User login

Painful Papules on the Arms

The Diagnosis: Piloleiomyoma

Leiomyoma cutis, also known as cutaneous leiomyoma, is a benign smooth muscle tumor first described in 1854.1 Cutaneous leiomyoma is comprised of 3 distinct types that depend on the origin of smooth muscle tumor: piloleiomyoma (arrector pili muscle), angioleiomyoma (tunica media of arteries/veins), and genital leiomyoma (dartos muscle of the scrotum and labia majora, erectile muscle of nipple).2 It affects both sexes equally, though some reports have noted an increased prevalence in females. Piloleiomyomas commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the extremities (solitary) and trunk (multiple).1 Tumors most often present as firm flesh-colored or pink-brown papulonodules. They can be linear, dermatomal, segmental, or diffuse, and often are painful. Clinical differential diagnosis for painful skin tumors is aided by the acronym "BLEND AN EGG": blue rubber bleb nevus, leiomyoma, eccrine spiradenoma, neuroma, dermatofibroma, angiolipoma, neurilemmoma, endometrioma, glomangioma, and granular cell tumor.3 For isolated lesions, surgical excision is the treatment of choice. For numerous lesions in which excision would not be feasible, intralesional corticosteroids, medications (eg, calcium channel blockers, alpha blockers, nitroglycerin), and botulinum toxin have been used for pain relief.4

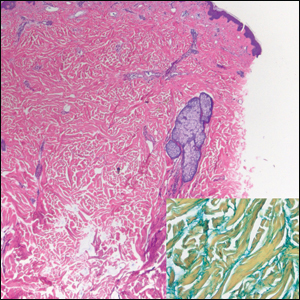

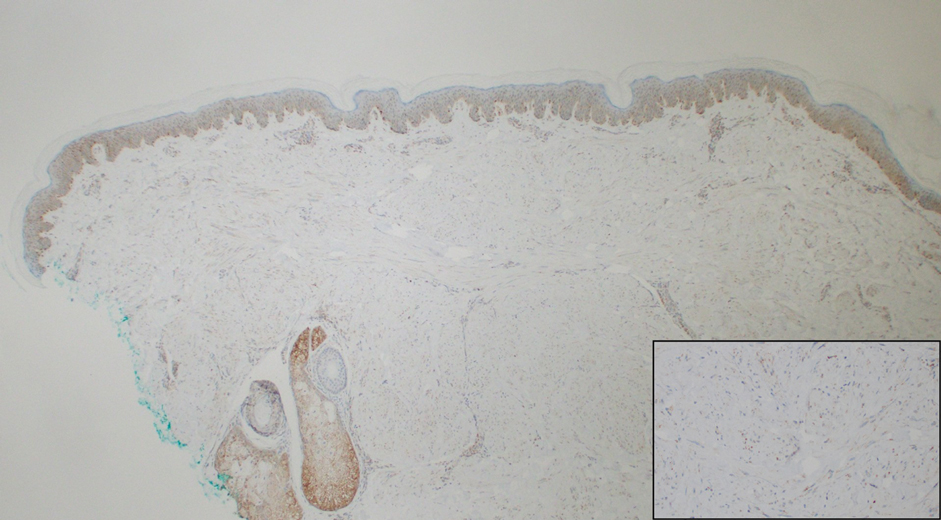

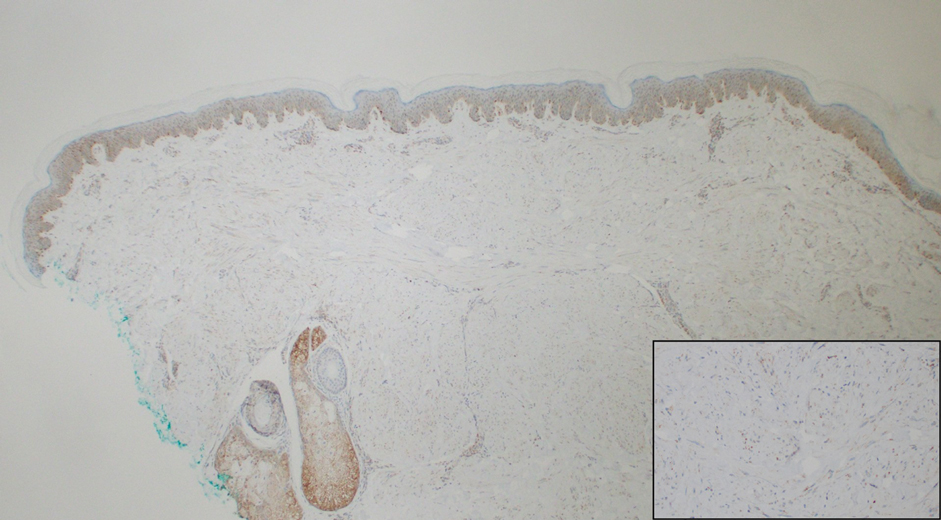

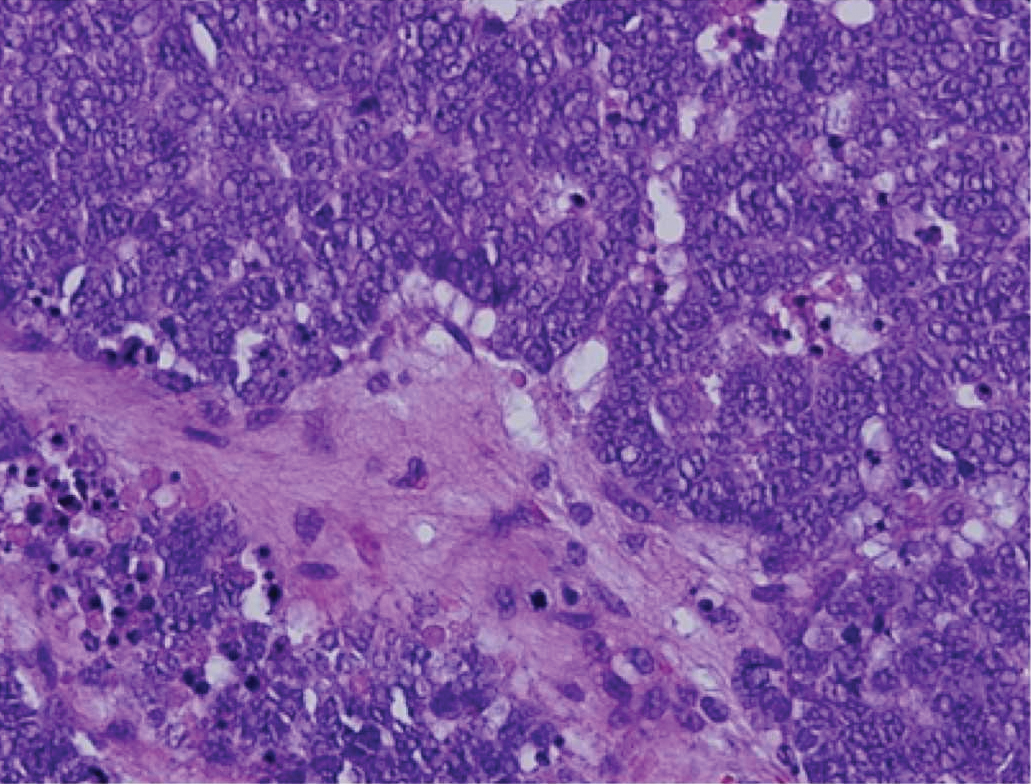

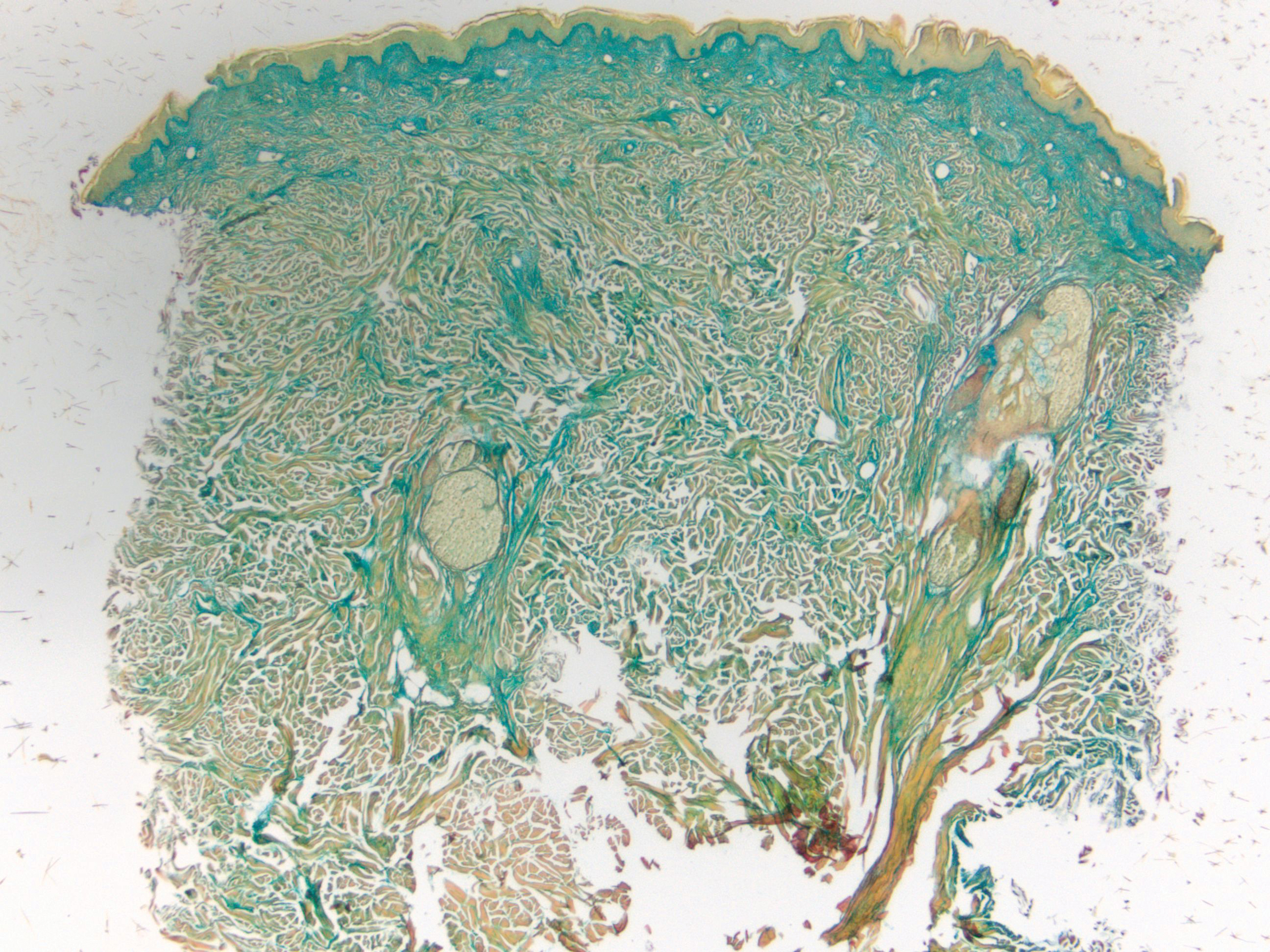

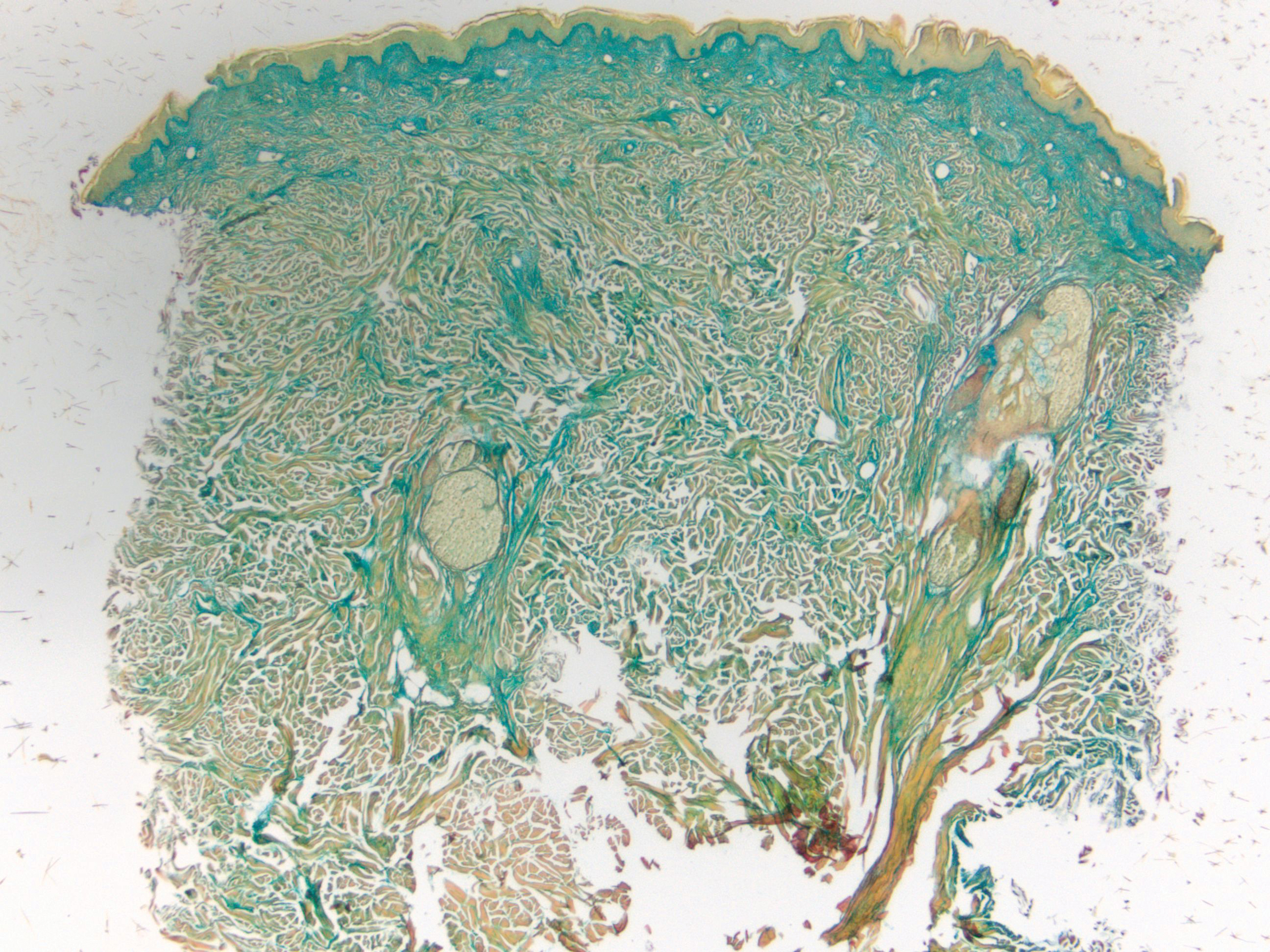

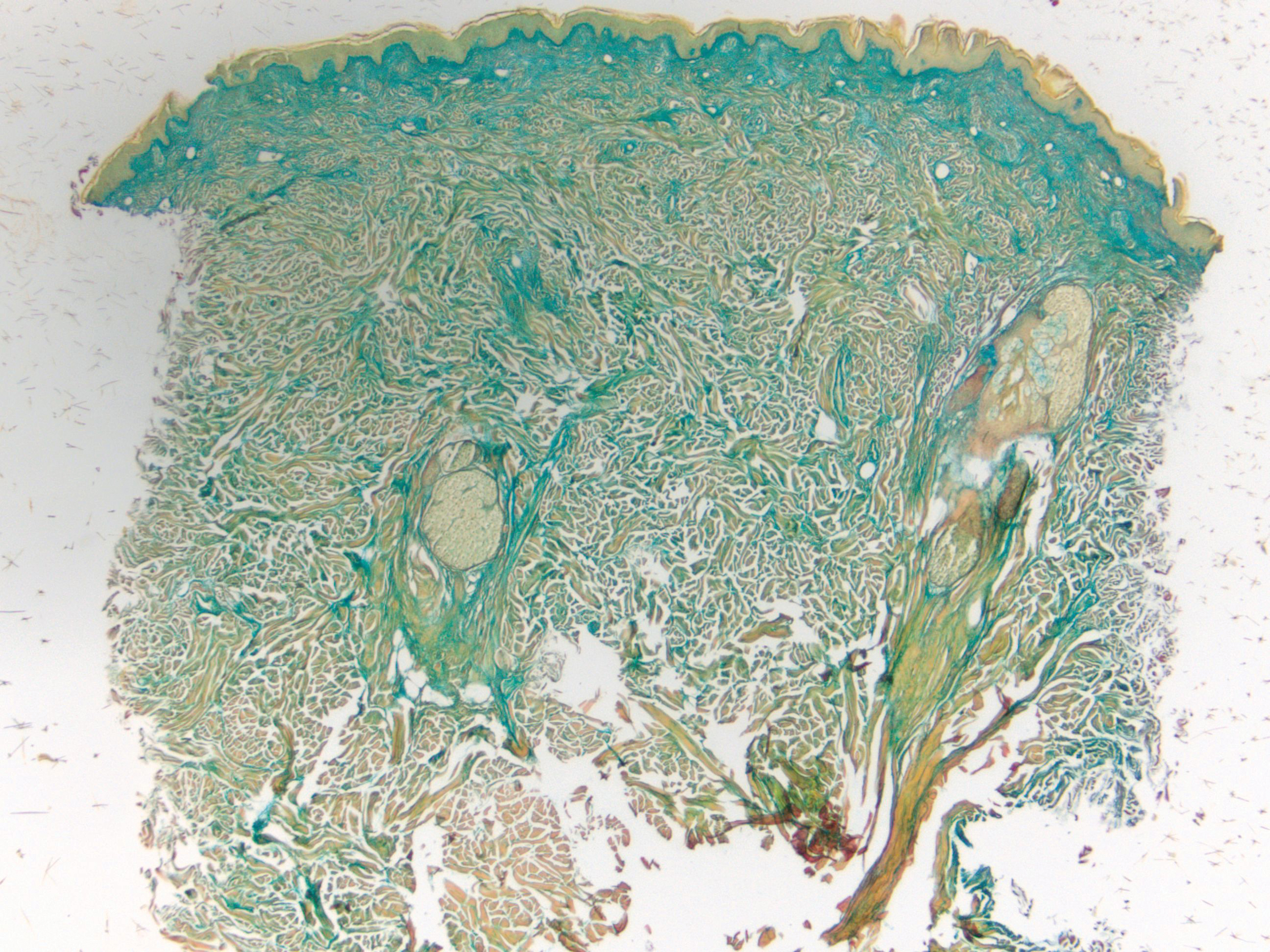

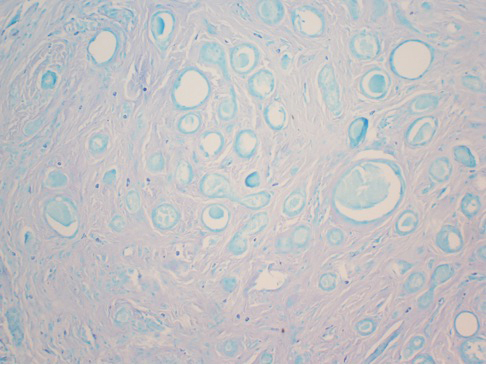

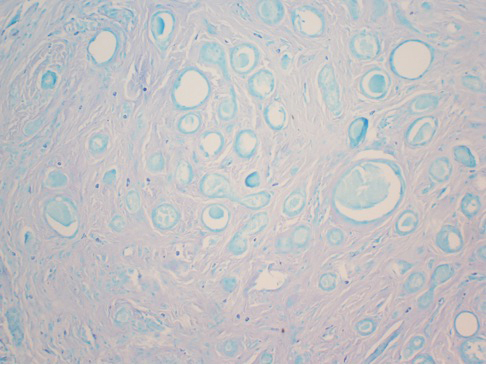

Notably, multiple cutaneous leiomyomas can be seen in association with uterine leiomyomas in Reed syndrome due to an autosomal-dominant or de novo mutation in the fumarate hydratase gene, FH. Reed syndrome is associated with a lifetime risk for renal cell carcinoma (hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer) in 15% of cases with FH mutations.5 In our patient, both immunohistochemical staining and blood testing for FH were performed. Immunohistochemistry revealed notably diminished staining with only weak patchy granular cytoplasmic staining present (Figure 1). Genetic testing revealed heterozygosity for a pathogenic variant of the FH gene, consistent with a diagnosis of Reed syndrome.

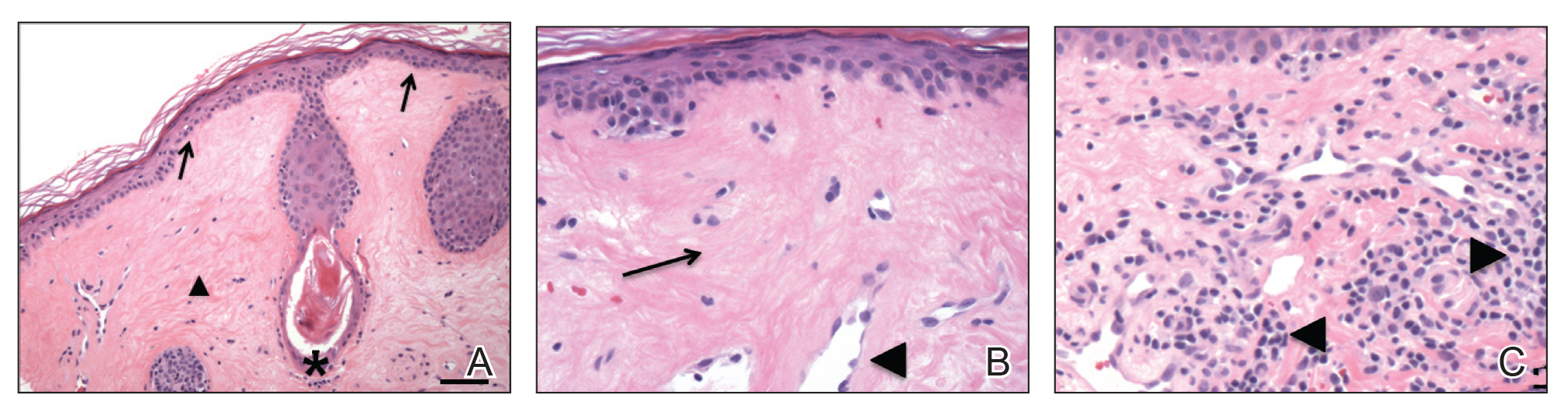

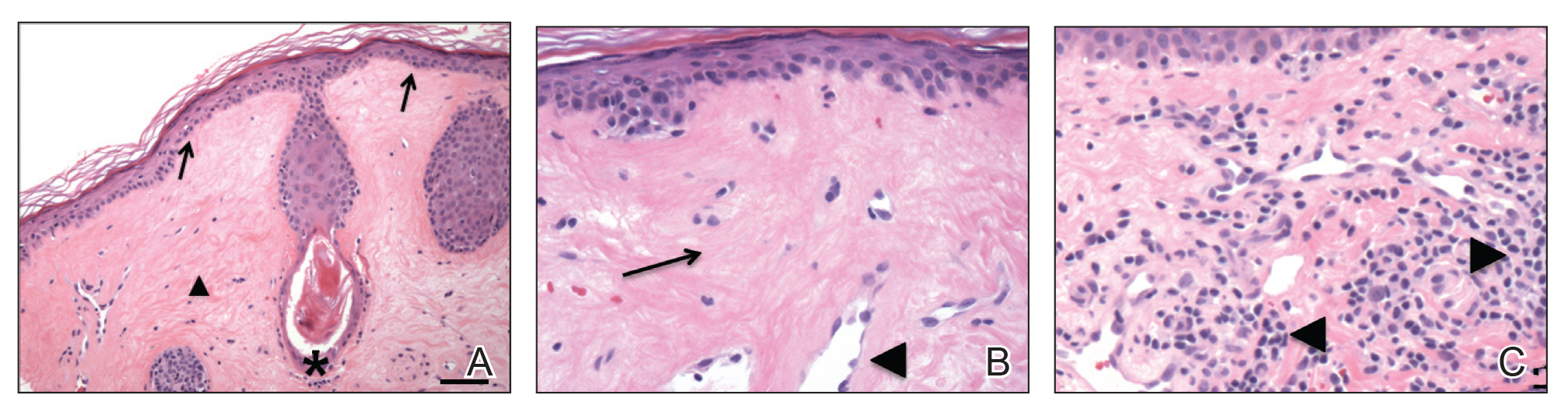

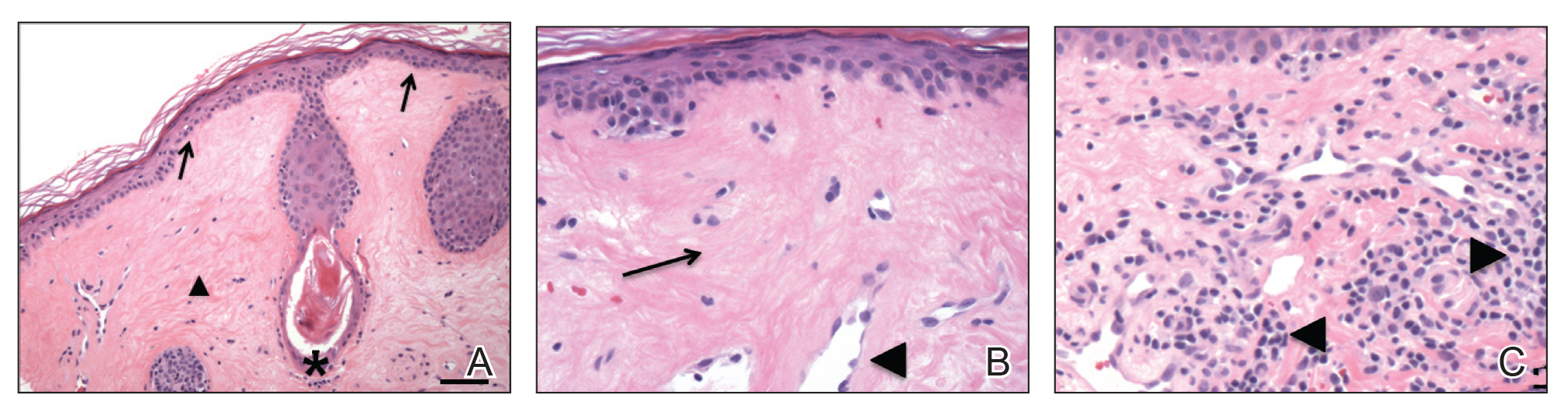

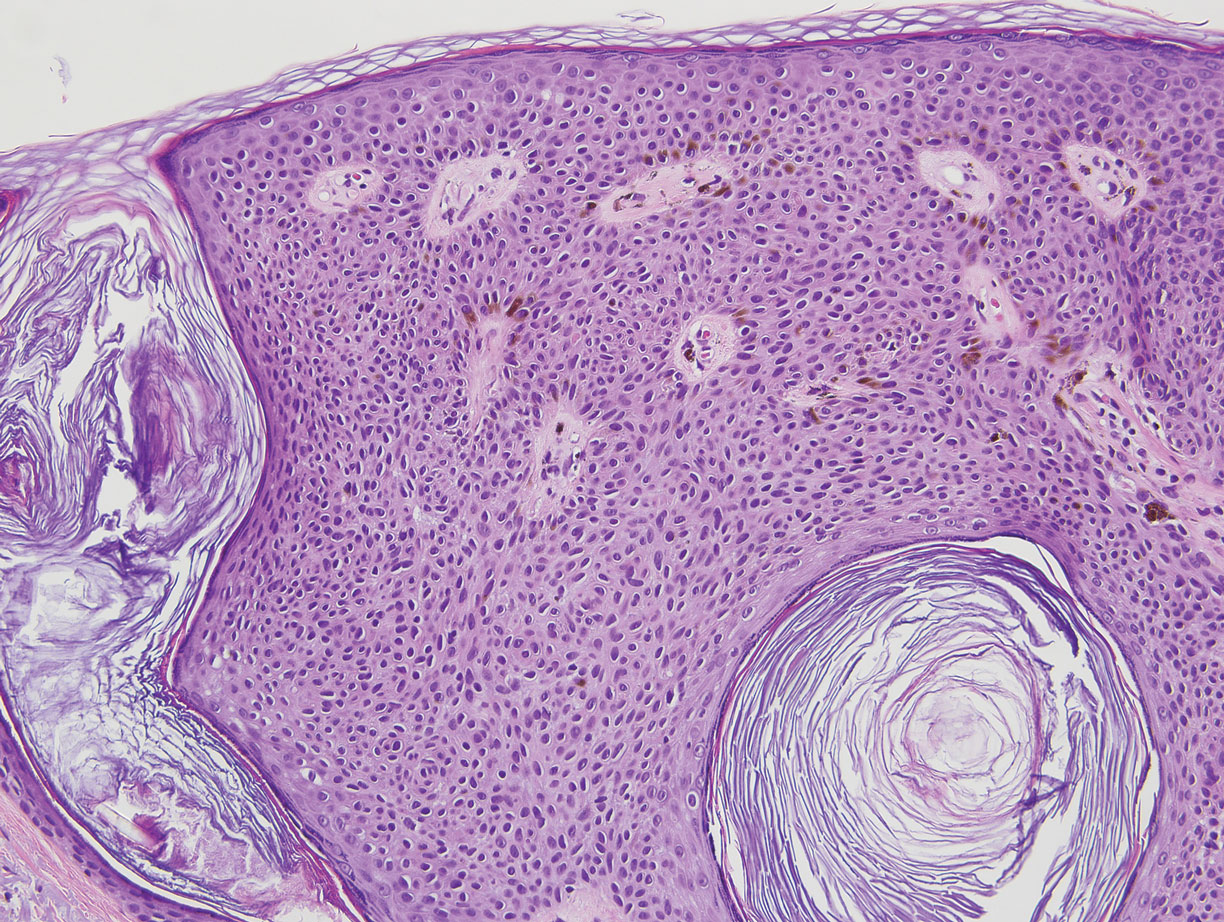

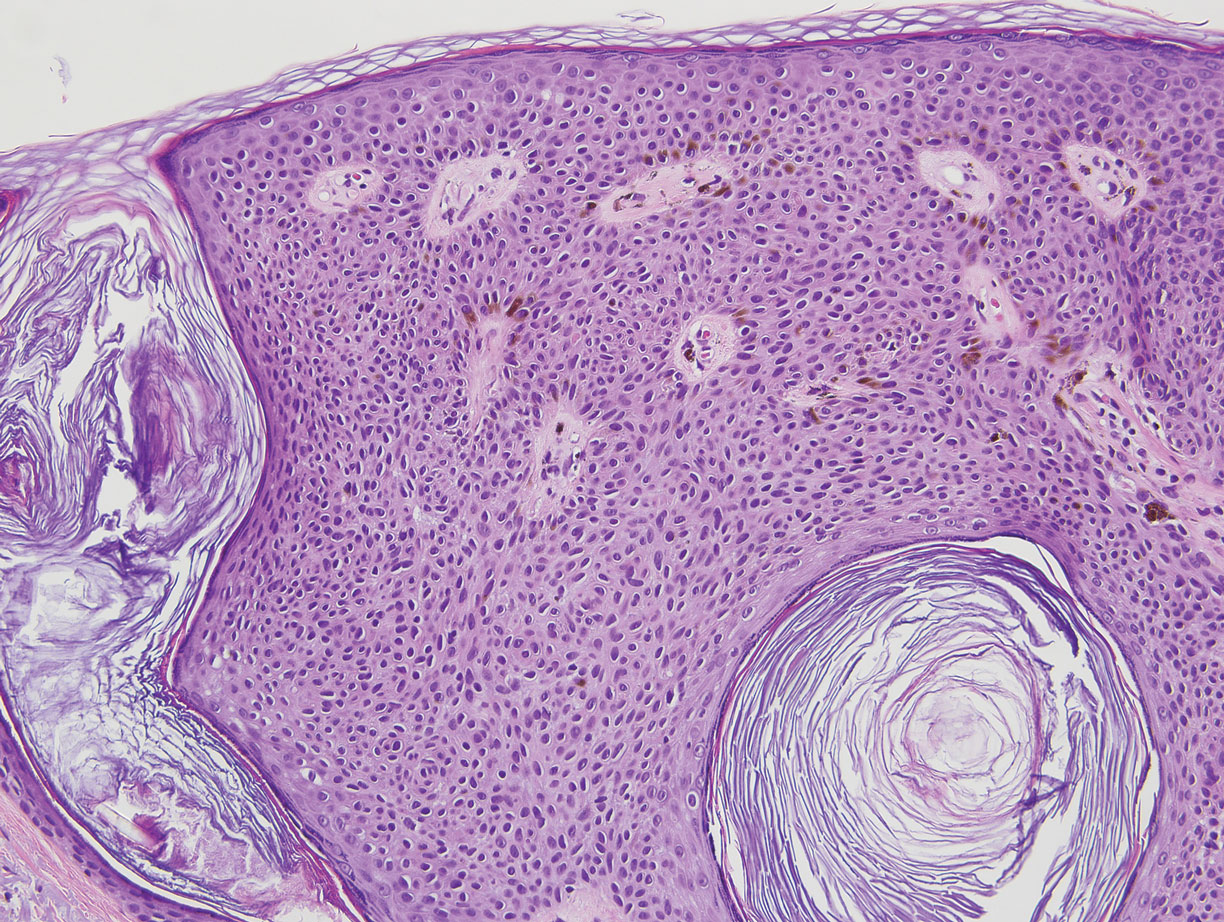

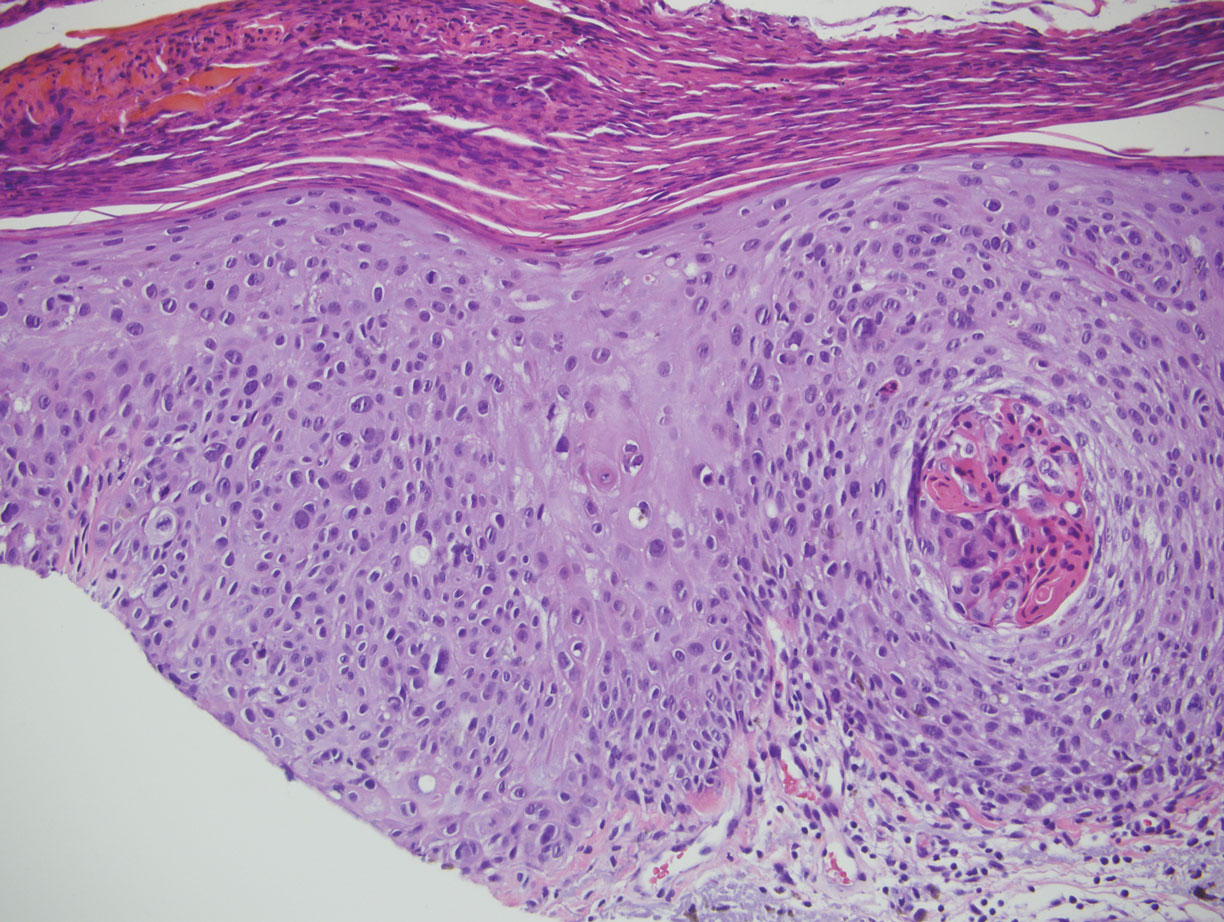

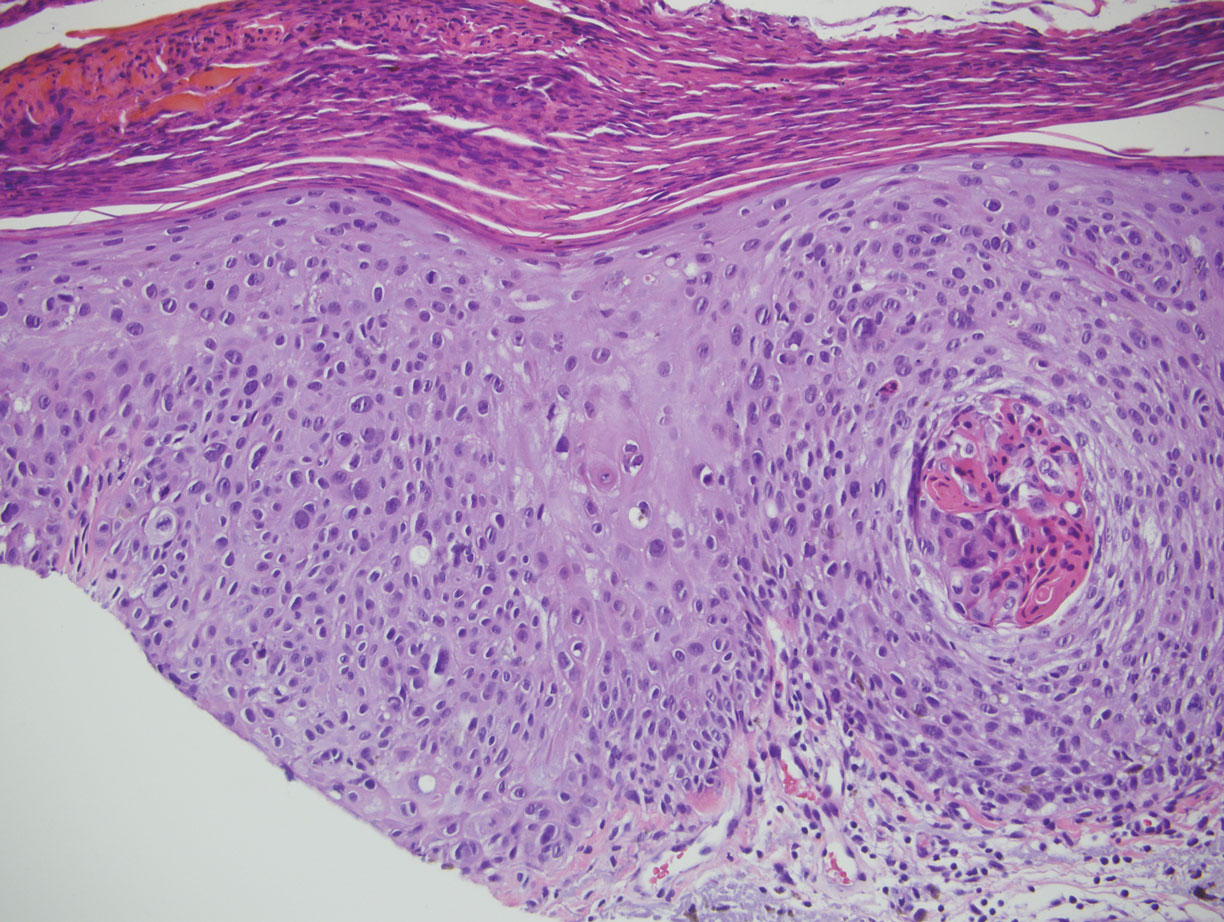

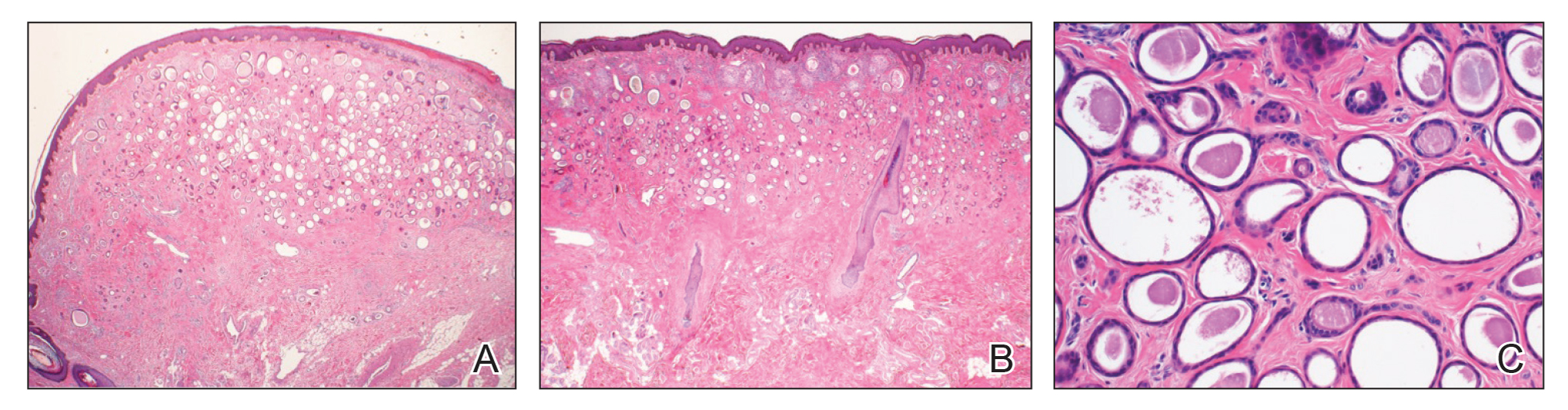

Histologically, the differential diagnosis includes other spindle cell tumors, such as dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, and dermatomyofibroma. The histologic appearance varies depending on the type, with piloleiomyoma typically located within the reticular dermis with possible subcutaneous extension. Fascicles of eosinophilic smooth muscle cells in an interlacing arrangement often ramify between neighboring dermal collagen; these smooth muscle cells contain cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei with a perinuclear clear vacuole. Marked epidermal hyperplasia is possible.6 A close association with a nearby hair follicle frequently is noted. Although differentiated smooth muscle cells usually are evident on hematoxylin and eosin, positive staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and desmin can aid in diagnosis.7 Immunohistochemical staining for FH has proven to be highly specific (97.6%) with moderate sensitivity (70.0%).8 Angioleiomyomas appear as well-demarcated dermal to subcutaneous tumors composed of smooth muscle cells surrounding thick-walled vaculature.9 Scrotal and vulvar leiomyomas are composed of eosinophilic spindle cells, though vulvar leiomyomas have shown epithelioid differentiation.10 Nipple leiomyomas appear similar to piloleiomyomas on histology with interlacing smooth muscle fiber bundles.

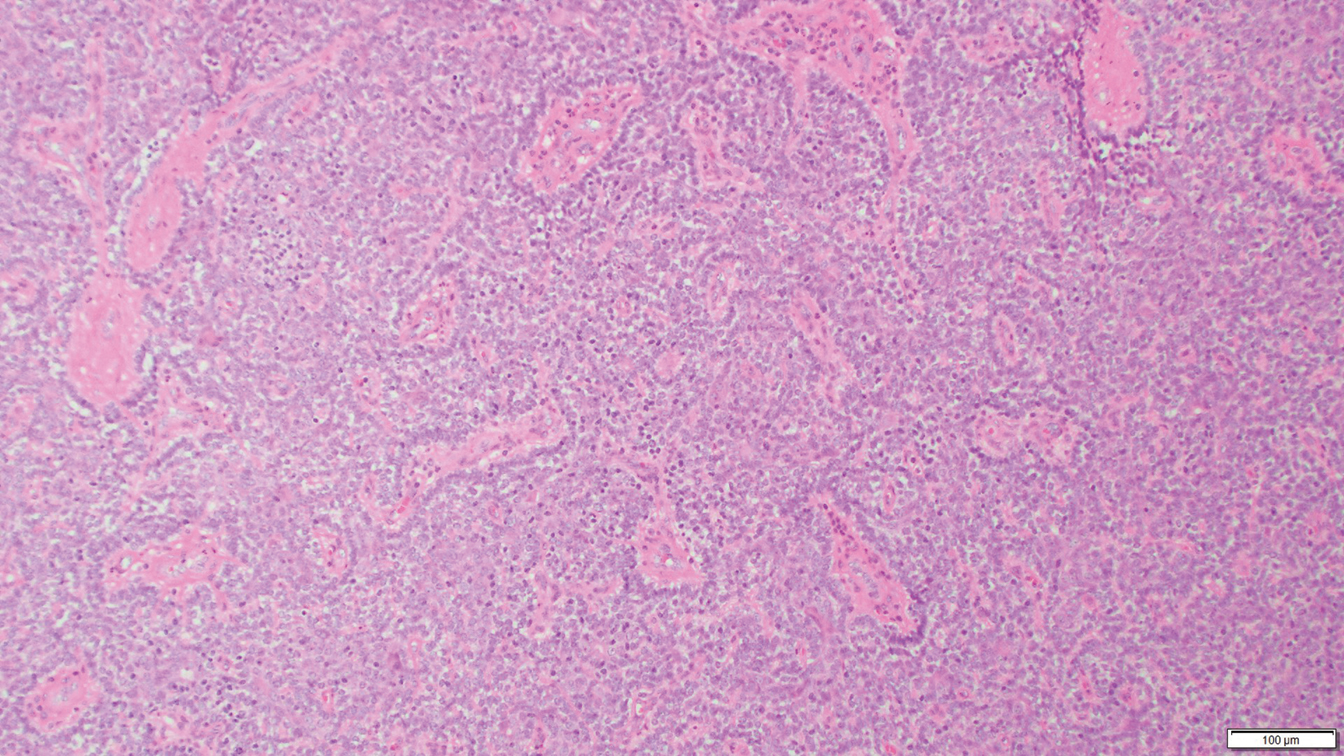

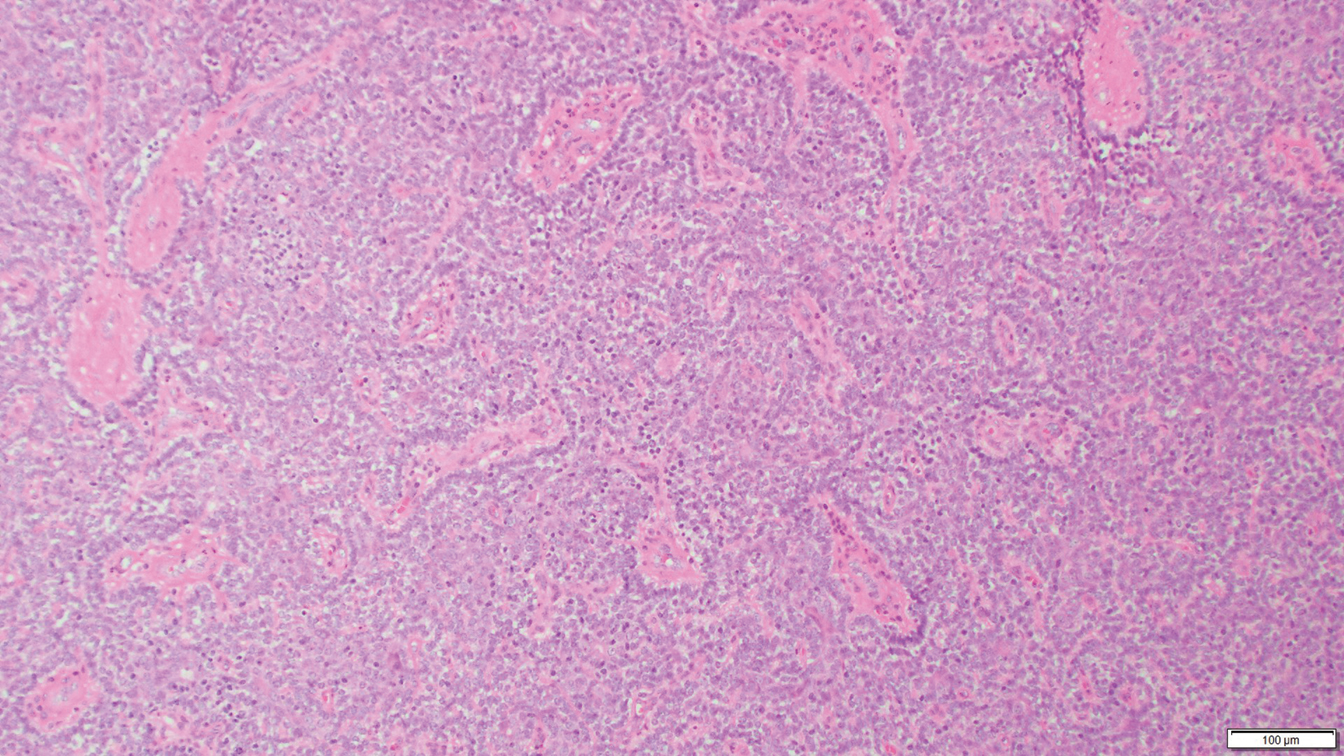

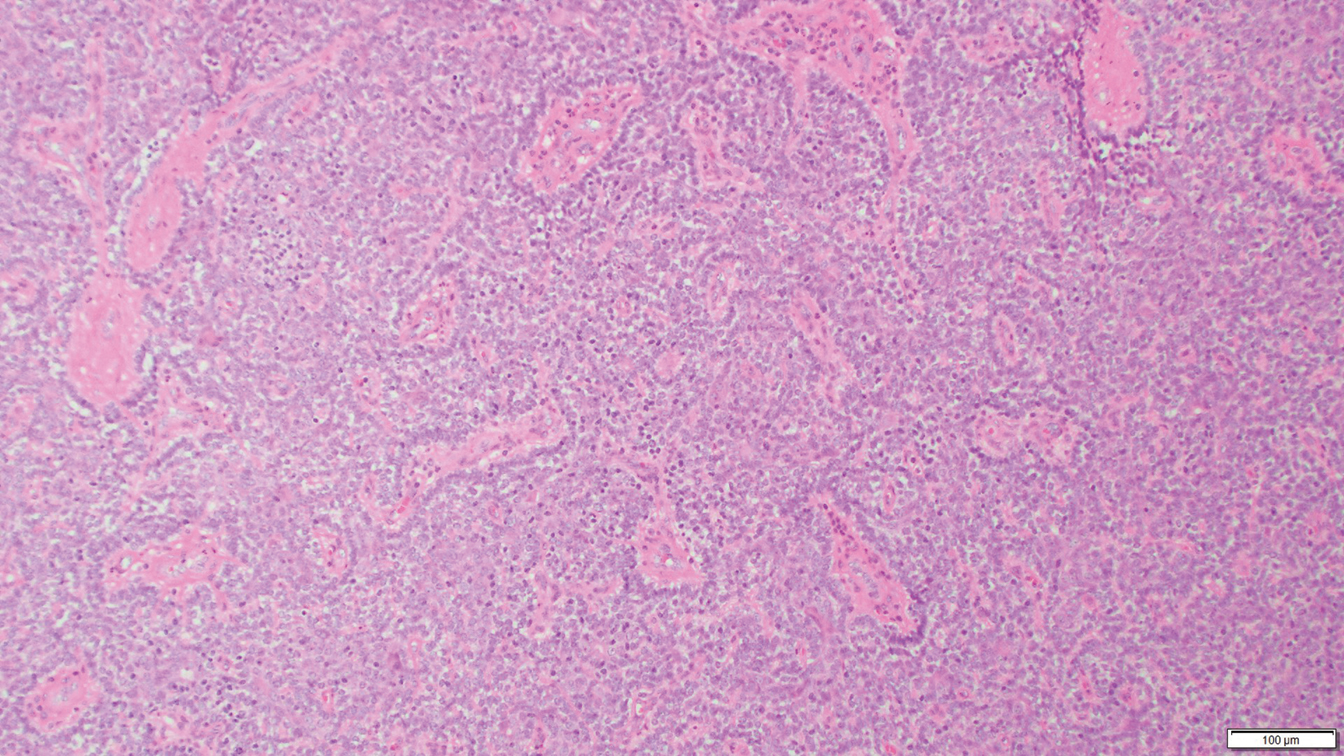

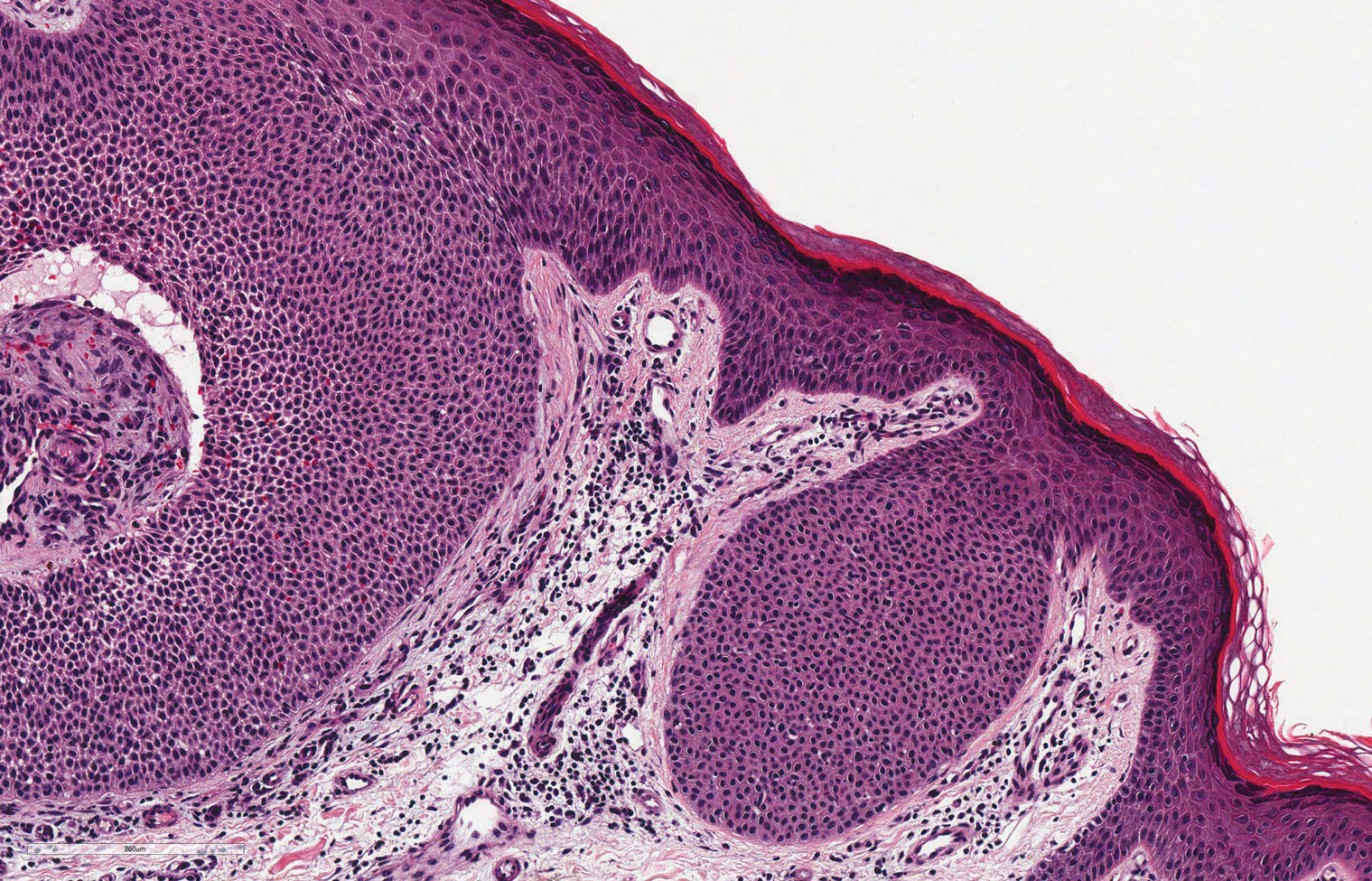

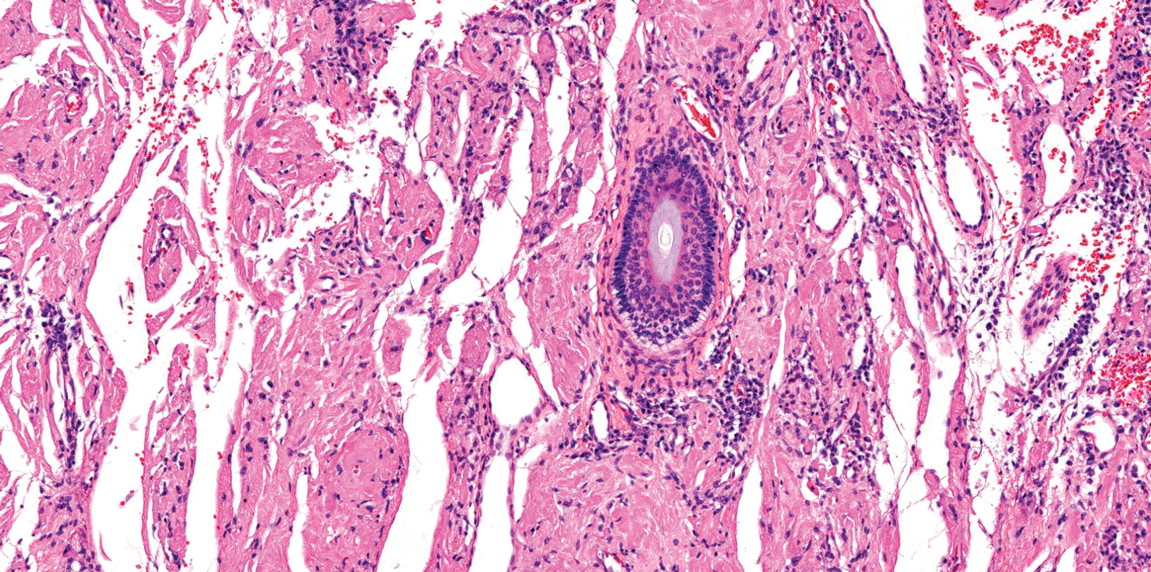

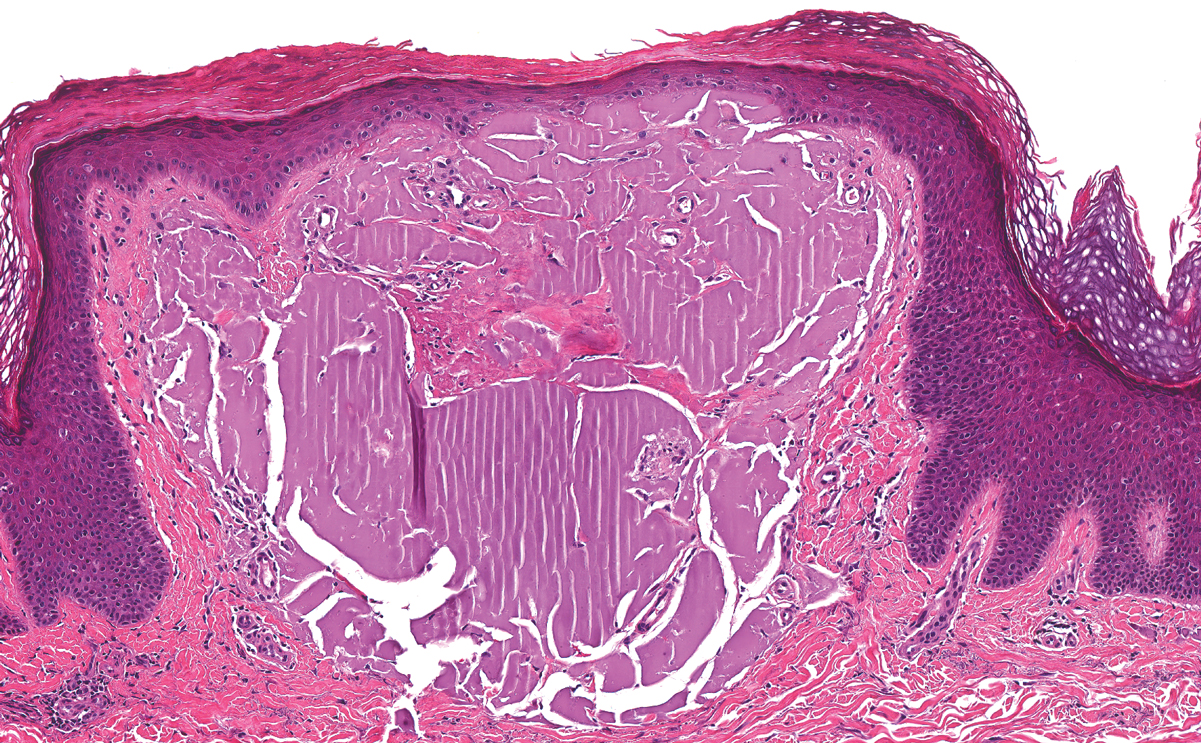

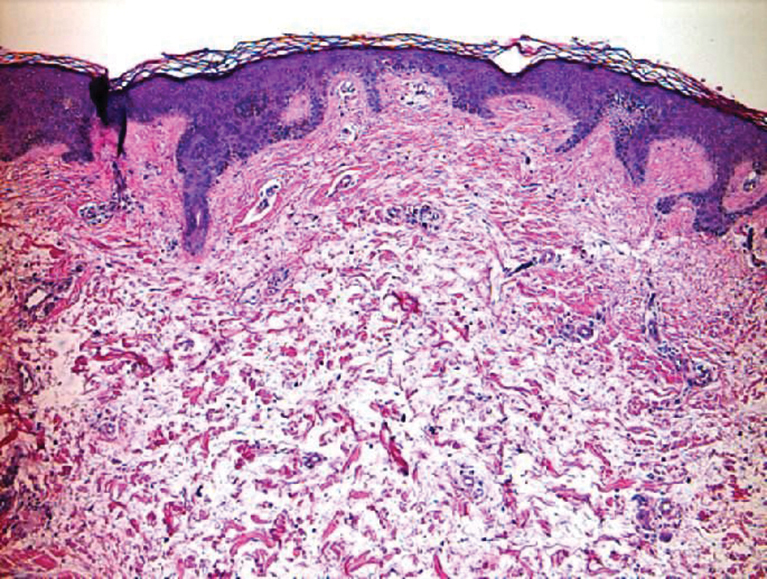

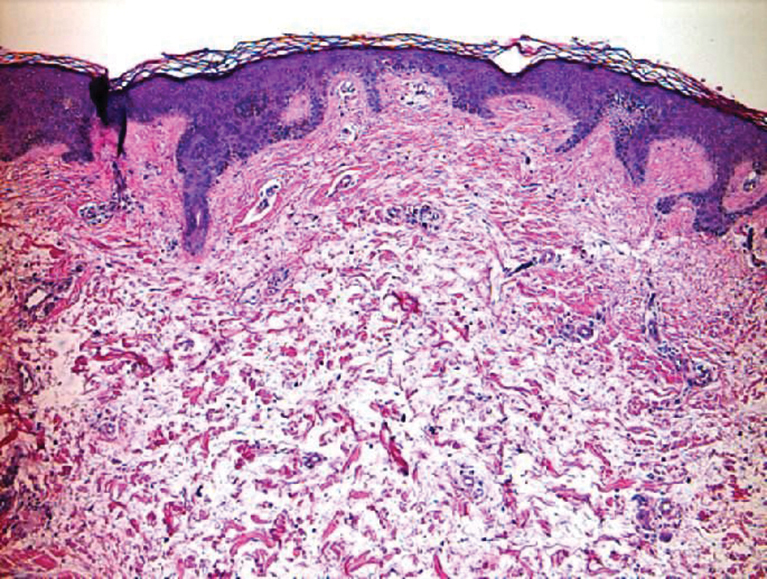

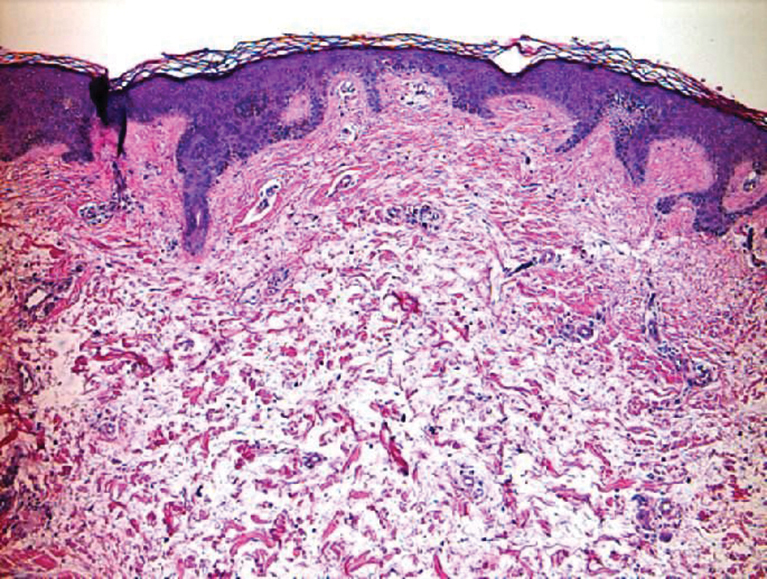

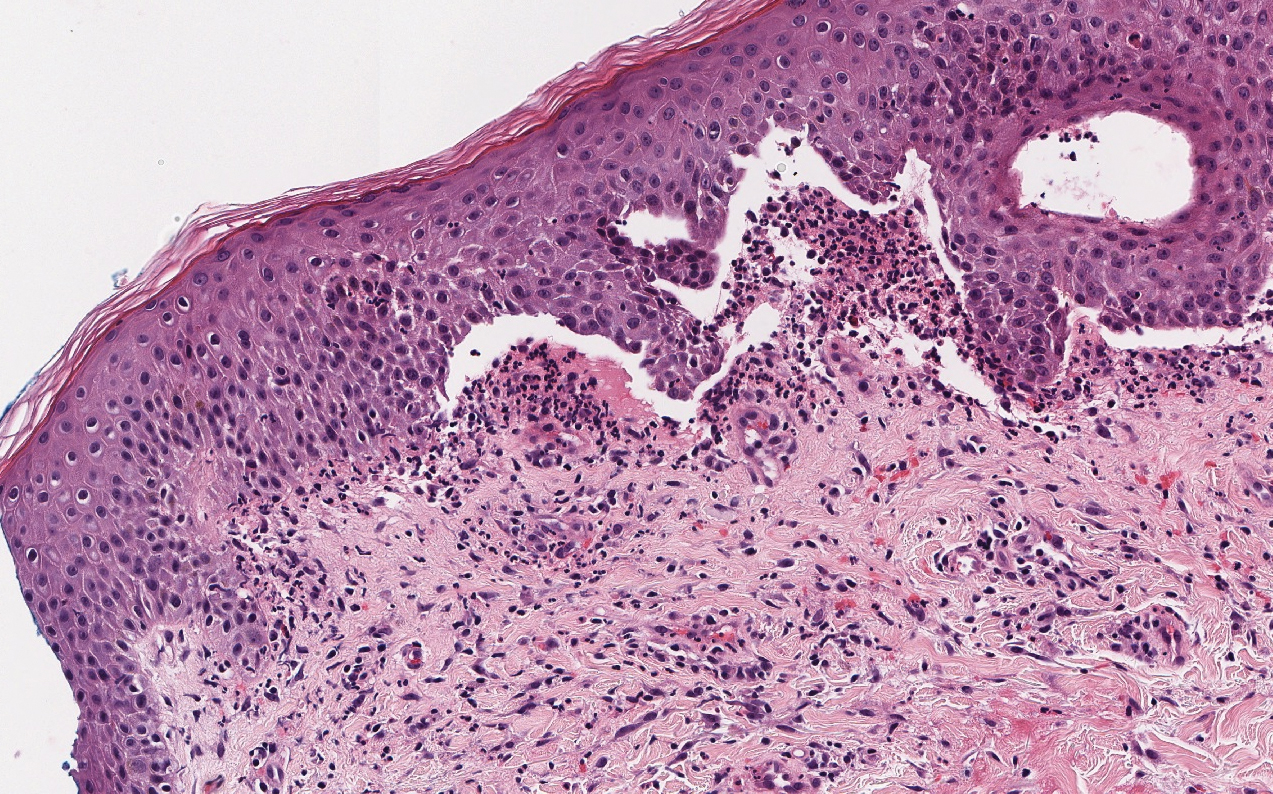

Eccrine spiradenoma is a relatively uncommon adnexal tumor derived from eccrine sweat glands. It most often presents as a small, painful or tender, intradermal nodule (or rarely as nodules) on the head or ventral trunk.11 There is no sexual predilection. It affects adults at any age but most often from 15 to 35 years. Although rare, malignant transformation is possible. Histologically, eccrine spiradenomas appear as a well-demarcated dermal tumor composed of bland basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm, often with numerous admixed lymphocytes and variably prominent vasculature (Figure 2). Eosinophilic basement membrane material can be seen within or surrounding the nodules of tumor cells. Multiple spiradenomas can occur in the setting of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant disorder due to an inherited mutation in the CYLD gene. Spiradenomas are benign neoplasms, and surgical excision with clear margins is the treatment of choice.12

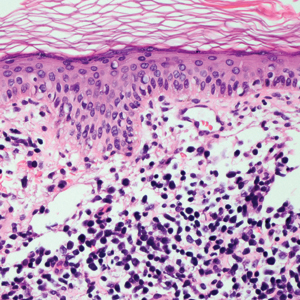

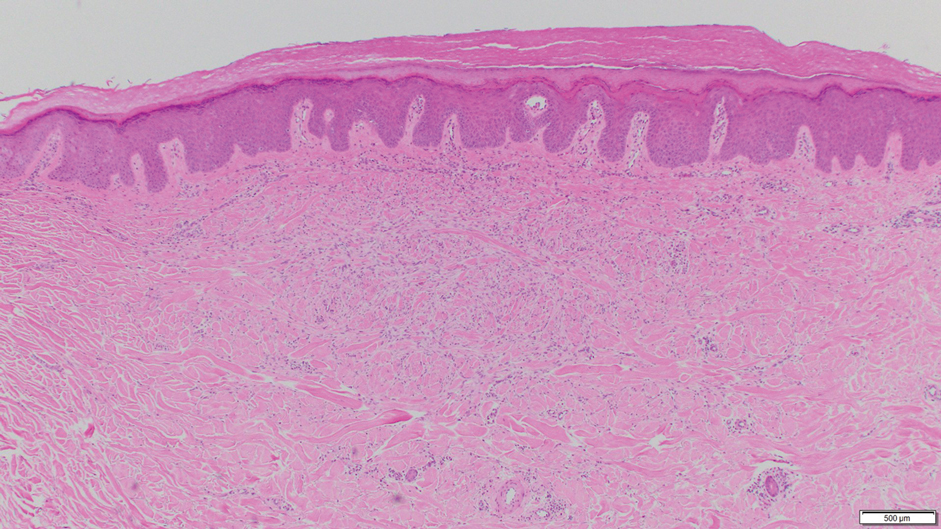

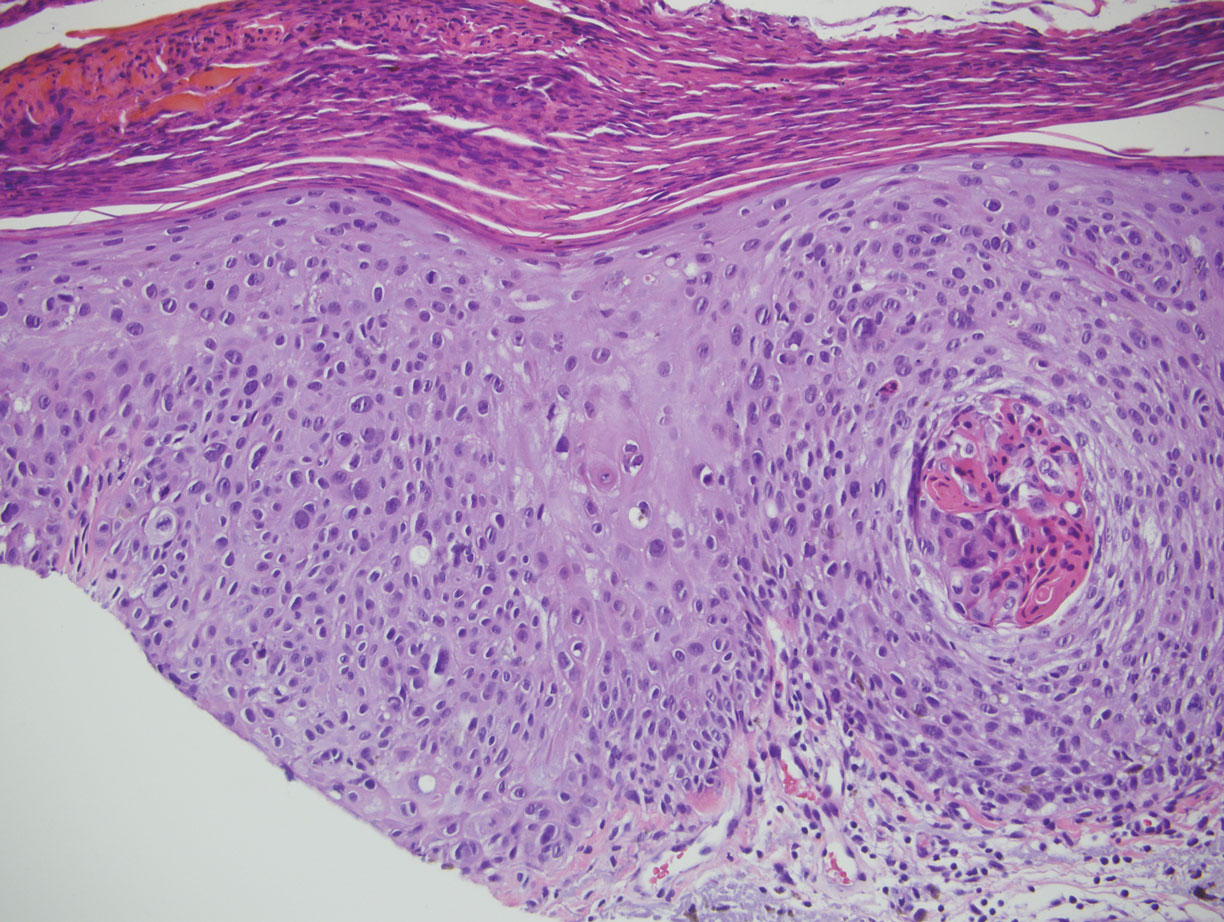

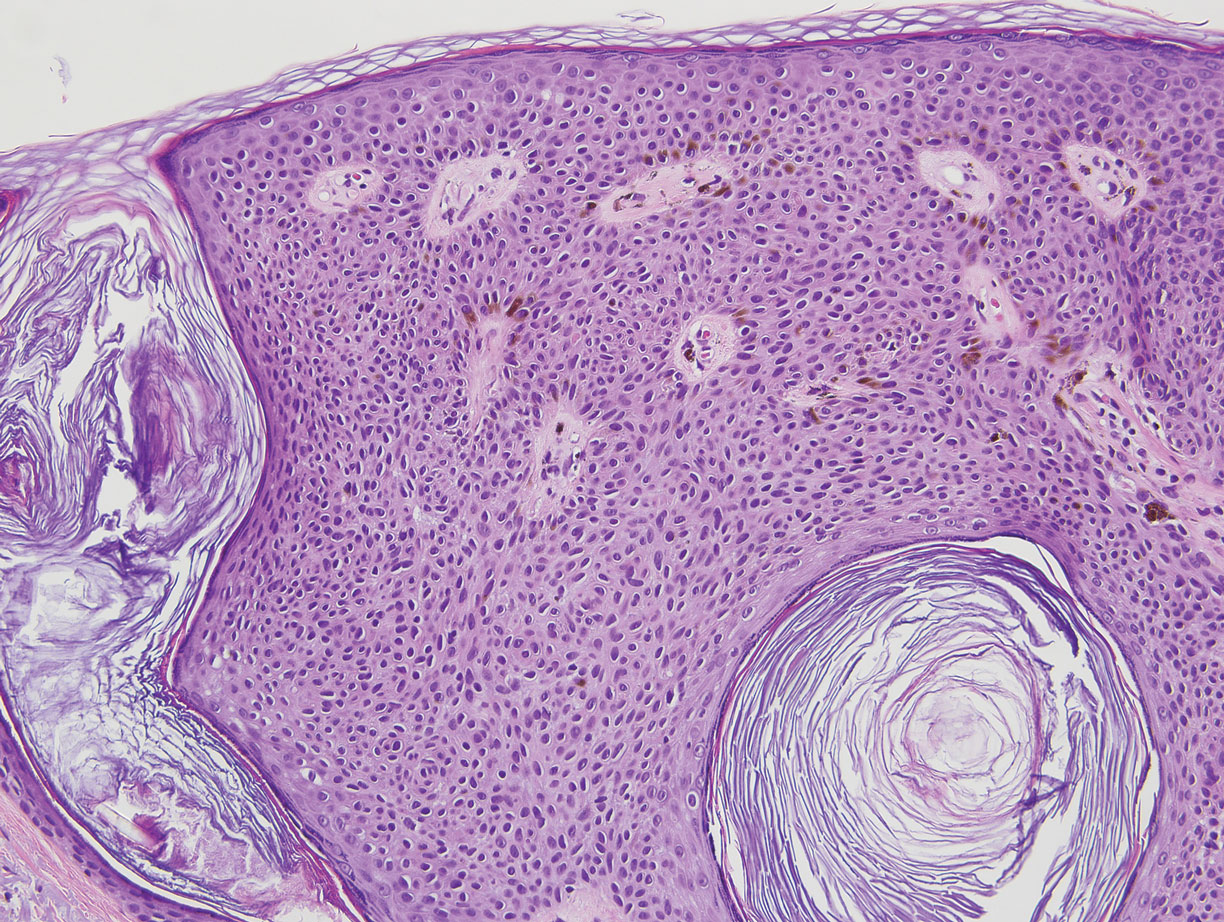

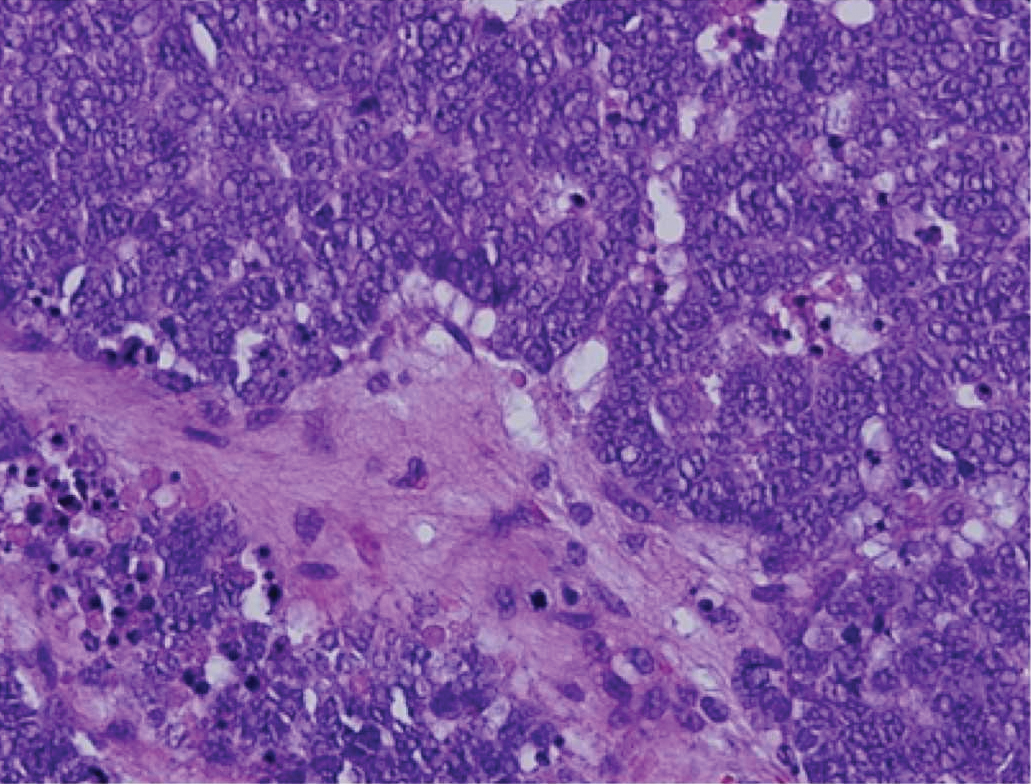

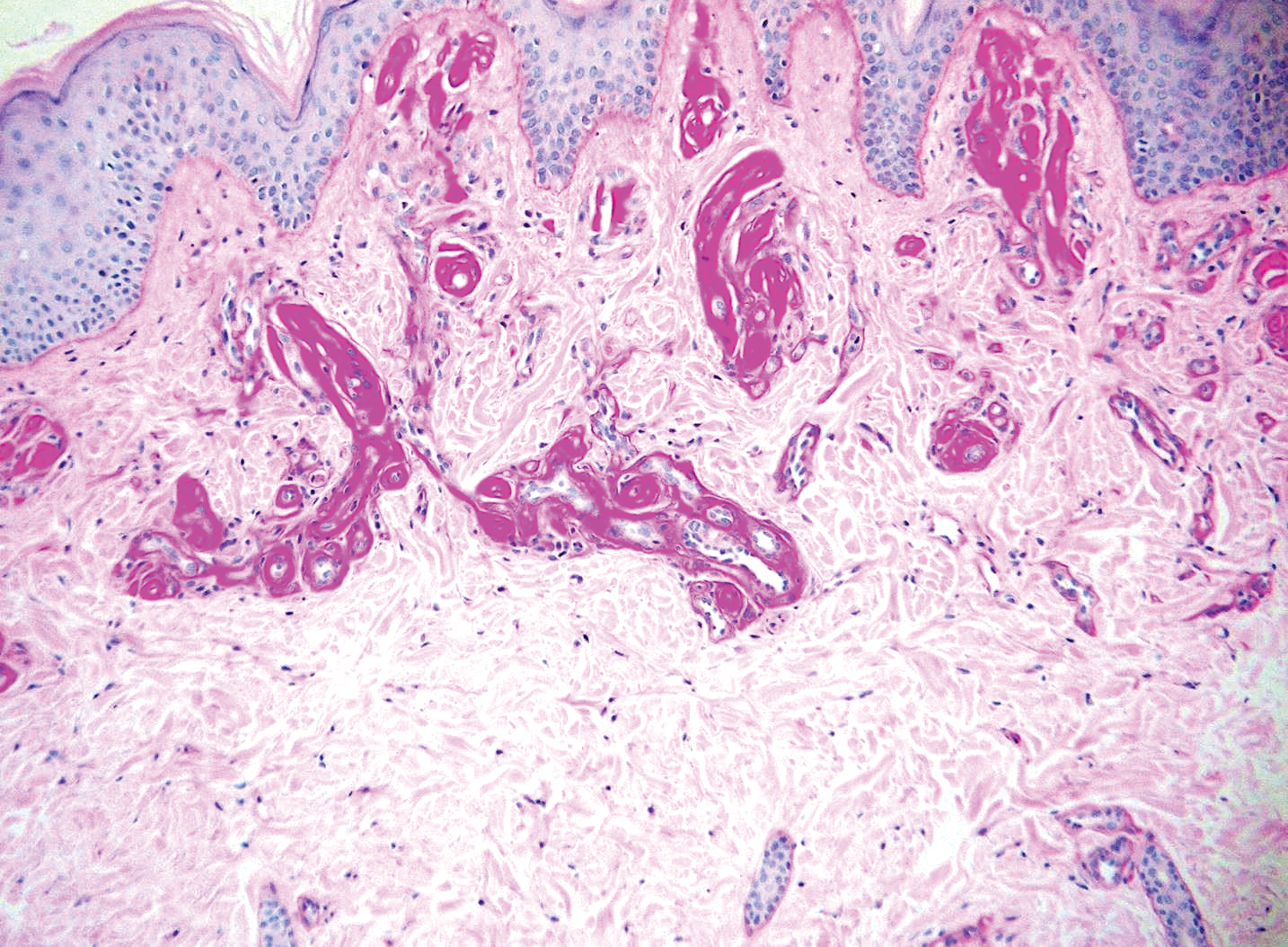

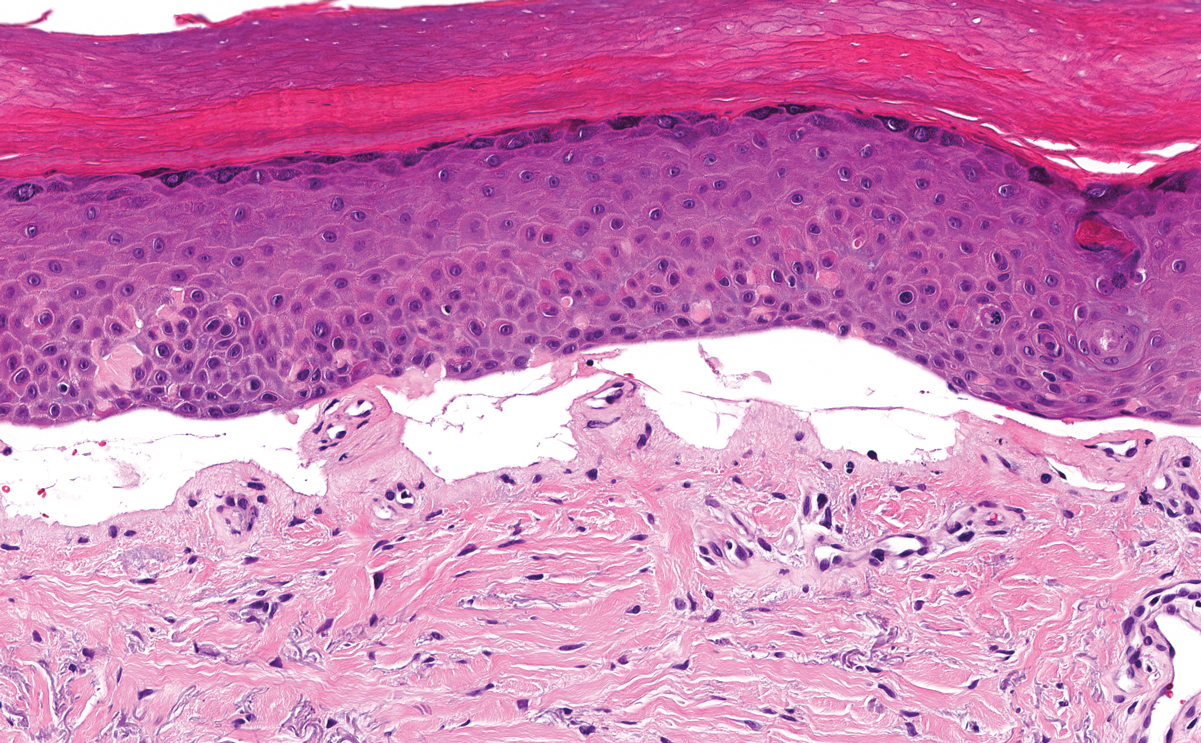

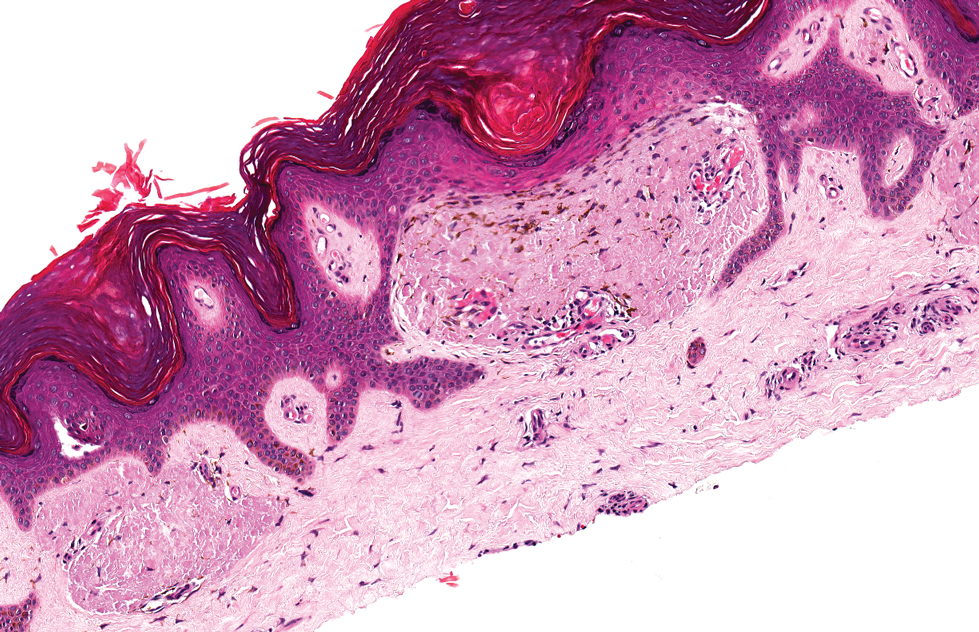

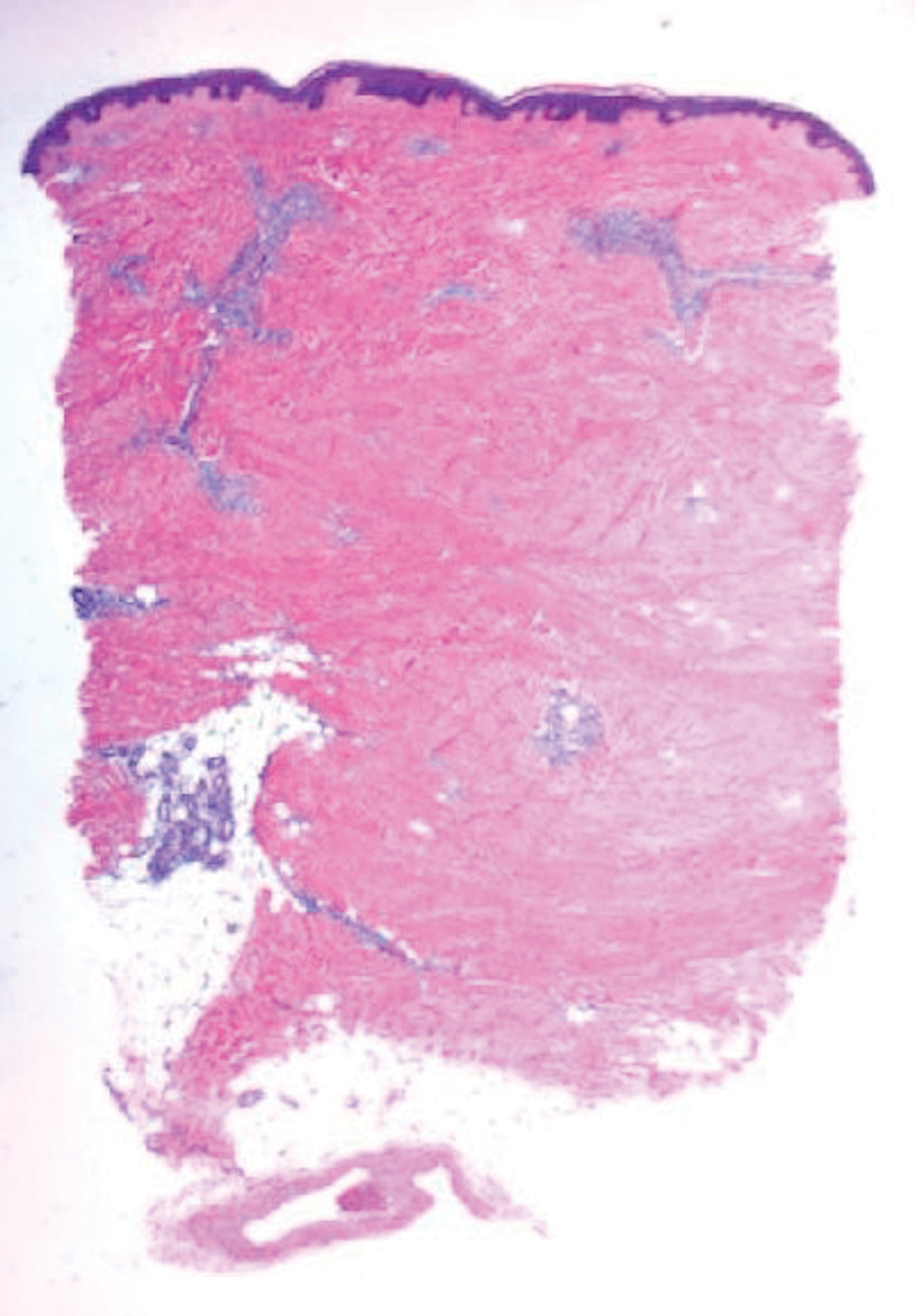

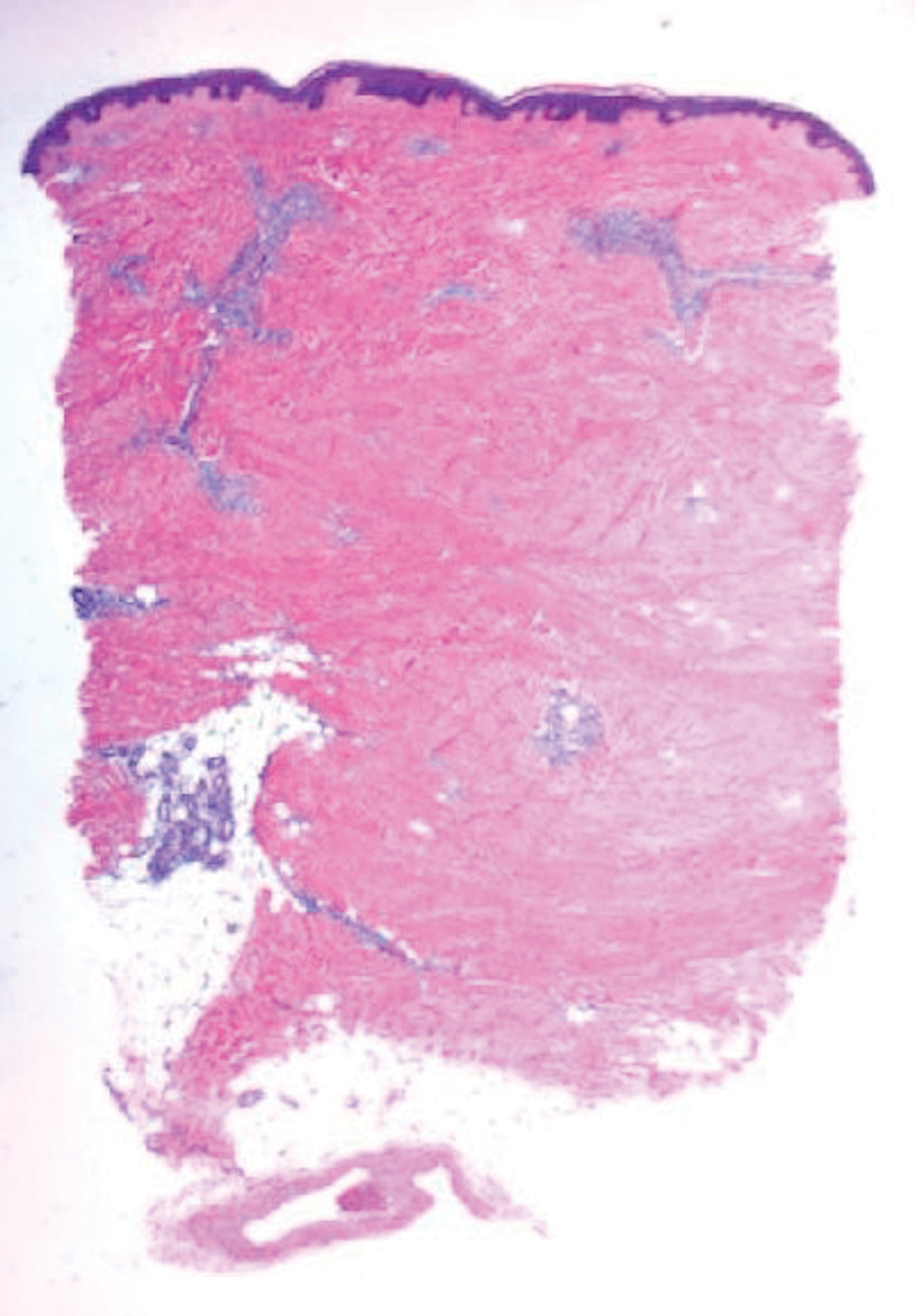

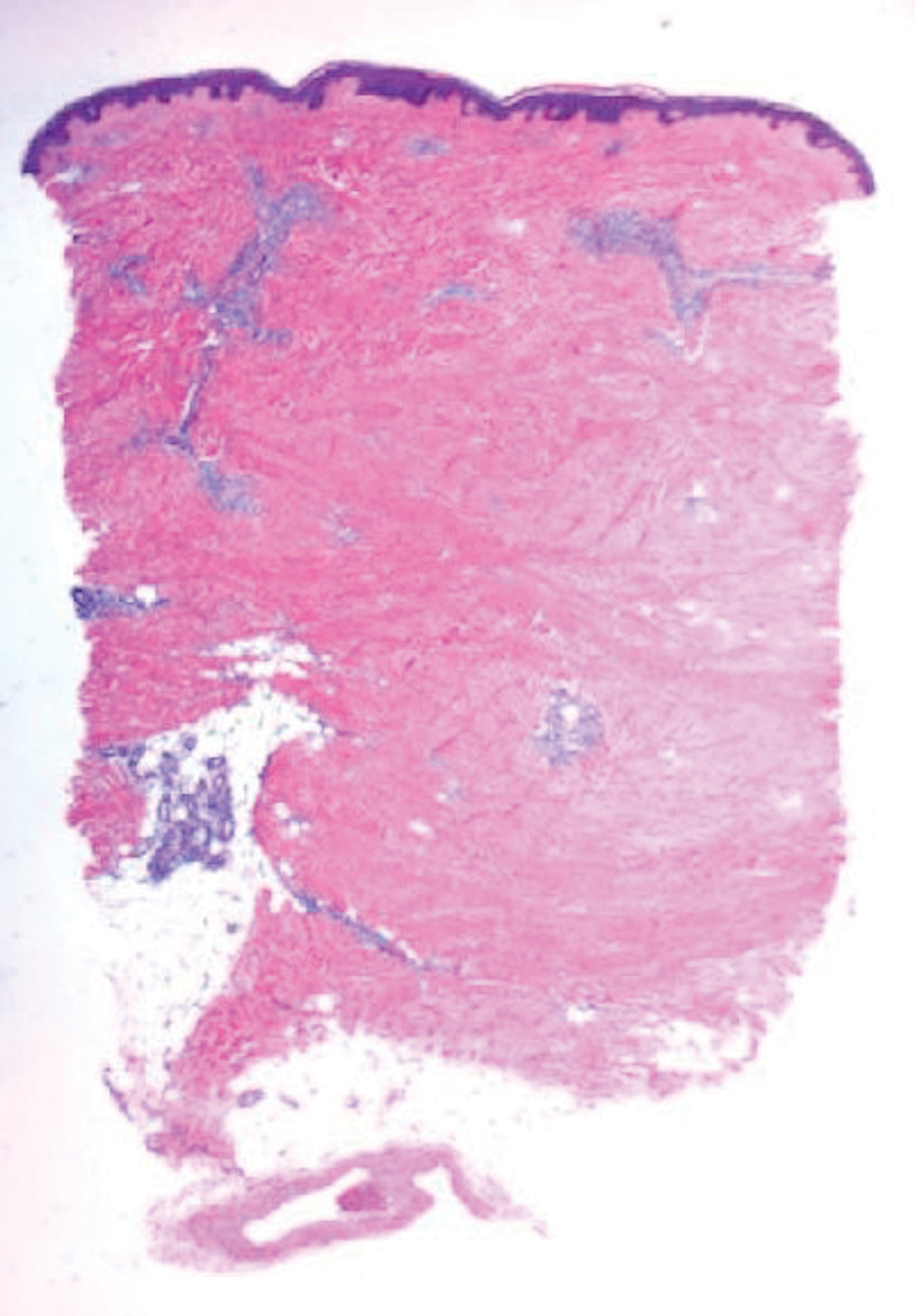

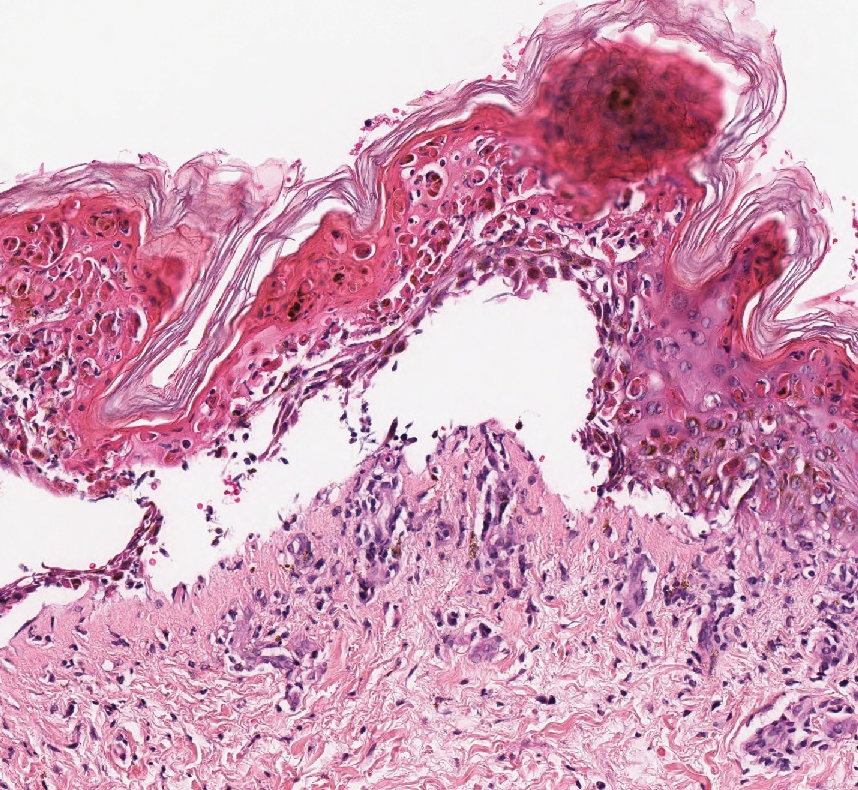

Dermatofibroma, also known as cutaneous benign fibrous histiocytoma, is a firm, flesh-colored papule or nodule that most often presents on the lower extremities. It typically is seen in women aged 20 to 40 years.13 The etiology is uncertain, and dermatofibromas often spontaneously develop, though there are inconsistent reports of development with local trauma including insect bites and puncture wounds. The dimple sign refers to skin dimpling with lateral pressure.13 Most commonly, dermatofibromas consist of a dermal proliferation of bland fibroblastic cells with entrapment of dermal collagen bundles at the periphery of the tumors (Figure 3). The fibroblastic cells often are paler and less eosinophilic than smooth muscle cells seen in cutaneous leiomyomas, with tapered nuclei that lack a perinuclear vacuole. Admixed histocytes and other inflammatory cells often are present. Overlying epidermal hyperplasia and/or hyperpigmentation also may be present. Numerous histologic variants have been described, including cellular, epithelioid, aneurysmal, atypical, and hemosiderotic types.14 Immunohistochemical stains may show patchy positive staining for SMA, but h-caldesmon and desmin typically are negative.

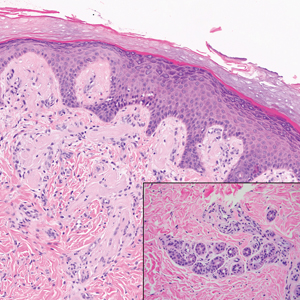

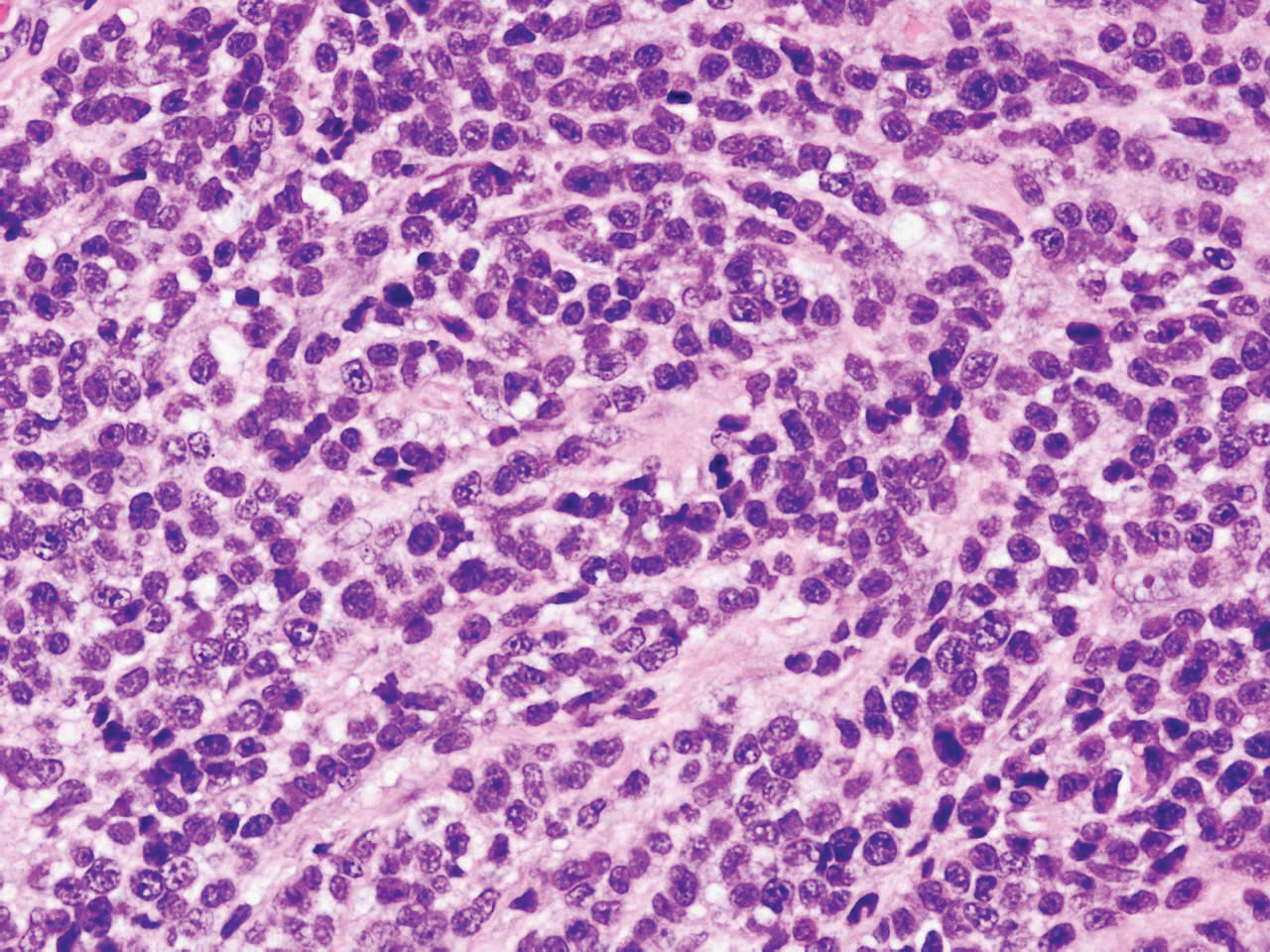

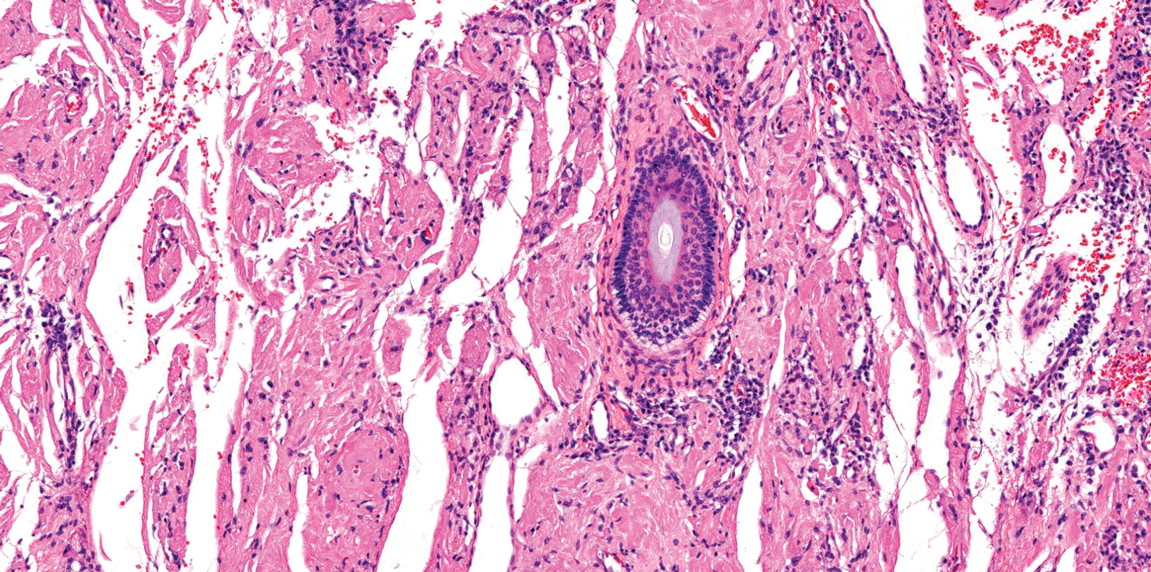

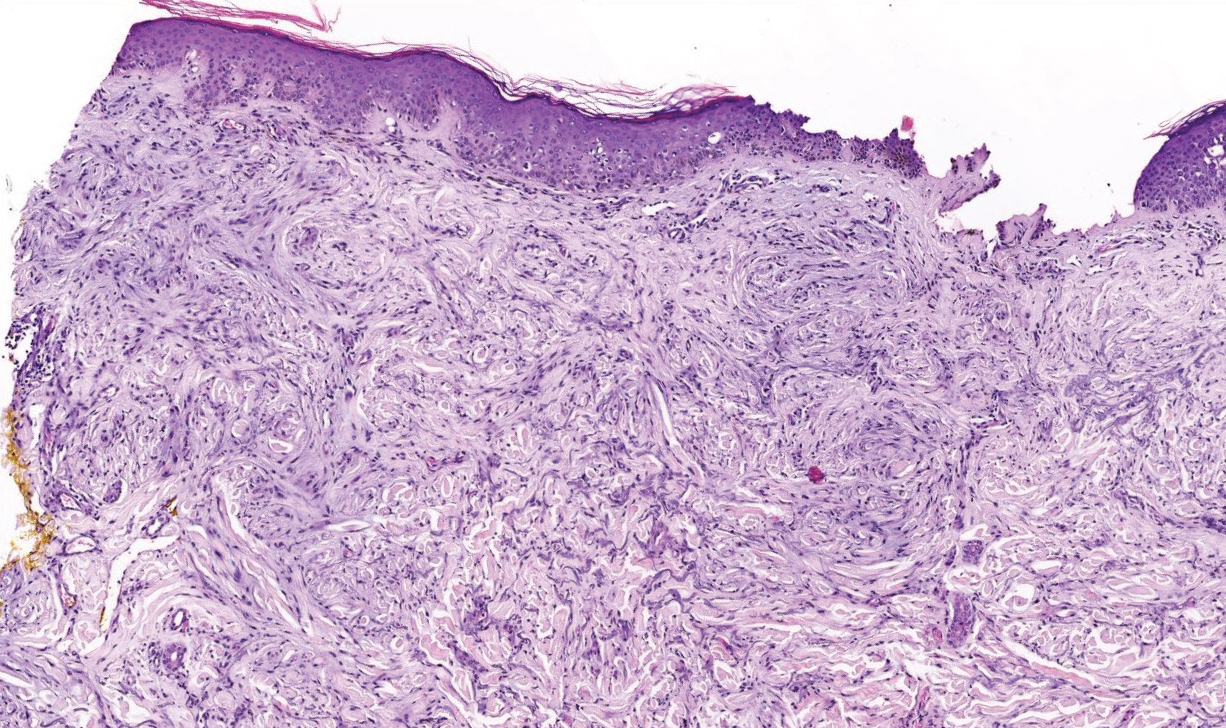

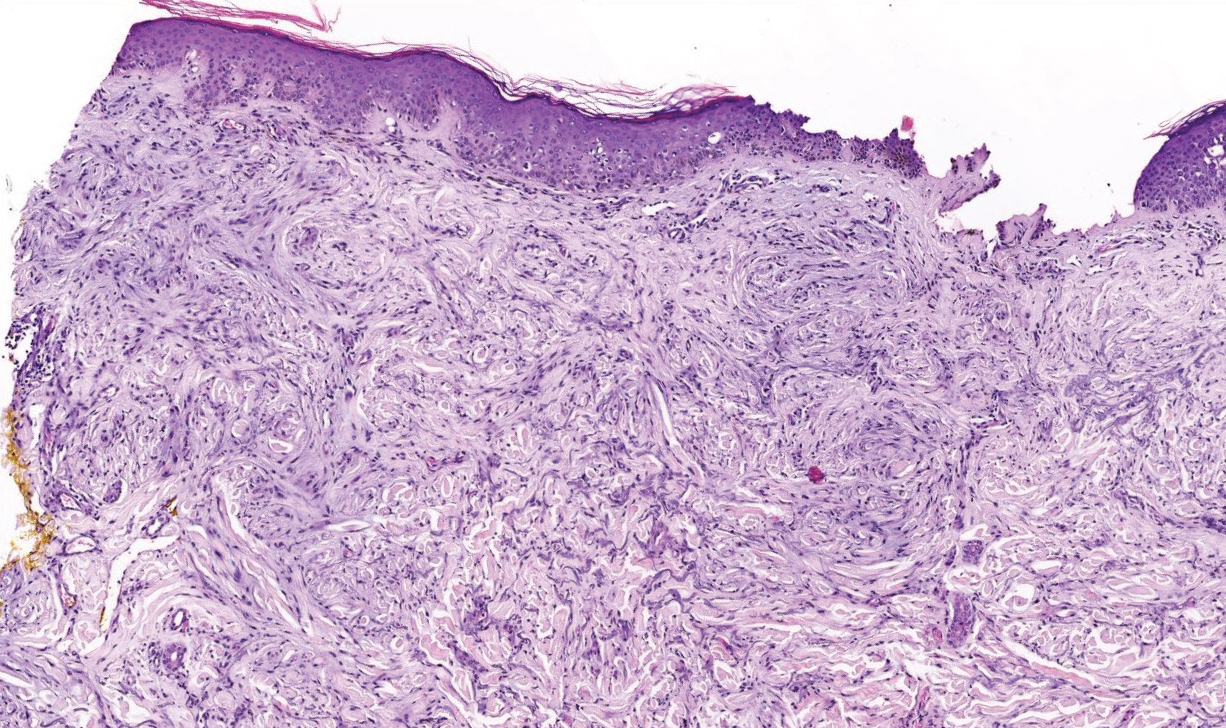

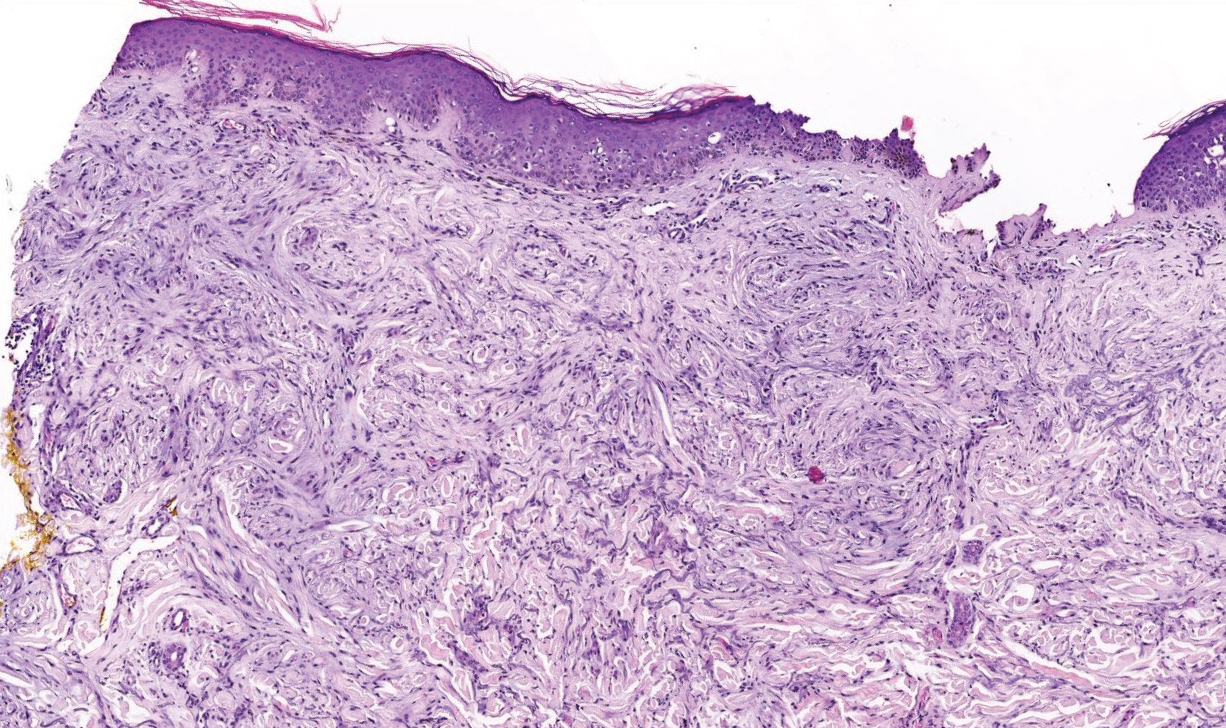

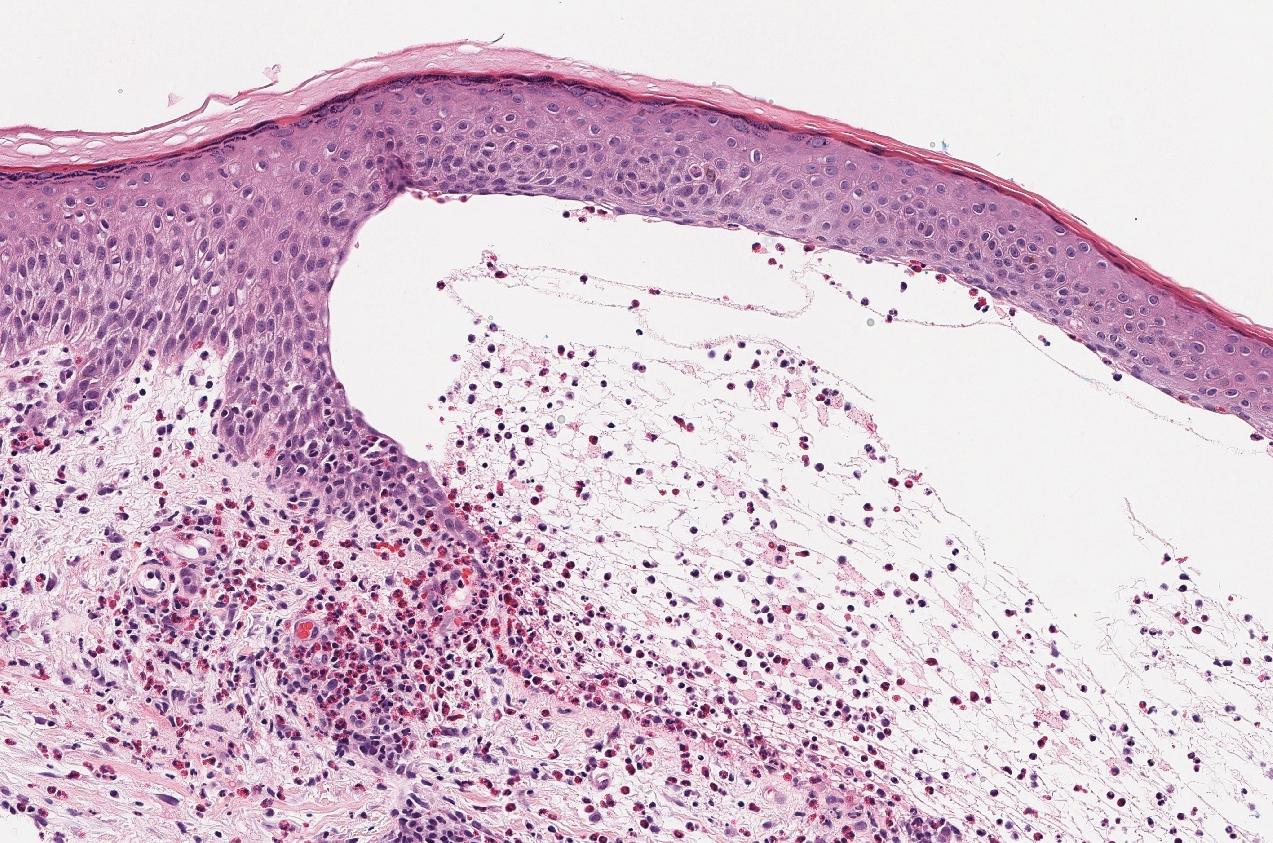

Neurofibroma is a tumor derived from neuromesenchymal tissue with nerve axons. They form through neuromesenchyme (eg, Schwann cells, mast cells, perineural cells, endoneural fibroblast) proliferation. Solitary neurofibromas occur most commonly in adults and have no gender predilection. The most common presentation is an asymptomatic, solitary, soft, flesh-colored papulonodule.15 Clinical variants include pigmented, diffuse, and plexiform, with plexiform neurofibromas almost always being consistent with a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. Histologically, neurofibromas present as dermal or subcutaneous nodules composed of randomly arranged spindle cells with wavy tapered nuclei within a loose collagenous stroma (Figure 4).16 The spindle cells in neurofibromas will stain positively for S-100 protein and SOX-10 and negatively for SMA and desmin.

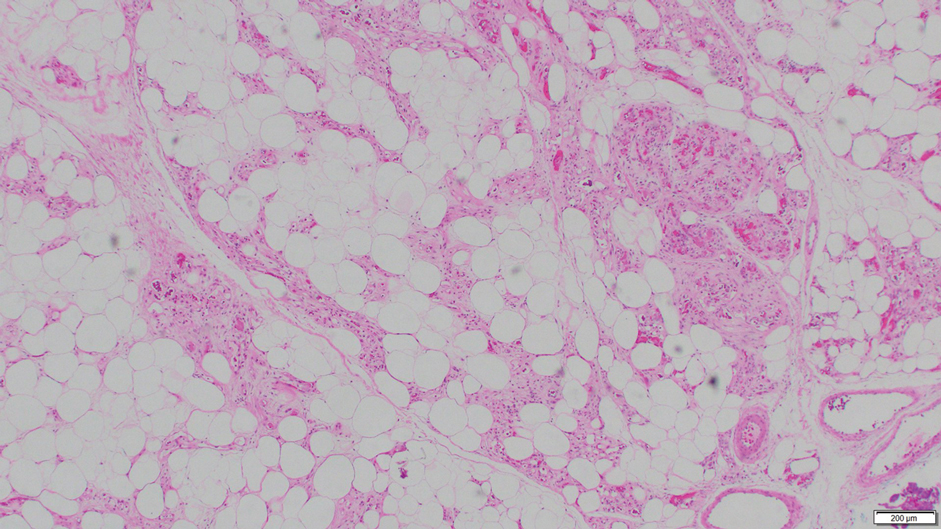

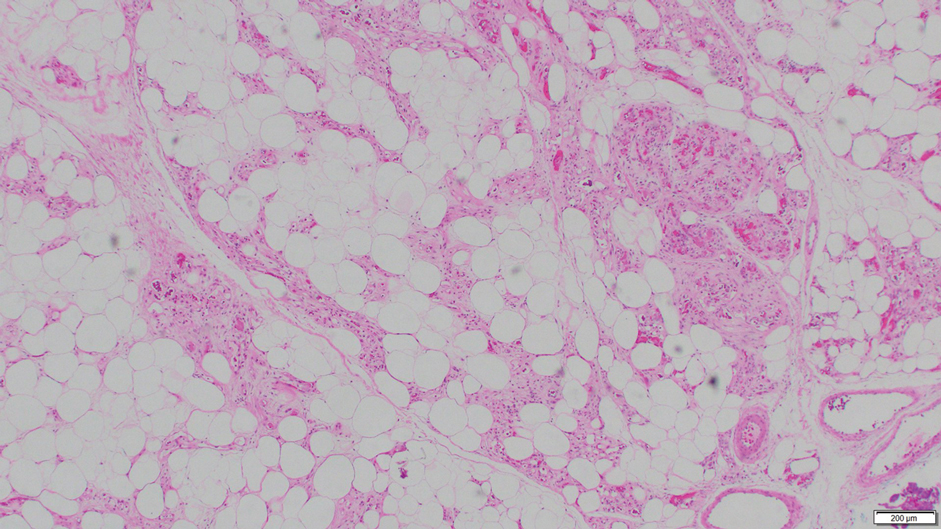

Angiolipoma is a benign tumor composed of adipocytes that also contains vasculature.17 The majority of cases are of unknown etiology, though familial cases have been described. They typically present as multiple painful or tender (differentiating from lipomas) subcutaneous swellings over the forearms in individuals aged 20 to 30 years.18 On histopathology, angiolipomas appear as well-circumscribed subcutaneous tumors containing mature adipocytes intermixed with small capillary vessels, some of which contain luminal fibrin thrombi (Figure 5).

- Malik K, Patel P, Chen J, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a focused review on presentation, management, and association with malignancy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:35-46.

- Malhotra P, Walia H, Singh A, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a clinicopathological series of 37 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:337-341.

- Delfino S, Toto V, Brunetti B, et al. Recurrent atypical eccrine spiradenoma of the forehead. In Vivo. 2008;22:821-823.

- Onder M, Adis¸en E. A new indication of botulinum toxin: leiomyoma-related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:325-328.

- Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:637-644.

- Raj S, Calonje E, Kraus M, et al. Cutaneous pilar leiomyoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 53 lesions in 45 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:2-9.

- Choi JH, Ro JY. Cutaneous spindle cell neoplasms: pattern-based diagnostic approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:958-972.

- Carter CS, Skala SL, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of fumarate hydratase (FH) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in cutaneous leiomyomas for detection of familial cancer syndromes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:801-809.

- Kanitakis J. Angioleiomyoma of the auricle: an unusual tumor on a rare location. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:1-3.

- Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ. Smooth muscle tumors of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53:213-217.

- Phukan J, Sinha A, Pal S. Fine needle aspiration cytology of eccrine spiradenoma of back: report of a rare case. J Lab Physicians. 2014;6:130.

- Zheng Y, Tian Q, Wang J, et al. Differential diagnosis of eccrine spiradenoma: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:1097-1101.

- Bandyopadhyay MR, Besra M, Dutta S, et al. Dermatofibroma: atypical presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:121.

- Commons JD, Parish L, Yazdanian S, et al. Dermatofibroma: a curious tumor. Skinmed. 2012;10:268-270.

- Lee YB, Lee JI, Park HJ, et al. Solitary neurofibromas: does an uncommon site exist? Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:101-102.

- Ortonne N, Wolkenstein P, Blakeley JO, et al. Cutaneous neurofibromas: current clinical and pathologic issues. Neurology. 2018;91:S5-S13.

- Howard WR. Angiolipoma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:924.

- Ghosh S, Haldar BA. Multiple angiolipomas. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1990;56:143-144.

The Diagnosis: Piloleiomyoma

Leiomyoma cutis, also known as cutaneous leiomyoma, is a benign smooth muscle tumor first described in 1854.1 Cutaneous leiomyoma is comprised of 3 distinct types that depend on the origin of smooth muscle tumor: piloleiomyoma (arrector pili muscle), angioleiomyoma (tunica media of arteries/veins), and genital leiomyoma (dartos muscle of the scrotum and labia majora, erectile muscle of nipple).2 It affects both sexes equally, though some reports have noted an increased prevalence in females. Piloleiomyomas commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the extremities (solitary) and trunk (multiple).1 Tumors most often present as firm flesh-colored or pink-brown papulonodules. They can be linear, dermatomal, segmental, or diffuse, and often are painful. Clinical differential diagnosis for painful skin tumors is aided by the acronym "BLEND AN EGG": blue rubber bleb nevus, leiomyoma, eccrine spiradenoma, neuroma, dermatofibroma, angiolipoma, neurilemmoma, endometrioma, glomangioma, and granular cell tumor.3 For isolated lesions, surgical excision is the treatment of choice. For numerous lesions in which excision would not be feasible, intralesional corticosteroids, medications (eg, calcium channel blockers, alpha blockers, nitroglycerin), and botulinum toxin have been used for pain relief.4

Notably, multiple cutaneous leiomyomas can be seen in association with uterine leiomyomas in Reed syndrome due to an autosomal-dominant or de novo mutation in the fumarate hydratase gene, FH. Reed syndrome is associated with a lifetime risk for renal cell carcinoma (hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer) in 15% of cases with FH mutations.5 In our patient, both immunohistochemical staining and blood testing for FH were performed. Immunohistochemistry revealed notably diminished staining with only weak patchy granular cytoplasmic staining present (Figure 1). Genetic testing revealed heterozygosity for a pathogenic variant of the FH gene, consistent with a diagnosis of Reed syndrome.

Histologically, the differential diagnosis includes other spindle cell tumors, such as dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, and dermatomyofibroma. The histologic appearance varies depending on the type, with piloleiomyoma typically located within the reticular dermis with possible subcutaneous extension. Fascicles of eosinophilic smooth muscle cells in an interlacing arrangement often ramify between neighboring dermal collagen; these smooth muscle cells contain cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei with a perinuclear clear vacuole. Marked epidermal hyperplasia is possible.6 A close association with a nearby hair follicle frequently is noted. Although differentiated smooth muscle cells usually are evident on hematoxylin and eosin, positive staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and desmin can aid in diagnosis.7 Immunohistochemical staining for FH has proven to be highly specific (97.6%) with moderate sensitivity (70.0%).8 Angioleiomyomas appear as well-demarcated dermal to subcutaneous tumors composed of smooth muscle cells surrounding thick-walled vaculature.9 Scrotal and vulvar leiomyomas are composed of eosinophilic spindle cells, though vulvar leiomyomas have shown epithelioid differentiation.10 Nipple leiomyomas appear similar to piloleiomyomas on histology with interlacing smooth muscle fiber bundles.

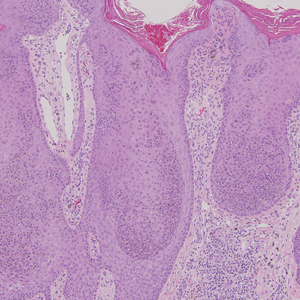

Eccrine spiradenoma is a relatively uncommon adnexal tumor derived from eccrine sweat glands. It most often presents as a small, painful or tender, intradermal nodule (or rarely as nodules) on the head or ventral trunk.11 There is no sexual predilection. It affects adults at any age but most often from 15 to 35 years. Although rare, malignant transformation is possible. Histologically, eccrine spiradenomas appear as a well-demarcated dermal tumor composed of bland basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm, often with numerous admixed lymphocytes and variably prominent vasculature (Figure 2). Eosinophilic basement membrane material can be seen within or surrounding the nodules of tumor cells. Multiple spiradenomas can occur in the setting of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant disorder due to an inherited mutation in the CYLD gene. Spiradenomas are benign neoplasms, and surgical excision with clear margins is the treatment of choice.12

Dermatofibroma, also known as cutaneous benign fibrous histiocytoma, is a firm, flesh-colored papule or nodule that most often presents on the lower extremities. It typically is seen in women aged 20 to 40 years.13 The etiology is uncertain, and dermatofibromas often spontaneously develop, though there are inconsistent reports of development with local trauma including insect bites and puncture wounds. The dimple sign refers to skin dimpling with lateral pressure.13 Most commonly, dermatofibromas consist of a dermal proliferation of bland fibroblastic cells with entrapment of dermal collagen bundles at the periphery of the tumors (Figure 3). The fibroblastic cells often are paler and less eosinophilic than smooth muscle cells seen in cutaneous leiomyomas, with tapered nuclei that lack a perinuclear vacuole. Admixed histocytes and other inflammatory cells often are present. Overlying epidermal hyperplasia and/or hyperpigmentation also may be present. Numerous histologic variants have been described, including cellular, epithelioid, aneurysmal, atypical, and hemosiderotic types.14 Immunohistochemical stains may show patchy positive staining for SMA, but h-caldesmon and desmin typically are negative.

Neurofibroma is a tumor derived from neuromesenchymal tissue with nerve axons. They form through neuromesenchyme (eg, Schwann cells, mast cells, perineural cells, endoneural fibroblast) proliferation. Solitary neurofibromas occur most commonly in adults and have no gender predilection. The most common presentation is an asymptomatic, solitary, soft, flesh-colored papulonodule.15 Clinical variants include pigmented, diffuse, and plexiform, with plexiform neurofibromas almost always being consistent with a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. Histologically, neurofibromas present as dermal or subcutaneous nodules composed of randomly arranged spindle cells with wavy tapered nuclei within a loose collagenous stroma (Figure 4).16 The spindle cells in neurofibromas will stain positively for S-100 protein and SOX-10 and negatively for SMA and desmin.

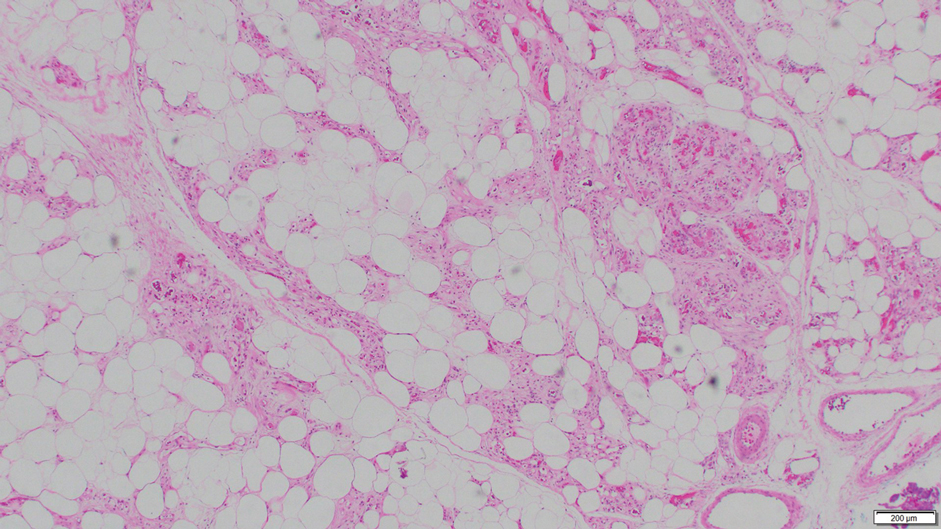

Angiolipoma is a benign tumor composed of adipocytes that also contains vasculature.17 The majority of cases are of unknown etiology, though familial cases have been described. They typically present as multiple painful or tender (differentiating from lipomas) subcutaneous swellings over the forearms in individuals aged 20 to 30 years.18 On histopathology, angiolipomas appear as well-circumscribed subcutaneous tumors containing mature adipocytes intermixed with small capillary vessels, some of which contain luminal fibrin thrombi (Figure 5).

The Diagnosis: Piloleiomyoma

Leiomyoma cutis, also known as cutaneous leiomyoma, is a benign smooth muscle tumor first described in 1854.1 Cutaneous leiomyoma is comprised of 3 distinct types that depend on the origin of smooth muscle tumor: piloleiomyoma (arrector pili muscle), angioleiomyoma (tunica media of arteries/veins), and genital leiomyoma (dartos muscle of the scrotum and labia majora, erectile muscle of nipple).2 It affects both sexes equally, though some reports have noted an increased prevalence in females. Piloleiomyomas commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the extremities (solitary) and trunk (multiple).1 Tumors most often present as firm flesh-colored or pink-brown papulonodules. They can be linear, dermatomal, segmental, or diffuse, and often are painful. Clinical differential diagnosis for painful skin tumors is aided by the acronym "BLEND AN EGG": blue rubber bleb nevus, leiomyoma, eccrine spiradenoma, neuroma, dermatofibroma, angiolipoma, neurilemmoma, endometrioma, glomangioma, and granular cell tumor.3 For isolated lesions, surgical excision is the treatment of choice. For numerous lesions in which excision would not be feasible, intralesional corticosteroids, medications (eg, calcium channel blockers, alpha blockers, nitroglycerin), and botulinum toxin have been used for pain relief.4

Notably, multiple cutaneous leiomyomas can be seen in association with uterine leiomyomas in Reed syndrome due to an autosomal-dominant or de novo mutation in the fumarate hydratase gene, FH. Reed syndrome is associated with a lifetime risk for renal cell carcinoma (hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer) in 15% of cases with FH mutations.5 In our patient, both immunohistochemical staining and blood testing for FH were performed. Immunohistochemistry revealed notably diminished staining with only weak patchy granular cytoplasmic staining present (Figure 1). Genetic testing revealed heterozygosity for a pathogenic variant of the FH gene, consistent with a diagnosis of Reed syndrome.

Histologically, the differential diagnosis includes other spindle cell tumors, such as dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, and dermatomyofibroma. The histologic appearance varies depending on the type, with piloleiomyoma typically located within the reticular dermis with possible subcutaneous extension. Fascicles of eosinophilic smooth muscle cells in an interlacing arrangement often ramify between neighboring dermal collagen; these smooth muscle cells contain cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei with a perinuclear clear vacuole. Marked epidermal hyperplasia is possible.6 A close association with a nearby hair follicle frequently is noted. Although differentiated smooth muscle cells usually are evident on hematoxylin and eosin, positive staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and desmin can aid in diagnosis.7 Immunohistochemical staining for FH has proven to be highly specific (97.6%) with moderate sensitivity (70.0%).8 Angioleiomyomas appear as well-demarcated dermal to subcutaneous tumors composed of smooth muscle cells surrounding thick-walled vaculature.9 Scrotal and vulvar leiomyomas are composed of eosinophilic spindle cells, though vulvar leiomyomas have shown epithelioid differentiation.10 Nipple leiomyomas appear similar to piloleiomyomas on histology with interlacing smooth muscle fiber bundles.

Eccrine spiradenoma is a relatively uncommon adnexal tumor derived from eccrine sweat glands. It most often presents as a small, painful or tender, intradermal nodule (or rarely as nodules) on the head or ventral trunk.11 There is no sexual predilection. It affects adults at any age but most often from 15 to 35 years. Although rare, malignant transformation is possible. Histologically, eccrine spiradenomas appear as a well-demarcated dermal tumor composed of bland basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm, often with numerous admixed lymphocytes and variably prominent vasculature (Figure 2). Eosinophilic basement membrane material can be seen within or surrounding the nodules of tumor cells. Multiple spiradenomas can occur in the setting of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant disorder due to an inherited mutation in the CYLD gene. Spiradenomas are benign neoplasms, and surgical excision with clear margins is the treatment of choice.12

Dermatofibroma, also known as cutaneous benign fibrous histiocytoma, is a firm, flesh-colored papule or nodule that most often presents on the lower extremities. It typically is seen in women aged 20 to 40 years.13 The etiology is uncertain, and dermatofibromas often spontaneously develop, though there are inconsistent reports of development with local trauma including insect bites and puncture wounds. The dimple sign refers to skin dimpling with lateral pressure.13 Most commonly, dermatofibromas consist of a dermal proliferation of bland fibroblastic cells with entrapment of dermal collagen bundles at the periphery of the tumors (Figure 3). The fibroblastic cells often are paler and less eosinophilic than smooth muscle cells seen in cutaneous leiomyomas, with tapered nuclei that lack a perinuclear vacuole. Admixed histocytes and other inflammatory cells often are present. Overlying epidermal hyperplasia and/or hyperpigmentation also may be present. Numerous histologic variants have been described, including cellular, epithelioid, aneurysmal, atypical, and hemosiderotic types.14 Immunohistochemical stains may show patchy positive staining for SMA, but h-caldesmon and desmin typically are negative.

Neurofibroma is a tumor derived from neuromesenchymal tissue with nerve axons. They form through neuromesenchyme (eg, Schwann cells, mast cells, perineural cells, endoneural fibroblast) proliferation. Solitary neurofibromas occur most commonly in adults and have no gender predilection. The most common presentation is an asymptomatic, solitary, soft, flesh-colored papulonodule.15 Clinical variants include pigmented, diffuse, and plexiform, with plexiform neurofibromas almost always being consistent with a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. Histologically, neurofibromas present as dermal or subcutaneous nodules composed of randomly arranged spindle cells with wavy tapered nuclei within a loose collagenous stroma (Figure 4).16 The spindle cells in neurofibromas will stain positively for S-100 protein and SOX-10 and negatively for SMA and desmin.

Angiolipoma is a benign tumor composed of adipocytes that also contains vasculature.17 The majority of cases are of unknown etiology, though familial cases have been described. They typically present as multiple painful or tender (differentiating from lipomas) subcutaneous swellings over the forearms in individuals aged 20 to 30 years.18 On histopathology, angiolipomas appear as well-circumscribed subcutaneous tumors containing mature adipocytes intermixed with small capillary vessels, some of which contain luminal fibrin thrombi (Figure 5).

- Malik K, Patel P, Chen J, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a focused review on presentation, management, and association with malignancy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:35-46.

- Malhotra P, Walia H, Singh A, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a clinicopathological series of 37 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:337-341.

- Delfino S, Toto V, Brunetti B, et al. Recurrent atypical eccrine spiradenoma of the forehead. In Vivo. 2008;22:821-823.

- Onder M, Adis¸en E. A new indication of botulinum toxin: leiomyoma-related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:325-328.

- Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:637-644.

- Raj S, Calonje E, Kraus M, et al. Cutaneous pilar leiomyoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 53 lesions in 45 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:2-9.

- Choi JH, Ro JY. Cutaneous spindle cell neoplasms: pattern-based diagnostic approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:958-972.

- Carter CS, Skala SL, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of fumarate hydratase (FH) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in cutaneous leiomyomas for detection of familial cancer syndromes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:801-809.

- Kanitakis J. Angioleiomyoma of the auricle: an unusual tumor on a rare location. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:1-3.

- Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ. Smooth muscle tumors of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53:213-217.

- Phukan J, Sinha A, Pal S. Fine needle aspiration cytology of eccrine spiradenoma of back: report of a rare case. J Lab Physicians. 2014;6:130.

- Zheng Y, Tian Q, Wang J, et al. Differential diagnosis of eccrine spiradenoma: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:1097-1101.

- Bandyopadhyay MR, Besra M, Dutta S, et al. Dermatofibroma: atypical presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:121.

- Commons JD, Parish L, Yazdanian S, et al. Dermatofibroma: a curious tumor. Skinmed. 2012;10:268-270.

- Lee YB, Lee JI, Park HJ, et al. Solitary neurofibromas: does an uncommon site exist? Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:101-102.

- Ortonne N, Wolkenstein P, Blakeley JO, et al. Cutaneous neurofibromas: current clinical and pathologic issues. Neurology. 2018;91:S5-S13.

- Howard WR. Angiolipoma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:924.

- Ghosh S, Haldar BA. Multiple angiolipomas. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1990;56:143-144.

- Malik K, Patel P, Chen J, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a focused review on presentation, management, and association with malignancy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:35-46.

- Malhotra P, Walia H, Singh A, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a clinicopathological series of 37 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:337-341.

- Delfino S, Toto V, Brunetti B, et al. Recurrent atypical eccrine spiradenoma of the forehead. In Vivo. 2008;22:821-823.

- Onder M, Adis¸en E. A new indication of botulinum toxin: leiomyoma-related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:325-328.

- Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:637-644.

- Raj S, Calonje E, Kraus M, et al. Cutaneous pilar leiomyoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 53 lesions in 45 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:2-9.

- Choi JH, Ro JY. Cutaneous spindle cell neoplasms: pattern-based diagnostic approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:958-972.

- Carter CS, Skala SL, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of fumarate hydratase (FH) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in cutaneous leiomyomas for detection of familial cancer syndromes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:801-809.

- Kanitakis J. Angioleiomyoma of the auricle: an unusual tumor on a rare location. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:1-3.

- Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ. Smooth muscle tumors of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53:213-217.

- Phukan J, Sinha A, Pal S. Fine needle aspiration cytology of eccrine spiradenoma of back: report of a rare case. J Lab Physicians. 2014;6:130.

- Zheng Y, Tian Q, Wang J, et al. Differential diagnosis of eccrine spiradenoma: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:1097-1101.

- Bandyopadhyay MR, Besra M, Dutta S, et al. Dermatofibroma: atypical presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:121.

- Commons JD, Parish L, Yazdanian S, et al. Dermatofibroma: a curious tumor. Skinmed. 2012;10:268-270.

- Lee YB, Lee JI, Park HJ, et al. Solitary neurofibromas: does an uncommon site exist? Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:101-102.

- Ortonne N, Wolkenstein P, Blakeley JO, et al. Cutaneous neurofibromas: current clinical and pathologic issues. Neurology. 2018;91:S5-S13.

- Howard WR. Angiolipoma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:924.

- Ghosh S, Haldar BA. Multiple angiolipomas. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1990;56:143-144.

A 36-year-old woman presented with multiple new-onset, firm, tender, subcutaneous papules and nodules involving the upper arms and shoulders.

Lichen Sclerosus of the Eyelid

To the Editor:

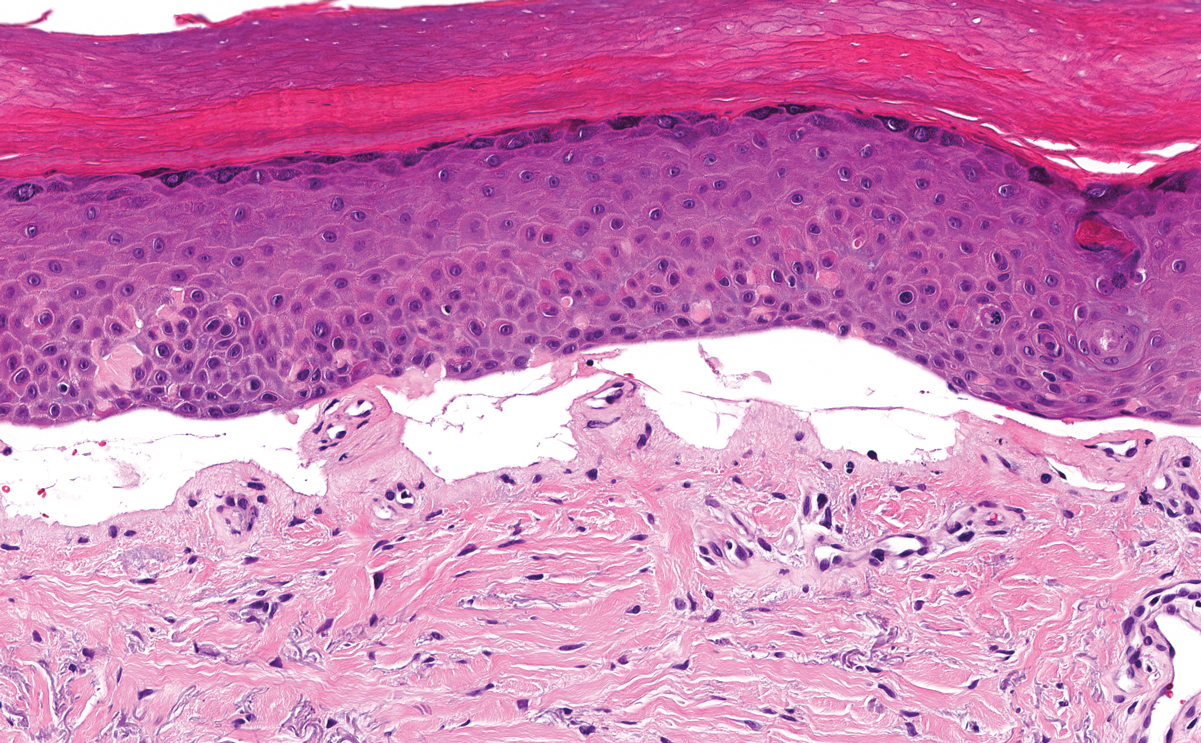

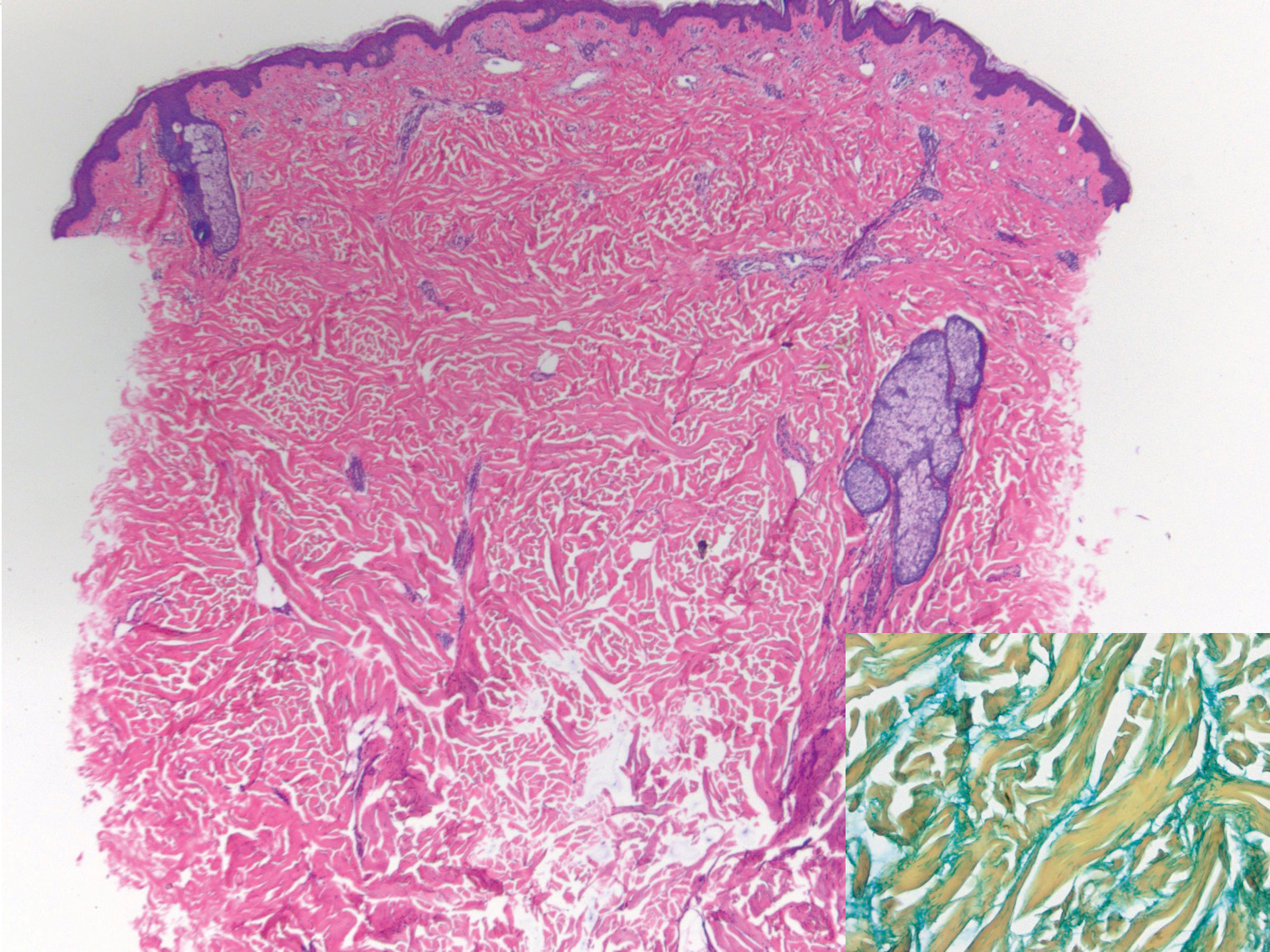

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory skin disease of unknown cause that predominantly affects the anogenital region, but isolated extragenital lesions occur in 6% to 15% of patients. The buttocks, thighs, neck, shoulder, upper torso, and wrists most commonly are involved; the face rarely is affected.1,2 Although the etiology of lichen sclerosus remains undetermined, there is growing evidence that autoimmunity may play a role.1 Lichen sclerosus more commonly is seen in women, and the disease can present at any age, with a bimodal onset in prepubertal children and in postmenopausal women and men in the fourth decade of life.1-3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms lichen and eyelid and manually screened revealed 6 cases of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid.2-4 We describe a case of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid and its histopathology.

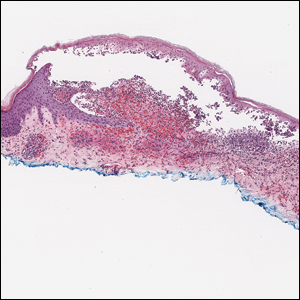

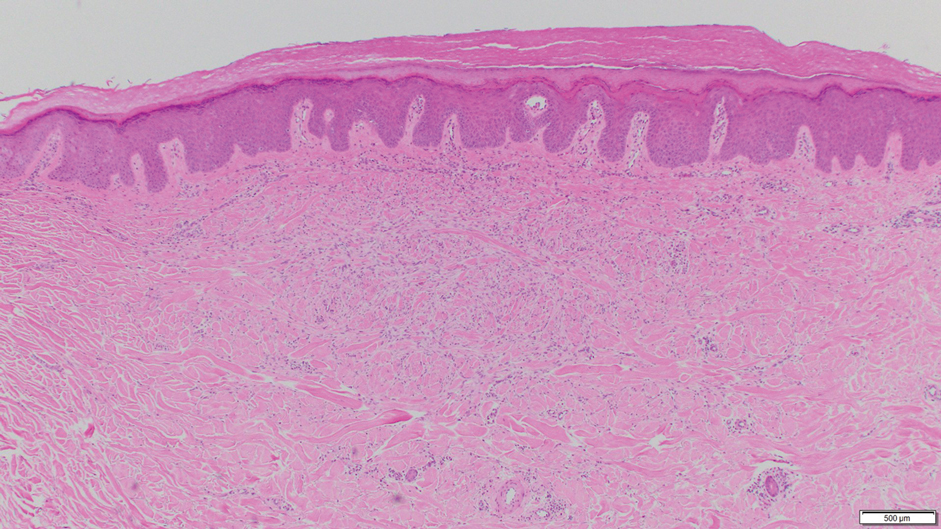

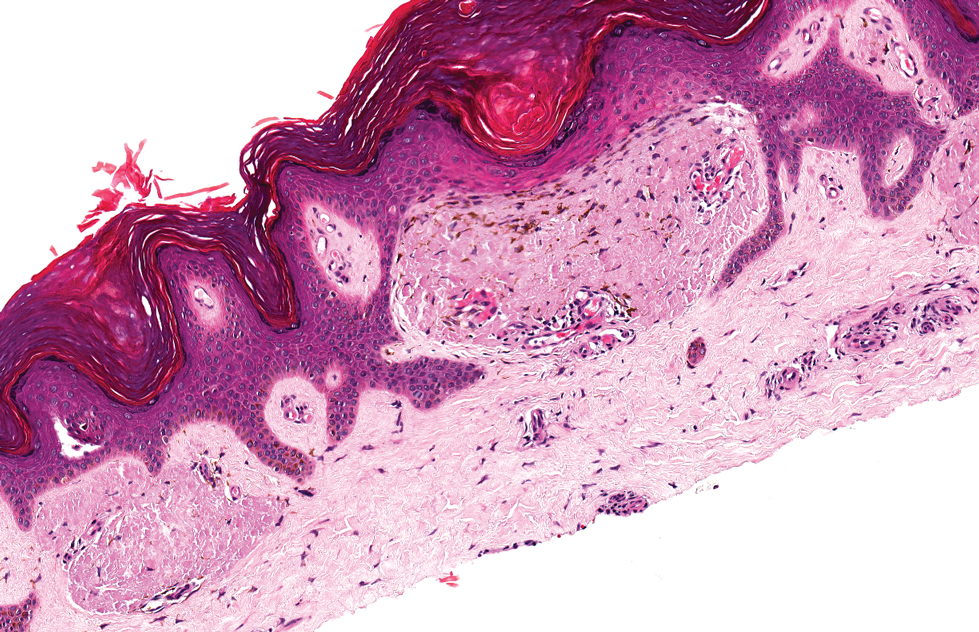

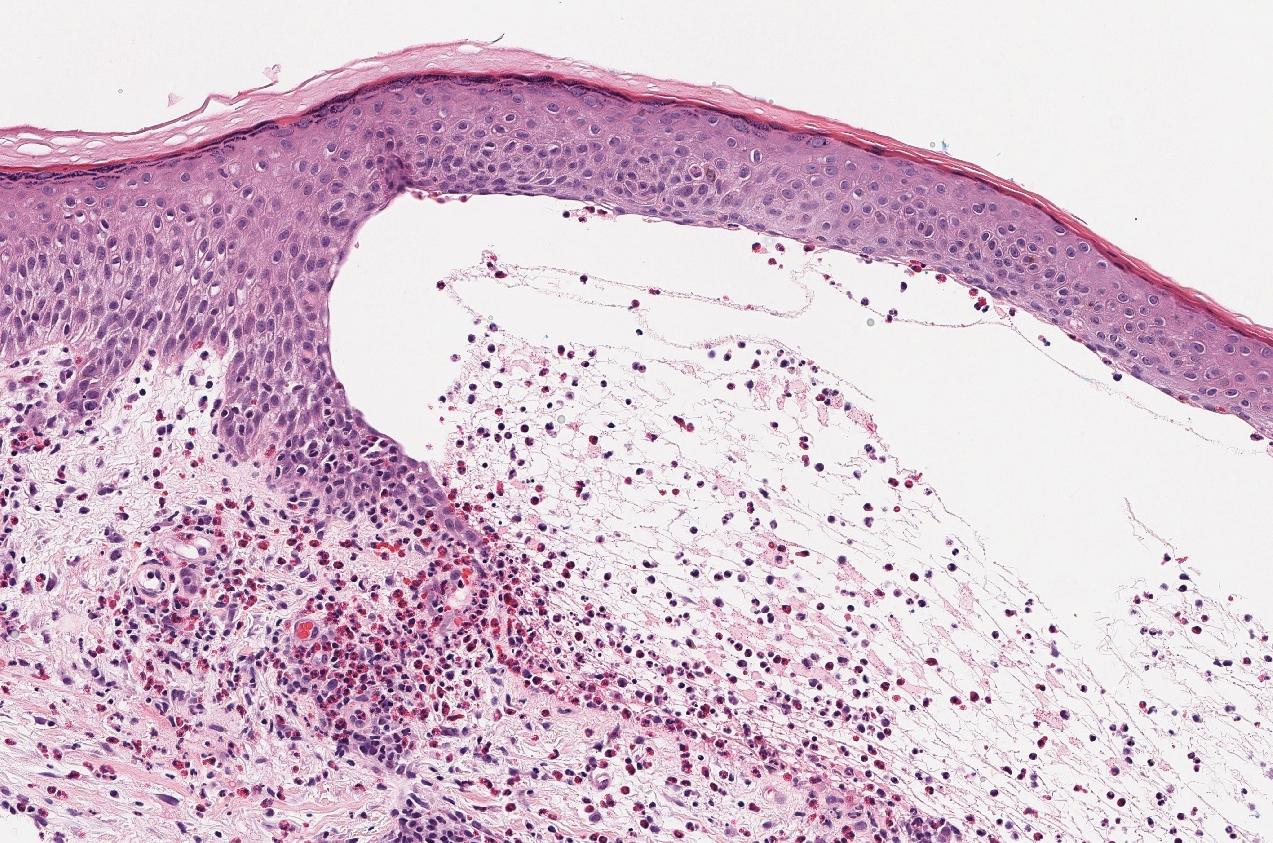

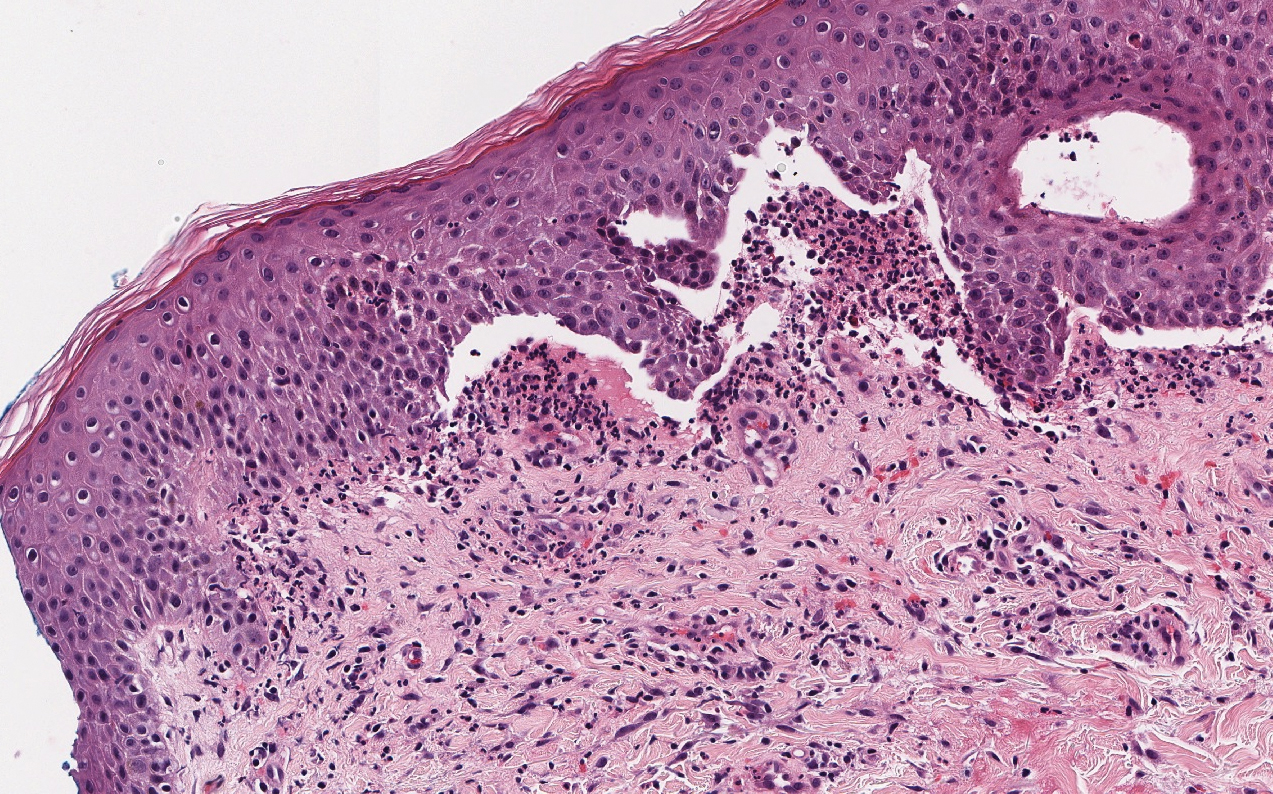

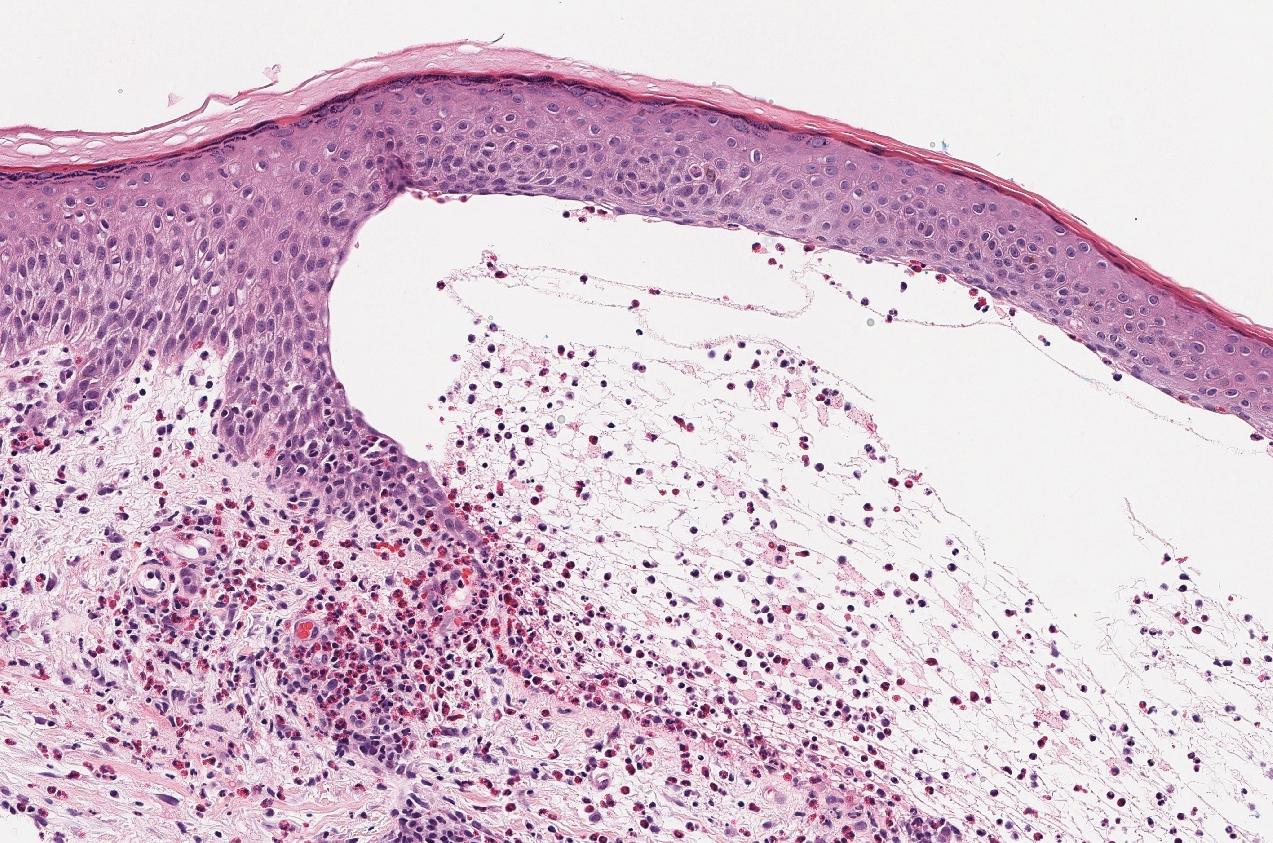

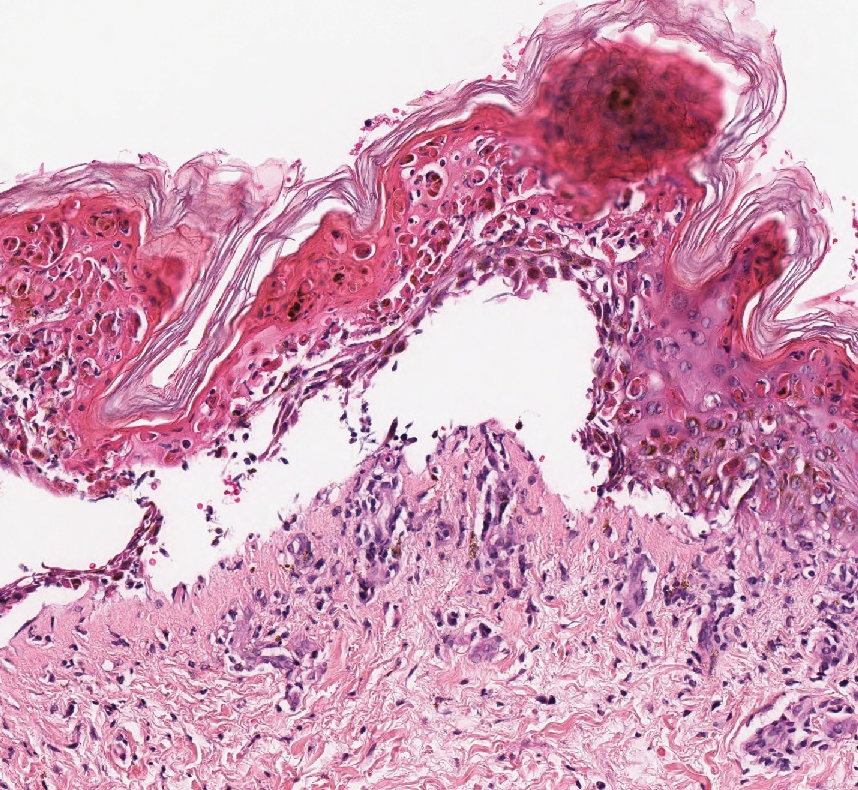

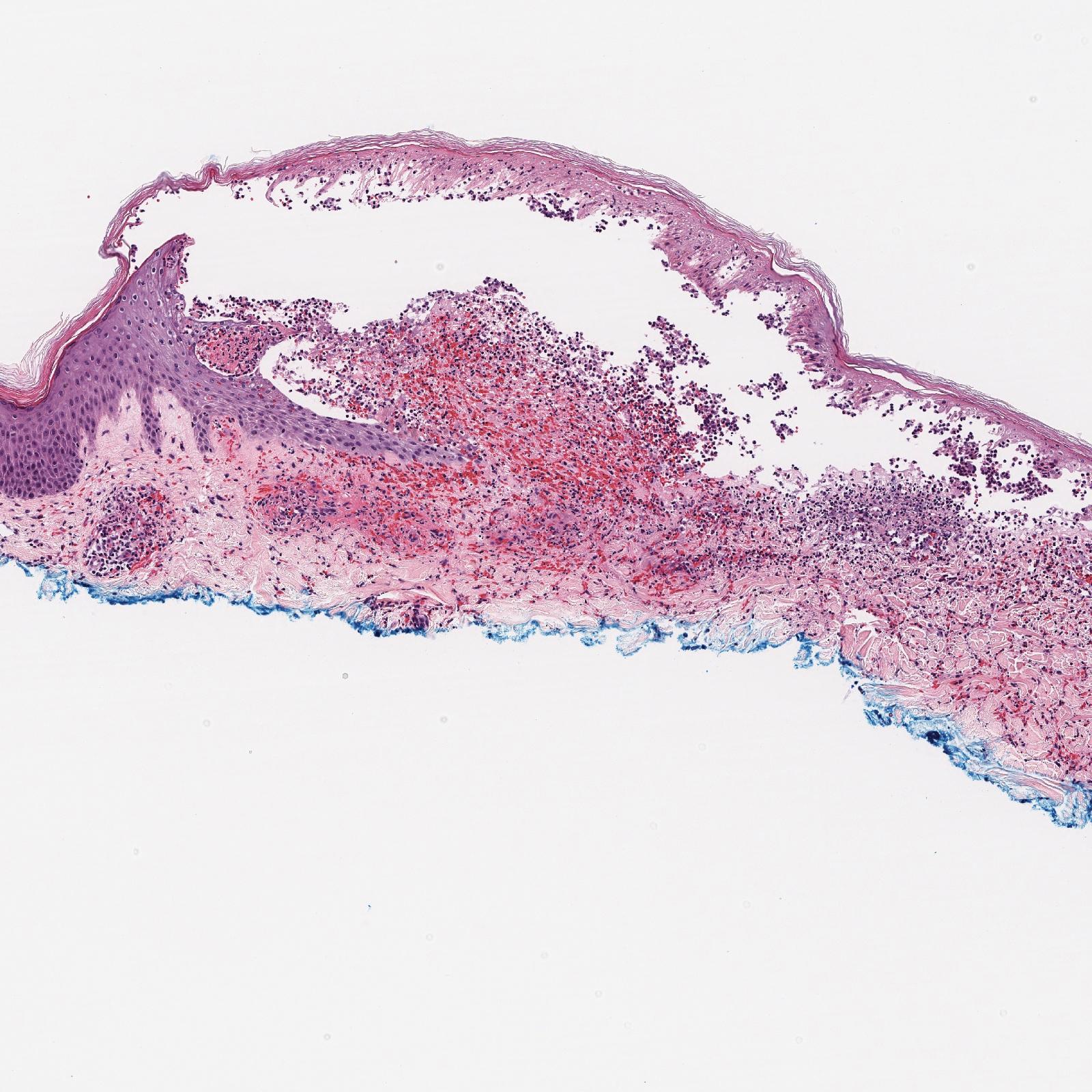

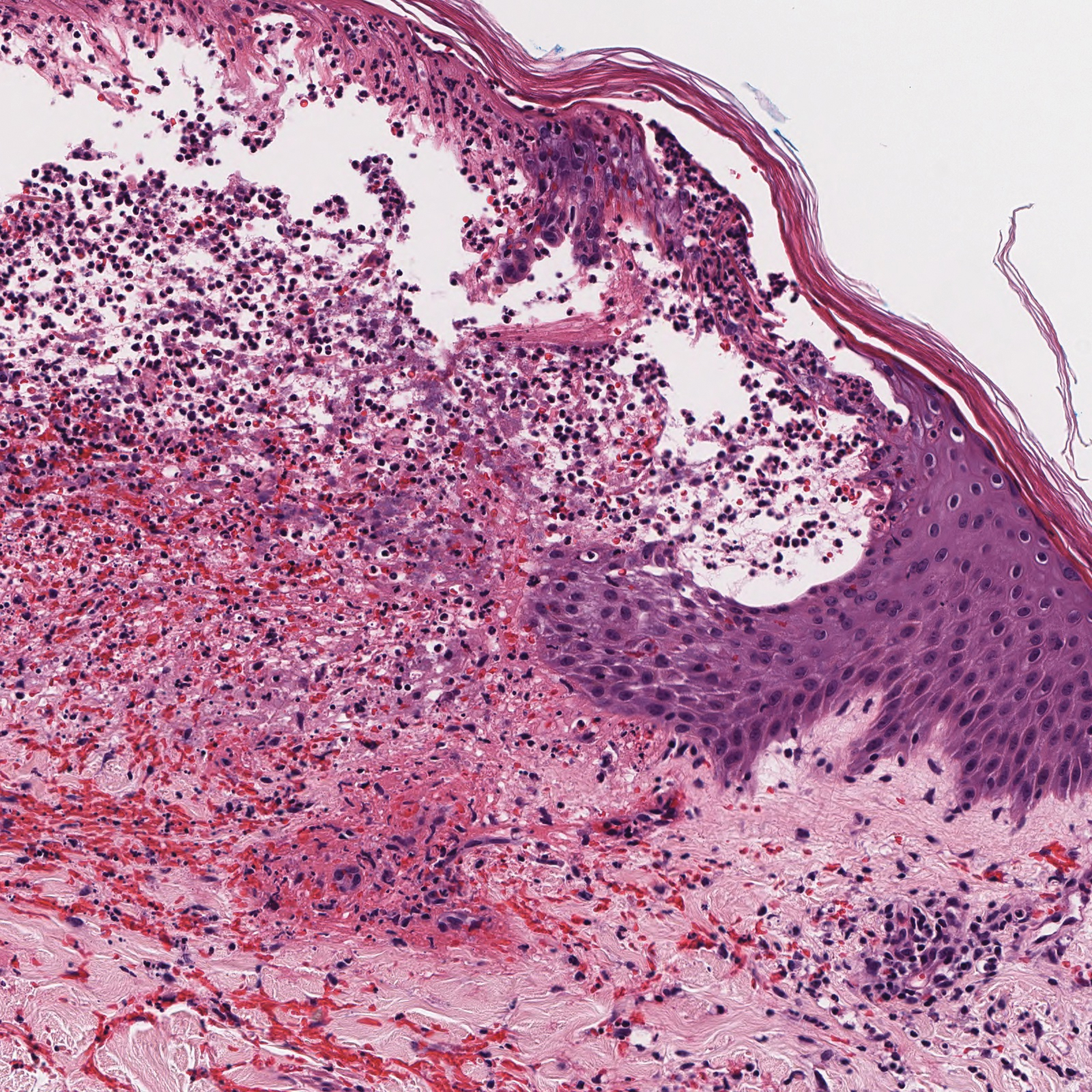

A 45-year-old woman was referred to dermatology for evaluation of a right lower eyelid lesion of 3 months’ duration. She first noted a small white patch under the eyelid that had doubled in size and felt firm without bleeding or ulceration. Her medical history was unremarkable, and there was no history of ophthalmic conditions, autoimmune disease, trauma, or cancer. An ophthalmic examination was normal, except for a 20×8-mm, flat, depigmented, firm papule with scalloped borders involving the right lower eyelid margin and extending inferiorly without evidence of madarosis or ulceration (Figure 1). She underwent an incisional biopsy that revealed the diagnosis of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (Figure 2). A full dermatologic evaluation included a genital examination and did not reveal any additional lesions. Tacrolimus ointment was started to avoid the need for long-term use of periocular steroids and their complications.

Extragenital lichen sclerosus typically is asymptomatic and only rarely presents with pruritus, in contrast to genital lichen sclerosus, which characteristically involves pruritus and dyspareunia. Although eyelid involvement is rare, ophthalmic manifestations of lichen sclerosus have included lid notching, ectropion, acquired Brown syndrome, and associated keratoconjunctivitis sicca.3-5 It characteristically appears as a well-demarcated hypopigmented papule. The differential diagnosis for a hypopigmented papule also includes amelanotic melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, vitiligo, tinea versicolor, lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, morphea (localized scleroderma), and systemic scleroderma with eyelid involvement.1,5

Differentiating lichen sclerosus from these conditions is of importance, as some of them can have notable morbidity and/or mortality. Of all the autoimmune connective tissue disorders, systemic sclerosus has the highest disease-specific mortality.6 Morphea, on the other hand, can have considerable morbidity. Morphea involving the head and neck notably increases the risk for neurologic complications such as seizures or central nervous system vasculitis as well as ocular complications such as anterior uveitis.6 Of note, genital lichen sclerosus carries an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma and verrucous carcinoma; however, there have been no reported cases of malignant transformation with extragenital lesions.2

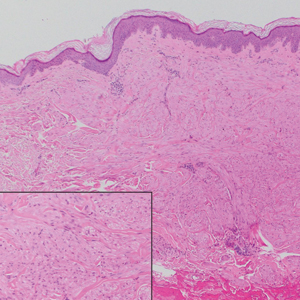

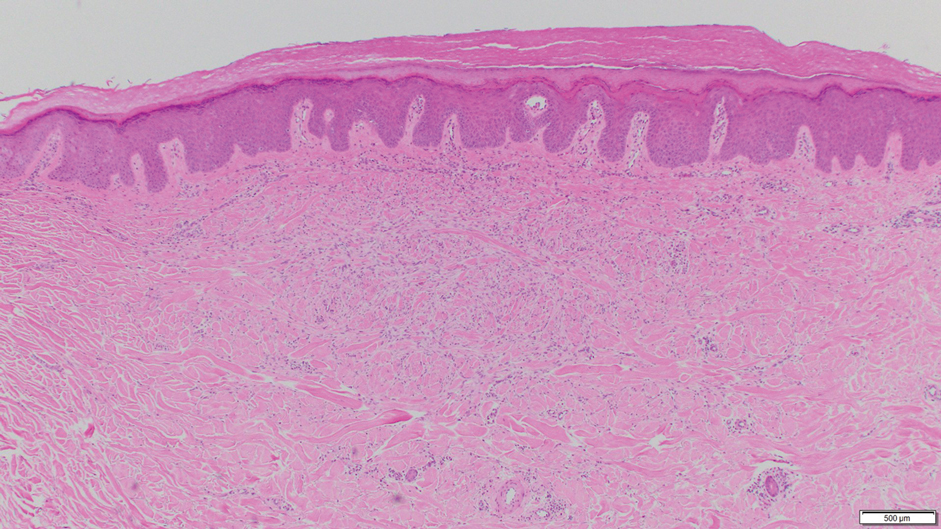

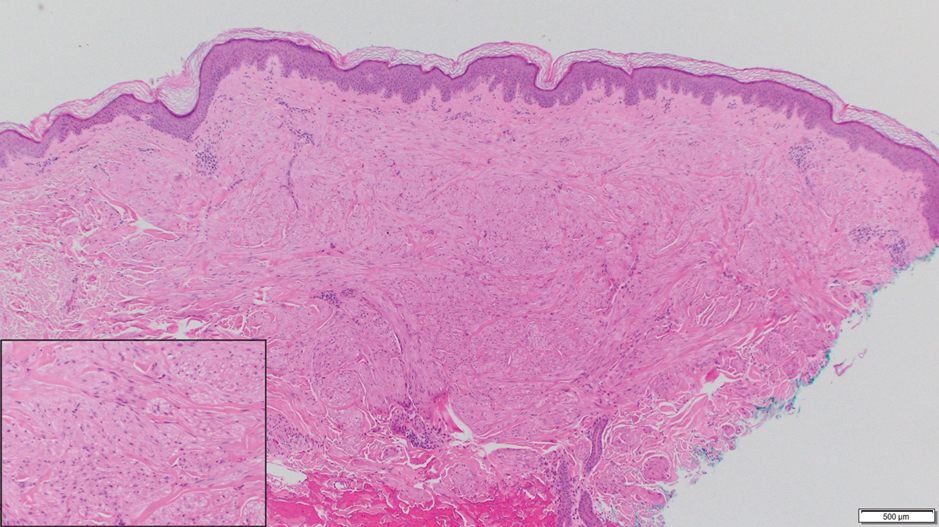

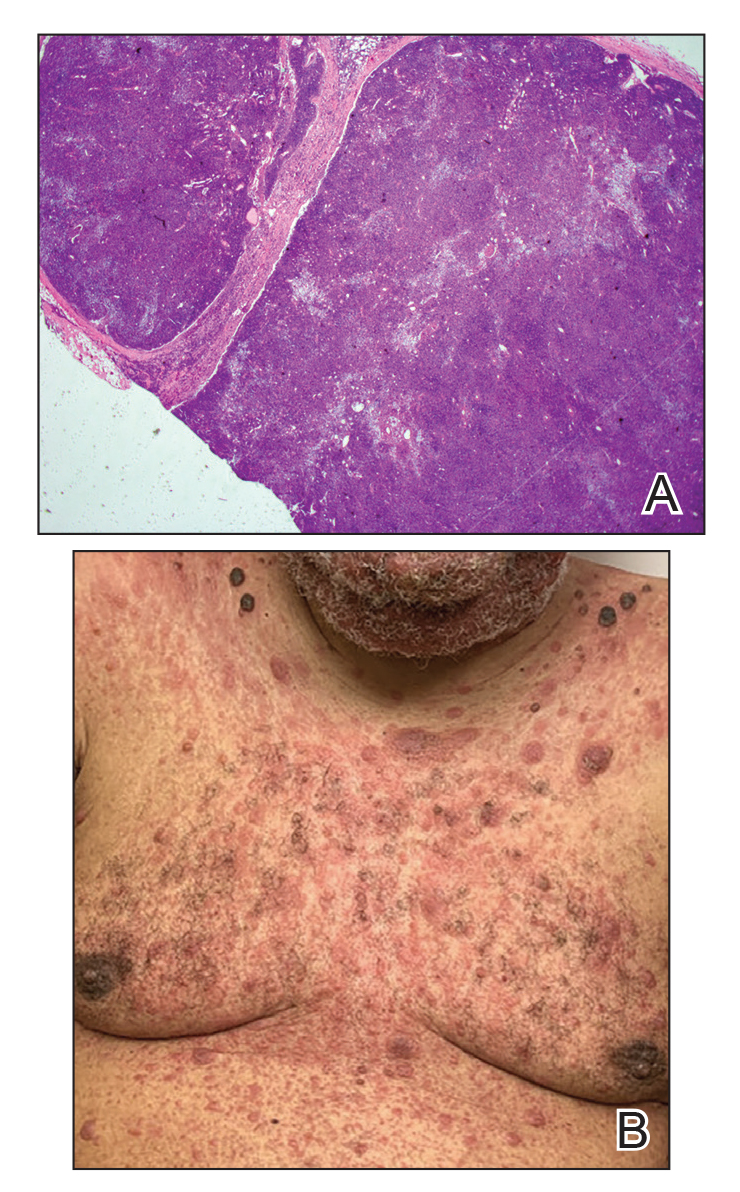

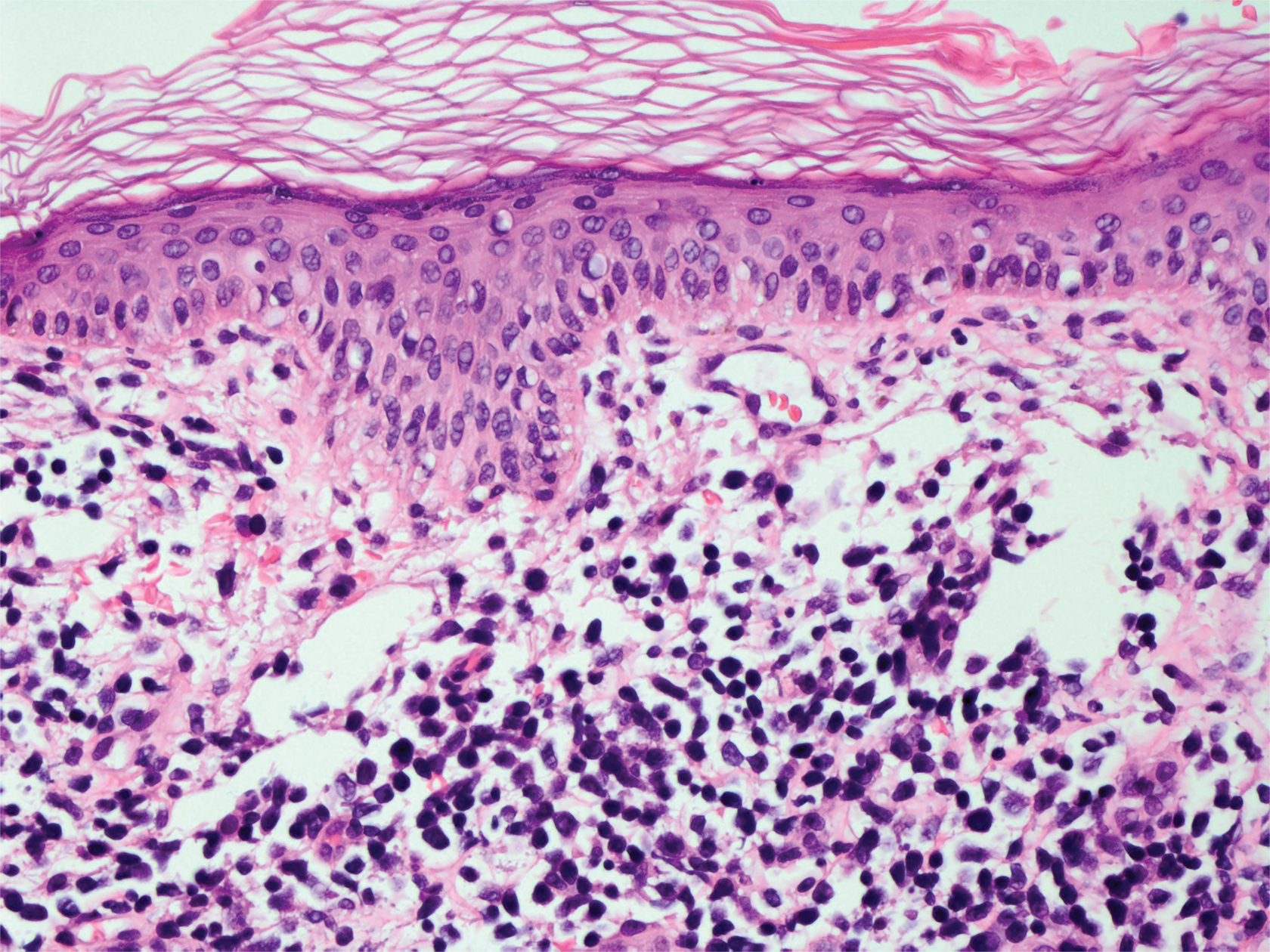

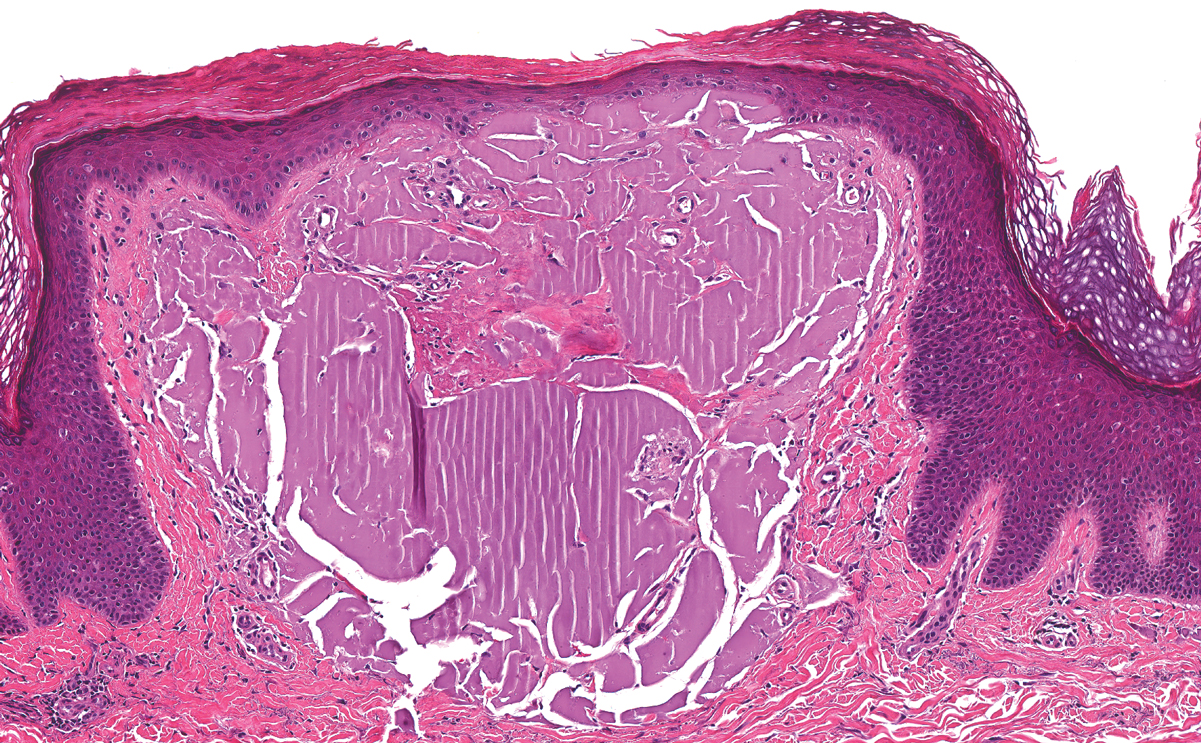

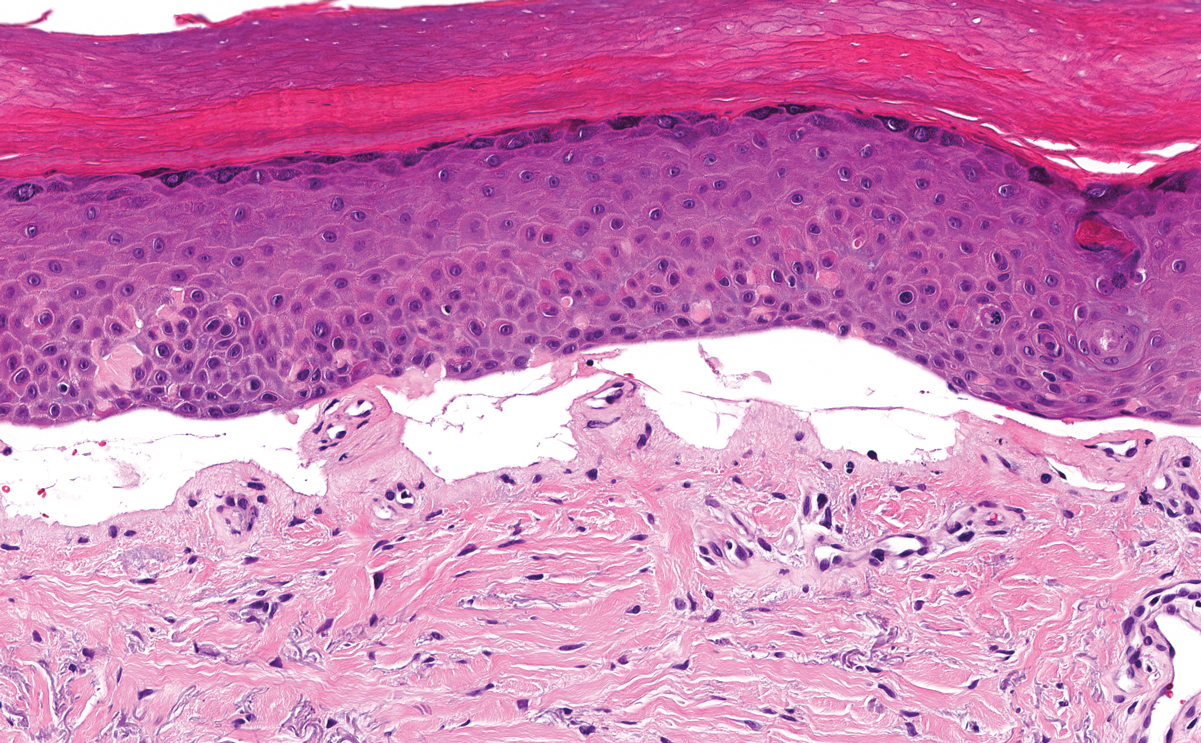

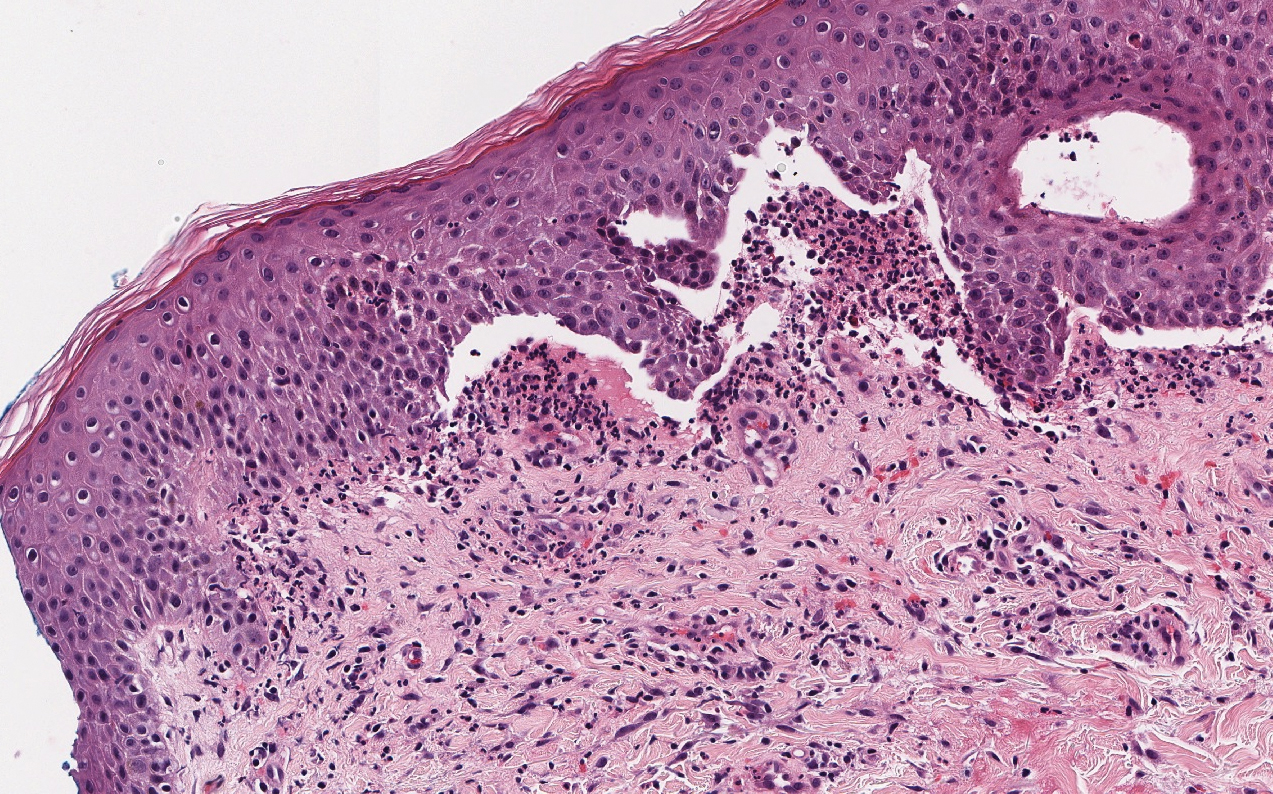

Histopathology is useful to distinguish among these entities. Although there are no specific features separating lichen sclerosus from a morphea overlap and both entities often are classified by clinical presentation, lichen sclerosus demonstrates epidermal atrophy, follicular plugging, homogenized collagen in the upper dermis with dermal edema, and lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2).1 Extragenital lesions in particular also have been noted to have more epidermal atrophy and decreased rete ridges.2

First-line treatment of lichen sclerosus includes topical corticosteroids with emollients for supportive therapy. A topical calcineurin inhibitor such as tacrolimus should be considered for patients who do not respond to corticosteroid therapy or in cases in which corticosteroid therapy is contraindicated to avoid steroid-induced glaucoma or undesirable skin atrophy and hypopigmentation.2 A collaborative approach including dermatology and internal medicine can help identify a systemic or multisystem process.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Rosenthal IM, Taube JM, Nelson DL, et al. A case of infraorbital lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20021.

- Rabinowitz R, Rosenthal G, Yerushalmy J, et al. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca associated with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Eye. 2000;14:103-104.

- Olver J, Laidler P. Acquired Brown’s syndrome in a patient with combined lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and morphea. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:552-557.

- El-Baba F, Frangieh GT, Iliff WJ, et al. Morphea of the eyelids. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:125-128.

- Fett N. Scleroderma: nomenclatures, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatment: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory skin disease of unknown cause that predominantly affects the anogenital region, but isolated extragenital lesions occur in 6% to 15% of patients. The buttocks, thighs, neck, shoulder, upper torso, and wrists most commonly are involved; the face rarely is affected.1,2 Although the etiology of lichen sclerosus remains undetermined, there is growing evidence that autoimmunity may play a role.1 Lichen sclerosus more commonly is seen in women, and the disease can present at any age, with a bimodal onset in prepubertal children and in postmenopausal women and men in the fourth decade of life.1-3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms lichen and eyelid and manually screened revealed 6 cases of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid.2-4 We describe a case of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid and its histopathology.

A 45-year-old woman was referred to dermatology for evaluation of a right lower eyelid lesion of 3 months’ duration. She first noted a small white patch under the eyelid that had doubled in size and felt firm without bleeding or ulceration. Her medical history was unremarkable, and there was no history of ophthalmic conditions, autoimmune disease, trauma, or cancer. An ophthalmic examination was normal, except for a 20×8-mm, flat, depigmented, firm papule with scalloped borders involving the right lower eyelid margin and extending inferiorly without evidence of madarosis or ulceration (Figure 1). She underwent an incisional biopsy that revealed the diagnosis of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (Figure 2). A full dermatologic evaluation included a genital examination and did not reveal any additional lesions. Tacrolimus ointment was started to avoid the need for long-term use of periocular steroids and their complications.

Extragenital lichen sclerosus typically is asymptomatic and only rarely presents with pruritus, in contrast to genital lichen sclerosus, which characteristically involves pruritus and dyspareunia. Although eyelid involvement is rare, ophthalmic manifestations of lichen sclerosus have included lid notching, ectropion, acquired Brown syndrome, and associated keratoconjunctivitis sicca.3-5 It characteristically appears as a well-demarcated hypopigmented papule. The differential diagnosis for a hypopigmented papule also includes amelanotic melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, vitiligo, tinea versicolor, lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, morphea (localized scleroderma), and systemic scleroderma with eyelid involvement.1,5

Differentiating lichen sclerosus from these conditions is of importance, as some of them can have notable morbidity and/or mortality. Of all the autoimmune connective tissue disorders, systemic sclerosus has the highest disease-specific mortality.6 Morphea, on the other hand, can have considerable morbidity. Morphea involving the head and neck notably increases the risk for neurologic complications such as seizures or central nervous system vasculitis as well as ocular complications such as anterior uveitis.6 Of note, genital lichen sclerosus carries an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma and verrucous carcinoma; however, there have been no reported cases of malignant transformation with extragenital lesions.2

Histopathology is useful to distinguish among these entities. Although there are no specific features separating lichen sclerosus from a morphea overlap and both entities often are classified by clinical presentation, lichen sclerosus demonstrates epidermal atrophy, follicular plugging, homogenized collagen in the upper dermis with dermal edema, and lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2).1 Extragenital lesions in particular also have been noted to have more epidermal atrophy and decreased rete ridges.2

First-line treatment of lichen sclerosus includes topical corticosteroids with emollients for supportive therapy. A topical calcineurin inhibitor such as tacrolimus should be considered for patients who do not respond to corticosteroid therapy or in cases in which corticosteroid therapy is contraindicated to avoid steroid-induced glaucoma or undesirable skin atrophy and hypopigmentation.2 A collaborative approach including dermatology and internal medicine can help identify a systemic or multisystem process.

To the Editor:

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory skin disease of unknown cause that predominantly affects the anogenital region, but isolated extragenital lesions occur in 6% to 15% of patients. The buttocks, thighs, neck, shoulder, upper torso, and wrists most commonly are involved; the face rarely is affected.1,2 Although the etiology of lichen sclerosus remains undetermined, there is growing evidence that autoimmunity may play a role.1 Lichen sclerosus more commonly is seen in women, and the disease can present at any age, with a bimodal onset in prepubertal children and in postmenopausal women and men in the fourth decade of life.1-3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms lichen and eyelid and manually screened revealed 6 cases of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid.2-4 We describe a case of lichen sclerosus involving the eyelid and its histopathology.

A 45-year-old woman was referred to dermatology for evaluation of a right lower eyelid lesion of 3 months’ duration. She first noted a small white patch under the eyelid that had doubled in size and felt firm without bleeding or ulceration. Her medical history was unremarkable, and there was no history of ophthalmic conditions, autoimmune disease, trauma, or cancer. An ophthalmic examination was normal, except for a 20×8-mm, flat, depigmented, firm papule with scalloped borders involving the right lower eyelid margin and extending inferiorly without evidence of madarosis or ulceration (Figure 1). She underwent an incisional biopsy that revealed the diagnosis of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (Figure 2). A full dermatologic evaluation included a genital examination and did not reveal any additional lesions. Tacrolimus ointment was started to avoid the need for long-term use of periocular steroids and their complications.

Extragenital lichen sclerosus typically is asymptomatic and only rarely presents with pruritus, in contrast to genital lichen sclerosus, which characteristically involves pruritus and dyspareunia. Although eyelid involvement is rare, ophthalmic manifestations of lichen sclerosus have included lid notching, ectropion, acquired Brown syndrome, and associated keratoconjunctivitis sicca.3-5 It characteristically appears as a well-demarcated hypopigmented papule. The differential diagnosis for a hypopigmented papule also includes amelanotic melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, vitiligo, tinea versicolor, lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, morphea (localized scleroderma), and systemic scleroderma with eyelid involvement.1,5

Differentiating lichen sclerosus from these conditions is of importance, as some of them can have notable morbidity and/or mortality. Of all the autoimmune connective tissue disorders, systemic sclerosus has the highest disease-specific mortality.6 Morphea, on the other hand, can have considerable morbidity. Morphea involving the head and neck notably increases the risk for neurologic complications such as seizures or central nervous system vasculitis as well as ocular complications such as anterior uveitis.6 Of note, genital lichen sclerosus carries an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma and verrucous carcinoma; however, there have been no reported cases of malignant transformation with extragenital lesions.2

Histopathology is useful to distinguish among these entities. Although there are no specific features separating lichen sclerosus from a morphea overlap and both entities often are classified by clinical presentation, lichen sclerosus demonstrates epidermal atrophy, follicular plugging, homogenized collagen in the upper dermis with dermal edema, and lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2).1 Extragenital lesions in particular also have been noted to have more epidermal atrophy and decreased rete ridges.2

First-line treatment of lichen sclerosus includes topical corticosteroids with emollients for supportive therapy. A topical calcineurin inhibitor such as tacrolimus should be considered for patients who do not respond to corticosteroid therapy or in cases in which corticosteroid therapy is contraindicated to avoid steroid-induced glaucoma or undesirable skin atrophy and hypopigmentation.2 A collaborative approach including dermatology and internal medicine can help identify a systemic or multisystem process.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Rosenthal IM, Taube JM, Nelson DL, et al. A case of infraorbital lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20021.

- Rabinowitz R, Rosenthal G, Yerushalmy J, et al. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca associated with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Eye. 2000;14:103-104.

- Olver J, Laidler P. Acquired Brown’s syndrome in a patient with combined lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and morphea. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:552-557.

- El-Baba F, Frangieh GT, Iliff WJ, et al. Morphea of the eyelids. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:125-128.

- Fett N. Scleroderma: nomenclatures, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatment: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Rosenthal IM, Taube JM, Nelson DL, et al. A case of infraorbital lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20021.

- Rabinowitz R, Rosenthal G, Yerushalmy J, et al. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca associated with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Eye. 2000;14:103-104.

- Olver J, Laidler P. Acquired Brown’s syndrome in a patient with combined lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and morphea. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:552-557.

- El-Baba F, Frangieh GT, Iliff WJ, et al. Morphea of the eyelids. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:125-128.

- Fett N. Scleroderma: nomenclatures, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatment: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

Practice Points

- Lichen sclerosus is not confined to only the anogenital area and can affect the face in rare cases.

Irritated Pigmented Plaque on the Scalp

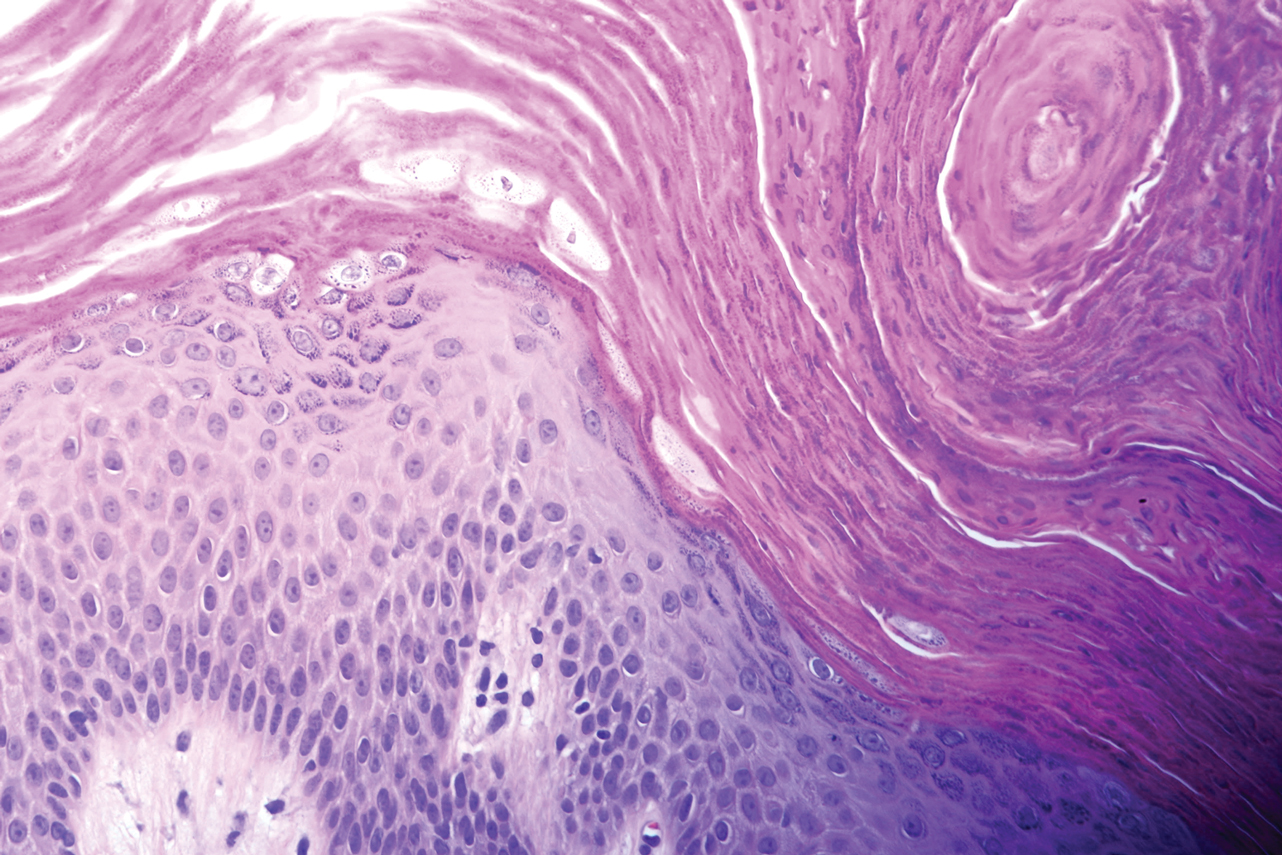

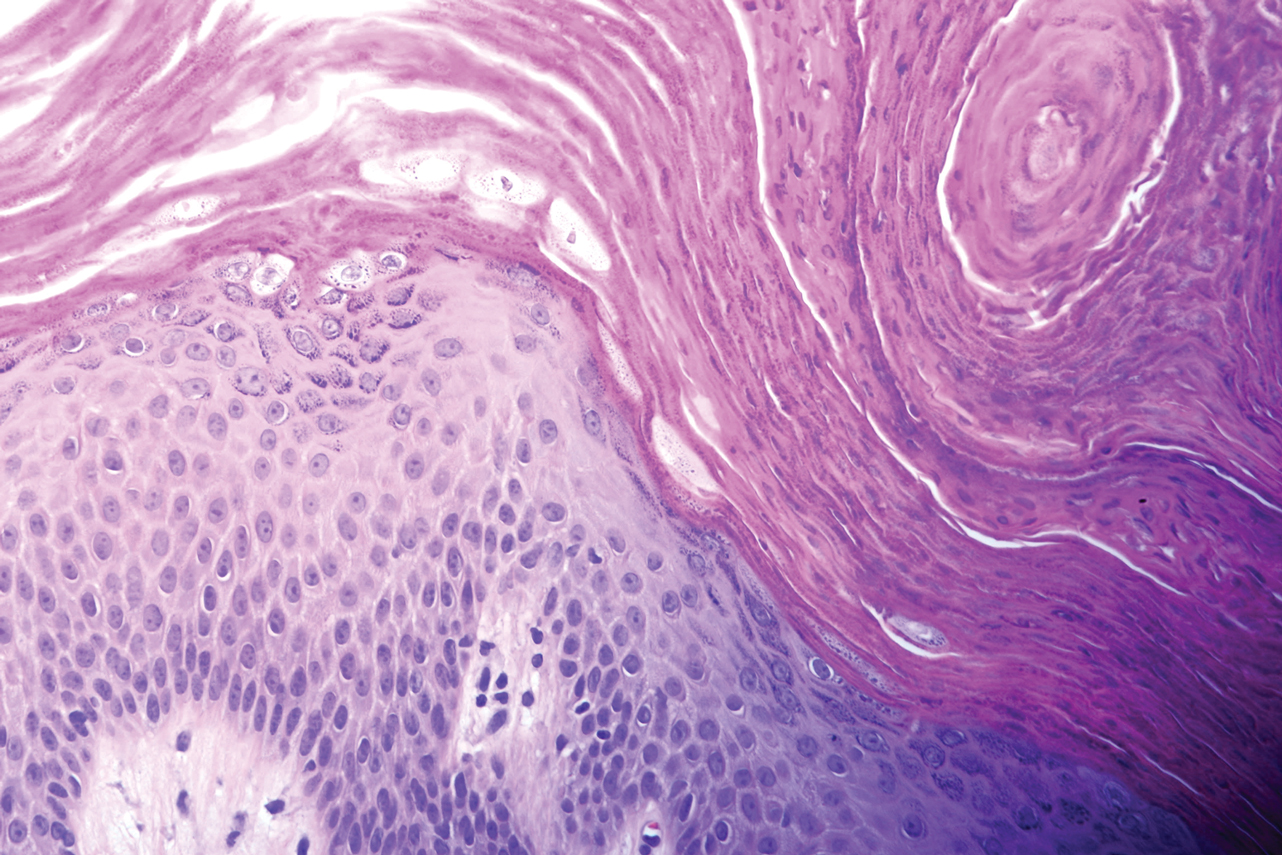

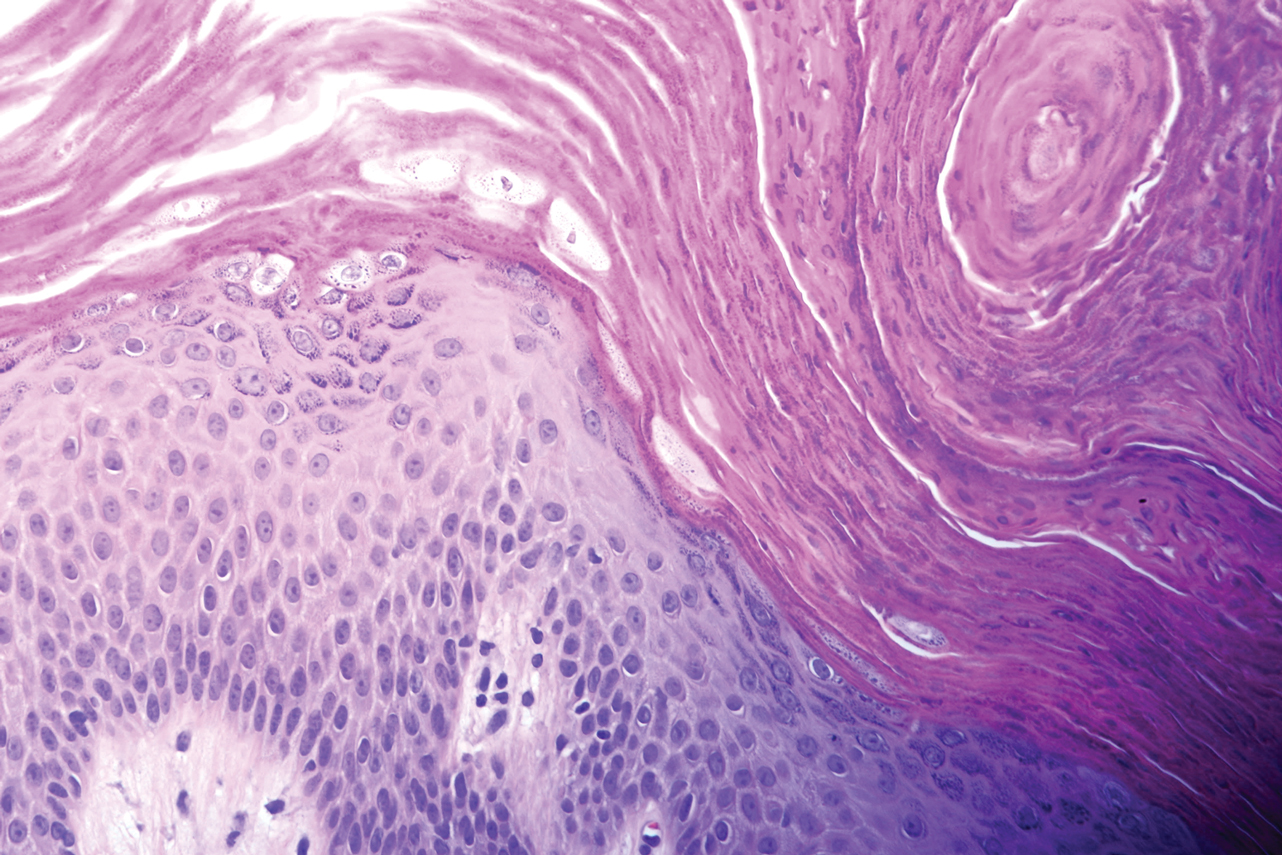

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

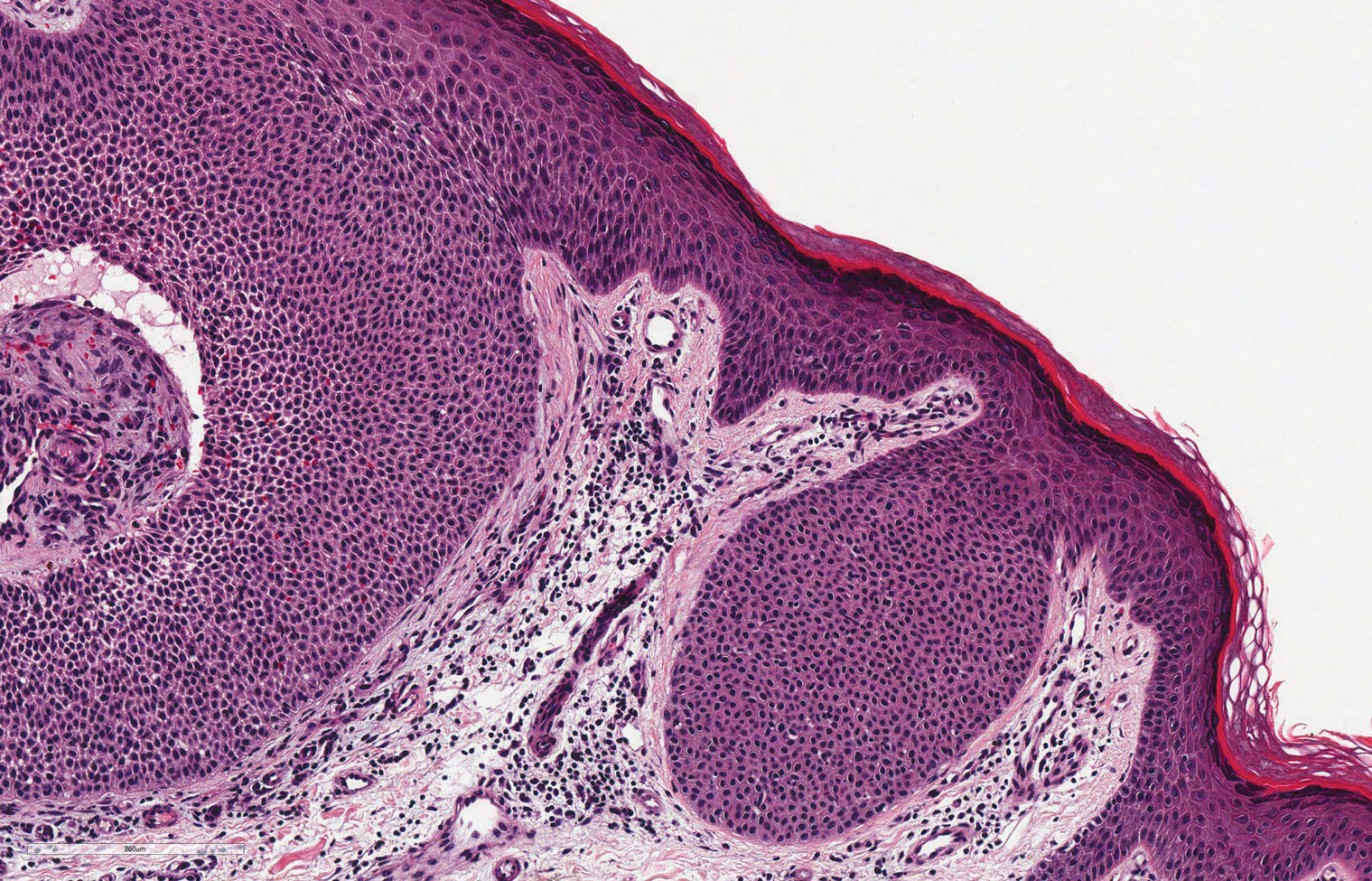

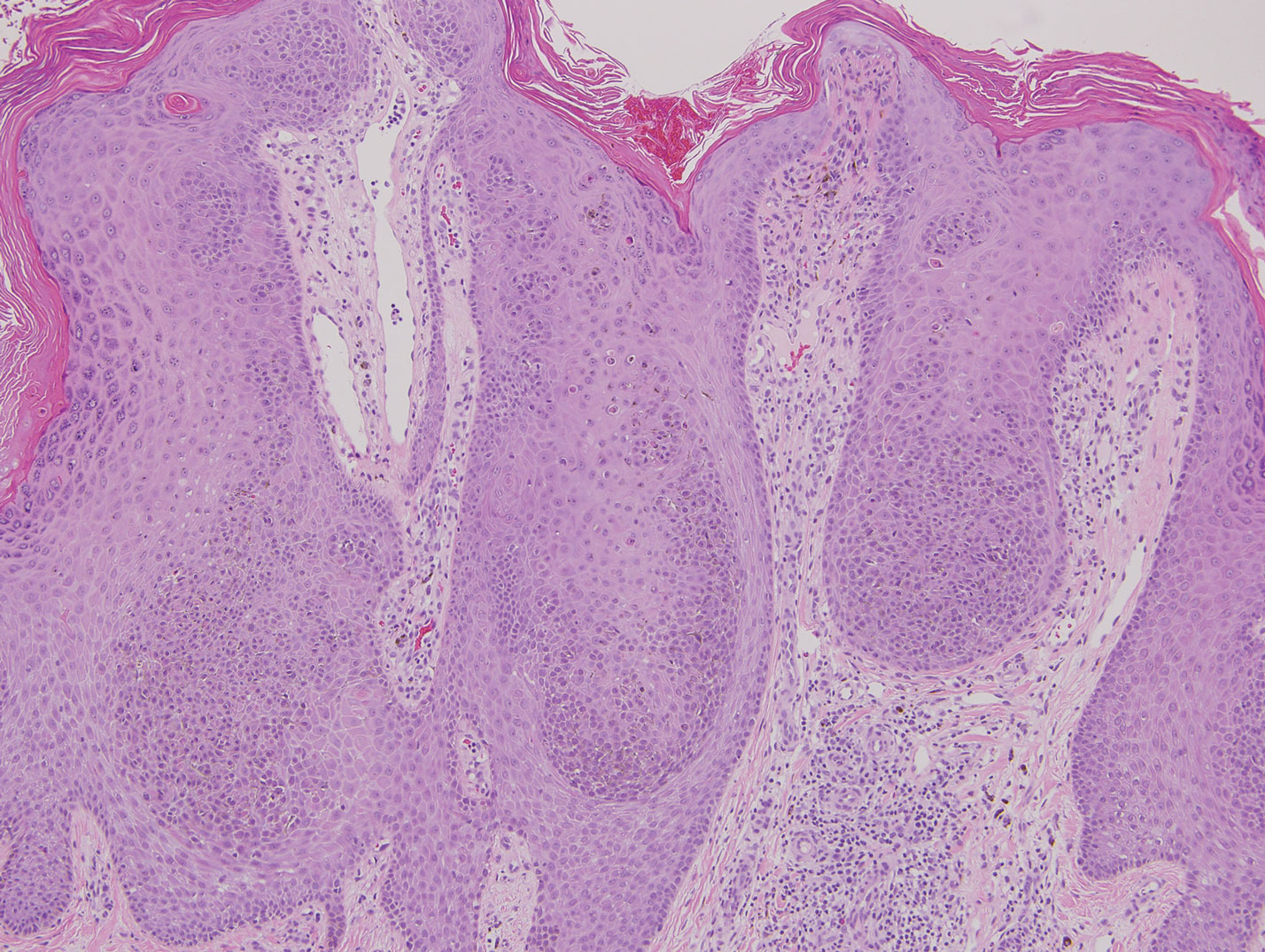

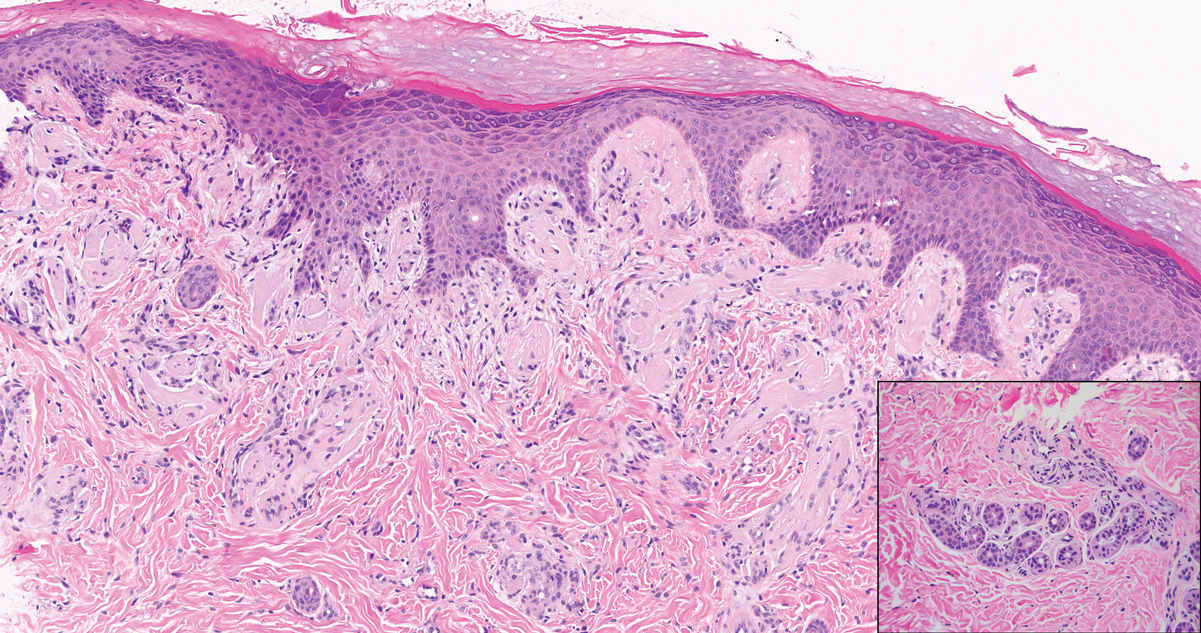

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

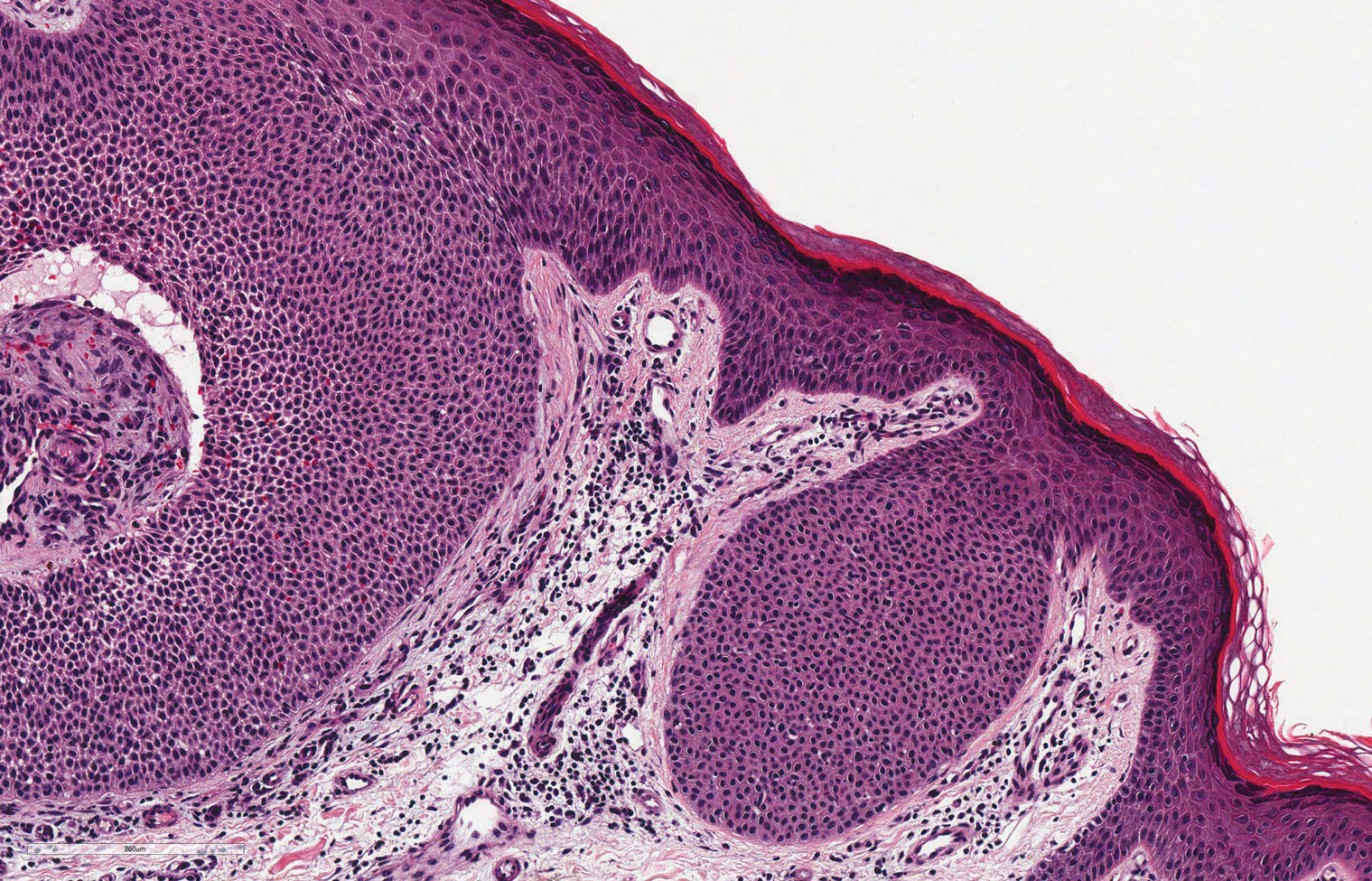

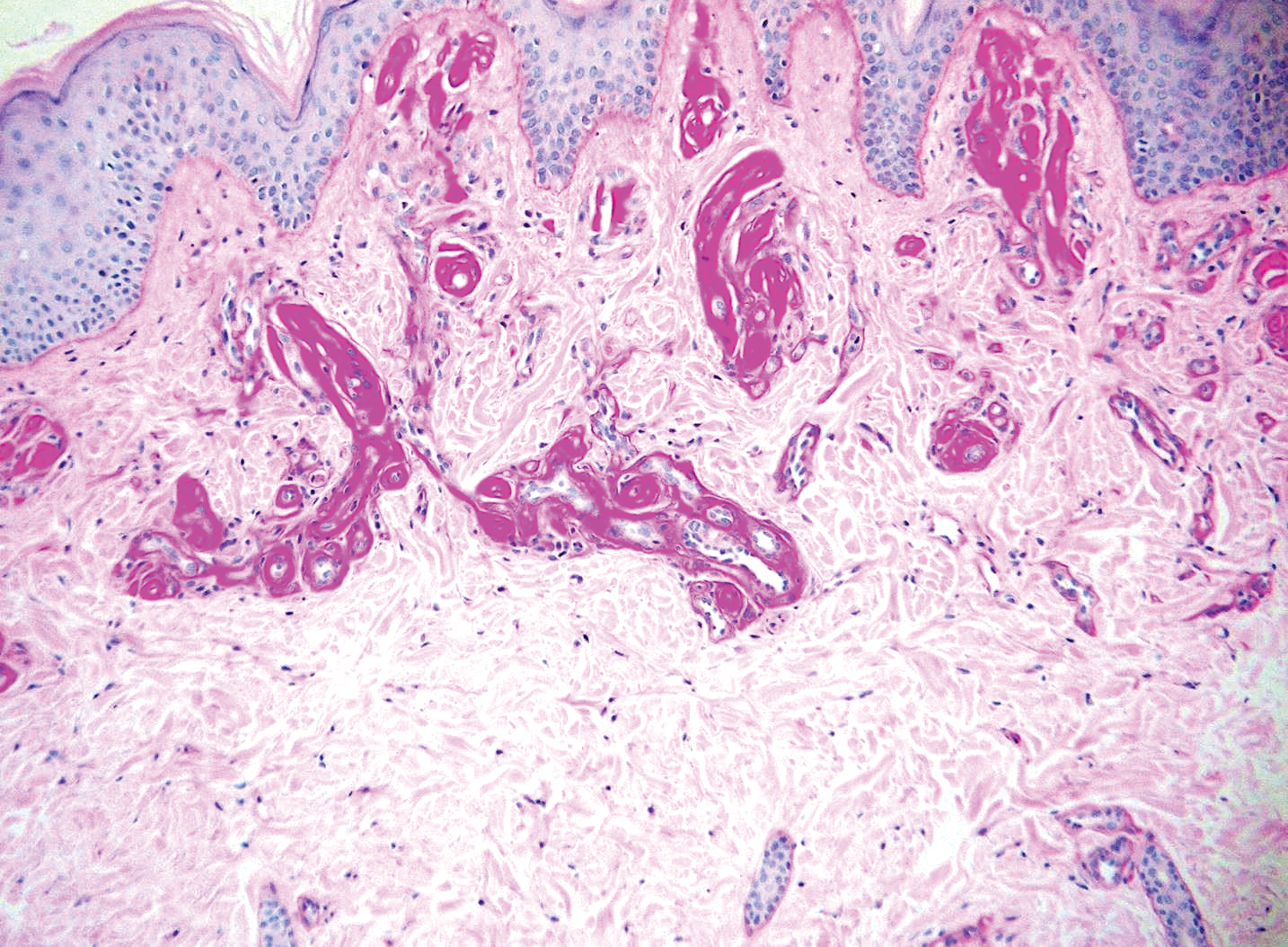

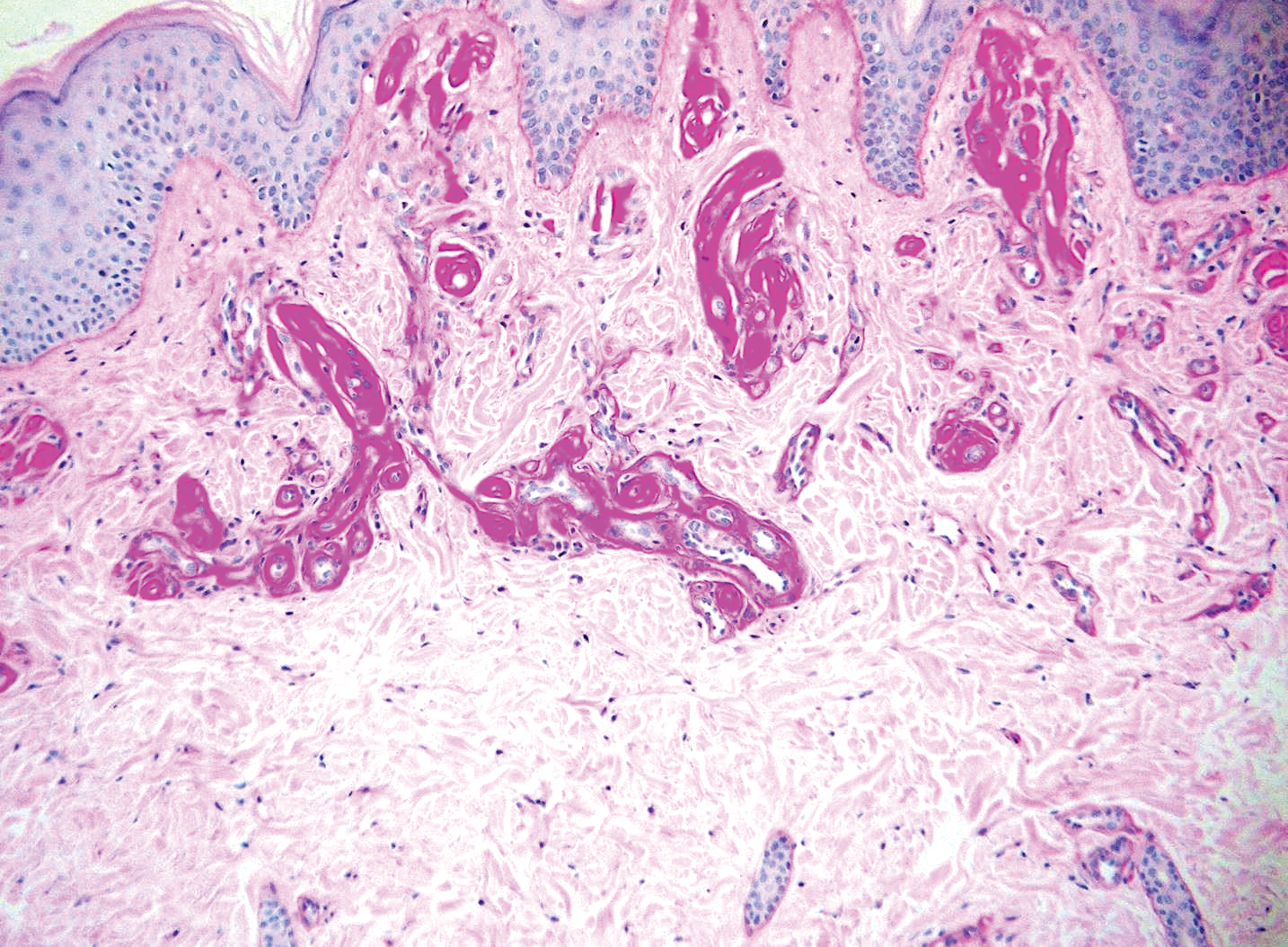

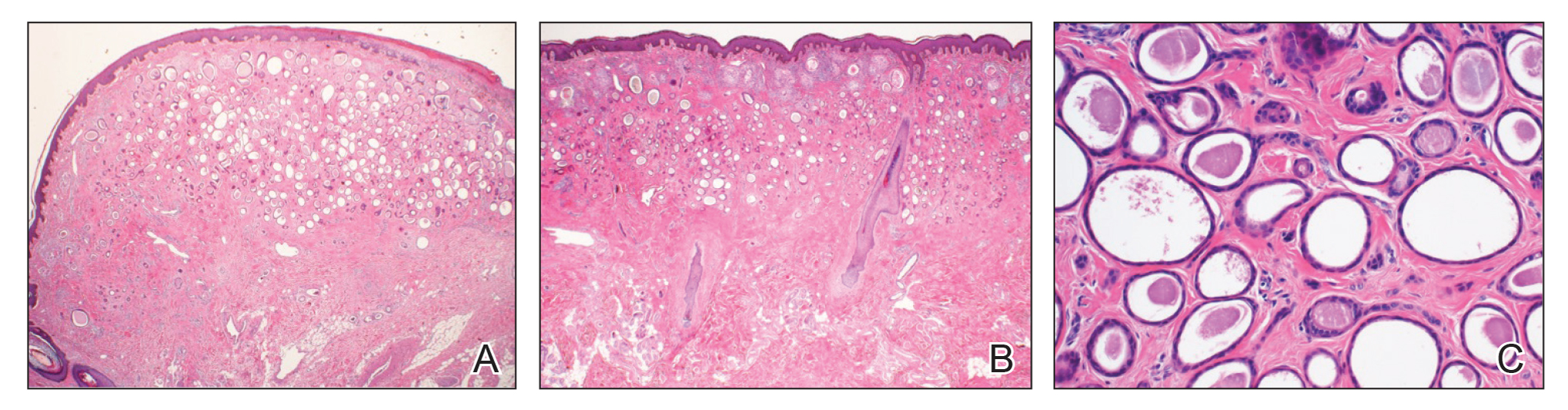

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

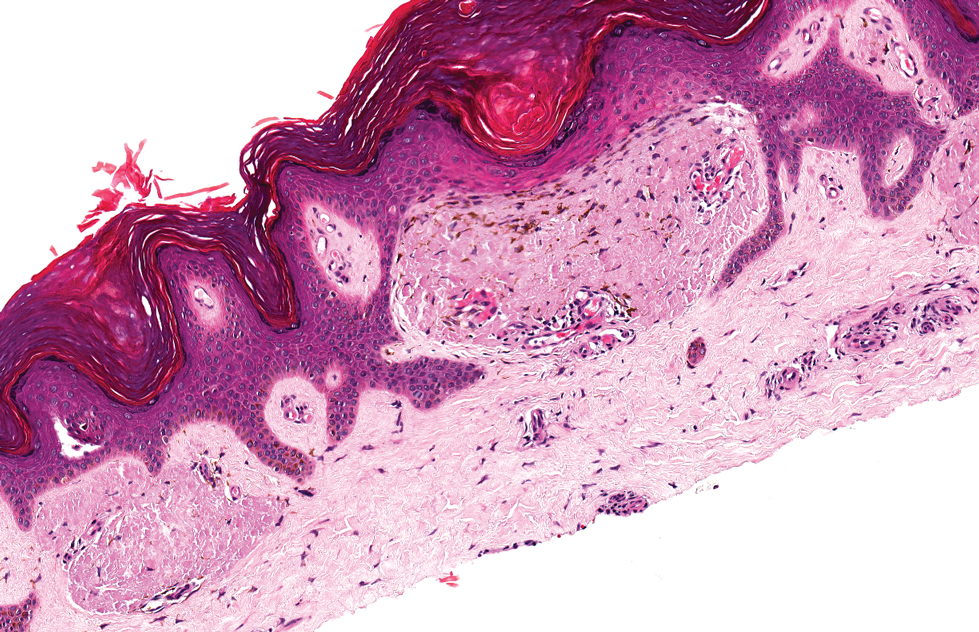

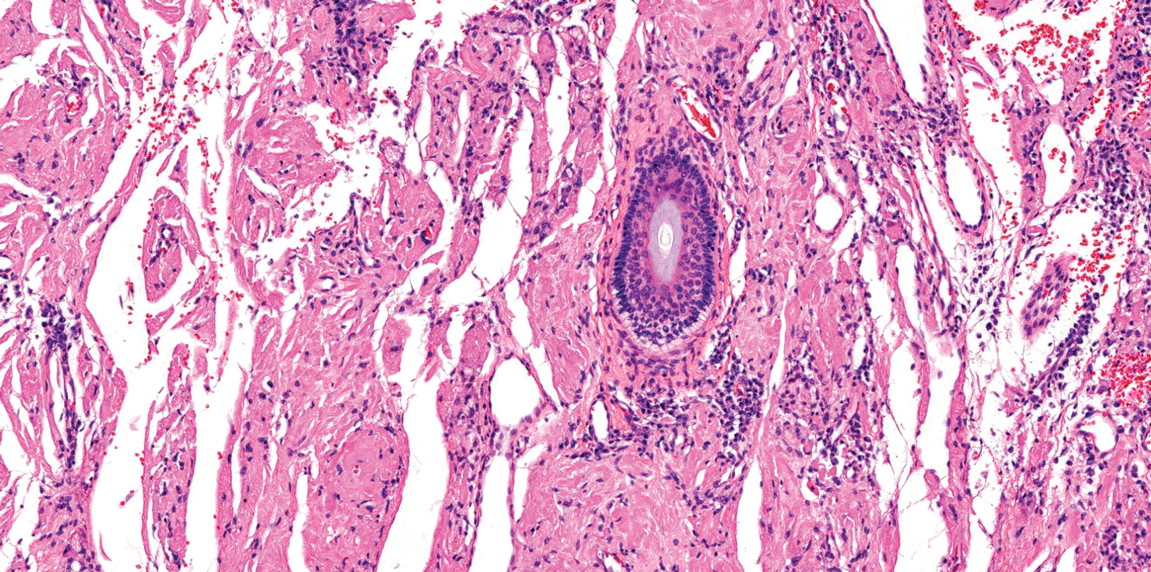

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

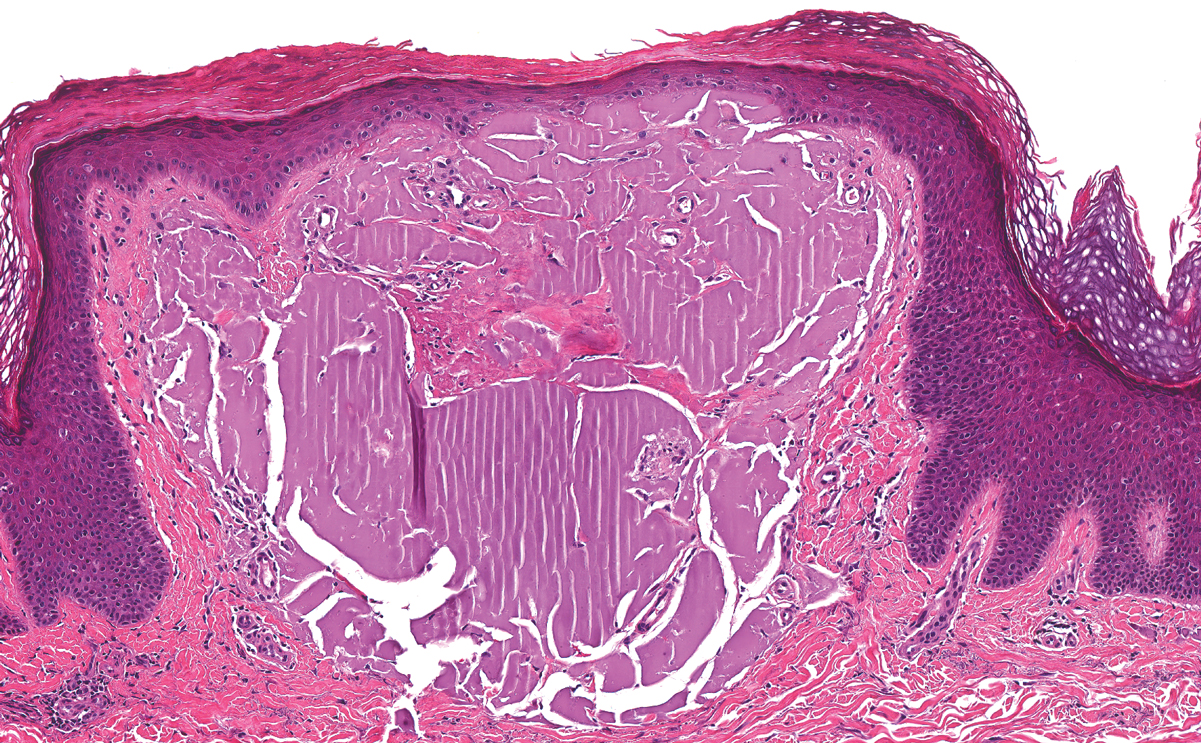

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

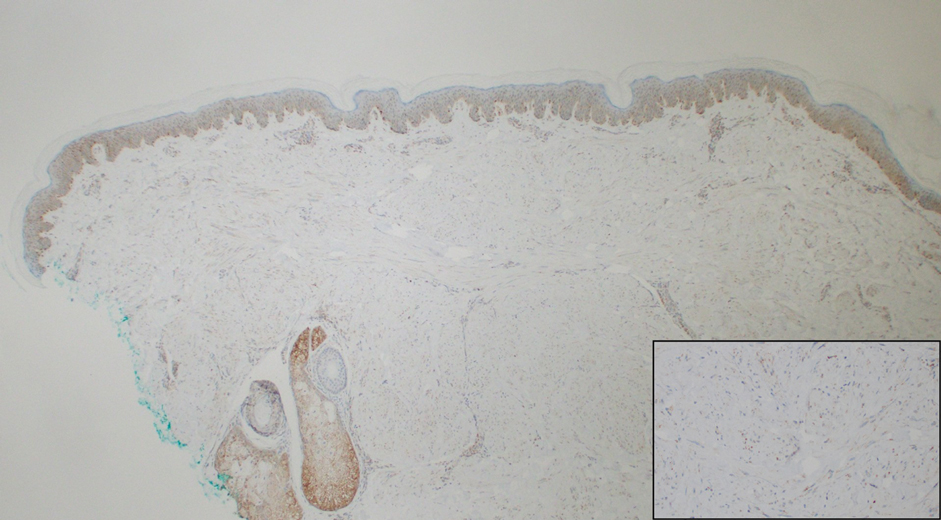

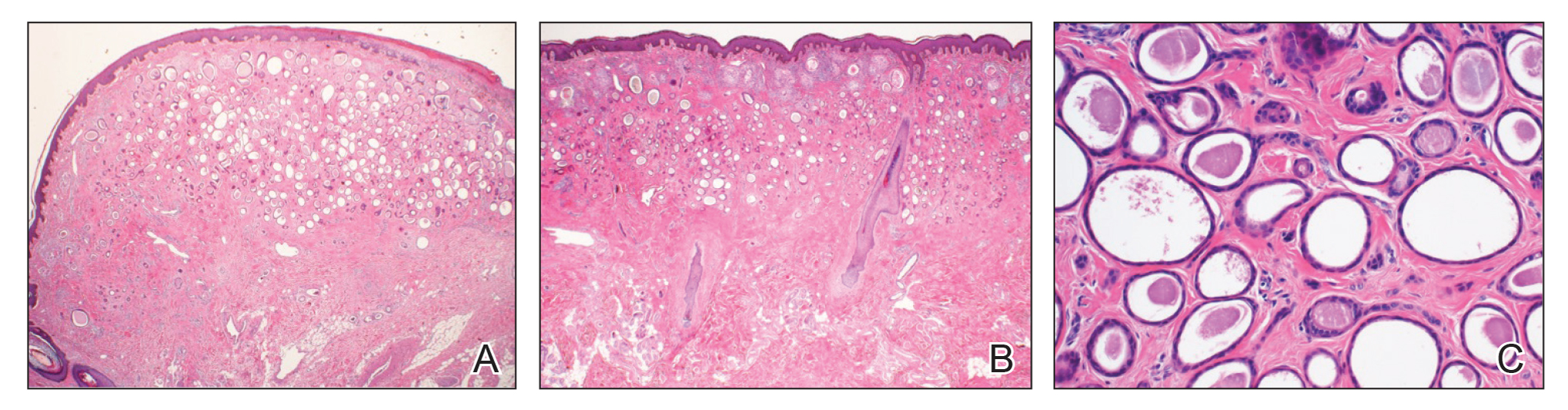

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

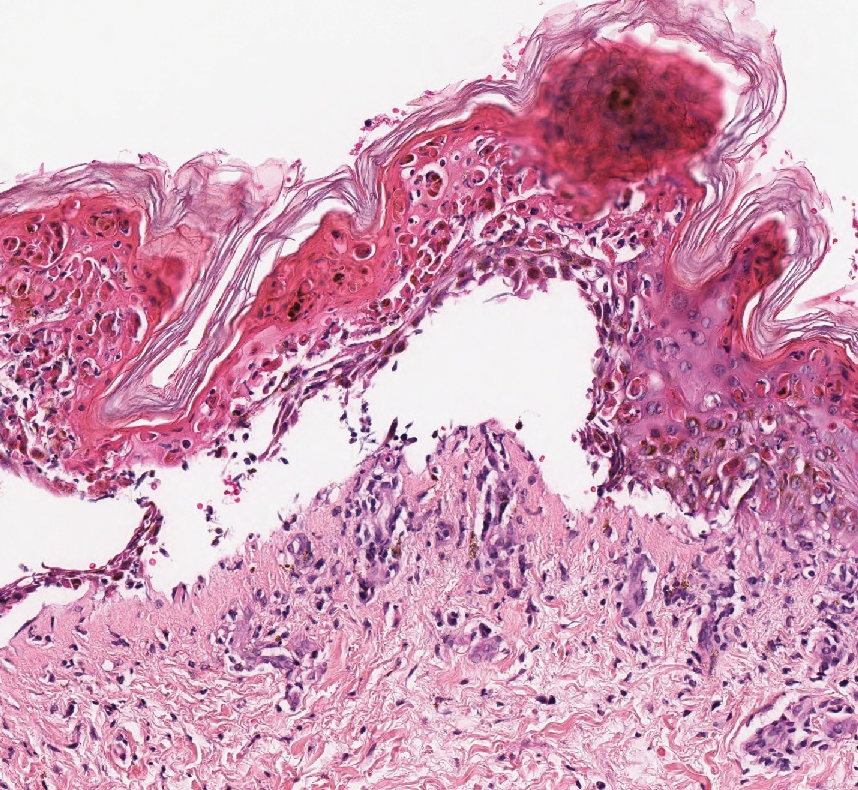

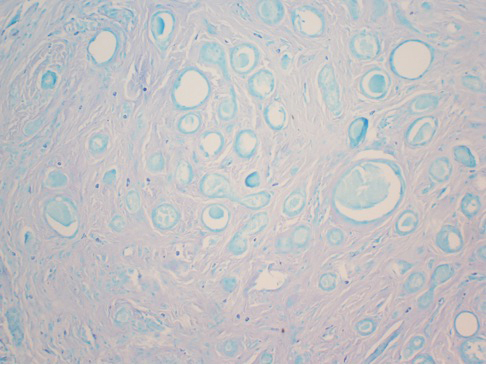

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

A 49-year-old man with light brown skin and no history of skin cancer presented with a pruritic lesion on the scalp of 3 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed a 7×3-cm, brown, mammillated plaque on the left parietal scalp. A shave biopsy of the scalp lesion was performed.

Rapid Onset of Widespread Nodules and Lymphadenopathy

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous γδ T-cell Lymphoma

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTL) is a distinct entity that can be confused with other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Often rapidly fatal, PCGDTL has a broad clinical spectrum that may include indolent variants—subcutaneous, epidermotropic, and dermal.1 Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma represents less than 1% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2 Diagnosis and treatment remain challenging. Patients typically present with nodular lesions that progress to ulceration and necrosis. Early lesions can be confused with erythema nodosum, mycosis fungoides, or infection on clinical examination; biopsy establishes the diagnosis. Typical findings include a cytotoxic phenotype, variable epidermotropism, dermal and subcutaneous involvement, and loss of CD4 and often CD8 expression. Testing for Epstein-Barr virus expression yields negative results. The neoplastic lymphocytes in dermal and subcutaneous PCGDTL typically are T-cell intracellular antigen-1 (TIA-1) and granzyme positive.1

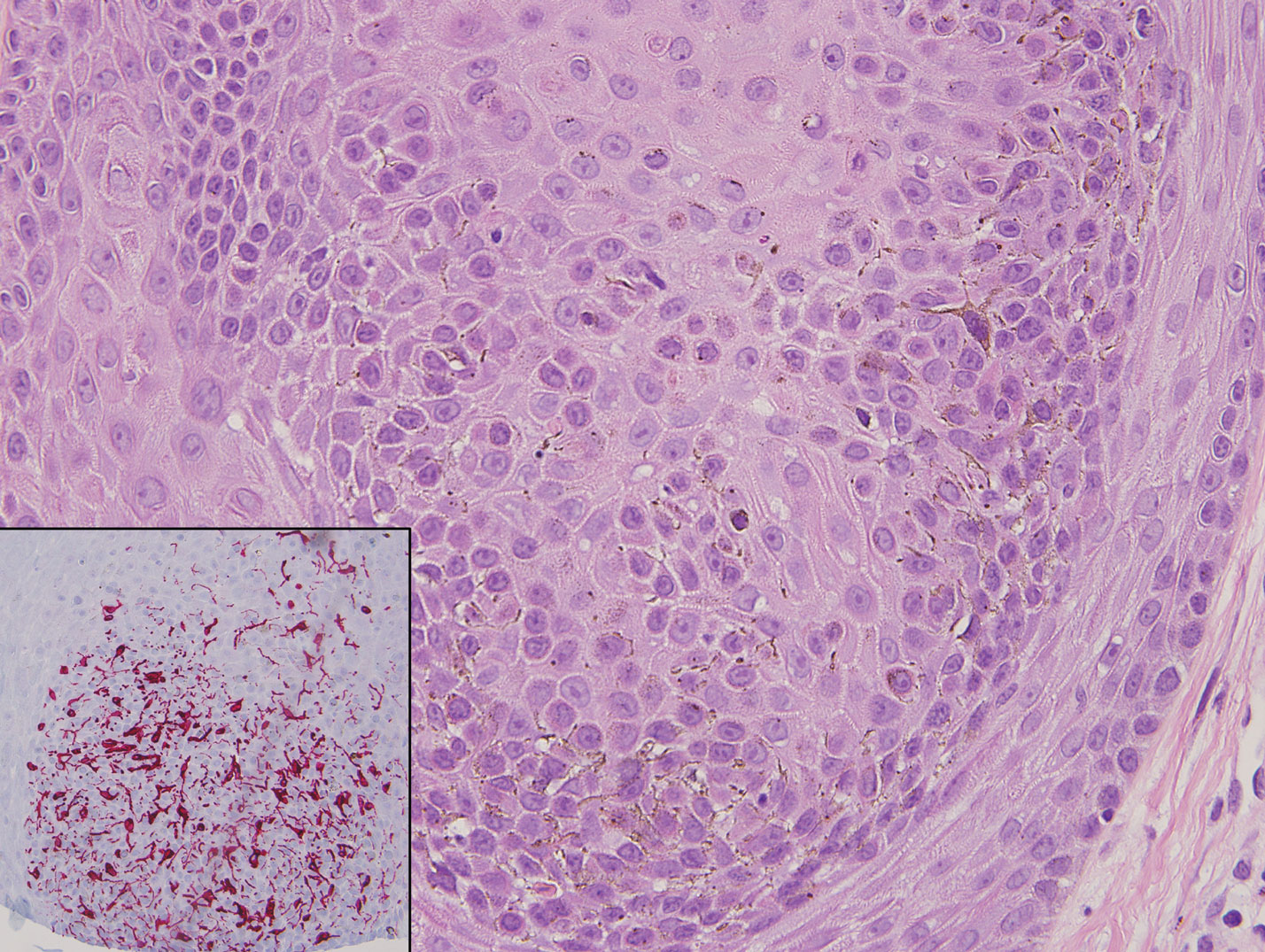

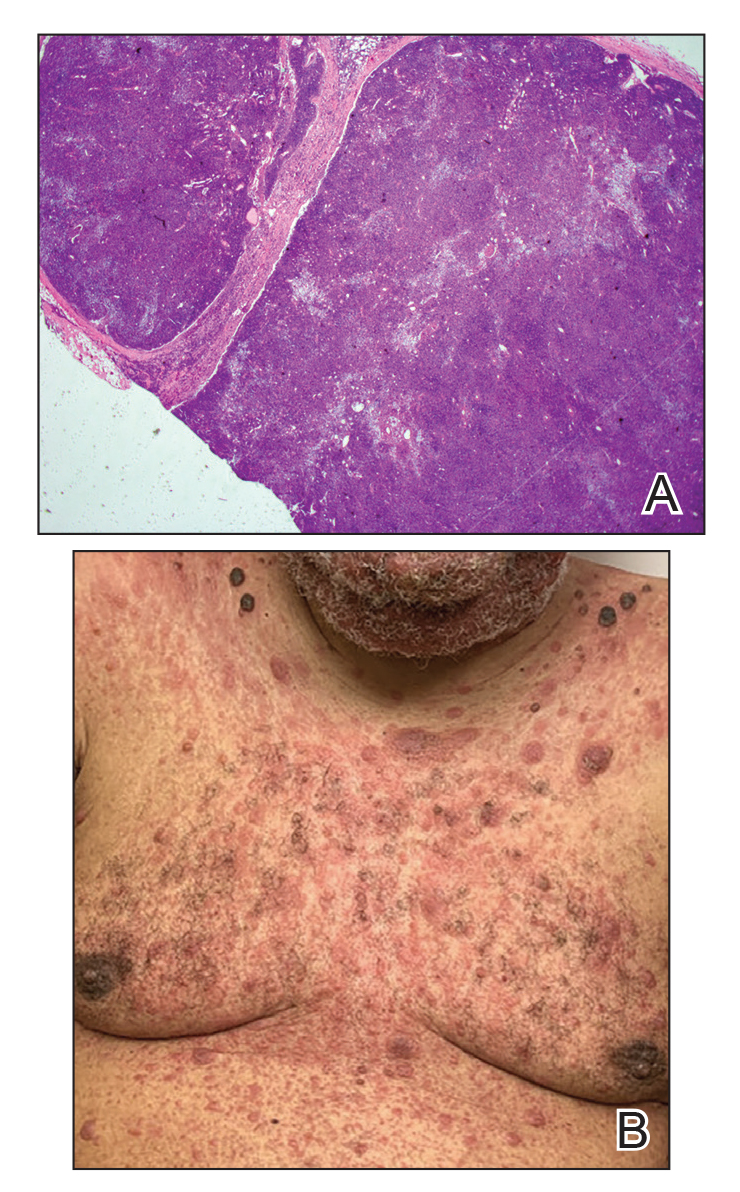

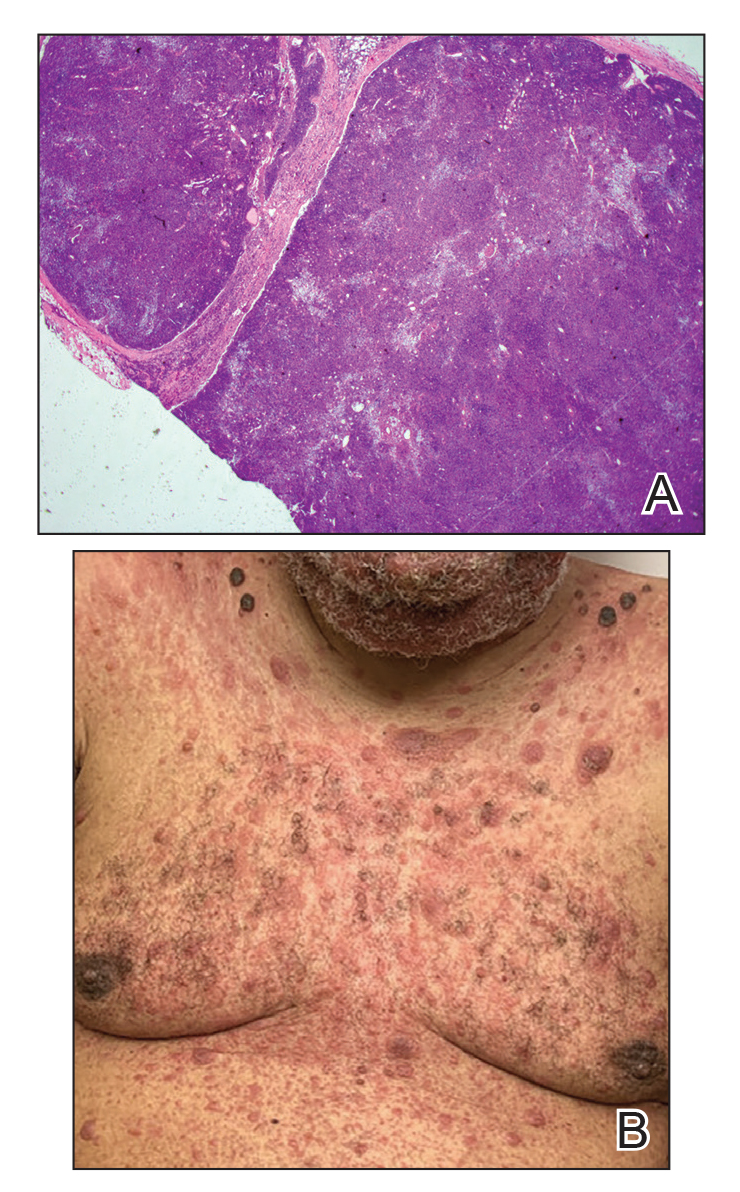

Immunohistochemistry failed to reveal CD8, CD56, granzyme, or T-cell intracellular antigen-1 staining of neoplastic cells in our patient but stained diffusely positive with CD3 and CD4. A CD20 stain decorated only a few dermal cells. The patient’s skin lesions continued to enlarge, and the massive lymphadenopathy made breathing difficult. Computed tomography revealed diffuse systemic involvement. An axillary lymph node biopsy revealed sinusoids with complete diffuse effacement of architecture as well as frequent mitotic figures and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 1A). Negative staining for T-cell receptor beta-F1 of the axillary lymph node biopsy and clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma chain supported the diagnosis of PCGDTL. Nuclear staining for Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA was negative. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 antibodies and polymerase chain reaction also were negative. Flow cytometry demonstrated an atypical population of CD3+, CD4+, and CD7− γδ T lymphocytes, further supporting the diagnosis of lymphoma.

The median life expectancy for patients with dermal or subcutaneous PCGDTL is 10 to 15 months after diagnosis.3 The 5-year life expectancy for PCGDTL is approximately 11%.2 Limited treatment options contribute to the poor outcome. Chemotherapy regimens such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) and EPOCH (etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) have yielded inconsistent results. Stem cell transplant has been tried in progressive disease and also has yielded mixed results.2 Brentuximab is indicated for individuals whose tumors express CD30.4 Associated hemophagic lymphohistiocytosis portends a poor prognosis.5

Despite treatment with etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and high-dose oral steroids, our patient developed progressive difficulty breathing, stridor, kidney injury, and anemia. Our patient died less than 1 month after diagnosis—after only 1 round of chemotherapy—secondary to progressive disease and an uncontrollable gastrointestinal tract bleed. The leonine facies (Figure 1B) encountered in our patient can raise a differential diagnosis that includes infectious as well as neoplastic etiologies; however, most infectious etiologies associated with leonine facies manifest in a chronic fashion rather than with a sudden eruption, as noted in our patient.

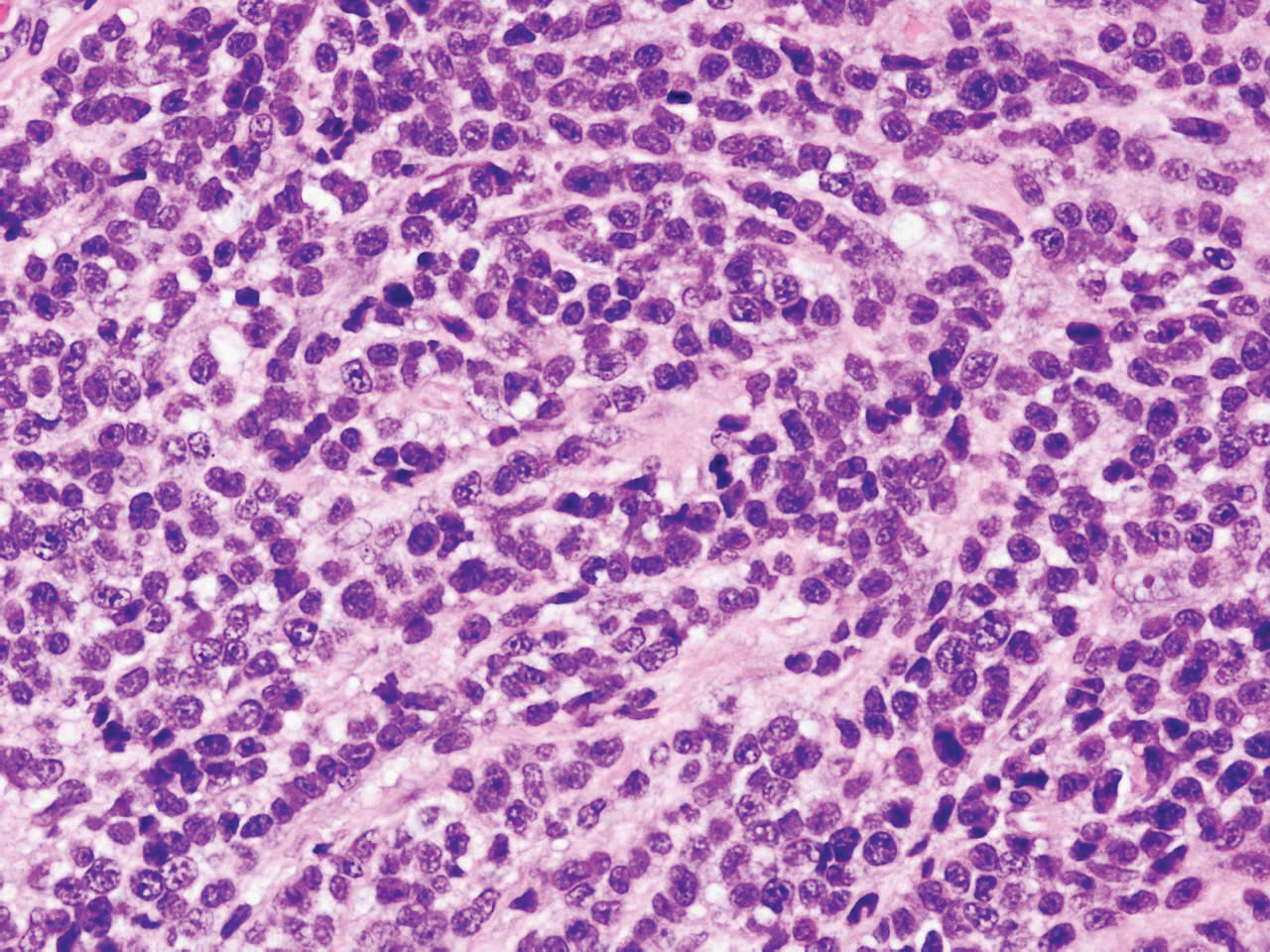

Leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae, a grampositive bacillus. The condition manifests across a spectrum, with the poles being tuberculoid and lepromatous, and borderline variants in between.6-8 Lepromatous leprosy arises in individuals who are unable to mount cellular immunity against M leprae secondary to anergy.6 Lepromatous leprosy often presents with numerous papules and nodules. Aside from cutaneous manifestations, lepromatous leprosy has a predilection for peripheral nerves and specifically Schwann cells. Histologically, biopsy reveals a flat epidermis and a cell-free subepidermal grenz zone. Within the dermis, there is a diffuse histiocytic infiltrate that typically is not centered around nerves (Figure 2).6,7 Mycobacterium leprae can appear scattered throughout or clustered in globi. Mycobacterium leprae stains red with Ziehl-Neelsen or Wade-Fite stains.6,7 Immunohistochemistry reveals a CD4+ helper T cell (TH2) predominance, supported by the increased expression of type 2 reaction cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13.8

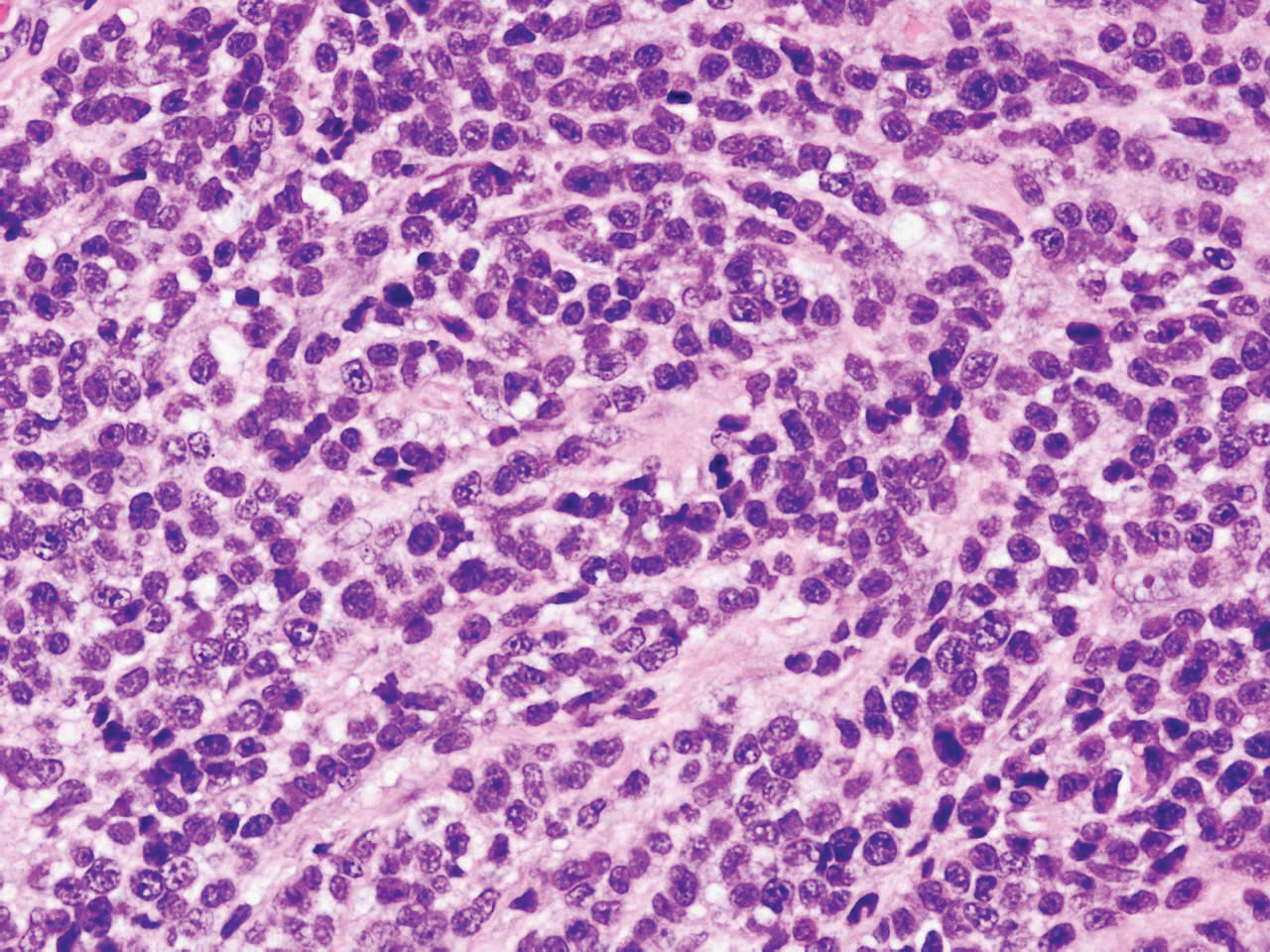

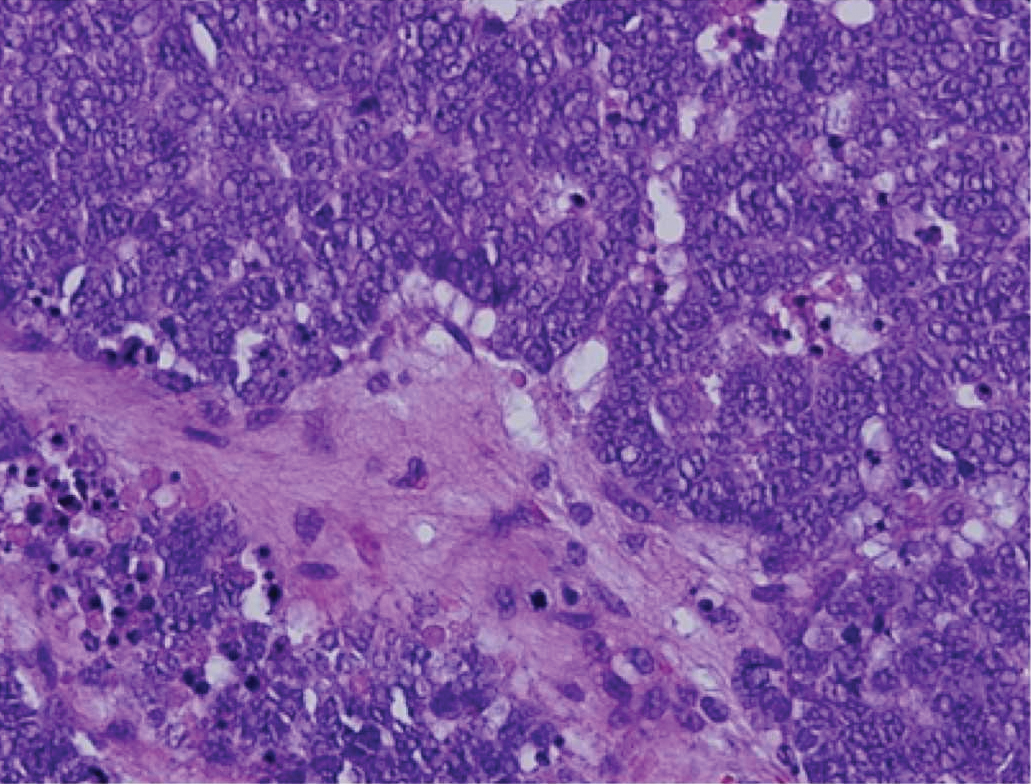

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) embodies 10% to 20% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas; it is more prevalent in older adults (age range, 70–82 years) and women. Clinically, DLBCL presents as either single or multiple rapidly progressing nodules or plaques, usually violaceous or blue-red in color.9,10 The most common area of presentation is on the legs, though it also can surface at other sites.9 On histology, DLBCL has clearly malignant features including frequent mitotic figures, large immunoblasts, and involvement throughout the dermis as well as perivascularly (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped cells and anaplastic features can be present. Immunohistochemically, DLBCL stains strongly positive for CD20 and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) along with other pan–B-cell markers.9-11 The aggressive leg type of DLBCL stains positively for multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1).9,11

Cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinoma from internal malignancies occurs in approximately 5% of cancer patients with metastatic spread.12 Most of these cutaneous lesions develop in close proximity to the primary tumor such as on the trunk, head, or neck. All cutaneous metastases carry a poor prognosis. Clinical presentation can vary greatly, ranging from painless, firm, or elastic nodules to lesions that mimic inflammatory skin conditions such as erysipelas or scleroderma. The majority of these metastases develop as painless firm nodules that are flesh colored, pink, red-brown, or purple.12,13 The histopathology of metastatic adenocarcinoma demonstrates an infiltrative nodular appearance, though there rarely are well-circumscribed nodules found.13 The lesion originates in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. It is a glandulartype lesion that may reflect the tissue of the primary tumor (Figure 4).12,14 Immunohistochemical stains likely will remain consistent with those of the primary tumor, which is not always the case.14

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive cutaneous malignancy of epithelial and neuroendocrine origin, first described as trabecular carcinoma due to the arrangement of tumor resembling cancellous bone.15,16 Merkel cells are mechanoreceptors found near nerve terminals.17 Approximately 80% of MCCs are associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus, which is a small, double-stranded DNA virus with an icosahedral capsid.17,18 Merkel cell polyomavirus–positive cases of MCC tend to have a better prognosis. In Merkel cell polyomavirus–negative MCC, there is an association with UV damage and increased chromosomal aberrations.18 Merkel cell carcinoma is known for its high rate of recurrence as well as local and distant metastasis. Nodal involvement is the most important prognostic indicator.15 Clinically, MCC is associated with the AEIOU mnemonic (asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years, UV exposed/fair skin).15-17 Lesions appear as red-blue papules on sun-exposed skin and usually are smaller than 2 cm by their greatest dimension. On histopathology, MCC demonstrates small, round, blue cells arranged in sheets or nests originating in the dermis and occasionally can infiltrate the subcutis and lymphovascular surroundings (Figure 5).16-19 Cells have scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may have fine granular chromatin. Numerous mitotic figures and apoptotic cells also are present. On immunohistochemistry, these cells will stain positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), CK20, and CD56. Due to their neuroendocrine derivation, they also are commonly synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, and chromogranin A positive. Notably, MCC will stain negative for leukocyte common antigen, CD20, CD3, CD34, and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1).16,17

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma can be difficult to diagnose and requires urgent treatment. Clinicians and dermatopathologists need to work together to establish the diagnosis. There is a high mortality rate associated with PCGDTL, making prompt recognition and timely treatment critical. Acknowledgments—Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

- Merrill ED, Agbay R, Miranda RN, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas showing gamma-delta (γδ) phenotype and predominantly epidermotropic pattern are clinicopathologically distinct from classic primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:204-215.

- Foppoli M, Ferreri AJ. Gamma‐delta T‐cell lymphomas. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:206-218.

- Toro JR, Liewehr DJ, Pabby N, et al. Gamma-delta T-cell phenotype is associated with significantly decreased survival in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:3407-3412.

- Rubio-Gonzalez B, Zain J, Garcia L, et al. Cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma successfully treated with brentuximab vedotin. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388-1390.

- Tong H, Ren Y, Liu H, et al. Clinical characteristics of T-cell lymphoma associated with hemophagocytic syndrome: comparison of T-cell lymphoma with and without hemophagocytic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:81-87.

- Brehmer-Andersson E. Leprosy. Dermatopathology. New York, NY: Springer; 2006:110-113.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Naafs B, Noto S. Reactions in leprosy. In: Nunzi E, Massone C, eds. Leprosy: A Practical Guide. Milan, Italy: Springer; 2012:219-239.

- Hope CB, Pincus LB. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:547-574.

- Billero VL, LaSenna CE, Romanelli M, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as chronic non-healing ulcer. Int Wound J. 2017;14:830-832.

- Testo N, Olson L, Subramaniyam S, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a MYC-IGH rearrangement and gain of BCL2: expanding the spectrum of MYC/BCL2 double hit lymphomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:769-774.

- Boyd AS. Pulmonary signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma metastatic to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:E66-E68.

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:758-761.

- Trinidad CM, Torres-Cabala CA, Prieto VG, et. Al. Update on eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer classification for Merkel Cell carcinoma and histopathological parameters that determine prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 2017;72:337-340.

- Bandino JP, Purvis CG, Shaffer BR, et al. A comparison of the histopathologic growth patterns between non-Merkel cell small round blue cell tumors and Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:815-818.

- Mauzo SH, Rerrarotto R, Bell D, et al. Molecular characteristics and potential therapeutic targets in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:382-390.

- Lowe G, Brewer J, Bordeaux J. Epidemiology and genetics. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:26-28.

- North J, McCalmont T. Histopathologic diagnosis. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:66-69.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous γδ T-cell Lymphoma

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTL) is a distinct entity that can be confused with other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Often rapidly fatal, PCGDTL has a broad clinical spectrum that may include indolent variants—subcutaneous, epidermotropic, and dermal.1 Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma represents less than 1% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2 Diagnosis and treatment remain challenging. Patients typically present with nodular lesions that progress to ulceration and necrosis. Early lesions can be confused with erythema nodosum, mycosis fungoides, or infection on clinical examination; biopsy establishes the diagnosis. Typical findings include a cytotoxic phenotype, variable epidermotropism, dermal and subcutaneous involvement, and loss of CD4 and often CD8 expression. Testing for Epstein-Barr virus expression yields negative results. The neoplastic lymphocytes in dermal and subcutaneous PCGDTL typically are T-cell intracellular antigen-1 (TIA-1) and granzyme positive.1

Immunohistochemistry failed to reveal CD8, CD56, granzyme, or T-cell intracellular antigen-1 staining of neoplastic cells in our patient but stained diffusely positive with CD3 and CD4. A CD20 stain decorated only a few dermal cells. The patient’s skin lesions continued to enlarge, and the massive lymphadenopathy made breathing difficult. Computed tomography revealed diffuse systemic involvement. An axillary lymph node biopsy revealed sinusoids with complete diffuse effacement of architecture as well as frequent mitotic figures and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 1A). Negative staining for T-cell receptor beta-F1 of the axillary lymph node biopsy and clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma chain supported the diagnosis of PCGDTL. Nuclear staining for Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA was negative. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 antibodies and polymerase chain reaction also were negative. Flow cytometry demonstrated an atypical population of CD3+, CD4+, and CD7− γδ T lymphocytes, further supporting the diagnosis of lymphoma.

The median life expectancy for patients with dermal or subcutaneous PCGDTL is 10 to 15 months after diagnosis.3 The 5-year life expectancy for PCGDTL is approximately 11%.2 Limited treatment options contribute to the poor outcome. Chemotherapy regimens such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) and EPOCH (etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) have yielded inconsistent results. Stem cell transplant has been tried in progressive disease and also has yielded mixed results.2 Brentuximab is indicated for individuals whose tumors express CD30.4 Associated hemophagic lymphohistiocytosis portends a poor prognosis.5