User login

Psoriasiform Dermatitis Associated With the Moderna COVID-19 Messenger RNA Vaccine

To the Editor:

The Moderna COVID-19 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine was authorized for use on December 18, 2020, with the second dose beginning on January 15, 2021.1-3 Some individuals who received the Moderna vaccine experienced an intense rash known as “COVID arm,” a harmless but bothersome adverse effect that typically appears within a week and is a localized and transient immunogenic response.4 COVID arm differs from most vaccine adverse effects. The rash emerges not immediately but 5 to 9 days after the initial dose—on average, 1 week later. Apart from being itchy, the rash does not appear to be harmful and is not a reason to hesitate getting vaccinated.

Dermatologists and allergists have been studying this adverse effect, which has been formally termed delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity. Of potential clinical consequence is that the efficacy of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine may be harmed if postvaccination dermal reactions necessitate systemic corticosteroid therapy. Because this vaccine stimulates an immune response as viral RNA integrates in cells secondary to production of the spike protein of the virus, the skin may be affected secondarily and manifestations of any underlying disease may be aggravated.5 We report a patient who developed a psoriasiform dermatitis after the first dose of the Moderna vaccine.

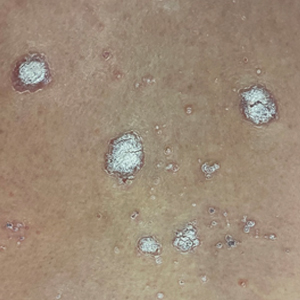

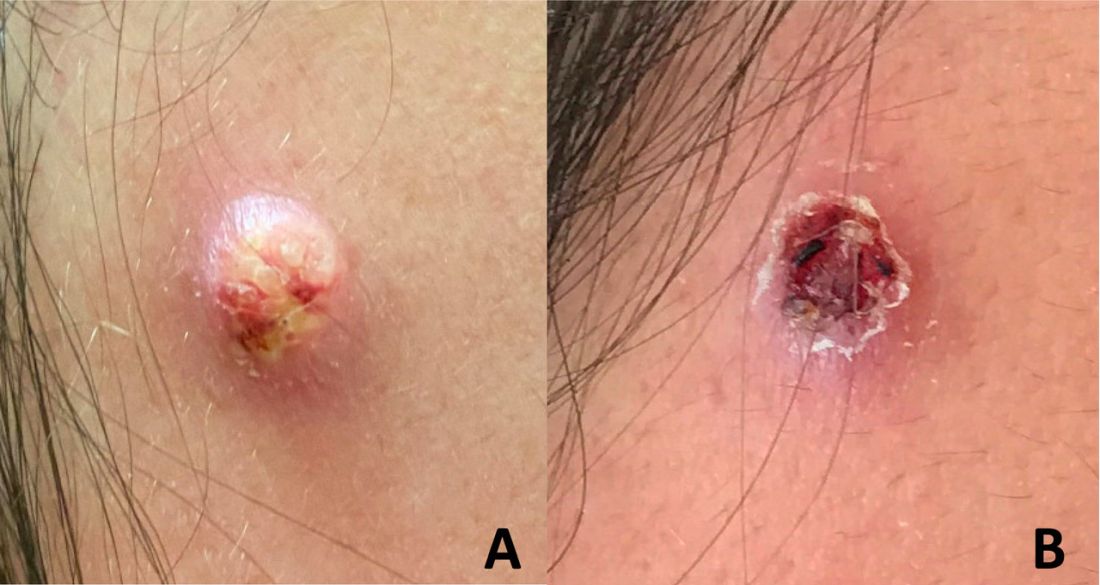

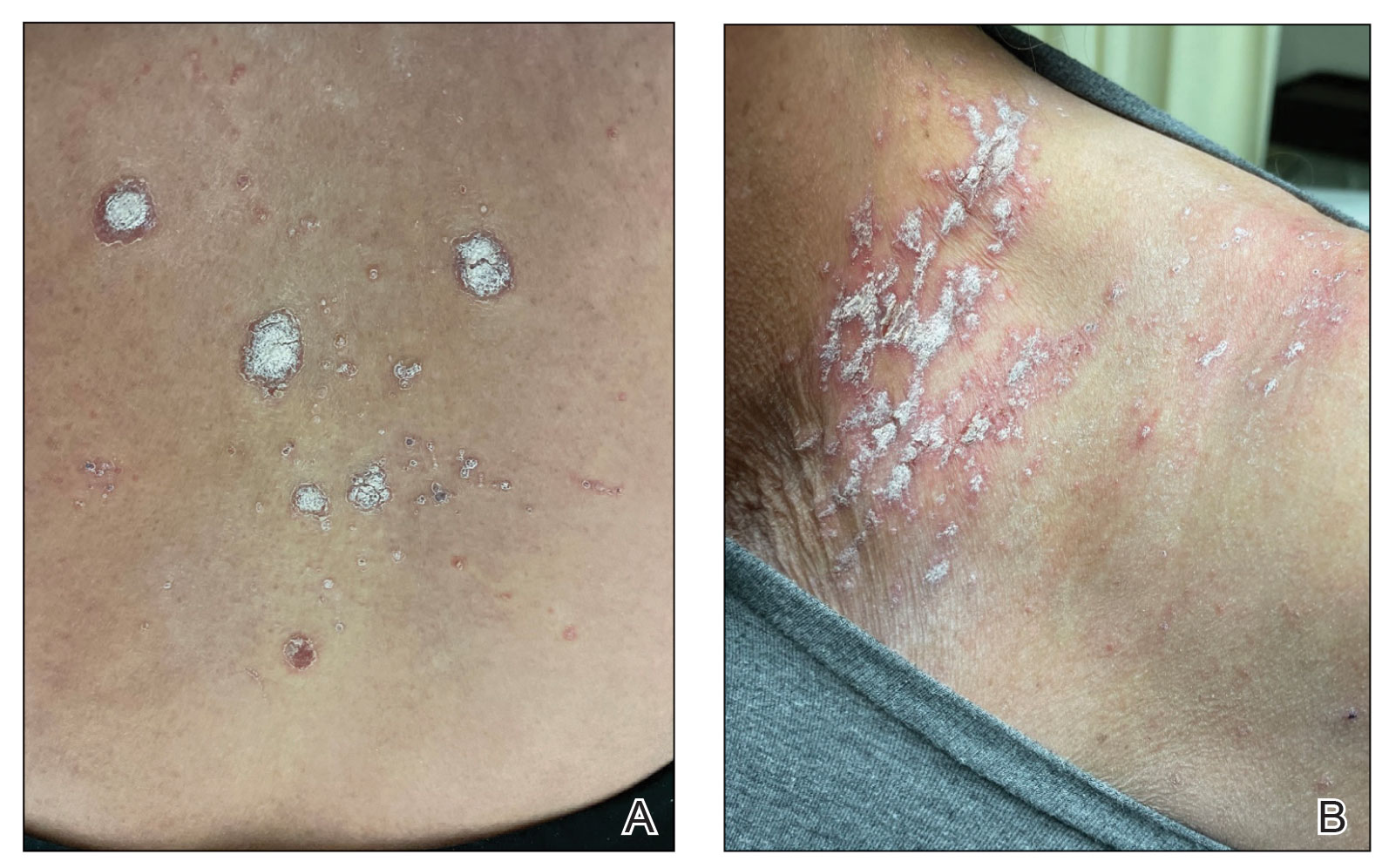

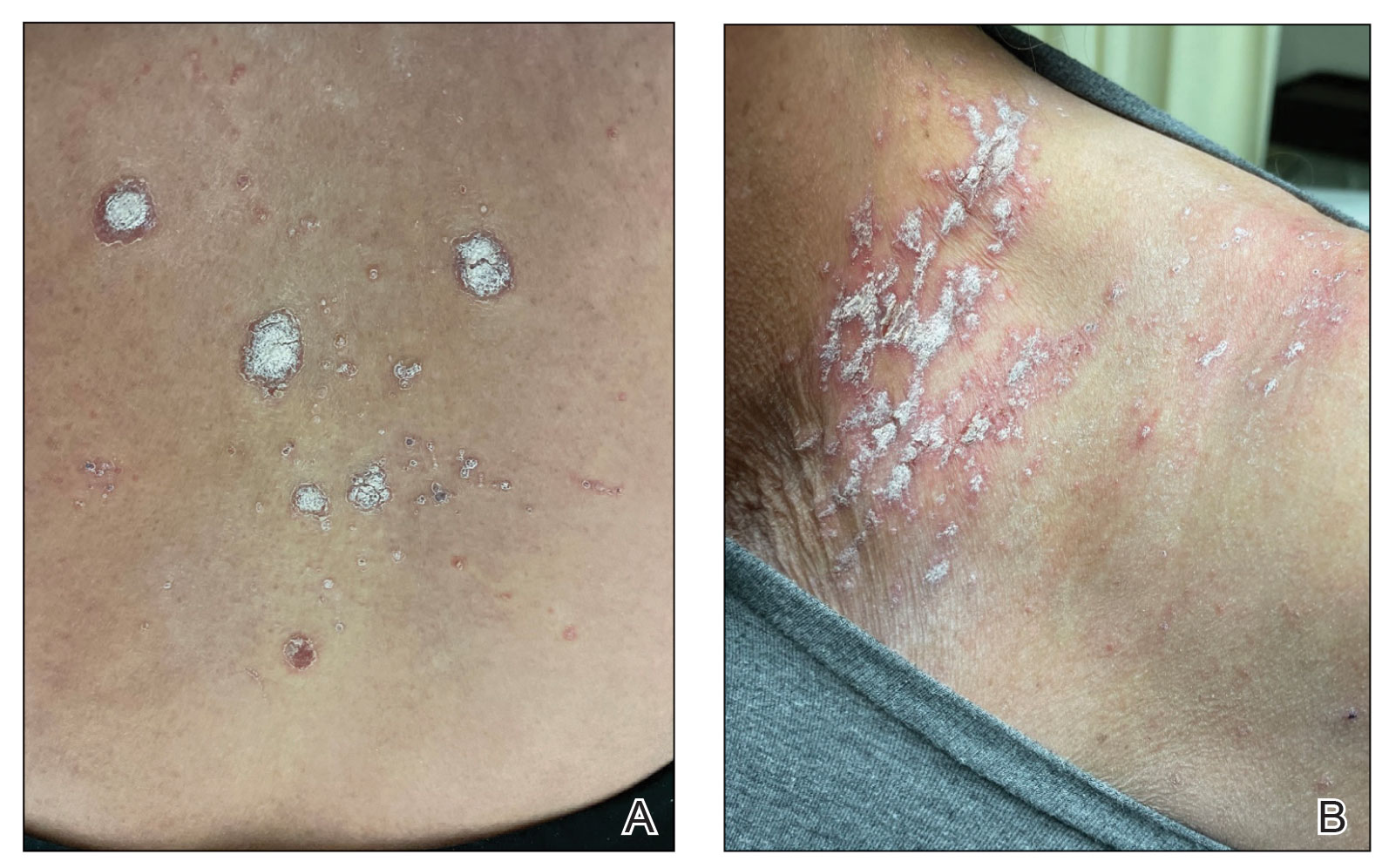

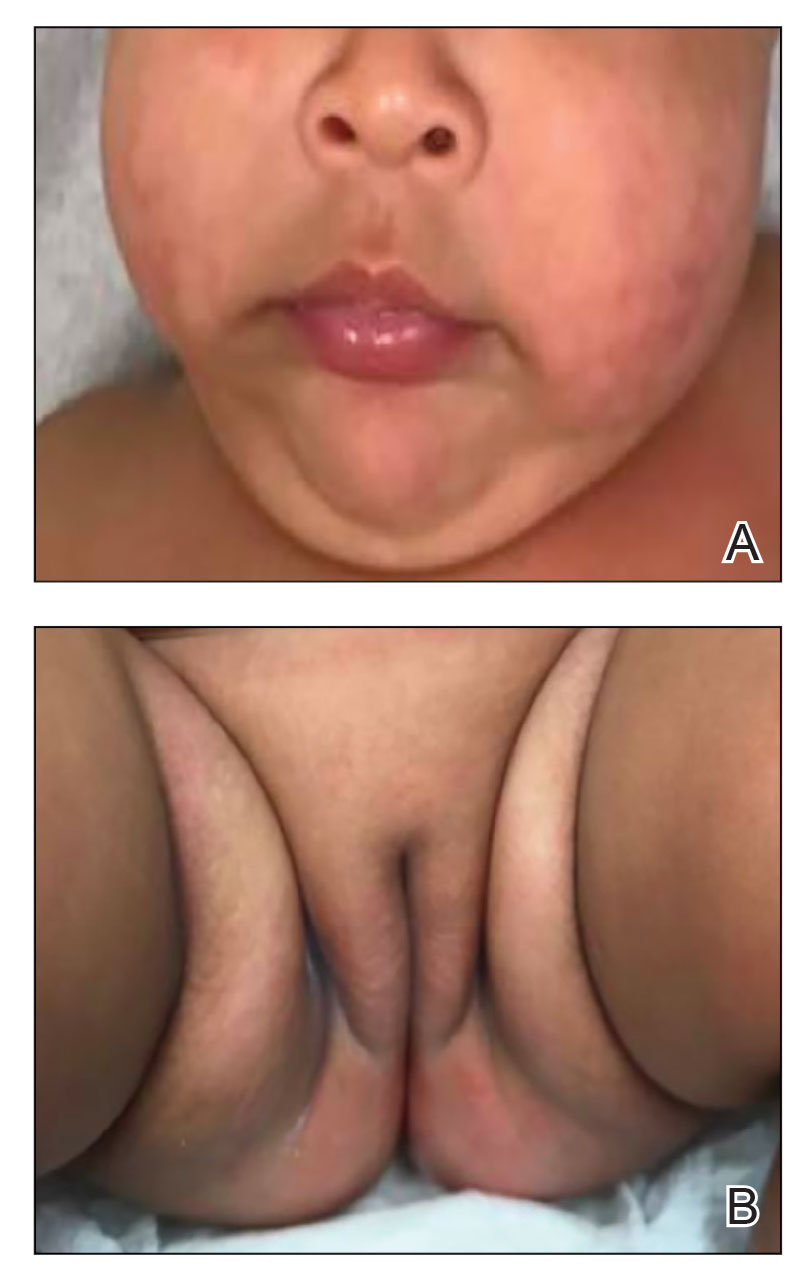

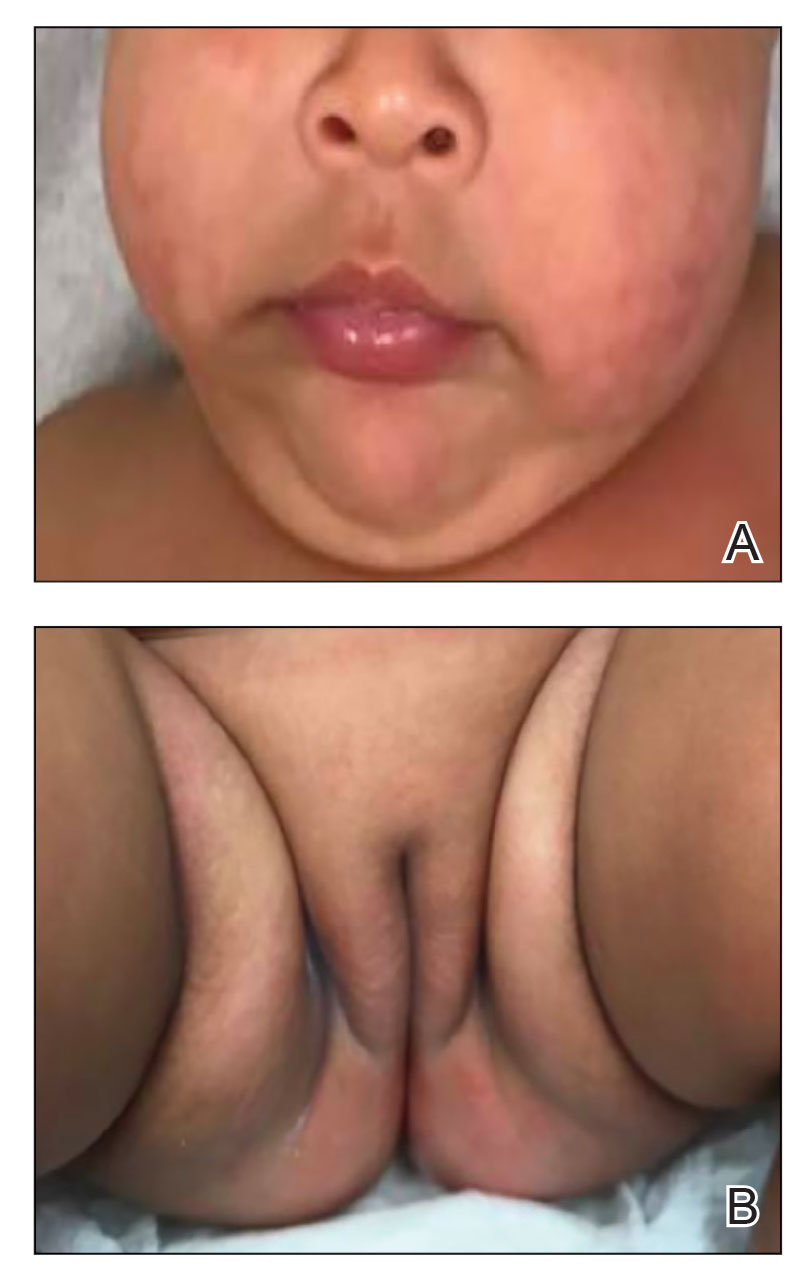

A 65-year-old woman presented to her primary care physician because of the severity of psoriasiform dermatitis that developed 5 days after she received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The patient had a medical history of Sjögren syndrome. Her medication history was negative, and her family history was negative for autoimmune disease. Physical examination by primary care revealed an erythematous scaly rash with plaques and papules on the neck and back (Figure 1). The patient presented again to primary care 2 days later with swollen, painful, discolored digits (Figure 2) and a stiff, sore neck.

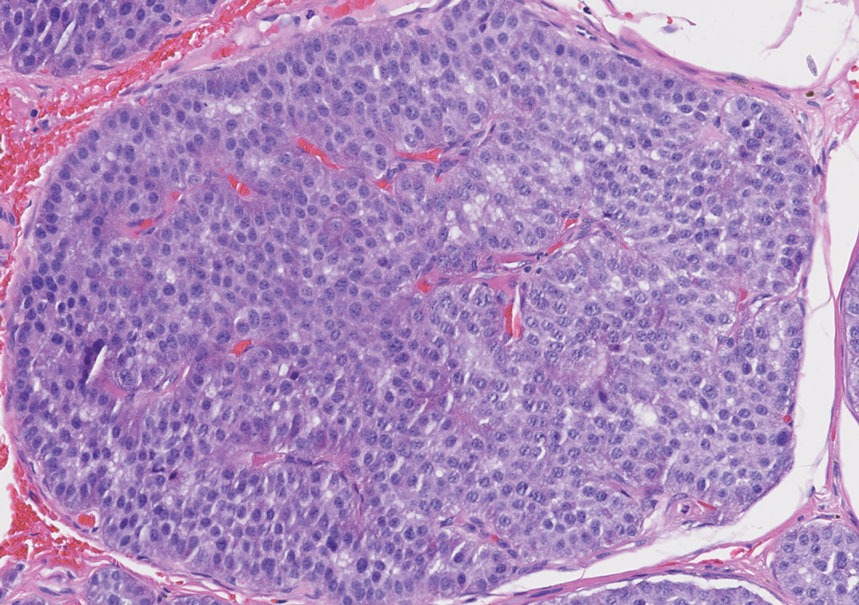

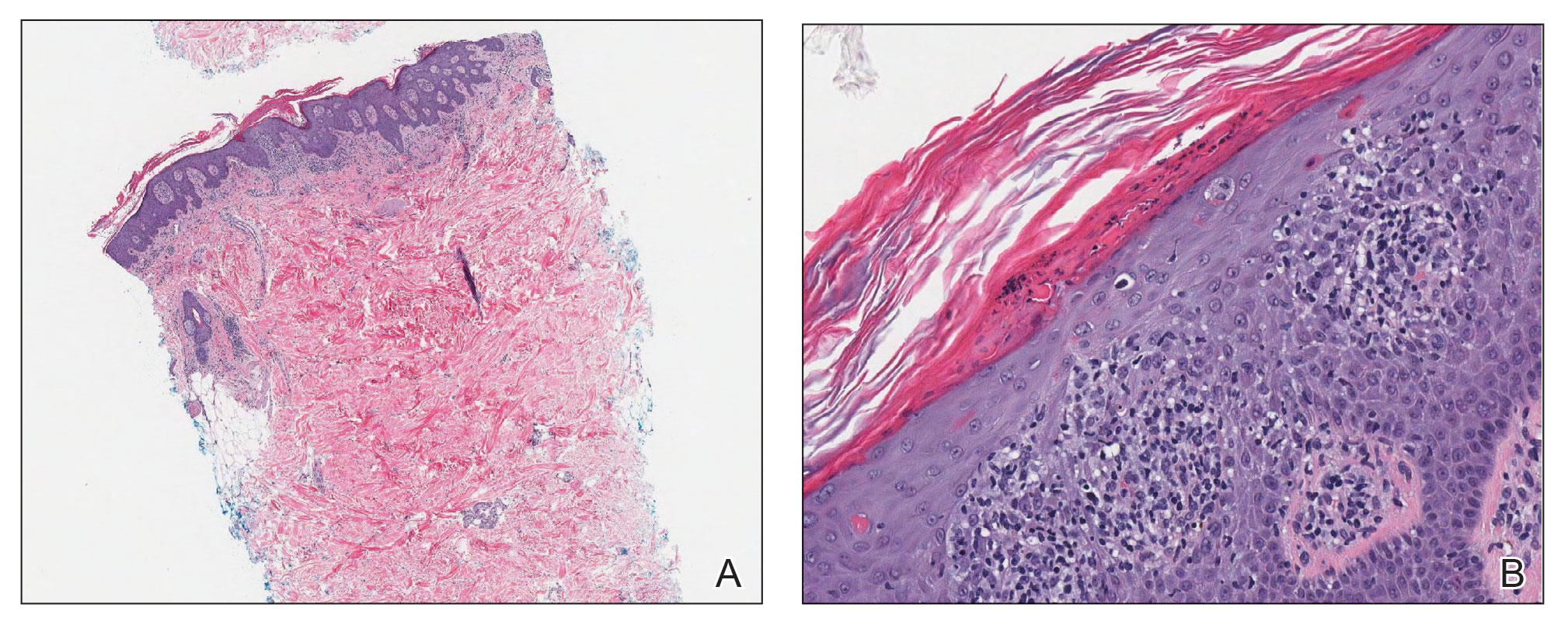

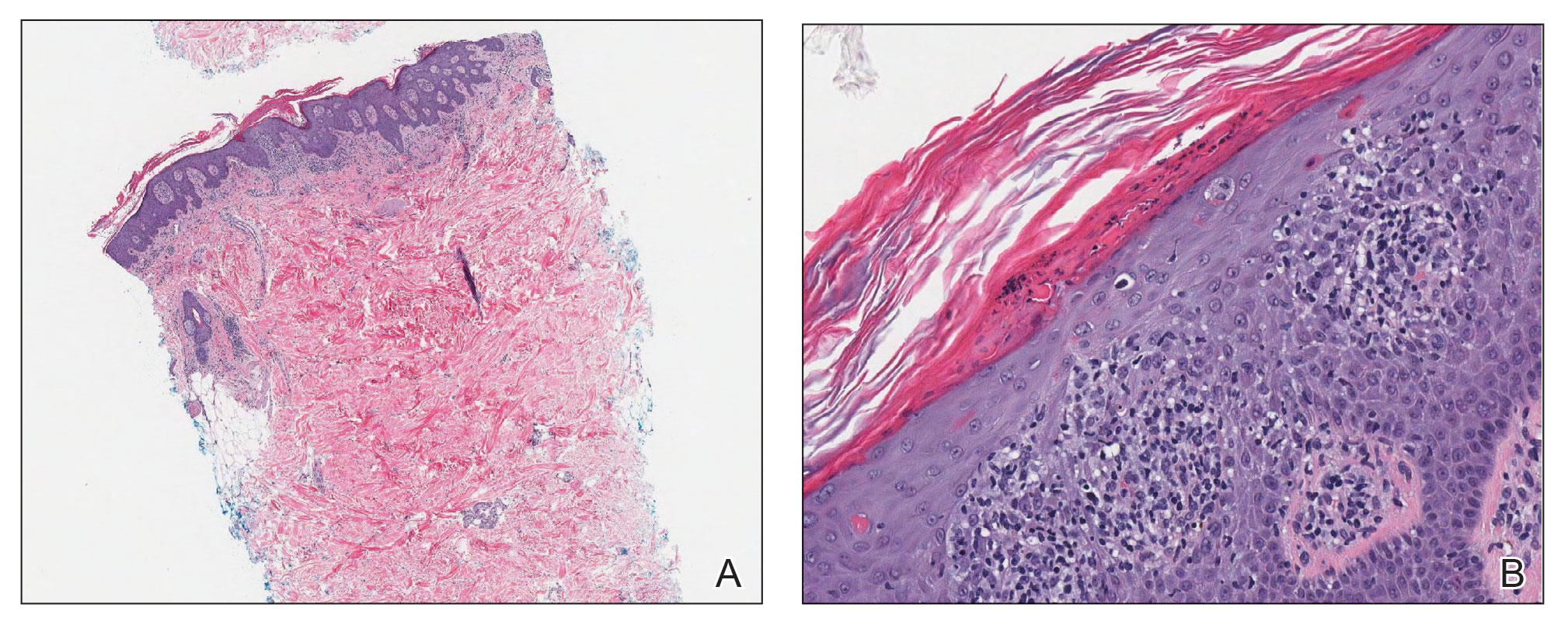

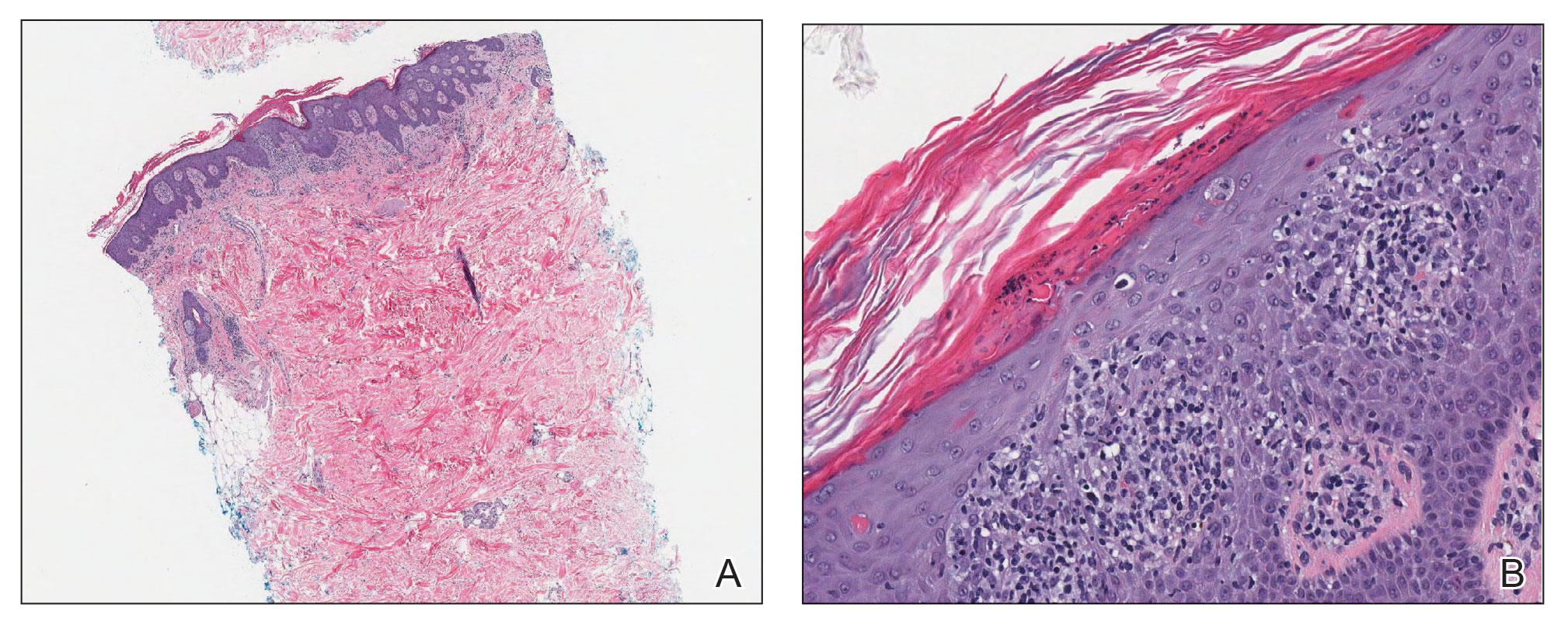

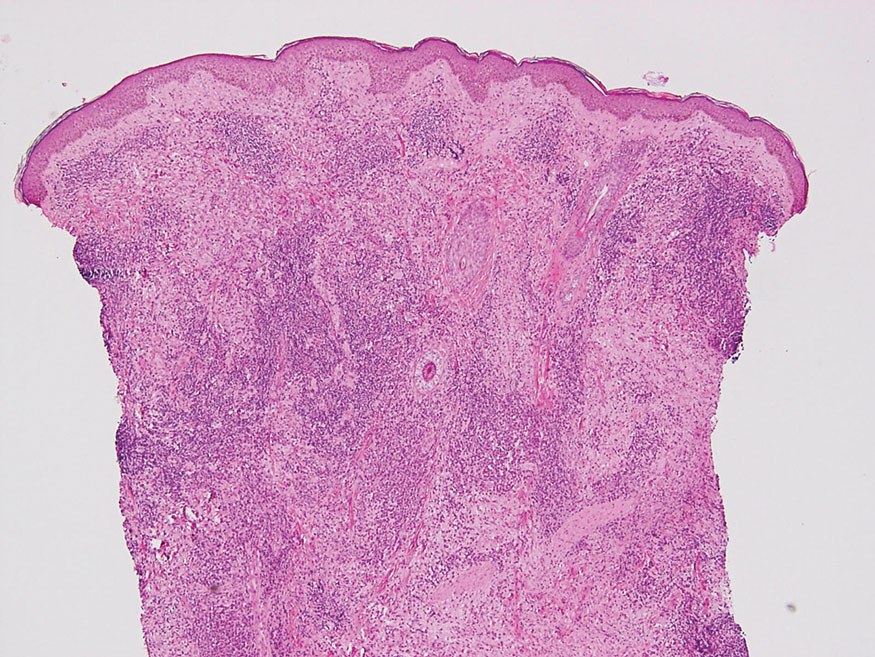

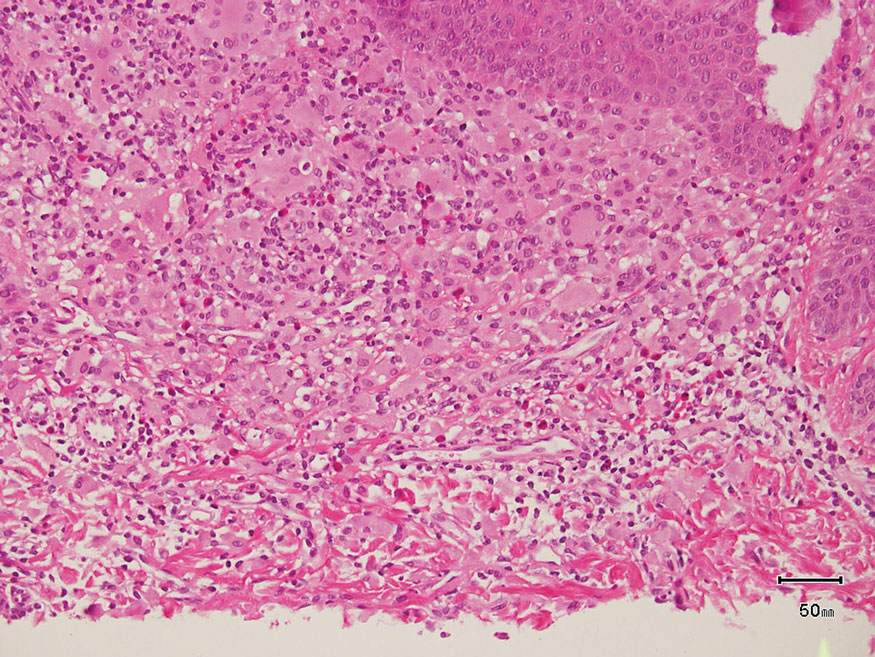

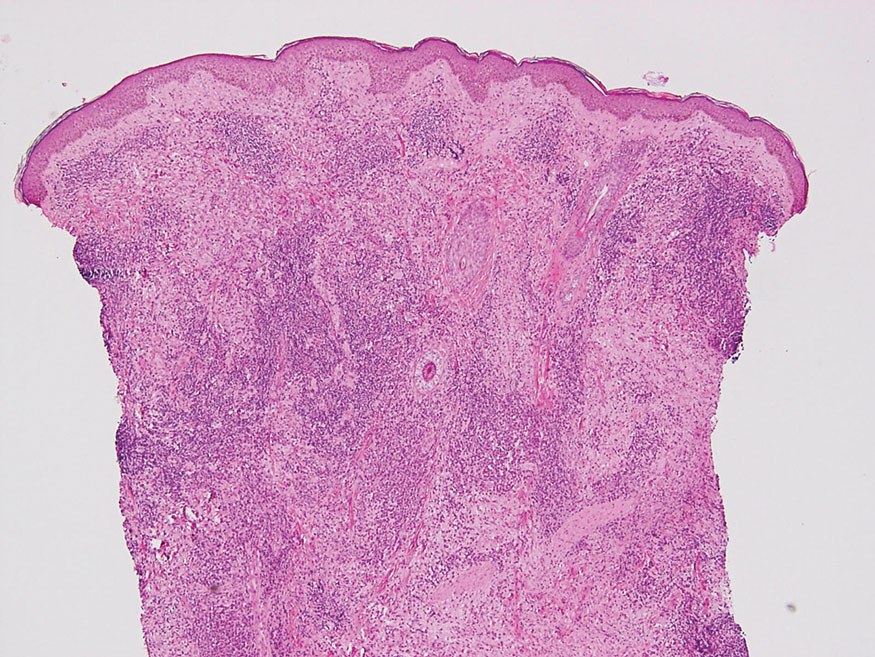

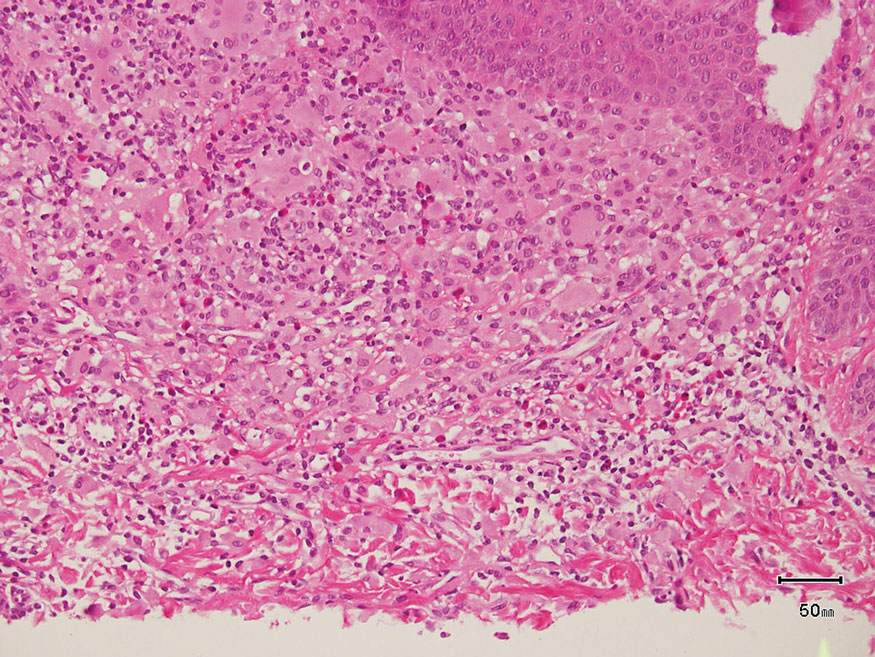

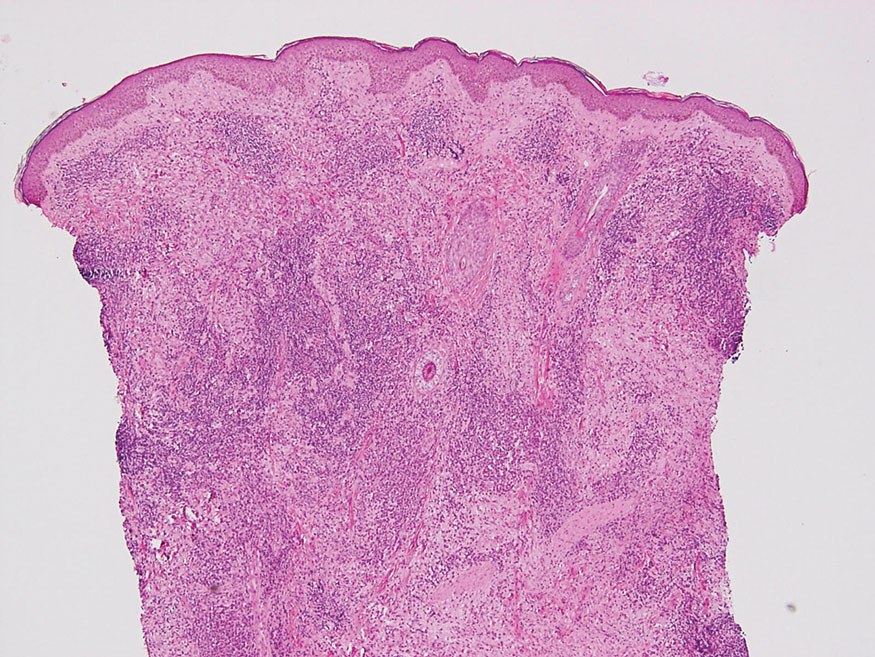

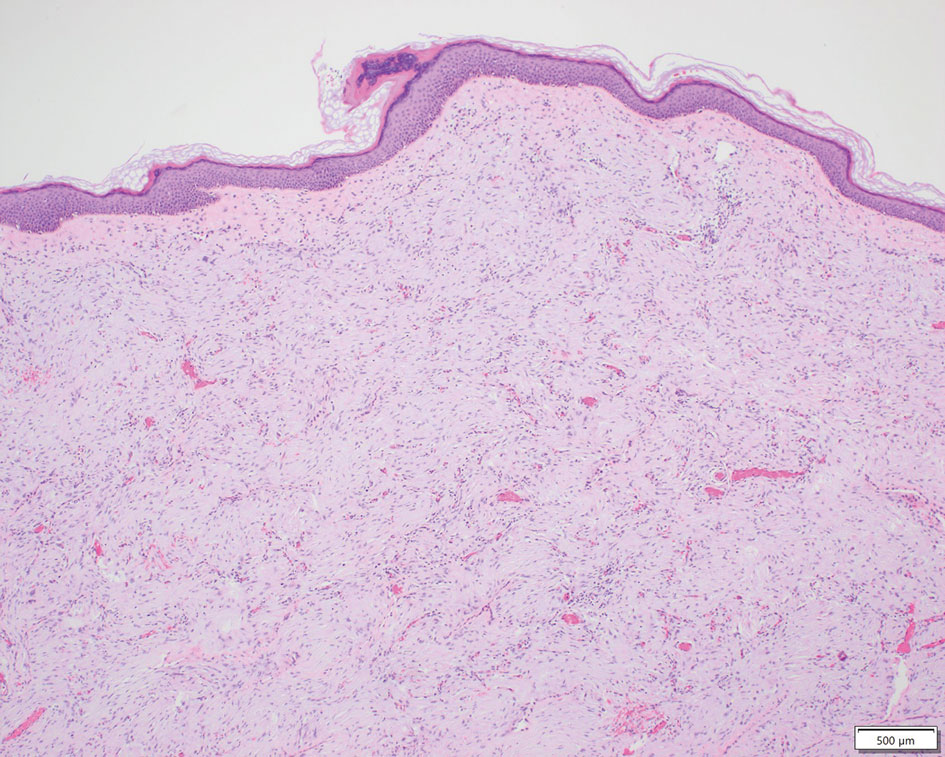

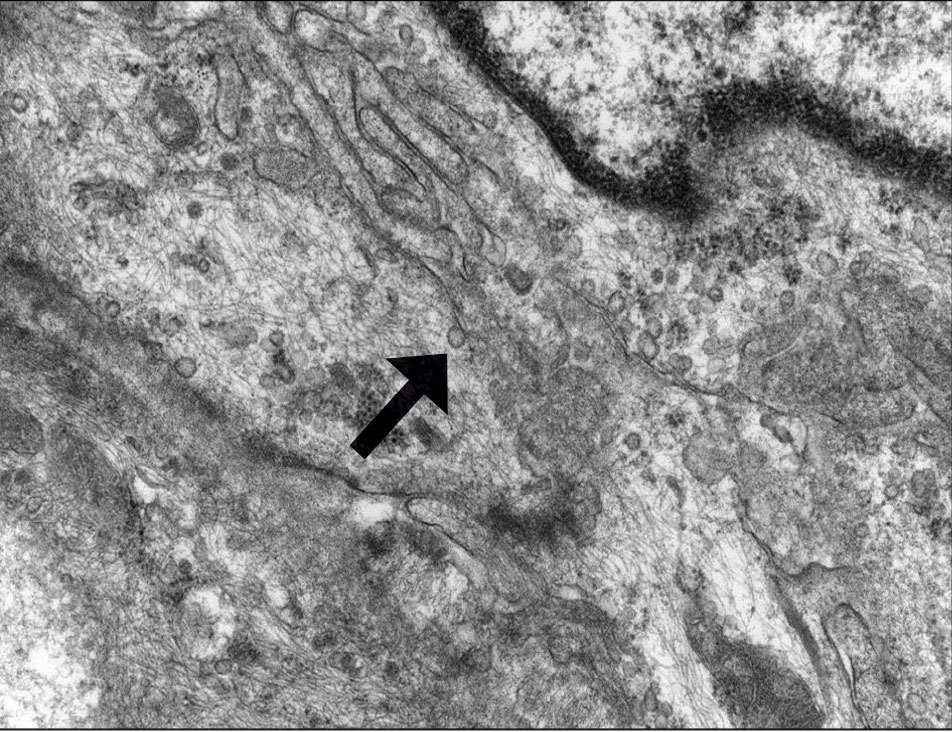

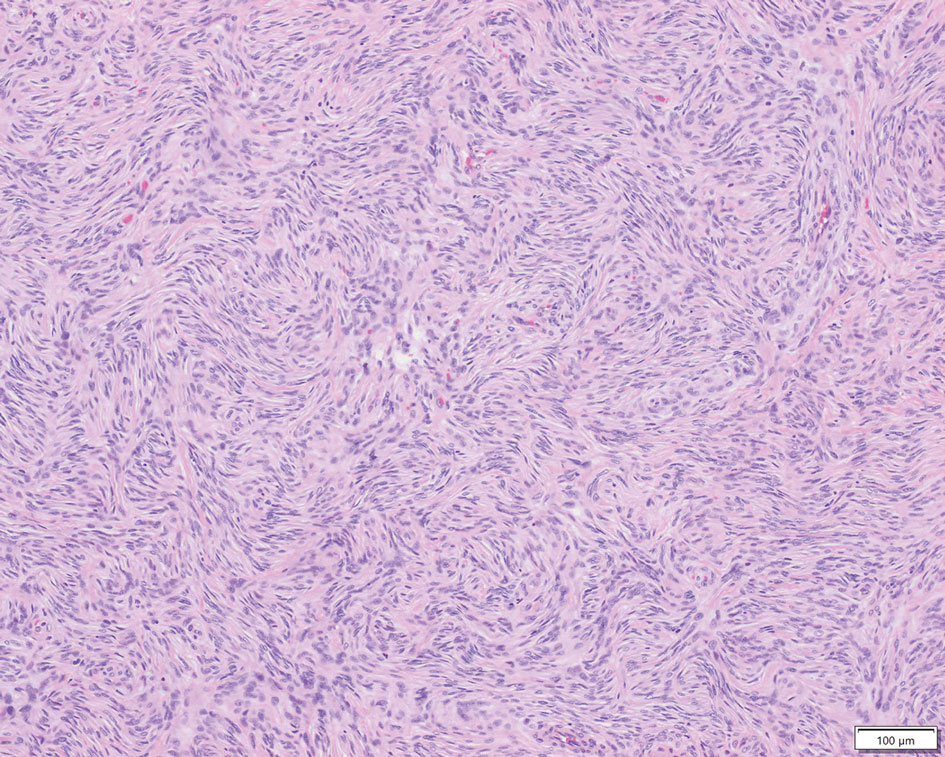

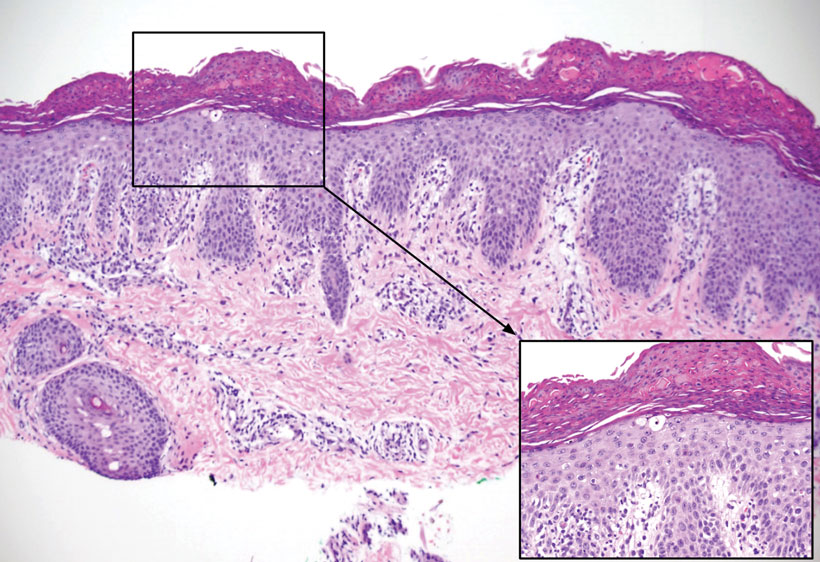

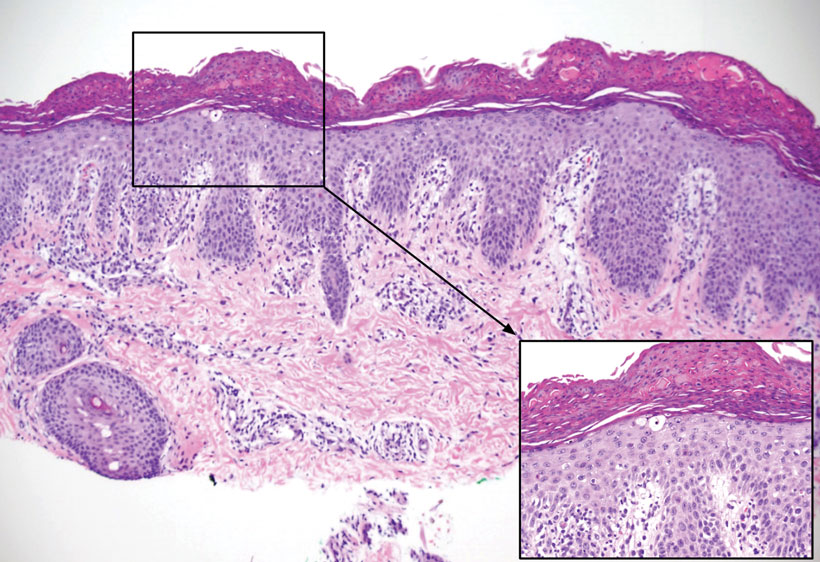

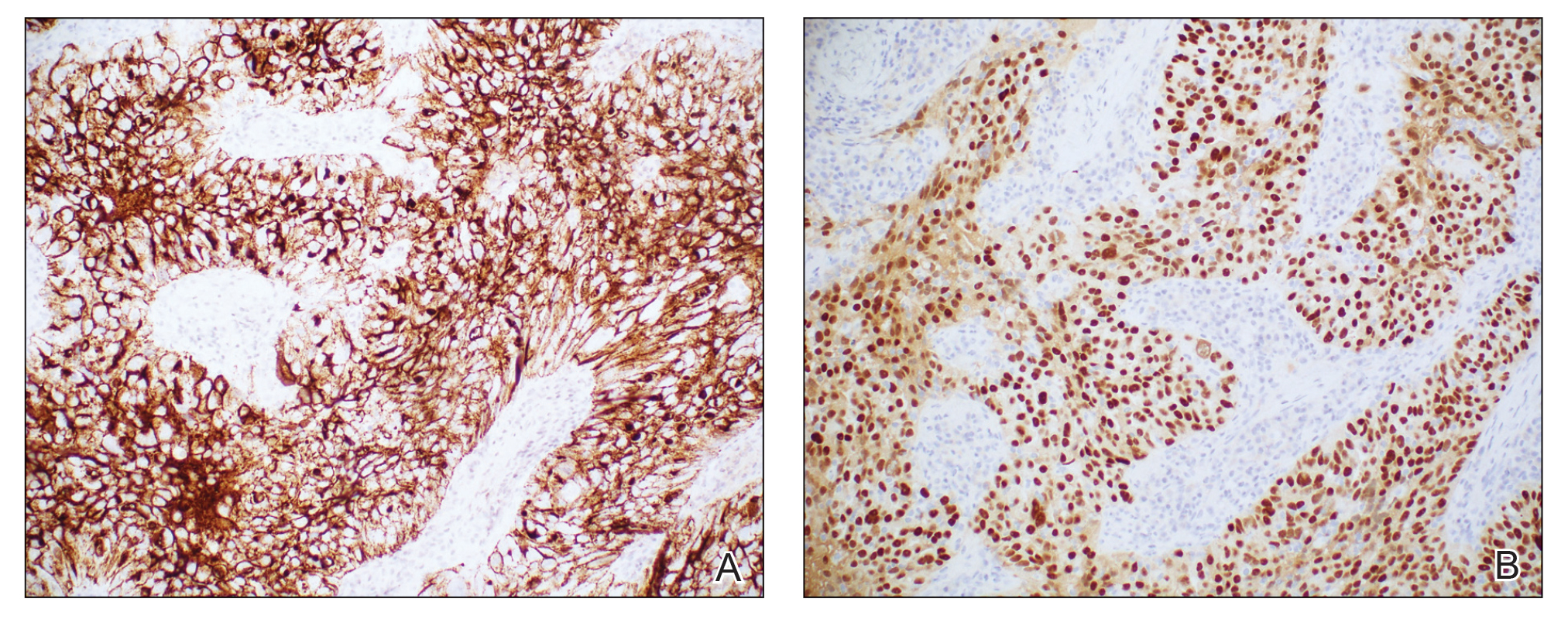

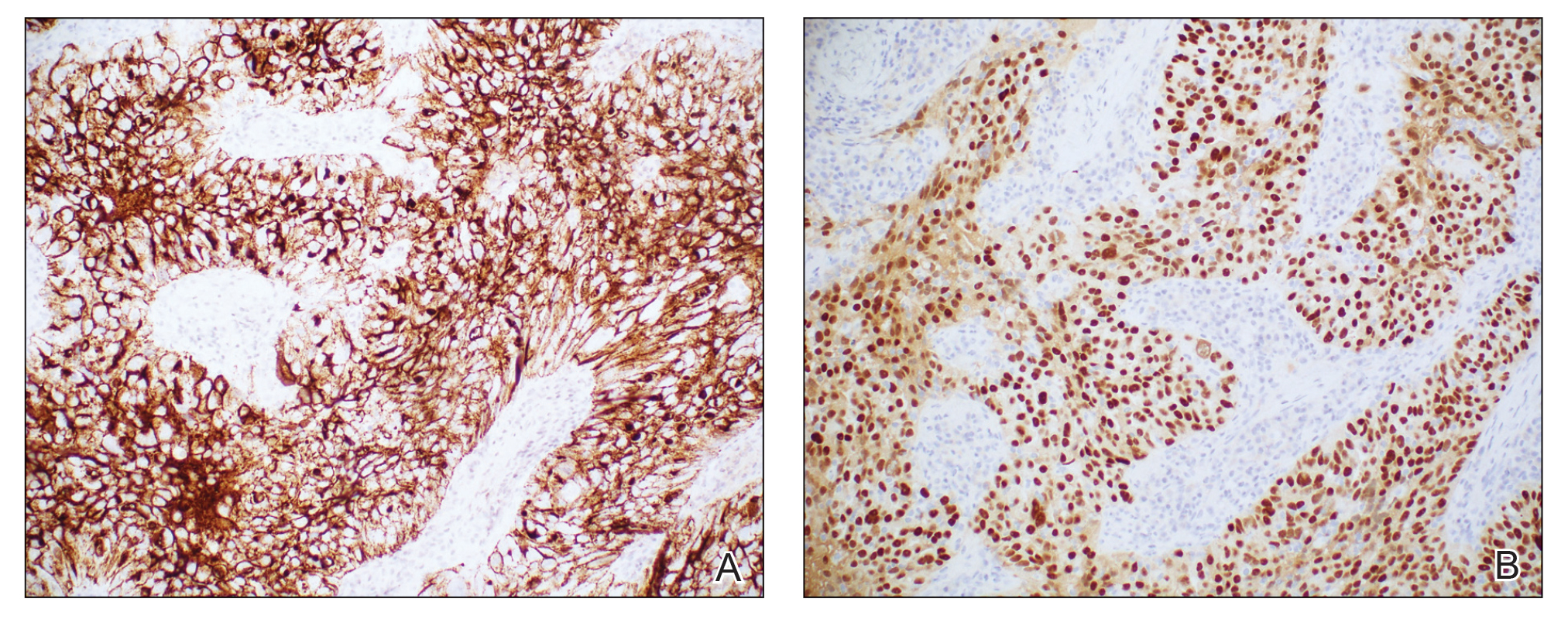

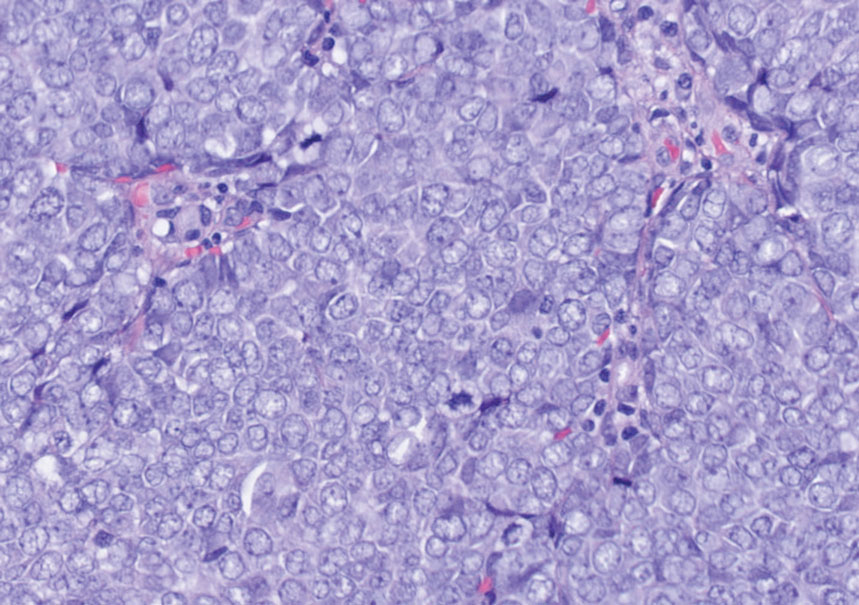

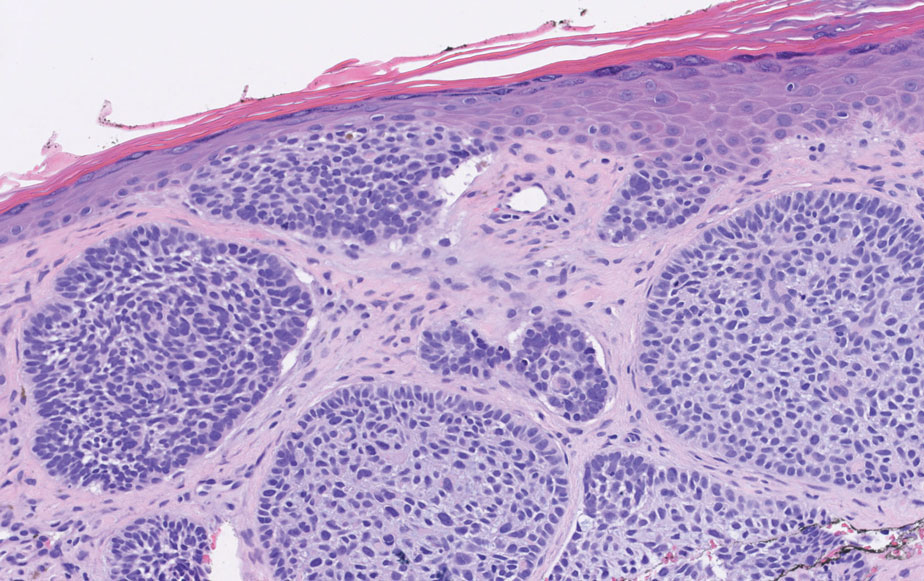

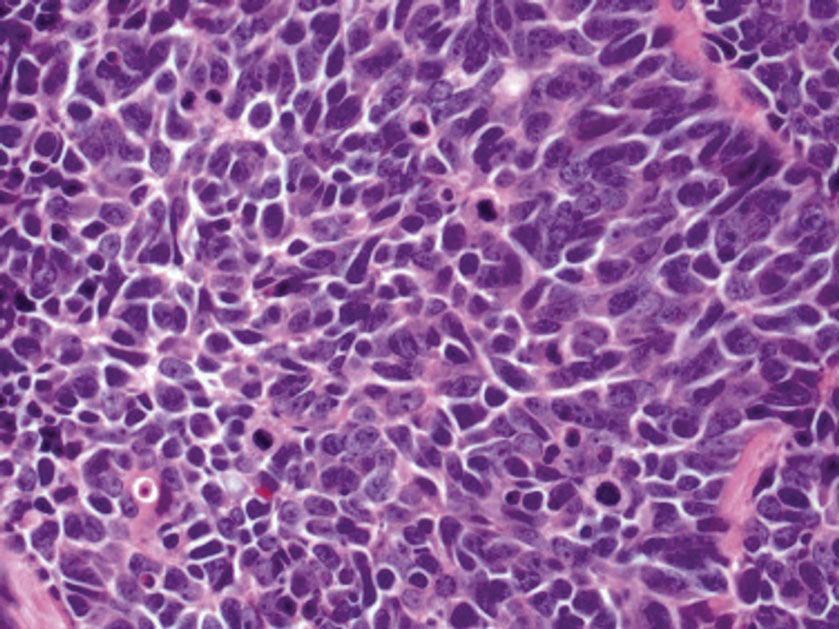

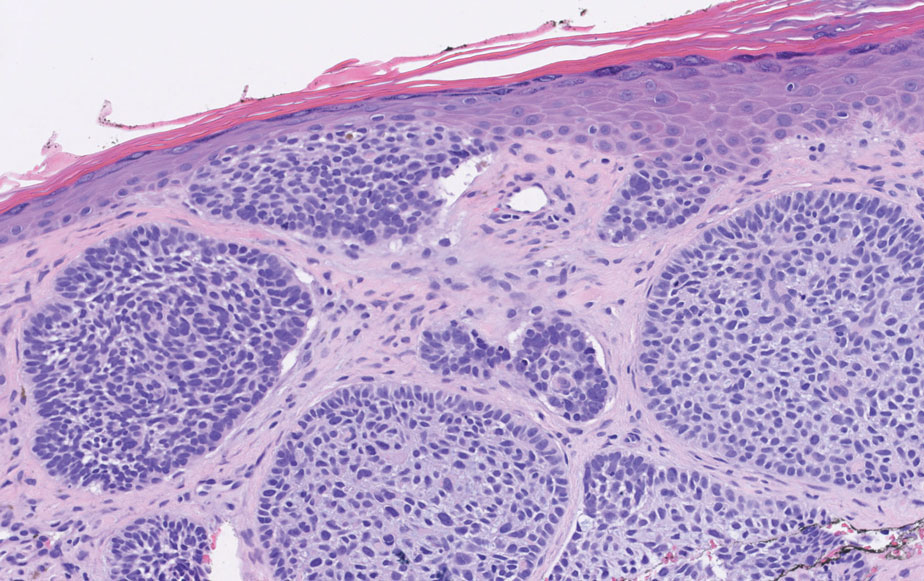

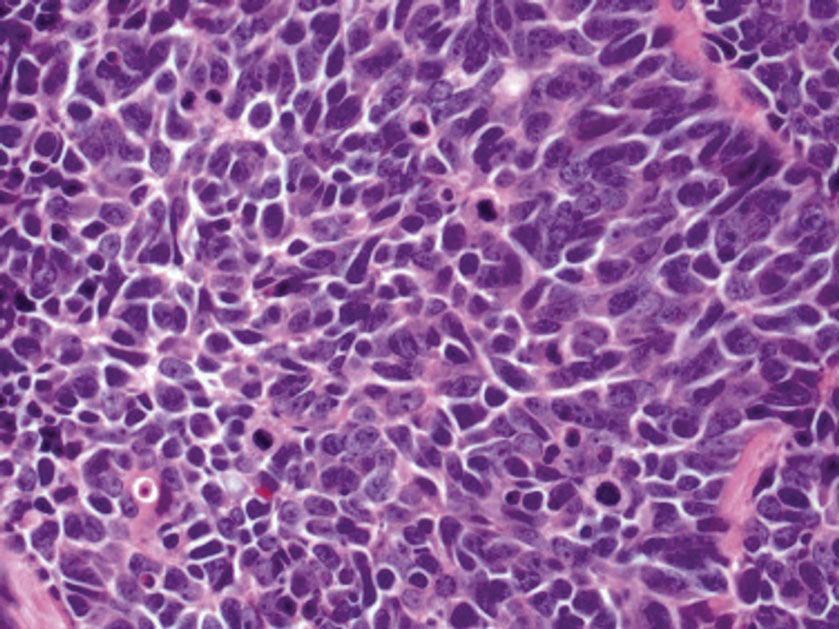

Laboratory results were positive for anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B. A complete blood cell count; comprehensive metabolic panel; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; and assays of rheumatoid factor, C-reactive protein, and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide were within reference range. A biopsy of a lesion on the back showed psoriasiform dermatitis with confluent parakeratosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes. There was superficial perivascular inflammation with rare eosinophils (Figure 3).

The patient was treated with a course of systemic corticosteroids. The rash resolved in 1 week. She did not receive the second dose due to the rash.

Two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines—Pfizer BioNTech and Moderna—have been granted emergency use authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration.6 The safety profile of the mRNA-1273 vaccine for the median 2-month follow-up showed no safety concerns.3 Minor localized adverse effects (eg, pain, redness, swelling) have been observed more frequently with the vaccines than with placebo. Systemic symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, headache, and muscle and joint pain, also were seen somewhat more often with the vaccines than with placebo; most such effects occurred 24 to 48 hours after vaccination.3,6,7 The frequency of unsolicited adverse events and serious adverse events reported during the 28-day period after vaccination generally was similar among participants in the vaccine and placebo groups.3

There are 2 types of reactions to COVID-19 vaccination: immediate and delayed. Immediate reactions usually are due to anaphylaxis, requiring prompt recognition and treatment with epinephrine to stop rapid progression of life-threatening symptoms. Delayed reactions include localized reactions, such as urticaria and benign exanthema; serum sickness and serum sickness–like reactions; fever; and rare skin, organ, and neurologic sequelae.1,6-8

Cutaneous manifestations, present in 16% to 50% of patients with Sjögren syndrome, are considered one of the most common extraglandular presentations of the syndrome. They are classified as nonvascular (eg, xerosis, angular cheilitis, eyelid dermatitis, annular erythema) and vascular (eg, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis).9-11 Our patient did not have any of those findings. She had not taken any medications before the rash appeared, thereby ruling out a drug reaction.

The differential for our patient included post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash, which is not typical with Escherichia coli infection but is described with infection with Chlamydia species and Salmonella species. Moreover, post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash appear mostly on the palms and soles. Systemic lupus erythematosus–like rashes have a different histology and appear on sun-exposed areas; our patient’s rash was found mainly on unexposed areas.12

Because our patient received the Moderna vaccine 5 days before the rash appeared and later developed swelling of the digits with morning stiffness, a delayed serum sickness–like reaction secondary to COVID-19 vaccination was possible.3,6

COVID-19 mRNA vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna incorporate a lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system that prevents rapid enzymatic degradation of mRNA and facilitates in vivo delivery of mRNA. This lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system is further stabilized by a polyethylene glycol 2000 lipid conjugate that provides a hydrophilic layer, thus prolonging half-life. The presence of lipid polyethylene glycol 2000 in mRNA vaccines has led to concern that this component could be implicated in anaphylaxis.6

COVID-19 antigens can give rise to varying clinical manifestations that are directly related to viral tissue damage or are indirectly induced by the antiviral immune response.13,14 Hyperactivation of the immune system to eradicate COVID-19 may trigger autoimmunity; several immune-mediated disorders have been described in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. Dermal manifestations include cutaneous rash and vasculitis.13-16 Crucial immunologic steps occur during SARS-CoV-2 infection that may link autoimmunity to COVID-19.13,14 In preliminary published data on the efficacy of the Moderna vaccine on 45 trial enrollees, 3 did not receive the second dose of vaccination, including 1 who developed urticaria on both legs 5 days after the first dose.1

Introduction of viral RNA can induce autoimmunity that can be explained by various phenomena, including epitope spreading, molecular mimicry, cryptic antigen, and bystander activation. Remarkably, more than one-third of immunogenic proteins in SARS-CoV-2 have potentially problematic homology to proteins that are key to the human adaptive immune system.5

Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 seems to induce organ injury through alternative mechanisms beyond direct viral infection, including immunologic injury. In some situations, hyperactivation of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 RNA can result in autoimmune disease. COVID-19 has been associated with immune-mediated systemic or organ-selective manifestations, some of which fulfill the diagnostic or classification criteria of specific autoimmune diseases. It is unclear whether those medical disorders are the result of transitory postinfectious epiphenomena.5

A few studies have shown that patients with rheumatic disease have an incidence and prevalence of COVID-19 that is similar to the general population. A similar pattern has been detected in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates, even among patients with an autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren syndrome.5,17 Furthermore, exacerbation of preexisting rheumatic symptoms may be due to hyperactivation of antiviral pathways in a person with an autoimmune disease.17-19 The findings in our patient suggested a direct role for the vaccine in skin manifestations, rather than for reactivation or development of new systemic autoimmune processes, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination has been described20; however, the case patient did not have a history of psoriasis. The mechanism(s) of such exacerbation remain unclear; COVID-19 vaccine–induced helper T cells (TH17) may play a role.21 Other skin manifestations encountered following COVID-19 vaccination include lichen planus, leukocytoclastic vasculitic rash, erythema multiforme–like rash, and pityriasis rosea–like rash.22-25 The immune mechanisms of these manifestations remain unclear.

The clinical presentation of delayed vaccination reactions can be attributed to the timing of symptoms and, in this case, the immune-mediated background of a psoriasiform reaction. Although adverse reactions to the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine are rare, more individuals should be studied after vaccination to confirm and better understand this phenomenon.

- Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, et al; . An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1920-1931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022483

- Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, et al; . Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2427-2438. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028436

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Weise E. ‘COVID arm’ rash seen after Moderna vaccine annoying but harmless, doctors say. USA Today. January 27, 2021. Accessed September 4, 2022. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2021/01/27/covid-arm-moderna-vaccine-rash-harmless-side-effect-doctors-say/4277725001/

- Talotta R, Robertson E. Autoimmunity as the comet tail of COVID-19 pandemic. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:3621-3644. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v8.i17.3621

- Castells MC, Phillips EJ. Maintaining safety with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:643-649. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2035343

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al; . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603-2615. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2034577

- Dooling K, McClung N, Chamberland M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID-19 vaccine—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1857-1859. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e1

- Roguedas AM, Misery L, Sassolas B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of primary Sjögren’s syndrome are underestimated. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:632-636.

- Katayama I. Dry skin manifestations in Sjögren syndrome and atopic dermatitis related to aberrant sudomotor function in inflammatory allergic skin diseases. Allergol Int. 2018;67:448-454. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2018.07.001

- Generali E, Costanzo A, Mainetti C, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:357-370. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8639-y

- Chanprapaph K, Tankunakorn J, Suchonwanit P, et al. Dermatologic manifestations, histologic features and disease progression among cutaneous lupus erythematosus subtypes: a prospective observational study in Asians. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:131-147. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00471-y

- Ortega-Quijano D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Selda-Enriquez G, et al. Algorithm for the classification of COVID-19 rashes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e103-e104. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.034

- Rahimi H, Tehranchinia Z. A comprehensive review of cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID-19. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1236520. doi:10.1155/2020/1236520

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:75-81. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.04.011

- Landa N, Mendieta-Eckert M, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Chilblain-like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:739-743. doi:10.1111/ijd.14937

- Dellavance A, Coelho Andrade LE. Immunologic derangement preceding clinical autoimmunity. Lupus. 2014;23:1305-1308. doi:10.1177/0961203314531346

- Parodi A, Gasparini G, Cozzani E. Could antiphospholipid antibodies contribute to coagulopathy in COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e249. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.003

- Zhou Y, Han T, Chen J, et al. Clinical and autoimmune characteristics of severe and critical cases of COVID-19. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13:1077-1086. doi:10.1111/cts.12805

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.812010

- Rouai M, Slimane MB, Sassi W, et al. Pustular rash triggered by Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022:e15465. doi:10.1111/dth.15465

- Altun E, Kuzucular E. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis after COVID-19 vaccination. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15279. doi:10.1111/dth.15279

- Buckley JE, Landis LN, Rapini RP. Pityriasis rosea-like rash after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination: a case report and review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2022;7:164-168. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.009

- Gökçek GE, Öksüm Solak E, Çölgeçen E. Pityriasis rosea like eruption: a dermatological manifestation of Coronavac-COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15256. doi:10.1111/dth.15256

- Kim MJ, Kim JW, Kim MS, et al. Generalized erythema multiforme-like skin rash following the first dose of COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:e98-e100. doi:10.1111/jdv.17757

To the Editor:

The Moderna COVID-19 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine was authorized for use on December 18, 2020, with the second dose beginning on January 15, 2021.1-3 Some individuals who received the Moderna vaccine experienced an intense rash known as “COVID arm,” a harmless but bothersome adverse effect that typically appears within a week and is a localized and transient immunogenic response.4 COVID arm differs from most vaccine adverse effects. The rash emerges not immediately but 5 to 9 days after the initial dose—on average, 1 week later. Apart from being itchy, the rash does not appear to be harmful and is not a reason to hesitate getting vaccinated.

Dermatologists and allergists have been studying this adverse effect, which has been formally termed delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity. Of potential clinical consequence is that the efficacy of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine may be harmed if postvaccination dermal reactions necessitate systemic corticosteroid therapy. Because this vaccine stimulates an immune response as viral RNA integrates in cells secondary to production of the spike protein of the virus, the skin may be affected secondarily and manifestations of any underlying disease may be aggravated.5 We report a patient who developed a psoriasiform dermatitis after the first dose of the Moderna vaccine.

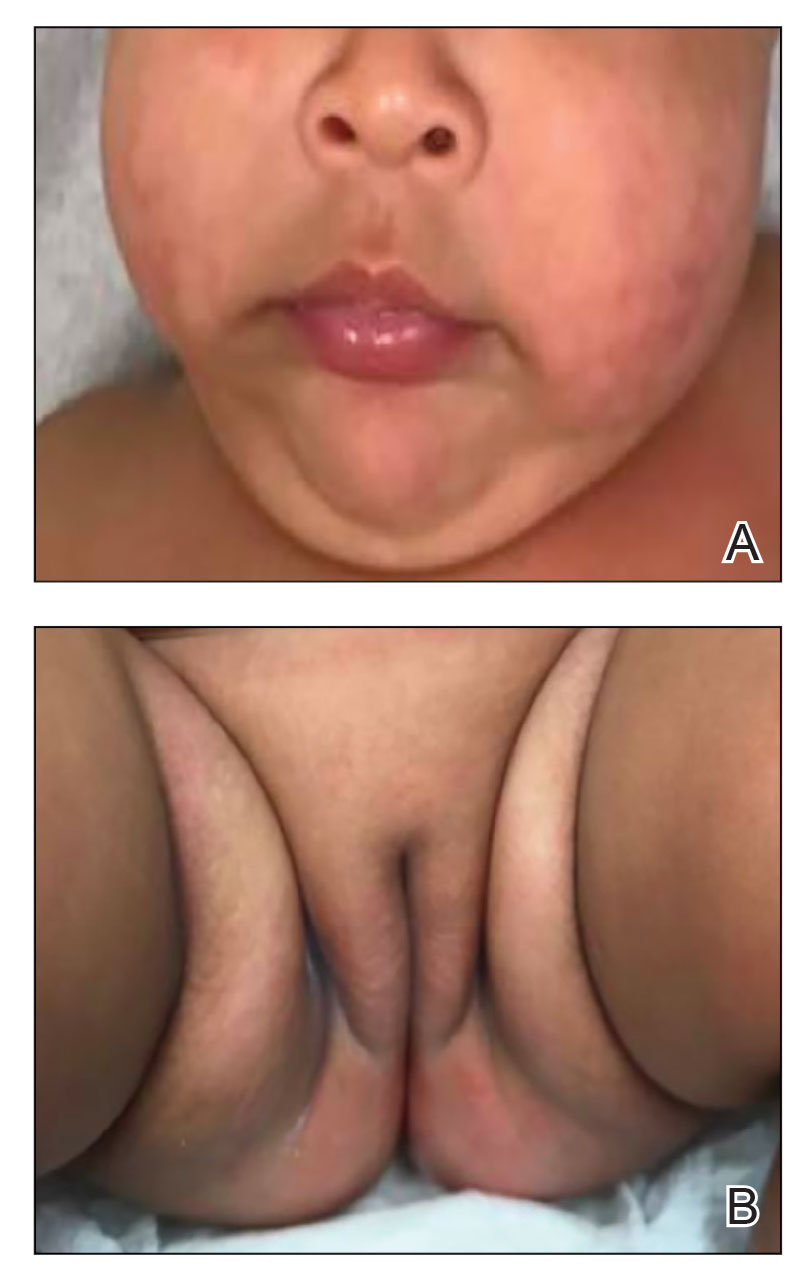

A 65-year-old woman presented to her primary care physician because of the severity of psoriasiform dermatitis that developed 5 days after she received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The patient had a medical history of Sjögren syndrome. Her medication history was negative, and her family history was negative for autoimmune disease. Physical examination by primary care revealed an erythematous scaly rash with plaques and papules on the neck and back (Figure 1). The patient presented again to primary care 2 days later with swollen, painful, discolored digits (Figure 2) and a stiff, sore neck.

Laboratory results were positive for anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B. A complete blood cell count; comprehensive metabolic panel; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; and assays of rheumatoid factor, C-reactive protein, and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide were within reference range. A biopsy of a lesion on the back showed psoriasiform dermatitis with confluent parakeratosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes. There was superficial perivascular inflammation with rare eosinophils (Figure 3).

The patient was treated with a course of systemic corticosteroids. The rash resolved in 1 week. She did not receive the second dose due to the rash.

Two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines—Pfizer BioNTech and Moderna—have been granted emergency use authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration.6 The safety profile of the mRNA-1273 vaccine for the median 2-month follow-up showed no safety concerns.3 Minor localized adverse effects (eg, pain, redness, swelling) have been observed more frequently with the vaccines than with placebo. Systemic symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, headache, and muscle and joint pain, also were seen somewhat more often with the vaccines than with placebo; most such effects occurred 24 to 48 hours after vaccination.3,6,7 The frequency of unsolicited adverse events and serious adverse events reported during the 28-day period after vaccination generally was similar among participants in the vaccine and placebo groups.3

There are 2 types of reactions to COVID-19 vaccination: immediate and delayed. Immediate reactions usually are due to anaphylaxis, requiring prompt recognition and treatment with epinephrine to stop rapid progression of life-threatening symptoms. Delayed reactions include localized reactions, such as urticaria and benign exanthema; serum sickness and serum sickness–like reactions; fever; and rare skin, organ, and neurologic sequelae.1,6-8

Cutaneous manifestations, present in 16% to 50% of patients with Sjögren syndrome, are considered one of the most common extraglandular presentations of the syndrome. They are classified as nonvascular (eg, xerosis, angular cheilitis, eyelid dermatitis, annular erythema) and vascular (eg, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis).9-11 Our patient did not have any of those findings. She had not taken any medications before the rash appeared, thereby ruling out a drug reaction.

The differential for our patient included post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash, which is not typical with Escherichia coli infection but is described with infection with Chlamydia species and Salmonella species. Moreover, post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash appear mostly on the palms and soles. Systemic lupus erythematosus–like rashes have a different histology and appear on sun-exposed areas; our patient’s rash was found mainly on unexposed areas.12

Because our patient received the Moderna vaccine 5 days before the rash appeared and later developed swelling of the digits with morning stiffness, a delayed serum sickness–like reaction secondary to COVID-19 vaccination was possible.3,6

COVID-19 mRNA vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna incorporate a lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system that prevents rapid enzymatic degradation of mRNA and facilitates in vivo delivery of mRNA. This lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system is further stabilized by a polyethylene glycol 2000 lipid conjugate that provides a hydrophilic layer, thus prolonging half-life. The presence of lipid polyethylene glycol 2000 in mRNA vaccines has led to concern that this component could be implicated in anaphylaxis.6

COVID-19 antigens can give rise to varying clinical manifestations that are directly related to viral tissue damage or are indirectly induced by the antiviral immune response.13,14 Hyperactivation of the immune system to eradicate COVID-19 may trigger autoimmunity; several immune-mediated disorders have been described in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. Dermal manifestations include cutaneous rash and vasculitis.13-16 Crucial immunologic steps occur during SARS-CoV-2 infection that may link autoimmunity to COVID-19.13,14 In preliminary published data on the efficacy of the Moderna vaccine on 45 trial enrollees, 3 did not receive the second dose of vaccination, including 1 who developed urticaria on both legs 5 days after the first dose.1

Introduction of viral RNA can induce autoimmunity that can be explained by various phenomena, including epitope spreading, molecular mimicry, cryptic antigen, and bystander activation. Remarkably, more than one-third of immunogenic proteins in SARS-CoV-2 have potentially problematic homology to proteins that are key to the human adaptive immune system.5

Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 seems to induce organ injury through alternative mechanisms beyond direct viral infection, including immunologic injury. In some situations, hyperactivation of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 RNA can result in autoimmune disease. COVID-19 has been associated with immune-mediated systemic or organ-selective manifestations, some of which fulfill the diagnostic or classification criteria of specific autoimmune diseases. It is unclear whether those medical disorders are the result of transitory postinfectious epiphenomena.5

A few studies have shown that patients with rheumatic disease have an incidence and prevalence of COVID-19 that is similar to the general population. A similar pattern has been detected in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates, even among patients with an autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren syndrome.5,17 Furthermore, exacerbation of preexisting rheumatic symptoms may be due to hyperactivation of antiviral pathways in a person with an autoimmune disease.17-19 The findings in our patient suggested a direct role for the vaccine in skin manifestations, rather than for reactivation or development of new systemic autoimmune processes, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination has been described20; however, the case patient did not have a history of psoriasis. The mechanism(s) of such exacerbation remain unclear; COVID-19 vaccine–induced helper T cells (TH17) may play a role.21 Other skin manifestations encountered following COVID-19 vaccination include lichen planus, leukocytoclastic vasculitic rash, erythema multiforme–like rash, and pityriasis rosea–like rash.22-25 The immune mechanisms of these manifestations remain unclear.

The clinical presentation of delayed vaccination reactions can be attributed to the timing of symptoms and, in this case, the immune-mediated background of a psoriasiform reaction. Although adverse reactions to the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine are rare, more individuals should be studied after vaccination to confirm and better understand this phenomenon.

To the Editor:

The Moderna COVID-19 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine was authorized for use on December 18, 2020, with the second dose beginning on January 15, 2021.1-3 Some individuals who received the Moderna vaccine experienced an intense rash known as “COVID arm,” a harmless but bothersome adverse effect that typically appears within a week and is a localized and transient immunogenic response.4 COVID arm differs from most vaccine adverse effects. The rash emerges not immediately but 5 to 9 days after the initial dose—on average, 1 week later. Apart from being itchy, the rash does not appear to be harmful and is not a reason to hesitate getting vaccinated.

Dermatologists and allergists have been studying this adverse effect, which has been formally termed delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity. Of potential clinical consequence is that the efficacy of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine may be harmed if postvaccination dermal reactions necessitate systemic corticosteroid therapy. Because this vaccine stimulates an immune response as viral RNA integrates in cells secondary to production of the spike protein of the virus, the skin may be affected secondarily and manifestations of any underlying disease may be aggravated.5 We report a patient who developed a psoriasiform dermatitis after the first dose of the Moderna vaccine.

A 65-year-old woman presented to her primary care physician because of the severity of psoriasiform dermatitis that developed 5 days after she received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The patient had a medical history of Sjögren syndrome. Her medication history was negative, and her family history was negative for autoimmune disease. Physical examination by primary care revealed an erythematous scaly rash with plaques and papules on the neck and back (Figure 1). The patient presented again to primary care 2 days later with swollen, painful, discolored digits (Figure 2) and a stiff, sore neck.

Laboratory results were positive for anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B. A complete blood cell count; comprehensive metabolic panel; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; and assays of rheumatoid factor, C-reactive protein, and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide were within reference range. A biopsy of a lesion on the back showed psoriasiform dermatitis with confluent parakeratosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes. There was superficial perivascular inflammation with rare eosinophils (Figure 3).

The patient was treated with a course of systemic corticosteroids. The rash resolved in 1 week. She did not receive the second dose due to the rash.

Two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines—Pfizer BioNTech and Moderna—have been granted emergency use authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration.6 The safety profile of the mRNA-1273 vaccine for the median 2-month follow-up showed no safety concerns.3 Minor localized adverse effects (eg, pain, redness, swelling) have been observed more frequently with the vaccines than with placebo. Systemic symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, headache, and muscle and joint pain, also were seen somewhat more often with the vaccines than with placebo; most such effects occurred 24 to 48 hours after vaccination.3,6,7 The frequency of unsolicited adverse events and serious adverse events reported during the 28-day period after vaccination generally was similar among participants in the vaccine and placebo groups.3

There are 2 types of reactions to COVID-19 vaccination: immediate and delayed. Immediate reactions usually are due to anaphylaxis, requiring prompt recognition and treatment with epinephrine to stop rapid progression of life-threatening symptoms. Delayed reactions include localized reactions, such as urticaria and benign exanthema; serum sickness and serum sickness–like reactions; fever; and rare skin, organ, and neurologic sequelae.1,6-8

Cutaneous manifestations, present in 16% to 50% of patients with Sjögren syndrome, are considered one of the most common extraglandular presentations of the syndrome. They are classified as nonvascular (eg, xerosis, angular cheilitis, eyelid dermatitis, annular erythema) and vascular (eg, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis).9-11 Our patient did not have any of those findings. She had not taken any medications before the rash appeared, thereby ruling out a drug reaction.

The differential for our patient included post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash, which is not typical with Escherichia coli infection but is described with infection with Chlamydia species and Salmonella species. Moreover, post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash appear mostly on the palms and soles. Systemic lupus erythematosus–like rashes have a different histology and appear on sun-exposed areas; our patient’s rash was found mainly on unexposed areas.12

Because our patient received the Moderna vaccine 5 days before the rash appeared and later developed swelling of the digits with morning stiffness, a delayed serum sickness–like reaction secondary to COVID-19 vaccination was possible.3,6

COVID-19 mRNA vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna incorporate a lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system that prevents rapid enzymatic degradation of mRNA and facilitates in vivo delivery of mRNA. This lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system is further stabilized by a polyethylene glycol 2000 lipid conjugate that provides a hydrophilic layer, thus prolonging half-life. The presence of lipid polyethylene glycol 2000 in mRNA vaccines has led to concern that this component could be implicated in anaphylaxis.6

COVID-19 antigens can give rise to varying clinical manifestations that are directly related to viral tissue damage or are indirectly induced by the antiviral immune response.13,14 Hyperactivation of the immune system to eradicate COVID-19 may trigger autoimmunity; several immune-mediated disorders have been described in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. Dermal manifestations include cutaneous rash and vasculitis.13-16 Crucial immunologic steps occur during SARS-CoV-2 infection that may link autoimmunity to COVID-19.13,14 In preliminary published data on the efficacy of the Moderna vaccine on 45 trial enrollees, 3 did not receive the second dose of vaccination, including 1 who developed urticaria on both legs 5 days after the first dose.1

Introduction of viral RNA can induce autoimmunity that can be explained by various phenomena, including epitope spreading, molecular mimicry, cryptic antigen, and bystander activation. Remarkably, more than one-third of immunogenic proteins in SARS-CoV-2 have potentially problematic homology to proteins that are key to the human adaptive immune system.5

Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 seems to induce organ injury through alternative mechanisms beyond direct viral infection, including immunologic injury. In some situations, hyperactivation of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 RNA can result in autoimmune disease. COVID-19 has been associated with immune-mediated systemic or organ-selective manifestations, some of which fulfill the diagnostic or classification criteria of specific autoimmune diseases. It is unclear whether those medical disorders are the result of transitory postinfectious epiphenomena.5

A few studies have shown that patients with rheumatic disease have an incidence and prevalence of COVID-19 that is similar to the general population. A similar pattern has been detected in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates, even among patients with an autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren syndrome.5,17 Furthermore, exacerbation of preexisting rheumatic symptoms may be due to hyperactivation of antiviral pathways in a person with an autoimmune disease.17-19 The findings in our patient suggested a direct role for the vaccine in skin manifestations, rather than for reactivation or development of new systemic autoimmune processes, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination has been described20; however, the case patient did not have a history of psoriasis. The mechanism(s) of such exacerbation remain unclear; COVID-19 vaccine–induced helper T cells (TH17) may play a role.21 Other skin manifestations encountered following COVID-19 vaccination include lichen planus, leukocytoclastic vasculitic rash, erythema multiforme–like rash, and pityriasis rosea–like rash.22-25 The immune mechanisms of these manifestations remain unclear.

The clinical presentation of delayed vaccination reactions can be attributed to the timing of symptoms and, in this case, the immune-mediated background of a psoriasiform reaction. Although adverse reactions to the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine are rare, more individuals should be studied after vaccination to confirm and better understand this phenomenon.

- Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, et al; . An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1920-1931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022483

- Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, et al; . Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2427-2438. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028436

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Weise E. ‘COVID arm’ rash seen after Moderna vaccine annoying but harmless, doctors say. USA Today. January 27, 2021. Accessed September 4, 2022. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2021/01/27/covid-arm-moderna-vaccine-rash-harmless-side-effect-doctors-say/4277725001/

- Talotta R, Robertson E. Autoimmunity as the comet tail of COVID-19 pandemic. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:3621-3644. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v8.i17.3621

- Castells MC, Phillips EJ. Maintaining safety with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:643-649. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2035343

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al; . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603-2615. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2034577

- Dooling K, McClung N, Chamberland M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID-19 vaccine—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1857-1859. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e1

- Roguedas AM, Misery L, Sassolas B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of primary Sjögren’s syndrome are underestimated. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:632-636.

- Katayama I. Dry skin manifestations in Sjögren syndrome and atopic dermatitis related to aberrant sudomotor function in inflammatory allergic skin diseases. Allergol Int. 2018;67:448-454. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2018.07.001

- Generali E, Costanzo A, Mainetti C, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:357-370. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8639-y

- Chanprapaph K, Tankunakorn J, Suchonwanit P, et al. Dermatologic manifestations, histologic features and disease progression among cutaneous lupus erythematosus subtypes: a prospective observational study in Asians. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:131-147. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00471-y

- Ortega-Quijano D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Selda-Enriquez G, et al. Algorithm for the classification of COVID-19 rashes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e103-e104. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.034

- Rahimi H, Tehranchinia Z. A comprehensive review of cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID-19. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1236520. doi:10.1155/2020/1236520

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:75-81. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.04.011

- Landa N, Mendieta-Eckert M, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Chilblain-like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:739-743. doi:10.1111/ijd.14937

- Dellavance A, Coelho Andrade LE. Immunologic derangement preceding clinical autoimmunity. Lupus. 2014;23:1305-1308. doi:10.1177/0961203314531346

- Parodi A, Gasparini G, Cozzani E. Could antiphospholipid antibodies contribute to coagulopathy in COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e249. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.003

- Zhou Y, Han T, Chen J, et al. Clinical and autoimmune characteristics of severe and critical cases of COVID-19. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13:1077-1086. doi:10.1111/cts.12805

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.812010

- Rouai M, Slimane MB, Sassi W, et al. Pustular rash triggered by Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022:e15465. doi:10.1111/dth.15465

- Altun E, Kuzucular E. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis after COVID-19 vaccination. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15279. doi:10.1111/dth.15279

- Buckley JE, Landis LN, Rapini RP. Pityriasis rosea-like rash after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination: a case report and review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2022;7:164-168. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.009

- Gökçek GE, Öksüm Solak E, Çölgeçen E. Pityriasis rosea like eruption: a dermatological manifestation of Coronavac-COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15256. doi:10.1111/dth.15256

- Kim MJ, Kim JW, Kim MS, et al. Generalized erythema multiforme-like skin rash following the first dose of COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:e98-e100. doi:10.1111/jdv.17757

- Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, et al; . An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1920-1931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022483

- Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, et al; . Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2427-2438. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028436

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Weise E. ‘COVID arm’ rash seen after Moderna vaccine annoying but harmless, doctors say. USA Today. January 27, 2021. Accessed September 4, 2022. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2021/01/27/covid-arm-moderna-vaccine-rash-harmless-side-effect-doctors-say/4277725001/

- Talotta R, Robertson E. Autoimmunity as the comet tail of COVID-19 pandemic. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:3621-3644. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v8.i17.3621

- Castells MC, Phillips EJ. Maintaining safety with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:643-649. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2035343

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al; . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603-2615. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2034577

- Dooling K, McClung N, Chamberland M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID-19 vaccine—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1857-1859. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e1

- Roguedas AM, Misery L, Sassolas B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of primary Sjögren’s syndrome are underestimated. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:632-636.

- Katayama I. Dry skin manifestations in Sjögren syndrome and atopic dermatitis related to aberrant sudomotor function in inflammatory allergic skin diseases. Allergol Int. 2018;67:448-454. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2018.07.001

- Generali E, Costanzo A, Mainetti C, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:357-370. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8639-y

- Chanprapaph K, Tankunakorn J, Suchonwanit P, et al. Dermatologic manifestations, histologic features and disease progression among cutaneous lupus erythematosus subtypes: a prospective observational study in Asians. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:131-147. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00471-y

- Ortega-Quijano D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Selda-Enriquez G, et al. Algorithm for the classification of COVID-19 rashes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e103-e104. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.034

- Rahimi H, Tehranchinia Z. A comprehensive review of cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID-19. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1236520. doi:10.1155/2020/1236520

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:75-81. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.04.011

- Landa N, Mendieta-Eckert M, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Chilblain-like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:739-743. doi:10.1111/ijd.14937

- Dellavance A, Coelho Andrade LE. Immunologic derangement preceding clinical autoimmunity. Lupus. 2014;23:1305-1308. doi:10.1177/0961203314531346

- Parodi A, Gasparini G, Cozzani E. Could antiphospholipid antibodies contribute to coagulopathy in COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e249. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.003

- Zhou Y, Han T, Chen J, et al. Clinical and autoimmune characteristics of severe and critical cases of COVID-19. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13:1077-1086. doi:10.1111/cts.12805

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.812010

- Rouai M, Slimane MB, Sassi W, et al. Pustular rash triggered by Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022:e15465. doi:10.1111/dth.15465

- Altun E, Kuzucular E. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis after COVID-19 vaccination. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15279. doi:10.1111/dth.15279

- Buckley JE, Landis LN, Rapini RP. Pityriasis rosea-like rash after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination: a case report and review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2022;7:164-168. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.009

- Gökçek GE, Öksüm Solak E, Çölgeçen E. Pityriasis rosea like eruption: a dermatological manifestation of Coronavac-COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15256. doi:10.1111/dth.15256

- Kim MJ, Kim JW, Kim MS, et al. Generalized erythema multiforme-like skin rash following the first dose of COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:e98-e100. doi:10.1111/jdv.17757

PRACTICE POINTS

- The differential diagnosis for a new-onset psoriasiform rash in an elderly patient should include a vaccine-related rash.

- A rash following vaccination that necessitates systemic corticosteroid therapy can decrease vaccine efficacy.

Yellow Papules and Plaques on a Child

The Diagnosis: Tuberous Xanthoma

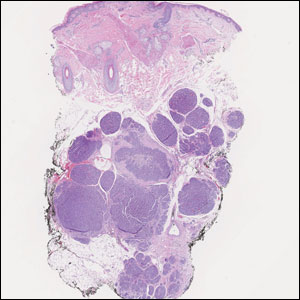

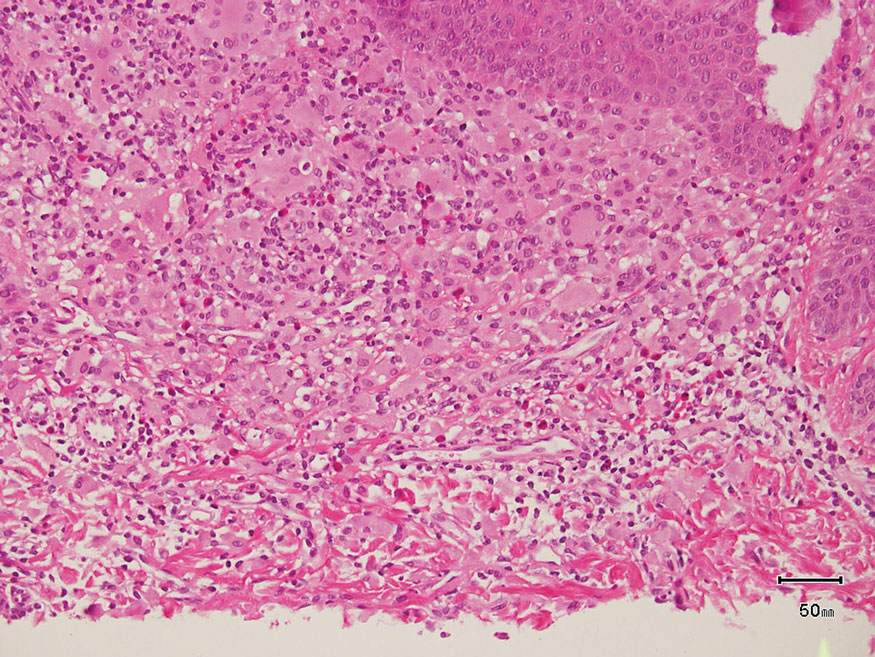

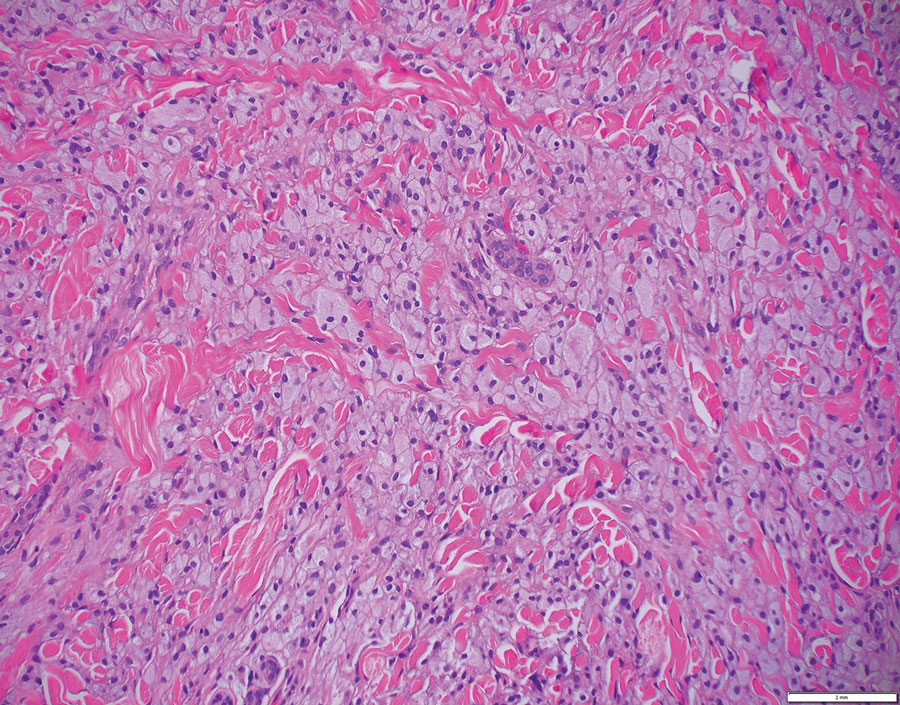

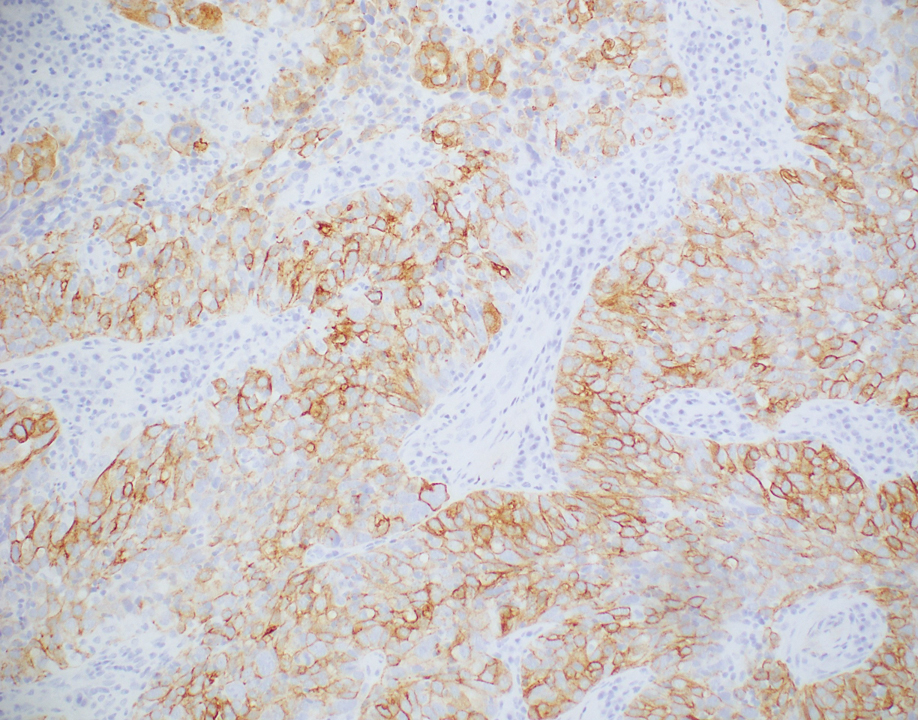

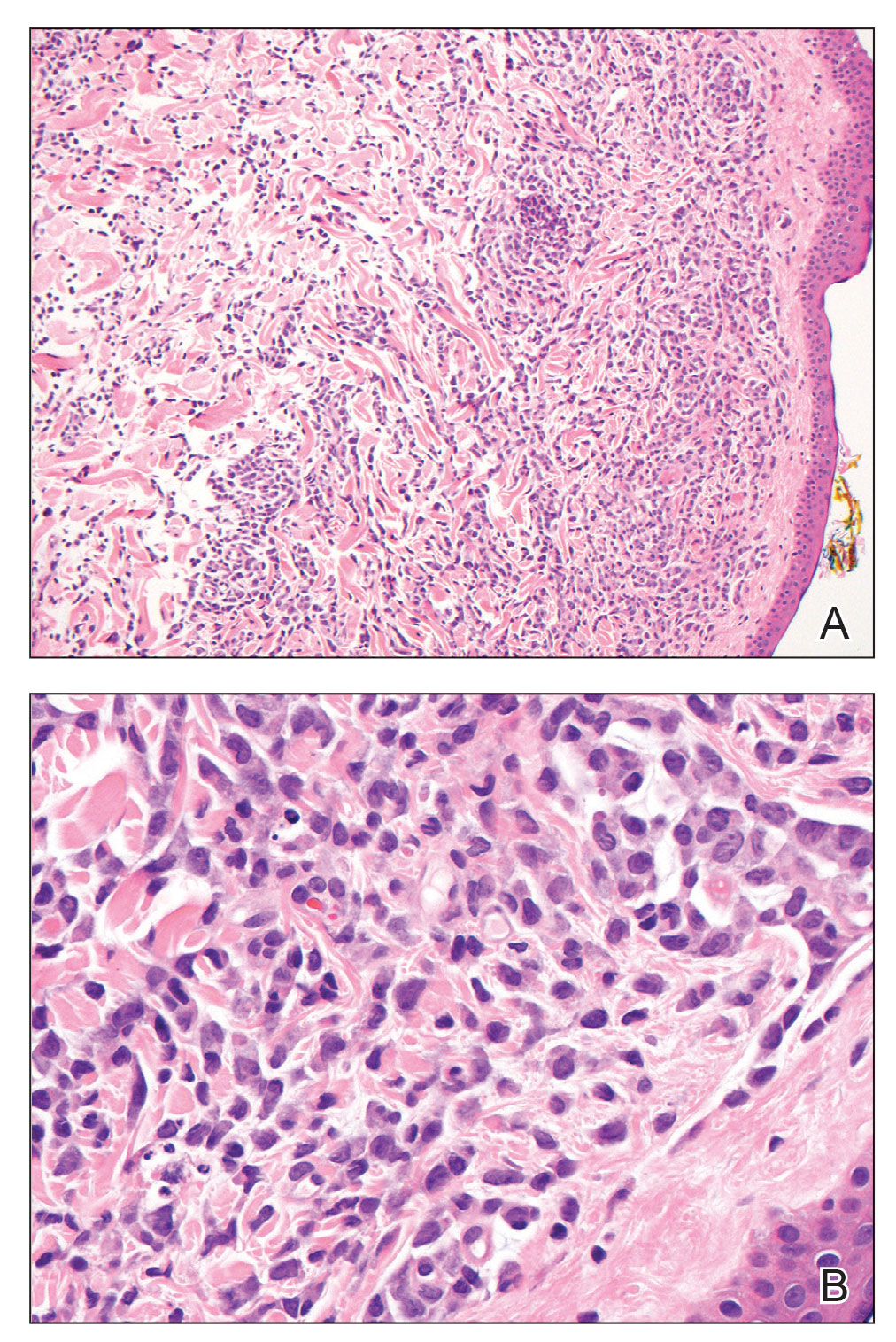

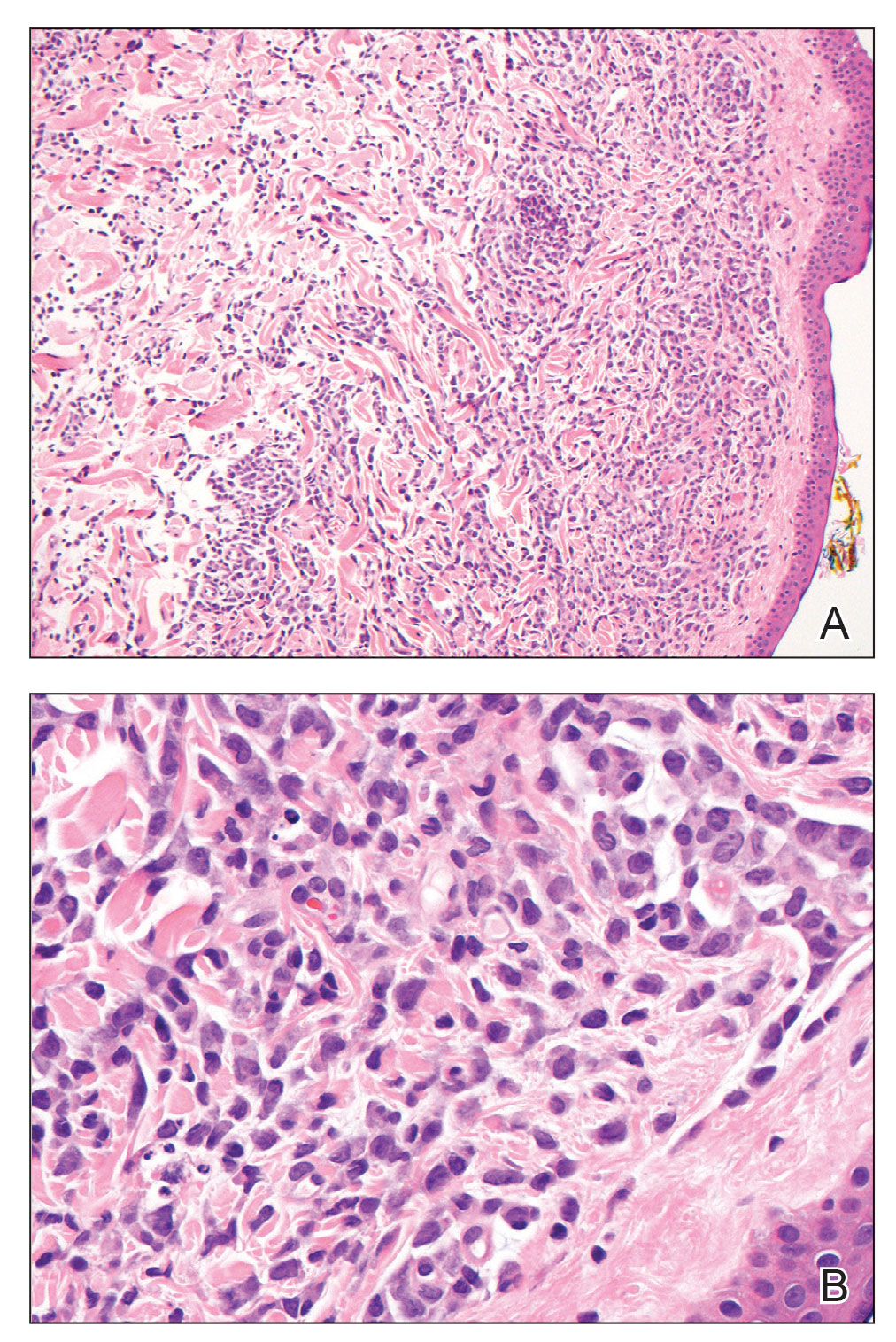

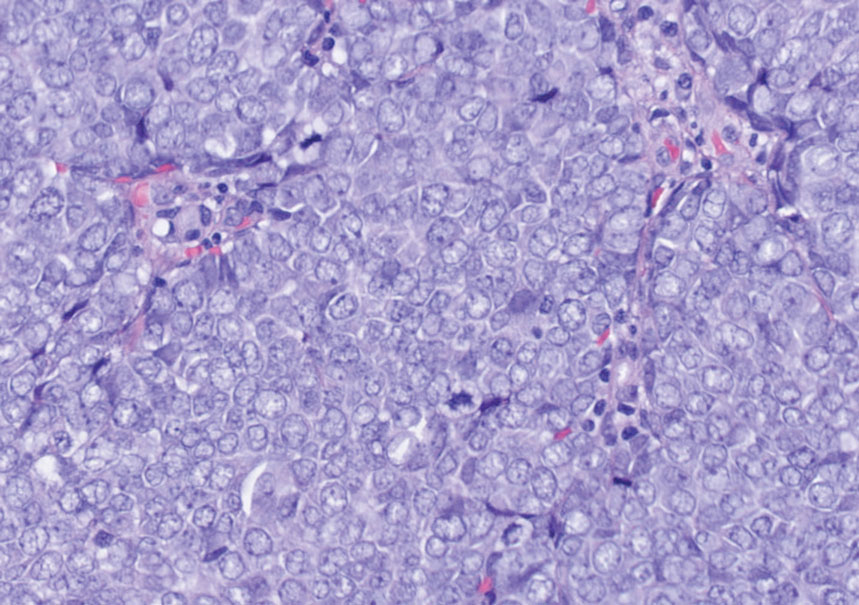

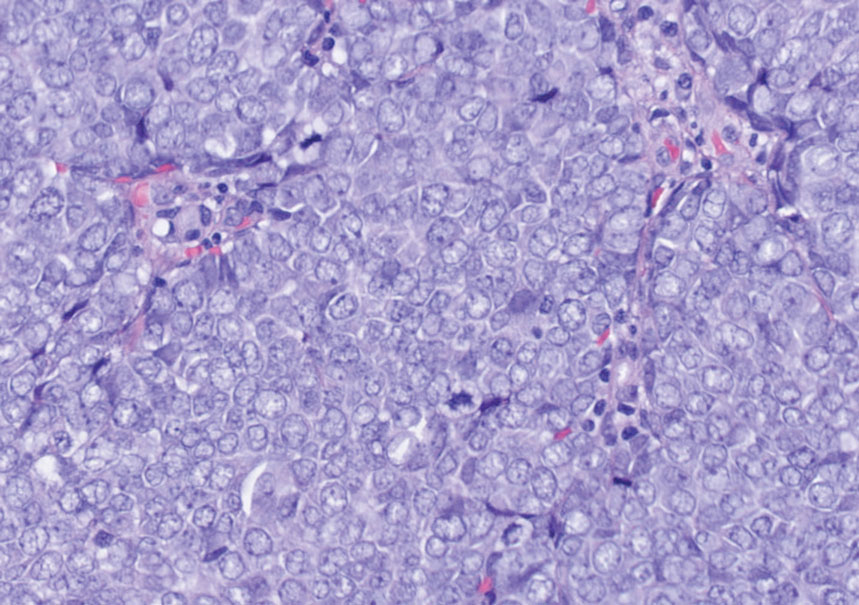

The skin biopsy revealed a nodular collection of foam cells (quiz image [bottom]). Tuberous xanthoma was the most likely diagnosis based on the patient’s history as well as the clinical and histologic findings. Tuberous xanthomas are flat or elevated nodules in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, commonly occurring on the skin over the joints.1 Smaller nodules and papules often are referred to as tuberoeruptive xanthomas and exist on a continuum with the larger tuberous xanthomas. All xanthomas appear histologically similar, with collections of foam cells present within the dermis.2 Foam cells form when serum lipoproteins diffuse through capillary walls, deposit in the skin or tendons, and are scavenged by monocytes.3 Tuberous xanthomas, along with tendinous, eruptive, and planar xanthomas, are the most likely to be associated with hyperlipidemia.4 They may indicate an underlying disorder of lipid metabolism, such as familial hypercholesterolemia.1,3 This is the most common cause of inheritable cardiovascular disease, with a prevalence of approximately 1:250.2 Premature cardiovascular disease risk increases 2 to 4 times in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia and tendinous xanthomas,1 illustrating that recognition of cutaneous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and prevention of patient morbidity and mortality.

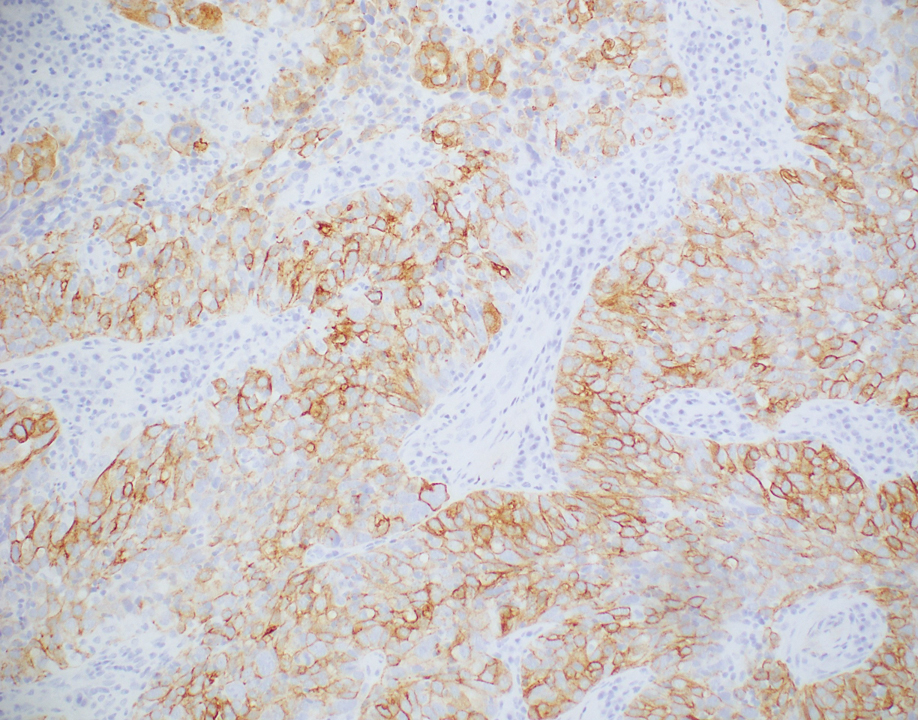

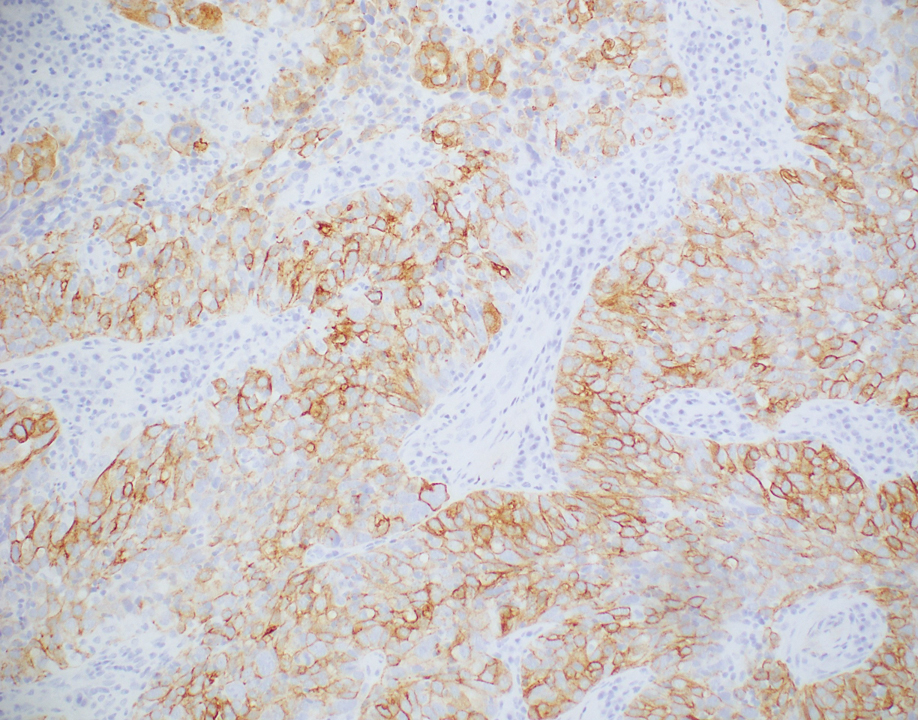

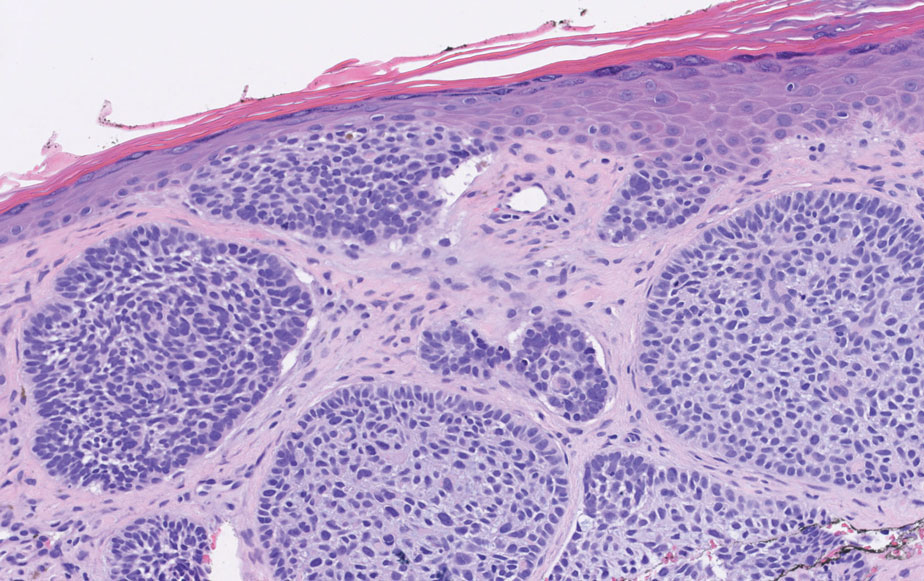

Juvenile xanthogranuloma typically presents as smooth yellow papules or nodules on the head and neck, with a characteristic “setting-sun” appearance (ie, yellow center with an erythematous halo) on dermoscopy.5 Histologically, juvenile xanthogranulomas are composed of foam cells and a mixed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils within the dermis. Giant cells with a ring of nuclei surrounded by cytoplasm containing lipid vacuoles (called Touton giant cells) are characteristic (Figure 1). In contrast to tuberous xanthomas, juvenile xanthogranulomas often present within the first year of life.6

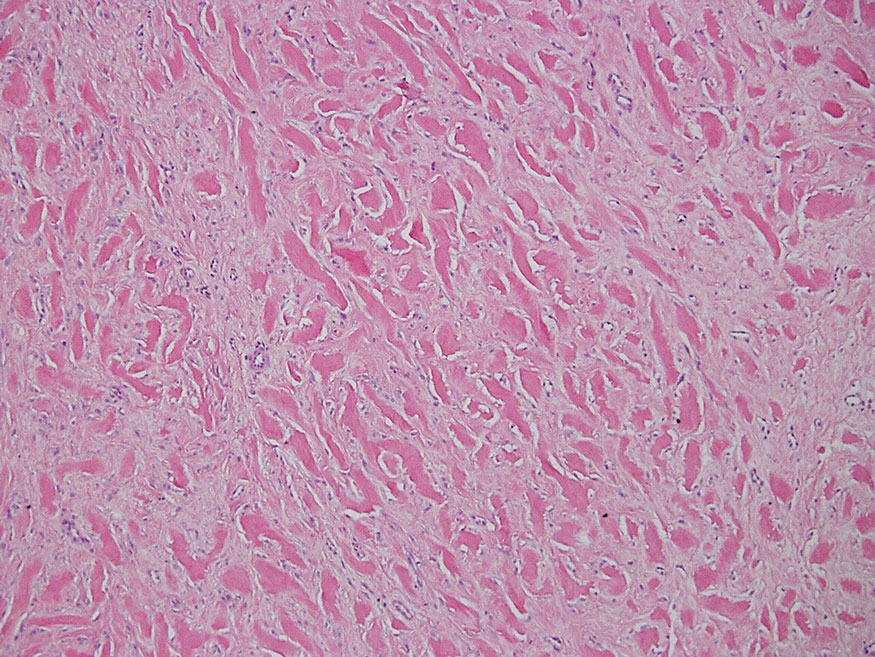

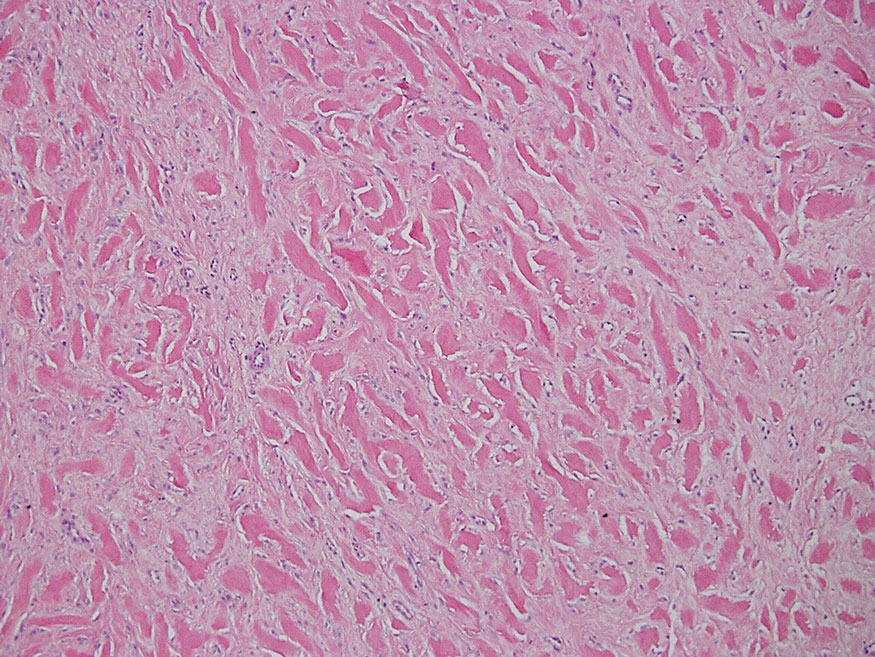

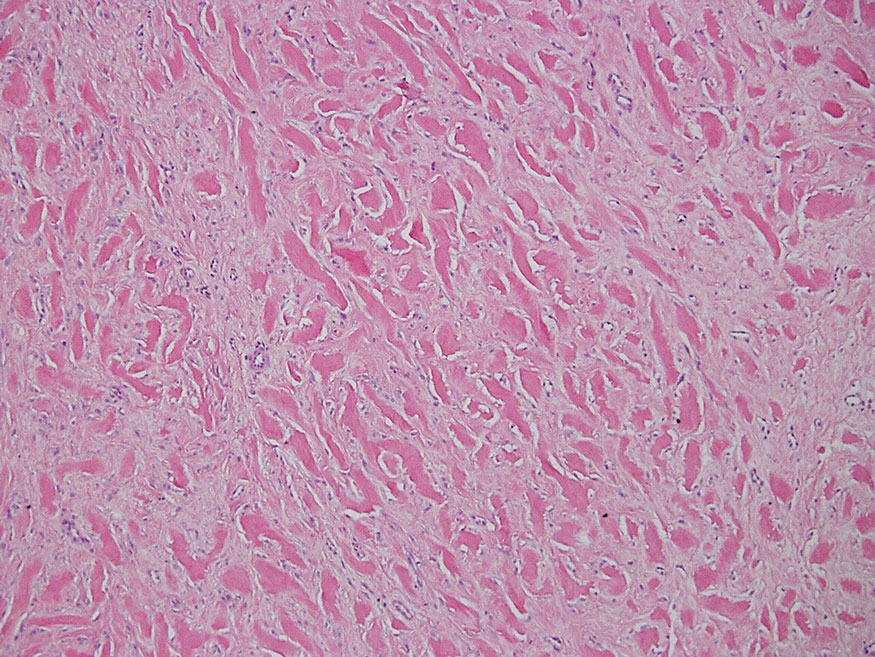

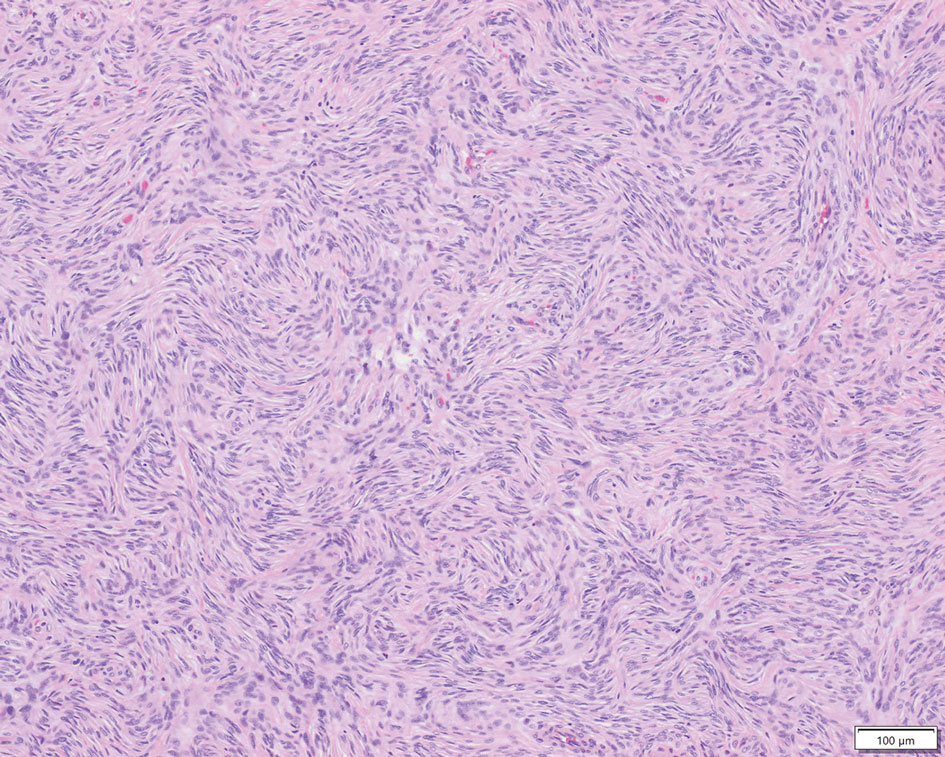

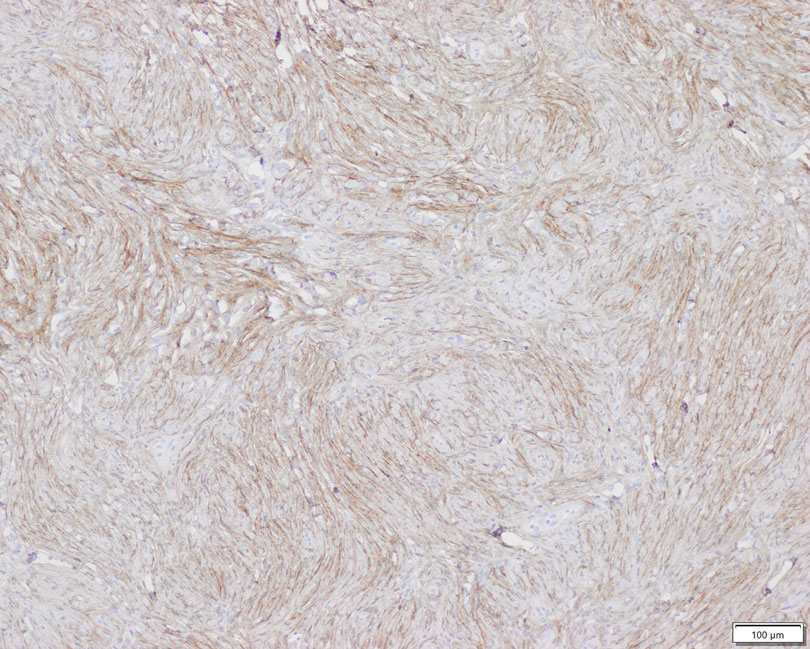

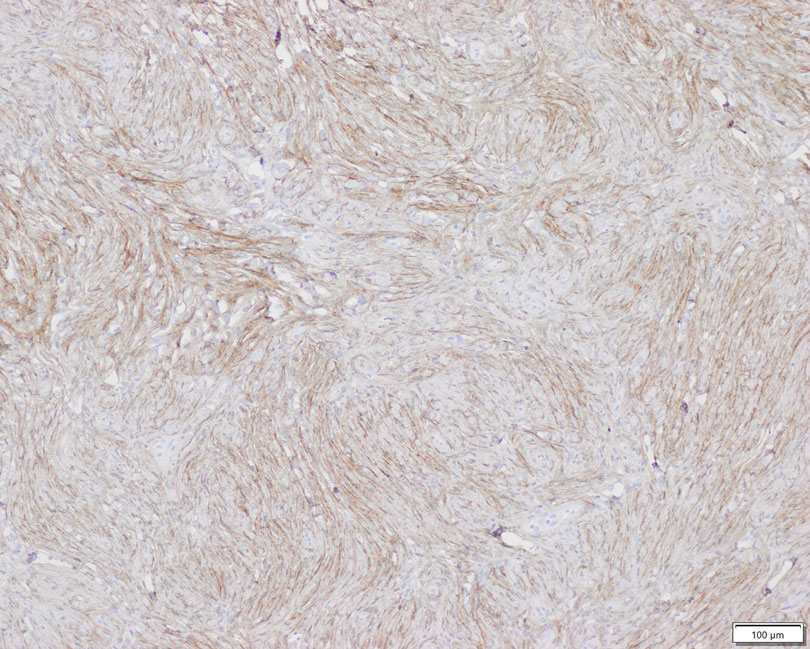

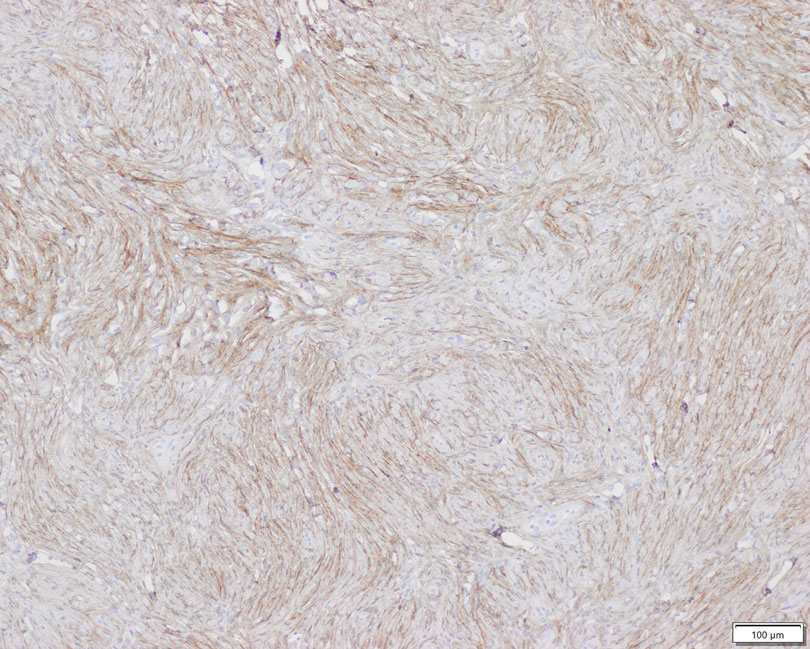

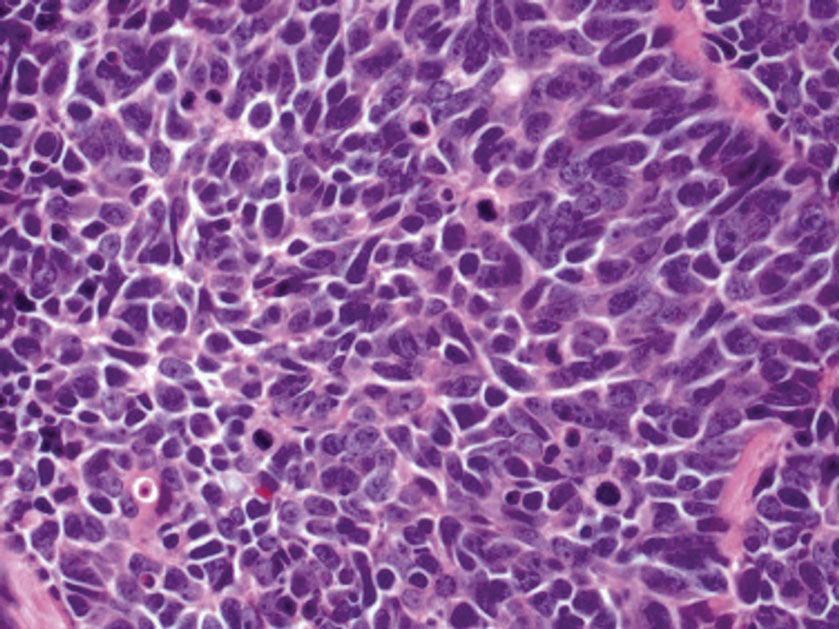

Keloid scars are more prevalent in patients with skin of color. They are characterized by eosinophilic keloidal collagen with a whorled proliferation of fibroblasts on histology (Figure 2).7 They occur spontaneously or at sites of injury and present as bluish-red or flesh-colored firm papules or nodules.8 In our patient, keloid scars were an unlikely diagnosis due to the lack of trauma and the absence of keloidal collagen on histology.

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum typically presents as an erythematous, yellow-brown, circular plaque on the anterior lower leg in patients with diabetes mellitus; it rarely occurs in children.9 Microscopy shows palisaded granulomas surrounding necrobiotic collagen arranged horizontally in a layer cake–like fashion (Figure 3).9,10 The etiology of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum currently is unknown, though immune complex deposition may contribute to its pathology. It has been associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus, though severity of the lesions is not associated with extent of glycemic control.10

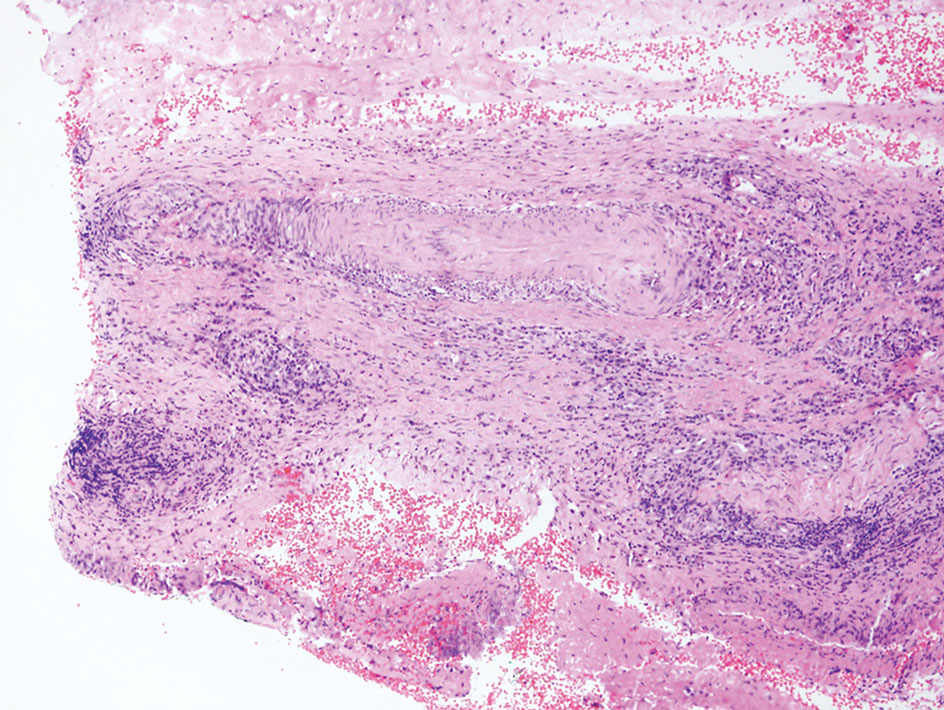

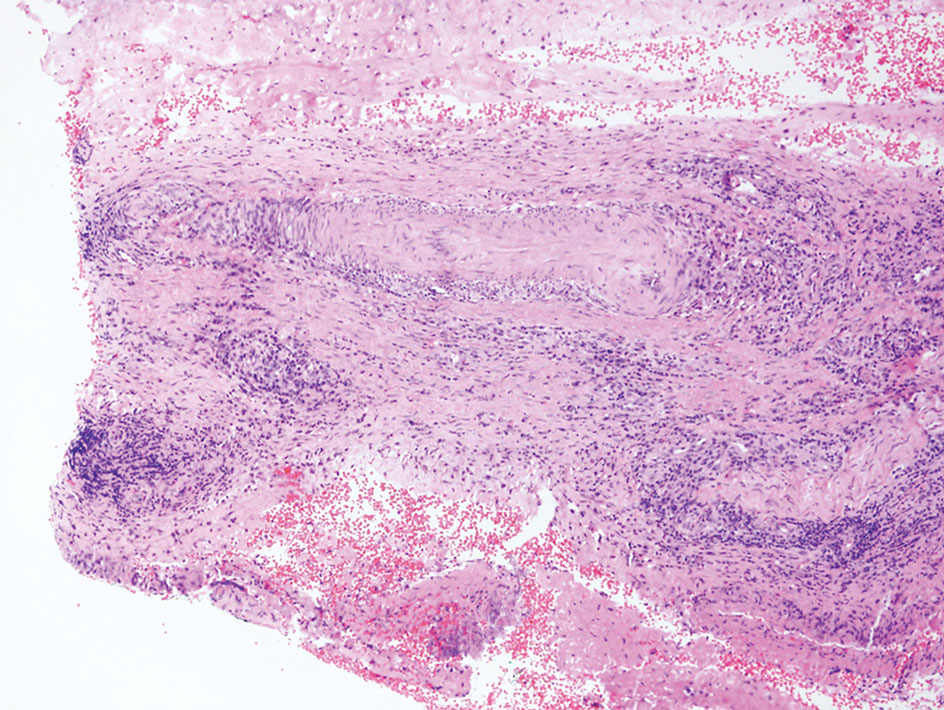

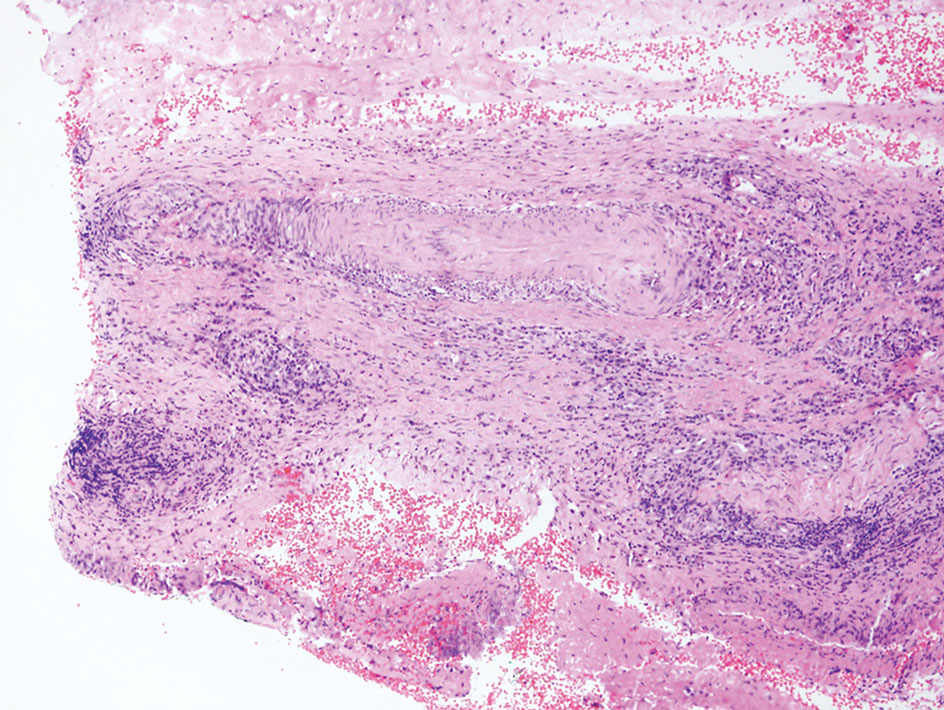

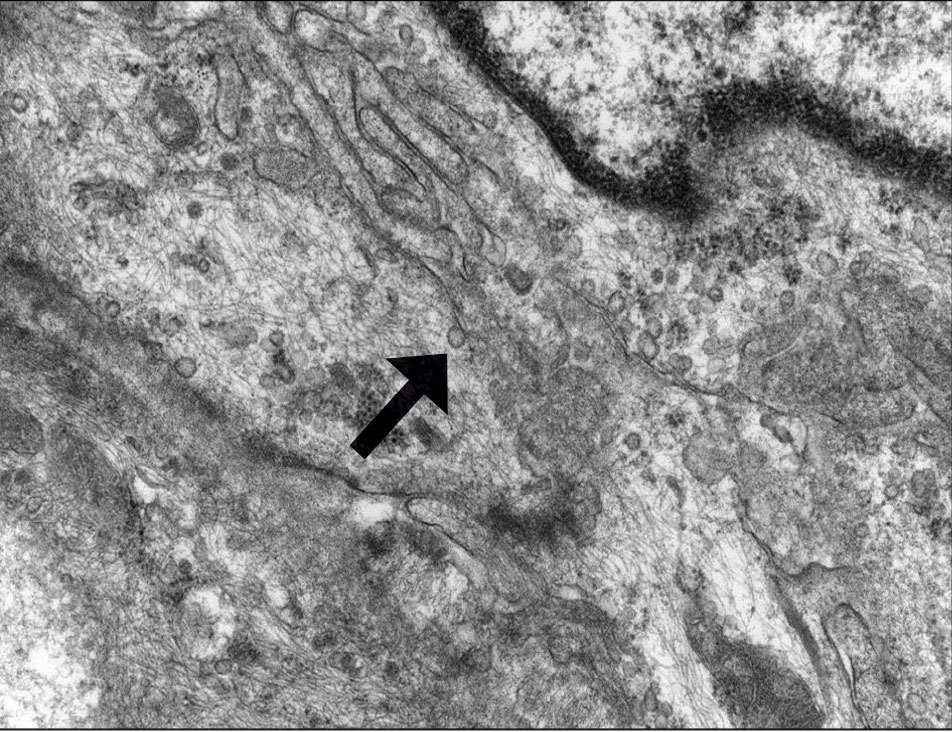

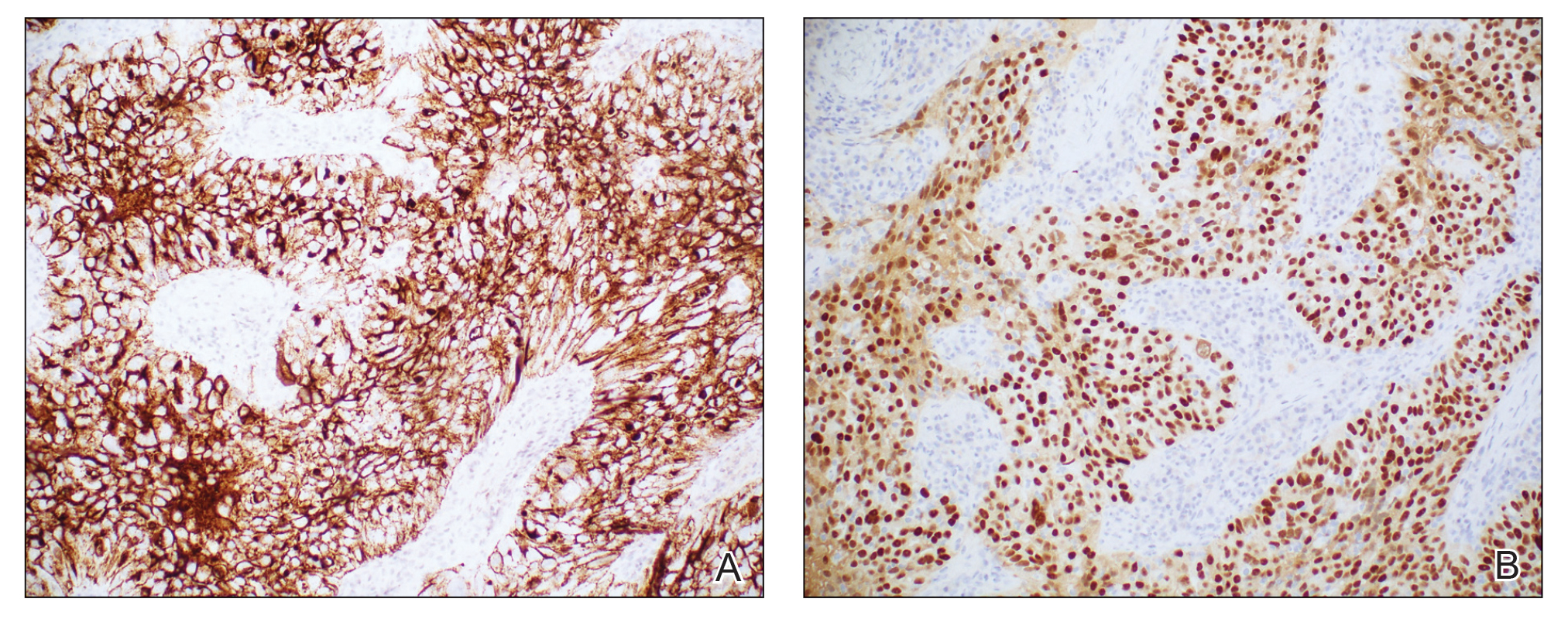

Rosai-Dorfman disease is an uncommon disorder characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes that most often presents as bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy in children and young adults but rarely can present with cutaneous lesions when extranodal involvement is present.11,12 The cutaneous form most commonly presents as red papules or nodules. On histology, the lesions exhibit a nodular dermal proliferation of histiocytes and smaller lymphocytoid cells with a marbled or starry sky–like appearance on low power (Figure 4). On higher magnification, the characteristic finding of emperipolesis can be seen.11 On immunohistochemistry, the histiocytes stain positively for CD68 and S-100. Although the pathogenesis currently is unknown, evidence of clonality indicates the disease may be related to a neoplastic process.12

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Ison HE, Clarke SL, Knowles JW. Familial hypercholesterolemia. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK174884/

- Sathiyakumar V, Jones SR, Martin SS. Xanthomas and lipoprotein disorders. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Massangale WT. Xanthomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, et al, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1634-1643.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526103/

- Hernández-San Martín MJ, Vargas-Mora P, Aranibar L. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: an entity with a wide clinical spectrum. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2020;111:725-733. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2020.07.004

- Lee JY, Yang C, Chao S, et al. Histopathological differential diagnosis of keloid and hypertrophic scar. Am J Dermatopathology. 2004;26:379-384.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP, et al. Benign neoplasms and hyperplasias. In: Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 8th ed. McGraw Hill; 2017:141-188.

- Bonura C, Frontino G, Rigamonti A, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a pediatric case report. Dermatoendocrinol. 2014;6:E27790. doi:10.4161/derm.27790

- Lepe K, Riley CA, Salazar FJ. Necrobiosis lipoidica. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kumc.edu/books/NBK459318/

- Parrent T, Clark T, Hall D. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Cutis. 2012;90:237-238.

- Bruce-Brand C, Schneider JW, Schubert P. Rosai-Dorfman disease: an overview. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73:697-705. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206733

The Diagnosis: Tuberous Xanthoma

The skin biopsy revealed a nodular collection of foam cells (quiz image [bottom]). Tuberous xanthoma was the most likely diagnosis based on the patient’s history as well as the clinical and histologic findings. Tuberous xanthomas are flat or elevated nodules in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, commonly occurring on the skin over the joints.1 Smaller nodules and papules often are referred to as tuberoeruptive xanthomas and exist on a continuum with the larger tuberous xanthomas. All xanthomas appear histologically similar, with collections of foam cells present within the dermis.2 Foam cells form when serum lipoproteins diffuse through capillary walls, deposit in the skin or tendons, and are scavenged by monocytes.3 Tuberous xanthomas, along with tendinous, eruptive, and planar xanthomas, are the most likely to be associated with hyperlipidemia.4 They may indicate an underlying disorder of lipid metabolism, such as familial hypercholesterolemia.1,3 This is the most common cause of inheritable cardiovascular disease, with a prevalence of approximately 1:250.2 Premature cardiovascular disease risk increases 2 to 4 times in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia and tendinous xanthomas,1 illustrating that recognition of cutaneous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and prevention of patient morbidity and mortality.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma typically presents as smooth yellow papules or nodules on the head and neck, with a characteristic “setting-sun” appearance (ie, yellow center with an erythematous halo) on dermoscopy.5 Histologically, juvenile xanthogranulomas are composed of foam cells and a mixed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils within the dermis. Giant cells with a ring of nuclei surrounded by cytoplasm containing lipid vacuoles (called Touton giant cells) are characteristic (Figure 1). In contrast to tuberous xanthomas, juvenile xanthogranulomas often present within the first year of life.6

Keloid scars are more prevalent in patients with skin of color. They are characterized by eosinophilic keloidal collagen with a whorled proliferation of fibroblasts on histology (Figure 2).7 They occur spontaneously or at sites of injury and present as bluish-red or flesh-colored firm papules or nodules.8 In our patient, keloid scars were an unlikely diagnosis due to the lack of trauma and the absence of keloidal collagen on histology.

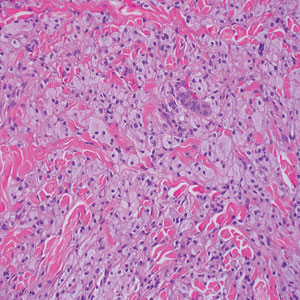

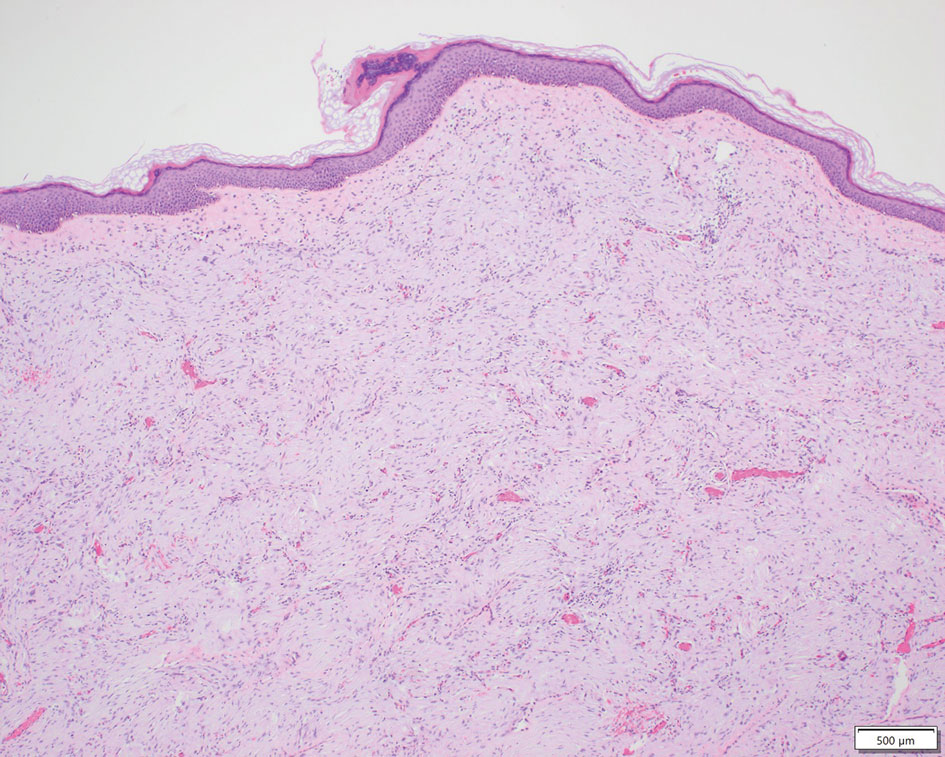

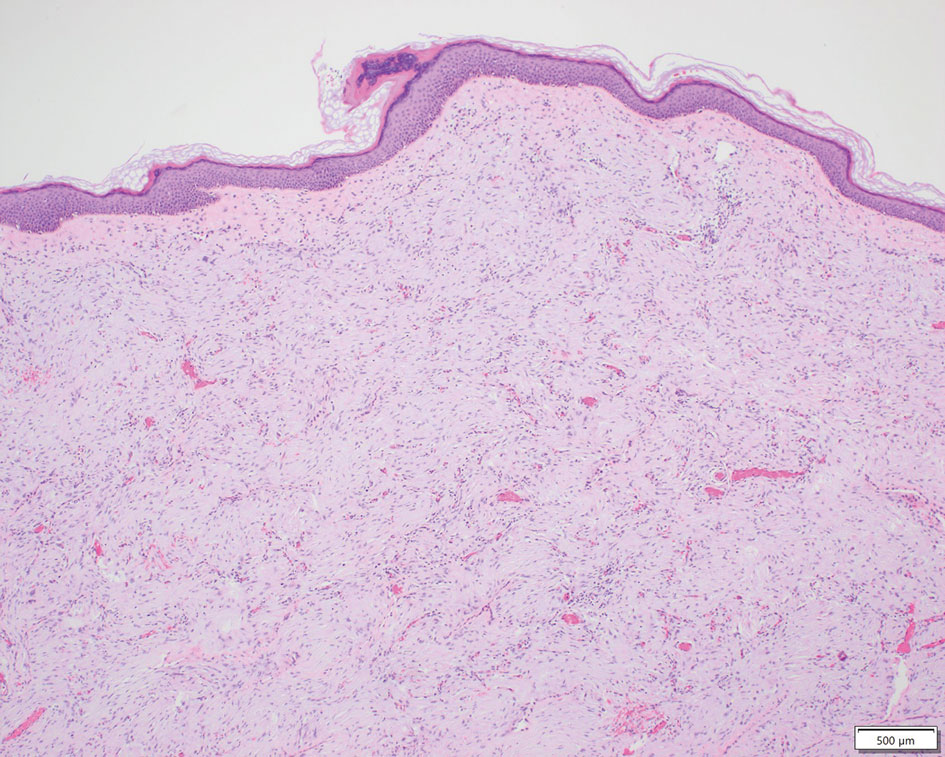

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum typically presents as an erythematous, yellow-brown, circular plaque on the anterior lower leg in patients with diabetes mellitus; it rarely occurs in children.9 Microscopy shows palisaded granulomas surrounding necrobiotic collagen arranged horizontally in a layer cake–like fashion (Figure 3).9,10 The etiology of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum currently is unknown, though immune complex deposition may contribute to its pathology. It has been associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus, though severity of the lesions is not associated with extent of glycemic control.10

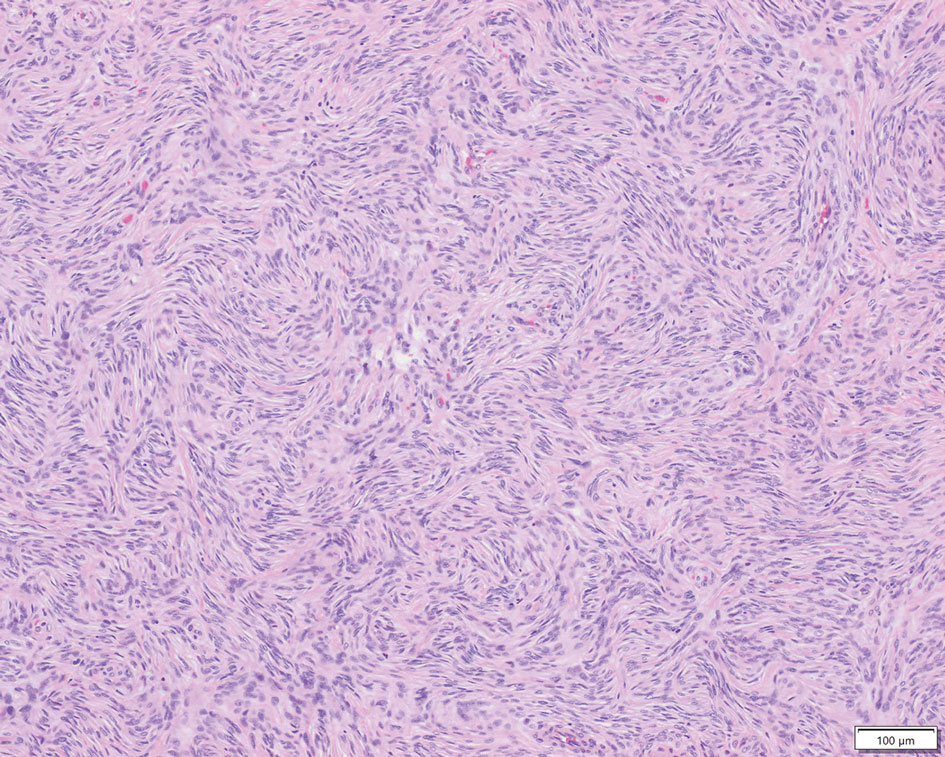

Rosai-Dorfman disease is an uncommon disorder characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes that most often presents as bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy in children and young adults but rarely can present with cutaneous lesions when extranodal involvement is present.11,12 The cutaneous form most commonly presents as red papules or nodules. On histology, the lesions exhibit a nodular dermal proliferation of histiocytes and smaller lymphocytoid cells with a marbled or starry sky–like appearance on low power (Figure 4). On higher magnification, the characteristic finding of emperipolesis can be seen.11 On immunohistochemistry, the histiocytes stain positively for CD68 and S-100. Although the pathogenesis currently is unknown, evidence of clonality indicates the disease may be related to a neoplastic process.12

The Diagnosis: Tuberous Xanthoma

The skin biopsy revealed a nodular collection of foam cells (quiz image [bottom]). Tuberous xanthoma was the most likely diagnosis based on the patient’s history as well as the clinical and histologic findings. Tuberous xanthomas are flat or elevated nodules in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, commonly occurring on the skin over the joints.1 Smaller nodules and papules often are referred to as tuberoeruptive xanthomas and exist on a continuum with the larger tuberous xanthomas. All xanthomas appear histologically similar, with collections of foam cells present within the dermis.2 Foam cells form when serum lipoproteins diffuse through capillary walls, deposit in the skin or tendons, and are scavenged by monocytes.3 Tuberous xanthomas, along with tendinous, eruptive, and planar xanthomas, are the most likely to be associated with hyperlipidemia.4 They may indicate an underlying disorder of lipid metabolism, such as familial hypercholesterolemia.1,3 This is the most common cause of inheritable cardiovascular disease, with a prevalence of approximately 1:250.2 Premature cardiovascular disease risk increases 2 to 4 times in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia and tendinous xanthomas,1 illustrating that recognition of cutaneous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and prevention of patient morbidity and mortality.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma typically presents as smooth yellow papules or nodules on the head and neck, with a characteristic “setting-sun” appearance (ie, yellow center with an erythematous halo) on dermoscopy.5 Histologically, juvenile xanthogranulomas are composed of foam cells and a mixed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils within the dermis. Giant cells with a ring of nuclei surrounded by cytoplasm containing lipid vacuoles (called Touton giant cells) are characteristic (Figure 1). In contrast to tuberous xanthomas, juvenile xanthogranulomas often present within the first year of life.6

Keloid scars are more prevalent in patients with skin of color. They are characterized by eosinophilic keloidal collagen with a whorled proliferation of fibroblasts on histology (Figure 2).7 They occur spontaneously or at sites of injury and present as bluish-red or flesh-colored firm papules or nodules.8 In our patient, keloid scars were an unlikely diagnosis due to the lack of trauma and the absence of keloidal collagen on histology.

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum typically presents as an erythematous, yellow-brown, circular plaque on the anterior lower leg in patients with diabetes mellitus; it rarely occurs in children.9 Microscopy shows palisaded granulomas surrounding necrobiotic collagen arranged horizontally in a layer cake–like fashion (Figure 3).9,10 The etiology of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum currently is unknown, though immune complex deposition may contribute to its pathology. It has been associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus, though severity of the lesions is not associated with extent of glycemic control.10

Rosai-Dorfman disease is an uncommon disorder characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes that most often presents as bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy in children and young adults but rarely can present with cutaneous lesions when extranodal involvement is present.11,12 The cutaneous form most commonly presents as red papules or nodules. On histology, the lesions exhibit a nodular dermal proliferation of histiocytes and smaller lymphocytoid cells with a marbled or starry sky–like appearance on low power (Figure 4). On higher magnification, the characteristic finding of emperipolesis can be seen.11 On immunohistochemistry, the histiocytes stain positively for CD68 and S-100. Although the pathogenesis currently is unknown, evidence of clonality indicates the disease may be related to a neoplastic process.12

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Ison HE, Clarke SL, Knowles JW. Familial hypercholesterolemia. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK174884/

- Sathiyakumar V, Jones SR, Martin SS. Xanthomas and lipoprotein disorders. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Massangale WT. Xanthomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, et al, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1634-1643.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526103/

- Hernández-San Martín MJ, Vargas-Mora P, Aranibar L. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: an entity with a wide clinical spectrum. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2020;111:725-733. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2020.07.004

- Lee JY, Yang C, Chao S, et al. Histopathological differential diagnosis of keloid and hypertrophic scar. Am J Dermatopathology. 2004;26:379-384.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP, et al. Benign neoplasms and hyperplasias. In: Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 8th ed. McGraw Hill; 2017:141-188.

- Bonura C, Frontino G, Rigamonti A, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a pediatric case report. Dermatoendocrinol. 2014;6:E27790. doi:10.4161/derm.27790

- Lepe K, Riley CA, Salazar FJ. Necrobiosis lipoidica. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kumc.edu/books/NBK459318/

- Parrent T, Clark T, Hall D. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Cutis. 2012;90:237-238.

- Bruce-Brand C, Schneider JW, Schubert P. Rosai-Dorfman disease: an overview. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73:697-705. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206733

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Ison HE, Clarke SL, Knowles JW. Familial hypercholesterolemia. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK174884/

- Sathiyakumar V, Jones SR, Martin SS. Xanthomas and lipoprotein disorders. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Massangale WT. Xanthomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, et al, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1634-1643.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526103/

- Hernández-San Martín MJ, Vargas-Mora P, Aranibar L. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: an entity with a wide clinical spectrum. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2020;111:725-733. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2020.07.004

- Lee JY, Yang C, Chao S, et al. Histopathological differential diagnosis of keloid and hypertrophic scar. Am J Dermatopathology. 2004;26:379-384.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP, et al. Benign neoplasms and hyperplasias. In: Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 8th ed. McGraw Hill; 2017:141-188.

- Bonura C, Frontino G, Rigamonti A, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a pediatric case report. Dermatoendocrinol. 2014;6:E27790. doi:10.4161/derm.27790

- Lepe K, Riley CA, Salazar FJ. Necrobiosis lipoidica. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kumc.edu/books/NBK459318/

- Parrent T, Clark T, Hall D. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Cutis. 2012;90:237-238.

- Bruce-Brand C, Schneider JW, Schubert P. Rosai-Dorfman disease: an overview. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73:697-705. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206733

A 3-year-old girl presented with raised, firm, enlarging, asymptomatic, well-defined, subcutaneous papules, plaques, and nodules on the hands, knees, and posterior ankles of 1 year’s duration. The patient’s mother stated that the lesions began on the ankles (top), and she initially believed them to be due to friction from the child’s shoes until the more recent involvement of the knees and hands. The patient’s father, paternal grandfather, and paternal great-grandfather had a history of elevated cholesterol levels. A shave biopsy was performed (bottom).

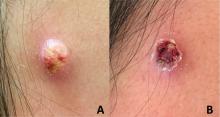

An adolescent male presents with an eroded bump on the temple

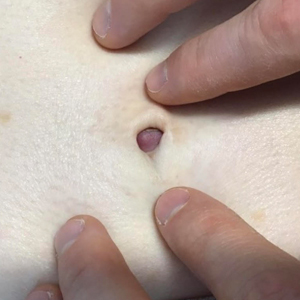

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign skin disorder caused by a pox virus and is frequently seen in children. This disease is transmitted primarily through direct skin contact with an infected individual.1 Contaminated fomites have been suggested as another source of infection.2 The typical lesion appears dome-shaped, round, and pinkish-purple in color.1 The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 6 months and is typically self-limited in immunocompetent hosts; however, in immunocompromised persons, molluscum contagiosum lesions may present atypically such that they are larger in size and/or resemble malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma (for single lesions), or other infectious diseases, such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis (for more numerous lesions).3,4 A giant atypical molluscum contagiosum is rarely seen in healthy individuals.

What’s on the differential?

The recent episode of bleeding raises concern for other neoplastic processes of the skin including squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma as well as cutaneous metastatic rhabdoid tumor, given the patient’s history.

Eruptive keratoacanthomas are also reported in patients taking nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which the patient has received for treatment of his recurrent metastatic rhabdoid tumor.5 More common entities such as a pyogenic granuloma or verruca are also included on the differential. The initial presentation of the lesion, however, is more consistent with the pearly umbilicated papules associated with molluscum contagiosum.

Comments from Dr. Eichenfield

This is a very hard diagnosis to make with the clinical findings and history.

Molluscum contagiosum infections are common, but with this patient’s medical history, biopsy and excision with pathologic examination was an appropriate approach to make a certain diagnosis.

Ms. Moyal is a research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

References

1. Brown J et al. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;45(2):93-9.

2. Hanson D and Diven DG. Dermatol Online J. 2003 Mar;9(2).

3. Badri T and Gandhi GR. Molluscum contagiosum. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing.

4. Schwartz JJ and Myskowski PL. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Oct 1;27(4):583-8.

5. Antonov NK et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Apr 5;5(4):342-5.

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign skin disorder caused by a pox virus and is frequently seen in children. This disease is transmitted primarily through direct skin contact with an infected individual.1 Contaminated fomites have been suggested as another source of infection.2 The typical lesion appears dome-shaped, round, and pinkish-purple in color.1 The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 6 months and is typically self-limited in immunocompetent hosts; however, in immunocompromised persons, molluscum contagiosum lesions may present atypically such that they are larger in size and/or resemble malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma (for single lesions), or other infectious diseases, such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis (for more numerous lesions).3,4 A giant atypical molluscum contagiosum is rarely seen in healthy individuals.

What’s on the differential?

The recent episode of bleeding raises concern for other neoplastic processes of the skin including squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma as well as cutaneous metastatic rhabdoid tumor, given the patient’s history.

Eruptive keratoacanthomas are also reported in patients taking nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which the patient has received for treatment of his recurrent metastatic rhabdoid tumor.5 More common entities such as a pyogenic granuloma or verruca are also included on the differential. The initial presentation of the lesion, however, is more consistent with the pearly umbilicated papules associated with molluscum contagiosum.

Comments from Dr. Eichenfield

This is a very hard diagnosis to make with the clinical findings and history.

Molluscum contagiosum infections are common, but with this patient’s medical history, biopsy and excision with pathologic examination was an appropriate approach to make a certain diagnosis.

Ms. Moyal is a research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

References

1. Brown J et al. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;45(2):93-9.

2. Hanson D and Diven DG. Dermatol Online J. 2003 Mar;9(2).

3. Badri T and Gandhi GR. Molluscum contagiosum. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing.

4. Schwartz JJ and Myskowski PL. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Oct 1;27(4):583-8.

5. Antonov NK et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Apr 5;5(4):342-5.

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign skin disorder caused by a pox virus and is frequently seen in children. This disease is transmitted primarily through direct skin contact with an infected individual.1 Contaminated fomites have been suggested as another source of infection.2 The typical lesion appears dome-shaped, round, and pinkish-purple in color.1 The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 6 months and is typically self-limited in immunocompetent hosts; however, in immunocompromised persons, molluscum contagiosum lesions may present atypically such that they are larger in size and/or resemble malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma (for single lesions), or other infectious diseases, such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis (for more numerous lesions).3,4 A giant atypical molluscum contagiosum is rarely seen in healthy individuals.

What’s on the differential?

The recent episode of bleeding raises concern for other neoplastic processes of the skin including squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma as well as cutaneous metastatic rhabdoid tumor, given the patient’s history.

Eruptive keratoacanthomas are also reported in patients taking nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which the patient has received for treatment of his recurrent metastatic rhabdoid tumor.5 More common entities such as a pyogenic granuloma or verruca are also included on the differential. The initial presentation of the lesion, however, is more consistent with the pearly umbilicated papules associated with molluscum contagiosum.

Comments from Dr. Eichenfield

This is a very hard diagnosis to make with the clinical findings and history.

Molluscum contagiosum infections are common, but with this patient’s medical history, biopsy and excision with pathologic examination was an appropriate approach to make a certain diagnosis.

Ms. Moyal is a research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

References

1. Brown J et al. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;45(2):93-9.

2. Hanson D and Diven DG. Dermatol Online J. 2003 Mar;9(2).

3. Badri T and Gandhi GR. Molluscum contagiosum. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing.

4. Schwartz JJ and Myskowski PL. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Oct 1;27(4):583-8.

5. Antonov NK et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Apr 5;5(4):342-5.

Painful and Pruritic Eruptions on the Entire Body

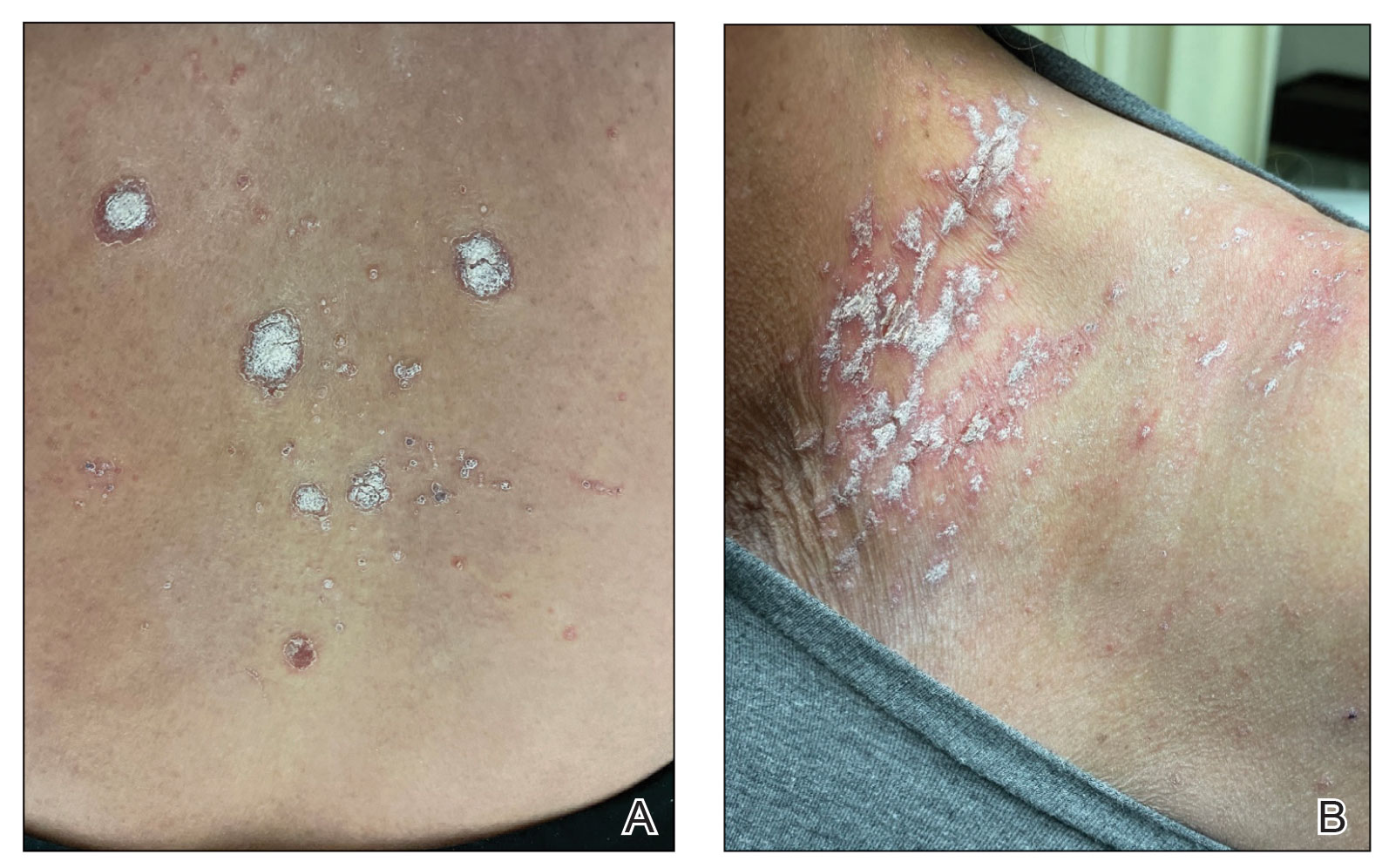

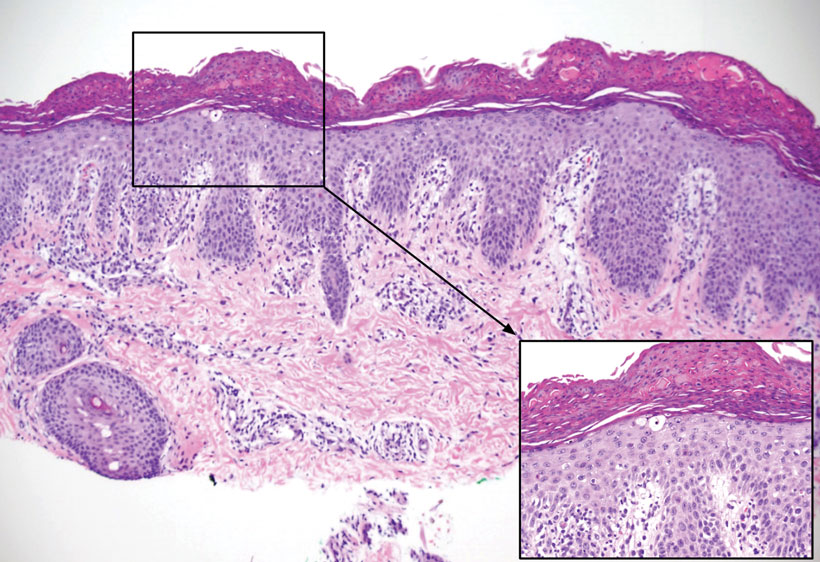

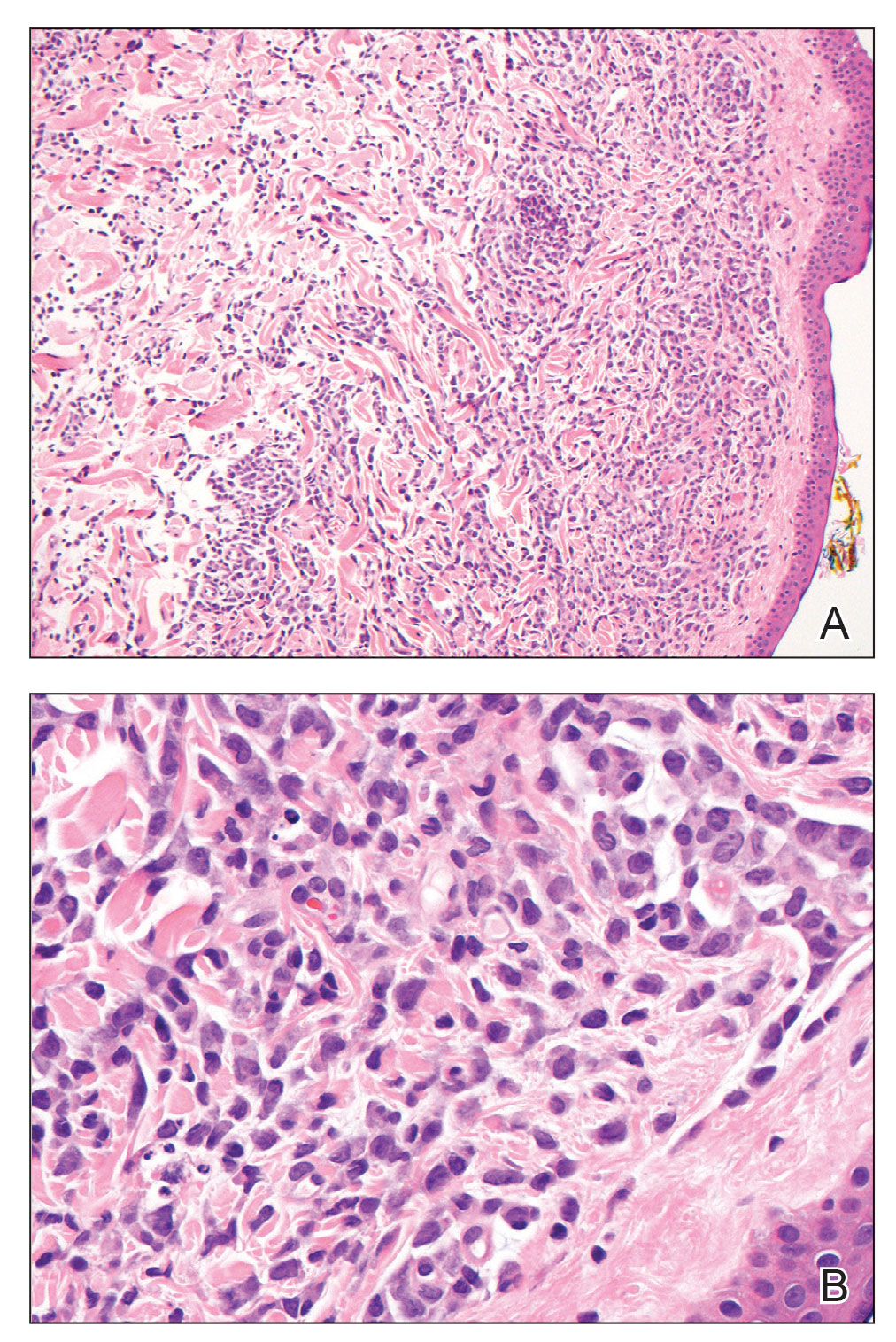

The Diagnosis: IgA Pemphigus

Histopathology revealed a neutrophilic pustule and vesicle formation underlying the corneal layer (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed weak positive staining for IgA within the intercellular keratinocyte in the epithelial compartment and a negative pattern with IgG, IgM, C3, and fibrinogen. The patient received a 40-mg intralesional triamcinolone injection and was placed on an oral prednisone 50-mg taper within 5 days. The plaques, bullae, and pustules began to resolve, but the lesions returned 1 day later. Oral prednisone 10 mg daily was initiated for 1 month, which resulted in full resolution of the lesions.

IgA pemphigus is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the occurrence of painful pruritic blisters caused by circulating IgA antibodies, which react against keratinocyte cellular components responsible for mediating cell-to-cell adherence.1 The etiology of IgA pemphigus presently remains elusive, though it has been reported to occur concomitantly with several chronic malignancies and inflammatory conditions. Although its etiology is unknown, IgA pemphigus most commonly is treated with oral dapsone and corticosteroids.2

IgA pemphigus can be divided into 2 primary subtypes: subcorneal pustular dermatosis and intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis.1,3 The former is characterized by intercellular deposition of IgA that reacts to the glycoprotein desmocollin-1 in the upper layer of the epidermis. Intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis is distinguished by the presence of autoantibodies against the desmoglein members of the cadherin superfamily of proteins. Additionally, unlike subcorneal pustular dermatosis, intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis autoantibody reactivity occurs in the lower epidermis.4

The differential includes dermatitis herpetiformis, which is commonly seen on the elbows, knees, and buttocks, with DIF showing IgA deposition at the dermal papillae. Pemphigus foliaceus is distributed on the scalp, face, and trunk, with DIF showing IgG intercellular deposition. Pustular psoriasis presents as erythematous sterile pustules in a more localized annular pattern. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) has similar clinical and histological findings to IgA pemphigus; however, DIF is negative.

- Kridin K, Patel PM, Jones VA, et al. IgA pemphigus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1386-1392.

- Moreno ACL, Santi CG, Gabbi TVB, et al. IgA pemphigus: case series with emphasis on therapeutic response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:200-201.

- Niimi Y, Kawana S, Kusunoki T. IgA pemphigus: a case report and its characteristic clinical features compared with subcorneal pustular dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:546-549.

- Aslanova M, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. IgA pemphigus. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

The Diagnosis: IgA Pemphigus

Histopathology revealed a neutrophilic pustule and vesicle formation underlying the corneal layer (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed weak positive staining for IgA within the intercellular keratinocyte in the epithelial compartment and a negative pattern with IgG, IgM, C3, and fibrinogen. The patient received a 40-mg intralesional triamcinolone injection and was placed on an oral prednisone 50-mg taper within 5 days. The plaques, bullae, and pustules began to resolve, but the lesions returned 1 day later. Oral prednisone 10 mg daily was initiated for 1 month, which resulted in full resolution of the lesions.

IgA pemphigus is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the occurrence of painful pruritic blisters caused by circulating IgA antibodies, which react against keratinocyte cellular components responsible for mediating cell-to-cell adherence.1 The etiology of IgA pemphigus presently remains elusive, though it has been reported to occur concomitantly with several chronic malignancies and inflammatory conditions. Although its etiology is unknown, IgA pemphigus most commonly is treated with oral dapsone and corticosteroids.2

IgA pemphigus can be divided into 2 primary subtypes: subcorneal pustular dermatosis and intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis.1,3 The former is characterized by intercellular deposition of IgA that reacts to the glycoprotein desmocollin-1 in the upper layer of the epidermis. Intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis is distinguished by the presence of autoantibodies against the desmoglein members of the cadherin superfamily of proteins. Additionally, unlike subcorneal pustular dermatosis, intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis autoantibody reactivity occurs in the lower epidermis.4

The differential includes dermatitis herpetiformis, which is commonly seen on the elbows, knees, and buttocks, with DIF showing IgA deposition at the dermal papillae. Pemphigus foliaceus is distributed on the scalp, face, and trunk, with DIF showing IgG intercellular deposition. Pustular psoriasis presents as erythematous sterile pustules in a more localized annular pattern. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) has similar clinical and histological findings to IgA pemphigus; however, DIF is negative.

The Diagnosis: IgA Pemphigus

Histopathology revealed a neutrophilic pustule and vesicle formation underlying the corneal layer (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed weak positive staining for IgA within the intercellular keratinocyte in the epithelial compartment and a negative pattern with IgG, IgM, C3, and fibrinogen. The patient received a 40-mg intralesional triamcinolone injection and was placed on an oral prednisone 50-mg taper within 5 days. The plaques, bullae, and pustules began to resolve, but the lesions returned 1 day later. Oral prednisone 10 mg daily was initiated for 1 month, which resulted in full resolution of the lesions.

IgA pemphigus is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the occurrence of painful pruritic blisters caused by circulating IgA antibodies, which react against keratinocyte cellular components responsible for mediating cell-to-cell adherence.1 The etiology of IgA pemphigus presently remains elusive, though it has been reported to occur concomitantly with several chronic malignancies and inflammatory conditions. Although its etiology is unknown, IgA pemphigus most commonly is treated with oral dapsone and corticosteroids.2

IgA pemphigus can be divided into 2 primary subtypes: subcorneal pustular dermatosis and intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis.1,3 The former is characterized by intercellular deposition of IgA that reacts to the glycoprotein desmocollin-1 in the upper layer of the epidermis. Intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis is distinguished by the presence of autoantibodies against the desmoglein members of the cadherin superfamily of proteins. Additionally, unlike subcorneal pustular dermatosis, intraepidermal neutrophilic dermatosis autoantibody reactivity occurs in the lower epidermis.4

The differential includes dermatitis herpetiformis, which is commonly seen on the elbows, knees, and buttocks, with DIF showing IgA deposition at the dermal papillae. Pemphigus foliaceus is distributed on the scalp, face, and trunk, with DIF showing IgG intercellular deposition. Pustular psoriasis presents as erythematous sterile pustules in a more localized annular pattern. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) has similar clinical and histological findings to IgA pemphigus; however, DIF is negative.

- Kridin K, Patel PM, Jones VA, et al. IgA pemphigus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1386-1392.

- Moreno ACL, Santi CG, Gabbi TVB, et al. IgA pemphigus: case series with emphasis on therapeutic response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:200-201.

- Niimi Y, Kawana S, Kusunoki T. IgA pemphigus: a case report and its characteristic clinical features compared with subcorneal pustular dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:546-549.

- Aslanova M, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. IgA pemphigus. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Kridin K, Patel PM, Jones VA, et al. IgA pemphigus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1386-1392.

- Moreno ACL, Santi CG, Gabbi TVB, et al. IgA pemphigus: case series with emphasis on therapeutic response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:200-201.

- Niimi Y, Kawana S, Kusunoki T. IgA pemphigus: a case report and its characteristic clinical features compared with subcorneal pustular dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:546-549.

- Aslanova M, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. IgA pemphigus. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

A 36-year-old man presented with painful tender blisters and rashes on the entire body, including the ears and tongue. The rash began as a few pinpointed red dots on the abdomen, which subsequently increased in size and spread over the last week. He initially felt red and flushed and noticed new lesions appearing throughout the day. He did not attempt any specific treatment for these lesions. The patient tested positive for COVID-19 four months prior to the skin eruption. He denied systemic symptoms, smoking, or recent travel. He had no history of skin cancer, skin disorders, HIV, or hepatitis. He had no known medication allergies. Physical examination revealed multiple disseminated pustules on the ears, superficial ulcerations on the tongue, and blisters on the right lip. Few lesions were tender to the touch and drained clear fluid. Bacterial, viral, HIV, herpes, and rapid plasma reagin culture and laboratory screenings were negative. He was started on valaciclovir and cephalexin; however, no improvement was noticed. Punch biopsies were taken from the blisters on the chest and perilesional area.

Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Perineuriomas in 2 Pediatric Patients

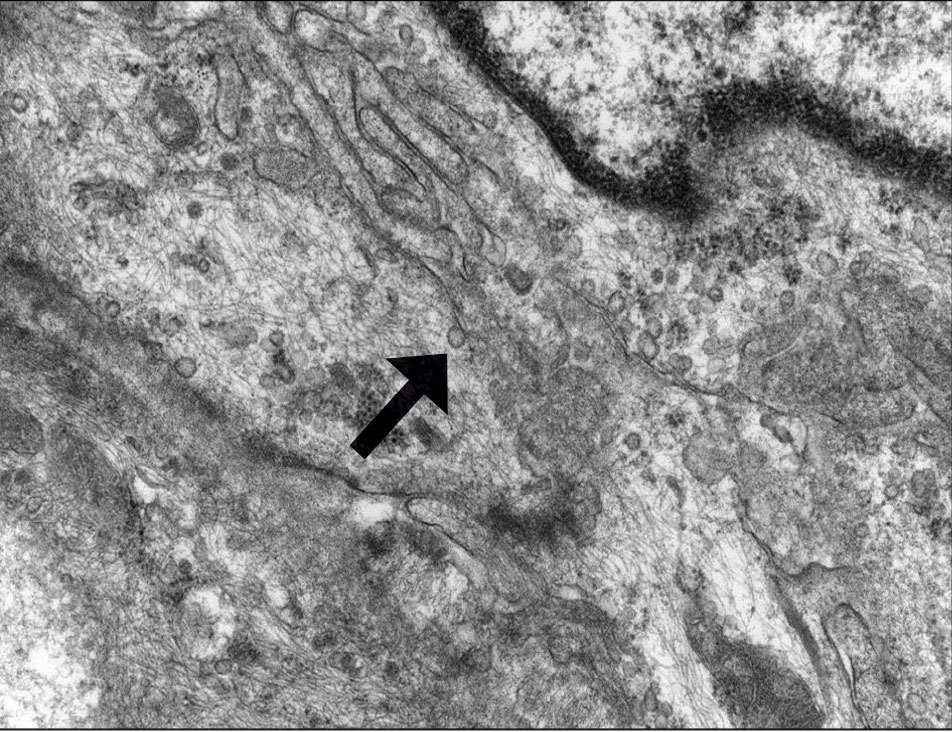

Perineuriomas are benign, slow-growing tumors derived from perineurial cells,1 which form the structurally supportive perineurium that surrounds individual nerve fascicles.2,3 Perineuriomas are classified into 2 main forms: intraneural or extraneural.4 Intraneural perineuriomas are found within the border of the peripheral nerve,5 while extraneural perineuriomas usually are found in soft tissue and skin. Extraneural perineuriomas can be further classified into variants based on their histologic appearance, including reticular, sclerosing, and plexiform subtypes. Extraneural perineuriomas usually present on the extremities or trunk of young to middle-aged adults as a well-circumscribed, painless, subcutaneous masses.1 These tumors are especially unusual in children.4 We present 2 extraneural perineurioma cases in children, and we review the pertinent diagnostic features of perineurioma as well as the presentation in the pediatric population.

Case Reports