User login

Top questions answered about COVID-19 boosters for your patients

Confusion continues to circulate in the wake of decisions on booster doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, all announced within 1 week. Many people – including those now eligible and those who officially have to wait for their shot at a third dose – have questions.

Multiple agencies are involved in the booster decisions, and they have put out multiple – and sometimes conflicting – messages about booster doses, leaving more questions than answers for many people.

On Sept. 22, the Food and Drug Administration granted an emergency use authorization (EUA) for a booster dose of the Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for those 65 and older and those at high risk for severe illness from the coronavirus, including essential workers whose jobs increase their risk for infection – such as frontline health care workers.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, then overruled advice from the agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) to recommend boosters for essential workers such as those working on the front lines during the pandemic.

As it stands now, the CDC recommends that the following groups should get a third dose of the Pfizer vaccine:

- People aged 65 years and older.

- People aged 18 years and older in long-term care settings.

- People aged 50-64 years with underlying medical conditions.

The CDC also recommends that the following groups may receive a booster shot of the Pfizer vaccine, based on their individual benefits and risks:

- People aged 18-49 years with underlying medical conditions.

- People aged 18-64 years at increased risk for COVID-19 exposure and transmission because of occupational or institutional setting.

The CDC currently considers the following groups at increased risk for COVID-19:

- First responders (health care workers, firefighters, police, congregate care staff).

- Education staff (teachers, support staff, day care workers).

- Food and agriculture workers.

- Manufacturing workers.

- Corrections workers.

- U.S. Postal Service workers.

- Public transit workers.

- Grocery store workers.

Health care professionals, among the most trusted sources of COVID-19 information, are likely to encounter a number of patients wondering how all this will work.

“It’s fantastic that boosters will be available for those who the data supports need [them],” Rachael Piltch-Loeb, PhD, said during a media briefing on Sept. 23, held between the FDA and CDC decisions.

“But we’re really in a place where we have a lot more questions and answers about what the next phase of the vaccine availability and updates are going to be in the United States,” added Dr. Piltch-Loeb, preparedness fellow in the division of policy translation and leadership development and a research associate in the department of biostatistics at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

1. What is the biggest concern you are hearing from patients about getting a booster?

“The biggest concerns are that everyone wants it and they don’t know where to get it. In health care’s defense, the CDC just figured out what to do,” said Janet Englund, MD, professor of pediatric infectious diseases and an infectious disease and virology expert at Seattle Children’s Hospital in Washington.

“Everyone thinks they should be eligible for a booster ... people in their 50s who are not yet 65+, people with young grandchildren, etc.,” she added. “I’m at Seattle Children’s Hospital, so people are asking about booster shots and about getting their children vaccinated.”

Boosters for all COVID-19 vaccines are completely free.

“All COVID-19 vaccines, including booster doses, will be provided free of charge to the U.S. population,” the CDC has said.

2. Will patients need to prove they meet eligibility criteria for a booster shot or will it be the honor system?

“No, patients will only need to attest that they fall into one of the high-risk groups for whom a booster vaccine is authorized,” said Robert Atmar, MD, professor of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Dr. Piltch-Loeb agreed. “It is likely to be an honor system. It is very unlikely that there will be punishments or other ramifications ... if doses are administered, beyond the approved usage.”

3. If a patient who had the Moderna or the Johnson and Johnson vaccination requests a booster, can health care workers give them Pfizer?

The short answer is no. “This only applies to individuals who have received the Pfizer vaccine,” Dr. Piltch-Loeb said.

More data will be needed before other vaccine boosters are authorized, she added.

“My understanding is the Moderna people have just recently submitted their information, all of their data to the FDA and J&J is in line to do that very shortly,” said William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. “I would hope that within the next month to 6 weeks, we will get information about both of those vaccines,” Dr. Schaffner said.

4. When are the “mix-and-match” vaccine study results expected to come out?

“We expect that data from the study will be available in the coming weeks,” said Dr. Atmar, who is the national co-principal investigator of a mix-and-match booster trial launched in June 2021.

5. Are side effects of a booster vaccine expected to be about the same as what people experienced during their first or second immunization?

“I’m expecting the side effects will be similar to the second dose,” Dr. Englund said.

“The data presented ... at ACIP suggests that the side effects from the third shot are either the same or actually less than the first two shots,” said Carlos del Rio, MD, distinguished professor of medicine, epidemiology, and global health, and executive associate dean of Emory University School of Medicine at Grady Health System in Atlanta.

”Everyone reacts very differently to vaccines, regardless of vaccine type,” said Eric Ascher, MD, a family medicine physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. “I have had patients (as well as personal experience) where there were none to minimal symptoms, and others who felt they had a mild flu for 24 hours.”

“I expect no side effects greater than what was felt with you prior doses,” he said. “The vaccine is very safe and the benefit of vaccination outweighs the risks of any mild side effects.”

6. Is it unethical to give a booster to someone outside the approved groups if there are doses remaining at the end of the day in an open vial?

“Offering a booster shot to someone outside of approved groups if remaining doses will go to waste at the end of the day seems like a prudent decision, and relatively harmless action,” said Faith Fletcher, PhD, assistant professor at the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Baylor College of Medicine.

“However, if doses continue to fall in the laps of unapproved groups, we must evaluate the vaccine systems and structures that advantage some groups and disadvantage others,” she added. “We know that the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines has not been equitable – and some groups have been left behind.”

“I am not an ethicist and there are many competing concerns that this question addresses,” Dr. Atmar said. For example, “there is not a limitation of vaccine supply in the U.S., so that using leftover vaccine to prevent waste is no longer a major concern in the U.S.”

It could be more of a legal than ethical question, Dr. Atmar said. For an individual outside the authorized groups, legally, the FDA’s EUA for boosting does not allow the vaccine to be administered to this person, he said.

“The rationale for the restricted use in the EUA is that at this time the safety and risks associated with such administration are not known, and the benefits also have not been determined,” Dr. Atmar said. “Members of the ACIP raised concerns about other individuals who may potentially benefit from a booster but are not eligible and the importance of making boosters available to them, but from a legal standpoint – I am also not a lawyer, so this is my understanding – administration of the vaccine is limited to those identified in the EUA.”

7. What is the likelihood that one shot will combine COVID and flu protection in the near future?

It is not likely, Dr. Englund said. “The reason is that the flu vaccine changes so much, and it already has four different antigens. This is assuming we keep the same method of making the flu vaccine – the answer could be different if the flu vaccine becomes an mRNA vaccine in the future.”

Companies such as Moderna and Novavax are testing single-dose shots for COVID-19 and influenza, but they are still far from having anything ready for this flu season in the United States.

8. Is there any chance a booster shot distributed now will need to be redesigned for a future variant?

“Absolutely,” Dr. Englund said. “And a booster dose is the time we may want to consider re-engineering a vaccine.”

9. Do you think the FDA/CDC limitations on who is eligible for a booster was in any way influenced by the World Health Organization call for prioritizing shots for the unvaccinated in lower-resource countries?

“This is absolutely still a global problem,” Dr. Piltch-Loeb said. “We need to get more vaccine to more countries and more people as soon as possible, because if there’s anything we’ve seen about the variants it is that ... they can come from all different places.”

“That being said, I think that it is unlikely to change the course of action in the U.S.,” she added, when it comes to comparing the global need with the domestic policy priorities of the administration.

Dr. Atmar was more direct. “No,” he said. “The WHO recommends against boosting of anyone. The U.S. decisions about boosting those in this country who are eligible are aimed toward addressing perceived needs domestically at the same time that vaccines are being provided to other countries.

“The philosophy is to address both ‘needs’ at the same time,” Dr. Atmar said.

10. What does the future hold for booster shots?

“Predicting the future is really hard, especially when it involves COVID,” Dr. del Rio said.

“Having said that, COVID is not the flu, so I doubt there will be need for annual boosters. I think the population eligible for boosters will be expanded ... and the major population not addressed at this point is the people that received either Moderna or J&J [vaccines].”

Kelly Davis contributed to this feature. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Confusion continues to circulate in the wake of decisions on booster doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, all announced within 1 week. Many people – including those now eligible and those who officially have to wait for their shot at a third dose – have questions.

Multiple agencies are involved in the booster decisions, and they have put out multiple – and sometimes conflicting – messages about booster doses, leaving more questions than answers for many people.

On Sept. 22, the Food and Drug Administration granted an emergency use authorization (EUA) for a booster dose of the Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for those 65 and older and those at high risk for severe illness from the coronavirus, including essential workers whose jobs increase their risk for infection – such as frontline health care workers.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, then overruled advice from the agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) to recommend boosters for essential workers such as those working on the front lines during the pandemic.

As it stands now, the CDC recommends that the following groups should get a third dose of the Pfizer vaccine:

- People aged 65 years and older.

- People aged 18 years and older in long-term care settings.

- People aged 50-64 years with underlying medical conditions.

The CDC also recommends that the following groups may receive a booster shot of the Pfizer vaccine, based on their individual benefits and risks:

- People aged 18-49 years with underlying medical conditions.

- People aged 18-64 years at increased risk for COVID-19 exposure and transmission because of occupational or institutional setting.

The CDC currently considers the following groups at increased risk for COVID-19:

- First responders (health care workers, firefighters, police, congregate care staff).

- Education staff (teachers, support staff, day care workers).

- Food and agriculture workers.

- Manufacturing workers.

- Corrections workers.

- U.S. Postal Service workers.

- Public transit workers.

- Grocery store workers.

Health care professionals, among the most trusted sources of COVID-19 information, are likely to encounter a number of patients wondering how all this will work.

“It’s fantastic that boosters will be available for those who the data supports need [them],” Rachael Piltch-Loeb, PhD, said during a media briefing on Sept. 23, held between the FDA and CDC decisions.

“But we’re really in a place where we have a lot more questions and answers about what the next phase of the vaccine availability and updates are going to be in the United States,” added Dr. Piltch-Loeb, preparedness fellow in the division of policy translation and leadership development and a research associate in the department of biostatistics at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

1. What is the biggest concern you are hearing from patients about getting a booster?

“The biggest concerns are that everyone wants it and they don’t know where to get it. In health care’s defense, the CDC just figured out what to do,” said Janet Englund, MD, professor of pediatric infectious diseases and an infectious disease and virology expert at Seattle Children’s Hospital in Washington.

“Everyone thinks they should be eligible for a booster ... people in their 50s who are not yet 65+, people with young grandchildren, etc.,” she added. “I’m at Seattle Children’s Hospital, so people are asking about booster shots and about getting their children vaccinated.”

Boosters for all COVID-19 vaccines are completely free.

“All COVID-19 vaccines, including booster doses, will be provided free of charge to the U.S. population,” the CDC has said.

2. Will patients need to prove they meet eligibility criteria for a booster shot or will it be the honor system?

“No, patients will only need to attest that they fall into one of the high-risk groups for whom a booster vaccine is authorized,” said Robert Atmar, MD, professor of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Dr. Piltch-Loeb agreed. “It is likely to be an honor system. It is very unlikely that there will be punishments or other ramifications ... if doses are administered, beyond the approved usage.”

3. If a patient who had the Moderna or the Johnson and Johnson vaccination requests a booster, can health care workers give them Pfizer?

The short answer is no. “This only applies to individuals who have received the Pfizer vaccine,” Dr. Piltch-Loeb said.

More data will be needed before other vaccine boosters are authorized, she added.

“My understanding is the Moderna people have just recently submitted their information, all of their data to the FDA and J&J is in line to do that very shortly,” said William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. “I would hope that within the next month to 6 weeks, we will get information about both of those vaccines,” Dr. Schaffner said.

4. When are the “mix-and-match” vaccine study results expected to come out?

“We expect that data from the study will be available in the coming weeks,” said Dr. Atmar, who is the national co-principal investigator of a mix-and-match booster trial launched in June 2021.

5. Are side effects of a booster vaccine expected to be about the same as what people experienced during their first or second immunization?

“I’m expecting the side effects will be similar to the second dose,” Dr. Englund said.

“The data presented ... at ACIP suggests that the side effects from the third shot are either the same or actually less than the first two shots,” said Carlos del Rio, MD, distinguished professor of medicine, epidemiology, and global health, and executive associate dean of Emory University School of Medicine at Grady Health System in Atlanta.

”Everyone reacts very differently to vaccines, regardless of vaccine type,” said Eric Ascher, MD, a family medicine physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. “I have had patients (as well as personal experience) where there were none to minimal symptoms, and others who felt they had a mild flu for 24 hours.”

“I expect no side effects greater than what was felt with you prior doses,” he said. “The vaccine is very safe and the benefit of vaccination outweighs the risks of any mild side effects.”

6. Is it unethical to give a booster to someone outside the approved groups if there are doses remaining at the end of the day in an open vial?

“Offering a booster shot to someone outside of approved groups if remaining doses will go to waste at the end of the day seems like a prudent decision, and relatively harmless action,” said Faith Fletcher, PhD, assistant professor at the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Baylor College of Medicine.

“However, if doses continue to fall in the laps of unapproved groups, we must evaluate the vaccine systems and structures that advantage some groups and disadvantage others,” she added. “We know that the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines has not been equitable – and some groups have been left behind.”

“I am not an ethicist and there are many competing concerns that this question addresses,” Dr. Atmar said. For example, “there is not a limitation of vaccine supply in the U.S., so that using leftover vaccine to prevent waste is no longer a major concern in the U.S.”

It could be more of a legal than ethical question, Dr. Atmar said. For an individual outside the authorized groups, legally, the FDA’s EUA for boosting does not allow the vaccine to be administered to this person, he said.

“The rationale for the restricted use in the EUA is that at this time the safety and risks associated with such administration are not known, and the benefits also have not been determined,” Dr. Atmar said. “Members of the ACIP raised concerns about other individuals who may potentially benefit from a booster but are not eligible and the importance of making boosters available to them, but from a legal standpoint – I am also not a lawyer, so this is my understanding – administration of the vaccine is limited to those identified in the EUA.”

7. What is the likelihood that one shot will combine COVID and flu protection in the near future?

It is not likely, Dr. Englund said. “The reason is that the flu vaccine changes so much, and it already has four different antigens. This is assuming we keep the same method of making the flu vaccine – the answer could be different if the flu vaccine becomes an mRNA vaccine in the future.”

Companies such as Moderna and Novavax are testing single-dose shots for COVID-19 and influenza, but they are still far from having anything ready for this flu season in the United States.

8. Is there any chance a booster shot distributed now will need to be redesigned for a future variant?

“Absolutely,” Dr. Englund said. “And a booster dose is the time we may want to consider re-engineering a vaccine.”

9. Do you think the FDA/CDC limitations on who is eligible for a booster was in any way influenced by the World Health Organization call for prioritizing shots for the unvaccinated in lower-resource countries?

“This is absolutely still a global problem,” Dr. Piltch-Loeb said. “We need to get more vaccine to more countries and more people as soon as possible, because if there’s anything we’ve seen about the variants it is that ... they can come from all different places.”

“That being said, I think that it is unlikely to change the course of action in the U.S.,” she added, when it comes to comparing the global need with the domestic policy priorities of the administration.

Dr. Atmar was more direct. “No,” he said. “The WHO recommends against boosting of anyone. The U.S. decisions about boosting those in this country who are eligible are aimed toward addressing perceived needs domestically at the same time that vaccines are being provided to other countries.

“The philosophy is to address both ‘needs’ at the same time,” Dr. Atmar said.

10. What does the future hold for booster shots?

“Predicting the future is really hard, especially when it involves COVID,” Dr. del Rio said.

“Having said that, COVID is not the flu, so I doubt there will be need for annual boosters. I think the population eligible for boosters will be expanded ... and the major population not addressed at this point is the people that received either Moderna or J&J [vaccines].”

Kelly Davis contributed to this feature. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Confusion continues to circulate in the wake of decisions on booster doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, all announced within 1 week. Many people – including those now eligible and those who officially have to wait for their shot at a third dose – have questions.

Multiple agencies are involved in the booster decisions, and they have put out multiple – and sometimes conflicting – messages about booster doses, leaving more questions than answers for many people.

On Sept. 22, the Food and Drug Administration granted an emergency use authorization (EUA) for a booster dose of the Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for those 65 and older and those at high risk for severe illness from the coronavirus, including essential workers whose jobs increase their risk for infection – such as frontline health care workers.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, then overruled advice from the agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) to recommend boosters for essential workers such as those working on the front lines during the pandemic.

As it stands now, the CDC recommends that the following groups should get a third dose of the Pfizer vaccine:

- People aged 65 years and older.

- People aged 18 years and older in long-term care settings.

- People aged 50-64 years with underlying medical conditions.

The CDC also recommends that the following groups may receive a booster shot of the Pfizer vaccine, based on their individual benefits and risks:

- People aged 18-49 years with underlying medical conditions.

- People aged 18-64 years at increased risk for COVID-19 exposure and transmission because of occupational or institutional setting.

The CDC currently considers the following groups at increased risk for COVID-19:

- First responders (health care workers, firefighters, police, congregate care staff).

- Education staff (teachers, support staff, day care workers).

- Food and agriculture workers.

- Manufacturing workers.

- Corrections workers.

- U.S. Postal Service workers.

- Public transit workers.

- Grocery store workers.

Health care professionals, among the most trusted sources of COVID-19 information, are likely to encounter a number of patients wondering how all this will work.

“It’s fantastic that boosters will be available for those who the data supports need [them],” Rachael Piltch-Loeb, PhD, said during a media briefing on Sept. 23, held between the FDA and CDC decisions.

“But we’re really in a place where we have a lot more questions and answers about what the next phase of the vaccine availability and updates are going to be in the United States,” added Dr. Piltch-Loeb, preparedness fellow in the division of policy translation and leadership development and a research associate in the department of biostatistics at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

1. What is the biggest concern you are hearing from patients about getting a booster?

“The biggest concerns are that everyone wants it and they don’t know where to get it. In health care’s defense, the CDC just figured out what to do,” said Janet Englund, MD, professor of pediatric infectious diseases and an infectious disease and virology expert at Seattle Children’s Hospital in Washington.

“Everyone thinks they should be eligible for a booster ... people in their 50s who are not yet 65+, people with young grandchildren, etc.,” she added. “I’m at Seattle Children’s Hospital, so people are asking about booster shots and about getting their children vaccinated.”

Boosters for all COVID-19 vaccines are completely free.

“All COVID-19 vaccines, including booster doses, will be provided free of charge to the U.S. population,” the CDC has said.

2. Will patients need to prove they meet eligibility criteria for a booster shot or will it be the honor system?

“No, patients will only need to attest that they fall into one of the high-risk groups for whom a booster vaccine is authorized,” said Robert Atmar, MD, professor of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Dr. Piltch-Loeb agreed. “It is likely to be an honor system. It is very unlikely that there will be punishments or other ramifications ... if doses are administered, beyond the approved usage.”

3. If a patient who had the Moderna or the Johnson and Johnson vaccination requests a booster, can health care workers give them Pfizer?

The short answer is no. “This only applies to individuals who have received the Pfizer vaccine,” Dr. Piltch-Loeb said.

More data will be needed before other vaccine boosters are authorized, she added.

“My understanding is the Moderna people have just recently submitted their information, all of their data to the FDA and J&J is in line to do that very shortly,” said William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. “I would hope that within the next month to 6 weeks, we will get information about both of those vaccines,” Dr. Schaffner said.

4. When are the “mix-and-match” vaccine study results expected to come out?

“We expect that data from the study will be available in the coming weeks,” said Dr. Atmar, who is the national co-principal investigator of a mix-and-match booster trial launched in June 2021.

5. Are side effects of a booster vaccine expected to be about the same as what people experienced during their first or second immunization?

“I’m expecting the side effects will be similar to the second dose,” Dr. Englund said.

“The data presented ... at ACIP suggests that the side effects from the third shot are either the same or actually less than the first two shots,” said Carlos del Rio, MD, distinguished professor of medicine, epidemiology, and global health, and executive associate dean of Emory University School of Medicine at Grady Health System in Atlanta.

”Everyone reacts very differently to vaccines, regardless of vaccine type,” said Eric Ascher, MD, a family medicine physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. “I have had patients (as well as personal experience) where there were none to minimal symptoms, and others who felt they had a mild flu for 24 hours.”

“I expect no side effects greater than what was felt with you prior doses,” he said. “The vaccine is very safe and the benefit of vaccination outweighs the risks of any mild side effects.”

6. Is it unethical to give a booster to someone outside the approved groups if there are doses remaining at the end of the day in an open vial?

“Offering a booster shot to someone outside of approved groups if remaining doses will go to waste at the end of the day seems like a prudent decision, and relatively harmless action,” said Faith Fletcher, PhD, assistant professor at the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Baylor College of Medicine.

“However, if doses continue to fall in the laps of unapproved groups, we must evaluate the vaccine systems and structures that advantage some groups and disadvantage others,” she added. “We know that the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines has not been equitable – and some groups have been left behind.”

“I am not an ethicist and there are many competing concerns that this question addresses,” Dr. Atmar said. For example, “there is not a limitation of vaccine supply in the U.S., so that using leftover vaccine to prevent waste is no longer a major concern in the U.S.”

It could be more of a legal than ethical question, Dr. Atmar said. For an individual outside the authorized groups, legally, the FDA’s EUA for boosting does not allow the vaccine to be administered to this person, he said.

“The rationale for the restricted use in the EUA is that at this time the safety and risks associated with such administration are not known, and the benefits also have not been determined,” Dr. Atmar said. “Members of the ACIP raised concerns about other individuals who may potentially benefit from a booster but are not eligible and the importance of making boosters available to them, but from a legal standpoint – I am also not a lawyer, so this is my understanding – administration of the vaccine is limited to those identified in the EUA.”

7. What is the likelihood that one shot will combine COVID and flu protection in the near future?

It is not likely, Dr. Englund said. “The reason is that the flu vaccine changes so much, and it already has four different antigens. This is assuming we keep the same method of making the flu vaccine – the answer could be different if the flu vaccine becomes an mRNA vaccine in the future.”

Companies such as Moderna and Novavax are testing single-dose shots for COVID-19 and influenza, but they are still far from having anything ready for this flu season in the United States.

8. Is there any chance a booster shot distributed now will need to be redesigned for a future variant?

“Absolutely,” Dr. Englund said. “And a booster dose is the time we may want to consider re-engineering a vaccine.”

9. Do you think the FDA/CDC limitations on who is eligible for a booster was in any way influenced by the World Health Organization call for prioritizing shots for the unvaccinated in lower-resource countries?

“This is absolutely still a global problem,” Dr. Piltch-Loeb said. “We need to get more vaccine to more countries and more people as soon as possible, because if there’s anything we’ve seen about the variants it is that ... they can come from all different places.”

“That being said, I think that it is unlikely to change the course of action in the U.S.,” she added, when it comes to comparing the global need with the domestic policy priorities of the administration.

Dr. Atmar was more direct. “No,” he said. “The WHO recommends against boosting of anyone. The U.S. decisions about boosting those in this country who are eligible are aimed toward addressing perceived needs domestically at the same time that vaccines are being provided to other countries.

“The philosophy is to address both ‘needs’ at the same time,” Dr. Atmar said.

10. What does the future hold for booster shots?

“Predicting the future is really hard, especially when it involves COVID,” Dr. del Rio said.

“Having said that, COVID is not the flu, so I doubt there will be need for annual boosters. I think the population eligible for boosters will be expanded ... and the major population not addressed at this point is the people that received either Moderna or J&J [vaccines].”

Kelly Davis contributed to this feature. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Virtual Visitation: Exploring the Impact on Patients and Families During COVID-19 and Beyond

From Northwell Health, Lake Success, NY.

Objective: Northwell Health, New York’s largest health care organization, rapidly adopted technology solutions to support patient and family communication during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: This case series outlines the pragmatic, interdisciplinary approach Northwell underwent to rapidly implement patient virtual visitation processes during the peak of the initial crisis.

Results: Implementation of large-scale virtual visitation required leadership, technology, and dedicated, empathetic frontline professionals. Patient and family feedback uncovered varied feelings and perspectives, from confusion to gratitude.

Conclusion: Subsequent efforts to obtain direct patient and family perspectives and insights helped Northwell identify areas of strength and ongoing performance improvement.

Keywords: virtual visitation; COVID-19; technology; communication; patient experience.

The power of human connection has become increasingly apparent throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent recovery phases. Due to the need for social distancing, people worldwide have turned to virtual means of communication, staying in touch with family, friends, and colleagues via digital technology platforms. On March 18, 2020, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) issued a health advisory, suspending all hospital visitation.1 As a result, hospitals rapidly transformed existing in-person visitation practices to meet large-scale virtual programming needs.

Family members often take on various roles—such as advocate, emotional support person, and postdischarge caregiver—for an ill or injured loved one.2 The Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, a nonprofit organization founded in 1992, has been leading a cultural transformation where families are valued as care partners, as opposed to “visitors.”3 Although widely adopted and well-received in specialized units, such as neonatal intensive care units,4 virtual visitation had not been widely implemented across adult care settings. The NYSDOH guidance therefore required organizational leadership, innovation, flexibility, and systems ingenuity to meet the evolving needs of patients, families, and health care professionals. An overarching goal was ensuring patients and families were afforded opportunities to stay connected throughout hospitalization.

Reflecting the impact of COVID-19 surges, hospital environments became increasingly depersonalized, with health care providers wearing extensive personal protective equipment (PPE) and taking remarkable measures to socially distance and minimize exposure. Patients’ room doors were kept primarily closed, while codes and alerts blared in the halls overhead. The lack of families and visitors became increasingly obvious, aiding feelings of isolation and confinement. With fear of nosocomial transmission, impactful modalities (such as sitting at the bedside) and empathetic, therapeutic touch were no longer taking place.

With those scenarios—common to so many health care systems during the pandemic—as a backdrop, comes our experience. Northwell Health is the largest health care system in New York State, geographically spread throughout New York City’s 5 boroughs, Westchester County, and Long Island. With 23 hospitals, approximately 820 medical practices, and over 72 000 employees, Northwell has cared for more than 100 000 COVID-positive patients to date. This case series outlines a pragmatic approach to implementing virtual visitation during the initial peak and obtaining patient and family perspectives to help inform performance improvement and future programming.

Methods

Implementing virtual visitation

Through swift and focused multidisciplinary collaboration, numerous Northwell teams came together to implement large-scale virtual visitation across the organization during the first wave of the COVID crisis. The initial priority involved securing devices that could support patient-family communication. Prior to COVID, each facility had only a handful of tablets that were used primarily during leadership rounding, so once visitation was restricted, we needed a large quantity of devices within a matter of days. Through diligent work from System Procurement and internal Foundation, Northwell was able to acquire nearly 900 devices, including iPads, PadInMotion tablets, and Samsung tablets.

Typically, the benefits of using wireless tablets within a health care setting include long battery life, powerful data processing, advanced operating systems, large screens, and easy end-user navigation.4 During COVID-19 and its associated isolation precautions, tablets offered a lifeline for effective and socially distant communication. With new devices in hand, the system Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO) and site-based Information Technology (IT) teams were engaged. They worked tirelessly to streamline connectivity, download necessary apps, test devices on approved WiFi networks, and troubleshoot issues. Once set up, devices were strategically deployed across all Northwell hospitals and post-acute rehabilitation facilities.

Frontline teams quickly realized that a model similar to mobile proning teams, who focus solely on turning and positioning COVID patients to promote optimal respiratory ventilation,5 was needed to support virtual visitation. During the initial COVID wave, elective surgeries were not permissible, as per the NYSDOH. As a result, large numbers of clinical and nonclinical ambulatory surgery employees were redeployed throughout the organization, with many assigned and dedicated to facilitating newly created virtual visitation processes. These employees were primarily responsible for creating unit-based schedules, coordinating logistics, navigating devices on behalf of patients, being present during video calls, and sanitizing the devices between uses. Finally, if necessary, virtual interpretation services were used to overcome language barriers between staff and patients.

What began as an ad hoc function quickly became a valued and meaningful role. Utilizing triage mentality, virtual visitation was first offered during unit-based rounding protocols to those patients with the highest acuity and need to connect with family. We had no formal script; instead, unit-based leaders and frontline team members had open dialogues with patients and families to gauge their interest in virtual visitation. That included patients with an active end-of-life care plan, critically ill patients within intensive care units, and those soon to be intubated or recently extubated. Utilization also occurred within specialty areas such as labor and delivery, pediatrics, inpatient psychiatry, medical units, and long-term rehab facilities. Frontline teams appreciated the supplementary support so they could prioritize ongoing physical assessments and medical interventions. Donned in PPE, virtual visitation team members often served as physical extensions of the patient’s loved ones—holding their hand, offering prayers, and, at times, bearing witness to a last breath. In reflecting on that time, this role required absolute professionalism, empathy, and compassion.

In summer 2020, although demand for virtual visitation was still at an all-time high when ambulatory surgery was reinstated, redeployed staff returned to their responsibilities. To fill this void without interruption to patients and their families, site leaders quickly pivoted and refined processes and protocols utilizing Patient & Customer Experience and Hospitality department team members. Throughout spring 2021, the NYSDOH offered guidance to open in-person visitation, and the institution’s Clinical Advisory Group has been taking a pragmatic approach to doing that in a measured and safe manner across care settings.

Listening to the ‘voice’ of patients and families

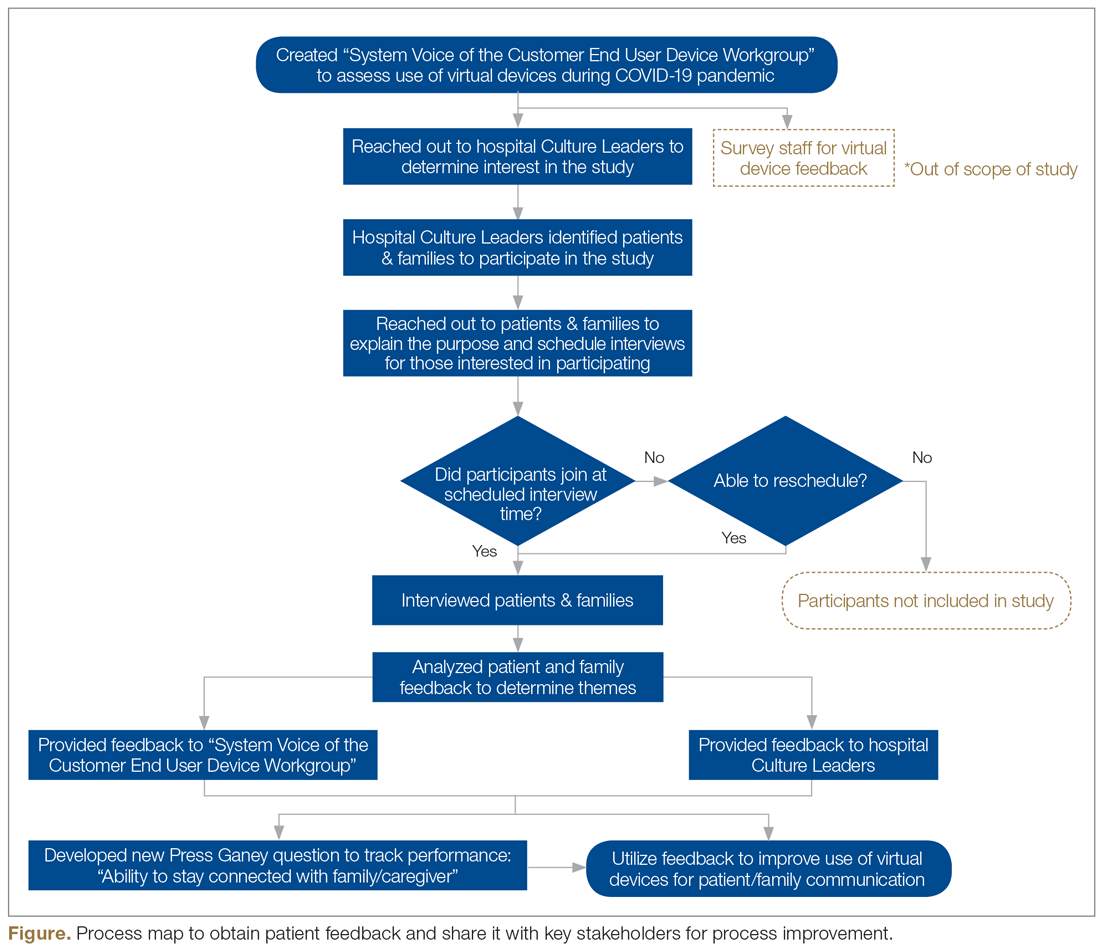

Our institution’s mission is grounded in providing “quality service and patient-centered care.” Honoring those tenets, during the initial COVID wave, the system “Voice of the Customer End User Device Workgroup” was created with system and site-based interdisciplinary representation. Despite challenging and unprecedented times, conscious attention and effort was undertaken to assess the use and impact of virtual devices. One of the major work streams was to capture and examine patient and family thoughts, feedback, and the overall experience as it relates to virtual visitation.

The system Office of Patient & Customer Experience (OPCE), led by Sven Gierlinger, SVP Chief Experience Officer, reached out to our colleagues at Press Ganey to add a custom question to patient experience surveys. Beginning on December 1, 2020, discharged inpatients were asked to rate the “Degree to which you were able to stay connected with your family/caregiver during your stay.” Potential answers include the Likert scale responses of Always, Usually, Sometimes, and Never, with “Always” representing the Top Box score. The OPCE team believes these quantitative insights are important to track and trend, particularly since in-person and virtual visitation remain in constant flux.

In an effort to obtain additional, focused, qualitative feedback, OPCE partnered with our institution’s Digital Patient Experience (dPX) colleagues. The approach consisted of voluntary, semistructured, interview-type conversations with patients and family members who engaged in virtual visitation multiple times while the patient was hospitalized. OPCE contacted site-based Patient Experience leads, also known as Culture Leaders, at 3 hospitals, asking them to identify potential participants. This convenience sample excluded instances where the patient passed away during and/or immediately following hospitalization.

The OPCE team phoned potential interview candidates to make a personalized connection, explain the purpose of the interviews, and schedule them, if interested. For consistency, the same Digital Customer Experience Researcher on the dPX team facilitated all sessions, which were 30-minute, semiscripted interviews conducted virtually via Microsoft Teams. The tone was intentionally conversational so that patients and family members would feel comfortable delving into themes that were most impactful during their experience. After some initial ice breakers, such as “What were some of your feelings about being a patient/having a loved one in the hospital during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic?” we moved on to some more pragmatic, implementation questions and rating scales. These included questions such as “How did you first learn about the option for virtual visitation? Was it something you inquired about or did someone offer it to you? How was it explained to you?” Patients were also asked, on a scale of 1 (easy) to 5 (difficult), to rate their experience with the technology aspect when connecting with their loved ones. They also provided verbal consent to be recorded and were given a $15 gift card upon completion of the interview.

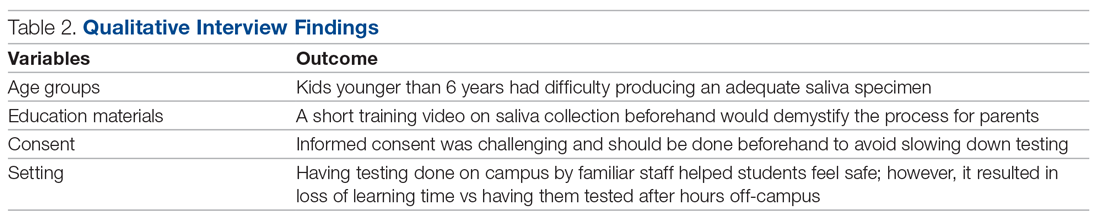

Transcriptions were generated by uploading the interview recordings to a platform called UserTesting. In addition to these transcriptions, this platform also allowed for a keyword mapping tool that organized high-level themes and adjectives into groupings along a sentiment axis from negative to neutral to positive. Transcripts were then read carefully and annotated by the Digital Customer Experience Researcher, which allowed for strengthening of some of the automated themes as well as the emergence of new, more nuanced themes. These themes were organized into those that we could address with design and/or procedure updates (actionable insights), those that came up most frequently overall (frequency), and those that came up across our 3 interview sessions (commonality).

This feedback, along with the responses to the new Press Ganey question, was presented to the system Voice of the Customer End User Device Workgroup. The results led to robust discussion and brainstorming regarding how to improve the process to be more patient-centered. Findings were also shared with our hospital-based Culture Leaders. As many of their local strategic plans focused on patient-family communication, this information was helpful to them in considering plans for expansion and/or sustaining virtual visitation efforts. The process map in the Figure outlines key milestones within this feedback loop.

Outcomes

During the height of the initial COVID-19 crisis, virtual visitation was a new and ever-evolving process. Amidst the chaos, mechanisms to capture the quantity and quality of virtual visits were not in place. Based on informal observation, a majority of patients utilized personal devices to connect with loved ones, and staff even offered their own cellular devices to facilitate timely patient-family communication. The technology primarily used included FaceTime, Zoom, and EZCall, as there was much public awareness and comfort with those platforms.

In the first quarter of 2021, our institution overall performed at a Top Box score of 60.2 for our ability to assist patients with staying connected to their family/caregiver during their inpatient visit. With more than 6700 returned surveys during that time period, our hospitals earned Top Box scores ranging between 48.0 and 75.3. At this time, obtaining a national benchmark ranking is not possible, because the question regarding connectedness is unique to Northwell inpatient settings. As other health care organizations adopt this customized question, further peer-to-peer measurements can be established.

Regarding virtual interviews, 25 patients were initially contacted to determine their interest in participating. Of that sample, 17 patients were engaged over the phone, representing a reach rate of 68%. Overall, 10 interviews were scheduled; 7 patients did not show up, resulting in 3 completed interviews. During follow-up, “no-show” participants either gave no response or stated they had a conflict at their originally scheduled time but were not interested in rescheduling due to personal circumstances. Through such conversations, ongoing health complications were found to be a reoccurring barrier to participation.

Each of the participating patients had experienced being placed on a ventilator. They described their hospitalization as a time of “confusion and despair” in the first days after extubation. After we reviewed interview recordings, a reoccurring theme across all interviews was the feeling of gratitude. Patients expressed deep and heartfelt appreciation for being given the opportunity to connect as a family. One patient described virtual visitation sessions as her “only tether to reality when nothing else made sense.”

Interestingly enough, none of the participants knew that virtual visitation was an option and/or thought to inquire about it before a hospital staff member offered to set up a session. Patients recounted how they were weak and physically unable to connect to the sessions without significant assistance. They reported examples of not having the physical strength to hold up the tablet or needing a staff member to facilitate the conversation because the patient could not speak loudly enough and/or they were having difficulty hearing over background medical equipment noises. Participants also described times when a nurse or social worker would stand and hold the tablet for 20 to 30 minutes at a time, further describing mixed feelings of gratitude, guilt for “taking up their time,” and a desire for more privacy to have those precious conversations.

Discussion

Our institution encountered various barriers when establishing, implementing, and sustaining virtual visitation. The acquisition and bulk purchasing of devices, so that each hospital unit and department had adequate par levels during a high-demand time frame, was an initial challenge. Ensuring appropriate safeguards, software programming, and access to WiFi required ingenuity from IT teams. Leaders sought to advocate for the importance of prioritizing virtual visitation alongside clinical interventions. For team members, education was needed to build awareness, learn how to navigate technology, and troubleshoot, in real-time, issues such as poor connectivity. However, despite these organizational struggles, the hospital’s frontline professionals fully recognized and understood the humanistic value of connecting ill patients with their loved ones. Harnessing their teamwork, empathy, and innovative spirits, they forged through such difficulties to create meaningful interactions.

Although virtual visitation occurred prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in subspecialty areas such as neonatal intensive care units,6 it was not commonplace in most adult inpatient care settings. However, now that virtual means to communication are widely accepted and preferred, our hospital anticipates these offerings will become a broad patient expectation and, therefore, part of standard hospital care and operations. Health care leaders and interdisciplinary teams must therefore prioritize virtual visitation protocols, efforts, and future programming. It is no longer an exception to the rule, but rather a critical approach when ensuring quality communication between patients, families, and care teams.

We strive to continually improve by including user feedback as part of an interactive design process. For a broader, more permanent installation of virtual visitation, health care organizations must proactively promote this capability as a valued option. Considering health literacy and comfort with technology, functionality, and logistics must be carefully explained to patients and their families. This may require additional staff training so that they are knowledgeable, comfortable with, and able to troubleshoot questions/concerns in real time. There needs to be an adequate number of mobile devices available at a unit or departmental level to meet short-term and long-term demands. Additionally, now that we have emerged from our initial crisis-based mentality, it is time to consider alternatives to alleviate the need for staff assistance, such as mounts to hold devices and enabling voice controls.

Conclusion

As an organization grounded in the spirit of innovation, Northwell has been able to quickly pivot, adopting virtual visitation to address emerging and complex communication needs. Taking a best practice established during a crisis period and engraining it into sustainable organizational culture and operations requires visionary leadership, strong teamwork, and an unbridled commitment to patient and family centeredness. Despite unprecedented challenges, our commitment to listening to the “voice” of patients and families never wavered. Using their insights and feedback as critical components to the decision-making process, there is much work ahead within the realm of virtual visitation.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge the Northwell Health providers, frontline health care professionals, and team members who worked tirelessly to care for its community during initial COVID-19 waves and every day thereafter. Heartfelt gratitude to Northwell’s senior leaders for the visionary leadership; the OCIO and hospital-based IT teams for their swift collaboration; and dedicated Culture Leaders, Patient Experience team members, and redeployed staff for their unbridled passion for caring for patients and families. Special thanks to Agnes Barden, DNP, RN, CPXP, Joseph Narvaez, MBA, and Natalie Bashkin, MBA, from the system Office of Patient & Customer Experience, and Carolyne Burgess, MPH, from the Digital Patient Experience teams, for their participation, leadership, and syngeristic partnerships.

Corresponding Author: Nicole Giammarinaro, MSN, RN, CPXP, Director, Patient & Customer Experience, Northwell Health, 2000 Marcus Ave, Lake Success, NY 11042; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Sven Gierlinger serves on the Speakers Bureau for Northwell Health and as an Executive Board Member for The Beryl Institute.

1. New York State Department of Health. Health advisory: COVID-19 guidance for hospital operators regarding visitation. March 18, 2020. https://coronavirus.health.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2020/03/covid19-hospital-visitation-guidance-3.18.20.pdf

2. Zhang Y. Family functioning in the context of an adult family member with illness: a concept analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(15-16):3205-3224. doi:10.1111/jocn.14500

3. Institute for Patient- & Family-Centered Care. Better Together: Partnering with Families. https://www.ipfcc.org/bestpractices/better-together-ny.html

4. Marceglia S, Bonacina S, Zaccaria V, et al. How might the iPad change healthcare? J R Soc Med. 2012;105(6):233-241. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2012.110296

5. Short B, Parekh M, Ryan P, et al. Rapid implementation of a mobile prone team during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Crit Care. 2020;60:230-234. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.08.020

6. Yeo C, Ho SK, Khong K, Lau Y. Virtual visitation in the neonatal intensive care: experience with the use of internet and telemedicine in a tertiary neonatal unit. Perm J. 2011;15(3):32-36.

From Northwell Health, Lake Success, NY.

Objective: Northwell Health, New York’s largest health care organization, rapidly adopted technology solutions to support patient and family communication during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: This case series outlines the pragmatic, interdisciplinary approach Northwell underwent to rapidly implement patient virtual visitation processes during the peak of the initial crisis.

Results: Implementation of large-scale virtual visitation required leadership, technology, and dedicated, empathetic frontline professionals. Patient and family feedback uncovered varied feelings and perspectives, from confusion to gratitude.

Conclusion: Subsequent efforts to obtain direct patient and family perspectives and insights helped Northwell identify areas of strength and ongoing performance improvement.

Keywords: virtual visitation; COVID-19; technology; communication; patient experience.

The power of human connection has become increasingly apparent throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent recovery phases. Due to the need for social distancing, people worldwide have turned to virtual means of communication, staying in touch with family, friends, and colleagues via digital technology platforms. On March 18, 2020, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) issued a health advisory, suspending all hospital visitation.1 As a result, hospitals rapidly transformed existing in-person visitation practices to meet large-scale virtual programming needs.

Family members often take on various roles—such as advocate, emotional support person, and postdischarge caregiver—for an ill or injured loved one.2 The Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, a nonprofit organization founded in 1992, has been leading a cultural transformation where families are valued as care partners, as opposed to “visitors.”3 Although widely adopted and well-received in specialized units, such as neonatal intensive care units,4 virtual visitation had not been widely implemented across adult care settings. The NYSDOH guidance therefore required organizational leadership, innovation, flexibility, and systems ingenuity to meet the evolving needs of patients, families, and health care professionals. An overarching goal was ensuring patients and families were afforded opportunities to stay connected throughout hospitalization.

Reflecting the impact of COVID-19 surges, hospital environments became increasingly depersonalized, with health care providers wearing extensive personal protective equipment (PPE) and taking remarkable measures to socially distance and minimize exposure. Patients’ room doors were kept primarily closed, while codes and alerts blared in the halls overhead. The lack of families and visitors became increasingly obvious, aiding feelings of isolation and confinement. With fear of nosocomial transmission, impactful modalities (such as sitting at the bedside) and empathetic, therapeutic touch were no longer taking place.

With those scenarios—common to so many health care systems during the pandemic—as a backdrop, comes our experience. Northwell Health is the largest health care system in New York State, geographically spread throughout New York City’s 5 boroughs, Westchester County, and Long Island. With 23 hospitals, approximately 820 medical practices, and over 72 000 employees, Northwell has cared for more than 100 000 COVID-positive patients to date. This case series outlines a pragmatic approach to implementing virtual visitation during the initial peak and obtaining patient and family perspectives to help inform performance improvement and future programming.

Methods

Implementing virtual visitation

Through swift and focused multidisciplinary collaboration, numerous Northwell teams came together to implement large-scale virtual visitation across the organization during the first wave of the COVID crisis. The initial priority involved securing devices that could support patient-family communication. Prior to COVID, each facility had only a handful of tablets that were used primarily during leadership rounding, so once visitation was restricted, we needed a large quantity of devices within a matter of days. Through diligent work from System Procurement and internal Foundation, Northwell was able to acquire nearly 900 devices, including iPads, PadInMotion tablets, and Samsung tablets.

Typically, the benefits of using wireless tablets within a health care setting include long battery life, powerful data processing, advanced operating systems, large screens, and easy end-user navigation.4 During COVID-19 and its associated isolation precautions, tablets offered a lifeline for effective and socially distant communication. With new devices in hand, the system Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO) and site-based Information Technology (IT) teams were engaged. They worked tirelessly to streamline connectivity, download necessary apps, test devices on approved WiFi networks, and troubleshoot issues. Once set up, devices were strategically deployed across all Northwell hospitals and post-acute rehabilitation facilities.

Frontline teams quickly realized that a model similar to mobile proning teams, who focus solely on turning and positioning COVID patients to promote optimal respiratory ventilation,5 was needed to support virtual visitation. During the initial COVID wave, elective surgeries were not permissible, as per the NYSDOH. As a result, large numbers of clinical and nonclinical ambulatory surgery employees were redeployed throughout the organization, with many assigned and dedicated to facilitating newly created virtual visitation processes. These employees were primarily responsible for creating unit-based schedules, coordinating logistics, navigating devices on behalf of patients, being present during video calls, and sanitizing the devices between uses. Finally, if necessary, virtual interpretation services were used to overcome language barriers between staff and patients.

What began as an ad hoc function quickly became a valued and meaningful role. Utilizing triage mentality, virtual visitation was first offered during unit-based rounding protocols to those patients with the highest acuity and need to connect with family. We had no formal script; instead, unit-based leaders and frontline team members had open dialogues with patients and families to gauge their interest in virtual visitation. That included patients with an active end-of-life care plan, critically ill patients within intensive care units, and those soon to be intubated or recently extubated. Utilization also occurred within specialty areas such as labor and delivery, pediatrics, inpatient psychiatry, medical units, and long-term rehab facilities. Frontline teams appreciated the supplementary support so they could prioritize ongoing physical assessments and medical interventions. Donned in PPE, virtual visitation team members often served as physical extensions of the patient’s loved ones—holding their hand, offering prayers, and, at times, bearing witness to a last breath. In reflecting on that time, this role required absolute professionalism, empathy, and compassion.

In summer 2020, although demand for virtual visitation was still at an all-time high when ambulatory surgery was reinstated, redeployed staff returned to their responsibilities. To fill this void without interruption to patients and their families, site leaders quickly pivoted and refined processes and protocols utilizing Patient & Customer Experience and Hospitality department team members. Throughout spring 2021, the NYSDOH offered guidance to open in-person visitation, and the institution’s Clinical Advisory Group has been taking a pragmatic approach to doing that in a measured and safe manner across care settings.

Listening to the ‘voice’ of patients and families

Our institution’s mission is grounded in providing “quality service and patient-centered care.” Honoring those tenets, during the initial COVID wave, the system “Voice of the Customer End User Device Workgroup” was created with system and site-based interdisciplinary representation. Despite challenging and unprecedented times, conscious attention and effort was undertaken to assess the use and impact of virtual devices. One of the major work streams was to capture and examine patient and family thoughts, feedback, and the overall experience as it relates to virtual visitation.

The system Office of Patient & Customer Experience (OPCE), led by Sven Gierlinger, SVP Chief Experience Officer, reached out to our colleagues at Press Ganey to add a custom question to patient experience surveys. Beginning on December 1, 2020, discharged inpatients were asked to rate the “Degree to which you were able to stay connected with your family/caregiver during your stay.” Potential answers include the Likert scale responses of Always, Usually, Sometimes, and Never, with “Always” representing the Top Box score. The OPCE team believes these quantitative insights are important to track and trend, particularly since in-person and virtual visitation remain in constant flux.

In an effort to obtain additional, focused, qualitative feedback, OPCE partnered with our institution’s Digital Patient Experience (dPX) colleagues. The approach consisted of voluntary, semistructured, interview-type conversations with patients and family members who engaged in virtual visitation multiple times while the patient was hospitalized. OPCE contacted site-based Patient Experience leads, also known as Culture Leaders, at 3 hospitals, asking them to identify potential participants. This convenience sample excluded instances where the patient passed away during and/or immediately following hospitalization.

The OPCE team phoned potential interview candidates to make a personalized connection, explain the purpose of the interviews, and schedule them, if interested. For consistency, the same Digital Customer Experience Researcher on the dPX team facilitated all sessions, which were 30-minute, semiscripted interviews conducted virtually via Microsoft Teams. The tone was intentionally conversational so that patients and family members would feel comfortable delving into themes that were most impactful during their experience. After some initial ice breakers, such as “What were some of your feelings about being a patient/having a loved one in the hospital during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic?” we moved on to some more pragmatic, implementation questions and rating scales. These included questions such as “How did you first learn about the option for virtual visitation? Was it something you inquired about or did someone offer it to you? How was it explained to you?” Patients were also asked, on a scale of 1 (easy) to 5 (difficult), to rate their experience with the technology aspect when connecting with their loved ones. They also provided verbal consent to be recorded and were given a $15 gift card upon completion of the interview.

Transcriptions were generated by uploading the interview recordings to a platform called UserTesting. In addition to these transcriptions, this platform also allowed for a keyword mapping tool that organized high-level themes and adjectives into groupings along a sentiment axis from negative to neutral to positive. Transcripts were then read carefully and annotated by the Digital Customer Experience Researcher, which allowed for strengthening of some of the automated themes as well as the emergence of new, more nuanced themes. These themes were organized into those that we could address with design and/or procedure updates (actionable insights), those that came up most frequently overall (frequency), and those that came up across our 3 interview sessions (commonality).

This feedback, along with the responses to the new Press Ganey question, was presented to the system Voice of the Customer End User Device Workgroup. The results led to robust discussion and brainstorming regarding how to improve the process to be more patient-centered. Findings were also shared with our hospital-based Culture Leaders. As many of their local strategic plans focused on patient-family communication, this information was helpful to them in considering plans for expansion and/or sustaining virtual visitation efforts. The process map in the Figure outlines key milestones within this feedback loop.

Outcomes

During the height of the initial COVID-19 crisis, virtual visitation was a new and ever-evolving process. Amidst the chaos, mechanisms to capture the quantity and quality of virtual visits were not in place. Based on informal observation, a majority of patients utilized personal devices to connect with loved ones, and staff even offered their own cellular devices to facilitate timely patient-family communication. The technology primarily used included FaceTime, Zoom, and EZCall, as there was much public awareness and comfort with those platforms.

In the first quarter of 2021, our institution overall performed at a Top Box score of 60.2 for our ability to assist patients with staying connected to their family/caregiver during their inpatient visit. With more than 6700 returned surveys during that time period, our hospitals earned Top Box scores ranging between 48.0 and 75.3. At this time, obtaining a national benchmark ranking is not possible, because the question regarding connectedness is unique to Northwell inpatient settings. As other health care organizations adopt this customized question, further peer-to-peer measurements can be established.

Regarding virtual interviews, 25 patients were initially contacted to determine their interest in participating. Of that sample, 17 patients were engaged over the phone, representing a reach rate of 68%. Overall, 10 interviews were scheduled; 7 patients did not show up, resulting in 3 completed interviews. During follow-up, “no-show” participants either gave no response or stated they had a conflict at their originally scheduled time but were not interested in rescheduling due to personal circumstances. Through such conversations, ongoing health complications were found to be a reoccurring barrier to participation.

Each of the participating patients had experienced being placed on a ventilator. They described their hospitalization as a time of “confusion and despair” in the first days after extubation. After we reviewed interview recordings, a reoccurring theme across all interviews was the feeling of gratitude. Patients expressed deep and heartfelt appreciation for being given the opportunity to connect as a family. One patient described virtual visitation sessions as her “only tether to reality when nothing else made sense.”

Interestingly enough, none of the participants knew that virtual visitation was an option and/or thought to inquire about it before a hospital staff member offered to set up a session. Patients recounted how they were weak and physically unable to connect to the sessions without significant assistance. They reported examples of not having the physical strength to hold up the tablet or needing a staff member to facilitate the conversation because the patient could not speak loudly enough and/or they were having difficulty hearing over background medical equipment noises. Participants also described times when a nurse or social worker would stand and hold the tablet for 20 to 30 minutes at a time, further describing mixed feelings of gratitude, guilt for “taking up their time,” and a desire for more privacy to have those precious conversations.

Discussion

Our institution encountered various barriers when establishing, implementing, and sustaining virtual visitation. The acquisition and bulk purchasing of devices, so that each hospital unit and department had adequate par levels during a high-demand time frame, was an initial challenge. Ensuring appropriate safeguards, software programming, and access to WiFi required ingenuity from IT teams. Leaders sought to advocate for the importance of prioritizing virtual visitation alongside clinical interventions. For team members, education was needed to build awareness, learn how to navigate technology, and troubleshoot, in real-time, issues such as poor connectivity. However, despite these organizational struggles, the hospital’s frontline professionals fully recognized and understood the humanistic value of connecting ill patients with their loved ones. Harnessing their teamwork, empathy, and innovative spirits, they forged through such difficulties to create meaningful interactions.

Although virtual visitation occurred prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in subspecialty areas such as neonatal intensive care units,6 it was not commonplace in most adult inpatient care settings. However, now that virtual means to communication are widely accepted and preferred, our hospital anticipates these offerings will become a broad patient expectation and, therefore, part of standard hospital care and operations. Health care leaders and interdisciplinary teams must therefore prioritize virtual visitation protocols, efforts, and future programming. It is no longer an exception to the rule, but rather a critical approach when ensuring quality communication between patients, families, and care teams.

We strive to continually improve by including user feedback as part of an interactive design process. For a broader, more permanent installation of virtual visitation, health care organizations must proactively promote this capability as a valued option. Considering health literacy and comfort with technology, functionality, and logistics must be carefully explained to patients and their families. This may require additional staff training so that they are knowledgeable, comfortable with, and able to troubleshoot questions/concerns in real time. There needs to be an adequate number of mobile devices available at a unit or departmental level to meet short-term and long-term demands. Additionally, now that we have emerged from our initial crisis-based mentality, it is time to consider alternatives to alleviate the need for staff assistance, such as mounts to hold devices and enabling voice controls.

Conclusion

As an organization grounded in the spirit of innovation, Northwell has been able to quickly pivot, adopting virtual visitation to address emerging and complex communication needs. Taking a best practice established during a crisis period and engraining it into sustainable organizational culture and operations requires visionary leadership, strong teamwork, and an unbridled commitment to patient and family centeredness. Despite unprecedented challenges, our commitment to listening to the “voice” of patients and families never wavered. Using their insights and feedback as critical components to the decision-making process, there is much work ahead within the realm of virtual visitation.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge the Northwell Health providers, frontline health care professionals, and team members who worked tirelessly to care for its community during initial COVID-19 waves and every day thereafter. Heartfelt gratitude to Northwell’s senior leaders for the visionary leadership; the OCIO and hospital-based IT teams for their swift collaboration; and dedicated Culture Leaders, Patient Experience team members, and redeployed staff for their unbridled passion for caring for patients and families. Special thanks to Agnes Barden, DNP, RN, CPXP, Joseph Narvaez, MBA, and Natalie Bashkin, MBA, from the system Office of Patient & Customer Experience, and Carolyne Burgess, MPH, from the Digital Patient Experience teams, for their participation, leadership, and syngeristic partnerships.

Corresponding Author: Nicole Giammarinaro, MSN, RN, CPXP, Director, Patient & Customer Experience, Northwell Health, 2000 Marcus Ave, Lake Success, NY 11042; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Sven Gierlinger serves on the Speakers Bureau for Northwell Health and as an Executive Board Member for The Beryl Institute.

From Northwell Health, Lake Success, NY.

Objective: Northwell Health, New York’s largest health care organization, rapidly adopted technology solutions to support patient and family communication during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: This case series outlines the pragmatic, interdisciplinary approach Northwell underwent to rapidly implement patient virtual visitation processes during the peak of the initial crisis.

Results: Implementation of large-scale virtual visitation required leadership, technology, and dedicated, empathetic frontline professionals. Patient and family feedback uncovered varied feelings and perspectives, from confusion to gratitude.

Conclusion: Subsequent efforts to obtain direct patient and family perspectives and insights helped Northwell identify areas of strength and ongoing performance improvement.

Keywords: virtual visitation; COVID-19; technology; communication; patient experience.

The power of human connection has become increasingly apparent throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent recovery phases. Due to the need for social distancing, people worldwide have turned to virtual means of communication, staying in touch with family, friends, and colleagues via digital technology platforms. On March 18, 2020, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) issued a health advisory, suspending all hospital visitation.1 As a result, hospitals rapidly transformed existing in-person visitation practices to meet large-scale virtual programming needs.

Family members often take on various roles—such as advocate, emotional support person, and postdischarge caregiver—for an ill or injured loved one.2 The Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, a nonprofit organization founded in 1992, has been leading a cultural transformation where families are valued as care partners, as opposed to “visitors.”3 Although widely adopted and well-received in specialized units, such as neonatal intensive care units,4 virtual visitation had not been widely implemented across adult care settings. The NYSDOH guidance therefore required organizational leadership, innovation, flexibility, and systems ingenuity to meet the evolving needs of patients, families, and health care professionals. An overarching goal was ensuring patients and families were afforded opportunities to stay connected throughout hospitalization.

Reflecting the impact of COVID-19 surges, hospital environments became increasingly depersonalized, with health care providers wearing extensive personal protective equipment (PPE) and taking remarkable measures to socially distance and minimize exposure. Patients’ room doors were kept primarily closed, while codes and alerts blared in the halls overhead. The lack of families and visitors became increasingly obvious, aiding feelings of isolation and confinement. With fear of nosocomial transmission, impactful modalities (such as sitting at the bedside) and empathetic, therapeutic touch were no longer taking place.

With those scenarios—common to so many health care systems during the pandemic—as a backdrop, comes our experience. Northwell Health is the largest health care system in New York State, geographically spread throughout New York City’s 5 boroughs, Westchester County, and Long Island. With 23 hospitals, approximately 820 medical practices, and over 72 000 employees, Northwell has cared for more than 100 000 COVID-positive patients to date. This case series outlines a pragmatic approach to implementing virtual visitation during the initial peak and obtaining patient and family perspectives to help inform performance improvement and future programming.

Methods

Implementing virtual visitation

Through swift and focused multidisciplinary collaboration, numerous Northwell teams came together to implement large-scale virtual visitation across the organization during the first wave of the COVID crisis. The initial priority involved securing devices that could support patient-family communication. Prior to COVID, each facility had only a handful of tablets that were used primarily during leadership rounding, so once visitation was restricted, we needed a large quantity of devices within a matter of days. Through diligent work from System Procurement and internal Foundation, Northwell was able to acquire nearly 900 devices, including iPads, PadInMotion tablets, and Samsung tablets.

Typically, the benefits of using wireless tablets within a health care setting include long battery life, powerful data processing, advanced operating systems, large screens, and easy end-user navigation.4 During COVID-19 and its associated isolation precautions, tablets offered a lifeline for effective and socially distant communication. With new devices in hand, the system Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO) and site-based Information Technology (IT) teams were engaged. They worked tirelessly to streamline connectivity, download necessary apps, test devices on approved WiFi networks, and troubleshoot issues. Once set up, devices were strategically deployed across all Northwell hospitals and post-acute rehabilitation facilities.