User login

FDA advisory committee supports birth control patch approval

Most of the committee members based their decisions on the need for additional contraceptive options for patients. However, most also expressed concerns about its efficacy and offered suggestions for product labeling that called attention to high rates of unintended pregnancies and increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in obese women.

The agency’s Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee reviewed safety and efficacy data for AG200-15, a combined hormonal contraceptive patch developed by Agile Therapeutics. The treatment regimen involves application of a patch to the abdomen, buttock, or upper torso, and the patch is changed weekly for 3 weeks, followed by 1 week without a patch.

Elizabeth Garner, MD, consultant and former chief medical officer of Agile, presented study data on safety and effectiveness of the patch. The key study (known as Study 23) considered by the FDA included 1,736 women aged 35 years and younger. The primary efficacy endpoint was the pregnancy rate in the women who used the patch. Women reported sexual activity and back-up contraception use in e-diaries.

A total of 68 pregnancies occurred in the study population after 15,165 evaluable cycles, yielding an overall Pearl Index of 5.83 across all weight and body mass index groups. Historically, a Pearl Index of 5 has been the standard measure for effectiveness in contraceptive products, with lower being better. The index is defined as the number of pregnancies per 100 woman-years of product use. For example, a Pearl Index of 0.1 means that 1 in 1,000 women who use the same contraceptive method for 1 year becomes pregnant.

A subgroup analysis showed reduced efficacy in women with a higher BMI. The Pearl Index for women with a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2 (defined as nonobese) was 4.34, whereas in women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 and higher (defined as obese), the index was 8.64, nearly double that of nonobese women. No significant differences in the index were noted based on race/ethnicity.

The company described the patch as filling a niche and providing an additional alternative for women seeking a noninvasive method of contraception. It proposed a limitation of use (LOU) as part of the product label that would provide detailed information on efficacy based on the Pearl Index for the different categories of BMI and would suggest that the patch may be less effective for women with obesity. Most of the committee members favored use of a LOU statement on the label, but some noted that it might limit prescriptions to nonobese women.

The committee expressed concern over the Pearl data in the study. The FDA has never approved a contraceptive product with a Pearl Index of greater than 5, said Yun Tang, PhD, a statistical reviewer for the agency’s Office of Translational Sciences, who presented the evaluation of the effectiveness of AG200-15.

Key safety concerns raised in discussion included the risk of venous thromboembolism and the risk of unscheduled bleeding. Both of those issues were significantly more common among obese women, said Nneka McNeal-Jackson, MD, clinical reviewer for the FDA, who presented details on the safety profile and risk-benefit considerations for the patch.

Overall, in Study 23, the incidence rate of VTE was 28/10,000 women-years, with cases in five participants. Four of those were deemed related to the patch, and all occurred in obese women.

Virginia C. “Jennie” Leslie, MD, of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, voted no to recommending approval of the patch mainly because of efficacy concerns. “My goal is to do no harm, and I have concerns regarding efficacy and giving our patients a false sense of hope,” she said.

Even those members who voted yes expressed concerns about the efficacy data and VTE risk in obese women and recommended postmarketing studies and appropriate labeling to help clinicians in shared decision making with their patients.

Esther Eisenberg, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, noted that the patch fills a need, certainly for women with a BMI less than 30 kg/m2, and suggested that use be limited to women in that lower BMI category.

Other committee members suggested that the product not be restricted based on BMI, but rather that the LOU provide clear explanations of how effectiveness decreases as BMI increases.

David J. Margolis, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, opted to abstain from voting, in part based on concerns about the study design and a lack of additional data from the company.

Most of the committee members based their decisions on the need for additional contraceptive options for patients. However, most also expressed concerns about its efficacy and offered suggestions for product labeling that called attention to high rates of unintended pregnancies and increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in obese women.

The agency’s Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee reviewed safety and efficacy data for AG200-15, a combined hormonal contraceptive patch developed by Agile Therapeutics. The treatment regimen involves application of a patch to the abdomen, buttock, or upper torso, and the patch is changed weekly for 3 weeks, followed by 1 week without a patch.

Elizabeth Garner, MD, consultant and former chief medical officer of Agile, presented study data on safety and effectiveness of the patch. The key study (known as Study 23) considered by the FDA included 1,736 women aged 35 years and younger. The primary efficacy endpoint was the pregnancy rate in the women who used the patch. Women reported sexual activity and back-up contraception use in e-diaries.

A total of 68 pregnancies occurred in the study population after 15,165 evaluable cycles, yielding an overall Pearl Index of 5.83 across all weight and body mass index groups. Historically, a Pearl Index of 5 has been the standard measure for effectiveness in contraceptive products, with lower being better. The index is defined as the number of pregnancies per 100 woman-years of product use. For example, a Pearl Index of 0.1 means that 1 in 1,000 women who use the same contraceptive method for 1 year becomes pregnant.

A subgroup analysis showed reduced efficacy in women with a higher BMI. The Pearl Index for women with a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2 (defined as nonobese) was 4.34, whereas in women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 and higher (defined as obese), the index was 8.64, nearly double that of nonobese women. No significant differences in the index were noted based on race/ethnicity.

The company described the patch as filling a niche and providing an additional alternative for women seeking a noninvasive method of contraception. It proposed a limitation of use (LOU) as part of the product label that would provide detailed information on efficacy based on the Pearl Index for the different categories of BMI and would suggest that the patch may be less effective for women with obesity. Most of the committee members favored use of a LOU statement on the label, but some noted that it might limit prescriptions to nonobese women.

The committee expressed concern over the Pearl data in the study. The FDA has never approved a contraceptive product with a Pearl Index of greater than 5, said Yun Tang, PhD, a statistical reviewer for the agency’s Office of Translational Sciences, who presented the evaluation of the effectiveness of AG200-15.

Key safety concerns raised in discussion included the risk of venous thromboembolism and the risk of unscheduled bleeding. Both of those issues were significantly more common among obese women, said Nneka McNeal-Jackson, MD, clinical reviewer for the FDA, who presented details on the safety profile and risk-benefit considerations for the patch.

Overall, in Study 23, the incidence rate of VTE was 28/10,000 women-years, with cases in five participants. Four of those were deemed related to the patch, and all occurred in obese women.

Virginia C. “Jennie” Leslie, MD, of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, voted no to recommending approval of the patch mainly because of efficacy concerns. “My goal is to do no harm, and I have concerns regarding efficacy and giving our patients a false sense of hope,” she said.

Even those members who voted yes expressed concerns about the efficacy data and VTE risk in obese women and recommended postmarketing studies and appropriate labeling to help clinicians in shared decision making with their patients.

Esther Eisenberg, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, noted that the patch fills a need, certainly for women with a BMI less than 30 kg/m2, and suggested that use be limited to women in that lower BMI category.

Other committee members suggested that the product not be restricted based on BMI, but rather that the LOU provide clear explanations of how effectiveness decreases as BMI increases.

David J. Margolis, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, opted to abstain from voting, in part based on concerns about the study design and a lack of additional data from the company.

Most of the committee members based their decisions on the need for additional contraceptive options for patients. However, most also expressed concerns about its efficacy and offered suggestions for product labeling that called attention to high rates of unintended pregnancies and increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in obese women.

The agency’s Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee reviewed safety and efficacy data for AG200-15, a combined hormonal contraceptive patch developed by Agile Therapeutics. The treatment regimen involves application of a patch to the abdomen, buttock, or upper torso, and the patch is changed weekly for 3 weeks, followed by 1 week without a patch.

Elizabeth Garner, MD, consultant and former chief medical officer of Agile, presented study data on safety and effectiveness of the patch. The key study (known as Study 23) considered by the FDA included 1,736 women aged 35 years and younger. The primary efficacy endpoint was the pregnancy rate in the women who used the patch. Women reported sexual activity and back-up contraception use in e-diaries.

A total of 68 pregnancies occurred in the study population after 15,165 evaluable cycles, yielding an overall Pearl Index of 5.83 across all weight and body mass index groups. Historically, a Pearl Index of 5 has been the standard measure for effectiveness in contraceptive products, with lower being better. The index is defined as the number of pregnancies per 100 woman-years of product use. For example, a Pearl Index of 0.1 means that 1 in 1,000 women who use the same contraceptive method for 1 year becomes pregnant.

A subgroup analysis showed reduced efficacy in women with a higher BMI. The Pearl Index for women with a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2 (defined as nonobese) was 4.34, whereas in women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 and higher (defined as obese), the index was 8.64, nearly double that of nonobese women. No significant differences in the index were noted based on race/ethnicity.

The company described the patch as filling a niche and providing an additional alternative for women seeking a noninvasive method of contraception. It proposed a limitation of use (LOU) as part of the product label that would provide detailed information on efficacy based on the Pearl Index for the different categories of BMI and would suggest that the patch may be less effective for women with obesity. Most of the committee members favored use of a LOU statement on the label, but some noted that it might limit prescriptions to nonobese women.

The committee expressed concern over the Pearl data in the study. The FDA has never approved a contraceptive product with a Pearl Index of greater than 5, said Yun Tang, PhD, a statistical reviewer for the agency’s Office of Translational Sciences, who presented the evaluation of the effectiveness of AG200-15.

Key safety concerns raised in discussion included the risk of venous thromboembolism and the risk of unscheduled bleeding. Both of those issues were significantly more common among obese women, said Nneka McNeal-Jackson, MD, clinical reviewer for the FDA, who presented details on the safety profile and risk-benefit considerations for the patch.

Overall, in Study 23, the incidence rate of VTE was 28/10,000 women-years, with cases in five participants. Four of those were deemed related to the patch, and all occurred in obese women.

Virginia C. “Jennie” Leslie, MD, of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, voted no to recommending approval of the patch mainly because of efficacy concerns. “My goal is to do no harm, and I have concerns regarding efficacy and giving our patients a false sense of hope,” she said.

Even those members who voted yes expressed concerns about the efficacy data and VTE risk in obese women and recommended postmarketing studies and appropriate labeling to help clinicians in shared decision making with their patients.

Esther Eisenberg, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, noted that the patch fills a need, certainly for women with a BMI less than 30 kg/m2, and suggested that use be limited to women in that lower BMI category.

Other committee members suggested that the product not be restricted based on BMI, but rather that the LOU provide clear explanations of how effectiveness decreases as BMI increases.

David J. Margolis, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, opted to abstain from voting, in part based on concerns about the study design and a lack of additional data from the company.

FROM THE FDA

2019 Update on contraception

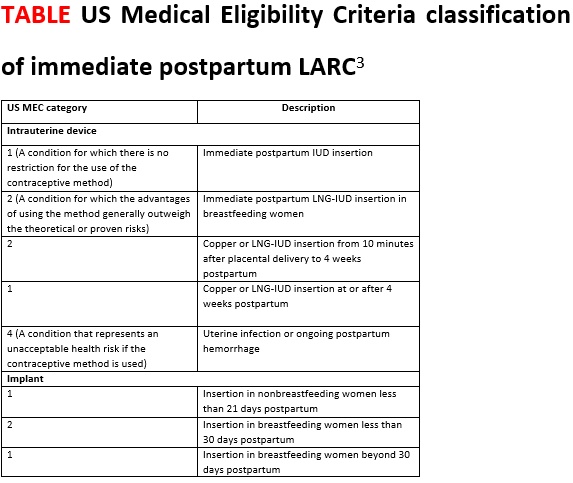

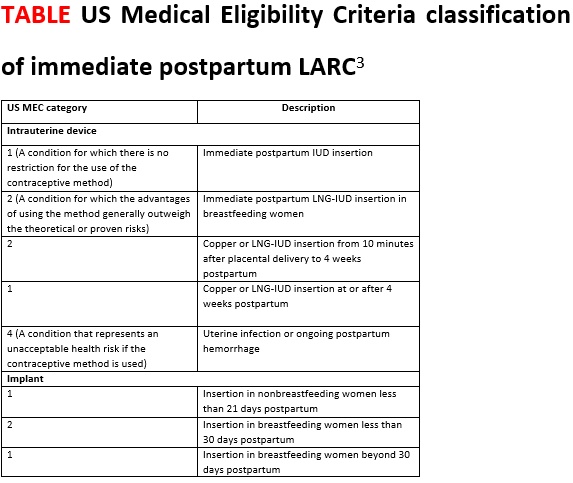

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) use continues to increase in the United States. According to the most recent estimates from 2014, 14% of women use either an intrauterine device (IUD) or the etonogestrel implant.1 Forms of LARC currently available in the United States include:

- 4 hormone-releasing IUDs

- 1 nonhormonal copper IUD, and

- 1 hormonal subdermal implant.

The hormone-releasing IUDs all contain levonorgestrel (LNG). These include two 52-mg LNG products and a 19.5-mg LNG IUD, which are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for contraception for 5 continuous years of use. In addition, a 13.5-mg LNG IUD is FDA-approved for 3 years of use. The hormonal subdermal implant, which contains etonogestrel, is FDA-approved for 3 years of use. Although major complications with IUDs (perforation, expulsion, intrauterine infection)and implants (subfascial implantation, distant migration) are rare, adverse effects that can affect continuation—such as irregular bleeding—are more common.2,3

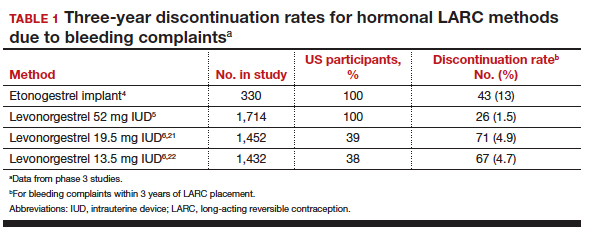

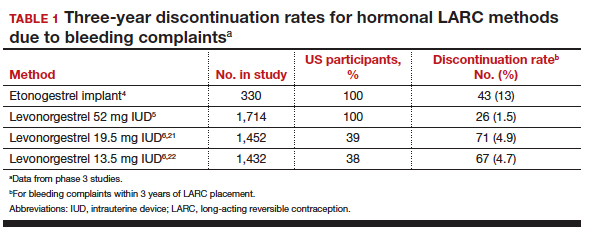

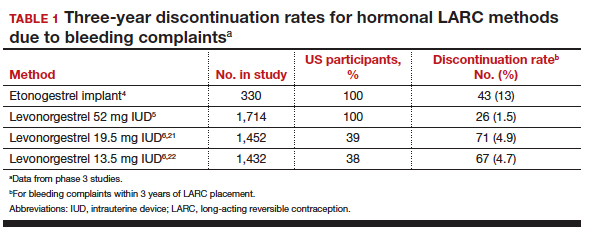

Contraceptive discontinuation due to bleeding concerns occurs more frequently with the etonogestrel implant than with LNG IUDs (TABLE 1). In a large prospective study in the United States, 13% of women discontinued the implant during 3 years of follow-up due to bleeding pattern changes.

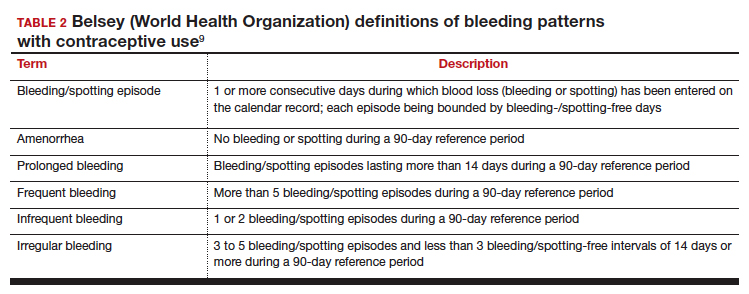

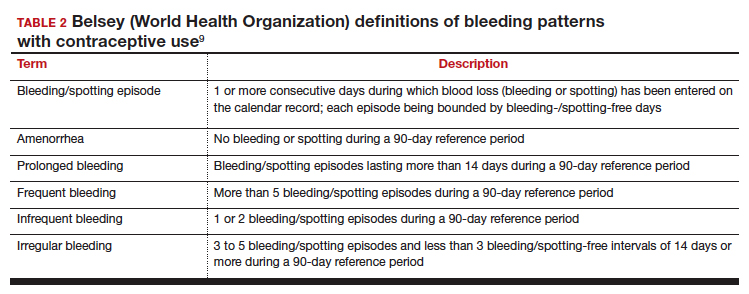

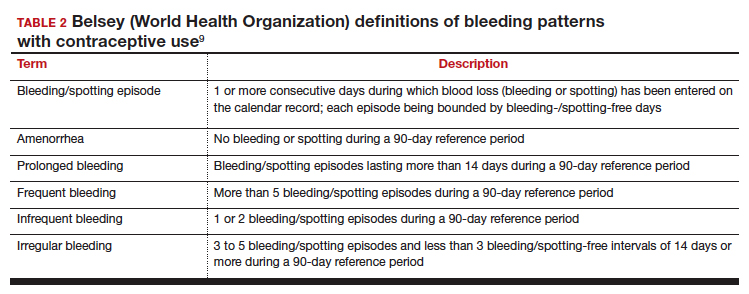

Notably, it is important to use standardized definitions to understand and compare bleeding concerns with LARC use. The Belsey criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO), a standard used for decades, describe bleeding patterns using 90-day reference periods or intervals (TABLE 2).9 Bleeding patterns that decrease flow (amenorrhea, infrequent bleeding) often are considered favorable, and those that increase bleeding or irregularity often are considered unfavorable. These criteria are commonly used in package labeling to describe bleeding patterns with extended use.

In this Update, we examine recent data evaluating differences in bleeding patterns with the 3 doses of the LNG IUD, predictors of abnormal bleeding with the etonogestrel implant, and the impact of timing on postpartum etonogestrel implant placement.

Continue to: Bleeding patterns with progestin-containing IUDs vary according to the LNG dose...

Bleeding patterns with progestin-containing IUDs vary according to the LNG dose

Goldthwaite LM, Creinin MD. Comparing bleeding patterns for the levonorgestrel 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg intrauterine systems. Contraception. 2019;100:128-131.

Counseling on IUDs' different hormonal doses requires an understanding of patients' desires for contraceptive efficacy and bleeding expectations. A recent study provides guidance on what patients typically can expect for their bleeding patterns over the first few years with the 3 different doses of LNG IUDs.

Goldthwaite and Creinin used existing published or publicly available data to analyze differences in bleeding patterns associated with the 52-mg, 19.5-mg, and 13.5-mg LNG IUDs. Although two 52-mg LNG IUDs are available, published data using the WHO Belsey criteria are available only for one (Liletta; Allergan, Medicines360). The 2 products have been shown previously to have similar drug-release rates and LNG levels over 5 years.8

Comparing favorable bleeding patterns: Amenorrhea and infrequent bleeding

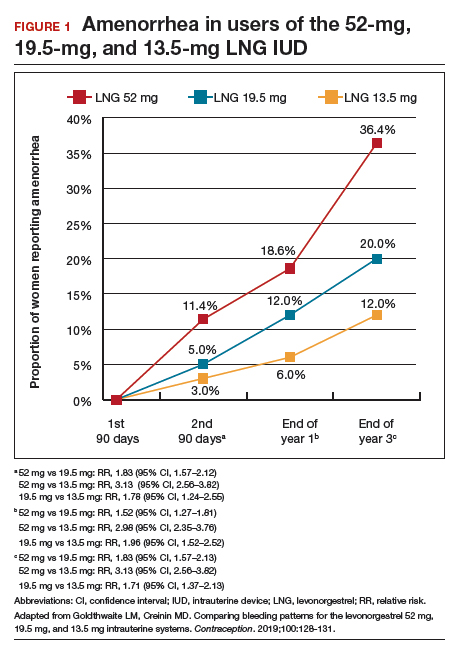

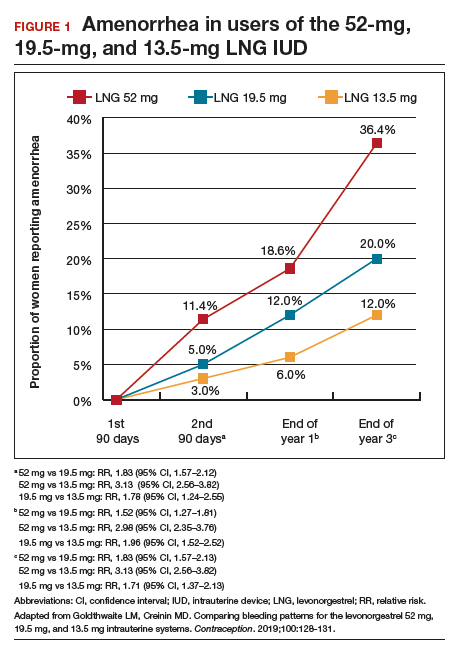

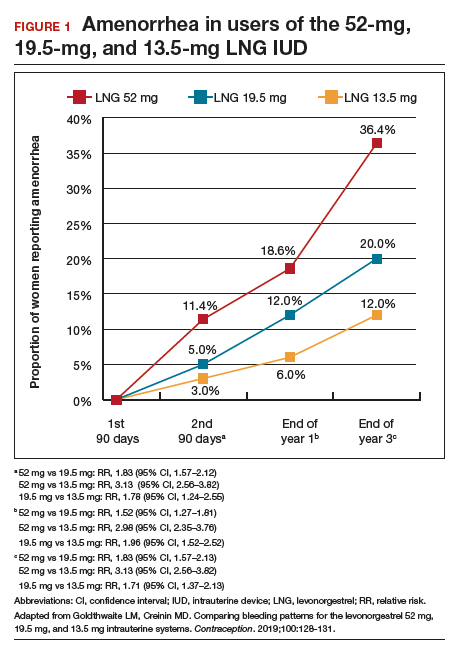

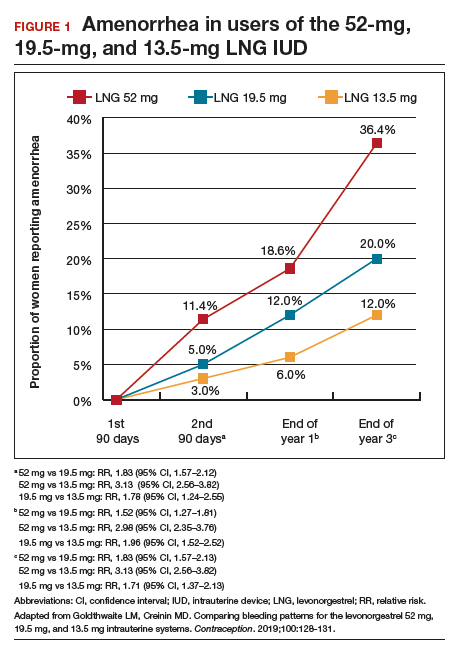

Among favorable bleeding patterns, amenorrhea was uncommon in the first 90 days and increased over time for all 3 IUDs. However, starting as soon as the second 90-day reference period, amenorrhea rates were significantly higher with the 52-mg LNG IUD compared with both of the lower-LNG dose IUDs, and this difference increased through 3 years of use (FIGURE 1).

Similarly, the 19.5-mg LNG IUD users had significantly higher rates of amenorrhea than the 13.5-mg LNG IUD users for all periods starting with the second 90-day reference period. At 3 years, 36% of women using the 52-mg LNG IUD had amenorrhea compared with 20% of those using the 19.5-mg LNG IUD (P<.0001) and 12% of those using the 13.5-mg LNG IUD (P<.0001).

Infrequent bleeding was similar for all 3 LNG IUDs in the first 90-day period, and it then increased most rapidly in the 52-mg LNG IUD users. At the end of year 1, 30% of the 52-mg LNG IUD users had infrequent bleeding compared with 26% of the 19.5-mg users (P = .01) and 20% of the 13.5-mg users (P<.0001). Although there was no difference in infrequent bleeding rates between the 52-mg and the 19.5-mg LNG IUD users at the end of year 1, those using a 52-mg LNG IUD had significantly higher rates of infrequent bleeding compared with the 13.5-mg LNG IUD at all time points.

Comparing unfavorable bleeding patterns: Frequent, prolonged, and irregular bleeding

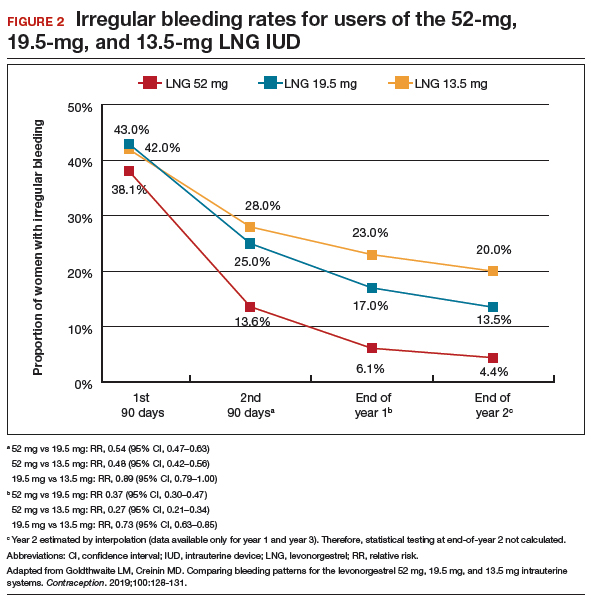

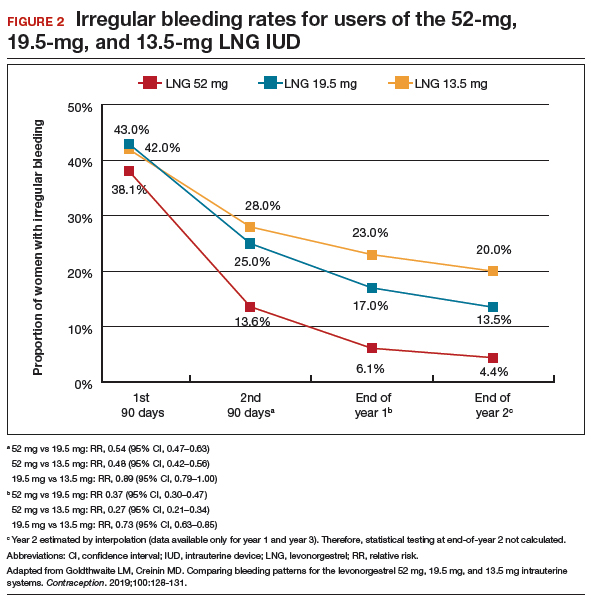

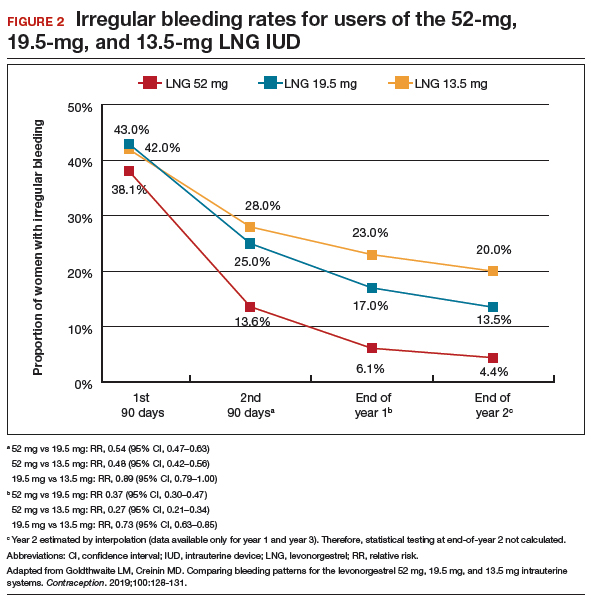

Frequent and prolonged bleeding were uncommon with all LNG doses. Irregular bleeding rates declined for users of the 3 IUDs over time. However, significantly fewer users of the 52-mg LNG IUD reported irregular bleeding at 1 year (6%) compared with users of the 19.5-mg (16.5%, P<.0001) and 13.5-mg (23%, P<.0001) LNG IUD (FIGURE 2).

Study limitations

Comparing the data from different studies has limitations. For example, the data were collected from different populations, with the lower-dose LNG products tested in women who had a lower body mass index (BMI) and higher parity. However, prior analysis of the data on the 52-mg LNG IUD demonstrated that bleeding pattern changes did not vary based on these factors.10

When considering the different progestin-based IUD options, it is important to counsel patients according to their preferences for potential adverse effects. A randomized trial during product development found no difference in systemic adverse effects with the 3 doses of LNG IUD, likely because the systemic hormone levels are incredibly low for all 3 products.11 The summary data in this report helps explain why women using the lower-dose LNG products have slightly higher discontinuation rates for bleeding complaints, a fact we can explain to our patients during counseling.

Overall, the 52-mg LNG IUD is associated with a higher likelihood of favorable bleeding patterns over the first few years of use, with higher rates of amenorrhea and infrequent bleeding and lower rates of irregular bleeding. For women who prefer to not have periods or to have infrequent periods, the 52-mg LNG IUD is most likely to provide that outcome. For a patient who prefers to have periods, there is no evidence that the lower-dose IUDs result in “regular” or “normal” menstrual bleeding, even though they do result in more bleeding/spotting days overall. To the contrary, the available data show that these women have a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing prolonged, frequent, and irregular bleeding. In fact, no studies have reported rates of “normal” bleeding with the progestin IUDs, likely because women uncommonly have “normal” bleeding with these contraception methods. If a patient does not desire amenorrhea or strongly prefers to have “regular bleeding,” alternative methods such as a copper IUD should be considered rather than counseling her toward a lower-dose progestin IUD.

Continue to: Predicting long-term bleeding patterns after etonogestrel implant insertion...

Predicting long-term bleeding patterns after etonogestrel implant insertion

Mansour D, Fraser IS, Edelman A, et al. Can initial vaginal bleeding patterns in etonogestrel implant users predict subsequent bleeding in the first two years of use? Contraception. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.017.

Data from 2014 indicate that the etonogestrel implant was used by nearly 1 million women in the United States and by 3% of women using contraception.1 The primary reason women discontinue implant use is because of changes in bleeding patterns. Given the high prevalence of bleeding concerns with the etonogestrel implant, we need more data to help counsel our patients on how they can expect their bleeding to change with implant use.

Etonogestral implant and bleeding pattern trends

Mansour and colleagues completed a secondary analysis of 12 phase 3 studies to evaluate the correlation between bleeding patterns early after placement of the etonogestrel implant (days 29-118) compared with bleeding patterns through 90-day intervals during the rest of the first year of use. To account for differences in timing of etonogestrel implant placement relative to the menstrual cycle and discontinuation of other methods like oral contraceptives, bleeding outcomes on days 0-28 were excluded. They also sought to investigate the correlation between bleeding patterns in year 1 compared with those in year 2.

Overall, these studies included 923 individuals across 11 countries; however, for the current analysis, the researchers excluded women from Asian countries who comprised more than 28% of the study population. These women report significantly fewer bleeding/spotting days with the etonogestrel implant and have a lower average body weight compared with European and American women.12

A prior analysis of the same data set looked at the number of bleeding/spotting days in groups of users rather than trends in individual patients, and, as mentioned, it also included Asian women, which diluted the overall number of bleeding days.12 In this new analysis, Mansour and colleagues used the Belsey criteria to analyze individual bleeding patterns as favorable (amenorrhea, infrequent bleeding, normal bleeding) or unfavorable (prolonged and/or frequent bleeding) from a patient perspective. In this way, we can understand trends in bleeding patterns for each patient over time, rather than seeing a static (cross-sectional) report of bleeding patterns at one point in time. Data were analyzed from 537 women in year 1 and 428 women in year 2. During the first 90-day reference period (days 29-118 after implant insertion), 61% of women reported favorable bleeding, and 39% reported unfavorable bleeding.

Favorable bleeding correlates with favorable patterns later

A favorable bleeding pattern in this first reference period correlated with favorable bleeding patterns through year 1, with 85%, 80%, and 80% of these women having a favorable pattern in reference periods 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Overall, 61% of women with a favorable pattern in reference period 1 had favorable bleeding throughout the entire first year of use. Only 3.7% of women with favorable bleeding in the first reference period discontinued the implant for bleeding in year 1. Further, women with favorable bleeding at year 1 commonly continued to have favorable bleeding in year 2, with a low discontinuation rate (2.5%) in year 2.

Individual patients who have a favorable bleeding pattern initially with etonogestrel implant placement are highly likely to continue having favorable bleeding at year 1 and year 2. Notably, of women with a favorable bleeding pattern in any 90-day reference period, about 80% will continue to have a favorable bleeding pattern in the next reference period. These women can be counseled that, even if they have a 90-day period with unfavorable bleeding, about two-thirds will have a favorable pattern in the next reference period. For those with initial unfavorable patterns, about one-third to one-half change to a favorable pattern in subsequent 90-day reference periods. For women who require intervention for unfavorable bleeding but wish to keep their etonogestrel implant, prior data support use of combined oral contraceptive pills, although bleeding resolution seems to be temporary, with 86% of women having bleeding recurrence within 10 days after treatment.13

Initial unfavorable bleeding portends less favorable patterns later

Women who had an unfavorable bleeding pattern initially, however, had a less predictable course over the first year. For those with an initial unfavorable pattern, only 37%, 47%, and 51% reported a favorable pattern in reference periods 2, 3, and 4. Despite these relatively low rates of favorable bleeding, only 13% of the women with an initial unfavorable bleeding pattern discontinued implant use for a bleeding complaint by the end of year 1; this rate was significantly higher than that for women with a favorable initial bleeding pattern (P<.0001). The discontinuation rate for bleeding complaints also remained higher in year 2, at 16.5%.

Limitations and strengths to consider

Although the etonogestrel implant is FDA-approved for 3 years of use, the bleeding data from the combined trials included information for only up to 2 years after placement. The studies included also did not uniformly assess BMI, which makes it difficult to find correlations between bleeding patterns and BMI. Importantly, the studies did not include women who were more than 30% above their ideal body weight, so these assessments do not apply to obese users.12 Exclusion of women from Southeast Asia in this analysis makes this study's findings more generalizable to populations in the United States and Europe.

Continue to: Early versus delayed postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion...

Early versus delayed postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion: Similar impacts on 12-month bleeding patterns

Vieira CS, de Nadai MN, de Melo Pereira do Carmo LS, et al. Timing of postpartum etonogestrel-releasing implant insertion and bleeding patterns, weight change, 12-month continuation and satisfaction rates: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.007.

Initiation of a desired LARC method shortly after delivery is associated with significant reductions in short interpregnancy intervals.14 With that goal in mind, Vieira and colleagues compared bleeding patterns in women who received an etonogestrel implant within 48 hours of delivery with those who received an implant at 6 weeks postdelivery.

The study was a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial of early versus delayed postpartum insertion of the etonogestrel implant conducted in Sao Paulo, Brazil. That primary trial's goal was to examine the impact of early versus delayed implant insertion on infant growth (100 women were randomly assigned to the 2 implant groups); no difference in infant growth at 12 months was seen in the 2 groups.15 In the secondary analysis, bleeding patterns and BMI were evaluated every 90 days for 12 months. The mean BMI at enrollment postpartum was 29.4 kg/m2 in the early-insertion group and 30.2 kg/m2 for the delayed-insertion group.

Bleeding patterns with early or delayed implant insertion were similar

Vieira and colleagues found similar bleeding patterns between the groups over 12 months of follow-up. Amenorrhea was reported by 56% of the early-insertion group in the first 90 days and by 62% in the delayed-insertion group. During the last 90 days of the year, 52% of the early-insertion and 46% of the delayed-insertion group reported amenorrhea. Amenorrhea rates did not differ between women who were exclusively breastfeeding and those nonexclusively breastfeeding.

Continuation rates were high at 1 year

Prolonged bleeding episodes were uncommon in both groups, with only 2% of women reporting prolonged bleeding in any given reference period. Twelve-month implant continuation rates were high in both groups: 98% in the early- and 100% in the delayed-insertion group. Additionally, the investigators found that both groups experienced a BMI decrease, with no difference between groups (10.3% and 11% in the early- and delayed-insertion groups, respectively).

Study limitations and strengths

This study included a larger number of participants than prior randomized, controlled trials that evaluated bleeding patterns with postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion, and it had very low rates of loss to follow-up. The study's low rate of 12-month implant discontinuation (2%) is lower than that of other studies that reported rates of 6% to 14%.16,17 Although the authors stated that this low rate may be due to thorough anticipatory counseling prior to placement, it is also possible that this study population does not reflect all populations. Regardless, the data clearly show that placing an etonogestrel implant prior to hospital discharge, compared with waiting for later placement, does not impact bleeding patterns over the ensuing year.

For patients who desire an etonogestrel implant for contraception postpartum, we now have additional information to counsel about the impact of implant placement on postpartum bleeding patterns. Overall, bleeding patterns are highly favorable and do not vary whether the implant is placed in the hospital or later. Additionally, the timing of placement does not impact implant continuation rates or BMI changes over 1 year. Further, the primary study assessed infant growth in the early- versus delayed-placement groups and found no differences in infant growth. Although the data are limited, immediate postpartum etonogestrel implant placement does not seem to affect the rate of breastfeeding or the volume of breast milk.18,19 Timing of implant placement, assuming adequate resources, should be based primarily on patient preference. And, given the correlation of immediate postpartum LARC placement to increased interpregnancy interval, particular efforts should be made to provide the implant in the immediate postpartum period, if the patient desires.20

- Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J. Contraceptive method use in the United States: trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014. Contraception. 2018;97:14-21.

- Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397-404.

- Odom EB, Eisenberg DL, Fox IK. Difficult removal of subdermal contraceptive implants: a multidisciplinary approach involving a peripheral nerve expert. Contraception. 2017;96: 89-95.

- Funk S, Miller MM, Mishell DR Jr, et al; Implanon US Study Group. Safety and efficacy of Implanon, a single-rod implantable contraceptive containing etonogestrel. Contraception. 2005;71:319-326.

- Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, et al; ACCESS IUS Investigators. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92:10-16.

- Nelson A, Apter D, Hauck B, et al. Two low-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive systems: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1205-1213.

- Beckert V, Ahlers C, Frenz AK, et al. Bleeding patterns with the 19.5mg LNG-IUS, with special focus on the first year of use: implications for counselling. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24:251-259.

- Teal SB, Turok DK, Chen BA, et al. Five-year contraceptive efficacy and safety of a levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine system. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:63-70.

- Belsey EM, Machines D, d’Arcangues C. The analysis of vaginal bleeding patterns induced by fertility regulating methods. Contraception. 1986;34:253-260.

- Schreiber CA, Teal SB, Blumenthal PD, et al. Bleeding patterns for the Liletta® levonorgestrel 52mg intrauterine system. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23:116–120.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized, phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:616-22.e1-3.

- Mansour D, Korver T, Marintcheva-Petrova M, et al. The effects of Implanon on menstrual bleeding patterns. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13(suppl 1):13-28.

- Guiahi M, McBride M, Sheeder J, et al. Short-term treatment of bothersome bleeding for etonogestrel implant users using a 14-day oral contraceptive pill regimen: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:508-513.

- Brunson MR, Klein DA, Olsen CH, et al. Postpartum contraception: initiation and effectiveness in a large universal healthcare system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:55.e1-55.e9

- de Melo Pereira Carmo LS, Braga GC, Ferriani RA, et al. Timing of etonogestrel-releasing implants and growth of breastfed infants: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:100-107.

- Crockett AH, Pickell LB, Heberlein EC, et al. Six- and twelve-month documented removal rates among women electing postpartum inpatient compared to delayed or interval contraceptive implant insertions after Medicaid payment reform. Contraception. 2017;95:71-76.

- Wilson S, Tennant C, Sammel MD, et al. Immediate postpartum etonogestrel implant: a contraception option with long-term continuation. Contraception. 2014;90:259-264.

- Sothornwit J, Werawatakul Y, Kaewrudee S, et al. Immediate versus delayed postpartum insertion of contraceptive implant for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011913.

- Braga GC, Ferriolli E, Quintana SM, et al. Immediate postpartum initiation of etonogestrel-releasing implant: a randomized controlled trial on breastfeeding impact. Contraception. 2015;92:536-542.

- Thiel de Bocanegra H, Chang R, Howell M, et al. Interpregnancy intervals: impact of postpartum contraceptive effectiveness and coverage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:311.e1-8.

- Kyleena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc;2016.

- Skyla [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2016.

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) use continues to increase in the United States. According to the most recent estimates from 2014, 14% of women use either an intrauterine device (IUD) or the etonogestrel implant.1 Forms of LARC currently available in the United States include:

- 4 hormone-releasing IUDs

- 1 nonhormonal copper IUD, and

- 1 hormonal subdermal implant.

The hormone-releasing IUDs all contain levonorgestrel (LNG). These include two 52-mg LNG products and a 19.5-mg LNG IUD, which are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for contraception for 5 continuous years of use. In addition, a 13.5-mg LNG IUD is FDA-approved for 3 years of use. The hormonal subdermal implant, which contains etonogestrel, is FDA-approved for 3 years of use. Although major complications with IUDs (perforation, expulsion, intrauterine infection)and implants (subfascial implantation, distant migration) are rare, adverse effects that can affect continuation—such as irregular bleeding—are more common.2,3

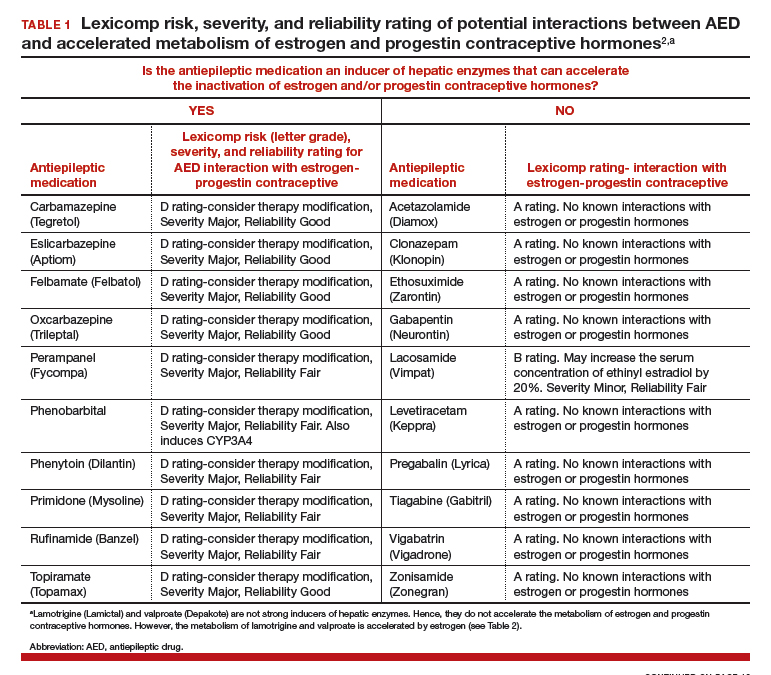

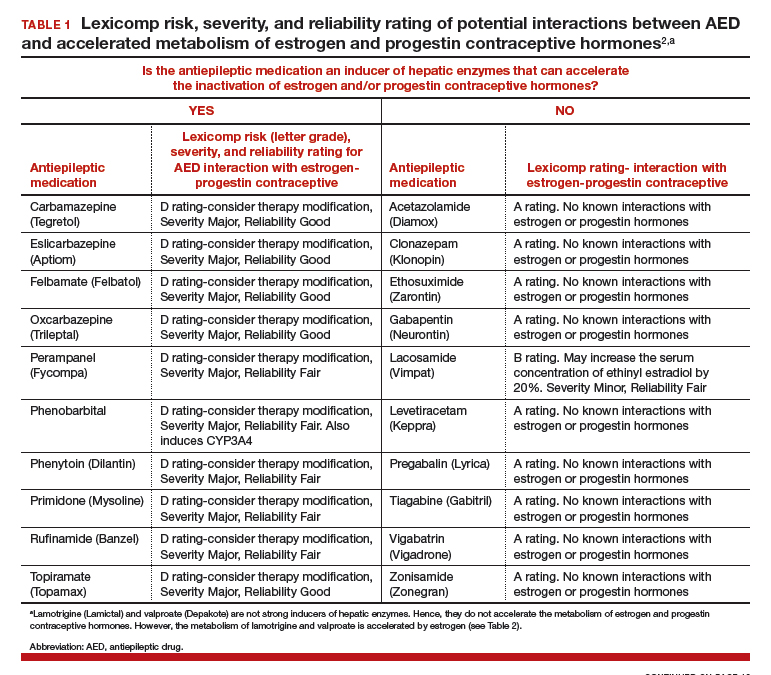

Contraceptive discontinuation due to bleeding concerns occurs more frequently with the etonogestrel implant than with LNG IUDs (TABLE 1). In a large prospective study in the United States, 13% of women discontinued the implant during 3 years of follow-up due to bleeding pattern changes.

Notably, it is important to use standardized definitions to understand and compare bleeding concerns with LARC use. The Belsey criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO), a standard used for decades, describe bleeding patterns using 90-day reference periods or intervals (TABLE 2).9 Bleeding patterns that decrease flow (amenorrhea, infrequent bleeding) often are considered favorable, and those that increase bleeding or irregularity often are considered unfavorable. These criteria are commonly used in package labeling to describe bleeding patterns with extended use.

In this Update, we examine recent data evaluating differences in bleeding patterns with the 3 doses of the LNG IUD, predictors of abnormal bleeding with the etonogestrel implant, and the impact of timing on postpartum etonogestrel implant placement.

Continue to: Bleeding patterns with progestin-containing IUDs vary according to the LNG dose...

Bleeding patterns with progestin-containing IUDs vary according to the LNG dose

Goldthwaite LM, Creinin MD. Comparing bleeding patterns for the levonorgestrel 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg intrauterine systems. Contraception. 2019;100:128-131.

Counseling on IUDs' different hormonal doses requires an understanding of patients' desires for contraceptive efficacy and bleeding expectations. A recent study provides guidance on what patients typically can expect for their bleeding patterns over the first few years with the 3 different doses of LNG IUDs.

Goldthwaite and Creinin used existing published or publicly available data to analyze differences in bleeding patterns associated with the 52-mg, 19.5-mg, and 13.5-mg LNG IUDs. Although two 52-mg LNG IUDs are available, published data using the WHO Belsey criteria are available only for one (Liletta; Allergan, Medicines360). The 2 products have been shown previously to have similar drug-release rates and LNG levels over 5 years.8

Comparing favorable bleeding patterns: Amenorrhea and infrequent bleeding

Among favorable bleeding patterns, amenorrhea was uncommon in the first 90 days and increased over time for all 3 IUDs. However, starting as soon as the second 90-day reference period, amenorrhea rates were significantly higher with the 52-mg LNG IUD compared with both of the lower-LNG dose IUDs, and this difference increased through 3 years of use (FIGURE 1).

Similarly, the 19.5-mg LNG IUD users had significantly higher rates of amenorrhea than the 13.5-mg LNG IUD users for all periods starting with the second 90-day reference period. At 3 years, 36% of women using the 52-mg LNG IUD had amenorrhea compared with 20% of those using the 19.5-mg LNG IUD (P<.0001) and 12% of those using the 13.5-mg LNG IUD (P<.0001).

Infrequent bleeding was similar for all 3 LNG IUDs in the first 90-day period, and it then increased most rapidly in the 52-mg LNG IUD users. At the end of year 1, 30% of the 52-mg LNG IUD users had infrequent bleeding compared with 26% of the 19.5-mg users (P = .01) and 20% of the 13.5-mg users (P<.0001). Although there was no difference in infrequent bleeding rates between the 52-mg and the 19.5-mg LNG IUD users at the end of year 1, those using a 52-mg LNG IUD had significantly higher rates of infrequent bleeding compared with the 13.5-mg LNG IUD at all time points.

Comparing unfavorable bleeding patterns: Frequent, prolonged, and irregular bleeding

Frequent and prolonged bleeding were uncommon with all LNG doses. Irregular bleeding rates declined for users of the 3 IUDs over time. However, significantly fewer users of the 52-mg LNG IUD reported irregular bleeding at 1 year (6%) compared with users of the 19.5-mg (16.5%, P<.0001) and 13.5-mg (23%, P<.0001) LNG IUD (FIGURE 2).

Study limitations

Comparing the data from different studies has limitations. For example, the data were collected from different populations, with the lower-dose LNG products tested in women who had a lower body mass index (BMI) and higher parity. However, prior analysis of the data on the 52-mg LNG IUD demonstrated that bleeding pattern changes did not vary based on these factors.10

When considering the different progestin-based IUD options, it is important to counsel patients according to their preferences for potential adverse effects. A randomized trial during product development found no difference in systemic adverse effects with the 3 doses of LNG IUD, likely because the systemic hormone levels are incredibly low for all 3 products.11 The summary data in this report helps explain why women using the lower-dose LNG products have slightly higher discontinuation rates for bleeding complaints, a fact we can explain to our patients during counseling.

Overall, the 52-mg LNG IUD is associated with a higher likelihood of favorable bleeding patterns over the first few years of use, with higher rates of amenorrhea and infrequent bleeding and lower rates of irregular bleeding. For women who prefer to not have periods or to have infrequent periods, the 52-mg LNG IUD is most likely to provide that outcome. For a patient who prefers to have periods, there is no evidence that the lower-dose IUDs result in “regular” or “normal” menstrual bleeding, even though they do result in more bleeding/spotting days overall. To the contrary, the available data show that these women have a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing prolonged, frequent, and irregular bleeding. In fact, no studies have reported rates of “normal” bleeding with the progestin IUDs, likely because women uncommonly have “normal” bleeding with these contraception methods. If a patient does not desire amenorrhea or strongly prefers to have “regular bleeding,” alternative methods such as a copper IUD should be considered rather than counseling her toward a lower-dose progestin IUD.

Continue to: Predicting long-term bleeding patterns after etonogestrel implant insertion...

Predicting long-term bleeding patterns after etonogestrel implant insertion

Mansour D, Fraser IS, Edelman A, et al. Can initial vaginal bleeding patterns in etonogestrel implant users predict subsequent bleeding in the first two years of use? Contraception. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.017.

Data from 2014 indicate that the etonogestrel implant was used by nearly 1 million women in the United States and by 3% of women using contraception.1 The primary reason women discontinue implant use is because of changes in bleeding patterns. Given the high prevalence of bleeding concerns with the etonogestrel implant, we need more data to help counsel our patients on how they can expect their bleeding to change with implant use.

Etonogestral implant and bleeding pattern trends

Mansour and colleagues completed a secondary analysis of 12 phase 3 studies to evaluate the correlation between bleeding patterns early after placement of the etonogestrel implant (days 29-118) compared with bleeding patterns through 90-day intervals during the rest of the first year of use. To account for differences in timing of etonogestrel implant placement relative to the menstrual cycle and discontinuation of other methods like oral contraceptives, bleeding outcomes on days 0-28 were excluded. They also sought to investigate the correlation between bleeding patterns in year 1 compared with those in year 2.

Overall, these studies included 923 individuals across 11 countries; however, for the current analysis, the researchers excluded women from Asian countries who comprised more than 28% of the study population. These women report significantly fewer bleeding/spotting days with the etonogestrel implant and have a lower average body weight compared with European and American women.12

A prior analysis of the same data set looked at the number of bleeding/spotting days in groups of users rather than trends in individual patients, and, as mentioned, it also included Asian women, which diluted the overall number of bleeding days.12 In this new analysis, Mansour and colleagues used the Belsey criteria to analyze individual bleeding patterns as favorable (amenorrhea, infrequent bleeding, normal bleeding) or unfavorable (prolonged and/or frequent bleeding) from a patient perspective. In this way, we can understand trends in bleeding patterns for each patient over time, rather than seeing a static (cross-sectional) report of bleeding patterns at one point in time. Data were analyzed from 537 women in year 1 and 428 women in year 2. During the first 90-day reference period (days 29-118 after implant insertion), 61% of women reported favorable bleeding, and 39% reported unfavorable bleeding.

Favorable bleeding correlates with favorable patterns later

A favorable bleeding pattern in this first reference period correlated with favorable bleeding patterns through year 1, with 85%, 80%, and 80% of these women having a favorable pattern in reference periods 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Overall, 61% of women with a favorable pattern in reference period 1 had favorable bleeding throughout the entire first year of use. Only 3.7% of women with favorable bleeding in the first reference period discontinued the implant for bleeding in year 1. Further, women with favorable bleeding at year 1 commonly continued to have favorable bleeding in year 2, with a low discontinuation rate (2.5%) in year 2.

Individual patients who have a favorable bleeding pattern initially with etonogestrel implant placement are highly likely to continue having favorable bleeding at year 1 and year 2. Notably, of women with a favorable bleeding pattern in any 90-day reference period, about 80% will continue to have a favorable bleeding pattern in the next reference period. These women can be counseled that, even if they have a 90-day period with unfavorable bleeding, about two-thirds will have a favorable pattern in the next reference period. For those with initial unfavorable patterns, about one-third to one-half change to a favorable pattern in subsequent 90-day reference periods. For women who require intervention for unfavorable bleeding but wish to keep their etonogestrel implant, prior data support use of combined oral contraceptive pills, although bleeding resolution seems to be temporary, with 86% of women having bleeding recurrence within 10 days after treatment.13

Initial unfavorable bleeding portends less favorable patterns later

Women who had an unfavorable bleeding pattern initially, however, had a less predictable course over the first year. For those with an initial unfavorable pattern, only 37%, 47%, and 51% reported a favorable pattern in reference periods 2, 3, and 4. Despite these relatively low rates of favorable bleeding, only 13% of the women with an initial unfavorable bleeding pattern discontinued implant use for a bleeding complaint by the end of year 1; this rate was significantly higher than that for women with a favorable initial bleeding pattern (P<.0001). The discontinuation rate for bleeding complaints also remained higher in year 2, at 16.5%.

Limitations and strengths to consider

Although the etonogestrel implant is FDA-approved for 3 years of use, the bleeding data from the combined trials included information for only up to 2 years after placement. The studies included also did not uniformly assess BMI, which makes it difficult to find correlations between bleeding patterns and BMI. Importantly, the studies did not include women who were more than 30% above their ideal body weight, so these assessments do not apply to obese users.12 Exclusion of women from Southeast Asia in this analysis makes this study's findings more generalizable to populations in the United States and Europe.

Continue to: Early versus delayed postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion...

Early versus delayed postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion: Similar impacts on 12-month bleeding patterns

Vieira CS, de Nadai MN, de Melo Pereira do Carmo LS, et al. Timing of postpartum etonogestrel-releasing implant insertion and bleeding patterns, weight change, 12-month continuation and satisfaction rates: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.007.

Initiation of a desired LARC method shortly after delivery is associated with significant reductions in short interpregnancy intervals.14 With that goal in mind, Vieira and colleagues compared bleeding patterns in women who received an etonogestrel implant within 48 hours of delivery with those who received an implant at 6 weeks postdelivery.

The study was a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial of early versus delayed postpartum insertion of the etonogestrel implant conducted in Sao Paulo, Brazil. That primary trial's goal was to examine the impact of early versus delayed implant insertion on infant growth (100 women were randomly assigned to the 2 implant groups); no difference in infant growth at 12 months was seen in the 2 groups.15 In the secondary analysis, bleeding patterns and BMI were evaluated every 90 days for 12 months. The mean BMI at enrollment postpartum was 29.4 kg/m2 in the early-insertion group and 30.2 kg/m2 for the delayed-insertion group.

Bleeding patterns with early or delayed implant insertion were similar

Vieira and colleagues found similar bleeding patterns between the groups over 12 months of follow-up. Amenorrhea was reported by 56% of the early-insertion group in the first 90 days and by 62% in the delayed-insertion group. During the last 90 days of the year, 52% of the early-insertion and 46% of the delayed-insertion group reported amenorrhea. Amenorrhea rates did not differ between women who were exclusively breastfeeding and those nonexclusively breastfeeding.

Continuation rates were high at 1 year

Prolonged bleeding episodes were uncommon in both groups, with only 2% of women reporting prolonged bleeding in any given reference period. Twelve-month implant continuation rates were high in both groups: 98% in the early- and 100% in the delayed-insertion group. Additionally, the investigators found that both groups experienced a BMI decrease, with no difference between groups (10.3% and 11% in the early- and delayed-insertion groups, respectively).

Study limitations and strengths

This study included a larger number of participants than prior randomized, controlled trials that evaluated bleeding patterns with postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion, and it had very low rates of loss to follow-up. The study's low rate of 12-month implant discontinuation (2%) is lower than that of other studies that reported rates of 6% to 14%.16,17 Although the authors stated that this low rate may be due to thorough anticipatory counseling prior to placement, it is also possible that this study population does not reflect all populations. Regardless, the data clearly show that placing an etonogestrel implant prior to hospital discharge, compared with waiting for later placement, does not impact bleeding patterns over the ensuing year.

For patients who desire an etonogestrel implant for contraception postpartum, we now have additional information to counsel about the impact of implant placement on postpartum bleeding patterns. Overall, bleeding patterns are highly favorable and do not vary whether the implant is placed in the hospital or later. Additionally, the timing of placement does not impact implant continuation rates or BMI changes over 1 year. Further, the primary study assessed infant growth in the early- versus delayed-placement groups and found no differences in infant growth. Although the data are limited, immediate postpartum etonogestrel implant placement does not seem to affect the rate of breastfeeding or the volume of breast milk.18,19 Timing of implant placement, assuming adequate resources, should be based primarily on patient preference. And, given the correlation of immediate postpartum LARC placement to increased interpregnancy interval, particular efforts should be made to provide the implant in the immediate postpartum period, if the patient desires.20

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) use continues to increase in the United States. According to the most recent estimates from 2014, 14% of women use either an intrauterine device (IUD) or the etonogestrel implant.1 Forms of LARC currently available in the United States include:

- 4 hormone-releasing IUDs

- 1 nonhormonal copper IUD, and

- 1 hormonal subdermal implant.

The hormone-releasing IUDs all contain levonorgestrel (LNG). These include two 52-mg LNG products and a 19.5-mg LNG IUD, which are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for contraception for 5 continuous years of use. In addition, a 13.5-mg LNG IUD is FDA-approved for 3 years of use. The hormonal subdermal implant, which contains etonogestrel, is FDA-approved for 3 years of use. Although major complications with IUDs (perforation, expulsion, intrauterine infection)and implants (subfascial implantation, distant migration) are rare, adverse effects that can affect continuation—such as irregular bleeding—are more common.2,3

Contraceptive discontinuation due to bleeding concerns occurs more frequently with the etonogestrel implant than with LNG IUDs (TABLE 1). In a large prospective study in the United States, 13% of women discontinued the implant during 3 years of follow-up due to bleeding pattern changes.

Notably, it is important to use standardized definitions to understand and compare bleeding concerns with LARC use. The Belsey criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO), a standard used for decades, describe bleeding patterns using 90-day reference periods or intervals (TABLE 2).9 Bleeding patterns that decrease flow (amenorrhea, infrequent bleeding) often are considered favorable, and those that increase bleeding or irregularity often are considered unfavorable. These criteria are commonly used in package labeling to describe bleeding patterns with extended use.

In this Update, we examine recent data evaluating differences in bleeding patterns with the 3 doses of the LNG IUD, predictors of abnormal bleeding with the etonogestrel implant, and the impact of timing on postpartum etonogestrel implant placement.

Continue to: Bleeding patterns with progestin-containing IUDs vary according to the LNG dose...

Bleeding patterns with progestin-containing IUDs vary according to the LNG dose

Goldthwaite LM, Creinin MD. Comparing bleeding patterns for the levonorgestrel 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg intrauterine systems. Contraception. 2019;100:128-131.

Counseling on IUDs' different hormonal doses requires an understanding of patients' desires for contraceptive efficacy and bleeding expectations. A recent study provides guidance on what patients typically can expect for their bleeding patterns over the first few years with the 3 different doses of LNG IUDs.

Goldthwaite and Creinin used existing published or publicly available data to analyze differences in bleeding patterns associated with the 52-mg, 19.5-mg, and 13.5-mg LNG IUDs. Although two 52-mg LNG IUDs are available, published data using the WHO Belsey criteria are available only for one (Liletta; Allergan, Medicines360). The 2 products have been shown previously to have similar drug-release rates and LNG levels over 5 years.8

Comparing favorable bleeding patterns: Amenorrhea and infrequent bleeding

Among favorable bleeding patterns, amenorrhea was uncommon in the first 90 days and increased over time for all 3 IUDs. However, starting as soon as the second 90-day reference period, amenorrhea rates were significantly higher with the 52-mg LNG IUD compared with both of the lower-LNG dose IUDs, and this difference increased through 3 years of use (FIGURE 1).

Similarly, the 19.5-mg LNG IUD users had significantly higher rates of amenorrhea than the 13.5-mg LNG IUD users for all periods starting with the second 90-day reference period. At 3 years, 36% of women using the 52-mg LNG IUD had amenorrhea compared with 20% of those using the 19.5-mg LNG IUD (P<.0001) and 12% of those using the 13.5-mg LNG IUD (P<.0001).

Infrequent bleeding was similar for all 3 LNG IUDs in the first 90-day period, and it then increased most rapidly in the 52-mg LNG IUD users. At the end of year 1, 30% of the 52-mg LNG IUD users had infrequent bleeding compared with 26% of the 19.5-mg users (P = .01) and 20% of the 13.5-mg users (P<.0001). Although there was no difference in infrequent bleeding rates between the 52-mg and the 19.5-mg LNG IUD users at the end of year 1, those using a 52-mg LNG IUD had significantly higher rates of infrequent bleeding compared with the 13.5-mg LNG IUD at all time points.

Comparing unfavorable bleeding patterns: Frequent, prolonged, and irregular bleeding

Frequent and prolonged bleeding were uncommon with all LNG doses. Irregular bleeding rates declined for users of the 3 IUDs over time. However, significantly fewer users of the 52-mg LNG IUD reported irregular bleeding at 1 year (6%) compared with users of the 19.5-mg (16.5%, P<.0001) and 13.5-mg (23%, P<.0001) LNG IUD (FIGURE 2).

Study limitations

Comparing the data from different studies has limitations. For example, the data were collected from different populations, with the lower-dose LNG products tested in women who had a lower body mass index (BMI) and higher parity. However, prior analysis of the data on the 52-mg LNG IUD demonstrated that bleeding pattern changes did not vary based on these factors.10

When considering the different progestin-based IUD options, it is important to counsel patients according to their preferences for potential adverse effects. A randomized trial during product development found no difference in systemic adverse effects with the 3 doses of LNG IUD, likely because the systemic hormone levels are incredibly low for all 3 products.11 The summary data in this report helps explain why women using the lower-dose LNG products have slightly higher discontinuation rates for bleeding complaints, a fact we can explain to our patients during counseling.

Overall, the 52-mg LNG IUD is associated with a higher likelihood of favorable bleeding patterns over the first few years of use, with higher rates of amenorrhea and infrequent bleeding and lower rates of irregular bleeding. For women who prefer to not have periods or to have infrequent periods, the 52-mg LNG IUD is most likely to provide that outcome. For a patient who prefers to have periods, there is no evidence that the lower-dose IUDs result in “regular” or “normal” menstrual bleeding, even though they do result in more bleeding/spotting days overall. To the contrary, the available data show that these women have a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing prolonged, frequent, and irregular bleeding. In fact, no studies have reported rates of “normal” bleeding with the progestin IUDs, likely because women uncommonly have “normal” bleeding with these contraception methods. If a patient does not desire amenorrhea or strongly prefers to have “regular bleeding,” alternative methods such as a copper IUD should be considered rather than counseling her toward a lower-dose progestin IUD.

Continue to: Predicting long-term bleeding patterns after etonogestrel implant insertion...

Predicting long-term bleeding patterns after etonogestrel implant insertion

Mansour D, Fraser IS, Edelman A, et al. Can initial vaginal bleeding patterns in etonogestrel implant users predict subsequent bleeding in the first two years of use? Contraception. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.017.

Data from 2014 indicate that the etonogestrel implant was used by nearly 1 million women in the United States and by 3% of women using contraception.1 The primary reason women discontinue implant use is because of changes in bleeding patterns. Given the high prevalence of bleeding concerns with the etonogestrel implant, we need more data to help counsel our patients on how they can expect their bleeding to change with implant use.

Etonogestral implant and bleeding pattern trends

Mansour and colleagues completed a secondary analysis of 12 phase 3 studies to evaluate the correlation between bleeding patterns early after placement of the etonogestrel implant (days 29-118) compared with bleeding patterns through 90-day intervals during the rest of the first year of use. To account for differences in timing of etonogestrel implant placement relative to the menstrual cycle and discontinuation of other methods like oral contraceptives, bleeding outcomes on days 0-28 were excluded. They also sought to investigate the correlation between bleeding patterns in year 1 compared with those in year 2.

Overall, these studies included 923 individuals across 11 countries; however, for the current analysis, the researchers excluded women from Asian countries who comprised more than 28% of the study population. These women report significantly fewer bleeding/spotting days with the etonogestrel implant and have a lower average body weight compared with European and American women.12

A prior analysis of the same data set looked at the number of bleeding/spotting days in groups of users rather than trends in individual patients, and, as mentioned, it also included Asian women, which diluted the overall number of bleeding days.12 In this new analysis, Mansour and colleagues used the Belsey criteria to analyze individual bleeding patterns as favorable (amenorrhea, infrequent bleeding, normal bleeding) or unfavorable (prolonged and/or frequent bleeding) from a patient perspective. In this way, we can understand trends in bleeding patterns for each patient over time, rather than seeing a static (cross-sectional) report of bleeding patterns at one point in time. Data were analyzed from 537 women in year 1 and 428 women in year 2. During the first 90-day reference period (days 29-118 after implant insertion), 61% of women reported favorable bleeding, and 39% reported unfavorable bleeding.

Favorable bleeding correlates with favorable patterns later

A favorable bleeding pattern in this first reference period correlated with favorable bleeding patterns through year 1, with 85%, 80%, and 80% of these women having a favorable pattern in reference periods 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Overall, 61% of women with a favorable pattern in reference period 1 had favorable bleeding throughout the entire first year of use. Only 3.7% of women with favorable bleeding in the first reference period discontinued the implant for bleeding in year 1. Further, women with favorable bleeding at year 1 commonly continued to have favorable bleeding in year 2, with a low discontinuation rate (2.5%) in year 2.

Individual patients who have a favorable bleeding pattern initially with etonogestrel implant placement are highly likely to continue having favorable bleeding at year 1 and year 2. Notably, of women with a favorable bleeding pattern in any 90-day reference period, about 80% will continue to have a favorable bleeding pattern in the next reference period. These women can be counseled that, even if they have a 90-day period with unfavorable bleeding, about two-thirds will have a favorable pattern in the next reference period. For those with initial unfavorable patterns, about one-third to one-half change to a favorable pattern in subsequent 90-day reference periods. For women who require intervention for unfavorable bleeding but wish to keep their etonogestrel implant, prior data support use of combined oral contraceptive pills, although bleeding resolution seems to be temporary, with 86% of women having bleeding recurrence within 10 days after treatment.13

Initial unfavorable bleeding portends less favorable patterns later

Women who had an unfavorable bleeding pattern initially, however, had a less predictable course over the first year. For those with an initial unfavorable pattern, only 37%, 47%, and 51% reported a favorable pattern in reference periods 2, 3, and 4. Despite these relatively low rates of favorable bleeding, only 13% of the women with an initial unfavorable bleeding pattern discontinued implant use for a bleeding complaint by the end of year 1; this rate was significantly higher than that for women with a favorable initial bleeding pattern (P<.0001). The discontinuation rate for bleeding complaints also remained higher in year 2, at 16.5%.

Limitations and strengths to consider

Although the etonogestrel implant is FDA-approved for 3 years of use, the bleeding data from the combined trials included information for only up to 2 years after placement. The studies included also did not uniformly assess BMI, which makes it difficult to find correlations between bleeding patterns and BMI. Importantly, the studies did not include women who were more than 30% above their ideal body weight, so these assessments do not apply to obese users.12 Exclusion of women from Southeast Asia in this analysis makes this study's findings more generalizable to populations in the United States and Europe.

Continue to: Early versus delayed postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion...

Early versus delayed postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion: Similar impacts on 12-month bleeding patterns

Vieira CS, de Nadai MN, de Melo Pereira do Carmo LS, et al. Timing of postpartum etonogestrel-releasing implant insertion and bleeding patterns, weight change, 12-month continuation and satisfaction rates: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.007.

Initiation of a desired LARC method shortly after delivery is associated with significant reductions in short interpregnancy intervals.14 With that goal in mind, Vieira and colleagues compared bleeding patterns in women who received an etonogestrel implant within 48 hours of delivery with those who received an implant at 6 weeks postdelivery.

The study was a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial of early versus delayed postpartum insertion of the etonogestrel implant conducted in Sao Paulo, Brazil. That primary trial's goal was to examine the impact of early versus delayed implant insertion on infant growth (100 women were randomly assigned to the 2 implant groups); no difference in infant growth at 12 months was seen in the 2 groups.15 In the secondary analysis, bleeding patterns and BMI were evaluated every 90 days for 12 months. The mean BMI at enrollment postpartum was 29.4 kg/m2 in the early-insertion group and 30.2 kg/m2 for the delayed-insertion group.

Bleeding patterns with early or delayed implant insertion were similar

Vieira and colleagues found similar bleeding patterns between the groups over 12 months of follow-up. Amenorrhea was reported by 56% of the early-insertion group in the first 90 days and by 62% in the delayed-insertion group. During the last 90 days of the year, 52% of the early-insertion and 46% of the delayed-insertion group reported amenorrhea. Amenorrhea rates did not differ between women who were exclusively breastfeeding and those nonexclusively breastfeeding.

Continuation rates were high at 1 year

Prolonged bleeding episodes were uncommon in both groups, with only 2% of women reporting prolonged bleeding in any given reference period. Twelve-month implant continuation rates were high in both groups: 98% in the early- and 100% in the delayed-insertion group. Additionally, the investigators found that both groups experienced a BMI decrease, with no difference between groups (10.3% and 11% in the early- and delayed-insertion groups, respectively).

Study limitations and strengths

This study included a larger number of participants than prior randomized, controlled trials that evaluated bleeding patterns with postpartum etonogestrel implant insertion, and it had very low rates of loss to follow-up. The study's low rate of 12-month implant discontinuation (2%) is lower than that of other studies that reported rates of 6% to 14%.16,17 Although the authors stated that this low rate may be due to thorough anticipatory counseling prior to placement, it is also possible that this study population does not reflect all populations. Regardless, the data clearly show that placing an etonogestrel implant prior to hospital discharge, compared with waiting for later placement, does not impact bleeding patterns over the ensuing year.

For patients who desire an etonogestrel implant for contraception postpartum, we now have additional information to counsel about the impact of implant placement on postpartum bleeding patterns. Overall, bleeding patterns are highly favorable and do not vary whether the implant is placed in the hospital or later. Additionally, the timing of placement does not impact implant continuation rates or BMI changes over 1 year. Further, the primary study assessed infant growth in the early- versus delayed-placement groups and found no differences in infant growth. Although the data are limited, immediate postpartum etonogestrel implant placement does not seem to affect the rate of breastfeeding or the volume of breast milk.18,19 Timing of implant placement, assuming adequate resources, should be based primarily on patient preference. And, given the correlation of immediate postpartum LARC placement to increased interpregnancy interval, particular efforts should be made to provide the implant in the immediate postpartum period, if the patient desires.20

- Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J. Contraceptive method use in the United States: trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014. Contraception. 2018;97:14-21.

- Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397-404.

- Odom EB, Eisenberg DL, Fox IK. Difficult removal of subdermal contraceptive implants: a multidisciplinary approach involving a peripheral nerve expert. Contraception. 2017;96: 89-95.

- Funk S, Miller MM, Mishell DR Jr, et al; Implanon US Study Group. Safety and efficacy of Implanon, a single-rod implantable contraceptive containing etonogestrel. Contraception. 2005;71:319-326.

- Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, et al; ACCESS IUS Investigators. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92:10-16.

- Nelson A, Apter D, Hauck B, et al. Two low-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive systems: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1205-1213.

- Beckert V, Ahlers C, Frenz AK, et al. Bleeding patterns with the 19.5mg LNG-IUS, with special focus on the first year of use: implications for counselling. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24:251-259.

- Teal SB, Turok DK, Chen BA, et al. Five-year contraceptive efficacy and safety of a levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine system. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:63-70.

- Belsey EM, Machines D, d’Arcangues C. The analysis of vaginal bleeding patterns induced by fertility regulating methods. Contraception. 1986;34:253-260.

- Schreiber CA, Teal SB, Blumenthal PD, et al. Bleeding patterns for the Liletta® levonorgestrel 52mg intrauterine system. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23:116–120.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized, phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:616-22.e1-3.

- Mansour D, Korver T, Marintcheva-Petrova M, et al. The effects of Implanon on menstrual bleeding patterns. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13(suppl 1):13-28.

- Guiahi M, McBride M, Sheeder J, et al. Short-term treatment of bothersome bleeding for etonogestrel implant users using a 14-day oral contraceptive pill regimen: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:508-513.

- Brunson MR, Klein DA, Olsen CH, et al. Postpartum contraception: initiation and effectiveness in a large universal healthcare system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:55.e1-55.e9

- de Melo Pereira Carmo LS, Braga GC, Ferriani RA, et al. Timing of etonogestrel-releasing implants and growth of breastfed infants: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:100-107.

- Crockett AH, Pickell LB, Heberlein EC, et al. Six- and twelve-month documented removal rates among women electing postpartum inpatient compared to delayed or interval contraceptive implant insertions after Medicaid payment reform. Contraception. 2017;95:71-76.

- Wilson S, Tennant C, Sammel MD, et al. Immediate postpartum etonogestrel implant: a contraception option with long-term continuation. Contraception. 2014;90:259-264.

- Sothornwit J, Werawatakul Y, Kaewrudee S, et al. Immediate versus delayed postpartum insertion of contraceptive implant for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011913.

- Braga GC, Ferriolli E, Quintana SM, et al. Immediate postpartum initiation of etonogestrel-releasing implant: a randomized controlled trial on breastfeeding impact. Contraception. 2015;92:536-542.

- Thiel de Bocanegra H, Chang R, Howell M, et al. Interpregnancy intervals: impact of postpartum contraceptive effectiveness and coverage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:311.e1-8.

- Kyleena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc;2016.

- Skyla [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2016.

- Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J. Contraceptive method use in the United States: trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014. Contraception. 2018;97:14-21.

- Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397-404.

- Odom EB, Eisenberg DL, Fox IK. Difficult removal of subdermal contraceptive implants: a multidisciplinary approach involving a peripheral nerve expert. Contraception. 2017;96: 89-95.

- Funk S, Miller MM, Mishell DR Jr, et al; Implanon US Study Group. Safety and efficacy of Implanon, a single-rod implantable contraceptive containing etonogestrel. Contraception. 2005;71:319-326.

- Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, et al; ACCESS IUS Investigators. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92:10-16.

- Nelson A, Apter D, Hauck B, et al. Two low-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive systems: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1205-1213.

- Beckert V, Ahlers C, Frenz AK, et al. Bleeding patterns with the 19.5mg LNG-IUS, with special focus on the first year of use: implications for counselling. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2019;24:251-259.

- Teal SB, Turok DK, Chen BA, et al. Five-year contraceptive efficacy and safety of a levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine system. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:63-70.

- Belsey EM, Machines D, d’Arcangues C. The analysis of vaginal bleeding patterns induced by fertility regulating methods. Contraception. 1986;34:253-260.

- Schreiber CA, Teal SB, Blumenthal PD, et al. Bleeding patterns for the Liletta® levonorgestrel 52mg intrauterine system. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23:116–120.

- Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized, phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:616-22.e1-3.

- Mansour D, Korver T, Marintcheva-Petrova M, et al. The effects of Implanon on menstrual bleeding patterns. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13(suppl 1):13-28.

- Guiahi M, McBride M, Sheeder J, et al. Short-term treatment of bothersome bleeding for etonogestrel implant users using a 14-day oral contraceptive pill regimen: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:508-513.

- Brunson MR, Klein DA, Olsen CH, et al. Postpartum contraception: initiation and effectiveness in a large universal healthcare system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:55.e1-55.e9

- de Melo Pereira Carmo LS, Braga GC, Ferriani RA, et al. Timing of etonogestrel-releasing implants and growth of breastfed infants: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:100-107.

- Crockett AH, Pickell LB, Heberlein EC, et al. Six- and twelve-month documented removal rates among women electing postpartum inpatient compared to delayed or interval contraceptive implant insertions after Medicaid payment reform. Contraception. 2017;95:71-76.

- Wilson S, Tennant C, Sammel MD, et al. Immediate postpartum etonogestrel implant: a contraception option with long-term continuation. Contraception. 2014;90:259-264.

- Sothornwit J, Werawatakul Y, Kaewrudee S, et al. Immediate versus delayed postpartum insertion of contraceptive implant for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011913.

- Braga GC, Ferriolli E, Quintana SM, et al. Immediate postpartum initiation of etonogestrel-releasing implant: a randomized controlled trial on breastfeeding impact. Contraception. 2015;92:536-542.

- Thiel de Bocanegra H, Chang R, Howell M, et al. Interpregnancy intervals: impact of postpartum contraceptive effectiveness and coverage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:311.e1-8.

- Kyleena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc;2016.

- Skyla [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2016.

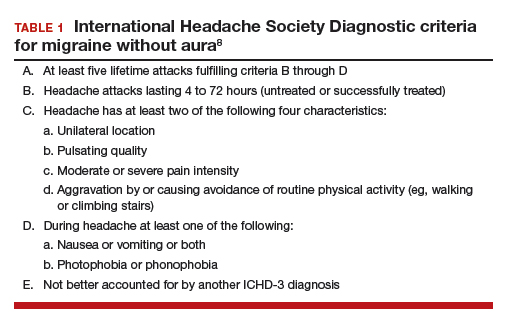

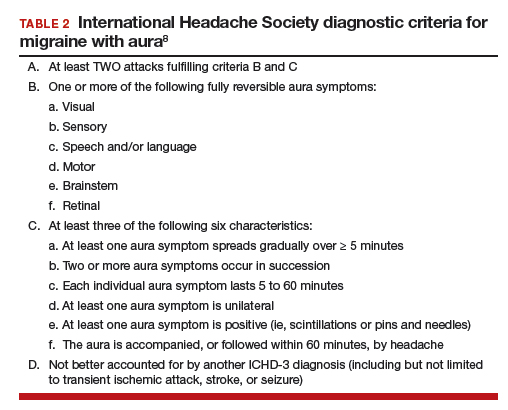

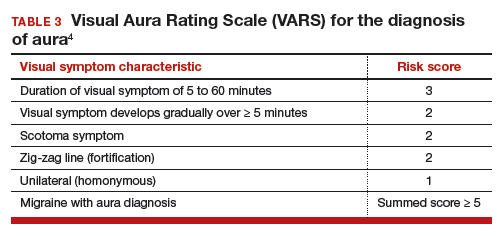

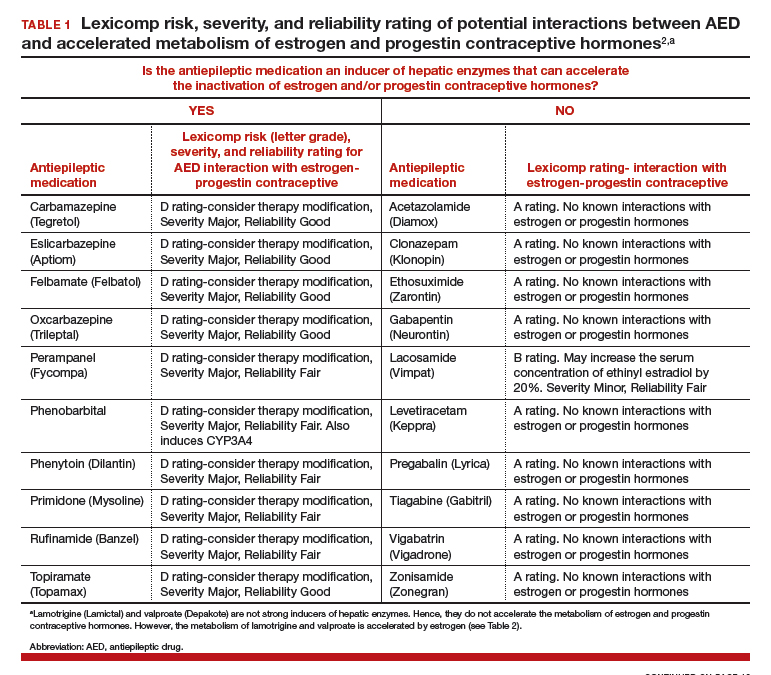

When providing contraceptive counseling to women with migraine headaches, how do you identify migraine with aura?

Most physicians know that migraine with aura is a risk factor for ischemic stroke and that the use of an estrogen-containing contraceptive further increases this risk.1-3 Additional important and prevalent risk factors for ischemic stroke include cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)2 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)3 recommend against the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives for women with migraine with aura because of the increased risk of ischemic stroke (Medical Eligibility Criteria [MEC] category 4—unacceptable health risk, method not to be used).