User login

Is Laundry Detergent a Common Cause of Allergic Contact Dermatitis?

Laundry detergent, a cleaning agent ubiquitous in the modern household, often is suspected as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

We provide a summary of the evidence for the potential allergenicity of laundry detergent, including common allergens present in laundry detergent, the role of machine washing, and the differential diagnosis for laundry detergent–associated ACD.

Allergenic Ingredients in Laundry Detergent

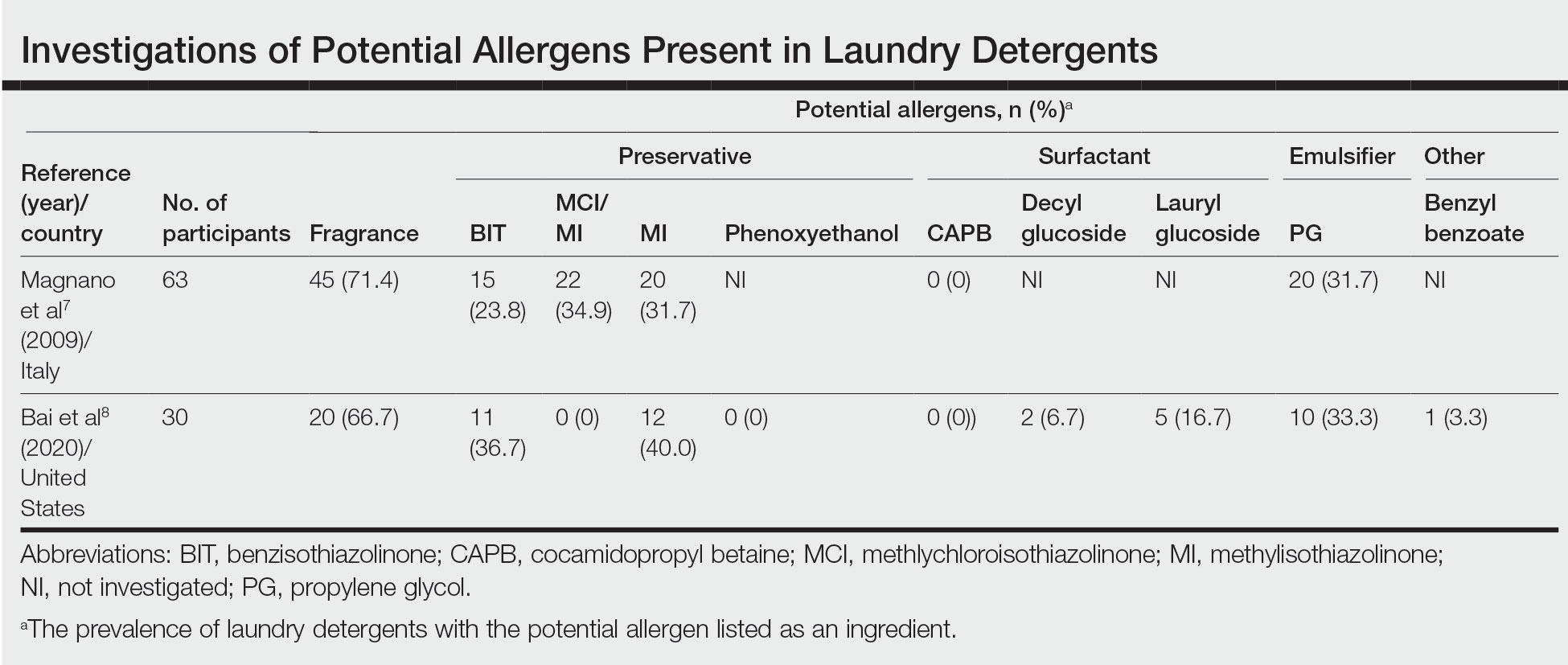

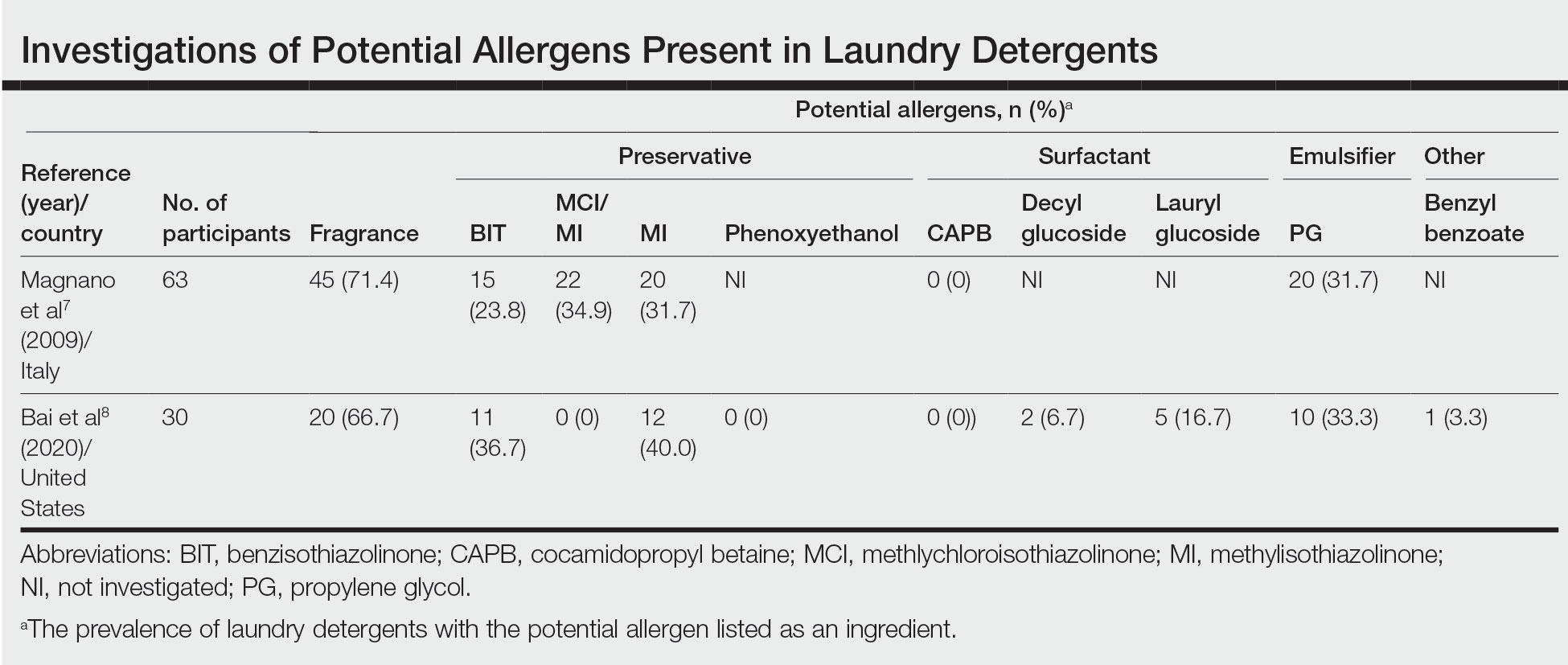

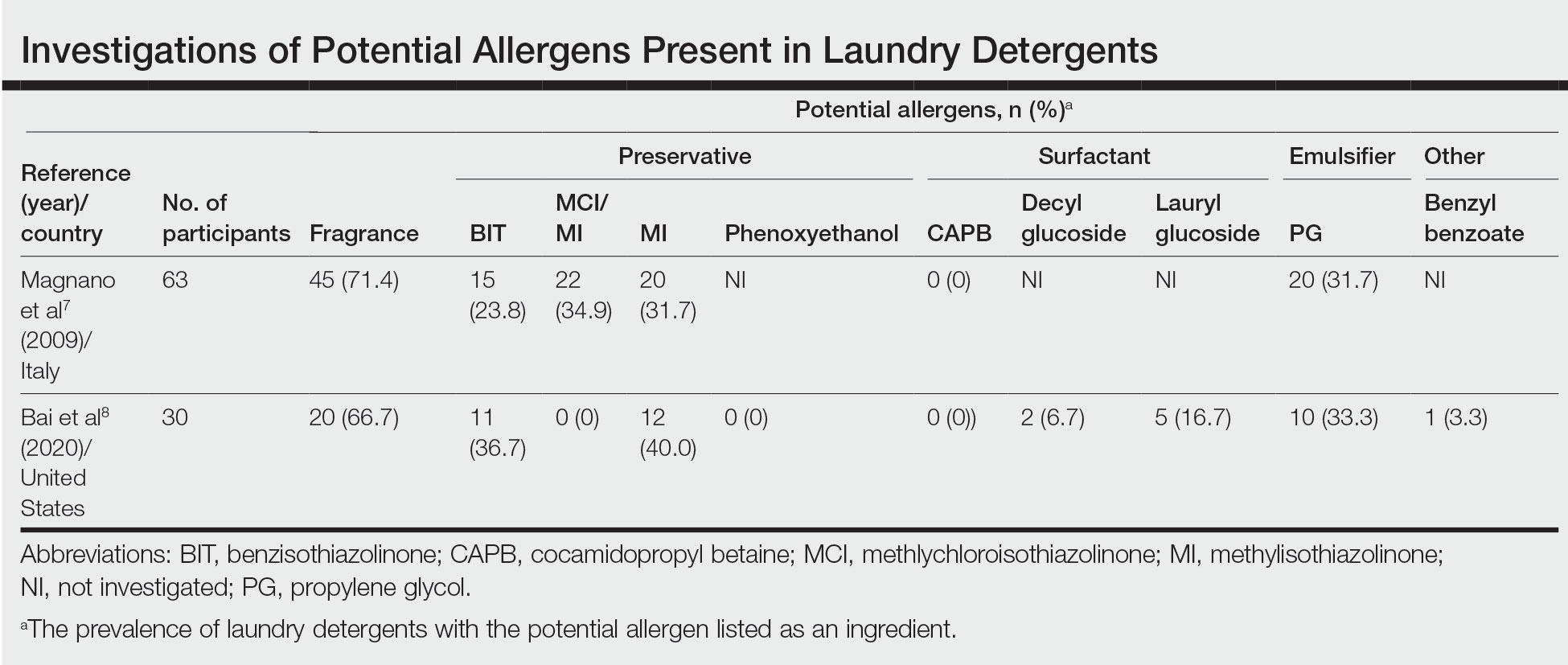

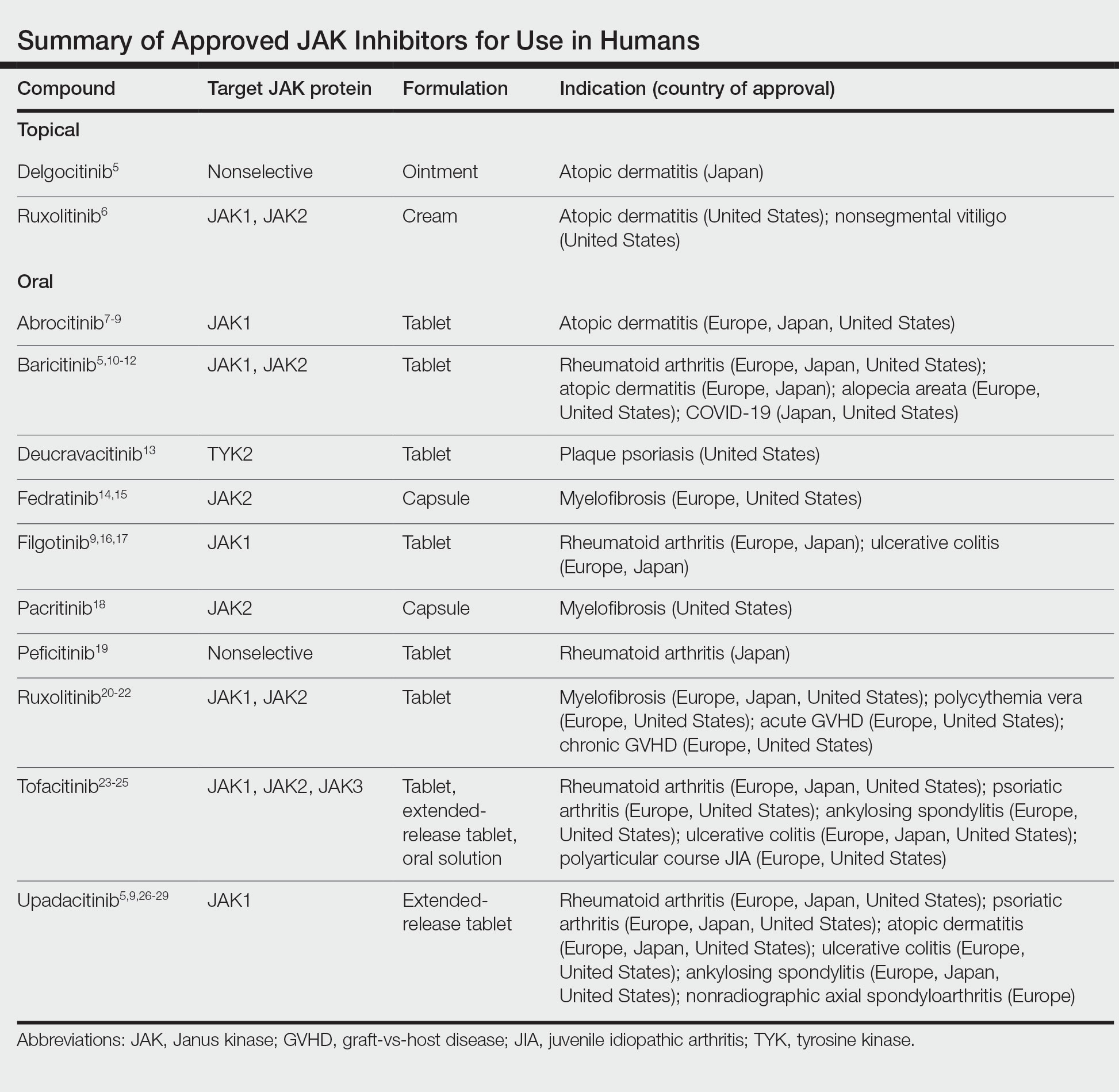

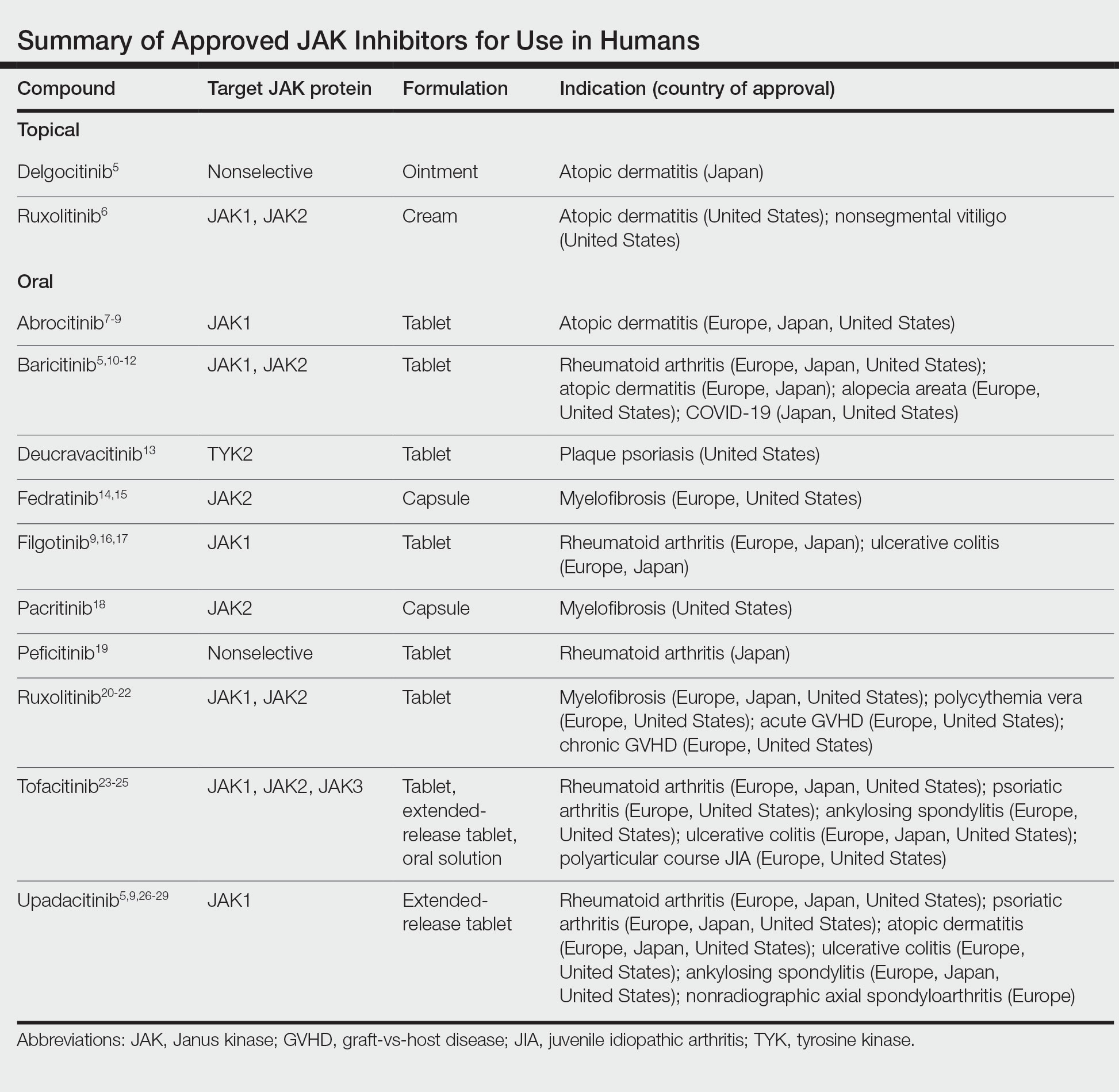

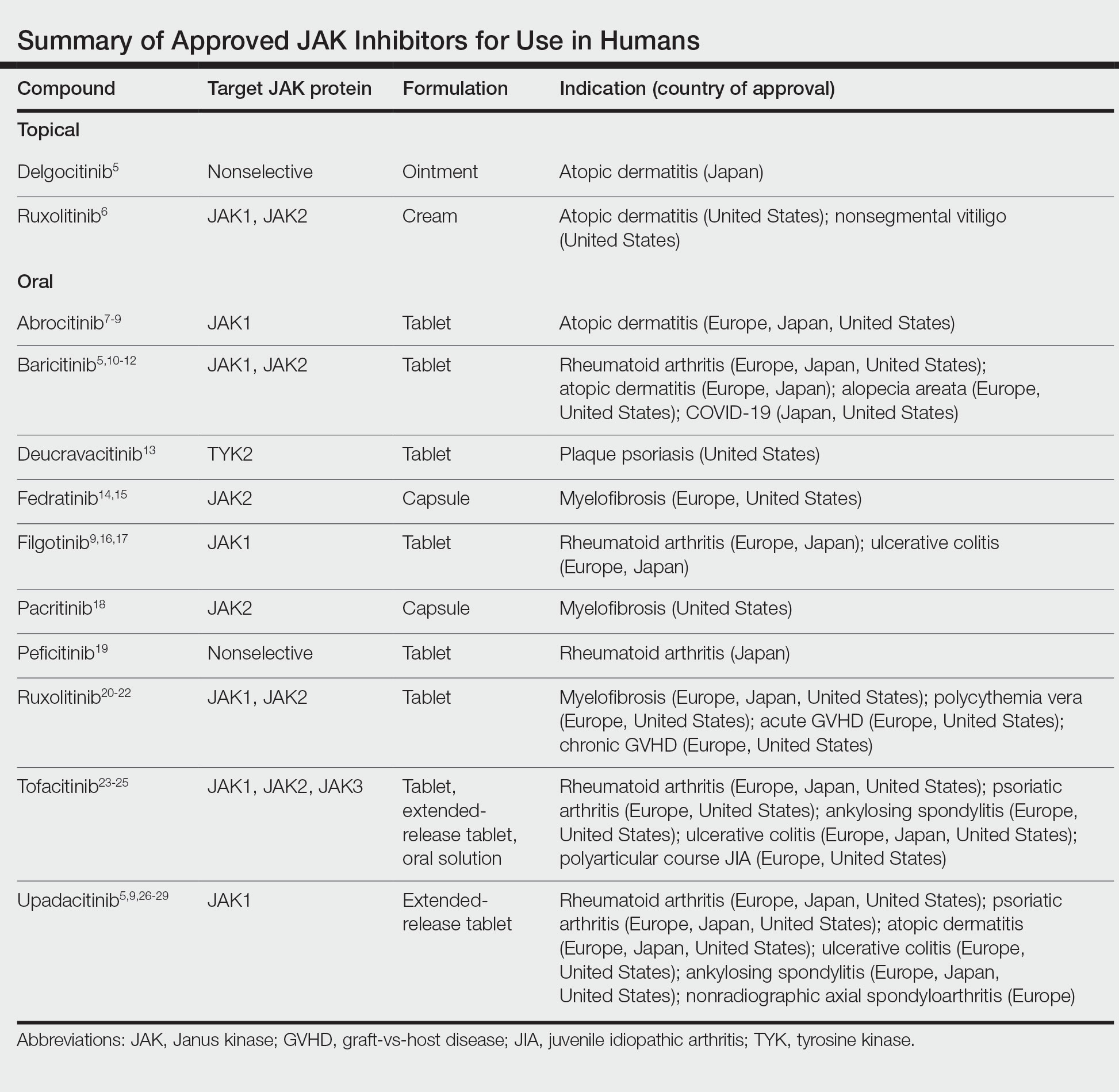

Potential allergens present in laundry detergent include fragrances, preservatives, surfactants, emulsifiers, bleaches, brighteners, enzymes, and dyes.6-8 In an analysis of allergens present in laundry detergents available in the United States, fragrances and preservatives were most common (eTable).7,8 Contact allergy to fragrances occurs in approximately 3.5% of the general population9 and is detected in as many as 9.2% of patients referred for patch testing in North America.10 Preservatives commonly found in laundry detergent include isothiazolinones, such as methylchloroisothiazolinone (MCI)/methylisothiazolinone (MI), MI alone, and benzisothiazolinone (BIT). Methylisothiazolinone has gained attention for causing an ACD epidemic beginning in the early 2000s and peaking in Europe between 2013 and 2014 and decreasing thereafter due to consumer personal care product regulatory changes enacted in the European Union.11 In contrast, rates of MI allergy in North America have continued to increase (reaching as high as 15% of patch tested patients in 2017-2018) due to a lack of similar regulation.10,12 More recently, the prevalence of positive patch tests to BIT has been rising, though it often is difficult to ascertain relevant sources of exposure, and some cases could represent cross-reactions to MCI/MI.10,13

Other allergens that may be present in laundry detergent include surfactants and propylene glycol. Alkyl glucosides such as decyl glucoside and lauryl glucoside are considered gentle surfactants and often are included in products marketed as safe for sensitive skin,14 such as “free and gentle” detergents.8 However, they actually may pose an increased risk for sensitization in patients with atopic dermatitis.14 In addition to being allergenic, surfactants and emulsifiers are known irritants.6,15 Although pathologically distinct, ACD and irritant contact dermatitis can be indistinguishable on clinical presentation.

How Commonly Does Laundry Detergent Cause ACD?

The mere presence of a contact allergen in laundry detergent does not necessarily imply that it is likely to cause ACD. To do so, the chemical in question must exceed the exposure thresholds for primary sensitization (ie, induction of contact allergy) and/or elicitation (ie, development of ACD in sensitized individuals). These depend on a complex interplay of product- and patient-specific factors, among them the concentration of the chemical in the detergent, the method of use, and the amount of detergent residue remaining on clothing after washing.

In the 1990s, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) attempted to determine the prevalence of ACD caused by laundry detergent.1 Among 738 patients patch tested to aqueous dilutions of granular and liquid laundry detergents, only 5 (0.7%) had a possible allergic patch test reaction. It was unclear what the culprit allergens in the detergents may have been; only 1 of the patients also tested positive to fragrance. Two patients underwent further testing to additional detergent dilutions, and the results called into question whether their initial reactions had truly been allergic (positive) or were actually irritant (negative). The investigators concluded that the prevalence of laundry detergent–associated ACD in this large group of patients was at most 0.7%, and possibly lower.1

Importantly, patch testing to laundry detergents should not be undertaken in routine clinical practice. Laundry detergents should never be tested “as is” (ie, undiluted) on the skin; they are inherently irritating and have a high likelihood of producing misleading false-positive reactions. Careful dilutions and testing of control subjects are necessary if patch testing with these products is to be appropriately conducted.

Isothiazolinones in Laundry Detergent

The extremely low prevalence of laundry detergent–associated ACD reported by the NACDG was determined prior to the start of the worldwide MI allergy epidemic, raising the possibility that laundry detergents containing isothiazolinones may be associated with ACD. There is no consensus about the minimum level at which isothiazolinones pose no risk to consumers,16-19 but the US Expert Panel for Cosmetic Ingredient Safety declared that MI is “safe for use in rinse-off cosmetic products at concentrations up to 100 ppm and safe in leave-on cosmetic products when they are formulated to be nonsensitizing.”18,19 Although ingredient lists do not always reveal when isothiazolinones are present, analyses of commercially available laundry detergents have shown MI concentrations ranging from undetectable to 65.7 ppm.20-23

Published reports suggest that MCI/MI in laundry detergent can elicit ACD in sensitized individuals. In one case, a 7-year-old girl with chronic truncal dermatitis (atopic history unspecified) was patch tested, revealing a strongly positive reaction to MCI/MI.24 Her laundry detergent was the only personal product found to contain MI. The dermatitis completely resolved after switching detergents and flared after wearing a jacket that had been washed in the implicated detergent, further supporting the relevance of the positive patch test. The investigators suspected initial sensitization to MI from wet wipes used earlier in childhood.24 In another case involving occupational exposure, a 39-year-old nonatopic factory worker was responsible for directly adding MI to laundry detergent.25 Although he wore disposable work gloves, he developed severe hand dermatitis, eczematous pretibial patches, and generalized pruritus. Patch testing revealed positive reactions to MCI/MI and MI, and he experienced improvement when reassigned to different work duties. It was hypothesized that the leg dermatitis and generalized pruritus may have been related to exposure to small concentrations of MI in work clothes washed with an MI-containing detergent.25 Notably, this patient’s level of exposure was much greater than that encountered by individuals in day-to-day life outside of specialized occupational settings.

Regarding other isothiazolinones, a toxicologic study estimated that BIT in laundry detergent would be unlikely to induce sensitization, even at the maximal acceptable concentration, as recommended by preservative manufacturers, and accounting for undiluted detergent spilling directly onto the skin.26

Does Machine Washing Impact Allergen Concentrations?

Two recent investigations have suggested that machine washing reduces concentrations of isothiazolinones to levels that are likely below clinical relevance. In the first study, 3 fabrics—cotton, polyester, cotton-polyester—were machine washed and line dried.27 A standard detergent was used with MI added at different concentrations: less than 1 ppm, 100 ppm, and 1000 ppm. This process was either performed once or 10 times. Following laundering and line drying, MI was undetectable in all fabrics regardless of MI concentration or number of times washed (detection limit, 0.5 ppm).27 In the second study, 4 fabrics—cotton, wool, polyester, linen—were washed with standard laundry detergent in 1 of 4 ways: handwashing (positive control), standard machine washing, standard machine washing with fabric softener, and standard machine washing with a double rinse.28 After laundering and line drying, concentrations of MI, MCI, and BIT were low or undetectable regardless of fabric type or method of laundering. The highest levels detected were in handwashed garments at a maximum of 0.5 ppm of MI. The study authors postulated that chemical concentrations near these maximum residual levels may pose a risk for eliciting ACD in highly sensitized individuals. Therefore, handwashing can be considered a much higher risk activity for isothiazolinone ACD compared with machine washing.28

It is intriguing that machine washing appears to reduce isothiazolinones to low concentrations that may have limited likelihood of causing ACD. Similar findings have been reported regarding fragrances. A quantitative risk assessment performed on 24 of 26 fragrance allergens regulated by the European Union determined that the amount of fragrance deposited on the skin from laundered garments would be less than the threshold for causing sensitization.29 Although this risk assessment was unable to address the threshold of elicitation, another study conducted in Europe investigated whether fragrance residues present on fabric, such as those deposited from laundry detergent, are present at high enough concentrations to elicit ACD in previously sensitized individuals.30 When 36 individuals were patch tested with increasing concentrations of a fragrance to which they were already sensitized, only 2 (5.6%) had a weakly positive reaction and then only to the highest concentration, which was estimated to be 20-fold higher than the level of skin exposure after normal laundering. No patient reacted at lower concentrations.30

Although machine washing may decrease isothiazolinone and/or fragrance concentrations in laundry detergent to below clinically relevant levels, these findings should not necessarily be extrapolated to all chemicals in laundry detergent. Indeed, a prior study observed that after washing cotton cloths in a detergent solution for 10 minutes, detergent residue was present at concentrations ranging from 139 to 2820 ppm and required a subsequent 20 to 22 washes in water to become undetectable.31 Another study produced a mathematical model of the residual concentration of sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), a surfactant and known irritant, in laundered clothing.32 It was estimated that after machine washing, the residual concentration of SDS on clothes would be too low to cause irritation; however, as the clothes dry (ie, as moisture evaporates but solutes remain), the concentration of SDS on the fabric’s surface would increase to potentially irritating levels. The extensive drying that is possible with electric dryers may further enhance this solute-concentrating effect.

Differential Diagnosis of Laundry Detergent ACD

The propensity for laundry detergent to cause ACD is a question that is nowhere near settled, but the prevalence of allergy likely is far less common than is generally suspected. In our experience, many patients presenting for patch testing have already made the change to “free and clear” detergents without noticeable improvement in their dermatitis, which could possibly relate to the ongoing presence of contact allergens in these “gentle” formulations.7 However, to avoid anchoring bias, more frequent causes of dermatitis should be included in the differential diagnosis. Textile ACD presents beneath clothing with accentuation at areas of closest contact with the skin, classically involving the axillary rim but sparing the vault. The most frequently implicated allergens in textile ACD are disperse dyes and less commonly textile resins.33,34 Between 2017 and 2018, 2.3% of 4882 patients patch tested by the NACDG reacted positively to disperse dye mix.10 There is evidence to suggest that the actual prevalence of disperse dye allergy might be higher due to inadequacy of screening allergens on baseline patch test series.35 Additional diagnoses that should be distinguished from presumed detergent contact dermatitis include atopic dermatitis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Final Interpretation

Although many patients and physicians consider laundry detergent to be a major cause of ACD, there is limited high-quality evidence to support this belief. Contact allergy to laundry detergent is probably much less common than is widely supposed. Although laundry detergents can contain common allergens such as fragrances and preservatives, evidence suggests that they are likely reduced to below clinically relevant levels during routine machine washing; however, we cannot assume that we are in the “free and clear,” as uncertainty remains about the impact of these low concentrationson individuals with strong contact allergy, and large studies of patch testing to modern detergents have yet to be carried out.

- Belsito DV, Fransway AF, Fowler JF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to detergents: a multicenter study to assess prevalence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:200-206. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.119665

- Dallas MJ, Wilson PA, Burns LD, et al. Dermatological and other health problems attributed by consumers to contact with laundry products. Home Econ Res J. 1992;21:34-49. doi:10.1177/1077727X9202100103

- Bailey A. An overview of laundry detergent allergies. Verywell Health. September 16, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.verywellhealth.com/laundry-detergent-allergies-signs-symptoms-and-treatment-5198934

- Fasanella K. How to tell if you laundry detergent is messing with your skin. Allure. June 15, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.allure.com/story/laundry-detergent-allergy-skin-reaction

- Oykhman P, Dookie J, Al-Rammahy et al. Dietary elimination for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Immunol Pract. 2022;10:2657-2666.e8. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2022.06.044

- Kwon S, Holland D, Kern P. Skin safety evaluation of laundry detergent products. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2009;72:1369-1379. doi:10.1080/1528739090321675

- Magnano M, Silvani S, Vincenzi C, et al. Contact allergens and irritants in household washing and cleaning products. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:337-341. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01647.x

- Bai H, Tam I, Yu J. Contact allergens in top-selling textile-care products. Dermatitis. 2020;31:53-58. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000566

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi:10.1111/cod.13119

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000729

- Havmose M, Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, et al. The epidemic of contact allergy to methylisothiazolinone–an analysis of Danish consecutive patients patch tested between 2005 and 2019. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84:254-262. doi:10.1111/cod.13717

- Atwater AR, Petty AJ, Liu B, et al. Contact dermatitis associated with preservatives: retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1994 through 2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:965-976. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.059

- King N, Latheef F, Wilkinson M. Trends in preservative allergy: benzisothiazolinone emerges from the pack. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:637-642. doi:10.1111/cod.13968

- Sasseville D. Alkyl glucosides: 2017 “allergen of the year.” Dermatitis. 2017;28:296. doi:10.1097/DER0000000000000290

- McGowan MA, Scheman A, Jacob SE. Propylene glycol in contact dermatitis: a systematic review. Dermatitis. 2018;29:6-12. doi:10.1097/DER0000000000000307

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Consumers. Opinion on methylisothiazolinone (P94) submission II (sensitisation only). Revised March 27, 2014. Accessed March 21, 2023. http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/consumer_safety/docs/sccs_o_145.pdf

- Cosmetic ingredient hotlist: list of ingredients that are restricted for use in cosmetic products. Government of Canada website. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredient-hotlist-prohibited-restricted-ingredients/hotlist.html#tbl2

- Burnett CL, Boyer I, Bergfeld WF, et al. Amended safety assessment of methylisothiazolinone as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2019;38(1 suppl):70S-84S. doi:10.1177/1091581819838792

- Burnett CL, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, et al. Amended safety assessment of methylisothiazolinone as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2021;40(1 suppl):5S-19S. doi:10.1177/10915818211015795

- Aerts O, Meert H, Goossens A, et al. Methylisothiazolinone in selected consumer products in Belgium: adding fuel to the fire? Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:142-149. doi:10.1111/cod.12449

- Garcia-Hidalgo E, Sottas V, von Goetz N, et al. Occurrence and concentrations of isothiazolinones in detergents and cosmetics in Switzerland. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:96-106. doi:10.1111/cod.12700

- Marrero-Alemán G, Borrego L, Antuña AG, et al. Isothiazolinones in cleaning products: analysis with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry of samples from sensitized patients and markets. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;82:94-100. doi:10.1111/cod.13430

- Alvarez-Rivera G, Dagnac T, Lores M, et al. Determination of isothiazolinone preservatives in cosmetics and household products by matrix solid-phase dispersion followed by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1270:41-50. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2012.10.063

- Cotton CH, Duah CG, Matiz C. Allergic contact dermatitis due to methylisothiazolinone in a young girl’s laundry detergent. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:486-487. doi:10.1111/pde.13122

- Sandvik A, Holm JO. Severe allergic contact dermatitis in a detergent production worker caused by exposure to methylisothiazolinone. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:243-245. doi:10.1111/cod.13182

- Novick RM, Nelson ML, Unice KM, et al. Estimation of safe use concentrations of the preservative 1,2-benziosothiazolin-3-one (BIT) in consumer cleaning products and sunscreens. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;56:60-66. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.02.006

- Hofmann MA, Giménez-Arnau A, Aberer W, et al. MI (2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one) contained in detergents is not detectable in machine washed textiles. Clin Transl Allergy. 2018;8:1. doi:10.1186/s13601-017-0187-2

- Marrero-Alemán G, Borrego L, Atuña AG, et al. Persistence of isothiazolinones in clothes after machine washing. Dermatitis. 2021;32:298-300. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000603

- Corea NV, Basketter DA, Clapp C, et al. Fragrance allergy: assessing the risk from washed fabrics. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:48-53. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00872.x

- Basketter DA, Pons-Guiraud A, van Asten A, et al. Fragrance allergy: assessing the safety of washed fabrics. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:349-354. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01728.x

- Agarwal C, Gupta BN, Mathur AK, et al. Residue analysis of detergent in crockery and clothes. Environmentalist. 1986;4:240-243.

- Broadbridge P, Tilley BS. Diffusion of dermatological irritant in drying laundered cloth. Math Med Biol. 2021;38:474-489. doi:10.1093/imammb/dqab014

- Lisi P, Stingeni L, Cristaudo A, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of textile contact dermatitis: an Italian multicentre study. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;70:344-350. doi:10.1111/cod.12179

- Mobolaji-Lawal M, Nedorost S. The role of textiles in dermatitis: an update. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:17. doi:10.1007/s11882-015-0518-0

- Nijman L, Rustemeyer T, Franken SM, et al. The prevalence and relevance of patch testing with textile dyes [published online December 3, 2022]. Contact Dermatitis. doi:10.1111/cod.14260

Laundry detergent, a cleaning agent ubiquitous in the modern household, often is suspected as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

We provide a summary of the evidence for the potential allergenicity of laundry detergent, including common allergens present in laundry detergent, the role of machine washing, and the differential diagnosis for laundry detergent–associated ACD.

Allergenic Ingredients in Laundry Detergent

Potential allergens present in laundry detergent include fragrances, preservatives, surfactants, emulsifiers, bleaches, brighteners, enzymes, and dyes.6-8 In an analysis of allergens present in laundry detergents available in the United States, fragrances and preservatives were most common (eTable).7,8 Contact allergy to fragrances occurs in approximately 3.5% of the general population9 and is detected in as many as 9.2% of patients referred for patch testing in North America.10 Preservatives commonly found in laundry detergent include isothiazolinones, such as methylchloroisothiazolinone (MCI)/methylisothiazolinone (MI), MI alone, and benzisothiazolinone (BIT). Methylisothiazolinone has gained attention for causing an ACD epidemic beginning in the early 2000s and peaking in Europe between 2013 and 2014 and decreasing thereafter due to consumer personal care product regulatory changes enacted in the European Union.11 In contrast, rates of MI allergy in North America have continued to increase (reaching as high as 15% of patch tested patients in 2017-2018) due to a lack of similar regulation.10,12 More recently, the prevalence of positive patch tests to BIT has been rising, though it often is difficult to ascertain relevant sources of exposure, and some cases could represent cross-reactions to MCI/MI.10,13

Other allergens that may be present in laundry detergent include surfactants and propylene glycol. Alkyl glucosides such as decyl glucoside and lauryl glucoside are considered gentle surfactants and often are included in products marketed as safe for sensitive skin,14 such as “free and gentle” detergents.8 However, they actually may pose an increased risk for sensitization in patients with atopic dermatitis.14 In addition to being allergenic, surfactants and emulsifiers are known irritants.6,15 Although pathologically distinct, ACD and irritant contact dermatitis can be indistinguishable on clinical presentation.

How Commonly Does Laundry Detergent Cause ACD?

The mere presence of a contact allergen in laundry detergent does not necessarily imply that it is likely to cause ACD. To do so, the chemical in question must exceed the exposure thresholds for primary sensitization (ie, induction of contact allergy) and/or elicitation (ie, development of ACD in sensitized individuals). These depend on a complex interplay of product- and patient-specific factors, among them the concentration of the chemical in the detergent, the method of use, and the amount of detergent residue remaining on clothing after washing.

In the 1990s, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) attempted to determine the prevalence of ACD caused by laundry detergent.1 Among 738 patients patch tested to aqueous dilutions of granular and liquid laundry detergents, only 5 (0.7%) had a possible allergic patch test reaction. It was unclear what the culprit allergens in the detergents may have been; only 1 of the patients also tested positive to fragrance. Two patients underwent further testing to additional detergent dilutions, and the results called into question whether their initial reactions had truly been allergic (positive) or were actually irritant (negative). The investigators concluded that the prevalence of laundry detergent–associated ACD in this large group of patients was at most 0.7%, and possibly lower.1

Importantly, patch testing to laundry detergents should not be undertaken in routine clinical practice. Laundry detergents should never be tested “as is” (ie, undiluted) on the skin; they are inherently irritating and have a high likelihood of producing misleading false-positive reactions. Careful dilutions and testing of control subjects are necessary if patch testing with these products is to be appropriately conducted.

Isothiazolinones in Laundry Detergent

The extremely low prevalence of laundry detergent–associated ACD reported by the NACDG was determined prior to the start of the worldwide MI allergy epidemic, raising the possibility that laundry detergents containing isothiazolinones may be associated with ACD. There is no consensus about the minimum level at which isothiazolinones pose no risk to consumers,16-19 but the US Expert Panel for Cosmetic Ingredient Safety declared that MI is “safe for use in rinse-off cosmetic products at concentrations up to 100 ppm and safe in leave-on cosmetic products when they are formulated to be nonsensitizing.”18,19 Although ingredient lists do not always reveal when isothiazolinones are present, analyses of commercially available laundry detergents have shown MI concentrations ranging from undetectable to 65.7 ppm.20-23

Published reports suggest that MCI/MI in laundry detergent can elicit ACD in sensitized individuals. In one case, a 7-year-old girl with chronic truncal dermatitis (atopic history unspecified) was patch tested, revealing a strongly positive reaction to MCI/MI.24 Her laundry detergent was the only personal product found to contain MI. The dermatitis completely resolved after switching detergents and flared after wearing a jacket that had been washed in the implicated detergent, further supporting the relevance of the positive patch test. The investigators suspected initial sensitization to MI from wet wipes used earlier in childhood.24 In another case involving occupational exposure, a 39-year-old nonatopic factory worker was responsible for directly adding MI to laundry detergent.25 Although he wore disposable work gloves, he developed severe hand dermatitis, eczematous pretibial patches, and generalized pruritus. Patch testing revealed positive reactions to MCI/MI and MI, and he experienced improvement when reassigned to different work duties. It was hypothesized that the leg dermatitis and generalized pruritus may have been related to exposure to small concentrations of MI in work clothes washed with an MI-containing detergent.25 Notably, this patient’s level of exposure was much greater than that encountered by individuals in day-to-day life outside of specialized occupational settings.

Regarding other isothiazolinones, a toxicologic study estimated that BIT in laundry detergent would be unlikely to induce sensitization, even at the maximal acceptable concentration, as recommended by preservative manufacturers, and accounting for undiluted detergent spilling directly onto the skin.26

Does Machine Washing Impact Allergen Concentrations?

Two recent investigations have suggested that machine washing reduces concentrations of isothiazolinones to levels that are likely below clinical relevance. In the first study, 3 fabrics—cotton, polyester, cotton-polyester—were machine washed and line dried.27 A standard detergent was used with MI added at different concentrations: less than 1 ppm, 100 ppm, and 1000 ppm. This process was either performed once or 10 times. Following laundering and line drying, MI was undetectable in all fabrics regardless of MI concentration or number of times washed (detection limit, 0.5 ppm).27 In the second study, 4 fabrics—cotton, wool, polyester, linen—were washed with standard laundry detergent in 1 of 4 ways: handwashing (positive control), standard machine washing, standard machine washing with fabric softener, and standard machine washing with a double rinse.28 After laundering and line drying, concentrations of MI, MCI, and BIT were low or undetectable regardless of fabric type or method of laundering. The highest levels detected were in handwashed garments at a maximum of 0.5 ppm of MI. The study authors postulated that chemical concentrations near these maximum residual levels may pose a risk for eliciting ACD in highly sensitized individuals. Therefore, handwashing can be considered a much higher risk activity for isothiazolinone ACD compared with machine washing.28

It is intriguing that machine washing appears to reduce isothiazolinones to low concentrations that may have limited likelihood of causing ACD. Similar findings have been reported regarding fragrances. A quantitative risk assessment performed on 24 of 26 fragrance allergens regulated by the European Union determined that the amount of fragrance deposited on the skin from laundered garments would be less than the threshold for causing sensitization.29 Although this risk assessment was unable to address the threshold of elicitation, another study conducted in Europe investigated whether fragrance residues present on fabric, such as those deposited from laundry detergent, are present at high enough concentrations to elicit ACD in previously sensitized individuals.30 When 36 individuals were patch tested with increasing concentrations of a fragrance to which they were already sensitized, only 2 (5.6%) had a weakly positive reaction and then only to the highest concentration, which was estimated to be 20-fold higher than the level of skin exposure after normal laundering. No patient reacted at lower concentrations.30

Although machine washing may decrease isothiazolinone and/or fragrance concentrations in laundry detergent to below clinically relevant levels, these findings should not necessarily be extrapolated to all chemicals in laundry detergent. Indeed, a prior study observed that after washing cotton cloths in a detergent solution for 10 minutes, detergent residue was present at concentrations ranging from 139 to 2820 ppm and required a subsequent 20 to 22 washes in water to become undetectable.31 Another study produced a mathematical model of the residual concentration of sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), a surfactant and known irritant, in laundered clothing.32 It was estimated that after machine washing, the residual concentration of SDS on clothes would be too low to cause irritation; however, as the clothes dry (ie, as moisture evaporates but solutes remain), the concentration of SDS on the fabric’s surface would increase to potentially irritating levels. The extensive drying that is possible with electric dryers may further enhance this solute-concentrating effect.

Differential Diagnosis of Laundry Detergent ACD

The propensity for laundry detergent to cause ACD is a question that is nowhere near settled, but the prevalence of allergy likely is far less common than is generally suspected. In our experience, many patients presenting for patch testing have already made the change to “free and clear” detergents without noticeable improvement in their dermatitis, which could possibly relate to the ongoing presence of contact allergens in these “gentle” formulations.7 However, to avoid anchoring bias, more frequent causes of dermatitis should be included in the differential diagnosis. Textile ACD presents beneath clothing with accentuation at areas of closest contact with the skin, classically involving the axillary rim but sparing the vault. The most frequently implicated allergens in textile ACD are disperse dyes and less commonly textile resins.33,34 Between 2017 and 2018, 2.3% of 4882 patients patch tested by the NACDG reacted positively to disperse dye mix.10 There is evidence to suggest that the actual prevalence of disperse dye allergy might be higher due to inadequacy of screening allergens on baseline patch test series.35 Additional diagnoses that should be distinguished from presumed detergent contact dermatitis include atopic dermatitis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Final Interpretation

Although many patients and physicians consider laundry detergent to be a major cause of ACD, there is limited high-quality evidence to support this belief. Contact allergy to laundry detergent is probably much less common than is widely supposed. Although laundry detergents can contain common allergens such as fragrances and preservatives, evidence suggests that they are likely reduced to below clinically relevant levels during routine machine washing; however, we cannot assume that we are in the “free and clear,” as uncertainty remains about the impact of these low concentrationson individuals with strong contact allergy, and large studies of patch testing to modern detergents have yet to be carried out.

Laundry detergent, a cleaning agent ubiquitous in the modern household, often is suspected as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

We provide a summary of the evidence for the potential allergenicity of laundry detergent, including common allergens present in laundry detergent, the role of machine washing, and the differential diagnosis for laundry detergent–associated ACD.

Allergenic Ingredients in Laundry Detergent

Potential allergens present in laundry detergent include fragrances, preservatives, surfactants, emulsifiers, bleaches, brighteners, enzymes, and dyes.6-8 In an analysis of allergens present in laundry detergents available in the United States, fragrances and preservatives were most common (eTable).7,8 Contact allergy to fragrances occurs in approximately 3.5% of the general population9 and is detected in as many as 9.2% of patients referred for patch testing in North America.10 Preservatives commonly found in laundry detergent include isothiazolinones, such as methylchloroisothiazolinone (MCI)/methylisothiazolinone (MI), MI alone, and benzisothiazolinone (BIT). Methylisothiazolinone has gained attention for causing an ACD epidemic beginning in the early 2000s and peaking in Europe between 2013 and 2014 and decreasing thereafter due to consumer personal care product regulatory changes enacted in the European Union.11 In contrast, rates of MI allergy in North America have continued to increase (reaching as high as 15% of patch tested patients in 2017-2018) due to a lack of similar regulation.10,12 More recently, the prevalence of positive patch tests to BIT has been rising, though it often is difficult to ascertain relevant sources of exposure, and some cases could represent cross-reactions to MCI/MI.10,13

Other allergens that may be present in laundry detergent include surfactants and propylene glycol. Alkyl glucosides such as decyl glucoside and lauryl glucoside are considered gentle surfactants and often are included in products marketed as safe for sensitive skin,14 such as “free and gentle” detergents.8 However, they actually may pose an increased risk for sensitization in patients with atopic dermatitis.14 In addition to being allergenic, surfactants and emulsifiers are known irritants.6,15 Although pathologically distinct, ACD and irritant contact dermatitis can be indistinguishable on clinical presentation.

How Commonly Does Laundry Detergent Cause ACD?

The mere presence of a contact allergen in laundry detergent does not necessarily imply that it is likely to cause ACD. To do so, the chemical in question must exceed the exposure thresholds for primary sensitization (ie, induction of contact allergy) and/or elicitation (ie, development of ACD in sensitized individuals). These depend on a complex interplay of product- and patient-specific factors, among them the concentration of the chemical in the detergent, the method of use, and the amount of detergent residue remaining on clothing after washing.

In the 1990s, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) attempted to determine the prevalence of ACD caused by laundry detergent.1 Among 738 patients patch tested to aqueous dilutions of granular and liquid laundry detergents, only 5 (0.7%) had a possible allergic patch test reaction. It was unclear what the culprit allergens in the detergents may have been; only 1 of the patients also tested positive to fragrance. Two patients underwent further testing to additional detergent dilutions, and the results called into question whether their initial reactions had truly been allergic (positive) or were actually irritant (negative). The investigators concluded that the prevalence of laundry detergent–associated ACD in this large group of patients was at most 0.7%, and possibly lower.1

Importantly, patch testing to laundry detergents should not be undertaken in routine clinical practice. Laundry detergents should never be tested “as is” (ie, undiluted) on the skin; they are inherently irritating and have a high likelihood of producing misleading false-positive reactions. Careful dilutions and testing of control subjects are necessary if patch testing with these products is to be appropriately conducted.

Isothiazolinones in Laundry Detergent

The extremely low prevalence of laundry detergent–associated ACD reported by the NACDG was determined prior to the start of the worldwide MI allergy epidemic, raising the possibility that laundry detergents containing isothiazolinones may be associated with ACD. There is no consensus about the minimum level at which isothiazolinones pose no risk to consumers,16-19 but the US Expert Panel for Cosmetic Ingredient Safety declared that MI is “safe for use in rinse-off cosmetic products at concentrations up to 100 ppm and safe in leave-on cosmetic products when they are formulated to be nonsensitizing.”18,19 Although ingredient lists do not always reveal when isothiazolinones are present, analyses of commercially available laundry detergents have shown MI concentrations ranging from undetectable to 65.7 ppm.20-23

Published reports suggest that MCI/MI in laundry detergent can elicit ACD in sensitized individuals. In one case, a 7-year-old girl with chronic truncal dermatitis (atopic history unspecified) was patch tested, revealing a strongly positive reaction to MCI/MI.24 Her laundry detergent was the only personal product found to contain MI. The dermatitis completely resolved after switching detergents and flared after wearing a jacket that had been washed in the implicated detergent, further supporting the relevance of the positive patch test. The investigators suspected initial sensitization to MI from wet wipes used earlier in childhood.24 In another case involving occupational exposure, a 39-year-old nonatopic factory worker was responsible for directly adding MI to laundry detergent.25 Although he wore disposable work gloves, he developed severe hand dermatitis, eczematous pretibial patches, and generalized pruritus. Patch testing revealed positive reactions to MCI/MI and MI, and he experienced improvement when reassigned to different work duties. It was hypothesized that the leg dermatitis and generalized pruritus may have been related to exposure to small concentrations of MI in work clothes washed with an MI-containing detergent.25 Notably, this patient’s level of exposure was much greater than that encountered by individuals in day-to-day life outside of specialized occupational settings.

Regarding other isothiazolinones, a toxicologic study estimated that BIT in laundry detergent would be unlikely to induce sensitization, even at the maximal acceptable concentration, as recommended by preservative manufacturers, and accounting for undiluted detergent spilling directly onto the skin.26

Does Machine Washing Impact Allergen Concentrations?

Two recent investigations have suggested that machine washing reduces concentrations of isothiazolinones to levels that are likely below clinical relevance. In the first study, 3 fabrics—cotton, polyester, cotton-polyester—were machine washed and line dried.27 A standard detergent was used with MI added at different concentrations: less than 1 ppm, 100 ppm, and 1000 ppm. This process was either performed once or 10 times. Following laundering and line drying, MI was undetectable in all fabrics regardless of MI concentration or number of times washed (detection limit, 0.5 ppm).27 In the second study, 4 fabrics—cotton, wool, polyester, linen—were washed with standard laundry detergent in 1 of 4 ways: handwashing (positive control), standard machine washing, standard machine washing with fabric softener, and standard machine washing with a double rinse.28 After laundering and line drying, concentrations of MI, MCI, and BIT were low or undetectable regardless of fabric type or method of laundering. The highest levels detected were in handwashed garments at a maximum of 0.5 ppm of MI. The study authors postulated that chemical concentrations near these maximum residual levels may pose a risk for eliciting ACD in highly sensitized individuals. Therefore, handwashing can be considered a much higher risk activity for isothiazolinone ACD compared with machine washing.28

It is intriguing that machine washing appears to reduce isothiazolinones to low concentrations that may have limited likelihood of causing ACD. Similar findings have been reported regarding fragrances. A quantitative risk assessment performed on 24 of 26 fragrance allergens regulated by the European Union determined that the amount of fragrance deposited on the skin from laundered garments would be less than the threshold for causing sensitization.29 Although this risk assessment was unable to address the threshold of elicitation, another study conducted in Europe investigated whether fragrance residues present on fabric, such as those deposited from laundry detergent, are present at high enough concentrations to elicit ACD in previously sensitized individuals.30 When 36 individuals were patch tested with increasing concentrations of a fragrance to which they were already sensitized, only 2 (5.6%) had a weakly positive reaction and then only to the highest concentration, which was estimated to be 20-fold higher than the level of skin exposure after normal laundering. No patient reacted at lower concentrations.30

Although machine washing may decrease isothiazolinone and/or fragrance concentrations in laundry detergent to below clinically relevant levels, these findings should not necessarily be extrapolated to all chemicals in laundry detergent. Indeed, a prior study observed that after washing cotton cloths in a detergent solution for 10 minutes, detergent residue was present at concentrations ranging from 139 to 2820 ppm and required a subsequent 20 to 22 washes in water to become undetectable.31 Another study produced a mathematical model of the residual concentration of sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), a surfactant and known irritant, in laundered clothing.32 It was estimated that after machine washing, the residual concentration of SDS on clothes would be too low to cause irritation; however, as the clothes dry (ie, as moisture evaporates but solutes remain), the concentration of SDS on the fabric’s surface would increase to potentially irritating levels. The extensive drying that is possible with electric dryers may further enhance this solute-concentrating effect.

Differential Diagnosis of Laundry Detergent ACD

The propensity for laundry detergent to cause ACD is a question that is nowhere near settled, but the prevalence of allergy likely is far less common than is generally suspected. In our experience, many patients presenting for patch testing have already made the change to “free and clear” detergents without noticeable improvement in their dermatitis, which could possibly relate to the ongoing presence of contact allergens in these “gentle” formulations.7 However, to avoid anchoring bias, more frequent causes of dermatitis should be included in the differential diagnosis. Textile ACD presents beneath clothing with accentuation at areas of closest contact with the skin, classically involving the axillary rim but sparing the vault. The most frequently implicated allergens in textile ACD are disperse dyes and less commonly textile resins.33,34 Between 2017 and 2018, 2.3% of 4882 patients patch tested by the NACDG reacted positively to disperse dye mix.10 There is evidence to suggest that the actual prevalence of disperse dye allergy might be higher due to inadequacy of screening allergens on baseline patch test series.35 Additional diagnoses that should be distinguished from presumed detergent contact dermatitis include atopic dermatitis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Final Interpretation

Although many patients and physicians consider laundry detergent to be a major cause of ACD, there is limited high-quality evidence to support this belief. Contact allergy to laundry detergent is probably much less common than is widely supposed. Although laundry detergents can contain common allergens such as fragrances and preservatives, evidence suggests that they are likely reduced to below clinically relevant levels during routine machine washing; however, we cannot assume that we are in the “free and clear,” as uncertainty remains about the impact of these low concentrationson individuals with strong contact allergy, and large studies of patch testing to modern detergents have yet to be carried out.

- Belsito DV, Fransway AF, Fowler JF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to detergents: a multicenter study to assess prevalence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:200-206. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.119665

- Dallas MJ, Wilson PA, Burns LD, et al. Dermatological and other health problems attributed by consumers to contact with laundry products. Home Econ Res J. 1992;21:34-49. doi:10.1177/1077727X9202100103

- Bailey A. An overview of laundry detergent allergies. Verywell Health. September 16, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.verywellhealth.com/laundry-detergent-allergies-signs-symptoms-and-treatment-5198934

- Fasanella K. How to tell if you laundry detergent is messing with your skin. Allure. June 15, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.allure.com/story/laundry-detergent-allergy-skin-reaction

- Oykhman P, Dookie J, Al-Rammahy et al. Dietary elimination for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Immunol Pract. 2022;10:2657-2666.e8. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2022.06.044

- Kwon S, Holland D, Kern P. Skin safety evaluation of laundry detergent products. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2009;72:1369-1379. doi:10.1080/1528739090321675

- Magnano M, Silvani S, Vincenzi C, et al. Contact allergens and irritants in household washing and cleaning products. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:337-341. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01647.x

- Bai H, Tam I, Yu J. Contact allergens in top-selling textile-care products. Dermatitis. 2020;31:53-58. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000566

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi:10.1111/cod.13119

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000729

- Havmose M, Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, et al. The epidemic of contact allergy to methylisothiazolinone–an analysis of Danish consecutive patients patch tested between 2005 and 2019. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84:254-262. doi:10.1111/cod.13717

- Atwater AR, Petty AJ, Liu B, et al. Contact dermatitis associated with preservatives: retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1994 through 2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:965-976. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.059

- King N, Latheef F, Wilkinson M. Trends in preservative allergy: benzisothiazolinone emerges from the pack. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:637-642. doi:10.1111/cod.13968

- Sasseville D. Alkyl glucosides: 2017 “allergen of the year.” Dermatitis. 2017;28:296. doi:10.1097/DER0000000000000290

- McGowan MA, Scheman A, Jacob SE. Propylene glycol in contact dermatitis: a systematic review. Dermatitis. 2018;29:6-12. doi:10.1097/DER0000000000000307

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Consumers. Opinion on methylisothiazolinone (P94) submission II (sensitisation only). Revised March 27, 2014. Accessed March 21, 2023. http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/consumer_safety/docs/sccs_o_145.pdf

- Cosmetic ingredient hotlist: list of ingredients that are restricted for use in cosmetic products. Government of Canada website. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredient-hotlist-prohibited-restricted-ingredients/hotlist.html#tbl2

- Burnett CL, Boyer I, Bergfeld WF, et al. Amended safety assessment of methylisothiazolinone as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2019;38(1 suppl):70S-84S. doi:10.1177/1091581819838792

- Burnett CL, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, et al. Amended safety assessment of methylisothiazolinone as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2021;40(1 suppl):5S-19S. doi:10.1177/10915818211015795

- Aerts O, Meert H, Goossens A, et al. Methylisothiazolinone in selected consumer products in Belgium: adding fuel to the fire? Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:142-149. doi:10.1111/cod.12449

- Garcia-Hidalgo E, Sottas V, von Goetz N, et al. Occurrence and concentrations of isothiazolinones in detergents and cosmetics in Switzerland. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:96-106. doi:10.1111/cod.12700

- Marrero-Alemán G, Borrego L, Antuña AG, et al. Isothiazolinones in cleaning products: analysis with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry of samples from sensitized patients and markets. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;82:94-100. doi:10.1111/cod.13430

- Alvarez-Rivera G, Dagnac T, Lores M, et al. Determination of isothiazolinone preservatives in cosmetics and household products by matrix solid-phase dispersion followed by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1270:41-50. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2012.10.063

- Cotton CH, Duah CG, Matiz C. Allergic contact dermatitis due to methylisothiazolinone in a young girl’s laundry detergent. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:486-487. doi:10.1111/pde.13122

- Sandvik A, Holm JO. Severe allergic contact dermatitis in a detergent production worker caused by exposure to methylisothiazolinone. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:243-245. doi:10.1111/cod.13182

- Novick RM, Nelson ML, Unice KM, et al. Estimation of safe use concentrations of the preservative 1,2-benziosothiazolin-3-one (BIT) in consumer cleaning products and sunscreens. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;56:60-66. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.02.006

- Hofmann MA, Giménez-Arnau A, Aberer W, et al. MI (2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one) contained in detergents is not detectable in machine washed textiles. Clin Transl Allergy. 2018;8:1. doi:10.1186/s13601-017-0187-2

- Marrero-Alemán G, Borrego L, Atuña AG, et al. Persistence of isothiazolinones in clothes after machine washing. Dermatitis. 2021;32:298-300. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000603

- Corea NV, Basketter DA, Clapp C, et al. Fragrance allergy: assessing the risk from washed fabrics. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:48-53. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00872.x

- Basketter DA, Pons-Guiraud A, van Asten A, et al. Fragrance allergy: assessing the safety of washed fabrics. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:349-354. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01728.x

- Agarwal C, Gupta BN, Mathur AK, et al. Residue analysis of detergent in crockery and clothes. Environmentalist. 1986;4:240-243.

- Broadbridge P, Tilley BS. Diffusion of dermatological irritant in drying laundered cloth. Math Med Biol. 2021;38:474-489. doi:10.1093/imammb/dqab014

- Lisi P, Stingeni L, Cristaudo A, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of textile contact dermatitis: an Italian multicentre study. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;70:344-350. doi:10.1111/cod.12179

- Mobolaji-Lawal M, Nedorost S. The role of textiles in dermatitis: an update. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:17. doi:10.1007/s11882-015-0518-0

- Nijman L, Rustemeyer T, Franken SM, et al. The prevalence and relevance of patch testing with textile dyes [published online December 3, 2022]. Contact Dermatitis. doi:10.1111/cod.14260

- Belsito DV, Fransway AF, Fowler JF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to detergents: a multicenter study to assess prevalence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:200-206. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.119665

- Dallas MJ, Wilson PA, Burns LD, et al. Dermatological and other health problems attributed by consumers to contact with laundry products. Home Econ Res J. 1992;21:34-49. doi:10.1177/1077727X9202100103

- Bailey A. An overview of laundry detergent allergies. Verywell Health. September 16, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.verywellhealth.com/laundry-detergent-allergies-signs-symptoms-and-treatment-5198934

- Fasanella K. How to tell if you laundry detergent is messing with your skin. Allure. June 15, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.allure.com/story/laundry-detergent-allergy-skin-reaction

- Oykhman P, Dookie J, Al-Rammahy et al. Dietary elimination for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Immunol Pract. 2022;10:2657-2666.e8. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2022.06.044

- Kwon S, Holland D, Kern P. Skin safety evaluation of laundry detergent products. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2009;72:1369-1379. doi:10.1080/1528739090321675

- Magnano M, Silvani S, Vincenzi C, et al. Contact allergens and irritants in household washing and cleaning products. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:337-341. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01647.x

- Bai H, Tam I, Yu J. Contact allergens in top-selling textile-care products. Dermatitis. 2020;31:53-58. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000566

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi:10.1111/cod.13119

- DeKoven JG, Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results 2017-2018. Dermatitis. 2021;32:111-123. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000729

- Havmose M, Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, et al. The epidemic of contact allergy to methylisothiazolinone–an analysis of Danish consecutive patients patch tested between 2005 and 2019. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84:254-262. doi:10.1111/cod.13717

- Atwater AR, Petty AJ, Liu B, et al. Contact dermatitis associated with preservatives: retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1994 through 2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:965-976. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.059

- King N, Latheef F, Wilkinson M. Trends in preservative allergy: benzisothiazolinone emerges from the pack. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:637-642. doi:10.1111/cod.13968

- Sasseville D. Alkyl glucosides: 2017 “allergen of the year.” Dermatitis. 2017;28:296. doi:10.1097/DER0000000000000290

- McGowan MA, Scheman A, Jacob SE. Propylene glycol in contact dermatitis: a systematic review. Dermatitis. 2018;29:6-12. doi:10.1097/DER0000000000000307

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Consumers. Opinion on methylisothiazolinone (P94) submission II (sensitisation only). Revised March 27, 2014. Accessed March 21, 2023. http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/consumer_safety/docs/sccs_o_145.pdf

- Cosmetic ingredient hotlist: list of ingredients that are restricted for use in cosmetic products. Government of Canada website. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredient-hotlist-prohibited-restricted-ingredients/hotlist.html#tbl2

- Burnett CL, Boyer I, Bergfeld WF, et al. Amended safety assessment of methylisothiazolinone as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2019;38(1 suppl):70S-84S. doi:10.1177/1091581819838792

- Burnett CL, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, et al. Amended safety assessment of methylisothiazolinone as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2021;40(1 suppl):5S-19S. doi:10.1177/10915818211015795

- Aerts O, Meert H, Goossens A, et al. Methylisothiazolinone in selected consumer products in Belgium: adding fuel to the fire? Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:142-149. doi:10.1111/cod.12449

- Garcia-Hidalgo E, Sottas V, von Goetz N, et al. Occurrence and concentrations of isothiazolinones in detergents and cosmetics in Switzerland. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:96-106. doi:10.1111/cod.12700

- Marrero-Alemán G, Borrego L, Antuña AG, et al. Isothiazolinones in cleaning products: analysis with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry of samples from sensitized patients and markets. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;82:94-100. doi:10.1111/cod.13430

- Alvarez-Rivera G, Dagnac T, Lores M, et al. Determination of isothiazolinone preservatives in cosmetics and household products by matrix solid-phase dispersion followed by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1270:41-50. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2012.10.063

- Cotton CH, Duah CG, Matiz C. Allergic contact dermatitis due to methylisothiazolinone in a young girl’s laundry detergent. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:486-487. doi:10.1111/pde.13122

- Sandvik A, Holm JO. Severe allergic contact dermatitis in a detergent production worker caused by exposure to methylisothiazolinone. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:243-245. doi:10.1111/cod.13182

- Novick RM, Nelson ML, Unice KM, et al. Estimation of safe use concentrations of the preservative 1,2-benziosothiazolin-3-one (BIT) in consumer cleaning products and sunscreens. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;56:60-66. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.02.006

- Hofmann MA, Giménez-Arnau A, Aberer W, et al. MI (2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one) contained in detergents is not detectable in machine washed textiles. Clin Transl Allergy. 2018;8:1. doi:10.1186/s13601-017-0187-2

- Marrero-Alemán G, Borrego L, Atuña AG, et al. Persistence of isothiazolinones in clothes after machine washing. Dermatitis. 2021;32:298-300. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000603

- Corea NV, Basketter DA, Clapp C, et al. Fragrance allergy: assessing the risk from washed fabrics. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:48-53. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00872.x

- Basketter DA, Pons-Guiraud A, van Asten A, et al. Fragrance allergy: assessing the safety of washed fabrics. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:349-354. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01728.x

- Agarwal C, Gupta BN, Mathur AK, et al. Residue analysis of detergent in crockery and clothes. Environmentalist. 1986;4:240-243.

- Broadbridge P, Tilley BS. Diffusion of dermatological irritant in drying laundered cloth. Math Med Biol. 2021;38:474-489. doi:10.1093/imammb/dqab014

- Lisi P, Stingeni L, Cristaudo A, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of textile contact dermatitis: an Italian multicentre study. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;70:344-350. doi:10.1111/cod.12179

- Mobolaji-Lawal M, Nedorost S. The role of textiles in dermatitis: an update. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:17. doi:10.1007/s11882-015-0518-0

- Nijman L, Rustemeyer T, Franken SM, et al. The prevalence and relevance of patch testing with textile dyes [published online December 3, 2022]. Contact Dermatitis. doi:10.1111/cod.14260

Practice Points

- Although laundry detergent commonly is believed to be a cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), the actual prevalence is quite low (<1%).

- Common allergens present in laundry detergent such as fragrances and isothiazolinone preservatives likely are reduced to clinically irrelevant levels during routine machine washing.

- Other diagnoses to consider when laundry detergent–associated ACD is suspected include textile ACD, atopic dermatitis, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Pilot study evaluates sensitive skin burden in persons of color

NEW ORLEANS – .

Respondents also reported high rates of reactions to skin care products marketed for sensitive skin, and most said they had visited a dermatologist about their condition.

Those are among the key findings of a pilot study designed to assess the prevalence, symptom burden, and behaviors of self-identified persons of color with sensitive skin, which senior author Adam Friedman, MD, and colleagues defined as a subjective syndrome of cutaneous hyperreactivity to otherwise innocuous stimuli. “Improved understanding of sensitive skin is essential, and we encourage additional research into pathophysiology and creating a consensus definition for sensitive skin,” Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where the study was presented during an e-poster session. The findings were also reported online in JAAD International.

In May of 2022, Dr. Friedman, first author Erika McCormick, a 4th-year medical student at George Washington University, and colleagues invited individuals attending a community health fair in an undeserved area of Washington, to complete the Sensitive Scale-10 (SS-10) and to answer other questions after receiving a brief education about sensitive skin. Of the 58 respondents, 78% were female, and 86% self-identified as a person of color.

“Our study population predominantly self-identified as Black, which only represents one piece of those who would be characterized as persons of color,” Dr. Friedman said. “That said, improved representation of both our study population, and furthermore persons of color, in all aspects of dermatology research is crucial to at a minimum ensure generalizability of findings to the U.S. population, and research on sensitive skin is but one component of this.”

Nearly two-thirds of all respondents (63.8%) reported having an underlying skin condition, most commonly acne (21%), eczema (17%), and rosacea (6%). More than half (57%) reported sensitive skin, 27% of whom reported no other skin disease. Individuals with sensitive skin had higher mean SS-10 scores, compared with those with nonsensitive skin (14.61 vs. 4.32; P = .002) and burning was the main symptom among those with sensitive skin (56%), followed by itch (50%), redness (39%), dryness (39%) and pain (17%).

Compared with those who did not meet criteria for sensitive skin, those who did were more likely to report a personal history of allergy (56.25% vs. 8.33%; P = .0002) and were nearly seven times more likely to have seen a dermatologist about their concerns (odds ratio, 6.857; P = .0012).

In other findings limited to respondents with sensitive skin, 72% who reported reactions to general consumer skin care products also reported reacting to products marketed for sensitive skin, and 94% reported reactivity to at least one trigger, most commonly extreme temperatures (34%), stress (34%), sweat (33%), sun exposure (29%), and diet (28%). “We were particularly surprised by the high rates of reactivity to skin care products designed for and marketed to those suffering with sensitive skin,” Ms. McCormick told this news organization. “Importantly, there is currently no federal or legal standard regulating ingredients in products marketed for sensitive skin, and many products lack testing in sensitive skin specifically. Our data suggest an opportunity for improvement of sensitive skin care.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its small sample size. “Reconducting this survey in a larger population will help validate our findings,” she said.

The research was supported by two independent research grants from Galderma: one supporting Ms. McCormick with a Sensitive Skin Research Fellowship and the other a Sensitive Skin Research Acceleration Fund. Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – .

Respondents also reported high rates of reactions to skin care products marketed for sensitive skin, and most said they had visited a dermatologist about their condition.

Those are among the key findings of a pilot study designed to assess the prevalence, symptom burden, and behaviors of self-identified persons of color with sensitive skin, which senior author Adam Friedman, MD, and colleagues defined as a subjective syndrome of cutaneous hyperreactivity to otherwise innocuous stimuli. “Improved understanding of sensitive skin is essential, and we encourage additional research into pathophysiology and creating a consensus definition for sensitive skin,” Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where the study was presented during an e-poster session. The findings were also reported online in JAAD International.

In May of 2022, Dr. Friedman, first author Erika McCormick, a 4th-year medical student at George Washington University, and colleagues invited individuals attending a community health fair in an undeserved area of Washington, to complete the Sensitive Scale-10 (SS-10) and to answer other questions after receiving a brief education about sensitive skin. Of the 58 respondents, 78% were female, and 86% self-identified as a person of color.

“Our study population predominantly self-identified as Black, which only represents one piece of those who would be characterized as persons of color,” Dr. Friedman said. “That said, improved representation of both our study population, and furthermore persons of color, in all aspects of dermatology research is crucial to at a minimum ensure generalizability of findings to the U.S. population, and research on sensitive skin is but one component of this.”

Nearly two-thirds of all respondents (63.8%) reported having an underlying skin condition, most commonly acne (21%), eczema (17%), and rosacea (6%). More than half (57%) reported sensitive skin, 27% of whom reported no other skin disease. Individuals with sensitive skin had higher mean SS-10 scores, compared with those with nonsensitive skin (14.61 vs. 4.32; P = .002) and burning was the main symptom among those with sensitive skin (56%), followed by itch (50%), redness (39%), dryness (39%) and pain (17%).

Compared with those who did not meet criteria for sensitive skin, those who did were more likely to report a personal history of allergy (56.25% vs. 8.33%; P = .0002) and were nearly seven times more likely to have seen a dermatologist about their concerns (odds ratio, 6.857; P = .0012).

In other findings limited to respondents with sensitive skin, 72% who reported reactions to general consumer skin care products also reported reacting to products marketed for sensitive skin, and 94% reported reactivity to at least one trigger, most commonly extreme temperatures (34%), stress (34%), sweat (33%), sun exposure (29%), and diet (28%). “We were particularly surprised by the high rates of reactivity to skin care products designed for and marketed to those suffering with sensitive skin,” Ms. McCormick told this news organization. “Importantly, there is currently no federal or legal standard regulating ingredients in products marketed for sensitive skin, and many products lack testing in sensitive skin specifically. Our data suggest an opportunity for improvement of sensitive skin care.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its small sample size. “Reconducting this survey in a larger population will help validate our findings,” she said.

The research was supported by two independent research grants from Galderma: one supporting Ms. McCormick with a Sensitive Skin Research Fellowship and the other a Sensitive Skin Research Acceleration Fund. Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – .

Respondents also reported high rates of reactions to skin care products marketed for sensitive skin, and most said they had visited a dermatologist about their condition.

Those are among the key findings of a pilot study designed to assess the prevalence, symptom burden, and behaviors of self-identified persons of color with sensitive skin, which senior author Adam Friedman, MD, and colleagues defined as a subjective syndrome of cutaneous hyperreactivity to otherwise innocuous stimuli. “Improved understanding of sensitive skin is essential, and we encourage additional research into pathophysiology and creating a consensus definition for sensitive skin,” Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where the study was presented during an e-poster session. The findings were also reported online in JAAD International.

In May of 2022, Dr. Friedman, first author Erika McCormick, a 4th-year medical student at George Washington University, and colleagues invited individuals attending a community health fair in an undeserved area of Washington, to complete the Sensitive Scale-10 (SS-10) and to answer other questions after receiving a brief education about sensitive skin. Of the 58 respondents, 78% were female, and 86% self-identified as a person of color.

“Our study population predominantly self-identified as Black, which only represents one piece of those who would be characterized as persons of color,” Dr. Friedman said. “That said, improved representation of both our study population, and furthermore persons of color, in all aspects of dermatology research is crucial to at a minimum ensure generalizability of findings to the U.S. population, and research on sensitive skin is but one component of this.”

Nearly two-thirds of all respondents (63.8%) reported having an underlying skin condition, most commonly acne (21%), eczema (17%), and rosacea (6%). More than half (57%) reported sensitive skin, 27% of whom reported no other skin disease. Individuals with sensitive skin had higher mean SS-10 scores, compared with those with nonsensitive skin (14.61 vs. 4.32; P = .002) and burning was the main symptom among those with sensitive skin (56%), followed by itch (50%), redness (39%), dryness (39%) and pain (17%).

Compared with those who did not meet criteria for sensitive skin, those who did were more likely to report a personal history of allergy (56.25% vs. 8.33%; P = .0002) and were nearly seven times more likely to have seen a dermatologist about their concerns (odds ratio, 6.857; P = .0012).

In other findings limited to respondents with sensitive skin, 72% who reported reactions to general consumer skin care products also reported reacting to products marketed for sensitive skin, and 94% reported reactivity to at least one trigger, most commonly extreme temperatures (34%), stress (34%), sweat (33%), sun exposure (29%), and diet (28%). “We were particularly surprised by the high rates of reactivity to skin care products designed for and marketed to those suffering with sensitive skin,” Ms. McCormick told this news organization. “Importantly, there is currently no federal or legal standard regulating ingredients in products marketed for sensitive skin, and many products lack testing in sensitive skin specifically. Our data suggest an opportunity for improvement of sensitive skin care.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its small sample size. “Reconducting this survey in a larger population will help validate our findings,” she said.

The research was supported by two independent research grants from Galderma: one supporting Ms. McCormick with a Sensitive Skin Research Fellowship and the other a Sensitive Skin Research Acceleration Fund. Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant disclosures.

AT AAD 2023

Papular Rash in a New Tattoo

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

This patient’s history and physical examination were most consistent with a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, likely from an additive or diluent solution within the tattoo ink. Her history of a similar transient reaction following tattooing 2 weeks prior lent credence to an allergic etiology. She was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1% as well as mupirocin ointment 2% for use as both an emollient and for precautionary antimicrobial coverage. The rash resolved within 2 days, and she reported no recurrence at a 6-month follow-up. The cosmesis of her tattoo was preserved.

Acute cellulitis may follow tattooing, but the absence of warmth, pain, or purulence on physical examination made this diagnosis less likely in this patient. Sarcoidosis or other granulomatous reactions may present as papules or nodules arising within a tattoo but would be unlikely to occur the next day. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection likewise tends to present subacutely or chronically rather than immediately following tattoo application.

Tattooing has existed for millennia and is becoming increasingly popular.1,2 The tattooing process entails introduction of insoluble pigment compounds into the dermis to create a permanent design on the skin, which most often is accomplished via needling. As a result, tattooed skin is susceptible to both acute and chronic complications. Acute complications prominently include allergic hypersensitivity reactions and pyogenic bacterial infections. Chronic granulomatous, inflammatory, or infectious complications also can occur.

Allergic eczematous reactions to tattooing are well documented in the literature and are thought to originate from sensitization to pigment molecules themselves or alternatively to ink diluent compounds.3 Although reactions to ink diluent chemicals typically are self-resolving, allergic reactions to pigment can persist beyond the acute phase, as these insoluble compounds intentionally remain embedded in the dermis. The mechanism of action may involve haptenization of pigment molecules that then induces allergic hypersensitivity.3,4 Black pigment typically is derived from carbon black (ie, amorphous combustion byproducts such as soot). Colored inks historically consisted of inorganic heavy metal–containing salts prior to the modern introduction of synthetic azo and polycyclic dyes. These newer colored pigments appear to be less allergenic than their metallic predecessors; however, epidemiologic studies have suggested that allergic reactions still occur more commonly in colored tattoos than black tattoos.1 Overall, these reactions may occur in as many as one-third of individuals who receive tattoos.2,4

As with any process that disrupts skin integrity, tattooing carries a risk for transmitting various infectious pathogens. Microbes may originate from adjacent skin, contaminated needles, ink bottles, or nonsterile ink diluents. Although tattoo parlors and artists may undergo licensing to demonstrate adherence to hygienic standards, regulations vary between states and do not include testing of ink or ink additives to ensure sterility.4,5 Staphylococci and streptococci commonly are implicated in acute pyogenic skin infections following tattooing.5,6 Nontuberculous mycobacteria increasingly are being recognized as causative organisms for granulomatous lesions developing subacutely or even months after receiving a new tattoo.5,7 Local and systemic viral infections also may be transmitted during tattooing; cases of tattoo-transmitted viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, and hepatitis B and C viruses all have been observed.5,6,8 Herpes simplex virus transmission (colloquially termed herpes compunctorum) and HIV transmission through tattooing also are hypothesized to be possible, though there is a paucity of known cases for each.8,9

Chronic inflammatory, granulomatous, or neoplastic lesions may arise within tattooed skin months or years after tattooing. Foreign body granulomas, sarcoidosis, pseudolymphoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and keratoacanthoma are some representative entities.3,5 Cases of cancerous lesions in tattooed skin have been documented, but their incidence appears similar to nontattooed skin.3 These broad categories of lesions are clinically diverse but may be difficult to definitively diagnose on examination alone; therefore, a biopsy should be strongly considered for any subacute to chronic skin lesions within a tattoo. Patients may be hesitant to disrupt the cosmesis of a tattoo but should be counseled on the attendant risks and benefits to make an informed decision regarding biopsy.

- Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, et al. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138-147.

- Liszewski W, Kream E, Helland S, et al. The demographics and rates of tattoo complications, regret, and unsafe tattooing practices: a crosssectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1283-1289.

- Islam PS, Chang C, Selmi C, et al. Medical complications of tattoos: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50:273-286.

- Serup J, Carlsen KH, Sepehri M. Tattoo complaints and complications: diagnosis and clinical spectrum. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:48-60.

- Simunovic C, Shinohara MM. Complications of decorative tattoos: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:525-536.

- Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. Tattoos: dermatological complications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:375-382.

- Sergeant A, Conaglen P, Laurenson IF, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection: a complication of tattooing. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:140-142.

- Cohen PR. Tattoo-associated viral infections: a review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:1529-1540.

- Doll DC. Tattooing in prison and HIV infection. Lancet. 1988;1:66-67.

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

This patient’s history and physical examination were most consistent with a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, likely from an additive or diluent solution within the tattoo ink. Her history of a similar transient reaction following tattooing 2 weeks prior lent credence to an allergic etiology. She was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1% as well as mupirocin ointment 2% for use as both an emollient and for precautionary antimicrobial coverage. The rash resolved within 2 days, and she reported no recurrence at a 6-month follow-up. The cosmesis of her tattoo was preserved.

Acute cellulitis may follow tattooing, but the absence of warmth, pain, or purulence on physical examination made this diagnosis less likely in this patient. Sarcoidosis or other granulomatous reactions may present as papules or nodules arising within a tattoo but would be unlikely to occur the next day. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection likewise tends to present subacutely or chronically rather than immediately following tattoo application.

Tattooing has existed for millennia and is becoming increasingly popular.1,2 The tattooing process entails introduction of insoluble pigment compounds into the dermis to create a permanent design on the skin, which most often is accomplished via needling. As a result, tattooed skin is susceptible to both acute and chronic complications. Acute complications prominently include allergic hypersensitivity reactions and pyogenic bacterial infections. Chronic granulomatous, inflammatory, or infectious complications also can occur.