User login

Pruritus: Diagnosing and Treating Older Adults

Chronic pruritus is a common problem among older individuals. During a session at the Dermatology Days of Paris 2024 conference dedicated to general practitioners, Juliette Delaunay, MD, a dermatologist and venereologist at Angers University Hospital Center in Angers, France, and Gabrielle Lisembard, MD, a general practitioner in the French town Grand-Fort-Philippe, discussed diagnostic approaches and key principles for the therapeutic management of pruritus.

Identifying Causes

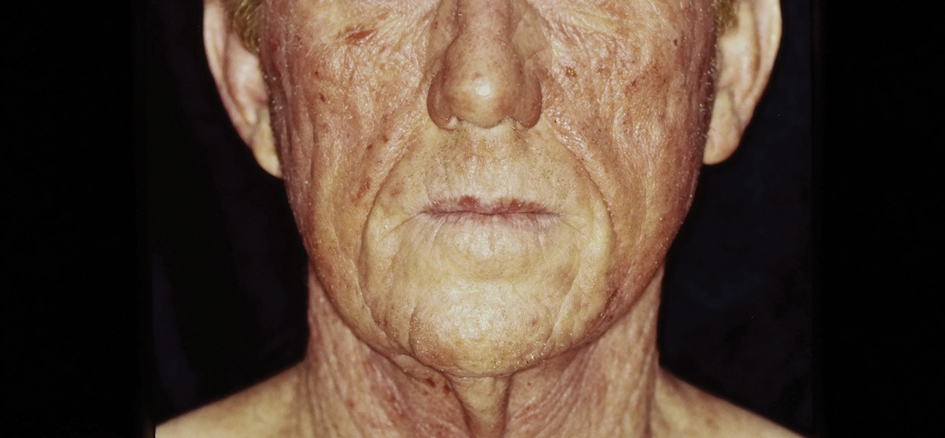

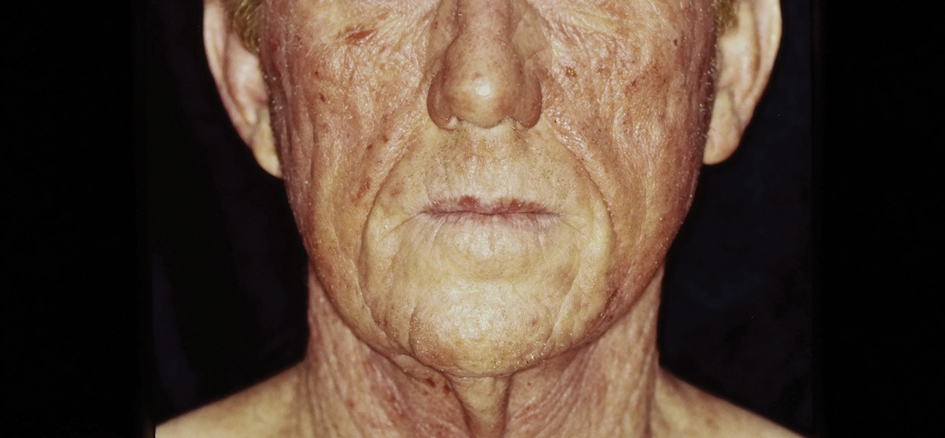

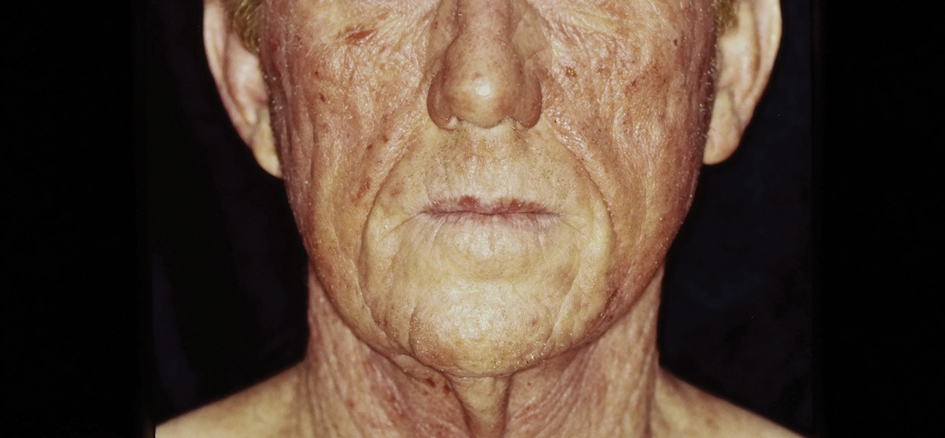

“Pruritus in older people is most often linked to physiological changes in the skin caused by aging, leading to significant xerosis. However, before attributing it to aging, we need to rule out several causes,” Delaunay noted.

Beyond simple aging, one must consider autoimmune bullous dermatoses (bullous pemphigoid), drug-related causes, metabolic disorders (can occur at any age), cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, scabies, lice, and HIV infection.

Senile Pruritus

Aging-related xerosis can cause senile pruritus, often presenting as itching with scratch marks and dry skin. “This is a diagnosis of exclusion,” Delaunay insisted.

In older individuals with pruritus, initial examinations should include complete blood cell count (CBC), liver function tests, and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels. Syphilis serology, HIV testing, and beta-2 microglobulin levels are secondary evaluations. Renal function analysis may also be performed, and imaging may be required to investigate neoplasia.

“Annual etiological reassessment is essential if the initial evaluation is negative, as patients may later develop or report a neoplasia or hematological disorder,” Delaunay emphasized.

Paraneoplastic pruritus can occur, particularly those linked to hematological disorders (lymphomas, polycythemia, or myeloma).

Bullous Pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid often begins with pruritus, which can be severe and lead to insomnia. General practitioners should consider bullous pemphigoids when there is a bullous rash (tense blisters with citrine content) or an urticarial or chronic eczematous rash that does not heal spontaneously within a few days. The first-line biologic test to confirm the diagnosis is the CBC, which may reveal significant hypereosinophilia.

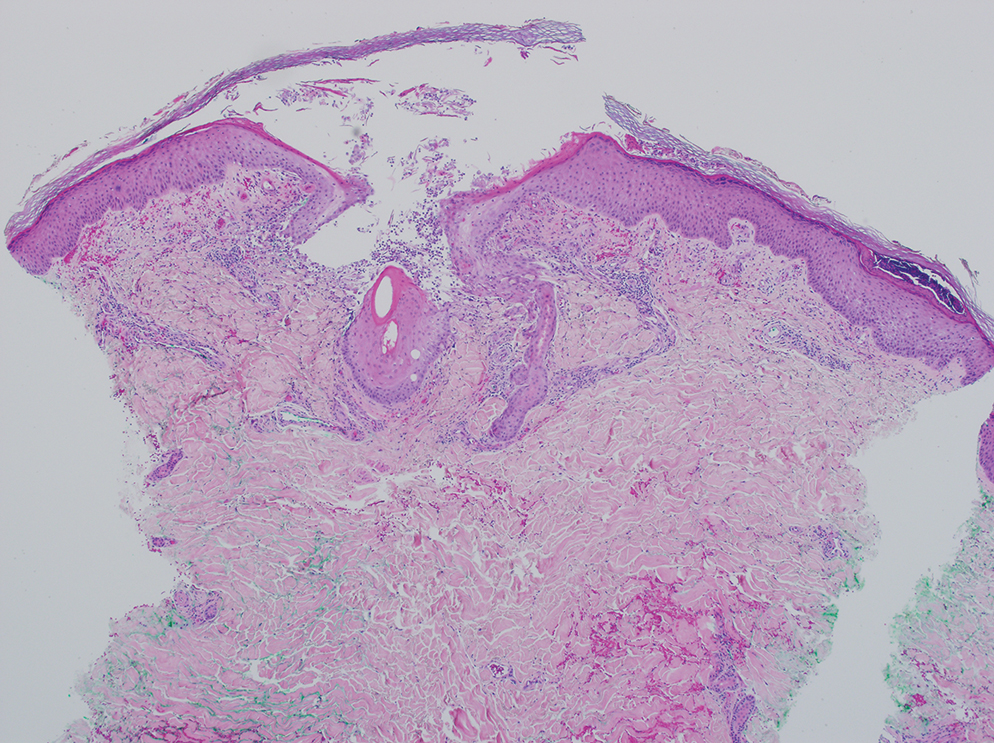

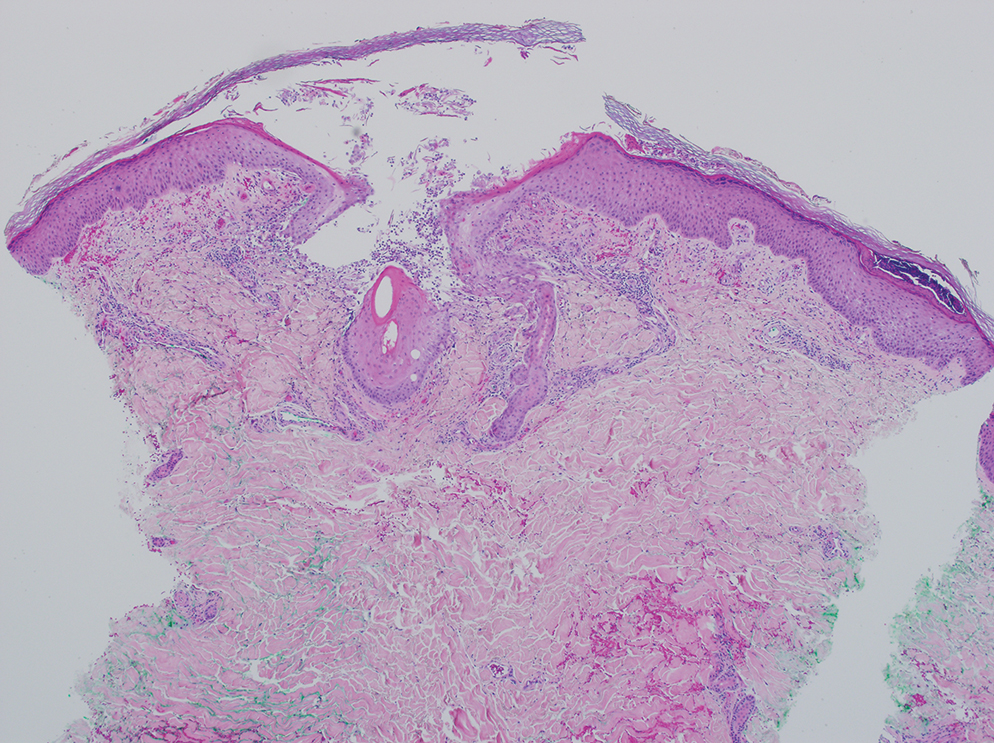

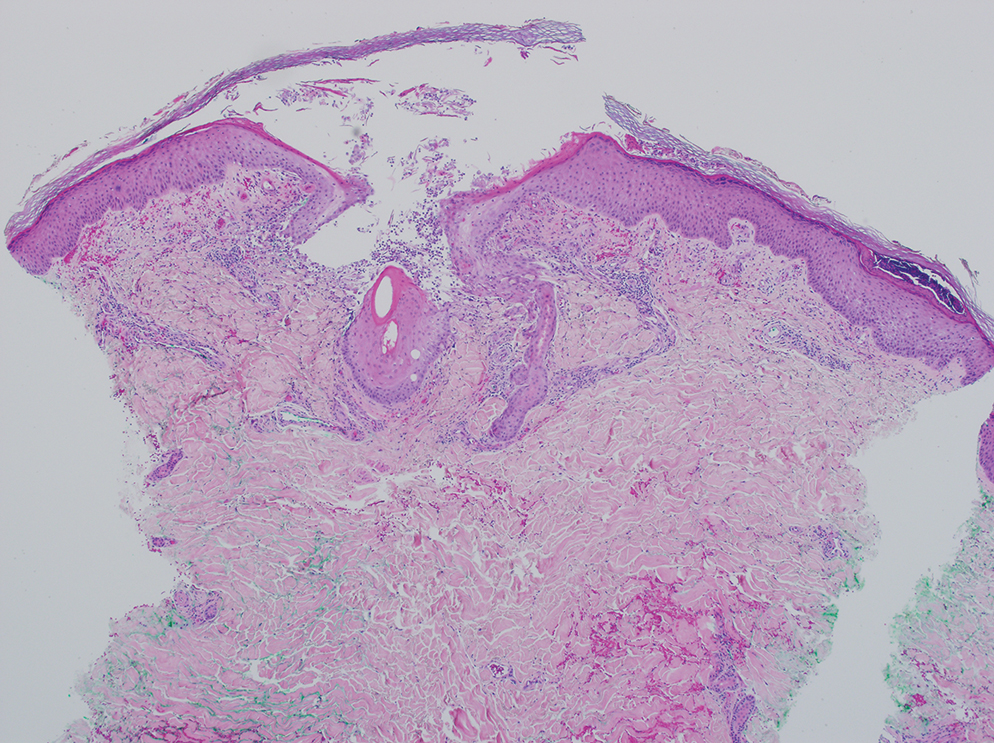

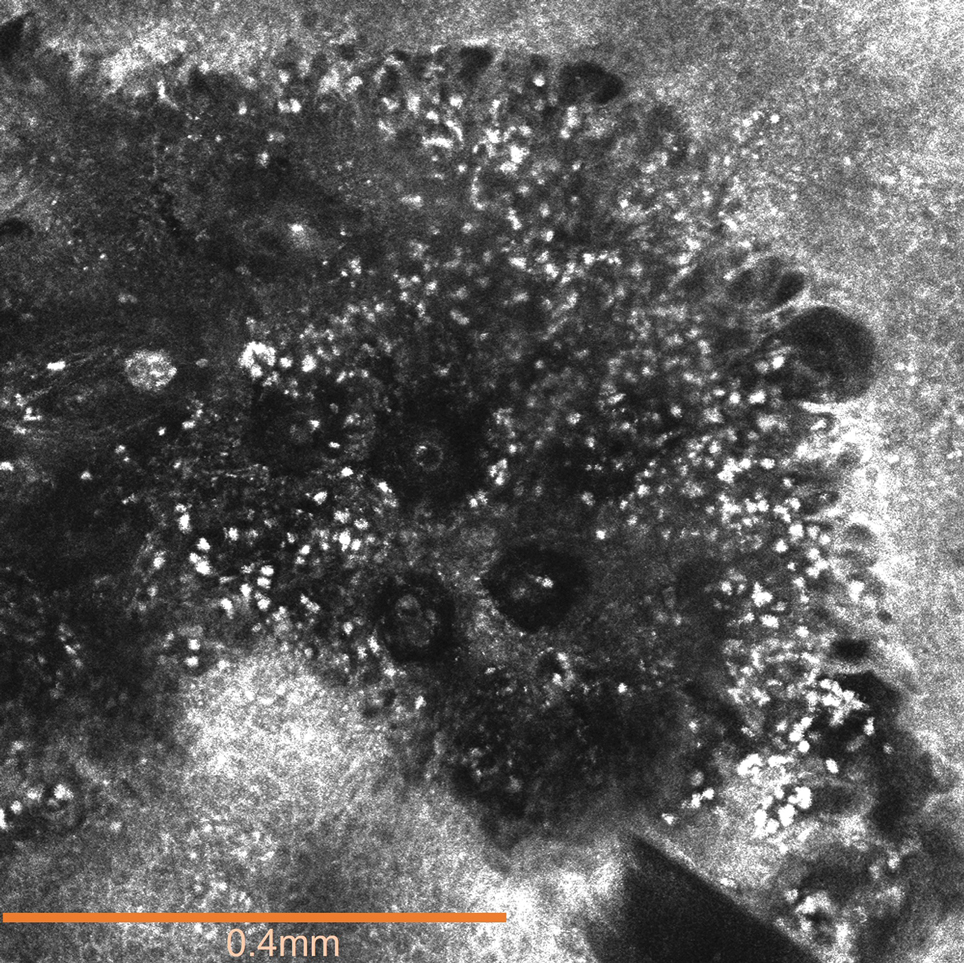

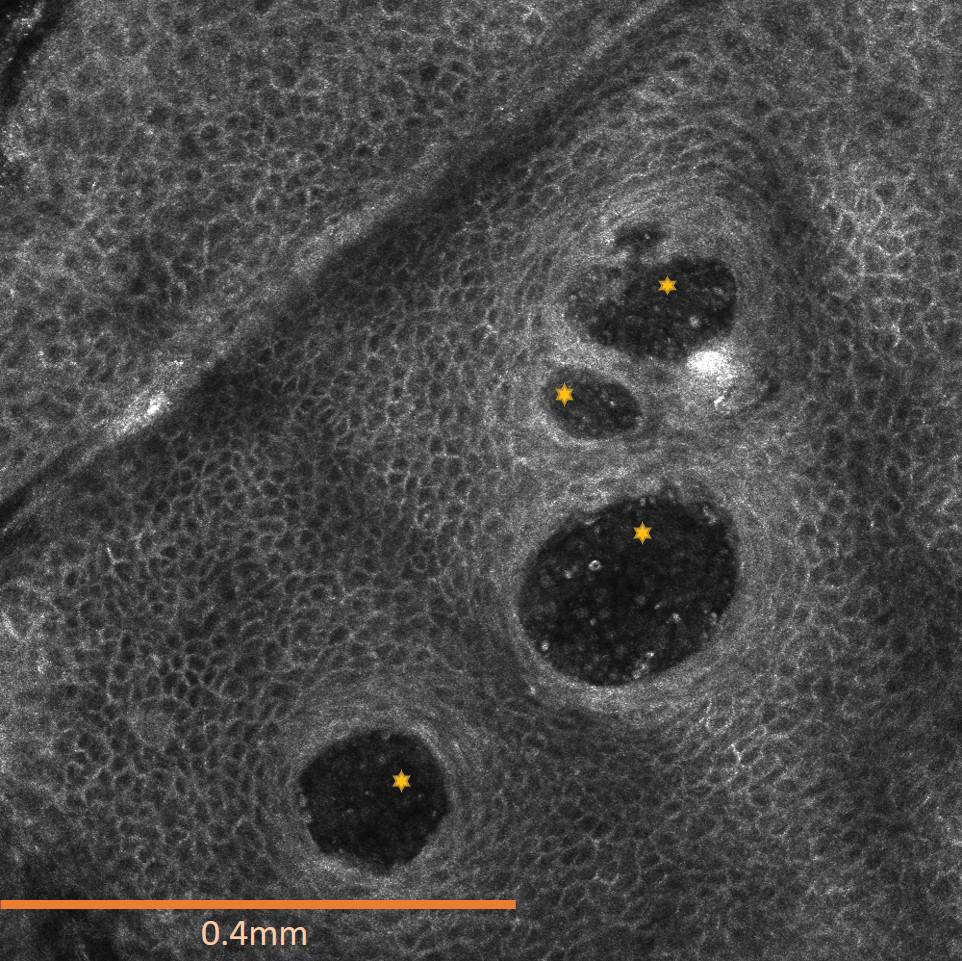

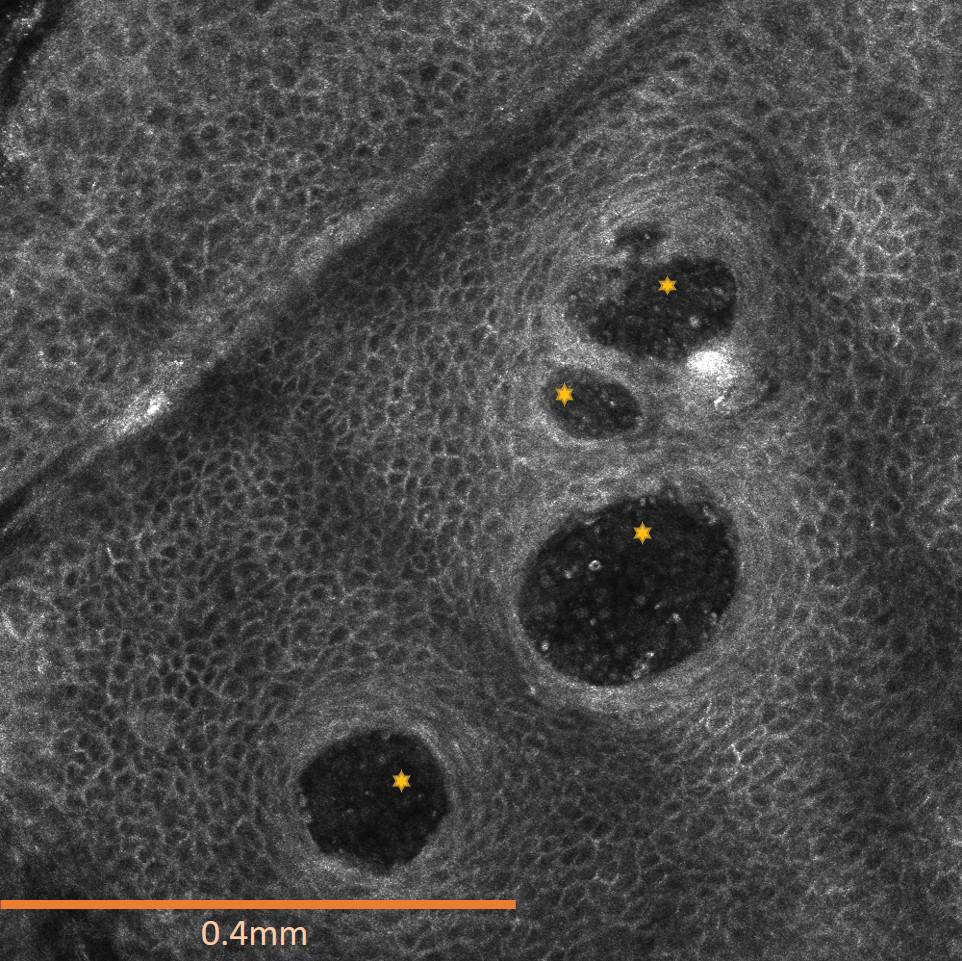

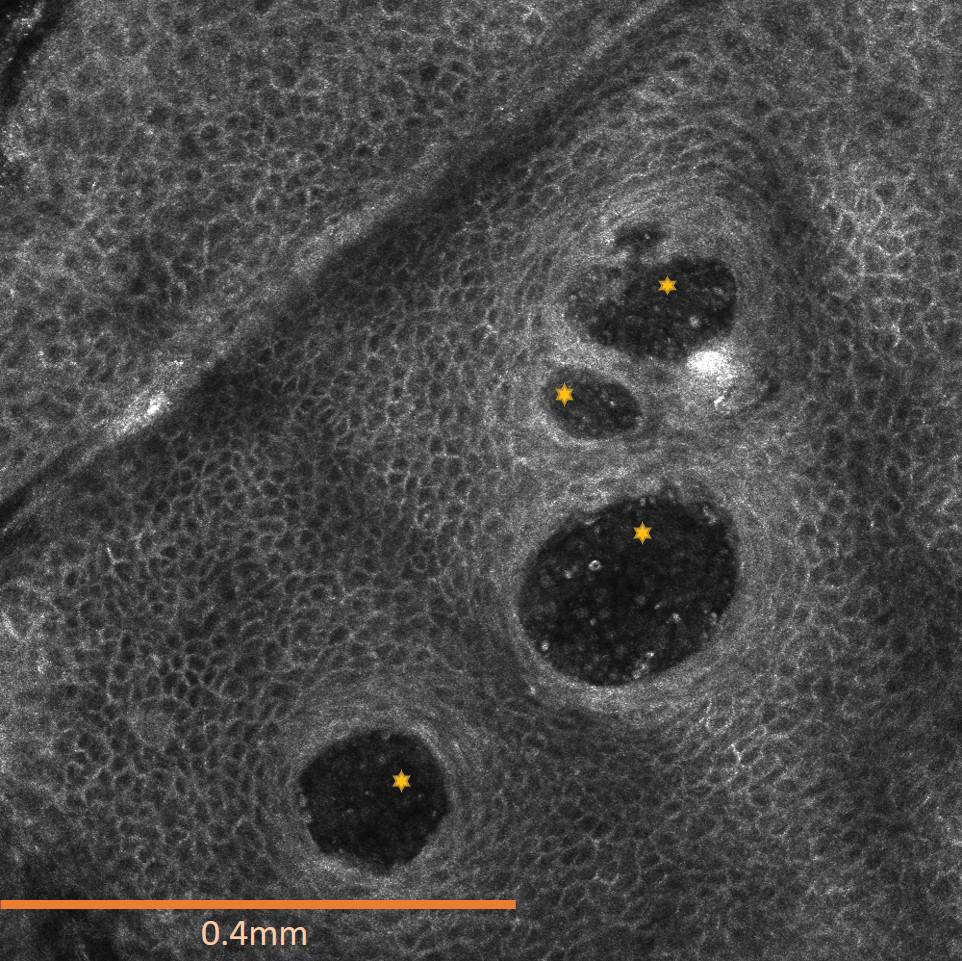

The diagnosis is confirmed by a skin biopsy showing a subepidermal blister with a preserved roof, unlike intraepidermal dermatoses, where the roof ruptures.

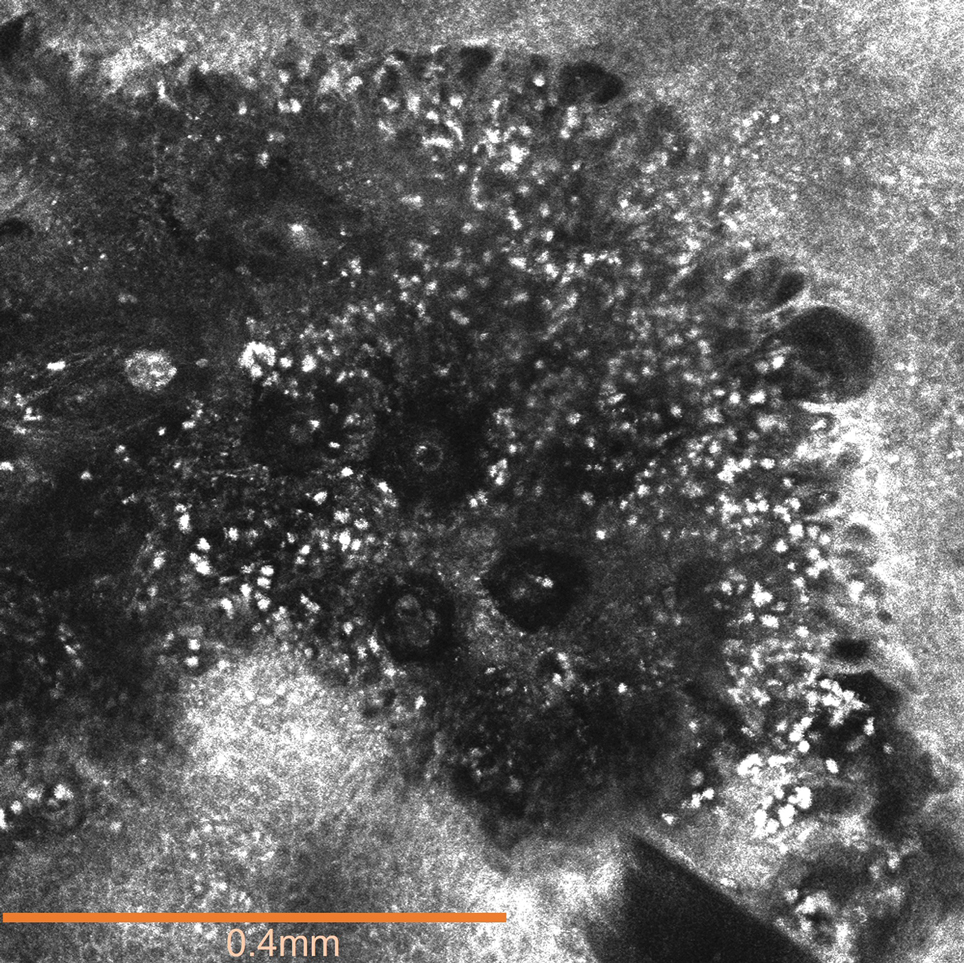

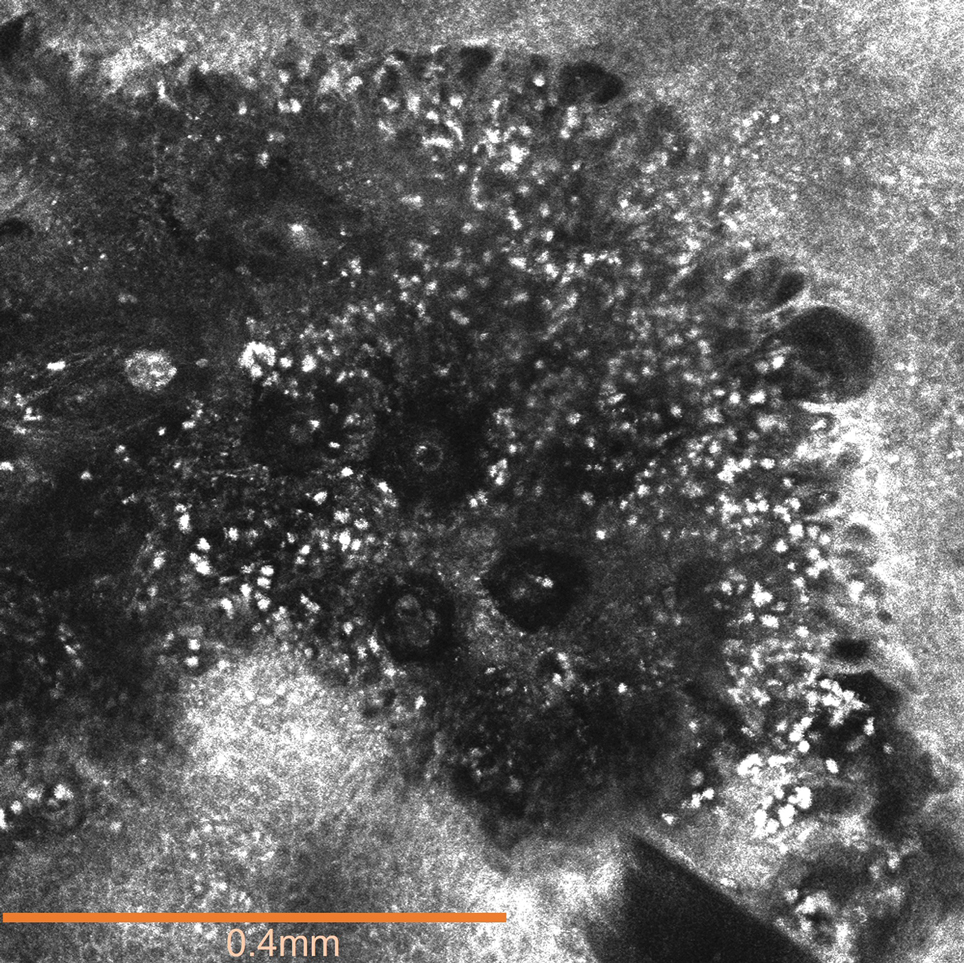

Direct immunofluorescence revealed deposits of immunoglobulin G antibodies along the dermoepidermal junction.

Approximately 40% of cases of bullous pemphigoid are associated with neurodegenerative diseases, such as stroke, parkinsonism, or dementia syndromes — occurring at a rate two to three times higher than in the general population.

It’s important to identify drugs that induce bullous pemphigoid, such as gliptins, anti-programmed cell death protein 1-programmed death-ligand 1 agents, loop diuretics (furosemide and bumetanide), anti-aldosterones (spironolactone), antiarrhythmics (amiodarone), and neuroleptics (phenothiazines).

“Stopping the medication is not mandatory if the bullous pemphigoid is well controlled by local or systemic treatments and the medication is essential. The decision to stop should be made on a case-by-case basis in consultation with the treating specialist,” Delaunay emphasized.

Treatment consists of very strong local corticosteroid therapy as the first-line treatment. If ineffective, systemic treatments based on methotrexate, oral corticosteroids, or immunomodulatory agents may be considered. Hospitalization is sometimes required.

Drug-Induced Pruritus

Drug-induced pruritus is common because older individuals often take multiple medications (antihypertensives, statins, oral hypoglycemics, psychotropic drugs, antiarrhythmics, etc.). “Sometimes, drug-induced pruritus can occur even if the medication was started several months or years ago,” Delaunay emphasized.

The lesions are generally nonspecific and scratching.

“This is a diagnosis of exclusion for other causes of pruritus. In the absence of specific lesions pointing to a dermatosis, eviction/reintroduction tests with treatments should be conducted one by one, which can be quite lengthy,” she explained.

Awareness for Scabies

Delaunay reminded attendees to consider scabies in older individuals when classic signs of pruritus flare up at night, with a rash affecting the face, scabs, or vesicles in the interdigital spaces of the hands, wrists, scrotal area, or the peri-mammary region.

“The incidence is increasing, particularly in nursing homes, where outbreaks pose a significant risk of rapid spread. Treatment involves three courses of topical and oral treatments administered on days 0, 7, and 14. All contact cases must also be treated. Sometimes, these thick lesions are stripped with 10% salicylated petroleum jelly. Environmental treatment with acaricides is essential, along with strict isolation measures,” Delaunay emphasized.

Adherent nits on the scalp or other hairy areas should raise suspicion of pediculosis.

Neurogenic and Psychogenic Origins

Neurogenic pruritus can occur during a stroke, presenting as contralateral pruritus, or in the presence of a brain tumor or following neurosurgery. Opioid-containing medications may also induce neurogenic pruritus.

The presence of unilateral painful or itchy sensations should prompt the investigation of shingles in older individuals.

Psychogenic pruritus is also common and can arise in the context of psychosis with parasitophobia or as part of anxiety-depression syndromes.

Supportive Measures

For managing pruritus, it is essential to:

- Keep nails trimmed short

- Wash with cold or lukewarm water

- Use lipid-rice soaps and syndets

- Avoid irritants, including antiseptics, cologne, no-rinse cleansers, and steroidal or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Limit bathing frequency

- Avoid wearing nylon, wool, or tight clothing

- Minimize exposure to heat and excessive heating

“Alternatives to scratching, such as applying a moisturizing emollient, can be beneficial and may have a placebo effect,” explained the dermatologist. She further emphasized that local corticosteroids are effective only in the presence of inflammatory dermatosis and should not be applied to healthy skin. Similarly, antihistamines should only be prescribed if the pruritus is histamine-mediated.

Capsaicin may be useful in the treatment of localized neuropathic pruritus.

In cases of neurogenic pruritus, gabapentin and pregabalin may be prescribed, but tolerance can be problematic at this age. Other measures include acupuncture, cryotherapy, relaxation, hypnosis, psychotherapy, and music therapy. In cases of repeated therapeutic failure, patients may be treated with biotherapy (dupilumab) by a dermatologist.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic pruritus is a common problem among older individuals. During a session at the Dermatology Days of Paris 2024 conference dedicated to general practitioners, Juliette Delaunay, MD, a dermatologist and venereologist at Angers University Hospital Center in Angers, France, and Gabrielle Lisembard, MD, a general practitioner in the French town Grand-Fort-Philippe, discussed diagnostic approaches and key principles for the therapeutic management of pruritus.

Identifying Causes

“Pruritus in older people is most often linked to physiological changes in the skin caused by aging, leading to significant xerosis. However, before attributing it to aging, we need to rule out several causes,” Delaunay noted.

Beyond simple aging, one must consider autoimmune bullous dermatoses (bullous pemphigoid), drug-related causes, metabolic disorders (can occur at any age), cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, scabies, lice, and HIV infection.

Senile Pruritus

Aging-related xerosis can cause senile pruritus, often presenting as itching with scratch marks and dry skin. “This is a diagnosis of exclusion,” Delaunay insisted.

In older individuals with pruritus, initial examinations should include complete blood cell count (CBC), liver function tests, and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels. Syphilis serology, HIV testing, and beta-2 microglobulin levels are secondary evaluations. Renal function analysis may also be performed, and imaging may be required to investigate neoplasia.

“Annual etiological reassessment is essential if the initial evaluation is negative, as patients may later develop or report a neoplasia or hematological disorder,” Delaunay emphasized.

Paraneoplastic pruritus can occur, particularly those linked to hematological disorders (lymphomas, polycythemia, or myeloma).

Bullous Pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid often begins with pruritus, which can be severe and lead to insomnia. General practitioners should consider bullous pemphigoids when there is a bullous rash (tense blisters with citrine content) or an urticarial or chronic eczematous rash that does not heal spontaneously within a few days. The first-line biologic test to confirm the diagnosis is the CBC, which may reveal significant hypereosinophilia.

The diagnosis is confirmed by a skin biopsy showing a subepidermal blister with a preserved roof, unlike intraepidermal dermatoses, where the roof ruptures.

Direct immunofluorescence revealed deposits of immunoglobulin G antibodies along the dermoepidermal junction.

Approximately 40% of cases of bullous pemphigoid are associated with neurodegenerative diseases, such as stroke, parkinsonism, or dementia syndromes — occurring at a rate two to three times higher than in the general population.

It’s important to identify drugs that induce bullous pemphigoid, such as gliptins, anti-programmed cell death protein 1-programmed death-ligand 1 agents, loop diuretics (furosemide and bumetanide), anti-aldosterones (spironolactone), antiarrhythmics (amiodarone), and neuroleptics (phenothiazines).

“Stopping the medication is not mandatory if the bullous pemphigoid is well controlled by local or systemic treatments and the medication is essential. The decision to stop should be made on a case-by-case basis in consultation with the treating specialist,” Delaunay emphasized.

Treatment consists of very strong local corticosteroid therapy as the first-line treatment. If ineffective, systemic treatments based on methotrexate, oral corticosteroids, or immunomodulatory agents may be considered. Hospitalization is sometimes required.

Drug-Induced Pruritus

Drug-induced pruritus is common because older individuals often take multiple medications (antihypertensives, statins, oral hypoglycemics, psychotropic drugs, antiarrhythmics, etc.). “Sometimes, drug-induced pruritus can occur even if the medication was started several months or years ago,” Delaunay emphasized.

The lesions are generally nonspecific and scratching.

“This is a diagnosis of exclusion for other causes of pruritus. In the absence of specific lesions pointing to a dermatosis, eviction/reintroduction tests with treatments should be conducted one by one, which can be quite lengthy,” she explained.

Awareness for Scabies

Delaunay reminded attendees to consider scabies in older individuals when classic signs of pruritus flare up at night, with a rash affecting the face, scabs, or vesicles in the interdigital spaces of the hands, wrists, scrotal area, or the peri-mammary region.

“The incidence is increasing, particularly in nursing homes, where outbreaks pose a significant risk of rapid spread. Treatment involves three courses of topical and oral treatments administered on days 0, 7, and 14. All contact cases must also be treated. Sometimes, these thick lesions are stripped with 10% salicylated petroleum jelly. Environmental treatment with acaricides is essential, along with strict isolation measures,” Delaunay emphasized.

Adherent nits on the scalp or other hairy areas should raise suspicion of pediculosis.

Neurogenic and Psychogenic Origins

Neurogenic pruritus can occur during a stroke, presenting as contralateral pruritus, or in the presence of a brain tumor or following neurosurgery. Opioid-containing medications may also induce neurogenic pruritus.

The presence of unilateral painful or itchy sensations should prompt the investigation of shingles in older individuals.

Psychogenic pruritus is also common and can arise in the context of psychosis with parasitophobia or as part of anxiety-depression syndromes.

Supportive Measures

For managing pruritus, it is essential to:

- Keep nails trimmed short

- Wash with cold or lukewarm water

- Use lipid-rice soaps and syndets

- Avoid irritants, including antiseptics, cologne, no-rinse cleansers, and steroidal or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Limit bathing frequency

- Avoid wearing nylon, wool, or tight clothing

- Minimize exposure to heat and excessive heating

“Alternatives to scratching, such as applying a moisturizing emollient, can be beneficial and may have a placebo effect,” explained the dermatologist. She further emphasized that local corticosteroids are effective only in the presence of inflammatory dermatosis and should not be applied to healthy skin. Similarly, antihistamines should only be prescribed if the pruritus is histamine-mediated.

Capsaicin may be useful in the treatment of localized neuropathic pruritus.

In cases of neurogenic pruritus, gabapentin and pregabalin may be prescribed, but tolerance can be problematic at this age. Other measures include acupuncture, cryotherapy, relaxation, hypnosis, psychotherapy, and music therapy. In cases of repeated therapeutic failure, patients may be treated with biotherapy (dupilumab) by a dermatologist.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic pruritus is a common problem among older individuals. During a session at the Dermatology Days of Paris 2024 conference dedicated to general practitioners, Juliette Delaunay, MD, a dermatologist and venereologist at Angers University Hospital Center in Angers, France, and Gabrielle Lisembard, MD, a general practitioner in the French town Grand-Fort-Philippe, discussed diagnostic approaches and key principles for the therapeutic management of pruritus.

Identifying Causes

“Pruritus in older people is most often linked to physiological changes in the skin caused by aging, leading to significant xerosis. However, before attributing it to aging, we need to rule out several causes,” Delaunay noted.

Beyond simple aging, one must consider autoimmune bullous dermatoses (bullous pemphigoid), drug-related causes, metabolic disorders (can occur at any age), cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, scabies, lice, and HIV infection.

Senile Pruritus

Aging-related xerosis can cause senile pruritus, often presenting as itching with scratch marks and dry skin. “This is a diagnosis of exclusion,” Delaunay insisted.

In older individuals with pruritus, initial examinations should include complete blood cell count (CBC), liver function tests, and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels. Syphilis serology, HIV testing, and beta-2 microglobulin levels are secondary evaluations. Renal function analysis may also be performed, and imaging may be required to investigate neoplasia.

“Annual etiological reassessment is essential if the initial evaluation is negative, as patients may later develop or report a neoplasia or hematological disorder,” Delaunay emphasized.

Paraneoplastic pruritus can occur, particularly those linked to hematological disorders (lymphomas, polycythemia, or myeloma).

Bullous Pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid often begins with pruritus, which can be severe and lead to insomnia. General practitioners should consider bullous pemphigoids when there is a bullous rash (tense blisters with citrine content) or an urticarial or chronic eczematous rash that does not heal spontaneously within a few days. The first-line biologic test to confirm the diagnosis is the CBC, which may reveal significant hypereosinophilia.

The diagnosis is confirmed by a skin biopsy showing a subepidermal blister with a preserved roof, unlike intraepidermal dermatoses, where the roof ruptures.

Direct immunofluorescence revealed deposits of immunoglobulin G antibodies along the dermoepidermal junction.

Approximately 40% of cases of bullous pemphigoid are associated with neurodegenerative diseases, such as stroke, parkinsonism, or dementia syndromes — occurring at a rate two to three times higher than in the general population.

It’s important to identify drugs that induce bullous pemphigoid, such as gliptins, anti-programmed cell death protein 1-programmed death-ligand 1 agents, loop diuretics (furosemide and bumetanide), anti-aldosterones (spironolactone), antiarrhythmics (amiodarone), and neuroleptics (phenothiazines).

“Stopping the medication is not mandatory if the bullous pemphigoid is well controlled by local or systemic treatments and the medication is essential. The decision to stop should be made on a case-by-case basis in consultation with the treating specialist,” Delaunay emphasized.

Treatment consists of very strong local corticosteroid therapy as the first-line treatment. If ineffective, systemic treatments based on methotrexate, oral corticosteroids, or immunomodulatory agents may be considered. Hospitalization is sometimes required.

Drug-Induced Pruritus

Drug-induced pruritus is common because older individuals often take multiple medications (antihypertensives, statins, oral hypoglycemics, psychotropic drugs, antiarrhythmics, etc.). “Sometimes, drug-induced pruritus can occur even if the medication was started several months or years ago,” Delaunay emphasized.

The lesions are generally nonspecific and scratching.

“This is a diagnosis of exclusion for other causes of pruritus. In the absence of specific lesions pointing to a dermatosis, eviction/reintroduction tests with treatments should be conducted one by one, which can be quite lengthy,” she explained.

Awareness for Scabies

Delaunay reminded attendees to consider scabies in older individuals when classic signs of pruritus flare up at night, with a rash affecting the face, scabs, or vesicles in the interdigital spaces of the hands, wrists, scrotal area, or the peri-mammary region.

“The incidence is increasing, particularly in nursing homes, where outbreaks pose a significant risk of rapid spread. Treatment involves three courses of topical and oral treatments administered on days 0, 7, and 14. All contact cases must also be treated. Sometimes, these thick lesions are stripped with 10% salicylated petroleum jelly. Environmental treatment with acaricides is essential, along with strict isolation measures,” Delaunay emphasized.

Adherent nits on the scalp or other hairy areas should raise suspicion of pediculosis.

Neurogenic and Psychogenic Origins

Neurogenic pruritus can occur during a stroke, presenting as contralateral pruritus, or in the presence of a brain tumor or following neurosurgery. Opioid-containing medications may also induce neurogenic pruritus.

The presence of unilateral painful or itchy sensations should prompt the investigation of shingles in older individuals.

Psychogenic pruritus is also common and can arise in the context of psychosis with parasitophobia or as part of anxiety-depression syndromes.

Supportive Measures

For managing pruritus, it is essential to:

- Keep nails trimmed short

- Wash with cold or lukewarm water

- Use lipid-rice soaps and syndets

- Avoid irritants, including antiseptics, cologne, no-rinse cleansers, and steroidal or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Limit bathing frequency

- Avoid wearing nylon, wool, or tight clothing

- Minimize exposure to heat and excessive heating

“Alternatives to scratching, such as applying a moisturizing emollient, can be beneficial and may have a placebo effect,” explained the dermatologist. She further emphasized that local corticosteroids are effective only in the presence of inflammatory dermatosis and should not be applied to healthy skin. Similarly, antihistamines should only be prescribed if the pruritus is histamine-mediated.

Capsaicin may be useful in the treatment of localized neuropathic pruritus.

In cases of neurogenic pruritus, gabapentin and pregabalin may be prescribed, but tolerance can be problematic at this age. Other measures include acupuncture, cryotherapy, relaxation, hypnosis, psychotherapy, and music therapy. In cases of repeated therapeutic failure, patients may be treated with biotherapy (dupilumab) by a dermatologist.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Central Line Skin Reactions in Children: Survey Addresses Treatment Protocols in Use

TOPLINE:

A and reported varying management approaches.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers developed and administered a 14-item Qualtrics survey to 107 dermatologists providing pediatric inpatient care through the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Inpatient Dermatology Section and Section Chief email lists.

- A total of 35 dermatologists (33%) from multiple institutions responded to the survey; most respondents (94%) specialized in pediatric dermatology.

- Researchers assessed management of CLD-associated adverse skin reactions.

TAKEAWAY:

- All respondents reported receiving CLD-related consults, but 66% indicated there was no personal or institutional standardized approach for managing CLD-associated skin reactions.

- Respondents said most reactions were in children aged 1-12 years (19 or 76% of 25 respondents) compared with those aged < 1 year (3 or 12% of 25 respondents).

- Management strategies included switching to alternative products, applying topical corticosteroids, and performing patch testing for allergies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Insights derived from this study, including variation in clinician familiarity with reaction patterns, underscore the necessity of a standardized protocol for classifying and managing cutaneous CLD reactions in pediatric patients,” the authors wrote. “Further investigation is needed to better characterize CLD-associated allergic CD [contact dermatitis], irritant CD, and skin infections, as well as at-risk populations, to better inform clinical approaches,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Mulinda, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and was published online on December 16 in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted variable respondent awareness of institutional CLD and potential recency bias as key limitations of the study.

DISCLOSURES:

Study funding source was not declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A and reported varying management approaches.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers developed and administered a 14-item Qualtrics survey to 107 dermatologists providing pediatric inpatient care through the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Inpatient Dermatology Section and Section Chief email lists.

- A total of 35 dermatologists (33%) from multiple institutions responded to the survey; most respondents (94%) specialized in pediatric dermatology.

- Researchers assessed management of CLD-associated adverse skin reactions.

TAKEAWAY:

- All respondents reported receiving CLD-related consults, but 66% indicated there was no personal or institutional standardized approach for managing CLD-associated skin reactions.

- Respondents said most reactions were in children aged 1-12 years (19 or 76% of 25 respondents) compared with those aged < 1 year (3 or 12% of 25 respondents).

- Management strategies included switching to alternative products, applying topical corticosteroids, and performing patch testing for allergies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Insights derived from this study, including variation in clinician familiarity with reaction patterns, underscore the necessity of a standardized protocol for classifying and managing cutaneous CLD reactions in pediatric patients,” the authors wrote. “Further investigation is needed to better characterize CLD-associated allergic CD [contact dermatitis], irritant CD, and skin infections, as well as at-risk populations, to better inform clinical approaches,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Mulinda, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and was published online on December 16 in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted variable respondent awareness of institutional CLD and potential recency bias as key limitations of the study.

DISCLOSURES:

Study funding source was not declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A and reported varying management approaches.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers developed and administered a 14-item Qualtrics survey to 107 dermatologists providing pediatric inpatient care through the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Inpatient Dermatology Section and Section Chief email lists.

- A total of 35 dermatologists (33%) from multiple institutions responded to the survey; most respondents (94%) specialized in pediatric dermatology.

- Researchers assessed management of CLD-associated adverse skin reactions.

TAKEAWAY:

- All respondents reported receiving CLD-related consults, but 66% indicated there was no personal or institutional standardized approach for managing CLD-associated skin reactions.

- Respondents said most reactions were in children aged 1-12 years (19 or 76% of 25 respondents) compared with those aged < 1 year (3 or 12% of 25 respondents).

- Management strategies included switching to alternative products, applying topical corticosteroids, and performing patch testing for allergies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Insights derived from this study, including variation in clinician familiarity with reaction patterns, underscore the necessity of a standardized protocol for classifying and managing cutaneous CLD reactions in pediatric patients,” the authors wrote. “Further investigation is needed to better characterize CLD-associated allergic CD [contact dermatitis], irritant CD, and skin infections, as well as at-risk populations, to better inform clinical approaches,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Mulinda, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and was published online on December 16 in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted variable respondent awareness of institutional CLD and potential recency bias as key limitations of the study.

DISCLOSURES:

Study funding source was not declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis: New Culprits

New allergens responsible for contact dermatitis emerge regularly. During the Dermatology Days of Paris 2024 conference, Angèle Soria, MD, PhD, a dermatologist at Tenon Hospital in Paris, France, outlined four major categories driving this trend. Among them are (meth)acrylates found in nail cosmetics used in salons or do-it-yourself false nail kits that can be bought online.

Isothiazolinones

a preservative used in many cosmetics; (meth)acrylates; essential oils; and epoxy resins used in industry and leisure activities.

Around 15 years ago, parabens, commonly used as preservatives in cosmetics, were identified as endocrine disruptors. In response, they were largely replaced by newer preservatives, notably MI. However, this led to a proliferation of allergic contact dermatitis in Europe between 2010 and 2013.

“About 10% of the population that we tested showed allergies to these preservatives, primarily found in cosmetics,” explained Soria. Since 2015, the use of MI in leave-on cosmetics has been prohibited in Europe and its concentration restricted in rinse-off products. However, cosmetics sold online from outside Europe may not comply with these regulations.

MI is also present in water-based paints to prevent mold. “A few years ago, we started seeing patients with facial angioedema, sometimes combined with asthma, caused by these isothiazolinone preservatives, including in patients who are not professional painters,” said Soria. More recently, attention has shifted to MI’s presence in household cleaning products. A 2020 Spanish study found MI in 76% of 34 analyzed cleaning products.

MI-based fungicides are also used to treat leather during transport, which can lead to contact allergies among professionals and consumers alike. Additionally, MI has been identified in children’s toys, including slime gels, and in florists’ gel cubes used to preserve flowers.

“We are therefore surrounded by these preservatives, which are no longer only in cosmetics,” warned the dermatologist.

(Meth)acrylates

Another major allergen category is (meth)acrylates, responsible for many cases of allergic contact dermatitis. Acrylates and their derivatives are widely used in everyday items. They are low–molecular weight monomers, sensitizing on contact with the skin. Their polymerized forms include materials like Plexiglas.

“We are currently witnessing an epidemic of contact dermatitis in the general population, mainly due to nail cosmetics, such as semipermanent nail polishes and at-home false nail kits,” reported Soria. Nail cosmetics account for 97% of new sensitization cases involving (meth)acrylates. These allergens often cause severe dermatitis, prompting the European Union to mandate labeling in 2020, warning that these products are “for professional use only” and can “cause allergic reactions.”

Beyond nail cosmetics, these allergens are also found in dental products (such as trays), ECG electrodes, prosthetics, glucose sensors, surgical adhesives, and some electronic devices like earbuds and phone screens. Notably, patients sensitized to acrylates via nail kits may experience reactions during dental treatments involving acrylates.

Investigating Essential Oil Use

Essential oils, distinct from vegetable oils like almond or argan, are another known allergen. Often considered risk-free due to their “natural” label, these products are widely used topically, orally, or via inhalation for various purposes, such as treating respiratory infections or creating relaxing atmospheres. However, essential oils contain fragrant molecules like terpenes, which can become highly allergenic over time, especially after repeated exposure.

Soria emphasized the importance of asking patients about their use of essential oils, especially tea tree and lavender oils, which are commonly used but rarely mentioned by patients unless prompted.

Epoxy Resins in Recreational Use

Epoxy resins are a growing cause of contact allergies, not just in professional settings such as aeronautics and construction work but also increasingly in recreational activities. Soria highlighted the case of a 12-year-old girl hospitalized for severe facial edema after engaging in resin crafts inspired by TikTok. For 6 months, she had been creating resin objects, such as bowls and cutting boards, using vinyl gloves and a Filtering FacePiece 2 mask under adult supervision.

“The growing popularity and online availability of epoxy resins mean that allergic reactions should now be considered even in nonprofessional contexts,” warned Soria.

Clinical Approach

When dermatologists suspect allergic contact dermatitis, the first step is to treat the condition with corticosteroid creams. This is followed by a detailed patient interview to identify suspected allergens in products they’ve used.

Patch testing is then conducted to confirm the allergen. Small chambers containing potential allergens are applied to the upper back for 48 hours without removal. Results are read 2-5 days later, with some cases requiring a 7-day follow-up.

The patient’s occupation is an important factor, as certain professions, such as hairdressing, healthcare, or beauty therapy, are known to trigger allergic contact dermatitis. Similarly, certain hobbies may also play a role.

A thorough approach ensures accurate diagnosis and targeted prevention strategies.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New allergens responsible for contact dermatitis emerge regularly. During the Dermatology Days of Paris 2024 conference, Angèle Soria, MD, PhD, a dermatologist at Tenon Hospital in Paris, France, outlined four major categories driving this trend. Among them are (meth)acrylates found in nail cosmetics used in salons or do-it-yourself false nail kits that can be bought online.

Isothiazolinones

a preservative used in many cosmetics; (meth)acrylates; essential oils; and epoxy resins used in industry and leisure activities.

Around 15 years ago, parabens, commonly used as preservatives in cosmetics, were identified as endocrine disruptors. In response, they were largely replaced by newer preservatives, notably MI. However, this led to a proliferation of allergic contact dermatitis in Europe between 2010 and 2013.

“About 10% of the population that we tested showed allergies to these preservatives, primarily found in cosmetics,” explained Soria. Since 2015, the use of MI in leave-on cosmetics has been prohibited in Europe and its concentration restricted in rinse-off products. However, cosmetics sold online from outside Europe may not comply with these regulations.

MI is also present in water-based paints to prevent mold. “A few years ago, we started seeing patients with facial angioedema, sometimes combined with asthma, caused by these isothiazolinone preservatives, including in patients who are not professional painters,” said Soria. More recently, attention has shifted to MI’s presence in household cleaning products. A 2020 Spanish study found MI in 76% of 34 analyzed cleaning products.

MI-based fungicides are also used to treat leather during transport, which can lead to contact allergies among professionals and consumers alike. Additionally, MI has been identified in children’s toys, including slime gels, and in florists’ gel cubes used to preserve flowers.

“We are therefore surrounded by these preservatives, which are no longer only in cosmetics,” warned the dermatologist.

(Meth)acrylates

Another major allergen category is (meth)acrylates, responsible for many cases of allergic contact dermatitis. Acrylates and their derivatives are widely used in everyday items. They are low–molecular weight monomers, sensitizing on contact with the skin. Their polymerized forms include materials like Plexiglas.

“We are currently witnessing an epidemic of contact dermatitis in the general population, mainly due to nail cosmetics, such as semipermanent nail polishes and at-home false nail kits,” reported Soria. Nail cosmetics account for 97% of new sensitization cases involving (meth)acrylates. These allergens often cause severe dermatitis, prompting the European Union to mandate labeling in 2020, warning that these products are “for professional use only” and can “cause allergic reactions.”

Beyond nail cosmetics, these allergens are also found in dental products (such as trays), ECG electrodes, prosthetics, glucose sensors, surgical adhesives, and some electronic devices like earbuds and phone screens. Notably, patients sensitized to acrylates via nail kits may experience reactions during dental treatments involving acrylates.

Investigating Essential Oil Use

Essential oils, distinct from vegetable oils like almond or argan, are another known allergen. Often considered risk-free due to their “natural” label, these products are widely used topically, orally, or via inhalation for various purposes, such as treating respiratory infections or creating relaxing atmospheres. However, essential oils contain fragrant molecules like terpenes, which can become highly allergenic over time, especially after repeated exposure.

Soria emphasized the importance of asking patients about their use of essential oils, especially tea tree and lavender oils, which are commonly used but rarely mentioned by patients unless prompted.

Epoxy Resins in Recreational Use

Epoxy resins are a growing cause of contact allergies, not just in professional settings such as aeronautics and construction work but also increasingly in recreational activities. Soria highlighted the case of a 12-year-old girl hospitalized for severe facial edema after engaging in resin crafts inspired by TikTok. For 6 months, she had been creating resin objects, such as bowls and cutting boards, using vinyl gloves and a Filtering FacePiece 2 mask under adult supervision.

“The growing popularity and online availability of epoxy resins mean that allergic reactions should now be considered even in nonprofessional contexts,” warned Soria.

Clinical Approach

When dermatologists suspect allergic contact dermatitis, the first step is to treat the condition with corticosteroid creams. This is followed by a detailed patient interview to identify suspected allergens in products they’ve used.

Patch testing is then conducted to confirm the allergen. Small chambers containing potential allergens are applied to the upper back for 48 hours without removal. Results are read 2-5 days later, with some cases requiring a 7-day follow-up.

The patient’s occupation is an important factor, as certain professions, such as hairdressing, healthcare, or beauty therapy, are known to trigger allergic contact dermatitis. Similarly, certain hobbies may also play a role.

A thorough approach ensures accurate diagnosis and targeted prevention strategies.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New allergens responsible for contact dermatitis emerge regularly. During the Dermatology Days of Paris 2024 conference, Angèle Soria, MD, PhD, a dermatologist at Tenon Hospital in Paris, France, outlined four major categories driving this trend. Among them are (meth)acrylates found in nail cosmetics used in salons or do-it-yourself false nail kits that can be bought online.

Isothiazolinones

a preservative used in many cosmetics; (meth)acrylates; essential oils; and epoxy resins used in industry and leisure activities.

Around 15 years ago, parabens, commonly used as preservatives in cosmetics, were identified as endocrine disruptors. In response, they were largely replaced by newer preservatives, notably MI. However, this led to a proliferation of allergic contact dermatitis in Europe between 2010 and 2013.

“About 10% of the population that we tested showed allergies to these preservatives, primarily found in cosmetics,” explained Soria. Since 2015, the use of MI in leave-on cosmetics has been prohibited in Europe and its concentration restricted in rinse-off products. However, cosmetics sold online from outside Europe may not comply with these regulations.

MI is also present in water-based paints to prevent mold. “A few years ago, we started seeing patients with facial angioedema, sometimes combined with asthma, caused by these isothiazolinone preservatives, including in patients who are not professional painters,” said Soria. More recently, attention has shifted to MI’s presence in household cleaning products. A 2020 Spanish study found MI in 76% of 34 analyzed cleaning products.

MI-based fungicides are also used to treat leather during transport, which can lead to contact allergies among professionals and consumers alike. Additionally, MI has been identified in children’s toys, including slime gels, and in florists’ gel cubes used to preserve flowers.

“We are therefore surrounded by these preservatives, which are no longer only in cosmetics,” warned the dermatologist.

(Meth)acrylates

Another major allergen category is (meth)acrylates, responsible for many cases of allergic contact dermatitis. Acrylates and their derivatives are widely used in everyday items. They are low–molecular weight monomers, sensitizing on contact with the skin. Their polymerized forms include materials like Plexiglas.

“We are currently witnessing an epidemic of contact dermatitis in the general population, mainly due to nail cosmetics, such as semipermanent nail polishes and at-home false nail kits,” reported Soria. Nail cosmetics account for 97% of new sensitization cases involving (meth)acrylates. These allergens often cause severe dermatitis, prompting the European Union to mandate labeling in 2020, warning that these products are “for professional use only” and can “cause allergic reactions.”

Beyond nail cosmetics, these allergens are also found in dental products (such as trays), ECG electrodes, prosthetics, glucose sensors, surgical adhesives, and some electronic devices like earbuds and phone screens. Notably, patients sensitized to acrylates via nail kits may experience reactions during dental treatments involving acrylates.

Investigating Essential Oil Use

Essential oils, distinct from vegetable oils like almond or argan, are another known allergen. Often considered risk-free due to their “natural” label, these products are widely used topically, orally, or via inhalation for various purposes, such as treating respiratory infections or creating relaxing atmospheres. However, essential oils contain fragrant molecules like terpenes, which can become highly allergenic over time, especially after repeated exposure.

Soria emphasized the importance of asking patients about their use of essential oils, especially tea tree and lavender oils, which are commonly used but rarely mentioned by patients unless prompted.

Epoxy Resins in Recreational Use

Epoxy resins are a growing cause of contact allergies, not just in professional settings such as aeronautics and construction work but also increasingly in recreational activities. Soria highlighted the case of a 12-year-old girl hospitalized for severe facial edema after engaging in resin crafts inspired by TikTok. For 6 months, she had been creating resin objects, such as bowls and cutting boards, using vinyl gloves and a Filtering FacePiece 2 mask under adult supervision.

“The growing popularity and online availability of epoxy resins mean that allergic reactions should now be considered even in nonprofessional contexts,” warned Soria.

Clinical Approach

When dermatologists suspect allergic contact dermatitis, the first step is to treat the condition with corticosteroid creams. This is followed by a detailed patient interview to identify suspected allergens in products they’ve used.

Patch testing is then conducted to confirm the allergen. Small chambers containing potential allergens are applied to the upper back for 48 hours without removal. Results are read 2-5 days later, with some cases requiring a 7-day follow-up.

The patient’s occupation is an important factor, as certain professions, such as hairdressing, healthcare, or beauty therapy, are known to trigger allergic contact dermatitis. Similarly, certain hobbies may also play a role.

A thorough approach ensures accurate diagnosis and targeted prevention strategies.

This story was translated from Medscape’s French edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Ob.Gyn. Says Collaboration with Dermatologists Essential for Managing Vulvar Dermatoses

— and she believes collaboration with dermatologists is essential, especially for complex cases in what she calls a neglected, data-poor area of medicine.

She also recommends that dermatologists have a good understanding of the vestibule, “one of the most important structures in vulvar medicine,” and that they become equipped to recognize generalized and localized causes of vulvar pain and/or itch.

“The problem is, we don’t talk about [vulvovaginal pain and itch] ... it’s taboo and we’re not taught about it in medical school,” Cigna, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at The George Washington University (GWU), Washington, DC, said in a grand rounds lecture held recently at the GWU School of Medicine and Health Sciences Department of Dermatology.

“There are dermatologists who don’t have much training in vulvar dermatology, and a lot of gyns don’t get as much training” as they should, she said in an interview after the lecture. “So who’s looking at people’s vulvar skin and figuring out what’s going on and giving them effective treatments and evidence-based education?”

Cigna and dermatologist Emily Murphy, MD, will be co-directors of a joint ob.gyn-dermatology Vulvar Dermatology Clinic at GWU that will be launched in 2025, with monthly clinics for particularly challenging cases where the etiology is unclear or treatment is ineffective. “We want to collaborate in a more systematic way and put our heads together and think creatively about what will improve patient care,” Cigna said in the interview.

Dermatologists have valuable expertise in the immunology and genetic factors involved in skin disorders, Cigna said. Moreover, Murphy, assistant professor of dermatology and director of the Vulvar Health Program at GWU, said in an interview, dermatologists “are comfortable in going to off-label systemic medications that ob.gyns may not use that often” and bring to the table expertise in various types of procedures.

Murphy recently trained with Melissa Mauskar, MD, associate of dermatology and obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and founder and director of the Gynecologic Dermatology Clinic there. “It’s so important for dermatologists to be involved. It just takes some extra training that residents aren’t getting right now,” said Murphy, a member of the newly formed Vulvar Dermatoses Research Consortium.

In her grand rounds lecture, Cigna offered pearls to dermatologists for approaching a history and exam and covered highlights of the diagnosis and treatment of various problems, from vulvar Candida infections and lichen simplex chronicus to vulvar lichen sclerosus (LS), vulvar lichen planus (LP), vulvar Crohn’s disease, pudendal neuralgia, and pelvic floor muscle spasm, as well as the role of mast cell proliferation in vulvar issues.

Approaching the History and Exam

A comprehensive history covers the start, duration, and location of pain and/or itching as well as a detailed timeline (such as timing of potential causes, including injuries or births) and symptoms (such as burning, cutting, aching, and stinging). The question of whether pain “is on the outside, at the entrance, or deeper inside” is “crucial, especially for those in dermatology,” Cigna emphasized.

“And if you’re seeing a patient for a vulvar condition, please ask them about sex. Ask, is this affecting your sexual or intimate life with your partner because this can also give you a clue about what’s going on and how you can help them,” she told the audience of dermatologists.

Queries about trauma history (physical and emotional/verbal), competitive sports (such as daily cycling, equestrian, and heavy weight lifting), endometriosis/gynecologic surgery, connective tissue disorders (such as Ehler-Danlos syndrome), and irritable bowel syndrome are all potentially important to consider. It is important to ask about anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, which do not cause — but are highly associated with — vulvar dermatoses, she said.

A surprisingly large number of people with vulvovaginal issues are being diagnosed with Ehler-Danlos syndrome, so “I’m always asking, are you hypermobile because this might be affecting the musculoskeletal system, which might be affecting the pelvis,” Cigna said. “Anything that affects the pelvis can affect the vulva as well.”

The pelvic examination should be “offered” rather than assumed to be part of the exam, as part of a trauma-informed approach that is crucial for earning trust, she advised. “Just saying, ‘we’re going to talk, and then I can offer you an exam if you like’…patients like it. It helps them feel safer and more open.”

Many diagnoses are differentiated by eliciting pain on the anterior vs the posterior half of the vulvar vestibule — the part of the vulva that lies between the labia minora and is composed of nonkeratinized tissue with embryonic origins in the endoderm. “If you touch on the keratinized skin (of the vulva) and they don’t have pain, but on the vestibule they do have pain, and there is no pain inside the vagina, this suggests there is a vestibular problem,” said Cigna.

Pain/tenderness isolated to the posterior half of the vestibule suggests a muscular cause, and pain in both the posterior and anterior parts of the vestibule suggests a cause that is more systemic or diffuse, which could be a result of a hormonal issue such as one related to oral contraceptives or decreased testosterone, or a nerve-related process.

Cigna uses gentle swipes of a Q-tip moistened with water or gel to examine the vulva rather than a poke or touch, with the exception being the posterior vestibule, which overlies muscle insertion sites. “Make sure to get a baseline in remote areas such as the inner thigh, and always distinguish between ‘scratchy/sensitive’ sensations and pain,” she said, noting the value of having the patient hold a mirror on her inner thigh.

Causes of Vulvar Itch: Infectious and Noninfectious

With vulvar candidiasis, a common infectious cause of vulvar itch, “you have to ask if they’re also itching on the inside because if you treat them with a topical and you don’t treat the vaginal yeast infection that may be co-occurring, they’ll keep reseeding their vulvar skin,” Cigna said, “and it will never be fully treated.”

Candida albicans is the most common cause of vulvar or vulvovaginal candidiasis, and resistance to antifungals has been rising. Non-albicans Candida “tends to have even higher resistance rates,” she said. Ordering a sensitivity panel along with the culture is helpful, but “comprehensive vaginal biome” panels are generally not useful. “It’s hard to correlate the information clinically,” she said, “and there’s not always a lot of information about susceptibilities, which is what I really like to know.”

Cigna’s treatments for vaginal infections include miconazole, terconazole, and fluconazole (and occasionally, itraconazole or voriconazole — a “decision we don’t take lightly”). Vulvar treatments include nystatin ointment, clotrimazole cream, and miconazole cream. Often, optimal treatment involves addressing “both inside and out,” she said, noting the importance of also killing yeast in undergarment fabric.

“In my experience, Diflucan [oral fluconazole] doesn’t treat persistent vulvar cutaneous skin yeast well, so while I might try Diflucan, I typically use something topical as well,” she said. “And with vaginal yeast, we do use boric acid from time to time, especially for non-albicans species because it tends to be a little more effective.”

Noninfectious causes of vulvar itch include allergic, neuropathic, and muscular causes, as well as autoimmune dermatoses and mast cell activation syndrome. Well known in dermatology are acute contact dermatitis and lichen simplex chronicus — both characterized by induration, thickening, and a “puffy” erythematous appearance, and worsening of pruritus at night. What may be less appreciated is the long list of implicated allergens , including Always menstrual pads made of a plastic-containing “dry weave” material, Cigna said. There are at least several cotton-only, low-preservative feminine products available on the market, she noted.

Common Autoimmune Vulvar Dermatoses: LS and LP

Vulvar LS has traditionally been thought to affect mainly prepubertal and postmenopausal women, but the autoimmune condition is now known to affect more reproductive-age people with vulvas than previously appreciated, Cigna said.

And notably, in an observational web-based study of premenopausal women (aged 18-50 years) with biopsy-confirmed vulvar LS, the leading symptom was not itch but dyspareunia and tearing with intercourse. This means “we’re missing people,” said Cigna, an author of the study. “We think the reason we’re not seeing itch as commonly in this population is that itch is likely mediated by the low estrogen state of pre- and postmenopausal people.”

Vulvar LS also occurs in pregnancy, with symptoms that are either stable or decrease during pregnancy and increase in the postpartum period, as demonstrated in a recently published online survey.

Patients with vulvar LS can present with hypopigmentation, lichenification, and scarring and architectural changes, the latter of which can involve clitoral phimosis, labial resorption, and narrowing of the introitus. (The vaginal mucosa is unaffected.) The presentation can be subtle, especially in premenopausal women, and differentiation between LS, vitiligo, and yeast is sometimes necessary.

A timely biopsy-driven definitive diagnosis is important because vulvar LS increases the risk for cancer if it’s not adequately treated and because long-term steroid use can affect the accuracy of pathology reports. “We really care about keeping this disease in remission as much as possible,” Cigna said. Experts in the field recommend long-term maintenance therapy with a mid-ultra-potent steroid one to three times/week or an alternative. “I’ve just started using ruxolitinib cream, a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, and tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor,” she said.

With vulvar LP, based on current evidence, the risk for malignant transformation is low, but “it crosses into the vagina and can cause vaginal adhesions, so if you’re diagnosing someone with lichen planus, you need to make sure you’re talking with them about dilators, and if you’re not comfortable, send them to [gyn],” she said.

The use of vulvoscopy is important for one’s ability to see the fine Wickham’s striae that often characterize vulvar LP, she noted. Medical treatments for vulvar LP include topical calcineurin inhibitors, high-potency steroids, and JAK inhibitors.

Surgical treatment of vulvar granuloma fissuratum caused by vulvar LS is possible (when the patient is in complete remission, to prevent koebnerization), with daily post-op application of clobetasol and retraction of tissues, noted Cigna, the author of a study on vulvar lysis of adhesions.

With both LS and LP, Cigna said, “don’t forget (consideration of) hormones” as an adjunctive treatment, especially in postmenopausal women. “Patients in a low hormone state will have more flares.”

Vulvar Crohn’s

“We all have to know how to look for this,” Cigna said. “Unilateral or asymmetric swelling is classic, but don’t rule out the diagnosis if you see symmetric swelling.” Patients also typically have linear “knife-like” fissures or ulcerations, the vulva “is very indurated,” and “swelling is so intense, the patients are miserable,” she said.

Vulvar Crohn’s disease may precede intestinal disease in 20%-30% of patients, so referral to a gastroenterologist — and ideally subsequent collaboration — is important, as vulvar manifestations are treated with systemic medications typical for Crohn’s.

A biopsy is required for diagnosis, and the pathologist should be advised to look for lichenified squamous mucosa with the Touton giant cell reaction. “Vulvar Crohn’s is a rare enough disorder that if you don’t have an experienced or informed pathologist looking at your specimen, they may miss it because they won’t be looking for it,” Cigna added in the interview. “You should be really clear about what you’re looking for.”

Neuropathic Itch, Pelvic Floor Muscle Spasm

Patients with pudendal neuralgia — caused by an injured, entrapped, or irritated pudendal nerve (originating from S2-S4) — typically present with chronic vulvar and pelvic pain that is often unprovoked and worsens with sitting. Itching upon touch is often another symptom, and some patients describe a foreign body sensation. The cause is often trauma (such as an accident or childbirth-related) as opposed to myofascial irritation, Cigna explained in her lecture.

“Your exam will be largely normal, with no skin findings, so patients will get sent away if you don’t know to look for pudendal neuralgia by pressing on the pudendal nerve or doing (or referring for) a diagnostic nerve block,” Cigna added in the interview.

Persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD) is “more global” in that it can also originate not only from the pudendal nerve but also from nerve roots higher in the spine or even from the brain. “People feel a sense of arousal, but some describe it as an itch,” Cigna said in her lecture, referring to a 2021 consensus document on PGAD/genito-pelvic dysesthesia by the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health as a valuable resource for understanding and managing the condition.

Diagnosis and treatment usually start with a pudendal nerve block with a combination of steroid and anesthetic. If this does not relieve arousal/itching, the next step may be an MRI to look higher in the spine.

Pelvic Floor Muscle Spasm

Vulvar pain, skin itching, and irritation can be symptoms of pelvic floor muscle spasm. “Oftentimes people come to me and say, ‘I have a dermatologic problem,’” Cigna said. “The skin may look red and erythematous, but it’s probably more likely a muscle problem when you’re not finding anything, and no amount of steroid will help the itch go away when the problem lies underneath.”

Co-occurring symptoms can include vaginal dryness, clitoral pain, urethral discomfort, bladder pain/irritation, increased urgency, constipation, and anal fissures. The first-line treatment approach is pelvic floor therapy.

“Pelvic floor therapy is not just for incontinence. It’s also for pain and discomfort from muscles,” she said, noting that most patients with vulvar disorders are referred for pelvic floor therapy. “Almost all of them end up having pelvic floor dysfunction because the pelvic floor muscles spasm whenever there’s pain or inflammation.”

A Cautionary Word on Vulvodynia, and a Mast Cell Paradigm to Explore

Vulvodynia is defined as persistent pain of at least 3 months’ duration with no clear cause. “These are the patients with no skin findings,” Cigna said. But in most cases, she said, careful investigation identifies causes that are musculoskeletal, hormonal, or nerve-related.

“It’s a term that’s thrown around a lot — it’s kind of a catchall. Yet it should be a small minority of patients who truly have a diagnosis of vulvodynia,” she said.

In the early stages of investigation is the idea that mast cell proliferation and mast cell activation may play a role in some cases of vulvar and vestibular pain and itching. “We see that some patients with vulvodynia and vestibulodynia have mast cells that are increased in number in the epithelium and beneath the epithelium, and nerve staining shows an increased number of nerve endings traveling into the epithelium,” Cigna said.

“We do diagnose some people clinically” based on urticaria and other symptoms suggestive of mast cell proliferation/activation (such as flushing, abdominal cramping, diarrhea, hypotensive syncope or near syncope, and tachycardia), and “then we send them to the allergist for testing,” Cigna said.

Cigna and Murphy have no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

— and she believes collaboration with dermatologists is essential, especially for complex cases in what she calls a neglected, data-poor area of medicine.

She also recommends that dermatologists have a good understanding of the vestibule, “one of the most important structures in vulvar medicine,” and that they become equipped to recognize generalized and localized causes of vulvar pain and/or itch.

“The problem is, we don’t talk about [vulvovaginal pain and itch] ... it’s taboo and we’re not taught about it in medical school,” Cigna, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at The George Washington University (GWU), Washington, DC, said in a grand rounds lecture held recently at the GWU School of Medicine and Health Sciences Department of Dermatology.

“There are dermatologists who don’t have much training in vulvar dermatology, and a lot of gyns don’t get as much training” as they should, she said in an interview after the lecture. “So who’s looking at people’s vulvar skin and figuring out what’s going on and giving them effective treatments and evidence-based education?”

Cigna and dermatologist Emily Murphy, MD, will be co-directors of a joint ob.gyn-dermatology Vulvar Dermatology Clinic at GWU that will be launched in 2025, with monthly clinics for particularly challenging cases where the etiology is unclear or treatment is ineffective. “We want to collaborate in a more systematic way and put our heads together and think creatively about what will improve patient care,” Cigna said in the interview.

Dermatologists have valuable expertise in the immunology and genetic factors involved in skin disorders, Cigna said. Moreover, Murphy, assistant professor of dermatology and director of the Vulvar Health Program at GWU, said in an interview, dermatologists “are comfortable in going to off-label systemic medications that ob.gyns may not use that often” and bring to the table expertise in various types of procedures.

Murphy recently trained with Melissa Mauskar, MD, associate of dermatology and obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, and founder and director of the Gynecologic Dermatology Clinic there. “It’s so important for dermatologists to be involved. It just takes some extra training that residents aren’t getting right now,” said Murphy, a member of the newly formed Vulvar Dermatoses Research Consortium.

In her grand rounds lecture, Cigna offered pearls to dermatologists for approaching a history and exam and covered highlights of the diagnosis and treatment of various problems, from vulvar Candida infections and lichen simplex chronicus to vulvar lichen sclerosus (LS), vulvar lichen planus (LP), vulvar Crohn’s disease, pudendal neuralgia, and pelvic floor muscle spasm, as well as the role of mast cell proliferation in vulvar issues.

Approaching the History and Exam

A comprehensive history covers the start, duration, and location of pain and/or itching as well as a detailed timeline (such as timing of potential causes, including injuries or births) and symptoms (such as burning, cutting, aching, and stinging). The question of whether pain “is on the outside, at the entrance, or deeper inside” is “crucial, especially for those in dermatology,” Cigna emphasized.

“And if you’re seeing a patient for a vulvar condition, please ask them about sex. Ask, is this affecting your sexual or intimate life with your partner because this can also give you a clue about what’s going on and how you can help them,” she told the audience of dermatologists.

Queries about trauma history (physical and emotional/verbal), competitive sports (such as daily cycling, equestrian, and heavy weight lifting), endometriosis/gynecologic surgery, connective tissue disorders (such as Ehler-Danlos syndrome), and irritable bowel syndrome are all potentially important to consider. It is important to ask about anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, which do not cause — but are highly associated with — vulvar dermatoses, she said.

A surprisingly large number of people with vulvovaginal issues are being diagnosed with Ehler-Danlos syndrome, so “I’m always asking, are you hypermobile because this might be affecting the musculoskeletal system, which might be affecting the pelvis,” Cigna said. “Anything that affects the pelvis can affect the vulva as well.”

The pelvic examination should be “offered” rather than assumed to be part of the exam, as part of a trauma-informed approach that is crucial for earning trust, she advised. “Just saying, ‘we’re going to talk, and then I can offer you an exam if you like’…patients like it. It helps them feel safer and more open.”

Many diagnoses are differentiated by eliciting pain on the anterior vs the posterior half of the vulvar vestibule — the part of the vulva that lies between the labia minora and is composed of nonkeratinized tissue with embryonic origins in the endoderm. “If you touch on the keratinized skin (of the vulva) and they don’t have pain, but on the vestibule they do have pain, and there is no pain inside the vagina, this suggests there is a vestibular problem,” said Cigna.

Pain/tenderness isolated to the posterior half of the vestibule suggests a muscular cause, and pain in both the posterior and anterior parts of the vestibule suggests a cause that is more systemic or diffuse, which could be a result of a hormonal issue such as one related to oral contraceptives or decreased testosterone, or a nerve-related process.

Cigna uses gentle swipes of a Q-tip moistened with water or gel to examine the vulva rather than a poke or touch, with the exception being the posterior vestibule, which overlies muscle insertion sites. “Make sure to get a baseline in remote areas such as the inner thigh, and always distinguish between ‘scratchy/sensitive’ sensations and pain,” she said, noting the value of having the patient hold a mirror on her inner thigh.

Causes of Vulvar Itch: Infectious and Noninfectious

With vulvar candidiasis, a common infectious cause of vulvar itch, “you have to ask if they’re also itching on the inside because if you treat them with a topical and you don’t treat the vaginal yeast infection that may be co-occurring, they’ll keep reseeding their vulvar skin,” Cigna said, “and it will never be fully treated.”

Candida albicans is the most common cause of vulvar or vulvovaginal candidiasis, and resistance to antifungals has been rising. Non-albicans Candida “tends to have even higher resistance rates,” she said. Ordering a sensitivity panel along with the culture is helpful, but “comprehensive vaginal biome” panels are generally not useful. “It’s hard to correlate the information clinically,” she said, “and there’s not always a lot of information about susceptibilities, which is what I really like to know.”

Cigna’s treatments for vaginal infections include miconazole, terconazole, and fluconazole (and occasionally, itraconazole or voriconazole — a “decision we don’t take lightly”). Vulvar treatments include nystatin ointment, clotrimazole cream, and miconazole cream. Often, optimal treatment involves addressing “both inside and out,” she said, noting the importance of also killing yeast in undergarment fabric.

“In my experience, Diflucan [oral fluconazole] doesn’t treat persistent vulvar cutaneous skin yeast well, so while I might try Diflucan, I typically use something topical as well,” she said. “And with vaginal yeast, we do use boric acid from time to time, especially for non-albicans species because it tends to be a little more effective.”

Noninfectious causes of vulvar itch include allergic, neuropathic, and muscular causes, as well as autoimmune dermatoses and mast cell activation syndrome. Well known in dermatology are acute contact dermatitis and lichen simplex chronicus — both characterized by induration, thickening, and a “puffy” erythematous appearance, and worsening of pruritus at night. What may be less appreciated is the long list of implicated allergens , including Always menstrual pads made of a plastic-containing “dry weave” material, Cigna said. There are at least several cotton-only, low-preservative feminine products available on the market, she noted.

Common Autoimmune Vulvar Dermatoses: LS and LP

Vulvar LS has traditionally been thought to affect mainly prepubertal and postmenopausal women, but the autoimmune condition is now known to affect more reproductive-age people with vulvas than previously appreciated, Cigna said.

And notably, in an observational web-based study of premenopausal women (aged 18-50 years) with biopsy-confirmed vulvar LS, the leading symptom was not itch but dyspareunia and tearing with intercourse. This means “we’re missing people,” said Cigna, an author of the study. “We think the reason we’re not seeing itch as commonly in this population is that itch is likely mediated by the low estrogen state of pre- and postmenopausal people.”

Vulvar LS also occurs in pregnancy, with symptoms that are either stable or decrease during pregnancy and increase in the postpartum period, as demonstrated in a recently published online survey.

Patients with vulvar LS can present with hypopigmentation, lichenification, and scarring and architectural changes, the latter of which can involve clitoral phimosis, labial resorption, and narrowing of the introitus. (The vaginal mucosa is unaffected.) The presentation can be subtle, especially in premenopausal women, and differentiation between LS, vitiligo, and yeast is sometimes necessary.

A timely biopsy-driven definitive diagnosis is important because vulvar LS increases the risk for cancer if it’s not adequately treated and because long-term steroid use can affect the accuracy of pathology reports. “We really care about keeping this disease in remission as much as possible,” Cigna said. Experts in the field recommend long-term maintenance therapy with a mid-ultra-potent steroid one to three times/week or an alternative. “I’ve just started using ruxolitinib cream, a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, and tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor,” she said.

With vulvar LP, based on current evidence, the risk for malignant transformation is low, but “it crosses into the vagina and can cause vaginal adhesions, so if you’re diagnosing someone with lichen planus, you need to make sure you’re talking with them about dilators, and if you’re not comfortable, send them to [gyn],” she said.

The use of vulvoscopy is important for one’s ability to see the fine Wickham’s striae that often characterize vulvar LP, she noted. Medical treatments for vulvar LP include topical calcineurin inhibitors, high-potency steroids, and JAK inhibitors.

Surgical treatment of vulvar granuloma fissuratum caused by vulvar LS is possible (when the patient is in complete remission, to prevent koebnerization), with daily post-op application of clobetasol and retraction of tissues, noted Cigna, the author of a study on vulvar lysis of adhesions.

With both LS and LP, Cigna said, “don’t forget (consideration of) hormones” as an adjunctive treatment, especially in postmenopausal women. “Patients in a low hormone state will have more flares.”

Vulvar Crohn’s

“We all have to know how to look for this,” Cigna said. “Unilateral or asymmetric swelling is classic, but don’t rule out the diagnosis if you see symmetric swelling.” Patients also typically have linear “knife-like” fissures or ulcerations, the vulva “is very indurated,” and “swelling is so intense, the patients are miserable,” she said.

Vulvar Crohn’s disease may precede intestinal disease in 20%-30% of patients, so referral to a gastroenterologist — and ideally subsequent collaboration — is important, as vulvar manifestations are treated with systemic medications typical for Crohn’s.

A biopsy is required for diagnosis, and the pathologist should be advised to look for lichenified squamous mucosa with the Touton giant cell reaction. “Vulvar Crohn’s is a rare enough disorder that if you don’t have an experienced or informed pathologist looking at your specimen, they may miss it because they won’t be looking for it,” Cigna added in the interview. “You should be really clear about what you’re looking for.”

Neuropathic Itch, Pelvic Floor Muscle Spasm

Patients with pudendal neuralgia — caused by an injured, entrapped, or irritated pudendal nerve (originating from S2-S4) — typically present with chronic vulvar and pelvic pain that is often unprovoked and worsens with sitting. Itching upon touch is often another symptom, and some patients describe a foreign body sensation. The cause is often trauma (such as an accident or childbirth-related) as opposed to myofascial irritation, Cigna explained in her lecture.

“Your exam will be largely normal, with no skin findings, so patients will get sent away if you don’t know to look for pudendal neuralgia by pressing on the pudendal nerve or doing (or referring for) a diagnostic nerve block,” Cigna added in the interview.

Persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD) is “more global” in that it can also originate not only from the pudendal nerve but also from nerve roots higher in the spine or even from the brain. “People feel a sense of arousal, but some describe it as an itch,” Cigna said in her lecture, referring to a 2021 consensus document on PGAD/genito-pelvic dysesthesia by the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health as a valuable resource for understanding and managing the condition.

Diagnosis and treatment usually start with a pudendal nerve block with a combination of steroid and anesthetic. If this does not relieve arousal/itching, the next step may be an MRI to look higher in the spine.

Pelvic Floor Muscle Spasm

Vulvar pain, skin itching, and irritation can be symptoms of pelvic floor muscle spasm. “Oftentimes people come to me and say, ‘I have a dermatologic problem,’” Cigna said. “The skin may look red and erythematous, but it’s probably more likely a muscle problem when you’re not finding anything, and no amount of steroid will help the itch go away when the problem lies underneath.”

Co-occurring symptoms can include vaginal dryness, clitoral pain, urethral discomfort, bladder pain/irritation, increased urgency, constipation, and anal fissures. The first-line treatment approach is pelvic floor therapy.

“Pelvic floor therapy is not just for incontinence. It’s also for pain and discomfort from muscles,” she said, noting that most patients with vulvar disorders are referred for pelvic floor therapy. “Almost all of them end up having pelvic floor dysfunction because the pelvic floor muscles spasm whenever there’s pain or inflammation.”

A Cautionary Word on Vulvodynia, and a Mast Cell Paradigm to Explore

Vulvodynia is defined as persistent pain of at least 3 months’ duration with no clear cause. “These are the patients with no skin findings,” Cigna said. But in most cases, she said, careful investigation identifies causes that are musculoskeletal, hormonal, or nerve-related.

“It’s a term that’s thrown around a lot — it’s kind of a catchall. Yet it should be a small minority of patients who truly have a diagnosis of vulvodynia,” she said.

In the early stages of investigation is the idea that mast cell proliferation and mast cell activation may play a role in some cases of vulvar and vestibular pain and itching. “We see that some patients with vulvodynia and vestibulodynia have mast cells that are increased in number in the epithelium and beneath the epithelium, and nerve staining shows an increased number of nerve endings traveling into the epithelium,” Cigna said.

“We do diagnose some people clinically” based on urticaria and other symptoms suggestive of mast cell proliferation/activation (such as flushing, abdominal cramping, diarrhea, hypotensive syncope or near syncope, and tachycardia), and “then we send them to the allergist for testing,” Cigna said.

Cigna and Murphy have no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

— and she believes collaboration with dermatologists is essential, especially for complex cases in what she calls a neglected, data-poor area of medicine.

She also recommends that dermatologists have a good understanding of the vestibule, “one of the most important structures in vulvar medicine,” and that they become equipped to recognize generalized and localized causes of vulvar pain and/or itch.

“The problem is, we don’t talk about [vulvovaginal pain and itch] ... it’s taboo and we’re not taught about it in medical school,” Cigna, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at The George Washington University (GWU), Washington, DC, said in a grand rounds lecture held recently at the GWU School of Medicine and Health Sciences Department of Dermatology.

“There are dermatologists who don’t have much training in vulvar dermatology, and a lot of gyns don’t get as much training” as they should, she said in an interview after the lecture. “So who’s looking at people’s vulvar skin and figuring out what’s going on and giving them effective treatments and evidence-based education?”

Cigna and dermatologist Emily Murphy, MD, will be co-directors of a joint ob.gyn-dermatology Vulvar Dermatology Clinic at GWU that will be launched in 2025, with monthly clinics for particularly challenging cases where the etiology is unclear or treatment is ineffective. “We want to collaborate in a more systematic way and put our heads together and think creatively about what will improve patient care,” Cigna said in the interview.