User login

Differences in right vs. left colon in Black vs. White individuals

The right colon appears to age faster in Black people than in White people, perhaps explaining the higher prevalence of right-side colon cancer among Black Americans, according to results from a biopsy study.

The findings were published online Dec. 30 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

For the study, investigators analyzed colon biopsy specimens from 128 individuals who underwent routine colorectal screening.

The researchers compared DNA methylation levels in right and left colon biopsy samples from the same patient. They then assigned epigenetic ages to the tissue samples using the Hovarth clock, which estimates tissue age on the basis of DNA methylation.

DNA methylation is influenced by age and environmental exposures. Aberrant DNA methylation is a hallmark of colorectal cancer, the researchers explained.

The epigenetic age of the right colon of the 88 Black patients was 1.51 years ahead of their left colon; the right colon of the 44 White patients was epigenetically 1.93 years younger than their left colon.

The right colon was epigenetically older than the left colon in 60.2% of Black patients; it was younger in more than 70% of White patients.

A unique pattern of DNA hypermethylation was found in the right colon of Black patients.

“Our results provide biological plausibility for the observed relative preponderance of right colon cancer and younger age of onset in African Americans as compared to European Americans,” wrote the investigators, led by Matthew Devall, PhD, a research associate at the Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“Side-specific colonic epigenetic aging may be a promising marker to guide interventions to reduce CRC [colorectal cancer] burden,” they suggested.

If these findings are “corroborated in African Americans in future studies, these results could potentially explain racial differences in the site predilection of colorectal cancers,” Amit Joshi, MBBS, PhD, and Andrew Chan, MD, gastrointestinal molecular epidemiologists at Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

However, “it is not clear if the higher epigenetic aging measured using the Horvath clock ... directly translates to a higher risk of colorectal cancer,” they noted.

Some differences between the Black patients and the White patients in the study could explain the methylation differences, they pointed out. A higher proportion of Black patients smoked (37.5% vs. 15%), and Black patients were younger (median age, 55.5 years, vs. 61.7 years). In addition, the study included more Black women than White women (67% vs. 58%), and body mass indexes were higher for Black patients than White patients (31.36 kg/m2 vs 28.29 kg/m2).

“One or more of these factors, or others that were not measured, may be linked to differential methylation in the right compared with left colon,” the editorialists wrote.

Even so, among the Black patients, almost 70% of differentially methylated positions in the right colon were hypermethylated, compared to less than half in the left colon. These included positions previously associated with colorectal cancer, aging, and ancestry, “suggesting a role for genetic variation in contributing to DNA methylation differences in AA right colon,” the investigators said.

The work was supported the National Cancer Institute Cancer, the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the University of Virginia Cancer Center. The authors and editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The right colon appears to age faster in Black people than in White people, perhaps explaining the higher prevalence of right-side colon cancer among Black Americans, according to results from a biopsy study.

The findings were published online Dec. 30 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

For the study, investigators analyzed colon biopsy specimens from 128 individuals who underwent routine colorectal screening.

The researchers compared DNA methylation levels in right and left colon biopsy samples from the same patient. They then assigned epigenetic ages to the tissue samples using the Hovarth clock, which estimates tissue age on the basis of DNA methylation.

DNA methylation is influenced by age and environmental exposures. Aberrant DNA methylation is a hallmark of colorectal cancer, the researchers explained.

The epigenetic age of the right colon of the 88 Black patients was 1.51 years ahead of their left colon; the right colon of the 44 White patients was epigenetically 1.93 years younger than their left colon.

The right colon was epigenetically older than the left colon in 60.2% of Black patients; it was younger in more than 70% of White patients.

A unique pattern of DNA hypermethylation was found in the right colon of Black patients.

“Our results provide biological plausibility for the observed relative preponderance of right colon cancer and younger age of onset in African Americans as compared to European Americans,” wrote the investigators, led by Matthew Devall, PhD, a research associate at the Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“Side-specific colonic epigenetic aging may be a promising marker to guide interventions to reduce CRC [colorectal cancer] burden,” they suggested.

If these findings are “corroborated in African Americans in future studies, these results could potentially explain racial differences in the site predilection of colorectal cancers,” Amit Joshi, MBBS, PhD, and Andrew Chan, MD, gastrointestinal molecular epidemiologists at Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

However, “it is not clear if the higher epigenetic aging measured using the Horvath clock ... directly translates to a higher risk of colorectal cancer,” they noted.

Some differences between the Black patients and the White patients in the study could explain the methylation differences, they pointed out. A higher proportion of Black patients smoked (37.5% vs. 15%), and Black patients were younger (median age, 55.5 years, vs. 61.7 years). In addition, the study included more Black women than White women (67% vs. 58%), and body mass indexes were higher for Black patients than White patients (31.36 kg/m2 vs 28.29 kg/m2).

“One or more of these factors, or others that were not measured, may be linked to differential methylation in the right compared with left colon,” the editorialists wrote.

Even so, among the Black patients, almost 70% of differentially methylated positions in the right colon were hypermethylated, compared to less than half in the left colon. These included positions previously associated with colorectal cancer, aging, and ancestry, “suggesting a role for genetic variation in contributing to DNA methylation differences in AA right colon,” the investigators said.

The work was supported the National Cancer Institute Cancer, the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the University of Virginia Cancer Center. The authors and editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The right colon appears to age faster in Black people than in White people, perhaps explaining the higher prevalence of right-side colon cancer among Black Americans, according to results from a biopsy study.

The findings were published online Dec. 30 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

For the study, investigators analyzed colon biopsy specimens from 128 individuals who underwent routine colorectal screening.

The researchers compared DNA methylation levels in right and left colon biopsy samples from the same patient. They then assigned epigenetic ages to the tissue samples using the Hovarth clock, which estimates tissue age on the basis of DNA methylation.

DNA methylation is influenced by age and environmental exposures. Aberrant DNA methylation is a hallmark of colorectal cancer, the researchers explained.

The epigenetic age of the right colon of the 88 Black patients was 1.51 years ahead of their left colon; the right colon of the 44 White patients was epigenetically 1.93 years younger than their left colon.

The right colon was epigenetically older than the left colon in 60.2% of Black patients; it was younger in more than 70% of White patients.

A unique pattern of DNA hypermethylation was found in the right colon of Black patients.

“Our results provide biological plausibility for the observed relative preponderance of right colon cancer and younger age of onset in African Americans as compared to European Americans,” wrote the investigators, led by Matthew Devall, PhD, a research associate at the Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“Side-specific colonic epigenetic aging may be a promising marker to guide interventions to reduce CRC [colorectal cancer] burden,” they suggested.

If these findings are “corroborated in African Americans in future studies, these results could potentially explain racial differences in the site predilection of colorectal cancers,” Amit Joshi, MBBS, PhD, and Andrew Chan, MD, gastrointestinal molecular epidemiologists at Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

However, “it is not clear if the higher epigenetic aging measured using the Horvath clock ... directly translates to a higher risk of colorectal cancer,” they noted.

Some differences between the Black patients and the White patients in the study could explain the methylation differences, they pointed out. A higher proportion of Black patients smoked (37.5% vs. 15%), and Black patients were younger (median age, 55.5 years, vs. 61.7 years). In addition, the study included more Black women than White women (67% vs. 58%), and body mass indexes were higher for Black patients than White patients (31.36 kg/m2 vs 28.29 kg/m2).

“One or more of these factors, or others that were not measured, may be linked to differential methylation in the right compared with left colon,” the editorialists wrote.

Even so, among the Black patients, almost 70% of differentially methylated positions in the right colon were hypermethylated, compared to less than half in the left colon. These included positions previously associated with colorectal cancer, aging, and ancestry, “suggesting a role for genetic variation in contributing to DNA methylation differences in AA right colon,” the investigators said.

The work was supported the National Cancer Institute Cancer, the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the University of Virginia Cancer Center. The authors and editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Left Ventricular Compression and Hypotension Due to Acute Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is a postsurgical dilatation of the colon that presents with abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea and may lead to colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

A cute colonic pseudo-obstruction, or Ogilvie syndrome, is dilatation of the colon without mechanical obstruction. It is often seen postoperatively after cesarean section , pelvic , spinal, or other orthopedic surgery, such as knee arthroplasty. 1 One study demonstrated an incidence of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction of 1.3% following hip replacement surgery. 2

The most common symptoms are abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. Bowel sounds are present in the majority of cases.3 It is important to recognize the varied presentations of ileus in the postoperative setting. The most serious complications of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction are colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old man underwent a total left hip arthroplasty revision. The evening after his surgery, his blood pressure (BP) decreased from 93/54 to 71/47 mm Hg, and his heart rate was 73 beats per minute. He was awake, in no acute distress, but reported loose stools. Results of cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, showing a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs and clear lungs. There was normal jugular venous pressure and chronic pitting edema of the lower extremities bilaterally.

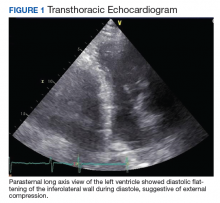

An abdominal examination revealed positive bowel sounds, a large ventral hernia, which was easily reducible, and a distended abdomen. His BP remained unchanged after IV normal saline 4 L, and urine output was 200 cc over 4 hours, which the care team determined represented adequate resuscitation. An infection workup, including chest X-ray, urinalysis, and blood and urine cultures, was unrevealing. Hemoglobin was stable at 8.5 g/dL (normal range 14-18), and creatinine level 0.66 mg/dL (normal range 0.7-1.2) at baseline. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed impaired diastolic filling suggestive of extrinsic compression of the left ventricle by mediastinal contents (Figure 1). An abdominal X-ray revealed diffuse dilatation of large bowel loops up to 10 cm, causing elevation and rightward shift of the heart (Figure 2A). A computed tomography scan of the abdomen showed total colonic dilatation without obstruction (Figure 2B).

The patient was diagnosed with postoperative ileus and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Nasogastric and rectal tubes were placed for decompression, and the patient was placed on nothing by mouth status. By postoperative day 3, his hypotension had resolved and his BP had improved to 111/58 mm Hg. The patient was able to resume a regular diet.

Discussion

We present an unusual case of left ventricular compression leading to hypotension due to acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Our patient presented with the rare complication of hypotension due to cardiac compression, which we have not previously seen reported in the literature. Analogous instance of cardiac compression may arise from hiatal hernias and diaphragmatic paralysis. 4-6

Management of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is through nothing by mouth status and abdominal decompression. For more severe cases, neostigmine, colonoscopic decompression, and surgery can be considered.

This surgical complication was diagnosed by internal medicine hospitalist consultants on a surgical comanagement service. In the comanagement model, the surgical specialties of orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, and podiatry at San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center in California have hospitalists who work with the team as active consultants for the medical care of the patients. Hospitalists develop a unique skill set in which they can anticipate new diagnoses, prevent or identify early complications, and individualize a patient’s postoperative care.7 One study found that a surgical comanagement service was associated with a decrease in the number of patients with at least 1 surgical complication, decrease in length of stay and 30-day readmissions for a medical cause, decreased consultant use, and an average cost savings per patient of about $2,600 to $4,300.8

Conclusions

With the increasing prevalence of hospitalist comanagement services, it is important for surgeons and nonsurgeons alike to recognize acute colonic pseudo-obstruction as a possible surgical complication.

1. Bernardi M, Warrier S, Lynch C, Heriot A. Acute and chronic pseudo-obstruction: a current update. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(10):709-714. doi:10.1111/ans.13148

2. Norwood MGA, Lykostratis H, Garcea G, Berry DP. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction following major orthopaedic surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7(5):496-499. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00790.x

3. Vanek VW, Al-Salti M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome). An analysis of 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29(3):203-210. doi:10.1007/BF02555027

4. Devabhandari MP, Khan MA, Hooper TL. Cardiac compression following cardiac surgery due to unrecognised hiatus hernia. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2007;32(5):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.08.002

5. Asti E, Bonavina L, Lombardi M, Bandera F, Secchi F, Guazzi M. Reversibility of cardiopulmonary impairment after laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:33-35. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.005

6. Tayyareci Y, Bayazit P, Taştan CP, Aksoy H. Right atrial compression due to idiopathic right diaphragm paralysis detected incidentally by transthoracic echocardiography. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2008;36(6):412-414.

7. Rohatgi N, Schulman K, Ahuja N. Comanagement by hospitalists: why it makes clinical and fiscal sense. Am J Med. 2020;133(3):257-258. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.07.053

8. Rohatgi N, Loftus P, Grujic O, Cullen M, Hopkins J, Ahuja N. Surgical comanagement by hospitalists improves patient outcomes: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):275-282. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001629

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is a postsurgical dilatation of the colon that presents with abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea and may lead to colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is a postsurgical dilatation of the colon that presents with abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea and may lead to colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

A cute colonic pseudo-obstruction, or Ogilvie syndrome, is dilatation of the colon without mechanical obstruction. It is often seen postoperatively after cesarean section , pelvic , spinal, or other orthopedic surgery, such as knee arthroplasty. 1 One study demonstrated an incidence of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction of 1.3% following hip replacement surgery. 2

The most common symptoms are abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. Bowel sounds are present in the majority of cases.3 It is important to recognize the varied presentations of ileus in the postoperative setting. The most serious complications of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction are colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old man underwent a total left hip arthroplasty revision. The evening after his surgery, his blood pressure (BP) decreased from 93/54 to 71/47 mm Hg, and his heart rate was 73 beats per minute. He was awake, in no acute distress, but reported loose stools. Results of cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, showing a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs and clear lungs. There was normal jugular venous pressure and chronic pitting edema of the lower extremities bilaterally.

An abdominal examination revealed positive bowel sounds, a large ventral hernia, which was easily reducible, and a distended abdomen. His BP remained unchanged after IV normal saline 4 L, and urine output was 200 cc over 4 hours, which the care team determined represented adequate resuscitation. An infection workup, including chest X-ray, urinalysis, and blood and urine cultures, was unrevealing. Hemoglobin was stable at 8.5 g/dL (normal range 14-18), and creatinine level 0.66 mg/dL (normal range 0.7-1.2) at baseline. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed impaired diastolic filling suggestive of extrinsic compression of the left ventricle by mediastinal contents (Figure 1). An abdominal X-ray revealed diffuse dilatation of large bowel loops up to 10 cm, causing elevation and rightward shift of the heart (Figure 2A). A computed tomography scan of the abdomen showed total colonic dilatation without obstruction (Figure 2B).

The patient was diagnosed with postoperative ileus and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Nasogastric and rectal tubes were placed for decompression, and the patient was placed on nothing by mouth status. By postoperative day 3, his hypotension had resolved and his BP had improved to 111/58 mm Hg. The patient was able to resume a regular diet.

Discussion

We present an unusual case of left ventricular compression leading to hypotension due to acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Our patient presented with the rare complication of hypotension due to cardiac compression, which we have not previously seen reported in the literature. Analogous instance of cardiac compression may arise from hiatal hernias and diaphragmatic paralysis. 4-6

Management of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is through nothing by mouth status and abdominal decompression. For more severe cases, neostigmine, colonoscopic decompression, and surgery can be considered.

This surgical complication was diagnosed by internal medicine hospitalist consultants on a surgical comanagement service. In the comanagement model, the surgical specialties of orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, and podiatry at San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center in California have hospitalists who work with the team as active consultants for the medical care of the patients. Hospitalists develop a unique skill set in which they can anticipate new diagnoses, prevent or identify early complications, and individualize a patient’s postoperative care.7 One study found that a surgical comanagement service was associated with a decrease in the number of patients with at least 1 surgical complication, decrease in length of stay and 30-day readmissions for a medical cause, decreased consultant use, and an average cost savings per patient of about $2,600 to $4,300.8

Conclusions

With the increasing prevalence of hospitalist comanagement services, it is important for surgeons and nonsurgeons alike to recognize acute colonic pseudo-obstruction as a possible surgical complication.

A cute colonic pseudo-obstruction, or Ogilvie syndrome, is dilatation of the colon without mechanical obstruction. It is often seen postoperatively after cesarean section , pelvic , spinal, or other orthopedic surgery, such as knee arthroplasty. 1 One study demonstrated an incidence of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction of 1.3% following hip replacement surgery. 2

The most common symptoms are abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. Bowel sounds are present in the majority of cases.3 It is important to recognize the varied presentations of ileus in the postoperative setting. The most serious complications of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction are colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old man underwent a total left hip arthroplasty revision. The evening after his surgery, his blood pressure (BP) decreased from 93/54 to 71/47 mm Hg, and his heart rate was 73 beats per minute. He was awake, in no acute distress, but reported loose stools. Results of cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, showing a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs and clear lungs. There was normal jugular venous pressure and chronic pitting edema of the lower extremities bilaterally.

An abdominal examination revealed positive bowel sounds, a large ventral hernia, which was easily reducible, and a distended abdomen. His BP remained unchanged after IV normal saline 4 L, and urine output was 200 cc over 4 hours, which the care team determined represented adequate resuscitation. An infection workup, including chest X-ray, urinalysis, and blood and urine cultures, was unrevealing. Hemoglobin was stable at 8.5 g/dL (normal range 14-18), and creatinine level 0.66 mg/dL (normal range 0.7-1.2) at baseline. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed impaired diastolic filling suggestive of extrinsic compression of the left ventricle by mediastinal contents (Figure 1). An abdominal X-ray revealed diffuse dilatation of large bowel loops up to 10 cm, causing elevation and rightward shift of the heart (Figure 2A). A computed tomography scan of the abdomen showed total colonic dilatation without obstruction (Figure 2B).

The patient was diagnosed with postoperative ileus and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Nasogastric and rectal tubes were placed for decompression, and the patient was placed on nothing by mouth status. By postoperative day 3, his hypotension had resolved and his BP had improved to 111/58 mm Hg. The patient was able to resume a regular diet.

Discussion

We present an unusual case of left ventricular compression leading to hypotension due to acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Our patient presented with the rare complication of hypotension due to cardiac compression, which we have not previously seen reported in the literature. Analogous instance of cardiac compression may arise from hiatal hernias and diaphragmatic paralysis. 4-6

Management of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is through nothing by mouth status and abdominal decompression. For more severe cases, neostigmine, colonoscopic decompression, and surgery can be considered.

This surgical complication was diagnosed by internal medicine hospitalist consultants on a surgical comanagement service. In the comanagement model, the surgical specialties of orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, and podiatry at San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center in California have hospitalists who work with the team as active consultants for the medical care of the patients. Hospitalists develop a unique skill set in which they can anticipate new diagnoses, prevent or identify early complications, and individualize a patient’s postoperative care.7 One study found that a surgical comanagement service was associated with a decrease in the number of patients with at least 1 surgical complication, decrease in length of stay and 30-day readmissions for a medical cause, decreased consultant use, and an average cost savings per patient of about $2,600 to $4,300.8

Conclusions

With the increasing prevalence of hospitalist comanagement services, it is important for surgeons and nonsurgeons alike to recognize acute colonic pseudo-obstruction as a possible surgical complication.

1. Bernardi M, Warrier S, Lynch C, Heriot A. Acute and chronic pseudo-obstruction: a current update. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(10):709-714. doi:10.1111/ans.13148

2. Norwood MGA, Lykostratis H, Garcea G, Berry DP. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction following major orthopaedic surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7(5):496-499. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00790.x

3. Vanek VW, Al-Salti M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome). An analysis of 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29(3):203-210. doi:10.1007/BF02555027

4. Devabhandari MP, Khan MA, Hooper TL. Cardiac compression following cardiac surgery due to unrecognised hiatus hernia. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2007;32(5):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.08.002

5. Asti E, Bonavina L, Lombardi M, Bandera F, Secchi F, Guazzi M. Reversibility of cardiopulmonary impairment after laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:33-35. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.005

6. Tayyareci Y, Bayazit P, Taştan CP, Aksoy H. Right atrial compression due to idiopathic right diaphragm paralysis detected incidentally by transthoracic echocardiography. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2008;36(6):412-414.

7. Rohatgi N, Schulman K, Ahuja N. Comanagement by hospitalists: why it makes clinical and fiscal sense. Am J Med. 2020;133(3):257-258. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.07.053

8. Rohatgi N, Loftus P, Grujic O, Cullen M, Hopkins J, Ahuja N. Surgical comanagement by hospitalists improves patient outcomes: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):275-282. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001629

1. Bernardi M, Warrier S, Lynch C, Heriot A. Acute and chronic pseudo-obstruction: a current update. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(10):709-714. doi:10.1111/ans.13148

2. Norwood MGA, Lykostratis H, Garcea G, Berry DP. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction following major orthopaedic surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7(5):496-499. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00790.x

3. Vanek VW, Al-Salti M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome). An analysis of 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29(3):203-210. doi:10.1007/BF02555027

4. Devabhandari MP, Khan MA, Hooper TL. Cardiac compression following cardiac surgery due to unrecognised hiatus hernia. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2007;32(5):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.08.002

5. Asti E, Bonavina L, Lombardi M, Bandera F, Secchi F, Guazzi M. Reversibility of cardiopulmonary impairment after laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:33-35. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.005

6. Tayyareci Y, Bayazit P, Taştan CP, Aksoy H. Right atrial compression due to idiopathic right diaphragm paralysis detected incidentally by transthoracic echocardiography. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2008;36(6):412-414.

7. Rohatgi N, Schulman K, Ahuja N. Comanagement by hospitalists: why it makes clinical and fiscal sense. Am J Med. 2020;133(3):257-258. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.07.053

8. Rohatgi N, Loftus P, Grujic O, Cullen M, Hopkins J, Ahuja N. Surgical comanagement by hospitalists improves patient outcomes: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):275-282. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001629

Surgery may not be needed with locally advanced rectal cancer

A short course of radiation therapy followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy resulted in a clinical complete response (CR) in almost half of 90 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer, allowing the majority of responders to skip surgical resection, a retrospective study indicates.

Specifically, at a median follow-up of 16.6 months for living patients, the initial clinical CR rate was 48% overall.

“While we do not have enough follow-up yet to know the late side-effect profile of this regimen, our preliminary results are promising,” Re-I Chin, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, told Medscape Medical News in an email.

The study was presented at the virtual 2020 meeting of the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO).

“Certainly, longer follow-up will be needed in this study, but none of the observed patients to date has experienced an unsalvageable failure,” said meeting discussant Amol Narang, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

He reminded conference attendees that, despite good evidence supporting equivalency in oncologic outcomes between short-course radiation and long-course chemoradiation, the former is “highly underutilized in the US” with a mere 1% usage rate between 2004 and 2014.

The current study’s short-course treatment approach was compared in this setting to long-course chemoradiation and adjuvant chemotherapy in the RAPIDO trial reported at the 2020 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), Narang pointed out.

Short-course patients had a higher rate of pathological complete response (pCR) and a lower rate of treatment failure compared with patients who received long-course chemoradiation and adjuvant chemotherapy; both patient groups underwent total mesorectal excision — which is different from the current analysis. The RAPIDO investigators concluded that the approach featuring the short course “can be considered as a new standard of care.”

Narang said the data collectively “begs the question as to whether the superiority of long-course chemoradiation should really have to be demonstrated to justify its use.”

But Chin highlighted toxicity issues. “Historically, there have been concerns regarding toxicity with short-course radiation therapy since it requires larger doses of radiation given over a shorter period of time,” Chin explained. “But [the short course] is particularly convenient for patients since it saves them more than a month of daily trips to the radiation oncology department.”

Seven local failures

The single-center study involved patients with newly diagnosed, nonmetastatic rectal adenocarcinoma treated with short-course radiation therapy followed by chemotherapy in 2018 and 2019. Nearly all (96%) had locally advanced disease, with either a T3/T4 tumor or node-positive disease. Median tumor size was 4.6 cm.

“Many of the patients in the study had low lying tumors,” Chin reported, with a median distance from the anal verge of 7 cm.

Radiation therapy was delivered in 25 Gy given in five fractions over 5 consecutive days, with the option to boost the dose to 30 Gy or 35 Gy in five fractions if extra-mesorectal lymph nodes were involved. Conventional 3D or intensity-modulated radiation was used and all patients completed treatment.

The median interval between diagnosis of rectal cancer and initiation of radiation therapy was 1.4 months, while the median interval between completion of radiation to initiation of chemotherapy was 2.7 weeks.

The most common chemotherapy regimen was FOLFOX – consisting of leucovorin, fluorouracil (5-FU), and oxaliplatin – or modified FOLFOX. For patients who received six or more cycles of chemotherapy, the median time spent on treatment was 3.9 months.

For those who completed at least six cycles of chemotherapy, the overall clinical CR was 51%, and, for patients with locally advanced disease, the clinical CR rate was 49%. Five of the 43 patients who achieved an initial clinical CR still underwent surgical resection because of patient or physician preference. Among this small group of patients, 4 of the 5 achieved a pCR, and the remaining patient achieved a pathological partial response (pPR).

A total of 42 patients (47% of the group) achieved a partial response following the radiation plus chemotherapy paradigm, and one patient had progressive disease. All underwent surgical resection. One patient did not complete chemotherapy and did not get surgery and subsequently died.

This left 38 patients to be managed nonoperatively. In this nonoperative cohort, 79% of patients continued to have a clinical CR at the end of follow-up. Of the 7 patients with local failure, 6 were salvaged by surgery, one was salvaged by chemotherapy, and all 7 treatment failures had no evidence of disease at last follow-up.

Of the small group of 5 patients who achieved an initial clinical CR following short-course radiation therapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, there were no further events in this group, whereas, for patients who achieved only an initial partial response or who had progressive disease, 72% remained event-free.

Approximately half of those who achieved a clinical CR to the treatment regimen had no late gastrointestinal toxicities, and no grade 3 or 4 toxicities were observed. “Surgical resection of tumors — even without a permanent stoma — can result in significantly decreased bowel function, so our goal is to treat patients without surgery and maintain good bowel function,” Chin noted.

“For rectal cancer, both short-course radiation therapy and nonoperative management are emerging treatment paradigms that may be more cost-effective and convenient compared to long-course chemoradiation followed by surgery, [especially since] the COVID-19 pandemic...has spurred changes in clinical practices in radiation oncology,” she said.

Chin has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Narang reports receiving research support from Boston Scientific.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A short course of radiation therapy followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy resulted in a clinical complete response (CR) in almost half of 90 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer, allowing the majority of responders to skip surgical resection, a retrospective study indicates.

Specifically, at a median follow-up of 16.6 months for living patients, the initial clinical CR rate was 48% overall.

“While we do not have enough follow-up yet to know the late side-effect profile of this regimen, our preliminary results are promising,” Re-I Chin, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, told Medscape Medical News in an email.

The study was presented at the virtual 2020 meeting of the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO).

“Certainly, longer follow-up will be needed in this study, but none of the observed patients to date has experienced an unsalvageable failure,” said meeting discussant Amol Narang, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

He reminded conference attendees that, despite good evidence supporting equivalency in oncologic outcomes between short-course radiation and long-course chemoradiation, the former is “highly underutilized in the US” with a mere 1% usage rate between 2004 and 2014.

The current study’s short-course treatment approach was compared in this setting to long-course chemoradiation and adjuvant chemotherapy in the RAPIDO trial reported at the 2020 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), Narang pointed out.

Short-course patients had a higher rate of pathological complete response (pCR) and a lower rate of treatment failure compared with patients who received long-course chemoradiation and adjuvant chemotherapy; both patient groups underwent total mesorectal excision — which is different from the current analysis. The RAPIDO investigators concluded that the approach featuring the short course “can be considered as a new standard of care.”

Narang said the data collectively “begs the question as to whether the superiority of long-course chemoradiation should really have to be demonstrated to justify its use.”

But Chin highlighted toxicity issues. “Historically, there have been concerns regarding toxicity with short-course radiation therapy since it requires larger doses of radiation given over a shorter period of time,” Chin explained. “But [the short course] is particularly convenient for patients since it saves them more than a month of daily trips to the radiation oncology department.”

Seven local failures

The single-center study involved patients with newly diagnosed, nonmetastatic rectal adenocarcinoma treated with short-course radiation therapy followed by chemotherapy in 2018 and 2019. Nearly all (96%) had locally advanced disease, with either a T3/T4 tumor or node-positive disease. Median tumor size was 4.6 cm.

“Many of the patients in the study had low lying tumors,” Chin reported, with a median distance from the anal verge of 7 cm.

Radiation therapy was delivered in 25 Gy given in five fractions over 5 consecutive days, with the option to boost the dose to 30 Gy or 35 Gy in five fractions if extra-mesorectal lymph nodes were involved. Conventional 3D or intensity-modulated radiation was used and all patients completed treatment.

The median interval between diagnosis of rectal cancer and initiation of radiation therapy was 1.4 months, while the median interval between completion of radiation to initiation of chemotherapy was 2.7 weeks.

The most common chemotherapy regimen was FOLFOX – consisting of leucovorin, fluorouracil (5-FU), and oxaliplatin – or modified FOLFOX. For patients who received six or more cycles of chemotherapy, the median time spent on treatment was 3.9 months.

For those who completed at least six cycles of chemotherapy, the overall clinical CR was 51%, and, for patients with locally advanced disease, the clinical CR rate was 49%. Five of the 43 patients who achieved an initial clinical CR still underwent surgical resection because of patient or physician preference. Among this small group of patients, 4 of the 5 achieved a pCR, and the remaining patient achieved a pathological partial response (pPR).

A total of 42 patients (47% of the group) achieved a partial response following the radiation plus chemotherapy paradigm, and one patient had progressive disease. All underwent surgical resection. One patient did not complete chemotherapy and did not get surgery and subsequently died.

This left 38 patients to be managed nonoperatively. In this nonoperative cohort, 79% of patients continued to have a clinical CR at the end of follow-up. Of the 7 patients with local failure, 6 were salvaged by surgery, one was salvaged by chemotherapy, and all 7 treatment failures had no evidence of disease at last follow-up.

Of the small group of 5 patients who achieved an initial clinical CR following short-course radiation therapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, there were no further events in this group, whereas, for patients who achieved only an initial partial response or who had progressive disease, 72% remained event-free.

Approximately half of those who achieved a clinical CR to the treatment regimen had no late gastrointestinal toxicities, and no grade 3 or 4 toxicities were observed. “Surgical resection of tumors — even without a permanent stoma — can result in significantly decreased bowel function, so our goal is to treat patients without surgery and maintain good bowel function,” Chin noted.

“For rectal cancer, both short-course radiation therapy and nonoperative management are emerging treatment paradigms that may be more cost-effective and convenient compared to long-course chemoradiation followed by surgery, [especially since] the COVID-19 pandemic...has spurred changes in clinical practices in radiation oncology,” she said.

Chin has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Narang reports receiving research support from Boston Scientific.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A short course of radiation therapy followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy resulted in a clinical complete response (CR) in almost half of 90 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer, allowing the majority of responders to skip surgical resection, a retrospective study indicates.

Specifically, at a median follow-up of 16.6 months for living patients, the initial clinical CR rate was 48% overall.

“While we do not have enough follow-up yet to know the late side-effect profile of this regimen, our preliminary results are promising,” Re-I Chin, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, told Medscape Medical News in an email.

The study was presented at the virtual 2020 meeting of the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO).

“Certainly, longer follow-up will be needed in this study, but none of the observed patients to date has experienced an unsalvageable failure,” said meeting discussant Amol Narang, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

He reminded conference attendees that, despite good evidence supporting equivalency in oncologic outcomes between short-course radiation and long-course chemoradiation, the former is “highly underutilized in the US” with a mere 1% usage rate between 2004 and 2014.

The current study’s short-course treatment approach was compared in this setting to long-course chemoradiation and adjuvant chemotherapy in the RAPIDO trial reported at the 2020 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), Narang pointed out.

Short-course patients had a higher rate of pathological complete response (pCR) and a lower rate of treatment failure compared with patients who received long-course chemoradiation and adjuvant chemotherapy; both patient groups underwent total mesorectal excision — which is different from the current analysis. The RAPIDO investigators concluded that the approach featuring the short course “can be considered as a new standard of care.”

Narang said the data collectively “begs the question as to whether the superiority of long-course chemoradiation should really have to be demonstrated to justify its use.”

But Chin highlighted toxicity issues. “Historically, there have been concerns regarding toxicity with short-course radiation therapy since it requires larger doses of radiation given over a shorter period of time,” Chin explained. “But [the short course] is particularly convenient for patients since it saves them more than a month of daily trips to the radiation oncology department.”

Seven local failures

The single-center study involved patients with newly diagnosed, nonmetastatic rectal adenocarcinoma treated with short-course radiation therapy followed by chemotherapy in 2018 and 2019. Nearly all (96%) had locally advanced disease, with either a T3/T4 tumor or node-positive disease. Median tumor size was 4.6 cm.

“Many of the patients in the study had low lying tumors,” Chin reported, with a median distance from the anal verge of 7 cm.

Radiation therapy was delivered in 25 Gy given in five fractions over 5 consecutive days, with the option to boost the dose to 30 Gy or 35 Gy in five fractions if extra-mesorectal lymph nodes were involved. Conventional 3D or intensity-modulated radiation was used and all patients completed treatment.

The median interval between diagnosis of rectal cancer and initiation of radiation therapy was 1.4 months, while the median interval between completion of radiation to initiation of chemotherapy was 2.7 weeks.

The most common chemotherapy regimen was FOLFOX – consisting of leucovorin, fluorouracil (5-FU), and oxaliplatin – or modified FOLFOX. For patients who received six or more cycles of chemotherapy, the median time spent on treatment was 3.9 months.

For those who completed at least six cycles of chemotherapy, the overall clinical CR was 51%, and, for patients with locally advanced disease, the clinical CR rate was 49%. Five of the 43 patients who achieved an initial clinical CR still underwent surgical resection because of patient or physician preference. Among this small group of patients, 4 of the 5 achieved a pCR, and the remaining patient achieved a pathological partial response (pPR).

A total of 42 patients (47% of the group) achieved a partial response following the radiation plus chemotherapy paradigm, and one patient had progressive disease. All underwent surgical resection. One patient did not complete chemotherapy and did not get surgery and subsequently died.

This left 38 patients to be managed nonoperatively. In this nonoperative cohort, 79% of patients continued to have a clinical CR at the end of follow-up. Of the 7 patients with local failure, 6 were salvaged by surgery, one was salvaged by chemotherapy, and all 7 treatment failures had no evidence of disease at last follow-up.

Of the small group of 5 patients who achieved an initial clinical CR following short-course radiation therapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, there were no further events in this group, whereas, for patients who achieved only an initial partial response or who had progressive disease, 72% remained event-free.

Approximately half of those who achieved a clinical CR to the treatment regimen had no late gastrointestinal toxicities, and no grade 3 or 4 toxicities were observed. “Surgical resection of tumors — even without a permanent stoma — can result in significantly decreased bowel function, so our goal is to treat patients without surgery and maintain good bowel function,” Chin noted.

“For rectal cancer, both short-course radiation therapy and nonoperative management are emerging treatment paradigms that may be more cost-effective and convenient compared to long-course chemoradiation followed by surgery, [especially since] the COVID-19 pandemic...has spurred changes in clinical practices in radiation oncology,” she said.

Chin has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Narang reports receiving research support from Boston Scientific.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Now USPSTF also suggests start CRC screening at age 45

that is open for public comment.

“This is the only change that was made,” said task force member Michael Barry, MD, director of the Informed Medical Decisions Program in the Health Decision Sciences Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

The recommendation is that all adults aged 45-75 years be screened for CRC.

This is an “A” recommendation for adults aged 50-75 and a “B” recommendation for adults aged 45-49. Dr. Barry explained that the reason for this difference is that the benefit is smaller for the 45- to 49-years age group. “But there’s not much difference between A and B from a practical standpoint,” he explained.

For adults aged 76-85, the benefits and harms of screening need to be weighed against the individual’s overall health and personal circumstances. This is a “C” recommendation.

Barry emphasized that the USPSTF document is not final. The draft recommendation and supporting evidence is posted on the task force website and will be available for public comments until Nov. 23.

Mounting pressure

The move comes after mounting evidence of an increase in CRC among younger adults and mounting pressure to lower the starting age.

Two years ago, the American Cancer Society (ACS) revised its own screening guidelines and lowered the starting age to 45 years. Soon afterward, a coalition of 22 public health and patient advocacy groups joined the ACS in submitting a letter to the USPSTF asking that the task force reconsider its 2016 guidance (which recommends starting at age 50 years).

The starting age for screening is an important issue, commented Judy Yee, MD, chair of radiology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the Montefiore Health System in New York and chair of the Colon Cancer Committee of the American College of Radiology.

“Right now it is very confusing to physicians and to the public,” Dr. Yee said in an interview at that time. “The USPSTF and the ACS differ as far as the age to begin screening, and insurers may not cover the cost of colorectal cancer screening before age 50.”

Dr. Barry said that the Task Force took notice of recent data showing an increase in the incidence of CRC among younger adults. “The risk now for age 45 to 49 is pretty similar to the risk for people in their early 50s. So in some ways, today’s late 40-year-olds are like yesterday’s 50-year-olds,” he commented.

The task force used simulation models that confirmed what the epidemiologic data suggested and “that we could prevent some additional colorectal cancer deaths by starting screening at age 45,” he said.

The rest of the new draft recommendation is similar to the 2016 guidelines, in which the task force says there is convincing evidence that CRC screening substantially reduces disease-related mortality. However, it does not recommend any one screening approach over another. It recommends both direct visualization, such as colonoscopy, as well as noninvasive stool-based tests. It does not recommend serum tests, urine tests, or capsule endoscopy because there is not yet enough evidence about the benefits and harms of these tests.

“The right test is the one a patient will do,” Dr. Barry commented.

Defining populations

CRC in young adults made the news in August 2020 when Chadwick Boseman, known for his role as King T’Challa in Marvel’s “Black Panther,” died of colon cancer. Diagnosed in 2016, he was only 43 years old.

“The recent passing of Chadwick Boseman is tragic, and our thoughts are with his loved ones during this difficult time,” said Dr. Barry. “As a Black man, the data show that Chadwick was at higher risk for developing colorectal cancer.”

Unfortunately, there is currently not enough evidence that screening Black men younger than 45 could help prevent tragic deaths such as Chadwick’s, he commented. “The task force is calling for more research on colorectal cancer screening in Black adults,” he added.

Limit screening to those at higher risk

In contrast to the USPSTF and ACS guidelines, which recommend screening for CRC for everyone over a certain age, a set of recommendations developed by an international panel of experts suggests screening only for individuals who are at higher risk for CRC.

As previously reported, these guidelines suggest restricting screening to adults whose cumulative cancer risk is 3% or more in the next 15 years, the point at which the balance between benefits and harms favors screening.

The authors, led by Lise Helsingen, MD, Clinical Effectiveness Research Group, University of Oslo, said “the optimal choice for each person requires shared decision-making.”

Such a risk-based approach is “increasingly regarded as the most appropriate way to discuss cancer screening.” That approach is already used in prostate and lung cancer screening, they noted.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians and researchers have actively debated the pros and cons of lowering the screening age to 45 years since 2018, when the American Cancer Society released its colorectal cancer (CRC) screening guidelines. The most compelling argument in support of lowering the screening age is that recent data from Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) show that the CRC incidence rates in 45- to 50-year-olds are similar to rates seen in 50- to 54-year-olds about 20 years ago, when the first guidelines to initiate screening at age 50 were widely established. Termed early-onset CRC (EOCRC), the underlying reasons for this increase are not completely understood, and while the absolute numbers of EOCRC cases are smaller than in older age groups, modeling studies show that screening this age group is both efficient and effective.

Over the last 20 years we have made major strides in reducing the incidence and mortality from CRC in ages 50 years and older, and now we must rise to the challenge of delivering CRC screening to this younger group in order to see similar dividends over time and curb the rising incidence curve of EOCRC. And we must do so without direct evidence to guide us as to the magnitude of the benefit of screening this younger group, the best modality to use, or tools to risk stratify who is likely to benefit from screening in this group. We must also be careful not to worsen racial and geographic disparities in CRC screening, which already exist for African Americans, Native Americans, and other minorities and rural residents. Finally, even though the goal posts are changing, our target remains to get to 80% screening rates for all age groups, and not neglect the currently underscreened 50- to 75-year-olds, who are at a much higher risk of CRC than their younger counterparts.

Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, is an investigator, Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research, section chief and staff physician, GI section, Minneapolis VA Health Care System; staff physician, Fairview University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis; and professor, University of Minnesota department of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Minneapolis. She has no conflicts of interest.

Clinicians and researchers have actively debated the pros and cons of lowering the screening age to 45 years since 2018, when the American Cancer Society released its colorectal cancer (CRC) screening guidelines. The most compelling argument in support of lowering the screening age is that recent data from Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) show that the CRC incidence rates in 45- to 50-year-olds are similar to rates seen in 50- to 54-year-olds about 20 years ago, when the first guidelines to initiate screening at age 50 were widely established. Termed early-onset CRC (EOCRC), the underlying reasons for this increase are not completely understood, and while the absolute numbers of EOCRC cases are smaller than in older age groups, modeling studies show that screening this age group is both efficient and effective.

Over the last 20 years we have made major strides in reducing the incidence and mortality from CRC in ages 50 years and older, and now we must rise to the challenge of delivering CRC screening to this younger group in order to see similar dividends over time and curb the rising incidence curve of EOCRC. And we must do so without direct evidence to guide us as to the magnitude of the benefit of screening this younger group, the best modality to use, or tools to risk stratify who is likely to benefit from screening in this group. We must also be careful not to worsen racial and geographic disparities in CRC screening, which already exist for African Americans, Native Americans, and other minorities and rural residents. Finally, even though the goal posts are changing, our target remains to get to 80% screening rates for all age groups, and not neglect the currently underscreened 50- to 75-year-olds, who are at a much higher risk of CRC than their younger counterparts.

Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, is an investigator, Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research, section chief and staff physician, GI section, Minneapolis VA Health Care System; staff physician, Fairview University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis; and professor, University of Minnesota department of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Minneapolis. She has no conflicts of interest.

Clinicians and researchers have actively debated the pros and cons of lowering the screening age to 45 years since 2018, when the American Cancer Society released its colorectal cancer (CRC) screening guidelines. The most compelling argument in support of lowering the screening age is that recent data from Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) show that the CRC incidence rates in 45- to 50-year-olds are similar to rates seen in 50- to 54-year-olds about 20 years ago, when the first guidelines to initiate screening at age 50 were widely established. Termed early-onset CRC (EOCRC), the underlying reasons for this increase are not completely understood, and while the absolute numbers of EOCRC cases are smaller than in older age groups, modeling studies show that screening this age group is both efficient and effective.

Over the last 20 years we have made major strides in reducing the incidence and mortality from CRC in ages 50 years and older, and now we must rise to the challenge of delivering CRC screening to this younger group in order to see similar dividends over time and curb the rising incidence curve of EOCRC. And we must do so without direct evidence to guide us as to the magnitude of the benefit of screening this younger group, the best modality to use, or tools to risk stratify who is likely to benefit from screening in this group. We must also be careful not to worsen racial and geographic disparities in CRC screening, which already exist for African Americans, Native Americans, and other minorities and rural residents. Finally, even though the goal posts are changing, our target remains to get to 80% screening rates for all age groups, and not neglect the currently underscreened 50- to 75-year-olds, who are at a much higher risk of CRC than their younger counterparts.

Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, is an investigator, Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research, section chief and staff physician, GI section, Minneapolis VA Health Care System; staff physician, Fairview University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis; and professor, University of Minnesota department of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Minneapolis. She has no conflicts of interest.

that is open for public comment.

“This is the only change that was made,” said task force member Michael Barry, MD, director of the Informed Medical Decisions Program in the Health Decision Sciences Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

The recommendation is that all adults aged 45-75 years be screened for CRC.

This is an “A” recommendation for adults aged 50-75 and a “B” recommendation for adults aged 45-49. Dr. Barry explained that the reason for this difference is that the benefit is smaller for the 45- to 49-years age group. “But there’s not much difference between A and B from a practical standpoint,” he explained.

For adults aged 76-85, the benefits and harms of screening need to be weighed against the individual’s overall health and personal circumstances. This is a “C” recommendation.

Barry emphasized that the USPSTF document is not final. The draft recommendation and supporting evidence is posted on the task force website and will be available for public comments until Nov. 23.

Mounting pressure

The move comes after mounting evidence of an increase in CRC among younger adults and mounting pressure to lower the starting age.

Two years ago, the American Cancer Society (ACS) revised its own screening guidelines and lowered the starting age to 45 years. Soon afterward, a coalition of 22 public health and patient advocacy groups joined the ACS in submitting a letter to the USPSTF asking that the task force reconsider its 2016 guidance (which recommends starting at age 50 years).

The starting age for screening is an important issue, commented Judy Yee, MD, chair of radiology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the Montefiore Health System in New York and chair of the Colon Cancer Committee of the American College of Radiology.

“Right now it is very confusing to physicians and to the public,” Dr. Yee said in an interview at that time. “The USPSTF and the ACS differ as far as the age to begin screening, and insurers may not cover the cost of colorectal cancer screening before age 50.”

Dr. Barry said that the Task Force took notice of recent data showing an increase in the incidence of CRC among younger adults. “The risk now for age 45 to 49 is pretty similar to the risk for people in their early 50s. So in some ways, today’s late 40-year-olds are like yesterday’s 50-year-olds,” he commented.

The task force used simulation models that confirmed what the epidemiologic data suggested and “that we could prevent some additional colorectal cancer deaths by starting screening at age 45,” he said.

The rest of the new draft recommendation is similar to the 2016 guidelines, in which the task force says there is convincing evidence that CRC screening substantially reduces disease-related mortality. However, it does not recommend any one screening approach over another. It recommends both direct visualization, such as colonoscopy, as well as noninvasive stool-based tests. It does not recommend serum tests, urine tests, or capsule endoscopy because there is not yet enough evidence about the benefits and harms of these tests.

“The right test is the one a patient will do,” Dr. Barry commented.

Defining populations

CRC in young adults made the news in August 2020 when Chadwick Boseman, known for his role as King T’Challa in Marvel’s “Black Panther,” died of colon cancer. Diagnosed in 2016, he was only 43 years old.

“The recent passing of Chadwick Boseman is tragic, and our thoughts are with his loved ones during this difficult time,” said Dr. Barry. “As a Black man, the data show that Chadwick was at higher risk for developing colorectal cancer.”

Unfortunately, there is currently not enough evidence that screening Black men younger than 45 could help prevent tragic deaths such as Chadwick’s, he commented. “The task force is calling for more research on colorectal cancer screening in Black adults,” he added.

Limit screening to those at higher risk

In contrast to the USPSTF and ACS guidelines, which recommend screening for CRC for everyone over a certain age, a set of recommendations developed by an international panel of experts suggests screening only for individuals who are at higher risk for CRC.

As previously reported, these guidelines suggest restricting screening to adults whose cumulative cancer risk is 3% or more in the next 15 years, the point at which the balance between benefits and harms favors screening.

The authors, led by Lise Helsingen, MD, Clinical Effectiveness Research Group, University of Oslo, said “the optimal choice for each person requires shared decision-making.”

Such a risk-based approach is “increasingly regarded as the most appropriate way to discuss cancer screening.” That approach is already used in prostate and lung cancer screening, they noted.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

that is open for public comment.

“This is the only change that was made,” said task force member Michael Barry, MD, director of the Informed Medical Decisions Program in the Health Decision Sciences Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

The recommendation is that all adults aged 45-75 years be screened for CRC.

This is an “A” recommendation for adults aged 50-75 and a “B” recommendation for adults aged 45-49. Dr. Barry explained that the reason for this difference is that the benefit is smaller for the 45- to 49-years age group. “But there’s not much difference between A and B from a practical standpoint,” he explained.

For adults aged 76-85, the benefits and harms of screening need to be weighed against the individual’s overall health and personal circumstances. This is a “C” recommendation.

Barry emphasized that the USPSTF document is not final. The draft recommendation and supporting evidence is posted on the task force website and will be available for public comments until Nov. 23.

Mounting pressure

The move comes after mounting evidence of an increase in CRC among younger adults and mounting pressure to lower the starting age.

Two years ago, the American Cancer Society (ACS) revised its own screening guidelines and lowered the starting age to 45 years. Soon afterward, a coalition of 22 public health and patient advocacy groups joined the ACS in submitting a letter to the USPSTF asking that the task force reconsider its 2016 guidance (which recommends starting at age 50 years).

The starting age for screening is an important issue, commented Judy Yee, MD, chair of radiology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the Montefiore Health System in New York and chair of the Colon Cancer Committee of the American College of Radiology.

“Right now it is very confusing to physicians and to the public,” Dr. Yee said in an interview at that time. “The USPSTF and the ACS differ as far as the age to begin screening, and insurers may not cover the cost of colorectal cancer screening before age 50.”

Dr. Barry said that the Task Force took notice of recent data showing an increase in the incidence of CRC among younger adults. “The risk now for age 45 to 49 is pretty similar to the risk for people in their early 50s. So in some ways, today’s late 40-year-olds are like yesterday’s 50-year-olds,” he commented.

The task force used simulation models that confirmed what the epidemiologic data suggested and “that we could prevent some additional colorectal cancer deaths by starting screening at age 45,” he said.

The rest of the new draft recommendation is similar to the 2016 guidelines, in which the task force says there is convincing evidence that CRC screening substantially reduces disease-related mortality. However, it does not recommend any one screening approach over another. It recommends both direct visualization, such as colonoscopy, as well as noninvasive stool-based tests. It does not recommend serum tests, urine tests, or capsule endoscopy because there is not yet enough evidence about the benefits and harms of these tests.

“The right test is the one a patient will do,” Dr. Barry commented.

Defining populations

CRC in young adults made the news in August 2020 when Chadwick Boseman, known for his role as King T’Challa in Marvel’s “Black Panther,” died of colon cancer. Diagnosed in 2016, he was only 43 years old.

“The recent passing of Chadwick Boseman is tragic, and our thoughts are with his loved ones during this difficult time,” said Dr. Barry. “As a Black man, the data show that Chadwick was at higher risk for developing colorectal cancer.”

Unfortunately, there is currently not enough evidence that screening Black men younger than 45 could help prevent tragic deaths such as Chadwick’s, he commented. “The task force is calling for more research on colorectal cancer screening in Black adults,” he added.

Limit screening to those at higher risk

In contrast to the USPSTF and ACS guidelines, which recommend screening for CRC for everyone over a certain age, a set of recommendations developed by an international panel of experts suggests screening only for individuals who are at higher risk for CRC.

As previously reported, these guidelines suggest restricting screening to adults whose cumulative cancer risk is 3% or more in the next 15 years, the point at which the balance between benefits and harms favors screening.

The authors, led by Lise Helsingen, MD, Clinical Effectiveness Research Group, University of Oslo, said “the optimal choice for each person requires shared decision-making.”

Such a risk-based approach is “increasingly regarded as the most appropriate way to discuss cancer screening.” That approach is already used in prostate and lung cancer screening, they noted.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Intensive surveillance after CRC resection does not improve survival

However, among patients with colon cancer recurrence, those randomized to intensive surveillance more often had a second surgery with curative intent. Even so, there was no overall survival benefit versus standard surveillance in this group.

In short, “none of the follow-up modalities resulted in a difference,” said investigator Come Lepage, MD, PhD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Dijon (France).

Dr. Lepage presented these findings at the European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Congress 2020.

Dr. Lepage said the study’s results suggest guidelines that include CT and CEA monitoring should be amended, and the standard surveillance methods should be ultrasound and chest x-ray. Dr. LePage called CEA surveillance “useless” and said CT scans should be performed only in cases of suspected recurrence.

However, study discussant Tim Price, MBBS, DHSc, of the University of Adelaide, noted that both the intensive and standard arms in this study had abdominal imaging every 3 months, be it ultrasound or CT, so even in the standard arms, surveillance “was still fairly aggressive.”

Because of that, the study does not “suggest we should decrease our intensity,” Dr. Price said.

He added that the study’s major finding was that more intensive surveillance led to higher rates of secondary surgery with curative intent, probably because recurrences were caught earlier than they would have been with standard surveillance, when curative surgery was still possible.

Patients in the study were treated during 2009-2015, and that might have also made a difference. “We need to remember that, in 2020, care is very different,” Dr. Price said. This includes increased surgical interventions and options for oligometastatic disease, plus systemic therapies such as pembrolizumab. With modern treatments, detecting recurrences earlier “may well have an impact on survival.”

Perhaps patients would live longer with “earlier diagnosis in today’s setting with more active agents and more aggressive surgery and radiotherapy [e.g., stereotactic ablative radiation therapy],” Dr. Price said in an interview.

Study details

The trial, dubbed PRODIGE 13, was done to bring clarity to the surveillance issue. Intensive follow-up after curative surgery for colorectal cancer, including CT and CEA monitoring, is recommended by various scientific societies, but it’s based mainly on expert opinion. Results of the few clinical trials on the issue have been controversial, Dr. Lepage explained.

PRODIGE 13 included 1,995 subjects with colorectal cancer. About half of patients had stage II disease, and the other half had stage III. Most patients were 75 years or younger at baseline, and there were more men in the study than women. All patients underwent resection with curative intent and had no evidence of residual disease 3 months after surgery. Some patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Patients were first randomized to no CEA monitoring or CEA monitoring every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for an additional 3 years. Members in both groups were then randomized a second time to either intensive or standard radiologic surveillance.

Surveillance in the standard arm consisted of an abdominal ultrasound every 3 months for the first 3 years, then biannually for an additional 2 years, plus chest x-rays every 6 months for 5 years. Intensive surveillance consisted of CT imaging, including thoracic imaging, alternating with abdominal ultrasound, every 3 months, then biannually for another 2 years.

At baseline, the surveillance groups were well balanced with regard to demographics, primary tumor location, and other factors, but stage III disease was more prevalent among patients randomized to standard radiologic monitoring without CEA.

Results

The median follow up was 6.5 years. There were no significant differences between the surveillance groups with regard to 5-year overall survival (P = .340) or recurrence-free survival (P = .473).

There were no significant differences in recurrence-free or overall survival when patients were stratified by age, sex, stage, CEA at a cut point of 5 mcg/L, and primary tumor characteristics including location, perineural invasion, and occlusion/perforation.

There were 356 recurrences in patients initially treated for colon cancer. CEA surveillance with or without CT scan was associated with an increased incidence of secondary resection with curative intent. The rate of secondary resection was 66.3% in the standard imaging with CEA arm, 59.5% in the CT plus CEA arm, 50.7% with CT imaging but no CEA, and 40.9% with standard imaging and no CEA (P = .0035).

The rates were similar among the 83 patients with recurrence after initial treatment for rectal cancer, but the between-arm differences were not significant. The rate of secondary resection with curative intent was 57.9% in the standard imaging with CEA arm, 47.8% in the CT plus CEA arm, 55% with CT imaging but no CEA, and 42.9% with standard imaging and no CEA.

The research is ongoing, and the team expects to report on secondary outcomes and ancillary studies of circulating tumor DNA, among other things, in 2021.

The study is being funded by the Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive. Dr. Lepage disclosed ties with Novartis, Amgen, Bayer, Servier, and AAA. Dr. Price disclosed institutional research funding from Amgen and being an uncompensated adviser to Pierre-Fabre and Merck.

SOURCE: Lepage C et al. ESMO 2020, Abstract 398O.

However, among patients with colon cancer recurrence, those randomized to intensive surveillance more often had a second surgery with curative intent. Even so, there was no overall survival benefit versus standard surveillance in this group.

In short, “none of the follow-up modalities resulted in a difference,” said investigator Come Lepage, MD, PhD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Dijon (France).

Dr. Lepage presented these findings at the European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Congress 2020.

Dr. Lepage said the study’s results suggest guidelines that include CT and CEA monitoring should be amended, and the standard surveillance methods should be ultrasound and chest x-ray. Dr. LePage called CEA surveillance “useless” and said CT scans should be performed only in cases of suspected recurrence.

However, study discussant Tim Price, MBBS, DHSc, of the University of Adelaide, noted that both the intensive and standard arms in this study had abdominal imaging every 3 months, be it ultrasound or CT, so even in the standard arms, surveillance “was still fairly aggressive.”

Because of that, the study does not “suggest we should decrease our intensity,” Dr. Price said.

He added that the study’s major finding was that more intensive surveillance led to higher rates of secondary surgery with curative intent, probably because recurrences were caught earlier than they would have been with standard surveillance, when curative surgery was still possible.

Patients in the study were treated during 2009-2015, and that might have also made a difference. “We need to remember that, in 2020, care is very different,” Dr. Price said. This includes increased surgical interventions and options for oligometastatic disease, plus systemic therapies such as pembrolizumab. With modern treatments, detecting recurrences earlier “may well have an impact on survival.”

Perhaps patients would live longer with “earlier diagnosis in today’s setting with more active agents and more aggressive surgery and radiotherapy [e.g., stereotactic ablative radiation therapy],” Dr. Price said in an interview.

Study details

The trial, dubbed PRODIGE 13, was done to bring clarity to the surveillance issue. Intensive follow-up after curative surgery for colorectal cancer, including CT and CEA monitoring, is recommended by various scientific societies, but it’s based mainly on expert opinion. Results of the few clinical trials on the issue have been controversial, Dr. Lepage explained.

PRODIGE 13 included 1,995 subjects with colorectal cancer. About half of patients had stage II disease, and the other half had stage III. Most patients were 75 years or younger at baseline, and there were more men in the study than women. All patients underwent resection with curative intent and had no evidence of residual disease 3 months after surgery. Some patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Patients were first randomized to no CEA monitoring or CEA monitoring every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for an additional 3 years. Members in both groups were then randomized a second time to either intensive or standard radiologic surveillance.

Surveillance in the standard arm consisted of an abdominal ultrasound every 3 months for the first 3 years, then biannually for an additional 2 years, plus chest x-rays every 6 months for 5 years. Intensive surveillance consisted of CT imaging, including thoracic imaging, alternating with abdominal ultrasound, every 3 months, then biannually for another 2 years.

At baseline, the surveillance groups were well balanced with regard to demographics, primary tumor location, and other factors, but stage III disease was more prevalent among patients randomized to standard radiologic monitoring without CEA.

Results

The median follow up was 6.5 years. There were no significant differences between the surveillance groups with regard to 5-year overall survival (P = .340) or recurrence-free survival (P = .473).

There were no significant differences in recurrence-free or overall survival when patients were stratified by age, sex, stage, CEA at a cut point of 5 mcg/L, and primary tumor characteristics including location, perineural invasion, and occlusion/perforation.