User login

EHR Tool Enhances Primary Aldosteronism Screening in Hypertensive Patients

Primary aldosteronism (PA) is a frequently overlooked yet common cause of secondary hypertension, presenting significant risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

But fewer than 4% of at-risk patients receive the recommended screening for PA, leaving a substantial gap in early detection and management, according to Adina F. Turcu, MD, MS, associate professor in endocrinology and internal medicine at University of Michigan Health in Ann Arbor.

In response to this clinical challenge, Dr. Turcu and her colleagues developed a best-practice advisory (BPA) to identify patients who were at risk for PA and embedded it into electronic health record at University of Michigan ambulatory clinics. Her team found that use of the tool led to increased rates of screening for PA, particularly among primary care physicians.

Over a 15-month period, Dr. Turcu and her colleagues tested the BPA through a quality improvement study, identifying 14,603 unique candidates for PA screening, with a mean age of 65.5 years and a diverse representation of ethnic backgrounds.

Notably, 48.1% of these candidates had treatment-resistant hypertension, 43.5% exhibited hypokalemia, 10.5% were younger than 35 years, and 3.1% had adrenal nodules. Of these candidates, 14.0% received orders for PA screening, with 70.5% completing the recommended screening within the system, and 17.4% receiving positive screening results.

The study, conducted over 6 months in 2023, targeted adults with hypertension and at least one of the following: Those who took four or more antihypertensive medications, exhibited hypokalemia, were younger than age 35 years, or had adrenal nodules. Patients previously tested for PA were excluded from the analysis.

The noninterruptive BPA was triggered during outpatient visits with clinicians who specialized in hypertension. The advisory would then offer an order set for PA screening and provide a link to interpretation guidance for results. Clinicians had the option to use, ignore, or decline the BPA.

“Although we were hoping for broader uptake of this EHR-embedded BPA, we were delighted to see an increase in PA screening rates to 14% of identified candidates as compared to an average of less than 3% in retrospective studies of similar populations, including in our own institution prior to implementing this BPA,” Dr. Turcu told this news organization.

Physician specialty played a crucial role in the utilization of the BPA. Internists and family medicine physicians accounted for the majority of screening orders, placing 40.0% and 28.1% of these, respectively. Family practitioners and internists predominantly used the embedded order set (80.3% and 68.9%, respectively).

“Hypertension often gets treated rather than screening for [causes of] secondary hypertension prior to treatment,” said Kaniksha Desai, MD, clinical associate professor and endocrinology quality director at Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, who was not involved in the research. But “primary hyperaldosteronism is a condition that can be treated surgically and has increased long term cardiovascular consequences if not identified. While guidelines recommend screening at-risk patients, this often can get lost in translation in clinical practice due to many factors, including time constraints and volume of patients.”

Patients who did vs did not undergo screening were more likely to be women, Black, and younger than age 35 years. Additionally, the likelihood of screening was higher among patients with obesity and dyslipidemia, whereas it was lower in those with chronic kidney disease and established cardiovascular complications.

According to Dr. Turcu, the findings from this study suggest that noninterruptive BPAs, especially when integrated into primary care workflows, hold promise as effective tools for PA screening.

When coupled with artificial intelligence to optimize detection yield, these refined BPAs could significantly contribute to personalized care for hypertension, the investigators said.

“Considering that in the United States almost one in two adults has hypertension, such automatized tools become instrumental to busy clinicians, particularly those in primary care,” Dr. Turcu said. “Our results indicate a promising opportunity to meaningfully improve PA awareness and enhance its diagnosis.”

Dr. Turcu reported receiving grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Doris Duke Foundation, served as an investigator in a CinCor Pharma clinical trial, and received financial support to her institution during the conduct of the study. Dr. Desai reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary aldosteronism (PA) is a frequently overlooked yet common cause of secondary hypertension, presenting significant risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

But fewer than 4% of at-risk patients receive the recommended screening for PA, leaving a substantial gap in early detection and management, according to Adina F. Turcu, MD, MS, associate professor in endocrinology and internal medicine at University of Michigan Health in Ann Arbor.

In response to this clinical challenge, Dr. Turcu and her colleagues developed a best-practice advisory (BPA) to identify patients who were at risk for PA and embedded it into electronic health record at University of Michigan ambulatory clinics. Her team found that use of the tool led to increased rates of screening for PA, particularly among primary care physicians.

Over a 15-month period, Dr. Turcu and her colleagues tested the BPA through a quality improvement study, identifying 14,603 unique candidates for PA screening, with a mean age of 65.5 years and a diverse representation of ethnic backgrounds.

Notably, 48.1% of these candidates had treatment-resistant hypertension, 43.5% exhibited hypokalemia, 10.5% were younger than 35 years, and 3.1% had adrenal nodules. Of these candidates, 14.0% received orders for PA screening, with 70.5% completing the recommended screening within the system, and 17.4% receiving positive screening results.

The study, conducted over 6 months in 2023, targeted adults with hypertension and at least one of the following: Those who took four or more antihypertensive medications, exhibited hypokalemia, were younger than age 35 years, or had adrenal nodules. Patients previously tested for PA were excluded from the analysis.

The noninterruptive BPA was triggered during outpatient visits with clinicians who specialized in hypertension. The advisory would then offer an order set for PA screening and provide a link to interpretation guidance for results. Clinicians had the option to use, ignore, or decline the BPA.

“Although we were hoping for broader uptake of this EHR-embedded BPA, we were delighted to see an increase in PA screening rates to 14% of identified candidates as compared to an average of less than 3% in retrospective studies of similar populations, including in our own institution prior to implementing this BPA,” Dr. Turcu told this news organization.

Physician specialty played a crucial role in the utilization of the BPA. Internists and family medicine physicians accounted for the majority of screening orders, placing 40.0% and 28.1% of these, respectively. Family practitioners and internists predominantly used the embedded order set (80.3% and 68.9%, respectively).

“Hypertension often gets treated rather than screening for [causes of] secondary hypertension prior to treatment,” said Kaniksha Desai, MD, clinical associate professor and endocrinology quality director at Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, who was not involved in the research. But “primary hyperaldosteronism is a condition that can be treated surgically and has increased long term cardiovascular consequences if not identified. While guidelines recommend screening at-risk patients, this often can get lost in translation in clinical practice due to many factors, including time constraints and volume of patients.”

Patients who did vs did not undergo screening were more likely to be women, Black, and younger than age 35 years. Additionally, the likelihood of screening was higher among patients with obesity and dyslipidemia, whereas it was lower in those with chronic kidney disease and established cardiovascular complications.

According to Dr. Turcu, the findings from this study suggest that noninterruptive BPAs, especially when integrated into primary care workflows, hold promise as effective tools for PA screening.

When coupled with artificial intelligence to optimize detection yield, these refined BPAs could significantly contribute to personalized care for hypertension, the investigators said.

“Considering that in the United States almost one in two adults has hypertension, such automatized tools become instrumental to busy clinicians, particularly those in primary care,” Dr. Turcu said. “Our results indicate a promising opportunity to meaningfully improve PA awareness and enhance its diagnosis.”

Dr. Turcu reported receiving grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Doris Duke Foundation, served as an investigator in a CinCor Pharma clinical trial, and received financial support to her institution during the conduct of the study. Dr. Desai reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary aldosteronism (PA) is a frequently overlooked yet common cause of secondary hypertension, presenting significant risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

But fewer than 4% of at-risk patients receive the recommended screening for PA, leaving a substantial gap in early detection and management, according to Adina F. Turcu, MD, MS, associate professor in endocrinology and internal medicine at University of Michigan Health in Ann Arbor.

In response to this clinical challenge, Dr. Turcu and her colleagues developed a best-practice advisory (BPA) to identify patients who were at risk for PA and embedded it into electronic health record at University of Michigan ambulatory clinics. Her team found that use of the tool led to increased rates of screening for PA, particularly among primary care physicians.

Over a 15-month period, Dr. Turcu and her colleagues tested the BPA through a quality improvement study, identifying 14,603 unique candidates for PA screening, with a mean age of 65.5 years and a diverse representation of ethnic backgrounds.

Notably, 48.1% of these candidates had treatment-resistant hypertension, 43.5% exhibited hypokalemia, 10.5% were younger than 35 years, and 3.1% had adrenal nodules. Of these candidates, 14.0% received orders for PA screening, with 70.5% completing the recommended screening within the system, and 17.4% receiving positive screening results.

The study, conducted over 6 months in 2023, targeted adults with hypertension and at least one of the following: Those who took four or more antihypertensive medications, exhibited hypokalemia, were younger than age 35 years, or had adrenal nodules. Patients previously tested for PA were excluded from the analysis.

The noninterruptive BPA was triggered during outpatient visits with clinicians who specialized in hypertension. The advisory would then offer an order set for PA screening and provide a link to interpretation guidance for results. Clinicians had the option to use, ignore, or decline the BPA.

“Although we were hoping for broader uptake of this EHR-embedded BPA, we were delighted to see an increase in PA screening rates to 14% of identified candidates as compared to an average of less than 3% in retrospective studies of similar populations, including in our own institution prior to implementing this BPA,” Dr. Turcu told this news organization.

Physician specialty played a crucial role in the utilization of the BPA. Internists and family medicine physicians accounted for the majority of screening orders, placing 40.0% and 28.1% of these, respectively. Family practitioners and internists predominantly used the embedded order set (80.3% and 68.9%, respectively).

“Hypertension often gets treated rather than screening for [causes of] secondary hypertension prior to treatment,” said Kaniksha Desai, MD, clinical associate professor and endocrinology quality director at Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, who was not involved in the research. But “primary hyperaldosteronism is a condition that can be treated surgically and has increased long term cardiovascular consequences if not identified. While guidelines recommend screening at-risk patients, this often can get lost in translation in clinical practice due to many factors, including time constraints and volume of patients.”

Patients who did vs did not undergo screening were more likely to be women, Black, and younger than age 35 years. Additionally, the likelihood of screening was higher among patients with obesity and dyslipidemia, whereas it was lower in those with chronic kidney disease and established cardiovascular complications.

According to Dr. Turcu, the findings from this study suggest that noninterruptive BPAs, especially when integrated into primary care workflows, hold promise as effective tools for PA screening.

When coupled with artificial intelligence to optimize detection yield, these refined BPAs could significantly contribute to personalized care for hypertension, the investigators said.

“Considering that in the United States almost one in two adults has hypertension, such automatized tools become instrumental to busy clinicians, particularly those in primary care,” Dr. Turcu said. “Our results indicate a promising opportunity to meaningfully improve PA awareness and enhance its diagnosis.”

Dr. Turcu reported receiving grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Doris Duke Foundation, served as an investigator in a CinCor Pharma clinical trial, and received financial support to her institution during the conduct of the study. Dr. Desai reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Continued Caution Needed Combining Nitrates With ED Drugs

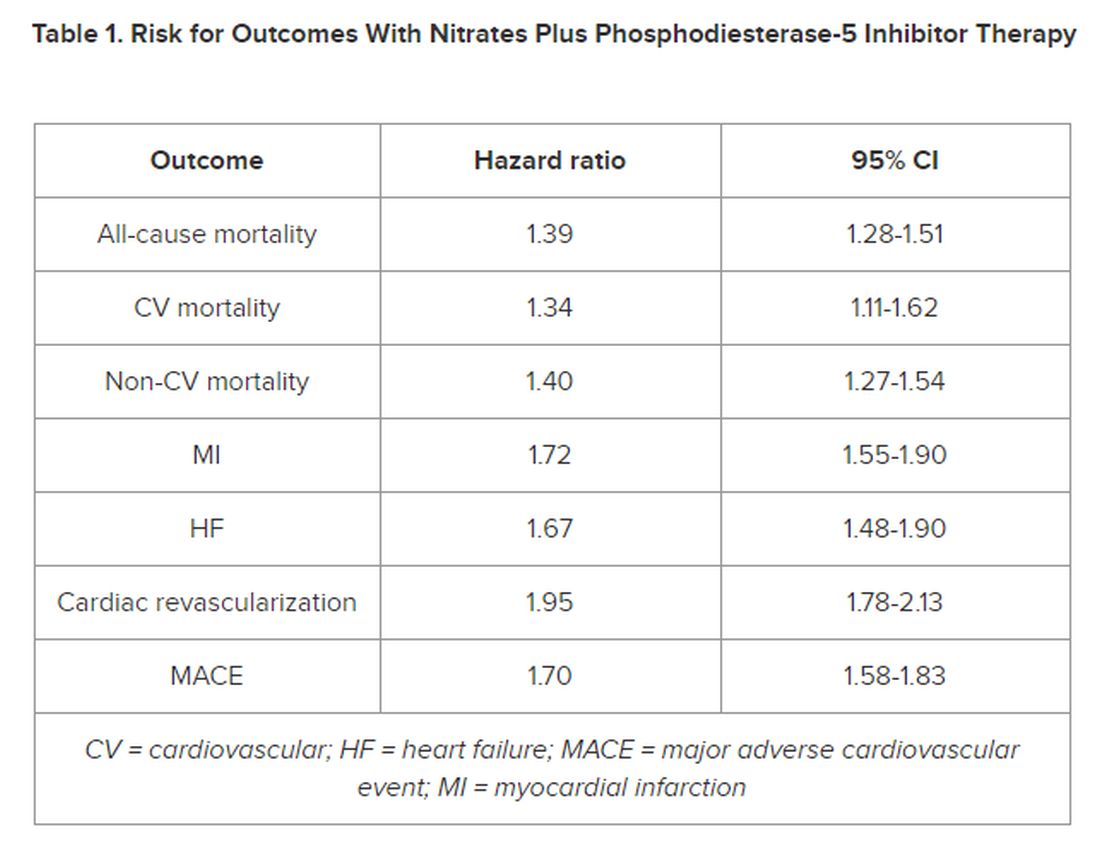

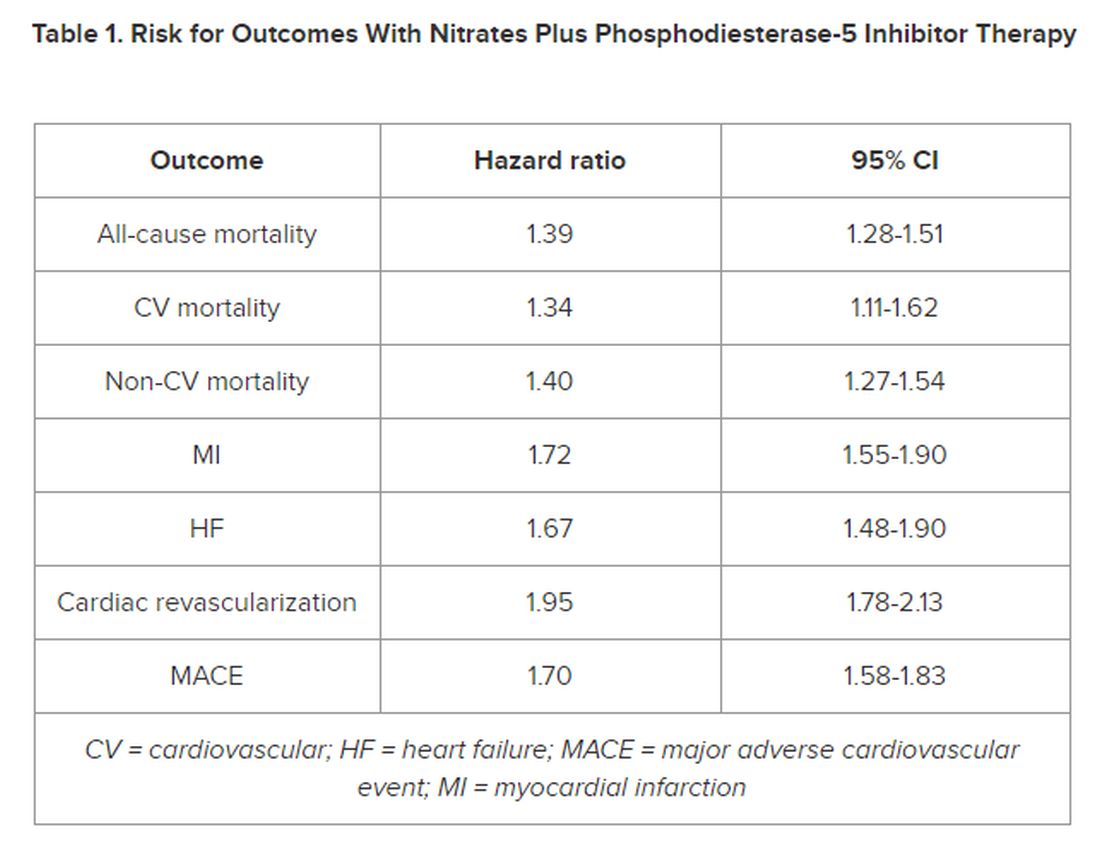

New research supports continued caution in prescribing a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE5i) to treat erectile dysfunction (ED) in men with heart disease using nitrate medications.

In a large Swedish population study of men with stable coronary artery disease (CAD), the combined use of a PDE5i and nitrates was associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality.

“According to current recommendations, PDE5i are contraindicated in patients taking organic nitrates; however, in clinical practice, both are commonly prescribed, and concomitant use has increased,” first author Ylva Trolle Lagerros, MD, PhD, with Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, told this news organization.

and weigh the benefits of the medication against the possible increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality given by this combination,” Dr. Lagerros said.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC).

The researchers used the Swedish Patient Register and the Prescribed Drug Register to assess the association between PDE5i treatment and CV outcomes in men with stable CAD treated with nitrate medication.

Among 55,777 men with a history of previous myocardial infarction (MI) or coronary revascularization who had filled at least two nitrate prescriptions (sublingual, oral, or both), 5710 also had at least two filled prescriptions of a PDE5i.

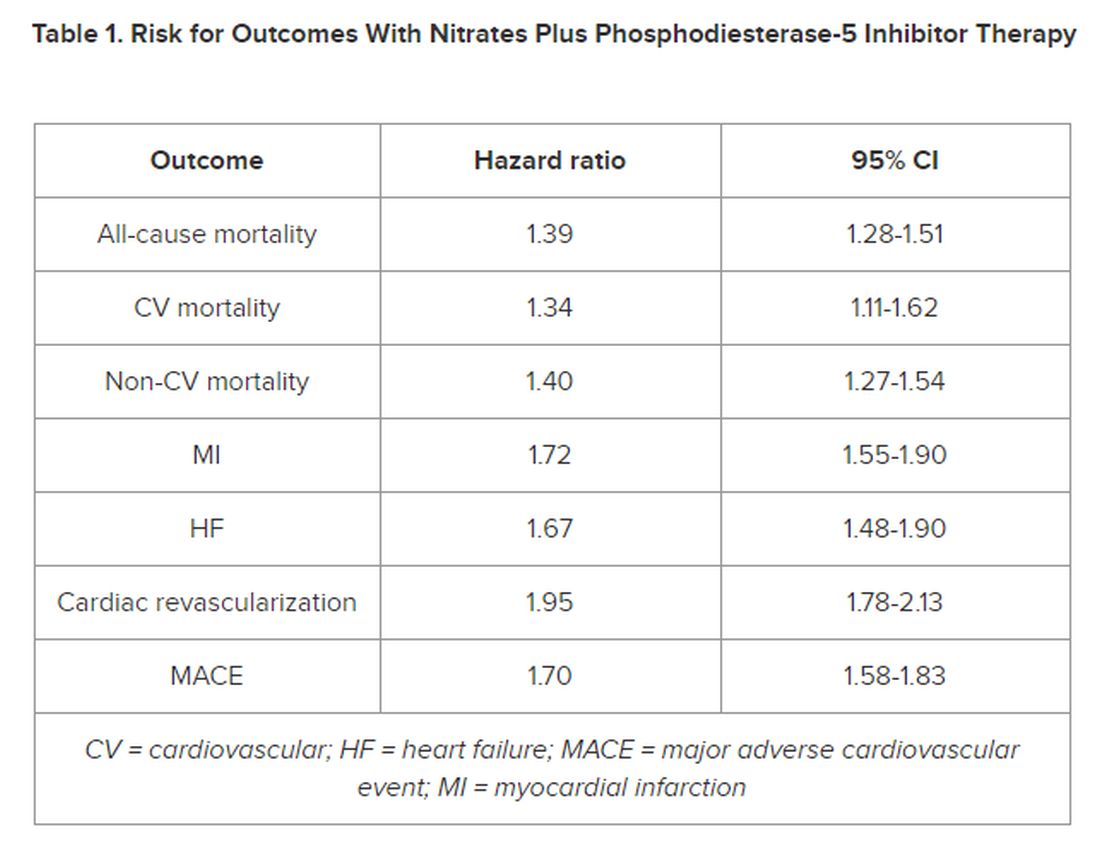

In multivariate-adjusted analysis, the combined use of PDE5i treatment with nitrates was associated with an increased relative risk for all studied outcomes, including all-cause mortality, CV and non-CV mortality, MI, heart failure, cardiac revascularization (hazard ratio), and major adverse cardiovascular events.

However, the number of events 28 days following a PDE5i prescription fill was “few, with lower incidence rates than in subjects taking nitrates only, indicating a low immediate risk for any event,” the authors noted in their article.

‘Common Bedfellows’

In a JACC editorial, Glenn N. Levine, MD, with Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, noted that, “ED and CAD are unfortunate, and all too common, bedfellows. But, as with most relationships, assuming proper precautions and care, they can coexist together for many years, perhaps even a lifetime.”

Dr. Levine noted that PDE5is are “reasonably safe” in most patients with stable CAD and only mild angina if not on chronic nitrate therapy. For those on chronic oral nitrate therapy, the use of PDE5is should continue to be regarded as “ill-advised at best and generally contraindicated.”

In some patients on oral nitrate therapy who want to use a PDE5i, particularly those who have undergone revascularization and have minimal or no angina, Dr. Levine said it may be reasonable to initiate a several-week trial of the nitrate therapy (or on a different class of antianginal therapy) and assess if the patient remains relatively angina-free.

In those patients with just rare exertional angina at generally higher levels of activity or those prescribed sublingual nitroglycerin “just in case,” it may be reasonable to prescribe PDE5i after a “clear and detailed” discussion with the patient of the risks for temporarily combining PDE5i and sublingual nitroglycerin.

Dr. Levine said these patients should be instructed not to take nitroglycerin within 24 hours of using a shorter-acting PDE5i and within 48 hours of using the longer-acting PDE5i tadalafil.

They should also be told to call 9-1-1 if angina develops during sexual intercourse and does not resolve upon cessation of such sexual activity, as well as to make medical personnel aware that they have recently used a PDE5i.

The study was funded by Region Stockholm, the Center for Innovative Medicine, and Karolinska Institutet. The researchers and editorial writer had declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New research supports continued caution in prescribing a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE5i) to treat erectile dysfunction (ED) in men with heart disease using nitrate medications.

In a large Swedish population study of men with stable coronary artery disease (CAD), the combined use of a PDE5i and nitrates was associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality.

“According to current recommendations, PDE5i are contraindicated in patients taking organic nitrates; however, in clinical practice, both are commonly prescribed, and concomitant use has increased,” first author Ylva Trolle Lagerros, MD, PhD, with Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, told this news organization.

and weigh the benefits of the medication against the possible increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality given by this combination,” Dr. Lagerros said.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC).

The researchers used the Swedish Patient Register and the Prescribed Drug Register to assess the association between PDE5i treatment and CV outcomes in men with stable CAD treated with nitrate medication.

Among 55,777 men with a history of previous myocardial infarction (MI) or coronary revascularization who had filled at least two nitrate prescriptions (sublingual, oral, or both), 5710 also had at least two filled prescriptions of a PDE5i.

In multivariate-adjusted analysis, the combined use of PDE5i treatment with nitrates was associated with an increased relative risk for all studied outcomes, including all-cause mortality, CV and non-CV mortality, MI, heart failure, cardiac revascularization (hazard ratio), and major adverse cardiovascular events.

However, the number of events 28 days following a PDE5i prescription fill was “few, with lower incidence rates than in subjects taking nitrates only, indicating a low immediate risk for any event,” the authors noted in their article.

‘Common Bedfellows’

In a JACC editorial, Glenn N. Levine, MD, with Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, noted that, “ED and CAD are unfortunate, and all too common, bedfellows. But, as with most relationships, assuming proper precautions and care, they can coexist together for many years, perhaps even a lifetime.”

Dr. Levine noted that PDE5is are “reasonably safe” in most patients with stable CAD and only mild angina if not on chronic nitrate therapy. For those on chronic oral nitrate therapy, the use of PDE5is should continue to be regarded as “ill-advised at best and generally contraindicated.”

In some patients on oral nitrate therapy who want to use a PDE5i, particularly those who have undergone revascularization and have minimal or no angina, Dr. Levine said it may be reasonable to initiate a several-week trial of the nitrate therapy (or on a different class of antianginal therapy) and assess if the patient remains relatively angina-free.

In those patients with just rare exertional angina at generally higher levels of activity or those prescribed sublingual nitroglycerin “just in case,” it may be reasonable to prescribe PDE5i after a “clear and detailed” discussion with the patient of the risks for temporarily combining PDE5i and sublingual nitroglycerin.

Dr. Levine said these patients should be instructed not to take nitroglycerin within 24 hours of using a shorter-acting PDE5i and within 48 hours of using the longer-acting PDE5i tadalafil.

They should also be told to call 9-1-1 if angina develops during sexual intercourse and does not resolve upon cessation of such sexual activity, as well as to make medical personnel aware that they have recently used a PDE5i.

The study was funded by Region Stockholm, the Center for Innovative Medicine, and Karolinska Institutet. The researchers and editorial writer had declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New research supports continued caution in prescribing a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE5i) to treat erectile dysfunction (ED) in men with heart disease using nitrate medications.

In a large Swedish population study of men with stable coronary artery disease (CAD), the combined use of a PDE5i and nitrates was associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality.

“According to current recommendations, PDE5i are contraindicated in patients taking organic nitrates; however, in clinical practice, both are commonly prescribed, and concomitant use has increased,” first author Ylva Trolle Lagerros, MD, PhD, with Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, told this news organization.

and weigh the benefits of the medication against the possible increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality given by this combination,” Dr. Lagerros said.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC).

The researchers used the Swedish Patient Register and the Prescribed Drug Register to assess the association between PDE5i treatment and CV outcomes in men with stable CAD treated with nitrate medication.

Among 55,777 men with a history of previous myocardial infarction (MI) or coronary revascularization who had filled at least two nitrate prescriptions (sublingual, oral, or both), 5710 also had at least two filled prescriptions of a PDE5i.

In multivariate-adjusted analysis, the combined use of PDE5i treatment with nitrates was associated with an increased relative risk for all studied outcomes, including all-cause mortality, CV and non-CV mortality, MI, heart failure, cardiac revascularization (hazard ratio), and major adverse cardiovascular events.

However, the number of events 28 days following a PDE5i prescription fill was “few, with lower incidence rates than in subjects taking nitrates only, indicating a low immediate risk for any event,” the authors noted in their article.

‘Common Bedfellows’

In a JACC editorial, Glenn N. Levine, MD, with Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, noted that, “ED and CAD are unfortunate, and all too common, bedfellows. But, as with most relationships, assuming proper precautions and care, they can coexist together for many years, perhaps even a lifetime.”

Dr. Levine noted that PDE5is are “reasonably safe” in most patients with stable CAD and only mild angina if not on chronic nitrate therapy. For those on chronic oral nitrate therapy, the use of PDE5is should continue to be regarded as “ill-advised at best and generally contraindicated.”

In some patients on oral nitrate therapy who want to use a PDE5i, particularly those who have undergone revascularization and have minimal or no angina, Dr. Levine said it may be reasonable to initiate a several-week trial of the nitrate therapy (or on a different class of antianginal therapy) and assess if the patient remains relatively angina-free.

In those patients with just rare exertional angina at generally higher levels of activity or those prescribed sublingual nitroglycerin “just in case,” it may be reasonable to prescribe PDE5i after a “clear and detailed” discussion with the patient of the risks for temporarily combining PDE5i and sublingual nitroglycerin.

Dr. Levine said these patients should be instructed not to take nitroglycerin within 24 hours of using a shorter-acting PDE5i and within 48 hours of using the longer-acting PDE5i tadalafil.

They should also be told to call 9-1-1 if angina develops during sexual intercourse and does not resolve upon cessation of such sexual activity, as well as to make medical personnel aware that they have recently used a PDE5i.

The study was funded by Region Stockholm, the Center for Innovative Medicine, and Karolinska Institutet. The researchers and editorial writer had declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New Insights Into Mortality in Takotsubo Syndrome

TOPLINE:

Mortality in patients with takotsubo syndrome (TTS), sometimes called broken heart syndrome or stress-induced cardiomyopathy is substantially higher than that in the general population and comparable with that in patients having myocardial infarction (MI), results of a new case-control study showed. The rates of medication use are similar for TTS and MI, despite no current clinical trials or recommendations to guide such therapies, the authors noted.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 620 Scottish patients (mean age, 66 years; 91% women) with TTS, a potentially fatal condition that mimics MI, predominantly affects middle-aged women, and is often triggered by stress.

- The analysis also included two age-, sex-, and geographically matched control groups: Representative participants from the general Scottish population (1:4) and patients with acute MI (1:1).

- Using comprehensive national data sets, researchers extracted information for all three cohorts on prescribing of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular medications, including the duration of dispensing and causes of death, and clustered the major causes of death into 17 major groups.

- At a median follow-up of 5.5 years, there were 722 deaths (153 in patients with TTS, 195 in those with MI, and 374 in the general population cohort).

TAKEAWAY:

- and slightly lower than that in patients having MI (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62-0.94; P = .012), with cardiovascular causes, particularly heart failure, being the most strongly associated with TTS (HR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.81-3.39; P < .0001 vs general population), followed by pulmonary causes. Noncardiovascular mortality was similar in TTS and MI.

- Prescription rates of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular medications were similar between patients with TTS and MI.

- The only cardiovascular therapy associated with lower mortality in patients with TTS was angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker therapy (P = .0056); in contrast, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers, antiplatelet agents, and statins were all associated with improved survival in patients with MI.

- Diuretics were associated with worse outcomes in both patients with TTS and MI, as was psychotropic therapy.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings may help to lay the foundations for further exploration of potential mechanisms and treatments” for TTS, an “increasingly recognized and potentially fatal condition,” the authors concluded.

In an accompanying comment, Rodolfo Citro, MD, PHD, Cardiovascular and Thoracic Department, San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’ Aragona University Hospital, Salerno, Italy, and colleagues said the authors should be commended for providing data on cardiovascular mortality “during one of the longest available follow-ups in TTS,” adding the study “suggests the importance of further research for more appropriate management of patients with acute and long-term TTS.”

SOURCE:

The research was led by Amelia E. Rudd, MSC, Aberdeen Cardiovascular and Diabetes Centre, University of Aberdeen and NHS Grampian, Aberdeen, Scotland. It was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Complete alignment of all variables related to clinical characteristics of patients with TTS and MI wasn’t feasible. During the study, TTS was still relatively unfamiliar to clinicians and underdiagnosed. As the study used a national data set of routinely collected data, not all desirable information was available, including indications of why drugs were prescribed or discontinued, which could have led to imprecise results. As the study used nonrandomized data, causality can’t be assumed.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Rudd had no relevant conflicts of interest. Study author Dana K. Dawson, Aberdeen Cardiovascular and Diabetes Centre, University of Aberdeen, Scotland, declared receiving the Chief Scientist Office Scotland award CGA-16-4 and the BHF Research Training Fellowship. Commentary authors had no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Mortality in patients with takotsubo syndrome (TTS), sometimes called broken heart syndrome or stress-induced cardiomyopathy is substantially higher than that in the general population and comparable with that in patients having myocardial infarction (MI), results of a new case-control study showed. The rates of medication use are similar for TTS and MI, despite no current clinical trials or recommendations to guide such therapies, the authors noted.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 620 Scottish patients (mean age, 66 years; 91% women) with TTS, a potentially fatal condition that mimics MI, predominantly affects middle-aged women, and is often triggered by stress.

- The analysis also included two age-, sex-, and geographically matched control groups: Representative participants from the general Scottish population (1:4) and patients with acute MI (1:1).

- Using comprehensive national data sets, researchers extracted information for all three cohorts on prescribing of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular medications, including the duration of dispensing and causes of death, and clustered the major causes of death into 17 major groups.

- At a median follow-up of 5.5 years, there were 722 deaths (153 in patients with TTS, 195 in those with MI, and 374 in the general population cohort).

TAKEAWAY:

- and slightly lower than that in patients having MI (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62-0.94; P = .012), with cardiovascular causes, particularly heart failure, being the most strongly associated with TTS (HR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.81-3.39; P < .0001 vs general population), followed by pulmonary causes. Noncardiovascular mortality was similar in TTS and MI.

- Prescription rates of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular medications were similar between patients with TTS and MI.

- The only cardiovascular therapy associated with lower mortality in patients with TTS was angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker therapy (P = .0056); in contrast, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers, antiplatelet agents, and statins were all associated with improved survival in patients with MI.

- Diuretics were associated with worse outcomes in both patients with TTS and MI, as was psychotropic therapy.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings may help to lay the foundations for further exploration of potential mechanisms and treatments” for TTS, an “increasingly recognized and potentially fatal condition,” the authors concluded.

In an accompanying comment, Rodolfo Citro, MD, PHD, Cardiovascular and Thoracic Department, San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’ Aragona University Hospital, Salerno, Italy, and colleagues said the authors should be commended for providing data on cardiovascular mortality “during one of the longest available follow-ups in TTS,” adding the study “suggests the importance of further research for more appropriate management of patients with acute and long-term TTS.”

SOURCE:

The research was led by Amelia E. Rudd, MSC, Aberdeen Cardiovascular and Diabetes Centre, University of Aberdeen and NHS Grampian, Aberdeen, Scotland. It was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Complete alignment of all variables related to clinical characteristics of patients with TTS and MI wasn’t feasible. During the study, TTS was still relatively unfamiliar to clinicians and underdiagnosed. As the study used a national data set of routinely collected data, not all desirable information was available, including indications of why drugs were prescribed or discontinued, which could have led to imprecise results. As the study used nonrandomized data, causality can’t be assumed.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Rudd had no relevant conflicts of interest. Study author Dana K. Dawson, Aberdeen Cardiovascular and Diabetes Centre, University of Aberdeen, Scotland, declared receiving the Chief Scientist Office Scotland award CGA-16-4 and the BHF Research Training Fellowship. Commentary authors had no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Mortality in patients with takotsubo syndrome (TTS), sometimes called broken heart syndrome or stress-induced cardiomyopathy is substantially higher than that in the general population and comparable with that in patients having myocardial infarction (MI), results of a new case-control study showed. The rates of medication use are similar for TTS and MI, despite no current clinical trials or recommendations to guide such therapies, the authors noted.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 620 Scottish patients (mean age, 66 years; 91% women) with TTS, a potentially fatal condition that mimics MI, predominantly affects middle-aged women, and is often triggered by stress.

- The analysis also included two age-, sex-, and geographically matched control groups: Representative participants from the general Scottish population (1:4) and patients with acute MI (1:1).

- Using comprehensive national data sets, researchers extracted information for all three cohorts on prescribing of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular medications, including the duration of dispensing and causes of death, and clustered the major causes of death into 17 major groups.

- At a median follow-up of 5.5 years, there were 722 deaths (153 in patients with TTS, 195 in those with MI, and 374 in the general population cohort).

TAKEAWAY:

- and slightly lower than that in patients having MI (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62-0.94; P = .012), with cardiovascular causes, particularly heart failure, being the most strongly associated with TTS (HR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.81-3.39; P < .0001 vs general population), followed by pulmonary causes. Noncardiovascular mortality was similar in TTS and MI.

- Prescription rates of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular medications were similar between patients with TTS and MI.

- The only cardiovascular therapy associated with lower mortality in patients with TTS was angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker therapy (P = .0056); in contrast, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers, antiplatelet agents, and statins were all associated with improved survival in patients with MI.

- Diuretics were associated with worse outcomes in both patients with TTS and MI, as was psychotropic therapy.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings may help to lay the foundations for further exploration of potential mechanisms and treatments” for TTS, an “increasingly recognized and potentially fatal condition,” the authors concluded.

In an accompanying comment, Rodolfo Citro, MD, PHD, Cardiovascular and Thoracic Department, San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’ Aragona University Hospital, Salerno, Italy, and colleagues said the authors should be commended for providing data on cardiovascular mortality “during one of the longest available follow-ups in TTS,” adding the study “suggests the importance of further research for more appropriate management of patients with acute and long-term TTS.”

SOURCE:

The research was led by Amelia E. Rudd, MSC, Aberdeen Cardiovascular and Diabetes Centre, University of Aberdeen and NHS Grampian, Aberdeen, Scotland. It was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Complete alignment of all variables related to clinical characteristics of patients with TTS and MI wasn’t feasible. During the study, TTS was still relatively unfamiliar to clinicians and underdiagnosed. As the study used a national data set of routinely collected data, not all desirable information was available, including indications of why drugs were prescribed or discontinued, which could have led to imprecise results. As the study used nonrandomized data, causality can’t be assumed.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Rudd had no relevant conflicts of interest. Study author Dana K. Dawson, Aberdeen Cardiovascular and Diabetes Centre, University of Aberdeen, Scotland, declared receiving the Chief Scientist Office Scotland award CGA-16-4 and the BHF Research Training Fellowship. Commentary authors had no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Severely Irregular Sleep Patterns and OSA Prompt Increased Odds of Hypertension

TOPLINE:

Severe sleep irregularity often occurs with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and this combination approximately doubled the odds of hypertension in middle-aged individuals.

METHODOLOGY:

- OSA has demonstrated an association with hypertension, but data on the impact of sleep irregularity on this relationship are lacking.

- The researchers used the recently developed sleep regularity index (SRI) to determine sleep patterns using a scale of 0-100 (with higher numbers indicating greater regularity) to assess relationships between OSA, sleep patterns, and hypertension in 602 adults with a mean age of 57 years.

- The study’s goal was an assessment of the associations between sleep regularity, OSA, and hypertension in a community sample of adults with normal circadian patterns.

TAKEAWAY:

- The odds of OSA were significantly greater for individuals with mildly irregular or severely irregular sleep than for regular sleepers (odds ratios, 1.97 and 2.06, respectively).

- Individuals with OSA and severely irregular sleep had the highest odds of hypertension compared with individuals with no OSA and regular sleep (OR, 2.34).

- However, participants with OSA and regular sleep or mildly irregular sleep had no significant increase in hypertension risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“Irregular sleep may be an important marker of OSA-related sleep disruption and may be an important modifiable health target,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Kelly Sansom, a PhD candidate at the Centre for Sleep Science at the University of Western Australia, Albany. The study was published online in the journal Sleep.

LIMITATIONS:

The cross-sectional design prevented conclusions of causality, and the SRI is a nonspecific measure that may capture a range of phenotypes with one score; other limitations included the small sample sizes of sleep regularity groups and the use of actigraphy to collect sleep times.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship and the Raine Study PhD Top-up Scholarship; the Raine Study Scholarship is supported by the NHMRC, the Centre for Sleep Science, School of Anatomy, Physiology & Human Biology of the University of Western Australia, and the Lions Eye Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Severe sleep irregularity often occurs with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and this combination approximately doubled the odds of hypertension in middle-aged individuals.

METHODOLOGY:

- OSA has demonstrated an association with hypertension, but data on the impact of sleep irregularity on this relationship are lacking.

- The researchers used the recently developed sleep regularity index (SRI) to determine sleep patterns using a scale of 0-100 (with higher numbers indicating greater regularity) to assess relationships between OSA, sleep patterns, and hypertension in 602 adults with a mean age of 57 years.

- The study’s goal was an assessment of the associations between sleep regularity, OSA, and hypertension in a community sample of adults with normal circadian patterns.

TAKEAWAY:

- The odds of OSA were significantly greater for individuals with mildly irregular or severely irregular sleep than for regular sleepers (odds ratios, 1.97 and 2.06, respectively).

- Individuals with OSA and severely irregular sleep had the highest odds of hypertension compared with individuals with no OSA and regular sleep (OR, 2.34).

- However, participants with OSA and regular sleep or mildly irregular sleep had no significant increase in hypertension risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“Irregular sleep may be an important marker of OSA-related sleep disruption and may be an important modifiable health target,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Kelly Sansom, a PhD candidate at the Centre for Sleep Science at the University of Western Australia, Albany. The study was published online in the journal Sleep.

LIMITATIONS:

The cross-sectional design prevented conclusions of causality, and the SRI is a nonspecific measure that may capture a range of phenotypes with one score; other limitations included the small sample sizes of sleep regularity groups and the use of actigraphy to collect sleep times.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship and the Raine Study PhD Top-up Scholarship; the Raine Study Scholarship is supported by the NHMRC, the Centre for Sleep Science, School of Anatomy, Physiology & Human Biology of the University of Western Australia, and the Lions Eye Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Severe sleep irregularity often occurs with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and this combination approximately doubled the odds of hypertension in middle-aged individuals.

METHODOLOGY:

- OSA has demonstrated an association with hypertension, but data on the impact of sleep irregularity on this relationship are lacking.

- The researchers used the recently developed sleep regularity index (SRI) to determine sleep patterns using a scale of 0-100 (with higher numbers indicating greater regularity) to assess relationships between OSA, sleep patterns, and hypertension in 602 adults with a mean age of 57 years.

- The study’s goal was an assessment of the associations between sleep regularity, OSA, and hypertension in a community sample of adults with normal circadian patterns.

TAKEAWAY:

- The odds of OSA were significantly greater for individuals with mildly irregular or severely irregular sleep than for regular sleepers (odds ratios, 1.97 and 2.06, respectively).

- Individuals with OSA and severely irregular sleep had the highest odds of hypertension compared with individuals with no OSA and regular sleep (OR, 2.34).

- However, participants with OSA and regular sleep or mildly irregular sleep had no significant increase in hypertension risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“Irregular sleep may be an important marker of OSA-related sleep disruption and may be an important modifiable health target,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Kelly Sansom, a PhD candidate at the Centre for Sleep Science at the University of Western Australia, Albany. The study was published online in the journal Sleep.

LIMITATIONS:

The cross-sectional design prevented conclusions of causality, and the SRI is a nonspecific measure that may capture a range of phenotypes with one score; other limitations included the small sample sizes of sleep regularity groups and the use of actigraphy to collect sleep times.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship and the Raine Study PhD Top-up Scholarship; the Raine Study Scholarship is supported by the NHMRC, the Centre for Sleep Science, School of Anatomy, Physiology & Human Biology of the University of Western Australia, and the Lions Eye Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Temporary Higher Stroke Rate After TAVR

TOPLINE:

Patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) have a higher risk for stroke for up to 2 years compared with an age- and sex-matched population, after which their risks are comparable, results of a large Swiss registry study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 11,957 patients from the prospective SwissTAVI Registry, an ongoing mandatory cohort study enrolling consecutive patients undergoing TAVR in Switzerland.

- The study population, which had a mean age of 81.8 years and mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS PROM) of 4.62, with 11.8% having a history of cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and 32.3% a history of atrial fibrillation, underwent TAVR at 15 centers between February 2011 and June 2021.

- The primary outcome was the incidence of stroke, with secondary outcomes including the incidence of CVA, a composite of stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA).

- Researchers calculated standardized stroke ratios (SSRs) and compared stroke trends in patients undergoing TAVR with those of an age- and sex-matched general population in Switzerland derived from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study.

TAKEAWAY:

- , accounting for 69% of these events.

- After excluding 30-day events, the 1-year incidence rates of CVA and stroke were 1.7% and 1.4%, respectively, followed by an annual stroke incidence of 1.2%, 0.8%, 0.9%, and 0.7% in the second, third, fourth, and fifth years post TAVR, respectively.

- Only increased age and moderate/severe paravalvular leakage (PVL) at discharge were associated with an increased risk for early stroke (up to 30 days post TAVR), whereas dyslipidemia and history of atrial fibrillation and of CVA were associated with an increased risk for late stroke (30 days to 5 years after TAVR).

- SSR in the study population returned to a level comparable to that expected in the general Swiss population after 2 years and through to 5 years post-TAVR.

IN PRACTICE:

Although the study results “are reassuring” with respect to stroke risk beyond 2 years post TAVR, “our findings underscore the continued efforts of stroke-prevention measures” early and longer term, wrote the authors.

In an accompanying editorial, Lauge Østergaard, MD, PhD, Department of Cardiology, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, noted the study suggests reduced PVL could lower the risk for early stroke following TAVR and “highlights how assessment of usual risk factors (dyslipidemia and atrial fibrillation) could help reduce the burden of stroke in the long term.”

SOURCE:

The study was carried out by Taishi Okuno, MD, Department of Cardiology, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Switzerland, and colleagues. It was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC): Cardiovascular Interventions.

LIMITATIONS:

The study couldn’t investigate the association between antithrombotic regimens and the risk for CVA. Definitions of CVA in the SwissTAVI Registry might differ from those used in the GBD study from which the matched population data were derived. The general population wasn’t matched on comorbidities usually associated with elevated stroke risk, which may have led to underestimation of stroke. As the mean age in the study was 82 years, results may not be extrapolated to a younger population.

DISCLOSURES:

The SwissTAVI registry is supported by the Swiss Heart Foundation, Swiss Working Group of Interventional Cardiology and Acute Coronary Syndromes, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, Boston Scientific/Symetis, JenaValve, and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Okuno has no relevant conflicts of interest; see paper for disclosures of other study authors. Dr. Østergaard has received an independent research grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) have a higher risk for stroke for up to 2 years compared with an age- and sex-matched population, after which their risks are comparable, results of a large Swiss registry study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 11,957 patients from the prospective SwissTAVI Registry, an ongoing mandatory cohort study enrolling consecutive patients undergoing TAVR in Switzerland.

- The study population, which had a mean age of 81.8 years and mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS PROM) of 4.62, with 11.8% having a history of cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and 32.3% a history of atrial fibrillation, underwent TAVR at 15 centers between February 2011 and June 2021.

- The primary outcome was the incidence of stroke, with secondary outcomes including the incidence of CVA, a composite of stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA).

- Researchers calculated standardized stroke ratios (SSRs) and compared stroke trends in patients undergoing TAVR with those of an age- and sex-matched general population in Switzerland derived from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study.

TAKEAWAY:

- , accounting for 69% of these events.

- After excluding 30-day events, the 1-year incidence rates of CVA and stroke were 1.7% and 1.4%, respectively, followed by an annual stroke incidence of 1.2%, 0.8%, 0.9%, and 0.7% in the second, third, fourth, and fifth years post TAVR, respectively.

- Only increased age and moderate/severe paravalvular leakage (PVL) at discharge were associated with an increased risk for early stroke (up to 30 days post TAVR), whereas dyslipidemia and history of atrial fibrillation and of CVA were associated with an increased risk for late stroke (30 days to 5 years after TAVR).

- SSR in the study population returned to a level comparable to that expected in the general Swiss population after 2 years and through to 5 years post-TAVR.

IN PRACTICE:

Although the study results “are reassuring” with respect to stroke risk beyond 2 years post TAVR, “our findings underscore the continued efforts of stroke-prevention measures” early and longer term, wrote the authors.

In an accompanying editorial, Lauge Østergaard, MD, PhD, Department of Cardiology, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, noted the study suggests reduced PVL could lower the risk for early stroke following TAVR and “highlights how assessment of usual risk factors (dyslipidemia and atrial fibrillation) could help reduce the burden of stroke in the long term.”

SOURCE:

The study was carried out by Taishi Okuno, MD, Department of Cardiology, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Switzerland, and colleagues. It was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC): Cardiovascular Interventions.

LIMITATIONS:

The study couldn’t investigate the association between antithrombotic regimens and the risk for CVA. Definitions of CVA in the SwissTAVI Registry might differ from those used in the GBD study from which the matched population data were derived. The general population wasn’t matched on comorbidities usually associated with elevated stroke risk, which may have led to underestimation of stroke. As the mean age in the study was 82 years, results may not be extrapolated to a younger population.

DISCLOSURES:

The SwissTAVI registry is supported by the Swiss Heart Foundation, Swiss Working Group of Interventional Cardiology and Acute Coronary Syndromes, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, Boston Scientific/Symetis, JenaValve, and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Okuno has no relevant conflicts of interest; see paper for disclosures of other study authors. Dr. Østergaard has received an independent research grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) have a higher risk for stroke for up to 2 years compared with an age- and sex-matched population, after which their risks are comparable, results of a large Swiss registry study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 11,957 patients from the prospective SwissTAVI Registry, an ongoing mandatory cohort study enrolling consecutive patients undergoing TAVR in Switzerland.

- The study population, which had a mean age of 81.8 years and mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS PROM) of 4.62, with 11.8% having a history of cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and 32.3% a history of atrial fibrillation, underwent TAVR at 15 centers between February 2011 and June 2021.

- The primary outcome was the incidence of stroke, with secondary outcomes including the incidence of CVA, a composite of stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA).

- Researchers calculated standardized stroke ratios (SSRs) and compared stroke trends in patients undergoing TAVR with those of an age- and sex-matched general population in Switzerland derived from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study.

TAKEAWAY:

- , accounting for 69% of these events.

- After excluding 30-day events, the 1-year incidence rates of CVA and stroke were 1.7% and 1.4%, respectively, followed by an annual stroke incidence of 1.2%, 0.8%, 0.9%, and 0.7% in the second, third, fourth, and fifth years post TAVR, respectively.

- Only increased age and moderate/severe paravalvular leakage (PVL) at discharge were associated with an increased risk for early stroke (up to 30 days post TAVR), whereas dyslipidemia and history of atrial fibrillation and of CVA were associated with an increased risk for late stroke (30 days to 5 years after TAVR).

- SSR in the study population returned to a level comparable to that expected in the general Swiss population after 2 years and through to 5 years post-TAVR.

IN PRACTICE:

Although the study results “are reassuring” with respect to stroke risk beyond 2 years post TAVR, “our findings underscore the continued efforts of stroke-prevention measures” early and longer term, wrote the authors.

In an accompanying editorial, Lauge Østergaard, MD, PhD, Department of Cardiology, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, noted the study suggests reduced PVL could lower the risk for early stroke following TAVR and “highlights how assessment of usual risk factors (dyslipidemia and atrial fibrillation) could help reduce the burden of stroke in the long term.”

SOURCE:

The study was carried out by Taishi Okuno, MD, Department of Cardiology, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Switzerland, and colleagues. It was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC): Cardiovascular Interventions.

LIMITATIONS:

The study couldn’t investigate the association between antithrombotic regimens and the risk for CVA. Definitions of CVA in the SwissTAVI Registry might differ from those used in the GBD study from which the matched population data were derived. The general population wasn’t matched on comorbidities usually associated with elevated stroke risk, which may have led to underestimation of stroke. As the mean age in the study was 82 years, results may not be extrapolated to a younger population.

DISCLOSURES:

The SwissTAVI registry is supported by the Swiss Heart Foundation, Swiss Working Group of Interventional Cardiology and Acute Coronary Syndromes, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, Boston Scientific/Symetis, JenaValve, and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Okuno has no relevant conflicts of interest; see paper for disclosures of other study authors. Dr. Østergaard has received an independent research grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical Cannabis for Chronic Pain Tied to Arrhythmia Risk

TOPLINE:

, mainly atrial fibrillation/flutter, a Danish registry study suggested. Cannabis use has been associated with increased cardiovascular (CV) risk, but data on CV side effects with use of medical cannabis for chronic pain are limited.

METHODOLOGY:

- To investigate, researchers identified 5391 patients with chronic pain (median age 59; 63% women) initiating first-time treatment with medical cannabis during 2018-2021 and matched them (1:5) to 26,941 control patients on age, sex, chronic pain diagnosis, and concomitant use of other noncannabis pain medication.

- They calculated and compared absolute risks for first-time arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation/flutter, conduction disorders, paroxysmal tachycardias, and ventricular arrhythmias) and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) between groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Within 180 days, 42 medical cannabis users and 107 control participants developed arrhythmia, most commonly atrial fibrillation/flutter.

- Medical cannabis users had a slightly elevated risk for new-onset arrhythmia compared with nonusers (180-day absolute risk, 0.8% vs 0.4%).

- The 180-day risk ratio with cannabis use was 2.07 (95% CI, 1.34-2.80), and the 1-year risk ratio was 1.36 (95% CI, 1.00-1.73).

- Adults with cancer or cardiometabolic disease had the highest risk for arrhythmia with cannabis use (180-day absolute risk difference, 1.1% and 0.8%). There was no significant association between medical cannabis use and ACS risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“With the investigated cohort’s low age and low prevalence of comorbidity in mind, the notable relative risk increase of new-onset arrhythmia, mainly driven by atrial fibrillation/flutter, could be a reason for concern, albeit the absolute risks in this study population were modest,” the authors wrote.

“Medical cannabis may not be a ‘one-size-fits-all’ therapeutic option for certain medical conditions and should be contextualized based on patient comorbidities and potential vulnerability to side effects,” added the author of an editorial.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Anders Holt, MD, Copenhagen University and Herlev-Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, was published online on January 11, 2024, in the European Heart Journal, with an editorial by Robert Page II, PharmD, MSPH, University of Colorado, Aurora.

LIMITATIONS:

Residual confounding is possible. The registers lack information on disease severity, clinical measures, blood tests, and lifestyle factors. The route of cannabis administration was not known.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by external and independent medical research grants. Holt had no relevant disclosures. Some coauthors reported research grants and speakers’ fees from various drug companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, mainly atrial fibrillation/flutter, a Danish registry study suggested. Cannabis use has been associated with increased cardiovascular (CV) risk, but data on CV side effects with use of medical cannabis for chronic pain are limited.

METHODOLOGY:

- To investigate, researchers identified 5391 patients with chronic pain (median age 59; 63% women) initiating first-time treatment with medical cannabis during 2018-2021 and matched them (1:5) to 26,941 control patients on age, sex, chronic pain diagnosis, and concomitant use of other noncannabis pain medication.

- They calculated and compared absolute risks for first-time arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation/flutter, conduction disorders, paroxysmal tachycardias, and ventricular arrhythmias) and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) between groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Within 180 days, 42 medical cannabis users and 107 control participants developed arrhythmia, most commonly atrial fibrillation/flutter.

- Medical cannabis users had a slightly elevated risk for new-onset arrhythmia compared with nonusers (180-day absolute risk, 0.8% vs 0.4%).

- The 180-day risk ratio with cannabis use was 2.07 (95% CI, 1.34-2.80), and the 1-year risk ratio was 1.36 (95% CI, 1.00-1.73).

- Adults with cancer or cardiometabolic disease had the highest risk for arrhythmia with cannabis use (180-day absolute risk difference, 1.1% and 0.8%). There was no significant association between medical cannabis use and ACS risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“With the investigated cohort’s low age and low prevalence of comorbidity in mind, the notable relative risk increase of new-onset arrhythmia, mainly driven by atrial fibrillation/flutter, could be a reason for concern, albeit the absolute risks in this study population were modest,” the authors wrote.

“Medical cannabis may not be a ‘one-size-fits-all’ therapeutic option for certain medical conditions and should be contextualized based on patient comorbidities and potential vulnerability to side effects,” added the author of an editorial.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Anders Holt, MD, Copenhagen University and Herlev-Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, was published online on January 11, 2024, in the European Heart Journal, with an editorial by Robert Page II, PharmD, MSPH, University of Colorado, Aurora.

LIMITATIONS:

Residual confounding is possible. The registers lack information on disease severity, clinical measures, blood tests, and lifestyle factors. The route of cannabis administration was not known.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by external and independent medical research grants. Holt had no relevant disclosures. Some coauthors reported research grants and speakers’ fees from various drug companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, mainly atrial fibrillation/flutter, a Danish registry study suggested. Cannabis use has been associated with increased cardiovascular (CV) risk, but data on CV side effects with use of medical cannabis for chronic pain are limited.

METHODOLOGY:

- To investigate, researchers identified 5391 patients with chronic pain (median age 59; 63% women) initiating first-time treatment with medical cannabis during 2018-2021 and matched them (1:5) to 26,941 control patients on age, sex, chronic pain diagnosis, and concomitant use of other noncannabis pain medication.

- They calculated and compared absolute risks for first-time arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation/flutter, conduction disorders, paroxysmal tachycardias, and ventricular arrhythmias) and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) between groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Within 180 days, 42 medical cannabis users and 107 control participants developed arrhythmia, most commonly atrial fibrillation/flutter.

- Medical cannabis users had a slightly elevated risk for new-onset arrhythmia compared with nonusers (180-day absolute risk, 0.8% vs 0.4%).

- The 180-day risk ratio with cannabis use was 2.07 (95% CI, 1.34-2.80), and the 1-year risk ratio was 1.36 (95% CI, 1.00-1.73).

- Adults with cancer or cardiometabolic disease had the highest risk for arrhythmia with cannabis use (180-day absolute risk difference, 1.1% and 0.8%). There was no significant association between medical cannabis use and ACS risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“With the investigated cohort’s low age and low prevalence of comorbidity in mind, the notable relative risk increase of new-onset arrhythmia, mainly driven by atrial fibrillation/flutter, could be a reason for concern, albeit the absolute risks in this study population were modest,” the authors wrote.

“Medical cannabis may not be a ‘one-size-fits-all’ therapeutic option for certain medical conditions and should be contextualized based on patient comorbidities and potential vulnerability to side effects,” added the author of an editorial.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Anders Holt, MD, Copenhagen University and Herlev-Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, was published online on January 11, 2024, in the European Heart Journal, with an editorial by Robert Page II, PharmD, MSPH, University of Colorado, Aurora.

LIMITATIONS:

Residual confounding is possible. The registers lack information on disease severity, clinical measures, blood tests, and lifestyle factors. The route of cannabis administration was not known.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by external and independent medical research grants. Holt had no relevant disclosures. Some coauthors reported research grants and speakers’ fees from various drug companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

What’s the Disease Burden From Plastic Exposure?

Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) via daily use of plastics is a major contributor to the overall disease burden in the United States and the associated costs to society amount to more than 1% of the gross domestic product, revealed a large-scale analysis.

The research, published in the Journal of the Endocrine Society, indicated that taken together, the disease burden attributable to EDCs used in the manufacture of plastics added up to almost $250 billion in 2018 alone.

“The diseases due to plastics run the entire life course from preterm birth to obesity, heart disease, and cancers,” commented lead author Leonardo Trasande, MD, MPP, Jim G. Hendrick, MD Professor of Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, in a release.

“Our study drives home the need to address chemicals used in plastic materials” through global treaties and other policy initiatives, he said, so as to “reduce these costs” in line with reductions in exposure to the chemicals.

Co-author Michael Belliveau, Executive Director at Defend Our Health in Portland, ME, agreed, saying: “We can reduce these health costs and the prevalence of chronic endocrine diseases such as diabetes and obesity if governments and companies enact policies that minimize exposure to EDCs to protect public health and the environment.”

Plastics may contain any one of a number of EDCs, such as polybrominated diphenylethers in flame retardant additives, phthalates in food packaging, bisphenols in can linings, and perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in nonstick cooking utensils.

in developing fetuses and children, and even death.

In March 2022, the United Nations Environment Assembly committed to a global plastics treaty to “end plastic pollution and forge an international legally binding agreement by 2024” that “addresses the full life cycle of plastic, including its production, design and disposal.”

Minimizing EDC Exposure

But what can doctors tell their patients today to help them reduce their exposure to EDCs?

“There are safe and simple steps that people can take to limit their exposure to the chemicals of greatest concern,” Dr. Trasande told this news organization.

This can be partly achieved by reducing plastic use down to its essentials. “To use an example, when you are flying, fill up a stainless steel container after clearing security. At home, use glass or stainless steel” rather than plastic bottles or containers.

In particular, “avoiding microwaving plastic is important,” Dr. Trasande said, “even if a container says it’s microwave-safe.”

He warned that “many chemicals used in plastic are not covalently bound, and heat facilitates leaching into food. Microscopic contaminants can also get into food when you microwave plastic.”

Dr. Trasande also suggests limiting canned food consumption and avoiding cleaning plastic food containers in machine dishwashers.

Calculating the Disease Burden

To accurately assess the “the tradeoffs involved in the ongoing reliance on plastic production as a source of economic productivity,” the current researchers calculated the attributable disease burden and cost related to EDCs used in plastic materials in the United States in 2018.

Building on previously published analyses, they used industry reports, publications by national and international governing bodies, and peer-reviewed publications to determine the usage of each type of EDC and its attributable disease and disability burden.

This plastic-related fraction (PRF) of disease burden was then used to calculate an updated cost estimate for each EDC, based on the assumption that the disease burden is directly proportional to its exposure.

They found that for bisphenol A, 97.5% of its use, and therefore its estimated PRF of disease burden, was related to the manufacture of plastics, while this figure was 98%-100% for phthalates. For PDBE, 98% of its use was in plastics vs 93% for PFAS.

The researchers then estimated that the total plastic-attributable disease burden in the United States in 2018 cost the nation $249 billion, or 1.22% of the gross domestic product. Of this, $159 billion was linked to PDBE exposure, which is associated with diseases such as cancer.

Moreover, $1.02 billion plastic-attributable disease burden was associated with bisphenol A exposure, which can have potentially harmful health effects on the immune system; followed by $66.7 billion due to phthalates, which are linked to preterm birth, reduced sperm count, and childhood obesity; and $22.4 billion due to PFAS, which are associated with kidney failure and gestational diabetes.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Passport Foundation.

Dr. Trasande declared relationships with Audible, Houghton Mifflin, Paidos, and Kobunsha, none of which relate to the present manuscript.

No other financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) via daily use of plastics is a major contributor to the overall disease burden in the United States and the associated costs to society amount to more than 1% of the gross domestic product, revealed a large-scale analysis.

The research, published in the Journal of the Endocrine Society, indicated that taken together, the disease burden attributable to EDCs used in the manufacture of plastics added up to almost $250 billion in 2018 alone.

“The diseases due to plastics run the entire life course from preterm birth to obesity, heart disease, and cancers,” commented lead author Leonardo Trasande, MD, MPP, Jim G. Hendrick, MD Professor of Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, in a release.

“Our study drives home the need to address chemicals used in plastic materials” through global treaties and other policy initiatives, he said, so as to “reduce these costs” in line with reductions in exposure to the chemicals.

Co-author Michael Belliveau, Executive Director at Defend Our Health in Portland, ME, agreed, saying: “We can reduce these health costs and the prevalence of chronic endocrine diseases such as diabetes and obesity if governments and companies enact policies that minimize exposure to EDCs to protect public health and the environment.”

Plastics may contain any one of a number of EDCs, such as polybrominated diphenylethers in flame retardant additives, phthalates in food packaging, bisphenols in can linings, and perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in nonstick cooking utensils.

in developing fetuses and children, and even death.

In March 2022, the United Nations Environment Assembly committed to a global plastics treaty to “end plastic pollution and forge an international legally binding agreement by 2024” that “addresses the full life cycle of plastic, including its production, design and disposal.”

Minimizing EDC Exposure

But what can doctors tell their patients today to help them reduce their exposure to EDCs?

“There are safe and simple steps that people can take to limit their exposure to the chemicals of greatest concern,” Dr. Trasande told this news organization.

This can be partly achieved by reducing plastic use down to its essentials. “To use an example, when you are flying, fill up a stainless steel container after clearing security. At home, use glass or stainless steel” rather than plastic bottles or containers.

In particular, “avoiding microwaving plastic is important,” Dr. Trasande said, “even if a container says it’s microwave-safe.”

He warned that “many chemicals used in plastic are not covalently bound, and heat facilitates leaching into food. Microscopic contaminants can also get into food when you microwave plastic.”

Dr. Trasande also suggests limiting canned food consumption and avoiding cleaning plastic food containers in machine dishwashers.

Calculating the Disease Burden

To accurately assess the “the tradeoffs involved in the ongoing reliance on plastic production as a source of economic productivity,” the current researchers calculated the attributable disease burden and cost related to EDCs used in plastic materials in the United States in 2018.

Building on previously published analyses, they used industry reports, publications by national and international governing bodies, and peer-reviewed publications to determine the usage of each type of EDC and its attributable disease and disability burden.

This plastic-related fraction (PRF) of disease burden was then used to calculate an updated cost estimate for each EDC, based on the assumption that the disease burden is directly proportional to its exposure.

They found that for bisphenol A, 97.5% of its use, and therefore its estimated PRF of disease burden, was related to the manufacture of plastics, while this figure was 98%-100% for phthalates. For PDBE, 98% of its use was in plastics vs 93% for PFAS.

The researchers then estimated that the total plastic-attributable disease burden in the United States in 2018 cost the nation $249 billion, or 1.22% of the gross domestic product. Of this, $159 billion was linked to PDBE exposure, which is associated with diseases such as cancer.

Moreover, $1.02 billion plastic-attributable disease burden was associated with bisphenol A exposure, which can have potentially harmful health effects on the immune system; followed by $66.7 billion due to phthalates, which are linked to preterm birth, reduced sperm count, and childhood obesity; and $22.4 billion due to PFAS, which are associated with kidney failure and gestational diabetes.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Passport Foundation.

Dr. Trasande declared relationships with Audible, Houghton Mifflin, Paidos, and Kobunsha, none of which relate to the present manuscript.

No other financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) via daily use of plastics is a major contributor to the overall disease burden in the United States and the associated costs to society amount to more than 1% of the gross domestic product, revealed a large-scale analysis.

The research, published in the Journal of the Endocrine Society, indicated that taken together, the disease burden attributable to EDCs used in the manufacture of plastics added up to almost $250 billion in 2018 alone.

“The diseases due to plastics run the entire life course from preterm birth to obesity, heart disease, and cancers,” commented lead author Leonardo Trasande, MD, MPP, Jim G. Hendrick, MD Professor of Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, in a release.

“Our study drives home the need to address chemicals used in plastic materials” through global treaties and other policy initiatives, he said, so as to “reduce these costs” in line with reductions in exposure to the chemicals.

Co-author Michael Belliveau, Executive Director at Defend Our Health in Portland, ME, agreed, saying: “We can reduce these health costs and the prevalence of chronic endocrine diseases such as diabetes and obesity if governments and companies enact policies that minimize exposure to EDCs to protect public health and the environment.”

Plastics may contain any one of a number of EDCs, such as polybrominated diphenylethers in flame retardant additives, phthalates in food packaging, bisphenols in can linings, and perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in nonstick cooking utensils.

in developing fetuses and children, and even death.

In March 2022, the United Nations Environment Assembly committed to a global plastics treaty to “end plastic pollution and forge an international legally binding agreement by 2024” that “addresses the full life cycle of plastic, including its production, design and disposal.”

Minimizing EDC Exposure

But what can doctors tell their patients today to help them reduce their exposure to EDCs?

“There are safe and simple steps that people can take to limit their exposure to the chemicals of greatest concern,” Dr. Trasande told this news organization.