User login

More conclusive link needed on teratogenicity and atypicals in pregnancy

CHICAGO – If you’re currently treating any pregnant patients who are taking atypical antipsychotics, Dr. Marlene P. Freeman and her colleagues, who’ve started a national registry for tracking these data, hope to hear from you.

"We also need information not just on patients who are taking antipsychotics but also on those who aren’t, so that we can expand the number of controls," Dr. Freeman said in an interview during Psychiatry Update 2014, cosponsored by the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists and Current Psychiatry.

"Our registry is carefully, prospectively done," said Dr. Freeman while speaking at the meeting. "It’s all done by phone, with two calls during pregnancy and one post partum."

Findings based on data collected before June 2013 and presented at a teratogenicity meeting last year were "not unblinded in terms of what medications were associated with what outcomes or who the controls were," she said. However, so far the trend is that antipsychotic use isn’t likely going to turn out to be as adverse as valproic acid, the anticonvulsant that ultimately was found associated with teratogenicity, said Dr. Freeman, who is the clinical director of Women’s Mental Health Center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where the registry is housed. "Rates of malformations [found in the registry data so far] were at or below the rates in the general population," she said, adding that definitive results are still needed.

At this time, more than 400 patients are enrolled in the registry, which began in 2011 in an effort to build a definitive database on teratogenicity and atypicals in pregnancy. According to Dr. Freeman, a German study published recently showed no significant difference between rates of major malformations between those exposed to first-generation antipsychotics or second-generation atypicals during the first trimester (J. Clin. Psychopharm. 2013;33:453-62). However, compared with controls, the major malformation rate was just over two times greater among those exposed to atypicals.

Meanwhile, a prospective Canadian study also cited by Dr. Freeman did not find a significant difference in congenital malformations between children born to mothers taking atypicals, compared with controls (BMJ Open 2013;3:e003062 [doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003062]).

According to Dr. Freeman, the need for clear, substantial data is important, because the use of atypicals in pregnancy is on the rise. A study published last year and cited by Dr. Freeman found that among 585,615 U.S. deliveries that occurred during 2001-2007 with prescriptions dispensed to the mother between 60 days before or on the date of delivery, 0.72% received an atypical antipsychotic and 0.09% received a typical antipsychotic (Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2013;16:149-57). There was a 2.5-fold increase in atypicals prescribed over the course of the study period. Depression was the most common mental health diagnosis (63%), followed by bipolar disorder (43%), and schizophrenia (13%).

Dr. Freeman disclosed she has industry relationships with GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda/Lundbeck, and Genentech, among others. Current Psychiatry and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

For more information on the National Pregnancy Registry, click here.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CHICAGO – If you’re currently treating any pregnant patients who are taking atypical antipsychotics, Dr. Marlene P. Freeman and her colleagues, who’ve started a national registry for tracking these data, hope to hear from you.

"We also need information not just on patients who are taking antipsychotics but also on those who aren’t, so that we can expand the number of controls," Dr. Freeman said in an interview during Psychiatry Update 2014, cosponsored by the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists and Current Psychiatry.

"Our registry is carefully, prospectively done," said Dr. Freeman while speaking at the meeting. "It’s all done by phone, with two calls during pregnancy and one post partum."

Findings based on data collected before June 2013 and presented at a teratogenicity meeting last year were "not unblinded in terms of what medications were associated with what outcomes or who the controls were," she said. However, so far the trend is that antipsychotic use isn’t likely going to turn out to be as adverse as valproic acid, the anticonvulsant that ultimately was found associated with teratogenicity, said Dr. Freeman, who is the clinical director of Women’s Mental Health Center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where the registry is housed. "Rates of malformations [found in the registry data so far] were at or below the rates in the general population," she said, adding that definitive results are still needed.

At this time, more than 400 patients are enrolled in the registry, which began in 2011 in an effort to build a definitive database on teratogenicity and atypicals in pregnancy. According to Dr. Freeman, a German study published recently showed no significant difference between rates of major malformations between those exposed to first-generation antipsychotics or second-generation atypicals during the first trimester (J. Clin. Psychopharm. 2013;33:453-62). However, compared with controls, the major malformation rate was just over two times greater among those exposed to atypicals.

Meanwhile, a prospective Canadian study also cited by Dr. Freeman did not find a significant difference in congenital malformations between children born to mothers taking atypicals, compared with controls (BMJ Open 2013;3:e003062 [doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003062]).

According to Dr. Freeman, the need for clear, substantial data is important, because the use of atypicals in pregnancy is on the rise. A study published last year and cited by Dr. Freeman found that among 585,615 U.S. deliveries that occurred during 2001-2007 with prescriptions dispensed to the mother between 60 days before or on the date of delivery, 0.72% received an atypical antipsychotic and 0.09% received a typical antipsychotic (Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2013;16:149-57). There was a 2.5-fold increase in atypicals prescribed over the course of the study period. Depression was the most common mental health diagnosis (63%), followed by bipolar disorder (43%), and schizophrenia (13%).

Dr. Freeman disclosed she has industry relationships with GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda/Lundbeck, and Genentech, among others. Current Psychiatry and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

For more information on the National Pregnancy Registry, click here.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CHICAGO – If you’re currently treating any pregnant patients who are taking atypical antipsychotics, Dr. Marlene P. Freeman and her colleagues, who’ve started a national registry for tracking these data, hope to hear from you.

"We also need information not just on patients who are taking antipsychotics but also on those who aren’t, so that we can expand the number of controls," Dr. Freeman said in an interview during Psychiatry Update 2014, cosponsored by the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists and Current Psychiatry.

"Our registry is carefully, prospectively done," said Dr. Freeman while speaking at the meeting. "It’s all done by phone, with two calls during pregnancy and one post partum."

Findings based on data collected before June 2013 and presented at a teratogenicity meeting last year were "not unblinded in terms of what medications were associated with what outcomes or who the controls were," she said. However, so far the trend is that antipsychotic use isn’t likely going to turn out to be as adverse as valproic acid, the anticonvulsant that ultimately was found associated with teratogenicity, said Dr. Freeman, who is the clinical director of Women’s Mental Health Center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where the registry is housed. "Rates of malformations [found in the registry data so far] were at or below the rates in the general population," she said, adding that definitive results are still needed.

At this time, more than 400 patients are enrolled in the registry, which began in 2011 in an effort to build a definitive database on teratogenicity and atypicals in pregnancy. According to Dr. Freeman, a German study published recently showed no significant difference between rates of major malformations between those exposed to first-generation antipsychotics or second-generation atypicals during the first trimester (J. Clin. Psychopharm. 2013;33:453-62). However, compared with controls, the major malformation rate was just over two times greater among those exposed to atypicals.

Meanwhile, a prospective Canadian study also cited by Dr. Freeman did not find a significant difference in congenital malformations between children born to mothers taking atypicals, compared with controls (BMJ Open 2013;3:e003062 [doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003062]).

According to Dr. Freeman, the need for clear, substantial data is important, because the use of atypicals in pregnancy is on the rise. A study published last year and cited by Dr. Freeman found that among 585,615 U.S. deliveries that occurred during 2001-2007 with prescriptions dispensed to the mother between 60 days before or on the date of delivery, 0.72% received an atypical antipsychotic and 0.09% received a typical antipsychotic (Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2013;16:149-57). There was a 2.5-fold increase in atypicals prescribed over the course of the study period. Depression was the most common mental health diagnosis (63%), followed by bipolar disorder (43%), and schizophrenia (13%).

Dr. Freeman disclosed she has industry relationships with GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda/Lundbeck, and Genentech, among others. Current Psychiatry and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

For more information on the National Pregnancy Registry, click here.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PSYCHIATRY UPDATE 2014

Tobacco use tied to 53% of deaths in schizophrenia patients

Patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression have a significantly increased risk of tobacco-related mortality.

Among more than 591,000 such patients, tobacco-related deaths were about doubled, compared with the general population, Russell C. Callaghan, Ph.D., and his colleagues reported (J. Psych. Res. 2014;48:102-10).

In the study, the researchers analyzed the death records of patients who had been hospitalized with an ICD-9 primary psychiatric diagnosis in California between 1990 and 2005. Mortality estimates for conditions related to tobacco use comprised 53% of the total deaths in the schizophrenia cohort, 48% of deaths in the bipolar cohort, and 50% in the depression cohort, wrote Dr. Callaghan, associate professor in the Northern Medical Program at the University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, and his associates.

The SMRs (standardized mortality ratios) for tobacco-related conditions were 2.45 for those in the schizophrenia group, 1.57 for the bipolar cohort, and 1.95 for the depression cohort. Cancer deaths were elevated among those with schizophrenia and depression, with SMRs of 1.3 among those with schizophrenia and 1.22 among those with depression. The risk was not increased among those with bipolar disorder, a finding that the investigators found to be surprising.

In addition, the schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression groups all had increased rates of cardiovascular disease (SMRs of 2.46, 1.56, and 1.95, respectively). They also showed significantly higher SMRs for respiratory diseases (3.7, 2.4, and 2.7), wrote Dr. Callaghan, who also is affiliated with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, and his associates.

Two factors are probably driving the excess mortality, they noted: insufficient tobacco use counseling and treatment, and the absence of regular cancer screenings.

The investigators cited several limitations. Because their cohort assignment algorithm "relied upon inpatient ICD-9 diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression," the sample is based on those with fairly severe illness and might not have included those who had limited access to care. In addition, the medical records that were examined did not include information about the "presence, frequency, intensity, or duration of tobacco use," they wrote.

Despite those limitations, the findings suggest that addressing tobacco use in those groups is a "critical clinical and public health concern," they said.

"Our results stand as a call for increased recognition of the full harmful impact of tobacco use in these populations, as well as the urgent need to develop and implement strategies to reduce tobacco-related harms," Dr. Callaghan and his associates wrote.

The study was sponsored by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression have a significantly increased risk of tobacco-related mortality.

Among more than 591,000 such patients, tobacco-related deaths were about doubled, compared with the general population, Russell C. Callaghan, Ph.D., and his colleagues reported (J. Psych. Res. 2014;48:102-10).

In the study, the researchers analyzed the death records of patients who had been hospitalized with an ICD-9 primary psychiatric diagnosis in California between 1990 and 2005. Mortality estimates for conditions related to tobacco use comprised 53% of the total deaths in the schizophrenia cohort, 48% of deaths in the bipolar cohort, and 50% in the depression cohort, wrote Dr. Callaghan, associate professor in the Northern Medical Program at the University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, and his associates.

The SMRs (standardized mortality ratios) for tobacco-related conditions were 2.45 for those in the schizophrenia group, 1.57 for the bipolar cohort, and 1.95 for the depression cohort. Cancer deaths were elevated among those with schizophrenia and depression, with SMRs of 1.3 among those with schizophrenia and 1.22 among those with depression. The risk was not increased among those with bipolar disorder, a finding that the investigators found to be surprising.

In addition, the schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression groups all had increased rates of cardiovascular disease (SMRs of 2.46, 1.56, and 1.95, respectively). They also showed significantly higher SMRs for respiratory diseases (3.7, 2.4, and 2.7), wrote Dr. Callaghan, who also is affiliated with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, and his associates.

Two factors are probably driving the excess mortality, they noted: insufficient tobacco use counseling and treatment, and the absence of regular cancer screenings.

The investigators cited several limitations. Because their cohort assignment algorithm "relied upon inpatient ICD-9 diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression," the sample is based on those with fairly severe illness and might not have included those who had limited access to care. In addition, the medical records that were examined did not include information about the "presence, frequency, intensity, or duration of tobacco use," they wrote.

Despite those limitations, the findings suggest that addressing tobacco use in those groups is a "critical clinical and public health concern," they said.

"Our results stand as a call for increased recognition of the full harmful impact of tobacco use in these populations, as well as the urgent need to develop and implement strategies to reduce tobacco-related harms," Dr. Callaghan and his associates wrote.

The study was sponsored by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression have a significantly increased risk of tobacco-related mortality.

Among more than 591,000 such patients, tobacco-related deaths were about doubled, compared with the general population, Russell C. Callaghan, Ph.D., and his colleagues reported (J. Psych. Res. 2014;48:102-10).

In the study, the researchers analyzed the death records of patients who had been hospitalized with an ICD-9 primary psychiatric diagnosis in California between 1990 and 2005. Mortality estimates for conditions related to tobacco use comprised 53% of the total deaths in the schizophrenia cohort, 48% of deaths in the bipolar cohort, and 50% in the depression cohort, wrote Dr. Callaghan, associate professor in the Northern Medical Program at the University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, and his associates.

The SMRs (standardized mortality ratios) for tobacco-related conditions were 2.45 for those in the schizophrenia group, 1.57 for the bipolar cohort, and 1.95 for the depression cohort. Cancer deaths were elevated among those with schizophrenia and depression, with SMRs of 1.3 among those with schizophrenia and 1.22 among those with depression. The risk was not increased among those with bipolar disorder, a finding that the investigators found to be surprising.

In addition, the schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression groups all had increased rates of cardiovascular disease (SMRs of 2.46, 1.56, and 1.95, respectively). They also showed significantly higher SMRs for respiratory diseases (3.7, 2.4, and 2.7), wrote Dr. Callaghan, who also is affiliated with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, and his associates.

Two factors are probably driving the excess mortality, they noted: insufficient tobacco use counseling and treatment, and the absence of regular cancer screenings.

The investigators cited several limitations. Because their cohort assignment algorithm "relied upon inpatient ICD-9 diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression," the sample is based on those with fairly severe illness and might not have included those who had limited access to care. In addition, the medical records that were examined did not include information about the "presence, frequency, intensity, or duration of tobacco use," they wrote.

Despite those limitations, the findings suggest that addressing tobacco use in those groups is a "critical clinical and public health concern," they said.

"Our results stand as a call for increased recognition of the full harmful impact of tobacco use in these populations, as well as the urgent need to develop and implement strategies to reduce tobacco-related harms," Dr. Callaghan and his associates wrote.

The study was sponsored by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

Major finding: The standardized mortality ratios for tobacco-related conditions were 2.45 for those in the schizophrenia group, 1.57 for the bipolar cohort, and 1.95 for the depression cohort.

Data source: The review included data on more than 591,000 patients extracted from California state records from 1990 to 2005.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Three key subdimensions of mania identified, validated

Mania, the defining feature of bipolar disorder, is not the monolithic entity it is portrayed to be in the DSM-5, but instead has at least three distinct "subdimensions" that distinguish it from other mental disorders, according to a report in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Researchers who found the DSM-5 portrayal of mania to be "unidimensional" and "misleading" sought to establish a more nuanced characterization by using detailed clinical interviews of 422 psychiatric outpatients to identify the key features unique to mania. These patients, predominantly women with a mean age of 42 years, were currently receiving mental health treatment; 17% had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and 6% were in a manic episode at the time of the interview, said Camilo J. Ruggero, Ph.D., of the department of psychology, University of North Texas, Denton, and his associates.

Using the Interview for Mood and Anxiety Symptoms; the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders; the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, Expanded Version; the Global Assessment of Functioning; and the Sheehan Disability Scale, the investigators identified three subdimensions that consistently characterized mania and distinguished it from other disorders: euphoric activation, which reflected increased energy; hyperactive cognition, which reflected flight of ideas, pressured speech, and distractibility; and reckless overconfidence, which reflected extreme overconfidence and resulting poor judgment and recklessness. The latter subdimension is similar to grandiosity but not necessarily delusional. A fourth subdimension, irritability, also was characteristic of mania but was not as unique to it as were the other three, since it can also occur in depression and other disorders (J. Affect. Disord. 2014;161:8-15).

After creating an instrument to reflect these four subdimensions of mania, Dr. Ruggero and his associates validated their findings in clinical interviews with a separate study population: 306 student volunteers who had a history of mental health treatment, 31% of whom were currently in treatment. All four subdimensions were highly prevalent in patients who had mania but not in those with other disorders.

Identifying these key subdimensions could elucidate the etiology of bipolar disorder. And, instead of focusing on "the higher-order syndrome" of mania, highlighting these subdimensions might help resolve discrepancies in results from pathophysiologic studies, since different facets of mania might reflect different pathophysiological processes, the researchers noted.

"Moreover, assessing distinct types of symptoms has important clinical implications; not all subdimensions affect functioning equally." For example, in these two patient populations, euphoric activation had little impact on participants’ daily functioning, compared with other symptoms, the researchers added.

Dr. Ruggero and his associates cited several limitations. Neither psychotic nor depressive symptoms were included in their analyses. Also, a few of the patients were in a current manic episode at the time of the study. Despite those limitations, their study "provides important new findings about mania. Future work can use these dimensions ... to better discern the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder," they wrote.

This work was supported in part by the Feldstein Medical Foundation. Dr. Ruggero and his associates reported no conflicts of interest.

Mania, the defining feature of bipolar disorder, is not the monolithic entity it is portrayed to be in the DSM-5, but instead has at least three distinct "subdimensions" that distinguish it from other mental disorders, according to a report in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Researchers who found the DSM-5 portrayal of mania to be "unidimensional" and "misleading" sought to establish a more nuanced characterization by using detailed clinical interviews of 422 psychiatric outpatients to identify the key features unique to mania. These patients, predominantly women with a mean age of 42 years, were currently receiving mental health treatment; 17% had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and 6% were in a manic episode at the time of the interview, said Camilo J. Ruggero, Ph.D., of the department of psychology, University of North Texas, Denton, and his associates.

Using the Interview for Mood and Anxiety Symptoms; the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders; the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, Expanded Version; the Global Assessment of Functioning; and the Sheehan Disability Scale, the investigators identified three subdimensions that consistently characterized mania and distinguished it from other disorders: euphoric activation, which reflected increased energy; hyperactive cognition, which reflected flight of ideas, pressured speech, and distractibility; and reckless overconfidence, which reflected extreme overconfidence and resulting poor judgment and recklessness. The latter subdimension is similar to grandiosity but not necessarily delusional. A fourth subdimension, irritability, also was characteristic of mania but was not as unique to it as were the other three, since it can also occur in depression and other disorders (J. Affect. Disord. 2014;161:8-15).

After creating an instrument to reflect these four subdimensions of mania, Dr. Ruggero and his associates validated their findings in clinical interviews with a separate study population: 306 student volunteers who had a history of mental health treatment, 31% of whom were currently in treatment. All four subdimensions were highly prevalent in patients who had mania but not in those with other disorders.

Identifying these key subdimensions could elucidate the etiology of bipolar disorder. And, instead of focusing on "the higher-order syndrome" of mania, highlighting these subdimensions might help resolve discrepancies in results from pathophysiologic studies, since different facets of mania might reflect different pathophysiological processes, the researchers noted.

"Moreover, assessing distinct types of symptoms has important clinical implications; not all subdimensions affect functioning equally." For example, in these two patient populations, euphoric activation had little impact on participants’ daily functioning, compared with other symptoms, the researchers added.

Dr. Ruggero and his associates cited several limitations. Neither psychotic nor depressive symptoms were included in their analyses. Also, a few of the patients were in a current manic episode at the time of the study. Despite those limitations, their study "provides important new findings about mania. Future work can use these dimensions ... to better discern the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder," they wrote.

This work was supported in part by the Feldstein Medical Foundation. Dr. Ruggero and his associates reported no conflicts of interest.

Mania, the defining feature of bipolar disorder, is not the monolithic entity it is portrayed to be in the DSM-5, but instead has at least three distinct "subdimensions" that distinguish it from other mental disorders, according to a report in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Researchers who found the DSM-5 portrayal of mania to be "unidimensional" and "misleading" sought to establish a more nuanced characterization by using detailed clinical interviews of 422 psychiatric outpatients to identify the key features unique to mania. These patients, predominantly women with a mean age of 42 years, were currently receiving mental health treatment; 17% had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and 6% were in a manic episode at the time of the interview, said Camilo J. Ruggero, Ph.D., of the department of psychology, University of North Texas, Denton, and his associates.

Using the Interview for Mood and Anxiety Symptoms; the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders; the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, Expanded Version; the Global Assessment of Functioning; and the Sheehan Disability Scale, the investigators identified three subdimensions that consistently characterized mania and distinguished it from other disorders: euphoric activation, which reflected increased energy; hyperactive cognition, which reflected flight of ideas, pressured speech, and distractibility; and reckless overconfidence, which reflected extreme overconfidence and resulting poor judgment and recklessness. The latter subdimension is similar to grandiosity but not necessarily delusional. A fourth subdimension, irritability, also was characteristic of mania but was not as unique to it as were the other three, since it can also occur in depression and other disorders (J. Affect. Disord. 2014;161:8-15).

After creating an instrument to reflect these four subdimensions of mania, Dr. Ruggero and his associates validated their findings in clinical interviews with a separate study population: 306 student volunteers who had a history of mental health treatment, 31% of whom were currently in treatment. All four subdimensions were highly prevalent in patients who had mania but not in those with other disorders.

Identifying these key subdimensions could elucidate the etiology of bipolar disorder. And, instead of focusing on "the higher-order syndrome" of mania, highlighting these subdimensions might help resolve discrepancies in results from pathophysiologic studies, since different facets of mania might reflect different pathophysiological processes, the researchers noted.

"Moreover, assessing distinct types of symptoms has important clinical implications; not all subdimensions affect functioning equally." For example, in these two patient populations, euphoric activation had little impact on participants’ daily functioning, compared with other symptoms, the researchers added.

Dr. Ruggero and his associates cited several limitations. Neither psychotic nor depressive symptoms were included in their analyses. Also, a few of the patients were in a current manic episode at the time of the study. Despite those limitations, their study "provides important new findings about mania. Future work can use these dimensions ... to better discern the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder," they wrote.

This work was supported in part by the Feldstein Medical Foundation. Dr. Ruggero and his associates reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Major finding: Three subdimensions of mania consistently characterize the disorder and distinguish it from other mental disorders: euphoric activation, which reflects increased energy; hyperactive cognition, which reflects flight of ideas, pressured speech, and distractibility; and reckless overconfidence, which reflects extreme overconfidence and the resulting poor judgment and recklessness. The latter is similar to grandiosity but is not necessarily delusional.

Data source: Clinical interviews with 422 psychiatric outpatients to identify subdimensions that are specific to mania, and separate interviews with 306 students with a history of mental health treatment to validate that four subdimensions characterize mania.

Disclosures: This work was supported in part by the Feldstein Medical Foundation. Dr. Ruggero and his associates reported no conflicts of interest.

Suicide at higher altitudes linked to bipolar disorder

Persons who committed suicide and lived at higher altitudes were significantly more likely to have bipolar disorder, compared with depression, schizophrenia, or anxiety disorders, researchers reported in the April issue of Medical Hypotheses.

Past research has found an association between altitude and suicide, even after controlling for gun ownership, rurality, age, and mental health access. The current study indicates that altitude preferentially affects suicide in bipolar disorder, said Rebekah S. Huber, a researcher at the University of Utah Brain Institute, Salt Lake City, and her associates.

The researchers performed random coefficient logistic regression modeling and least squares means on data for 35,725 suicides in 16 states and 809 counties that occurred during 2005-2008 and were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Violent Death Reporting System. The investigators assigned every decedent a single major diagnosis of bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, or anxiety disorder, and excluded infrequent diagnoses such as posttraumatic stress disorder or eating disorder.

Living at higher altitude was significantly associated with having coefficient (P = .004) and logistic regression (P = .001) models. Persons with bipolar disorder committed suicide at a higher mean altitude (1,205 meters) than did decedents with anxiety disorders (1,181), major depressive disorder (1,116), or schizophrenia (1,057).

The reason for the effect merits further study but might be tied to underlying mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder, lower levels of environmental lithium at higher altitudes, or diminished efficacy of bipolar disorder treatments at higher elevations, the investigators said (Med. Hypotheses 2014;82:377-81).

"Metabolic stress due to hypoxia may have important considerations for individuals with [bipolar disorder]," they added. "Hypoxia due to reduced oxygen partial pressure at higher altitudes may further decrease mitochondrial function in individuals with BD. For these individuals, metabolic changes associated with hypoxia may lead to depression, instability of mood, and increased risk of suicide."

The researchers cited several limitations. For example, the findings are based on results from far less than half of the 50 states, but "many states in the intermountain West are included," they wrote.

The VISN 19 Mental Illness Research and Education Center, the Utah Science Technology and Research Initiative, and the National Institutes of Health funded the research. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Persons who committed suicide and lived at higher altitudes were significantly more likely to have bipolar disorder, compared with depression, schizophrenia, or anxiety disorders, researchers reported in the April issue of Medical Hypotheses.

Past research has found an association between altitude and suicide, even after controlling for gun ownership, rurality, age, and mental health access. The current study indicates that altitude preferentially affects suicide in bipolar disorder, said Rebekah S. Huber, a researcher at the University of Utah Brain Institute, Salt Lake City, and her associates.

The researchers performed random coefficient logistic regression modeling and least squares means on data for 35,725 suicides in 16 states and 809 counties that occurred during 2005-2008 and were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Violent Death Reporting System. The investigators assigned every decedent a single major diagnosis of bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, or anxiety disorder, and excluded infrequent diagnoses such as posttraumatic stress disorder or eating disorder.

Living at higher altitude was significantly associated with having coefficient (P = .004) and logistic regression (P = .001) models. Persons with bipolar disorder committed suicide at a higher mean altitude (1,205 meters) than did decedents with anxiety disorders (1,181), major depressive disorder (1,116), or schizophrenia (1,057).

The reason for the effect merits further study but might be tied to underlying mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder, lower levels of environmental lithium at higher altitudes, or diminished efficacy of bipolar disorder treatments at higher elevations, the investigators said (Med. Hypotheses 2014;82:377-81).

"Metabolic stress due to hypoxia may have important considerations for individuals with [bipolar disorder]," they added. "Hypoxia due to reduced oxygen partial pressure at higher altitudes may further decrease mitochondrial function in individuals with BD. For these individuals, metabolic changes associated with hypoxia may lead to depression, instability of mood, and increased risk of suicide."

The researchers cited several limitations. For example, the findings are based on results from far less than half of the 50 states, but "many states in the intermountain West are included," they wrote.

The VISN 19 Mental Illness Research and Education Center, the Utah Science Technology and Research Initiative, and the National Institutes of Health funded the research. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Persons who committed suicide and lived at higher altitudes were significantly more likely to have bipolar disorder, compared with depression, schizophrenia, or anxiety disorders, researchers reported in the April issue of Medical Hypotheses.

Past research has found an association between altitude and suicide, even after controlling for gun ownership, rurality, age, and mental health access. The current study indicates that altitude preferentially affects suicide in bipolar disorder, said Rebekah S. Huber, a researcher at the University of Utah Brain Institute, Salt Lake City, and her associates.

The researchers performed random coefficient logistic regression modeling and least squares means on data for 35,725 suicides in 16 states and 809 counties that occurred during 2005-2008 and were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Violent Death Reporting System. The investigators assigned every decedent a single major diagnosis of bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, or anxiety disorder, and excluded infrequent diagnoses such as posttraumatic stress disorder or eating disorder.

Living at higher altitude was significantly associated with having coefficient (P = .004) and logistic regression (P = .001) models. Persons with bipolar disorder committed suicide at a higher mean altitude (1,205 meters) than did decedents with anxiety disorders (1,181), major depressive disorder (1,116), or schizophrenia (1,057).

The reason for the effect merits further study but might be tied to underlying mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder, lower levels of environmental lithium at higher altitudes, or diminished efficacy of bipolar disorder treatments at higher elevations, the investigators said (Med. Hypotheses 2014;82:377-81).

"Metabolic stress due to hypoxia may have important considerations for individuals with [bipolar disorder]," they added. "Hypoxia due to reduced oxygen partial pressure at higher altitudes may further decrease mitochondrial function in individuals with BD. For these individuals, metabolic changes associated with hypoxia may lead to depression, instability of mood, and increased risk of suicide."

The researchers cited several limitations. For example, the findings are based on results from far less than half of the 50 states, but "many states in the intermountain West are included," they wrote.

The VISN 19 Mental Illness Research and Education Center, the Utah Science Technology and Research Initiative, and the National Institutes of Health funded the research. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM MEDICAL HYPOTHESES

Major finding: Among persons who committed suicide, living at higher altitude was significantly associated with having bipolar disorder instead of another mental health diagnosis in both random coefficient (P = .004) and logistic regression (P = .001) models.

Data source: The study looked at 12,861 suicides by persons with mental health diagnoses reported to the National Violent Death Reporting System. Decedents lived in 16 states and committed suicide during 2005-2008.

Disclosures: The VISN 19 Mental Illness Research and Education Center, the Utah Science Technology and Research Initiative, and the National Institutes of Health funded the research. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Asenapine often beneficial in geriatric bipolar disorder

ORLANDO – Low-dose asenapine provided global improvement in symptoms and mood in older nondemented patients with bipolar disorder with prior suboptimal response to other therapies, according to a pilot study.

This atypical antipsychotic agent, which was used in the study at a mean daily dose of just 7.4 mg, is a novel therapy worth considering in selected geriatric patients with bipolar disorder, Dr. Martha N. Sajatovic said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

She presented a 12-week, prospective, open-label pilot study of asenapine (Saphris) in 15 nondemented patients over age 60 years with type 1 or 2 bipolar disorder who had a poor response to previous treatments. Patients started on asenapine at 5 mg/day and were titrated as indicated to a maximum of 20 mg/day, although the mean dose used was 7.4 mg/day.

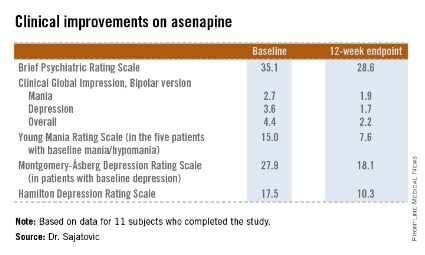

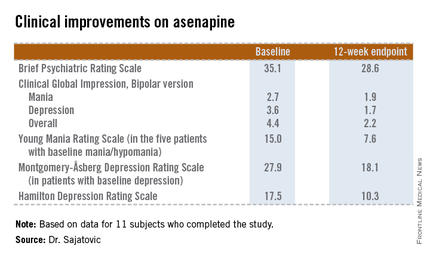

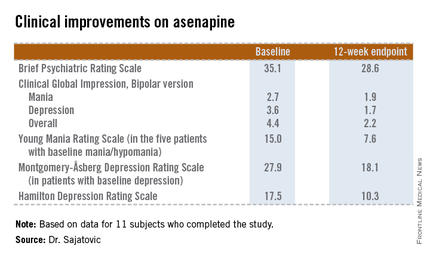

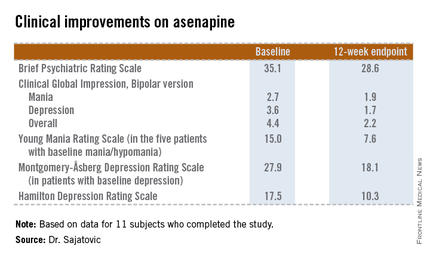

The 11 subjects who completed the study showed significant improvements on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, on the Clinical Global Impression, Bipolar version, and on measures of mood symptoms. No changes were found from baseline in terms of mean body mass index, abnormal movement scores, blood glucose levels, lipid levels, or functional status as measured by the Short Form–12, or on the WHO-Disability Assessment Scale II.

Of the four study dropouts, one left because of elevated liver function test results, another because of the emergence of manic symptoms while on asenapine, and two others for reasons unrelated to the study medication, according to Dr. Sajatovic, professor of psychiatry and director of the geropsychiatry program at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse event was mild, transient GI discomfort, which affected one-third of participants.

The addition of asenapine to the armamentarium for bipolar disorder in later life is a welcome development, she said. Of the 6 million American adults with bipolar disorder, roughly 1 million are over the age of 60. Traditional mood stabilizers such as lithium often have limiting side effects in the older population, and treatment failures are common, she noted.

This pilot study was sponsored by NV Organon/Merck. Dr. Satajovic reported receiving research grants from Merck and other companies, as well as serving as a consultant to Prophase, Otsuka, Pfizer, Amgen, and United BioSource.

ORLANDO – Low-dose asenapine provided global improvement in symptoms and mood in older nondemented patients with bipolar disorder with prior suboptimal response to other therapies, according to a pilot study.

This atypical antipsychotic agent, which was used in the study at a mean daily dose of just 7.4 mg, is a novel therapy worth considering in selected geriatric patients with bipolar disorder, Dr. Martha N. Sajatovic said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

She presented a 12-week, prospective, open-label pilot study of asenapine (Saphris) in 15 nondemented patients over age 60 years with type 1 or 2 bipolar disorder who had a poor response to previous treatments. Patients started on asenapine at 5 mg/day and were titrated as indicated to a maximum of 20 mg/day, although the mean dose used was 7.4 mg/day.

The 11 subjects who completed the study showed significant improvements on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, on the Clinical Global Impression, Bipolar version, and on measures of mood symptoms. No changes were found from baseline in terms of mean body mass index, abnormal movement scores, blood glucose levels, lipid levels, or functional status as measured by the Short Form–12, or on the WHO-Disability Assessment Scale II.

Of the four study dropouts, one left because of elevated liver function test results, another because of the emergence of manic symptoms while on asenapine, and two others for reasons unrelated to the study medication, according to Dr. Sajatovic, professor of psychiatry and director of the geropsychiatry program at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse event was mild, transient GI discomfort, which affected one-third of participants.

The addition of asenapine to the armamentarium for bipolar disorder in later life is a welcome development, she said. Of the 6 million American adults with bipolar disorder, roughly 1 million are over the age of 60. Traditional mood stabilizers such as lithium often have limiting side effects in the older population, and treatment failures are common, she noted.

This pilot study was sponsored by NV Organon/Merck. Dr. Satajovic reported receiving research grants from Merck and other companies, as well as serving as a consultant to Prophase, Otsuka, Pfizer, Amgen, and United BioSource.

ORLANDO – Low-dose asenapine provided global improvement in symptoms and mood in older nondemented patients with bipolar disorder with prior suboptimal response to other therapies, according to a pilot study.

This atypical antipsychotic agent, which was used in the study at a mean daily dose of just 7.4 mg, is a novel therapy worth considering in selected geriatric patients with bipolar disorder, Dr. Martha N. Sajatovic said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

She presented a 12-week, prospective, open-label pilot study of asenapine (Saphris) in 15 nondemented patients over age 60 years with type 1 or 2 bipolar disorder who had a poor response to previous treatments. Patients started on asenapine at 5 mg/day and were titrated as indicated to a maximum of 20 mg/day, although the mean dose used was 7.4 mg/day.

The 11 subjects who completed the study showed significant improvements on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, on the Clinical Global Impression, Bipolar version, and on measures of mood symptoms. No changes were found from baseline in terms of mean body mass index, abnormal movement scores, blood glucose levels, lipid levels, or functional status as measured by the Short Form–12, or on the WHO-Disability Assessment Scale II.

Of the four study dropouts, one left because of elevated liver function test results, another because of the emergence of manic symptoms while on asenapine, and two others for reasons unrelated to the study medication, according to Dr. Sajatovic, professor of psychiatry and director of the geropsychiatry program at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse event was mild, transient GI discomfort, which affected one-third of participants.

The addition of asenapine to the armamentarium for bipolar disorder in later life is a welcome development, she said. Of the 6 million American adults with bipolar disorder, roughly 1 million are over the age of 60. Traditional mood stabilizers such as lithium often have limiting side effects in the older population, and treatment failures are common, she noted.

This pilot study was sponsored by NV Organon/Merck. Dr. Satajovic reported receiving research grants from Merck and other companies, as well as serving as a consultant to Prophase, Otsuka, Pfizer, Amgen, and United BioSource.

AT THE AAGP ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: The atypical antipsychotic asenapine produced significant improvement in symptoms and mood in patients with later-life bipolar disorder that previously had shown a poor response to other therapies.

Data source: A prospective, 12-week, open-label pilot study in which 15 nondemented patients over age 60 with bipolar disorder suboptimally responsive to other therapies were treated with asenapine starting at 5 mg/day.

Disclosures: This pilot study was sponsored by NV Organon/Merck. Dr. Satajovic reported receiving research grants from Merck and other companies, as well as serving as a consultant to Prophase, Otsuka, Pfizer, Amgen, and United BioSource.

High medication burden persists in bipolar disorder

Almost one-third of patients with bipolar I disorder were taking at least four psychotropic medications when admitted to a psychiatric hospital, researchers reported in the April issue of Psychiatry Research.

The findings "reflect the enormous challenge of symptom management" in bipolar I disorder and the "fine line between help and harm that clinicians face" because monotherapies for [bipolar disorder] often are ineffective, said Dr. Lauren M. Weinstock and her associates at Brown University and Butler Hospital in Providence, R.I.

Using a computer algorithm, the investigators reviewed the charts of 218 adults with bipolar I disorder presenting for admission to a single psychiatric hospital. Patients averaged 42 years in age (range, 18-77), and 58% were female (Psychiatry Res. 2014;216:24-30).

In all, 82 patients (32%) were taking at least four psychotropic medications on admission. Taking this many medications was significantly associated with comorbid anxiety disorder (P less than .001), depression on admission (P = .002), a past suicide attempt (P = .010), and female gender (P = .025). Women were more likely than men to be prescribed benzodiazepines (P = .008), antidepressants (P = .012), and stimulants (P = .052), even after depressed mood was controlled for.

The results highlight concerns about an "increased risk of adverse side effects, drug interactions, medication error, and poor treatment adherence," and the complex polypharmacy’s "high cost burden to both patients and the health care system," said Dr. Weinstock and her associates. They emphasized the need for more research on outpatient prescribing for bipolar disorder patients and "the potential risks, especially for women, of iatrogenic complications without evidence of potential benefits."

The researchers did not use supplementary methods to confirm chart data and could not distinguish between long-standing treatment patterns or recent changes to medications. Because 94% of patients were white and most had health insurance, the findings could not be generalized to other patient populations.

A grant from the National Institute of Mental Health funded manuscript preparation. The authors did not disclose conflicts of interest.

Almost one-third of patients with bipolar I disorder were taking at least four psychotropic medications when admitted to a psychiatric hospital, researchers reported in the April issue of Psychiatry Research.

The findings "reflect the enormous challenge of symptom management" in bipolar I disorder and the "fine line between help and harm that clinicians face" because monotherapies for [bipolar disorder] often are ineffective, said Dr. Lauren M. Weinstock and her associates at Brown University and Butler Hospital in Providence, R.I.

Using a computer algorithm, the investigators reviewed the charts of 218 adults with bipolar I disorder presenting for admission to a single psychiatric hospital. Patients averaged 42 years in age (range, 18-77), and 58% were female (Psychiatry Res. 2014;216:24-30).

In all, 82 patients (32%) were taking at least four psychotropic medications on admission. Taking this many medications was significantly associated with comorbid anxiety disorder (P less than .001), depression on admission (P = .002), a past suicide attempt (P = .010), and female gender (P = .025). Women were more likely than men to be prescribed benzodiazepines (P = .008), antidepressants (P = .012), and stimulants (P = .052), even after depressed mood was controlled for.

The results highlight concerns about an "increased risk of adverse side effects, drug interactions, medication error, and poor treatment adherence," and the complex polypharmacy’s "high cost burden to both patients and the health care system," said Dr. Weinstock and her associates. They emphasized the need for more research on outpatient prescribing for bipolar disorder patients and "the potential risks, especially for women, of iatrogenic complications without evidence of potential benefits."

The researchers did not use supplementary methods to confirm chart data and could not distinguish between long-standing treatment patterns or recent changes to medications. Because 94% of patients were white and most had health insurance, the findings could not be generalized to other patient populations.

A grant from the National Institute of Mental Health funded manuscript preparation. The authors did not disclose conflicts of interest.

Almost one-third of patients with bipolar I disorder were taking at least four psychotropic medications when admitted to a psychiatric hospital, researchers reported in the April issue of Psychiatry Research.

The findings "reflect the enormous challenge of symptom management" in bipolar I disorder and the "fine line between help and harm that clinicians face" because monotherapies for [bipolar disorder] often are ineffective, said Dr. Lauren M. Weinstock and her associates at Brown University and Butler Hospital in Providence, R.I.

Using a computer algorithm, the investigators reviewed the charts of 218 adults with bipolar I disorder presenting for admission to a single psychiatric hospital. Patients averaged 42 years in age (range, 18-77), and 58% were female (Psychiatry Res. 2014;216:24-30).

In all, 82 patients (32%) were taking at least four psychotropic medications on admission. Taking this many medications was significantly associated with comorbid anxiety disorder (P less than .001), depression on admission (P = .002), a past suicide attempt (P = .010), and female gender (P = .025). Women were more likely than men to be prescribed benzodiazepines (P = .008), antidepressants (P = .012), and stimulants (P = .052), even after depressed mood was controlled for.

The results highlight concerns about an "increased risk of adverse side effects, drug interactions, medication error, and poor treatment adherence," and the complex polypharmacy’s "high cost burden to both patients and the health care system," said Dr. Weinstock and her associates. They emphasized the need for more research on outpatient prescribing for bipolar disorder patients and "the potential risks, especially for women, of iatrogenic complications without evidence of potential benefits."

The researchers did not use supplementary methods to confirm chart data and could not distinguish between long-standing treatment patterns or recent changes to medications. Because 94% of patients were white and most had health insurance, the findings could not be generalized to other patient populations.

A grant from the National Institute of Mental Health funded manuscript preparation. The authors did not disclose conflicts of interest.

FROM PSYCHIATRY RESEARCH

Major finding: Eight-two patients (32%) were taking at least four psychotropic medications. Taking this many medications was significantly associated with comorbid anxiety disorder (P less than .001), depression on admission (P = .002), a past suicide attempt (P = .010), and female gender (P = .025).

Data source: A retrospective chart study of 218 patients with bipolar I disorder who were presenting for psychiatric hospital admission.

Disclosures: A grant from the National Institute of Mental Health funded manuscript preparation. The authors did not disclose conflicts of interest.

Deaf and self-signing

CASE Self Signing

Mrs. H, a 47-year-old, deaf, African American woman, is brought into the emergency room because she is becoming increasingly withdrawn and is signing to herself. She was hospitalized more than 10 years ago after developing psychotic symptoms and received a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, not otherwise specified. She was treated with olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, but she has not seen a psychiatrist or taken any psychotropics in 8 years. Upon admission to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Mrs. H reports, through an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter, that she has had “problems with her parents” and with “being fair” and that she is 18 months pregnant. Urine pregnancy test is negative. Mrs. H also reports that her mother is pregnant. She indicates that it is difficult for her to describe what she is trying to say and that it is difficult to be deaf.

She endorses “very strong” racing thoughts, which she first states have been present for 15 years, then reports it has been 20 months. She endorses high-energy levels, feeling like there is “work to do,” and poor sleep. However, when asked, she indicates that she sleeps for 15 hours a day.

Which is critical when conducting a psychiatric assessment for a deaf patient?

a) rely only on the ASL interpreter

b) inquire about the patient’s communication preferences

c) use written language to communicate instead of speech

d) use a family member as interpreter

The authors’ observations

Mental health assessment of a deaf a patient involves a unique set of challenges and requires a specialized skill set for mental health practitioners—a skill set that is not routinely covered in psychiatric training programs.

a We use the term “deaf” to describe patients who have severe hearing loss. Other terms, such as “hearing impaired,” might be considered pejorative in the Deaf community. The term “Deaf” (capitalized) refers to Deaf culture and community, which deaf patients may or may not identify with.

Deafness history

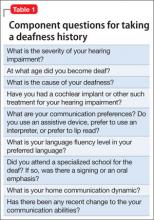

It is important to assess the cause of deafness,1,2 if known, and its age of onset (Table 1). A person is considered to be prelingually deaf if hearing loss was diagnosed before age 3.2 Clinicians should establish the patient’s communication preferences (use of assistive devices or interpreters or preference for lip reading), home communication dynamic,2 and language fluency level.1-3 Ask the patient if she attended a specialized school for the deaf and, if so, if there was an emphasis on oral communication or signing.2

HISTORY Conflicting reports

Mrs. H reports that she has been deaf since age 9, and that she learned sign language in India, where she became the “star king.” Mrs. H states that she then moved to the United States where she went to a school for the deaf. When asked if her family is able to communicate with her in sign language, she nods and indicates that they speak to her in “African and Indian.”

Mrs. H’s husband, who is hearing, says that Mrs. H is congenitally deaf, and was raised in the Midwestern United States where she attended a specialized school for the deaf. Mr. H and his 2 adult sons are hearing but communicate with Mrs. H in basic ASL. He states that Mrs. H sometimes uses signs that he and his sons cannot interpret. In addition to increased self-preoccupation and self-signing, Mrs. H has become more impulsive.

What are limitations of the mental status examination when evaluating a deaf patient?

a) facial expressions have a specific linguistic function in ASL

b) there is no differentiation in the mental status exam of deaf patients from that of hearing patients

c) the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a validated tool to assess cognition in deaf patients

d) the clinician should not rely on the interpreter to assist with the mental status examination

The authors’ observation

Performing a mental status examination of a deaf patient without recognizing some of the challenges inherent to this task can lead to misleading findings. For example, signing and gesturing can give the clinician an impression of psychomotor agitation.2 What appears to be socially withdrawn behavior might be a reaction to the patient’s inability to communicate with others.2,3 Social skills may be affected by language deprivation, if present.3 In ASL, facial expressions have specific linguistic functions in addition to representing emotions,2 and can affect the meaning of the sign used. An exaggerated or intense facial expression with the sign “quiet,” for example, usually means “very quiet.”4 In assessing cognition, the MMSE is not available in ASL and has not been validated in deaf patients.5 Also, deaf people have reduced access to information, and a lack of knowledge does not necessarily correlate with low IQ.2

The interpreter’s role

An ASL interpreter can aid in assessing a deaf patient’s communication skills. The interpreter can help with a thorough language evaluation1,6 and provide information about socio-cultural norms in the Deaf community.7 Using an ASL interpreter with special training in mental health1,3,6,7 is important to accurately diagnose thought disorders in deaf patients.1

EVALUATION Mental status exam

Mrs. H is poorly groomed and is wearing a pink housecoat, with her hair in disarray. She seems to be distracted by something next to the interpreter, because her eyes keep roving in this direction. She has moderate psychomotor agitation, based on the rapidity of her signing and gesturing. Mrs. H makes indecipherable vocalizations while signing, often loud and with an urgent quality. Her affect is elevated and expansive. She is not oriented to place or time and when asked where she is, signs, “many times, every day, 6-9-9, 2-5, more trouble…”

The ASL interpreter notes that Mrs. H signs so quickly that only about one-half of her signs are interpretable. Mrs. H’s grammar is not always correct and that her syntax is, at times, inappropriate. Mrs. H’s letters are difficult to interpret because she often starts and concludes a word with a clear sign, but the intervening letters are rapid and uninterpretable. She also uses several non-alphabet signs that cannot be interpreted (approximately 10% to 15% of signs) and repeats signs without clear context, such as “nothing off.” Mrs. H can pause to clarify for the interpreter at the beginning of the interview but is not able to do so by the end of the interview.

How does assessment of psychosis differ when evaluating deaf patients?

a) language dysfluency must be carefully differentiated from a thought disorder

b) signing to oneself does not necessarily indicate a response to internal stimuli

c) norms in Deaf culture might be misconstrued as delusions

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

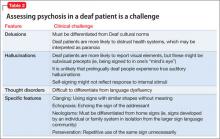

The prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients is unknown.8 Although older studies have reported an increased prevalence of psychotic disorders among deaf patients, these studies suffer from methodological problems.1 Other studies are at odds with each other, variably reporting a greater,9 equivalent,10 and lesser incidence of psychotic disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients.11 Deaf patients with psychotic disorders experience delusions, hallucinations, and thought disorders,1,3 and assessing for these symptoms in deaf patients can present a diagnostic challenge (Table 2).

Delusions are thought to present similarly in deaf patients with psychotic disorders compared with hearing patients.1,3 Paranoia may be increased in patients who are postlingually deaf, but has not been associated with prelingual deafness. Deficits in theory of mind related to hearing impairment have been thought to contribute to delusions in deaf patients.1,12

Many deaf patients distrust health care systems and providers,2,3,13 which may be misinterpreted as paranoia. Poor communication between deaf patients and clinicians and poor health literacy among deaf patients contribute to feelings of mistrust. Deaf patients often report experiencing prejudice within the health care system, and think that providers lack sufficient knowledge of deafness.13 Care must be taken to ensure that Deaf cultural norms are not misinterpreted as delusions.

Hallucinations. How deaf patients experience hallucinations, especially in prelingual deafness, likely is different from hallucinatory experiences of hearing patients.1,14 Deaf people with psychosis have described ”ideas coming into one’s head” and an almost “telepathic” process of “knowing.”14 Deaf patients with schizophrenia are more likely to report visual elements to their hallucinations; however, these may be subvisual precepts rather than true visual hallucinations.1,15 For example, hallucination might include the perception of being signed to.1

Deaf patients’ experience of auditory hallucinations is thought to be closely related to past auditory experiences. It is unlikely that prelingually deaf patients experience true auditory hallucinations.1,14 An endorsement of hearing a “voice” in ASL does not necessarily translate to an audiological experience.15 If profoundly prelingually deaf patients endorse hearing voices, generally they cannot assign acoustic properties (pitch, tone, volume, accent, etc.).1,14,15 It may not be necessary to fully comprehend the precise modality of how hallucinations are experienced by deaf patients to provide therapy.14

Self-signing, or signing to oneself, does not necessarily indicate that a deaf person is responding to a hallucinatory experience. Non-verbal patients may gesture to themselves without clear evidence of psychosis. When considering whether a patient is experiencing hallucinations, it is important to look for other evidence of psychosis.3

Possible approaches to evaluating hallucinations in deaf patients include asking,, “is someone signing in your head?” or “Is someone who is not in the room trying to communicate with you?”

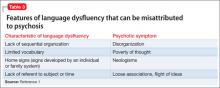

Thought disorders in deaf psychiatric inpatients are difficult to diagnose, in part because of a high rate of language dysfluency in deaf patients; in samples of psychiatric inpatients, 75% are not fluent in ASL, 66% are not fluent in any language).1,3,11 Commonly, language dysfluency is related to language deprivation because of late or inadequate exposure to ASL, although it may be related to neurologic damage or aphasia.1,3,6,16 Deaf patients can have additional disabilities, including learning disabilities, that might contribute to language dysfluency.2 Language dysfluency can be misattributed to a psychotic process1-3,7 (Table 3).1

Language dysfluency and thought disorders can be difficult to differentiate and may be comorbid. Loose associations and flight of ideas can be hard to assess in patients with language dysfluency. In general, increasing looseness of association between concepts corresponds to an increasing likelihood that a patient has true loose associations rather than language dysfluency alone.3 Deaf patients with schizophrenia can be identified by the presence of associated symptoms of psychosis, especially if delusions are present.1,3

EVALUATION Psychotic symptoms

Mrs. H’s thought process appears disorganized and illogical, with flight of ideas. She might have an underlying language dysfluency. It is likely that Mrs. H is using neologisms to communicate because of her family’s lack of familiarity with some of her signs. She also demonstrates perseveration, with use of certain signs repeatedly without clear context (ie, “nothing off”).

Her thought content includes racial themes—she mentions Russia, Germany, and Vietnam without clear context—and delusions of being the “star king” and of being pregnant. She endorses paranoid feelings that people on the inpatient unit are trying to hurt her, although it isn’t clear whether this represents a true paranoid delusion because of the hectic climate of the unit, and she did not show unnecessarily defensive or guarded behaviors.

She is seen signing to herself in the dayroom and endorses feeling as though someone who is not in the room—described as an Indian teacher (and sometimes as a boss or principal) known as “Mr. Smith” or “Mr. Donald”—is trying to communicate with her. She describes this person as being male and female. She mentions that sometimes she sees an Indian man and another man fighting. It is likely that Mrs. H is experiencing hallucinations from decompensated psychosis, because of the constellation and trajectory of her symptoms. Her nonverbal behavior—her eyes rove around the room during interviews—also supports this conclusion.

Because of evidence of mood and psychotic symptoms, and with a collateral history that suggests significant baseline disorganization, Mrs. H receives a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. She is restarted on olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d.

Mrs. H’s psychomotor acceleration and affective elevation gradually improve with pharmacotherapy. After a 2-week hospitalization, despite ongoing disorganization and self-signing, Mrs. H’s husband says that he feels she is improved enough to return home, with plans to continue to take her medications and to reestablish outpatient follow-up.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric assessment of deaf patients presents distinctive challenges related to cultural and language barriers—making it important to engage an ASL interpreter with training in mental health during assessment of a deaf patient. Clinicians must become familiar with these challenges to provide effective care for mentally ill deaf patients.

Related Resources

• Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Communicating with deaf patients: 10 tips to deliver appropriate care. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):36-37.

• Deaf Wellness Center. University of Rochester School of Medicine. www.urmc.rochester.edu/deaf-wellness-center.

• Gallaudet University Mental Health Center. www.gallaudet.edu/

mental_health_center.html.

Drug Brand Names

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Identifying and assessing psychosis in deaf psychiatric patients. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):198-202.

2. Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Pollard R. Mental health of deaf people. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1037-1044.

3. Glickman N. Do you hear voices? Problems in assessment of mental status in deaf persons with severe language deprivation. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12(2):127-147.

4. Vicars W. ASL University. Facial expressions. http://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/pages-layout/facialexpressions.htm. Accessed April 2, 2013.

5. Dean PM, Feldman DM, Morere D, et al. Clinical evaluation of the mini-mental state exam with culturally deaf senior citizens. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24(8):753-760.

6. Crump C, Glickman N. Mental health interpreting with language dysfluent deaf clients. Journal of Interpretation. 2011;21(1):21-36.

7. Leigh IW, Pollard RQ Jr. Mental health and deaf adults. In: Marschark M, Spencer PE, eds. Oxford handbook of deaf studies, language, and education. Vol 1. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2011:214-226.

8. Øhre B, von Tezchner S, Falkum E. Deaf adults and mental health: A review of recent research on the prevalence and distribution of psychiatric symptoms and disorders in the prelingually deaf adult population. International Journal on Mental Health and Deafness. 2011;1(1):3-22.

9. Appleford J. Clinical activity within a specialist mental health service for deaf people: comparison with a general psychiatric service. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2003;27(10): 375-377.

10. Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Inpatient psychiatric treatment of deaf adults: demographic and diagnostic comparisons with hearing inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):196-199.

11. Black PA, Glickman NS. Demographics, psychiatric diagnoses, and other characteristics of North American deaf and hard-of-hearing inpatients. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2006; 11(3):303-321.

12. Thewissen V, Myin-Germeys I, Bentall R, et al. Hearing impairment and psychosis revisited. Schizophr Res. 2005; 76(1):99-103.

13. Steinberg AG, Barnett S, Meador HE, et al. Health care system accessibility. Experiences and perceptions of deaf people. J Gen Inter Med. 2006;21(3):260-266.

14. Paijmans R, Cromwell J, Austen S. Do profoundly prelingually deaf patients with psychosis really hear voices? Am Ann Deaf. 2006;151(1):42-48.

15. Atkinson JR. The perceptual characteristics of voice-hallucinations in deaf people: insights into the nature of subvocal thought and sensory feedback loops. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):701-708.

16. Trumbetta SL, Bonvillian JD, Siedlecki T, et al. Language-related symptoms in persons with schizophrenia and how deaf persons may manifest these symptoms. Sign Language Studies. 2001;1(3):228-253.

CASE Self Signing

Mrs. H, a 47-year-old, deaf, African American woman, is brought into the emergency room because she is becoming increasingly withdrawn and is signing to herself. She was hospitalized more than 10 years ago after developing psychotic symptoms and received a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, not otherwise specified. She was treated with olanzapine, 10 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,000 mg/d, but she has not seen a psychiatrist or taken any psychotropics in 8 years. Upon admission to the inpatient psychiatric unit, Mrs. H reports, through an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter, that she has had “problems with her parents” and with “being fair” and that she is 18 months pregnant. Urine pregnancy test is negative. Mrs. H also reports that her mother is pregnant. She indicates that it is difficult for her to describe what she is trying to say and that it is difficult to be deaf.

She endorses “very strong” racing thoughts, which she first states have been present for 15 years, then reports it has been 20 months. She endorses high-energy levels, feeling like there is “work to do,” and poor sleep. However, when asked, she indicates that she sleeps for 15 hours a day.

Which is critical when conducting a psychiatric assessment for a deaf patient?

a) rely only on the ASL interpreter

b) inquire about the patient’s communication preferences

c) use written language to communicate instead of speech

d) use a family member as interpreter

The authors’ observations

Mental health assessment of a deaf a patient involves a unique set of challenges and requires a specialized skill set for mental health practitioners—a skill set that is not routinely covered in psychiatric training programs.

a We use the term “deaf” to describe patients who have severe hearing loss. Other terms, such as “hearing impaired,” might be considered pejorative in the Deaf community. The term “Deaf” (capitalized) refers to Deaf culture and community, which deaf patients may or may not identify with.

Deafness history

It is important to assess the cause of deafness,1,2 if known, and its age of onset (Table 1). A person is considered to be prelingually deaf if hearing loss was diagnosed before age 3.2 Clinicians should establish the patient’s communication preferences (use of assistive devices or interpreters or preference for lip reading), home communication dynamic,2 and language fluency level.1-3 Ask the patient if she attended a specialized school for the deaf and, if so, if there was an emphasis on oral communication or signing.2

HISTORY Conflicting reports

Mrs. H reports that she has been deaf since age 9, and that she learned sign language in India, where she became the “star king.” Mrs. H states that she then moved to the United States where she went to a school for the deaf. When asked if her family is able to communicate with her in sign language, she nods and indicates that they speak to her in “African and Indian.”

Mrs. H’s husband, who is hearing, says that Mrs. H is congenitally deaf, and was raised in the Midwestern United States where she attended a specialized school for the deaf. Mr. H and his 2 adult sons are hearing but communicate with Mrs. H in basic ASL. He states that Mrs. H sometimes uses signs that he and his sons cannot interpret. In addition to increased self-preoccupation and self-signing, Mrs. H has become more impulsive.

What are limitations of the mental status examination when evaluating a deaf patient?

a) facial expressions have a specific linguistic function in ASL

b) there is no differentiation in the mental status exam of deaf patients from that of hearing patients

c) the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a validated tool to assess cognition in deaf patients

d) the clinician should not rely on the interpreter to assist with the mental status examination

The authors’ observation

Performing a mental status examination of a deaf patient without recognizing some of the challenges inherent to this task can lead to misleading findings. For example, signing and gesturing can give the clinician an impression of psychomotor agitation.2 What appears to be socially withdrawn behavior might be a reaction to the patient’s inability to communicate with others.2,3 Social skills may be affected by language deprivation, if present.3 In ASL, facial expressions have specific linguistic functions in addition to representing emotions,2 and can affect the meaning of the sign used. An exaggerated or intense facial expression with the sign “quiet,” for example, usually means “very quiet.”4 In assessing cognition, the MMSE is not available in ASL and has not been validated in deaf patients.5 Also, deaf people have reduced access to information, and a lack of knowledge does not necessarily correlate with low IQ.2

The interpreter’s role

An ASL interpreter can aid in assessing a deaf patient’s communication skills. The interpreter can help with a thorough language evaluation1,6 and provide information about socio-cultural norms in the Deaf community.7 Using an ASL interpreter with special training in mental health1,3,6,7 is important to accurately diagnose thought disorders in deaf patients.1

EVALUATION Mental status exam

Mrs. H is poorly groomed and is wearing a pink housecoat, with her hair in disarray. She seems to be distracted by something next to the interpreter, because her eyes keep roving in this direction. She has moderate psychomotor agitation, based on the rapidity of her signing and gesturing. Mrs. H makes indecipherable vocalizations while signing, often loud and with an urgent quality. Her affect is elevated and expansive. She is not oriented to place or time and when asked where she is, signs, “many times, every day, 6-9-9, 2-5, more trouble…”

The ASL interpreter notes that Mrs. H signs so quickly that only about one-half of her signs are interpretable. Mrs. H’s grammar is not always correct and that her syntax is, at times, inappropriate. Mrs. H’s letters are difficult to interpret because she often starts and concludes a word with a clear sign, but the intervening letters are rapid and uninterpretable. She also uses several non-alphabet signs that cannot be interpreted (approximately 10% to 15% of signs) and repeats signs without clear context, such as “nothing off.” Mrs. H can pause to clarify for the interpreter at the beginning of the interview but is not able to do so by the end of the interview.

How does assessment of psychosis differ when evaluating deaf patients?

a) language dysfluency must be carefully differentiated from a thought disorder

b) signing to oneself does not necessarily indicate a response to internal stimuli

c) norms in Deaf culture might be misconstrued as delusions

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations