User login

Lithium may reduce melanoma risk

Adults with a history of lithium exposure had a 32% lower risk of melanoma than did those who were not exposed in an unadjusted analysis of data from more than 2 million patients.

Microarray gene profiling techniques suggest that Wnt genes, which “encode a family of secreted glycoproteins that activate cellular signaling pathways to control cell differentiation, proliferation, and motility,” may be involved in melanoma development, wrote Maryam M. Asgari, MD, of the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital and the department of population medicine at Harvard University, both in Boston, and her colleagues. In particular, “transcriptional profiling of melanoma cell lines has suggested that Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates a transcriptional signature predictive of less aggressive melanoma,” they wrote.

The psychiatric medication lithium activates the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway and has shown an ability to inhibit the proliferation of melanoma cells in a mouse model, but “to our knowledge, no published epidemiologic studies have examined the association of melanoma risk with lithium exposure,” they wrote.

The researchers reviewed data from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California database of 2,213,848 adult white patients who were members during 1997-2012, which included 11,317 with lithium exposure. They evaluated the association between lithium exposure and both incident melanoma risk and melanoma-associated mortality (J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Oct;137[10]:2087-91.).

Individuals exposed to lithium had a 32% reduced risk of melanoma in an unadjusted analysis; in an adjusted analysis, the reduced risk was 23% and was not significant.

However, there was a significant difference in melanoma incidence per 100,000 person-years in lithium-exposed individuals, compared with unexposed individuals (67.4 vs. 92.5, respectively; P = .027).

Among patients with melanoma, those with exposure to lithium had a lower mortality rate than those not exposed (4.68 vs. 7.21 per 1,000 person-years, respectively), but the sample size for this subgroup was too small to determine statistical significance. In addition, lithium exposure was associated with reduced likelihood of developing skin tumors greater than 4 mm and of presenting with extensive disease. Among those exposed to lithium, none presented with a thick tumor (Breslow depth greater than 4 mm), and none had regional or distant disease when they were diagnosed, compared with 2.8% and 6.3%, respectively, of those not exposed to lithium.

The findings were limited by several factors, including reliance on prescription information to determine lithium exposure, a homogeneous study population, and confounding variables, such as sun exposure behaviors, the researchers noted. However, the large study population adds strength to the results, and “our conclusions provide evidence that lithium, a relatively inexpensive and readily available drug, warrants further study in melanoma,” they said.

Lead author Dr. Asgari and one of the other four authors disclosed serving as investigators for studies funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer. This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Asgari is principal investigator in the Patient-Oriented Research in the Epidemiology of Skin Diseases lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Adults with a history of lithium exposure had a 32% lower risk of melanoma than did those who were not exposed in an unadjusted analysis of data from more than 2 million patients.

Microarray gene profiling techniques suggest that Wnt genes, which “encode a family of secreted glycoproteins that activate cellular signaling pathways to control cell differentiation, proliferation, and motility,” may be involved in melanoma development, wrote Maryam M. Asgari, MD, of the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital and the department of population medicine at Harvard University, both in Boston, and her colleagues. In particular, “transcriptional profiling of melanoma cell lines has suggested that Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates a transcriptional signature predictive of less aggressive melanoma,” they wrote.

The psychiatric medication lithium activates the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway and has shown an ability to inhibit the proliferation of melanoma cells in a mouse model, but “to our knowledge, no published epidemiologic studies have examined the association of melanoma risk with lithium exposure,” they wrote.

The researchers reviewed data from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California database of 2,213,848 adult white patients who were members during 1997-2012, which included 11,317 with lithium exposure. They evaluated the association between lithium exposure and both incident melanoma risk and melanoma-associated mortality (J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Oct;137[10]:2087-91.).

Individuals exposed to lithium had a 32% reduced risk of melanoma in an unadjusted analysis; in an adjusted analysis, the reduced risk was 23% and was not significant.

However, there was a significant difference in melanoma incidence per 100,000 person-years in lithium-exposed individuals, compared with unexposed individuals (67.4 vs. 92.5, respectively; P = .027).

Among patients with melanoma, those with exposure to lithium had a lower mortality rate than those not exposed (4.68 vs. 7.21 per 1,000 person-years, respectively), but the sample size for this subgroup was too small to determine statistical significance. In addition, lithium exposure was associated with reduced likelihood of developing skin tumors greater than 4 mm and of presenting with extensive disease. Among those exposed to lithium, none presented with a thick tumor (Breslow depth greater than 4 mm), and none had regional or distant disease when they were diagnosed, compared with 2.8% and 6.3%, respectively, of those not exposed to lithium.

The findings were limited by several factors, including reliance on prescription information to determine lithium exposure, a homogeneous study population, and confounding variables, such as sun exposure behaviors, the researchers noted. However, the large study population adds strength to the results, and “our conclusions provide evidence that lithium, a relatively inexpensive and readily available drug, warrants further study in melanoma,” they said.

Lead author Dr. Asgari and one of the other four authors disclosed serving as investigators for studies funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer. This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Asgari is principal investigator in the Patient-Oriented Research in the Epidemiology of Skin Diseases lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Adults with a history of lithium exposure had a 32% lower risk of melanoma than did those who were not exposed in an unadjusted analysis of data from more than 2 million patients.

Microarray gene profiling techniques suggest that Wnt genes, which “encode a family of secreted glycoproteins that activate cellular signaling pathways to control cell differentiation, proliferation, and motility,” may be involved in melanoma development, wrote Maryam M. Asgari, MD, of the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital and the department of population medicine at Harvard University, both in Boston, and her colleagues. In particular, “transcriptional profiling of melanoma cell lines has suggested that Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates a transcriptional signature predictive of less aggressive melanoma,” they wrote.

The psychiatric medication lithium activates the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway and has shown an ability to inhibit the proliferation of melanoma cells in a mouse model, but “to our knowledge, no published epidemiologic studies have examined the association of melanoma risk with lithium exposure,” they wrote.

The researchers reviewed data from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California database of 2,213,848 adult white patients who were members during 1997-2012, which included 11,317 with lithium exposure. They evaluated the association between lithium exposure and both incident melanoma risk and melanoma-associated mortality (J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Oct;137[10]:2087-91.).

Individuals exposed to lithium had a 32% reduced risk of melanoma in an unadjusted analysis; in an adjusted analysis, the reduced risk was 23% and was not significant.

However, there was a significant difference in melanoma incidence per 100,000 person-years in lithium-exposed individuals, compared with unexposed individuals (67.4 vs. 92.5, respectively; P = .027).

Among patients with melanoma, those with exposure to lithium had a lower mortality rate than those not exposed (4.68 vs. 7.21 per 1,000 person-years, respectively), but the sample size for this subgroup was too small to determine statistical significance. In addition, lithium exposure was associated with reduced likelihood of developing skin tumors greater than 4 mm and of presenting with extensive disease. Among those exposed to lithium, none presented with a thick tumor (Breslow depth greater than 4 mm), and none had regional or distant disease when they were diagnosed, compared with 2.8% and 6.3%, respectively, of those not exposed to lithium.

The findings were limited by several factors, including reliance on prescription information to determine lithium exposure, a homogeneous study population, and confounding variables, such as sun exposure behaviors, the researchers noted. However, the large study population adds strength to the results, and “our conclusions provide evidence that lithium, a relatively inexpensive and readily available drug, warrants further study in melanoma,” they said.

Lead author Dr. Asgari and one of the other four authors disclosed serving as investigators for studies funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer. This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Asgari is principal investigator in the Patient-Oriented Research in the Epidemiology of Skin Diseases lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Lithium may reduce the risk of melanoma and melanoma mortality.

Major finding: The incidence of melanoma was significantly lower among adults exposed to lithium (67/100,000 person-years) than those not exposed (93/100,000 person-years).

Data source: The data come from a population-based, retrospective cohort study of 11,317 white adults in Northern California.

Disclosures: The lead author and one of the other four authors disclosed serving as investigators for studies funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer. The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute.

Austedo approved for treatment of tardive dyskinesia

The Food and Drug Administration has approved deutetrabenazine (Austedo) for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia in adults, according to an announcement from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries.

The agency’s approval of Austedo was based on results from two phase 3 clinical trials in which the drug was shown to be safe and effective at reducing involuntary movements collectively termed tardive dyskinesia, a debilitating and sometimes irreversible movement disorder which affects about 500,000 people in the United States. Austedo was first approved in April 2017 to treat chorea associated with Huntington’s disease.

“Physicians treating tardive dyskinesia will appreciate the therapy’s dosing flexibility and the ability to focus on directly treating the movement disorder and not disrupt the ongoing treatment for the underlying condition,” Michael Hayden, MD, PhD, President of Global R&D and Chief Scientific Officer at Teva, said in the announcement.

The full prescribing information can be viewed here.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved deutetrabenazine (Austedo) for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia in adults, according to an announcement from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries.

The agency’s approval of Austedo was based on results from two phase 3 clinical trials in which the drug was shown to be safe and effective at reducing involuntary movements collectively termed tardive dyskinesia, a debilitating and sometimes irreversible movement disorder which affects about 500,000 people in the United States. Austedo was first approved in April 2017 to treat chorea associated with Huntington’s disease.

“Physicians treating tardive dyskinesia will appreciate the therapy’s dosing flexibility and the ability to focus on directly treating the movement disorder and not disrupt the ongoing treatment for the underlying condition,” Michael Hayden, MD, PhD, President of Global R&D and Chief Scientific Officer at Teva, said in the announcement.

The full prescribing information can be viewed here.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved deutetrabenazine (Austedo) for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia in adults, according to an announcement from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries.

The agency’s approval of Austedo was based on results from two phase 3 clinical trials in which the drug was shown to be safe and effective at reducing involuntary movements collectively termed tardive dyskinesia, a debilitating and sometimes irreversible movement disorder which affects about 500,000 people in the United States. Austedo was first approved in April 2017 to treat chorea associated with Huntington’s disease.

“Physicians treating tardive dyskinesia will appreciate the therapy’s dosing flexibility and the ability to focus on directly treating the movement disorder and not disrupt the ongoing treatment for the underlying condition,” Michael Hayden, MD, PhD, President of Global R&D and Chief Scientific Officer at Teva, said in the announcement.

The full prescribing information can be viewed here.

Abilify Maintena OK’d by FDA for adults with bipolar I disorder

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a monthly injectable formulation of aripiprazole, (Abilify Maintena) , for a maintenance monotherapy treatment of bipolar I disorder for adults, Otsuka and Lundbeck have announced.

Patients treated with the injectable formulation of the atypical antipsychotic must continue to take a daily oral antipsychotic for the first 14 days. After that, however, the long-acting injectable (LAI) – which must be administered by a health care professional – can replace the daily medication.

Joseph R. Calabrese, MD, director of the mood disorders program at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, said in the July 28 announcement that the LAI is a new treatment option for bipolar I patients “who have established tolerability with oral aripiprazole.”

The drug label includes a warning that elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis who are treated with antipsychotics are at a higher mortality risk. Adverse reactions that have been associated with treatment with aripiprazole include weight gain, akathisia, injection site pain, sedation, and certain compulsive behaviors.

Created by Otsuka, and marketed by Otsuka and Lundbeck, the LAI was approved in the United States for treating adults with schizophrenia in 2013.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a monthly injectable formulation of aripiprazole, (Abilify Maintena) , for a maintenance monotherapy treatment of bipolar I disorder for adults, Otsuka and Lundbeck have announced.

Patients treated with the injectable formulation of the atypical antipsychotic must continue to take a daily oral antipsychotic for the first 14 days. After that, however, the long-acting injectable (LAI) – which must be administered by a health care professional – can replace the daily medication.

Joseph R. Calabrese, MD, director of the mood disorders program at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, said in the July 28 announcement that the LAI is a new treatment option for bipolar I patients “who have established tolerability with oral aripiprazole.”

The drug label includes a warning that elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis who are treated with antipsychotics are at a higher mortality risk. Adverse reactions that have been associated with treatment with aripiprazole include weight gain, akathisia, injection site pain, sedation, and certain compulsive behaviors.

Created by Otsuka, and marketed by Otsuka and Lundbeck, the LAI was approved in the United States for treating adults with schizophrenia in 2013.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a monthly injectable formulation of aripiprazole, (Abilify Maintena) , for a maintenance monotherapy treatment of bipolar I disorder for adults, Otsuka and Lundbeck have announced.

Patients treated with the injectable formulation of the atypical antipsychotic must continue to take a daily oral antipsychotic for the first 14 days. After that, however, the long-acting injectable (LAI) – which must be administered by a health care professional – can replace the daily medication.

Joseph R. Calabrese, MD, director of the mood disorders program at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, said in the July 28 announcement that the LAI is a new treatment option for bipolar I patients “who have established tolerability with oral aripiprazole.”

The drug label includes a warning that elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis who are treated with antipsychotics are at a higher mortality risk. Adverse reactions that have been associated with treatment with aripiprazole include weight gain, akathisia, injection site pain, sedation, and certain compulsive behaviors.

Created by Otsuka, and marketed by Otsuka and Lundbeck, the LAI was approved in the United States for treating adults with schizophrenia in 2013.

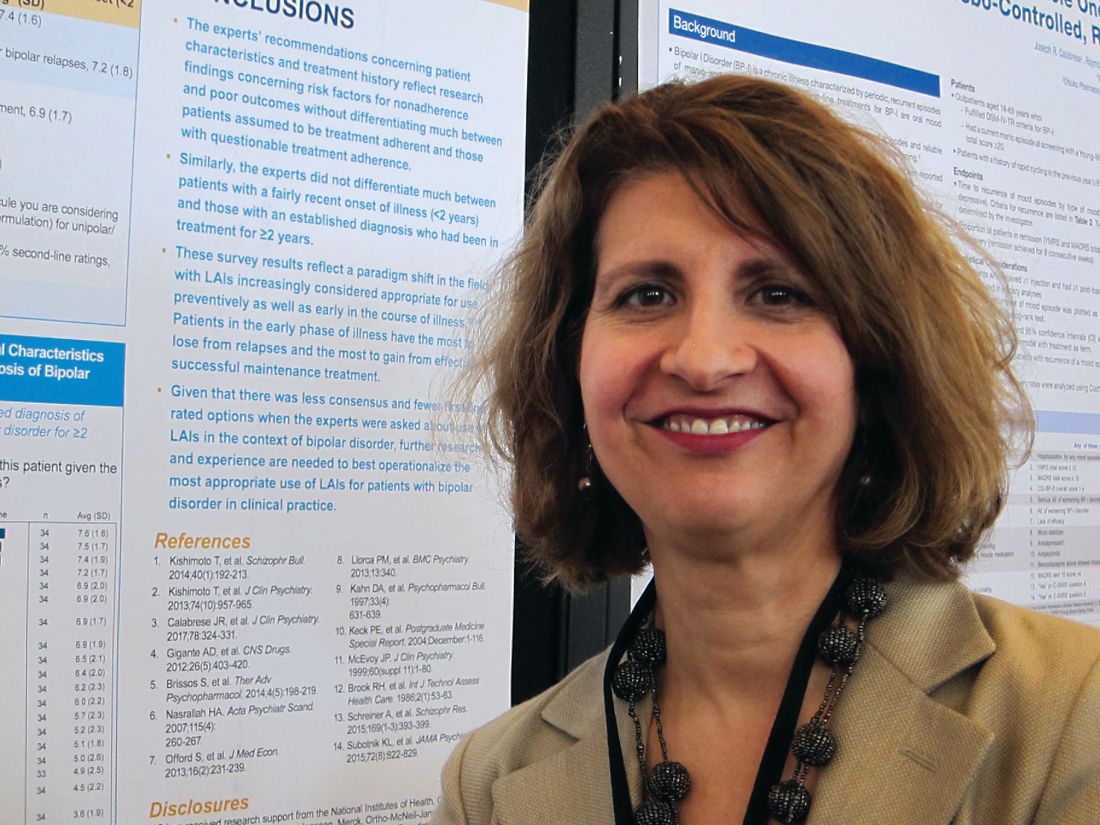

Patients’ profile deemed best criteria for LAIs in bipolar disorder

MIAMI – Expert clinicians endorsed long-acting injectables as a preferred treatment for bipolar I disorder on the basis of patient characteristics and treatment history, rather than on an assumed level of treatment adherence, according to a small survey.

“Just over three-quarters of the experts we surveyed said they were ‘somewhat’ or ‘not very’ confident about their ability to assess their patients’ adherence,” said Martha Sajatovic, MD, who presented the data during a poster session at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting.

The finding reflects a shift, according to Dr. Sajatovic, professor of psychiatry and neurology, and the Willard Brown Chair in Neurological Outcomes Research, at Case Western University in Cleveland.

The traditional view of using long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) for patients with bipolar I disorder is that they are appropriate only in certain cohorts, such as patients with very severe illness or at the more extreme spectrum in terms of risk, and those who are homeless or pose a risk to themselves or others, Dr. Sajatovic said. Also, when it comes to the use of LAIs, there is a lack of guidance – which might contribute to clinicians’ reluctance to prescribe or recommend them, she said.

In the survey, of the 42 experts contacted by Dr. Sajatovic and her colleagues, 34 responded. According to those respondents, 11% of their patients with bipolar disorder were being treated with LAIs, compared with one-third of all patients with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder.

Using a scale of 1-9, with 1 being “extremely inappropriate,” 2-3 being “usually inappropriate,” 4-6 being “sometimes appropriate,” 7-8 being “usually appropriate,” and 9 being “extremely appropriate,” all tended to favor patient characteristics and treatment history over adherence when rating criteria for treatment selection. This was true regardless of whether patients were newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder, or whether their diagnosis was established and treated with an antipsychotic for 2 or more years.

For comparison, Dr. Sajatovic and her colleagues also surveyed the expert panel members on their use of LAIs in established schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

Patients with a history of two or more hospitalizations for bipolar relapses and those who were either homeless or had unstable housing were rated by most respondents as usually appropriate for LAIs as first-line treatment. For those with dubious treatment adherence, the profile was similar: LAIs were considered by a majority of respondents as usually appropriate if there was a history of two or more hospitalizations for bipolar relapses, as well as homelessness or an unstable housing situation. LAIs also were considered by a majority as usually appropriate in this cohort if there was a history of violence to others, and if patients had poor insight into their illness.

Spotty treatment adherence to medications was the most common treatment history characteristic cited for first-line prescription of LAIs in patients with an established bipolar disorder diagnosis. Other first-line LAI criteria cited by most respondents for this cohort were if they previously had done well on an LAI, and if they frequently missed clinic appointments.

Virtually all the criteria above applied to patients with established illness and questionable adherence, although the expert clinicians also largely cited a failure to respond to lithium or an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer, a predominant history of manic relapse, and a strong therapeutic alliance as additional reasons to view LAIs as usually appropriate.

Regardless of the assumption of adherence or nonadherence, in most cases in which patients had an established bipolar diagnosis, more than half of the expert panel said use of an LAI was extremely appropriate.

In patients with an established diagnosis of bipolar disorder with questionable treatment adherence, respondents strongly endorsed the idea that it was usually appropriate to use LAIs as first-line treatment if the patients had a history of two or more hospitalizations for bipolar relapses, homelessness or an otherwise unstable living arrangement, violence toward others, and poor insight into their illness.

The panel members were blinded to the study’s sponsor, which was Otsuka. All respondents had an average of 25 years of clinical experience and an average of 22 years of research experience, and all had extensive expertise in the use of two or more LAIs, although no specific antipsychotic brand names were included in the survey.

Just more than one-third of respondents reported spending all or most of their professional time seeing patients, and one-fifth reported that they saw patients half of the time. The average age of patients seen by the respondents was 35-65 years.

Dr. Sajatovic disclosed receiving research grants from the National Institutes of Health, Alkermes, Janssen, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies and foundations; serving as a consultant for numerous entities, including Otsuka; and receiving royalties from UpToDate, and several publishing companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

MIAMI – Expert clinicians endorsed long-acting injectables as a preferred treatment for bipolar I disorder on the basis of patient characteristics and treatment history, rather than on an assumed level of treatment adherence, according to a small survey.

“Just over three-quarters of the experts we surveyed said they were ‘somewhat’ or ‘not very’ confident about their ability to assess their patients’ adherence,” said Martha Sajatovic, MD, who presented the data during a poster session at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting.

The finding reflects a shift, according to Dr. Sajatovic, professor of psychiatry and neurology, and the Willard Brown Chair in Neurological Outcomes Research, at Case Western University in Cleveland.

The traditional view of using long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) for patients with bipolar I disorder is that they are appropriate only in certain cohorts, such as patients with very severe illness or at the more extreme spectrum in terms of risk, and those who are homeless or pose a risk to themselves or others, Dr. Sajatovic said. Also, when it comes to the use of LAIs, there is a lack of guidance – which might contribute to clinicians’ reluctance to prescribe or recommend them, she said.

In the survey, of the 42 experts contacted by Dr. Sajatovic and her colleagues, 34 responded. According to those respondents, 11% of their patients with bipolar disorder were being treated with LAIs, compared with one-third of all patients with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder.

Using a scale of 1-9, with 1 being “extremely inappropriate,” 2-3 being “usually inappropriate,” 4-6 being “sometimes appropriate,” 7-8 being “usually appropriate,” and 9 being “extremely appropriate,” all tended to favor patient characteristics and treatment history over adherence when rating criteria for treatment selection. This was true regardless of whether patients were newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder, or whether their diagnosis was established and treated with an antipsychotic for 2 or more years.

For comparison, Dr. Sajatovic and her colleagues also surveyed the expert panel members on their use of LAIs in established schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

Patients with a history of two or more hospitalizations for bipolar relapses and those who were either homeless or had unstable housing were rated by most respondents as usually appropriate for LAIs as first-line treatment. For those with dubious treatment adherence, the profile was similar: LAIs were considered by a majority of respondents as usually appropriate if there was a history of two or more hospitalizations for bipolar relapses, as well as homelessness or an unstable housing situation. LAIs also were considered by a majority as usually appropriate in this cohort if there was a history of violence to others, and if patients had poor insight into their illness.

Spotty treatment adherence to medications was the most common treatment history characteristic cited for first-line prescription of LAIs in patients with an established bipolar disorder diagnosis. Other first-line LAI criteria cited by most respondents for this cohort were if they previously had done well on an LAI, and if they frequently missed clinic appointments.

Virtually all the criteria above applied to patients with established illness and questionable adherence, although the expert clinicians also largely cited a failure to respond to lithium or an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer, a predominant history of manic relapse, and a strong therapeutic alliance as additional reasons to view LAIs as usually appropriate.

Regardless of the assumption of adherence or nonadherence, in most cases in which patients had an established bipolar diagnosis, more than half of the expert panel said use of an LAI was extremely appropriate.

In patients with an established diagnosis of bipolar disorder with questionable treatment adherence, respondents strongly endorsed the idea that it was usually appropriate to use LAIs as first-line treatment if the patients had a history of two or more hospitalizations for bipolar relapses, homelessness or an otherwise unstable living arrangement, violence toward others, and poor insight into their illness.

The panel members were blinded to the study’s sponsor, which was Otsuka. All respondents had an average of 25 years of clinical experience and an average of 22 years of research experience, and all had extensive expertise in the use of two or more LAIs, although no specific antipsychotic brand names were included in the survey.

Just more than one-third of respondents reported spending all or most of their professional time seeing patients, and one-fifth reported that they saw patients half of the time. The average age of patients seen by the respondents was 35-65 years.

Dr. Sajatovic disclosed receiving research grants from the National Institutes of Health, Alkermes, Janssen, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies and foundations; serving as a consultant for numerous entities, including Otsuka; and receiving royalties from UpToDate, and several publishing companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

MIAMI – Expert clinicians endorsed long-acting injectables as a preferred treatment for bipolar I disorder on the basis of patient characteristics and treatment history, rather than on an assumed level of treatment adherence, according to a small survey.

“Just over three-quarters of the experts we surveyed said they were ‘somewhat’ or ‘not very’ confident about their ability to assess their patients’ adherence,” said Martha Sajatovic, MD, who presented the data during a poster session at a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting.

The finding reflects a shift, according to Dr. Sajatovic, professor of psychiatry and neurology, and the Willard Brown Chair in Neurological Outcomes Research, at Case Western University in Cleveland.

The traditional view of using long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) for patients with bipolar I disorder is that they are appropriate only in certain cohorts, such as patients with very severe illness or at the more extreme spectrum in terms of risk, and those who are homeless or pose a risk to themselves or others, Dr. Sajatovic said. Also, when it comes to the use of LAIs, there is a lack of guidance – which might contribute to clinicians’ reluctance to prescribe or recommend them, she said.

In the survey, of the 42 experts contacted by Dr. Sajatovic and her colleagues, 34 responded. According to those respondents, 11% of their patients with bipolar disorder were being treated with LAIs, compared with one-third of all patients with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder.

Using a scale of 1-9, with 1 being “extremely inappropriate,” 2-3 being “usually inappropriate,” 4-6 being “sometimes appropriate,” 7-8 being “usually appropriate,” and 9 being “extremely appropriate,” all tended to favor patient characteristics and treatment history over adherence when rating criteria for treatment selection. This was true regardless of whether patients were newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder, or whether their diagnosis was established and treated with an antipsychotic for 2 or more years.

For comparison, Dr. Sajatovic and her colleagues also surveyed the expert panel members on their use of LAIs in established schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

Patients with a history of two or more hospitalizations for bipolar relapses and those who were either homeless or had unstable housing were rated by most respondents as usually appropriate for LAIs as first-line treatment. For those with dubious treatment adherence, the profile was similar: LAIs were considered by a majority of respondents as usually appropriate if there was a history of two or more hospitalizations for bipolar relapses, as well as homelessness or an unstable housing situation. LAIs also were considered by a majority as usually appropriate in this cohort if there was a history of violence to others, and if patients had poor insight into their illness.

Spotty treatment adherence to medications was the most common treatment history characteristic cited for first-line prescription of LAIs in patients with an established bipolar disorder diagnosis. Other first-line LAI criteria cited by most respondents for this cohort were if they previously had done well on an LAI, and if they frequently missed clinic appointments.

Virtually all the criteria above applied to patients with established illness and questionable adherence, although the expert clinicians also largely cited a failure to respond to lithium or an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer, a predominant history of manic relapse, and a strong therapeutic alliance as additional reasons to view LAIs as usually appropriate.

Regardless of the assumption of adherence or nonadherence, in most cases in which patients had an established bipolar diagnosis, more than half of the expert panel said use of an LAI was extremely appropriate.

In patients with an established diagnosis of bipolar disorder with questionable treatment adherence, respondents strongly endorsed the idea that it was usually appropriate to use LAIs as first-line treatment if the patients had a history of two or more hospitalizations for bipolar relapses, homelessness or an otherwise unstable living arrangement, violence toward others, and poor insight into their illness.

The panel members were blinded to the study’s sponsor, which was Otsuka. All respondents had an average of 25 years of clinical experience and an average of 22 years of research experience, and all had extensive expertise in the use of two or more LAIs, although no specific antipsychotic brand names were included in the survey.

Just more than one-third of respondents reported spending all or most of their professional time seeing patients, and one-fifth reported that they saw patients half of the time. The average age of patients seen by the respondents was 35-65 years.

Dr. Sajatovic disclosed receiving research grants from the National Institutes of Health, Alkermes, Janssen, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies and foundations; serving as a consultant for numerous entities, including Otsuka; and receiving royalties from UpToDate, and several publishing companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT THE ASCP ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Clinicians very strongly endorsed the use long-acting injectables as first-line treatment in patients with bipolar disorder who met several criteria, including having a history of two or more hospitalizations for bipolar relapses.

Data source: A blinded, consensus survey of 34 high-prescribing clinicians experienced in treating mood and psychotic disorders.

Disclosures: Dr. Sajatovic disclosed receiving research grants from the National Institutes of Health, Alkermes, Janssen, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies and foundations; serving as a consultant for numerous entities, including Otsuka, which sponsored the study; and receiving royalties from UpToDate, and several publishing companies.

Most veterans with schizophrenia or bipolar I report suicide attempts

SAN DIEGO – A new study reports that about half of assessed U.S. veterans with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder have tried to kill themselves. Nearly 70% of those with schizophrenia had documented suicidal behavior or ideation, as did more than 82% of those with bipolar I disorder.

“The VA struggles to predict suicidal ideation and behavior,” said study lead author Philip D. Harvey, PhD, of the Carter VA Medical Center in Miami, in an interview. “These data suggest that having one of these diagnoses is a major risk factor. Regular assessment makes considerable sense.”

Dr. Harvey released the study findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

For the study, Dr. Harvey and his colleagues examined findings from a VA research project into the genetics behind functional disability in schizophrenia and bipolar illness.

“We know that suicide risk is higher in veterans than in the general population. We also know that the current focus is on returning veterans who were deployed in combat operations,” said Dr. Harvey, who also is affiliated with the University of Miami. “We wanted to evaluate the risk for suicidal ideation and behavior in the segment of the veteran population who have recently or ever been exposed to military trauma.”

The project assessed VA patients with schizophrenia (N = 3,941) or bipolar I disorder (N = 5,414) through in-person evaluations regarding issues like cognitive and functional status, and history of posttraumatic stress disorder. All of the subjects were outpatients at 26 VA medical centers.

Combined, the mean age of the study participants was 53.6 years, plus or minus 11 years, and 86.2% were male. Whites made up 57.4% of the sample, followed by blacks (37.0%) and other (5.6%). A total of 27% had no comorbid psychiatric conditions.

The study authors found documented suicidal ideation or suicidal behavior in 69.9% of veterans with schizophrenia and 82.3% of those with bipolar disorder; the percentages who reported making actual suicide attempts was 46.1% schizophrenia and 54.5% bipolar disorder.

The risk of suicidal ideation was lower in schizophrenia vs. bipolar disorder (odds ratio, 0.82; 95% confidence interval, 0.71-0.95), as was suicidal behavior (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71-0.93).

Dr. Harvey said this is not surprising. “The combination of a history of euphoric mood and significant depression [characteristic of bipolar disorder] is very challenging.”

Other factors lowered risk: College education vs. high school or less (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.67-1.00 for ideation; OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.58-0.84 for behavior). In addition, lower risk was found among black vs. white patients (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.63-0.84 for ideation; OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72-0.93, for behavior).

These factors boosted risk: multiple psychiatric comorbidities vs. none (OR, 2.61; 95% CI, 2.22-3.07 for ideation; OR, 3.82; 95% CI, 3.30-4.41, for behavior), and those with a history of being ever vs. never married (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.02-1.37 for ideation; OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.19-1.55, for behavior). Most of those who had been married later were divorced.

“These findings underscore the need for continuous monitoring for suicidality in veteran populations, regardless of age or psychiatric diagnosis, and especially with multiple psychiatric comorbidities,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Program. Dr. Harvey reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – A new study reports that about half of assessed U.S. veterans with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder have tried to kill themselves. Nearly 70% of those with schizophrenia had documented suicidal behavior or ideation, as did more than 82% of those with bipolar I disorder.

“The VA struggles to predict suicidal ideation and behavior,” said study lead author Philip D. Harvey, PhD, of the Carter VA Medical Center in Miami, in an interview. “These data suggest that having one of these diagnoses is a major risk factor. Regular assessment makes considerable sense.”

Dr. Harvey released the study findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

For the study, Dr. Harvey and his colleagues examined findings from a VA research project into the genetics behind functional disability in schizophrenia and bipolar illness.

“We know that suicide risk is higher in veterans than in the general population. We also know that the current focus is on returning veterans who were deployed in combat operations,” said Dr. Harvey, who also is affiliated with the University of Miami. “We wanted to evaluate the risk for suicidal ideation and behavior in the segment of the veteran population who have recently or ever been exposed to military trauma.”

The project assessed VA patients with schizophrenia (N = 3,941) or bipolar I disorder (N = 5,414) through in-person evaluations regarding issues like cognitive and functional status, and history of posttraumatic stress disorder. All of the subjects were outpatients at 26 VA medical centers.

Combined, the mean age of the study participants was 53.6 years, plus or minus 11 years, and 86.2% were male. Whites made up 57.4% of the sample, followed by blacks (37.0%) and other (5.6%). A total of 27% had no comorbid psychiatric conditions.

The study authors found documented suicidal ideation or suicidal behavior in 69.9% of veterans with schizophrenia and 82.3% of those with bipolar disorder; the percentages who reported making actual suicide attempts was 46.1% schizophrenia and 54.5% bipolar disorder.

The risk of suicidal ideation was lower in schizophrenia vs. bipolar disorder (odds ratio, 0.82; 95% confidence interval, 0.71-0.95), as was suicidal behavior (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71-0.93).

Dr. Harvey said this is not surprising. “The combination of a history of euphoric mood and significant depression [characteristic of bipolar disorder] is very challenging.”

Other factors lowered risk: College education vs. high school or less (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.67-1.00 for ideation; OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.58-0.84 for behavior). In addition, lower risk was found among black vs. white patients (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.63-0.84 for ideation; OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72-0.93, for behavior).

These factors boosted risk: multiple psychiatric comorbidities vs. none (OR, 2.61; 95% CI, 2.22-3.07 for ideation; OR, 3.82; 95% CI, 3.30-4.41, for behavior), and those with a history of being ever vs. never married (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.02-1.37 for ideation; OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.19-1.55, for behavior). Most of those who had been married later were divorced.

“These findings underscore the need for continuous monitoring for suicidality in veteran populations, regardless of age or psychiatric diagnosis, and especially with multiple psychiatric comorbidities,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Program. Dr. Harvey reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – A new study reports that about half of assessed U.S. veterans with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder have tried to kill themselves. Nearly 70% of those with schizophrenia had documented suicidal behavior or ideation, as did more than 82% of those with bipolar I disorder.

“The VA struggles to predict suicidal ideation and behavior,” said study lead author Philip D. Harvey, PhD, of the Carter VA Medical Center in Miami, in an interview. “These data suggest that having one of these diagnoses is a major risk factor. Regular assessment makes considerable sense.”

Dr. Harvey released the study findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

For the study, Dr. Harvey and his colleagues examined findings from a VA research project into the genetics behind functional disability in schizophrenia and bipolar illness.

“We know that suicide risk is higher in veterans than in the general population. We also know that the current focus is on returning veterans who were deployed in combat operations,” said Dr. Harvey, who also is affiliated with the University of Miami. “We wanted to evaluate the risk for suicidal ideation and behavior in the segment of the veteran population who have recently or ever been exposed to military trauma.”

The project assessed VA patients with schizophrenia (N = 3,941) or bipolar I disorder (N = 5,414) through in-person evaluations regarding issues like cognitive and functional status, and history of posttraumatic stress disorder. All of the subjects were outpatients at 26 VA medical centers.

Combined, the mean age of the study participants was 53.6 years, plus or minus 11 years, and 86.2% were male. Whites made up 57.4% of the sample, followed by blacks (37.0%) and other (5.6%). A total of 27% had no comorbid psychiatric conditions.

The study authors found documented suicidal ideation or suicidal behavior in 69.9% of veterans with schizophrenia and 82.3% of those with bipolar disorder; the percentages who reported making actual suicide attempts was 46.1% schizophrenia and 54.5% bipolar disorder.

The risk of suicidal ideation was lower in schizophrenia vs. bipolar disorder (odds ratio, 0.82; 95% confidence interval, 0.71-0.95), as was suicidal behavior (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71-0.93).

Dr. Harvey said this is not surprising. “The combination of a history of euphoric mood and significant depression [characteristic of bipolar disorder] is very challenging.”

Other factors lowered risk: College education vs. high school or less (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.67-1.00 for ideation; OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.58-0.84 for behavior). In addition, lower risk was found among black vs. white patients (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.63-0.84 for ideation; OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72-0.93, for behavior).

These factors boosted risk: multiple psychiatric comorbidities vs. none (OR, 2.61; 95% CI, 2.22-3.07 for ideation; OR, 3.82; 95% CI, 3.30-4.41, for behavior), and those with a history of being ever vs. never married (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.02-1.37 for ideation; OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.19-1.55, for behavior). Most of those who had been married later were divorced.

“These findings underscore the need for continuous monitoring for suicidality in veteran populations, regardless of age or psychiatric diagnosis, and especially with multiple psychiatric comorbidities,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Program. Dr. Harvey reported no relevant disclosures.

AT APA

Key clinical point: Roughly half of U.S. veterans with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder have tried to kill themselves, and most of these veterans have histories of suicidal ideation or behavior.

Major finding: Suicide attempts are reported in 46.1% of patients with schizophrenia and 54.5% of those with bipolar I disorder. Documented suicidal ideation or behavior is reported in 69.9% of veterans with schizophrenia and 82.3% of those with bipolar disorder.

Data source: A genomic study with in-person assessments of VA patients with schizophrenia (N = 3,941) or bipolar disorder (N = 5,414). The mean age was 53.6 years, plus or minus 11 years; 86.2% were male, and 57.4% were white.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Program.

Treatment response rates for psychotic bipolar depression similar to those without

MIAMI – Response rates for psychotic and nonpsychotic depression in bipolar disorder were statistically similar, regardless of treatment, an ad hoc analysis has shown.

Over a 6 month period, results from the multisite, randomized, controlled Bipolar CHOICE (Clinical Health Outcomes Initiative in Comparative Effectiveness for Bipolar Disorder) study showed that 482 patients anywhere on the bipolar spectrum, given either lithium or quetiapine, had similar treatment response rates over 6 months.

“When you look at the course of the improvement for those with psychosis, they had more severe disorder at baseline,and presented with these symptoms throughout the study. But, when we compare curves of improvement, those with severe disorder responded to treatment at the same pace [as those without psychosis],” Dr. Caldieraro said.

The overall scores for the Bipolar Inventory of Symptoms Scale (BISS) at baseline were 75.2 plus or minus 17.6 percentage points for those with psychosis, vs. 54.9 plus or minus 16.3 for those without (P less than .001). At 6 months, the scores were more in range with one another: 37.2 plus or minus 19.7 for those with psychosis and 26.3 plus or minus 18.0 for those without (P = .003). The BISS depression scores at baseline for those with psychosis were 29.5 plus or minus 7.0, compared with 24.9 plus or minus 8.0 for those without (P = .002). At study end, the scores were 13.0 plus or minus 8.6, vs. 10.9 plus or minus 9.5 (P = .253).

Overall Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scores for bipolar disorder at baseline in the group with psychosis were 5.1 plus or minus 0.9, compared with 4.5 plus or minus 0.8 in those without (P less than .001). At 6 months, the scores were 3.4 plus or minus 1.3, vs. 2.8 plus or minus 1.3 (P = .032). The CGI scores for depression in the psychosis group at baseline were 4.9 plus or minus 0.9, compared with 4.4 plus or minus 0.9 in the nonpsychosis group (P = .006). At 6 months, the psychosis groups’ scores were 3.1 plus or minus 1.4, compared with 2.6 plus or minus 1.3 in the nonpsychosis group (P = .07).

In addition to either lithium or quetiapine, patients in the CHOICE study also received adjunctive personalized treatment. Patients who received lithium plus APT were not given second-generation antipsychotics, while those given quetiapine plus APT were not given lithium or any other second-generation antipsychotic.

In the quetiapine group, 21 people had psychotic depression at baseline. In the lithium group, there were 11. The time to remission was numerically, although not statistically, similar between the patients with psychosis in the lithium and the quetiapine groups.

Compared with the CHOICE study participants without psychosis, the subanalysis showed that the 32 people with psychotic features were far more likely to be single or never married (P = .036), employed at half the rate (P = .035), twice as likely to suffer from generalized anxiety disorder (P = .028), and more likely to have social phobias (P = .018). People with psychotic depression in the study also were more likely to suffer from agoraphobia.

One reason for his interest in the study, Dr. Caldieraro said, was that, despite the worse prognosis for people on the bipolar spectrum with psychotic depression, the literature on treatment outcomes for this cohort is scant.

“Ours is a small sample, so you could say that we didn’t have enough power, but we have some interesting results,” he said during his presentation. “The results need replication, but the study suggests that maybe, if we make the patient better, it doesn’t matter which medication we use.”

Dr. Caldieraro had no relevant disclosures. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded the CHOICE study, NCT01331304.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

MIAMI – Response rates for psychotic and nonpsychotic depression in bipolar disorder were statistically similar, regardless of treatment, an ad hoc analysis has shown.

Over a 6 month period, results from the multisite, randomized, controlled Bipolar CHOICE (Clinical Health Outcomes Initiative in Comparative Effectiveness for Bipolar Disorder) study showed that 482 patients anywhere on the bipolar spectrum, given either lithium or quetiapine, had similar treatment response rates over 6 months.

“When you look at the course of the improvement for those with psychosis, they had more severe disorder at baseline,and presented with these symptoms throughout the study. But, when we compare curves of improvement, those with severe disorder responded to treatment at the same pace [as those without psychosis],” Dr. Caldieraro said.

The overall scores for the Bipolar Inventory of Symptoms Scale (BISS) at baseline were 75.2 plus or minus 17.6 percentage points for those with psychosis, vs. 54.9 plus or minus 16.3 for those without (P less than .001). At 6 months, the scores were more in range with one another: 37.2 plus or minus 19.7 for those with psychosis and 26.3 plus or minus 18.0 for those without (P = .003). The BISS depression scores at baseline for those with psychosis were 29.5 plus or minus 7.0, compared with 24.9 plus or minus 8.0 for those without (P = .002). At study end, the scores were 13.0 plus or minus 8.6, vs. 10.9 plus or minus 9.5 (P = .253).

Overall Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scores for bipolar disorder at baseline in the group with psychosis were 5.1 plus or minus 0.9, compared with 4.5 plus or minus 0.8 in those without (P less than .001). At 6 months, the scores were 3.4 plus or minus 1.3, vs. 2.8 plus or minus 1.3 (P = .032). The CGI scores for depression in the psychosis group at baseline were 4.9 plus or minus 0.9, compared with 4.4 plus or minus 0.9 in the nonpsychosis group (P = .006). At 6 months, the psychosis groups’ scores were 3.1 plus or minus 1.4, compared with 2.6 plus or minus 1.3 in the nonpsychosis group (P = .07).

In addition to either lithium or quetiapine, patients in the CHOICE study also received adjunctive personalized treatment. Patients who received lithium plus APT were not given second-generation antipsychotics, while those given quetiapine plus APT were not given lithium or any other second-generation antipsychotic.

In the quetiapine group, 21 people had psychotic depression at baseline. In the lithium group, there were 11. The time to remission was numerically, although not statistically, similar between the patients with psychosis in the lithium and the quetiapine groups.

Compared with the CHOICE study participants without psychosis, the subanalysis showed that the 32 people with psychotic features were far more likely to be single or never married (P = .036), employed at half the rate (P = .035), twice as likely to suffer from generalized anxiety disorder (P = .028), and more likely to have social phobias (P = .018). People with psychotic depression in the study also were more likely to suffer from agoraphobia.

One reason for his interest in the study, Dr. Caldieraro said, was that, despite the worse prognosis for people on the bipolar spectrum with psychotic depression, the literature on treatment outcomes for this cohort is scant.

“Ours is a small sample, so you could say that we didn’t have enough power, but we have some interesting results,” he said during his presentation. “The results need replication, but the study suggests that maybe, if we make the patient better, it doesn’t matter which medication we use.”

Dr. Caldieraro had no relevant disclosures. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded the CHOICE study, NCT01331304.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

MIAMI – Response rates for psychotic and nonpsychotic depression in bipolar disorder were statistically similar, regardless of treatment, an ad hoc analysis has shown.

Over a 6 month period, results from the multisite, randomized, controlled Bipolar CHOICE (Clinical Health Outcomes Initiative in Comparative Effectiveness for Bipolar Disorder) study showed that 482 patients anywhere on the bipolar spectrum, given either lithium or quetiapine, had similar treatment response rates over 6 months.

“When you look at the course of the improvement for those with psychosis, they had more severe disorder at baseline,and presented with these symptoms throughout the study. But, when we compare curves of improvement, those with severe disorder responded to treatment at the same pace [as those without psychosis],” Dr. Caldieraro said.

The overall scores for the Bipolar Inventory of Symptoms Scale (BISS) at baseline were 75.2 plus or minus 17.6 percentage points for those with psychosis, vs. 54.9 plus or minus 16.3 for those without (P less than .001). At 6 months, the scores were more in range with one another: 37.2 plus or minus 19.7 for those with psychosis and 26.3 plus or minus 18.0 for those without (P = .003). The BISS depression scores at baseline for those with psychosis were 29.5 plus or minus 7.0, compared with 24.9 plus or minus 8.0 for those without (P = .002). At study end, the scores were 13.0 plus or minus 8.6, vs. 10.9 plus or minus 9.5 (P = .253).

Overall Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scores for bipolar disorder at baseline in the group with psychosis were 5.1 plus or minus 0.9, compared with 4.5 plus or minus 0.8 in those without (P less than .001). At 6 months, the scores were 3.4 plus or minus 1.3, vs. 2.8 plus or minus 1.3 (P = .032). The CGI scores for depression in the psychosis group at baseline were 4.9 plus or minus 0.9, compared with 4.4 plus or minus 0.9 in the nonpsychosis group (P = .006). At 6 months, the psychosis groups’ scores were 3.1 plus or minus 1.4, compared with 2.6 plus or minus 1.3 in the nonpsychosis group (P = .07).

In addition to either lithium or quetiapine, patients in the CHOICE study also received adjunctive personalized treatment. Patients who received lithium plus APT were not given second-generation antipsychotics, while those given quetiapine plus APT were not given lithium or any other second-generation antipsychotic.

In the quetiapine group, 21 people had psychotic depression at baseline. In the lithium group, there were 11. The time to remission was numerically, although not statistically, similar between the patients with psychosis in the lithium and the quetiapine groups.

Compared with the CHOICE study participants without psychosis, the subanalysis showed that the 32 people with psychotic features were far more likely to be single or never married (P = .036), employed at half the rate (P = .035), twice as likely to suffer from generalized anxiety disorder (P = .028), and more likely to have social phobias (P = .018). People with psychotic depression in the study also were more likely to suffer from agoraphobia.

One reason for his interest in the study, Dr. Caldieraro said, was that, despite the worse prognosis for people on the bipolar spectrum with psychotic depression, the literature on treatment outcomes for this cohort is scant.

“Ours is a small sample, so you could say that we didn’t have enough power, but we have some interesting results,” he said during his presentation. “The results need replication, but the study suggests that maybe, if we make the patient better, it doesn’t matter which medication we use.”

Dr. Caldieraro had no relevant disclosures. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded the CHOICE study, NCT01331304.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT THE ASCP ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients with psychotic or nonpsychotic bipolar depression responded equally well to lithium and quetiapine when compared with response rates in patients without bipolar depression.

Data source: A secondary analysis of 32 patients from a multisite, randomized, controlled trial of 482 patients with bipolar disorder I or bipolar II and psychosis, assigned to receive either lithium or quetiapine for 6 months.

Disclosures: Dr. Caldieraro had no relevant disclosures. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded the CHOICE study, NCT01331304.

First trimester lithium exposure ups risk of cardiac malformations

Cardiac malformations are three times more likely to occur in infants exposed to lithium during the first trimester of gestation than in unexposed infants.

The increased risk could account for one additional cardiac malformation per 100 live births, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, and her colleagues wrote in the June 8 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine (2017;376:2245-54).

Dr. Patorno’s study is the largest conducted since then. It comprised more than 1.3 million pregnancies included in the U.S. Medicaid Analytic eXtract database during 2000-2010. Of these, 663 had first trimester lithium exposure. These were compared with 1,945 pregnancies with first trimester exposure to lamotrigine, another mood stabilizer, and to the remaining 1.3 million pregnancies unexposed to either drug.

There were 16 cardiac malformations in the lithium group (2.41%); 27 in the lamotrigine group (1.39%); and 15,251 in the unexposed group (1.15%). Lithium conferred a 65% increased risk of cardiac defect, compared with unexposed pregnancies. It more than doubled the risk when compared with lamotrigine-exposed pregnancies (risk ratio, 2.25).

The risk was dose dependent, however, with an 11% increase associated with 600 mg/day or less and a 60% increase associated with 601-900 mg/day. Infants exposed to more than 900 mg per day in the first trimester, however, were more than 300% more likely to have a cardiac malformation (RR, 3.22).

The investigators also examined the association of lithium with cardiac defects consistent with Ebstein’s anomaly. Lithium more than doubled the risk, compared with unexposed infants (RR, 2.66). This risk was also dose dependent; all of the right ventricular outflow defects occurred in infants exposed to more than 600 mg/day.

Dr. Patorno reported grant support from National Institute of Mental Health during the study and grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline outside of the study. Other authors reported receiving grants or personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

Cardiac malformations are three times more likely to occur in infants exposed to lithium during the first trimester of gestation than in unexposed infants.

The increased risk could account for one additional cardiac malformation per 100 live births, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, and her colleagues wrote in the June 8 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine (2017;376:2245-54).

Dr. Patorno’s study is the largest conducted since then. It comprised more than 1.3 million pregnancies included in the U.S. Medicaid Analytic eXtract database during 2000-2010. Of these, 663 had first trimester lithium exposure. These were compared with 1,945 pregnancies with first trimester exposure to lamotrigine, another mood stabilizer, and to the remaining 1.3 million pregnancies unexposed to either drug.

There were 16 cardiac malformations in the lithium group (2.41%); 27 in the lamotrigine group (1.39%); and 15,251 in the unexposed group (1.15%). Lithium conferred a 65% increased risk of cardiac defect, compared with unexposed pregnancies. It more than doubled the risk when compared with lamotrigine-exposed pregnancies (risk ratio, 2.25).

The risk was dose dependent, however, with an 11% increase associated with 600 mg/day or less and a 60% increase associated with 601-900 mg/day. Infants exposed to more than 900 mg per day in the first trimester, however, were more than 300% more likely to have a cardiac malformation (RR, 3.22).

The investigators also examined the association of lithium with cardiac defects consistent with Ebstein’s anomaly. Lithium more than doubled the risk, compared with unexposed infants (RR, 2.66). This risk was also dose dependent; all of the right ventricular outflow defects occurred in infants exposed to more than 600 mg/day.

Dr. Patorno reported grant support from National Institute of Mental Health during the study and grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline outside of the study. Other authors reported receiving grants or personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

Cardiac malformations are three times more likely to occur in infants exposed to lithium during the first trimester of gestation than in unexposed infants.

The increased risk could account for one additional cardiac malformation per 100 live births, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, and her colleagues wrote in the June 8 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine (2017;376:2245-54).

Dr. Patorno’s study is the largest conducted since then. It comprised more than 1.3 million pregnancies included in the U.S. Medicaid Analytic eXtract database during 2000-2010. Of these, 663 had first trimester lithium exposure. These were compared with 1,945 pregnancies with first trimester exposure to lamotrigine, another mood stabilizer, and to the remaining 1.3 million pregnancies unexposed to either drug.

There were 16 cardiac malformations in the lithium group (2.41%); 27 in the lamotrigine group (1.39%); and 15,251 in the unexposed group (1.15%). Lithium conferred a 65% increased risk of cardiac defect, compared with unexposed pregnancies. It more than doubled the risk when compared with lamotrigine-exposed pregnancies (risk ratio, 2.25).

The risk was dose dependent, however, with an 11% increase associated with 600 mg/day or less and a 60% increase associated with 601-900 mg/day. Infants exposed to more than 900 mg per day in the first trimester, however, were more than 300% more likely to have a cardiac malformation (RR, 3.22).

The investigators also examined the association of lithium with cardiac defects consistent with Ebstein’s anomaly. Lithium more than doubled the risk, compared with unexposed infants (RR, 2.66). This risk was also dose dependent; all of the right ventricular outflow defects occurred in infants exposed to more than 600 mg/day.

Dr. Patorno reported grant support from National Institute of Mental Health during the study and grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline outside of the study. Other authors reported receiving grants or personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The dose-dependent increased risks ranged from 11% to more than 300%, compared with unexposed pregnancies.

Data source: The Medicaid database review comprised more than 1.3 million pregnancies.

Disclosures: Dr. Patorno reported grant support from National Institute of Mental Health during the study and grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline outside of the study. Other authors reported receiving grants or personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

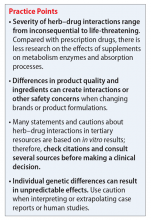

Herb–drug interactions: Caution patients when changing supplements

Ms. X, age 41, has a history of bipolar disorder and presents with extreme sleepiness, constipation with mild abdominal cramping, occasional dizziness, and “palpitations.” Although usually she is quite articulate, Ms. X seems to have trouble describing her symptoms and reports that they have been worsening over 4 to 6 days. She is worried because she is making mistakes at work and repeatedly misunderstanding directions.

Ms. X has a family history of hyperlipidemia, heart disease, and diabetes, and she has been employing a healthy diet, exercise, and use of supplements for cardiovascular health since her early 20s. Her medication regimen includes lithium, 600 mg, twice a day, quetiapine, 1,200 mg/d, a multivitamin and mineral tablet once a day, a brand name garlic supplement (garlic powder, 300 mg, vitamin C, 80 mg, vitamin E, 20 IU, vitamin A, 2,640 IU) twice a day, and fish oil, 2 g/d, at bedtime. Lithium levels consistently have been 0.8 to 0.9 mEq/L for the last 3 years.

Factors of drug–supplement interactions

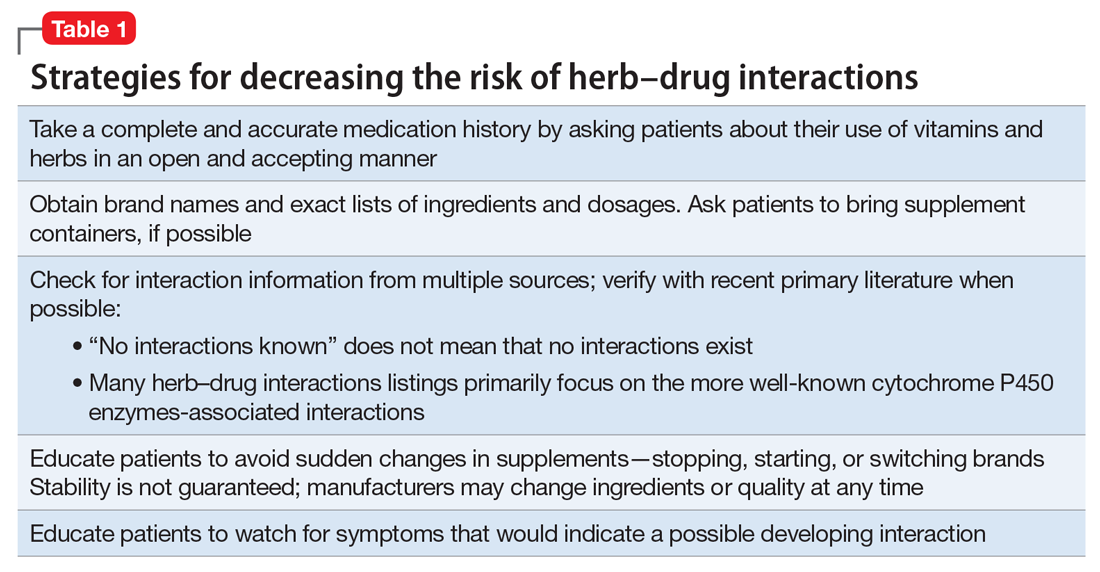

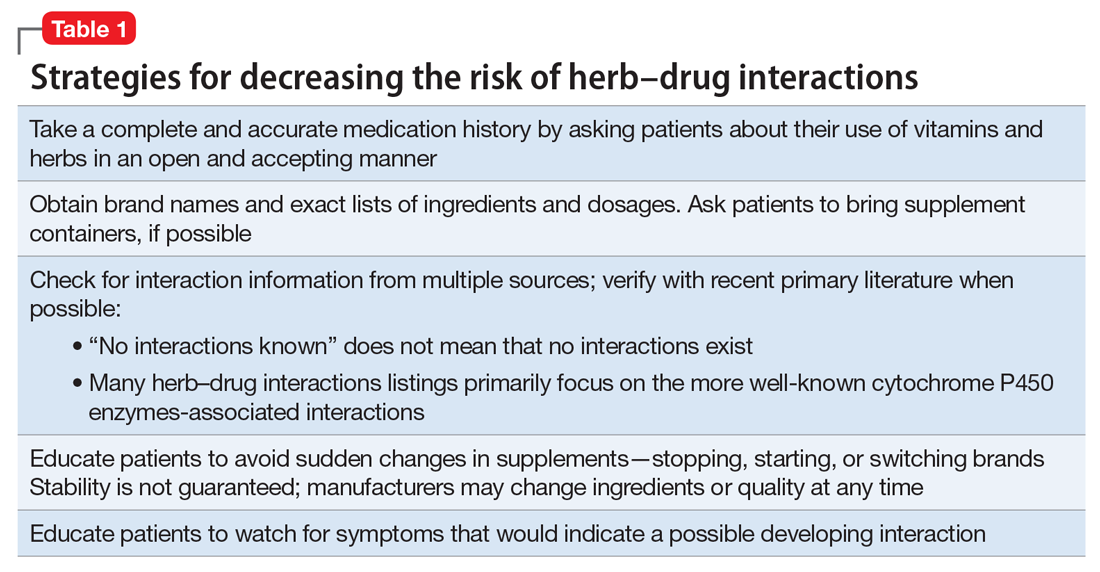

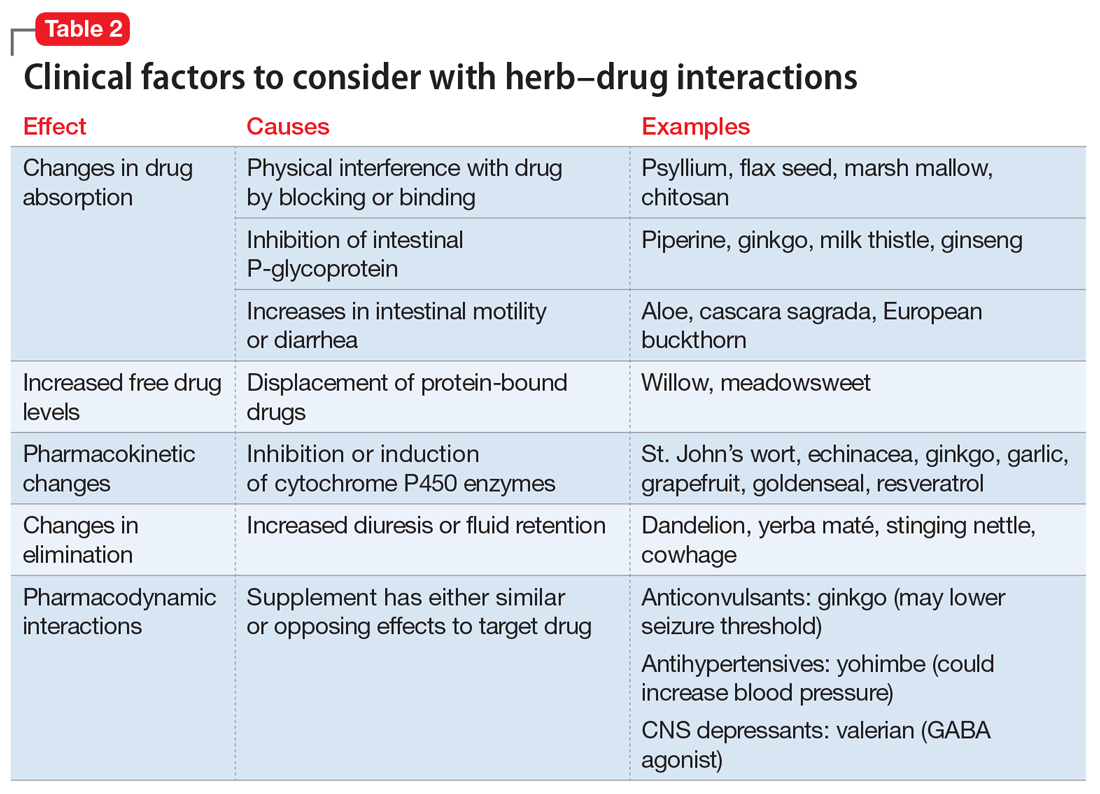

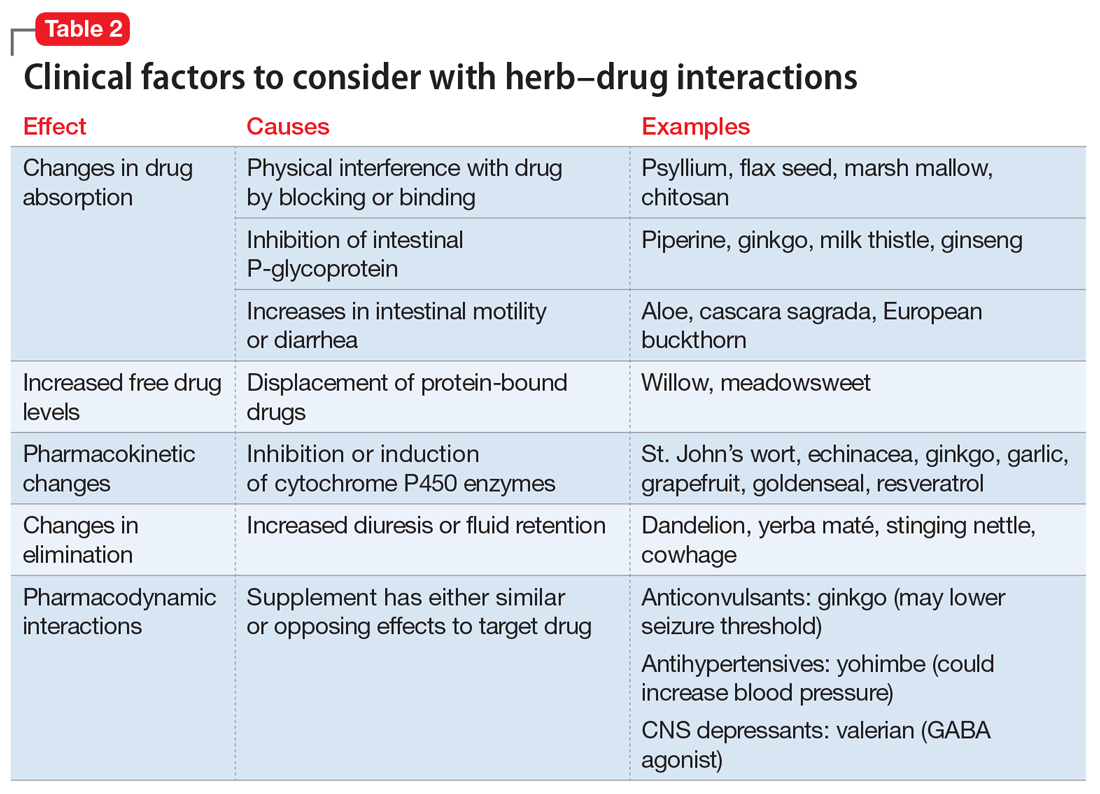

Because an interaction is possible doesn’t always mean that a drug and an offending botanical cannot be used together. With awareness and planning, possible interactions can be safely managed (Table 1). Such was the case of Ms. X, who was stable on a higher-than-usual dosage of quetiapine (average target is 600 mg/d for bipolar disorder) because of presumed moderate enzyme induction by the brand name garlic supplement. Ms. X did not want to stop taking this supplement when she started quetiapine. Although garlic is listed as a possible moderate cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inducer, there is conflicting evidence.1 Ms. X’s clinician advised her to avoid changes in dosage, because it could affect her quetiapine levels. However, the change in the botanical preparation from dried, powdered garlic to garlic oil likely removed the CYP3A4 enzyme induction, leading to a lower rate of metabolism and accumulation of the drug to toxic levels.

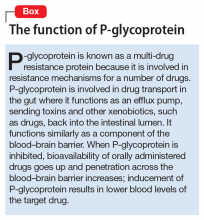

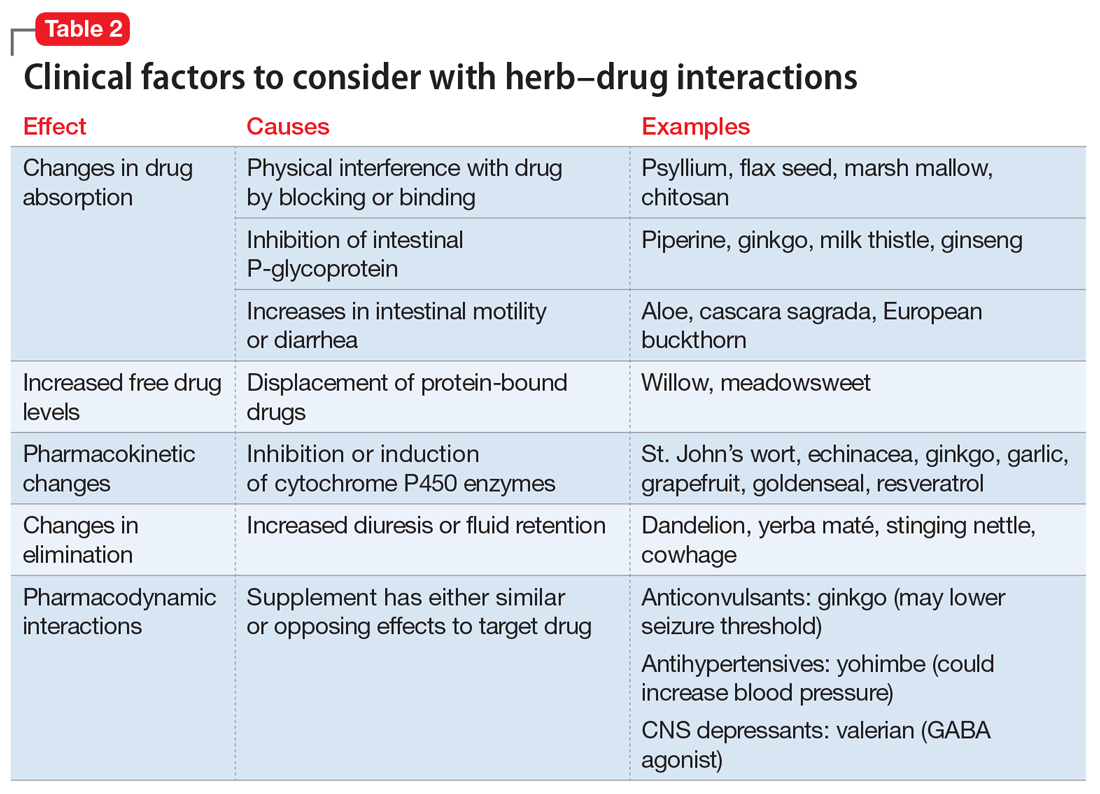

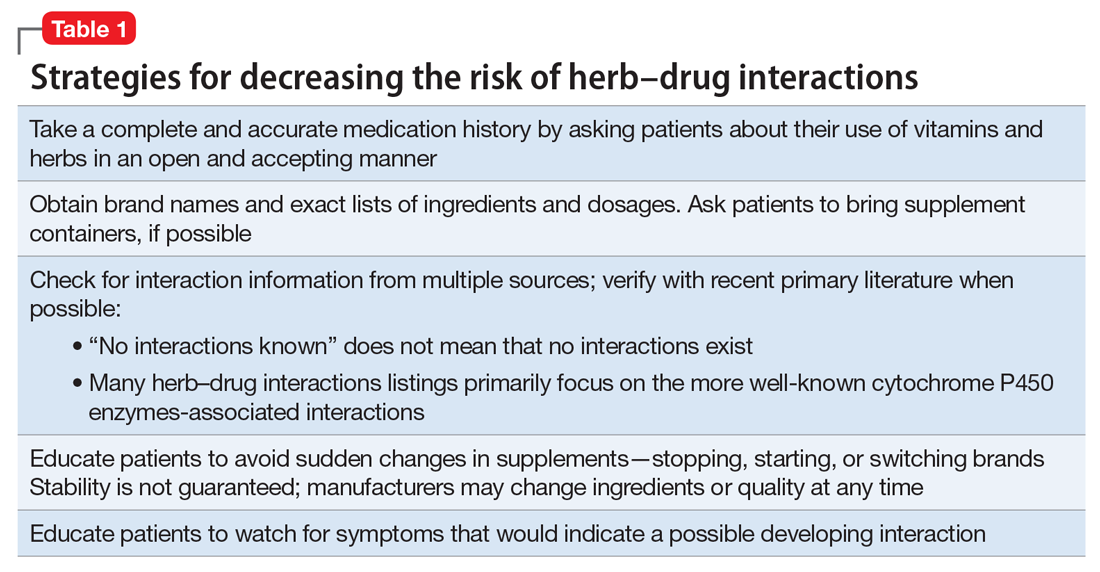

Drug metabolism. Practitioners are increasingly aware that St. John’s wort can significantly affect concomitantly administered drug levels by induction of the CYP isoenzyme 3A4 and more resources are listing this same possible induction for garlic.1 However, what is less understood is the extent to which different preparations of the same plant possess different chemical profiles (Table 2).

Clinical studies with different garlic preparations—dried powder, aqueous extracts, deodorized preparations, oils—have demonstrated diverse and highly variable results in tests of effects on CYP isoenzymes and other metabolism activities.

Drug absorption. Small differences in amounts of vitamins in the supplement are unlikely to be clinically significant, but the addition of piperine could be affecting quetiapine absorption. Piperine, a constituent of black pepper and long pepper, is used in Ayurvedic medicine for:

- pain

- influenza

- rheumatoid arthritis

- asthma

- loss of appetite

- stimulating peristalsis.6

Animal studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory, anticonvulsant, anticarcinogenic, and antioxidant effects, as well as stimulation of digestion via digestive enzyme secretion and increased gastromotility.3,6

Because piperine is known to increase intestinal absorption by various mechanisms, it often is added to botanical medicines to increase bioavailability of active components. BioPerine is a 95% piperine extract marketed to be included in vitamin and herbal supplements for that purpose.3 This allows use of lower dosages to achieve outcomes, which, for expensive botanicals, could be a cost savings for the manufacturer. Studies examining piperine’s influence on drug absorption have demonstrated significant increases in carbamazepine, rifampin, phenytoin, nevirapine, and many other drugs.

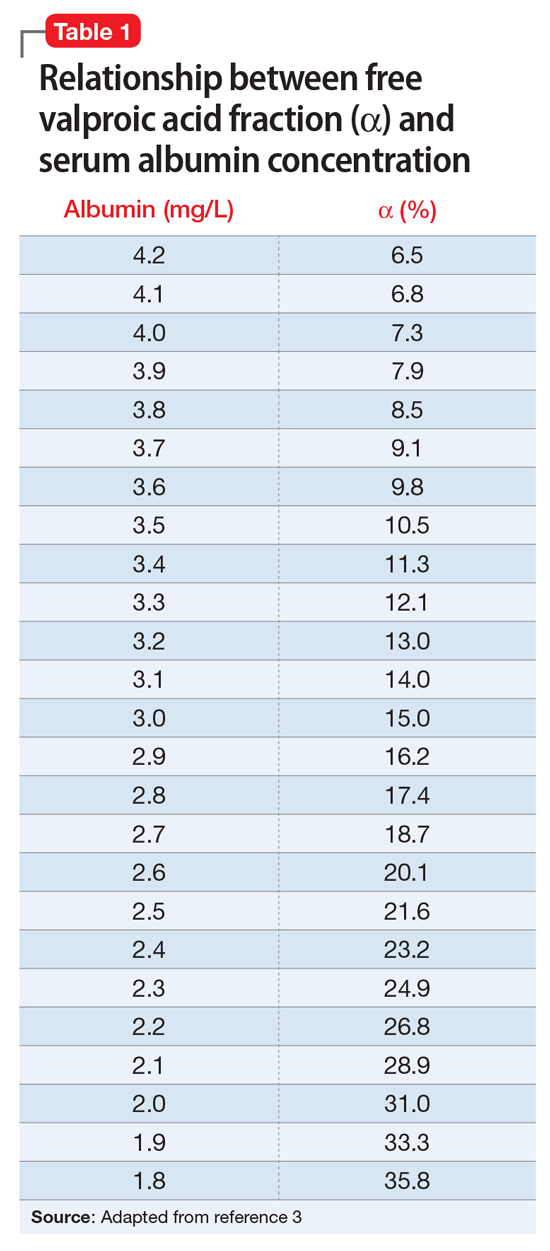

In addition to increased absorption, piperine seems to be a non-specific general inhibitor of CYP isoenzymes; IV phenytoin levels also were higher among test participants.6,8 Piperine reduces intestinal glucuronidation via uridine 5’-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase inhibition, and the small or moderate effects on lithium levels seem to be the result of diuretic activities.3,7

Patients often are motivated to control at least 1 aspect of their medical treatment, such as the supplements they choose to take. Being open to patient use of non-harmful or low-risk supplements, even when they are unlikely to have any medicinal benefit, helps preserve a relationship in which patients are more likely to consider your recommendation to avoid a harmful or high-risk supplement.

Related Resources

1. Natural Medicines Database. Garlic monograph. http://naturaldatabase.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed May 1, 2017.

2. Wanwimolruk S, Prachayasittikul V. Cytochrome P450 enzyme mediated herbal drug interactions (part 1). EXCLI J. 2014;13:347-391.

3. Colalto C. Herbal interactions on absorption of drugs: mechanism of action and clinical risk assessment. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62(3):207-227.

4. Gurley BJ, Gardner SF, Hubbard MA, et al. Clinical assessment of effects of botanical supplementation on cytochrome P450 phenotypes in the elderly: St. John’s wort, garlic oil, Panax ginseng and Ginkgo biloba. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(6):525-539.

5. Gallicano K, Foster B, Choudhri S. Effect of short-term administration of garlic supplements on single-dose ritonavir pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55(2):199-202.

6. Meghwal M, Goswami TK. Piper nigrum and piperine: an update. Phytother Res. 2013;27(8):1121-1130.

7. Natural Medicines Database. Black pepper monograph. https://www.naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed May 1, 2017.

8. Zhou S, Lim LY, Chowbay B. Herbal modulation of p-glycoprotein. Drug Metab Rev. 2004;36(1):57-104.

9. Chinta G, Syed B, Coumar MS, et al. Piperine: a comprehensive review of pre-clinical and clinical investigations. Curr Bioact Compd. 2015;11(3):156-169.

Ms. X, age 41, has a history of bipolar disorder and presents with extreme sleepiness, constipation with mild abdominal cramping, occasional dizziness, and “palpitations.” Although usually she is quite articulate, Ms. X seems to have trouble describing her symptoms and reports that they have been worsening over 4 to 6 days. She is worried because she is making mistakes at work and repeatedly misunderstanding directions.

Ms. X has a family history of hyperlipidemia, heart disease, and diabetes, and she has been employing a healthy diet, exercise, and use of supplements for cardiovascular health since her early 20s. Her medication regimen includes lithium, 600 mg, twice a day, quetiapine, 1,200 mg/d, a multivitamin and mineral tablet once a day, a brand name garlic supplement (garlic powder, 300 mg, vitamin C, 80 mg, vitamin E, 20 IU, vitamin A, 2,640 IU) twice a day, and fish oil, 2 g/d, at bedtime. Lithium levels consistently have been 0.8 to 0.9 mEq/L for the last 3 years.

Factors of drug–supplement interactions

Because an interaction is possible doesn’t always mean that a drug and an offending botanical cannot be used together. With awareness and planning, possible interactions can be safely managed (Table 1). Such was the case of Ms. X, who was stable on a higher-than-usual dosage of quetiapine (average target is 600 mg/d for bipolar disorder) because of presumed moderate enzyme induction by the brand name garlic supplement. Ms. X did not want to stop taking this supplement when she started quetiapine. Although garlic is listed as a possible moderate cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inducer, there is conflicting evidence.1 Ms. X’s clinician advised her to avoid changes in dosage, because it could affect her quetiapine levels. However, the change in the botanical preparation from dried, powdered garlic to garlic oil likely removed the CYP3A4 enzyme induction, leading to a lower rate of metabolism and accumulation of the drug to toxic levels.

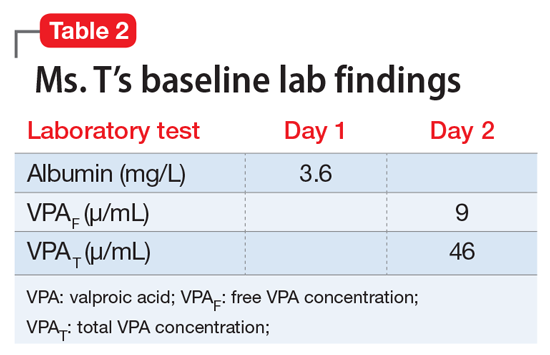

Drug metabolism. Practitioners are increasingly aware that St. John’s wort can significantly affect concomitantly administered drug levels by induction of the CYP isoenzyme 3A4 and more resources are listing this same possible induction for garlic.1 However, what is less understood is the extent to which different preparations of the same plant possess different chemical profiles (Table 2).

Clinical studies with different garlic preparations—dried powder, aqueous extracts, deodorized preparations, oils—have demonstrated diverse and highly variable results in tests of effects on CYP isoenzymes and other metabolism activities.

Drug absorption. Small differences in amounts of vitamins in the supplement are unlikely to be clinically significant, but the addition of piperine could be affecting quetiapine absorption. Piperine, a constituent of black pepper and long pepper, is used in Ayurvedic medicine for:

- pain

- influenza

- rheumatoid arthritis

- asthma

- loss of appetite

- stimulating peristalsis.6

Animal studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory, anticonvulsant, anticarcinogenic, and antioxidant effects, as well as stimulation of digestion via digestive enzyme secretion and increased gastromotility.3,6

Because piperine is known to increase intestinal absorption by various mechanisms, it often is added to botanical medicines to increase bioavailability of active components. BioPerine is a 95% piperine extract marketed to be included in vitamin and herbal supplements for that purpose.3 This allows use of lower dosages to achieve outcomes, which, for expensive botanicals, could be a cost savings for the manufacturer. Studies examining piperine’s influence on drug absorption have demonstrated significant increases in carbamazepine, rifampin, phenytoin, nevirapine, and many other drugs.

In addition to increased absorption, piperine seems to be a non-specific general inhibitor of CYP isoenzymes; IV phenytoin levels also were higher among test participants.6,8 Piperine reduces intestinal glucuronidation via uridine 5’-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase inhibition, and the small or moderate effects on lithium levels seem to be the result of diuretic activities.3,7

Patients often are motivated to control at least 1 aspect of their medical treatment, such as the supplements they choose to take. Being open to patient use of non-harmful or low-risk supplements, even when they are unlikely to have any medicinal benefit, helps preserve a relationship in which patients are more likely to consider your recommendation to avoid a harmful or high-risk supplement.

Related Resources

Ms. X, age 41, has a history of bipolar disorder and presents with extreme sleepiness, constipation with mild abdominal cramping, occasional dizziness, and “palpitations.” Although usually she is quite articulate, Ms. X seems to have trouble describing her symptoms and reports that they have been worsening over 4 to 6 days. She is worried because she is making mistakes at work and repeatedly misunderstanding directions.

Ms. X has a family history of hyperlipidemia, heart disease, and diabetes, and she has been employing a healthy diet, exercise, and use of supplements for cardiovascular health since her early 20s. Her medication regimen includes lithium, 600 mg, twice a day, quetiapine, 1,200 mg/d, a multivitamin and mineral tablet once a day, a brand name garlic supplement (garlic powder, 300 mg, vitamin C, 80 mg, vitamin E, 20 IU, vitamin A, 2,640 IU) twice a day, and fish oil, 2 g/d, at bedtime. Lithium levels consistently have been 0.8 to 0.9 mEq/L for the last 3 years.

Factors of drug–supplement interactions

Because an interaction is possible doesn’t always mean that a drug and an offending botanical cannot be used together. With awareness and planning, possible interactions can be safely managed (Table 1). Such was the case of Ms. X, who was stable on a higher-than-usual dosage of quetiapine (average target is 600 mg/d for bipolar disorder) because of presumed moderate enzyme induction by the brand name garlic supplement. Ms. X did not want to stop taking this supplement when she started quetiapine. Although garlic is listed as a possible moderate cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inducer, there is conflicting evidence.1 Ms. X’s clinician advised her to avoid changes in dosage, because it could affect her quetiapine levels. However, the change in the botanical preparation from dried, powdered garlic to garlic oil likely removed the CYP3A4 enzyme induction, leading to a lower rate of metabolism and accumulation of the drug to toxic levels.

Drug metabolism. Practitioners are increasingly aware that St. John’s wort can significantly affect concomitantly administered drug levels by induction of the CYP isoenzyme 3A4 and more resources are listing this same possible induction for garlic.1 However, what is less understood is the extent to which different preparations of the same plant possess different chemical profiles (Table 2).

Clinical studies with different garlic preparations—dried powder, aqueous extracts, deodorized preparations, oils—have demonstrated diverse and highly variable results in tests of effects on CYP isoenzymes and other metabolism activities.

Drug absorption. Small differences in amounts of vitamins in the supplement are unlikely to be clinically significant, but the addition of piperine could be affecting quetiapine absorption. Piperine, a constituent of black pepper and long pepper, is used in Ayurvedic medicine for:

- pain

- influenza

- rheumatoid arthritis

- asthma

- loss of appetite

- stimulating peristalsis.6