User login

Minimizing use of antipsychotics

Treating psychopathology in developmentally disabled tricky

LAS VEGAS – Individuals with intellectual disability experience behavioral and psychiatric illness at higher rates than the general population, according to Bryan H. King, MD.

“Increasingly, these individuals are showing up in all of our clinical practices,” Dr. King said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “In this area, it’s not so much that the population doesn’t experience psychiatric illness, but the diagnosis can be challenging because the presentation of symptoms may be different. For someone who can’t articulate whether they’re feeling anxious, fearful, or nervous, it’s more challenging to make a diagnosis.”

More than 10 years ago, researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill compared health disparities between adults with developmental disabilities in North Carolina and adults in the state with other disabilities and adults without disabilities (Public Health Rep. 2004;114[4]:418-26). They found those in the developmental disability group had a similar or greater risk of having high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic pain, compared with nondisabled adults. In addition, 24% of adults in the developmental disability group reported having either no one to talk to about personal things or often felt lonely.

A more recent, large national study found that, compared with adults with no autism diagnoses, those diagnosed with autism had significantly increased rates for all psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia (a more than 20-fold increased rate), and suicide attempts (Autism. 2015;19[7]:814-23). In addition, nearly all medical conditions such as obesity and dyslipidemia were significantly more common in adults with autism.

Results from a separate study of 371 adults with intellectual disabilities found that 40% had at least one mental health disorder and 45% had at least one moderate or severe behavior problem (Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:767-76). In addition, the highest ratios of unmet to met need were found with respect to sexuality issues and with respect to mental health problems.

Once a diagnosis is made, Dr. King said patients who have developmental disabilities should be treated in the same way as patients who do not. “There is a tremendous amount of heterogeneity in this population,” he said. “If you are confident that you have someone before you who has depression, the treatment for depression is going to proceed in the same ways it does for someone without the condition. Let that guide the way for medications you are going to use.”

In a recent edition of Current Opinion in Psychiatry, authors Na Young Ji, MD, and Robert L. Findling, MD, reviewed current evidence-based pharmacotherapy options for mental health problems in people with intellectual disability (Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29:103-25). Their five key points were:

1. “Antipsychotics, particularly risperidone, appear to be effective in reducing problem behaviors associated with intellectual disability.

2. “For attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, methylphenidate has been shown to be effective, and atomoxetine and alpha-agonists might be beneficial.

3. “Lithium might be effective in reducing aggression. Evidence for the use of antiepileptic drugs, anxiolytics, and naltrexone for management of problem behaviors is insufficient to draw conclusions.

4. “Antidepressants are often poorly tolerated and do not appear to be effective in decreasing repetitive or stereotypic behaviors associated with intellectual disability.

5. “Melatonin appears to improve sleep in people with intellectual disability.”

Dr. King noted that the data for using lithium in people with intellectual disability “are very old. There’s been nothing recent to help us fine-tune the indications.” He said naltrexone is among the best studied in this population, “especially for self-injurious behavior. The two large placebo-controlled trials were negative. In my own clinical experience, I have not seen it helpful.”

Dr. King disclosed that he has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Janssen, and Roche. He also is a consultant for Care Management Technologies and Neurotrope.

LAS VEGAS – Individuals with intellectual disability experience behavioral and psychiatric illness at higher rates than the general population, according to Bryan H. King, MD.

“Increasingly, these individuals are showing up in all of our clinical practices,” Dr. King said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “In this area, it’s not so much that the population doesn’t experience psychiatric illness, but the diagnosis can be challenging because the presentation of symptoms may be different. For someone who can’t articulate whether they’re feeling anxious, fearful, or nervous, it’s more challenging to make a diagnosis.”

More than 10 years ago, researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill compared health disparities between adults with developmental disabilities in North Carolina and adults in the state with other disabilities and adults without disabilities (Public Health Rep. 2004;114[4]:418-26). They found those in the developmental disability group had a similar or greater risk of having high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic pain, compared with nondisabled adults. In addition, 24% of adults in the developmental disability group reported having either no one to talk to about personal things or often felt lonely.

A more recent, large national study found that, compared with adults with no autism diagnoses, those diagnosed with autism had significantly increased rates for all psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia (a more than 20-fold increased rate), and suicide attempts (Autism. 2015;19[7]:814-23). In addition, nearly all medical conditions such as obesity and dyslipidemia were significantly more common in adults with autism.

Results from a separate study of 371 adults with intellectual disabilities found that 40% had at least one mental health disorder and 45% had at least one moderate or severe behavior problem (Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:767-76). In addition, the highest ratios of unmet to met need were found with respect to sexuality issues and with respect to mental health problems.

Once a diagnosis is made, Dr. King said patients who have developmental disabilities should be treated in the same way as patients who do not. “There is a tremendous amount of heterogeneity in this population,” he said. “If you are confident that you have someone before you who has depression, the treatment for depression is going to proceed in the same ways it does for someone without the condition. Let that guide the way for medications you are going to use.”

In a recent edition of Current Opinion in Psychiatry, authors Na Young Ji, MD, and Robert L. Findling, MD, reviewed current evidence-based pharmacotherapy options for mental health problems in people with intellectual disability (Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29:103-25). Their five key points were:

1. “Antipsychotics, particularly risperidone, appear to be effective in reducing problem behaviors associated with intellectual disability.

2. “For attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, methylphenidate has been shown to be effective, and atomoxetine and alpha-agonists might be beneficial.

3. “Lithium might be effective in reducing aggression. Evidence for the use of antiepileptic drugs, anxiolytics, and naltrexone for management of problem behaviors is insufficient to draw conclusions.

4. “Antidepressants are often poorly tolerated and do not appear to be effective in decreasing repetitive or stereotypic behaviors associated with intellectual disability.

5. “Melatonin appears to improve sleep in people with intellectual disability.”

Dr. King noted that the data for using lithium in people with intellectual disability “are very old. There’s been nothing recent to help us fine-tune the indications.” He said naltrexone is among the best studied in this population, “especially for self-injurious behavior. The two large placebo-controlled trials were negative. In my own clinical experience, I have not seen it helpful.”

Dr. King disclosed that he has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Janssen, and Roche. He also is a consultant for Care Management Technologies and Neurotrope.

LAS VEGAS – Individuals with intellectual disability experience behavioral and psychiatric illness at higher rates than the general population, according to Bryan H. King, MD.

“Increasingly, these individuals are showing up in all of our clinical practices,” Dr. King said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “In this area, it’s not so much that the population doesn’t experience psychiatric illness, but the diagnosis can be challenging because the presentation of symptoms may be different. For someone who can’t articulate whether they’re feeling anxious, fearful, or nervous, it’s more challenging to make a diagnosis.”

More than 10 years ago, researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill compared health disparities between adults with developmental disabilities in North Carolina and adults in the state with other disabilities and adults without disabilities (Public Health Rep. 2004;114[4]:418-26). They found those in the developmental disability group had a similar or greater risk of having high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic pain, compared with nondisabled adults. In addition, 24% of adults in the developmental disability group reported having either no one to talk to about personal things or often felt lonely.

A more recent, large national study found that, compared with adults with no autism diagnoses, those diagnosed with autism had significantly increased rates for all psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia (a more than 20-fold increased rate), and suicide attempts (Autism. 2015;19[7]:814-23). In addition, nearly all medical conditions such as obesity and dyslipidemia were significantly more common in adults with autism.

Results from a separate study of 371 adults with intellectual disabilities found that 40% had at least one mental health disorder and 45% had at least one moderate or severe behavior problem (Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:767-76). In addition, the highest ratios of unmet to met need were found with respect to sexuality issues and with respect to mental health problems.

Once a diagnosis is made, Dr. King said patients who have developmental disabilities should be treated in the same way as patients who do not. “There is a tremendous amount of heterogeneity in this population,” he said. “If you are confident that you have someone before you who has depression, the treatment for depression is going to proceed in the same ways it does for someone without the condition. Let that guide the way for medications you are going to use.”

In a recent edition of Current Opinion in Psychiatry, authors Na Young Ji, MD, and Robert L. Findling, MD, reviewed current evidence-based pharmacotherapy options for mental health problems in people with intellectual disability (Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29:103-25). Their five key points were:

1. “Antipsychotics, particularly risperidone, appear to be effective in reducing problem behaviors associated with intellectual disability.

2. “For attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, methylphenidate has been shown to be effective, and atomoxetine and alpha-agonists might be beneficial.

3. “Lithium might be effective in reducing aggression. Evidence for the use of antiepileptic drugs, anxiolytics, and naltrexone for management of problem behaviors is insufficient to draw conclusions.

4. “Antidepressants are often poorly tolerated and do not appear to be effective in decreasing repetitive or stereotypic behaviors associated with intellectual disability.

5. “Melatonin appears to improve sleep in people with intellectual disability.”

Dr. King noted that the data for using lithium in people with intellectual disability “are very old. There’s been nothing recent to help us fine-tune the indications.” He said naltrexone is among the best studied in this population, “especially for self-injurious behavior. The two large placebo-controlled trials were negative. In my own clinical experience, I have not seen it helpful.”

Dr. King disclosed that he has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Janssen, and Roche. He also is a consultant for Care Management Technologies and Neurotrope.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE NPA PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY UPDATE

SSRI activation in children, adolescents often misdiagnosed as bipolar

SAN FRANCISCO – It’s not uncommon for children to arrive at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor activation that was misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder, according to Boris Birmaher, MD.

“We get many kids into our clinic with a diagnosis of bipolar because of this, and they are not bipolar. You have to be careful,” he said during a talk about pediatric depression at a psychopharmacology update held by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

SSRIs activate about 5%-10% of children. There might be sleep problems, fast speech, hyperactivity, agitation, aggression, and even suicidality, he said.

Younger children and those with autism or developmental disabilities are particularly at risk. Occasionally, a child might be a slow metabolizer so that even low SSRI doses cause problems. “Once in a blue moon,” Dr. Birmaher said he will screen for genetic cytochrome P450 deficiency, especially if a child doesn’t seem able to tolerate medications in general, not just psychiatric ones. He’s found a few slow metabolizers over the years.

Psychiatrists also have to be careful when children and adolescents are tagged as “treatment resistant.” It’s important to teach parents what treatment resistance would actually look like for their child, so they don’t jump to conclusions and misdirect therapy, he said.

For example, when a child has been prescribed an SSRI for anxiety, parents might come in and say it’s not helping, when in fact they’re concerned about homework not getting done and restlessness in class. “There’s no treatment resistance. You teach the parent how to measure improvement of anxiety” and tackle the ADHD if it’s truly a problem, said Dr. Birmaher, also professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh.

If there really is SSRI treatment resistance, he said he first ensures that a maximum dose of the drug has been tried, so long as it’s tolerated. If it doesn’t work after 4-6 weeks, he’ll switch to another SSRI or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or combination treatment with, for instance, bupropion (Wellbutrin) or an atypical antipsychotic, which are particularly helpful for irritability, even in small doses. Atypicals seem to take the edge off, he said.

It’s trial and error, since there aren’t much data in children to guide treatment. “The only thing I highly recommend is to make one change at a time. Sometimes we see kids who’ve had two or three changes at the same time.” In those cases, he said, it’s impossible to know what to blame if there are side effects or what to credit if depression improves.

Dr. Birmaher said he had no pharmaceutical industry ties.

SAN FRANCISCO – It’s not uncommon for children to arrive at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor activation that was misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder, according to Boris Birmaher, MD.

“We get many kids into our clinic with a diagnosis of bipolar because of this, and they are not bipolar. You have to be careful,” he said during a talk about pediatric depression at a psychopharmacology update held by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

SSRIs activate about 5%-10% of children. There might be sleep problems, fast speech, hyperactivity, agitation, aggression, and even suicidality, he said.

Younger children and those with autism or developmental disabilities are particularly at risk. Occasionally, a child might be a slow metabolizer so that even low SSRI doses cause problems. “Once in a blue moon,” Dr. Birmaher said he will screen for genetic cytochrome P450 deficiency, especially if a child doesn’t seem able to tolerate medications in general, not just psychiatric ones. He’s found a few slow metabolizers over the years.

Psychiatrists also have to be careful when children and adolescents are tagged as “treatment resistant.” It’s important to teach parents what treatment resistance would actually look like for their child, so they don’t jump to conclusions and misdirect therapy, he said.

For example, when a child has been prescribed an SSRI for anxiety, parents might come in and say it’s not helping, when in fact they’re concerned about homework not getting done and restlessness in class. “There’s no treatment resistance. You teach the parent how to measure improvement of anxiety” and tackle the ADHD if it’s truly a problem, said Dr. Birmaher, also professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh.

If there really is SSRI treatment resistance, he said he first ensures that a maximum dose of the drug has been tried, so long as it’s tolerated. If it doesn’t work after 4-6 weeks, he’ll switch to another SSRI or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or combination treatment with, for instance, bupropion (Wellbutrin) or an atypical antipsychotic, which are particularly helpful for irritability, even in small doses. Atypicals seem to take the edge off, he said.

It’s trial and error, since there aren’t much data in children to guide treatment. “The only thing I highly recommend is to make one change at a time. Sometimes we see kids who’ve had two or three changes at the same time.” In those cases, he said, it’s impossible to know what to blame if there are side effects or what to credit if depression improves.

Dr. Birmaher said he had no pharmaceutical industry ties.

SAN FRANCISCO – It’s not uncommon for children to arrive at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor activation that was misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder, according to Boris Birmaher, MD.

“We get many kids into our clinic with a diagnosis of bipolar because of this, and they are not bipolar. You have to be careful,” he said during a talk about pediatric depression at a psychopharmacology update held by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

SSRIs activate about 5%-10% of children. There might be sleep problems, fast speech, hyperactivity, agitation, aggression, and even suicidality, he said.

Younger children and those with autism or developmental disabilities are particularly at risk. Occasionally, a child might be a slow metabolizer so that even low SSRI doses cause problems. “Once in a blue moon,” Dr. Birmaher said he will screen for genetic cytochrome P450 deficiency, especially if a child doesn’t seem able to tolerate medications in general, not just psychiatric ones. He’s found a few slow metabolizers over the years.

Psychiatrists also have to be careful when children and adolescents are tagged as “treatment resistant.” It’s important to teach parents what treatment resistance would actually look like for their child, so they don’t jump to conclusions and misdirect therapy, he said.

For example, when a child has been prescribed an SSRI for anxiety, parents might come in and say it’s not helping, when in fact they’re concerned about homework not getting done and restlessness in class. “There’s no treatment resistance. You teach the parent how to measure improvement of anxiety” and tackle the ADHD if it’s truly a problem, said Dr. Birmaher, also professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh.

If there really is SSRI treatment resistance, he said he first ensures that a maximum dose of the drug has been tried, so long as it’s tolerated. If it doesn’t work after 4-6 weeks, he’ll switch to another SSRI or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or combination treatment with, for instance, bupropion (Wellbutrin) or an atypical antipsychotic, which are particularly helpful for irritability, even in small doses. Atypicals seem to take the edge off, he said.

It’s trial and error, since there aren’t much data in children to guide treatment. “The only thing I highly recommend is to make one change at a time. Sometimes we see kids who’ve had two or three changes at the same time.” In those cases, he said, it’s impossible to know what to blame if there are side effects or what to credit if depression improves.

Dr. Birmaher said he had no pharmaceutical industry ties.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY UPDATE INSTITUTE

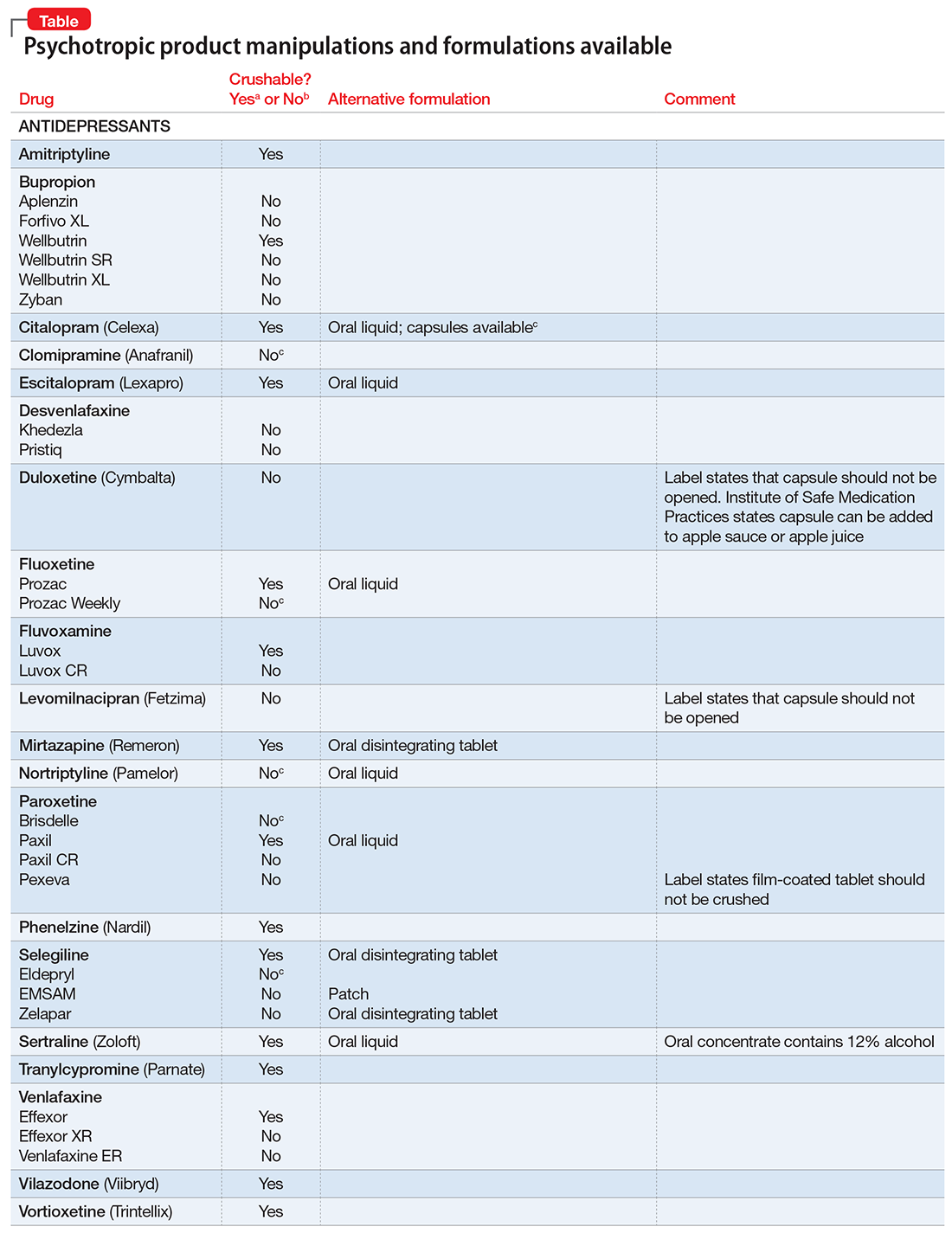

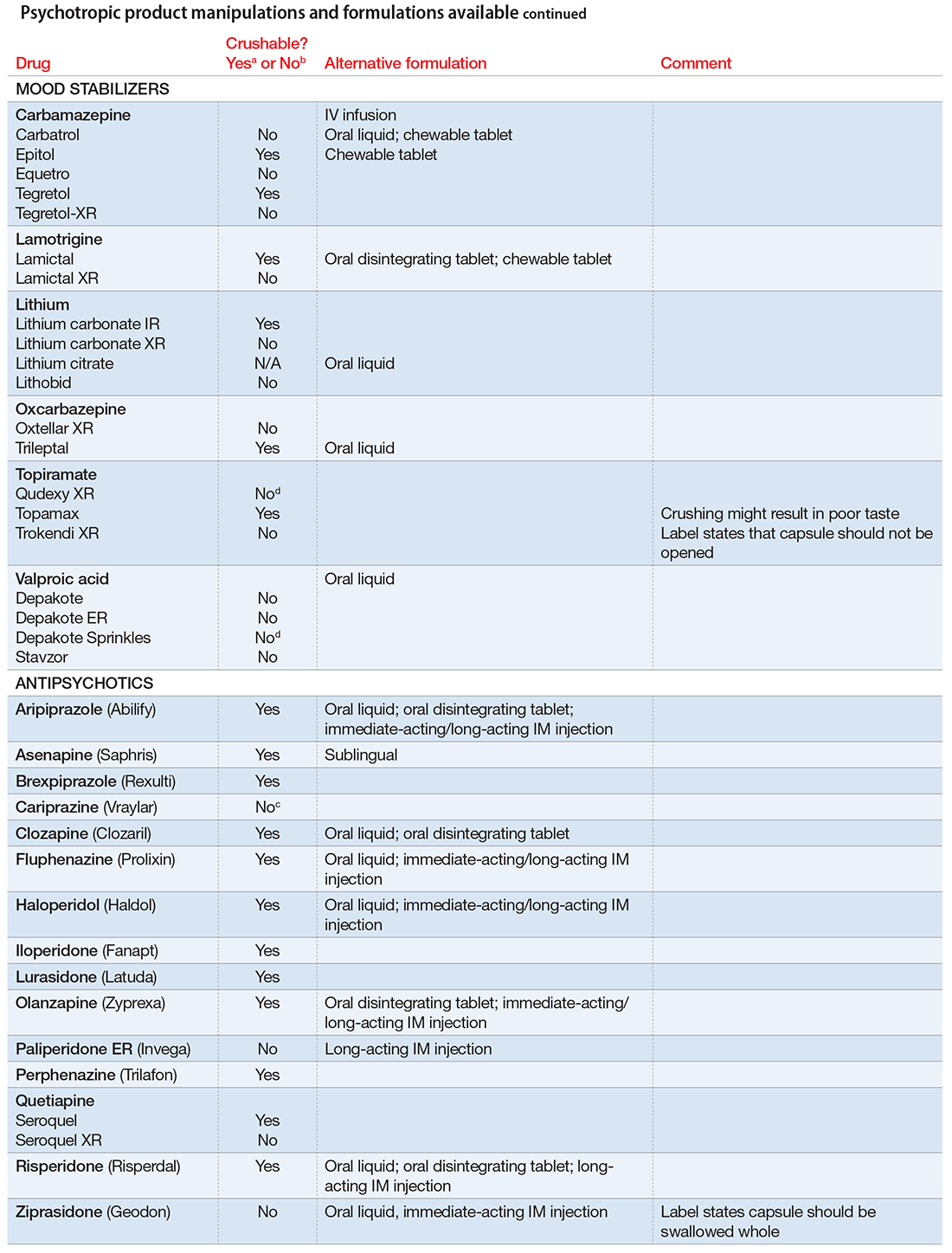

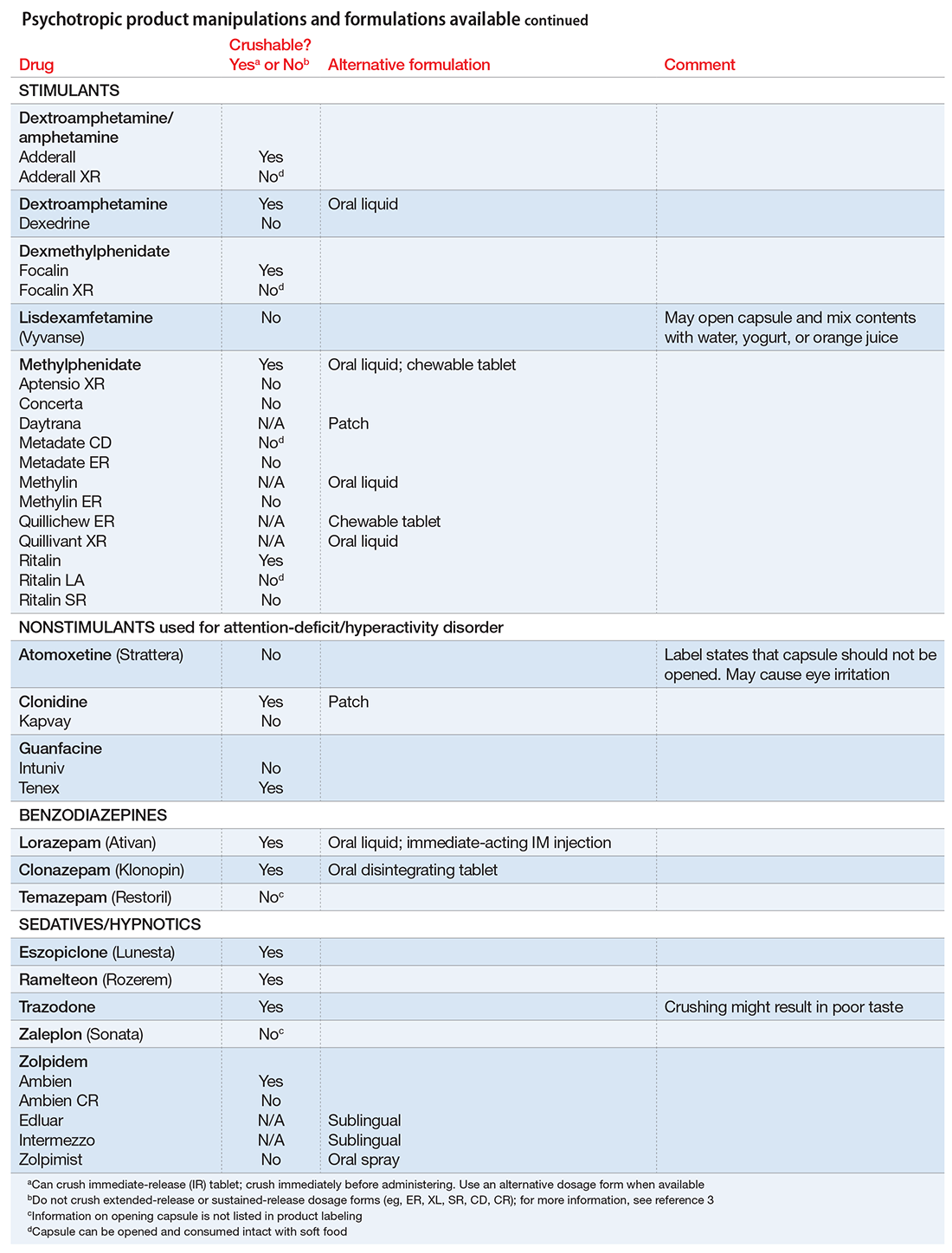

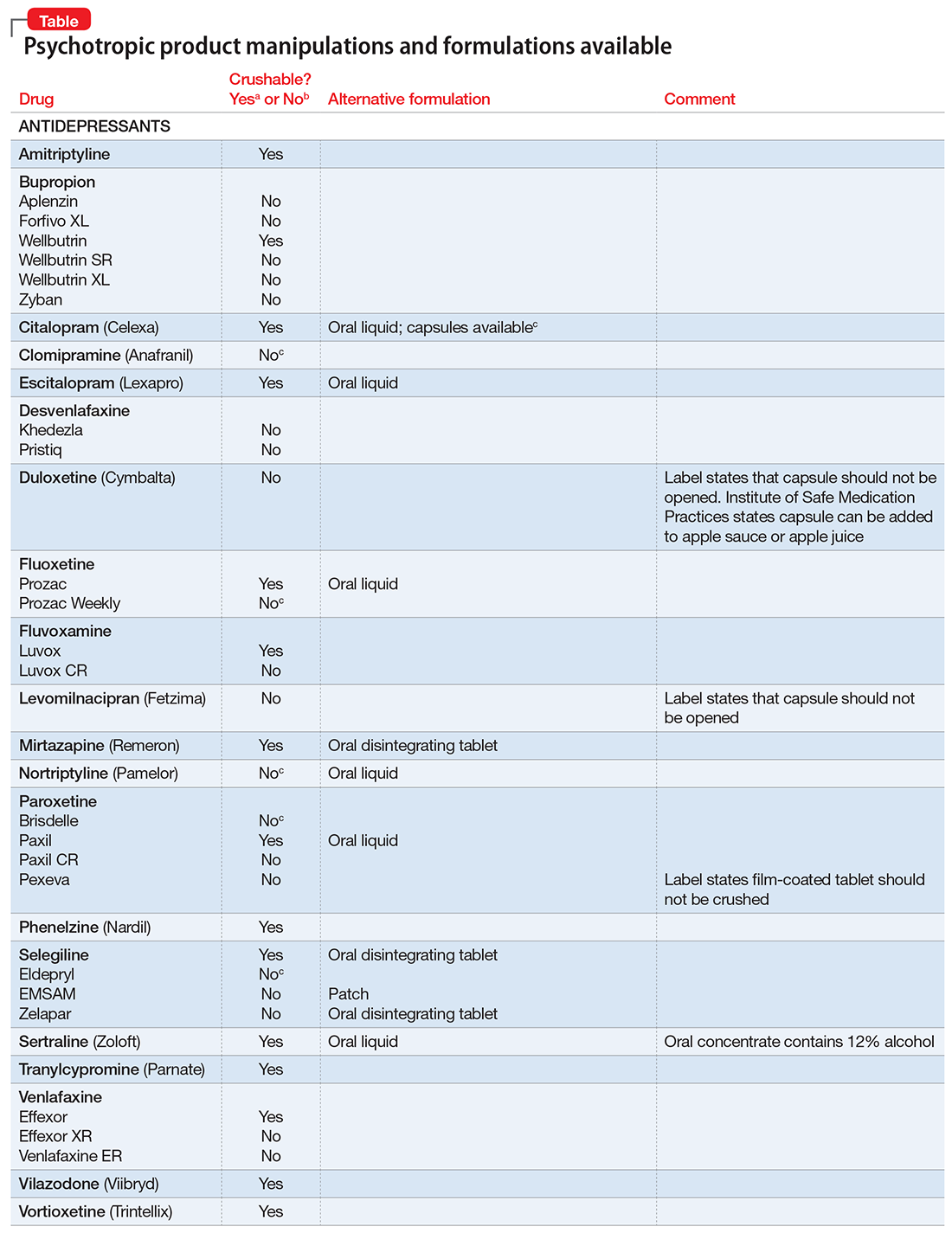

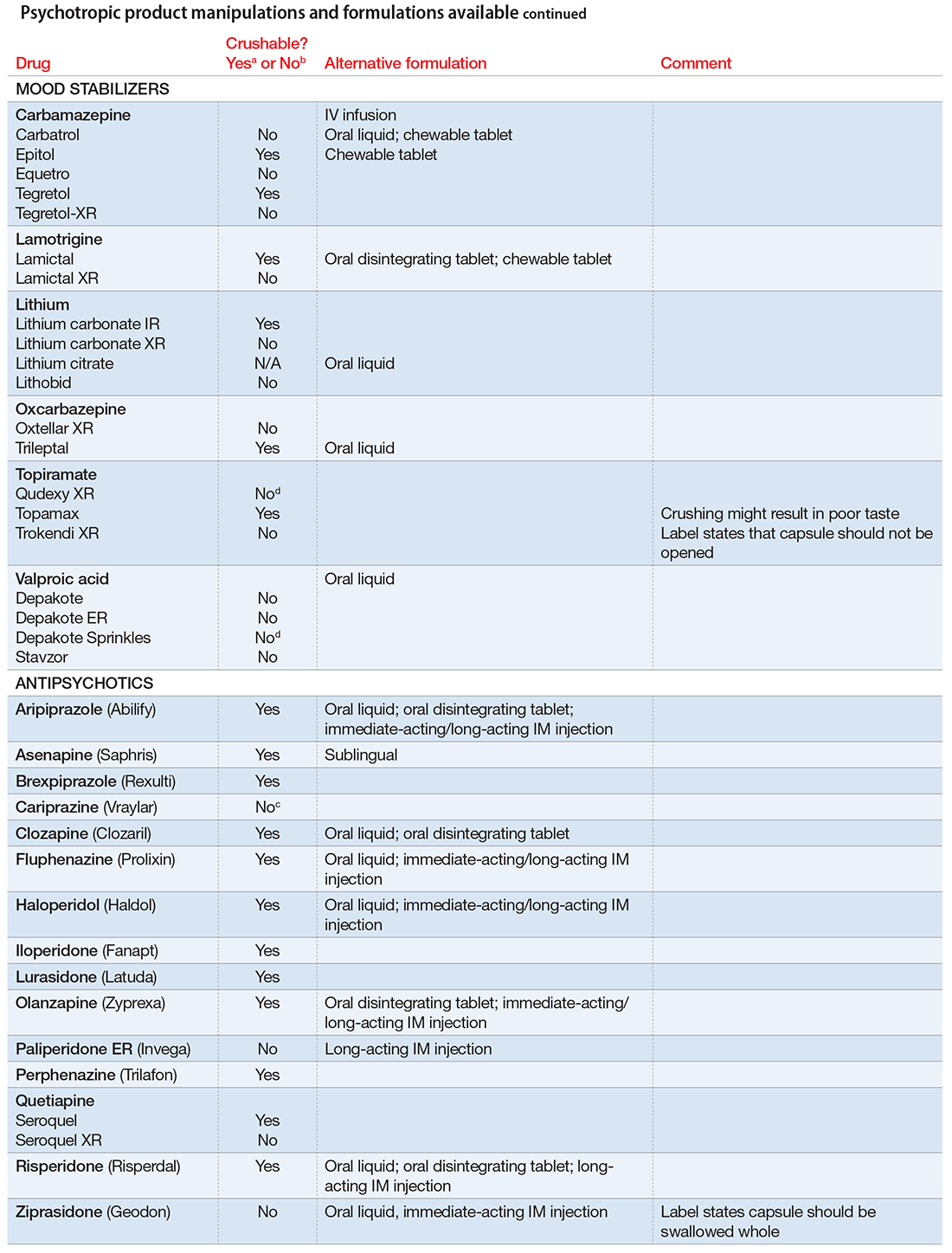

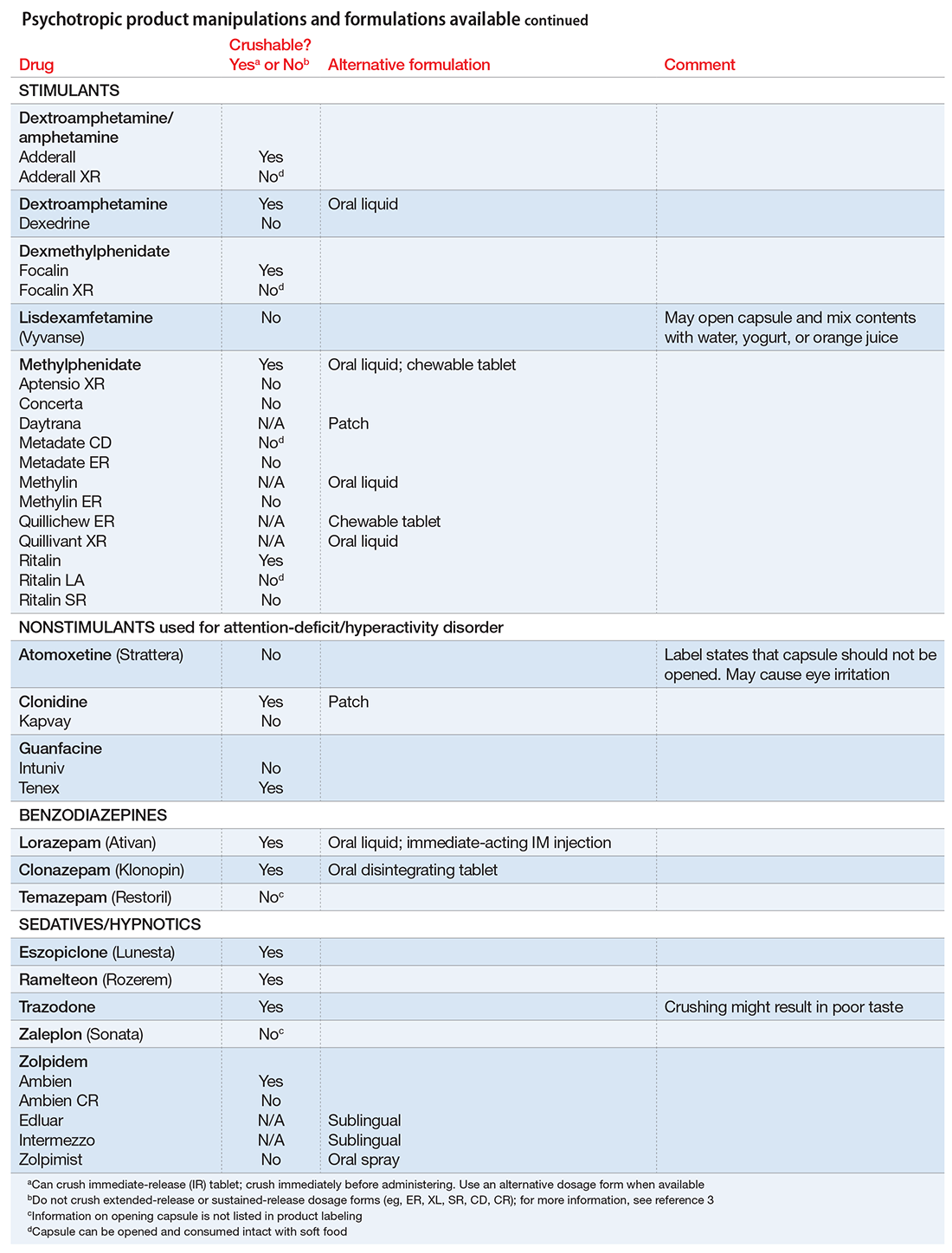

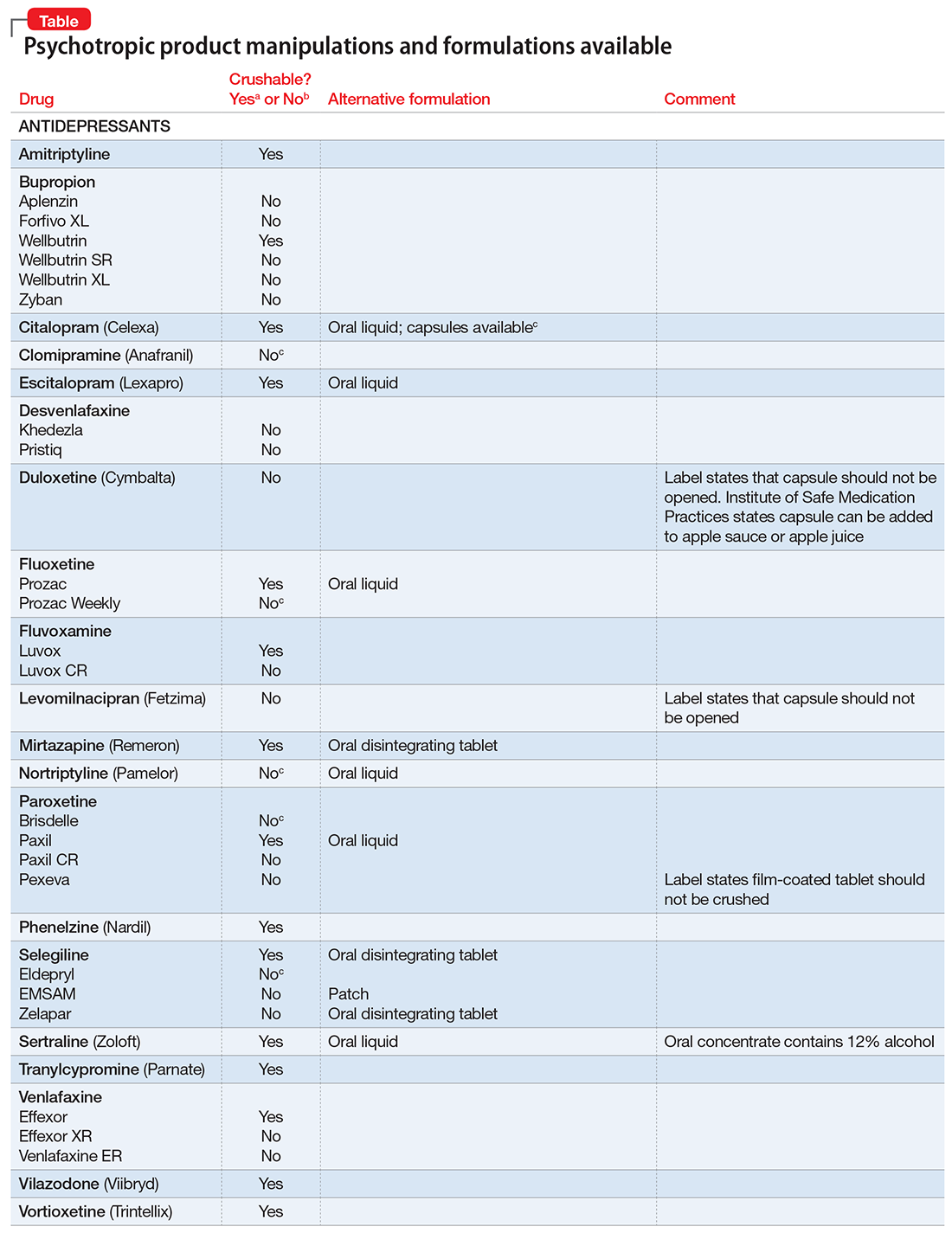

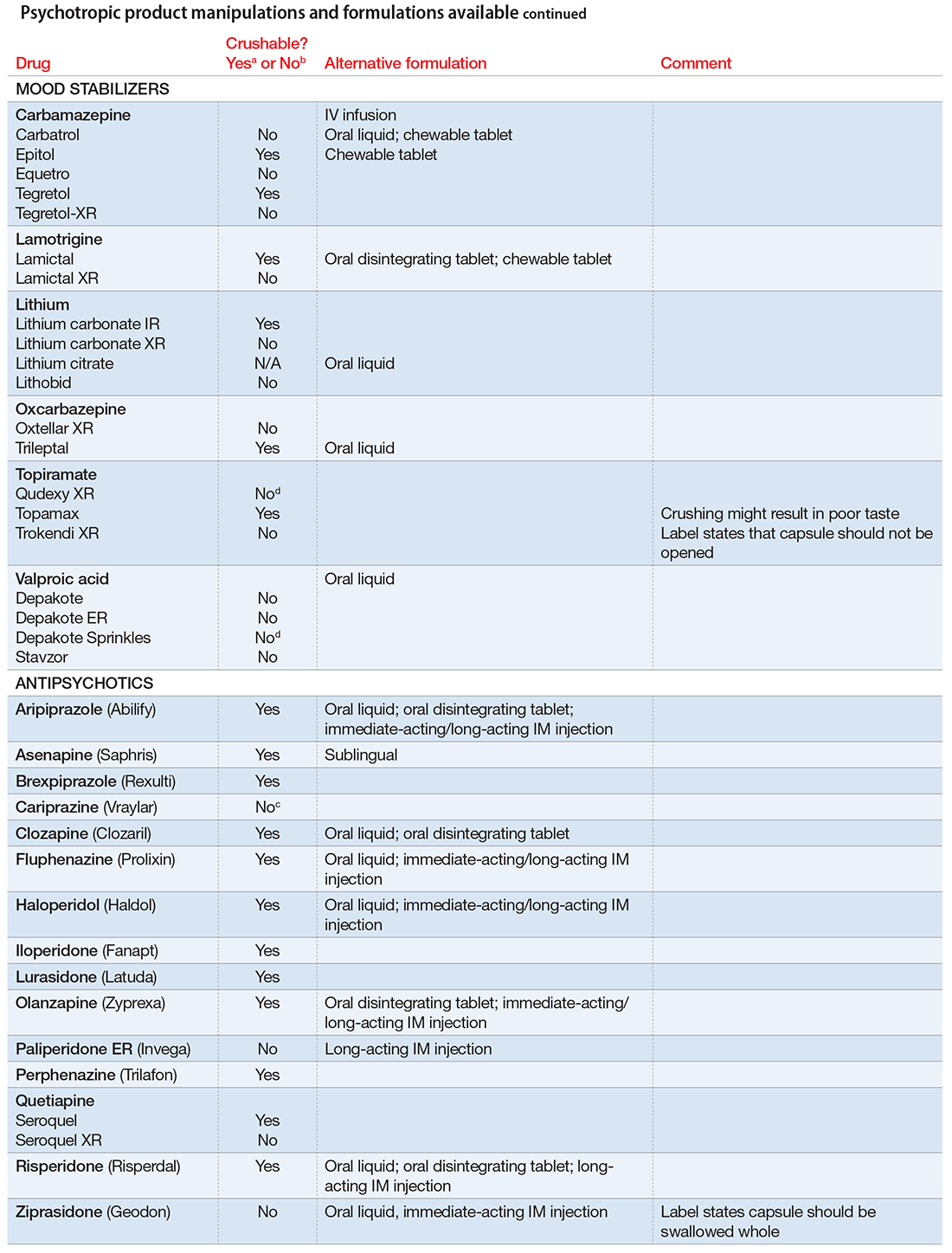

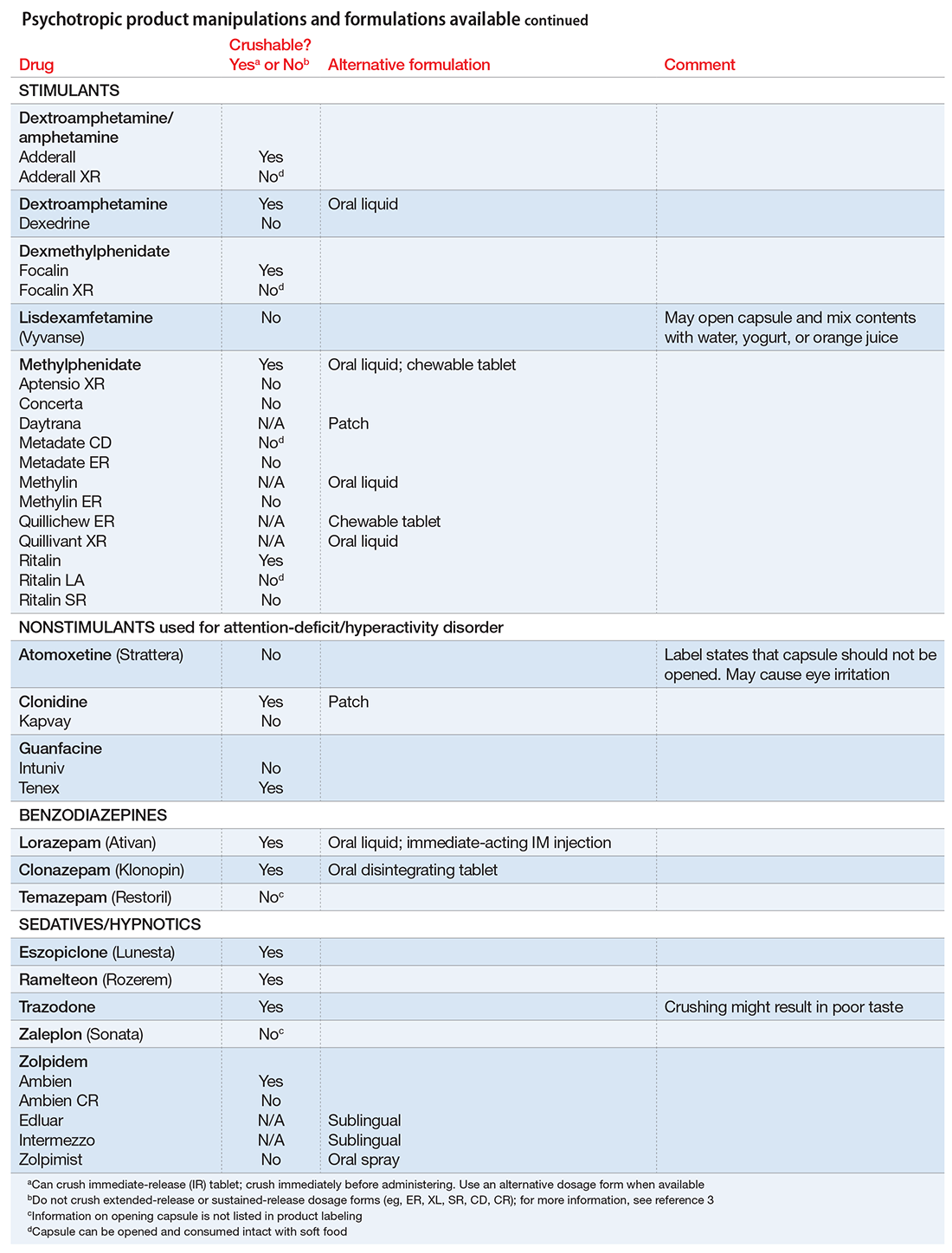

Pills to powder: An updated clinician’s reference for crushable psychotropics

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

- discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

- postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

- dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

- odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

- a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

- Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

- Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

- Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

- Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

- Capsules generally can be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’sLetter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp.org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2015. Accessed January 17, 2017.

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

- discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

- postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

- dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

- odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

- a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

- Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

- Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

- Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

- Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

- Capsules generally can be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

Many patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, for various reasons:

- discomfort (particularly pediatric and geriatric patients)

- postsurgical need for an alternate route of enteral intake (nasogastric tube, gastrostomy, jejunostomy)

- dysphagia due to a neurologic disorder (multiple sclerosis, impaired gag reflex, dementing processes)

- odynophagia (pain upon swallowing) due to gastroesophageal reflux or a structural abnormality

- a structural abnormality of the head or neck that impairs swallowing.1

If these difficulties are not addressed, they can interfere with medication adherence. In those instances, using an alternative dosage form or manipulating an available formulation might be required.

Crushing guidelines

There are limited data on crushed-form products and their impact on efficacy. Therefore, when patients have difficulty taking pills, switching to liquid solution or orally disintegrating forms is recommended. However, most psychotropics are available only as tablets or capsules. Patients can crush their pills immediately before administration for easier intake. The following are some general guidelines for doing so:2

- Scored tablets typically can be crushed.

- Crushing sublingual and buccal tablets can alter their effectiveness.

- Crushing sustained-release medications can eliminate the sustained-release action.3

- Enteric-coated medications should not be crushed, because this can alter drug absorption.

- Capsules generally can be opened to administer powdered contents, unless the capsule has time-release properties or an enteric coating.

The accompanying Table, organized by drug class, indicates whether a drug can be crushed to a powdered form, which usually is mixed with food or liquid for easier intake. The Table also lists liquid and orally disintegrating forms available, and other routes, including injectable immediate and long-acting formulations. Helping patients find a medication formulation that suits their needs strengthens adherence and the therapeutic relationship.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’sLetter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp.org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2015. Accessed January 17, 2017.

1. Schiele JT, Quinzler R, Klimm HD, et al. Difficulties swallowing solid oral dosage forms in a general practice population: prevalence, causes, and relationship to dosage forms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(4): 937-948.

2. PL Detail-Document, Meds That Should Not Be Crushed. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’sLetter. July 2012.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. http://www.ismp.org/tools/donotcrush.pdf. Updated January 2015. Accessed January 17, 2017.

Lower BDNF levels found in older adults with bipolar I

Older patients with bipolar I disorder appear to have lower serum levels of brain-deprived neurotrophic factor than similarly aged adults without bipolar I, a study showed.

At the beginning of the study, Aline T. Soares, MD, and her colleagues recruited 118 patients from clinics in the United States and Canada with bipolar disorder who were aged 50 and over and a similar control group of 76 healthy patients. Twenty-seven of the 118 patients had type II bipolar disorder, and 91 had type I bipolar disorder; all had been clinically euthymic for at least 4 weeks when they were evaluated, reported Dr. Soares of the department of internal medicine at the University of São Paulo (Brazil).

The results showed that patients positively identified with bipolar I disorder had lowered brain-deprived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels, compared with their control group counterparts. Lower levels of BDNF were not detected in those with bipolar II disorder, the investigators reported (Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016 Aug;24[8]:596-601).

“Our study represents a continuation of the [bipolar disorder] and BDNF story: Prolonged bipolar illness appears to lead to decreased BDNF, even in the euthymic state,” Dr. Soares and her colleagues wrote. “This reduces the brain’s capacity for neurogenesis and neuroplasticity and theoretically increases the risk of hippocampal shrinkage, cognitive deficits, and dementia.”

Future studies are needed to look into how BDNF levels affect mood, cognitive abilities, and other areas of life related to bipolar disorder, they said.

Dr. Soares and her colleagues reported that they had no conflicts to disclose.

To read more about the study, click here.

Older patients with bipolar I disorder appear to have lower serum levels of brain-deprived neurotrophic factor than similarly aged adults without bipolar I, a study showed.

At the beginning of the study, Aline T. Soares, MD, and her colleagues recruited 118 patients from clinics in the United States and Canada with bipolar disorder who were aged 50 and over and a similar control group of 76 healthy patients. Twenty-seven of the 118 patients had type II bipolar disorder, and 91 had type I bipolar disorder; all had been clinically euthymic for at least 4 weeks when they were evaluated, reported Dr. Soares of the department of internal medicine at the University of São Paulo (Brazil).

The results showed that patients positively identified with bipolar I disorder had lowered brain-deprived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels, compared with their control group counterparts. Lower levels of BDNF were not detected in those with bipolar II disorder, the investigators reported (Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016 Aug;24[8]:596-601).

“Our study represents a continuation of the [bipolar disorder] and BDNF story: Prolonged bipolar illness appears to lead to decreased BDNF, even in the euthymic state,” Dr. Soares and her colleagues wrote. “This reduces the brain’s capacity for neurogenesis and neuroplasticity and theoretically increases the risk of hippocampal shrinkage, cognitive deficits, and dementia.”

Future studies are needed to look into how BDNF levels affect mood, cognitive abilities, and other areas of life related to bipolar disorder, they said.

Dr. Soares and her colleagues reported that they had no conflicts to disclose.

To read more about the study, click here.

Older patients with bipolar I disorder appear to have lower serum levels of brain-deprived neurotrophic factor than similarly aged adults without bipolar I, a study showed.

At the beginning of the study, Aline T. Soares, MD, and her colleagues recruited 118 patients from clinics in the United States and Canada with bipolar disorder who were aged 50 and over and a similar control group of 76 healthy patients. Twenty-seven of the 118 patients had type II bipolar disorder, and 91 had type I bipolar disorder; all had been clinically euthymic for at least 4 weeks when they were evaluated, reported Dr. Soares of the department of internal medicine at the University of São Paulo (Brazil).

The results showed that patients positively identified with bipolar I disorder had lowered brain-deprived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels, compared with their control group counterparts. Lower levels of BDNF were not detected in those with bipolar II disorder, the investigators reported (Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016 Aug;24[8]:596-601).

“Our study represents a continuation of the [bipolar disorder] and BDNF story: Prolonged bipolar illness appears to lead to decreased BDNF, even in the euthymic state,” Dr. Soares and her colleagues wrote. “This reduces the brain’s capacity for neurogenesis and neuroplasticity and theoretically increases the risk of hippocampal shrinkage, cognitive deficits, and dementia.”

Future studies are needed to look into how BDNF levels affect mood, cognitive abilities, and other areas of life related to bipolar disorder, they said.

Dr. Soares and her colleagues reported that they had no conflicts to disclose.

To read more about the study, click here.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GERIATRIC PSYCHIATRY

Depression in pediatric bipolar disorder

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Revisiting delirious mania; Correcting an error

Revisiting delirious mania

After treating a young woman with delirious mania, we were compelled to comment on the case report “Confused and nearly naked after going on spending sprees” (Cases That Test Your Skills,

A young woman with bipolar I disorder and mild intellectual disability was brought to our inpatient psychiatric unit after she disappeared from her home. Her family reported she was not compliant with her medications, and she recently showed deterioration marked by bizarre and violent behaviors for the previous month.

Although her presentation was consistent with earlier manic episodes, additional behaviors indicated an increase in severity. The patient was only oriented to name, was disrobing, had urinary and fecal incontinence, and showed purposeless hyperactivity such as continuously dancing in circles.

Because we thought she was experiencing a severe exacerbation of bipolar disorder, the patient was started on 4 different antipsychotic trials (typical and atypical) and 2 mood stabilizers, all of which did not produce adequate response. Even after augmentation with nightly long-acting benzodiazepines, the patient’s symptoms remained unchanged.

The patient received a diagnosis of delirious mania, with the underlying mechanism being severe catatonia. A literature search revealed electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and benzodiazepines as first-line treatments, and discouraged use of typical antipsychotics because of an increased risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome and malignant delirious mania.1 Because ECT was not available at our facility, we initiated benzodiazepines,

We agree it is prudent to rule out any medical illnesses that could cause delirium. Interestingly, in our patient a head CT revealed small calcifications suggestive of cysticercosis, which have been seen on imaging since age 13. We suggest that this finding contributed to her disinhibition, prolonged her recovery, and could explain why she did not respond adequately to medications.

Diagnosing and treating delirious mania in our patient was challenging. As mentioned by Davis et al, there is no classification of delirious mania in DSM-5. In addition, there are no large-scale studies to educate psychiatrists about the prevalence and appropriate treatment of this disorder.

Our treatment approach differed from that of Davis et al in that we chose scheduled benzodiazepines rather than antipsychotics to target the patient’s catatonia. However, both patients improved, prompting us to further question the mechanism behind this presentation.

We encourage the addition of delirious mania to the next edition of DSM. Without classification and establishment of this diagnosis, psychiatrists are unlikely to consider this serious and potentially fatal syndrome. Delirious mania is mysterious and rare and its inner workings are not fully elucidated.

Sabina Bera, MD MSc

PGY-2 Psychiatry Resident

Mohammed Molla, MD, DFAPA

Interim Joint Chair and Program Director

University of California Los Angeles-Kern

Psychiatry Training Program

Bakersfield, California

Reference

1. Jacobowski NL, Heckers S, Bobo WV. Delirious mania: detection, diagnosis, and clinical management in the acute setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):15-28.

Correcting an error

In his informative guest editorial "

David A. Gorelick, MD, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry

Maryland Psychiatric Research Center

University of Maryland

Baltimore, Maryland

Revisiting delirious mania

After treating a young woman with delirious mania, we were compelled to comment on the case report “Confused and nearly naked after going on spending sprees” (Cases That Test Your Skills,

A young woman with bipolar I disorder and mild intellectual disability was brought to our inpatient psychiatric unit after she disappeared from her home. Her family reported she was not compliant with her medications, and she recently showed deterioration marked by bizarre and violent behaviors for the previous month.

Although her presentation was consistent with earlier manic episodes, additional behaviors indicated an increase in severity. The patient was only oriented to name, was disrobing, had urinary and fecal incontinence, and showed purposeless hyperactivity such as continuously dancing in circles.

Because we thought she was experiencing a severe exacerbation of bipolar disorder, the patient was started on 4 different antipsychotic trials (typical and atypical) and 2 mood stabilizers, all of which did not produce adequate response. Even after augmentation with nightly long-acting benzodiazepines, the patient’s symptoms remained unchanged.

The patient received a diagnosis of delirious mania, with the underlying mechanism being severe catatonia. A literature search revealed electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and benzodiazepines as first-line treatments, and discouraged use of typical antipsychotics because of an increased risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome and malignant delirious mania.1 Because ECT was not available at our facility, we initiated benzodiazepines,

We agree it is prudent to rule out any medical illnesses that could cause delirium. Interestingly, in our patient a head CT revealed small calcifications suggestive of cysticercosis, which have been seen on imaging since age 13. We suggest that this finding contributed to her disinhibition, prolonged her recovery, and could explain why she did not respond adequately to medications.

Diagnosing and treating delirious mania in our patient was challenging. As mentioned by Davis et al, there is no classification of delirious mania in DSM-5. In addition, there are no large-scale studies to educate psychiatrists about the prevalence and appropriate treatment of this disorder.

Our treatment approach differed from that of Davis et al in that we chose scheduled benzodiazepines rather than antipsychotics to target the patient’s catatonia. However, both patients improved, prompting us to further question the mechanism behind this presentation.

We encourage the addition of delirious mania to the next edition of DSM. Without classification and establishment of this diagnosis, psychiatrists are unlikely to consider this serious and potentially fatal syndrome. Delirious mania is mysterious and rare and its inner workings are not fully elucidated.

Sabina Bera, MD MSc

PGY-2 Psychiatry Resident

Mohammed Molla, MD, DFAPA

Interim Joint Chair and Program Director

University of California Los Angeles-Kern

Psychiatry Training Program

Bakersfield, California

Reference

1. Jacobowski NL, Heckers S, Bobo WV. Delirious mania: detection, diagnosis, and clinical management in the acute setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):15-28.

Correcting an error

In his informative guest editorial "

David A. Gorelick, MD, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry

Maryland Psychiatric Research Center

University of Maryland

Baltimore, Maryland

Revisiting delirious mania

After treating a young woman with delirious mania, we were compelled to comment on the case report “Confused and nearly naked after going on spending sprees” (Cases That Test Your Skills,

A young woman with bipolar I disorder and mild intellectual disability was brought to our inpatient psychiatric unit after she disappeared from her home. Her family reported she was not compliant with her medications, and she recently showed deterioration marked by bizarre and violent behaviors for the previous month.

Although her presentation was consistent with earlier manic episodes, additional behaviors indicated an increase in severity. The patient was only oriented to name, was disrobing, had urinary and fecal incontinence, and showed purposeless hyperactivity such as continuously dancing in circles.

Because we thought she was experiencing a severe exacerbation of bipolar disorder, the patient was started on 4 different antipsychotic trials (typical and atypical) and 2 mood stabilizers, all of which did not produce adequate response. Even after augmentation with nightly long-acting benzodiazepines, the patient’s symptoms remained unchanged.

The patient received a diagnosis of delirious mania, with the underlying mechanism being severe catatonia. A literature search revealed electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and benzodiazepines as first-line treatments, and discouraged use of typical antipsychotics because of an increased risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome and malignant delirious mania.1 Because ECT was not available at our facility, we initiated benzodiazepines,

We agree it is prudent to rule out any medical illnesses that could cause delirium. Interestingly, in our patient a head CT revealed small calcifications suggestive of cysticercosis, which have been seen on imaging since age 13. We suggest that this finding contributed to her disinhibition, prolonged her recovery, and could explain why she did not respond adequately to medications.

Diagnosing and treating delirious mania in our patient was challenging. As mentioned by Davis et al, there is no classification of delirious mania in DSM-5. In addition, there are no large-scale studies to educate psychiatrists about the prevalence and appropriate treatment of this disorder.

Our treatment approach differed from that of Davis et al in that we chose scheduled benzodiazepines rather than antipsychotics to target the patient’s catatonia. However, both patients improved, prompting us to further question the mechanism behind this presentation.

We encourage the addition of delirious mania to the next edition of DSM. Without classification and establishment of this diagnosis, psychiatrists are unlikely to consider this serious and potentially fatal syndrome. Delirious mania is mysterious and rare and its inner workings are not fully elucidated.

Sabina Bera, MD MSc

PGY-2 Psychiatry Resident

Mohammed Molla, MD, DFAPA

Interim Joint Chair and Program Director

University of California Los Angeles-Kern

Psychiatry Training Program

Bakersfield, California

Reference

1. Jacobowski NL, Heckers S, Bobo WV. Delirious mania: detection, diagnosis, and clinical management in the acute setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):15-28.

Correcting an error

In his informative guest editorial "

David A. Gorelick, MD, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry

Maryland Psychiatric Research Center

University of Maryland

Baltimore, Maryland

Differentiating ADHD and bipolar disorder

New bipolar disorder algorithm changes ranking of first-line therapies

CEQUEL: Combo therapy a win in bipolar depression

VIENNA – Psychiatrists have received a welcome gift in the form of CEQUEL, a randomized trial that offers much needed guidance on how to proceed when quetiapine for bipolar depression isn’t achieving sufficient response, Eduard Vieta, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The answer provided by CEQUEL is to add lamotrigine.

“Quetiapine is indicated for treatment of symptoms of bipolar depression, but many clinicians – including myself – are a bit underwhelmed about the practical results. In the clinical trials, quetiapine looks great, but when we use it in practice we’re not so happy with the results. The trials are consistently positive with a large effect size, whereas in clinical practice many patients respond only partially to quetiapine. The question has been what to do next,” observed Dr. Vieta, professor of psychiatry and head of the bipolar disorders program at the University of Barcelona.

Increasing the dose of quetiapine (Seroquel) above the recommended 300 mg/day in an effort to boost efficacy is problematic. Patients become extremely sedated. The CEQUEL (Comparative Evaluation of Quetiapine plus Lamotrigine) investigators decided to examine combination therapy with two drugs having completely different mechanisms of action.

A total of 202 patients with bipolar depression at 27 U.K. sites were placed on quetiapine and randomized double-blind to lamotrigine or placebo. Lamotrigine (Lamictal) was started at 25 mg/day and gradually increased to 200 mg daily. Because there is some limited evidence that folic acid is effective in unipolar depression, the investigators employed a 2x2 factorial design, further randomizing participants to 500 mcg/day of folic acid or placebo.

The primary endpoint was improvement in depressive symptoms at 12 weeks, with 52-week outcomes as a secondary endpoint. The group on combination therapy with quetiapine and lamotrigine showed significantly greater improvement both on mean depressive symptoms as measured with the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-self report version 16 (QIDS-SR16), and on rates of remission at 12 and 52 weeks, compared with patients on quetiapine and placebo. The combination also reduced the risk of relapse in patients with bipolar I disorder with predominantly depressive symptoms.

Folic acid proved to be not only ineffective, it actually interfered with lamotrigine’s effectiveness. The mean reduction from baseline to 12 weeks on the QIDS-SR16 was 4.4 points in patients who received lamotrigine without folic acid, compared with a 0.12-point increase in those receiving lamotrigine plus folic acid (Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Jan;3[1]:31-9).

Dr. Vieta wasn’t involved in CEQUEL, but he considers the study one of the highlights of the year in the field of affective disorders and urged his colleagues to consider lamotrigine/quetiapine combination therapy for bipolar depression.

“Quetiapine and lamotrigine are both now generic drugs. CEQUEL showed both are superior to quetiapine alone. It’s good news – a not-expensive treatment combining quetiapine with a drug, lamotrigine, that’s quite well tolerated,” he said.

CEQUEL was funded by the Medical Research Council. Dr. Vieta reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

VIENNA – Psychiatrists have received a welcome gift in the form of CEQUEL, a randomized trial that offers much needed guidance on how to proceed when quetiapine for bipolar depression isn’t achieving sufficient response, Eduard Vieta, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The answer provided by CEQUEL is to add lamotrigine.

“Quetiapine is indicated for treatment of symptoms of bipolar depression, but many clinicians – including myself – are a bit underwhelmed about the practical results. In the clinical trials, quetiapine looks great, but when we use it in practice we’re not so happy with the results. The trials are consistently positive with a large effect size, whereas in clinical practice many patients respond only partially to quetiapine. The question has been what to do next,” observed Dr. Vieta, professor of psychiatry and head of the bipolar disorders program at the University of Barcelona.

Increasing the dose of quetiapine (Seroquel) above the recommended 300 mg/day in an effort to boost efficacy is problematic. Patients become extremely sedated. The CEQUEL (Comparative Evaluation of Quetiapine plus Lamotrigine) investigators decided to examine combination therapy with two drugs having completely different mechanisms of action.

A total of 202 patients with bipolar depression at 27 U.K. sites were placed on quetiapine and randomized double-blind to lamotrigine or placebo. Lamotrigine (Lamictal) was started at 25 mg/day and gradually increased to 200 mg daily. Because there is some limited evidence that folic acid is effective in unipolar depression, the investigators employed a 2x2 factorial design, further randomizing participants to 500 mcg/day of folic acid or placebo.

The primary endpoint was improvement in depressive symptoms at 12 weeks, with 52-week outcomes as a secondary endpoint. The group on combination therapy with quetiapine and lamotrigine showed significantly greater improvement both on mean depressive symptoms as measured with the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-self report version 16 (QIDS-SR16), and on rates of remission at 12 and 52 weeks, compared with patients on quetiapine and placebo. The combination also reduced the risk of relapse in patients with bipolar I disorder with predominantly depressive symptoms.

Folic acid proved to be not only ineffective, it actually interfered with lamotrigine’s effectiveness. The mean reduction from baseline to 12 weeks on the QIDS-SR16 was 4.4 points in patients who received lamotrigine without folic acid, compared with a 0.12-point increase in those receiving lamotrigine plus folic acid (Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Jan;3[1]:31-9).

Dr. Vieta wasn’t involved in CEQUEL, but he considers the study one of the highlights of the year in the field of affective disorders and urged his colleagues to consider lamotrigine/quetiapine combination therapy for bipolar depression.

“Quetiapine and lamotrigine are both now generic drugs. CEQUEL showed both are superior to quetiapine alone. It’s good news – a not-expensive treatment combining quetiapine with a drug, lamotrigine, that’s quite well tolerated,” he said.

CEQUEL was funded by the Medical Research Council. Dr. Vieta reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

VIENNA – Psychiatrists have received a welcome gift in the form of CEQUEL, a randomized trial that offers much needed guidance on how to proceed when quetiapine for bipolar depression isn’t achieving sufficient response, Eduard Vieta, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The answer provided by CEQUEL is to add lamotrigine.

“Quetiapine is indicated for treatment of symptoms of bipolar depression, but many clinicians – including myself – are a bit underwhelmed about the practical results. In the clinical trials, quetiapine looks great, but when we use it in practice we’re not so happy with the results. The trials are consistently positive with a large effect size, whereas in clinical practice many patients respond only partially to quetiapine. The question has been what to do next,” observed Dr. Vieta, professor of psychiatry and head of the bipolar disorders program at the University of Barcelona.

Increasing the dose of quetiapine (Seroquel) above the recommended 300 mg/day in an effort to boost efficacy is problematic. Patients become extremely sedated. The CEQUEL (Comparative Evaluation of Quetiapine plus Lamotrigine) investigators decided to examine combination therapy with two drugs having completely different mechanisms of action.

A total of 202 patients with bipolar depression at 27 U.K. sites were placed on quetiapine and randomized double-blind to lamotrigine or placebo. Lamotrigine (Lamictal) was started at 25 mg/day and gradually increased to 200 mg daily. Because there is some limited evidence that folic acid is effective in unipolar depression, the investigators employed a 2x2 factorial design, further randomizing participants to 500 mcg/day of folic acid or placebo.

The primary endpoint was improvement in depressive symptoms at 12 weeks, with 52-week outcomes as a secondary endpoint. The group on combination therapy with quetiapine and lamotrigine showed significantly greater improvement both on mean depressive symptoms as measured with the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-self report version 16 (QIDS-SR16), and on rates of remission at 12 and 52 weeks, compared with patients on quetiapine and placebo. The combination also reduced the risk of relapse in patients with bipolar I disorder with predominantly depressive symptoms.

Folic acid proved to be not only ineffective, it actually interfered with lamotrigine’s effectiveness. The mean reduction from baseline to 12 weeks on the QIDS-SR16 was 4.4 points in patients who received lamotrigine without folic acid, compared with a 0.12-point increase in those receiving lamotrigine plus folic acid (Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Jan;3[1]:31-9).

Dr. Vieta wasn’t involved in CEQUEL, but he considers the study one of the highlights of the year in the field of affective disorders and urged his colleagues to consider lamotrigine/quetiapine combination therapy for bipolar depression.

“Quetiapine and lamotrigine are both now generic drugs. CEQUEL showed both are superior to quetiapine alone. It’s good news – a not-expensive treatment combining quetiapine with a drug, lamotrigine, that’s quite well tolerated,” he said.

CEQUEL was funded by the Medical Research Council. Dr. Vieta reported having no financial conflicts of interest.