User login

Hydroxychloroquine-triggered QTc-interval prolongations mount in COVID-19 patients

The potential for serious arrhythmias from hydroxychloroquine treatment of COVID-19 patients received further documentation from a pair of studies released on May 1, casting further doubt on whether the uncertain benefit from this or related drugs to infected patients is worth the clear risks the agents pose.

A report from 90 confirmed COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine at one Boston hospital during March-April 2020 identified a significantly prolonged, corrected QT (QTc) interval of at least 500 msec in 18 patients (20%), which included 10 patients whose QTc rose by at least 60 msec above baseline, and a total of 21 patients (23%) having a notable prolongation (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May 4. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1834). This series included one patient who developed torsades de pointes following treatment with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, “which to our knowledge has yet to be reported elsewhere in the literature,” the report said.

The second report, from a single center in Lyon, France, included 40 confirmed COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine during 2 weeks in late March, and found that 37 (93%) had some increase in the QTc interval, including 14 patients (36%) with an increase of at least 60 msec, and 7 patients (18%) whose QTc rose to at least 500 msec (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1787). However, none of the 40 patients in this series developed an identified ventricular arrhythmia. All patients in both studies received hydroxychloroquine for at least 1 day, and roughly half the patients in each series also received concurrent azithromycin, another drug that can prolong the QTc interval and that has been frequently used in combination with hydroxychloroquine as an unproven COVID-19 treatment cocktail.

These two reports, as well as prior report from Brazil on COVID-19 patients treated with chloroquine diphosphate (JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3[4]:e208857), “underscore the potential risk associated with widespread use of hydroxychloroquine and the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in ambulatory patients with known or suspected COVID-19. Understanding whether this risk is worth taking in the absence of evidence of therapeutic efficacy creates a knowledge gap that needs to be addressed,” wrote Robert O. Bonow, MD, a professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, and coauthors in an editorial that accompanied the two reports (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May 4;doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1782). The editorial cited two recently-begun prospective trials, ORCHID and RECOVERY, that are more systematically assessing the safety and efficacy of hydroxychloroquine treatment in COVID-19 patients.

The findings lend further support to a Safety Communication from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on April 24 that reminded clinicians that the Emergency Use Authorization for hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in COVID-19 patients that the FDA issued on March 28 applied to only certain hospitalized patients or those enrolled in clinical trials. The Safety Communication also said that agency was aware of reports of adverse arrhythmia events when COVID-19 patients received these drugs outside a hospital setting as well as uninfected people who had received one of these drugs for preventing infection.

In addition, leaders of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society on April 10 issued a summary of considerations when using hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to treat COVID-19 patients, and noted that a way to minimized the risk from these drugs is to withhold them from patients with a QTc interval of 500 msec or greater at baseline (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.016). The summary also highlighted the need for regular ECG monitoring of COVID-19 patients who receive drugs that can prolong the QTc interval, and recommended withdrawing treatment from patients when their QTc exceeds the 500 msec threshold.

None of the authors of the two reports and editorial had relevant commercial disclosures.

The potential for serious arrhythmias from hydroxychloroquine treatment of COVID-19 patients received further documentation from a pair of studies released on May 1, casting further doubt on whether the uncertain benefit from this or related drugs to infected patients is worth the clear risks the agents pose.

A report from 90 confirmed COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine at one Boston hospital during March-April 2020 identified a significantly prolonged, corrected QT (QTc) interval of at least 500 msec in 18 patients (20%), which included 10 patients whose QTc rose by at least 60 msec above baseline, and a total of 21 patients (23%) having a notable prolongation (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May 4. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1834). This series included one patient who developed torsades de pointes following treatment with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, “which to our knowledge has yet to be reported elsewhere in the literature,” the report said.

The second report, from a single center in Lyon, France, included 40 confirmed COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine during 2 weeks in late March, and found that 37 (93%) had some increase in the QTc interval, including 14 patients (36%) with an increase of at least 60 msec, and 7 patients (18%) whose QTc rose to at least 500 msec (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1787). However, none of the 40 patients in this series developed an identified ventricular arrhythmia. All patients in both studies received hydroxychloroquine for at least 1 day, and roughly half the patients in each series also received concurrent azithromycin, another drug that can prolong the QTc interval and that has been frequently used in combination with hydroxychloroquine as an unproven COVID-19 treatment cocktail.

These two reports, as well as prior report from Brazil on COVID-19 patients treated with chloroquine diphosphate (JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3[4]:e208857), “underscore the potential risk associated with widespread use of hydroxychloroquine and the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in ambulatory patients with known or suspected COVID-19. Understanding whether this risk is worth taking in the absence of evidence of therapeutic efficacy creates a knowledge gap that needs to be addressed,” wrote Robert O. Bonow, MD, a professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, and coauthors in an editorial that accompanied the two reports (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May 4;doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1782). The editorial cited two recently-begun prospective trials, ORCHID and RECOVERY, that are more systematically assessing the safety and efficacy of hydroxychloroquine treatment in COVID-19 patients.

The findings lend further support to a Safety Communication from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on April 24 that reminded clinicians that the Emergency Use Authorization for hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in COVID-19 patients that the FDA issued on March 28 applied to only certain hospitalized patients or those enrolled in clinical trials. The Safety Communication also said that agency was aware of reports of adverse arrhythmia events when COVID-19 patients received these drugs outside a hospital setting as well as uninfected people who had received one of these drugs for preventing infection.

In addition, leaders of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society on April 10 issued a summary of considerations when using hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to treat COVID-19 patients, and noted that a way to minimized the risk from these drugs is to withhold them from patients with a QTc interval of 500 msec or greater at baseline (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.016). The summary also highlighted the need for regular ECG monitoring of COVID-19 patients who receive drugs that can prolong the QTc interval, and recommended withdrawing treatment from patients when their QTc exceeds the 500 msec threshold.

None of the authors of the two reports and editorial had relevant commercial disclosures.

The potential for serious arrhythmias from hydroxychloroquine treatment of COVID-19 patients received further documentation from a pair of studies released on May 1, casting further doubt on whether the uncertain benefit from this or related drugs to infected patients is worth the clear risks the agents pose.

A report from 90 confirmed COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine at one Boston hospital during March-April 2020 identified a significantly prolonged, corrected QT (QTc) interval of at least 500 msec in 18 patients (20%), which included 10 patients whose QTc rose by at least 60 msec above baseline, and a total of 21 patients (23%) having a notable prolongation (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May 4. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1834). This series included one patient who developed torsades de pointes following treatment with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, “which to our knowledge has yet to be reported elsewhere in the literature,” the report said.

The second report, from a single center in Lyon, France, included 40 confirmed COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine during 2 weeks in late March, and found that 37 (93%) had some increase in the QTc interval, including 14 patients (36%) with an increase of at least 60 msec, and 7 patients (18%) whose QTc rose to at least 500 msec (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1787). However, none of the 40 patients in this series developed an identified ventricular arrhythmia. All patients in both studies received hydroxychloroquine for at least 1 day, and roughly half the patients in each series also received concurrent azithromycin, another drug that can prolong the QTc interval and that has been frequently used in combination with hydroxychloroquine as an unproven COVID-19 treatment cocktail.

These two reports, as well as prior report from Brazil on COVID-19 patients treated with chloroquine diphosphate (JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3[4]:e208857), “underscore the potential risk associated with widespread use of hydroxychloroquine and the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in ambulatory patients with known or suspected COVID-19. Understanding whether this risk is worth taking in the absence of evidence of therapeutic efficacy creates a knowledge gap that needs to be addressed,” wrote Robert O. Bonow, MD, a professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, and coauthors in an editorial that accompanied the two reports (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 May 4;doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1782). The editorial cited two recently-begun prospective trials, ORCHID and RECOVERY, that are more systematically assessing the safety and efficacy of hydroxychloroquine treatment in COVID-19 patients.

The findings lend further support to a Safety Communication from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on April 24 that reminded clinicians that the Emergency Use Authorization for hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in COVID-19 patients that the FDA issued on March 28 applied to only certain hospitalized patients or those enrolled in clinical trials. The Safety Communication also said that agency was aware of reports of adverse arrhythmia events when COVID-19 patients received these drugs outside a hospital setting as well as uninfected people who had received one of these drugs for preventing infection.

In addition, leaders of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society on April 10 issued a summary of considerations when using hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to treat COVID-19 patients, and noted that a way to minimized the risk from these drugs is to withhold them from patients with a QTc interval of 500 msec or greater at baseline (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.016). The summary also highlighted the need for regular ECG monitoring of COVID-19 patients who receive drugs that can prolong the QTc interval, and recommended withdrawing treatment from patients when their QTc exceeds the 500 msec threshold.

None of the authors of the two reports and editorial had relevant commercial disclosures.

FROM JAMA CARDIOLOGY

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests soar during COVID-19 in Italy

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests increased 58% during the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak in the hard-hit region of Lombardy, Italy, compared with the same period last year, a new analysis shows.

During the first 40 days of the outbreak beginning Feb. 21, four provinces in northern Italy reported 362 cases of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest compared with 229 during the same period in 2019.

The increases in these provinces varied in magnitude from 18% in Mantua, where there were 1,688 confirmed COVID-19 cases, to 187% in Lodi, which had 2,116 COVID-19 cases. The Cremona province, which had the highest number of COVID-19 cases at 3,869, saw a 143% increase in out-of-hospital cardiac arrests.

The mortality rate in the field was 14.9 percentage points higher in 2020 than in 2019 among patients in whom resuscitation was attempted by emergency medical services (EMS), Enrico Baldi, MD, University of Pavia, Italy, and colleagues reported in a letter April 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The sex and age of the patients were similar in the 2020 and 2019 periods, but in 2020, the incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to a medical cause was 6.5 percentage points higher, the incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest at home was 7.3 percentage points higher, and the incidence of unwitnessed cardiac arrest was 11.3 percentage points higher,” the authors wrote.

Patients were also less likely to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation from bystanders in 2020 vs 2019 (–15.6 percentage points) and were more likely to die before reaching the hospital when resuscitation was attempted by EMS (+14.9 percentage points).

Among all patients, the death rate in the field increased 11.4 percentage points during the outbreak, from 77.3% in 2019 to 88.7% in 2020.

The cumulative incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in 2020 was “strongly associated” with the cumulative incidence of COVID-19 (Spearman rank correlation coefficient, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.91) and the spike in cases “followed the time course of the COVID-19 outbreak,” the researchers noted.

A total of 103 patients, who arrested out of hospital and were diagnosed with or suspected of having COVID-19, “account for 77.4% of the increase in cases of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest observed in these provinces in 2020,” the investigators noted.

As the pandemic has taken hold, hospitals and physicians across the United States are also voicing concerns about the drop in the number of patients presenting with myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke.

Nearly one-third of Americans (29%) report having delayed or avoided medical care because of concerns of catching COVID-19, according to a new poll released April 28 from the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and Morning Consult, a global data research firm.

Despite many emergency departments reporting a decline in patient volume, 74% of respondents said they were worried about hospital wait times and overcrowding. Another 59% expressed concerns about being turned away from the hospital or doctor’s office.

At the same time, the survey found strong support for emergency physicians and 73% of respondents said they were concerned about overstressing the health care system.

The drop-off in Americans seeking care for MI and strokes nationally prompted eight professional societies – including ACEP, the American Heart Association, and the Association of Black Cardiologists – to issue a joint statement urging those experiencing symptoms to call 911 and seek care for these life-threatening events.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests increased 58% during the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak in the hard-hit region of Lombardy, Italy, compared with the same period last year, a new analysis shows.

During the first 40 days of the outbreak beginning Feb. 21, four provinces in northern Italy reported 362 cases of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest compared with 229 during the same period in 2019.

The increases in these provinces varied in magnitude from 18% in Mantua, where there were 1,688 confirmed COVID-19 cases, to 187% in Lodi, which had 2,116 COVID-19 cases. The Cremona province, which had the highest number of COVID-19 cases at 3,869, saw a 143% increase in out-of-hospital cardiac arrests.

The mortality rate in the field was 14.9 percentage points higher in 2020 than in 2019 among patients in whom resuscitation was attempted by emergency medical services (EMS), Enrico Baldi, MD, University of Pavia, Italy, and colleagues reported in a letter April 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The sex and age of the patients were similar in the 2020 and 2019 periods, but in 2020, the incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to a medical cause was 6.5 percentage points higher, the incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest at home was 7.3 percentage points higher, and the incidence of unwitnessed cardiac arrest was 11.3 percentage points higher,” the authors wrote.

Patients were also less likely to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation from bystanders in 2020 vs 2019 (–15.6 percentage points) and were more likely to die before reaching the hospital when resuscitation was attempted by EMS (+14.9 percentage points).

Among all patients, the death rate in the field increased 11.4 percentage points during the outbreak, from 77.3% in 2019 to 88.7% in 2020.

The cumulative incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in 2020 was “strongly associated” with the cumulative incidence of COVID-19 (Spearman rank correlation coefficient, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.91) and the spike in cases “followed the time course of the COVID-19 outbreak,” the researchers noted.

A total of 103 patients, who arrested out of hospital and were diagnosed with or suspected of having COVID-19, “account for 77.4% of the increase in cases of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest observed in these provinces in 2020,” the investigators noted.

As the pandemic has taken hold, hospitals and physicians across the United States are also voicing concerns about the drop in the number of patients presenting with myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke.

Nearly one-third of Americans (29%) report having delayed or avoided medical care because of concerns of catching COVID-19, according to a new poll released April 28 from the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and Morning Consult, a global data research firm.

Despite many emergency departments reporting a decline in patient volume, 74% of respondents said they were worried about hospital wait times and overcrowding. Another 59% expressed concerns about being turned away from the hospital or doctor’s office.

At the same time, the survey found strong support for emergency physicians and 73% of respondents said they were concerned about overstressing the health care system.

The drop-off in Americans seeking care for MI and strokes nationally prompted eight professional societies – including ACEP, the American Heart Association, and the Association of Black Cardiologists – to issue a joint statement urging those experiencing symptoms to call 911 and seek care for these life-threatening events.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests increased 58% during the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak in the hard-hit region of Lombardy, Italy, compared with the same period last year, a new analysis shows.

During the first 40 days of the outbreak beginning Feb. 21, four provinces in northern Italy reported 362 cases of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest compared with 229 during the same period in 2019.

The increases in these provinces varied in magnitude from 18% in Mantua, where there were 1,688 confirmed COVID-19 cases, to 187% in Lodi, which had 2,116 COVID-19 cases. The Cremona province, which had the highest number of COVID-19 cases at 3,869, saw a 143% increase in out-of-hospital cardiac arrests.

The mortality rate in the field was 14.9 percentage points higher in 2020 than in 2019 among patients in whom resuscitation was attempted by emergency medical services (EMS), Enrico Baldi, MD, University of Pavia, Italy, and colleagues reported in a letter April 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“The sex and age of the patients were similar in the 2020 and 2019 periods, but in 2020, the incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to a medical cause was 6.5 percentage points higher, the incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest at home was 7.3 percentage points higher, and the incidence of unwitnessed cardiac arrest was 11.3 percentage points higher,” the authors wrote.

Patients were also less likely to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation from bystanders in 2020 vs 2019 (–15.6 percentage points) and were more likely to die before reaching the hospital when resuscitation was attempted by EMS (+14.9 percentage points).

Among all patients, the death rate in the field increased 11.4 percentage points during the outbreak, from 77.3% in 2019 to 88.7% in 2020.

The cumulative incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in 2020 was “strongly associated” with the cumulative incidence of COVID-19 (Spearman rank correlation coefficient, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.91) and the spike in cases “followed the time course of the COVID-19 outbreak,” the researchers noted.

A total of 103 patients, who arrested out of hospital and were diagnosed with or suspected of having COVID-19, “account for 77.4% of the increase in cases of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest observed in these provinces in 2020,” the investigators noted.

As the pandemic has taken hold, hospitals and physicians across the United States are also voicing concerns about the drop in the number of patients presenting with myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke.

Nearly one-third of Americans (29%) report having delayed or avoided medical care because of concerns of catching COVID-19, according to a new poll released April 28 from the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and Morning Consult, a global data research firm.

Despite many emergency departments reporting a decline in patient volume, 74% of respondents said they were worried about hospital wait times and overcrowding. Another 59% expressed concerns about being turned away from the hospital or doctor’s office.

At the same time, the survey found strong support for emergency physicians and 73% of respondents said they were concerned about overstressing the health care system.

The drop-off in Americans seeking care for MI and strokes nationally prompted eight professional societies – including ACEP, the American Heart Association, and the Association of Black Cardiologists – to issue a joint statement urging those experiencing symptoms to call 911 and seek care for these life-threatening events.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

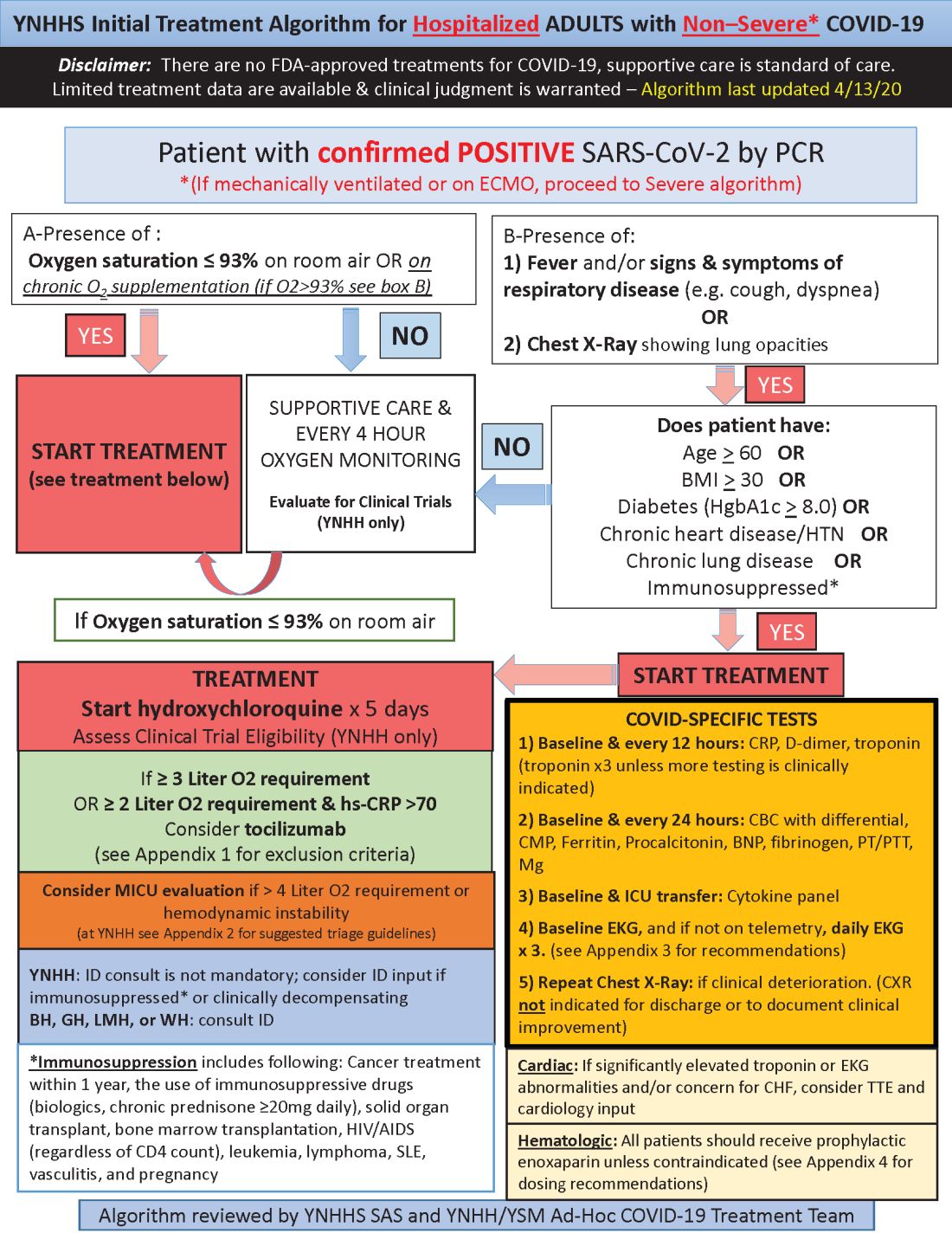

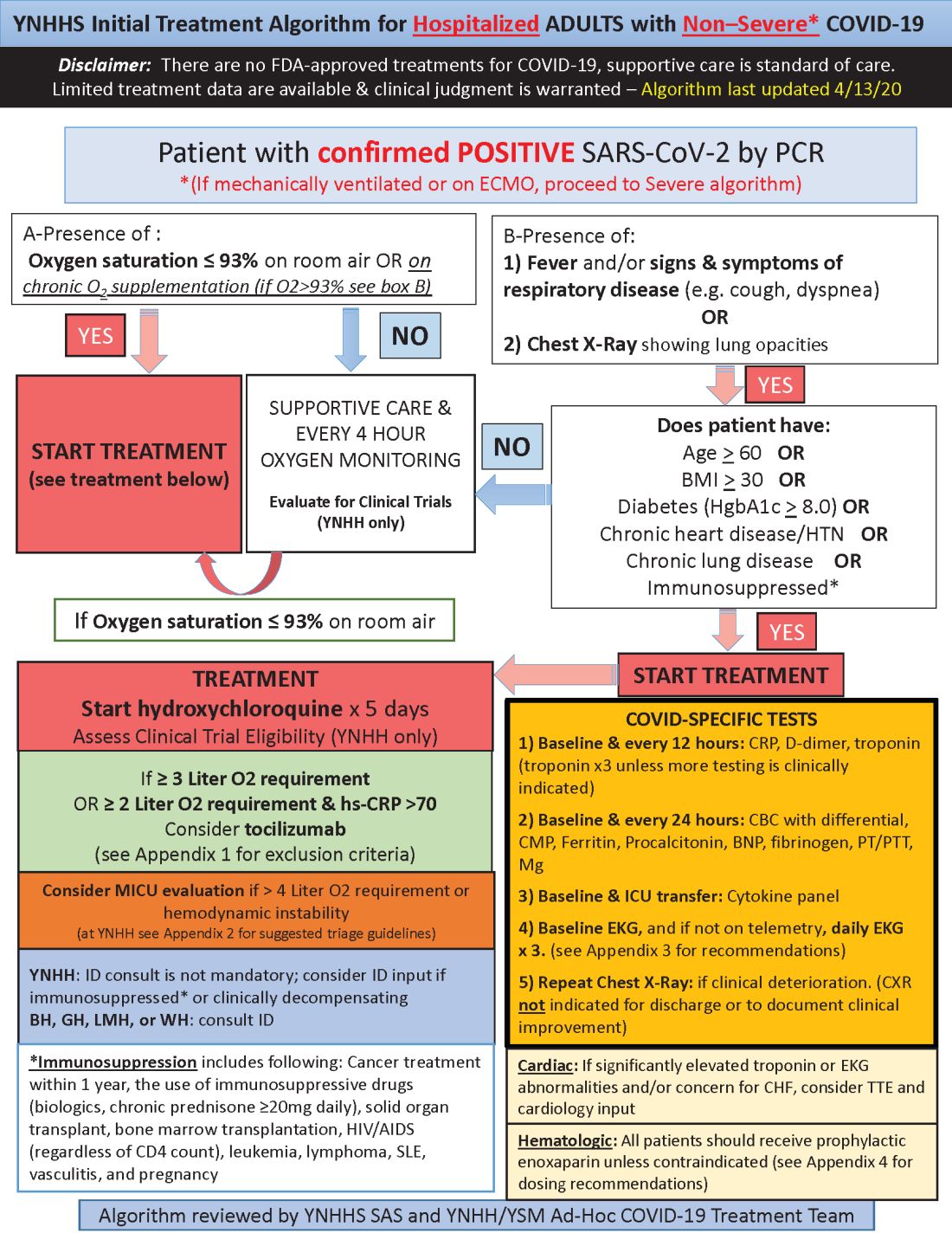

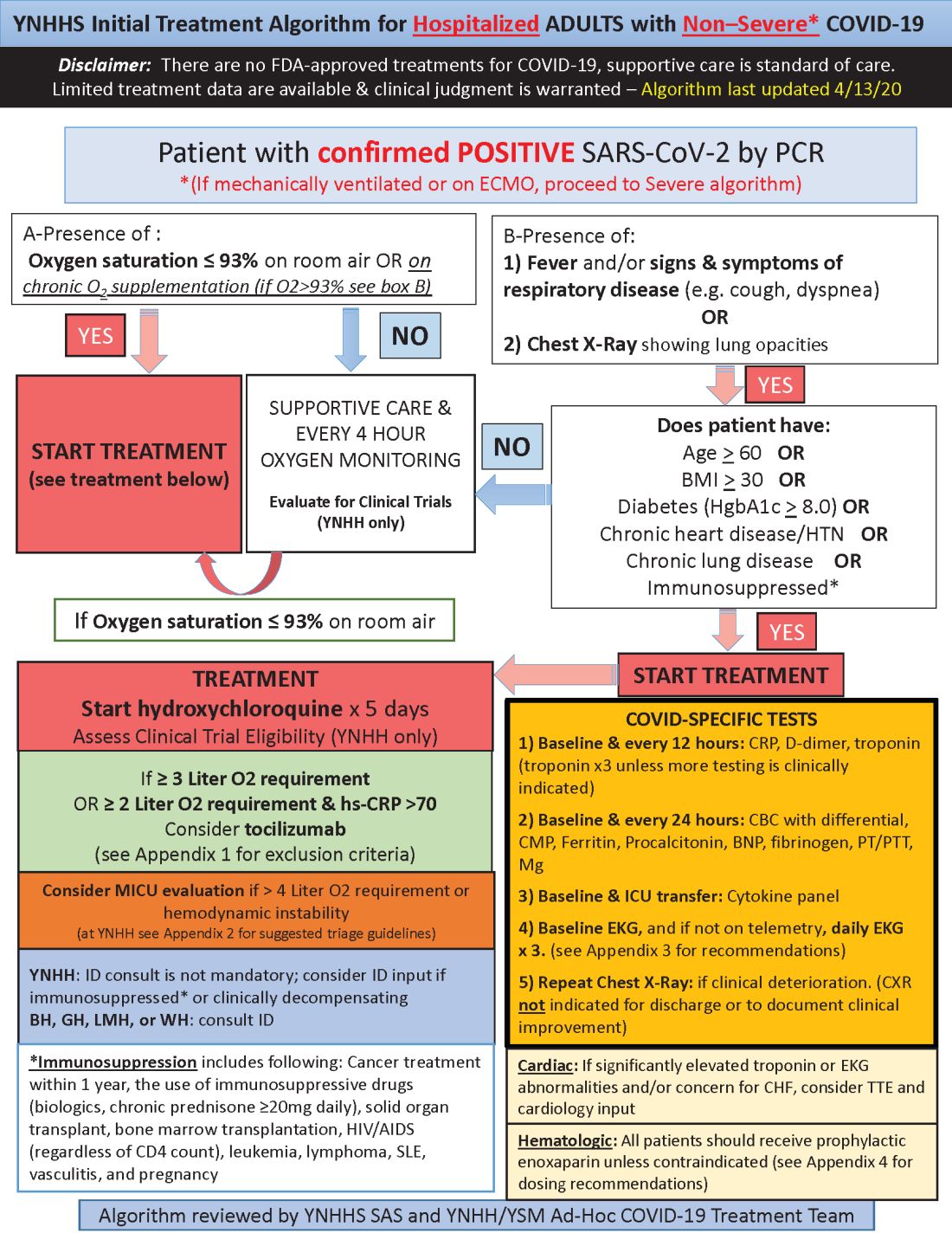

Yale’s COVID-19 inpatient protocol: Hydroxychloroquine plus/minus tocilizumab

Hydroxychloroquine is currently first-line, and tocilizumab second-line, for people hospitalized with polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19 in the Yale New Haven (Conn.) Health System, which operates hospitals across Connecticut, many of them hard hit by the pandemic.

Patients enter the treatment algorithm if they have an oxygen saturation at or below 93% on room air or chronic supplementation, or by being acutely ill with fever, respiratory signs, or opacities on chest x-ray, plus risk factors for severe illness such as age over 60 years, chronic heart or lung disease, immunosuppression, diabetes, hypertension, or obesity, which makes it harder to ventilate.

Physicians at Yale have seen both presentations – oxygen desaturation and frank illness – and “wanted to make sure we weren’t missing anyone,” said Nihar Desai, MD, a Yale cardiologist who is helping to coordinate the health system’s response to COVID-19.

In either case, the initial treatment is the same at Yale hospitals: hydroxychloroquine for 5 days, with tocilizumab (Actemra) considered when not contraindicated and oxygen requirements reach or pass 3 L, or 2 L with C-reactive protein levels above 70 mg/L.

Patients are put on prophylactic enoxaparin to thin the blood unless contraindicated; inflammatory, cardiac, kidney, and other markers are checked every 12 or 24 hours; and ECGs are taken daily if telemetry isn’t used. Chest x-rays are repeated if clinical signs worsen, and transthoracic echocardiograms are ordered for suspected heart problems.

ICUs are notified early if the clinical situation worsens because patients “can deteriorate very quickly; at the first sign of trouble, people are really aggressive,” said Dr. Desai, also the associate chief of clinical operations in the Section of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Yale University, New Haven.

The haze of battle

Yale has updated its algorithm several times since the virus first hit Connecticut weeks ago. A team including pulmonologists, critical care physicians, pharmacologists, infectious disease experts, and cardiologists, including Dr. Desai, are constantly monitoring the situation and making changes as new information comes in.

Much of what’s being done at Yale and elsewhere is empiric because there are simply not much data to go on. “We are trying to do the best we can” in “the haze of battle. People really came together quickly to develop this. One hopes we never have to go through anything like this again,” he said.

Hydroxychloroquine is first-line at Yale because in-vitro data show potent inhibition of the virus and possible clinical benefit, which is about as good as evidence gets at the moment. Also, “it’s cheap, it’s been used for decades, and people are relatively comfortable with it,” Dr. Desai said.

Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor antagonist, is second-line because it might counter the cytokine storm thought to be at least partly responsible for severe complications, and retrospective data suggest possible benefit. The antiviral remdesivir and IL-6 blocker sarulimab (Kevzara) are also potential candidates, available through clinical trials.

Dr. Desai wanted to share the algorithm with other providers because, he noted, “there are a lot of places that may not have all the resources we have.”

His home institution, Yale New Haven Hospital, is almost half full with COVID-19 patients, at more than 400.

A moving target

Yale’s approach is similar in confirmed COVID-19 cases already in respiratory failure, including those on mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: hydroxychloroquine and possibly tocilizumab, but also methylprednisolone if clinical status worsens or inflammatory markers go up. The steroid is for additional help battling the cytokine storm, Dr. Desai said.

The degree of anticoagulation in the ICU is based on d-dimer levels or suspicion or confirmation of venous thromboembolism. Telemetry is monitored closely for QTc prolongation, and point of care ultrasound is considered to check left ventricular function in the setting of markedly increased cardiac troponin levels, ECG abnormalities, or hemodynamic instability.

Previous versions of Yale’s algorithm included HIV protease inhibitors, but they were pulled after a recent trial found no benefit. Frequency of monitoring was also reduced from every 8 hours because it didn’t improve decision making and put staff collecting specimens at risk (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282).

Anticoagulation was added to newer versions after it became clear that COVID-19 is prothrombotic. “We are still seeing thrombotic events that might warrant further intensification,” Dr. Desai said.

Newer algorithms also have Yale watching QTc intervals more closely. It’s unclear if the prolongation risk is caused by the infection or hydroxychloroquine.

On April 24, the Food and Drug Administration reiterated it’s concern about the arrhythmia risk with hydroxychloroquine and emphasized that it should only be used for COVID-19 patients when they are hospitalized and it is not feasible for them to participate in a clinical trial.

To help keep patients safe, ECGs from confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases are now first in line to be reviewed by cardiologists across Yale hospitals to pick up prolongations and notify providers as soon as possible. Hydroxychloroquine is held if there are no other explanations.

Cardiologists are on the fontline at Yale and elsewhere, Dr. Desai said, because heart complications like myocarditis and arrhythmias emerged early as common problems in hospitalized patients.

[email protected]

This article was updated with the latest treatment algorithm on 5/6/2020.

Hydroxychloroquine is currently first-line, and tocilizumab second-line, for people hospitalized with polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19 in the Yale New Haven (Conn.) Health System, which operates hospitals across Connecticut, many of them hard hit by the pandemic.

Patients enter the treatment algorithm if they have an oxygen saturation at or below 93% on room air or chronic supplementation, or by being acutely ill with fever, respiratory signs, or opacities on chest x-ray, plus risk factors for severe illness such as age over 60 years, chronic heart or lung disease, immunosuppression, diabetes, hypertension, or obesity, which makes it harder to ventilate.

Physicians at Yale have seen both presentations – oxygen desaturation and frank illness – and “wanted to make sure we weren’t missing anyone,” said Nihar Desai, MD, a Yale cardiologist who is helping to coordinate the health system’s response to COVID-19.

In either case, the initial treatment is the same at Yale hospitals: hydroxychloroquine for 5 days, with tocilizumab (Actemra) considered when not contraindicated and oxygen requirements reach or pass 3 L, or 2 L with C-reactive protein levels above 70 mg/L.

Patients are put on prophylactic enoxaparin to thin the blood unless contraindicated; inflammatory, cardiac, kidney, and other markers are checked every 12 or 24 hours; and ECGs are taken daily if telemetry isn’t used. Chest x-rays are repeated if clinical signs worsen, and transthoracic echocardiograms are ordered for suspected heart problems.

ICUs are notified early if the clinical situation worsens because patients “can deteriorate very quickly; at the first sign of trouble, people are really aggressive,” said Dr. Desai, also the associate chief of clinical operations in the Section of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Yale University, New Haven.

The haze of battle

Yale has updated its algorithm several times since the virus first hit Connecticut weeks ago. A team including pulmonologists, critical care physicians, pharmacologists, infectious disease experts, and cardiologists, including Dr. Desai, are constantly monitoring the situation and making changes as new information comes in.

Much of what’s being done at Yale and elsewhere is empiric because there are simply not much data to go on. “We are trying to do the best we can” in “the haze of battle. People really came together quickly to develop this. One hopes we never have to go through anything like this again,” he said.

Hydroxychloroquine is first-line at Yale because in-vitro data show potent inhibition of the virus and possible clinical benefit, which is about as good as evidence gets at the moment. Also, “it’s cheap, it’s been used for decades, and people are relatively comfortable with it,” Dr. Desai said.

Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor antagonist, is second-line because it might counter the cytokine storm thought to be at least partly responsible for severe complications, and retrospective data suggest possible benefit. The antiviral remdesivir and IL-6 blocker sarulimab (Kevzara) are also potential candidates, available through clinical trials.

Dr. Desai wanted to share the algorithm with other providers because, he noted, “there are a lot of places that may not have all the resources we have.”

His home institution, Yale New Haven Hospital, is almost half full with COVID-19 patients, at more than 400.

A moving target

Yale’s approach is similar in confirmed COVID-19 cases already in respiratory failure, including those on mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: hydroxychloroquine and possibly tocilizumab, but also methylprednisolone if clinical status worsens or inflammatory markers go up. The steroid is for additional help battling the cytokine storm, Dr. Desai said.

The degree of anticoagulation in the ICU is based on d-dimer levels or suspicion or confirmation of venous thromboembolism. Telemetry is monitored closely for QTc prolongation, and point of care ultrasound is considered to check left ventricular function in the setting of markedly increased cardiac troponin levels, ECG abnormalities, or hemodynamic instability.

Previous versions of Yale’s algorithm included HIV protease inhibitors, but they were pulled after a recent trial found no benefit. Frequency of monitoring was also reduced from every 8 hours because it didn’t improve decision making and put staff collecting specimens at risk (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282).

Anticoagulation was added to newer versions after it became clear that COVID-19 is prothrombotic. “We are still seeing thrombotic events that might warrant further intensification,” Dr. Desai said.

Newer algorithms also have Yale watching QTc intervals more closely. It’s unclear if the prolongation risk is caused by the infection or hydroxychloroquine.

On April 24, the Food and Drug Administration reiterated it’s concern about the arrhythmia risk with hydroxychloroquine and emphasized that it should only be used for COVID-19 patients when they are hospitalized and it is not feasible for them to participate in a clinical trial.

To help keep patients safe, ECGs from confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases are now first in line to be reviewed by cardiologists across Yale hospitals to pick up prolongations and notify providers as soon as possible. Hydroxychloroquine is held if there are no other explanations.

Cardiologists are on the fontline at Yale and elsewhere, Dr. Desai said, because heart complications like myocarditis and arrhythmias emerged early as common problems in hospitalized patients.

[email protected]

This article was updated with the latest treatment algorithm on 5/6/2020.

Hydroxychloroquine is currently first-line, and tocilizumab second-line, for people hospitalized with polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19 in the Yale New Haven (Conn.) Health System, which operates hospitals across Connecticut, many of them hard hit by the pandemic.

Patients enter the treatment algorithm if they have an oxygen saturation at or below 93% on room air or chronic supplementation, or by being acutely ill with fever, respiratory signs, or opacities on chest x-ray, plus risk factors for severe illness such as age over 60 years, chronic heart or lung disease, immunosuppression, diabetes, hypertension, or obesity, which makes it harder to ventilate.

Physicians at Yale have seen both presentations – oxygen desaturation and frank illness – and “wanted to make sure we weren’t missing anyone,” said Nihar Desai, MD, a Yale cardiologist who is helping to coordinate the health system’s response to COVID-19.

In either case, the initial treatment is the same at Yale hospitals: hydroxychloroquine for 5 days, with tocilizumab (Actemra) considered when not contraindicated and oxygen requirements reach or pass 3 L, or 2 L with C-reactive protein levels above 70 mg/L.

Patients are put on prophylactic enoxaparin to thin the blood unless contraindicated; inflammatory, cardiac, kidney, and other markers are checked every 12 or 24 hours; and ECGs are taken daily if telemetry isn’t used. Chest x-rays are repeated if clinical signs worsen, and transthoracic echocardiograms are ordered for suspected heart problems.

ICUs are notified early if the clinical situation worsens because patients “can deteriorate very quickly; at the first sign of trouble, people are really aggressive,” said Dr. Desai, also the associate chief of clinical operations in the Section of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Yale University, New Haven.

The haze of battle

Yale has updated its algorithm several times since the virus first hit Connecticut weeks ago. A team including pulmonologists, critical care physicians, pharmacologists, infectious disease experts, and cardiologists, including Dr. Desai, are constantly monitoring the situation and making changes as new information comes in.

Much of what’s being done at Yale and elsewhere is empiric because there are simply not much data to go on. “We are trying to do the best we can” in “the haze of battle. People really came together quickly to develop this. One hopes we never have to go through anything like this again,” he said.

Hydroxychloroquine is first-line at Yale because in-vitro data show potent inhibition of the virus and possible clinical benefit, which is about as good as evidence gets at the moment. Also, “it’s cheap, it’s been used for decades, and people are relatively comfortable with it,” Dr. Desai said.

Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor antagonist, is second-line because it might counter the cytokine storm thought to be at least partly responsible for severe complications, and retrospective data suggest possible benefit. The antiviral remdesivir and IL-6 blocker sarulimab (Kevzara) are also potential candidates, available through clinical trials.

Dr. Desai wanted to share the algorithm with other providers because, he noted, “there are a lot of places that may not have all the resources we have.”

His home institution, Yale New Haven Hospital, is almost half full with COVID-19 patients, at more than 400.

A moving target

Yale’s approach is similar in confirmed COVID-19 cases already in respiratory failure, including those on mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: hydroxychloroquine and possibly tocilizumab, but also methylprednisolone if clinical status worsens or inflammatory markers go up. The steroid is for additional help battling the cytokine storm, Dr. Desai said.

The degree of anticoagulation in the ICU is based on d-dimer levels or suspicion or confirmation of venous thromboembolism. Telemetry is monitored closely for QTc prolongation, and point of care ultrasound is considered to check left ventricular function in the setting of markedly increased cardiac troponin levels, ECG abnormalities, or hemodynamic instability.

Previous versions of Yale’s algorithm included HIV protease inhibitors, but they were pulled after a recent trial found no benefit. Frequency of monitoring was also reduced from every 8 hours because it didn’t improve decision making and put staff collecting specimens at risk (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282).

Anticoagulation was added to newer versions after it became clear that COVID-19 is prothrombotic. “We are still seeing thrombotic events that might warrant further intensification,” Dr. Desai said.

Newer algorithms also have Yale watching QTc intervals more closely. It’s unclear if the prolongation risk is caused by the infection or hydroxychloroquine.

On April 24, the Food and Drug Administration reiterated it’s concern about the arrhythmia risk with hydroxychloroquine and emphasized that it should only be used for COVID-19 patients when they are hospitalized and it is not feasible for them to participate in a clinical trial.

To help keep patients safe, ECGs from confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases are now first in line to be reviewed by cardiologists across Yale hospitals to pick up prolongations and notify providers as soon as possible. Hydroxychloroquine is held if there are no other explanations.

Cardiologists are on the fontline at Yale and elsewhere, Dr. Desai said, because heart complications like myocarditis and arrhythmias emerged early as common problems in hospitalized patients.

[email protected]

This article was updated with the latest treatment algorithm on 5/6/2020.

Survey: Hydroxychloroquine use fairly common in COVID-19

One of five physicians in front-line treatment roles has prescribed hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, according to a new survey from health care market research company InCrowd.

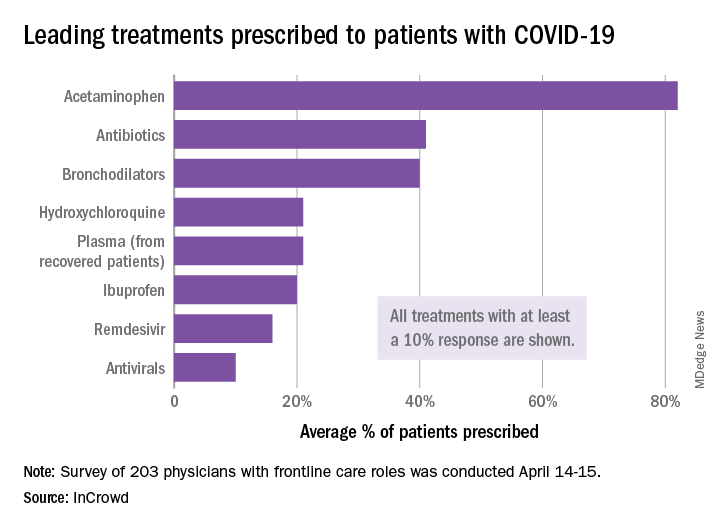

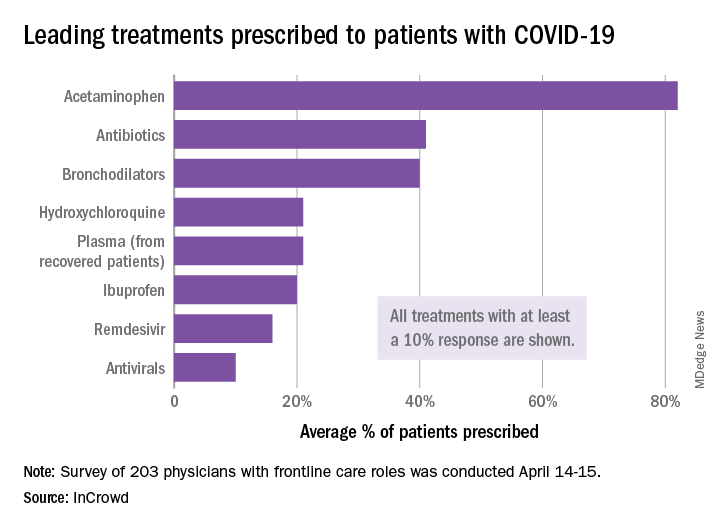

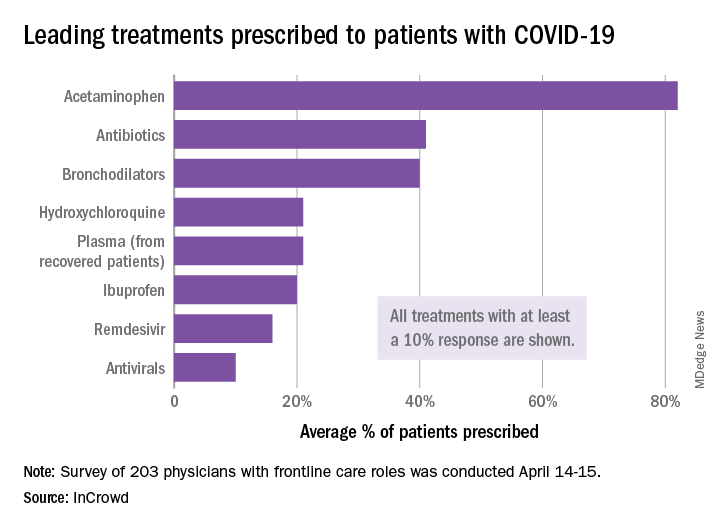

The most common treatments were acetaminophen, prescribed to 82% of patients, antibiotics (41%), and bronchodilators (40%), InCrowd said after surveying 203 primary care physicians, pediatricians, and emergency medicine or critical care physicians who are treating at least 20 patients with flulike symptoms.

On April 24, the Food and Drug Administration warned against the use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine outside of hospitals and clinical trials.

The InCrowd survey, which took place April 14-15 and is the fourth in a series investigating COVID-19’s impact on physicians, showed that access to testing was up to 82% in mid-April, compared with 67% in March and 20% in late February. The April respondents also were twice as likely (59% vs. 24% in March) to say that their facilities were prepared to treat patients, InCrowd reported.

“U.S. physicians report sluggish optimism around preparedness, safety, and institutional efforts, while many worry about the future, including a second outbreak and job security,” the company said in a separate written statement.

The average estimate for a return to normal was just over 6 months among respondents, and only 28% believed that their facility was prepared for a second outbreak later in the year, InCrowd noted.

On a personal level, 45% of the respondents were concerned about the safety of their job. An emergency/critical care physician from Tennessee said, “We’ve been cutting back on staff due to overall revenue reductions, but have increased acuity and complexity which requires more staffing. This puts even more of a burden on those of us still here.”

Support for institutional responses to slow the pandemic was strongest for state governments, which gained approval from 54% of front-line physicians, up from 33% in March. Actions taken by the federal government were supported by 21% of respondents, compared with 38% for the World Health Organization and 46% for governments outside the United States, InCrowd reported.

Suggestions for further actions by state and local authorities included this comment from an emergency/critical care physician in Florida: “Continued, broad and properly enforced stay at home and social distancing measures MUST remain in place to keep citizens and healthcare workers safe, and the latter alive and in adequate supply.”

One of five physicians in front-line treatment roles has prescribed hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, according to a new survey from health care market research company InCrowd.

The most common treatments were acetaminophen, prescribed to 82% of patients, antibiotics (41%), and bronchodilators (40%), InCrowd said after surveying 203 primary care physicians, pediatricians, and emergency medicine or critical care physicians who are treating at least 20 patients with flulike symptoms.

On April 24, the Food and Drug Administration warned against the use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine outside of hospitals and clinical trials.

The InCrowd survey, which took place April 14-15 and is the fourth in a series investigating COVID-19’s impact on physicians, showed that access to testing was up to 82% in mid-April, compared with 67% in March and 20% in late February. The April respondents also were twice as likely (59% vs. 24% in March) to say that their facilities were prepared to treat patients, InCrowd reported.

“U.S. physicians report sluggish optimism around preparedness, safety, and institutional efforts, while many worry about the future, including a second outbreak and job security,” the company said in a separate written statement.

The average estimate for a return to normal was just over 6 months among respondents, and only 28% believed that their facility was prepared for a second outbreak later in the year, InCrowd noted.

On a personal level, 45% of the respondents were concerned about the safety of their job. An emergency/critical care physician from Tennessee said, “We’ve been cutting back on staff due to overall revenue reductions, but have increased acuity and complexity which requires more staffing. This puts even more of a burden on those of us still here.”

Support for institutional responses to slow the pandemic was strongest for state governments, which gained approval from 54% of front-line physicians, up from 33% in March. Actions taken by the federal government were supported by 21% of respondents, compared with 38% for the World Health Organization and 46% for governments outside the United States, InCrowd reported.

Suggestions for further actions by state and local authorities included this comment from an emergency/critical care physician in Florida: “Continued, broad and properly enforced stay at home and social distancing measures MUST remain in place to keep citizens and healthcare workers safe, and the latter alive and in adequate supply.”

One of five physicians in front-line treatment roles has prescribed hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, according to a new survey from health care market research company InCrowd.

The most common treatments were acetaminophen, prescribed to 82% of patients, antibiotics (41%), and bronchodilators (40%), InCrowd said after surveying 203 primary care physicians, pediatricians, and emergency medicine or critical care physicians who are treating at least 20 patients with flulike symptoms.

On April 24, the Food and Drug Administration warned against the use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine outside of hospitals and clinical trials.

The InCrowd survey, which took place April 14-15 and is the fourth in a series investigating COVID-19’s impact on physicians, showed that access to testing was up to 82% in mid-April, compared with 67% in March and 20% in late February. The April respondents also were twice as likely (59% vs. 24% in March) to say that their facilities were prepared to treat patients, InCrowd reported.

“U.S. physicians report sluggish optimism around preparedness, safety, and institutional efforts, while many worry about the future, including a second outbreak and job security,” the company said in a separate written statement.

The average estimate for a return to normal was just over 6 months among respondents, and only 28% believed that their facility was prepared for a second outbreak later in the year, InCrowd noted.

On a personal level, 45% of the respondents were concerned about the safety of their job. An emergency/critical care physician from Tennessee said, “We’ve been cutting back on staff due to overall revenue reductions, but have increased acuity and complexity which requires more staffing. This puts even more of a burden on those of us still here.”

Support for institutional responses to slow the pandemic was strongest for state governments, which gained approval from 54% of front-line physicians, up from 33% in March. Actions taken by the federal government were supported by 21% of respondents, compared with 38% for the World Health Organization and 46% for governments outside the United States, InCrowd reported.

Suggestions for further actions by state and local authorities included this comment from an emergency/critical care physician in Florida: “Continued, broad and properly enforced stay at home and social distancing measures MUST remain in place to keep citizens and healthcare workers safe, and the latter alive and in adequate supply.”

FDA reiterates hydroxychloroquine limitations for COVID-19

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration reinforced its March guidance on when it’s permissible to use hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine to treat COVID-19 patients and on the multiple risks these drugs pose in a Safety Communication on April 24.

The new communication reiterated the agency’s position from the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) it granted on March 28 to allow hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine treatment of COVID-19 patients only when they are hospitalized and participation in a clinical trial is “not available,” or “not feasible.” The April 24 update to the EUA noted that “the FDA is aware of reports of serious heart rhythm problems in patients with COVID-19 treated with hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, often in combination with azithromycin and other QT-prolonging medicines. We are also aware of increased use of these medicines through outpatient prescriptions.”

In addition to reiterating the prior limitations on permissible patients for these treatment the agency also said in the new communication that “close supervision is strongly recommended, “ specifying that “we recommend initial evaluation and monitoring when using hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine under the EUA or in clinical trials that investigate these medicines for the treatment or prevention of COVID-19. Monitoring may include baseline ECG, electrolytes, renal function, and hepatic tests.” The communication also highlighted several potential serious adverse effects from hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine that include QT prolongation with increased risk in patients with renal insufficiency or failure, increased insulin levels and insulin action causing increased risk of severe hypoglycemia, hemolysis in selected patients, and interaction with other medicines that cause QT prolongation.

“If a healthcare professional is considering use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine to treat or prevent COVID-19, FDA recommends checking www.clinicaltrials.gov for a suitable clinical trial and consider enrolling the patient,” the statement added.

The FDA’s Safety Communication came a day after the European Medicines Agency issued a similar reminder about the risk for serious adverse effects from treatment with hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, the need for adverse effect monitoring, and the unproven status of purported benefits from these agents.

The statement came after ongoing promotion by the Trump administration of hydroxychloroquine, in particular, for COVID-19 despite a lack of evidence.

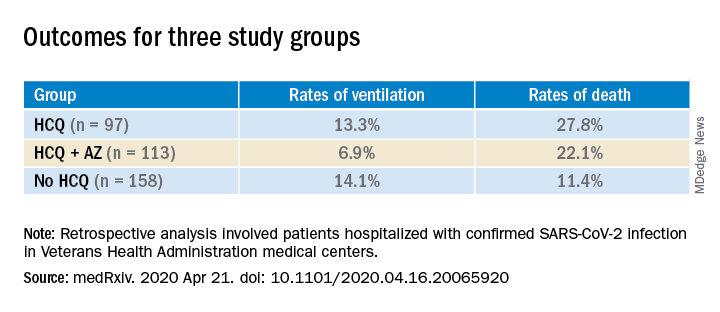

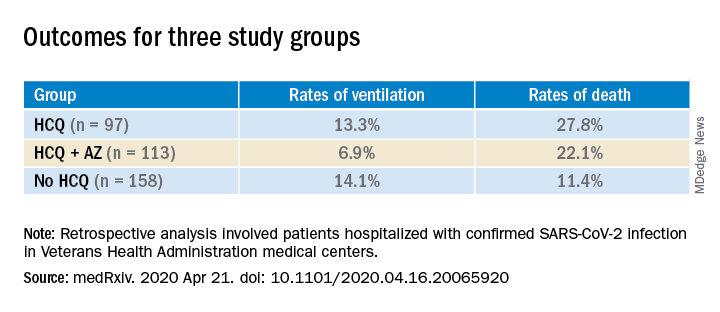

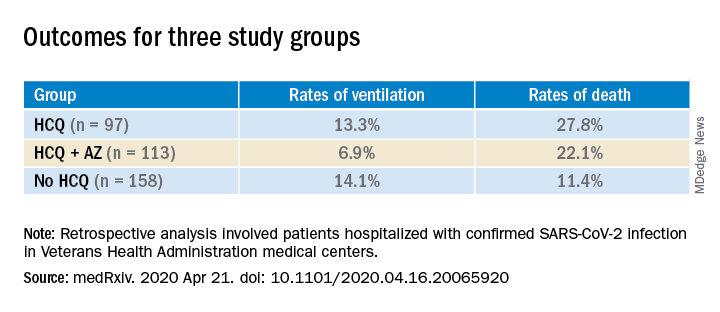

The FDA’s communication cited recent case reports sent to the FDA, as well as published findings, and reports to the National Poison Data System that have described serious, heart-related adverse events and death in COVID-19 patients who received hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, alone or in combination with azithromycin or another QT-prolonging drug. One recent, notable but not peer-reviewed report on 368 patients treated at any of several U.S. VA medical centers showed no apparent benefit to hospitalized COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and a signal for increased mortality among certain patients on this drug (medRxiv. 2020 Apr 23; doi: 10.1101/2020.04.16.20065920). Several cardiology societies have also highlighted the cardiac considerations for using these drugs in patients with COVID-19, including a summary coauthored by the presidents of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society (Circulation. 2020 Apr 8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047521), and in guidance from the European Society of Cardiology.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration reinforced its March guidance on when it’s permissible to use hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine to treat COVID-19 patients and on the multiple risks these drugs pose in a Safety Communication on April 24.

The new communication reiterated the agency’s position from the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) it granted on March 28 to allow hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine treatment of COVID-19 patients only when they are hospitalized and participation in a clinical trial is “not available,” or “not feasible.” The April 24 update to the EUA noted that “the FDA is aware of reports of serious heart rhythm problems in patients with COVID-19 treated with hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, often in combination with azithromycin and other QT-prolonging medicines. We are also aware of increased use of these medicines through outpatient prescriptions.”

In addition to reiterating the prior limitations on permissible patients for these treatment the agency also said in the new communication that “close supervision is strongly recommended, “ specifying that “we recommend initial evaluation and monitoring when using hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine under the EUA or in clinical trials that investigate these medicines for the treatment or prevention of COVID-19. Monitoring may include baseline ECG, electrolytes, renal function, and hepatic tests.” The communication also highlighted several potential serious adverse effects from hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine that include QT prolongation with increased risk in patients with renal insufficiency or failure, increased insulin levels and insulin action causing increased risk of severe hypoglycemia, hemolysis in selected patients, and interaction with other medicines that cause QT prolongation.

“If a healthcare professional is considering use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine to treat or prevent COVID-19, FDA recommends checking www.clinicaltrials.gov for a suitable clinical trial and consider enrolling the patient,” the statement added.

The FDA’s Safety Communication came a day after the European Medicines Agency issued a similar reminder about the risk for serious adverse effects from treatment with hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, the need for adverse effect monitoring, and the unproven status of purported benefits from these agents.

The statement came after ongoing promotion by the Trump administration of hydroxychloroquine, in particular, for COVID-19 despite a lack of evidence.

The FDA’s communication cited recent case reports sent to the FDA, as well as published findings, and reports to the National Poison Data System that have described serious, heart-related adverse events and death in COVID-19 patients who received hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, alone or in combination with azithromycin or another QT-prolonging drug. One recent, notable but not peer-reviewed report on 368 patients treated at any of several U.S. VA medical centers showed no apparent benefit to hospitalized COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and a signal for increased mortality among certain patients on this drug (medRxiv. 2020 Apr 23; doi: 10.1101/2020.04.16.20065920). Several cardiology societies have also highlighted the cardiac considerations for using these drugs in patients with COVID-19, including a summary coauthored by the presidents of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society (Circulation. 2020 Apr 8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047521), and in guidance from the European Society of Cardiology.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration reinforced its March guidance on when it’s permissible to use hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine to treat COVID-19 patients and on the multiple risks these drugs pose in a Safety Communication on April 24.

The new communication reiterated the agency’s position from the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) it granted on March 28 to allow hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine treatment of COVID-19 patients only when they are hospitalized and participation in a clinical trial is “not available,” or “not feasible.” The April 24 update to the EUA noted that “the FDA is aware of reports of serious heart rhythm problems in patients with COVID-19 treated with hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, often in combination with azithromycin and other QT-prolonging medicines. We are also aware of increased use of these medicines through outpatient prescriptions.”

In addition to reiterating the prior limitations on permissible patients for these treatment the agency also said in the new communication that “close supervision is strongly recommended, “ specifying that “we recommend initial evaluation and monitoring when using hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine under the EUA or in clinical trials that investigate these medicines for the treatment or prevention of COVID-19. Monitoring may include baseline ECG, electrolytes, renal function, and hepatic tests.” The communication also highlighted several potential serious adverse effects from hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine that include QT prolongation with increased risk in patients with renal insufficiency or failure, increased insulin levels and insulin action causing increased risk of severe hypoglycemia, hemolysis in selected patients, and interaction with other medicines that cause QT prolongation.

“If a healthcare professional is considering use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine to treat or prevent COVID-19, FDA recommends checking www.clinicaltrials.gov for a suitable clinical trial and consider enrolling the patient,” the statement added.

The FDA’s Safety Communication came a day after the European Medicines Agency issued a similar reminder about the risk for serious adverse effects from treatment with hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, the need for adverse effect monitoring, and the unproven status of purported benefits from these agents.

The statement came after ongoing promotion by the Trump administration of hydroxychloroquine, in particular, for COVID-19 despite a lack of evidence.

The FDA’s communication cited recent case reports sent to the FDA, as well as published findings, and reports to the National Poison Data System that have described serious, heart-related adverse events and death in COVID-19 patients who received hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, alone or in combination with azithromycin or another QT-prolonging drug. One recent, notable but not peer-reviewed report on 368 patients treated at any of several U.S. VA medical centers showed no apparent benefit to hospitalized COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and a signal for increased mortality among certain patients on this drug (medRxiv. 2020 Apr 23; doi: 10.1101/2020.04.16.20065920). Several cardiology societies have also highlighted the cardiac considerations for using these drugs in patients with COVID-19, including a summary coauthored by the presidents of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society (Circulation. 2020 Apr 8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047521), and in guidance from the European Society of Cardiology.

FROM THE FDA

Angiotensin drugs and COVID-19: More reassuring data

Initial data from one Chinese center on the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 appear to give some further reassurance about continued use of these drugs.

The report from one hospital in Wuhan found that among patients with hypertension hospitalized with the COVID-19 virus, there was no difference in disease severity or death rate in patients taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs and those not taking such medications.

The data were published online April 23 in JAMA Cardiology.

The study adds to another recent report in a larger number of COVID-19 patients from nine Chinese hospitals that suggested a beneficial effect of ACE inhibitors or ARBs on mortality.

Additional studies

Two other similar studies have also been recently released. Another study from China, published online March 31 in Emerging Microbes & Infections, included a small sample of 42 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 on antihypertensive therapy. Those on ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy had a lower rate of severe disease and a trend toward a lower level of IL-6 in peripheral blood. In addition, patients on ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy had increased CD3+ and CD8+ T-cell counts in peripheral blood and decreased peak viral load compared with other antihypertensive drugs.

And a preliminary study from the UK, which has not yet been peer reviewed, found that treatment with ACE inhibitors was associated with a reduced risk of rapidly deteriorating severe COVID-19 disease.

The study, available online on MedRxiv, a preprint server for health sciences, reports on 205 acute inpatients with COVID-19 at King’s College Hospital and Princess Royal University Hospital, London.

Of these, 51.2% had hypertension, 30.2% had diabetes, and 14.6% had ischemic heart disease or heart failure. Of the 37 patients on ACE inhibitors, five (14%) died or required critical care support compared with 29% (48/168) of patients not taking an ACE inhibitor.

New Wuhan study

The authors of the new article published in JAMA Cardiology, led by Juyi Li, MD, reported on a case series of 1,178 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 at the Central Hospital of Wuhan, Hubei, China, between Jan. 15 and March 15, 2020.

Patients were a median age of 55 years, and 46% were men. They had an overall in-hospital mortality rate of 11%.

Of the 1,178 patients, 362 (30.7%) had a diagnosis of hypertension. These patients were older (median age, 66 years) and had a greater prevalence of chronic diseases. Patients with hypertension also had more severe manifestations of COVID-19 compared to those without hypertension, including higher rates of acute respiratory distress syndrome and in-hospital mortality (21.3% vs. 6.5%).

Of the 362 patients with hypertension, 31.8% were taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

Apart from a greater prevalence of coronary artery disease, patients taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs had similar comorbidities to those not taking these medications, and also similar laboratory profile results including blood counts, inflammatory markers, renal and liver function tests, and cardiac biomarkers, although those taking ACE inhibitors/ARBs had higher levels of alkaline phosphatase.

The most commonly used antihypertensive drugs were calcium blockers. The percentage of patients with hypertension taking any drug or drug combination did not differ between those with severe and nonsevere infections and between those who survived and those who died.

Specifically regarding ACE inhibitors/ARBs, there was no difference between those with severe versus nonsevere illness in the use of ACE inhibitors (9.2% vs. 10.1%; P = .80), ARBs (24.9% vs. 21.2%; P = .40), or the composite of ACE inhibitors or ARBs (32.9% vs. 30.7%; P = .65).

Similarly, there were no differences in nonsurvivors and survivors in the use of ACE inhibitors (9.1% vs. 9.8%; P = .85); ARBs (19.5% vs. 23.9%; P = .42), or the composite of ACE inhibitors or ARBs (27.3% vs. 33.0%; P = .34).

The frequency of severe illness and death also did not differ between those treated with and without ACE inhibitors/ARBs in patients with hypertension and other various chronic conditions including coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, neurological disease, and chronic renal disease.

The authors noted that these data confirm previous reports showing that patients with hypertension have more severe illness and higher mortality rates associated with COVID-19 than those without hypertension.

But they added: “Our data provide some reassurance that ACE inhibitors/ARBs are not associated with the progression or outcome of COVID-19 hospitalizations in patients with hypertension.”

They also noted that these results support the recommendations from almost all major cardiovascular societies that patients do not discontinue ACE inhibitors or ARBs because of worries about COVID-19.

However, the authors did point out some limitations of their study, which included a small number of patients with hypertension taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs and the fact that a nonsevere disease course was still severe enough to require hospitalization. In addition, it was not clear whether ACE inhibitor/ARB treatment at baseline was maintained throughout hospitalization for all patients.

This was also an observational comparison and may be biased by differences in patients taking versus not taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs at the time of hospitalization, although the measured baseline characteristics were similar in both groups.

But the authors also highlighted the finding that, in this cohort, patients with hypertension had three times the mortality rate of all other patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

“Hypertension combined with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease would predispose patients to an increased risk of severity and mortality of COVID-19. Therefore, patients with these underlying conditions who develop COVID-19 require particularly intensive surveillance and care,” they wrote.

Experts cautiously optimistic

Some cardiovascular experts were cautiously optimistic about these latest results.

Michael A. Weber, MD, professor of medicine at the State University of New York, Brooklyn, and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Clinical Hypertension, said: “This new report from Wuhan, China, gives modest reassurance that the use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in hypertensive patients with COVID-19 disease does not increase the risk of clinical deterioration or death.

“Ongoing, more definitive studies should help resolve competing hypotheses regarding the effects of these agents: whether the increased ACE2 enzyme levels they produce can worsen outcomes by increasing access of the COVID virus to lung tissue; or whether there is a benefit linked to a protective effect of increased ACE2 on alveolar cell function,” Dr. Weber noted.

“Though the number of patients included in this new report is small, it is startling that hypertensive patients were three times as likely as nonhypertensives to have a fatal outcome, presumably reflecting vulnerability due to the cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidities associated with hypertension,” he added.

“In any case, for now, clinicians should continue treating hypertensive patients with whichever drugs, including ACE inhibitors and ARBs, best provide protection from adverse outcomes,” Dr. Weber concluded.

John McMurray, MD, professor of medical cardiology, University of Glasgow, Scotland, commented: “This study from Wuhan provides some reassurance about one of the two questions about ACEI/ARBs: Do these drugs increase susceptibility to infection? And if [the patient is] infected, do they increase the severity of infection? This study addresses the latter question and appears to suggest no increased severity.”

However, Dr. McMurray pointed out that the study had many limitations. There were only small patient numbers and the data were unadjusted, “although it looks like the ACE inhibitor/ARB treated patients were higher risk to start with.” It was an observational study, and patients were not randomized and were predominantly treated with ARBs, and not ACE inhibitors, so “we don’t know if the concerns apply equally to these two classes of drug.

“Other data published and unpublished supporting this (even showing better outcomes in patients treated with an ACE inhibitor/ARB), and, to date, any concerns about these drugs remain unsubstantiated and the guidance from medical societies to continue treatment with these agents in patients prescribed them seems wise,” Dr. McMurray added.

Franz H. Messerli, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Bern, Switzerland, commented: “The study from Wuhan is not a great study. They didn’t even do a multivariable analysis. They could have done a bit more with the data, but it still gives some reassurance.”

Dr. Messerli said it was “interesting” that 30% of the patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the sample had hypertension. “That corresponds to the general population, so does not suggest that having hypertension increases susceptibility to infection – but it does seem to increase the risk of a bad outcome.”

Dr. Messerli noted that there are two more similar studies due to be published soon, both said to suggest either a beneficial or neutral effect of ACE inhibitors/ARBs on COVID-19 outcomes in hospitalized patients.

“This does help with confidence in prescribing these agents and reinforces the recommendations for patients to stay on these drugs,” he said.

“However, none of these studies address the infectivity issue – whether their use upregulates the ACE2 receptor, which the virus uses to gain entry to cells, thereby increasing susceptibility to the infection,” Dr. Messerli cautioned. “But the similar or better outcomes on these drugs are encouraging,” he added.

The Wuhan study was supported by the Health and Family Planning Commission of Wuhan City, China. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Initial data from one Chinese center on the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 appear to give some further reassurance about continued use of these drugs.

The report from one hospital in Wuhan found that among patients with hypertension hospitalized with the COVID-19 virus, there was no difference in disease severity or death rate in patients taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs and those not taking such medications.

The data were published online April 23 in JAMA Cardiology.

The study adds to another recent report in a larger number of COVID-19 patients from nine Chinese hospitals that suggested a beneficial effect of ACE inhibitors or ARBs on mortality.

Additional studies

Two other similar studies have also been recently released. Another study from China, published online March 31 in Emerging Microbes & Infections, included a small sample of 42 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 on antihypertensive therapy. Those on ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy had a lower rate of severe disease and a trend toward a lower level of IL-6 in peripheral blood. In addition, patients on ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy had increased CD3+ and CD8+ T-cell counts in peripheral blood and decreased peak viral load compared with other antihypertensive drugs.

And a preliminary study from the UK, which has not yet been peer reviewed, found that treatment with ACE inhibitors was associated with a reduced risk of rapidly deteriorating severe COVID-19 disease.

The study, available online on MedRxiv, a preprint server for health sciences, reports on 205 acute inpatients with COVID-19 at King’s College Hospital and Princess Royal University Hospital, London.

Of these, 51.2% had hypertension, 30.2% had diabetes, and 14.6% had ischemic heart disease or heart failure. Of the 37 patients on ACE inhibitors, five (14%) died or required critical care support compared with 29% (48/168) of patients not taking an ACE inhibitor.

New Wuhan study

The authors of the new article published in JAMA Cardiology, led by Juyi Li, MD, reported on a case series of 1,178 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 at the Central Hospital of Wuhan, Hubei, China, between Jan. 15 and March 15, 2020.

Patients were a median age of 55 years, and 46% were men. They had an overall in-hospital mortality rate of 11%.

Of the 1,178 patients, 362 (30.7%) had a diagnosis of hypertension. These patients were older (median age, 66 years) and had a greater prevalence of chronic diseases. Patients with hypertension also had more severe manifestations of COVID-19 compared to those without hypertension, including higher rates of acute respiratory distress syndrome and in-hospital mortality (21.3% vs. 6.5%).

Of the 362 patients with hypertension, 31.8% were taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

Apart from a greater prevalence of coronary artery disease, patients taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs had similar comorbidities to those not taking these medications, and also similar laboratory profile results including blood counts, inflammatory markers, renal and liver function tests, and cardiac biomarkers, although those taking ACE inhibitors/ARBs had higher levels of alkaline phosphatase.

The most commonly used antihypertensive drugs were calcium blockers. The percentage of patients with hypertension taking any drug or drug combination did not differ between those with severe and nonsevere infections and between those who survived and those who died.

Specifically regarding ACE inhibitors/ARBs, there was no difference between those with severe versus nonsevere illness in the use of ACE inhibitors (9.2% vs. 10.1%; P = .80), ARBs (24.9% vs. 21.2%; P = .40), or the composite of ACE inhibitors or ARBs (32.9% vs. 30.7%; P = .65).

Similarly, there were no differences in nonsurvivors and survivors in the use of ACE inhibitors (9.1% vs. 9.8%; P = .85); ARBs (19.5% vs. 23.9%; P = .42), or the composite of ACE inhibitors or ARBs (27.3% vs. 33.0%; P = .34).

The frequency of severe illness and death also did not differ between those treated with and without ACE inhibitors/ARBs in patients with hypertension and other various chronic conditions including coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, neurological disease, and chronic renal disease.

The authors noted that these data confirm previous reports showing that patients with hypertension have more severe illness and higher mortality rates associated with COVID-19 than those without hypertension.

But they added: “Our data provide some reassurance that ACE inhibitors/ARBs are not associated with the progression or outcome of COVID-19 hospitalizations in patients with hypertension.”

They also noted that these results support the recommendations from almost all major cardiovascular societies that patients do not discontinue ACE inhibitors or ARBs because of worries about COVID-19.

However, the authors did point out some limitations of their study, which included a small number of patients with hypertension taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs and the fact that a nonsevere disease course was still severe enough to require hospitalization. In addition, it was not clear whether ACE inhibitor/ARB treatment at baseline was maintained throughout hospitalization for all patients.

This was also an observational comparison and may be biased by differences in patients taking versus not taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs at the time of hospitalization, although the measured baseline characteristics were similar in both groups.

But the authors also highlighted the finding that, in this cohort, patients with hypertension had three times the mortality rate of all other patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

“Hypertension combined with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease would predispose patients to an increased risk of severity and mortality of COVID-19. Therefore, patients with these underlying conditions who develop COVID-19 require particularly intensive surveillance and care,” they wrote.

Experts cautiously optimistic

Some cardiovascular experts were cautiously optimistic about these latest results.

Michael A. Weber, MD, professor of medicine at the State University of New York, Brooklyn, and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Clinical Hypertension, said: “This new report from Wuhan, China, gives modest reassurance that the use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in hypertensive patients with COVID-19 disease does not increase the risk of clinical deterioration or death.

“Ongoing, more definitive studies should help resolve competing hypotheses regarding the effects of these agents: whether the increased ACE2 enzyme levels they produce can worsen outcomes by increasing access of the COVID virus to lung tissue; or whether there is a benefit linked to a protective effect of increased ACE2 on alveolar cell function,” Dr. Weber noted.

“Though the number of patients included in this new report is small, it is startling that hypertensive patients were three times as likely as nonhypertensives to have a fatal outcome, presumably reflecting vulnerability due to the cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidities associated with hypertension,” he added.

“In any case, for now, clinicians should continue treating hypertensive patients with whichever drugs, including ACE inhibitors and ARBs, best provide protection from adverse outcomes,” Dr. Weber concluded.

John McMurray, MD, professor of medical cardiology, University of Glasgow, Scotland, commented: “This study from Wuhan provides some reassurance about one of the two questions about ACEI/ARBs: Do these drugs increase susceptibility to infection? And if [the patient is] infected, do they increase the severity of infection? This study addresses the latter question and appears to suggest no increased severity.”

However, Dr. McMurray pointed out that the study had many limitations. There were only small patient numbers and the data were unadjusted, “although it looks like the ACE inhibitor/ARB treated patients were higher risk to start with.” It was an observational study, and patients were not randomized and were predominantly treated with ARBs, and not ACE inhibitors, so “we don’t know if the concerns apply equally to these two classes of drug.

“Other data published and unpublished supporting this (even showing better outcomes in patients treated with an ACE inhibitor/ARB), and, to date, any concerns about these drugs remain unsubstantiated and the guidance from medical societies to continue treatment with these agents in patients prescribed them seems wise,” Dr. McMurray added.

Franz H. Messerli, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Bern, Switzerland, commented: “The study from Wuhan is not a great study. They didn’t even do a multivariable analysis. They could have done a bit more with the data, but it still gives some reassurance.”