User login

Pediatric community-acquired pneumonia: 5 days of antibiotics better than 10 days

The evidence is in: and had the added benefit of a lower risk of inducing antibiotic resistance, according to the randomized, controlled SCOUT-CAP trial.

“Several studies have shown shorter antibiotic courses to be non-inferior to the standard treatment strategy, but in our study, we show that a shortened 5-day course of therapy was superior to standard therapy because the short course achieved similar outcomes with fewer days of antibiotics,” Derek Williams, MD, MPH, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said in an email.

“These data are immediately applicable to frontline clinicians, and we hope this study will shift the paradigm towards more judicious treatment approaches for childhood pneumonia, resulting in care that is safer and more effective,” he added.

The study was published online Jan. 18 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Uncomplicated CAP

The study enrolled children aged 6 months to 71 months diagnosed with uncomplicated CAP who demonstrated early clinical improvement in response to 5 days of antibiotic treatment. Participants were prescribed either amoxicillin, amoxicillin and clavulanate, or cefdinir according to standard of care and were randomized on day 6 to another 5 days of their initially prescribed antibiotic course or to placebo.

“Those assessed on day 6 were eligible only if they had not yet received a dose of antibiotic therapy on that day,” the authors write. The primary endpoint was end-of-treatment response, adjusted for the duration of antibiotic risk as assessed by RADAR. As the authors explain, RADAR is a composite endpoint that ranks each child’s clinical response, resolution of symptoms, and antibiotic-associated adverse effects (AEs) in an ordinal desirability of outcome ranking, or DOOR.

“There were no differences between strategies in the DOOR or in its individual components,” Dr. Williams and colleagues point out. A total of 380 children took part in the study. The mean age of participants was 35.7 months, and half were male.

Over 90% of children randomized to active therapy were prescribed amoxicillin. “Fewer than 10% of children in either strategy had an inadequate clinical response,” the authors report.

However, the 5-day antibiotic strategy had a 69% (95% CI, 63%-75%) probability of children achieving a more desirable RADAR outcome compared with the standard, 10-day course, as assessed either on days 6 to 10 at outcome assessment visit one (OAV1) or at OAV2 on days 19 to 25.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in the percentage of participants with persistent symptoms at either assessment point, they note. At assessment visit one, 40% of children assigned to the short-course strategy and 37% of children assigned to the 10-day strategy reported an antibiotic-related AE, most of which were mild.

Resistome analysis

Some 171 children were included in a resistome analysis in which throat swabs were collected between study days 19 and 25 to quantify antibiotic resistance genes in oropharyngeal flora. The total number of resistance genes per prokaryotic cell (RGPC) was significantly lower in children treated with antibiotics for 5 days compared with children who were treated for 10 days.

Specifically, the median number of total RGPC was 1.17 (95% CI, 0.35-2.43) for the short-course strategy and 1.33 (95% CI, 0.46-11.08) for the standard-course strategy (P = .01). Similarly, the median number of β-lactamase RGPC was 0.55 (0.18-1.24) for the short-course strategy and 0.60 (0.21-2.45) for the standard-course strategy (P = .03).

“Providing the shortest duration of antibiotics necessary to effectively treat an infection is a central tenet of antimicrobial stewardship and a convenient and cost-effective strategy for caregivers,” the authors observe. For example, reducing treatment from 10 to 5 days for outpatient CAP could reduce the number of days spent on antibiotics by up to 7.5 million days in the U.S. each year.

“If we can safely reduce antibiotic exposure, we can minimize antibiotic side effects while also helping to slow antibiotic resistance,” Dr. Williams pointed out.

Fewer days of having to give their child repeated doses of antibiotics is also more convenient for families, he added.

Asked to comment on the study, David Greenberg, MD, professor of pediatrics and infectious diseases, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Israel, explained that the length of antibiotic therapy as recommended by various guidelines is more or less arbitrary, some infections being excepted.

“There have been no studies evaluating the recommendation for a 100-day treatment course, and it’s kind of a joke because if you look at the treatment of just about any infection, it’s either for 7 days or 14 days or even 20 days because it’s easy to calculate – it’s not that anybody proved that treatment of whatever infection it is should last this long,” he told this news organization.

Moreover, adherence to a shorter antibiotic course is much better than it is to a longer course. If, for example, physicians tell a mother to take two bottles of antibiotics for a treatment course of 10 days, she’ll finish the first bottle which is good for 5 days and, because the child is fine, “she forgets about the second bottle,” Dr. Greenberg said.

In one of the first studies to compare a short versus long course of antibiotic therapy in uncomplicated CAP in young children, Dr. Greenberg and colleagues initially compared a 3-day course of high-dose amoxicillin to a 10-day course of the same treatment, but the 3-day course was associated with an unacceptable failure rate. (At the time, the World Health Organization was recommending a 3-day course of antibiotics for the treatment of uncomplicated CAP in children.)

They stopped the study and then initiated a second study in which they compared a 5-day course of the same antibiotic to a 10-day course and found the 5-day course was comparable to the 10-day course in terms of clinical cure rates. As a result of his study, Dr. Greenberg has long since prescribed a 5-day course of antibiotics for his own patients.

“Five days is good,” he affirmed. “And if patients start a 10-day course of an antibiotic for, say, a urinary tract infection and a subsequent culture comes back negative, they don’t have to finish the antibiotics either.” Dr. Greenberg said.

Dr. Williams said he has no financial ties to industry. Dr. Greenberg said he has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, and AstraZeneca. He is also a founder of the company Beyond Air.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The evidence is in: and had the added benefit of a lower risk of inducing antibiotic resistance, according to the randomized, controlled SCOUT-CAP trial.

“Several studies have shown shorter antibiotic courses to be non-inferior to the standard treatment strategy, but in our study, we show that a shortened 5-day course of therapy was superior to standard therapy because the short course achieved similar outcomes with fewer days of antibiotics,” Derek Williams, MD, MPH, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said in an email.

“These data are immediately applicable to frontline clinicians, and we hope this study will shift the paradigm towards more judicious treatment approaches for childhood pneumonia, resulting in care that is safer and more effective,” he added.

The study was published online Jan. 18 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Uncomplicated CAP

The study enrolled children aged 6 months to 71 months diagnosed with uncomplicated CAP who demonstrated early clinical improvement in response to 5 days of antibiotic treatment. Participants were prescribed either amoxicillin, amoxicillin and clavulanate, or cefdinir according to standard of care and were randomized on day 6 to another 5 days of their initially prescribed antibiotic course or to placebo.

“Those assessed on day 6 were eligible only if they had not yet received a dose of antibiotic therapy on that day,” the authors write. The primary endpoint was end-of-treatment response, adjusted for the duration of antibiotic risk as assessed by RADAR. As the authors explain, RADAR is a composite endpoint that ranks each child’s clinical response, resolution of symptoms, and antibiotic-associated adverse effects (AEs) in an ordinal desirability of outcome ranking, or DOOR.

“There were no differences between strategies in the DOOR or in its individual components,” Dr. Williams and colleagues point out. A total of 380 children took part in the study. The mean age of participants was 35.7 months, and half were male.

Over 90% of children randomized to active therapy were prescribed amoxicillin. “Fewer than 10% of children in either strategy had an inadequate clinical response,” the authors report.

However, the 5-day antibiotic strategy had a 69% (95% CI, 63%-75%) probability of children achieving a more desirable RADAR outcome compared with the standard, 10-day course, as assessed either on days 6 to 10 at outcome assessment visit one (OAV1) or at OAV2 on days 19 to 25.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in the percentage of participants with persistent symptoms at either assessment point, they note. At assessment visit one, 40% of children assigned to the short-course strategy and 37% of children assigned to the 10-day strategy reported an antibiotic-related AE, most of which were mild.

Resistome analysis

Some 171 children were included in a resistome analysis in which throat swabs were collected between study days 19 and 25 to quantify antibiotic resistance genes in oropharyngeal flora. The total number of resistance genes per prokaryotic cell (RGPC) was significantly lower in children treated with antibiotics for 5 days compared with children who were treated for 10 days.

Specifically, the median number of total RGPC was 1.17 (95% CI, 0.35-2.43) for the short-course strategy and 1.33 (95% CI, 0.46-11.08) for the standard-course strategy (P = .01). Similarly, the median number of β-lactamase RGPC was 0.55 (0.18-1.24) for the short-course strategy and 0.60 (0.21-2.45) for the standard-course strategy (P = .03).

“Providing the shortest duration of antibiotics necessary to effectively treat an infection is a central tenet of antimicrobial stewardship and a convenient and cost-effective strategy for caregivers,” the authors observe. For example, reducing treatment from 10 to 5 days for outpatient CAP could reduce the number of days spent on antibiotics by up to 7.5 million days in the U.S. each year.

“If we can safely reduce antibiotic exposure, we can minimize antibiotic side effects while also helping to slow antibiotic resistance,” Dr. Williams pointed out.

Fewer days of having to give their child repeated doses of antibiotics is also more convenient for families, he added.

Asked to comment on the study, David Greenberg, MD, professor of pediatrics and infectious diseases, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Israel, explained that the length of antibiotic therapy as recommended by various guidelines is more or less arbitrary, some infections being excepted.

“There have been no studies evaluating the recommendation for a 100-day treatment course, and it’s kind of a joke because if you look at the treatment of just about any infection, it’s either for 7 days or 14 days or even 20 days because it’s easy to calculate – it’s not that anybody proved that treatment of whatever infection it is should last this long,” he told this news organization.

Moreover, adherence to a shorter antibiotic course is much better than it is to a longer course. If, for example, physicians tell a mother to take two bottles of antibiotics for a treatment course of 10 days, she’ll finish the first bottle which is good for 5 days and, because the child is fine, “she forgets about the second bottle,” Dr. Greenberg said.

In one of the first studies to compare a short versus long course of antibiotic therapy in uncomplicated CAP in young children, Dr. Greenberg and colleagues initially compared a 3-day course of high-dose amoxicillin to a 10-day course of the same treatment, but the 3-day course was associated with an unacceptable failure rate. (At the time, the World Health Organization was recommending a 3-day course of antibiotics for the treatment of uncomplicated CAP in children.)

They stopped the study and then initiated a second study in which they compared a 5-day course of the same antibiotic to a 10-day course and found the 5-day course was comparable to the 10-day course in terms of clinical cure rates. As a result of his study, Dr. Greenberg has long since prescribed a 5-day course of antibiotics for his own patients.

“Five days is good,” he affirmed. “And if patients start a 10-day course of an antibiotic for, say, a urinary tract infection and a subsequent culture comes back negative, they don’t have to finish the antibiotics either.” Dr. Greenberg said.

Dr. Williams said he has no financial ties to industry. Dr. Greenberg said he has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, and AstraZeneca. He is also a founder of the company Beyond Air.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The evidence is in: and had the added benefit of a lower risk of inducing antibiotic resistance, according to the randomized, controlled SCOUT-CAP trial.

“Several studies have shown shorter antibiotic courses to be non-inferior to the standard treatment strategy, but in our study, we show that a shortened 5-day course of therapy was superior to standard therapy because the short course achieved similar outcomes with fewer days of antibiotics,” Derek Williams, MD, MPH, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said in an email.

“These data are immediately applicable to frontline clinicians, and we hope this study will shift the paradigm towards more judicious treatment approaches for childhood pneumonia, resulting in care that is safer and more effective,” he added.

The study was published online Jan. 18 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Uncomplicated CAP

The study enrolled children aged 6 months to 71 months diagnosed with uncomplicated CAP who demonstrated early clinical improvement in response to 5 days of antibiotic treatment. Participants were prescribed either amoxicillin, amoxicillin and clavulanate, or cefdinir according to standard of care and were randomized on day 6 to another 5 days of their initially prescribed antibiotic course or to placebo.

“Those assessed on day 6 were eligible only if they had not yet received a dose of antibiotic therapy on that day,” the authors write. The primary endpoint was end-of-treatment response, adjusted for the duration of antibiotic risk as assessed by RADAR. As the authors explain, RADAR is a composite endpoint that ranks each child’s clinical response, resolution of symptoms, and antibiotic-associated adverse effects (AEs) in an ordinal desirability of outcome ranking, or DOOR.

“There were no differences between strategies in the DOOR or in its individual components,” Dr. Williams and colleagues point out. A total of 380 children took part in the study. The mean age of participants was 35.7 months, and half were male.

Over 90% of children randomized to active therapy were prescribed amoxicillin. “Fewer than 10% of children in either strategy had an inadequate clinical response,” the authors report.

However, the 5-day antibiotic strategy had a 69% (95% CI, 63%-75%) probability of children achieving a more desirable RADAR outcome compared with the standard, 10-day course, as assessed either on days 6 to 10 at outcome assessment visit one (OAV1) or at OAV2 on days 19 to 25.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in the percentage of participants with persistent symptoms at either assessment point, they note. At assessment visit one, 40% of children assigned to the short-course strategy and 37% of children assigned to the 10-day strategy reported an antibiotic-related AE, most of which were mild.

Resistome analysis

Some 171 children were included in a resistome analysis in which throat swabs were collected between study days 19 and 25 to quantify antibiotic resistance genes in oropharyngeal flora. The total number of resistance genes per prokaryotic cell (RGPC) was significantly lower in children treated with antibiotics for 5 days compared with children who were treated for 10 days.

Specifically, the median number of total RGPC was 1.17 (95% CI, 0.35-2.43) for the short-course strategy and 1.33 (95% CI, 0.46-11.08) for the standard-course strategy (P = .01). Similarly, the median number of β-lactamase RGPC was 0.55 (0.18-1.24) for the short-course strategy and 0.60 (0.21-2.45) for the standard-course strategy (P = .03).

“Providing the shortest duration of antibiotics necessary to effectively treat an infection is a central tenet of antimicrobial stewardship and a convenient and cost-effective strategy for caregivers,” the authors observe. For example, reducing treatment from 10 to 5 days for outpatient CAP could reduce the number of days spent on antibiotics by up to 7.5 million days in the U.S. each year.

“If we can safely reduce antibiotic exposure, we can minimize antibiotic side effects while also helping to slow antibiotic resistance,” Dr. Williams pointed out.

Fewer days of having to give their child repeated doses of antibiotics is also more convenient for families, he added.

Asked to comment on the study, David Greenberg, MD, professor of pediatrics and infectious diseases, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Israel, explained that the length of antibiotic therapy as recommended by various guidelines is more or less arbitrary, some infections being excepted.

“There have been no studies evaluating the recommendation for a 100-day treatment course, and it’s kind of a joke because if you look at the treatment of just about any infection, it’s either for 7 days or 14 days or even 20 days because it’s easy to calculate – it’s not that anybody proved that treatment of whatever infection it is should last this long,” he told this news organization.

Moreover, adherence to a shorter antibiotic course is much better than it is to a longer course. If, for example, physicians tell a mother to take two bottles of antibiotics for a treatment course of 10 days, she’ll finish the first bottle which is good for 5 days and, because the child is fine, “she forgets about the second bottle,” Dr. Greenberg said.

In one of the first studies to compare a short versus long course of antibiotic therapy in uncomplicated CAP in young children, Dr. Greenberg and colleagues initially compared a 3-day course of high-dose amoxicillin to a 10-day course of the same treatment, but the 3-day course was associated with an unacceptable failure rate. (At the time, the World Health Organization was recommending a 3-day course of antibiotics for the treatment of uncomplicated CAP in children.)

They stopped the study and then initiated a second study in which they compared a 5-day course of the same antibiotic to a 10-day course and found the 5-day course was comparable to the 10-day course in terms of clinical cure rates. As a result of his study, Dr. Greenberg has long since prescribed a 5-day course of antibiotics for his own patients.

“Five days is good,” he affirmed. “And if patients start a 10-day course of an antibiotic for, say, a urinary tract infection and a subsequent culture comes back negative, they don’t have to finish the antibiotics either.” Dr. Greenberg said.

Dr. Williams said he has no financial ties to industry. Dr. Greenberg said he has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, and AstraZeneca. He is also a founder of the company Beyond Air.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antibiotics used in newborns despite low risk for sepsis

Antibiotics were administered to newborns at low risk for early-onset sepsis as frequently as to newborns with EOS risk factors, based on data from approximately 7,500 infants.

EOS remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, and predicting which newborns are at risk remains a challenge for neonatal care that often drives high rates of antibiotic use, Dustin D. Flannery, DO, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and colleagues wrote.

Antibiotic exposures are associated with short- and long-term adverse effects in both preterm and term infants, which highlights the need for improved risk assessment in this population, the researchers said.

“A robust estimate of EOS risk in relation to delivery characteristics among infants of all gestational ages at birth could significantly contribute to newborn clinical management by identifying newborns unlikely to benefit from empirical antibiotic therapy,” they emphasized.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers identified 7,540 infants born between Jan. 1, 2009, and Dec. 31, 2014, at two high-risk perinatal units in Philadelphia. Gestational age ranged from 22 to 43 weeks. Criteria for low risk of EOS were determined via an algorithm that included cesarean delivery (with or without labor or membrane rupture), and no antepartum concerns for intra-amniotic infection or nonreassuring fetal status.

A total of 6,428 infants did not meet the low-risk criteria; another 1,121 infants met the low-risk criteria. The primary outcome of EOS was defined as growth of a pathogen in at least 1 blood and/or cerebrospinal fluid culture obtained at 72 hours or less after birth. Overall, 41 infants who did not meet the low-risk criteria developed EOS; none of the infants who met the low-risk criteria developed EOS. Secondary outcomes included initiation of empirical antibiotics at 72 hours or less after birth and the duration of antibiotic use.

Although fewer low-risk infants received antibiotics, compared with infants with EOS (80.4% vs. 91.0%, P < .001), the duration of antibiotic use was not significantly different between the groups, with an adjusted difference of 0.6 hours.

Among infants who did not meet low-risk criteria, 157 were started on antibiotics for each case of EOS, the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Because no cases of EOS were identified in the low-risk group, this proportion could not be calculated but suggests that antibiotic exposure in this group was disproportionately higher for incidence of EOS.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the possible lack of generalizability to other centers and the use of data from a period before more refined EOS strategies, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the inability to assess the effect of lab results on antibiotic use, a lack of data on the exact indication for delivery, and potential misclassification bias.

Risk assessment tools should not be used alone, but should be used to inform clinical decision-making, the researchers emphasized. However, the results were strengthened by the inclusion of moderately preterm infants, who are rarely studied, and the clinical utility of the risk algorithm used in the study. “The implications of our study include potential adjustments to sepsis risk assessment in term infants, and confirmation and enhancement of previous studies that identify a subset of lower-risk preterm infants,” who may be spared empirical or prolonged antibiotic exposure, they concluded.

Data inform intelligent antibiotic use

“Early-onset sepsis is predominantly caused by exposure of the fetus or neonate to ascending maternal colonization or infection by gastrointestinal or genitourinary bacteria,” Iris Krishna, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview. “Scenarios where there is limited neonatal exposure to these organisms would decrease the risk of development of EOS, therefore it is not surprising that delivery characteristics of low-risk deliveries as defined by investigators – the absence of labor, absence of intra-amniotic infection, rupture of membranes at time of delivery, and cesarean delivery – would have resulted in decreased likelihood of EOS.”

Inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to the development of resistant and more virulent strains of bacteria. A growing body of literature also suggests that early antibiotic usage in newborns may affect the neonatal gut microbiome, which is important for development of the neonatal immune system. Early alterations of the microbiome may have long-term implications,” Dr. Krishna said.

“Understanding the delivery characteristics that increase the risk of EOS are crucial to optimizing the use of antibiotics and thereby minimize potential harm to newborns,” she said. “Studies such as the current study are needed develop EOS prediction tools to improve antibiotic utilization.” More research is needed not only to adequately predict EOS, but to explore how antibiotics affect the neonatal microbiome, and how clinicians can circumvent potential adverse implications with antibiotic use to improve long-term health, Dr. Krishna concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Krishna had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn. News.

Antibiotics were administered to newborns at low risk for early-onset sepsis as frequently as to newborns with EOS risk factors, based on data from approximately 7,500 infants.

EOS remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, and predicting which newborns are at risk remains a challenge for neonatal care that often drives high rates of antibiotic use, Dustin D. Flannery, DO, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and colleagues wrote.

Antibiotic exposures are associated with short- and long-term adverse effects in both preterm and term infants, which highlights the need for improved risk assessment in this population, the researchers said.

“A robust estimate of EOS risk in relation to delivery characteristics among infants of all gestational ages at birth could significantly contribute to newborn clinical management by identifying newborns unlikely to benefit from empirical antibiotic therapy,” they emphasized.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers identified 7,540 infants born between Jan. 1, 2009, and Dec. 31, 2014, at two high-risk perinatal units in Philadelphia. Gestational age ranged from 22 to 43 weeks. Criteria for low risk of EOS were determined via an algorithm that included cesarean delivery (with or without labor or membrane rupture), and no antepartum concerns for intra-amniotic infection or nonreassuring fetal status.

A total of 6,428 infants did not meet the low-risk criteria; another 1,121 infants met the low-risk criteria. The primary outcome of EOS was defined as growth of a pathogen in at least 1 blood and/or cerebrospinal fluid culture obtained at 72 hours or less after birth. Overall, 41 infants who did not meet the low-risk criteria developed EOS; none of the infants who met the low-risk criteria developed EOS. Secondary outcomes included initiation of empirical antibiotics at 72 hours or less after birth and the duration of antibiotic use.

Although fewer low-risk infants received antibiotics, compared with infants with EOS (80.4% vs. 91.0%, P < .001), the duration of antibiotic use was not significantly different between the groups, with an adjusted difference of 0.6 hours.

Among infants who did not meet low-risk criteria, 157 were started on antibiotics for each case of EOS, the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Because no cases of EOS were identified in the low-risk group, this proportion could not be calculated but suggests that antibiotic exposure in this group was disproportionately higher for incidence of EOS.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the possible lack of generalizability to other centers and the use of data from a period before more refined EOS strategies, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the inability to assess the effect of lab results on antibiotic use, a lack of data on the exact indication for delivery, and potential misclassification bias.

Risk assessment tools should not be used alone, but should be used to inform clinical decision-making, the researchers emphasized. However, the results were strengthened by the inclusion of moderately preterm infants, who are rarely studied, and the clinical utility of the risk algorithm used in the study. “The implications of our study include potential adjustments to sepsis risk assessment in term infants, and confirmation and enhancement of previous studies that identify a subset of lower-risk preterm infants,” who may be spared empirical or prolonged antibiotic exposure, they concluded.

Data inform intelligent antibiotic use

“Early-onset sepsis is predominantly caused by exposure of the fetus or neonate to ascending maternal colonization or infection by gastrointestinal or genitourinary bacteria,” Iris Krishna, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview. “Scenarios where there is limited neonatal exposure to these organisms would decrease the risk of development of EOS, therefore it is not surprising that delivery characteristics of low-risk deliveries as defined by investigators – the absence of labor, absence of intra-amniotic infection, rupture of membranes at time of delivery, and cesarean delivery – would have resulted in decreased likelihood of EOS.”

Inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to the development of resistant and more virulent strains of bacteria. A growing body of literature also suggests that early antibiotic usage in newborns may affect the neonatal gut microbiome, which is important for development of the neonatal immune system. Early alterations of the microbiome may have long-term implications,” Dr. Krishna said.

“Understanding the delivery characteristics that increase the risk of EOS are crucial to optimizing the use of antibiotics and thereby minimize potential harm to newborns,” she said. “Studies such as the current study are needed develop EOS prediction tools to improve antibiotic utilization.” More research is needed not only to adequately predict EOS, but to explore how antibiotics affect the neonatal microbiome, and how clinicians can circumvent potential adverse implications with antibiotic use to improve long-term health, Dr. Krishna concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Krishna had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn. News.

Antibiotics were administered to newborns at low risk for early-onset sepsis as frequently as to newborns with EOS risk factors, based on data from approximately 7,500 infants.

EOS remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, and predicting which newborns are at risk remains a challenge for neonatal care that often drives high rates of antibiotic use, Dustin D. Flannery, DO, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and colleagues wrote.

Antibiotic exposures are associated with short- and long-term adverse effects in both preterm and term infants, which highlights the need for improved risk assessment in this population, the researchers said.

“A robust estimate of EOS risk in relation to delivery characteristics among infants of all gestational ages at birth could significantly contribute to newborn clinical management by identifying newborns unlikely to benefit from empirical antibiotic therapy,” they emphasized.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers identified 7,540 infants born between Jan. 1, 2009, and Dec. 31, 2014, at two high-risk perinatal units in Philadelphia. Gestational age ranged from 22 to 43 weeks. Criteria for low risk of EOS were determined via an algorithm that included cesarean delivery (with or without labor or membrane rupture), and no antepartum concerns for intra-amniotic infection or nonreassuring fetal status.

A total of 6,428 infants did not meet the low-risk criteria; another 1,121 infants met the low-risk criteria. The primary outcome of EOS was defined as growth of a pathogen in at least 1 blood and/or cerebrospinal fluid culture obtained at 72 hours or less after birth. Overall, 41 infants who did not meet the low-risk criteria developed EOS; none of the infants who met the low-risk criteria developed EOS. Secondary outcomes included initiation of empirical antibiotics at 72 hours or less after birth and the duration of antibiotic use.

Although fewer low-risk infants received antibiotics, compared with infants with EOS (80.4% vs. 91.0%, P < .001), the duration of antibiotic use was not significantly different between the groups, with an adjusted difference of 0.6 hours.

Among infants who did not meet low-risk criteria, 157 were started on antibiotics for each case of EOS, the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Because no cases of EOS were identified in the low-risk group, this proportion could not be calculated but suggests that antibiotic exposure in this group was disproportionately higher for incidence of EOS.”

The study findings were limited by several factors including the possible lack of generalizability to other centers and the use of data from a period before more refined EOS strategies, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the inability to assess the effect of lab results on antibiotic use, a lack of data on the exact indication for delivery, and potential misclassification bias.

Risk assessment tools should not be used alone, but should be used to inform clinical decision-making, the researchers emphasized. However, the results were strengthened by the inclusion of moderately preterm infants, who are rarely studied, and the clinical utility of the risk algorithm used in the study. “The implications of our study include potential adjustments to sepsis risk assessment in term infants, and confirmation and enhancement of previous studies that identify a subset of lower-risk preterm infants,” who may be spared empirical or prolonged antibiotic exposure, they concluded.

Data inform intelligent antibiotic use

“Early-onset sepsis is predominantly caused by exposure of the fetus or neonate to ascending maternal colonization or infection by gastrointestinal or genitourinary bacteria,” Iris Krishna, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview. “Scenarios where there is limited neonatal exposure to these organisms would decrease the risk of development of EOS, therefore it is not surprising that delivery characteristics of low-risk deliveries as defined by investigators – the absence of labor, absence of intra-amniotic infection, rupture of membranes at time of delivery, and cesarean delivery – would have resulted in decreased likelihood of EOS.”

Inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to the development of resistant and more virulent strains of bacteria. A growing body of literature also suggests that early antibiotic usage in newborns may affect the neonatal gut microbiome, which is important for development of the neonatal immune system. Early alterations of the microbiome may have long-term implications,” Dr. Krishna said.

“Understanding the delivery characteristics that increase the risk of EOS are crucial to optimizing the use of antibiotics and thereby minimize potential harm to newborns,” she said. “Studies such as the current study are needed develop EOS prediction tools to improve antibiotic utilization.” More research is needed not only to adequately predict EOS, but to explore how antibiotics affect the neonatal microbiome, and how clinicians can circumvent potential adverse implications with antibiotic use to improve long-term health, Dr. Krishna concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Krishna had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn. News.

FROM PEDIATRICS

The etiology of acute otitis media in young children in recent years

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, pediatricians have been seeing fewer cases of all respiratory illnesses, including acute otitis media (AOM). However, as I prepare this column, an uptick has commenced and likely will continue in an upward trajectory as we emerge from the pandemic into an endemic coronavirus era. Our group in Rochester, N.Y., has continued prospective studies of AOM throughout the pandemic. We found that nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis remained prevalent in our study cohort of children aged 6-36 months. However, with all the precautions of masking, social distancing, hand washing, and quick exclusion from day care when illness occurred, the frequency of detecting these common otopathogens decreased, as one might expect.1

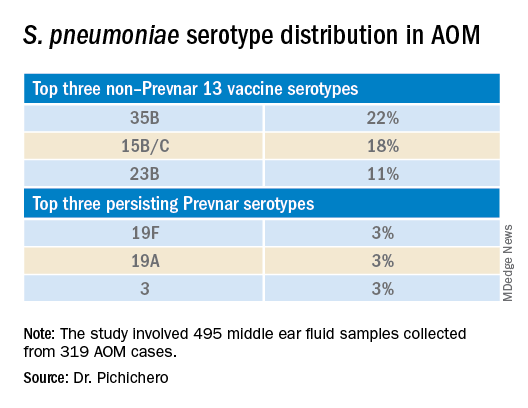

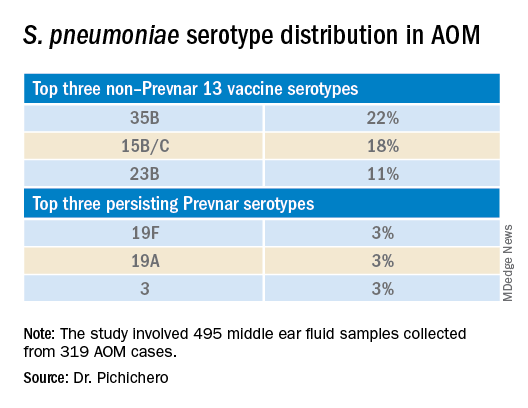

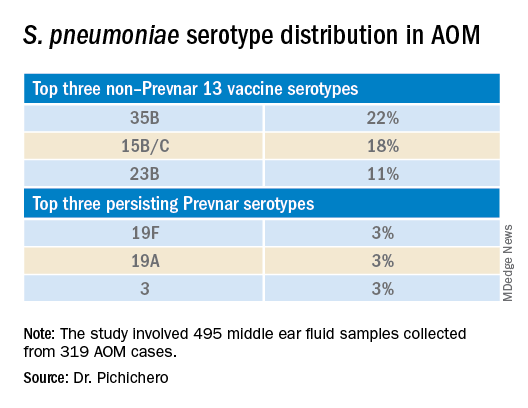

Leading up to the pandemic, we had an abundance of data to characterize AOM etiology and found that the cause of AOM continues to change following the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar 13). Our most recent report on otopathogen distribution and antibiotic susceptibility covered the years 2015-2019.2 A total of 589 children were enrolled prospectively and we collected 495 middle ear fluid samples (MEF) from 319 AOM cases using tympanocentesis. The frequency of isolates was H. influenzae (34%), pneumococcus (24%), and M. catarrhalis (15%). Beta-lactamase–positive H. influenzae strains were identified among 49% of the isolates, rendering them resistant to amoxicillin. PCV13 serotypes were infrequently isolated. However, we did isolate vaccine types (VTs) in some children from MEF, notably serotypes 19F, 19A, and 3. Non-PCV13 pneumococcus serotypes 35B, 23B, and 15B/C emerged as the most common serotypes. Amoxicillin resistance was identified among 25% of pneumococcal strains. Out of 16 antibiotics tested, 9 (56%) showed a significant increase in nonsusceptibility among pneumococcal isolates. 100% of M. catarrhalis isolates were beta-lactamase producers and therefore resistant to amoxicillin.

PCV13 has resulted in a decline in both invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal infections caused by strains expressing the 13 capsular serotypes included in the vaccine. However, the emergence of replacement serotypes occurred after introduction of PCV73,4 and continues to occur during the PCV13 era, as shown from the results presented here. Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for more than 90% of MEF isolates during 2015-2019, with 35B, 21 and 23B being the most commonly isolated. Other emergent serotypes of potential importance were nonvaccine serotypes 15A, 15B, 15C, 23A and 11A. This is highly relevant because forthcoming higher-valency PCVs – PCV15 (manufactured by Merck) and PCV20 (manufactured by Pfizer) will not include many of the dominant capsular serotypes of pneumococcus strains causing AOM. Consequently, the impact of higher-valency PCVs on AOM will not be as great as was observed with the introduction of PCV7 or PCV13.

Of special interest, 22% of pneumococcus isolates from MEF were serotype 35B, making it the most prevalent. Recently we reported a significant rise in antibiotic nonsusceptibility in Spn isolates, contributed mainly by serotype 35B5 and we have been studying how 35B strains transitioned from commensal to otopathogen in children.6 Because serotype 35B strains are increasingly prevalent and often antibiotic resistant, absence of this serotype from PCV15 and PCV20 is cause for concern.

The frequency of isolation of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis has remained stable across the PCV13 era as the No. 1 and No. 3 pathogens. Similarly, the production of beta-lactamase among strains causing AOM has remained stable at close to 50% and 100%, respectively. Use of amoxicillin, either high dose or standard dose, would not be expected to kill these bacteria.

Our study design has limitations. The population is derived from a predominantly middle-class, suburban population of children in upstate New York and may not be representative of other types of populations in the United States. The children are 6-36 months old, the age when most AOM occurs. MEF samples that were culture negative for bacteria were not further tested by polymerase chain reaction methods.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:722483.

2. Kaur R et al. Euro J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44

3. Pelton SI et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2004;23:1015-22.

4. Farrell DJ et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2007;26:123-8..

5. Kaur R et al. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(5):797-805.

6. Fuji N et al. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:744742.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, pediatricians have been seeing fewer cases of all respiratory illnesses, including acute otitis media (AOM). However, as I prepare this column, an uptick has commenced and likely will continue in an upward trajectory as we emerge from the pandemic into an endemic coronavirus era. Our group in Rochester, N.Y., has continued prospective studies of AOM throughout the pandemic. We found that nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis remained prevalent in our study cohort of children aged 6-36 months. However, with all the precautions of masking, social distancing, hand washing, and quick exclusion from day care when illness occurred, the frequency of detecting these common otopathogens decreased, as one might expect.1

Leading up to the pandemic, we had an abundance of data to characterize AOM etiology and found that the cause of AOM continues to change following the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar 13). Our most recent report on otopathogen distribution and antibiotic susceptibility covered the years 2015-2019.2 A total of 589 children were enrolled prospectively and we collected 495 middle ear fluid samples (MEF) from 319 AOM cases using tympanocentesis. The frequency of isolates was H. influenzae (34%), pneumococcus (24%), and M. catarrhalis (15%). Beta-lactamase–positive H. influenzae strains were identified among 49% of the isolates, rendering them resistant to amoxicillin. PCV13 serotypes were infrequently isolated. However, we did isolate vaccine types (VTs) in some children from MEF, notably serotypes 19F, 19A, and 3. Non-PCV13 pneumococcus serotypes 35B, 23B, and 15B/C emerged as the most common serotypes. Amoxicillin resistance was identified among 25% of pneumococcal strains. Out of 16 antibiotics tested, 9 (56%) showed a significant increase in nonsusceptibility among pneumococcal isolates. 100% of M. catarrhalis isolates were beta-lactamase producers and therefore resistant to amoxicillin.

PCV13 has resulted in a decline in both invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal infections caused by strains expressing the 13 capsular serotypes included in the vaccine. However, the emergence of replacement serotypes occurred after introduction of PCV73,4 and continues to occur during the PCV13 era, as shown from the results presented here. Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for more than 90% of MEF isolates during 2015-2019, with 35B, 21 and 23B being the most commonly isolated. Other emergent serotypes of potential importance were nonvaccine serotypes 15A, 15B, 15C, 23A and 11A. This is highly relevant because forthcoming higher-valency PCVs – PCV15 (manufactured by Merck) and PCV20 (manufactured by Pfizer) will not include many of the dominant capsular serotypes of pneumococcus strains causing AOM. Consequently, the impact of higher-valency PCVs on AOM will not be as great as was observed with the introduction of PCV7 or PCV13.

Of special interest, 22% of pneumococcus isolates from MEF were serotype 35B, making it the most prevalent. Recently we reported a significant rise in antibiotic nonsusceptibility in Spn isolates, contributed mainly by serotype 35B5 and we have been studying how 35B strains transitioned from commensal to otopathogen in children.6 Because serotype 35B strains are increasingly prevalent and often antibiotic resistant, absence of this serotype from PCV15 and PCV20 is cause for concern.

The frequency of isolation of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis has remained stable across the PCV13 era as the No. 1 and No. 3 pathogens. Similarly, the production of beta-lactamase among strains causing AOM has remained stable at close to 50% and 100%, respectively. Use of amoxicillin, either high dose or standard dose, would not be expected to kill these bacteria.

Our study design has limitations. The population is derived from a predominantly middle-class, suburban population of children in upstate New York and may not be representative of other types of populations in the United States. The children are 6-36 months old, the age when most AOM occurs. MEF samples that were culture negative for bacteria were not further tested by polymerase chain reaction methods.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:722483.

2. Kaur R et al. Euro J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44

3. Pelton SI et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2004;23:1015-22.

4. Farrell DJ et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2007;26:123-8..

5. Kaur R et al. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(5):797-805.

6. Fuji N et al. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:744742.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, pediatricians have been seeing fewer cases of all respiratory illnesses, including acute otitis media (AOM). However, as I prepare this column, an uptick has commenced and likely will continue in an upward trajectory as we emerge from the pandemic into an endemic coronavirus era. Our group in Rochester, N.Y., has continued prospective studies of AOM throughout the pandemic. We found that nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis remained prevalent in our study cohort of children aged 6-36 months. However, with all the precautions of masking, social distancing, hand washing, and quick exclusion from day care when illness occurred, the frequency of detecting these common otopathogens decreased, as one might expect.1

Leading up to the pandemic, we had an abundance of data to characterize AOM etiology and found that the cause of AOM continues to change following the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar 13). Our most recent report on otopathogen distribution and antibiotic susceptibility covered the years 2015-2019.2 A total of 589 children were enrolled prospectively and we collected 495 middle ear fluid samples (MEF) from 319 AOM cases using tympanocentesis. The frequency of isolates was H. influenzae (34%), pneumococcus (24%), and M. catarrhalis (15%). Beta-lactamase–positive H. influenzae strains were identified among 49% of the isolates, rendering them resistant to amoxicillin. PCV13 serotypes were infrequently isolated. However, we did isolate vaccine types (VTs) in some children from MEF, notably serotypes 19F, 19A, and 3. Non-PCV13 pneumococcus serotypes 35B, 23B, and 15B/C emerged as the most common serotypes. Amoxicillin resistance was identified among 25% of pneumococcal strains. Out of 16 antibiotics tested, 9 (56%) showed a significant increase in nonsusceptibility among pneumococcal isolates. 100% of M. catarrhalis isolates were beta-lactamase producers and therefore resistant to amoxicillin.

PCV13 has resulted in a decline in both invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal infections caused by strains expressing the 13 capsular serotypes included in the vaccine. However, the emergence of replacement serotypes occurred after introduction of PCV73,4 and continues to occur during the PCV13 era, as shown from the results presented here. Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for more than 90% of MEF isolates during 2015-2019, with 35B, 21 and 23B being the most commonly isolated. Other emergent serotypes of potential importance were nonvaccine serotypes 15A, 15B, 15C, 23A and 11A. This is highly relevant because forthcoming higher-valency PCVs – PCV15 (manufactured by Merck) and PCV20 (manufactured by Pfizer) will not include many of the dominant capsular serotypes of pneumococcus strains causing AOM. Consequently, the impact of higher-valency PCVs on AOM will not be as great as was observed with the introduction of PCV7 or PCV13.

Of special interest, 22% of pneumococcus isolates from MEF were serotype 35B, making it the most prevalent. Recently we reported a significant rise in antibiotic nonsusceptibility in Spn isolates, contributed mainly by serotype 35B5 and we have been studying how 35B strains transitioned from commensal to otopathogen in children.6 Because serotype 35B strains are increasingly prevalent and often antibiotic resistant, absence of this serotype from PCV15 and PCV20 is cause for concern.

The frequency of isolation of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis has remained stable across the PCV13 era as the No. 1 and No. 3 pathogens. Similarly, the production of beta-lactamase among strains causing AOM has remained stable at close to 50% and 100%, respectively. Use of amoxicillin, either high dose or standard dose, would not be expected to kill these bacteria.

Our study design has limitations. The population is derived from a predominantly middle-class, suburban population of children in upstate New York and may not be representative of other types of populations in the United States. The children are 6-36 months old, the age when most AOM occurs. MEF samples that were culture negative for bacteria were not further tested by polymerase chain reaction methods.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:722483.

2. Kaur R et al. Euro J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44

3. Pelton SI et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2004;23:1015-22.

4. Farrell DJ et al. Pediatr Infect Disease J. 2007;26:123-8..

5. Kaur R et al. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(5):797-805.

6. Fuji N et al. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:744742.

What makes a urinary tract infection complicated?

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

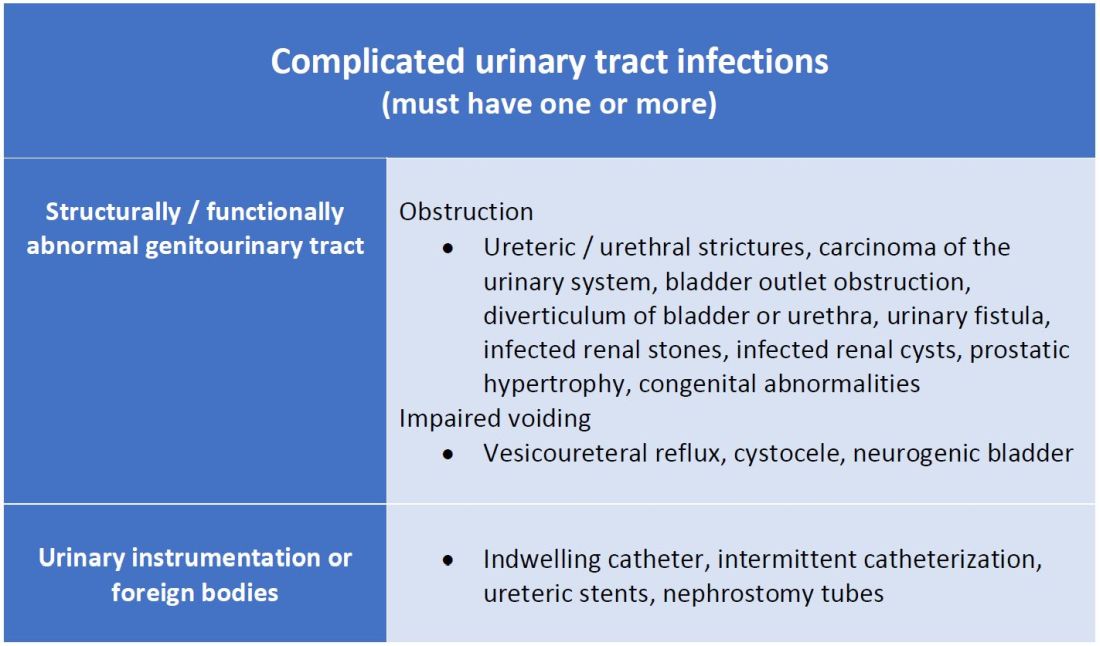

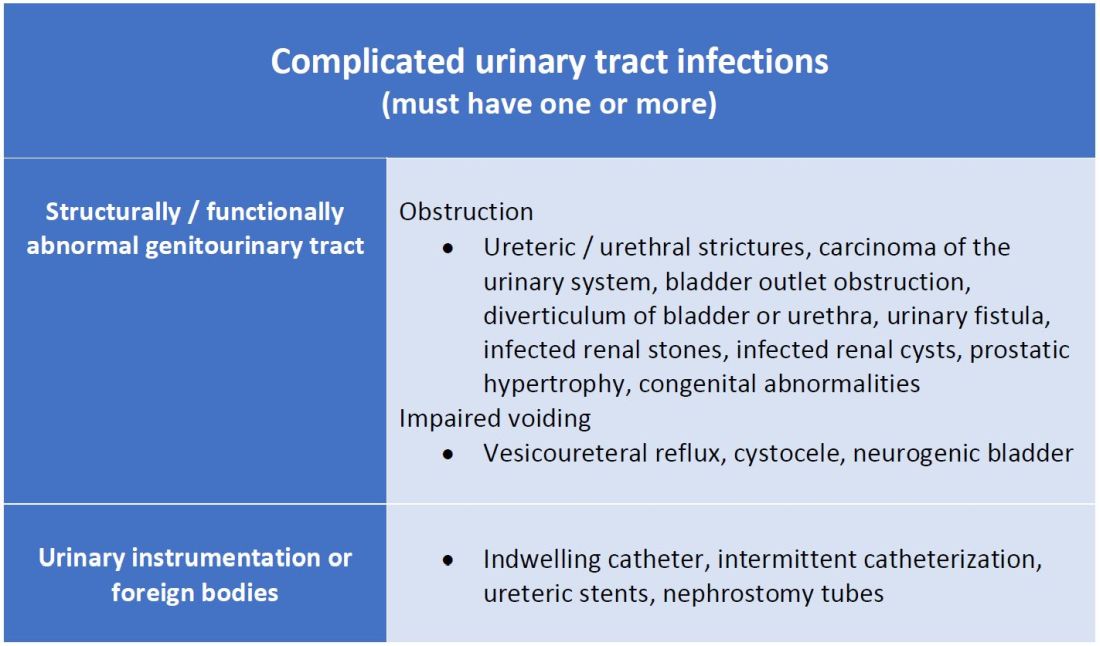

Anatomic approach

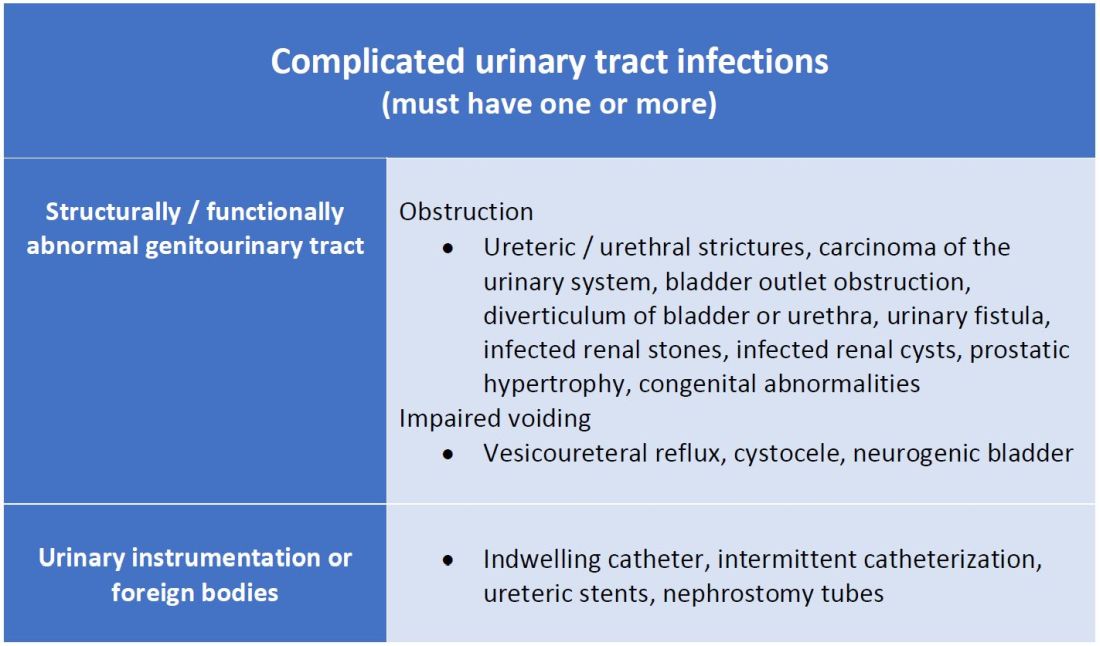

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.

This population of patients is at high risk of infections with more resistant bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli since they often lack the natural genitourinary barriers to infection. In addition, these patients more often undergo multiple antibiotic courses for their frequent infections, which also contributes to their risk of ESBL infections. Genitourinary abnormalities interfere with normal voiding, resulting in impaired flushing of bacteria. For instance, obstruction inhibits complete urinary drainage and increases the persistence of bacteria in biofilms, especially if there are stones or indwelling devices present. Biofilms usually contain a high concentration of organisms including Proteus mirabilis, Morgenella morganii, and Providencia spp.4 Keep in mind that, if there is an obstruction, the urinalysis might be without pyuria or bacteriuria.

Instrumentation increases infection risks through the direct introduction of bacteria into the genitourinary tract. Despite the efforts in maintaining sterility in urinary catheter placement, catheters provide a nidus for infection. Catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is defined by the Infectious Disease Society of America as UTIs that occur in patients with an indwelling catheter or who had a catheter removed for less than 48 hours who develop urinary symptoms and cultures positive for uropathogenic bacteria.4 Studies show that in general, patients with indwelling catheters will develop bacteriuria over time, with 10%-25% eventually developing symptoms.

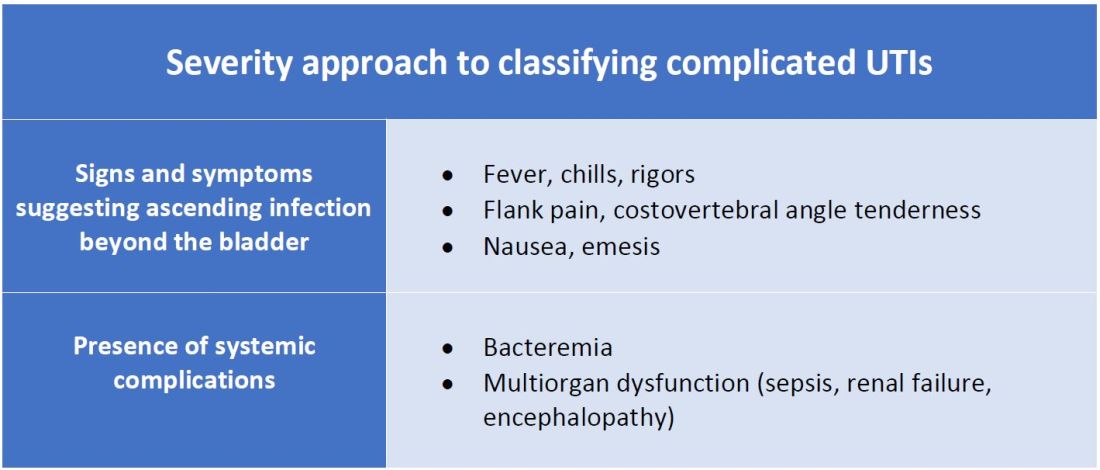

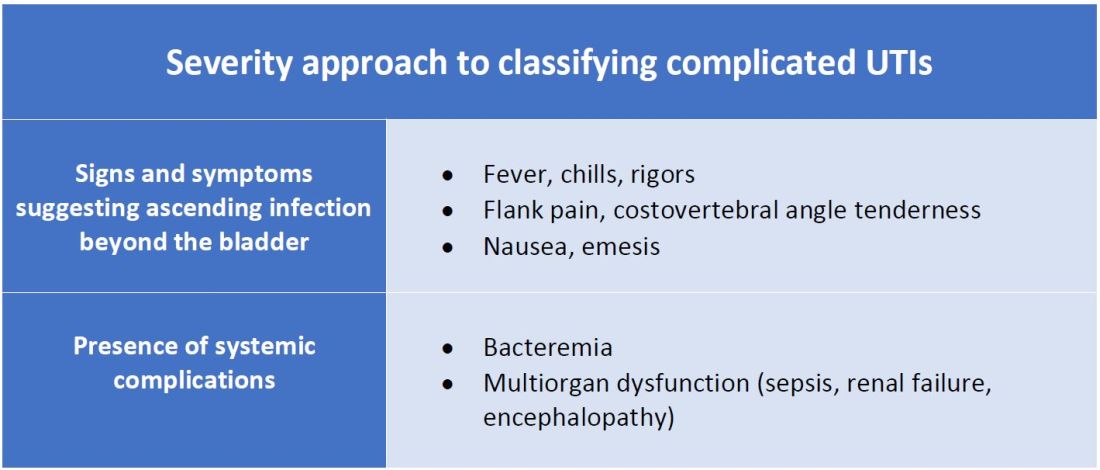

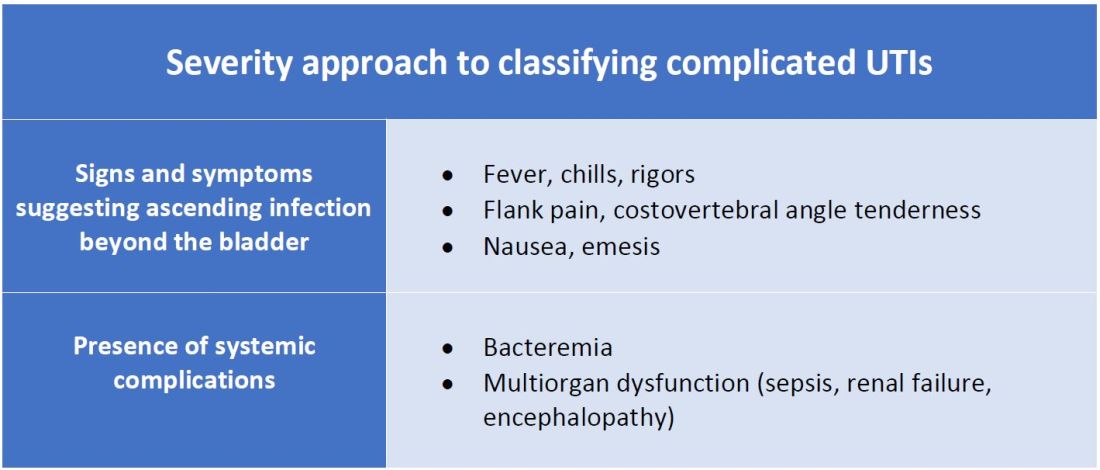

Severity approach

There are other schools of thought that categorize uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs based on the severity of presentation (see Table 2). An uncomplicated UTI would be classified as symptoms and signs of simple cystitis limited to dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. Using a symptom severity approach, systemic findings such as fever, chills, emesis, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or other findings of sepsis would be classified as a complicated UTI. These systemic findings would suggest an extension of infection beyond the bladder.

The argument for a symptomatic-based approach of classification is that the severity of symptoms should dictate the degree of management. Not all UTIs in the anatomic approach are severe. In fact, populations that are considered at risk for complicated UTIs by the AUA guidelines in Table 1 often have mild symptomatic cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the colonization of organisms in the urinary tract without active infection. For instance, bacteriuria is present in almost 100% of people with chronic indwelling catheters, 30%-40% of neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent catheterization, and 50% of elderly nursing home residents.4 Not all bacteriuria triggers enough of an inflammatory response to cause symptoms that require treatment.

Ultimate clinical judgment

Although there are multiple different society recommendations in distinguishing uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, considering both anatomical and severity risk factors can better aid in clinical decision-making rather than abiding by one classification method alone.

Uncomplicated UTIs from the AUA guidelines can cause severe infections that might require longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On the other hand, people with anatomic abnormalities can present with mild symptoms that can be treated with a narrow-spectrum antibiotic for a standard time course. Recognizing the severity of the infection and using clinical judgment aids in antibiotic stewardship.

Although the existence of algorithmic approaches can help guide clinical judgment, accounting for the spectrum of host and bacterial factors should ultimately determine the complexity of the disease and management.3 Using clinical suspicion to determine when a UTI should be treated as a complicated infection can ensure effective treatment and decrease the likelihood of sepsis, renal scarring, or end-stage disease.5

Back to the case

The case presents an elderly woman with diabetes presenting with sepsis from a UTI. Because of a normal urinary tract and no prior instrumentation, by the AUA definition, she would be classified as an uncomplicated UTI; however, we would classify her as a complicated UTI based on the severity of her presentation. She has a fever, tachycardia, flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness that are evidence of infection extending beyond the bladder. She has sepsis warranting inpatient management. Prior urine culture results could aid in determining empiric treatment while waiting for new cultures. In her case, an intravenous antibiotic with broad gram-negative coverage such as ceftriaxone would be appropriate.

Bottom line

There are multiple interpretations of complicated UTIs including both an anatomical and severity approach. Clinical judgment regarding infection severity should determine the depth of management.

Dr. Vu is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Gray is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky and the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

1. Folk CS. AUA Core Curriculum: Urinary Tract Infection (Adult). 2021 Mar 1. https://university.auanet.org/core_topic.cfm?coreid=92.

2. Gupta K et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257.

3. Johnson JR. Definition of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 February 15;64(4):529. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw751.

4. Nicolle LE, AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768.

5. Melekos MD and Naber KG. Complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15(4):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00168-0.

Key points

- The anatomical approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the presence of underlying, predisposing conditions such as structurally or functionally abnormal genitourinary tract or urinary instrumentation or foreign bodies.

- The severity approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the severity of presentation including the presence of systemic manifestations.

- Both approaches should consider populations that are at risk for recurrent or multidrug-resistant infections and infections that can lead to high morbidity.

- Either approach can be used as a guide, but neither should replace clinical suspicion and judgment in determining the depth of treatment.

Additional reading

Choe HS et al. Summary of the UAA‐AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018 Mar;25(3):175-85. doi:10.1111/iju.13493.

Nicolle LE et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;40(5):643-54. doi: 10.1086/427507.

Wagenlehner FME et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Oct;17:586-600. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0362-4.

Wallace DW et al. Urinalysis: A simple test with complicated interpretation. J Urgent Care Med. 2020 July-Aug;14(10):11-4.

Quiz

A 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with acute fever, chills, dysuria, frequency, and suprapubic pain. She has associated nausea, malaise, and fatigue. She takes metformin and denies recent antibiotic use. Her temperature is 102.8° F, heart rate 118 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/71 mm Hg, and her respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute. She is ill-appearing and has mild suprapubic tenderness. White blood cell count is 18 k/mcL. Urinalysis is positive for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria. Urine microscopy has 120 white blood cells per high power field. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Azithromycin

B. Ceftriaxone

C. Cefepime and vancomycin

D. Nitrofurantoin

The answer is B. The patient presents with sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Using the anatomic approach this would be classified as uncomplicated. Using the severity approach, this would be classified as a complicated urinary tract infection. With fever, chills, and signs of sepsis, it’s likely her infection extends beyond the bladder. Given the severity of her presentation, we’d favor treating her as a complicated urinary tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone. There is no suggestion of resistance or additional MRSA risk factors requiring intravenous vancomycin or cefepime. Nitrofurantoin, although a first-line treatment for uncomplicated cystitis, would not be appropriate if there is suspicion infection extends beyond the bladder. Azithromycin is a first-line option for chlamydia trachomatis, but not a urinary tract infection.

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Consider anatomical and severity risk factors

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

Anatomic approach

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.

This population of patients is at high risk of infections with more resistant bacteria such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli since they often lack the natural genitourinary barriers to infection. In addition, these patients more often undergo multiple antibiotic courses for their frequent infections, which also contributes to their risk of ESBL infections. Genitourinary abnormalities interfere with normal voiding, resulting in impaired flushing of bacteria. For instance, obstruction inhibits complete urinary drainage and increases the persistence of bacteria in biofilms, especially if there are stones or indwelling devices present. Biofilms usually contain a high concentration of organisms including Proteus mirabilis, Morgenella morganii, and Providencia spp.4 Keep in mind that, if there is an obstruction, the urinalysis might be without pyuria or bacteriuria.

Instrumentation increases infection risks through the direct introduction of bacteria into the genitourinary tract. Despite the efforts in maintaining sterility in urinary catheter placement, catheters provide a nidus for infection. Catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) is defined by the Infectious Disease Society of America as UTIs that occur in patients with an indwelling catheter or who had a catheter removed for less than 48 hours who develop urinary symptoms and cultures positive for uropathogenic bacteria.4 Studies show that in general, patients with indwelling catheters will develop bacteriuria over time, with 10%-25% eventually developing symptoms.

Severity approach

There are other schools of thought that categorize uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs based on the severity of presentation (see Table 2). An uncomplicated UTI would be classified as symptoms and signs of simple cystitis limited to dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain. Using a symptom severity approach, systemic findings such as fever, chills, emesis, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, or other findings of sepsis would be classified as a complicated UTI. These systemic findings would suggest an extension of infection beyond the bladder.

The argument for a symptomatic-based approach of classification is that the severity of symptoms should dictate the degree of management. Not all UTIs in the anatomic approach are severe. In fact, populations that are considered at risk for complicated UTIs by the AUA guidelines in Table 1 often have mild symptomatic cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the colonization of organisms in the urinary tract without active infection. For instance, bacteriuria is present in almost 100% of people with chronic indwelling catheters, 30%-40% of neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent catheterization, and 50% of elderly nursing home residents.4 Not all bacteriuria triggers enough of an inflammatory response to cause symptoms that require treatment.

Ultimate clinical judgment

Although there are multiple different society recommendations in distinguishing uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, considering both anatomical and severity risk factors can better aid in clinical decision-making rather than abiding by one classification method alone.

Uncomplicated UTIs from the AUA guidelines can cause severe infections that might require longer courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On the other hand, people with anatomic abnormalities can present with mild symptoms that can be treated with a narrow-spectrum antibiotic for a standard time course. Recognizing the severity of the infection and using clinical judgment aids in antibiotic stewardship.

Although the existence of algorithmic approaches can help guide clinical judgment, accounting for the spectrum of host and bacterial factors should ultimately determine the complexity of the disease and management.3 Using clinical suspicion to determine when a UTI should be treated as a complicated infection can ensure effective treatment and decrease the likelihood of sepsis, renal scarring, or end-stage disease.5

Back to the case

The case presents an elderly woman with diabetes presenting with sepsis from a UTI. Because of a normal urinary tract and no prior instrumentation, by the AUA definition, she would be classified as an uncomplicated UTI; however, we would classify her as a complicated UTI based on the severity of her presentation. She has a fever, tachycardia, flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness that are evidence of infection extending beyond the bladder. She has sepsis warranting inpatient management. Prior urine culture results could aid in determining empiric treatment while waiting for new cultures. In her case, an intravenous antibiotic with broad gram-negative coverage such as ceftriaxone would be appropriate.

Bottom line

There are multiple interpretations of complicated UTIs including both an anatomical and severity approach. Clinical judgment regarding infection severity should determine the depth of management.

Dr. Vu is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Gray is a hospitalist at the University of Kentucky and the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

1. Folk CS. AUA Core Curriculum: Urinary Tract Infection (Adult). 2021 Mar 1. https://university.auanet.org/core_topic.cfm?coreid=92.

2. Gupta K et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257.

3. Johnson JR. Definition of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 February 15;64(4):529. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw751.

4. Nicolle LE, AMMI Canada Guidelines Committee. Complicated urinary tract infection in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(6):349-60. doi: 10.1155/2005/385768.

5. Melekos MD and Naber KG. Complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15(4):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00168-0.

Key points

- The anatomical approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the presence of underlying, predisposing conditions such as structurally or functionally abnormal genitourinary tract or urinary instrumentation or foreign bodies.

- The severity approach to defining complicated UTIs considers the severity of presentation including the presence of systemic manifestations.

- Both approaches should consider populations that are at risk for recurrent or multidrug-resistant infections and infections that can lead to high morbidity.

- Either approach can be used as a guide, but neither should replace clinical suspicion and judgment in determining the depth of treatment.

Additional reading

Choe HS et al. Summary of the UAA‐AAUS guidelines for urinary tract infections. Int J Urol. 2018 Mar;25(3):175-85. doi:10.1111/iju.13493.

Nicolle LE et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar;40(5):643-54. doi: 10.1086/427507.

Wagenlehner FME et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Oct;17:586-600. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0362-4.

Wallace DW et al. Urinalysis: A simple test with complicated interpretation. J Urgent Care Med. 2020 July-Aug;14(10):11-4.

Quiz

A 68-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with acute fever, chills, dysuria, frequency, and suprapubic pain. She has associated nausea, malaise, and fatigue. She takes metformin and denies recent antibiotic use. Her temperature is 102.8° F, heart rate 118 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/71 mm Hg, and her respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute. She is ill-appearing and has mild suprapubic tenderness. White blood cell count is 18 k/mcL. Urinalysis is positive for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria. Urine microscopy has 120 white blood cells per high power field. What is the most appropriate treatment?

A. Azithromycin

B. Ceftriaxone

C. Cefepime and vancomycin

D. Nitrofurantoin

The answer is B. The patient presents with sepsis secondary to a urinary tract infection. Using the anatomic approach this would be classified as uncomplicated. Using the severity approach, this would be classified as a complicated urinary tract infection. With fever, chills, and signs of sepsis, it’s likely her infection extends beyond the bladder. Given the severity of her presentation, we’d favor treating her as a complicated urinary tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone. There is no suggestion of resistance or additional MRSA risk factors requiring intravenous vancomycin or cefepime. Nitrofurantoin, although a first-line treatment for uncomplicated cystitis, would not be appropriate if there is suspicion infection extends beyond the bladder. Azithromycin is a first-line option for chlamydia trachomatis, but not a urinary tract infection.

Case

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presents with acute dysuria, fever, and flank pain. She had a urinary tract infection (UTI) 3 months prior treated with nitrofurantoin. Temperature is 102° F, heart rate 112 beats per minute, and the remainder of vital signs are normal. She has left costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine microscopy shows 70 WBCs per high power field and bacteria. Is this urinary tract infection complicated?

Background

The urinary tract is divided into the upper tract, which includes the kidneys and ureters, and the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Infection of the lower urinary tract is referred to as cystitis while infection of the upper urinary tract is pyelonephritis. A UTI is the colonization of pathogen(s) within the urinary system that causes an inflammatory response resulting in symptoms and requiring treatment. UTIs occur when there is reduced urine flow, an increase in colonization risk, and when there are factors that facilitate ascent such as catheterization or incontinence.

There are an estimated 150 million cases of UTIs worldwide per year, accounting for $6 billion in health care expenditures.1 In the inpatient setting, about 40% of nosocomial infections are associated with urinary catheters. This equates to about 1 million catheter-associated UTIs per year in the United States, and up to 40% of hospital gram-negative bacteremia per year are caused by UTIs.1

UTIs are often classified as either uncomplicated or complicated infections, which can influence the depth of management. UTIs have a wide spectrum of symptoms and can manifest anywhere from mild dysuria treated successfully with outpatient antibiotics to florid sepsis. Uncomplicated simple cystitis is often treated as an outpatient with oral nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.2 Complicated UTIs are treated with broader antimicrobial coverage, and depending on severity, could require intravenous antibiotics. Many factors affect how a UTI manifests and determining whether an infection is “uncomplicated” or “complicated” is an important first step in guiding management. Unfortunately, there are differing classifications of “complicated” UTIs, making it a complicated issue itself. We outline two common approaches.

Anatomic approach

A commonly recognized definition is from the American Urological Association, which states that complicated UTIs are symptomatic cases associated with the presence of “underlying, predisposing conditions and not necessarily clinical severity, invasiveness, or complications.”3 These factors include structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities or urinary instrumentation (see Table 1). These predisposing conditions can increase microbial colonization and decrease therapy efficacy, thus increasing the frequency of infection and relapse.