User login

When fecal transplants for C. diff. fail, try, try again

CHICAGO – The best remedy for a failed fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection is most likely a second – or even a third or fourth attempt, according to Monika Fischer, MD.

Fecal microbiota transplants (FMTs) cure the large majority of those with recurrent C. difficile. But for those who don’t respond or who have an early recurrence, repeating the procedure will almost always effect cure, she said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

“My recommendation would be to repeat FMT once you make sure the diagnosis actually is recurrent C. difficile,” said Dr. Fischer of Indiana University, Indianapolis. “There are sufficient data showing that the success rate after two FMTs significantly increases independent of the delivery route. But the effectiveness rate is highest when FMT is delivered via colonoscopy, so I recommend the second FMT be delivered that way.”

Recurrent failures can also be a sign that something else is amiss clinically, she said. So before proceeding with multiple procedures, some detective work may be in order. It’s best to start with confirmatory testing for the organism, she said.

“We have seen that about 25% of patients referred for FMT don’t actually have C. difficile at all,” Dr. Fischer said. “Be thinking about an alternative diagnosis when the stool tests negative, but the patient is still symptomatic, or if, before the FMT, there was less than a 50% improvement with vancomycin or fidaxomicin therapy.”

“When evaluating a patient for FMT failure, it should be confirmed by stool testing, preferably by toxin testing. Recent studies suggest that PCR [polymerase chain reaction]–positive but toxin-negative patients may be colonized with C. difficile but that an alternative pathology is driving the symptoms. Toxin-negative patients’ outcome is similar with or without treatment, and it is very rare that toxin-negative patients develop CDI [C. difficile infection]–related complications.”

For these patients, the problem could be any of the conditions that cause chronic diarrhea: inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease, microscopic colitis, bile salt malabsorption, chronic pancreatitis, or some other kind of infection. If C. difficile is the confirmed etiology, repeated FMTs are the way to go, Dr. Fischer said.

However, it may be worth mixing up the delivery method. The ever-expanding data on FMT continue to show that colonoscopy delivery has the lowest failure rate – about 10%. Enema is the least successful, with a 40% failure rate. In between those are nasoduodenal tube delivery, which is associated with a 20% failure rate, and oral capsules, with a failure rate varying from 12% to 30%. Fresh stool is also more effective than frozen, which, in turn, is more effective than the lyophilized preparation, Dr. Fischer said.

“Options are to repeat FMT via colonoscopy, but for patients who have had several failures, consider using the upper and lower route at the same time, and give fresh stool, especially if the first transplants used frozen.”

Although the efficacy of FMT doesn’t appear to depend on donor characteristics, patient characteristics do seem to play a role. Dr. Fischer and her colleagues have created an assessment tool to predict who may be at risk for failure. The model was developed in a 300-patient FMT cohort at two centers and validated in a third academic center FMT population. Of 24 clinical variables, three were incorporated into the failure risk model: severe disease (odds ratio, 6), inpatient status (OR, 3.8), and the number of prior C. difficile–related hospitalizations (OR, 1.4 for each one). For severe disease, patients got 5 points on the scale; for inpatient status, 4 points; and for each prior hospitalization, 1 point.

“Patients in the low-risk category [0] had up to 5% chance of failing. Patients with intermediate risk [1-2] had a 15% chance of failing, and patients in the high-risk category [3 or more points] had higher than 35% chance of not responding to single FMT,” Dr. Fischer said.

She also examined this tool in an extended cohort of nearly 500 patients at four additional sites; about 5% had failed more than two FMTs. “We identified two additional risk factors for failing multiple transplants,” Dr. Fischer said. “These were immunocompromised state, which increased the risk by 4 times, and male gender, which increased the risk by 2.5 times.”

She offered some options for the rare patient who has failed repeat FMTs and doesn’t want to try again. “There are some alternative or adjunctive therapies to repeat FMTs that may be considered, in lieu of repeating FMT for the third or fourth time or even following the first FMT failure, if dictated by patient preference. We sometimes offer these for elderly or frail patients or those with a limited life expectancy. These therapy options are from small, nonrandomized trials in multiply recurrent C. difficile infections but have not been vetted in the FMT nonresponder population.”

These include a vancomycin taper, or a vancomycin taper followed by fidaxomicin. Another option, albeit with limited applicability, is suppressive low-dose vancomycin 125 mg given every day, every other day, or every third day, indefinitely. “This can be especially good for elderly, frail patients with limited life expectancy, needing ongoing antibiotic therapy for urinary tract infections,” she said.

Finally, an 8-week vancomycin taper with daily kefir ingestion has been helpful for some patients. Although probiotics have never been proven helpful in C. difficile infections or FMT success, kefir is a different sort of supplement, she said.

“Kefir is different from yogurt. It contains bacteriocins like nisin, a protein with antibacterial properties produced by Lactococcus lactis.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

CHICAGO – The best remedy for a failed fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection is most likely a second – or even a third or fourth attempt, according to Monika Fischer, MD.

Fecal microbiota transplants (FMTs) cure the large majority of those with recurrent C. difficile. But for those who don’t respond or who have an early recurrence, repeating the procedure will almost always effect cure, she said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

“My recommendation would be to repeat FMT once you make sure the diagnosis actually is recurrent C. difficile,” said Dr. Fischer of Indiana University, Indianapolis. “There are sufficient data showing that the success rate after two FMTs significantly increases independent of the delivery route. But the effectiveness rate is highest when FMT is delivered via colonoscopy, so I recommend the second FMT be delivered that way.”

Recurrent failures can also be a sign that something else is amiss clinically, she said. So before proceeding with multiple procedures, some detective work may be in order. It’s best to start with confirmatory testing for the organism, she said.

“We have seen that about 25% of patients referred for FMT don’t actually have C. difficile at all,” Dr. Fischer said. “Be thinking about an alternative diagnosis when the stool tests negative, but the patient is still symptomatic, or if, before the FMT, there was less than a 50% improvement with vancomycin or fidaxomicin therapy.”

“When evaluating a patient for FMT failure, it should be confirmed by stool testing, preferably by toxin testing. Recent studies suggest that PCR [polymerase chain reaction]–positive but toxin-negative patients may be colonized with C. difficile but that an alternative pathology is driving the symptoms. Toxin-negative patients’ outcome is similar with or without treatment, and it is very rare that toxin-negative patients develop CDI [C. difficile infection]–related complications.”

For these patients, the problem could be any of the conditions that cause chronic diarrhea: inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease, microscopic colitis, bile salt malabsorption, chronic pancreatitis, or some other kind of infection. If C. difficile is the confirmed etiology, repeated FMTs are the way to go, Dr. Fischer said.

However, it may be worth mixing up the delivery method. The ever-expanding data on FMT continue to show that colonoscopy delivery has the lowest failure rate – about 10%. Enema is the least successful, with a 40% failure rate. In between those are nasoduodenal tube delivery, which is associated with a 20% failure rate, and oral capsules, with a failure rate varying from 12% to 30%. Fresh stool is also more effective than frozen, which, in turn, is more effective than the lyophilized preparation, Dr. Fischer said.

“Options are to repeat FMT via colonoscopy, but for patients who have had several failures, consider using the upper and lower route at the same time, and give fresh stool, especially if the first transplants used frozen.”

Although the efficacy of FMT doesn’t appear to depend on donor characteristics, patient characteristics do seem to play a role. Dr. Fischer and her colleagues have created an assessment tool to predict who may be at risk for failure. The model was developed in a 300-patient FMT cohort at two centers and validated in a third academic center FMT population. Of 24 clinical variables, three were incorporated into the failure risk model: severe disease (odds ratio, 6), inpatient status (OR, 3.8), and the number of prior C. difficile–related hospitalizations (OR, 1.4 for each one). For severe disease, patients got 5 points on the scale; for inpatient status, 4 points; and for each prior hospitalization, 1 point.

“Patients in the low-risk category [0] had up to 5% chance of failing. Patients with intermediate risk [1-2] had a 15% chance of failing, and patients in the high-risk category [3 or more points] had higher than 35% chance of not responding to single FMT,” Dr. Fischer said.

She also examined this tool in an extended cohort of nearly 500 patients at four additional sites; about 5% had failed more than two FMTs. “We identified two additional risk factors for failing multiple transplants,” Dr. Fischer said. “These were immunocompromised state, which increased the risk by 4 times, and male gender, which increased the risk by 2.5 times.”

She offered some options for the rare patient who has failed repeat FMTs and doesn’t want to try again. “There are some alternative or adjunctive therapies to repeat FMTs that may be considered, in lieu of repeating FMT for the third or fourth time or even following the first FMT failure, if dictated by patient preference. We sometimes offer these for elderly or frail patients or those with a limited life expectancy. These therapy options are from small, nonrandomized trials in multiply recurrent C. difficile infections but have not been vetted in the FMT nonresponder population.”

These include a vancomycin taper, or a vancomycin taper followed by fidaxomicin. Another option, albeit with limited applicability, is suppressive low-dose vancomycin 125 mg given every day, every other day, or every third day, indefinitely. “This can be especially good for elderly, frail patients with limited life expectancy, needing ongoing antibiotic therapy for urinary tract infections,” she said.

Finally, an 8-week vancomycin taper with daily kefir ingestion has been helpful for some patients. Although probiotics have never been proven helpful in C. difficile infections or FMT success, kefir is a different sort of supplement, she said.

“Kefir is different from yogurt. It contains bacteriocins like nisin, a protein with antibacterial properties produced by Lactococcus lactis.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

CHICAGO – The best remedy for a failed fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection is most likely a second – or even a third or fourth attempt, according to Monika Fischer, MD.

Fecal microbiota transplants (FMTs) cure the large majority of those with recurrent C. difficile. But for those who don’t respond or who have an early recurrence, repeating the procedure will almost always effect cure, she said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

“My recommendation would be to repeat FMT once you make sure the diagnosis actually is recurrent C. difficile,” said Dr. Fischer of Indiana University, Indianapolis. “There are sufficient data showing that the success rate after two FMTs significantly increases independent of the delivery route. But the effectiveness rate is highest when FMT is delivered via colonoscopy, so I recommend the second FMT be delivered that way.”

Recurrent failures can also be a sign that something else is amiss clinically, she said. So before proceeding with multiple procedures, some detective work may be in order. It’s best to start with confirmatory testing for the organism, she said.

“We have seen that about 25% of patients referred for FMT don’t actually have C. difficile at all,” Dr. Fischer said. “Be thinking about an alternative diagnosis when the stool tests negative, but the patient is still symptomatic, or if, before the FMT, there was less than a 50% improvement with vancomycin or fidaxomicin therapy.”

“When evaluating a patient for FMT failure, it should be confirmed by stool testing, preferably by toxin testing. Recent studies suggest that PCR [polymerase chain reaction]–positive but toxin-negative patients may be colonized with C. difficile but that an alternative pathology is driving the symptoms. Toxin-negative patients’ outcome is similar with or without treatment, and it is very rare that toxin-negative patients develop CDI [C. difficile infection]–related complications.”

For these patients, the problem could be any of the conditions that cause chronic diarrhea: inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease, microscopic colitis, bile salt malabsorption, chronic pancreatitis, or some other kind of infection. If C. difficile is the confirmed etiology, repeated FMTs are the way to go, Dr. Fischer said.

However, it may be worth mixing up the delivery method. The ever-expanding data on FMT continue to show that colonoscopy delivery has the lowest failure rate – about 10%. Enema is the least successful, with a 40% failure rate. In between those are nasoduodenal tube delivery, which is associated with a 20% failure rate, and oral capsules, with a failure rate varying from 12% to 30%. Fresh stool is also more effective than frozen, which, in turn, is more effective than the lyophilized preparation, Dr. Fischer said.

“Options are to repeat FMT via colonoscopy, but for patients who have had several failures, consider using the upper and lower route at the same time, and give fresh stool, especially if the first transplants used frozen.”

Although the efficacy of FMT doesn’t appear to depend on donor characteristics, patient characteristics do seem to play a role. Dr. Fischer and her colleagues have created an assessment tool to predict who may be at risk for failure. The model was developed in a 300-patient FMT cohort at two centers and validated in a third academic center FMT population. Of 24 clinical variables, three were incorporated into the failure risk model: severe disease (odds ratio, 6), inpatient status (OR, 3.8), and the number of prior C. difficile–related hospitalizations (OR, 1.4 for each one). For severe disease, patients got 5 points on the scale; for inpatient status, 4 points; and for each prior hospitalization, 1 point.

“Patients in the low-risk category [0] had up to 5% chance of failing. Patients with intermediate risk [1-2] had a 15% chance of failing, and patients in the high-risk category [3 or more points] had higher than 35% chance of not responding to single FMT,” Dr. Fischer said.

She also examined this tool in an extended cohort of nearly 500 patients at four additional sites; about 5% had failed more than two FMTs. “We identified two additional risk factors for failing multiple transplants,” Dr. Fischer said. “These were immunocompromised state, which increased the risk by 4 times, and male gender, which increased the risk by 2.5 times.”

She offered some options for the rare patient who has failed repeat FMTs and doesn’t want to try again. “There are some alternative or adjunctive therapies to repeat FMTs that may be considered, in lieu of repeating FMT for the third or fourth time or even following the first FMT failure, if dictated by patient preference. We sometimes offer these for elderly or frail patients or those with a limited life expectancy. These therapy options are from small, nonrandomized trials in multiply recurrent C. difficile infections but have not been vetted in the FMT nonresponder population.”

These include a vancomycin taper, or a vancomycin taper followed by fidaxomicin. Another option, albeit with limited applicability, is suppressive low-dose vancomycin 125 mg given every day, every other day, or every third day, indefinitely. “This can be especially good for elderly, frail patients with limited life expectancy, needing ongoing antibiotic therapy for urinary tract infections,” she said.

Finally, an 8-week vancomycin taper with daily kefir ingestion has been helpful for some patients. Although probiotics have never been proven helpful in C. difficile infections or FMT success, kefir is a different sort of supplement, she said.

“Kefir is different from yogurt. It contains bacteriocins like nisin, a protein with antibacterial properties produced by Lactococcus lactis.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT DDW 2017

E. coli, GBS account for majority of neonatal bacterial meningitis in Canada

No major shifts appear to have occurred in the bacteria that cause meningitis in Canada, said Lynda Ouchenir, MD, University of Montreal, and her associates.

“There is a paucity of information on the characteristics of neonatal meningitis in the era of infant Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) and pneumococcal immunization, maternal group B Streptococcus (GBS) prophylaxis, and emerging antimicrobial resistance,” the researchers said. So, they undertook a retrospective study of infants with onset of bacterial meningitis in the first 90 days of life at seven Canadian hospitals to find out the major pathogens involved and best empirical antibiotics to use.

This substitution of a carbapenem for the cephalosporin was considered prudent if the birth hospitalization was complicated and if the cerebrospinal fluid Gram-stain or the blood culture was suggestive of Gram-negative meningitis, Dr. Ouchenir and her associates said.

Read more at (Pediatrics. 2017;140[1)]:e20170476).

No major shifts appear to have occurred in the bacteria that cause meningitis in Canada, said Lynda Ouchenir, MD, University of Montreal, and her associates.

“There is a paucity of information on the characteristics of neonatal meningitis in the era of infant Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) and pneumococcal immunization, maternal group B Streptococcus (GBS) prophylaxis, and emerging antimicrobial resistance,” the researchers said. So, they undertook a retrospective study of infants with onset of bacterial meningitis in the first 90 days of life at seven Canadian hospitals to find out the major pathogens involved and best empirical antibiotics to use.

This substitution of a carbapenem for the cephalosporin was considered prudent if the birth hospitalization was complicated and if the cerebrospinal fluid Gram-stain or the blood culture was suggestive of Gram-negative meningitis, Dr. Ouchenir and her associates said.

Read more at (Pediatrics. 2017;140[1)]:e20170476).

No major shifts appear to have occurred in the bacteria that cause meningitis in Canada, said Lynda Ouchenir, MD, University of Montreal, and her associates.

“There is a paucity of information on the characteristics of neonatal meningitis in the era of infant Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) and pneumococcal immunization, maternal group B Streptococcus (GBS) prophylaxis, and emerging antimicrobial resistance,” the researchers said. So, they undertook a retrospective study of infants with onset of bacterial meningitis in the first 90 days of life at seven Canadian hospitals to find out the major pathogens involved and best empirical antibiotics to use.

This substitution of a carbapenem for the cephalosporin was considered prudent if the birth hospitalization was complicated and if the cerebrospinal fluid Gram-stain or the blood culture was suggestive of Gram-negative meningitis, Dr. Ouchenir and her associates said.

Read more at (Pediatrics. 2017;140[1)]:e20170476).

FROM PEDIATRICS

Sneak Peek: Journal of Hospital Medicine

BACKGROUND: Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have been advocated to improve antimicrobial utilization, but program implementation is variable.

OBJECTIVE: To determine associations of ASPs with facility characteristics and inpatient antimicrobial utilization measures in the Veterans Affairs (VA) system in 2012.

SETTING: All 130 VA facilities with acute care services.

RESULTS: Variables associated with at least three favorable changes in antimicrobial utilization included presence of postgraduate physician/pharmacy training programs, number of antimicrobial-specific order sets, frequency of systematic de-escalation review, presence of pharmacists and/or infectious diseases (ID) attendings on acute care ward teams, and formal ID training of the lead ASP pharmacist. Variables associated with two unfavorable measures included bed size, the level of engagement with VA Antimicrobial Stewardship Task Force online resources, and utilization of antimicrobial stop orders.

CONCLUSIONS: Formalization of ASP processes and presence of pharmacy and ID expertise are associated with favorable utilization. Systematic de-escalation review and order set establishment may be high-yield interventions.

Also in JHM

High prevalence of inappropriate benzodiazepine and sedative hypnotic prescriptions among hospitalized older adults

AUTHORS: Elisabeth Anna Pek, MD, Andrew Remfry, MD, Ciara Pendrith, MSc, Chris Fan-Lun, BScPhm, R. Sacha Bhatia, MD, and Christine Soong, MD, MSc, SFHM

Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of hospital-acquired anemia

AUTHORS: Anil N. Makam, MD, MAS, Oanh K. Nguyen, MD, MAS, Christopher Clark, MPA, and Ethan A. Halm, MD, MPH

Association between radiologic incidental findings and resource utilization in patients admitted with chest pain in an urban medical center

AUTHORS: Venkat P. Gundareddy, MD, MPH, SFHM, Nisa M. Maruthur, MD, MHS, Abednego Chibungu, MD, Preetam Bollampally, MD, Regina Landis, MS, abd Shaker M. Eid, MD, MBA

Clinical utility of routine CBC testing in patients with community-acquired pneumonia

AUTHORS: Neelaysh Vukkadala, BS, and Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM

Overuse of troponin? A comprehensive evaluation of testing in a large hospital system

AUTHORS: Gibbs Wilson, MD, Kyler Barkley, MD, Kipp Slicker, DO, Robert Kowal, MD, PhD, Brandon Pope, PhD, and Jeffrey Michel, MD

BACKGROUND: Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have been advocated to improve antimicrobial utilization, but program implementation is variable.

OBJECTIVE: To determine associations of ASPs with facility characteristics and inpatient antimicrobial utilization measures in the Veterans Affairs (VA) system in 2012.

SETTING: All 130 VA facilities with acute care services.

RESULTS: Variables associated with at least three favorable changes in antimicrobial utilization included presence of postgraduate physician/pharmacy training programs, number of antimicrobial-specific order sets, frequency of systematic de-escalation review, presence of pharmacists and/or infectious diseases (ID) attendings on acute care ward teams, and formal ID training of the lead ASP pharmacist. Variables associated with two unfavorable measures included bed size, the level of engagement with VA Antimicrobial Stewardship Task Force online resources, and utilization of antimicrobial stop orders.

CONCLUSIONS: Formalization of ASP processes and presence of pharmacy and ID expertise are associated with favorable utilization. Systematic de-escalation review and order set establishment may be high-yield interventions.

Also in JHM

High prevalence of inappropriate benzodiazepine and sedative hypnotic prescriptions among hospitalized older adults

AUTHORS: Elisabeth Anna Pek, MD, Andrew Remfry, MD, Ciara Pendrith, MSc, Chris Fan-Lun, BScPhm, R. Sacha Bhatia, MD, and Christine Soong, MD, MSc, SFHM

Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of hospital-acquired anemia

AUTHORS: Anil N. Makam, MD, MAS, Oanh K. Nguyen, MD, MAS, Christopher Clark, MPA, and Ethan A. Halm, MD, MPH

Association between radiologic incidental findings and resource utilization in patients admitted with chest pain in an urban medical center

AUTHORS: Venkat P. Gundareddy, MD, MPH, SFHM, Nisa M. Maruthur, MD, MHS, Abednego Chibungu, MD, Preetam Bollampally, MD, Regina Landis, MS, abd Shaker M. Eid, MD, MBA

Clinical utility of routine CBC testing in patients with community-acquired pneumonia

AUTHORS: Neelaysh Vukkadala, BS, and Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM

Overuse of troponin? A comprehensive evaluation of testing in a large hospital system

AUTHORS: Gibbs Wilson, MD, Kyler Barkley, MD, Kipp Slicker, DO, Robert Kowal, MD, PhD, Brandon Pope, PhD, and Jeffrey Michel, MD

BACKGROUND: Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have been advocated to improve antimicrobial utilization, but program implementation is variable.

OBJECTIVE: To determine associations of ASPs with facility characteristics and inpatient antimicrobial utilization measures in the Veterans Affairs (VA) system in 2012.

SETTING: All 130 VA facilities with acute care services.

RESULTS: Variables associated with at least three favorable changes in antimicrobial utilization included presence of postgraduate physician/pharmacy training programs, number of antimicrobial-specific order sets, frequency of systematic de-escalation review, presence of pharmacists and/or infectious diseases (ID) attendings on acute care ward teams, and formal ID training of the lead ASP pharmacist. Variables associated with two unfavorable measures included bed size, the level of engagement with VA Antimicrobial Stewardship Task Force online resources, and utilization of antimicrobial stop orders.

CONCLUSIONS: Formalization of ASP processes and presence of pharmacy and ID expertise are associated with favorable utilization. Systematic de-escalation review and order set establishment may be high-yield interventions.

Also in JHM

High prevalence of inappropriate benzodiazepine and sedative hypnotic prescriptions among hospitalized older adults

AUTHORS: Elisabeth Anna Pek, MD, Andrew Remfry, MD, Ciara Pendrith, MSc, Chris Fan-Lun, BScPhm, R. Sacha Bhatia, MD, and Christine Soong, MD, MSc, SFHM

Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of hospital-acquired anemia

AUTHORS: Anil N. Makam, MD, MAS, Oanh K. Nguyen, MD, MAS, Christopher Clark, MPA, and Ethan A. Halm, MD, MPH

Association between radiologic incidental findings and resource utilization in patients admitted with chest pain in an urban medical center

AUTHORS: Venkat P. Gundareddy, MD, MPH, SFHM, Nisa M. Maruthur, MD, MHS, Abednego Chibungu, MD, Preetam Bollampally, MD, Regina Landis, MS, abd Shaker M. Eid, MD, MBA

Clinical utility of routine CBC testing in patients with community-acquired pneumonia

AUTHORS: Neelaysh Vukkadala, BS, and Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM

Overuse of troponin? A comprehensive evaluation of testing in a large hospital system

AUTHORS: Gibbs Wilson, MD, Kyler Barkley, MD, Kipp Slicker, DO, Robert Kowal, MD, PhD, Brandon Pope, PhD, and Jeffrey Michel, MD

Ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections by protecting microbiome

VIENNA – An investigational beta-lactamase reduced Clostridium difficile infections by 71% in patients receiving extended antibiotic therapy for respiratory infections but not by killing the opportunistic bacteria.

Rather, ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections (CDI) by breaking down excess therapeutic antibiotics in the gut before they could injure an otherwise healthy microbiome, John Kokai-Kun, PhD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Ribaxamase is an oral enzyme that breaks the lactam ring in penicillins and cephalosporins. It’s formulated to release at a pH of 5.5 or higher, an environment that begins to develop in the upper small intestine near the bile duct – the same place that excess antibiotics are excreted.

“The drug is intended to be administered during, and for a short time after, intravenous administration of specific beta-lactam–containing antibiotics,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase doesn’t work on carbapenem-type antibiotics, he noted, and Synthetic Biologics is working on an effective enzyme for those as well.

In early human studies, ribaxamase was well tolerated and didn’t interfere with the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic antibiotics (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Mar;61[3]:e02197-16). It’s also effective in patients who are taking a proton pump inhibitor, he said.

Dr. Kokai-Kun reported the results of a phase IIb study of 412 patients who received IV ceftriaxone for lower respiratory infections. They were assigned 1:1 to either 150 mg ribaxamase daily or placebo throughout the IV treatment and for 3 days after.

The primary endpoint was prevention of C. difficile infection. The secondary endpoint was prevention of non–C. difficile antibiotic-associated diarrhea. An exploratory endpoint examined the drug’s ability to protect the microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks after treatment stopped.

The cohort was a mean 70 years old. One-third of patients also received a macrolide during their hospitalization, and one-third were taking proton pump inhibitors. The respiratory infection cure rate was about 99% in both groups at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

Eight patients in the placebo group (3.8%) and two in the active group (less than 1%) developed C. difficile infection. That translated to a statistically significant 71% risk reduction, with a P value of .027, Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase did not hit its secondary endpoint of preventing all-cause diarrhea or antibiotic-associated diarrhea that was not caused by C. difficile infection.

Although not a primary finding, ribaxamase also inhibited colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which occurred in about 70 (40%) patients in the placebo group and 40 (20%) in the ribaxamase group at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

All patients contributed stool samples at baseline and after treatment for microbiome analysis. That portion of the study is still ongoing, Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

VIENNA – An investigational beta-lactamase reduced Clostridium difficile infections by 71% in patients receiving extended antibiotic therapy for respiratory infections but not by killing the opportunistic bacteria.

Rather, ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections (CDI) by breaking down excess therapeutic antibiotics in the gut before they could injure an otherwise healthy microbiome, John Kokai-Kun, PhD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Ribaxamase is an oral enzyme that breaks the lactam ring in penicillins and cephalosporins. It’s formulated to release at a pH of 5.5 or higher, an environment that begins to develop in the upper small intestine near the bile duct – the same place that excess antibiotics are excreted.

“The drug is intended to be administered during, and for a short time after, intravenous administration of specific beta-lactam–containing antibiotics,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase doesn’t work on carbapenem-type antibiotics, he noted, and Synthetic Biologics is working on an effective enzyme for those as well.

In early human studies, ribaxamase was well tolerated and didn’t interfere with the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic antibiotics (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Mar;61[3]:e02197-16). It’s also effective in patients who are taking a proton pump inhibitor, he said.

Dr. Kokai-Kun reported the results of a phase IIb study of 412 patients who received IV ceftriaxone for lower respiratory infections. They were assigned 1:1 to either 150 mg ribaxamase daily or placebo throughout the IV treatment and for 3 days after.

The primary endpoint was prevention of C. difficile infection. The secondary endpoint was prevention of non–C. difficile antibiotic-associated diarrhea. An exploratory endpoint examined the drug’s ability to protect the microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks after treatment stopped.

The cohort was a mean 70 years old. One-third of patients also received a macrolide during their hospitalization, and one-third were taking proton pump inhibitors. The respiratory infection cure rate was about 99% in both groups at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

Eight patients in the placebo group (3.8%) and two in the active group (less than 1%) developed C. difficile infection. That translated to a statistically significant 71% risk reduction, with a P value of .027, Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase did not hit its secondary endpoint of preventing all-cause diarrhea or antibiotic-associated diarrhea that was not caused by C. difficile infection.

Although not a primary finding, ribaxamase also inhibited colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which occurred in about 70 (40%) patients in the placebo group and 40 (20%) in the ribaxamase group at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

All patients contributed stool samples at baseline and after treatment for microbiome analysis. That portion of the study is still ongoing, Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

VIENNA – An investigational beta-lactamase reduced Clostridium difficile infections by 71% in patients receiving extended antibiotic therapy for respiratory infections but not by killing the opportunistic bacteria.

Rather, ribaxamase prevented C. difficile infections (CDI) by breaking down excess therapeutic antibiotics in the gut before they could injure an otherwise healthy microbiome, John Kokai-Kun, PhD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Ribaxamase is an oral enzyme that breaks the lactam ring in penicillins and cephalosporins. It’s formulated to release at a pH of 5.5 or higher, an environment that begins to develop in the upper small intestine near the bile duct – the same place that excess antibiotics are excreted.

“The drug is intended to be administered during, and for a short time after, intravenous administration of specific beta-lactam–containing antibiotics,” Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase doesn’t work on carbapenem-type antibiotics, he noted, and Synthetic Biologics is working on an effective enzyme for those as well.

In early human studies, ribaxamase was well tolerated and didn’t interfere with the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic antibiotics (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Mar;61[3]:e02197-16). It’s also effective in patients who are taking a proton pump inhibitor, he said.

Dr. Kokai-Kun reported the results of a phase IIb study of 412 patients who received IV ceftriaxone for lower respiratory infections. They were assigned 1:1 to either 150 mg ribaxamase daily or placebo throughout the IV treatment and for 3 days after.

The primary endpoint was prevention of C. difficile infection. The secondary endpoint was prevention of non–C. difficile antibiotic-associated diarrhea. An exploratory endpoint examined the drug’s ability to protect the microbiome. Patients were monitored for 6 weeks after treatment stopped.

The cohort was a mean 70 years old. One-third of patients also received a macrolide during their hospitalization, and one-third were taking proton pump inhibitors. The respiratory infection cure rate was about 99% in both groups at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

Eight patients in the placebo group (3.8%) and two in the active group (less than 1%) developed C. difficile infection. That translated to a statistically significant 71% risk reduction, with a P value of .027, Dr. Kokai-Kun said. Ribaxamase did not hit its secondary endpoint of preventing all-cause diarrhea or antibiotic-associated diarrhea that was not caused by C. difficile infection.

Although not a primary finding, ribaxamase also inhibited colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which occurred in about 70 (40%) patients in the placebo group and 40 (20%) in the ribaxamase group at both 72 hours and 4 weeks.

All patients contributed stool samples at baseline and after treatment for microbiome analysis. That portion of the study is still ongoing, Dr. Kokai-Kun said.

Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT ECCMID 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Ribaxamase reduced C. difficile infections by 71%, relative to a placebo.

Data source: The study randomized 412 patients to either placebo or ribaxamase in addition to their therapeutic antibiotics.

Disclosures: Synthetic Biologics sponsored the study and is developing ribaxamase. Dr. Kokai-Kun is the company’s vice president of nonclinical affairs.

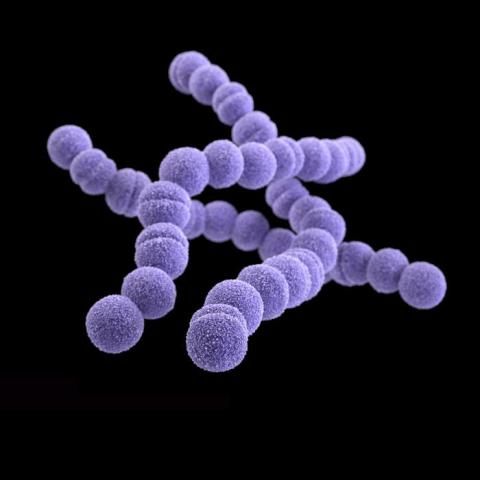

Molecular tests for GAS pharyngitis could spur overuse of antibiotics

SAN FRANCISCO – The diagnosis of pharyngitis due to infection by group A streptococcus (GAS) based on the detection of nucleic acid is fast and accurate. But this benefit brings the possibility of overuse of antibiotics, with treatment offered to those who, in the era of growth-based detection of the bacteria, would not have received treatment, according to Robert R. Tanz, MD.

Dr. Tanz, professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, delivered this cautionary note at the meeting of the Pediatrics Academics Societies.

“The short turnaround time, high sensitivity, and high specificity of newer molecular tests for GAS will make their use increasingly common. Many of the additional patients identified by molecular testing may not have an illness attributable to GAS. The increase in positive tests will probably be associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may not be beneficial, especially in areas with low rates of acute rheumatic fever,” said Dr. Tanz, who practices at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

Nowadays, diagnosis of GAS at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital uses the Illumigene system. Its use has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for diagnosis without the need for backup culture of throat swabs. Results are available in about 1 hour.

Dr. Tanz and his colleagues took a retrospective look at patient records during 2013, when testing was still growth-based, and in 2014 and 2015, after the hospital had shifted to the molecular analysis of throat swabs. The aim was to determine the proportion of tests positive for GAS prior to and after the switch.

The positive detection rate of 9.6% (96 of 997 samples) in 2013 climbed to 17% (152 of 894) in 2014 and 16% (138 of 859) in 2015. The difference was highly significant (P less than .00001).

Sore throats increase in the colder months when people tend to be indoors more often, and this seasonality was evident in 2013. However, detection was more consistent throughout the 12 months in 2014 (2013 vs 2014, P less than .000001) and 2015 (2013 vs 2015, P less than .00001). The detection rates in 2014 and 2015 were similar (P equal to .59), according to Dr. Tanz.

The new era of molecular testing circumvents what is known as the spectrum effect, in which culture-based tests are more often positive in patients with symptoms that are consistent with the infection, he said. In contrast, molecular tests can increase the identification of the target bacterium, here GAS, in patients who have sore throat caused by a viral infection.

Preliminary results presented by Dr. Tanz indicated a significantly greater detection of GAS in children not displaying symptoms of infection. In decades past, these children would not have been treated.

“The increase in positive tests for group A strep is likely associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may or may not represent a benefit to patients, as the additional identified patients may not have an illness actually attributable to group A strep,” said Dr. Tanz.

“Our findings support rigorous selectivity in choosing which patients to test, specifically excluding those with overt viral symptoms, as recommended in the guidelines from the [Infectious Diseases Society of America], [American Academy of Pediatrics], and other groups,” he said, adding that clinician guidance on the use of molecular diagnostic tests for pharyngitis caused by group A strep is a prudent step.

Features suggestive of GAS may include sudden onset of sore throat, age 5-15 years, fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, tonsillopharyngeal inflammation and patchy tonsillopharyngeal exudates, palatal petechiae, tender nodes, and scarlatiniform rash. Viral pharyngitis features include conjunctivitis, coryza, cough, diarrhea, discrete ulcerative stomatitis, viral exanthema, and hoarseness, according to the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of American guidelines (Clin Infect Dis. 2012. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629).

For most people, a sore throat is more of a temporary inconvenience rather than a looming health threat, but GAS easily spreads from person to person and can lead to the more serious condition of acute rheumatic fever, Dr. Tanz said. Hence the concern with diagnosing the cause of sore throat and, when the cause is bacterial, alleviating the infection using antibiotics.

The study was conducted at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and was not funded. Dr. Tanz reported having received support from Meridian Bioscience, manufacturer of the Illumigene Group A Streptococcus assay. Meridian Bioscience did not support this study.

SAN FRANCISCO – The diagnosis of pharyngitis due to infection by group A streptococcus (GAS) based on the detection of nucleic acid is fast and accurate. But this benefit brings the possibility of overuse of antibiotics, with treatment offered to those who, in the era of growth-based detection of the bacteria, would not have received treatment, according to Robert R. Tanz, MD.

Dr. Tanz, professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, delivered this cautionary note at the meeting of the Pediatrics Academics Societies.

“The short turnaround time, high sensitivity, and high specificity of newer molecular tests for GAS will make their use increasingly common. Many of the additional patients identified by molecular testing may not have an illness attributable to GAS. The increase in positive tests will probably be associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may not be beneficial, especially in areas with low rates of acute rheumatic fever,” said Dr. Tanz, who practices at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

Nowadays, diagnosis of GAS at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital uses the Illumigene system. Its use has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for diagnosis without the need for backup culture of throat swabs. Results are available in about 1 hour.

Dr. Tanz and his colleagues took a retrospective look at patient records during 2013, when testing was still growth-based, and in 2014 and 2015, after the hospital had shifted to the molecular analysis of throat swabs. The aim was to determine the proportion of tests positive for GAS prior to and after the switch.

The positive detection rate of 9.6% (96 of 997 samples) in 2013 climbed to 17% (152 of 894) in 2014 and 16% (138 of 859) in 2015. The difference was highly significant (P less than .00001).

Sore throats increase in the colder months when people tend to be indoors more often, and this seasonality was evident in 2013. However, detection was more consistent throughout the 12 months in 2014 (2013 vs 2014, P less than .000001) and 2015 (2013 vs 2015, P less than .00001). The detection rates in 2014 and 2015 were similar (P equal to .59), according to Dr. Tanz.

The new era of molecular testing circumvents what is known as the spectrum effect, in which culture-based tests are more often positive in patients with symptoms that are consistent with the infection, he said. In contrast, molecular tests can increase the identification of the target bacterium, here GAS, in patients who have sore throat caused by a viral infection.

Preliminary results presented by Dr. Tanz indicated a significantly greater detection of GAS in children not displaying symptoms of infection. In decades past, these children would not have been treated.

“The increase in positive tests for group A strep is likely associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may or may not represent a benefit to patients, as the additional identified patients may not have an illness actually attributable to group A strep,” said Dr. Tanz.

“Our findings support rigorous selectivity in choosing which patients to test, specifically excluding those with overt viral symptoms, as recommended in the guidelines from the [Infectious Diseases Society of America], [American Academy of Pediatrics], and other groups,” he said, adding that clinician guidance on the use of molecular diagnostic tests for pharyngitis caused by group A strep is a prudent step.

Features suggestive of GAS may include sudden onset of sore throat, age 5-15 years, fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, tonsillopharyngeal inflammation and patchy tonsillopharyngeal exudates, palatal petechiae, tender nodes, and scarlatiniform rash. Viral pharyngitis features include conjunctivitis, coryza, cough, diarrhea, discrete ulcerative stomatitis, viral exanthema, and hoarseness, according to the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of American guidelines (Clin Infect Dis. 2012. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629).

For most people, a sore throat is more of a temporary inconvenience rather than a looming health threat, but GAS easily spreads from person to person and can lead to the more serious condition of acute rheumatic fever, Dr. Tanz said. Hence the concern with diagnosing the cause of sore throat and, when the cause is bacterial, alleviating the infection using antibiotics.

The study was conducted at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and was not funded. Dr. Tanz reported having received support from Meridian Bioscience, manufacturer of the Illumigene Group A Streptococcus assay. Meridian Bioscience did not support this study.

SAN FRANCISCO – The diagnosis of pharyngitis due to infection by group A streptococcus (GAS) based on the detection of nucleic acid is fast and accurate. But this benefit brings the possibility of overuse of antibiotics, with treatment offered to those who, in the era of growth-based detection of the bacteria, would not have received treatment, according to Robert R. Tanz, MD.

Dr. Tanz, professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, delivered this cautionary note at the meeting of the Pediatrics Academics Societies.

“The short turnaround time, high sensitivity, and high specificity of newer molecular tests for GAS will make their use increasingly common. Many of the additional patients identified by molecular testing may not have an illness attributable to GAS. The increase in positive tests will probably be associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may not be beneficial, especially in areas with low rates of acute rheumatic fever,” said Dr. Tanz, who practices at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

Nowadays, diagnosis of GAS at Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital uses the Illumigene system. Its use has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for diagnosis without the need for backup culture of throat swabs. Results are available in about 1 hour.

Dr. Tanz and his colleagues took a retrospective look at patient records during 2013, when testing was still growth-based, and in 2014 and 2015, after the hospital had shifted to the molecular analysis of throat swabs. The aim was to determine the proportion of tests positive for GAS prior to and after the switch.

The positive detection rate of 9.6% (96 of 997 samples) in 2013 climbed to 17% (152 of 894) in 2014 and 16% (138 of 859) in 2015. The difference was highly significant (P less than .00001).

Sore throats increase in the colder months when people tend to be indoors more often, and this seasonality was evident in 2013. However, detection was more consistent throughout the 12 months in 2014 (2013 vs 2014, P less than .000001) and 2015 (2013 vs 2015, P less than .00001). The detection rates in 2014 and 2015 were similar (P equal to .59), according to Dr. Tanz.

The new era of molecular testing circumvents what is known as the spectrum effect, in which culture-based tests are more often positive in patients with symptoms that are consistent with the infection, he said. In contrast, molecular tests can increase the identification of the target bacterium, here GAS, in patients who have sore throat caused by a viral infection.

Preliminary results presented by Dr. Tanz indicated a significantly greater detection of GAS in children not displaying symptoms of infection. In decades past, these children would not have been treated.

“The increase in positive tests for group A strep is likely associated with increased antibiotic prescribing. This may or may not represent a benefit to patients, as the additional identified patients may not have an illness actually attributable to group A strep,” said Dr. Tanz.

“Our findings support rigorous selectivity in choosing which patients to test, specifically excluding those with overt viral symptoms, as recommended in the guidelines from the [Infectious Diseases Society of America], [American Academy of Pediatrics], and other groups,” he said, adding that clinician guidance on the use of molecular diagnostic tests for pharyngitis caused by group A strep is a prudent step.

Features suggestive of GAS may include sudden onset of sore throat, age 5-15 years, fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, tonsillopharyngeal inflammation and patchy tonsillopharyngeal exudates, palatal petechiae, tender nodes, and scarlatiniform rash. Viral pharyngitis features include conjunctivitis, coryza, cough, diarrhea, discrete ulcerative stomatitis, viral exanthema, and hoarseness, according to the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of American guidelines (Clin Infect Dis. 2012. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629).

For most people, a sore throat is more of a temporary inconvenience rather than a looming health threat, but GAS easily spreads from person to person and can lead to the more serious condition of acute rheumatic fever, Dr. Tanz said. Hence the concern with diagnosing the cause of sore throat and, when the cause is bacterial, alleviating the infection using antibiotics.

The study was conducted at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and was not funded. Dr. Tanz reported having received support from Meridian Bioscience, manufacturer of the Illumigene Group A Streptococcus assay. Meridian Bioscience did not support this study.

Key clinical point: The increased molecular-based detection of group A streptococci could led to antibiotic overuse, with prescriptions for patients who do not have bacterial infections.

Major finding: In the most recent year of culture-based testing at Lurie Children’s Hospital, the detection rate of group A streptococci was 9.6%; detection rates were 17.0% and 16.1% in the next 2 years when molecular-based analysis was implemented.

Data source: Quality assessment study involving a retrospective review of hospital electronic medical records.

Disclosures: The study was conducted at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and was not funded. Dr. Tanz reported having received support from Meridian Bioscience, manufacturer of the Illumigene Group A Streptococcus assay. Meridian Bioscience did not support this study.

VIDEO: Registry study will follow 4,000 fecal transplant patients for 10 years

CHICAGO – A 10-year registry study aims to gather clinical and patient-reported outcomes on 4,000 adult and pediatric patients who undergo fecal microbiota transplant in the United States, officials of the American Gastroenterological Association announced during Digestive Disease Week®.

The AGA Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry will be the first study to assess both short- and long-term patient outcomes associated with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in both adults and children, Colleen Kelly, MD, said in an video interview. Most subjects will have received FMT for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infections – the only indication for which Food and Drug Administration currently allows independent clinician action. But the investigational uses of FMT are expanding rapidly, and patients who undergo the procedure during any registered study will be eligible for enrollment, said Dr. Kelly, co-chair of the study’s steering committee.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The study’s primary objectives are short- and long-term safety outcomes, said Dr. Kelly of Brown University, Providence, R.I. While generally considered quite safe, short-term adverse events have been reported with FMT, and some of them have been serious – including one death from aspiration pneumonia in a patient who received donor stool via nasogastric tube (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Mar;61[1]:136-7). Other adverse events are usually self-limited but can include low-grade fever, abdominal pain, distention, bloating, and diarrhea.

Researchers seek to illuminate many of the unknowns associated with this relatively new procedure. Scientists are only now beginning to unravel the myriad ways the human microbiome promotes both health and disease. Specific alterations, for example, have been associated with obesity and other conditions; there is concern that transplanting a new microbial population could induce a disease phenotype in a recipient who might not have otherwise been at risk.

With the planned cohort size and follow-up period, the study should be able to detect any unanticipated adverse events that occur in more than 1% of the population, Dr. Kelly said. It will include a comparator group of patients with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection from a large insurance claims database to allow comparison between patients treated with FMT and those treated with antibiotics only.

The registry study also aims to discover which method or methods of transplant material delivery are best, she said. Right now, there are a number of methods (colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy, enema, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, nasogastric or nasoduodenal tube, and capsules), and no consensus on which is the best. As indications for FMT expand, there may be no single best method. The approach will probably be matched to the disorder being treated, and the study may help illuminate this as well.

For the first 2 years after a transplant, clinicians will follow patients and enter data into the registry. After that, an electronic patient-reported outcomes system will automatically contact the patient annually for follow-up information by email or text message. When patients enter their data, they can access educational material that will help keep them up-to-date on potential adverse events.

The study will also include a biobank of stool samples obtained during the procedures, hosted by the American Gut Project and the Microbiome Initiative at the University of California, San Diego. This arm of the project will analyze the microbiome of 3,000 stool samples from recipients, both before and after their transplant, as well as the corresponding donors whose material was used in the fecal transplant.

The registry study, a project of the AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education, is funded by a $3.3 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. It will be conducted in partnership with the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, Infectious Diseases Society, and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

The registry study currently is accepting applications. Physicians who perform FMT for C. difficile infections, and centers that conduct FMT research for other potential indications, can fill out a short survey to indicate their interest.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

This article was updated June 8, 2017.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

CHICAGO – A 10-year registry study aims to gather clinical and patient-reported outcomes on 4,000 adult and pediatric patients who undergo fecal microbiota transplant in the United States, officials of the American Gastroenterological Association announced during Digestive Disease Week®.

The AGA Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry will be the first study to assess both short- and long-term patient outcomes associated with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in both adults and children, Colleen Kelly, MD, said in an video interview. Most subjects will have received FMT for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infections – the only indication for which Food and Drug Administration currently allows independent clinician action. But the investigational uses of FMT are expanding rapidly, and patients who undergo the procedure during any registered study will be eligible for enrollment, said Dr. Kelly, co-chair of the study’s steering committee.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The study’s primary objectives are short- and long-term safety outcomes, said Dr. Kelly of Brown University, Providence, R.I. While generally considered quite safe, short-term adverse events have been reported with FMT, and some of them have been serious – including one death from aspiration pneumonia in a patient who received donor stool via nasogastric tube (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Mar;61[1]:136-7). Other adverse events are usually self-limited but can include low-grade fever, abdominal pain, distention, bloating, and diarrhea.

Researchers seek to illuminate many of the unknowns associated with this relatively new procedure. Scientists are only now beginning to unravel the myriad ways the human microbiome promotes both health and disease. Specific alterations, for example, have been associated with obesity and other conditions; there is concern that transplanting a new microbial population could induce a disease phenotype in a recipient who might not have otherwise been at risk.

With the planned cohort size and follow-up period, the study should be able to detect any unanticipated adverse events that occur in more than 1% of the population, Dr. Kelly said. It will include a comparator group of patients with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection from a large insurance claims database to allow comparison between patients treated with FMT and those treated with antibiotics only.

The registry study also aims to discover which method or methods of transplant material delivery are best, she said. Right now, there are a number of methods (colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy, enema, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, nasogastric or nasoduodenal tube, and capsules), and no consensus on which is the best. As indications for FMT expand, there may be no single best method. The approach will probably be matched to the disorder being treated, and the study may help illuminate this as well.

For the first 2 years after a transplant, clinicians will follow patients and enter data into the registry. After that, an electronic patient-reported outcomes system will automatically contact the patient annually for follow-up information by email or text message. When patients enter their data, they can access educational material that will help keep them up-to-date on potential adverse events.

The study will also include a biobank of stool samples obtained during the procedures, hosted by the American Gut Project and the Microbiome Initiative at the University of California, San Diego. This arm of the project will analyze the microbiome of 3,000 stool samples from recipients, both before and after their transplant, as well as the corresponding donors whose material was used in the fecal transplant.

The registry study, a project of the AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education, is funded by a $3.3 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. It will be conducted in partnership with the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, Infectious Diseases Society, and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

The registry study currently is accepting applications. Physicians who perform FMT for C. difficile infections, and centers that conduct FMT research for other potential indications, can fill out a short survey to indicate their interest.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

This article was updated June 8, 2017.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

CHICAGO – A 10-year registry study aims to gather clinical and patient-reported outcomes on 4,000 adult and pediatric patients who undergo fecal microbiota transplant in the United States, officials of the American Gastroenterological Association announced during Digestive Disease Week®.

The AGA Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry will be the first study to assess both short- and long-term patient outcomes associated with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in both adults and children, Colleen Kelly, MD, said in an video interview. Most subjects will have received FMT for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infections – the only indication for which Food and Drug Administration currently allows independent clinician action. But the investigational uses of FMT are expanding rapidly, and patients who undergo the procedure during any registered study will be eligible for enrollment, said Dr. Kelly, co-chair of the study’s steering committee.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The study’s primary objectives are short- and long-term safety outcomes, said Dr. Kelly of Brown University, Providence, R.I. While generally considered quite safe, short-term adverse events have been reported with FMT, and some of them have been serious – including one death from aspiration pneumonia in a patient who received donor stool via nasogastric tube (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Mar;61[1]:136-7). Other adverse events are usually self-limited but can include low-grade fever, abdominal pain, distention, bloating, and diarrhea.

Researchers seek to illuminate many of the unknowns associated with this relatively new procedure. Scientists are only now beginning to unravel the myriad ways the human microbiome promotes both health and disease. Specific alterations, for example, have been associated with obesity and other conditions; there is concern that transplanting a new microbial population could induce a disease phenotype in a recipient who might not have otherwise been at risk.

With the planned cohort size and follow-up period, the study should be able to detect any unanticipated adverse events that occur in more than 1% of the population, Dr. Kelly said. It will include a comparator group of patients with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection from a large insurance claims database to allow comparison between patients treated with FMT and those treated with antibiotics only.

The registry study also aims to discover which method or methods of transplant material delivery are best, she said. Right now, there are a number of methods (colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy, enema, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, nasogastric or nasoduodenal tube, and capsules), and no consensus on which is the best. As indications for FMT expand, there may be no single best method. The approach will probably be matched to the disorder being treated, and the study may help illuminate this as well.

For the first 2 years after a transplant, clinicians will follow patients and enter data into the registry. After that, an electronic patient-reported outcomes system will automatically contact the patient annually for follow-up information by email or text message. When patients enter their data, they can access educational material that will help keep them up-to-date on potential adverse events.

The study will also include a biobank of stool samples obtained during the procedures, hosted by the American Gut Project and the Microbiome Initiative at the University of California, San Diego. This arm of the project will analyze the microbiome of 3,000 stool samples from recipients, both before and after their transplant, as well as the corresponding donors whose material was used in the fecal transplant.

The registry study, a project of the AGA Center for Gut Microbiome Research and Education, is funded by a $3.3 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. It will be conducted in partnership with the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, Infectious Diseases Society, and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

The registry study currently is accepting applications. Physicians who perform FMT for C. difficile infections, and centers that conduct FMT research for other potential indications, can fill out a short survey to indicate their interest.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

This article was updated June 8, 2017.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

AT DDW

VIDEO: Rifamycin matches ciprofloxacin’s efficacy in travelers’ diarrhea with less antibiotic resistance

CHICAGO – An investigational antibiotic was just as effective as ciprofloxacin at curing travelers’ diarrhea but was associated with a significantly lower rate of colonization with extended spectrum beta-lactam–resistant Escherichia coli, a phase III trial has determined.

“Rifamycin was noninferior to ciprofloxacin on every endpoint in this trial,” Robert Steffen, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. “However, there was no increase in extended spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-E) associated with rifamycin, and significantly less new acquisition of these pathogens than in the ciprofloxacin group.”

Rifamycin is a poorly absorbed, broad-spectrum antibiotic in the same chemical family as rifaximin. It’s designed, both molecularly and in packaging, to become active only in the lower ileum and colon with limited systemic absorption. The drug is approved in Europe for infectious colitis, Clostridium difficile, diverticulitis, and also as supportive treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases and hepatic encephalopathy.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Subjects were randomized to 3 days of rifamycin 800 mg, or ciprofloxacin 1,000 mg. Follow-up visits occurred on days 2, 5, and 6, with a final follow-up by mail 4 weeks later. The primary endpoint was time to last unformed stool from the first dose of study medication. Secondary endpoints were clinical cure (24 hours with no clinical symptoms, fever, or watery stools, or 48 hours with no fever; and either no stools or only formed stools), need for rescue therapy, treatment failure, pathogen eradication in posttreatment stool, and the rate of ESBL-E colonization.

The time to last unformed stool was 43 hours in the rifamycin group and 37 hours in the ciprofloxacin group, which were not significantly different. The results were similar when broken down by infective organism, by gender, and by study location.

Rifamycin was also noninferior to ciprofloxacin in several secondary endpoints, including clinical cure (85% each), treatment failure (15% each), and need for rescue therapy (1% vs. 2.6%). The drugs were also virtually identical in the number of unformed stools per 24-hour interval, which fell precipitously from 5.5 on day 1, to 1 by day 5, and in complete resolution of gastrointestinal symptoms, which were about 75% resolved in each group by day 5.

Rifamycin was equally effective in eradicating all of the pathogens identified in the cohort. This included all pathogens in the E. coli group, all in the potentially invasive group (Shigella, Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Aeromonas), norovirus, giardia, and Cryptosporidium.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 12% of each group; none were serious. About 8% of each group experienced an adverse drug reaction.

Where the drugs did differ, and sharply so, was in antibiotic resistance, said Dr. Steffen, of the University of Zürich and the University of Texas School of Public Health, Houston. At baseline, about 16% of the group was infected with ESBL–E coli. At last follow-up, those species were present in 16% of the rifamycin group, but in 21% of the ciprofloxacin group. Similarly, there was less new ESBL–E. coli colonization in patients who had been negative at baseline (10% vs. 17%).

The findings are particularly important in light of the increasing worldwide emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, Dr. Steffen said. In fact, new guidelines released April 29 by the International Society of Travel Medicine recommend that antibiotics be reserved for moderate to severe cases of traveler’s diarrhea and not be used at all in milder cases (J Travel Med. 2017 Apr 29;24[suppl. 1]:S57-S74).

“The widespread use of ciprofloxacin and other antibiotics for travelers’ diarrhea has contributed to the rise of these resistant bacteria,” Dr. Steffen said in an interview. “We need to rethink the way we use these drugs and to focus instead on drugs that are not systemically absorbed. If rifamycin is eventually approved for this indication, it would be a good alternative to systemic antibiotics, curing the acute illness, and not contributing as much to the emergence of these worrisome pathogens.”

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Steffen spoke about the trial and concerns about antibiotic resistance that are addressed in the new guidelines and by this new study.

Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH of Freiburg, Germany, is developing rifamycin and conducted the study. Dr. Steffen has received consulting and travel fees from the company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

CHICAGO – An investigational antibiotic was just as effective as ciprofloxacin at curing travelers’ diarrhea but was associated with a significantly lower rate of colonization with extended spectrum beta-lactam–resistant Escherichia coli, a phase III trial has determined.

“Rifamycin was noninferior to ciprofloxacin on every endpoint in this trial,” Robert Steffen, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. “However, there was no increase in extended spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-E) associated with rifamycin, and significantly less new acquisition of these pathogens than in the ciprofloxacin group.”

Rifamycin is a poorly absorbed, broad-spectrum antibiotic in the same chemical family as rifaximin. It’s designed, both molecularly and in packaging, to become active only in the lower ileum and colon with limited systemic absorption. The drug is approved in Europe for infectious colitis, Clostridium difficile, diverticulitis, and also as supportive treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases and hepatic encephalopathy.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Subjects were randomized to 3 days of rifamycin 800 mg, or ciprofloxacin 1,000 mg. Follow-up visits occurred on days 2, 5, and 6, with a final follow-up by mail 4 weeks later. The primary endpoint was time to last unformed stool from the first dose of study medication. Secondary endpoints were clinical cure (24 hours with no clinical symptoms, fever, or watery stools, or 48 hours with no fever; and either no stools or only formed stools), need for rescue therapy, treatment failure, pathogen eradication in posttreatment stool, and the rate of ESBL-E colonization.

The time to last unformed stool was 43 hours in the rifamycin group and 37 hours in the ciprofloxacin group, which were not significantly different. The results were similar when broken down by infective organism, by gender, and by study location.

Rifamycin was also noninferior to ciprofloxacin in several secondary endpoints, including clinical cure (85% each), treatment failure (15% each), and need for rescue therapy (1% vs. 2.6%). The drugs were also virtually identical in the number of unformed stools per 24-hour interval, which fell precipitously from 5.5 on day 1, to 1 by day 5, and in complete resolution of gastrointestinal symptoms, which were about 75% resolved in each group by day 5.

Rifamycin was equally effective in eradicating all of the pathogens identified in the cohort. This included all pathogens in the E. coli group, all in the potentially invasive group (Shigella, Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Aeromonas), norovirus, giardia, and Cryptosporidium.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 12% of each group; none were serious. About 8% of each group experienced an adverse drug reaction.

Where the drugs did differ, and sharply so, was in antibiotic resistance, said Dr. Steffen, of the University of Zürich and the University of Texas School of Public Health, Houston. At baseline, about 16% of the group was infected with ESBL–E coli. At last follow-up, those species were present in 16% of the rifamycin group, but in 21% of the ciprofloxacin group. Similarly, there was less new ESBL–E. coli colonization in patients who had been negative at baseline (10% vs. 17%).

The findings are particularly important in light of the increasing worldwide emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, Dr. Steffen said. In fact, new guidelines released April 29 by the International Society of Travel Medicine recommend that antibiotics be reserved for moderate to severe cases of traveler’s diarrhea and not be used at all in milder cases (J Travel Med. 2017 Apr 29;24[suppl. 1]:S57-S74).

“The widespread use of ciprofloxacin and other antibiotics for travelers’ diarrhea has contributed to the rise of these resistant bacteria,” Dr. Steffen said in an interview. “We need to rethink the way we use these drugs and to focus instead on drugs that are not systemically absorbed. If rifamycin is eventually approved for this indication, it would be a good alternative to systemic antibiotics, curing the acute illness, and not contributing as much to the emergence of these worrisome pathogens.”

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Steffen spoke about the trial and concerns about antibiotic resistance that are addressed in the new guidelines and by this new study.

Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH of Freiburg, Germany, is developing rifamycin and conducted the study. Dr. Steffen has received consulting and travel fees from the company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

CHICAGO – An investigational antibiotic was just as effective as ciprofloxacin at curing travelers’ diarrhea but was associated with a significantly lower rate of colonization with extended spectrum beta-lactam–resistant Escherichia coli, a phase III trial has determined.

“Rifamycin was noninferior to ciprofloxacin on every endpoint in this trial,” Robert Steffen, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. “However, there was no increase in extended spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-E) associated with rifamycin, and significantly less new acquisition of these pathogens than in the ciprofloxacin group.”

Rifamycin is a poorly absorbed, broad-spectrum antibiotic in the same chemical family as rifaximin. It’s designed, both molecularly and in packaging, to become active only in the lower ileum and colon with limited systemic absorption. The drug is approved in Europe for infectious colitis, Clostridium difficile, diverticulitis, and also as supportive treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases and hepatic encephalopathy.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel