User login

Changes in metabolism tied to risk of subsequent dementia

in new findings that may provide a prevention target.

Investigators found one of the clusters includes small high-density lipoprotein (HDL) metabolites associated with vascular dementia, while another cluster involves ketone bodies and citrate that are primarily associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Ketone bodies, or ketones, are three related compounds – acetone, acetoacetic acid, and beta-hydroxybutyric acid (BHB) – produced by the liver during fat metabolism. Citrate is a salt or ester of citric acid.

These metabolite clusters are not only linked to the future development of dementia but also correlate with early pathology in those under age 60 years, said study investigator Cornelia M. van Duijn, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Nuffield Department of Population Health, Oxford (England) University.

“These metabolites flag early and late pathology and may be relevant as targets for prevention of dementia,” she noted.

The findings were presented at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Weight loss before dementia explained?

For the study, investigators included 125,000 patients from the UK Biobank, which includes 51,031 who were over age 60 at baseline. Of these, 1,188 developed dementia during a follow-up of about 10 years; 553 were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and 298 with vascular dementia.

Researchers used a platform that covers 249 metabolic measures, including small molecules, fatty acids, and lipoprotein lipids.

They estimated risk associated with these metabolites, adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, technical variables, ethnicity, smoking, alcohol, education, metabolic and neuropsychiatric medication, and APOE4 genotypes.

Of the 249 metabolites, 47 (19%) were associated with dementia risk in those over age 60, after adjustment.

The investigators examined effect estimates for associations of metabolites with both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia over age 60 versus hippocampal volume under age 60. They found a “very strong, very significant” association for Alzheimer’s disease, and a “marginally significant” association for vascular dementia, said Dr. van Duijn.

This would be expected, as there is a much stronger correlation between hippocampal and Alzheimer’s disease versus vascular dementia, she added.

“We not only see that the metabolites predict dementia, but also early pathology. This makes these findings rather interesting for targeting prevention,” she said. An analysis of total brain volume showed “very strong, very similar, very significant associations” for both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia,” added Dr. van Duijn.

The researchers found a major shift in various metabolites involved in energy metabolism in the 10-year period before the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. These changes include low levels of branched-chain amino acids and omega-3 fatty acids and high levels of glucose, citrate, acetone, beta-hydroxybutyrate, and acetate. “This finding is in line with that in APOE models that show reduced energy metabolism over age in the brain,” said Dr. van Duijn.

She added that high levels of some of these metabolites are associated with low body weight before dementia onset, which may explain the weight loss seen in patients before developing the disease. “Our hypothesis is that the liver is burning the fat reserves of the patients in order to provide the brain with fuel,” she explained.

Diet a prevention target?

The results also showed ketone bodies increase with age, which may represent the aging brain’s “compensation mechanism” to deal with an energy shortage, said Dr. van Duijn. “Supplementation of ketone bodies, branched-chain amino and omega-3 fatty acids may help support brain function.”

The fact that ketone bodies were positively associated with the risk of dementia is “a very important finding,” she said.

Following this and other presentations, session cochair Rima Kaddurah-Daouk, PhD, professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Institute for Brain Sciences, Duke University, Durham, N.C., noted the research is “an important part of trying to decipher some of the mysteries in Alzheimer’s disease.”

The research contributes to the understanding of how nutrition and diet could influence metabolism and then the brain and is “opening the horizon” for thinking about “strategies for therapeutic interventions,” she said.

The study received funding support from the National Institute on Aging. The investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in new findings that may provide a prevention target.

Investigators found one of the clusters includes small high-density lipoprotein (HDL) metabolites associated with vascular dementia, while another cluster involves ketone bodies and citrate that are primarily associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Ketone bodies, or ketones, are three related compounds – acetone, acetoacetic acid, and beta-hydroxybutyric acid (BHB) – produced by the liver during fat metabolism. Citrate is a salt or ester of citric acid.

These metabolite clusters are not only linked to the future development of dementia but also correlate with early pathology in those under age 60 years, said study investigator Cornelia M. van Duijn, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Nuffield Department of Population Health, Oxford (England) University.

“These metabolites flag early and late pathology and may be relevant as targets for prevention of dementia,” she noted.

The findings were presented at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Weight loss before dementia explained?

For the study, investigators included 125,000 patients from the UK Biobank, which includes 51,031 who were over age 60 at baseline. Of these, 1,188 developed dementia during a follow-up of about 10 years; 553 were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and 298 with vascular dementia.

Researchers used a platform that covers 249 metabolic measures, including small molecules, fatty acids, and lipoprotein lipids.

They estimated risk associated with these metabolites, adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, technical variables, ethnicity, smoking, alcohol, education, metabolic and neuropsychiatric medication, and APOE4 genotypes.

Of the 249 metabolites, 47 (19%) were associated with dementia risk in those over age 60, after adjustment.

The investigators examined effect estimates for associations of metabolites with both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia over age 60 versus hippocampal volume under age 60. They found a “very strong, very significant” association for Alzheimer’s disease, and a “marginally significant” association for vascular dementia, said Dr. van Duijn.

This would be expected, as there is a much stronger correlation between hippocampal and Alzheimer’s disease versus vascular dementia, she added.

“We not only see that the metabolites predict dementia, but also early pathology. This makes these findings rather interesting for targeting prevention,” she said. An analysis of total brain volume showed “very strong, very similar, very significant associations” for both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia,” added Dr. van Duijn.

The researchers found a major shift in various metabolites involved in energy metabolism in the 10-year period before the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. These changes include low levels of branched-chain amino acids and omega-3 fatty acids and high levels of glucose, citrate, acetone, beta-hydroxybutyrate, and acetate. “This finding is in line with that in APOE models that show reduced energy metabolism over age in the brain,” said Dr. van Duijn.

She added that high levels of some of these metabolites are associated with low body weight before dementia onset, which may explain the weight loss seen in patients before developing the disease. “Our hypothesis is that the liver is burning the fat reserves of the patients in order to provide the brain with fuel,” she explained.

Diet a prevention target?

The results also showed ketone bodies increase with age, which may represent the aging brain’s “compensation mechanism” to deal with an energy shortage, said Dr. van Duijn. “Supplementation of ketone bodies, branched-chain amino and omega-3 fatty acids may help support brain function.”

The fact that ketone bodies were positively associated with the risk of dementia is “a very important finding,” she said.

Following this and other presentations, session cochair Rima Kaddurah-Daouk, PhD, professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Institute for Brain Sciences, Duke University, Durham, N.C., noted the research is “an important part of trying to decipher some of the mysteries in Alzheimer’s disease.”

The research contributes to the understanding of how nutrition and diet could influence metabolism and then the brain and is “opening the horizon” for thinking about “strategies for therapeutic interventions,” she said.

The study received funding support from the National Institute on Aging. The investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in new findings that may provide a prevention target.

Investigators found one of the clusters includes small high-density lipoprotein (HDL) metabolites associated with vascular dementia, while another cluster involves ketone bodies and citrate that are primarily associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Ketone bodies, or ketones, are three related compounds – acetone, acetoacetic acid, and beta-hydroxybutyric acid (BHB) – produced by the liver during fat metabolism. Citrate is a salt or ester of citric acid.

These metabolite clusters are not only linked to the future development of dementia but also correlate with early pathology in those under age 60 years, said study investigator Cornelia M. van Duijn, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Nuffield Department of Population Health, Oxford (England) University.

“These metabolites flag early and late pathology and may be relevant as targets for prevention of dementia,” she noted.

The findings were presented at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Weight loss before dementia explained?

For the study, investigators included 125,000 patients from the UK Biobank, which includes 51,031 who were over age 60 at baseline. Of these, 1,188 developed dementia during a follow-up of about 10 years; 553 were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and 298 with vascular dementia.

Researchers used a platform that covers 249 metabolic measures, including small molecules, fatty acids, and lipoprotein lipids.

They estimated risk associated with these metabolites, adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, technical variables, ethnicity, smoking, alcohol, education, metabolic and neuropsychiatric medication, and APOE4 genotypes.

Of the 249 metabolites, 47 (19%) were associated with dementia risk in those over age 60, after adjustment.

The investigators examined effect estimates for associations of metabolites with both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia over age 60 versus hippocampal volume under age 60. They found a “very strong, very significant” association for Alzheimer’s disease, and a “marginally significant” association for vascular dementia, said Dr. van Duijn.

This would be expected, as there is a much stronger correlation between hippocampal and Alzheimer’s disease versus vascular dementia, she added.

“We not only see that the metabolites predict dementia, but also early pathology. This makes these findings rather interesting for targeting prevention,” she said. An analysis of total brain volume showed “very strong, very similar, very significant associations” for both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia,” added Dr. van Duijn.

The researchers found a major shift in various metabolites involved in energy metabolism in the 10-year period before the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. These changes include low levels of branched-chain amino acids and omega-3 fatty acids and high levels of glucose, citrate, acetone, beta-hydroxybutyrate, and acetate. “This finding is in line with that in APOE models that show reduced energy metabolism over age in the brain,” said Dr. van Duijn.

She added that high levels of some of these metabolites are associated with low body weight before dementia onset, which may explain the weight loss seen in patients before developing the disease. “Our hypothesis is that the liver is burning the fat reserves of the patients in order to provide the brain with fuel,” she explained.

Diet a prevention target?

The results also showed ketone bodies increase with age, which may represent the aging brain’s “compensation mechanism” to deal with an energy shortage, said Dr. van Duijn. “Supplementation of ketone bodies, branched-chain amino and omega-3 fatty acids may help support brain function.”

The fact that ketone bodies were positively associated with the risk of dementia is “a very important finding,” she said.

Following this and other presentations, session cochair Rima Kaddurah-Daouk, PhD, professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Institute for Brain Sciences, Duke University, Durham, N.C., noted the research is “an important part of trying to decipher some of the mysteries in Alzheimer’s disease.”

The research contributes to the understanding of how nutrition and diet could influence metabolism and then the brain and is “opening the horizon” for thinking about “strategies for therapeutic interventions,” she said.

The study received funding support from the National Institute on Aging. The investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAIC 2021

‘Staggering’ increase in global dementia cases predicted by 2050

, new global prevalence data show. “These extreme increases are due largely to demographic trends, including population growth and aging,” said study investigator Emma Nichols, MPH, a researcher at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington in Seattle.

“Our estimates of expected increases can and should inform policy and planning efforts that will be needed to address the needs of the growing number of individuals with dementia in the future,” Ms. Nichols said.

The latest global prevalence data were reported at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“The numbers are staggering: Nearly 153 million cases of dementia are predicted worldwide by the year 2050. To put that in context, that number is equal to approximately half of the U.S. population in 2020,” Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said in a statement.

Prevalence by country

To more accurately forecast global dementia prevalence and produce country-level estimates, the investigators leveraged data from 1999 to 2019 from the Global Burden of Disease study, a comprehensive set of estimates of worldwide health trends.

These data suggest global dementia cases will increase from 57.4 million (50.4 to 65.1) in 2019 to 152.8 million (130.8 to 175.9) in 2050.

Regions that will experience the worst of the increase are eastern Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and the Middle East.

The researchers also factored into the forecasts expected trends in obesity, diabetes, smoking, and educational attainment.

Increases in better education around the world are projected to decrease dementia prevalence by 6.2 million cases worldwide by 2050. However, anticipated trends in smoking, high body mass index, and diabetes will offset this gain, increasing global dementia cases by 6.8 million cases.

“A reversal of these expected trends in cardiovascular risks would be necessary to alter the anticipated trends,” Ms. Nichols said. “Interventions targeted at modifiable risk factors for dementia represent a viable strategy to help address the anticipated trends in dementia burden,” she added.

Need for effective prevention, treatment

Commenting on the research, Rebecca M. Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the global increase in dementia cases is something the association has been following for many years. “We know that if we do not find effective treatments that are going to stop, slow, or prevent Alzheimer’s disease, this number will continue to grow and it will continue to impact people globally,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

She noted that although there are some positive trends, including the fact that increased education may drive down dementia risk, other factors, such as smoking, high body mass index, and high blood sugar level, are predicted to increase in prevalence.

“Some of these factors are actually counterbalancing each other, and in the end, if we don’t continue to develop culturally tailored interventions or even risk reduction strategies for individuals across the globe, we will continue to see those numbers rise overall,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new global prevalence data show. “These extreme increases are due largely to demographic trends, including population growth and aging,” said study investigator Emma Nichols, MPH, a researcher at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington in Seattle.

“Our estimates of expected increases can and should inform policy and planning efforts that will be needed to address the needs of the growing number of individuals with dementia in the future,” Ms. Nichols said.

The latest global prevalence data were reported at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“The numbers are staggering: Nearly 153 million cases of dementia are predicted worldwide by the year 2050. To put that in context, that number is equal to approximately half of the U.S. population in 2020,” Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said in a statement.

Prevalence by country

To more accurately forecast global dementia prevalence and produce country-level estimates, the investigators leveraged data from 1999 to 2019 from the Global Burden of Disease study, a comprehensive set of estimates of worldwide health trends.

These data suggest global dementia cases will increase from 57.4 million (50.4 to 65.1) in 2019 to 152.8 million (130.8 to 175.9) in 2050.

Regions that will experience the worst of the increase are eastern Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and the Middle East.

The researchers also factored into the forecasts expected trends in obesity, diabetes, smoking, and educational attainment.

Increases in better education around the world are projected to decrease dementia prevalence by 6.2 million cases worldwide by 2050. However, anticipated trends in smoking, high body mass index, and diabetes will offset this gain, increasing global dementia cases by 6.8 million cases.

“A reversal of these expected trends in cardiovascular risks would be necessary to alter the anticipated trends,” Ms. Nichols said. “Interventions targeted at modifiable risk factors for dementia represent a viable strategy to help address the anticipated trends in dementia burden,” she added.

Need for effective prevention, treatment

Commenting on the research, Rebecca M. Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the global increase in dementia cases is something the association has been following for many years. “We know that if we do not find effective treatments that are going to stop, slow, or prevent Alzheimer’s disease, this number will continue to grow and it will continue to impact people globally,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

She noted that although there are some positive trends, including the fact that increased education may drive down dementia risk, other factors, such as smoking, high body mass index, and high blood sugar level, are predicted to increase in prevalence.

“Some of these factors are actually counterbalancing each other, and in the end, if we don’t continue to develop culturally tailored interventions or even risk reduction strategies for individuals across the globe, we will continue to see those numbers rise overall,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new global prevalence data show. “These extreme increases are due largely to demographic trends, including population growth and aging,” said study investigator Emma Nichols, MPH, a researcher at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington in Seattle.

“Our estimates of expected increases can and should inform policy and planning efforts that will be needed to address the needs of the growing number of individuals with dementia in the future,” Ms. Nichols said.

The latest global prevalence data were reported at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“The numbers are staggering: Nearly 153 million cases of dementia are predicted worldwide by the year 2050. To put that in context, that number is equal to approximately half of the U.S. population in 2020,” Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said in a statement.

Prevalence by country

To more accurately forecast global dementia prevalence and produce country-level estimates, the investigators leveraged data from 1999 to 2019 from the Global Burden of Disease study, a comprehensive set of estimates of worldwide health trends.

These data suggest global dementia cases will increase from 57.4 million (50.4 to 65.1) in 2019 to 152.8 million (130.8 to 175.9) in 2050.

Regions that will experience the worst of the increase are eastern Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and the Middle East.

The researchers also factored into the forecasts expected trends in obesity, diabetes, smoking, and educational attainment.

Increases in better education around the world are projected to decrease dementia prevalence by 6.2 million cases worldwide by 2050. However, anticipated trends in smoking, high body mass index, and diabetes will offset this gain, increasing global dementia cases by 6.8 million cases.

“A reversal of these expected trends in cardiovascular risks would be necessary to alter the anticipated trends,” Ms. Nichols said. “Interventions targeted at modifiable risk factors for dementia represent a viable strategy to help address the anticipated trends in dementia burden,” she added.

Need for effective prevention, treatment

Commenting on the research, Rebecca M. Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the global increase in dementia cases is something the association has been following for many years. “We know that if we do not find effective treatments that are going to stop, slow, or prevent Alzheimer’s disease, this number will continue to grow and it will continue to impact people globally,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

She noted that although there are some positive trends, including the fact that increased education may drive down dementia risk, other factors, such as smoking, high body mass index, and high blood sugar level, are predicted to increase in prevalence.

“Some of these factors are actually counterbalancing each other, and in the end, if we don’t continue to develop culturally tailored interventions or even risk reduction strategies for individuals across the globe, we will continue to see those numbers rise overall,” Dr. Edelmayer said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From AAIC 2021

Coffee and the brain: ‘Concerning’ new data

according to the results of a large study.

“With coffee intake, moderation is the key, and especially high levels of consumption may have adverse long-term effects on the brain,” said study investigator Elina Hypponen, PhD, professor of nutritional and genetic epidemiology and director of the Australian Center for Precision Health at the University of South Australia.

“These new data are concerning, and there is a need to conduct further carefully controlled studies to clarify the effects of coffee on the brain.”

The study was published online June 24 in Nutritional Neuroscience.

Potent stimulant

Coffee is a potent nervous system stimulant and is among the most popular nonalcoholic beverages. Some previous research suggests it benefits the brain, but the investigators noted that other research shows a negative or U-shaped relationship.

To investigate, the researchers examined data from the U.K. Biobank, a long-term prospective epidemiologic study of more than 500,000 participants aged 37-73 years who were recruited in 22 assessment centers in the United Kingdom between March 2006 and October 2010.

During the baseline assessment, information was gathered using touchscreen questionnaires, verbal interviews, and physical examinations that involved collection of blood, urine, and saliva samples. An imaging substudy was incorporated in 2014, the goal of which was to conduct brain, heart, and body MRI imaging for 100,000 participants.

The investigators conducted analyses on disease outcomes for 398,646 participants for whom information on habitual coffee consumption was available. Brain volume analyses were conducted in 17,702 participants for whom valid brain imaging data were available.

Participants reported coffee intake in cups per day. Researchers grouped coffee consumption into seven categories: nondrinkers, decaffeinated coffee drinkers, and caffeinated coffee drinkers who consumed less than 1 cup/d, 1-2 cups/d, 3-4 cups/d, 5-6 cups/d, and more than 6 cups/d.

The reference category was those who consumed 1-2 cups/d, rather than those who abstained from coffee, because persons who abstain are more likely to be at suboptimal health.

“Comparing the health of coffee drinkers to the health of those choosing to abstain from coffee will typically lead to an impression of a health benefit, even if there would not be one,” said Dr. Hypponen.

The researchers obtained total and regional brain volumes from the MRI imaging substudy starting 4-6 years after baseline assessment. They accessed information on incident dementia and stroke using primary care data, hospital admission electronic health records, national death registers, and self-reported medical conditions.

Covariates included socioeconomic, health, and other factors, such as smoking, alcohol and tea consumption, physical activity, stressful life events, and body mass index.

The investigators found that there was a linear inverse association between coffee consumption and total brain volume (fully adjusted beta per cup, –1.42; 95% confidence interval, –1.89 to –0.94), with consistent patterns for gray matter, white matter, and hippocampal volumes.

There was no evidence to support an association with white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume (beta –0.01; 95% CI, –0.07 to 0.05).

Higher consumption, higher risk

The analysis also revealed a nonlinear association between coffee consumption and the odds of dementia (P nonlinearity = .0001), with slightly higher odds seen with non–coffee drinkers and decaffeinated-coffee drinkers and more notable increases for participants in the highest categories of coffee consumption compared with light coffee drinkers.

After adjustment for all covariates, the odds ratio of dementia among persons in the category of coffee intake was 1.53 (95% CI, 1.28-1.83). After full adjustments, the association with heavy coffee consumption and stroke was not significant, although “we can’t exclude a weak effect,” said Dr. Hypponen.

“For the highest coffee consumption group, the data support an association which may be anywhere from 0% to 37% higher odds of stroke after full adjustment,” she added.

People at risk for hypertension may develop “unpleasant sensations” and stop drinking coffee before a serious adverse event occurs, said Dr. Hypponen. In a previous study, she and her colleagues showed that those who have genetically higher blood pressure tend to drink less coffee than their counterparts without the condition.

“This type of effect might be expected to naturally limit the adverse effects of coffee on the risk of stroke,” said Dr. Hypponen.

The odds remained elevated for participants drinking more than 6 cups/d after the researchers accounted for sleep quality. There were no differences in risk between men and women or by age.

An examination of the consumption of tea, which often contains caffeine, did not show an association with brain volume or the odds of dementia or stroke.

“We don’t know whether the difference between associations seen for coffee and tea intake reflects the difference in related caffeine intake or some other explanation, such as dehydration or effects operating through blood cholesterol,” said Dr. Hypponen.

Although reverse causation is possible, there’s no reason to believe that it is relevant to the study results. Genetic evidence suggests a causal role of higher coffee intake on risk for Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, results of a clinical trial support the association between higher caffeine intake and smaller gray matter volume, said Dr. Hypponen.

The mechanisms linking coffee consumption to brain volumes and dementia are not well established. However, Dr. Hypponen noted that caffeine has been used to induce apoptosis in cancer studies using glial cells.

“Furthermore, adenosine receptors, which mediate many of the effects of caffeine in the brain, have been suggested to influence the release of growth factors, which in turn can have an influence on astrocyte proliferation and angiogenesis in the brain,” she said.

Some types of coffee contain cafestol, which increases blood cholesterol and can have adverse effects though related mechanisms, said Dr. Hypponen.

The mechanism may also involve dehydration, which may have a harmful effect on the brain. The study suggested a correlation between dehydration and high coffee intake. “Of course, if this is the case, it is good news, as then we can do something about it simply by drinking some water every time we have a cup of coffee,” she said.

Misleading conclusions

Coffee contains antioxidants, and although previous studies have suggested it might be beneficial, this hypothesis is “too simplistic,” said Dr. Hypponen. “While coffee is not going to be all ‘bad’ either, there are a lot of controversies and suggestions about beneficial effects of coffee which may not be true, or at least do not reflect the full story.”

If the drinking of coffee is at least partly determined by an individual’s health status, then that would often lead to misleading conclusions in observational studies, said Dr. Hypponen.

“When one uses as a comparison people who already have poor health and who do not drink coffee because of that, coffee intake will by default appear beneficial simply because there are more people with disease among those choosing abstinence,” she said.

Before now, there was “very little evidence about the association between coffee intake and brain morphology,” and the studies that were conducted were relatively small, said Dr. Hypponen.

One of these smaller studies included a group of women aged 13-30 years. It found that coffee consumption was not associated with total brain volumes, but the findings suggested a U-shaped association with hippocampal volume; higher values were seen both for nondrinkers and the groups with higher consumption.

A small study of elderly patients with diabetes showed no evidence of an association with white matter volume, but there was a possible age-dependent association with gray matter volume.

The largest of the earlier studies had results that were very similar to those of the current study, suggesting that increasing coffee intake is associated with smaller hippocampal volumes, said Dr. Hypponen.

One of the study’s limitations included the fact that full dietary information was available only for a subsample and that factors such as dehydration were measured at baseline rather than at the time of brain MRI.

Another possible study limitation was the use of self-reported data and the fact that lifestyle changes may have occurred between baseline and MRI or covariate measurement.

In addition, the study is subject to a healthy-volunteer bias, and its implications are restricted to White British persons. The association needs to be studied in other ethnic populations, the authors noted.

A reason to cut back?

Commenting on the findings, Walter Willett, MD, DrPH, professor of epidemiology and nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, said the study is large and quite well done.

“It does raise questions about an increase in risk of dementia with six or more cups of coffee per day,” said Dr. Willett. “At the same time, it provides reassurance about lack of adverse effects of coffee for those consuming three or four cups per day, and little increase in risk, if any, with five cups per day.”

It’s not entirely clear whether the increase in risk with six or more cups of coffee per day represents a “true effect” of coffee, inasmuch as the study did not seem to adjust fully for dietary factors, high consumption of alcohol, or past smoking, said Dr. Willett.

The findings don’t suggest that coffee lovers should give up their Java. “But six or more cups per day is a lot, and those who drink that much might consider cutting back a bit while research continues,” said Dr. Willett.

The study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to the results of a large study.

“With coffee intake, moderation is the key, and especially high levels of consumption may have adverse long-term effects on the brain,” said study investigator Elina Hypponen, PhD, professor of nutritional and genetic epidemiology and director of the Australian Center for Precision Health at the University of South Australia.

“These new data are concerning, and there is a need to conduct further carefully controlled studies to clarify the effects of coffee on the brain.”

The study was published online June 24 in Nutritional Neuroscience.

Potent stimulant

Coffee is a potent nervous system stimulant and is among the most popular nonalcoholic beverages. Some previous research suggests it benefits the brain, but the investigators noted that other research shows a negative or U-shaped relationship.

To investigate, the researchers examined data from the U.K. Biobank, a long-term prospective epidemiologic study of more than 500,000 participants aged 37-73 years who were recruited in 22 assessment centers in the United Kingdom between March 2006 and October 2010.

During the baseline assessment, information was gathered using touchscreen questionnaires, verbal interviews, and physical examinations that involved collection of blood, urine, and saliva samples. An imaging substudy was incorporated in 2014, the goal of which was to conduct brain, heart, and body MRI imaging for 100,000 participants.

The investigators conducted analyses on disease outcomes for 398,646 participants for whom information on habitual coffee consumption was available. Brain volume analyses were conducted in 17,702 participants for whom valid brain imaging data were available.

Participants reported coffee intake in cups per day. Researchers grouped coffee consumption into seven categories: nondrinkers, decaffeinated coffee drinkers, and caffeinated coffee drinkers who consumed less than 1 cup/d, 1-2 cups/d, 3-4 cups/d, 5-6 cups/d, and more than 6 cups/d.

The reference category was those who consumed 1-2 cups/d, rather than those who abstained from coffee, because persons who abstain are more likely to be at suboptimal health.

“Comparing the health of coffee drinkers to the health of those choosing to abstain from coffee will typically lead to an impression of a health benefit, even if there would not be one,” said Dr. Hypponen.

The researchers obtained total and regional brain volumes from the MRI imaging substudy starting 4-6 years after baseline assessment. They accessed information on incident dementia and stroke using primary care data, hospital admission electronic health records, national death registers, and self-reported medical conditions.

Covariates included socioeconomic, health, and other factors, such as smoking, alcohol and tea consumption, physical activity, stressful life events, and body mass index.

The investigators found that there was a linear inverse association between coffee consumption and total brain volume (fully adjusted beta per cup, –1.42; 95% confidence interval, –1.89 to –0.94), with consistent patterns for gray matter, white matter, and hippocampal volumes.

There was no evidence to support an association with white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume (beta –0.01; 95% CI, –0.07 to 0.05).

Higher consumption, higher risk

The analysis also revealed a nonlinear association between coffee consumption and the odds of dementia (P nonlinearity = .0001), with slightly higher odds seen with non–coffee drinkers and decaffeinated-coffee drinkers and more notable increases for participants in the highest categories of coffee consumption compared with light coffee drinkers.

After adjustment for all covariates, the odds ratio of dementia among persons in the category of coffee intake was 1.53 (95% CI, 1.28-1.83). After full adjustments, the association with heavy coffee consumption and stroke was not significant, although “we can’t exclude a weak effect,” said Dr. Hypponen.

“For the highest coffee consumption group, the data support an association which may be anywhere from 0% to 37% higher odds of stroke after full adjustment,” she added.

People at risk for hypertension may develop “unpleasant sensations” and stop drinking coffee before a serious adverse event occurs, said Dr. Hypponen. In a previous study, she and her colleagues showed that those who have genetically higher blood pressure tend to drink less coffee than their counterparts without the condition.

“This type of effect might be expected to naturally limit the adverse effects of coffee on the risk of stroke,” said Dr. Hypponen.

The odds remained elevated for participants drinking more than 6 cups/d after the researchers accounted for sleep quality. There were no differences in risk between men and women or by age.

An examination of the consumption of tea, which often contains caffeine, did not show an association with brain volume or the odds of dementia or stroke.

“We don’t know whether the difference between associations seen for coffee and tea intake reflects the difference in related caffeine intake or some other explanation, such as dehydration or effects operating through blood cholesterol,” said Dr. Hypponen.

Although reverse causation is possible, there’s no reason to believe that it is relevant to the study results. Genetic evidence suggests a causal role of higher coffee intake on risk for Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, results of a clinical trial support the association between higher caffeine intake and smaller gray matter volume, said Dr. Hypponen.

The mechanisms linking coffee consumption to brain volumes and dementia are not well established. However, Dr. Hypponen noted that caffeine has been used to induce apoptosis in cancer studies using glial cells.

“Furthermore, adenosine receptors, which mediate many of the effects of caffeine in the brain, have been suggested to influence the release of growth factors, which in turn can have an influence on astrocyte proliferation and angiogenesis in the brain,” she said.

Some types of coffee contain cafestol, which increases blood cholesterol and can have adverse effects though related mechanisms, said Dr. Hypponen.

The mechanism may also involve dehydration, which may have a harmful effect on the brain. The study suggested a correlation between dehydration and high coffee intake. “Of course, if this is the case, it is good news, as then we can do something about it simply by drinking some water every time we have a cup of coffee,” she said.

Misleading conclusions

Coffee contains antioxidants, and although previous studies have suggested it might be beneficial, this hypothesis is “too simplistic,” said Dr. Hypponen. “While coffee is not going to be all ‘bad’ either, there are a lot of controversies and suggestions about beneficial effects of coffee which may not be true, or at least do not reflect the full story.”

If the drinking of coffee is at least partly determined by an individual’s health status, then that would often lead to misleading conclusions in observational studies, said Dr. Hypponen.

“When one uses as a comparison people who already have poor health and who do not drink coffee because of that, coffee intake will by default appear beneficial simply because there are more people with disease among those choosing abstinence,” she said.

Before now, there was “very little evidence about the association between coffee intake and brain morphology,” and the studies that were conducted were relatively small, said Dr. Hypponen.

One of these smaller studies included a group of women aged 13-30 years. It found that coffee consumption was not associated with total brain volumes, but the findings suggested a U-shaped association with hippocampal volume; higher values were seen both for nondrinkers and the groups with higher consumption.

A small study of elderly patients with diabetes showed no evidence of an association with white matter volume, but there was a possible age-dependent association with gray matter volume.

The largest of the earlier studies had results that were very similar to those of the current study, suggesting that increasing coffee intake is associated with smaller hippocampal volumes, said Dr. Hypponen.

One of the study’s limitations included the fact that full dietary information was available only for a subsample and that factors such as dehydration were measured at baseline rather than at the time of brain MRI.

Another possible study limitation was the use of self-reported data and the fact that lifestyle changes may have occurred between baseline and MRI or covariate measurement.

In addition, the study is subject to a healthy-volunteer bias, and its implications are restricted to White British persons. The association needs to be studied in other ethnic populations, the authors noted.

A reason to cut back?

Commenting on the findings, Walter Willett, MD, DrPH, professor of epidemiology and nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, said the study is large and quite well done.

“It does raise questions about an increase in risk of dementia with six or more cups of coffee per day,” said Dr. Willett. “At the same time, it provides reassurance about lack of adverse effects of coffee for those consuming three or four cups per day, and little increase in risk, if any, with five cups per day.”

It’s not entirely clear whether the increase in risk with six or more cups of coffee per day represents a “true effect” of coffee, inasmuch as the study did not seem to adjust fully for dietary factors, high consumption of alcohol, or past smoking, said Dr. Willett.

The findings don’t suggest that coffee lovers should give up their Java. “But six or more cups per day is a lot, and those who drink that much might consider cutting back a bit while research continues,” said Dr. Willett.

The study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to the results of a large study.

“With coffee intake, moderation is the key, and especially high levels of consumption may have adverse long-term effects on the brain,” said study investigator Elina Hypponen, PhD, professor of nutritional and genetic epidemiology and director of the Australian Center for Precision Health at the University of South Australia.

“These new data are concerning, and there is a need to conduct further carefully controlled studies to clarify the effects of coffee on the brain.”

The study was published online June 24 in Nutritional Neuroscience.

Potent stimulant

Coffee is a potent nervous system stimulant and is among the most popular nonalcoholic beverages. Some previous research suggests it benefits the brain, but the investigators noted that other research shows a negative or U-shaped relationship.

To investigate, the researchers examined data from the U.K. Biobank, a long-term prospective epidemiologic study of more than 500,000 participants aged 37-73 years who were recruited in 22 assessment centers in the United Kingdom between March 2006 and October 2010.

During the baseline assessment, information was gathered using touchscreen questionnaires, verbal interviews, and physical examinations that involved collection of blood, urine, and saliva samples. An imaging substudy was incorporated in 2014, the goal of which was to conduct brain, heart, and body MRI imaging for 100,000 participants.

The investigators conducted analyses on disease outcomes for 398,646 participants for whom information on habitual coffee consumption was available. Brain volume analyses were conducted in 17,702 participants for whom valid brain imaging data were available.

Participants reported coffee intake in cups per day. Researchers grouped coffee consumption into seven categories: nondrinkers, decaffeinated coffee drinkers, and caffeinated coffee drinkers who consumed less than 1 cup/d, 1-2 cups/d, 3-4 cups/d, 5-6 cups/d, and more than 6 cups/d.

The reference category was those who consumed 1-2 cups/d, rather than those who abstained from coffee, because persons who abstain are more likely to be at suboptimal health.

“Comparing the health of coffee drinkers to the health of those choosing to abstain from coffee will typically lead to an impression of a health benefit, even if there would not be one,” said Dr. Hypponen.

The researchers obtained total and regional brain volumes from the MRI imaging substudy starting 4-6 years after baseline assessment. They accessed information on incident dementia and stroke using primary care data, hospital admission electronic health records, national death registers, and self-reported medical conditions.

Covariates included socioeconomic, health, and other factors, such as smoking, alcohol and tea consumption, physical activity, stressful life events, and body mass index.

The investigators found that there was a linear inverse association between coffee consumption and total brain volume (fully adjusted beta per cup, –1.42; 95% confidence interval, –1.89 to –0.94), with consistent patterns for gray matter, white matter, and hippocampal volumes.

There was no evidence to support an association with white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume (beta –0.01; 95% CI, –0.07 to 0.05).

Higher consumption, higher risk

The analysis also revealed a nonlinear association between coffee consumption and the odds of dementia (P nonlinearity = .0001), with slightly higher odds seen with non–coffee drinkers and decaffeinated-coffee drinkers and more notable increases for participants in the highest categories of coffee consumption compared with light coffee drinkers.

After adjustment for all covariates, the odds ratio of dementia among persons in the category of coffee intake was 1.53 (95% CI, 1.28-1.83). After full adjustments, the association with heavy coffee consumption and stroke was not significant, although “we can’t exclude a weak effect,” said Dr. Hypponen.

“For the highest coffee consumption group, the data support an association which may be anywhere from 0% to 37% higher odds of stroke after full adjustment,” she added.

People at risk for hypertension may develop “unpleasant sensations” and stop drinking coffee before a serious adverse event occurs, said Dr. Hypponen. In a previous study, she and her colleagues showed that those who have genetically higher blood pressure tend to drink less coffee than their counterparts without the condition.

“This type of effect might be expected to naturally limit the adverse effects of coffee on the risk of stroke,” said Dr. Hypponen.

The odds remained elevated for participants drinking more than 6 cups/d after the researchers accounted for sleep quality. There were no differences in risk between men and women or by age.

An examination of the consumption of tea, which often contains caffeine, did not show an association with brain volume or the odds of dementia or stroke.

“We don’t know whether the difference between associations seen for coffee and tea intake reflects the difference in related caffeine intake or some other explanation, such as dehydration or effects operating through blood cholesterol,” said Dr. Hypponen.

Although reverse causation is possible, there’s no reason to believe that it is relevant to the study results. Genetic evidence suggests a causal role of higher coffee intake on risk for Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, results of a clinical trial support the association between higher caffeine intake and smaller gray matter volume, said Dr. Hypponen.

The mechanisms linking coffee consumption to brain volumes and dementia are not well established. However, Dr. Hypponen noted that caffeine has been used to induce apoptosis in cancer studies using glial cells.

“Furthermore, adenosine receptors, which mediate many of the effects of caffeine in the brain, have been suggested to influence the release of growth factors, which in turn can have an influence on astrocyte proliferation and angiogenesis in the brain,” she said.

Some types of coffee contain cafestol, which increases blood cholesterol and can have adverse effects though related mechanisms, said Dr. Hypponen.

The mechanism may also involve dehydration, which may have a harmful effect on the brain. The study suggested a correlation between dehydration and high coffee intake. “Of course, if this is the case, it is good news, as then we can do something about it simply by drinking some water every time we have a cup of coffee,” she said.

Misleading conclusions

Coffee contains antioxidants, and although previous studies have suggested it might be beneficial, this hypothesis is “too simplistic,” said Dr. Hypponen. “While coffee is not going to be all ‘bad’ either, there are a lot of controversies and suggestions about beneficial effects of coffee which may not be true, or at least do not reflect the full story.”

If the drinking of coffee is at least partly determined by an individual’s health status, then that would often lead to misleading conclusions in observational studies, said Dr. Hypponen.

“When one uses as a comparison people who already have poor health and who do not drink coffee because of that, coffee intake will by default appear beneficial simply because there are more people with disease among those choosing abstinence,” she said.

Before now, there was “very little evidence about the association between coffee intake and brain morphology,” and the studies that were conducted were relatively small, said Dr. Hypponen.

One of these smaller studies included a group of women aged 13-30 years. It found that coffee consumption was not associated with total brain volumes, but the findings suggested a U-shaped association with hippocampal volume; higher values were seen both for nondrinkers and the groups with higher consumption.

A small study of elderly patients with diabetes showed no evidence of an association with white matter volume, but there was a possible age-dependent association with gray matter volume.

The largest of the earlier studies had results that were very similar to those of the current study, suggesting that increasing coffee intake is associated with smaller hippocampal volumes, said Dr. Hypponen.

One of the study’s limitations included the fact that full dietary information was available only for a subsample and that factors such as dehydration were measured at baseline rather than at the time of brain MRI.

Another possible study limitation was the use of self-reported data and the fact that lifestyle changes may have occurred between baseline and MRI or covariate measurement.

In addition, the study is subject to a healthy-volunteer bias, and its implications are restricted to White British persons. The association needs to be studied in other ethnic populations, the authors noted.

A reason to cut back?

Commenting on the findings, Walter Willett, MD, DrPH, professor of epidemiology and nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, said the study is large and quite well done.

“It does raise questions about an increase in risk of dementia with six or more cups of coffee per day,” said Dr. Willett. “At the same time, it provides reassurance about lack of adverse effects of coffee for those consuming three or four cups per day, and little increase in risk, if any, with five cups per day.”

It’s not entirely clear whether the increase in risk with six or more cups of coffee per day represents a “true effect” of coffee, inasmuch as the study did not seem to adjust fully for dietary factors, high consumption of alcohol, or past smoking, said Dr. Willett.

The findings don’t suggest that coffee lovers should give up their Java. “But six or more cups per day is a lot, and those who drink that much might consider cutting back a bit while research continues,” said Dr. Willett.

The study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NUTRITIONAL NEUROSCIENCE

Remote cognitive assessments get positive mark

That is the message behind numerous publications in recent years, and the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated that trend.

“The publications have just skyrocketed since 2018, but I think there are still some additional tests that we need to validate using this medium of assessment. Also, I think we need to kind of put on our thinking caps as a field and think outside the box. What novel tests can we develop that will capitalize upon the telehealth environment – interactive tests that are monitoring [the individuals’] performance in real time and giving the examiner feedback, things like that,” said Munro Cullum, PhD, in an interview. Dr. Cullum spoke on the topic at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Still, challenges remain, especially factors in the home environment that can adversely affect testing. “Some of our tests are a question-answer, pencil-paper sort of tests that can be well suited to a telemedicine environment, [but] other tests don’t translate as well. So we still have a ways to go to kind of get our test to the next generation when being administered during this type of assessment. But a lot of the verbal tests work extremely well,” said Dr. Cullum, who is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

Preliminary evidence of equivalence

Some years ago, Dr. Cullum was interested in getting a better understanding of what existing tests could best be performed remotely, and what populations could most benefit from remote assessments. Existing studies were generally supportive of remote testing, but varied significantly in their methodology and design. He went on to publish a study in 2014 showing equivalency of existing tests in the in-person and remote environment, and that helped pave the way for a wave of more recent studies that seem to confirm equivalence of in-person methods.

“If you look at the literature overall, there is a nice, growing body of evidence suggesting support for a host of neuropsychological test instruments. For the most part, almost all have shown good reliability across test conditions,” Dr. Cullum said during the talk.

He said that he is often asked if different test norms will be required for remote tests, but that doesn’t seem to be a concern. “It looks like the regular old neuropsych test norms should serve as well in this remote assessment environment. Although as within hospital testing of patients, conservative use of norms is always an order. They are interpretive guidelines,” he added.

One concern is potential threats to validity within the home environment. He posted an image of a woman at home, taking a remote cognitive test. The desk she sat at overlooked a wooded scene, and had a sewing machine on it. A small dog lay in her lap. “So assessing the home environment, ensuring that it is as close to a clinical standard setting as possible, is certainly advised,” said Dr. Cullum.

Although much progress has been made in studying existing tests in a telemedicine environment, many commonly used tests still haven’t been studied. The risk of intrusions and distractions, and even connectivity issues, can be limiting factors. Some tests may be ineligible for remote use due to copyright issues that might prevent required materials from being displayed online. For those reasons and others, not all individuals are suited for a remote test.

Finally, remote tests should be viewed with healthy skepticism. “In doing clinical evaluations this way, we have to be extra careful to not mis- or overinterpret the findings in case there were any distractions or glitches in the examination that came up during the test,” said Dr. Cullum.

Looking toward the future

Moving forward, Dr. Cullum called for more research to design new tests to exploit the telehealth format. “I think this is a really important opportunity for new test development in neuropsychology with increasing incorporation of computerized measures and integration with more cognitive neuroscience and clinical neuropsychology principles.”

He also suggested that remote testing could be combined with neuroimaging, neuromodulation, and even portable magnetoencephalography. “These opportunities for research can enhance compliance, enhance large-scale studies to allow for the inclusion of brief cognitive outcome metrics that might not have other otherwise been [possible],” said Dr. Cullum.

During the question-and-answer session, someone asked if the momentum towards telehealth will continue once the COVID-19 pandemic recedes. “We believe telehealth is here to stay, or at least I do,” said session moderator Allison Lindauer, PhD, who was asked to comment. Dr. Lindauer is an associate professor at the Layton Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Center in Portland, Ore.

Dr. Lindauer has also conducted studies on telehealth-delivered assessments and also found encouraging results. “Work like this says, we have confidence in our work, we can believe that what we’re assessing and what we’re doing – if we did it face to face, we would get similar results,” Dr. Lindauer said in an interview.

Plenty of challenges remain, and the most important is widely available broadband internet, said Dr. Lindauer. “We need a huge push to get broadband everywhere. Granted, you’re going to have people that don’t want to use the computer, or they’re nervous about doing it online. But in my experience, most people with enough coaching can do it and are fine with it.”

Dr. Cullum and Dr. Lindauer have no relevant financial disclosures.

That is the message behind numerous publications in recent years, and the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated that trend.

“The publications have just skyrocketed since 2018, but I think there are still some additional tests that we need to validate using this medium of assessment. Also, I think we need to kind of put on our thinking caps as a field and think outside the box. What novel tests can we develop that will capitalize upon the telehealth environment – interactive tests that are monitoring [the individuals’] performance in real time and giving the examiner feedback, things like that,” said Munro Cullum, PhD, in an interview. Dr. Cullum spoke on the topic at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Still, challenges remain, especially factors in the home environment that can adversely affect testing. “Some of our tests are a question-answer, pencil-paper sort of tests that can be well suited to a telemedicine environment, [but] other tests don’t translate as well. So we still have a ways to go to kind of get our test to the next generation when being administered during this type of assessment. But a lot of the verbal tests work extremely well,” said Dr. Cullum, who is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

Preliminary evidence of equivalence

Some years ago, Dr. Cullum was interested in getting a better understanding of what existing tests could best be performed remotely, and what populations could most benefit from remote assessments. Existing studies were generally supportive of remote testing, but varied significantly in their methodology and design. He went on to publish a study in 2014 showing equivalency of existing tests in the in-person and remote environment, and that helped pave the way for a wave of more recent studies that seem to confirm equivalence of in-person methods.

“If you look at the literature overall, there is a nice, growing body of evidence suggesting support for a host of neuropsychological test instruments. For the most part, almost all have shown good reliability across test conditions,” Dr. Cullum said during the talk.

He said that he is often asked if different test norms will be required for remote tests, but that doesn’t seem to be a concern. “It looks like the regular old neuropsych test norms should serve as well in this remote assessment environment. Although as within hospital testing of patients, conservative use of norms is always an order. They are interpretive guidelines,” he added.

One concern is potential threats to validity within the home environment. He posted an image of a woman at home, taking a remote cognitive test. The desk she sat at overlooked a wooded scene, and had a sewing machine on it. A small dog lay in her lap. “So assessing the home environment, ensuring that it is as close to a clinical standard setting as possible, is certainly advised,” said Dr. Cullum.

Although much progress has been made in studying existing tests in a telemedicine environment, many commonly used tests still haven’t been studied. The risk of intrusions and distractions, and even connectivity issues, can be limiting factors. Some tests may be ineligible for remote use due to copyright issues that might prevent required materials from being displayed online. For those reasons and others, not all individuals are suited for a remote test.

Finally, remote tests should be viewed with healthy skepticism. “In doing clinical evaluations this way, we have to be extra careful to not mis- or overinterpret the findings in case there were any distractions or glitches in the examination that came up during the test,” said Dr. Cullum.

Looking toward the future

Moving forward, Dr. Cullum called for more research to design new tests to exploit the telehealth format. “I think this is a really important opportunity for new test development in neuropsychology with increasing incorporation of computerized measures and integration with more cognitive neuroscience and clinical neuropsychology principles.”

He also suggested that remote testing could be combined with neuroimaging, neuromodulation, and even portable magnetoencephalography. “These opportunities for research can enhance compliance, enhance large-scale studies to allow for the inclusion of brief cognitive outcome metrics that might not have other otherwise been [possible],” said Dr. Cullum.

During the question-and-answer session, someone asked if the momentum towards telehealth will continue once the COVID-19 pandemic recedes. “We believe telehealth is here to stay, or at least I do,” said session moderator Allison Lindauer, PhD, who was asked to comment. Dr. Lindauer is an associate professor at the Layton Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Center in Portland, Ore.

Dr. Lindauer has also conducted studies on telehealth-delivered assessments and also found encouraging results. “Work like this says, we have confidence in our work, we can believe that what we’re assessing and what we’re doing – if we did it face to face, we would get similar results,” Dr. Lindauer said in an interview.

Plenty of challenges remain, and the most important is widely available broadband internet, said Dr. Lindauer. “We need a huge push to get broadband everywhere. Granted, you’re going to have people that don’t want to use the computer, or they’re nervous about doing it online. But in my experience, most people with enough coaching can do it and are fine with it.”

Dr. Cullum and Dr. Lindauer have no relevant financial disclosures.

That is the message behind numerous publications in recent years, and the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated that trend.

“The publications have just skyrocketed since 2018, but I think there are still some additional tests that we need to validate using this medium of assessment. Also, I think we need to kind of put on our thinking caps as a field and think outside the box. What novel tests can we develop that will capitalize upon the telehealth environment – interactive tests that are monitoring [the individuals’] performance in real time and giving the examiner feedback, things like that,” said Munro Cullum, PhD, in an interview. Dr. Cullum spoke on the topic at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Still, challenges remain, especially factors in the home environment that can adversely affect testing. “Some of our tests are a question-answer, pencil-paper sort of tests that can be well suited to a telemedicine environment, [but] other tests don’t translate as well. So we still have a ways to go to kind of get our test to the next generation when being administered during this type of assessment. But a lot of the verbal tests work extremely well,” said Dr. Cullum, who is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

Preliminary evidence of equivalence

Some years ago, Dr. Cullum was interested in getting a better understanding of what existing tests could best be performed remotely, and what populations could most benefit from remote assessments. Existing studies were generally supportive of remote testing, but varied significantly in their methodology and design. He went on to publish a study in 2014 showing equivalency of existing tests in the in-person and remote environment, and that helped pave the way for a wave of more recent studies that seem to confirm equivalence of in-person methods.

“If you look at the literature overall, there is a nice, growing body of evidence suggesting support for a host of neuropsychological test instruments. For the most part, almost all have shown good reliability across test conditions,” Dr. Cullum said during the talk.

He said that he is often asked if different test norms will be required for remote tests, but that doesn’t seem to be a concern. “It looks like the regular old neuropsych test norms should serve as well in this remote assessment environment. Although as within hospital testing of patients, conservative use of norms is always an order. They are interpretive guidelines,” he added.

One concern is potential threats to validity within the home environment. He posted an image of a woman at home, taking a remote cognitive test. The desk she sat at overlooked a wooded scene, and had a sewing machine on it. A small dog lay in her lap. “So assessing the home environment, ensuring that it is as close to a clinical standard setting as possible, is certainly advised,” said Dr. Cullum.

Although much progress has been made in studying existing tests in a telemedicine environment, many commonly used tests still haven’t been studied. The risk of intrusions and distractions, and even connectivity issues, can be limiting factors. Some tests may be ineligible for remote use due to copyright issues that might prevent required materials from being displayed online. For those reasons and others, not all individuals are suited for a remote test.

Finally, remote tests should be viewed with healthy skepticism. “In doing clinical evaluations this way, we have to be extra careful to not mis- or overinterpret the findings in case there were any distractions or glitches in the examination that came up during the test,” said Dr. Cullum.

Looking toward the future

Moving forward, Dr. Cullum called for more research to design new tests to exploit the telehealth format. “I think this is a really important opportunity for new test development in neuropsychology with increasing incorporation of computerized measures and integration with more cognitive neuroscience and clinical neuropsychology principles.”

He also suggested that remote testing could be combined with neuroimaging, neuromodulation, and even portable magnetoencephalography. “These opportunities for research can enhance compliance, enhance large-scale studies to allow for the inclusion of brief cognitive outcome metrics that might not have other otherwise been [possible],” said Dr. Cullum.

During the question-and-answer session, someone asked if the momentum towards telehealth will continue once the COVID-19 pandemic recedes. “We believe telehealth is here to stay, or at least I do,” said session moderator Allison Lindauer, PhD, who was asked to comment. Dr. Lindauer is an associate professor at the Layton Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Center in Portland, Ore.

Dr. Lindauer has also conducted studies on telehealth-delivered assessments and also found encouraging results. “Work like this says, we have confidence in our work, we can believe that what we’re assessing and what we’re doing – if we did it face to face, we would get similar results,” Dr. Lindauer said in an interview.

Plenty of challenges remain, and the most important is widely available broadband internet, said Dr. Lindauer. “We need a huge push to get broadband everywhere. Granted, you’re going to have people that don’t want to use the computer, or they’re nervous about doing it online. But in my experience, most people with enough coaching can do it and are fine with it.”

Dr. Cullum and Dr. Lindauer have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AAIC 2021

Reducing air pollution is linked to slowed brain aging and lower dementia risk

, new research reveals. The findings have implications for individual behaviors, such as avoiding areas with poor air quality, but they also have implications for public policy, said study investigator, Xinhui Wang, PhD, assistant professor of research neurology, department of neurology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“Controlling air quality has great benefits not only for the short-term, for example for pulmonary function or very broadly mortality, but can impact brain function and slow memory function decline and in the long run may reduce dementia cases.”

The findings were presented at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

New approach

Previous research examining the impact of reducing air pollution, which has primarily examined respiratory illnesses and mortality, showed it is beneficial. However, no previous studies have examined the impact of improved air quality on cognitive function.

The current study used a subset of participants from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study-Epidemiology of Cognitive Health Outcomes (WHIMS-ECHO), which evaluated whether postmenopausal women derive cognitive benefit from hormone therapy.

The analysis included 2,232 community-dwelling older women aged 74-92 (mean age, 81.5 years) who did not have dementia at study enrollment.

Researchers obtained measures of participants’ annual cognitive function from 2008 to 2018. These measures included general cognitive status assessed using the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified (TICSm) and episodic memory assessed by the telephone-based California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT).

The investigators used complex geographical covariates to estimate exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), in areas where individual participants lived from 1996 to 2012. The investigators averaged measures over 3-year periods immediately preceding (recent exposure) and 10 years prior to (remote exposure) enrollment, then calculated individual-level improvements in air quality as the reduction from remote to recent exposures.

The researchers examined pollution exposure and cognitive outcomes at different times to determine causation.

“Maybe the relationship isn’t causal and is just an association, so we tried to separate the timeframe for exposure and outcome and make sure the exposure was before we measured the outcome,” said Dr. Wang.

The investigators adjusted for multiple sociodemographic, lifestyle, and clinical characteristics.

Reduced dementia risk

The analysis showed air quality improved significantly for both PM2.5 and NO2 before study enrollment. “For almost 95% of the subjects in our study, air quality improved over the 10 years,” said Dr. Wang.

During a median follow-up of 6.2 years, there was a significant decline in cognitive status and episodic memory in study participants, which makes sense, said Dr. Wang, because cognitive function naturally declines with age.

However, a 10% improvement in air quality PM2.5 and NO2 resulted in a respective 14% and 26% decreased risk for dementia. This translates into a level of risk seen in women 2 to 3 years younger.

Greater air quality improvement was associated with slower decline in both general cognitive status and episodic memory.

“Participants all declined in cognitive function, but living in areas with the greatest air quality improvement slowed this decline,” said Dr. Wang.

“Whether you look at global cognitive function or memory-specific function, and whether you look at PM2.5 or NO2, slower decline was in the range of someone who is 1-2 years younger.”

The associations did not significantly differ by age, region, education, APOE ε4 genotypes, or cardiovascular risk factors.

Patients concerned about cognitive decline can take steps to avoid exposure to pollution by wearing a mask; avoiding heavy traffic, fires, and smoke; or moving to an area with better air quality, said Dr. Wang.

“But our study mainly tried to provide some evidence for policymakers and regulators,” she added.

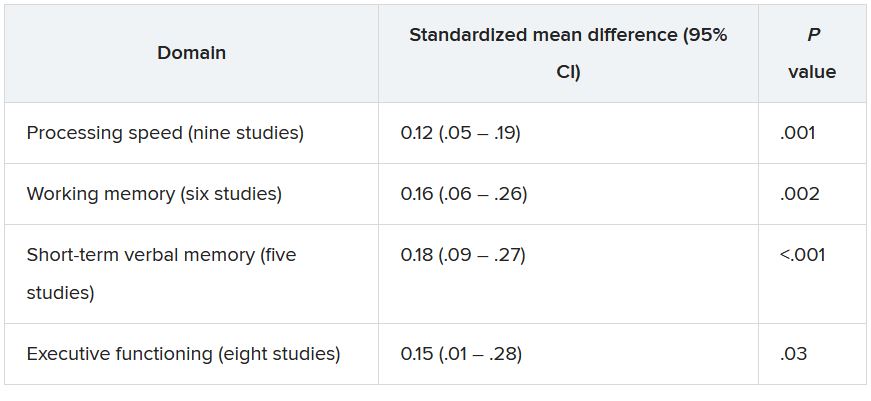

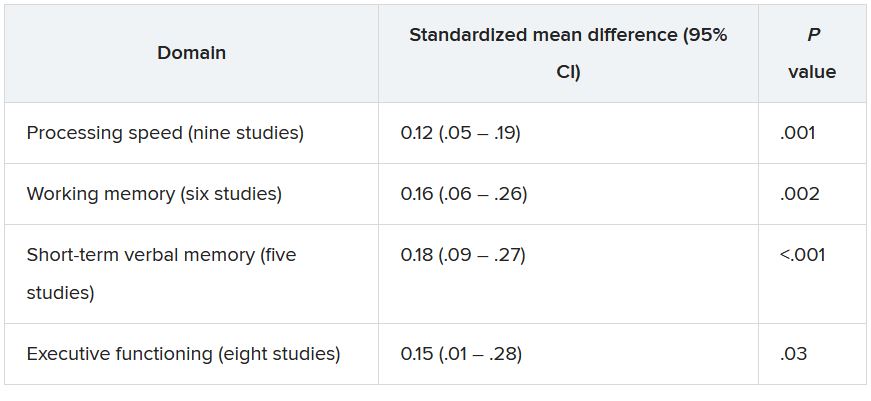

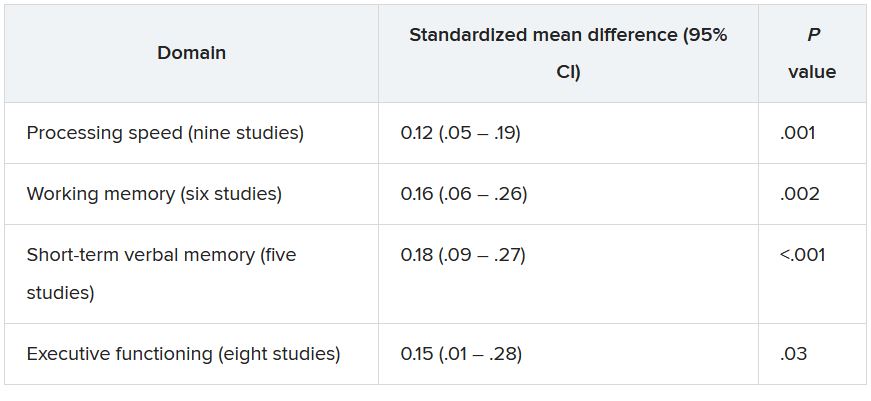

Another study carried out by the same investigators suggests pollution may affect various cognitive functions differently. This analysis used the same cohort, timeframe, and air quality improvement indicators as the first study but examined the association with specific cognitive domains, including episodic memory, working memory, attention/executive function, and language.

The investigators found women living in locations with greater PM2.5 improvement performed better on tests of episodic memory (P = .002), working memory (P = .01) and attention/executive function (P = .01), but not language. Findings were similar for improved NO2.

When looking at air quality improvement and trajectory slopes of decline across cognitive functions, only the association between improved NO2 and slower episodic memory decline was statistically significant (P < 0.001). “The other domains were marginal or not significant,” said Dr. Wang.

“This suggests that brain regions are impacted differently,” she said, adding that various brain areas oversee different cognitive functions.

Important policy implications

Commenting on the research, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement, Alzheimer’s Association, said she welcomes new research on environmental factors that affect Alzheimer’s disease.

Whereas previous studies have linked longterm air pollution exposure to accumulation of Alzheimer’s disease-related brain plaques and increased risk of dementia, “these newer studies provide some of the first evidence to suggest that actually reducing pollution is associated with lower risk of all-cause dementia,” said Dr. Edelmayer.

Individuals can control some factors that contribute to dementia risk, such as exercise, diet, and physical activity, but it’s more difficult for them to control exposure to smog and pollution, she said.

“This is probably going to require changes to policy from federal and local governments and businesses, to start addressing the need to improve air quality to help reduce risk for dementia.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research reveals. The findings have implications for individual behaviors, such as avoiding areas with poor air quality, but they also have implications for public policy, said study investigator, Xinhui Wang, PhD, assistant professor of research neurology, department of neurology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“Controlling air quality has great benefits not only for the short-term, for example for pulmonary function or very broadly mortality, but can impact brain function and slow memory function decline and in the long run may reduce dementia cases.”

The findings were presented at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

New approach

Previous research examining the impact of reducing air pollution, which has primarily examined respiratory illnesses and mortality, showed it is beneficial. However, no previous studies have examined the impact of improved air quality on cognitive function.

The current study used a subset of participants from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study-Epidemiology of Cognitive Health Outcomes (WHIMS-ECHO), which evaluated whether postmenopausal women derive cognitive benefit from hormone therapy.