User login

Clinical Pearl: Advantages of the Scalp as a Split-Thickness Skin Graft Donor Site

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

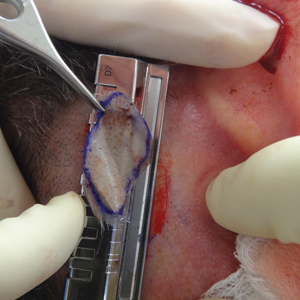

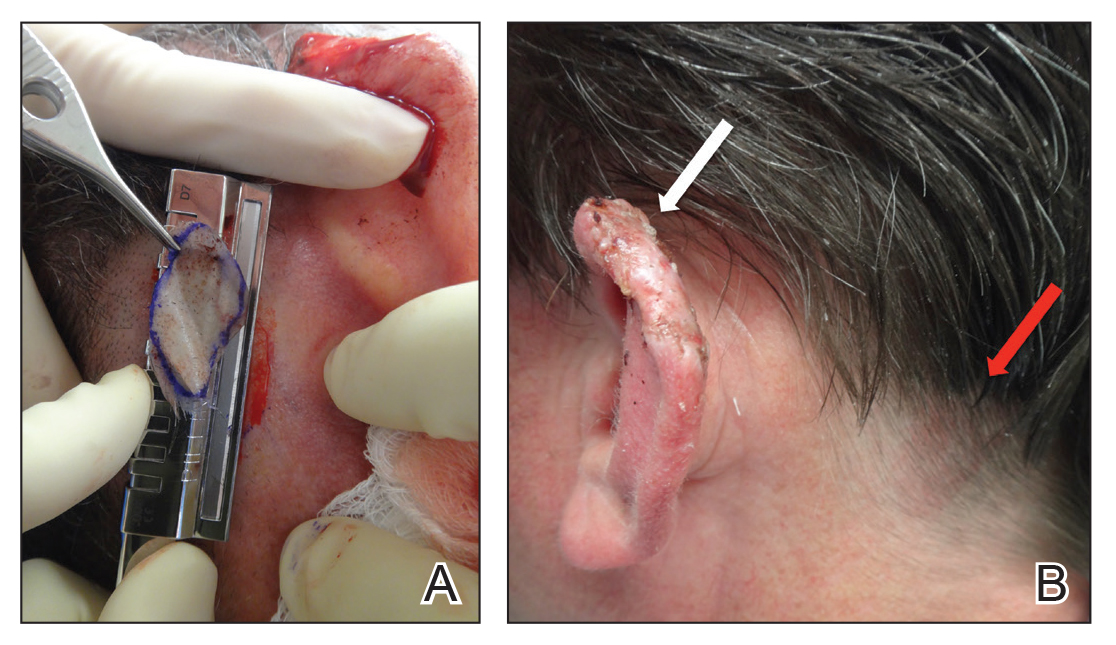

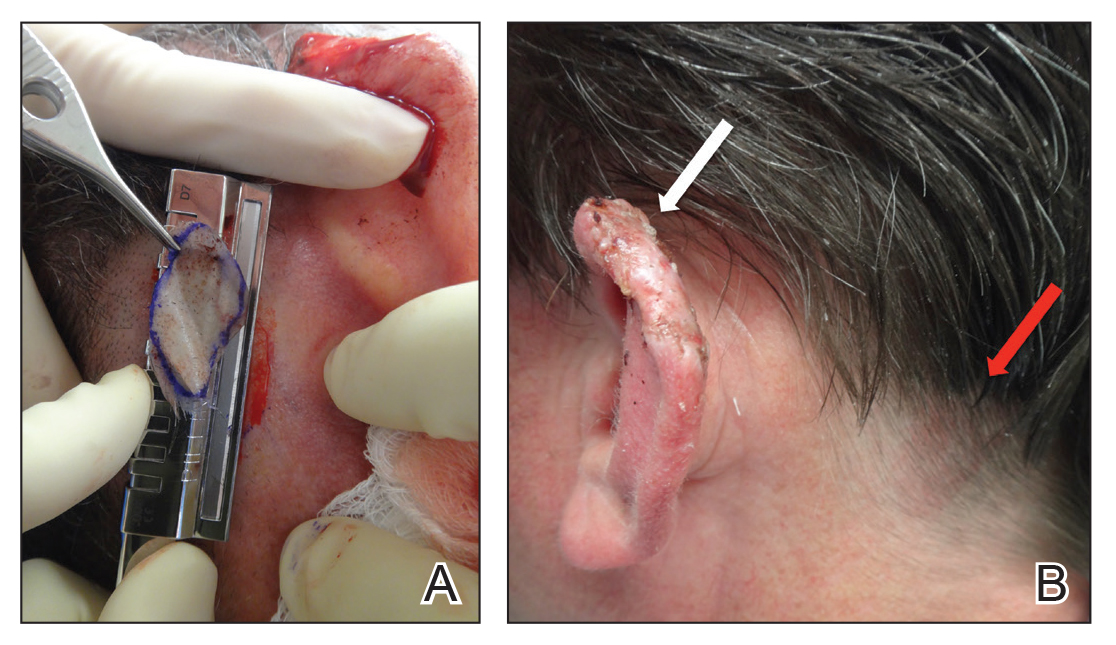

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

- Aneer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:28-35.

- Goulian D. A new economical dermatome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42:85-86.

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

- Aneer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:28-35.

- Goulian D. A new economical dermatome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42:85-86.

- Aneer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:28-35.

- Goulian D. A new economical dermatome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42:85-86.

Ocular Chemical Burns in the Dermatology Office: A Practical Approach to Managing Safety Precautions

Many dermatologic procedures are performed on the face, such as skin biopsies, surgical excisions, and cosmetic procedures, which can increase the risk for accidental ocular injuries.1,2 Ocular chemical burns have been reported to account for approximately 3% to 20% of ocular injuries3,4 and are one of the few ocular emergencies dermatologists may encounter in practice. Given the potentially severe consequences of permanent vision changes or loss, it is important to take precautionary steps in preventing chemical exposures and know how to appropriately manage ophthalmic emergencies when they occur.1,5-8 In this article, we describe a patient with a transient ocular chemical injury from exposure to aluminum chloride hexahydrate that completely resolved with immediate care. We also offer practical guidance for the general dermatologist in the acute management of acidic chemical burns to the eye, highlighting immediate copious irrigation as the most important step in preventing severe permanent damage. Given that aluminum chloride hexahydrate is an acidic solution, we focus predominantly on the approach to acidic chemical exposures to the eye.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman was seen in the dermatology outpatient clinic for a shave biopsy on the left cheek followed by aluminum chloride application for hemostasis. Following the biopsy, the patient stated she felt the sensation that something had dripped into the left eye and she felt a burning pain. There was a 30- to 60-second delay in irrigation of the eye, as it was at first unclear what had occurred. The patient reported an increased burning sensation, and at that point she was instructed to begin flushing the eye with tap water from the examination room sink for 15 to 20 minutes; she wanted to stop irrigation after a few minutes, and convincing her to continue thorough irrigation was somewhat challenging. It was determined that aluminum chloride hexahydrate had dripped from an oversaturated cotton swab in transit from the tray to the biopsy site.

The patient was urgently directed to the ophthalmology clinic and evaluated by an ophthalmologist within 1 to 2 hours of chemical exposure. Visual acuity of the affected left eye was noted to be 20/30 -2 with correctional glasses, and slit lamp examination revealed moderate injection of the conjunctiva and sclera, and at least 3 punctate epithelial erosions and punctate staining of the inferior aspects of the cornea, consistent with a chemical injury. The remaining ocular examination was normal for both eyes. She was diagnosed with keratitis of the left eye from chemical exposure to aluminum chloride and was prescribed loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 0.5% and tobramycin ophthalmic solution 0.3% to be applied to the left eye 4 times daily, with follow-up 4 days later.

At follow-up, the patient denied any pain, though she was not using the prescribed eye drops consistently. On examination, the patient showed improvement in visual acuity to 20/20 -2 and complete resolution of the keratitis, with slit lamp examination showing clear conjunctiva, sclera, and cornea. Given complete resolution, the eye drops were discontinued.

Comment

Factors Contributing to Ocular Chemical Injuries

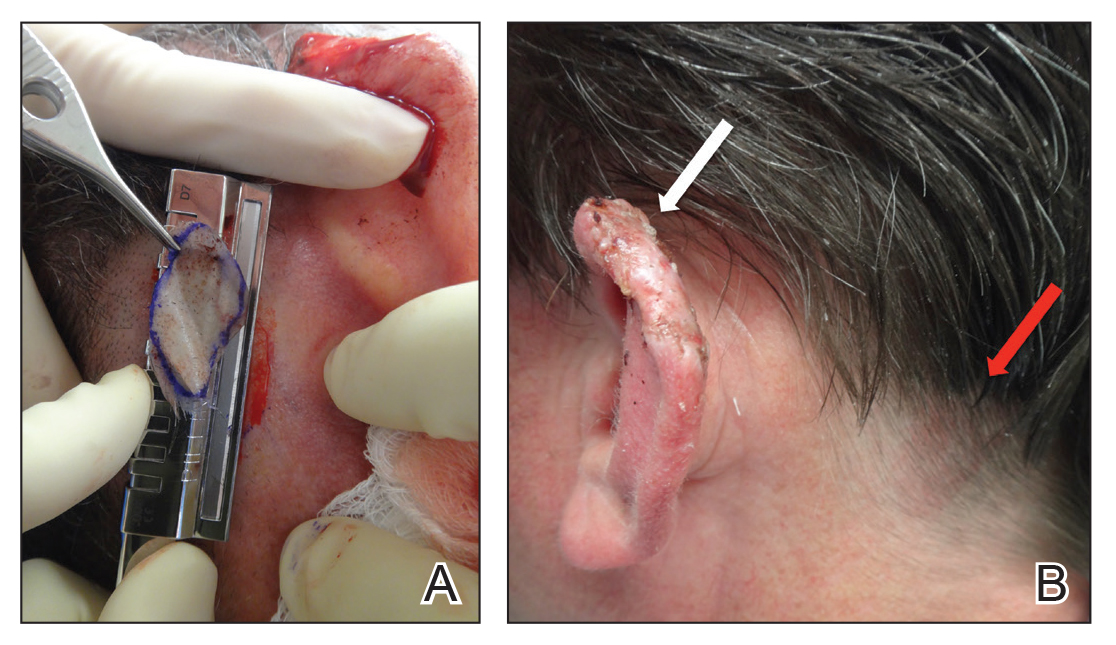

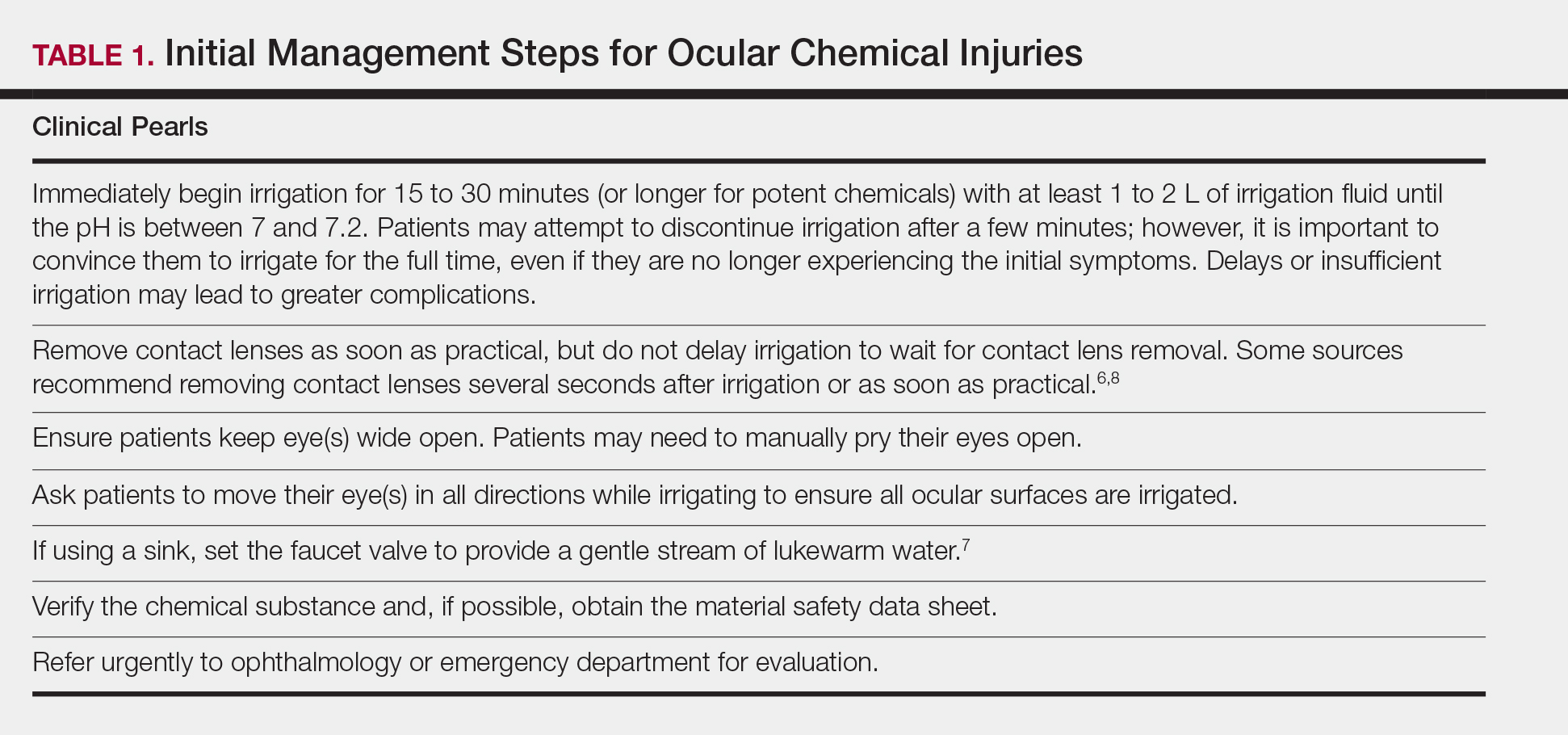

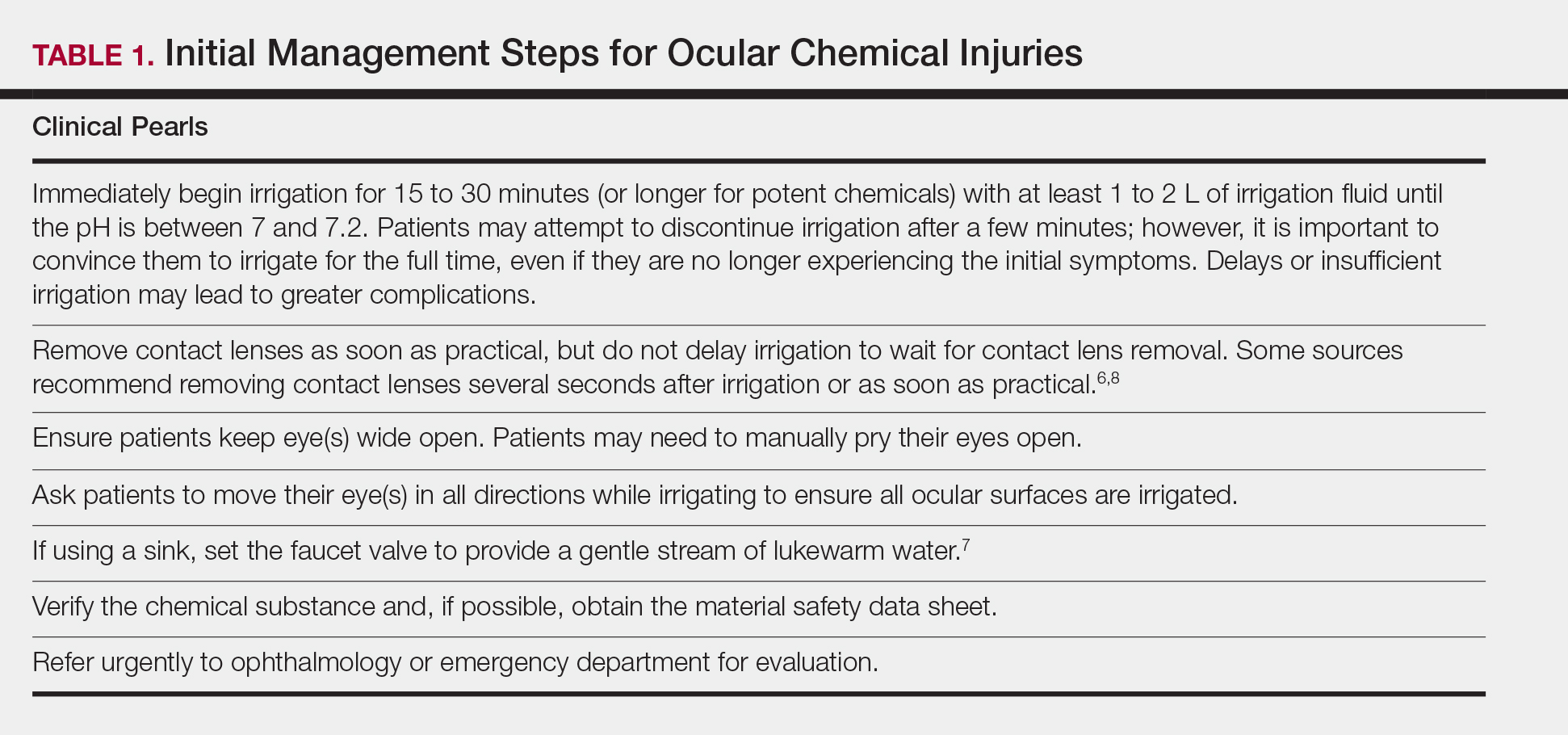

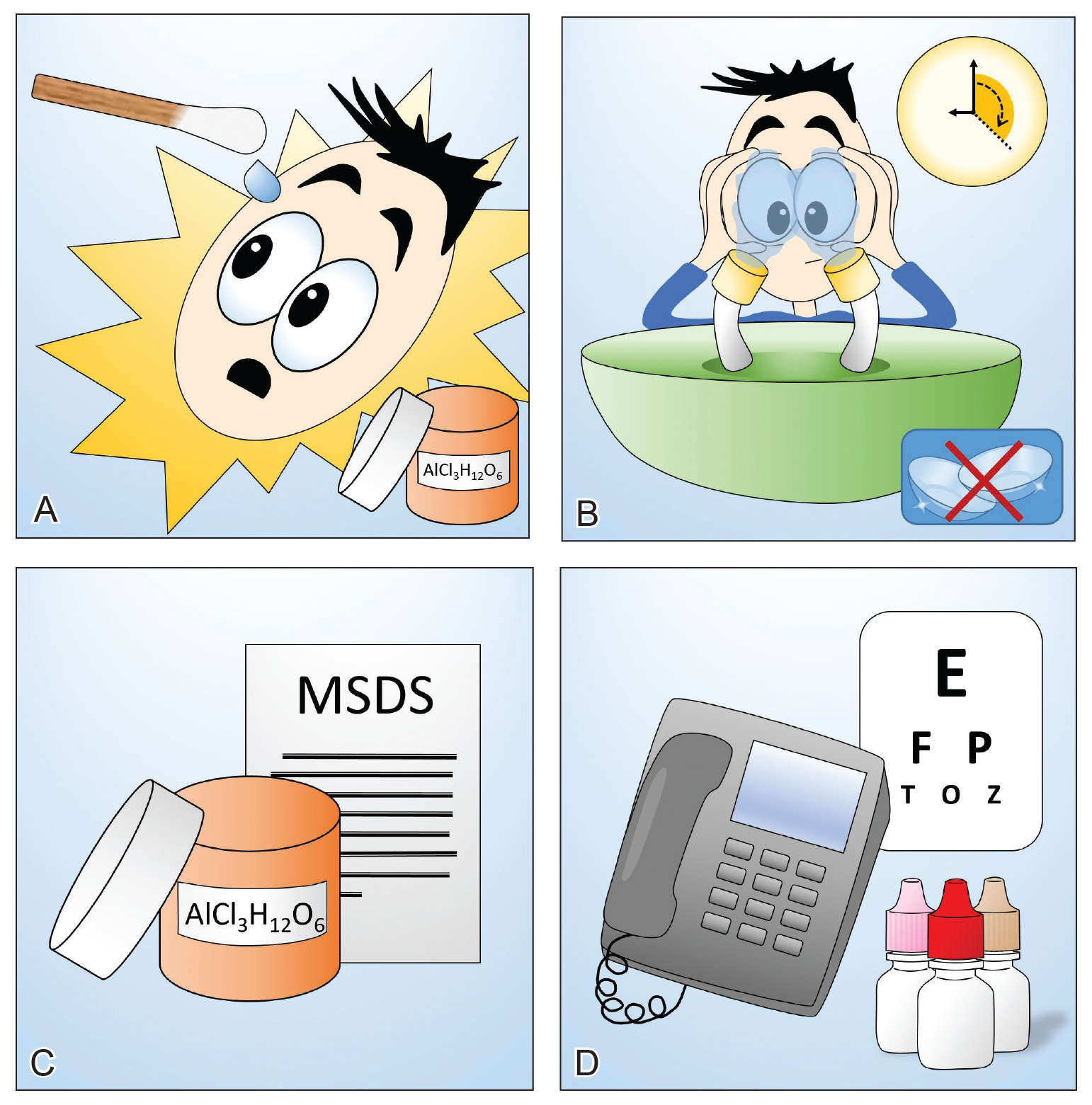

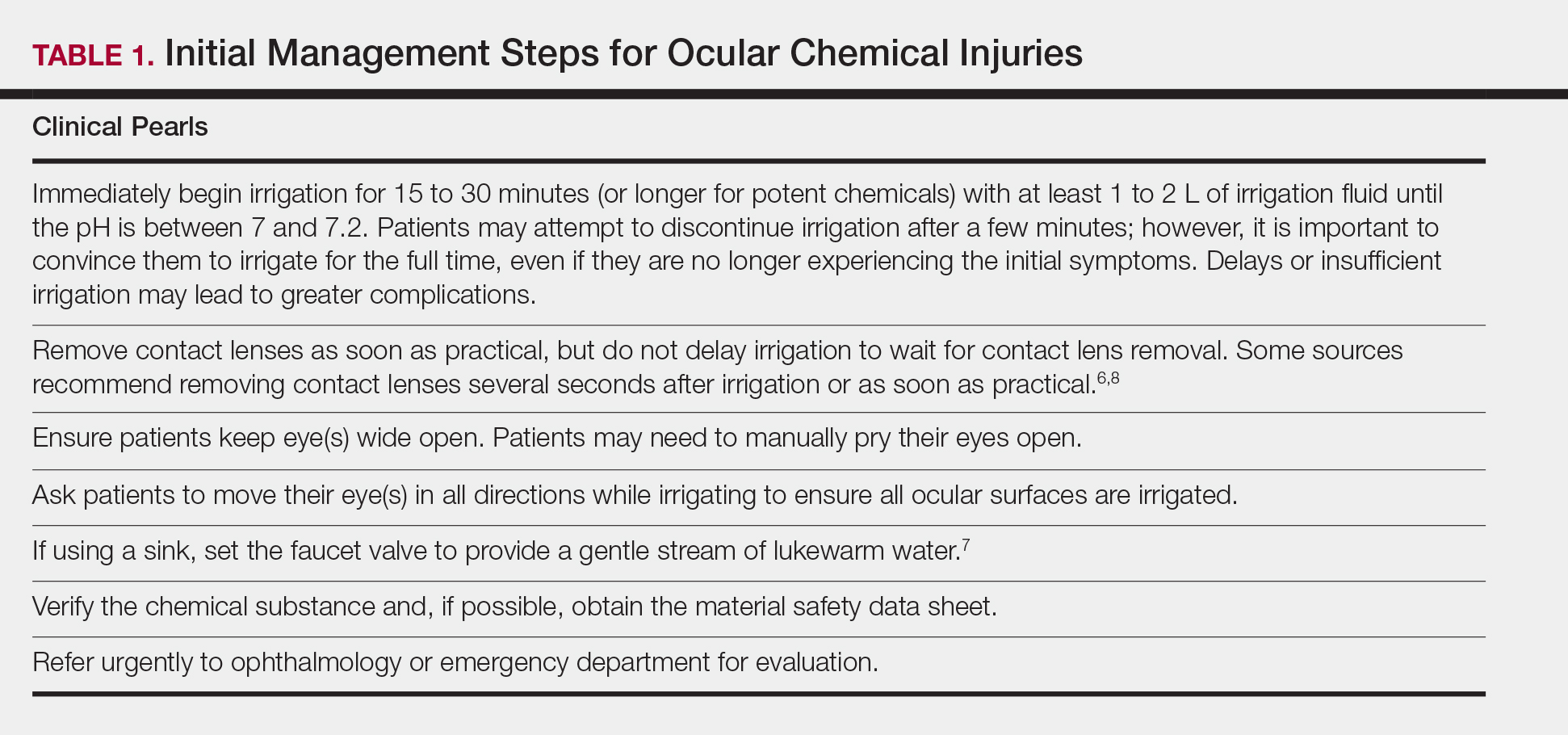

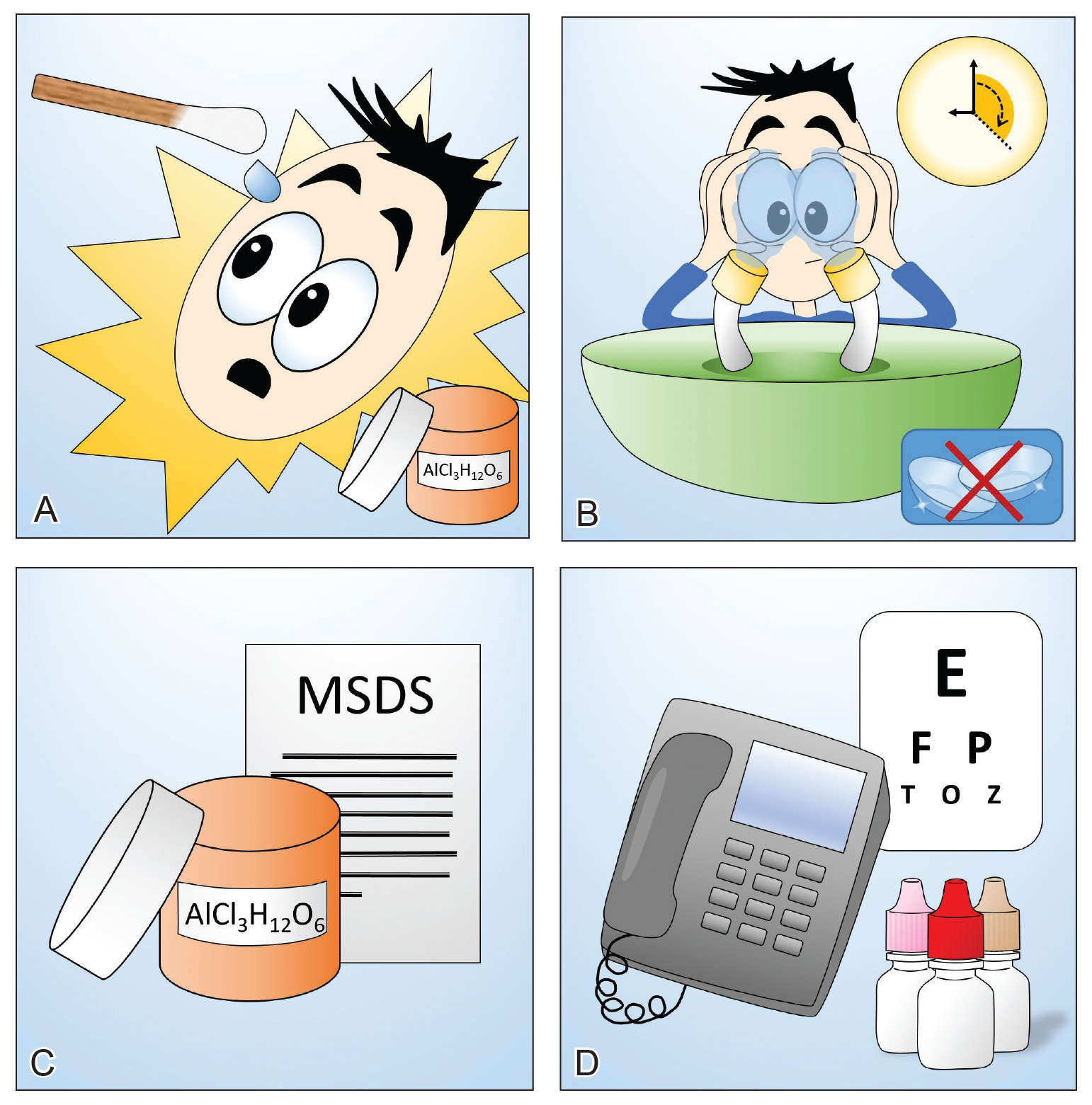

Chemical burns to the eyes during cosmetic or surgical procedures are one of the few acute ocular emergencies dermatologists may encounter in practice. If not managed properly, the eye may be permanently damaged. Therefore, dermatologists must be confident in the initial management of ocular chemical burns (Table 1; Figure).

obtain the material safety data sheet. D, Refer the patient urgently to ophthalmology for a visual acuity test and treatment. Images courtesy of Deborah J. Moon, MD (Los Angeles, California).

Mechanism of Ocular Chemical Burns

The extent of injury is predominantly determined by 2 factors: (1) the chemical properties of the substance, and (2) the length of exposure.5,9,10 Potential chemical exposures and their reported ocular effects are listed in Table 2.11-21 Alkaline chemical burns often have the gravest outcome, as they can rapidly penetrate into the internal ocular structures, potentially leading to cataracts and glaucoma.9 Hydroxyl ions, often found in alkaline chemicals, are capable of rapidly denaturing the corneal matrix and triggering release of proteolytic enzymes through a series of inflammatory responses. Conversely, ocular damage from most acidic chemicals often is limited to the more superficial structures, such as the cornea and conjunctiva, given that acids may cause corneal proteins to coagulate, thus forming a barrier that slows further penetration into deeper structures.9 Nonetheless, corneal damage can still have a devastating impact on visual acuity, as the cornea provides 65% to 75% of the eye’s total focusing power.22 For both alkaline and acidic chemicals, immediate profuse irrigation is most critical in determining the clinical course.23-26 To provide perspective, potent alkaline chemicals may penetrate into the anterior chamber of the eye within 15 seconds,9 and delayed initiation of irrigation by even 5 to 15 minutes may lead to irreversible intraocular damage.27

Symptoms of Ocular Chemical Exposure

Signs and symptoms associated with ocular chemical exposures include erythema, pain, tearing, photosensitivity, eyelid swelling, foreign body sensation, changes in vision, and corneal clouding.3,5,9,28 Specifically, aluminum chloride hexahydrate, a hemostatic agent commonly used by dermatologists, has potentially caused eye irritation and conjunctivitis, according to its material safety data sheet,29 as well as blepharospasms, transient disturbances in corneal epithelium, and a persistent faint nebula in the corneal stroma.30 Similar antiperspirants also showed damaging effects to bovine lenses, ocular irritation, and subjective reports of burning and watery eyes.31-33

Immediate Management

If potential chemical exposure to the eye is suspected either by the health care provider or patient, immediately irrigate the affected eye(s) for at least 15 to 30 minutes (longer for alkaline burns) with at least 1 to 2 L of irrigation fluid until the pH is between 7 and 7.2.3-5,9,27,34,35 Irrigation fluids reported to be used include normal saline, Ringer lactate solution, normal saline with sodium bicarbonate, and balanced salt solution.5 If no solutions are readily available, immediate irrigation with tap water is sufficient for diluting and washing away the chemical and has been reported to have better clinical outcomes than delaying irrigation.5,24-26 Studies have shown that prolonged irrigation corresponded with reduced severity, shortened healing time, shorter in-hospital treatment duration, and quicker return to work.5,26

If an eye wash station is not available, the patient can gently flush the eye under a sink faucet set to a gentle stream of lukewarm water.6,7 The health care provider also may manually irrigate the eye. Necessary equipment includes a large syringe or clean eyecup, irrigating fluid, local anesthetic drops for comfort, a towel to soak up excessive fluid, and a bowl or kidney dish to collect the irrigated fluid.34 Providers should first wash their hands. If necessary, anesthetic eye drops may be added for comfort. Lay a towel over the patient’s neck and shoulders and position the patient at a comfortable angle. Place a bowl adjacent to the patient’s cheek to collect the irrigating fluid and have the patient tilt his/her head such that the irrigated fluid would flow into the bowl. Pour a steady stream of the irrigating fluid over the eye from a height of no more than 5 cm.6,7,34

During irrigation, ensure that the patient’s eye(s) is wide open and that all ocular surfaces, including the area underneath the eyelids, are thoroughly washed; everting the eyelids may be beneficial. Ask the patient to move his/her eye(s) in all directions while irrigating. If available, place a litmus strip in the conjunctival fornix to ensure that the goal pH of 7 to 7.2 is reached.9 The pH should be rechecked every 15 to 30 minutes to ensure there has been no change, as hidden crystalized chemical particles may continue to elute chemicals, causing further injury.3 Contact lenses, if present, should be removed as soon as practical, as lenses can trap chemicals; however, immediate initiation of irrigation should not be delayed8 (Table 1).

Identify and verify the chemical suspected to have been exposed to the patient’s eye. The material safety data sheet, which may often be found online if a hard copy is not available, may provide valuable information for the ophthalmologist.36 After thorough irrigation, refer the patient urgently to ophthalmology or the emergency department for prompt evaluation. The emergency department is frequently equipped with polymethylmethacrylate scleral lenses, also called Morgan Lens, which consist of a plastic lens connected via tubing to a bag of irrigation fluid (eg, Ringer lactate solution), allowing for prolonged continuous irrigation of the conjunctiva and cornea. The ophthalmologist will conduct a visual acuity test and complete a thorough eye examination to assess the extent of ischemic injury to the conjunctiva or sclera and damage to the corneal epithelium and internal ocular structures.9

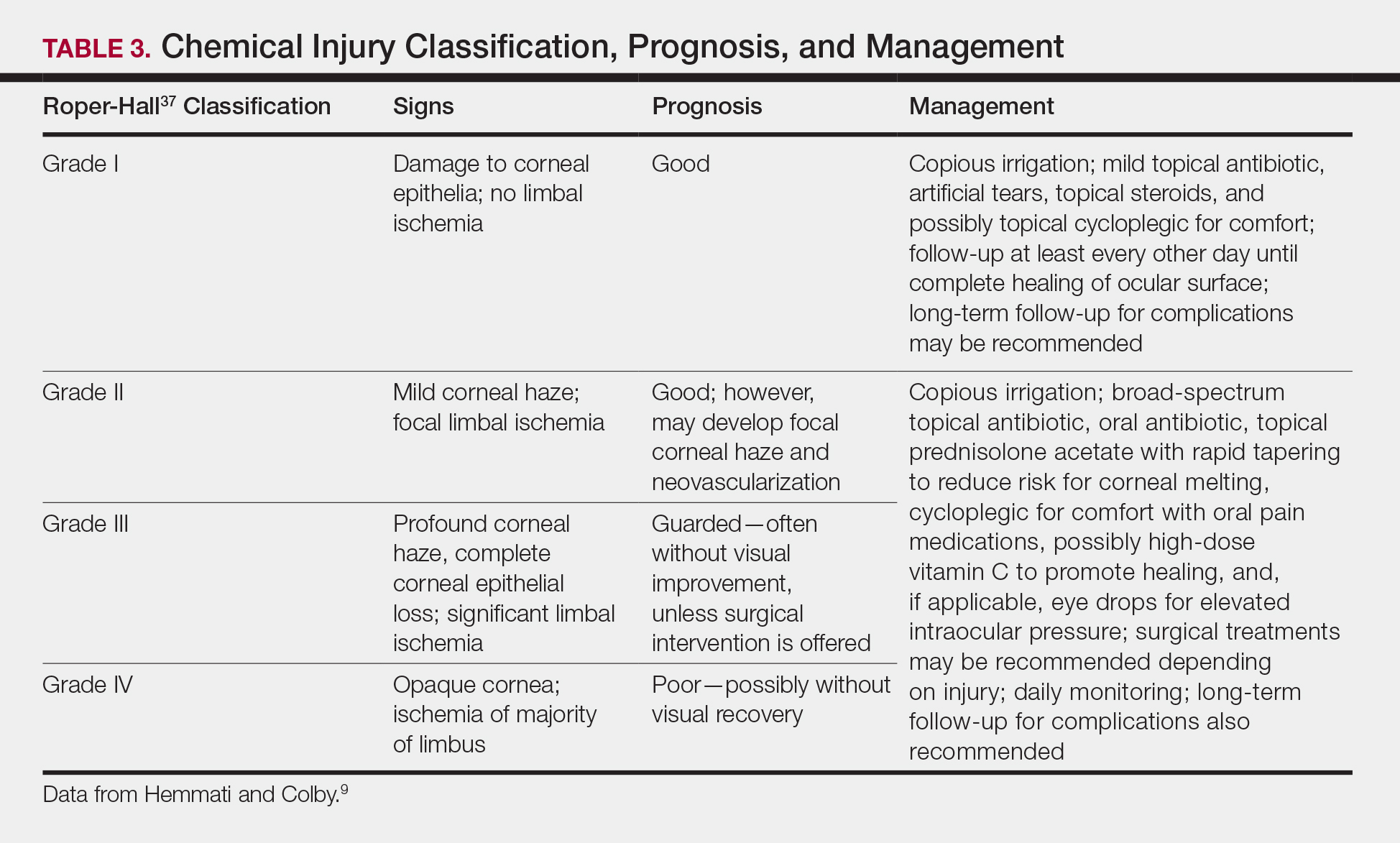

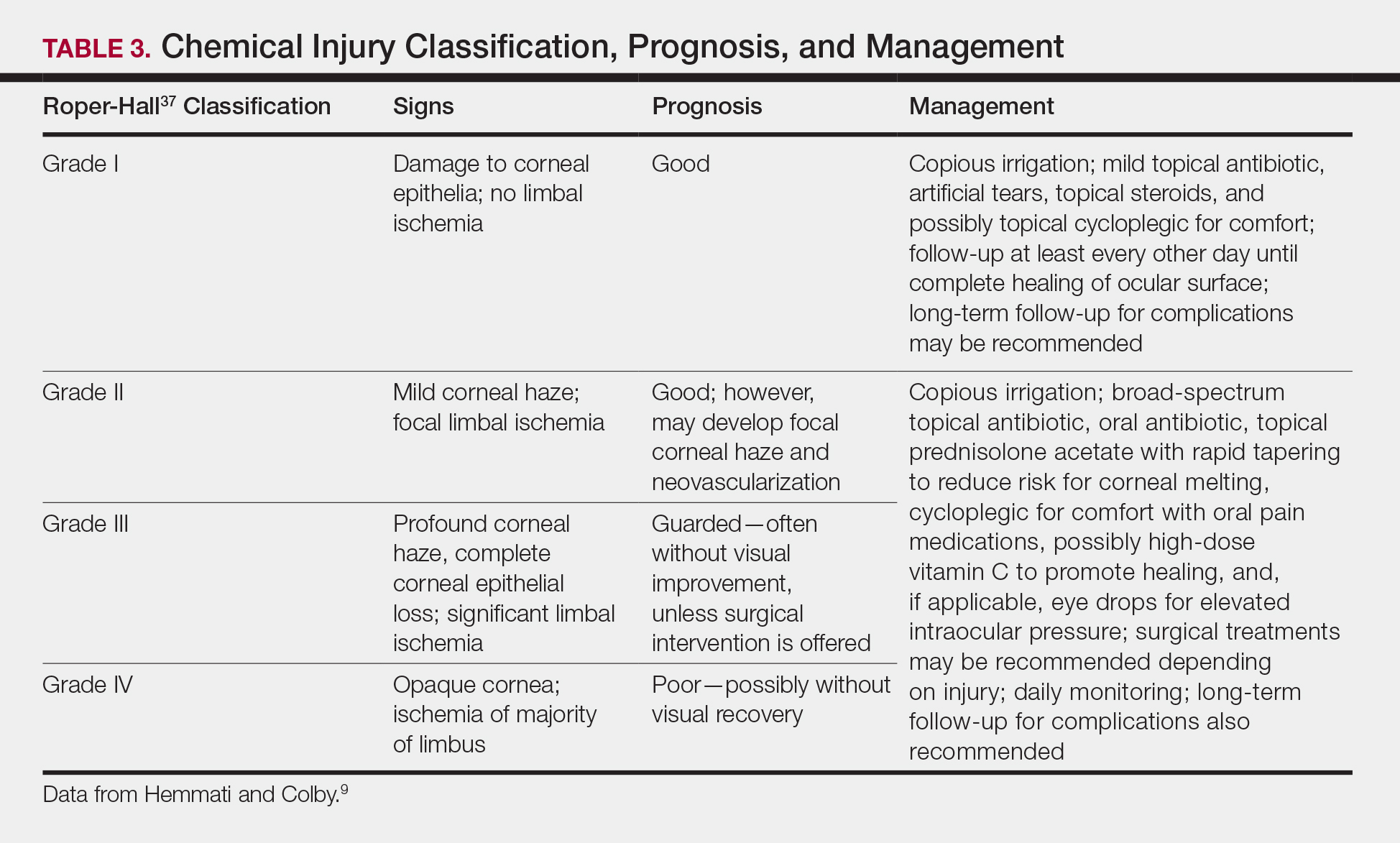

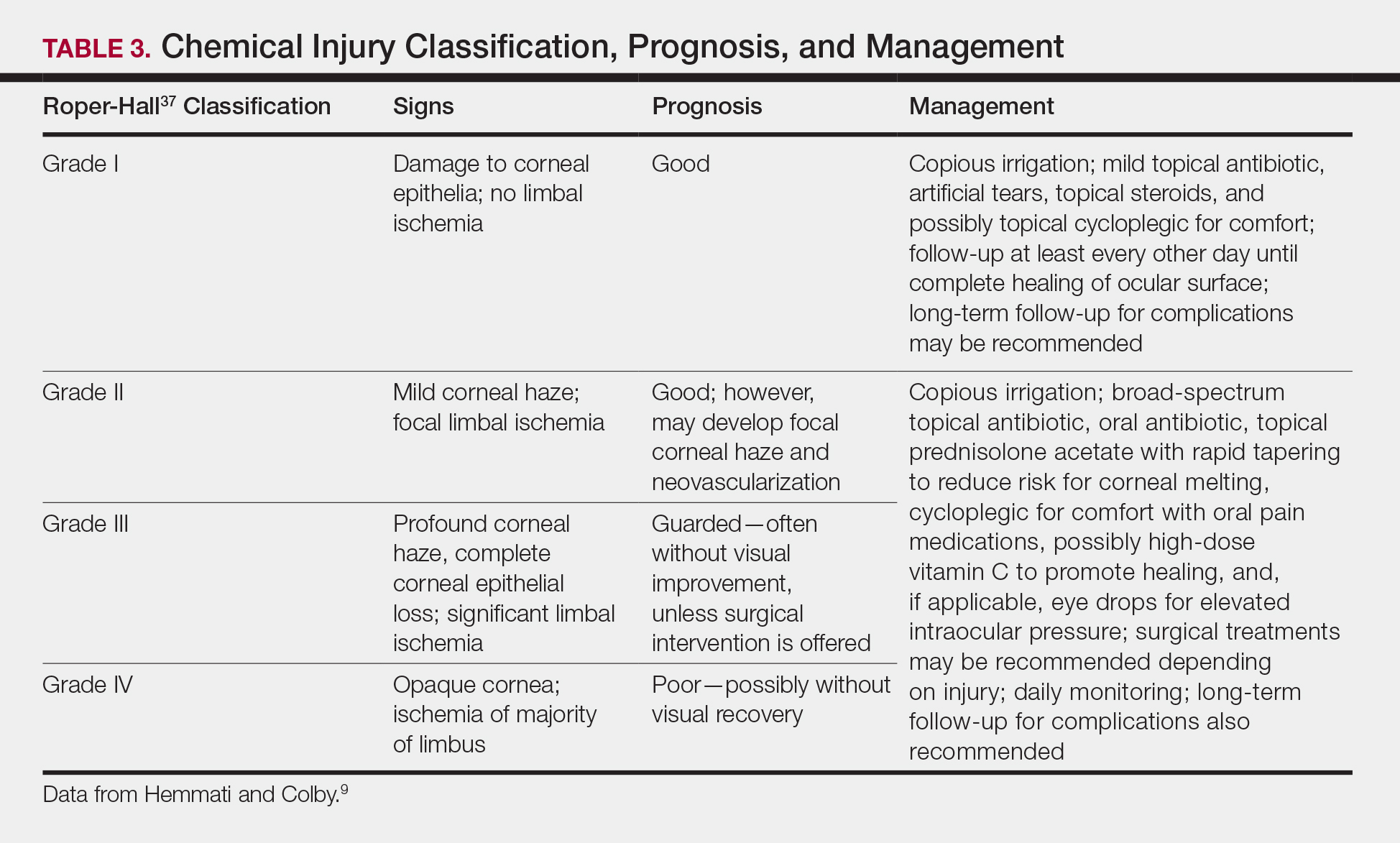

Generally, topical antibiotics, artificial tears, and topical steroids may be provided to patients with mild injury with close follow-up.9,37 For higher-grade injuries, broad-spectrum topical antibiotics, oral antibiotics, topical corticosteroids, vitamin C, and surgical treatments may be additionally recommended (Table 3). Long-term follow-up may be recommended by the ophthalmologist to monitor for potential late complications, such as glaucoma from damage to the trabecular meshwork, corneal abnormalities and limbal stem cell deficiency, symblepharon formation, or eyelid abnormalities.9

Conclusion

We report a case of a transient chemical burn to the eye secondary to exposure to aluminum chloride hexahydrate. Complete resolution of the injury was achieved with prompt irrigation and urgent medical management by ophthalmology. This case emphasizes the potential for ocular emergencies in the dermatology setting and highlights the steps for appropriate management should a chemical burn to the eye occur. We emphasize the importance of immediate profuse irrigation for 15 to 30 minutes and urgent evaluation by an ophthalmologist. Dermatologists should be cognizant of potential hazards to the eye during facial procedures and always take proper precautions to decrease the risk for ocular injuries.

- Ricci LH, Navajas SV, Carneiro PR, et al. Ocular adverse effects after facial cosmetic procedures: a review of case reports. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:145-151.

- Boonsiri M, Marks KC, Ditre CM. Benzocaine/lidocaine/tetracainecream: report of corneal damage and review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:48-50.

- Gelston CD. Common eye emergencies. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:515-519.

- Sharma N, Kaur M, Agarwal T, et al. Treatment of acute ocular chemical burns. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018;63:214-235.

- Chau JP, Lee DT, Lo SH. A systematic review of methods of eye irrigation for adults and children with ocular chemical burns. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2012;9:129-138.

- Sears W, Sears M, Sears R, et al. The Portable Pediatrician: Everything You Need to Know About Your Child’s Health. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2011.

- Kuckelkorn R, Schrage N, Keller G, et al. Emergency treatment of chemical and thermal eye burns. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80:4-10.

- Schulte PA, Ahlers HW, Jackson LL, et al. Contact Lens Use in a Chemical Environment. Cincinnati, OH: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. NIOSH publication 2005-139.

- Hemmati HD, Colby KA. Treating acute chemical injuries of the cornea. Eyenet. October 2012. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/treating-acute-chemical-injuries-of-cornea. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- Schrage NF, Langefeld S, Zschocke J, et al. Eye burns: an emergency and continuing problem. Burns. 2000;26:689-699.

- Gattey D. Chemical-induced ocular side effects. In: Fraunfelder FT, Fraunfelder FW, Chambers WA, eds. Clinical Ocular Toxicology. Edinburgh, Scotland: W.B. Saunders; 2008:289-306.

- Apt L, Isenberg SJ. Hibiclens keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:670-671.

- Tabor E, Bostwick DC, Evans C. Corneal damage due to eye contact with chlorhexidine gluconate. JAMA. 1989;261:557-558.

- Galor A, Jeng BH, Lowder CY. A curious case of corneal edema. Eyenet. January 2007. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/curious-case-of-corneal-edema. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- Hamed LM, Ellis FD, Boudreault G, et al. Hibiclens keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:50-56.

- Haring R, Sheffield ID, Channa R, et al. Epidemiologic trends of chemical ocular burns in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:1119-1124.

- Racioppi F, Daskaleros PA, Besbelli N, et al. Household bleaches based on sodium hypochlorite: review of acute toxicology and poison control center experience. Food Chem Toxicol. 1994;32:845-861.

- Shazly TA. Ocular acid burn due to 20% concentrated salicylic acid. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2011;30:84-86.

- Speaker MG, Menikoff JA. Prophylaxis of endophthalmitis with topical povidone-iodine. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1769-1775.

- Apt L, Isenberg S, Yoshimori R, et al. Chemical preparation of the eye in ophthalmic surgery: III. effect of povidone-iodine on the conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:728-729.

- Stroman DW, Mintun K, Epstein AB, et al. Reduction in bacterial load using hypochlorous acid hygiene solution on ocular skin. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:707-714.

- Paul M, Sieving A. Facts about the cornea and corneal disease. National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health website. https://nei.nih.gov/health/cornealdisease. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Khaw P, Shah P, Elkington A. Injury to the eye. BMJ. 2004;328:36-38.

- Duffy B. Managing chemical eye injuries: Bernice Duffy says initial management of potentially devastating chemical eye injuries by emergency nurses can affect patients’ future prognosis as much as subsequent ophthalmic treatment. Emerg Nurse. 2008;16:25-30.

- Burns F, Paterson C. Prompt irrigation of chemical eye injuries may avert severe damage. Occup Health Saf. 1989;58:33-36.

- Ikeda N, Hayasaka S, Hayasaka Y, et al. Alkali burns of the eye: effect of immediate copious irrigation with tap water on their severity. Ophthalmologica. 2006;220:225-228.

- Eslani M, Baradaran-Rafii A, Movahedan A, et al. The ocular surface chemical burns. J Ophthalmol. 2014;2014:196827.

- Pokhrel PK, Loftus SA. Ocular emergencies. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:829-836.

- Drysol. MSDS No. BLVCL; Glendale, CA: Person & Covey Inc; March 9, 1991. http://msdsreport.com/msds/blvcl. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Grant WM, Schuman JS. Toxicology of the Eye: Effects on the Eyes and Visual System From Chemicals, Drugs, Metals and Minerals, Plants, Toxins and Venoms: Also Systemic Side Effects From Eye Medications. Vol 1. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher; 1993.

- Wong W, Sivak JG, Moran KL. Optical response of the cultured bovine lens; testing opaque or partially transparent semi-solid/solid common consumer hygiene products. Toxicol In Vitro. 2003;17:785-790.

- Donahue DA, Kaufman LE, Avalos J, et al. Survey of ocular irritation predictive capacity using chorioallantoic membrane vascular assay (CAMVA) and bovine corneal opacity and permeability (BCOP) test historical data for 319 personal care products over fourteen years. Toxicol In Vitro. 2011;25:563-572.

- Groot AC, Nater JP, Lender R, et al. Adverse effects of cosmetics and toiletries: a retrospective study in the general population. Int J Cosmet Sci. 1987;9:255-259.

- Stevens S. Ophthalmic practice. Community Eye Health. 2005;18:109-110.

- Hoyt KS, Haley RJ. Innovations in advanced practice: assessment and management of eye emergencies. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2005;27:101-117.

- LaDou J, Harrison RJ, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2013.

- Roper-Hall M. Thermal and chemical burns. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1965;85:631-653.

Many dermatologic procedures are performed on the face, such as skin biopsies, surgical excisions, and cosmetic procedures, which can increase the risk for accidental ocular injuries.1,2 Ocular chemical burns have been reported to account for approximately 3% to 20% of ocular injuries3,4 and are one of the few ocular emergencies dermatologists may encounter in practice. Given the potentially severe consequences of permanent vision changes or loss, it is important to take precautionary steps in preventing chemical exposures and know how to appropriately manage ophthalmic emergencies when they occur.1,5-8 In this article, we describe a patient with a transient ocular chemical injury from exposure to aluminum chloride hexahydrate that completely resolved with immediate care. We also offer practical guidance for the general dermatologist in the acute management of acidic chemical burns to the eye, highlighting immediate copious irrigation as the most important step in preventing severe permanent damage. Given that aluminum chloride hexahydrate is an acidic solution, we focus predominantly on the approach to acidic chemical exposures to the eye.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman was seen in the dermatology outpatient clinic for a shave biopsy on the left cheek followed by aluminum chloride application for hemostasis. Following the biopsy, the patient stated she felt the sensation that something had dripped into the left eye and she felt a burning pain. There was a 30- to 60-second delay in irrigation of the eye, as it was at first unclear what had occurred. The patient reported an increased burning sensation, and at that point she was instructed to begin flushing the eye with tap water from the examination room sink for 15 to 20 minutes; she wanted to stop irrigation after a few minutes, and convincing her to continue thorough irrigation was somewhat challenging. It was determined that aluminum chloride hexahydrate had dripped from an oversaturated cotton swab in transit from the tray to the biopsy site.

The patient was urgently directed to the ophthalmology clinic and evaluated by an ophthalmologist within 1 to 2 hours of chemical exposure. Visual acuity of the affected left eye was noted to be 20/30 -2 with correctional glasses, and slit lamp examination revealed moderate injection of the conjunctiva and sclera, and at least 3 punctate epithelial erosions and punctate staining of the inferior aspects of the cornea, consistent with a chemical injury. The remaining ocular examination was normal for both eyes. She was diagnosed with keratitis of the left eye from chemical exposure to aluminum chloride and was prescribed loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 0.5% and tobramycin ophthalmic solution 0.3% to be applied to the left eye 4 times daily, with follow-up 4 days later.

At follow-up, the patient denied any pain, though she was not using the prescribed eye drops consistently. On examination, the patient showed improvement in visual acuity to 20/20 -2 and complete resolution of the keratitis, with slit lamp examination showing clear conjunctiva, sclera, and cornea. Given complete resolution, the eye drops were discontinued.

Comment

Factors Contributing to Ocular Chemical Injuries

Chemical burns to the eyes during cosmetic or surgical procedures are one of the few acute ocular emergencies dermatologists may encounter in practice. If not managed properly, the eye may be permanently damaged. Therefore, dermatologists must be confident in the initial management of ocular chemical burns (Table 1; Figure).

obtain the material safety data sheet. D, Refer the patient urgently to ophthalmology for a visual acuity test and treatment. Images courtesy of Deborah J. Moon, MD (Los Angeles, California).

Mechanism of Ocular Chemical Burns

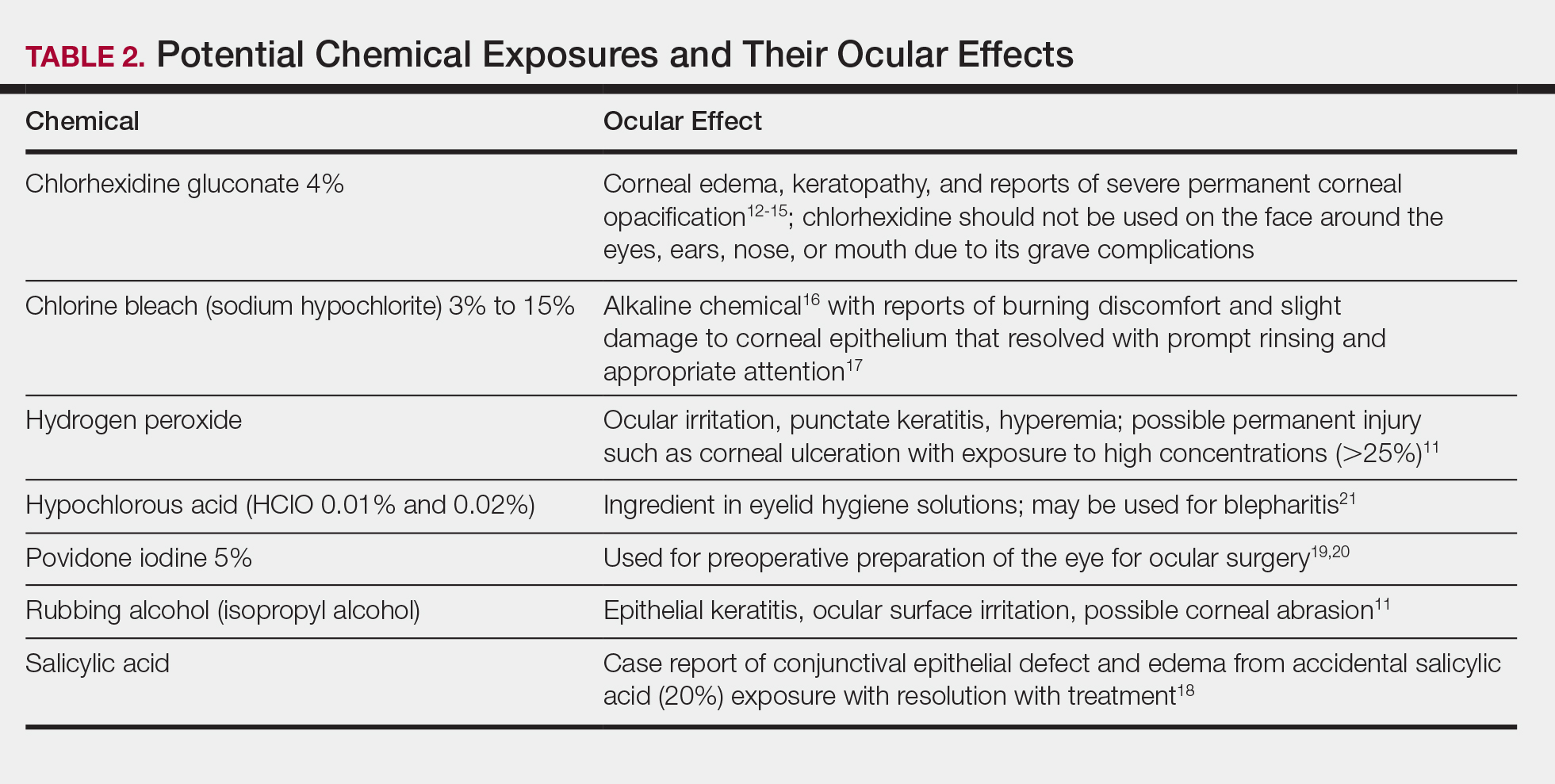

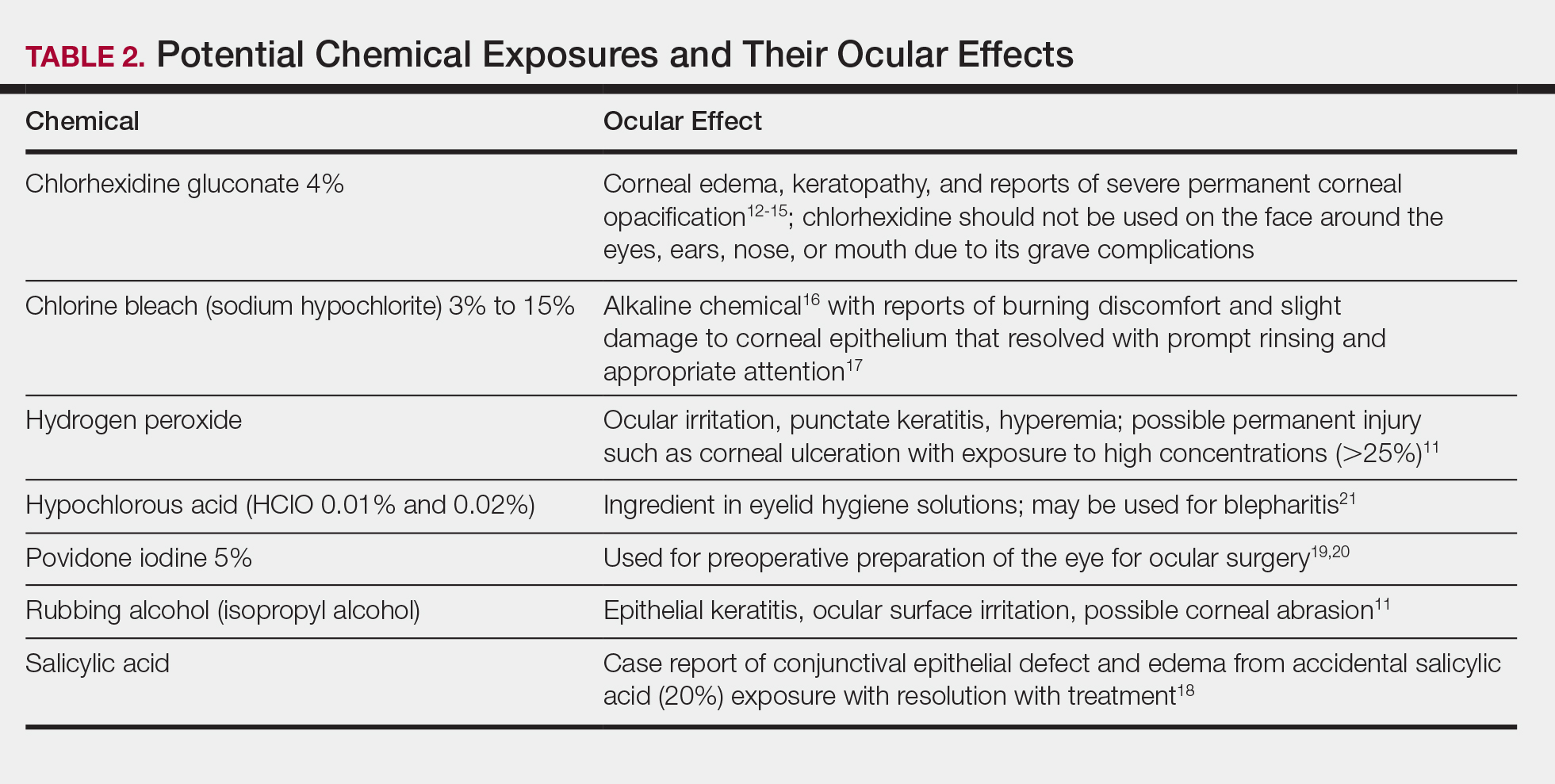

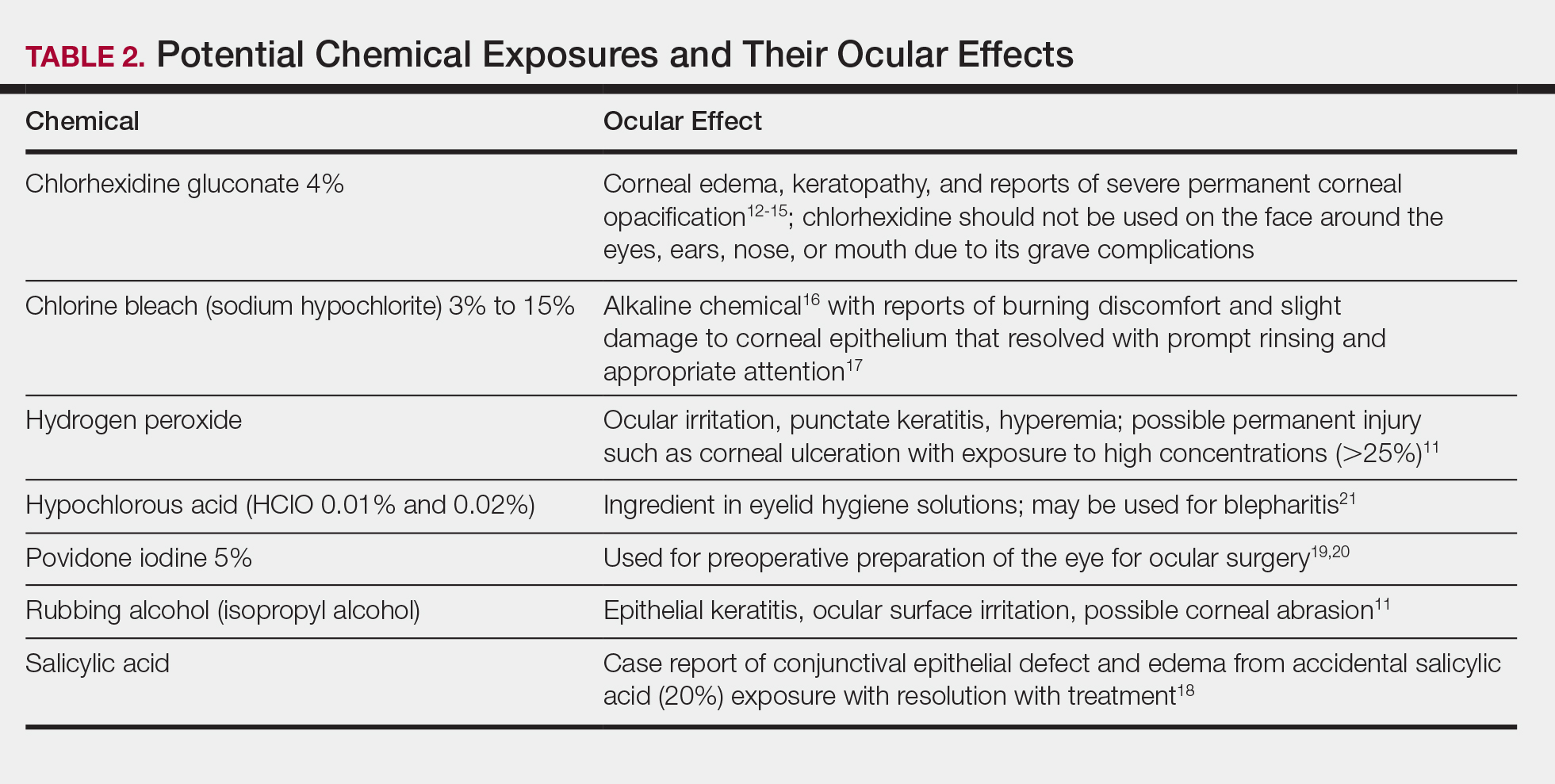

The extent of injury is predominantly determined by 2 factors: (1) the chemical properties of the substance, and (2) the length of exposure.5,9,10 Potential chemical exposures and their reported ocular effects are listed in Table 2.11-21 Alkaline chemical burns often have the gravest outcome, as they can rapidly penetrate into the internal ocular structures, potentially leading to cataracts and glaucoma.9 Hydroxyl ions, often found in alkaline chemicals, are capable of rapidly denaturing the corneal matrix and triggering release of proteolytic enzymes through a series of inflammatory responses. Conversely, ocular damage from most acidic chemicals often is limited to the more superficial structures, such as the cornea and conjunctiva, given that acids may cause corneal proteins to coagulate, thus forming a barrier that slows further penetration into deeper structures.9 Nonetheless, corneal damage can still have a devastating impact on visual acuity, as the cornea provides 65% to 75% of the eye’s total focusing power.22 For both alkaline and acidic chemicals, immediate profuse irrigation is most critical in determining the clinical course.23-26 To provide perspective, potent alkaline chemicals may penetrate into the anterior chamber of the eye within 15 seconds,9 and delayed initiation of irrigation by even 5 to 15 minutes may lead to irreversible intraocular damage.27

Symptoms of Ocular Chemical Exposure

Signs and symptoms associated with ocular chemical exposures include erythema, pain, tearing, photosensitivity, eyelid swelling, foreign body sensation, changes in vision, and corneal clouding.3,5,9,28 Specifically, aluminum chloride hexahydrate, a hemostatic agent commonly used by dermatologists, has potentially caused eye irritation and conjunctivitis, according to its material safety data sheet,29 as well as blepharospasms, transient disturbances in corneal epithelium, and a persistent faint nebula in the corneal stroma.30 Similar antiperspirants also showed damaging effects to bovine lenses, ocular irritation, and subjective reports of burning and watery eyes.31-33

Immediate Management

If potential chemical exposure to the eye is suspected either by the health care provider or patient, immediately irrigate the affected eye(s) for at least 15 to 30 minutes (longer for alkaline burns) with at least 1 to 2 L of irrigation fluid until the pH is between 7 and 7.2.3-5,9,27,34,35 Irrigation fluids reported to be used include normal saline, Ringer lactate solution, normal saline with sodium bicarbonate, and balanced salt solution.5 If no solutions are readily available, immediate irrigation with tap water is sufficient for diluting and washing away the chemical and has been reported to have better clinical outcomes than delaying irrigation.5,24-26 Studies have shown that prolonged irrigation corresponded with reduced severity, shortened healing time, shorter in-hospital treatment duration, and quicker return to work.5,26

If an eye wash station is not available, the patient can gently flush the eye under a sink faucet set to a gentle stream of lukewarm water.6,7 The health care provider also may manually irrigate the eye. Necessary equipment includes a large syringe or clean eyecup, irrigating fluid, local anesthetic drops for comfort, a towel to soak up excessive fluid, and a bowl or kidney dish to collect the irrigated fluid.34 Providers should first wash their hands. If necessary, anesthetic eye drops may be added for comfort. Lay a towel over the patient’s neck and shoulders and position the patient at a comfortable angle. Place a bowl adjacent to the patient’s cheek to collect the irrigating fluid and have the patient tilt his/her head such that the irrigated fluid would flow into the bowl. Pour a steady stream of the irrigating fluid over the eye from a height of no more than 5 cm.6,7,34

During irrigation, ensure that the patient’s eye(s) is wide open and that all ocular surfaces, including the area underneath the eyelids, are thoroughly washed; everting the eyelids may be beneficial. Ask the patient to move his/her eye(s) in all directions while irrigating. If available, place a litmus strip in the conjunctival fornix to ensure that the goal pH of 7 to 7.2 is reached.9 The pH should be rechecked every 15 to 30 minutes to ensure there has been no change, as hidden crystalized chemical particles may continue to elute chemicals, causing further injury.3 Contact lenses, if present, should be removed as soon as practical, as lenses can trap chemicals; however, immediate initiation of irrigation should not be delayed8 (Table 1).

Identify and verify the chemical suspected to have been exposed to the patient’s eye. The material safety data sheet, which may often be found online if a hard copy is not available, may provide valuable information for the ophthalmologist.36 After thorough irrigation, refer the patient urgently to ophthalmology or the emergency department for prompt evaluation. The emergency department is frequently equipped with polymethylmethacrylate scleral lenses, also called Morgan Lens, which consist of a plastic lens connected via tubing to a bag of irrigation fluid (eg, Ringer lactate solution), allowing for prolonged continuous irrigation of the conjunctiva and cornea. The ophthalmologist will conduct a visual acuity test and complete a thorough eye examination to assess the extent of ischemic injury to the conjunctiva or sclera and damage to the corneal epithelium and internal ocular structures.9

Generally, topical antibiotics, artificial tears, and topical steroids may be provided to patients with mild injury with close follow-up.9,37 For higher-grade injuries, broad-spectrum topical antibiotics, oral antibiotics, topical corticosteroids, vitamin C, and surgical treatments may be additionally recommended (Table 3). Long-term follow-up may be recommended by the ophthalmologist to monitor for potential late complications, such as glaucoma from damage to the trabecular meshwork, corneal abnormalities and limbal stem cell deficiency, symblepharon formation, or eyelid abnormalities.9

Conclusion

We report a case of a transient chemical burn to the eye secondary to exposure to aluminum chloride hexahydrate. Complete resolution of the injury was achieved with prompt irrigation and urgent medical management by ophthalmology. This case emphasizes the potential for ocular emergencies in the dermatology setting and highlights the steps for appropriate management should a chemical burn to the eye occur. We emphasize the importance of immediate profuse irrigation for 15 to 30 minutes and urgent evaluation by an ophthalmologist. Dermatologists should be cognizant of potential hazards to the eye during facial procedures and always take proper precautions to decrease the risk for ocular injuries.

Many dermatologic procedures are performed on the face, such as skin biopsies, surgical excisions, and cosmetic procedures, which can increase the risk for accidental ocular injuries.1,2 Ocular chemical burns have been reported to account for approximately 3% to 20% of ocular injuries3,4 and are one of the few ocular emergencies dermatologists may encounter in practice. Given the potentially severe consequences of permanent vision changes or loss, it is important to take precautionary steps in preventing chemical exposures and know how to appropriately manage ophthalmic emergencies when they occur.1,5-8 In this article, we describe a patient with a transient ocular chemical injury from exposure to aluminum chloride hexahydrate that completely resolved with immediate care. We also offer practical guidance for the general dermatologist in the acute management of acidic chemical burns to the eye, highlighting immediate copious irrigation as the most important step in preventing severe permanent damage. Given that aluminum chloride hexahydrate is an acidic solution, we focus predominantly on the approach to acidic chemical exposures to the eye.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman was seen in the dermatology outpatient clinic for a shave biopsy on the left cheek followed by aluminum chloride application for hemostasis. Following the biopsy, the patient stated she felt the sensation that something had dripped into the left eye and she felt a burning pain. There was a 30- to 60-second delay in irrigation of the eye, as it was at first unclear what had occurred. The patient reported an increased burning sensation, and at that point she was instructed to begin flushing the eye with tap water from the examination room sink for 15 to 20 minutes; she wanted to stop irrigation after a few minutes, and convincing her to continue thorough irrigation was somewhat challenging. It was determined that aluminum chloride hexahydrate had dripped from an oversaturated cotton swab in transit from the tray to the biopsy site.

The patient was urgently directed to the ophthalmology clinic and evaluated by an ophthalmologist within 1 to 2 hours of chemical exposure. Visual acuity of the affected left eye was noted to be 20/30 -2 with correctional glasses, and slit lamp examination revealed moderate injection of the conjunctiva and sclera, and at least 3 punctate epithelial erosions and punctate staining of the inferior aspects of the cornea, consistent with a chemical injury. The remaining ocular examination was normal for both eyes. She was diagnosed with keratitis of the left eye from chemical exposure to aluminum chloride and was prescribed loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 0.5% and tobramycin ophthalmic solution 0.3% to be applied to the left eye 4 times daily, with follow-up 4 days later.

At follow-up, the patient denied any pain, though she was not using the prescribed eye drops consistently. On examination, the patient showed improvement in visual acuity to 20/20 -2 and complete resolution of the keratitis, with slit lamp examination showing clear conjunctiva, sclera, and cornea. Given complete resolution, the eye drops were discontinued.

Comment

Factors Contributing to Ocular Chemical Injuries

Chemical burns to the eyes during cosmetic or surgical procedures are one of the few acute ocular emergencies dermatologists may encounter in practice. If not managed properly, the eye may be permanently damaged. Therefore, dermatologists must be confident in the initial management of ocular chemical burns (Table 1; Figure).

obtain the material safety data sheet. D, Refer the patient urgently to ophthalmology for a visual acuity test and treatment. Images courtesy of Deborah J. Moon, MD (Los Angeles, California).

Mechanism of Ocular Chemical Burns

The extent of injury is predominantly determined by 2 factors: (1) the chemical properties of the substance, and (2) the length of exposure.5,9,10 Potential chemical exposures and their reported ocular effects are listed in Table 2.11-21 Alkaline chemical burns often have the gravest outcome, as they can rapidly penetrate into the internal ocular structures, potentially leading to cataracts and glaucoma.9 Hydroxyl ions, often found in alkaline chemicals, are capable of rapidly denaturing the corneal matrix and triggering release of proteolytic enzymes through a series of inflammatory responses. Conversely, ocular damage from most acidic chemicals often is limited to the more superficial structures, such as the cornea and conjunctiva, given that acids may cause corneal proteins to coagulate, thus forming a barrier that slows further penetration into deeper structures.9 Nonetheless, corneal damage can still have a devastating impact on visual acuity, as the cornea provides 65% to 75% of the eye’s total focusing power.22 For both alkaline and acidic chemicals, immediate profuse irrigation is most critical in determining the clinical course.23-26 To provide perspective, potent alkaline chemicals may penetrate into the anterior chamber of the eye within 15 seconds,9 and delayed initiation of irrigation by even 5 to 15 minutes may lead to irreversible intraocular damage.27

Symptoms of Ocular Chemical Exposure

Signs and symptoms associated with ocular chemical exposures include erythema, pain, tearing, photosensitivity, eyelid swelling, foreign body sensation, changes in vision, and corneal clouding.3,5,9,28 Specifically, aluminum chloride hexahydrate, a hemostatic agent commonly used by dermatologists, has potentially caused eye irritation and conjunctivitis, according to its material safety data sheet,29 as well as blepharospasms, transient disturbances in corneal epithelium, and a persistent faint nebula in the corneal stroma.30 Similar antiperspirants also showed damaging effects to bovine lenses, ocular irritation, and subjective reports of burning and watery eyes.31-33

Immediate Management

If potential chemical exposure to the eye is suspected either by the health care provider or patient, immediately irrigate the affected eye(s) for at least 15 to 30 minutes (longer for alkaline burns) with at least 1 to 2 L of irrigation fluid until the pH is between 7 and 7.2.3-5,9,27,34,35 Irrigation fluids reported to be used include normal saline, Ringer lactate solution, normal saline with sodium bicarbonate, and balanced salt solution.5 If no solutions are readily available, immediate irrigation with tap water is sufficient for diluting and washing away the chemical and has been reported to have better clinical outcomes than delaying irrigation.5,24-26 Studies have shown that prolonged irrigation corresponded with reduced severity, shortened healing time, shorter in-hospital treatment duration, and quicker return to work.5,26

If an eye wash station is not available, the patient can gently flush the eye under a sink faucet set to a gentle stream of lukewarm water.6,7 The health care provider also may manually irrigate the eye. Necessary equipment includes a large syringe or clean eyecup, irrigating fluid, local anesthetic drops for comfort, a towel to soak up excessive fluid, and a bowl or kidney dish to collect the irrigated fluid.34 Providers should first wash their hands. If necessary, anesthetic eye drops may be added for comfort. Lay a towel over the patient’s neck and shoulders and position the patient at a comfortable angle. Place a bowl adjacent to the patient’s cheek to collect the irrigating fluid and have the patient tilt his/her head such that the irrigated fluid would flow into the bowl. Pour a steady stream of the irrigating fluid over the eye from a height of no more than 5 cm.6,7,34

During irrigation, ensure that the patient’s eye(s) is wide open and that all ocular surfaces, including the area underneath the eyelids, are thoroughly washed; everting the eyelids may be beneficial. Ask the patient to move his/her eye(s) in all directions while irrigating. If available, place a litmus strip in the conjunctival fornix to ensure that the goal pH of 7 to 7.2 is reached.9 The pH should be rechecked every 15 to 30 minutes to ensure there has been no change, as hidden crystalized chemical particles may continue to elute chemicals, causing further injury.3 Contact lenses, if present, should be removed as soon as practical, as lenses can trap chemicals; however, immediate initiation of irrigation should not be delayed8 (Table 1).

Identify and verify the chemical suspected to have been exposed to the patient’s eye. The material safety data sheet, which may often be found online if a hard copy is not available, may provide valuable information for the ophthalmologist.36 After thorough irrigation, refer the patient urgently to ophthalmology or the emergency department for prompt evaluation. The emergency department is frequently equipped with polymethylmethacrylate scleral lenses, also called Morgan Lens, which consist of a plastic lens connected via tubing to a bag of irrigation fluid (eg, Ringer lactate solution), allowing for prolonged continuous irrigation of the conjunctiva and cornea. The ophthalmologist will conduct a visual acuity test and complete a thorough eye examination to assess the extent of ischemic injury to the conjunctiva or sclera and damage to the corneal epithelium and internal ocular structures.9

Generally, topical antibiotics, artificial tears, and topical steroids may be provided to patients with mild injury with close follow-up.9,37 For higher-grade injuries, broad-spectrum topical antibiotics, oral antibiotics, topical corticosteroids, vitamin C, and surgical treatments may be additionally recommended (Table 3). Long-term follow-up may be recommended by the ophthalmologist to monitor for potential late complications, such as glaucoma from damage to the trabecular meshwork, corneal abnormalities and limbal stem cell deficiency, symblepharon formation, or eyelid abnormalities.9

Conclusion

We report a case of a transient chemical burn to the eye secondary to exposure to aluminum chloride hexahydrate. Complete resolution of the injury was achieved with prompt irrigation and urgent medical management by ophthalmology. This case emphasizes the potential for ocular emergencies in the dermatology setting and highlights the steps for appropriate management should a chemical burn to the eye occur. We emphasize the importance of immediate profuse irrigation for 15 to 30 minutes and urgent evaluation by an ophthalmologist. Dermatologists should be cognizant of potential hazards to the eye during facial procedures and always take proper precautions to decrease the risk for ocular injuries.

- Ricci LH, Navajas SV, Carneiro PR, et al. Ocular adverse effects after facial cosmetic procedures: a review of case reports. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:145-151.

- Boonsiri M, Marks KC, Ditre CM. Benzocaine/lidocaine/tetracainecream: report of corneal damage and review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:48-50.

- Gelston CD. Common eye emergencies. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:515-519.

- Sharma N, Kaur M, Agarwal T, et al. Treatment of acute ocular chemical burns. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018;63:214-235.

- Chau JP, Lee DT, Lo SH. A systematic review of methods of eye irrigation for adults and children with ocular chemical burns. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2012;9:129-138.

- Sears W, Sears M, Sears R, et al. The Portable Pediatrician: Everything You Need to Know About Your Child’s Health. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2011.

- Kuckelkorn R, Schrage N, Keller G, et al. Emergency treatment of chemical and thermal eye burns. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80:4-10.

- Schulte PA, Ahlers HW, Jackson LL, et al. Contact Lens Use in a Chemical Environment. Cincinnati, OH: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. NIOSH publication 2005-139.

- Hemmati HD, Colby KA. Treating acute chemical injuries of the cornea. Eyenet. October 2012. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/treating-acute-chemical-injuries-of-cornea. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- Schrage NF, Langefeld S, Zschocke J, et al. Eye burns: an emergency and continuing problem. Burns. 2000;26:689-699.

- Gattey D. Chemical-induced ocular side effects. In: Fraunfelder FT, Fraunfelder FW, Chambers WA, eds. Clinical Ocular Toxicology. Edinburgh, Scotland: W.B. Saunders; 2008:289-306.

- Apt L, Isenberg SJ. Hibiclens keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:670-671.

- Tabor E, Bostwick DC, Evans C. Corneal damage due to eye contact with chlorhexidine gluconate. JAMA. 1989;261:557-558.

- Galor A, Jeng BH, Lowder CY. A curious case of corneal edema. Eyenet. January 2007. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/curious-case-of-corneal-edema. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- Hamed LM, Ellis FD, Boudreault G, et al. Hibiclens keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:50-56.

- Haring R, Sheffield ID, Channa R, et al. Epidemiologic trends of chemical ocular burns in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:1119-1124.

- Racioppi F, Daskaleros PA, Besbelli N, et al. Household bleaches based on sodium hypochlorite: review of acute toxicology and poison control center experience. Food Chem Toxicol. 1994;32:845-861.

- Shazly TA. Ocular acid burn due to 20% concentrated salicylic acid. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2011;30:84-86.

- Speaker MG, Menikoff JA. Prophylaxis of endophthalmitis with topical povidone-iodine. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1769-1775.

- Apt L, Isenberg S, Yoshimori R, et al. Chemical preparation of the eye in ophthalmic surgery: III. effect of povidone-iodine on the conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:728-729.

- Stroman DW, Mintun K, Epstein AB, et al. Reduction in bacterial load using hypochlorous acid hygiene solution on ocular skin. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:707-714.

- Paul M, Sieving A. Facts about the cornea and corneal disease. National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health website. https://nei.nih.gov/health/cornealdisease. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Khaw P, Shah P, Elkington A. Injury to the eye. BMJ. 2004;328:36-38.

- Duffy B. Managing chemical eye injuries: Bernice Duffy says initial management of potentially devastating chemical eye injuries by emergency nurses can affect patients’ future prognosis as much as subsequent ophthalmic treatment. Emerg Nurse. 2008;16:25-30.

- Burns F, Paterson C. Prompt irrigation of chemical eye injuries may avert severe damage. Occup Health Saf. 1989;58:33-36.

- Ikeda N, Hayasaka S, Hayasaka Y, et al. Alkali burns of the eye: effect of immediate copious irrigation with tap water on their severity. Ophthalmologica. 2006;220:225-228.

- Eslani M, Baradaran-Rafii A, Movahedan A, et al. The ocular surface chemical burns. J Ophthalmol. 2014;2014:196827.

- Pokhrel PK, Loftus SA. Ocular emergencies. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:829-836.

- Drysol. MSDS No. BLVCL; Glendale, CA: Person & Covey Inc; March 9, 1991. http://msdsreport.com/msds/blvcl. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Grant WM, Schuman JS. Toxicology of the Eye: Effects on the Eyes and Visual System From Chemicals, Drugs, Metals and Minerals, Plants, Toxins and Venoms: Also Systemic Side Effects From Eye Medications. Vol 1. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher; 1993.

- Wong W, Sivak JG, Moran KL. Optical response of the cultured bovine lens; testing opaque or partially transparent semi-solid/solid common consumer hygiene products. Toxicol In Vitro. 2003;17:785-790.

- Donahue DA, Kaufman LE, Avalos J, et al. Survey of ocular irritation predictive capacity using chorioallantoic membrane vascular assay (CAMVA) and bovine corneal opacity and permeability (BCOP) test historical data for 319 personal care products over fourteen years. Toxicol In Vitro. 2011;25:563-572.

- Groot AC, Nater JP, Lender R, et al. Adverse effects of cosmetics and toiletries: a retrospective study in the general population. Int J Cosmet Sci. 1987;9:255-259.

- Stevens S. Ophthalmic practice. Community Eye Health. 2005;18:109-110.

- Hoyt KS, Haley RJ. Innovations in advanced practice: assessment and management of eye emergencies. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2005;27:101-117.

- LaDou J, Harrison RJ, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2013.

- Roper-Hall M. Thermal and chemical burns. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1965;85:631-653.

- Ricci LH, Navajas SV, Carneiro PR, et al. Ocular adverse effects after facial cosmetic procedures: a review of case reports. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14:145-151.

- Boonsiri M, Marks KC, Ditre CM. Benzocaine/lidocaine/tetracainecream: report of corneal damage and review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:48-50.

- Gelston CD. Common eye emergencies. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:515-519.

- Sharma N, Kaur M, Agarwal T, et al. Treatment of acute ocular chemical burns. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018;63:214-235.

- Chau JP, Lee DT, Lo SH. A systematic review of methods of eye irrigation for adults and children with ocular chemical burns. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2012;9:129-138.

- Sears W, Sears M, Sears R, et al. The Portable Pediatrician: Everything You Need to Know About Your Child’s Health. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2011.

- Kuckelkorn R, Schrage N, Keller G, et al. Emergency treatment of chemical and thermal eye burns. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80:4-10.

- Schulte PA, Ahlers HW, Jackson LL, et al. Contact Lens Use in a Chemical Environment. Cincinnati, OH: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. NIOSH publication 2005-139.

- Hemmati HD, Colby KA. Treating acute chemical injuries of the cornea. Eyenet. October 2012. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/treating-acute-chemical-injuries-of-cornea. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- Schrage NF, Langefeld S, Zschocke J, et al. Eye burns: an emergency and continuing problem. Burns. 2000;26:689-699.

- Gattey D. Chemical-induced ocular side effects. In: Fraunfelder FT, Fraunfelder FW, Chambers WA, eds. Clinical Ocular Toxicology. Edinburgh, Scotland: W.B. Saunders; 2008:289-306.

- Apt L, Isenberg SJ. Hibiclens keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:670-671.

- Tabor E, Bostwick DC, Evans C. Corneal damage due to eye contact with chlorhexidine gluconate. JAMA. 1989;261:557-558.

- Galor A, Jeng BH, Lowder CY. A curious case of corneal edema. Eyenet. January 2007. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/curious-case-of-corneal-edema. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- Hamed LM, Ellis FD, Boudreault G, et al. Hibiclens keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:50-56.

- Haring R, Sheffield ID, Channa R, et al. Epidemiologic trends of chemical ocular burns in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:1119-1124.

- Racioppi F, Daskaleros PA, Besbelli N, et al. Household bleaches based on sodium hypochlorite: review of acute toxicology and poison control center experience. Food Chem Toxicol. 1994;32:845-861.

- Shazly TA. Ocular acid burn due to 20% concentrated salicylic acid. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2011;30:84-86.

- Speaker MG, Menikoff JA. Prophylaxis of endophthalmitis with topical povidone-iodine. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1769-1775.

- Apt L, Isenberg S, Yoshimori R, et al. Chemical preparation of the eye in ophthalmic surgery: III. effect of povidone-iodine on the conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:728-729.

- Stroman DW, Mintun K, Epstein AB, et al. Reduction in bacterial load using hypochlorous acid hygiene solution on ocular skin. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:707-714.

- Paul M, Sieving A. Facts about the cornea and corneal disease. National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health website. https://nei.nih.gov/health/cornealdisease. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Khaw P, Shah P, Elkington A. Injury to the eye. BMJ. 2004;328:36-38.

- Duffy B. Managing chemical eye injuries: Bernice Duffy says initial management of potentially devastating chemical eye injuries by emergency nurses can affect patients’ future prognosis as much as subsequent ophthalmic treatment. Emerg Nurse. 2008;16:25-30.

- Burns F, Paterson C. Prompt irrigation of chemical eye injuries may avert severe damage. Occup Health Saf. 1989;58:33-36.

- Ikeda N, Hayasaka S, Hayasaka Y, et al. Alkali burns of the eye: effect of immediate copious irrigation with tap water on their severity. Ophthalmologica. 2006;220:225-228.

- Eslani M, Baradaran-Rafii A, Movahedan A, et al. The ocular surface chemical burns. J Ophthalmol. 2014;2014:196827.

- Pokhrel PK, Loftus SA. Ocular emergencies. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:829-836.

- Drysol. MSDS No. BLVCL; Glendale, CA: Person & Covey Inc; March 9, 1991. http://msdsreport.com/msds/blvcl. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- Grant WM, Schuman JS. Toxicology of the Eye: Effects on the Eyes and Visual System From Chemicals, Drugs, Metals and Minerals, Plants, Toxins and Venoms: Also Systemic Side Effects From Eye Medications. Vol 1. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher; 1993.

- Wong W, Sivak JG, Moran KL. Optical response of the cultured bovine lens; testing opaque or partially transparent semi-solid/solid common consumer hygiene products. Toxicol In Vitro. 2003;17:785-790.

- Donahue DA, Kaufman LE, Avalos J, et al. Survey of ocular irritation predictive capacity using chorioallantoic membrane vascular assay (CAMVA) and bovine corneal opacity and permeability (BCOP) test historical data for 319 personal care products over fourteen years. Toxicol In Vitro. 2011;25:563-572.

- Groot AC, Nater JP, Lender R, et al. Adverse effects of cosmetics and toiletries: a retrospective study in the general population. Int J Cosmet Sci. 1987;9:255-259.

- Stevens S. Ophthalmic practice. Community Eye Health. 2005;18:109-110.

- Hoyt KS, Haley RJ. Innovations in advanced practice: assessment and management of eye emergencies. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2005;27:101-117.

- LaDou J, Harrison RJ, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2013.

- Roper-Hall M. Thermal and chemical burns. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1965;85:631-653.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be cognizant of potential hazards to the eyes during facial procedures and always take proper precautions to decrease the risk for ocular injuries.

- If a patient’s eye(s) becomes exposed to a chemical during a dermatologic procedure, immediate copious irrigation for at least 15 to 30 minutes (longer for alkaline burns) is crucial, followed by prompt evaluation by an ophthalmologist.

- The patient should be instructed to manually hold open the eye and move the eyeball in all directions to achieve the most effective irrigation of the chemical.

- If the patient is wearing contact lenses, they should be removed promptly, but do not delay the irrigation to do so. Lenses should be removed once irrigation is underway.

The great sunscreen ingredient debate

In a commentary issued on May 6, the Food and Drug Administration stated that “with sunscreens now being used with greater frequency, in larger amounts, and by broader populations, it is more important than ever to ensure that sunscreens are safe and effective for daily, lifelong use.” The statement coincided with the publication of the randomized study, “Effect of sunscreen application under maximal use conditions on plasma concentrations of sunscreen active ingredients,” by Matta et al. of the FDA and others in JAMA (2019 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5586). A maximal usage trial examines the systemic absorption of a topical drug when used according to the guidelines given for the product’s maximum usage. In this study, adult participants were randomized to one of four commercially available sunscreen products: spray 1 (n = 6), spray 2 (n = 6), a lotion (n = 6), and a cream (n = 6). Two mg of sunscreen per 1 cm2 was applied to 75% of body surface area four times per day for 4 days, and blood samples were collected from each individual over 7 days.

The FDA’s guidance for industry and proposed rule on OTC sunscreens state that active ingredients with systemic absorption at 0.5 ng/mL or higher or with possible safety concerns need to undergo further nonclinical toxicology assessment to evaluate risk of systemic carcinogenicity, developmental/reproductive abnormalities, or other adverse effects.

Absorption of some sunscreen ingredients has been detected in other studies. Despite systemic absorption, two active ingredients – zinc oxide and titanium dioxide – have been found by the FDA to be generally recognized as safe and effective. But for 12 other active ingredients (cinoxate, dioxybenzone, ensulizole, homosalate, meradimate, octinoxate, octisalate, octocrylene, padimate O, sulisobenzone, oxybenzone, and avobenzone), there are insufficient data to make a “generally recognized as safe and effective” determination; thus, more data have been requested from the manufacturers. While physical blocking sunscreens have improved in their UV-blocking ability without compromising cosmesis over the past several years, some sunscreens containing chemical blockers are able to achieve higher SPFs with good cosmesis when applied to the skin.

Our skin acts as the ultimate barrier between ourselves and the environment, and it is not uncommon for substances to be blocked, absorbed, or excreted from the skin. Absorption of an ingredient through the skin and into the body does not indicate that the ingredient is unsafe. Rather, findings such as these call for further testing and research to determine the safety of that ingredient with repeated use. Per the FDA, such testing is part of the standard premarket safety evaluation of most chronically administered drugs with appreciable systemic absorption.

In February 2019, the FDA’s proposed rule was issued to “update regulatory requirements for most sunscreen products in the United States,” with the goal of bringing OTC sunscreens “up to date with the latest scientific standards,” according to the FDA May 6 commentary. “As part of this rule, the FDA is asking industry and other interested parties for additional safety data on the 12 active sunscreen ingredients currently available in marketed products” mentioned previously. These rules are being put into place to address the “key data gap” for these 12 ingredients, which is “understanding whether, and to what extent the ingredient is absorbed into the body after topical application.”

In other previously published studies, oxybenzone, along with some other sunscreen active ingredients including octocrylene, have been found in human breast milk. In addition, oxybenzone has been detected in amniotic fluid, urine, and blood. Whether these findings have any clinical implications needs to be further assessed. Some studies in the literature have raised questions about the potential for oxybenzone to affect endocrine activity.

Another issue that has been raised is the potential impact of sunscreen on the environment, specifically, coral reefs. In July 2018, Hawaii Governor David Ige (D) signed a bill (SB 2571) that bans the sale of sunscreens containing oxybenzone and octinoxate beginning in 2021, making Hawaii the first state to ban the sale of sunscreens containing these two chemicals. Shortly afterward, the Republic of Palau and city of Key West, Fla., also took action to ban sunscreens containing chemicals potentially harmful to marine life. In Hawaii, what’s know as “reef safe” sunscreen is sold.

More research in this area is needed, but studies have linked these ingredients to harming coral by bleaching, disease, and damage to DNA, and also to decreasing fertility in fish, impairing algae growth, inducing defects in mussel and sea urchin young, and accumulating in the tissues of dolphins. According to NASA, as much as 27% of monitored reef formation have already been lost and over the following 32 years, 32% more are at risk. Reefs cover a mere 0.2% of the ocean’s floor, but it is estimated that reefs are home to and protect nearly 1 million species of fish, invertebrates, and algae.

In early May, Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-Hawaii) and Sen. Tim Ryan (D-Ohio) introduced legislation known as the Oxybenzone and Octinoxate Impact Study Act of 2019 (H.R. 2588) to require the Environmental Protection Agency to study the impact of those two chemicals on human health and the environment and to provide findings to Congress and the public within 18 months.

The importance of sun protection and prevention of sunburns is paramount. We know that multiple sunburn events during childhood double a child’s risk of developing skin cancer later in life, and skin cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in the United States, with 5 million cases treated every year. One in five Americans will develop skin cancer by age 70 years.

As a Mohs and a cosmetic dermatologic surgeon, I appreciate the unquestionable protective effects of sunscreen products with regards to skin cancer, dyspigmentation, solar elastosis, and rhytids associated with photoaging. We can applaud the FDA for improving testing and regulation of OTC ingredients, including those in sunscreen. These types of studies are important and monumental in ensuring that we are utilizing the right type of ingredients to protect our patients, our oceans, and our reefs.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

- Matta MK et al. JAMA. 2019 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5586.

- Shedding new light on sunscreen absorption, by Janet Woodcock, MD, director, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, and Theresa M. Michele, MD, director, CDER’s Division of Nonprescription Drug Products, Office of New Drugs

- Food and Drug Administration. Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use: Proposed rule. Fed Regist. 2019;84(38):6204-75.

- Schlumpf M et al. Chemosphere. 2010 Nov;81(10):1171-83.

- Krause M et al. Int J Androl. 2012 Jun;35(3):424-36.

In a commentary issued on May 6, the Food and Drug Administration stated that “with sunscreens now being used with greater frequency, in larger amounts, and by broader populations, it is more important than ever to ensure that sunscreens are safe and effective for daily, lifelong use.” The statement coincided with the publication of the randomized study, “Effect of sunscreen application under maximal use conditions on plasma concentrations of sunscreen active ingredients,” by Matta et al. of the FDA and others in JAMA (2019 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5586). A maximal usage trial examines the systemic absorption of a topical drug when used according to the guidelines given for the product’s maximum usage. In this study, adult participants were randomized to one of four commercially available sunscreen products: spray 1 (n = 6), spray 2 (n = 6), a lotion (n = 6), and a cream (n = 6). Two mg of sunscreen per 1 cm2 was applied to 75% of body surface area four times per day for 4 days, and blood samples were collected from each individual over 7 days.

The FDA’s guidance for industry and proposed rule on OTC sunscreens state that active ingredients with systemic absorption at 0.5 ng/mL or higher or with possible safety concerns need to undergo further nonclinical toxicology assessment to evaluate risk of systemic carcinogenicity, developmental/reproductive abnormalities, or other adverse effects.

Absorption of some sunscreen ingredients has been detected in other studies. Despite systemic absorption, two active ingredients – zinc oxide and titanium dioxide – have been found by the FDA to be generally recognized as safe and effective. But for 12 other active ingredients (cinoxate, dioxybenzone, ensulizole, homosalate, meradimate, octinoxate, octisalate, octocrylene, padimate O, sulisobenzone, oxybenzone, and avobenzone), there are insufficient data to make a “generally recognized as safe and effective” determination; thus, more data have been requested from the manufacturers. While physical blocking sunscreens have improved in their UV-blocking ability without compromising cosmesis over the past several years, some sunscreens containing chemical blockers are able to achieve higher SPFs with good cosmesis when applied to the skin.

Our skin acts as the ultimate barrier between ourselves and the environment, and it is not uncommon for substances to be blocked, absorbed, or excreted from the skin. Absorption of an ingredient through the skin and into the body does not indicate that the ingredient is unsafe. Rather, findings such as these call for further testing and research to determine the safety of that ingredient with repeated use. Per the FDA, such testing is part of the standard premarket safety evaluation of most chronically administered drugs with appreciable systemic absorption.

In February 2019, the FDA’s proposed rule was issued to “update regulatory requirements for most sunscreen products in the United States,” with the goal of bringing OTC sunscreens “up to date with the latest scientific standards,” according to the FDA May 6 commentary. “As part of this rule, the FDA is asking industry and other interested parties for additional safety data on the 12 active sunscreen ingredients currently available in marketed products” mentioned previously. These rules are being put into place to address the “key data gap” for these 12 ingredients, which is “understanding whether, and to what extent the ingredient is absorbed into the body after topical application.”

In other previously published studies, oxybenzone, along with some other sunscreen active ingredients including octocrylene, have been found in human breast milk. In addition, oxybenzone has been detected in amniotic fluid, urine, and blood. Whether these findings have any clinical implications needs to be further assessed. Some studies in the literature have raised questions about the potential for oxybenzone to affect endocrine activity.

Another issue that has been raised is the potential impact of sunscreen on the environment, specifically, coral reefs. In July 2018, Hawaii Governor David Ige (D) signed a bill (SB 2571) that bans the sale of sunscreens containing oxybenzone and octinoxate beginning in 2021, making Hawaii the first state to ban the sale of sunscreens containing these two chemicals. Shortly afterward, the Republic of Palau and city of Key West, Fla., also took action to ban sunscreens containing chemicals potentially harmful to marine life. In Hawaii, what’s know as “reef safe” sunscreen is sold.

More research in this area is needed, but studies have linked these ingredients to harming coral by bleaching, disease, and damage to DNA, and also to decreasing fertility in fish, impairing algae growth, inducing defects in mussel and sea urchin young, and accumulating in the tissues of dolphins. According to NASA, as much as 27% of monitored reef formation have already been lost and over the following 32 years, 32% more are at risk. Reefs cover a mere 0.2% of the ocean’s floor, but it is estimated that reefs are home to and protect nearly 1 million species of fish, invertebrates, and algae.

In early May, Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-Hawaii) and Sen. Tim Ryan (D-Ohio) introduced legislation known as the Oxybenzone and Octinoxate Impact Study Act of 2019 (H.R. 2588) to require the Environmental Protection Agency to study the impact of those two chemicals on human health and the environment and to provide findings to Congress and the public within 18 months.

The importance of sun protection and prevention of sunburns is paramount. We know that multiple sunburn events during childhood double a child’s risk of developing skin cancer later in life, and skin cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in the United States, with 5 million cases treated every year. One in five Americans will develop skin cancer by age 70 years.

As a Mohs and a cosmetic dermatologic surgeon, I appreciate the unquestionable protective effects of sunscreen products with regards to skin cancer, dyspigmentation, solar elastosis, and rhytids associated with photoaging. We can applaud the FDA for improving testing and regulation of OTC ingredients, including those in sunscreen. These types of studies are important and monumental in ensuring that we are utilizing the right type of ingredients to protect our patients, our oceans, and our reefs.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

- Matta MK et al. JAMA. 2019 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5586.

- Shedding new light on sunscreen absorption, by Janet Woodcock, MD, director, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, and Theresa M. Michele, MD, director, CDER’s Division of Nonprescription Drug Products, Office of New Drugs

- Food and Drug Administration. Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use: Proposed rule. Fed Regist. 2019;84(38):6204-75.

- Schlumpf M et al. Chemosphere. 2010 Nov;81(10):1171-83.

- Krause M et al. Int J Androl. 2012 Jun;35(3):424-36.

In a commentary issued on May 6, the Food and Drug Administration stated that “with sunscreens now being used with greater frequency, in larger amounts, and by broader populations, it is more important than ever to ensure that sunscreens are safe and effective for daily, lifelong use.” The statement coincided with the publication of the randomized study, “Effect of sunscreen application under maximal use conditions on plasma concentrations of sunscreen active ingredients,” by Matta et al. of the FDA and others in JAMA (2019 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5586). A maximal usage trial examines the systemic absorption of a topical drug when used according to the guidelines given for the product’s maximum usage. In this study, adult participants were randomized to one of four commercially available sunscreen products: spray 1 (n = 6), spray 2 (n = 6), a lotion (n = 6), and a cream (n = 6). Two mg of sunscreen per 1 cm2 was applied to 75% of body surface area four times per day for 4 days, and blood samples were collected from each individual over 7 days.

The FDA’s guidance for industry and proposed rule on OTC sunscreens state that active ingredients with systemic absorption at 0.5 ng/mL or higher or with possible safety concerns need to undergo further nonclinical toxicology assessment to evaluate risk of systemic carcinogenicity, developmental/reproductive abnormalities, or other adverse effects.