User login

Graying of hair: Could it be reversed?

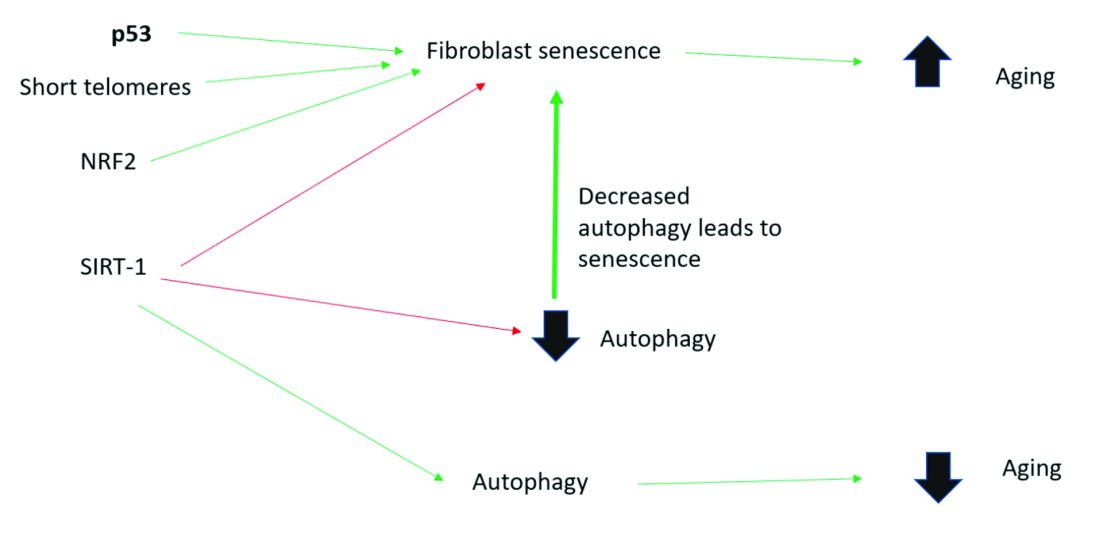

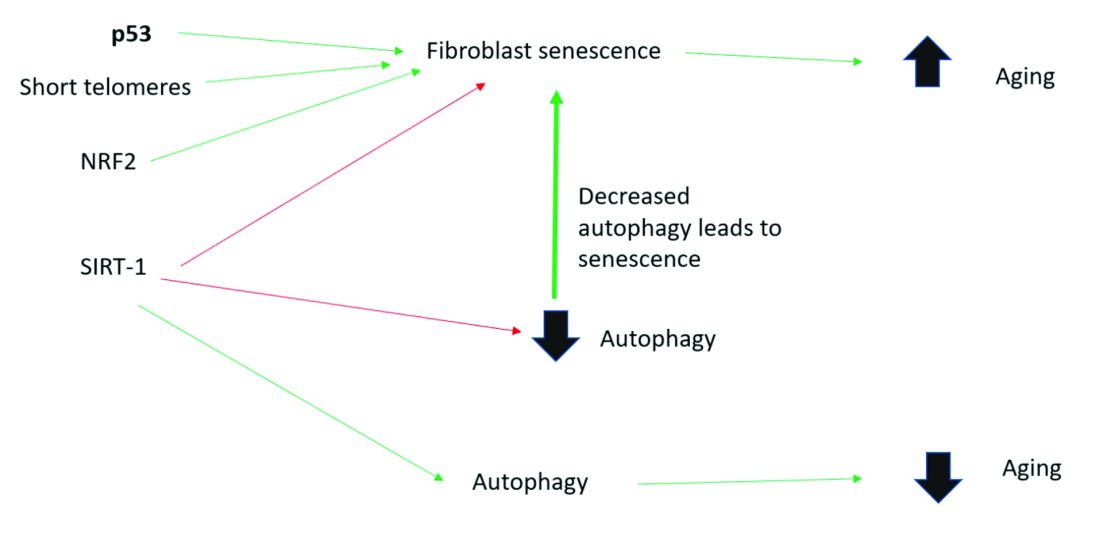

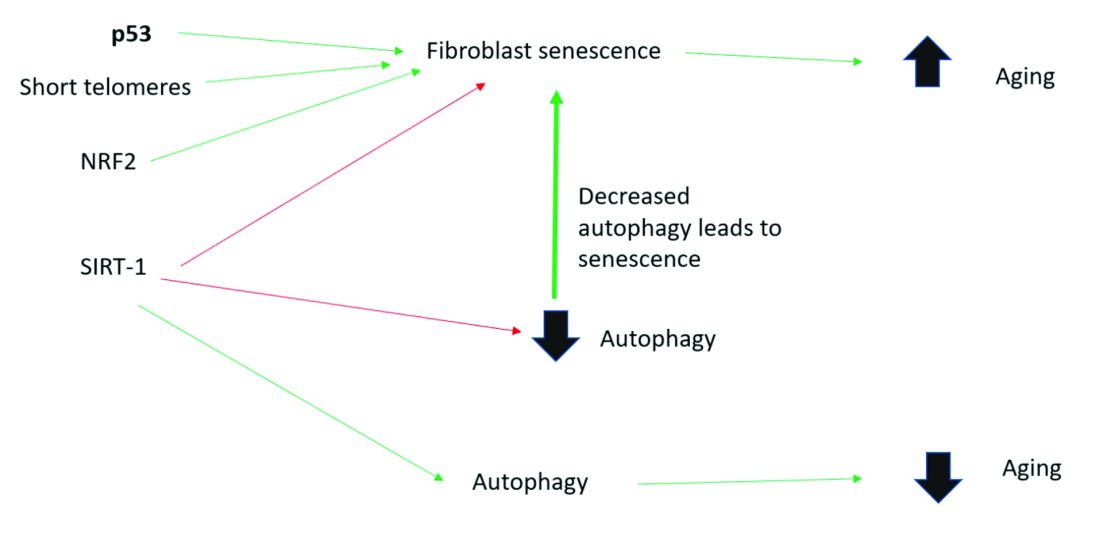

as hair pigment goes through its natural progression of senescence.

However, the recent publication that is a collaboration between the department of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York; and the departments of dermatology at the University College Dublin, University of Miami, and the University of Manchester (England); and the Monasterium Laboratory in Münster, Germany, demonstrates a quantitative mapping of human hair graying – and its reversal – in relation to stress.

In the study, hair color of single strands of hair from seven healthy females and seven healthy males, whose mean age was 35 years (range, 9-65 years), were analyzed. In addition to hair pigment analysis, study subjects documented the stress they were experiencing each week in diaries. Using either high resolution image scanners, electron microscopy, and/or hair shaft proteomics, the investigators were able to evaluate loss of pigment within fragments small enough to have grown over one hour.

When changes in hair color were noted, variations in up to 300 proteins were documented, including an up-regulation of the fatty acid synthesis and metabolism machinery in graying. Recent studies also corroborate that fatty acid synthesis by fatty acid synthase and “transport by CPT1A ... are sufficient drivers of cell senescence, and that fatty acid metabolism regulates melanocyte aging biology” the authors wrote.

Molecularly, the investigators found that gray hairs up-regulate proteins associated with energy metabolism, mitochondria, and antioxidant defenses. The graying correlated with stress was also reversible, “at least temporarily,” based on their retrospective analysis and analysis over the 2.5-year recruitment period, the investigators wrote. Specifically, they found that graying hair “may be acutely triggered by stressful life experiences, the removal of which can trigger reversal.” From the data, they also developed a mathematical model to predict what might happen to human hair over time.

Through this study, proof-of-concept evidence is provided indicating that biobehavioral factors are linked to human hair graying dynamics. Future analysis with larger sample sizes and incorporating neuroendocrine markers may further support these correlations. This is an interesting study that elucidates the mechanisms responsible for how stress and other life exposures manifest in human biology, and, if we as human beings effectively manage that stress, how it may both reverse the negative impact and outcomes affecting our body and health.

The study was supported by the Wharton Fund and grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Lily Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They have no relevant disclosures.

as hair pigment goes through its natural progression of senescence.

However, the recent publication that is a collaboration between the department of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York; and the departments of dermatology at the University College Dublin, University of Miami, and the University of Manchester (England); and the Monasterium Laboratory in Münster, Germany, demonstrates a quantitative mapping of human hair graying – and its reversal – in relation to stress.

In the study, hair color of single strands of hair from seven healthy females and seven healthy males, whose mean age was 35 years (range, 9-65 years), were analyzed. In addition to hair pigment analysis, study subjects documented the stress they were experiencing each week in diaries. Using either high resolution image scanners, electron microscopy, and/or hair shaft proteomics, the investigators were able to evaluate loss of pigment within fragments small enough to have grown over one hour.

When changes in hair color were noted, variations in up to 300 proteins were documented, including an up-regulation of the fatty acid synthesis and metabolism machinery in graying. Recent studies also corroborate that fatty acid synthesis by fatty acid synthase and “transport by CPT1A ... are sufficient drivers of cell senescence, and that fatty acid metabolism regulates melanocyte aging biology” the authors wrote.

Molecularly, the investigators found that gray hairs up-regulate proteins associated with energy metabolism, mitochondria, and antioxidant defenses. The graying correlated with stress was also reversible, “at least temporarily,” based on their retrospective analysis and analysis over the 2.5-year recruitment period, the investigators wrote. Specifically, they found that graying hair “may be acutely triggered by stressful life experiences, the removal of which can trigger reversal.” From the data, they also developed a mathematical model to predict what might happen to human hair over time.

Through this study, proof-of-concept evidence is provided indicating that biobehavioral factors are linked to human hair graying dynamics. Future analysis with larger sample sizes and incorporating neuroendocrine markers may further support these correlations. This is an interesting study that elucidates the mechanisms responsible for how stress and other life exposures manifest in human biology, and, if we as human beings effectively manage that stress, how it may both reverse the negative impact and outcomes affecting our body and health.

The study was supported by the Wharton Fund and grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Lily Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They have no relevant disclosures.

as hair pigment goes through its natural progression of senescence.

However, the recent publication that is a collaboration between the department of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York; and the departments of dermatology at the University College Dublin, University of Miami, and the University of Manchester (England); and the Monasterium Laboratory in Münster, Germany, demonstrates a quantitative mapping of human hair graying – and its reversal – in relation to stress.

In the study, hair color of single strands of hair from seven healthy females and seven healthy males, whose mean age was 35 years (range, 9-65 years), were analyzed. In addition to hair pigment analysis, study subjects documented the stress they were experiencing each week in diaries. Using either high resolution image scanners, electron microscopy, and/or hair shaft proteomics, the investigators were able to evaluate loss of pigment within fragments small enough to have grown over one hour.

When changes in hair color were noted, variations in up to 300 proteins were documented, including an up-regulation of the fatty acid synthesis and metabolism machinery in graying. Recent studies also corroborate that fatty acid synthesis by fatty acid synthase and “transport by CPT1A ... are sufficient drivers of cell senescence, and that fatty acid metabolism regulates melanocyte aging biology” the authors wrote.

Molecularly, the investigators found that gray hairs up-regulate proteins associated with energy metabolism, mitochondria, and antioxidant defenses. The graying correlated with stress was also reversible, “at least temporarily,” based on their retrospective analysis and analysis over the 2.5-year recruitment period, the investigators wrote. Specifically, they found that graying hair “may be acutely triggered by stressful life experiences, the removal of which can trigger reversal.” From the data, they also developed a mathematical model to predict what might happen to human hair over time.

Through this study, proof-of-concept evidence is provided indicating that biobehavioral factors are linked to human hair graying dynamics. Future analysis with larger sample sizes and incorporating neuroendocrine markers may further support these correlations. This is an interesting study that elucidates the mechanisms responsible for how stress and other life exposures manifest in human biology, and, if we as human beings effectively manage that stress, how it may both reverse the negative impact and outcomes affecting our body and health.

The study was supported by the Wharton Fund and grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Lily Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They have no relevant disclosures.

Synthetic snake venom to the rescue? Potential uses in skin health and rejuvenation

1 This column discusses some of the emerging data in this novel area of medical and dermatologic research. For more detailed information, a review on the therapeutic potential of peptides in animal venom was published in 2003 (Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003 Oct;2[10]:790-802).

The potential of peptides found in snake venom

Snake venom is known to contain carbohydrates, nucleosides, amino acids, and lipids, as well as enzymatic and nonenzymatic proteins and peptides, with proteins and peptides comprising the primary components.2

There are many different types of peptides in snake venom. The peptides and the small proteins found in snake venoms are known to confer a wide range of biologic activities, including antimicrobial, antihypertensive, analgesic, antitumor, and analgesic, in addition to several others. These peptides have been included in antiaging skin care products.3Pennington et al. have observed that venom-derived peptides appear to have potential as effective therapeutic agents in cosmetic formulations.4 In particular, Waglerin peptides appear to act with a Botox-like paralyzing effect and purportedly diminish skin wrinkles.5

Issues with efficacy of snake venom in skin care products

As with many skin care ingredients, what is seen in cell cultures or a laboratory setting may not translate to real life use. Shelf life, issues during manufacturing, interaction with other ingredients in the product, interactions with other products in the regimen, exposure to air and light, and difficulty of penetration can all affect efficacy. With snake venom in particular, stability and penetration make the efficacy in skin care products questionable.

The problem with many peptides in skin care products is that they are usually larger than 500 Dalton and, therefore, cannot penetrate into the skin. Bos et al. described the “500 Dalton rule” in 2000.6 Regardless of these issues, there are several publications looking at snake venom that will be discussed here.

Antimicrobial and wound healing activity

In 2011, Samy et al. found that phospholipase A2 purified from crotalid snake venom expressed antibacterial activity in vitro against various clinical human pathogens. The investigators synthesized peptides based on the sequence homology and ascertained that the synthetic peptides exhibited potent microbicidal properties against Gram-negative and Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria with diminished toxicity against normal human cells. Subsequently, the investigators used a BALB/c mouse model to show that peptide-treated animals displayed accelerated healing of full-thickness skin wounds, with increased re-epithelialization, collagen production, and angiogenesis. They concluded that the protein/peptide complex developed from snake venoms was effective at fostering wound healing.7

In that same year, Samy et al. showed in vivo that the snake venom phospholipase A₂ (svPLA₂) proteins from Viperidae and Elapidae snakes activated innate immunity in the animals tested, providing protection against skin infection caused by S. aureus. In vitro experiments also revealed that svPLA₂ proteins dose dependently exerted bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects on S. aureus.8 In 2015, Al-Asmari et al. comparatively assessed the venoms of two cobras, four vipers, a standard antibiotic, and an antimycotic as antimicrobial agents. The methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacterium was the most susceptible, followed by Gram-positive S. aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. While the antibiotic vancomycin was more effective against P. aeruginosa, the venoms more efficiently suppressed the resistant bacteria. The snake venoms had minimal effect on the fungus Candida albicans. The investigators concluded that the snake venoms exhibited antibacterial activity comparable to antibiotics and were more efficient in tackling resistant bacteria.9 In a review of animal venoms in 2017, Samy et al. reported that snake venom–derived synthetic peptide/snake cathelicidin exhibits robust antimicrobial and wound healing capacity, despite its instability and risk, and presents as a possible new treatment for S. aureus infections. They indicated that antimicrobial peptides derived from various animal venoms, including snakes, spiders, and scorpions, are in early experimental and preclinical development stages, and these cysteine-rich substances share hydrophobic alpha-helices or beta-sheets that yield lethal pores and membrane-impairing results on bacteria.10

New drugs and emerging indications

An ingredient that is said to mimic waglerin-1, a snake venom–derived peptide, is the main active ingredient in the Hanskin Syn-Ake Peptide Renewal Mask, a Korean product, which reportedly promotes facial muscle relaxation and wrinkle reduction, as the waglerin-1 provokes neuromuscular blockade via reversible antagonism of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.2,4,5

Waheed et al. reported in 2017 that recent innovations in molecular research have led to scientific harnessing of the various proteins and peptides found in snake venoms to render them salutary, rather than toxic. Most of the drug development focuses on coagulopathy, hemostasis, and anticancer functions, but research continues in other areas.11 According to An et al., several studies have also been performed on the use of snake venom to treat atopic dermatitis.12

Conclusion

Snake venom is a substance known primarily for its extreme toxicity, but it seems to offer promise for having beneficial effects in medicine. Due to its size and instability, it is doubtful that snake venom will have utility as a topical application in the dermatologic arsenal. In spite of the lack of convincing evidence, a search on Amazon.com brings up dozens of various skin care products containing snake venom. Much more research is necessary, of course, to see if there are methods to facilitate entry of snake venom into the dermis and if this is even desirable.

Snake venom is, in fact, my favorite example of a skin care ingredient that is a waste of money in skin care products. Do you have any favorite “charlatan skincare ingredients”? If so, feel free to contact me, and I will write a column. As dermatologists, we have a responsibility to debunk skin care marketing claims not supported by scientific evidence. I am here to help.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

2. Munawar A et al. Snake venom peptides: tools of biodiscovery. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Nov 14;10(11):474.

3. Almeida JR et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(30):3254-82.

4. Pennington MW et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018 Jun 1;26(10):2738-58.

5. Debono J et al. J Mol Evol. 2017 Jan;84(1):8-11.

6. Bos JD, Meinardi MM. Exp Dermatol. 2000 Jun;9(3):165-9.

7. Samy RP et al. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;716:245-65.

8. Samy RP et al. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(33):5104-13.

9. Al-Asmari AK et al. Open Microbiol J. 2015 Jul;9:18-25.

10. Perumal Samy R et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 15;134:127-38.

11. Waheed H et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(17):1874-91.

12. An HJ et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Dec;175(23):4310-24.

1 This column discusses some of the emerging data in this novel area of medical and dermatologic research. For more detailed information, a review on the therapeutic potential of peptides in animal venom was published in 2003 (Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003 Oct;2[10]:790-802).

The potential of peptides found in snake venom

Snake venom is known to contain carbohydrates, nucleosides, amino acids, and lipids, as well as enzymatic and nonenzymatic proteins and peptides, with proteins and peptides comprising the primary components.2

There are many different types of peptides in snake venom. The peptides and the small proteins found in snake venoms are known to confer a wide range of biologic activities, including antimicrobial, antihypertensive, analgesic, antitumor, and analgesic, in addition to several others. These peptides have been included in antiaging skin care products.3Pennington et al. have observed that venom-derived peptides appear to have potential as effective therapeutic agents in cosmetic formulations.4 In particular, Waglerin peptides appear to act with a Botox-like paralyzing effect and purportedly diminish skin wrinkles.5

Issues with efficacy of snake venom in skin care products

As with many skin care ingredients, what is seen in cell cultures or a laboratory setting may not translate to real life use. Shelf life, issues during manufacturing, interaction with other ingredients in the product, interactions with other products in the regimen, exposure to air and light, and difficulty of penetration can all affect efficacy. With snake venom in particular, stability and penetration make the efficacy in skin care products questionable.

The problem with many peptides in skin care products is that they are usually larger than 500 Dalton and, therefore, cannot penetrate into the skin. Bos et al. described the “500 Dalton rule” in 2000.6 Regardless of these issues, there are several publications looking at snake venom that will be discussed here.

Antimicrobial and wound healing activity

In 2011, Samy et al. found that phospholipase A2 purified from crotalid snake venom expressed antibacterial activity in vitro against various clinical human pathogens. The investigators synthesized peptides based on the sequence homology and ascertained that the synthetic peptides exhibited potent microbicidal properties against Gram-negative and Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria with diminished toxicity against normal human cells. Subsequently, the investigators used a BALB/c mouse model to show that peptide-treated animals displayed accelerated healing of full-thickness skin wounds, with increased re-epithelialization, collagen production, and angiogenesis. They concluded that the protein/peptide complex developed from snake venoms was effective at fostering wound healing.7

In that same year, Samy et al. showed in vivo that the snake venom phospholipase A₂ (svPLA₂) proteins from Viperidae and Elapidae snakes activated innate immunity in the animals tested, providing protection against skin infection caused by S. aureus. In vitro experiments also revealed that svPLA₂ proteins dose dependently exerted bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects on S. aureus.8 In 2015, Al-Asmari et al. comparatively assessed the venoms of two cobras, four vipers, a standard antibiotic, and an antimycotic as antimicrobial agents. The methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacterium was the most susceptible, followed by Gram-positive S. aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. While the antibiotic vancomycin was more effective against P. aeruginosa, the venoms more efficiently suppressed the resistant bacteria. The snake venoms had minimal effect on the fungus Candida albicans. The investigators concluded that the snake venoms exhibited antibacterial activity comparable to antibiotics and were more efficient in tackling resistant bacteria.9 In a review of animal venoms in 2017, Samy et al. reported that snake venom–derived synthetic peptide/snake cathelicidin exhibits robust antimicrobial and wound healing capacity, despite its instability and risk, and presents as a possible new treatment for S. aureus infections. They indicated that antimicrobial peptides derived from various animal venoms, including snakes, spiders, and scorpions, are in early experimental and preclinical development stages, and these cysteine-rich substances share hydrophobic alpha-helices or beta-sheets that yield lethal pores and membrane-impairing results on bacteria.10

New drugs and emerging indications

An ingredient that is said to mimic waglerin-1, a snake venom–derived peptide, is the main active ingredient in the Hanskin Syn-Ake Peptide Renewal Mask, a Korean product, which reportedly promotes facial muscle relaxation and wrinkle reduction, as the waglerin-1 provokes neuromuscular blockade via reversible antagonism of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.2,4,5

Waheed et al. reported in 2017 that recent innovations in molecular research have led to scientific harnessing of the various proteins and peptides found in snake venoms to render them salutary, rather than toxic. Most of the drug development focuses on coagulopathy, hemostasis, and anticancer functions, but research continues in other areas.11 According to An et al., several studies have also been performed on the use of snake venom to treat atopic dermatitis.12

Conclusion

Snake venom is a substance known primarily for its extreme toxicity, but it seems to offer promise for having beneficial effects in medicine. Due to its size and instability, it is doubtful that snake venom will have utility as a topical application in the dermatologic arsenal. In spite of the lack of convincing evidence, a search on Amazon.com brings up dozens of various skin care products containing snake venom. Much more research is necessary, of course, to see if there are methods to facilitate entry of snake venom into the dermis and if this is even desirable.

Snake venom is, in fact, my favorite example of a skin care ingredient that is a waste of money in skin care products. Do you have any favorite “charlatan skincare ingredients”? If so, feel free to contact me, and I will write a column. As dermatologists, we have a responsibility to debunk skin care marketing claims not supported by scientific evidence. I am here to help.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

2. Munawar A et al. Snake venom peptides: tools of biodiscovery. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Nov 14;10(11):474.

3. Almeida JR et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(30):3254-82.

4. Pennington MW et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018 Jun 1;26(10):2738-58.

5. Debono J et al. J Mol Evol. 2017 Jan;84(1):8-11.

6. Bos JD, Meinardi MM. Exp Dermatol. 2000 Jun;9(3):165-9.

7. Samy RP et al. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;716:245-65.

8. Samy RP et al. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(33):5104-13.

9. Al-Asmari AK et al. Open Microbiol J. 2015 Jul;9:18-25.

10. Perumal Samy R et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 15;134:127-38.

11. Waheed H et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(17):1874-91.

12. An HJ et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Dec;175(23):4310-24.

1 This column discusses some of the emerging data in this novel area of medical and dermatologic research. For more detailed information, a review on the therapeutic potential of peptides in animal venom was published in 2003 (Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003 Oct;2[10]:790-802).

The potential of peptides found in snake venom

Snake venom is known to contain carbohydrates, nucleosides, amino acids, and lipids, as well as enzymatic and nonenzymatic proteins and peptides, with proteins and peptides comprising the primary components.2

There are many different types of peptides in snake venom. The peptides and the small proteins found in snake venoms are known to confer a wide range of biologic activities, including antimicrobial, antihypertensive, analgesic, antitumor, and analgesic, in addition to several others. These peptides have been included in antiaging skin care products.3Pennington et al. have observed that venom-derived peptides appear to have potential as effective therapeutic agents in cosmetic formulations.4 In particular, Waglerin peptides appear to act with a Botox-like paralyzing effect and purportedly diminish skin wrinkles.5

Issues with efficacy of snake venom in skin care products

As with many skin care ingredients, what is seen in cell cultures or a laboratory setting may not translate to real life use. Shelf life, issues during manufacturing, interaction with other ingredients in the product, interactions with other products in the regimen, exposure to air and light, and difficulty of penetration can all affect efficacy. With snake venom in particular, stability and penetration make the efficacy in skin care products questionable.

The problem with many peptides in skin care products is that they are usually larger than 500 Dalton and, therefore, cannot penetrate into the skin. Bos et al. described the “500 Dalton rule” in 2000.6 Regardless of these issues, there are several publications looking at snake venom that will be discussed here.

Antimicrobial and wound healing activity

In 2011, Samy et al. found that phospholipase A2 purified from crotalid snake venom expressed antibacterial activity in vitro against various clinical human pathogens. The investigators synthesized peptides based on the sequence homology and ascertained that the synthetic peptides exhibited potent microbicidal properties against Gram-negative and Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria with diminished toxicity against normal human cells. Subsequently, the investigators used a BALB/c mouse model to show that peptide-treated animals displayed accelerated healing of full-thickness skin wounds, with increased re-epithelialization, collagen production, and angiogenesis. They concluded that the protein/peptide complex developed from snake venoms was effective at fostering wound healing.7

In that same year, Samy et al. showed in vivo that the snake venom phospholipase A₂ (svPLA₂) proteins from Viperidae and Elapidae snakes activated innate immunity in the animals tested, providing protection against skin infection caused by S. aureus. In vitro experiments also revealed that svPLA₂ proteins dose dependently exerted bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects on S. aureus.8 In 2015, Al-Asmari et al. comparatively assessed the venoms of two cobras, four vipers, a standard antibiotic, and an antimycotic as antimicrobial agents. The methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacterium was the most susceptible, followed by Gram-positive S. aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. While the antibiotic vancomycin was more effective against P. aeruginosa, the venoms more efficiently suppressed the resistant bacteria. The snake venoms had minimal effect on the fungus Candida albicans. The investigators concluded that the snake venoms exhibited antibacterial activity comparable to antibiotics and were more efficient in tackling resistant bacteria.9 In a review of animal venoms in 2017, Samy et al. reported that snake venom–derived synthetic peptide/snake cathelicidin exhibits robust antimicrobial and wound healing capacity, despite its instability and risk, and presents as a possible new treatment for S. aureus infections. They indicated that antimicrobial peptides derived from various animal venoms, including snakes, spiders, and scorpions, are in early experimental and preclinical development stages, and these cysteine-rich substances share hydrophobic alpha-helices or beta-sheets that yield lethal pores and membrane-impairing results on bacteria.10

New drugs and emerging indications

An ingredient that is said to mimic waglerin-1, a snake venom–derived peptide, is the main active ingredient in the Hanskin Syn-Ake Peptide Renewal Mask, a Korean product, which reportedly promotes facial muscle relaxation and wrinkle reduction, as the waglerin-1 provokes neuromuscular blockade via reversible antagonism of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.2,4,5

Waheed et al. reported in 2017 that recent innovations in molecular research have led to scientific harnessing of the various proteins and peptides found in snake venoms to render them salutary, rather than toxic. Most of the drug development focuses on coagulopathy, hemostasis, and anticancer functions, but research continues in other areas.11 According to An et al., several studies have also been performed on the use of snake venom to treat atopic dermatitis.12

Conclusion

Snake venom is a substance known primarily for its extreme toxicity, but it seems to offer promise for having beneficial effects in medicine. Due to its size and instability, it is doubtful that snake venom will have utility as a topical application in the dermatologic arsenal. In spite of the lack of convincing evidence, a search on Amazon.com brings up dozens of various skin care products containing snake venom. Much more research is necessary, of course, to see if there are methods to facilitate entry of snake venom into the dermis and if this is even desirable.

Snake venom is, in fact, my favorite example of a skin care ingredient that is a waste of money in skin care products. Do you have any favorite “charlatan skincare ingredients”? If so, feel free to contact me, and I will write a column. As dermatologists, we have a responsibility to debunk skin care marketing claims not supported by scientific evidence. I am here to help.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

2. Munawar A et al. Snake venom peptides: tools of biodiscovery. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Nov 14;10(11):474.

3. Almeida JR et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(30):3254-82.

4. Pennington MW et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018 Jun 1;26(10):2738-58.

5. Debono J et al. J Mol Evol. 2017 Jan;84(1):8-11.

6. Bos JD, Meinardi MM. Exp Dermatol. 2000 Jun;9(3):165-9.

7. Samy RP et al. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;716:245-65.

8. Samy RP et al. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(33):5104-13.

9. Al-Asmari AK et al. Open Microbiol J. 2015 Jul;9:18-25.

10. Perumal Samy R et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 15;134:127-38.

11. Waheed H et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(17):1874-91.

12. An HJ et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Dec;175(23):4310-24.

Understanding the alpha hydroxy acids: Glycolic acid

. The extent of exfoliation with any of the alpha hydroxy acids depends on the type of acid, its concentration, and the pH of the preparations. Glycolic acid inhibits tyrosinase and chelates calcium ion concentration between the cells in the epidermis, which results in exfoliation of the skin.

Over-the-counter glycolic acid is available in concentrations up to 30%, and in professional products up to 70%. Clinically, glycolic acid above a concentration of 30% causes local burning, erythema, and dryness.

However, overuse of glycolic acid among consumers has increased the incidence of skin reactions and hyperpigmentation. Professional-grade products containing up to 70% glycolic acid are widely available on the Internet and without proper guidelines on use and sun avoidance, adverse events and long term scarring are becoming prevalent.

The overuse of acids and overexfoliation of the skin in patients with skin types I-IV is a growing problem as consumers are purchasing more “at-home peels,” peel pads, glow pads, and at-home exfoliation regimens. This overexfoliation of the skin and the resulting erythema induces rapid postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Consumers then often mistakenly try to self-treat the hyperpigmentation with increasing concentrations of acids, retinols, and/or hydroquinone on top of an already compromised skin barrier, further worsening the problem. In addition, these acids increase sensitivity to UV light and increase the risk of sunburns in all skin types.

Although glycolic acids are generally safe, standardized recommendations for their use in the skin care market are necessary. More is not always better. In our clinic, we do not treat patients with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from acids or peels with more exfoliation. We focus on repairing the barrier for 1-3 months, which includes use of gentle cleansers and occlusive moisturizers, and avoidance of acids, retinols, or scrubs, and aggressive sun protection, and then using gentle fade ingredients – such as kojic acid, licorice root extract, and vitamin C – at low concentrations to slowly decrease melanin production. Barrier repair is the first and most important step and it is often overlooked when clinicians try to lighten the skin in haste.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan O. Wesley and are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. They had no relevant disclosures. Write to them at [email protected].

. The extent of exfoliation with any of the alpha hydroxy acids depends on the type of acid, its concentration, and the pH of the preparations. Glycolic acid inhibits tyrosinase and chelates calcium ion concentration between the cells in the epidermis, which results in exfoliation of the skin.

Over-the-counter glycolic acid is available in concentrations up to 30%, and in professional products up to 70%. Clinically, glycolic acid above a concentration of 30% causes local burning, erythema, and dryness.

However, overuse of glycolic acid among consumers has increased the incidence of skin reactions and hyperpigmentation. Professional-grade products containing up to 70% glycolic acid are widely available on the Internet and without proper guidelines on use and sun avoidance, adverse events and long term scarring are becoming prevalent.

The overuse of acids and overexfoliation of the skin in patients with skin types I-IV is a growing problem as consumers are purchasing more “at-home peels,” peel pads, glow pads, and at-home exfoliation regimens. This overexfoliation of the skin and the resulting erythema induces rapid postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Consumers then often mistakenly try to self-treat the hyperpigmentation with increasing concentrations of acids, retinols, and/or hydroquinone on top of an already compromised skin barrier, further worsening the problem. In addition, these acids increase sensitivity to UV light and increase the risk of sunburns in all skin types.

Although glycolic acids are generally safe, standardized recommendations for their use in the skin care market are necessary. More is not always better. In our clinic, we do not treat patients with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from acids or peels with more exfoliation. We focus on repairing the barrier for 1-3 months, which includes use of gentle cleansers and occlusive moisturizers, and avoidance of acids, retinols, or scrubs, and aggressive sun protection, and then using gentle fade ingredients – such as kojic acid, licorice root extract, and vitamin C – at low concentrations to slowly decrease melanin production. Barrier repair is the first and most important step and it is often overlooked when clinicians try to lighten the skin in haste.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan O. Wesley and are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. They had no relevant disclosures. Write to them at [email protected].

. The extent of exfoliation with any of the alpha hydroxy acids depends on the type of acid, its concentration, and the pH of the preparations. Glycolic acid inhibits tyrosinase and chelates calcium ion concentration between the cells in the epidermis, which results in exfoliation of the skin.

Over-the-counter glycolic acid is available in concentrations up to 30%, and in professional products up to 70%. Clinically, glycolic acid above a concentration of 30% causes local burning, erythema, and dryness.

However, overuse of glycolic acid among consumers has increased the incidence of skin reactions and hyperpigmentation. Professional-grade products containing up to 70% glycolic acid are widely available on the Internet and without proper guidelines on use and sun avoidance, adverse events and long term scarring are becoming prevalent.

The overuse of acids and overexfoliation of the skin in patients with skin types I-IV is a growing problem as consumers are purchasing more “at-home peels,” peel pads, glow pads, and at-home exfoliation regimens. This overexfoliation of the skin and the resulting erythema induces rapid postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Consumers then often mistakenly try to self-treat the hyperpigmentation with increasing concentrations of acids, retinols, and/or hydroquinone on top of an already compromised skin barrier, further worsening the problem. In addition, these acids increase sensitivity to UV light and increase the risk of sunburns in all skin types.

Although glycolic acids are generally safe, standardized recommendations for their use in the skin care market are necessary. More is not always better. In our clinic, we do not treat patients with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from acids or peels with more exfoliation. We focus on repairing the barrier for 1-3 months, which includes use of gentle cleansers and occlusive moisturizers, and avoidance of acids, retinols, or scrubs, and aggressive sun protection, and then using gentle fade ingredients – such as kojic acid, licorice root extract, and vitamin C – at low concentrations to slowly decrease melanin production. Barrier repair is the first and most important step and it is often overlooked when clinicians try to lighten the skin in haste.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan O. Wesley and are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. They had no relevant disclosures. Write to them at [email protected].

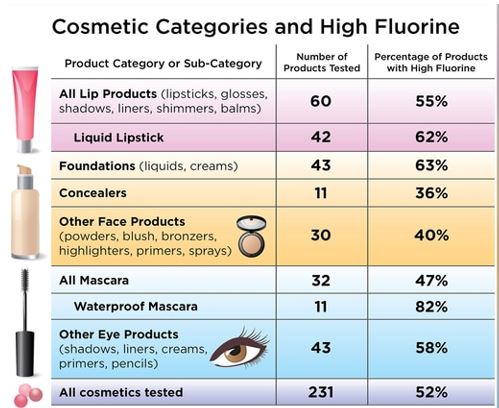

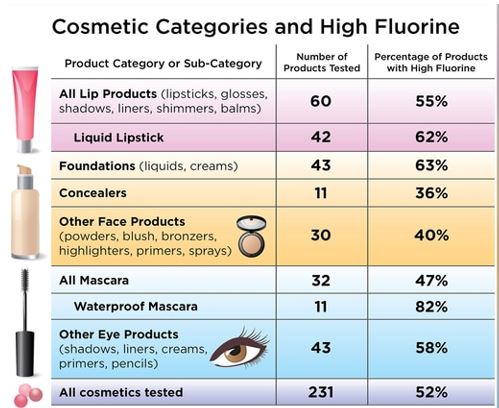

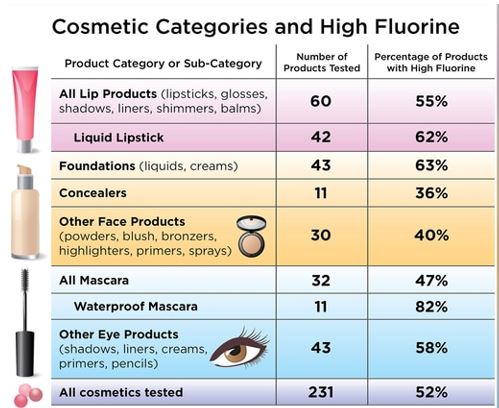

Toxic chemicals found in many cosmetics

People may be absorbing and ingesting potentially toxic chemicals from their cosmetic products, a new study suggests.

– per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Many of these chemicals were not included on the product labels, making it difficult for consumers to consciously avoid them.

“This study is very helpful for elucidating the PFAS content of different types of cosmetics in the U.S. and Canadian markets,” said Elsie Sunderland, PhD, an environmental scientist who was not involved with the study.

“Previously, all the data had been collected in Europe, and this study shows we are dealing with similar problems in the North American marketplace,” said Dr. Sunderland, a professor of environmental chemistry at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

PFAS are a class of chemicals used in a variety of consumer products, such as nonstick cookware, stain-resistant carpeting, and water-repellent clothing, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They are added to cosmetics to make the products more durable and spreadable, researchers said in the study.

“[PFAS] are added to change the properties of surfaces, to make them nonstick or resistant to stay in water or oils,” said study coauthor Tom Bruton, PhD, senior scientist at the Green Science Policy Institute in Berkeley, Calif. “The concerning thing about cosmetics is that these are products that you’re applying to your skin and face every day, so there’s the skin absorption route that’s of concern, but also incidental ingestion of cosmetics is also a concern as well.”

The CDC says some of the potential health effects of PFAS exposure includes increased cholesterol levels, increased risk of kidney and testicular cancer, changes in liver enzymes, decreased vaccine response in children, and a higher risk of high blood pressure or preeclampsia in pregnant women.

“PFAS are a large class of chemicals. In humans, exposure to some of these chemicals has been associated with impaired immune function, certain cancers, increased risks of diabetes, obesity and endocrine disruption,” Dr. Sunderland said. “They appear to be harmful to every major organ system in the human body.”

For the current study, published online in Environmental Science & Technology Letters, Dr. Bruton and colleagues purchased 231 cosmetic products in the United States and Canada from retailers such as Ulta Beauty, Sephora, Target, and Bed Bath & Beyond. They then screened them for fluorine.Three-quarters of waterproof mascara samples contained high fluorine concentrations, as did nearly two-thirds of foundations and liquid lipsticks, and more than half of the eye and lip products tested.

The authors found that different categories of makeup tended to have higher or lower fluorine concentrations. “High fluorine levels were found in products commonly advertised as ‘wear-resistant’ to water and oils or ‘long-lasting,’ including foundations, liquid lipsticks, and waterproof mascaras,” Dr. Bruton and colleagues wrote.

When they further analyzed a subset of 29 products to determine what types of chemicals were present, they found that each cosmetic product contained at least 4 PFAS, with one product containing 13.The PFAS substances found included some that break down into other chemicals that are known to be highly toxic and environmentally harmful.

“It’s concerning that some of the products we tested appear to be intentionally using PFAS, but not listing those ingredients on the label,” Dr. Bruton said. “I do think that it is helpful for consumers to read labels, but beyond that, there’s not a lot of ways that consumers themselves can solve this problem. ... We think that the industry needs to be more proactive about moving away from this group of chemicals.”

Dr. Sunderland said a resource people can use when trying to avoid PFAS is the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit organization that maintains an extensive database of cosmetics and personal care products.

“At this point, there is very little regulatory activity related to PFAS in cosmetics,” Dr. Sunderland said. “The best thing to happen now would be for consumers to indicate that they prefer products without PFAS and to demand better transparency in product ingredient lists.”

A similar study done in 2018 by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency found high levels of PFAS in nearly one-third of the cosmetics products it tested.

People can also be exposed to PFAS by eating or drinking contaminated food or water and through food packaging. Dr. Sunderland said some wild foods like seafood are known to accumulate these compounds in the environment.

“There are examples of contaminated biosolids leading to accumulation of PFAS in vegetables and milk,” Dr. Sunderland explained. “Food packaging is another concern because it can also result in PFAS accumulation in the foods we eat.”

Although it’s difficult to avoid PFAS altogether, the CDC suggests lowering exposure rates by avoiding contaminated water and food. If you’re not sure if your water is contaminated, you should ask your local or state health and environmental quality departments for fish or water advisories in your area.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

People may be absorbing and ingesting potentially toxic chemicals from their cosmetic products, a new study suggests.

– per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Many of these chemicals were not included on the product labels, making it difficult for consumers to consciously avoid them.

“This study is very helpful for elucidating the PFAS content of different types of cosmetics in the U.S. and Canadian markets,” said Elsie Sunderland, PhD, an environmental scientist who was not involved with the study.

“Previously, all the data had been collected in Europe, and this study shows we are dealing with similar problems in the North American marketplace,” said Dr. Sunderland, a professor of environmental chemistry at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

PFAS are a class of chemicals used in a variety of consumer products, such as nonstick cookware, stain-resistant carpeting, and water-repellent clothing, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They are added to cosmetics to make the products more durable and spreadable, researchers said in the study.

“[PFAS] are added to change the properties of surfaces, to make them nonstick or resistant to stay in water or oils,” said study coauthor Tom Bruton, PhD, senior scientist at the Green Science Policy Institute in Berkeley, Calif. “The concerning thing about cosmetics is that these are products that you’re applying to your skin and face every day, so there’s the skin absorption route that’s of concern, but also incidental ingestion of cosmetics is also a concern as well.”

The CDC says some of the potential health effects of PFAS exposure includes increased cholesterol levels, increased risk of kidney and testicular cancer, changes in liver enzymes, decreased vaccine response in children, and a higher risk of high blood pressure or preeclampsia in pregnant women.

“PFAS are a large class of chemicals. In humans, exposure to some of these chemicals has been associated with impaired immune function, certain cancers, increased risks of diabetes, obesity and endocrine disruption,” Dr. Sunderland said. “They appear to be harmful to every major organ system in the human body.”

For the current study, published online in Environmental Science & Technology Letters, Dr. Bruton and colleagues purchased 231 cosmetic products in the United States and Canada from retailers such as Ulta Beauty, Sephora, Target, and Bed Bath & Beyond. They then screened them for fluorine.Three-quarters of waterproof mascara samples contained high fluorine concentrations, as did nearly two-thirds of foundations and liquid lipsticks, and more than half of the eye and lip products tested.

The authors found that different categories of makeup tended to have higher or lower fluorine concentrations. “High fluorine levels were found in products commonly advertised as ‘wear-resistant’ to water and oils or ‘long-lasting,’ including foundations, liquid lipsticks, and waterproof mascaras,” Dr. Bruton and colleagues wrote.

When they further analyzed a subset of 29 products to determine what types of chemicals were present, they found that each cosmetic product contained at least 4 PFAS, with one product containing 13.The PFAS substances found included some that break down into other chemicals that are known to be highly toxic and environmentally harmful.

“It’s concerning that some of the products we tested appear to be intentionally using PFAS, but not listing those ingredients on the label,” Dr. Bruton said. “I do think that it is helpful for consumers to read labels, but beyond that, there’s not a lot of ways that consumers themselves can solve this problem. ... We think that the industry needs to be more proactive about moving away from this group of chemicals.”

Dr. Sunderland said a resource people can use when trying to avoid PFAS is the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit organization that maintains an extensive database of cosmetics and personal care products.

“At this point, there is very little regulatory activity related to PFAS in cosmetics,” Dr. Sunderland said. “The best thing to happen now would be for consumers to indicate that they prefer products without PFAS and to demand better transparency in product ingredient lists.”

A similar study done in 2018 by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency found high levels of PFAS in nearly one-third of the cosmetics products it tested.

People can also be exposed to PFAS by eating or drinking contaminated food or water and through food packaging. Dr. Sunderland said some wild foods like seafood are known to accumulate these compounds in the environment.

“There are examples of contaminated biosolids leading to accumulation of PFAS in vegetables and milk,” Dr. Sunderland explained. “Food packaging is another concern because it can also result in PFAS accumulation in the foods we eat.”

Although it’s difficult to avoid PFAS altogether, the CDC suggests lowering exposure rates by avoiding contaminated water and food. If you’re not sure if your water is contaminated, you should ask your local or state health and environmental quality departments for fish or water advisories in your area.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

People may be absorbing and ingesting potentially toxic chemicals from their cosmetic products, a new study suggests.

– per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Many of these chemicals were not included on the product labels, making it difficult for consumers to consciously avoid them.

“This study is very helpful for elucidating the PFAS content of different types of cosmetics in the U.S. and Canadian markets,” said Elsie Sunderland, PhD, an environmental scientist who was not involved with the study.

“Previously, all the data had been collected in Europe, and this study shows we are dealing with similar problems in the North American marketplace,” said Dr. Sunderland, a professor of environmental chemistry at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

PFAS are a class of chemicals used in a variety of consumer products, such as nonstick cookware, stain-resistant carpeting, and water-repellent clothing, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They are added to cosmetics to make the products more durable and spreadable, researchers said in the study.

“[PFAS] are added to change the properties of surfaces, to make them nonstick or resistant to stay in water or oils,” said study coauthor Tom Bruton, PhD, senior scientist at the Green Science Policy Institute in Berkeley, Calif. “The concerning thing about cosmetics is that these are products that you’re applying to your skin and face every day, so there’s the skin absorption route that’s of concern, but also incidental ingestion of cosmetics is also a concern as well.”

The CDC says some of the potential health effects of PFAS exposure includes increased cholesterol levels, increased risk of kidney and testicular cancer, changes in liver enzymes, decreased vaccine response in children, and a higher risk of high blood pressure or preeclampsia in pregnant women.

“PFAS are a large class of chemicals. In humans, exposure to some of these chemicals has been associated with impaired immune function, certain cancers, increased risks of diabetes, obesity and endocrine disruption,” Dr. Sunderland said. “They appear to be harmful to every major organ system in the human body.”

For the current study, published online in Environmental Science & Technology Letters, Dr. Bruton and colleagues purchased 231 cosmetic products in the United States and Canada from retailers such as Ulta Beauty, Sephora, Target, and Bed Bath & Beyond. They then screened them for fluorine.Three-quarters of waterproof mascara samples contained high fluorine concentrations, as did nearly two-thirds of foundations and liquid lipsticks, and more than half of the eye and lip products tested.

The authors found that different categories of makeup tended to have higher or lower fluorine concentrations. “High fluorine levels were found in products commonly advertised as ‘wear-resistant’ to water and oils or ‘long-lasting,’ including foundations, liquid lipsticks, and waterproof mascaras,” Dr. Bruton and colleagues wrote.

When they further analyzed a subset of 29 products to determine what types of chemicals were present, they found that each cosmetic product contained at least 4 PFAS, with one product containing 13.The PFAS substances found included some that break down into other chemicals that are known to be highly toxic and environmentally harmful.

“It’s concerning that some of the products we tested appear to be intentionally using PFAS, but not listing those ingredients on the label,” Dr. Bruton said. “I do think that it is helpful for consumers to read labels, but beyond that, there’s not a lot of ways that consumers themselves can solve this problem. ... We think that the industry needs to be more proactive about moving away from this group of chemicals.”

Dr. Sunderland said a resource people can use when trying to avoid PFAS is the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit organization that maintains an extensive database of cosmetics and personal care products.

“At this point, there is very little regulatory activity related to PFAS in cosmetics,” Dr. Sunderland said. “The best thing to happen now would be for consumers to indicate that they prefer products without PFAS and to demand better transparency in product ingredient lists.”

A similar study done in 2018 by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency found high levels of PFAS in nearly one-third of the cosmetics products it tested.

People can also be exposed to PFAS by eating or drinking contaminated food or water and through food packaging. Dr. Sunderland said some wild foods like seafood are known to accumulate these compounds in the environment.

“There are examples of contaminated biosolids leading to accumulation of PFAS in vegetables and milk,” Dr. Sunderland explained. “Food packaging is another concern because it can also result in PFAS accumulation in the foods we eat.”

Although it’s difficult to avoid PFAS altogether, the CDC suggests lowering exposure rates by avoiding contaminated water and food. If you’re not sure if your water is contaminated, you should ask your local or state health and environmental quality departments for fish or water advisories in your area.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Photobiomodulation: Evaluation in a wide range of medical specialties underway

according to Juanita J. Anders, PhD.

During the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, Dr. Anders, professor of anatomy, physiology, and genetics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., defined photobiomodulation (PBM) as the mechanism by which nonionizing optical radiation in the visible and near-infrared spectral range is absorbed by endogenous chromophores to elicit photophysical and photochemical events at various biological scales. Photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT) involves the use of light sources including lasers, LEDs, and broadband light, that emit visible and/or near-infrared light to cause physiological changes in cells and tissues and result in therapeutic benefits.

In dermatology, LED light therapy devices are commonly used for PBMT in wavelengths that range from blue (415 nm) and red (633 nm) to near infrared (830 nm). “Often, when PBMT is referred to by dermatologists it’s called LED therapy or LED light therapy,” Dr. Anders noted. “Some people are under the impression that this is different from PBMT. But remember: It’s not the device that’s producing the photons that is clinically relevant, but it’s the photons themselves. In both cases, the same radiances and fluence ranges are being used and the mechanisms are the same, so it’s all PBMT.”

The therapy is used to treat a wide variety of medical and aesthetic disorders including acne vulgaris, psoriasis, burns, and wound healing. It has also been used in conjunction with surgical aesthetic and resurfacing procedures and has been reported to reduce erythema, edema, bruising, and days to healing. It’s been shown that PBMT stimulates fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, and extracellular matrix resulting in lifting and tightening lax skin.

According to Dr. Anders, French dermatologists Linda Fouque, MD, and Michele Pelletier, MD, performed a series of in vivo and in vitro studies in which they tested the effects of yellow and red light for skin rejuvenation when used individually or in combination. “They found that fibroblasts and keratinocytes in vitro had great improvement in their morphology both with the yellow and red light, but the best improvement was seen with combination therapy,” Dr. Anders said. “This held true in their work looking at epidermal and dermal markers in the skin, where they found the best up-regulation in protein synthesis of such markers as collagens and fibronectin were produced when a combination wavelength light was used.”

Oral mucositis and pain

PBMT is also being used to treat oral mucositis (OM), a common adverse response to chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, which causes pain, difficulty in swallowing and eating, and oral ulceration, and often interrupts the course of treatments. Authors of a recently published review on the risks and benefits of PBMT concluded that there is consistent evidence from a small number of high-quality studies that PBMT can help prevent the development of cancer therapy–induced OM, reduce pain intensity, as well as promote healing, and enhance patient quality of life.

“They also cautioned that, due to the limited long-term follow-up of patients, there is still concern for the potential long-term risks of PBMT in cancer cell mutation and amplification,” Dr. Anders said. “They advised that PBMT should be used carefully when the irradiation beam is in the direction of the tumor zone.”

Using PBMT for modulation of pain is another area of active research. Based on work from the laboratory of Dr. Anders and others, there are two methods to modulate pain. The first is to target tissue at irradiances below 100 mW/cm2.

“In my laboratory, based on in vivo preclinical animal models of neuropathic pain, we used a 980-nm wavelength laser at 43.25 mW/cm2 transcutaneously delivered to the level of the nerve for 20 seconds,” said Dr. Anders, who is a past president of the ASLMS. “Essentially, we found that the pain was modulated by reducing sensitivity to mechanical stimulation and also by causing an anti-inflammatory shift in microglial and macrophage phenotype in the dorsal root ganglion and spinal cord of affected segments.”

The second way to modulate pain, she continued, is to target tissue at irradiances above 250 mW/cm2. She and her colleagues have conducted in vitro and in vivo studies, which indicate that treatment with an irradiance/fluence rate at 270 mW/cm2 or higher at the nerve can rapidly block pain transmission.

“In vitro, we found that if we used an 810-nm wavelength light at 300 mW/cm2, we got a disruption of microtubules in the DRG neurons in culture, specifically the small neurons, the nociceptive fibers, but we did not affect the proprioceptive fibers unless we increased the length of the treatment,” she said. “We essentially found the same thing in vivo in a rodent model of neuropathic pain.”

In a pilot study, Dr. Anders and coauthors examined the efficacy of laser irradiation of the dorsal root ganglion of the second lumbar spinal nerve for patients with chronic back pain.

They found that PBMT effectively reduced back pain equal to the effects of lidocaine.

Based on these two irradiation approaches of targeting tissue, Dr. Anders recommends that a combination therapy be used to modulate neuropathic pain going forward. “This approach would involve the initial use of a high-irradiance treatment [at least 250 mW/cm2] at the nerve to block the pain transmission,” she said. “That treatment would be followed by a series of low-irradiance treatments [10-100 mW/cm2] along the course of the involved nerve to alter chronic pathology and inflammation.”

Potential applications in neurology

Dr. Anders also discussed research efforts under way involving transcranial PBMT: the delivery of near-infrared light through the tissues of the scalp and skull to targeted brain regions to treat neurologic injuries and disorders. “There have been some exciting results in preclinical animal work and in small clinical pilot work that show that there could be possible beneficial effects in Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and improvement in cognition and memory after a brain injury, such as a TBI,” she said.

“Initially, though, there were a lot of questions about whether you could really deliver light to the brain through the scalp. In my laboratory, we used slices of nonfixed brain and found that the sulci within the human brain act as light-wave guides. We used an 808-nm near-infrared wavelength of light, so that the light could penetrate more deeply.” Using nonfixed cadaver heads, where the light was applied at the scalp surface, Dr. Anders and colleagues were able to measure photons down to the depth of 4 cm. “It’s generally agreed now, though, that it’s to a maximum depth of 2.5-3 cm that enough photons are delivered that would cause a beneficial therapeutic effect,” she said.

Dr. Anders disclosed that she has received equipment from LiteCure, grant funding from the Department of Defense, and that she holds advisory board roles with LiteCure and Neurothera. She has also served in leadership roles for the Optical Society and holds intellectual property rights for the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine.

according to Juanita J. Anders, PhD.

During the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, Dr. Anders, professor of anatomy, physiology, and genetics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., defined photobiomodulation (PBM) as the mechanism by which nonionizing optical radiation in the visible and near-infrared spectral range is absorbed by endogenous chromophores to elicit photophysical and photochemical events at various biological scales. Photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT) involves the use of light sources including lasers, LEDs, and broadband light, that emit visible and/or near-infrared light to cause physiological changes in cells and tissues and result in therapeutic benefits.

In dermatology, LED light therapy devices are commonly used for PBMT in wavelengths that range from blue (415 nm) and red (633 nm) to near infrared (830 nm). “Often, when PBMT is referred to by dermatologists it’s called LED therapy or LED light therapy,” Dr. Anders noted. “Some people are under the impression that this is different from PBMT. But remember: It’s not the device that’s producing the photons that is clinically relevant, but it’s the photons themselves. In both cases, the same radiances and fluence ranges are being used and the mechanisms are the same, so it’s all PBMT.”

The therapy is used to treat a wide variety of medical and aesthetic disorders including acne vulgaris, psoriasis, burns, and wound healing. It has also been used in conjunction with surgical aesthetic and resurfacing procedures and has been reported to reduce erythema, edema, bruising, and days to healing. It’s been shown that PBMT stimulates fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, and extracellular matrix resulting in lifting and tightening lax skin.

According to Dr. Anders, French dermatologists Linda Fouque, MD, and Michele Pelletier, MD, performed a series of in vivo and in vitro studies in which they tested the effects of yellow and red light for skin rejuvenation when used individually or in combination. “They found that fibroblasts and keratinocytes in vitro had great improvement in their morphology both with the yellow and red light, but the best improvement was seen with combination therapy,” Dr. Anders said. “This held true in their work looking at epidermal and dermal markers in the skin, where they found the best up-regulation in protein synthesis of such markers as collagens and fibronectin were produced when a combination wavelength light was used.”

Oral mucositis and pain

PBMT is also being used to treat oral mucositis (OM), a common adverse response to chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, which causes pain, difficulty in swallowing and eating, and oral ulceration, and often interrupts the course of treatments. Authors of a recently published review on the risks and benefits of PBMT concluded that there is consistent evidence from a small number of high-quality studies that PBMT can help prevent the development of cancer therapy–induced OM, reduce pain intensity, as well as promote healing, and enhance patient quality of life.

“They also cautioned that, due to the limited long-term follow-up of patients, there is still concern for the potential long-term risks of PBMT in cancer cell mutation and amplification,” Dr. Anders said. “They advised that PBMT should be used carefully when the irradiation beam is in the direction of the tumor zone.”

Using PBMT for modulation of pain is another area of active research. Based on work from the laboratory of Dr. Anders and others, there are two methods to modulate pain. The first is to target tissue at irradiances below 100 mW/cm2.

“In my laboratory, based on in vivo preclinical animal models of neuropathic pain, we used a 980-nm wavelength laser at 43.25 mW/cm2 transcutaneously delivered to the level of the nerve for 20 seconds,” said Dr. Anders, who is a past president of the ASLMS. “Essentially, we found that the pain was modulated by reducing sensitivity to mechanical stimulation and also by causing an anti-inflammatory shift in microglial and macrophage phenotype in the dorsal root ganglion and spinal cord of affected segments.”

The second way to modulate pain, she continued, is to target tissue at irradiances above 250 mW/cm2. She and her colleagues have conducted in vitro and in vivo studies, which indicate that treatment with an irradiance/fluence rate at 270 mW/cm2 or higher at the nerve can rapidly block pain transmission.

“In vitro, we found that if we used an 810-nm wavelength light at 300 mW/cm2, we got a disruption of microtubules in the DRG neurons in culture, specifically the small neurons, the nociceptive fibers, but we did not affect the proprioceptive fibers unless we increased the length of the treatment,” she said. “We essentially found the same thing in vivo in a rodent model of neuropathic pain.”

In a pilot study, Dr. Anders and coauthors examined the efficacy of laser irradiation of the dorsal root ganglion of the second lumbar spinal nerve for patients with chronic back pain.

They found that PBMT effectively reduced back pain equal to the effects of lidocaine.

Based on these two irradiation approaches of targeting tissue, Dr. Anders recommends that a combination therapy be used to modulate neuropathic pain going forward. “This approach would involve the initial use of a high-irradiance treatment [at least 250 mW/cm2] at the nerve to block the pain transmission,” she said. “That treatment would be followed by a series of low-irradiance treatments [10-100 mW/cm2] along the course of the involved nerve to alter chronic pathology and inflammation.”

Potential applications in neurology

Dr. Anders also discussed research efforts under way involving transcranial PBMT: the delivery of near-infrared light through the tissues of the scalp and skull to targeted brain regions to treat neurologic injuries and disorders. “There have been some exciting results in preclinical animal work and in small clinical pilot work that show that there could be possible beneficial effects in Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and improvement in cognition and memory after a brain injury, such as a TBI,” she said.

“Initially, though, there were a lot of questions about whether you could really deliver light to the brain through the scalp. In my laboratory, we used slices of nonfixed brain and found that the sulci within the human brain act as light-wave guides. We used an 808-nm near-infrared wavelength of light, so that the light could penetrate more deeply.” Using nonfixed cadaver heads, where the light was applied at the scalp surface, Dr. Anders and colleagues were able to measure photons down to the depth of 4 cm. “It’s generally agreed now, though, that it’s to a maximum depth of 2.5-3 cm that enough photons are delivered that would cause a beneficial therapeutic effect,” she said.

Dr. Anders disclosed that she has received equipment from LiteCure, grant funding from the Department of Defense, and that she holds advisory board roles with LiteCure and Neurothera. She has also served in leadership roles for the Optical Society and holds intellectual property rights for the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine.

according to Juanita J. Anders, PhD.

During the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, Dr. Anders, professor of anatomy, physiology, and genetics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., defined photobiomodulation (PBM) as the mechanism by which nonionizing optical radiation in the visible and near-infrared spectral range is absorbed by endogenous chromophores to elicit photophysical and photochemical events at various biological scales. Photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT) involves the use of light sources including lasers, LEDs, and broadband light, that emit visible and/or near-infrared light to cause physiological changes in cells and tissues and result in therapeutic benefits.

In dermatology, LED light therapy devices are commonly used for PBMT in wavelengths that range from blue (415 nm) and red (633 nm) to near infrared (830 nm). “Often, when PBMT is referred to by dermatologists it’s called LED therapy or LED light therapy,” Dr. Anders noted. “Some people are under the impression that this is different from PBMT. But remember: It’s not the device that’s producing the photons that is clinically relevant, but it’s the photons themselves. In both cases, the same radiances and fluence ranges are being used and the mechanisms are the same, so it’s all PBMT.”

The therapy is used to treat a wide variety of medical and aesthetic disorders including acne vulgaris, psoriasis, burns, and wound healing. It has also been used in conjunction with surgical aesthetic and resurfacing procedures and has been reported to reduce erythema, edema, bruising, and days to healing. It’s been shown that PBMT stimulates fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, and extracellular matrix resulting in lifting and tightening lax skin.

According to Dr. Anders, French dermatologists Linda Fouque, MD, and Michele Pelletier, MD, performed a series of in vivo and in vitro studies in which they tested the effects of yellow and red light for skin rejuvenation when used individually or in combination. “They found that fibroblasts and keratinocytes in vitro had great improvement in their morphology both with the yellow and red light, but the best improvement was seen with combination therapy,” Dr. Anders said. “This held true in their work looking at epidermal and dermal markers in the skin, where they found the best up-regulation in protein synthesis of such markers as collagens and fibronectin were produced when a combination wavelength light was used.”

Oral mucositis and pain

PBMT is also being used to treat oral mucositis (OM), a common adverse response to chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, which causes pain, difficulty in swallowing and eating, and oral ulceration, and often interrupts the course of treatments. Authors of a recently published review on the risks and benefits of PBMT concluded that there is consistent evidence from a small number of high-quality studies that PBMT can help prevent the development of cancer therapy–induced OM, reduce pain intensity, as well as promote healing, and enhance patient quality of life.

“They also cautioned that, due to the limited long-term follow-up of patients, there is still concern for the potential long-term risks of PBMT in cancer cell mutation and amplification,” Dr. Anders said. “They advised that PBMT should be used carefully when the irradiation beam is in the direction of the tumor zone.”

Using PBMT for modulation of pain is another area of active research. Based on work from the laboratory of Dr. Anders and others, there are two methods to modulate pain. The first is to target tissue at irradiances below 100 mW/cm2.

“In my laboratory, based on in vivo preclinical animal models of neuropathic pain, we used a 980-nm wavelength laser at 43.25 mW/cm2 transcutaneously delivered to the level of the nerve for 20 seconds,” said Dr. Anders, who is a past president of the ASLMS. “Essentially, we found that the pain was modulated by reducing sensitivity to mechanical stimulation and also by causing an anti-inflammatory shift in microglial and macrophage phenotype in the dorsal root ganglion and spinal cord of affected segments.”

The second way to modulate pain, she continued, is to target tissue at irradiances above 250 mW/cm2. She and her colleagues have conducted in vitro and in vivo studies, which indicate that treatment with an irradiance/fluence rate at 270 mW/cm2 or higher at the nerve can rapidly block pain transmission.

“In vitro, we found that if we used an 810-nm wavelength light at 300 mW/cm2, we got a disruption of microtubules in the DRG neurons in culture, specifically the small neurons, the nociceptive fibers, but we did not affect the proprioceptive fibers unless we increased the length of the treatment,” she said. “We essentially found the same thing in vivo in a rodent model of neuropathic pain.”

In a pilot study, Dr. Anders and coauthors examined the efficacy of laser irradiation of the dorsal root ganglion of the second lumbar spinal nerve for patients with chronic back pain.

They found that PBMT effectively reduced back pain equal to the effects of lidocaine.

Based on these two irradiation approaches of targeting tissue, Dr. Anders recommends that a combination therapy be used to modulate neuropathic pain going forward. “This approach would involve the initial use of a high-irradiance treatment [at least 250 mW/cm2] at the nerve to block the pain transmission,” she said. “That treatment would be followed by a series of low-irradiance treatments [10-100 mW/cm2] along the course of the involved nerve to alter chronic pathology and inflammation.”

Potential applications in neurology

Dr. Anders also discussed research efforts under way involving transcranial PBMT: the delivery of near-infrared light through the tissues of the scalp and skull to targeted brain regions to treat neurologic injuries and disorders. “There have been some exciting results in preclinical animal work and in small clinical pilot work that show that there could be possible beneficial effects in Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and improvement in cognition and memory after a brain injury, such as a TBI,” she said.

“Initially, though, there were a lot of questions about whether you could really deliver light to the brain through the scalp. In my laboratory, we used slices of nonfixed brain and found that the sulci within the human brain act as light-wave guides. We used an 808-nm near-infrared wavelength of light, so that the light could penetrate more deeply.” Using nonfixed cadaver heads, where the light was applied at the scalp surface, Dr. Anders and colleagues were able to measure photons down to the depth of 4 cm. “It’s generally agreed now, though, that it’s to a maximum depth of 2.5-3 cm that enough photons are delivered that would cause a beneficial therapeutic effect,” she said.

Dr. Anders disclosed that she has received equipment from LiteCure, grant funding from the Department of Defense, and that she holds advisory board roles with LiteCure and Neurothera. She has also served in leadership roles for the Optical Society and holds intellectual property rights for the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine.

FROM ASLMS 2021

Expert offers 10 ‘tips and tricks’ for everyday cosmetic practice

, based on nearly 10 years of experience treating patients on both coasts of the United States.

They are as follows:

1. Know your clinical endpoints. “One of the things that was drilled into me during my fellowship in lasers and cosmetics at Mass General was to know your clinical endpoints and to avoid a cookbook approach,” said Dr. Jalian, who practices dermatology in Los Angeles. “You should treat based on the pathology that you’re seeing on the skin and let the endpoints be your guide. The skin will tell you what you’re doing right, and the skin will tell you what you’re doing wrong. Picking up on these cues will allow you to deliver a safe and effective treatment to your patients.”