User login

Teens likely to mimic parents’ opioid use

reported Pamela C. Griesler, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates.

Given the significant link between parental and adolescent smoking and adolescent nonmedical prescription opioid (NMPO) use, smoking also should be included in targeted interventions, they wrote in Pediatrics.

Dr. Griesler and her colleagues noted that there actually are three classes of factors influencing the association between parent and adolescent NMPO use: phenotypic heritability, parental role modeling, and parental socialization and other environmental influences.

In the first known study to explore the relationship of parent-adolescent NMPO use within a nationally representative sampling of parent-child dyads taken from the National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, Dr. Griesler and her colleagues examined the intergenerational association of lifetime NMPO use among 35,000 parent-adolescent dyads (21,200 mothers, 13,800 fathers). Of the 35,000 children aged 12-17 years included in the sample, 90% were biological, 8% were stepchildren, and 2% were adopted.

Given the absence of previous studies exploring the relationship between parent-adolescent NMPO use, Dr. Griesler and her associates used established findings for smoking and substance use to hypothesize that there would be stronger associations for mothers than fathers, daughters than sons, and for whites than African Americans.

The investigators posed three questions that formed the basis of their research: 1) What is the association between lifetime parental and child NMPO use? 2) What is the unique association between parental and child NMPO use, controlling for other factors? 3) Do parental/adolescent NMPO use associations differ by parent/child gender and race and/or ethnicity?

About 14% of parents reported ever using an NMPO; fathers (14%) had slightly higher rates of usage than mothers (13%), and white parents had higher rates of use (16%) than African American (10%) or Hispanic (9%) parents. Among adolescents, 9% reported ever having used an NMPO; this included similar rates for boys (9%) and girls (9%), as well as whites (9%), Hispanics (9%), and African Americans (8%). Use increased with age over time, from 4% among 12-year-olds to 15% among 17-year-olds.

Dr. Griesler and her colleagues did find “a significant positive association between NMPO use by parents and adolescents.” Adolescents were more likely to use an NMPO in their lifetime (14%) if a parent had a history of any use than adolescents whose parents did not have a history (8%). This association persisted even when controlling for other factors (adjusted odds ratio, 1.3).

Adolescent reporting identified low levels of parental support and monitoring, as well as parent approval of drug use, as the primary factors contributing to perceptions of subpar parent-child relationship quality and subsequent NMPO use. Additional adolescent behaviors contributing to increased risk of drug use included delinquency, depression, anxiety, reduced academic and religious involvement, and perceptions around peer drug use and approval of drug use, as well as being older.

Consistent with their original hypothesis, “only maternal NMPO use was significantly associated with adolescent NMPO use,” the investigators wrote (aOR, 1.62), which was not correlated either way concerning the gender of the child. The authors did note, however, “a marginally significant negative association among sons, [aOR, 0.71],” even though no overall paternal-child NMPO correlation was found (aOR, 0.98). They speculated that this negative association might be explained “by the father’s use of other drugs, particularly marijuana.”

Parental factors independently associated with adolescent NMPO use included smoking, alcohol and/or marijuana use, as well as other illicit drug use. When controlling for their use of different drugs and other covariates, only smoking remained associated with adolescent NMPO use (aOR, 1.24). Importantly, higher NMPO usage was observed in cases of poor parenting quality, especially for low levels of monitoring and high incidence of conflict between parents and adolescents. Adolescent NMPO usage were conversely lower in cases where parents self-reported their belief that drug use was risky.

Adolescent behaviors that predicted lifetime NMPO use included starting to smoke cigarettes or marijuana before using NMPO, being depressed or delinquent, having the perception that most peers use drugs, and being older in age. Dr. Griesler and her associates also observed that adolescents who began using alcohol before NMPO were likely to experiment first with smoking cigarettes and marijuana before NMPO.

The lack of differences observed with regard to child gender, race, or ethnicity warrants further investigation, but the authors speculated that “such differences might be detected with measures of current or heavy use.”

One limitation of the study was the focus on lifetime use, Dr. Griesler and her colleagues wrote. Observing patterns of current or heavy use, as well as disorder and “genetically informative samples,” might shed light on the role that familial environmental and genetic influences could play. Additionally, limiting households to one parent and one adolescent discounts the possible combined influence of mother and father NMPO usage on adolescent usage. The research also did not explore the role that adolescent NMPO use could play in influencing “parent-child interactions.”

The authors reported no financial relationships or potential conflicts of interest. The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the New York State Psychiatric Institute; it was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Griesler PC et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182354.

reported Pamela C. Griesler, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates.

Given the significant link between parental and adolescent smoking and adolescent nonmedical prescription opioid (NMPO) use, smoking also should be included in targeted interventions, they wrote in Pediatrics.

Dr. Griesler and her colleagues noted that there actually are three classes of factors influencing the association between parent and adolescent NMPO use: phenotypic heritability, parental role modeling, and parental socialization and other environmental influences.

In the first known study to explore the relationship of parent-adolescent NMPO use within a nationally representative sampling of parent-child dyads taken from the National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, Dr. Griesler and her colleagues examined the intergenerational association of lifetime NMPO use among 35,000 parent-adolescent dyads (21,200 mothers, 13,800 fathers). Of the 35,000 children aged 12-17 years included in the sample, 90% were biological, 8% were stepchildren, and 2% were adopted.

Given the absence of previous studies exploring the relationship between parent-adolescent NMPO use, Dr. Griesler and her associates used established findings for smoking and substance use to hypothesize that there would be stronger associations for mothers than fathers, daughters than sons, and for whites than African Americans.

The investigators posed three questions that formed the basis of their research: 1) What is the association between lifetime parental and child NMPO use? 2) What is the unique association between parental and child NMPO use, controlling for other factors? 3) Do parental/adolescent NMPO use associations differ by parent/child gender and race and/or ethnicity?

About 14% of parents reported ever using an NMPO; fathers (14%) had slightly higher rates of usage than mothers (13%), and white parents had higher rates of use (16%) than African American (10%) or Hispanic (9%) parents. Among adolescents, 9% reported ever having used an NMPO; this included similar rates for boys (9%) and girls (9%), as well as whites (9%), Hispanics (9%), and African Americans (8%). Use increased with age over time, from 4% among 12-year-olds to 15% among 17-year-olds.

Dr. Griesler and her colleagues did find “a significant positive association between NMPO use by parents and adolescents.” Adolescents were more likely to use an NMPO in their lifetime (14%) if a parent had a history of any use than adolescents whose parents did not have a history (8%). This association persisted even when controlling for other factors (adjusted odds ratio, 1.3).

Adolescent reporting identified low levels of parental support and monitoring, as well as parent approval of drug use, as the primary factors contributing to perceptions of subpar parent-child relationship quality and subsequent NMPO use. Additional adolescent behaviors contributing to increased risk of drug use included delinquency, depression, anxiety, reduced academic and religious involvement, and perceptions around peer drug use and approval of drug use, as well as being older.

Consistent with their original hypothesis, “only maternal NMPO use was significantly associated with adolescent NMPO use,” the investigators wrote (aOR, 1.62), which was not correlated either way concerning the gender of the child. The authors did note, however, “a marginally significant negative association among sons, [aOR, 0.71],” even though no overall paternal-child NMPO correlation was found (aOR, 0.98). They speculated that this negative association might be explained “by the father’s use of other drugs, particularly marijuana.”

Parental factors independently associated with adolescent NMPO use included smoking, alcohol and/or marijuana use, as well as other illicit drug use. When controlling for their use of different drugs and other covariates, only smoking remained associated with adolescent NMPO use (aOR, 1.24). Importantly, higher NMPO usage was observed in cases of poor parenting quality, especially for low levels of monitoring and high incidence of conflict between parents and adolescents. Adolescent NMPO usage were conversely lower in cases where parents self-reported their belief that drug use was risky.

Adolescent behaviors that predicted lifetime NMPO use included starting to smoke cigarettes or marijuana before using NMPO, being depressed or delinquent, having the perception that most peers use drugs, and being older in age. Dr. Griesler and her associates also observed that adolescents who began using alcohol before NMPO were likely to experiment first with smoking cigarettes and marijuana before NMPO.

The lack of differences observed with regard to child gender, race, or ethnicity warrants further investigation, but the authors speculated that “such differences might be detected with measures of current or heavy use.”

One limitation of the study was the focus on lifetime use, Dr. Griesler and her colleagues wrote. Observing patterns of current or heavy use, as well as disorder and “genetically informative samples,” might shed light on the role that familial environmental and genetic influences could play. Additionally, limiting households to one parent and one adolescent discounts the possible combined influence of mother and father NMPO usage on adolescent usage. The research also did not explore the role that adolescent NMPO use could play in influencing “parent-child interactions.”

The authors reported no financial relationships or potential conflicts of interest. The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the New York State Psychiatric Institute; it was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Griesler PC et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182354.

reported Pamela C. Griesler, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates.

Given the significant link between parental and adolescent smoking and adolescent nonmedical prescription opioid (NMPO) use, smoking also should be included in targeted interventions, they wrote in Pediatrics.

Dr. Griesler and her colleagues noted that there actually are three classes of factors influencing the association between parent and adolescent NMPO use: phenotypic heritability, parental role modeling, and parental socialization and other environmental influences.

In the first known study to explore the relationship of parent-adolescent NMPO use within a nationally representative sampling of parent-child dyads taken from the National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, Dr. Griesler and her colleagues examined the intergenerational association of lifetime NMPO use among 35,000 parent-adolescent dyads (21,200 mothers, 13,800 fathers). Of the 35,000 children aged 12-17 years included in the sample, 90% were biological, 8% were stepchildren, and 2% were adopted.

Given the absence of previous studies exploring the relationship between parent-adolescent NMPO use, Dr. Griesler and her associates used established findings for smoking and substance use to hypothesize that there would be stronger associations for mothers than fathers, daughters than sons, and for whites than African Americans.

The investigators posed three questions that formed the basis of their research: 1) What is the association between lifetime parental and child NMPO use? 2) What is the unique association between parental and child NMPO use, controlling for other factors? 3) Do parental/adolescent NMPO use associations differ by parent/child gender and race and/or ethnicity?

About 14% of parents reported ever using an NMPO; fathers (14%) had slightly higher rates of usage than mothers (13%), and white parents had higher rates of use (16%) than African American (10%) or Hispanic (9%) parents. Among adolescents, 9% reported ever having used an NMPO; this included similar rates for boys (9%) and girls (9%), as well as whites (9%), Hispanics (9%), and African Americans (8%). Use increased with age over time, from 4% among 12-year-olds to 15% among 17-year-olds.

Dr. Griesler and her colleagues did find “a significant positive association between NMPO use by parents and adolescents.” Adolescents were more likely to use an NMPO in their lifetime (14%) if a parent had a history of any use than adolescents whose parents did not have a history (8%). This association persisted even when controlling for other factors (adjusted odds ratio, 1.3).

Adolescent reporting identified low levels of parental support and monitoring, as well as parent approval of drug use, as the primary factors contributing to perceptions of subpar parent-child relationship quality and subsequent NMPO use. Additional adolescent behaviors contributing to increased risk of drug use included delinquency, depression, anxiety, reduced academic and religious involvement, and perceptions around peer drug use and approval of drug use, as well as being older.

Consistent with their original hypothesis, “only maternal NMPO use was significantly associated with adolescent NMPO use,” the investigators wrote (aOR, 1.62), which was not correlated either way concerning the gender of the child. The authors did note, however, “a marginally significant negative association among sons, [aOR, 0.71],” even though no overall paternal-child NMPO correlation was found (aOR, 0.98). They speculated that this negative association might be explained “by the father’s use of other drugs, particularly marijuana.”

Parental factors independently associated with adolescent NMPO use included smoking, alcohol and/or marijuana use, as well as other illicit drug use. When controlling for their use of different drugs and other covariates, only smoking remained associated with adolescent NMPO use (aOR, 1.24). Importantly, higher NMPO usage was observed in cases of poor parenting quality, especially for low levels of monitoring and high incidence of conflict between parents and adolescents. Adolescent NMPO usage were conversely lower in cases where parents self-reported their belief that drug use was risky.

Adolescent behaviors that predicted lifetime NMPO use included starting to smoke cigarettes or marijuana before using NMPO, being depressed or delinquent, having the perception that most peers use drugs, and being older in age. Dr. Griesler and her associates also observed that adolescents who began using alcohol before NMPO were likely to experiment first with smoking cigarettes and marijuana before NMPO.

The lack of differences observed with regard to child gender, race, or ethnicity warrants further investigation, but the authors speculated that “such differences might be detected with measures of current or heavy use.”

One limitation of the study was the focus on lifetime use, Dr. Griesler and her colleagues wrote. Observing patterns of current or heavy use, as well as disorder and “genetically informative samples,” might shed light on the role that familial environmental and genetic influences could play. Additionally, limiting households to one parent and one adolescent discounts the possible combined influence of mother and father NMPO usage on adolescent usage. The research also did not explore the role that adolescent NMPO use could play in influencing “parent-child interactions.”

The authors reported no financial relationships or potential conflicts of interest. The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the New York State Psychiatric Institute; it was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Griesler PC et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182354.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Trump bars abortion referrals from family planning program

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services has finalized sweeping changes to the federal Title X family planning program, pulling back funds from clinics that provide abortion counseling or that refer patients for abortion services, regardless of whether the money is used for other health care services.

Under the final rule, announced Feb. 22 by HHS, women’s health clinics are ineligible for Title X funding if they offer, promote, or support abortion as a method of family planning. Title X grants generally go to health centers that provide reproductive health care – such as STD-testing, cancer screenings, and contraception – to low-income families.

In a fact sheet, HHS stated the final rule will provide for clear financial and physical separation between Title X and non-Title X activities, reduce confusion on the part of Title X clinics and the public about permissible Title X activities, and improve program transparency by requiring more complete reporting by grantees about their partnerships with referral agencies.

“The final rule ensures compliance with statutory program integrity provisions governing the program and, in particular, the statutory prohibition on funding programs where abortion is a method of family planning,” department officials said in a statement. “The final rule amends the Title X regulation, which had not been substantially updated in nearly 2 decades, and makes notable improvements designed to increase the number of patients served and improve the quality of their care.”

Lisa Hollier, MD, president for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) said the final rule threatens the ability of women’s health care providers to deliver medically accurate and comprehensive reproductive health care and poses significant harms to women’s health.

“As the only federal program exclusively dedicated to providing low-income patients with access to family planning and preventive health services and information, [Title X] plays a vital role in the landscape of women’s health care,” Dr. Hollier said during a Feb. 22 press conference. “By weakening the requirements for the scope of contraceptive care provided by grant recipients and restricting the types of care recipients can discuss with patients, the final rule fundamentally harms the scope and purpose of this historic program.”

The American Medical Association also expressed disappointment, referring to the final requirement as a “gag rule” between physicians and patients.

“This rule interferes with and imposes restrictions on the patient-physician relationship,” Barbara L. McAneny, MD, AMA President said in a statement. “For all intents and purposes, it imposes a gag rule on what information physicians can provide to their patients. The patient-physician relationship relies on trust, open conversation and informed decision making and the government should not be telling physicians what they can and cannot say to their patients.”

Under the rule, proposed last year, physicians are prohibited from discussing abortion options with pregnant women, from sharing abortion information, and from making abortion referrals if the clinic receives Title X funds. The regulation permits, but no longer requires, nondirective pregnancy counseling, including nondirective counseling on abortion. In its statement, HHS officials said the new rule ensures “conscience protections” for Title X health providers by eliminating the requirement for providers to counsel on and refer for abortion.

Susan B. Anthony List, an anti-abortion group, praised the final rule as a measure that disentangles taxpayers from the “big abortion industry led by Planned Parenthood.”

“The Protect Life Rule does not cut family planning funding by a single dime, and instead directs tax dollars to entities that provide health care to women but do not perform abortions,” said SBA List President Marjorie Dannenfelser in a statement. “The Title X program was not intended to be a slush fund for abortion businesses like Planned Parenthood, which violently ends the lives of more than 332,000 unborn babies a year and receives almost $60 million a year in Title X taxpayer dollars.”

Emily Stewart, vice president of public policy for the Planned Parenthood Federation of America indicated that the group plans to fight the rule in court.

“Since day one, the Trump-Pence administration has aggressively targeted the health, rights, and bodily autonomy of people of color, people with low incomes, and women,” she said in a statement. “We’re going to fight this rule through every possible avenue.”

The final rule has been submitted to the Federal Register for publication.

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services has finalized sweeping changes to the federal Title X family planning program, pulling back funds from clinics that provide abortion counseling or that refer patients for abortion services, regardless of whether the money is used for other health care services.

Under the final rule, announced Feb. 22 by HHS, women’s health clinics are ineligible for Title X funding if they offer, promote, or support abortion as a method of family planning. Title X grants generally go to health centers that provide reproductive health care – such as STD-testing, cancer screenings, and contraception – to low-income families.

In a fact sheet, HHS stated the final rule will provide for clear financial and physical separation between Title X and non-Title X activities, reduce confusion on the part of Title X clinics and the public about permissible Title X activities, and improve program transparency by requiring more complete reporting by grantees about their partnerships with referral agencies.

“The final rule ensures compliance with statutory program integrity provisions governing the program and, in particular, the statutory prohibition on funding programs where abortion is a method of family planning,” department officials said in a statement. “The final rule amends the Title X regulation, which had not been substantially updated in nearly 2 decades, and makes notable improvements designed to increase the number of patients served and improve the quality of their care.”

Lisa Hollier, MD, president for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) said the final rule threatens the ability of women’s health care providers to deliver medically accurate and comprehensive reproductive health care and poses significant harms to women’s health.

“As the only federal program exclusively dedicated to providing low-income patients with access to family planning and preventive health services and information, [Title X] plays a vital role in the landscape of women’s health care,” Dr. Hollier said during a Feb. 22 press conference. “By weakening the requirements for the scope of contraceptive care provided by grant recipients and restricting the types of care recipients can discuss with patients, the final rule fundamentally harms the scope and purpose of this historic program.”

The American Medical Association also expressed disappointment, referring to the final requirement as a “gag rule” between physicians and patients.

“This rule interferes with and imposes restrictions on the patient-physician relationship,” Barbara L. McAneny, MD, AMA President said in a statement. “For all intents and purposes, it imposes a gag rule on what information physicians can provide to their patients. The patient-physician relationship relies on trust, open conversation and informed decision making and the government should not be telling physicians what they can and cannot say to their patients.”

Under the rule, proposed last year, physicians are prohibited from discussing abortion options with pregnant women, from sharing abortion information, and from making abortion referrals if the clinic receives Title X funds. The regulation permits, but no longer requires, nondirective pregnancy counseling, including nondirective counseling on abortion. In its statement, HHS officials said the new rule ensures “conscience protections” for Title X health providers by eliminating the requirement for providers to counsel on and refer for abortion.

Susan B. Anthony List, an anti-abortion group, praised the final rule as a measure that disentangles taxpayers from the “big abortion industry led by Planned Parenthood.”

“The Protect Life Rule does not cut family planning funding by a single dime, and instead directs tax dollars to entities that provide health care to women but do not perform abortions,” said SBA List President Marjorie Dannenfelser in a statement. “The Title X program was not intended to be a slush fund for abortion businesses like Planned Parenthood, which violently ends the lives of more than 332,000 unborn babies a year and receives almost $60 million a year in Title X taxpayer dollars.”

Emily Stewart, vice president of public policy for the Planned Parenthood Federation of America indicated that the group plans to fight the rule in court.

“Since day one, the Trump-Pence administration has aggressively targeted the health, rights, and bodily autonomy of people of color, people with low incomes, and women,” she said in a statement. “We’re going to fight this rule through every possible avenue.”

The final rule has been submitted to the Federal Register for publication.

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services has finalized sweeping changes to the federal Title X family planning program, pulling back funds from clinics that provide abortion counseling or that refer patients for abortion services, regardless of whether the money is used for other health care services.

Under the final rule, announced Feb. 22 by HHS, women’s health clinics are ineligible for Title X funding if they offer, promote, or support abortion as a method of family planning. Title X grants generally go to health centers that provide reproductive health care – such as STD-testing, cancer screenings, and contraception – to low-income families.

In a fact sheet, HHS stated the final rule will provide for clear financial and physical separation between Title X and non-Title X activities, reduce confusion on the part of Title X clinics and the public about permissible Title X activities, and improve program transparency by requiring more complete reporting by grantees about their partnerships with referral agencies.

“The final rule ensures compliance with statutory program integrity provisions governing the program and, in particular, the statutory prohibition on funding programs where abortion is a method of family planning,” department officials said in a statement. “The final rule amends the Title X regulation, which had not been substantially updated in nearly 2 decades, and makes notable improvements designed to increase the number of patients served and improve the quality of their care.”

Lisa Hollier, MD, president for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) said the final rule threatens the ability of women’s health care providers to deliver medically accurate and comprehensive reproductive health care and poses significant harms to women’s health.

“As the only federal program exclusively dedicated to providing low-income patients with access to family planning and preventive health services and information, [Title X] plays a vital role in the landscape of women’s health care,” Dr. Hollier said during a Feb. 22 press conference. “By weakening the requirements for the scope of contraceptive care provided by grant recipients and restricting the types of care recipients can discuss with patients, the final rule fundamentally harms the scope and purpose of this historic program.”

The American Medical Association also expressed disappointment, referring to the final requirement as a “gag rule” between physicians and patients.

“This rule interferes with and imposes restrictions on the patient-physician relationship,” Barbara L. McAneny, MD, AMA President said in a statement. “For all intents and purposes, it imposes a gag rule on what information physicians can provide to their patients. The patient-physician relationship relies on trust, open conversation and informed decision making and the government should not be telling physicians what they can and cannot say to their patients.”

Under the rule, proposed last year, physicians are prohibited from discussing abortion options with pregnant women, from sharing abortion information, and from making abortion referrals if the clinic receives Title X funds. The regulation permits, but no longer requires, nondirective pregnancy counseling, including nondirective counseling on abortion. In its statement, HHS officials said the new rule ensures “conscience protections” for Title X health providers by eliminating the requirement for providers to counsel on and refer for abortion.

Susan B. Anthony List, an anti-abortion group, praised the final rule as a measure that disentangles taxpayers from the “big abortion industry led by Planned Parenthood.”

“The Protect Life Rule does not cut family planning funding by a single dime, and instead directs tax dollars to entities that provide health care to women but do not perform abortions,” said SBA List President Marjorie Dannenfelser in a statement. “The Title X program was not intended to be a slush fund for abortion businesses like Planned Parenthood, which violently ends the lives of more than 332,000 unborn babies a year and receives almost $60 million a year in Title X taxpayer dollars.”

Emily Stewart, vice president of public policy for the Planned Parenthood Federation of America indicated that the group plans to fight the rule in court.

“Since day one, the Trump-Pence administration has aggressively targeted the health, rights, and bodily autonomy of people of color, people with low incomes, and women,” she said in a statement. “We’re going to fight this rule through every possible avenue.”

The final rule has been submitted to the Federal Register for publication.

Mediterranean diet cut Parkinson’s risk

‘Telereferrals’ improved mental health referral follow-through for children. How to take action to cut cardiovascular disease risk in rheumatoid patients. And the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends counseling for perinatal depression prevention.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

‘Telereferrals’ improved mental health referral follow-through for children. How to take action to cut cardiovascular disease risk in rheumatoid patients. And the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends counseling for perinatal depression prevention.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

‘Telereferrals’ improved mental health referral follow-through for children. How to take action to cut cardiovascular disease risk in rheumatoid patients. And the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends counseling for perinatal depression prevention.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Tranexamic acid shows improvements in heavy menstrual bleeding

new research suggests.

Writing in the Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, Sarah H. O’Brien, MD, from Nationwide Children’s Hospital and the Ohio State University, both in Columbus, and her coauthors presented the results of an open-label efficacy study of the competitive plasminogen inhibitor in 25 adolescent girls aged 10-19 years who attended pediatric hematology clinics for evaluation or management of heavy menstrual bleeding. The study participants were instructed to take 1,300 mg of tranexamic acid (two tablets) three times a day for up to 5 days during their monthly menstruation for three cycles.

The study found a significant improvement in mean menstrual impact questionnaire (MIQ) scores, which improved from a mean of 3 at baseline to 1.91 (P less than .001). Two-thirds of patients reported at least a one-point improvement from baseline, and all reported that this was clinically meaningful. At baseline, 84% of patients reported heavy to very heavy blood loss, but this decreased to 23% after treatment with tranexamic acid (P less than .001).

The study population included ten individuals (40%) with bleeding disorders. However, the researchers did not see a significant difference in response between those with bleeding disorders and those without.

While the treatment did not significantly affect school attendance (only 24% reported that their heavy bleeding limited school attendance), researchers did see a significant improvement in limitations on physical activities and on social and leisure activities. Patients who reported at baseline that their menstrual bleeding significantly affected their social and leisure activities had an average score improvement of 1.74, a greater than or equal to one point improvement. Participants also reported significant improvements in their Pictorial Blood Assessment Chart scores, which dropped from an average of 255 to 155 (P less than .001).

The treatment did not show any significant effects on hemoglobin or ferritin. The most common adverse events were sinonasal symptoms, such as nasal congestion, headache, and sinus pain, but no thrombotic or ocular adverse events were seen.

Dr. O’Brien and her coauthors wrote that one limitation of their study was using the MIQ score as their primary endpoint as opposed to a more objective measure, such as change in measured blood loss.

“However, a major factor that motivates patients with heavy menstrual bleeding to seek medical care is the negative impact of heavy menstrual bleeding on daily life,” they wrote.

The study drug was supplied by Ferring pharmaceuticals, and the study was supported by the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society. One author disclosed receiving the Joan Fellowship in Pediatric Hemostasis and Thrombosis at Nationwide Children’s Hospital; no other authors said they had relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: O’Brien SH et al. J Pediatr Adol Gynec. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.01.009.

new research suggests.

Writing in the Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, Sarah H. O’Brien, MD, from Nationwide Children’s Hospital and the Ohio State University, both in Columbus, and her coauthors presented the results of an open-label efficacy study of the competitive plasminogen inhibitor in 25 adolescent girls aged 10-19 years who attended pediatric hematology clinics for evaluation or management of heavy menstrual bleeding. The study participants were instructed to take 1,300 mg of tranexamic acid (two tablets) three times a day for up to 5 days during their monthly menstruation for three cycles.

The study found a significant improvement in mean menstrual impact questionnaire (MIQ) scores, which improved from a mean of 3 at baseline to 1.91 (P less than .001). Two-thirds of patients reported at least a one-point improvement from baseline, and all reported that this was clinically meaningful. At baseline, 84% of patients reported heavy to very heavy blood loss, but this decreased to 23% after treatment with tranexamic acid (P less than .001).

The study population included ten individuals (40%) with bleeding disorders. However, the researchers did not see a significant difference in response between those with bleeding disorders and those without.

While the treatment did not significantly affect school attendance (only 24% reported that their heavy bleeding limited school attendance), researchers did see a significant improvement in limitations on physical activities and on social and leisure activities. Patients who reported at baseline that their menstrual bleeding significantly affected their social and leisure activities had an average score improvement of 1.74, a greater than or equal to one point improvement. Participants also reported significant improvements in their Pictorial Blood Assessment Chart scores, which dropped from an average of 255 to 155 (P less than .001).

The treatment did not show any significant effects on hemoglobin or ferritin. The most common adverse events were sinonasal symptoms, such as nasal congestion, headache, and sinus pain, but no thrombotic or ocular adverse events were seen.

Dr. O’Brien and her coauthors wrote that one limitation of their study was using the MIQ score as their primary endpoint as opposed to a more objective measure, such as change in measured blood loss.

“However, a major factor that motivates patients with heavy menstrual bleeding to seek medical care is the negative impact of heavy menstrual bleeding on daily life,” they wrote.

The study drug was supplied by Ferring pharmaceuticals, and the study was supported by the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society. One author disclosed receiving the Joan Fellowship in Pediatric Hemostasis and Thrombosis at Nationwide Children’s Hospital; no other authors said they had relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: O’Brien SH et al. J Pediatr Adol Gynec. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.01.009.

new research suggests.

Writing in the Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, Sarah H. O’Brien, MD, from Nationwide Children’s Hospital and the Ohio State University, both in Columbus, and her coauthors presented the results of an open-label efficacy study of the competitive plasminogen inhibitor in 25 adolescent girls aged 10-19 years who attended pediatric hematology clinics for evaluation or management of heavy menstrual bleeding. The study participants were instructed to take 1,300 mg of tranexamic acid (two tablets) three times a day for up to 5 days during their monthly menstruation for three cycles.

The study found a significant improvement in mean menstrual impact questionnaire (MIQ) scores, which improved from a mean of 3 at baseline to 1.91 (P less than .001). Two-thirds of patients reported at least a one-point improvement from baseline, and all reported that this was clinically meaningful. At baseline, 84% of patients reported heavy to very heavy blood loss, but this decreased to 23% after treatment with tranexamic acid (P less than .001).

The study population included ten individuals (40%) with bleeding disorders. However, the researchers did not see a significant difference in response between those with bleeding disorders and those without.

While the treatment did not significantly affect school attendance (only 24% reported that their heavy bleeding limited school attendance), researchers did see a significant improvement in limitations on physical activities and on social and leisure activities. Patients who reported at baseline that their menstrual bleeding significantly affected their social and leisure activities had an average score improvement of 1.74, a greater than or equal to one point improvement. Participants also reported significant improvements in their Pictorial Blood Assessment Chart scores, which dropped from an average of 255 to 155 (P less than .001).

The treatment did not show any significant effects on hemoglobin or ferritin. The most common adverse events were sinonasal symptoms, such as nasal congestion, headache, and sinus pain, but no thrombotic or ocular adverse events were seen.

Dr. O’Brien and her coauthors wrote that one limitation of their study was using the MIQ score as their primary endpoint as opposed to a more objective measure, such as change in measured blood loss.

“However, a major factor that motivates patients with heavy menstrual bleeding to seek medical care is the negative impact of heavy menstrual bleeding on daily life,” they wrote.

The study drug was supplied by Ferring pharmaceuticals, and the study was supported by the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society. One author disclosed receiving the Joan Fellowship in Pediatric Hemostasis and Thrombosis at Nationwide Children’s Hospital; no other authors said they had relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: O’Brien SH et al. J Pediatr Adol Gynec. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.01.009.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC & ADOLESCENT GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Tranexamic acid appears to improve quality of life for adolescents with heavy menstrual bleeding.

Major finding: Patients treated with tranexamic acid reported significant improvements in mean menstrual impact questionnaire scores.

Study details: Open-label efficacy study in 25 adolescent girls with heavy menstrual bleeding.

Disclosures: The study drug was supplied by Ferring pharmaceuticals, and the study was supported by the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society. One author disclosed receiving the Joan Fellowship in Pediatric Hemostasis and Thrombosis at Nationwide Children’s Hospital; no other authors said they had relevant financial disclosures.

Source: O’Brien SH et al. J Pediatr Adol Gynec. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.01.009.

Conservatism spreads in prostate cancer

, the United States now has more than 100 measles cases for the year, e-cigarette use reverses progress in reducing teens’ tobacco use, and consider adopting the MESA 10-year coronary heart disease risk calculator.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

, the United States now has more than 100 measles cases for the year, e-cigarette use reverses progress in reducing teens’ tobacco use, and consider adopting the MESA 10-year coronary heart disease risk calculator.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

, the United States now has more than 100 measles cases for the year, e-cigarette use reverses progress in reducing teens’ tobacco use, and consider adopting the MESA 10-year coronary heart disease risk calculator.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Failure to launch can happen to college students

March often is the time of year when college freshmen truly begin to feel comfortable in their new settings. Many students report feeling excited to get back to campus after the long winter break, and once into their second semester, they feel more comfortable with the independence from family and high school supports. It also is a time for some college freshmen to return home after failing to manage this major transition.

Of the latter group, many will have had difficult months of depression, anxiety, or substance use, and most will be suffering from a deep sense of shame after failing to navigate this long-anticipated transition. Asking detailed questions about their academic challenges, social lives, self-care, and sleep while they were on campus will help you make thoughtful recommendations to your patients and their parents about how they might best get back on track.

Some students will report a great social experience, but academic struggles. They will report some normal ups and downs emotionally, but most of their distress will have been focused on their academic performance. Many 18-year-olds have not had to organize their time and effort around homework without the attention and support of parents and teachers. College often has much bigger classes, with less personal attention. There is a lot of assigned reading, but no regular incremental homework, only a major midterm and final exam, or a substantial paper. For a student who gets anxious about performance, or one with organizational challenges, this can lead to procrastination and poor performance.

Find out details about how they did academically. Did they fail one class or many classes? Did they receive some incompletes in their first semester and then struggle to catch up with them while keeping up with their second semester work? Did they have tutoring or support? Were they unrealistic about their course load? Or did they have their first serious relationship and not spend enough time on homework? Did they spend too much time partying with their new friends and not enough time sleeping and getting their homework done?

It is important to dig deeper if patients report regular or binge drug and alcohol use that interfered with their academic performance, as they may need more substantial substance use disorder treatment. Most students, though, will not have a substance use disorder. Instead, their academic failure could represent something as simple as the need for more academic support and time management support. Many schools have such programs to help students learn how to better manage their time and effort as they take fuller responsibility than they had for it in high school.

For other students, you will learn that their emotional distress preceded their academic troubles. The stress of the transition to college may be enough to trigger an episode of depression or to exacerbate a mood or anxiety disorder that was subclinical or in remission before school started. These students usually will report that sadness, intense anxiety, or loss of interest came early in their semester; perhaps they were even doing well academically when these problems started.

Ask about how their sleep was. Often they had difficulty falling asleep or woke up often at night, unlike most college students, whose sleep is compromised because they stay up late with new friends or because they are hard at work, but could easily sleep at any time.

Find out about their eating habits. Did they lose their appetite? Lose weight? Did they become preoccupied with weight or body image issues and begin restricting their intake? Eating disorders can begin in college when vulnerable students are stressed and have more control over their diet. While weight gain is more common in freshman year, it often is connected to poor stress management skills, and is more often a marker of a student who was struggling academically and then managing stress by overeating.

In the case where the distress came first, it is critical that your patients have a thorough psychiatric evaluation and treatment. It may be possible for them to return to school quickly, but it is most important that they are engaged in effective treatment and in at last partial remission before adding to their stress by attempting to return to school. Often, ambitious students and their parents need to hear this message very clearly from a pediatrician. A rushed return to school may be a set-up for a more protracted and difficult course of illness. For these students, it may be better to have a fresh start in a new semester. Help them (and their parents) to understand that they should use their time off to focus on treatment and good self-care so they might benefit from the many opportunities of college.

For a small minority of college students who do not succeed at college, their social withdrawal, academic deterioration, anxiety, and loss of interest in previous passions may occur alongside more serious psychiatric symptoms such as auditory hallucinations, paranoia, or grandiosity. Any time there is a suggestion of psychotic symptoms in a previously healthy person in the late teens or early 20s, a prompt comprehensive psychiatric evaluation is critical. These years are when most chronic psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, are likely to emerge. These patients require a thorough evaluation to distinguish these disorders from other illnesses, especially when they occur with substance use. And these patients require specialized care.

If your patient appears to have any psychotic symptoms, it is critical that you help the family find an excellent psychiatrist, or even a clinic that specializes in thought disorders so that he or she may get the best possible care early.

There is another class of students who withdraw from college who will need more comprehensive remediation, but not connected to any psychiatric diagnosis. Some young people may not be developmentally ready for college. These are your patients who often were excellent performers in high school, perhaps academically and athletically, but whose performance was more connected to pleasing important adults than to genuine motivating passions or sense of purpose. These young adults may have been drawn into the intense, results-oriented forces that are powerful in many of our high schools. If they did not have enough time or space to explore a host of interests, and to then manage the routine failures, setbacks, and disappointments that are essential to healthy adolescent development, they are going to run out of fuel in college. Such students often are quite dependent on their parents, and struggle with the independence college offers.

If your patients report that they could not muster the same intense work ethic they previously had, without any evidence of a psychiatric illness interfering with motivation, they may need time to finish the developmental work of cultivating a deep and rich sense of their own identity. Some students can do this at college, provided they, their parents and their school offer them adequate time before they have to declare a major. Other students will need to get a job and explore interests with a few courses at a community college, cultivating independence while learning about their own strengths and weaknesses and their genuine interests. This way, when they return to school, they will be motivated by a genuine sense of purpose and self-knowledge.

“Failure to launch” is a critical symptom at a key transitional moment. Pediatric providers can be essential to their patients and families by clarifying the nature of the difficulty and coordinating a reasonable plan to get these young adults back on track to healthy adulthood.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

March often is the time of year when college freshmen truly begin to feel comfortable in their new settings. Many students report feeling excited to get back to campus after the long winter break, and once into their second semester, they feel more comfortable with the independence from family and high school supports. It also is a time for some college freshmen to return home after failing to manage this major transition.

Of the latter group, many will have had difficult months of depression, anxiety, or substance use, and most will be suffering from a deep sense of shame after failing to navigate this long-anticipated transition. Asking detailed questions about their academic challenges, social lives, self-care, and sleep while they were on campus will help you make thoughtful recommendations to your patients and their parents about how they might best get back on track.

Some students will report a great social experience, but academic struggles. They will report some normal ups and downs emotionally, but most of their distress will have been focused on their academic performance. Many 18-year-olds have not had to organize their time and effort around homework without the attention and support of parents and teachers. College often has much bigger classes, with less personal attention. There is a lot of assigned reading, but no regular incremental homework, only a major midterm and final exam, or a substantial paper. For a student who gets anxious about performance, or one with organizational challenges, this can lead to procrastination and poor performance.

Find out details about how they did academically. Did they fail one class or many classes? Did they receive some incompletes in their first semester and then struggle to catch up with them while keeping up with their second semester work? Did they have tutoring or support? Were they unrealistic about their course load? Or did they have their first serious relationship and not spend enough time on homework? Did they spend too much time partying with their new friends and not enough time sleeping and getting their homework done?

It is important to dig deeper if patients report regular or binge drug and alcohol use that interfered with their academic performance, as they may need more substantial substance use disorder treatment. Most students, though, will not have a substance use disorder. Instead, their academic failure could represent something as simple as the need for more academic support and time management support. Many schools have such programs to help students learn how to better manage their time and effort as they take fuller responsibility than they had for it in high school.

For other students, you will learn that their emotional distress preceded their academic troubles. The stress of the transition to college may be enough to trigger an episode of depression or to exacerbate a mood or anxiety disorder that was subclinical or in remission before school started. These students usually will report that sadness, intense anxiety, or loss of interest came early in their semester; perhaps they were even doing well academically when these problems started.

Ask about how their sleep was. Often they had difficulty falling asleep or woke up often at night, unlike most college students, whose sleep is compromised because they stay up late with new friends or because they are hard at work, but could easily sleep at any time.

Find out about their eating habits. Did they lose their appetite? Lose weight? Did they become preoccupied with weight or body image issues and begin restricting their intake? Eating disorders can begin in college when vulnerable students are stressed and have more control over their diet. While weight gain is more common in freshman year, it often is connected to poor stress management skills, and is more often a marker of a student who was struggling academically and then managing stress by overeating.

In the case where the distress came first, it is critical that your patients have a thorough psychiatric evaluation and treatment. It may be possible for them to return to school quickly, but it is most important that they are engaged in effective treatment and in at last partial remission before adding to their stress by attempting to return to school. Often, ambitious students and their parents need to hear this message very clearly from a pediatrician. A rushed return to school may be a set-up for a more protracted and difficult course of illness. For these students, it may be better to have a fresh start in a new semester. Help them (and their parents) to understand that they should use their time off to focus on treatment and good self-care so they might benefit from the many opportunities of college.

For a small minority of college students who do not succeed at college, their social withdrawal, academic deterioration, anxiety, and loss of interest in previous passions may occur alongside more serious psychiatric symptoms such as auditory hallucinations, paranoia, or grandiosity. Any time there is a suggestion of psychotic symptoms in a previously healthy person in the late teens or early 20s, a prompt comprehensive psychiatric evaluation is critical. These years are when most chronic psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, are likely to emerge. These patients require a thorough evaluation to distinguish these disorders from other illnesses, especially when they occur with substance use. And these patients require specialized care.

If your patient appears to have any psychotic symptoms, it is critical that you help the family find an excellent psychiatrist, or even a clinic that specializes in thought disorders so that he or she may get the best possible care early.

There is another class of students who withdraw from college who will need more comprehensive remediation, but not connected to any psychiatric diagnosis. Some young people may not be developmentally ready for college. These are your patients who often were excellent performers in high school, perhaps academically and athletically, but whose performance was more connected to pleasing important adults than to genuine motivating passions or sense of purpose. These young adults may have been drawn into the intense, results-oriented forces that are powerful in many of our high schools. If they did not have enough time or space to explore a host of interests, and to then manage the routine failures, setbacks, and disappointments that are essential to healthy adolescent development, they are going to run out of fuel in college. Such students often are quite dependent on their parents, and struggle with the independence college offers.

If your patients report that they could not muster the same intense work ethic they previously had, without any evidence of a psychiatric illness interfering with motivation, they may need time to finish the developmental work of cultivating a deep and rich sense of their own identity. Some students can do this at college, provided they, their parents and their school offer them adequate time before they have to declare a major. Other students will need to get a job and explore interests with a few courses at a community college, cultivating independence while learning about their own strengths and weaknesses and their genuine interests. This way, when they return to school, they will be motivated by a genuine sense of purpose and self-knowledge.

“Failure to launch” is a critical symptom at a key transitional moment. Pediatric providers can be essential to their patients and families by clarifying the nature of the difficulty and coordinating a reasonable plan to get these young adults back on track to healthy adulthood.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

March often is the time of year when college freshmen truly begin to feel comfortable in their new settings. Many students report feeling excited to get back to campus after the long winter break, and once into their second semester, they feel more comfortable with the independence from family and high school supports. It also is a time for some college freshmen to return home after failing to manage this major transition.

Of the latter group, many will have had difficult months of depression, anxiety, or substance use, and most will be suffering from a deep sense of shame after failing to navigate this long-anticipated transition. Asking detailed questions about their academic challenges, social lives, self-care, and sleep while they were on campus will help you make thoughtful recommendations to your patients and their parents about how they might best get back on track.

Some students will report a great social experience, but academic struggles. They will report some normal ups and downs emotionally, but most of their distress will have been focused on their academic performance. Many 18-year-olds have not had to organize their time and effort around homework without the attention and support of parents and teachers. College often has much bigger classes, with less personal attention. There is a lot of assigned reading, but no regular incremental homework, only a major midterm and final exam, or a substantial paper. For a student who gets anxious about performance, or one with organizational challenges, this can lead to procrastination and poor performance.

Find out details about how they did academically. Did they fail one class or many classes? Did they receive some incompletes in their first semester and then struggle to catch up with them while keeping up with their second semester work? Did they have tutoring or support? Were they unrealistic about their course load? Or did they have their first serious relationship and not spend enough time on homework? Did they spend too much time partying with their new friends and not enough time sleeping and getting their homework done?

It is important to dig deeper if patients report regular or binge drug and alcohol use that interfered with their academic performance, as they may need more substantial substance use disorder treatment. Most students, though, will not have a substance use disorder. Instead, their academic failure could represent something as simple as the need for more academic support and time management support. Many schools have such programs to help students learn how to better manage their time and effort as they take fuller responsibility than they had for it in high school.

For other students, you will learn that their emotional distress preceded their academic troubles. The stress of the transition to college may be enough to trigger an episode of depression or to exacerbate a mood or anxiety disorder that was subclinical or in remission before school started. These students usually will report that sadness, intense anxiety, or loss of interest came early in their semester; perhaps they were even doing well academically when these problems started.

Ask about how their sleep was. Often they had difficulty falling asleep or woke up often at night, unlike most college students, whose sleep is compromised because they stay up late with new friends or because they are hard at work, but could easily sleep at any time.

Find out about their eating habits. Did they lose their appetite? Lose weight? Did they become preoccupied with weight or body image issues and begin restricting their intake? Eating disorders can begin in college when vulnerable students are stressed and have more control over their diet. While weight gain is more common in freshman year, it often is connected to poor stress management skills, and is more often a marker of a student who was struggling academically and then managing stress by overeating.

In the case where the distress came first, it is critical that your patients have a thorough psychiatric evaluation and treatment. It may be possible for them to return to school quickly, but it is most important that they are engaged in effective treatment and in at last partial remission before adding to their stress by attempting to return to school. Often, ambitious students and their parents need to hear this message very clearly from a pediatrician. A rushed return to school may be a set-up for a more protracted and difficult course of illness. For these students, it may be better to have a fresh start in a new semester. Help them (and their parents) to understand that they should use their time off to focus on treatment and good self-care so they might benefit from the many opportunities of college.

For a small minority of college students who do not succeed at college, their social withdrawal, academic deterioration, anxiety, and loss of interest in previous passions may occur alongside more serious psychiatric symptoms such as auditory hallucinations, paranoia, or grandiosity. Any time there is a suggestion of psychotic symptoms in a previously healthy person in the late teens or early 20s, a prompt comprehensive psychiatric evaluation is critical. These years are when most chronic psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, are likely to emerge. These patients require a thorough evaluation to distinguish these disorders from other illnesses, especially when they occur with substance use. And these patients require specialized care.

If your patient appears to have any psychotic symptoms, it is critical that you help the family find an excellent psychiatrist, or even a clinic that specializes in thought disorders so that he or she may get the best possible care early.

There is another class of students who withdraw from college who will need more comprehensive remediation, but not connected to any psychiatric diagnosis. Some young people may not be developmentally ready for college. These are your patients who often were excellent performers in high school, perhaps academically and athletically, but whose performance was more connected to pleasing important adults than to genuine motivating passions or sense of purpose. These young adults may have been drawn into the intense, results-oriented forces that are powerful in many of our high schools. If they did not have enough time or space to explore a host of interests, and to then manage the routine failures, setbacks, and disappointments that are essential to healthy adolescent development, they are going to run out of fuel in college. Such students often are quite dependent on their parents, and struggle with the independence college offers.

If your patients report that they could not muster the same intense work ethic they previously had, without any evidence of a psychiatric illness interfering with motivation, they may need time to finish the developmental work of cultivating a deep and rich sense of their own identity. Some students can do this at college, provided they, their parents and their school offer them adequate time before they have to declare a major. Other students will need to get a job and explore interests with a few courses at a community college, cultivating independence while learning about their own strengths and weaknesses and their genuine interests. This way, when they return to school, they will be motivated by a genuine sense of purpose and self-knowledge.

“Failure to launch” is a critical symptom at a key transitional moment. Pediatric providers can be essential to their patients and families by clarifying the nature of the difficulty and coordinating a reasonable plan to get these young adults back on track to healthy adulthood.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

Interactive parenting, life skill intervention improves self-esteem in teen mothers

than did those who received standard care, according to Joanne E. Cox, MD, director of primary care at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and her associates.

A total of 140 mothers who were aged less than 19 years when they delivered and whose child was aged less than 12 months were included in the study published in Pediatrics. Of this group, 72 received the intervention, which included a series of five 1-hour, one-on-one, interactive modules adapted from the Nurturing and Ansell-Casey Life Skills curricula, delivered over the infant’s first 15 months, in addition to standard teen-tot clinic care. The remaining 68 mothers received teen-tot care alone.

While overall maternal self-esteem decreased in both the intervention and control groups when measured at 36 months, the intervention group experienced a significantly smaller decrease from baseline (P = .011). Similarly, the intervention group had higher scores regarding preparedness for motherhood (P = .011), acceptance of infant (P = .008), and expected relationship with infant (P = .029).

Of the 52 mothers in the intervention group and 48 mothers in the control group for whom pregnancy data was available at 36 months, 42% in the intervention group had a repeat pregnancy, compared with 67% in the control group (adjusted odds ratio, 0.20; 95% confidence interval, 0.06-0.75; P = .017).

The study findings “highlight the positive impact of pairing medical services with comprehensive social services and parenting education and can inform future policy and services for teen parents. These positive effects also have potential to improve long-term outcomes for teens and their children,” Dr. Cox and her associates concluded.

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest. The study was supported in part by a grant from the Office of Adolescent Pregnancy Programs, the Edgerley Family Endowment, a Leadership Education in Adolescent Health training grant, the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, and the Health Resources and Services Administration.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Cox JE et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Feb 12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2303.

than did those who received standard care, according to Joanne E. Cox, MD, director of primary care at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and her associates.

A total of 140 mothers who were aged less than 19 years when they delivered and whose child was aged less than 12 months were included in the study published in Pediatrics. Of this group, 72 received the intervention, which included a series of five 1-hour, one-on-one, interactive modules adapted from the Nurturing and Ansell-Casey Life Skills curricula, delivered over the infant’s first 15 months, in addition to standard teen-tot clinic care. The remaining 68 mothers received teen-tot care alone.

While overall maternal self-esteem decreased in both the intervention and control groups when measured at 36 months, the intervention group experienced a significantly smaller decrease from baseline (P = .011). Similarly, the intervention group had higher scores regarding preparedness for motherhood (P = .011), acceptance of infant (P = .008), and expected relationship with infant (P = .029).

Of the 52 mothers in the intervention group and 48 mothers in the control group for whom pregnancy data was available at 36 months, 42% in the intervention group had a repeat pregnancy, compared with 67% in the control group (adjusted odds ratio, 0.20; 95% confidence interval, 0.06-0.75; P = .017).

The study findings “highlight the positive impact of pairing medical services with comprehensive social services and parenting education and can inform future policy and services for teen parents. These positive effects also have potential to improve long-term outcomes for teens and their children,” Dr. Cox and her associates concluded.

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest. The study was supported in part by a grant from the Office of Adolescent Pregnancy Programs, the Edgerley Family Endowment, a Leadership Education in Adolescent Health training grant, the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, and the Health Resources and Services Administration.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Cox JE et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Feb 12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2303.

than did those who received standard care, according to Joanne E. Cox, MD, director of primary care at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and her associates.

A total of 140 mothers who were aged less than 19 years when they delivered and whose child was aged less than 12 months were included in the study published in Pediatrics. Of this group, 72 received the intervention, which included a series of five 1-hour, one-on-one, interactive modules adapted from the Nurturing and Ansell-Casey Life Skills curricula, delivered over the infant’s first 15 months, in addition to standard teen-tot clinic care. The remaining 68 mothers received teen-tot care alone.

While overall maternal self-esteem decreased in both the intervention and control groups when measured at 36 months, the intervention group experienced a significantly smaller decrease from baseline (P = .011). Similarly, the intervention group had higher scores regarding preparedness for motherhood (P = .011), acceptance of infant (P = .008), and expected relationship with infant (P = .029).

Of the 52 mothers in the intervention group and 48 mothers in the control group for whom pregnancy data was available at 36 months, 42% in the intervention group had a repeat pregnancy, compared with 67% in the control group (adjusted odds ratio, 0.20; 95% confidence interval, 0.06-0.75; P = .017).

The study findings “highlight the positive impact of pairing medical services with comprehensive social services and parenting education and can inform future policy and services for teen parents. These positive effects also have potential to improve long-term outcomes for teens and their children,” Dr. Cox and her associates concluded.

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest. The study was supported in part by a grant from the Office of Adolescent Pregnancy Programs, the Edgerley Family Endowment, a Leadership Education in Adolescent Health training grant, the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, and the Health Resources and Services Administration.

[email protected]

SOURCE: Cox JE et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Feb 12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2303.

FROM PEDIATRICS

E-cig use reverses progress in reducing tobacco use in teens

A significant increase during 2017-2018 in e-cigarette use among U.S. youths has erased recent progress in reducing overall tobacco product use in this age group, a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found.

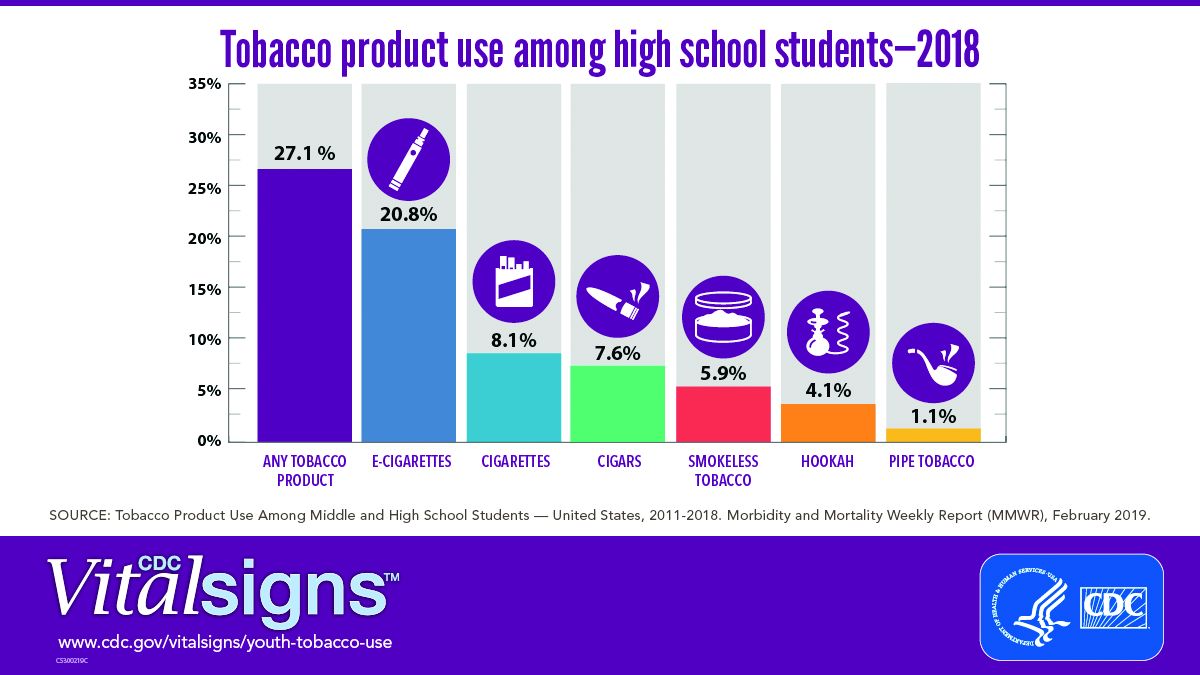

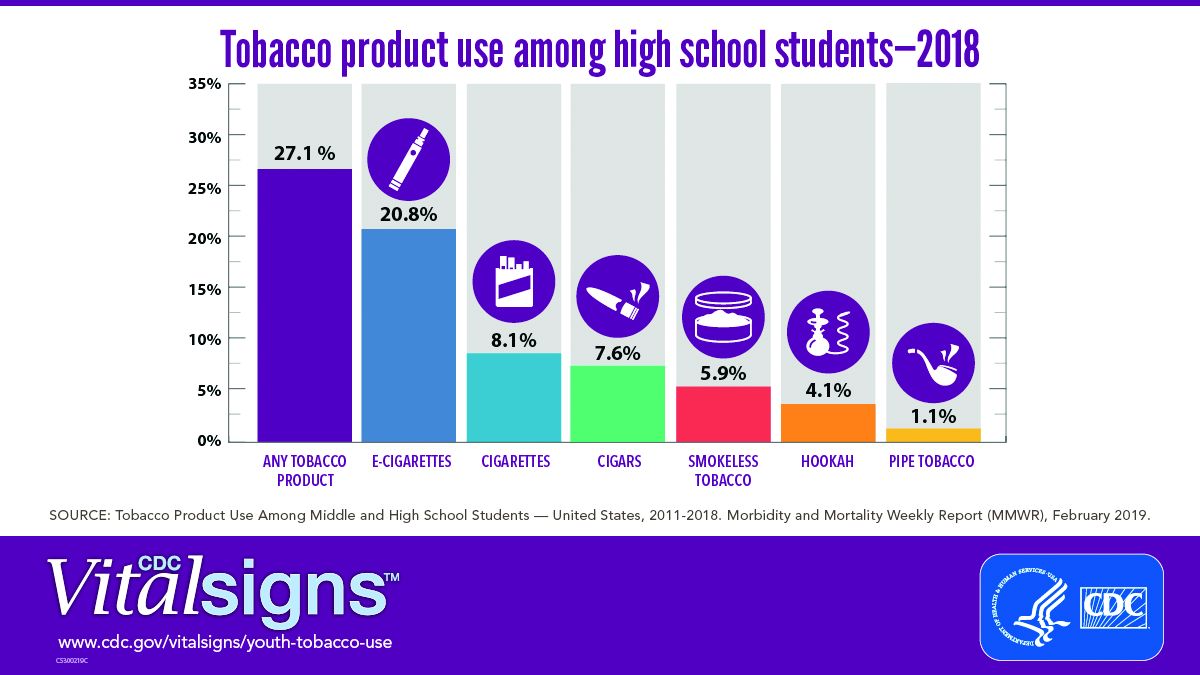

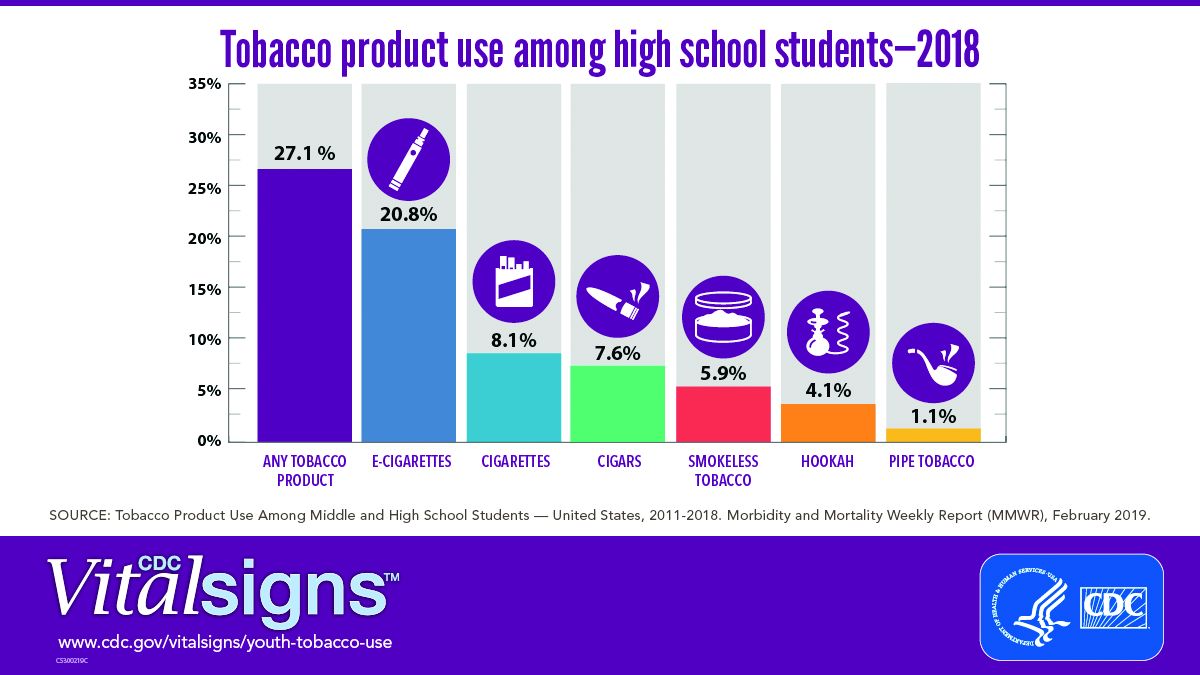

E-cigarettes are driving the trend. About 4 million high school students in the United States reported using any tobacco product in the last 30 days, and 3 million of them reported using e-cigarettes, according to a Vital Signs document published by the CDC on Feb. 11 in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.*

In addition, many high school students who use e-cigarettes use them often; 28% reported using the products at least 20 times in the past 28 days, up from 20% in 2017.

“Any use of any tobacco product is unsafe for teens,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, said in a teleconference to present the findings. Nicotine is highly addictive and can harm brain development in youth, including capacity for learning, memory, and attention, she said.

The rise in e-cigarette use corresponds with the rise in marketing and availability of e-cigarette devices such as JUUL, which dispense nicotine via liquid refill pods available in flavors including strawberry and cotton candy, said Brian King, MPH, PhD, deputy director for research translation at the CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health.

“The advertising will lead a horse to water, the flavors will make them drink, and the nicotine will keep them coming back for more,” said Dr. King.

Approximately 27.1% of high school students and 7.2% of middle school students used a tobacco product in 2018, a significant increase from 2017 data, and with a major increase in e-cigarette use.

No change was noted in the use of other tobacco products, including cigarettes, from 2017 to 2018, according to the report. However, conventional cigarettes remained the most common companion product to e-cigarettes for youth who use two or more tobacco products (two in five high school students and one in three middle school students in 2018). From a demographic standpoint, e-cigarette use was highest among males, whites, and high school students.

Tobacco use in teens is trending in the direction of wiping out the progress made in recent years to reduce exposure to youths. The report noted, “The prevalence of e-cigarette use by U.S. high school students had peaked in 2015 before declining by 29% during 2015-2016 (from 16% to 11.3%); this decline was the first ever recorded for e-cigarette use among youths in the NYTS since monitoring began, and it was subsequently sustained during 2016-2017). However, current e-cigarette use increased by 77.8% among high school students and 48.5% among middle school students during 2017-2018, erasing the progress in reducing e-cigarette use, as well as any tobacco product use, that had occurred in prior years.”

The CDC and the Food and Drug Administration are taking action to curb the rise in e-cigarette use in youth in particular by seeking regulations to make the products less accessible, raising prices, and banning most flavorings, said Dr. Schuchat.

“We have targeted companies engaged in kid friendly marketing,” said Mitch Zeller, JD, director of the Center for Tobacco Products for the FDA.

In a statement published simultaneously with the Vital Signs study, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, emphasized the link between e-cigarette use in teens and the potential for future tobacco use. “The kids using e-cigarettes are children who rejected conventional cigarettes, but don’t see the same stigma associated with the use of e-cigarettes. But now, having become exposed to nicotine through e-cigs, they will be more likely to smoke.” Dr. Gottlieb declared, “I will not allow a generation of children to become addicted to nicotine through e-cigarettes. We must stop the trends of youth e-cigarette use from continuing to build and will take whatever action is necessary to ensure these kids don’t become future smokers.” He reviewed steps taken in the past year by the FDA to counter tobacco use in teens but he warned of future actions that may need to be taken: “If these youth use trends continue, we’ll be forced to consider regulatory steps that could constrain or even foreclose the opportunities for currently addicted adult smokers to have the same level of access to these products that they now enjoy. I recognize that such a move could come with significant impacts to adult smokers.”

In the meantime, however, parents, teachers, community leaders, and health care providers are on the front lines and can make a difference in protecting youth and curbing nicotine use, Dr. King said.