User login

Study Provides Insight Into Alcohol’s Effects on the Brain

The findings could lead the way to understanding the brain’s intake and output of energy in good health and bad and the part that alcohol plays.

In previous studies, the researchers have shown that alcohol significantly affects brain glucose metabolism, a measure of energy use, as well as regional brain activity, assessed through changes in blood oxygenation. But regional differences in glucose metabolism are hard to interpret, they say. In a study with healthy volunteers, they used brain imaging techniques to help quantify “match and mismatch” in energy consumption and expenditure across the brain—what they termed power and cost.

The researchers assessed power by observing to what extent brain regions are active and use energy, and cost by observing how brain regions expended energy. They found that different brain regions that serve distinct functions have “notably different power and different cost.”

Next, they tested a group of light drinkers and heavy drinkers and found both acute and chronic exposure to alcohol affected power and cost. In heavy drinkers, the researchers say, they saw less regional power, for example, in the thalamus, the sensory gateway, and frontal cortex. The researchers interpreted the decreases in power as reflecting the toxic effects of long-term exposure to alcohol on the brain cells.

They also found power dropped in the visual regions during acute alcohol exposure, which was related to disruption of visual processing. Visual regions also had the most significant drops in cost of activity during intoxication. That is consistent with the reliance of those regions on alternative energy sources, such as acetate (a byproduct of alcohol metabolism), the researchers say.

Their approach for characterizing brain energetic patterns related to alcohol use could be useful in other ways, the researchers say. “Studying energetic signatures of brain regions in different neuropsychiatric diseases is an important future direction,” said co-lead investigator Dr. Ehsan Schokri-Kojori. “The measures of power and cost may provide new multimodal biomarkers.”

The findings could lead the way to understanding the brain’s intake and output of energy in good health and bad and the part that alcohol plays.

In previous studies, the researchers have shown that alcohol significantly affects brain glucose metabolism, a measure of energy use, as well as regional brain activity, assessed through changes in blood oxygenation. But regional differences in glucose metabolism are hard to interpret, they say. In a study with healthy volunteers, they used brain imaging techniques to help quantify “match and mismatch” in energy consumption and expenditure across the brain—what they termed power and cost.

The researchers assessed power by observing to what extent brain regions are active and use energy, and cost by observing how brain regions expended energy. They found that different brain regions that serve distinct functions have “notably different power and different cost.”

Next, they tested a group of light drinkers and heavy drinkers and found both acute and chronic exposure to alcohol affected power and cost. In heavy drinkers, the researchers say, they saw less regional power, for example, in the thalamus, the sensory gateway, and frontal cortex. The researchers interpreted the decreases in power as reflecting the toxic effects of long-term exposure to alcohol on the brain cells.

They also found power dropped in the visual regions during acute alcohol exposure, which was related to disruption of visual processing. Visual regions also had the most significant drops in cost of activity during intoxication. That is consistent with the reliance of those regions on alternative energy sources, such as acetate (a byproduct of alcohol metabolism), the researchers say.

Their approach for characterizing brain energetic patterns related to alcohol use could be useful in other ways, the researchers say. “Studying energetic signatures of brain regions in different neuropsychiatric diseases is an important future direction,” said co-lead investigator Dr. Ehsan Schokri-Kojori. “The measures of power and cost may provide new multimodal biomarkers.”

The findings could lead the way to understanding the brain’s intake and output of energy in good health and bad and the part that alcohol plays.

In previous studies, the researchers have shown that alcohol significantly affects brain glucose metabolism, a measure of energy use, as well as regional brain activity, assessed through changes in blood oxygenation. But regional differences in glucose metabolism are hard to interpret, they say. In a study with healthy volunteers, they used brain imaging techniques to help quantify “match and mismatch” in energy consumption and expenditure across the brain—what they termed power and cost.

The researchers assessed power by observing to what extent brain regions are active and use energy, and cost by observing how brain regions expended energy. They found that different brain regions that serve distinct functions have “notably different power and different cost.”

Next, they tested a group of light drinkers and heavy drinkers and found both acute and chronic exposure to alcohol affected power and cost. In heavy drinkers, the researchers say, they saw less regional power, for example, in the thalamus, the sensory gateway, and frontal cortex. The researchers interpreted the decreases in power as reflecting the toxic effects of long-term exposure to alcohol on the brain cells.

They also found power dropped in the visual regions during acute alcohol exposure, which was related to disruption of visual processing. Visual regions also had the most significant drops in cost of activity during intoxication. That is consistent with the reliance of those regions on alternative energy sources, such as acetate (a byproduct of alcohol metabolism), the researchers say.

Their approach for characterizing brain energetic patterns related to alcohol use could be useful in other ways, the researchers say. “Studying energetic signatures of brain regions in different neuropsychiatric diseases is an important future direction,” said co-lead investigator Dr. Ehsan Schokri-Kojori. “The measures of power and cost may provide new multimodal biomarkers.”

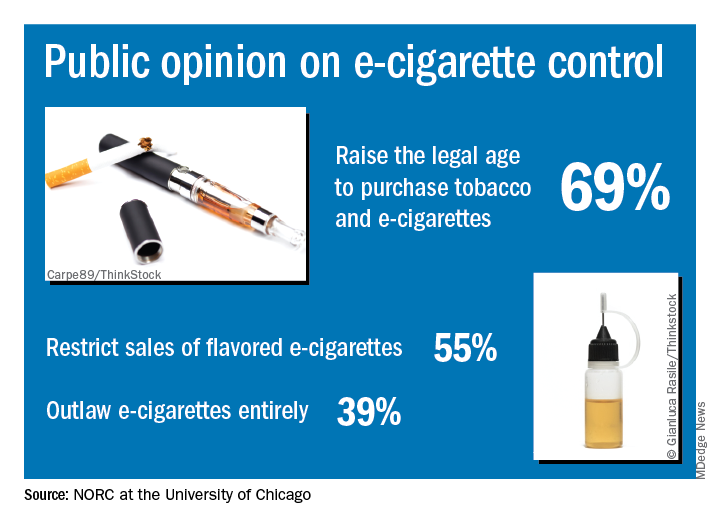

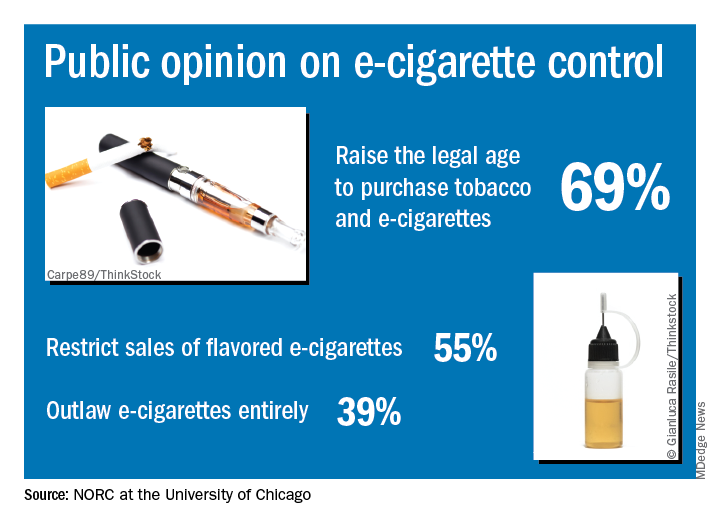

Survey: Americans support regulation of vaping products

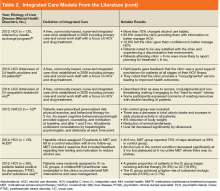

Almost 70% of adults believe that the Food and Drug Administration should raise the legal age to purchase e-cigarettes and tobacco, according to a new survey by NORC at the University of Chicago, a nonpartisan research institution.

“Americans are particularly concerned about teens becoming newly addicted to e-cigarettes, and they support a range of actions the federal government could take to make vaping products less available, less addictive, and less appealing,” Caroline Pearson, senior vice president at NORC, said in a written statement.

The AmeriSpeak Spotlight on Health Poll, conducted Feb. 14-18, 2019 (margin of error, plus or minus 4.12%), showed that 69% of adults strongly or somewhat support raising the age limit to purchase e-cigarettes and tobacco and 55% support restricting sales of flavored e-cigarettes, NORC reported. Almost 40% of the 1,004 respondents expressed support for a complete ban on e-cigarettes.

Despite FDA efforts under Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, to raise awareness of teen vaping, only 21% of those surveyed correctly responded that e-cigarettes generally contain more nicotine that regular cigarettes. Dr. Gottlieb announced his resignation recently, “but he indicated that the Trump Administration will continue efforts to increase regulation of e-cigarettes,” NORC said.

Almost 70% of adults believe that the Food and Drug Administration should raise the legal age to purchase e-cigarettes and tobacco, according to a new survey by NORC at the University of Chicago, a nonpartisan research institution.

“Americans are particularly concerned about teens becoming newly addicted to e-cigarettes, and they support a range of actions the federal government could take to make vaping products less available, less addictive, and less appealing,” Caroline Pearson, senior vice president at NORC, said in a written statement.

The AmeriSpeak Spotlight on Health Poll, conducted Feb. 14-18, 2019 (margin of error, plus or minus 4.12%), showed that 69% of adults strongly or somewhat support raising the age limit to purchase e-cigarettes and tobacco and 55% support restricting sales of flavored e-cigarettes, NORC reported. Almost 40% of the 1,004 respondents expressed support for a complete ban on e-cigarettes.

Despite FDA efforts under Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, to raise awareness of teen vaping, only 21% of those surveyed correctly responded that e-cigarettes generally contain more nicotine that regular cigarettes. Dr. Gottlieb announced his resignation recently, “but he indicated that the Trump Administration will continue efforts to increase regulation of e-cigarettes,” NORC said.

Almost 70% of adults believe that the Food and Drug Administration should raise the legal age to purchase e-cigarettes and tobacco, according to a new survey by NORC at the University of Chicago, a nonpartisan research institution.

“Americans are particularly concerned about teens becoming newly addicted to e-cigarettes, and they support a range of actions the federal government could take to make vaping products less available, less addictive, and less appealing,” Caroline Pearson, senior vice president at NORC, said in a written statement.

The AmeriSpeak Spotlight on Health Poll, conducted Feb. 14-18, 2019 (margin of error, plus or minus 4.12%), showed that 69% of adults strongly or somewhat support raising the age limit to purchase e-cigarettes and tobacco and 55% support restricting sales of flavored e-cigarettes, NORC reported. Almost 40% of the 1,004 respondents expressed support for a complete ban on e-cigarettes.

Despite FDA efforts under Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, to raise awareness of teen vaping, only 21% of those surveyed correctly responded that e-cigarettes generally contain more nicotine that regular cigarettes. Dr. Gottlieb announced his resignation recently, “but he indicated that the Trump Administration will continue efforts to increase regulation of e-cigarettes,” NORC said.

Integrating Care for Patients With Chronic Liver Disease and Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders (FULL)

Chronic liver disease (CLD) encompasses a spectrum of common diseases associated with high morbidity and mortality. In 2010, cirrhosis, or advanced-stage CLD, was the eighth leading cause of death in the U.S., accounting for about 49,500 deaths.1 The leading causes of CLD are hepatitis C virus (HCV), which affects about 3.6 million people in the US; nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which has been increasing in prevalence in up to 75% of CLD cases; and alcohol misuse.2,3 Substance use disorders (SUDs) are a common cause of CLD. About one-third of cirrhosis cases can be attributed to alcohol use, and there is a strong association between IV drug use and HCV. Individual studies point to the high prevalence of mental health disorders (MHDs) among patients with CLD.4-19 It is clear that mental health disorders and SUDs impact outcomes for patients with CLD such that addressing these co-occurring disorders is critical to caring for this population.

An integrated or multidisciplinary approach to medical care attempts to coordinate the delivery of health and social care to patients with complex disease and comorbidities.20 Integrated care models have been shown to positively impact outcomes in many chronic diseases. For example, in patients with heart failure, multidisciplinary interventions such as home visits, remote physiologic monitoring, telehealth, telephone follow-up, or a hospital/clinic team-based intervention have been shown to reduce both hospital admissions and all-cause mortality.21 Similarly, there have been studies in patients with CLD exploring integrated care models. Although individual studies have assessed outcomes associated with various MHDs/SUDs among patients with different etiologies of liver disease, this review assesses the role of integrated care models for patients with CLD and MHDs/SUDs across etiologies.

Methods

A search of the PubMed database was conducted in November 2016 with the following keywords: “liver disease” and “mental health,” “liver disease” and “depression,” “liver disease” and “integrated care,” “substance use” and “liver disease,” “integrated care” and “hepatitis,” “integrated care” and “cirrhosis,” “integrated care” and “advanced liver disease,” and “integrated care” and “alcoholic liver disease” or “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.” Articles covered a range of study types, including qualitative and quantitative analyses as well as other systematic reviews on focused topics within the area of interest. The authors reviewed the abstracts for eligibility criteria, which included topics focused on the study of mental health or substance use aspects and/or integrated mental health/substance use care for liver diseases (across etiologies and stages), published from January 2004 to November 2016, written in English, and focused on an adult population. Five members of the research team reviewed abstracts and eliminated any that did not meet the eligibility criteria.

A total of 636 records were screened and 378 were excluded based on abstract relevance to the stated topics as well as eligibility criteria. Following this review, full articles (N = 263) were reviewed by at least 2 members of the research team. For both levels of review, articles were removed for the criteria above and additional exclusion criteria: editorial style articles, duplicates, transplant focus, or primarily focused on health-related quality of life (QOL) not specific to MHDs. Although many articles fit more than one exclusion criteria, an article was removed once it met one exclusion criteria. After individual assessment by members of the research team, 71 articles were kept in the review. The team identified 14 additional articles that contributed to the topic but were not located through the original database search. The final analysis included 85 articles that fell into 3 key areas: (1) prevalence of comorbid MHD/SUD in liver disease; (2) associations between MHD/SUD and disease progression/management; and (3) the use of integrated care models in patients with CLD.

Results

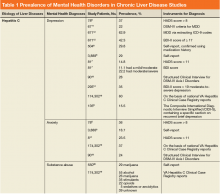

In general, depression and anxiety were common among patients with CLD regardless of etiology.5 Across VA and non-VA studies, depressive disorders were found in one-third to two-thirds of patients with CLD and anxiety disorders in about one-third of patients with CLD. 5,7,8,10,15,16, 22-25Results of the studies that assess the prevalence of MHDs in patients with CLD are shown in Table 1.

MHDs and SUDs in Patients With CLD

Mental health symptoms have been associated with the severity of liver disease in some but not all studies.17,18,26 Mental health disorders also may have more dire consequences in this population. In a national survey of adults, 1.6% of patients with depression were found to have liver disease. Among this group with depression, suicide attempts were 3-fold higher among patients with CLD vs patients without CLD.19

Substance use disorders (including alcohol) are common among patients with CLD. This has been best studied in the context of patients with HCV.22, 27-32 For example among patients with HCV, the prevalence of injection drug use (IDU) was 48% to 65%, and the prevalence of marijuana use was 29%.33-36 In a report of 174,302 veterans with HCV receiving VA care, the following SUDs were reported as diagnosis in this patient population: alcohol, 55%; cannabis, 26%; stimulants, 35%; opioids, 22%; sedatives or anxiolytics, 5%; and other drug use, 39%.10

Both Non-VA and VA studies have found overlap between HCV and alcohol-related liver disease with a number of patients with HCV using alcohol and a number of patients with alcohol-related liver disease having a past history of IDU and HCV.37,38 Across VA and non-VA studies, patients with HIV/HCV co-infection have been found to have particularly high rates of MHDs and SUDs. One VA retrospective cohort study of 18,349 HIV-infected patients noted 37% were seropositive for HCV as well.39-41 These patients with HIV/HCV infection when compared with patients with only HIV infection were more likely to have a diagnosis of mental health illness (76.1% vs 63.1%), depression (56.6% vs 45.6%), alcohol abuse (64.2% vs 30.1%), substance abuse (68.0% vs 25.7%), and hard drug use (62.9% vs 20.6%).42 Patients with CLD and ongoing alcohol use have been found to have increased mental health symptoms compared with patients without ongoing alcohol use.17 Thus MHDs and SUDs are common and often coexist among patients with CLD.

MHDs Impact Patient Outcomes

Mental health disorders can affect how providers care for patients. In the past, for example, in both VA and non-VA studies, patients were often excluded from interferon-based HCV treatments due to MHDs.22,35,43-45 These exclusions included psychiatric issues (35%), alcohol abuse (31%), drug abuse (9%), or > 1 of these reasons (26%).46 Depression also has been associated with decreased care seeking by patients. Patients with cirrhosis and depression often do not seek medical care due to perceived stigma.47 Nearly one-fifth of patients with HCV in one study reported that they did not share information about their disease with others to avoid being stigmatized.48 Other studies have noted similar difficulty with patients’ seeking HCV treatment, advances in medications notwithstanding.49-52

Depression among patients with cirrhosis has been associated with reduced QOL, worsened cognitive function, increased mortality, and frailty.18,53,54 Psychiatric symptoms have been associated with disability and pain among patients with cirrhosis and with weight gain among patients with NAFLD.5,55 Mental health symptoms also predicted lower work productivity in patients with HCV.8 Histologic changes in the liver have been described among patients with psychiatric disorders, although the mechanism is not well understood.15,16

Although not a focus of this review, it is well established that MHDs are associated with increased substance use. Since there is a well-established connection between alcohol and adverse liver-related outcomes regardless of etiology of liver disease, mental health is thus indirectly linked to poor liver outcomes through this mechanism.37,38,56-67

Integrated Care in Liver Disease

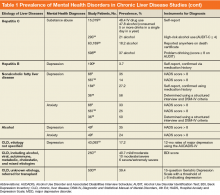

Although there are no set guidelines on how to approach patients with liver disease and MHD/SUD comorbidities, integrated care approaches that include attention to both CLD and psychiatric needs seem promising. Integrated care models have been recommended by several authors specifically for patients with HCV and co-occurring MHDs and SUDs.4,33,42,43,45,68-72 Various integrated care models for CLD and psychiatric comorbidities have been studied and are detailed in Table 2.

The most well described models of integrated care in CLD have been used for patients with HCV as noted in prior reviews.22,34,49,73 These studies included liver care integrated with substance abuse clinics/specialists, mental health professionals, and/or case managers. Outcomes that have been assessed include adherence, HCV treatment completion, HCV treatment eligibility/initiation, and reduction in alcohol use.31,46, 74-77 A large randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing integrated care with usual care found that integrated care, including collaborative consultation with mental health providers and case managers, was associated with increased antiviral treatment and sustained virologic response (SVR).50,78 One study of integrated care in the era of direct-acting antiviral treatment for HCV found that twice as many veterans initiated treatment with integrated care (with case management and a mental health provider) as opposed to usual care. In this integrated care model, mental health providers provided ongoing brief psychological interventions designed to address the specific risk factors identified at screening, facilitated treatment, and served as a regular contact.79 Overall, integrating mental health care and HCV care has resulted in increased adherence, increased treatment eligibility/initiation, treatment completion, higher rates of SVR, and reduction in alcohol use.31,46,74-77

In addition to positive medical outcomes with integrated care models, patients and providers generally have favorable impressions of the clinics using an integrated care approach. For example, multiple qualitative studies of the Hepatitis C Community Clinic in New Zealand have described that patients and providers have positive feelings about integrated care models for HCV.80-82 Another study evaluating integrated care at 4 hepatitis clinics in British Columbia, Canada found that clients overall valued the clinic and viewed it favorably; however, they identified several areas for continued improvement, including communication and time spent with clients, follow-up and access to care, as well as education on coping and managing their disease.83

Beyond HCV, other patients with CLD could benefit from integrated care approaches. Given the association of psychiatric symptoms with weight outcomes among patients with NAFLD, integrating behavioral support has been recommended.55 Multidisciplinary care has been trialed in patients with NAFLD. One model included behavioral therapy with psychological counseling, motivation for lifestyle changes, and support by a trained expert cognitive behavioral psychologist. Although this study did not include a control group, the patients in the study experienced an 8% weight reduction, reduction in aminotransferases, and decreased hepatic steatosis by ultrasound.84

Integrated care also has been advocated for patients with alcohol-related liver disease. One study recommended creating a personalized framework to support self-management for this population.85 Another study assessed patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy and recommended integrating individual coping strategies and support into liver care for this group of patients.86

A United Kingdom study of multidisciplinary care that included a team of gastroenterologists, psychiatrists, and a psychiatric liaison nurse, found improved accessibility to care and patient/family satisfaction using this model. Outpatient appointments were offered to 84% of patients after collaborative care was introduced as opposed to 12% previously. Patients and family members reported that this approach decreased the stigma of mental health care, allowing patients to be more open to intervention and education in this setting.87 A systematic review of patients with alcohol-related CLD found that among 5 RCTs with 1,945 cumulative patients, integrated care was associated with increased short-term abstinence but not sustained abstinence.88 Thus integrated care has been used most in patients with HCV-related CLD, but growing evidence supports its use for patients with other etiologies of CLD, including NAFLD and alcohol.

Discussion

This review found that MHDs are common among patients with CLD and that there is an association between the worsening of liver disease outcomes for patients with comorbid mental health and substance use diagnoses as well as an association of poor MHD/SUD outcomes among patients with CLD (eg, increased suicide attempts among those with comorbid CLD and depression). These data synthesis support screening for MHDs in patients with CLD and providing integrated or multidisciplinary care where possible. Integrated care provides both mental health and CLD care in a combined setting. Integrated care models have been associated with improved health outcomes in patients with CLD and psychiatric comorbidities, including increased adherence, increased HCV treatment eligibility; initiation, and completion; higher rates of HCV treatment cure; reduction in alcohol use; and increased weight loss among patients with NAFLD.

Integrated care is becoming the standard of care for patients with CLD in many countries with national medical care systems. Scotland, for example, initiated an HCV action plan that included mental health and social care. It reported a reduced incidence of HCV infection among patients with a history of IDU, increased treatment initiation, and increased HCV testing with this approach.89 Multidisciplinary care is a class 1 level B recommendation for HCV care in Canada, meaning that it is the highest class of evidence and is supported by at least 1 randomized or multiple nonrandomized studies.90 Similarly, the US Department of Health and Human Services has developed a “National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan” with more than 20 participating federal agencies. The plan highlights the importance of integrating public health and clinical services to successfully improve viral hepatitis care, prevention, and treatment across the US.

The content of the integrated care interventions has been variable. Models with the highest success of liver disease outcomes in this study seem to have screened patients for MHDs and/or SUDs and then used trained professionals to address these issues while also focusing on liver care. An approach that includes evidence-based treatments or intervention for MHDs/SUDs is likely preferable to nonspecific support or information giving. However, it is notable that even minimal interventions (eg, providing informational materials) have been associated with improved outcomes in CLD. The actual implementation of integrated care for MHDs/SUDs into liver care likely has to be tailored to the context and available resources.

One study proposed several models of integrated care that can be adapted to the available resources of a given clinical practice setting. These included fully integrated models where services are colocated, collaborative practice models in which there is a strong relationship between providers in hepatology and mental health and SUD clinics, and then hybrid models that integrate/colocate when possible and collaborate when colocation isn’t available. Although the fully integrated care model likely is the most ideal, any multidisciplinary approach has the potential to decrease barriers and increase access to treatment.91

Another study used modeling to develop an integrated care framework for vulnerable veterans with HCV that incorporated both implementation factors (eg, research evidence, clinical experience, facilitation, and leadership) based on the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services framework and patients’ factors from the Andersen Behavioral Model (eg, geography and finances) to form a hybrid framework for this population.92

Limitations

There are several notable limitations of this review. Although the review focused on depression, anxiety, and SUDs, given the high prevalence of these disorders, other MHDs are also common among patients with CLD and were not addressed. For example, veterans with HCV also commonly had posttraumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.10 Further investigation should focus on these disorders and their impacts. Additionally, the authors did not specifically search for alcohol-related care in the search terms. This review also did not address nonpsychiatric types of integrated care, which could be the focus of future reviews. Despite these limitations, this review provides support for the use of integrated care in the context of CLD and co-occurring MHDs and SUDs.

Conclusion

Several studies support integrated care for patients with liver disease and co-occurring psychiatric disorders. There are multiple integrated care models in place, although they have largely been used in patients with HCV. More studies are needed to assess the role of integrated mental health care in other populations of patients with CLD. There is an abundance of research supporting the role of integrated care in improving health outcomes across many chronic diseases, including implementation of mental health into primary care in large health care systems like the VA health care system.93 Health care systems should work toward alignment of resources to meet these needs in specialty care settings, such as liver disease care in order optimize both liver disease and MHD/SUD outcomes for these patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al; US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591-608.

2. Davis GL, Alter MJ, El-Serag H, Poynard T, Jennings LW. Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2):513-521.e1-e6.

3. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, et al. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(6):524-530.e1; quiz e60.

4. Neuman MG, Monteiro M, Rehm J. Drug interactions between psychoactive substances and antiretroviral therapy in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency and hepatitis viruses. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(10-12):1395-1463.

5. Rogal SS, Bielefeldt K, Wasan AD, et al. Inflammation, psychiatric symptoms, and opioid use are associated with pain and disability in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(5):1009-1016.

6. Weinstein AA, Kallman Price J, Stepanova M, et al. Depression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(2):127-132.

7. Erim Y, Tagay S, Beckmann M, et al. Depression and protective factors of mental health in people with hepatitis C: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(3):342-349.

8. Younossi I, Weinstein A, Stepanova M, Hunt S, Younossi ZM. Mental and emotional impairment in patients with hepatitis C is related to lower work productivity. Psychosomatics. 2016;57(1):82-88.

9. Carta MG, Angst J, Moro MF, et al. Association of chronic hepatitis C with recurrent brief depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2-3):361-366.

10. Beste LA, Ioannou GN. Prevalence and treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37(1):131-143.

11. Birerdinc A, Afendy A, Stepanova M, Younossi I, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Gene expression profiles associated with depression in patients with chronic hepatitis C (CH-C). Brain Behav. 2012;2(5):525-531.

12. Patterson AL, Morasco BJ, Fuller BE, Indest DW, Loftis JM, Hauser P. Screening for depression in patients with hepatitis C using the Beck Depression Inventory-II: do somatic symptoms compromise validity? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(4):354-362.

13. Golden J, O’Dwyer AM, Conroy RM. Depression and anxiety in patients with hepatitis C: prevalence, detection rates and risk factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27(6):431-438.

14. Fireman M, Indest DW, Blackwell A, Whitehead AJ, Hauser P. Addressing tri-morbidity (hepatitis C, psychiatric disorders, and substance use): the importance of routine mental health screening as a component of a comanagement model of care. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(suppl 5):S286-S291.

15. Elwing JE, Lustman PJ, Wang HL, Clouse RE. Depression, anxiety, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(4):563-569.

16. Youssef NA, Abdelmalek MF, Binks M, et al. Associations of depression, anxiety and antidepressants with histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2013;33(7):1062-1070.

17. Bianchi G, Marchesini G, Nicolino F, et al. Psychological status and depression in patients with liver cirrhosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37(8):593-600.

18. Cron DC, Friedman JF, Winder GS, et al. Depression and frailty in patients with end-stage liver disease referred for transplant evaluation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(6):1805-1811.

19. Le Strat Y, Le Foll B, Dubertret C. Major depression and suicide attempts in patients with liver disease in the United States. Liver Int. 2015;35(7):1910-1916.

20. Lemmens LC, Molema CC, Versnel N, Baan CA, de Bruin SR. Integrated care programs for patients with psychological comorbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(6):580-594.

21. Holland R, Battersby J, Harvey I, Lenaghan E, Smith J, Hay L. Systematic review of multidisciplinary interventions in heart failure. Heart. 2005;91(7):899-906.

22. Ho SB, Groessl E, Dollarhide A, Robinson S, Kravetz D, Dieperink E. Management of chronic hepatitis C in veterans: the potential of integrated care models. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(7):1810-1823.

23. Adinolfi LE, Nevola R, Lus G, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection and neurological and psychiatric disorders: an overview. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(8):2269-2280.

24. Lee K, Otgonsuren M, Younoszai Z, Mir HM, Younossi ZM. Association of chronic liver disease with depression: a population-based study. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(1):52-59.

25. Rosenthal E, Cacoub P. Extrahepatic manifestations in chronic hepatitis C virus carriers. Lupus. 2015;24(4-5):469-482.

26. Duan Z, Kong Y, Zhang J, Guo H. Psychological comorbidities in Chinese patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(3):276-281.

27. Cariello R, Federico A, Sapone A, et al. Intestinal permeability in patients with chronic liver diseases: its relationship with the aetiology and the entity of liver damage. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42(3):200-204.

28. Wise M, Finelli L, Sorvillo F. Prognostic factors associated with hepatitis C disease: a case-control study utilizing U.S. multiple-cause-of-death data. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(3):414-422.

29. Wurst FM, Dürsteler-MacFarland KM, Auwaerter V, et al. Assessment of alcohol use among methadone maintenance patients by direct ethanol metabolites and self-reports. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(9):1552-1557.

30. Campbell JV, Hagan H, Latka MH, et al; The STRIVE Project. High prevalence of alcohol use among hepatitis C virus antibody positive injection drug users in three US cities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81(3):259-265.

31. Dieperink E, Fuller B, Isenhart C, et al. Efficacy of motivational enhancement therapy on alcohol use disorders in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2014;109(11):1869-1877.

32. Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):705-714

33. Arain A, Robaeys G. Eligibility of persons who inject drugs for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(36):12722-12733.

34. North CS, Hong BA, Kerr T. Hepatitis C and substance use: new treatments and novel approaches. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(3):206-212.

35. Coffin PO, Reynolds A. Ending hepatitis C in the United States: the role of screening. Hepat Med. 2014;6:79-87.

36. Liu T, Howell GT, Turner L, Corace K, Garber G, Cooper C. Marijuana use in hepatitis C infection does not affect liver biopsy histology or treatment outcomes. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(7):381-384.

37. Kamal A, Cheung R. Positive CAGE screen correlates with cirrhosis in veterans with chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(10):2564-2569.

38. Fuster D, Sanvisens A, Bolao F, et al. Impact of hepatitis C virus infection on the risk of death of alcohol-dependent patients. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22(1):18-24.

39. Klein MB, Rollet KC, Saeed S, et al; Canadian HIV-HCV Cohort Investigators. HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfection in Canada: challenges and opportunities for reducing preventable morbidity and mortality. HIV Med. 2013;14(1):10-20.

40. Weiss JJ, Gorman JM. Psychiatric behavioral aspects of comanagement of hepatitis C virus and HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2006;3(4):176-181.

41. Goulet JL, Fultz SL, McGinnis KA, Justice AC. Relative prevalence of comorbidities and treatment contraindications in HIV-mono-infected and HIV/HCV-co-infected veterans. AIDS. 2005;19(suppl 3):S99-S105.

42. Backus LI, Boothroyd D, Deyton LR. HIV, hepatitis C and HIV/hepatitis C virus co-infection in vulnerable populations. AIDS. 2005;19(suppl 3):S13-S19.

43. Mehta SH, Genberg BL, Astemborski J, et al. Limited uptake of hepatitis C treatment among injection drug users. J Community Health. 2008;33(3):126-133.

44. Gidding HF, Law MG, Amin J, et al; ACHOS Investigator Team. Predictors of deferral of treatment for hepatitis C infection in Australian clinics. Med J Aust. 2011;194(8):398-402.

45. Chainuvati S, Khalid SK, Kancir S, et al. Comparison of hepatitis C treatment patterns in patients with and without psychiatric and/or substance use disorders. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13(4):235-241.

46. Evon DM, Simpson K, Kixmiller S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an integrated care intervention to increase eligibility for chronic hepatitis C treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011; 106(10):1777-1786.

47. Vaughn-Sandler V, Sherman C, Aronsohn A, Volk ML. Consequences of perceived stigma among patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(3):681-686.

48. Blasiole JA, Shinkunas L, Labrecque DR, Arnold RM, Zickmund SL. Mental and physical symptoms associated with lower social support for patients with hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(29):4665-4672.

49. Bruggmann P, Litwin AH. Models of care for the management of hepatitis C virus among people who inject drugs: one size does not fit all. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(suppl 2):S56-S61.

50. Groessl EJ, Sklar M, Cheung RC, Bräu N, Ho SB. Increasing antiviral treatment through integrated hepatitis C care: a randomized multicenter trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35(2):97-107.

51. Alavi M, Grebely J, Micallef M, et al; Enhancing Treatment for Hepatitis C in Opioid Substitution Settings (ETHOS) Study Group. Assessment and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs in the opioid substitution setting: ETHOS study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(suppl 2):S62-S69.

52. Evon DM, Golin CE, Fried MW, Keefe FJ. Chronic hepatitis C and antiviral treatment regimens: where can psychology contribute? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(2):361-374.

53. Mullish BH, Kabir MS, Thursz MR, Dhar A. Review article: depression and the use of antidepressants in patients with chronic liver disease or liver transplantation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(8):880-892.

54. Stewart CA, Enders FT, Mitchell MM, Felmlee-Devine D, Smith GE. The cognitive profile of depressed patients with cirrhosis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13(3):pii. PCC.10m01090

55. Stewart KE, Haller DL, Sargeant C, Levenson JL, Puri P, Sanyal AJ. Readiness for behaviour change in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: implications for multidisciplinary care models. Liver Int. 2015;35(3):936-943.

56. Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM, Goldberg DJ. Influence of alcohol on the progression of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(11):1150-1159.

57. Chaudhry AA, Sulkowski MS, Chander G, Moore RD. Hazardous drinking is associated with an elevated aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index in an urban HIV-infected clinical cohort. HIV Med. 2009;10(3):133-142.

58. McMahon BJ, Bruden D, Bruce MG, et al. Adverse outcomes in Alaska natives who recovered from or have chronic hepatitis C infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(3):922-931.e1.

59. Anand BS, Thornby J. Alcohol has no effect on hepatitis C virus replication: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2005;54(10):1468-1472.

60. Au DH, Kivlahan DR, Bryson CL, Blough D, Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores and risk of hospitalizations for GI conditions in men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(3):443-451.

61. Orman ES, Odena G, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis, management, and novel targets for therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(suppl 1):77-84.

62. Liu J, Lewohl JM, Harris RA, Dodd PR, Mayfield RD. Altered gene expression profiles in the frontal cortex of cirrhotic alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(9):1460-1466.

63. Barve S, Kapoor R, Moghe A, et al. Focus on the liver: alcohol use, highly active antiretroviral therapy, and liver disease in HIV-infected patients. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33(3):229-236.

64. Trimble G, Zheng L, Mishra A, Kalwaney S, Mir HM, Younossi ZM. Mortality associated with alcohol-related liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(6):596-602.

65. Loomba R, Yang HI, Su J, Brenner D, Iloeje U, Chen CJ. Obesity and alcohol synergize to increase the risk of incident hepatocellular carcinoma in men. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(10):891-898.e1-e2.

66. Zakhari S, Li TK. Determinants of alcohol use and abuse: impact of quantity and frequency patterns on liver disease. Hepatology. 2007;46(6):2032-2039.

67. Lim JK, Tate JP, Fultz SL, et al. Relationship between alcohol use categories and noninvasive markers of advanced hepatic fibrosis in HIV-infected, chronic hepatitis C virus-infected, and uninfected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(10):1449-1458.

68. Kanwal F, White DL, Tavakoli-Tabasi S, et al. Many patients with interleukin 28B genotypes associated with response to therapy are ineligible for treatment because of comorbidities. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(2):327-333.e1.

69. Mehta SH, Thomas DL, Sulkowski MS, Safaein M, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA. A framework for understanding factors that affect access and utilization of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection among HCV-mono-infected and HIV/HCV-co-infected injection drug users. AIDS. 2005;19(suppl 3):S179-S189.

70. McLaren M, Garber G, Cooper C. Barriers to hepatitis C virus treatment in a Canadian HIV-hepatitis C virus coinfection tertiary care clinic. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22(2):133-137.

71. Treloar C, Rance J, Dore GJ, Grebely J; ETHOS Study Group. Barriers and facilitators for assessment and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in the opioid substitution treatment setting: insights from the ETHOS study. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(8):560-567.

72. Treloar C, Rance J, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Client and staff experiences of a co-located service for hepatitis C care in opioid substitution treatment settings in New South Wales, Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(2):529-534.

73. Edlin BR, Kresina TF, Raymond DB, et al. Overcoming barriers to prevention, care, and treatment of hepatitis C in illicit drug users. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(suppl 5):S276-S285.

74. Martinez AD, Dimova R, Marks KM, et al. Integrated internist—addiction medicine— hepatology model for hepatitis C management for individuals on methadone maintenance. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19(1):47-54.

75. Fahey S. Developing a nursing service for patients with hepatitis C. Nurs Stand. 2007;21(43):35-40.

76. Knott A, Dieperink E, Willenbring ML, et al. Integrated psychiatric/medical care in a chronic hepatitis C clinic: effect on antiviral treatment evaluation and outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2254-2262.

77. Dieperink E, Ho SB, Heit S, Durfee JM, Thuras P, Willenbring ML. Significant reductions in drinking following brief alcohol treatment provided in a hepatitis C clinic. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(2):149-156.

78. Ho SB, Bräu N, Cheung R, et al. Integrated care increases treatment and improves outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection and psychiatric illness or substance abuse. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(11):2005-2014.e1-e3.

79. Groessl EJ, Liu L, Sklar M, Ho SB. HCV integrated care: a randomized trial to increase treatment initiation and SVR with direct acting antivirals. Int J Hepatol. 2017;2017:5834182.

80. Treloar C, Gray R, Brener L. A piece of the jigsaw of primary care: health professional perceptions of an integrated care model of hepatitis C management in the community. J Prim Health Care. 2014;6(2):129-134.

81. Brener L, Gray R, Cama EJ, Treloar C. “Makes you wanna do treatment”: benefits of a hepatitis C specialist clinic to clients in Christchurch, New Zealand. Health Soc Care Community. 2013;21(2):216-223.

82. Horwitz R, Brener L, Treloar C. Evaluation of an integrated care service facility for people living with hepatitis C in New Zealand. Int J Integr Care. 2012;12(Spec Ed Integrated Care Pathways):e229.

83. Christianson TM, Moralejo D. Assessing the quality of care in a regional integrated viral hepatitis clinic in British Columbia: a cross-sectional study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2009;32(5):315-324.

84. Scaglioni F, Marino M, Ciccia S, et al. Short-term multidisciplinary non-pharmacological intervention is effective in reducing liver fat content assessed non-invasively in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37(4):353-358.

85. Lau-Walker M, Presky J, Webzell I, Murrells T, Heaton N. Patients with alcohol-related liver disease—beliefs about their illness and factors that influence their self-management. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(1):173-185.

86. Mikkelsen MR, Hendriksen C, Schiødt FV, Rydahl-Hansen S. Coping and rehabilitation in alcoholic liver disease patients after hepatic encephalopathy—in interaction with professionals and relatives. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(23-24):3627-3637.

87. Moriarty KJ, Platt H, Crompton S, et al. Collaborative care for alcohol-related liver disease. Clin Med (Lond). 2007;7(2):125-128.

88. Khan A, Tansel A, White DL, et al. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in inducing and maintaining alcohol abstinence in patients with chronic liver disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(2):191-202.e1-e4;quiz e20.

89. Wylie L, Hutchinson S, Liddell D, Rowan N. The successful implementation of Scotland’s Hepatitis C Action Plan: what can other European stakeholders learn from the experience? A Scottish voluntary sector perspective. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(suppl 6):S7.

90. Hull M, Shafran S, Wong A, et al. CIHR Canadian HIV trials network coinfection and concurrent diseases core research group: 2016 updated Canadian HIV/hepatitis C adult guidelines for management and treatment. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2016;2016:4385643.

91. Bonner JE, Barritt AS 4th, Fried MW, Evon DM. Time to rethink antiviral treatment for hepatitis C in patients with coexisting mental health/substance abuse issues. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(6):1469-1474.

92. Rongey C, Asch S, Knight SJ. Access to care for vulnerable veterans with hepatitis C: a hybrid conceptual framework and a case study to guide translation. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(4):644-651.

93. Zeiss AM, Karlin BE. Integrating mental health and primary care services in the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2008;15(1):73-78.

94. Drumright LN, Hagan H, Thomas DL, et al. Predictors and effects of alcohol use on liver function among young HCV-infected injection drug users in a behavioral intervention. J Hepatol. 2011;55(1):45-52.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) encompasses a spectrum of common diseases associated with high morbidity and mortality. In 2010, cirrhosis, or advanced-stage CLD, was the eighth leading cause of death in the U.S., accounting for about 49,500 deaths.1 The leading causes of CLD are hepatitis C virus (HCV), which affects about 3.6 million people in the US; nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which has been increasing in prevalence in up to 75% of CLD cases; and alcohol misuse.2,3 Substance use disorders (SUDs) are a common cause of CLD. About one-third of cirrhosis cases can be attributed to alcohol use, and there is a strong association between IV drug use and HCV. Individual studies point to the high prevalence of mental health disorders (MHDs) among patients with CLD.4-19 It is clear that mental health disorders and SUDs impact outcomes for patients with CLD such that addressing these co-occurring disorders is critical to caring for this population.

An integrated or multidisciplinary approach to medical care attempts to coordinate the delivery of health and social care to patients with complex disease and comorbidities.20 Integrated care models have been shown to positively impact outcomes in many chronic diseases. For example, in patients with heart failure, multidisciplinary interventions such as home visits, remote physiologic monitoring, telehealth, telephone follow-up, or a hospital/clinic team-based intervention have been shown to reduce both hospital admissions and all-cause mortality.21 Similarly, there have been studies in patients with CLD exploring integrated care models. Although individual studies have assessed outcomes associated with various MHDs/SUDs among patients with different etiologies of liver disease, this review assesses the role of integrated care models for patients with CLD and MHDs/SUDs across etiologies.

Methods

A search of the PubMed database was conducted in November 2016 with the following keywords: “liver disease” and “mental health,” “liver disease” and “depression,” “liver disease” and “integrated care,” “substance use” and “liver disease,” “integrated care” and “hepatitis,” “integrated care” and “cirrhosis,” “integrated care” and “advanced liver disease,” and “integrated care” and “alcoholic liver disease” or “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.” Articles covered a range of study types, including qualitative and quantitative analyses as well as other systematic reviews on focused topics within the area of interest. The authors reviewed the abstracts for eligibility criteria, which included topics focused on the study of mental health or substance use aspects and/or integrated mental health/substance use care for liver diseases (across etiologies and stages), published from January 2004 to November 2016, written in English, and focused on an adult population. Five members of the research team reviewed abstracts and eliminated any that did not meet the eligibility criteria.

A total of 636 records were screened and 378 were excluded based on abstract relevance to the stated topics as well as eligibility criteria. Following this review, full articles (N = 263) were reviewed by at least 2 members of the research team. For both levels of review, articles were removed for the criteria above and additional exclusion criteria: editorial style articles, duplicates, transplant focus, or primarily focused on health-related quality of life (QOL) not specific to MHDs. Although many articles fit more than one exclusion criteria, an article was removed once it met one exclusion criteria. After individual assessment by members of the research team, 71 articles were kept in the review. The team identified 14 additional articles that contributed to the topic but were not located through the original database search. The final analysis included 85 articles that fell into 3 key areas: (1) prevalence of comorbid MHD/SUD in liver disease; (2) associations between MHD/SUD and disease progression/management; and (3) the use of integrated care models in patients with CLD.

Results

In general, depression and anxiety were common among patients with CLD regardless of etiology.5 Across VA and non-VA studies, depressive disorders were found in one-third to two-thirds of patients with CLD and anxiety disorders in about one-third of patients with CLD. 5,7,8,10,15,16, 22-25Results of the studies that assess the prevalence of MHDs in patients with CLD are shown in Table 1.

MHDs and SUDs in Patients With CLD

Mental health symptoms have been associated with the severity of liver disease in some but not all studies.17,18,26 Mental health disorders also may have more dire consequences in this population. In a national survey of adults, 1.6% of patients with depression were found to have liver disease. Among this group with depression, suicide attempts were 3-fold higher among patients with CLD vs patients without CLD.19

Substance use disorders (including alcohol) are common among patients with CLD. This has been best studied in the context of patients with HCV.22, 27-32 For example among patients with HCV, the prevalence of injection drug use (IDU) was 48% to 65%, and the prevalence of marijuana use was 29%.33-36 In a report of 174,302 veterans with HCV receiving VA care, the following SUDs were reported as diagnosis in this patient population: alcohol, 55%; cannabis, 26%; stimulants, 35%; opioids, 22%; sedatives or anxiolytics, 5%; and other drug use, 39%.10

Both Non-VA and VA studies have found overlap between HCV and alcohol-related liver disease with a number of patients with HCV using alcohol and a number of patients with alcohol-related liver disease having a past history of IDU and HCV.37,38 Across VA and non-VA studies, patients with HIV/HCV co-infection have been found to have particularly high rates of MHDs and SUDs. One VA retrospective cohort study of 18,349 HIV-infected patients noted 37% were seropositive for HCV as well.39-41 These patients with HIV/HCV infection when compared with patients with only HIV infection were more likely to have a diagnosis of mental health illness (76.1% vs 63.1%), depression (56.6% vs 45.6%), alcohol abuse (64.2% vs 30.1%), substance abuse (68.0% vs 25.7%), and hard drug use (62.9% vs 20.6%).42 Patients with CLD and ongoing alcohol use have been found to have increased mental health symptoms compared with patients without ongoing alcohol use.17 Thus MHDs and SUDs are common and often coexist among patients with CLD.

MHDs Impact Patient Outcomes

Mental health disorders can affect how providers care for patients. In the past, for example, in both VA and non-VA studies, patients were often excluded from interferon-based HCV treatments due to MHDs.22,35,43-45 These exclusions included psychiatric issues (35%), alcohol abuse (31%), drug abuse (9%), or > 1 of these reasons (26%).46 Depression also has been associated with decreased care seeking by patients. Patients with cirrhosis and depression often do not seek medical care due to perceived stigma.47 Nearly one-fifth of patients with HCV in one study reported that they did not share information about their disease with others to avoid being stigmatized.48 Other studies have noted similar difficulty with patients’ seeking HCV treatment, advances in medications notwithstanding.49-52

Depression among patients with cirrhosis has been associated with reduced QOL, worsened cognitive function, increased mortality, and frailty.18,53,54 Psychiatric symptoms have been associated with disability and pain among patients with cirrhosis and with weight gain among patients with NAFLD.5,55 Mental health symptoms also predicted lower work productivity in patients with HCV.8 Histologic changes in the liver have been described among patients with psychiatric disorders, although the mechanism is not well understood.15,16

Although not a focus of this review, it is well established that MHDs are associated with increased substance use. Since there is a well-established connection between alcohol and adverse liver-related outcomes regardless of etiology of liver disease, mental health is thus indirectly linked to poor liver outcomes through this mechanism.37,38,56-67

Integrated Care in Liver Disease

Although there are no set guidelines on how to approach patients with liver disease and MHD/SUD comorbidities, integrated care approaches that include attention to both CLD and psychiatric needs seem promising. Integrated care models have been recommended by several authors specifically for patients with HCV and co-occurring MHDs and SUDs.4,33,42,43,45,68-72 Various integrated care models for CLD and psychiatric comorbidities have been studied and are detailed in Table 2.

The most well described models of integrated care in CLD have been used for patients with HCV as noted in prior reviews.22,34,49,73 These studies included liver care integrated with substance abuse clinics/specialists, mental health professionals, and/or case managers. Outcomes that have been assessed include adherence, HCV treatment completion, HCV treatment eligibility/initiation, and reduction in alcohol use.31,46, 74-77 A large randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing integrated care with usual care found that integrated care, including collaborative consultation with mental health providers and case managers, was associated with increased antiviral treatment and sustained virologic response (SVR).50,78 One study of integrated care in the era of direct-acting antiviral treatment for HCV found that twice as many veterans initiated treatment with integrated care (with case management and a mental health provider) as opposed to usual care. In this integrated care model, mental health providers provided ongoing brief psychological interventions designed to address the specific risk factors identified at screening, facilitated treatment, and served as a regular contact.79 Overall, integrating mental health care and HCV care has resulted in increased adherence, increased treatment eligibility/initiation, treatment completion, higher rates of SVR, and reduction in alcohol use.31,46,74-77

In addition to positive medical outcomes with integrated care models, patients and providers generally have favorable impressions of the clinics using an integrated care approach. For example, multiple qualitative studies of the Hepatitis C Community Clinic in New Zealand have described that patients and providers have positive feelings about integrated care models for HCV.80-82 Another study evaluating integrated care at 4 hepatitis clinics in British Columbia, Canada found that clients overall valued the clinic and viewed it favorably; however, they identified several areas for continued improvement, including communication and time spent with clients, follow-up and access to care, as well as education on coping and managing their disease.83

Beyond HCV, other patients with CLD could benefit from integrated care approaches. Given the association of psychiatric symptoms with weight outcomes among patients with NAFLD, integrating behavioral support has been recommended.55 Multidisciplinary care has been trialed in patients with NAFLD. One model included behavioral therapy with psychological counseling, motivation for lifestyle changes, and support by a trained expert cognitive behavioral psychologist. Although this study did not include a control group, the patients in the study experienced an 8% weight reduction, reduction in aminotransferases, and decreased hepatic steatosis by ultrasound.84

Integrated care also has been advocated for patients with alcohol-related liver disease. One study recommended creating a personalized framework to support self-management for this population.85 Another study assessed patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy and recommended integrating individual coping strategies and support into liver care for this group of patients.86

A United Kingdom study of multidisciplinary care that included a team of gastroenterologists, psychiatrists, and a psychiatric liaison nurse, found improved accessibility to care and patient/family satisfaction using this model. Outpatient appointments were offered to 84% of patients after collaborative care was introduced as opposed to 12% previously. Patients and family members reported that this approach decreased the stigma of mental health care, allowing patients to be more open to intervention and education in this setting.87 A systematic review of patients with alcohol-related CLD found that among 5 RCTs with 1,945 cumulative patients, integrated care was associated with increased short-term abstinence but not sustained abstinence.88 Thus integrated care has been used most in patients with HCV-related CLD, but growing evidence supports its use for patients with other etiologies of CLD, including NAFLD and alcohol.

Discussion

This review found that MHDs are common among patients with CLD and that there is an association between the worsening of liver disease outcomes for patients with comorbid mental health and substance use diagnoses as well as an association of poor MHD/SUD outcomes among patients with CLD (eg, increased suicide attempts among those with comorbid CLD and depression). These data synthesis support screening for MHDs in patients with CLD and providing integrated or multidisciplinary care where possible. Integrated care provides both mental health and CLD care in a combined setting. Integrated care models have been associated with improved health outcomes in patients with CLD and psychiatric comorbidities, including increased adherence, increased HCV treatment eligibility; initiation, and completion; higher rates of HCV treatment cure; reduction in alcohol use; and increased weight loss among patients with NAFLD.

Integrated care is becoming the standard of care for patients with CLD in many countries with national medical care systems. Scotland, for example, initiated an HCV action plan that included mental health and social care. It reported a reduced incidence of HCV infection among patients with a history of IDU, increased treatment initiation, and increased HCV testing with this approach.89 Multidisciplinary care is a class 1 level B recommendation for HCV care in Canada, meaning that it is the highest class of evidence and is supported by at least 1 randomized or multiple nonrandomized studies.90 Similarly, the US Department of Health and Human Services has developed a “National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan” with more than 20 participating federal agencies. The plan highlights the importance of integrating public health and clinical services to successfully improve viral hepatitis care, prevention, and treatment across the US.

The content of the integrated care interventions has been variable. Models with the highest success of liver disease outcomes in this study seem to have screened patients for MHDs and/or SUDs and then used trained professionals to address these issues while also focusing on liver care. An approach that includes evidence-based treatments or intervention for MHDs/SUDs is likely preferable to nonspecific support or information giving. However, it is notable that even minimal interventions (eg, providing informational materials) have been associated with improved outcomes in CLD. The actual implementation of integrated care for MHDs/SUDs into liver care likely has to be tailored to the context and available resources.

One study proposed several models of integrated care that can be adapted to the available resources of a given clinical practice setting. These included fully integrated models where services are colocated, collaborative practice models in which there is a strong relationship between providers in hepatology and mental health and SUD clinics, and then hybrid models that integrate/colocate when possible and collaborate when colocation isn’t available. Although the fully integrated care model likely is the most ideal, any multidisciplinary approach has the potential to decrease barriers and increase access to treatment.91

Another study used modeling to develop an integrated care framework for vulnerable veterans with HCV that incorporated both implementation factors (eg, research evidence, clinical experience, facilitation, and leadership) based on the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services framework and patients’ factors from the Andersen Behavioral Model (eg, geography and finances) to form a hybrid framework for this population.92

Limitations

There are several notable limitations of this review. Although the review focused on depression, anxiety, and SUDs, given the high prevalence of these disorders, other MHDs are also common among patients with CLD and were not addressed. For example, veterans with HCV also commonly had posttraumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.10 Further investigation should focus on these disorders and their impacts. Additionally, the authors did not specifically search for alcohol-related care in the search terms. This review also did not address nonpsychiatric types of integrated care, which could be the focus of future reviews. Despite these limitations, this review provides support for the use of integrated care in the context of CLD and co-occurring MHDs and SUDs.

Conclusion

Several studies support integrated care for patients with liver disease and co-occurring psychiatric disorders. There are multiple integrated care models in place, although they have largely been used in patients with HCV. More studies are needed to assess the role of integrated mental health care in other populations of patients with CLD. There is an abundance of research supporting the role of integrated care in improving health outcomes across many chronic diseases, including implementation of mental health into primary care in large health care systems like the VA health care system.93 Health care systems should work toward alignment of resources to meet these needs in specialty care settings, such as liver disease care in order optimize both liver disease and MHD/SUD outcomes for these patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) encompasses a spectrum of common diseases associated with high morbidity and mortality. In 2010, cirrhosis, or advanced-stage CLD, was the eighth leading cause of death in the U.S., accounting for about 49,500 deaths.1 The leading causes of CLD are hepatitis C virus (HCV), which affects about 3.6 million people in the US; nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which has been increasing in prevalence in up to 75% of CLD cases; and alcohol misuse.2,3 Substance use disorders (SUDs) are a common cause of CLD. About one-third of cirrhosis cases can be attributed to alcohol use, and there is a strong association between IV drug use and HCV. Individual studies point to the high prevalence of mental health disorders (MHDs) among patients with CLD.4-19 It is clear that mental health disorders and SUDs impact outcomes for patients with CLD such that addressing these co-occurring disorders is critical to caring for this population.

An integrated or multidisciplinary approach to medical care attempts to coordinate the delivery of health and social care to patients with complex disease and comorbidities.20 Integrated care models have been shown to positively impact outcomes in many chronic diseases. For example, in patients with heart failure, multidisciplinary interventions such as home visits, remote physiologic monitoring, telehealth, telephone follow-up, or a hospital/clinic team-based intervention have been shown to reduce both hospital admissions and all-cause mortality.21 Similarly, there have been studies in patients with CLD exploring integrated care models. Although individual studies have assessed outcomes associated with various MHDs/SUDs among patients with different etiologies of liver disease, this review assesses the role of integrated care models for patients with CLD and MHDs/SUDs across etiologies.

Methods

A search of the PubMed database was conducted in November 2016 with the following keywords: “liver disease” and “mental health,” “liver disease” and “depression,” “liver disease” and “integrated care,” “substance use” and “liver disease,” “integrated care” and “hepatitis,” “integrated care” and “cirrhosis,” “integrated care” and “advanced liver disease,” and “integrated care” and “alcoholic liver disease” or “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.” Articles covered a range of study types, including qualitative and quantitative analyses as well as other systematic reviews on focused topics within the area of interest. The authors reviewed the abstracts for eligibility criteria, which included topics focused on the study of mental health or substance use aspects and/or integrated mental health/substance use care for liver diseases (across etiologies and stages), published from January 2004 to November 2016, written in English, and focused on an adult population. Five members of the research team reviewed abstracts and eliminated any that did not meet the eligibility criteria.

A total of 636 records were screened and 378 were excluded based on abstract relevance to the stated topics as well as eligibility criteria. Following this review, full articles (N = 263) were reviewed by at least 2 members of the research team. For both levels of review, articles were removed for the criteria above and additional exclusion criteria: editorial style articles, duplicates, transplant focus, or primarily focused on health-related quality of life (QOL) not specific to MHDs. Although many articles fit more than one exclusion criteria, an article was removed once it met one exclusion criteria. After individual assessment by members of the research team, 71 articles were kept in the review. The team identified 14 additional articles that contributed to the topic but were not located through the original database search. The final analysis included 85 articles that fell into 3 key areas: (1) prevalence of comorbid MHD/SUD in liver disease; (2) associations between MHD/SUD and disease progression/management; and (3) the use of integrated care models in patients with CLD.

Results

In general, depression and anxiety were common among patients with CLD regardless of etiology.5 Across VA and non-VA studies, depressive disorders were found in one-third to two-thirds of patients with CLD and anxiety disorders in about one-third of patients with CLD. 5,7,8,10,15,16, 22-25Results of the studies that assess the prevalence of MHDs in patients with CLD are shown in Table 1.

MHDs and SUDs in Patients With CLD

Mental health symptoms have been associated with the severity of liver disease in some but not all studies.17,18,26 Mental health disorders also may have more dire consequences in this population. In a national survey of adults, 1.6% of patients with depression were found to have liver disease. Among this group with depression, suicide attempts were 3-fold higher among patients with CLD vs patients without CLD.19

Substance use disorders (including alcohol) are common among patients with CLD. This has been best studied in the context of patients with HCV.22, 27-32 For example among patients with HCV, the prevalence of injection drug use (IDU) was 48% to 65%, and the prevalence of marijuana use was 29%.33-36 In a report of 174,302 veterans with HCV receiving VA care, the following SUDs were reported as diagnosis in this patient population: alcohol, 55%; cannabis, 26%; stimulants, 35%; opioids, 22%; sedatives or anxiolytics, 5%; and other drug use, 39%.10

Both Non-VA and VA studies have found overlap between HCV and alcohol-related liver disease with a number of patients with HCV using alcohol and a number of patients with alcohol-related liver disease having a past history of IDU and HCV.37,38 Across VA and non-VA studies, patients with HIV/HCV co-infection have been found to have particularly high rates of MHDs and SUDs. One VA retrospective cohort study of 18,349 HIV-infected patients noted 37% were seropositive for HCV as well.39-41 These patients with HIV/HCV infection when compared with patients with only HIV infection were more likely to have a diagnosis of mental health illness (76.1% vs 63.1%), depression (56.6% vs 45.6%), alcohol abuse (64.2% vs 30.1%), substance abuse (68.0% vs 25.7%), and hard drug use (62.9% vs 20.6%).42 Patients with CLD and ongoing alcohol use have been found to have increased mental health symptoms compared with patients without ongoing alcohol use.17 Thus MHDs and SUDs are common and often coexist among patients with CLD.

MHDs Impact Patient Outcomes

Mental health disorders can affect how providers care for patients. In the past, for example, in both VA and non-VA studies, patients were often excluded from interferon-based HCV treatments due to MHDs.22,35,43-45 These exclusions included psychiatric issues (35%), alcohol abuse (31%), drug abuse (9%), or > 1 of these reasons (26%).46 Depression also has been associated with decreased care seeking by patients. Patients with cirrhosis and depression often do not seek medical care due to perceived stigma.47 Nearly one-fifth of patients with HCV in one study reported that they did not share information about their disease with others to avoid being stigmatized.48 Other studies have noted similar difficulty with patients’ seeking HCV treatment, advances in medications notwithstanding.49-52

Depression among patients with cirrhosis has been associated with reduced QOL, worsened cognitive function, increased mortality, and frailty.18,53,54 Psychiatric symptoms have been associated with disability and pain among patients with cirrhosis and with weight gain among patients with NAFLD.5,55 Mental health symptoms also predicted lower work productivity in patients with HCV.8 Histologic changes in the liver have been described among patients with psychiatric disorders, although the mechanism is not well understood.15,16

Although not a focus of this review, it is well established that MHDs are associated with increased substance use. Since there is a well-established connection between alcohol and adverse liver-related outcomes regardless of etiology of liver disease, mental health is thus indirectly linked to poor liver outcomes through this mechanism.37,38,56-67

Integrated Care in Liver Disease

Although there are no set guidelines on how to approach patients with liver disease and MHD/SUD comorbidities, integrated care approaches that include attention to both CLD and psychiatric needs seem promising. Integrated care models have been recommended by several authors specifically for patients with HCV and co-occurring MHDs and SUDs.4,33,42,43,45,68-72 Various integrated care models for CLD and psychiatric comorbidities have been studied and are detailed in Table 2.

The most well described models of integrated care in CLD have been used for patients with HCV as noted in prior reviews.22,34,49,73 These studies included liver care integrated with substance abuse clinics/specialists, mental health professionals, and/or case managers. Outcomes that have been assessed include adherence, HCV treatment completion, HCV treatment eligibility/initiation, and reduction in alcohol use.31,46, 74-77 A large randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing integrated care with usual care found that integrated care, including collaborative consultation with mental health providers and case managers, was associated with increased antiviral treatment and sustained virologic response (SVR).50,78 One study of integrated care in the era of direct-acting antiviral treatment for HCV found that twice as many veterans initiated treatment with integrated care (with case management and a mental health provider) as opposed to usual care. In this integrated care model, mental health providers provided ongoing brief psychological interventions designed to address the specific risk factors identified at screening, facilitated treatment, and served as a regular contact.79 Overall, integrating mental health care and HCV care has resulted in increased adherence, increased treatment eligibility/initiation, treatment completion, higher rates of SVR, and reduction in alcohol use.31,46,74-77

In addition to positive medical outcomes with integrated care models, patients and providers generally have favorable impressions of the clinics using an integrated care approach. For example, multiple qualitative studies of the Hepatitis C Community Clinic in New Zealand have described that patients and providers have positive feelings about integrated care models for HCV.80-82 Another study evaluating integrated care at 4 hepatitis clinics in British Columbia, Canada found that clients overall valued the clinic and viewed it favorably; however, they identified several areas for continued improvement, including communication and time spent with clients, follow-up and access to care, as well as education on coping and managing their disease.83

Beyond HCV, other patients with CLD could benefit from integrated care approaches. Given the association of psychiatric symptoms with weight outcomes among patients with NAFLD, integrating behavioral support has been recommended.55 Multidisciplinary care has been trialed in patients with NAFLD. One model included behavioral therapy with psychological counseling, motivation for lifestyle changes, and support by a trained expert cognitive behavioral psychologist. Although this study did not include a control group, the patients in the study experienced an 8% weight reduction, reduction in aminotransferases, and decreased hepatic steatosis by ultrasound.84

Integrated care also has been advocated for patients with alcohol-related liver disease. One study recommended creating a personalized framework to support self-management for this population.85 Another study assessed patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy and recommended integrating individual coping strategies and support into liver care for this group of patients.86

A United Kingdom study of multidisciplinary care that included a team of gastroenterologists, psychiatrists, and a psychiatric liaison nurse, found improved accessibility to care and patient/family satisfaction using this model. Outpatient appointments were offered to 84% of patients after collaborative care was introduced as opposed to 12% previously. Patients and family members reported that this approach decreased the stigma of mental health care, allowing patients to be more open to intervention and education in this setting.87 A systematic review of patients with alcohol-related CLD found that among 5 RCTs with 1,945 cumulative patients, integrated care was associated with increased short-term abstinence but not sustained abstinence.88 Thus integrated care has been used most in patients with HCV-related CLD, but growing evidence supports its use for patients with other etiologies of CLD, including NAFLD and alcohol.

Discussion