User login

Chronic opioid use linked to low testosterone levels

NEW ORLEANS – About two thirds of men who chronically use opioids have low testosterone levels, based on a literature search of more than 50 randomized and observational studies that examined endocrine function in patients on chronic opioid therapy.

Hypocortisolism, seen in about 20% of the men in these studies, was among the other potentially significant deficiencies in endocrine function, Amir H. Zamanipoor Najafabadi, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Najafabadi of Leiden University in the Netherlands, and Friso de Vries, PhD, analyzed the link between opioid use and changes in the gonadal axis. Most of the subjects in their study were men (J Endocr Soc. 2019. doi. 10.1210/js.2019-SUN-489).

While the data do not support firm conclusions on the health consequences of these endocrine observations, Dr. Najafabadi said that a prospective trial is needed to determine whether there is a potential benefit from screening patients on chronic opioids for potentially treatable endocrine deficiencies.

NEW ORLEANS – About two thirds of men who chronically use opioids have low testosterone levels, based on a literature search of more than 50 randomized and observational studies that examined endocrine function in patients on chronic opioid therapy.

Hypocortisolism, seen in about 20% of the men in these studies, was among the other potentially significant deficiencies in endocrine function, Amir H. Zamanipoor Najafabadi, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Najafabadi of Leiden University in the Netherlands, and Friso de Vries, PhD, analyzed the link between opioid use and changes in the gonadal axis. Most of the subjects in their study were men (J Endocr Soc. 2019. doi. 10.1210/js.2019-SUN-489).

While the data do not support firm conclusions on the health consequences of these endocrine observations, Dr. Najafabadi said that a prospective trial is needed to determine whether there is a potential benefit from screening patients on chronic opioids for potentially treatable endocrine deficiencies.

NEW ORLEANS – About two thirds of men who chronically use opioids have low testosterone levels, based on a literature search of more than 50 randomized and observational studies that examined endocrine function in patients on chronic opioid therapy.

Hypocortisolism, seen in about 20% of the men in these studies, was among the other potentially significant deficiencies in endocrine function, Amir H. Zamanipoor Najafabadi, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Najafabadi of Leiden University in the Netherlands, and Friso de Vries, PhD, analyzed the link between opioid use and changes in the gonadal axis. Most of the subjects in their study were men (J Endocr Soc. 2019. doi. 10.1210/js.2019-SUN-489).

While the data do not support firm conclusions on the health consequences of these endocrine observations, Dr. Najafabadi said that a prospective trial is needed to determine whether there is a potential benefit from screening patients on chronic opioids for potentially treatable endocrine deficiencies.

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2019

Smoking rates remain steady among the poor

While an increasing number of U.S. citizens are saying no to cigarettes, a recent study shows.

The odds of current smoking, versus never smoking, declined significantly during 2008-2017 for individuals with none of six disadvantages tied to cigarette use, including disability, unemployment, poverty, low education, psychological distress, and heavy alcohol intake, according to researchers.

Individuals with one or two of those disadvantages have also been cutting back, the data suggest. But, by contrast, odds of current versus never smoking did not significantly change for those with three or more disadvantages, according to Adam M. Leventhal, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and coinvestigators.

“How this pattern can inform a cohesive policy agenda is unknown, but it is clear from these findings that the crux of the recently expanding tobacco-related health disparity problem in the United States is not tied to groups facing merely a single form of disadvantage,” Dr. Leventhal and coauthors wrote in a report on the study in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The cross-sectional analysis by Dr. Leventhal and colleagues was based on National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 2008-2017 including more than 278,000 respondents aged 25 years or older.

A snapshot of that 10-year period showed that current smoking prevalence was successively higher depending on the number of socioeconomic or health-related disadvantages.

The mean prevalence of current smoking over that entire time period was just 13.8% for people with zero of the six disadvantages, 21.4% for those with one disadvantage, and so on, up to 58.2% for those with all six disadvantages, according to data in the published report.

Encouragingly, overall smoking prevalence fell from 20.8% in 2008-2009 to 15.8% in 2016-2017, the researchers found. However, the decreasing trend was not apparent for individuals with many disadvantages.

The odds ratio for change in odds of smoking per year was 0.951 (95% confidence interval, 0.944-0.958) for those with zero disadvantages, 0.96 (95% CI, 0.95-0.97) for one disadvantage, and 0.98 (95% CI, 0.97-0.99) for two, all representing significant annual reductions in current versus never smoking, investigators said. By contrast, no such significant changes were apparent for those with three, four, five, or six such disadvantages.

Tobacco control or regulatory policies that consider these disadvantages separately may be overlooking a “broader pattern” showing that the cumulative number of disadvantages correlates with the magnitude of disparity, wrote Dr. Leventhal and colleagues in their report.

“Successful prevention of smoking initiation and promotion of smoking cessation in multi-disadvantaged populations would substantially reduce the smoking-related public health burden in the United States,” they concluded.

Dr. Leventhal and colleagues reported no conflicts related to their research, which was supported in part by a Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science award from the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration, among other sources.

SOURCE: Leventhal AM et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Apr 22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0192.

While an increasing number of U.S. citizens are saying no to cigarettes, a recent study shows.

The odds of current smoking, versus never smoking, declined significantly during 2008-2017 for individuals with none of six disadvantages tied to cigarette use, including disability, unemployment, poverty, low education, psychological distress, and heavy alcohol intake, according to researchers.

Individuals with one or two of those disadvantages have also been cutting back, the data suggest. But, by contrast, odds of current versus never smoking did not significantly change for those with three or more disadvantages, according to Adam M. Leventhal, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and coinvestigators.

“How this pattern can inform a cohesive policy agenda is unknown, but it is clear from these findings that the crux of the recently expanding tobacco-related health disparity problem in the United States is not tied to groups facing merely a single form of disadvantage,” Dr. Leventhal and coauthors wrote in a report on the study in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The cross-sectional analysis by Dr. Leventhal and colleagues was based on National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 2008-2017 including more than 278,000 respondents aged 25 years or older.

A snapshot of that 10-year period showed that current smoking prevalence was successively higher depending on the number of socioeconomic or health-related disadvantages.

The mean prevalence of current smoking over that entire time period was just 13.8% for people with zero of the six disadvantages, 21.4% for those with one disadvantage, and so on, up to 58.2% for those with all six disadvantages, according to data in the published report.

Encouragingly, overall smoking prevalence fell from 20.8% in 2008-2009 to 15.8% in 2016-2017, the researchers found. However, the decreasing trend was not apparent for individuals with many disadvantages.

The odds ratio for change in odds of smoking per year was 0.951 (95% confidence interval, 0.944-0.958) for those with zero disadvantages, 0.96 (95% CI, 0.95-0.97) for one disadvantage, and 0.98 (95% CI, 0.97-0.99) for two, all representing significant annual reductions in current versus never smoking, investigators said. By contrast, no such significant changes were apparent for those with three, four, five, or six such disadvantages.

Tobacco control or regulatory policies that consider these disadvantages separately may be overlooking a “broader pattern” showing that the cumulative number of disadvantages correlates with the magnitude of disparity, wrote Dr. Leventhal and colleagues in their report.

“Successful prevention of smoking initiation and promotion of smoking cessation in multi-disadvantaged populations would substantially reduce the smoking-related public health burden in the United States,” they concluded.

Dr. Leventhal and colleagues reported no conflicts related to their research, which was supported in part by a Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science award from the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration, among other sources.

SOURCE: Leventhal AM et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Apr 22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0192.

While an increasing number of U.S. citizens are saying no to cigarettes, a recent study shows.

The odds of current smoking, versus never smoking, declined significantly during 2008-2017 for individuals with none of six disadvantages tied to cigarette use, including disability, unemployment, poverty, low education, psychological distress, and heavy alcohol intake, according to researchers.

Individuals with one or two of those disadvantages have also been cutting back, the data suggest. But, by contrast, odds of current versus never smoking did not significantly change for those with three or more disadvantages, according to Adam M. Leventhal, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and coinvestigators.

“How this pattern can inform a cohesive policy agenda is unknown, but it is clear from these findings that the crux of the recently expanding tobacco-related health disparity problem in the United States is not tied to groups facing merely a single form of disadvantage,” Dr. Leventhal and coauthors wrote in a report on the study in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The cross-sectional analysis by Dr. Leventhal and colleagues was based on National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 2008-2017 including more than 278,000 respondents aged 25 years or older.

A snapshot of that 10-year period showed that current smoking prevalence was successively higher depending on the number of socioeconomic or health-related disadvantages.

The mean prevalence of current smoking over that entire time period was just 13.8% for people with zero of the six disadvantages, 21.4% for those with one disadvantage, and so on, up to 58.2% for those with all six disadvantages, according to data in the published report.

Encouragingly, overall smoking prevalence fell from 20.8% in 2008-2009 to 15.8% in 2016-2017, the researchers found. However, the decreasing trend was not apparent for individuals with many disadvantages.

The odds ratio for change in odds of smoking per year was 0.951 (95% confidence interval, 0.944-0.958) for those with zero disadvantages, 0.96 (95% CI, 0.95-0.97) for one disadvantage, and 0.98 (95% CI, 0.97-0.99) for two, all representing significant annual reductions in current versus never smoking, investigators said. By contrast, no such significant changes were apparent for those with three, four, five, or six such disadvantages.

Tobacco control or regulatory policies that consider these disadvantages separately may be overlooking a “broader pattern” showing that the cumulative number of disadvantages correlates with the magnitude of disparity, wrote Dr. Leventhal and colleagues in their report.

“Successful prevention of smoking initiation and promotion of smoking cessation in multi-disadvantaged populations would substantially reduce the smoking-related public health burden in the United States,” they concluded.

Dr. Leventhal and colleagues reported no conflicts related to their research, which was supported in part by a Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science award from the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration, among other sources.

SOURCE: Leventhal AM et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Apr 22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0192.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Current U.S. smoking rates have not declined among individuals with multiple socioeconomic or health-related disadvantages.

Major finding: The odds ratio for change in odds of smoking per year was 0.951 for individuals with zero disadvantages, 0.96 for one disadvantage, and 0.97-0.99 for two, with no significant annual reductions in those with three or more disadvantages.

Study details: Cross-sectional analysis of 278,048 respondents aged 25 years or older in the National Health Interview Survey during 2008-2017.

Disclosures: Authors reported no conflicts of interest related to the study, which was supported in part by a Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science award from the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration, among other sources.

Source: Leventhal AM et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Apr 22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0192.

More than 40% of U.K. physicians report binge drinking

Many doctors say they cope with job-related stress by drinking alcohol or taking drugs

Occupational distress among physicians is tied to increased odds of substance use, sleep disturbance, binge eating, and poor health in general, a cross-sectional study of 417 U.K. doctors shows.

Burned-out or depressed doctors had higher risks of those health problems regardless of whether or not they worked in a hospital setting, according to Asta Medisauskaite, PhD, of University College London and Caroline Kamau, PhD, of the University of London. The study was published in BMJ Open.

The investigators asked the participants to answer a battery of validated questionnaires online, including the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale, and the Insomnia Severity Index.

The odds of many health problems were increased among the physicians with emotional exhaustion, as indicated by the Maslach Burnout Inventory, as was also the case with psychiatric disorders, according to the General Health Questionnaire-12, which investigators noted has been used extensively to examine medical doctors and other working populations.

Sleep disturbances were, for example, more likely in physicians with burnout or psychiatric morbidity, with odds ratios ranging from 1.344 to 3.826, the investigators reported. Likewise, these indicators of occupational distress increased the risk of suffering from frequent poor health, with odds ratios from 1.050 to 3.544, and of binge eating, with odds ratios from 1.311 to 1.841, Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau reported.

Distressed doctors more often used alcohol, according to the researchers, who said that they found a higher risk of alcohol dependence (odds ratio, 6.165) among physicians reporting that they used substances to feel better or cope with stress. Those doctors also had higher risk of binge drinking, drinking larger quantities, and using alcohol more often, the data show. In fact, 44% of the physicians reported binge drinking, and 5% met the criteria for alcohol dependence, Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau wrote. Binge drinking was defined as consuming more than six drinks on a single occasion.

Previous studies have indicated that occupational distress among physicians has negative effects on quality of care and patient safety, the authors noted. This latest cross-sectional study builds on those findings by showing that occupational distress increases risk of health problems among doctors. “The impact of occupational distress or ill health could increase levels of sickness-absence among doctors, thus reducing patient safety because of understaffing,” Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau wrote.

Similarly, physicians with sleep problems or substance use related to occupational distress could perform poorly on the job because of being groggy, intoxicated, or hung over, they said.

“We recommend that doctors’ mentors, supervisors, peers, and occupational health support services recognize and act on (1) the prevalence of occupational distress and health problems among doctors; (2) the possibility that occupational distress raises the risk of several health problems; and (3) the need to provide early interventions,” Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau wrote. Such interventions could help prevent physicians who are experiencing occupational distress from suffering the long-term health effects from sleep disturbances, binge drinking and binge eating, and ill health, they suggested.

One limitation cited was the study’s cross-sectional design, which makes it impossible to draw conclusions about causation. The researchers also conceded that some participants might not have been comfortable answering questions about illicit use of drugs or alcohol. Nevertheless, they said,

Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau declared no competing interests related to the study.

SOURCE: Medisauskaite A, Kamau C. BMJ Open. 2019 May 15. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027362.

Many doctors say they cope with job-related stress by drinking alcohol or taking drugs

Many doctors say they cope with job-related stress by drinking alcohol or taking drugs

Occupational distress among physicians is tied to increased odds of substance use, sleep disturbance, binge eating, and poor health in general, a cross-sectional study of 417 U.K. doctors shows.

Burned-out or depressed doctors had higher risks of those health problems regardless of whether or not they worked in a hospital setting, according to Asta Medisauskaite, PhD, of University College London and Caroline Kamau, PhD, of the University of London. The study was published in BMJ Open.

The investigators asked the participants to answer a battery of validated questionnaires online, including the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale, and the Insomnia Severity Index.

The odds of many health problems were increased among the physicians with emotional exhaustion, as indicated by the Maslach Burnout Inventory, as was also the case with psychiatric disorders, according to the General Health Questionnaire-12, which investigators noted has been used extensively to examine medical doctors and other working populations.

Sleep disturbances were, for example, more likely in physicians with burnout or psychiatric morbidity, with odds ratios ranging from 1.344 to 3.826, the investigators reported. Likewise, these indicators of occupational distress increased the risk of suffering from frequent poor health, with odds ratios from 1.050 to 3.544, and of binge eating, with odds ratios from 1.311 to 1.841, Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau reported.

Distressed doctors more often used alcohol, according to the researchers, who said that they found a higher risk of alcohol dependence (odds ratio, 6.165) among physicians reporting that they used substances to feel better or cope with stress. Those doctors also had higher risk of binge drinking, drinking larger quantities, and using alcohol more often, the data show. In fact, 44% of the physicians reported binge drinking, and 5% met the criteria for alcohol dependence, Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau wrote. Binge drinking was defined as consuming more than six drinks on a single occasion.

Previous studies have indicated that occupational distress among physicians has negative effects on quality of care and patient safety, the authors noted. This latest cross-sectional study builds on those findings by showing that occupational distress increases risk of health problems among doctors. “The impact of occupational distress or ill health could increase levels of sickness-absence among doctors, thus reducing patient safety because of understaffing,” Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau wrote.

Similarly, physicians with sleep problems or substance use related to occupational distress could perform poorly on the job because of being groggy, intoxicated, or hung over, they said.

“We recommend that doctors’ mentors, supervisors, peers, and occupational health support services recognize and act on (1) the prevalence of occupational distress and health problems among doctors; (2) the possibility that occupational distress raises the risk of several health problems; and (3) the need to provide early interventions,” Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau wrote. Such interventions could help prevent physicians who are experiencing occupational distress from suffering the long-term health effects from sleep disturbances, binge drinking and binge eating, and ill health, they suggested.

One limitation cited was the study’s cross-sectional design, which makes it impossible to draw conclusions about causation. The researchers also conceded that some participants might not have been comfortable answering questions about illicit use of drugs or alcohol. Nevertheless, they said,

Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau declared no competing interests related to the study.

SOURCE: Medisauskaite A, Kamau C. BMJ Open. 2019 May 15. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027362.

Occupational distress among physicians is tied to increased odds of substance use, sleep disturbance, binge eating, and poor health in general, a cross-sectional study of 417 U.K. doctors shows.

Burned-out or depressed doctors had higher risks of those health problems regardless of whether or not they worked in a hospital setting, according to Asta Medisauskaite, PhD, of University College London and Caroline Kamau, PhD, of the University of London. The study was published in BMJ Open.

The investigators asked the participants to answer a battery of validated questionnaires online, including the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale, and the Insomnia Severity Index.

The odds of many health problems were increased among the physicians with emotional exhaustion, as indicated by the Maslach Burnout Inventory, as was also the case with psychiatric disorders, according to the General Health Questionnaire-12, which investigators noted has been used extensively to examine medical doctors and other working populations.

Sleep disturbances were, for example, more likely in physicians with burnout or psychiatric morbidity, with odds ratios ranging from 1.344 to 3.826, the investigators reported. Likewise, these indicators of occupational distress increased the risk of suffering from frequent poor health, with odds ratios from 1.050 to 3.544, and of binge eating, with odds ratios from 1.311 to 1.841, Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau reported.

Distressed doctors more often used alcohol, according to the researchers, who said that they found a higher risk of alcohol dependence (odds ratio, 6.165) among physicians reporting that they used substances to feel better or cope with stress. Those doctors also had higher risk of binge drinking, drinking larger quantities, and using alcohol more often, the data show. In fact, 44% of the physicians reported binge drinking, and 5% met the criteria for alcohol dependence, Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau wrote. Binge drinking was defined as consuming more than six drinks on a single occasion.

Previous studies have indicated that occupational distress among physicians has negative effects on quality of care and patient safety, the authors noted. This latest cross-sectional study builds on those findings by showing that occupational distress increases risk of health problems among doctors. “The impact of occupational distress or ill health could increase levels of sickness-absence among doctors, thus reducing patient safety because of understaffing,” Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau wrote.

Similarly, physicians with sleep problems or substance use related to occupational distress could perform poorly on the job because of being groggy, intoxicated, or hung over, they said.

“We recommend that doctors’ mentors, supervisors, peers, and occupational health support services recognize and act on (1) the prevalence of occupational distress and health problems among doctors; (2) the possibility that occupational distress raises the risk of several health problems; and (3) the need to provide early interventions,” Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau wrote. Such interventions could help prevent physicians who are experiencing occupational distress from suffering the long-term health effects from sleep disturbances, binge drinking and binge eating, and ill health, they suggested.

One limitation cited was the study’s cross-sectional design, which makes it impossible to draw conclusions about causation. The researchers also conceded that some participants might not have been comfortable answering questions about illicit use of drugs or alcohol. Nevertheless, they said,

Dr. Medisauskaite and Dr. Kamau declared no competing interests related to the study.

SOURCE: Medisauskaite A, Kamau C. BMJ Open. 2019 May 15. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027362.

FROM BMJ OPEN

Key clinical point: Occupational distress increased the odds of substance use, sleep disturbance, binge eating, and poor health among medical doctors in the United Kingdom.

Major finding: Distressed medical doctors had a higher risk of binge drinking. In fact, 44% reported binge drinking, defined as consuming more than six drinks on a single occasion.

Study details: A U.K. cross-sectional study of 417 doctors who answered a series of validated health-related questionnaires online.

Disclosures: The authors declared no competing interests related to the study.

Source: Medisauskaite A, Kamau C. BMJ Open. 2019 May 15. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027362.

Racial, economic disparities found in buprenorphine prescriptions

Buprenorphine for opioid use disorder is much less likely to be prescribed to patients who are black or who do not have health insurance, an analysis of two national surveys shows.

Researchers analyzed data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2004 to 2015, including 13.4 million visits in which buprenorphine was prescribed. The analysis was published as a research letter in JAMA Psychiatry.

From 2012 to 2015, the number of ambulatory visits involving buprenorphine rose from 0.04% to 0.36%. Black patients were 77% less likely to receive a prescription for buprenorphine at their visit – even after adjustment for payment method, sex, and age – while the number of prescription received by white patients was considerably higher than for patients of any other ethnicity, wrote Pooja A. Lagisetty, MD, and coauthors.

, and the age group with the highest incidence of buprenorphine prescriptions was 30-50 years.

Self-pay and private health insurance were the most common payment methods, but the number of self-paying patients receiving buprenorphine prescriptions dramatically increased from 585,568 in 2004-2007 to 5.3 million in 2012-2015.

“This finding in nationally representative data builds on a previous study that reported buprenorphine treatment disparities on the basis of race/ethnicity and income in New York City,” said Dr. Lagisetty of the department of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and coauthors.

However, they acknowledged that it was unclear whether the treatment disparity might in fact reflect a difference in the prevalence of opioid use disorder across ethnicities.

Commenting on the differences in payment methods, the authors noted that, despite the enactment of mental health parity legislation and the expansion of Medicaid, the proportion of self-pay visits remained relatively unchanged across the study period.

“A recent study demonstrated that half of the physicians prescribing buprenorphine in Ohio accepted cash alone, and our findings suggest that this practice may be widespread and may be associated with additional financial barriers for low-income populations,” the researchers wrote. “With rising rates of opioid overdoses, it is imperative that policy and research efforts specifically address racial/ethnic and economic differences in treatment access and engagement.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lagisetty P et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 May 8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0876.

Buprenorphine for opioid use disorder is much less likely to be prescribed to patients who are black or who do not have health insurance, an analysis of two national surveys shows.

Researchers analyzed data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2004 to 2015, including 13.4 million visits in which buprenorphine was prescribed. The analysis was published as a research letter in JAMA Psychiatry.

From 2012 to 2015, the number of ambulatory visits involving buprenorphine rose from 0.04% to 0.36%. Black patients were 77% less likely to receive a prescription for buprenorphine at their visit – even after adjustment for payment method, sex, and age – while the number of prescription received by white patients was considerably higher than for patients of any other ethnicity, wrote Pooja A. Lagisetty, MD, and coauthors.

, and the age group with the highest incidence of buprenorphine prescriptions was 30-50 years.

Self-pay and private health insurance were the most common payment methods, but the number of self-paying patients receiving buprenorphine prescriptions dramatically increased from 585,568 in 2004-2007 to 5.3 million in 2012-2015.

“This finding in nationally representative data builds on a previous study that reported buprenorphine treatment disparities on the basis of race/ethnicity and income in New York City,” said Dr. Lagisetty of the department of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and coauthors.

However, they acknowledged that it was unclear whether the treatment disparity might in fact reflect a difference in the prevalence of opioid use disorder across ethnicities.

Commenting on the differences in payment methods, the authors noted that, despite the enactment of mental health parity legislation and the expansion of Medicaid, the proportion of self-pay visits remained relatively unchanged across the study period.

“A recent study demonstrated that half of the physicians prescribing buprenorphine in Ohio accepted cash alone, and our findings suggest that this practice may be widespread and may be associated with additional financial barriers for low-income populations,” the researchers wrote. “With rising rates of opioid overdoses, it is imperative that policy and research efforts specifically address racial/ethnic and economic differences in treatment access and engagement.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lagisetty P et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 May 8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0876.

Buprenorphine for opioid use disorder is much less likely to be prescribed to patients who are black or who do not have health insurance, an analysis of two national surveys shows.

Researchers analyzed data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2004 to 2015, including 13.4 million visits in which buprenorphine was prescribed. The analysis was published as a research letter in JAMA Psychiatry.

From 2012 to 2015, the number of ambulatory visits involving buprenorphine rose from 0.04% to 0.36%. Black patients were 77% less likely to receive a prescription for buprenorphine at their visit – even after adjustment for payment method, sex, and age – while the number of prescription received by white patients was considerably higher than for patients of any other ethnicity, wrote Pooja A. Lagisetty, MD, and coauthors.

, and the age group with the highest incidence of buprenorphine prescriptions was 30-50 years.

Self-pay and private health insurance were the most common payment methods, but the number of self-paying patients receiving buprenorphine prescriptions dramatically increased from 585,568 in 2004-2007 to 5.3 million in 2012-2015.

“This finding in nationally representative data builds on a previous study that reported buprenorphine treatment disparities on the basis of race/ethnicity and income in New York City,” said Dr. Lagisetty of the department of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and coauthors.

However, they acknowledged that it was unclear whether the treatment disparity might in fact reflect a difference in the prevalence of opioid use disorder across ethnicities.

Commenting on the differences in payment methods, the authors noted that, despite the enactment of mental health parity legislation and the expansion of Medicaid, the proportion of self-pay visits remained relatively unchanged across the study period.

“A recent study demonstrated that half of the physicians prescribing buprenorphine in Ohio accepted cash alone, and our findings suggest that this practice may be widespread and may be associated with additional financial barriers for low-income populations,” the researchers wrote. “With rising rates of opioid overdoses, it is imperative that policy and research efforts specifically address racial/ethnic and economic differences in treatment access and engagement.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lagisetty P et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 May 8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0876.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Overdoses are driving down life expectancy

The average life expectancy in the United States declined from 78.9 years in 2014 to 78.6 years in 2017.1 The 2017 figure—78.6 years—means life expectancy is shorter in the United States than in other countries.1 The decline is due, in part, to the drug overdose epidemic in the United States.2 In 2017, 70,237 people died by drug overdose2—with prescription drugs, heroin, and opioids (especially fentanyl) being the major threats.3 From 2016 to 2017, overdoses from synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol, increased from 6.2 to 9 per 100,000 people.2

These statistics should motivate all health care professionals to improve the general public’s health metrics, especially when treating patients with substance use disorders. But to best do so, we need a collaborative effort across many professions—not just health care providers, but also public health officials, elected government leaders, and law enforcement. To better define what this would entail, we suggest ways in which these groups could expand their roles to help reduce overdose deaths.

Health care professionals:

- implement safer opioid prescribing for patients who have chronic pain;

- educate patients about the risks of opioid use;

- consider alternative therapies for pain management; and

- utilize electronic databases to monitor controlled substance prescribing.

Public health officials:

- expand naloxone distribution; and

- enhance harm reduction (eg, syringe exchange programs, substance abuse treatment options).

Government leaders:

- draft legislation that allows the use of better interventions for treating individuals with drug dependence or those who overdose; and

- improve criminal justice approaches so that laws are less punitive and more therapeutic for individuals who suffer from drug dependence.

Law enforcement:

- supply naltrexone kits to first responders and provide appropriate training.

Kuldeep Ghosh, MD, MS

Rajashekhar Yeruva, MD

Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, Ky

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Table 15. Life expectancy at birth, at age 65, and at age 75, by sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, selected years 1900-2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2016/015.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. NCHS Data Brief No 329. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm. Published November 2019. Accessed April 24, 2019.

3. United States Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA releases 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment. https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2018/11/02/dea-releases-2018-national-drug-threat-assessment-0. Published November 2, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

The average life expectancy in the United States declined from 78.9 years in 2014 to 78.6 years in 2017.1 The 2017 figure—78.6 years—means life expectancy is shorter in the United States than in other countries.1 The decline is due, in part, to the drug overdose epidemic in the United States.2 In 2017, 70,237 people died by drug overdose2—with prescription drugs, heroin, and opioids (especially fentanyl) being the major threats.3 From 2016 to 2017, overdoses from synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol, increased from 6.2 to 9 per 100,000 people.2

These statistics should motivate all health care professionals to improve the general public’s health metrics, especially when treating patients with substance use disorders. But to best do so, we need a collaborative effort across many professions—not just health care providers, but also public health officials, elected government leaders, and law enforcement. To better define what this would entail, we suggest ways in which these groups could expand their roles to help reduce overdose deaths.

Health care professionals:

- implement safer opioid prescribing for patients who have chronic pain;

- educate patients about the risks of opioid use;

- consider alternative therapies for pain management; and

- utilize electronic databases to monitor controlled substance prescribing.

Public health officials:

- expand naloxone distribution; and

- enhance harm reduction (eg, syringe exchange programs, substance abuse treatment options).

Government leaders:

- draft legislation that allows the use of better interventions for treating individuals with drug dependence or those who overdose; and

- improve criminal justice approaches so that laws are less punitive and more therapeutic for individuals who suffer from drug dependence.

Law enforcement:

- supply naltrexone kits to first responders and provide appropriate training.

Kuldeep Ghosh, MD, MS

Rajashekhar Yeruva, MD

Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, Ky

The average life expectancy in the United States declined from 78.9 years in 2014 to 78.6 years in 2017.1 The 2017 figure—78.6 years—means life expectancy is shorter in the United States than in other countries.1 The decline is due, in part, to the drug overdose epidemic in the United States.2 In 2017, 70,237 people died by drug overdose2—with prescription drugs, heroin, and opioids (especially fentanyl) being the major threats.3 From 2016 to 2017, overdoses from synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol, increased from 6.2 to 9 per 100,000 people.2

These statistics should motivate all health care professionals to improve the general public’s health metrics, especially when treating patients with substance use disorders. But to best do so, we need a collaborative effort across many professions—not just health care providers, but also public health officials, elected government leaders, and law enforcement. To better define what this would entail, we suggest ways in which these groups could expand their roles to help reduce overdose deaths.

Health care professionals:

- implement safer opioid prescribing for patients who have chronic pain;

- educate patients about the risks of opioid use;

- consider alternative therapies for pain management; and

- utilize electronic databases to monitor controlled substance prescribing.

Public health officials:

- expand naloxone distribution; and

- enhance harm reduction (eg, syringe exchange programs, substance abuse treatment options).

Government leaders:

- draft legislation that allows the use of better interventions for treating individuals with drug dependence or those who overdose; and

- improve criminal justice approaches so that laws are less punitive and more therapeutic for individuals who suffer from drug dependence.

Law enforcement:

- supply naltrexone kits to first responders and provide appropriate training.

Kuldeep Ghosh, MD, MS

Rajashekhar Yeruva, MD

Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, Ky

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Table 15. Life expectancy at birth, at age 65, and at age 75, by sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, selected years 1900-2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2016/015.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. NCHS Data Brief No 329. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm. Published November 2019. Accessed April 24, 2019.

3. United States Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA releases 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment. https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2018/11/02/dea-releases-2018-national-drug-threat-assessment-0. Published November 2, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Table 15. Life expectancy at birth, at age 65, and at age 75, by sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, selected years 1900-2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2016/015.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed April 24, 2019.

2. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. NCHS Data Brief No 329. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm. Published November 2019. Accessed April 24, 2019.

3. United States Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA releases 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment. https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2018/11/02/dea-releases-2018-national-drug-threat-assessment-0. Published November 2, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

Direct pharmacy dispensing of naloxone linked to drop in fatal overdoses

investigators reported.

By contrast, state laws that stopped short of allowing pharmacists to directly dispense the opioid antagonist did not appear to impact mortality, according to the report, which appears in JAMA Internal Medicine (2019 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0272).

The report, based on state-level trends tracked from 2005 to 2016, indicates that fatal opioid overdoses fell by nearly one-third in states that adopted direct dispensing laws as compared with states that adopted other naloxone laws.

That finding suggests that the policy type determines whether a naloxone law is useful in combating fatal opioid overdoses, said Rahi Abouk, PhD, of William Paterson University, Wayne, N.J. and co-authors of the paper.

“Enabling distribution through various sources, or requiring gatekeepers, will not be as beneficial,” Dr. Abouk and co-authors said in their report.

The current rate of deaths from fentanyl, heroin, and prescription analgesic overdose has outpaced all previous drug epidemics on record, and even surpasses the number of deaths in the peak year of the HIV epidemic of the 1980s, Dr. Abouk and colleagues wrote in their paper.

The number of states with naloxone access laws grew from just 2 in 2005 to 47 by 2016, including 9 states that granted direct authority to pharmacists and 38 that granted indirect authority, according to the researchers.

The analysis of overdose trends from 2005 to 2016 was based on naloxone distribution data from state Medicaid agencies and opioid-related mortality data from a national statistics system. Forty percent of nonelderly adults with an opioid addiction are covered by Medicaid, the researchers said.

They found that naloxone laws granting pharmacists direct dispensing authority were linked to a drop in opioid deaths that increased in magnitude over time, according to researchers. The mean number of opioid deaths dropped by 27% in the second year after adoption of direct authority laws, relative to opioid deaths in states with indirect access laws, while in subsequent years, deaths dropped by 34%.

Emergency department visits related to opioids increased by 15% in direct authority states 3 or more years after adoption, as compared to states that did not adopt direct authority laws. According to investigators, that translated into 15 additional opioid-related emergency department visits each month.

That increase suggests that, alongside direct dispensing laws, “useful interventions” and connections to treatment are needed for the emergency department, according to Dr. Abouk and colleagues.

“This is the location where such programs may be the most effective,” they said in their report.

Future research should be done to determine whether removing gatekeepers increases the value of naloxone distribution policies, they concluded in the report.

Dr. Abouk had no disclosures. Co-authors on the study reported funding and conflict of interest disclosures related to the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

SOURCE: Abouk R, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 May 6. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0272.

investigators reported.

By contrast, state laws that stopped short of allowing pharmacists to directly dispense the opioid antagonist did not appear to impact mortality, according to the report, which appears in JAMA Internal Medicine (2019 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0272).

The report, based on state-level trends tracked from 2005 to 2016, indicates that fatal opioid overdoses fell by nearly one-third in states that adopted direct dispensing laws as compared with states that adopted other naloxone laws.

That finding suggests that the policy type determines whether a naloxone law is useful in combating fatal opioid overdoses, said Rahi Abouk, PhD, of William Paterson University, Wayne, N.J. and co-authors of the paper.

“Enabling distribution through various sources, or requiring gatekeepers, will not be as beneficial,” Dr. Abouk and co-authors said in their report.

The current rate of deaths from fentanyl, heroin, and prescription analgesic overdose has outpaced all previous drug epidemics on record, and even surpasses the number of deaths in the peak year of the HIV epidemic of the 1980s, Dr. Abouk and colleagues wrote in their paper.

The number of states with naloxone access laws grew from just 2 in 2005 to 47 by 2016, including 9 states that granted direct authority to pharmacists and 38 that granted indirect authority, according to the researchers.

The analysis of overdose trends from 2005 to 2016 was based on naloxone distribution data from state Medicaid agencies and opioid-related mortality data from a national statistics system. Forty percent of nonelderly adults with an opioid addiction are covered by Medicaid, the researchers said.

They found that naloxone laws granting pharmacists direct dispensing authority were linked to a drop in opioid deaths that increased in magnitude over time, according to researchers. The mean number of opioid deaths dropped by 27% in the second year after adoption of direct authority laws, relative to opioid deaths in states with indirect access laws, while in subsequent years, deaths dropped by 34%.

Emergency department visits related to opioids increased by 15% in direct authority states 3 or more years after adoption, as compared to states that did not adopt direct authority laws. According to investigators, that translated into 15 additional opioid-related emergency department visits each month.

That increase suggests that, alongside direct dispensing laws, “useful interventions” and connections to treatment are needed for the emergency department, according to Dr. Abouk and colleagues.

“This is the location where such programs may be the most effective,” they said in their report.

Future research should be done to determine whether removing gatekeepers increases the value of naloxone distribution policies, they concluded in the report.

Dr. Abouk had no disclosures. Co-authors on the study reported funding and conflict of interest disclosures related to the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

SOURCE: Abouk R, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 May 6. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0272.

investigators reported.

By contrast, state laws that stopped short of allowing pharmacists to directly dispense the opioid antagonist did not appear to impact mortality, according to the report, which appears in JAMA Internal Medicine (2019 May 6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0272).

The report, based on state-level trends tracked from 2005 to 2016, indicates that fatal opioid overdoses fell by nearly one-third in states that adopted direct dispensing laws as compared with states that adopted other naloxone laws.

That finding suggests that the policy type determines whether a naloxone law is useful in combating fatal opioid overdoses, said Rahi Abouk, PhD, of William Paterson University, Wayne, N.J. and co-authors of the paper.

“Enabling distribution through various sources, or requiring gatekeepers, will not be as beneficial,” Dr. Abouk and co-authors said in their report.

The current rate of deaths from fentanyl, heroin, and prescription analgesic overdose has outpaced all previous drug epidemics on record, and even surpasses the number of deaths in the peak year of the HIV epidemic of the 1980s, Dr. Abouk and colleagues wrote in their paper.

The number of states with naloxone access laws grew from just 2 in 2005 to 47 by 2016, including 9 states that granted direct authority to pharmacists and 38 that granted indirect authority, according to the researchers.

The analysis of overdose trends from 2005 to 2016 was based on naloxone distribution data from state Medicaid agencies and opioid-related mortality data from a national statistics system. Forty percent of nonelderly adults with an opioid addiction are covered by Medicaid, the researchers said.

They found that naloxone laws granting pharmacists direct dispensing authority were linked to a drop in opioid deaths that increased in magnitude over time, according to researchers. The mean number of opioid deaths dropped by 27% in the second year after adoption of direct authority laws, relative to opioid deaths in states with indirect access laws, while in subsequent years, deaths dropped by 34%.

Emergency department visits related to opioids increased by 15% in direct authority states 3 or more years after adoption, as compared to states that did not adopt direct authority laws. According to investigators, that translated into 15 additional opioid-related emergency department visits each month.

That increase suggests that, alongside direct dispensing laws, “useful interventions” and connections to treatment are needed for the emergency department, according to Dr. Abouk and colleagues.

“This is the location where such programs may be the most effective,” they said in their report.

Future research should be done to determine whether removing gatekeepers increases the value of naloxone distribution policies, they concluded in the report.

Dr. Abouk had no disclosures. Co-authors on the study reported funding and conflict of interest disclosures related to the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

SOURCE: Abouk R, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 May 6. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0272.

FROM JAMA Internal Medicine

Key clinical point: State laws granting pharmacists direct authority to dispense naloxone were linked to significant drops in opioid-related fatal overdoses.

Major finding: The mean number of opioid deaths dropped by 27% in the second year after adoption of direct authority laws relative to opioid deaths in states with indirect access laws, while in subsequent years, deaths dropped by 34%.

Study details: Analysis of naloxone distribution data and opioid-related mortality data from 2005 to 2016 for all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Disclosures: Study authors reported funding and conflict of interest disclosures related to the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Source: Abouk R, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 May 6.

Only 1.5% of individuals at high risk of opioid overdose receive naloxone

The vast majority of individuals at high risk for opioid overdose do not receive naloxone, despite numerous opportunities, according to Sarah Follman and associates from the University of Chicago.

In a retrospective study published in JAMA Network Open, the study authors analyzed data from individuals in the Truven Health MarketScan Research Database who had ICD-10 codes related to opioid use, misuse, dependence, and overdose. Data from Oct. 1, 2015, through Dec. 31, 2016, were included; a total of 138,108 high-risk individuals were identified as interacting with the health care system nearly 1.2 million times (88,618 hospitalizations, 229,680 ED visits, 298,058 internal medicine visits, and 568,448 family practice visits).

Of the 138,108 individuals in the study, only 2,135 (1.5%) were prescribed naloxone during the study period. Patients who had prior diagnoses of both opioid misuse/dependence and overdose were significantly more likely to receive naloxone than were those who only had a history of opioid dependence (odds ratio, 2.32; 95% confidence interval, 1.98-2.72; P less than .001). In addition, having a history of overdose alone was associated with a decreased chance of receiving naloxone, compared with those with a history of opioid misuse alone (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57-0.94; P = .01).

Other factors that significantly reduced the odds of receiving naloxone included being aged 30-44 years and being from the Midwest or West. Factors that reduced the odds include having received treatment for opioid use disorder, visiting a detoxification facility, receiving other substance use disorder treatment; and having received outpatient care from a pain specialist, psychologist, or surgeon.

“Most individuals at high risk of opioid overdose do not receive naloxone through direct prescribing,” Ms. Follman and associates wrote. “Clinicians can address this gap by regularly prescribing naloxone to eligible patients. To address barriers to prescribing, hospital systems and medical schools can support clinicians by improving education on screening and treating substance use disorders, clarifying legal concerns, and developing policies and protocols to guide implementation of increased prescribing.

No conflicts of interest were reported; one coauthor reported receiving a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Follman S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 May 3. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3209.

The vast majority of individuals at high risk for opioid overdose do not receive naloxone, despite numerous opportunities, according to Sarah Follman and associates from the University of Chicago.

In a retrospective study published in JAMA Network Open, the study authors analyzed data from individuals in the Truven Health MarketScan Research Database who had ICD-10 codes related to opioid use, misuse, dependence, and overdose. Data from Oct. 1, 2015, through Dec. 31, 2016, were included; a total of 138,108 high-risk individuals were identified as interacting with the health care system nearly 1.2 million times (88,618 hospitalizations, 229,680 ED visits, 298,058 internal medicine visits, and 568,448 family practice visits).

Of the 138,108 individuals in the study, only 2,135 (1.5%) were prescribed naloxone during the study period. Patients who had prior diagnoses of both opioid misuse/dependence and overdose were significantly more likely to receive naloxone than were those who only had a history of opioid dependence (odds ratio, 2.32; 95% confidence interval, 1.98-2.72; P less than .001). In addition, having a history of overdose alone was associated with a decreased chance of receiving naloxone, compared with those with a history of opioid misuse alone (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57-0.94; P = .01).

Other factors that significantly reduced the odds of receiving naloxone included being aged 30-44 years and being from the Midwest or West. Factors that reduced the odds include having received treatment for opioid use disorder, visiting a detoxification facility, receiving other substance use disorder treatment; and having received outpatient care from a pain specialist, psychologist, or surgeon.

“Most individuals at high risk of opioid overdose do not receive naloxone through direct prescribing,” Ms. Follman and associates wrote. “Clinicians can address this gap by regularly prescribing naloxone to eligible patients. To address barriers to prescribing, hospital systems and medical schools can support clinicians by improving education on screening and treating substance use disorders, clarifying legal concerns, and developing policies and protocols to guide implementation of increased prescribing.

No conflicts of interest were reported; one coauthor reported receiving a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Follman S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 May 3. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3209.

The vast majority of individuals at high risk for opioid overdose do not receive naloxone, despite numerous opportunities, according to Sarah Follman and associates from the University of Chicago.

In a retrospective study published in JAMA Network Open, the study authors analyzed data from individuals in the Truven Health MarketScan Research Database who had ICD-10 codes related to opioid use, misuse, dependence, and overdose. Data from Oct. 1, 2015, through Dec. 31, 2016, were included; a total of 138,108 high-risk individuals were identified as interacting with the health care system nearly 1.2 million times (88,618 hospitalizations, 229,680 ED visits, 298,058 internal medicine visits, and 568,448 family practice visits).

Of the 138,108 individuals in the study, only 2,135 (1.5%) were prescribed naloxone during the study period. Patients who had prior diagnoses of both opioid misuse/dependence and overdose were significantly more likely to receive naloxone than were those who only had a history of opioid dependence (odds ratio, 2.32; 95% confidence interval, 1.98-2.72; P less than .001). In addition, having a history of overdose alone was associated with a decreased chance of receiving naloxone, compared with those with a history of opioid misuse alone (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57-0.94; P = .01).

Other factors that significantly reduced the odds of receiving naloxone included being aged 30-44 years and being from the Midwest or West. Factors that reduced the odds include having received treatment for opioid use disorder, visiting a detoxification facility, receiving other substance use disorder treatment; and having received outpatient care from a pain specialist, psychologist, or surgeon.

“Most individuals at high risk of opioid overdose do not receive naloxone through direct prescribing,” Ms. Follman and associates wrote. “Clinicians can address this gap by regularly prescribing naloxone to eligible patients. To address barriers to prescribing, hospital systems and medical schools can support clinicians by improving education on screening and treating substance use disorders, clarifying legal concerns, and developing policies and protocols to guide implementation of increased prescribing.

No conflicts of interest were reported; one coauthor reported receiving a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Follman S et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 May 3. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3209.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Outpatient program successfully tackles substance use and chronic pain

MILWAUKEE – An interdisciplinary intensive outpatient treatment program addressing chronic pain and substance use disorder effectively addressed both diagnoses in a military population.

Intensive outpatient programs (IOPs) frequently address these conditions within a biopsychosocial format, but it’s not common for IOPs to have this dual focus on chronic pain and substance use disorder (SUD), said Michael Stockin, MD, speaking in an interview at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Dr. Stockin said he and his collaborators recognized that, especially among a military population, the two conditions have considerable overlap, so it made sense to integrate behavioral treatment for both conditions in an intensive outpatient program. “Our hypothesis was that if you can use an intensive outpatient program to address substance use disorder, maybe you can actually add a chronic pain curriculum – like a functional restoration program to it.

“As a result of our study, we did find that there were significant differences in worst pain scores as a result of the program. In the people who took both the substance use disorder and chronic pain curriculum, we found significant reductions in total impairment, worst pain, and they also had less … substance use as well,” said Dr. Stockin.

In a quality improvement project, Dr. Stockin and collaborators compared short-term outcomes for patients who received IOP treatment addressing both chronic pain and SUD with those receiving SUD-only IOP.

For those participating in the joint IOP, scores indicating worst pain on the 0-10 numeric rating scale were reduced significantly, from 7.55 to 6.23 (P = .013). Scores on a functional measure of impairment, the Pain Outcomes Questionnaire Short Form (POQ-SF) also dropped significantly, from 84.92 to 63.50 (P = .034). The vitality domain of the POQ-SF also showed that patients had less impairment after participation in the joint IOP, with scores in that domain dropping from 20.17 to 17.25 (P = .024).

Looking at the total cohort, patient scores on the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM) dropped significantly from baseline to the end of the intervention, indicating reduced substance use (P = .041). Mean scores for participants in the joint IOP were higher at baseline than for those in the SUD-only IOP (1.000 vs. 0.565). However, those participating in the joint IOP had lower mean postintervention BAM scores than the SUD-only cohort (0.071 vs. 0.174).

American veterans experience more severe pain and have a higher prevalence of chronic pain than nonveterans. Similarly, wrote Dr. Stockin, a chronic pain fellow in pain management at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues in the poster presentation.

The project enrolled a total of 66 patients (10 female and 56 male). Of these, 18 participated in the joint SUD–chronic pain program, and 48 received usual treatment of the SUD-only IOP treatment. The mean overall age was 33.2 years, and 71.2% of participants were white.

Overall, 51 patients (77.3%) of participants had alcohol use disorder. Participants included active duty service members, veterans, and their dependents. Opioid and cannabis use disorders were experienced by a total of eight patients, and seven more patients had diagnoses of alcohol use disorder along with other substance use disorders.

All patients completed the BAM and received urine toxicology and alcohol breath testing at enrollment; drug and alcohol screening was completed at other points during the IOP treatment for both groups as well.

The joint IOP ran 3 full days a week, with a substance use curriculum in the morning and a pain management program in the afternoon; the SUD-only participants had three morning sessions weekly. Both interventions lasted 6 weeks, and Dr. Stockin said he and his colleagues would like to acquire longitudinal data to assess the durability of gains seen from the joint IOP.

The multidisciplinary team running the joint IOP was made up of an addiction/pain medicine physician, a clinical health psychologist, a physical therapist, social workers, and a nurse.

“This project is the first of its kind to find a significant reduction in pain burden while concurrently treating addiction and pain in an outpatient military health care setting,” Dr. Stockin and colleagues wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

“We had outcomes in both substance use and chronic pain that were positive, so it suggests that in the military health system, people may actually benefit from treating both chronic pain and substance use disorder concurrently. If you could harmonize those programs, you might be able to get good outcomes for soldiers and their families,” Dr. Stockin said.

Dr. Stockin reported no conflicts of interest. The project was funded by the Defense Health Agency.

MILWAUKEE – An interdisciplinary intensive outpatient treatment program addressing chronic pain and substance use disorder effectively addressed both diagnoses in a military population.

Intensive outpatient programs (IOPs) frequently address these conditions within a biopsychosocial format, but it’s not common for IOPs to have this dual focus on chronic pain and substance use disorder (SUD), said Michael Stockin, MD, speaking in an interview at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Dr. Stockin said he and his collaborators recognized that, especially among a military population, the two conditions have considerable overlap, so it made sense to integrate behavioral treatment for both conditions in an intensive outpatient program. “Our hypothesis was that if you can use an intensive outpatient program to address substance use disorder, maybe you can actually add a chronic pain curriculum – like a functional restoration program to it.

“As a result of our study, we did find that there were significant differences in worst pain scores as a result of the program. In the people who took both the substance use disorder and chronic pain curriculum, we found significant reductions in total impairment, worst pain, and they also had less … substance use as well,” said Dr. Stockin.

In a quality improvement project, Dr. Stockin and collaborators compared short-term outcomes for patients who received IOP treatment addressing both chronic pain and SUD with those receiving SUD-only IOP.

For those participating in the joint IOP, scores indicating worst pain on the 0-10 numeric rating scale were reduced significantly, from 7.55 to 6.23 (P = .013). Scores on a functional measure of impairment, the Pain Outcomes Questionnaire Short Form (POQ-SF) also dropped significantly, from 84.92 to 63.50 (P = .034). The vitality domain of the POQ-SF also showed that patients had less impairment after participation in the joint IOP, with scores in that domain dropping from 20.17 to 17.25 (P = .024).

Looking at the total cohort, patient scores on the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM) dropped significantly from baseline to the end of the intervention, indicating reduced substance use (P = .041). Mean scores for participants in the joint IOP were higher at baseline than for those in the SUD-only IOP (1.000 vs. 0.565). However, those participating in the joint IOP had lower mean postintervention BAM scores than the SUD-only cohort (0.071 vs. 0.174).

American veterans experience more severe pain and have a higher prevalence of chronic pain than nonveterans. Similarly, wrote Dr. Stockin, a chronic pain fellow in pain management at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues in the poster presentation.

The project enrolled a total of 66 patients (10 female and 56 male). Of these, 18 participated in the joint SUD–chronic pain program, and 48 received usual treatment of the SUD-only IOP treatment. The mean overall age was 33.2 years, and 71.2% of participants were white.

Overall, 51 patients (77.3%) of participants had alcohol use disorder. Participants included active duty service members, veterans, and their dependents. Opioid and cannabis use disorders were experienced by a total of eight patients, and seven more patients had diagnoses of alcohol use disorder along with other substance use disorders.

All patients completed the BAM and received urine toxicology and alcohol breath testing at enrollment; drug and alcohol screening was completed at other points during the IOP treatment for both groups as well.

The joint IOP ran 3 full days a week, with a substance use curriculum in the morning and a pain management program in the afternoon; the SUD-only participants had three morning sessions weekly. Both interventions lasted 6 weeks, and Dr. Stockin said he and his colleagues would like to acquire longitudinal data to assess the durability of gains seen from the joint IOP.

The multidisciplinary team running the joint IOP was made up of an addiction/pain medicine physician, a clinical health psychologist, a physical therapist, social workers, and a nurse.

“This project is the first of its kind to find a significant reduction in pain burden while concurrently treating addiction and pain in an outpatient military health care setting,” Dr. Stockin and colleagues wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

“We had outcomes in both substance use and chronic pain that were positive, so it suggests that in the military health system, people may actually benefit from treating both chronic pain and substance use disorder concurrently. If you could harmonize those programs, you might be able to get good outcomes for soldiers and their families,” Dr. Stockin said.

Dr. Stockin reported no conflicts of interest. The project was funded by the Defense Health Agency.

MILWAUKEE – An interdisciplinary intensive outpatient treatment program addressing chronic pain and substance use disorder effectively addressed both diagnoses in a military population.

Intensive outpatient programs (IOPs) frequently address these conditions within a biopsychosocial format, but it’s not common for IOPs to have this dual focus on chronic pain and substance use disorder (SUD), said Michael Stockin, MD, speaking in an interview at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Dr. Stockin said he and his collaborators recognized that, especially among a military population, the two conditions have considerable overlap, so it made sense to integrate behavioral treatment for both conditions in an intensive outpatient program. “Our hypothesis was that if you can use an intensive outpatient program to address substance use disorder, maybe you can actually add a chronic pain curriculum – like a functional restoration program to it.

“As a result of our study, we did find that there were significant differences in worst pain scores as a result of the program. In the people who took both the substance use disorder and chronic pain curriculum, we found significant reductions in total impairment, worst pain, and they also had less … substance use as well,” said Dr. Stockin.

In a quality improvement project, Dr. Stockin and collaborators compared short-term outcomes for patients who received IOP treatment addressing both chronic pain and SUD with those receiving SUD-only IOP.

For those participating in the joint IOP, scores indicating worst pain on the 0-10 numeric rating scale were reduced significantly, from 7.55 to 6.23 (P = .013). Scores on a functional measure of impairment, the Pain Outcomes Questionnaire Short Form (POQ-SF) also dropped significantly, from 84.92 to 63.50 (P = .034). The vitality domain of the POQ-SF also showed that patients had less impairment after participation in the joint IOP, with scores in that domain dropping from 20.17 to 17.25 (P = .024).

Looking at the total cohort, patient scores on the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM) dropped significantly from baseline to the end of the intervention, indicating reduced substance use (P = .041). Mean scores for participants in the joint IOP were higher at baseline than for those in the SUD-only IOP (1.000 vs. 0.565). However, those participating in the joint IOP had lower mean postintervention BAM scores than the SUD-only cohort (0.071 vs. 0.174).

American veterans experience more severe pain and have a higher prevalence of chronic pain than nonveterans. Similarly, wrote Dr. Stockin, a chronic pain fellow in pain management at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues in the poster presentation.

The project enrolled a total of 66 patients (10 female and 56 male). Of these, 18 participated in the joint SUD–chronic pain program, and 48 received usual treatment of the SUD-only IOP treatment. The mean overall age was 33.2 years, and 71.2% of participants were white.

Overall, 51 patients (77.3%) of participants had alcohol use disorder. Participants included active duty service members, veterans, and their dependents. Opioid and cannabis use disorders were experienced by a total of eight patients, and seven more patients had diagnoses of alcohol use disorder along with other substance use disorders.

All patients completed the BAM and received urine toxicology and alcohol breath testing at enrollment; drug and alcohol screening was completed at other points during the IOP treatment for both groups as well.

The joint IOP ran 3 full days a week, with a substance use curriculum in the morning and a pain management program in the afternoon; the SUD-only participants had three morning sessions weekly. Both interventions lasted 6 weeks, and Dr. Stockin said he and his colleagues would like to acquire longitudinal data to assess the durability of gains seen from the joint IOP.

The multidisciplinary team running the joint IOP was made up of an addiction/pain medicine physician, a clinical health psychologist, a physical therapist, social workers, and a nurse.

“This project is the first of its kind to find a significant reduction in pain burden while concurrently treating addiction and pain in an outpatient military health care setting,” Dr. Stockin and colleagues wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

“We had outcomes in both substance use and chronic pain that were positive, so it suggests that in the military health system, people may actually benefit from treating both chronic pain and substance use disorder concurrently. If you could harmonize those programs, you might be able to get good outcomes for soldiers and their families,” Dr. Stockin said.

Dr. Stockin reported no conflicts of interest. The project was funded by the Defense Health Agency.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

Key clinical point: An intensive, 6-week joint substance use disorder and chronic pain intensive outpatient program significantly reduced both substance use and pain.

Major finding: Patients had less pain and reduced substance use after completing the program, compared with baseline (P = .013 and .041, respectively).

Study details: A quality improvement project including 66 patients at a military health facility.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Defense Health Agency. Dr. Stockin reported no conflicts of interest.

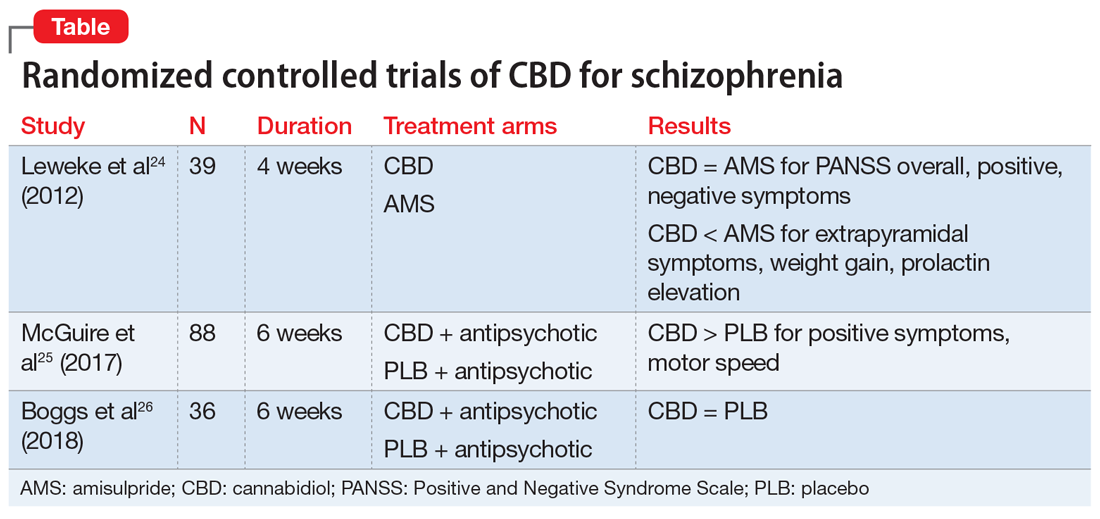

Cannabidiol (CBD) for schizophrenia: Promise or pipe dream?

Over the past few decades, it has become increasingly clear that cannabis use can increase the risk of developing a psychotic disorder and worsen the course of existing schizophrenia in a dose-dependent fashion.1-3 Beyond psychosis, although many patients with mental illness use cannabis for recreational purposes or as purported “self-medication,” currently available evidence suggests that marijuana is more likely to represent a harm than a benefit for psychiatric disorders4 (Box4-8). Our current state of knowledge therefore suggests that psychiatrists should caution their patients against using cannabis and prioritize interventions to reduce or discontinue use, especially among those with psychotic disorders.

Box

Data from California in 2006—a decade after the state’s legalization of “medical marijuana”—revealed that 23% of patients in a sample enrolled in medical marijuana clinics were receiving cannabis to treat a mental disorder.5 That was a striking statistic given the dearth of evidence to support a benefit of cannabis for psychiatric conditions at the time, leaving clinicians who provided the necessary recommendations to obtain medical marijuana largely unable to give informed consent about the risks and benefits, much less recommendations about specific products, routes of administration, or dosing. In 2019, we know considerably more about the interaction between cannabinoids and mental health, but research findings thus far warrant more caution than enthusiasm, with one recent review concluding that “whenever an association is observed between cannabis use and psychiatric disorders, the relationship is generally an adverse one.”4