User login

A patient-centered approach to tapering opioids

Many Americans who are treated with prescription opioid analgesics would be better off with less opioid or none at all. To that end, published opioid prescribing guidelines do provide guidance on the mechanics of tapering patients off opioids1-4—but they have a major flaw: They do not adequately account for the fact that people who have a diagnosis of chronic pain are a heterogeneous group and require diagnosis-specific treatment planning. A patient-centered approach to opioid tapers must account for the reality that many people who are given a prescription for an opioid to treat pain have significant mental health conditions—for which opioids act as a psychotropic agent. An opioid taper must therefore address psychological trauma, in particular.5 (See “Tapering and harm-reduction strategies have failed.”6-14)

SIDEBAR

Tapering and harm-reduction strategies have failed

Efforts to address the rising number of overdose events that involve opioids began in earnest in 2010. In a 2011 Government Accountability Office report to Congress, the Drug Enforcement Agency reported that “the number of regulatory investigations (of medical providers who prescribed opioids) tripled between fiscal years 2009- 2010.”6

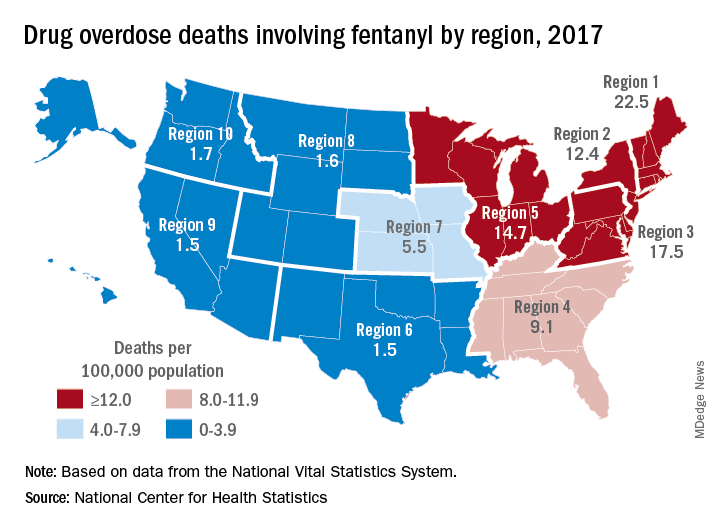

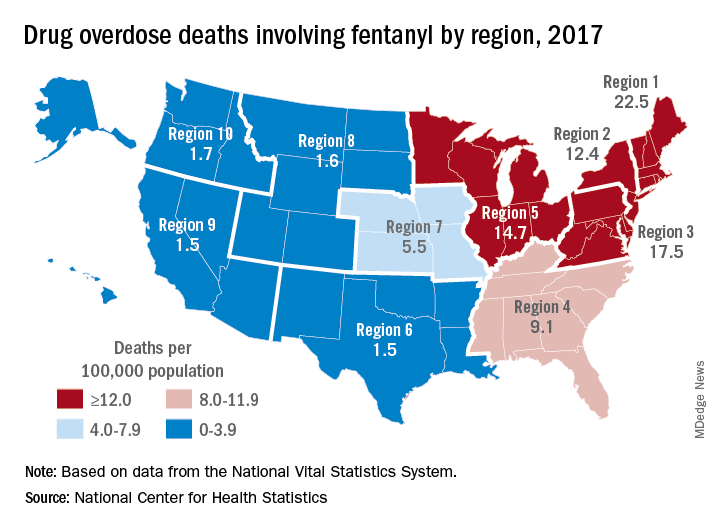

How has it gone since 2010? High-dosage prescribing of opioids has fallen by 48% since 2011, yet the decline has not reduced overdose events of any kind.7,8 Just the opposite: The 19,000 overdose deaths recorded in 2010 involving any opioid increased to 49,068 by 2017, the National Institute on Drug Abuse reports.9 The increase in opioid overdose deaths is fueled by a recent 9-fold increase in consumption of the synthetic opioid fentanyl: “The rate of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone … increased on average by 8% per year from 1999 through 2013 and by 71% per year from 2013 through 2017.”10

These and other statistics document only a modest rise in deaths that involve prescription opioids: from 15,000 in 2010 to 19,000 in 2016.9,10 Since 2010, the crisis of opioid overdose deaths burns hotter, and the pattern of opioid use has shifted from prescription drugs to much deadlier illicit drugs, such as heroin.

Interventions have not been successful overall. Results of research focused on the impact of opioid tapering and harm-reduction strategies implemented this decade are likewise discouraging. In 2018, the US Department of Veterans Affairs reported that opioid discontinuation was not associated with a reduction in overdose but was associated with an increase in suicide.11,12 Von Korff and colleagues, in a 2017 report, concluded that “Long-term implementation of opioid dose and risk reduction initiatives [in Washington state] was not associated with lower rates of prescription opioid use disorder among prevalent [chronic opioid therapy] patients.”13

Evidence suggests that efforts to address the opioid crisis of the past decade have had an effect that is the opposite of what was intended. The federal government recognized this in April 2019 in a Drug Safety Communication: “The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has received reports of serious harm in patients who are physically dependent on opioid pain medicines suddenly having these medicines discontinued or the dose rapidly decreased. These include serious withdrawal symptoms, uncontrolled pain, psychological distress, and suicide.”14

In this article, we present an evidence-based consensus approach to opioid tapering for your practice that is informed by a broader understanding of why patients take prescription opioids and why they, occasionally, switch to illicit drugs when their prescription is tapered. This consensus approach is based on the experience of the authors, members of the pain faculty of Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) of the ECHO Institute, a worldwide initiative that uses adult learning techniques and interactive video technology to connect community providers with specialists at centers of excellence in regular real-time collaborative sessions. We are variously experts in pain medicine, primary care, psychology, addiction medicine, pharmacy, behavioral health therapy, occupational medicine, and Chinese medicine.

Why Americans obtain prescription opioids

There are 4 principal reasons why patients obtain prescription opioids, beyond indicated analgesic uses:

1. Patients seek the antianxiety and antidepressant effects of opioids. Multiple converging lines of evidence suggest that antianxiety and antidepressant effects of opioids are a significant reason that patients in the United States persist in requesting prescriptions for opioids:

- In our experience with more than 500 primary care telemedicine case presentations, at least 50% of patients say that the main effect of opioids prescribed for them is “it makes me feel calm” or “more relaxed.”

- In a 2007 survey of 91,823 US residents older than 18 years, nonmedical use of opioids was statistically associated with panic, social anxiety, and depressive symptoms.15

- Ten years later, Von Korff and colleagues found that more than half of opioid prescriptions written in the United States were for the small percentage of patients who have a diagnosis of serious anxiety or depression.13

- In 2016, Yovell and colleagues reported that ultra-low-dosage buprenorphine markedly reduced suicidal ideation over 4 weeks in 62 patients with varied levels of depression.16

There is also mechanistic evidence that the antianxiety and antidepressant effects of opioids are significant reasons Americans persist in requesting prescription opioids. The literature suggests that opioid receptors play a role in mood regulation, including alleviation of depression and anxiety; recent research suggests that oxycodone might be a unique mood-altering drug compared to other common prescription opioids because of its ability to affect mood through the δ opioid receptor.17-20

It should not be a surprise that Americans often turn to opioids to address posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression. A recent study of the state of the US mental health system concluded that mental health services in the United States are inadequate—despite evidence that > 50% of Americans seek, or consider seeking, treatment for mental health problems for themselves or others.21

2. Patients experience pain unrelated to tissue damage. Rather, they are in pain “for psychological reasons.”22 In 2016, Davis and Vanderah wrote: “We theorize that a functional change in the [central nervous system] can occur in response to certain emotional states or traumatic experiences (eg, child abuse, assault, accidents).” They connect this change to central sensitization and a reduced pain-perception threshold,23 and strongly suspect that many patients with chronic pain have undiagnosed and untreated psychological trauma that has changed the way their central nervous system processes sensory stimuli. The authors call this “trauma-induced hyperalgesia.”

Continue to: Psychological trauma...

Psychological trauma is uniquely capable of producing hyperalgesia, compared to anxiety or depression. In a study of veterans, Defrin and colleagues demonstrated hyperalgesia in patients who had a diagnosis of PTSD but not in controls group who had an anxiety disorder only.24

To support successful opioid tapering, trauma-induced hyperalgesia, when present, must be addressed. Treatment of what the International Association for the Study of Pain calls “pain due to psychological factors”22 requires specific trauma therapy. However, our experience validates what researchers have to say about access to treatment of psychological trauma in the United States: “…[C]linical research has identified certain psychological interventions that effectively ameliorate the symptoms of PTSD. But most people struggling with PTSD don’t receive those treatments.”25

We have no doubt that this is due, in part, to underdiagnosis of psychological trauma, even in mental health clinics. According to Miele and colleagues, “PTSD remains largely undiagnosed and undertreated in mental health outpatients, even in teaching hospitals, with diagnosis rates as low as 4% while published prevalence is between 7% and 50% in this population.”26

3. Patients suffer from opioid use disorder (OUD) and complain of pain to obtain opioids by prescription. For patients with OUD, their use is out of control; they devote increasing mental and physical resources to obtaining, using, and recovering from substances; and they continue to use despite adverse consequences.27 The prevalence of OUD in primary care clinics varies strikingly by the location of clinics. In Washington state, the prevalence of moderate and severe OUD in a large population of patients who had been prescribed opioids through primary care clinics was recently determined to be between 21.5% and 23.9%.13

4. Patients are obtaining opioid prescriptions for people other than themselves. While this is a reason that patients obtain opioid prescriptions, it is not necessarily common. Statistics show that the likelihood of a prescription being diverted intentionally is low: Dart and colleagues found that diversion has become uncommon in the general population.28

Continue to: Why we taper opioid analgesics

Why we taper opioid analgesics

Reasons for an opioid taper include concern that the patient has, or will develop, an OUD; will experience accidental or intentional overdose; might be diverting opioids; is not benefiting from opioid therapy for pain; or is experiencing severe adverse effects. A patient who has nociceptive pain and might have opioid-induced hyperalgesia will require a much different opioid taper plan than a patient with untreated PTSD or a patient with severe OUD.

Misunderstanding can lead to inappropriate tapering

We often encounter primary care providers who believe that a large percentage of patients on chronic opioid therapy inevitably develop OUD. This is a common reason for initiating opioid taper. Most patients on a chronic opioid do become physically dependent, but only a small percentage of patients develop psychological dependence (ie, addiction or OUD).29

Physical dependence is “a state of adaptation that is manifested by a drug class–specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist.”30 Symptoms of opioid withdrawal include muscle aches; abdominal cramping; increased lacrimation, rhinorrhea, and perspiration; diarrhea; agitation and anxiety; insomnia; and piloerection. Opioid withdrawal symptoms are caused by physical dependence, not by addiction. They can be mitigated by tapering slowly and instituting adjuvant medications, such as clonidine, to attenuate symptoms.

Psychological dependence, or addiction (that is, OUD, as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition27), comprises primarily 3 behavioral criteria:

- Loss of control of the medication, with compulsive use

- Continued use despite adverse consequences of using opioids, such as arrest for driving under the influence and deterioration of social, family, or work performance

- Obsession or preoccupation with obtaining and using the substance. In properly selected chronic opioid therapy patients, there is evidence that new-onset OUD is not as common as has been thought. A recent study of the risk for opioid addiction after use of an opioid for ≥ 90 days for chronic noncancer pain found that the absolute rate of de novo OUD among patients treated for 90 days was 0.72%.29 A systematic review by Fishbain and colleagues of 24 studies of opioid-exposed patients found a risk of 3.27% overall—0.19% for patients who did not have a history of abuse or addiction.31 As Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Norma Volkow, MD, wrote in 2016: “Addiction occurs in only a small percentage of people who are exposed to opioids—even among those with preexisting vulnerabilities.”32

Assessment should focus on why the patient is taking an opioid

A strong case can be made that less opioid is better for many of the people for whom these medications are prescribed for chronic noncancer pain. However, a one-size-fits-all dosage reduction and addiction-focused approach to opioid tapering has not worked: The assessment and treatment paradigm must change, in our view.

Continue to: During assessment...

During assessment, we must adopt the means to identify the reason that a patient is using a prescription opioid. It is of particular importance that we identify patients using opioids for their psychotropic properties, particularly when the goal is to cope with the effects of psychological trauma. The subsequent treatment protocol will then need to include time for effective, evidence-based behavioral health treatment of anxiety, PTSD, or depression. If opioids are serving primarily as psychotropic medication, an attempt to taper before establishing effective behavioral health treatment might lead the patient to pursue illegal means of procuring opioid medication.

We acknowledge that primary care physicians are not reimbursed for trauma screening and that evidence-based intensive trauma treatment is generally unavailable in the United States. Both of these shortcomings must be corrected if we want to stem the opioid crisis.

If diversion is suspected and there is evidence that the patient is not currently taking prescribed opioids (eg, a negative urine drug screen), discontinuing the opioid prescription is the immediate next step for the sake of public safety.

SIDEBAR

2 decisions to make before continuing to prescribe an opioid for chronic noncancer pain

#1 Should I provide the patient with a prescription for an opioid for a few days, while I await more information?a

Yes. Writing a prescription is a reasonable decision if all of the following apply:

- You do not have significant suspicion of diversion (based on a clinical interview).

- You do not suspect an active addiction disorder, based on the score of the 10-question Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) and on a clinical interview. (DAST-10 is available at: https://cde.drugabuse.gov/instrument/e9053390-ee9c-9140-e040-bb89ad433d69.)

- The patient is likely to experience withdrawal symptoms if you don’t provide the medication immediately.

- The patient’s pain and function are likely to be impaired if you do not provide the medication.

- The patient does not display altered mental status during the visit (eg, drowsy, slurred speech).

No. If writing a prescription for an opioid for a few days does not seem to be a reasonable decision because the criteria above are not met, but withdrawal symptoms are likely, you can prescribe medication to mitigate symptoms or refer the patient for treatment of withdrawal.

#2 I’ve decided to provide the patient with a prescription for an opioid. For how many days should I write it?

The usual practice, for a patient whose case is familiar to you, is to prescribe a 1-month supply.

However, if any 1 of the following criteria is met, prescribing a 1-month supply is unsafe under most circumstances:

- An unstable social or living environment places the patient at risk by possessing a supply of opioids (based on a clinical interview).

- You suspect an unstable or severe behavioral health condition or a mental health diagnosis (based on a clinical interview or on the patient record from outside your practice).

- The patient scores as “high risk” on the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT; www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/OpioidRiskTool.pdf), Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4706778/), or a similar opioid risk assessment tool.

When 1 or more of these exclusionary criteria are met, you have 3 options:

- Prescribe an opioid for a brief duration and see the patient often.

- Do not prescribe an opioid; instead, refer the patient as necessary for treatment of withdrawal.

- Refer the patient for treatment of the underlying behavioral health condition.

a Additional information might include findings from consultants you’ve engaged regarding the patient’s diagnosis; a response to your call from a past prescriber; urine drug screen results; and results of a prescription monitoring program check.

Considering a taper? Take this 5-step approach

Once it appears that tapering an opioid is indicated, we propose that you take the following steps:

- Establish whether it is safe to continue prescribing (follow the route provided in “2 decisions to make before continuing to prescribe an opioid for chronic noncancer pain”); if continuing it is not safe, take steps to protect the patient and the community

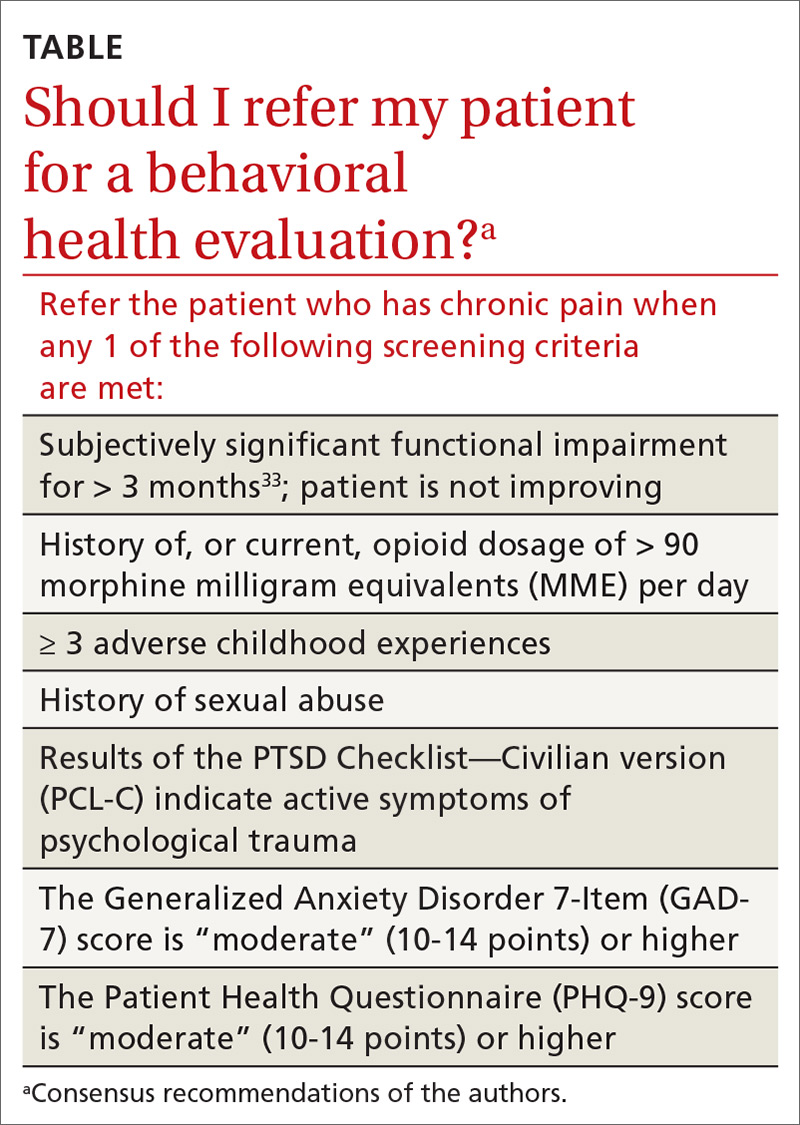

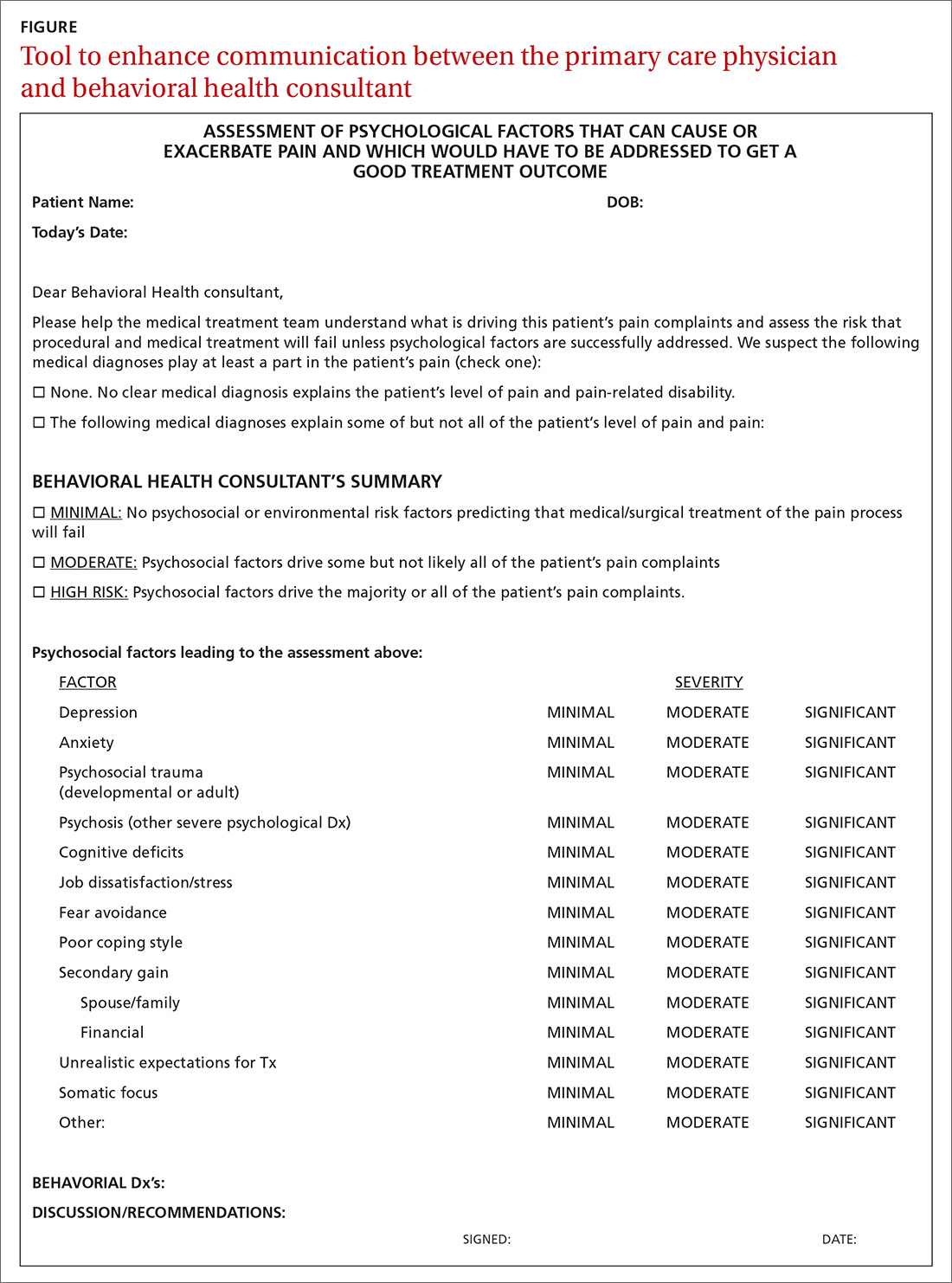

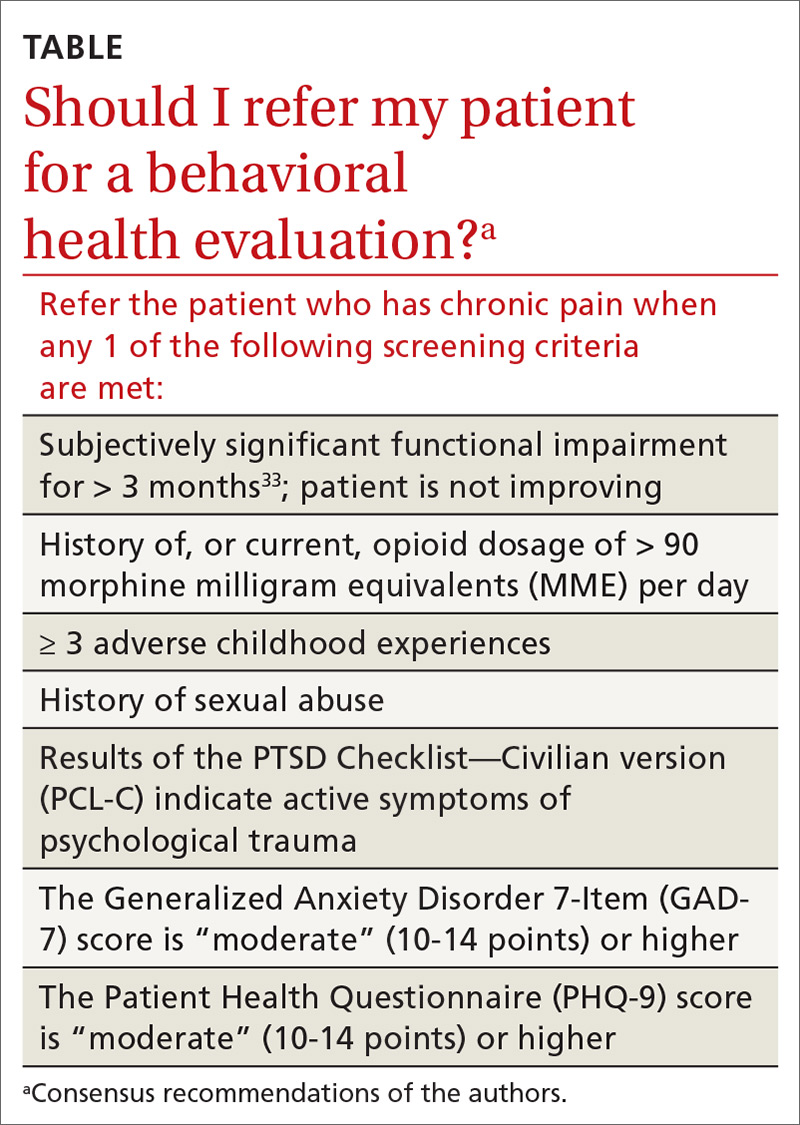

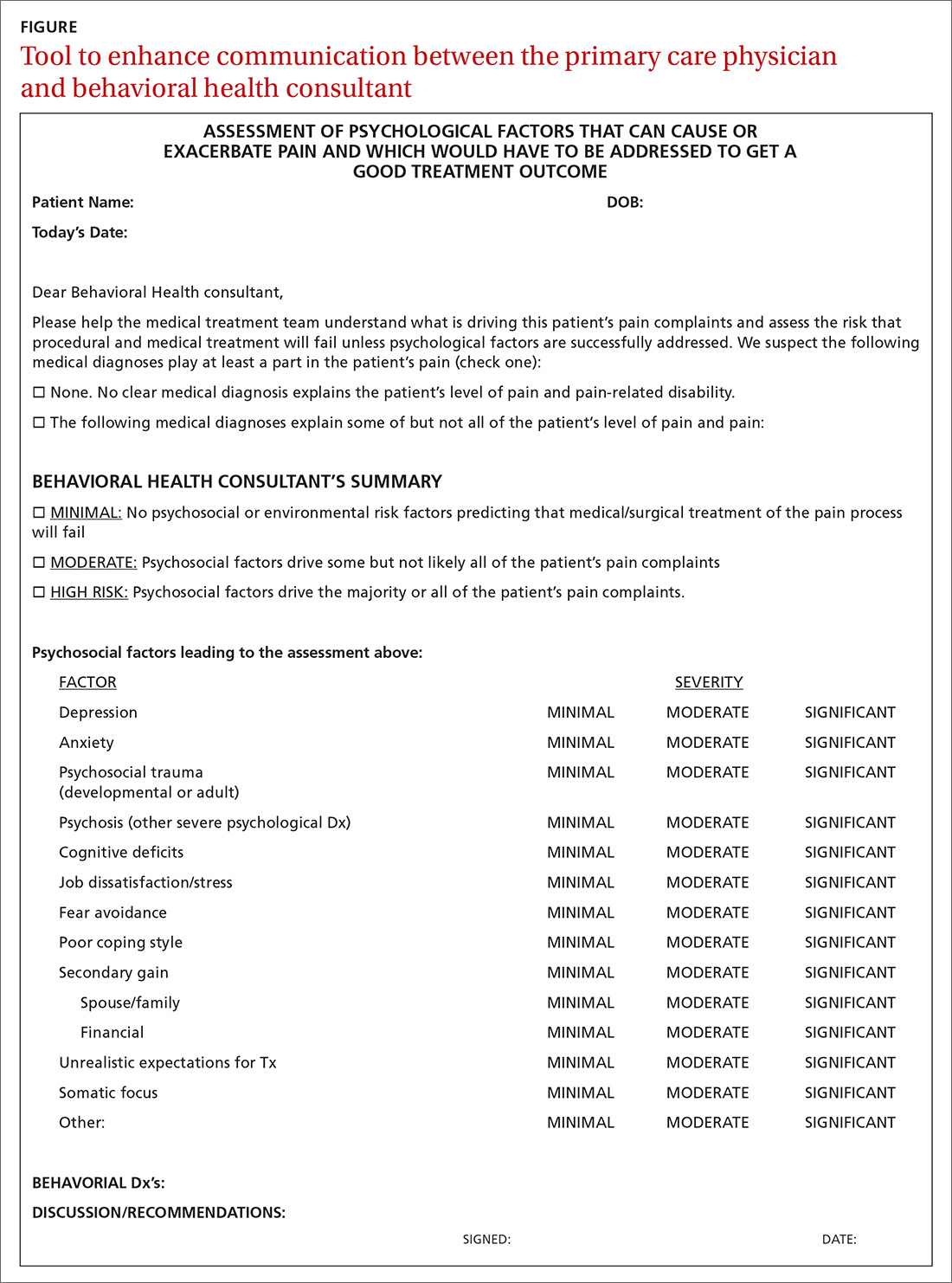

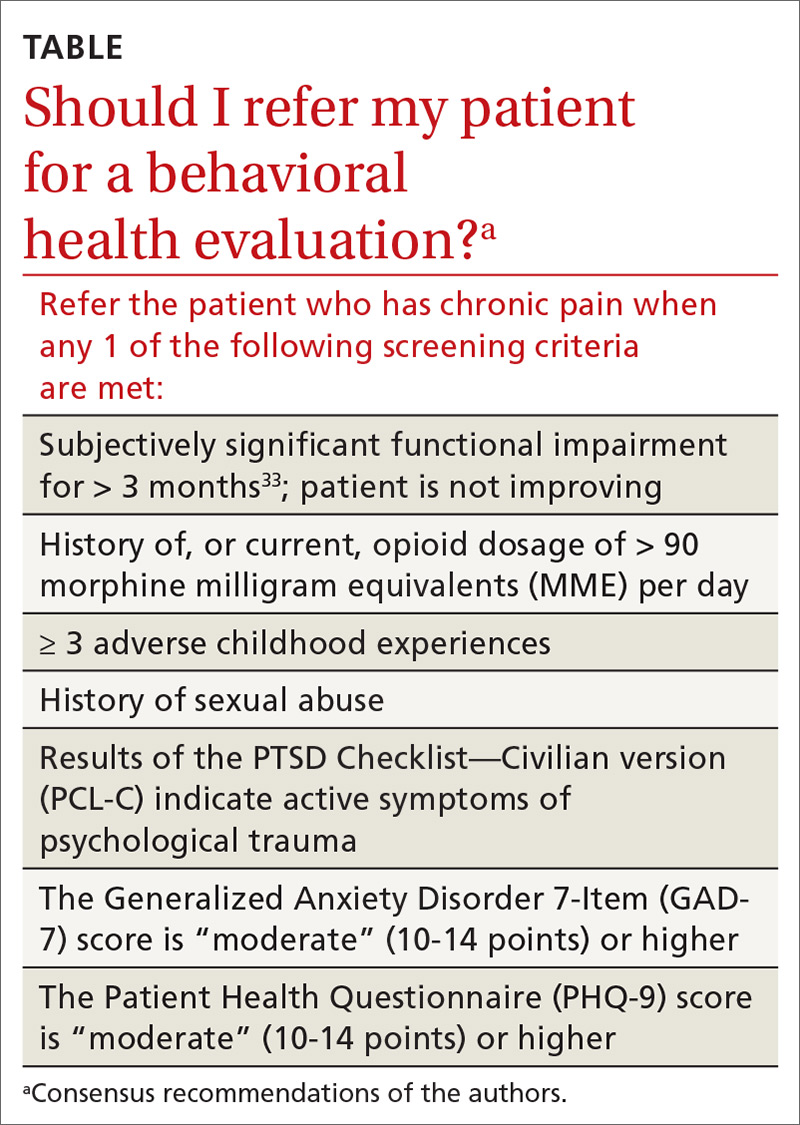

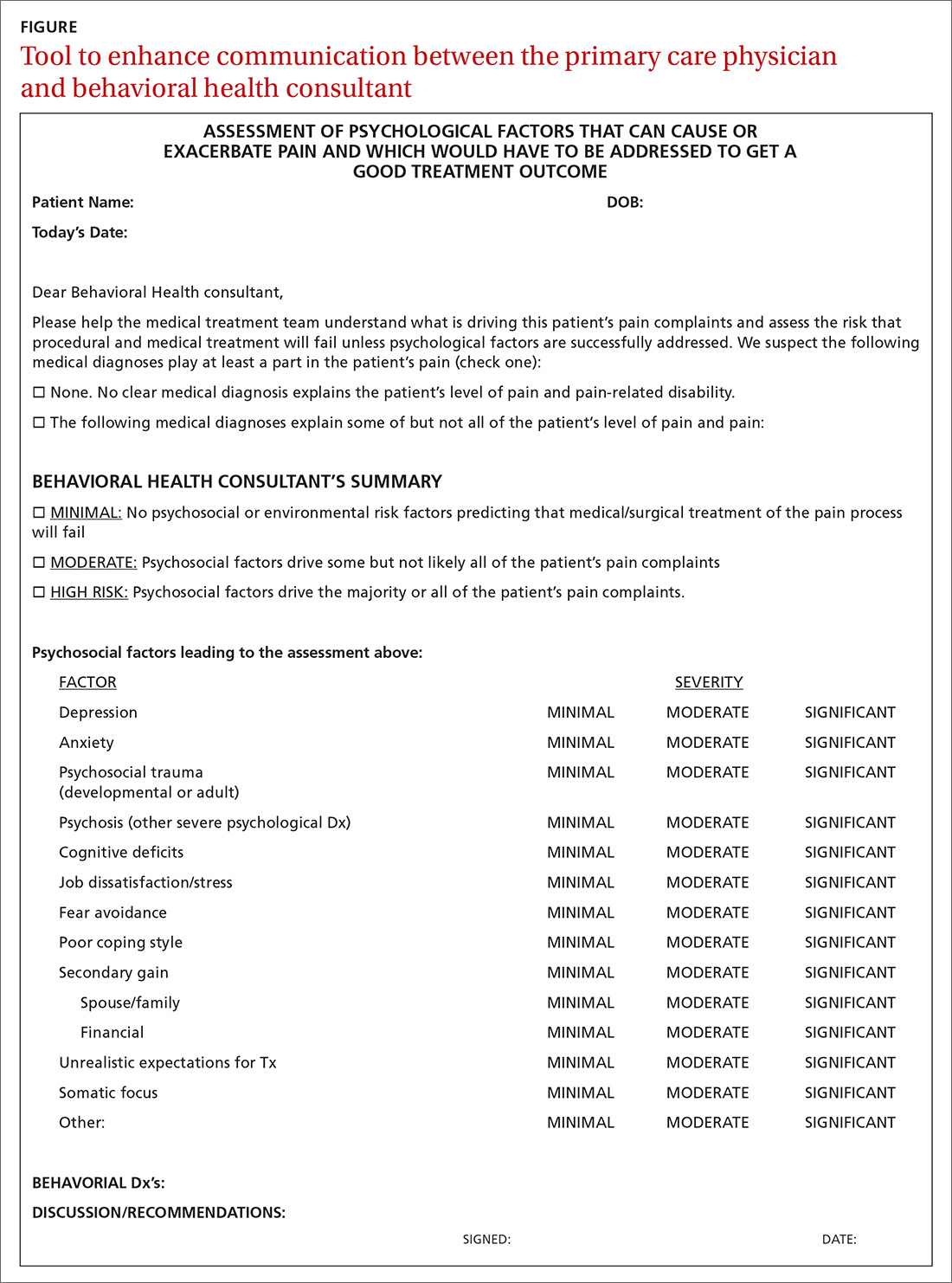

- Determine whether assessment by a trauma-informed behavioral health expert is needed, assuming that, in your judgment, it is safe to continue the opioid (TABLE33). When behavioral health assessment is needed, you need 3 questions answered by that assessment: (1) Are psychological factors present that might put the patient at risk during an opioid taper? (2) What are those factors? (3) What needs to done about them before the taper is started? Recalling that psychological trauma often is not assessed by behavioral health colleagues, it is necessary to provide the behavioral health provider with a specific request to assess trauma burden, and state the physical diagnoses that are causing pain or provide a clear statement that no such diagnoses can be made. (See the FIGURE, which we developed in conjunction with behavioral health colleagues to help the consultant understand what the primary care physician needs from a behavioral health assessment.)

- Obtain consultation from a physical therapist, pain medicine specialist, and, if possible, an alternative or complementary medicine provider to determine what nonpharmacotherapeutic modalities can be instituted to treat pain before tapering the opioid.

- Initiate the Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) approach if OUD is suspected (www.samhsa.gov/sbirt).34 This motivational interviewing tool identifies patients with a substance use disorder, severity of use, and appropriate level of treatment. (If OUD is suspected during assessment, next steps are to stop prescribing and implement harm-reduction strategies, such as primary care level medically assisted treatment [MAT] with buprenorphine, followed by expert behavioral health-centered addiction treatment.)

- Experiment with dosage reduction according to published guidance, if (1) psychological factors are absent or have been adequately addressed, according to the behavioral health consultant, and (2) nonpharmacotherapeutic strategies are in place.8-11

Shifting to a patient-centered approach

The timing and choice of opioid tapers, in relation to harm reduction and intervention targeting the root cause of a patient’s complaint of pain, have not been adequately explored. In our practice, we’ve shifted from an addiction-centered, dosage-centered approach to opioid taper to a patient-centered approach35 that emphasizes behavioral-medical integration—an approach that we broadly endorse. Such an approach (1) is based on a clear understanding of why the patient is taking opioid pain medication, (2) engages medical and complementary or alternative medicine specialists, (3) addresses underdiagnosis of psychological trauma, and (4) requires a quantum leap in access to trauma-specific behavioral health treatment resources. 36

Continue to: To underscore the case...

To underscore the case for shifting to a patient-centered approach35 we present sample cases in “How a patient-centered approach to tapering opioids looks in practice.”

SIDEBAR

How a patient-centered approach to tapering opioids looks in practice

Five hypothetical cases illustrate what might happen when a practice shifts from an addiction-centered, dosage-centered approach to one that places the individual at the center of care.

CASE #1: Brett F

Mr. F appears to use medication responsibly; benefits functionally from an opioid; has tolerable adverse effects; does not have significant psychosocial risk factors (based on the score of the Opioid Risk Tool [ORT] or the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised [SOAPP-R]); and is engaged in effective self-management. Most of Mr. F’s pain is thought to have a nociceptive or neuropathic source.

Mr F could reasonably contemplate continuing current opioid treatment.

Action: If the daily morphine milligram equivalent (MME) dosage is high, Mr. F should be referred to a pain medicine specialist. We recommend a periodic (at least annually) empiric trial of dosage reduction to see whether he is indeed best served by the current dosage.

CASE #2: Brett F (version 2.0)

Envision Mr. F having the same profile in all respects except that he is not engaged in effective self-management.

Optimal treatment of chronic pain often requires supplemental modalities beyond opioids.

Action: Physical therapy; an individualized, ongoing exercise regimen; interventional procedures; weight loss (if the patient is obese); smoking cessation; and improving coping skills for anxiety and depression without pharmacotherapy might not only temporarily alleviate the pain but, over time, improve Mr. F’s physical condition.

If Mr. F is not willing to do more than take the prescribed opioids, nothing is likely to change: Over time, his condition is likely to deteriorate. A patient like Mr. F can be harmed if opioids continue to be prescribed for him long-term.

Further action: If Mr. F won’t engage in broadening the approach to treating his pain, the opioid medication should be tapered, in his long-term best interest. A carrot-and-stick approach can facilitate Mr. F’s involvement in his care.

CASE #3: Clark S

Mr. S has a significant psychosocial component driving his pain: depression.a

Prescribing opioids without addressing the root cause of trauma is not in the patient’s best interest.

Action: Because of Mr. S’s depression, refer him to a behavioral health provider. If you determine that he is emotionally stable, wait until he is engaged in trauma treatment to begin the taper. If he appears unstable (eg, crying in the office, recent psychological stressors, recent impulsive behaviors, poor insight) consider (1) urgent behavioral health referral and (2) prescribing only enough opioid medication (ie, at close intervals) to prevent withdrawal and panic. Consider whether a psychotropic medication might be of benefit (eg, a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor).

Further action: Harm-reduction steps, such as close monitoring and, perhaps, a change to a buprenorphine product, is indicated, especially when the patient is overwhelmed by recent psychosocial stressors. Harm-reduction treatment is available through Medication-Assisted Therapy (MAT) programs; however, patients often run into difficulty obtaining access to these programs because regulations and laws restrict MAT to patients who have a diagnosis of opioid use disorder (OUD) and because some health plans and pharmacy benefit managers require prior authorization.

CASE #4: Gloria B

Ms. B isn’t managing her medications responsibly—although you don’t suspect OUD.

When a patient has shown the inability to manage opioid medication responsibly, you should delve into the reason to determine your next step.

Action: Evaluate Ms. B for a cognitive disorder or a thought disorder. Alternatively, as in the case of Mr. S, a psychosocial component might underlie her pain; in that case, the same recommendations can be made for her. In addition, you can propose that she identify a responsible person to dispense her medication.

CASE #5: Nicole L

You suspect that Ms. L, who is taking opioid medication to alleviate pain, also has a substance use disorder.

Action: Implement harm-reduction early for Ms. L: Obtain addiction medicine consultation and implement behavioral health strategies for addiction treatment.

A key characteristic of a substance use disorder is loss of control over use of the substance. A patient like Ms. L—who is in pain and who has an active OUD—cannot be expected to manage her opioid use responsibly.

Further action: We recommend that Ms. L be referred to an addiction specialist for MAT. Evidence of the harmreduction benefit of MAT is sufficient to strongly recommend it. Continue any other treatment modalities for pain that Ms. L has been using, such as non-opioid medication, physical therapy, alternative treatments, and behavioral therapy, or begin such treatments as appropriate.

a Depression is not the only psychosocial component that can underlie pain. Others include anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and grief.

An eye toward the future. To inform future approaches to opioid tapering, more resources need to be deployed to

- support screening and risk stratification for PTSD, anxiety, and related disorders at the primary care level,

- continue the effort to identify and treat OUD,

- develop best-practice responses to screening, and

- make harm-reduction strategies that are now reserved for patients with OUD available to those who don't have OUD.

We urge that research be pursued into best practices for chronic pain interventions that target psychological trauma, anxiety, and depression.

CORRESPONDENCE

Bennet Davis MD, 2092 East Calle de Dulcinea, Tucson, AZ 85718; [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pocket guide: tapering for chronic pain. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/clinical_pocket_guide_tapering-a.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2019.

2. Kral LA, Jackson K, Uritsky TJ. A practical guide to tapering opioids. Ment Health Clin. 2015;5:102-108.

3. Murphy L, Babaei-Rad R, Buna D, et al. Guidance on opioid tapering in the context of chronic pain: evidence, practical advice and frequently asked questions. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2018;151:114-120.

4. Berna C, Kulich RJ, Rathmell JP. Tapering long-term opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain: evidence and recommendations for everyday practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;90:828-842.

5. Davis M. Prescription opioid use among adults with mental health disorders in the United States. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:407-417.

6. US Government Accountability Office. Report to Congressional Requestors. Prescription drug control: DEA has enhanced efforts to combat diversion, but could better assess and report program results. August 2011. www.gao.gov/assets/520/511464.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2019.

7. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Annual surveillance report of drug-related risks and outcomes. United States, 2017. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2017-cdc-drug-surveillance-report.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2019.

8. Hedegaard H, Warner M, Miniño AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2016, NCHS Data Brief No. 294. December 21, 2017. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm. Accessed November 25, 2019.

9. Overdose death rates. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. January 2019. www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Accessed November 25, 2019.

10. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. NCHS Data Brief No. 329. November 2018. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db329-h.pdf . Accessed November 25, 2019.

11. Manhapra A, Kertesz S, Oliva A, et al. VA data about Rx opioids and overdose and suicide: clinical implications. Presented at the 2018 National Rx Drug Abuse and Heroin Summit, Atlanta Georgia, April 4, 2018.

12. Demidenko M, Dobscha SK, Morasco BJ, et al. Suicidal ideation and suicidal self-directed violence following clinician-initiated prescription opioid discontinuation among long-term opioid users. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;47:29-35.

13. Von Korff M, Walker RL, Saunders K, et al. Prevalence of prescription opioid use disorder among chronic opioid therapy patients after health plan opioid dose and risk reduction initiatives. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:90-98.

14. United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA identifies harm reported from sudden discontinuation of opioid pain medicines and requires label changes to guide prescribers on gradual, individualized tapering. April 9, 2019. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm635038.htm. Accessed November 25, 2019.

15. Becker W, Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, et al. Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among U.S. adults: psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:38-47.

16. Yovell Y, Bar G, Mashiah M, et al. Ultra-low-dose buprenorphine as a time-limited treatment for severe suicidal ideation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:491-498.

17. Pradhan AA, Befort K, Nozaki C, et al. The delta opioid receptor: an evolving target for the treatment of brain disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:581-590.

18. Sugiyama A, Yamada M, Saitoh A, et al. Administration of a delta opioid receptor agonist KNT-127 to the basolateral amygdala has robust anxiolytic-like effects in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235:2947-2955.

19. Richards EM, Mathews DC, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled pilot trial of the delta opioid receptor agonist AZD2327 in anxious depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233:1119-1130.

20. Yang PP, Yeh GC, Yeh TK, et al. Activation of delta-opioid receptor contributes to the antinociceptive effect of oxycodone in mice. Pharmacol Res. 2016;111:867-876.

21. America’s mental health 2018. Stamford, CT: Cohen Veterans Network. October 10, 2018. https://www.cohenveteransnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Research-Summary-10-10-2018.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2019.

22. Classification of Chronic Pain, Second Edition (Revised). Washington, DC: International Association for the Study of Pain. Updated 2012. www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1673. Accessed November 25, 2019.

23. Davis B, Vanderah TW. A new paradigm for pain? J Fam Pract. 2016 65:598-605.

24. Defrin R, Ginzburg K, Solomon Z, et al. Quantitative testing of pain perception in subjects with PTSD—implications for the mechanism of the coexistence between PTSD and chronic pain. Pain. 2008;138:450-459.

25. Foa EB, Gillihan SJ, Bryant RA. Challenges and successes in dissemination of evidence-based treatments for posttraumatic stress: lessons learned from prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Psychol Science Public Interest. 2013;14:65-111.

26. Miele D, O’Brien EJ. Underdiagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder in at risk youth. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:591-598.

27. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013:541.

28. Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:241-248.

29. Schuchat A, Houry D, Guy GP Jr. New data on opioid use and prescribing in the United States. JAMA. 2017;318:425-426.

30. American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society, American Society of Addiction Medicine. Definitions related to the use of opioids for the treatment of pain. 2001. www.naabt.org/documents/APS_consensus_document.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2019.

31. Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J, et al. What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med. 2008;9:444-459.

32. Volkow ND, McClellan AT. Opioid abuse in chronic pain—misconceptions and mitigation strategies. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1253-1263.

33. Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain. 2015;156:1003-1007.

34. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. www.samhsa.gov/sbirt. Accessed November 25, 2019.

35. Schneider JP, Davis B. How well do you know your patient? Pract Pain Manag. 2017;17(2). www.practicalpainmanagement.com/resources/practice-management/how-well-do-you-know-your-patient. Accessed November 25, 2019.

36. Schneider JP. A patient-centered approach to the opioid overdose crisis. J Miss State Med Assoc. 2018;59:232-233.

Many Americans who are treated with prescription opioid analgesics would be better off with less opioid or none at all. To that end, published opioid prescribing guidelines do provide guidance on the mechanics of tapering patients off opioids1-4—but they have a major flaw: They do not adequately account for the fact that people who have a diagnosis of chronic pain are a heterogeneous group and require diagnosis-specific treatment planning. A patient-centered approach to opioid tapers must account for the reality that many people who are given a prescription for an opioid to treat pain have significant mental health conditions—for which opioids act as a psychotropic agent. An opioid taper must therefore address psychological trauma, in particular.5 (See “Tapering and harm-reduction strategies have failed.”6-14)

SIDEBAR

Tapering and harm-reduction strategies have failed

Efforts to address the rising number of overdose events that involve opioids began in earnest in 2010. In a 2011 Government Accountability Office report to Congress, the Drug Enforcement Agency reported that “the number of regulatory investigations (of medical providers who prescribed opioids) tripled between fiscal years 2009- 2010.”6

How has it gone since 2010? High-dosage prescribing of opioids has fallen by 48% since 2011, yet the decline has not reduced overdose events of any kind.7,8 Just the opposite: The 19,000 overdose deaths recorded in 2010 involving any opioid increased to 49,068 by 2017, the National Institute on Drug Abuse reports.9 The increase in opioid overdose deaths is fueled by a recent 9-fold increase in consumption of the synthetic opioid fentanyl: “The rate of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone … increased on average by 8% per year from 1999 through 2013 and by 71% per year from 2013 through 2017.”10

These and other statistics document only a modest rise in deaths that involve prescription opioids: from 15,000 in 2010 to 19,000 in 2016.9,10 Since 2010, the crisis of opioid overdose deaths burns hotter, and the pattern of opioid use has shifted from prescription drugs to much deadlier illicit drugs, such as heroin.

Interventions have not been successful overall. Results of research focused on the impact of opioid tapering and harm-reduction strategies implemented this decade are likewise discouraging. In 2018, the US Department of Veterans Affairs reported that opioid discontinuation was not associated with a reduction in overdose but was associated with an increase in suicide.11,12 Von Korff and colleagues, in a 2017 report, concluded that “Long-term implementation of opioid dose and risk reduction initiatives [in Washington state] was not associated with lower rates of prescription opioid use disorder among prevalent [chronic opioid therapy] patients.”13

Evidence suggests that efforts to address the opioid crisis of the past decade have had an effect that is the opposite of what was intended. The federal government recognized this in April 2019 in a Drug Safety Communication: “The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has received reports of serious harm in patients who are physically dependent on opioid pain medicines suddenly having these medicines discontinued or the dose rapidly decreased. These include serious withdrawal symptoms, uncontrolled pain, psychological distress, and suicide.”14

In this article, we present an evidence-based consensus approach to opioid tapering for your practice that is informed by a broader understanding of why patients take prescription opioids and why they, occasionally, switch to illicit drugs when their prescription is tapered. This consensus approach is based on the experience of the authors, members of the pain faculty of Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) of the ECHO Institute, a worldwide initiative that uses adult learning techniques and interactive video technology to connect community providers with specialists at centers of excellence in regular real-time collaborative sessions. We are variously experts in pain medicine, primary care, psychology, addiction medicine, pharmacy, behavioral health therapy, occupational medicine, and Chinese medicine.

Why Americans obtain prescription opioids

There are 4 principal reasons why patients obtain prescription opioids, beyond indicated analgesic uses:

1. Patients seek the antianxiety and antidepressant effects of opioids. Multiple converging lines of evidence suggest that antianxiety and antidepressant effects of opioids are a significant reason that patients in the United States persist in requesting prescriptions for opioids:

- In our experience with more than 500 primary care telemedicine case presentations, at least 50% of patients say that the main effect of opioids prescribed for them is “it makes me feel calm” or “more relaxed.”

- In a 2007 survey of 91,823 US residents older than 18 years, nonmedical use of opioids was statistically associated with panic, social anxiety, and depressive symptoms.15

- Ten years later, Von Korff and colleagues found that more than half of opioid prescriptions written in the United States were for the small percentage of patients who have a diagnosis of serious anxiety or depression.13

- In 2016, Yovell and colleagues reported that ultra-low-dosage buprenorphine markedly reduced suicidal ideation over 4 weeks in 62 patients with varied levels of depression.16

There is also mechanistic evidence that the antianxiety and antidepressant effects of opioids are significant reasons Americans persist in requesting prescription opioids. The literature suggests that opioid receptors play a role in mood regulation, including alleviation of depression and anxiety; recent research suggests that oxycodone might be a unique mood-altering drug compared to other common prescription opioids because of its ability to affect mood through the δ opioid receptor.17-20

It should not be a surprise that Americans often turn to opioids to address posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression. A recent study of the state of the US mental health system concluded that mental health services in the United States are inadequate—despite evidence that > 50% of Americans seek, or consider seeking, treatment for mental health problems for themselves or others.21

2. Patients experience pain unrelated to tissue damage. Rather, they are in pain “for psychological reasons.”22 In 2016, Davis and Vanderah wrote: “We theorize that a functional change in the [central nervous system] can occur in response to certain emotional states or traumatic experiences (eg, child abuse, assault, accidents).” They connect this change to central sensitization and a reduced pain-perception threshold,23 and strongly suspect that many patients with chronic pain have undiagnosed and untreated psychological trauma that has changed the way their central nervous system processes sensory stimuli. The authors call this “trauma-induced hyperalgesia.”

Continue to: Psychological trauma...

Psychological trauma is uniquely capable of producing hyperalgesia, compared to anxiety or depression. In a study of veterans, Defrin and colleagues demonstrated hyperalgesia in patients who had a diagnosis of PTSD but not in controls group who had an anxiety disorder only.24

To support successful opioid tapering, trauma-induced hyperalgesia, when present, must be addressed. Treatment of what the International Association for the Study of Pain calls “pain due to psychological factors”22 requires specific trauma therapy. However, our experience validates what researchers have to say about access to treatment of psychological trauma in the United States: “…[C]linical research has identified certain psychological interventions that effectively ameliorate the symptoms of PTSD. But most people struggling with PTSD don’t receive those treatments.”25

We have no doubt that this is due, in part, to underdiagnosis of psychological trauma, even in mental health clinics. According to Miele and colleagues, “PTSD remains largely undiagnosed and undertreated in mental health outpatients, even in teaching hospitals, with diagnosis rates as low as 4% while published prevalence is between 7% and 50% in this population.”26

3. Patients suffer from opioid use disorder (OUD) and complain of pain to obtain opioids by prescription. For patients with OUD, their use is out of control; they devote increasing mental and physical resources to obtaining, using, and recovering from substances; and they continue to use despite adverse consequences.27 The prevalence of OUD in primary care clinics varies strikingly by the location of clinics. In Washington state, the prevalence of moderate and severe OUD in a large population of patients who had been prescribed opioids through primary care clinics was recently determined to be between 21.5% and 23.9%.13

4. Patients are obtaining opioid prescriptions for people other than themselves. While this is a reason that patients obtain opioid prescriptions, it is not necessarily common. Statistics show that the likelihood of a prescription being diverted intentionally is low: Dart and colleagues found that diversion has become uncommon in the general population.28

Continue to: Why we taper opioid analgesics

Why we taper opioid analgesics

Reasons for an opioid taper include concern that the patient has, or will develop, an OUD; will experience accidental or intentional overdose; might be diverting opioids; is not benefiting from opioid therapy for pain; or is experiencing severe adverse effects. A patient who has nociceptive pain and might have opioid-induced hyperalgesia will require a much different opioid taper plan than a patient with untreated PTSD or a patient with severe OUD.

Misunderstanding can lead to inappropriate tapering

We often encounter primary care providers who believe that a large percentage of patients on chronic opioid therapy inevitably develop OUD. This is a common reason for initiating opioid taper. Most patients on a chronic opioid do become physically dependent, but only a small percentage of patients develop psychological dependence (ie, addiction or OUD).29

Physical dependence is “a state of adaptation that is manifested by a drug class–specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist.”30 Symptoms of opioid withdrawal include muscle aches; abdominal cramping; increased lacrimation, rhinorrhea, and perspiration; diarrhea; agitation and anxiety; insomnia; and piloerection. Opioid withdrawal symptoms are caused by physical dependence, not by addiction. They can be mitigated by tapering slowly and instituting adjuvant medications, such as clonidine, to attenuate symptoms.

Psychological dependence, or addiction (that is, OUD, as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition27), comprises primarily 3 behavioral criteria:

- Loss of control of the medication, with compulsive use

- Continued use despite adverse consequences of using opioids, such as arrest for driving under the influence and deterioration of social, family, or work performance

- Obsession or preoccupation with obtaining and using the substance. In properly selected chronic opioid therapy patients, there is evidence that new-onset OUD is not as common as has been thought. A recent study of the risk for opioid addiction after use of an opioid for ≥ 90 days for chronic noncancer pain found that the absolute rate of de novo OUD among patients treated for 90 days was 0.72%.29 A systematic review by Fishbain and colleagues of 24 studies of opioid-exposed patients found a risk of 3.27% overall—0.19% for patients who did not have a history of abuse or addiction.31 As Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Norma Volkow, MD, wrote in 2016: “Addiction occurs in only a small percentage of people who are exposed to opioids—even among those with preexisting vulnerabilities.”32

Assessment should focus on why the patient is taking an opioid

A strong case can be made that less opioid is better for many of the people for whom these medications are prescribed for chronic noncancer pain. However, a one-size-fits-all dosage reduction and addiction-focused approach to opioid tapering has not worked: The assessment and treatment paradigm must change, in our view.

Continue to: During assessment...

During assessment, we must adopt the means to identify the reason that a patient is using a prescription opioid. It is of particular importance that we identify patients using opioids for their psychotropic properties, particularly when the goal is to cope with the effects of psychological trauma. The subsequent treatment protocol will then need to include time for effective, evidence-based behavioral health treatment of anxiety, PTSD, or depression. If opioids are serving primarily as psychotropic medication, an attempt to taper before establishing effective behavioral health treatment might lead the patient to pursue illegal means of procuring opioid medication.

We acknowledge that primary care physicians are not reimbursed for trauma screening and that evidence-based intensive trauma treatment is generally unavailable in the United States. Both of these shortcomings must be corrected if we want to stem the opioid crisis.

If diversion is suspected and there is evidence that the patient is not currently taking prescribed opioids (eg, a negative urine drug screen), discontinuing the opioid prescription is the immediate next step for the sake of public safety.

SIDEBAR

2 decisions to make before continuing to prescribe an opioid for chronic noncancer pain

#1 Should I provide the patient with a prescription for an opioid for a few days, while I await more information?a

Yes. Writing a prescription is a reasonable decision if all of the following apply:

- You do not have significant suspicion of diversion (based on a clinical interview).

- You do not suspect an active addiction disorder, based on the score of the 10-question Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) and on a clinical interview. (DAST-10 is available at: https://cde.drugabuse.gov/instrument/e9053390-ee9c-9140-e040-bb89ad433d69.)

- The patient is likely to experience withdrawal symptoms if you don’t provide the medication immediately.

- The patient’s pain and function are likely to be impaired if you do not provide the medication.

- The patient does not display altered mental status during the visit (eg, drowsy, slurred speech).

No. If writing a prescription for an opioid for a few days does not seem to be a reasonable decision because the criteria above are not met, but withdrawal symptoms are likely, you can prescribe medication to mitigate symptoms or refer the patient for treatment of withdrawal.

#2 I’ve decided to provide the patient with a prescription for an opioid. For how many days should I write it?

The usual practice, for a patient whose case is familiar to you, is to prescribe a 1-month supply.

However, if any 1 of the following criteria is met, prescribing a 1-month supply is unsafe under most circumstances:

- An unstable social or living environment places the patient at risk by possessing a supply of opioids (based on a clinical interview).

- You suspect an unstable or severe behavioral health condition or a mental health diagnosis (based on a clinical interview or on the patient record from outside your practice).

- The patient scores as “high risk” on the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT; www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/OpioidRiskTool.pdf), Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4706778/), or a similar opioid risk assessment tool.

When 1 or more of these exclusionary criteria are met, you have 3 options:

- Prescribe an opioid for a brief duration and see the patient often.

- Do not prescribe an opioid; instead, refer the patient as necessary for treatment of withdrawal.

- Refer the patient for treatment of the underlying behavioral health condition.

a Additional information might include findings from consultants you’ve engaged regarding the patient’s diagnosis; a response to your call from a past prescriber; urine drug screen results; and results of a prescription monitoring program check.

Considering a taper? Take this 5-step approach

Once it appears that tapering an opioid is indicated, we propose that you take the following steps:

- Establish whether it is safe to continue prescribing (follow the route provided in “2 decisions to make before continuing to prescribe an opioid for chronic noncancer pain”); if continuing it is not safe, take steps to protect the patient and the community

- Determine whether assessment by a trauma-informed behavioral health expert is needed, assuming that, in your judgment, it is safe to continue the opioid (TABLE33). When behavioral health assessment is needed, you need 3 questions answered by that assessment: (1) Are psychological factors present that might put the patient at risk during an opioid taper? (2) What are those factors? (3) What needs to done about them before the taper is started? Recalling that psychological trauma often is not assessed by behavioral health colleagues, it is necessary to provide the behavioral health provider with a specific request to assess trauma burden, and state the physical diagnoses that are causing pain or provide a clear statement that no such diagnoses can be made. (See the FIGURE, which we developed in conjunction with behavioral health colleagues to help the consultant understand what the primary care physician needs from a behavioral health assessment.)

- Obtain consultation from a physical therapist, pain medicine specialist, and, if possible, an alternative or complementary medicine provider to determine what nonpharmacotherapeutic modalities can be instituted to treat pain before tapering the opioid.

- Initiate the Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) approach if OUD is suspected (www.samhsa.gov/sbirt).34 This motivational interviewing tool identifies patients with a substance use disorder, severity of use, and appropriate level of treatment. (If OUD is suspected during assessment, next steps are to stop prescribing and implement harm-reduction strategies, such as primary care level medically assisted treatment [MAT] with buprenorphine, followed by expert behavioral health-centered addiction treatment.)

- Experiment with dosage reduction according to published guidance, if (1) psychological factors are absent or have been adequately addressed, according to the behavioral health consultant, and (2) nonpharmacotherapeutic strategies are in place.8-11

Shifting to a patient-centered approach

The timing and choice of opioid tapers, in relation to harm reduction and intervention targeting the root cause of a patient’s complaint of pain, have not been adequately explored. In our practice, we’ve shifted from an addiction-centered, dosage-centered approach to opioid taper to a patient-centered approach35 that emphasizes behavioral-medical integration—an approach that we broadly endorse. Such an approach (1) is based on a clear understanding of why the patient is taking opioid pain medication, (2) engages medical and complementary or alternative medicine specialists, (3) addresses underdiagnosis of psychological trauma, and (4) requires a quantum leap in access to trauma-specific behavioral health treatment resources. 36

Continue to: To underscore the case...

To underscore the case for shifting to a patient-centered approach35 we present sample cases in “How a patient-centered approach to tapering opioids looks in practice.”

SIDEBAR

How a patient-centered approach to tapering opioids looks in practice

Five hypothetical cases illustrate what might happen when a practice shifts from an addiction-centered, dosage-centered approach to one that places the individual at the center of care.

CASE #1: Brett F

Mr. F appears to use medication responsibly; benefits functionally from an opioid; has tolerable adverse effects; does not have significant psychosocial risk factors (based on the score of the Opioid Risk Tool [ORT] or the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised [SOAPP-R]); and is engaged in effective self-management. Most of Mr. F’s pain is thought to have a nociceptive or neuropathic source.

Mr F could reasonably contemplate continuing current opioid treatment.

Action: If the daily morphine milligram equivalent (MME) dosage is high, Mr. F should be referred to a pain medicine specialist. We recommend a periodic (at least annually) empiric trial of dosage reduction to see whether he is indeed best served by the current dosage.

CASE #2: Brett F (version 2.0)

Envision Mr. F having the same profile in all respects except that he is not engaged in effective self-management.

Optimal treatment of chronic pain often requires supplemental modalities beyond opioids.

Action: Physical therapy; an individualized, ongoing exercise regimen; interventional procedures; weight loss (if the patient is obese); smoking cessation; and improving coping skills for anxiety and depression without pharmacotherapy might not only temporarily alleviate the pain but, over time, improve Mr. F’s physical condition.

If Mr. F is not willing to do more than take the prescribed opioids, nothing is likely to change: Over time, his condition is likely to deteriorate. A patient like Mr. F can be harmed if opioids continue to be prescribed for him long-term.

Further action: If Mr. F won’t engage in broadening the approach to treating his pain, the opioid medication should be tapered, in his long-term best interest. A carrot-and-stick approach can facilitate Mr. F’s involvement in his care.

CASE #3: Clark S

Mr. S has a significant psychosocial component driving his pain: depression.a

Prescribing opioids without addressing the root cause of trauma is not in the patient’s best interest.

Action: Because of Mr. S’s depression, refer him to a behavioral health provider. If you determine that he is emotionally stable, wait until he is engaged in trauma treatment to begin the taper. If he appears unstable (eg, crying in the office, recent psychological stressors, recent impulsive behaviors, poor insight) consider (1) urgent behavioral health referral and (2) prescribing only enough opioid medication (ie, at close intervals) to prevent withdrawal and panic. Consider whether a psychotropic medication might be of benefit (eg, a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor).

Further action: Harm-reduction steps, such as close monitoring and, perhaps, a change to a buprenorphine product, is indicated, especially when the patient is overwhelmed by recent psychosocial stressors. Harm-reduction treatment is available through Medication-Assisted Therapy (MAT) programs; however, patients often run into difficulty obtaining access to these programs because regulations and laws restrict MAT to patients who have a diagnosis of opioid use disorder (OUD) and because some health plans and pharmacy benefit managers require prior authorization.

CASE #4: Gloria B

Ms. B isn’t managing her medications responsibly—although you don’t suspect OUD.

When a patient has shown the inability to manage opioid medication responsibly, you should delve into the reason to determine your next step.

Action: Evaluate Ms. B for a cognitive disorder or a thought disorder. Alternatively, as in the case of Mr. S, a psychosocial component might underlie her pain; in that case, the same recommendations can be made for her. In addition, you can propose that she identify a responsible person to dispense her medication.

CASE #5: Nicole L

You suspect that Ms. L, who is taking opioid medication to alleviate pain, also has a substance use disorder.

Action: Implement harm-reduction early for Ms. L: Obtain addiction medicine consultation and implement behavioral health strategies for addiction treatment.

A key characteristic of a substance use disorder is loss of control over use of the substance. A patient like Ms. L—who is in pain and who has an active OUD—cannot be expected to manage her opioid use responsibly.

Further action: We recommend that Ms. L be referred to an addiction specialist for MAT. Evidence of the harmreduction benefit of MAT is sufficient to strongly recommend it. Continue any other treatment modalities for pain that Ms. L has been using, such as non-opioid medication, physical therapy, alternative treatments, and behavioral therapy, or begin such treatments as appropriate.

a Depression is not the only psychosocial component that can underlie pain. Others include anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and grief.

An eye toward the future. To inform future approaches to opioid tapering, more resources need to be deployed to

- support screening and risk stratification for PTSD, anxiety, and related disorders at the primary care level,

- continue the effort to identify and treat OUD,

- develop best-practice responses to screening, and

- make harm-reduction strategies that are now reserved for patients with OUD available to those who don't have OUD.

We urge that research be pursued into best practices for chronic pain interventions that target psychological trauma, anxiety, and depression.

CORRESPONDENCE

Bennet Davis MD, 2092 East Calle de Dulcinea, Tucson, AZ 85718; [email protected].

Many Americans who are treated with prescription opioid analgesics would be better off with less opioid or none at all. To that end, published opioid prescribing guidelines do provide guidance on the mechanics of tapering patients off opioids1-4—but they have a major flaw: They do not adequately account for the fact that people who have a diagnosis of chronic pain are a heterogeneous group and require diagnosis-specific treatment planning. A patient-centered approach to opioid tapers must account for the reality that many people who are given a prescription for an opioid to treat pain have significant mental health conditions—for which opioids act as a psychotropic agent. An opioid taper must therefore address psychological trauma, in particular.5 (See “Tapering and harm-reduction strategies have failed.”6-14)

SIDEBAR

Tapering and harm-reduction strategies have failed

Efforts to address the rising number of overdose events that involve opioids began in earnest in 2010. In a 2011 Government Accountability Office report to Congress, the Drug Enforcement Agency reported that “the number of regulatory investigations (of medical providers who prescribed opioids) tripled between fiscal years 2009- 2010.”6

How has it gone since 2010? High-dosage prescribing of opioids has fallen by 48% since 2011, yet the decline has not reduced overdose events of any kind.7,8 Just the opposite: The 19,000 overdose deaths recorded in 2010 involving any opioid increased to 49,068 by 2017, the National Institute on Drug Abuse reports.9 The increase in opioid overdose deaths is fueled by a recent 9-fold increase in consumption of the synthetic opioid fentanyl: “The rate of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone … increased on average by 8% per year from 1999 through 2013 and by 71% per year from 2013 through 2017.”10

These and other statistics document only a modest rise in deaths that involve prescription opioids: from 15,000 in 2010 to 19,000 in 2016.9,10 Since 2010, the crisis of opioid overdose deaths burns hotter, and the pattern of opioid use has shifted from prescription drugs to much deadlier illicit drugs, such as heroin.

Interventions have not been successful overall. Results of research focused on the impact of opioid tapering and harm-reduction strategies implemented this decade are likewise discouraging. In 2018, the US Department of Veterans Affairs reported that opioid discontinuation was not associated with a reduction in overdose but was associated with an increase in suicide.11,12 Von Korff and colleagues, in a 2017 report, concluded that “Long-term implementation of opioid dose and risk reduction initiatives [in Washington state] was not associated with lower rates of prescription opioid use disorder among prevalent [chronic opioid therapy] patients.”13

Evidence suggests that efforts to address the opioid crisis of the past decade have had an effect that is the opposite of what was intended. The federal government recognized this in April 2019 in a Drug Safety Communication: “The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has received reports of serious harm in patients who are physically dependent on opioid pain medicines suddenly having these medicines discontinued or the dose rapidly decreased. These include serious withdrawal symptoms, uncontrolled pain, psychological distress, and suicide.”14

In this article, we present an evidence-based consensus approach to opioid tapering for your practice that is informed by a broader understanding of why patients take prescription opioids and why they, occasionally, switch to illicit drugs when their prescription is tapered. This consensus approach is based on the experience of the authors, members of the pain faculty of Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) of the ECHO Institute, a worldwide initiative that uses adult learning techniques and interactive video technology to connect community providers with specialists at centers of excellence in regular real-time collaborative sessions. We are variously experts in pain medicine, primary care, psychology, addiction medicine, pharmacy, behavioral health therapy, occupational medicine, and Chinese medicine.

Why Americans obtain prescription opioids

There are 4 principal reasons why patients obtain prescription opioids, beyond indicated analgesic uses:

1. Patients seek the antianxiety and antidepressant effects of opioids. Multiple converging lines of evidence suggest that antianxiety and antidepressant effects of opioids are a significant reason that patients in the United States persist in requesting prescriptions for opioids:

- In our experience with more than 500 primary care telemedicine case presentations, at least 50% of patients say that the main effect of opioids prescribed for them is “it makes me feel calm” or “more relaxed.”

- In a 2007 survey of 91,823 US residents older than 18 years, nonmedical use of opioids was statistically associated with panic, social anxiety, and depressive symptoms.15

- Ten years later, Von Korff and colleagues found that more than half of opioid prescriptions written in the United States were for the small percentage of patients who have a diagnosis of serious anxiety or depression.13

- In 2016, Yovell and colleagues reported that ultra-low-dosage buprenorphine markedly reduced suicidal ideation over 4 weeks in 62 patients with varied levels of depression.16

There is also mechanistic evidence that the antianxiety and antidepressant effects of opioids are significant reasons Americans persist in requesting prescription opioids. The literature suggests that opioid receptors play a role in mood regulation, including alleviation of depression and anxiety; recent research suggests that oxycodone might be a unique mood-altering drug compared to other common prescription opioids because of its ability to affect mood through the δ opioid receptor.17-20

It should not be a surprise that Americans often turn to opioids to address posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression. A recent study of the state of the US mental health system concluded that mental health services in the United States are inadequate—despite evidence that > 50% of Americans seek, or consider seeking, treatment for mental health problems for themselves or others.21

2. Patients experience pain unrelated to tissue damage. Rather, they are in pain “for psychological reasons.”22 In 2016, Davis and Vanderah wrote: “We theorize that a functional change in the [central nervous system] can occur in response to certain emotional states or traumatic experiences (eg, child abuse, assault, accidents).” They connect this change to central sensitization and a reduced pain-perception threshold,23 and strongly suspect that many patients with chronic pain have undiagnosed and untreated psychological trauma that has changed the way their central nervous system processes sensory stimuli. The authors call this “trauma-induced hyperalgesia.”

Continue to: Psychological trauma...

Psychological trauma is uniquely capable of producing hyperalgesia, compared to anxiety or depression. In a study of veterans, Defrin and colleagues demonstrated hyperalgesia in patients who had a diagnosis of PTSD but not in controls group who had an anxiety disorder only.24

To support successful opioid tapering, trauma-induced hyperalgesia, when present, must be addressed. Treatment of what the International Association for the Study of Pain calls “pain due to psychological factors”22 requires specific trauma therapy. However, our experience validates what researchers have to say about access to treatment of psychological trauma in the United States: “…[C]linical research has identified certain psychological interventions that effectively ameliorate the symptoms of PTSD. But most people struggling with PTSD don’t receive those treatments.”25

We have no doubt that this is due, in part, to underdiagnosis of psychological trauma, even in mental health clinics. According to Miele and colleagues, “PTSD remains largely undiagnosed and undertreated in mental health outpatients, even in teaching hospitals, with diagnosis rates as low as 4% while published prevalence is between 7% and 50% in this population.”26

3. Patients suffer from opioid use disorder (OUD) and complain of pain to obtain opioids by prescription. For patients with OUD, their use is out of control; they devote increasing mental and physical resources to obtaining, using, and recovering from substances; and they continue to use despite adverse consequences.27 The prevalence of OUD in primary care clinics varies strikingly by the location of clinics. In Washington state, the prevalence of moderate and severe OUD in a large population of patients who had been prescribed opioids through primary care clinics was recently determined to be between 21.5% and 23.9%.13

4. Patients are obtaining opioid prescriptions for people other than themselves. While this is a reason that patients obtain opioid prescriptions, it is not necessarily common. Statistics show that the likelihood of a prescription being diverted intentionally is low: Dart and colleagues found that diversion has become uncommon in the general population.28

Continue to: Why we taper opioid analgesics

Why we taper opioid analgesics

Reasons for an opioid taper include concern that the patient has, or will develop, an OUD; will experience accidental or intentional overdose; might be diverting opioids; is not benefiting from opioid therapy for pain; or is experiencing severe adverse effects. A patient who has nociceptive pain and might have opioid-induced hyperalgesia will require a much different opioid taper plan than a patient with untreated PTSD or a patient with severe OUD.

Misunderstanding can lead to inappropriate tapering

We often encounter primary care providers who believe that a large percentage of patients on chronic opioid therapy inevitably develop OUD. This is a common reason for initiating opioid taper. Most patients on a chronic opioid do become physically dependent, but only a small percentage of patients develop psychological dependence (ie, addiction or OUD).29

Physical dependence is “a state of adaptation that is manifested by a drug class–specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist.”30 Symptoms of opioid withdrawal include muscle aches; abdominal cramping; increased lacrimation, rhinorrhea, and perspiration; diarrhea; agitation and anxiety; insomnia; and piloerection. Opioid withdrawal symptoms are caused by physical dependence, not by addiction. They can be mitigated by tapering slowly and instituting adjuvant medications, such as clonidine, to attenuate symptoms.

Psychological dependence, or addiction (that is, OUD, as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition27), comprises primarily 3 behavioral criteria:

- Loss of control of the medication, with compulsive use

- Continued use despite adverse consequences of using opioids, such as arrest for driving under the influence and deterioration of social, family, or work performance

- Obsession or preoccupation with obtaining and using the substance. In properly selected chronic opioid therapy patients, there is evidence that new-onset OUD is not as common as has been thought. A recent study of the risk for opioid addiction after use of an opioid for ≥ 90 days for chronic noncancer pain found that the absolute rate of de novo OUD among patients treated for 90 days was 0.72%.29 A systematic review by Fishbain and colleagues of 24 studies of opioid-exposed patients found a risk of 3.27% overall—0.19% for patients who did not have a history of abuse or addiction.31 As Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Norma Volkow, MD, wrote in 2016: “Addiction occurs in only a small percentage of people who are exposed to opioids—even among those with preexisting vulnerabilities.”32

Assessment should focus on why the patient is taking an opioid

A strong case can be made that less opioid is better for many of the people for whom these medications are prescribed for chronic noncancer pain. However, a one-size-fits-all dosage reduction and addiction-focused approach to opioid tapering has not worked: The assessment and treatment paradigm must change, in our view.

Continue to: During assessment...

During assessment, we must adopt the means to identify the reason that a patient is using a prescription opioid. It is of particular importance that we identify patients using opioids for their psychotropic properties, particularly when the goal is to cope with the effects of psychological trauma. The subsequent treatment protocol will then need to include time for effective, evidence-based behavioral health treatment of anxiety, PTSD, or depression. If opioids are serving primarily as psychotropic medication, an attempt to taper before establishing effective behavioral health treatment might lead the patient to pursue illegal means of procuring opioid medication.

We acknowledge that primary care physicians are not reimbursed for trauma screening and that evidence-based intensive trauma treatment is generally unavailable in the United States. Both of these shortcomings must be corrected if we want to stem the opioid crisis.

If diversion is suspected and there is evidence that the patient is not currently taking prescribed opioids (eg, a negative urine drug screen), discontinuing the opioid prescription is the immediate next step for the sake of public safety.

SIDEBAR

2 decisions to make before continuing to prescribe an opioid for chronic noncancer pain

#1 Should I provide the patient with a prescription for an opioid for a few days, while I await more information?a

Yes. Writing a prescription is a reasonable decision if all of the following apply:

- You do not have significant suspicion of diversion (based on a clinical interview).

- You do not suspect an active addiction disorder, based on the score of the 10-question Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) and on a clinical interview. (DAST-10 is available at: https://cde.drugabuse.gov/instrument/e9053390-ee9c-9140-e040-bb89ad433d69.)

- The patient is likely to experience withdrawal symptoms if you don’t provide the medication immediately.

- The patient’s pain and function are likely to be impaired if you do not provide the medication.

- The patient does not display altered mental status during the visit (eg, drowsy, slurred speech).

No. If writing a prescription for an opioid for a few days does not seem to be a reasonable decision because the criteria above are not met, but withdrawal symptoms are likely, you can prescribe medication to mitigate symptoms or refer the patient for treatment of withdrawal.

#2 I’ve decided to provide the patient with a prescription for an opioid. For how many days should I write it?

The usual practice, for a patient whose case is familiar to you, is to prescribe a 1-month supply.

However, if any 1 of the following criteria is met, prescribing a 1-month supply is unsafe under most circumstances:

- An unstable social or living environment places the patient at risk by possessing a supply of opioids (based on a clinical interview).

- You suspect an unstable or severe behavioral health condition or a mental health diagnosis (based on a clinical interview or on the patient record from outside your practice).

- The patient scores as “high risk” on the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT; www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/OpioidRiskTool.pdf), Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4706778/), or a similar opioid risk assessment tool.

When 1 or more of these exclusionary criteria are met, you have 3 options:

- Prescribe an opioid for a brief duration and see the patient often.

- Do not prescribe an opioid; instead, refer the patient as necessary for treatment of withdrawal.

- Refer the patient for treatment of the underlying behavioral health condition.

a Additional information might include findings from consultants you’ve engaged regarding the patient’s diagnosis; a response to your call from a past prescriber; urine drug screen results; and results of a prescription monitoring program check.

Considering a taper? Take this 5-step approach

Once it appears that tapering an opioid is indicated, we propose that you take the following steps:

- Establish whether it is safe to continue prescribing (follow the route provided in “2 decisions to make before continuing to prescribe an opioid for chronic noncancer pain”); if continuing it is not safe, take steps to protect the patient and the community

- Determine whether assessment by a trauma-informed behavioral health expert is needed, assuming that, in your judgment, it is safe to continue the opioid (TABLE33). When behavioral health assessment is needed, you need 3 questions answered by that assessment: (1) Are psychological factors present that might put the patient at risk during an opioid taper? (2) What are those factors? (3) What needs to done about them before the taper is started? Recalling that psychological trauma often is not assessed by behavioral health colleagues, it is necessary to provide the behavioral health provider with a specific request to assess trauma burden, and state the physical diagnoses that are causing pain or provide a clear statement that no such diagnoses can be made. (See the FIGURE, which we developed in conjunction with behavioral health colleagues to help the consultant understand what the primary care physician needs from a behavioral health assessment.)

- Obtain consultation from a physical therapist, pain medicine specialist, and, if possible, an alternative or complementary medicine provider to determine what nonpharmacotherapeutic modalities can be instituted to treat pain before tapering the opioid.

- Initiate the Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) approach if OUD is suspected (www.samhsa.gov/sbirt).34 This motivational interviewing tool identifies patients with a substance use disorder, severity of use, and appropriate level of treatment. (If OUD is suspected during assessment, next steps are to stop prescribing and implement harm-reduction strategies, such as primary care level medically assisted treatment [MAT] with buprenorphine, followed by expert behavioral health-centered addiction treatment.)

- Experiment with dosage reduction according to published guidance, if (1) psychological factors are absent or have been adequately addressed, according to the behavioral health consultant, and (2) nonpharmacotherapeutic strategies are in place.8-11

Shifting to a patient-centered approach

The timing and choice of opioid tapers, in relation to harm reduction and intervention targeting the root cause of a patient’s complaint of pain, have not been adequately explored. In our practice, we’ve shifted from an addiction-centered, dosage-centered approach to opioid taper to a patient-centered approach35 that emphasizes behavioral-medical integration—an approach that we broadly endorse. Such an approach (1) is based on a clear understanding of why the patient is taking opioid pain medication, (2) engages medical and complementary or alternative medicine specialists, (3) addresses underdiagnosis of psychological trauma, and (4) requires a quantum leap in access to trauma-specific behavioral health treatment resources. 36

Continue to: To underscore the case...

To underscore the case for shifting to a patient-centered approach35 we present sample cases in “How a patient-centered approach to tapering opioids looks in practice.”

SIDEBAR

How a patient-centered approach to tapering opioids looks in practice