User login

Adolescent alcohol, opioid misuse linked to risky behaviors

Binge drinking and misuse of opioids led to risky behavior during adolescence, two studies from the journal Pediatrics highlighted. And the binge drinking in high school may predict risky driving behaviors up to 4 years after high school.

Federico E. Vaca, MD, of the developmental neurocognitive driving simulation research center at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues examined the associations between risky driving behaviors and binge drinking of 2,785 adolescents in the nationally representative, longitudinal NEXT Generation Health Study. The researchers studied the effects of binge drinking on driving while impaired (DWI), riding with an impaired driver (RWI), blackouts, extreme binge drinking, and risky driving.

The adolescents were studied across seven waves, with Wave 1 beginning in the 2009-2010 school year (10th grade; mean age, 16 years), and data extended up to 4 years after high school. Of all adolescents enrolled, 91% completed Wave 1, 88% completed Wave 2, 86% completed Wave 3 (12th grade), 78% completed Wave 4, 79% completed Wave 5, 84% completed Wave 6, and 83% completed Wave 7 (4 years after leaving high school) of the study.

High school binge drinking predicts later risky behavior

About one-quarter of adolescents reported binge drinking in Waves 1-3, with an incidence of 27% in Wave 1, 24% in Wave 2, and 27% in Wave 3. Adolescents who reported binge drinking in Wave 3 had a higher likelihood of DWI in subsequent waves, with nearly six times higher odds in Wave 5 and more than twice as likely in Wave 7, researchers said. Binge drinking in Wave 3 also was associated with greater than four times higher odds of RWI in Wave 4, and more than two and a half times higher odds of RWI in Wave 7. Among adolescents who reported binge drinking across 3 years in high school, there was a higher likelihood of extreme binge drinking in Wave 7, and higher likelihood of risky driving after graduating.

Impact of parental knowledge of drinking

in some waves. Father monitoring knowledge of drinking in Waves 1-3 lowered the odds of DWI by 30% in Wave 5 and 20% in Wave 6, while also lowering the odds of RWI in Wave 4 and Wave 7 by 20%.

Mother knowledge of drinking in Waves 1-3 was associated with 60% lower odds of DWI in Wave 4, but did not lower odds in any wave for RWI.

Overall, parental support for not drinking lowered odds for DWI by 40% in Waves 4 and 5, and by 30% in Wave 7 while also lowering odds of RWI in Wave 4 by 20%.

The results are consistent with other studies examining risky driving behavior and binge drinking in adolescent populations, but researchers noted that “to an important but limited extent, parental practices while the teenager is in high school may protect against DWI, RWI, and blackouts as adolescents move into early adulthood.”

“Our findings are relevant to prevention programs that seek to incorporate alcohol screening with intentional inquiry about binge drinking. Moreover, our results may be instructive to programs that seek to leverage facets of parental practices to reduce health-risk contexts for youth,” Dr. Vaca and colleagues concluded. “Such prevention activities coupled with strengthening of policies and practices reducing adolescents’ access to alcohol could reduce later major alcohol-related health-risk behaviors and their consequences.”

Opioid misuse and risky behavior

In a second study, Devika Bhatia, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues examined opioid misuse in a nationally-representative sample of 14,765 adolescents from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey. The researchers measured opioid misuse by categorizing adolescents into groups based on whether they had ever misused prescription opioids and whether they had engaged in risky driving behavior, violent behavior, risky sexual behavior, had a history of substance abuse, or attempted suicide.

Dr. Bhatia and colleagues found 14% of adolescents in the study reported misusing opioids, with an overrepresentation of 17-year-old and 18-year-old participants reporting opioid misuse (P less than .0001). there were no statistically significant difference between those who misused opioids and those who did not in terms of race, ethnicity, or sex.

Those adolescents who reported misusing opioids were 2.8 times more likely to not use a seatbelt; were 2.8 times more likely to have RWI; were 5.8 times more likely to have DWI; or 2.3 times more likely to have texted or emailed while driving. In each of these cases, P was less than .0001.

Adolescents who misused opioids also had significantly increased odds of engaging in risky sexual behaviors such as having sex before 13 years (3.9 times); having sex with four or more partners (4.8 times); using substances before sex (3.6 times); and not using a condom before sex (2.0 times). In each of these cases, P was less than .0001.

Additionally, adolescents in this category were between 5.4 times and 22.3 times more likely to use other substances (P less than .0001 for 10 variables); 4.9 times more likely to have attempted suicide (P less than .0001); or more likely to have engaged in violent behavior such as getting into physical fights (4.0 times), carrying a weapon (3.4 times) or a gun (5.1 times) within the last 30 days. In the four latter cases, P was less than .0001.

“With the ongoing opioid epidemic, pediatricians and child psychiatrists are likely to be more attuned to opioid misuse in their patients,” Dr. Bhatia and colleagues concluded. “If youth are screening positive for opioid misuse, pediatricians, nurses, social workers, child psychiatrists, and other providers assessing adolescents may have a new, broad range of other risky behaviors for which to screen regardless of the direction of the association.”

Substance use screening for treating substance use disorder traditionally has been is provided by a specialist, Jessica A. Kulak, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “However, integration of care services may help to change societal norms around problematic substance use – both by decreasing stigma associated with substance use, as well as increasing clinicians’ preparedness, knowledge, and confidence in preventing and intervening on adolescents’ substance experimentation and use.” She recommended that clinicians in primary care improve their training by using the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment program, which is available as a free online course.

Confidentiality is important in adolescent health, said Dr. Kulak, who is an assistant professor in the department of health, nutrition, and dietetics at State University of New York at Buffalo. “When discussing sensitive topics, such as binge drinking and opioid misuse, adolescents may fear that these or other risky activities may be disclosed to parents or law enforcement officials. Therefore, adolescent health providers should be aware of local, state, and federal laws pertaining to the confidentiality of minors.”

She added, “adolescents are often susceptible to others’ influences, so having open communication and support from a trusted adult – be it a parent or clinician – may also be protective against risky behaviors.”

The study by Vaca et al. was funded by the National Institutes of Health with support from the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; the National Institute on Drug Abuse; and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration. The study by Bhatia et al. had no external funding. The authors from both studies reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Kulak said she had no financial disclosures or other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vaca FE et al. Pediatrics. 2020; doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-4095. Bhatia D et al. Pediatrics. 2020; doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2470.

These newly published reports indicate the high prevalence of risky behaviors and their associations – cross-sectionally and longitudinally – with major threats to adolescent health – so asking about alcohol use, opioid misuse, and associated health risks is truly “in the lane” of clinicians, school professionals, and parents who see and care about adolescents.

At this point, I think it’s incontrovertible that clinicians should screen adolescents to learn about their physical, emotional, and behavioral health. And they should seek opportunities for professional training, skills development, and expansion of their professional networks so they are able to address – individually or collaboratively via referrals – the behavioral and psychosocial health risks of their patients.

The good news is that there is growing awareness of the importance of using validated screening tools to identify patient behavioral health risks – including those pertaining to adolescent and young adult alcohol use and opioid misuse. “Best practice” dictates that screening approaches rely on asking questions using structured tools; intuition and “just winging it” are not effective or reliable for identifying patient behavior. Forward-looking clinics and practices could be asking patients to report about health behaviors in the waiting room (on a computer tablet, for example), or even remotely (using a secure app or data collection tool) in advance of a visit. Asking should be periodic – since behaviors can change fairly rapidly among young people. The benefit is that patient-reported information can be processed in advance to cue clinician follow-up and intervention. And youth tend to share more about their behaviors when they are asked electronically, rather than face to face. Intelligent screens can provide near real-time estimation of risk – to support in-office brief intervention tailored to the risk level of a young person or to trigger follow-up.

These studies indicate that binge alcohol use and misuse of prescription opioids among adolescents are real, pervasive, and deserving of our considered attention. There is no magic bullet. However busy clinicians may have a significant role to play in identifying and addressing these problems.

Elissa Weitzman, ScD, MSc, is an associate professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and an associate scientist based in adolescent/young adult medicine and the computational health informatics program at Boston Children’s Hospital. She was asked to comment on the articles by Vaca et al. and Bhatia et al. Dr. Weitzman said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

These newly published reports indicate the high prevalence of risky behaviors and their associations – cross-sectionally and longitudinally – with major threats to adolescent health – so asking about alcohol use, opioid misuse, and associated health risks is truly “in the lane” of clinicians, school professionals, and parents who see and care about adolescents.

At this point, I think it’s incontrovertible that clinicians should screen adolescents to learn about their physical, emotional, and behavioral health. And they should seek opportunities for professional training, skills development, and expansion of their professional networks so they are able to address – individually or collaboratively via referrals – the behavioral and psychosocial health risks of their patients.

The good news is that there is growing awareness of the importance of using validated screening tools to identify patient behavioral health risks – including those pertaining to adolescent and young adult alcohol use and opioid misuse. “Best practice” dictates that screening approaches rely on asking questions using structured tools; intuition and “just winging it” are not effective or reliable for identifying patient behavior. Forward-looking clinics and practices could be asking patients to report about health behaviors in the waiting room (on a computer tablet, for example), or even remotely (using a secure app or data collection tool) in advance of a visit. Asking should be periodic – since behaviors can change fairly rapidly among young people. The benefit is that patient-reported information can be processed in advance to cue clinician follow-up and intervention. And youth tend to share more about their behaviors when they are asked electronically, rather than face to face. Intelligent screens can provide near real-time estimation of risk – to support in-office brief intervention tailored to the risk level of a young person or to trigger follow-up.

These studies indicate that binge alcohol use and misuse of prescription opioids among adolescents are real, pervasive, and deserving of our considered attention. There is no magic bullet. However busy clinicians may have a significant role to play in identifying and addressing these problems.

Elissa Weitzman, ScD, MSc, is an associate professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and an associate scientist based in adolescent/young adult medicine and the computational health informatics program at Boston Children’s Hospital. She was asked to comment on the articles by Vaca et al. and Bhatia et al. Dr. Weitzman said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

These newly published reports indicate the high prevalence of risky behaviors and their associations – cross-sectionally and longitudinally – with major threats to adolescent health – so asking about alcohol use, opioid misuse, and associated health risks is truly “in the lane” of clinicians, school professionals, and parents who see and care about adolescents.

At this point, I think it’s incontrovertible that clinicians should screen adolescents to learn about their physical, emotional, and behavioral health. And they should seek opportunities for professional training, skills development, and expansion of their professional networks so they are able to address – individually or collaboratively via referrals – the behavioral and psychosocial health risks of their patients.

The good news is that there is growing awareness of the importance of using validated screening tools to identify patient behavioral health risks – including those pertaining to adolescent and young adult alcohol use and opioid misuse. “Best practice” dictates that screening approaches rely on asking questions using structured tools; intuition and “just winging it” are not effective or reliable for identifying patient behavior. Forward-looking clinics and practices could be asking patients to report about health behaviors in the waiting room (on a computer tablet, for example), or even remotely (using a secure app or data collection tool) in advance of a visit. Asking should be periodic – since behaviors can change fairly rapidly among young people. The benefit is that patient-reported information can be processed in advance to cue clinician follow-up and intervention. And youth tend to share more about their behaviors when they are asked electronically, rather than face to face. Intelligent screens can provide near real-time estimation of risk – to support in-office brief intervention tailored to the risk level of a young person or to trigger follow-up.

These studies indicate that binge alcohol use and misuse of prescription opioids among adolescents are real, pervasive, and deserving of our considered attention. There is no magic bullet. However busy clinicians may have a significant role to play in identifying and addressing these problems.

Elissa Weitzman, ScD, MSc, is an associate professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and an associate scientist based in adolescent/young adult medicine and the computational health informatics program at Boston Children’s Hospital. She was asked to comment on the articles by Vaca et al. and Bhatia et al. Dr. Weitzman said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Binge drinking and misuse of opioids led to risky behavior during adolescence, two studies from the journal Pediatrics highlighted. And the binge drinking in high school may predict risky driving behaviors up to 4 years after high school.

Federico E. Vaca, MD, of the developmental neurocognitive driving simulation research center at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues examined the associations between risky driving behaviors and binge drinking of 2,785 adolescents in the nationally representative, longitudinal NEXT Generation Health Study. The researchers studied the effects of binge drinking on driving while impaired (DWI), riding with an impaired driver (RWI), blackouts, extreme binge drinking, and risky driving.

The adolescents were studied across seven waves, with Wave 1 beginning in the 2009-2010 school year (10th grade; mean age, 16 years), and data extended up to 4 years after high school. Of all adolescents enrolled, 91% completed Wave 1, 88% completed Wave 2, 86% completed Wave 3 (12th grade), 78% completed Wave 4, 79% completed Wave 5, 84% completed Wave 6, and 83% completed Wave 7 (4 years after leaving high school) of the study.

High school binge drinking predicts later risky behavior

About one-quarter of adolescents reported binge drinking in Waves 1-3, with an incidence of 27% in Wave 1, 24% in Wave 2, and 27% in Wave 3. Adolescents who reported binge drinking in Wave 3 had a higher likelihood of DWI in subsequent waves, with nearly six times higher odds in Wave 5 and more than twice as likely in Wave 7, researchers said. Binge drinking in Wave 3 also was associated with greater than four times higher odds of RWI in Wave 4, and more than two and a half times higher odds of RWI in Wave 7. Among adolescents who reported binge drinking across 3 years in high school, there was a higher likelihood of extreme binge drinking in Wave 7, and higher likelihood of risky driving after graduating.

Impact of parental knowledge of drinking

in some waves. Father monitoring knowledge of drinking in Waves 1-3 lowered the odds of DWI by 30% in Wave 5 and 20% in Wave 6, while also lowering the odds of RWI in Wave 4 and Wave 7 by 20%.

Mother knowledge of drinking in Waves 1-3 was associated with 60% lower odds of DWI in Wave 4, but did not lower odds in any wave for RWI.

Overall, parental support for not drinking lowered odds for DWI by 40% in Waves 4 and 5, and by 30% in Wave 7 while also lowering odds of RWI in Wave 4 by 20%.

The results are consistent with other studies examining risky driving behavior and binge drinking in adolescent populations, but researchers noted that “to an important but limited extent, parental practices while the teenager is in high school may protect against DWI, RWI, and blackouts as adolescents move into early adulthood.”

“Our findings are relevant to prevention programs that seek to incorporate alcohol screening with intentional inquiry about binge drinking. Moreover, our results may be instructive to programs that seek to leverage facets of parental practices to reduce health-risk contexts for youth,” Dr. Vaca and colleagues concluded. “Such prevention activities coupled with strengthening of policies and practices reducing adolescents’ access to alcohol could reduce later major alcohol-related health-risk behaviors and their consequences.”

Opioid misuse and risky behavior

In a second study, Devika Bhatia, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues examined opioid misuse in a nationally-representative sample of 14,765 adolescents from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey. The researchers measured opioid misuse by categorizing adolescents into groups based on whether they had ever misused prescription opioids and whether they had engaged in risky driving behavior, violent behavior, risky sexual behavior, had a history of substance abuse, or attempted suicide.

Dr. Bhatia and colleagues found 14% of adolescents in the study reported misusing opioids, with an overrepresentation of 17-year-old and 18-year-old participants reporting opioid misuse (P less than .0001). there were no statistically significant difference between those who misused opioids and those who did not in terms of race, ethnicity, or sex.

Those adolescents who reported misusing opioids were 2.8 times more likely to not use a seatbelt; were 2.8 times more likely to have RWI; were 5.8 times more likely to have DWI; or 2.3 times more likely to have texted or emailed while driving. In each of these cases, P was less than .0001.

Adolescents who misused opioids also had significantly increased odds of engaging in risky sexual behaviors such as having sex before 13 years (3.9 times); having sex with four or more partners (4.8 times); using substances before sex (3.6 times); and not using a condom before sex (2.0 times). In each of these cases, P was less than .0001.

Additionally, adolescents in this category were between 5.4 times and 22.3 times more likely to use other substances (P less than .0001 for 10 variables); 4.9 times more likely to have attempted suicide (P less than .0001); or more likely to have engaged in violent behavior such as getting into physical fights (4.0 times), carrying a weapon (3.4 times) or a gun (5.1 times) within the last 30 days. In the four latter cases, P was less than .0001.

“With the ongoing opioid epidemic, pediatricians and child psychiatrists are likely to be more attuned to opioid misuse in their patients,” Dr. Bhatia and colleagues concluded. “If youth are screening positive for opioid misuse, pediatricians, nurses, social workers, child psychiatrists, and other providers assessing adolescents may have a new, broad range of other risky behaviors for which to screen regardless of the direction of the association.”

Substance use screening for treating substance use disorder traditionally has been is provided by a specialist, Jessica A. Kulak, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “However, integration of care services may help to change societal norms around problematic substance use – both by decreasing stigma associated with substance use, as well as increasing clinicians’ preparedness, knowledge, and confidence in preventing and intervening on adolescents’ substance experimentation and use.” She recommended that clinicians in primary care improve their training by using the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment program, which is available as a free online course.

Confidentiality is important in adolescent health, said Dr. Kulak, who is an assistant professor in the department of health, nutrition, and dietetics at State University of New York at Buffalo. “When discussing sensitive topics, such as binge drinking and opioid misuse, adolescents may fear that these or other risky activities may be disclosed to parents or law enforcement officials. Therefore, adolescent health providers should be aware of local, state, and federal laws pertaining to the confidentiality of minors.”

She added, “adolescents are often susceptible to others’ influences, so having open communication and support from a trusted adult – be it a parent or clinician – may also be protective against risky behaviors.”

The study by Vaca et al. was funded by the National Institutes of Health with support from the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; the National Institute on Drug Abuse; and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration. The study by Bhatia et al. had no external funding. The authors from both studies reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Kulak said she had no financial disclosures or other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vaca FE et al. Pediatrics. 2020; doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-4095. Bhatia D et al. Pediatrics. 2020; doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2470.

Binge drinking and misuse of opioids led to risky behavior during adolescence, two studies from the journal Pediatrics highlighted. And the binge drinking in high school may predict risky driving behaviors up to 4 years after high school.

Federico E. Vaca, MD, of the developmental neurocognitive driving simulation research center at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues examined the associations between risky driving behaviors and binge drinking of 2,785 adolescents in the nationally representative, longitudinal NEXT Generation Health Study. The researchers studied the effects of binge drinking on driving while impaired (DWI), riding with an impaired driver (RWI), blackouts, extreme binge drinking, and risky driving.

The adolescents were studied across seven waves, with Wave 1 beginning in the 2009-2010 school year (10th grade; mean age, 16 years), and data extended up to 4 years after high school. Of all adolescents enrolled, 91% completed Wave 1, 88% completed Wave 2, 86% completed Wave 3 (12th grade), 78% completed Wave 4, 79% completed Wave 5, 84% completed Wave 6, and 83% completed Wave 7 (4 years after leaving high school) of the study.

High school binge drinking predicts later risky behavior

About one-quarter of adolescents reported binge drinking in Waves 1-3, with an incidence of 27% in Wave 1, 24% in Wave 2, and 27% in Wave 3. Adolescents who reported binge drinking in Wave 3 had a higher likelihood of DWI in subsequent waves, with nearly six times higher odds in Wave 5 and more than twice as likely in Wave 7, researchers said. Binge drinking in Wave 3 also was associated with greater than four times higher odds of RWI in Wave 4, and more than two and a half times higher odds of RWI in Wave 7. Among adolescents who reported binge drinking across 3 years in high school, there was a higher likelihood of extreme binge drinking in Wave 7, and higher likelihood of risky driving after graduating.

Impact of parental knowledge of drinking

in some waves. Father monitoring knowledge of drinking in Waves 1-3 lowered the odds of DWI by 30% in Wave 5 and 20% in Wave 6, while also lowering the odds of RWI in Wave 4 and Wave 7 by 20%.

Mother knowledge of drinking in Waves 1-3 was associated with 60% lower odds of DWI in Wave 4, but did not lower odds in any wave for RWI.

Overall, parental support for not drinking lowered odds for DWI by 40% in Waves 4 and 5, and by 30% in Wave 7 while also lowering odds of RWI in Wave 4 by 20%.

The results are consistent with other studies examining risky driving behavior and binge drinking in adolescent populations, but researchers noted that “to an important but limited extent, parental practices while the teenager is in high school may protect against DWI, RWI, and blackouts as adolescents move into early adulthood.”

“Our findings are relevant to prevention programs that seek to incorporate alcohol screening with intentional inquiry about binge drinking. Moreover, our results may be instructive to programs that seek to leverage facets of parental practices to reduce health-risk contexts for youth,” Dr. Vaca and colleagues concluded. “Such prevention activities coupled with strengthening of policies and practices reducing adolescents’ access to alcohol could reduce later major alcohol-related health-risk behaviors and their consequences.”

Opioid misuse and risky behavior

In a second study, Devika Bhatia, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues examined opioid misuse in a nationally-representative sample of 14,765 adolescents from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey. The researchers measured opioid misuse by categorizing adolescents into groups based on whether they had ever misused prescription opioids and whether they had engaged in risky driving behavior, violent behavior, risky sexual behavior, had a history of substance abuse, or attempted suicide.

Dr. Bhatia and colleagues found 14% of adolescents in the study reported misusing opioids, with an overrepresentation of 17-year-old and 18-year-old participants reporting opioid misuse (P less than .0001). there were no statistically significant difference between those who misused opioids and those who did not in terms of race, ethnicity, or sex.

Those adolescents who reported misusing opioids were 2.8 times more likely to not use a seatbelt; were 2.8 times more likely to have RWI; were 5.8 times more likely to have DWI; or 2.3 times more likely to have texted or emailed while driving. In each of these cases, P was less than .0001.

Adolescents who misused opioids also had significantly increased odds of engaging in risky sexual behaviors such as having sex before 13 years (3.9 times); having sex with four or more partners (4.8 times); using substances before sex (3.6 times); and not using a condom before sex (2.0 times). In each of these cases, P was less than .0001.

Additionally, adolescents in this category were between 5.4 times and 22.3 times more likely to use other substances (P less than .0001 for 10 variables); 4.9 times more likely to have attempted suicide (P less than .0001); or more likely to have engaged in violent behavior such as getting into physical fights (4.0 times), carrying a weapon (3.4 times) or a gun (5.1 times) within the last 30 days. In the four latter cases, P was less than .0001.

“With the ongoing opioid epidemic, pediatricians and child psychiatrists are likely to be more attuned to opioid misuse in their patients,” Dr. Bhatia and colleagues concluded. “If youth are screening positive for opioid misuse, pediatricians, nurses, social workers, child psychiatrists, and other providers assessing adolescents may have a new, broad range of other risky behaviors for which to screen regardless of the direction of the association.”

Substance use screening for treating substance use disorder traditionally has been is provided by a specialist, Jessica A. Kulak, PhD, MPH, said in an interview. “However, integration of care services may help to change societal norms around problematic substance use – both by decreasing stigma associated with substance use, as well as increasing clinicians’ preparedness, knowledge, and confidence in preventing and intervening on adolescents’ substance experimentation and use.” She recommended that clinicians in primary care improve their training by using the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment program, which is available as a free online course.

Confidentiality is important in adolescent health, said Dr. Kulak, who is an assistant professor in the department of health, nutrition, and dietetics at State University of New York at Buffalo. “When discussing sensitive topics, such as binge drinking and opioid misuse, adolescents may fear that these or other risky activities may be disclosed to parents or law enforcement officials. Therefore, adolescent health providers should be aware of local, state, and federal laws pertaining to the confidentiality of minors.”

She added, “adolescents are often susceptible to others’ influences, so having open communication and support from a trusted adult – be it a parent or clinician – may also be protective against risky behaviors.”

The study by Vaca et al. was funded by the National Institutes of Health with support from the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; the National Institute on Drug Abuse; and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration. The study by Bhatia et al. had no external funding. The authors from both studies reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Kulak said she had no financial disclosures or other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vaca FE et al. Pediatrics. 2020; doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-4095. Bhatia D et al. Pediatrics. 2020; doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2470.

FROM PEDIATRICS

FDA targets flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes, but says it is not a ‘ban’

but states it is not a “ban.”

On Jan. 2, the agency issued enforcement guidance alerting companies that manufacture, distribute, and sell unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes within the next 30 days will risk FDA enforcement action.

FDA has had the authority to require premarket authorization of all e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) since August 2016, but thus far has exercised enforcement discretion regarding the need for premarket authorization for these types of products.

“By prioritizing enforcement against the products that are most widely used by children, our action today seeks to strike the right public health balance by maintaining e-cigarettes as a potential off-ramp for adults using combustible tobacco while ensuring these products don’t provide an on-ramp to nicotine addiction for our youth,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement.

The action comes in the wake of more than 2,500 vaping-related injuries being reported, including more than 50 deaths associated with vaping reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (although many are related to the use of tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] within vaping products) and a continued rise in youth use of e-cigarettes noted in government surveys.

The agency noted in a Jan. 2 statement announcing the enforcement action that, to date, no ENDS products have received a premarket authorization, “meaning that all ENDS products currently on the market are considered illegally marketed and are subject to enforcement, at any time, in the FDA’s discretion.”

FDA said it is prioritizing enforcement in 30 days against:

- Any flavored, cartridge-based ENDS product, other than those with a tobacco or menthol flavoring.

- All other ENDS products for which manufacturers are failing to take adequate measures to prevent access by minors.

- Any ENDS product that is targeted to minors or is likely to promote use by minors.

In the last category, this might include labeling or advertising resembling “kid-friendly food and drinks such as juice boxes or kid-friendly cereal; products marketed directly to minors by promoting ease of concealing the product or disguising it as another product; and products marketed with characters designed to appeal to youth,” according to the FDA statement.

As of May 12, FDA also will prioritize enforcement against any ENDS product for which the manufacturer has not submitted a premarket application. The agency will continue to exercise enforcement discretion for up to 1 year on these products if an application has been submitted, pending the review of that application.

“By not prioritizing enforcement against other flavored ENDS products in the same way as flavored cartridge-based ENDS products, the FDA has attempted to balance the public health concerns related to youth use of ENDS products with consideration regarding addicted adult cigarette smokers who may try to use ENDS products to transition away from combustible tobacco products,” the agency stated, adding that cartridge-based ENDS products are most commonly used among youth.

The FDA statement noted that the enforcement priorities outlined in the guidance document were not a “ban” on flavored or cartridge-based ENDS, noting the agency “has already accepted and begun review of several premarket applications for flavored ENDS products through the pathway that Congress established in the Tobacco Control Act. ... If a company can demonstrate to the FDA that a specific product meets the applicable standard set forth by Congress, including considering how the marketing of the product may affect youth initiation and use, then the FDA could authorize that product for sale.”

“Coupled with the recently signed legislation increasing the minimum age of sale of tobacco to 21, we believe this policy balances the urgency with which we must address the public health threat of youth use of e-cigarette products with the potential role that e-cigarettes may play in helping adult smokers transition completely away from combustible tobacco to a potentially less risky form of nicotine delivery,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “While we expect that responsible members of industry will comply with premarket requirements, we’re ready to take action against any unauthorized e-cigarette products as outlined in our priorities. We’ll also closely monitor the use rates of all e-cigarette products and take additional steps to address youth use as necessary.”

The American Medical Association criticized the action as not going far enough, even though it was a step in the right direction.

“The AMA is disappointed that menthol flavors, one of the most popular, will still be allowed, and that flavored e-liquids will remain on the market, leaving young people with easy access to alternative flavored e-cigarette products,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “If we are serious about tackling this epidemic and keeping these harmful products out of the hands of young people, a total ban on all flavored e-cigarettes, in all forms and at all locations, is prudent and urgently needed. We are pleased the administration committed today to closely monitoring the situation and trends in e-cigarette use among young people, and to taking further action if needed.”

but states it is not a “ban.”

On Jan. 2, the agency issued enforcement guidance alerting companies that manufacture, distribute, and sell unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes within the next 30 days will risk FDA enforcement action.

FDA has had the authority to require premarket authorization of all e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) since August 2016, but thus far has exercised enforcement discretion regarding the need for premarket authorization for these types of products.

“By prioritizing enforcement against the products that are most widely used by children, our action today seeks to strike the right public health balance by maintaining e-cigarettes as a potential off-ramp for adults using combustible tobacco while ensuring these products don’t provide an on-ramp to nicotine addiction for our youth,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement.

The action comes in the wake of more than 2,500 vaping-related injuries being reported, including more than 50 deaths associated with vaping reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (although many are related to the use of tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] within vaping products) and a continued rise in youth use of e-cigarettes noted in government surveys.

The agency noted in a Jan. 2 statement announcing the enforcement action that, to date, no ENDS products have received a premarket authorization, “meaning that all ENDS products currently on the market are considered illegally marketed and are subject to enforcement, at any time, in the FDA’s discretion.”

FDA said it is prioritizing enforcement in 30 days against:

- Any flavored, cartridge-based ENDS product, other than those with a tobacco or menthol flavoring.

- All other ENDS products for which manufacturers are failing to take adequate measures to prevent access by minors.

- Any ENDS product that is targeted to minors or is likely to promote use by minors.

In the last category, this might include labeling or advertising resembling “kid-friendly food and drinks such as juice boxes or kid-friendly cereal; products marketed directly to minors by promoting ease of concealing the product or disguising it as another product; and products marketed with characters designed to appeal to youth,” according to the FDA statement.

As of May 12, FDA also will prioritize enforcement against any ENDS product for which the manufacturer has not submitted a premarket application. The agency will continue to exercise enforcement discretion for up to 1 year on these products if an application has been submitted, pending the review of that application.

“By not prioritizing enforcement against other flavored ENDS products in the same way as flavored cartridge-based ENDS products, the FDA has attempted to balance the public health concerns related to youth use of ENDS products with consideration regarding addicted adult cigarette smokers who may try to use ENDS products to transition away from combustible tobacco products,” the agency stated, adding that cartridge-based ENDS products are most commonly used among youth.

The FDA statement noted that the enforcement priorities outlined in the guidance document were not a “ban” on flavored or cartridge-based ENDS, noting the agency “has already accepted and begun review of several premarket applications for flavored ENDS products through the pathway that Congress established in the Tobacco Control Act. ... If a company can demonstrate to the FDA that a specific product meets the applicable standard set forth by Congress, including considering how the marketing of the product may affect youth initiation and use, then the FDA could authorize that product for sale.”

“Coupled with the recently signed legislation increasing the minimum age of sale of tobacco to 21, we believe this policy balances the urgency with which we must address the public health threat of youth use of e-cigarette products with the potential role that e-cigarettes may play in helping adult smokers transition completely away from combustible tobacco to a potentially less risky form of nicotine delivery,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “While we expect that responsible members of industry will comply with premarket requirements, we’re ready to take action against any unauthorized e-cigarette products as outlined in our priorities. We’ll also closely monitor the use rates of all e-cigarette products and take additional steps to address youth use as necessary.”

The American Medical Association criticized the action as not going far enough, even though it was a step in the right direction.

“The AMA is disappointed that menthol flavors, one of the most popular, will still be allowed, and that flavored e-liquids will remain on the market, leaving young people with easy access to alternative flavored e-cigarette products,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “If we are serious about tackling this epidemic and keeping these harmful products out of the hands of young people, a total ban on all flavored e-cigarettes, in all forms and at all locations, is prudent and urgently needed. We are pleased the administration committed today to closely monitoring the situation and trends in e-cigarette use among young people, and to taking further action if needed.”

but states it is not a “ban.”

On Jan. 2, the agency issued enforcement guidance alerting companies that manufacture, distribute, and sell unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes within the next 30 days will risk FDA enforcement action.

FDA has had the authority to require premarket authorization of all e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) since August 2016, but thus far has exercised enforcement discretion regarding the need for premarket authorization for these types of products.

“By prioritizing enforcement against the products that are most widely used by children, our action today seeks to strike the right public health balance by maintaining e-cigarettes as a potential off-ramp for adults using combustible tobacco while ensuring these products don’t provide an on-ramp to nicotine addiction for our youth,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement.

The action comes in the wake of more than 2,500 vaping-related injuries being reported, including more than 50 deaths associated with vaping reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (although many are related to the use of tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] within vaping products) and a continued rise in youth use of e-cigarettes noted in government surveys.

The agency noted in a Jan. 2 statement announcing the enforcement action that, to date, no ENDS products have received a premarket authorization, “meaning that all ENDS products currently on the market are considered illegally marketed and are subject to enforcement, at any time, in the FDA’s discretion.”

FDA said it is prioritizing enforcement in 30 days against:

- Any flavored, cartridge-based ENDS product, other than those with a tobacco or menthol flavoring.

- All other ENDS products for which manufacturers are failing to take adequate measures to prevent access by minors.

- Any ENDS product that is targeted to minors or is likely to promote use by minors.

In the last category, this might include labeling or advertising resembling “kid-friendly food and drinks such as juice boxes or kid-friendly cereal; products marketed directly to minors by promoting ease of concealing the product or disguising it as another product; and products marketed with characters designed to appeal to youth,” according to the FDA statement.

As of May 12, FDA also will prioritize enforcement against any ENDS product for which the manufacturer has not submitted a premarket application. The agency will continue to exercise enforcement discretion for up to 1 year on these products if an application has been submitted, pending the review of that application.

“By not prioritizing enforcement against other flavored ENDS products in the same way as flavored cartridge-based ENDS products, the FDA has attempted to balance the public health concerns related to youth use of ENDS products with consideration regarding addicted adult cigarette smokers who may try to use ENDS products to transition away from combustible tobacco products,” the agency stated, adding that cartridge-based ENDS products are most commonly used among youth.

The FDA statement noted that the enforcement priorities outlined in the guidance document were not a “ban” on flavored or cartridge-based ENDS, noting the agency “has already accepted and begun review of several premarket applications for flavored ENDS products through the pathway that Congress established in the Tobacco Control Act. ... If a company can demonstrate to the FDA that a specific product meets the applicable standard set forth by Congress, including considering how the marketing of the product may affect youth initiation and use, then the FDA could authorize that product for sale.”

“Coupled with the recently signed legislation increasing the minimum age of sale of tobacco to 21, we believe this policy balances the urgency with which we must address the public health threat of youth use of e-cigarette products with the potential role that e-cigarettes may play in helping adult smokers transition completely away from combustible tobacco to a potentially less risky form of nicotine delivery,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “While we expect that responsible members of industry will comply with premarket requirements, we’re ready to take action against any unauthorized e-cigarette products as outlined in our priorities. We’ll also closely monitor the use rates of all e-cigarette products and take additional steps to address youth use as necessary.”

The American Medical Association criticized the action as not going far enough, even though it was a step in the right direction.

“The AMA is disappointed that menthol flavors, one of the most popular, will still be allowed, and that flavored e-liquids will remain on the market, leaving young people with easy access to alternative flavored e-cigarette products,” AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in a statement. “If we are serious about tackling this epidemic and keeping these harmful products out of the hands of young people, a total ban on all flavored e-cigarettes, in all forms and at all locations, is prudent and urgently needed. We are pleased the administration committed today to closely monitoring the situation and trends in e-cigarette use among young people, and to taking further action if needed.”

Lofexidine: An option for treating opioid withdrawal

Opioid use disorder (OUD) and deaths by opioid overdose are a major public health concern, especially with the advent of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.1 Enrolling patients with OUD into substance abuse treatment programs can be a difficult hurdle to cross because patients do not want to experience withdrawal. The fear of withdrawal leads many individuals to refuse appropriate interventions. For these patients, consider the alpha-2 agonist lofexidine, which was FDA-approved in 2018 to help diminish the signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal.1-3 Use of lofexidine might encourage more patients with OUD to accept substance abuse treatment.1,4,5

How to prescribe lofexidine

For decades, clinicians in Britain have prescribed lofexidine to attenuate opioid withdrawal.1An analog of clonidine, lofexidine is reportedly less likely than clonidine to induce hypotension.1,4 While this agent does not diminish drug toxicity, it can provide symptomatic relief for patients undergoing opioid withdrawal, and is efficacious as a supplement to and/or replacement for methadone, buprenorphine, clonidine, or other symptomatic pharmacotherapies.1,4,5

Lofexidine is available in 0.18-mg tablets. For patients experiencing overt symptoms of opioid withdrawal, initially prescribe 3 0.18-mg tablets, 4 times a day.3 The recommended maximum dosage is 2.88 mg/d, and each dose generally should not exceed 0.72 mg/d. Lofexidine may be continued for up to 14 days, with dosing guided by symptoms. Initiate a taper once the patient no longer experiences withdrawal symptoms.3

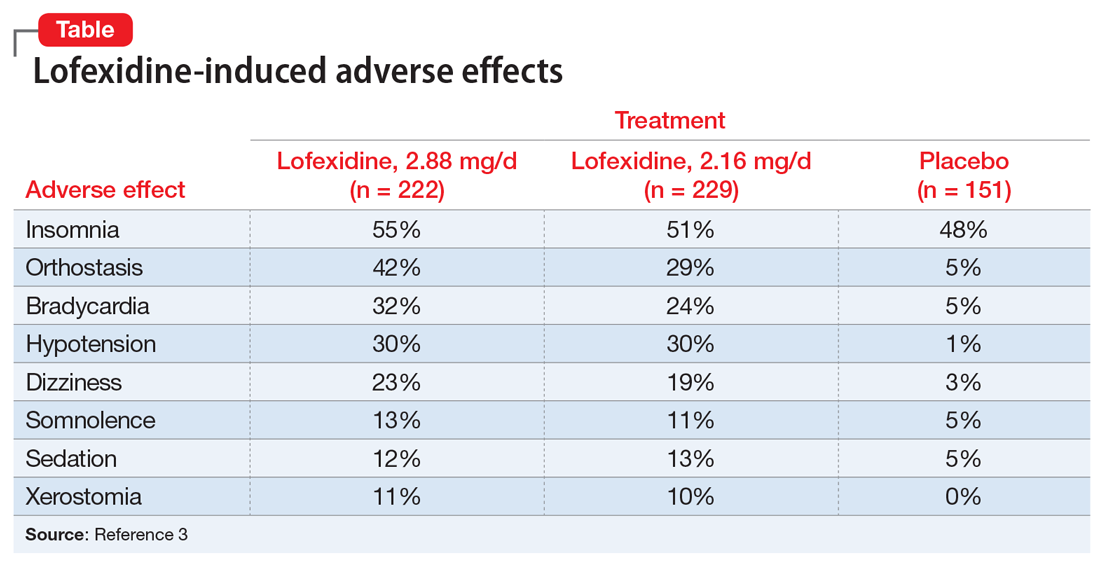

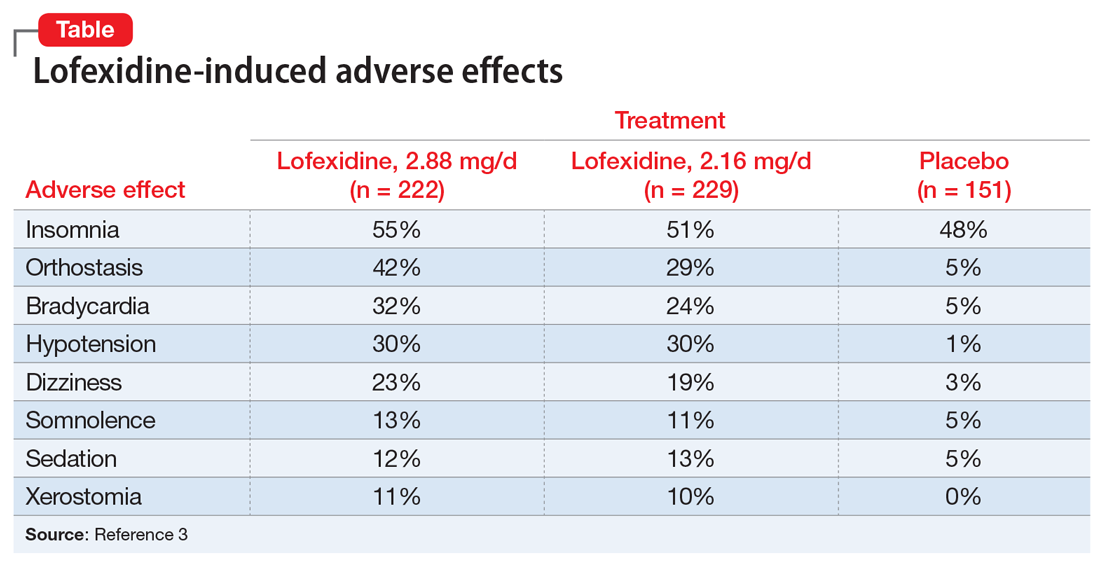

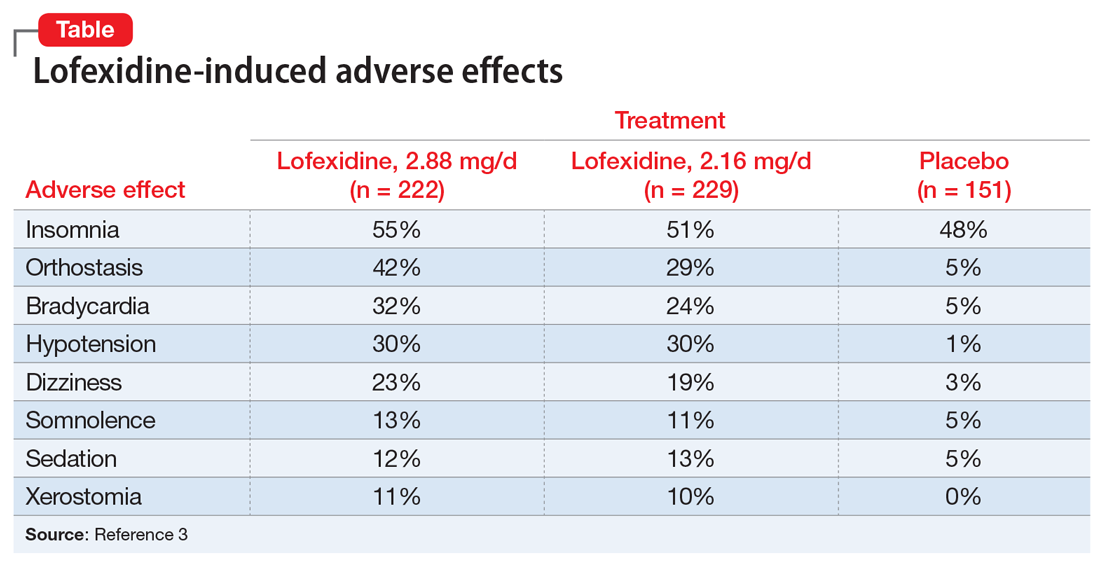

Adverse effects. Lofexidine’s efficacy and safety were evaluated in 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that included 935 participants dependent on short-acting opioids who were experiencing abrupt opioid withdrawal and received lofexidine, 2.16 or 2.88 mg/d, or placebo.3 The most common adverse effects of lofexidine were insomnia, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, hypotension, dizziness, somnolence, sedation, and dry mouth.3 In the 3 trials, these effects were reported by ≥10% of patients receiving lofexidine, and occurred more frequently compared with placebo (Table3).

Take precautions when prescribing lofexidine because it can cause QT prolongation and CNS depression, especially when co-administered with sedative agents.3 It also can result in rebound hypertension once discontinued. This may be minimized by gradually reducing the dosage.3

A pathway to OUD treatment

Lofexidine can help relieve symptoms of opioid withdrawal, such as stomach cramps, muscle spasms or twitching, feeling cold, muscular tension, and aches and pains.1-5 This new option might help clinicians encourage more patients with OUD to fully engage in substance abuse treatment.

1. Rehman SU, Maqsood MH, Bajwa H, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety profile of lofexidine hydrochloride in treating opioid withdrawal symptoms: a review of literature. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4827. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4827.

2. FDA approves the first non-opioid treatment for management of opioid withdrawal symptoms in adults. US Food & Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm607884.htm. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed December 13, 2019.

3. Lucemyra [package insert]. Louisville, KY: US WorldMeds, LLC; 2018.

4. Carnwath T, Hardman J. Randomized double-blind comparison of lofexidine and clonidine in the out-patient treatment of opiate withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50(3):251-254.

5. Gonzalez G, Oliveto A, Kosten TR. Combating opiate dependence: a comparison among the available pharmacological options. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5(4):713-725.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) and deaths by opioid overdose are a major public health concern, especially with the advent of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.1 Enrolling patients with OUD into substance abuse treatment programs can be a difficult hurdle to cross because patients do not want to experience withdrawal. The fear of withdrawal leads many individuals to refuse appropriate interventions. For these patients, consider the alpha-2 agonist lofexidine, which was FDA-approved in 2018 to help diminish the signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal.1-3 Use of lofexidine might encourage more patients with OUD to accept substance abuse treatment.1,4,5

How to prescribe lofexidine

For decades, clinicians in Britain have prescribed lofexidine to attenuate opioid withdrawal.1An analog of clonidine, lofexidine is reportedly less likely than clonidine to induce hypotension.1,4 While this agent does not diminish drug toxicity, it can provide symptomatic relief for patients undergoing opioid withdrawal, and is efficacious as a supplement to and/or replacement for methadone, buprenorphine, clonidine, or other symptomatic pharmacotherapies.1,4,5

Lofexidine is available in 0.18-mg tablets. For patients experiencing overt symptoms of opioid withdrawal, initially prescribe 3 0.18-mg tablets, 4 times a day.3 The recommended maximum dosage is 2.88 mg/d, and each dose generally should not exceed 0.72 mg/d. Lofexidine may be continued for up to 14 days, with dosing guided by symptoms. Initiate a taper once the patient no longer experiences withdrawal symptoms.3

Adverse effects. Lofexidine’s efficacy and safety were evaluated in 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that included 935 participants dependent on short-acting opioids who were experiencing abrupt opioid withdrawal and received lofexidine, 2.16 or 2.88 mg/d, or placebo.3 The most common adverse effects of lofexidine were insomnia, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, hypotension, dizziness, somnolence, sedation, and dry mouth.3 In the 3 trials, these effects were reported by ≥10% of patients receiving lofexidine, and occurred more frequently compared with placebo (Table3).

Take precautions when prescribing lofexidine because it can cause QT prolongation and CNS depression, especially when co-administered with sedative agents.3 It also can result in rebound hypertension once discontinued. This may be minimized by gradually reducing the dosage.3

A pathway to OUD treatment

Lofexidine can help relieve symptoms of opioid withdrawal, such as stomach cramps, muscle spasms or twitching, feeling cold, muscular tension, and aches and pains.1-5 This new option might help clinicians encourage more patients with OUD to fully engage in substance abuse treatment.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) and deaths by opioid overdose are a major public health concern, especially with the advent of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.1 Enrolling patients with OUD into substance abuse treatment programs can be a difficult hurdle to cross because patients do not want to experience withdrawal. The fear of withdrawal leads many individuals to refuse appropriate interventions. For these patients, consider the alpha-2 agonist lofexidine, which was FDA-approved in 2018 to help diminish the signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal.1-3 Use of lofexidine might encourage more patients with OUD to accept substance abuse treatment.1,4,5

How to prescribe lofexidine

For decades, clinicians in Britain have prescribed lofexidine to attenuate opioid withdrawal.1An analog of clonidine, lofexidine is reportedly less likely than clonidine to induce hypotension.1,4 While this agent does not diminish drug toxicity, it can provide symptomatic relief for patients undergoing opioid withdrawal, and is efficacious as a supplement to and/or replacement for methadone, buprenorphine, clonidine, or other symptomatic pharmacotherapies.1,4,5

Lofexidine is available in 0.18-mg tablets. For patients experiencing overt symptoms of opioid withdrawal, initially prescribe 3 0.18-mg tablets, 4 times a day.3 The recommended maximum dosage is 2.88 mg/d, and each dose generally should not exceed 0.72 mg/d. Lofexidine may be continued for up to 14 days, with dosing guided by symptoms. Initiate a taper once the patient no longer experiences withdrawal symptoms.3

Adverse effects. Lofexidine’s efficacy and safety were evaluated in 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that included 935 participants dependent on short-acting opioids who were experiencing abrupt opioid withdrawal and received lofexidine, 2.16 or 2.88 mg/d, or placebo.3 The most common adverse effects of lofexidine were insomnia, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, hypotension, dizziness, somnolence, sedation, and dry mouth.3 In the 3 trials, these effects were reported by ≥10% of patients receiving lofexidine, and occurred more frequently compared with placebo (Table3).

Take precautions when prescribing lofexidine because it can cause QT prolongation and CNS depression, especially when co-administered with sedative agents.3 It also can result in rebound hypertension once discontinued. This may be minimized by gradually reducing the dosage.3

A pathway to OUD treatment

Lofexidine can help relieve symptoms of opioid withdrawal, such as stomach cramps, muscle spasms or twitching, feeling cold, muscular tension, and aches and pains.1-5 This new option might help clinicians encourage more patients with OUD to fully engage in substance abuse treatment.

1. Rehman SU, Maqsood MH, Bajwa H, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety profile of lofexidine hydrochloride in treating opioid withdrawal symptoms: a review of literature. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4827. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4827.

2. FDA approves the first non-opioid treatment for management of opioid withdrawal symptoms in adults. US Food & Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm607884.htm. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed December 13, 2019.

3. Lucemyra [package insert]. Louisville, KY: US WorldMeds, LLC; 2018.

4. Carnwath T, Hardman J. Randomized double-blind comparison of lofexidine and clonidine in the out-patient treatment of opiate withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50(3):251-254.

5. Gonzalez G, Oliveto A, Kosten TR. Combating opiate dependence: a comparison among the available pharmacological options. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5(4):713-725.

1. Rehman SU, Maqsood MH, Bajwa H, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety profile of lofexidine hydrochloride in treating opioid withdrawal symptoms: a review of literature. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4827. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4827.

2. FDA approves the first non-opioid treatment for management of opioid withdrawal symptoms in adults. US Food & Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm607884.htm. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed December 13, 2019.

3. Lucemyra [package insert]. Louisville, KY: US WorldMeds, LLC; 2018.

4. Carnwath T, Hardman J. Randomized double-blind comparison of lofexidine and clonidine in the out-patient treatment of opiate withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50(3):251-254.

5. Gonzalez G, Oliveto A, Kosten TR. Combating opiate dependence: a comparison among the available pharmacological options. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5(4):713-725.

Dual e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use compound respiratory disease risk

according to recent longitudinal analysis published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

E-cigarettes have been promoted as a safer alternative to combustible tobacco, and until recently, there has been little and conflicting evidence by which to test this hypothesis. This study conducted by Dharma N. Bhatta, PhD, and Stanton A. Glantz, PhD, of the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco, is one of the first longitudinal examinations of e-cigarette use and controlling for combustible tobacco use.

Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz performed a multivariable, logistic regression analysis of adults enrolled in the nationally representative, population-based, longitudinal Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study. The researchers analyzed the tobacco use of adults in the study in three waves, following them through wave 1 (September 2013 to December 2014), wave 2 (October 2014 to October 2015), and wave 3 (October 2015 to October 2016), analyzing the data between 2018 and 2019. Overall, wave 1 began with 32,320 participants, and 15.1% of adults reported respiratory disease at baseline.

Lung or respiratory disease was assessed by asking participants whether they had been told by a health professional that they had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or asthma. The researchers defined e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use as participants who never, currently, or formerly used e-cigarettes or smoked combustible tobacco. Participants who indicated they used e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco frequently or infrequently were placed in the current-user group, while past users were those participants who said they used to, but no longer use e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco.

The results showed former e-cigarette use (adjusted odds ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.46) and current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.17-1.49) were associated with an increased risk of having incident respiratory disease.

The data showed a not unexpected statistically significant association between former combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.14-1.47) as well as current combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.42-1.82) and incident respiratory disease risk.

There was a statistically significant association between respiratory disease and former or current e-cigarette use for adults who did not have respiratory disease at baseline, after adjusting for factors such as current combustible tobacco use, clinical variables, and demographic differences. Participants in wave 1 who reported former (aOR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07-1.60) or current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.03-1.61) had a significantly higher risk of developing incident respiratory disease in subsequent waves. There was also a statistically significant association between use of combustible tobacco and subsequent respiratory disease in later waves of the study (aOR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.92-3.41), which the researchers noted was independent of the usual risks associated with combustible tobacco.

The investigators also looked at the link between dual use of e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco and respiratory disease risk. “The much more common pattern is dual use, in which an e-cigarette user continues to smoke combusted tobacco products at the same time (93.7% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 91.2% at wave 3 also used combustible tobacco; 73.3% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 64.9% at wave 3 also smoked cigarettes),” they wrote.

The odds of developing respiratory disease for participants who used both e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco were 3.30, compared with a participant who never used e-cigarettes, with similar results seen when comparing e-cigarettes and cigarettes.

“Although switching from combustible tobacco, including cigarettes, to e-cigarettes theoretically could reduce the risk of developing respiratory disease, current evidence indicates a high prevalence of dual use, which is associated with in-creased risk beyond combustible tobacco use,” the investigators wrote.

Harold J. Farber, MD, FCCP, professor of pediatrics in the pulmonary section at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, said in an interview that the increased respiratory risk among dual users, who are likely using e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco together as a way to quit smoking, is particularly concerning.

“There is substantial reason to be concerned about efficacy of electronic cigarette products. Real-world observational studies have shown that, on average, tobacco smokers who use electronic cigarettes are less likely to stop smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes,” he said. “People who have stopped tobacco smoking but use electronic cigarettes are more likely to relapse to tobacco smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes.”

Dr. Farber noted that there are other Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for treating tobacco addiction. In addition, the World Health Organization, American Medical Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and FDA have all advised that e-cigarettes should not be used as smoking cessation aids, he said, especially in light of current outbreak of life-threatening e-cigarette and vaping lung injuries currently being investigated by the CDC and FDA.

“These study results suggest that the CDC reports of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury are likely to be just the tip of the iceberg,” he said. “Although the CDC has identified vitamin E acetate–containing products as an important culprit, it is unlikely to be the only one. There are many substances in the emissions of e-cigarettes that have known irritant and/or toxic effects on the airways.”

Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz acknowledged several limitations in their analysis, including the possibility of recall bias, not distinguishing between nondaily and daily e-cigarette or combustible tobacco use, and combining respiratory conditions together to achieve adequate power. The study shows an association, but the mechanism by which e-cigarettes may contribute to the development of lung disease remains under investigation.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse; the National Cancer Institute; the FDA Center for Tobacco Products; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the University of California, San Francisco Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Global Cancer Program. Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bhatta DN, Glantz SA. Am J Prev Med. 2019 Dec 16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.028.

according to recent longitudinal analysis published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

E-cigarettes have been promoted as a safer alternative to combustible tobacco, and until recently, there has been little and conflicting evidence by which to test this hypothesis. This study conducted by Dharma N. Bhatta, PhD, and Stanton A. Glantz, PhD, of the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco, is one of the first longitudinal examinations of e-cigarette use and controlling for combustible tobacco use.

Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz performed a multivariable, logistic regression analysis of adults enrolled in the nationally representative, population-based, longitudinal Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study. The researchers analyzed the tobacco use of adults in the study in three waves, following them through wave 1 (September 2013 to December 2014), wave 2 (October 2014 to October 2015), and wave 3 (October 2015 to October 2016), analyzing the data between 2018 and 2019. Overall, wave 1 began with 32,320 participants, and 15.1% of adults reported respiratory disease at baseline.

Lung or respiratory disease was assessed by asking participants whether they had been told by a health professional that they had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or asthma. The researchers defined e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use as participants who never, currently, or formerly used e-cigarettes or smoked combustible tobacco. Participants who indicated they used e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco frequently or infrequently were placed in the current-user group, while past users were those participants who said they used to, but no longer use e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco.

The results showed former e-cigarette use (adjusted odds ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.46) and current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.17-1.49) were associated with an increased risk of having incident respiratory disease.

The data showed a not unexpected statistically significant association between former combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.14-1.47) as well as current combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.42-1.82) and incident respiratory disease risk.

There was a statistically significant association between respiratory disease and former or current e-cigarette use for adults who did not have respiratory disease at baseline, after adjusting for factors such as current combustible tobacco use, clinical variables, and demographic differences. Participants in wave 1 who reported former (aOR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07-1.60) or current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.03-1.61) had a significantly higher risk of developing incident respiratory disease in subsequent waves. There was also a statistically significant association between use of combustible tobacco and subsequent respiratory disease in later waves of the study (aOR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.92-3.41), which the researchers noted was independent of the usual risks associated with combustible tobacco.

The investigators also looked at the link between dual use of e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco and respiratory disease risk. “The much more common pattern is dual use, in which an e-cigarette user continues to smoke combusted tobacco products at the same time (93.7% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 91.2% at wave 3 also used combustible tobacco; 73.3% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 64.9% at wave 3 also smoked cigarettes),” they wrote.

The odds of developing respiratory disease for participants who used both e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco were 3.30, compared with a participant who never used e-cigarettes, with similar results seen when comparing e-cigarettes and cigarettes.

“Although switching from combustible tobacco, including cigarettes, to e-cigarettes theoretically could reduce the risk of developing respiratory disease, current evidence indicates a high prevalence of dual use, which is associated with in-creased risk beyond combustible tobacco use,” the investigators wrote.

Harold J. Farber, MD, FCCP, professor of pediatrics in the pulmonary section at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, said in an interview that the increased respiratory risk among dual users, who are likely using e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco together as a way to quit smoking, is particularly concerning.

“There is substantial reason to be concerned about efficacy of electronic cigarette products. Real-world observational studies have shown that, on average, tobacco smokers who use electronic cigarettes are less likely to stop smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes,” he said. “People who have stopped tobacco smoking but use electronic cigarettes are more likely to relapse to tobacco smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes.”

Dr. Farber noted that there are other Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for treating tobacco addiction. In addition, the World Health Organization, American Medical Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and FDA have all advised that e-cigarettes should not be used as smoking cessation aids, he said, especially in light of current outbreak of life-threatening e-cigarette and vaping lung injuries currently being investigated by the CDC and FDA.

“These study results suggest that the CDC reports of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury are likely to be just the tip of the iceberg,” he said. “Although the CDC has identified vitamin E acetate–containing products as an important culprit, it is unlikely to be the only one. There are many substances in the emissions of e-cigarettes that have known irritant and/or toxic effects on the airways.”

Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz acknowledged several limitations in their analysis, including the possibility of recall bias, not distinguishing between nondaily and daily e-cigarette or combustible tobacco use, and combining respiratory conditions together to achieve adequate power. The study shows an association, but the mechanism by which e-cigarettes may contribute to the development of lung disease remains under investigation.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse; the National Cancer Institute; the FDA Center for Tobacco Products; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the University of California, San Francisco Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Global Cancer Program. Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bhatta DN, Glantz SA. Am J Prev Med. 2019 Dec 16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.028.

according to recent longitudinal analysis published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

E-cigarettes have been promoted as a safer alternative to combustible tobacco, and until recently, there has been little and conflicting evidence by which to test this hypothesis. This study conducted by Dharma N. Bhatta, PhD, and Stanton A. Glantz, PhD, of the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco, is one of the first longitudinal examinations of e-cigarette use and controlling for combustible tobacco use.

Dr. Bhatta and Dr. Glantz performed a multivariable, logistic regression analysis of adults enrolled in the nationally representative, population-based, longitudinal Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study. The researchers analyzed the tobacco use of adults in the study in three waves, following them through wave 1 (September 2013 to December 2014), wave 2 (October 2014 to October 2015), and wave 3 (October 2015 to October 2016), analyzing the data between 2018 and 2019. Overall, wave 1 began with 32,320 participants, and 15.1% of adults reported respiratory disease at baseline.

Lung or respiratory disease was assessed by asking participants whether they had been told by a health professional that they had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or asthma. The researchers defined e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use as participants who never, currently, or formerly used e-cigarettes or smoked combustible tobacco. Participants who indicated they used e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco frequently or infrequently were placed in the current-user group, while past users were those participants who said they used to, but no longer use e-cigarettes or combustible tobacco.

The results showed former e-cigarette use (adjusted odds ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-1.46) and current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.17-1.49) were associated with an increased risk of having incident respiratory disease.

The data showed a not unexpected statistically significant association between former combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.14-1.47) as well as current combustible tobacco use (aOR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.42-1.82) and incident respiratory disease risk.

There was a statistically significant association between respiratory disease and former or current e-cigarette use for adults who did not have respiratory disease at baseline, after adjusting for factors such as current combustible tobacco use, clinical variables, and demographic differences. Participants in wave 1 who reported former (aOR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07-1.60) or current e-cigarette use (aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.03-1.61) had a significantly higher risk of developing incident respiratory disease in subsequent waves. There was also a statistically significant association between use of combustible tobacco and subsequent respiratory disease in later waves of the study (aOR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.92-3.41), which the researchers noted was independent of the usual risks associated with combustible tobacco.

The investigators also looked at the link between dual use of e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco and respiratory disease risk. “The much more common pattern is dual use, in which an e-cigarette user continues to smoke combusted tobacco products at the same time (93.7% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 91.2% at wave 3 also used combustible tobacco; 73.3% of e-cigarette users at wave 2 and 64.9% at wave 3 also smoked cigarettes),” they wrote.

The odds of developing respiratory disease for participants who used both e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco were 3.30, compared with a participant who never used e-cigarettes, with similar results seen when comparing e-cigarettes and cigarettes.

“Although switching from combustible tobacco, including cigarettes, to e-cigarettes theoretically could reduce the risk of developing respiratory disease, current evidence indicates a high prevalence of dual use, which is associated with in-creased risk beyond combustible tobacco use,” the investigators wrote.

Harold J. Farber, MD, FCCP, professor of pediatrics in the pulmonary section at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, said in an interview that the increased respiratory risk among dual users, who are likely using e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco together as a way to quit smoking, is particularly concerning.

“There is substantial reason to be concerned about efficacy of electronic cigarette products. Real-world observational studies have shown that, on average, tobacco smokers who use electronic cigarettes are less likely to stop smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes,” he said. “People who have stopped tobacco smoking but use electronic cigarettes are more likely to relapse to tobacco smoking than those who do not use electronic cigarettes.”

Dr. Farber noted that there are other Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for treating tobacco addiction. In addition, the World Health Organization, American Medical Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and FDA have all advised that e-cigarettes should not be used as smoking cessation aids, he said, especially in light of current outbreak of life-threatening e-cigarette and vaping lung injuries currently being investigated by the CDC and FDA.