User login

CDC: Opioid prescribing and use rates down since 2010

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

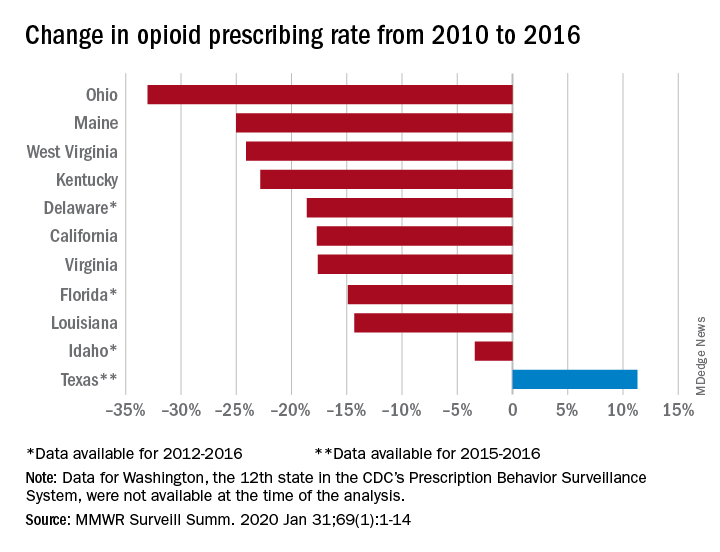

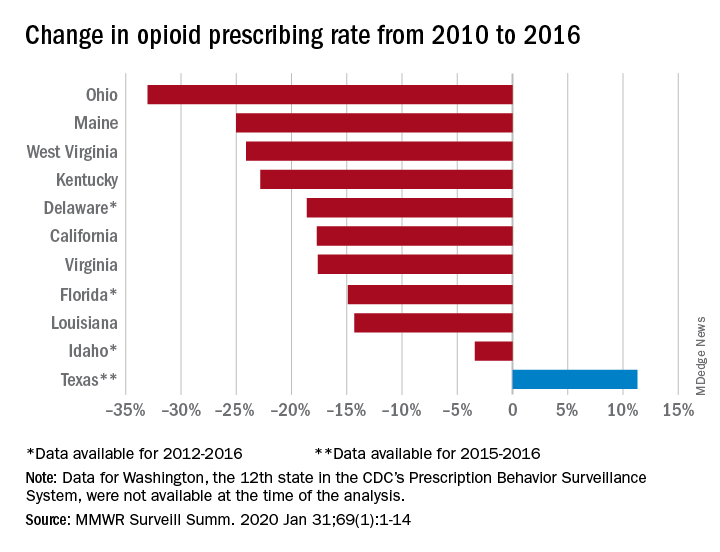

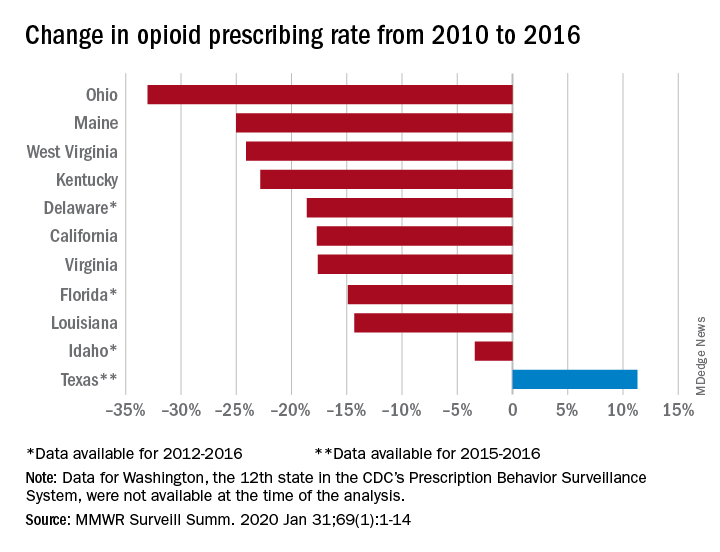

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

FROM MMWR SURVEILLANCE SUMMARIES

Rural treatment of opioid use disorder increasingly driven by nonphysician workforce

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants, rather than physicians, are the clinicians who have boosted capacity for buprenorphine prescribing in rural America, according to a study in a rural health–focused issue of the journal Health Affairs.

In the face of an ongoing crisis of opioid use disorder, and associated overdoses and deaths that have spared no sector of the U.S. population, the federal government expanded its waiver program for buprenorphine prescribing in 2017. The waiver expansion allows nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) – along with clinical nurse specialists, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and certified nurse-midwives – to use the drug for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder after completing 24 hours of mandated training; physicians are required to complete 8 hours of training to receive their waiver.

From 2016 to 2019, capacity for MAT in rural areas increased, with the number of clinicians with buprenorphine waivers more than doubling. Of the newly waivered prescribers accounting for this 111% increase, more than half were NPs and PAs.

In many areas, NPs and PAs led the way forward, wrote the study’s lead author Michael L. Barnett, MD, and coauthors, noting in the abstract accompanying the paper that “NPs and PAs accounted for more than half of this increase and were the first waivered clinicians in 285 rural counties with 5.7 million residents.” Overall, the proportion of people living in a county without a waivered clinician has decreased by 36% since NPs and PAs were permitted to obtain waivers.

SAMHSA data identifies trends

In an in-depth interview, Dr. Barnett, an internal medicine physician and health services researcher at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, said the issue today is “not so much continuing to dissect the risks and benefits of opioids as a treatment for pain, but more trying to address the current overdose crisis, and the fact that our patient treatment infrastructure is woefully inadequate for the magnitude of the problem that we face.”

Dr. Barnett’s chief intention for this study, he said, was to generate information that will drive policy to implement effective opioid treatment. He’d always been interested in models of care delivery that move beyond seeing just the physician-patient dyad.

“There are a whole range of nonphysician providers that are probably better at providing many different types of care – things that physicians aren’t necessarily that well trained to do,” he said.

Expansion of buprenorphine waivers to NPs and PAs, said Dr. Barnett, presented “a very interesting opportunity to see: How does a nonphysician workforce respond to a new practice opportunity, to really be engaged in areas that many physicians really were neglecting?”

The researchers used information drawn from what Dr. Barnett characterized as a “gold-standard” dataset maintained by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. They found that, by March 2019, 52% of U.S. rural residents lived in counties with at least one NP or PA holding a buprenorphine waiver, though there was wide geographic variation: Every county in Maine and New Hampshire had waivered NPs or PAs, but in Tennessee, just 3 of 95 counties had an NP or PA with a waiver.

Scope-of-practice regulations matter

The scope of practice permitted NPs and PAs varies by state, and Dr. Barnett and coauthors also looked to see whether broader scope of practice meant that more advanced practice clinicians were getting buprenorphine waivers. This did appear to be the case: In an analysis that dichotomized scope of practice into “broad” and “restricted,” states with broader practice scope saw twice as many waivered NPs per 100,000 rural residents as those with restrictive practice scope. This association was not seen for PAs, but Dr. Barnett pointed out that PAs are less likely overall to work in primary care.

This, he added, is where scope of practice starts to matter. “A lot of states are still bickering about scope of practice. We show in our paper the clear relationship between scope of practice and the degree to which providers are able to take up these waivers. We can’t prove causality, but I think it’s not a big stretch to think that these policies are playing a big role. I hope we’re working to try to advance that conversation.”

Helping address the unmet need for evidence-based treatment of opioid use disorder, he said, “is one of the more important examples, because doctors have been leaving rural areas in droves. We are lucky that there is a workforce of NPs that still seem to recognize the market opportunity; rural areas still need providers, and they have been willing to fill the gap.”

Waivered NPs or PAs can apply for an expanded waiver, permitting expansion of the buprenorphine panel from 30 to 100 patients after 1 year of holding their initial waiver. Physicians may apply for a waiver to treat up to 275 patients.

Effect on quality of care

The evidence doesn’t support big worries about quality of care, he said. “We don’t have any data on this in the clinical context of addiction, but all of the data that are out there in terms of evaluating the quality of care and level of care being offered by NPs and PAs versus primary care doctors – the types of things that we think of as within the scope of NP and PA practice typically – have shown that they are the same.” Dr. Barnett acknowledged that “there are a little bit of mixed results here and there in one direction or another, but largely, the care being delivered is much more the same than different.”

In addressing the opioid crisis as in the rest of medicine, it’s a mistake not to include this sector of the health care workforce when policies are being crafted, said Dr. Barnett. “People who are making policy and aren’t familiar with the workforce in rural areas could miss the boat. ... NPs aren’t just an asterisk to the workforce – they are an essential part of delivering medicine, just as much as physicians are.”

Dr. Barnett said that, in his estimation, “a lot of protectionist myths get physicians worked up around increased scope of practice for NPs.” However, “The truth is that there’s enough health care spending to go around for everybody and there’s plenty of work to go around.”

Dr. Barnett acknowledged that the current study captured only prescribing capacity, and not actual prescription volume. But, based on some preliminary data, “my sense is that NPs and PAs who acquire waivers are more likely to be prescribing to a larger number of patients proportionately than MDs.” He wasn’t surprised to see this, since the many more hours of training required for NPs and PAs to acquire a waiver means they’re likely to be committed to using the waiver in practice.

Stepping back to look at the bigger picture, Dr. Barnett remarked that, “taking a look at the waiver requirement, a part of me feels that it’s a bit of an anachronistic regulation, anyway – it’s really hard to justify clinically or ethically versus other things that we do.” The waiver program he said, is “a regulation barrier whose time should be limited. ... I’m hoping that the waiver disappears soon.”

Prescribing issues will linger beyond any future abolition of the waiver program, since many clinicians will still not be comfortable prescribing medication for MAT of opioid use disorder, said Dr. Barnett. “It’ll be a lot of the same stigma and structural barriers that were in place prior to the waiver.”

Dr. Barnett reported that he has been retained as an expert witness for plaintiffs in lawsuits against opioid manufacturers. The study was partly funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Barnett ML et al. Health Aff. 2019 Jan;38(12):2048-56.

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants, rather than physicians, are the clinicians who have boosted capacity for buprenorphine prescribing in rural America, according to a study in a rural health–focused issue of the journal Health Affairs.

In the face of an ongoing crisis of opioid use disorder, and associated overdoses and deaths that have spared no sector of the U.S. population, the federal government expanded its waiver program for buprenorphine prescribing in 2017. The waiver expansion allows nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) – along with clinical nurse specialists, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and certified nurse-midwives – to use the drug for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder after completing 24 hours of mandated training; physicians are required to complete 8 hours of training to receive their waiver.

From 2016 to 2019, capacity for MAT in rural areas increased, with the number of clinicians with buprenorphine waivers more than doubling. Of the newly waivered prescribers accounting for this 111% increase, more than half were NPs and PAs.

In many areas, NPs and PAs led the way forward, wrote the study’s lead author Michael L. Barnett, MD, and coauthors, noting in the abstract accompanying the paper that “NPs and PAs accounted for more than half of this increase and were the first waivered clinicians in 285 rural counties with 5.7 million residents.” Overall, the proportion of people living in a county without a waivered clinician has decreased by 36% since NPs and PAs were permitted to obtain waivers.

SAMHSA data identifies trends

In an in-depth interview, Dr. Barnett, an internal medicine physician and health services researcher at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, said the issue today is “not so much continuing to dissect the risks and benefits of opioids as a treatment for pain, but more trying to address the current overdose crisis, and the fact that our patient treatment infrastructure is woefully inadequate for the magnitude of the problem that we face.”

Dr. Barnett’s chief intention for this study, he said, was to generate information that will drive policy to implement effective opioid treatment. He’d always been interested in models of care delivery that move beyond seeing just the physician-patient dyad.

“There are a whole range of nonphysician providers that are probably better at providing many different types of care – things that physicians aren’t necessarily that well trained to do,” he said.

Expansion of buprenorphine waivers to NPs and PAs, said Dr. Barnett, presented “a very interesting opportunity to see: How does a nonphysician workforce respond to a new practice opportunity, to really be engaged in areas that many physicians really were neglecting?”

The researchers used information drawn from what Dr. Barnett characterized as a “gold-standard” dataset maintained by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. They found that, by March 2019, 52% of U.S. rural residents lived in counties with at least one NP or PA holding a buprenorphine waiver, though there was wide geographic variation: Every county in Maine and New Hampshire had waivered NPs or PAs, but in Tennessee, just 3 of 95 counties had an NP or PA with a waiver.

Scope-of-practice regulations matter

The scope of practice permitted NPs and PAs varies by state, and Dr. Barnett and coauthors also looked to see whether broader scope of practice meant that more advanced practice clinicians were getting buprenorphine waivers. This did appear to be the case: In an analysis that dichotomized scope of practice into “broad” and “restricted,” states with broader practice scope saw twice as many waivered NPs per 100,000 rural residents as those with restrictive practice scope. This association was not seen for PAs, but Dr. Barnett pointed out that PAs are less likely overall to work in primary care.

This, he added, is where scope of practice starts to matter. “A lot of states are still bickering about scope of practice. We show in our paper the clear relationship between scope of practice and the degree to which providers are able to take up these waivers. We can’t prove causality, but I think it’s not a big stretch to think that these policies are playing a big role. I hope we’re working to try to advance that conversation.”

Helping address the unmet need for evidence-based treatment of opioid use disorder, he said, “is one of the more important examples, because doctors have been leaving rural areas in droves. We are lucky that there is a workforce of NPs that still seem to recognize the market opportunity; rural areas still need providers, and they have been willing to fill the gap.”

Waivered NPs or PAs can apply for an expanded waiver, permitting expansion of the buprenorphine panel from 30 to 100 patients after 1 year of holding their initial waiver. Physicians may apply for a waiver to treat up to 275 patients.

Effect on quality of care

The evidence doesn’t support big worries about quality of care, he said. “We don’t have any data on this in the clinical context of addiction, but all of the data that are out there in terms of evaluating the quality of care and level of care being offered by NPs and PAs versus primary care doctors – the types of things that we think of as within the scope of NP and PA practice typically – have shown that they are the same.” Dr. Barnett acknowledged that “there are a little bit of mixed results here and there in one direction or another, but largely, the care being delivered is much more the same than different.”

In addressing the opioid crisis as in the rest of medicine, it’s a mistake not to include this sector of the health care workforce when policies are being crafted, said Dr. Barnett. “People who are making policy and aren’t familiar with the workforce in rural areas could miss the boat. ... NPs aren’t just an asterisk to the workforce – they are an essential part of delivering medicine, just as much as physicians are.”

Dr. Barnett said that, in his estimation, “a lot of protectionist myths get physicians worked up around increased scope of practice for NPs.” However, “The truth is that there’s enough health care spending to go around for everybody and there’s plenty of work to go around.”

Dr. Barnett acknowledged that the current study captured only prescribing capacity, and not actual prescription volume. But, based on some preliminary data, “my sense is that NPs and PAs who acquire waivers are more likely to be prescribing to a larger number of patients proportionately than MDs.” He wasn’t surprised to see this, since the many more hours of training required for NPs and PAs to acquire a waiver means they’re likely to be committed to using the waiver in practice.

Stepping back to look at the bigger picture, Dr. Barnett remarked that, “taking a look at the waiver requirement, a part of me feels that it’s a bit of an anachronistic regulation, anyway – it’s really hard to justify clinically or ethically versus other things that we do.” The waiver program he said, is “a regulation barrier whose time should be limited. ... I’m hoping that the waiver disappears soon.”

Prescribing issues will linger beyond any future abolition of the waiver program, since many clinicians will still not be comfortable prescribing medication for MAT of opioid use disorder, said Dr. Barnett. “It’ll be a lot of the same stigma and structural barriers that were in place prior to the waiver.”

Dr. Barnett reported that he has been retained as an expert witness for plaintiffs in lawsuits against opioid manufacturers. The study was partly funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Barnett ML et al. Health Aff. 2019 Jan;38(12):2048-56.

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants, rather than physicians, are the clinicians who have boosted capacity for buprenorphine prescribing in rural America, according to a study in a rural health–focused issue of the journal Health Affairs.

In the face of an ongoing crisis of opioid use disorder, and associated overdoses and deaths that have spared no sector of the U.S. population, the federal government expanded its waiver program for buprenorphine prescribing in 2017. The waiver expansion allows nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) – along with clinical nurse specialists, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and certified nurse-midwives – to use the drug for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder after completing 24 hours of mandated training; physicians are required to complete 8 hours of training to receive their waiver.

From 2016 to 2019, capacity for MAT in rural areas increased, with the number of clinicians with buprenorphine waivers more than doubling. Of the newly waivered prescribers accounting for this 111% increase, more than half were NPs and PAs.

In many areas, NPs and PAs led the way forward, wrote the study’s lead author Michael L. Barnett, MD, and coauthors, noting in the abstract accompanying the paper that “NPs and PAs accounted for more than half of this increase and were the first waivered clinicians in 285 rural counties with 5.7 million residents.” Overall, the proportion of people living in a county without a waivered clinician has decreased by 36% since NPs and PAs were permitted to obtain waivers.

SAMHSA data identifies trends

In an in-depth interview, Dr. Barnett, an internal medicine physician and health services researcher at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, said the issue today is “not so much continuing to dissect the risks and benefits of opioids as a treatment for pain, but more trying to address the current overdose crisis, and the fact that our patient treatment infrastructure is woefully inadequate for the magnitude of the problem that we face.”

Dr. Barnett’s chief intention for this study, he said, was to generate information that will drive policy to implement effective opioid treatment. He’d always been interested in models of care delivery that move beyond seeing just the physician-patient dyad.

“There are a whole range of nonphysician providers that are probably better at providing many different types of care – things that physicians aren’t necessarily that well trained to do,” he said.

Expansion of buprenorphine waivers to NPs and PAs, said Dr. Barnett, presented “a very interesting opportunity to see: How does a nonphysician workforce respond to a new practice opportunity, to really be engaged in areas that many physicians really were neglecting?”

The researchers used information drawn from what Dr. Barnett characterized as a “gold-standard” dataset maintained by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. They found that, by March 2019, 52% of U.S. rural residents lived in counties with at least one NP or PA holding a buprenorphine waiver, though there was wide geographic variation: Every county in Maine and New Hampshire had waivered NPs or PAs, but in Tennessee, just 3 of 95 counties had an NP or PA with a waiver.

Scope-of-practice regulations matter

The scope of practice permitted NPs and PAs varies by state, and Dr. Barnett and coauthors also looked to see whether broader scope of practice meant that more advanced practice clinicians were getting buprenorphine waivers. This did appear to be the case: In an analysis that dichotomized scope of practice into “broad” and “restricted,” states with broader practice scope saw twice as many waivered NPs per 100,000 rural residents as those with restrictive practice scope. This association was not seen for PAs, but Dr. Barnett pointed out that PAs are less likely overall to work in primary care.

This, he added, is where scope of practice starts to matter. “A lot of states are still bickering about scope of practice. We show in our paper the clear relationship between scope of practice and the degree to which providers are able to take up these waivers. We can’t prove causality, but I think it’s not a big stretch to think that these policies are playing a big role. I hope we’re working to try to advance that conversation.”

Helping address the unmet need for evidence-based treatment of opioid use disorder, he said, “is one of the more important examples, because doctors have been leaving rural areas in droves. We are lucky that there is a workforce of NPs that still seem to recognize the market opportunity; rural areas still need providers, and they have been willing to fill the gap.”

Waivered NPs or PAs can apply for an expanded waiver, permitting expansion of the buprenorphine panel from 30 to 100 patients after 1 year of holding their initial waiver. Physicians may apply for a waiver to treat up to 275 patients.

Effect on quality of care

The evidence doesn’t support big worries about quality of care, he said. “We don’t have any data on this in the clinical context of addiction, but all of the data that are out there in terms of evaluating the quality of care and level of care being offered by NPs and PAs versus primary care doctors – the types of things that we think of as within the scope of NP and PA practice typically – have shown that they are the same.” Dr. Barnett acknowledged that “there are a little bit of mixed results here and there in one direction or another, but largely, the care being delivered is much more the same than different.”

In addressing the opioid crisis as in the rest of medicine, it’s a mistake not to include this sector of the health care workforce when policies are being crafted, said Dr. Barnett. “People who are making policy and aren’t familiar with the workforce in rural areas could miss the boat. ... NPs aren’t just an asterisk to the workforce – they are an essential part of delivering medicine, just as much as physicians are.”

Dr. Barnett said that, in his estimation, “a lot of protectionist myths get physicians worked up around increased scope of practice for NPs.” However, “The truth is that there’s enough health care spending to go around for everybody and there’s plenty of work to go around.”

Dr. Barnett acknowledged that the current study captured only prescribing capacity, and not actual prescription volume. But, based on some preliminary data, “my sense is that NPs and PAs who acquire waivers are more likely to be prescribing to a larger number of patients proportionately than MDs.” He wasn’t surprised to see this, since the many more hours of training required for NPs and PAs to acquire a waiver means they’re likely to be committed to using the waiver in practice.

Stepping back to look at the bigger picture, Dr. Barnett remarked that, “taking a look at the waiver requirement, a part of me feels that it’s a bit of an anachronistic regulation, anyway – it’s really hard to justify clinically or ethically versus other things that we do.” The waiver program he said, is “a regulation barrier whose time should be limited. ... I’m hoping that the waiver disappears soon.”

Prescribing issues will linger beyond any future abolition of the waiver program, since many clinicians will still not be comfortable prescribing medication for MAT of opioid use disorder, said Dr. Barnett. “It’ll be a lot of the same stigma and structural barriers that were in place prior to the waiver.”

Dr. Barnett reported that he has been retained as an expert witness for plaintiffs in lawsuits against opioid manufacturers. The study was partly funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Barnett ML et al. Health Aff. 2019 Jan;38(12):2048-56.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Opioid deaths boost donor heart supply

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The tragic opioid epidemic has “one small bright spot”: an expanding pool of eligible donor hearts for transplantation, Akshay S. Desai, MD, said at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

For decades, the annual volume of heart transplantations performed in the U.S. was static because of the huge mismatch between donor organ supply and demand. But heart transplant volume has increased steadily in the last few years – a result of the opioid epidemic.

Data from the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network show that the proportion of donor hearts obtained from individuals who died from drug intoxication climbed from a mere 1.5% in 1999 to 17.6% in 2017, the most recent year for which data are available. Meanwhile, the size of the heart transplant waiting list, which rose year after year in 2009-2015, has since declined (N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 7;380[6]:597-9).

“What’s amazing is that, even though these patients might have historically been considered high risk in general, the organs recovered from these patients – and particularly the hearts – don’t seem to be any worse in terms of allograft survival than the organs recovered from patients who died from other causes, which are the traditional sources, like blunt head trauma, gunshot wounds, or stroke, that lead to brain death. In general, these organs are useful and do quite well,” according to Dr. Desai, medical director of the cardiomyopathy and heart failure program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

He highlighted several other recent developments in the field of cardiac transplantation that promise to further expand the donor heart pool, including acceptance of hepatitis C–infected donors and organ donation after circulatory rather than brain death. Dr. Desai also drew attention to the unintended perverse consequences of a recent redesign of the U.S. donor heart allocation system and discussed the impressive improvement in clinical outcomes with mechanical circulatory support. He noted that, while relatively few cardiologists practice in the highly specialized centers where heart transplants take place, virtually all cardiologists are affected by advances in heart transplantation since hundreds of thousands of the estimated 7 million Americans with heart failure have advanced disease.

Heart transplantation, he emphasized, is becoming increasingly complex. Recipients are on average older, sicker, and have more comorbidities than in times past. As a result, there is greater need for dual organ transplants: heart/lung, heart/liver, or heart/kidney. Plus, more patients come to transplantation after prior cardiac surgery for implantation of a ventricular assist device, so sensitization to blood products is a growing issue. And, of course, the pool of transplant candidates has expanded.

“We’re now forced to take patients previously considered to have contraindications to transplant; for example, diabetes was a contraindication to transplant in the early years, but now it’s the rule in 35%-40% of our patients who present with advanced heart failure,” the cardiologist noted.

Transplants from HCV-infected donors to uninfected recipients

Hearts and lungs from donors with hepatitis C viremia were traditionally deemed unsuitable for transplant. That’s all changed in the current era of highly effective direct-acting antiviral agents for the treatment of HCV infection.

In the DONATE HCV trial, Dr. Desai’s colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital showed that giving HCV-uninfected recipients of hearts or lungs from HCV-viremic donors a shortened 4-week course of treatment with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir (Epclusa) beginning within a few hours after transplantation uniformly blocked viral replication. Six months after transplantation, none of the study participants had a detectable HCV viral load, and all had excellent graft function (N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 25;380[17]:1606-17).

“This is effective prevention of HCV infection by aggressive upfront therapy,” Dr. Desai explained. “We can now take organs from HCV-viremic patients and use them in solid organ transplantation. This has led to a skyrocketing increase in donors with HCV infection, and those donations have helped us clear the waiting list.”

Donation after circulatory death

Australian transplant physicians have pioneered the use of donor hearts obtained after circulatory death in individuals with devastating neurologic injury who didn’t quite meet the criteria for brain death, which is the traditional prerequisite. In the new scenario, withdrawal of life-supporting therapy is followed by circulatory death, then the donor heart is procured and preserved via extracorporeal perfusion until transplantation.

The Australians report excellent outcomes, with rates of overall survival and rejection episodes similar to outcomes from brain-dead donors (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Apr 2;73[12]:1447-59). The first U.S. heart transplant involving donation after circulatory death took place at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. A multicenter U.S. clinical trial of this practice is underway.

If the results are positive and the practice of donation after circulatory death becomes widely implemented, the U.S. heart donor pool could increase by 30%.

Recent overhaul of donor heart allocation system may have backfired

The U.S. donor heart allocation system was redesigned in the fall of 2018 in an effort to reduce waiting times. One of the biggest changes involved breaking down the category with the highest urgency status into three new subcategories based upon sickness. Now, the highest-urgency category is for patients in cardiogenic shock who are supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or other temporary mechanical circulatory support devices.

But an analysis of United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) data suggests this change has unintended adverse consequences for clinical outcomes.

Indeed, the investigators reported that the use of ECMO support is fourfold greater in the new system, the use of durable left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as a bridge to transplant is down, and outcomes are worse. The 180-day rate of freedom from death or retransplantation was 77.9%, down significantly from 93.4% in the former system. In a multivariate analysis, patients transplanted in the new system had an adjusted 2.1-fold increased risk of death or retransplantation (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 Jan;39[1]:1-4).

“When you create a new listing system, you create new incentives, and people start to manage patients differently,” Dr. Desai observed. “Increasingly now, the path direct to transplant is through temporary mechanical circulatory support rather than durable mechanical circulatory support. Is that a good idea? We don’t know, but if you look at the best data, those on ECMO or percutaneous VADs have the worst outcomes. So the question of whether we should take the sickest of sick patients directly to transplant as a standard strategy has come under scrutiny.”

Improved durable LVAD technology brings impressive clinical outcomes

Results of the landmark MOMENTUM 3 randomized trial showed that 2-year clinical outcomes with the magnetically levitated centrifugal-flow HeartMate 3 LVAD now rival those of percutaneous mitral valve repair using the MitraClip device. Two-year all-cause mortality in the LVAD recipients was 22% versus 29.1% with the MitraClip in the COAPT trial and 34.9% in the MITRA-FR trial. The HeartMate 3 reduces the hemocompatibility issues that plagued earlier-generation durable LVADs, with resultant lower rates of pump thrombosis, stroke, and GI bleeding. Indeed, the outcomes in MOMENTUM 3 were so good – and so similar – with the HeartMate 3, regardless of whether the intended treatment goal was as a bridge to transplant or as lifelong destination therapy, that the investigators have recently proposed doing away with those distinctions.

“It is possible that use of arbitrary categorizations based on current or future transplant eligibility should be clinically abandoned in favor of a single preimplant strategy: to extend the survival and improve the quality of life of patients with medically refractory heart failure,” according to the investigators (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Jan 15. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5323).

The next step forward in LVAD technology is already on the horizon: a fully implantable device that eliminates the transcutaneous drive-line for the power supply, which is prone to infection and diminishes overall quality of life. This investigational device utilizes wireless coplanar energy transfer, with a coil ring placed around the lung and fixed to the chest wall. The implanted battery provides more than 6 hours of power without a recharge (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019 Apr;38[4]:339-43).

“The first LVAD patient has gone swimming in Kazakhstan,” according to Dr. Desai.

Myocardial recovery in LVAD recipients remains elusive

The initial hope for LVADs was that they would not only be able to serve as a bridge to transplantation or as lifetime therapy, but that the prolonged unloading of the ventricle would enable potent medical therapy to rescue myocardial function so that the device could eventually be explanted. That does happen, but only rarely. In a large registry study, myocardial recovery occurred in only about 1% of patients on mechanical circulatory support. Attempts to enhance the process by add-on stem cell therapy have thus far been ineffective.

“For the moment, recovery is still a hope, not a reality,” the cardiologist said.

He reported serving as a consultant to more than a dozen pharmaceutical or medical device companies and receiving research grants from Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare, MyoKardia, and Novartis.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The tragic opioid epidemic has “one small bright spot”: an expanding pool of eligible donor hearts for transplantation, Akshay S. Desai, MD, said at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

For decades, the annual volume of heart transplantations performed in the U.S. was static because of the huge mismatch between donor organ supply and demand. But heart transplant volume has increased steadily in the last few years – a result of the opioid epidemic.

Data from the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network show that the proportion of donor hearts obtained from individuals who died from drug intoxication climbed from a mere 1.5% in 1999 to 17.6% in 2017, the most recent year for which data are available. Meanwhile, the size of the heart transplant waiting list, which rose year after year in 2009-2015, has since declined (N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 7;380[6]:597-9).

“What’s amazing is that, even though these patients might have historically been considered high risk in general, the organs recovered from these patients – and particularly the hearts – don’t seem to be any worse in terms of allograft survival than the organs recovered from patients who died from other causes, which are the traditional sources, like blunt head trauma, gunshot wounds, or stroke, that lead to brain death. In general, these organs are useful and do quite well,” according to Dr. Desai, medical director of the cardiomyopathy and heart failure program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

He highlighted several other recent developments in the field of cardiac transplantation that promise to further expand the donor heart pool, including acceptance of hepatitis C–infected donors and organ donation after circulatory rather than brain death. Dr. Desai also drew attention to the unintended perverse consequences of a recent redesign of the U.S. donor heart allocation system and discussed the impressive improvement in clinical outcomes with mechanical circulatory support. He noted that, while relatively few cardiologists practice in the highly specialized centers where heart transplants take place, virtually all cardiologists are affected by advances in heart transplantation since hundreds of thousands of the estimated 7 million Americans with heart failure have advanced disease.

Heart transplantation, he emphasized, is becoming increasingly complex. Recipients are on average older, sicker, and have more comorbidities than in times past. As a result, there is greater need for dual organ transplants: heart/lung, heart/liver, or heart/kidney. Plus, more patients come to transplantation after prior cardiac surgery for implantation of a ventricular assist device, so sensitization to blood products is a growing issue. And, of course, the pool of transplant candidates has expanded.

“We’re now forced to take patients previously considered to have contraindications to transplant; for example, diabetes was a contraindication to transplant in the early years, but now it’s the rule in 35%-40% of our patients who present with advanced heart failure,” the cardiologist noted.

Transplants from HCV-infected donors to uninfected recipients

Hearts and lungs from donors with hepatitis C viremia were traditionally deemed unsuitable for transplant. That’s all changed in the current era of highly effective direct-acting antiviral agents for the treatment of HCV infection.

In the DONATE HCV trial, Dr. Desai’s colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital showed that giving HCV-uninfected recipients of hearts or lungs from HCV-viremic donors a shortened 4-week course of treatment with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir (Epclusa) beginning within a few hours after transplantation uniformly blocked viral replication. Six months after transplantation, none of the study participants had a detectable HCV viral load, and all had excellent graft function (N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 25;380[17]:1606-17).

“This is effective prevention of HCV infection by aggressive upfront therapy,” Dr. Desai explained. “We can now take organs from HCV-viremic patients and use them in solid organ transplantation. This has led to a skyrocketing increase in donors with HCV infection, and those donations have helped us clear the waiting list.”

Donation after circulatory death

Australian transplant physicians have pioneered the use of donor hearts obtained after circulatory death in individuals with devastating neurologic injury who didn’t quite meet the criteria for brain death, which is the traditional prerequisite. In the new scenario, withdrawal of life-supporting therapy is followed by circulatory death, then the donor heart is procured and preserved via extracorporeal perfusion until transplantation.

The Australians report excellent outcomes, with rates of overall survival and rejection episodes similar to outcomes from brain-dead donors (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Apr 2;73[12]:1447-59). The first U.S. heart transplant involving donation after circulatory death took place at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. A multicenter U.S. clinical trial of this practice is underway.

If the results are positive and the practice of donation after circulatory death becomes widely implemented, the U.S. heart donor pool could increase by 30%.

Recent overhaul of donor heart allocation system may have backfired

The U.S. donor heart allocation system was redesigned in the fall of 2018 in an effort to reduce waiting times. One of the biggest changes involved breaking down the category with the highest urgency status into three new subcategories based upon sickness. Now, the highest-urgency category is for patients in cardiogenic shock who are supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or other temporary mechanical circulatory support devices.

But an analysis of United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) data suggests this change has unintended adverse consequences for clinical outcomes.

Indeed, the investigators reported that the use of ECMO support is fourfold greater in the new system, the use of durable left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as a bridge to transplant is down, and outcomes are worse. The 180-day rate of freedom from death or retransplantation was 77.9%, down significantly from 93.4% in the former system. In a multivariate analysis, patients transplanted in the new system had an adjusted 2.1-fold increased risk of death or retransplantation (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 Jan;39[1]:1-4).

“When you create a new listing system, you create new incentives, and people start to manage patients differently,” Dr. Desai observed. “Increasingly now, the path direct to transplant is through temporary mechanical circulatory support rather than durable mechanical circulatory support. Is that a good idea? We don’t know, but if you look at the best data, those on ECMO or percutaneous VADs have the worst outcomes. So the question of whether we should take the sickest of sick patients directly to transplant as a standard strategy has come under scrutiny.”

Improved durable LVAD technology brings impressive clinical outcomes

Results of the landmark MOMENTUM 3 randomized trial showed that 2-year clinical outcomes with the magnetically levitated centrifugal-flow HeartMate 3 LVAD now rival those of percutaneous mitral valve repair using the MitraClip device. Two-year all-cause mortality in the LVAD recipients was 22% versus 29.1% with the MitraClip in the COAPT trial and 34.9% in the MITRA-FR trial. The HeartMate 3 reduces the hemocompatibility issues that plagued earlier-generation durable LVADs, with resultant lower rates of pump thrombosis, stroke, and GI bleeding. Indeed, the outcomes in MOMENTUM 3 were so good – and so similar – with the HeartMate 3, regardless of whether the intended treatment goal was as a bridge to transplant or as lifelong destination therapy, that the investigators have recently proposed doing away with those distinctions.

“It is possible that use of arbitrary categorizations based on current or future transplant eligibility should be clinically abandoned in favor of a single preimplant strategy: to extend the survival and improve the quality of life of patients with medically refractory heart failure,” according to the investigators (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Jan 15. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5323).

The next step forward in LVAD technology is already on the horizon: a fully implantable device that eliminates the transcutaneous drive-line for the power supply, which is prone to infection and diminishes overall quality of life. This investigational device utilizes wireless coplanar energy transfer, with a coil ring placed around the lung and fixed to the chest wall. The implanted battery provides more than 6 hours of power without a recharge (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019 Apr;38[4]:339-43).

“The first LVAD patient has gone swimming in Kazakhstan,” according to Dr. Desai.

Myocardial recovery in LVAD recipients remains elusive

The initial hope for LVADs was that they would not only be able to serve as a bridge to transplantation or as lifetime therapy, but that the prolonged unloading of the ventricle would enable potent medical therapy to rescue myocardial function so that the device could eventually be explanted. That does happen, but only rarely. In a large registry study, myocardial recovery occurred in only about 1% of patients on mechanical circulatory support. Attempts to enhance the process by add-on stem cell therapy have thus far been ineffective.

“For the moment, recovery is still a hope, not a reality,” the cardiologist said.

He reported serving as a consultant to more than a dozen pharmaceutical or medical device companies and receiving research grants from Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare, MyoKardia, and Novartis.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The tragic opioid epidemic has “one small bright spot”: an expanding pool of eligible donor hearts for transplantation, Akshay S. Desai, MD, said at the annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

For decades, the annual volume of heart transplantations performed in the U.S. was static because of the huge mismatch between donor organ supply and demand. But heart transplant volume has increased steadily in the last few years – a result of the opioid epidemic.

Data from the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network show that the proportion of donor hearts obtained from individuals who died from drug intoxication climbed from a mere 1.5% in 1999 to 17.6% in 2017, the most recent year for which data are available. Meanwhile, the size of the heart transplant waiting list, which rose year after year in 2009-2015, has since declined (N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 7;380[6]:597-9).

“What’s amazing is that, even though these patients might have historically been considered high risk in general, the organs recovered from these patients – and particularly the hearts – don’t seem to be any worse in terms of allograft survival than the organs recovered from patients who died from other causes, which are the traditional sources, like blunt head trauma, gunshot wounds, or stroke, that lead to brain death. In general, these organs are useful and do quite well,” according to Dr. Desai, medical director of the cardiomyopathy and heart failure program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

He highlighted several other recent developments in the field of cardiac transplantation that promise to further expand the donor heart pool, including acceptance of hepatitis C–infected donors and organ donation after circulatory rather than brain death. Dr. Desai also drew attention to the unintended perverse consequences of a recent redesign of the U.S. donor heart allocation system and discussed the impressive improvement in clinical outcomes with mechanical circulatory support. He noted that, while relatively few cardiologists practice in the highly specialized centers where heart transplants take place, virtually all cardiologists are affected by advances in heart transplantation since hundreds of thousands of the estimated 7 million Americans with heart failure have advanced disease.

Heart transplantation, he emphasized, is becoming increasingly complex. Recipients are on average older, sicker, and have more comorbidities than in times past. As a result, there is greater need for dual organ transplants: heart/lung, heart/liver, or heart/kidney. Plus, more patients come to transplantation after prior cardiac surgery for implantation of a ventricular assist device, so sensitization to blood products is a growing issue. And, of course, the pool of transplant candidates has expanded.

“We’re now forced to take patients previously considered to have contraindications to transplant; for example, diabetes was a contraindication to transplant in the early years, but now it’s the rule in 35%-40% of our patients who present with advanced heart failure,” the cardiologist noted.

Transplants from HCV-infected donors to uninfected recipients

Hearts and lungs from donors with hepatitis C viremia were traditionally deemed unsuitable for transplant. That’s all changed in the current era of highly effective direct-acting antiviral agents for the treatment of HCV infection.

In the DONATE HCV trial, Dr. Desai’s colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital showed that giving HCV-uninfected recipients of hearts or lungs from HCV-viremic donors a shortened 4-week course of treatment with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir (Epclusa) beginning within a few hours after transplantation uniformly blocked viral replication. Six months after transplantation, none of the study participants had a detectable HCV viral load, and all had excellent graft function (N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 25;380[17]:1606-17).

“This is effective prevention of HCV infection by aggressive upfront therapy,” Dr. Desai explained. “We can now take organs from HCV-viremic patients and use them in solid organ transplantation. This has led to a skyrocketing increase in donors with HCV infection, and those donations have helped us clear the waiting list.”

Donation after circulatory death

Australian transplant physicians have pioneered the use of donor hearts obtained after circulatory death in individuals with devastating neurologic injury who didn’t quite meet the criteria for brain death, which is the traditional prerequisite. In the new scenario, withdrawal of life-supporting therapy is followed by circulatory death, then the donor heart is procured and preserved via extracorporeal perfusion until transplantation.

The Australians report excellent outcomes, with rates of overall survival and rejection episodes similar to outcomes from brain-dead donors (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Apr 2;73[12]:1447-59). The first U.S. heart transplant involving donation after circulatory death took place at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. A multicenter U.S. clinical trial of this practice is underway.

If the results are positive and the practice of donation after circulatory death becomes widely implemented, the U.S. heart donor pool could increase by 30%.

Recent overhaul of donor heart allocation system may have backfired

The U.S. donor heart allocation system was redesigned in the fall of 2018 in an effort to reduce waiting times. One of the biggest changes involved breaking down the category with the highest urgency status into three new subcategories based upon sickness. Now, the highest-urgency category is for patients in cardiogenic shock who are supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or other temporary mechanical circulatory support devices.

But an analysis of United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) data suggests this change has unintended adverse consequences for clinical outcomes.

Indeed, the investigators reported that the use of ECMO support is fourfold greater in the new system, the use of durable left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as a bridge to transplant is down, and outcomes are worse. The 180-day rate of freedom from death or retransplantation was 77.9%, down significantly from 93.4% in the former system. In a multivariate analysis, patients transplanted in the new system had an adjusted 2.1-fold increased risk of death or retransplantation (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 Jan;39[1]:1-4).

“When you create a new listing system, you create new incentives, and people start to manage patients differently,” Dr. Desai observed. “Increasingly now, the path direct to transplant is through temporary mechanical circulatory support rather than durable mechanical circulatory support. Is that a good idea? We don’t know, but if you look at the best data, those on ECMO or percutaneous VADs have the worst outcomes. So the question of whether we should take the sickest of sick patients directly to transplant as a standard strategy has come under scrutiny.”

Improved durable LVAD technology brings impressive clinical outcomes

Results of the landmark MOMENTUM 3 randomized trial showed that 2-year clinical outcomes with the magnetically levitated centrifugal-flow HeartMate 3 LVAD now rival those of percutaneous mitral valve repair using the MitraClip device. Two-year all-cause mortality in the LVAD recipients was 22% versus 29.1% with the MitraClip in the COAPT trial and 34.9% in the MITRA-FR trial. The HeartMate 3 reduces the hemocompatibility issues that plagued earlier-generation durable LVADs, with resultant lower rates of pump thrombosis, stroke, and GI bleeding. Indeed, the outcomes in MOMENTUM 3 were so good – and so similar – with the HeartMate 3, regardless of whether the intended treatment goal was as a bridge to transplant or as lifelong destination therapy, that the investigators have recently proposed doing away with those distinctions.

“It is possible that use of arbitrary categorizations based on current or future transplant eligibility should be clinically abandoned in favor of a single preimplant strategy: to extend the survival and improve the quality of life of patients with medically refractory heart failure,” according to the investigators (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Jan 15. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5323).

The next step forward in LVAD technology is already on the horizon: a fully implantable device that eliminates the transcutaneous drive-line for the power supply, which is prone to infection and diminishes overall quality of life. This investigational device utilizes wireless coplanar energy transfer, with a coil ring placed around the lung and fixed to the chest wall. The implanted battery provides more than 6 hours of power without a recharge (J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019 Apr;38[4]:339-43).

“The first LVAD patient has gone swimming in Kazakhstan,” according to Dr. Desai.

Myocardial recovery in LVAD recipients remains elusive

The initial hope for LVADs was that they would not only be able to serve as a bridge to transplantation or as lifetime therapy, but that the prolonged unloading of the ventricle would enable potent medical therapy to rescue myocardial function so that the device could eventually be explanted. That does happen, but only rarely. In a large registry study, myocardial recovery occurred in only about 1% of patients on mechanical circulatory support. Attempts to enhance the process by add-on stem cell therapy have thus far been ineffective.

“For the moment, recovery is still a hope, not a reality,” the cardiologist said.

He reported serving as a consultant to more than a dozen pharmaceutical or medical device companies and receiving research grants from Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare, MyoKardia, and Novartis.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACC SNOWMASS 2020

Cannabis use in pregnancy and lactation: A changing landscape

National survey data from 2007-2012 of more than 93,000 pregnant women suggest that around 7% of pregnant respondents reported any cannabis use in the last 2-12 months; of those, 16% reported daily or almost daily use. Among pregnant past-year users in the same survey, 70% perceived slight or no risk of harm from cannabis use 1-2 times a week in pregnancy.1

Data from the Kaiser Northern California health plan involving more than 279,000 pregnancies followed during 2009-2016 suggest that there has been a significant upward trend in use of cannabis during pregnancy, from 4% to 7%, as reported by the mother and/or identified by routine urine screening. The highest prevalence in that study was seen among 18- to 24-year-old pregnant women, increasing from 13% to 22% over the 7-year study period. Importantly, more than 50% of cannabis users in the sample were identified by toxicology screening alone.2,3 Common reasons given for use of cannabis in pregnancy include anxiety, pain, and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.4

With respect to adverse perinatal outcomes, several case-control studies have examined risks for major birth defects with maternal self-report of cannabis use. Some have noted very modest increased risks for selected major birth defects (odds ratios less than 2); however, data still are very limited.5,6

A number of prospective studies have addressed risks of preterm birth and growth restriction, accounting for mother’s concomitant tobacco use.7-11 Some of these studies have suggested about a twofold to threefold increased risk for preterm delivery and an increased risk for reduced birth weight – particularly with heavier or regular cannabis use – but study findings have not been entirely consistent.

Given its psychoactive properties, there has been high interest in understanding whether there are any short- or long-term neurodevelopmental effects on children prenatally exposed to cannabis. These outcomes have been studied in two small older cohorts in the United States and Canada and one more recent cohort in the Netherlands.12-15 Deficits in several measures of cognition and behavior were noted in follow-up of those children from birth to adulthood. However, it is unclear to what extent these findings may have been influenced by heredity, environment, or other factors.

There have been limitations in almost all studies published to date, including small sample sizes, no biomarker validation of maternal report of dose and gestational timing of cannabis use, and lack of detailed data on common coexposures, such as alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. In addition, newer studies of pregnancy outcomes in women who use currently available cannabis products are needed, given the substantial increase in the potency of cannabis used today, compared with that of 20 years ago. For example, the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration in commonly cultivated marijuana plants has increased threefold from 4% to 12% between 1995 and 2014.16

There are very limited data on the presence of cannabis in breast milk and the potential effects of exposure to THC and other metabolites for breastfed infants. However, two recent studies have demonstrated there are low but measurable levels of some cannabis metabolites in breast milk.17-18 Further work is needed to determine if these metabolites accumulate in milk and if at a given dose and age of the breastfed infant, there are any growth, neurodevelopmental, or other clinically important adverse effects.

Related questions, such as potential differences in the effects of exposure during pregnancy or lactation based on the route of administration (edible vs. inhaled) and the use of cannabidiol (CBD) products, have not been studied.

At the present time, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women who are pregnant or contemplating pregnancy be encouraged to discontinue marijuana use. With respect to lactation and breastfeeding, ACOG concludes there are insufficient data to evaluate the effects on infants, and in the absence of such data, marijuana use is discouraged. Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends women of childbearing age abstain from marijuana use while pregnant or breastfeeding because of potential adverse consequences to the fetus, infant, or child.

In August 2019, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory regarding potential harm to developing brains from the use of marijuana during pregnancy and lactation. The Food and Drug Administration issued a similar statement in October 2019 strongly advising against the use of CBD, THC, and marijuana in any form during pregnancy or while breastfeeding.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Aug;213(2):201.e1-10.

2. JAMA. 2017 Dec 26;318(24):2490-1.

3. JAMA. 2017 Jan 10;317(2):207-9.

4. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009 Nov;15(4)242-6.

5. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014 Sep; 28(5): 424-33.

6. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2007 Jan;70(1):7-18.

7. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983 Aug 15;146(8):992-4.

8. Clin Perinatol. 1991 Mar;18(1):77-91.

9. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Dec;124(6):986-93.

10. Pediatr Res. 2012 Feb;71(2):215-9.

11. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;62:77-86.

12. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1987 Jan-Feb;9(1):1-7.

13. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1994 Mar-Apr;16(2):169-75.

14. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Jun 15;79(12):971-9.

15. Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Feb;182:133-51.

16. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 1;79(7):613-9.

17. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):783-8.

18. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep;142(3):e20181076.

National survey data from 2007-2012 of more than 93,000 pregnant women suggest that around 7% of pregnant respondents reported any cannabis use in the last 2-12 months; of those, 16% reported daily or almost daily use. Among pregnant past-year users in the same survey, 70% perceived slight or no risk of harm from cannabis use 1-2 times a week in pregnancy.1

Data from the Kaiser Northern California health plan involving more than 279,000 pregnancies followed during 2009-2016 suggest that there has been a significant upward trend in use of cannabis during pregnancy, from 4% to 7%, as reported by the mother and/or identified by routine urine screening. The highest prevalence in that study was seen among 18- to 24-year-old pregnant women, increasing from 13% to 22% over the 7-year study period. Importantly, more than 50% of cannabis users in the sample were identified by toxicology screening alone.2,3 Common reasons given for use of cannabis in pregnancy include anxiety, pain, and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.4

With respect to adverse perinatal outcomes, several case-control studies have examined risks for major birth defects with maternal self-report of cannabis use. Some have noted very modest increased risks for selected major birth defects (odds ratios less than 2); however, data still are very limited.5,6

A number of prospective studies have addressed risks of preterm birth and growth restriction, accounting for mother’s concomitant tobacco use.7-11 Some of these studies have suggested about a twofold to threefold increased risk for preterm delivery and an increased risk for reduced birth weight – particularly with heavier or regular cannabis use – but study findings have not been entirely consistent.

Given its psychoactive properties, there has been high interest in understanding whether there are any short- or long-term neurodevelopmental effects on children prenatally exposed to cannabis. These outcomes have been studied in two small older cohorts in the United States and Canada and one more recent cohort in the Netherlands.12-15 Deficits in several measures of cognition and behavior were noted in follow-up of those children from birth to adulthood. However, it is unclear to what extent these findings may have been influenced by heredity, environment, or other factors.

There have been limitations in almost all studies published to date, including small sample sizes, no biomarker validation of maternal report of dose and gestational timing of cannabis use, and lack of detailed data on common coexposures, such as alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. In addition, newer studies of pregnancy outcomes in women who use currently available cannabis products are needed, given the substantial increase in the potency of cannabis used today, compared with that of 20 years ago. For example, the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration in commonly cultivated marijuana plants has increased threefold from 4% to 12% between 1995 and 2014.16

There are very limited data on the presence of cannabis in breast milk and the potential effects of exposure to THC and other metabolites for breastfed infants. However, two recent studies have demonstrated there are low but measurable levels of some cannabis metabolites in breast milk.17-18 Further work is needed to determine if these metabolites accumulate in milk and if at a given dose and age of the breastfed infant, there are any growth, neurodevelopmental, or other clinically important adverse effects.

Related questions, such as potential differences in the effects of exposure during pregnancy or lactation based on the route of administration (edible vs. inhaled) and the use of cannabidiol (CBD) products, have not been studied.

At the present time, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women who are pregnant or contemplating pregnancy be encouraged to discontinue marijuana use. With respect to lactation and breastfeeding, ACOG concludes there are insufficient data to evaluate the effects on infants, and in the absence of such data, marijuana use is discouraged. Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends women of childbearing age abstain from marijuana use while pregnant or breastfeeding because of potential adverse consequences to the fetus, infant, or child.

In August 2019, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory regarding potential harm to developing brains from the use of marijuana during pregnancy and lactation. The Food and Drug Administration issued a similar statement in October 2019 strongly advising against the use of CBD, THC, and marijuana in any form during pregnancy or while breastfeeding.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Aug;213(2):201.e1-10.

2. JAMA. 2017 Dec 26;318(24):2490-1.

3. JAMA. 2017 Jan 10;317(2):207-9.

4. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009 Nov;15(4)242-6.

5. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014 Sep; 28(5): 424-33.

6. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2007 Jan;70(1):7-18.

7. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983 Aug 15;146(8):992-4.

8. Clin Perinatol. 1991 Mar;18(1):77-91.

9. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Dec;124(6):986-93.

10. Pediatr Res. 2012 Feb;71(2):215-9.

11. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;62:77-86.

12. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1987 Jan-Feb;9(1):1-7.

13. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1994 Mar-Apr;16(2):169-75.

14. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Jun 15;79(12):971-9.

15. Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Feb;182:133-51.

16. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 1;79(7):613-9.

17. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):783-8.

18. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep;142(3):e20181076.

National survey data from 2007-2012 of more than 93,000 pregnant women suggest that around 7% of pregnant respondents reported any cannabis use in the last 2-12 months; of those, 16% reported daily or almost daily use. Among pregnant past-year users in the same survey, 70% perceived slight or no risk of harm from cannabis use 1-2 times a week in pregnancy.1

Data from the Kaiser Northern California health plan involving more than 279,000 pregnancies followed during 2009-2016 suggest that there has been a significant upward trend in use of cannabis during pregnancy, from 4% to 7%, as reported by the mother and/or identified by routine urine screening. The highest prevalence in that study was seen among 18- to 24-year-old pregnant women, increasing from 13% to 22% over the 7-year study period. Importantly, more than 50% of cannabis users in the sample were identified by toxicology screening alone.2,3 Common reasons given for use of cannabis in pregnancy include anxiety, pain, and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.4

With respect to adverse perinatal outcomes, several case-control studies have examined risks for major birth defects with maternal self-report of cannabis use. Some have noted very modest increased risks for selected major birth defects (odds ratios less than 2); however, data still are very limited.5,6

A number of prospective studies have addressed risks of preterm birth and growth restriction, accounting for mother’s concomitant tobacco use.7-11 Some of these studies have suggested about a twofold to threefold increased risk for preterm delivery and an increased risk for reduced birth weight – particularly with heavier or regular cannabis use – but study findings have not been entirely consistent.

Given its psychoactive properties, there has been high interest in understanding whether there are any short- or long-term neurodevelopmental effects on children prenatally exposed to cannabis. These outcomes have been studied in two small older cohorts in the United States and Canada and one more recent cohort in the Netherlands.12-15 Deficits in several measures of cognition and behavior were noted in follow-up of those children from birth to adulthood. However, it is unclear to what extent these findings may have been influenced by heredity, environment, or other factors.

There have been limitations in almost all studies published to date, including small sample sizes, no biomarker validation of maternal report of dose and gestational timing of cannabis use, and lack of detailed data on common coexposures, such as alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. In addition, newer studies of pregnancy outcomes in women who use currently available cannabis products are needed, given the substantial increase in the potency of cannabis used today, compared with that of 20 years ago. For example, the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentration in commonly cultivated marijuana plants has increased threefold from 4% to 12% between 1995 and 2014.16

There are very limited data on the presence of cannabis in breast milk and the potential effects of exposure to THC and other metabolites for breastfed infants. However, two recent studies have demonstrated there are low but measurable levels of some cannabis metabolites in breast milk.17-18 Further work is needed to determine if these metabolites accumulate in milk and if at a given dose and age of the breastfed infant, there are any growth, neurodevelopmental, or other clinically important adverse effects.

Related questions, such as potential differences in the effects of exposure during pregnancy or lactation based on the route of administration (edible vs. inhaled) and the use of cannabidiol (CBD) products, have not been studied.

At the present time, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women who are pregnant or contemplating pregnancy be encouraged to discontinue marijuana use. With respect to lactation and breastfeeding, ACOG concludes there are insufficient data to evaluate the effects on infants, and in the absence of such data, marijuana use is discouraged. Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends women of childbearing age abstain from marijuana use while pregnant or breastfeeding because of potential adverse consequences to the fetus, infant, or child.

In August 2019, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory regarding potential harm to developing brains from the use of marijuana during pregnancy and lactation. The Food and Drug Administration issued a similar statement in October 2019 strongly advising against the use of CBD, THC, and marijuana in any form during pregnancy or while breastfeeding.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Aug;213(2):201.e1-10.

2. JAMA. 2017 Dec 26;318(24):2490-1.

3. JAMA. 2017 Jan 10;317(2):207-9.

4. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009 Nov;15(4)242-6.

5. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014 Sep; 28(5): 424-33.

6. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2007 Jan;70(1):7-18.

7. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983 Aug 15;146(8):992-4.

8. Clin Perinatol. 1991 Mar;18(1):77-91.

9. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Dec;124(6):986-93.

10. Pediatr Res. 2012 Feb;71(2):215-9.

11. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;62:77-86.

12. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1987 Jan-Feb;9(1):1-7.

13. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1994 Mar-Apr;16(2):169-75.

14. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Jun 15;79(12):971-9.

15. Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Feb;182:133-51.

16. Biol Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 1;79(7):613-9.

17. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):783-8.

18. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep;142(3):e20181076.

EVALI update warns of chemicals in vaping products

A report issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirms that 82% of patients presenting with e-cigarette– or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) used products containing tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).