User login

6 ‘D’s: Next steps after an insufficient antipsychotic response

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

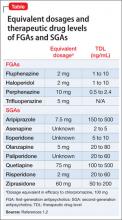

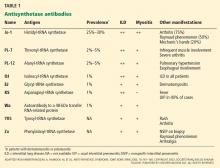

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

Auditory musical hallucinations: When a patient complains, ‘I hear a symphony!’

Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations—hearing singing voices, musical tones, song lyrics, or instrumental music—occur in >20% of outpatients who have a diagnosis of an anxiety, affective, or schizophrenic disorder, with the highest prevalence (41%) in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).1 OCD comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders increases the frequency of auditory musical hallucinations. Auditory musical hallucinations mainly affect older (mean age, 61.5 years) females who have tinnitus and severe, high-frequency, sensorineural hearing loss.1 Auditory musical hallucinations occur in psychiatric diseases, ictal states of complex partial seizures, abnormalities of the auditory cortex, thalamic infarcts, subarachnoid hemorrhage, tumors of the brain stem, intoxication, and progressive deafness.1,2

What patients report hearing

Some patients identify 1 musical instrument that dominates others. The musical tones are reported to have a vibrating quality, similar to the sound produced by blowing air through a paper-covered comb. Some patients hear singing voices, predominantly deep in tone, although the words usually are not clear.

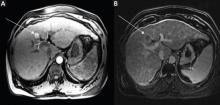

Patients with auditory musical hallucinations associated with deafness may not have dementia or psychosis. Both sensorineural and conductive involvement indicates a mixed type of deafness. Pure tone audiograms show a bilateral loss of >30 decibels, affecting the higher and lower ranges.2,3 Cerebral atrophy and microangiopathic changes are common co-occurring findings on MRI.

Treatment options

Reassure your patient that the experience is not necessarily associated with a psychotic disorder. Perform a complete history, physical, and neurologic examination. Rule out unilateral symptoms, tinnitus, and hearing loss. If she (he) is experiencing unilateral symptoms, pulsatile tinnitus, unilateral hearing loss, and a constant feeling of unsteadiness, further evaluation is necessary to exclude underlying pathology. Treating concurrent insomnia, depression, or anxiety might resolve the hallucinations.4

Nonpharmacotherapeutic treatments include hearing amplification, and masking tinnitus with a hearing aid emitting low-volume music or sounds of nature (ie, rainfall).4 Two cases have reported successful carbamazepine therapy; 2 other cases demonstrated success with clomipramine.5 Frequently, symptoms spontaneously remit.

Consider electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with musical hallucinations that are refractory to medical treatment and cause distress; 3 patients with concurrent major depressive disorder showed improvement after ECT.6 Antipsychotics are not recommended as first-line treatment.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Hermesh H, Konas S, Shiloh R, et al. Musical hallucinations: prevalence in psychotic and nonpsychotic outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):191-197.

2. Schakenraad SM, Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MG. Musical hallucinations in psychiatric patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(4):394-397.

3. Evers S, Ellger T. The clinical spectrum of musical hallucinations. J Neurol Sci. 2004;227(1):55-65.

4. Zegarra NM, Cuetter AC, Briones DF, et al. Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations in elderly persons with progressive deafness. Clin Geriatr. 2007;15(11):33-37.

5. Mahendran R. The psychopathology of musical hallucinations. Singapore Med J. 2007;48(2):e68-e70.

6. Wengel SP, Burke WJ, Holemon D. Musical hallucinations. The sounds of silence? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(2):163-166.

Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations—hearing singing voices, musical tones, song lyrics, or instrumental music—occur in >20% of outpatients who have a diagnosis of an anxiety, affective, or schizophrenic disorder, with the highest prevalence (41%) in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).1 OCD comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders increases the frequency of auditory musical hallucinations. Auditory musical hallucinations mainly affect older (mean age, 61.5 years) females who have tinnitus and severe, high-frequency, sensorineural hearing loss.1 Auditory musical hallucinations occur in psychiatric diseases, ictal states of complex partial seizures, abnormalities of the auditory cortex, thalamic infarcts, subarachnoid hemorrhage, tumors of the brain stem, intoxication, and progressive deafness.1,2

What patients report hearing

Some patients identify 1 musical instrument that dominates others. The musical tones are reported to have a vibrating quality, similar to the sound produced by blowing air through a paper-covered comb. Some patients hear singing voices, predominantly deep in tone, although the words usually are not clear.

Patients with auditory musical hallucinations associated with deafness may not have dementia or psychosis. Both sensorineural and conductive involvement indicates a mixed type of deafness. Pure tone audiograms show a bilateral loss of >30 decibels, affecting the higher and lower ranges.2,3 Cerebral atrophy and microangiopathic changes are common co-occurring findings on MRI.

Treatment options

Reassure your patient that the experience is not necessarily associated with a psychotic disorder. Perform a complete history, physical, and neurologic examination. Rule out unilateral symptoms, tinnitus, and hearing loss. If she (he) is experiencing unilateral symptoms, pulsatile tinnitus, unilateral hearing loss, and a constant feeling of unsteadiness, further evaluation is necessary to exclude underlying pathology. Treating concurrent insomnia, depression, or anxiety might resolve the hallucinations.4

Nonpharmacotherapeutic treatments include hearing amplification, and masking tinnitus with a hearing aid emitting low-volume music or sounds of nature (ie, rainfall).4 Two cases have reported successful carbamazepine therapy; 2 other cases demonstrated success with clomipramine.5 Frequently, symptoms spontaneously remit.

Consider electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with musical hallucinations that are refractory to medical treatment and cause distress; 3 patients with concurrent major depressive disorder showed improvement after ECT.6 Antipsychotics are not recommended as first-line treatment.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations—hearing singing voices, musical tones, song lyrics, or instrumental music—occur in >20% of outpatients who have a diagnosis of an anxiety, affective, or schizophrenic disorder, with the highest prevalence (41%) in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).1 OCD comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders increases the frequency of auditory musical hallucinations. Auditory musical hallucinations mainly affect older (mean age, 61.5 years) females who have tinnitus and severe, high-frequency, sensorineural hearing loss.1 Auditory musical hallucinations occur in psychiatric diseases, ictal states of complex partial seizures, abnormalities of the auditory cortex, thalamic infarcts, subarachnoid hemorrhage, tumors of the brain stem, intoxication, and progressive deafness.1,2

What patients report hearing

Some patients identify 1 musical instrument that dominates others. The musical tones are reported to have a vibrating quality, similar to the sound produced by blowing air through a paper-covered comb. Some patients hear singing voices, predominantly deep in tone, although the words usually are not clear.

Patients with auditory musical hallucinations associated with deafness may not have dementia or psychosis. Both sensorineural and conductive involvement indicates a mixed type of deafness. Pure tone audiograms show a bilateral loss of >30 decibels, affecting the higher and lower ranges.2,3 Cerebral atrophy and microangiopathic changes are common co-occurring findings on MRI.

Treatment options

Reassure your patient that the experience is not necessarily associated with a psychotic disorder. Perform a complete history, physical, and neurologic examination. Rule out unilateral symptoms, tinnitus, and hearing loss. If she (he) is experiencing unilateral symptoms, pulsatile tinnitus, unilateral hearing loss, and a constant feeling of unsteadiness, further evaluation is necessary to exclude underlying pathology. Treating concurrent insomnia, depression, or anxiety might resolve the hallucinations.4

Nonpharmacotherapeutic treatments include hearing amplification, and masking tinnitus with a hearing aid emitting low-volume music or sounds of nature (ie, rainfall).4 Two cases have reported successful carbamazepine therapy; 2 other cases demonstrated success with clomipramine.5 Frequently, symptoms spontaneously remit.

Consider electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with musical hallucinations that are refractory to medical treatment and cause distress; 3 patients with concurrent major depressive disorder showed improvement after ECT.6 Antipsychotics are not recommended as first-line treatment.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Hermesh H, Konas S, Shiloh R, et al. Musical hallucinations: prevalence in psychotic and nonpsychotic outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):191-197.

2. Schakenraad SM, Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MG. Musical hallucinations in psychiatric patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(4):394-397.

3. Evers S, Ellger T. The clinical spectrum of musical hallucinations. J Neurol Sci. 2004;227(1):55-65.

4. Zegarra NM, Cuetter AC, Briones DF, et al. Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations in elderly persons with progressive deafness. Clin Geriatr. 2007;15(11):33-37.

5. Mahendran R. The psychopathology of musical hallucinations. Singapore Med J. 2007;48(2):e68-e70.

6. Wengel SP, Burke WJ, Holemon D. Musical hallucinations. The sounds of silence? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(2):163-166.

1. Hermesh H, Konas S, Shiloh R, et al. Musical hallucinations: prevalence in psychotic and nonpsychotic outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):191-197.

2. Schakenraad SM, Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MG. Musical hallucinations in psychiatric patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(4):394-397.

3. Evers S, Ellger T. The clinical spectrum of musical hallucinations. J Neurol Sci. 2004;227(1):55-65.

4. Zegarra NM, Cuetter AC, Briones DF, et al. Nonpsychotic auditory musical hallucinations in elderly persons with progressive deafness. Clin Geriatr. 2007;15(11):33-37.

5. Mahendran R. The psychopathology of musical hallucinations. Singapore Med J. 2007;48(2):e68-e70.

6. Wengel SP, Burke WJ, Holemon D. Musical hallucinations. The sounds of silence? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(2):163-166.

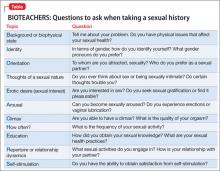

Know your BIOTEACHERS when you assess sexual health

Psychiatrists often are required to obtain basic sexual information as part of a thorough clinical assessment.1 Although a detailed sexual health assessment comprises multiple elaborate domains,2 it’s important that mental health professionals remember a set of topics and related questions (Table) that can help investigate, diagnose, and treat sexual dysfunction, and contribute to a biopsychosocial formulation of your patient’s sexuality. The BIOTEACHERS mnemonic can remind you what to ask when taking a patient’s sexual history; it is not intended to be an alternative to a comprehensive sexual health evaluation.

Each letter stands for a component of the sexual assessment. The grouped letters of the acronym break down into different relevant areas that aid in remembering each category.

BIO

Background of the problem or the patient’s biophysical state

Identity

Orientation

BIO gathers basic medical information, then creates an opportunity to understand the patient’s gender identity. This step allows for nonjudgmental discussions about the patient’s sexual orientation.

TEACH

Thoughts of a sexual nature

Erotic desire or sexual interest

Arousal

Climax during sex

How often

TEACH incorporates a common chronology of sexual response and activity, starting with sexual thoughts, feelings of erotic desire, development of sexual arousal, ability and quality of a patient’s orgasm, as well as frequency of sexual activity.

ERS

Education

Repertoire or relationship dynamics

Self-stimulation

ERS comprises somewhat more complicated subjects: education (questions about a person’s sexual awareness and communication style); formal sexual knowledge; and health practices. These areas of questioning also normalize discussion of the patient’s sexual repertoire (what activities he [she] does and avoids), reviews qualities of the sexual relationship, and broaches the issue of self-stimulation.

Remember: All discussions of sexuality should be appropriate to the clinical context and considerate of the deeply personal nature of the information.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Sallie Foley, LMSW, Daniela Wittmann, LMSW, and the University of Michigan Sexual Health Certificate program for their assistance.

1. Levine SB, Scott DL. Sexual education for psychiatric residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(5):349-352.

2. Downey JI, Friedman RC. Taking a sexual history: the adult psychiatric patient. Focus. 2009;7(4):435-440.

Psychiatrists often are required to obtain basic sexual information as part of a thorough clinical assessment.1 Although a detailed sexual health assessment comprises multiple elaborate domains,2 it’s important that mental health professionals remember a set of topics and related questions (Table) that can help investigate, diagnose, and treat sexual dysfunction, and contribute to a biopsychosocial formulation of your patient’s sexuality. The BIOTEACHERS mnemonic can remind you what to ask when taking a patient’s sexual history; it is not intended to be an alternative to a comprehensive sexual health evaluation.

Each letter stands for a component of the sexual assessment. The grouped letters of the acronym break down into different relevant areas that aid in remembering each category.

BIO

Background of the problem or the patient’s biophysical state

Identity

Orientation

BIO gathers basic medical information, then creates an opportunity to understand the patient’s gender identity. This step allows for nonjudgmental discussions about the patient’s sexual orientation.

TEACH

Thoughts of a sexual nature

Erotic desire or sexual interest

Arousal

Climax during sex

How often

TEACH incorporates a common chronology of sexual response and activity, starting with sexual thoughts, feelings of erotic desire, development of sexual arousal, ability and quality of a patient’s orgasm, as well as frequency of sexual activity.

ERS

Education

Repertoire or relationship dynamics

Self-stimulation

ERS comprises somewhat more complicated subjects: education (questions about a person’s sexual awareness and communication style); formal sexual knowledge; and health practices. These areas of questioning also normalize discussion of the patient’s sexual repertoire (what activities he [she] does and avoids), reviews qualities of the sexual relationship, and broaches the issue of self-stimulation.

Remember: All discussions of sexuality should be appropriate to the clinical context and considerate of the deeply personal nature of the information.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Sallie Foley, LMSW, Daniela Wittmann, LMSW, and the University of Michigan Sexual Health Certificate program for their assistance.

Psychiatrists often are required to obtain basic sexual information as part of a thorough clinical assessment.1 Although a detailed sexual health assessment comprises multiple elaborate domains,2 it’s important that mental health professionals remember a set of topics and related questions (Table) that can help investigate, diagnose, and treat sexual dysfunction, and contribute to a biopsychosocial formulation of your patient’s sexuality. The BIOTEACHERS mnemonic can remind you what to ask when taking a patient’s sexual history; it is not intended to be an alternative to a comprehensive sexual health evaluation.

Each letter stands for a component of the sexual assessment. The grouped letters of the acronym break down into different relevant areas that aid in remembering each category.

BIO

Background of the problem or the patient’s biophysical state

Identity

Orientation

BIO gathers basic medical information, then creates an opportunity to understand the patient’s gender identity. This step allows for nonjudgmental discussions about the patient’s sexual orientation.

TEACH

Thoughts of a sexual nature

Erotic desire or sexual interest

Arousal

Climax during sex

How often

TEACH incorporates a common chronology of sexual response and activity, starting with sexual thoughts, feelings of erotic desire, development of sexual arousal, ability and quality of a patient’s orgasm, as well as frequency of sexual activity.

ERS

Education

Repertoire or relationship dynamics

Self-stimulation

ERS comprises somewhat more complicated subjects: education (questions about a person’s sexual awareness and communication style); formal sexual knowledge; and health practices. These areas of questioning also normalize discussion of the patient’s sexual repertoire (what activities he [she] does and avoids), reviews qualities of the sexual relationship, and broaches the issue of self-stimulation.

Remember: All discussions of sexuality should be appropriate to the clinical context and considerate of the deeply personal nature of the information.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Sallie Foley, LMSW, Daniela Wittmann, LMSW, and the University of Michigan Sexual Health Certificate program for their assistance.

1. Levine SB, Scott DL. Sexual education for psychiatric residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(5):349-352.

2. Downey JI, Friedman RC. Taking a sexual history: the adult psychiatric patient. Focus. 2009;7(4):435-440.

1. Levine SB, Scott DL. Sexual education for psychiatric residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(5):349-352.

2. Downey JI, Friedman RC. Taking a sexual history: the adult psychiatric patient. Focus. 2009;7(4):435-440.

Use of the JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib in the treatment of patients with myelofibrosis

Myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF and MF secondary to polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia, is a chronic, clinically heterogeneous hematologic malignancy characterized by inefficient hematopoiesis, bone marrow fibrosis, and shortened survival. Typical clinical manifestations include progressive splenomegaly, debilitating symptoms, and anemia. MF is associated with dysregulation of Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway affecting hematopoiesis and inflammation. Ruxolitinib, an oral JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, was approved for the treatment of patients with intermediate or high-risk MF based on the results of 2 phase 3 studies (Controlled MyeloFibrosis Study with Oral JAK Inhibitor Treatment [COMFORT]-I and COMFORT-II). In these trials, ruxolitinib treatment was associated with reductions in spleen size and symptom burden, and improvements in quality of life. The most common adverse events were dose-dependent cytopenias, which were managed by dose modifications, treatment interruptions, and red blood cell transfusions (for anemia). Ruxolitinib was effective regardless of MF type, risk status, or JAK2V617F mutation status, and across various other MF subpopulations. Two-year follow-up data from the COMFORT trials also demonstrate that ruxolitinib has durable efficacy and may be associated with a survival advantage relative to placebo and best available therapy. Preliminary data from ongoing studies support possible dosing strategies for patients with low platelet counts.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF and MF secondary to polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia, is a chronic, clinically heterogeneous hematologic malignancy characterized by inefficient hematopoiesis, bone marrow fibrosis, and shortened survival. Typical clinical manifestations include progressive splenomegaly, debilitating symptoms, and anemia. MF is associated with dysregulation of Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway affecting hematopoiesis and inflammation. Ruxolitinib, an oral JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, was approved for the treatment of patients with intermediate or high-risk MF based on the results of 2 phase 3 studies (Controlled MyeloFibrosis Study with Oral JAK Inhibitor Treatment [COMFORT]-I and COMFORT-II). In these trials, ruxolitinib treatment was associated with reductions in spleen size and symptom burden, and improvements in quality of life. The most common adverse events were dose-dependent cytopenias, which were managed by dose modifications, treatment interruptions, and red blood cell transfusions (for anemia). Ruxolitinib was effective regardless of MF type, risk status, or JAK2V617F mutation status, and across various other MF subpopulations. Two-year follow-up data from the COMFORT trials also demonstrate that ruxolitinib has durable efficacy and may be associated with a survival advantage relative to placebo and best available therapy. Preliminary data from ongoing studies support possible dosing strategies for patients with low platelet counts.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF and MF secondary to polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia, is a chronic, clinically heterogeneous hematologic malignancy characterized by inefficient hematopoiesis, bone marrow fibrosis, and shortened survival. Typical clinical manifestations include progressive splenomegaly, debilitating symptoms, and anemia. MF is associated with dysregulation of Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway affecting hematopoiesis and inflammation. Ruxolitinib, an oral JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, was approved for the treatment of patients with intermediate or high-risk MF based on the results of 2 phase 3 studies (Controlled MyeloFibrosis Study with Oral JAK Inhibitor Treatment [COMFORT]-I and COMFORT-II). In these trials, ruxolitinib treatment was associated with reductions in spleen size and symptom burden, and improvements in quality of life. The most common adverse events were dose-dependent cytopenias, which were managed by dose modifications, treatment interruptions, and red blood cell transfusions (for anemia). Ruxolitinib was effective regardless of MF type, risk status, or JAK2V617F mutation status, and across various other MF subpopulations. Two-year follow-up data from the COMFORT trials also demonstrate that ruxolitinib has durable efficacy and may be associated with a survival advantage relative to placebo and best available therapy. Preliminary data from ongoing studies support possible dosing strategies for patients with low platelet counts.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Electronic Communication

INTRODUCTION

Coordination of care within a practice, during transitions of care, and between primary and specialty care teams requires more than data exchange; it requires effective communication among healthcare providers.[1, 2, 3] In clinical terms, data exchange, communication, and care coordination are related, but they represent distinct concepts.[4] Data exchange refers to transfer of information between settings, independent of the individuals involved, whereas communication is the multistep process that enables information exchange between two people.[5] Care coordination, as defined by O'Malley, is integration of care in consultation with patients, their families and caregivers across all of a patient's conditions, needs, clinicians and settings.[3]

Strong collaboration among providers has been associated with improved patient outcomes.[2, 6] Yet, despite the significant role of communication in healthcare, communication may not take place at all, even at high‐stakes events like transitions of care,[7, 8] or it may be done poorly at the risk of substantial clinical morbidity and mortality.[9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]

Proof of the global effectiveness of health information technology (HIT) to improve patient care is lacking, but data from some studies demonstrate real improvements in quality and safety in specific areas,[17, 18, 19] especially with computerized physician order entry[20] and electronic prescribing.[21]

The limited information about the effect of HIT on communication focuses largely on the anticipated improvements in patient‐physician communication[22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]; provider‐to‐provider communication within the electronic domain is not as well understood. A recent review of interventions involving communication devices such as pagers and mobile phones found limited high‐quality evidence in the literature.[28] Clinicians have described what they consider to be key characteristics of clinical electronic communications systems such as security/reliability, cross coverage, overall convenience, and message prioritization.[29] Although the electronic health record (EHR) is expected to assist with this communication,[30] it also has the potential to impede effective communication, leading physicians to resort to more traditional workarounds.[31, 32, 33]

Measuring and improving the use of EHRs nationally were driving forces behind the creation of the Meaningful Use incentive program in the United States.[34] To receive the incentive payments, providers must meet and report on a series of measures set in three stages over the course of five years.[35] In the current state, Meaningful Use does not reward provider‐to‐provider communication within the EHR.[36, 37] The main communication objectives for stages 1 and 2 concentrate on patient‐to‐provider communication, such as patient portals and patient‐to‐provider messaging.[36, 37]

Understanding the current evidence for provider‐to‐provider communication within EHRs, its reported effectiveness, and its shortcomings may help to develop a roadmap for identifying next‐generation solutions to support coordination of care.[38, 39] This review assesses the literature regarding provider‐to‐provider electronic communication tools (as supported within or external to an EHR). It is intended as a comprehensive view of studies reporting quantitative measures of the impact of electronic communication on providers and patients.

METHODS

Definitions and Conceptual Model of Provider‐to‐Provider Communication

We conducted a systematic review of studies of provider‐to‐provider electronic communication. This review included only formal clinical communication between providers and was informed by the Coiera communications paradigm.[5] This paradigm consists of four steps: (1) task identification, when a task is identified and associated with the appropriate individual; (2) connection, when an attempt is made to contact that person; (3) communication, when task‐specific information is exchanged between the parties; and (4) disconnection, when the task reaches some stage of completion.

Literature Review

We examined written electronic communication between providers including e‐mail, text messaging, and instant messaging. We did not review provider‐to‐provider telephone or telehealth communication, as these are not generally supported within EHR systems. Communication in all clinical contexts was included among providers within an individual clinic or hospital and among providers across specialties or practice settings.[40] We excluded physician handoff communication because it has been extensively reviewed elsewhere and because handoff occurs largely through verbal exchange not recorded in the EHR.[41, 42] Communication from clinical information systems to providers, such as automated notification of unacknowledged orders, was also excluded, as it is not within the scope of provider‐to‐provider interaction.

Data Sources and Searches

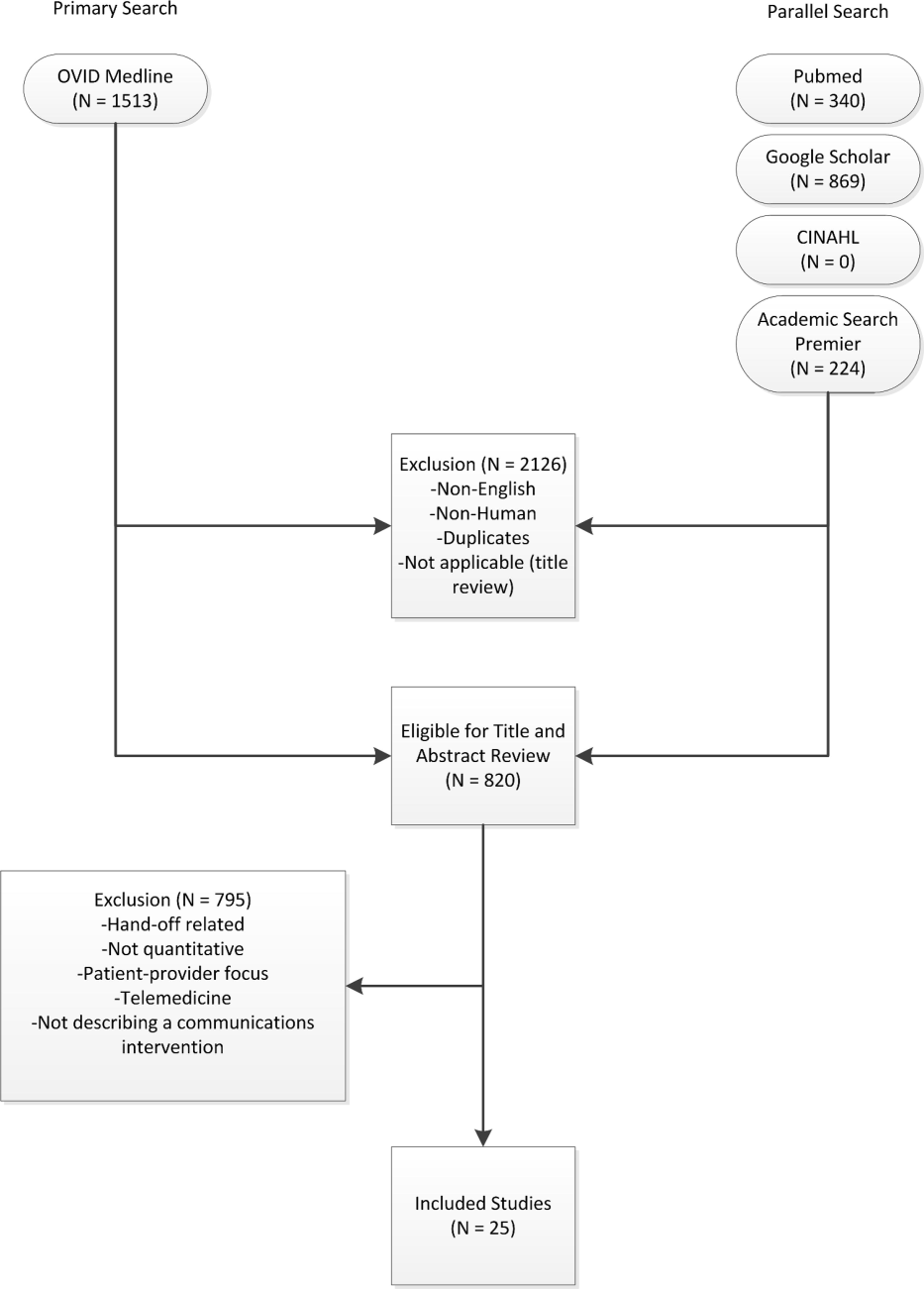

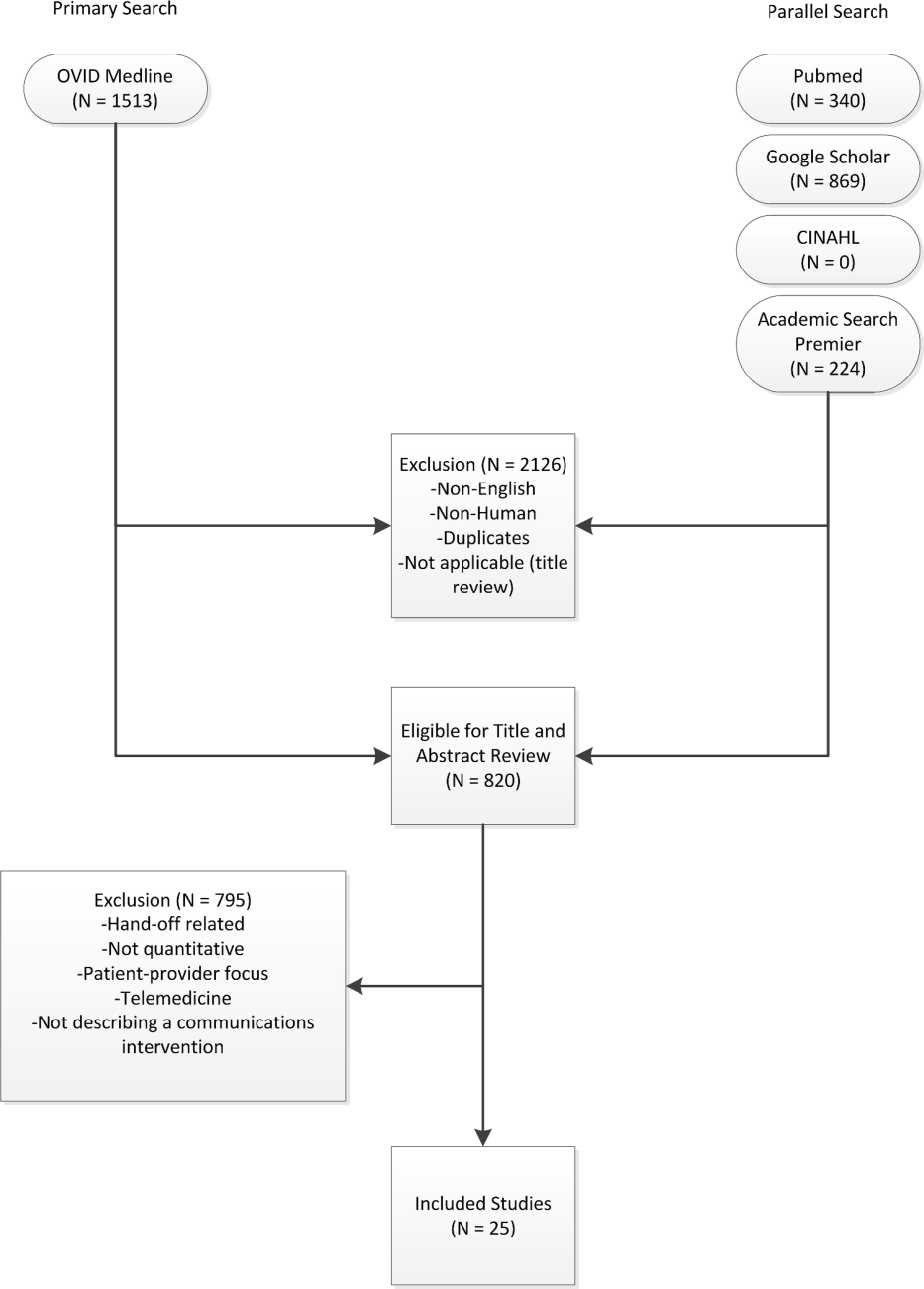

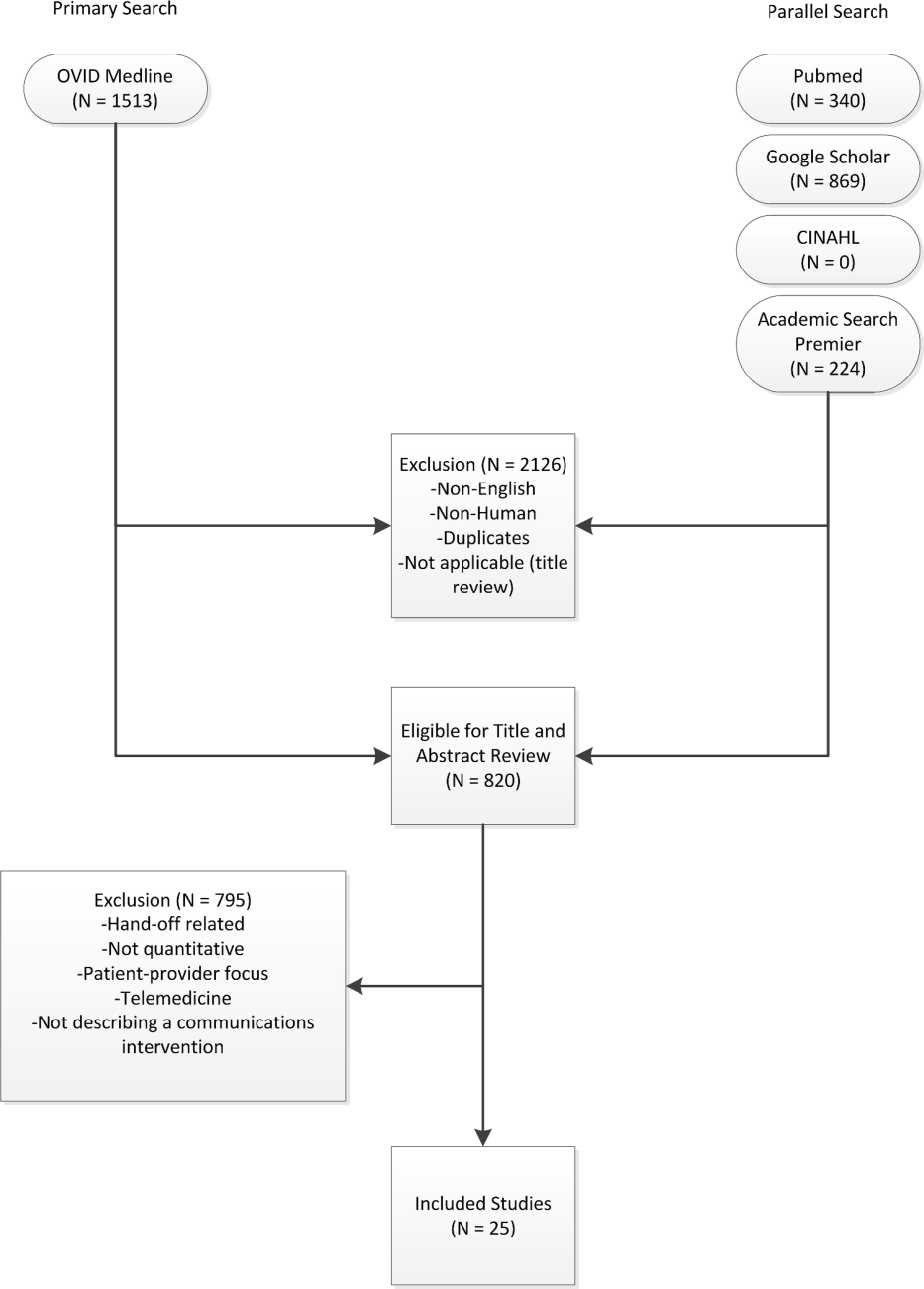

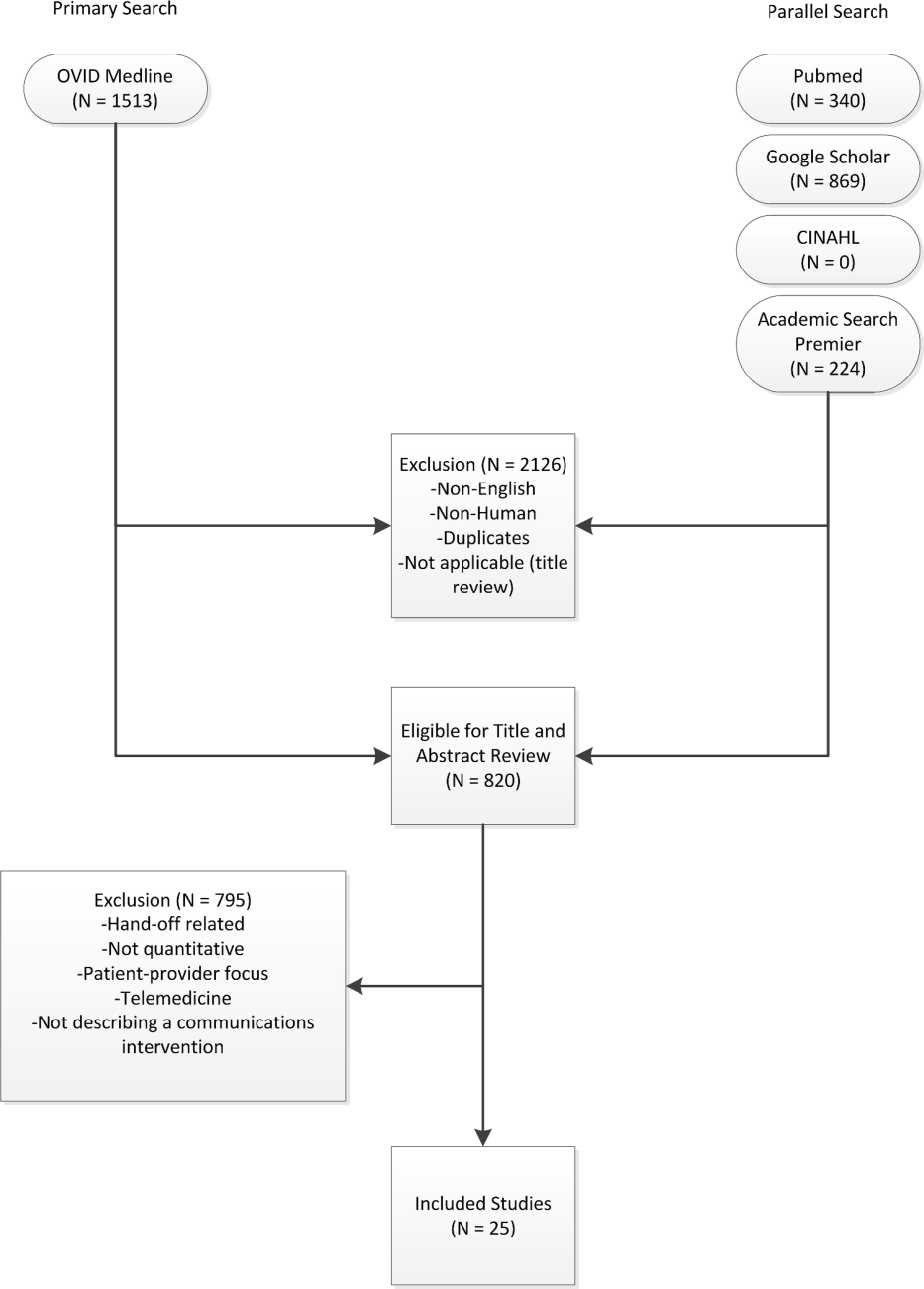

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in Ovid MEDLINE with the input of a medical librarian, and a parallel search was performed using PubMed. The Ovid MEDLINE query and parallel database search terms are documented in Table 1. Subsearches were conducted in Google Scholar, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Academic Search Premier for peer‐reviewed journals. Subsequent studies citing the initially detected articles were found through citation maps.

| Database | Strategy | Items Reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Ovid MEDLINE | Query terms: exp medicine/ or physicians or exp outpatient clinics/ or exp hospitals/ AND *communication/ or *computer communication networks/ or *interprofessional relations/ or *continuity of patient care/ AND electronic mail or referral and consultation or text messaging/ or reminder systems. | 1513 |

| PubMed | Healthcare, provider, communication, messaging, e‐mail, texting, text messaging, instant messaging, paging, coordination, referral, EHR, EMR, electronic health record, electronic medical record, electronic, and physician. Excluding patient‐provider and patient‐physician | 340 |

| Google Scholar | Physician‐physician electronic communication excluding physician‐patient | 940 |

| CINAHL | Medical records and communication; or computerized patient records and communication | None |

| Academic Search Premier (peer‐reviewed journals) | Electronic health record and communication | 54 |

| Communication and electronic health record | 80 | |

| Physician‐physician communication | 2 | |

| Physicians and electronic health records | 88 | |

Study Selection

Paper Inclusion Criteria

Requirements included publication in English‐language peer‐reviewed journals. Included studies provided quantitative provider‐to‐provider communication data, provider satisfaction statistics, or EHR communication data. Provider‐to‐staff communication was also included if it fell within the scope of studies of communication between providers.

Paper Exclusion Criteria

Studies excluded in this review were articles that reviewed EHR systems without any focus on communication between providers and those that discussed EHR models and strategies but did not include actual testing and quantitative results. Results that included nontraditional online documents or that were found on nonpeer‐reviewed websites were also discarded. Duplicate records or publications that covered the same study were also removed. The most common reason for exclusion was the lack of quantitative evaluation.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Three authors (Walsh, Siegler, Stetson) reviewed titles and abstracts of resultant studies against inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Studies were evaluated qualitatively and findings summarized. Given the heterogeneous nature of data reported, statistical analysis was not possible.

RESULTS

The primary and parallel searches produced 2946 results that were weaned through title review and exclusion of duplicates, nonEnglish‐language, and nonhuman studies to 820 articles for title and abstract review (Figure 1). After careful review of the articles' titles, abstracts, or full content (where appropriate), twenty‐five articles met inclusion criteria and presented data about provider‐to‐provider electronic communication, either within an EHR or through a system designed to promote provider‐to‐provider communication. All of the studies that met inclusion criteria focused on physicians as providers. Five studies (20%) described trial design, three (12%) were pilot studies, and seventeen (68%) were observational studies. Thirteen of twenty‐five articles (52%) described studies conducted in the United States and twelve in Europe.

Most of the studies (56%) focused on electronic referrals between primary care and subspecialty providers. The clinical need was to communicate information on a specific patient with a specialist who shared responsibility for the overall plan of care. Only two studies evaluated curbside consultation, where providers ask for clinical recommendations without formally engaging a specialist in the plan of care for a particular patient. Table 2 summarizes included studies and has been organized with respect to clinical need under evaluation. The major themes that emerged from this review included: studies of penetration of communication tools either within the EHR system (intra‐EHR IT) or external to the EHR (extra‐EHR IT); electronic referrals; curbside consultations; and test results reporting (results notification).

| Primary Author, Year | Design | Intervention | Measurement | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Need: Communicate care across clinical settings (inpatient‐outpatient) | ||||

| Branger, 1992[4, 6] | Observational study | Introduction of electronic messaging system in the Netherlands between hospital and PCPs. | Satisfaction survey data using Likert scale of usefulness. | Free text messaging to exchange patient data was rated very useful or useful by 20 of 27 PCP respondents. |

| Reponen, 2004[66] | Observational study | Finnish study of electronic referrals XML messages between EHRs or secure web links. | User questionnaire. No description of respondents was provided. | Internists surveyed estimated that electronic referrals accelerate the referral process by 1 week. |

| Need: Communicate care across specialties (primary care physicians‐specialists) | ||||

| Kooijman, 1998[67] | Observational study | Survey of 45 PCPs who received notes from specialists via Electronic Data Interchange. | User questionnaire with 5‐point Likert scale of satisfaction, from 1 (much better) to 5 (much worse). | Highest satisfaction scores for speed (1.51.8) and efficiency (1.51.7) for electronic messages, with lower scores for reliability (2.52.7) and clarity (2.5). |

| Harno, 2000[4][8] | Nonrandomized trial | Eight‐month prospective comparative study in Finland of outpatient clinics in hospitals with and without intranet referral systems. | Comparison of numbers of electronic referrals, clinic visits, costs. | There were 43% of electronic referrals and 79% of outpatient referrals that resulted in outpatient visits. A 3‐fold increase in productivity overall and 7‐fold reduction in visit costs per patient using e‐mail consultation. |

| Moorman, 2001[4][7] | Observational study | Supersedes Branger, 1999.[68] Analyzes intra‐EHR communications between PCPs and consultant in Netherlands re: diabetes management of patients (19941998). | Descriptive statistics of number of messages, content, whether message had been copied into EMR; survey of PCPs (12 of 15 responded). | Decline in integration by PCPs of messages in the EHR from 75% to 51% over first 3 years. Despite this, most PCPs wanted to extend messaging to other patient groups. |

| Bergus, 2006[69] | Observational study | Follow‐up of Bergus, 1998[54]; evaluated formulation of clinical referrals to specialists at the University of Iowa by retrospective review of e‐mail transcripts. | Analyzed taxonomy of clinical questions; assessed need for clinical consultation of 1618 clinical questions. | Specialists less likely to recommend clinic consultation if referral specified the clinical task (OR: 0.36, P<0.001), intervention (OR: 0.62, P=0.004), or outcome (OR: 0.49, P<0.001). This effect was independent of clinical content (P>0.05). |

| Dennison, 2006[70] | Pilot study | Construction of an electronic referral pro forma to facilitate referral of patients to colorectal surgeons. | Descriptive statistics. Comparisons of patient attendance rate, delays to booking and to actual appointment between 54 electronic referrals and 189 paper referrals. | Compared to paper referrals, electronic referrals were booked more quickly (same day vs 1 week later on average) and patients had lower nonattendance rates (8.5% vs 22.5%). Both results stated as statistically significant, but P values were not provided. |

| Shaw, 2007[49] | Observational study | Dermatology electronic referral in England. | Content of 131 electronic vs 139 paper referrals to dermatologists(NHS Choose and Book).[71] | Paper superior to electronic for clinical data such as current treatments (included in 68% of paper vs 39% of electronic referrals, P<0.001); electronic superior for demographic data. |

| Gandhi, 2008[50] | Nonrandomized trial | Electronic referral tool in the Partners Healthcare System in Massachusetts that included a structured referral‐letter generator and referral status tracker. Assigned to 1 intervention site and 1 control site. | Survey assessment. Fifty‐four of 117 PCPs responded (46%), 235 of 430 specialists responded (55%), 143 out of 210 patients responded (69%). | Intervention group showed high voluntary adoption (99%), higher information transfer rates prior to subspecialty visit (62% vs 12%), and lower rates of conflicting information being given to patients (6% vs 20%). |

| John, 2008[72] | Pilot study | Validation study of the Lower Gastrointestinal e‐RP (through the Choose and Book System in the United Kingdom) intended to improve yield of colon cancers diagnosed and to reduce delays in diagnosis. | Comparison of actual to simulated referral patterns through e‐RP for 300 patients divided into colorectal cancer, 2‐week wait suspected cancer, and routine referral groups. | e‐RP was more accurate than traditional referral at upgrading patients who had cancer to the appropriate suspected cancer referral group (85% vs 43%, P=0.002). |

| Kim, 2009[73] | Observational study | Electronic referrals via a portal to San Francisco General Hospital. Included reply functionality and ability to forward messaging to a scheduler for calendaring. | Impact of electronic referral system as measured by questionnaire to referring providers. A total of 298/368 participated (24 clinics); 53.5% attending physicians. | Electronic referrals improved overall quality of care (reported by 72%), guidance of presubspecialty visit (73%), and the ability to track referrals (89%). Small change in access for urgent issues (35% better, 49% reported no change). |

| Scott, 2009[74] | Pilot study | Pilot of urgent electronic referral system from PCPs to oncologists at South West Wales Cancer Centre. | Satisfaction statistics (10‐point Likert scale) collected from PCPs via interview. | Over 6 months, 99 referrals submitted; 81% were processed within 1 hour with high satisfaction scores. |

| Were, 2009[75] | Nonrandomized trial | Geriatrics consultants were provided system to make electronic recommendations (consultant‐recommended orders) in the native CPOE system along with consult notes in the intervention vs consult notes alone in the control. | Rates of implementation of consultant recommendations. Qualitative survey of users of the new system. | Higher total number of recommendations (247 vs 192, P<0.05) and higher implementation rates of consultant‐recommended orders in the intervention group vs control (78% vs 59%, P=0.01). High satisfaction scores on 5‐point Likert scale for the intervention system with good survey response rate (83%). |

| Dixon, 2010[52] | Observational study | Comparison of 2 extra‐EHR systems (NHS Choose and Book, Dutch ZorgDomein) for booking referrals. Patients choose doctor or hospital and the system transfers demographic and clinical information between PCP and specialist. | National data, patient and provider surveys, focus groups, observational studies. Focus was on patient choice, but evaluations included all aspects of the systems. | Resistance from PCPs during implementation; 78% of ZorgDomein PCPs felt referrals took more time; general displeasure on the part of specialists re: quality of referrals, although not quantified. |

| Patterson, 2010[51] | Observational study | E‐mail referral system to a neurologist in Northern Ireland. Referrals were template based and recorded as clinical episode in the patient administration system. Comparison of this system to conventional referrals to another neurologist. | Evaluated effectiveness, cost, safety for period 20022007. | Decreased referral wait times (4 vs 13 weeks) and 35% cost reduction per patient for the e‐mail referral vs conventional referrals. |

| No diminution in safety. Limitation: single neurologist participated. | ||||

| Singh, 2011[76] | Observational study | Chart review of electronic referrals to specialist practices in a Veterans Affairs outpatient system. | Follow‐up actions taken by subspecialists within 30 days of receiving referral. | An intra‐EHR referral system was still affected by communication breakdowns. Of 61,931 referrals, 36.4% were discontinued for inappropriate or incomplete referral requests. |

| Kim‐Hwang, 2010[77] | Observational study | Electronic referrals via a portal to San Francisco General Hospital. Follow‐up to Kim, 2009.[73] | Survey of medical and surgical subspecialty consultants. | Statistically significant differences in clarity of consult request in both medical and surgical clinics, in decreased inappropriate referrals in surgical clinics, in decreased use of follow‐up appointments by surgical specialists, and in decreased avoidable follow‐up surgical visits. |

| Warren, 2011[53] | Observational study | Electronic referrals from general medical practices to public referral network of Hutt Hospital in New Zealand (20072010). | Retrospective analysis of transactional data from messaging system and from general inpatient tracking system. Qualitative data collection via interviews. | Estimated 71% of 10,367 referrals were electronic referrals over 3 years. Statistically significant improvement in referral latency without change in staffing. Clinicians appreciate shared transparency of referrals but cite usability issues as barriers. |

| Need: Curbside consults (primary care physicians‐specialists) | ||||

| Bergus, 1998[54] | Observational study | Evaluation of the ECS for curbside consultations between family physicians and subspecialists. | Descriptive statistics of usage data; survey of users. | Median response time 16.1 hours; 92% of questions answered; almost 90% concerned specific patients. Both groups expressed satisfaction. |

| Abbott, 2002[55] | Observational study | Evaluation of Department of Defense Ask a Doc physician‐to‐physicians e‐mail consultation system over network of 21 states (19982000). | Descriptive statistics; qualitative assessment. | There were 3121 consultations. Average response time <12 hours. Minimal cost and effort to initiate and sustain. Felt to mirror clinical practice. Barriers were security and assignation of credit for consultation. |

| Need: Communication of results (primary care physicians ‐specialists) | ||||

| Singh, 2007[5][6] | Nonrandomized trial | Concurrent prospective evaluation of responses to 1017 critical imaging alert notifications in a Veterans Affairs outpatient system (2006). Radiologists generated alerts. Included receipt system. | Measured percentage of unacknowledged alerts and imaging lost to follow‐up. | There were 368 of 1017 transmitted alerts unacknowledged (36%); 45 were completely lost to follow‐up. There were 0.2% outpatient imaging results lost to follow‐up overall. |

| Singh, 2009[5][7] | Nonrandomized trial | Concurrent evaluation of responses to 1196 critical imaging alert notifications in a Veterans Affairs outpatient system (20072008). Similar coding system to Singh, 2007.[56] | Measured percentage of alerts acknowledged, timely follow‐up; compared electronic alerts alone to combination of alerts and phone calls or admission. | Percentage of alerts acknowledged did not differ by type of communication; combination of electronic alerts with phone follow‐up (OR: 0.12, P<0.001) or admission (OR: 0.22, P<0.001) decreased likelihood of delayed follow‐up. Alerts to 2 providers increased the likelihood of delayed follow‐up (OR: 1.99, P=0.03). |

| Abujudeh, 2009[5][8] | Observational study | Retrospective review of e‐mailbased alert system for abnormal imaging results at Massachusetts General Hospital 20052007. E‐mail alerting by radiologist to ordering physician of nonurgent findings. | Descriptive statistics; survey of referring physicians (12/26). | There were 56,691 out of 1,540,254 reports for important but not urgent findings; 93.3% generated e‐mail message (6.7% failure rate); 80% of alerts were viewed. Higher satisfaction for e‐mail alerts over conventional methods (eg, facsimile) for nonurgent but important findings. |

| Need: Communicate within 1 care setting (primary care physicians) | ||||

| Lanham, 2012[78] | Observational study | Comparison of practice‐level EHR use with communication patterns among physicians, nurses, medical assistants, practice managers, and nonclinical staff within individual practices in Texas. | Observation and semistructured interviews. Within‐practice communication patterns were categorized as fragmented or cohesive. Practice‐level EHR use was categorized as homogeneous or heterogeneous. | Clinical practices with cohesive within‐practice communication patterns were associated with homogeneous patterns of practice‐level EHR use. |

| Murphy, 2012[79] | Observational study | Review of note‐based messaging within the EHR in outpatient clinics of large tertiary Veterans Affairs facility. Clinic staff send additional signature request alerts linked to parent notes in the EHR to primary care physicians. | Reason for and origin of alerts. Parent note linked to alert was also reviewed for 3 value attributes: urgency; potential harm if alert was missed; subjective value to PCP of the alert. | Of the alerts reviewed, 53.7% of 525 were deemed of high value but required PCPs to review significant amounts of extraneous text (80.3% of words in parent notes) to get relevant information. Most alerts (40%) were medication, prescription, or refill related. |

Extra‐EHR IT

A review of electronic communication in 2000 examined electronic communication among primary care physicians but notably did not distinguish between communication and data exchange.[43] Of the thirty included publications in that review, seventeen publications dealt with electronically communicated information in general; the remaining studies focused on notifications of test results or transitions of care, reports from specialists, or electronic communication as replacement of traditional referral.[43] Although many studies of electronic communication described positive benefits, few included objective data, and most did not analyze provider‐to‐provider communication specifically. A survey of IT use outside of the EHR in 2006 documented that approximately 30% of clinicians used e‐mail to communicate with other clinicians, fewer than those who consulted on‐line journals (40.8%), but many more than those who communicated with patients by e‐mail at that time (3.6%).[44]

Intra‐EHR IT

A comparison of two physician surveys of EHR use in Massachusetts (the first in 2005 and the second in 2007) documented an increase in the percentage of practices with an EHR, from 23% to 35%; in those practices with EHRs, only the use of electronic prescribing increased over time. Use of secure electronic referrals or messaging including secure e‐mail remained unchanged; of note, referrals and messaging were considered a singular clinical function in that study. Between 2005 and 2007, referrals or clinical messaging were available in 62% and 63% of EHR systems, respectively, and they were used most or all of the time by 29% to 33% of the physicians who had an EHR.[45]

Electronic Referrals

Fourteen articles focused on electronic referrals. Two had a prepost or longitudinal study design,[46, 47] and five included a control group.[48, 49, 50, 51] The rest were descriptive. In most cases, electronic referral improved the transfer of information, especially when standardized message templates were created. Use of electronic referral appeared to result in reduced waiting time for appointments and enabled more efficient triage.

Barriers to integration of electronic referral in the EHR were also assessed. An intra‐EHR communication system requiring a primary care physician to integrate information e‐mailed by the consultant into the record showed the percentage of integrated notes decreasing over time.[47] Practitioners had mixed feelings about the system; although the majority (92% of respondents) felt that the system improved patient care and wanted to extend messaging to other patient groups, they also felt that electronic messaging decreased the ease of reviewing data (83%) and confused tasks and responsibilities (59%). A study of British and Dutch electronic referral systems described significant resistance on the part of practitioners to electronic referrals and concern on the part of specialists about the quality of referrals.[52] Another study demonstrated improvement in quality of demographic data but degradation in quality of clinical information when referrals were submitted electronically.[49] A recent transactional analysis of electronic referrals in New Zealand showed high uptake and reduced referral latency compared to conventional referral; clinicians cited usability concerns as the major barrier to use.[53]

Curbside Consultations via E‐mail

Two studies evaluated curbside consultations via e‐mail and documented high provider satisfaction and rapid turnaround.[54, 55] The preliminary nature of these studies raises questions of sustainability and long‐term implementation.

Results Notification

Three studies focused on test‐result reporting from radiologists. In these studies, a radiologist could designate a result as high priority and have an e‐mail notification sent to the ordering physicians.[56, 57, 58] Urgent results were relayed by telephone. Lack of acknowledgement of alerts impacted the results of every study, and in one of these studies, alerting two physicians, rather than just one, decreased the likelihood that the results would be followed up.[57] Providers did prefer e‐mail to fax notification.[58]

DISCUSSION

The principal findings of the literature review demonstrate the paucity of quantitative data surrounding provider‐to‐provider communication. The majority of studies focused on physicians as providers without emphasis on other provider types on the care team. Most of the quantitative studies investigated electronic referrals. Data collected largely represented measures of provider satisfaction and process measures. Few quantitative studies used established models or measures of team coordination or communication.

This study extends the work of others by compiling a comprehensive view of electronic provider‐to‐provider communication. A recent review of devices for clinical communication tells a part of the story,[28] and our review adds a comprehensive, device‐agnostic look at the systems physicians and other providers use every day.

Limitations of this review include the small number of eligible studies and a homogenous provider type (physicians). The latter is both an important finding and a limitation to generalizability of our results. Reviewed studies were in English only. The literature review by its nature is subject to publication bias.

Intra‐EHR communication cannot serve all purposes, and is it not a panacea for effective care coordination. One recent qualitative study warns about the pitfalls of electronic communication. Interviews with physicians from twenty‐six practices elicited some concerns about the resulting decrease in face‐to‐face communication that has resulted from the adoption of electronic communication tools.[32] This finding brings implications: (1) a false sense of security may reduce verbal communications when they are needed mostduring emergencies or when caring for complex patients who require detailed, nuanced discussion; and (2) fewer conversations within a practice can reduce both knowledge sharing and basic social interactions necessary for the maintenance of a collaboration. Last, privacy and confidentiality are top priorities. Common electronic communication tools are susceptible to security breaches,[47, 59] and innovations within this domain must conform to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act regulations.[60]

Although electronic communication is not a complete solution for clinical collaboration, it is difficult to use face‐to‐face communication and telephone communication to convey large amounts of patient information while simultaneously generating a record of the transaction. Moreover, paging functions, telephone calls, and face‐to‐face encounters can be highly interruptive, increasing cognitive load, burdening working memory, and shifting attention from the task at hand.[14] Interruptions contribute to inefficiency and to the potential for errors.[61]

Effective coordination of care for the chronically ill is one of the essential goals of the health system; it is an ongoing process that depends on constant, effective communication. Bates and Bitton have recognized this and described the crucial role that HIT will play in creating an effective medical home by enumerating seven domains of HIT especially in need of research.[62] In particular, they note that effective team care and care transitions will depend on an EHR that promotes both implicit and real‐time communication: it will be essential to develop communication tools that allow practices to record goals shared by providers and patients alike, and to track medical interventions and progress.[62]

Future research could investigate a number of open questions. Overall, an emphasis should be placed on rigorous qualitative and quantitative evaluation of electronic communication. Process measures, such as length of stay, hospital readmission rates, and measures of care coordination, should be framed ultimately with respect to patient health outcomes. Such data are beginning to be reported.[63]

It is unclear which types of communications would be best served within the EHR and which should remain external to it. Instant communication or chat has not been studied sufficiently to show a demonstrable impact on patient care. Cross‐coverage and team identification within the EHR can be further studied with respect to workflows and best practices. Studies using structured observation or time‐and‐motion analysis could provide insight into use cases and workflows that providers implement to discuss patients. Future research should incorporate established models of communication[5] and coordination.[64] Data on unintended consequences or harms of provider‐to‐provider electronic communication have been limited, and this area should be considered in subsequent work. Finally, although the scope of this review focused on communication between providers, transformative electronic communication systems should bridge communication gaps between providers and patients as well.

As adoption of EHRs in US hospitals has increased from 15.1% of US hospitals in 2010 to 26.6% in 2011 for any type of EHR and 3.6% to 8.7% for comprehensive EHRs,[65] it is worth noting that Meaningful Use, as it stands, incentivizes patient‐provider communication, but not communication between providers. Inclusion of certification criteria focused on provider‐to‐provider communication may spur additional innovation.

CONCLUSIONS

The optimal features to support electronic communication between providers remain under‐assessed, although there is preliminary evidence for the acceptability of electronic referrals. Without better understanding of electronic communication on workflow, provider satisfaction, and patient outcomes, the impact of such tools on coordination of complex medical care will be an open question, and it remains an important one to answer.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Thomas Payne, Medical Director of IT Services at the University of Washington, for sharing his expertise, and to Marina Chilov, medical librarian at Columbia University, for her assistance with the literature search. The authors would like to thank Paul Sun, MA, for his assistance with the literature review.

Disclosures: This work was funded by 5K22LM8805 (PDS) and T15 LM007079 (CW, SC) grants. Dr. Stetson serves on the advisory board of the Allscripts Enterprise EHR.

- , . Physician‐physician communication: what's the hang‐up? J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:437–439.

- , , , et al. Meta‐analysis: effect of interactive communication between collaborating primary care physicians and specialists. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(4):247–258.

- , , , , . Are electronic medical records helpful for care coordination? Experiences of physician practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;25:177–185.

- , , , , , . Development of an ontology to model medical errors, information needs, and the clinical communication space. Proc AMIA Symp. 2001:672–676.

- . Clinical communication: a new informatics paradigm. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1996:17–21.

- , , . Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice‐based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD000072.

- , , , . Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4):218–229.

- , , , et al. Association of communication between hospital‐based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381–386.

- , , , et al. Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA. 1998;280(15):1311–1316.

- , , , . Analysing potential harm in Australian general practice: an incident‐monitoring study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;169:73–76.

- . When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):277–286.

- , , , , . Communication loads on clinical staff in the emergency department. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;176(9):415–418.

- , , , , , . Deficit in communicaiton and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians. JAMA. 2007;297:831–841.

- , . Improving clinical communication: a view from psychology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(5):453–461.

- , , . Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186–194.

- , , , , , . The Quality in Australian Health Care Study. Med J Aust. 1995;163:458–471.

- , , , et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):742–752.

- , , . Costs and benefits of health information technology. Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2006;132:1–71.

- , , , et al. Relationship between use of electronic health record features and health care quality: results of a statewide survey. Med Care. 2010;48:203–209.

- , , , et al. Decrease in hospital‐wide mortality rate after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1–e8.

- , , , , . Electronic prescribing improves medication safety in community‐based office practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:530–536.

- . Patient‐centered Care. Radiol Technol. 2009;81(2):133–147.

- , . The missing link: bridging the patient‐provider health information gap. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(5):1290–1295.

- , , , , . Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(2):121–126.

- , . Web messaging: a new tool for patient‐physician communication. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(3):260–270.

- , , , . Expanding the guidelines for electronic communication with patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2001;8(4):344–348.

- , , , . The utility of electronic mail as a medium for patient‐physician communication. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(3):268–271.

- , , , et al. Effects of clinical communication interventions in hospitals: a systematic review of information and communication technology adoptions for improved communication between clinicians. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(11):723–732.

- , . Desiderata for personal electronic communication in clinical systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;9(3):209–216.

- . When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7:277–286.

- . Getting in step: electronic health records and their role in care coordination. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:174–176.

- , , . Electronic medical records and communication with patients and other clinicians: are we talking less? Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change. 2010;(131):1–4.

- , . Referral and consultation communication between primary care and specialist physicians: finding common ground. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(1):56–65.

- , . The "meaningful use" regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):501–504.

- Centers for Medicare 25(3):177–185.

- . Getting in step: electronic health records and their role in care coordination. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):174–176.

- , , , . A framework for clinical communication supporting healthcare delivery. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:375–379.

- Understanding and improving patient handoffs. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2010:49–96.

- , , , . Signout: a collaborative document with implications for the future of clinical information systems. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2007:696–700.

- , , . Effects of electronic communication in general practice. Int J Med Inform. 2000;60(1):59–70.

- , , , , . Prevalence of basic information technology use by U.S. physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1150–1155.

- , , , et al. Physicians' use of key functions in electronic health records from 2005 to 2007: a statewide survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:465–470.

- , , , et al. Electronic communication between providers of primary and secondary care. BMJ. 1992;305(6861):1068–1070.

- , , , . Electronic messaging between primary and secondary care: a four‐year case report. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2001;8(4):372–378.

- , , , . Patient referral by telemedicine: effectiveness and cost anslysis of an intranet system. J Telemed Telecare. 2000;6(6):320–329.

- , . Strengths and weaknesses of electronic referral: comparison of data content and clinical value of electronic and paper referrals in dermatology. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(536):223–224.

- , , , et al. Improving referral communication using a referral tool within an electronic medical record. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, eds. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches. Vol. 3. Performance and Tools. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008:63–74.

- , , , . Email triage is an effective, efficient, and safe way of managing new referrals to a neurologist. Qual Safety Health Care. 2010;19(5):e51.