User login

A Multi-Disciplinary Approach to Increasing Germline Genetic Testing for Prostate Cancer

PURPOSE

This quality improvement project aims to enhance the rate of germline genetic testing for prostate cancer at the Stratton VA Medical Center, improving risk reduction strategies and therapeutic options for patients.

BACKGROUND

Prostate cancer is prevalent at the Stratton VA Medical Center, yet the rate of genetic evaluation for prostate cancer remains suboptimal. National guidelines recommend genetic counseling and testing in specific patient populations. To address this gap, an interdisciplinary working group conducted gap analysis and root cause analysis, identifying four significant barriers.

METHODS

The working group comprised medical oncologists, urologists, primary care physicians, genetics counselors, data experts, and a LEAN coach. Interventions included implementing a prostate cancer pathway to educate staff on genetic testing indications and integrating genetic testing screening into clinic visits. After the interventions were implemented in January 2022, patient charts were reviewed for all genetic referrals and new prostate cancer diagnoses from January to December 2022.

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive analysis was conducted on referral rates, evaluation visit completion rates, and genetic testing outcomes among prostate cancer patients.

RESULTS

During the study period, 59 prostate cancer patients were referred for genetic evaluation. Notably, this was a large increase from no genetic referrals for prostate cancer in the previous year. Among them, 43 completed the evaluation visit, and 34 underwent genetic testing. Noteworthy findings were observed in 5 patients, including 3 variants of unknown significance and 2 pathogenic germline variants: HOXB13 and BRCA2 mutations.

IMPLICATIONS

This project highlights the power of a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to overcome barriers and enhance the quality of care for prostate cancer patients. The team’s use of gap analysis and root cause analysis successfully identified barriers and proposed solutions, leading to increased referrals and the identification of significant genetic findings. Continued efforts to improve access to germline genetic testing are crucial for enhanced patient care and improved outcomes.

PURPOSE

This quality improvement project aims to enhance the rate of germline genetic testing for prostate cancer at the Stratton VA Medical Center, improving risk reduction strategies and therapeutic options for patients.

BACKGROUND

Prostate cancer is prevalent at the Stratton VA Medical Center, yet the rate of genetic evaluation for prostate cancer remains suboptimal. National guidelines recommend genetic counseling and testing in specific patient populations. To address this gap, an interdisciplinary working group conducted gap analysis and root cause analysis, identifying four significant barriers.

METHODS

The working group comprised medical oncologists, urologists, primary care physicians, genetics counselors, data experts, and a LEAN coach. Interventions included implementing a prostate cancer pathway to educate staff on genetic testing indications and integrating genetic testing screening into clinic visits. After the interventions were implemented in January 2022, patient charts were reviewed for all genetic referrals and new prostate cancer diagnoses from January to December 2022.

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive analysis was conducted on referral rates, evaluation visit completion rates, and genetic testing outcomes among prostate cancer patients.

RESULTS

During the study period, 59 prostate cancer patients were referred for genetic evaluation. Notably, this was a large increase from no genetic referrals for prostate cancer in the previous year. Among them, 43 completed the evaluation visit, and 34 underwent genetic testing. Noteworthy findings were observed in 5 patients, including 3 variants of unknown significance and 2 pathogenic germline variants: HOXB13 and BRCA2 mutations.

IMPLICATIONS

This project highlights the power of a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to overcome barriers and enhance the quality of care for prostate cancer patients. The team’s use of gap analysis and root cause analysis successfully identified barriers and proposed solutions, leading to increased referrals and the identification of significant genetic findings. Continued efforts to improve access to germline genetic testing are crucial for enhanced patient care and improved outcomes.

PURPOSE

This quality improvement project aims to enhance the rate of germline genetic testing for prostate cancer at the Stratton VA Medical Center, improving risk reduction strategies and therapeutic options for patients.

BACKGROUND

Prostate cancer is prevalent at the Stratton VA Medical Center, yet the rate of genetic evaluation for prostate cancer remains suboptimal. National guidelines recommend genetic counseling and testing in specific patient populations. To address this gap, an interdisciplinary working group conducted gap analysis and root cause analysis, identifying four significant barriers.

METHODS

The working group comprised medical oncologists, urologists, primary care physicians, genetics counselors, data experts, and a LEAN coach. Interventions included implementing a prostate cancer pathway to educate staff on genetic testing indications and integrating genetic testing screening into clinic visits. After the interventions were implemented in January 2022, patient charts were reviewed for all genetic referrals and new prostate cancer diagnoses from January to December 2022.

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive analysis was conducted on referral rates, evaluation visit completion rates, and genetic testing outcomes among prostate cancer patients.

RESULTS

During the study period, 59 prostate cancer patients were referred for genetic evaluation. Notably, this was a large increase from no genetic referrals for prostate cancer in the previous year. Among them, 43 completed the evaluation visit, and 34 underwent genetic testing. Noteworthy findings were observed in 5 patients, including 3 variants of unknown significance and 2 pathogenic germline variants: HOXB13 and BRCA2 mutations.

IMPLICATIONS

This project highlights the power of a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to overcome barriers and enhance the quality of care for prostate cancer patients. The team’s use of gap analysis and root cause analysis successfully identified barriers and proposed solutions, leading to increased referrals and the identification of significant genetic findings. Continued efforts to improve access to germline genetic testing are crucial for enhanced patient care and improved outcomes.

Improving Germline Genetic Testing Among Veterans With High Risk, Very High Risk and Metastatic Prostate Cancer

PURPOSE

To improve germline genetic testing among Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer.

BACKGROUND

During our Commission on Cancer survey in 2021, it was noted that the Detroit VA’s referrals for germline genetic testing and counseling were extremely low. In 2020, only 1 Veteran was referred for prostate germline genetic testing and counseling and only 8 Veterans were referred in 2021. It was felt that the need to refer Veterans outside of the Detroit VA may have contributed to these low numbers. Our Cancer Committee chose prostate cancer as a disease to focus on. We chose a timeline of one year to implement our process.

METHODS

We made testing and counseling locally accessible to Veterans and encouraged medical oncology providers to make it part of the care of Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer. We sought the assistance of the VA’s National Precision Oncology Program and were able to secure financial and logistical support to perform germline molecular prostate panel testing at the Detroit VA. We were also able to identify a cancer genetic specialist at the Ann Arbor VA that would perform genetic counseling among this group of patients based on their test results. Our medical oncology providers identified Veterans meeting the criteria for testing. Education regarding germline testing, its benefits and implications were conducted with Veterans, and performed after obtaining their informed consent in collaboration with our pathology department. The specimen is then sent to a VA central laboratory for processing. Detroit VA providers are alerted by the local laboratory once results are available. Veterans are then referred to the genetic counseling specialist based on the results. Some of these counseling visits are done virtually for the Veteran’s convenience.

DATA ANALYSIS

A retrospective chart analysis was used to collect the data.

RESULTS

After the implementation of our initiative, 97 Veterans with high risk, very high risk or metastatic prostate cancer were educated on the benefits of germline genetic testing, 87 of whom agreed to be tested. As of 4/2/23, 48 tests have already been performed. Pathogenic variants were recorded on 2 Veterans so far. One was for BRCA2 and KDM6A, and the other was for ATM. Data collection and recording is on-going.

IMPLICATIONS

Improving accessibility and incorporating genetic testing and counseling in cancer care can improve their utilization.

PURPOSE

To improve germline genetic testing among Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer.

BACKGROUND

During our Commission on Cancer survey in 2021, it was noted that the Detroit VA’s referrals for germline genetic testing and counseling were extremely low. In 2020, only 1 Veteran was referred for prostate germline genetic testing and counseling and only 8 Veterans were referred in 2021. It was felt that the need to refer Veterans outside of the Detroit VA may have contributed to these low numbers. Our Cancer Committee chose prostate cancer as a disease to focus on. We chose a timeline of one year to implement our process.

METHODS

We made testing and counseling locally accessible to Veterans and encouraged medical oncology providers to make it part of the care of Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer. We sought the assistance of the VA’s National Precision Oncology Program and were able to secure financial and logistical support to perform germline molecular prostate panel testing at the Detroit VA. We were also able to identify a cancer genetic specialist at the Ann Arbor VA that would perform genetic counseling among this group of patients based on their test results. Our medical oncology providers identified Veterans meeting the criteria for testing. Education regarding germline testing, its benefits and implications were conducted with Veterans, and performed after obtaining their informed consent in collaboration with our pathology department. The specimen is then sent to a VA central laboratory for processing. Detroit VA providers are alerted by the local laboratory once results are available. Veterans are then referred to the genetic counseling specialist based on the results. Some of these counseling visits are done virtually for the Veteran’s convenience.

DATA ANALYSIS

A retrospective chart analysis was used to collect the data.

RESULTS

After the implementation of our initiative, 97 Veterans with high risk, very high risk or metastatic prostate cancer were educated on the benefits of germline genetic testing, 87 of whom agreed to be tested. As of 4/2/23, 48 tests have already been performed. Pathogenic variants were recorded on 2 Veterans so far. One was for BRCA2 and KDM6A, and the other was for ATM. Data collection and recording is on-going.

IMPLICATIONS

Improving accessibility and incorporating genetic testing and counseling in cancer care can improve their utilization.

PURPOSE

To improve germline genetic testing among Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer.

BACKGROUND

During our Commission on Cancer survey in 2021, it was noted that the Detroit VA’s referrals for germline genetic testing and counseling were extremely low. In 2020, only 1 Veteran was referred for prostate germline genetic testing and counseling and only 8 Veterans were referred in 2021. It was felt that the need to refer Veterans outside of the Detroit VA may have contributed to these low numbers. Our Cancer Committee chose prostate cancer as a disease to focus on. We chose a timeline of one year to implement our process.

METHODS

We made testing and counseling locally accessible to Veterans and encouraged medical oncology providers to make it part of the care of Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer. We sought the assistance of the VA’s National Precision Oncology Program and were able to secure financial and logistical support to perform germline molecular prostate panel testing at the Detroit VA. We were also able to identify a cancer genetic specialist at the Ann Arbor VA that would perform genetic counseling among this group of patients based on their test results. Our medical oncology providers identified Veterans meeting the criteria for testing. Education regarding germline testing, its benefits and implications were conducted with Veterans, and performed after obtaining their informed consent in collaboration with our pathology department. The specimen is then sent to a VA central laboratory for processing. Detroit VA providers are alerted by the local laboratory once results are available. Veterans are then referred to the genetic counseling specialist based on the results. Some of these counseling visits are done virtually for the Veteran’s convenience.

DATA ANALYSIS

A retrospective chart analysis was used to collect the data.

RESULTS

After the implementation of our initiative, 97 Veterans with high risk, very high risk or metastatic prostate cancer were educated on the benefits of germline genetic testing, 87 of whom agreed to be tested. As of 4/2/23, 48 tests have already been performed. Pathogenic variants were recorded on 2 Veterans so far. One was for BRCA2 and KDM6A, and the other was for ATM. Data collection and recording is on-going.

IMPLICATIONS

Improving accessibility and incorporating genetic testing and counseling in cancer care can improve their utilization.

Implementing a Telehealth Shared Counseling and Decision-Making Visit for Lung Cancer Screening in a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Lung cancer is the second most frequently diagnosed cancer among US veterans and the leading cause of cancer death.1 Clinical trials have shown that annual screening of high-risk persons with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) can reduce the risk of dying of lung cancer.2 In 2011, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) reported that over a 3-year period, annual LDCT screening reduced the risk of dying of lung cancer by 20% compared with chest radiograph screening.3 Lung cancer screening (LCS), however, was associated with harms, including false-positive results, complications from invasive diagnostic procedures, incidental findings, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) began recommending annual screening of high-risk persons after publication of the NLST results.4 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) recommended implementing LCS in 2017.5 Guidelines, however, have consistently highlighted the complexity of the decision and the importance of engaging patients in thorough discussions about the potential benefits and harms of screening (shared decision making [SDM]). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has issued coverage determinations mandating that eligible patients undergo a counseling visit that uses a decision aid to support SDM for LCS and addresses tobacco use.6,7 However, primary care practitioners (PCPs) face many challenges in delivering SDM, including a lack of awareness of clinical trial results and screening guidelines, competing clinical demands, being untrained in SDM, and not having educational resources.8 Patients in rural locations face travel burdens in attending counseling visits.9

We conducted a pilot study to address concerns with delivering SDM for LCS to veterans. We implemented a centralized screening model in which veterans were referred by clinicians to a trained decision coach who conducted telephone visits to discuss the initial LCS decision, addressed tobacco cessation, and placed LDCT orders. We evaluated the outcomes of this telemedicine visit by using decision quality metrics and tracking LCS uptake, referrals for tobacco cessation, and clinical outcomes. The University of Iowa Institutional Review Board considered this study to be a quality improvement project and waived informed consent and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) authorization requirements.

Implementation

We implemented the LCS program at the Iowa City Veterans Affairs Health Care System (ICVAHCS), which has both resident and staff clinicians, and 2 community-based outpatient clinics (Coralville, Cedar Rapids) with staff clinicians. The pilot study, conducted from November 2020 through July 2022, was led by a multidisciplinary team that included a nurse, primary care physician, pulmonologist, and radiologist. The team conducted online presentations to educate PCPs about the epidemiology of lung cancer, results of screening trials, LCS guidelines, the rationale for a centralized model of SDM, and the ICVAHCS screening protocols.

Screening Referrals

When the study began in 2020, we used the 2015 USPSTF criteria for annual LCS: individuals aged 55 to 80 years with a 30 pack-year smoking history and current tobacco user or who had quit within 15 years.4 We lowered the starting age to 50 years and the pack-year requirement to 20 after the USPSTF issued updated guidelines in 2021.10 Clinicians were notified about potentially eligible patients through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Computerized Personal Record System (CPRS) reminders or by the nurse program coordinator (NPC) who reviewed health records of patients with upcoming appointments. If the clinician determined that screening was appropriate, they ordered an LCS consult. The NPC called the veteran to confirm eligibility, mailed a decision aid, and scheduled a telephone visit to conduct SDM. We used the VA decision aid developed for the LCS demonstration project conducted at 8 academic VA medical centers between 2013 and 2017.11

Shared Decision-Making Telephone Visit

The NPC adapted a telephone script developed for a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas–funded project conducted by 2 coauthors (RJV and LML).12 The NPC asked about receipt/review of the decision aid, described the screening process, and addressed benefits and potential harms of screening. The NPC also offered smoking cessation interventions for veterans who were currently smoking, including referrals to the VA patient aligned care team clinical pharmacist for management of tobacco cessation or to the national VA Quit Line. The encounter ended by assessing the veteran’s understanding of screening issues and eliciting the veteran’s preferences for LDCT and willingness to adhere with the LCS program.

LDCT Imaging

The NPC placed LDCT orders for veterans interested in screening and alerted the referring clinician to sign the order. Veterans who agreed to be screened were placed in an LCS dashboard developed by the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) 23 LCS program that was used as a patient management tool. The dashboard allowed the NPC to track patients, ensuring that veterans were being scheduled for and completing initial and follow-up testing. Radiologists used the Lung-RADS (Lung Imaging Reporting and Data System) to categorize LDCT results (1, normal; 2, benign nodule; 3, probably benign nodule; 4, suspicious nodule).13 Veterans with Lung-RADS 1 or 2 results were scheduled for an annual LDCT (if they remained eligible). Veterans with Lung-RADS 3 results were scheduled for a 6-month follow-up CT. The screening program sent electronic consults to pulmonary for veterans with Lung-RADS 4 to determine whether they should undergo additional imaging or be evaluated in the pulmonary clinic.

Evaluating Shared Decision Making

We audio taped and transcribed randomly selected SDM encounters to assess fidelity with the 2016 CMS required discussion elements for counseling about lung cancer, including the benefit of reducing lung cancer mortality; the potential for harms from false alarms, incidental findings, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure; the need for annual screening; the importance of smoking cessation; and the possibility of undergoing follow-up testing and diagnostic procedures. An investigator coded the transcripts to assess for the presence of each required element and scored the encounter from 0 to 7.

We also surveyed veterans completing SDM, using a convenience sampling strategy to evaluate knowledge, the quality of the SDM process, and decisional conflict. Initially, we sent mailed surveys to subjects to be completed 1 week after the SDM visit. To increase the response rate, we subsequently called patients to complete the surveys by telephone 1 week after the SDM visit.

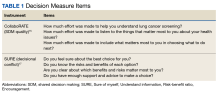

We used the validated LCS-12 knowledge measure to assess awareness of lung cancer risks, screening eligibility, and the benefits and harms of screening.14 We evaluated the quality of the SDM visit by using the 3-item CollaboRATE scale (Table 1).15

The NPC also took field notes during interviews to help identify additional SDM issues. After each call, the NPC noted her impressions of the veteran’s engagement with SDM and understanding of the screening issues.

Clinical Outcomes

We used the screening dashboard and CPRS to track clinical outcomes, including screening uptake, referrals for tobacco cessation, appropriate (screening or diagnostic) follow-up testing, and cancer diagnoses. We used descriptive statistics to characterize demographic data and survey responses.

Initial Findings

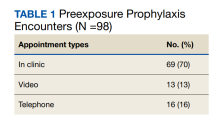

We conducted 105 SDM telephone visits from November 2020 through July 2022 (Table 2).

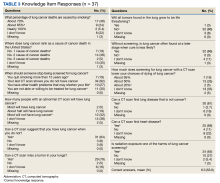

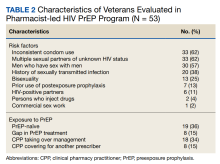

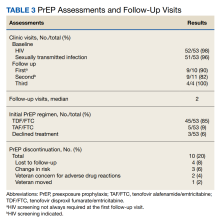

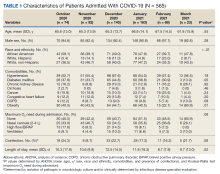

We surveyed 47 of the veterans completing SDM visits (45%) and received 37 completed surveys (79%). All respondents were male, mean age 61.9 years, 89% White, 38% married/partnered, 70% rural, 65% currently smoking, with a mean 44.8 pack-years smoking history. On average, veterans answered 6.3 (53%) of knowledge questions correctly (Table 3).

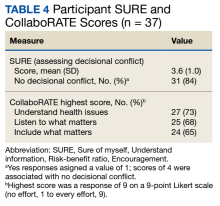

Only 1 respondent (3%) correctly answered the multiple-choice question about indications for stopping screening. Two (5%) correctly answered the question on the magnitude of benefit, most overestimated or did not know. Similarly, 23 (62%) overestimated or did not know the predictive value of an abnormal scan. About two-thirds of veterans underestimated or did not know the attributable risk of lung cancer from tobacco, and about four-fifths did not know the mortality rank of lung cancer. Among the 37 respondents, 31 (84%) indicated not having any decisional conflict as defined by a score of 4 on the SURE scale.

Implementing SDM

The NPC’s field notes indicated that many veterans did not perceive any need to discuss the screening decision and believed that their PCP had referred them just for screening. However, they reported having cursory discussions with their PCP, being told that only their history of heavy tobacco use meant they should be screened. For veterans who had not read the decision aid, the NPC attempted to summarize benefits and harms. However, the discussions were often inadequate because the veterans were not interested in receiving information, particularly numerical data, or indicated that they had limited time for the call.

Seventy-two (69%) of the veterans who met with the NPC were currently smoking. Tobacco cessation counseling was offered to 66; 29 were referred to the VA Quit Line, 10 were referred to the tobacco cessation pharmacist, and the NPC contacted the PCPs for 9 patients who wanted prescriptions for nicotine replacement therapy.

After the SDM visit, 91 veterans (87%) agreed to screening. By the end of the study period, 73 veterans (80%) completed testing. Most veterans had Lung-RADS 1 or 2 results, 11 (1%) had a Lung-RADS 3, and 7 (10%) had a Lung-RADS 4. All 9 veterans with Lung-RADS 3 results and at least 6 months of follow-up underwent repeat imaging within 4 to 13 months (median, 7). All veterans with a Lung-RADS 4 result were referred to pulmonary. One patient was diagnosed with an early-stage non–small cell lung cancer.

We identified several problems with LDCT coding. Radiologists did not consistently use Lung-RADS when interpreting screening LDCTs; some used the Fleischner lung nodule criteria.18 We also found discordant readings for abnormal LDCTs, where the assigned Lung-RADS score was not consistent with the nodule description in the radiology report.

Discussion

Efforts to implement LCS with a telemedicine SDM intervention were mixed. An NPC-led SDM phone call was successfully incorporated into the clinical workflow. Most veterans identified as being eligible for screening participated in the counseling visit and underwent screening. However, they were often reluctant to engage in SDM, feeling that their clinician had already recommended screening and that there was no need for further discussion. Unfortunately, many veterans had not received or reviewed the decision aid and were not interested in receiving information about benefits and harms. Because we relied on telephone calls, we could not share visual information in real time.

Overall, the surveys indicated that most veterans were very satisfied with the quality of the discussion and reported feeling no decisional conflict. However, based on the NPC’s field notes and audio recordings, we believe that the responses may have reflected earlier discussions with the PCP that reportedly emphasized only the veteran’s eligibility for screening. The fidelity assessments indicated that the NPC consistently addressed the harms and benefits of screening.

Nonetheless, the performance on knowledge measures was uneven. Veterans were generally aware of harms, including false alarms, overdiagnosis, radiation exposure, and incidental findings. They did not, however, appreciate when screening should stop. They also underestimated the risks of developing lung cancer and the portion of that risk attributable to tobacco use, and overestimated the benefits of screening. These results suggest that the veterans, at least those who completed the surveys, may not be making well-informed decisions.

Our findings echo those of other VA investigators in finding knowledge deficits among screened veterans, including being unaware that LDCT was for LCS, believing that screening could prevent cancer, receiving little information about screening harms, and feeling that negative tests meant they were among the “lucky ones” who would avoid harm from continued smoking.19,20

The VA is currently implementing centralized screening models with the Lung Precision Oncology Program and the VA partnership to increase access to lung screening (VA-PALS).5 The centralized model, which readily supports the tracking, monitoring, and reporting needs of a screening program, also has advantages in delivering SDM because counselors have been trained in SDM, are more familiar with LCS evidence and processes, can better incorporate decision tools, and do not face the same time constraints as clinicians.21 However, studies have shown that most patients have already decided to be screened when they show up for the SDM visit.22 In contrast, about one-third of patients in primary care settings who receive decision support chose not to be screened.23,24 We found that 13% of our patients decided against screening after a telephone discussion, suggesting that a virtually conducted SDM visit can meaningfully support decision making. Telemedicine also may reduce health inequities in centralized models arising from patients having limited access to screening centers.

Our results suggest that PCPs referring patients to a centralized program, even for virtual visits, should frame the decision to initiate LCS as SDM, where an informed patient is being supported in making a decision consistent with their values and preferences. Furthermore, engaging patients in SDM should not be construed as endorsing screening. When centralized support is less available, individual clinics may need to provide SDM, perhaps using a nonclinician decision coach if clinicians lack the time to lead the discussions. Decision coaches have been effectively used to increase patients’ knowledge about the benefits and harms of screening.12 Regardless of the program model, PCPs will also be responsible for determining whether patients are healthy enough to undergo invasive diagnostic testing and treatment and ensuring that tobacco use is addressed.

SDM delivered in any setting will be enhanced by ensuring that patients are provided with decision aids before a counseling visit. This will help them better understand the benefits and harms of screening and the need to elicit values. The discussion can then focus on areas of concern or questions raised by reviewing the decision aid. The clinician and patient could also use a decision aid during either a face-to-face or video clinical encounter to facilitate SDM. A Cochrane review has shown that using decision aids for people facing screening decisions increases knowledge, reduces decisional conflict, and effectively elicits values and preferences.25 Providing high-quality decision support is a patient-centered approach that respects a patient’s autonomy and may promote health equity and improve adherence.

We recognized the importance of having a multidisciplinary team, involving primary care, radiology, pulmonary, and nursing, with a shared understanding of the screening processes. These are essential features for a high-quality screening program where eligible veterans are readily identified and receive prompt and appropriate follow-up. Radiologists need to use Lung-RADS categories consistently and appropriately when reading LDCTs. This may require ongoing educational efforts, particularly given the new CMS guidelines accepting nonsubspecialist chest readers.7 Additionally, fellows and board-eligible residents may interpret images in academic settings and at VA facilities. The program needs to work closely with the pulmonary service to ensure that Lung-RADS 4 patients are promptly assessed. Radiologists and pulmonologists should calibrate the application of Lung-RADS categories to pulmonary nodules through jointly participating in meetings to review selected cases.

Challenges and Limitations

We faced some notable implementation challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic was extremely disruptive to LCS as it was to all health care. In addition, screening workflow processes were hampered by a lack of clinical reminders, which ideally would trigger for clinicians based on the tobacco history. The absence of this reminder meant that numerous patients were found to be ineligible for screening. We have a long-standing lung nodule clinic, and clinicians were confused about whether to order a surveillance imaging for an incidental nodule or a screening LDCT.

The radiology service was able to update order sets in CPRS to help guide clinicians in distinguishing indications and prerequisites for enrolling in LCS. This helped reduce the number of inappropriate orders and crossover orders between the VISN nodule tracking program and the LCS program.

Our results were preliminary and based on a small sample. We did not survey all veterans who underwent SDM, though the response rate was 79% and patient characteristics were similar to the larger cohort. Our results were potentially subject to selection bias, which could inflate the positive responses about decision quality and decisional conflict. However, the knowledge deficits are likely to be valid and suggest a need to better inform eligible veterans about the benefits and harms of screening. We did not have sufficient follow-up time to determine whether veterans were adherent to annual screenings. We showed that almost all those with abnormal imaging results completed diagnostic evaluations and/or were evaluated by pulmonary. As the program matures, we will be able to track outcomes related to cancer diagnoses and treatment.

Conclusions

A centralized LCS program was able to deliver SDM and enroll veterans in a screening program. While veterans were confident in their decision to screen and felt that they participated in decision making, knowledge testing indicated important deficits. Furthermore, we observed that many veterans did not meaningfully engage in SDM. Clinicians will need to frame the decision as patient centered at the time of referral, highlight the role of the NPC and importance of SDM, and be able to provide adequate decision support. The SDM visits can be enhanced by ensuring that veterans are able to review decision aids. Telemedicine is an acceptable and effective approach for supporting screening discussions, particularly for rural veterans.26

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals for their contributions to the study: John Paul Hornbeck, program support specialist; Kelly Miell, PhD; Bradley Mecham, PhD; Christopher C. Richards, MA; Bailey Noble, NP; Rebecca Barnhart, program analyst.

1. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693-701. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-11-00434

2. Hoffman RM, Atallah RP, Struble RD, Badgett RG. Lung cancer screening with low-dose CT: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3015-3025. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05951-7

3. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395-409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

4. Moyer VA, US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):330-338. doi:10.7326/M13-2771

5. Maurice NM, Tanner NT. Lung cancer screening at the VA: past, present and future. Semin Oncol. 2022;S0093-7754(22)00041-0. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.06.001

6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N). Published 2015. Accessed July 10, 2023. http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439R). Published 2022. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncacal-decision-memo.aspx?proposed=N&ncaid=304

8. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; National Cancer Policy Forum. Implementation of Lung Cancer Screening: Proceedings of a Workshop. The National Academies Press; November 17, 2016. doi:10.172216/23680

9. Bernstein E, Bade BC, Akgün KM, Rose MG, Cain HC. Barriers and facilitators to lung cancer screening and follow-up. Semin Oncol. 2022;S0093-7754(22)00058-6. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.07.004

10. US Preventive Services Task Force, Krist AH, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(10):962-970. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.1117

11. Kinsinger LS, Atkins D, Provenzale D, Anderson C, Petzel R. Implementation of a new screening recommendation in health care: the Veterans Health Administration’s approach to lung cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):597-598. doi:10.7326/M14-1070

12. Lowenstein LM, Godoy MCB, Erasmus JJ, et al. Implementing decision coaching for lung cancer screening in the low-dose computed tomography setting. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(8):e703-e725. doi:10.1200/JOP.19.00453

13. American College of Radiology Committee on Lung-RADS. Lung-RADS assessment categories 2022. Published November 2022. Accessed July 3, 2023. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/RADS/Lung-RADS/Lung-RADS-2022.pdf

14. Lowenstein LM, Richards VF, Leal VB, et al. A brief measure of smokers’ knowledge of lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:351-356. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.07.008

15. Elwyn G, Barr PJ, Grande SW, Thompson R, Walsh T, Ozanne EM. Developing CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of shared decision making in clinical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(1):102-107. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.05.009

16. Barr PJ, Thompson R, Walsh T, Grande SW, Ozanne EM, Elwyn G. The psychometric properties of CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of the shared decision-making process. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(1):e2. doi:10.2196/jmir.3085

17. Légaré F, Kearing S, Clay K, et al. Are you SURE?: Assessing patient decisional conflict with a 4-item screening test. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(8):e308-e314.

18. MacMahon H, Naidich DP, Goo JM, et al. Guidelines for management of incidental pulmonary nodules detected on CT images: from the Fleischner Society 2017. Radiology. 2017;284(1):228-243. doi:10.1148/radiol.2017161659

19. Wiener RS, Koppelman E, Bolton R, et al. Patient and clinician perspectives on shared decision-making in early adopting lung cancer screening programs: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1035-1042. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4350-9

20. Zeliadt SB, Heffner JL, Sayre G, et al. Attitudes and perceptions about smoking cessation in the context of lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1530-1537. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3558

21. Mazzone PJ, White CS, Kazerooni EA, Smith RA, Thomson CC. Proposed quality metrics for lung cancer screening programs: a National Lung Cancer Roundtable Project. Chest. 2021;160(1):368-378. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.063

22. Mazzone PJ, Tenenbaum A, Seeley M, et al. Impact of a lung cancer screening counseling and shared decision-making visit. Chest. 2017;151(3):572-578. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.027

23. Reuland DS, Cubillos L, Brenner AT, Harris RP, Minish B, Pignone MP. A pre-post study testing a lung cancer screening decision aid in primary care. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2018;18(1):5. doi:10.1186/s12911-018-0582-1

24. Dharod A, Bellinger C, Foley K, Case LD, Miller D. The reach and feasibility of an interactive lung cancer screening decision aid delivered by patient portal. Appl Clin Inform. 2019;10(1):19-27. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1676807

25. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5

26. Tanner NT, Banas E, Yeager D, Dai L, Hughes Halbert C, Silvestri GA. In-person and telephonic shared decision-making visits for people considering lung cancer screening: an assessment of decision quality. Chest. 2019;155(1):236-238. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2018.07.046

Lung cancer is the second most frequently diagnosed cancer among US veterans and the leading cause of cancer death.1 Clinical trials have shown that annual screening of high-risk persons with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) can reduce the risk of dying of lung cancer.2 In 2011, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) reported that over a 3-year period, annual LDCT screening reduced the risk of dying of lung cancer by 20% compared with chest radiograph screening.3 Lung cancer screening (LCS), however, was associated with harms, including false-positive results, complications from invasive diagnostic procedures, incidental findings, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) began recommending annual screening of high-risk persons after publication of the NLST results.4 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) recommended implementing LCS in 2017.5 Guidelines, however, have consistently highlighted the complexity of the decision and the importance of engaging patients in thorough discussions about the potential benefits and harms of screening (shared decision making [SDM]). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has issued coverage determinations mandating that eligible patients undergo a counseling visit that uses a decision aid to support SDM for LCS and addresses tobacco use.6,7 However, primary care practitioners (PCPs) face many challenges in delivering SDM, including a lack of awareness of clinical trial results and screening guidelines, competing clinical demands, being untrained in SDM, and not having educational resources.8 Patients in rural locations face travel burdens in attending counseling visits.9

We conducted a pilot study to address concerns with delivering SDM for LCS to veterans. We implemented a centralized screening model in which veterans were referred by clinicians to a trained decision coach who conducted telephone visits to discuss the initial LCS decision, addressed tobacco cessation, and placed LDCT orders. We evaluated the outcomes of this telemedicine visit by using decision quality metrics and tracking LCS uptake, referrals for tobacco cessation, and clinical outcomes. The University of Iowa Institutional Review Board considered this study to be a quality improvement project and waived informed consent and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) authorization requirements.

Implementation

We implemented the LCS program at the Iowa City Veterans Affairs Health Care System (ICVAHCS), which has both resident and staff clinicians, and 2 community-based outpatient clinics (Coralville, Cedar Rapids) with staff clinicians. The pilot study, conducted from November 2020 through July 2022, was led by a multidisciplinary team that included a nurse, primary care physician, pulmonologist, and radiologist. The team conducted online presentations to educate PCPs about the epidemiology of lung cancer, results of screening trials, LCS guidelines, the rationale for a centralized model of SDM, and the ICVAHCS screening protocols.

Screening Referrals

When the study began in 2020, we used the 2015 USPSTF criteria for annual LCS: individuals aged 55 to 80 years with a 30 pack-year smoking history and current tobacco user or who had quit within 15 years.4 We lowered the starting age to 50 years and the pack-year requirement to 20 after the USPSTF issued updated guidelines in 2021.10 Clinicians were notified about potentially eligible patients through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Computerized Personal Record System (CPRS) reminders or by the nurse program coordinator (NPC) who reviewed health records of patients with upcoming appointments. If the clinician determined that screening was appropriate, they ordered an LCS consult. The NPC called the veteran to confirm eligibility, mailed a decision aid, and scheduled a telephone visit to conduct SDM. We used the VA decision aid developed for the LCS demonstration project conducted at 8 academic VA medical centers between 2013 and 2017.11

Shared Decision-Making Telephone Visit

The NPC adapted a telephone script developed for a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas–funded project conducted by 2 coauthors (RJV and LML).12 The NPC asked about receipt/review of the decision aid, described the screening process, and addressed benefits and potential harms of screening. The NPC also offered smoking cessation interventions for veterans who were currently smoking, including referrals to the VA patient aligned care team clinical pharmacist for management of tobacco cessation or to the national VA Quit Line. The encounter ended by assessing the veteran’s understanding of screening issues and eliciting the veteran’s preferences for LDCT and willingness to adhere with the LCS program.

LDCT Imaging

The NPC placed LDCT orders for veterans interested in screening and alerted the referring clinician to sign the order. Veterans who agreed to be screened were placed in an LCS dashboard developed by the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) 23 LCS program that was used as a patient management tool. The dashboard allowed the NPC to track patients, ensuring that veterans were being scheduled for and completing initial and follow-up testing. Radiologists used the Lung-RADS (Lung Imaging Reporting and Data System) to categorize LDCT results (1, normal; 2, benign nodule; 3, probably benign nodule; 4, suspicious nodule).13 Veterans with Lung-RADS 1 or 2 results were scheduled for an annual LDCT (if they remained eligible). Veterans with Lung-RADS 3 results were scheduled for a 6-month follow-up CT. The screening program sent electronic consults to pulmonary for veterans with Lung-RADS 4 to determine whether they should undergo additional imaging or be evaluated in the pulmonary clinic.

Evaluating Shared Decision Making

We audio taped and transcribed randomly selected SDM encounters to assess fidelity with the 2016 CMS required discussion elements for counseling about lung cancer, including the benefit of reducing lung cancer mortality; the potential for harms from false alarms, incidental findings, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure; the need for annual screening; the importance of smoking cessation; and the possibility of undergoing follow-up testing and diagnostic procedures. An investigator coded the transcripts to assess for the presence of each required element and scored the encounter from 0 to 7.

We also surveyed veterans completing SDM, using a convenience sampling strategy to evaluate knowledge, the quality of the SDM process, and decisional conflict. Initially, we sent mailed surveys to subjects to be completed 1 week after the SDM visit. To increase the response rate, we subsequently called patients to complete the surveys by telephone 1 week after the SDM visit.

We used the validated LCS-12 knowledge measure to assess awareness of lung cancer risks, screening eligibility, and the benefits and harms of screening.14 We evaluated the quality of the SDM visit by using the 3-item CollaboRATE scale (Table 1).15

The NPC also took field notes during interviews to help identify additional SDM issues. After each call, the NPC noted her impressions of the veteran’s engagement with SDM and understanding of the screening issues.

Clinical Outcomes

We used the screening dashboard and CPRS to track clinical outcomes, including screening uptake, referrals for tobacco cessation, appropriate (screening or diagnostic) follow-up testing, and cancer diagnoses. We used descriptive statistics to characterize demographic data and survey responses.

Initial Findings

We conducted 105 SDM telephone visits from November 2020 through July 2022 (Table 2).

We surveyed 47 of the veterans completing SDM visits (45%) and received 37 completed surveys (79%). All respondents were male, mean age 61.9 years, 89% White, 38% married/partnered, 70% rural, 65% currently smoking, with a mean 44.8 pack-years smoking history. On average, veterans answered 6.3 (53%) of knowledge questions correctly (Table 3).

Only 1 respondent (3%) correctly answered the multiple-choice question about indications for stopping screening. Two (5%) correctly answered the question on the magnitude of benefit, most overestimated or did not know. Similarly, 23 (62%) overestimated or did not know the predictive value of an abnormal scan. About two-thirds of veterans underestimated or did not know the attributable risk of lung cancer from tobacco, and about four-fifths did not know the mortality rank of lung cancer. Among the 37 respondents, 31 (84%) indicated not having any decisional conflict as defined by a score of 4 on the SURE scale.

Implementing SDM

The NPC’s field notes indicated that many veterans did not perceive any need to discuss the screening decision and believed that their PCP had referred them just for screening. However, they reported having cursory discussions with their PCP, being told that only their history of heavy tobacco use meant they should be screened. For veterans who had not read the decision aid, the NPC attempted to summarize benefits and harms. However, the discussions were often inadequate because the veterans were not interested in receiving information, particularly numerical data, or indicated that they had limited time for the call.

Seventy-two (69%) of the veterans who met with the NPC were currently smoking. Tobacco cessation counseling was offered to 66; 29 were referred to the VA Quit Line, 10 were referred to the tobacco cessation pharmacist, and the NPC contacted the PCPs for 9 patients who wanted prescriptions for nicotine replacement therapy.

After the SDM visit, 91 veterans (87%) agreed to screening. By the end of the study period, 73 veterans (80%) completed testing. Most veterans had Lung-RADS 1 or 2 results, 11 (1%) had a Lung-RADS 3, and 7 (10%) had a Lung-RADS 4. All 9 veterans with Lung-RADS 3 results and at least 6 months of follow-up underwent repeat imaging within 4 to 13 months (median, 7). All veterans with a Lung-RADS 4 result were referred to pulmonary. One patient was diagnosed with an early-stage non–small cell lung cancer.

We identified several problems with LDCT coding. Radiologists did not consistently use Lung-RADS when interpreting screening LDCTs; some used the Fleischner lung nodule criteria.18 We also found discordant readings for abnormal LDCTs, where the assigned Lung-RADS score was not consistent with the nodule description in the radiology report.

Discussion

Efforts to implement LCS with a telemedicine SDM intervention were mixed. An NPC-led SDM phone call was successfully incorporated into the clinical workflow. Most veterans identified as being eligible for screening participated in the counseling visit and underwent screening. However, they were often reluctant to engage in SDM, feeling that their clinician had already recommended screening and that there was no need for further discussion. Unfortunately, many veterans had not received or reviewed the decision aid and were not interested in receiving information about benefits and harms. Because we relied on telephone calls, we could not share visual information in real time.

Overall, the surveys indicated that most veterans were very satisfied with the quality of the discussion and reported feeling no decisional conflict. However, based on the NPC’s field notes and audio recordings, we believe that the responses may have reflected earlier discussions with the PCP that reportedly emphasized only the veteran’s eligibility for screening. The fidelity assessments indicated that the NPC consistently addressed the harms and benefits of screening.

Nonetheless, the performance on knowledge measures was uneven. Veterans were generally aware of harms, including false alarms, overdiagnosis, radiation exposure, and incidental findings. They did not, however, appreciate when screening should stop. They also underestimated the risks of developing lung cancer and the portion of that risk attributable to tobacco use, and overestimated the benefits of screening. These results suggest that the veterans, at least those who completed the surveys, may not be making well-informed decisions.

Our findings echo those of other VA investigators in finding knowledge deficits among screened veterans, including being unaware that LDCT was for LCS, believing that screening could prevent cancer, receiving little information about screening harms, and feeling that negative tests meant they were among the “lucky ones” who would avoid harm from continued smoking.19,20

The VA is currently implementing centralized screening models with the Lung Precision Oncology Program and the VA partnership to increase access to lung screening (VA-PALS).5 The centralized model, which readily supports the tracking, monitoring, and reporting needs of a screening program, also has advantages in delivering SDM because counselors have been trained in SDM, are more familiar with LCS evidence and processes, can better incorporate decision tools, and do not face the same time constraints as clinicians.21 However, studies have shown that most patients have already decided to be screened when they show up for the SDM visit.22 In contrast, about one-third of patients in primary care settings who receive decision support chose not to be screened.23,24 We found that 13% of our patients decided against screening after a telephone discussion, suggesting that a virtually conducted SDM visit can meaningfully support decision making. Telemedicine also may reduce health inequities in centralized models arising from patients having limited access to screening centers.

Our results suggest that PCPs referring patients to a centralized program, even for virtual visits, should frame the decision to initiate LCS as SDM, where an informed patient is being supported in making a decision consistent with their values and preferences. Furthermore, engaging patients in SDM should not be construed as endorsing screening. When centralized support is less available, individual clinics may need to provide SDM, perhaps using a nonclinician decision coach if clinicians lack the time to lead the discussions. Decision coaches have been effectively used to increase patients’ knowledge about the benefits and harms of screening.12 Regardless of the program model, PCPs will also be responsible for determining whether patients are healthy enough to undergo invasive diagnostic testing and treatment and ensuring that tobacco use is addressed.

SDM delivered in any setting will be enhanced by ensuring that patients are provided with decision aids before a counseling visit. This will help them better understand the benefits and harms of screening and the need to elicit values. The discussion can then focus on areas of concern or questions raised by reviewing the decision aid. The clinician and patient could also use a decision aid during either a face-to-face or video clinical encounter to facilitate SDM. A Cochrane review has shown that using decision aids for people facing screening decisions increases knowledge, reduces decisional conflict, and effectively elicits values and preferences.25 Providing high-quality decision support is a patient-centered approach that respects a patient’s autonomy and may promote health equity and improve adherence.

We recognized the importance of having a multidisciplinary team, involving primary care, radiology, pulmonary, and nursing, with a shared understanding of the screening processes. These are essential features for a high-quality screening program where eligible veterans are readily identified and receive prompt and appropriate follow-up. Radiologists need to use Lung-RADS categories consistently and appropriately when reading LDCTs. This may require ongoing educational efforts, particularly given the new CMS guidelines accepting nonsubspecialist chest readers.7 Additionally, fellows and board-eligible residents may interpret images in academic settings and at VA facilities. The program needs to work closely with the pulmonary service to ensure that Lung-RADS 4 patients are promptly assessed. Radiologists and pulmonologists should calibrate the application of Lung-RADS categories to pulmonary nodules through jointly participating in meetings to review selected cases.

Challenges and Limitations

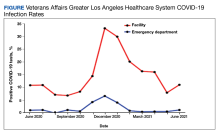

We faced some notable implementation challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic was extremely disruptive to LCS as it was to all health care. In addition, screening workflow processes were hampered by a lack of clinical reminders, which ideally would trigger for clinicians based on the tobacco history. The absence of this reminder meant that numerous patients were found to be ineligible for screening. We have a long-standing lung nodule clinic, and clinicians were confused about whether to order a surveillance imaging for an incidental nodule or a screening LDCT.

The radiology service was able to update order sets in CPRS to help guide clinicians in distinguishing indications and prerequisites for enrolling in LCS. This helped reduce the number of inappropriate orders and crossover orders between the VISN nodule tracking program and the LCS program.

Our results were preliminary and based on a small sample. We did not survey all veterans who underwent SDM, though the response rate was 79% and patient characteristics were similar to the larger cohort. Our results were potentially subject to selection bias, which could inflate the positive responses about decision quality and decisional conflict. However, the knowledge deficits are likely to be valid and suggest a need to better inform eligible veterans about the benefits and harms of screening. We did not have sufficient follow-up time to determine whether veterans were adherent to annual screenings. We showed that almost all those with abnormal imaging results completed diagnostic evaluations and/or were evaluated by pulmonary. As the program matures, we will be able to track outcomes related to cancer diagnoses and treatment.

Conclusions

A centralized LCS program was able to deliver SDM and enroll veterans in a screening program. While veterans were confident in their decision to screen and felt that they participated in decision making, knowledge testing indicated important deficits. Furthermore, we observed that many veterans did not meaningfully engage in SDM. Clinicians will need to frame the decision as patient centered at the time of referral, highlight the role of the NPC and importance of SDM, and be able to provide adequate decision support. The SDM visits can be enhanced by ensuring that veterans are able to review decision aids. Telemedicine is an acceptable and effective approach for supporting screening discussions, particularly for rural veterans.26

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals for their contributions to the study: John Paul Hornbeck, program support specialist; Kelly Miell, PhD; Bradley Mecham, PhD; Christopher C. Richards, MA; Bailey Noble, NP; Rebecca Barnhart, program analyst.

Lung cancer is the second most frequently diagnosed cancer among US veterans and the leading cause of cancer death.1 Clinical trials have shown that annual screening of high-risk persons with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) can reduce the risk of dying of lung cancer.2 In 2011, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) reported that over a 3-year period, annual LDCT screening reduced the risk of dying of lung cancer by 20% compared with chest radiograph screening.3 Lung cancer screening (LCS), however, was associated with harms, including false-positive results, complications from invasive diagnostic procedures, incidental findings, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) began recommending annual screening of high-risk persons after publication of the NLST results.4 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) recommended implementing LCS in 2017.5 Guidelines, however, have consistently highlighted the complexity of the decision and the importance of engaging patients in thorough discussions about the potential benefits and harms of screening (shared decision making [SDM]). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has issued coverage determinations mandating that eligible patients undergo a counseling visit that uses a decision aid to support SDM for LCS and addresses tobacco use.6,7 However, primary care practitioners (PCPs) face many challenges in delivering SDM, including a lack of awareness of clinical trial results and screening guidelines, competing clinical demands, being untrained in SDM, and not having educational resources.8 Patients in rural locations face travel burdens in attending counseling visits.9

We conducted a pilot study to address concerns with delivering SDM for LCS to veterans. We implemented a centralized screening model in which veterans were referred by clinicians to a trained decision coach who conducted telephone visits to discuss the initial LCS decision, addressed tobacco cessation, and placed LDCT orders. We evaluated the outcomes of this telemedicine visit by using decision quality metrics and tracking LCS uptake, referrals for tobacco cessation, and clinical outcomes. The University of Iowa Institutional Review Board considered this study to be a quality improvement project and waived informed consent and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) authorization requirements.

Implementation

We implemented the LCS program at the Iowa City Veterans Affairs Health Care System (ICVAHCS), which has both resident and staff clinicians, and 2 community-based outpatient clinics (Coralville, Cedar Rapids) with staff clinicians. The pilot study, conducted from November 2020 through July 2022, was led by a multidisciplinary team that included a nurse, primary care physician, pulmonologist, and radiologist. The team conducted online presentations to educate PCPs about the epidemiology of lung cancer, results of screening trials, LCS guidelines, the rationale for a centralized model of SDM, and the ICVAHCS screening protocols.

Screening Referrals

When the study began in 2020, we used the 2015 USPSTF criteria for annual LCS: individuals aged 55 to 80 years with a 30 pack-year smoking history and current tobacco user or who had quit within 15 years.4 We lowered the starting age to 50 years and the pack-year requirement to 20 after the USPSTF issued updated guidelines in 2021.10 Clinicians were notified about potentially eligible patients through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Computerized Personal Record System (CPRS) reminders or by the nurse program coordinator (NPC) who reviewed health records of patients with upcoming appointments. If the clinician determined that screening was appropriate, they ordered an LCS consult. The NPC called the veteran to confirm eligibility, mailed a decision aid, and scheduled a telephone visit to conduct SDM. We used the VA decision aid developed for the LCS demonstration project conducted at 8 academic VA medical centers between 2013 and 2017.11

Shared Decision-Making Telephone Visit

The NPC adapted a telephone script developed for a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas–funded project conducted by 2 coauthors (RJV and LML).12 The NPC asked about receipt/review of the decision aid, described the screening process, and addressed benefits and potential harms of screening. The NPC also offered smoking cessation interventions for veterans who were currently smoking, including referrals to the VA patient aligned care team clinical pharmacist for management of tobacco cessation or to the national VA Quit Line. The encounter ended by assessing the veteran’s understanding of screening issues and eliciting the veteran’s preferences for LDCT and willingness to adhere with the LCS program.

LDCT Imaging

The NPC placed LDCT orders for veterans interested in screening and alerted the referring clinician to sign the order. Veterans who agreed to be screened were placed in an LCS dashboard developed by the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) 23 LCS program that was used as a patient management tool. The dashboard allowed the NPC to track patients, ensuring that veterans were being scheduled for and completing initial and follow-up testing. Radiologists used the Lung-RADS (Lung Imaging Reporting and Data System) to categorize LDCT results (1, normal; 2, benign nodule; 3, probably benign nodule; 4, suspicious nodule).13 Veterans with Lung-RADS 1 or 2 results were scheduled for an annual LDCT (if they remained eligible). Veterans with Lung-RADS 3 results were scheduled for a 6-month follow-up CT. The screening program sent electronic consults to pulmonary for veterans with Lung-RADS 4 to determine whether they should undergo additional imaging or be evaluated in the pulmonary clinic.

Evaluating Shared Decision Making

We audio taped and transcribed randomly selected SDM encounters to assess fidelity with the 2016 CMS required discussion elements for counseling about lung cancer, including the benefit of reducing lung cancer mortality; the potential for harms from false alarms, incidental findings, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure; the need for annual screening; the importance of smoking cessation; and the possibility of undergoing follow-up testing and diagnostic procedures. An investigator coded the transcripts to assess for the presence of each required element and scored the encounter from 0 to 7.

We also surveyed veterans completing SDM, using a convenience sampling strategy to evaluate knowledge, the quality of the SDM process, and decisional conflict. Initially, we sent mailed surveys to subjects to be completed 1 week after the SDM visit. To increase the response rate, we subsequently called patients to complete the surveys by telephone 1 week after the SDM visit.

We used the validated LCS-12 knowledge measure to assess awareness of lung cancer risks, screening eligibility, and the benefits and harms of screening.14 We evaluated the quality of the SDM visit by using the 3-item CollaboRATE scale (Table 1).15

The NPC also took field notes during interviews to help identify additional SDM issues. After each call, the NPC noted her impressions of the veteran’s engagement with SDM and understanding of the screening issues.

Clinical Outcomes

We used the screening dashboard and CPRS to track clinical outcomes, including screening uptake, referrals for tobacco cessation, appropriate (screening or diagnostic) follow-up testing, and cancer diagnoses. We used descriptive statistics to characterize demographic data and survey responses.

Initial Findings

We conducted 105 SDM telephone visits from November 2020 through July 2022 (Table 2).

We surveyed 47 of the veterans completing SDM visits (45%) and received 37 completed surveys (79%). All respondents were male, mean age 61.9 years, 89% White, 38% married/partnered, 70% rural, 65% currently smoking, with a mean 44.8 pack-years smoking history. On average, veterans answered 6.3 (53%) of knowledge questions correctly (Table 3).

Only 1 respondent (3%) correctly answered the multiple-choice question about indications for stopping screening. Two (5%) correctly answered the question on the magnitude of benefit, most overestimated or did not know. Similarly, 23 (62%) overestimated or did not know the predictive value of an abnormal scan. About two-thirds of veterans underestimated or did not know the attributable risk of lung cancer from tobacco, and about four-fifths did not know the mortality rank of lung cancer. Among the 37 respondents, 31 (84%) indicated not having any decisional conflict as defined by a score of 4 on the SURE scale.

Implementing SDM

The NPC’s field notes indicated that many veterans did not perceive any need to discuss the screening decision and believed that their PCP had referred them just for screening. However, they reported having cursory discussions with their PCP, being told that only their history of heavy tobacco use meant they should be screened. For veterans who had not read the decision aid, the NPC attempted to summarize benefits and harms. However, the discussions were often inadequate because the veterans were not interested in receiving information, particularly numerical data, or indicated that they had limited time for the call.

Seventy-two (69%) of the veterans who met with the NPC were currently smoking. Tobacco cessation counseling was offered to 66; 29 were referred to the VA Quit Line, 10 were referred to the tobacco cessation pharmacist, and the NPC contacted the PCPs for 9 patients who wanted prescriptions for nicotine replacement therapy.

After the SDM visit, 91 veterans (87%) agreed to screening. By the end of the study period, 73 veterans (80%) completed testing. Most veterans had Lung-RADS 1 or 2 results, 11 (1%) had a Lung-RADS 3, and 7 (10%) had a Lung-RADS 4. All 9 veterans with Lung-RADS 3 results and at least 6 months of follow-up underwent repeat imaging within 4 to 13 months (median, 7). All veterans with a Lung-RADS 4 result were referred to pulmonary. One patient was diagnosed with an early-stage non–small cell lung cancer.

We identified several problems with LDCT coding. Radiologists did not consistently use Lung-RADS when interpreting screening LDCTs; some used the Fleischner lung nodule criteria.18 We also found discordant readings for abnormal LDCTs, where the assigned Lung-RADS score was not consistent with the nodule description in the radiology report.

Discussion

Efforts to implement LCS with a telemedicine SDM intervention were mixed. An NPC-led SDM phone call was successfully incorporated into the clinical workflow. Most veterans identified as being eligible for screening participated in the counseling visit and underwent screening. However, they were often reluctant to engage in SDM, feeling that their clinician had already recommended screening and that there was no need for further discussion. Unfortunately, many veterans had not received or reviewed the decision aid and were not interested in receiving information about benefits and harms. Because we relied on telephone calls, we could not share visual information in real time.

Overall, the surveys indicated that most veterans were very satisfied with the quality of the discussion and reported feeling no decisional conflict. However, based on the NPC’s field notes and audio recordings, we believe that the responses may have reflected earlier discussions with the PCP that reportedly emphasized only the veteran’s eligibility for screening. The fidelity assessments indicated that the NPC consistently addressed the harms and benefits of screening.

Nonetheless, the performance on knowledge measures was uneven. Veterans were generally aware of harms, including false alarms, overdiagnosis, radiation exposure, and incidental findings. They did not, however, appreciate when screening should stop. They also underestimated the risks of developing lung cancer and the portion of that risk attributable to tobacco use, and overestimated the benefits of screening. These results suggest that the veterans, at least those who completed the surveys, may not be making well-informed decisions.

Our findings echo those of other VA investigators in finding knowledge deficits among screened veterans, including being unaware that LDCT was for LCS, believing that screening could prevent cancer, receiving little information about screening harms, and feeling that negative tests meant they were among the “lucky ones” who would avoid harm from continued smoking.19,20

The VA is currently implementing centralized screening models with the Lung Precision Oncology Program and the VA partnership to increase access to lung screening (VA-PALS).5 The centralized model, which readily supports the tracking, monitoring, and reporting needs of a screening program, also has advantages in delivering SDM because counselors have been trained in SDM, are more familiar with LCS evidence and processes, can better incorporate decision tools, and do not face the same time constraints as clinicians.21 However, studies have shown that most patients have already decided to be screened when they show up for the SDM visit.22 In contrast, about one-third of patients in primary care settings who receive decision support chose not to be screened.23,24 We found that 13% of our patients decided against screening after a telephone discussion, suggesting that a virtually conducted SDM visit can meaningfully support decision making. Telemedicine also may reduce health inequities in centralized models arising from patients having limited access to screening centers.

Our results suggest that PCPs referring patients to a centralized program, even for virtual visits, should frame the decision to initiate LCS as SDM, where an informed patient is being supported in making a decision consistent with their values and preferences. Furthermore, engaging patients in SDM should not be construed as endorsing screening. When centralized support is less available, individual clinics may need to provide SDM, perhaps using a nonclinician decision coach if clinicians lack the time to lead the discussions. Decision coaches have been effectively used to increase patients’ knowledge about the benefits and harms of screening.12 Regardless of the program model, PCPs will also be responsible for determining whether patients are healthy enough to undergo invasive diagnostic testing and treatment and ensuring that tobacco use is addressed.

SDM delivered in any setting will be enhanced by ensuring that patients are provided with decision aids before a counseling visit. This will help them better understand the benefits and harms of screening and the need to elicit values. The discussion can then focus on areas of concern or questions raised by reviewing the decision aid. The clinician and patient could also use a decision aid during either a face-to-face or video clinical encounter to facilitate SDM. A Cochrane review has shown that using decision aids for people facing screening decisions increases knowledge, reduces decisional conflict, and effectively elicits values and preferences.25 Providing high-quality decision support is a patient-centered approach that respects a patient’s autonomy and may promote health equity and improve adherence.

We recognized the importance of having a multidisciplinary team, involving primary care, radiology, pulmonary, and nursing, with a shared understanding of the screening processes. These are essential features for a high-quality screening program where eligible veterans are readily identified and receive prompt and appropriate follow-up. Radiologists need to use Lung-RADS categories consistently and appropriately when reading LDCTs. This may require ongoing educational efforts, particularly given the new CMS guidelines accepting nonsubspecialist chest readers.7 Additionally, fellows and board-eligible residents may interpret images in academic settings and at VA facilities. The program needs to work closely with the pulmonary service to ensure that Lung-RADS 4 patients are promptly assessed. Radiologists and pulmonologists should calibrate the application of Lung-RADS categories to pulmonary nodules through jointly participating in meetings to review selected cases.

Challenges and Limitations

We faced some notable implementation challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic was extremely disruptive to LCS as it was to all health care. In addition, screening workflow processes were hampered by a lack of clinical reminders, which ideally would trigger for clinicians based on the tobacco history. The absence of this reminder meant that numerous patients were found to be ineligible for screening. We have a long-standing lung nodule clinic, and clinicians were confused about whether to order a surveillance imaging for an incidental nodule or a screening LDCT.

The radiology service was able to update order sets in CPRS to help guide clinicians in distinguishing indications and prerequisites for enrolling in LCS. This helped reduce the number of inappropriate orders and crossover orders between the VISN nodule tracking program and the LCS program.

Our results were preliminary and based on a small sample. We did not survey all veterans who underwent SDM, though the response rate was 79% and patient characteristics were similar to the larger cohort. Our results were potentially subject to selection bias, which could inflate the positive responses about decision quality and decisional conflict. However, the knowledge deficits are likely to be valid and suggest a need to better inform eligible veterans about the benefits and harms of screening. We did not have sufficient follow-up time to determine whether veterans were adherent to annual screenings. We showed that almost all those with abnormal imaging results completed diagnostic evaluations and/or were evaluated by pulmonary. As the program matures, we will be able to track outcomes related to cancer diagnoses and treatment.

Conclusions

A centralized LCS program was able to deliver SDM and enroll veterans in a screening program. While veterans were confident in their decision to screen and felt that they participated in decision making, knowledge testing indicated important deficits. Furthermore, we observed that many veterans did not meaningfully engage in SDM. Clinicians will need to frame the decision as patient centered at the time of referral, highlight the role of the NPC and importance of SDM, and be able to provide adequate decision support. The SDM visits can be enhanced by ensuring that veterans are able to review decision aids. Telemedicine is an acceptable and effective approach for supporting screening discussions, particularly for rural veterans.26

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals for their contributions to the study: John Paul Hornbeck, program support specialist; Kelly Miell, PhD; Bradley Mecham, PhD; Christopher C. Richards, MA; Bailey Noble, NP; Rebecca Barnhart, program analyst.

1. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693-701. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-11-00434

2. Hoffman RM, Atallah RP, Struble RD, Badgett RG. Lung cancer screening with low-dose CT: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3015-3025. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05951-7

3. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395-409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

4. Moyer VA, US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):330-338. doi:10.7326/M13-2771

5. Maurice NM, Tanner NT. Lung cancer screening at the VA: past, present and future. Semin Oncol. 2022;S0093-7754(22)00041-0. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2022.06.001

6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N). Published 2015. Accessed July 10, 2023. http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274