User login

The Hospitalist only

A “Ray of light”

Finding inspiration in our patients

I rush into the room at 4:30 p.m., hoping for a quick visit and maybe an early exit from the hospital; I had been asked to see Mr. Bryant in room 6765 with sigmoid volvulus.

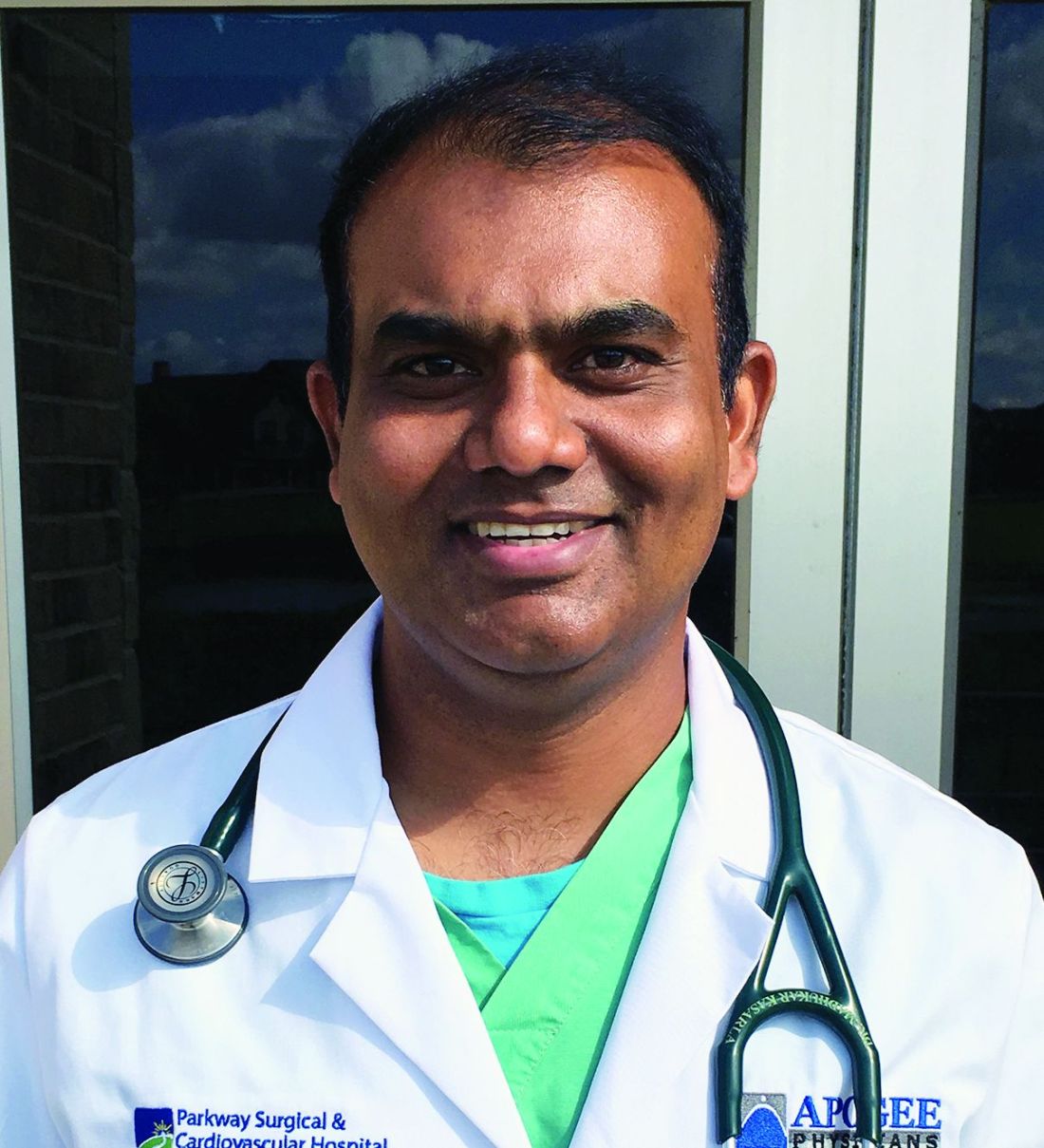

“Hey, Dr. Hass, my brother!” he says with a huge smile. Somehow, he must have gotten a glimpse of me before I could see him. I peek over the nurse’s shoulder, and then I see that unforgettable smile with only a few teeth and big bright eyes. Immediately I recognize him and think, “How could I have forgotten his name? Ray – like a beam of light.” He certainly had not forgotten me.

“It’s been more than a year since I was last here,” he says proudly.

When we met during his last hospitalization, I was struck by a thought that implanted itself deep in my brain: This guy is the happiest person I have ever met. And after what must have been 18 hard months for him, he is still smiling – and more than that, he is radiating love.

The fact that he is the “happiest person” is made more remarkable by all the hardship he has endured. Ray was born with cerebral palsy and didn’t walk until he was 10. The continuous spasms in his muscles led to severe cervical disc disease. His worsening pain and weakness were missed by his health care providers until he had lost significant strength in his hands and legs. When he finally got an MRI and then emergency surgery, it was too late. He never regained the dexterity of his hands or the ability to walk. He can climb onto his scooter chair only with the help of a lift.

“Wow! How you been, Ray?”

He replies with a phrase that jumped back out from my memory as he was saying it: “I just wake up every day and think about what I can do to make people happy.”

The goosebumps rise on my arms; I remember feeling this same sense of awe the last time we met – a feeling of real spiritual love for this guy.

“Today I feel so much better, too. I want to thank y’all who helped my stomach go down. Man, it got so huge, I thought I might blow up.” One of the consequences of the nerve damage he sustained is a very slow gut that has led to a stretched-out colon. The other day, his big, floppy colon got twisted, and neither our gastroenterologist nor radiologist was able to untwist it. He still has a tube in his rectum to help decompress his bowel.

Ray fills me in on the details in the slightly strained and slurred speech that sometimes comes with cerebral palsy. As he relays his story, my mind goes to work trying to diagnosis this mysterious case of happiness. How can I not try to get to the origins of this wellspring of love? I can’t help but thinking: Was it Ray’s joy and his speech impediment that made him seem childlike, or was it some brain injury that blessedly knocked out his self-pity? I would be wallowing in self-pity if I were as gravely disabled as him.

After a moment’s reflection, I recall the research on the amazing stability of our happiness set point: Good things and bad only move our happiness for a while before we return to our innate level of happiness. I see I had likely fallen prey to a stereotype of the disabled as heroic for just being themselves. Ray’s happiness is largely because of his lack of self-absorption and his focus on service and love.

Finishing our conversation and leaving the room feeling enlivened, I realize that Ray‘s generous spirit is a gift.

That night, my heart aches. I think about the inadequate care that led to Ray’s profound loss of function, leading to a surge of anger toward our flawed health care system – one that routinely lets down the most vulnerable among us.

The next day, two sisters and an aunt join Ray in his room. They ask for hugs, and I happily supply them. “Ray told us about you,” says Sheila, one of his sisters.

“Well, we have been talking about him here at the hospital, because he brightens everyone’s day. He is truly amazing. Has Ray always been so full of love?” I say, hoping to get some insight into his remarkable spirit.

Tonya, his aunt, responds first. “We were raised that way – to look for the good and keep love in our hearts. But Ray has always been the best. He never, ever complains. He brings joy to so many people. You should see him every day out on his scooter. That’s how he got that big sore on his butt.”

Ray indeed had developed a pressure sore, one that was going to need some thoughtful, ongoing care.

“But I finally got the right kind of cushion, before it was real hard,” he says.

I move from hospitalist mode to primary care mode and ask about his home equipment and his dental care. But they all want to keep talking about love.

“If doctors showed more love and their human side, they could bring more healing,” his sister says.

After 20 minutes of chatting, I pause. It is my last day on service, I had run out of medical reason to stay and I have others to see. So, I reluctantly give my goodbye hugs and leave. At the door, I turn back around. “Hey, Ray, can I get a picture with you?”

“Yeah, I want one with you, too!”

So, not surprisingly, Ray never complains. Maybe his spinal cord injury wasn’t from negligent care. Maybe he was so accustomed to looking past discomfort and too busy with his ministry of love, it didn’t occur to him to seek care.

Still, such a tragedy that he lost so much of the little mobility he did have. But maybe not so bad. His injury brought him back in contact with me and our staff. He is still waking up trying to make people happy and I can see his efforts are working. “He made my day!” I hear from a nurse. There is a healthy buzz at the nurses’ station after visits to his room.

Before walking out the door, he gives me an awkward fist bump from the bed and says, “I want to thank y’all again for everything. And I want you to know I love you.”

I find myself tearing up. “I love you too, my brother. And I am the one who should be grateful, Ray.” Saying it, I feel myself playing a part in the cycle of gratitude. Even small gifts put us under an obligation to give back. With great gifts, the desire to give is inescapable.

There is only one Ray, but he has given me something to aspire toward and what feels like urgency to do it. I want to “wake up each day thinking about ways to make other people happy.”

And understanding the potency of the gift from him has alerted me to the value of looking for other gifts and other inspirations from those I care for – something those of us who tend to be in the “doing” part of the provider-patient relationship can easy miss.

I will never be the beacon of light and love that Ray is, but being compelled to be my most authentic caring self with him, I see that for years I have held back – in the name of professionalism – the positive emotions that naturally arise from the work I do. I will try to shine and try to connect with that “Ray of light” residing in all my patients. I hope, too, that the cycle of giving Ray started will continue spreading to all those I care for.

Dr. Hass is a hospitalist at Sutter Health in Oakland, Calif. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

Finding inspiration in our patients

Finding inspiration in our patients

I rush into the room at 4:30 p.m., hoping for a quick visit and maybe an early exit from the hospital; I had been asked to see Mr. Bryant in room 6765 with sigmoid volvulus.

“Hey, Dr. Hass, my brother!” he says with a huge smile. Somehow, he must have gotten a glimpse of me before I could see him. I peek over the nurse’s shoulder, and then I see that unforgettable smile with only a few teeth and big bright eyes. Immediately I recognize him and think, “How could I have forgotten his name? Ray – like a beam of light.” He certainly had not forgotten me.

“It’s been more than a year since I was last here,” he says proudly.

When we met during his last hospitalization, I was struck by a thought that implanted itself deep in my brain: This guy is the happiest person I have ever met. And after what must have been 18 hard months for him, he is still smiling – and more than that, he is radiating love.

The fact that he is the “happiest person” is made more remarkable by all the hardship he has endured. Ray was born with cerebral palsy and didn’t walk until he was 10. The continuous spasms in his muscles led to severe cervical disc disease. His worsening pain and weakness were missed by his health care providers until he had lost significant strength in his hands and legs. When he finally got an MRI and then emergency surgery, it was too late. He never regained the dexterity of his hands or the ability to walk. He can climb onto his scooter chair only with the help of a lift.

“Wow! How you been, Ray?”

He replies with a phrase that jumped back out from my memory as he was saying it: “I just wake up every day and think about what I can do to make people happy.”

The goosebumps rise on my arms; I remember feeling this same sense of awe the last time we met – a feeling of real spiritual love for this guy.

“Today I feel so much better, too. I want to thank y’all who helped my stomach go down. Man, it got so huge, I thought I might blow up.” One of the consequences of the nerve damage he sustained is a very slow gut that has led to a stretched-out colon. The other day, his big, floppy colon got twisted, and neither our gastroenterologist nor radiologist was able to untwist it. He still has a tube in his rectum to help decompress his bowel.

Ray fills me in on the details in the slightly strained and slurred speech that sometimes comes with cerebral palsy. As he relays his story, my mind goes to work trying to diagnosis this mysterious case of happiness. How can I not try to get to the origins of this wellspring of love? I can’t help but thinking: Was it Ray’s joy and his speech impediment that made him seem childlike, or was it some brain injury that blessedly knocked out his self-pity? I would be wallowing in self-pity if I were as gravely disabled as him.

After a moment’s reflection, I recall the research on the amazing stability of our happiness set point: Good things and bad only move our happiness for a while before we return to our innate level of happiness. I see I had likely fallen prey to a stereotype of the disabled as heroic for just being themselves. Ray’s happiness is largely because of his lack of self-absorption and his focus on service and love.

Finishing our conversation and leaving the room feeling enlivened, I realize that Ray‘s generous spirit is a gift.

That night, my heart aches. I think about the inadequate care that led to Ray’s profound loss of function, leading to a surge of anger toward our flawed health care system – one that routinely lets down the most vulnerable among us.

The next day, two sisters and an aunt join Ray in his room. They ask for hugs, and I happily supply them. “Ray told us about you,” says Sheila, one of his sisters.

“Well, we have been talking about him here at the hospital, because he brightens everyone’s day. He is truly amazing. Has Ray always been so full of love?” I say, hoping to get some insight into his remarkable spirit.

Tonya, his aunt, responds first. “We were raised that way – to look for the good and keep love in our hearts. But Ray has always been the best. He never, ever complains. He brings joy to so many people. You should see him every day out on his scooter. That’s how he got that big sore on his butt.”

Ray indeed had developed a pressure sore, one that was going to need some thoughtful, ongoing care.

“But I finally got the right kind of cushion, before it was real hard,” he says.

I move from hospitalist mode to primary care mode and ask about his home equipment and his dental care. But they all want to keep talking about love.

“If doctors showed more love and their human side, they could bring more healing,” his sister says.

After 20 minutes of chatting, I pause. It is my last day on service, I had run out of medical reason to stay and I have others to see. So, I reluctantly give my goodbye hugs and leave. At the door, I turn back around. “Hey, Ray, can I get a picture with you?”

“Yeah, I want one with you, too!”

So, not surprisingly, Ray never complains. Maybe his spinal cord injury wasn’t from negligent care. Maybe he was so accustomed to looking past discomfort and too busy with his ministry of love, it didn’t occur to him to seek care.

Still, such a tragedy that he lost so much of the little mobility he did have. But maybe not so bad. His injury brought him back in contact with me and our staff. He is still waking up trying to make people happy and I can see his efforts are working. “He made my day!” I hear from a nurse. There is a healthy buzz at the nurses’ station after visits to his room.

Before walking out the door, he gives me an awkward fist bump from the bed and says, “I want to thank y’all again for everything. And I want you to know I love you.”

I find myself tearing up. “I love you too, my brother. And I am the one who should be grateful, Ray.” Saying it, I feel myself playing a part in the cycle of gratitude. Even small gifts put us under an obligation to give back. With great gifts, the desire to give is inescapable.

There is only one Ray, but he has given me something to aspire toward and what feels like urgency to do it. I want to “wake up each day thinking about ways to make other people happy.”

And understanding the potency of the gift from him has alerted me to the value of looking for other gifts and other inspirations from those I care for – something those of us who tend to be in the “doing” part of the provider-patient relationship can easy miss.

I will never be the beacon of light and love that Ray is, but being compelled to be my most authentic caring self with him, I see that for years I have held back – in the name of professionalism – the positive emotions that naturally arise from the work I do. I will try to shine and try to connect with that “Ray of light” residing in all my patients. I hope, too, that the cycle of giving Ray started will continue spreading to all those I care for.

Dr. Hass is a hospitalist at Sutter Health in Oakland, Calif. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

I rush into the room at 4:30 p.m., hoping for a quick visit and maybe an early exit from the hospital; I had been asked to see Mr. Bryant in room 6765 with sigmoid volvulus.

“Hey, Dr. Hass, my brother!” he says with a huge smile. Somehow, he must have gotten a glimpse of me before I could see him. I peek over the nurse’s shoulder, and then I see that unforgettable smile with only a few teeth and big bright eyes. Immediately I recognize him and think, “How could I have forgotten his name? Ray – like a beam of light.” He certainly had not forgotten me.

“It’s been more than a year since I was last here,” he says proudly.

When we met during his last hospitalization, I was struck by a thought that implanted itself deep in my brain: This guy is the happiest person I have ever met. And after what must have been 18 hard months for him, he is still smiling – and more than that, he is radiating love.

The fact that he is the “happiest person” is made more remarkable by all the hardship he has endured. Ray was born with cerebral palsy and didn’t walk until he was 10. The continuous spasms in his muscles led to severe cervical disc disease. His worsening pain and weakness were missed by his health care providers until he had lost significant strength in his hands and legs. When he finally got an MRI and then emergency surgery, it was too late. He never regained the dexterity of his hands or the ability to walk. He can climb onto his scooter chair only with the help of a lift.

“Wow! How you been, Ray?”

He replies with a phrase that jumped back out from my memory as he was saying it: “I just wake up every day and think about what I can do to make people happy.”

The goosebumps rise on my arms; I remember feeling this same sense of awe the last time we met – a feeling of real spiritual love for this guy.

“Today I feel so much better, too. I want to thank y’all who helped my stomach go down. Man, it got so huge, I thought I might blow up.” One of the consequences of the nerve damage he sustained is a very slow gut that has led to a stretched-out colon. The other day, his big, floppy colon got twisted, and neither our gastroenterologist nor radiologist was able to untwist it. He still has a tube in his rectum to help decompress his bowel.

Ray fills me in on the details in the slightly strained and slurred speech that sometimes comes with cerebral palsy. As he relays his story, my mind goes to work trying to diagnosis this mysterious case of happiness. How can I not try to get to the origins of this wellspring of love? I can’t help but thinking: Was it Ray’s joy and his speech impediment that made him seem childlike, or was it some brain injury that blessedly knocked out his self-pity? I would be wallowing in self-pity if I were as gravely disabled as him.

After a moment’s reflection, I recall the research on the amazing stability of our happiness set point: Good things and bad only move our happiness for a while before we return to our innate level of happiness. I see I had likely fallen prey to a stereotype of the disabled as heroic for just being themselves. Ray’s happiness is largely because of his lack of self-absorption and his focus on service and love.

Finishing our conversation and leaving the room feeling enlivened, I realize that Ray‘s generous spirit is a gift.

That night, my heart aches. I think about the inadequate care that led to Ray’s profound loss of function, leading to a surge of anger toward our flawed health care system – one that routinely lets down the most vulnerable among us.

The next day, two sisters and an aunt join Ray in his room. They ask for hugs, and I happily supply them. “Ray told us about you,” says Sheila, one of his sisters.

“Well, we have been talking about him here at the hospital, because he brightens everyone’s day. He is truly amazing. Has Ray always been so full of love?” I say, hoping to get some insight into his remarkable spirit.

Tonya, his aunt, responds first. “We were raised that way – to look for the good and keep love in our hearts. But Ray has always been the best. He never, ever complains. He brings joy to so many people. You should see him every day out on his scooter. That’s how he got that big sore on his butt.”

Ray indeed had developed a pressure sore, one that was going to need some thoughtful, ongoing care.

“But I finally got the right kind of cushion, before it was real hard,” he says.

I move from hospitalist mode to primary care mode and ask about his home equipment and his dental care. But they all want to keep talking about love.

“If doctors showed more love and their human side, they could bring more healing,” his sister says.

After 20 minutes of chatting, I pause. It is my last day on service, I had run out of medical reason to stay and I have others to see. So, I reluctantly give my goodbye hugs and leave. At the door, I turn back around. “Hey, Ray, can I get a picture with you?”

“Yeah, I want one with you, too!”

So, not surprisingly, Ray never complains. Maybe his spinal cord injury wasn’t from negligent care. Maybe he was so accustomed to looking past discomfort and too busy with his ministry of love, it didn’t occur to him to seek care.

Still, such a tragedy that he lost so much of the little mobility he did have. But maybe not so bad. His injury brought him back in contact with me and our staff. He is still waking up trying to make people happy and I can see his efforts are working. “He made my day!” I hear from a nurse. There is a healthy buzz at the nurses’ station after visits to his room.

Before walking out the door, he gives me an awkward fist bump from the bed and says, “I want to thank y’all again for everything. And I want you to know I love you.”

I find myself tearing up. “I love you too, my brother. And I am the one who should be grateful, Ray.” Saying it, I feel myself playing a part in the cycle of gratitude. Even small gifts put us under an obligation to give back. With great gifts, the desire to give is inescapable.

There is only one Ray, but he has given me something to aspire toward and what feels like urgency to do it. I want to “wake up each day thinking about ways to make other people happy.”

And understanding the potency of the gift from him has alerted me to the value of looking for other gifts and other inspirations from those I care for – something those of us who tend to be in the “doing” part of the provider-patient relationship can easy miss.

I will never be the beacon of light and love that Ray is, but being compelled to be my most authentic caring self with him, I see that for years I have held back – in the name of professionalism – the positive emotions that naturally arise from the work I do. I will try to shine and try to connect with that “Ray of light” residing in all my patients. I hope, too, that the cycle of giving Ray started will continue spreading to all those I care for.

Dr. Hass is a hospitalist at Sutter Health in Oakland, Calif. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

Are hospitalists being more highly valued?

An uptrend in financial support

Since the inception of hospital medicine more than 2 decades ago, the total number of hospitalists has rapidly increased to more than 60,000. The Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM), published biennially, captures new changes in our growing field and sheds light on current practice trends.

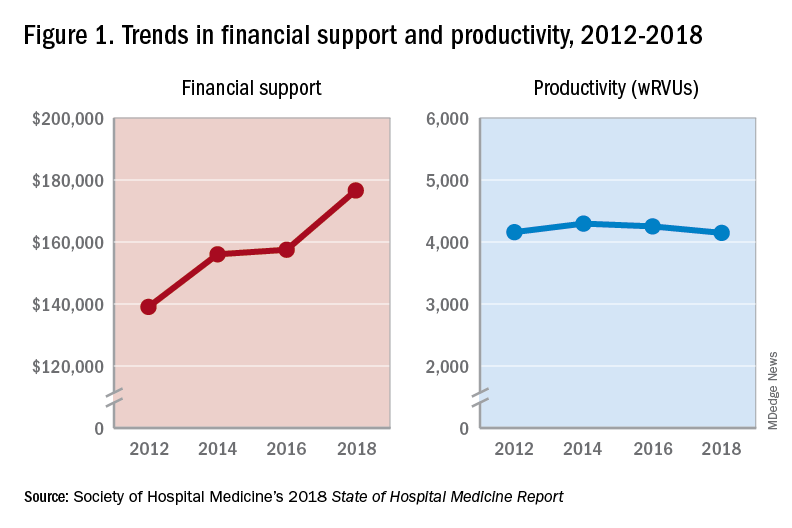

Among its findings, the 2018 SoHM Report reassuringly reveals that financial support from hospitals to hospital medicine groups (HMGs) continues to climb, even in the setting of rising health care costs and ongoing budget pressure.

The median amount of financial support per full-time equivalent (FTE) physician for HMGs serving adults was $176,658, according to the 2018 SoHM Report, which is up 12% from the 2016 median of $157,535. While there is no correlation between group sizes and the amount of financial support per FTE physician, there are significant differences across regions, with HMGs in the Midwest garnering the highest median support, at $193,121 per FTE physician.

The report also reveals big differences by employment model. For example, private multispecialty and primary care medical groups receive much less financial support ($58,396 per FTE physician) than HMGs employed by hospitals. This likely signifies that their main source of revenue is from professional service fees. Regardless of the types of employment models, past surveys have reported more than 95% of HMGs receive support from their hospitals to help cover expenses.

The median amount of financial support per FTE provider (including nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and locum tenens) was $134,300, which represents a 3.3% decrease, compared with the 2016 SoHM Report. For the first time, the 2018 SoHM also collected data on financial support per “work relative value unit” (wRVU) in addition to support per FTE physician and support per FTE provider. HMGs and their hospitals can use support per wRVU data to evaluate the support per unit of work, regardless of who (whether it is a physician, an advanced practice provider, and/or others) performed that work.

The median amount of financial support per wRVU for HMGs serving adults in 2018 was $41.92, with academic HMGs reporting a higher amount ($45.81) than nonacademic HMGs ($41.28). It will be interesting to track these numbers over time.

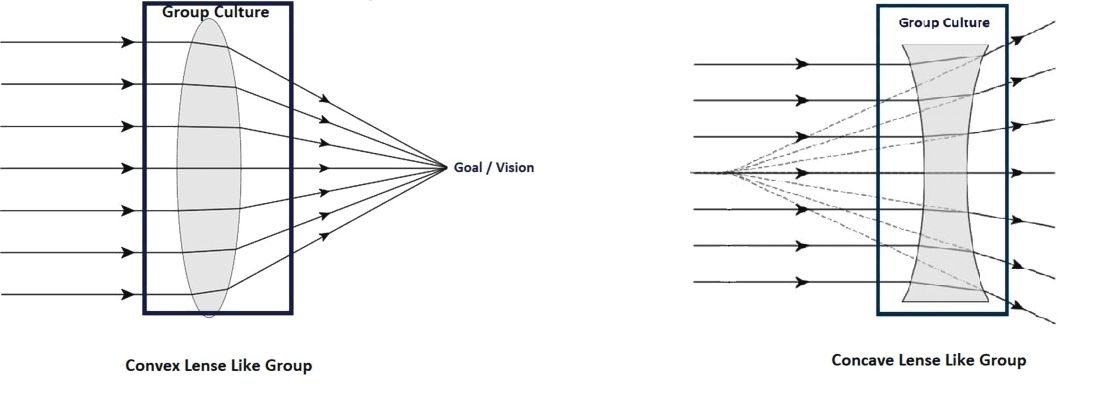

One of the most intriguing findings from the SHM’s 2018 SoHM Report is that financial support has risen despite relatively flat professional fee productivity (see Figure 1). Productivity, calculated as work relative value units (wRVUs) per physician declined slightly from 4,252 in 2016 to 4,147 in 2018.

There may be a few reasons why wRVUs per physician has remained relatively unchanged over the years. Many hospitals emphasize quality of care above provider productivity. The volume-to-value shift in theory serves as a means to reduce hospital-associated complications, length of stay, and readmission rates, thereby avoiding penalties and saving the overall costs for the hospitals in the long run.

Hospitalists involved in quality improvement projects and other essential nonclinical work perform tasks that are rarely captured in the wRVU metric. Improving patient experience, one of the Triple Aim components, necessitates extra time and effort, which also are nonbillable. In addition, increasing productivity can be challenging, a double-edged sword that may further escalate burnout and turnover rates. The static productivity may portend that it has leveled off or hit the ceiling in spite of ongoing efforts to improve efficacy.

In my view, the decision to invest in hospitalists for their contributions and dedications should not be determined based on a single metric such as wRVUs per physician. Hospitalist work on quality improvements; patient safety; efficiency, from direct bedside patient care to nonclinical efforts; teaching; research; involvements in various committees; administrative tasks; and leadership roles in improving health care systems are immeasurable. These are the reasons that most hospitals chose to adopt the hospitalist model and continue to support it. In fact, demand for hospitalists still outstrips supply, as evidenced by more than half of the hospital medicine groups with unfilled positions and an overall high turnover rate per 2018 SoHM data.

Although hospitalists are needed for the value that they provide, they should not take the status quo for granted. Instead, in return for the favorable financial support and in appreciation of being valued, hospitalists have a responsibility to prove that they are the right group chosen to do the work and help achieve their hospital’s mission and goals.

Dr. Vuong is a hospitalist at HealthPartners Medical Group in St Paul, Minn., and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

References

Afsar N. Looking into the Future and Making History. Hospitalist. 2019;23(1):31.

Beresford L. The State of Hospital Medicine in 2018. Hospitalist. 2019;23(1):1-11.

FitzGerald S. Not a Time for Modesty. Oct. 2009. Retrieved from https://acphospitalist.org/archives/2009/10/value.htm.

Watcher RM et al. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Eng J Med. 2016. 375(11):1009-11.

An uptrend in financial support

An uptrend in financial support

Since the inception of hospital medicine more than 2 decades ago, the total number of hospitalists has rapidly increased to more than 60,000. The Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM), published biennially, captures new changes in our growing field and sheds light on current practice trends.

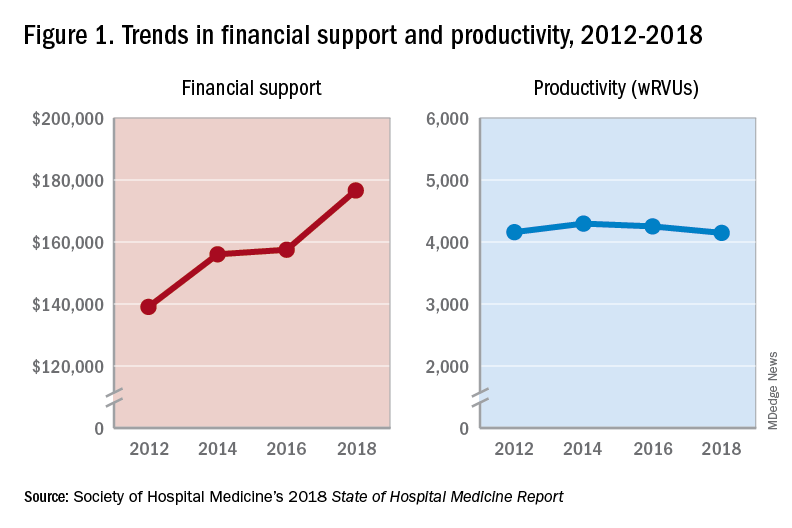

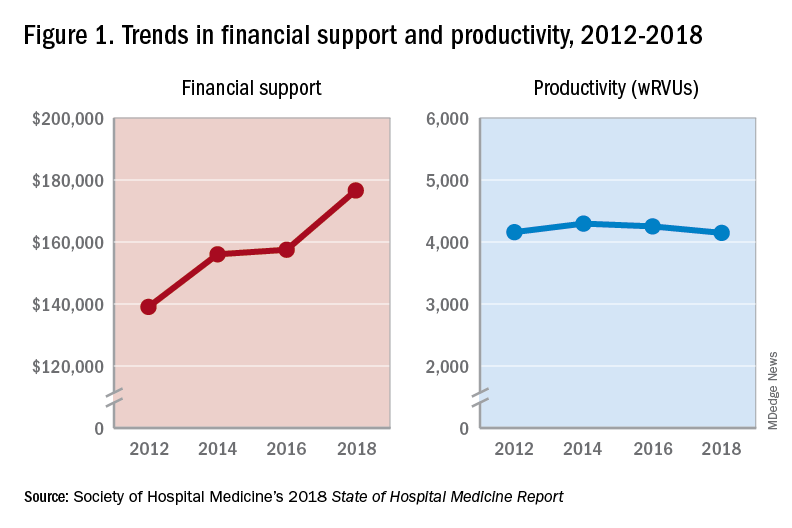

Among its findings, the 2018 SoHM Report reassuringly reveals that financial support from hospitals to hospital medicine groups (HMGs) continues to climb, even in the setting of rising health care costs and ongoing budget pressure.

The median amount of financial support per full-time equivalent (FTE) physician for HMGs serving adults was $176,658, according to the 2018 SoHM Report, which is up 12% from the 2016 median of $157,535. While there is no correlation between group sizes and the amount of financial support per FTE physician, there are significant differences across regions, with HMGs in the Midwest garnering the highest median support, at $193,121 per FTE physician.

The report also reveals big differences by employment model. For example, private multispecialty and primary care medical groups receive much less financial support ($58,396 per FTE physician) than HMGs employed by hospitals. This likely signifies that their main source of revenue is from professional service fees. Regardless of the types of employment models, past surveys have reported more than 95% of HMGs receive support from their hospitals to help cover expenses.

The median amount of financial support per FTE provider (including nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and locum tenens) was $134,300, which represents a 3.3% decrease, compared with the 2016 SoHM Report. For the first time, the 2018 SoHM also collected data on financial support per “work relative value unit” (wRVU) in addition to support per FTE physician and support per FTE provider. HMGs and their hospitals can use support per wRVU data to evaluate the support per unit of work, regardless of who (whether it is a physician, an advanced practice provider, and/or others) performed that work.

The median amount of financial support per wRVU for HMGs serving adults in 2018 was $41.92, with academic HMGs reporting a higher amount ($45.81) than nonacademic HMGs ($41.28). It will be interesting to track these numbers over time.

One of the most intriguing findings from the SHM’s 2018 SoHM Report is that financial support has risen despite relatively flat professional fee productivity (see Figure 1). Productivity, calculated as work relative value units (wRVUs) per physician declined slightly from 4,252 in 2016 to 4,147 in 2018.

There may be a few reasons why wRVUs per physician has remained relatively unchanged over the years. Many hospitals emphasize quality of care above provider productivity. The volume-to-value shift in theory serves as a means to reduce hospital-associated complications, length of stay, and readmission rates, thereby avoiding penalties and saving the overall costs for the hospitals in the long run.

Hospitalists involved in quality improvement projects and other essential nonclinical work perform tasks that are rarely captured in the wRVU metric. Improving patient experience, one of the Triple Aim components, necessitates extra time and effort, which also are nonbillable. In addition, increasing productivity can be challenging, a double-edged sword that may further escalate burnout and turnover rates. The static productivity may portend that it has leveled off or hit the ceiling in spite of ongoing efforts to improve efficacy.

In my view, the decision to invest in hospitalists for their contributions and dedications should not be determined based on a single metric such as wRVUs per physician. Hospitalist work on quality improvements; patient safety; efficiency, from direct bedside patient care to nonclinical efforts; teaching; research; involvements in various committees; administrative tasks; and leadership roles in improving health care systems are immeasurable. These are the reasons that most hospitals chose to adopt the hospitalist model and continue to support it. In fact, demand for hospitalists still outstrips supply, as evidenced by more than half of the hospital medicine groups with unfilled positions and an overall high turnover rate per 2018 SoHM data.

Although hospitalists are needed for the value that they provide, they should not take the status quo for granted. Instead, in return for the favorable financial support and in appreciation of being valued, hospitalists have a responsibility to prove that they are the right group chosen to do the work and help achieve their hospital’s mission and goals.

Dr. Vuong is a hospitalist at HealthPartners Medical Group in St Paul, Minn., and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

References

Afsar N. Looking into the Future and Making History. Hospitalist. 2019;23(1):31.

Beresford L. The State of Hospital Medicine in 2018. Hospitalist. 2019;23(1):1-11.

FitzGerald S. Not a Time for Modesty. Oct. 2009. Retrieved from https://acphospitalist.org/archives/2009/10/value.htm.

Watcher RM et al. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Eng J Med. 2016. 375(11):1009-11.

Since the inception of hospital medicine more than 2 decades ago, the total number of hospitalists has rapidly increased to more than 60,000. The Society of Hospital Medicine’s State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM), published biennially, captures new changes in our growing field and sheds light on current practice trends.

Among its findings, the 2018 SoHM Report reassuringly reveals that financial support from hospitals to hospital medicine groups (HMGs) continues to climb, even in the setting of rising health care costs and ongoing budget pressure.

The median amount of financial support per full-time equivalent (FTE) physician for HMGs serving adults was $176,658, according to the 2018 SoHM Report, which is up 12% from the 2016 median of $157,535. While there is no correlation between group sizes and the amount of financial support per FTE physician, there are significant differences across regions, with HMGs in the Midwest garnering the highest median support, at $193,121 per FTE physician.

The report also reveals big differences by employment model. For example, private multispecialty and primary care medical groups receive much less financial support ($58,396 per FTE physician) than HMGs employed by hospitals. This likely signifies that their main source of revenue is from professional service fees. Regardless of the types of employment models, past surveys have reported more than 95% of HMGs receive support from their hospitals to help cover expenses.

The median amount of financial support per FTE provider (including nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and locum tenens) was $134,300, which represents a 3.3% decrease, compared with the 2016 SoHM Report. For the first time, the 2018 SoHM also collected data on financial support per “work relative value unit” (wRVU) in addition to support per FTE physician and support per FTE provider. HMGs and their hospitals can use support per wRVU data to evaluate the support per unit of work, regardless of who (whether it is a physician, an advanced practice provider, and/or others) performed that work.

The median amount of financial support per wRVU for HMGs serving adults in 2018 was $41.92, with academic HMGs reporting a higher amount ($45.81) than nonacademic HMGs ($41.28). It will be interesting to track these numbers over time.

One of the most intriguing findings from the SHM’s 2018 SoHM Report is that financial support has risen despite relatively flat professional fee productivity (see Figure 1). Productivity, calculated as work relative value units (wRVUs) per physician declined slightly from 4,252 in 2016 to 4,147 in 2018.

There may be a few reasons why wRVUs per physician has remained relatively unchanged over the years. Many hospitals emphasize quality of care above provider productivity. The volume-to-value shift in theory serves as a means to reduce hospital-associated complications, length of stay, and readmission rates, thereby avoiding penalties and saving the overall costs for the hospitals in the long run.

Hospitalists involved in quality improvement projects and other essential nonclinical work perform tasks that are rarely captured in the wRVU metric. Improving patient experience, one of the Triple Aim components, necessitates extra time and effort, which also are nonbillable. In addition, increasing productivity can be challenging, a double-edged sword that may further escalate burnout and turnover rates. The static productivity may portend that it has leveled off or hit the ceiling in spite of ongoing efforts to improve efficacy.

In my view, the decision to invest in hospitalists for their contributions and dedications should not be determined based on a single metric such as wRVUs per physician. Hospitalist work on quality improvements; patient safety; efficiency, from direct bedside patient care to nonclinical efforts; teaching; research; involvements in various committees; administrative tasks; and leadership roles in improving health care systems are immeasurable. These are the reasons that most hospitals chose to adopt the hospitalist model and continue to support it. In fact, demand for hospitalists still outstrips supply, as evidenced by more than half of the hospital medicine groups with unfilled positions and an overall high turnover rate per 2018 SoHM data.

Although hospitalists are needed for the value that they provide, they should not take the status quo for granted. Instead, in return for the favorable financial support and in appreciation of being valued, hospitalists have a responsibility to prove that they are the right group chosen to do the work and help achieve their hospital’s mission and goals.

Dr. Vuong is a hospitalist at HealthPartners Medical Group in St Paul, Minn., and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

References

Afsar N. Looking into the Future and Making History. Hospitalist. 2019;23(1):31.

Beresford L. The State of Hospital Medicine in 2018. Hospitalist. 2019;23(1):1-11.

FitzGerald S. Not a Time for Modesty. Oct. 2009. Retrieved from https://acphospitalist.org/archives/2009/10/value.htm.

Watcher RM et al. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Eng J Med. 2016. 375(11):1009-11.

Discharge before noon: An appropriate metric for efficiency?

I first heard the term “discharge before noon” (DCBN) as a third-year medical student starting my internal medicine rotation. The basic idea made sense: Get patients out of the hospital early so rooms can be cleaned more quickly and new patients wouldn’t have to wait so long in the ED.

It quickly became apparent, however, that a lot of moving parts had to align perfectly for DCBN. Even if we prioritized rounding on dischargeable patients (starting 8-9 a.m. depending on the service/day), they still needed prescriptions filled, normal clothes to wear, and a way to get home, which wasn’t easy to coordinate while we were still trying to see all the other patients.

Fast forward through 5 years of residency/fellowship experience and DCBN seems even more unrealistic in hospitalized pediatric patients. As a simple example, discharge criteria for dehydration (one of the most common reasons for pediatric hospitalization) include demonstrating the ability to drink enough liquids to stay hydrated. Who’s going to force children to stay up all night sipping fluids (plus changing all those diapers or taking them to the bathroom)? If the child stays on intravenous fluids overnight, we have to monitor at least through breakfast, likely lunch, thus making DCBN nearly impossible.

In a January 2019 article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Hailey James, MHA, (@Haileyjms on Twitter) and her colleagues demonstrated an association between DCBN and decreased length of stay (LOS) for medical but not surgical pediatric discharges.1 This made them question if DCBN is an appropriate metric for discharge efficiency, as well as workflow differences between services. Many hospitals, however, still try to push DCBN as a goal (see Destino et al in the same January 2019 issue of JHM2), which could potentially lead to people trying to game the system.

How does your institution try to make discharge processes more efficient? Is it actually possible to do everything more quickly without sacrificing quality or trainee education? Whether your patients are kids, adults, or both, there are likely many issues in common where we could all learn from each other.

We discussed this topic in #JHMChat on April 15 on Twitter. New to Twitter or not familiar with #JHMChat? Since October 2015, JHM has reviewed and discussed dozens of articles spanning a wide variety of topics related to caring for hospitalized patients. All are welcome to join, including medical students, residents, nurses, practicing hospitalists, and more. It’s a great opportunity to virtually meet and learn from others while earning free CME.

To participate in future chats, type #JHMChat in the search box on the top right corner of your Twitter homepage, click on the “Latest” tab at the top left to see the most recent tweets, and join the conversation (don’t forget the hashtag)!

Dr. Chen is a pediatric hospital medicine fellow at Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego. She is one of the cofounders/moderators of #PHMFellowJC, serves as a fellow district representative for the American Academy of Pediatrics, and is an active #tweetiatrician at @DrJenChen4kids. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

References

1. James HJ et al. The Association of Discharge Before Noon and Length of Stay in Hospitalized Pediatric Patients. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):28-32. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3111.

2. Destino L et al. Improving Patient Flow: Analysis of an Initiative to Improve Early Discharge. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):22-7. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3133.

I first heard the term “discharge before noon” (DCBN) as a third-year medical student starting my internal medicine rotation. The basic idea made sense: Get patients out of the hospital early so rooms can be cleaned more quickly and new patients wouldn’t have to wait so long in the ED.

It quickly became apparent, however, that a lot of moving parts had to align perfectly for DCBN. Even if we prioritized rounding on dischargeable patients (starting 8-9 a.m. depending on the service/day), they still needed prescriptions filled, normal clothes to wear, and a way to get home, which wasn’t easy to coordinate while we were still trying to see all the other patients.

Fast forward through 5 years of residency/fellowship experience and DCBN seems even more unrealistic in hospitalized pediatric patients. As a simple example, discharge criteria for dehydration (one of the most common reasons for pediatric hospitalization) include demonstrating the ability to drink enough liquids to stay hydrated. Who’s going to force children to stay up all night sipping fluids (plus changing all those diapers or taking them to the bathroom)? If the child stays on intravenous fluids overnight, we have to monitor at least through breakfast, likely lunch, thus making DCBN nearly impossible.

In a January 2019 article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Hailey James, MHA, (@Haileyjms on Twitter) and her colleagues demonstrated an association between DCBN and decreased length of stay (LOS) for medical but not surgical pediatric discharges.1 This made them question if DCBN is an appropriate metric for discharge efficiency, as well as workflow differences between services. Many hospitals, however, still try to push DCBN as a goal (see Destino et al in the same January 2019 issue of JHM2), which could potentially lead to people trying to game the system.

How does your institution try to make discharge processes more efficient? Is it actually possible to do everything more quickly without sacrificing quality or trainee education? Whether your patients are kids, adults, or both, there are likely many issues in common where we could all learn from each other.

We discussed this topic in #JHMChat on April 15 on Twitter. New to Twitter or not familiar with #JHMChat? Since October 2015, JHM has reviewed and discussed dozens of articles spanning a wide variety of topics related to caring for hospitalized patients. All are welcome to join, including medical students, residents, nurses, practicing hospitalists, and more. It’s a great opportunity to virtually meet and learn from others while earning free CME.

To participate in future chats, type #JHMChat in the search box on the top right corner of your Twitter homepage, click on the “Latest” tab at the top left to see the most recent tweets, and join the conversation (don’t forget the hashtag)!

Dr. Chen is a pediatric hospital medicine fellow at Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego. She is one of the cofounders/moderators of #PHMFellowJC, serves as a fellow district representative for the American Academy of Pediatrics, and is an active #tweetiatrician at @DrJenChen4kids. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

References

1. James HJ et al. The Association of Discharge Before Noon and Length of Stay in Hospitalized Pediatric Patients. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):28-32. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3111.

2. Destino L et al. Improving Patient Flow: Analysis of an Initiative to Improve Early Discharge. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):22-7. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3133.

I first heard the term “discharge before noon” (DCBN) as a third-year medical student starting my internal medicine rotation. The basic idea made sense: Get patients out of the hospital early so rooms can be cleaned more quickly and new patients wouldn’t have to wait so long in the ED.

It quickly became apparent, however, that a lot of moving parts had to align perfectly for DCBN. Even if we prioritized rounding on dischargeable patients (starting 8-9 a.m. depending on the service/day), they still needed prescriptions filled, normal clothes to wear, and a way to get home, which wasn’t easy to coordinate while we were still trying to see all the other patients.

Fast forward through 5 years of residency/fellowship experience and DCBN seems even more unrealistic in hospitalized pediatric patients. As a simple example, discharge criteria for dehydration (one of the most common reasons for pediatric hospitalization) include demonstrating the ability to drink enough liquids to stay hydrated. Who’s going to force children to stay up all night sipping fluids (plus changing all those diapers or taking them to the bathroom)? If the child stays on intravenous fluids overnight, we have to monitor at least through breakfast, likely lunch, thus making DCBN nearly impossible.

In a January 2019 article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Hailey James, MHA, (@Haileyjms on Twitter) and her colleagues demonstrated an association between DCBN and decreased length of stay (LOS) for medical but not surgical pediatric discharges.1 This made them question if DCBN is an appropriate metric for discharge efficiency, as well as workflow differences between services. Many hospitals, however, still try to push DCBN as a goal (see Destino et al in the same January 2019 issue of JHM2), which could potentially lead to people trying to game the system.

How does your institution try to make discharge processes more efficient? Is it actually possible to do everything more quickly without sacrificing quality or trainee education? Whether your patients are kids, adults, or both, there are likely many issues in common where we could all learn from each other.

We discussed this topic in #JHMChat on April 15 on Twitter. New to Twitter or not familiar with #JHMChat? Since October 2015, JHM has reviewed and discussed dozens of articles spanning a wide variety of topics related to caring for hospitalized patients. All are welcome to join, including medical students, residents, nurses, practicing hospitalists, and more. It’s a great opportunity to virtually meet and learn from others while earning free CME.

To participate in future chats, type #JHMChat in the search box on the top right corner of your Twitter homepage, click on the “Latest” tab at the top left to see the most recent tweets, and join the conversation (don’t forget the hashtag)!

Dr. Chen is a pediatric hospital medicine fellow at Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego. She is one of the cofounders/moderators of #PHMFellowJC, serves as a fellow district representative for the American Academy of Pediatrics, and is an active #tweetiatrician at @DrJenChen4kids. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

References

1. James HJ et al. The Association of Discharge Before Noon and Length of Stay in Hospitalized Pediatric Patients. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):28-32. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3111.

2. Destino L et al. Improving Patient Flow: Analysis of an Initiative to Improve Early Discharge. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):22-7. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3133.

A warning song to keep our children safe

Pay heed to “The House of the Rising Sun”

“There is a house in New Orleans. They call the Rising Sun. And it’s been the ruin of many a poor boy. And, God, I know I’m one.”

The 1960s rock band the Animals will tell you a tale to convince you to get vaccinated. Don’t believe me? Follow along.

The first hints of the song “House of the Rising Sun” rolled out of the hills of Appalachia.

Somewhere in the Golden Triangle, far away from New Orleans, where Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee rise in quiet desolation, a warning song about a tailor and a drunk emerged. Sometime around the Civil War, a hint of a tune began. Over the next century, it evolved, until it became cemented in rock culture 50 years ago by The Animals, existing as the version played most commonly today.

In the mid-19th century, medicine shows rambled through the South, stopping in places like Noetown or Daisy. The small towns would empty out for the day to see the entertainers, singers, and jugglers perform. Hundreds gathered in the hot summer day, the entertainment solely a pretext for the traveling doctors to sell their wares, the snake oil, and cure-alls, as well as various patent medicines.

These were isolated towns, with no deliveries, few visitors, and the railroad yet to arrive. Frequently, the only news from outside came from these caravans of entertainers and con men who swept into town. They were like Professor Marvel from The Wizard of Oz, or a current-day Dr. Oz, luring the crowd with false advertising, selling colored water, and then disappearing before you realized you were duped. Today, traveling doctors of the same ilk convince parents to not vaccinate their children, tell them to visit stem cell centers that claim false cures, and offer them a shiny object with one hand while taking their cash with the other.

Yet, there was a positive development in the wake of these patent medicine shows: the entertainment lingered. New songs traveled the same journeys as these medicine shows – new earworms that would then be warbled in the local bars, while doing chores around the barn, or simply during walks on the Appalachian trails.

In 1937, Alan Lomax arrived in Noetown, Ky., with a microphone and an acetate record and recorded the voice of 16-year-old Georgia Turner singing “House of the Rising Sun.” She didn’t know where she heard that song, but most likely picked it up at the medicine show.

One of those singers was Clarence Ashley, who would croon about the Rising Sun Blues. He sang with Doc Cloud and Doc Hauer, who offered tonics for whatever ailed you. Perhaps Georgia Turner heard the song in the early 1900s as well. Her 1937 version contains the lyrics most closely related to the Animals’ tune.

Lomax spent the 1940s gathering songs around the Appalachian South. He put these songs into a songbook and spread them throughout the country. He would also return to New York City and gather in a room with legendary folk singers. They would hear these new lyrics, new sounds, and make them their own.

In that room would be Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Josh White, the fathers of folk music. The music Lomax pulled out of the mountains in small towns would become new again in the guitars and harmonicas of the Greenwich Village singers and musicians. Pete Seeger performed with the Weavers, named because they would weave songs from the past into new versions.

“House of the Rising Sun” was woven into the folk music landscape, evolving and growing. Josh White is credited with changing the song from a major key into the minor key we know today. Bob Dylan sang a version. And then in 1964, Eric Burdon and The Animals released their version, which became the standard. An arpeggio guitar opening, the rhythm sped up, a louder sound, and that minor key provides an emotional wallop for this warning song.

Numerous covers followed, including a beautiful version of “Amazing Grace”, sung to the tune of “House of the Rising Sun” by the Blind Boys of Alabama.

The song endures for its melody as well as for its lyrics. This was a warning song, a universal song, “not to do what I have done.” The small towns in Kentucky may have heard of the sinful ways of New Orleans and would spread the message with these songs to avoid the brothels, the drink, and the broken marriages that would reverberate with visits to the Crescent City.

“House of the Rising Sun” is one of the most covered songs, traveling wide and far, no longer with the need for a medicine show. It was a pivotal moment in rock ‘n roll, turning folk music into rock music. The Animals became huge because of this song, and their version became the standard on which all subsequent covers based their version. It made Bob Dylan’s older version seem quaint.

The song has been in my head for a while now. My wife is hoping writing about it will keep it from being played in our household any more. There are various reasons it has been resonating with me, including the following:

- It traces the origins of folk music and the importance of people like Lomax and Guthrie to collect and save Americana.

- The magic of musical evolution – a reminder of how art is built on the work of those who came before, each version with its unique personality.

- The release of “House of the Rising Sun” was a seminal, transformative moment when folk became rock music.

- The lasting power of warning songs.

- The hucksters that enabled this song to be kept alive.

That last one has really stuck with me. The medicine shows are an important part of American history. For instance, Coca-Cola started as one of those patent medicines; it was one of the many concoctions of the Atlanta pharmacist John Stith Pemberton, sold to treat all that ails us. Dr. Pepper, too, was a medicine in a sugary bottle – another that often contained alcohol or cocaine. Society wants a cure-all, and the marketing and selling done during these medicine shows offered placebos.

The hucksters exist in various forms today, selling detoxifications, magic diet cures, psychic powers of healing, or convincing parents that their kids don’t need vaccines. We need a warning song that goes viral to keep our children safe. We are blessed to be in a world without smallpox, almost rid of polio, and we have the knowledge and opportunity to rid the world of other preventable illnesses. Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000; now, outbreaks emerge in every news cycle.

The CDC admits they have not been targeting misinformation well. How can we spread the science, the truth, the message faster than the lies? Better marketing? The answer may be through stories and narratives and song, with the backing of good science. “House of the Rising Sun” is a warning song. Maybe we need more. We need that deep history, that long trail to remind us of the world before vaccines, when everyone knew someone, either in their own household or next door, who succumbed to one of the childhood illnesses.

Let the “House of the Rising Sun” play on. Create a new version, and let that message reverberate, too.

Tell your children; they need to be vaccinated.

Dr. Messler is a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. He previously chaired SHM’s Quality and Patient Safety Committee and has been active in several SHM mentoring programs, most recently with Project BOOST and Glycemic Control. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

Pay heed to “The House of the Rising Sun”

Pay heed to “The House of the Rising Sun”

“There is a house in New Orleans. They call the Rising Sun. And it’s been the ruin of many a poor boy. And, God, I know I’m one.”

The 1960s rock band the Animals will tell you a tale to convince you to get vaccinated. Don’t believe me? Follow along.

The first hints of the song “House of the Rising Sun” rolled out of the hills of Appalachia.

Somewhere in the Golden Triangle, far away from New Orleans, where Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee rise in quiet desolation, a warning song about a tailor and a drunk emerged. Sometime around the Civil War, a hint of a tune began. Over the next century, it evolved, until it became cemented in rock culture 50 years ago by The Animals, existing as the version played most commonly today.

In the mid-19th century, medicine shows rambled through the South, stopping in places like Noetown or Daisy. The small towns would empty out for the day to see the entertainers, singers, and jugglers perform. Hundreds gathered in the hot summer day, the entertainment solely a pretext for the traveling doctors to sell their wares, the snake oil, and cure-alls, as well as various patent medicines.

These were isolated towns, with no deliveries, few visitors, and the railroad yet to arrive. Frequently, the only news from outside came from these caravans of entertainers and con men who swept into town. They were like Professor Marvel from The Wizard of Oz, or a current-day Dr. Oz, luring the crowd with false advertising, selling colored water, and then disappearing before you realized you were duped. Today, traveling doctors of the same ilk convince parents to not vaccinate their children, tell them to visit stem cell centers that claim false cures, and offer them a shiny object with one hand while taking their cash with the other.

Yet, there was a positive development in the wake of these patent medicine shows: the entertainment lingered. New songs traveled the same journeys as these medicine shows – new earworms that would then be warbled in the local bars, while doing chores around the barn, or simply during walks on the Appalachian trails.

In 1937, Alan Lomax arrived in Noetown, Ky., with a microphone and an acetate record and recorded the voice of 16-year-old Georgia Turner singing “House of the Rising Sun.” She didn’t know where she heard that song, but most likely picked it up at the medicine show.

One of those singers was Clarence Ashley, who would croon about the Rising Sun Blues. He sang with Doc Cloud and Doc Hauer, who offered tonics for whatever ailed you. Perhaps Georgia Turner heard the song in the early 1900s as well. Her 1937 version contains the lyrics most closely related to the Animals’ tune.

Lomax spent the 1940s gathering songs around the Appalachian South. He put these songs into a songbook and spread them throughout the country. He would also return to New York City and gather in a room with legendary folk singers. They would hear these new lyrics, new sounds, and make them their own.

In that room would be Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Josh White, the fathers of folk music. The music Lomax pulled out of the mountains in small towns would become new again in the guitars and harmonicas of the Greenwich Village singers and musicians. Pete Seeger performed with the Weavers, named because they would weave songs from the past into new versions.

“House of the Rising Sun” was woven into the folk music landscape, evolving and growing. Josh White is credited with changing the song from a major key into the minor key we know today. Bob Dylan sang a version. And then in 1964, Eric Burdon and The Animals released their version, which became the standard. An arpeggio guitar opening, the rhythm sped up, a louder sound, and that minor key provides an emotional wallop for this warning song.

Numerous covers followed, including a beautiful version of “Amazing Grace”, sung to the tune of “House of the Rising Sun” by the Blind Boys of Alabama.

The song endures for its melody as well as for its lyrics. This was a warning song, a universal song, “not to do what I have done.” The small towns in Kentucky may have heard of the sinful ways of New Orleans and would spread the message with these songs to avoid the brothels, the drink, and the broken marriages that would reverberate with visits to the Crescent City.

“House of the Rising Sun” is one of the most covered songs, traveling wide and far, no longer with the need for a medicine show. It was a pivotal moment in rock ‘n roll, turning folk music into rock music. The Animals became huge because of this song, and their version became the standard on which all subsequent covers based their version. It made Bob Dylan’s older version seem quaint.

The song has been in my head for a while now. My wife is hoping writing about it will keep it from being played in our household any more. There are various reasons it has been resonating with me, including the following:

- It traces the origins of folk music and the importance of people like Lomax and Guthrie to collect and save Americana.

- The magic of musical evolution – a reminder of how art is built on the work of those who came before, each version with its unique personality.

- The release of “House of the Rising Sun” was a seminal, transformative moment when folk became rock music.

- The lasting power of warning songs.

- The hucksters that enabled this song to be kept alive.

That last one has really stuck with me. The medicine shows are an important part of American history. For instance, Coca-Cola started as one of those patent medicines; it was one of the many concoctions of the Atlanta pharmacist John Stith Pemberton, sold to treat all that ails us. Dr. Pepper, too, was a medicine in a sugary bottle – another that often contained alcohol or cocaine. Society wants a cure-all, and the marketing and selling done during these medicine shows offered placebos.

The hucksters exist in various forms today, selling detoxifications, magic diet cures, psychic powers of healing, or convincing parents that their kids don’t need vaccines. We need a warning song that goes viral to keep our children safe. We are blessed to be in a world without smallpox, almost rid of polio, and we have the knowledge and opportunity to rid the world of other preventable illnesses. Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000; now, outbreaks emerge in every news cycle.

The CDC admits they have not been targeting misinformation well. How can we spread the science, the truth, the message faster than the lies? Better marketing? The answer may be through stories and narratives and song, with the backing of good science. “House of the Rising Sun” is a warning song. Maybe we need more. We need that deep history, that long trail to remind us of the world before vaccines, when everyone knew someone, either in their own household or next door, who succumbed to one of the childhood illnesses.

Let the “House of the Rising Sun” play on. Create a new version, and let that message reverberate, too.

Tell your children; they need to be vaccinated.

Dr. Messler is a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. He previously chaired SHM’s Quality and Patient Safety Committee and has been active in several SHM mentoring programs, most recently with Project BOOST and Glycemic Control. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

“There is a house in New Orleans. They call the Rising Sun. And it’s been the ruin of many a poor boy. And, God, I know I’m one.”

The 1960s rock band the Animals will tell you a tale to convince you to get vaccinated. Don’t believe me? Follow along.

The first hints of the song “House of the Rising Sun” rolled out of the hills of Appalachia.

Somewhere in the Golden Triangle, far away from New Orleans, where Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee rise in quiet desolation, a warning song about a tailor and a drunk emerged. Sometime around the Civil War, a hint of a tune began. Over the next century, it evolved, until it became cemented in rock culture 50 years ago by The Animals, existing as the version played most commonly today.

In the mid-19th century, medicine shows rambled through the South, stopping in places like Noetown or Daisy. The small towns would empty out for the day to see the entertainers, singers, and jugglers perform. Hundreds gathered in the hot summer day, the entertainment solely a pretext for the traveling doctors to sell their wares, the snake oil, and cure-alls, as well as various patent medicines.

These were isolated towns, with no deliveries, few visitors, and the railroad yet to arrive. Frequently, the only news from outside came from these caravans of entertainers and con men who swept into town. They were like Professor Marvel from The Wizard of Oz, or a current-day Dr. Oz, luring the crowd with false advertising, selling colored water, and then disappearing before you realized you were duped. Today, traveling doctors of the same ilk convince parents to not vaccinate their children, tell them to visit stem cell centers that claim false cures, and offer them a shiny object with one hand while taking their cash with the other.

Yet, there was a positive development in the wake of these patent medicine shows: the entertainment lingered. New songs traveled the same journeys as these medicine shows – new earworms that would then be warbled in the local bars, while doing chores around the barn, or simply during walks on the Appalachian trails.

In 1937, Alan Lomax arrived in Noetown, Ky., with a microphone and an acetate record and recorded the voice of 16-year-old Georgia Turner singing “House of the Rising Sun.” She didn’t know where she heard that song, but most likely picked it up at the medicine show.

One of those singers was Clarence Ashley, who would croon about the Rising Sun Blues. He sang with Doc Cloud and Doc Hauer, who offered tonics for whatever ailed you. Perhaps Georgia Turner heard the song in the early 1900s as well. Her 1937 version contains the lyrics most closely related to the Animals’ tune.

Lomax spent the 1940s gathering songs around the Appalachian South. He put these songs into a songbook and spread them throughout the country. He would also return to New York City and gather in a room with legendary folk singers. They would hear these new lyrics, new sounds, and make them their own.

In that room would be Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and Josh White, the fathers of folk music. The music Lomax pulled out of the mountains in small towns would become new again in the guitars and harmonicas of the Greenwich Village singers and musicians. Pete Seeger performed with the Weavers, named because they would weave songs from the past into new versions.

“House of the Rising Sun” was woven into the folk music landscape, evolving and growing. Josh White is credited with changing the song from a major key into the minor key we know today. Bob Dylan sang a version. And then in 1964, Eric Burdon and The Animals released their version, which became the standard. An arpeggio guitar opening, the rhythm sped up, a louder sound, and that minor key provides an emotional wallop for this warning song.

Numerous covers followed, including a beautiful version of “Amazing Grace”, sung to the tune of “House of the Rising Sun” by the Blind Boys of Alabama.

The song endures for its melody as well as for its lyrics. This was a warning song, a universal song, “not to do what I have done.” The small towns in Kentucky may have heard of the sinful ways of New Orleans and would spread the message with these songs to avoid the brothels, the drink, and the broken marriages that would reverberate with visits to the Crescent City.

“House of the Rising Sun” is one of the most covered songs, traveling wide and far, no longer with the need for a medicine show. It was a pivotal moment in rock ‘n roll, turning folk music into rock music. The Animals became huge because of this song, and their version became the standard on which all subsequent covers based their version. It made Bob Dylan’s older version seem quaint.

The song has been in my head for a while now. My wife is hoping writing about it will keep it from being played in our household any more. There are various reasons it has been resonating with me, including the following:

- It traces the origins of folk music and the importance of people like Lomax and Guthrie to collect and save Americana.

- The magic of musical evolution – a reminder of how art is built on the work of those who came before, each version with its unique personality.

- The release of “House of the Rising Sun” was a seminal, transformative moment when folk became rock music.

- The lasting power of warning songs.

- The hucksters that enabled this song to be kept alive.

That last one has really stuck with me. The medicine shows are an important part of American history. For instance, Coca-Cola started as one of those patent medicines; it was one of the many concoctions of the Atlanta pharmacist John Stith Pemberton, sold to treat all that ails us. Dr. Pepper, too, was a medicine in a sugary bottle – another that often contained alcohol or cocaine. Society wants a cure-all, and the marketing and selling done during these medicine shows offered placebos.

The hucksters exist in various forms today, selling detoxifications, magic diet cures, psychic powers of healing, or convincing parents that their kids don’t need vaccines. We need a warning song that goes viral to keep our children safe. We are blessed to be in a world without smallpox, almost rid of polio, and we have the knowledge and opportunity to rid the world of other preventable illnesses. Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000; now, outbreaks emerge in every news cycle.

The CDC admits they have not been targeting misinformation well. How can we spread the science, the truth, the message faster than the lies? Better marketing? The answer may be through stories and narratives and song, with the backing of good science. “House of the Rising Sun” is a warning song. Maybe we need more. We need that deep history, that long trail to remind us of the world before vaccines, when everyone knew someone, either in their own household or next door, who succumbed to one of the childhood illnesses.

Let the “House of the Rising Sun” play on. Create a new version, and let that message reverberate, too.

Tell your children; they need to be vaccinated.

Dr. Messler is a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. He previously chaired SHM’s Quality and Patient Safety Committee and has been active in several SHM mentoring programs, most recently with Project BOOST and Glycemic Control. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

Why you should re-credential with Medicare as a hospitalist

CMS needs a better database of hospitalist information

In April 2017, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services implemented the new physician specialty code C6, specifically for hospitalists. There has been a lot of confusion about what this means and some uncertainty about why clinicians should bother to use it.

Some folks thought initially that it was a new CPT code they could use to bill hospitalist services, which might recognize the increased intensity of services hospitalists often provide to their hospitalized patients compared to many traditional internal medicine and family medicine primary care physicians. Others thought it was a code that was added to the HCFA 1500 billing form somewhere to designate that the service was provided by a hospitalist.

Neither is true. The C6 physician specialty code is one of a large number of such codes used by physicians to designate their primary physician specialty when they enroll with Medicare via the PECOS online enrollment system. It describes the unique type of medicine practiced by the enrolling physician and is used by the CMS both for claims processing purposes and for “programmatic” purposes (whatever that means).

It doesn’t change how your claim is processed or how much you get paid. So why bother going through the laborious process of re-credentialing with CMS via PECOS just to change your specialty code? Well, I believe there are several ways in which the C6 specialty code provides value – both to you and to the specialty of hospital medicine.

Reduce concurrent care denials

First, it distinguishes you from a general internal medicine or general family medicine practitioner by recognizing “hospitalist” as a distinct specialty. This can be valuable from a financial perspective because it may reduce the risk that claims for your services might be denied due to “concurrent care” by another provider in the same specialty on the same calendar day.

And it’s not just a general internist or family medicine physician that you might run into concurrent care trouble with. I’ve seen situations where doctors completed critical care or cardiology fellowships but never got around to re-credentialing with Medicare in their new specialty, so their claims still showed up with an “internal medicine” physician specialty code, resulting in denied “concurrent care” claims for either the hospitalist or the specialist.

While Medicare may still see unnecessary overlap between services provided by you and an internal medicine or family physician to the same patient on the same calendar day, you can make a better argument that your services were unique and complementary to (not duplicative of) the services of others if you are credentialed as a hospitalist.

Ensure “apples to apples” comparisons

A second reason to re-credential as a hospitalist is to ensure that when the CMS looks at the services you are providing and the CPT codes you are selecting, it is comparing you to an appropriate peer group for compliance purposes.

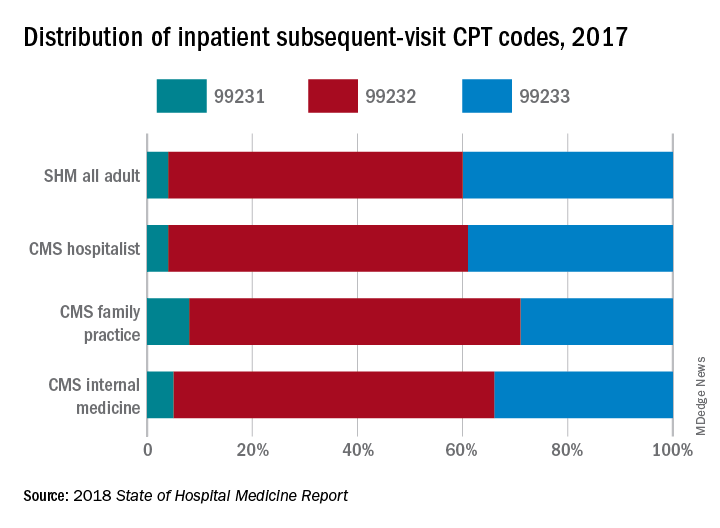

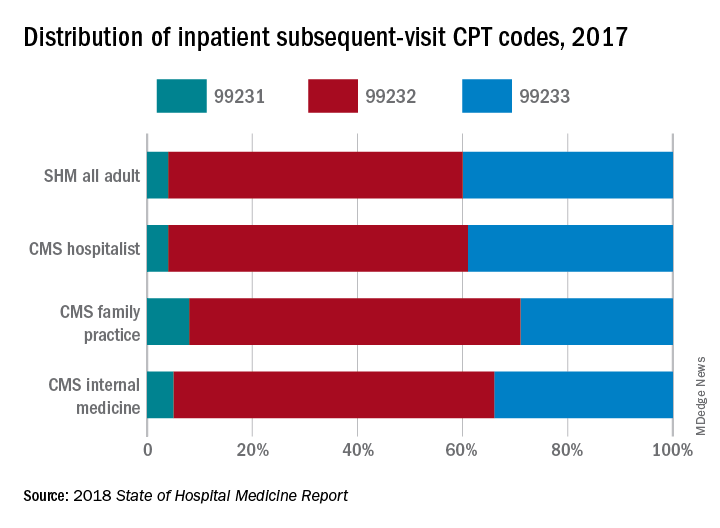

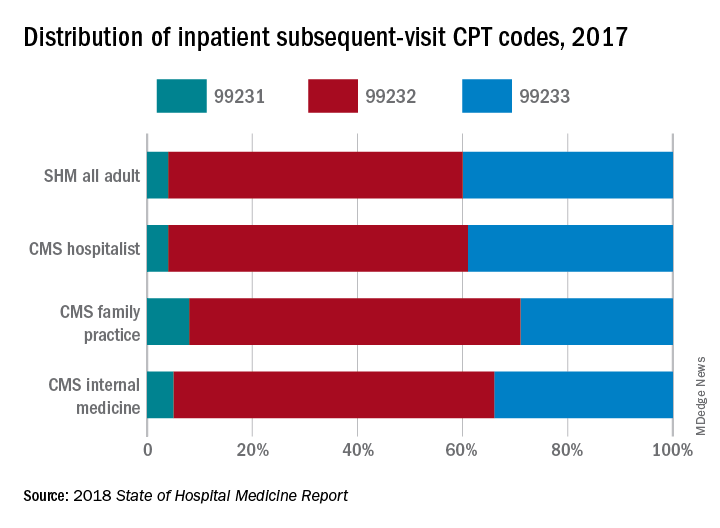

The mix of CPT codes reported by hospitalists in the SHM State of Hospital Medicine Survey has historically tilted toward higher-level care than has the mix of CPT codes reported by the CMS for internal medicine or family medicine physicians. But last year when Medicare released the utilization of evaluation and management services by specialty for calendar year 2017, CPT utilization was shown separately for hospitalists for the first time!

The volume of services reported for physicians credentialed as hospitalists was very small relative to the volume of inpatient services provided by internal medicine and family medicine physicians, but the distribution of inpatient admission, subsequent visit, and discharge codes for hospitalists closely mirrored those reported by SHM in its 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report (see graphic).

If you’re going to be targeted in a RAC audit for the high proportion of 99233s you bill, you want to be sure the CMS is looking at your performance compared to those who are truly your peers, caring for patients of the same type and complexity.

Improve CMS data used for research purposes

Finally, the ability of academic hospitalists and other health services researchers to utilize Medicare claims data to better understand the care provided by hospitalists and its impact on the overall health care system will be significantly enhanced by a more robust presence of physicians who have identified themselves as hospitalists in the PECOS credentialing system.

We care for the majority of patients in most hospitals these days, yet “hospitalists” billed only 2,009,869 inpatient subsequent visits (CPT codes 99231, 99232, and 99233) in 2017 compared to 25,903,829 billed by internal medicine physicians and 4,678,111 billed by family medicine physicians. And regardless of what you think about using claims data as a proxy for health care services and quality, it’s undeniably the best data set we currently have.

So, let’s work together to build a bigger, better database of hospitalist information at the CMS. I urge you to go to your credentialing folks today and find out how you can work with them to get yourself re-credentialed in PECOS using the C6 “hospitalist” physician specialty.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Meeting Committees, and helps to coordinate SHM’s bi-annual State of Hospital Medicine Survey. This article appeared originally in SHM's official blog The Hospital Leader. Read more recent posts here.

CMS needs a better database of hospitalist information

CMS needs a better database of hospitalist information

In April 2017, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services implemented the new physician specialty code C6, specifically for hospitalists. There has been a lot of confusion about what this means and some uncertainty about why clinicians should bother to use it.

Some folks thought initially that it was a new CPT code they could use to bill hospitalist services, which might recognize the increased intensity of services hospitalists often provide to their hospitalized patients compared to many traditional internal medicine and family medicine primary care physicians. Others thought it was a code that was added to the HCFA 1500 billing form somewhere to designate that the service was provided by a hospitalist.

Neither is true. The C6 physician specialty code is one of a large number of such codes used by physicians to designate their primary physician specialty when they enroll with Medicare via the PECOS online enrollment system. It describes the unique type of medicine practiced by the enrolling physician and is used by the CMS both for claims processing purposes and for “programmatic” purposes (whatever that means).

It doesn’t change how your claim is processed or how much you get paid. So why bother going through the laborious process of re-credentialing with CMS via PECOS just to change your specialty code? Well, I believe there are several ways in which the C6 specialty code provides value – both to you and to the specialty of hospital medicine.

Reduce concurrent care denials

First, it distinguishes you from a general internal medicine or general family medicine practitioner by recognizing “hospitalist” as a distinct specialty. This can be valuable from a financial perspective because it may reduce the risk that claims for your services might be denied due to “concurrent care” by another provider in the same specialty on the same calendar day.