User login

The Hospitalist only

MIPS: Nearly all eligible clinicians got a bonus for 2018

Nearly all clinicians who are eligible to participate in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program did so in 2018; most scored above the performance threshold and got a bonus.

According to the most recent data released this month by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 98.37% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated in the program. In the small/solo practice space, 89.20% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated.

But more importantly, the clinicians are performing better one year later with the program, even though fewer are participating.

In 2018, 97.63% of clinicians scored above the performance threshold, up from 93.12% in 2017. There also were fewer clinicians performing at the threshold (0.42% in 2018, down from 2.01% in the previous year) and fewer clinicians scoring below the threshold (1.95%, down from 4.87%).

Exceeding the performance threshold resulted in a bonus to fee schedule payments in 2018, although the agency did not disclose how much money was paid out in performance bonuses.

MIPS scored “improved across performance categories, with the biggest gain in the Quality performance category, which highlights the program’s effectiveness in measuring outcomes for beneficiaries,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma wrote in a blog post.

The total number of eligible clinicians decreased in 2018 to 916,058, down from 1,057,824 in 2017 because CMS broadened the low-volume threshold to exempt providers from participation requirements.

Participants in a MIPS alternative payment model saw even more success in 2018. Participation increased from 341,220 clinicians in 2017 to 356,828 clinicians in 2018, while virtually all performed above the performance threshold (100% in 2017 and 99.99% in 2018). The 0.01% that was not above the threshold still met it, while no clinicians in either year that participated in a MIPS alternative payment model performed below the threshold.

Participation in the advanced alternative payment model track increased as well, going from 99,026 in 2017 to 183,306 in 2018.

Nearly all clinicians who are eligible to participate in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program did so in 2018; most scored above the performance threshold and got a bonus.

According to the most recent data released this month by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 98.37% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated in the program. In the small/solo practice space, 89.20% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated.

But more importantly, the clinicians are performing better one year later with the program, even though fewer are participating.

In 2018, 97.63% of clinicians scored above the performance threshold, up from 93.12% in 2017. There also were fewer clinicians performing at the threshold (0.42% in 2018, down from 2.01% in the previous year) and fewer clinicians scoring below the threshold (1.95%, down from 4.87%).

Exceeding the performance threshold resulted in a bonus to fee schedule payments in 2018, although the agency did not disclose how much money was paid out in performance bonuses.

MIPS scored “improved across performance categories, with the biggest gain in the Quality performance category, which highlights the program’s effectiveness in measuring outcomes for beneficiaries,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma wrote in a blog post.

The total number of eligible clinicians decreased in 2018 to 916,058, down from 1,057,824 in 2017 because CMS broadened the low-volume threshold to exempt providers from participation requirements.

Participants in a MIPS alternative payment model saw even more success in 2018. Participation increased from 341,220 clinicians in 2017 to 356,828 clinicians in 2018, while virtually all performed above the performance threshold (100% in 2017 and 99.99% in 2018). The 0.01% that was not above the threshold still met it, while no clinicians in either year that participated in a MIPS alternative payment model performed below the threshold.

Participation in the advanced alternative payment model track increased as well, going from 99,026 in 2017 to 183,306 in 2018.

Nearly all clinicians who are eligible to participate in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program did so in 2018; most scored above the performance threshold and got a bonus.

According to the most recent data released this month by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 98.37% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated in the program. In the small/solo practice space, 89.20% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated.

But more importantly, the clinicians are performing better one year later with the program, even though fewer are participating.

In 2018, 97.63% of clinicians scored above the performance threshold, up from 93.12% in 2017. There also were fewer clinicians performing at the threshold (0.42% in 2018, down from 2.01% in the previous year) and fewer clinicians scoring below the threshold (1.95%, down from 4.87%).

Exceeding the performance threshold resulted in a bonus to fee schedule payments in 2018, although the agency did not disclose how much money was paid out in performance bonuses.

MIPS scored “improved across performance categories, with the biggest gain in the Quality performance category, which highlights the program’s effectiveness in measuring outcomes for beneficiaries,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma wrote in a blog post.

The total number of eligible clinicians decreased in 2018 to 916,058, down from 1,057,824 in 2017 because CMS broadened the low-volume threshold to exempt providers from participation requirements.

Participants in a MIPS alternative payment model saw even more success in 2018. Participation increased from 341,220 clinicians in 2017 to 356,828 clinicians in 2018, while virtually all performed above the performance threshold (100% in 2017 and 99.99% in 2018). The 0.01% that was not above the threshold still met it, while no clinicians in either year that participated in a MIPS alternative payment model performed below the threshold.

Participation in the advanced alternative payment model track increased as well, going from 99,026 in 2017 to 183,306 in 2018.

Recertification: The FPHM option

ABIM now offers increased flexibility

Everyone always told me that my time in residency would fly by, and the 3 years of internal medicine training really did seem to pass in just a few moments. Before I knew it, I had passed my internal medicine boards and practiced hospital medicine at an academic medical center.

One day last fall, I received notice from the American Board of Internal Medicine that it was time to recertify. I was surprised – had it already been 10 years? What did I have to do to maintain my certification?

As I investigated what it would take to maintain certification, I discovered that the recertification process provided more flexibility, compared with original board certification. I now had the option to recertify in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM). Beginning in 2014, ABIM offered hospitalists, or internists whose clinical practice is mainly in the inpatient setting, the option to recertify in internal medicine, but with the designation that highlighted their clinical practice in the inpatient setting.

The first step in recertification for me was deciding to recertify with the focus in hospital medicine or maintain the traditional internal medicine certification. I talked with several colleagues who are also practicing hospitalists and weighed their reasons for opting for FPHM. Ultimately, my decision to pursue a recertification with a focus in hospital medicine relied on three factors: First, my clinical practice since completing residency was exclusively in the inpatient setting. Day in and day out, I care for patients who are acutely ill and require inpatient medical care. Second, I wanted my board certification to reflect what I consider to be my area of clinical expertise, which is inpatient adult medicine. Pursuing the FPHM would provide that recognition. Finally, I wanted to study and be tested on topics that I could utilize in my day-to-day practice. Because I exclusively practiced hospital medicine since graduation, areas of clinical internal medicine that I did not frequently encounter in my daily practice became less accessible in my knowledge base.

The next step then was to enter the FPHM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program.

The ABIM requires two attestations to verify that I met the requirements to be a hospitalist. First was a self-attestation confirming at least 3 years of unsupervised inpatient care practice experience, and meeting patient encounter thresholds in the inpatient setting. The second attestation was from a “Senior Hospital Officer” confirming the information in the self-attestation was accurate.

Once entered into the program and having an unrestricted medical license to practice, I had to complete the remaining requirements of earning MOC points and then passing a knowledge-based assessment. I had to accumulate a total of 100 MOC points in the past 5 years, which I succeeded in doing through participating in quality improvement projects, recording CME credits, studying for the exam, and even taking the exam. I could track my point totals through the ABIM Physician Portal, which updated my point tally automatically for activities that counted toward MOC, such as attending SHM’s annual conference.

The final component was to pass the knowledge assessment, the dreaded exam. In 2018, I had the option to take the 10-year FPHM exam or do a general internal medicine Knowledge Check-In. Beginning in 2020, candidates will be able to sit for either the 10-year Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam or begin the Hospital Medicine Knowledge Check-In pathway. I had already decided to pursue FPHM and began to prepare to sit for an exam. I scheduled my exam through the ABIM portal at a local testing center.

The exam was scheduled for a full day, consisting of four sections broken up by a lunch break and section breaks. Specifically, the 220 single best answer, multiple-choice exam covered diagnosis, testing, treatment decisions, epidemiology, and basic science content through patient scenarios that reflected the scope of practice of a hospitalist. The ABIM provided an exam blueprint that detailed the specific clinical topics and the likelihood that a question pertaining to that topic would show up on the exam. Content was described as high, medium, or low importance and the number of questions related to the content was 75% for high importance, no more than 25% for medium importance, and no questions for low-importance content. In addition, content was distributed in a way that was reflective of my clinical practice as a hospitalist: 63.5% inpatient and traditional care; 6.5% palliative care; 15% consultative comanagement; and 15% quality, safety, and clinical reasoning.

Beginning 6 months prior to my scheduled exam, I purchased two critical resources to guide my studying efforts: the SHM Spark Self-Assessment Tool and the American College of Physicians Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program to review subject matter content and also do practice questions.

The latest version of SHM’s program, Spark Edition 2, provides updated questions and resources tailored to the hospital medicine exams. I appreciated the ability to answer questions online, as well as on my phone so I could do questions on the go. Moreover, I was able to track which content areas were stronger or weaker for me, and focus attention on areas that needed more work. Importantly, the questions I answered using the Spark self-assessment tool closely aligned with the subject matter I encountered in the exam, as well as the clinical cases I encounter every day in my practice.

While the day-long exam was challenging, I was gratified to receive notice from the ABIM that I had successfully recertified in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine!

Dr. Tad-y is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and associate vice chair of quality in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado.

ABIM now offers increased flexibility

ABIM now offers increased flexibility

Everyone always told me that my time in residency would fly by, and the 3 years of internal medicine training really did seem to pass in just a few moments. Before I knew it, I had passed my internal medicine boards and practiced hospital medicine at an academic medical center.

One day last fall, I received notice from the American Board of Internal Medicine that it was time to recertify. I was surprised – had it already been 10 years? What did I have to do to maintain my certification?

As I investigated what it would take to maintain certification, I discovered that the recertification process provided more flexibility, compared with original board certification. I now had the option to recertify in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM). Beginning in 2014, ABIM offered hospitalists, or internists whose clinical practice is mainly in the inpatient setting, the option to recertify in internal medicine, but with the designation that highlighted their clinical practice in the inpatient setting.

The first step in recertification for me was deciding to recertify with the focus in hospital medicine or maintain the traditional internal medicine certification. I talked with several colleagues who are also practicing hospitalists and weighed their reasons for opting for FPHM. Ultimately, my decision to pursue a recertification with a focus in hospital medicine relied on three factors: First, my clinical practice since completing residency was exclusively in the inpatient setting. Day in and day out, I care for patients who are acutely ill and require inpatient medical care. Second, I wanted my board certification to reflect what I consider to be my area of clinical expertise, which is inpatient adult medicine. Pursuing the FPHM would provide that recognition. Finally, I wanted to study and be tested on topics that I could utilize in my day-to-day practice. Because I exclusively practiced hospital medicine since graduation, areas of clinical internal medicine that I did not frequently encounter in my daily practice became less accessible in my knowledge base.

The next step then was to enter the FPHM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program.

The ABIM requires two attestations to verify that I met the requirements to be a hospitalist. First was a self-attestation confirming at least 3 years of unsupervised inpatient care practice experience, and meeting patient encounter thresholds in the inpatient setting. The second attestation was from a “Senior Hospital Officer” confirming the information in the self-attestation was accurate.

Once entered into the program and having an unrestricted medical license to practice, I had to complete the remaining requirements of earning MOC points and then passing a knowledge-based assessment. I had to accumulate a total of 100 MOC points in the past 5 years, which I succeeded in doing through participating in quality improvement projects, recording CME credits, studying for the exam, and even taking the exam. I could track my point totals through the ABIM Physician Portal, which updated my point tally automatically for activities that counted toward MOC, such as attending SHM’s annual conference.

The final component was to pass the knowledge assessment, the dreaded exam. In 2018, I had the option to take the 10-year FPHM exam or do a general internal medicine Knowledge Check-In. Beginning in 2020, candidates will be able to sit for either the 10-year Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam or begin the Hospital Medicine Knowledge Check-In pathway. I had already decided to pursue FPHM and began to prepare to sit for an exam. I scheduled my exam through the ABIM portal at a local testing center.

The exam was scheduled for a full day, consisting of four sections broken up by a lunch break and section breaks. Specifically, the 220 single best answer, multiple-choice exam covered diagnosis, testing, treatment decisions, epidemiology, and basic science content through patient scenarios that reflected the scope of practice of a hospitalist. The ABIM provided an exam blueprint that detailed the specific clinical topics and the likelihood that a question pertaining to that topic would show up on the exam. Content was described as high, medium, or low importance and the number of questions related to the content was 75% for high importance, no more than 25% for medium importance, and no questions for low-importance content. In addition, content was distributed in a way that was reflective of my clinical practice as a hospitalist: 63.5% inpatient and traditional care; 6.5% palliative care; 15% consultative comanagement; and 15% quality, safety, and clinical reasoning.

Beginning 6 months prior to my scheduled exam, I purchased two critical resources to guide my studying efforts: the SHM Spark Self-Assessment Tool and the American College of Physicians Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program to review subject matter content and also do practice questions.

The latest version of SHM’s program, Spark Edition 2, provides updated questions and resources tailored to the hospital medicine exams. I appreciated the ability to answer questions online, as well as on my phone so I could do questions on the go. Moreover, I was able to track which content areas were stronger or weaker for me, and focus attention on areas that needed more work. Importantly, the questions I answered using the Spark self-assessment tool closely aligned with the subject matter I encountered in the exam, as well as the clinical cases I encounter every day in my practice.

While the day-long exam was challenging, I was gratified to receive notice from the ABIM that I had successfully recertified in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine!

Dr. Tad-y is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and associate vice chair of quality in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado.

Everyone always told me that my time in residency would fly by, and the 3 years of internal medicine training really did seem to pass in just a few moments. Before I knew it, I had passed my internal medicine boards and practiced hospital medicine at an academic medical center.

One day last fall, I received notice from the American Board of Internal Medicine that it was time to recertify. I was surprised – had it already been 10 years? What did I have to do to maintain my certification?

As I investigated what it would take to maintain certification, I discovered that the recertification process provided more flexibility, compared with original board certification. I now had the option to recertify in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM). Beginning in 2014, ABIM offered hospitalists, or internists whose clinical practice is mainly in the inpatient setting, the option to recertify in internal medicine, but with the designation that highlighted their clinical practice in the inpatient setting.

The first step in recertification for me was deciding to recertify with the focus in hospital medicine or maintain the traditional internal medicine certification. I talked with several colleagues who are also practicing hospitalists and weighed their reasons for opting for FPHM. Ultimately, my decision to pursue a recertification with a focus in hospital medicine relied on three factors: First, my clinical practice since completing residency was exclusively in the inpatient setting. Day in and day out, I care for patients who are acutely ill and require inpatient medical care. Second, I wanted my board certification to reflect what I consider to be my area of clinical expertise, which is inpatient adult medicine. Pursuing the FPHM would provide that recognition. Finally, I wanted to study and be tested on topics that I could utilize in my day-to-day practice. Because I exclusively practiced hospital medicine since graduation, areas of clinical internal medicine that I did not frequently encounter in my daily practice became less accessible in my knowledge base.

The next step then was to enter the FPHM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program.

The ABIM requires two attestations to verify that I met the requirements to be a hospitalist. First was a self-attestation confirming at least 3 years of unsupervised inpatient care practice experience, and meeting patient encounter thresholds in the inpatient setting. The second attestation was from a “Senior Hospital Officer” confirming the information in the self-attestation was accurate.

Once entered into the program and having an unrestricted medical license to practice, I had to complete the remaining requirements of earning MOC points and then passing a knowledge-based assessment. I had to accumulate a total of 100 MOC points in the past 5 years, which I succeeded in doing through participating in quality improvement projects, recording CME credits, studying for the exam, and even taking the exam. I could track my point totals through the ABIM Physician Portal, which updated my point tally automatically for activities that counted toward MOC, such as attending SHM’s annual conference.

The final component was to pass the knowledge assessment, the dreaded exam. In 2018, I had the option to take the 10-year FPHM exam or do a general internal medicine Knowledge Check-In. Beginning in 2020, candidates will be able to sit for either the 10-year Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam or begin the Hospital Medicine Knowledge Check-In pathway. I had already decided to pursue FPHM and began to prepare to sit for an exam. I scheduled my exam through the ABIM portal at a local testing center.

The exam was scheduled for a full day, consisting of four sections broken up by a lunch break and section breaks. Specifically, the 220 single best answer, multiple-choice exam covered diagnosis, testing, treatment decisions, epidemiology, and basic science content through patient scenarios that reflected the scope of practice of a hospitalist. The ABIM provided an exam blueprint that detailed the specific clinical topics and the likelihood that a question pertaining to that topic would show up on the exam. Content was described as high, medium, or low importance and the number of questions related to the content was 75% for high importance, no more than 25% for medium importance, and no questions for low-importance content. In addition, content was distributed in a way that was reflective of my clinical practice as a hospitalist: 63.5% inpatient and traditional care; 6.5% palliative care; 15% consultative comanagement; and 15% quality, safety, and clinical reasoning.

Beginning 6 months prior to my scheduled exam, I purchased two critical resources to guide my studying efforts: the SHM Spark Self-Assessment Tool and the American College of Physicians Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program to review subject matter content and also do practice questions.

The latest version of SHM’s program, Spark Edition 2, provides updated questions and resources tailored to the hospital medicine exams. I appreciated the ability to answer questions online, as well as on my phone so I could do questions on the go. Moreover, I was able to track which content areas were stronger or weaker for me, and focus attention on areas that needed more work. Importantly, the questions I answered using the Spark self-assessment tool closely aligned with the subject matter I encountered in the exam, as well as the clinical cases I encounter every day in my practice.

While the day-long exam was challenging, I was gratified to receive notice from the ABIM that I had successfully recertified in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine!

Dr. Tad-y is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and associate vice chair of quality in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado.

Value-based metrics gain ground in physician employment contracts

Physician employment contracts increasingly include value- and quality-based metrics as bases for production bonuses, according to an analysis of recruitment searches from April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2019.

Metrics such as physician satisfaction rates, proper use of EHRs, following treatment protocols, and others that don’t directly measure volume are becoming more commonplace in employment contracts, though volume measures still are included, according to Phil Miller, vice president of communications at health care recruiting firm Merritt Hawkins and author of the company’s 2019 report on physician and advanced practitioner recruiting incentives, released July 8.

Of 70% of searches that offered a production bonus, 56% featured a bonus based at least in part on quality metrics, up from 43% in 2018. The finding represents the highest percent of contracts offering a quality-based bonus that the company has tracked, according to the report.

Merritt Hawkins’ review is based on a sample of the 3,131 permanent physician and advanced practitioner search assignments that Merritt Hawkins and its sister physician staffing companies at AMN Healthcare have ongoing or were engaged to conduct from April 1, 2018 to March 31, 2019.

Other common value-based metrics include reduction in hospital readmissions, cost containment, and proper coding.

While value-based incentives are on the rise, “facilities that employ physicians want to ensure they stay productive, and ‘productivity’ still is measured in part by what are essentially fee-for-service metrics, including relative value units [RVUs], net collections, and number of patients seen.”

RVUs were used in 70% of production formulas tracked in the 2019 review, up from 50% in the previous year and also a record high.

Mr. Miller noted that employers are seeking the “Goldilocks’ zone,” a balance point between traditional productivity measures and value-based metrics, very much a work in progress right now.

A possible corollary to the increase in production bonuses is a flattening of signing bonuses. During the current review period, 71% of contracts came with a signing bonus, up slightly from 70% in the previous year’s report and down from 76% 2 years ago.

Signing bonuses in the review period for the 2019 report averaged $32,692, down from $33,707 during the 2018 report’s review period.

Overall, family practice physicians remain the highest in demand for job searches, but specialty practice is gaining ground.

For the 2018-2019 review, family medicine was the most requested search by specialty, with 457 searches requested. While the ranking remains No. 1, as it has for the past 13 years, the number of searches has been on a steady decline. Last year, there were 497 searches, which was down from 607 2 years ago and 734 4 years ago.

Mr. Miller said there were a few reasons for the lower number of searches. “One is just the momentum shifts that are kind of inherent to recruiting. People put all of their resources into one area, typically, and in this case it was primary care and they realized, ‘Hey wait a minute, we need some specialists for these doctors to refer to, so now we have to put some of our chips in the specialty basket.’ ”

The Baby Boomers also is having an effect – as they age and are experiencing more health issues, more specialists are needed.

“[Older patients] visit the doctor twice or three times the rate of a younger person and they also generate a much higher percentage of inpatient procedures and tests and diagnoses,” he said.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, “younger people are less likely to have a primary care doctor who coordinates their care,” Mr. Miller said. “What they typically do is go to an urgent care center, a retail clinic, maybe even [use] telemedicine so they are not accessing the system in the same way or necessarily through the same provider.”

Demand for psychiatrists remained strong for the fourth year in a row, but the number of searches has declined for the last several years. For the current review period, there were 199 searches, down from 243 the previous year, 256 2 years ago, and 250 3 years ago.

There is “pretty much a crisis in behavioral health care now because there are so few psychiatrists and the demand has increased,” Mr. Miller noted.

Physician employment contracts increasingly include value- and quality-based metrics as bases for production bonuses, according to an analysis of recruitment searches from April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2019.

Metrics such as physician satisfaction rates, proper use of EHRs, following treatment protocols, and others that don’t directly measure volume are becoming more commonplace in employment contracts, though volume measures still are included, according to Phil Miller, vice president of communications at health care recruiting firm Merritt Hawkins and author of the company’s 2019 report on physician and advanced practitioner recruiting incentives, released July 8.

Of 70% of searches that offered a production bonus, 56% featured a bonus based at least in part on quality metrics, up from 43% in 2018. The finding represents the highest percent of contracts offering a quality-based bonus that the company has tracked, according to the report.

Merritt Hawkins’ review is based on a sample of the 3,131 permanent physician and advanced practitioner search assignments that Merritt Hawkins and its sister physician staffing companies at AMN Healthcare have ongoing or were engaged to conduct from April 1, 2018 to March 31, 2019.

Other common value-based metrics include reduction in hospital readmissions, cost containment, and proper coding.

While value-based incentives are on the rise, “facilities that employ physicians want to ensure they stay productive, and ‘productivity’ still is measured in part by what are essentially fee-for-service metrics, including relative value units [RVUs], net collections, and number of patients seen.”

RVUs were used in 70% of production formulas tracked in the 2019 review, up from 50% in the previous year and also a record high.

Mr. Miller noted that employers are seeking the “Goldilocks’ zone,” a balance point between traditional productivity measures and value-based metrics, very much a work in progress right now.

A possible corollary to the increase in production bonuses is a flattening of signing bonuses. During the current review period, 71% of contracts came with a signing bonus, up slightly from 70% in the previous year’s report and down from 76% 2 years ago.

Signing bonuses in the review period for the 2019 report averaged $32,692, down from $33,707 during the 2018 report’s review period.

Overall, family practice physicians remain the highest in demand for job searches, but specialty practice is gaining ground.

For the 2018-2019 review, family medicine was the most requested search by specialty, with 457 searches requested. While the ranking remains No. 1, as it has for the past 13 years, the number of searches has been on a steady decline. Last year, there were 497 searches, which was down from 607 2 years ago and 734 4 years ago.

Mr. Miller said there were a few reasons for the lower number of searches. “One is just the momentum shifts that are kind of inherent to recruiting. People put all of their resources into one area, typically, and in this case it was primary care and they realized, ‘Hey wait a minute, we need some specialists for these doctors to refer to, so now we have to put some of our chips in the specialty basket.’ ”

The Baby Boomers also is having an effect – as they age and are experiencing more health issues, more specialists are needed.

“[Older patients] visit the doctor twice or three times the rate of a younger person and they also generate a much higher percentage of inpatient procedures and tests and diagnoses,” he said.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, “younger people are less likely to have a primary care doctor who coordinates their care,” Mr. Miller said. “What they typically do is go to an urgent care center, a retail clinic, maybe even [use] telemedicine so they are not accessing the system in the same way or necessarily through the same provider.”

Demand for psychiatrists remained strong for the fourth year in a row, but the number of searches has declined for the last several years. For the current review period, there were 199 searches, down from 243 the previous year, 256 2 years ago, and 250 3 years ago.

There is “pretty much a crisis in behavioral health care now because there are so few psychiatrists and the demand has increased,” Mr. Miller noted.

Physician employment contracts increasingly include value- and quality-based metrics as bases for production bonuses, according to an analysis of recruitment searches from April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2019.

Metrics such as physician satisfaction rates, proper use of EHRs, following treatment protocols, and others that don’t directly measure volume are becoming more commonplace in employment contracts, though volume measures still are included, according to Phil Miller, vice president of communications at health care recruiting firm Merritt Hawkins and author of the company’s 2019 report on physician and advanced practitioner recruiting incentives, released July 8.

Of 70% of searches that offered a production bonus, 56% featured a bonus based at least in part on quality metrics, up from 43% in 2018. The finding represents the highest percent of contracts offering a quality-based bonus that the company has tracked, according to the report.

Merritt Hawkins’ review is based on a sample of the 3,131 permanent physician and advanced practitioner search assignments that Merritt Hawkins and its sister physician staffing companies at AMN Healthcare have ongoing or were engaged to conduct from April 1, 2018 to March 31, 2019.

Other common value-based metrics include reduction in hospital readmissions, cost containment, and proper coding.

While value-based incentives are on the rise, “facilities that employ physicians want to ensure they stay productive, and ‘productivity’ still is measured in part by what are essentially fee-for-service metrics, including relative value units [RVUs], net collections, and number of patients seen.”

RVUs were used in 70% of production formulas tracked in the 2019 review, up from 50% in the previous year and also a record high.

Mr. Miller noted that employers are seeking the “Goldilocks’ zone,” a balance point between traditional productivity measures and value-based metrics, very much a work in progress right now.

A possible corollary to the increase in production bonuses is a flattening of signing bonuses. During the current review period, 71% of contracts came with a signing bonus, up slightly from 70% in the previous year’s report and down from 76% 2 years ago.

Signing bonuses in the review period for the 2019 report averaged $32,692, down from $33,707 during the 2018 report’s review period.

Overall, family practice physicians remain the highest in demand for job searches, but specialty practice is gaining ground.

For the 2018-2019 review, family medicine was the most requested search by specialty, with 457 searches requested. While the ranking remains No. 1, as it has for the past 13 years, the number of searches has been on a steady decline. Last year, there were 497 searches, which was down from 607 2 years ago and 734 4 years ago.

Mr. Miller said there were a few reasons for the lower number of searches. “One is just the momentum shifts that are kind of inherent to recruiting. People put all of their resources into one area, typically, and in this case it was primary care and they realized, ‘Hey wait a minute, we need some specialists for these doctors to refer to, so now we have to put some of our chips in the specialty basket.’ ”

The Baby Boomers also is having an effect – as they age and are experiencing more health issues, more specialists are needed.

“[Older patients] visit the doctor twice or three times the rate of a younger person and they also generate a much higher percentage of inpatient procedures and tests and diagnoses,” he said.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, “younger people are less likely to have a primary care doctor who coordinates their care,” Mr. Miller said. “What they typically do is go to an urgent care center, a retail clinic, maybe even [use] telemedicine so they are not accessing the system in the same way or necessarily through the same provider.”

Demand for psychiatrists remained strong for the fourth year in a row, but the number of searches has declined for the last several years. For the current review period, there were 199 searches, down from 243 the previous year, 256 2 years ago, and 250 3 years ago.

There is “pretty much a crisis in behavioral health care now because there are so few psychiatrists and the demand has increased,” Mr. Miller noted.

A third of serious malpractice claims due to diagnostic error

A third of medical malpractice cases associated with patient death or permanent disability result from diagnostic errors by health providers, an analysis finds.

Lead investigator David E. Newman-Toker, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues reviewed malpractice claims during 2006-2015 from medical liability insurer CRICO’s Comparative Benchmarking System database, which represents 30% of all malpractice claims in the United States.

Investigators sought to identify diseases accounting for the majority of serious diagnosis-related harms associated with the claims. Of 55,377 closed claims, researchers identified 11,592 diagnostic error cases, of which 7,379 resulted in high-severity harm.

Of the high-severity claims, 34% stemmed from inaccurate or delayed diagnosis (Diagnosis 2019 Jul 11. doi. org/10.1515/dx-2019-0019).

The majority of diagnostic mistakes (74%) causing the most severe harm were attributable to cancer (38%), vascular events (23%), and infection (14%). These cases resulted in nearly $2 billion in malpractice payouts over a 10-year period, investigators found.

Clinical judgment factors were the primary reason behind the alleged errors, specifically: failure or delay in ordering a diagnostic test, narrow diagnostic focus with failure to establish a differential diagnosis, failure to appreciate and reconcile relevant symptoms or test results, and failure or delay in obtaining consultation or referral and misinterpretation of diagnostic studies.

“Diagnostic errors are the most common, the most catastrophic, and the most costly of medical errors,” Dr. Newman-Toker said at a press conference July 11. “We know that this is a major problem, at an individual, personal level, but also at a societal level and something we really have to take action toward fixing.”

This study breaks new ground by drilling into the major diseases most commonly associated with diagnostic errors, Dr. Newman-Toker said. In the cancer category, the most common cancers linked to severe harm were lung, breast, colorectal, prostate, and melanoma. In the vascular category, the most common conditions were stroke; myocardial infarction; venous thromboembolism; aortic aneurysm and dissection; and arterial thromboembolism. In the area of infection, sepsis; meningitis and encephalitis; spinal abscess; pneumonia; and endocarditis were the most common infections identified.

The findings provide a starting point to make improvements in the area of medical errors, said Dr. Newman-Toker, president of the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, an organization that aims to improve diagnosis and eliminate harm from diagnostic error.

“Although diagnostic errors happen everywhere, across all of medicine in every discipline with every disease, we might be able to take a big chunk out of this problem if we save a lot of lives and prevent a lot disability and if we focus some energy on tackling these problems,” he said. “It at least gives us a starting place and a roadmap for how to move the ball forward in this regard.”

The Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine has called on Congress to invest more funding into research to address diagnostic errors. Society CEO and cofounder Paul L. Epner noted that the 2019 House appropriations bill proposes not less than $4 million for diagnostic safety and quality research, which is up from $2 million last year.

“It’s a small step, but in the right direction,” Mr. Epner said. “[However,] the federal investment in research remains trivially small in relation to the public burden. That’s why we urge Congress to commit to research funding levels proportionate to the societal cost, in both human lives and in dollars.”

[email protected]

A third of medical malpractice cases associated with patient death or permanent disability result from diagnostic errors by health providers, an analysis finds.

Lead investigator David E. Newman-Toker, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues reviewed malpractice claims during 2006-2015 from medical liability insurer CRICO’s Comparative Benchmarking System database, which represents 30% of all malpractice claims in the United States.

Investigators sought to identify diseases accounting for the majority of serious diagnosis-related harms associated with the claims. Of 55,377 closed claims, researchers identified 11,592 diagnostic error cases, of which 7,379 resulted in high-severity harm.

Of the high-severity claims, 34% stemmed from inaccurate or delayed diagnosis (Diagnosis 2019 Jul 11. doi. org/10.1515/dx-2019-0019).

The majority of diagnostic mistakes (74%) causing the most severe harm were attributable to cancer (38%), vascular events (23%), and infection (14%). These cases resulted in nearly $2 billion in malpractice payouts over a 10-year period, investigators found.

Clinical judgment factors were the primary reason behind the alleged errors, specifically: failure or delay in ordering a diagnostic test, narrow diagnostic focus with failure to establish a differential diagnosis, failure to appreciate and reconcile relevant symptoms or test results, and failure or delay in obtaining consultation or referral and misinterpretation of diagnostic studies.

“Diagnostic errors are the most common, the most catastrophic, and the most costly of medical errors,” Dr. Newman-Toker said at a press conference July 11. “We know that this is a major problem, at an individual, personal level, but also at a societal level and something we really have to take action toward fixing.”

This study breaks new ground by drilling into the major diseases most commonly associated with diagnostic errors, Dr. Newman-Toker said. In the cancer category, the most common cancers linked to severe harm were lung, breast, colorectal, prostate, and melanoma. In the vascular category, the most common conditions were stroke; myocardial infarction; venous thromboembolism; aortic aneurysm and dissection; and arterial thromboembolism. In the area of infection, sepsis; meningitis and encephalitis; spinal abscess; pneumonia; and endocarditis were the most common infections identified.

The findings provide a starting point to make improvements in the area of medical errors, said Dr. Newman-Toker, president of the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, an organization that aims to improve diagnosis and eliminate harm from diagnostic error.

“Although diagnostic errors happen everywhere, across all of medicine in every discipline with every disease, we might be able to take a big chunk out of this problem if we save a lot of lives and prevent a lot disability and if we focus some energy on tackling these problems,” he said. “It at least gives us a starting place and a roadmap for how to move the ball forward in this regard.”

The Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine has called on Congress to invest more funding into research to address diagnostic errors. Society CEO and cofounder Paul L. Epner noted that the 2019 House appropriations bill proposes not less than $4 million for diagnostic safety and quality research, which is up from $2 million last year.

“It’s a small step, but in the right direction,” Mr. Epner said. “[However,] the federal investment in research remains trivially small in relation to the public burden. That’s why we urge Congress to commit to research funding levels proportionate to the societal cost, in both human lives and in dollars.”

[email protected]

A third of medical malpractice cases associated with patient death or permanent disability result from diagnostic errors by health providers, an analysis finds.

Lead investigator David E. Newman-Toker, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues reviewed malpractice claims during 2006-2015 from medical liability insurer CRICO’s Comparative Benchmarking System database, which represents 30% of all malpractice claims in the United States.

Investigators sought to identify diseases accounting for the majority of serious diagnosis-related harms associated with the claims. Of 55,377 closed claims, researchers identified 11,592 diagnostic error cases, of which 7,379 resulted in high-severity harm.

Of the high-severity claims, 34% stemmed from inaccurate or delayed diagnosis (Diagnosis 2019 Jul 11. doi. org/10.1515/dx-2019-0019).

The majority of diagnostic mistakes (74%) causing the most severe harm were attributable to cancer (38%), vascular events (23%), and infection (14%). These cases resulted in nearly $2 billion in malpractice payouts over a 10-year period, investigators found.

Clinical judgment factors were the primary reason behind the alleged errors, specifically: failure or delay in ordering a diagnostic test, narrow diagnostic focus with failure to establish a differential diagnosis, failure to appreciate and reconcile relevant symptoms or test results, and failure or delay in obtaining consultation or referral and misinterpretation of diagnostic studies.

“Diagnostic errors are the most common, the most catastrophic, and the most costly of medical errors,” Dr. Newman-Toker said at a press conference July 11. “We know that this is a major problem, at an individual, personal level, but also at a societal level and something we really have to take action toward fixing.”

This study breaks new ground by drilling into the major diseases most commonly associated with diagnostic errors, Dr. Newman-Toker said. In the cancer category, the most common cancers linked to severe harm were lung, breast, colorectal, prostate, and melanoma. In the vascular category, the most common conditions were stroke; myocardial infarction; venous thromboembolism; aortic aneurysm and dissection; and arterial thromboembolism. In the area of infection, sepsis; meningitis and encephalitis; spinal abscess; pneumonia; and endocarditis were the most common infections identified.

The findings provide a starting point to make improvements in the area of medical errors, said Dr. Newman-Toker, president of the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, an organization that aims to improve diagnosis and eliminate harm from diagnostic error.

“Although diagnostic errors happen everywhere, across all of medicine in every discipline with every disease, we might be able to take a big chunk out of this problem if we save a lot of lives and prevent a lot disability and if we focus some energy on tackling these problems,” he said. “It at least gives us a starting place and a roadmap for how to move the ball forward in this regard.”

The Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine has called on Congress to invest more funding into research to address diagnostic errors. Society CEO and cofounder Paul L. Epner noted that the 2019 House appropriations bill proposes not less than $4 million for diagnostic safety and quality research, which is up from $2 million last year.

“It’s a small step, but in the right direction,” Mr. Epner said. “[However,] the federal investment in research remains trivially small in relation to the public burden. That’s why we urge Congress to commit to research funding levels proportionate to the societal cost, in both human lives and in dollars.”

[email protected]

Dealing with staffing shortfalls

Five options for covering unfilled positions

Being in stressful situations is part of being a hospitalist. During a hospitalist’s work shift, one of the key determinants of stress is adequate staffing. With use of survey data from 569 hospital medicine groups (HMGs) across the nation, one of the topics examined in the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report is how HMGs cope with unfilled hospitalist physician positions.

The survey presented five options for covering unfilled hospitalist physician positions: use of locum tenens, use of moonlighters, use of voluntary extra shifts by the HMG’s existing hospitalists, use of required extra shifts, and leaving some shifts uncovered. Recipients were instructed to select all options that applied, so totals exceeded 100%. The data is organized according to HMGs that serve adults only, children only, and both adults and children.

For all three types of HMGs, the most common tactic to fill coverage gaps is through voluntary extra shifts by existing clinicians, reportedly used by 70.3% of HMGs that cover adults only, 66.7% by those that cover children only, and 76.9% by those that cover both adults and children. Data for adults-only HMGs was further broken down by geographic region, academic status, teaching status, group size, and employment model. Among adults-only HMGs, there is a direct correlation between group size and having members voluntarily work extra shifts, with 91.1% of groups with 30 or more full-time equivalent positions employing this tactic.

For HMGs that cover adults only and those that cover children only, the second most common tactic is to use moonlighters (57.4% and 53.3% respectively), while use of moonlighters is the third most commonly employed surveyed tactic for HMGs that cover both adults and children (53.8%).

HMGs that serve both adults and children were much more likely to utilize locum tenens to cover unfilled positions (69.2%) than were groups that serve adults only (44.0%) or children only (26.7%). The variability in the use of locum tenens is likely because of the willingness and/or ability of the respective groups to afford this option because it is generally the most expensive option of those surveyed.

Requiring that members of the group work extra shifts is the least popular staffing method among adults-only HMGs (10.0%) and HMGs serving both children and adults (7.7%). This strategy is unpopular, especially when there is little advance warning. Surprisingly, 40.0% of HMGs that see children only require members to work extra shifts to cover unfilled slots. This could be because pediatric HMGs are often smaller, and it would be more difficult to absorb the work if the shift is left uncovered. In fact, many pediatric HMGs staff with only one clinician at a time, so there may be no option besides requiring someone else in the group to come in and work.Of the options surveyed, perhaps the most uncomfortable for those hospitalist physicians on duty is to leave some shifts uncovered. The rapid growth and development of the specialty of hospital medicine has made it difficult for HMGs to continuously hire qualified hospitalists fast enough to meet demand. The survey found 46.2% of HMGs that serve both adults and children and 31.4% of groups that serve adults only have employed the staffing model of going short-staffed for at least some shifts. HMGs serving children-only are much less likely to go short-staffed (20.0%).

I work with a large HMG that has more than 70 members, and when it has been short-staffed, it tries to ensure a full complement of evening and night staff as the top priority because these shifts are typically more stressful. Since we have more hospitalist capacity during the day to absorb the loss of a physician, we pull staff from their daytime rounding schedules to execute this strategy. While going short-staffed is not ideal, this option has worked for many groups out of sheer necessity.

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Allina Health’s Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and is a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Five options for covering unfilled positions

Five options for covering unfilled positions

Being in stressful situations is part of being a hospitalist. During a hospitalist’s work shift, one of the key determinants of stress is adequate staffing. With use of survey data from 569 hospital medicine groups (HMGs) across the nation, one of the topics examined in the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report is how HMGs cope with unfilled hospitalist physician positions.

The survey presented five options for covering unfilled hospitalist physician positions: use of locum tenens, use of moonlighters, use of voluntary extra shifts by the HMG’s existing hospitalists, use of required extra shifts, and leaving some shifts uncovered. Recipients were instructed to select all options that applied, so totals exceeded 100%. The data is organized according to HMGs that serve adults only, children only, and both adults and children.

For all three types of HMGs, the most common tactic to fill coverage gaps is through voluntary extra shifts by existing clinicians, reportedly used by 70.3% of HMGs that cover adults only, 66.7% by those that cover children only, and 76.9% by those that cover both adults and children. Data for adults-only HMGs was further broken down by geographic region, academic status, teaching status, group size, and employment model. Among adults-only HMGs, there is a direct correlation between group size and having members voluntarily work extra shifts, with 91.1% of groups with 30 or more full-time equivalent positions employing this tactic.

For HMGs that cover adults only and those that cover children only, the second most common tactic is to use moonlighters (57.4% and 53.3% respectively), while use of moonlighters is the third most commonly employed surveyed tactic for HMGs that cover both adults and children (53.8%).

HMGs that serve both adults and children were much more likely to utilize locum tenens to cover unfilled positions (69.2%) than were groups that serve adults only (44.0%) or children only (26.7%). The variability in the use of locum tenens is likely because of the willingness and/or ability of the respective groups to afford this option because it is generally the most expensive option of those surveyed.

Requiring that members of the group work extra shifts is the least popular staffing method among adults-only HMGs (10.0%) and HMGs serving both children and adults (7.7%). This strategy is unpopular, especially when there is little advance warning. Surprisingly, 40.0% of HMGs that see children only require members to work extra shifts to cover unfilled slots. This could be because pediatric HMGs are often smaller, and it would be more difficult to absorb the work if the shift is left uncovered. In fact, many pediatric HMGs staff with only one clinician at a time, so there may be no option besides requiring someone else in the group to come in and work.Of the options surveyed, perhaps the most uncomfortable for those hospitalist physicians on duty is to leave some shifts uncovered. The rapid growth and development of the specialty of hospital medicine has made it difficult for HMGs to continuously hire qualified hospitalists fast enough to meet demand. The survey found 46.2% of HMGs that serve both adults and children and 31.4% of groups that serve adults only have employed the staffing model of going short-staffed for at least some shifts. HMGs serving children-only are much less likely to go short-staffed (20.0%).

I work with a large HMG that has more than 70 members, and when it has been short-staffed, it tries to ensure a full complement of evening and night staff as the top priority because these shifts are typically more stressful. Since we have more hospitalist capacity during the day to absorb the loss of a physician, we pull staff from their daytime rounding schedules to execute this strategy. While going short-staffed is not ideal, this option has worked for many groups out of sheer necessity.

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Allina Health’s Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and is a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Being in stressful situations is part of being a hospitalist. During a hospitalist’s work shift, one of the key determinants of stress is adequate staffing. With use of survey data from 569 hospital medicine groups (HMGs) across the nation, one of the topics examined in the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report is how HMGs cope with unfilled hospitalist physician positions.

The survey presented five options for covering unfilled hospitalist physician positions: use of locum tenens, use of moonlighters, use of voluntary extra shifts by the HMG’s existing hospitalists, use of required extra shifts, and leaving some shifts uncovered. Recipients were instructed to select all options that applied, so totals exceeded 100%. The data is organized according to HMGs that serve adults only, children only, and both adults and children.

For all three types of HMGs, the most common tactic to fill coverage gaps is through voluntary extra shifts by existing clinicians, reportedly used by 70.3% of HMGs that cover adults only, 66.7% by those that cover children only, and 76.9% by those that cover both adults and children. Data for adults-only HMGs was further broken down by geographic region, academic status, teaching status, group size, and employment model. Among adults-only HMGs, there is a direct correlation between group size and having members voluntarily work extra shifts, with 91.1% of groups with 30 or more full-time equivalent positions employing this tactic.

For HMGs that cover adults only and those that cover children only, the second most common tactic is to use moonlighters (57.4% and 53.3% respectively), while use of moonlighters is the third most commonly employed surveyed tactic for HMGs that cover both adults and children (53.8%).

HMGs that serve both adults and children were much more likely to utilize locum tenens to cover unfilled positions (69.2%) than were groups that serve adults only (44.0%) or children only (26.7%). The variability in the use of locum tenens is likely because of the willingness and/or ability of the respective groups to afford this option because it is generally the most expensive option of those surveyed.

Requiring that members of the group work extra shifts is the least popular staffing method among adults-only HMGs (10.0%) and HMGs serving both children and adults (7.7%). This strategy is unpopular, especially when there is little advance warning. Surprisingly, 40.0% of HMGs that see children only require members to work extra shifts to cover unfilled slots. This could be because pediatric HMGs are often smaller, and it would be more difficult to absorb the work if the shift is left uncovered. In fact, many pediatric HMGs staff with only one clinician at a time, so there may be no option besides requiring someone else in the group to come in and work.Of the options surveyed, perhaps the most uncomfortable for those hospitalist physicians on duty is to leave some shifts uncovered. The rapid growth and development of the specialty of hospital medicine has made it difficult for HMGs to continuously hire qualified hospitalists fast enough to meet demand. The survey found 46.2% of HMGs that serve both adults and children and 31.4% of groups that serve adults only have employed the staffing model of going short-staffed for at least some shifts. HMGs serving children-only are much less likely to go short-staffed (20.0%).

I work with a large HMG that has more than 70 members, and when it has been short-staffed, it tries to ensure a full complement of evening and night staff as the top priority because these shifts are typically more stressful. Since we have more hospitalist capacity during the day to absorb the loss of a physician, we pull staff from their daytime rounding schedules to execute this strategy. While going short-staffed is not ideal, this option has worked for many groups out of sheer necessity.

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Allina Health’s Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and is a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Some burnout factors are within a physician’s control

SAN DIEGO – Eat a healthy lunch. Get more sleep. Move your body. How many times in the course of a week do you give patients gentle reminders to practice these most basic steps of self-care? And how many times in the course of a week do you allow these basics to go by the wayside for yourself?

Self-care is one of the elements that can defend against physician burnout, Carol Burke, MD, said at a session on physician burnout held during the annual Digestive Disease Week®. Personal self-care can make a real difference, and shouldn’t be ignored as the profession works to reel back some of the institutional changes that challenge physicians today.

In the workplace, unhealthy stress levels can contribute to burnout, disruptive behavior, decreased productivity, and disengagement. Burnout – a response to chronic stress characterized by a diminished sense of personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion – can result in cynicism, a lack of compassion, and feelings of depersonalization, said Dr. Burke.

Contributors to physician stress have been well documented, said Dr. Burke, a professor of gastroenterology at the Cleveland Clinic. These range from personal debt and the struggle for work-life balance to an increased focus on metrics and documentation at the expense of authentic patient engagement. All of these factors are measurable by means of the validated Maslach Burnout Inventory, said Dr. Burke. A recent survey that used this measure indicated that nearly half of physician respondents report experiencing burnout.

In 2017, Dr. Burke led a survey of American College of Gastroenterology members that showed 49.3% of respondents reported feeling emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization. Some key themes emerged from the survey, she said. Women and younger physicians were more likely to experience burnout. Having children in the middle years (11-15 years old) and spending more time on domestic duties and child care increased the risk of burnout.

And doing patient-related work at home or having a spouse or partner bring work home also upped burnout risk. Skipping breakfast and lunch during the workweek was another risk factor, which highlights the importance of basic self-care as armor against the administrative onslaught, said Dr. Burke.

Measured by volume alone, physician work can be overwhelming: 45% of physicians in the United States work more than 60 hours weekly, compared with fewer than 10% of the general workforce, said Dr. Burke.

What factors within the control of an individual practitioner can reduce the risk of debilitating burnout and improve quality of life? Physicians who do report a high quality of life, said Dr. Burke, are more likely to have a positive outlook. They also practice basic self-care like taking vacations, exercising regularly, and engaging in hobbies outside of work.

For exhausted, overworked clinicians, getting a good night’s sleep is a critical form of self-care. But erratic schedules, stress, and family demands can all sabotage plans for better sleep hygiene. Still, attending to sleep is important, said Dr. Burke. Individuals with disturbed sleep are less mindful and have less self-compassion. Sleep disturbance is also strongly correlated with perceived stress.

She also reported that the odds ratio for burnout was 14.7 for physicians who reported insomnia when compared with those without sleep disturbance, and it was 9.9 for those who reported nonrestorative sleep.

Physical activity can help sleep and also help other markers of burnout. Dr. Burke pointed to a recent study of 4,402 medical students. Participants were able to reduce burnout risk when they met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations of achieving at least 150 minutes/week of moderate exercise or 75 minutes/week of vigorous exercise, plus at least 2 days/week of strength training (P less than .001; Acad Med. 2017;92:1006).

These physician-targeted programs can work, she said: “Faciliated interventions improve well-being, attitudes associated with patient-centered care, meaning and engagement in work, and reduce burnout.”

Practice-focused interventions to reclaim a semblance of control over one’s time are varied, and some are easier to implement than others. Virtual visits and group visits are surprisingly well received by patients, and each can be huge time-savers for physicians, said Dr. Burke. There are billing and workflow pitfalls to avoid, but group visits, in particular, can be practice changing for those who have heavy backlogs and see many patients with the same condition.

Medical scribes can improve productivity and reduce physician time spent on documentation. Also, said Dr. Burke, visits can appropriately be billed at a higher level of complexity when contemporaneous documentation is thorough. Clinicians overall feel that they can engage more fully with patients, and also feel more effective, when well-trained scribes are integrated into a practice, she said.

Female physicians have repeatedly been shown to have patient panels that are more demanding, and male and female patients alike expect more empathy and social support from their physicians, said Dr. Burke. When psychosocial complexities are interwoven with patient care, as they are more frequently for female providers, a 15-minute visit can easily run twice that – or more. Dr. Burke is among the physicians advocating for recognition of this invisible burden on female clinicians, either through adaptive scheduling or differential productivity expectations. This approach is not without controversy, she acknowledged; still, practices should acknowledge that clinic flow can be very different for male and female gastroenterologists, she said.

Dr. Burke reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Eat a healthy lunch. Get more sleep. Move your body. How many times in the course of a week do you give patients gentle reminders to practice these most basic steps of self-care? And how many times in the course of a week do you allow these basics to go by the wayside for yourself?

Self-care is one of the elements that can defend against physician burnout, Carol Burke, MD, said at a session on physician burnout held during the annual Digestive Disease Week®. Personal self-care can make a real difference, and shouldn’t be ignored as the profession works to reel back some of the institutional changes that challenge physicians today.

In the workplace, unhealthy stress levels can contribute to burnout, disruptive behavior, decreased productivity, and disengagement. Burnout – a response to chronic stress characterized by a diminished sense of personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion – can result in cynicism, a lack of compassion, and feelings of depersonalization, said Dr. Burke.

Contributors to physician stress have been well documented, said Dr. Burke, a professor of gastroenterology at the Cleveland Clinic. These range from personal debt and the struggle for work-life balance to an increased focus on metrics and documentation at the expense of authentic patient engagement. All of these factors are measurable by means of the validated Maslach Burnout Inventory, said Dr. Burke. A recent survey that used this measure indicated that nearly half of physician respondents report experiencing burnout.

In 2017, Dr. Burke led a survey of American College of Gastroenterology members that showed 49.3% of respondents reported feeling emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization. Some key themes emerged from the survey, she said. Women and younger physicians were more likely to experience burnout. Having children in the middle years (11-15 years old) and spending more time on domestic duties and child care increased the risk of burnout.

And doing patient-related work at home or having a spouse or partner bring work home also upped burnout risk. Skipping breakfast and lunch during the workweek was another risk factor, which highlights the importance of basic self-care as armor against the administrative onslaught, said Dr. Burke.

Measured by volume alone, physician work can be overwhelming: 45% of physicians in the United States work more than 60 hours weekly, compared with fewer than 10% of the general workforce, said Dr. Burke.

What factors within the control of an individual practitioner can reduce the risk of debilitating burnout and improve quality of life? Physicians who do report a high quality of life, said Dr. Burke, are more likely to have a positive outlook. They also practice basic self-care like taking vacations, exercising regularly, and engaging in hobbies outside of work.

For exhausted, overworked clinicians, getting a good night’s sleep is a critical form of self-care. But erratic schedules, stress, and family demands can all sabotage plans for better sleep hygiene. Still, attending to sleep is important, said Dr. Burke. Individuals with disturbed sleep are less mindful and have less self-compassion. Sleep disturbance is also strongly correlated with perceived stress.

She also reported that the odds ratio for burnout was 14.7 for physicians who reported insomnia when compared with those without sleep disturbance, and it was 9.9 for those who reported nonrestorative sleep.

Physical activity can help sleep and also help other markers of burnout. Dr. Burke pointed to a recent study of 4,402 medical students. Participants were able to reduce burnout risk when they met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations of achieving at least 150 minutes/week of moderate exercise or 75 minutes/week of vigorous exercise, plus at least 2 days/week of strength training (P less than .001; Acad Med. 2017;92:1006).

These physician-targeted programs can work, she said: “Faciliated interventions improve well-being, attitudes associated with patient-centered care, meaning and engagement in work, and reduce burnout.”

Practice-focused interventions to reclaim a semblance of control over one’s time are varied, and some are easier to implement than others. Virtual visits and group visits are surprisingly well received by patients, and each can be huge time-savers for physicians, said Dr. Burke. There are billing and workflow pitfalls to avoid, but group visits, in particular, can be practice changing for those who have heavy backlogs and see many patients with the same condition.

Medical scribes can improve productivity and reduce physician time spent on documentation. Also, said Dr. Burke, visits can appropriately be billed at a higher level of complexity when contemporaneous documentation is thorough. Clinicians overall feel that they can engage more fully with patients, and also feel more effective, when well-trained scribes are integrated into a practice, she said.

Female physicians have repeatedly been shown to have patient panels that are more demanding, and male and female patients alike expect more empathy and social support from their physicians, said Dr. Burke. When psychosocial complexities are interwoven with patient care, as they are more frequently for female providers, a 15-minute visit can easily run twice that – or more. Dr. Burke is among the physicians advocating for recognition of this invisible burden on female clinicians, either through adaptive scheduling or differential productivity expectations. This approach is not without controversy, she acknowledged; still, practices should acknowledge that clinic flow can be very different for male and female gastroenterologists, she said.

Dr. Burke reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Eat a healthy lunch. Get more sleep. Move your body. How many times in the course of a week do you give patients gentle reminders to practice these most basic steps of self-care? And how many times in the course of a week do you allow these basics to go by the wayside for yourself?

Self-care is one of the elements that can defend against physician burnout, Carol Burke, MD, said at a session on physician burnout held during the annual Digestive Disease Week®. Personal self-care can make a real difference, and shouldn’t be ignored as the profession works to reel back some of the institutional changes that challenge physicians today.

In the workplace, unhealthy stress levels can contribute to burnout, disruptive behavior, decreased productivity, and disengagement. Burnout – a response to chronic stress characterized by a diminished sense of personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion – can result in cynicism, a lack of compassion, and feelings of depersonalization, said Dr. Burke.

Contributors to physician stress have been well documented, said Dr. Burke, a professor of gastroenterology at the Cleveland Clinic. These range from personal debt and the struggle for work-life balance to an increased focus on metrics and documentation at the expense of authentic patient engagement. All of these factors are measurable by means of the validated Maslach Burnout Inventory, said Dr. Burke. A recent survey that used this measure indicated that nearly half of physician respondents report experiencing burnout.

In 2017, Dr. Burke led a survey of American College of Gastroenterology members that showed 49.3% of respondents reported feeling emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization. Some key themes emerged from the survey, she said. Women and younger physicians were more likely to experience burnout. Having children in the middle years (11-15 years old) and spending more time on domestic duties and child care increased the risk of burnout.

And doing patient-related work at home or having a spouse or partner bring work home also upped burnout risk. Skipping breakfast and lunch during the workweek was another risk factor, which highlights the importance of basic self-care as armor against the administrative onslaught, said Dr. Burke.

Measured by volume alone, physician work can be overwhelming: 45% of physicians in the United States work more than 60 hours weekly, compared with fewer than 10% of the general workforce, said Dr. Burke.

What factors within the control of an individual practitioner can reduce the risk of debilitating burnout and improve quality of life? Physicians who do report a high quality of life, said Dr. Burke, are more likely to have a positive outlook. They also practice basic self-care like taking vacations, exercising regularly, and engaging in hobbies outside of work.

For exhausted, overworked clinicians, getting a good night’s sleep is a critical form of self-care. But erratic schedules, stress, and family demands can all sabotage plans for better sleep hygiene. Still, attending to sleep is important, said Dr. Burke. Individuals with disturbed sleep are less mindful and have less self-compassion. Sleep disturbance is also strongly correlated with perceived stress.

She also reported that the odds ratio for burnout was 14.7 for physicians who reported insomnia when compared with those without sleep disturbance, and it was 9.9 for those who reported nonrestorative sleep.

Physical activity can help sleep and also help other markers of burnout. Dr. Burke pointed to a recent study of 4,402 medical students. Participants were able to reduce burnout risk when they met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations of achieving at least 150 minutes/week of moderate exercise or 75 minutes/week of vigorous exercise, plus at least 2 days/week of strength training (P less than .001; Acad Med. 2017;92:1006).

These physician-targeted programs can work, she said: “Faciliated interventions improve well-being, attitudes associated with patient-centered care, meaning and engagement in work, and reduce burnout.”

Practice-focused interventions to reclaim a semblance of control over one’s time are varied, and some are easier to implement than others. Virtual visits and group visits are surprisingly well received by patients, and each can be huge time-savers for physicians, said Dr. Burke. There are billing and workflow pitfalls to avoid, but group visits, in particular, can be practice changing for those who have heavy backlogs and see many patients with the same condition.

Medical scribes can improve productivity and reduce physician time spent on documentation. Also, said Dr. Burke, visits can appropriately be billed at a higher level of complexity when contemporaneous documentation is thorough. Clinicians overall feel that they can engage more fully with patients, and also feel more effective, when well-trained scribes are integrated into a practice, she said.

Female physicians have repeatedly been shown to have patient panels that are more demanding, and male and female patients alike expect more empathy and social support from their physicians, said Dr. Burke. When psychosocial complexities are interwoven with patient care, as they are more frequently for female providers, a 15-minute visit can easily run twice that – or more. Dr. Burke is among the physicians advocating for recognition of this invisible burden on female clinicians, either through adaptive scheduling or differential productivity expectations. This approach is not without controversy, she acknowledged; still, practices should acknowledge that clinic flow can be very different for male and female gastroenterologists, she said.

Dr. Burke reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM DDW 2019

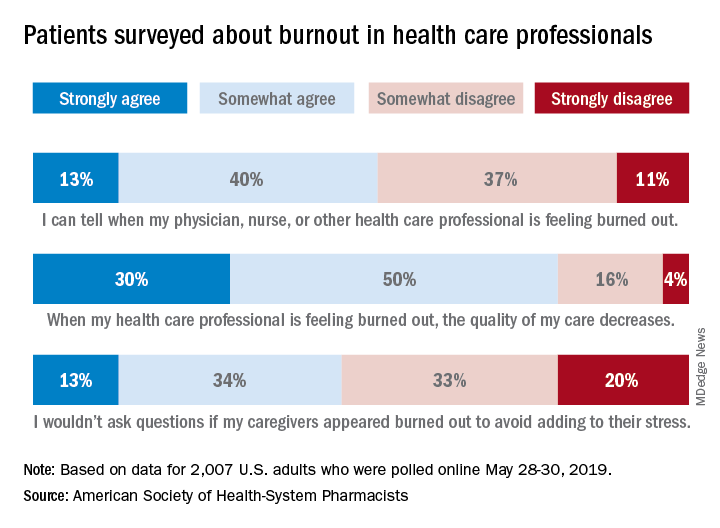

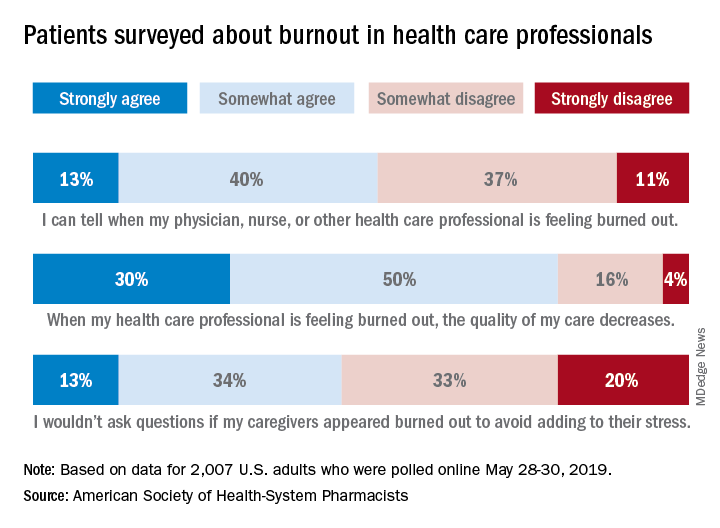

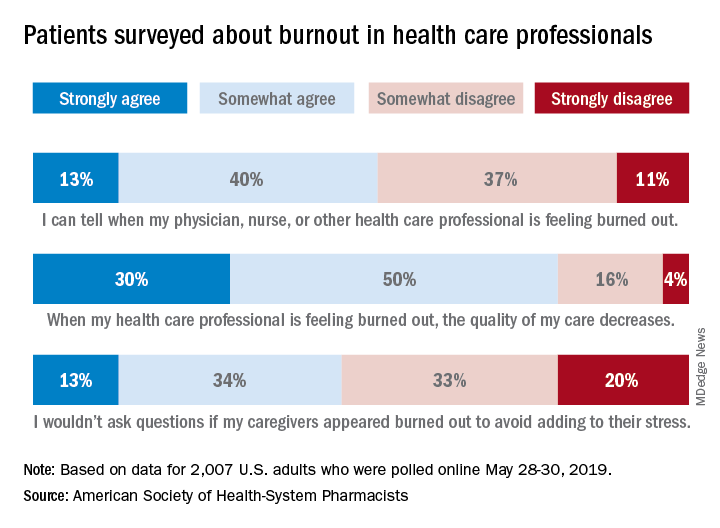

Patients concerned about clinician burnout

Almost three-quarters of Americans are concerned about burnout among health care professionals, according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.