User login

Utilization of a Stress Ball to Diminish Anxiety During Nail Surgery

Practice Gap

Anxiety is common in patients undergoing surgery with general anesthesia and may be exacerbated in patients undergoing dermatologic surgery with local anesthesia. Apprehension might be worse for nail surgery patients because the nail unit is highly innervated and vascular. Many patients fear the anesthetic injections, and there often is pain postoperatively. Perioperative anxiety correlates with increased postoperative pain,1 analgesic use,2 and delayed recovery.3 Several alternatives have been proposed to decrease perioperative anxiety, including nonpharmacologic interventions such as using educational videos, personalized music, hand holding, art activities, and virtual reality, as well as pharmacologic interventions such as benzodiazepines. However, these techniques have not been well studied for nail surgery.

The Technique

Patients generally are anxious about nail surgery secondary to the pain associated with the local anesthetic infiltration; hence, it is crucial to decrease anxiety during this initial step. In our practice, we provide patients with a palm-sized stress ball made of closed-cell polyurethane foam rubber before surgery. Patients are then instructed to hold the stress ball with the free hand and squeeze it whenever they feel anxious or when they feel any discomfort related to the procedure (Figure). A variety of balls can be bought for less than $1 each, thus making it a cost-effective option.

Practice Implications

Holding a stress ball has been found to reduce both pain and anxiety in patients undergoing conscious surgery.4 Furthermore, squeezing a stress ball perioperatively may increase feelings of empowerment, given that patients have direct control over the object, which in turn may have a positive effect on anxiety and patient satisfaction without interfering with the surgical procedure.5 Holding a stress ball is a safe, widely accessible, and inexpensive technique that may aid in decreasing patients’ anxiety related to nail surgery. Nonetheless, controlled clinical trials assessing the efficacy of this method in reducing anxiety related to nail surgery are needed to determine its benefit compared to other methods.

- Carr EC, Nicky Thomas V, Wilson-Barnet J. Patient experiences of anxiety, depression and acute pain after surgery: a longitudinal perspective. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:521-530.

- Powell R, Johnston M, Smith WC, et al. Psychological risk factors for chronic post-surgical pain after inguinal hernia repair surgery: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:600-610.

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:e20306.

- Hudson BF, Ogden J, Whiteley MS. Randomized controlled trial to compare the effect of simple distraction interventions on pain and anxiety experienced during conscious surgery. Eur J Pain. 2015;19:1447-1455.

- Foy CR, Timmins F. Improving communication in day surgery settings. Nurs Stand. 2004;19:37-42.

Practice Gap

Anxiety is common in patients undergoing surgery with general anesthesia and may be exacerbated in patients undergoing dermatologic surgery with local anesthesia. Apprehension might be worse for nail surgery patients because the nail unit is highly innervated and vascular. Many patients fear the anesthetic injections, and there often is pain postoperatively. Perioperative anxiety correlates with increased postoperative pain,1 analgesic use,2 and delayed recovery.3 Several alternatives have been proposed to decrease perioperative anxiety, including nonpharmacologic interventions such as using educational videos, personalized music, hand holding, art activities, and virtual reality, as well as pharmacologic interventions such as benzodiazepines. However, these techniques have not been well studied for nail surgery.

The Technique

Patients generally are anxious about nail surgery secondary to the pain associated with the local anesthetic infiltration; hence, it is crucial to decrease anxiety during this initial step. In our practice, we provide patients with a palm-sized stress ball made of closed-cell polyurethane foam rubber before surgery. Patients are then instructed to hold the stress ball with the free hand and squeeze it whenever they feel anxious or when they feel any discomfort related to the procedure (Figure). A variety of balls can be bought for less than $1 each, thus making it a cost-effective option.

Practice Implications

Holding a stress ball has been found to reduce both pain and anxiety in patients undergoing conscious surgery.4 Furthermore, squeezing a stress ball perioperatively may increase feelings of empowerment, given that patients have direct control over the object, which in turn may have a positive effect on anxiety and patient satisfaction without interfering with the surgical procedure.5 Holding a stress ball is a safe, widely accessible, and inexpensive technique that may aid in decreasing patients’ anxiety related to nail surgery. Nonetheless, controlled clinical trials assessing the efficacy of this method in reducing anxiety related to nail surgery are needed to determine its benefit compared to other methods.

Practice Gap

Anxiety is common in patients undergoing surgery with general anesthesia and may be exacerbated in patients undergoing dermatologic surgery with local anesthesia. Apprehension might be worse for nail surgery patients because the nail unit is highly innervated and vascular. Many patients fear the anesthetic injections, and there often is pain postoperatively. Perioperative anxiety correlates with increased postoperative pain,1 analgesic use,2 and delayed recovery.3 Several alternatives have been proposed to decrease perioperative anxiety, including nonpharmacologic interventions such as using educational videos, personalized music, hand holding, art activities, and virtual reality, as well as pharmacologic interventions such as benzodiazepines. However, these techniques have not been well studied for nail surgery.

The Technique

Patients generally are anxious about nail surgery secondary to the pain associated with the local anesthetic infiltration; hence, it is crucial to decrease anxiety during this initial step. In our practice, we provide patients with a palm-sized stress ball made of closed-cell polyurethane foam rubber before surgery. Patients are then instructed to hold the stress ball with the free hand and squeeze it whenever they feel anxious or when they feel any discomfort related to the procedure (Figure). A variety of balls can be bought for less than $1 each, thus making it a cost-effective option.

Practice Implications

Holding a stress ball has been found to reduce both pain and anxiety in patients undergoing conscious surgery.4 Furthermore, squeezing a stress ball perioperatively may increase feelings of empowerment, given that patients have direct control over the object, which in turn may have a positive effect on anxiety and patient satisfaction without interfering with the surgical procedure.5 Holding a stress ball is a safe, widely accessible, and inexpensive technique that may aid in decreasing patients’ anxiety related to nail surgery. Nonetheless, controlled clinical trials assessing the efficacy of this method in reducing anxiety related to nail surgery are needed to determine its benefit compared to other methods.

- Carr EC, Nicky Thomas V, Wilson-Barnet J. Patient experiences of anxiety, depression and acute pain after surgery: a longitudinal perspective. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:521-530.

- Powell R, Johnston M, Smith WC, et al. Psychological risk factors for chronic post-surgical pain after inguinal hernia repair surgery: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:600-610.

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:e20306.

- Hudson BF, Ogden J, Whiteley MS. Randomized controlled trial to compare the effect of simple distraction interventions on pain and anxiety experienced during conscious surgery. Eur J Pain. 2015;19:1447-1455.

- Foy CR, Timmins F. Improving communication in day surgery settings. Nurs Stand. 2004;19:37-42.

- Carr EC, Nicky Thomas V, Wilson-Barnet J. Patient experiences of anxiety, depression and acute pain after surgery: a longitudinal perspective. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:521-530.

- Powell R, Johnston M, Smith WC, et al. Psychological risk factors for chronic post-surgical pain after inguinal hernia repair surgery: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:600-610.

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:e20306.

- Hudson BF, Ogden J, Whiteley MS. Randomized controlled trial to compare the effect of simple distraction interventions on pain and anxiety experienced during conscious surgery. Eur J Pain. 2015;19:1447-1455.

- Foy CR, Timmins F. Improving communication in day surgery settings. Nurs Stand. 2004;19:37-42.

Cartilage Sutures for a Large Nasal Defect

Practice Gap

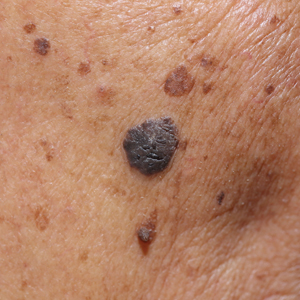

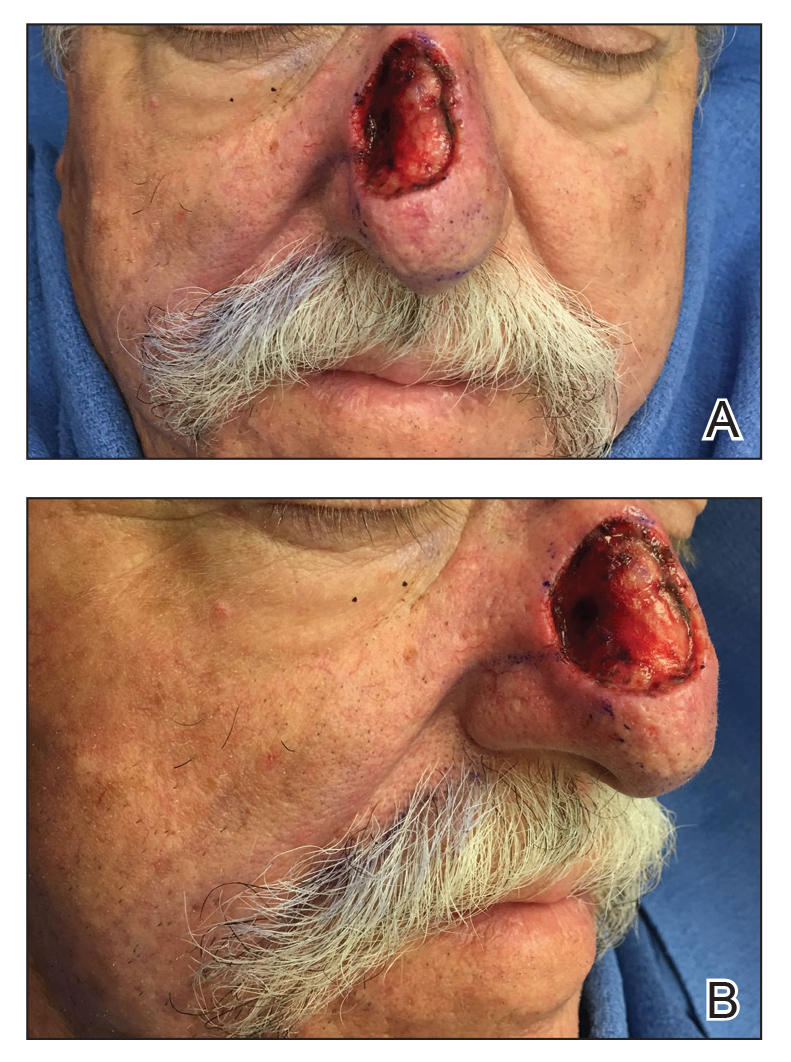

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

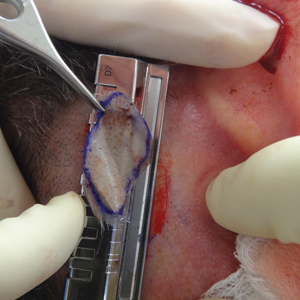

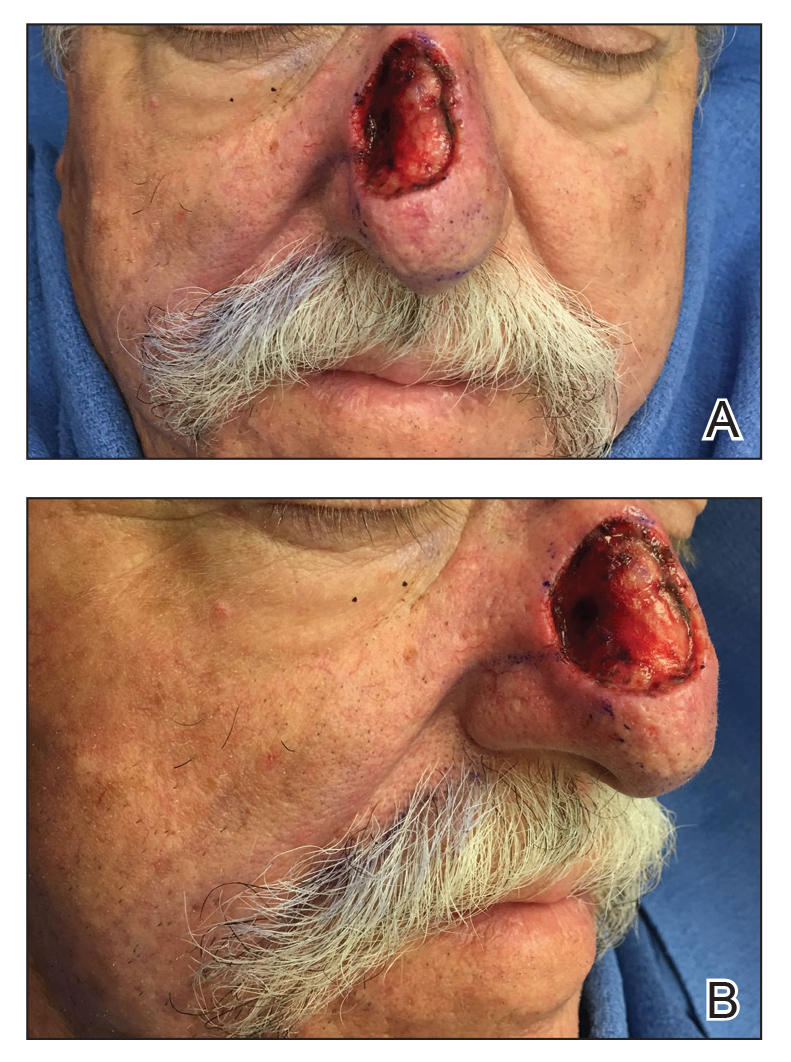

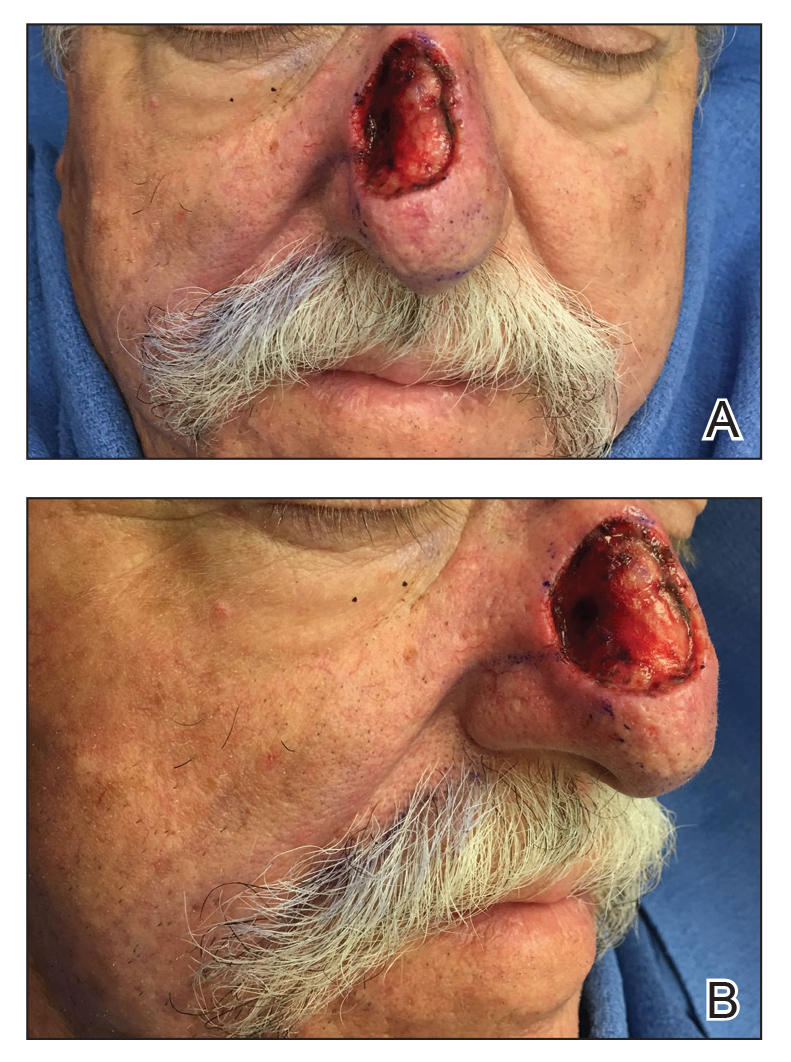

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

Practice Gap

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

Practice Gap

A 69-year-old man underwent staged excision for an invasive melanoma (0.4-mm Breslow depth; stage Ia) of the right dorsal nose. Two stages were required to achieve clear margins, leaving a 3.0×2.5-cm defect involving the nasal dorsum, right nasal sidewall, and nasal supratip (Figure 1). He declined any multistage repair and preferred a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) over any interpolation flap.

Given the size of our patient’s defect, primary repair was not possible and second intention healing may have resulted in a suboptimal cosmetic outcome, potential alar distortion, and prolonged healing. No single local flap, such as the dorsal nasal rotation flap, crescentic advancement flap, bilobed flap, and Rintala flap, would have provided adequate coverage. A FTSG of the entire defect would not have been an ideal tissue match, and given the limited surrounding laxity, a Burow FTSG would have required the linear repair to extend well into the forehead with a questionable cosmetic outcome.

The Technique

We opted to repair the defect using a combination of local flaps for a single-stage repair. Using the right cheek reservoir, a crescentic advancement flap was performed to restore the right nasal sidewall as best as possible with a standing cone taken superiorly. To execute this flap, an incision was made extending from the alar sulcus into the nasolabial fold while preserving the apical triangle of the upper cutaneous lip. The flap was elevated submuscularly on the nose, and broad undermining was performed in the subcutaneous plane of the medial cheek. A crescentic redundancy above the alar sulcus was excised, and periosteal tacking sutures were placed to both help advance the flap and to recreate the nasofacial sulcus.1

Next, a nasal tip spiral/rotation flap was designed to restore the remaining nasal defect.2 An incision was made at the right inferiormost aspect of the defect and extended along the inferior border of the nasal tip as it crossed the midline to the left side of the nose. After incising and elevating the flap in the submuscular plane, there was not enough of a tissue reservoir to cover the entire remaining nasal defect.

To resolve this intraoperative conundrum, simple interrupted sutures were placed into the nasal cartilage at midline to narrow the structure of the nose (Figure 2). Three 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures were placed beginning with the upper lateral cartilages and extending inferiorly to the lower lateral cartilages. Narrowing the nasal cartilages allowed for a smaller residual defect. The nasal tip rotation flap was then spiraled into place with adequate coverage. Some of the flap tip was trimmed after the superior aspect of the rotation flap was sutured to the inferior edge of the crescentic advancement flap. The immediate postoperative appearance is shown in Figure 3.

At 4-month follow-up, intralesional triamcinolone was injected into the slight induration at the right nasal tip. At 7-month follow-up, the patient was pleased with the cosmetic and functional result (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Cartilage sutures highlight an underutilized technique in nasal reconstruction, with few cases reported

A combination of local flaps may be used to repair large nasal defects involving multiple subunits, especially in patients who decline multistage reconstruction. A nasal tip rotation/spiral flap can be considered for the appropriate nasal tip defect. Suturing the nasal cartilage with either permanent or long-lasting suture can narrow the cartilage and facilitate flap coverage for nasal defects while also improving the appearance of patients with wide prominent lower noses.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

- Smith JM, Orseth ML, Nijhawan RI. Reconstruction of large nasal dorsum defects. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1607-1610.

- Snow SN. Rotation flaps to reconstruct nasal tip defects following Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:916-919.

- Malone CH, Hays JP, Tausend WE, et al. Interdomal sutures for nasal tip refinement and reduced wound size. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:E107-E108.

- Pelster MW, Behshad R, Maher IA. Large nasal tip defects-utilization of interdomal sutures before Burow’s graft for optimization of nasal contour. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:743-746.

- Gruber RP, Chang E, Buchanan E. Suture techniques in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37:231-243.

Hydrogen Peroxide as a Hemostatic Agent During Dermatologic Surgery

The number of skin cancer surgeries continues to rise, especially in the older population, many of whom are on blood thinners. The sequela of bleeding, even in minor cases, is one of the most frequently encountered complications of cutaneous surgery. Surgical site bleeding can increase the risk for infection, skin graft failure, wound dehiscence, and hematoma formation, which may lead to disrupted wound healing and eventual poor scar outcome. Although achieving hemostasis is important, it is recommended to limit certain alternative modalities such as electrosurgery due to the accompanied thermal tissue damage that in turn can prolong healing time, worsen scarring, and increase the risk for infection.1

Practice Gap

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a common topical antiseptic used to clean wounds by killing pathogens through oxidation burst and local oxygen production.2 It is generally affordable, nonallergenic, and easy to obtain. We describe our positive experience using H2O2 as a hemostatic agent during dermatologic surgery, highlighting the agent’s underutilization as well as the recent literature negating traditional viewpoints that it probably causes tissue necrosis and impaired wound healing through its high oxidative property.

The Technique

Before surgery, the site is prepared with chlorhexidine gluconate. A stack of 4×4-in gauze on the surgical tray is saturated with 3% H2O2 and used by the surgeon and surgical assistant throughout the procedure. We currently use this technique during standard excisions, Mohs micrographic surgery stages, repairs, and dermabrasion. Additionally, as a first measure of hemostasis, we recommend H2O2 soaks immediately postoperatively in patients with active bleeding.

We have been utilizing this technique since H2O2 was described as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent during manual dermabrasion.3 Hydrogen peroxide is known to facilitate hemostasis with several accepted mechanisms that include regulating the contractility and barrier function of endothelial cells, activating latent cell surface tissue factor and platelet aggregation, and stimulating platelet-derived growth factor activation.4 It has been reported that increasing H2O2 levels leads to a dose-response increase in aggregation in the presence of subaggregating amounts of collagen.5 This concept was described in an article that utilizes H2O2 as a way to obtain hemostasis before skin grafting burn patients.6 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms h202, hydrogen peroxide, hemostasis, wound healing, surgery, and wound produced several surgical specialties—neurosurgery, orthopedics, gastroenterology, and maxillofacial surgery—that also utilize H2O2 as a hemostatic agent.7,8 One article described a dual-enzyme H2O2 generation machinery in hydrogels as a novel antimicrobial wound treatment.9

Practice Implications

The use of H2O2 as a topical hemostatic agent during surgery was described in 1984.2 The use of H2O2 is not suggested as a substitute for other strong and well-known hemostatic agents, such as aluminum chloride and ferric subsulfate, but rather as a technique that can be used in conjunction with standard methods of hemostasis and antisepsis. For surgical sites that are intended to be closed, we do not suggest these hemostatic agents, as they are known to be caustic, irritating, and pigmenting. In addition to H2O2’s known hemostatic and antiseptic properties, more recent literature invalidates wound impairment concerns and describes its possible role in signaling effector cells to respond downstream, contributing to tissue formation and remodeling.4 The use of H2O2 in wound and incision care has been controversial and avoided due to described skin irritation and possible premature removal of suture10; however, positive biochemical effects of H2O2 on acute wounds have been reported and dispel arguments that this agent causes tissue damage.4 Contrary to the traditional viewpoint that H2O2 probably impairs tissue through its high oxidative property, a proper level of H2O2 is considered an important requirement for normal wound healing. The report published in 1985 that raised concerns of H2O2 causing impaired wound healing through its effect on fibroblasts has been challenged given that the killed cultured fibroblasts were in an in vitro model and not likely representative of the complexities of a healing wound.10 In our experience, the use of H2O2 has not demonstrated any impairments or delays in wound healing, and we postulate that the exposure to H2O2 as described in our technique is not sufficient to cause notable impairment in fibroblast function in vivo. In addition, the role of H2O2 promoting oxidative stress as well as resolving inflammation may suggest it serves as a bidirectional regulator.

Future Directions

Additional studies are needed to assess this precise balance of H2O2 forming a favorable microenvironment in wounds. Similarly, although we discuss minimal and brief use of H2O2 during a procedure, the lack of data on the role of H2O2 as a prophylactic anti-infective agent for postoperative wound care also may be an area of future exploration.

- Henley J, Brewer JD. Newer hemostatic agents used in the practice of dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Res Pract. 2013;2013:279289.

- Hankin FM, Campbell SE, Goldstein SA, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as a topical hemostatic agent. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;186:244-247.

- Weiss J, Winkleman FJ, Titone A, et al. Evaluation of hydrogen peroxide as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent in manual dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1601-1603.

- Zhu G, Wang Q, Lu S, et al. Hydrogen peroxide: a potential wound therapeutic target? Med Princ Pract. 2017;26:301-308.

- Practicò D, Iuliano L, Ghiselli A, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as trigger of platelet aggregation. Haemostasis. 1991;21:169-174.

- Potyondy L, Lottenberg L, Anderson J, et al. The use of hydrogen peroxide for achieving dermal hemostasis after burn excision in a patient with platelet dysfunction. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:99-101.

- Mawk JR. Hydrogen peroxide for hemostasis. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:827.

- Arakeri G, Brennan PA. Povidone-iodine and hydrogen peroxide mixture soaked gauze pack: a novel hemostatic technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1833.e1-1833.e3.

- Huber D, Tegl G, Mensah A, et al. A dual-enzyme hydrogen peroxide generation machinery in hydrogels supports antimicrobial wound treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:15307-15316.

- Lineaweaver W, McMorris S, Soucy D, et al. Cellular and bacterial toxicities of topical antimicrobials. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75:394-396.

The number of skin cancer surgeries continues to rise, especially in the older population, many of whom are on blood thinners. The sequela of bleeding, even in minor cases, is one of the most frequently encountered complications of cutaneous surgery. Surgical site bleeding can increase the risk for infection, skin graft failure, wound dehiscence, and hematoma formation, which may lead to disrupted wound healing and eventual poor scar outcome. Although achieving hemostasis is important, it is recommended to limit certain alternative modalities such as electrosurgery due to the accompanied thermal tissue damage that in turn can prolong healing time, worsen scarring, and increase the risk for infection.1

Practice Gap

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a common topical antiseptic used to clean wounds by killing pathogens through oxidation burst and local oxygen production.2 It is generally affordable, nonallergenic, and easy to obtain. We describe our positive experience using H2O2 as a hemostatic agent during dermatologic surgery, highlighting the agent’s underutilization as well as the recent literature negating traditional viewpoints that it probably causes tissue necrosis and impaired wound healing through its high oxidative property.

The Technique

Before surgery, the site is prepared with chlorhexidine gluconate. A stack of 4×4-in gauze on the surgical tray is saturated with 3% H2O2 and used by the surgeon and surgical assistant throughout the procedure. We currently use this technique during standard excisions, Mohs micrographic surgery stages, repairs, and dermabrasion. Additionally, as a first measure of hemostasis, we recommend H2O2 soaks immediately postoperatively in patients with active bleeding.

We have been utilizing this technique since H2O2 was described as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent during manual dermabrasion.3 Hydrogen peroxide is known to facilitate hemostasis with several accepted mechanisms that include regulating the contractility and barrier function of endothelial cells, activating latent cell surface tissue factor and platelet aggregation, and stimulating platelet-derived growth factor activation.4 It has been reported that increasing H2O2 levels leads to a dose-response increase in aggregation in the presence of subaggregating amounts of collagen.5 This concept was described in an article that utilizes H2O2 as a way to obtain hemostasis before skin grafting burn patients.6 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms h202, hydrogen peroxide, hemostasis, wound healing, surgery, and wound produced several surgical specialties—neurosurgery, orthopedics, gastroenterology, and maxillofacial surgery—that also utilize H2O2 as a hemostatic agent.7,8 One article described a dual-enzyme H2O2 generation machinery in hydrogels as a novel antimicrobial wound treatment.9

Practice Implications

The use of H2O2 as a topical hemostatic agent during surgery was described in 1984.2 The use of H2O2 is not suggested as a substitute for other strong and well-known hemostatic agents, such as aluminum chloride and ferric subsulfate, but rather as a technique that can be used in conjunction with standard methods of hemostasis and antisepsis. For surgical sites that are intended to be closed, we do not suggest these hemostatic agents, as they are known to be caustic, irritating, and pigmenting. In addition to H2O2’s known hemostatic and antiseptic properties, more recent literature invalidates wound impairment concerns and describes its possible role in signaling effector cells to respond downstream, contributing to tissue formation and remodeling.4 The use of H2O2 in wound and incision care has been controversial and avoided due to described skin irritation and possible premature removal of suture10; however, positive biochemical effects of H2O2 on acute wounds have been reported and dispel arguments that this agent causes tissue damage.4 Contrary to the traditional viewpoint that H2O2 probably impairs tissue through its high oxidative property, a proper level of H2O2 is considered an important requirement for normal wound healing. The report published in 1985 that raised concerns of H2O2 causing impaired wound healing through its effect on fibroblasts has been challenged given that the killed cultured fibroblasts were in an in vitro model and not likely representative of the complexities of a healing wound.10 In our experience, the use of H2O2 has not demonstrated any impairments or delays in wound healing, and we postulate that the exposure to H2O2 as described in our technique is not sufficient to cause notable impairment in fibroblast function in vivo. In addition, the role of H2O2 promoting oxidative stress as well as resolving inflammation may suggest it serves as a bidirectional regulator.

Future Directions

Additional studies are needed to assess this precise balance of H2O2 forming a favorable microenvironment in wounds. Similarly, although we discuss minimal and brief use of H2O2 during a procedure, the lack of data on the role of H2O2 as a prophylactic anti-infective agent for postoperative wound care also may be an area of future exploration.

The number of skin cancer surgeries continues to rise, especially in the older population, many of whom are on blood thinners. The sequela of bleeding, even in minor cases, is one of the most frequently encountered complications of cutaneous surgery. Surgical site bleeding can increase the risk for infection, skin graft failure, wound dehiscence, and hematoma formation, which may lead to disrupted wound healing and eventual poor scar outcome. Although achieving hemostasis is important, it is recommended to limit certain alternative modalities such as electrosurgery due to the accompanied thermal tissue damage that in turn can prolong healing time, worsen scarring, and increase the risk for infection.1

Practice Gap

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a common topical antiseptic used to clean wounds by killing pathogens through oxidation burst and local oxygen production.2 It is generally affordable, nonallergenic, and easy to obtain. We describe our positive experience using H2O2 as a hemostatic agent during dermatologic surgery, highlighting the agent’s underutilization as well as the recent literature negating traditional viewpoints that it probably causes tissue necrosis and impaired wound healing through its high oxidative property.

The Technique

Before surgery, the site is prepared with chlorhexidine gluconate. A stack of 4×4-in gauze on the surgical tray is saturated with 3% H2O2 and used by the surgeon and surgical assistant throughout the procedure. We currently use this technique during standard excisions, Mohs micrographic surgery stages, repairs, and dermabrasion. Additionally, as a first measure of hemostasis, we recommend H2O2 soaks immediately postoperatively in patients with active bleeding.

We have been utilizing this technique since H2O2 was described as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent during manual dermabrasion.3 Hydrogen peroxide is known to facilitate hemostasis with several accepted mechanisms that include regulating the contractility and barrier function of endothelial cells, activating latent cell surface tissue factor and platelet aggregation, and stimulating platelet-derived growth factor activation.4 It has been reported that increasing H2O2 levels leads to a dose-response increase in aggregation in the presence of subaggregating amounts of collagen.5 This concept was described in an article that utilizes H2O2 as a way to obtain hemostasis before skin grafting burn patients.6 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms h202, hydrogen peroxide, hemostasis, wound healing, surgery, and wound produced several surgical specialties—neurosurgery, orthopedics, gastroenterology, and maxillofacial surgery—that also utilize H2O2 as a hemostatic agent.7,8 One article described a dual-enzyme H2O2 generation machinery in hydrogels as a novel antimicrobial wound treatment.9

Practice Implications

The use of H2O2 as a topical hemostatic agent during surgery was described in 1984.2 The use of H2O2 is not suggested as a substitute for other strong and well-known hemostatic agents, such as aluminum chloride and ferric subsulfate, but rather as a technique that can be used in conjunction with standard methods of hemostasis and antisepsis. For surgical sites that are intended to be closed, we do not suggest these hemostatic agents, as they are known to be caustic, irritating, and pigmenting. In addition to H2O2’s known hemostatic and antiseptic properties, more recent literature invalidates wound impairment concerns and describes its possible role in signaling effector cells to respond downstream, contributing to tissue formation and remodeling.4 The use of H2O2 in wound and incision care has been controversial and avoided due to described skin irritation and possible premature removal of suture10; however, positive biochemical effects of H2O2 on acute wounds have been reported and dispel arguments that this agent causes tissue damage.4 Contrary to the traditional viewpoint that H2O2 probably impairs tissue through its high oxidative property, a proper level of H2O2 is considered an important requirement for normal wound healing. The report published in 1985 that raised concerns of H2O2 causing impaired wound healing through its effect on fibroblasts has been challenged given that the killed cultured fibroblasts were in an in vitro model and not likely representative of the complexities of a healing wound.10 In our experience, the use of H2O2 has not demonstrated any impairments or delays in wound healing, and we postulate that the exposure to H2O2 as described in our technique is not sufficient to cause notable impairment in fibroblast function in vivo. In addition, the role of H2O2 promoting oxidative stress as well as resolving inflammation may suggest it serves as a bidirectional regulator.

Future Directions

Additional studies are needed to assess this precise balance of H2O2 forming a favorable microenvironment in wounds. Similarly, although we discuss minimal and brief use of H2O2 during a procedure, the lack of data on the role of H2O2 as a prophylactic anti-infective agent for postoperative wound care also may be an area of future exploration.

- Henley J, Brewer JD. Newer hemostatic agents used in the practice of dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Res Pract. 2013;2013:279289.

- Hankin FM, Campbell SE, Goldstein SA, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as a topical hemostatic agent. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;186:244-247.

- Weiss J, Winkleman FJ, Titone A, et al. Evaluation of hydrogen peroxide as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent in manual dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1601-1603.

- Zhu G, Wang Q, Lu S, et al. Hydrogen peroxide: a potential wound therapeutic target? Med Princ Pract. 2017;26:301-308.

- Practicò D, Iuliano L, Ghiselli A, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as trigger of platelet aggregation. Haemostasis. 1991;21:169-174.

- Potyondy L, Lottenberg L, Anderson J, et al. The use of hydrogen peroxide for achieving dermal hemostasis after burn excision in a patient with platelet dysfunction. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:99-101.

- Mawk JR. Hydrogen peroxide for hemostasis. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:827.

- Arakeri G, Brennan PA. Povidone-iodine and hydrogen peroxide mixture soaked gauze pack: a novel hemostatic technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1833.e1-1833.e3.

- Huber D, Tegl G, Mensah A, et al. A dual-enzyme hydrogen peroxide generation machinery in hydrogels supports antimicrobial wound treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:15307-15316.

- Lineaweaver W, McMorris S, Soucy D, et al. Cellular and bacterial toxicities of topical antimicrobials. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75:394-396.

- Henley J, Brewer JD. Newer hemostatic agents used in the practice of dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Res Pract. 2013;2013:279289.

- Hankin FM, Campbell SE, Goldstein SA, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as a topical hemostatic agent. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;186:244-247.

- Weiss J, Winkleman FJ, Titone A, et al. Evaluation of hydrogen peroxide as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent in manual dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1601-1603.

- Zhu G, Wang Q, Lu S, et al. Hydrogen peroxide: a potential wound therapeutic target? Med Princ Pract. 2017;26:301-308.

- Practicò D, Iuliano L, Ghiselli A, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as trigger of platelet aggregation. Haemostasis. 1991;21:169-174.

- Potyondy L, Lottenberg L, Anderson J, et al. The use of hydrogen peroxide for achieving dermal hemostasis after burn excision in a patient with platelet dysfunction. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:99-101.

- Mawk JR. Hydrogen peroxide for hemostasis. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:827.

- Arakeri G, Brennan PA. Povidone-iodine and hydrogen peroxide mixture soaked gauze pack: a novel hemostatic technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1833.e1-1833.e3.

- Huber D, Tegl G, Mensah A, et al. A dual-enzyme hydrogen peroxide generation machinery in hydrogels supports antimicrobial wound treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:15307-15316.

- Lineaweaver W, McMorris S, Soucy D, et al. Cellular and bacterial toxicities of topical antimicrobials. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75:394-396.

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy to Facilitate Knifeless Skin Cancer Management

Practice Gap

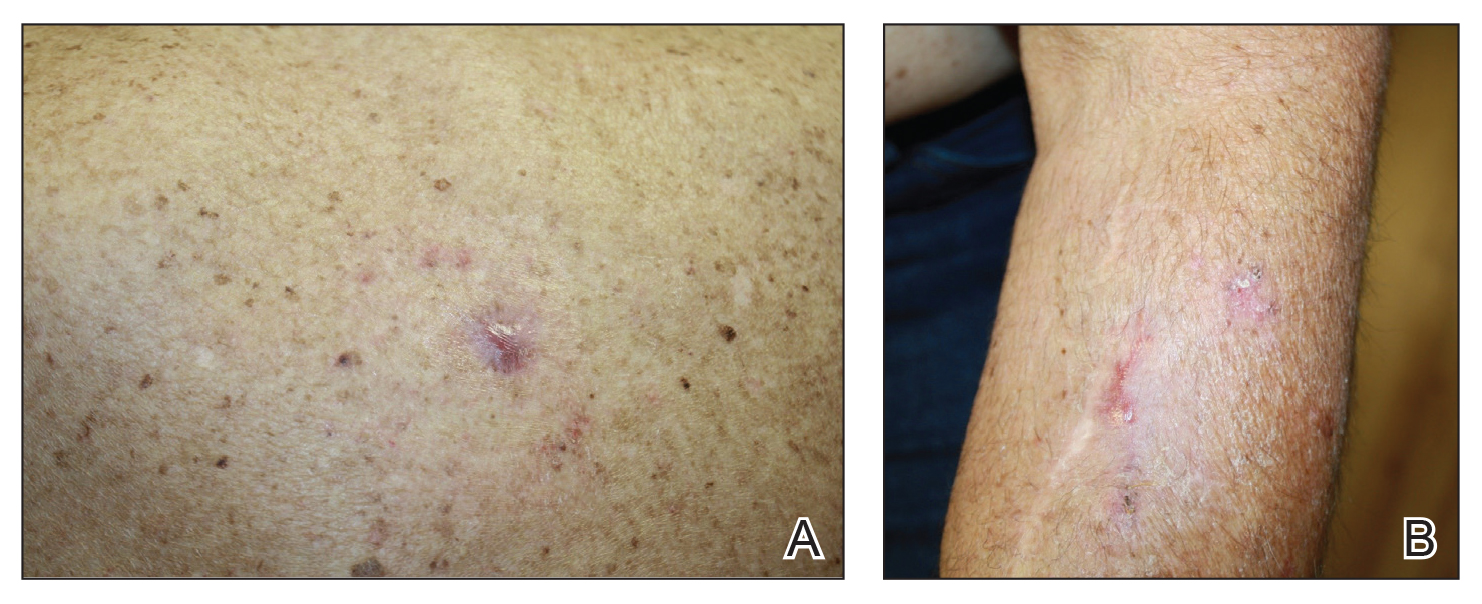

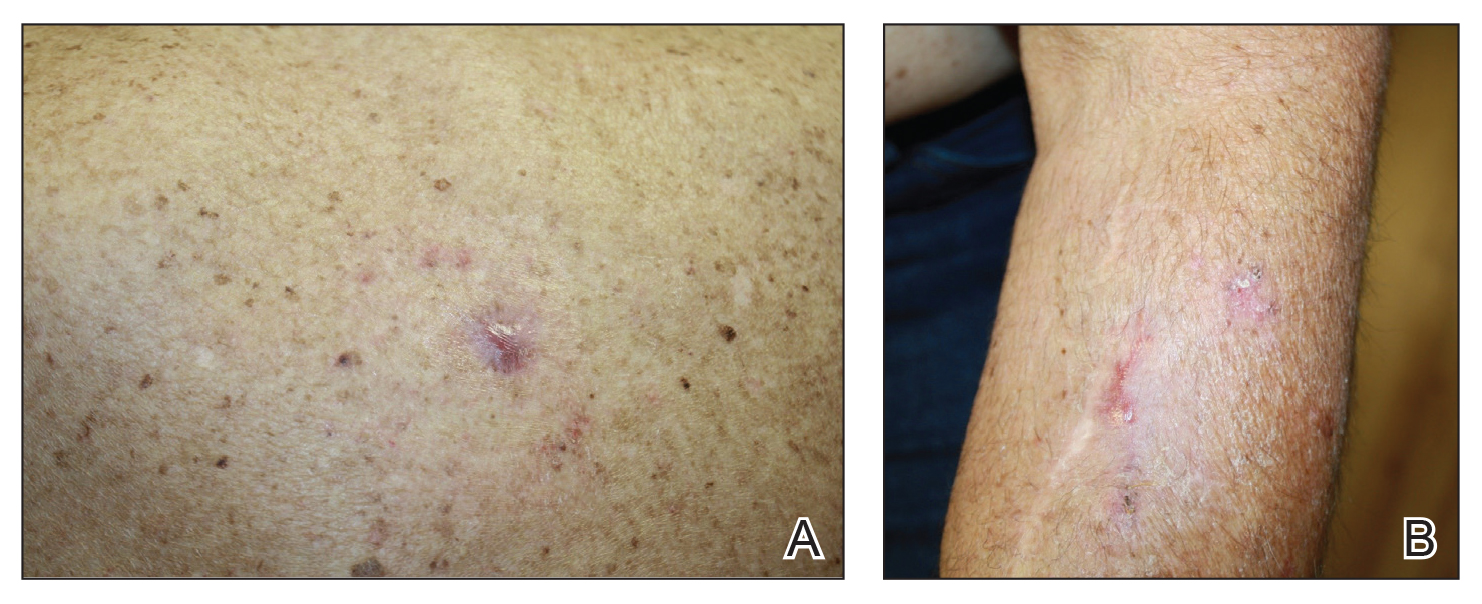

Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in elderly patients can cause morbidity because these patients frequently struggle to care for their biopsy sites and experience biopsy- and surgery-related complications. To minimize this treatment-related morbidity, we designed a knifeless treatment approach that employs reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) in lieu of skin biopsy to establish the diagnosis of NMSC, then uses either intralesional or topical chemotherapy or immunotherapy (as appropriate, depending on depth of invasion) to cure the NMSC. With this approach, the patient is spared both biopsy- and surgery-related difficulties, though both intralesional and topical chemotherapy are accompanied by their own risks for adverse effects.

The Technique

Elderly patients, diabetic patients, and patients with lesions suspicious for NMSC on areas prone to poor wound healing or to notable treatment-related morbidity (eg, lower legs, genitals, the face of younger patients) are offered skin biopsy or RCM; the latter is performed during the appointment by an RC

When resolution is uncertain, RCM is repeated to assess for tumor clearance. Repeat RCM is performed at least 4 weeks after termination of treatment to avoid misinterpretation caused by treatment-related tissue inflammation. Patients who are not cured using this management approach are offered appropriate surgical management.

Practice Implications

Reflectance confocal microscopy has emerged as an effective modality for confirming the diagnosis of NMSC with high sensitivity and specificity.1,2 Emergence of this technology presents an opportunity for improving the way the NMSC is managed because RCM allows dermatologists to confirm the diagnosis of BCC and SCC by interpretation of RCM mosaics rather than by histopathologic examination of biopsied tissue. Our knifeless approach to skin cancer management is especially beneficial when biopsy and dermatologic surgery are likely to confer notable morbidity, such as managing NMSC on the face of a young adult, in the frail elderly population, or in diabetic patients, and when treating sites on the lower extremity prone to poor wound healing.

- Song E, Grant-Kels JM, Swede H, et al. Paired comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis and reflectance confocal microscopy in the detection of melanoma in vivo: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1187-1192.

- Ferrari B, Salgarelli AC, Mandel VD, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: the aid of reflectance confocal microscopy for the accurate diagnosis and management. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152:169-177.

Practice Gap

Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in elderly patients can cause morbidity because these patients frequently struggle to care for their biopsy sites and experience biopsy- and surgery-related complications. To minimize this treatment-related morbidity, we designed a knifeless treatment approach that employs reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) in lieu of skin biopsy to establish the diagnosis of NMSC, then uses either intralesional or topical chemotherapy or immunotherapy (as appropriate, depending on depth of invasion) to cure the NMSC. With this approach, the patient is spared both biopsy- and surgery-related difficulties, though both intralesional and topical chemotherapy are accompanied by their own risks for adverse effects.

The Technique

Elderly patients, diabetic patients, and patients with lesions suspicious for NMSC on areas prone to poor wound healing or to notable treatment-related morbidity (eg, lower legs, genitals, the face of younger patients) are offered skin biopsy or RCM; the latter is performed during the appointment by an RC

When resolution is uncertain, RCM is repeated to assess for tumor clearance. Repeat RCM is performed at least 4 weeks after termination of treatment to avoid misinterpretation caused by treatment-related tissue inflammation. Patients who are not cured using this management approach are offered appropriate surgical management.

Practice Implications

Reflectance confocal microscopy has emerged as an effective modality for confirming the diagnosis of NMSC with high sensitivity and specificity.1,2 Emergence of this technology presents an opportunity for improving the way the NMSC is managed because RCM allows dermatologists to confirm the diagnosis of BCC and SCC by interpretation of RCM mosaics rather than by histopathologic examination of biopsied tissue. Our knifeless approach to skin cancer management is especially beneficial when biopsy and dermatologic surgery are likely to confer notable morbidity, such as managing NMSC on the face of a young adult, in the frail elderly population, or in diabetic patients, and when treating sites on the lower extremity prone to poor wound healing.

Practice Gap

Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in elderly patients can cause morbidity because these patients frequently struggle to care for their biopsy sites and experience biopsy- and surgery-related complications. To minimize this treatment-related morbidity, we designed a knifeless treatment approach that employs reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) in lieu of skin biopsy to establish the diagnosis of NMSC, then uses either intralesional or topical chemotherapy or immunotherapy (as appropriate, depending on depth of invasion) to cure the NMSC. With this approach, the patient is spared both biopsy- and surgery-related difficulties, though both intralesional and topical chemotherapy are accompanied by their own risks for adverse effects.

The Technique

Elderly patients, diabetic patients, and patients with lesions suspicious for NMSC on areas prone to poor wound healing or to notable treatment-related morbidity (eg, lower legs, genitals, the face of younger patients) are offered skin biopsy or RCM; the latter is performed during the appointment by an RC

When resolution is uncertain, RCM is repeated to assess for tumor clearance. Repeat RCM is performed at least 4 weeks after termination of treatment to avoid misinterpretation caused by treatment-related tissue inflammation. Patients who are not cured using this management approach are offered appropriate surgical management.

Practice Implications

Reflectance confocal microscopy has emerged as an effective modality for confirming the diagnosis of NMSC with high sensitivity and specificity.1,2 Emergence of this technology presents an opportunity for improving the way the NMSC is managed because RCM allows dermatologists to confirm the diagnosis of BCC and SCC by interpretation of RCM mosaics rather than by histopathologic examination of biopsied tissue. Our knifeless approach to skin cancer management is especially beneficial when biopsy and dermatologic surgery are likely to confer notable morbidity, such as managing NMSC on the face of a young adult, in the frail elderly population, or in diabetic patients, and when treating sites on the lower extremity prone to poor wound healing.

- Song E, Grant-Kels JM, Swede H, et al. Paired comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis and reflectance confocal microscopy in the detection of melanoma in vivo: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1187-1192.

- Ferrari B, Salgarelli AC, Mandel VD, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: the aid of reflectance confocal microscopy for the accurate diagnosis and management. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152:169-177.

- Song E, Grant-Kels JM, Swede H, et al. Paired comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis and reflectance confocal microscopy in the detection of melanoma in vivo: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1187-1192.

- Ferrari B, Salgarelli AC, Mandel VD, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: the aid of reflectance confocal microscopy for the accurate diagnosis and management. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152:169-177.

Clinical Pearl: Topical Timolol for Refractory Hypergranulation

Practice Gap

Hypergranulation is a frequent complication of dermatologic surgery, especially when surgical defects are left to heal by secondary intention (eg, after electrodesiccation and curettage). Although management of postoperative hypergranulation with routine wound care, superpotent topical corticosteroids, and/or topical silver nitrate often is effective, refractory cases pose a difficult challenge given the paucity of treatment options. Effective management of these cases is important because hypergranulation can delay wound healing, cause patient discomfort, and lead to poor wound cosmesis.

The Technique

If refractory hypergranulation fails to respond to treatment with routine wound care and topical silver nitrate, we prescribe twice-daily application of timolol maleate ophthalmic gel forming solution 0.5% for up to 14 days or until complete resolution of the hypergranulation is achieved. We counsel patients to continue routine wound care with daily dressing changes in conjunction with topical timolol application.

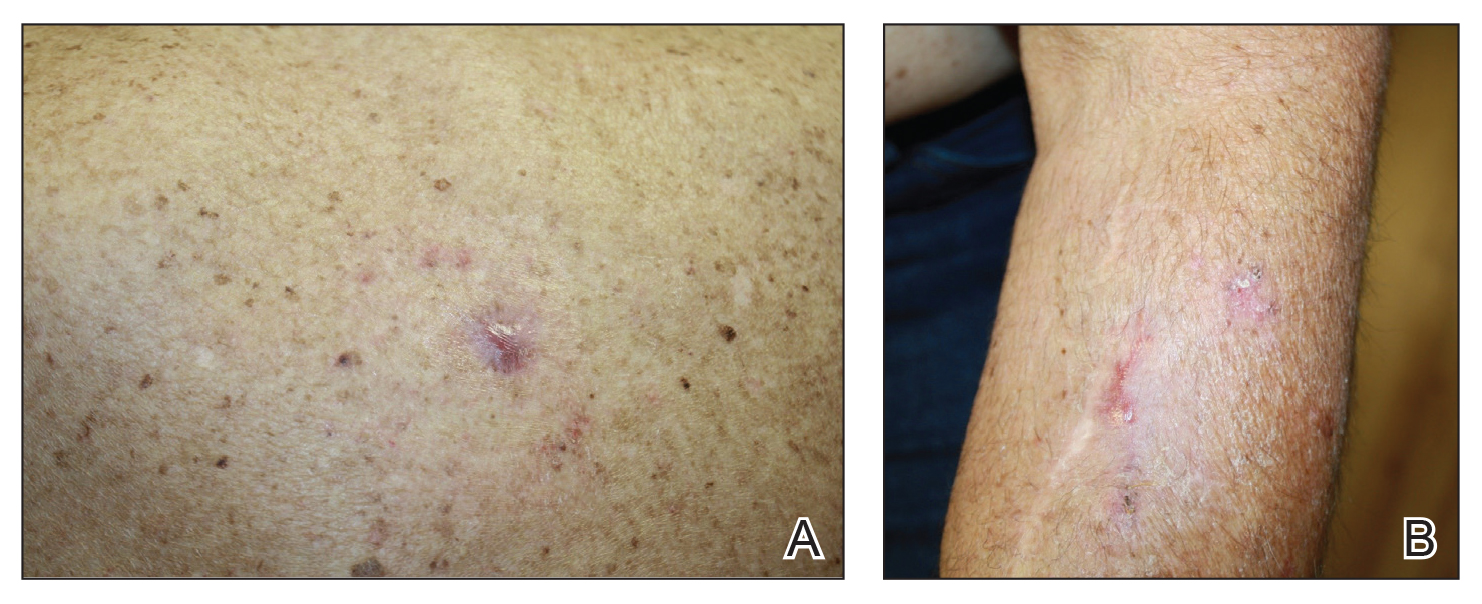

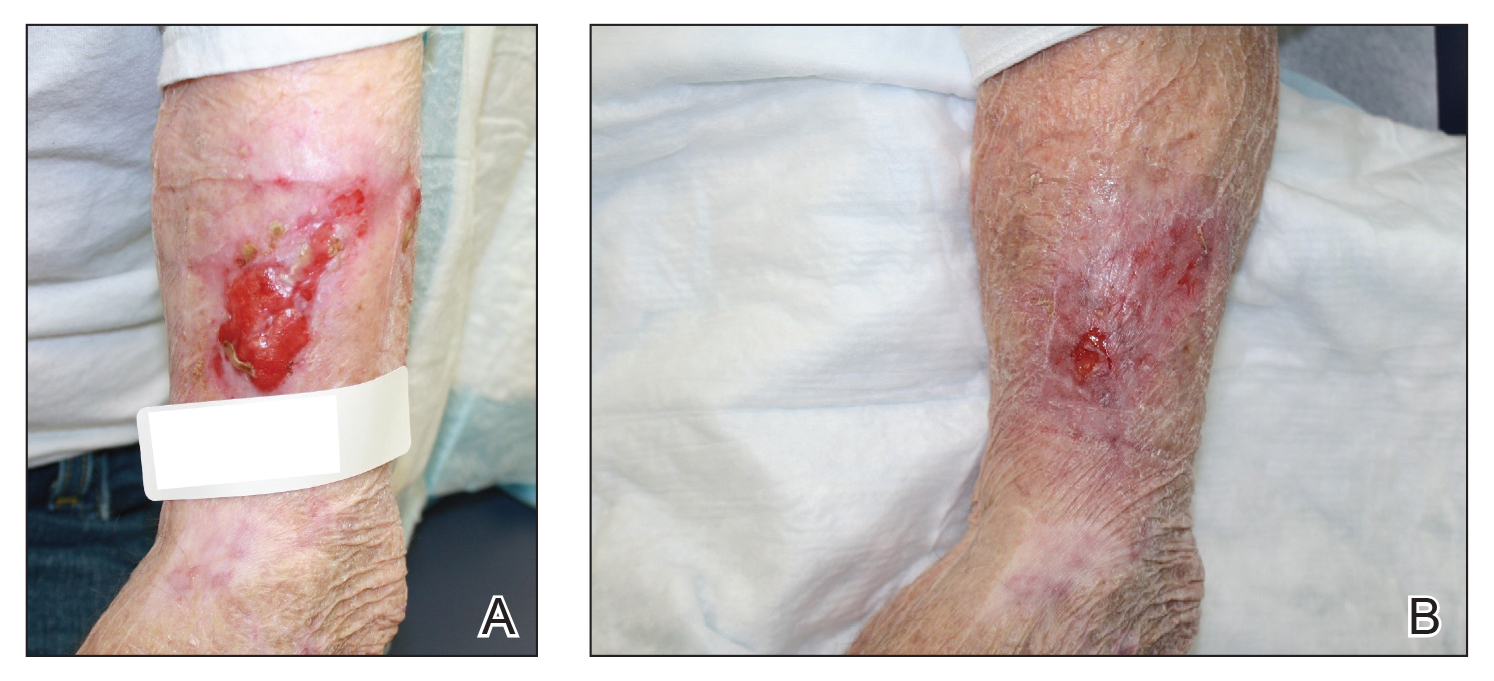

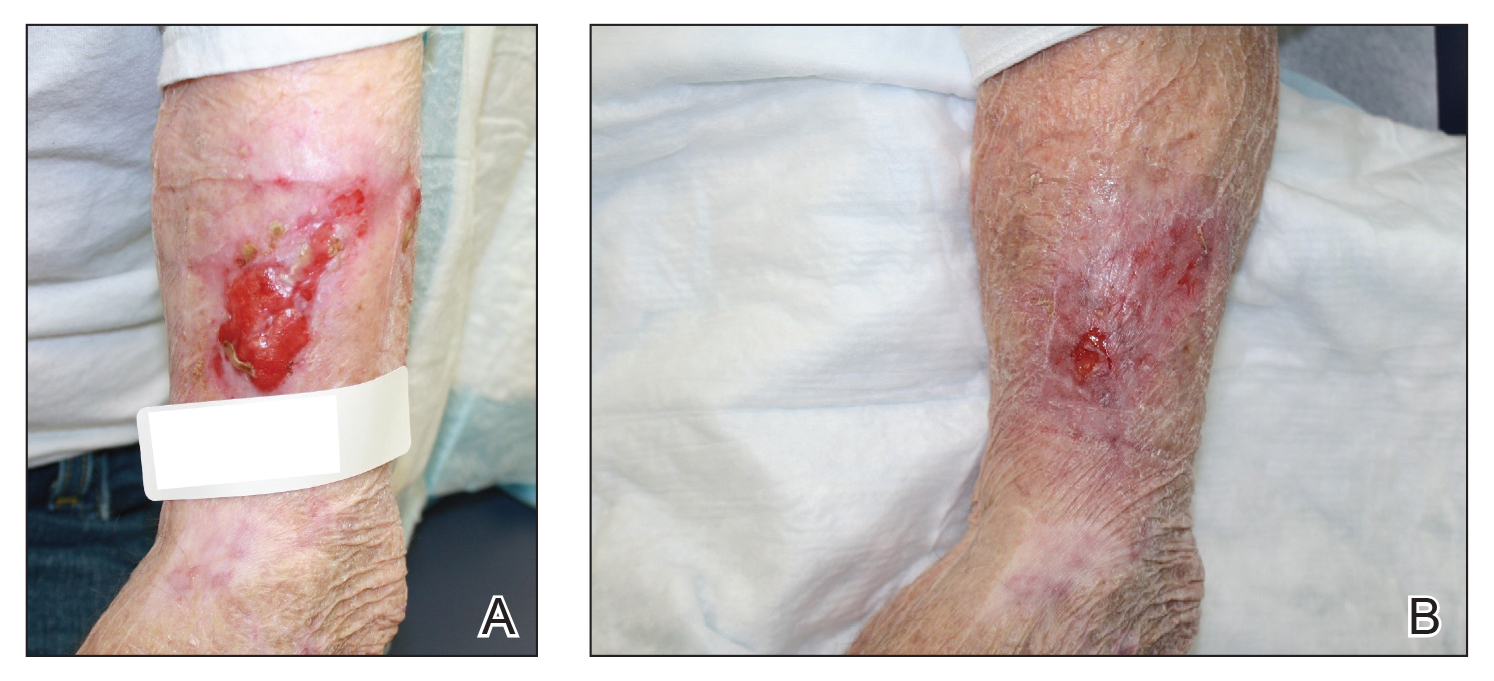

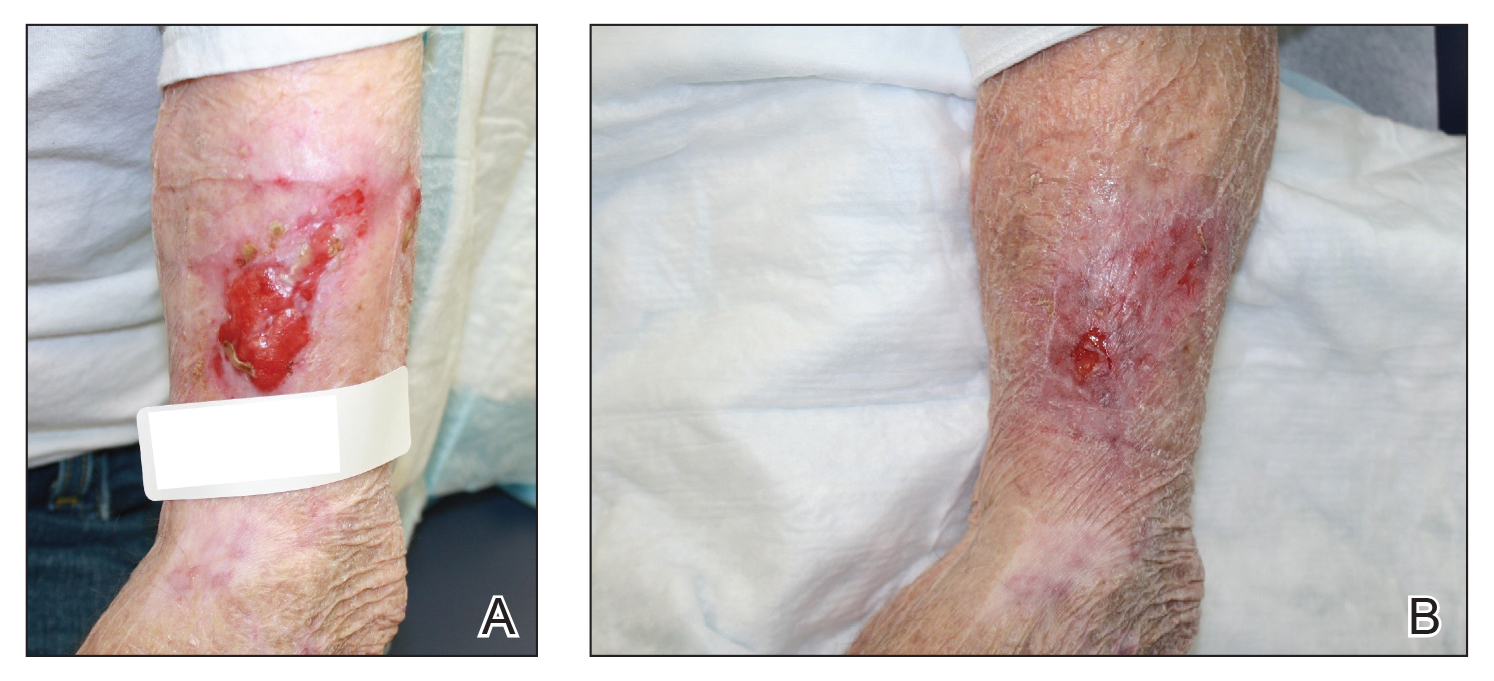

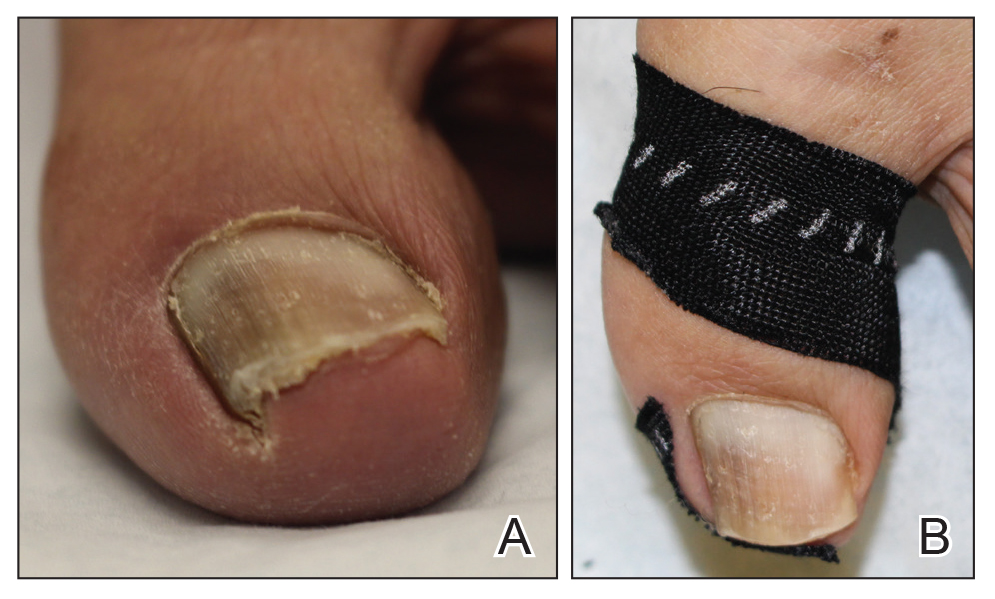

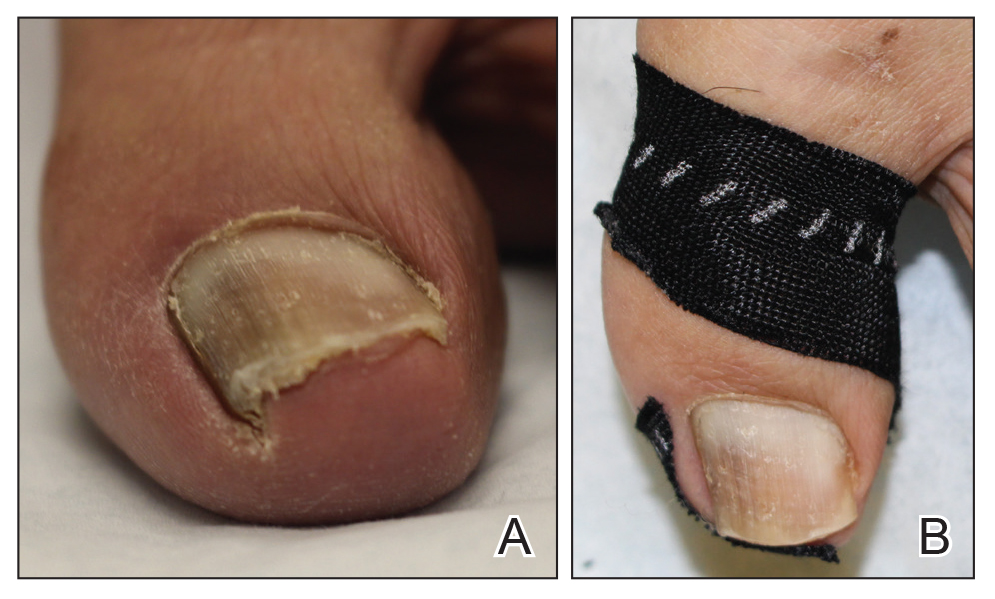

We initiated treatment with topical timolol in a patient who developed hypergranulation at 2 separate electrodesiccation and curettage sites that was refractory to 6 weeks of routine wound care with white petrolatum under nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and 2 subsequent topical silver nitrate applications (Figure 1). After 2 weeks of treatment with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 2). Another patient presented with hypergranulation that developed following a traumatic injury on the left upper arm and had been treated unsuccessfully for several months at a wound care clinic with daily nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and both topical and oral antibiotics (Figure 3A). After treatment for 9 days with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Beta-blockers are increasingly being used for management of chronic nonhealing wounds since the 1990s when oral administration of propranolol initially was reported to be an effective adjuvant therapy for managing severe burns.1 Since then, topical beta-blockers have been reported to be effective for management of ulcerated hemangiomas, venous stasis ulcers, chronic diabetic ulcers, and chronic nonhealing surgical wounds; however, there are no known reports of using topical beta-blockers for management of hypergranulation.2-5 We found timolol ophthalmic gel to be an excellent second-line therapy for management of postoperative hypergranulation if prior treatment with routine wound care and superpotent topical corticosteroids has failed. To date, we have found no reported adverse effects from the use of topical timolol for this indication that have required discontinuation of the medication. Use of this simple and safe intervention can be effective as a solution to a common postoperative condition.

- Herndon DN, Hart DW, Wolf SE, et al. Reversal of catabolism by beta-blockade after severe burns. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1223-1229.

- Pope E, Chakkittakandiyil A. Topical timolol gel for infantile hemangiomas: a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:564-565.

- Braun L, Lamel S, Richmond N, et al. Topical timolol for recalcitrant wounds. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1400-1402.

- Thomas B, Kurien J, Jose T, et al. Topical timolol promotes healing of chronic leg ulcer. J Vasc Surg. 2017;5:844-850.

- Tang J, Dosal J, Kirsner RS. Topical timolol for a refractory wound. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:135-138.

Practice Gap

Hypergranulation is a frequent complication of dermatologic surgery, especially when surgical defects are left to heal by secondary intention (eg, after electrodesiccation and curettage). Although management of postoperative hypergranulation with routine wound care, superpotent topical corticosteroids, and/or topical silver nitrate often is effective, refractory cases pose a difficult challenge given the paucity of treatment options. Effective management of these cases is important because hypergranulation can delay wound healing, cause patient discomfort, and lead to poor wound cosmesis.

The Technique

If refractory hypergranulation fails to respond to treatment with routine wound care and topical silver nitrate, we prescribe twice-daily application of timolol maleate ophthalmic gel forming solution 0.5% for up to 14 days or until complete resolution of the hypergranulation is achieved. We counsel patients to continue routine wound care with daily dressing changes in conjunction with topical timolol application.

We initiated treatment with topical timolol in a patient who developed hypergranulation at 2 separate electrodesiccation and curettage sites that was refractory to 6 weeks of routine wound care with white petrolatum under nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and 2 subsequent topical silver nitrate applications (Figure 1). After 2 weeks of treatment with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 2). Another patient presented with hypergranulation that developed following a traumatic injury on the left upper arm and had been treated unsuccessfully for several months at a wound care clinic with daily nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and both topical and oral antibiotics (Figure 3A). After treatment for 9 days with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Beta-blockers are increasingly being used for management of chronic nonhealing wounds since the 1990s when oral administration of propranolol initially was reported to be an effective adjuvant therapy for managing severe burns.1 Since then, topical beta-blockers have been reported to be effective for management of ulcerated hemangiomas, venous stasis ulcers, chronic diabetic ulcers, and chronic nonhealing surgical wounds; however, there are no known reports of using topical beta-blockers for management of hypergranulation.2-5 We found timolol ophthalmic gel to be an excellent second-line therapy for management of postoperative hypergranulation if prior treatment with routine wound care and superpotent topical corticosteroids has failed. To date, we have found no reported adverse effects from the use of topical timolol for this indication that have required discontinuation of the medication. Use of this simple and safe intervention can be effective as a solution to a common postoperative condition.

Practice Gap

Hypergranulation is a frequent complication of dermatologic surgery, especially when surgical defects are left to heal by secondary intention (eg, after electrodesiccation and curettage). Although management of postoperative hypergranulation with routine wound care, superpotent topical corticosteroids, and/or topical silver nitrate often is effective, refractory cases pose a difficult challenge given the paucity of treatment options. Effective management of these cases is important because hypergranulation can delay wound healing, cause patient discomfort, and lead to poor wound cosmesis.

The Technique

If refractory hypergranulation fails to respond to treatment with routine wound care and topical silver nitrate, we prescribe twice-daily application of timolol maleate ophthalmic gel forming solution 0.5% for up to 14 days or until complete resolution of the hypergranulation is achieved. We counsel patients to continue routine wound care with daily dressing changes in conjunction with topical timolol application.

We initiated treatment with topical timolol in a patient who developed hypergranulation at 2 separate electrodesiccation and curettage sites that was refractory to 6 weeks of routine wound care with white petrolatum under nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and 2 subsequent topical silver nitrate applications (Figure 1). After 2 weeks of treatment with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 2). Another patient presented with hypergranulation that developed following a traumatic injury on the left upper arm and had been treated unsuccessfully for several months at a wound care clinic with daily nonadherent sterile gauze dressings and both topical and oral antibiotics (Figure 3A). After treatment for 9 days with topical timolol, resolution of the hypergranulation and re-epithelialization of the surgical sites was observed (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Beta-blockers are increasingly being used for management of chronic nonhealing wounds since the 1990s when oral administration of propranolol initially was reported to be an effective adjuvant therapy for managing severe burns.1 Since then, topical beta-blockers have been reported to be effective for management of ulcerated hemangiomas, venous stasis ulcers, chronic diabetic ulcers, and chronic nonhealing surgical wounds; however, there are no known reports of using topical beta-blockers for management of hypergranulation.2-5 We found timolol ophthalmic gel to be an excellent second-line therapy for management of postoperative hypergranulation if prior treatment with routine wound care and superpotent topical corticosteroids has failed. To date, we have found no reported adverse effects from the use of topical timolol for this indication that have required discontinuation of the medication. Use of this simple and safe intervention can be effective as a solution to a common postoperative condition.

- Herndon DN, Hart DW, Wolf SE, et al. Reversal of catabolism by beta-blockade after severe burns. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1223-1229.

- Pope E, Chakkittakandiyil A. Topical timolol gel for infantile hemangiomas: a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:564-565.

- Braun L, Lamel S, Richmond N, et al. Topical timolol for recalcitrant wounds. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1400-1402.

- Thomas B, Kurien J, Jose T, et al. Topical timolol promotes healing of chronic leg ulcer. J Vasc Surg. 2017;5:844-850.

- Tang J, Dosal J, Kirsner RS. Topical timolol for a refractory wound. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:135-138.

- Herndon DN, Hart DW, Wolf SE, et al. Reversal of catabolism by beta-blockade after severe burns. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1223-1229.

- Pope E, Chakkittakandiyil A. Topical timolol gel for infantile hemangiomas: a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:564-565.

- Braun L, Lamel S, Richmond N, et al. Topical timolol for recalcitrant wounds. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1400-1402.

- Thomas B, Kurien J, Jose T, et al. Topical timolol promotes healing of chronic leg ulcer. J Vasc Surg. 2017;5:844-850.

- Tang J, Dosal J, Kirsner RS. Topical timolol for a refractory wound. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:135-138.

Clinical Pearl: Benzethonium Chloride for Habit-Tic Nail Deformity

Practice Gap

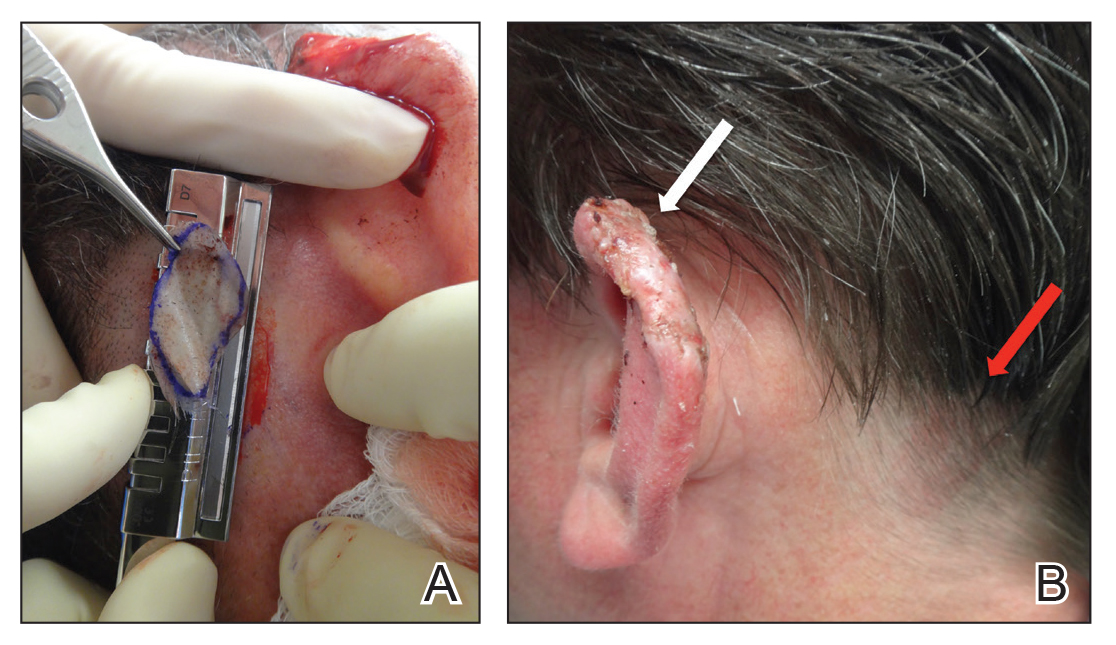

Habit-tic nail deformity results from repetitive manipulation of the cuticle and/or proximal nail fold. It most commonly affects one or both thumbnails and presents with a characteristic longitudinal midline furrow with parallel transverse ridges in the nail plate. Complications may include permanent onychodystrophy, frictional melanonychia, and infections. Treatment is challenging, as diagnosis first requires patient insight to the cause of symptoms. Therapeutic options include nonpharmacologic techniques (eg, occlusion of the nails to prevent trauma, cyanoacrylate adhesives, cognitive behavioral therapy) and pharmacologic techniques (eg, N-acetyl cysteine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, antipsychotics), with limited supporting data and potential adverse effects.1

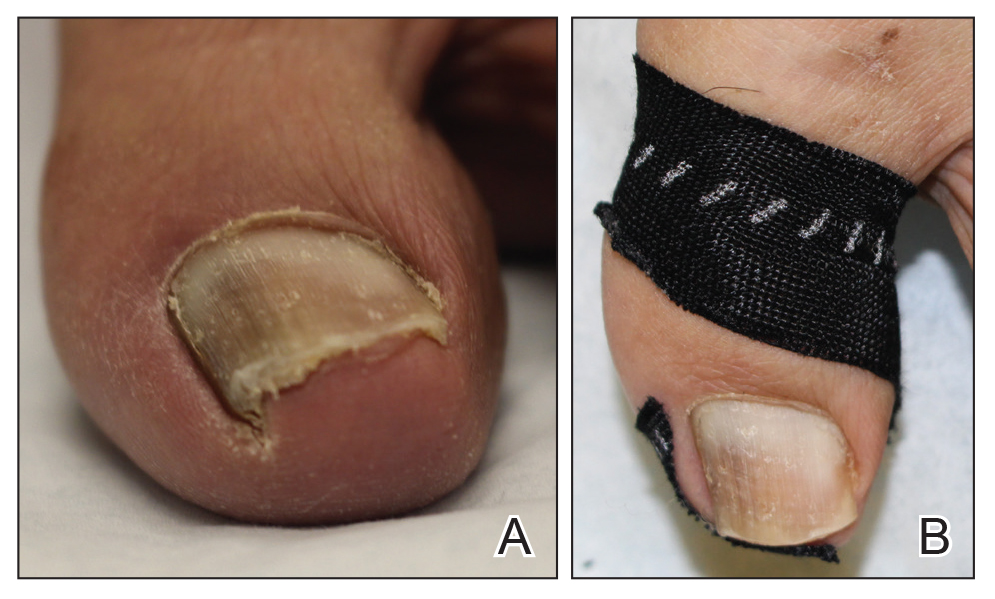

The Technique

Benzethonium chloride solution 0.2% is an antiseptic that creates a polymeric layer that binds to the skin. It normally is used to treat small skin erosions and prevent blisters. In patients with habit-tic nail deformity, we recommend once-daily application of benzethonium chloride to the proximal nail fold, thereby artificially recreating the cuticle and forming a sustainable barrier from trauma (Figure, A). Patients should be reminded not to manipulate the cuticle and/or nail fold during treatment. In one 36-year-old man with habit tic nail deformity, we saw clear nail growth after 4 months of treatment (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Successful treatment of habit-tic nail deformity requires patients to have some insight into their behavior. The benzethonium chloride serves as a reminder for patients to stop picking as an unfamiliar artificial barrier and reminds them to substitute the picking behavior for another more positive behavior. Therefore, benzethonium chloride may be offered to patients as a novel therapy to both protect the cuticle and alter behavior in patients with habit-tic nail deformity, as it can be difficult to treat with few available therapies.

Allergic contact dermatitis to benzethonium chloride is a potential side effect and patients should be cautioned prior to treatment; however, it is extremely rare with 6 cases reported to date based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms allergic contact dermatitis and benzethonium chloride,2 and much rarer than contact allergy to cyanoacrylates.

- Halteh P, Scher RK, Lipner SR. Onychotillomania: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:763-770.

- Hirata Y, Yanagi T, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Ulcerative contact dermatitis caused by benzethonium chloride. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:188-190.

Practice Gap

Habit-tic nail deformity results from repetitive manipulation of the cuticle and/or proximal nail fold. It most commonly affects one or both thumbnails and presents with a characteristic longitudinal midline furrow with parallel transverse ridges in the nail plate. Complications may include permanent onychodystrophy, frictional melanonychia, and infections. Treatment is challenging, as diagnosis first requires patient insight to the cause of symptoms. Therapeutic options include nonpharmacologic techniques (eg, occlusion of the nails to prevent trauma, cyanoacrylate adhesives, cognitive behavioral therapy) and pharmacologic techniques (eg, N-acetyl cysteine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, antipsychotics), with limited supporting data and potential adverse effects.1

The Technique

Benzethonium chloride solution 0.2% is an antiseptic that creates a polymeric layer that binds to the skin. It normally is used to treat small skin erosions and prevent blisters. In patients with habit-tic nail deformity, we recommend once-daily application of benzethonium chloride to the proximal nail fold, thereby artificially recreating the cuticle and forming a sustainable barrier from trauma (Figure, A). Patients should be reminded not to manipulate the cuticle and/or nail fold during treatment. In one 36-year-old man with habit tic nail deformity, we saw clear nail growth after 4 months of treatment (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Successful treatment of habit-tic nail deformity requires patients to have some insight into their behavior. The benzethonium chloride serves as a reminder for patients to stop picking as an unfamiliar artificial barrier and reminds them to substitute the picking behavior for another more positive behavior. Therefore, benzethonium chloride may be offered to patients as a novel therapy to both protect the cuticle and alter behavior in patients with habit-tic nail deformity, as it can be difficult to treat with few available therapies.

Allergic contact dermatitis to benzethonium chloride is a potential side effect and patients should be cautioned prior to treatment; however, it is extremely rare with 6 cases reported to date based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms allergic contact dermatitis and benzethonium chloride,2 and much rarer than contact allergy to cyanoacrylates.

Practice Gap

Habit-tic nail deformity results from repetitive manipulation of the cuticle and/or proximal nail fold. It most commonly affects one or both thumbnails and presents with a characteristic longitudinal midline furrow with parallel transverse ridges in the nail plate. Complications may include permanent onychodystrophy, frictional melanonychia, and infections. Treatment is challenging, as diagnosis first requires patient insight to the cause of symptoms. Therapeutic options include nonpharmacologic techniques (eg, occlusion of the nails to prevent trauma, cyanoacrylate adhesives, cognitive behavioral therapy) and pharmacologic techniques (eg, N-acetyl cysteine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, antipsychotics), with limited supporting data and potential adverse effects.1

The Technique

Benzethonium chloride solution 0.2% is an antiseptic that creates a polymeric layer that binds to the skin. It normally is used to treat small skin erosions and prevent blisters. In patients with habit-tic nail deformity, we recommend once-daily application of benzethonium chloride to the proximal nail fold, thereby artificially recreating the cuticle and forming a sustainable barrier from trauma (Figure, A). Patients should be reminded not to manipulate the cuticle and/or nail fold during treatment. In one 36-year-old man with habit tic nail deformity, we saw clear nail growth after 4 months of treatment (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Successful treatment of habit-tic nail deformity requires patients to have some insight into their behavior. The benzethonium chloride serves as a reminder for patients to stop picking as an unfamiliar artificial barrier and reminds them to substitute the picking behavior for another more positive behavior. Therefore, benzethonium chloride may be offered to patients as a novel therapy to both protect the cuticle and alter behavior in patients with habit-tic nail deformity, as it can be difficult to treat with few available therapies.

Allergic contact dermatitis to benzethonium chloride is a potential side effect and patients should be cautioned prior to treatment; however, it is extremely rare with 6 cases reported to date based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms allergic contact dermatitis and benzethonium chloride,2 and much rarer than contact allergy to cyanoacrylates.

- Halteh P, Scher RK, Lipner SR. Onychotillomania: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:763-770.

- Hirata Y, Yanagi T, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Ulcerative contact dermatitis caused by benzethonium chloride. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:188-190.

- Halteh P, Scher RK, Lipner SR. Onychotillomania: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:763-770.

- Hirata Y, Yanagi T, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Ulcerative contact dermatitis caused by benzethonium chloride. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:188-190.

Clinical Pearl: Advantages of the Scalp as a Split-Thickness Skin Graft Donor Site

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

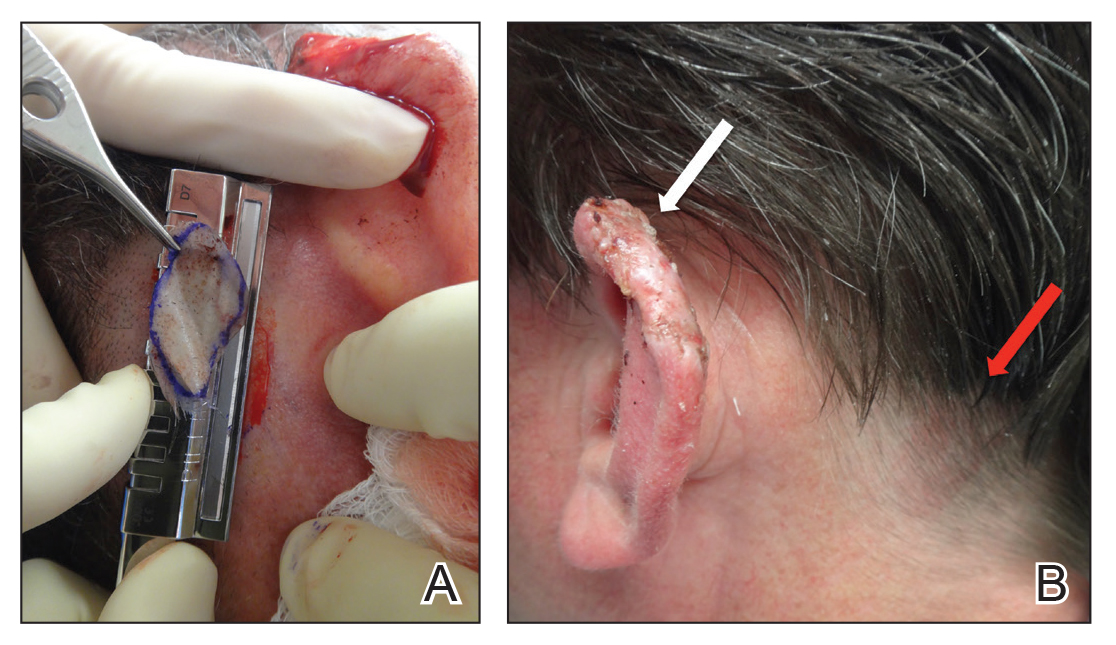

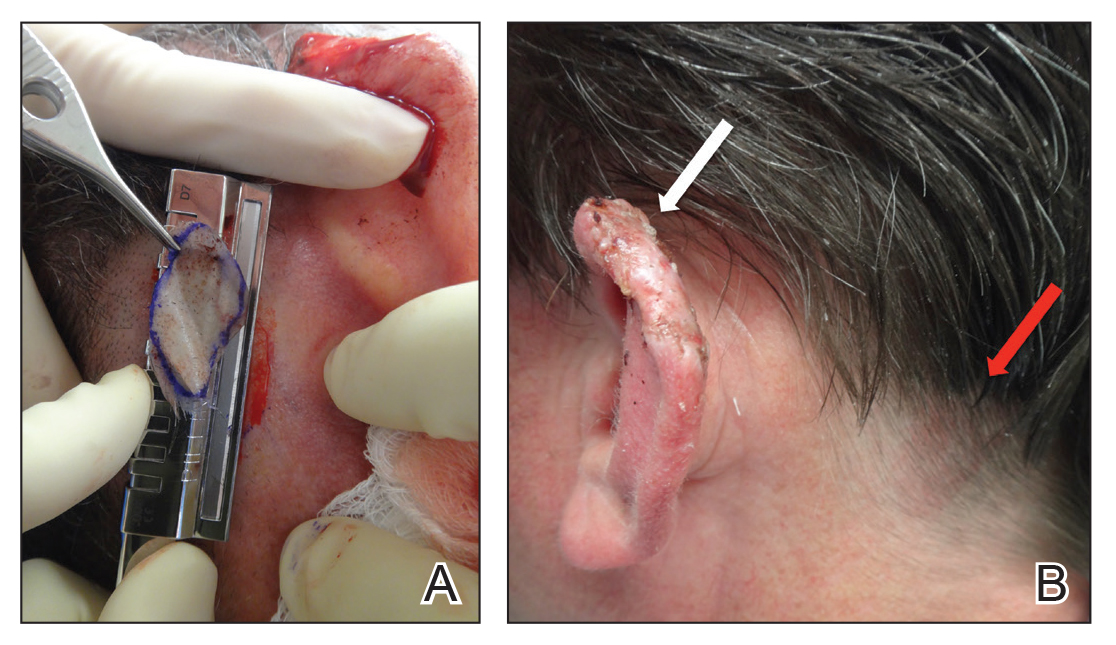

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

- Aneer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:28-35.

- Goulian D. A new economical dermatome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42:85-86.

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique

The donor site is lubricated with a sterile mineral oil. An assistant provides tension, leading the trajectory of the Weck knife with a guard. Small, gentle, back-and-forth strokes are made with the Weck knife to harvest the graft, which is then meshed with a No. 15 blade by placing the belly of the blade on the tissue and rolling it to-and-fro. The recipient site cartilage is fenestrated with a 2-mm punch biopsy.

A 48-year-old man underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of a primary basal cell carcinoma of the left helix, resulting in a 2.5×1.3-cm defect after 2 stages. A Weck knife with a 0.012-in guard was used to harvest an STSG from the postauricular scalp (Figure, A), and the graft was inset to the recipient wound bed. Hemostasis at the scalp donor site was achieved through application of pressure and sterile gauze that was saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine. Both recipient and donor sites were dressed with tie-over bolsters that were sutured into place. At 2-week follow-up, the donor site was fully reepithelialized and hair regrowth obscured the defect (Figure, B).

Practice Implications

Our case demonstrates the advantages of the scalp as an STSG donor site with prompt healing time and excellent cosmesis. Because grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, the hair regrows to conceal the donor site scar. Additionally, the robust blood supply of the scalp and hair follicle density optimize healing time. The location of the donor site at the postauricular scalp facilitates accessibility for wound care by the patient. Electrocautery or chemical styptics used for hemostasis may traumatize the hair follicles and risk causing alopecia; therefore, as demonstrated in our case, the preferred method to achieve hemostasis is the use of pressure or application of sterile gauze that has been saturated with local 1% lidocaine anesthesia containing 1:400,000 epinephrine, followed by a pressure dressing provided by a sutured bolster.

Our case also demonstrates the utility of the Weck knife, which was introduced in 1968 as a modification of existing instruments to improve the ease of harvesting STSGs by appending a fixed handle and interchangeable depth gauges to a straight razor.1,2 The Weck knife can obtain grafts up to 5.5 cm in width (length may be as long as anatomically available), often circumventing the need to overlap grafts of smaller widths for repair of larger defects. Furthermore, grafts are harvested at a depth superficial to the hair follicle, averting donor site alopecia. These characteristics make the technique an ideal option for harvesting grafts from the scalp and other large donor sites.

Limitations of the Weck knife technique include the inability to harvest grafts from small donor sites in difficult-to-access anatomic regions or from areas with notable 3-dimensional structure. For harvesting such grafts, we prefer the DermaBlade (AccuTec Blades). Furthermore, assistance for providing tension along the trajectory of the Weck blade with a guard is optimal when performing the procedure. For practices not already utilizing a Weck knife, the technique necessitates additional training and cost. Nonetheless, for STSGs in which large donor site surface area, adjustable thickness, and convenient and timely operational technique are desired, the Weck knife should be considered as part of the dermatologic surgeon’s armamentarium.

Practice Gap

Common donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) include the abdomen, buttocks, inner upper arms and forearms, and thighs. Challenges associated with donor site wounds in these areas include slow healing times and poor scar cosmesis. Although the scalp is not commonly considered when selecting a STSG donor site, harvesting from this area yields optimal results to improve these shortcomings.

Tools

A Weck knife facilitates STSG harvesting in an operationally timely, convenient fashion from larger donor sites up to 5.5 cm in width, such as the scalp, using adjustable thickness control guards.

The Technique