User login

Severe itching in 2-year-old

The FP recognized that the boy had a case of severe atopic dermatitis. There was considerable inflammation of the skin, but the erythema was less visible because of the boy’s darker skin color.

The father had the full atopic triad: asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis. This explained the son’s inheritance of atopic dermatitis. The FP recommended aggressive treatment and the father was relieved, as it hurt him to see his son suffer.

The FP prescribed a tub (454 g) of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be used twice daily all over the involved skin, especially after bathing. The FP said that the child should be given a daily bath with mild soap. (There is no data to support the notion that bathing dries out the skin; bathing before the use of topical steroids actually helps the steroids absorb into the skin.)

Oral hydroxyzine was prescribed for use before bedtime, as this sedating antihistamine can improve sleep and diminish pruritus. Considering the severity of the condition, the FP decided to prescribe a short course of oral prednisolone for one week (1 mg/kg/d). There is some evidence that dilute bleach baths help atopic dermatitis, but the FP decided to discuss this at a future visit—after the flare had subsided. There was no evidence of a secondary infection, so antibiotics weren’t prescribed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that the boy had a case of severe atopic dermatitis. There was considerable inflammation of the skin, but the erythema was less visible because of the boy’s darker skin color.

The father had the full atopic triad: asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis. This explained the son’s inheritance of atopic dermatitis. The FP recommended aggressive treatment and the father was relieved, as it hurt him to see his son suffer.

The FP prescribed a tub (454 g) of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be used twice daily all over the involved skin, especially after bathing. The FP said that the child should be given a daily bath with mild soap. (There is no data to support the notion that bathing dries out the skin; bathing before the use of topical steroids actually helps the steroids absorb into the skin.)

Oral hydroxyzine was prescribed for use before bedtime, as this sedating antihistamine can improve sleep and diminish pruritus. Considering the severity of the condition, the FP decided to prescribe a short course of oral prednisolone for one week (1 mg/kg/d). There is some evidence that dilute bleach baths help atopic dermatitis, but the FP decided to discuss this at a future visit—after the flare had subsided. There was no evidence of a secondary infection, so antibiotics weren’t prescribed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that the boy had a case of severe atopic dermatitis. There was considerable inflammation of the skin, but the erythema was less visible because of the boy’s darker skin color.

The father had the full atopic triad: asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis. This explained the son’s inheritance of atopic dermatitis. The FP recommended aggressive treatment and the father was relieved, as it hurt him to see his son suffer.

The FP prescribed a tub (454 g) of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be used twice daily all over the involved skin, especially after bathing. The FP said that the child should be given a daily bath with mild soap. (There is no data to support the notion that bathing dries out the skin; bathing before the use of topical steroids actually helps the steroids absorb into the skin.)

Oral hydroxyzine was prescribed for use before bedtime, as this sedating antihistamine can improve sleep and diminish pruritus. Considering the severity of the condition, the FP decided to prescribe a short course of oral prednisolone for one week (1 mg/kg/d). There is some evidence that dilute bleach baths help atopic dermatitis, but the FP decided to discuss this at a future visit—after the flare had subsided. There was no evidence of a secondary infection, so antibiotics weren’t prescribed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Child with various rashes

The FP made the diagnoses of atopic dermatitis (especially in the popliteal fossae) and pityriasis alba, which was seen on the child’s face and arms. Pityriasis alba is very common in children (especially in those who also have atopic dermatitis), but it can occur in children without atopic dermatitis, as well. The condition is characterized by hypopigmented patches of skin and is of cosmetic concern only.

The FP prescribed 2.5% hydrocortisone ointment for both conditions and told the mother that she would need to apply it once to twice daily, as needed. The FP explained that the hypopigmentation would take longer to resolve than the inflammatory erythema. Fortunately, atopic dermatitis in children typically resolves by adulthood.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP made the diagnoses of atopic dermatitis (especially in the popliteal fossae) and pityriasis alba, which was seen on the child’s face and arms. Pityriasis alba is very common in children (especially in those who also have atopic dermatitis), but it can occur in children without atopic dermatitis, as well. The condition is characterized by hypopigmented patches of skin and is of cosmetic concern only.

The FP prescribed 2.5% hydrocortisone ointment for both conditions and told the mother that she would need to apply it once to twice daily, as needed. The FP explained that the hypopigmentation would take longer to resolve than the inflammatory erythema. Fortunately, atopic dermatitis in children typically resolves by adulthood.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP made the diagnoses of atopic dermatitis (especially in the popliteal fossae) and pityriasis alba, which was seen on the child’s face and arms. Pityriasis alba is very common in children (especially in those who also have atopic dermatitis), but it can occur in children without atopic dermatitis, as well. The condition is characterized by hypopigmented patches of skin and is of cosmetic concern only.

The FP prescribed 2.5% hydrocortisone ointment for both conditions and told the mother that she would need to apply it once to twice daily, as needed. The FP explained that the hypopigmentation would take longer to resolve than the inflammatory erythema. Fortunately, atopic dermatitis in children typically resolves by adulthood.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Hemodialysis patient with finger ulcerations

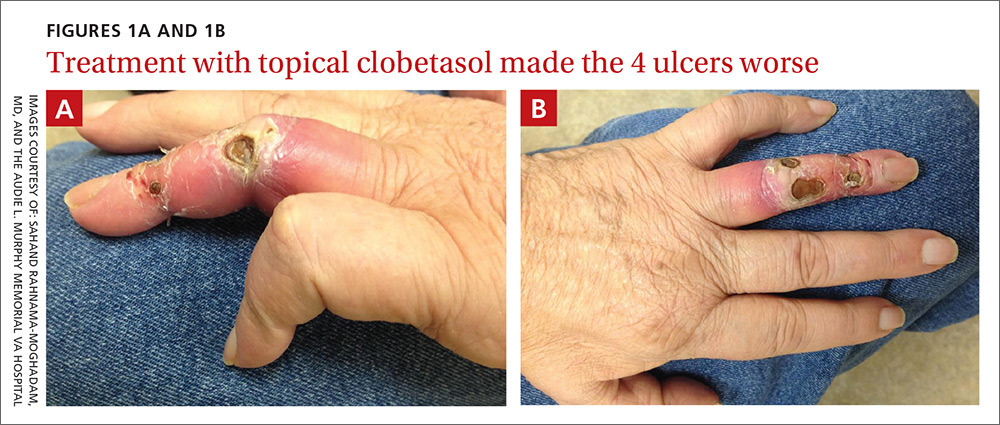

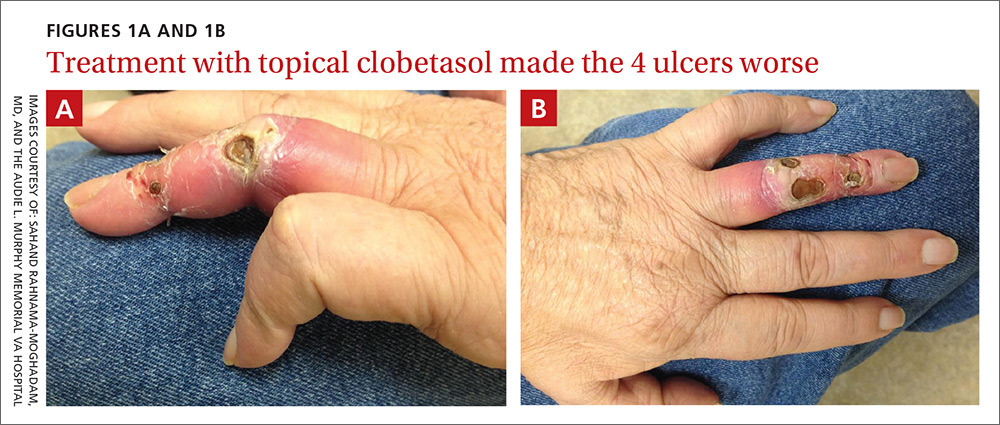

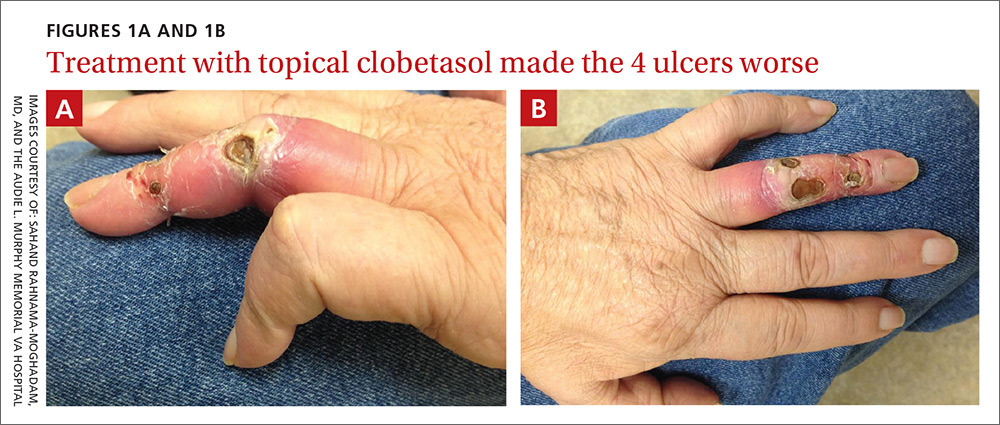

A 62-year-old man with end-stage renal disease presented to our dermatology clinic with 2-month-old ulcerations on his distal left ring finger. He was on hemodialysis and had a radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF) on his left arm. He had been empirically treated elsewhere with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a presumed bacterial infection, without improvement. He was then treated for contact dermatitis with topical clobetasol, which led to ulcer expansion and worsening pain.

At our clinic, the patient reported intermittent pain in his finger and paresthesias during activity and dialysis, but no tenderness of the ulcers. He had atrophy of the intrinsic left hand muscles (his non-dominant hand) with associated weakness. Three weeks earlier, he’d received a blood transfusion for anemia. Afterward, the pain in his hand improved and the ulcers decreased in size.

On exam, the AVF had a palpable thrill over the left forearm. The radial pulses were palpable bilaterally (2+) and the left ulnar artery was palpable, but diminished (1+). The patient’s left hand was cooler than the right (with a slight cyanotic hue and visible intrinsic muscle atrophy) and had decreased sensation to pain and temperature. Four ulcers with dry yellow eschar were located over the dorsal interphalangeal joints (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). They were essentially non-tender, but there was tenderness in the adjacent intact skin. There was violaceous blue edematous congestion noted on the fourth finger, and the distal phalange was constricted, giving it a “pseudoainhum” appearance.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Dialysis access steal syndrome

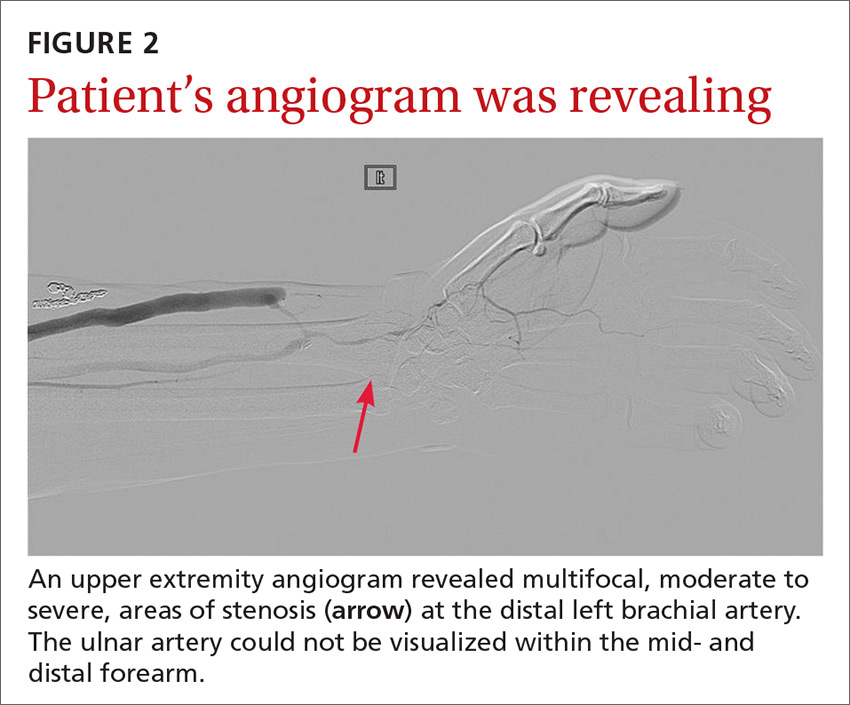

We suspected dialysis access steal syndrome (also known as AVF steal syndrome), so a duplex ultrasound was performed. The ultrasound was inconclusive. (We couldn’t confirm a limitation in blood flow, nor delineate anatomy.) So, we referred the patient for a thoracic and upper extremity angiogram.

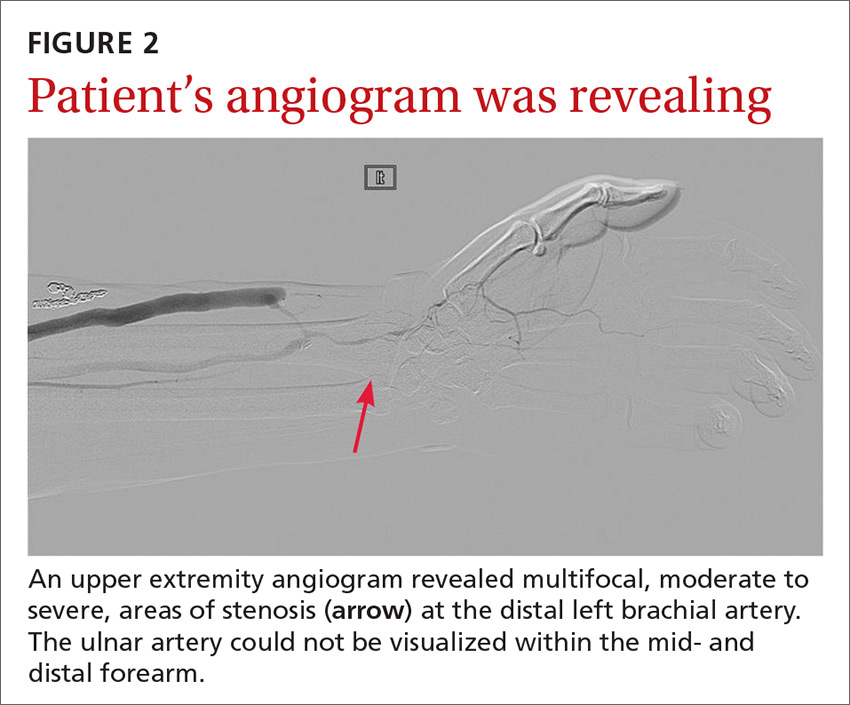

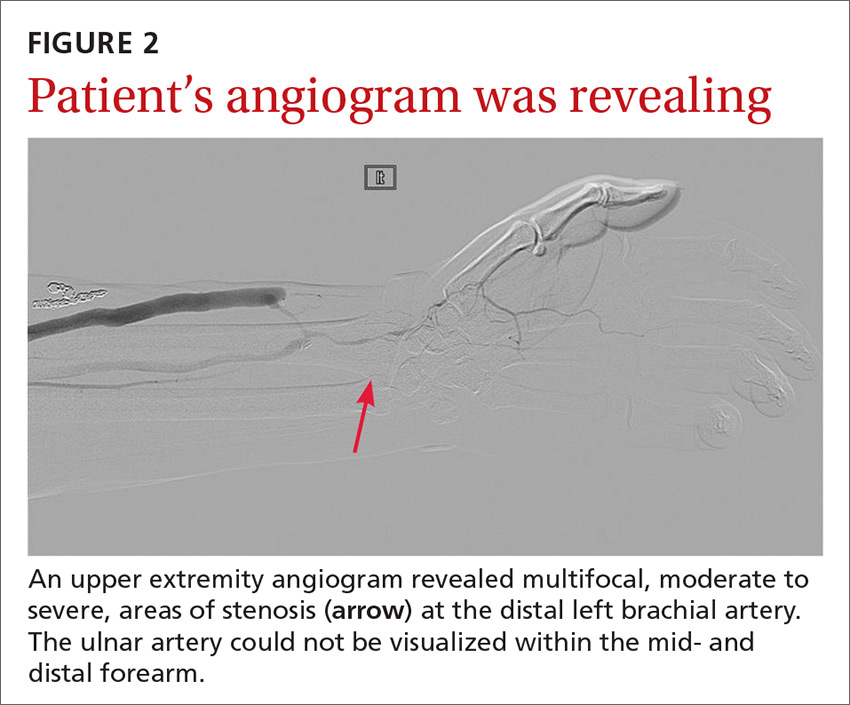

The angiogram demonstrated multifocal, moderate to severe, areas of stenosis at the distal left brachial artery. The radial artery was patent at the level of the wrist, but showed diffuse narrowing beyond the level of the arteriovenous (AV) anastomosis. There was only a faint palmar arch identified on the radial aspect of the hand with digital branches feeding the radial portion of the hand. In contrast, the ulnar artery was not seen within the mid- and distal forearm (FIGURE 2). Palmar branches to the ulnar half of the hand were not identified. The fistula itself didn’t show any stenosis.

Based on these findings, our suspicions of dialysis access steal syndrome were confirmed.

Dialysis access steal syndrome is caused by a significant decrease or reversal of blood flow in the arterial segment distal to the AVF or graft, which is induced by the low resistance of the fistula outflow. Patients with adequate collateral vasculature are able to compensate for the steal effect; however, patients with end-stage renal disease typically have preexisting vascular disease that increases the risk for vascular steal and, ultimately, demand ischemia after placement of an AVF.1 Interestingly, a steal effect occurs in 73% of patients after AVF construction, yet it is estimated that only 10% of patients demonstrating a steal phenomenon become symptomatic.2

In our patient’s case, the vaso-occlusive properties of topical steroids explain why the superpotent steroid (clobetasol) he was prescribed increased his pain and worsened the underlying problem.

A broad differential; a useful exam maneuver

The differential diagnosis of ulcers includes infection (mainly from bacterial or mycobacterial sources), trauma facilitated by neuropathy (neuropathic ulceration), vasculitis, and ischemia. When the history and physical exam suggest ischemic ulceration, then thromboembolism, thoracic outlet syndrome, vasculitis, atherosclerosis, and steal syndrome become more likely causes.

Signs and symptoms of ischemic steal syndrome are initially subtle and include extremity coolness, neurosensory changes, intrinsic muscle weakness, ulceration, and ultimately, gangrene of the affected extremity.3,4 A cold, numb, and/or painful hand during dialysis is another clue.3 Factors that increase the likelihood of the syndrome include age >60 years, female sex, and the presence of diabetes or peripheral artery disease.2,3,5,6

One physical exam maneuver that can help make the diagnosis of steal syndrome is manual occlusion of the AVF. If palpable distal pulses disappear when the AVF is patent and reappear when the fistula is occluded with downward pressure, then AVF steal syndrome is likely.4 Pain at rest, sensory loss, loss of pulse, and digital gangrene are emergency symptoms that warrant immediate surgical evaluation.3

Tests will confirm suspicions. Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess changes in the blood flow rate of the affected vessels when the AVF is patent vs when it is occluded. Similarly, pulse oximetry can be used with and without AVF occlusion to compare changes in oxygen saturation. The confirmatory diagnosis, however, is made via a fistulogram (angiography) with and without manual compression.6 Images taken after dye injection into the AVF show dramatic improvement of distal blood flow with AVF compression.

Treatment requires surgery

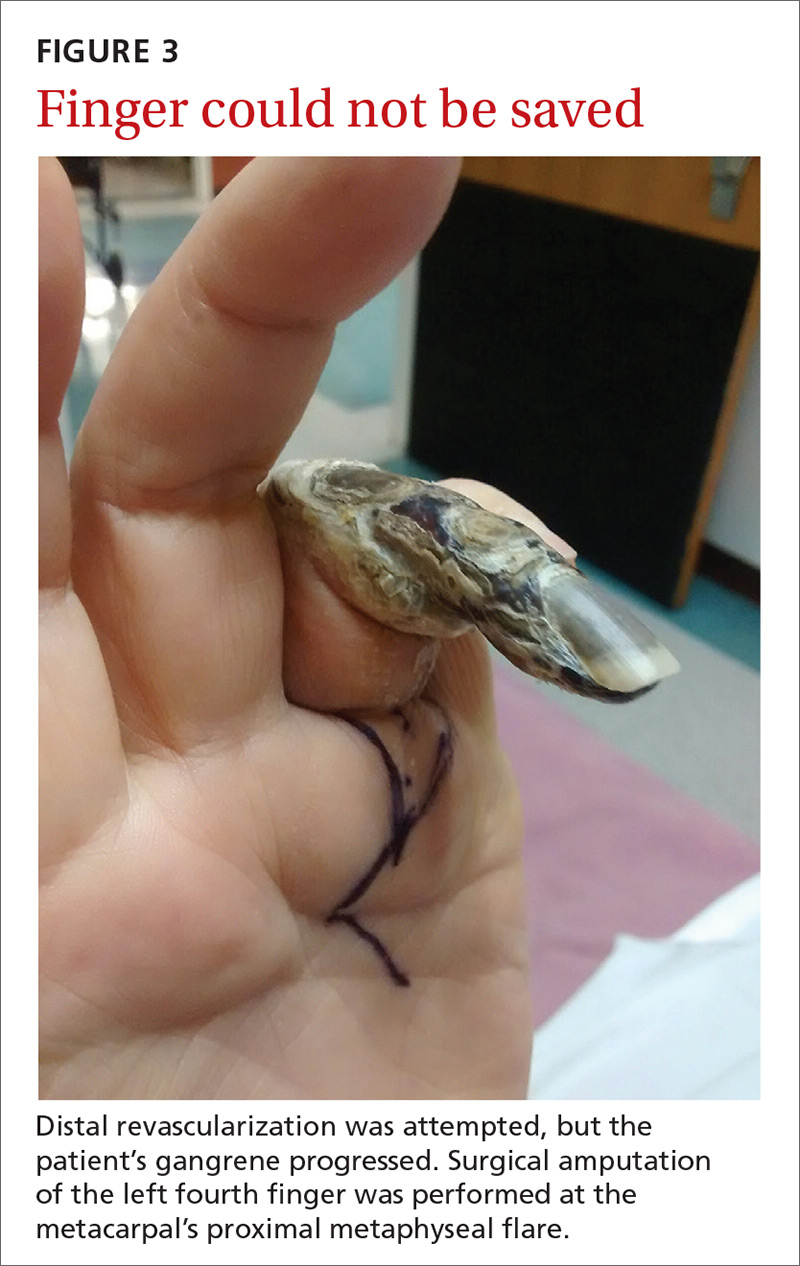

Severe steal-related ischemic manifestations that threaten the function and viability of digits require surgical treatment that is primarily directed toward improving distal blood flow and secondarily toward preserving hemodialysis access. Several surgical treatments are commonly used, including access ligation, banding, elongation, distal arterial ligation, and distal revascularization and interval ligation.2-5,7

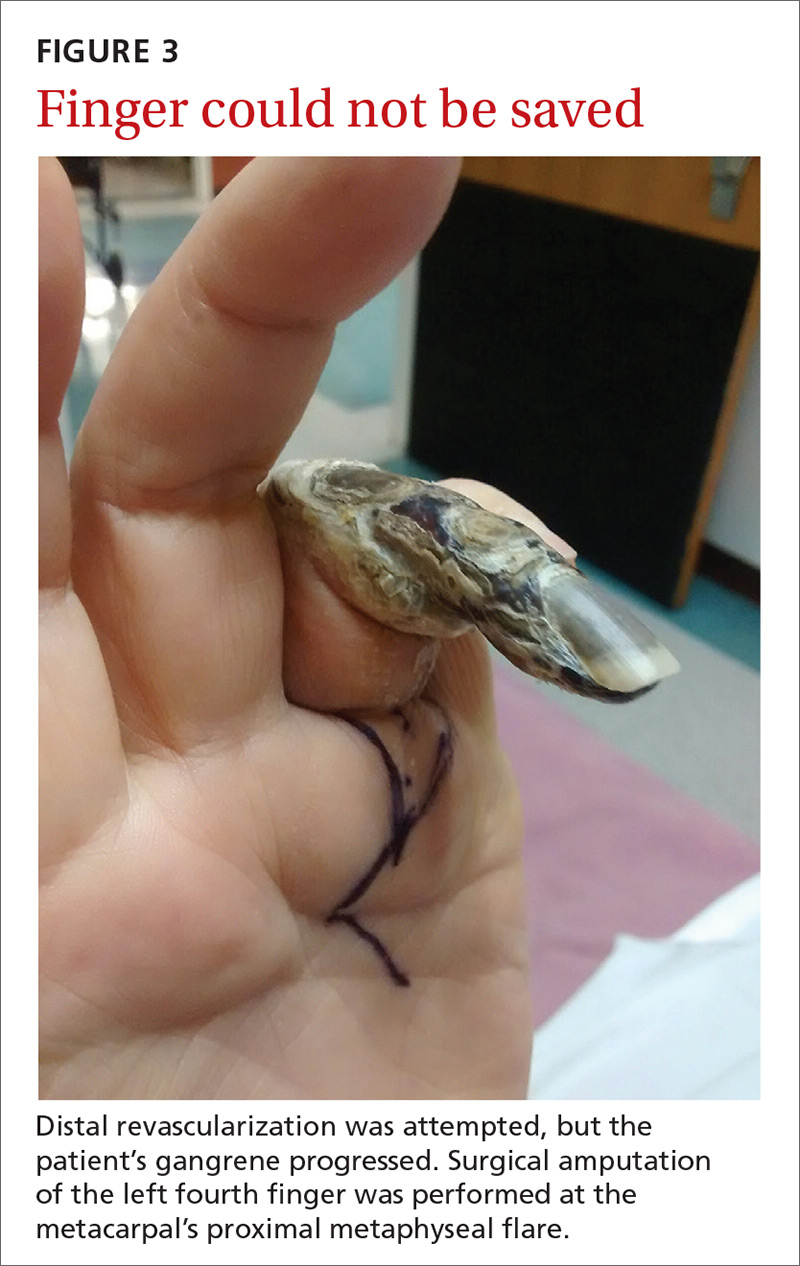

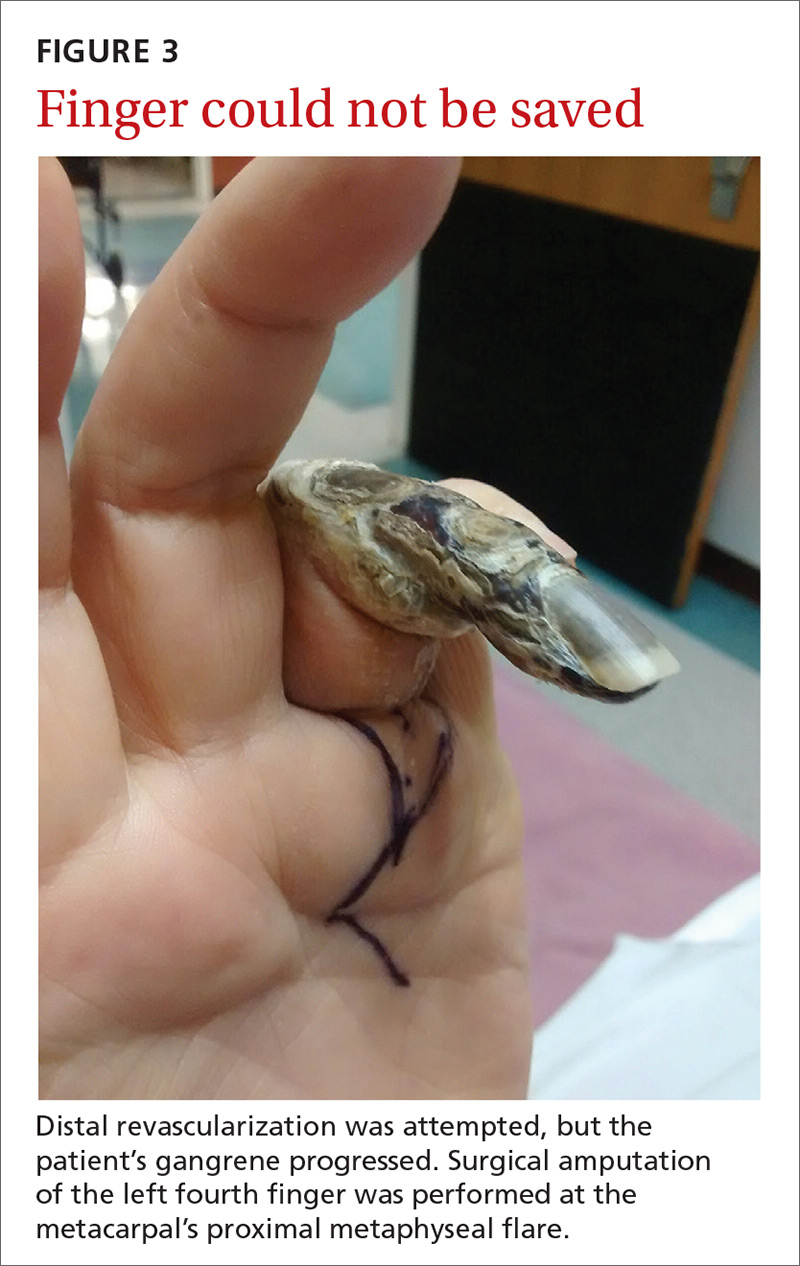

Our patient. Distal revascularization was attempted, but unfortunately, the patient’s gangrene was progressive (FIGURE 3) and surgical amputation of the left fourth finger was performed at the metacarpal’s proximal metaphyseal flare. The patient was transitioned to peritoneal dialysis to avoid further ischemia.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, Department of Dermatology, Indiana University, 545 Barnhill Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46202; [email protected].

1. Morsy AH, Kulbaski M, Chen C, et al. Incidence and characteristics of patients with hand ischemia after a hemodialysis access procedure. J Surg Res. 1998;74:8-10.

2. Puryear A, Villarreal S, Wells MJ, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. Hand ischemia in a hemodialysis patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:393-395.

3. Pelle MT, Miller OF 3rd. Dermatologic manifestations and management of vascular steal syndrome in hemodialysis patients with arteriovenous fistulas. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1296-1298.

4. Wixon CL, Hughes JD, Mills JL. Understanding strategies for the treatment of ischemic steal syndrome after hemodialysis access. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:301-310.

5. Gupta N, Yuo TH, Konig G 4th, et al. Treatment strategies of arterial steal after arteriovenous access. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:162-167.

6. Zamani P, Kaufman J, Kinlay S. Ischemic steal syndrome following arm arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis. Vasc Med. 2009;14:371-376.

7. Leake AE, Winger DG, Leers SA, et al. Management and outcomes of dialysis access-associated steal syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:754-760.

A 62-year-old man with end-stage renal disease presented to our dermatology clinic with 2-month-old ulcerations on his distal left ring finger. He was on hemodialysis and had a radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF) on his left arm. He had been empirically treated elsewhere with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a presumed bacterial infection, without improvement. He was then treated for contact dermatitis with topical clobetasol, which led to ulcer expansion and worsening pain.

At our clinic, the patient reported intermittent pain in his finger and paresthesias during activity and dialysis, but no tenderness of the ulcers. He had atrophy of the intrinsic left hand muscles (his non-dominant hand) with associated weakness. Three weeks earlier, he’d received a blood transfusion for anemia. Afterward, the pain in his hand improved and the ulcers decreased in size.

On exam, the AVF had a palpable thrill over the left forearm. The radial pulses were palpable bilaterally (2+) and the left ulnar artery was palpable, but diminished (1+). The patient’s left hand was cooler than the right (with a slight cyanotic hue and visible intrinsic muscle atrophy) and had decreased sensation to pain and temperature. Four ulcers with dry yellow eschar were located over the dorsal interphalangeal joints (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). They were essentially non-tender, but there was tenderness in the adjacent intact skin. There was violaceous blue edematous congestion noted on the fourth finger, and the distal phalange was constricted, giving it a “pseudoainhum” appearance.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Dialysis access steal syndrome

We suspected dialysis access steal syndrome (also known as AVF steal syndrome), so a duplex ultrasound was performed. The ultrasound was inconclusive. (We couldn’t confirm a limitation in blood flow, nor delineate anatomy.) So, we referred the patient for a thoracic and upper extremity angiogram.

The angiogram demonstrated multifocal, moderate to severe, areas of stenosis at the distal left brachial artery. The radial artery was patent at the level of the wrist, but showed diffuse narrowing beyond the level of the arteriovenous (AV) anastomosis. There was only a faint palmar arch identified on the radial aspect of the hand with digital branches feeding the radial portion of the hand. In contrast, the ulnar artery was not seen within the mid- and distal forearm (FIGURE 2). Palmar branches to the ulnar half of the hand were not identified. The fistula itself didn’t show any stenosis.

Based on these findings, our suspicions of dialysis access steal syndrome were confirmed.

Dialysis access steal syndrome is caused by a significant decrease or reversal of blood flow in the arterial segment distal to the AVF or graft, which is induced by the low resistance of the fistula outflow. Patients with adequate collateral vasculature are able to compensate for the steal effect; however, patients with end-stage renal disease typically have preexisting vascular disease that increases the risk for vascular steal and, ultimately, demand ischemia after placement of an AVF.1 Interestingly, a steal effect occurs in 73% of patients after AVF construction, yet it is estimated that only 10% of patients demonstrating a steal phenomenon become symptomatic.2

In our patient’s case, the vaso-occlusive properties of topical steroids explain why the superpotent steroid (clobetasol) he was prescribed increased his pain and worsened the underlying problem.

A broad differential; a useful exam maneuver

The differential diagnosis of ulcers includes infection (mainly from bacterial or mycobacterial sources), trauma facilitated by neuropathy (neuropathic ulceration), vasculitis, and ischemia. When the history and physical exam suggest ischemic ulceration, then thromboembolism, thoracic outlet syndrome, vasculitis, atherosclerosis, and steal syndrome become more likely causes.

Signs and symptoms of ischemic steal syndrome are initially subtle and include extremity coolness, neurosensory changes, intrinsic muscle weakness, ulceration, and ultimately, gangrene of the affected extremity.3,4 A cold, numb, and/or painful hand during dialysis is another clue.3 Factors that increase the likelihood of the syndrome include age >60 years, female sex, and the presence of diabetes or peripheral artery disease.2,3,5,6

One physical exam maneuver that can help make the diagnosis of steal syndrome is manual occlusion of the AVF. If palpable distal pulses disappear when the AVF is patent and reappear when the fistula is occluded with downward pressure, then AVF steal syndrome is likely.4 Pain at rest, sensory loss, loss of pulse, and digital gangrene are emergency symptoms that warrant immediate surgical evaluation.3

Tests will confirm suspicions. Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess changes in the blood flow rate of the affected vessels when the AVF is patent vs when it is occluded. Similarly, pulse oximetry can be used with and without AVF occlusion to compare changes in oxygen saturation. The confirmatory diagnosis, however, is made via a fistulogram (angiography) with and without manual compression.6 Images taken after dye injection into the AVF show dramatic improvement of distal blood flow with AVF compression.

Treatment requires surgery

Severe steal-related ischemic manifestations that threaten the function and viability of digits require surgical treatment that is primarily directed toward improving distal blood flow and secondarily toward preserving hemodialysis access. Several surgical treatments are commonly used, including access ligation, banding, elongation, distal arterial ligation, and distal revascularization and interval ligation.2-5,7

Our patient. Distal revascularization was attempted, but unfortunately, the patient’s gangrene was progressive (FIGURE 3) and surgical amputation of the left fourth finger was performed at the metacarpal’s proximal metaphyseal flare. The patient was transitioned to peritoneal dialysis to avoid further ischemia.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, Department of Dermatology, Indiana University, 545 Barnhill Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46202; [email protected].

A 62-year-old man with end-stage renal disease presented to our dermatology clinic with 2-month-old ulcerations on his distal left ring finger. He was on hemodialysis and had a radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF) on his left arm. He had been empirically treated elsewhere with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a presumed bacterial infection, without improvement. He was then treated for contact dermatitis with topical clobetasol, which led to ulcer expansion and worsening pain.

At our clinic, the patient reported intermittent pain in his finger and paresthesias during activity and dialysis, but no tenderness of the ulcers. He had atrophy of the intrinsic left hand muscles (his non-dominant hand) with associated weakness. Three weeks earlier, he’d received a blood transfusion for anemia. Afterward, the pain in his hand improved and the ulcers decreased in size.

On exam, the AVF had a palpable thrill over the left forearm. The radial pulses were palpable bilaterally (2+) and the left ulnar artery was palpable, but diminished (1+). The patient’s left hand was cooler than the right (with a slight cyanotic hue and visible intrinsic muscle atrophy) and had decreased sensation to pain and temperature. Four ulcers with dry yellow eschar were located over the dorsal interphalangeal joints (FIGURES 1A AND 1B). They were essentially non-tender, but there was tenderness in the adjacent intact skin. There was violaceous blue edematous congestion noted on the fourth finger, and the distal phalange was constricted, giving it a “pseudoainhum” appearance.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Dialysis access steal syndrome

We suspected dialysis access steal syndrome (also known as AVF steal syndrome), so a duplex ultrasound was performed. The ultrasound was inconclusive. (We couldn’t confirm a limitation in blood flow, nor delineate anatomy.) So, we referred the patient for a thoracic and upper extremity angiogram.

The angiogram demonstrated multifocal, moderate to severe, areas of stenosis at the distal left brachial artery. The radial artery was patent at the level of the wrist, but showed diffuse narrowing beyond the level of the arteriovenous (AV) anastomosis. There was only a faint palmar arch identified on the radial aspect of the hand with digital branches feeding the radial portion of the hand. In contrast, the ulnar artery was not seen within the mid- and distal forearm (FIGURE 2). Palmar branches to the ulnar half of the hand were not identified. The fistula itself didn’t show any stenosis.

Based on these findings, our suspicions of dialysis access steal syndrome were confirmed.

Dialysis access steal syndrome is caused by a significant decrease or reversal of blood flow in the arterial segment distal to the AVF or graft, which is induced by the low resistance of the fistula outflow. Patients with adequate collateral vasculature are able to compensate for the steal effect; however, patients with end-stage renal disease typically have preexisting vascular disease that increases the risk for vascular steal and, ultimately, demand ischemia after placement of an AVF.1 Interestingly, a steal effect occurs in 73% of patients after AVF construction, yet it is estimated that only 10% of patients demonstrating a steal phenomenon become symptomatic.2

In our patient’s case, the vaso-occlusive properties of topical steroids explain why the superpotent steroid (clobetasol) he was prescribed increased his pain and worsened the underlying problem.

A broad differential; a useful exam maneuver

The differential diagnosis of ulcers includes infection (mainly from bacterial or mycobacterial sources), trauma facilitated by neuropathy (neuropathic ulceration), vasculitis, and ischemia. When the history and physical exam suggest ischemic ulceration, then thromboembolism, thoracic outlet syndrome, vasculitis, atherosclerosis, and steal syndrome become more likely causes.

Signs and symptoms of ischemic steal syndrome are initially subtle and include extremity coolness, neurosensory changes, intrinsic muscle weakness, ulceration, and ultimately, gangrene of the affected extremity.3,4 A cold, numb, and/or painful hand during dialysis is another clue.3 Factors that increase the likelihood of the syndrome include age >60 years, female sex, and the presence of diabetes or peripheral artery disease.2,3,5,6

One physical exam maneuver that can help make the diagnosis of steal syndrome is manual occlusion of the AVF. If palpable distal pulses disappear when the AVF is patent and reappear when the fistula is occluded with downward pressure, then AVF steal syndrome is likely.4 Pain at rest, sensory loss, loss of pulse, and digital gangrene are emergency symptoms that warrant immediate surgical evaluation.3

Tests will confirm suspicions. Doppler ultrasound can be used to assess changes in the blood flow rate of the affected vessels when the AVF is patent vs when it is occluded. Similarly, pulse oximetry can be used with and without AVF occlusion to compare changes in oxygen saturation. The confirmatory diagnosis, however, is made via a fistulogram (angiography) with and without manual compression.6 Images taken after dye injection into the AVF show dramatic improvement of distal blood flow with AVF compression.

Treatment requires surgery

Severe steal-related ischemic manifestations that threaten the function and viability of digits require surgical treatment that is primarily directed toward improving distal blood flow and secondarily toward preserving hemodialysis access. Several surgical treatments are commonly used, including access ligation, banding, elongation, distal arterial ligation, and distal revascularization and interval ligation.2-5,7

Our patient. Distal revascularization was attempted, but unfortunately, the patient’s gangrene was progressive (FIGURE 3) and surgical amputation of the left fourth finger was performed at the metacarpal’s proximal metaphyseal flare. The patient was transitioned to peritoneal dialysis to avoid further ischemia.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sahand Rahnama-Moghadam, MD, Department of Dermatology, Indiana University, 545 Barnhill Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46202; [email protected].

1. Morsy AH, Kulbaski M, Chen C, et al. Incidence and characteristics of patients with hand ischemia after a hemodialysis access procedure. J Surg Res. 1998;74:8-10.

2. Puryear A, Villarreal S, Wells MJ, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. Hand ischemia in a hemodialysis patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:393-395.

3. Pelle MT, Miller OF 3rd. Dermatologic manifestations and management of vascular steal syndrome in hemodialysis patients with arteriovenous fistulas. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1296-1298.

4. Wixon CL, Hughes JD, Mills JL. Understanding strategies for the treatment of ischemic steal syndrome after hemodialysis access. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:301-310.

5. Gupta N, Yuo TH, Konig G 4th, et al. Treatment strategies of arterial steal after arteriovenous access. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:162-167.

6. Zamani P, Kaufman J, Kinlay S. Ischemic steal syndrome following arm arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis. Vasc Med. 2009;14:371-376.

7. Leake AE, Winger DG, Leers SA, et al. Management and outcomes of dialysis access-associated steal syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:754-760.

1. Morsy AH, Kulbaski M, Chen C, et al. Incidence and characteristics of patients with hand ischemia after a hemodialysis access procedure. J Surg Res. 1998;74:8-10.

2. Puryear A, Villarreal S, Wells MJ, et al. JAAD grand rounds quiz. Hand ischemia in a hemodialysis patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:393-395.

3. Pelle MT, Miller OF 3rd. Dermatologic manifestations and management of vascular steal syndrome in hemodialysis patients with arteriovenous fistulas. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1296-1298.

4. Wixon CL, Hughes JD, Mills JL. Understanding strategies for the treatment of ischemic steal syndrome after hemodialysis access. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:301-310.

5. Gupta N, Yuo TH, Konig G 4th, et al. Treatment strategies of arterial steal after arteriovenous access. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:162-167.

6. Zamani P, Kaufman J, Kinlay S. Ischemic steal syndrome following arm arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis. Vasc Med. 2009;14:371-376.

7. Leake AE, Winger DG, Leers SA, et al. Management and outcomes of dialysis access-associated steal syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:754-760.

Pruritic nodules in axillae

The FP suspected scabies, realizing that in addition to the classic burrows seen between the fingers, scabies may present with pruritic nodules in the axilla or genital region. This child did not have any visible burrows between his fingers and there was no involvement of the genital area. Using dermoscopy, scabies mites were seen as triangular structures with trailing burrows over some of the nodules. The mother agreed to have her hands examined and scabies mites were seen between her fingers.

The child weighed less than 33 pounds, so he was not an appropriate candidate for oral ivermectin. The physician prescribed 5% permethrin cream for the child, mother, and other household members. The FP explained the importance of applying the cream from the neck down to the toes overnight and washing it off in the morning. Toddlers often have the scabies mites above the neck, so the mother was counseled to apply the 5% permethrin cream on her son’s head and face, being careful to avoid his mouth and eyes. The FP also gave the family directions to wash their clothes and bedclothes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Chanoine P, Smith M. Scabies. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:575-580.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected scabies, realizing that in addition to the classic burrows seen between the fingers, scabies may present with pruritic nodules in the axilla or genital region. This child did not have any visible burrows between his fingers and there was no involvement of the genital area. Using dermoscopy, scabies mites were seen as triangular structures with trailing burrows over some of the nodules. The mother agreed to have her hands examined and scabies mites were seen between her fingers.

The child weighed less than 33 pounds, so he was not an appropriate candidate for oral ivermectin. The physician prescribed 5% permethrin cream for the child, mother, and other household members. The FP explained the importance of applying the cream from the neck down to the toes overnight and washing it off in the morning. Toddlers often have the scabies mites above the neck, so the mother was counseled to apply the 5% permethrin cream on her son’s head and face, being careful to avoid his mouth and eyes. The FP also gave the family directions to wash their clothes and bedclothes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Chanoine P, Smith M. Scabies. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:575-580.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected scabies, realizing that in addition to the classic burrows seen between the fingers, scabies may present with pruritic nodules in the axilla or genital region. This child did not have any visible burrows between his fingers and there was no involvement of the genital area. Using dermoscopy, scabies mites were seen as triangular structures with trailing burrows over some of the nodules. The mother agreed to have her hands examined and scabies mites were seen between her fingers.

The child weighed less than 33 pounds, so he was not an appropriate candidate for oral ivermectin. The physician prescribed 5% permethrin cream for the child, mother, and other household members. The FP explained the importance of applying the cream from the neck down to the toes overnight and washing it off in the morning. Toddlers often have the scabies mites above the neck, so the mother was counseled to apply the 5% permethrin cream on her son’s head and face, being careful to avoid his mouth and eyes. The FP also gave the family directions to wash their clothes and bedclothes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Chanoine P, Smith M. Scabies. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:575-580.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Crusty rash from head to toe

The FP diagnosed crusted scabies based on the patient’s clinical appearance and the distribution of crusting. He happened to have a dermatoscope and was able to see scabies mites moving and creating burrows under the skin. The mites generally appeared as dark triangles with light oval bodies. Crusted scabies is also known as "Norwegian scabies," but the preferred term is crusted scabies. Crusted scabies is more common in individuals who are immunosuppressed, chronically ill (for any reason), or who live in nursing homes.

The child's HIV test was negative and the FP never found out the cause of the cachexia. The diagnosis of crusted scabies was important for everyone involved in the transportation and care of this child. Once the diagnosis was known, everyone was careful to use gloves when caring for her so as to avoid acquiring scabies. The mother was almost certainly infested, along with other family members who’d been in direct contact with the child.

The recommended treatment for crusted scabies is oral ivermectin at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg (maximum dose, 12 mg) once for each infested person to be repeated in 10 days. Fortunately, the global health team had oral ivermectin to give to the child and the family. The FP also told the family to wash all of their clothes and bedclothes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Chanoine P, Smith M. Scabies. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:575-580.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed crusted scabies based on the patient’s clinical appearance and the distribution of crusting. He happened to have a dermatoscope and was able to see scabies mites moving and creating burrows under the skin. The mites generally appeared as dark triangles with light oval bodies. Crusted scabies is also known as "Norwegian scabies," but the preferred term is crusted scabies. Crusted scabies is more common in individuals who are immunosuppressed, chronically ill (for any reason), or who live in nursing homes.

The child's HIV test was negative and the FP never found out the cause of the cachexia. The diagnosis of crusted scabies was important for everyone involved in the transportation and care of this child. Once the diagnosis was known, everyone was careful to use gloves when caring for her so as to avoid acquiring scabies. The mother was almost certainly infested, along with other family members who’d been in direct contact with the child.

The recommended treatment for crusted scabies is oral ivermectin at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg (maximum dose, 12 mg) once for each infested person to be repeated in 10 days. Fortunately, the global health team had oral ivermectin to give to the child and the family. The FP also told the family to wash all of their clothes and bedclothes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Chanoine P, Smith M. Scabies. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:575-580.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed crusted scabies based on the patient’s clinical appearance and the distribution of crusting. He happened to have a dermatoscope and was able to see scabies mites moving and creating burrows under the skin. The mites generally appeared as dark triangles with light oval bodies. Crusted scabies is also known as "Norwegian scabies," but the preferred term is crusted scabies. Crusted scabies is more common in individuals who are immunosuppressed, chronically ill (for any reason), or who live in nursing homes.

The child's HIV test was negative and the FP never found out the cause of the cachexia. The diagnosis of crusted scabies was important for everyone involved in the transportation and care of this child. Once the diagnosis was known, everyone was careful to use gloves when caring for her so as to avoid acquiring scabies. The mother was almost certainly infested, along with other family members who’d been in direct contact with the child.

The recommended treatment for crusted scabies is oral ivermectin at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg (maximum dose, 12 mg) once for each infested person to be repeated in 10 days. Fortunately, the global health team had oral ivermectin to give to the child and the family. The FP also told the family to wash all of their clothes and bedclothes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Chanoine P, Smith M. Scabies. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:575-580.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Itchy scalp

Based on the patient’s history, the FP suspected that this was a case of either head lice or seborrhea. He put on gloves to examine the hair and found nits (eggs) glued to the hair. There was an especially high density of them behind her ears (which is always a good place to begin the exam for head lice). The nits were pearly as expected, but no live adult head lice were found.

The FP was aware that nits are far more numerous than adult head lice. The scalp itself was unremarkable and there was no seborrhea. While it is possible to look at nits under a microscope to see if there are live larvae inside, the history of 2 weeks of symptoms without treatment was sufficient to assume that this was an active case of head lice, rather than dead or hatched nits from a previous case.

The mother confirmed that the child hadn’t been treated for head lice in the past and claimed that she washed her daughter's hair every night. The FP explained that any child in school or around other children can easily get head lice—regardless of their personal hygiene habits. The FP asked if it was okay to check the mother’s hair, and found a few nits behind her ears, as well.

There are many treatment options for head lice, including 2 nonprescription products that cost less than $15 each: 1% permethrin cream rinse (Nix) and pyrethrins with piperonyl butoxide (RID) shampoo. There are also more expensive prescription products, including malathion 0.5%, benzyl alcohol 5% lotion, spinosad, and ivermectin 0.5% lotion. A 2001 Cochrane review found no evidence that any one pediculicide was better than another.1 However, the review only included studies of permethrin, synergized pyrethrin, and malathion.

In this case, the mother chose to buy the over-the-counter 1% permethrin cream rinse for herself and her daughter. While the FP was not able to examine the patient’s father or older brother, he did suggest that they all do the treatment simultaneously to avoid one family member remaining infested (and then reinfesting the rest of the family).

1. Dodd CS. Interventions for treating headlice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;CD001165.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Lice. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 570-574.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the patient’s history, the FP suspected that this was a case of either head lice or seborrhea. He put on gloves to examine the hair and found nits (eggs) glued to the hair. There was an especially high density of them behind her ears (which is always a good place to begin the exam for head lice). The nits were pearly as expected, but no live adult head lice were found.

The FP was aware that nits are far more numerous than adult head lice. The scalp itself was unremarkable and there was no seborrhea. While it is possible to look at nits under a microscope to see if there are live larvae inside, the history of 2 weeks of symptoms without treatment was sufficient to assume that this was an active case of head lice, rather than dead or hatched nits from a previous case.

The mother confirmed that the child hadn’t been treated for head lice in the past and claimed that she washed her daughter's hair every night. The FP explained that any child in school or around other children can easily get head lice—regardless of their personal hygiene habits. The FP asked if it was okay to check the mother’s hair, and found a few nits behind her ears, as well.

There are many treatment options for head lice, including 2 nonprescription products that cost less than $15 each: 1% permethrin cream rinse (Nix) and pyrethrins with piperonyl butoxide (RID) shampoo. There are also more expensive prescription products, including malathion 0.5%, benzyl alcohol 5% lotion, spinosad, and ivermectin 0.5% lotion. A 2001 Cochrane review found no evidence that any one pediculicide was better than another.1 However, the review only included studies of permethrin, synergized pyrethrin, and malathion.

In this case, the mother chose to buy the over-the-counter 1% permethrin cream rinse for herself and her daughter. While the FP was not able to examine the patient’s father or older brother, he did suggest that they all do the treatment simultaneously to avoid one family member remaining infested (and then reinfesting the rest of the family).

1. Dodd CS. Interventions for treating headlice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;CD001165.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Lice. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 570-574.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the patient’s history, the FP suspected that this was a case of either head lice or seborrhea. He put on gloves to examine the hair and found nits (eggs) glued to the hair. There was an especially high density of them behind her ears (which is always a good place to begin the exam for head lice). The nits were pearly as expected, but no live adult head lice were found.

The FP was aware that nits are far more numerous than adult head lice. The scalp itself was unremarkable and there was no seborrhea. While it is possible to look at nits under a microscope to see if there are live larvae inside, the history of 2 weeks of symptoms without treatment was sufficient to assume that this was an active case of head lice, rather than dead or hatched nits from a previous case.

The mother confirmed that the child hadn’t been treated for head lice in the past and claimed that she washed her daughter's hair every night. The FP explained that any child in school or around other children can easily get head lice—regardless of their personal hygiene habits. The FP asked if it was okay to check the mother’s hair, and found a few nits behind her ears, as well.

There are many treatment options for head lice, including 2 nonprescription products that cost less than $15 each: 1% permethrin cream rinse (Nix) and pyrethrins with piperonyl butoxide (RID) shampoo. There are also more expensive prescription products, including malathion 0.5%, benzyl alcohol 5% lotion, spinosad, and ivermectin 0.5% lotion. A 2001 Cochrane review found no evidence that any one pediculicide was better than another.1 However, the review only included studies of permethrin, synergized pyrethrin, and malathion.

In this case, the mother chose to buy the over-the-counter 1% permethrin cream rinse for herself and her daughter. While the FP was not able to examine the patient’s father or older brother, he did suggest that they all do the treatment simultaneously to avoid one family member remaining infested (and then reinfesting the rest of the family).

1. Dodd CS. Interventions for treating headlice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;CD001165.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Lice. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 570-574.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

White spots on back

The FP considered the diagnoses of vitiligo and tinea versicolor. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and saw the “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern of Malassezia furfur. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) The “spaghetti” or “ziti” is the short mycelial form of M furfur and the “meatballs” are the round yeast form (Pityrosporum).

This was definitive proof that the patient had tinea versicolor caused by M furfur, a lipophilic yeast that can be found on healthy skin. Tinea versicolor starts when the yeast that normally colonizes the skin changes from the round form to the pathologic mycelial form and then invades the stratum corneum. M furfur thrives on sebum and moisture and tends to grow on the skin in areas where there are sebaceous follicles secreting sebum. Patients with tinea versicolor present with skin discolorations that are white, pink, or brown.

The patient in this case chose a single oral dose of 400 mg fluconazole to be repeated one week later. The condition cleared and the patient's skin color returned to normal in the following months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Tinea versicolor. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:566-569.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP considered the diagnoses of vitiligo and tinea versicolor. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and saw the “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern of Malassezia furfur. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) The “spaghetti” or “ziti” is the short mycelial form of M furfur and the “meatballs” are the round yeast form (Pityrosporum).

This was definitive proof that the patient had tinea versicolor caused by M furfur, a lipophilic yeast that can be found on healthy skin. Tinea versicolor starts when the yeast that normally colonizes the skin changes from the round form to the pathologic mycelial form and then invades the stratum corneum. M furfur thrives on sebum and moisture and tends to grow on the skin in areas where there are sebaceous follicles secreting sebum. Patients with tinea versicolor present with skin discolorations that are white, pink, or brown.

The patient in this case chose a single oral dose of 400 mg fluconazole to be repeated one week later. The condition cleared and the patient's skin color returned to normal in the following months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Tinea versicolor. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:566-569.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP considered the diagnoses of vitiligo and tinea versicolor. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and saw the “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern of Malassezia furfur. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) The “spaghetti” or “ziti” is the short mycelial form of M furfur and the “meatballs” are the round yeast form (Pityrosporum).

This was definitive proof that the patient had tinea versicolor caused by M furfur, a lipophilic yeast that can be found on healthy skin. Tinea versicolor starts when the yeast that normally colonizes the skin changes from the round form to the pathologic mycelial form and then invades the stratum corneum. M furfur thrives on sebum and moisture and tends to grow on the skin in areas where there are sebaceous follicles secreting sebum. Patients with tinea versicolor present with skin discolorations that are white, pink, or brown.

The patient in this case chose a single oral dose of 400 mg fluconazole to be repeated one week later. The condition cleared and the patient's skin color returned to normal in the following months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Tinea versicolor. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:566-569.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Malodorous discharge, redness, and crusting of the feet

A 50-year-old man who worked in construction presented to a local urgent care facility complaining of 2 weeks of bilateral foot discomfort associated with local malodorous discharge, redness, and crusting. He had a past medical history of recurrent tinea pedis and had previously been treated with intravenous (IV) antibiotics for a severe episode of cellulitis. He denied recent fever, trauma, or swelling. Physical examination revealed extensive malodorous crusting of the interdigital webs of both feet, in addition to tenderness, erythema, and serous discharge. He was treated with topical clotrimazole and oral terbinafine for a presumed tinea pedis recurrence; cephalexin and triamcinolone were added a week later after minimal response. Two days later, he sought care at a local emergency department with progressive cellulitis, bullae formation, and extensive desquamation (FIGURES 1A AND 1B) and was hospitalized.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gram-negative foot intertrigo

Plain x-rays and computed tomography imaging did not reveal evidence of abscess formation, subcutaneous gas/air formation, or osteomyelitis. Laboratory testing was normal. The patient was empirically started on cefepime, clindamycin, and ketoconazole. Wound therapy, consisting of normal saline washes, use of xeroform gauze to cover the wound, and frequent absorbent dressing changes, was also initiated. Wound cultures were obtained, which later grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus faecalis. (P aeruginosa was the predominant organism.) We made the diagnosis of gram-negative foot intertrigo.

First described in 1973, researchers have found that P aeruginosa, as well as E faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus, are commonly associated with tinea pedis1 and toe web intertrigo.2 The infection usually involves the lateral 3 toe webs, and can present with malodorous discharge, itchy maceration, edema, and erythema of the surrounding tissue. Non-purulent lower extremity cellulitis is typically caused by beta-hemolytic streptococci residing in the toe webs, and is usually treated empirically with cephalexin or similar antibiotics.3 The presentation of foot intertrigo varies along a spectrum that includes tinea pedis, superinfected maceration, and infectious eczematoid dermatitis, all of which can encourage bacterial superinfections.

In this patient, it is likely that sweating (and consequent skin maceration), tinea pedis, and perhaps even friction between the affected area and the patient’s shoes led to skin ulceration. This then became colonized and infected with bacteria, including gram-negative varieties, which sometimes harbor at the edges of ulcerations. Addressing each of these factors is important to heal the infection.

Differential diagnosis includes other bacterial skin infections

The differential diagnosis includes erysipelas, cellulitis, lipodermatosclerosis, venous eczema, and burns. Erysipelas affects the superficial dermis with well demarcated borders, while cellulitis involves the subcutaneous fat.4 Both are more likely to be caused by beta-hemolytic streptococci, but at first may be difficult to differentiate from similar appearing gram-negative skin/soft tissue infection without microbiologic data.

Patients with lipodermatosclerosis and venous eczema often have a history of chronic venous insufficiency. Lipodermatosclerosis often presents with a subcutaneous panniculitis and hyperpigmentation; venous eczema is often associated with scaling of the involved areas. Although burns can become secondarily superinfected with bacteria, they can be differentiated from a primary bacterial infection by the history or presentation.

Gram-negative infections (especially those caused by Pseudomonas species) should be suspected if a toe web infection does not respond to empiric antimicrobial therapy with first- or second-generation cephalosporins, as their spectrum of antimicrobial activity does not include P aeruginosa. If the infection is severe, it may impact ambulation.2 Predisposing factors for gram-negative toe web infections include obesity, diabetes, moist environments, tight interdigital spaces, and recurrent tinea pedis.4

Administer appropriate wound care and start antimicrobial therapy

Foot intertrigo provides an easy portal of entry for pathogenic organisms.5 Therefore, it is important to modify risk factors from the outset to help prevent superinfection (as occurred with this patient) and other complications. Aggressive treatment of tinea pedis and use of compression stockings to reduce lymphedema are vital for prevention of recurrent infections.3

Physicians should be aware of likely, as well as unlikely, causative pathogens; “typical” skin and soft tissue infections that do not resolve may be due to atypical or gram-negative organisms, and typical first-line antibiotics will do nothing to eradicate them. Antimicrobial susceptibilities and a bacterial culture will steer you to the appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Debridement of the edge of the ulceration is necessary to remove any lingering bacteria.6 And appropriate wound care is paramount and should include the use of techniques to keep the affected areas dry, such as the use of astringent powders along with avoidance of damp shoes and socks.

Our patient was switched from empiric therapy to culture-specific IV therapy with vancomycin 2 g every 12 hours, ciprofloxacin 400 mg every 12 hours, and fluconazole 400 mg daily. Two weeks later, he was discharged from the hospital on topical antifungals, oral fluconazole, and daily acetic acid soaks. He did, however, require further advanced topical treatments (miconazole 2% twice daily) due to recurrent flare-ups before complete resolution was achieved 6 weeks after presentation (FIGURES 2A AND 2B).

CORRESPONDENCE

Alberto Marcelin, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic Health System, 1000 1st Dr NW, Austin, MN 55912; [email protected].

1. Westmoreland TA, Ross EV, Yeager JK. Pseudomonas toe web infections. Cutis. 1992;49:185-186.

2. Lin JY, Shih YL, Ho HC. Foot bacterial intertrigo mimicking interdigital tinea pedis. Chang Gung Med J. 2011;34:44-49.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:e10-e52.

4. Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Lower limb cellulitis and its mimics: part II. Conditions that simulate lower limb cellulitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:177, e1-e9; quiz 185-186.

5. Semel JD, Goldin H. Association of athlete’s foot with cellulitis of the lower extremities: diagnostic value of bacterial cultures of ipsilateral interdigital space samples. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1162-1164.

6. Fangman W, Burton C. Hyperkeratotic rim of gram-negative toe web infections. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:658.

A 50-year-old man who worked in construction presented to a local urgent care facility complaining of 2 weeks of bilateral foot discomfort associated with local malodorous discharge, redness, and crusting. He had a past medical history of recurrent tinea pedis and had previously been treated with intravenous (IV) antibiotics for a severe episode of cellulitis. He denied recent fever, trauma, or swelling. Physical examination revealed extensive malodorous crusting of the interdigital webs of both feet, in addition to tenderness, erythema, and serous discharge. He was treated with topical clotrimazole and oral terbinafine for a presumed tinea pedis recurrence; cephalexin and triamcinolone were added a week later after minimal response. Two days later, he sought care at a local emergency department with progressive cellulitis, bullae formation, and extensive desquamation (FIGURES 1A AND 1B) and was hospitalized.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gram-negative foot intertrigo

Plain x-rays and computed tomography imaging did not reveal evidence of abscess formation, subcutaneous gas/air formation, or osteomyelitis. Laboratory testing was normal. The patient was empirically started on cefepime, clindamycin, and ketoconazole. Wound therapy, consisting of normal saline washes, use of xeroform gauze to cover the wound, and frequent absorbent dressing changes, was also initiated. Wound cultures were obtained, which later grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus faecalis. (P aeruginosa was the predominant organism.) We made the diagnosis of gram-negative foot intertrigo.

First described in 1973, researchers have found that P aeruginosa, as well as E faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus, are commonly associated with tinea pedis1 and toe web intertrigo.2 The infection usually involves the lateral 3 toe webs, and can present with malodorous discharge, itchy maceration, edema, and erythema of the surrounding tissue. Non-purulent lower extremity cellulitis is typically caused by beta-hemolytic streptococci residing in the toe webs, and is usually treated empirically with cephalexin or similar antibiotics.3 The presentation of foot intertrigo varies along a spectrum that includes tinea pedis, superinfected maceration, and infectious eczematoid dermatitis, all of which can encourage bacterial superinfections.

In this patient, it is likely that sweating (and consequent skin maceration), tinea pedis, and perhaps even friction between the affected area and the patient’s shoes led to skin ulceration. This then became colonized and infected with bacteria, including gram-negative varieties, which sometimes harbor at the edges of ulcerations. Addressing each of these factors is important to heal the infection.

Differential diagnosis includes other bacterial skin infections

The differential diagnosis includes erysipelas, cellulitis, lipodermatosclerosis, venous eczema, and burns. Erysipelas affects the superficial dermis with well demarcated borders, while cellulitis involves the subcutaneous fat.4 Both are more likely to be caused by beta-hemolytic streptococci, but at first may be difficult to differentiate from similar appearing gram-negative skin/soft tissue infection without microbiologic data.

Patients with lipodermatosclerosis and venous eczema often have a history of chronic venous insufficiency. Lipodermatosclerosis often presents with a subcutaneous panniculitis and hyperpigmentation; venous eczema is often associated with scaling of the involved areas. Although burns can become secondarily superinfected with bacteria, they can be differentiated from a primary bacterial infection by the history or presentation.

Gram-negative infections (especially those caused by Pseudomonas species) should be suspected if a toe web infection does not respond to empiric antimicrobial therapy with first- or second-generation cephalosporins, as their spectrum of antimicrobial activity does not include P aeruginosa. If the infection is severe, it may impact ambulation.2 Predisposing factors for gram-negative toe web infections include obesity, diabetes, moist environments, tight interdigital spaces, and recurrent tinea pedis.4

Administer appropriate wound care and start antimicrobial therapy

Foot intertrigo provides an easy portal of entry for pathogenic organisms.5 Therefore, it is important to modify risk factors from the outset to help prevent superinfection (as occurred with this patient) and other complications. Aggressive treatment of tinea pedis and use of compression stockings to reduce lymphedema are vital for prevention of recurrent infections.3

Physicians should be aware of likely, as well as unlikely, causative pathogens; “typical” skin and soft tissue infections that do not resolve may be due to atypical or gram-negative organisms, and typical first-line antibiotics will do nothing to eradicate them. Antimicrobial susceptibilities and a bacterial culture will steer you to the appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Debridement of the edge of the ulceration is necessary to remove any lingering bacteria.6 And appropriate wound care is paramount and should include the use of techniques to keep the affected areas dry, such as the use of astringent powders along with avoidance of damp shoes and socks.

Our patient was switched from empiric therapy to culture-specific IV therapy with vancomycin 2 g every 12 hours, ciprofloxacin 400 mg every 12 hours, and fluconazole 400 mg daily. Two weeks later, he was discharged from the hospital on topical antifungals, oral fluconazole, and daily acetic acid soaks. He did, however, require further advanced topical treatments (miconazole 2% twice daily) due to recurrent flare-ups before complete resolution was achieved 6 weeks after presentation (FIGURES 2A AND 2B).

CORRESPONDENCE

Alberto Marcelin, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic Health System, 1000 1st Dr NW, Austin, MN 55912; [email protected].

A 50-year-old man who worked in construction presented to a local urgent care facility complaining of 2 weeks of bilateral foot discomfort associated with local malodorous discharge, redness, and crusting. He had a past medical history of recurrent tinea pedis and had previously been treated with intravenous (IV) antibiotics for a severe episode of cellulitis. He denied recent fever, trauma, or swelling. Physical examination revealed extensive malodorous crusting of the interdigital webs of both feet, in addition to tenderness, erythema, and serous discharge. He was treated with topical clotrimazole and oral terbinafine for a presumed tinea pedis recurrence; cephalexin and triamcinolone were added a week later after minimal response. Two days later, he sought care at a local emergency department with progressive cellulitis, bullae formation, and extensive desquamation (FIGURES 1A AND 1B) and was hospitalized.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gram-negative foot intertrigo

Plain x-rays and computed tomography imaging did not reveal evidence of abscess formation, subcutaneous gas/air formation, or osteomyelitis. Laboratory testing was normal. The patient was empirically started on cefepime, clindamycin, and ketoconazole. Wound therapy, consisting of normal saline washes, use of xeroform gauze to cover the wound, and frequent absorbent dressing changes, was also initiated. Wound cultures were obtained, which later grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus faecalis. (P aeruginosa was the predominant organism.) We made the diagnosis of gram-negative foot intertrigo.

First described in 1973, researchers have found that P aeruginosa, as well as E faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus, are commonly associated with tinea pedis1 and toe web intertrigo.2 The infection usually involves the lateral 3 toe webs, and can present with malodorous discharge, itchy maceration, edema, and erythema of the surrounding tissue. Non-purulent lower extremity cellulitis is typically caused by beta-hemolytic streptococci residing in the toe webs, and is usually treated empirically with cephalexin or similar antibiotics.3 The presentation of foot intertrigo varies along a spectrum that includes tinea pedis, superinfected maceration, and infectious eczematoid dermatitis, all of which can encourage bacterial superinfections.

In this patient, it is likely that sweating (and consequent skin maceration), tinea pedis, and perhaps even friction between the affected area and the patient’s shoes led to skin ulceration. This then became colonized and infected with bacteria, including gram-negative varieties, which sometimes harbor at the edges of ulcerations. Addressing each of these factors is important to heal the infection.

Differential diagnosis includes other bacterial skin infections

The differential diagnosis includes erysipelas, cellulitis, lipodermatosclerosis, venous eczema, and burns. Erysipelas affects the superficial dermis with well demarcated borders, while cellulitis involves the subcutaneous fat.4 Both are more likely to be caused by beta-hemolytic streptococci, but at first may be difficult to differentiate from similar appearing gram-negative skin/soft tissue infection without microbiologic data.

Patients with lipodermatosclerosis and venous eczema often have a history of chronic venous insufficiency. Lipodermatosclerosis often presents with a subcutaneous panniculitis and hyperpigmentation; venous eczema is often associated with scaling of the involved areas. Although burns can become secondarily superinfected with bacteria, they can be differentiated from a primary bacterial infection by the history or presentation.

Gram-negative infections (especially those caused by Pseudomonas species) should be suspected if a toe web infection does not respond to empiric antimicrobial therapy with first- or second-generation cephalosporins, as their spectrum of antimicrobial activity does not include P aeruginosa. If the infection is severe, it may impact ambulation.2 Predisposing factors for gram-negative toe web infections include obesity, diabetes, moist environments, tight interdigital spaces, and recurrent tinea pedis.4

Administer appropriate wound care and start antimicrobial therapy

Foot intertrigo provides an easy portal of entry for pathogenic organisms.5 Therefore, it is important to modify risk factors from the outset to help prevent superinfection (as occurred with this patient) and other complications. Aggressive treatment of tinea pedis and use of compression stockings to reduce lymphedema are vital for prevention of recurrent infections.3

Physicians should be aware of likely, as well as unlikely, causative pathogens; “typical” skin and soft tissue infections that do not resolve may be due to atypical or gram-negative organisms, and typical first-line antibiotics will do nothing to eradicate them. Antimicrobial susceptibilities and a bacterial culture will steer you to the appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Debridement of the edge of the ulceration is necessary to remove any lingering bacteria.6 And appropriate wound care is paramount and should include the use of techniques to keep the affected areas dry, such as the use of astringent powders along with avoidance of damp shoes and socks.

Our patient was switched from empiric therapy to culture-specific IV therapy with vancomycin 2 g every 12 hours, ciprofloxacin 400 mg every 12 hours, and fluconazole 400 mg daily. Two weeks later, he was discharged from the hospital on topical antifungals, oral fluconazole, and daily acetic acid soaks. He did, however, require further advanced topical treatments (miconazole 2% twice daily) due to recurrent flare-ups before complete resolution was achieved 6 weeks after presentation (FIGURES 2A AND 2B).

CORRESPONDENCE

Alberto Marcelin, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic Health System, 1000 1st Dr NW, Austin, MN 55912; [email protected].

1. Westmoreland TA, Ross EV, Yeager JK. Pseudomonas toe web infections. Cutis. 1992;49:185-186.

2. Lin JY, Shih YL, Ho HC. Foot bacterial intertrigo mimicking interdigital tinea pedis. Chang Gung Med J. 2011;34:44-49.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:e10-e52.

4. Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Lower limb cellulitis and its mimics: part II. Conditions that simulate lower limb cellulitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:177, e1-e9; quiz 185-186.

5. Semel JD, Goldin H. Association of athlete’s foot with cellulitis of the lower extremities: diagnostic value of bacterial cultures of ipsilateral interdigital space samples. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1162-1164.

6. Fangman W, Burton C. Hyperkeratotic rim of gram-negative toe web infections. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:658.

1. Westmoreland TA, Ross EV, Yeager JK. Pseudomonas toe web infections. Cutis. 1992;49:185-186.

2. Lin JY, Shih YL, Ho HC. Foot bacterial intertrigo mimicking interdigital tinea pedis. Chang Gung Med J. 2011;34:44-49.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:e10-e52.

4. Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Lower limb cellulitis and its mimics: part II. Conditions that simulate lower limb cellulitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:177, e1-e9; quiz 185-186.

5. Semel JD, Goldin H. Association of athlete’s foot with cellulitis of the lower extremities: diagnostic value of bacterial cultures of ipsilateral interdigital space samples. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1162-1164.

6. Fangman W, Burton C. Hyperkeratotic rim of gram-negative toe web infections. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:658.

Rash on eyebrows and periumbilical region

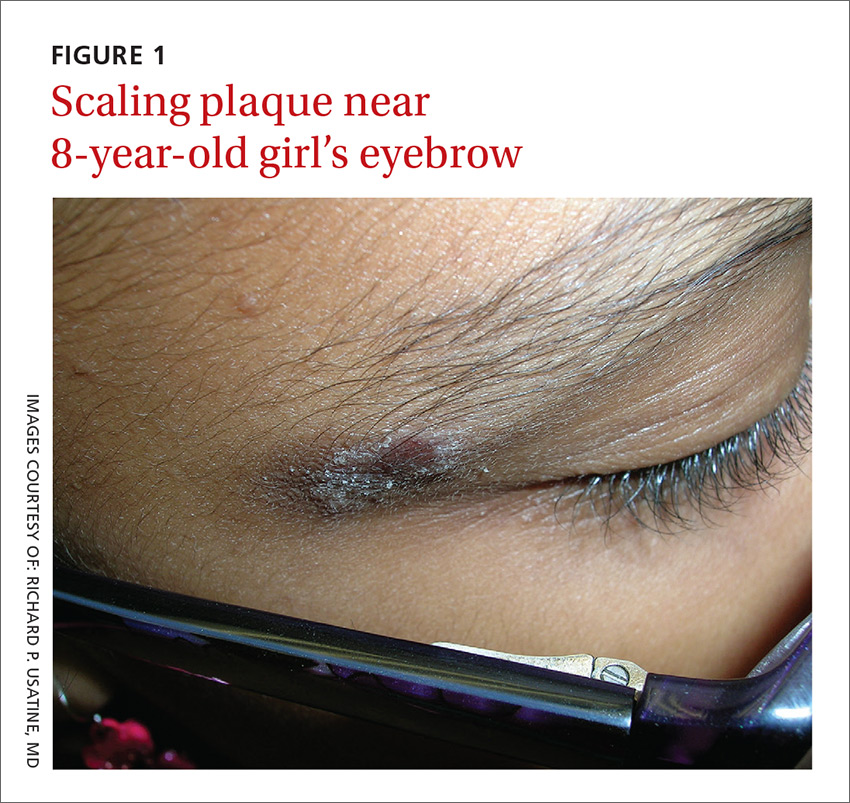

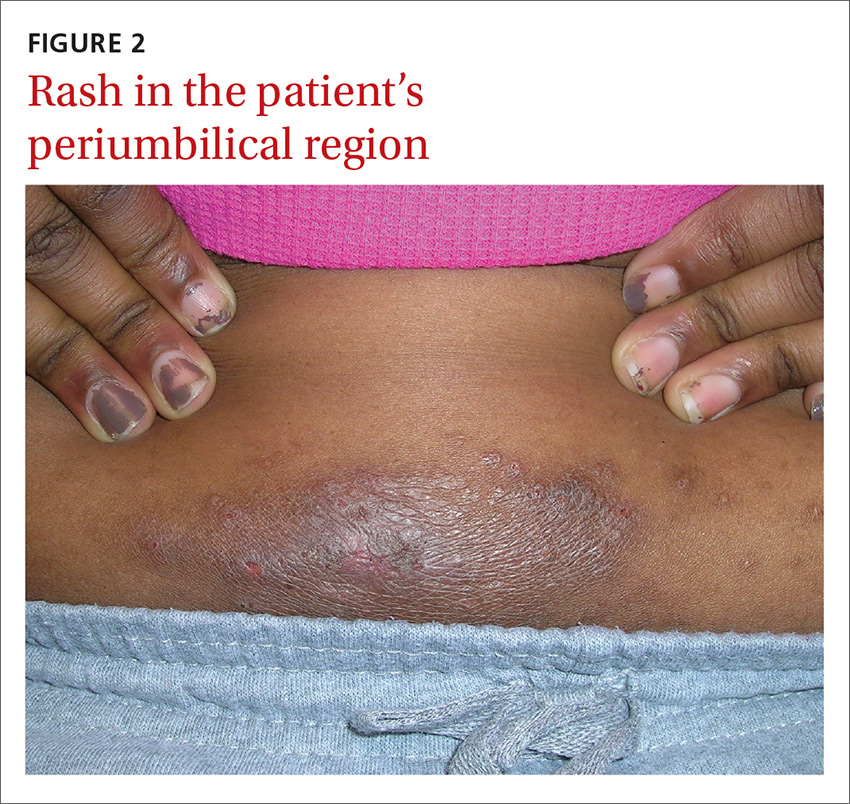

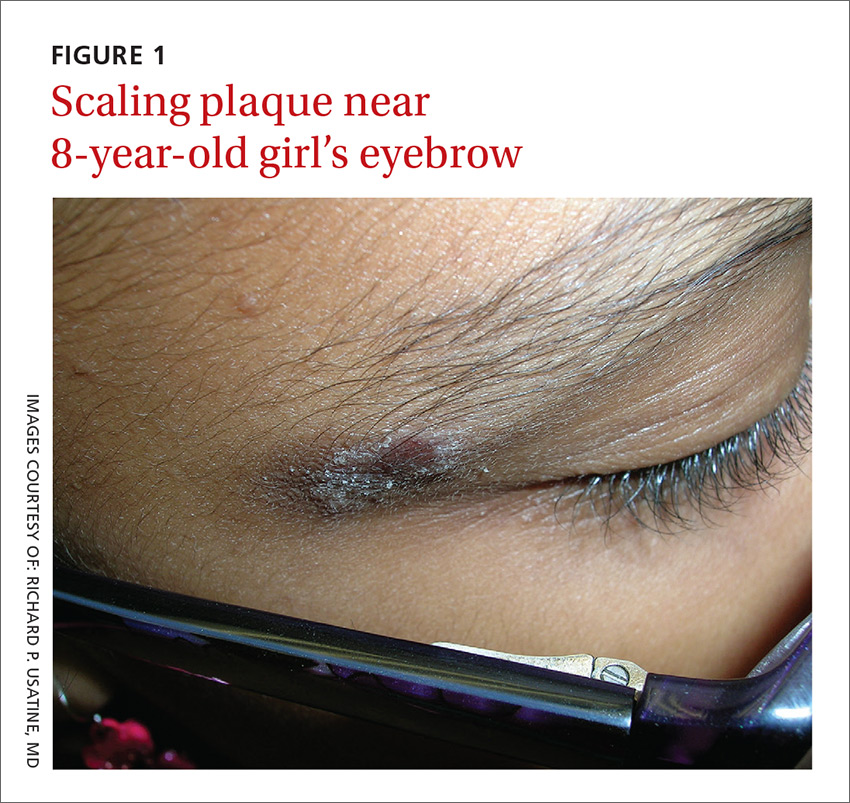

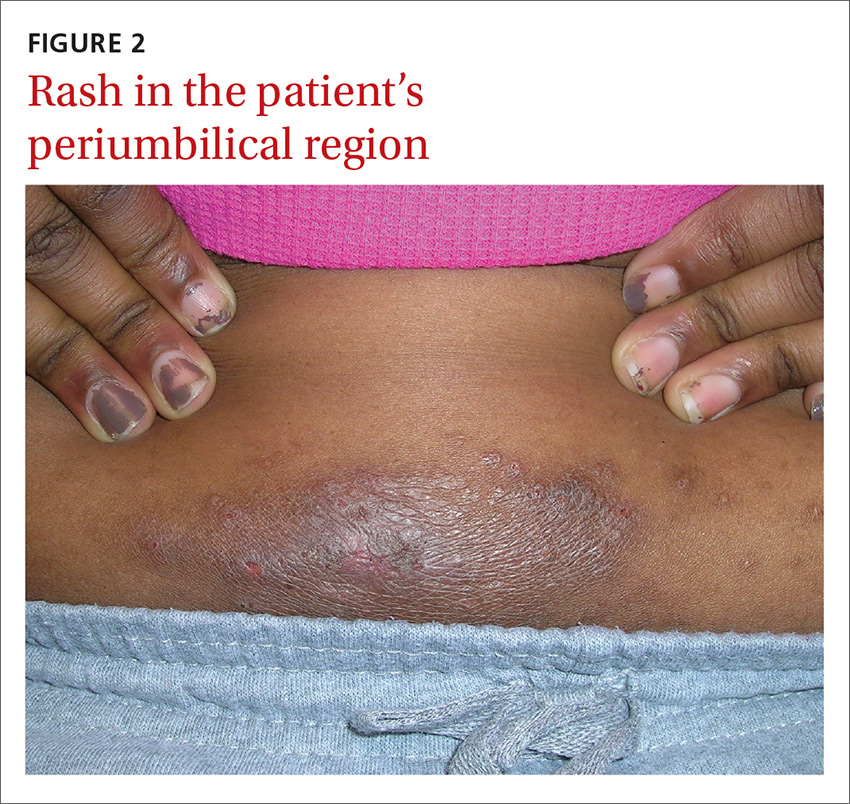

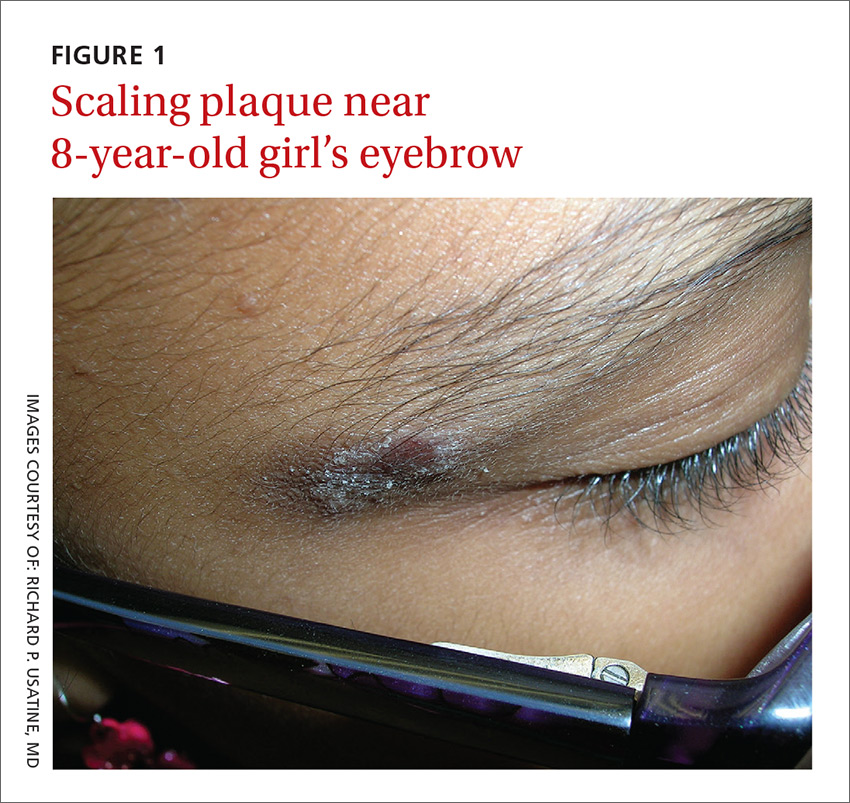

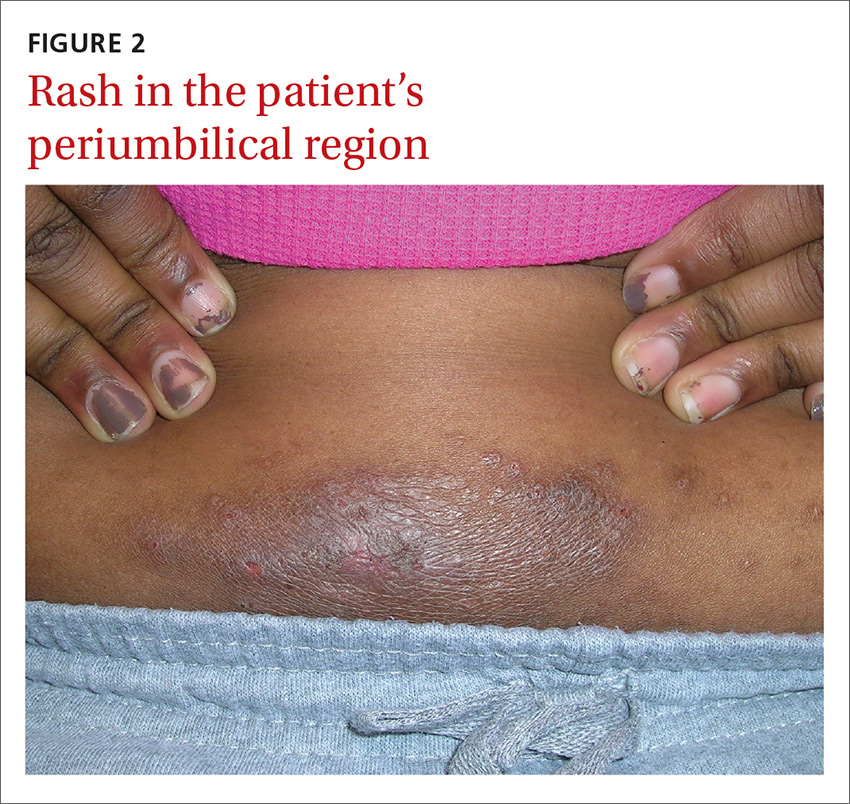

An 8-year-old girl was brought to her family physician’s office (RU) because of a persistent rash on her lateral eyebrows and periumbilical region. The family indicated that she’d had the rash for more than 6 months. They also mentioned that the child had received a new pair of eyeglasses 8 months earlier. The child was otherwise in good health. The physical examination revealed erythematous scaling plaques near both lateral eyebrows and around the belly button (FIGURES 1 AND 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Allergic contact dermatitis

We recognized that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), based on the clinical presentation. The distribution of the erythema, scale, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was highly suggestive of an ACD to nickel. In this case, the nickel in the patient’s eyeglasses and the snaps found on her pants were the culprits.

The lichenification of the plaque near the umbilicus suggested that the dermatitis was not acute and that the patient had likely been scratching the area due to itching. The plaque near the patient’s eye was actually in the shape of the metal on the inside of her glasses.

Most prevalent contact allergens. Patch testing data indicate that the 5 most prevalent contact allergens out of more than 3700 that are known are: nickel (14.3% of patients tested), fragrance mix (14%), the topical antibiotic neomycin (11.6%), balsam of Peru (used in some perfumes, toiletries, and pharmaceutical items) (10.4%), and the mercury-based vaccine preservative thimerosal (10.4%).1

ACD is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction in which a foreign substance comes into contact with the skin and is linked to skin proteins forming an antigen complex that leads to sensitization. When the epidermis is re-exposed to the antigen, the sensitized T cells initiate an inflammatory cascade, leading to the skin changes seen in ACD.2

Silverberg et al reported that in 30 children with a personal history of umbilical or wrist dermatitis or a family history of nickel ACD, 100% demonstrated a positive reaction to nickel sulfate.3 Nickel continues to be used (and unregulated) in a wide range of products, including costume jewelry, piercing posts, belt buckles, eyeglasses, and personal electronics (eg, tablets, cell phones, and laptop computers).

Making the diagnosis. Contact dermatitis can sometimes be diagnosed clinically with a good history and physical exam. However, there are many cases in which patch testing is needed to find the offending allergens or confirm the suspicion regarding a specific allergen. The only convenient and ready-to-use patch test in the United States is the T.R.U.E. test.

The differential includes other superficial skin infections