User login

Rash on top of feet

The FP suspected that contact dermatitis was to blame for the rash on the dorsum of the patient’s feet. This would have been an unlikely location for tinea pedis and the patient had already tried topical antifungal medications without any benefit. The FP asked the patient if he had purchased any new shoes or boots before the rash started, and the patient indicated that he’d purchased new running shoes about a year earlier.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily. The FP recognized that patch testing might be indicated, but did not perform this in her office. She also recommended that the patient stay away from the running shoes at this time. One month later, the rash was 95% better, except for some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that was likely to take months to fade. The patient was happy with the results, but wanted to know the cause of his allergy and what shoes would be safe to wear.

The FP offered the patient a referral to a local dermatologist who performed patch testing. The patient went for patch testing and learned he was allergic to chromates found in many types of leather. Statistically, the most likely offending allergens for a rash in this location would be formaldehyde or a chromate. Both are found in leather and are common allergens that cause contact dermatitis on the feet.

Allergic contact dermatitis to chromate in leather shoes may be seasonal as a result of the allergen being leached out by perspiration in warmer months. There are leather shoes that are made free of chromates for people who suffer from allergic contact dermatitis due to this allergen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that contact dermatitis was to blame for the rash on the dorsum of the patient’s feet. This would have been an unlikely location for tinea pedis and the patient had already tried topical antifungal medications without any benefit. The FP asked the patient if he had purchased any new shoes or boots before the rash started, and the patient indicated that he’d purchased new running shoes about a year earlier.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily. The FP recognized that patch testing might be indicated, but did not perform this in her office. She also recommended that the patient stay away from the running shoes at this time. One month later, the rash was 95% better, except for some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that was likely to take months to fade. The patient was happy with the results, but wanted to know the cause of his allergy and what shoes would be safe to wear.

The FP offered the patient a referral to a local dermatologist who performed patch testing. The patient went for patch testing and learned he was allergic to chromates found in many types of leather. Statistically, the most likely offending allergens for a rash in this location would be formaldehyde or a chromate. Both are found in leather and are common allergens that cause contact dermatitis on the feet.

Allergic contact dermatitis to chromate in leather shoes may be seasonal as a result of the allergen being leached out by perspiration in warmer months. There are leather shoes that are made free of chromates for people who suffer from allergic contact dermatitis due to this allergen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that contact dermatitis was to blame for the rash on the dorsum of the patient’s feet. This would have been an unlikely location for tinea pedis and the patient had already tried topical antifungal medications without any benefit. The FP asked the patient if he had purchased any new shoes or boots before the rash started, and the patient indicated that he’d purchased new running shoes about a year earlier.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily. The FP recognized that patch testing might be indicated, but did not perform this in her office. She also recommended that the patient stay away from the running shoes at this time. One month later, the rash was 95% better, except for some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that was likely to take months to fade. The patient was happy with the results, but wanted to know the cause of his allergy and what shoes would be safe to wear.

The FP offered the patient a referral to a local dermatologist who performed patch testing. The patient went for patch testing and learned he was allergic to chromates found in many types of leather. Statistically, the most likely offending allergens for a rash in this location would be formaldehyde or a chromate. Both are found in leather and are common allergens that cause contact dermatitis on the feet.

Allergic contact dermatitis to chromate in leather shoes may be seasonal as a result of the allergen being leached out by perspiration in warmer months. There are leather shoes that are made free of chromates for people who suffer from allergic contact dermatitis due to this allergen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Malodorous, itchy feet

This patient was suffering from pitted keratolysis and interdigital tinea pedis. Pitted keratolysis is caused by the bacterium Kytococcus sedentarius. Like tinea pedis, moist and sweaty feet provide a great environment for growth of this organism. The patient admitted to having sweaty feet—especially while playing soccer for hours. He also didn’t use shower shoes in the gym shower.

In pitted keratolysis, the bacteria live on the dead cells of the stratum corneum of the sole and form visible pits. In interdigital tinea pedis, the skin between the toes is white in appearance.

The FP recommended that the patient wear shower shoes and change his socks during the day if they become sweaty. He also prescribed topical 2% erythromycin solution to apply twice daily to the area with visible pits. In addition, the FP recommended that the patient buy over-the-counter topical terbinafine cream and apply it between the toes once or twice daily—especially after drying his feet well after a shower. A month later, both infections were clear.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient was suffering from pitted keratolysis and interdigital tinea pedis. Pitted keratolysis is caused by the bacterium Kytococcus sedentarius. Like tinea pedis, moist and sweaty feet provide a great environment for growth of this organism. The patient admitted to having sweaty feet—especially while playing soccer for hours. He also didn’t use shower shoes in the gym shower.

In pitted keratolysis, the bacteria live on the dead cells of the stratum corneum of the sole and form visible pits. In interdigital tinea pedis, the skin between the toes is white in appearance.

The FP recommended that the patient wear shower shoes and change his socks during the day if they become sweaty. He also prescribed topical 2% erythromycin solution to apply twice daily to the area with visible pits. In addition, the FP recommended that the patient buy over-the-counter topical terbinafine cream and apply it between the toes once or twice daily—especially after drying his feet well after a shower. A month later, both infections were clear.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient was suffering from pitted keratolysis and interdigital tinea pedis. Pitted keratolysis is caused by the bacterium Kytococcus sedentarius. Like tinea pedis, moist and sweaty feet provide a great environment for growth of this organism. The patient admitted to having sweaty feet—especially while playing soccer for hours. He also didn’t use shower shoes in the gym shower.

In pitted keratolysis, the bacteria live on the dead cells of the stratum corneum of the sole and form visible pits. In interdigital tinea pedis, the skin between the toes is white in appearance.

The FP recommended that the patient wear shower shoes and change his socks during the day if they become sweaty. He also prescribed topical 2% erythromycin solution to apply twice daily to the area with visible pits. In addition, the FP recommended that the patient buy over-the-counter topical terbinafine cream and apply it between the toes once or twice daily—especially after drying his feet well after a shower. A month later, both infections were clear.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Painful rash on feet

The FP told the patient that he had ulcerative tinea pedis related to a bacterial superinfection. The FP performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was positive for branching septate hyphae. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) The small ulcerations and crusts were due to a bacterial superinfection on top of the standard tinea pedis.

Ulcerative tinea pedis is uncommon and, thus, is not always mentioned when describing the standard types of tinea pedis (interdigital, moccasin distribution, and vesicular [vesiculobullous]). Ulcerative tinea pedis does not have to have large ulcers, but there is usually disruption in the skin barrier along with signs of bacterial superinfection (such as crusting and exudate).

This patient demonstrated these signs and the FP chose to treat the patient with an antibiotic that would cover typical skin organisms. There was no need for a culture, as it was likely to grow out many types of skin flora found on the foot. This case was unlikely to be the result of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, so a first-generation cephalosporin was adequate.

The FP treated the patient with oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 2 weeks, along with a course of oral cephalexin 500 mg 3 times daily for one week. Three weeks later, the skin on the patient’s feet was clear, except for some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that was likely to fade over time.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP told the patient that he had ulcerative tinea pedis related to a bacterial superinfection. The FP performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was positive for branching septate hyphae. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) The small ulcerations and crusts were due to a bacterial superinfection on top of the standard tinea pedis.

Ulcerative tinea pedis is uncommon and, thus, is not always mentioned when describing the standard types of tinea pedis (interdigital, moccasin distribution, and vesicular [vesiculobullous]). Ulcerative tinea pedis does not have to have large ulcers, but there is usually disruption in the skin barrier along with signs of bacterial superinfection (such as crusting and exudate).

This patient demonstrated these signs and the FP chose to treat the patient with an antibiotic that would cover typical skin organisms. There was no need for a culture, as it was likely to grow out many types of skin flora found on the foot. This case was unlikely to be the result of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, so a first-generation cephalosporin was adequate.

The FP treated the patient with oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 2 weeks, along with a course of oral cephalexin 500 mg 3 times daily for one week. Three weeks later, the skin on the patient’s feet was clear, except for some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that was likely to fade over time.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP told the patient that he had ulcerative tinea pedis related to a bacterial superinfection. The FP performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was positive for branching septate hyphae. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) The small ulcerations and crusts were due to a bacterial superinfection on top of the standard tinea pedis.

Ulcerative tinea pedis is uncommon and, thus, is not always mentioned when describing the standard types of tinea pedis (interdigital, moccasin distribution, and vesicular [vesiculobullous]). Ulcerative tinea pedis does not have to have large ulcers, but there is usually disruption in the skin barrier along with signs of bacterial superinfection (such as crusting and exudate).

This patient demonstrated these signs and the FP chose to treat the patient with an antibiotic that would cover typical skin organisms. There was no need for a culture, as it was likely to grow out many types of skin flora found on the foot. This case was unlikely to be the result of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, so a first-generation cephalosporin was adequate.

The FP treated the patient with oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 2 weeks, along with a course of oral cephalexin 500 mg 3 times daily for one week. Three weeks later, the skin on the patient’s feet was clear, except for some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that was likely to fade over time.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Itchy blisters on feet

The patient was given a diagnosis of vesicular (vesiculobullous) tinea pedis, based on the vesicles and bullae over the arch region of the foot. The arch is a typical location for vesiculobullous tinea pedis. There are 3 main types of tinea pedis: interdigital, moccasin distribution, and vesiculobullous (which is the least common type). Interdigital tinea pedis is the most common type and is typically seen between the fourth and fifth digits. The moccasin distribution tends to involve more erythema and scale—especially on the sides of the feet—giving the appearance of moccasins.

In general, tinea pedis is most commonly caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Other causative organisms include Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum. The vesiculobullous type of tinea pedis is usually caused by T mentagrophytes. The FP made this diagnosis clinically and did not perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, as this type of tinea pedis has minimal scale and the dermatophyte may be harder to identify with the superficial scraping.

The FP prescribed 2 weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d instead of relying on topical antifungal medicine because a better response can be expected with it. One month later, the vesiculobullous tinea pedis was fully resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The patient was given a diagnosis of vesicular (vesiculobullous) tinea pedis, based on the vesicles and bullae over the arch region of the foot. The arch is a typical location for vesiculobullous tinea pedis. There are 3 main types of tinea pedis: interdigital, moccasin distribution, and vesiculobullous (which is the least common type). Interdigital tinea pedis is the most common type and is typically seen between the fourth and fifth digits. The moccasin distribution tends to involve more erythema and scale—especially on the sides of the feet—giving the appearance of moccasins.

In general, tinea pedis is most commonly caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Other causative organisms include Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum. The vesiculobullous type of tinea pedis is usually caused by T mentagrophytes. The FP made this diagnosis clinically and did not perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, as this type of tinea pedis has minimal scale and the dermatophyte may be harder to identify with the superficial scraping.

The FP prescribed 2 weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d instead of relying on topical antifungal medicine because a better response can be expected with it. One month later, the vesiculobullous tinea pedis was fully resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The patient was given a diagnosis of vesicular (vesiculobullous) tinea pedis, based on the vesicles and bullae over the arch region of the foot. The arch is a typical location for vesiculobullous tinea pedis. There are 3 main types of tinea pedis: interdigital, moccasin distribution, and vesiculobullous (which is the least common type). Interdigital tinea pedis is the most common type and is typically seen between the fourth and fifth digits. The moccasin distribution tends to involve more erythema and scale—especially on the sides of the feet—giving the appearance of moccasins.

In general, tinea pedis is most commonly caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Other causative organisms include Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum. The vesiculobullous type of tinea pedis is usually caused by T mentagrophytes. The FP made this diagnosis clinically and did not perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, as this type of tinea pedis has minimal scale and the dermatophyte may be harder to identify with the superficial scraping.

The FP prescribed 2 weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d instead of relying on topical antifungal medicine because a better response can be expected with it. One month later, the vesiculobullous tinea pedis was fully resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Reppa R. Tinea pedis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:799-804.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Perifollicular petechiae and easy bruising

A 45-year-old woman presented to our hospital with recurrent cirrhosis and sepsis secondary to a hepatic abscess from Pseudomonas aeromonas and Candida albicans. Ten years earlier, she had received a liver transplant due to sclerosing cholangitis. The patient had a history of nausea from her liver disease and malnutrition due to a diet that consisted predominantly of cereal with minimal fresh fruits and vegetables. Her family reported that she bruised easily and had worsening dry, flaky skin.

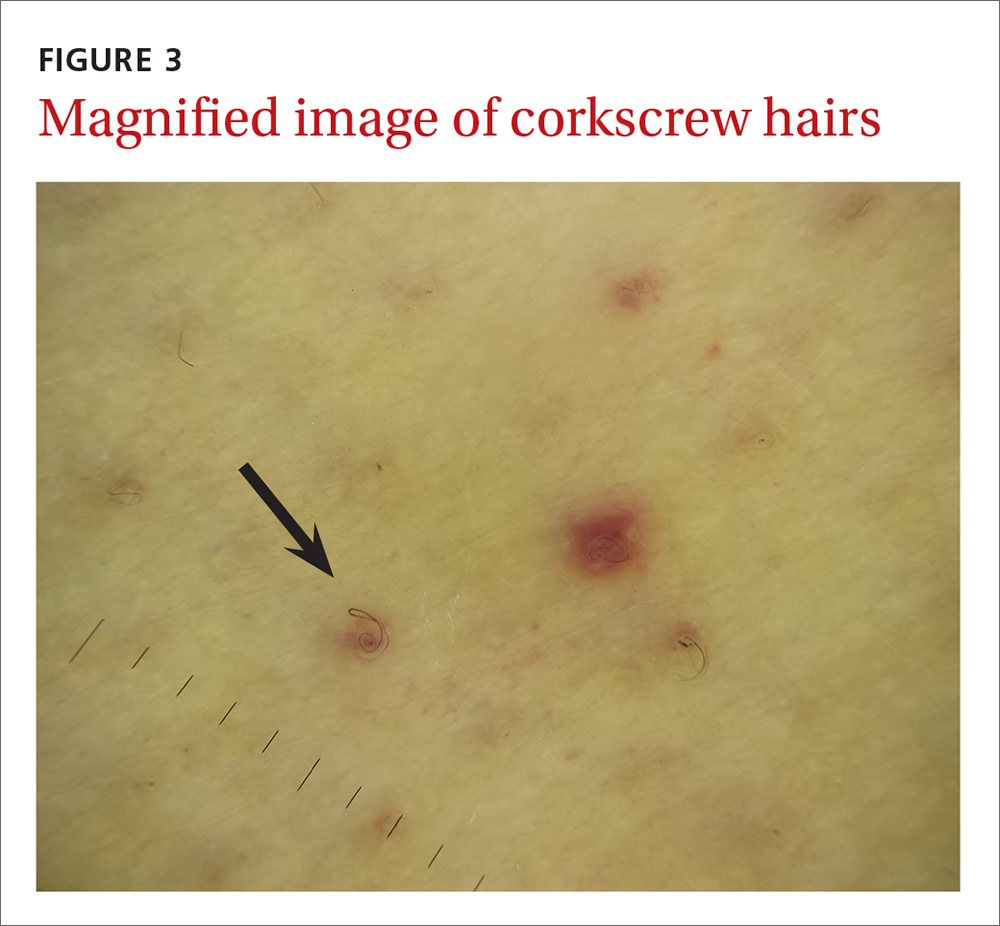

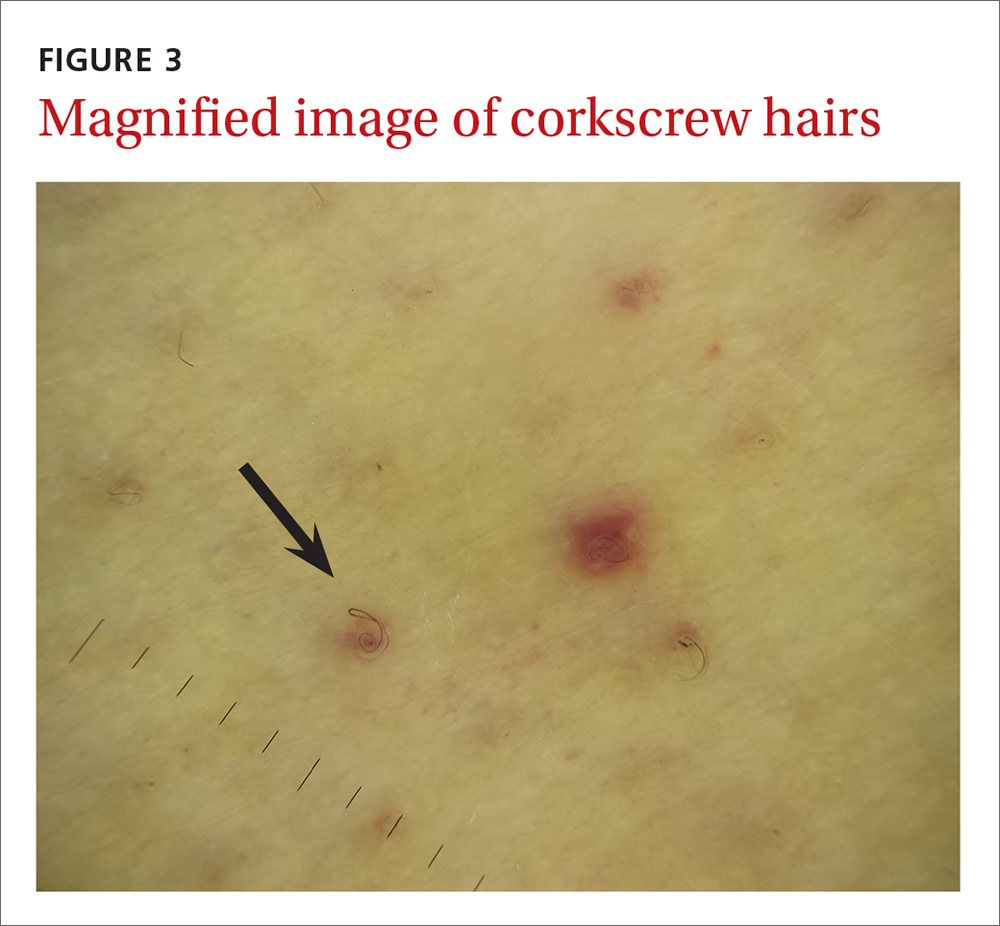

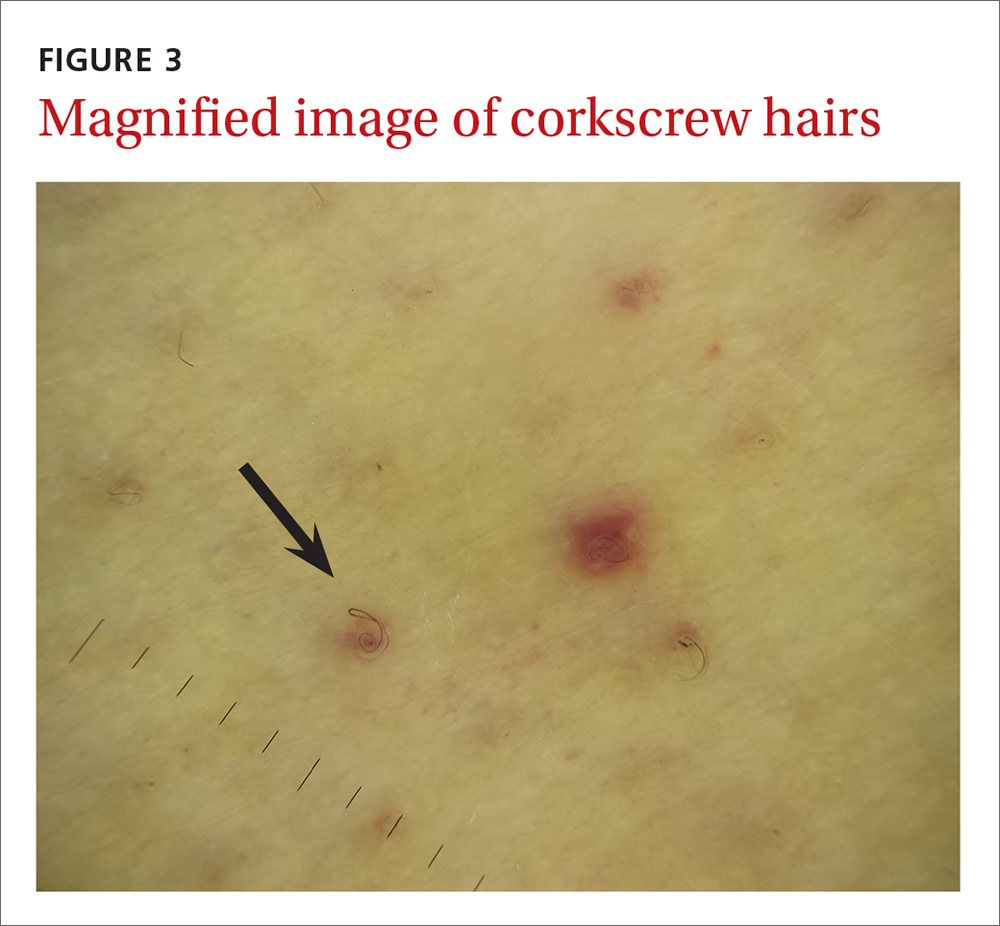

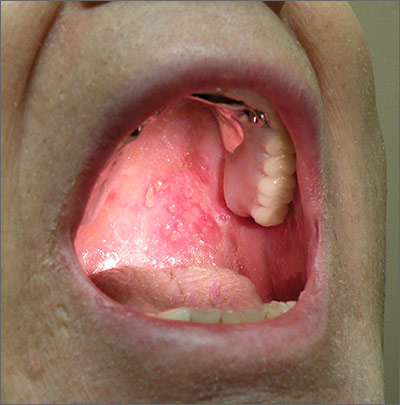

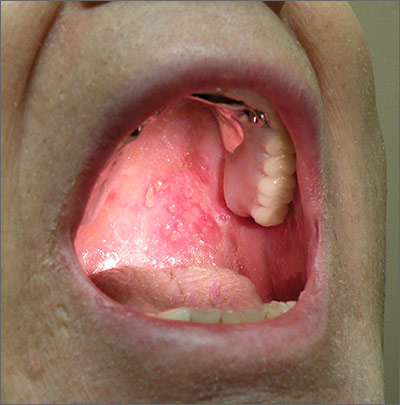

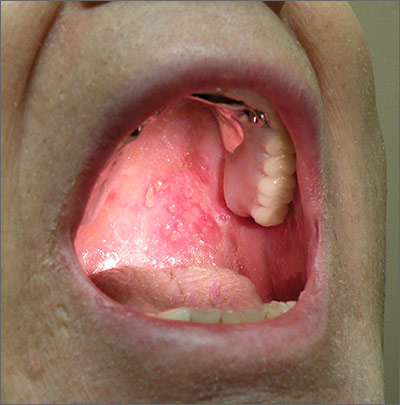

The physical examination revealed jaundice, scleral icterus, purpuric macules, superficial desquamation, gingivitis (FIGURE 1), and perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs (FIGURES 2 and 3). The patient also had acute kidney injury, delirium, and pancytopenia. She was admitted to the hospital and was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole for sepsis, as well as rifaximin and lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Vitamin C deficiency

We diagnosed this patient with vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) based on the fact that she had perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs, which is a pathognomonic feature of the deficiency. The diagnosis was confirmed with a blood vitamin C level of 10 mcmol/L (normal range: 11-114 mcmol/L). It’s important to note that a vitamin C level drawn after hospitalization may be falsely normal due to an improved diet during hospitalization, so a normal vitamin C level doesn’t always rule out a deficiency.

Vitamin C is absorbed from the small intestine and excreted renally. A low vitamin C level occurs in the presence of several conditions—specifically alcoholism and critical illnesses such as sepsis, trauma, major surgery, or stroke—possibly due to decreased absorption and increased oxidative stress. Vitamin C is necessary for multiple hydroxylation reactions, including hydroxylation of proline and lysine in collagen synthesis, beta-hydroxybutyric acid in carnitine synthesis, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in catecholamine synthesis.1

Early vitamin C deficiency presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as malaise, fatigue, and lethargy, followed by the development of anemia, myalgia, bone pain, easy bruising, edema, petechiae, perifollicular hemorrhages, corkscrew hairs, gingivitis, poor wound healing, and mood changes. If untreated, jaundice, neuropathy, hemolysis, seizures, and death can occur.2-4

Perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs are characteristic of the Dx

The differential diagnosis of vitamin C deficiency includes vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, multiple myeloma, and folliculitis.

Vasculitis typically presents with palpable purpura and is not exclusively perifollicular.5 Thrombocytopenia may present with petechiae, but the petechiae are generally not perifollicular and hair shaft abnormalities are generally absent. Multiple myeloma may present with purpura with minimal trauma and larger ecchymosis that isn’t petechial in appearance. Folliculitis typically presents with folliculocentric pustules that have surrounding erythema, but no hemorrhaging.

Suspect vitamin C deficiency in patients with alcoholism, a poor diet, and those who are critically ill.6 During the physical exam, look for ecchymosis, edema, gingivitis, impaired wound healing, jaundice, and the tell-tale sign of perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs.7

If lab values and/or circumstances leave doubt as to whether a true vitamin C deficiency exists, a punch biopsy of an area of perifollicular hemorrhage may be performed. The punch biopsy should demonstrate follicular hyperkeratosis overlying multiple fragmented hair shafts that are surrounded by a perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells.4

Treat with vitamin C

Vitamin C can be replaced via the oral or intravenous (IV) route. There is currently no consensus on a single best replacement regimen, but several effective regimens have been reported in the literature.8,9

We started our patient on IV vitamin C 1 g/d, which improved her cutaneous lesions. Unfortunately, though, she succumbed to complications of her liver disease shortly after starting the therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Krishna AJ Mutgi, MD, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 555 S. 18th Street, Columbus, OH 43205; [email protected].

1. Chambial S, Dwivedi S, Shukla KK, et al. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2013;28:314-328.

2. Touyz LZ. Oral scurvy and periodontal disease. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997;63:837-845.

3. Singh S, Richards SJ, Lykins M, et al. An underdiagnosed ailment: scurvy in a tertiary care academic center. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:372-373.

4. Al-Dabagh A, Milliron BJ, Strowd L, et al. A disease of the present: scurvy in “well-nourished” patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e246-e247.

5. Francescone MA, Levitt J. Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2005;76:261-266.

6. Holley AD, Osland E, Barnes J, et al. Scurvy: historically a plague of the sailor that remains a consideration in the modern intensive care unit. Intern Med J. 2011;41:283-285.

7. Cinotti E, Perrot JL, Labeille B, et al. A dermoscopic clue for scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:S37-S38.

8. De Luna RH, Colley BJ 3rd, Smith K, et al. Scurvy: an often forgotten cause of bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:85-87.

9. Stephen R, Utecht T. Scurvy identified in the emergency department: a case report. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:235-237.

A 45-year-old woman presented to our hospital with recurrent cirrhosis and sepsis secondary to a hepatic abscess from Pseudomonas aeromonas and Candida albicans. Ten years earlier, she had received a liver transplant due to sclerosing cholangitis. The patient had a history of nausea from her liver disease and malnutrition due to a diet that consisted predominantly of cereal with minimal fresh fruits and vegetables. Her family reported that she bruised easily and had worsening dry, flaky skin.

The physical examination revealed jaundice, scleral icterus, purpuric macules, superficial desquamation, gingivitis (FIGURE 1), and perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs (FIGURES 2 and 3). The patient also had acute kidney injury, delirium, and pancytopenia. She was admitted to the hospital and was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole for sepsis, as well as rifaximin and lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Vitamin C deficiency

We diagnosed this patient with vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) based on the fact that she had perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs, which is a pathognomonic feature of the deficiency. The diagnosis was confirmed with a blood vitamin C level of 10 mcmol/L (normal range: 11-114 mcmol/L). It’s important to note that a vitamin C level drawn after hospitalization may be falsely normal due to an improved diet during hospitalization, so a normal vitamin C level doesn’t always rule out a deficiency.

Vitamin C is absorbed from the small intestine and excreted renally. A low vitamin C level occurs in the presence of several conditions—specifically alcoholism and critical illnesses such as sepsis, trauma, major surgery, or stroke—possibly due to decreased absorption and increased oxidative stress. Vitamin C is necessary for multiple hydroxylation reactions, including hydroxylation of proline and lysine in collagen synthesis, beta-hydroxybutyric acid in carnitine synthesis, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in catecholamine synthesis.1

Early vitamin C deficiency presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as malaise, fatigue, and lethargy, followed by the development of anemia, myalgia, bone pain, easy bruising, edema, petechiae, perifollicular hemorrhages, corkscrew hairs, gingivitis, poor wound healing, and mood changes. If untreated, jaundice, neuropathy, hemolysis, seizures, and death can occur.2-4

Perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs are characteristic of the Dx

The differential diagnosis of vitamin C deficiency includes vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, multiple myeloma, and folliculitis.

Vasculitis typically presents with palpable purpura and is not exclusively perifollicular.5 Thrombocytopenia may present with petechiae, but the petechiae are generally not perifollicular and hair shaft abnormalities are generally absent. Multiple myeloma may present with purpura with minimal trauma and larger ecchymosis that isn’t petechial in appearance. Folliculitis typically presents with folliculocentric pustules that have surrounding erythema, but no hemorrhaging.

Suspect vitamin C deficiency in patients with alcoholism, a poor diet, and those who are critically ill.6 During the physical exam, look for ecchymosis, edema, gingivitis, impaired wound healing, jaundice, and the tell-tale sign of perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs.7

If lab values and/or circumstances leave doubt as to whether a true vitamin C deficiency exists, a punch biopsy of an area of perifollicular hemorrhage may be performed. The punch biopsy should demonstrate follicular hyperkeratosis overlying multiple fragmented hair shafts that are surrounded by a perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells.4

Treat with vitamin C

Vitamin C can be replaced via the oral or intravenous (IV) route. There is currently no consensus on a single best replacement regimen, but several effective regimens have been reported in the literature.8,9

We started our patient on IV vitamin C 1 g/d, which improved her cutaneous lesions. Unfortunately, though, she succumbed to complications of her liver disease shortly after starting the therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Krishna AJ Mutgi, MD, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 555 S. 18th Street, Columbus, OH 43205; [email protected].

A 45-year-old woman presented to our hospital with recurrent cirrhosis and sepsis secondary to a hepatic abscess from Pseudomonas aeromonas and Candida albicans. Ten years earlier, she had received a liver transplant due to sclerosing cholangitis. The patient had a history of nausea from her liver disease and malnutrition due to a diet that consisted predominantly of cereal with minimal fresh fruits and vegetables. Her family reported that she bruised easily and had worsening dry, flaky skin.

The physical examination revealed jaundice, scleral icterus, purpuric macules, superficial desquamation, gingivitis (FIGURE 1), and perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs (FIGURES 2 and 3). The patient also had acute kidney injury, delirium, and pancytopenia. She was admitted to the hospital and was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole for sepsis, as well as rifaximin and lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Vitamin C deficiency

We diagnosed this patient with vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) based on the fact that she had perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs, which is a pathognomonic feature of the deficiency. The diagnosis was confirmed with a blood vitamin C level of 10 mcmol/L (normal range: 11-114 mcmol/L). It’s important to note that a vitamin C level drawn after hospitalization may be falsely normal due to an improved diet during hospitalization, so a normal vitamin C level doesn’t always rule out a deficiency.

Vitamin C is absorbed from the small intestine and excreted renally. A low vitamin C level occurs in the presence of several conditions—specifically alcoholism and critical illnesses such as sepsis, trauma, major surgery, or stroke—possibly due to decreased absorption and increased oxidative stress. Vitamin C is necessary for multiple hydroxylation reactions, including hydroxylation of proline and lysine in collagen synthesis, beta-hydroxybutyric acid in carnitine synthesis, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in catecholamine synthesis.1

Early vitamin C deficiency presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as malaise, fatigue, and lethargy, followed by the development of anemia, myalgia, bone pain, easy bruising, edema, petechiae, perifollicular hemorrhages, corkscrew hairs, gingivitis, poor wound healing, and mood changes. If untreated, jaundice, neuropathy, hemolysis, seizures, and death can occur.2-4

Perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs are characteristic of the Dx

The differential diagnosis of vitamin C deficiency includes vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, multiple myeloma, and folliculitis.

Vasculitis typically presents with palpable purpura and is not exclusively perifollicular.5 Thrombocytopenia may present with petechiae, but the petechiae are generally not perifollicular and hair shaft abnormalities are generally absent. Multiple myeloma may present with purpura with minimal trauma and larger ecchymosis that isn’t petechial in appearance. Folliculitis typically presents with folliculocentric pustules that have surrounding erythema, but no hemorrhaging.

Suspect vitamin C deficiency in patients with alcoholism, a poor diet, and those who are critically ill.6 During the physical exam, look for ecchymosis, edema, gingivitis, impaired wound healing, jaundice, and the tell-tale sign of perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs.7

If lab values and/or circumstances leave doubt as to whether a true vitamin C deficiency exists, a punch biopsy of an area of perifollicular hemorrhage may be performed. The punch biopsy should demonstrate follicular hyperkeratosis overlying multiple fragmented hair shafts that are surrounded by a perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells.4

Treat with vitamin C

Vitamin C can be replaced via the oral or intravenous (IV) route. There is currently no consensus on a single best replacement regimen, but several effective regimens have been reported in the literature.8,9

We started our patient on IV vitamin C 1 g/d, which improved her cutaneous lesions. Unfortunately, though, she succumbed to complications of her liver disease shortly after starting the therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Krishna AJ Mutgi, MD, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 555 S. 18th Street, Columbus, OH 43205; [email protected].

1. Chambial S, Dwivedi S, Shukla KK, et al. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2013;28:314-328.

2. Touyz LZ. Oral scurvy and periodontal disease. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997;63:837-845.

3. Singh S, Richards SJ, Lykins M, et al. An underdiagnosed ailment: scurvy in a tertiary care academic center. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:372-373.

4. Al-Dabagh A, Milliron BJ, Strowd L, et al. A disease of the present: scurvy in “well-nourished” patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e246-e247.

5. Francescone MA, Levitt J. Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2005;76:261-266.

6. Holley AD, Osland E, Barnes J, et al. Scurvy: historically a plague of the sailor that remains a consideration in the modern intensive care unit. Intern Med J. 2011;41:283-285.

7. Cinotti E, Perrot JL, Labeille B, et al. A dermoscopic clue for scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:S37-S38.

8. De Luna RH, Colley BJ 3rd, Smith K, et al. Scurvy: an often forgotten cause of bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:85-87.

9. Stephen R, Utecht T. Scurvy identified in the emergency department: a case report. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:235-237.

1. Chambial S, Dwivedi S, Shukla KK, et al. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2013;28:314-328.

2. Touyz LZ. Oral scurvy and periodontal disease. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997;63:837-845.

3. Singh S, Richards SJ, Lykins M, et al. An underdiagnosed ailment: scurvy in a tertiary care academic center. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:372-373.

4. Al-Dabagh A, Milliron BJ, Strowd L, et al. A disease of the present: scurvy in “well-nourished” patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e246-e247.

5. Francescone MA, Levitt J. Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2005;76:261-266.

6. Holley AD, Osland E, Barnes J, et al. Scurvy: historically a plague of the sailor that remains a consideration in the modern intensive care unit. Intern Med J. 2011;41:283-285.

7. Cinotti E, Perrot JL, Labeille B, et al. A dermoscopic clue for scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:S37-S38.

8. De Luna RH, Colley BJ 3rd, Smith K, et al. Scurvy: an often forgotten cause of bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:85-87.

9. Stephen R, Utecht T. Scurvy identified in the emergency department: a case report. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:235-237.

Sore throat and ear pain

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, he was given a diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus—also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome typically develop unilateral facial paralysis and erythematous vesicles that appear ipsilaterally on the ear and/or in the mouth. This syndrome is a rare complication of herpes zoster that occurs when latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection reactivates and spreads to affect the geniculate ganglion.

An estimated 5 out of every 100,000 people develop Ramsay Hunt syndrome each year in the United States; men and women are equally affected. Any patient who’s had VZV infection runs the risk of developing Ramsay Hunt syndrome, but it most often develops in individuals older than age 60.

Vesicles in the mouth usually develop on the tongue or hard palate. Other symptoms may include tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and nystagmus. Because the symptoms of Ramsay Hunt syndrome suggest a possible infection, the differential diagnosis should include herpes simplex virus type 1, Epstein-Barr virus, group A Streptococcus, and measles.

A diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome is typically made clinically, but can be confirmed with direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) analysis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, or viral culture of vesicular exudates. DFA for VZV has an 87% sensitivity. PCR has a higher sensitivity (92%), is widely available, and is the diagnostic test of choice, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Treatment with an oral steroid, such as prednisone, in addition to an antiviral such as acyclovir or valacyclovir, may reduce the likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia and improve facial motor function. However, these benefits have not been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times a day for 7 days and oral prednisone 50 mg/d for 5 days for the patient. After one week of treatment, the patient’s symptoms resolved and the vesicles in his mouth crusted over. He did not experience postherpetic neuralgia or have a recurrence.

Adapted from: Moss DA, Crawford P. Sore throat and left ear pain. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:117-119.

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, he was given a diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus—also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome typically develop unilateral facial paralysis and erythematous vesicles that appear ipsilaterally on the ear and/or in the mouth. This syndrome is a rare complication of herpes zoster that occurs when latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection reactivates and spreads to affect the geniculate ganglion.

An estimated 5 out of every 100,000 people develop Ramsay Hunt syndrome each year in the United States; men and women are equally affected. Any patient who’s had VZV infection runs the risk of developing Ramsay Hunt syndrome, but it most often develops in individuals older than age 60.

Vesicles in the mouth usually develop on the tongue or hard palate. Other symptoms may include tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and nystagmus. Because the symptoms of Ramsay Hunt syndrome suggest a possible infection, the differential diagnosis should include herpes simplex virus type 1, Epstein-Barr virus, group A Streptococcus, and measles.

A diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome is typically made clinically, but can be confirmed with direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) analysis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, or viral culture of vesicular exudates. DFA for VZV has an 87% sensitivity. PCR has a higher sensitivity (92%), is widely available, and is the diagnostic test of choice, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Treatment with an oral steroid, such as prednisone, in addition to an antiviral such as acyclovir or valacyclovir, may reduce the likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia and improve facial motor function. However, these benefits have not been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times a day for 7 days and oral prednisone 50 mg/d for 5 days for the patient. After one week of treatment, the patient’s symptoms resolved and the vesicles in his mouth crusted over. He did not experience postherpetic neuralgia or have a recurrence.

Adapted from: Moss DA, Crawford P. Sore throat and left ear pain. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:117-119.

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, he was given a diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus—also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome typically develop unilateral facial paralysis and erythematous vesicles that appear ipsilaterally on the ear and/or in the mouth. This syndrome is a rare complication of herpes zoster that occurs when latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection reactivates and spreads to affect the geniculate ganglion.

An estimated 5 out of every 100,000 people develop Ramsay Hunt syndrome each year in the United States; men and women are equally affected. Any patient who’s had VZV infection runs the risk of developing Ramsay Hunt syndrome, but it most often develops in individuals older than age 60.

Vesicles in the mouth usually develop on the tongue or hard palate. Other symptoms may include tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and nystagmus. Because the symptoms of Ramsay Hunt syndrome suggest a possible infection, the differential diagnosis should include herpes simplex virus type 1, Epstein-Barr virus, group A Streptococcus, and measles.

A diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome is typically made clinically, but can be confirmed with direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) analysis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, or viral culture of vesicular exudates. DFA for VZV has an 87% sensitivity. PCR has a higher sensitivity (92%), is widely available, and is the diagnostic test of choice, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Treatment with an oral steroid, such as prednisone, in addition to an antiviral such as acyclovir or valacyclovir, may reduce the likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia and improve facial motor function. However, these benefits have not been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times a day for 7 days and oral prednisone 50 mg/d for 5 days for the patient. After one week of treatment, the patient’s symptoms resolved and the vesicles in his mouth crusted over. He did not experience postherpetic neuralgia or have a recurrence.

Adapted from: Moss DA, Crawford P. Sore throat and left ear pain. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:117-119.

Itchy rash in groin

The FP examined the rash closely and considered a diagnosis of inverse psoriasis. He looked at the patient’s nails for further clues and found that the patient had nail pitting and some onycholysis, which are both found in psoriasis. There were also some psoriatic plaques over the dorsum of his fingers. The remainder of the patient’s skin was clear.

Between the nail findings and the fact that the rash didn’t respond to antifungal medicine, the FP realized that this was truly inverse psoriasis and decided not to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation.

The partial response to hydrocortisone supported the psoriasis diagnosis as well, but the FP knew that hydrocortisone was rarely potent enough to treat psoriasis, so he prescribed topical triamcinolone cream. While ointments are frequently more potent, the choice of the cream was made to avoid the greasiness that the patient would feel with an ointment in the groin.

Triamcinolone was chosen to avoid issues of atrophy that could occur with a higher potency steroid in an intertriginous area. However, if the triamcinolone was not effective, the FP was prepared to prescribe a stronger potency topical steroid for a short period of time until the psoriasis cleared. Then, the moderate potency triamcinolone could be used to prevent recurrence. The patient was also told he could use the triamcinolone on his fingers.

The physician counseled the patient on quitting smoking because smoking worsens psoriasis and, of course, has many health risks. The patient was not willing to completely stop, but said he would try to cut down. The FP encouraged him to have a long-term goal of complete smoking cessation.

At a follow-up visit one month later, the rash was 90% better, but the psoriasis over the fingers was only 50% better. The FP then prescribed clobetasol ointment for the fingers and told the patient to also use it in the inguinal area for one week. Two months later, the patient had 95% clearance in both areas. The FP told the patient that this is a lifelong disease that can often be controlled, but not cured.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP examined the rash closely and considered a diagnosis of inverse psoriasis. He looked at the patient’s nails for further clues and found that the patient had nail pitting and some onycholysis, which are both found in psoriasis. There were also some psoriatic plaques over the dorsum of his fingers. The remainder of the patient’s skin was clear.

Between the nail findings and the fact that the rash didn’t respond to antifungal medicine, the FP realized that this was truly inverse psoriasis and decided not to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation.

The partial response to hydrocortisone supported the psoriasis diagnosis as well, but the FP knew that hydrocortisone was rarely potent enough to treat psoriasis, so he prescribed topical triamcinolone cream. While ointments are frequently more potent, the choice of the cream was made to avoid the greasiness that the patient would feel with an ointment in the groin.

Triamcinolone was chosen to avoid issues of atrophy that could occur with a higher potency steroid in an intertriginous area. However, if the triamcinolone was not effective, the FP was prepared to prescribe a stronger potency topical steroid for a short period of time until the psoriasis cleared. Then, the moderate potency triamcinolone could be used to prevent recurrence. The patient was also told he could use the triamcinolone on his fingers.

The physician counseled the patient on quitting smoking because smoking worsens psoriasis and, of course, has many health risks. The patient was not willing to completely stop, but said he would try to cut down. The FP encouraged him to have a long-term goal of complete smoking cessation.

At a follow-up visit one month later, the rash was 90% better, but the psoriasis over the fingers was only 50% better. The FP then prescribed clobetasol ointment for the fingers and told the patient to also use it in the inguinal area for one week. Two months later, the patient had 95% clearance in both areas. The FP told the patient that this is a lifelong disease that can often be controlled, but not cured.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP examined the rash closely and considered a diagnosis of inverse psoriasis. He looked at the patient’s nails for further clues and found that the patient had nail pitting and some onycholysis, which are both found in psoriasis. There were also some psoriatic plaques over the dorsum of his fingers. The remainder of the patient’s skin was clear.

Between the nail findings and the fact that the rash didn’t respond to antifungal medicine, the FP realized that this was truly inverse psoriasis and decided not to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation.

The partial response to hydrocortisone supported the psoriasis diagnosis as well, but the FP knew that hydrocortisone was rarely potent enough to treat psoriasis, so he prescribed topical triamcinolone cream. While ointments are frequently more potent, the choice of the cream was made to avoid the greasiness that the patient would feel with an ointment in the groin.

Triamcinolone was chosen to avoid issues of atrophy that could occur with a higher potency steroid in an intertriginous area. However, if the triamcinolone was not effective, the FP was prepared to prescribe a stronger potency topical steroid for a short period of time until the psoriasis cleared. Then, the moderate potency triamcinolone could be used to prevent recurrence. The patient was also told he could use the triamcinolone on his fingers.

The physician counseled the patient on quitting smoking because smoking worsens psoriasis and, of course, has many health risks. The patient was not willing to completely stop, but said he would try to cut down. The FP encouraged him to have a long-term goal of complete smoking cessation.

At a follow-up visit one month later, the rash was 90% better, but the psoriasis over the fingers was only 50% better. The FP then prescribed clobetasol ointment for the fingers and told the patient to also use it in the inguinal area for one week. Two months later, the patient had 95% clearance in both areas. The FP told the patient that this is a lifelong disease that can often be controlled, but not cured.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

“Jock itch” or something else?

The family physician (FP) agreed that this could be a tinea cruris infection. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, but did not see any hyphae or fungal elements. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

He told the patient that there was no evidence of fungus under the microscope, and took out his Woods lamp (ultraviolet light) to check for erythrasma. The involved area fluoresced a coral red, confirming the diagnosis of erythrasma. Erythrasma is a bacterial infection caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum.

Treatment options include topical erythromycin, topical clindamycin, oral erythromycin, or oral clarithromycin. The patient decided to take oral erythromycin and the FP prescribed 250 mg twice a day for 2 weeks. At a follow-up visit one month later, the rash had completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) agreed that this could be a tinea cruris infection. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, but did not see any hyphae or fungal elements. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

He told the patient that there was no evidence of fungus under the microscope, and took out his Woods lamp (ultraviolet light) to check for erythrasma. The involved area fluoresced a coral red, confirming the diagnosis of erythrasma. Erythrasma is a bacterial infection caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum.

Treatment options include topical erythromycin, topical clindamycin, oral erythromycin, or oral clarithromycin. The patient decided to take oral erythromycin and the FP prescribed 250 mg twice a day for 2 weeks. At a follow-up visit one month later, the rash had completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) agreed that this could be a tinea cruris infection. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, but did not see any hyphae or fungal elements. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

He told the patient that there was no evidence of fungus under the microscope, and took out his Woods lamp (ultraviolet light) to check for erythrasma. The involved area fluoresced a coral red, confirming the diagnosis of erythrasma. Erythrasma is a bacterial infection caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum.

Treatment options include topical erythromycin, topical clindamycin, oral erythromycin, or oral clarithromycin. The patient decided to take oral erythromycin and the FP prescribed 250 mg twice a day for 2 weeks. At a follow-up visit one month later, the rash had completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com