User login

Rash for 20 years

Based on the pattern of the rash and the patient’s history, the family physician (FP) considered tinea corporis and cruris, but the history of failing treatment seemed unusual. The FP also considered a diagnosis of pityriasis rubra pilaris because he observed a “skip” area on the left thigh.

The FP performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation using a fungal stain and found branching septate hyphae. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.) He also wondered if the failed treatment was secondary to inadequate dosing or duration of the oral medicines previously used, given that the patient was 6 feet, 5 inches tall and weighed more than 250 pounds. The patient didn’t have liver disease and rarely drank alcohol. Baseline liver function tests (LFTs) were within normal limits.

The FP told the patient to use oral terbinafine for one month rather than the recommended 2 weeks. One month later, there was less erythema and scaling, but the rash had not completely resolved. At that time, the FP and patient decided together to do a punch biopsy to make sure the diagnosis was correct. The punch biopsy supported the diagnosis of tinea with a positive periodic acid–Schiff stain for fungal elements; no other pathology was noted.

Since the LFTs were still normal, the FP and patient discussed a second month of treatment. The FP also performed a fungal culture and requested that the lab test the fungus for identification and sensitivities. Two weeks later, the results showed Trichophyton rubrum that was sensitive to all oral antifungal medications tested, including terbinafine.

At this point, the FP became concerned about the patient’s immune system, so he ordered a complete blood count (CBC) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test. The CBC came back normal and the HIV test was negative. At the end of the second month, the fungal infection was still present clinically and the KOH preparation was still positive.

The FP offered oral itraconazole 100 mg/d and the patient was happy to try another therapy. The LFTs remained normal and after one month of itraconazole, the tinea was still present. At this point, the patient decided that he could live with the condition and would use a topical antifungal when the rash was itchy.

This case demonstrates a situation in which the patient’s immune system is “blind” to the foreign fungus. This has been known to happen with human papillomavirus, when patients have warts that do not resolve even with the most aggressive therapies.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the pattern of the rash and the patient’s history, the family physician (FP) considered tinea corporis and cruris, but the history of failing treatment seemed unusual. The FP also considered a diagnosis of pityriasis rubra pilaris because he observed a “skip” area on the left thigh.

The FP performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation using a fungal stain and found branching septate hyphae. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.) He also wondered if the failed treatment was secondary to inadequate dosing or duration of the oral medicines previously used, given that the patient was 6 feet, 5 inches tall and weighed more than 250 pounds. The patient didn’t have liver disease and rarely drank alcohol. Baseline liver function tests (LFTs) were within normal limits.

The FP told the patient to use oral terbinafine for one month rather than the recommended 2 weeks. One month later, there was less erythema and scaling, but the rash had not completely resolved. At that time, the FP and patient decided together to do a punch biopsy to make sure the diagnosis was correct. The punch biopsy supported the diagnosis of tinea with a positive periodic acid–Schiff stain for fungal elements; no other pathology was noted.

Since the LFTs were still normal, the FP and patient discussed a second month of treatment. The FP also performed a fungal culture and requested that the lab test the fungus for identification and sensitivities. Two weeks later, the results showed Trichophyton rubrum that was sensitive to all oral antifungal medications tested, including terbinafine.

At this point, the FP became concerned about the patient’s immune system, so he ordered a complete blood count (CBC) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test. The CBC came back normal and the HIV test was negative. At the end of the second month, the fungal infection was still present clinically and the KOH preparation was still positive.

The FP offered oral itraconazole 100 mg/d and the patient was happy to try another therapy. The LFTs remained normal and after one month of itraconazole, the tinea was still present. At this point, the patient decided that he could live with the condition and would use a topical antifungal when the rash was itchy.

This case demonstrates a situation in which the patient’s immune system is “blind” to the foreign fungus. This has been known to happen with human papillomavirus, when patients have warts that do not resolve even with the most aggressive therapies.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the pattern of the rash and the patient’s history, the family physician (FP) considered tinea corporis and cruris, but the history of failing treatment seemed unusual. The FP also considered a diagnosis of pityriasis rubra pilaris because he observed a “skip” area on the left thigh.

The FP performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation using a fungal stain and found branching septate hyphae. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.) He also wondered if the failed treatment was secondary to inadequate dosing or duration of the oral medicines previously used, given that the patient was 6 feet, 5 inches tall and weighed more than 250 pounds. The patient didn’t have liver disease and rarely drank alcohol. Baseline liver function tests (LFTs) were within normal limits.

The FP told the patient to use oral terbinafine for one month rather than the recommended 2 weeks. One month later, there was less erythema and scaling, but the rash had not completely resolved. At that time, the FP and patient decided together to do a punch biopsy to make sure the diagnosis was correct. The punch biopsy supported the diagnosis of tinea with a positive periodic acid–Schiff stain for fungal elements; no other pathology was noted.

Since the LFTs were still normal, the FP and patient discussed a second month of treatment. The FP also performed a fungal culture and requested that the lab test the fungus for identification and sensitivities. Two weeks later, the results showed Trichophyton rubrum that was sensitive to all oral antifungal medications tested, including terbinafine.

At this point, the FP became concerned about the patient’s immune system, so he ordered a complete blood count (CBC) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test. The CBC came back normal and the HIV test was negative. At the end of the second month, the fungal infection was still present clinically and the KOH preparation was still positive.

The FP offered oral itraconazole 100 mg/d and the patient was happy to try another therapy. The LFTs remained normal and after one month of itraconazole, the tinea was still present. At this point, the patient decided that he could live with the condition and would use a topical antifungal when the rash was itchy.

This case demonstrates a situation in which the patient’s immune system is “blind” to the foreign fungus. This has been known to happen with human papillomavirus, when patients have warts that do not resolve even with the most aggressive therapies.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Woman with rash in groin

The family physician (FP) suspected that the patient had tinea cruris, but hadn’t ever seen it spread so far from the inguinal area. The rash had central clearing, which is typical of tinea corporis, but is not seen as often with tinea cruris. The FP performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was positive for branching septate hyphae. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

The FP discussed the treatment options, which consisted of topical antifungal medicine vs oral antifungal medicine. The patient was willing to try the topical terbinafine and return for a follow-up appointment in a month. The FP told the patient that he would give her oral terbinafine if the topical terbinafine didn’t work. One month later, the skin had cleared and the patient was happy with the results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) suspected that the patient had tinea cruris, but hadn’t ever seen it spread so far from the inguinal area. The rash had central clearing, which is typical of tinea corporis, but is not seen as often with tinea cruris. The FP performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was positive for branching septate hyphae. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

The FP discussed the treatment options, which consisted of topical antifungal medicine vs oral antifungal medicine. The patient was willing to try the topical terbinafine and return for a follow-up appointment in a month. The FP told the patient that he would give her oral terbinafine if the topical terbinafine didn’t work. One month later, the skin had cleared and the patient was happy with the results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) suspected that the patient had tinea cruris, but hadn’t ever seen it spread so far from the inguinal area. The rash had central clearing, which is typical of tinea corporis, but is not seen as often with tinea cruris. The FP performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was positive for branching septate hyphae. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

The FP discussed the treatment options, which consisted of topical antifungal medicine vs oral antifungal medicine. The patient was willing to try the topical terbinafine and return for a follow-up appointment in a month. The FP told the patient that he would give her oral terbinafine if the topical terbinafine didn’t work. One month later, the skin had cleared and the patient was happy with the results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Two cases of asymmetric papules

CASE 1 ›

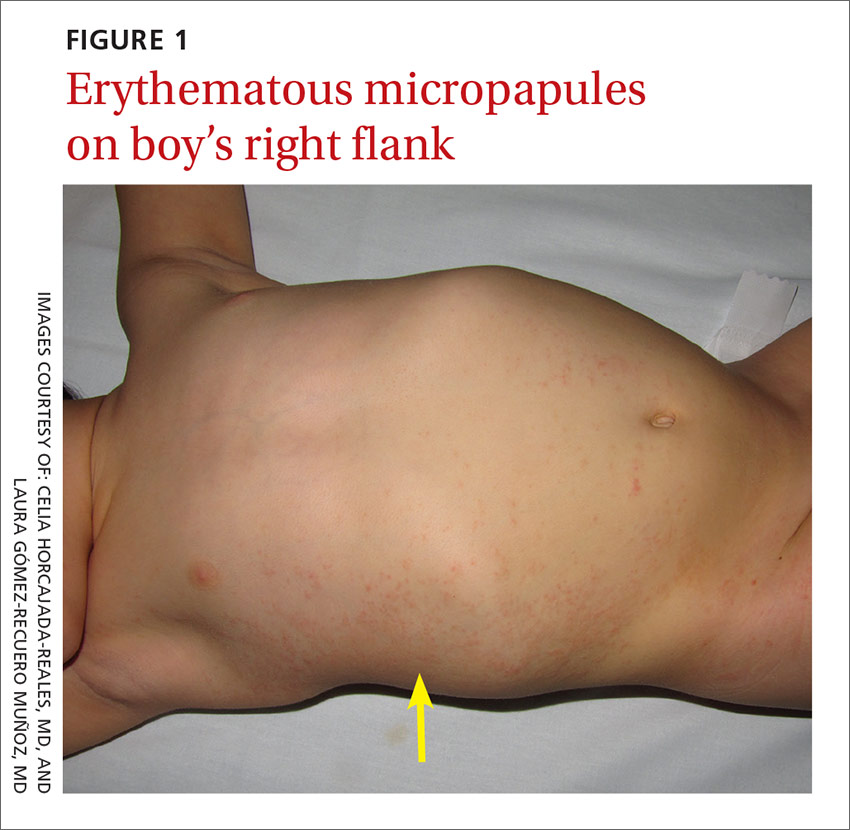

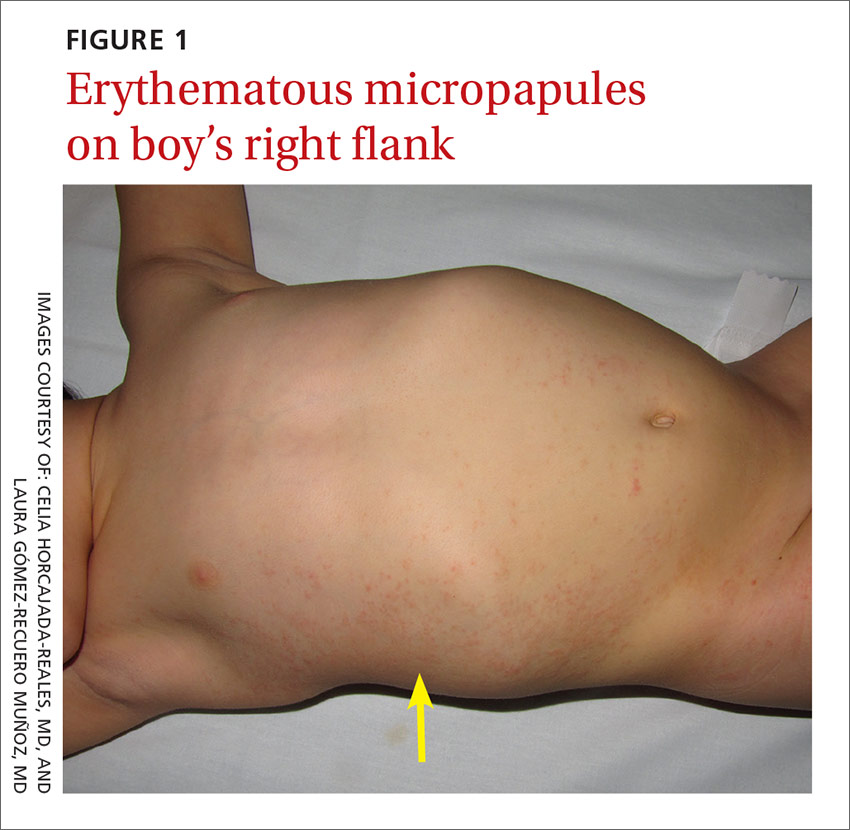

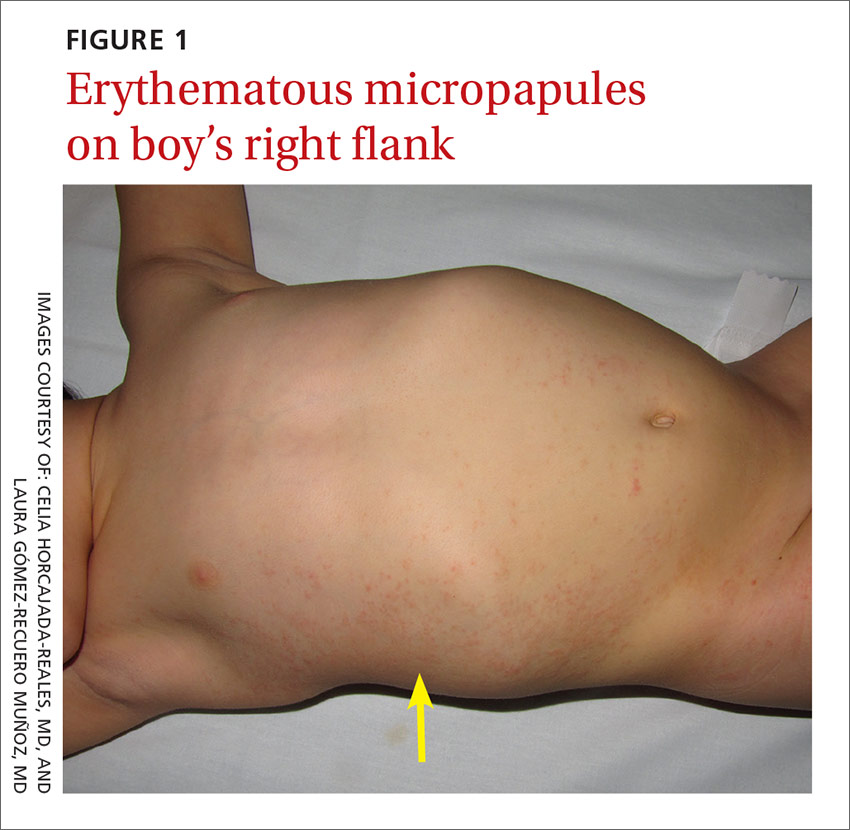

A 3-year-old boy was brought to our emergency department for evaluation of skin lesions that he’d had for 7 days. The boy would sometimes scratch the lesions, which began on his right flank as erythematous micropapules and later spread to his right lateral thigh and inner arm (FIGURE 1). His lymph nodes were not palpable.

The boy’s parents had been told to use a topical corticosteroid, but the rash did not improve. His family denied fever or other previous infectious or systemic symptoms, and said that he hadn’t come into contact with any irritants or allergenic substances.

CASE 2 ›

A 13-year-old girl came to our emergency department with a pruriginous rash on her right leg and abdomen that she’d had for 4 days (FIGURE 2). The millimetric papules had also spread to the right side of her trunk, her right arm and armpit, and her inner thigh. Before the rash, she’d had a fever, otalgia, and conjunctivitis. We noted redness of her left conjunctiva, eardrum, and pharynx. The girl’s lymph nodes were not palpable. Serologic examinations for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, rubella, parvovirus B19, and Mycoplasma were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood

Both of these patients were given a diagnosis of asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood (APEC), based on the appearance and distribution of the rashes.

A rare condition that mostly affects young children

APEC is a rash of unknown cause, although epidemiologic and clinical findings support a viral etiology. Cases of this rash were first reported in 1992 by Bodemer et al, and a year later, Taïeb et al reported new cases, establishing the term “asymmetric periflexural exanthem.”1,2 Several viruses have been related to APEC (including adenovirus, parvovirus B19, parainfluenza 2 and 3, and human herpesvirus 7), but none of these has been consistently associated with the rash.3-5

APEC tends to affect children between one and 5 years of age, but adult cases have been reported.6,7 The condition occurs slightly more frequently among females and more often in winter and spring.8,9 APEC is a rare condition; since 1992, there have only been about 300 cases reported in the literature.10

What you’ll see. The erythematous rash appears as an asymmetrical or unilateral papular, scarlatiniform, or eczematous exanthema. It initially affects the axilla or groin and may then progress to the extremities and trunk. Minor lesions infrequently present on the contralateral side. Most children who are affected by APEC are otherwise healthy and asymptomatic at presentation. The exanthem is occasionally pruritic and can be preceded by short respiratory or gastrointestinal prodromes or a low-grade fever.2,9 If the rash predominantly affects the lateral thoracic wall, it may be referred to as unilateral laterothoracic exanthem.11 Regional lymphadenopathies can often be found, and there is no systemic involvement.

The distribution of the rash helps to distinguish the condition

The differential diagnosis for this type of exanthem includes drug eruptions, pityriasis rosea, miliaria, scarlet fever, papular acrodermatitis of childhood, and other viral rashes. The asymmetric distribution of APEC helps to distinguish the condition. Other possible asymmetric skin lesions, such as contact dermatitis, tinea corporis, or lichen striatus, can be differentiated by the characteristics of the cutaneous lesions. Contact dermatitis lesions are more vesicular, pruritic, and related to the contact area. Tinea corporis lesions tend to be smaller, circular, well-limited, and often have pustules. Lichen striatus starts as small pink-, red-, or flesh-colored spots that join together to form a dull red and slightly scaly linear band over the course of one or 2 weeks.12 Because APEC is self-limiting, a skin biopsy is usually not necessary.13

Lesions usually persist for one to 6 weeks and resolve with no sequelae. Only symptomatic treatment is required.9 Topical emollients, topical corticosteroids, or oral antihistamines can be used, if necessary.

Our patients. Both patients were treated with oral antihistamines and the rashes completely resolved within 2 to 3 weeks.

CORRESPONDENCE

Celia Horcajada-Reales, MD, Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Calle del Dr. Esquerdo, 46, 28007 Madrid, Spain; [email protected].

1. Bodemer C, de Prost Y. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem in children: a new disease? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:693-696.

2. Taïeb A, Mégraud F, Legrain V, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:391-393.

3. Al Yousef Ali A, Farhi D, De Maricourt S, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema associated with HHV7 infection. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:230-231.

4. Coustou D, Masquelier B, Lafon ME, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: microbiologic case-control study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:169-173.

5. Harangi F, Várszegi D, Szücs G. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood and viral examinations. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995;12:112-115.

6. Zawar VP. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema: a report in an adult patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:401-404.

7. Pauluzzi P, Festini G, Gelmetti C. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood in an adult patient with parvovirus B19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:372-374.

8. McCuaig CC, Russo P, Powell J, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. A clinicopathologic study of forty-eight patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:979-984.

9. Coustou D, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: a clinical, pathologic, and epidemiologic prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:799-803.

10. Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Ramírez-Romero VS, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthema of childhood. An infrequently diagnosed disease entity. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2007;64:65-68.

11. Chuh AA, Chan HH. Unilateral mediothoracic exanthem: a variant of unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. Cutis. 2006;77:29-32.

12. Chuh A, Zawar V, Law M, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, pityriasis rosea, asymmetrical periflexural exanthem, unilateral mediothoracic exanthem, eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, and papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome: a brief review and arguments for diagnostic criteria. Infect Dis Rep. 2012;4:e12.

13. Gelmetti C, Caputo R. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: who are you? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:293-294.

CASE 1 ›

A 3-year-old boy was brought to our emergency department for evaluation of skin lesions that he’d had for 7 days. The boy would sometimes scratch the lesions, which began on his right flank as erythematous micropapules and later spread to his right lateral thigh and inner arm (FIGURE 1). His lymph nodes were not palpable.

The boy’s parents had been told to use a topical corticosteroid, but the rash did not improve. His family denied fever or other previous infectious or systemic symptoms, and said that he hadn’t come into contact with any irritants or allergenic substances.

CASE 2 ›

A 13-year-old girl came to our emergency department with a pruriginous rash on her right leg and abdomen that she’d had for 4 days (FIGURE 2). The millimetric papules had also spread to the right side of her trunk, her right arm and armpit, and her inner thigh. Before the rash, she’d had a fever, otalgia, and conjunctivitis. We noted redness of her left conjunctiva, eardrum, and pharynx. The girl’s lymph nodes were not palpable. Serologic examinations for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, rubella, parvovirus B19, and Mycoplasma were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood

Both of these patients were given a diagnosis of asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood (APEC), based on the appearance and distribution of the rashes.

A rare condition that mostly affects young children

APEC is a rash of unknown cause, although epidemiologic and clinical findings support a viral etiology. Cases of this rash were first reported in 1992 by Bodemer et al, and a year later, Taïeb et al reported new cases, establishing the term “asymmetric periflexural exanthem.”1,2 Several viruses have been related to APEC (including adenovirus, parvovirus B19, parainfluenza 2 and 3, and human herpesvirus 7), but none of these has been consistently associated with the rash.3-5

APEC tends to affect children between one and 5 years of age, but adult cases have been reported.6,7 The condition occurs slightly more frequently among females and more often in winter and spring.8,9 APEC is a rare condition; since 1992, there have only been about 300 cases reported in the literature.10

What you’ll see. The erythematous rash appears as an asymmetrical or unilateral papular, scarlatiniform, or eczematous exanthema. It initially affects the axilla or groin and may then progress to the extremities and trunk. Minor lesions infrequently present on the contralateral side. Most children who are affected by APEC are otherwise healthy and asymptomatic at presentation. The exanthem is occasionally pruritic and can be preceded by short respiratory or gastrointestinal prodromes or a low-grade fever.2,9 If the rash predominantly affects the lateral thoracic wall, it may be referred to as unilateral laterothoracic exanthem.11 Regional lymphadenopathies can often be found, and there is no systemic involvement.

The distribution of the rash helps to distinguish the condition

The differential diagnosis for this type of exanthem includes drug eruptions, pityriasis rosea, miliaria, scarlet fever, papular acrodermatitis of childhood, and other viral rashes. The asymmetric distribution of APEC helps to distinguish the condition. Other possible asymmetric skin lesions, such as contact dermatitis, tinea corporis, or lichen striatus, can be differentiated by the characteristics of the cutaneous lesions. Contact dermatitis lesions are more vesicular, pruritic, and related to the contact area. Tinea corporis lesions tend to be smaller, circular, well-limited, and often have pustules. Lichen striatus starts as small pink-, red-, or flesh-colored spots that join together to form a dull red and slightly scaly linear band over the course of one or 2 weeks.12 Because APEC is self-limiting, a skin biopsy is usually not necessary.13

Lesions usually persist for one to 6 weeks and resolve with no sequelae. Only symptomatic treatment is required.9 Topical emollients, topical corticosteroids, or oral antihistamines can be used, if necessary.

Our patients. Both patients were treated with oral antihistamines and the rashes completely resolved within 2 to 3 weeks.

CORRESPONDENCE

Celia Horcajada-Reales, MD, Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Calle del Dr. Esquerdo, 46, 28007 Madrid, Spain; [email protected].

CASE 1 ›

A 3-year-old boy was brought to our emergency department for evaluation of skin lesions that he’d had for 7 days. The boy would sometimes scratch the lesions, which began on his right flank as erythematous micropapules and later spread to his right lateral thigh and inner arm (FIGURE 1). His lymph nodes were not palpable.

The boy’s parents had been told to use a topical corticosteroid, but the rash did not improve. His family denied fever or other previous infectious or systemic symptoms, and said that he hadn’t come into contact with any irritants or allergenic substances.

CASE 2 ›

A 13-year-old girl came to our emergency department with a pruriginous rash on her right leg and abdomen that she’d had for 4 days (FIGURE 2). The millimetric papules had also spread to the right side of her trunk, her right arm and armpit, and her inner thigh. Before the rash, she’d had a fever, otalgia, and conjunctivitis. We noted redness of her left conjunctiva, eardrum, and pharynx. The girl’s lymph nodes were not palpable. Serologic examinations for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, rubella, parvovirus B19, and Mycoplasma were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood

Both of these patients were given a diagnosis of asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood (APEC), based on the appearance and distribution of the rashes.

A rare condition that mostly affects young children

APEC is a rash of unknown cause, although epidemiologic and clinical findings support a viral etiology. Cases of this rash were first reported in 1992 by Bodemer et al, and a year later, Taïeb et al reported new cases, establishing the term “asymmetric periflexural exanthem.”1,2 Several viruses have been related to APEC (including adenovirus, parvovirus B19, parainfluenza 2 and 3, and human herpesvirus 7), but none of these has been consistently associated with the rash.3-5

APEC tends to affect children between one and 5 years of age, but adult cases have been reported.6,7 The condition occurs slightly more frequently among females and more often in winter and spring.8,9 APEC is a rare condition; since 1992, there have only been about 300 cases reported in the literature.10

What you’ll see. The erythematous rash appears as an asymmetrical or unilateral papular, scarlatiniform, or eczematous exanthema. It initially affects the axilla or groin and may then progress to the extremities and trunk. Minor lesions infrequently present on the contralateral side. Most children who are affected by APEC are otherwise healthy and asymptomatic at presentation. The exanthem is occasionally pruritic and can be preceded by short respiratory or gastrointestinal prodromes or a low-grade fever.2,9 If the rash predominantly affects the lateral thoracic wall, it may be referred to as unilateral laterothoracic exanthem.11 Regional lymphadenopathies can often be found, and there is no systemic involvement.

The distribution of the rash helps to distinguish the condition

The differential diagnosis for this type of exanthem includes drug eruptions, pityriasis rosea, miliaria, scarlet fever, papular acrodermatitis of childhood, and other viral rashes. The asymmetric distribution of APEC helps to distinguish the condition. Other possible asymmetric skin lesions, such as contact dermatitis, tinea corporis, or lichen striatus, can be differentiated by the characteristics of the cutaneous lesions. Contact dermatitis lesions are more vesicular, pruritic, and related to the contact area. Tinea corporis lesions tend to be smaller, circular, well-limited, and often have pustules. Lichen striatus starts as small pink-, red-, or flesh-colored spots that join together to form a dull red and slightly scaly linear band over the course of one or 2 weeks.12 Because APEC is self-limiting, a skin biopsy is usually not necessary.13

Lesions usually persist for one to 6 weeks and resolve with no sequelae. Only symptomatic treatment is required.9 Topical emollients, topical corticosteroids, or oral antihistamines can be used, if necessary.

Our patients. Both patients were treated with oral antihistamines and the rashes completely resolved within 2 to 3 weeks.

CORRESPONDENCE

Celia Horcajada-Reales, MD, Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Calle del Dr. Esquerdo, 46, 28007 Madrid, Spain; [email protected].

1. Bodemer C, de Prost Y. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem in children: a new disease? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:693-696.

2. Taïeb A, Mégraud F, Legrain V, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:391-393.

3. Al Yousef Ali A, Farhi D, De Maricourt S, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema associated with HHV7 infection. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:230-231.

4. Coustou D, Masquelier B, Lafon ME, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: microbiologic case-control study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:169-173.

5. Harangi F, Várszegi D, Szücs G. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood and viral examinations. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995;12:112-115.

6. Zawar VP. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema: a report in an adult patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:401-404.

7. Pauluzzi P, Festini G, Gelmetti C. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood in an adult patient with parvovirus B19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:372-374.

8. McCuaig CC, Russo P, Powell J, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. A clinicopathologic study of forty-eight patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:979-984.

9. Coustou D, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: a clinical, pathologic, and epidemiologic prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:799-803.

10. Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Ramírez-Romero VS, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthema of childhood. An infrequently diagnosed disease entity. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2007;64:65-68.

11. Chuh AA, Chan HH. Unilateral mediothoracic exanthem: a variant of unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. Cutis. 2006;77:29-32.

12. Chuh A, Zawar V, Law M, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, pityriasis rosea, asymmetrical periflexural exanthem, unilateral mediothoracic exanthem, eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, and papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome: a brief review and arguments for diagnostic criteria. Infect Dis Rep. 2012;4:e12.

13. Gelmetti C, Caputo R. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: who are you? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:293-294.

1. Bodemer C, de Prost Y. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem in children: a new disease? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:693-696.

2. Taïeb A, Mégraud F, Legrain V, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:391-393.

3. Al Yousef Ali A, Farhi D, De Maricourt S, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema associated with HHV7 infection. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:230-231.

4. Coustou D, Masquelier B, Lafon ME, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: microbiologic case-control study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:169-173.

5. Harangi F, Várszegi D, Szücs G. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood and viral examinations. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995;12:112-115.

6. Zawar VP. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema: a report in an adult patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:401-404.

7. Pauluzzi P, Festini G, Gelmetti C. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood in an adult patient with parvovirus B19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:372-374.

8. McCuaig CC, Russo P, Powell J, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. A clinicopathologic study of forty-eight patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:979-984.

9. Coustou D, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: a clinical, pathologic, and epidemiologic prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:799-803.

10. Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Ramírez-Romero VS, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthema of childhood. An infrequently diagnosed disease entity. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2007;64:65-68.

11. Chuh AA, Chan HH. Unilateral mediothoracic exanthem: a variant of unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. Cutis. 2006;77:29-32.

12. Chuh A, Zawar V, Law M, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, pityriasis rosea, asymmetrical periflexural exanthem, unilateral mediothoracic exanthem, eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, and papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome: a brief review and arguments for diagnostic criteria. Infect Dis Rep. 2012;4:e12.

13. Gelmetti C, Caputo R. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: who are you? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:293-294.

Mildly pruritic palmar rash

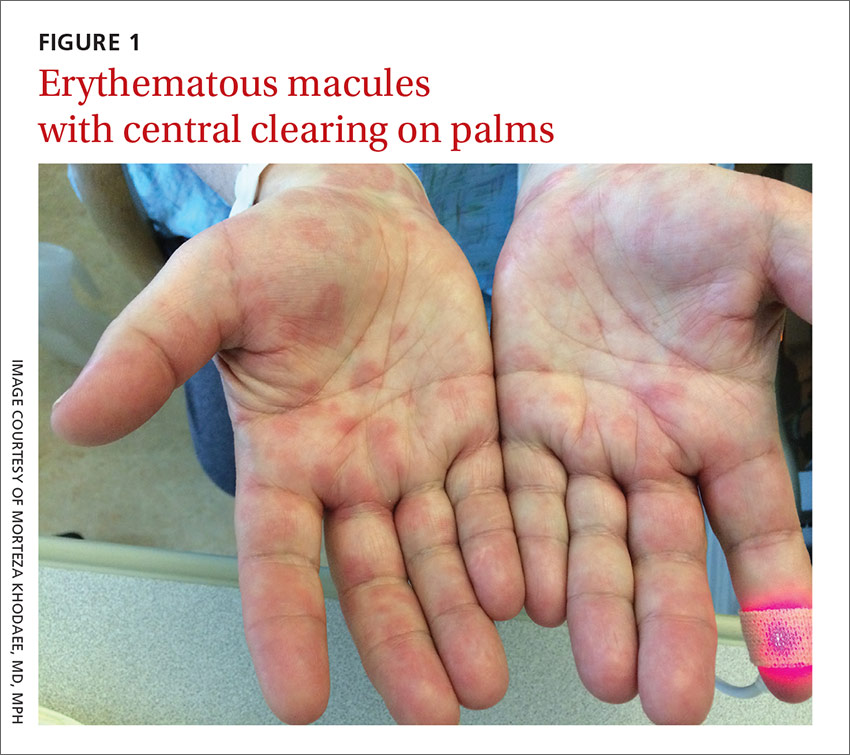

A 62-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a swollen, red, and painful right lower leg. He’d had bilateral lower leg swelling for 2 months, but the left leg became increasingly painful and red over the past 3 days. The patient also had a 3-day history of a diffuse rash that began on his right upper arm and spread to his left arm, both palms, both legs, and his back. It was mildly pruritic, but not painful.

The patient indicated that he had recently sought care from his primary care physician for lower respiratory symptoms. He had just completed a 5-day course of azithromycin and prednisone (50 mg/d for 5 days) the day before his ED visit.

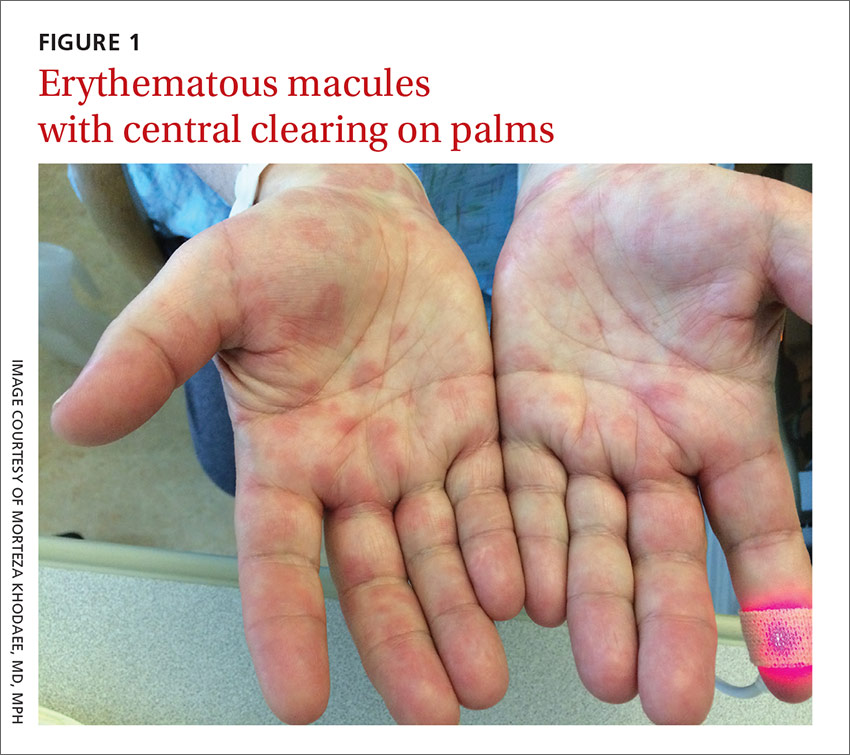

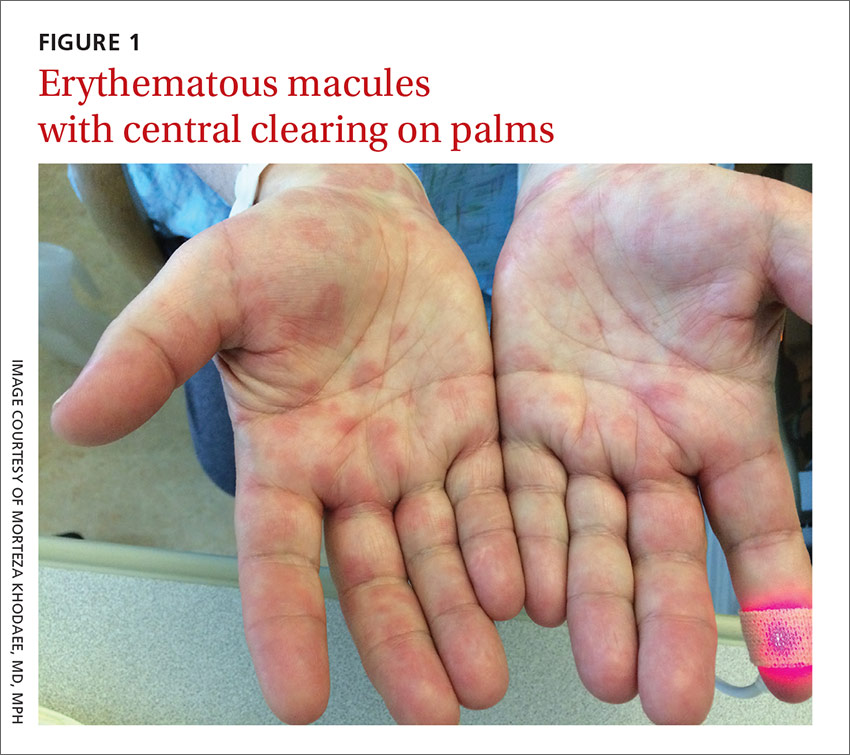

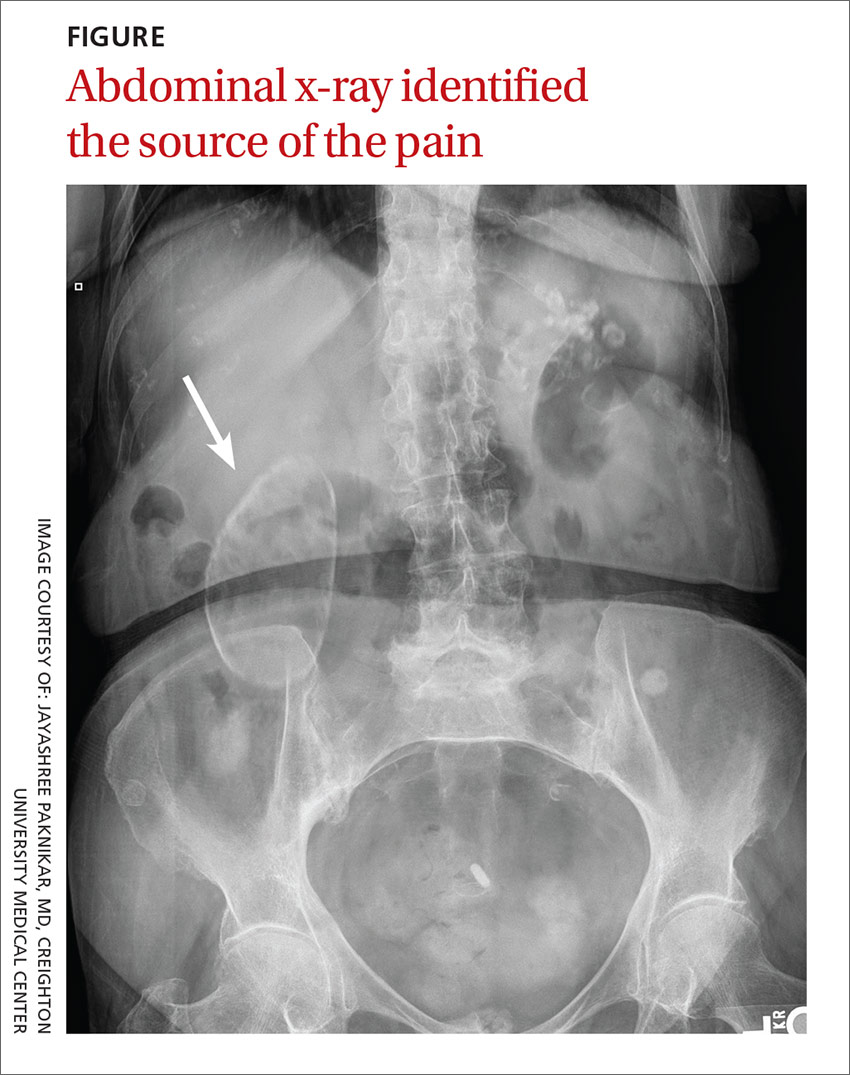

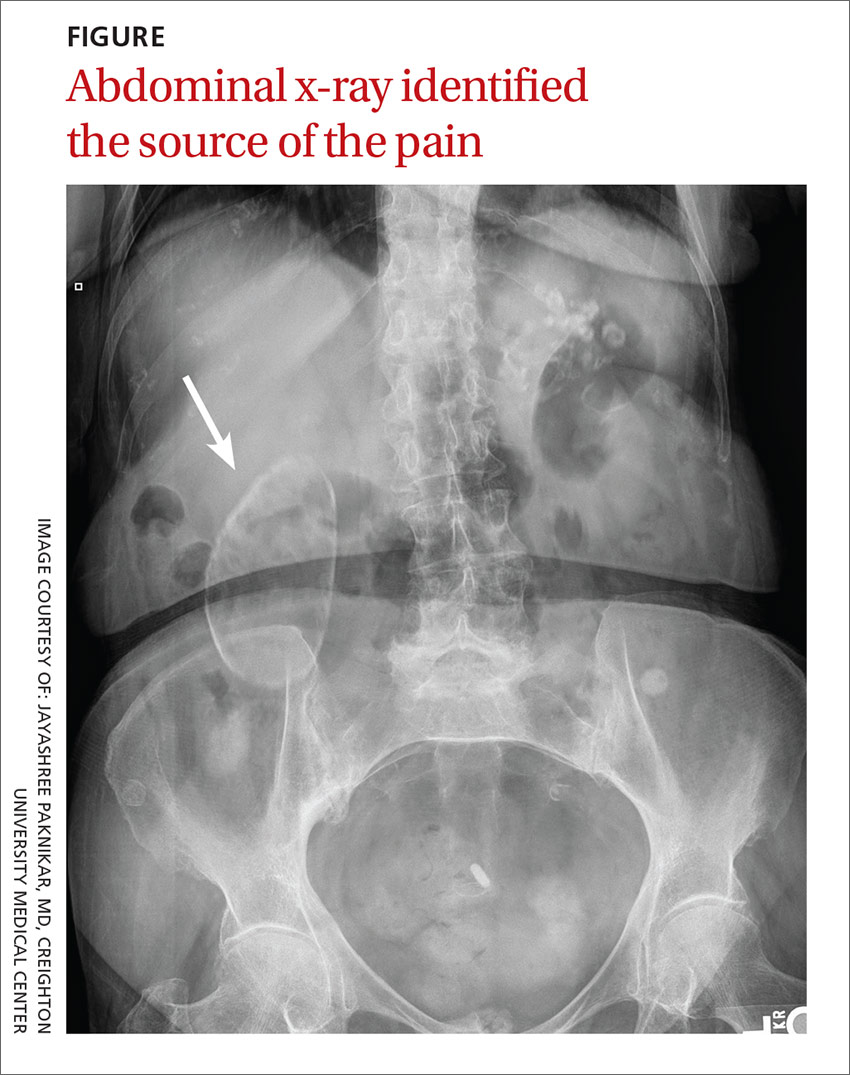

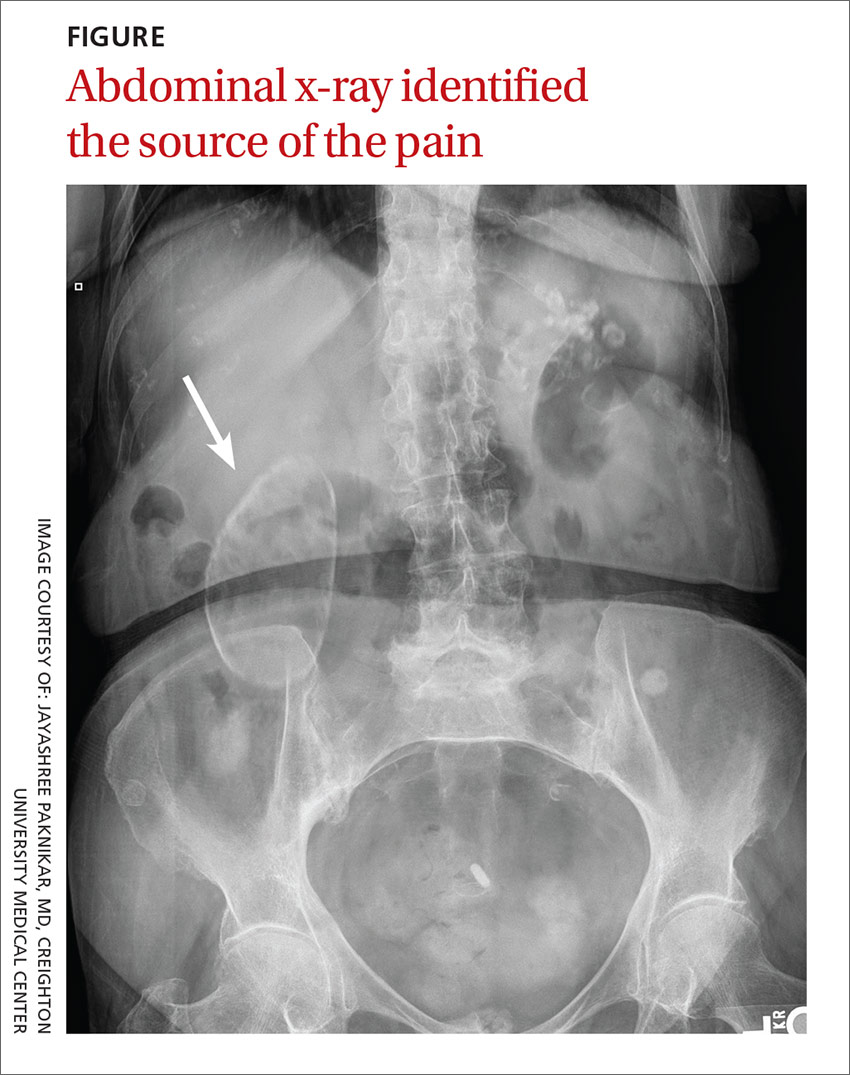

A lower extremity venous ultrasound revealed that the patient had a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the chest with contrast revealed pulmonary emboli. He was treated with enoxaparin and warfarin. We diagnosed the rash based on the patient’s history and the appearance of the rash, which was comprised of blanching and erythematous macules with central clearing (FIGURE 1). (There were no blisters or mucosal involvement.)

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema multiforme

The clinical exam was consistent with the diagnosis of erythema multiforme (EM). A diagnosis of EM can usually be made based on the clinical exam alone.1 Typical targetoid lesions have a round shape and 3 concentric zones: A central dusky area of epidermal necrosis that may involve bullae, a paler pink or edematous zone, and a peripheral erythematous ring.2 Atypical lesions, such as raised papules, may also be seen.2

The skin lesions of EM usually appear symmetrically on the distal extremities and spread in a centripetal manner.1 Palms, soles, and mucosa can be involved.1 EM with mucosal involvement is called “erythema multiforme major,” and EM without mucosal disease (as in our patient’s case) is called “erythema multiforme minor.”2

EM is an acute, immune-mediated eruption thought to be caused by a cell-mediated hypersensitivity to certain infections or drugs.2 Ninety percent of cases are associated with an infection; herpes simplex virus (HSV) is the most common infectious agent.3 Mycoplasma pneumoniae is another culprit, especially in children. Medications are inciting factors about 10% of the time; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, sulfonamides, antiepileptics, and antibiotics have been linked to EM eruptions.3

Interestingly, while azithromycin—the medication our patient had taken most recently—can cause EM, it has been mainly linked to cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS).4 So, while we suspect that azithromycin was the trigger in our patient’s case, we can’t be sure. It’s also possible that Mycoplasma pneumoniae was the trigger for our patient’s EM. However, Mycoplasma pneumoniae is more common in adolescents.

Differential includes life-threatening conditions like SJS

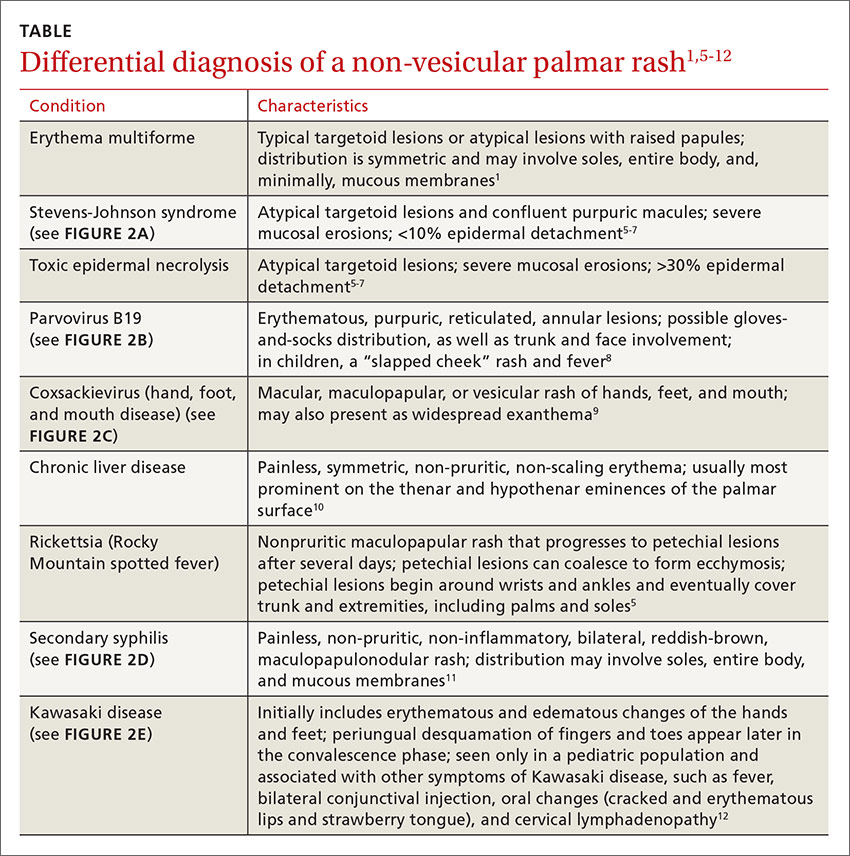

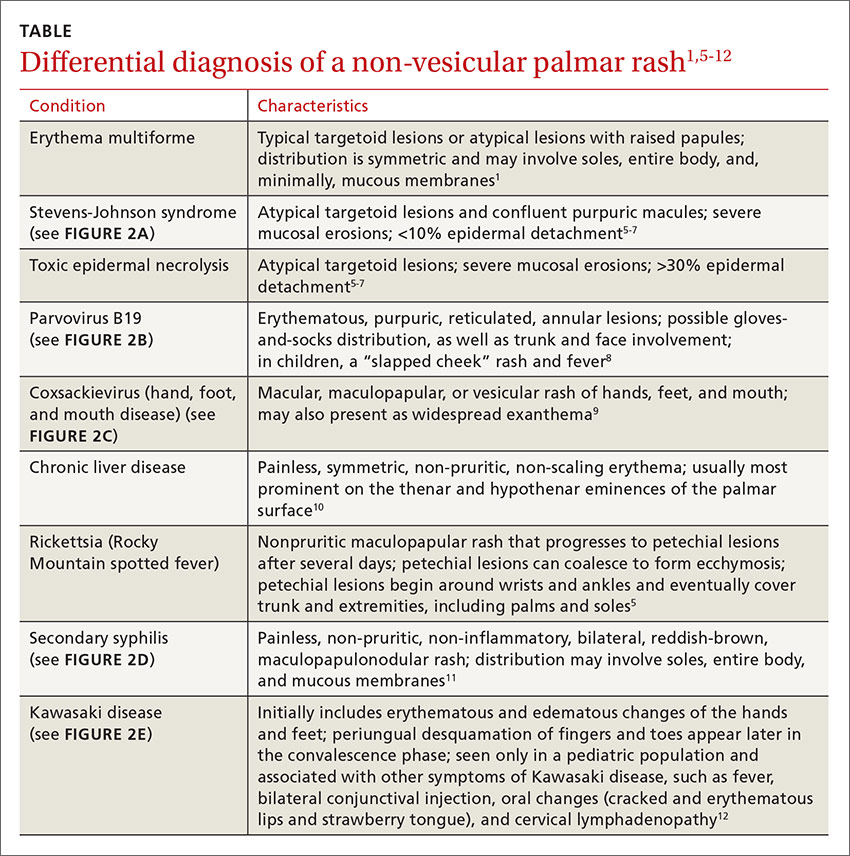

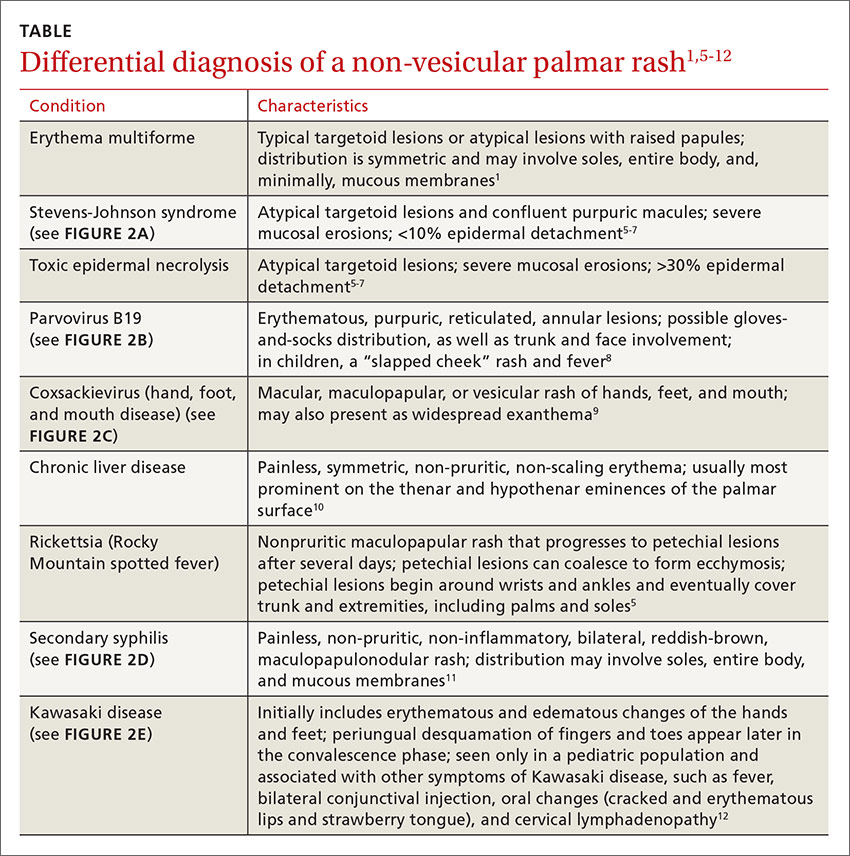

The differential diagnosis for a non-vesicular palmar rash is discussed in the TABLE.1,5-12 There is a wide spectrum of possible etiologies—from infectious and rheumatologic disorders to chronic liver disease. Histologic testing may be useful in differentiating EM from other diseases, but in most cases, it is not required to make a diagnosis.1 Laboratory testing may reveal leukocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and elevated liver function test results, but these are nonspecific.1

It’s important to differentiate EM from life-threatening conditions like SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).5 EM is characterized by typical and atypical targetoid lesions with minimal mucosal involvement.6,7 SJS is characterized by flat atypical targetoid lesions, confluent purpuric macules, severe mucosal erosions, and <10% epidermal detachment.6,7 TEN is characterized by severe mucosal erosions and >30% epidermal detachment.6,7

Lesions resolve on their own, but topical steroids can provide relief

EM is a self-limiting disease; lesions resolve within about 2 weeks.3 Management begins by treating any suspected infection or discontinuing any suspected drugs.1 In patients with co-existing or recurrent HSV infection, early treatment with an oral antiviral (such as acyclovir) may lessen the number and duration of lesions.1,6 In addition, oral antihistamines and topical steroids may be used to provide symptomatic relief.1,6 Use of oral corticosteroids can be considered in severe mucosal disease, although such use is considered controversial due to a lack of evidence.1,6

Our patient remained hospitalized for 4 days. As noted earlier, his DVT and pulmonary embolism were treated with enoxaparin and the patient was sent home with a prescription for warfarin. Regarding the EM, his rash and itching

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, Colorado 80238; [email protected].

1. Lamoreux MR, Sternbach MR, Hsu WT. Erythema multiforme. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1883-1888.

2. Patel NN, Patel DN. Erythema multiforme syndrome. Am J Med. 2009;122:623-625.

3. Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902.

4. Nambudiri VE. More than skin deep—the costs of antibiotic overuse: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1724-1725.

5. Usatine RP, Sandy N. Dermatologic emergencies. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:773-780.

6. Al-Johani KA, Fedele S, Porter SR. Erythema multiforme andrelated disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:642-654.

7. Assier H, Bastuji-Garin S, Revuz J, et al. Erythema multiforme with mucous membrane involvement and Stevens-Johnson syndrome are clinically different disorders with distinct causes. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:539-543.

8. Mage V, Lipsker D, Barbarot S, et al. Different patterns of skin manifestations associated with parvovirus B19 primary infection in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:62-69.

9. Hubiche T, Schuffenecker I, Boralevi F, et al; Clinical Research Group of the French Society of Pediatric Dermatology Groupe de Recherche Clinique de la Société Française de Dermatologie Pédiatrique. Dermatological spectrum of hand, foot and mouth disease from classical to generalized exanthema. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:e92-e98.

10. Serrao R, Zirwas M, English JC. Palmar erythema. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:347-356.

11. Meffert JJ. Photo quiz. A palmar rash. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:1259-1260.

12. Saguil A, Fargo M, Grogan S. Diagnosis and management of Kawasaki disease. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:365-371.

A 62-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a swollen, red, and painful right lower leg. He’d had bilateral lower leg swelling for 2 months, but the left leg became increasingly painful and red over the past 3 days. The patient also had a 3-day history of a diffuse rash that began on his right upper arm and spread to his left arm, both palms, both legs, and his back. It was mildly pruritic, but not painful.

The patient indicated that he had recently sought care from his primary care physician for lower respiratory symptoms. He had just completed a 5-day course of azithromycin and prednisone (50 mg/d for 5 days) the day before his ED visit.

A lower extremity venous ultrasound revealed that the patient had a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the chest with contrast revealed pulmonary emboli. He was treated with enoxaparin and warfarin. We diagnosed the rash based on the patient’s history and the appearance of the rash, which was comprised of blanching and erythematous macules with central clearing (FIGURE 1). (There were no blisters or mucosal involvement.)

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema multiforme

The clinical exam was consistent with the diagnosis of erythema multiforme (EM). A diagnosis of EM can usually be made based on the clinical exam alone.1 Typical targetoid lesions have a round shape and 3 concentric zones: A central dusky area of epidermal necrosis that may involve bullae, a paler pink or edematous zone, and a peripheral erythematous ring.2 Atypical lesions, such as raised papules, may also be seen.2

The skin lesions of EM usually appear symmetrically on the distal extremities and spread in a centripetal manner.1 Palms, soles, and mucosa can be involved.1 EM with mucosal involvement is called “erythema multiforme major,” and EM without mucosal disease (as in our patient’s case) is called “erythema multiforme minor.”2

EM is an acute, immune-mediated eruption thought to be caused by a cell-mediated hypersensitivity to certain infections or drugs.2 Ninety percent of cases are associated with an infection; herpes simplex virus (HSV) is the most common infectious agent.3 Mycoplasma pneumoniae is another culprit, especially in children. Medications are inciting factors about 10% of the time; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, sulfonamides, antiepileptics, and antibiotics have been linked to EM eruptions.3

Interestingly, while azithromycin—the medication our patient had taken most recently—can cause EM, it has been mainly linked to cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS).4 So, while we suspect that azithromycin was the trigger in our patient’s case, we can’t be sure. It’s also possible that Mycoplasma pneumoniae was the trigger for our patient’s EM. However, Mycoplasma pneumoniae is more common in adolescents.

Differential includes life-threatening conditions like SJS

The differential diagnosis for a non-vesicular palmar rash is discussed in the TABLE.1,5-12 There is a wide spectrum of possible etiologies—from infectious and rheumatologic disorders to chronic liver disease. Histologic testing may be useful in differentiating EM from other diseases, but in most cases, it is not required to make a diagnosis.1 Laboratory testing may reveal leukocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and elevated liver function test results, but these are nonspecific.1

It’s important to differentiate EM from life-threatening conditions like SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).5 EM is characterized by typical and atypical targetoid lesions with minimal mucosal involvement.6,7 SJS is characterized by flat atypical targetoid lesions, confluent purpuric macules, severe mucosal erosions, and <10% epidermal detachment.6,7 TEN is characterized by severe mucosal erosions and >30% epidermal detachment.6,7

Lesions resolve on their own, but topical steroids can provide relief

EM is a self-limiting disease; lesions resolve within about 2 weeks.3 Management begins by treating any suspected infection or discontinuing any suspected drugs.1 In patients with co-existing or recurrent HSV infection, early treatment with an oral antiviral (such as acyclovir) may lessen the number and duration of lesions.1,6 In addition, oral antihistamines and topical steroids may be used to provide symptomatic relief.1,6 Use of oral corticosteroids can be considered in severe mucosal disease, although such use is considered controversial due to a lack of evidence.1,6

Our patient remained hospitalized for 4 days. As noted earlier, his DVT and pulmonary embolism were treated with enoxaparin and the patient was sent home with a prescription for warfarin. Regarding the EM, his rash and itching

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, Colorado 80238; [email protected].

A 62-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a swollen, red, and painful right lower leg. He’d had bilateral lower leg swelling for 2 months, but the left leg became increasingly painful and red over the past 3 days. The patient also had a 3-day history of a diffuse rash that began on his right upper arm and spread to his left arm, both palms, both legs, and his back. It was mildly pruritic, but not painful.

The patient indicated that he had recently sought care from his primary care physician for lower respiratory symptoms. He had just completed a 5-day course of azithromycin and prednisone (50 mg/d for 5 days) the day before his ED visit.

A lower extremity venous ultrasound revealed that the patient had a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the chest with contrast revealed pulmonary emboli. He was treated with enoxaparin and warfarin. We diagnosed the rash based on the patient’s history and the appearance of the rash, which was comprised of blanching and erythematous macules with central clearing (FIGURE 1). (There were no blisters or mucosal involvement.)

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema multiforme

The clinical exam was consistent with the diagnosis of erythema multiforme (EM). A diagnosis of EM can usually be made based on the clinical exam alone.1 Typical targetoid lesions have a round shape and 3 concentric zones: A central dusky area of epidermal necrosis that may involve bullae, a paler pink or edematous zone, and a peripheral erythematous ring.2 Atypical lesions, such as raised papules, may also be seen.2

The skin lesions of EM usually appear symmetrically on the distal extremities and spread in a centripetal manner.1 Palms, soles, and mucosa can be involved.1 EM with mucosal involvement is called “erythema multiforme major,” and EM without mucosal disease (as in our patient’s case) is called “erythema multiforme minor.”2

EM is an acute, immune-mediated eruption thought to be caused by a cell-mediated hypersensitivity to certain infections or drugs.2 Ninety percent of cases are associated with an infection; herpes simplex virus (HSV) is the most common infectious agent.3 Mycoplasma pneumoniae is another culprit, especially in children. Medications are inciting factors about 10% of the time; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, sulfonamides, antiepileptics, and antibiotics have been linked to EM eruptions.3

Interestingly, while azithromycin—the medication our patient had taken most recently—can cause EM, it has been mainly linked to cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS).4 So, while we suspect that azithromycin was the trigger in our patient’s case, we can’t be sure. It’s also possible that Mycoplasma pneumoniae was the trigger for our patient’s EM. However, Mycoplasma pneumoniae is more common in adolescents.

Differential includes life-threatening conditions like SJS

The differential diagnosis for a non-vesicular palmar rash is discussed in the TABLE.1,5-12 There is a wide spectrum of possible etiologies—from infectious and rheumatologic disorders to chronic liver disease. Histologic testing may be useful in differentiating EM from other diseases, but in most cases, it is not required to make a diagnosis.1 Laboratory testing may reveal leukocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and elevated liver function test results, but these are nonspecific.1

It’s important to differentiate EM from life-threatening conditions like SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).5 EM is characterized by typical and atypical targetoid lesions with minimal mucosal involvement.6,7 SJS is characterized by flat atypical targetoid lesions, confluent purpuric macules, severe mucosal erosions, and <10% epidermal detachment.6,7 TEN is characterized by severe mucosal erosions and >30% epidermal detachment.6,7

Lesions resolve on their own, but topical steroids can provide relief

EM is a self-limiting disease; lesions resolve within about 2 weeks.3 Management begins by treating any suspected infection or discontinuing any suspected drugs.1 In patients with co-existing or recurrent HSV infection, early treatment with an oral antiviral (such as acyclovir) may lessen the number and duration of lesions.1,6 In addition, oral antihistamines and topical steroids may be used to provide symptomatic relief.1,6 Use of oral corticosteroids can be considered in severe mucosal disease, although such use is considered controversial due to a lack of evidence.1,6

Our patient remained hospitalized for 4 days. As noted earlier, his DVT and pulmonary embolism were treated with enoxaparin and the patient was sent home with a prescription for warfarin. Regarding the EM, his rash and itching

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, Colorado 80238; [email protected].

1. Lamoreux MR, Sternbach MR, Hsu WT. Erythema multiforme. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1883-1888.

2. Patel NN, Patel DN. Erythema multiforme syndrome. Am J Med. 2009;122:623-625.

3. Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902.

4. Nambudiri VE. More than skin deep—the costs of antibiotic overuse: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1724-1725.

5. Usatine RP, Sandy N. Dermatologic emergencies. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:773-780.

6. Al-Johani KA, Fedele S, Porter SR. Erythema multiforme andrelated disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:642-654.

7. Assier H, Bastuji-Garin S, Revuz J, et al. Erythema multiforme with mucous membrane involvement and Stevens-Johnson syndrome are clinically different disorders with distinct causes. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:539-543.

8. Mage V, Lipsker D, Barbarot S, et al. Different patterns of skin manifestations associated with parvovirus B19 primary infection in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:62-69.

9. Hubiche T, Schuffenecker I, Boralevi F, et al; Clinical Research Group of the French Society of Pediatric Dermatology Groupe de Recherche Clinique de la Société Française de Dermatologie Pédiatrique. Dermatological spectrum of hand, foot and mouth disease from classical to generalized exanthema. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:e92-e98.

10. Serrao R, Zirwas M, English JC. Palmar erythema. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:347-356.

11. Meffert JJ. Photo quiz. A palmar rash. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:1259-1260.

12. Saguil A, Fargo M, Grogan S. Diagnosis and management of Kawasaki disease. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:365-371.

1. Lamoreux MR, Sternbach MR, Hsu WT. Erythema multiforme. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1883-1888.

2. Patel NN, Patel DN. Erythema multiforme syndrome. Am J Med. 2009;122:623-625.

3. Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902.

4. Nambudiri VE. More than skin deep—the costs of antibiotic overuse: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1724-1725.

5. Usatine RP, Sandy N. Dermatologic emergencies. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:773-780.

6. Al-Johani KA, Fedele S, Porter SR. Erythema multiforme andrelated disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:642-654.

7. Assier H, Bastuji-Garin S, Revuz J, et al. Erythema multiforme with mucous membrane involvement and Stevens-Johnson syndrome are clinically different disorders with distinct causes. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:539-543.

8. Mage V, Lipsker D, Barbarot S, et al. Different patterns of skin manifestations associated with parvovirus B19 primary infection in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:62-69.

9. Hubiche T, Schuffenecker I, Boralevi F, et al; Clinical Research Group of the French Society of Pediatric Dermatology Groupe de Recherche Clinique de la Société Française de Dermatologie Pédiatrique. Dermatological spectrum of hand, foot and mouth disease from classical to generalized exanthema. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:e92-e98.

10. Serrao R, Zirwas M, English JC. Palmar erythema. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:347-356.

11. Meffert JJ. Photo quiz. A palmar rash. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:1259-1260.

12. Saguil A, Fargo M, Grogan S. Diagnosis and management of Kawasaki disease. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:365-371.

Itching in groin

The FP suspected tinea cruris and asked the patient if he had athlete’s foot. The patient stated that his feet were fine, but the FP asked to examine them anyway and found signs of tinea pedis between the toes (especially in the interspace between toes 4 and 5). While this supported the diagnosis of tinea cruris, the FP decided to confirm his diagnosis with a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.) The KOH preparation showed branching hyphae with septate and visible nuclei, confirming the tinea infection.

Tinea cruris is an intensely pruritic superficial fungal infection of the groin and adjacent skin that is more common in men than women and rarely affects children. It is most commonly caused by the dermatophytes Trichophyton rubrum, Epidermophyton floccosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton verrucosum. T rubrum is the most common organism and can be spread by fomites, such as contaminated towels. Autoinoculation can occur from fungus on the feet or hands. Risk factors include obesity and diabetes.

Most topical antifungals can be used to treat tinea cruris, except for nystatin, which only works for Candida. The fungicidal allylamines (naftifine and terbinafine) and butenafine (allylamine derivative) are more convenient, as they allow for a shorter duration of treatment compared with fungistatic azoles (clotrimazole, econazole, ketoconazole, oxiconazole, miconazole, and sulconazole). Topical azoles should be continued for 4 weeks and topical allylamines for 2 weeks or until clinical cure. Fluconazole 150 mg once weekly for 2 to 4 weeks can effectively treat tinea cruris when topical agents are failing. If there are multiple sites infected with fungus, such as the groin and feet, it helps to treat all active areas of infection simultaneously to prevent reinfection of the groin from other body sites.

For this patient, the FP suggested that he buy over-the-counter topical terbinafine to treat the groin and feet twice daily for a minimum of 2 weeks until the fungal infection was no longer visible and symptomatic. At a follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the tinea had resolved and the patient was very happy with the results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected tinea cruris and asked the patient if he had athlete’s foot. The patient stated that his feet were fine, but the FP asked to examine them anyway and found signs of tinea pedis between the toes (especially in the interspace between toes 4 and 5). While this supported the diagnosis of tinea cruris, the FP decided to confirm his diagnosis with a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.) The KOH preparation showed branching hyphae with septate and visible nuclei, confirming the tinea infection.

Tinea cruris is an intensely pruritic superficial fungal infection of the groin and adjacent skin that is more common in men than women and rarely affects children. It is most commonly caused by the dermatophytes Trichophyton rubrum, Epidermophyton floccosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton verrucosum. T rubrum is the most common organism and can be spread by fomites, such as contaminated towels. Autoinoculation can occur from fungus on the feet or hands. Risk factors include obesity and diabetes.

Most topical antifungals can be used to treat tinea cruris, except for nystatin, which only works for Candida. The fungicidal allylamines (naftifine and terbinafine) and butenafine (allylamine derivative) are more convenient, as they allow for a shorter duration of treatment compared with fungistatic azoles (clotrimazole, econazole, ketoconazole, oxiconazole, miconazole, and sulconazole). Topical azoles should be continued for 4 weeks and topical allylamines for 2 weeks or until clinical cure. Fluconazole 150 mg once weekly for 2 to 4 weeks can effectively treat tinea cruris when topical agents are failing. If there are multiple sites infected with fungus, such as the groin and feet, it helps to treat all active areas of infection simultaneously to prevent reinfection of the groin from other body sites.

For this patient, the FP suggested that he buy over-the-counter topical terbinafine to treat the groin and feet twice daily for a minimum of 2 weeks until the fungal infection was no longer visible and symptomatic. At a follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the tinea had resolved and the patient was very happy with the results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected tinea cruris and asked the patient if he had athlete’s foot. The patient stated that his feet were fine, but the FP asked to examine them anyway and found signs of tinea pedis between the toes (especially in the interspace between toes 4 and 5). While this supported the diagnosis of tinea cruris, the FP decided to confirm his diagnosis with a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.) The KOH preparation showed branching hyphae with septate and visible nuclei, confirming the tinea infection.

Tinea cruris is an intensely pruritic superficial fungal infection of the groin and adjacent skin that is more common in men than women and rarely affects children. It is most commonly caused by the dermatophytes Trichophyton rubrum, Epidermophyton floccosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton verrucosum. T rubrum is the most common organism and can be spread by fomites, such as contaminated towels. Autoinoculation can occur from fungus on the feet or hands. Risk factors include obesity and diabetes.

Most topical antifungals can be used to treat tinea cruris, except for nystatin, which only works for Candida. The fungicidal allylamines (naftifine and terbinafine) and butenafine (allylamine derivative) are more convenient, as they allow for a shorter duration of treatment compared with fungistatic azoles (clotrimazole, econazole, ketoconazole, oxiconazole, miconazole, and sulconazole). Topical azoles should be continued for 4 weeks and topical allylamines for 2 weeks or until clinical cure. Fluconazole 150 mg once weekly for 2 to 4 weeks can effectively treat tinea cruris when topical agents are failing. If there are multiple sites infected with fungus, such as the groin and feet, it helps to treat all active areas of infection simultaneously to prevent reinfection of the groin from other body sites.

For this patient, the FP suggested that he buy over-the-counter topical terbinafine to treat the groin and feet twice daily for a minimum of 2 weeks until the fungal infection was no longer visible and symptomatic. At a follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the tinea had resolved and the patient was very happy with the results.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Smith M. Tinea cruris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:795-798.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Dark rash on chest

The FP suspected tinea incognito (fungus caused by steroids because of a misdiagnosis) and wanted to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

Unfortunately, the FP’s health system had removed microscopes from all of the offices because of regulatory issues from The Joint Commission. So the physician did the next best thing: He scraped the outer edge of the rash and put the scale in a sterile urine cup to send to the lab for fungal stain and culture. He recommended that the patient stop using the triamcinolone cream and start using a topical terbinafine (now an over-the-counter antifungal cream). He also made a mental note that most topical steroids only need to be used twice daily, even when the electronic medical record populates 3 times a day as the default setting.

The FP set up an appointment to see the patient the following week, hoping to have some answers from the laboratory. Two days later, the KOH with Calcofluor white fungal stain was positive for fungal elements. When the patient returned, the culture was growing Trichophyton rubrum. The patient noted that the rash had improved a little, but wondered if there was something stronger to help her.

Now that the diagnosis of tinea incognito was finalized, the FP offered her oral terbinafine. The patient did not have any liver disease and rarely drank alcohol, so the FP prescribed terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks. One month later, the patient was pleased that the itching, scaling, and raised areas had resolved. However, she asked if the dark area on her chest would remain that way forever. The FP told her that the postinflammatory hyperpigmentation would likely fade over time, but might not ever return to her normal skin color. The patient was upset, as she’d been wearing different clothes to hide the dark mark, and was hoping it would go away completely.

The FP suggested that she return in 2 months to see how her skin was doing. He told her about the use of an over-the-counter 3% hydroquinone cream, but warned her that it sometimes darkened skin rather than lightening it. He also suggested keeping the area protected from the sun and told her to stop using the bleaching cream if it caused irritation or darkened her skin.

This case is a dramatic example of how treating an unknown rash with topical steroids can have potentially permanent consequences for the patient. Even FPs who don't have microscopes or don't know how to create a KOH preparation can do what this doctor did (send a specimen to the laboratory). It’s always better to have a diagnosis before treatment, as topical steroids are not the answer to all pruritic rashes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Jimenez A. Tinea corporis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:788-794.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected tinea incognito (fungus caused by steroids because of a misdiagnosis) and wanted to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

Unfortunately, the FP’s health system had removed microscopes from all of the offices because of regulatory issues from The Joint Commission. So the physician did the next best thing: He scraped the outer edge of the rash and put the scale in a sterile urine cup to send to the lab for fungal stain and culture. He recommended that the patient stop using the triamcinolone cream and start using a topical terbinafine (now an over-the-counter antifungal cream). He also made a mental note that most topical steroids only need to be used twice daily, even when the electronic medical record populates 3 times a day as the default setting.

The FP set up an appointment to see the patient the following week, hoping to have some answers from the laboratory. Two days later, the KOH with Calcofluor white fungal stain was positive for fungal elements. When the patient returned, the culture was growing Trichophyton rubrum. The patient noted that the rash had improved a little, but wondered if there was something stronger to help her.

Now that the diagnosis of tinea incognito was finalized, the FP offered her oral terbinafine. The patient did not have any liver disease and rarely drank alcohol, so the FP prescribed terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks. One month later, the patient was pleased that the itching, scaling, and raised areas had resolved. However, she asked if the dark area on her chest would remain that way forever. The FP told her that the postinflammatory hyperpigmentation would likely fade over time, but might not ever return to her normal skin color. The patient was upset, as she’d been wearing different clothes to hide the dark mark, and was hoping it would go away completely.

The FP suggested that she return in 2 months to see how her skin was doing. He told her about the use of an over-the-counter 3% hydroquinone cream, but warned her that it sometimes darkened skin rather than lightening it. He also suggested keeping the area protected from the sun and told her to stop using the bleaching cream if it caused irritation or darkened her skin.

This case is a dramatic example of how treating an unknown rash with topical steroids can have potentially permanent consequences for the patient. Even FPs who don't have microscopes or don't know how to create a KOH preparation can do what this doctor did (send a specimen to the laboratory). It’s always better to have a diagnosis before treatment, as topical steroids are not the answer to all pruritic rashes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Jimenez A. Tinea corporis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:788-794.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected tinea incognito (fungus caused by steroids because of a misdiagnosis) and wanted to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

Unfortunately, the FP’s health system had removed microscopes from all of the offices because of regulatory issues from The Joint Commission. So the physician did the next best thing: He scraped the outer edge of the rash and put the scale in a sterile urine cup to send to the lab for fungal stain and culture. He recommended that the patient stop using the triamcinolone cream and start using a topical terbinafine (now an over-the-counter antifungal cream). He also made a mental note that most topical steroids only need to be used twice daily, even when the electronic medical record populates 3 times a day as the default setting.

The FP set up an appointment to see the patient the following week, hoping to have some answers from the laboratory. Two days later, the KOH with Calcofluor white fungal stain was positive for fungal elements. When the patient returned, the culture was growing Trichophyton rubrum. The patient noted that the rash had improved a little, but wondered if there was something stronger to help her.

Now that the diagnosis of tinea incognito was finalized, the FP offered her oral terbinafine. The patient did not have any liver disease and rarely drank alcohol, so the FP prescribed terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks. One month later, the patient was pleased that the itching, scaling, and raised areas had resolved. However, she asked if the dark area on her chest would remain that way forever. The FP told her that the postinflammatory hyperpigmentation would likely fade over time, but might not ever return to her normal skin color. The patient was upset, as she’d been wearing different clothes to hide the dark mark, and was hoping it would go away completely.

The FP suggested that she return in 2 months to see how her skin was doing. He told her about the use of an over-the-counter 3% hydroquinone cream, but warned her that it sometimes darkened skin rather than lightening it. He also suggested keeping the area protected from the sun and told her to stop using the bleaching cream if it caused irritation or darkened her skin.

This case is a dramatic example of how treating an unknown rash with topical steroids can have potentially permanent consequences for the patient. Even FPs who don't have microscopes or don't know how to create a KOH preparation can do what this doctor did (send a specimen to the laboratory). It’s always better to have a diagnosis before treatment, as topical steroids are not the answer to all pruritic rashes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Jimenez A. Tinea corporis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:788-794.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash from waist to below knees

The FP suspected a fungal infection that was worsened by topical triamcinolone. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and it was positive for branching septate hyphae, confirming the diagnosis of tinea corporis (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here).

Knowing something about fungal epidemiology, he realized that this was most likely Trichophyton rubrum. He looked at the patient’s feet as well, but she did not have evidence of tinea pedis or onychomycosis. This patient’s diagnosis could also be called tinea incognito because a topical steroid was applied to the area, potentially changing the appearance of the infection. Since the infection was also in the groin, the term tinea cruris would describe that part of the rash. The hyperpigmentation seen is one form of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and may or may not resolve after the tinea is eradicated.

The FP knew that a topical antifungal cream wouldn’t be able to cure this massive case of tinea corporis, so he prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks. He also advised the patient to discontinue the hydroxyzine and the triamcinolone. The patient returned for a follow-up visit 3 weeks later and was delighted by the results. She had been able to sleep well—without incessant itching—for the first time in a year.

One month later, she returned to the FP with regrowth of fungus in the involved area. It wasn’t as bad as when she first presented, but the KOH preparation was again positive. The FP reassessed the situation and realized that large tinea infections may require more than the recommended duration of therapy. As she had no risk factors for liver disease and previous liver function tests were normal, the FP gave the patient an additional 4 weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. A 2-month follow-up appointment was arranged, at which time there was no further evidence of an active fungal infection. The post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation was lighter, but not fully gone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Jimenez A. Tinea corporis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:788-794.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected a fungal infection that was worsened by topical triamcinolone. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and it was positive for branching septate hyphae, confirming the diagnosis of tinea corporis (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here).

Knowing something about fungal epidemiology, he realized that this was most likely Trichophyton rubrum. He looked at the patient’s feet as well, but she did not have evidence of tinea pedis or onychomycosis. This patient’s diagnosis could also be called tinea incognito because a topical steroid was applied to the area, potentially changing the appearance of the infection. Since the infection was also in the groin, the term tinea cruris would describe that part of the rash. The hyperpigmentation seen is one form of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and may or may not resolve after the tinea is eradicated.

The FP knew that a topical antifungal cream wouldn’t be able to cure this massive case of tinea corporis, so he prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks. He also advised the patient to discontinue the hydroxyzine and the triamcinolone. The patient returned for a follow-up visit 3 weeks later and was delighted by the results. She had been able to sleep well—without incessant itching—for the first time in a year.

One month later, she returned to the FP with regrowth of fungus in the involved area. It wasn’t as bad as when she first presented, but the KOH preparation was again positive. The FP reassessed the situation and realized that large tinea infections may require more than the recommended duration of therapy. As she had no risk factors for liver disease and previous liver function tests were normal, the FP gave the patient an additional 4 weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. A 2-month follow-up appointment was arranged, at which time there was no further evidence of an active fungal infection. The post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation was lighter, but not fully gone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Jimenez A. Tinea corporis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:788-794.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected a fungal infection that was worsened by topical triamcinolone. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and it was positive for branching septate hyphae, confirming the diagnosis of tinea corporis (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here).

Knowing something about fungal epidemiology, he realized that this was most likely Trichophyton rubrum. He looked at the patient’s feet as well, but she did not have evidence of tinea pedis or onychomycosis. This patient’s diagnosis could also be called tinea incognito because a topical steroid was applied to the area, potentially changing the appearance of the infection. Since the infection was also in the groin, the term tinea cruris would describe that part of the rash. The hyperpigmentation seen is one form of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and may or may not resolve after the tinea is eradicated.

The FP knew that a topical antifungal cream wouldn’t be able to cure this massive case of tinea corporis, so he prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks. He also advised the patient to discontinue the hydroxyzine and the triamcinolone. The patient returned for a follow-up visit 3 weeks later and was delighted by the results. She had been able to sleep well—without incessant itching—for the first time in a year.

One month later, she returned to the FP with regrowth of fungus in the involved area. It wasn’t as bad as when she first presented, but the KOH preparation was again positive. The FP reassessed the situation and realized that large tinea infections may require more than the recommended duration of therapy. As she had no risk factors for liver disease and previous liver function tests were normal, the FP gave the patient an additional 4 weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. A 2-month follow-up appointment was arranged, at which time there was no further evidence of an active fungal infection. The post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation was lighter, but not fully gone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Jimenez A. Tinea corporis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:788-794.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Pruritic rash in armpit