User login

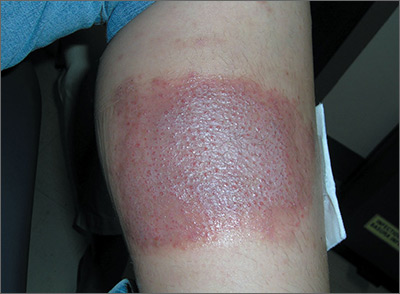

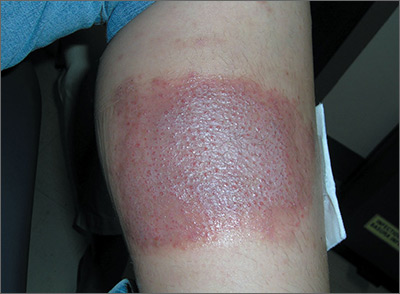

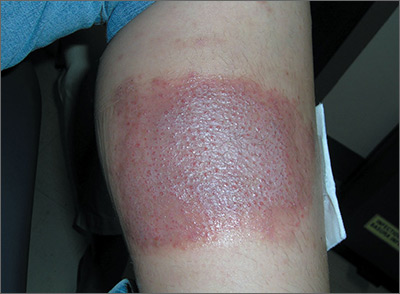

Large leg rash

The family physician (FP) asked some more questions about the antibiotic ointment and discovered that it was a triple antibiotic ointment (which typically contains neomycin, bacitracin, and polymyxin). The patient acknowledged that after applying the ointment to the bug bite, she’d used a bandage that was rectangular in shape—just like the patch of erythematous skin with papules.

The FP deduced that this was a case of contact dermatitis and the patient was reacting to at least one of the topical antibiotics in the triple antibiotic preparation. The most likely offending topical antibiotic was neomycin, as it’s a common contact allergen. However, bacitracin is also a common contact allergen.

The FP told the patient to stop using the triple antibiotic ointment and to avoid using any preparations that contain neomycin, bacitracin—or both—in the future. The FP explained that most minor skin injuries, including bug bites and minor scrapes, do not require topical antibiotics.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily to treat the erythema and itching caused by the contact dermatitis. At a follow-up visit one month later, the only skin problem that persisted was some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The FP explained that this would likely fade over time.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:591-596.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) asked some more questions about the antibiotic ointment and discovered that it was a triple antibiotic ointment (which typically contains neomycin, bacitracin, and polymyxin). The patient acknowledged that after applying the ointment to the bug bite, she’d used a bandage that was rectangular in shape—just like the patch of erythematous skin with papules.

The FP deduced that this was a case of contact dermatitis and the patient was reacting to at least one of the topical antibiotics in the triple antibiotic preparation. The most likely offending topical antibiotic was neomycin, as it’s a common contact allergen. However, bacitracin is also a common contact allergen.

The FP told the patient to stop using the triple antibiotic ointment and to avoid using any preparations that contain neomycin, bacitracin—or both—in the future. The FP explained that most minor skin injuries, including bug bites and minor scrapes, do not require topical antibiotics.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily to treat the erythema and itching caused by the contact dermatitis. At a follow-up visit one month later, the only skin problem that persisted was some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The FP explained that this would likely fade over time.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:591-596.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) asked some more questions about the antibiotic ointment and discovered that it was a triple antibiotic ointment (which typically contains neomycin, bacitracin, and polymyxin). The patient acknowledged that after applying the ointment to the bug bite, she’d used a bandage that was rectangular in shape—just like the patch of erythematous skin with papules.

The FP deduced that this was a case of contact dermatitis and the patient was reacting to at least one of the topical antibiotics in the triple antibiotic preparation. The most likely offending topical antibiotic was neomycin, as it’s a common contact allergen. However, bacitracin is also a common contact allergen.

The FP told the patient to stop using the triple antibiotic ointment and to avoid using any preparations that contain neomycin, bacitracin—or both—in the future. The FP explained that most minor skin injuries, including bug bites and minor scrapes, do not require topical antibiotics.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily to treat the erythema and itching caused by the contact dermatitis. At a follow-up visit one month later, the only skin problem that persisted was some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The FP explained that this would likely fade over time.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:591-596.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash in both axillae

The family physician (FP) suspected that the patient had a contact dermatitis to his deodorant. After further questioning, the patient said he had changed his deodorant about one month before the rash started. The FP explained that an ingredient in this new deodorant was likely causing the allergic reaction.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily. He suggested that the patient either go back to his original deodorant or read the ingredients on the new deodorant and choose a deodorant that does not have the same ingredients.

At a follow-up visit one month later, the patient's skin had cleared and he was very happy with the results. He said he’d gone back to using his original deodorant, which didn’t have the same ingredients as the new one.

This is a typical case of contact dermatitis in which the history and physical exam were sufficient to make the diagnosis. No patch testing or referrals to Dermatology were required.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:591-596.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) suspected that the patient had a contact dermatitis to his deodorant. After further questioning, the patient said he had changed his deodorant about one month before the rash started. The FP explained that an ingredient in this new deodorant was likely causing the allergic reaction.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily. He suggested that the patient either go back to his original deodorant or read the ingredients on the new deodorant and choose a deodorant that does not have the same ingredients.

At a follow-up visit one month later, the patient's skin had cleared and he was very happy with the results. He said he’d gone back to using his original deodorant, which didn’t have the same ingredients as the new one.

This is a typical case of contact dermatitis in which the history and physical exam were sufficient to make the diagnosis. No patch testing or referrals to Dermatology were required.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:591-596.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) suspected that the patient had a contact dermatitis to his deodorant. After further questioning, the patient said he had changed his deodorant about one month before the rash started. The FP explained that an ingredient in this new deodorant was likely causing the allergic reaction.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily. He suggested that the patient either go back to his original deodorant or read the ingredients on the new deodorant and choose a deodorant that does not have the same ingredients.

At a follow-up visit one month later, the patient's skin had cleared and he was very happy with the results. He said he’d gone back to using his original deodorant, which didn’t have the same ingredients as the new one.

This is a typical case of contact dermatitis in which the history and physical exam were sufficient to make the diagnosis. No patch testing or referrals to Dermatology were required.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:591-596.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

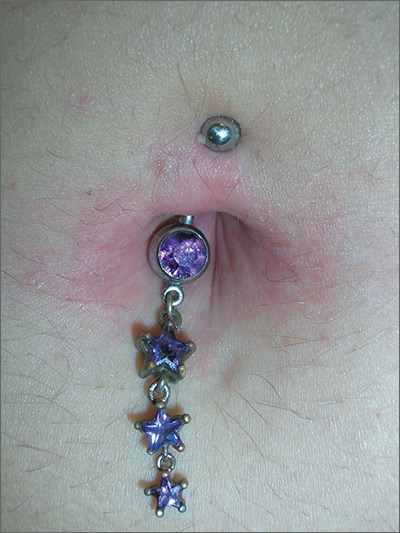

Rash around belly button

The family physician (FP) recognized that the patient’s new belly ring was the cause of this case of contact dermatitis. The FP suspected that the belly ring contained nickel—a common culprit in cases of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

ACD is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction that occurs when skin proteins form an antigen complex in reaction to a foreign substance. Upon reexposure of the epidermis to the antigen, the sensitized T cells initiate an inflammatory cascade, leading to the skin changes seen in ACD.

The FP told the patient that patch testing could be used to confirm her allergy, but it required wearing patches on her back for 3 days and involved 3 office visits to complete the testing. He also asked her if she wanted to have her jewelry tested for nickel content.

The patient removed the belly button jewelry and the FP used a nickel testing kit, which showed the jewelry was, in fact, positive for nickel. The patient asked if she could still wear the jewelry if she got medication to treat the allergy, but the FP explained that it was unlikely that the rash would go away completely with a topical cream if the jewelry remained in place. The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily to the area. He also suggested that she look for a jewelry replacement that was nickel-free.

At a one-month follow-up visit, the patient acknowledged that the FP had been right: While she was able to wear the jewelry for another 2 weeks with decreased erythema and pruritus while using the triamcinolone cream, the rash never went away. The patient switched to a nickel-free belly button ring and her rash cleared completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:591-596.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) recognized that the patient’s new belly ring was the cause of this case of contact dermatitis. The FP suspected that the belly ring contained nickel—a common culprit in cases of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

ACD is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction that occurs when skin proteins form an antigen complex in reaction to a foreign substance. Upon reexposure of the epidermis to the antigen, the sensitized T cells initiate an inflammatory cascade, leading to the skin changes seen in ACD.

The FP told the patient that patch testing could be used to confirm her allergy, but it required wearing patches on her back for 3 days and involved 3 office visits to complete the testing. He also asked her if she wanted to have her jewelry tested for nickel content.

The patient removed the belly button jewelry and the FP used a nickel testing kit, which showed the jewelry was, in fact, positive for nickel. The patient asked if she could still wear the jewelry if she got medication to treat the allergy, but the FP explained that it was unlikely that the rash would go away completely with a topical cream if the jewelry remained in place. The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily to the area. He also suggested that she look for a jewelry replacement that was nickel-free.

At a one-month follow-up visit, the patient acknowledged that the FP had been right: While she was able to wear the jewelry for another 2 weeks with decreased erythema and pruritus while using the triamcinolone cream, the rash never went away. The patient switched to a nickel-free belly button ring and her rash cleared completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:591-596.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) recognized that the patient’s new belly ring was the cause of this case of contact dermatitis. The FP suspected that the belly ring contained nickel—a common culprit in cases of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

ACD is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction that occurs when skin proteins form an antigen complex in reaction to a foreign substance. Upon reexposure of the epidermis to the antigen, the sensitized T cells initiate an inflammatory cascade, leading to the skin changes seen in ACD.

The FP told the patient that patch testing could be used to confirm her allergy, but it required wearing patches on her back for 3 days and involved 3 office visits to complete the testing. He also asked her if she wanted to have her jewelry tested for nickel content.

The patient removed the belly button jewelry and the FP used a nickel testing kit, which showed the jewelry was, in fact, positive for nickel. The patient asked if she could still wear the jewelry if she got medication to treat the allergy, but the FP explained that it was unlikely that the rash would go away completely with a topical cream if the jewelry remained in place. The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily to the area. He also suggested that she look for a jewelry replacement that was nickel-free.

At a one-month follow-up visit, the patient acknowledged that the FP had been right: While she was able to wear the jewelry for another 2 weeks with decreased erythema and pruritus while using the triamcinolone cream, the rash never went away. The patient switched to a nickel-free belly button ring and her rash cleared completely.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Contact dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:591-596.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Scalp papules in a teenage boy

The patient was given a diagnosis of acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN), a chronic folliculitis that is characterized by smooth, dome-shaped papules on the posterior scalp and neck that become confluent and form firm papules and hairless, keloid-like plaques. Seen almost exclusively in young, postpubescent African American males, the condition is often asymptomatic, although some patients complain of itching at the affected area.

The cause of AKN may be associated with an acute pseudofolliculitis secondary to close-shaved curly hair reentering the skin; this leads to a foreign body reaction to hair protein and subsequent fibrosis. AKN is diagnosed based on the appearance and location of the papules, as well as the patient’s history.

Treatment of AKN is often difficult, but early treatment decreases the potential of developing larger lesions and long-term disfigurement. Topical steroid therapy is indicated for mild to moderate AKN. Application of tretinoin 0.01% gel once or twice daily for several months has an anti-inflammatory effect and alters keratinocyte differentiation, which may discharge ingrown hairs. Topical and systemic antibiotics minimize infection associated with pseudofolliculitis and have anti-inflammatory effects. Intralesional steroid injections (triamcinolone acetonide 2.5-5 mg/cc) with 0.1 cc injected into each lesion every 2 to 3 weeks for 3 to 6 injections can reduce inflammation and pruritus and reduce the thickness of keloidal scars. (For a how-to video that illustrates intralesional injections, go to http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/88050/dermatology/intralesional-injections.)

Surgical management is generally reserved for large lesions that do not respond to medical management. The use of CO2 laser ablation can be considered for advanced cases.

Patients with AKN can prevent further irritation of the affected area by not wearing anything on their head that rubs on the involved area. Patients should also refrain from shaving the posterior scalp and neck to prevent the pseudofolliculitis that may be causing this condition. Electric barber trimmers that leave a short stubble (but do not cleanly shave the skin) are OK.

In this case, the patient’s papules flattened and became asymptomatic over several months of treatment with tretinoin 0.01% gel, doxycycline 100 mg/d, and a series of biweekly intralesional steroid injections. A flat-scarred patch remained.

Adapted from: Rafferty E, Brodell R. Occipital scalp papules in a teenage boy. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:739-740.

The patient was given a diagnosis of acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN), a chronic folliculitis that is characterized by smooth, dome-shaped papules on the posterior scalp and neck that become confluent and form firm papules and hairless, keloid-like plaques. Seen almost exclusively in young, postpubescent African American males, the condition is often asymptomatic, although some patients complain of itching at the affected area.

The cause of AKN may be associated with an acute pseudofolliculitis secondary to close-shaved curly hair reentering the skin; this leads to a foreign body reaction to hair protein and subsequent fibrosis. AKN is diagnosed based on the appearance and location of the papules, as well as the patient’s history.

Treatment of AKN is often difficult, but early treatment decreases the potential of developing larger lesions and long-term disfigurement. Topical steroid therapy is indicated for mild to moderate AKN. Application of tretinoin 0.01% gel once or twice daily for several months has an anti-inflammatory effect and alters keratinocyte differentiation, which may discharge ingrown hairs. Topical and systemic antibiotics minimize infection associated with pseudofolliculitis and have anti-inflammatory effects. Intralesional steroid injections (triamcinolone acetonide 2.5-5 mg/cc) with 0.1 cc injected into each lesion every 2 to 3 weeks for 3 to 6 injections can reduce inflammation and pruritus and reduce the thickness of keloidal scars. (For a how-to video that illustrates intralesional injections, go to http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/88050/dermatology/intralesional-injections.)

Surgical management is generally reserved for large lesions that do not respond to medical management. The use of CO2 laser ablation can be considered for advanced cases.

Patients with AKN can prevent further irritation of the affected area by not wearing anything on their head that rubs on the involved area. Patients should also refrain from shaving the posterior scalp and neck to prevent the pseudofolliculitis that may be causing this condition. Electric barber trimmers that leave a short stubble (but do not cleanly shave the skin) are OK.

In this case, the patient’s papules flattened and became asymptomatic over several months of treatment with tretinoin 0.01% gel, doxycycline 100 mg/d, and a series of biweekly intralesional steroid injections. A flat-scarred patch remained.

Adapted from: Rafferty E, Brodell R. Occipital scalp papules in a teenage boy. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:739-740.

The patient was given a diagnosis of acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN), a chronic folliculitis that is characterized by smooth, dome-shaped papules on the posterior scalp and neck that become confluent and form firm papules and hairless, keloid-like plaques. Seen almost exclusively in young, postpubescent African American males, the condition is often asymptomatic, although some patients complain of itching at the affected area.

The cause of AKN may be associated with an acute pseudofolliculitis secondary to close-shaved curly hair reentering the skin; this leads to a foreign body reaction to hair protein and subsequent fibrosis. AKN is diagnosed based on the appearance and location of the papules, as well as the patient’s history.

Treatment of AKN is often difficult, but early treatment decreases the potential of developing larger lesions and long-term disfigurement. Topical steroid therapy is indicated for mild to moderate AKN. Application of tretinoin 0.01% gel once or twice daily for several months has an anti-inflammatory effect and alters keratinocyte differentiation, which may discharge ingrown hairs. Topical and systemic antibiotics minimize infection associated with pseudofolliculitis and have anti-inflammatory effects. Intralesional steroid injections (triamcinolone acetonide 2.5-5 mg/cc) with 0.1 cc injected into each lesion every 2 to 3 weeks for 3 to 6 injections can reduce inflammation and pruritus and reduce the thickness of keloidal scars. (For a how-to video that illustrates intralesional injections, go to http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/88050/dermatology/intralesional-injections.)

Surgical management is generally reserved for large lesions that do not respond to medical management. The use of CO2 laser ablation can be considered for advanced cases.

Patients with AKN can prevent further irritation of the affected area by not wearing anything on their head that rubs on the involved area. Patients should also refrain from shaving the posterior scalp and neck to prevent the pseudofolliculitis that may be causing this condition. Electric barber trimmers that leave a short stubble (but do not cleanly shave the skin) are OK.

In this case, the patient’s papules flattened and became asymptomatic over several months of treatment with tretinoin 0.01% gel, doxycycline 100 mg/d, and a series of biweekly intralesional steroid injections. A flat-scarred patch remained.

Adapted from: Rafferty E, Brodell R. Occipital scalp papules in a teenage boy. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:739-740.

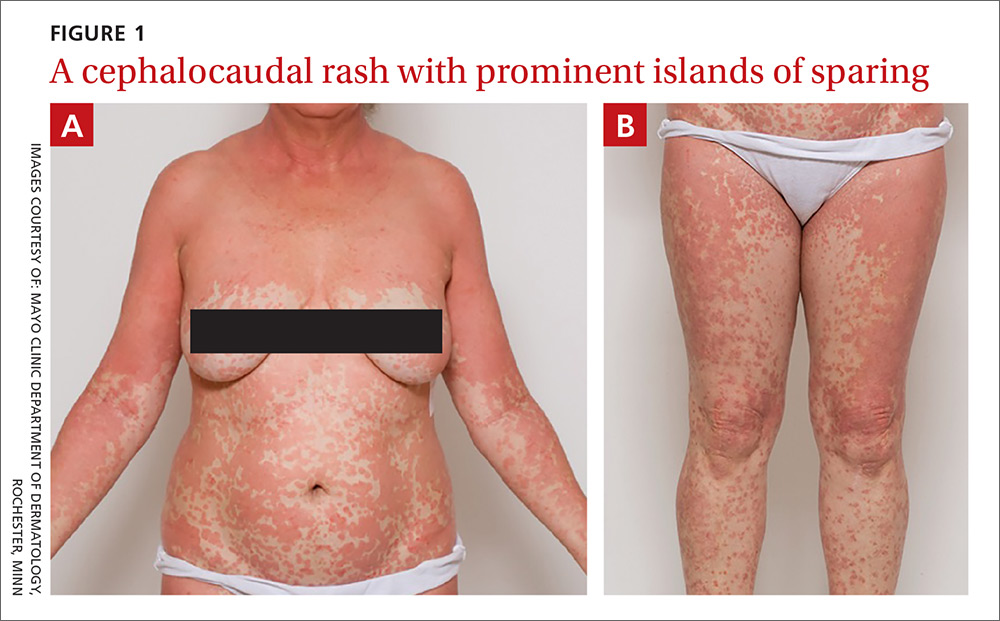

Widespread erythematous skin eruption

A 48-year-old woman sought care for a widespread pruritic skin eruption that began on her upper back and spread to her arms, lower trunk, and lower legs. She’d had the rash for approximately 2 months and didn’t have any systemic symptoms. A course of prednisone prior to her presentation failed to improve the rash. She denied a personal or family history of rheumatologic or dermatologic disease and reported no new medications or exposures.

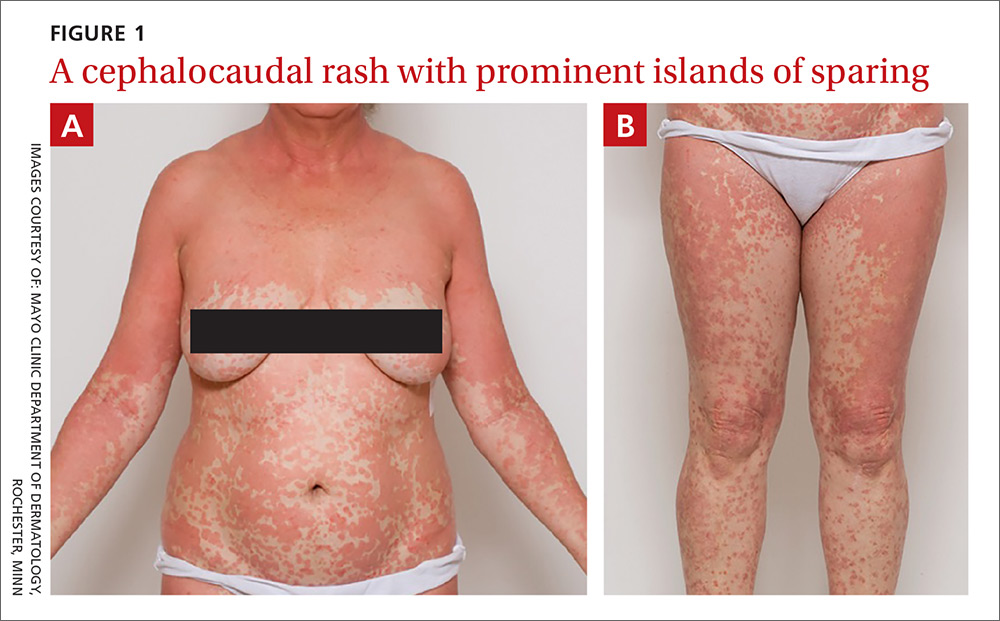

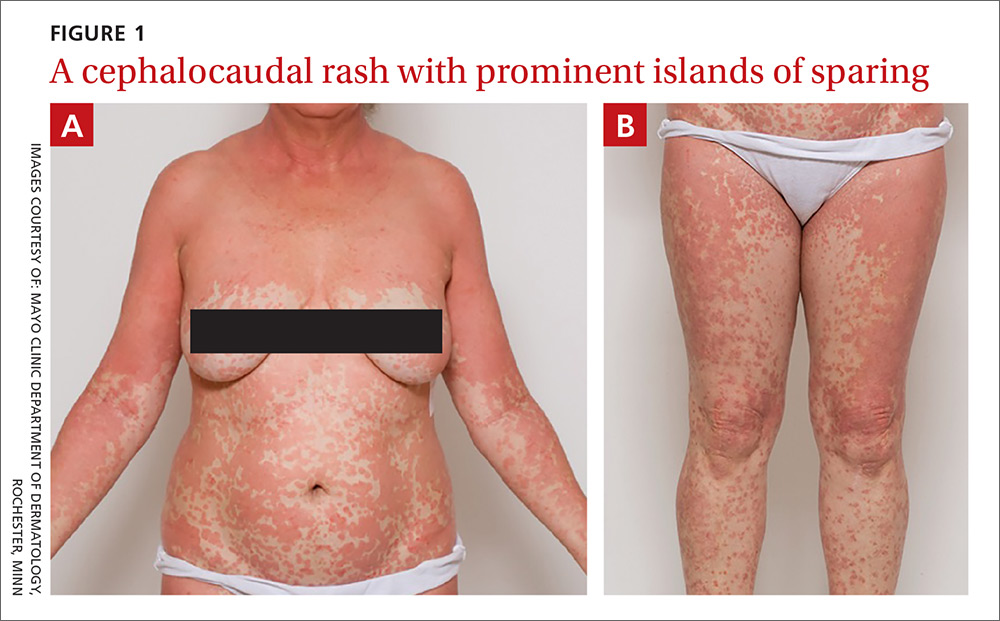

On physical exam, she was afebrile and her vital signs were normal. The rash had red-to-salmon–colored scaling patches with discrete and coalescing follicular papules. There were prominent islands of sparing (FIGURE 1).

The patient’s palms were waxy and erythematous and her feet had hyperkeratosis. A complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipid panel were normal. A skin biopsy demonstrated psoriasiform dermatitis with alternating areas of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis (the presence of keratinocyte nuclei within the stratum corneum where nuclei typically aren’t found).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pityriasis rubra pilaris

The patient was given a diagnosis of pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) based on her distinctive clinical presentation. This included the presence of prominent islands of sparing, the red-to-salmon scaling patches with follicular papules, the waxy erythema of her palms, and the cephalocaudal progression of her rash. The patient’s skin biopsy findings (in particular, the alternating orthokeratosis/parakeratosis) were also supportive of the diagnosis and helpful to exclude other potential causes of erythroderma (described below).

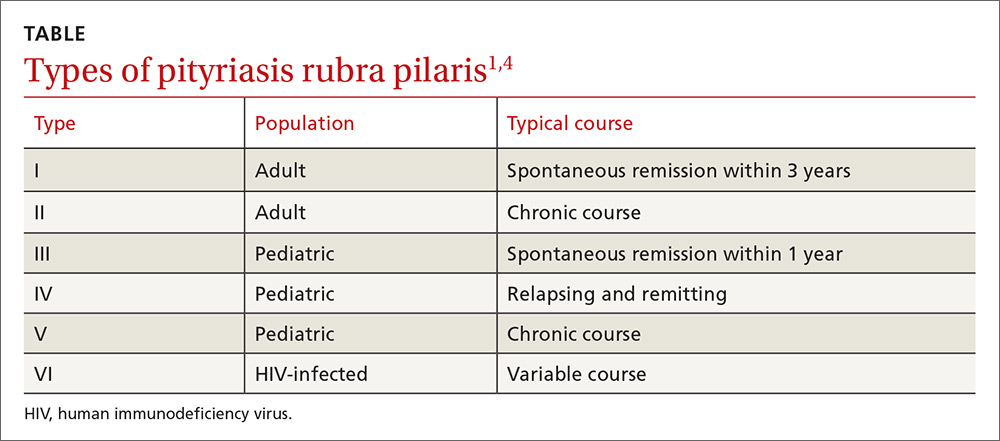

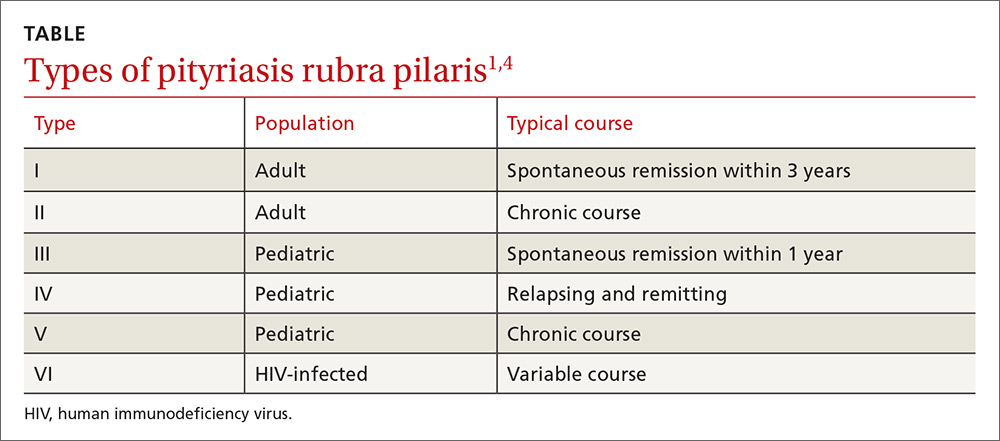

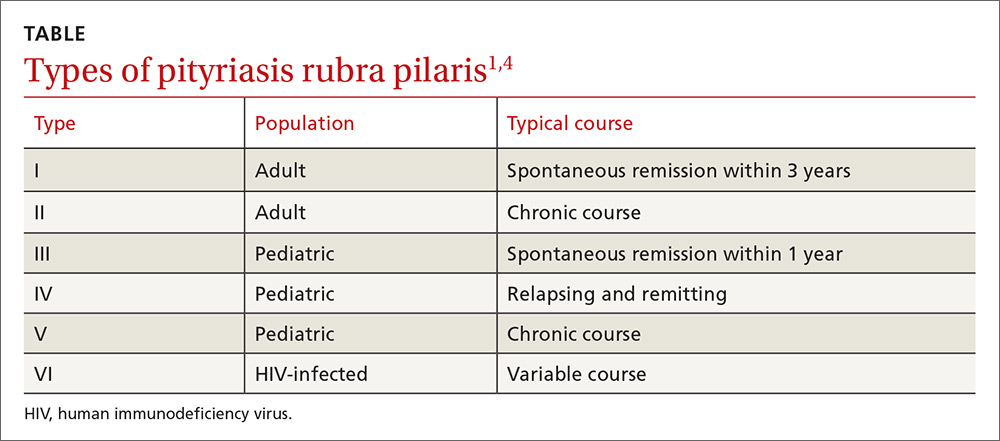

PRP most often affects middle-aged individuals with an equal sex distribution. The etiology and pathogenesis of PRP are not well understood. In rare cases, it has been associated with internal malignancy and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1,2 PRP may stem from a combination of a dysfunction in vitamin A metabolism, genetic factors, and immune dysregulation.3 Six types of PRP have been identified; they differ in the way they present and the populations affected (TABLE).1,4

PRP can be confused with other causes of erythroderma

PRP can cause erythroderma (also known as exfoliative dermatitis), which is the term applied to an erythematous eruption with scaling that covers ≥90% of the body’s surface area. Akhyani et al found that PRP is responsible for approximately 8% of all erythrodermas;5 the other causes of erythroderma are manifestations of numerous conditions, including psoriasis, dermatitis, drug eruptions, and malignancy. The course and prognosis of the erythroderma varies with the underlying condition causing it.6

Psoriasis is a common cause of exfoliative dermatitis in adults. Erythroderma may occur in patients with underlying psoriasis after discontinuing, or rapidly tapering, systemic corticosteroids.7 Because PRP is a papulosquamous eruption, it is often confused with psoriasis.1,3

Dermatitis. Several subtypes of dermatitis can be associated with erythroderma. These include atopic, seborrheic, allergic contact, airborne, and photosensitivity dermatitis.

Drug eruptions. Numerous pharmacologic agents have been associated with the development of widespread drug-induced skin eruptions. These eruptions include the severe reaction of toxic epidermal necrolysis, which always involves sloughing of skin.

Malignancy. Both cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (including mycosis fungoides) and internal malignancies can lead to erythroderma.6,8,9

PRP has several distinguishing features from other causes of erythroderma

Treatment includes oral retinoids

In the initial evaluation of most cases of erythroderma, it is important to perform a skin biopsy (a 4-mm punch is often best) with a request for a rush reading to avoid missing a possibly severe and life-threatening diagnosis. Skin biopsy is often not diagnostic, but may show alternating parakeratosis and orthokeratosis (as in this case). Careful correlation of the histopathologic findings with the clinical presentation is what usually leads to the diagnosis. Obtaining 2 punch biopsies may be helpful if there are multiple morphologies present or if mycosis fungoides is suspected. If the patient is not physiologically stable, hospitalization is warranted.

Oral retinoids (eg, acitretin) are the first-line treatment for PRP. PRP is a rare disease, so the best treatment data available include studies involving small case series. Other treatments include methotrexate and phototherapy, but results are mixed and patient-dependent.1,3 In fact, some patients have experienced flare-ups when treated with phototherapy; therefore, it is not a commonly used treatment for PRP.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors, including infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept, have been used increasingly with varying degrees of success.10-12 TNF-alpha inhibitors have a relatively good safety profile and should be considered in refractory cases. If there are associated conditions, such as HIV, treating these may also result in remission.2

Our patient was treated with oral acitretin 70 mg/d. At a 3-month follow-up visit, her skin showed signs of partial improvement.

CORRESPONDENCE

André D. Généreux, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Abbott-Northwestern Hospital, 800 East 28th Street, Minneapolis, MN 55407-3799; [email protected].

1. Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

2. González-López A, Velasco E, Pozo T, et al. HIV-associated pityriasis rubra pilaris responsive to triple antiretroviral therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:931-934.

3. Bruch-Gerharz D, Ruzicka T. Chapter 24. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY:McGraw-Hill;2012.

4. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. (Juvenile) Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:438-446.

5. Akhyani M, Ghodsi ZS, Toosi S, et al. Erythroderma: a clinical study of 97 cases. BMC Dermatol. 2005;5:5.

6. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Sardana K. Erythroderma/exfoliative dermatitis: a synopsis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:39-47.

7. Rosenbach M, Hsu S, Korman NJ, et al; National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board. Treatment of erythrodermic psoriasis: from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:655-662.

8. Chong VH, Lim CC. Erythroderma as the first manifestation of colon cancer. South Med J. 2009;102:334-335.

9. Ge W, Teng BW, Yu DC, et al. Dermatosis as the initial presentation of gastric cancer: two cases. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:632-638.

10. Garcovich S, Di Giampetruzzi AR, Antonelli G, et al. Treatment of refractory adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris with TNF-alpha antagonists: a case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:881-884.

11. Walling HW, Swick BL. Pityriasis rubra pilaris responding rapidly to adalimumab. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:99-101.

12. Eastham AB, Femia AN, Qureshi A, et al. Treatment options for pityriasis rubra pilaris including biologic agents: a retrospective analysis from an academic medical center. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:92-94.

A 48-year-old woman sought care for a widespread pruritic skin eruption that began on her upper back and spread to her arms, lower trunk, and lower legs. She’d had the rash for approximately 2 months and didn’t have any systemic symptoms. A course of prednisone prior to her presentation failed to improve the rash. She denied a personal or family history of rheumatologic or dermatologic disease and reported no new medications or exposures.

On physical exam, she was afebrile and her vital signs were normal. The rash had red-to-salmon–colored scaling patches with discrete and coalescing follicular papules. There were prominent islands of sparing (FIGURE 1).

The patient’s palms were waxy and erythematous and her feet had hyperkeratosis. A complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipid panel were normal. A skin biopsy demonstrated psoriasiform dermatitis with alternating areas of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis (the presence of keratinocyte nuclei within the stratum corneum where nuclei typically aren’t found).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pityriasis rubra pilaris

The patient was given a diagnosis of pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) based on her distinctive clinical presentation. This included the presence of prominent islands of sparing, the red-to-salmon scaling patches with follicular papules, the waxy erythema of her palms, and the cephalocaudal progression of her rash. The patient’s skin biopsy findings (in particular, the alternating orthokeratosis/parakeratosis) were also supportive of the diagnosis and helpful to exclude other potential causes of erythroderma (described below).

PRP most often affects middle-aged individuals with an equal sex distribution. The etiology and pathogenesis of PRP are not well understood. In rare cases, it has been associated with internal malignancy and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1,2 PRP may stem from a combination of a dysfunction in vitamin A metabolism, genetic factors, and immune dysregulation.3 Six types of PRP have been identified; they differ in the way they present and the populations affected (TABLE).1,4

PRP can be confused with other causes of erythroderma

PRP can cause erythroderma (also known as exfoliative dermatitis), which is the term applied to an erythematous eruption with scaling that covers ≥90% of the body’s surface area. Akhyani et al found that PRP is responsible for approximately 8% of all erythrodermas;5 the other causes of erythroderma are manifestations of numerous conditions, including psoriasis, dermatitis, drug eruptions, and malignancy. The course and prognosis of the erythroderma varies with the underlying condition causing it.6

Psoriasis is a common cause of exfoliative dermatitis in adults. Erythroderma may occur in patients with underlying psoriasis after discontinuing, or rapidly tapering, systemic corticosteroids.7 Because PRP is a papulosquamous eruption, it is often confused with psoriasis.1,3

Dermatitis. Several subtypes of dermatitis can be associated with erythroderma. These include atopic, seborrheic, allergic contact, airborne, and photosensitivity dermatitis.

Drug eruptions. Numerous pharmacologic agents have been associated with the development of widespread drug-induced skin eruptions. These eruptions include the severe reaction of toxic epidermal necrolysis, which always involves sloughing of skin.

Malignancy. Both cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (including mycosis fungoides) and internal malignancies can lead to erythroderma.6,8,9

PRP has several distinguishing features from other causes of erythroderma

Treatment includes oral retinoids

In the initial evaluation of most cases of erythroderma, it is important to perform a skin biopsy (a 4-mm punch is often best) with a request for a rush reading to avoid missing a possibly severe and life-threatening diagnosis. Skin biopsy is often not diagnostic, but may show alternating parakeratosis and orthokeratosis (as in this case). Careful correlation of the histopathologic findings with the clinical presentation is what usually leads to the diagnosis. Obtaining 2 punch biopsies may be helpful if there are multiple morphologies present or if mycosis fungoides is suspected. If the patient is not physiologically stable, hospitalization is warranted.

Oral retinoids (eg, acitretin) are the first-line treatment for PRP. PRP is a rare disease, so the best treatment data available include studies involving small case series. Other treatments include methotrexate and phototherapy, but results are mixed and patient-dependent.1,3 In fact, some patients have experienced flare-ups when treated with phototherapy; therefore, it is not a commonly used treatment for PRP.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors, including infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept, have been used increasingly with varying degrees of success.10-12 TNF-alpha inhibitors have a relatively good safety profile and should be considered in refractory cases. If there are associated conditions, such as HIV, treating these may also result in remission.2

Our patient was treated with oral acitretin 70 mg/d. At a 3-month follow-up visit, her skin showed signs of partial improvement.

CORRESPONDENCE

André D. Généreux, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Abbott-Northwestern Hospital, 800 East 28th Street, Minneapolis, MN 55407-3799; [email protected].

A 48-year-old woman sought care for a widespread pruritic skin eruption that began on her upper back and spread to her arms, lower trunk, and lower legs. She’d had the rash for approximately 2 months and didn’t have any systemic symptoms. A course of prednisone prior to her presentation failed to improve the rash. She denied a personal or family history of rheumatologic or dermatologic disease and reported no new medications or exposures.

On physical exam, she was afebrile and her vital signs were normal. The rash had red-to-salmon–colored scaling patches with discrete and coalescing follicular papules. There were prominent islands of sparing (FIGURE 1).

The patient’s palms were waxy and erythematous and her feet had hyperkeratosis. A complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipid panel were normal. A skin biopsy demonstrated psoriasiform dermatitis with alternating areas of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis (the presence of keratinocyte nuclei within the stratum corneum where nuclei typically aren’t found).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pityriasis rubra pilaris

The patient was given a diagnosis of pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) based on her distinctive clinical presentation. This included the presence of prominent islands of sparing, the red-to-salmon scaling patches with follicular papules, the waxy erythema of her palms, and the cephalocaudal progression of her rash. The patient’s skin biopsy findings (in particular, the alternating orthokeratosis/parakeratosis) were also supportive of the diagnosis and helpful to exclude other potential causes of erythroderma (described below).

PRP most often affects middle-aged individuals with an equal sex distribution. The etiology and pathogenesis of PRP are not well understood. In rare cases, it has been associated with internal malignancy and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1,2 PRP may stem from a combination of a dysfunction in vitamin A metabolism, genetic factors, and immune dysregulation.3 Six types of PRP have been identified; they differ in the way they present and the populations affected (TABLE).1,4

PRP can be confused with other causes of erythroderma

PRP can cause erythroderma (also known as exfoliative dermatitis), which is the term applied to an erythematous eruption with scaling that covers ≥90% of the body’s surface area. Akhyani et al found that PRP is responsible for approximately 8% of all erythrodermas;5 the other causes of erythroderma are manifestations of numerous conditions, including psoriasis, dermatitis, drug eruptions, and malignancy. The course and prognosis of the erythroderma varies with the underlying condition causing it.6

Psoriasis is a common cause of exfoliative dermatitis in adults. Erythroderma may occur in patients with underlying psoriasis after discontinuing, or rapidly tapering, systemic corticosteroids.7 Because PRP is a papulosquamous eruption, it is often confused with psoriasis.1,3

Dermatitis. Several subtypes of dermatitis can be associated with erythroderma. These include atopic, seborrheic, allergic contact, airborne, and photosensitivity dermatitis.

Drug eruptions. Numerous pharmacologic agents have been associated with the development of widespread drug-induced skin eruptions. These eruptions include the severe reaction of toxic epidermal necrolysis, which always involves sloughing of skin.

Malignancy. Both cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (including mycosis fungoides) and internal malignancies can lead to erythroderma.6,8,9

PRP has several distinguishing features from other causes of erythroderma

Treatment includes oral retinoids

In the initial evaluation of most cases of erythroderma, it is important to perform a skin biopsy (a 4-mm punch is often best) with a request for a rush reading to avoid missing a possibly severe and life-threatening diagnosis. Skin biopsy is often not diagnostic, but may show alternating parakeratosis and orthokeratosis (as in this case). Careful correlation of the histopathologic findings with the clinical presentation is what usually leads to the diagnosis. Obtaining 2 punch biopsies may be helpful if there are multiple morphologies present or if mycosis fungoides is suspected. If the patient is not physiologically stable, hospitalization is warranted.

Oral retinoids (eg, acitretin) are the first-line treatment for PRP. PRP is a rare disease, so the best treatment data available include studies involving small case series. Other treatments include methotrexate and phototherapy, but results are mixed and patient-dependent.1,3 In fact, some patients have experienced flare-ups when treated with phototherapy; therefore, it is not a commonly used treatment for PRP.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors, including infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept, have been used increasingly with varying degrees of success.10-12 TNF-alpha inhibitors have a relatively good safety profile and should be considered in refractory cases. If there are associated conditions, such as HIV, treating these may also result in remission.2

Our patient was treated with oral acitretin 70 mg/d. At a 3-month follow-up visit, her skin showed signs of partial improvement.

CORRESPONDENCE

André D. Généreux, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Abbott-Northwestern Hospital, 800 East 28th Street, Minneapolis, MN 55407-3799; [email protected].

1. Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

2. González-López A, Velasco E, Pozo T, et al. HIV-associated pityriasis rubra pilaris responsive to triple antiretroviral therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:931-934.

3. Bruch-Gerharz D, Ruzicka T. Chapter 24. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY:McGraw-Hill;2012.

4. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. (Juvenile) Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:438-446.

5. Akhyani M, Ghodsi ZS, Toosi S, et al. Erythroderma: a clinical study of 97 cases. BMC Dermatol. 2005;5:5.

6. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Sardana K. Erythroderma/exfoliative dermatitis: a synopsis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:39-47.

7. Rosenbach M, Hsu S, Korman NJ, et al; National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board. Treatment of erythrodermic psoriasis: from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:655-662.

8. Chong VH, Lim CC. Erythroderma as the first manifestation of colon cancer. South Med J. 2009;102:334-335.

9. Ge W, Teng BW, Yu DC, et al. Dermatosis as the initial presentation of gastric cancer: two cases. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:632-638.

10. Garcovich S, Di Giampetruzzi AR, Antonelli G, et al. Treatment of refractory adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris with TNF-alpha antagonists: a case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:881-884.

11. Walling HW, Swick BL. Pityriasis rubra pilaris responding rapidly to adalimumab. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:99-101.

12. Eastham AB, Femia AN, Qureshi A, et al. Treatment options for pityriasis rubra pilaris including biologic agents: a retrospective analysis from an academic medical center. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:92-94.

1. Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

2. González-López A, Velasco E, Pozo T, et al. HIV-associated pityriasis rubra pilaris responsive to triple antiretroviral therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:931-934.

3. Bruch-Gerharz D, Ruzicka T. Chapter 24. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY:McGraw-Hill;2012.

4. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. (Juvenile) Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:438-446.

5. Akhyani M, Ghodsi ZS, Toosi S, et al. Erythroderma: a clinical study of 97 cases. BMC Dermatol. 2005;5:5.

6. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Sardana K. Erythroderma/exfoliative dermatitis: a synopsis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:39-47.

7. Rosenbach M, Hsu S, Korman NJ, et al; National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board. Treatment of erythrodermic psoriasis: from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:655-662.

8. Chong VH, Lim CC. Erythroderma as the first manifestation of colon cancer. South Med J. 2009;102:334-335.

9. Ge W, Teng BW, Yu DC, et al. Dermatosis as the initial presentation of gastric cancer: two cases. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:632-638.

10. Garcovich S, Di Giampetruzzi AR, Antonelli G, et al. Treatment of refractory adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris with TNF-alpha antagonists: a case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:881-884.

11. Walling HW, Swick BL. Pityriasis rubra pilaris responding rapidly to adalimumab. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:99-101.

12. Eastham AB, Femia AN, Qureshi A, et al. Treatment options for pityriasis rubra pilaris including biologic agents: a retrospective analysis from an academic medical center. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:92-94.

Healthy infant with a blistering rash

A 4-month-old girl was brought to our clinic with a 4-week history of blisters on her arms and legs. The eruption started on her right posterior and lateral calf and then appeared on her left calf and bilateral elbows. Other than the blisters, the girl appeared well and was eating and growing normally. Her parents said she had not been in contact with anyone with a similar rash or itching. They also denied recent outdoor activities, camping trips, or environmental exposures.

The child had been previously treated with topical and oral steroids and oral antibiotics by a pediatrician, but the rash barely improved. On physical examination, she was afebrile with well-demarcated erythematous papules and plaques with bullae, and erosions with honey-colored crusts. The rash was distributed symmetrically on the bilateral posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat

The appearance and distribution of the rash on the infant’s posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms prompted us to conclude that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat, along with secondary impetiginization.

The incidence of car seat contact dermatitis is unknown, although it is suspected to be both under-recognized and under-reported. In fact, the number of cases may be on the rise,1 given the increasing number of synthetic liners now being used in car seats, high chairs, and other infant support products.

More common in summer months. Car seat dermatitis is commonly reported in warmer months, when an infant’s skin is more likely to be in direct contact with the car seat and sweating is increased.1 In the acute setting, clinical morphology usually takes the form of inflamed papules or vesicles, while in chronic presentations, lichenified eczematous plaques may be seen. Distribution is typically symmetric and involves areas in direct contact with the car seat, such as the elbows, upper lateral or posterior thighs, lower lateral legs, and sometimes, the occipital scalp.1 The presence of a secondary infection or autoeczematization can complicate the clinical presentation.

Which car seat materials are to blame? Previous reports have described the shiny, nylon-like material overlying the car seat cushion as the cause of the contact allergy, but no specific allergens have yet been identified.1 Attempts at identifying specific allergens in car seat liners have been thwarted by the proprietary nature of manufacturers’ formulas and the unwillingness of companies to divulge the chemicals used in the manufacture of their car seats. Potential allergens include bromine, chlorine, and flame-retardants.1 These allergens differ from the usual contact allergens in children and adolescents, which include nickel sulfate, cobalt chloride, potassium dichromate, fragrance mix, thimerosal, neomycin sulfate, and para-tertiary-butylphenol formaldehyde resin.2

Differential includes other conditions with blisters, plaques

The differential diagnosis includes eczema herpeticum, bullous impetigo, and psoriasis.

Infants with eczema herpeticum usually have eczematous plaques in locations such as the cheeks, neck, antecubital fossa, popliteal fossa, and ankles, with numerous “punched-out” shallow erosions. Children with extensive eczema herpeticum can be systemically ill.

Bullous impetigo is seen as flaccid bullae in infants, which can easily rupture and leave behind superficial erosions. These blisters tend to appear on normal skin. (This is quite different from the thick, erythematous plaques seen in contact dermatitis.) In patients with superficial erosions, a polymerase chain reaction test for the herpes virus and a bacterial culture should be obtained.

Psoriasis often presents with well-demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale. Although it can be symmetric on extensor surfaces, the weeping vesicles with acute onset that were seen in this case would be unusual.

Look for a pattern. The well-demarcated symmetric plaques corresponding directly to areas in contact with the car seat should be a strong clue for contact dermatitis. While patch testing for relevant chemicals is often indicated in patients for whom there is a clinical suspicion of a contact allergy,3,4 we did not perform such testing because the specific chemicals involved in car seat manufacturing are unknown.

Topical steroids and avoidance of the allergen help resolve the rash

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoiding the contact allergen. In car seat contact dermatitis, parents should be counseled to avoid contact between the child’s bare skin and the car seat liner. Given that the precise allergen is unknown, it is impossible to know if a new car seat would contain the same material. Instead, we recommend covering the car seat with a cotton blanket to avoid irritation/allergens.

Depending on the extent of the rash, the patient should be treated with a mid- or high-potency topical steroid until the erythema and blistering resolve.5-8 A 3-week prednisone taper can also be considered for severe cases. For patients who have >25% of their body surface involved, oral steroids are recommended.6 Any secondary infection should be treated with topical and oral antibiotics, as appropriate.

Our patient. Due to the extent and severity of the eruption, we put the patient on a 3-week oral prednisone taper and advised the parents to apply clobetasol 0.05% ointment to the affected areas 2 times a day. We also prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 50 mg/kg divided in 3 doses a day and topical mupirocin ointment (to be applied 2 times a day) for the secondary impetiginization.

We advised the parents to use a cotton blanket over the baby’s car seat to prevent further outbreaks. The eruption resolved within 2 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karolyn A. Wanat, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Drive, 40000 PFP, Iowa City, IA 52242; [email protected].

1. Ghali FE. “Car seat dermatitis”: a newly described form of contact dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:321-326.

2. Mortz CG, Andersen KE. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and adolescents. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:121-130.

3. van der Valk PG, Devos SA, Coenraads PJ. Evidence-based diagnosis in patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:121-125.

4. Krob HA, Fleischer AB Jr, D’Agostino R Jr, et al. Prevalence and relevance of contact dermatitis allergens: a meta-analysis of 15 years of published T.R.U.E. test data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:349-353.

5. Cohen DE, Heidary N. Treatment of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:334-340.

6. Belsito DV. The diagnostic evaluation, treatment, and prevention of allergic contact dermatitis in the new millennium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:409-420.

7. Hachem JP, De Paepe K, Vanpée E, et al. Efficacy of topical corticosteroids in nickel-induced contact allergy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:47-50.

8. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

A 4-month-old girl was brought to our clinic with a 4-week history of blisters on her arms and legs. The eruption started on her right posterior and lateral calf and then appeared on her left calf and bilateral elbows. Other than the blisters, the girl appeared well and was eating and growing normally. Her parents said she had not been in contact with anyone with a similar rash or itching. They also denied recent outdoor activities, camping trips, or environmental exposures.

The child had been previously treated with topical and oral steroids and oral antibiotics by a pediatrician, but the rash barely improved. On physical examination, she was afebrile with well-demarcated erythematous papules and plaques with bullae, and erosions with honey-colored crusts. The rash was distributed symmetrically on the bilateral posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat

The appearance and distribution of the rash on the infant’s posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms prompted us to conclude that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat, along with secondary impetiginization.

The incidence of car seat contact dermatitis is unknown, although it is suspected to be both under-recognized and under-reported. In fact, the number of cases may be on the rise,1 given the increasing number of synthetic liners now being used in car seats, high chairs, and other infant support products.

More common in summer months. Car seat dermatitis is commonly reported in warmer months, when an infant’s skin is more likely to be in direct contact with the car seat and sweating is increased.1 In the acute setting, clinical morphology usually takes the form of inflamed papules or vesicles, while in chronic presentations, lichenified eczematous plaques may be seen. Distribution is typically symmetric and involves areas in direct contact with the car seat, such as the elbows, upper lateral or posterior thighs, lower lateral legs, and sometimes, the occipital scalp.1 The presence of a secondary infection or autoeczematization can complicate the clinical presentation.

Which car seat materials are to blame? Previous reports have described the shiny, nylon-like material overlying the car seat cushion as the cause of the contact allergy, but no specific allergens have yet been identified.1 Attempts at identifying specific allergens in car seat liners have been thwarted by the proprietary nature of manufacturers’ formulas and the unwillingness of companies to divulge the chemicals used in the manufacture of their car seats. Potential allergens include bromine, chlorine, and flame-retardants.1 These allergens differ from the usual contact allergens in children and adolescents, which include nickel sulfate, cobalt chloride, potassium dichromate, fragrance mix, thimerosal, neomycin sulfate, and para-tertiary-butylphenol formaldehyde resin.2

Differential includes other conditions with blisters, plaques

The differential diagnosis includes eczema herpeticum, bullous impetigo, and psoriasis.

Infants with eczema herpeticum usually have eczematous plaques in locations such as the cheeks, neck, antecubital fossa, popliteal fossa, and ankles, with numerous “punched-out” shallow erosions. Children with extensive eczema herpeticum can be systemically ill.

Bullous impetigo is seen as flaccid bullae in infants, which can easily rupture and leave behind superficial erosions. These blisters tend to appear on normal skin. (This is quite different from the thick, erythematous plaques seen in contact dermatitis.) In patients with superficial erosions, a polymerase chain reaction test for the herpes virus and a bacterial culture should be obtained.

Psoriasis often presents with well-demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale. Although it can be symmetric on extensor surfaces, the weeping vesicles with acute onset that were seen in this case would be unusual.

Look for a pattern. The well-demarcated symmetric plaques corresponding directly to areas in contact with the car seat should be a strong clue for contact dermatitis. While patch testing for relevant chemicals is often indicated in patients for whom there is a clinical suspicion of a contact allergy,3,4 we did not perform such testing because the specific chemicals involved in car seat manufacturing are unknown.

Topical steroids and avoidance of the allergen help resolve the rash

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoiding the contact allergen. In car seat contact dermatitis, parents should be counseled to avoid contact between the child’s bare skin and the car seat liner. Given that the precise allergen is unknown, it is impossible to know if a new car seat would contain the same material. Instead, we recommend covering the car seat with a cotton blanket to avoid irritation/allergens.

Depending on the extent of the rash, the patient should be treated with a mid- or high-potency topical steroid until the erythema and blistering resolve.5-8 A 3-week prednisone taper can also be considered for severe cases. For patients who have >25% of their body surface involved, oral steroids are recommended.6 Any secondary infection should be treated with topical and oral antibiotics, as appropriate.

Our patient. Due to the extent and severity of the eruption, we put the patient on a 3-week oral prednisone taper and advised the parents to apply clobetasol 0.05% ointment to the affected areas 2 times a day. We also prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 50 mg/kg divided in 3 doses a day and topical mupirocin ointment (to be applied 2 times a day) for the secondary impetiginization.

We advised the parents to use a cotton blanket over the baby’s car seat to prevent further outbreaks. The eruption resolved within 2 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karolyn A. Wanat, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Drive, 40000 PFP, Iowa City, IA 52242; [email protected].

A 4-month-old girl was brought to our clinic with a 4-week history of blisters on her arms and legs. The eruption started on her right posterior and lateral calf and then appeared on her left calf and bilateral elbows. Other than the blisters, the girl appeared well and was eating and growing normally. Her parents said she had not been in contact with anyone with a similar rash or itching. They also denied recent outdoor activities, camping trips, or environmental exposures.

The child had been previously treated with topical and oral steroids and oral antibiotics by a pediatrician, but the rash barely improved. On physical examination, she was afebrile with well-demarcated erythematous papules and plaques with bullae, and erosions with honey-colored crusts. The rash was distributed symmetrically on the bilateral posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat

The appearance and distribution of the rash on the infant’s posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms prompted us to conclude that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat, along with secondary impetiginization.

The incidence of car seat contact dermatitis is unknown, although it is suspected to be both under-recognized and under-reported. In fact, the number of cases may be on the rise,1 given the increasing number of synthetic liners now being used in car seats, high chairs, and other infant support products.

More common in summer months. Car seat dermatitis is commonly reported in warmer months, when an infant’s skin is more likely to be in direct contact with the car seat and sweating is increased.1 In the acute setting, clinical morphology usually takes the form of inflamed papules or vesicles, while in chronic presentations, lichenified eczematous plaques may be seen. Distribution is typically symmetric and involves areas in direct contact with the car seat, such as the elbows, upper lateral or posterior thighs, lower lateral legs, and sometimes, the occipital scalp.1 The presence of a secondary infection or autoeczematization can complicate the clinical presentation.

Which car seat materials are to blame? Previous reports have described the shiny, nylon-like material overlying the car seat cushion as the cause of the contact allergy, but no specific allergens have yet been identified.1 Attempts at identifying specific allergens in car seat liners have been thwarted by the proprietary nature of manufacturers’ formulas and the unwillingness of companies to divulge the chemicals used in the manufacture of their car seats. Potential allergens include bromine, chlorine, and flame-retardants.1 These allergens differ from the usual contact allergens in children and adolescents, which include nickel sulfate, cobalt chloride, potassium dichromate, fragrance mix, thimerosal, neomycin sulfate, and para-tertiary-butylphenol formaldehyde resin.2

Differential includes other conditions with blisters, plaques

The differential diagnosis includes eczema herpeticum, bullous impetigo, and psoriasis.

Infants with eczema herpeticum usually have eczematous plaques in locations such as the cheeks, neck, antecubital fossa, popliteal fossa, and ankles, with numerous “punched-out” shallow erosions. Children with extensive eczema herpeticum can be systemically ill.

Bullous impetigo is seen as flaccid bullae in infants, which can easily rupture and leave behind superficial erosions. These blisters tend to appear on normal skin. (This is quite different from the thick, erythematous plaques seen in contact dermatitis.) In patients with superficial erosions, a polymerase chain reaction test for the herpes virus and a bacterial culture should be obtained.

Psoriasis often presents with well-demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale. Although it can be symmetric on extensor surfaces, the weeping vesicles with acute onset that were seen in this case would be unusual.

Look for a pattern. The well-demarcated symmetric plaques corresponding directly to areas in contact with the car seat should be a strong clue for contact dermatitis. While patch testing for relevant chemicals is often indicated in patients for whom there is a clinical suspicion of a contact allergy,3,4 we did not perform such testing because the specific chemicals involved in car seat manufacturing are unknown.

Topical steroids and avoidance of the allergen help resolve the rash

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoiding the contact allergen. In car seat contact dermatitis, parents should be counseled to avoid contact between the child’s bare skin and the car seat liner. Given that the precise allergen is unknown, it is impossible to know if a new car seat would contain the same material. Instead, we recommend covering the car seat with a cotton blanket to avoid irritation/allergens.

Depending on the extent of the rash, the patient should be treated with a mid- or high-potency topical steroid until the erythema and blistering resolve.5-8 A 3-week prednisone taper can also be considered for severe cases. For patients who have >25% of their body surface involved, oral steroids are recommended.6 Any secondary infection should be treated with topical and oral antibiotics, as appropriate.

Our patient. Due to the extent and severity of the eruption, we put the patient on a 3-week oral prednisone taper and advised the parents to apply clobetasol 0.05% ointment to the affected areas 2 times a day. We also prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 50 mg/kg divided in 3 doses a day and topical mupirocin ointment (to be applied 2 times a day) for the secondary impetiginization.

We advised the parents to use a cotton blanket over the baby’s car seat to prevent further outbreaks. The eruption resolved within 2 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karolyn A. Wanat, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Drive, 40000 PFP, Iowa City, IA 52242; [email protected].

1. Ghali FE. “Car seat dermatitis”: a newly described form of contact dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:321-326.

2. Mortz CG, Andersen KE. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and adolescents. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:121-130.

3. van der Valk PG, Devos SA, Coenraads PJ. Evidence-based diagnosis in patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:121-125.

4. Krob HA, Fleischer AB Jr, D’Agostino R Jr, et al. Prevalence and relevance of contact dermatitis allergens: a meta-analysis of 15 years of published T.R.U.E. test data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:349-353.

5. Cohen DE, Heidary N. Treatment of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:334-340.

6. Belsito DV. The diagnostic evaluation, treatment, and prevention of allergic contact dermatitis in the new millennium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:409-420.

7. Hachem JP, De Paepe K, Vanpée E, et al. Efficacy of topical corticosteroids in nickel-induced contact allergy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:47-50.

8. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

1. Ghali FE. “Car seat dermatitis”: a newly described form of contact dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:321-326.

2. Mortz CG, Andersen KE. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and adolescents. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:121-130.

3. van der Valk PG, Devos SA, Coenraads PJ. Evidence-based diagnosis in patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:121-125.

4. Krob HA, Fleischer AB Jr, D’Agostino R Jr, et al. Prevalence and relevance of contact dermatitis allergens: a meta-analysis of 15 years of published T.R.U.E. test data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:349-353.

5. Cohen DE, Heidary N. Treatment of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:334-340.

6. Belsito DV. The diagnostic evaluation, treatment, and prevention of allergic contact dermatitis in the new millennium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:409-420.

7. Hachem JP, De Paepe K, Vanpée E, et al. Efficacy of topical corticosteroids in nickel-induced contact allergy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:47-50.

8. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

Dark line across nose

The FP recognized the dark line on the patient’s face as a hyperpigmented horizontal nasal crease based on the fact that she had the atopic triad and repeatedly wiped her nose in an upward motion (an “allergic salute”) whenever her nose felt itchy. There is no specific treatment for a hyperpigmented horizontal nose crease, except to help control the allergic rhinitis. It also helps to control any atopic dermatitis, which can lead to pruritus.

The patient was happy to know the cause of the condition and did not request treatment for the cosmetic aspect of it. For patients who want treatment, a good place to start is with an over-the-counter 3% hydroquinone bleaching agent, along with 1% hydrocortisone cream. (These can both be applied twice daily.)

The FP in this case also recommended sun protection and sun avoidance to avoid further darkening of the hyperpigmented crease.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized the dark line on the patient’s face as a hyperpigmented horizontal nasal crease based on the fact that she had the atopic triad and repeatedly wiped her nose in an upward motion (an “allergic salute”) whenever her nose felt itchy. There is no specific treatment for a hyperpigmented horizontal nose crease, except to help control the allergic rhinitis. It also helps to control any atopic dermatitis, which can lead to pruritus.

The patient was happy to know the cause of the condition and did not request treatment for the cosmetic aspect of it. For patients who want treatment, a good place to start is with an over-the-counter 3% hydroquinone bleaching agent, along with 1% hydrocortisone cream. (These can both be applied twice daily.)

The FP in this case also recommended sun protection and sun avoidance to avoid further darkening of the hyperpigmented crease.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized the dark line on the patient’s face as a hyperpigmented horizontal nasal crease based on the fact that she had the atopic triad and repeatedly wiped her nose in an upward motion (an “allergic salute”) whenever her nose felt itchy. There is no specific treatment for a hyperpigmented horizontal nose crease, except to help control the allergic rhinitis. It also helps to control any atopic dermatitis, which can lead to pruritus.

The patient was happy to know the cause of the condition and did not request treatment for the cosmetic aspect of it. For patients who want treatment, a good place to start is with an over-the-counter 3% hydroquinone bleaching agent, along with 1% hydrocortisone cream. (These can both be applied twice daily.)

The FP in this case also recommended sun protection and sun avoidance to avoid further darkening of the hyperpigmented crease.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

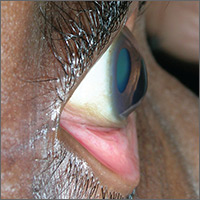

Blurred vision

The FP advised the patient that she had keratoconus, a condition in which the cornea bulges out in the middle (like a cone). Keratoconus, which can adversely affect the health of the eye, is one of several eye findings related to atopic dermatitis. Others include recurrent conjunctivitis, cataracts, and periorbital darkening.

The patient in this case was referred to her ophthalmologist for further evaluation and the FP advised her to avoid rubbing her eyes. In some severe cases, keratoconus treatment requires corneal transplantation.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP advised the patient that she had keratoconus, a condition in which the cornea bulges out in the middle (like a cone). Keratoconus, which can adversely affect the health of the eye, is one of several eye findings related to atopic dermatitis. Others include recurrent conjunctivitis, cataracts, and periorbital darkening.

The patient in this case was referred to her ophthalmologist for further evaluation and the FP advised her to avoid rubbing her eyes. In some severe cases, keratoconus treatment requires corneal transplantation.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP advised the patient that she had keratoconus, a condition in which the cornea bulges out in the middle (like a cone). Keratoconus, which can adversely affect the health of the eye, is one of several eye findings related to atopic dermatitis. Others include recurrent conjunctivitis, cataracts, and periorbital darkening.

The patient in this case was referred to her ophthalmologist for further evaluation and the FP advised her to avoid rubbing her eyes. In some severe cases, keratoconus treatment requires corneal transplantation.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Finklea L. Atopic dermatitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:584-590.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com