User login

Coin-shaped lesions on arm

The FP noted the coin-like shape of the lesions and made a presumptive diagnosis of nummular eczema (nummular dermatitis). He was also concerned about a possible bacterial superinfection because yellow crusting was visible. However, upon further inquiry, the FP learned that the patient had just completed a 10-day course of doxycycline that was given to him by doctors in the emergency room, who suspected that this was a case of impetigo; the lesions had not improved. The patient also indicated that when the rash first erupted, he had tried an over-the-counter antifungal cream, but it had not helped. The FP still went ahead, though, and scraped the skin for a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.)

Since the patient hadn’t seen any improvement with either the antibiotic or the antifungal cream, the FP felt confident that this was a case of nummular eczema and not impetigo or tinea corporis. He believed that the vesicles, oozing, and crusting were all secondary to the inflammatory process. (And the KOH prep subsequently came back negative.)

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

Secondary morphology includes excoriations from scratching, weeping and crusting after the vesicles leak, and scaling and lichenification in more chronic lesions. Excessive weeping and crusting may indicate secondary bacterial infection, but this weeping is often part of the primary inflammatory dermatosis.

In this case, the FP prescribed a high-potency corticosteroid ointment to be applied twice daily. One month later, the patient’s skin was more than 95% improved. Some post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation remained, but the FP reassured the patient that this would likely fade over time. He also explained that the nummular eczema could return and that the steroid could be used again if that were to happen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP noted the coin-like shape of the lesions and made a presumptive diagnosis of nummular eczema (nummular dermatitis). He was also concerned about a possible bacterial superinfection because yellow crusting was visible. However, upon further inquiry, the FP learned that the patient had just completed a 10-day course of doxycycline that was given to him by doctors in the emergency room, who suspected that this was a case of impetigo; the lesions had not improved. The patient also indicated that when the rash first erupted, he had tried an over-the-counter antifungal cream, but it had not helped. The FP still went ahead, though, and scraped the skin for a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.)

Since the patient hadn’t seen any improvement with either the antibiotic or the antifungal cream, the FP felt confident that this was a case of nummular eczema and not impetigo or tinea corporis. He believed that the vesicles, oozing, and crusting were all secondary to the inflammatory process. (And the KOH prep subsequently came back negative.)

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

Secondary morphology includes excoriations from scratching, weeping and crusting after the vesicles leak, and scaling and lichenification in more chronic lesions. Excessive weeping and crusting may indicate secondary bacterial infection, but this weeping is often part of the primary inflammatory dermatosis.

In this case, the FP prescribed a high-potency corticosteroid ointment to be applied twice daily. One month later, the patient’s skin was more than 95% improved. Some post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation remained, but the FP reassured the patient that this would likely fade over time. He also explained that the nummular eczema could return and that the steroid could be used again if that were to happen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP noted the coin-like shape of the lesions and made a presumptive diagnosis of nummular eczema (nummular dermatitis). He was also concerned about a possible bacterial superinfection because yellow crusting was visible. However, upon further inquiry, the FP learned that the patient had just completed a 10-day course of doxycycline that was given to him by doctors in the emergency room, who suspected that this was a case of impetigo; the lesions had not improved. The patient also indicated that when the rash first erupted, he had tried an over-the-counter antifungal cream, but it had not helped. The FP still went ahead, though, and scraped the skin for a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.)

Since the patient hadn’t seen any improvement with either the antibiotic or the antifungal cream, the FP felt confident that this was a case of nummular eczema and not impetigo or tinea corporis. He believed that the vesicles, oozing, and crusting were all secondary to the inflammatory process. (And the KOH prep subsequently came back negative.)

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

Secondary morphology includes excoriations from scratching, weeping and crusting after the vesicles leak, and scaling and lichenification in more chronic lesions. Excessive weeping and crusting may indicate secondary bacterial infection, but this weeping is often part of the primary inflammatory dermatosis.

In this case, the FP prescribed a high-potency corticosteroid ointment to be applied twice daily. One month later, the patient’s skin was more than 95% improved. Some post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation remained, but the FP reassured the patient that this would likely fade over time. He also explained that the nummular eczema could return and that the steroid could be used again if that were to happen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Green fingernail

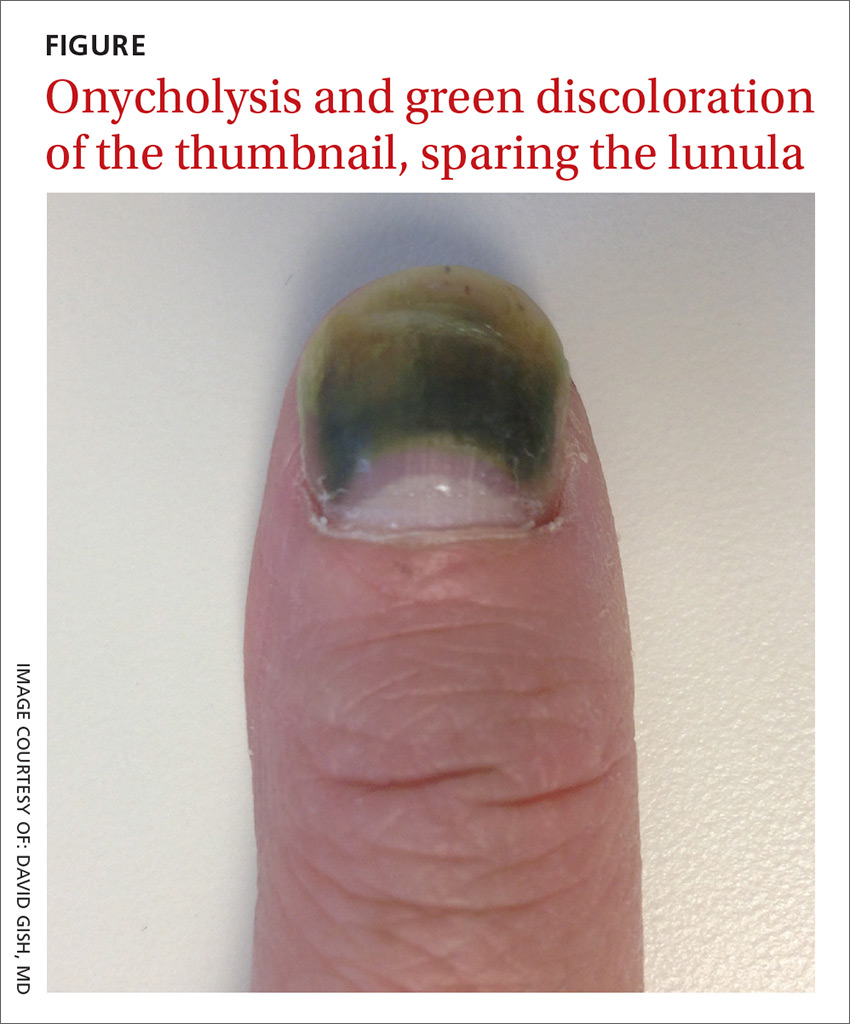

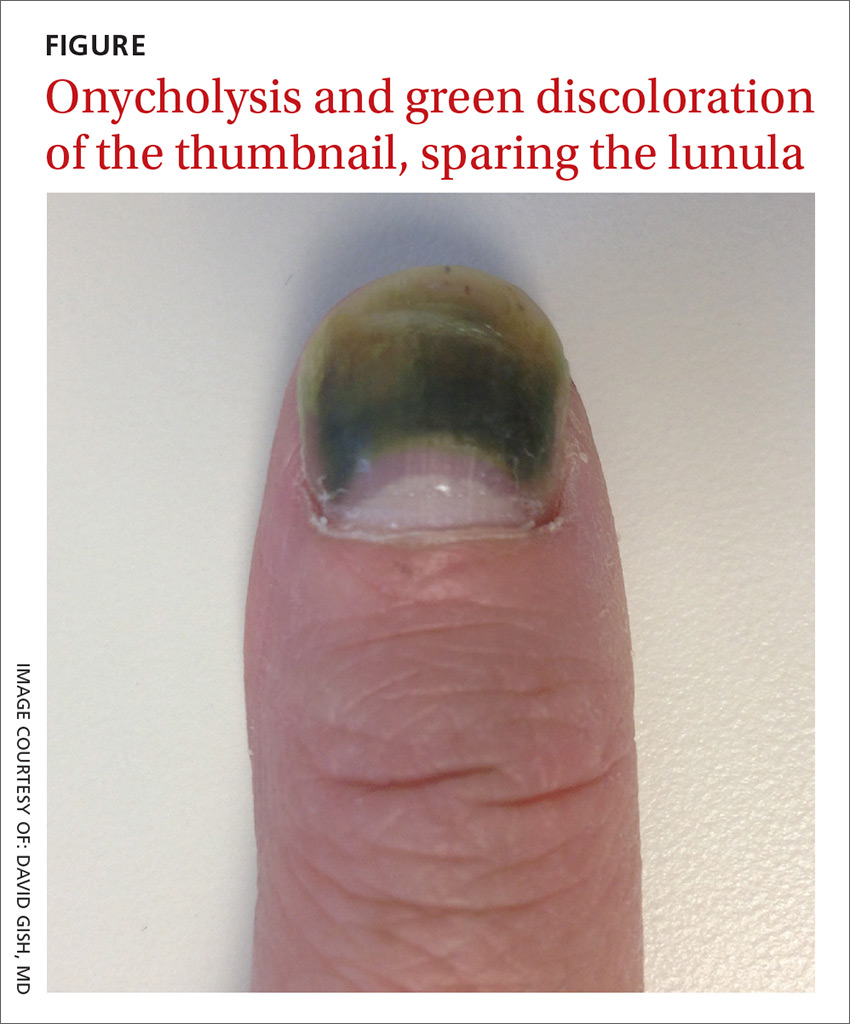

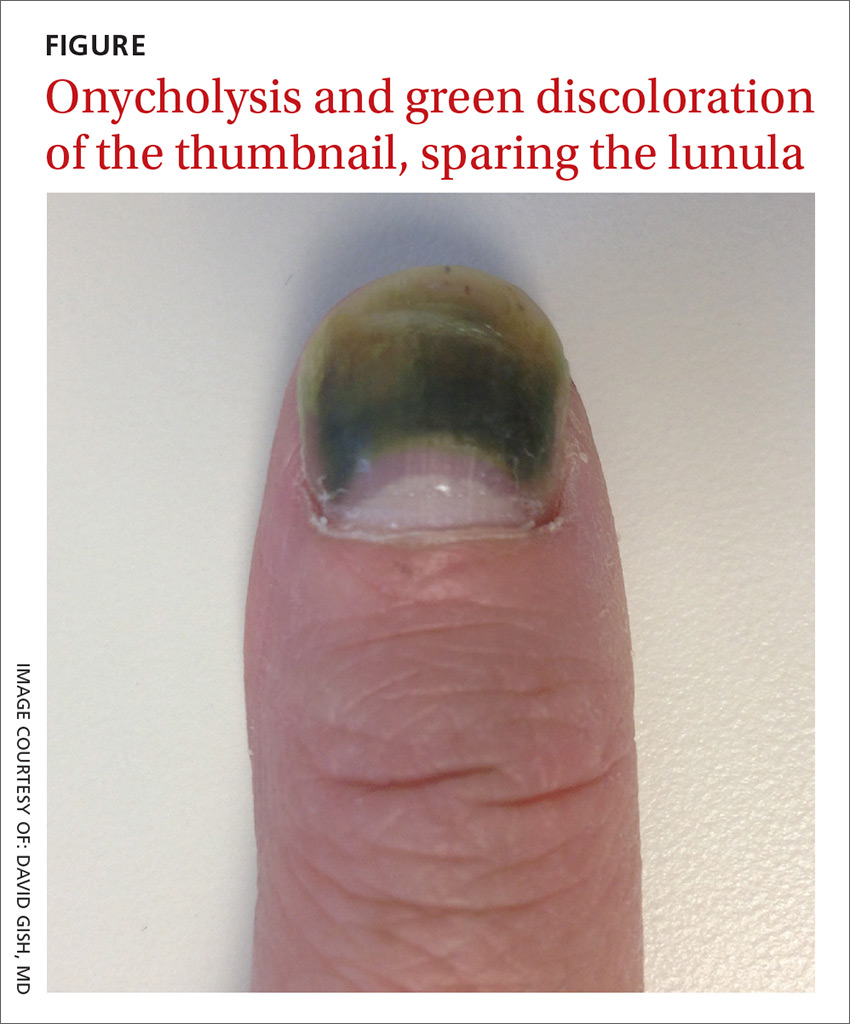

A 34-year-old woman came to our clinic because she was concerned about her thumbnail, which had turned green. Although her finger didn’t hurt, she was bothered by its appearance. Several months earlier, the woman had sought care at a different clinic because the same nail had become brittle and come loose from the nail bed, which was spongy. The physician advised her that she had onychomycosis and prescribed ciclopirox lacquer, but it didn’t help.

Over the next 3 weeks, she noticed a faint green hue developing at the tip of the nail, which expanded and intensified in color (FIGURE). The patient was a mother who worked at home, washed dishes by hand daily, and bathed her children. Her past medical history was significant for type 1 diabetes mellitus and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. She had no other symptoms.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Green nail syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa

This patient had green nail syndrome (GNS), an infection of the nail bed caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These bacteria produce pyocyanin, a blue-green pigment that discolors the nail.1 GNS often occurs in patients with prior nail problems, such as onychomycosis, onycholysis, trauma, chronic paronychia, or psoriasis.

Nail disease disrupts the integumentary barrier and allows a portal of entry for bacteria. Scanning electron microscopy of patients with GNS has shown that fungal infections create tunnel-like structures in the nail keratin, and P aeruginosa grows in these spaces.2 Nails with prior nail disease that are chronically exposed to moisture are at greatest risk of developing GNS,3,4 and it is typical for only one nail to be involved.5Pseudomonas is the most common bacterial infection of the nails, but is not well known because it is rarely reported and patients often don’t seek care.6

In our patient’s case, her prior onychomycosis helped to create a favorable environment for the growth of the bacteria. Onycholysis—characterized by separation of the nail plate from the nail bed—was also present in our patient, based on her description of a “spongy” nail bed and loose nail, allowing moisture and bacteria to infiltrate the space. Onycholysis is associated with hypothyroidism, which the patient also had.7 The frequent soaking of her hands during dishwashing and bathing her children helped to provide the moist environment in which Pseudomonas thrives.

As was the case in this patient, GNS is often painless, or may be accompanied by mild tenderness of the nail. Patients may seek treatment primarily for cosmetic reasons.

GNS can be diagnosed by clinical observation and characteristic pigmentation along with an appropriate patient history.4 Culture of the nail bed may be helpful if bacterial resistance or co-infection with fungal organisms is suspected.

Changes in nail color can be a sign of many conditions

Nail discoloration, or chromonychia, can present in a variety of colors. Nail findings may represent an isolated disease or provide an important clinical clue to other systemic diseases.8 The specific shade of discoloration helps to differentiate the underlying pathology.

Yellow nail syndrome. As the name implies, this syndrome typically causes yellow discoloration of the nail (although yellow-green is also possible). Yellow nail syndrome is believed to be due to microvascular permeability, which also accounts for its associated clinical triad: hypoalbuminemia, pleural effusion, and lymphedema. Yellow nail syndrome may be seen in patients with bronchiectasis, internal malignancies, immunodeficiency, and rheumatoid arthritis.8

Nail bed hematoma. Among the most common causes of nail discoloration, these lesions typically appear as reddish to reddish-black, depending on the age of the bleed, and will often have streaks at the distal margin of the lesion.9 Risk factors for hemorrhage include blood thinners and clotting disorders. Subungual hemorrhages that do not grow out with the nail, or that recur in the same place, may require biopsy.9

Subungual melanoma causes black-brown discoloration of the nails, and may form a longitudinal band in the nail.9 Longitudinal melanonychia is a common variant in African American individuals.10 Features that increase the likelihood of melanoma include a family history of melanoma, a sudden change in the appearance of the lesion, band width greater than 3 mm, pigment changes extending into the cuticle (known as Hutchinson’s sign), and nail plate disruption.

Dermoscopy, the technique of using surface microscopy to examine the skin, may be helpful in distinguishing nail lesions. (See a video on how to perform dermoscopy here: http://bit.ly/2pyJ3xN.)

Nonmelanocytic lesions tend to have homogeneously distributed pigment, while melanocytic lesions contain granules of pigment in cellular inclusions. Any suspicion of melanoma warrants a punch biopsy.11

Medication-induced effects. Minocycline may cause bluish nail discoloration similar to that produced by infection with P aeruginosa, but it is rare for only a single nail to be involved. In addition, pigmentation changes are often present elsewhere on the body, including the sclerae, teeth, and pinna.

Another medication known to color the nails blue is colloidal silver, which is still sold as a dietary supplement or homeopathic remedy to treat a wide range of ailments.6 (Of note: In 1999, the Food and Drug Administration issued a final rule saying that colloidal silver isn’t safe or effective for treating any disease or condition.12)

Glomus tumor. Another cause of blue nails is glomus tumors, relatively uncommon perivascular neoplasms that are typically found in the subungual region. These tumors are generally accompanied by localized tenderness, cold sensitivity, and paroxysms of excruciating pain that are disproportional to the size of the tumor.

Imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis, in addition to pathologic confirmation. Magnetic resonance imaging is the most sensitive imaging modality; if a glomus tumor is present, it most often appears as a well-circumscribed T2 hyperintense lesion.13

Exogenous pigmentation. Nails may become discolored due to exposure to various toxins or chemicals. Frequent culprits include eosin, methylene blue, henna, hair dye, and tobacco.9

Antibiotics and measures to keep the nail dry will help resolve infection

When chronic nail wetness is a contributing factor, treatment begins with measures to keep the nails dry. In addition, either topical or systemic antibiotics may be used to eradicate the infection. Topical applications with agents such as nadifloxacin have been shown to be effective in several case reports,3 but large-scale controlled trials are lacking. Fluoroquinolones are regarded as first-line systemic treatment.5 Briefly soaking the nail in a diluted sodium hypochlorite (bleach) solution also helps to suppress bacterial growth. Nail extraction may be required in refractory cases.

For our patient, we prescribed ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day for 10 days, plus bleach soaks (one part bleach to 4 parts water) twice a day. We recommended that our patient wear gloves for household tasks that involved immersing her hands in water, and drying her finger with a hair dryer after bathing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Gish, MD, University of Virginia Health System, 1215 Lee St. Charlottesville, VA 22908; [email protected].

1. Greene SL, Su WP, Muller SA. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections of the skin. Am Fam Physician. 1984;29:193-200.

2. de Almeida HL Jr, Duquia RP, de Castro LA, et al. Scanning electron microscopy of the green nail. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:962-963.

3. Hengge UR, Bardeli V. Images in clinical medicine. Green nails. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1125.

4. Chiriac A, Brzezinski P, Foia L, et al. Chloronychia: green nail syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in elderly persons. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:265-267.

5. Müller S, Ebnöther M, Itin P. Green nail syndrome (Pseudomonas aeruginosa nail infection): Two cases successfully treated with topical nadifloxacin, an acne medication. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:180-184.

6. Raam R, DeClerck B, Jhun P, et al. That’s some weird nail polish you got there! Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:585-588.

7. Gregoriou S, Argyriou G, Larios G, et al. Nail disorders and systemic disease: what the nails tell us. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:509-514.

8. Fawcett RS, Linford S, Stulberg DL. Nail abnormalities: clues to systemic disease. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1417-1424.

9. Braun RP, Baran R, Le Gal FA, et al. Diagnosis and management of nail pigmentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:835-847.

10. Buka R, Friedman KA, Phelps RG, et al. Childhood longitudinal melanonychia: case reports and review of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68:331-335.

11. Tully AS, Trayes KP, Studdiford JS. Evaluation of nail abnormalities. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:779-787.

12. US Food and Drug Administration. Over-the-counter drug products containing colloidal silver ingredients or silver salts. 1999. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/081799a.txt. Accessed April 11, 2017.

13. Glazebrook KN, Laundre BJ, Schiefer TK, et al. Imaging features of glomus tumors. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:855-862.

A 34-year-old woman came to our clinic because she was concerned about her thumbnail, which had turned green. Although her finger didn’t hurt, she was bothered by its appearance. Several months earlier, the woman had sought care at a different clinic because the same nail had become brittle and come loose from the nail bed, which was spongy. The physician advised her that she had onychomycosis and prescribed ciclopirox lacquer, but it didn’t help.

Over the next 3 weeks, she noticed a faint green hue developing at the tip of the nail, which expanded and intensified in color (FIGURE). The patient was a mother who worked at home, washed dishes by hand daily, and bathed her children. Her past medical history was significant for type 1 diabetes mellitus and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. She had no other symptoms.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Green nail syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa

This patient had green nail syndrome (GNS), an infection of the nail bed caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These bacteria produce pyocyanin, a blue-green pigment that discolors the nail.1 GNS often occurs in patients with prior nail problems, such as onychomycosis, onycholysis, trauma, chronic paronychia, or psoriasis.

Nail disease disrupts the integumentary barrier and allows a portal of entry for bacteria. Scanning electron microscopy of patients with GNS has shown that fungal infections create tunnel-like structures in the nail keratin, and P aeruginosa grows in these spaces.2 Nails with prior nail disease that are chronically exposed to moisture are at greatest risk of developing GNS,3,4 and it is typical for only one nail to be involved.5Pseudomonas is the most common bacterial infection of the nails, but is not well known because it is rarely reported and patients often don’t seek care.6

In our patient’s case, her prior onychomycosis helped to create a favorable environment for the growth of the bacteria. Onycholysis—characterized by separation of the nail plate from the nail bed—was also present in our patient, based on her description of a “spongy” nail bed and loose nail, allowing moisture and bacteria to infiltrate the space. Onycholysis is associated with hypothyroidism, which the patient also had.7 The frequent soaking of her hands during dishwashing and bathing her children helped to provide the moist environment in which Pseudomonas thrives.

As was the case in this patient, GNS is often painless, or may be accompanied by mild tenderness of the nail. Patients may seek treatment primarily for cosmetic reasons.

GNS can be diagnosed by clinical observation and characteristic pigmentation along with an appropriate patient history.4 Culture of the nail bed may be helpful if bacterial resistance or co-infection with fungal organisms is suspected.

Changes in nail color can be a sign of many conditions

Nail discoloration, or chromonychia, can present in a variety of colors. Nail findings may represent an isolated disease or provide an important clinical clue to other systemic diseases.8 The specific shade of discoloration helps to differentiate the underlying pathology.

Yellow nail syndrome. As the name implies, this syndrome typically causes yellow discoloration of the nail (although yellow-green is also possible). Yellow nail syndrome is believed to be due to microvascular permeability, which also accounts for its associated clinical triad: hypoalbuminemia, pleural effusion, and lymphedema. Yellow nail syndrome may be seen in patients with bronchiectasis, internal malignancies, immunodeficiency, and rheumatoid arthritis.8

Nail bed hematoma. Among the most common causes of nail discoloration, these lesions typically appear as reddish to reddish-black, depending on the age of the bleed, and will often have streaks at the distal margin of the lesion.9 Risk factors for hemorrhage include blood thinners and clotting disorders. Subungual hemorrhages that do not grow out with the nail, or that recur in the same place, may require biopsy.9

Subungual melanoma causes black-brown discoloration of the nails, and may form a longitudinal band in the nail.9 Longitudinal melanonychia is a common variant in African American individuals.10 Features that increase the likelihood of melanoma include a family history of melanoma, a sudden change in the appearance of the lesion, band width greater than 3 mm, pigment changes extending into the cuticle (known as Hutchinson’s sign), and nail plate disruption.

Dermoscopy, the technique of using surface microscopy to examine the skin, may be helpful in distinguishing nail lesions. (See a video on how to perform dermoscopy here: http://bit.ly/2pyJ3xN.)

Nonmelanocytic lesions tend to have homogeneously distributed pigment, while melanocytic lesions contain granules of pigment in cellular inclusions. Any suspicion of melanoma warrants a punch biopsy.11

Medication-induced effects. Minocycline may cause bluish nail discoloration similar to that produced by infection with P aeruginosa, but it is rare for only a single nail to be involved. In addition, pigmentation changes are often present elsewhere on the body, including the sclerae, teeth, and pinna.

Another medication known to color the nails blue is colloidal silver, which is still sold as a dietary supplement or homeopathic remedy to treat a wide range of ailments.6 (Of note: In 1999, the Food and Drug Administration issued a final rule saying that colloidal silver isn’t safe or effective for treating any disease or condition.12)

Glomus tumor. Another cause of blue nails is glomus tumors, relatively uncommon perivascular neoplasms that are typically found in the subungual region. These tumors are generally accompanied by localized tenderness, cold sensitivity, and paroxysms of excruciating pain that are disproportional to the size of the tumor.

Imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis, in addition to pathologic confirmation. Magnetic resonance imaging is the most sensitive imaging modality; if a glomus tumor is present, it most often appears as a well-circumscribed T2 hyperintense lesion.13

Exogenous pigmentation. Nails may become discolored due to exposure to various toxins or chemicals. Frequent culprits include eosin, methylene blue, henna, hair dye, and tobacco.9

Antibiotics and measures to keep the nail dry will help resolve infection

When chronic nail wetness is a contributing factor, treatment begins with measures to keep the nails dry. In addition, either topical or systemic antibiotics may be used to eradicate the infection. Topical applications with agents such as nadifloxacin have been shown to be effective in several case reports,3 but large-scale controlled trials are lacking. Fluoroquinolones are regarded as first-line systemic treatment.5 Briefly soaking the nail in a diluted sodium hypochlorite (bleach) solution also helps to suppress bacterial growth. Nail extraction may be required in refractory cases.

For our patient, we prescribed ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day for 10 days, plus bleach soaks (one part bleach to 4 parts water) twice a day. We recommended that our patient wear gloves for household tasks that involved immersing her hands in water, and drying her finger with a hair dryer after bathing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Gish, MD, University of Virginia Health System, 1215 Lee St. Charlottesville, VA 22908; [email protected].

A 34-year-old woman came to our clinic because she was concerned about her thumbnail, which had turned green. Although her finger didn’t hurt, she was bothered by its appearance. Several months earlier, the woman had sought care at a different clinic because the same nail had become brittle and come loose from the nail bed, which was spongy. The physician advised her that she had onychomycosis and prescribed ciclopirox lacquer, but it didn’t help.

Over the next 3 weeks, she noticed a faint green hue developing at the tip of the nail, which expanded and intensified in color (FIGURE). The patient was a mother who worked at home, washed dishes by hand daily, and bathed her children. Her past medical history was significant for type 1 diabetes mellitus and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. She had no other symptoms.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Green nail syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa

This patient had green nail syndrome (GNS), an infection of the nail bed caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These bacteria produce pyocyanin, a blue-green pigment that discolors the nail.1 GNS often occurs in patients with prior nail problems, such as onychomycosis, onycholysis, trauma, chronic paronychia, or psoriasis.

Nail disease disrupts the integumentary barrier and allows a portal of entry for bacteria. Scanning electron microscopy of patients with GNS has shown that fungal infections create tunnel-like structures in the nail keratin, and P aeruginosa grows in these spaces.2 Nails with prior nail disease that are chronically exposed to moisture are at greatest risk of developing GNS,3,4 and it is typical for only one nail to be involved.5Pseudomonas is the most common bacterial infection of the nails, but is not well known because it is rarely reported and patients often don’t seek care.6

In our patient’s case, her prior onychomycosis helped to create a favorable environment for the growth of the bacteria. Onycholysis—characterized by separation of the nail plate from the nail bed—was also present in our patient, based on her description of a “spongy” nail bed and loose nail, allowing moisture and bacteria to infiltrate the space. Onycholysis is associated with hypothyroidism, which the patient also had.7 The frequent soaking of her hands during dishwashing and bathing her children helped to provide the moist environment in which Pseudomonas thrives.

As was the case in this patient, GNS is often painless, or may be accompanied by mild tenderness of the nail. Patients may seek treatment primarily for cosmetic reasons.

GNS can be diagnosed by clinical observation and characteristic pigmentation along with an appropriate patient history.4 Culture of the nail bed may be helpful if bacterial resistance or co-infection with fungal organisms is suspected.

Changes in nail color can be a sign of many conditions

Nail discoloration, or chromonychia, can present in a variety of colors. Nail findings may represent an isolated disease or provide an important clinical clue to other systemic diseases.8 The specific shade of discoloration helps to differentiate the underlying pathology.

Yellow nail syndrome. As the name implies, this syndrome typically causes yellow discoloration of the nail (although yellow-green is also possible). Yellow nail syndrome is believed to be due to microvascular permeability, which also accounts for its associated clinical triad: hypoalbuminemia, pleural effusion, and lymphedema. Yellow nail syndrome may be seen in patients with bronchiectasis, internal malignancies, immunodeficiency, and rheumatoid arthritis.8

Nail bed hematoma. Among the most common causes of nail discoloration, these lesions typically appear as reddish to reddish-black, depending on the age of the bleed, and will often have streaks at the distal margin of the lesion.9 Risk factors for hemorrhage include blood thinners and clotting disorders. Subungual hemorrhages that do not grow out with the nail, or that recur in the same place, may require biopsy.9

Subungual melanoma causes black-brown discoloration of the nails, and may form a longitudinal band in the nail.9 Longitudinal melanonychia is a common variant in African American individuals.10 Features that increase the likelihood of melanoma include a family history of melanoma, a sudden change in the appearance of the lesion, band width greater than 3 mm, pigment changes extending into the cuticle (known as Hutchinson’s sign), and nail plate disruption.

Dermoscopy, the technique of using surface microscopy to examine the skin, may be helpful in distinguishing nail lesions. (See a video on how to perform dermoscopy here: http://bit.ly/2pyJ3xN.)

Nonmelanocytic lesions tend to have homogeneously distributed pigment, while melanocytic lesions contain granules of pigment in cellular inclusions. Any suspicion of melanoma warrants a punch biopsy.11

Medication-induced effects. Minocycline may cause bluish nail discoloration similar to that produced by infection with P aeruginosa, but it is rare for only a single nail to be involved. In addition, pigmentation changes are often present elsewhere on the body, including the sclerae, teeth, and pinna.

Another medication known to color the nails blue is colloidal silver, which is still sold as a dietary supplement or homeopathic remedy to treat a wide range of ailments.6 (Of note: In 1999, the Food and Drug Administration issued a final rule saying that colloidal silver isn’t safe or effective for treating any disease or condition.12)

Glomus tumor. Another cause of blue nails is glomus tumors, relatively uncommon perivascular neoplasms that are typically found in the subungual region. These tumors are generally accompanied by localized tenderness, cold sensitivity, and paroxysms of excruciating pain that are disproportional to the size of the tumor.

Imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis, in addition to pathologic confirmation. Magnetic resonance imaging is the most sensitive imaging modality; if a glomus tumor is present, it most often appears as a well-circumscribed T2 hyperintense lesion.13

Exogenous pigmentation. Nails may become discolored due to exposure to various toxins or chemicals. Frequent culprits include eosin, methylene blue, henna, hair dye, and tobacco.9

Antibiotics and measures to keep the nail dry will help resolve infection

When chronic nail wetness is a contributing factor, treatment begins with measures to keep the nails dry. In addition, either topical or systemic antibiotics may be used to eradicate the infection. Topical applications with agents such as nadifloxacin have been shown to be effective in several case reports,3 but large-scale controlled trials are lacking. Fluoroquinolones are regarded as first-line systemic treatment.5 Briefly soaking the nail in a diluted sodium hypochlorite (bleach) solution also helps to suppress bacterial growth. Nail extraction may be required in refractory cases.

For our patient, we prescribed ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day for 10 days, plus bleach soaks (one part bleach to 4 parts water) twice a day. We recommended that our patient wear gloves for household tasks that involved immersing her hands in water, and drying her finger with a hair dryer after bathing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Gish, MD, University of Virginia Health System, 1215 Lee St. Charlottesville, VA 22908; [email protected].

1. Greene SL, Su WP, Muller SA. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections of the skin. Am Fam Physician. 1984;29:193-200.

2. de Almeida HL Jr, Duquia RP, de Castro LA, et al. Scanning electron microscopy of the green nail. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:962-963.

3. Hengge UR, Bardeli V. Images in clinical medicine. Green nails. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1125.

4. Chiriac A, Brzezinski P, Foia L, et al. Chloronychia: green nail syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in elderly persons. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:265-267.

5. Müller S, Ebnöther M, Itin P. Green nail syndrome (Pseudomonas aeruginosa nail infection): Two cases successfully treated with topical nadifloxacin, an acne medication. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:180-184.

6. Raam R, DeClerck B, Jhun P, et al. That’s some weird nail polish you got there! Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:585-588.

7. Gregoriou S, Argyriou G, Larios G, et al. Nail disorders and systemic disease: what the nails tell us. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:509-514.

8. Fawcett RS, Linford S, Stulberg DL. Nail abnormalities: clues to systemic disease. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1417-1424.

9. Braun RP, Baran R, Le Gal FA, et al. Diagnosis and management of nail pigmentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:835-847.

10. Buka R, Friedman KA, Phelps RG, et al. Childhood longitudinal melanonychia: case reports and review of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68:331-335.

11. Tully AS, Trayes KP, Studdiford JS. Evaluation of nail abnormalities. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:779-787.

12. US Food and Drug Administration. Over-the-counter drug products containing colloidal silver ingredients or silver salts. 1999. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/081799a.txt. Accessed April 11, 2017.

13. Glazebrook KN, Laundre BJ, Schiefer TK, et al. Imaging features of glomus tumors. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:855-862.

1. Greene SL, Su WP, Muller SA. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections of the skin. Am Fam Physician. 1984;29:193-200.

2. de Almeida HL Jr, Duquia RP, de Castro LA, et al. Scanning electron microscopy of the green nail. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:962-963.

3. Hengge UR, Bardeli V. Images in clinical medicine. Green nails. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1125.

4. Chiriac A, Brzezinski P, Foia L, et al. Chloronychia: green nail syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in elderly persons. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:265-267.

5. Müller S, Ebnöther M, Itin P. Green nail syndrome (Pseudomonas aeruginosa nail infection): Two cases successfully treated with topical nadifloxacin, an acne medication. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:180-184.

6. Raam R, DeClerck B, Jhun P, et al. That’s some weird nail polish you got there! Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66:585-588.

7. Gregoriou S, Argyriou G, Larios G, et al. Nail disorders and systemic disease: what the nails tell us. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:509-514.

8. Fawcett RS, Linford S, Stulberg DL. Nail abnormalities: clues to systemic disease. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1417-1424.

9. Braun RP, Baran R, Le Gal FA, et al. Diagnosis and management of nail pigmentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:835-847.

10. Buka R, Friedman KA, Phelps RG, et al. Childhood longitudinal melanonychia: case reports and review of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68:331-335.

11. Tully AS, Trayes KP, Studdiford JS. Evaluation of nail abnormalities. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:779-787.

12. US Food and Drug Administration. Over-the-counter drug products containing colloidal silver ingredients or silver salts. 1999. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/081799a.txt. Accessed April 11, 2017.

13. Glazebrook KN, Laundre BJ, Schiefer TK, et al. Imaging features of glomus tumors. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:855-862.

Fever, petechiae, and joint pain

A 59-year-old woman presented to our emergency department with a rash, severe acute pain in her left hip and lower back, and dyspnea on exertion. She denied having a headache and her mental status was at baseline. The woman reported exposure to rats and snakes one week prior to presentation, and mentioned getting bitten by a rat multiple times on the back of both of her hands while feeding it to her son’s pet snake. The patient had a history of a left hip replacement, with a revision and bone graft 5 years earlier.

The patient had a fever of 103° F during the physical examination. She had erythematous papules and central hemorrhagic eschars at the sites of the bites (FIGURE 1). She also had nonblanching petechiae on both of her lower legs (FIGURE 2) and on the dorsal and palmar aspects of her hands.

The patient’s lab work showed mild normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 11.4 g/dL (normal, 12-16 g/dL) and a platelet count of 129,000/mcL (normal, 130,000-400,000/mcL). Her white blood cell count, chemistries, brain natriuretic peptide test, and chest x-ray were normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Rat bite fever

Based on the patient’s symptoms, history, and lab work, we concluded that this was a case of rat bite fever. RBF is a zoonotic systemic illness caused by infection from either the gram-negative bacillus Streptobacillus moniliformis, commonly found in the United States, or the gram-negative rod Spirillum minus, commonly seen in Asia. Anyone with exposure to rats is at risk for RBF, especially pet shop employees, lab workers, and people living in areas with rat infestations.1

The rash associated with RBF can be petechial, purpuric, or maculopapular, but the presence of hemorrhagic nodules and ulcers at the site of the bite is especially indicative of the illness. The rash often involves the hands and feet, including the palms and soles.

To make the diagnosis of RBF, a careful history and a high index of suspicion are important. Fever and rigor are often the first symptoms to appear, beginning 3 to 10 days after the bite. Three to 4 days after the onset of fever, up to 75% of patients will develop a rash.2 Joint and muscle aches are also common, as is a migrating pattern of arthritis.2,3

Rule out other infections related to animal exposure

The differential diagnosis for RBF includes other animal-related infections, such as those from snake bites, leptospirosis, rabies, and pasteurellosis.

Symptoms associated with snake bite injuries appear rapidly after the bite and vary with the type of snake toxin. Hemotoxic symptoms may include intense pain, edema, petechiae, and ecchymosis from coagulopathy. Neurotoxic symptoms may include ptosis, weakness, and paresthesias. All snake bites should be treated with supportive care, and antivenin is indicated when symptoms or history indicate a bite from a venomous snake. Venomous snakes are rarely intentionally kept as pets.2

Leptospirosis is a zoonotic bacterial infection that may be spread through the urine of rats, dogs, or other mammals. Symptoms may be mild and limited to conjunctivitis, vomiting, and fever; life-threatening symptoms include hemorrhage and kidney failure. A petechial rash is not typical.4 Beta-lactam antibiotics are the treatment of choice.

Rabies is a viral infection that occurs after exposure to infected animals (most commonly raccoons, bats, skunks, and foxes). Symptoms include fever and mental status changes that can lead to death; rash is not a typical symptom. Exposed patients should receive post-exposure prophylaxis with immune globulin or a rabies vaccine.5

Pasteurellosis may also cause hemorrhagic nodules at the site of the bite or scratch, but bites are typically caused by larger animals such as dogs and livestock. Other symptoms include fever, sepsis, and osteomyelitis. Treatment includes amoxicillin-clavulanate or a fluoroquinolone-clindamycin combination.6

In cases of high suspicion, special culture tubes may be needed

Blood cultures and cerebrospinal fluid cultures are often falsely negative. Special culture tubes without polyanethol sulfonate preservative, which inhibits the growth of S moniliformis, may be required in cases of high suspicion. S moniliformis polymerase chain reaction may be available in some specialized labs.7,8

Treatment options include 7 to 10 days of antibiotic therapy with oral penicillin 500 mg 4 times daily, amoxicillin-clavulanate 875/125 mg twice daily, or oral doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours.9

RBF may be fatal if not treated.3 Complications may include bacteremia, septicemia, meningitis, and endocarditis.

Our patient received empiric intravenous ceftriaxone 1 g every 24 hours and her fever and joint pain resolved within 48 hours. On Day 3 she was discharged home to complete a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate 875/125 mg. Her primary care physician reported that the rash resolved and the patient made a full recovery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kate Rowland, MD, MS, Rush-Copley Family Medicine Residency, 2020 Ogden Ave. Suite 325, Aurora, IL 60504; [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rat-bite fever (RBF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/rat-bite-fever/index.html. Accessed December 1, 2015.

2. Elliott SP. Rat bite fever and Streptobacillus moniliformis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:13-22.

3. Juckett G, Hancox JG. Venomous snakebites in the United States: management review and update. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1367-1374.

4. Rabinowitz PM, Gordon Z, Odofin L. Pet-related infections. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:1314-1322.

5. Fishbein DB, Robinson LE. Rabies. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1632-1638.

6. Wilson BA, Ho M. Pasteurella multocida: from zoonosis to cellular microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:631-655.

7. Eng J. Effect of sodium polyanethol sulfonate in blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1975;1:119-123.

8. Nakagomi D, Deguchi N, Yagasaki A, et al. Rat-bite fever identified by polymerase chain reaction detection of Streptobacillus moniliformis DNA. J Dermatol. 2008;35:667-670.

9. Bush LM, Perez MT. Rat-bite fever. In: The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; 2011.

A 59-year-old woman presented to our emergency department with a rash, severe acute pain in her left hip and lower back, and dyspnea on exertion. She denied having a headache and her mental status was at baseline. The woman reported exposure to rats and snakes one week prior to presentation, and mentioned getting bitten by a rat multiple times on the back of both of her hands while feeding it to her son’s pet snake. The patient had a history of a left hip replacement, with a revision and bone graft 5 years earlier.

The patient had a fever of 103° F during the physical examination. She had erythematous papules and central hemorrhagic eschars at the sites of the bites (FIGURE 1). She also had nonblanching petechiae on both of her lower legs (FIGURE 2) and on the dorsal and palmar aspects of her hands.

The patient’s lab work showed mild normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 11.4 g/dL (normal, 12-16 g/dL) and a platelet count of 129,000/mcL (normal, 130,000-400,000/mcL). Her white blood cell count, chemistries, brain natriuretic peptide test, and chest x-ray were normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Rat bite fever

Based on the patient’s symptoms, history, and lab work, we concluded that this was a case of rat bite fever. RBF is a zoonotic systemic illness caused by infection from either the gram-negative bacillus Streptobacillus moniliformis, commonly found in the United States, or the gram-negative rod Spirillum minus, commonly seen in Asia. Anyone with exposure to rats is at risk for RBF, especially pet shop employees, lab workers, and people living in areas with rat infestations.1

The rash associated with RBF can be petechial, purpuric, or maculopapular, but the presence of hemorrhagic nodules and ulcers at the site of the bite is especially indicative of the illness. The rash often involves the hands and feet, including the palms and soles.

To make the diagnosis of RBF, a careful history and a high index of suspicion are important. Fever and rigor are often the first symptoms to appear, beginning 3 to 10 days after the bite. Three to 4 days after the onset of fever, up to 75% of patients will develop a rash.2 Joint and muscle aches are also common, as is a migrating pattern of arthritis.2,3

Rule out other infections related to animal exposure

The differential diagnosis for RBF includes other animal-related infections, such as those from snake bites, leptospirosis, rabies, and pasteurellosis.

Symptoms associated with snake bite injuries appear rapidly after the bite and vary with the type of snake toxin. Hemotoxic symptoms may include intense pain, edema, petechiae, and ecchymosis from coagulopathy. Neurotoxic symptoms may include ptosis, weakness, and paresthesias. All snake bites should be treated with supportive care, and antivenin is indicated when symptoms or history indicate a bite from a venomous snake. Venomous snakes are rarely intentionally kept as pets.2

Leptospirosis is a zoonotic bacterial infection that may be spread through the urine of rats, dogs, or other mammals. Symptoms may be mild and limited to conjunctivitis, vomiting, and fever; life-threatening symptoms include hemorrhage and kidney failure. A petechial rash is not typical.4 Beta-lactam antibiotics are the treatment of choice.

Rabies is a viral infection that occurs after exposure to infected animals (most commonly raccoons, bats, skunks, and foxes). Symptoms include fever and mental status changes that can lead to death; rash is not a typical symptom. Exposed patients should receive post-exposure prophylaxis with immune globulin or a rabies vaccine.5

Pasteurellosis may also cause hemorrhagic nodules at the site of the bite or scratch, but bites are typically caused by larger animals such as dogs and livestock. Other symptoms include fever, sepsis, and osteomyelitis. Treatment includes amoxicillin-clavulanate or a fluoroquinolone-clindamycin combination.6

In cases of high suspicion, special culture tubes may be needed

Blood cultures and cerebrospinal fluid cultures are often falsely negative. Special culture tubes without polyanethol sulfonate preservative, which inhibits the growth of S moniliformis, may be required in cases of high suspicion. S moniliformis polymerase chain reaction may be available in some specialized labs.7,8

Treatment options include 7 to 10 days of antibiotic therapy with oral penicillin 500 mg 4 times daily, amoxicillin-clavulanate 875/125 mg twice daily, or oral doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours.9

RBF may be fatal if not treated.3 Complications may include bacteremia, septicemia, meningitis, and endocarditis.

Our patient received empiric intravenous ceftriaxone 1 g every 24 hours and her fever and joint pain resolved within 48 hours. On Day 3 she was discharged home to complete a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate 875/125 mg. Her primary care physician reported that the rash resolved and the patient made a full recovery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kate Rowland, MD, MS, Rush-Copley Family Medicine Residency, 2020 Ogden Ave. Suite 325, Aurora, IL 60504; [email protected].

A 59-year-old woman presented to our emergency department with a rash, severe acute pain in her left hip and lower back, and dyspnea on exertion. She denied having a headache and her mental status was at baseline. The woman reported exposure to rats and snakes one week prior to presentation, and mentioned getting bitten by a rat multiple times on the back of both of her hands while feeding it to her son’s pet snake. The patient had a history of a left hip replacement, with a revision and bone graft 5 years earlier.

The patient had a fever of 103° F during the physical examination. She had erythematous papules and central hemorrhagic eschars at the sites of the bites (FIGURE 1). She also had nonblanching petechiae on both of her lower legs (FIGURE 2) and on the dorsal and palmar aspects of her hands.

The patient’s lab work showed mild normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 11.4 g/dL (normal, 12-16 g/dL) and a platelet count of 129,000/mcL (normal, 130,000-400,000/mcL). Her white blood cell count, chemistries, brain natriuretic peptide test, and chest x-ray were normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Rat bite fever

Based on the patient’s symptoms, history, and lab work, we concluded that this was a case of rat bite fever. RBF is a zoonotic systemic illness caused by infection from either the gram-negative bacillus Streptobacillus moniliformis, commonly found in the United States, or the gram-negative rod Spirillum minus, commonly seen in Asia. Anyone with exposure to rats is at risk for RBF, especially pet shop employees, lab workers, and people living in areas with rat infestations.1

The rash associated with RBF can be petechial, purpuric, or maculopapular, but the presence of hemorrhagic nodules and ulcers at the site of the bite is especially indicative of the illness. The rash often involves the hands and feet, including the palms and soles.

To make the diagnosis of RBF, a careful history and a high index of suspicion are important. Fever and rigor are often the first symptoms to appear, beginning 3 to 10 days after the bite. Three to 4 days after the onset of fever, up to 75% of patients will develop a rash.2 Joint and muscle aches are also common, as is a migrating pattern of arthritis.2,3

Rule out other infections related to animal exposure

The differential diagnosis for RBF includes other animal-related infections, such as those from snake bites, leptospirosis, rabies, and pasteurellosis.

Symptoms associated with snake bite injuries appear rapidly after the bite and vary with the type of snake toxin. Hemotoxic symptoms may include intense pain, edema, petechiae, and ecchymosis from coagulopathy. Neurotoxic symptoms may include ptosis, weakness, and paresthesias. All snake bites should be treated with supportive care, and antivenin is indicated when symptoms or history indicate a bite from a venomous snake. Venomous snakes are rarely intentionally kept as pets.2

Leptospirosis is a zoonotic bacterial infection that may be spread through the urine of rats, dogs, or other mammals. Symptoms may be mild and limited to conjunctivitis, vomiting, and fever; life-threatening symptoms include hemorrhage and kidney failure. A petechial rash is not typical.4 Beta-lactam antibiotics are the treatment of choice.

Rabies is a viral infection that occurs after exposure to infected animals (most commonly raccoons, bats, skunks, and foxes). Symptoms include fever and mental status changes that can lead to death; rash is not a typical symptom. Exposed patients should receive post-exposure prophylaxis with immune globulin or a rabies vaccine.5

Pasteurellosis may also cause hemorrhagic nodules at the site of the bite or scratch, but bites are typically caused by larger animals such as dogs and livestock. Other symptoms include fever, sepsis, and osteomyelitis. Treatment includes amoxicillin-clavulanate or a fluoroquinolone-clindamycin combination.6

In cases of high suspicion, special culture tubes may be needed

Blood cultures and cerebrospinal fluid cultures are often falsely negative. Special culture tubes without polyanethol sulfonate preservative, which inhibits the growth of S moniliformis, may be required in cases of high suspicion. S moniliformis polymerase chain reaction may be available in some specialized labs.7,8

Treatment options include 7 to 10 days of antibiotic therapy with oral penicillin 500 mg 4 times daily, amoxicillin-clavulanate 875/125 mg twice daily, or oral doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours.9

RBF may be fatal if not treated.3 Complications may include bacteremia, septicemia, meningitis, and endocarditis.

Our patient received empiric intravenous ceftriaxone 1 g every 24 hours and her fever and joint pain resolved within 48 hours. On Day 3 she was discharged home to complete a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate 875/125 mg. Her primary care physician reported that the rash resolved and the patient made a full recovery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kate Rowland, MD, MS, Rush-Copley Family Medicine Residency, 2020 Ogden Ave. Suite 325, Aurora, IL 60504; [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rat-bite fever (RBF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/rat-bite-fever/index.html. Accessed December 1, 2015.

2. Elliott SP. Rat bite fever and Streptobacillus moniliformis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:13-22.

3. Juckett G, Hancox JG. Venomous snakebites in the United States: management review and update. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1367-1374.

4. Rabinowitz PM, Gordon Z, Odofin L. Pet-related infections. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:1314-1322.

5. Fishbein DB, Robinson LE. Rabies. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1632-1638.

6. Wilson BA, Ho M. Pasteurella multocida: from zoonosis to cellular microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:631-655.

7. Eng J. Effect of sodium polyanethol sulfonate in blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1975;1:119-123.

8. Nakagomi D, Deguchi N, Yagasaki A, et al. Rat-bite fever identified by polymerase chain reaction detection of Streptobacillus moniliformis DNA. J Dermatol. 2008;35:667-670.

9. Bush LM, Perez MT. Rat-bite fever. In: The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; 2011.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rat-bite fever (RBF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/rat-bite-fever/index.html. Accessed December 1, 2015.

2. Elliott SP. Rat bite fever and Streptobacillus moniliformis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:13-22.

3. Juckett G, Hancox JG. Venomous snakebites in the United States: management review and update. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1367-1374.

4. Rabinowitz PM, Gordon Z, Odofin L. Pet-related infections. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:1314-1322.

5. Fishbein DB, Robinson LE. Rabies. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1632-1638.

6. Wilson BA, Ho M. Pasteurella multocida: from zoonosis to cellular microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:631-655.

7. Eng J. Effect of sodium polyanethol sulfonate in blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1975;1:119-123.

8. Nakagomi D, Deguchi N, Yagasaki A, et al. Rat-bite fever identified by polymerase chain reaction detection of Streptobacillus moniliformis DNA. J Dermatol. 2008;35:667-670.

9. Bush LM, Perez MT. Rat-bite fever. In: The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; 2011.

Severely painful vesicular rash

The family physician (FP) recognized the multiple vesicles on the patient’s hands as pompholyx, also known as dyshidrotic eczema. The term “pompholyx” means bubble, while the term “dyshidrotic” means "difficult sweating," as problems with sweating were once believed to be the cause of this condition. Some dermatologists prefer the name “vesicular hand dermatitis.” Regardless of the terminology, this can be a mild condition that is a minor nuisance or a severe chronic condition that impairs the patient's quality of life.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily and gave the patient a referral to a dermatologist. While waiting for the dermatology appointment, the patient was not improving, so she went to an emergency room, where she received a prescription for oral prednisone.

When she arrived at the dermatology office, she stated that neither the topical cream nor the oral prednisone helped to improve the rash on her hands. The dermatologist performed patch testing and discovered that she had a contact allergy to topical steroids. He withdrew the steroids and started her on oral cyclosporine, which cleared the rash.

One major lesson from this case is that patients can actually be allergic to topical steroids. Referral to Dermatology was appropriate as the complexity of this case was beyond the scope of family medicine.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) recognized the multiple vesicles on the patient’s hands as pompholyx, also known as dyshidrotic eczema. The term “pompholyx” means bubble, while the term “dyshidrotic” means "difficult sweating," as problems with sweating were once believed to be the cause of this condition. Some dermatologists prefer the name “vesicular hand dermatitis.” Regardless of the terminology, this can be a mild condition that is a minor nuisance or a severe chronic condition that impairs the patient's quality of life.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily and gave the patient a referral to a dermatologist. While waiting for the dermatology appointment, the patient was not improving, so she went to an emergency room, where she received a prescription for oral prednisone.

When she arrived at the dermatology office, she stated that neither the topical cream nor the oral prednisone helped to improve the rash on her hands. The dermatologist performed patch testing and discovered that she had a contact allergy to topical steroids. He withdrew the steroids and started her on oral cyclosporine, which cleared the rash.

One major lesson from this case is that patients can actually be allergic to topical steroids. Referral to Dermatology was appropriate as the complexity of this case was beyond the scope of family medicine.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The family physician (FP) recognized the multiple vesicles on the patient’s hands as pompholyx, also known as dyshidrotic eczema. The term “pompholyx” means bubble, while the term “dyshidrotic” means "difficult sweating," as problems with sweating were once believed to be the cause of this condition. Some dermatologists prefer the name “vesicular hand dermatitis.” Regardless of the terminology, this can be a mild condition that is a minor nuisance or a severe chronic condition that impairs the patient's quality of life.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily and gave the patient a referral to a dermatologist. While waiting for the dermatology appointment, the patient was not improving, so she went to an emergency room, where she received a prescription for oral prednisone.

When she arrived at the dermatology office, she stated that neither the topical cream nor the oral prednisone helped to improve the rash on her hands. The dermatologist performed patch testing and discovered that she had a contact allergy to topical steroids. He withdrew the steroids and started her on oral cyclosporine, which cleared the rash.

One major lesson from this case is that patients can actually be allergic to topical steroids. Referral to Dermatology was appropriate as the complexity of this case was beyond the scope of family medicine.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Painful, red hands

The FP suspected contact dermatitis, but also noted that the patient had white material between his fingers and performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) Under the microscope, the FP found budding yeast and the pseudohyphae of Candida albicans. Candida in the interdigital space is called erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica.

Patients with diabetes are at higher risk for this condition, as are those who perform “wet work.” The FP discussed the importance of hand protection with the patient and ways to better control his diabetes.

Fortunately, the patient had the next 2 days off of work so he was able to begin his treatment while avoiding the irritating environment at work. The FP recommended that the patient purchase over-the-counter clotrimazole cream to apply between his fingers. He also prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily and discussed the use of protective gloves with cotton liners whenever possible.

The FP also referred the patient to Dermatology for further evaluation of the suspected contact dermatitis (including patch testing).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected contact dermatitis, but also noted that the patient had white material between his fingers and performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) Under the microscope, the FP found budding yeast and the pseudohyphae of Candida albicans. Candida in the interdigital space is called erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica.

Patients with diabetes are at higher risk for this condition, as are those who perform “wet work.” The FP discussed the importance of hand protection with the patient and ways to better control his diabetes.

Fortunately, the patient had the next 2 days off of work so he was able to begin his treatment while avoiding the irritating environment at work. The FP recommended that the patient purchase over-the-counter clotrimazole cream to apply between his fingers. He also prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily and discussed the use of protective gloves with cotton liners whenever possible.

The FP also referred the patient to Dermatology for further evaluation of the suspected contact dermatitis (including patch testing).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected contact dermatitis, but also noted that the patient had white material between his fingers and performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) Under the microscope, the FP found budding yeast and the pseudohyphae of Candida albicans. Candida in the interdigital space is called erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica.

Patients with diabetes are at higher risk for this condition, as are those who perform “wet work.” The FP discussed the importance of hand protection with the patient and ways to better control his diabetes.

Fortunately, the patient had the next 2 days off of work so he was able to begin his treatment while avoiding the irritating environment at work. The FP recommended that the patient purchase over-the-counter clotrimazole cream to apply between his fingers. He also prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily and discussed the use of protective gloves with cotton liners whenever possible.

The FP also referred the patient to Dermatology for further evaluation of the suspected contact dermatitis (including patch testing).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Dry, thickened skin on hand

The FP asked the patient to show him how he moved about and immediately noticed that the involved area corresponded directly to the part of the hand that pressed upon his cane. He then diagnosed the patient with unilateral hand eczema related to friction.

The FP asked the patient if he would be willing to get a soft glove to wear on his hand while walking. The patient was amenable to this suggestion, but also asked if something could be done for the dry, thickened area that had already built up on his palm.

The FP prescribed ammonium lactate 12% to be applied twice daily, as it is a good moisturizing keratolytic that helps to break down keratin and soften the skin. He also gave the patient a prescription for 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to rub into the affected area at night before going to sleep. The FP recommended not using this during the daytime as it might make the patient’s hand slippery, leading to a fall if he lost his grip on the cane. At a follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient had improved and was very happy with the result.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP asked the patient to show him how he moved about and immediately noticed that the involved area corresponded directly to the part of the hand that pressed upon his cane. He then diagnosed the patient with unilateral hand eczema related to friction.

The FP asked the patient if he would be willing to get a soft glove to wear on his hand while walking. The patient was amenable to this suggestion, but also asked if something could be done for the dry, thickened area that had already built up on his palm.

The FP prescribed ammonium lactate 12% to be applied twice daily, as it is a good moisturizing keratolytic that helps to break down keratin and soften the skin. He also gave the patient a prescription for 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to rub into the affected area at night before going to sleep. The FP recommended not using this during the daytime as it might make the patient’s hand slippery, leading to a fall if he lost his grip on the cane. At a follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient had improved and was very happy with the result.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP asked the patient to show him how he moved about and immediately noticed that the involved area corresponded directly to the part of the hand that pressed upon his cane. He then diagnosed the patient with unilateral hand eczema related to friction.

The FP asked the patient if he would be willing to get a soft glove to wear on his hand while walking. The patient was amenable to this suggestion, but also asked if something could be done for the dry, thickened area that had already built up on his palm.

The FP prescribed ammonium lactate 12% to be applied twice daily, as it is a good moisturizing keratolytic that helps to break down keratin and soften the skin. He also gave the patient a prescription for 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to rub into the affected area at night before going to sleep. The FP recommended not using this during the daytime as it might make the patient’s hand slippery, leading to a fall if he lost his grip on the cane. At a follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient had improved and was very happy with the result.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Itchy rash on sides of fingers

The FP recognized the multiple tapioca-like vesicles on the sides of the patient’s fingers as pompholyx, also known as dyshidrotic eczema. One of the classic findings of dyshidrotic eczema is the vesicles that resemble the small spheres in tapioca pudding. (The FP considered scabies, but ruled it out because no one in the family had a similar rash and there were no signs of any burrows.)

The term “pompholyx” means bubble, while the term “dyshidrotic” means “difficult sweating,” as problems with sweating were once believed to be the cause of this condition. Some dermatologists prefer the name “vesicular hand dermatitis.” Regardless of the terminology, this can be a very mild condition that is a minor nuisance or a very severe chronic condition that impairs the patient’s quality of life.

The FP explained that dyshidrotic eczema is not curable and may be worsened by stress and substances that come into contact with the hands. He discussed the possibility of avoiding washing the dishes and other “wet work,” but the patient said that wasn’t possible, so he told her to use nitrile gloves with cotton liners. (Using gloves without cotton liners often leads to sweating in the gloves that can worsen dyshidrotic eczema.)

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily. During a follow-up visit one month later, the patient’s rash had improved considerably. She was still working on lifestyle changes to minimize her contact with water and other substances. If the patient’s condition hadn’t improved with basic treatment, she would have been referred to a dermatologist for patch testing to rule out contact dermatitis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized the multiple tapioca-like vesicles on the sides of the patient’s fingers as pompholyx, also known as dyshidrotic eczema. One of the classic findings of dyshidrotic eczema is the vesicles that resemble the small spheres in tapioca pudding. (The FP considered scabies, but ruled it out because no one in the family had a similar rash and there were no signs of any burrows.)

The term “pompholyx” means bubble, while the term “dyshidrotic” means “difficult sweating,” as problems with sweating were once believed to be the cause of this condition. Some dermatologists prefer the name “vesicular hand dermatitis.” Regardless of the terminology, this can be a very mild condition that is a minor nuisance or a very severe chronic condition that impairs the patient’s quality of life.

The FP explained that dyshidrotic eczema is not curable and may be worsened by stress and substances that come into contact with the hands. He discussed the possibility of avoiding washing the dishes and other “wet work,” but the patient said that wasn’t possible, so he told her to use nitrile gloves with cotton liners. (Using gloves without cotton liners often leads to sweating in the gloves that can worsen dyshidrotic eczema.)

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily. During a follow-up visit one month later, the patient’s rash had improved considerably. She was still working on lifestyle changes to minimize her contact with water and other substances. If the patient’s condition hadn’t improved with basic treatment, she would have been referred to a dermatologist for patch testing to rule out contact dermatitis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized the multiple tapioca-like vesicles on the sides of the patient’s fingers as pompholyx, also known as dyshidrotic eczema. One of the classic findings of dyshidrotic eczema is the vesicles that resemble the small spheres in tapioca pudding. (The FP considered scabies, but ruled it out because no one in the family had a similar rash and there were no signs of any burrows.)

The term “pompholyx” means bubble, while the term “dyshidrotic” means “difficult sweating,” as problems with sweating were once believed to be the cause of this condition. Some dermatologists prefer the name “vesicular hand dermatitis.” Regardless of the terminology, this can be a very mild condition that is a minor nuisance or a very severe chronic condition that impairs the patient’s quality of life.

The FP explained that dyshidrotic eczema is not curable and may be worsened by stress and substances that come into contact with the hands. He discussed the possibility of avoiding washing the dishes and other “wet work,” but the patient said that wasn’t possible, so he told her to use nitrile gloves with cotton liners. (Using gloves without cotton liners often leads to sweating in the gloves that can worsen dyshidrotic eczema.)

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone cream to be applied twice daily. During a follow-up visit one month later, the patient’s rash had improved considerably. She was still working on lifestyle changes to minimize her contact with water and other substances. If the patient’s condition hadn’t improved with basic treatment, she would have been referred to a dermatologist for patch testing to rule out contact dermatitis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Single nontender ulcer on the glans

A 42-year-old gay man sought care for a nonhealing lesion on his penis that he’d had for 6 weeks. The patient acknowledged having unprotected sex with several partners in the month prior to the onset of the lesion. The lesion was asymptomatic and small, but rapidly developed into a superficial ulcer. The examination revealed a 1-cm ulcerated, erythematous plaque with raised and indurated edges on the glans (FIGURE). There was minimal drainage in the periurethral area. The patient didn’t have any other rashes or lesions on the skin or mucous membranes, or any regional lymphadenopathies.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Primary syphilis

The patient was given a diagnosis of primary syphilis based on his history and the clinical appearance of a syphilitic chancre. While chancres often occur on the shaft of the penis, they can also occur in the periurethral area, as was the case with this patient. The diagnosis of syphilis was confirmed with a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA).

Although the primary route of transmission is sexual contact, syphilis may also be transmitted from mother to fetus during pregnancy or birth, resulting in congenital syphilis. In addition, a considerable number of men who are diagnosed with syphilis are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies.1 (Our patient was tested for HIV; the result was negative.)