User login

Red line when skin is rubbed

The FP suspected that this was a case of dermatographism. To confirm his suspicions, he used the end of a cotton-tipped applicator and wrote on the patient’s skin. Within 3 minutes, the writing turned into a triple reaction with some erythema, blanching, and swelling—confirming the diagnosis.

Dermatographism often accompanies urticaria, but can occur without it. If one writes on the skin, one is able to see the resulting words or shapes. The cause of this condition is unknown, but the pathophysiology involves degranulation of mast cells and the release of histamine.

No treatment is required for asymptomatic dermatographism. If patients are symptomatic, they should be advised to avoid precipitating physical stimuli. Dry skin may stimulate scratching, so the use of emollients can help. If the patient wants a medication, start with a second-generation antihistamine such as loratadine or cetirizine. While the recommended over-the-counter dose of these 2 medications is 10 mg/d, the dose may be increased to 20 mg twice daily. It is best to start at the lowest dose and then titrate up according to response and tolerance of adverse effects. (The second-generation antihistamines can still be sedating.) If this doesn’t work, a sedating antihistamine can be added before bedtime.

Dermatographism is not life-threatening and does not lead to anaphylaxis. The patient in this case didn’t want treatment and was pleased to know what was going on with his skin.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Urticaria and angioedema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 863-870.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was a case of dermatographism. To confirm his suspicions, he used the end of a cotton-tipped applicator and wrote on the patient’s skin. Within 3 minutes, the writing turned into a triple reaction with some erythema, blanching, and swelling—confirming the diagnosis.

Dermatographism often accompanies urticaria, but can occur without it. If one writes on the skin, one is able to see the resulting words or shapes. The cause of this condition is unknown, but the pathophysiology involves degranulation of mast cells and the release of histamine.

No treatment is required for asymptomatic dermatographism. If patients are symptomatic, they should be advised to avoid precipitating physical stimuli. Dry skin may stimulate scratching, so the use of emollients can help. If the patient wants a medication, start with a second-generation antihistamine such as loratadine or cetirizine. While the recommended over-the-counter dose of these 2 medications is 10 mg/d, the dose may be increased to 20 mg twice daily. It is best to start at the lowest dose and then titrate up according to response and tolerance of adverse effects. (The second-generation antihistamines can still be sedating.) If this doesn’t work, a sedating antihistamine can be added before bedtime.

Dermatographism is not life-threatening and does not lead to anaphylaxis. The patient in this case didn’t want treatment and was pleased to know what was going on with his skin.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Urticaria and angioedema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 863-870.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was a case of dermatographism. To confirm his suspicions, he used the end of a cotton-tipped applicator and wrote on the patient’s skin. Within 3 minutes, the writing turned into a triple reaction with some erythema, blanching, and swelling—confirming the diagnosis.

Dermatographism often accompanies urticaria, but can occur without it. If one writes on the skin, one is able to see the resulting words or shapes. The cause of this condition is unknown, but the pathophysiology involves degranulation of mast cells and the release of histamine.

No treatment is required for asymptomatic dermatographism. If patients are symptomatic, they should be advised to avoid precipitating physical stimuli. Dry skin may stimulate scratching, so the use of emollients can help. If the patient wants a medication, start with a second-generation antihistamine such as loratadine or cetirizine. While the recommended over-the-counter dose of these 2 medications is 10 mg/d, the dose may be increased to 20 mg twice daily. It is best to start at the lowest dose and then titrate up according to response and tolerance of adverse effects. (The second-generation antihistamines can still be sedating.) If this doesn’t work, a sedating antihistamine can be added before bedtime.

Dermatographism is not life-threatening and does not lead to anaphylaxis. The patient in this case didn’t want treatment and was pleased to know what was going on with his skin.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Urticaria and angioedema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 863-870.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Itchy nodules on legs

The FP did a 4-mm punch biopsy to confirm that this was a case of prurigo nodularis and prescribed clobetasol cream to be applied twice daily to the pruritic nodules. The FP recommended that the patient apply the cream instead of scratching the area. The FP also said that if the patient couldn’t avoid touching the area, it would be better to lightly rub the area over his clothing instead.

The biopsy results subsequently confirmed a diagnosis of prurigo nodularis. At the patient’s 2-week follow-up, he indicated that his symptoms were 50% better since using the clobetasol. The FP explained to the patient the nature of prurigo nodularis, including the patient’s itch-scratch cycle and how stress was making it worse. The patient acknowledged that his symptoms had become worse when he began having financial trouble. The FP asked the patient if he wanted to see a counselor, but the patient declined, saying that he just needed to get more work.

At a one-month follow-up, 90% of the nodules were resolved, although there were still some stubborn areas that continued to itch. The patient could not control scratching these areas at times. The FP offered intralesional injections with triamcinolone and/or cryotherapy. The patient consented to liquid nitrogen therapy and the remaining nodules were frozen for approximately 10 seconds each using a liquid nitrogen spray.

Four weeks later, the patient had 4 remaining nodules. The FP injected the nodules with 10 mg/mL triamcinolone and refilled the clobetasol cream. At the next appointment, 2 nodules remained. The patient indicated that he would continue using the cream until the nodules went away. In many cases, prurigo nodularis does not respond especially well to treatment, so this patient was fortunate that standard treatments provided a good outcome.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Johnson A. Self-inflicted dermatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 856-862.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP did a 4-mm punch biopsy to confirm that this was a case of prurigo nodularis and prescribed clobetasol cream to be applied twice daily to the pruritic nodules. The FP recommended that the patient apply the cream instead of scratching the area. The FP also said that if the patient couldn’t avoid touching the area, it would be better to lightly rub the area over his clothing instead.

The biopsy results subsequently confirmed a diagnosis of prurigo nodularis. At the patient’s 2-week follow-up, he indicated that his symptoms were 50% better since using the clobetasol. The FP explained to the patient the nature of prurigo nodularis, including the patient’s itch-scratch cycle and how stress was making it worse. The patient acknowledged that his symptoms had become worse when he began having financial trouble. The FP asked the patient if he wanted to see a counselor, but the patient declined, saying that he just needed to get more work.

At a one-month follow-up, 90% of the nodules were resolved, although there were still some stubborn areas that continued to itch. The patient could not control scratching these areas at times. The FP offered intralesional injections with triamcinolone and/or cryotherapy. The patient consented to liquid nitrogen therapy and the remaining nodules were frozen for approximately 10 seconds each using a liquid nitrogen spray.

Four weeks later, the patient had 4 remaining nodules. The FP injected the nodules with 10 mg/mL triamcinolone and refilled the clobetasol cream. At the next appointment, 2 nodules remained. The patient indicated that he would continue using the cream until the nodules went away. In many cases, prurigo nodularis does not respond especially well to treatment, so this patient was fortunate that standard treatments provided a good outcome.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Johnson A. Self-inflicted dermatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 856-862.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP did a 4-mm punch biopsy to confirm that this was a case of prurigo nodularis and prescribed clobetasol cream to be applied twice daily to the pruritic nodules. The FP recommended that the patient apply the cream instead of scratching the area. The FP also said that if the patient couldn’t avoid touching the area, it would be better to lightly rub the area over his clothing instead.

The biopsy results subsequently confirmed a diagnosis of prurigo nodularis. At the patient’s 2-week follow-up, he indicated that his symptoms were 50% better since using the clobetasol. The FP explained to the patient the nature of prurigo nodularis, including the patient’s itch-scratch cycle and how stress was making it worse. The patient acknowledged that his symptoms had become worse when he began having financial trouble. The FP asked the patient if he wanted to see a counselor, but the patient declined, saying that he just needed to get more work.

At a one-month follow-up, 90% of the nodules were resolved, although there were still some stubborn areas that continued to itch. The patient could not control scratching these areas at times. The FP offered intralesional injections with triamcinolone and/or cryotherapy. The patient consented to liquid nitrogen therapy and the remaining nodules were frozen for approximately 10 seconds each using a liquid nitrogen spray.

Four weeks later, the patient had 4 remaining nodules. The FP injected the nodules with 10 mg/mL triamcinolone and refilled the clobetasol cream. At the next appointment, 2 nodules remained. The patient indicated that he would continue using the cream until the nodules went away. In many cases, prurigo nodularis does not respond especially well to treatment, so this patient was fortunate that standard treatments provided a good outcome.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Johnson A. Self-inflicted dermatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 856-862.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Itchy rash on neck

The FP diagnosed lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) in this patient, based on the lesion’s clinical appearance and location, as well as the patient’s history of repeated daily scratching. LSC is more common in women than in men, and occurs mostly in mid- to late-adulthood, with the highest prevalence in people who are 30 to 50 years of age.

A very common location for LSC in women is the back of the neck. In this case the LSC was coexisting with acanthosis nigricans. Fortunately, this patient did not have diabetes, but her obesity and family history predisposed her to acanthosis nigricans.

The treatment for LSC is topical mid- to high-potency corticosteroids. Oral sedating antihistamines can be added at night if pruritus is bad during the evening. If the patient acknowledges that stress is involved, obtain a good psychosocial history and offer the patient treatment for any problems you uncover.

Patients need to minimize touching, scratching, and rubbing of the affected areas. Explain to patients that they are unintentionally hurting their own skin. Suggest that they gently apply their medication or a moisturizer instead of scratching the pruritic areas.

In this case, the FP prescribed topical triamcinolone ointment and stressed the importance of not rubbing or scratching the area. The patient’s LSC healed well.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Johnson A. Self-inflicted dermatoses. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 856-862.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) in this patient, based on the lesion’s clinical appearance and location, as well as the patient’s history of repeated daily scratching. LSC is more common in women than in men, and occurs mostly in mid- to late-adulthood, with the highest prevalence in people who are 30 to 50 years of age.

A very common location for LSC in women is the back of the neck. In this case the LSC was coexisting with acanthosis nigricans. Fortunately, this patient did not have diabetes, but her obesity and family history predisposed her to acanthosis nigricans.

The treatment for LSC is topical mid- to high-potency corticosteroids. Oral sedating antihistamines can be added at night if pruritus is bad during the evening. If the patient acknowledges that stress is involved, obtain a good psychosocial history and offer the patient treatment for any problems you uncover.

Patients need to minimize touching, scratching, and rubbing of the affected areas. Explain to patients that they are unintentionally hurting their own skin. Suggest that they gently apply their medication or a moisturizer instead of scratching the pruritic areas.

In this case, the FP prescribed topical triamcinolone ointment and stressed the importance of not rubbing or scratching the area. The patient’s LSC healed well.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Johnson A. Self-inflicted dermatoses. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 856-862.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) in this patient, based on the lesion’s clinical appearance and location, as well as the patient’s history of repeated daily scratching. LSC is more common in women than in men, and occurs mostly in mid- to late-adulthood, with the highest prevalence in people who are 30 to 50 years of age.

A very common location for LSC in women is the back of the neck. In this case the LSC was coexisting with acanthosis nigricans. Fortunately, this patient did not have diabetes, but her obesity and family history predisposed her to acanthosis nigricans.

The treatment for LSC is topical mid- to high-potency corticosteroids. Oral sedating antihistamines can be added at night if pruritus is bad during the evening. If the patient acknowledges that stress is involved, obtain a good psychosocial history and offer the patient treatment for any problems you uncover.

Patients need to minimize touching, scratching, and rubbing of the affected areas. Explain to patients that they are unintentionally hurting their own skin. Suggest that they gently apply their medication or a moisturizer instead of scratching the pruritic areas.

In this case, the FP prescribed topical triamcinolone ointment and stressed the importance of not rubbing or scratching the area. The patient’s LSC healed well.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Johnson A. Self-inflicted dermatoses. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 856-862.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Nodules on nose and tattoos

Based on the clinical presentation and skin biopsy results, the patient was given a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. The biopsy from the right side of his nose demonstrated sarcoidal granulomas. A biopsy of one of the tattoo nodules showed sarcoidal granulomas, and close inspection revealed red tattoo pigment within the granulomatous inflammation. X-rays showed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, which was consistent with pulmonary sarcoidosis, and the lace-like appearance of the middle and distal phalanges was consistent with skeletal sarcoidosis.

Systemic sarcoidosis is an idiopathic, granulomatous disease that affects multiple organ systems, but primarily the lungs and lymphatic system. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can occur as a manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis. It may present as asymptomatic red or skin-colored papules and firm nodules within tattoos, old scars, or permanent makeup. Sarcoidosis usually occurs in red, black, or blue-black areas of tattoos, in which the pigment acts as a nidus for granuloma formation.

The first-line treatment for limited papules is a high-potency topical corticosteroid (eg, clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied twice weekly) and an intralesional corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone, one 5-10 mg/mL injection every 4 weeks). Antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine or methotrexate can also be helpful. Midpotency topical corticosteroids such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream and doxycycline hyclate have been reported to clear cutaneous lesions in tattoos. Oral corticosteroids are often effective for severe cutaneous sarcoidosis, but their multiple adverse effects (eg, diabetes and adrenal suppression) prevent prolonged use except in very low doses in conjunction with other therapies.

The nodules on this patient’s nose were successfully treated with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL. No treatment was initiated for the tattoo nodules because they were asymptomatic and the patient wasn’t bothered by their appearance. The patient’s hand swelling improved with a treatment of prednisone 10 mg/d. The rheumatologist considered a steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agent such as methotrexate; however, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Adapted from: Zhang J, Jansen R, Lim HW. Nodules on nose and tattoos. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:241-243.

Based on the clinical presentation and skin biopsy results, the patient was given a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. The biopsy from the right side of his nose demonstrated sarcoidal granulomas. A biopsy of one of the tattoo nodules showed sarcoidal granulomas, and close inspection revealed red tattoo pigment within the granulomatous inflammation. X-rays showed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, which was consistent with pulmonary sarcoidosis, and the lace-like appearance of the middle and distal phalanges was consistent with skeletal sarcoidosis.

Systemic sarcoidosis is an idiopathic, granulomatous disease that affects multiple organ systems, but primarily the lungs and lymphatic system. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can occur as a manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis. It may present as asymptomatic red or skin-colored papules and firm nodules within tattoos, old scars, or permanent makeup. Sarcoidosis usually occurs in red, black, or blue-black areas of tattoos, in which the pigment acts as a nidus for granuloma formation.

The first-line treatment for limited papules is a high-potency topical corticosteroid (eg, clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied twice weekly) and an intralesional corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone, one 5-10 mg/mL injection every 4 weeks). Antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine or methotrexate can also be helpful. Midpotency topical corticosteroids such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream and doxycycline hyclate have been reported to clear cutaneous lesions in tattoos. Oral corticosteroids are often effective for severe cutaneous sarcoidosis, but their multiple adverse effects (eg, diabetes and adrenal suppression) prevent prolonged use except in very low doses in conjunction with other therapies.

The nodules on this patient’s nose were successfully treated with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL. No treatment was initiated for the tattoo nodules because they were asymptomatic and the patient wasn’t bothered by their appearance. The patient’s hand swelling improved with a treatment of prednisone 10 mg/d. The rheumatologist considered a steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agent such as methotrexate; however, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Adapted from: Zhang J, Jansen R, Lim HW. Nodules on nose and tattoos. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:241-243.

Based on the clinical presentation and skin biopsy results, the patient was given a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. The biopsy from the right side of his nose demonstrated sarcoidal granulomas. A biopsy of one of the tattoo nodules showed sarcoidal granulomas, and close inspection revealed red tattoo pigment within the granulomatous inflammation. X-rays showed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, which was consistent with pulmonary sarcoidosis, and the lace-like appearance of the middle and distal phalanges was consistent with skeletal sarcoidosis.

Systemic sarcoidosis is an idiopathic, granulomatous disease that affects multiple organ systems, but primarily the lungs and lymphatic system. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can occur as a manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis. It may present as asymptomatic red or skin-colored papules and firm nodules within tattoos, old scars, or permanent makeup. Sarcoidosis usually occurs in red, black, or blue-black areas of tattoos, in which the pigment acts as a nidus for granuloma formation.

The first-line treatment for limited papules is a high-potency topical corticosteroid (eg, clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied twice weekly) and an intralesional corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone, one 5-10 mg/mL injection every 4 weeks). Antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine or methotrexate can also be helpful. Midpotency topical corticosteroids such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream and doxycycline hyclate have been reported to clear cutaneous lesions in tattoos. Oral corticosteroids are often effective for severe cutaneous sarcoidosis, but their multiple adverse effects (eg, diabetes and adrenal suppression) prevent prolonged use except in very low doses in conjunction with other therapies.

The nodules on this patient’s nose were successfully treated with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL. No treatment was initiated for the tattoo nodules because they were asymptomatic and the patient wasn’t bothered by their appearance. The patient’s hand swelling improved with a treatment of prednisone 10 mg/d. The rheumatologist considered a steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agent such as methotrexate; however, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Adapted from: Zhang J, Jansen R, Lim HW. Nodules on nose and tattoos. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:241-243.

Severe right hip pain

A 63-year-old woman with a 3-year history of osteoporosis presented to our clinic with a 2-week history of severe right hip pain. She had been taking a bisphosphonate—oral ibandronate sodium, 150 mg, once monthly—for about 6 years. The postmenopausal patient had a history of degenerative disc disease and lumbar back pain, but no known history of recent trauma or falls.

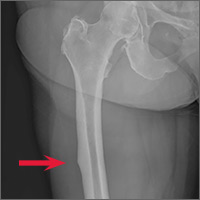

A clinical exam revealed full passive and active range of motion; however, she had pain with weight bearing. A full metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities. A leg length discrepancy was noted, so a bone length study was ordered. Anteroposterior x-rays of the bilateral lower extremities demonstrated a focal convexity along the lateral cortical junction of the proximal right femur (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Bisphosphonate-associated proximal insufficiency fracture

Based on the patient’s clinical history and x-ray findings, we determined that the patient had sustained a bisphosphonate-associated proximal femoral insufficiency fracture. Insufficiency fractures arise from normal physiologic stress on abnormal bone. They commonly occur in conditions that impair normal bone physiology and remodeling, such as osteoporosis, renal insufficiency, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes.1

Could a bisphosphonate be to blame? Bisphosphonate therapy has been associated with significant benefits, including increased bone mineral density (BMD), decreased incidence of fracture, and improved mortality.2-4 But it’s been postulated that the global suppression of bone turnover caused by these drugs may also impair the bone remodeling process.5 Some case reports have suggested an association between chronic bisphosphonate use and atypical insufficiency fractures. These atypical femur fractures are characterized by their location (along the diaphysis in the region distal to the lesser trochanter), the patient’s history (there may be minimal to no trauma), and the potential for “beaking” (localized periosteal or endosteal thickening of the lateral cortex).6,7

Several large, population-based, case-control studies have found a temporal relationship between bisphosphonate therapy and a statistically significant increased risk of subtrochanteric fractures.8-10 These studies do note, however, that the absolute risk of insufficiency fracture is very low, and that the benefits of bisphosphonate therapy greatly outweigh the risks. A 2013 meta-analysis came to the same conclusion.11

Treatment options include PT, surgical intervention

When an insufficiency fracture is identified in a patient taking a bisphosphonate, the medication should be discontinued and a consultation with Endocrinology should be arranged. Nonsurgical management ranges from physical therapy to alternative medication regimens, such as teriparatide—a recombinant human parathyroid hormone used to restore bone quality. A variety of surgical stabilization options are also available.6

In contrast to typical subtrochanteric fractures, about half of patients with atypical insufficiency fractures demonstrate poor fracture healing that requires surgical intervention.12 Complete fractures almost always require surgery, while incomplete subtrochanteric femur fractures can usually be managed conservatively by altering pharmacologic prophylaxis (interval dosing or discontinuation of the bisphosphonate and initiation of an alternative therapy like teriparatide) in conjunction with routine radiologic surveillance. Internal fixation may be considered for cases of persistent pain or those that progress to an unstable fracture.13

Our patient declined surgical intervention. We switched her monthly ibandronate dosage to a periodic dosing schedule (6 months on, followed by 6 months off) and advised her to rest and take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs when needed. While consensus guidelines exist for the management of osteoporosis (see Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient’s risk), there is still debate over the optimal length of bisphosphonate therapy and the impact of drug holidays; a recent review in The BMJ discusses bisphosphonate use in detail.5

SIDEBAR

Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient's riskApproximately 9.9 million Americans have osteoporosis, and while the disease is more common in Caucasian females, patients with osteoporosis have the same elevated fracture risk regardless of their race.14 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends bone mineral density (BMD) testing for all women ages 65 years and older (earlier if risk factor profile warrants).15

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), patients with BMD T-scores at the hip or lumbar spine that are ≤2.5 standard deviations below the mean BMD of a young-adult reference population are at highest risk for osteoporotic fractures.16 There are also free online risk assessment tools, like the WHO’s FRAX calculator (available at: http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp?locationValue=9), which integrate clinical data to generate an evidence-based assessment of fracture risk.17

Follow-up x-rays 14 months later revealed that the insufficiency fracture had healed with a bony callus.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joseph S. McMonagle, MD, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Department of Radiology, P.O. Box 1980, Norfolk, VA; [email protected].

1. Sheehan SE, Shyu JY, Weaver MJ, et al. Proximal femoral fractures: what the orthopedic surgeon wants to know. Radiographics. 2015;35:1563-1584.

2. Wells G, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Risedronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD004523.

3. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001155.

4. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Etidronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD003376.

5. Maraka S, Kennel KA. Bisphosphonates for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. BMJ. 2015;351:h3783.

6. Balach T, Baldwin PC, Intravia J. Atypical femur fractures associated with diphosphonate use. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:550-557.

7. Porrino JA Jr, Kohl CA, Taljanovic M, et al. Diagnosis of proximal femoral insufficiency fractures in patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:1061-1064.

8. Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Lane J, et al. Bisphosphonates and nonhealing femoral fractures: analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and international safety efforts: a systematic review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events And Reports (RADAR) project. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:297-307.

9. Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, et al. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. JAMA. 2011;305:783-789.

10. Schilcher J, Michaëlsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1728-1737.

11. Gedmintas L, Solomon DH, Kim SC. Bisphosphonates and risk of subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femur fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1729-1737.

12. Weil YA, Rivkin G, Safran O, et al. The outcome of surgically treated femur fractures associated with long-term bisphosphonate use. J Trauma. 2011;71:186-190.

13. Khan AA, Leslie WD, Lentle B, et al. Atypical femoral fractures: a teaching perspective. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2015;66:102-107.

14. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359-2381.

15. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:356-364.

16. World Health Organization (WHO). 1994. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: report of a WHO study group. WHO Technical Report Series, Report No. 843. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

17. Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, et al. Development and use of FRAX in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:S407-S413.

A 63-year-old woman with a 3-year history of osteoporosis presented to our clinic with a 2-week history of severe right hip pain. She had been taking a bisphosphonate—oral ibandronate sodium, 150 mg, once monthly—for about 6 years. The postmenopausal patient had a history of degenerative disc disease and lumbar back pain, but no known history of recent trauma or falls.

A clinical exam revealed full passive and active range of motion; however, she had pain with weight bearing. A full metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities. A leg length discrepancy was noted, so a bone length study was ordered. Anteroposterior x-rays of the bilateral lower extremities demonstrated a focal convexity along the lateral cortical junction of the proximal right femur (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Bisphosphonate-associated proximal insufficiency fracture

Based on the patient’s clinical history and x-ray findings, we determined that the patient had sustained a bisphosphonate-associated proximal femoral insufficiency fracture. Insufficiency fractures arise from normal physiologic stress on abnormal bone. They commonly occur in conditions that impair normal bone physiology and remodeling, such as osteoporosis, renal insufficiency, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes.1

Could a bisphosphonate be to blame? Bisphosphonate therapy has been associated with significant benefits, including increased bone mineral density (BMD), decreased incidence of fracture, and improved mortality.2-4 But it’s been postulated that the global suppression of bone turnover caused by these drugs may also impair the bone remodeling process.5 Some case reports have suggested an association between chronic bisphosphonate use and atypical insufficiency fractures. These atypical femur fractures are characterized by their location (along the diaphysis in the region distal to the lesser trochanter), the patient’s history (there may be minimal to no trauma), and the potential for “beaking” (localized periosteal or endosteal thickening of the lateral cortex).6,7

Several large, population-based, case-control studies have found a temporal relationship between bisphosphonate therapy and a statistically significant increased risk of subtrochanteric fractures.8-10 These studies do note, however, that the absolute risk of insufficiency fracture is very low, and that the benefits of bisphosphonate therapy greatly outweigh the risks. A 2013 meta-analysis came to the same conclusion.11

Treatment options include PT, surgical intervention

When an insufficiency fracture is identified in a patient taking a bisphosphonate, the medication should be discontinued and a consultation with Endocrinology should be arranged. Nonsurgical management ranges from physical therapy to alternative medication regimens, such as teriparatide—a recombinant human parathyroid hormone used to restore bone quality. A variety of surgical stabilization options are also available.6

In contrast to typical subtrochanteric fractures, about half of patients with atypical insufficiency fractures demonstrate poor fracture healing that requires surgical intervention.12 Complete fractures almost always require surgery, while incomplete subtrochanteric femur fractures can usually be managed conservatively by altering pharmacologic prophylaxis (interval dosing or discontinuation of the bisphosphonate and initiation of an alternative therapy like teriparatide) in conjunction with routine radiologic surveillance. Internal fixation may be considered for cases of persistent pain or those that progress to an unstable fracture.13

Our patient declined surgical intervention. We switched her monthly ibandronate dosage to a periodic dosing schedule (6 months on, followed by 6 months off) and advised her to rest and take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs when needed. While consensus guidelines exist for the management of osteoporosis (see Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient’s risk), there is still debate over the optimal length of bisphosphonate therapy and the impact of drug holidays; a recent review in The BMJ discusses bisphosphonate use in detail.5

SIDEBAR

Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient's riskApproximately 9.9 million Americans have osteoporosis, and while the disease is more common in Caucasian females, patients with osteoporosis have the same elevated fracture risk regardless of their race.14 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends bone mineral density (BMD) testing for all women ages 65 years and older (earlier if risk factor profile warrants).15

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), patients with BMD T-scores at the hip or lumbar spine that are ≤2.5 standard deviations below the mean BMD of a young-adult reference population are at highest risk for osteoporotic fractures.16 There are also free online risk assessment tools, like the WHO’s FRAX calculator (available at: http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp?locationValue=9), which integrate clinical data to generate an evidence-based assessment of fracture risk.17

Follow-up x-rays 14 months later revealed that the insufficiency fracture had healed with a bony callus.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joseph S. McMonagle, MD, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Department of Radiology, P.O. Box 1980, Norfolk, VA; [email protected].

A 63-year-old woman with a 3-year history of osteoporosis presented to our clinic with a 2-week history of severe right hip pain. She had been taking a bisphosphonate—oral ibandronate sodium, 150 mg, once monthly—for about 6 years. The postmenopausal patient had a history of degenerative disc disease and lumbar back pain, but no known history of recent trauma or falls.

A clinical exam revealed full passive and active range of motion; however, she had pain with weight bearing. A full metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities. A leg length discrepancy was noted, so a bone length study was ordered. Anteroposterior x-rays of the bilateral lower extremities demonstrated a focal convexity along the lateral cortical junction of the proximal right femur (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Bisphosphonate-associated proximal insufficiency fracture

Based on the patient’s clinical history and x-ray findings, we determined that the patient had sustained a bisphosphonate-associated proximal femoral insufficiency fracture. Insufficiency fractures arise from normal physiologic stress on abnormal bone. They commonly occur in conditions that impair normal bone physiology and remodeling, such as osteoporosis, renal insufficiency, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes.1

Could a bisphosphonate be to blame? Bisphosphonate therapy has been associated with significant benefits, including increased bone mineral density (BMD), decreased incidence of fracture, and improved mortality.2-4 But it’s been postulated that the global suppression of bone turnover caused by these drugs may also impair the bone remodeling process.5 Some case reports have suggested an association between chronic bisphosphonate use and atypical insufficiency fractures. These atypical femur fractures are characterized by their location (along the diaphysis in the region distal to the lesser trochanter), the patient’s history (there may be minimal to no trauma), and the potential for “beaking” (localized periosteal or endosteal thickening of the lateral cortex).6,7

Several large, population-based, case-control studies have found a temporal relationship between bisphosphonate therapy and a statistically significant increased risk of subtrochanteric fractures.8-10 These studies do note, however, that the absolute risk of insufficiency fracture is very low, and that the benefits of bisphosphonate therapy greatly outweigh the risks. A 2013 meta-analysis came to the same conclusion.11

Treatment options include PT, surgical intervention

When an insufficiency fracture is identified in a patient taking a bisphosphonate, the medication should be discontinued and a consultation with Endocrinology should be arranged. Nonsurgical management ranges from physical therapy to alternative medication regimens, such as teriparatide—a recombinant human parathyroid hormone used to restore bone quality. A variety of surgical stabilization options are also available.6

In contrast to typical subtrochanteric fractures, about half of patients with atypical insufficiency fractures demonstrate poor fracture healing that requires surgical intervention.12 Complete fractures almost always require surgery, while incomplete subtrochanteric femur fractures can usually be managed conservatively by altering pharmacologic prophylaxis (interval dosing or discontinuation of the bisphosphonate and initiation of an alternative therapy like teriparatide) in conjunction with routine radiologic surveillance. Internal fixation may be considered for cases of persistent pain or those that progress to an unstable fracture.13

Our patient declined surgical intervention. We switched her monthly ibandronate dosage to a periodic dosing schedule (6 months on, followed by 6 months off) and advised her to rest and take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs when needed. While consensus guidelines exist for the management of osteoporosis (see Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient’s risk), there is still debate over the optimal length of bisphosphonate therapy and the impact of drug holidays; a recent review in The BMJ discusses bisphosphonate use in detail.5

SIDEBAR

Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient's riskApproximately 9.9 million Americans have osteoporosis, and while the disease is more common in Caucasian females, patients with osteoporosis have the same elevated fracture risk regardless of their race.14 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends bone mineral density (BMD) testing for all women ages 65 years and older (earlier if risk factor profile warrants).15

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), patients with BMD T-scores at the hip or lumbar spine that are ≤2.5 standard deviations below the mean BMD of a young-adult reference population are at highest risk for osteoporotic fractures.16 There are also free online risk assessment tools, like the WHO’s FRAX calculator (available at: http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp?locationValue=9), which integrate clinical data to generate an evidence-based assessment of fracture risk.17

Follow-up x-rays 14 months later revealed that the insufficiency fracture had healed with a bony callus.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joseph S. McMonagle, MD, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Department of Radiology, P.O. Box 1980, Norfolk, VA; [email protected].

1. Sheehan SE, Shyu JY, Weaver MJ, et al. Proximal femoral fractures: what the orthopedic surgeon wants to know. Radiographics. 2015;35:1563-1584.

2. Wells G, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Risedronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD004523.

3. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001155.

4. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Etidronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD003376.

5. Maraka S, Kennel KA. Bisphosphonates for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. BMJ. 2015;351:h3783.

6. Balach T, Baldwin PC, Intravia J. Atypical femur fractures associated with diphosphonate use. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:550-557.

7. Porrino JA Jr, Kohl CA, Taljanovic M, et al. Diagnosis of proximal femoral insufficiency fractures in patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:1061-1064.

8. Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Lane J, et al. Bisphosphonates and nonhealing femoral fractures: analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and international safety efforts: a systematic review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events And Reports (RADAR) project. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:297-307.

9. Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, et al. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. JAMA. 2011;305:783-789.

10. Schilcher J, Michaëlsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1728-1737.

11. Gedmintas L, Solomon DH, Kim SC. Bisphosphonates and risk of subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femur fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1729-1737.

12. Weil YA, Rivkin G, Safran O, et al. The outcome of surgically treated femur fractures associated with long-term bisphosphonate use. J Trauma. 2011;71:186-190.

13. Khan AA, Leslie WD, Lentle B, et al. Atypical femoral fractures: a teaching perspective. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2015;66:102-107.

14. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359-2381.

15. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:356-364.

16. World Health Organization (WHO). 1994. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: report of a WHO study group. WHO Technical Report Series, Report No. 843. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

17. Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, et al. Development and use of FRAX in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:S407-S413.

1. Sheehan SE, Shyu JY, Weaver MJ, et al. Proximal femoral fractures: what the orthopedic surgeon wants to know. Radiographics. 2015;35:1563-1584.

2. Wells G, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Risedronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD004523.

3. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001155.

4. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Etidronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD003376.

5. Maraka S, Kennel KA. Bisphosphonates for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. BMJ. 2015;351:h3783.

6. Balach T, Baldwin PC, Intravia J. Atypical femur fractures associated with diphosphonate use. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:550-557.

7. Porrino JA Jr, Kohl CA, Taljanovic M, et al. Diagnosis of proximal femoral insufficiency fractures in patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:1061-1064.

8. Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Lane J, et al. Bisphosphonates and nonhealing femoral fractures: analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and international safety efforts: a systematic review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events And Reports (RADAR) project. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:297-307.

9. Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, et al. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. JAMA. 2011;305:783-789.

10. Schilcher J, Michaëlsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1728-1737.

11. Gedmintas L, Solomon DH, Kim SC. Bisphosphonates and risk of subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femur fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1729-1737.

12. Weil YA, Rivkin G, Safran O, et al. The outcome of surgically treated femur fractures associated with long-term bisphosphonate use. J Trauma. 2011;71:186-190.

13. Khan AA, Leslie WD, Lentle B, et al. Atypical femoral fractures: a teaching perspective. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2015;66:102-107.

14. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359-2381.

15. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:356-364.

16. World Health Organization (WHO). 1994. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: report of a WHO study group. WHO Technical Report Series, Report No. 843. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

17. Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, et al. Development and use of FRAX in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:S407-S413.

Annular lesions on abdomen

The FP concluded that this was a case of nummular eczema, after exploring other elements of the differential diagnosis, which included psoriasis, tinea corporis, and contact dermatitis. The FP looked at the patient's nails and scalp and saw no other signs of psoriasis. He then performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and found no evidence of hyphae or fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) He ruled out contact dermatitis because the history did not support it, and this wouldn’t have been a common location for it.

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

In this case, the FP offered to do a biopsy to confirm the clinical diagnosis, but noted that treatment could be started empirically and the biopsy could be reserved for the next visit only if the treatment was not successful. The patient preferred to start with topical treatment and hold off on the biopsy.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily. The FP knew that this was a mid-potency steroid and a high-potency steroid might work more rapidly and effectively, but the patient's insurance had a large deductible and the patient was going to have to pay for the medication out-of-pocket. Generic 0.1% triamcinolone is far less expensive than any of the high-potency steroids, including generic clobetasol.

Fortunately, at the one-month follow-up, the patient had improved by 95% and the only remaining problem was the hyperpigmentation, which was secondary to the inflammation. The FP suggested that the patient continue using the triamcinolone until there was a full resolution of the erythema, scaling, and itching. He explained that the post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation might take months (to a year) to resolve, and in some cases never resolves. The patient was not worried about this issue and was happy that his symptoms had improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP concluded that this was a case of nummular eczema, after exploring other elements of the differential diagnosis, which included psoriasis, tinea corporis, and contact dermatitis. The FP looked at the patient's nails and scalp and saw no other signs of psoriasis. He then performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and found no evidence of hyphae or fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) He ruled out contact dermatitis because the history did not support it, and this wouldn’t have been a common location for it.

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

In this case, the FP offered to do a biopsy to confirm the clinical diagnosis, but noted that treatment could be started empirically and the biopsy could be reserved for the next visit only if the treatment was not successful. The patient preferred to start with topical treatment and hold off on the biopsy.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily. The FP knew that this was a mid-potency steroid and a high-potency steroid might work more rapidly and effectively, but the patient's insurance had a large deductible and the patient was going to have to pay for the medication out-of-pocket. Generic 0.1% triamcinolone is far less expensive than any of the high-potency steroids, including generic clobetasol.

Fortunately, at the one-month follow-up, the patient had improved by 95% and the only remaining problem was the hyperpigmentation, which was secondary to the inflammation. The FP suggested that the patient continue using the triamcinolone until there was a full resolution of the erythema, scaling, and itching. He explained that the post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation might take months (to a year) to resolve, and in some cases never resolves. The patient was not worried about this issue and was happy that his symptoms had improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP concluded that this was a case of nummular eczema, after exploring other elements of the differential diagnosis, which included psoriasis, tinea corporis, and contact dermatitis. The FP looked at the patient's nails and scalp and saw no other signs of psoriasis. He then performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and found no evidence of hyphae or fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) He ruled out contact dermatitis because the history did not support it, and this wouldn’t have been a common location for it.

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

In this case, the FP offered to do a biopsy to confirm the clinical diagnosis, but noted that treatment could be started empirically and the biopsy could be reserved for the next visit only if the treatment was not successful. The patient preferred to start with topical treatment and hold off on the biopsy.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily. The FP knew that this was a mid-potency steroid and a high-potency steroid might work more rapidly and effectively, but the patient's insurance had a large deductible and the patient was going to have to pay for the medication out-of-pocket. Generic 0.1% triamcinolone is far less expensive than any of the high-potency steroids, including generic clobetasol.

Fortunately, at the one-month follow-up, the patient had improved by 95% and the only remaining problem was the hyperpigmentation, which was secondary to the inflammation. The FP suggested that the patient continue using the triamcinolone until there was a full resolution of the erythema, scaling, and itching. He explained that the post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation might take months (to a year) to resolve, and in some cases never resolves. The patient was not worried about this issue and was happy that his symptoms had improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Itchy rash on forearms

The FP strongly suspected that this was a case of nummular eczema, based on the round shape of the plaques, but the location of the lesions suggested psoriasis. The FP also considered tinea corporis with psoriasis in the differential.

The FP checked the patient's scalp, nails, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis and found none. He also performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) To be sure that this wasn’t psoriasis, the FP also performed a punch biopsy. (The pathology subsequently came back positive for nummular eczema.) Ultimately, the yellow crusting, along with the round shape of the plaques, supported a diagnosis of nummular eczema. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”)

Treatment for nummular eczema typically includes clobetasol, an ultra-high-potency corticosteroid. (The patient’s lack of response to the over-the-counter [1%] hydrocortisone was not unusual for nummular eczema because it is a low-potency steroid.) The FP in this case prescribed 0.05% clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily to the lesions until the follow-up appointment 10 days later. At follow-up, the patient reported that the itching had almost completely resolved and the lesions were looking much better. The stitch from the biopsy was removed and the patient was told to continue using the clobetasol until the lesions completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP strongly suspected that this was a case of nummular eczema, based on the round shape of the plaques, but the location of the lesions suggested psoriasis. The FP also considered tinea corporis with psoriasis in the differential.

The FP checked the patient's scalp, nails, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis and found none. He also performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) To be sure that this wasn’t psoriasis, the FP also performed a punch biopsy. (The pathology subsequently came back positive for nummular eczema.) Ultimately, the yellow crusting, along with the round shape of the plaques, supported a diagnosis of nummular eczema. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”)

Treatment for nummular eczema typically includes clobetasol, an ultra-high-potency corticosteroid. (The patient’s lack of response to the over-the-counter [1%] hydrocortisone was not unusual for nummular eczema because it is a low-potency steroid.) The FP in this case prescribed 0.05% clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily to the lesions until the follow-up appointment 10 days later. At follow-up, the patient reported that the itching had almost completely resolved and the lesions were looking much better. The stitch from the biopsy was removed and the patient was told to continue using the clobetasol until the lesions completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP strongly suspected that this was a case of nummular eczema, based on the round shape of the plaques, but the location of the lesions suggested psoriasis. The FP also considered tinea corporis with psoriasis in the differential.

The FP checked the patient's scalp, nails, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis and found none. He also performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) To be sure that this wasn’t psoriasis, the FP also performed a punch biopsy. (The pathology subsequently came back positive for nummular eczema.) Ultimately, the yellow crusting, along with the round shape of the plaques, supported a diagnosis of nummular eczema. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”)

Treatment for nummular eczema typically includes clobetasol, an ultra-high-potency corticosteroid. (The patient’s lack of response to the over-the-counter [1%] hydrocortisone was not unusual for nummular eczema because it is a low-potency steroid.) The FP in this case prescribed 0.05% clobetasol ointment to be applied twice daily to the lesions until the follow-up appointment 10 days later. At follow-up, the patient reported that the itching had almost completely resolved and the lesions were looking much better. The stitch from the biopsy was removed and the patient was told to continue using the clobetasol until the lesions completely resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Dry spots on lower legs

The FP made the presumptive diagnosis of nummular eczema, but recognized that a fungal infection and psoriasis were part of the differential diagnosis. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) In order to explore whether this might be a case of guttate psoriasis, the FP asked about any preceding strep pharyngitis or other respiratory infections. The patient, however, had not had any preceding infections. The FP also checked her nails, scalp, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis, but found none. The FP was now confident in making a clinical diagnosis of nummular eczema (also known as nummular dermatitis).

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

Patients who have a history of atopic dermatitis are more likely to get nummular eczema even after they outgrow the atopic dermatitis. The 2 conditions involve problems with the barrier function of the skin, and emollients are helpful for the prevention and treatment of both.

In this case, the FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily until the lesions resolved. At a one-month follow-up appointment, the patient indicated that her legs were now smooth and she was happy that she could shave them again. The FP told her that it would be a good idea to use emollients after bathing to keep the skin moist in order to prevent future episodes of nummular eczema.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP made the presumptive diagnosis of nummular eczema, but recognized that a fungal infection and psoriasis were part of the differential diagnosis. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) In order to explore whether this might be a case of guttate psoriasis, the FP asked about any preceding strep pharyngitis or other respiratory infections. The patient, however, had not had any preceding infections. The FP also checked her nails, scalp, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis, but found none. The FP was now confident in making a clinical diagnosis of nummular eczema (also known as nummular dermatitis).

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

Patients who have a history of atopic dermatitis are more likely to get nummular eczema even after they outgrow the atopic dermatitis. The 2 conditions involve problems with the barrier function of the skin, and emollients are helpful for the prevention and treatment of both.

In this case, the FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily until the lesions resolved. At a one-month follow-up appointment, the patient indicated that her legs were now smooth and she was happy that she could shave them again. The FP told her that it would be a good idea to use emollients after bathing to keep the skin moist in order to prevent future episodes of nummular eczema.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP made the presumptive diagnosis of nummular eczema, but recognized that a fungal infection and psoriasis were part of the differential diagnosis. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, which was negative for hyphae and fungal elements. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation here: http://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/100603/dermatology/koh-preparation.) In order to explore whether this might be a case of guttate psoriasis, the FP asked about any preceding strep pharyngitis or other respiratory infections. The patient, however, had not had any preceding infections. The FP also checked her nails, scalp, and umbilicus for other signs of psoriasis, but found none. The FP was now confident in making a clinical diagnosis of nummular eczema (also known as nummular dermatitis).

Nummular eczema is a type of eczema characterized by circular or oval-shaped scaling plaques with well-defined borders. (“Nummus” is Latin for “coin.”) Nummular eczema produces multiple lesions that are most commonly found on the dorsa of the hands, arms, and legs.

Patients who have a history of atopic dermatitis are more likely to get nummular eczema even after they outgrow the atopic dermatitis. The 2 conditions involve problems with the barrier function of the skin, and emollients are helpful for the prevention and treatment of both.

In this case, the FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily until the lesions resolved. At a one-month follow-up appointment, the patient indicated that her legs were now smooth and she was happy that she could shave them again. The FP told her that it would be a good idea to use emollients after bathing to keep the skin moist in order to prevent future episodes of nummular eczema.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Wah Y, Usatine R. Eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com