User login

Recognition of skin cancer patterns

This Photo Rounds aims to help you hone your visual diagnostic skills to recognize the 3 most common types of skin cancer (in order of prevalence): basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. (See also “Diagnosis of skin malignancy,”.)

Pattern recognition informs us about the initial differential diagnosis and the appropriate biopsy method.

Basal cell carcinoma

The most common basal cell carcinoma is nodular. Figure 1 shows nodular basal cell carcinoma with a raised pearly pink and white nodule with a smooth, shiny, translucent surface. The smooth surface reflects a loss of the normal pore pattern. Telangiectasias can be seen within the lesion, and the border may appear to be rolled.

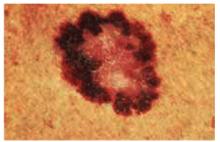

Figure 2 shows a nodular basal cell carcinoma that is both pigmented and has some central ulceration. This figure demonstrates how difficult it is to distinguish a melanoma from a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Figure 3 shows the next most frequently seen basal cell carcinoma, the superficial basal cell carcinoma. These lesions are found most often on the trunk and extremities rather than the face, and may appear as a pink scaling plaque. Sometimes shallow crusts or erosions may be seen within the lesion. Note the thready border present around this scaling plaque. This slightly elevated border is the best tip-off to recognizing this scaling plaque as a skin cancer rather than a plaque of psoriasis or nummular eczema.

Figure 4 shows the least prevalent basal cell carcinoma, the sclerosing type. These lesions are often ivory-colored or colorless. The skin may be appear atrophic and feel indurated. A sclerosing basal cell carcinoma may resemble a scar and can be easily overlooked. These carcinomas are often called morpheaform because of the resemblance to localized scleroderma (morphea). They are also called infiltrating basal cell carcinoma because they infiltrate into the surrounding normal skin in a way not easily visible to the naked eye.

FIGURE 1

Squamous cell carcinoma

The next most common type of skin cancer is squamous cell carcinoma. These cancers are most often found on the lips, ears, and scalp. Figure 5 shows a squamous cell carcinoma on the lower lip. The lower lip catches more ultraviolet rays from the sun than the upper lip, and therefore is the more prevalent site for this carcinoma.

Figure 6 shows a squamous cell carcinoma on the face in an area of sun exposure. This carcinoma looks very much like the superficial basal cell carcinoma in Figure 3, except that the squamous cell carcinoma has one area of crusting. The only way to make a definitive diagnosis is to perform biopsy and get a pathologic reading.

FIGURE 5

There are many different types of melanomas. Figure 7 shows one version of the most common melanoma, the superficial spreading melanoma. The dark pigmentation around the outside of this melanoma is where the lesion is superficially spreading away from the center (which has lost its pigmentation). This lesion meets all of the ABCDE criteria for malignant melanoma.

Figure 8 shows a melanoma arising in a lentigo maligna on the face of an older patient. It is not necessary to know the type of melanoma before the biopsy, but you should recognize that the lesion may be melanoma and perform a full-thickness biopsy. What may have started off as a simple age spot in this patient has become a malignant melanoma (see page 214).

Figure 9 shows a very thick and deadly nodular melanoma. One can recognize a nodular melanoma by the increased thickness and its darker pigmentation.

Figure 10 shows an uncommon type of melanoma but one of the deadliest—the acrallentiginous melanoma. This melanoma is often not detected until it has metastasized. Any pigmented lesion on the hands, feet, or under the fingernails that looks like melanoma should be biopsied early before it gets to this deadly stage.

FIGURE 7

Choice of biopsy technique

Choice of biopsy technique depends on the type of skin lesion. Most basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas can be adequately biopsied by the shave technique because the pathology is superficial and the prognosis is not determined by thickness. Exceptions include sclerosing basal cell carcinomas and very flat superficial basal cell carcinomas, which are best biopsied with a full-thickness specimen in the form of a punch biopsy or excisional biopsy.

All lesions you suspect may be melanoma should be biopsied with a full-thickness specimen. Very small and very large lesions can initially be biopsied using a punch instrument. The excisional biopsy is preferred when the lesion can be removed with one surgical procedure. Depending upon the depth of the melanoma, you may need to perform a second surgery to get adequate margins.

This Photo Rounds aims to help you hone your visual diagnostic skills to recognize the 3 most common types of skin cancer (in order of prevalence): basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. (See also “Diagnosis of skin malignancy,”.)

Pattern recognition informs us about the initial differential diagnosis and the appropriate biopsy method.

Basal cell carcinoma

The most common basal cell carcinoma is nodular. Figure 1 shows nodular basal cell carcinoma with a raised pearly pink and white nodule with a smooth, shiny, translucent surface. The smooth surface reflects a loss of the normal pore pattern. Telangiectasias can be seen within the lesion, and the border may appear to be rolled.

Figure 2 shows a nodular basal cell carcinoma that is both pigmented and has some central ulceration. This figure demonstrates how difficult it is to distinguish a melanoma from a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Figure 3 shows the next most frequently seen basal cell carcinoma, the superficial basal cell carcinoma. These lesions are found most often on the trunk and extremities rather than the face, and may appear as a pink scaling plaque. Sometimes shallow crusts or erosions may be seen within the lesion. Note the thready border present around this scaling plaque. This slightly elevated border is the best tip-off to recognizing this scaling plaque as a skin cancer rather than a plaque of psoriasis or nummular eczema.

Figure 4 shows the least prevalent basal cell carcinoma, the sclerosing type. These lesions are often ivory-colored or colorless. The skin may be appear atrophic and feel indurated. A sclerosing basal cell carcinoma may resemble a scar and can be easily overlooked. These carcinomas are often called morpheaform because of the resemblance to localized scleroderma (morphea). They are also called infiltrating basal cell carcinoma because they infiltrate into the surrounding normal skin in a way not easily visible to the naked eye.

FIGURE 1

Squamous cell carcinoma

The next most common type of skin cancer is squamous cell carcinoma. These cancers are most often found on the lips, ears, and scalp. Figure 5 shows a squamous cell carcinoma on the lower lip. The lower lip catches more ultraviolet rays from the sun than the upper lip, and therefore is the more prevalent site for this carcinoma.

Figure 6 shows a squamous cell carcinoma on the face in an area of sun exposure. This carcinoma looks very much like the superficial basal cell carcinoma in Figure 3, except that the squamous cell carcinoma has one area of crusting. The only way to make a definitive diagnosis is to perform biopsy and get a pathologic reading.

FIGURE 5

There are many different types of melanomas. Figure 7 shows one version of the most common melanoma, the superficial spreading melanoma. The dark pigmentation around the outside of this melanoma is where the lesion is superficially spreading away from the center (which has lost its pigmentation). This lesion meets all of the ABCDE criteria for malignant melanoma.

Figure 8 shows a melanoma arising in a lentigo maligna on the face of an older patient. It is not necessary to know the type of melanoma before the biopsy, but you should recognize that the lesion may be melanoma and perform a full-thickness biopsy. What may have started off as a simple age spot in this patient has become a malignant melanoma (see page 214).

Figure 9 shows a very thick and deadly nodular melanoma. One can recognize a nodular melanoma by the increased thickness and its darker pigmentation.

Figure 10 shows an uncommon type of melanoma but one of the deadliest—the acrallentiginous melanoma. This melanoma is often not detected until it has metastasized. Any pigmented lesion on the hands, feet, or under the fingernails that looks like melanoma should be biopsied early before it gets to this deadly stage.

FIGURE 7

Choice of biopsy technique

Choice of biopsy technique depends on the type of skin lesion. Most basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas can be adequately biopsied by the shave technique because the pathology is superficial and the prognosis is not determined by thickness. Exceptions include sclerosing basal cell carcinomas and very flat superficial basal cell carcinomas, which are best biopsied with a full-thickness specimen in the form of a punch biopsy or excisional biopsy.

All lesions you suspect may be melanoma should be biopsied with a full-thickness specimen. Very small and very large lesions can initially be biopsied using a punch instrument. The excisional biopsy is preferred when the lesion can be removed with one surgical procedure. Depending upon the depth of the melanoma, you may need to perform a second surgery to get adequate margins.

This Photo Rounds aims to help you hone your visual diagnostic skills to recognize the 3 most common types of skin cancer (in order of prevalence): basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. (See also “Diagnosis of skin malignancy,”.)

Pattern recognition informs us about the initial differential diagnosis and the appropriate biopsy method.

Basal cell carcinoma

The most common basal cell carcinoma is nodular. Figure 1 shows nodular basal cell carcinoma with a raised pearly pink and white nodule with a smooth, shiny, translucent surface. The smooth surface reflects a loss of the normal pore pattern. Telangiectasias can be seen within the lesion, and the border may appear to be rolled.

Figure 2 shows a nodular basal cell carcinoma that is both pigmented and has some central ulceration. This figure demonstrates how difficult it is to distinguish a melanoma from a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Figure 3 shows the next most frequently seen basal cell carcinoma, the superficial basal cell carcinoma. These lesions are found most often on the trunk and extremities rather than the face, and may appear as a pink scaling plaque. Sometimes shallow crusts or erosions may be seen within the lesion. Note the thready border present around this scaling plaque. This slightly elevated border is the best tip-off to recognizing this scaling plaque as a skin cancer rather than a plaque of psoriasis or nummular eczema.

Figure 4 shows the least prevalent basal cell carcinoma, the sclerosing type. These lesions are often ivory-colored or colorless. The skin may be appear atrophic and feel indurated. A sclerosing basal cell carcinoma may resemble a scar and can be easily overlooked. These carcinomas are often called morpheaform because of the resemblance to localized scleroderma (morphea). They are also called infiltrating basal cell carcinoma because they infiltrate into the surrounding normal skin in a way not easily visible to the naked eye.

FIGURE 1

Squamous cell carcinoma

The next most common type of skin cancer is squamous cell carcinoma. These cancers are most often found on the lips, ears, and scalp. Figure 5 shows a squamous cell carcinoma on the lower lip. The lower lip catches more ultraviolet rays from the sun than the upper lip, and therefore is the more prevalent site for this carcinoma.

Figure 6 shows a squamous cell carcinoma on the face in an area of sun exposure. This carcinoma looks very much like the superficial basal cell carcinoma in Figure 3, except that the squamous cell carcinoma has one area of crusting. The only way to make a definitive diagnosis is to perform biopsy and get a pathologic reading.

FIGURE 5

There are many different types of melanomas. Figure 7 shows one version of the most common melanoma, the superficial spreading melanoma. The dark pigmentation around the outside of this melanoma is where the lesion is superficially spreading away from the center (which has lost its pigmentation). This lesion meets all of the ABCDE criteria for malignant melanoma.

Figure 8 shows a melanoma arising in a lentigo maligna on the face of an older patient. It is not necessary to know the type of melanoma before the biopsy, but you should recognize that the lesion may be melanoma and perform a full-thickness biopsy. What may have started off as a simple age spot in this patient has become a malignant melanoma (see page 214).

Figure 9 shows a very thick and deadly nodular melanoma. One can recognize a nodular melanoma by the increased thickness and its darker pigmentation.

Figure 10 shows an uncommon type of melanoma but one of the deadliest—the acrallentiginous melanoma. This melanoma is often not detected until it has metastasized. Any pigmented lesion on the hands, feet, or under the fingernails that looks like melanoma should be biopsied early before it gets to this deadly stage.

FIGURE 7

Choice of biopsy technique

Choice of biopsy technique depends on the type of skin lesion. Most basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas can be adequately biopsied by the shave technique because the pathology is superficial and the prognosis is not determined by thickness. Exceptions include sclerosing basal cell carcinomas and very flat superficial basal cell carcinomas, which are best biopsied with a full-thickness specimen in the form of a punch biopsy or excisional biopsy.

All lesions you suspect may be melanoma should be biopsied with a full-thickness specimen. Very small and very large lesions can initially be biopsied using a punch instrument. The excisional biopsy is preferred when the lesion can be removed with one surgical procedure. Depending upon the depth of the melanoma, you may need to perform a second surgery to get adequate margins.

Abnormal fingernails

A 48-year-old African American woman came to our office because the discoloration of one fingernail that began months earlier had spread to a second finger, and the first finger to become discolored had begun to hurt.

The patient had initially seen another physician, who prescribed itraconazole for presumptive onychomycosis. The patient received a pulse therapy course of itraconazole for 3 months and had no improvement. Therapy ended 4 months ago, and a month ago the end of her left index finger began to ache.

The patient works at a computer, and typing causes pain in the left index finger. A review of her chart reveals she is taking a diuretic for hypertension; there are no other health problems.

What is the diagnosis?

Before taking a more extensive history, it is appropriate to look at her fingers more closely to collect data that will inform questioning. By applying pattern recognition skills first, you can form hypotheses and use the remainder of the exam to test them.

How would you describe the abnormalities seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2 (pattern recognition), and what would be the differential diagnosis (hypotheses)?

What further history, physical exam, or laboratory tests should be completed (hypothesis testing)?

FIGURE 1

This patient’s fingernail had been discolored for months and the fingertip had recently begun to hurt.

A brown discoloration (oil spot) in the patient’s proximal nail.

Figure 1 shows a brownish discoloration of the fingernail, with small pits particularly prominent around the lunula (the semicircular light area adjacent to the proximal nail fold). There is also evidence of onycholysis (separation of the nail from the nail bed). The vertical ridging is not abnormal.

Figure 2 shows a well-circumscribed brown discoloration in the proximal nail called an oil spot. These nail findings are classic for psoriasis.1

Figure 1 also shows subtle swelling of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. It is this area the patient said was painful, and she had joint tenderness to palpation over this DIP joint only.

Hypotheses

The 2 most likely diagnoses are:

- psoriasis causing nail changes while psoriatic arthritis is developing

- onychomycosis with incidental joint pain of the DIP joint.

Other causes of nail changes include lichen planus, chronic candida paronychia, and Reiter’s disease. Epidemiologically the most likely diagnosis is onychomycosis, which is far more prevalent than the other conditions. However, this patient has already failed a course of an oral antifungal agent, and her nail changes are more consistent with psoriasis.

Hypothesis testing

Questions and physical examination focus on collecting data to determine the more likely of the two diagnoses, psoriasis and fungal nail disease. The patient denied having any skin lesions and a history of psoriasis. She also said she had no athlete’s foot or problems with her toenails or other hand. Her knees ache from time to time, which she attributed to aging.

Physical exam revealed no evidence of psoriasis on the skin and no tinea pedis or onychomycosis of the toenails. She had no other skin findings suggestive of lichen planus or Reiter’s disease. Looking more closely at the fingernails, we saw no evidence of subungual keratoses, which are frequently found in onychomycosis.

A scraping and clipping of the fingernail was sent for fungal culture, and an x-ray film of that digit revealed no bony changes. The fungal culture results 2 weeks later were negative.

Patient follow-up

We made a presumptive diagnosis of psoriatic nail changes and psoriatic arthritis, and the patient was sent to a rheumatologist for consultation. The rheumatologist agreed with the diagnosis and placed the patient on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to treat the early psoriatic arthritis.

The patient developed more areas of psoriatic arthritis involvement over the subsequent years and became less concerned about the appearance of her nails. Eventually the psoriatic arthritis progressed to the point where the patient was taking remititive agents for inflammatory arthropathy. She never did develop the skin lesions of psoriasis.

Nail changes of psoriasis

It has been reported that 30% of patients with psoriasis have nail changes, the most common being pitting. Onycholysis is the next most frequent change, and the oil spot is less frequent but not rare.

Not everyone with nail pitting has psoriasis; however, there is a high correlation between psoriatic arthritis and nail pitting.

Patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis have a higher percentage of nail changes than patients with psoriasis of the skin only. In 1 study, nail changes were noted in 86.5% of patients affected by arthropathic psoriasis, and the most common fingernail change was pitting.2

This particular case shows it is possible to have psoriatic arthritis and psoriatic nail changes without psoriasis of the skin. Fortunately, the patient did not have an adverse reaction to the itraconazole prescribed for the incorrectly diagnosed onychomycosis.

It is debatable whether fungal cultures are needed before prescribing oral antifungal agents for onychomycosis. This was 1 case in which the nail findings may have steered the clinician toward getting a nail scraping for microscopic analysis using potassium hydroxide or a fungal culture. Negative findings would have spared the patient the treatment with an expensive agent with known liver toxicity.

The onset of pain, swelling, and tenderness of the DIP joint of the affected nail helped to make the diagnosis. It is the finger joint most commonly affected by psoriatic arthritis.

Treatment of psoriasis of the nails

There is no good treatment for psoriasis of the nails. Treatment regimens that have been studied include injection of steroids into the nail matrix and use of topical retinoids. Intralesional steroid injections are very painful, and the results are not adequate to recommend this treatment.

A study of topical retinoid tazorotene showed some promise.3 The study size was small, however, and the measured change was not great. But for patients desperately looking for help for psoriatic nail changes, the topical treatment may be worth a try.

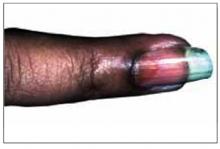

Figure 3 shows a different patient with an interesting connection between involvement of psoriatic arthritis in the finger and accompanying nail changes. This man had psoriatic plaques over his fingers and a severely swollen DIP joint of the middle finger with significant accompanying nail changes. The inflammatory reaction in the DIP joint is accompanied by abnormal changes in the nail matrix, producing a psoriatic nail on the same finger.

FIGURE 3

Another patient’s hand, with psoriatic plaques and swollen distal interphalangeal joint.

1. Habif T. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1996.

2. Lavaroni G, Kokelj F, Pauluzzi P, Trevisan G. The nails in psoriatic arthritis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1994;186:113.-

3. Scher RK, Stiller M, Zhu YI. Tazarotene 0.1% gel in the treatment of fingernail psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study. Cutis 2001;68:355-8.

A 48-year-old African American woman came to our office because the discoloration of one fingernail that began months earlier had spread to a second finger, and the first finger to become discolored had begun to hurt.

The patient had initially seen another physician, who prescribed itraconazole for presumptive onychomycosis. The patient received a pulse therapy course of itraconazole for 3 months and had no improvement. Therapy ended 4 months ago, and a month ago the end of her left index finger began to ache.

The patient works at a computer, and typing causes pain in the left index finger. A review of her chart reveals she is taking a diuretic for hypertension; there are no other health problems.

What is the diagnosis?

Before taking a more extensive history, it is appropriate to look at her fingers more closely to collect data that will inform questioning. By applying pattern recognition skills first, you can form hypotheses and use the remainder of the exam to test them.

How would you describe the abnormalities seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2 (pattern recognition), and what would be the differential diagnosis (hypotheses)?

What further history, physical exam, or laboratory tests should be completed (hypothesis testing)?

FIGURE 1

This patient’s fingernail had been discolored for months and the fingertip had recently begun to hurt.

A brown discoloration (oil spot) in the patient’s proximal nail.

Figure 1 shows a brownish discoloration of the fingernail, with small pits particularly prominent around the lunula (the semicircular light area adjacent to the proximal nail fold). There is also evidence of onycholysis (separation of the nail from the nail bed). The vertical ridging is not abnormal.

Figure 2 shows a well-circumscribed brown discoloration in the proximal nail called an oil spot. These nail findings are classic for psoriasis.1

Figure 1 also shows subtle swelling of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. It is this area the patient said was painful, and she had joint tenderness to palpation over this DIP joint only.

Hypotheses

The 2 most likely diagnoses are:

- psoriasis causing nail changes while psoriatic arthritis is developing

- onychomycosis with incidental joint pain of the DIP joint.

Other causes of nail changes include lichen planus, chronic candida paronychia, and Reiter’s disease. Epidemiologically the most likely diagnosis is onychomycosis, which is far more prevalent than the other conditions. However, this patient has already failed a course of an oral antifungal agent, and her nail changes are more consistent with psoriasis.

Hypothesis testing

Questions and physical examination focus on collecting data to determine the more likely of the two diagnoses, psoriasis and fungal nail disease. The patient denied having any skin lesions and a history of psoriasis. She also said she had no athlete’s foot or problems with her toenails or other hand. Her knees ache from time to time, which she attributed to aging.

Physical exam revealed no evidence of psoriasis on the skin and no tinea pedis or onychomycosis of the toenails. She had no other skin findings suggestive of lichen planus or Reiter’s disease. Looking more closely at the fingernails, we saw no evidence of subungual keratoses, which are frequently found in onychomycosis.

A scraping and clipping of the fingernail was sent for fungal culture, and an x-ray film of that digit revealed no bony changes. The fungal culture results 2 weeks later were negative.

Patient follow-up

We made a presumptive diagnosis of psoriatic nail changes and psoriatic arthritis, and the patient was sent to a rheumatologist for consultation. The rheumatologist agreed with the diagnosis and placed the patient on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to treat the early psoriatic arthritis.

The patient developed more areas of psoriatic arthritis involvement over the subsequent years and became less concerned about the appearance of her nails. Eventually the psoriatic arthritis progressed to the point where the patient was taking remititive agents for inflammatory arthropathy. She never did develop the skin lesions of psoriasis.

Nail changes of psoriasis

It has been reported that 30% of patients with psoriasis have nail changes, the most common being pitting. Onycholysis is the next most frequent change, and the oil spot is less frequent but not rare.

Not everyone with nail pitting has psoriasis; however, there is a high correlation between psoriatic arthritis and nail pitting.

Patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis have a higher percentage of nail changes than patients with psoriasis of the skin only. In 1 study, nail changes were noted in 86.5% of patients affected by arthropathic psoriasis, and the most common fingernail change was pitting.2

This particular case shows it is possible to have psoriatic arthritis and psoriatic nail changes without psoriasis of the skin. Fortunately, the patient did not have an adverse reaction to the itraconazole prescribed for the incorrectly diagnosed onychomycosis.

It is debatable whether fungal cultures are needed before prescribing oral antifungal agents for onychomycosis. This was 1 case in which the nail findings may have steered the clinician toward getting a nail scraping for microscopic analysis using potassium hydroxide or a fungal culture. Negative findings would have spared the patient the treatment with an expensive agent with known liver toxicity.

The onset of pain, swelling, and tenderness of the DIP joint of the affected nail helped to make the diagnosis. It is the finger joint most commonly affected by psoriatic arthritis.

Treatment of psoriasis of the nails

There is no good treatment for psoriasis of the nails. Treatment regimens that have been studied include injection of steroids into the nail matrix and use of topical retinoids. Intralesional steroid injections are very painful, and the results are not adequate to recommend this treatment.

A study of topical retinoid tazorotene showed some promise.3 The study size was small, however, and the measured change was not great. But for patients desperately looking for help for psoriatic nail changes, the topical treatment may be worth a try.

Figure 3 shows a different patient with an interesting connection between involvement of psoriatic arthritis in the finger and accompanying nail changes. This man had psoriatic plaques over his fingers and a severely swollen DIP joint of the middle finger with significant accompanying nail changes. The inflammatory reaction in the DIP joint is accompanied by abnormal changes in the nail matrix, producing a psoriatic nail on the same finger.

FIGURE 3

Another patient’s hand, with psoriatic plaques and swollen distal interphalangeal joint.

A 48-year-old African American woman came to our office because the discoloration of one fingernail that began months earlier had spread to a second finger, and the first finger to become discolored had begun to hurt.

The patient had initially seen another physician, who prescribed itraconazole for presumptive onychomycosis. The patient received a pulse therapy course of itraconazole for 3 months and had no improvement. Therapy ended 4 months ago, and a month ago the end of her left index finger began to ache.

The patient works at a computer, and typing causes pain in the left index finger. A review of her chart reveals she is taking a diuretic for hypertension; there are no other health problems.

What is the diagnosis?

Before taking a more extensive history, it is appropriate to look at her fingers more closely to collect data that will inform questioning. By applying pattern recognition skills first, you can form hypotheses and use the remainder of the exam to test them.

How would you describe the abnormalities seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2 (pattern recognition), and what would be the differential diagnosis (hypotheses)?

What further history, physical exam, or laboratory tests should be completed (hypothesis testing)?

FIGURE 1

This patient’s fingernail had been discolored for months and the fingertip had recently begun to hurt.

A brown discoloration (oil spot) in the patient’s proximal nail.

Figure 1 shows a brownish discoloration of the fingernail, with small pits particularly prominent around the lunula (the semicircular light area adjacent to the proximal nail fold). There is also evidence of onycholysis (separation of the nail from the nail bed). The vertical ridging is not abnormal.

Figure 2 shows a well-circumscribed brown discoloration in the proximal nail called an oil spot. These nail findings are classic for psoriasis.1

Figure 1 also shows subtle swelling of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. It is this area the patient said was painful, and she had joint tenderness to palpation over this DIP joint only.

Hypotheses

The 2 most likely diagnoses are:

- psoriasis causing nail changes while psoriatic arthritis is developing

- onychomycosis with incidental joint pain of the DIP joint.

Other causes of nail changes include lichen planus, chronic candida paronychia, and Reiter’s disease. Epidemiologically the most likely diagnosis is onychomycosis, which is far more prevalent than the other conditions. However, this patient has already failed a course of an oral antifungal agent, and her nail changes are more consistent with psoriasis.

Hypothesis testing

Questions and physical examination focus on collecting data to determine the more likely of the two diagnoses, psoriasis and fungal nail disease. The patient denied having any skin lesions and a history of psoriasis. She also said she had no athlete’s foot or problems with her toenails or other hand. Her knees ache from time to time, which she attributed to aging.

Physical exam revealed no evidence of psoriasis on the skin and no tinea pedis or onychomycosis of the toenails. She had no other skin findings suggestive of lichen planus or Reiter’s disease. Looking more closely at the fingernails, we saw no evidence of subungual keratoses, which are frequently found in onychomycosis.

A scraping and clipping of the fingernail was sent for fungal culture, and an x-ray film of that digit revealed no bony changes. The fungal culture results 2 weeks later were negative.

Patient follow-up

We made a presumptive diagnosis of psoriatic nail changes and psoriatic arthritis, and the patient was sent to a rheumatologist for consultation. The rheumatologist agreed with the diagnosis and placed the patient on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to treat the early psoriatic arthritis.

The patient developed more areas of psoriatic arthritis involvement over the subsequent years and became less concerned about the appearance of her nails. Eventually the psoriatic arthritis progressed to the point where the patient was taking remititive agents for inflammatory arthropathy. She never did develop the skin lesions of psoriasis.

Nail changes of psoriasis

It has been reported that 30% of patients with psoriasis have nail changes, the most common being pitting. Onycholysis is the next most frequent change, and the oil spot is less frequent but not rare.

Not everyone with nail pitting has psoriasis; however, there is a high correlation between psoriatic arthritis and nail pitting.

Patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis have a higher percentage of nail changes than patients with psoriasis of the skin only. In 1 study, nail changes were noted in 86.5% of patients affected by arthropathic psoriasis, and the most common fingernail change was pitting.2

This particular case shows it is possible to have psoriatic arthritis and psoriatic nail changes without psoriasis of the skin. Fortunately, the patient did not have an adverse reaction to the itraconazole prescribed for the incorrectly diagnosed onychomycosis.

It is debatable whether fungal cultures are needed before prescribing oral antifungal agents for onychomycosis. This was 1 case in which the nail findings may have steered the clinician toward getting a nail scraping for microscopic analysis using potassium hydroxide or a fungal culture. Negative findings would have spared the patient the treatment with an expensive agent with known liver toxicity.

The onset of pain, swelling, and tenderness of the DIP joint of the affected nail helped to make the diagnosis. It is the finger joint most commonly affected by psoriatic arthritis.

Treatment of psoriasis of the nails

There is no good treatment for psoriasis of the nails. Treatment regimens that have been studied include injection of steroids into the nail matrix and use of topical retinoids. Intralesional steroid injections are very painful, and the results are not adequate to recommend this treatment.

A study of topical retinoid tazorotene showed some promise.3 The study size was small, however, and the measured change was not great. But for patients desperately looking for help for psoriatic nail changes, the topical treatment may be worth a try.

Figure 3 shows a different patient with an interesting connection between involvement of psoriatic arthritis in the finger and accompanying nail changes. This man had psoriatic plaques over his fingers and a severely swollen DIP joint of the middle finger with significant accompanying nail changes. The inflammatory reaction in the DIP joint is accompanied by abnormal changes in the nail matrix, producing a psoriatic nail on the same finger.

FIGURE 3

Another patient’s hand, with psoriatic plaques and swollen distal interphalangeal joint.

1. Habif T. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1996.

2. Lavaroni G, Kokelj F, Pauluzzi P, Trevisan G. The nails in psoriatic arthritis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1994;186:113.-

3. Scher RK, Stiller M, Zhu YI. Tazarotene 0.1% gel in the treatment of fingernail psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study. Cutis 2001;68:355-8.

1. Habif T. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1996.

2. Lavaroni G, Kokelj F, Pauluzzi P, Trevisan G. The nails in psoriatic arthritis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1994;186:113.-

3. Scher RK, Stiller M, Zhu YI. Tazarotene 0.1% gel in the treatment of fingernail psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study. Cutis 2001;68:355-8.

A swollen knee

A 52-year-old African American homeless man visited a clinic at the local shelter, complaining of pain in his left knee for the past 2 days. He denied trauma or any history of knee injuries. He also denied any recent sexual activity. The patient was limping from significant pain. The patient’s clothes and hygiene were in poor condition. He worked in the fish market and had taken on the odor of his workplace. He admitted to a history of alcohol and substance abuse and was unwilling to discuss his psychiatric history. His chart indicated he had been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

The patient was afebrile and had a swollen warm left knee (Figure 1). A crusty skin lesion with a small amount of purulence was seen over his patella. There was evidence of a joint effusion and the skin appeared red around the whole knee region. The patient could not fully flex his knee. The physical exam demonstrated normal ligamentous stability.

What procedure would be appropriate to perform?

What diagnostic tests would be helpful?

We offered to take the patient to the county hospital to obtain the appropriate diagnostic procedure and to initiate inpatient care. He adamantly refused treatment in a hospital, stating he was “too busy” to go the hospital and he only wanted “some pills.”

What else could you now do to care for this patient?

The differential diagnosis includes septic arthritis (such as staphylococcal and gonococcal infections of the knee joint), inflammatory types of arthritis, septic bursitis, cellulitis, and impetigo. Joint aspiration was performed in the clinic because the patient refused to go to the emergency room for diagnosis and treatment.

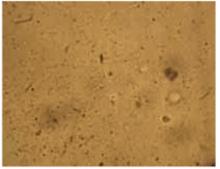

As seen in Figure 2, 10 mL of clear viscous yellow fluid was aspirated from the affected joint. Nine mL of aspirate was sent to a clinical laboratory for cell count, Gram stain, culture and sensitivity, crystal analysis, and microscopic examination. A drop of aspirate was placed on a wet mount and examined with plain light microscopy (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2

10 mL of clear viscous yellow fluid was aspirated from the joint.

Numerous refractile needle-shaped crystals were visualized.

Epidemiology of acute gout

Acute gout is predominantly a disease of the lower extremity, but any joint of any extremity may be involved. Ninety percent of patients experience acute attacks in the great toe at some time during the course of their disease. Next in order of frequency are the insteps, ankles, heels, knees, wrists, fingers, and elbows. The incidence of gout varies in populations from 0.20 to 0.35 per thousand per year, with an overall prevalence of 1.6 to 13.6 per thousand. The prevalence seems to increase substantially with age and increasing serum urate concentration.1 Prevalence is 3/100,000 for those 18 to 44 years of age; 21/100,000 for those 45 to 64, and 35/100,000 for those over 65. Men are 20 times more likely to have gout than women.2

Diagnosis

Most cases of gout are characterized by rapid onset of monoarticular arthritis resulting from deposition of urate crystals and a subsequent inflammatory response. The joint most commonly affected by gout is the first metatarsal phalangeal joint; the knee is the second most commonly involved joint. The diagnosis of acute gout was made based on the presence of the characteristic clinical history with urate crystals in the joint fluid.3

Management

Three treatments are available for patients suffering from acute gouty arthritis.

Colchicine inhibits microtubule formation and thus interferes with phagocytosis of the crystals, attenuating the inflammatory response. It also inhibits the release of chemotactic factors reducing the migration of neutrophils into the joint. In a randomized controlled trial, two thirds of patients treated with colchicine improved after 48 hours, but only one third of the patients receiving placebo demonstrated similar improvement. Improvement occurred earlier in the colchicine-treated patients. There were significant differences compared with placebo after 18–30 hours. All patients given colchicine (mean dose of 6.7 mg) developed diarrhea after a median time of 24 hours. Diarrhea occurred before relief of pain in most patients.4

The principal side effects of colchicine are gastrointestinal symptoms including abdominal pain and diarrhea. The dose associated with these symptoms is very close to the therapeutic dose.

Generally the initial dose is 1 mg, with 0.5 mg added every 2 hours until a total dose of up to 8 mg has been reached, or abdominal symptoms develop3 (Level of evidence, 1b; single RCT).4

Another option for treatment of acute gout is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Indomethacin has been the standard for years but there is no proof that it is better than other NSAIDs5-8 (Level of evidence, 1b; a set of RCTs). The starting dose is 50 mg tid, tapered over approximately 1 week as symptoms subside. NSAIDs are also limited by their gastrointestinal and renal side effects.

Intra-articular injection of corticosteroids is an additional treatment for acute gout. The dose given depends on the size of the affected joint. The appropriate dose of methylprednisolone would be 5–10 mg for a small joint and 20–60 mg for a large joint such as the knee1 (Level of evidence, 5; expert opinion).

The patient’s treatment and outcome

The patient had a history of gastric ulcers and intolerance to NSAIDs. Therefore, he was started on oral colchicine for the probable gout. He was also given 500 mg of cephalexin po, qid, for the cellulitis and impetigo. He refused any blood tests, but accepted a follow-up appointment for the next day.

When we thought the patient had a septic joint, the optimal treatment would have involved hospitalization. The patient’s fear of hospitalization and losing his job made the choice of hospitalization a nonoption for this mentally ill homeless man. Instead of doing nothing, we began the diagnostic process in the outpatient setting.

If we had obtained purulent joint fluid it would have been incumbent upon us to press once again for hospitalization for septic arthritis. The appearance of yellow fluid and joint crystals gave us the option of attempting outpatient care.

Unfortunately, the patient never returned. Joint fluid Gram stain and culture results were negative, and the cell counts were consistent with inflammation. The hospital lab read the crystal analysis as negative even though our photograph documents the presence of crystals consistent with urate crystals.

Health care delivery must be flexible and creative in the setting of a shelter clinic. We can only hope that the oral medications he received allowed him full recovery from his acute illnesses.

1. Rudy D, Kurowski K. Family Medicine (House Officer Series). Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins;1997.

2. Dambro M. Griffith’s 5 Minute Clinical Consult. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins;2002.

3. Emmerson BT. The management of gout. N Engl J Med 1996;334:445-51. Review.

4. Ahern MJ, Reid C, Gordon TP, et al. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. Aust N Z J Med 1987;17:301-4.

5. Shrestha M, Morgan DL, Moreden JM, et al. Randomized double-blind comparison of the analgesic efficacy of intramuscular ketorolac and oral indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26:682-6.

6. Maccagno A, Di Giorgio E, Romanowicz A. Effectiveness of etodolac (‘Lodine’) compared with naproxen in patients with acute gout. Curr Med Res Opin 1991;12:423-9.

7. Altman RD, Honig S, Levin JM, Lightfoot RW. Ketoprofen versus indomethacin in patients with acute gouty arthritis: a multicenter, double blind comparative study. J Rheumatol 1988;15:1422-6.

8. Fraser RC, Davis RH, Walker FS. Comparative trial of azapropazone and indomethacin plus allopurinol in acute gout and hyperuricaemia. J R Coll Gen Pract 1987;37:409-11.

A 52-year-old African American homeless man visited a clinic at the local shelter, complaining of pain in his left knee for the past 2 days. He denied trauma or any history of knee injuries. He also denied any recent sexual activity. The patient was limping from significant pain. The patient’s clothes and hygiene were in poor condition. He worked in the fish market and had taken on the odor of his workplace. He admitted to a history of alcohol and substance abuse and was unwilling to discuss his psychiatric history. His chart indicated he had been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

The patient was afebrile and had a swollen warm left knee (Figure 1). A crusty skin lesion with a small amount of purulence was seen over his patella. There was evidence of a joint effusion and the skin appeared red around the whole knee region. The patient could not fully flex his knee. The physical exam demonstrated normal ligamentous stability.

What procedure would be appropriate to perform?

What diagnostic tests would be helpful?

We offered to take the patient to the county hospital to obtain the appropriate diagnostic procedure and to initiate inpatient care. He adamantly refused treatment in a hospital, stating he was “too busy” to go the hospital and he only wanted “some pills.”

What else could you now do to care for this patient?

The differential diagnosis includes septic arthritis (such as staphylococcal and gonococcal infections of the knee joint), inflammatory types of arthritis, septic bursitis, cellulitis, and impetigo. Joint aspiration was performed in the clinic because the patient refused to go to the emergency room for diagnosis and treatment.

As seen in Figure 2, 10 mL of clear viscous yellow fluid was aspirated from the affected joint. Nine mL of aspirate was sent to a clinical laboratory for cell count, Gram stain, culture and sensitivity, crystal analysis, and microscopic examination. A drop of aspirate was placed on a wet mount and examined with plain light microscopy (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2

10 mL of clear viscous yellow fluid was aspirated from the joint.

Numerous refractile needle-shaped crystals were visualized.

Epidemiology of acute gout

Acute gout is predominantly a disease of the lower extremity, but any joint of any extremity may be involved. Ninety percent of patients experience acute attacks in the great toe at some time during the course of their disease. Next in order of frequency are the insteps, ankles, heels, knees, wrists, fingers, and elbows. The incidence of gout varies in populations from 0.20 to 0.35 per thousand per year, with an overall prevalence of 1.6 to 13.6 per thousand. The prevalence seems to increase substantially with age and increasing serum urate concentration.1 Prevalence is 3/100,000 for those 18 to 44 years of age; 21/100,000 for those 45 to 64, and 35/100,000 for those over 65. Men are 20 times more likely to have gout than women.2

Diagnosis

Most cases of gout are characterized by rapid onset of monoarticular arthritis resulting from deposition of urate crystals and a subsequent inflammatory response. The joint most commonly affected by gout is the first metatarsal phalangeal joint; the knee is the second most commonly involved joint. The diagnosis of acute gout was made based on the presence of the characteristic clinical history with urate crystals in the joint fluid.3

Management

Three treatments are available for patients suffering from acute gouty arthritis.

Colchicine inhibits microtubule formation and thus interferes with phagocytosis of the crystals, attenuating the inflammatory response. It also inhibits the release of chemotactic factors reducing the migration of neutrophils into the joint. In a randomized controlled trial, two thirds of patients treated with colchicine improved after 48 hours, but only one third of the patients receiving placebo demonstrated similar improvement. Improvement occurred earlier in the colchicine-treated patients. There were significant differences compared with placebo after 18–30 hours. All patients given colchicine (mean dose of 6.7 mg) developed diarrhea after a median time of 24 hours. Diarrhea occurred before relief of pain in most patients.4

The principal side effects of colchicine are gastrointestinal symptoms including abdominal pain and diarrhea. The dose associated with these symptoms is very close to the therapeutic dose.

Generally the initial dose is 1 mg, with 0.5 mg added every 2 hours until a total dose of up to 8 mg has been reached, or abdominal symptoms develop3 (Level of evidence, 1b; single RCT).4

Another option for treatment of acute gout is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Indomethacin has been the standard for years but there is no proof that it is better than other NSAIDs5-8 (Level of evidence, 1b; a set of RCTs). The starting dose is 50 mg tid, tapered over approximately 1 week as symptoms subside. NSAIDs are also limited by their gastrointestinal and renal side effects.

Intra-articular injection of corticosteroids is an additional treatment for acute gout. The dose given depends on the size of the affected joint. The appropriate dose of methylprednisolone would be 5–10 mg for a small joint and 20–60 mg for a large joint such as the knee1 (Level of evidence, 5; expert opinion).

The patient’s treatment and outcome

The patient had a history of gastric ulcers and intolerance to NSAIDs. Therefore, he was started on oral colchicine for the probable gout. He was also given 500 mg of cephalexin po, qid, for the cellulitis and impetigo. He refused any blood tests, but accepted a follow-up appointment for the next day.

When we thought the patient had a septic joint, the optimal treatment would have involved hospitalization. The patient’s fear of hospitalization and losing his job made the choice of hospitalization a nonoption for this mentally ill homeless man. Instead of doing nothing, we began the diagnostic process in the outpatient setting.

If we had obtained purulent joint fluid it would have been incumbent upon us to press once again for hospitalization for septic arthritis. The appearance of yellow fluid and joint crystals gave us the option of attempting outpatient care.

Unfortunately, the patient never returned. Joint fluid Gram stain and culture results were negative, and the cell counts were consistent with inflammation. The hospital lab read the crystal analysis as negative even though our photograph documents the presence of crystals consistent with urate crystals.

Health care delivery must be flexible and creative in the setting of a shelter clinic. We can only hope that the oral medications he received allowed him full recovery from his acute illnesses.

A 52-year-old African American homeless man visited a clinic at the local shelter, complaining of pain in his left knee for the past 2 days. He denied trauma or any history of knee injuries. He also denied any recent sexual activity. The patient was limping from significant pain. The patient’s clothes and hygiene were in poor condition. He worked in the fish market and had taken on the odor of his workplace. He admitted to a history of alcohol and substance abuse and was unwilling to discuss his psychiatric history. His chart indicated he had been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

The patient was afebrile and had a swollen warm left knee (Figure 1). A crusty skin lesion with a small amount of purulence was seen over his patella. There was evidence of a joint effusion and the skin appeared red around the whole knee region. The patient could not fully flex his knee. The physical exam demonstrated normal ligamentous stability.

What procedure would be appropriate to perform?

What diagnostic tests would be helpful?

We offered to take the patient to the county hospital to obtain the appropriate diagnostic procedure and to initiate inpatient care. He adamantly refused treatment in a hospital, stating he was “too busy” to go the hospital and he only wanted “some pills.”

What else could you now do to care for this patient?

The differential diagnosis includes septic arthritis (such as staphylococcal and gonococcal infections of the knee joint), inflammatory types of arthritis, septic bursitis, cellulitis, and impetigo. Joint aspiration was performed in the clinic because the patient refused to go to the emergency room for diagnosis and treatment.

As seen in Figure 2, 10 mL of clear viscous yellow fluid was aspirated from the affected joint. Nine mL of aspirate was sent to a clinical laboratory for cell count, Gram stain, culture and sensitivity, crystal analysis, and microscopic examination. A drop of aspirate was placed on a wet mount and examined with plain light microscopy (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2

10 mL of clear viscous yellow fluid was aspirated from the joint.

Numerous refractile needle-shaped crystals were visualized.

Epidemiology of acute gout

Acute gout is predominantly a disease of the lower extremity, but any joint of any extremity may be involved. Ninety percent of patients experience acute attacks in the great toe at some time during the course of their disease. Next in order of frequency are the insteps, ankles, heels, knees, wrists, fingers, and elbows. The incidence of gout varies in populations from 0.20 to 0.35 per thousand per year, with an overall prevalence of 1.6 to 13.6 per thousand. The prevalence seems to increase substantially with age and increasing serum urate concentration.1 Prevalence is 3/100,000 for those 18 to 44 years of age; 21/100,000 for those 45 to 64, and 35/100,000 for those over 65. Men are 20 times more likely to have gout than women.2

Diagnosis

Most cases of gout are characterized by rapid onset of monoarticular arthritis resulting from deposition of urate crystals and a subsequent inflammatory response. The joint most commonly affected by gout is the first metatarsal phalangeal joint; the knee is the second most commonly involved joint. The diagnosis of acute gout was made based on the presence of the characteristic clinical history with urate crystals in the joint fluid.3

Management

Three treatments are available for patients suffering from acute gouty arthritis.

Colchicine inhibits microtubule formation and thus interferes with phagocytosis of the crystals, attenuating the inflammatory response. It also inhibits the release of chemotactic factors reducing the migration of neutrophils into the joint. In a randomized controlled trial, two thirds of patients treated with colchicine improved after 48 hours, but only one third of the patients receiving placebo demonstrated similar improvement. Improvement occurred earlier in the colchicine-treated patients. There were significant differences compared with placebo after 18–30 hours. All patients given colchicine (mean dose of 6.7 mg) developed diarrhea after a median time of 24 hours. Diarrhea occurred before relief of pain in most patients.4

The principal side effects of colchicine are gastrointestinal symptoms including abdominal pain and diarrhea. The dose associated with these symptoms is very close to the therapeutic dose.

Generally the initial dose is 1 mg, with 0.5 mg added every 2 hours until a total dose of up to 8 mg has been reached, or abdominal symptoms develop3 (Level of evidence, 1b; single RCT).4

Another option for treatment of acute gout is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Indomethacin has been the standard for years but there is no proof that it is better than other NSAIDs5-8 (Level of evidence, 1b; a set of RCTs). The starting dose is 50 mg tid, tapered over approximately 1 week as symptoms subside. NSAIDs are also limited by their gastrointestinal and renal side effects.

Intra-articular injection of corticosteroids is an additional treatment for acute gout. The dose given depends on the size of the affected joint. The appropriate dose of methylprednisolone would be 5–10 mg for a small joint and 20–60 mg for a large joint such as the knee1 (Level of evidence, 5; expert opinion).

The patient’s treatment and outcome

The patient had a history of gastric ulcers and intolerance to NSAIDs. Therefore, he was started on oral colchicine for the probable gout. He was also given 500 mg of cephalexin po, qid, for the cellulitis and impetigo. He refused any blood tests, but accepted a follow-up appointment for the next day.

When we thought the patient had a septic joint, the optimal treatment would have involved hospitalization. The patient’s fear of hospitalization and losing his job made the choice of hospitalization a nonoption for this mentally ill homeless man. Instead of doing nothing, we began the diagnostic process in the outpatient setting.

If we had obtained purulent joint fluid it would have been incumbent upon us to press once again for hospitalization for septic arthritis. The appearance of yellow fluid and joint crystals gave us the option of attempting outpatient care.

Unfortunately, the patient never returned. Joint fluid Gram stain and culture results were negative, and the cell counts were consistent with inflammation. The hospital lab read the crystal analysis as negative even though our photograph documents the presence of crystals consistent with urate crystals.

Health care delivery must be flexible and creative in the setting of a shelter clinic. We can only hope that the oral medications he received allowed him full recovery from his acute illnesses.

1. Rudy D, Kurowski K. Family Medicine (House Officer Series). Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins;1997.

2. Dambro M. Griffith’s 5 Minute Clinical Consult. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins;2002.

3. Emmerson BT. The management of gout. N Engl J Med 1996;334:445-51. Review.

4. Ahern MJ, Reid C, Gordon TP, et al. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. Aust N Z J Med 1987;17:301-4.

5. Shrestha M, Morgan DL, Moreden JM, et al. Randomized double-blind comparison of the analgesic efficacy of intramuscular ketorolac and oral indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26:682-6.

6. Maccagno A, Di Giorgio E, Romanowicz A. Effectiveness of etodolac (‘Lodine’) compared with naproxen in patients with acute gout. Curr Med Res Opin 1991;12:423-9.

7. Altman RD, Honig S, Levin JM, Lightfoot RW. Ketoprofen versus indomethacin in patients with acute gouty arthritis: a multicenter, double blind comparative study. J Rheumatol 1988;15:1422-6.

8. Fraser RC, Davis RH, Walker FS. Comparative trial of azapropazone and indomethacin plus allopurinol in acute gout and hyperuricaemia. J R Coll Gen Pract 1987;37:409-11.

1. Rudy D, Kurowski K. Family Medicine (House Officer Series). Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins;1997.

2. Dambro M. Griffith’s 5 Minute Clinical Consult. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins;2002.

3. Emmerson BT. The management of gout. N Engl J Med 1996;334:445-51. Review.

4. Ahern MJ, Reid C, Gordon TP, et al. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. Aust N Z J Med 1987;17:301-4.

5. Shrestha M, Morgan DL, Moreden JM, et al. Randomized double-blind comparison of the analgesic efficacy of intramuscular ketorolac and oral indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26:682-6.

6. Maccagno A, Di Giorgio E, Romanowicz A. Effectiveness of etodolac (‘Lodine’) compared with naproxen in patients with acute gout. Curr Med Res Opin 1991;12:423-9.

7. Altman RD, Honig S, Levin JM, Lightfoot RW. Ketoprofen versus indomethacin in patients with acute gouty arthritis: a multicenter, double blind comparative study. J Rheumatol 1988;15:1422-6.

8. Fraser RC, Davis RH, Walker FS. Comparative trial of azapropazone and indomethacin plus allopurinol in acute gout and hyperuricaemia. J R Coll Gen Pract 1987;37:409-11.

Learning from images in clinical medicine

Photo Rounds is a new feature in The Journal of Family Practice designed to enhance your clinical diagnosis skills. Each month we will feature a medical problem commonly seen by family physicians. Many of the photographs will show conditions I personally have encountered and recorded over the past 17 years. The images will be accompanied by a clinical question, followed by an answer and a description of the diagnosis and management of the case, applying the principles of evidence-based medicine.

Your skill as a diagnostician is enhanced as your personal image bank grows and is committed to memory. Our image banks begin in medical school as we view pictures in lectures and textbooks, and they expand during our own clinical experiences. Studying and learning image patterns from any atlas—print or electronic—can enhance your expertise. Not all images, however, are retained and retrievable. Grotesque and disturbing images are retained because they are processed with strong emotional content. I contend that, in a similar way, images you photograph of patients who share their stories with you are likely to become memorable because of the highly personal context. These images will give you a wealth of material for self-instruction, teaching, and medical chart documentation.

If clinical photography is one of your interests, we encourage you to submit your best images and case descriptions for possible inclusion in this column. We are interested in clear, well-lit photographs accompanied by interesting stories that teach important practice principles.

Whether or not you use photography in your own clinical work, we hope the detailed, informative cases in the new JFP Photo Rounds will become an important resource for you in building your image bank.

Photo Rounds is a new feature in The Journal of Family Practice designed to enhance your clinical diagnosis skills. Each month we will feature a medical problem commonly seen by family physicians. Many of the photographs will show conditions I personally have encountered and recorded over the past 17 years. The images will be accompanied by a clinical question, followed by an answer and a description of the diagnosis and management of the case, applying the principles of evidence-based medicine.

Your skill as a diagnostician is enhanced as your personal image bank grows and is committed to memory. Our image banks begin in medical school as we view pictures in lectures and textbooks, and they expand during our own clinical experiences. Studying and learning image patterns from any atlas—print or electronic—can enhance your expertise. Not all images, however, are retained and retrievable. Grotesque and disturbing images are retained because they are processed with strong emotional content. I contend that, in a similar way, images you photograph of patients who share their stories with you are likely to become memorable because of the highly personal context. These images will give you a wealth of material for self-instruction, teaching, and medical chart documentation.

If clinical photography is one of your interests, we encourage you to submit your best images and case descriptions for possible inclusion in this column. We are interested in clear, well-lit photographs accompanied by interesting stories that teach important practice principles.

Whether or not you use photography in your own clinical work, we hope the detailed, informative cases in the new JFP Photo Rounds will become an important resource for you in building your image bank.

Photo Rounds is a new feature in The Journal of Family Practice designed to enhance your clinical diagnosis skills. Each month we will feature a medical problem commonly seen by family physicians. Many of the photographs will show conditions I personally have encountered and recorded over the past 17 years. The images will be accompanied by a clinical question, followed by an answer and a description of the diagnosis and management of the case, applying the principles of evidence-based medicine.

Your skill as a diagnostician is enhanced as your personal image bank grows and is committed to memory. Our image banks begin in medical school as we view pictures in lectures and textbooks, and they expand during our own clinical experiences. Studying and learning image patterns from any atlas—print or electronic—can enhance your expertise. Not all images, however, are retained and retrievable. Grotesque and disturbing images are retained because they are processed with strong emotional content. I contend that, in a similar way, images you photograph of patients who share their stories with you are likely to become memorable because of the highly personal context. These images will give you a wealth of material for self-instruction, teaching, and medical chart documentation.

If clinical photography is one of your interests, we encourage you to submit your best images and case descriptions for possible inclusion in this column. We are interested in clear, well-lit photographs accompanied by interesting stories that teach important practice principles.

Whether or not you use photography in your own clinical work, we hope the detailed, informative cases in the new JFP Photo Rounds will become an important resource for you in building your image bank.