User login

Black Linear Streaks on the Face With Pruritic Plaques on the Trunk and Arms

The Diagnosis: Toxicodendron Dermatitis

Toxicodendron dermatitis is an allergic contact dermatitis that can occur after exposure to a plant from the Toxicodendron genus including poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum), and poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix). These plants produce urushiol in their oleoresinous sap, which causes intense pruritus, streaks of erythema, and edematous papules followed by vesicles and bullae. Previously sensitized individuals develop symptoms as quickly as 24 to 48 hours after exposure, with a range of 5 hours to 15 days.1-3 Rarely, black spots also can be found on the skin, most prominently after 72 hours of exposure.4

The color change of urushiol-containing sap from pale to black was first documented by Peter Kalm, a Swedish botanist who traveled to North America in the 1700s.5 The black-spot test can be used to identify Toxicodendron species because the sap will turn black when expressed on white paper after a few minutes.6 Manifestation of black lacquer streaks on the skin is rare because concentrated sap is necessary, which typically requires an unusually prolonged exposure with Toxicodendron plants.7

Without treatment, typical Toxicodendron dermatitis resolves in approximately 3 weeks, though it may take up to 6 weeks to clear.2 Early intervention is critical, as urushiol will fully absorb after 30 minutes.2 After contact, complete removal of the oleoresin by washing with mild soap and water within 10 minutes can prevent dermatitis. Early topical corticosteroid application can reduce erythema and pruritus. Extensive or severe involvement, which includes Toxicodendron dermatitis with black spots, is treated with systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone that is tapered over 2 to 3 weeks.1

Our patient had classic findings of Toxicodendron dermatitis; however, initially there was concern for levamisole toxicity by the emergency department, as well-demarcated purpuric or dark skin lesions can be due to morbid conditions such as leukocytoclastic vasculitis or skin necrosis from drug toxicities or infectious etiologies. Dermatology was consulted and these concerns were alleviated on closer skin examination and further questioning. The patient reported that he spent several hours cutting brush that was known to be T vernix (poison sumac) 3 days prior to presentation. Interestingly, the patient did not have similar black streaks on the left side of the face, as he held the weed-trimming saw in his right hand and in effect protected the left side of the face from debris. Furthermore, he had pruritic erythematous plaques on both forearms. The facial black lacquer-like streaks were the result of urushiol oxidation in the setting of prolonged exposure to the poison sumac oleoresin sap during weed trimming. After dermatologic evaluation, the patient was discharged from the emergency department on a 15-day taper of oral prednisone, and he was instructed to wash involved areas and exposed clothing with soap and water, which led to complete resolution.

- Lee NP, Arriola ER. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis. West J Med. 1999;171:354-355.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128.

- Gross M, Baer H, Fales H. Urushiols of poisonous anacardiaceae. Phytochemistry. 1975;14:2263-2266.

- Mallory SB, Miller OF 3dU, Tyler WB. Toxicodendron radicans dermatitis with black lacquer deposit on the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:363-368.

- Benson AB. Peter Kalm's Travels in North America: The English Version of 1770. New York, NY: Dover Publications; 1937.

- Guin JD. The black spot test for recognizing poison ivy and related species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;2:332-333.

- Kurlan JG, Lucky AW. Black spot poison ivy: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:246-249.

The Diagnosis: Toxicodendron Dermatitis

Toxicodendron dermatitis is an allergic contact dermatitis that can occur after exposure to a plant from the Toxicodendron genus including poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum), and poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix). These plants produce urushiol in their oleoresinous sap, which causes intense pruritus, streaks of erythema, and edematous papules followed by vesicles and bullae. Previously sensitized individuals develop symptoms as quickly as 24 to 48 hours after exposure, with a range of 5 hours to 15 days.1-3 Rarely, black spots also can be found on the skin, most prominently after 72 hours of exposure.4

The color change of urushiol-containing sap from pale to black was first documented by Peter Kalm, a Swedish botanist who traveled to North America in the 1700s.5 The black-spot test can be used to identify Toxicodendron species because the sap will turn black when expressed on white paper after a few minutes.6 Manifestation of black lacquer streaks on the skin is rare because concentrated sap is necessary, which typically requires an unusually prolonged exposure with Toxicodendron plants.7

Without treatment, typical Toxicodendron dermatitis resolves in approximately 3 weeks, though it may take up to 6 weeks to clear.2 Early intervention is critical, as urushiol will fully absorb after 30 minutes.2 After contact, complete removal of the oleoresin by washing with mild soap and water within 10 minutes can prevent dermatitis. Early topical corticosteroid application can reduce erythema and pruritus. Extensive or severe involvement, which includes Toxicodendron dermatitis with black spots, is treated with systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone that is tapered over 2 to 3 weeks.1

Our patient had classic findings of Toxicodendron dermatitis; however, initially there was concern for levamisole toxicity by the emergency department, as well-demarcated purpuric or dark skin lesions can be due to morbid conditions such as leukocytoclastic vasculitis or skin necrosis from drug toxicities or infectious etiologies. Dermatology was consulted and these concerns were alleviated on closer skin examination and further questioning. The patient reported that he spent several hours cutting brush that was known to be T vernix (poison sumac) 3 days prior to presentation. Interestingly, the patient did not have similar black streaks on the left side of the face, as he held the weed-trimming saw in his right hand and in effect protected the left side of the face from debris. Furthermore, he had pruritic erythematous plaques on both forearms. The facial black lacquer-like streaks were the result of urushiol oxidation in the setting of prolonged exposure to the poison sumac oleoresin sap during weed trimming. After dermatologic evaluation, the patient was discharged from the emergency department on a 15-day taper of oral prednisone, and he was instructed to wash involved areas and exposed clothing with soap and water, which led to complete resolution.

The Diagnosis: Toxicodendron Dermatitis

Toxicodendron dermatitis is an allergic contact dermatitis that can occur after exposure to a plant from the Toxicodendron genus including poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum), and poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix). These plants produce urushiol in their oleoresinous sap, which causes intense pruritus, streaks of erythema, and edematous papules followed by vesicles and bullae. Previously sensitized individuals develop symptoms as quickly as 24 to 48 hours after exposure, with a range of 5 hours to 15 days.1-3 Rarely, black spots also can be found on the skin, most prominently after 72 hours of exposure.4

The color change of urushiol-containing sap from pale to black was first documented by Peter Kalm, a Swedish botanist who traveled to North America in the 1700s.5 The black-spot test can be used to identify Toxicodendron species because the sap will turn black when expressed on white paper after a few minutes.6 Manifestation of black lacquer streaks on the skin is rare because concentrated sap is necessary, which typically requires an unusually prolonged exposure with Toxicodendron plants.7

Without treatment, typical Toxicodendron dermatitis resolves in approximately 3 weeks, though it may take up to 6 weeks to clear.2 Early intervention is critical, as urushiol will fully absorb after 30 minutes.2 After contact, complete removal of the oleoresin by washing with mild soap and water within 10 minutes can prevent dermatitis. Early topical corticosteroid application can reduce erythema and pruritus. Extensive or severe involvement, which includes Toxicodendron dermatitis with black spots, is treated with systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone that is tapered over 2 to 3 weeks.1

Our patient had classic findings of Toxicodendron dermatitis; however, initially there was concern for levamisole toxicity by the emergency department, as well-demarcated purpuric or dark skin lesions can be due to morbid conditions such as leukocytoclastic vasculitis or skin necrosis from drug toxicities or infectious etiologies. Dermatology was consulted and these concerns were alleviated on closer skin examination and further questioning. The patient reported that he spent several hours cutting brush that was known to be T vernix (poison sumac) 3 days prior to presentation. Interestingly, the patient did not have similar black streaks on the left side of the face, as he held the weed-trimming saw in his right hand and in effect protected the left side of the face from debris. Furthermore, he had pruritic erythematous plaques on both forearms. The facial black lacquer-like streaks were the result of urushiol oxidation in the setting of prolonged exposure to the poison sumac oleoresin sap during weed trimming. After dermatologic evaluation, the patient was discharged from the emergency department on a 15-day taper of oral prednisone, and he was instructed to wash involved areas and exposed clothing with soap and water, which led to complete resolution.

- Lee NP, Arriola ER. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis. West J Med. 1999;171:354-355.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128.

- Gross M, Baer H, Fales H. Urushiols of poisonous anacardiaceae. Phytochemistry. 1975;14:2263-2266.

- Mallory SB, Miller OF 3dU, Tyler WB. Toxicodendron radicans dermatitis with black lacquer deposit on the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:363-368.

- Benson AB. Peter Kalm's Travels in North America: The English Version of 1770. New York, NY: Dover Publications; 1937.

- Guin JD. The black spot test for recognizing poison ivy and related species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;2:332-333.

- Kurlan JG, Lucky AW. Black spot poison ivy: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:246-249.

- Lee NP, Arriola ER. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis. West J Med. 1999;171:354-355.

- Gladman AC. Toxicodendron dermatitis: poison ivy, oak, and sumac. Wilderness Environ Med. 2006;17:120-128.

- Gross M, Baer H, Fales H. Urushiols of poisonous anacardiaceae. Phytochemistry. 1975;14:2263-2266.

- Mallory SB, Miller OF 3dU, Tyler WB. Toxicodendron radicans dermatitis with black lacquer deposit on the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:363-368.

- Benson AB. Peter Kalm's Travels in North America: The English Version of 1770. New York, NY: Dover Publications; 1937.

- Guin JD. The black spot test for recognizing poison ivy and related species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;2:332-333.

- Kurlan JG, Lucky AW. Black spot poison ivy: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:246-249.

A 68-year-old man presented to the emergency department with pruritic, edematous, pink plaques on the trunk and arms, as well as black linear streaks on the face, prompting dermatology consultation for possible tissue necrosis. The patient reported working outdoors in his garden 3 days prior to presentation.

Recalcitrant Solitary Erythematous Scaly Patch on the Foot

The Diagnosis: Pagetoid Reticulosis

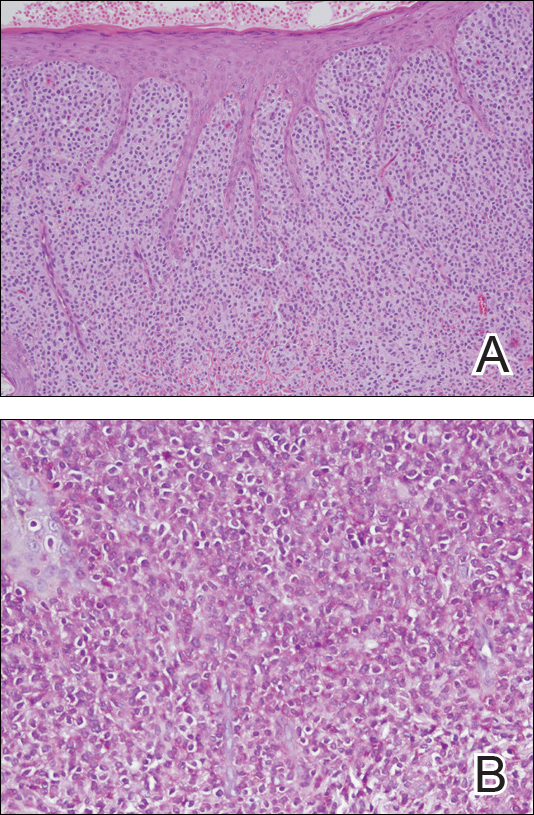

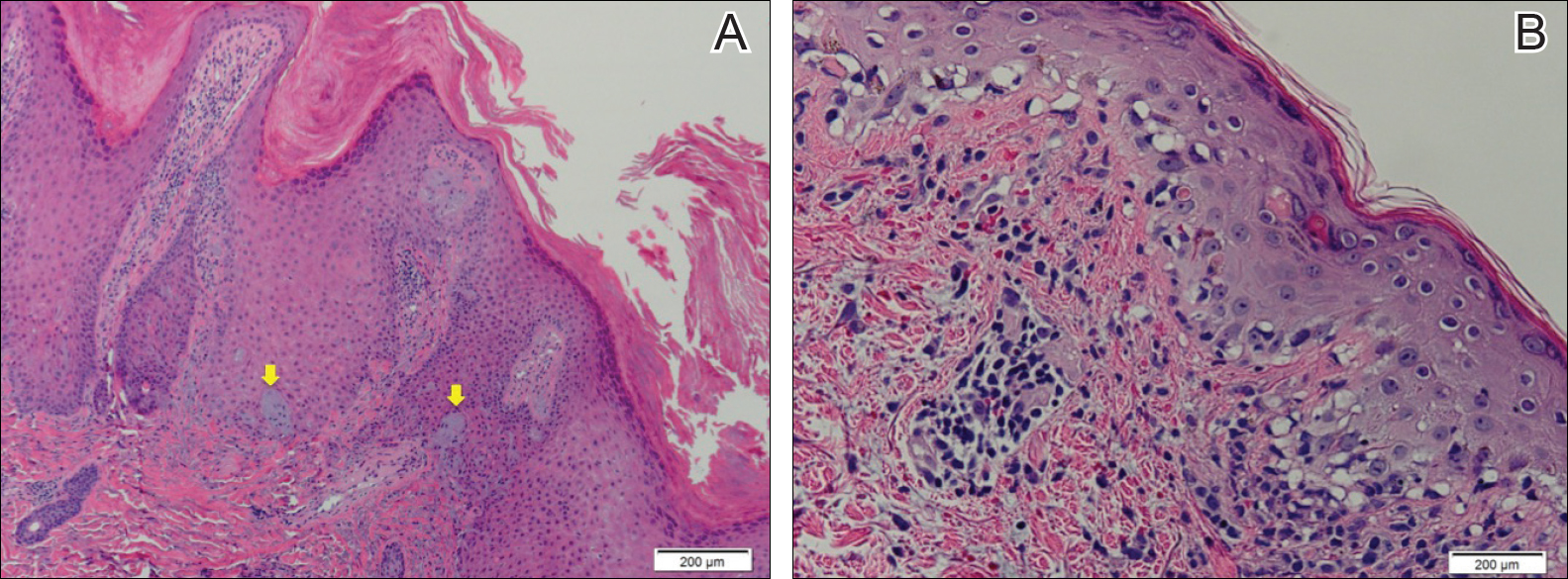

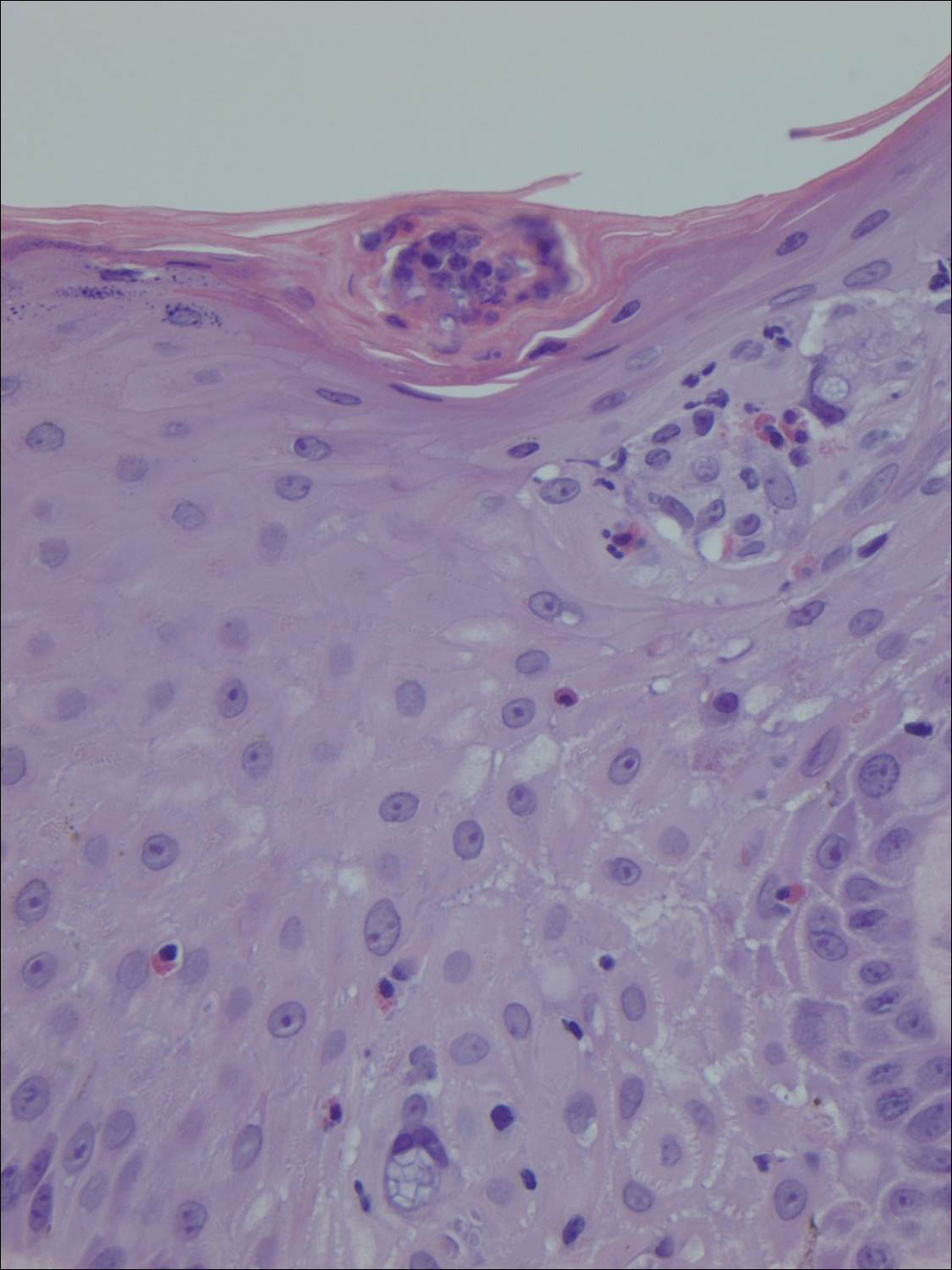

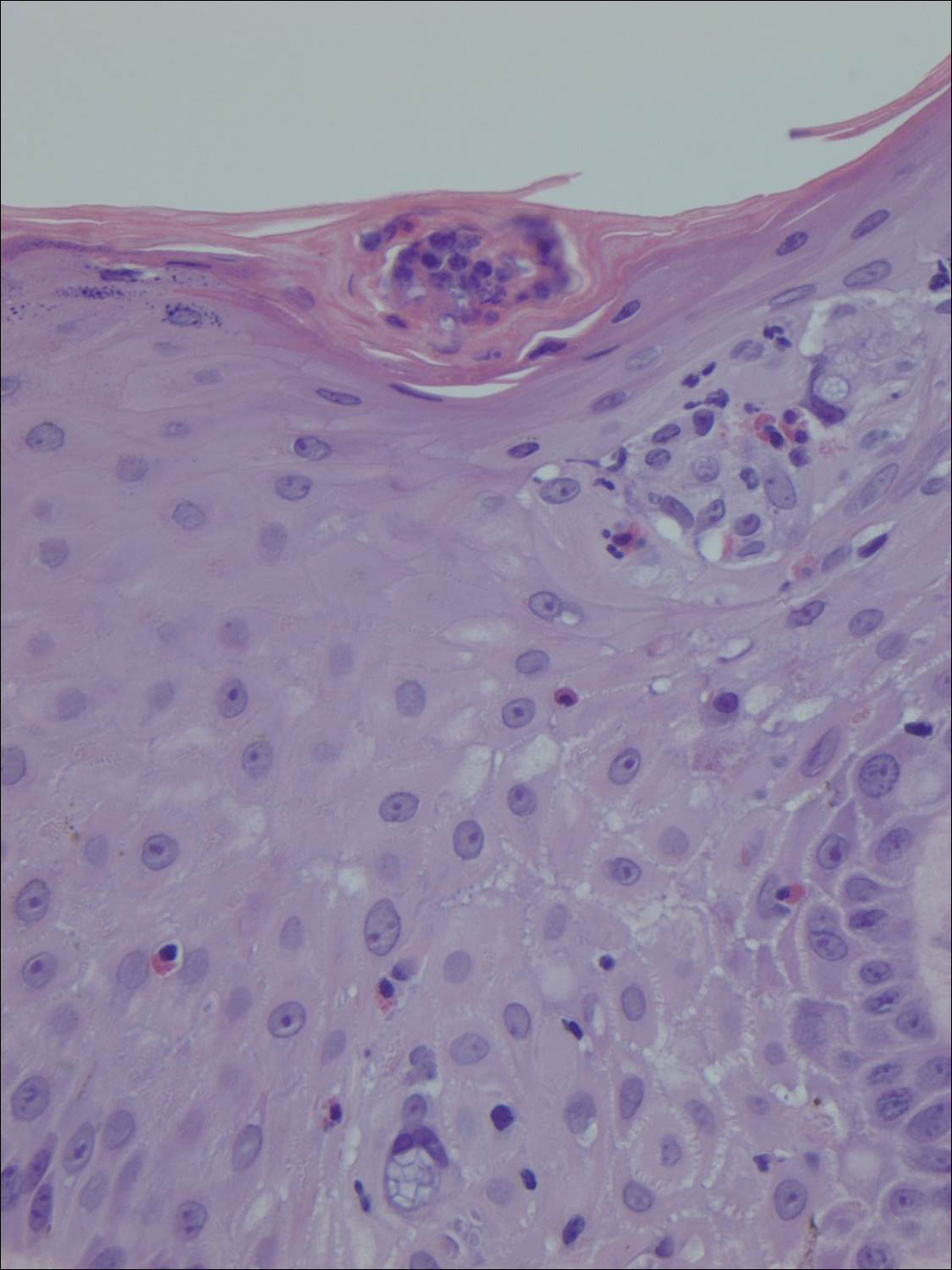

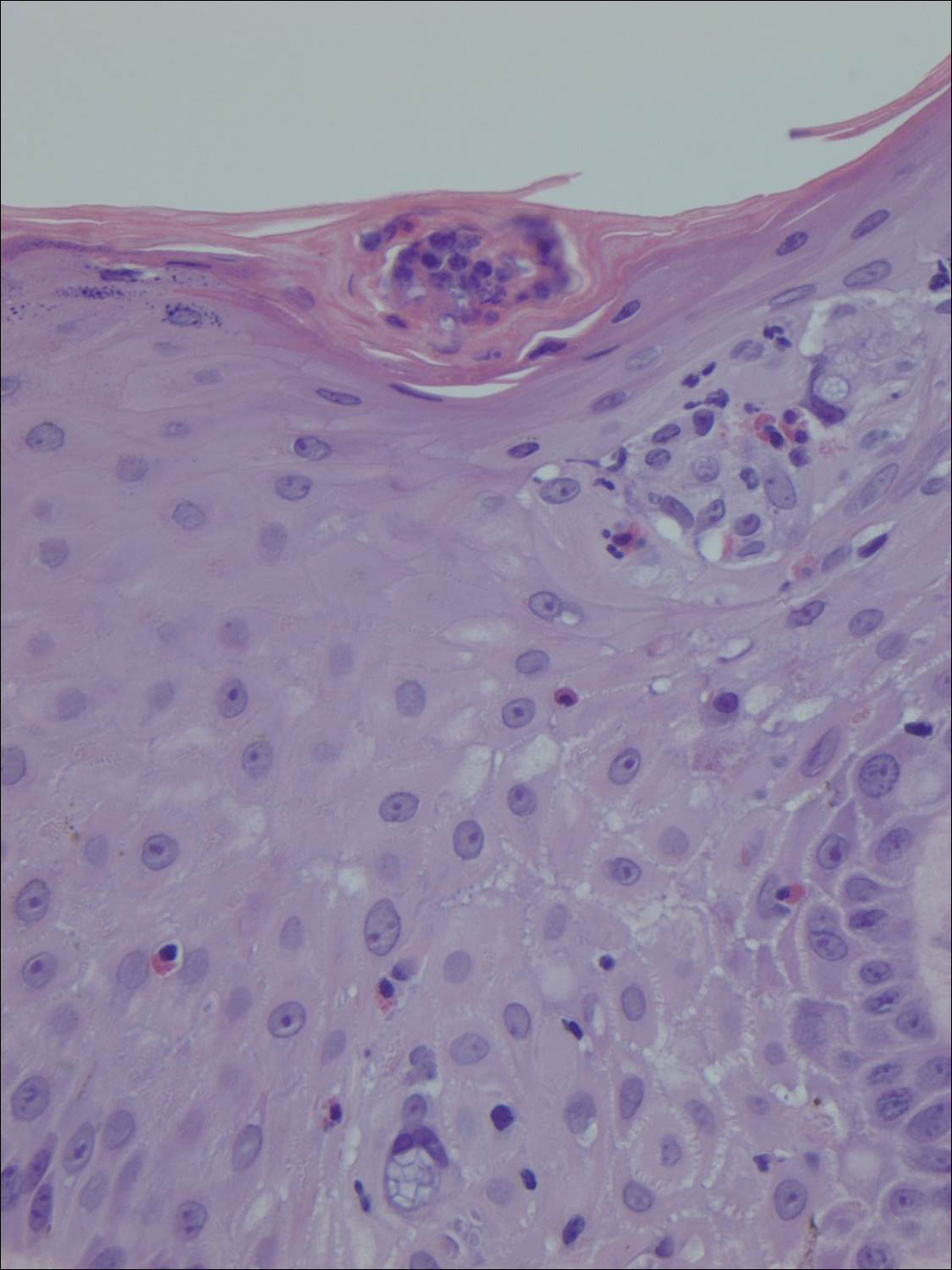

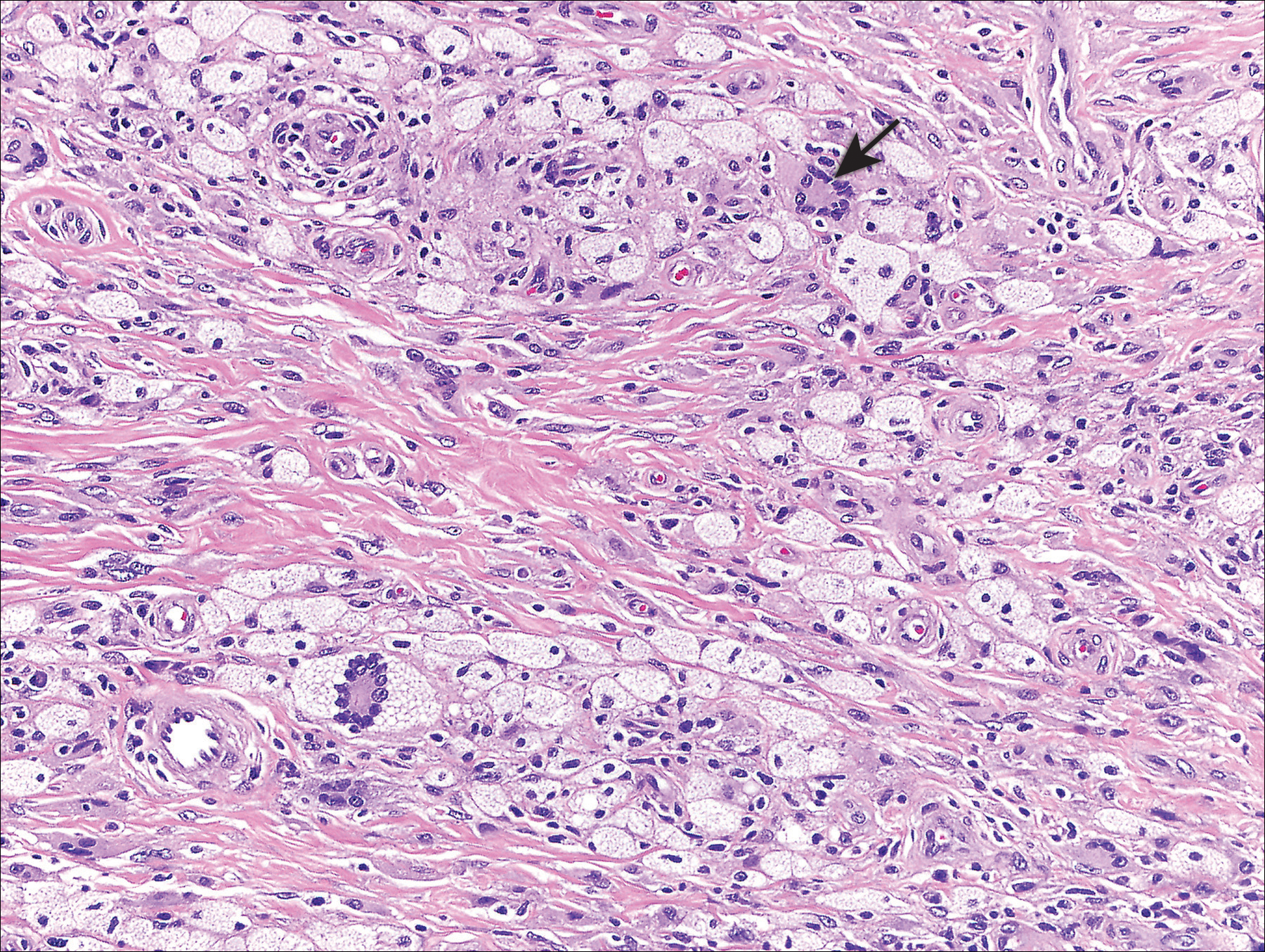

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dense infiltrate and psoriasiform pattern epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). There was conspicuous epidermotropism of moderately enlarged, hyperchromatic lymphocytes. Intraepidermal lymphocytes were slightly larger, darker, and more convoluted than those in the subjacent dermis (Figure, B). These cells exhibited CD3+ T-cell differentiation with an abnormal CD4-CD7-CD8- phenotype (Figure, C). The histopathologic finding of atypical epidermotropic T-cell infiltrate was compatible with a rare variant of mycosis fungoides known as pagetoid reticulosis (PR). After discussing the diagnosis and treatment options, the patient elected to begin with a conservative approach to therapy. We prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily under occlusion. At 1 month follow-up, the patient experienced marked improvement of the erythema and scaling of the lesion.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that has been categorized as an indolent localized variant of mycosis fungoides. This rare skin disorder was originally described by Woringer and Kolopp in 19391 and was further renamed in 1973 by Braun-Falco et al.2 At that time the term pagetoid reticulosis was introduced due to similarities in histopathologic findings seen in Paget disease of the nipple. Two variants of the disease have been described since then: the localized type and the disseminated type. The localized type, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease (WKD), typically presents as a persistent, sharply localized, scaly patch that slowly expands over several years. The lesion is classically located on the extensor surface of the hand or foot and often is asymptomatic. Due to the benign presentation, WKD can easily be confused with much more common diseases, such as psoriasis or fungal infections, resulting in a substantial delay in the diagnosis. The patient will often report a medical history notable for frequent office visits and numerous failed therapies. Even though it is exceedingly uncommon, these findings should prompt the practitioner to add WKD to their differential. The disseminated type of PR (also known as Ketron-Goodman disease) is characterized by diffuse cutaneous involvement, carries a much more progressive course, and often leads to a poor outcome.3 The histopathologic features of WKD and Ketron-Goodman disease are identical, and the 2 types are distinguished on clinical grounds alone.

Histopathologic features of PR are unique and often distinct in comparison to mycosis fungoides. Pagetoid reticulosis often is described as epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis, prominent acanthosis, and excessive epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes scattered throughout the epidermis.3 The distinct pattern of epidermotropism seen in PR is the characteristic finding. Review of immunocytochemistry from reported cases has shown that CD marker expression of neoplastic T cells in PR can be variable in nature.4 Although it is known that immunophenotyping can be useful in diagnosing and distinguishing PR from other types of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the clinical significance of the observed phenotypic variation remains a mystery. As of now, it appears to be prognostically irrelevant.5

There are numerous therapeutic options available for PR. Depending on the size and extent of the disease, surgical excision and radiotherapy may be an option and are the most effective.6 For patients who are not good candidates or opt out of these options, there are various pharmacotherapies that also have proven to work. Traditional therapies include topical corticosteroids, corticosteroid injections, and phototherapy. However, more recent trials with retinoids, such as alitretinoin or bexarotene, appear to offer a promising therapeutic approach.7

Pagetoid reticulosis is a true malignant lymphoma of T-cell lineage, but it typically carries an excellent prognosis. Rare cases have been reported to progress to disseminated lymphoma.8 Therefore, long-term follow-up for a patient diagnosed with PR is recommended.

- Woringer FR, Kolopp P. Lésion érythémato-squameuse polycyclique de l'avant-bras évoluantdepuis 6 ans chez un garçonnet de 13 ans. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1939;10:945-948.

- Braun-Falco O, Marghescu S, Wolff HH. Pagetoid reticulosis--Woringer-Kolopp's disease [in German]. Hautarzt. 1973;24:11-21.

- Haghighi B, Smoller BR, Leboit PE, et al. Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease): an immunophenotypic, molecular, and clinicopathologic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:502-510.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Mourtzinos N, Puri PK, Wang G, et al. CD4/CD8 double negative pagetoid reticulosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:491-496.

- Lee J, Viakhireva N, Cesca C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Woringer-Kolopp disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:706-712.

- Schmitz L, Bierhoff E, Dirschka T. Alitretinoin: an effective treatment option for pagetoid reticulosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1194-1195.

- Ioannides G, Engel MF, Rywlin AM. Woringer-Kolopp disease (pagetoid reticulosis). Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:153-158.

The Diagnosis: Pagetoid Reticulosis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dense infiltrate and psoriasiform pattern epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). There was conspicuous epidermotropism of moderately enlarged, hyperchromatic lymphocytes. Intraepidermal lymphocytes were slightly larger, darker, and more convoluted than those in the subjacent dermis (Figure, B). These cells exhibited CD3+ T-cell differentiation with an abnormal CD4-CD7-CD8- phenotype (Figure, C). The histopathologic finding of atypical epidermotropic T-cell infiltrate was compatible with a rare variant of mycosis fungoides known as pagetoid reticulosis (PR). After discussing the diagnosis and treatment options, the patient elected to begin with a conservative approach to therapy. We prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily under occlusion. At 1 month follow-up, the patient experienced marked improvement of the erythema and scaling of the lesion.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that has been categorized as an indolent localized variant of mycosis fungoides. This rare skin disorder was originally described by Woringer and Kolopp in 19391 and was further renamed in 1973 by Braun-Falco et al.2 At that time the term pagetoid reticulosis was introduced due to similarities in histopathologic findings seen in Paget disease of the nipple. Two variants of the disease have been described since then: the localized type and the disseminated type. The localized type, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease (WKD), typically presents as a persistent, sharply localized, scaly patch that slowly expands over several years. The lesion is classically located on the extensor surface of the hand or foot and often is asymptomatic. Due to the benign presentation, WKD can easily be confused with much more common diseases, such as psoriasis or fungal infections, resulting in a substantial delay in the diagnosis. The patient will often report a medical history notable for frequent office visits and numerous failed therapies. Even though it is exceedingly uncommon, these findings should prompt the practitioner to add WKD to their differential. The disseminated type of PR (also known as Ketron-Goodman disease) is characterized by diffuse cutaneous involvement, carries a much more progressive course, and often leads to a poor outcome.3 The histopathologic features of WKD and Ketron-Goodman disease are identical, and the 2 types are distinguished on clinical grounds alone.

Histopathologic features of PR are unique and often distinct in comparison to mycosis fungoides. Pagetoid reticulosis often is described as epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis, prominent acanthosis, and excessive epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes scattered throughout the epidermis.3 The distinct pattern of epidermotropism seen in PR is the characteristic finding. Review of immunocytochemistry from reported cases has shown that CD marker expression of neoplastic T cells in PR can be variable in nature.4 Although it is known that immunophenotyping can be useful in diagnosing and distinguishing PR from other types of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the clinical significance of the observed phenotypic variation remains a mystery. As of now, it appears to be prognostically irrelevant.5

There are numerous therapeutic options available for PR. Depending on the size and extent of the disease, surgical excision and radiotherapy may be an option and are the most effective.6 For patients who are not good candidates or opt out of these options, there are various pharmacotherapies that also have proven to work. Traditional therapies include topical corticosteroids, corticosteroid injections, and phototherapy. However, more recent trials with retinoids, such as alitretinoin or bexarotene, appear to offer a promising therapeutic approach.7

Pagetoid reticulosis is a true malignant lymphoma of T-cell lineage, but it typically carries an excellent prognosis. Rare cases have been reported to progress to disseminated lymphoma.8 Therefore, long-term follow-up for a patient diagnosed with PR is recommended.

The Diagnosis: Pagetoid Reticulosis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dense infiltrate and psoriasiform pattern epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). There was conspicuous epidermotropism of moderately enlarged, hyperchromatic lymphocytes. Intraepidermal lymphocytes were slightly larger, darker, and more convoluted than those in the subjacent dermis (Figure, B). These cells exhibited CD3+ T-cell differentiation with an abnormal CD4-CD7-CD8- phenotype (Figure, C). The histopathologic finding of atypical epidermotropic T-cell infiltrate was compatible with a rare variant of mycosis fungoides known as pagetoid reticulosis (PR). After discussing the diagnosis and treatment options, the patient elected to begin with a conservative approach to therapy. We prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily under occlusion. At 1 month follow-up, the patient experienced marked improvement of the erythema and scaling of the lesion.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that has been categorized as an indolent localized variant of mycosis fungoides. This rare skin disorder was originally described by Woringer and Kolopp in 19391 and was further renamed in 1973 by Braun-Falco et al.2 At that time the term pagetoid reticulosis was introduced due to similarities in histopathologic findings seen in Paget disease of the nipple. Two variants of the disease have been described since then: the localized type and the disseminated type. The localized type, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease (WKD), typically presents as a persistent, sharply localized, scaly patch that slowly expands over several years. The lesion is classically located on the extensor surface of the hand or foot and often is asymptomatic. Due to the benign presentation, WKD can easily be confused with much more common diseases, such as psoriasis or fungal infections, resulting in a substantial delay in the diagnosis. The patient will often report a medical history notable for frequent office visits and numerous failed therapies. Even though it is exceedingly uncommon, these findings should prompt the practitioner to add WKD to their differential. The disseminated type of PR (also known as Ketron-Goodman disease) is characterized by diffuse cutaneous involvement, carries a much more progressive course, and often leads to a poor outcome.3 The histopathologic features of WKD and Ketron-Goodman disease are identical, and the 2 types are distinguished on clinical grounds alone.

Histopathologic features of PR are unique and often distinct in comparison to mycosis fungoides. Pagetoid reticulosis often is described as epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis, prominent acanthosis, and excessive epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes scattered throughout the epidermis.3 The distinct pattern of epidermotropism seen in PR is the characteristic finding. Review of immunocytochemistry from reported cases has shown that CD marker expression of neoplastic T cells in PR can be variable in nature.4 Although it is known that immunophenotyping can be useful in diagnosing and distinguishing PR from other types of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the clinical significance of the observed phenotypic variation remains a mystery. As of now, it appears to be prognostically irrelevant.5

There are numerous therapeutic options available for PR. Depending on the size and extent of the disease, surgical excision and radiotherapy may be an option and are the most effective.6 For patients who are not good candidates or opt out of these options, there are various pharmacotherapies that also have proven to work. Traditional therapies include topical corticosteroids, corticosteroid injections, and phototherapy. However, more recent trials with retinoids, such as alitretinoin or bexarotene, appear to offer a promising therapeutic approach.7

Pagetoid reticulosis is a true malignant lymphoma of T-cell lineage, but it typically carries an excellent prognosis. Rare cases have been reported to progress to disseminated lymphoma.8 Therefore, long-term follow-up for a patient diagnosed with PR is recommended.

- Woringer FR, Kolopp P. Lésion érythémato-squameuse polycyclique de l'avant-bras évoluantdepuis 6 ans chez un garçonnet de 13 ans. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1939;10:945-948.

- Braun-Falco O, Marghescu S, Wolff HH. Pagetoid reticulosis--Woringer-Kolopp's disease [in German]. Hautarzt. 1973;24:11-21.

- Haghighi B, Smoller BR, Leboit PE, et al. Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease): an immunophenotypic, molecular, and clinicopathologic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:502-510.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Mourtzinos N, Puri PK, Wang G, et al. CD4/CD8 double negative pagetoid reticulosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:491-496.

- Lee J, Viakhireva N, Cesca C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Woringer-Kolopp disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:706-712.

- Schmitz L, Bierhoff E, Dirschka T. Alitretinoin: an effective treatment option for pagetoid reticulosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1194-1195.

- Ioannides G, Engel MF, Rywlin AM. Woringer-Kolopp disease (pagetoid reticulosis). Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:153-158.

- Woringer FR, Kolopp P. Lésion érythémato-squameuse polycyclique de l'avant-bras évoluantdepuis 6 ans chez un garçonnet de 13 ans. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1939;10:945-948.

- Braun-Falco O, Marghescu S, Wolff HH. Pagetoid reticulosis--Woringer-Kolopp's disease [in German]. Hautarzt. 1973;24:11-21.

- Haghighi B, Smoller BR, Leboit PE, et al. Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease): an immunophenotypic, molecular, and clinicopathologic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:502-510.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Mourtzinos N, Puri PK, Wang G, et al. CD4/CD8 double negative pagetoid reticulosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:491-496.

- Lee J, Viakhireva N, Cesca C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Woringer-Kolopp disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:706-712.

- Schmitz L, Bierhoff E, Dirschka T. Alitretinoin: an effective treatment option for pagetoid reticulosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1194-1195.

- Ioannides G, Engel MF, Rywlin AM. Woringer-Kolopp disease (pagetoid reticulosis). Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:153-158.

An 80-year-old man with a history of malignant melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma presented to the dermatology clinic with a chronic rash of 20 years' duration on the right ankle that extended to the instep of the right foot. His medical history was notable for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Family history was unremarkable. The patient described the rash as red and scaly but denied associated pain or pruritus. Over the last 2 to 3 years he had tried treating the affected area with petroleum jelly, topical and oral antifungals, and mild topical steroids with minimal improvement. Complete review of systems was performed and was negative other than some mild constipation. Physical examination revealed an erythematous scaly patch on the dorsal aspect of the right ankle. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal culture swab yielded negative results, and a shave biopsy was performed.

Flesh-Colored Nodule With Underlying Sclerotic Plaque

The Diagnosis: Collision Tumor

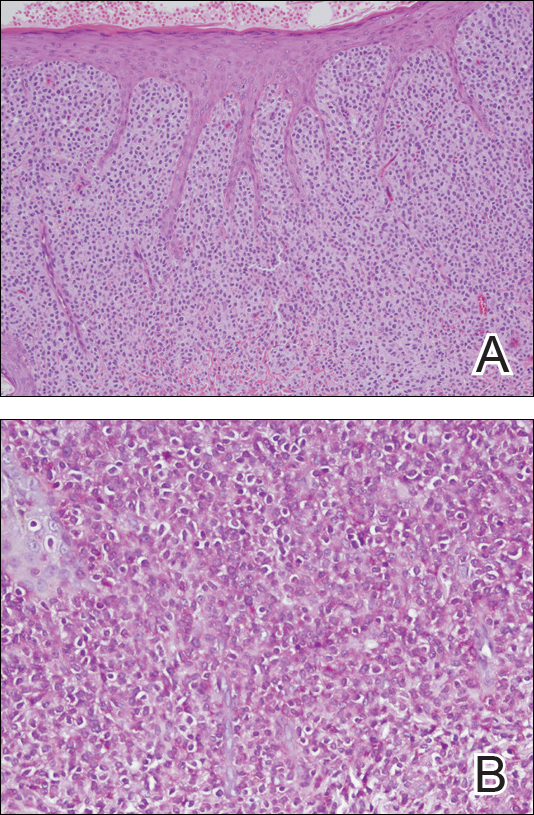

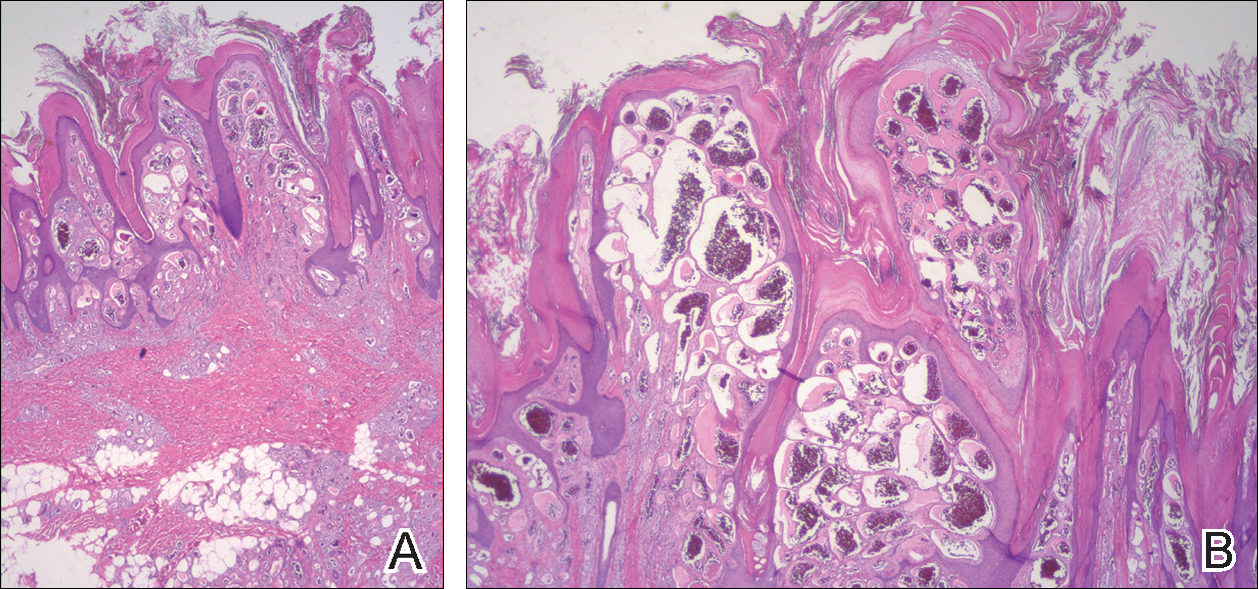

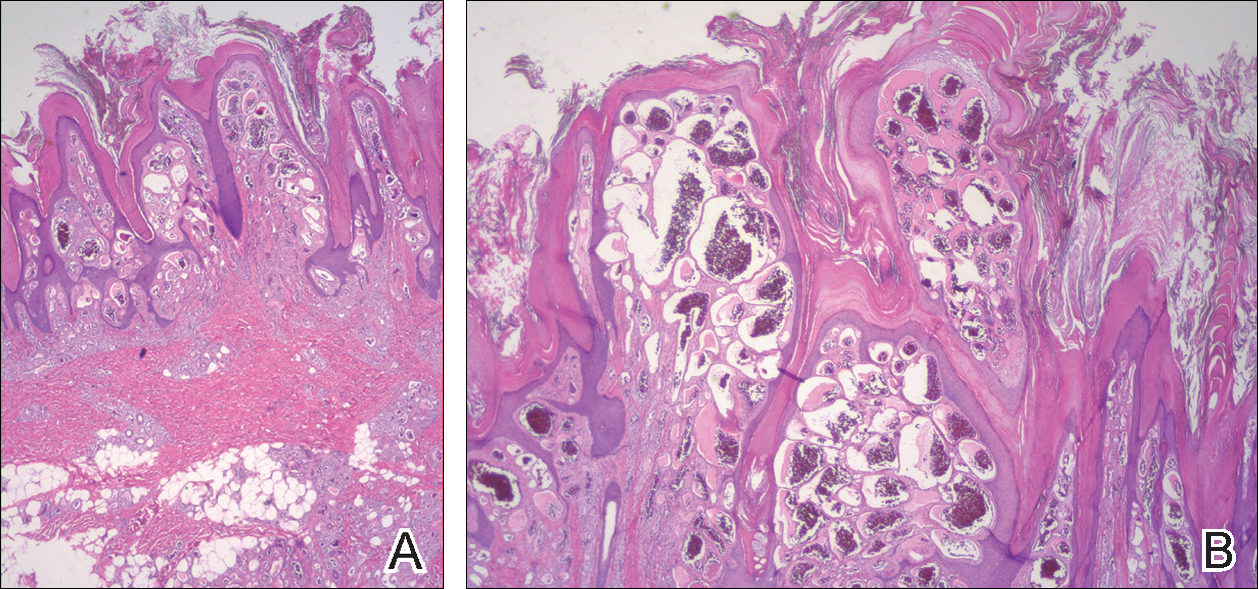

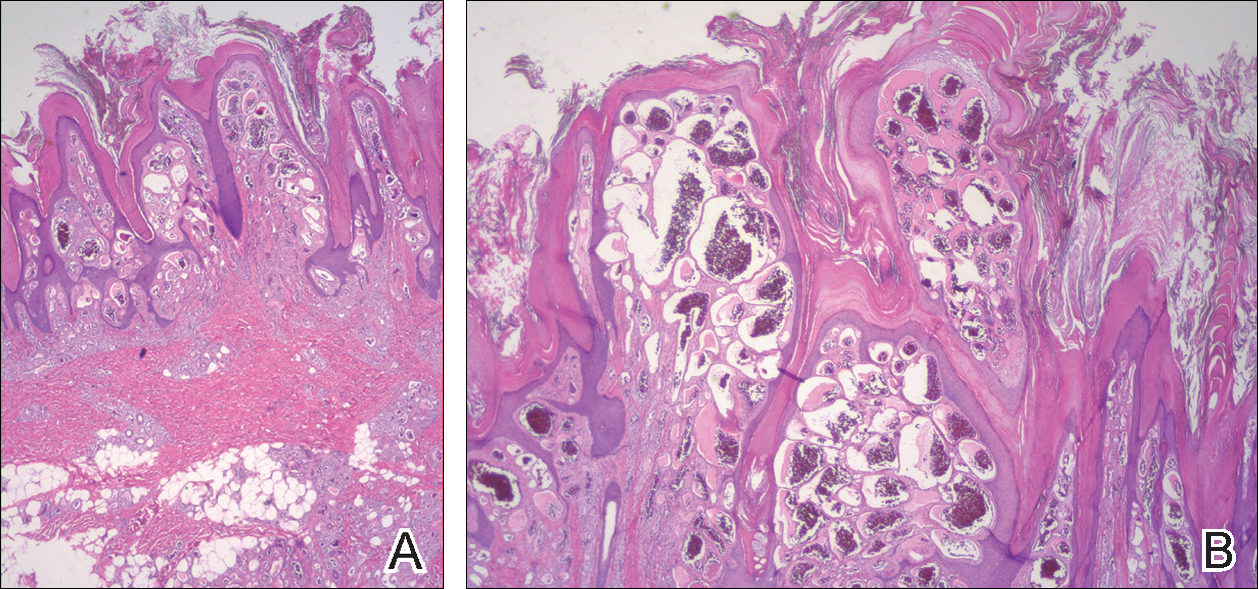

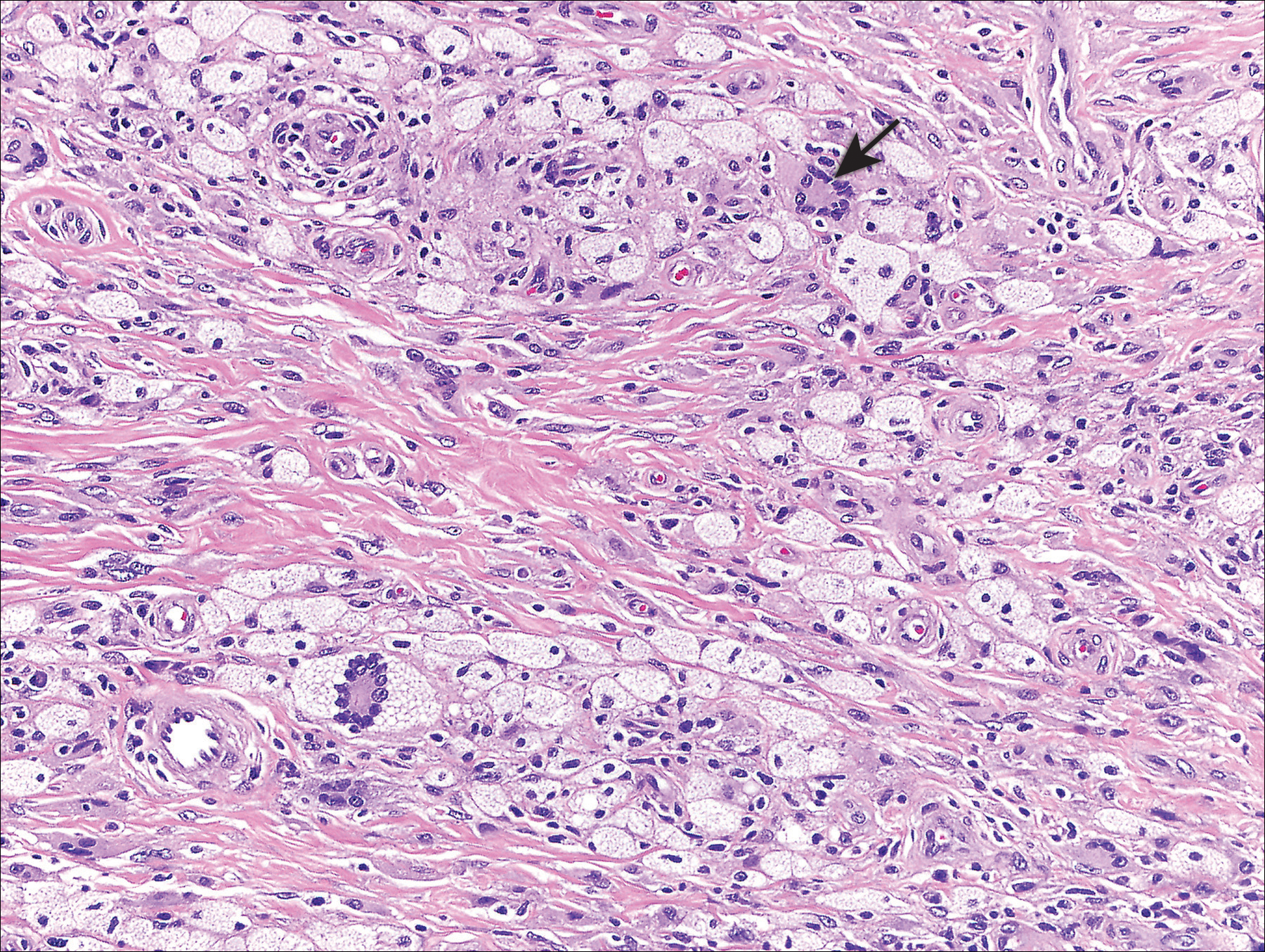

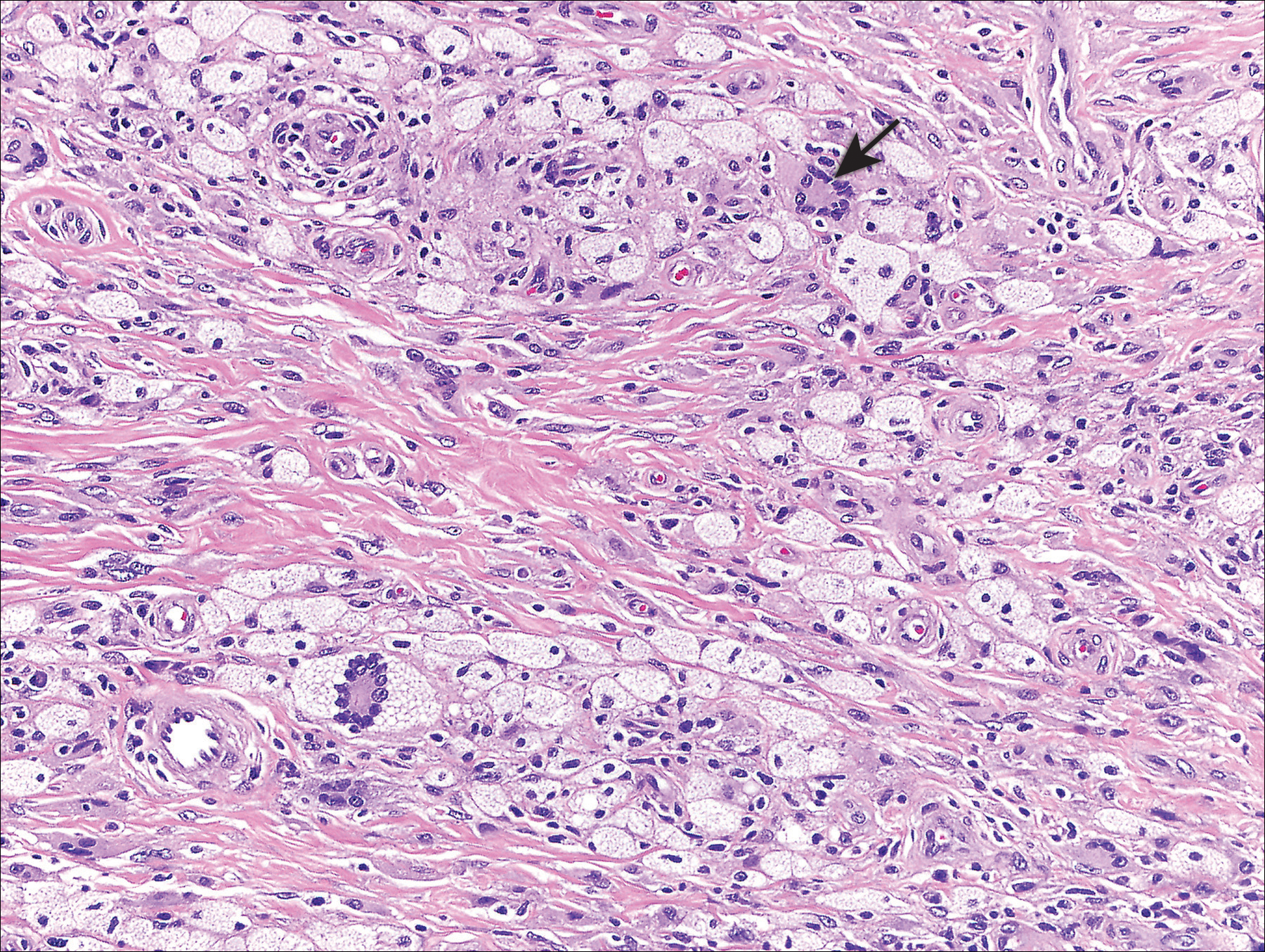

Excisional biopsy and histopathological examination demonstrated a collision tumor composed of a benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, tumor of follicular infundibulum, and an underlying sclerosing epithelial neoplasm, with a differential diagnosis of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma (Figure).

Common acquired melanocytic nevus presents clinically as a macule, papule, or nodule with smooth regular borders. The pigmented variant displays an evenly distributed pigment on the lesion. Intradermal melanocytic nevus often presents as a flesh-colored nodule, as in our case. Histopathologically, benign intradermal nevus typically is composed of a proliferation of melanocytes that exhibit dispersion as they go deeper in the dermis and maturation that manifests as melanocytes becoming smaller and more spindled in the deeper portions of the lesion.1 These 2 characteristics plus the bland cytology seen in the present case confirm the benign characteristic of this lesion (Figure, B).

In addition to the benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, an adjacent tumor of follicular infundibulum was noted. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is a rare adnexal tumor. It occurs frequently on the head and neck and shows some female predominance.2,3 Multiple lesions and eruptive lesions are rare forms that also have been reported.4 Histopathologically, the tumor demonstrates an epithelial plate that is present in the papillary dermis and is connected to the epidermis at multiple points with attachment to the follicular outer root sheath. Peripheral palisading is characteristically present above an eosinophilic basement membrane (Figure, A). Rare reports have documented sebaceous and eccrine differentiation.5,6

Tumor of follicular infundibulum has been reported to be associated with other tumors. Organoid nevus (nevus sebaceous), trichilemmal tumor, and fibroma have been reported to occur as a collision tumor with tumor of follicular infundibulum. An association with Cowden disease also has been described.7 Biopsies that represent partial samples should be interpreted cautiously, as step sections can reveal basal cell carcinoma.

The term sclerosing epithelial neoplasm describes tumors that share a paisley tielike epithelial pattern and sclerotic stroma. Small specimens often require clinicopathologic correlation (Figure, C). The differential diagnosis includes morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. A panel of stains using Ber-EP4, PHLDA1, cytokeratin 15, and cytokeratin 19 has been proposed to help differentiate these entities.8 CD34 and cytokeratin 20 also have been used with varying success in small specimens.9,10

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Melanocytic neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:105-109.

- Headington JT. Tumors of the hair follicle. Am J Pathol. 1976;85:480-505.

- Davis DA, Cohen PR. Hair follicle nevus: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:135-138.

- Ikeda S, Kawada J, Yaguchi H, et al. A case of unilateral, systematized linear hair follicle nevi associated with epidermal nevus-like lesions. Dermatology. 2003;206:172-174.

- Mehregan AH. Hair follicle tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:189-195.

- Mahalingam M, Bhawan J, Finn R, et al. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum with sebaceous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:314-317.

- Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

The Diagnosis: Collision Tumor

Excisional biopsy and histopathological examination demonstrated a collision tumor composed of a benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, tumor of follicular infundibulum, and an underlying sclerosing epithelial neoplasm, with a differential diagnosis of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma (Figure).

Common acquired melanocytic nevus presents clinically as a macule, papule, or nodule with smooth regular borders. The pigmented variant displays an evenly distributed pigment on the lesion. Intradermal melanocytic nevus often presents as a flesh-colored nodule, as in our case. Histopathologically, benign intradermal nevus typically is composed of a proliferation of melanocytes that exhibit dispersion as they go deeper in the dermis and maturation that manifests as melanocytes becoming smaller and more spindled in the deeper portions of the lesion.1 These 2 characteristics plus the bland cytology seen in the present case confirm the benign characteristic of this lesion (Figure, B).

In addition to the benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, an adjacent tumor of follicular infundibulum was noted. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is a rare adnexal tumor. It occurs frequently on the head and neck and shows some female predominance.2,3 Multiple lesions and eruptive lesions are rare forms that also have been reported.4 Histopathologically, the tumor demonstrates an epithelial plate that is present in the papillary dermis and is connected to the epidermis at multiple points with attachment to the follicular outer root sheath. Peripheral palisading is characteristically present above an eosinophilic basement membrane (Figure, A). Rare reports have documented sebaceous and eccrine differentiation.5,6

Tumor of follicular infundibulum has been reported to be associated with other tumors. Organoid nevus (nevus sebaceous), trichilemmal tumor, and fibroma have been reported to occur as a collision tumor with tumor of follicular infundibulum. An association with Cowden disease also has been described.7 Biopsies that represent partial samples should be interpreted cautiously, as step sections can reveal basal cell carcinoma.

The term sclerosing epithelial neoplasm describes tumors that share a paisley tielike epithelial pattern and sclerotic stroma. Small specimens often require clinicopathologic correlation (Figure, C). The differential diagnosis includes morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. A panel of stains using Ber-EP4, PHLDA1, cytokeratin 15, and cytokeratin 19 has been proposed to help differentiate these entities.8 CD34 and cytokeratin 20 also have been used with varying success in small specimens.9,10

The Diagnosis: Collision Tumor

Excisional biopsy and histopathological examination demonstrated a collision tumor composed of a benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, tumor of follicular infundibulum, and an underlying sclerosing epithelial neoplasm, with a differential diagnosis of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma (Figure).

Common acquired melanocytic nevus presents clinically as a macule, papule, or nodule with smooth regular borders. The pigmented variant displays an evenly distributed pigment on the lesion. Intradermal melanocytic nevus often presents as a flesh-colored nodule, as in our case. Histopathologically, benign intradermal nevus typically is composed of a proliferation of melanocytes that exhibit dispersion as they go deeper in the dermis and maturation that manifests as melanocytes becoming smaller and more spindled in the deeper portions of the lesion.1 These 2 characteristics plus the bland cytology seen in the present case confirm the benign characteristic of this lesion (Figure, B).

In addition to the benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, an adjacent tumor of follicular infundibulum was noted. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is a rare adnexal tumor. It occurs frequently on the head and neck and shows some female predominance.2,3 Multiple lesions and eruptive lesions are rare forms that also have been reported.4 Histopathologically, the tumor demonstrates an epithelial plate that is present in the papillary dermis and is connected to the epidermis at multiple points with attachment to the follicular outer root sheath. Peripheral palisading is characteristically present above an eosinophilic basement membrane (Figure, A). Rare reports have documented sebaceous and eccrine differentiation.5,6

Tumor of follicular infundibulum has been reported to be associated with other tumors. Organoid nevus (nevus sebaceous), trichilemmal tumor, and fibroma have been reported to occur as a collision tumor with tumor of follicular infundibulum. An association with Cowden disease also has been described.7 Biopsies that represent partial samples should be interpreted cautiously, as step sections can reveal basal cell carcinoma.

The term sclerosing epithelial neoplasm describes tumors that share a paisley tielike epithelial pattern and sclerotic stroma. Small specimens often require clinicopathologic correlation (Figure, C). The differential diagnosis includes morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. A panel of stains using Ber-EP4, PHLDA1, cytokeratin 15, and cytokeratin 19 has been proposed to help differentiate these entities.8 CD34 and cytokeratin 20 also have been used with varying success in small specimens.9,10

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Melanocytic neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:105-109.

- Headington JT. Tumors of the hair follicle. Am J Pathol. 1976;85:480-505.

- Davis DA, Cohen PR. Hair follicle nevus: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:135-138.

- Ikeda S, Kawada J, Yaguchi H, et al. A case of unilateral, systematized linear hair follicle nevi associated with epidermal nevus-like lesions. Dermatology. 2003;206:172-174.

- Mehregan AH. Hair follicle tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:189-195.

- Mahalingam M, Bhawan J, Finn R, et al. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum with sebaceous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:314-317.

- Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Melanocytic neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:105-109.

- Headington JT. Tumors of the hair follicle. Am J Pathol. 1976;85:480-505.

- Davis DA, Cohen PR. Hair follicle nevus: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:135-138.

- Ikeda S, Kawada J, Yaguchi H, et al. A case of unilateral, systematized linear hair follicle nevi associated with epidermal nevus-like lesions. Dermatology. 2003;206:172-174.

- Mehregan AH. Hair follicle tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:189-195.

- Mahalingam M, Bhawan J, Finn R, et al. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum with sebaceous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:314-317.

- Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

A 54-year-old man presented with a flesh-colored lesion on the chin. The nodule measured 0.6 cm in diameter. There was an underlying sclerotic plaque with indistinct borders.

Redness and Painful Ulcerations in the Perineal Area

The Diagnosis: PELVIS Syndrome

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are present in up to 10% of infants by 1 year of age and are most commonly located on the face and upper extremities. Less than 10% of IHs develop in the perineum.1 Perineal IHs are benign tumors of the vascular endothelium that present as plaques and commonly are accompanied by painful ulcerations. Ulceration is more common in the diaper area secondary to irritation from urine, stool, and friction.2 Although most IHs are benign isolated findings, facial IHs have been associated with several syndromes including Sturge-Weber and PHACE (posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies and coarctation of the aorta, and eye and endocrine abnormalities) syndromes.3 Researchers also have identified an association between lumbosacral IHs and spinal dysraphism (tethered spinal cord).4

A smaller number of studies have investigated congenital anomalies related to perineal IH,1,5 specifically PELVIS syndrome. The acronym PELVIS has been used to describe a syndrome of congenital malformations including perineal hemangioma, external genital malformations, lipomyelomeningocele, vesicorenal abnormalities, imperforate anus, and skin tag.1 An alternative description of similar findings is LUMBAR (lower body hemangioma and other cutaneous defects; urogenital anomalies, ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations, arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies).5 Researchers have suggested that both of these acronyms describe the same syndrome, and it is common for the syndrome to be incomplete.6 One study (N=11) found that perineal hemangiomas are most commonly associated with anal malformations (8 patients), followed by urinary tract abnormalities (7 patients) and malformation of the external genitalia (7 patients). A skin tag was present in 5 patients.1 The pathogenesis of PELVIS syndrome is unknown.

When an infant presents with a perineal hemangioma and physical examination suggests PELVIS syndrome, imaging should be performed to evaluate for other anomalies. Before 4 months of age, ultrasound should be utilized to investigate the presence of reno-genitourinary or spinal malformations. Magnetic resonance imaging is the preferred imaging modality in children older than 4 months.7 Management of PELVIS syndrome requires a multidisciplinary approach and early recognition of the full extent of congenital malformations. Pediatric dermatologists, urologists, endocrinologists, and neonatologists have a role in its diagnosis and treatment.

- Girard C, Bigorre M, Guillot B, et al. PELVIS syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:884-888.

- Bruckner AL, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:477-496.

- Frieden IJ, Reese V, Cohen D. PHACE syndrome: the association of posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:307-311.

- Albright AL, Gartner JC, Wiener ES. Lumbar cutaneous hemangiomas as indicators of tethered spinal cords. Pediatrics. 1989;83:977-980.

- Iacobas I, Burrows PE, Frieden IJ, et al. LUMBAR: association between cutaneous infantile hemangiomas of the lower body and regional congenital anomalies. J Pediatr. 2010;157:795-801.

- Frade FN, Kadlub V, Soupre S, et al. PELVIS or LUMBAR syndrome: the same entity. two case reports. Arch Pediatr. 2012;19:55-58.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ, Merritt DF. Management quandary: extensive perineal infantile hemangioma with associated congenital anomalies: an example of the PELVIS syndrome. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20:105-108.

The Diagnosis: PELVIS Syndrome

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are present in up to 10% of infants by 1 year of age and are most commonly located on the face and upper extremities. Less than 10% of IHs develop in the perineum.1 Perineal IHs are benign tumors of the vascular endothelium that present as plaques and commonly are accompanied by painful ulcerations. Ulceration is more common in the diaper area secondary to irritation from urine, stool, and friction.2 Although most IHs are benign isolated findings, facial IHs have been associated with several syndromes including Sturge-Weber and PHACE (posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies and coarctation of the aorta, and eye and endocrine abnormalities) syndromes.3 Researchers also have identified an association between lumbosacral IHs and spinal dysraphism (tethered spinal cord).4

A smaller number of studies have investigated congenital anomalies related to perineal IH,1,5 specifically PELVIS syndrome. The acronym PELVIS has been used to describe a syndrome of congenital malformations including perineal hemangioma, external genital malformations, lipomyelomeningocele, vesicorenal abnormalities, imperforate anus, and skin tag.1 An alternative description of similar findings is LUMBAR (lower body hemangioma and other cutaneous defects; urogenital anomalies, ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations, arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies).5 Researchers have suggested that both of these acronyms describe the same syndrome, and it is common for the syndrome to be incomplete.6 One study (N=11) found that perineal hemangiomas are most commonly associated with anal malformations (8 patients), followed by urinary tract abnormalities (7 patients) and malformation of the external genitalia (7 patients). A skin tag was present in 5 patients.1 The pathogenesis of PELVIS syndrome is unknown.

When an infant presents with a perineal hemangioma and physical examination suggests PELVIS syndrome, imaging should be performed to evaluate for other anomalies. Before 4 months of age, ultrasound should be utilized to investigate the presence of reno-genitourinary or spinal malformations. Magnetic resonance imaging is the preferred imaging modality in children older than 4 months.7 Management of PELVIS syndrome requires a multidisciplinary approach and early recognition of the full extent of congenital malformations. Pediatric dermatologists, urologists, endocrinologists, and neonatologists have a role in its diagnosis and treatment.

The Diagnosis: PELVIS Syndrome

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are present in up to 10% of infants by 1 year of age and are most commonly located on the face and upper extremities. Less than 10% of IHs develop in the perineum.1 Perineal IHs are benign tumors of the vascular endothelium that present as plaques and commonly are accompanied by painful ulcerations. Ulceration is more common in the diaper area secondary to irritation from urine, stool, and friction.2 Although most IHs are benign isolated findings, facial IHs have been associated with several syndromes including Sturge-Weber and PHACE (posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies and coarctation of the aorta, and eye and endocrine abnormalities) syndromes.3 Researchers also have identified an association between lumbosacral IHs and spinal dysraphism (tethered spinal cord).4

A smaller number of studies have investigated congenital anomalies related to perineal IH,1,5 specifically PELVIS syndrome. The acronym PELVIS has been used to describe a syndrome of congenital malformations including perineal hemangioma, external genital malformations, lipomyelomeningocele, vesicorenal abnormalities, imperforate anus, and skin tag.1 An alternative description of similar findings is LUMBAR (lower body hemangioma and other cutaneous defects; urogenital anomalies, ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations, arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies).5 Researchers have suggested that both of these acronyms describe the same syndrome, and it is common for the syndrome to be incomplete.6 One study (N=11) found that perineal hemangiomas are most commonly associated with anal malformations (8 patients), followed by urinary tract abnormalities (7 patients) and malformation of the external genitalia (7 patients). A skin tag was present in 5 patients.1 The pathogenesis of PELVIS syndrome is unknown.

When an infant presents with a perineal hemangioma and physical examination suggests PELVIS syndrome, imaging should be performed to evaluate for other anomalies. Before 4 months of age, ultrasound should be utilized to investigate the presence of reno-genitourinary or spinal malformations. Magnetic resonance imaging is the preferred imaging modality in children older than 4 months.7 Management of PELVIS syndrome requires a multidisciplinary approach and early recognition of the full extent of congenital malformations. Pediatric dermatologists, urologists, endocrinologists, and neonatologists have a role in its diagnosis and treatment.

- Girard C, Bigorre M, Guillot B, et al. PELVIS syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:884-888.

- Bruckner AL, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:477-496.

- Frieden IJ, Reese V, Cohen D. PHACE syndrome: the association of posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:307-311.

- Albright AL, Gartner JC, Wiener ES. Lumbar cutaneous hemangiomas as indicators of tethered spinal cords. Pediatrics. 1989;83:977-980.

- Iacobas I, Burrows PE, Frieden IJ, et al. LUMBAR: association between cutaneous infantile hemangiomas of the lower body and regional congenital anomalies. J Pediatr. 2010;157:795-801.

- Frade FN, Kadlub V, Soupre S, et al. PELVIS or LUMBAR syndrome: the same entity. two case reports. Arch Pediatr. 2012;19:55-58.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ, Merritt DF. Management quandary: extensive perineal infantile hemangioma with associated congenital anomalies: an example of the PELVIS syndrome. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20:105-108.

- Girard C, Bigorre M, Guillot B, et al. PELVIS syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:884-888.

- Bruckner AL, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:477-496.

- Frieden IJ, Reese V, Cohen D. PHACE syndrome: the association of posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:307-311.

- Albright AL, Gartner JC, Wiener ES. Lumbar cutaneous hemangiomas as indicators of tethered spinal cords. Pediatrics. 1989;83:977-980.

- Iacobas I, Burrows PE, Frieden IJ, et al. LUMBAR: association between cutaneous infantile hemangiomas of the lower body and regional congenital anomalies. J Pediatr. 2010;157:795-801.

- Frade FN, Kadlub V, Soupre S, et al. PELVIS or LUMBAR syndrome: the same entity. two case reports. Arch Pediatr. 2012;19:55-58.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ, Merritt DF. Management quandary: extensive perineal infantile hemangioma with associated congenital anomalies: an example of the PELVIS syndrome. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20:105-108.

A 7-week-old boy with ambiguous genitalia presented for evaluation of what the parents described as progressively worsening diaper rash. The patient was born at full-term after an uncomplicated gestation via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. Examination of the external genitalia revealed microphallus with phimosis and a bifid scrotum. Two weeks after birth, the patient developed redness and painful ulcerations in the diaper area. At the time of presentation, the patient had bright red plaques along the suprapubic lines, inguinal creases, and in the perineal region. Physical examination also was notable for tender ulcerations of the inguinal creases and perineum and a perineal skin tag.

Large Hyperpigmented Plaques on the Trunk of a Newborn

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Mastocytoma

Physical examination revealed a 58×51-mm hyperpigmented plaque with central pink coloration and scale on the right side of the back as well as a 39×33-mm pink plaque with a hyperpigmented border on the left side of the flank (Figure 1). At follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient's parents reported that blisters formed within both of the plaques. The blisters ruptured a few hours after forming and drained clear fluid with scant blood. Both plaques contained erosions from the ruptured bullae but remained the same size with no surrounding erythema or warmth. A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of intact skin from the back lesion (Figure 2A). Histologic examination revealed a cellular infiltrate of monotonous bland cells that completely filled the dermis without epidermal involvement, along with occasional intermixed eosinophils. The morphology of these infiltrating cells was compatible with mast cells confirmed by strongly positive Leder staining (Figure 2B).

Mastocytosis encompasses a rare group of disorders characterized by abnormal mast cell accumulation or mast cell mediator release in various tissues. These disorders can be classified as either systemic mastocytosis with mast cell infiltration into bone marrow or other extracutaneous organs, or cutaneous mastocytosis with disease limited to the skin.1 Mutations involving activation of the c-Kit receptor in stimulating mast cell growth and development have been implicated in both systemic and cutaneous forms of the disease.2,3

Cutaneous mastocytosis is most often diagnosed in childhood and typically is characterized by spontaneous regression before puberty in a majority of cases.1,4 Under the World Health Organization classification system, cutaneous mastocytosis can be further subdivided into 3 disorders (listed in order of most to least common): urticaria pigmentosa (also known as maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis) with typical, plaque, and nodular forms; cutaneous mastocytoma (as seen in this patient); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis.5 Compared to the widespread distribution of small macules and papules in urticaria pigmentosa, the cutaneous mastocytoma subtype presents with 1 to 6 brown to orange-yellow plaques or nodules measuring more than 1 cm in diameter. Cutaneous mastocytoma typically presents in infancy and is located most commonly on the trunk and extremities, though it may be found on the face or scalp. The plaques of mastocytoma often have well-defined margins, and these lesions may become bullous or demonstrate Darier sign of urtication and erythema on physical stimulation. Patients most commonly experience pruritus from mast cell degranulation and rarely exhibit systemic symptoms of mast cell mediator release; however, generalized flushing, hypotension, headaches, and gastrointestinal symptoms may occur, particularly if the lesion is vigorously rubbed.6,7 Conditions in the differential include aplasia cutis congenita, connective tissue nevus, epidermal nevus, and epidermolysis bullosa. They should not elicit a blister if rubbed, except for epidermolysis bullosa, which can easily be differentiated based on histology.

The workup for cutaneous mastocytosis in the pediatric population may include a biopsy of lesional skin, though in many cases the characteristic cutaneous manifestations are sufficient to make a diagnosis. Histologically, biopsy results often reveal abundant diffuse dermal infiltration of mast cells, which are characterized by their large pink granular cytoplasm and round dense central nuclei. In pediatric patients, mast cells typically are restricted to the dermis, and there is a low risk for hematologic abnormalities, thereby precluding the need for bone marrow examination in the absence of organomegaly or notable peripheral blood abnormalities such as severe cytopenia.5,6

Management of cutaneous mastocytosis consists of avoidance of mast cell degranulation triggers and symptomatic treatment of histamine release. Triggers include certain medications (eg, narcotic analgesics, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, iodinated contrast agents, antibiotics, muscle relaxants), mechanical irritation, insect stings, spicy foods, stress, or extreme temperature changes.8 Symptomatic treatment can be achieved through topical corticosteroid or oral antihistamine use. Along with decreasing pruritus, topical corticosteroids also may be helpful in decreasing time to spontaneous resolution and healing.7 The patient in this case was treated with desonide ointment 0.05% daily to both lesions as well as mupirocin ointment 2% as needed for erosions. These treatments helped reduce the patient's symptoms, but her lesions persisted over a follow-up period of 4 months.

- Valent P, Sperr WR, Schwartz LB, et al. Diagnosis and classification of mast cell proliferative disorders: delineation from immunologic diseases and non-mast cell hematopoietic neoplasms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:3-11.

- Bibi S, Langenfeld F, Jeanningros S, et al. Molecular defects in mastocytosis: KIT and beyond KIT. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014;34:239-262.

- Yavuz AS, Lipsky PE, Yavuz S, et al. Evidence for the involvement of a hematopoietic progenitor cell in systemic mastocytosis from single-cell analysis of mutations in the c-kit gene. Blood. 2002;100:661-665.

- Méni C, Bruneau J, Georgin-Lavialle S, et al. Paediatric mastocytosis: a systematic review of 1747 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:642-651.

- Valent P, Horny HP, Escribano L, et al. Diagnostic criteria and classification of mastocytosis: a consensus proposal. Leuk Res. 2001;25:603-625.

- Wolff K, Komar M, Petzelbauer P. Clinical and histopathological aspects of cutaneous mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2001;25:519-528.

- Patrizi A, Tabanelli M, Neri I, et al. Topical corticosteroids versus "wait and see" in the management of solitary mastocytoma in pediatric patients: a long-term follow-up. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:57-61.

- Bonadonna P, Lombardo C. Drug allergy in mastocytosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014;34:397-405.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Mastocytoma

Physical examination revealed a 58×51-mm hyperpigmented plaque with central pink coloration and scale on the right side of the back as well as a 39×33-mm pink plaque with a hyperpigmented border on the left side of the flank (Figure 1). At follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient's parents reported that blisters formed within both of the plaques. The blisters ruptured a few hours after forming and drained clear fluid with scant blood. Both plaques contained erosions from the ruptured bullae but remained the same size with no surrounding erythema or warmth. A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of intact skin from the back lesion (Figure 2A). Histologic examination revealed a cellular infiltrate of monotonous bland cells that completely filled the dermis without epidermal involvement, along with occasional intermixed eosinophils. The morphology of these infiltrating cells was compatible with mast cells confirmed by strongly positive Leder staining (Figure 2B).

Mastocytosis encompasses a rare group of disorders characterized by abnormal mast cell accumulation or mast cell mediator release in various tissues. These disorders can be classified as either systemic mastocytosis with mast cell infiltration into bone marrow or other extracutaneous organs, or cutaneous mastocytosis with disease limited to the skin.1 Mutations involving activation of the c-Kit receptor in stimulating mast cell growth and development have been implicated in both systemic and cutaneous forms of the disease.2,3

Cutaneous mastocytosis is most often diagnosed in childhood and typically is characterized by spontaneous regression before puberty in a majority of cases.1,4 Under the World Health Organization classification system, cutaneous mastocytosis can be further subdivided into 3 disorders (listed in order of most to least common): urticaria pigmentosa (also known as maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis) with typical, plaque, and nodular forms; cutaneous mastocytoma (as seen in this patient); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis.5 Compared to the widespread distribution of small macules and papules in urticaria pigmentosa, the cutaneous mastocytoma subtype presents with 1 to 6 brown to orange-yellow plaques or nodules measuring more than 1 cm in diameter. Cutaneous mastocytoma typically presents in infancy and is located most commonly on the trunk and extremities, though it may be found on the face or scalp. The plaques of mastocytoma often have well-defined margins, and these lesions may become bullous or demonstrate Darier sign of urtication and erythema on physical stimulation. Patients most commonly experience pruritus from mast cell degranulation and rarely exhibit systemic symptoms of mast cell mediator release; however, generalized flushing, hypotension, headaches, and gastrointestinal symptoms may occur, particularly if the lesion is vigorously rubbed.6,7 Conditions in the differential include aplasia cutis congenita, connective tissue nevus, epidermal nevus, and epidermolysis bullosa. They should not elicit a blister if rubbed, except for epidermolysis bullosa, which can easily be differentiated based on histology.

The workup for cutaneous mastocytosis in the pediatric population may include a biopsy of lesional skin, though in many cases the characteristic cutaneous manifestations are sufficient to make a diagnosis. Histologically, biopsy results often reveal abundant diffuse dermal infiltration of mast cells, which are characterized by their large pink granular cytoplasm and round dense central nuclei. In pediatric patients, mast cells typically are restricted to the dermis, and there is a low risk for hematologic abnormalities, thereby precluding the need for bone marrow examination in the absence of organomegaly or notable peripheral blood abnormalities such as severe cytopenia.5,6

Management of cutaneous mastocytosis consists of avoidance of mast cell degranulation triggers and symptomatic treatment of histamine release. Triggers include certain medications (eg, narcotic analgesics, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, iodinated contrast agents, antibiotics, muscle relaxants), mechanical irritation, insect stings, spicy foods, stress, or extreme temperature changes.8 Symptomatic treatment can be achieved through topical corticosteroid or oral antihistamine use. Along with decreasing pruritus, topical corticosteroids also may be helpful in decreasing time to spontaneous resolution and healing.7 The patient in this case was treated with desonide ointment 0.05% daily to both lesions as well as mupirocin ointment 2% as needed for erosions. These treatments helped reduce the patient's symptoms, but her lesions persisted over a follow-up period of 4 months.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Mastocytoma

Physical examination revealed a 58×51-mm hyperpigmented plaque with central pink coloration and scale on the right side of the back as well as a 39×33-mm pink plaque with a hyperpigmented border on the left side of the flank (Figure 1). At follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient's parents reported that blisters formed within both of the plaques. The blisters ruptured a few hours after forming and drained clear fluid with scant blood. Both plaques contained erosions from the ruptured bullae but remained the same size with no surrounding erythema or warmth. A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of intact skin from the back lesion (Figure 2A). Histologic examination revealed a cellular infiltrate of monotonous bland cells that completely filled the dermis without epidermal involvement, along with occasional intermixed eosinophils. The morphology of these infiltrating cells was compatible with mast cells confirmed by strongly positive Leder staining (Figure 2B).

Mastocytosis encompasses a rare group of disorders characterized by abnormal mast cell accumulation or mast cell mediator release in various tissues. These disorders can be classified as either systemic mastocytosis with mast cell infiltration into bone marrow or other extracutaneous organs, or cutaneous mastocytosis with disease limited to the skin.1 Mutations involving activation of the c-Kit receptor in stimulating mast cell growth and development have been implicated in both systemic and cutaneous forms of the disease.2,3

Cutaneous mastocytosis is most often diagnosed in childhood and typically is characterized by spontaneous regression before puberty in a majority of cases.1,4 Under the World Health Organization classification system, cutaneous mastocytosis can be further subdivided into 3 disorders (listed in order of most to least common): urticaria pigmentosa (also known as maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis) with typical, plaque, and nodular forms; cutaneous mastocytoma (as seen in this patient); and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis.5 Compared to the widespread distribution of small macules and papules in urticaria pigmentosa, the cutaneous mastocytoma subtype presents with 1 to 6 brown to orange-yellow plaques or nodules measuring more than 1 cm in diameter. Cutaneous mastocytoma typically presents in infancy and is located most commonly on the trunk and extremities, though it may be found on the face or scalp. The plaques of mastocytoma often have well-defined margins, and these lesions may become bullous or demonstrate Darier sign of urtication and erythema on physical stimulation. Patients most commonly experience pruritus from mast cell degranulation and rarely exhibit systemic symptoms of mast cell mediator release; however, generalized flushing, hypotension, headaches, and gastrointestinal symptoms may occur, particularly if the lesion is vigorously rubbed.6,7 Conditions in the differential include aplasia cutis congenita, connective tissue nevus, epidermal nevus, and epidermolysis bullosa. They should not elicit a blister if rubbed, except for epidermolysis bullosa, which can easily be differentiated based on histology.

The workup for cutaneous mastocytosis in the pediatric population may include a biopsy of lesional skin, though in many cases the characteristic cutaneous manifestations are sufficient to make a diagnosis. Histologically, biopsy results often reveal abundant diffuse dermal infiltration of mast cells, which are characterized by their large pink granular cytoplasm and round dense central nuclei. In pediatric patients, mast cells typically are restricted to the dermis, and there is a low risk for hematologic abnormalities, thereby precluding the need for bone marrow examination in the absence of organomegaly or notable peripheral blood abnormalities such as severe cytopenia.5,6

Management of cutaneous mastocytosis consists of avoidance of mast cell degranulation triggers and symptomatic treatment of histamine release. Triggers include certain medications (eg, narcotic analgesics, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, iodinated contrast agents, antibiotics, muscle relaxants), mechanical irritation, insect stings, spicy foods, stress, or extreme temperature changes.8 Symptomatic treatment can be achieved through topical corticosteroid or oral antihistamine use. Along with decreasing pruritus, topical corticosteroids also may be helpful in decreasing time to spontaneous resolution and healing.7 The patient in this case was treated with desonide ointment 0.05% daily to both lesions as well as mupirocin ointment 2% as needed for erosions. These treatments helped reduce the patient's symptoms, but her lesions persisted over a follow-up period of 4 months.

- Valent P, Sperr WR, Schwartz LB, et al. Diagnosis and classification of mast cell proliferative disorders: delineation from immunologic diseases and non-mast cell hematopoietic neoplasms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:3-11.

- Bibi S, Langenfeld F, Jeanningros S, et al. Molecular defects in mastocytosis: KIT and beyond KIT. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014;34:239-262.

- Yavuz AS, Lipsky PE, Yavuz S, et al. Evidence for the involvement of a hematopoietic progenitor cell in systemic mastocytosis from single-cell analysis of mutations in the c-kit gene. Blood. 2002;100:661-665.

- Méni C, Bruneau J, Georgin-Lavialle S, et al. Paediatric mastocytosis: a systematic review of 1747 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:642-651.

- Valent P, Horny HP, Escribano L, et al. Diagnostic criteria and classification of mastocytosis: a consensus proposal. Leuk Res. 2001;25:603-625.

- Wolff K, Komar M, Petzelbauer P. Clinical and histopathological aspects of cutaneous mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2001;25:519-528.

- Patrizi A, Tabanelli M, Neri I, et al. Topical corticosteroids versus "wait and see" in the management of solitary mastocytoma in pediatric patients: a long-term follow-up. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:57-61.

- Bonadonna P, Lombardo C. Drug allergy in mastocytosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014;34:397-405.

- Valent P, Sperr WR, Schwartz LB, et al. Diagnosis and classification of mast cell proliferative disorders: delineation from immunologic diseases and non-mast cell hematopoietic neoplasms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:3-11.

- Bibi S, Langenfeld F, Jeanningros S, et al. Molecular defects in mastocytosis: KIT and beyond KIT. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014;34:239-262.

- Yavuz AS, Lipsky PE, Yavuz S, et al. Evidence for the involvement of a hematopoietic progenitor cell in systemic mastocytosis from single-cell analysis of mutations in the c-kit gene. Blood. 2002;100:661-665.

- Méni C, Bruneau J, Georgin-Lavialle S, et al. Paediatric mastocytosis: a systematic review of 1747 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:642-651.

- Valent P, Horny HP, Escribano L, et al. Diagnostic criteria and classification of mastocytosis: a consensus proposal. Leuk Res. 2001;25:603-625.

- Wolff K, Komar M, Petzelbauer P. Clinical and histopathological aspects of cutaneous mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2001;25:519-528.

- Patrizi A, Tabanelli M, Neri I, et al. Topical corticosteroids versus "wait and see" in the management of solitary mastocytoma in pediatric patients: a long-term follow-up. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:57-61.

- Bonadonna P, Lombardo C. Drug allergy in mastocytosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014;34:397-405.

A 4-day-old girl with no notable medical history presented with 2 pink lesions on the right side of the back and left side of the flank. Both lesions were present at birth and had not changed in size, shape, or color in the first 4 days of life. She had no constitutional symptoms. The child was a full-term newborn, and her mother experienced no pregnancy or delivery complications. She had no family history of similar skin findings.

Bluish Gray Hyperpigmentation on the Face and Neck

The Diagnosis: Erythema Dyschromicum Perstans

Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), also referred to as ashy dermatosis, was first described by Ramirez1 in 1957 who labeled the patients los cenicientos (the ashen ones). It preferentially affects women in the second decade of life; however, patients of all ages can be affected, with reported cases occurring in children as young as 2 years of age.2 Most patients have Fitzpatrick skin type IV, mainly Amerindian, Hispanic South Asian, and Southwest Asian; however, there are cases reported worldwide.3 A genetic predisposition is proposed, as major histocompatibility complex genes associated with HLA-DR4⁎0407 are frequent in Mexican patients with ashy dermatosis and in the Amerindian population.4

The etiology of EDP is unknown. Various contributing factors have been reported including alimentary, occupational, and climatic factors,5,6 yet none have been conclusively demonstrated. High expression of CD36 (thrombospondin receptor not found in normal skin) in spinous and granular layers, CD94 (cytotoxic cell marker) in the basal cell layer and in the inflammatory dermal infiltrate,7 and focal keratinocytic expression of intercellular adhesion molecule I (CD54) in the active lesions of EDP, as well as the absence of these findings in normal skin, suggests an immunologic role in the development of the disease.8

Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents clinically with blue-gray hyperpigmented macules varying in size and shape and developing symmetrically in both sun-exposed and sun-protected areas of the face, neck, trunk, arms, and sometimes the dorsal hands (Figures 1 and 2). Notable sparing of the palms, soles, scalp, and mucous membranes occurs.

Occasionally, in the early active stage of the disease, elevated erythematous borders are noted surrounding the hyperpigmented macules. Eventually a hypopigmented halo develops after a prolonged duration of disease.9 The eruption typically is chronic and asymptomatic, though some cases may be pruritic.10

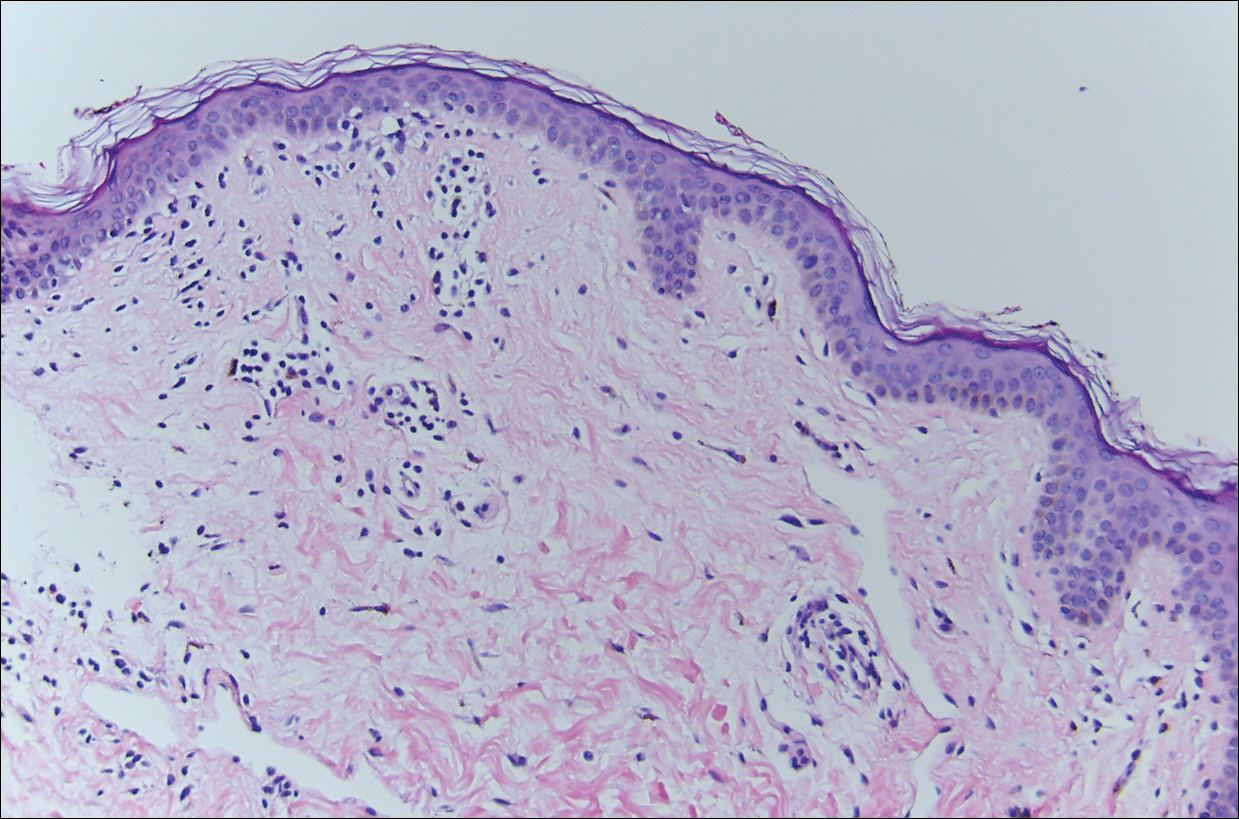

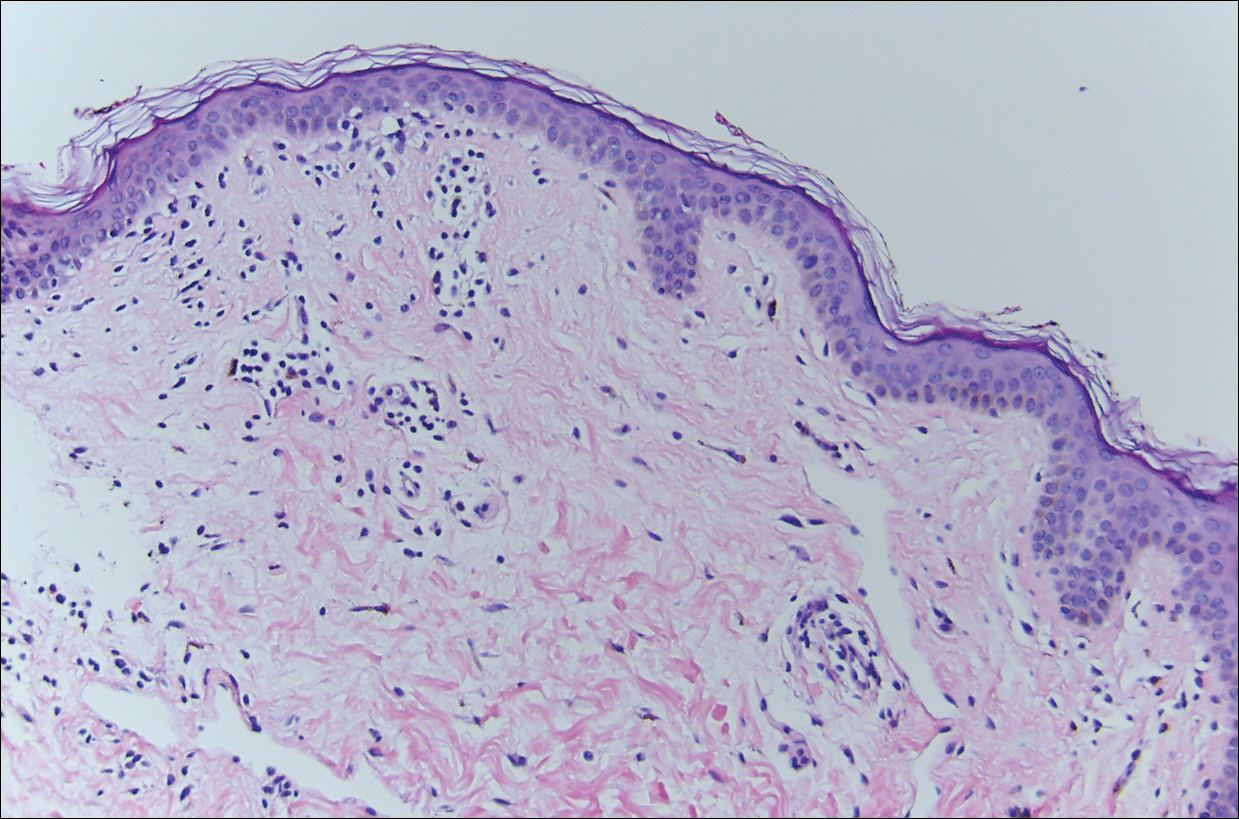

Histopathologically, the early lesions of EDP with an erythematous active border reveal lichenoid dermatitis with basal vacuolar change and occasional Civatte bodies. A mild to moderate perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate admixed with melanophages can be seen in the papillary dermis (Figure 3). In older lesions, the inflammatory infiltrate is sparse, and pigment incontinence consistent with postinflammatory pigmentation is prominent, though melanophages extending deep into the reticular dermis may aid in distinguishing EDP from other causes of postinflammatory pigment alteration.7,11

Erythema dyschromicum perstans and lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) may be indistinguishable histopathologically and may both be variants of lichen planus actinicus. Lichen planus pigmentosus often differs from EDP in that it presents with brown-black macules and patches often on the face and flexural areas. A subset of cases of LPP also may have mucous membrane involvement. The erythematous border that characterizes the active lesion of EDP is characteristically absent in LPP. In addition, pruritus often is reported with LPP. Direct immunofluorescence is not a beneficial tool in distinguishing the entities.12

Other differential diagnoses of predominantly facial hyperpigmentation include a lichenoid drug eruption; drug-induced hyperpigmentation (deposition disorder); postinflammatory hyperpigmentation following atopic dermatitis; contact dermatitis or photosensitivity reaction; early pinta; and cutaneous findings of systemic diseases manifesting with diffuse hyperpigmentation such as lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, hemochromatosis, and Addison disease. A detailed history including medication use, thorough clinical examination, and careful histopathologic evaluation will help distinguish these conditions.

Chrysiasis is a rare bluish to slate gray discoloration of the skin that predominantly occurs in sun-exposed areas. It is caused by chronic use of gold salts, which have been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. UV light may contribute to induce the uptake of gold and subsequently stimulate tyrosinase activity.13 Histologic features of chrysiasis include dermal and perivascular gold deposition within the macrophages and endothelial cells as well as extracellular granules. It demonstrates an orange-red birefringence on fluorescent microscopy.14,15

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is a well-recognized side effect of this drug. It is dose dependent and appears as a blue-black pigmentation that most frequently affects the shins, ankles, and arms.16 Three distinct types were documented: abnormal discoloration of the skin that has been linked to deposition of pigmented metabolites of minocycline producing blue-black pigmentation at the site of scarring or prior inflammation (type 1); blue-gray pigmentation affecting normal skin, mainly the legs (type 2); and elevated levels of melanin on the sun-exposed areas producing dirty skin syndrome (type 3).17,18

Topical and systemic corticosteroids, UV light therapy, oral dapsone, griseofulvin, retinoids, and clofazimine are reported as treatment options for ashy dermatosis, though results typically are disappointing.7

- Ramirez CO. Los cenicientos: problema clinica. In: Memoria del Primer Congresso Centroamericano de Dermatologica, December 5-8, 1957. San Salvador, El Salvador; 1957:122-130.

- Lee SJ, Chung KY. Erythema dyschromicum perstans in early childhood. J Dermatol. 1999;26:119-121.

- Homez-Chacin, Barroso C. On the etiopathogenic of the erythema dyschromicum perstans: possibility of a melanosis neurocutaneous. Dermatol Venez. 1996;4:149-151.

- Correa MC, Memije EV, Vargas-Alarcon G, et al. HLA-DR association with the genetic susceptibility to develop ashy dermatosis in Mexican Mestizo patients [published online November 20, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:617-620.

- Jablonska S. Ingestion of ammonium nitrate as a possible cause of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Dermatologica. 1975;150:287-291.

- Stevenson JR, Miura M. Erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:196-199.