User login

Caring for the aging transgender patient

The elderly transgender population is rapidly expanding and remains significantly overlooked. Although emerging evidence provides some guidance for medical and surgical treatment for transgender youth, there is still a paucity of research directed at the management of gender-diverse elders.

To a large extent, the challenges that transgender elders face are no different from those experienced by the general elder population. Irrespective of gender identity, patients begin to undergo cognitive and physical changes, encounter difficulties with activities of daily living, suffer the loss of social networks and friends, and face end-of-life issues.1 Attributes that contribute to successful aging in the general population include good health, social engagement and support, and having a positive outlook on life.1 Yet, stigma surrounding gender identity and sexual orientation continues to negatively affect elder transgender people.

Many members of the LGBTQIA+ population have higher rates of obesity, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, cardiovascular disease, substance abuse, depression, suicide, and intimate partner violence than the general same-age cohort.2 Compared with lesbian, gay, and bisexual elders of age-matched cohorts, transgender elders have significantly poorer overall physical health, disability, depressive symptoms, and perceived stress.2

Rates of sexually transmitted infections are also rising in the aging general population and increased by 30% between 2014 and 2017.2 There have been no current studies examining these rates in the LGBTQIA+ population. As providers interact more frequently with these patients, it’s not only essential to screen for conditions such as diabetes, lipid disorders, and sexually transmitted infections, but also to evaluate current gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) regimens and order appropriate screening tests.

Hormonal therapy for transfeminine patients should be continued as patients age. One of the biggest concerns providers have in continuing hormone therapy is the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and increasing thromboembolic risk, both of which tend to occur naturally as patients age. Overall, studies on the prevalence of CVD or stroke in gender-diverse individuals indicate an elevated risk independent of GAHT.3 While the overall rates of thromboembolic events are low in transfeminine populations, estrogen therapy does confer an increased risk. However, most transgender women who have experienced cardiac events or stroke were over the age of 50, had one or more CVD risk factors, or were using synthetic estrogens.3

How these studies affect screening is unclear. Current guidelines recommend using tailored risk-based calculators, which take into consideration the patient’s sex assigned at birth, hormone regimen, length of hormone usage, and additional modifiable risk factors, such as diabetes, obesity, and smoking.3 For transfeminine patients who want to continue GAHT but either develop a venous thromboembolism on estrogen or have increased risk for VTE, providers should consider transitioning them to a transdermal application. Patients who stay on GAHT should be counseled accordingly on the heightened risk of VTE recurrence. It is not unreasonable to consider life-long anticoagulation for patients who remain on estrogen therapy after a VTE.4

While exogenous estrogen exposure is one risk factor for the development of breast cancer in cisgender females, the role of GAHT in breast cancer in transgender women is ambiguous. Therefore, breast screening guidelines should follow current recommendations for cisgender female patients with some caveats. The provider must also take into consideration current estrogen dosage, the age at which hormones were initiated, and whether a patient has undergone an augmentation mammaplasty.3

Both estrogen and testosterone play an important role in bone formation and health. Patients who undergo either medical or surgical interventions that alter sex hormone production, such as GAHT, orchiectomy, or androgen blockade, may be at elevated risk for osteoporosis. Providers should take a thorough medical history to determine patients who may be at risk for osteoporosis and treat them accordingly. Overall, GAHT has a positive effect on bone mineral density. Conversely, gonadectomy, particularly if a patient is not taking GAHT, can decrease bone density. Generally, transgender women, like cisgender women, should undergo DEXA scans starting at the age of 65, with earlier screening considered if they have undergone an orchiectomy and are not currently taking GAHT.3

There is no evidence that GAHT or surgery increases the rate of prostate cancer. Providers should note that the prostate is not removed at the time of gender-affirming surgery and that malignancy or benign prostatic hypertrophy can still occur. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that clinicians have a discussion with cisgender men between the ages of 55 and 69 about the risks and benefits of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening.5 For cisgender men aged 70 and older, the USPSTF recommends against PSA-based screening.5 If digital examination of the prostate is warranted for transfeminine patients, the examination is performed through the neovaginal canal.

Caring for elderly transgender patients is complex. Even though evidence guiding the management of elderly transgender patients is improving, there are still not enough definitive long-term data on this dynamic demographic. Like clinical approaches with hormonal or surgical treatments, caring for transgender elders is also multidisciplinary. Providers should be prepared to work with social workers, geriatric care physicians, endocrinologists, surgeons, and other relevant specialists to assist with potential knowledge gaps. The goals for the aging transgender population are the same as those for cisgender patients – preventing preventable diseases and reducing overall mortality so our patients can enjoy their golden years.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa. Contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Carroll L. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2017;40:127-40.

2. Selix NW et al. Clinical care of the aging LGBT population. J Nurse Pract. 2020;16(7):349-54.

3. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people. 2022;8th version.

4. Shatzel JJ et al. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(2):204-8.

5. Wolf-Gould CS and Wolf-Gould CH. Primary and preventative care for transgender patients. In: Ferrando CA, ed. Comprehensive Care of the Transgender Patient. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020, p. 114-30.

The elderly transgender population is rapidly expanding and remains significantly overlooked. Although emerging evidence provides some guidance for medical and surgical treatment for transgender youth, there is still a paucity of research directed at the management of gender-diverse elders.

To a large extent, the challenges that transgender elders face are no different from those experienced by the general elder population. Irrespective of gender identity, patients begin to undergo cognitive and physical changes, encounter difficulties with activities of daily living, suffer the loss of social networks and friends, and face end-of-life issues.1 Attributes that contribute to successful aging in the general population include good health, social engagement and support, and having a positive outlook on life.1 Yet, stigma surrounding gender identity and sexual orientation continues to negatively affect elder transgender people.

Many members of the LGBTQIA+ population have higher rates of obesity, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, cardiovascular disease, substance abuse, depression, suicide, and intimate partner violence than the general same-age cohort.2 Compared with lesbian, gay, and bisexual elders of age-matched cohorts, transgender elders have significantly poorer overall physical health, disability, depressive symptoms, and perceived stress.2

Rates of sexually transmitted infections are also rising in the aging general population and increased by 30% between 2014 and 2017.2 There have been no current studies examining these rates in the LGBTQIA+ population. As providers interact more frequently with these patients, it’s not only essential to screen for conditions such as diabetes, lipid disorders, and sexually transmitted infections, but also to evaluate current gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) regimens and order appropriate screening tests.

Hormonal therapy for transfeminine patients should be continued as patients age. One of the biggest concerns providers have in continuing hormone therapy is the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and increasing thromboembolic risk, both of which tend to occur naturally as patients age. Overall, studies on the prevalence of CVD or stroke in gender-diverse individuals indicate an elevated risk independent of GAHT.3 While the overall rates of thromboembolic events are low in transfeminine populations, estrogen therapy does confer an increased risk. However, most transgender women who have experienced cardiac events or stroke were over the age of 50, had one or more CVD risk factors, or were using synthetic estrogens.3

How these studies affect screening is unclear. Current guidelines recommend using tailored risk-based calculators, which take into consideration the patient’s sex assigned at birth, hormone regimen, length of hormone usage, and additional modifiable risk factors, such as diabetes, obesity, and smoking.3 For transfeminine patients who want to continue GAHT but either develop a venous thromboembolism on estrogen or have increased risk for VTE, providers should consider transitioning them to a transdermal application. Patients who stay on GAHT should be counseled accordingly on the heightened risk of VTE recurrence. It is not unreasonable to consider life-long anticoagulation for patients who remain on estrogen therapy after a VTE.4

While exogenous estrogen exposure is one risk factor for the development of breast cancer in cisgender females, the role of GAHT in breast cancer in transgender women is ambiguous. Therefore, breast screening guidelines should follow current recommendations for cisgender female patients with some caveats. The provider must also take into consideration current estrogen dosage, the age at which hormones were initiated, and whether a patient has undergone an augmentation mammaplasty.3

Both estrogen and testosterone play an important role in bone formation and health. Patients who undergo either medical or surgical interventions that alter sex hormone production, such as GAHT, orchiectomy, or androgen blockade, may be at elevated risk for osteoporosis. Providers should take a thorough medical history to determine patients who may be at risk for osteoporosis and treat them accordingly. Overall, GAHT has a positive effect on bone mineral density. Conversely, gonadectomy, particularly if a patient is not taking GAHT, can decrease bone density. Generally, transgender women, like cisgender women, should undergo DEXA scans starting at the age of 65, with earlier screening considered if they have undergone an orchiectomy and are not currently taking GAHT.3

There is no evidence that GAHT or surgery increases the rate of prostate cancer. Providers should note that the prostate is not removed at the time of gender-affirming surgery and that malignancy or benign prostatic hypertrophy can still occur. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that clinicians have a discussion with cisgender men between the ages of 55 and 69 about the risks and benefits of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening.5 For cisgender men aged 70 and older, the USPSTF recommends against PSA-based screening.5 If digital examination of the prostate is warranted for transfeminine patients, the examination is performed through the neovaginal canal.

Caring for elderly transgender patients is complex. Even though evidence guiding the management of elderly transgender patients is improving, there are still not enough definitive long-term data on this dynamic demographic. Like clinical approaches with hormonal or surgical treatments, caring for transgender elders is also multidisciplinary. Providers should be prepared to work with social workers, geriatric care physicians, endocrinologists, surgeons, and other relevant specialists to assist with potential knowledge gaps. The goals for the aging transgender population are the same as those for cisgender patients – preventing preventable diseases and reducing overall mortality so our patients can enjoy their golden years.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa. Contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Carroll L. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2017;40:127-40.

2. Selix NW et al. Clinical care of the aging LGBT population. J Nurse Pract. 2020;16(7):349-54.

3. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people. 2022;8th version.

4. Shatzel JJ et al. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(2):204-8.

5. Wolf-Gould CS and Wolf-Gould CH. Primary and preventative care for transgender patients. In: Ferrando CA, ed. Comprehensive Care of the Transgender Patient. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020, p. 114-30.

The elderly transgender population is rapidly expanding and remains significantly overlooked. Although emerging evidence provides some guidance for medical and surgical treatment for transgender youth, there is still a paucity of research directed at the management of gender-diverse elders.

To a large extent, the challenges that transgender elders face are no different from those experienced by the general elder population. Irrespective of gender identity, patients begin to undergo cognitive and physical changes, encounter difficulties with activities of daily living, suffer the loss of social networks and friends, and face end-of-life issues.1 Attributes that contribute to successful aging in the general population include good health, social engagement and support, and having a positive outlook on life.1 Yet, stigma surrounding gender identity and sexual orientation continues to negatively affect elder transgender people.

Many members of the LGBTQIA+ population have higher rates of obesity, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, cardiovascular disease, substance abuse, depression, suicide, and intimate partner violence than the general same-age cohort.2 Compared with lesbian, gay, and bisexual elders of age-matched cohorts, transgender elders have significantly poorer overall physical health, disability, depressive symptoms, and perceived stress.2

Rates of sexually transmitted infections are also rising in the aging general population and increased by 30% between 2014 and 2017.2 There have been no current studies examining these rates in the LGBTQIA+ population. As providers interact more frequently with these patients, it’s not only essential to screen for conditions such as diabetes, lipid disorders, and sexually transmitted infections, but also to evaluate current gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) regimens and order appropriate screening tests.

Hormonal therapy for transfeminine patients should be continued as patients age. One of the biggest concerns providers have in continuing hormone therapy is the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and increasing thromboembolic risk, both of which tend to occur naturally as patients age. Overall, studies on the prevalence of CVD or stroke in gender-diverse individuals indicate an elevated risk independent of GAHT.3 While the overall rates of thromboembolic events are low in transfeminine populations, estrogen therapy does confer an increased risk. However, most transgender women who have experienced cardiac events or stroke were over the age of 50, had one or more CVD risk factors, or were using synthetic estrogens.3

How these studies affect screening is unclear. Current guidelines recommend using tailored risk-based calculators, which take into consideration the patient’s sex assigned at birth, hormone regimen, length of hormone usage, and additional modifiable risk factors, such as diabetes, obesity, and smoking.3 For transfeminine patients who want to continue GAHT but either develop a venous thromboembolism on estrogen or have increased risk for VTE, providers should consider transitioning them to a transdermal application. Patients who stay on GAHT should be counseled accordingly on the heightened risk of VTE recurrence. It is not unreasonable to consider life-long anticoagulation for patients who remain on estrogen therapy after a VTE.4

While exogenous estrogen exposure is one risk factor for the development of breast cancer in cisgender females, the role of GAHT in breast cancer in transgender women is ambiguous. Therefore, breast screening guidelines should follow current recommendations for cisgender female patients with some caveats. The provider must also take into consideration current estrogen dosage, the age at which hormones were initiated, and whether a patient has undergone an augmentation mammaplasty.3

Both estrogen and testosterone play an important role in bone formation and health. Patients who undergo either medical or surgical interventions that alter sex hormone production, such as GAHT, orchiectomy, or androgen blockade, may be at elevated risk for osteoporosis. Providers should take a thorough medical history to determine patients who may be at risk for osteoporosis and treat them accordingly. Overall, GAHT has a positive effect on bone mineral density. Conversely, gonadectomy, particularly if a patient is not taking GAHT, can decrease bone density. Generally, transgender women, like cisgender women, should undergo DEXA scans starting at the age of 65, with earlier screening considered if they have undergone an orchiectomy and are not currently taking GAHT.3

There is no evidence that GAHT or surgery increases the rate of prostate cancer. Providers should note that the prostate is not removed at the time of gender-affirming surgery and that malignancy or benign prostatic hypertrophy can still occur. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that clinicians have a discussion with cisgender men between the ages of 55 and 69 about the risks and benefits of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening.5 For cisgender men aged 70 and older, the USPSTF recommends against PSA-based screening.5 If digital examination of the prostate is warranted for transfeminine patients, the examination is performed through the neovaginal canal.

Caring for elderly transgender patients is complex. Even though evidence guiding the management of elderly transgender patients is improving, there are still not enough definitive long-term data on this dynamic demographic. Like clinical approaches with hormonal or surgical treatments, caring for transgender elders is also multidisciplinary. Providers should be prepared to work with social workers, geriatric care physicians, endocrinologists, surgeons, and other relevant specialists to assist with potential knowledge gaps. The goals for the aging transgender population are the same as those for cisgender patients – preventing preventable diseases and reducing overall mortality so our patients can enjoy their golden years.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa. Contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Carroll L. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2017;40:127-40.

2. Selix NW et al. Clinical care of the aging LGBT population. J Nurse Pract. 2020;16(7):349-54.

3. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people. 2022;8th version.

4. Shatzel JJ et al. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(2):204-8.

5. Wolf-Gould CS and Wolf-Gould CH. Primary and preventative care for transgender patients. In: Ferrando CA, ed. Comprehensive Care of the Transgender Patient. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020, p. 114-30.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines 2022: Management and treatment

In the United States and around the globe, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) remains one of the leading causes of death. In addition to new diagnostic guidelines, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2022 Report, or GOLD report, sets forth recommendations for management and treatment.

According to the GOLD report, initial management of COPD should aim at reducing exposure to risk factors such as smoking or other chemical exposures. In addition to medications, stable COPD patients should be evaluated for inhaler technique, adherence to prescribed therapies, smoking status, and continued exposure to other risk factors. Also, physical activity should be advised and pulmonary rehabilitation should be considered. Spirometry should be performed annually.

These guidelines offer very practical advice but often are difficult to implement in clinical practice. Everyone knows smoking is harmful and quitting provides huge health benefits, not only regarding COPD. However, nicotine is very addictive, and most smokers cannot just quit. Many need smoking cessation aids and counseling. Additionally, some smokers just don’t want to quit. Regarding workplace exposures, it often is not easy for someone just to change their job. Many are afraid to speak because they are afraid of losing their jobs. Everyone, not just patients with COPD, can benefit from increased physical activity, and all doctors know how difficult it is to motivate patients to do this.

The decision to initiate medications should be based on an individual patient’s symptoms and risk of exacerbations. In general, long-acting bronchodilators, including long-acting beta agonists (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), are preferred except when immediate relief of dyspnea is needed, and then short-acting bronchodilators should be used. Either a single long-acting or dual long-acting bronchodilator can be initiated. If a patient continues to have dyspnea on a single long-acting bronchodilator, treatment should be switched to a dual therapy.

In general, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are not recommended for stable COPD patients. If a patient has exacerbations despite appropriate treatment with LABAs, an ICS may be added to the LABA, the GOLD guidelines say. Oral corticosteroids are not recommended for long-term use. PDE4 inhibitors should be considered in patents with severe to very severe airflow obstruction, chronic bronchitis, and exacerbations. Macrolide antibiotics, especially azithromycin, can be considered in acute exacerbations. There is no evidence to support the use of antitussives and mucolytics are advised in only certain patients. Inhaled bronchodilators are advised over oral ones and theophylline is recommended when long-acting bronchodilators are unavailable or unaffordable.

In clinical practice, I see many patients treated based on symptomatology with spirometry testing not being done. This may help control many symptoms, but unless my patient has an accurate diagnosis, I won’t know if my patient is receiving the correct treatment.

It is important to keep in mind that COPD is a progressive disease and without appropriate treatment and monitoring, it will just get worse, and this is most likely to be irreversible.

Medications and treatment goals for patients with COPD

Patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency may benefit from the addition of alpha-1 antitrypsin augmentation therapy, the new guidelines say. In patients with severe disease experiencing dyspnea, oral and parental opioids can be considered. Medications that are used to treat primary pulmonary hypertension are not advised to treat pulmonary hypertension secondary to COPD.

The treatment goals of COPD should be to decrease severity of symptoms, reduce the occurrence of exacerbations, and improve exercise tolerance. Peripheral eosinophil counts can be used to guide the use of ICS to prevent exacerbations. However, the best predictor of exacerbations is previous exacerbations. Frequent exacerbations are defined as two or more annually. Additionally, deteriorating airflow is correlated with increased risk of exacerbations, hospitalizations, and death. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) alone lacks precision to predict exacerbations or death.

Vaccines and pulmonary rehabilitation recommended

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization recommend several vaccines for stable patients with COPD. Influenza vaccine was shown to reduce serious complications in COPD patients. Pneumococcal vaccines (PCV13 and PPSV23) reduced the likelihood of COPD exacerbations. The COVID-19 vaccine also has been effective at reducing hospitalizations, in particular ICU admissions, and death in patients with COPD. The CDC also recommends TdaP and Zoster vaccines.

An acute exacerbation of COPD occurs when a patient experiences worsening of respiratory symptoms that requires additional treatment, according to the updated GOLD guidelines. They are usually associated with increased airway inflammation, mucous productions, and trapping of gases. They are often triggered by viral infections, but bacterial and environment factors play a role as well. Less commonly, fungi such as Aspergillus can be observed as well. COPD exacerbations contribute to overall progression of the disease.

In patients with hypoxemia, supplemental oxygen should be titrated to a target O2 saturation of 88%-92%. It is important to follow blood gases to be sure adequate oxygenation is taking place while at the same time avoiding carbon dioxide retention and/or worsening acidosis. In patients with severe exacerbations whose dyspnea does not respond to initial emergency therapy, ICU admission is warranted. Other factors indicating the need for ICU admission include mental status changes, persistent or worsening hypoxemia, severe or worsening respiratory acidosis, the need for mechanical ventilation, and hemodynamic instability. Following an acute exacerbation, steps to prevent further exacerbations should be initiated.

Systemic glucocorticoids are indicated during acute exacerbations. They have been shown to hasten recovery time and improve functioning of the lungs as well as oxygenation. It is recommended to give prednisone 40 mg per day for 5 days. Antibiotics should be used in exacerbations if patients have dyspnea, sputum production, and purulence of the sputum or require mechanical ventilation. The choice of which antibiotic to use should be based on local bacterial resistance.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is an important component of COPD management. It incorporates exercise, education, and self-management aimed to change behavior and improve conditioning. The benefits of rehab have been shown to be considerable. The optimal length is 6-8 weeks. Palliative and end-of-life care are also very important factors to consider when treating COPD patients, according to the GOLD guidelines.

COPD is a very common disease and cause of mortality seen by family physicians. The GOLD report is an extensive document providing very clear guidelines and evidence to support these guidelines in every level of the treatment of COPD patients. As primary care doctors, we are often the first to treat patients with COPD and it is important to know the latest guidelines.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

In the United States and around the globe, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) remains one of the leading causes of death. In addition to new diagnostic guidelines, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2022 Report, or GOLD report, sets forth recommendations for management and treatment.

According to the GOLD report, initial management of COPD should aim at reducing exposure to risk factors such as smoking or other chemical exposures. In addition to medications, stable COPD patients should be evaluated for inhaler technique, adherence to prescribed therapies, smoking status, and continued exposure to other risk factors. Also, physical activity should be advised and pulmonary rehabilitation should be considered. Spirometry should be performed annually.

These guidelines offer very practical advice but often are difficult to implement in clinical practice. Everyone knows smoking is harmful and quitting provides huge health benefits, not only regarding COPD. However, nicotine is very addictive, and most smokers cannot just quit. Many need smoking cessation aids and counseling. Additionally, some smokers just don’t want to quit. Regarding workplace exposures, it often is not easy for someone just to change their job. Many are afraid to speak because they are afraid of losing their jobs. Everyone, not just patients with COPD, can benefit from increased physical activity, and all doctors know how difficult it is to motivate patients to do this.

The decision to initiate medications should be based on an individual patient’s symptoms and risk of exacerbations. In general, long-acting bronchodilators, including long-acting beta agonists (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), are preferred except when immediate relief of dyspnea is needed, and then short-acting bronchodilators should be used. Either a single long-acting or dual long-acting bronchodilator can be initiated. If a patient continues to have dyspnea on a single long-acting bronchodilator, treatment should be switched to a dual therapy.

In general, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are not recommended for stable COPD patients. If a patient has exacerbations despite appropriate treatment with LABAs, an ICS may be added to the LABA, the GOLD guidelines say. Oral corticosteroids are not recommended for long-term use. PDE4 inhibitors should be considered in patents with severe to very severe airflow obstruction, chronic bronchitis, and exacerbations. Macrolide antibiotics, especially azithromycin, can be considered in acute exacerbations. There is no evidence to support the use of antitussives and mucolytics are advised in only certain patients. Inhaled bronchodilators are advised over oral ones and theophylline is recommended when long-acting bronchodilators are unavailable or unaffordable.

In clinical practice, I see many patients treated based on symptomatology with spirometry testing not being done. This may help control many symptoms, but unless my patient has an accurate diagnosis, I won’t know if my patient is receiving the correct treatment.

It is important to keep in mind that COPD is a progressive disease and without appropriate treatment and monitoring, it will just get worse, and this is most likely to be irreversible.

Medications and treatment goals for patients with COPD

Patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency may benefit from the addition of alpha-1 antitrypsin augmentation therapy, the new guidelines say. In patients with severe disease experiencing dyspnea, oral and parental opioids can be considered. Medications that are used to treat primary pulmonary hypertension are not advised to treat pulmonary hypertension secondary to COPD.

The treatment goals of COPD should be to decrease severity of symptoms, reduce the occurrence of exacerbations, and improve exercise tolerance. Peripheral eosinophil counts can be used to guide the use of ICS to prevent exacerbations. However, the best predictor of exacerbations is previous exacerbations. Frequent exacerbations are defined as two or more annually. Additionally, deteriorating airflow is correlated with increased risk of exacerbations, hospitalizations, and death. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) alone lacks precision to predict exacerbations or death.

Vaccines and pulmonary rehabilitation recommended

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization recommend several vaccines for stable patients with COPD. Influenza vaccine was shown to reduce serious complications in COPD patients. Pneumococcal vaccines (PCV13 and PPSV23) reduced the likelihood of COPD exacerbations. The COVID-19 vaccine also has been effective at reducing hospitalizations, in particular ICU admissions, and death in patients with COPD. The CDC also recommends TdaP and Zoster vaccines.

An acute exacerbation of COPD occurs when a patient experiences worsening of respiratory symptoms that requires additional treatment, according to the updated GOLD guidelines. They are usually associated with increased airway inflammation, mucous productions, and trapping of gases. They are often triggered by viral infections, but bacterial and environment factors play a role as well. Less commonly, fungi such as Aspergillus can be observed as well. COPD exacerbations contribute to overall progression of the disease.

In patients with hypoxemia, supplemental oxygen should be titrated to a target O2 saturation of 88%-92%. It is important to follow blood gases to be sure adequate oxygenation is taking place while at the same time avoiding carbon dioxide retention and/or worsening acidosis. In patients with severe exacerbations whose dyspnea does not respond to initial emergency therapy, ICU admission is warranted. Other factors indicating the need for ICU admission include mental status changes, persistent or worsening hypoxemia, severe or worsening respiratory acidosis, the need for mechanical ventilation, and hemodynamic instability. Following an acute exacerbation, steps to prevent further exacerbations should be initiated.

Systemic glucocorticoids are indicated during acute exacerbations. They have been shown to hasten recovery time and improve functioning of the lungs as well as oxygenation. It is recommended to give prednisone 40 mg per day for 5 days. Antibiotics should be used in exacerbations if patients have dyspnea, sputum production, and purulence of the sputum or require mechanical ventilation. The choice of which antibiotic to use should be based on local bacterial resistance.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is an important component of COPD management. It incorporates exercise, education, and self-management aimed to change behavior and improve conditioning. The benefits of rehab have been shown to be considerable. The optimal length is 6-8 weeks. Palliative and end-of-life care are also very important factors to consider when treating COPD patients, according to the GOLD guidelines.

COPD is a very common disease and cause of mortality seen by family physicians. The GOLD report is an extensive document providing very clear guidelines and evidence to support these guidelines in every level of the treatment of COPD patients. As primary care doctors, we are often the first to treat patients with COPD and it is important to know the latest guidelines.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

In the United States and around the globe, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) remains one of the leading causes of death. In addition to new diagnostic guidelines, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2022 Report, or GOLD report, sets forth recommendations for management and treatment.

According to the GOLD report, initial management of COPD should aim at reducing exposure to risk factors such as smoking or other chemical exposures. In addition to medications, stable COPD patients should be evaluated for inhaler technique, adherence to prescribed therapies, smoking status, and continued exposure to other risk factors. Also, physical activity should be advised and pulmonary rehabilitation should be considered. Spirometry should be performed annually.

These guidelines offer very practical advice but often are difficult to implement in clinical practice. Everyone knows smoking is harmful and quitting provides huge health benefits, not only regarding COPD. However, nicotine is very addictive, and most smokers cannot just quit. Many need smoking cessation aids and counseling. Additionally, some smokers just don’t want to quit. Regarding workplace exposures, it often is not easy for someone just to change their job. Many are afraid to speak because they are afraid of losing their jobs. Everyone, not just patients with COPD, can benefit from increased physical activity, and all doctors know how difficult it is to motivate patients to do this.

The decision to initiate medications should be based on an individual patient’s symptoms and risk of exacerbations. In general, long-acting bronchodilators, including long-acting beta agonists (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), are preferred except when immediate relief of dyspnea is needed, and then short-acting bronchodilators should be used. Either a single long-acting or dual long-acting bronchodilator can be initiated. If a patient continues to have dyspnea on a single long-acting bronchodilator, treatment should be switched to a dual therapy.

In general, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are not recommended for stable COPD patients. If a patient has exacerbations despite appropriate treatment with LABAs, an ICS may be added to the LABA, the GOLD guidelines say. Oral corticosteroids are not recommended for long-term use. PDE4 inhibitors should be considered in patents with severe to very severe airflow obstruction, chronic bronchitis, and exacerbations. Macrolide antibiotics, especially azithromycin, can be considered in acute exacerbations. There is no evidence to support the use of antitussives and mucolytics are advised in only certain patients. Inhaled bronchodilators are advised over oral ones and theophylline is recommended when long-acting bronchodilators are unavailable or unaffordable.

In clinical practice, I see many patients treated based on symptomatology with spirometry testing not being done. This may help control many symptoms, but unless my patient has an accurate diagnosis, I won’t know if my patient is receiving the correct treatment.

It is important to keep in mind that COPD is a progressive disease and without appropriate treatment and monitoring, it will just get worse, and this is most likely to be irreversible.

Medications and treatment goals for patients with COPD

Patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency may benefit from the addition of alpha-1 antitrypsin augmentation therapy, the new guidelines say. In patients with severe disease experiencing dyspnea, oral and parental opioids can be considered. Medications that are used to treat primary pulmonary hypertension are not advised to treat pulmonary hypertension secondary to COPD.

The treatment goals of COPD should be to decrease severity of symptoms, reduce the occurrence of exacerbations, and improve exercise tolerance. Peripheral eosinophil counts can be used to guide the use of ICS to prevent exacerbations. However, the best predictor of exacerbations is previous exacerbations. Frequent exacerbations are defined as two or more annually. Additionally, deteriorating airflow is correlated with increased risk of exacerbations, hospitalizations, and death. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) alone lacks precision to predict exacerbations or death.

Vaccines and pulmonary rehabilitation recommended

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization recommend several vaccines for stable patients with COPD. Influenza vaccine was shown to reduce serious complications in COPD patients. Pneumococcal vaccines (PCV13 and PPSV23) reduced the likelihood of COPD exacerbations. The COVID-19 vaccine also has been effective at reducing hospitalizations, in particular ICU admissions, and death in patients with COPD. The CDC also recommends TdaP and Zoster vaccines.

An acute exacerbation of COPD occurs when a patient experiences worsening of respiratory symptoms that requires additional treatment, according to the updated GOLD guidelines. They are usually associated with increased airway inflammation, mucous productions, and trapping of gases. They are often triggered by viral infections, but bacterial and environment factors play a role as well. Less commonly, fungi such as Aspergillus can be observed as well. COPD exacerbations contribute to overall progression of the disease.

In patients with hypoxemia, supplemental oxygen should be titrated to a target O2 saturation of 88%-92%. It is important to follow blood gases to be sure adequate oxygenation is taking place while at the same time avoiding carbon dioxide retention and/or worsening acidosis. In patients with severe exacerbations whose dyspnea does not respond to initial emergency therapy, ICU admission is warranted. Other factors indicating the need for ICU admission include mental status changes, persistent or worsening hypoxemia, severe or worsening respiratory acidosis, the need for mechanical ventilation, and hemodynamic instability. Following an acute exacerbation, steps to prevent further exacerbations should be initiated.

Systemic glucocorticoids are indicated during acute exacerbations. They have been shown to hasten recovery time and improve functioning of the lungs as well as oxygenation. It is recommended to give prednisone 40 mg per day for 5 days. Antibiotics should be used in exacerbations if patients have dyspnea, sputum production, and purulence of the sputum or require mechanical ventilation. The choice of which antibiotic to use should be based on local bacterial resistance.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is an important component of COPD management. It incorporates exercise, education, and self-management aimed to change behavior and improve conditioning. The benefits of rehab have been shown to be considerable. The optimal length is 6-8 weeks. Palliative and end-of-life care are also very important factors to consider when treating COPD patients, according to the GOLD guidelines.

COPD is a very common disease and cause of mortality seen by family physicians. The GOLD report is an extensive document providing very clear guidelines and evidence to support these guidelines in every level of the treatment of COPD patients. As primary care doctors, we are often the first to treat patients with COPD and it is important to know the latest guidelines.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. You can contact her at [email protected].

Germline genetic testing: Why it matters and where we are failing

Historically, the role of genetic testing has been to identify familial cancer syndromes and initiate cascade testing. If a germline pathogenic variant is found in an individual, cascade testing involves genetic counseling and testing of blood relatives, starting with those closest in relation to the proband, to identify other family members at high hereditary cancer risk. Once testing identifies those family members at higher cancer risk, these individuals can be referred for risk-reducing procedures. They can undergo screening tests starting at an earlier age and/or increased frequency to help prevent invasive cancer or diagnose it at an earlier stage.

Genetic testing can also inform prognosis. While women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation are at higher risk of developing ovarian cancer compared with the baseline population, the presence of a germline BRCA mutation has been shown to confer improved survival compared with no BRCA mutation (BRCA wild type). However, more recent data have shown that when long-term survival was analyzed, the prognostic benefit seen in patients with a germline BRCA mutation was lost. The initial survival advantage seen in this population may be related to increased sensitivity to treatment. There appears to be improved response to platinum therapy, which is the standard of care for upfront treatment, in germline BRCA mutation carriers.

Most recently, genetic testing has been used to guide treatment decisions in gynecologic cancers. In 2014, the first poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, olaparib, received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer in the presence of a germline BRCA mutation. Now there are multiple PARP inhibitors that have FDA approval for ovarian cancer treatment, some as frontline treatment.

Previous data indicate that 13%-18% of women with ovarian cancer have a germline BRCA mutation that places them at increased risk of hereditary ovarian cancer.1 Current guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend universal genetic counseling and testing for patients diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer. Despite these guidelines, rates of referral for genetic counseling and completion of genetic testing are low.

There has been improvement for both referrals and testing since the publication of the 2014 SGO clinical practice statement on genetic testing for ovarian cancer patients, which recommended that all women, even those without any significant family history, should receive genetic counseling and be offered genetic testing.2 When including only studies that collected data after the publication of the 2014 SGO clinical practice statement on genetic testing, a recent systematic review found that 64% of patients were referred for genetic counseling and 63% underwent testing.3

Clinical interventions to target genetic evaluation appear to improve uptake of both counseling and testing. These interventions include using telemedicine to deliver genetic counseling services, mainstreaming (counseling and testing are provided in an oncology clinic by nongenetics specialists), having a genetic counselor within the clinic, and performing reflex testing. With limited numbers of genetic counselors (and even further limited numbers of cancer-specific genetic counselors),4 referral for genetic counseling before testing is often challenging and may not be feasible. There is continued need for strategies to help overcome the barrier to accessing genetic counseling.

While the data are limited, there appear to be significant disparities in rates of genetic testing. Genetic counseling and testing were completed by White (43% and 40%) patients more frequently than by either Black (24% and 26%) or Asian (23% and 14%) patients.4 Uninsured patients were about half as likely (23% vs. 47%) to complete genetic testing as were those with private insurance.4

Genetic testing is an important tool to help identify individuals and families at risk of having hereditary cancer syndromes. This identification allows us to prevent many cancers and identify others while still early stage, significantly decreasing the health care and financial burden on our society and improving outcomes for patients. While we have seen improvement in rates of referral for genetic counseling and testing, we are still falling short. Given the shortage of genetic counselors, it is imperative that we find solutions to ensure continued and improved access to genetic testing for our patients.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Norquist BM et al. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(4):482-90.

2. SGO Clinical Practice Statement. 2014 Oct 1.

3. Lin J et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162(2):506-16.

4. American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2016 Apr;12(4):339-83.

Historically, the role of genetic testing has been to identify familial cancer syndromes and initiate cascade testing. If a germline pathogenic variant is found in an individual, cascade testing involves genetic counseling and testing of blood relatives, starting with those closest in relation to the proband, to identify other family members at high hereditary cancer risk. Once testing identifies those family members at higher cancer risk, these individuals can be referred for risk-reducing procedures. They can undergo screening tests starting at an earlier age and/or increased frequency to help prevent invasive cancer or diagnose it at an earlier stage.

Genetic testing can also inform prognosis. While women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation are at higher risk of developing ovarian cancer compared with the baseline population, the presence of a germline BRCA mutation has been shown to confer improved survival compared with no BRCA mutation (BRCA wild type). However, more recent data have shown that when long-term survival was analyzed, the prognostic benefit seen in patients with a germline BRCA mutation was lost. The initial survival advantage seen in this population may be related to increased sensitivity to treatment. There appears to be improved response to platinum therapy, which is the standard of care for upfront treatment, in germline BRCA mutation carriers.

Most recently, genetic testing has been used to guide treatment decisions in gynecologic cancers. In 2014, the first poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, olaparib, received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer in the presence of a germline BRCA mutation. Now there are multiple PARP inhibitors that have FDA approval for ovarian cancer treatment, some as frontline treatment.

Previous data indicate that 13%-18% of women with ovarian cancer have a germline BRCA mutation that places them at increased risk of hereditary ovarian cancer.1 Current guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend universal genetic counseling and testing for patients diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer. Despite these guidelines, rates of referral for genetic counseling and completion of genetic testing are low.

There has been improvement for both referrals and testing since the publication of the 2014 SGO clinical practice statement on genetic testing for ovarian cancer patients, which recommended that all women, even those without any significant family history, should receive genetic counseling and be offered genetic testing.2 When including only studies that collected data after the publication of the 2014 SGO clinical practice statement on genetic testing, a recent systematic review found that 64% of patients were referred for genetic counseling and 63% underwent testing.3

Clinical interventions to target genetic evaluation appear to improve uptake of both counseling and testing. These interventions include using telemedicine to deliver genetic counseling services, mainstreaming (counseling and testing are provided in an oncology clinic by nongenetics specialists), having a genetic counselor within the clinic, and performing reflex testing. With limited numbers of genetic counselors (and even further limited numbers of cancer-specific genetic counselors),4 referral for genetic counseling before testing is often challenging and may not be feasible. There is continued need for strategies to help overcome the barrier to accessing genetic counseling.

While the data are limited, there appear to be significant disparities in rates of genetic testing. Genetic counseling and testing were completed by White (43% and 40%) patients more frequently than by either Black (24% and 26%) or Asian (23% and 14%) patients.4 Uninsured patients were about half as likely (23% vs. 47%) to complete genetic testing as were those with private insurance.4

Genetic testing is an important tool to help identify individuals and families at risk of having hereditary cancer syndromes. This identification allows us to prevent many cancers and identify others while still early stage, significantly decreasing the health care and financial burden on our society and improving outcomes for patients. While we have seen improvement in rates of referral for genetic counseling and testing, we are still falling short. Given the shortage of genetic counselors, it is imperative that we find solutions to ensure continued and improved access to genetic testing for our patients.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Norquist BM et al. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(4):482-90.

2. SGO Clinical Practice Statement. 2014 Oct 1.

3. Lin J et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162(2):506-16.

4. American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2016 Apr;12(4):339-83.

Historically, the role of genetic testing has been to identify familial cancer syndromes and initiate cascade testing. If a germline pathogenic variant is found in an individual, cascade testing involves genetic counseling and testing of blood relatives, starting with those closest in relation to the proband, to identify other family members at high hereditary cancer risk. Once testing identifies those family members at higher cancer risk, these individuals can be referred for risk-reducing procedures. They can undergo screening tests starting at an earlier age and/or increased frequency to help prevent invasive cancer or diagnose it at an earlier stage.

Genetic testing can also inform prognosis. While women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation are at higher risk of developing ovarian cancer compared with the baseline population, the presence of a germline BRCA mutation has been shown to confer improved survival compared with no BRCA mutation (BRCA wild type). However, more recent data have shown that when long-term survival was analyzed, the prognostic benefit seen in patients with a germline BRCA mutation was lost. The initial survival advantage seen in this population may be related to increased sensitivity to treatment. There appears to be improved response to platinum therapy, which is the standard of care for upfront treatment, in germline BRCA mutation carriers.

Most recently, genetic testing has been used to guide treatment decisions in gynecologic cancers. In 2014, the first poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, olaparib, received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer in the presence of a germline BRCA mutation. Now there are multiple PARP inhibitors that have FDA approval for ovarian cancer treatment, some as frontline treatment.

Previous data indicate that 13%-18% of women with ovarian cancer have a germline BRCA mutation that places them at increased risk of hereditary ovarian cancer.1 Current guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend universal genetic counseling and testing for patients diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer. Despite these guidelines, rates of referral for genetic counseling and completion of genetic testing are low.

There has been improvement for both referrals and testing since the publication of the 2014 SGO clinical practice statement on genetic testing for ovarian cancer patients, which recommended that all women, even those without any significant family history, should receive genetic counseling and be offered genetic testing.2 When including only studies that collected data after the publication of the 2014 SGO clinical practice statement on genetic testing, a recent systematic review found that 64% of patients were referred for genetic counseling and 63% underwent testing.3

Clinical interventions to target genetic evaluation appear to improve uptake of both counseling and testing. These interventions include using telemedicine to deliver genetic counseling services, mainstreaming (counseling and testing are provided in an oncology clinic by nongenetics specialists), having a genetic counselor within the clinic, and performing reflex testing. With limited numbers of genetic counselors (and even further limited numbers of cancer-specific genetic counselors),4 referral for genetic counseling before testing is often challenging and may not be feasible. There is continued need for strategies to help overcome the barrier to accessing genetic counseling.

While the data are limited, there appear to be significant disparities in rates of genetic testing. Genetic counseling and testing were completed by White (43% and 40%) patients more frequently than by either Black (24% and 26%) or Asian (23% and 14%) patients.4 Uninsured patients were about half as likely (23% vs. 47%) to complete genetic testing as were those with private insurance.4

Genetic testing is an important tool to help identify individuals and families at risk of having hereditary cancer syndromes. This identification allows us to prevent many cancers and identify others while still early stage, significantly decreasing the health care and financial burden on our society and improving outcomes for patients. While we have seen improvement in rates of referral for genetic counseling and testing, we are still falling short. Given the shortage of genetic counselors, it is imperative that we find solutions to ensure continued and improved access to genetic testing for our patients.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Norquist BM et al. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(4):482-90.

2. SGO Clinical Practice Statement. 2014 Oct 1.

3. Lin J et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162(2):506-16.

4. American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2016 Apr;12(4):339-83.

Rules for performing research with children

The road to hell is paved with good intentions – especially true in clinical research. A Food and Drug Administration press release notes, “Historically, children were not included in clinical trials because of a misperception that excluding them from research was in fact protecting them. This resulted in many FDA-approved, licensed, cleared, or authorized drugs, biological products, and medical devices lacking pediatric-specific labeling information.” In an effort to improve on this situation, the FDA published in September 2022 a proposed new draft guidance on performing research with children that is open for public comment for 3 months.

There is a long history of government attempts to promote research and development for the benefit of society. Sometimes government succeeds and sometimes not. For instance, when the U.S. federal government funded scientific research in the 1960s, it sought to increase the common good by promulgating those discoveries. The government insisted that all federally funded research be in the public domain. The funding produced a spectacular number of technological advancements that have enriched society. However, a decade later, the government concluded that too many good research ideas were never developed into beneficial products because without the ability to patent the results, the costs and risks of product development were not profitable for industry. By the late 1970s, new laws were enacted to enable universities and their faculty to patent the results of government-funded research and share in any wealth created.

Pharmaceutical research in the 1970s and 1980s was mostly performed on men in order to reduce the risk of giving treatments of unknown safety to pregnant women. The unintended consequence was that the new drugs frequently were less effective for women. This was particularly true for cardiac medications for which lifestyle risk factors differed between the sexes.

Similarly, children were often excluded from research because of the unknown risks of new drugs on growing bodies and brains. Children were also seen as a vulnerable population for whom informed consent was problematic. The result of these well-intentioned restrictions was the creation of new products that did not have pediatric dosing recommendations, pediatric safety assessments, or approval for pediatric indications. To remediate these deficiencies, in 1997 and 2007 the FDA offered a 6-month extension on patent protection as motivation for companies to develop those pediatric recommendations. Alas, those laws were primarily used to extend the profitability of blockbuster products rather than truly benefit children.

Over the past 4 decades, pediatric ethicists proposed and refined rules to govern research on children. The Common Rule used by institutional review boards (IRBs) to protect human research subjects was expanded with guidelines covering children. The new draft guidance is the latest iteration of this effort. Nothing in the 14 pages of draft regulation appears revolutionary to me. The ideas are tweaks, based on theory and experience, of principles agreed upon 30 years ago. Finding the optimal social moral contract involves some empirical assessment of praxis and effectiveness.

I am loathe to summarize this new document, which itself is a summary of a vast body of literature, that supports the Code of Federal Regulations Title 21 Part 50 and 45 CFR Part 46. The draft document is well organized and I recommend it as an excellent primer for the area of pediatric research ethics if the subject is new to you. I also recommend it as required reading for anyone serving on an IRB.

IRBs usually review and approve any research on people. Generally, the selection of people for research should be done equitably. However, children should not be enrolled unless it is necessary to answer an important question relevant to children. For the past 2 decades, there has been an emphasis on obtaining the assent of the child as well as informed consent by the parents.

An important determination is whether the research is likely to help that particular child or whether it is aimed at advancing general knowledge. If there is no prospect of direct benefit, research is still permissible but more restricted for safety and comfort reasons. Next is determining whether the research carries only minimal risk or a minor increase over minimal risk. The draft defines and provides anchor examples of these situations. For instance, oral placebos and single blood draws are typically minimal risk. Multiple injections and blood draws over a year fall into the second category. One MRI is minimal risk but a minor increase in risk if it involves sedation or contrast.

I strongly support the ideals expressed in these guidelines. They represent the best blend of intentions and practical experience. They will become the law of the land. In ethics, there is merit in striving to do things properly, orderly, and enforceably.

The cynic in me sees two weaknesses in the stated approach. First, the volume of harm to children occurring during organized clinical research is extremely small. The greater harms come from off-label use, nonsystematic research, and the ignorance resulting from a lack of research. Second, my observation in all endeavors of morality is, “Raise the bar high enough and people walk under it.”

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

The road to hell is paved with good intentions – especially true in clinical research. A Food and Drug Administration press release notes, “Historically, children were not included in clinical trials because of a misperception that excluding them from research was in fact protecting them. This resulted in many FDA-approved, licensed, cleared, or authorized drugs, biological products, and medical devices lacking pediatric-specific labeling information.” In an effort to improve on this situation, the FDA published in September 2022 a proposed new draft guidance on performing research with children that is open for public comment for 3 months.

There is a long history of government attempts to promote research and development for the benefit of society. Sometimes government succeeds and sometimes not. For instance, when the U.S. federal government funded scientific research in the 1960s, it sought to increase the common good by promulgating those discoveries. The government insisted that all federally funded research be in the public domain. The funding produced a spectacular number of technological advancements that have enriched society. However, a decade later, the government concluded that too many good research ideas were never developed into beneficial products because without the ability to patent the results, the costs and risks of product development were not profitable for industry. By the late 1970s, new laws were enacted to enable universities and their faculty to patent the results of government-funded research and share in any wealth created.

Pharmaceutical research in the 1970s and 1980s was mostly performed on men in order to reduce the risk of giving treatments of unknown safety to pregnant women. The unintended consequence was that the new drugs frequently were less effective for women. This was particularly true for cardiac medications for which lifestyle risk factors differed between the sexes.

Similarly, children were often excluded from research because of the unknown risks of new drugs on growing bodies and brains. Children were also seen as a vulnerable population for whom informed consent was problematic. The result of these well-intentioned restrictions was the creation of new products that did not have pediatric dosing recommendations, pediatric safety assessments, or approval for pediatric indications. To remediate these deficiencies, in 1997 and 2007 the FDA offered a 6-month extension on patent protection as motivation for companies to develop those pediatric recommendations. Alas, those laws were primarily used to extend the profitability of blockbuster products rather than truly benefit children.

Over the past 4 decades, pediatric ethicists proposed and refined rules to govern research on children. The Common Rule used by institutional review boards (IRBs) to protect human research subjects was expanded with guidelines covering children. The new draft guidance is the latest iteration of this effort. Nothing in the 14 pages of draft regulation appears revolutionary to me. The ideas are tweaks, based on theory and experience, of principles agreed upon 30 years ago. Finding the optimal social moral contract involves some empirical assessment of praxis and effectiveness.

I am loathe to summarize this new document, which itself is a summary of a vast body of literature, that supports the Code of Federal Regulations Title 21 Part 50 and 45 CFR Part 46. The draft document is well organized and I recommend it as an excellent primer for the area of pediatric research ethics if the subject is new to you. I also recommend it as required reading for anyone serving on an IRB.

IRBs usually review and approve any research on people. Generally, the selection of people for research should be done equitably. However, children should not be enrolled unless it is necessary to answer an important question relevant to children. For the past 2 decades, there has been an emphasis on obtaining the assent of the child as well as informed consent by the parents.

An important determination is whether the research is likely to help that particular child or whether it is aimed at advancing general knowledge. If there is no prospect of direct benefit, research is still permissible but more restricted for safety and comfort reasons. Next is determining whether the research carries only minimal risk or a minor increase over minimal risk. The draft defines and provides anchor examples of these situations. For instance, oral placebos and single blood draws are typically minimal risk. Multiple injections and blood draws over a year fall into the second category. One MRI is minimal risk but a minor increase in risk if it involves sedation or contrast.

I strongly support the ideals expressed in these guidelines. They represent the best blend of intentions and practical experience. They will become the law of the land. In ethics, there is merit in striving to do things properly, orderly, and enforceably.

The cynic in me sees two weaknesses in the stated approach. First, the volume of harm to children occurring during organized clinical research is extremely small. The greater harms come from off-label use, nonsystematic research, and the ignorance resulting from a lack of research. Second, my observation in all endeavors of morality is, “Raise the bar high enough and people walk under it.”

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

The road to hell is paved with good intentions – especially true in clinical research. A Food and Drug Administration press release notes, “Historically, children were not included in clinical trials because of a misperception that excluding them from research was in fact protecting them. This resulted in many FDA-approved, licensed, cleared, or authorized drugs, biological products, and medical devices lacking pediatric-specific labeling information.” In an effort to improve on this situation, the FDA published in September 2022 a proposed new draft guidance on performing research with children that is open for public comment for 3 months.

There is a long history of government attempts to promote research and development for the benefit of society. Sometimes government succeeds and sometimes not. For instance, when the U.S. federal government funded scientific research in the 1960s, it sought to increase the common good by promulgating those discoveries. The government insisted that all federally funded research be in the public domain. The funding produced a spectacular number of technological advancements that have enriched society. However, a decade later, the government concluded that too many good research ideas were never developed into beneficial products because without the ability to patent the results, the costs and risks of product development were not profitable for industry. By the late 1970s, new laws were enacted to enable universities and their faculty to patent the results of government-funded research and share in any wealth created.

Pharmaceutical research in the 1970s and 1980s was mostly performed on men in order to reduce the risk of giving treatments of unknown safety to pregnant women. The unintended consequence was that the new drugs frequently were less effective for women. This was particularly true for cardiac medications for which lifestyle risk factors differed between the sexes.

Similarly, children were often excluded from research because of the unknown risks of new drugs on growing bodies and brains. Children were also seen as a vulnerable population for whom informed consent was problematic. The result of these well-intentioned restrictions was the creation of new products that did not have pediatric dosing recommendations, pediatric safety assessments, or approval for pediatric indications. To remediate these deficiencies, in 1997 and 2007 the FDA offered a 6-month extension on patent protection as motivation for companies to develop those pediatric recommendations. Alas, those laws were primarily used to extend the profitability of blockbuster products rather than truly benefit children.

Over the past 4 decades, pediatric ethicists proposed and refined rules to govern research on children. The Common Rule used by institutional review boards (IRBs) to protect human research subjects was expanded with guidelines covering children. The new draft guidance is the latest iteration of this effort. Nothing in the 14 pages of draft regulation appears revolutionary to me. The ideas are tweaks, based on theory and experience, of principles agreed upon 30 years ago. Finding the optimal social moral contract involves some empirical assessment of praxis and effectiveness.

I am loathe to summarize this new document, which itself is a summary of a vast body of literature, that supports the Code of Federal Regulations Title 21 Part 50 and 45 CFR Part 46. The draft document is well organized and I recommend it as an excellent primer for the area of pediatric research ethics if the subject is new to you. I also recommend it as required reading for anyone serving on an IRB.

IRBs usually review and approve any research on people. Generally, the selection of people for research should be done equitably. However, children should not be enrolled unless it is necessary to answer an important question relevant to children. For the past 2 decades, there has been an emphasis on obtaining the assent of the child as well as informed consent by the parents.

An important determination is whether the research is likely to help that particular child or whether it is aimed at advancing general knowledge. If there is no prospect of direct benefit, research is still permissible but more restricted for safety and comfort reasons. Next is determining whether the research carries only minimal risk or a minor increase over minimal risk. The draft defines and provides anchor examples of these situations. For instance, oral placebos and single blood draws are typically minimal risk. Multiple injections and blood draws over a year fall into the second category. One MRI is minimal risk but a minor increase in risk if it involves sedation or contrast.

I strongly support the ideals expressed in these guidelines. They represent the best blend of intentions and practical experience. They will become the law of the land. In ethics, there is merit in striving to do things properly, orderly, and enforceably.

The cynic in me sees two weaknesses in the stated approach. First, the volume of harm to children occurring during organized clinical research is extremely small. The greater harms come from off-label use, nonsystematic research, and the ignorance resulting from a lack of research. Second, my observation in all endeavors of morality is, “Raise the bar high enough and people walk under it.”

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

Why the 5-day isolation period for COVID makes no sense

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

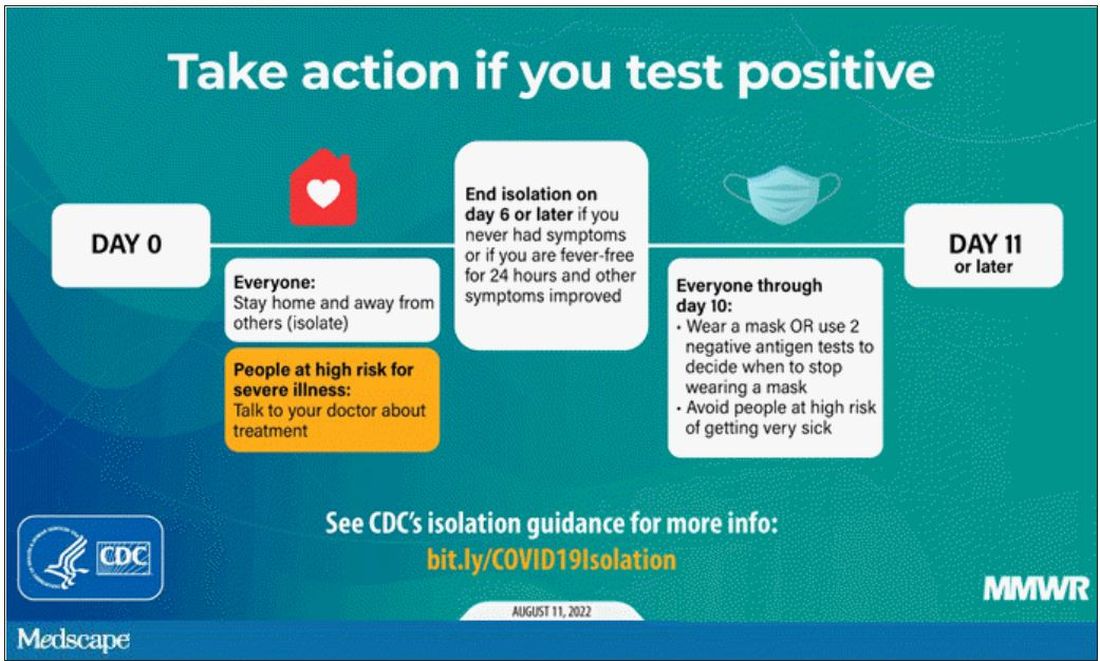

One of the more baffling decisions the CDC made during this pandemic was when they reduced the duration of isolation after a positive COVID test from 10 days to 5 days and did not require a negative antigen test to end isolation.

Multiple studies had suggested, after all, that positive antigen tests, while not perfect, were a decent proxy for infectivity. And if the purpose of isolation is to keep other community members safe, why not use a readily available test to know when it might be safe to go out in public again?

Also, 5 days just wasn’t that much time. Many individuals are symptomatic long after that point. Many people test positive long after that point. What exactly is the point of the 5-day isolation period?

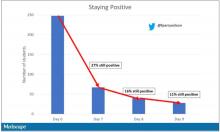

We got some hard numbers this week to show just how good (or bad) an arbitrary-seeming 5-day isolation period is, thanks to this study from JAMA Network Open, which gives us a low-end estimate for the proportion of people who remain positive on antigen tests, which is to say infectious, after an isolation period.

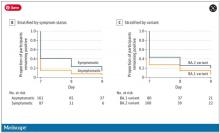

This study estimates the low end of postisolation infectivity because of the study population: student athletes at an NCAA Division I school, which may or may not be Stanford. These athletes tested positive for COVID after having at least one dose of vaccine from January to May 2022. School protocol was to put the students in isolation for 7 days, at which time they could “test out” with a negative antigen test.

Put simply, these were healthy people. They were young. They were athletes. They were vaccinated. If anyone is going to have a brief, easy COVID course, it would be them. And they are doing at least a week of isolation, not 5 days.

So – isolation for 7 days. Antigen testing on day 7. How many still tested positive? Of 248 individuals tested, 67 (27%) tested positive. One in four.

More than half of those positive on day 7 tested positive on day 8, and more than half of those tested positive again on day 9. By day 10, they were released from isolation without further testing.

So, right there .

There were some predictors of prolonged positivity.

Symptomatic athletes were much more likely to test positive than asymptomatic athletes.

And the particular variant seemed to matter as well. In this time period, BA.1 and BA.2 were dominant, and it was pretty clear that BA.2 persisted longer than BA.1.

This brings me back to my original question: What is the point of the 5-day isolation period? On the basis of this study, you could imagine a guideline based on symptoms: Stay home until you feel better. You could imagine a guideline based on testing: Stay home until you test negative. A guideline based on time alone just doesn’t comport with the data. The benefit of policies based on symptoms or testing are obvious; some people would be out of isolation even before 5 days. But the downside, of course, is that some people would be stuck in isolation for much longer.

Maybe we should just say it. At this point, you could even imagine there being no recommendation at all – no isolation period. Like, you just stay home if you feel like you should stay home. I’m not entirely sure that such a policy would necessarily result in a greater number of infectious people out in the community.

In any case, as the arbitrariness of this particular 5-day isolation policy becomes more clear, the policy itself may be living on borrowed time.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and hosts a repository of his communication work at www.methodsman.com. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.