User login

More Young Women Being Diagnosed With Breast Cancer Than Ever Before

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

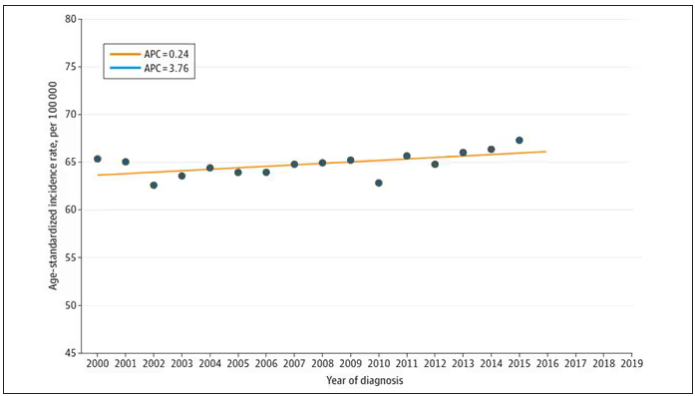

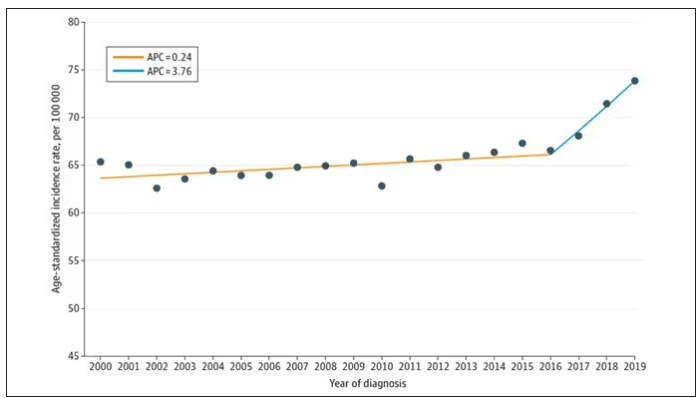

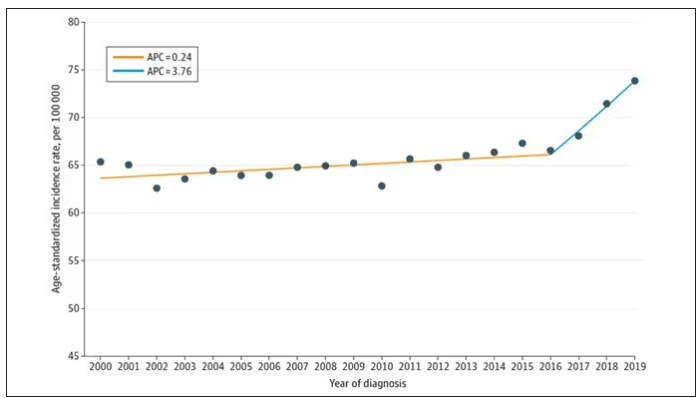

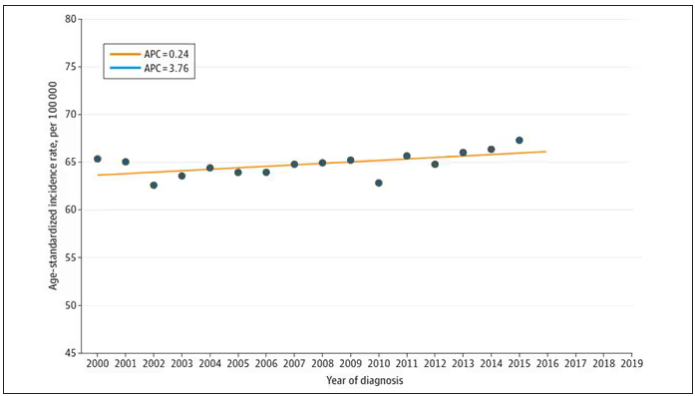

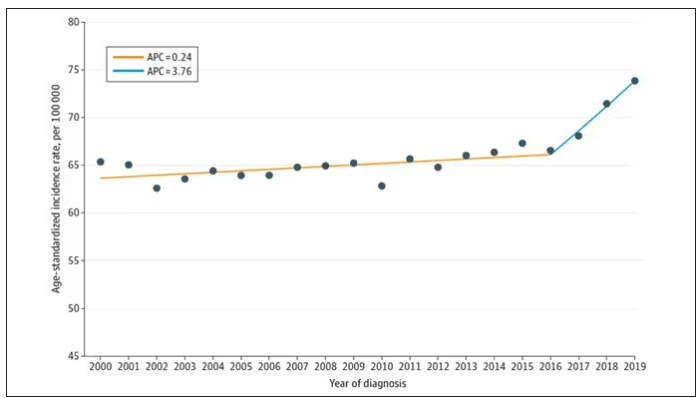

From the year 2000 until around 2016, the incidence of breast cancer among young women — those under age 50 — rose steadily, if slowly.

And then this happened:

I look at a lot of graphs in my line of work, and it’s not too often that one actually makes me say “What the hell?” out loud. But this one did. Why are young women all of a sudden more likely to get breast cancer?

The graph comes from this paper, Breast cancer incidence among us women aged 20 to 49 years by race, stage, and hormone receptor status, appearing in JAMA Network Open

Researchers from Washington University in St. Louis utilized SEER registries to conduct their analyses. SEER is a public database from the National Cancer Institute with coverage of 27% of the US population and a long track record of statistical backbone to translate the data from SEER to numbers that are representative of the population at large.

From 2000 to 2019, more than 200,000 women were diagnosed with primary invasive breast cancer in the dataset, and I’ve already given you the top-line results. Of course, when you see a graph like this, the next question really needs to be why?

Fortunately, the SEER dataset contains a lot more information than simply whether someone was diagnosed with cancer. In the case of breast cancer, there is information about the patient’s demographics, the hormone status of the cancer, the stage, and so on. Using those additional data points can help the authors, and us, start to formulate some hypotheses as to what is happening here.

Let’s start with something a bit tricky about this kind of data. We see an uptick in new breast cancer diagnoses among young women in recent years. We need to tease that uptick apart a bit. It could be that it is the year that is the key factor here. In other words, it is simply that more women are getting breast cancer since 2016 and so more young women are getting breast cancer since 2016. These are known as period effects.

Or is there something unique to young women — something about their environmental exposures that put them at higher risk than they would have been had they been born at some other time? These are known as cohort effects.

The researchers teased these two effects apart, as you can see here, and concluded that, well, it’s both.

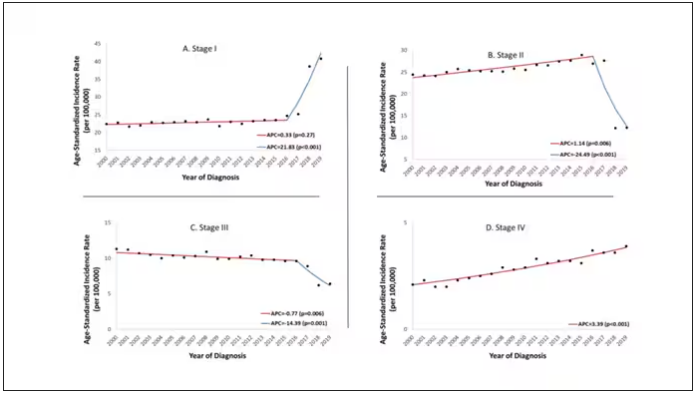

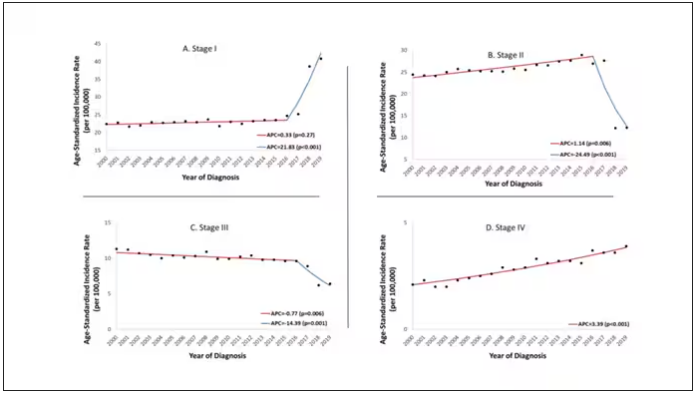

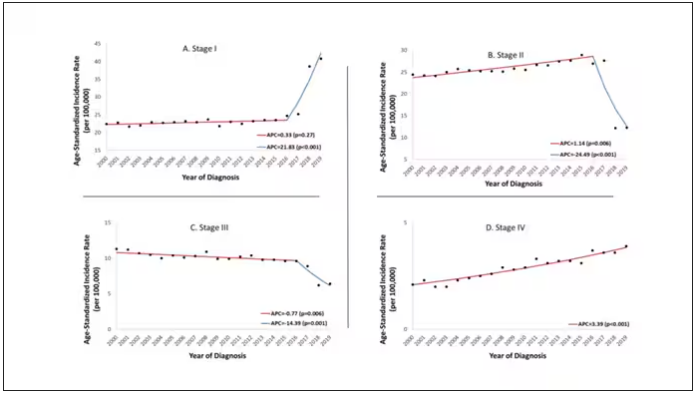

Stage of cancer at diagnosis can give us some more insight into what is happening. These results are pretty interesting. These higher cancer rates are due primarily to stage I and stage IV cancers, not stage II and stage III cancers.

The rising incidence of stage I cancers could reflect better detection, though many of the women in this cohort would not have been old enough to quality for screening mammograms. That said, increased awareness about genetic risk and family history might be leading younger women to get screened, picking up more early cancers. Additionally, much of the increased incidence was with estrogen receptor–positive tumors, which might reflect the fact that women in this cohort are tending to have fewer children, and children later in life.

So why the rise in stage IV breast cancer? Well, precisely because younger women are not recommended to get screening mammograms; those who detect a lump on their own are likely to be at a more advanced stage. But I’m not sure why that would be changing recently. The authors argue that an increase in overweight and obesity in the country might be to blame here. Prior studies have shown that higher BMI is associated with higher stage at breast cancer diagnosis.

Of course, we can speculate as to multiple other causes as well: environmental toxins, pollution, hormone exposures, and so on. Figuring this out will be the work of multiple other studies. In the meantime, we should remember that the landscape of cancer is continuously changing. And that means we need to adapt to it. If these trends continue, national agencies may need to reconsider their guidelines for when screening mammography should begin — at least in some groups of young women.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

From the year 2000 until around 2016, the incidence of breast cancer among young women — those under age 50 — rose steadily, if slowly.

And then this happened:

I look at a lot of graphs in my line of work, and it’s not too often that one actually makes me say “What the hell?” out loud. But this one did. Why are young women all of a sudden more likely to get breast cancer?

The graph comes from this paper, Breast cancer incidence among us women aged 20 to 49 years by race, stage, and hormone receptor status, appearing in JAMA Network Open

Researchers from Washington University in St. Louis utilized SEER registries to conduct their analyses. SEER is a public database from the National Cancer Institute with coverage of 27% of the US population and a long track record of statistical backbone to translate the data from SEER to numbers that are representative of the population at large.

From 2000 to 2019, more than 200,000 women were diagnosed with primary invasive breast cancer in the dataset, and I’ve already given you the top-line results. Of course, when you see a graph like this, the next question really needs to be why?

Fortunately, the SEER dataset contains a lot more information than simply whether someone was diagnosed with cancer. In the case of breast cancer, there is information about the patient’s demographics, the hormone status of the cancer, the stage, and so on. Using those additional data points can help the authors, and us, start to formulate some hypotheses as to what is happening here.

Let’s start with something a bit tricky about this kind of data. We see an uptick in new breast cancer diagnoses among young women in recent years. We need to tease that uptick apart a bit. It could be that it is the year that is the key factor here. In other words, it is simply that more women are getting breast cancer since 2016 and so more young women are getting breast cancer since 2016. These are known as period effects.

Or is there something unique to young women — something about their environmental exposures that put them at higher risk than they would have been had they been born at some other time? These are known as cohort effects.

The researchers teased these two effects apart, as you can see here, and concluded that, well, it’s both.

Stage of cancer at diagnosis can give us some more insight into what is happening. These results are pretty interesting. These higher cancer rates are due primarily to stage I and stage IV cancers, not stage II and stage III cancers.

The rising incidence of stage I cancers could reflect better detection, though many of the women in this cohort would not have been old enough to quality for screening mammograms. That said, increased awareness about genetic risk and family history might be leading younger women to get screened, picking up more early cancers. Additionally, much of the increased incidence was with estrogen receptor–positive tumors, which might reflect the fact that women in this cohort are tending to have fewer children, and children later in life.

So why the rise in stage IV breast cancer? Well, precisely because younger women are not recommended to get screening mammograms; those who detect a lump on their own are likely to be at a more advanced stage. But I’m not sure why that would be changing recently. The authors argue that an increase in overweight and obesity in the country might be to blame here. Prior studies have shown that higher BMI is associated with higher stage at breast cancer diagnosis.

Of course, we can speculate as to multiple other causes as well: environmental toxins, pollution, hormone exposures, and so on. Figuring this out will be the work of multiple other studies. In the meantime, we should remember that the landscape of cancer is continuously changing. And that means we need to adapt to it. If these trends continue, national agencies may need to reconsider their guidelines for when screening mammography should begin — at least in some groups of young women.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

From the year 2000 until around 2016, the incidence of breast cancer among young women — those under age 50 — rose steadily, if slowly.

And then this happened:

I look at a lot of graphs in my line of work, and it’s not too often that one actually makes me say “What the hell?” out loud. But this one did. Why are young women all of a sudden more likely to get breast cancer?

The graph comes from this paper, Breast cancer incidence among us women aged 20 to 49 years by race, stage, and hormone receptor status, appearing in JAMA Network Open

Researchers from Washington University in St. Louis utilized SEER registries to conduct their analyses. SEER is a public database from the National Cancer Institute with coverage of 27% of the US population and a long track record of statistical backbone to translate the data from SEER to numbers that are representative of the population at large.

From 2000 to 2019, more than 200,000 women were diagnosed with primary invasive breast cancer in the dataset, and I’ve already given you the top-line results. Of course, when you see a graph like this, the next question really needs to be why?

Fortunately, the SEER dataset contains a lot more information than simply whether someone was diagnosed with cancer. In the case of breast cancer, there is information about the patient’s demographics, the hormone status of the cancer, the stage, and so on. Using those additional data points can help the authors, and us, start to formulate some hypotheses as to what is happening here.

Let’s start with something a bit tricky about this kind of data. We see an uptick in new breast cancer diagnoses among young women in recent years. We need to tease that uptick apart a bit. It could be that it is the year that is the key factor here. In other words, it is simply that more women are getting breast cancer since 2016 and so more young women are getting breast cancer since 2016. These are known as period effects.

Or is there something unique to young women — something about their environmental exposures that put them at higher risk than they would have been had they been born at some other time? These are known as cohort effects.

The researchers teased these two effects apart, as you can see here, and concluded that, well, it’s both.

Stage of cancer at diagnosis can give us some more insight into what is happening. These results are pretty interesting. These higher cancer rates are due primarily to stage I and stage IV cancers, not stage II and stage III cancers.

The rising incidence of stage I cancers could reflect better detection, though many of the women in this cohort would not have been old enough to quality for screening mammograms. That said, increased awareness about genetic risk and family history might be leading younger women to get screened, picking up more early cancers. Additionally, much of the increased incidence was with estrogen receptor–positive tumors, which might reflect the fact that women in this cohort are tending to have fewer children, and children later in life.

So why the rise in stage IV breast cancer? Well, precisely because younger women are not recommended to get screening mammograms; those who detect a lump on their own are likely to be at a more advanced stage. But I’m not sure why that would be changing recently. The authors argue that an increase in overweight and obesity in the country might be to blame here. Prior studies have shown that higher BMI is associated with higher stage at breast cancer diagnosis.

Of course, we can speculate as to multiple other causes as well: environmental toxins, pollution, hormone exposures, and so on. Figuring this out will be the work of multiple other studies. In the meantime, we should remember that the landscape of cancer is continuously changing. And that means we need to adapt to it. If these trends continue, national agencies may need to reconsider their guidelines for when screening mammography should begin — at least in some groups of young women.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How to Motivate Pain Patients to Try Nondrug Options

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Neha Pathak, MD: Hello. Today, we’re talking to Dr. Daniel Clauw, a professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, who is running a major trial on treatments for chronic back pain. We’re talking today about managing back pain in the post-opioid world. Thank you so much, Dr. Clauw, for taking the time to be our resident pain consultant today. Managing chronic pain can lead to a large amount of burnout and helplessness in the clinic setting. That’s the reality with some of the modalities that patients are requesting; there is still confusion about what is optimal for a particular type of patient, this feeling that we’re not really helping people get better, and whenever patients come in, that’s always still their chief complaint.

How would you advise providers to think about that and to settle into their role as communicators about better strategies without the burnout?

Daniel Clauw, MD: The first thing is to broaden the number of other providers that you get involved in these individuals’ care as the evidence base for all of these nonpharmacologic therapies being effective in chronic pain increases and increases. As third-party payers begin to reimburse for more and more of these therapies, it’s really difficult to manage chronic pain patients if you’re trying to do it alone on an island.

If you can, identify the good physical therapists in your community that are going to really work with people to give them an exercise program that they can use at home; find a pain psychologist that can offer some cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for insomnia and some CBT for pain; and in the subset of patients with trauma, give them the emotional awareness of the neural reprocessing therapy for that specific subset.

As you start to identify more and more of these nonpharmacologic therapies that you want your patients to try, each of those has a set of providers and they can be incredibly helpful so that you, as the primary care provider (PCP), don’t really feel overwhelmed that you’re it, that you’re the only one.

Many of these individuals have more time to spend, and they have more one-on-one in-person time than you do as a primary care physician in the current healthcare system. Many of those providers have become really good at doing amateur CBT, goal-setting, and some of the other things that you need to do when you manage chronic pain patients. Try to find that other group of people that you can send your patients to that are going to be offering some of these nonpharmacologic therapies, and they’ll really help you manage these individuals.

Dr. Pathak: I think a couple of things come up for me. One is that we have to maybe broaden thinking about pain management, not only as multimodal strategies but also as multidisciplinary strategies. To your point, I think that’s really important. I also worry and wonder about health equity concerns, because just as overburdened as many PCPs are, we’re seeing it’s very difficult to get into physical therapy or to get into a setting where you’d be able to receive CBT for your pain. Any thoughts on those types of considerations?

Dr. Clauw: That’s a huge problem. Our group and many other groups in the pain space are developing websites, smartphone apps, and things like that to try to get some of these things directly to individuals with pain, not only for the reasons that you stated but also so that persons with pain don’t have to become patients. Our healthcare systems often make pain worse rather than better.

There were some great articles in The Lancet about 5 years ago talking about low back pain and that in different countries, the healthcare systems, for different reasons, have a tendency to actually make low back pain worse because they do too much surgery, immobilize people, or things like that rather than just not make them better. I think we’ve overmedicalized chronic pain in some settings, and much of what we’re trying to lead people to are things that are parts of wellness programs. The NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health director talks about whole person health often.

I think that these interdisciplinary, integrative approaches are what we have to be using for chronic pain patients. I tell pain patients that, among acupuncture, acupressure, mindfulness, five different forms of CBT, yoga, and tai chi, I don’t know which of those is going to work, but I know that about 1 in 3 individuals that tries each of those therapies gets a benefit. What I really should be doing most is incentivizing people and motivating people to keep trying some of those nonpharmacologic approaches that they haven’t yet tried, because when they find one that works for them, then they will integrate it into their day-to-day life.

The other trick I would use for primary care physicians or anyone managing chronic pain patients is, don’t try to incentivize a pain patient to go try a new nonpharmacologic therapy or start an exercise program because you want their pain score to go from a 6 to a 3. Incentivize them by asking them, what are two or three things that you’re not able to do now because you have chronic pain that you’d really like to be able to do?

You’d like to play nine holes of golf; you’d like to be able to hug your grandchild; or you’d like to be able to do something else. Use those functional goals that are patient0driven to motivate your patients to do these things, because that will work much better. Again, any of us are inherently more likely to take the time and the effort to do some of these nonpharmacologic therapies if it’s for a reason that internally motivates us.

Dr. Pathak: I think that’s great. I’m very privileged to work within the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system. I think that there’s been a huge shift within VA healthcare to provide these ancillary services, whether it’s yoga, tai chi, or acupuncture, as an adjunct to the pain management strategy.

Also, what comes up for me, as you’re saying, is grounding the point that instead of relying on a pain score — which can be objective and different from patient to patient and even within a patient — we should choose a smart goal that is almost more objective when it’s functional. Your goal is to walk two blocks to the mailbox. Can we achieve that as part of your pain control strategy?

I so appreciate your taking the time to be our pain consultant today. I really appreciate our discussion, and I’d like to hand it over to you for any final thoughts.

Dr. Clauw: I’d add that when you’re seeing chronic pain patients, many of them are going to have comorbid sleep problems. They’re going to have comorbid problems with fatigue and memory problems, especially the central nervous system–driven forms of pain that we now call nociplastic pain. Look at those as therapeutic targets.

If you’re befuddled because you’ve tried many different things for pain in this individual you’ve been seeing for a while, focus on their sleep and focus on getting them more active. Don’t use the word exercise — because that scares chronic pain patients — but focus on getting them more active.

There are many different tactics and strategies that you can use to motivate the patients to try some of these new nonpharmacologic approaches as the evidence base continues to increase.

Dr. Pathak: Thank you so much, again, to Dr. Clauw for joining us and being our pain consultant, really helping us to think about managing back pain in the postopioid world.

Dr. Pathak is Chief Physician Editor, Health and Lifestyle Medicine, WebMD. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Clauw is Director, Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center, Department of Anesthesia, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He disclosed ties with Tonix and Viatris.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Neha Pathak, MD: Hello. Today, we’re talking to Dr. Daniel Clauw, a professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, who is running a major trial on treatments for chronic back pain. We’re talking today about managing back pain in the post-opioid world. Thank you so much, Dr. Clauw, for taking the time to be our resident pain consultant today. Managing chronic pain can lead to a large amount of burnout and helplessness in the clinic setting. That’s the reality with some of the modalities that patients are requesting; there is still confusion about what is optimal for a particular type of patient, this feeling that we’re not really helping people get better, and whenever patients come in, that’s always still their chief complaint.

How would you advise providers to think about that and to settle into their role as communicators about better strategies without the burnout?

Daniel Clauw, MD: The first thing is to broaden the number of other providers that you get involved in these individuals’ care as the evidence base for all of these nonpharmacologic therapies being effective in chronic pain increases and increases. As third-party payers begin to reimburse for more and more of these therapies, it’s really difficult to manage chronic pain patients if you’re trying to do it alone on an island.

If you can, identify the good physical therapists in your community that are going to really work with people to give them an exercise program that they can use at home; find a pain psychologist that can offer some cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for insomnia and some CBT for pain; and in the subset of patients with trauma, give them the emotional awareness of the neural reprocessing therapy for that specific subset.

As you start to identify more and more of these nonpharmacologic therapies that you want your patients to try, each of those has a set of providers and they can be incredibly helpful so that you, as the primary care provider (PCP), don’t really feel overwhelmed that you’re it, that you’re the only one.

Many of these individuals have more time to spend, and they have more one-on-one in-person time than you do as a primary care physician in the current healthcare system. Many of those providers have become really good at doing amateur CBT, goal-setting, and some of the other things that you need to do when you manage chronic pain patients. Try to find that other group of people that you can send your patients to that are going to be offering some of these nonpharmacologic therapies, and they’ll really help you manage these individuals.

Dr. Pathak: I think a couple of things come up for me. One is that we have to maybe broaden thinking about pain management, not only as multimodal strategies but also as multidisciplinary strategies. To your point, I think that’s really important. I also worry and wonder about health equity concerns, because just as overburdened as many PCPs are, we’re seeing it’s very difficult to get into physical therapy or to get into a setting where you’d be able to receive CBT for your pain. Any thoughts on those types of considerations?

Dr. Clauw: That’s a huge problem. Our group and many other groups in the pain space are developing websites, smartphone apps, and things like that to try to get some of these things directly to individuals with pain, not only for the reasons that you stated but also so that persons with pain don’t have to become patients. Our healthcare systems often make pain worse rather than better.

There were some great articles in The Lancet about 5 years ago talking about low back pain and that in different countries, the healthcare systems, for different reasons, have a tendency to actually make low back pain worse because they do too much surgery, immobilize people, or things like that rather than just not make them better. I think we’ve overmedicalized chronic pain in some settings, and much of what we’re trying to lead people to are things that are parts of wellness programs. The NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health director talks about whole person health often.

I think that these interdisciplinary, integrative approaches are what we have to be using for chronic pain patients. I tell pain patients that, among acupuncture, acupressure, mindfulness, five different forms of CBT, yoga, and tai chi, I don’t know which of those is going to work, but I know that about 1 in 3 individuals that tries each of those therapies gets a benefit. What I really should be doing most is incentivizing people and motivating people to keep trying some of those nonpharmacologic approaches that they haven’t yet tried, because when they find one that works for them, then they will integrate it into their day-to-day life.

The other trick I would use for primary care physicians or anyone managing chronic pain patients is, don’t try to incentivize a pain patient to go try a new nonpharmacologic therapy or start an exercise program because you want their pain score to go from a 6 to a 3. Incentivize them by asking them, what are two or three things that you’re not able to do now because you have chronic pain that you’d really like to be able to do?

You’d like to play nine holes of golf; you’d like to be able to hug your grandchild; or you’d like to be able to do something else. Use those functional goals that are patient0driven to motivate your patients to do these things, because that will work much better. Again, any of us are inherently more likely to take the time and the effort to do some of these nonpharmacologic therapies if it’s for a reason that internally motivates us.

Dr. Pathak: I think that’s great. I’m very privileged to work within the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system. I think that there’s been a huge shift within VA healthcare to provide these ancillary services, whether it’s yoga, tai chi, or acupuncture, as an adjunct to the pain management strategy.

Also, what comes up for me, as you’re saying, is grounding the point that instead of relying on a pain score — which can be objective and different from patient to patient and even within a patient — we should choose a smart goal that is almost more objective when it’s functional. Your goal is to walk two blocks to the mailbox. Can we achieve that as part of your pain control strategy?

I so appreciate your taking the time to be our pain consultant today. I really appreciate our discussion, and I’d like to hand it over to you for any final thoughts.

Dr. Clauw: I’d add that when you’re seeing chronic pain patients, many of them are going to have comorbid sleep problems. They’re going to have comorbid problems with fatigue and memory problems, especially the central nervous system–driven forms of pain that we now call nociplastic pain. Look at those as therapeutic targets.

If you’re befuddled because you’ve tried many different things for pain in this individual you’ve been seeing for a while, focus on their sleep and focus on getting them more active. Don’t use the word exercise — because that scares chronic pain patients — but focus on getting them more active.

There are many different tactics and strategies that you can use to motivate the patients to try some of these new nonpharmacologic approaches as the evidence base continues to increase.

Dr. Pathak: Thank you so much, again, to Dr. Clauw for joining us and being our pain consultant, really helping us to think about managing back pain in the postopioid world.

Dr. Pathak is Chief Physician Editor, Health and Lifestyle Medicine, WebMD. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Clauw is Director, Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center, Department of Anesthesia, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He disclosed ties with Tonix and Viatris.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Neha Pathak, MD: Hello. Today, we’re talking to Dr. Daniel Clauw, a professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, who is running a major trial on treatments for chronic back pain. We’re talking today about managing back pain in the post-opioid world. Thank you so much, Dr. Clauw, for taking the time to be our resident pain consultant today. Managing chronic pain can lead to a large amount of burnout and helplessness in the clinic setting. That’s the reality with some of the modalities that patients are requesting; there is still confusion about what is optimal for a particular type of patient, this feeling that we’re not really helping people get better, and whenever patients come in, that’s always still their chief complaint.

How would you advise providers to think about that and to settle into their role as communicators about better strategies without the burnout?

Daniel Clauw, MD: The first thing is to broaden the number of other providers that you get involved in these individuals’ care as the evidence base for all of these nonpharmacologic therapies being effective in chronic pain increases and increases. As third-party payers begin to reimburse for more and more of these therapies, it’s really difficult to manage chronic pain patients if you’re trying to do it alone on an island.

If you can, identify the good physical therapists in your community that are going to really work with people to give them an exercise program that they can use at home; find a pain psychologist that can offer some cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for insomnia and some CBT for pain; and in the subset of patients with trauma, give them the emotional awareness of the neural reprocessing therapy for that specific subset.

As you start to identify more and more of these nonpharmacologic therapies that you want your patients to try, each of those has a set of providers and they can be incredibly helpful so that you, as the primary care provider (PCP), don’t really feel overwhelmed that you’re it, that you’re the only one.

Many of these individuals have more time to spend, and they have more one-on-one in-person time than you do as a primary care physician in the current healthcare system. Many of those providers have become really good at doing amateur CBT, goal-setting, and some of the other things that you need to do when you manage chronic pain patients. Try to find that other group of people that you can send your patients to that are going to be offering some of these nonpharmacologic therapies, and they’ll really help you manage these individuals.

Dr. Pathak: I think a couple of things come up for me. One is that we have to maybe broaden thinking about pain management, not only as multimodal strategies but also as multidisciplinary strategies. To your point, I think that’s really important. I also worry and wonder about health equity concerns, because just as overburdened as many PCPs are, we’re seeing it’s very difficult to get into physical therapy or to get into a setting where you’d be able to receive CBT for your pain. Any thoughts on those types of considerations?

Dr. Clauw: That’s a huge problem. Our group and many other groups in the pain space are developing websites, smartphone apps, and things like that to try to get some of these things directly to individuals with pain, not only for the reasons that you stated but also so that persons with pain don’t have to become patients. Our healthcare systems often make pain worse rather than better.

There were some great articles in The Lancet about 5 years ago talking about low back pain and that in different countries, the healthcare systems, for different reasons, have a tendency to actually make low back pain worse because they do too much surgery, immobilize people, or things like that rather than just not make them better. I think we’ve overmedicalized chronic pain in some settings, and much of what we’re trying to lead people to are things that are parts of wellness programs. The NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health director talks about whole person health often.

I think that these interdisciplinary, integrative approaches are what we have to be using for chronic pain patients. I tell pain patients that, among acupuncture, acupressure, mindfulness, five different forms of CBT, yoga, and tai chi, I don’t know which of those is going to work, but I know that about 1 in 3 individuals that tries each of those therapies gets a benefit. What I really should be doing most is incentivizing people and motivating people to keep trying some of those nonpharmacologic approaches that they haven’t yet tried, because when they find one that works for them, then they will integrate it into their day-to-day life.

The other trick I would use for primary care physicians or anyone managing chronic pain patients is, don’t try to incentivize a pain patient to go try a new nonpharmacologic therapy or start an exercise program because you want their pain score to go from a 6 to a 3. Incentivize them by asking them, what are two or three things that you’re not able to do now because you have chronic pain that you’d really like to be able to do?

You’d like to play nine holes of golf; you’d like to be able to hug your grandchild; or you’d like to be able to do something else. Use those functional goals that are patient0driven to motivate your patients to do these things, because that will work much better. Again, any of us are inherently more likely to take the time and the effort to do some of these nonpharmacologic therapies if it’s for a reason that internally motivates us.

Dr. Pathak: I think that’s great. I’m very privileged to work within the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system. I think that there’s been a huge shift within VA healthcare to provide these ancillary services, whether it’s yoga, tai chi, or acupuncture, as an adjunct to the pain management strategy.

Also, what comes up for me, as you’re saying, is grounding the point that instead of relying on a pain score — which can be objective and different from patient to patient and even within a patient — we should choose a smart goal that is almost more objective when it’s functional. Your goal is to walk two blocks to the mailbox. Can we achieve that as part of your pain control strategy?

I so appreciate your taking the time to be our pain consultant today. I really appreciate our discussion, and I’d like to hand it over to you for any final thoughts.

Dr. Clauw: I’d add that when you’re seeing chronic pain patients, many of them are going to have comorbid sleep problems. They’re going to have comorbid problems with fatigue and memory problems, especially the central nervous system–driven forms of pain that we now call nociplastic pain. Look at those as therapeutic targets.

If you’re befuddled because you’ve tried many different things for pain in this individual you’ve been seeing for a while, focus on their sleep and focus on getting them more active. Don’t use the word exercise — because that scares chronic pain patients — but focus on getting them more active.

There are many different tactics and strategies that you can use to motivate the patients to try some of these new nonpharmacologic approaches as the evidence base continues to increase.

Dr. Pathak: Thank you so much, again, to Dr. Clauw for joining us and being our pain consultant, really helping us to think about managing back pain in the postopioid world.

Dr. Pathak is Chief Physician Editor, Health and Lifestyle Medicine, WebMD. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Clauw is Director, Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center, Department of Anesthesia, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He disclosed ties with Tonix and Viatris.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

VA Versus the Private Sector — No Contest? Think Again

Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals are a stepchild in the bizarre mishmash of the U.S. healthcare system. They’re best known (often justifiably so) for rather cantankerous patients, rigid rules, and other oddities (such as patients being able to go on leave and come back).

The majority of American doctors, including myself, did at least part of our training at a VA and have no shortage of stories about them. One I worked at (Omaha VA) was powered by its own nuclear reactor in the basement (no, really, it was, though sadly it’s since been taken out).

VA hospitals, in general, are no-frills — linoleum floors, no piano player in the lobby, very few private rooms, and occasionally in the news for scandals like the one at my hometown Carl T. Hayden VA hospital (I trained there, too).

Yet, . Their focus on patient care, rather than profits, allows them to run with 8% fewer administrative staff since they generally don’t have to deal with insurance billings, denials, and other paperwork (they also don’t have to deal with shareholders and investor demands or ridiculous CEO salaries, though the study didn’t address that).

On a national scale, this would mean roughly 900,000 fewer administrative jobs in the private sector. Granted, that also would mean those people would have to find other jobs, but let’s look at the patient side. If you had 900,000 fewer desk workers, you’d have the money to hire more nurses, respiratory techs, therapists, and other people directly involved in patient care. You’d also need a lot less office space, which further brings down overhead.

Part of the problem is that a lot of the current medical business is in marketing — how many ads do you see each day for different hospitals in your area? — and upcoding to extract more money from each billing. Neither of these has any clinical value on the patient side of things.

You don’t have to look back too far (2020) for the study that found U.S. healthcare spent four times as much money ($812 billion) per capita than our northern neighbors.

And, for all the jokes we make about the VA (myself included), a study last year found its care was on par (or even better than) most hospitals .

I’m not saying the VA is perfect. All of us who worked there can think of times it wasn’t. But we also remember plenty of issues we’ve had at other places we’ve practiced, too.

Maybe it’s time to stop laughing at the VA and realize they’re doing something right — and learn from it to make healthcare better at the other 6,000 or so hospitals in the U.S.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals are a stepchild in the bizarre mishmash of the U.S. healthcare system. They’re best known (often justifiably so) for rather cantankerous patients, rigid rules, and other oddities (such as patients being able to go on leave and come back).

The majority of American doctors, including myself, did at least part of our training at a VA and have no shortage of stories about them. One I worked at (Omaha VA) was powered by its own nuclear reactor in the basement (no, really, it was, though sadly it’s since been taken out).

VA hospitals, in general, are no-frills — linoleum floors, no piano player in the lobby, very few private rooms, and occasionally in the news for scandals like the one at my hometown Carl T. Hayden VA hospital (I trained there, too).

Yet, . Their focus on patient care, rather than profits, allows them to run with 8% fewer administrative staff since they generally don’t have to deal with insurance billings, denials, and other paperwork (they also don’t have to deal with shareholders and investor demands or ridiculous CEO salaries, though the study didn’t address that).

On a national scale, this would mean roughly 900,000 fewer administrative jobs in the private sector. Granted, that also would mean those people would have to find other jobs, but let’s look at the patient side. If you had 900,000 fewer desk workers, you’d have the money to hire more nurses, respiratory techs, therapists, and other people directly involved in patient care. You’d also need a lot less office space, which further brings down overhead.

Part of the problem is that a lot of the current medical business is in marketing — how many ads do you see each day for different hospitals in your area? — and upcoding to extract more money from each billing. Neither of these has any clinical value on the patient side of things.

You don’t have to look back too far (2020) for the study that found U.S. healthcare spent four times as much money ($812 billion) per capita than our northern neighbors.

And, for all the jokes we make about the VA (myself included), a study last year found its care was on par (or even better than) most hospitals .

I’m not saying the VA is perfect. All of us who worked there can think of times it wasn’t. But we also remember plenty of issues we’ve had at other places we’ve practiced, too.

Maybe it’s time to stop laughing at the VA and realize they’re doing something right — and learn from it to make healthcare better at the other 6,000 or so hospitals in the U.S.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals are a stepchild in the bizarre mishmash of the U.S. healthcare system. They’re best known (often justifiably so) for rather cantankerous patients, rigid rules, and other oddities (such as patients being able to go on leave and come back).

The majority of American doctors, including myself, did at least part of our training at a VA and have no shortage of stories about them. One I worked at (Omaha VA) was powered by its own nuclear reactor in the basement (no, really, it was, though sadly it’s since been taken out).

VA hospitals, in general, are no-frills — linoleum floors, no piano player in the lobby, very few private rooms, and occasionally in the news for scandals like the one at my hometown Carl T. Hayden VA hospital (I trained there, too).

Yet, . Their focus on patient care, rather than profits, allows them to run with 8% fewer administrative staff since they generally don’t have to deal with insurance billings, denials, and other paperwork (they also don’t have to deal with shareholders and investor demands or ridiculous CEO salaries, though the study didn’t address that).

On a national scale, this would mean roughly 900,000 fewer administrative jobs in the private sector. Granted, that also would mean those people would have to find other jobs, but let’s look at the patient side. If you had 900,000 fewer desk workers, you’d have the money to hire more nurses, respiratory techs, therapists, and other people directly involved in patient care. You’d also need a lot less office space, which further brings down overhead.

Part of the problem is that a lot of the current medical business is in marketing — how many ads do you see each day for different hospitals in your area? — and upcoding to extract more money from each billing. Neither of these has any clinical value on the patient side of things.

You don’t have to look back too far (2020) for the study that found U.S. healthcare spent four times as much money ($812 billion) per capita than our northern neighbors.

And, for all the jokes we make about the VA (myself included), a study last year found its care was on par (or even better than) most hospitals .

I’m not saying the VA is perfect. All of us who worked there can think of times it wasn’t. But we also remember plenty of issues we’ve had at other places we’ve practiced, too.

Maybe it’s time to stop laughing at the VA and realize they’re doing something right — and learn from it to make healthcare better at the other 6,000 or so hospitals in the U.S.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Medical Aid in Dying Should Be Legal, Says Ethicist

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the Division of Medical Ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Right now, there are 10 states and the District of Columbia that have had some version of medical assistance in dying approved and on the books. That basically means that about 20% of Americans have access where they live to a physician who can prescribe a lethal dose of medication to them if they’re terminally ill and can ingest the medication themselves. That leaves many Americans not covered by this kind of access to this kind of service.

Many of you watching this may live in states where it is legal, like Oregon, Washington, New Jersey, Colorado, and Hawaii. I know many doctors say, “I’m not going to do that.” It’s not something that anyone is compelling a doctor to do. For some Americans, access is not just about where they live but whether there is a doctor willing to participate with them in bringing about their accelerated death, knowing that they’re inevitably going to die.

There’s not much we can do about that. It’s up to the conscience of each physician as to what they’re comfortable with. Certainly, there are other things that can be done to extend the possibility of having this available.

One thing that’s taking place is that, after lawsuits were filed, Vermont and Oregon have given up on their residency requirement, so you don’t have to be there 6 months or a year in order to use this opportunity. It’s legal now to move to the state or visit the state, and as soon as you get there, sign up for this kind of end-of-life intervention.

New Jersey is also being sued. I’ll predict that every state that has a residency requirement, when sued in court, is going to lose because we’ve long recognized the right of Americans to seek out healthcare in the United States, wherever they want to go.

If some states have made this a legitimate medical procedure, courts are going to say you can’t restrict it only to state residents. If someone wants to use a service, they’re entitled to show up from another state or another place and use it. I’m not sure about foreign nationals, but I’m very sure that Americans can go state to state in search of legitimate medical procedures.

The other bills that are out there, however, are basically saying they want to emulate Oregon, Washington, and the other states and say that the terminally ill, with severe restrictions, are going to be able to get this service without going anywhere.

The restrictions include a diagnosis of terminal illness and that you have to be deemed mentally competent. You can’t use this if you have Alzheimer’s or severe depression. You have to make a request twice with a week or two in between to make sure that your request is authentic. And obviously, everyone is on board to make sure that you’re not being coerced or pushed somehow into requesting a somewhat earlier death than you would have experienced without having the availability of the pills.

You also have to take the pills yourself or be able to pull a switch so that you could use a feeding tube–type administration. If you can’t do that, say due to ALS, you’re not eligible to use medical aid in dying. It’s a pretty restricted intervention.

Many people who get pills after going through these restrictions in the states that permit it don’t use it. As many as one third say they like having it there as a safety valve or a parachute, but once they know they could end their life sooner, then they’re going to stick it out.

Should states make this legal? New York, Massachusetts, Florida, and many other states have bills that are moving through. I’m going to say yes. We’ve had Oregon and Washington since the late 1990s with medical aid in dying on the books. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence of pushing people to use this, of bias against the disabled, or bigotry against particular ethnic or racial groups being used to encourage people to end their life sooner.

I think it is an option that Americans want. I think it’s an option that makes some sense. I’m well aware that we also have to make sure that people know about hospice. In some of these states, medical aid in dying is offered as a part of hospice — not all, but a few. Not everybody wants hospice once they realize that they’re dying and that it is coming relatively soon. They may want to leave with family present, with a ceremony, or with a quality of life that they desire.

Past experience says let’s continue to expand availability in each state. Let’s also realize that we have to keep the restrictions in place on how it’s used because they have protected us against abuse. Let’s understand that every doctor has an option to do this or not do this. It’s a matter of conscience and a matter of comfort.

I think legalization is the direction we’re going to be going in. Getting rid of the residency requirements that have been around, as I think courts are going to overturn them, also gives a push to the idea that once the service is in this many states, it’s something that should be available if there are doctors willing to do it.

I’m Art Caplan at the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. New York, NY. Thank you for watching.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

- Served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position)

- Serves as a contributing author and adviser for: Medscape

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the Division of Medical Ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Right now, there are 10 states and the District of Columbia that have had some version of medical assistance in dying approved and on the books. That basically means that about 20% of Americans have access where they live to a physician who can prescribe a lethal dose of medication to them if they’re terminally ill and can ingest the medication themselves. That leaves many Americans not covered by this kind of access to this kind of service.

Many of you watching this may live in states where it is legal, like Oregon, Washington, New Jersey, Colorado, and Hawaii. I know many doctors say, “I’m not going to do that.” It’s not something that anyone is compelling a doctor to do. For some Americans, access is not just about where they live but whether there is a doctor willing to participate with them in bringing about their accelerated death, knowing that they’re inevitably going to die.

There’s not much we can do about that. It’s up to the conscience of each physician as to what they’re comfortable with. Certainly, there are other things that can be done to extend the possibility of having this available.

One thing that’s taking place is that, after lawsuits were filed, Vermont and Oregon have given up on their residency requirement, so you don’t have to be there 6 months or a year in order to use this opportunity. It’s legal now to move to the state or visit the state, and as soon as you get there, sign up for this kind of end-of-life intervention.

New Jersey is also being sued. I’ll predict that every state that has a residency requirement, when sued in court, is going to lose because we’ve long recognized the right of Americans to seek out healthcare in the United States, wherever they want to go.

If some states have made this a legitimate medical procedure, courts are going to say you can’t restrict it only to state residents. If someone wants to use a service, they’re entitled to show up from another state or another place and use it. I’m not sure about foreign nationals, but I’m very sure that Americans can go state to state in search of legitimate medical procedures.

The other bills that are out there, however, are basically saying they want to emulate Oregon, Washington, and the other states and say that the terminally ill, with severe restrictions, are going to be able to get this service without going anywhere.

The restrictions include a diagnosis of terminal illness and that you have to be deemed mentally competent. You can’t use this if you have Alzheimer’s or severe depression. You have to make a request twice with a week or two in between to make sure that your request is authentic. And obviously, everyone is on board to make sure that you’re not being coerced or pushed somehow into requesting a somewhat earlier death than you would have experienced without having the availability of the pills.

You also have to take the pills yourself or be able to pull a switch so that you could use a feeding tube–type administration. If you can’t do that, say due to ALS, you’re not eligible to use medical aid in dying. It’s a pretty restricted intervention.

Many people who get pills after going through these restrictions in the states that permit it don’t use it. As many as one third say they like having it there as a safety valve or a parachute, but once they know they could end their life sooner, then they’re going to stick it out.

Should states make this legal? New York, Massachusetts, Florida, and many other states have bills that are moving through. I’m going to say yes. We’ve had Oregon and Washington since the late 1990s with medical aid in dying on the books. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence of pushing people to use this, of bias against the disabled, or bigotry against particular ethnic or racial groups being used to encourage people to end their life sooner.

I think it is an option that Americans want. I think it’s an option that makes some sense. I’m well aware that we also have to make sure that people know about hospice. In some of these states, medical aid in dying is offered as a part of hospice — not all, but a few. Not everybody wants hospice once they realize that they’re dying and that it is coming relatively soon. They may want to leave with family present, with a ceremony, or with a quality of life that they desire.

Past experience says let’s continue to expand availability in each state. Let’s also realize that we have to keep the restrictions in place on how it’s used because they have protected us against abuse. Let’s understand that every doctor has an option to do this or not do this. It’s a matter of conscience and a matter of comfort.

I think legalization is the direction we’re going to be going in. Getting rid of the residency requirements that have been around, as I think courts are going to overturn them, also gives a push to the idea that once the service is in this many states, it’s something that should be available if there are doctors willing to do it.

I’m Art Caplan at the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. New York, NY. Thank you for watching.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

- Served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position)

- Serves as a contributing author and adviser for: Medscape

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the Division of Medical Ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Right now, there are 10 states and the District of Columbia that have had some version of medical assistance in dying approved and on the books. That basically means that about 20% of Americans have access where they live to a physician who can prescribe a lethal dose of medication to them if they’re terminally ill and can ingest the medication themselves. That leaves many Americans not covered by this kind of access to this kind of service.

Many of you watching this may live in states where it is legal, like Oregon, Washington, New Jersey, Colorado, and Hawaii. I know many doctors say, “I’m not going to do that.” It’s not something that anyone is compelling a doctor to do. For some Americans, access is not just about where they live but whether there is a doctor willing to participate with them in bringing about their accelerated death, knowing that they’re inevitably going to die.

There’s not much we can do about that. It’s up to the conscience of each physician as to what they’re comfortable with. Certainly, there are other things that can be done to extend the possibility of having this available.

One thing that’s taking place is that, after lawsuits were filed, Vermont and Oregon have given up on their residency requirement, so you don’t have to be there 6 months or a year in order to use this opportunity. It’s legal now to move to the state or visit the state, and as soon as you get there, sign up for this kind of end-of-life intervention.

New Jersey is also being sued. I’ll predict that every state that has a residency requirement, when sued in court, is going to lose because we’ve long recognized the right of Americans to seek out healthcare in the United States, wherever they want to go.

If some states have made this a legitimate medical procedure, courts are going to say you can’t restrict it only to state residents. If someone wants to use a service, they’re entitled to show up from another state or another place and use it. I’m not sure about foreign nationals, but I’m very sure that Americans can go state to state in search of legitimate medical procedures.

The other bills that are out there, however, are basically saying they want to emulate Oregon, Washington, and the other states and say that the terminally ill, with severe restrictions, are going to be able to get this service without going anywhere.

The restrictions include a diagnosis of terminal illness and that you have to be deemed mentally competent. You can’t use this if you have Alzheimer’s or severe depression. You have to make a request twice with a week or two in between to make sure that your request is authentic. And obviously, everyone is on board to make sure that you’re not being coerced or pushed somehow into requesting a somewhat earlier death than you would have experienced without having the availability of the pills.

You also have to take the pills yourself or be able to pull a switch so that you could use a feeding tube–type administration. If you can’t do that, say due to ALS, you’re not eligible to use medical aid in dying. It’s a pretty restricted intervention.

Many people who get pills after going through these restrictions in the states that permit it don’t use it. As many as one third say they like having it there as a safety valve or a parachute, but once they know they could end their life sooner, then they’re going to stick it out.

Should states make this legal? New York, Massachusetts, Florida, and many other states have bills that are moving through. I’m going to say yes. We’ve had Oregon and Washington since the late 1990s with medical aid in dying on the books. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence of pushing people to use this, of bias against the disabled, or bigotry against particular ethnic or racial groups being used to encourage people to end their life sooner.

I think it is an option that Americans want. I think it’s an option that makes some sense. I’m well aware that we also have to make sure that people know about hospice. In some of these states, medical aid in dying is offered as a part of hospice — not all, but a few. Not everybody wants hospice once they realize that they’re dying and that it is coming relatively soon. They may want to leave with family present, with a ceremony, or with a quality of life that they desire.

Past experience says let’s continue to expand availability in each state. Let’s also realize that we have to keep the restrictions in place on how it’s used because they have protected us against abuse. Let’s understand that every doctor has an option to do this or not do this. It’s a matter of conscience and a matter of comfort.

I think legalization is the direction we’re going to be going in. Getting rid of the residency requirements that have been around, as I think courts are going to overturn them, also gives a push to the idea that once the service is in this many states, it’s something that should be available if there are doctors willing to do it.

I’m Art Caplan at the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. New York, NY. Thank you for watching.

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

- Served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position)

- Serves as a contributing author and adviser for: Medscape

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The Breakthrough Drug Whose Full Promise Remains Unrealized

Celebrating a Decade of Sofosbuvir for Hepatitis C

Prior to 2013, the backbone of hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy was pegylated interferon (PEG) in combination with ribavirin (RBV). This year-long therapy was associated with significant side effects and abysmal cure rates. Although efficacy improved with the addition of first-generation protease inhibitors, cure rates remained suboptimal and treatment side effects continued to be significant.

Clinicians and patients needed better options and looked to the drug pipeline with hope. However, even among the most optimistic, the idea that HCV therapy could evolve into an all-oral option seemed a relative pipe dream.

The Sofosbuvir Revolution Begins

The Liver Meeting held in 2013 changed everything.

Several presentations featured compelling data with sofosbuvir, a new polymerase inhibitor that, when combined with RBV, offered an all-oral option to patients with genotypes 2 and 3, as well as improved efficacy for patients with genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6 when it was combined with 12 weeks of PEG/RBV.

However, the glass ceiling of HCV care was truly shattered with the randomized COSMOS trial, a late-breaker abstract that revealed 12-week functional cure rates in patients receiving sofosbuvir in combination with the protease inhibitor simeprevir.

This phase 2a trial in treatment-naive and -experienced genotype 1 patients with and without cirrhosis showed that an all-oral option was not only viable for the most common strain of HCV but was also safe and efficacious, even in difficult-to-treat populations.

On December 6, 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved sofosbuvir for the treatment of HCV, ushering in a new era of therapy.

Guidelines quickly changed to advocate for both expansive HCV screening and generous treatment. Yet, as this more permissive approach was being recommended, the high price tag and large anticipated volume of those seeking prescriptions were setting off alarms. The drug cost triggered extensive restrictions based on degree of fibrosis, sobriety, and provider type in an effort to prevent immediate healthcare expenditures.

Given its high cost, rules restricting a patient to only one course of sofosbuvir-based therapy also surfaced. Although treatment with first-generation protease inhibitors carried a hefty price of $161,813.49 per sustained virologic response (SVR), compared with $66,000-$100,000 for 12 weeks of all-oral therapy, its uptake was low and limited by side effects and comorbid conditions. All-oral treatment appeared to have few medical barriers, leading payers to find ways to slow utilization. These restrictions are now gradually being eliminated.

Because of high SVR rates and few contraindications to therapy, most patients who gained access to treatment achieved cure. This included patients who had previously not responded to treatment and prioritized those with more advanced disease.

This quickly led to a significant shift in the population in need of treatment. Prior to 2013, many patients with HCV had advanced disease and did not respond to prior treatment options. After uptake of all-oral therapy, individuals in need were typically treatment naive without advanced disease.

This shift also added new psychosocial dimensions, as many of the newly infected individuals were struggling with active substance abuse. HCV treatment providers needed to change, with increasing recruitment of advanced practice providers, primary care physicians, and addiction medication specialists.

Progress, but Far From Reaching Targets

Fast-forward to 2023.

Ten years after FDA approval, 13.2 million individuals infected with HCV have been treated globally, 82% with sofosbuvir-based regimens and most in lower-middle-income countries. This is absolutely cause for celebration, but not complacency.

In 2016, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution of elimination of viral hepatitis by 2030. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined elimination of HCV as 90% reduction in new cases of infection, 90% diagnosis of those infected, 80% of eligible individuals treated, and 65% reduction of deaths by 2030.

Despite all the success thus far, the CDA Foundation estimates that the WHO elimination targets will not be achieved until after the year 2050. They also note that in 2020, over 50 million individuals were infected with HCV, of which only 20% were diagnosed and 1% annually treated.

The HCV care cascade, by which the patient journeys from screening to cure, is complicated, and a one-size-fits-all solution is not possible. Reflex testing (an automatic transition to HCV polymerase chain reaction [PCR] testing in the lab for those who are HCV antibody positive) has significantly improved diagnosis. However, communicating these results and linking a patient to curative therapy remain significant obstacles.

Models and real-life experience show that multiple strategies can be successful. They include leveraging the electronic medical record, simplified treatment algorithms, test-and-treat strategies (screening high-risk populations with a point-of-care test that allows treatment initiation at the same visit), and co-localizing HCV screening and treatment with addiction services and relinkage programs (finding those who are already diagnosed and linking them to treatment).

In addition, focusing on populations at high risk for HCV infection — such as people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, and incarcerated individuals — allows for better resource utilization.

Though daunting, HCV elimination is not impossible. There are several examples of success, including in the countries of Georgia and Iceland. Although, comparatively, the United States remains behind the curve, the White House has asked Congress for $11 billion to fund HCV elimination domestically.

As we await action at the national level, clinicians are reminded that there are several things we can do in caring for patients with HCV:

- A one-time HCV screening is recommended in all individuals aged 18 or older, including pregnant people with each pregnancy.

- HCV antibody testing with reflex to PCR should be used as the screening test.

- Pan-genotypic all-oral therapy is recommended for patients with HCV. Cure rates are greater than 95%, and there are few contraindications to treatment.

- Most people are eligible for simplified treatment algorithms that allow minimal on-treatment monitoring.

Without increased screening and linkage to curative therapy, we will not meet the WHO goals for HCV elimination.

Dr. Reau is chief of the hepatology section at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and a regular contributor to this news organization. She serves as editor of Clinical Liver Disease, a multimedia review journal, and recently as a member of HCVGuidelines.org, a web-based resource from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, as well as educational chair of the AASLD hepatitis C special interest group. She continues to have an active role in the hepatology interest group of the World Gastroenterology Organisation and the American Liver Foundation at the regional and national levels. She disclosed ties with AbbVie, Gilead, Arbutus, Intercept, and Salix.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Celebrating a Decade of Sofosbuvir for Hepatitis C

Celebrating a Decade of Sofosbuvir for Hepatitis C

Prior to 2013, the backbone of hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy was pegylated interferon (PEG) in combination with ribavirin (RBV). This year-long therapy was associated with significant side effects and abysmal cure rates. Although efficacy improved with the addition of first-generation protease inhibitors, cure rates remained suboptimal and treatment side effects continued to be significant.

Clinicians and patients needed better options and looked to the drug pipeline with hope. However, even among the most optimistic, the idea that HCV therapy could evolve into an all-oral option seemed a relative pipe dream.

The Sofosbuvir Revolution Begins

The Liver Meeting held in 2013 changed everything.

Several presentations featured compelling data with sofosbuvir, a new polymerase inhibitor that, when combined with RBV, offered an all-oral option to patients with genotypes 2 and 3, as well as improved efficacy for patients with genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6 when it was combined with 12 weeks of PEG/RBV.

However, the glass ceiling of HCV care was truly shattered with the randomized COSMOS trial, a late-breaker abstract that revealed 12-week functional cure rates in patients receiving sofosbuvir in combination with the protease inhibitor simeprevir.

This phase 2a trial in treatment-naive and -experienced genotype 1 patients with and without cirrhosis showed that an all-oral option was not only viable for the most common strain of HCV but was also safe and efficacious, even in difficult-to-treat populations.

On December 6, 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved sofosbuvir for the treatment of HCV, ushering in a new era of therapy.

Guidelines quickly changed to advocate for both expansive HCV screening and generous treatment. Yet, as this more permissive approach was being recommended, the high price tag and large anticipated volume of those seeking prescriptions were setting off alarms. The drug cost triggered extensive restrictions based on degree of fibrosis, sobriety, and provider type in an effort to prevent immediate healthcare expenditures.

Given its high cost, rules restricting a patient to only one course of sofosbuvir-based therapy also surfaced. Although treatment with first-generation protease inhibitors carried a hefty price of $161,813.49 per sustained virologic response (SVR), compared with $66,000-$100,000 for 12 weeks of all-oral therapy, its uptake was low and limited by side effects and comorbid conditions. All-oral treatment appeared to have few medical barriers, leading payers to find ways to slow utilization. These restrictions are now gradually being eliminated.

Because of high SVR rates and few contraindications to therapy, most patients who gained access to treatment achieved cure. This included patients who had previously not responded to treatment and prioritized those with more advanced disease.

This quickly led to a significant shift in the population in need of treatment. Prior to 2013, many patients with HCV had advanced disease and did not respond to prior treatment options. After uptake of all-oral therapy, individuals in need were typically treatment naive without advanced disease.

This shift also added new psychosocial dimensions, as many of the newly infected individuals were struggling with active substance abuse. HCV treatment providers needed to change, with increasing recruitment of advanced practice providers, primary care physicians, and addiction medication specialists.

Progress, but Far From Reaching Targets

Fast-forward to 2023.

Ten years after FDA approval, 13.2 million individuals infected with HCV have been treated globally, 82% with sofosbuvir-based regimens and most in lower-middle-income countries. This is absolutely cause for celebration, but not complacency.

In 2016, the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution of elimination of viral hepatitis by 2030. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined elimination of HCV as 90% reduction in new cases of infection, 90% diagnosis of those infected, 80% of eligible individuals treated, and 65% reduction of deaths by 2030.

Despite all the success thus far, the CDA Foundation estimates that the WHO elimination targets will not be achieved until after the year 2050. They also note that in 2020, over 50 million individuals were infected with HCV, of which only 20% were diagnosed and 1% annually treated.

The HCV care cascade, by which the patient journeys from screening to cure, is complicated, and a one-size-fits-all solution is not possible. Reflex testing (an automatic transition to HCV polymerase chain reaction [PCR] testing in the lab for those who are HCV antibody positive) has significantly improved diagnosis. However, communicating these results and linking a patient to curative therapy remain significant obstacles.

Models and real-life experience show that multiple strategies can be successful. They include leveraging the electronic medical record, simplified treatment algorithms, test-and-treat strategies (screening high-risk populations with a point-of-care test that allows treatment initiation at the same visit), and co-localizing HCV screening and treatment with addiction services and relinkage programs (finding those who are already diagnosed and linking them to treatment).

In addition, focusing on populations at high risk for HCV infection — such as people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, and incarcerated individuals — allows for better resource utilization.

Though daunting, HCV elimination is not impossible. There are several examples of success, including in the countries of Georgia and Iceland. Although, comparatively, the United States remains behind the curve, the White House has asked Congress for $11 billion to fund HCV elimination domestically.

As we await action at the national level, clinicians are reminded that there are several things we can do in caring for patients with HCV:

- A one-time HCV screening is recommended in all individuals aged 18 or older, including pregnant people with each pregnancy.

- HCV antibody testing with reflex to PCR should be used as the screening test.

- Pan-genotypic all-oral therapy is recommended for patients with HCV. Cure rates are greater than 95%, and there are few contraindications to treatment.

- Most people are eligible for simplified treatment algorithms that allow minimal on-treatment monitoring.

Without increased screening and linkage to curative therapy, we will not meet the WHO goals for HCV elimination.

Dr. Reau is chief of the hepatology section at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and a regular contributor to this news organization. She serves as editor of Clinical Liver Disease, a multimedia review journal, and recently as a member of HCVGuidelines.org, a web-based resource from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, as well as educational chair of the AASLD hepatitis C special interest group. She continues to have an active role in the hepatology interest group of the World Gastroenterology Organisation and the American Liver Foundation at the regional and national levels. She disclosed ties with AbbVie, Gilead, Arbutus, Intercept, and Salix.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Prior to 2013, the backbone of hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy was pegylated interferon (PEG) in combination with ribavirin (RBV). This year-long therapy was associated with significant side effects and abysmal cure rates. Although efficacy improved with the addition of first-generation protease inhibitors, cure rates remained suboptimal and treatment side effects continued to be significant.

Clinicians and patients needed better options and looked to the drug pipeline with hope. However, even among the most optimistic, the idea that HCV therapy could evolve into an all-oral option seemed a relative pipe dream.

The Sofosbuvir Revolution Begins

The Liver Meeting held in 2013 changed everything.

Several presentations featured compelling data with sofosbuvir, a new polymerase inhibitor that, when combined with RBV, offered an all-oral option to patients with genotypes 2 and 3, as well as improved efficacy for patients with genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6 when it was combined with 12 weeks of PEG/RBV.

However, the glass ceiling of HCV care was truly shattered with the randomized COSMOS trial, a late-breaker abstract that revealed 12-week functional cure rates in patients receiving sofosbuvir in combination with the protease inhibitor simeprevir.

This phase 2a trial in treatment-naive and -experienced genotype 1 patients with and without cirrhosis showed that an all-oral option was not only viable for the most common strain of HCV but was also safe and efficacious, even in difficult-to-treat populations.

On December 6, 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved sofosbuvir for the treatment of HCV, ushering in a new era of therapy.

Guidelines quickly changed to advocate for both expansive HCV screening and generous treatment. Yet, as this more permissive approach was being recommended, the high price tag and large anticipated volume of those seeking prescriptions were setting off alarms. The drug cost triggered extensive restrictions based on degree of fibrosis, sobriety, and provider type in an effort to prevent immediate healthcare expenditures.