User login

How are your otoscopy skills?

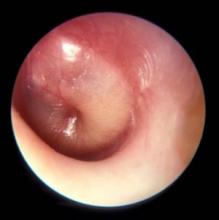

If the name Michael E. Pichichero, MD, is unfamiliar, you haven’t been reading some of the best articles on this website . Dr. Pichichero, an infectious disease specialist at the Research Institute at the Rochester General Hospital in New York, reports in his most recent ID Consult column on new research presented at the June 2019 meeting of the International Society for Otitis Media, including topics such as transtympanic antibiotic delivery, biofilms, probiotics, and biomarkers.

Dr. Pichichero described work he and his colleagues have been doing on the impact of overdiagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM). They found when “validated otoscopists” evaluated children, half as many reached the diagnostic threshold of being labeled “otitis prone” as when community-based pediatricians performed the exams.

Looking around at the colleagues with whom you share patients, do you find that some of them diagnose AOM much more frequently than does the coverage group average? How often do you see a child a day or two after he has been diagnosed with AOM by a colleague and find that the child’s tympanic membranes are transparent and mobile? Do you or your practice group keep track of each provider’s diagnostic tendencies? If these data exists, is there a mechanism for addressing apparent outliers? I suspect that the answer to those last two questions is a firm “No.”

I don’t have the stomach this morning to open those two cans of worms. But certainly Dr. Pichichero’s findings suggest that these are issues that need to be addressed. How the process should proceed in a nonthreatening way is a story for another day. But I’m not sure that involving your community ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist as a resource is the best answer. The scenarios in which pediatricians and ENTs perform otoscopies couldn’t be more different. In the pediatrician’s office, the child is generally sick, feverish, and possibly in pain. In the ENT’s office, the acute process has probably passed and the assessment may lean more heavily on history. The child is more likely to accept the exam without resistance, and the findings are not those of AOM but of a chronic process. The fact that Dr. Pichichero has been able to find and train “validated otoscopists” suggests that improving the quality of otoscopy among the physicians in communities like yours and mine is achievable.

How are your otoscopy skills? Do feel comfortable that you can do a good exam and accurately diagnose AOM? When did you acquire that comfort level? Probably not in medical school. More likely as a house officer when you were guided by a more senior house officer who may nor not been a master otoscopist. How would you rate your training? Or were you self-taught? Do you insufflate? Are you a skilled cerumen extractor? Or do you give up after one attempt? Be honest. How is your equipment? Are the bulbs and batteries fresh? Do you find yourself frustrated by an otoscope that is tethered to the wall charger by a cord that ensnarls you, the parent, and the patient? Have you complained to the practice administrators that your otoscopes are inadequate?

These are not minor issues. It is clear that overdiagnosis of AOM happens. It may occur even more often than Dr. Pichichero suggests, but I doubt it is less. Overdiagnosis can result in overtreatment with antibiotics, and the cascade of consequences both for the patient, the community, and the environment. Overdiagnosis can be the first step on the path to unnecessary surgery. It is incumbent on all of us to make sure that our otoscopy skills and those of our colleagues are sharp, that our equipment is well maintained and that we remain abreast of the latest developments in the diagnosis and treatment of AOM.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

If the name Michael E. Pichichero, MD, is unfamiliar, you haven’t been reading some of the best articles on this website . Dr. Pichichero, an infectious disease specialist at the Research Institute at the Rochester General Hospital in New York, reports in his most recent ID Consult column on new research presented at the June 2019 meeting of the International Society for Otitis Media, including topics such as transtympanic antibiotic delivery, biofilms, probiotics, and biomarkers.

Dr. Pichichero described work he and his colleagues have been doing on the impact of overdiagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM). They found when “validated otoscopists” evaluated children, half as many reached the diagnostic threshold of being labeled “otitis prone” as when community-based pediatricians performed the exams.

Looking around at the colleagues with whom you share patients, do you find that some of them diagnose AOM much more frequently than does the coverage group average? How often do you see a child a day or two after he has been diagnosed with AOM by a colleague and find that the child’s tympanic membranes are transparent and mobile? Do you or your practice group keep track of each provider’s diagnostic tendencies? If these data exists, is there a mechanism for addressing apparent outliers? I suspect that the answer to those last two questions is a firm “No.”

I don’t have the stomach this morning to open those two cans of worms. But certainly Dr. Pichichero’s findings suggest that these are issues that need to be addressed. How the process should proceed in a nonthreatening way is a story for another day. But I’m not sure that involving your community ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist as a resource is the best answer. The scenarios in which pediatricians and ENTs perform otoscopies couldn’t be more different. In the pediatrician’s office, the child is generally sick, feverish, and possibly in pain. In the ENT’s office, the acute process has probably passed and the assessment may lean more heavily on history. The child is more likely to accept the exam without resistance, and the findings are not those of AOM but of a chronic process. The fact that Dr. Pichichero has been able to find and train “validated otoscopists” suggests that improving the quality of otoscopy among the physicians in communities like yours and mine is achievable.

How are your otoscopy skills? Do feel comfortable that you can do a good exam and accurately diagnose AOM? When did you acquire that comfort level? Probably not in medical school. More likely as a house officer when you were guided by a more senior house officer who may nor not been a master otoscopist. How would you rate your training? Or were you self-taught? Do you insufflate? Are you a skilled cerumen extractor? Or do you give up after one attempt? Be honest. How is your equipment? Are the bulbs and batteries fresh? Do you find yourself frustrated by an otoscope that is tethered to the wall charger by a cord that ensnarls you, the parent, and the patient? Have you complained to the practice administrators that your otoscopes are inadequate?

These are not minor issues. It is clear that overdiagnosis of AOM happens. It may occur even more often than Dr. Pichichero suggests, but I doubt it is less. Overdiagnosis can result in overtreatment with antibiotics, and the cascade of consequences both for the patient, the community, and the environment. Overdiagnosis can be the first step on the path to unnecessary surgery. It is incumbent on all of us to make sure that our otoscopy skills and those of our colleagues are sharp, that our equipment is well maintained and that we remain abreast of the latest developments in the diagnosis and treatment of AOM.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

If the name Michael E. Pichichero, MD, is unfamiliar, you haven’t been reading some of the best articles on this website . Dr. Pichichero, an infectious disease specialist at the Research Institute at the Rochester General Hospital in New York, reports in his most recent ID Consult column on new research presented at the June 2019 meeting of the International Society for Otitis Media, including topics such as transtympanic antibiotic delivery, biofilms, probiotics, and biomarkers.

Dr. Pichichero described work he and his colleagues have been doing on the impact of overdiagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM). They found when “validated otoscopists” evaluated children, half as many reached the diagnostic threshold of being labeled “otitis prone” as when community-based pediatricians performed the exams.

Looking around at the colleagues with whom you share patients, do you find that some of them diagnose AOM much more frequently than does the coverage group average? How often do you see a child a day or two after he has been diagnosed with AOM by a colleague and find that the child’s tympanic membranes are transparent and mobile? Do you or your practice group keep track of each provider’s diagnostic tendencies? If these data exists, is there a mechanism for addressing apparent outliers? I suspect that the answer to those last two questions is a firm “No.”

I don’t have the stomach this morning to open those two cans of worms. But certainly Dr. Pichichero’s findings suggest that these are issues that need to be addressed. How the process should proceed in a nonthreatening way is a story for another day. But I’m not sure that involving your community ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist as a resource is the best answer. The scenarios in which pediatricians and ENTs perform otoscopies couldn’t be more different. In the pediatrician’s office, the child is generally sick, feverish, and possibly in pain. In the ENT’s office, the acute process has probably passed and the assessment may lean more heavily on history. The child is more likely to accept the exam without resistance, and the findings are not those of AOM but of a chronic process. The fact that Dr. Pichichero has been able to find and train “validated otoscopists” suggests that improving the quality of otoscopy among the physicians in communities like yours and mine is achievable.

How are your otoscopy skills? Do feel comfortable that you can do a good exam and accurately diagnose AOM? When did you acquire that comfort level? Probably not in medical school. More likely as a house officer when you were guided by a more senior house officer who may nor not been a master otoscopist. How would you rate your training? Or were you self-taught? Do you insufflate? Are you a skilled cerumen extractor? Or do you give up after one attempt? Be honest. How is your equipment? Are the bulbs and batteries fresh? Do you find yourself frustrated by an otoscope that is tethered to the wall charger by a cord that ensnarls you, the parent, and the patient? Have you complained to the practice administrators that your otoscopes are inadequate?

These are not minor issues. It is clear that overdiagnosis of AOM happens. It may occur even more often than Dr. Pichichero suggests, but I doubt it is less. Overdiagnosis can result in overtreatment with antibiotics, and the cascade of consequences both for the patient, the community, and the environment. Overdiagnosis can be the first step on the path to unnecessary surgery. It is incumbent on all of us to make sure that our otoscopy skills and those of our colleagues are sharp, that our equipment is well maintained and that we remain abreast of the latest developments in the diagnosis and treatment of AOM.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Living small

I’m sitting on the porch looking out at our little harbor, listening to the murmurings of the family of renters who have just moved into the cottage next door. We are on the cusp of the tourist season that draws millions of visitors – more than 36 million in 2017 – to a state that has less than a million and a half year-round residents during the other 9 months. Why do the “people from away” come?

The water is too cold for swimming most of the summer in Maine. But we have forested mountains, rocky shores, and we’re small. When I chat with the visitors sharing our stony little beach, they often ask if I live here and tell me how lucky I am because they envy the quiet, the friendly people, the lack of traffic, and the sense of community that they feel here in Vacationland.

My being here in Maine wasn’t a stroke of luck. It was a conscious decision that my wife and I made when I finished my training. The lucky part was meeting my wife who was born here. Through her I learned what Maine was about. I had grown up in a small town of 5,000 (although it was the suburb of a city of millions) and went to a small college in rural New Hampshire with an enrollment of a little more than 3,000. I turned down residencies in pediatric radiology and dermatology because I knew that to have a sustainable patient base we would have needed to live in a major metropolitan center.

I was accustomed to the benefits of living small. In the 1970s, the local economy in mid-coast Maine was shaky, the biggest employer had not yet secured the large military contracts it needed to thrive. But we decided it was a risk worth taking, and we have never regretted for a second living and practicing in a town of less than 20,000.

With this history as a backdrop, you can understand why I am a bit puzzled and disappointed by the results of a 2019 survey final-year medical residents recently published by the medical search and consulting firm Merritt Hawkins. Although the sample size is small (391 respondents out of 20,000 email surveys), the responses probably are a reasonable reflection of the opinions of the entire population of final-year residents. More than 80% of the respondents said that they would most like to practice in a community with a population of more than 100,000, and 65% would prefer a population base of more than 250,000. This would automatically rule out Maine, where our largest city has less than 80,000 people.

I can easily understand why physicians finishing their residency would avoid practice opportunities in remote, thinly populated regions in which they might find themselves as the only, or one of only two physicians serving a medically needy, economically depressed population spread out over a wide geographic area. That kind of challenge has some appeal for the saintly few, or the dreamy-eyed idealists. But in my experience, those work environments require so much energy that most physicians last only a few years because being on call is so taxing.

However, I know of several right here in Maine. What is driving young physicians to seek larger communities? It may be that because teaching hospitals are usually in more densely populated communities, many residents lack sufficient exposure to role models who are practicing in smaller settings. Compounding this dearth of role models is the unfortunate and often inaccurate image in which local doctors are cast as bumbling and clueless. I was fortunate because where I did my first 2 years of training, the local pediatricians played an active role and were very visible role models of how one can enjoy practice in a smaller community.

I guess I can’t ignore the obvious that a larger population base may be able guarantee an income that could sound appealing to the more than 50% of residents who will complete their training with a sizable debt.

However, I fear that too many residents nearing the end of their training believe that the “quality of life” that they claim to be seeking can’t be found in a small community practice. They would do well to speak to a few of us who have enjoyed and prospered by living small.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

I’m sitting on the porch looking out at our little harbor, listening to the murmurings of the family of renters who have just moved into the cottage next door. We are on the cusp of the tourist season that draws millions of visitors – more than 36 million in 2017 – to a state that has less than a million and a half year-round residents during the other 9 months. Why do the “people from away” come?

The water is too cold for swimming most of the summer in Maine. But we have forested mountains, rocky shores, and we’re small. When I chat with the visitors sharing our stony little beach, they often ask if I live here and tell me how lucky I am because they envy the quiet, the friendly people, the lack of traffic, and the sense of community that they feel here in Vacationland.

My being here in Maine wasn’t a stroke of luck. It was a conscious decision that my wife and I made when I finished my training. The lucky part was meeting my wife who was born here. Through her I learned what Maine was about. I had grown up in a small town of 5,000 (although it was the suburb of a city of millions) and went to a small college in rural New Hampshire with an enrollment of a little more than 3,000. I turned down residencies in pediatric radiology and dermatology because I knew that to have a sustainable patient base we would have needed to live in a major metropolitan center.

I was accustomed to the benefits of living small. In the 1970s, the local economy in mid-coast Maine was shaky, the biggest employer had not yet secured the large military contracts it needed to thrive. But we decided it was a risk worth taking, and we have never regretted for a second living and practicing in a town of less than 20,000.

With this history as a backdrop, you can understand why I am a bit puzzled and disappointed by the results of a 2019 survey final-year medical residents recently published by the medical search and consulting firm Merritt Hawkins. Although the sample size is small (391 respondents out of 20,000 email surveys), the responses probably are a reasonable reflection of the opinions of the entire population of final-year residents. More than 80% of the respondents said that they would most like to practice in a community with a population of more than 100,000, and 65% would prefer a population base of more than 250,000. This would automatically rule out Maine, where our largest city has less than 80,000 people.

I can easily understand why physicians finishing their residency would avoid practice opportunities in remote, thinly populated regions in which they might find themselves as the only, or one of only two physicians serving a medically needy, economically depressed population spread out over a wide geographic area. That kind of challenge has some appeal for the saintly few, or the dreamy-eyed idealists. But in my experience, those work environments require so much energy that most physicians last only a few years because being on call is so taxing.

However, I know of several right here in Maine. What is driving young physicians to seek larger communities? It may be that because teaching hospitals are usually in more densely populated communities, many residents lack sufficient exposure to role models who are practicing in smaller settings. Compounding this dearth of role models is the unfortunate and often inaccurate image in which local doctors are cast as bumbling and clueless. I was fortunate because where I did my first 2 years of training, the local pediatricians played an active role and were very visible role models of how one can enjoy practice in a smaller community.

I guess I can’t ignore the obvious that a larger population base may be able guarantee an income that could sound appealing to the more than 50% of residents who will complete their training with a sizable debt.

However, I fear that too many residents nearing the end of their training believe that the “quality of life” that they claim to be seeking can’t be found in a small community practice. They would do well to speak to a few of us who have enjoyed and prospered by living small.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

I’m sitting on the porch looking out at our little harbor, listening to the murmurings of the family of renters who have just moved into the cottage next door. We are on the cusp of the tourist season that draws millions of visitors – more than 36 million in 2017 – to a state that has less than a million and a half year-round residents during the other 9 months. Why do the “people from away” come?

The water is too cold for swimming most of the summer in Maine. But we have forested mountains, rocky shores, and we’re small. When I chat with the visitors sharing our stony little beach, they often ask if I live here and tell me how lucky I am because they envy the quiet, the friendly people, the lack of traffic, and the sense of community that they feel here in Vacationland.

My being here in Maine wasn’t a stroke of luck. It was a conscious decision that my wife and I made when I finished my training. The lucky part was meeting my wife who was born here. Through her I learned what Maine was about. I had grown up in a small town of 5,000 (although it was the suburb of a city of millions) and went to a small college in rural New Hampshire with an enrollment of a little more than 3,000. I turned down residencies in pediatric radiology and dermatology because I knew that to have a sustainable patient base we would have needed to live in a major metropolitan center.

I was accustomed to the benefits of living small. In the 1970s, the local economy in mid-coast Maine was shaky, the biggest employer had not yet secured the large military contracts it needed to thrive. But we decided it was a risk worth taking, and we have never regretted for a second living and practicing in a town of less than 20,000.

With this history as a backdrop, you can understand why I am a bit puzzled and disappointed by the results of a 2019 survey final-year medical residents recently published by the medical search and consulting firm Merritt Hawkins. Although the sample size is small (391 respondents out of 20,000 email surveys), the responses probably are a reasonable reflection of the opinions of the entire population of final-year residents. More than 80% of the respondents said that they would most like to practice in a community with a population of more than 100,000, and 65% would prefer a population base of more than 250,000. This would automatically rule out Maine, where our largest city has less than 80,000 people.

I can easily understand why physicians finishing their residency would avoid practice opportunities in remote, thinly populated regions in which they might find themselves as the only, or one of only two physicians serving a medically needy, economically depressed population spread out over a wide geographic area. That kind of challenge has some appeal for the saintly few, or the dreamy-eyed idealists. But in my experience, those work environments require so much energy that most physicians last only a few years because being on call is so taxing.

However, I know of several right here in Maine. What is driving young physicians to seek larger communities? It may be that because teaching hospitals are usually in more densely populated communities, many residents lack sufficient exposure to role models who are practicing in smaller settings. Compounding this dearth of role models is the unfortunate and often inaccurate image in which local doctors are cast as bumbling and clueless. I was fortunate because where I did my first 2 years of training, the local pediatricians played an active role and were very visible role models of how one can enjoy practice in a smaller community.

I guess I can’t ignore the obvious that a larger population base may be able guarantee an income that could sound appealing to the more than 50% of residents who will complete their training with a sizable debt.

However, I fear that too many residents nearing the end of their training believe that the “quality of life” that they claim to be seeking can’t be found in a small community practice. They would do well to speak to a few of us who have enjoyed and prospered by living small.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Potential improvements in convenience, tolerability of hematologic treatment

In this edition of “How I will treat my next patient,” I highlight two recent presentations regarding potential improvements in the convenience and tolerability of treatment for two hematologic malignancies: multiple myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL).

SC-Dara in myeloma

At the 2019 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Maria-Victoria Mateos, MD, PhD, and colleagues, reported the results of COLUMBA, a phase 3 evaluation in 522 patients with multiple myeloma who were randomized to subcutaneous daratumumab (SC-Dara) or standard intravenous infusions of daratumumab (IV-Dara). A previous phase 1b study (Blood. 2017;130:838) had suggested comparable efficacy from the more convenient SC regime. Whereas conventional infusions of IV-Dara (16 mg/kg) take several hours, the SC formulation (1,800 mg–flat dose) is delivered in minutes. In COLUMBA, patients were randomized between SC- and IV-Dara weekly (cycles 1-2), then every 2 weeks (cycles 3-6), then every 4 weeks until disease progression.

Among the IV-Dara patients, the median duration of the first infusion was 421 minutes in cycle 1, 255 minutes in cycle 2, and 205 minutes in subsequent cycles – compatible with standard practice in the United States. As reported, at a median follow-up of 7.46 months, the efficacy (overall response rate, complete response rate, stringent-complete response rate, very good-partial response rate, progression-free survival, and 6-month overall survival) and safety profile were non-inferior for SC-Dara. SC-Dara patients also reported higher satisfaction with therapy.

What this means in practice

It is always a good idea to await publication of the manuscript because there may be study details and statistical nuances that make SC-Dara appear better than it will prove to be. For example, patient characteristics were slightly different between the two arms. Peer review of the final manuscript could be important in placing these results in context.

However, for treatments that demand frequent office visits over many months, reducing treatment burden for patients has value. Based on COLUMBA, it appears likely that SC-Dara will be a major convenience for patients, without obvious drawbacks in efficacy or toxicity. Meanwhile, flat dosing will be a time-saver for physicians, nursing, and pharmacy staff. If the price of the SC formulation is not exorbitant, I would expect a “win-win” that will support converting from IV- to SC-Dara as standard practice.

Acalabrutinib in CLL/SLL

Preclinical studies have shown acalabrutinib (Acala) to be more selective for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) than the first-in-class agent ibrutinib, with less off-target kinase inhibition. As reported at the 2019 annual congress of the European Hematology Association by Paolo Ghia, MD, PhD, and colleagues in the phase 3 ASCEND trial, 310 patients with previously treated CLL were randomized between oral Acala twice daily and treatment of physician’s choice (TPC) – either idelalisib plus rituximab (maximum of seven infusions) or bendamustine plus rituximab (maximum of six cycles).

Progression-free survival was the primary endpoint. At a median of 16.1 months, progression-free survival had not been reached for Acala, in comparison with 16.5 months for TPC. Significant benefit of Acala was observed in all prognostic subsets.

Although there was no difference in overall survival at a median follow-up of about 16 months, 85% of Acala patients had a response lasting at least 12 months, compared with 60% of TPC patients. Adverse events of any grade occurred in 94% of patients treated with Acala, with 45% being grade 3-4 toxicities and six treatment-related deaths.

What this means in practice

The vast majority of CLL/SLL patients will relapse after primary therapy and will require further treatment, so the progression-free survival improvement associated with Acala in ASCEND is eye-catching. However, there are important considerations that demand closer scrutiny.

With oral agents administered until progression or unacceptable toxicity, low-grade toxicities can influence patient adherence, quality of life, and potentially the need for dose reduction or treatment interruptions. Regimens of finite duration and easy adherence monitoring may be, on balance, preferred by patients and providers – especially if the oral agent can be given in later-line with comparable overall survival.

With ibrutinib (Blood. 2017;129:2612-5), Paul M. Barr, MD, and colleagues demonstrated that higher dose intensity was associated with improved progression-free survival and that holds were associated with worsened progression-free survival. Acala’s promise of high efficacy and lower off-target toxicity will be solidified if the large (more than 500 patients) phase 3 ACE-CL-006 study (Acala vs. ibrutinib) demonstrates its relative benefit from efficacy, toxicity, and adherence perspectives, in comparison with a standard therapy that similarly demands adherence until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Dr. Lyss has been a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years, practicing in St. Louis. His clinical and research interests are in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of breast and lung cancers and in expanding access to clinical trials to medically underserved populations.

In this edition of “How I will treat my next patient,” I highlight two recent presentations regarding potential improvements in the convenience and tolerability of treatment for two hematologic malignancies: multiple myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL).

SC-Dara in myeloma

At the 2019 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Maria-Victoria Mateos, MD, PhD, and colleagues, reported the results of COLUMBA, a phase 3 evaluation in 522 patients with multiple myeloma who were randomized to subcutaneous daratumumab (SC-Dara) or standard intravenous infusions of daratumumab (IV-Dara). A previous phase 1b study (Blood. 2017;130:838) had suggested comparable efficacy from the more convenient SC regime. Whereas conventional infusions of IV-Dara (16 mg/kg) take several hours, the SC formulation (1,800 mg–flat dose) is delivered in minutes. In COLUMBA, patients were randomized between SC- and IV-Dara weekly (cycles 1-2), then every 2 weeks (cycles 3-6), then every 4 weeks until disease progression.

Among the IV-Dara patients, the median duration of the first infusion was 421 minutes in cycle 1, 255 minutes in cycle 2, and 205 minutes in subsequent cycles – compatible with standard practice in the United States. As reported, at a median follow-up of 7.46 months, the efficacy (overall response rate, complete response rate, stringent-complete response rate, very good-partial response rate, progression-free survival, and 6-month overall survival) and safety profile were non-inferior for SC-Dara. SC-Dara patients also reported higher satisfaction with therapy.

What this means in practice

It is always a good idea to await publication of the manuscript because there may be study details and statistical nuances that make SC-Dara appear better than it will prove to be. For example, patient characteristics were slightly different between the two arms. Peer review of the final manuscript could be important in placing these results in context.

However, for treatments that demand frequent office visits over many months, reducing treatment burden for patients has value. Based on COLUMBA, it appears likely that SC-Dara will be a major convenience for patients, without obvious drawbacks in efficacy or toxicity. Meanwhile, flat dosing will be a time-saver for physicians, nursing, and pharmacy staff. If the price of the SC formulation is not exorbitant, I would expect a “win-win” that will support converting from IV- to SC-Dara as standard practice.

Acalabrutinib in CLL/SLL

Preclinical studies have shown acalabrutinib (Acala) to be more selective for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) than the first-in-class agent ibrutinib, with less off-target kinase inhibition. As reported at the 2019 annual congress of the European Hematology Association by Paolo Ghia, MD, PhD, and colleagues in the phase 3 ASCEND trial, 310 patients with previously treated CLL were randomized between oral Acala twice daily and treatment of physician’s choice (TPC) – either idelalisib plus rituximab (maximum of seven infusions) or bendamustine plus rituximab (maximum of six cycles).

Progression-free survival was the primary endpoint. At a median of 16.1 months, progression-free survival had not been reached for Acala, in comparison with 16.5 months for TPC. Significant benefit of Acala was observed in all prognostic subsets.

Although there was no difference in overall survival at a median follow-up of about 16 months, 85% of Acala patients had a response lasting at least 12 months, compared with 60% of TPC patients. Adverse events of any grade occurred in 94% of patients treated with Acala, with 45% being grade 3-4 toxicities and six treatment-related deaths.

What this means in practice

The vast majority of CLL/SLL patients will relapse after primary therapy and will require further treatment, so the progression-free survival improvement associated with Acala in ASCEND is eye-catching. However, there are important considerations that demand closer scrutiny.

With oral agents administered until progression or unacceptable toxicity, low-grade toxicities can influence patient adherence, quality of life, and potentially the need for dose reduction or treatment interruptions. Regimens of finite duration and easy adherence monitoring may be, on balance, preferred by patients and providers – especially if the oral agent can be given in later-line with comparable overall survival.

With ibrutinib (Blood. 2017;129:2612-5), Paul M. Barr, MD, and colleagues demonstrated that higher dose intensity was associated with improved progression-free survival and that holds were associated with worsened progression-free survival. Acala’s promise of high efficacy and lower off-target toxicity will be solidified if the large (more than 500 patients) phase 3 ACE-CL-006 study (Acala vs. ibrutinib) demonstrates its relative benefit from efficacy, toxicity, and adherence perspectives, in comparison with a standard therapy that similarly demands adherence until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Dr. Lyss has been a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years, practicing in St. Louis. His clinical and research interests are in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of breast and lung cancers and in expanding access to clinical trials to medically underserved populations.

In this edition of “How I will treat my next patient,” I highlight two recent presentations regarding potential improvements in the convenience and tolerability of treatment for two hematologic malignancies: multiple myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL).

SC-Dara in myeloma

At the 2019 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Maria-Victoria Mateos, MD, PhD, and colleagues, reported the results of COLUMBA, a phase 3 evaluation in 522 patients with multiple myeloma who were randomized to subcutaneous daratumumab (SC-Dara) or standard intravenous infusions of daratumumab (IV-Dara). A previous phase 1b study (Blood. 2017;130:838) had suggested comparable efficacy from the more convenient SC regime. Whereas conventional infusions of IV-Dara (16 mg/kg) take several hours, the SC formulation (1,800 mg–flat dose) is delivered in minutes. In COLUMBA, patients were randomized between SC- and IV-Dara weekly (cycles 1-2), then every 2 weeks (cycles 3-6), then every 4 weeks until disease progression.

Among the IV-Dara patients, the median duration of the first infusion was 421 minutes in cycle 1, 255 minutes in cycle 2, and 205 minutes in subsequent cycles – compatible with standard practice in the United States. As reported, at a median follow-up of 7.46 months, the efficacy (overall response rate, complete response rate, stringent-complete response rate, very good-partial response rate, progression-free survival, and 6-month overall survival) and safety profile were non-inferior for SC-Dara. SC-Dara patients also reported higher satisfaction with therapy.

What this means in practice

It is always a good idea to await publication of the manuscript because there may be study details and statistical nuances that make SC-Dara appear better than it will prove to be. For example, patient characteristics were slightly different between the two arms. Peer review of the final manuscript could be important in placing these results in context.

However, for treatments that demand frequent office visits over many months, reducing treatment burden for patients has value. Based on COLUMBA, it appears likely that SC-Dara will be a major convenience for patients, without obvious drawbacks in efficacy or toxicity. Meanwhile, flat dosing will be a time-saver for physicians, nursing, and pharmacy staff. If the price of the SC formulation is not exorbitant, I would expect a “win-win” that will support converting from IV- to SC-Dara as standard practice.

Acalabrutinib in CLL/SLL

Preclinical studies have shown acalabrutinib (Acala) to be more selective for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) than the first-in-class agent ibrutinib, with less off-target kinase inhibition. As reported at the 2019 annual congress of the European Hematology Association by Paolo Ghia, MD, PhD, and colleagues in the phase 3 ASCEND trial, 310 patients with previously treated CLL were randomized between oral Acala twice daily and treatment of physician’s choice (TPC) – either idelalisib plus rituximab (maximum of seven infusions) or bendamustine plus rituximab (maximum of six cycles).

Progression-free survival was the primary endpoint. At a median of 16.1 months, progression-free survival had not been reached for Acala, in comparison with 16.5 months for TPC. Significant benefit of Acala was observed in all prognostic subsets.

Although there was no difference in overall survival at a median follow-up of about 16 months, 85% of Acala patients had a response lasting at least 12 months, compared with 60% of TPC patients. Adverse events of any grade occurred in 94% of patients treated with Acala, with 45% being grade 3-4 toxicities and six treatment-related deaths.

What this means in practice

The vast majority of CLL/SLL patients will relapse after primary therapy and will require further treatment, so the progression-free survival improvement associated with Acala in ASCEND is eye-catching. However, there are important considerations that demand closer scrutiny.

With oral agents administered until progression or unacceptable toxicity, low-grade toxicities can influence patient adherence, quality of life, and potentially the need for dose reduction or treatment interruptions. Regimens of finite duration and easy adherence monitoring may be, on balance, preferred by patients and providers – especially if the oral agent can be given in later-line with comparable overall survival.

With ibrutinib (Blood. 2017;129:2612-5), Paul M. Barr, MD, and colleagues demonstrated that higher dose intensity was associated with improved progression-free survival and that holds were associated with worsened progression-free survival. Acala’s promise of high efficacy and lower off-target toxicity will be solidified if the large (more than 500 patients) phase 3 ACE-CL-006 study (Acala vs. ibrutinib) demonstrates its relative benefit from efficacy, toxicity, and adherence perspectives, in comparison with a standard therapy that similarly demands adherence until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Dr. Lyss has been a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years, practicing in St. Louis. His clinical and research interests are in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of breast and lung cancers and in expanding access to clinical trials to medically underserved populations.

When’s the right time to use dementia as a diagnosis?

Is dementia a diagnosis?

I use it myself, although I find that some neurologists consider this blasphemy.

The problem is that there aren’t many terms to cover cognitive disorders beyond mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Phrases like “cortical degeneration” and “frontotemporal disorder” are difficult for families and patients. They aren’t medically trained and want something easy to write down.

“Alzheimer’s,” or – as one patient’s family member says, “the A-word” – is often more accurate, but has stigma attached to it that many don’t want, especially at a first visit. It also immediately conjures up feared images of nursing homes, wheelchairs, and bed-bound people.

So I use a diagnosis of dementia with many families, at least initially. Since, with occasional exceptions, we tend to perform a work-up of all cognitive disorders the same way, I don’t have a problem with using a more generic blanket term. As I sometimes try to simplify things, I’ll say, “It’s like squares and rectangles. Alzheimer’s disease is a dementia, but not all dementias are Alzheimer’s disease.”

I don’t do this to avoid confrontation, be dishonest, mislead patients and families, or avoid telling the truth. I still make it very clear that this is a progressive neurologic illness that will cause worsening cognitive problems over time. But many times families aren’t ready for “the A-word” early on, or there’s a concern the patient will harm themselves while they still have that capacity. Sometimes, it’s better to use a different phrase.

It may all be semantics, but on a personal level, a word can make a huge difference.

So I say dementia. In spite of some editorials I’ve seen saying we should retire the phrase, I argue that in many circumstances it’s still valid and useful.

It may not be a final, or even specific, diagnosis, but it is often the best and most socially acceptable one at the beginning of the doctor-patient-family relationship. When you’re trying to build rapport with them, that’s equally critical when you know what’s to come down the road.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Is dementia a diagnosis?

I use it myself, although I find that some neurologists consider this blasphemy.

The problem is that there aren’t many terms to cover cognitive disorders beyond mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Phrases like “cortical degeneration” and “frontotemporal disorder” are difficult for families and patients. They aren’t medically trained and want something easy to write down.

“Alzheimer’s,” or – as one patient’s family member says, “the A-word” – is often more accurate, but has stigma attached to it that many don’t want, especially at a first visit. It also immediately conjures up feared images of nursing homes, wheelchairs, and bed-bound people.

So I use a diagnosis of dementia with many families, at least initially. Since, with occasional exceptions, we tend to perform a work-up of all cognitive disorders the same way, I don’t have a problem with using a more generic blanket term. As I sometimes try to simplify things, I’ll say, “It’s like squares and rectangles. Alzheimer’s disease is a dementia, but not all dementias are Alzheimer’s disease.”

I don’t do this to avoid confrontation, be dishonest, mislead patients and families, or avoid telling the truth. I still make it very clear that this is a progressive neurologic illness that will cause worsening cognitive problems over time. But many times families aren’t ready for “the A-word” early on, or there’s a concern the patient will harm themselves while they still have that capacity. Sometimes, it’s better to use a different phrase.

It may all be semantics, but on a personal level, a word can make a huge difference.

So I say dementia. In spite of some editorials I’ve seen saying we should retire the phrase, I argue that in many circumstances it’s still valid and useful.

It may not be a final, or even specific, diagnosis, but it is often the best and most socially acceptable one at the beginning of the doctor-patient-family relationship. When you’re trying to build rapport with them, that’s equally critical when you know what’s to come down the road.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Is dementia a diagnosis?

I use it myself, although I find that some neurologists consider this blasphemy.

The problem is that there aren’t many terms to cover cognitive disorders beyond mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Phrases like “cortical degeneration” and “frontotemporal disorder” are difficult for families and patients. They aren’t medically trained and want something easy to write down.

“Alzheimer’s,” or – as one patient’s family member says, “the A-word” – is often more accurate, but has stigma attached to it that many don’t want, especially at a first visit. It also immediately conjures up feared images of nursing homes, wheelchairs, and bed-bound people.

So I use a diagnosis of dementia with many families, at least initially. Since, with occasional exceptions, we tend to perform a work-up of all cognitive disorders the same way, I don’t have a problem with using a more generic blanket term. As I sometimes try to simplify things, I’ll say, “It’s like squares and rectangles. Alzheimer’s disease is a dementia, but not all dementias are Alzheimer’s disease.”

I don’t do this to avoid confrontation, be dishonest, mislead patients and families, or avoid telling the truth. I still make it very clear that this is a progressive neurologic illness that will cause worsening cognitive problems over time. But many times families aren’t ready for “the A-word” early on, or there’s a concern the patient will harm themselves while they still have that capacity. Sometimes, it’s better to use a different phrase.

It may all be semantics, but on a personal level, a word can make a huge difference.

So I say dementia. In spite of some editorials I’ve seen saying we should retire the phrase, I argue that in many circumstances it’s still valid and useful.

It may not be a final, or even specific, diagnosis, but it is often the best and most socially acceptable one at the beginning of the doctor-patient-family relationship. When you’re trying to build rapport with them, that’s equally critical when you know what’s to come down the road.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The pool is closed!

At a recent Recreation Commission meeting here in Brunswick, the first agenda item under new business was “Coffin Pond Pool Closing.” As I and my fellow commissioners listened, we were told that for the first time in the last 3 decades the town’s only public swimming area would not be opening. While in the past there have been delayed openings and temporary closings due to water conditions, this year the pool would not open, period. The cause of the pool’s closure was the Parks and Recreation Department’s failure to fill even a skeleton crew of lifeguards.

We learned that the situation here in Brunswick was not unique and most other communities around the state and even around the country were struggling to find lifeguards. The shortage of trained staff has been nationwide for several years, and many beaches and pools particularly in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states were being forced to close or shorten hours of operation (“During the Pool Season Even Lifeguard Numbers are Taking a Dive,” by Leoneda Inge, July 28, 2015, NPR’s All Thing Considered).

You might think that here on the coast we would have ample places for children to swim, but in Brunswick our shore is rocky and often inaccessible. At the few sandy beaches, the water temperature is too cold for all but the hardy souls until late August. Lower-income families will be particularly affected by the loss of the pool.

When I was growing up, lifeguarding was a plum job that was highly coveted. While it did not pay as well as working construction, the perks of a pleasant atmosphere, the chance to swim every day, and the opportunity to work outside with children prompted me at age 16 to sell my lawn mower and bequeath my lucrative landscaping customers to a couple of preteens. Looking back, my 4 years of lifeguarding were probably a major influence when it came time to choose a specialty.

However, a perfect storm of socioeconomic factors has combined to create a climate in which being a lifeguard has lost its appeal as a summertime job. First, there is record low unemployment nationwide. Young people looking for work have their pick, and while wages still remain low, they can be choosy when it comes to hours and benefits. Lifeguarding does require a skill set and several hoops of certification to be navigated. I don’t recall having to pay much of anything to become certified. But I understand that the process now costs hundreds of dollars of upfront investment with no guarantee of passing the test.

In May, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy paper titled “Prevention of Drowning” (Pediatrics. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0850) in which the authors offer the troubling statistics on the toll that water-related accidents take on the children of this country annually. They go on to provide a broad list of actions that parents, communities, and pediatricians can take to prevent drownings. Under the category of Community Interventions and Advocacy Opportunities, recommendation No. 4 is “Pediatricians should work with community partners to provide access to programs that develop water-competency swim skills for all children.”

Obviously, these programs can’t happen without an adequate supply of lifeguards.

Unfortunately, the AAP’s statement fails to acknowledge or directly address the lifeguard shortage that has been going on for several years. While an adequate supply of lifeguards is probably not as important as increasing parental attentiveness and mandating pool fences in the overall scheme of drowning prevention, it is an issue that demands action both by the academy and those of us practicing in communities both large and small.

For my part, I am going to work here in Brunswick to see that we can offer lifeguards pay that is more than competitive and then develop an in-house training program to ensure a continuing supply for the future. If we are committed to encouraging our patients to be active, swimming is one of the best activities we should promote and support.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

At a recent Recreation Commission meeting here in Brunswick, the first agenda item under new business was “Coffin Pond Pool Closing.” As I and my fellow commissioners listened, we were told that for the first time in the last 3 decades the town’s only public swimming area would not be opening. While in the past there have been delayed openings and temporary closings due to water conditions, this year the pool would not open, period. The cause of the pool’s closure was the Parks and Recreation Department’s failure to fill even a skeleton crew of lifeguards.

We learned that the situation here in Brunswick was not unique and most other communities around the state and even around the country were struggling to find lifeguards. The shortage of trained staff has been nationwide for several years, and many beaches and pools particularly in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states were being forced to close or shorten hours of operation (“During the Pool Season Even Lifeguard Numbers are Taking a Dive,” by Leoneda Inge, July 28, 2015, NPR’s All Thing Considered).

You might think that here on the coast we would have ample places for children to swim, but in Brunswick our shore is rocky and often inaccessible. At the few sandy beaches, the water temperature is too cold for all but the hardy souls until late August. Lower-income families will be particularly affected by the loss of the pool.

When I was growing up, lifeguarding was a plum job that was highly coveted. While it did not pay as well as working construction, the perks of a pleasant atmosphere, the chance to swim every day, and the opportunity to work outside with children prompted me at age 16 to sell my lawn mower and bequeath my lucrative landscaping customers to a couple of preteens. Looking back, my 4 years of lifeguarding were probably a major influence when it came time to choose a specialty.

However, a perfect storm of socioeconomic factors has combined to create a climate in which being a lifeguard has lost its appeal as a summertime job. First, there is record low unemployment nationwide. Young people looking for work have their pick, and while wages still remain low, they can be choosy when it comes to hours and benefits. Lifeguarding does require a skill set and several hoops of certification to be navigated. I don’t recall having to pay much of anything to become certified. But I understand that the process now costs hundreds of dollars of upfront investment with no guarantee of passing the test.

In May, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy paper titled “Prevention of Drowning” (Pediatrics. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0850) in which the authors offer the troubling statistics on the toll that water-related accidents take on the children of this country annually. They go on to provide a broad list of actions that parents, communities, and pediatricians can take to prevent drownings. Under the category of Community Interventions and Advocacy Opportunities, recommendation No. 4 is “Pediatricians should work with community partners to provide access to programs that develop water-competency swim skills for all children.”

Obviously, these programs can’t happen without an adequate supply of lifeguards.

Unfortunately, the AAP’s statement fails to acknowledge or directly address the lifeguard shortage that has been going on for several years. While an adequate supply of lifeguards is probably not as important as increasing parental attentiveness and mandating pool fences in the overall scheme of drowning prevention, it is an issue that demands action both by the academy and those of us practicing in communities both large and small.

For my part, I am going to work here in Brunswick to see that we can offer lifeguards pay that is more than competitive and then develop an in-house training program to ensure a continuing supply for the future. If we are committed to encouraging our patients to be active, swimming is one of the best activities we should promote and support.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

At a recent Recreation Commission meeting here in Brunswick, the first agenda item under new business was “Coffin Pond Pool Closing.” As I and my fellow commissioners listened, we were told that for the first time in the last 3 decades the town’s only public swimming area would not be opening. While in the past there have been delayed openings and temporary closings due to water conditions, this year the pool would not open, period. The cause of the pool’s closure was the Parks and Recreation Department’s failure to fill even a skeleton crew of lifeguards.

We learned that the situation here in Brunswick was not unique and most other communities around the state and even around the country were struggling to find lifeguards. The shortage of trained staff has been nationwide for several years, and many beaches and pools particularly in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states were being forced to close or shorten hours of operation (“During the Pool Season Even Lifeguard Numbers are Taking a Dive,” by Leoneda Inge, July 28, 2015, NPR’s All Thing Considered).

You might think that here on the coast we would have ample places for children to swim, but in Brunswick our shore is rocky and often inaccessible. At the few sandy beaches, the water temperature is too cold for all but the hardy souls until late August. Lower-income families will be particularly affected by the loss of the pool.

When I was growing up, lifeguarding was a plum job that was highly coveted. While it did not pay as well as working construction, the perks of a pleasant atmosphere, the chance to swim every day, and the opportunity to work outside with children prompted me at age 16 to sell my lawn mower and bequeath my lucrative landscaping customers to a couple of preteens. Looking back, my 4 years of lifeguarding were probably a major influence when it came time to choose a specialty.

However, a perfect storm of socioeconomic factors has combined to create a climate in which being a lifeguard has lost its appeal as a summertime job. First, there is record low unemployment nationwide. Young people looking for work have their pick, and while wages still remain low, they can be choosy when it comes to hours and benefits. Lifeguarding does require a skill set and several hoops of certification to be navigated. I don’t recall having to pay much of anything to become certified. But I understand that the process now costs hundreds of dollars of upfront investment with no guarantee of passing the test.

In May, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy paper titled “Prevention of Drowning” (Pediatrics. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0850) in which the authors offer the troubling statistics on the toll that water-related accidents take on the children of this country annually. They go on to provide a broad list of actions that parents, communities, and pediatricians can take to prevent drownings. Under the category of Community Interventions and Advocacy Opportunities, recommendation No. 4 is “Pediatricians should work with community partners to provide access to programs that develop water-competency swim skills for all children.”

Obviously, these programs can’t happen without an adequate supply of lifeguards.

Unfortunately, the AAP’s statement fails to acknowledge or directly address the lifeguard shortage that has been going on for several years. While an adequate supply of lifeguards is probably not as important as increasing parental attentiveness and mandating pool fences in the overall scheme of drowning prevention, it is an issue that demands action both by the academy and those of us practicing in communities both large and small.

For my part, I am going to work here in Brunswick to see that we can offer lifeguards pay that is more than competitive and then develop an in-house training program to ensure a continuing supply for the future. If we are committed to encouraging our patients to be active, swimming is one of the best activities we should promote and support.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

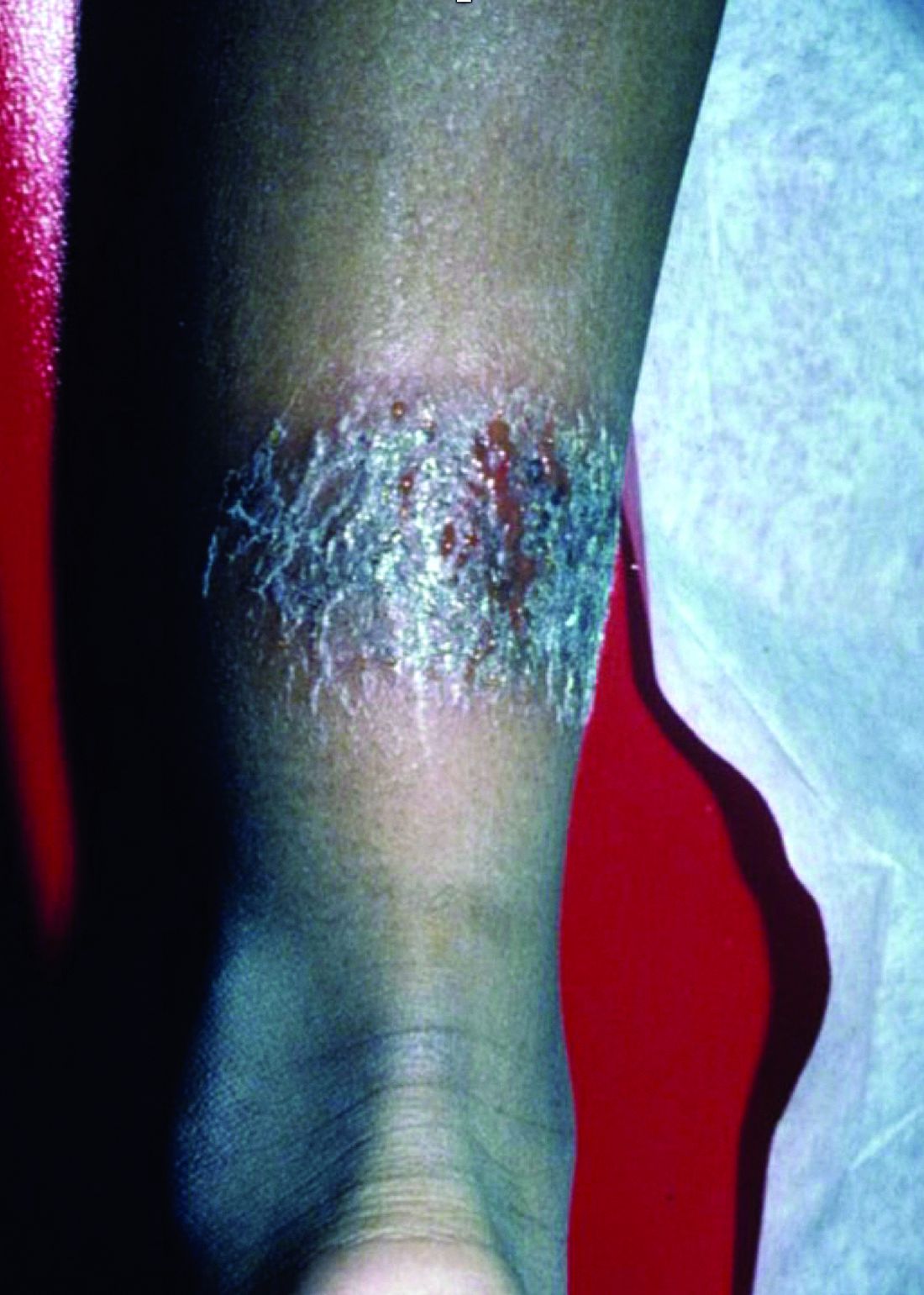

A 3-year-old is brought to the clinic for evaluation of a localized, scaling inflamed lesion on the left leg

Nummular dermatitis, or nummular eczema, is an inflammatory skin condition that is considered to be a distinctive form of idiopathic eczema, while the term also is used to describe lesional morphology associated with other conditions.

The term nummular derives from the Latin word for “coin,” as lesions are commonly annular plaques. Lesions of nummular dermatitis can be single or multiple. The typical distribution involves the extremities and, although less common, it can affect the trunk as well.

Nummular dermatitis may be associated with atopic dermatitis, or it can be an isolated condition.1 While the pathogenesis is uncertain, instigating factors include xerotic skin, insect bites, or scratches or scrapes.1Staphylococcus infection or colonization, contact allergies to metals such as nickel and less commonly mercury, sensitivity to formaldehyde or medicines such as neomycin, and sensitization to an environmental aeroallergen (such as Candida albicans, dust mites) are considered risk factors.2

The diagnosis of nummular dermatitis is clinical. Laboratory testing and/or biopsy generally are not necessary, although a bacterial culture can be considered in patients with exudative and/or crusted lesions to rule out impetigo as a primary process of secondary infection. In some cases, patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis may be useful.

The differential diagnosis of nummular dermatitis includes tinea corporis (ringworm), atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, impetigo, and psoriasis. Tinea corporis usually presents as annular lesions with a distinct peripheral scaling, rather than the diffuse induration of nummular dermatitis. Potassium hydroxide preparation or fungal culture can identify tinea species. Nummular dermatitis may be seen in patients with atopic dermatitis, who should have typical history, morphology, and course consistent with standard diagnostic criteria. Allergic contact dermatitis can present with regional, localized eczematous plaques in areas exposed to contact allergens. Patterns of lesions in areas of contact and worsening with repeat exposures can be clues to this diagnosis. Impetigo can present with honey-colored crusted lesions and/or superficial erosions, or purulent pyoderma. Lesions can be single or multiple and generally appear less inflammatory than nummular dermatitis. Psoriasis lesions may be annular, are more common on extensor surfaces, and usually have more prominent overlying pinkish, silvery white or micaceous scale.

Management of nummular dermatitis requires strong anti-inflammatory medications, usually mid-potency or higher topical corticosteroids, along with moisturizers and limiting exposure to skin irritants. “Wet wraps,” with application of topical corticosteroids to wet skin with occlusive wet dressings can enhance response. Transition from higher strength topical corticosteroids to lower strength agents used intermittently can help achieve remission or cure. Management practices include less frequent bathing with lukewarm water, using hypoallergenic cleansers and detergents, and applying moisturizers frequently. If plaques do recur, they tend to do so in the same location and in some patients resolution may result in hyper or hypopigmentation. Refractory disease may be managed with intralesional steroid injections, or systemic medications such as methotrexate.3

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Tracy nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Sep-Oct;29(5):580-3.

2. American Academy of Dermatology. Nummular Dermatitis Overview

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Sep;35(5):611-5.

Nummular dermatitis, or nummular eczema, is an inflammatory skin condition that is considered to be a distinctive form of idiopathic eczema, while the term also is used to describe lesional morphology associated with other conditions.

The term nummular derives from the Latin word for “coin,” as lesions are commonly annular plaques. Lesions of nummular dermatitis can be single or multiple. The typical distribution involves the extremities and, although less common, it can affect the trunk as well.

Nummular dermatitis may be associated with atopic dermatitis, or it can be an isolated condition.1 While the pathogenesis is uncertain, instigating factors include xerotic skin, insect bites, or scratches or scrapes.1Staphylococcus infection or colonization, contact allergies to metals such as nickel and less commonly mercury, sensitivity to formaldehyde or medicines such as neomycin, and sensitization to an environmental aeroallergen (such as Candida albicans, dust mites) are considered risk factors.2

The diagnosis of nummular dermatitis is clinical. Laboratory testing and/or biopsy generally are not necessary, although a bacterial culture can be considered in patients with exudative and/or crusted lesions to rule out impetigo as a primary process of secondary infection. In some cases, patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis may be useful.

The differential diagnosis of nummular dermatitis includes tinea corporis (ringworm), atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, impetigo, and psoriasis. Tinea corporis usually presents as annular lesions with a distinct peripheral scaling, rather than the diffuse induration of nummular dermatitis. Potassium hydroxide preparation or fungal culture can identify tinea species. Nummular dermatitis may be seen in patients with atopic dermatitis, who should have typical history, morphology, and course consistent with standard diagnostic criteria. Allergic contact dermatitis can present with regional, localized eczematous plaques in areas exposed to contact allergens. Patterns of lesions in areas of contact and worsening with repeat exposures can be clues to this diagnosis. Impetigo can present with honey-colored crusted lesions and/or superficial erosions, or purulent pyoderma. Lesions can be single or multiple and generally appear less inflammatory than nummular dermatitis. Psoriasis lesions may be annular, are more common on extensor surfaces, and usually have more prominent overlying pinkish, silvery white or micaceous scale.

Management of nummular dermatitis requires strong anti-inflammatory medications, usually mid-potency or higher topical corticosteroids, along with moisturizers and limiting exposure to skin irritants. “Wet wraps,” with application of topical corticosteroids to wet skin with occlusive wet dressings can enhance response. Transition from higher strength topical corticosteroids to lower strength agents used intermittently can help achieve remission or cure. Management practices include less frequent bathing with lukewarm water, using hypoallergenic cleansers and detergents, and applying moisturizers frequently. If plaques do recur, they tend to do so in the same location and in some patients resolution may result in hyper or hypopigmentation. Refractory disease may be managed with intralesional steroid injections, or systemic medications such as methotrexate.3

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Tracy nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Sep-Oct;29(5):580-3.

2. American Academy of Dermatology. Nummular Dermatitis Overview

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Sep;35(5):611-5.

Nummular dermatitis, or nummular eczema, is an inflammatory skin condition that is considered to be a distinctive form of idiopathic eczema, while the term also is used to describe lesional morphology associated with other conditions.

The term nummular derives from the Latin word for “coin,” as lesions are commonly annular plaques. Lesions of nummular dermatitis can be single or multiple. The typical distribution involves the extremities and, although less common, it can affect the trunk as well.

Nummular dermatitis may be associated with atopic dermatitis, or it can be an isolated condition.1 While the pathogenesis is uncertain, instigating factors include xerotic skin, insect bites, or scratches or scrapes.1Staphylococcus infection or colonization, contact allergies to metals such as nickel and less commonly mercury, sensitivity to formaldehyde or medicines such as neomycin, and sensitization to an environmental aeroallergen (such as Candida albicans, dust mites) are considered risk factors.2

The diagnosis of nummular dermatitis is clinical. Laboratory testing and/or biopsy generally are not necessary, although a bacterial culture can be considered in patients with exudative and/or crusted lesions to rule out impetigo as a primary process of secondary infection. In some cases, patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis may be useful.

The differential diagnosis of nummular dermatitis includes tinea corporis (ringworm), atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, impetigo, and psoriasis. Tinea corporis usually presents as annular lesions with a distinct peripheral scaling, rather than the diffuse induration of nummular dermatitis. Potassium hydroxide preparation or fungal culture can identify tinea species. Nummular dermatitis may be seen in patients with atopic dermatitis, who should have typical history, morphology, and course consistent with standard diagnostic criteria. Allergic contact dermatitis can present with regional, localized eczematous plaques in areas exposed to contact allergens. Patterns of lesions in areas of contact and worsening with repeat exposures can be clues to this diagnosis. Impetigo can present with honey-colored crusted lesions and/or superficial erosions, or purulent pyoderma. Lesions can be single or multiple and generally appear less inflammatory than nummular dermatitis. Psoriasis lesions may be annular, are more common on extensor surfaces, and usually have more prominent overlying pinkish, silvery white or micaceous scale.

Management of nummular dermatitis requires strong anti-inflammatory medications, usually mid-potency or higher topical corticosteroids, along with moisturizers and limiting exposure to skin irritants. “Wet wraps,” with application of topical corticosteroids to wet skin with occlusive wet dressings can enhance response. Transition from higher strength topical corticosteroids to lower strength agents used intermittently can help achieve remission or cure. Management practices include less frequent bathing with lukewarm water, using hypoallergenic cleansers and detergents, and applying moisturizers frequently. If plaques do recur, they tend to do so in the same location and in some patients resolution may result in hyper or hypopigmentation. Refractory disease may be managed with intralesional steroid injections, or systemic medications such as methotrexate.3

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Tracy nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Sep-Oct;29(5):580-3.

2. American Academy of Dermatology. Nummular Dermatitis Overview

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Sep;35(5):611-5.

On physical exam, he is noted to have a localized eczematous plaque with erythema and edema. Also, he is noted to have diffuse, fine xerosis of the bilateral lower extremities. His skin is otherwise nonremarkable.

Mothers, migraine, colic ... and sleep

In a recent article on this website, Jake Remaly reports on a study suggesting that maternal migraine is associated with infant colic. In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society, Amy Gelfand, MD, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, reported the results of a national survey of more than 1,400 parents (827 mothers, 592 fathers) collected via social media. She and her colleagues found that mothers with migraine were more likely to have an infant with colic, with an odds ratio of 1.7 that increased to 2.5 for mothers with more frequent migraine. Fathers with migraine were no more likely to have an infant with colic.

In a video clip included in the article, Dr. Gelfand discusses the possibilities that she and her group considered as they attempted to explain the study’s findings. Are there such things as “migraine genes?” If so, the failure to discover a paternal association might suggest that these would be mitochondrial genes. The researchers wondered if a substance in breast milk was acting as trigger, but they found that the association between colic and migraine was unrelated to whether the baby was fed by breast or bottle.

In full disclosure, I was not one of the investigators. Neither my wife nor I have migraine, and although our children cried as infants, they wouldn’t have qualified as having colic. However, I spent more than 40 years immersed in more than 300,000 patient encounters and can claim membership in the International Brother/Sisterhood of Anecdotal Observers. And, as such will offer up my explanation for Dr. Gelfand’s findings.

It is clear to me that most, if not all, children with migraine have their headaches when they are sleep deprived. While my sample size is smaller, I believe the same association also is true for many of the adults I know who have migraine. At least in children, restorative sleep ends the migraine much as it does for an epileptic seizure.

Traditionally, colic has been thought to be somehow related to a gastrointestinal phenomenon by many extended family members and some physicians. However, in my experience, it is usually a symptom of sleep deprivation compounded by the failure of those around the children to realize the obvious and take appropriate action. Of course, some babies are reacting to sore tummies, but my guess is that most are having headaches. We may never know. Dr. Gelfand also shares my observation that colicky crying is more likely to occur “at the end of the day,” a time when we are tired and are less tolerant of overstimulation.

However, the presentation varies depending on the age of the patients. Remember, infants can’t talk. It already has been shown that adults with migraine often were more likely to have been colicky infants. (Dr. Gelfand mentions this as well.) These unfortunate individuals probably have inherited a vulnerability to sleep deprivation that manifests itself as a headache. I hope to live long enough to be around when someone discovers the wrinkle in the genome that creates this vulnerability.

So, why did the researchers fail to find an association between fathers and colic? The answer is simple. We fathers are beginning to take on a larger role in parenting of infants and like to complain about how difficult it is. However, it is mothers who still have the lioness’ share of the work. They lose the most sleep and are starting off parenthood with 9 months of less than optimal sleep followed by who knows how many hours of energy-sapping labor. It’s surprising they all don’t have migraines.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

In a recent article on this website, Jake Remaly reports on a study suggesting that maternal migraine is associated with infant colic. In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society, Amy Gelfand, MD, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, reported the results of a national survey of more than 1,400 parents (827 mothers, 592 fathers) collected via social media. She and her colleagues found that mothers with migraine were more likely to have an infant with colic, with an odds ratio of 1.7 that increased to 2.5 for mothers with more frequent migraine. Fathers with migraine were no more likely to have an infant with colic.

In a video clip included in the article, Dr. Gelfand discusses the possibilities that she and her group considered as they attempted to explain the study’s findings. Are there such things as “migraine genes?” If so, the failure to discover a paternal association might suggest that these would be mitochondrial genes. The researchers wondered if a substance in breast milk was acting as trigger, but they found that the association between colic and migraine was unrelated to whether the baby was fed by breast or bottle.

In full disclosure, I was not one of the investigators. Neither my wife nor I have migraine, and although our children cried as infants, they wouldn’t have qualified as having colic. However, I spent more than 40 years immersed in more than 300,000 patient encounters and can claim membership in the International Brother/Sisterhood of Anecdotal Observers. And, as such will offer up my explanation for Dr. Gelfand’s findings.

It is clear to me that most, if not all, children with migraine have their headaches when they are sleep deprived. While my sample size is smaller, I believe the same association also is true for many of the adults I know who have migraine. At least in children, restorative sleep ends the migraine much as it does for an epileptic seizure.