User login

Why is AOM frequency decreasing in the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era?

In 2000, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine 7 (PCV7) was introduced in the United States, and in 2010, PCV13 was introduced. When each of those vaccines were used, they reduced acute otitis media (AOM) incidence caused by the pneumococcal types included in the vaccines. In the time frame of those vaccine introductions, about one-third of AOM cases occurred because of pneumococci and half of those cases occurred because of strains expressing the serotypes in the two formulations of the vaccines. Efficacy is about 70% for AOM prevention for PCVs. The math matches clinical trial results that have shown about an 11%-12% reduction of all AOM attributable to PCVs. However, our group continues to do tympanocentesis to track the etiology of AOM, and we have reported that elimination of strains of pneumococci expressing capsular types included in the PCVs has been followed by emergence of replacement strains of pneumococci that express non-PCV capsules. We also have shown that Haemophilus influenzae has increased proportionally as a cause of AOM and is the most frequent cause of recurrent AOM. So what else is going on?

My colleague, Stephen I. Pelton, MD, – another ID Consult columnist – is a coauthor of a paper along with Ron Dagan, MD; Lauren Bakaletz, PhD; and Robert Cohen, MD, (all major figures in pneumococcal disease or AOM) that was published in Lancet Infectious Diseases (Dagan R et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Apr;16[4]:480-92.). They gathered evidence suggesting that prevention of early AOM episodes caused by pneumococci expressing PCV serotypes resulted in a reduction of subsequent complex cases caused by nonvaccine serotypes and other otopathogens. Thus, PCVs may have an impact on AOM indirectly attributable to vaccination.

However, the American Academy of Pediatrics made several recommendations in the 2004 and 2013 guidelines for diagnosis and management of AOM that had a remarkable impact in reducing the frequency that this infection is diagnosed and treated as well. The recommendations included:

- Stricter diagnostic criteria in 2004 that became more strict in 2013 requiring bulging of the eardrum.

- Introduction of “watchful waiting” as an option in management that possibly led to no antibiotic treatment.

- Introduction of delayed prescription of antibiotic when diagnosis was uncertain that possibly led to no antibiotic treatment.

- Endorsement of specific antibiotics with the greatest anticipated efficacy taking into consideration spectrum of activity, safety, and costs.

In the same general time frame, a second development occurred: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched a national campaign to reduce unnecessary and inappropriate antibiotic use in an effort to reduce rising antibiotic resistance among bacteria. The public media and professional communication campaign emphasized that antibiotic treatment carried with it risks that should be considered by patients and clinicians.

Because of the AAP and CDC recommendations, clinicians diagnosed AOM less frequently, and they treated it less frequently. Parents of children took note of the fact that their children with viral upper respiratory infections suspected to have AOM were diagnosed with AOM less often; even when a diagnosis was made, an antibiotic was prescribed less often. Therefore, parents brought their children to clinicians less often when their child had a viral upper respiratory infections or when they suspected AOM.

In addition, guidelines endorsed specific antibiotics that had better efficacy in treatment of AOM. Therefore, when clinicians did treat the infection with antibiotics, they used more effective drugs resulting in fewer treatment failures. This gives the impression of less-frequent AOM as well.

Both universal PCV use and universal influenza vaccine use have been endorsed in recent years, and uptake of that recommendation has increased over time. Clinical trials have shown that influenza is a common virus associated with secondary bacterial AOM.

Lastly, returning to antibiotic use, we now increasingly appreciate the adverse effect on the natural microbiome of the nasopharynx and gut when antibiotics are given. Natural resistance provided by commensals is disrupted when antibiotics are given. This may allow otopathogens to colonize the nasopharynx more readily, an effect that may last for months after a single antibiotic course. We also appreciate more that the microbiome modulates our immune system favorably, so antibiotics that disrupt the microbiome may have an adverse effect on innate or adaptive immunity as well. These adverse consequences of antibiotic use on microbiome and immunity are reduced when less antibiotics are given to children, as has been occurring over the past 2 decades.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He said he had no relevent financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

In 2000, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine 7 (PCV7) was introduced in the United States, and in 2010, PCV13 was introduced. When each of those vaccines were used, they reduced acute otitis media (AOM) incidence caused by the pneumococcal types included in the vaccines. In the time frame of those vaccine introductions, about one-third of AOM cases occurred because of pneumococci and half of those cases occurred because of strains expressing the serotypes in the two formulations of the vaccines. Efficacy is about 70% for AOM prevention for PCVs. The math matches clinical trial results that have shown about an 11%-12% reduction of all AOM attributable to PCVs. However, our group continues to do tympanocentesis to track the etiology of AOM, and we have reported that elimination of strains of pneumococci expressing capsular types included in the PCVs has been followed by emergence of replacement strains of pneumococci that express non-PCV capsules. We also have shown that Haemophilus influenzae has increased proportionally as a cause of AOM and is the most frequent cause of recurrent AOM. So what else is going on?

My colleague, Stephen I. Pelton, MD, – another ID Consult columnist – is a coauthor of a paper along with Ron Dagan, MD; Lauren Bakaletz, PhD; and Robert Cohen, MD, (all major figures in pneumococcal disease or AOM) that was published in Lancet Infectious Diseases (Dagan R et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Apr;16[4]:480-92.). They gathered evidence suggesting that prevention of early AOM episodes caused by pneumococci expressing PCV serotypes resulted in a reduction of subsequent complex cases caused by nonvaccine serotypes and other otopathogens. Thus, PCVs may have an impact on AOM indirectly attributable to vaccination.

However, the American Academy of Pediatrics made several recommendations in the 2004 and 2013 guidelines for diagnosis and management of AOM that had a remarkable impact in reducing the frequency that this infection is diagnosed and treated as well. The recommendations included:

- Stricter diagnostic criteria in 2004 that became more strict in 2013 requiring bulging of the eardrum.

- Introduction of “watchful waiting” as an option in management that possibly led to no antibiotic treatment.

- Introduction of delayed prescription of antibiotic when diagnosis was uncertain that possibly led to no antibiotic treatment.

- Endorsement of specific antibiotics with the greatest anticipated efficacy taking into consideration spectrum of activity, safety, and costs.

In the same general time frame, a second development occurred: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched a national campaign to reduce unnecessary and inappropriate antibiotic use in an effort to reduce rising antibiotic resistance among bacteria. The public media and professional communication campaign emphasized that antibiotic treatment carried with it risks that should be considered by patients and clinicians.

Because of the AAP and CDC recommendations, clinicians diagnosed AOM less frequently, and they treated it less frequently. Parents of children took note of the fact that their children with viral upper respiratory infections suspected to have AOM were diagnosed with AOM less often; even when a diagnosis was made, an antibiotic was prescribed less often. Therefore, parents brought their children to clinicians less often when their child had a viral upper respiratory infections or when they suspected AOM.

In addition, guidelines endorsed specific antibiotics that had better efficacy in treatment of AOM. Therefore, when clinicians did treat the infection with antibiotics, they used more effective drugs resulting in fewer treatment failures. This gives the impression of less-frequent AOM as well.

Both universal PCV use and universal influenza vaccine use have been endorsed in recent years, and uptake of that recommendation has increased over time. Clinical trials have shown that influenza is a common virus associated with secondary bacterial AOM.

Lastly, returning to antibiotic use, we now increasingly appreciate the adverse effect on the natural microbiome of the nasopharynx and gut when antibiotics are given. Natural resistance provided by commensals is disrupted when antibiotics are given. This may allow otopathogens to colonize the nasopharynx more readily, an effect that may last for months after a single antibiotic course. We also appreciate more that the microbiome modulates our immune system favorably, so antibiotics that disrupt the microbiome may have an adverse effect on innate or adaptive immunity as well. These adverse consequences of antibiotic use on microbiome and immunity are reduced when less antibiotics are given to children, as has been occurring over the past 2 decades.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He said he had no relevent financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

In 2000, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine 7 (PCV7) was introduced in the United States, and in 2010, PCV13 was introduced. When each of those vaccines were used, they reduced acute otitis media (AOM) incidence caused by the pneumococcal types included in the vaccines. In the time frame of those vaccine introductions, about one-third of AOM cases occurred because of pneumococci and half of those cases occurred because of strains expressing the serotypes in the two formulations of the vaccines. Efficacy is about 70% for AOM prevention for PCVs. The math matches clinical trial results that have shown about an 11%-12% reduction of all AOM attributable to PCVs. However, our group continues to do tympanocentesis to track the etiology of AOM, and we have reported that elimination of strains of pneumococci expressing capsular types included in the PCVs has been followed by emergence of replacement strains of pneumococci that express non-PCV capsules. We also have shown that Haemophilus influenzae has increased proportionally as a cause of AOM and is the most frequent cause of recurrent AOM. So what else is going on?

My colleague, Stephen I. Pelton, MD, – another ID Consult columnist – is a coauthor of a paper along with Ron Dagan, MD; Lauren Bakaletz, PhD; and Robert Cohen, MD, (all major figures in pneumococcal disease or AOM) that was published in Lancet Infectious Diseases (Dagan R et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Apr;16[4]:480-92.). They gathered evidence suggesting that prevention of early AOM episodes caused by pneumococci expressing PCV serotypes resulted in a reduction of subsequent complex cases caused by nonvaccine serotypes and other otopathogens. Thus, PCVs may have an impact on AOM indirectly attributable to vaccination.

However, the American Academy of Pediatrics made several recommendations in the 2004 and 2013 guidelines for diagnosis and management of AOM that had a remarkable impact in reducing the frequency that this infection is diagnosed and treated as well. The recommendations included:

- Stricter diagnostic criteria in 2004 that became more strict in 2013 requiring bulging of the eardrum.

- Introduction of “watchful waiting” as an option in management that possibly led to no antibiotic treatment.

- Introduction of delayed prescription of antibiotic when diagnosis was uncertain that possibly led to no antibiotic treatment.

- Endorsement of specific antibiotics with the greatest anticipated efficacy taking into consideration spectrum of activity, safety, and costs.

In the same general time frame, a second development occurred: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched a national campaign to reduce unnecessary and inappropriate antibiotic use in an effort to reduce rising antibiotic resistance among bacteria. The public media and professional communication campaign emphasized that antibiotic treatment carried with it risks that should be considered by patients and clinicians.

Because of the AAP and CDC recommendations, clinicians diagnosed AOM less frequently, and they treated it less frequently. Parents of children took note of the fact that their children with viral upper respiratory infections suspected to have AOM were diagnosed with AOM less often; even when a diagnosis was made, an antibiotic was prescribed less often. Therefore, parents brought their children to clinicians less often when their child had a viral upper respiratory infections or when they suspected AOM.

In addition, guidelines endorsed specific antibiotics that had better efficacy in treatment of AOM. Therefore, when clinicians did treat the infection with antibiotics, they used more effective drugs resulting in fewer treatment failures. This gives the impression of less-frequent AOM as well.

Both universal PCV use and universal influenza vaccine use have been endorsed in recent years, and uptake of that recommendation has increased over time. Clinical trials have shown that influenza is a common virus associated with secondary bacterial AOM.

Lastly, returning to antibiotic use, we now increasingly appreciate the adverse effect on the natural microbiome of the nasopharynx and gut when antibiotics are given. Natural resistance provided by commensals is disrupted when antibiotics are given. This may allow otopathogens to colonize the nasopharynx more readily, an effect that may last for months after a single antibiotic course. We also appreciate more that the microbiome modulates our immune system favorably, so antibiotics that disrupt the microbiome may have an adverse effect on innate or adaptive immunity as well. These adverse consequences of antibiotic use on microbiome and immunity are reduced when less antibiotics are given to children, as has been occurring over the past 2 decades.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He said he had no relevent financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Provide appropriate sexual, reproductive health care for transgender patients

I recently was on a panel of experts discussing how to prevent HIV among transgender youth. Preventing HIV among transgender youth, especially transgender youth of color, remains a challenge for multiple reasons – racism, poverty, stigma, marginalization, and discrimination play a role in the HIV epidemic. A barrier to preventing HIV infections among transgender youth is a lack of knowledge on how to provide them with comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care. Here are some tips and resources that can help you ensure that transgender youth are safe and healthy.

One of the challenges of obtaining a sexual history is asking the right questions For example, if you have a transgender male assigned female at birth, ask whether their partners produce sperm instead of asking about the sex of their partners. A transgender male’s partner may identify as female but is assigned male at birth and uses her penis during sex. Furthermore, a transgender male may be on testosterone, but he still can get pregnant. Asking how they use their organs is just as important. A transgender male who has condomless penile-vaginal sex with multiple partners is at a higher risk for HIV infection than is a transgender male who shares sex toys with his only partner.

Normalizing that you ask a comprehensive sexual history to all your patients regardless of gender identity may put the patient at ease. Many transgender people are reluctant to disclose their gender identity to their provider because they are afraid that the provider may fixate on their sexuality once they do. Stating that you ask sexual health questions to all your patients may prevent the transgender patient from feeling singled out.

Finally, you don’t have to ask a sexual history with every transgender patient, just as you wouldn’t for your cisgender patients. If a patient is complaining of a sprained ankle, a sexual history may not be helpful, compared with obtaining one when a patient comes in with pelvic pain. Many transgender patients avoid care because they are frequently asked about their sexual history or gender identity when these are not relevant to their chief complaint.

Here are some helpful questions to ask when taking a sexual history, according to the University of California, San Francisco, Transgender Care & Treatment Guidelines.1

- Are you having sex? How many sex partners have you had in the past year?

- Who are you having sex with? What types of sex are you having? What parts of your anatomy do you use for sex?

- How do you protect yourself from STIs?

- What STIs have you had in the past, if any? When were you last tested for STIs?

- Has your partner(s) ever been diagnosed with any STIs?

- Do you use alcohol or any drugs when you have sex?

- Do you exchange sex for money, drugs, or a place to stay?

Also, use a trauma-informed approach when working with transgender patients. Many have been victims of sexual trauma. Always have a chaperone accompany you during the exam, explain to the patient what you plan to do and why it is necessary, and allow them to decline (and document their declining the physical exam). Also consider having your patient self-swab for STI screening if appropriate.1

Like obtaining a sexual history, routine screenings for certain types of cancers will be based on the organs the patient has. For example, a transgender woman assigned male at birth will not need a cervical cancer screening, but a transgender man assigned female at birth may need one – if the patient still has a cervix. Cervical cancer screening guidelines are similar for transgender men as it is for nontransgender women, and one should use the same guidelines endorsed by the American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathologists, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the World Health Organization.2-4

Cervical screenings should never be a requirement for testosterone therapy, and no transgender male under the age of 21 years will need cervical screening. The University of California guidelines offers tips on how to make transgender men more comfortable during cervical cancer screening.5

Contraception and menstrual management also are important for transgender patients. Testosterone can induce amenorrhea for transgender men, but it is not good birth control. If a transgender male patient has sex with partners that produce sperm, then the physician should discuss effective birth control options. There is no ideal birth control option for transgender men. One must consider multiple factors including the patient’s desire for pregnancy, desire to cease periods, ease of administration, and risk for thrombosis.

Most transgender men may balk at the idea of taking estrogen-containing contraception, but it is more effective than oral progestin-only pills. Intrauterine devices are highly effective in pregnancy prevention and can achieve amenorrhea in 50% of users within 1 year,but some transmen may become dysphoric with the procedure. 6 The etonogestrel implants also are highly effective birth control, but irregular periods are common, leading to discontinuation. Depot medroxyprogesterone is highly effective in preventing pregnancy and can induce amenorrhea in 70% of users within 1 year and 80% of users in 2 years, but also is associated with weight gain in one-third of users.7 Finally, pubertal blockers can rapidly stop periods for transmen who are severely dysphoric from their menses; however, before achieving amenorrhea, a flare bleed can occur 4-6 weeks after administration.8 Support from a mental health therapist during this time is critical. Pubertal blockers, nevertheless, are not suitable birth control.

When providing affirming sexual and reproductive health care for transgender patients, key principles include focusing on organs and activities over identity. Additionally, screening for certain types of cancers also is dependent on organs. Finally, do not neglect the importance of contraception among transgender men. Taking these principles in consideration will help you provide excellent care for transgender youth.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Transgender people and sexually transmitted infections (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/stis).

2. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 May-Jun;62(3):147-72.

3. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880-91.

4. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries: Report of a WHO consultation. 2002. World Health Organization, Geneva.

5. Screening for cervical cancer for transgender men (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/cervical-cancer).

6. Contraception. 2002 Feb;65(2):129-32.

7. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011 Jun;12(2):93-106.

8. Int J Womens Health. 2014 Jun 23;6:631-7.

Resources

Breast cancer screening in transgender men. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-men).

Screening for breast cancer in transgender women. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-women).

Transgender health and HIV (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/hiv).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV and Transgender People (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html).

I recently was on a panel of experts discussing how to prevent HIV among transgender youth. Preventing HIV among transgender youth, especially transgender youth of color, remains a challenge for multiple reasons – racism, poverty, stigma, marginalization, and discrimination play a role in the HIV epidemic. A barrier to preventing HIV infections among transgender youth is a lack of knowledge on how to provide them with comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care. Here are some tips and resources that can help you ensure that transgender youth are safe and healthy.

One of the challenges of obtaining a sexual history is asking the right questions For example, if you have a transgender male assigned female at birth, ask whether their partners produce sperm instead of asking about the sex of their partners. A transgender male’s partner may identify as female but is assigned male at birth and uses her penis during sex. Furthermore, a transgender male may be on testosterone, but he still can get pregnant. Asking how they use their organs is just as important. A transgender male who has condomless penile-vaginal sex with multiple partners is at a higher risk for HIV infection than is a transgender male who shares sex toys with his only partner.

Normalizing that you ask a comprehensive sexual history to all your patients regardless of gender identity may put the patient at ease. Many transgender people are reluctant to disclose their gender identity to their provider because they are afraid that the provider may fixate on their sexuality once they do. Stating that you ask sexual health questions to all your patients may prevent the transgender patient from feeling singled out.

Finally, you don’t have to ask a sexual history with every transgender patient, just as you wouldn’t for your cisgender patients. If a patient is complaining of a sprained ankle, a sexual history may not be helpful, compared with obtaining one when a patient comes in with pelvic pain. Many transgender patients avoid care because they are frequently asked about their sexual history or gender identity when these are not relevant to their chief complaint.

Here are some helpful questions to ask when taking a sexual history, according to the University of California, San Francisco, Transgender Care & Treatment Guidelines.1

- Are you having sex? How many sex partners have you had in the past year?

- Who are you having sex with? What types of sex are you having? What parts of your anatomy do you use for sex?

- How do you protect yourself from STIs?

- What STIs have you had in the past, if any? When were you last tested for STIs?

- Has your partner(s) ever been diagnosed with any STIs?

- Do you use alcohol or any drugs when you have sex?

- Do you exchange sex for money, drugs, or a place to stay?

Also, use a trauma-informed approach when working with transgender patients. Many have been victims of sexual trauma. Always have a chaperone accompany you during the exam, explain to the patient what you plan to do and why it is necessary, and allow them to decline (and document their declining the physical exam). Also consider having your patient self-swab for STI screening if appropriate.1

Like obtaining a sexual history, routine screenings for certain types of cancers will be based on the organs the patient has. For example, a transgender woman assigned male at birth will not need a cervical cancer screening, but a transgender man assigned female at birth may need one – if the patient still has a cervix. Cervical cancer screening guidelines are similar for transgender men as it is for nontransgender women, and one should use the same guidelines endorsed by the American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathologists, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the World Health Organization.2-4

Cervical screenings should never be a requirement for testosterone therapy, and no transgender male under the age of 21 years will need cervical screening. The University of California guidelines offers tips on how to make transgender men more comfortable during cervical cancer screening.5

Contraception and menstrual management also are important for transgender patients. Testosterone can induce amenorrhea for transgender men, but it is not good birth control. If a transgender male patient has sex with partners that produce sperm, then the physician should discuss effective birth control options. There is no ideal birth control option for transgender men. One must consider multiple factors including the patient’s desire for pregnancy, desire to cease periods, ease of administration, and risk for thrombosis.

Most transgender men may balk at the idea of taking estrogen-containing contraception, but it is more effective than oral progestin-only pills. Intrauterine devices are highly effective in pregnancy prevention and can achieve amenorrhea in 50% of users within 1 year,but some transmen may become dysphoric with the procedure. 6 The etonogestrel implants also are highly effective birth control, but irregular periods are common, leading to discontinuation. Depot medroxyprogesterone is highly effective in preventing pregnancy and can induce amenorrhea in 70% of users within 1 year and 80% of users in 2 years, but also is associated with weight gain in one-third of users.7 Finally, pubertal blockers can rapidly stop periods for transmen who are severely dysphoric from their menses; however, before achieving amenorrhea, a flare bleed can occur 4-6 weeks after administration.8 Support from a mental health therapist during this time is critical. Pubertal blockers, nevertheless, are not suitable birth control.

When providing affirming sexual and reproductive health care for transgender patients, key principles include focusing on organs and activities over identity. Additionally, screening for certain types of cancers also is dependent on organs. Finally, do not neglect the importance of contraception among transgender men. Taking these principles in consideration will help you provide excellent care for transgender youth.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Transgender people and sexually transmitted infections (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/stis).

2. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 May-Jun;62(3):147-72.

3. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880-91.

4. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries: Report of a WHO consultation. 2002. World Health Organization, Geneva.

5. Screening for cervical cancer for transgender men (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/cervical-cancer).

6. Contraception. 2002 Feb;65(2):129-32.

7. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011 Jun;12(2):93-106.

8. Int J Womens Health. 2014 Jun 23;6:631-7.

Resources

Breast cancer screening in transgender men. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-men).

Screening for breast cancer in transgender women. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-women).

Transgender health and HIV (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/hiv).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV and Transgender People (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html).

I recently was on a panel of experts discussing how to prevent HIV among transgender youth. Preventing HIV among transgender youth, especially transgender youth of color, remains a challenge for multiple reasons – racism, poverty, stigma, marginalization, and discrimination play a role in the HIV epidemic. A barrier to preventing HIV infections among transgender youth is a lack of knowledge on how to provide them with comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care. Here are some tips and resources that can help you ensure that transgender youth are safe and healthy.

One of the challenges of obtaining a sexual history is asking the right questions For example, if you have a transgender male assigned female at birth, ask whether their partners produce sperm instead of asking about the sex of their partners. A transgender male’s partner may identify as female but is assigned male at birth and uses her penis during sex. Furthermore, a transgender male may be on testosterone, but he still can get pregnant. Asking how they use their organs is just as important. A transgender male who has condomless penile-vaginal sex with multiple partners is at a higher risk for HIV infection than is a transgender male who shares sex toys with his only partner.

Normalizing that you ask a comprehensive sexual history to all your patients regardless of gender identity may put the patient at ease. Many transgender people are reluctant to disclose their gender identity to their provider because they are afraid that the provider may fixate on their sexuality once they do. Stating that you ask sexual health questions to all your patients may prevent the transgender patient from feeling singled out.

Finally, you don’t have to ask a sexual history with every transgender patient, just as you wouldn’t for your cisgender patients. If a patient is complaining of a sprained ankle, a sexual history may not be helpful, compared with obtaining one when a patient comes in with pelvic pain. Many transgender patients avoid care because they are frequently asked about their sexual history or gender identity when these are not relevant to their chief complaint.

Here are some helpful questions to ask when taking a sexual history, according to the University of California, San Francisco, Transgender Care & Treatment Guidelines.1

- Are you having sex? How many sex partners have you had in the past year?

- Who are you having sex with? What types of sex are you having? What parts of your anatomy do you use for sex?

- How do you protect yourself from STIs?

- What STIs have you had in the past, if any? When were you last tested for STIs?

- Has your partner(s) ever been diagnosed with any STIs?

- Do you use alcohol or any drugs when you have sex?

- Do you exchange sex for money, drugs, or a place to stay?

Also, use a trauma-informed approach when working with transgender patients. Many have been victims of sexual trauma. Always have a chaperone accompany you during the exam, explain to the patient what you plan to do and why it is necessary, and allow them to decline (and document their declining the physical exam). Also consider having your patient self-swab for STI screening if appropriate.1

Like obtaining a sexual history, routine screenings for certain types of cancers will be based on the organs the patient has. For example, a transgender woman assigned male at birth will not need a cervical cancer screening, but a transgender man assigned female at birth may need one – if the patient still has a cervix. Cervical cancer screening guidelines are similar for transgender men as it is for nontransgender women, and one should use the same guidelines endorsed by the American Cancer Society, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society of Clinical Pathologists, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the World Health Organization.2-4

Cervical screenings should never be a requirement for testosterone therapy, and no transgender male under the age of 21 years will need cervical screening. The University of California guidelines offers tips on how to make transgender men more comfortable during cervical cancer screening.5

Contraception and menstrual management also are important for transgender patients. Testosterone can induce amenorrhea for transgender men, but it is not good birth control. If a transgender male patient has sex with partners that produce sperm, then the physician should discuss effective birth control options. There is no ideal birth control option for transgender men. One must consider multiple factors including the patient’s desire for pregnancy, desire to cease periods, ease of administration, and risk for thrombosis.

Most transgender men may balk at the idea of taking estrogen-containing contraception, but it is more effective than oral progestin-only pills. Intrauterine devices are highly effective in pregnancy prevention and can achieve amenorrhea in 50% of users within 1 year,but some transmen may become dysphoric with the procedure. 6 The etonogestrel implants also are highly effective birth control, but irregular periods are common, leading to discontinuation. Depot medroxyprogesterone is highly effective in preventing pregnancy and can induce amenorrhea in 70% of users within 1 year and 80% of users in 2 years, but also is associated with weight gain in one-third of users.7 Finally, pubertal blockers can rapidly stop periods for transmen who are severely dysphoric from their menses; however, before achieving amenorrhea, a flare bleed can occur 4-6 weeks after administration.8 Support from a mental health therapist during this time is critical. Pubertal blockers, nevertheless, are not suitable birth control.

When providing affirming sexual and reproductive health care for transgender patients, key principles include focusing on organs and activities over identity. Additionally, screening for certain types of cancers also is dependent on organs. Finally, do not neglect the importance of contraception among transgender men. Taking these principles in consideration will help you provide excellent care for transgender youth.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Transgender people and sexually transmitted infections (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/stis).

2. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 May-Jun;62(3):147-72.

3. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880-91.

4. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries: Report of a WHO consultation. 2002. World Health Organization, Geneva.

5. Screening for cervical cancer for transgender men (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/cervical-cancer).

6. Contraception. 2002 Feb;65(2):129-32.

7. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011 Jun;12(2):93-106.

8. Int J Womens Health. 2014 Jun 23;6:631-7.

Resources

Breast cancer screening in transgender men. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-men).

Screening for breast cancer in transgender women. (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-women).

Transgender health and HIV (https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/hiv).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV and Transgender People (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html).

A Veteran With a Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

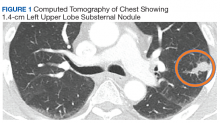

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.

Armed conflict disproportionately affects children

I was asked recently about the trauma of 9/11 by a teen patient who was too young to remember the terrorist attacks. I was surprised that even today I become teary eyed thinking about it. My son was in his first week of college at Georgetown, and in the early confusion about what was going on I was panicked at reports of bombings in Washington. Fortunately, for me and my family at least, none of us were physically harmed. But the mental trauma still is with us. It was a momentary panic for me, but it’s not so fleeting for many families around the world today.

I can’t imagine what it is like today to be a parent in an armed conflict zone, or even in an area with very high levels of criminal violence. At a meeting of the International Society for Social Pediatrics (ISSOP), I learned that an estimated 1.5 billion residents of Earth, or about one in five inhabitants, lived in war zones or in areas of tremendous violence, according to the World Bank’s 2011 World Development Report. And I learned that children are disproportionately affected – physically, mentally, and developmentally – from Stella Tsitoura, MD, of the Network for Children’s Rights, Athens, and others at the ISSOP meeting in Beirut, Lebanon, where pediatricians from around the world gathered in Oct. 2019 to consider what we as a profession should be doing in the context of armed conflict’s impact on so many children. The meeting was held in the Middle East because it is an especially hot conflict area, but children in South Asia, central Africa, South America, Central America, even rough inner-city areas in the United States are also affected.

Child soldiers in some parts of the world particularly are affected, sometimes being forced to commit violence on neighbors and kin. One country that I worked in years ago, Yemen, is a horrifying example of the complex impact of war on children and families. In 2017, over 2,100 children had been recruited as soldiers during the 3-year conflict in Yemen, a UNICEF representative reported. The death toll in Yemen was over 17,500 by Nov. 2018, according to a Human Rights Watch report.

Samuel Perlo-Freeman, PhD, an expert on the economics of arms trade, noted at the ISSOP meeting that two-thirds of civilian casualties in Yemen are caused by Coalition air strikes, whose members include Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and United Arab Emirates. He also said rebel groups in Yemen and elsewhere acquire their arms by capture, by smuggling, or through the aid of foreign backers. Six countries – the United States, Russia, and several western European countries – account for the majority of war tools used in armed conflict zones. In June 2019, courts in Great Britain ruled that British arms sales to the parties involved in Yemen were illegal without an assessment as to whether any violation of internal humanitarian law had taken place.

Many of us feel impotent when facing the magnitude of this problem, and the lives of despair that affected children lead are sometimes too heart breaking to dwell on. ISSOP, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the International Pediatric Association (IPA) are teaching us differently: Standing up for the human rights of children living in areas of conflict or refugees from those areas is our responsibility, both as individuals and as members of our pediatric associations. At a basic level we need to witness – we need to share what we see with our patients who have immigrated legally or illegally in our practices, our hospitals, and our communities. It’s important to be knowledgeable of current standards of clinical care outlined by both ISSOP and the AAP to ensure our patients affected by conflict and violence get appropriate treatment.

Some of the most lasting health impacts for children in conflict are their mental health needs; the World Health Organization prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings is 22%, according to a 2019 report in the Lancet (2019 Jun;394[10194]:240-8). Not only do mental health conditions last throughout a lifetime, the impact of war can affect generations through epigenetic forces.

Arms manufacturers should be held accountable as the courts are doing in Great Britain. Too often American-made armaments are falling into the wrong hands. More can be done to limit the sale of weapons that go into conflict zones. Chemical weapons, cluster bombs, and biologic weapons are banned by international agreement; shouldn’t we do the same with nuclear weapons?

Some pediatric health care facilities are impacted by the needs of traumatized children more than others. Countries at the front line of conflict – like Lebanon, Jordon, Turkey, Greece, Italy, and Mexico – should be supported in their efforts on behalf of child refugees. We need to share the burden and support entities such as Doctors Without Borders, Save the Children, and the Red Cross/Crescent as they present themselves in crisis zones. We recognize that the fundamental human rights of children are being ignored by warring parties. especially Goal 16, which asks the world community to make real progress in promoting peace and justice by 2030. Pediatricians may not be experts in armed conflict, but we are experts in what warfare does to the health and well-being of young children. It’s time to speak out and act.

I was asked recently about the trauma of 9/11 by a teen patient who was too young to remember the terrorist attacks. I was surprised that even today I become teary eyed thinking about it. My son was in his first week of college at Georgetown, and in the early confusion about what was going on I was panicked at reports of bombings in Washington. Fortunately, for me and my family at least, none of us were physically harmed. But the mental trauma still is with us. It was a momentary panic for me, but it’s not so fleeting for many families around the world today.