User login

Harassment of health care workers: A survey

During the course of my residency training, I have experienced and witnessed patients and visitors harassing health care workers (HCWs) by cursing or directing racial slurs at them, making sexist comments, or threatening their lives. What should be the correct response to this harassment? To say nothing may avoid conflict, but the silence perpetuates such abuse. To speak up may provoke aggression or even a physical assault. Further, does our response change if it is not the patient but someone who is accompanying them who exhibits this behavior?

I conducted a survey of psychiatry HCWs at our institution to evaluate the prevalence of and factors associated with such harassment.

An all-too-common problem

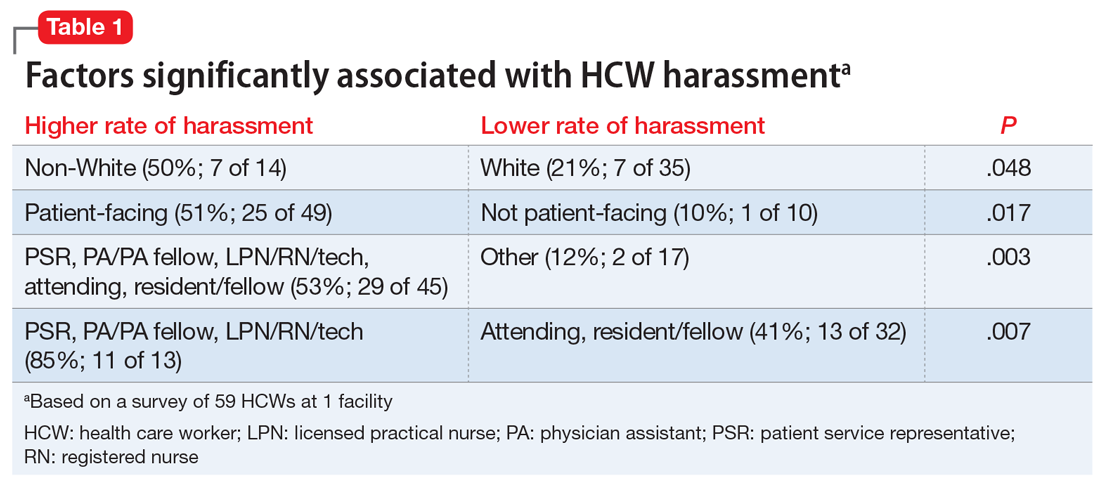

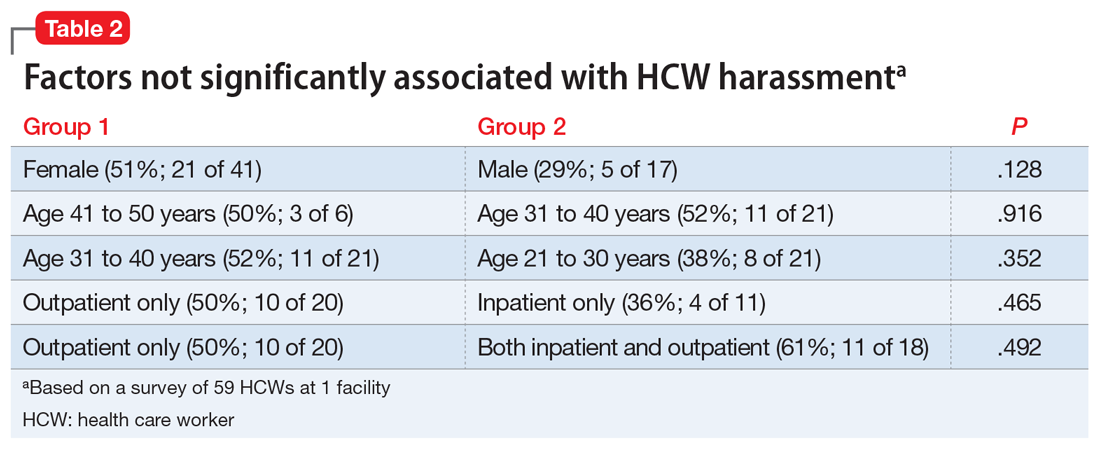

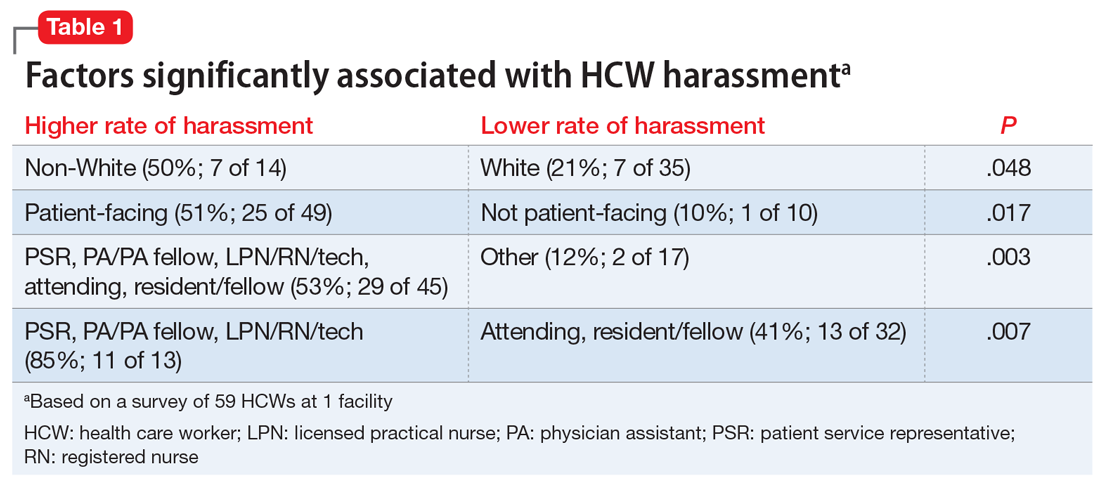

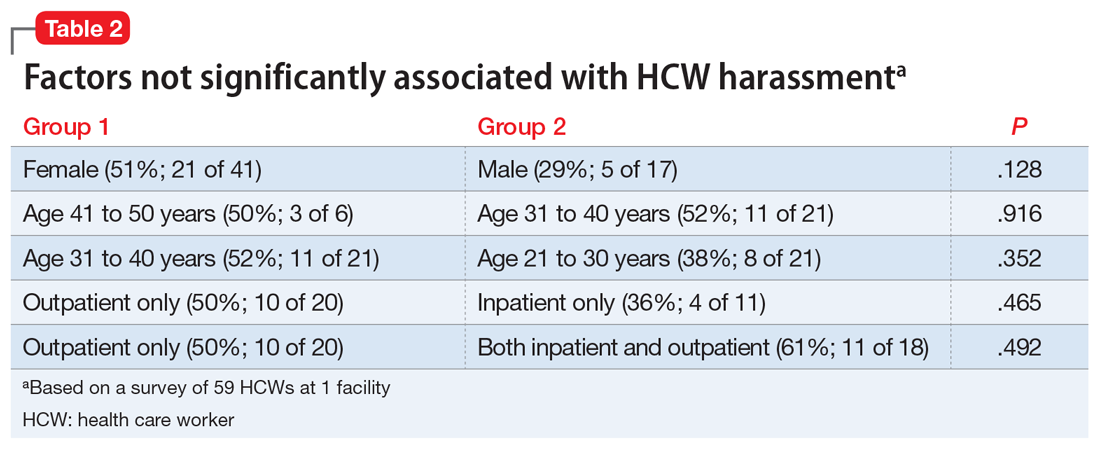

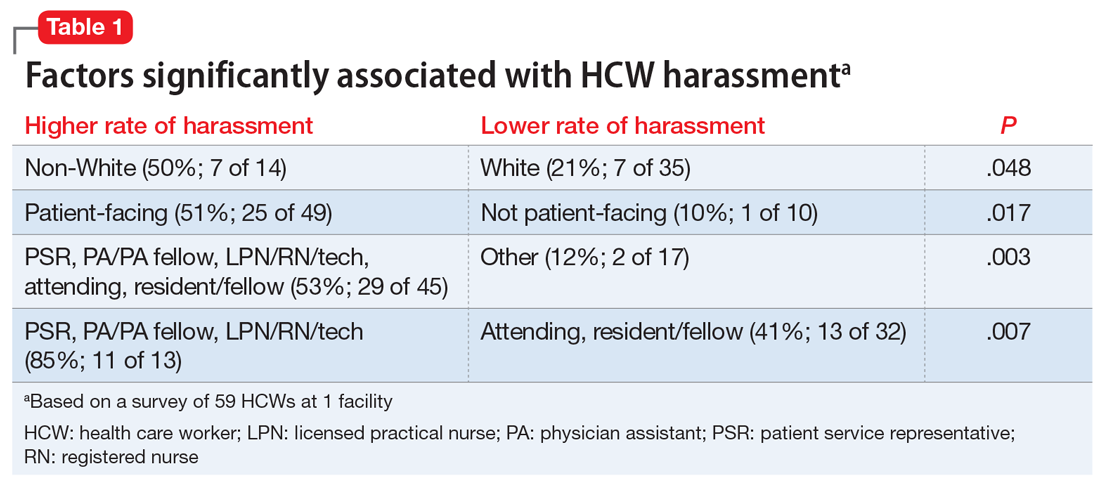

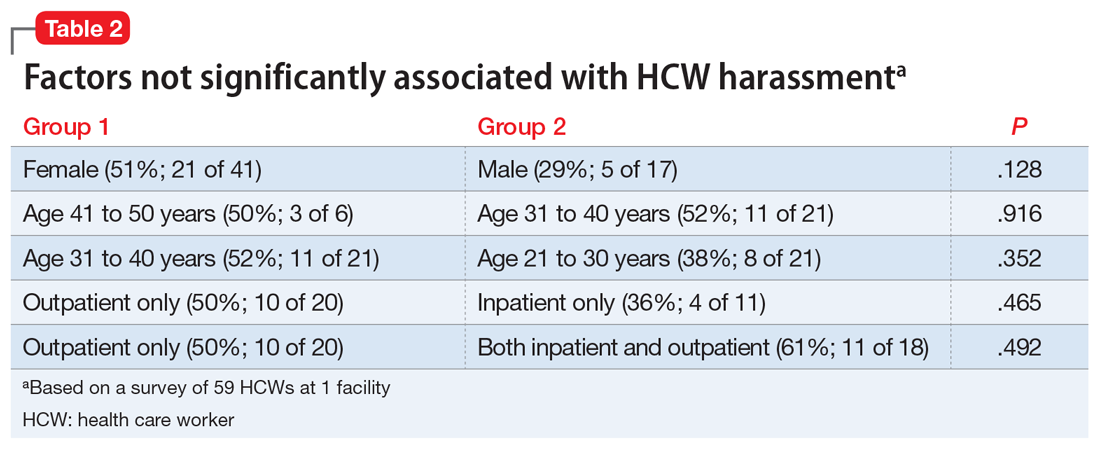

In a December 2020 internal survey at the University of Missouri Department of Psychiatry, 59 of 158 HCWs responded, and 26 (44%) reported experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse. Factors that were statistically significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included being non-White, working in a patient-facing position, and being a nonphysician patient-facing HCW (Table 1). Factors that were not significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included clinical setting, HCW age, and HCW gender (Table 2).

In addition to comments from patients and visitors, respondents stated that the harassment or abuse also included:

- physically threatening behavior and assault

- reporting a HCW for HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) violations after the HCW declined to provide an early refill of a controlled substance

- being accused of being a bad person for declining to prescribe a specific medication

- insults about not being intelligent enough to be on the treatment team

- comments from colleagues.

At the most basic level of response, the emergency department (ED) remains under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) obligation to see, screen, and stabilize any patient, and if psychiatry is consulted in the ED, we should similarly provide this standard of care. Beyond this, we can create behavioral plans for when a relevant diagnosis exists or does not exist, and patients and/or visitors can be terminated from their stay at the location/service/health care system. Whether or not a patient is receiving psychiatric care and/or treatment is irrelevant to the responses to harassment we might consider.

During the incident itself, we are empowered to remove ourselves from the patient encounter. Historically, HCWs have had strong opinions on the next steps, either deciding, “Yes, I am a professional and I will not be bullied,” or “No, I am a professional and I don’t need to deal with this.” Just as we prioritize our patients’ dignities, we should also respect our own and our colleagues’ dignities.

How harassment is handled at our facility

HCWs are commonly unsure whether to “call out” abusive comments during the encounter itself or afterwards. In our hospital, HCWs are encouraged to independently choose to immediately respond, immediately report to a supervisor or hospital security, or defer and report to leadership afterwards via the Patient Safety Network (PSN). The PSN is our hospital’s reporting system for medical errors, near misses, and abuse, neglect, and workplace violence. Relevant examples of abuse, neglect, and workplace violence include:

- Threats. Expression of intent to cause harm, including verbal or written threats and threatening body language

- Physical assault. Attacks ranging from slapping and beating to rape, the use of weapons, or homicide

- Sexual assault. Any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient, such as forced sexual intercourse, forcible sodomy, child molestation, incest, fondling, and attempted rape.

Continue to: Once complete...

Once complete, the PSN report is sent to Risk Management and other relevant groups, such as a 5-person team of security investigators, who are trained in trauma-informed interviewing and re-directive techniques. This team can immediately speak to the patient face-to-face in the inpatient setting or follow-up via phone in the outpatient setting.

The PSN report may result in the creation of a behavior plan for the patient that outlines the behaviors of concern, staff interventions, and consequences for persistent violations. The behavior plan is saved in the patient’s medical chart, and an alert pops up every time the chart is opened. The behavior plan is reviewed once annually for revision or deletion, as appropriate.

Lessons from our facility’s policy

In our health care system, our primary response to HCW harassment is to create a patient behavior plan that lays out specific expectations, care parameters, and consequences (up to terminating a patient from the entire health care system, except for EMTALA-level care). Clinicians are encouraged to report harassment to hospital administration, and a team of security investigators discusses expectations with the patient and/or visitors to prevent further abuse. We believe that describing our policies may be helpful to other health care systems and HCWs who confront this widespread issue.

During the course of my residency training, I have experienced and witnessed patients and visitors harassing health care workers (HCWs) by cursing or directing racial slurs at them, making sexist comments, or threatening their lives. What should be the correct response to this harassment? To say nothing may avoid conflict, but the silence perpetuates such abuse. To speak up may provoke aggression or even a physical assault. Further, does our response change if it is not the patient but someone who is accompanying them who exhibits this behavior?

I conducted a survey of psychiatry HCWs at our institution to evaluate the prevalence of and factors associated with such harassment.

An all-too-common problem

In a December 2020 internal survey at the University of Missouri Department of Psychiatry, 59 of 158 HCWs responded, and 26 (44%) reported experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse. Factors that were statistically significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included being non-White, working in a patient-facing position, and being a nonphysician patient-facing HCW (Table 1). Factors that were not significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included clinical setting, HCW age, and HCW gender (Table 2).

In addition to comments from patients and visitors, respondents stated that the harassment or abuse also included:

- physically threatening behavior and assault

- reporting a HCW for HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) violations after the HCW declined to provide an early refill of a controlled substance

- being accused of being a bad person for declining to prescribe a specific medication

- insults about not being intelligent enough to be on the treatment team

- comments from colleagues.

At the most basic level of response, the emergency department (ED) remains under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) obligation to see, screen, and stabilize any patient, and if psychiatry is consulted in the ED, we should similarly provide this standard of care. Beyond this, we can create behavioral plans for when a relevant diagnosis exists or does not exist, and patients and/or visitors can be terminated from their stay at the location/service/health care system. Whether or not a patient is receiving psychiatric care and/or treatment is irrelevant to the responses to harassment we might consider.

During the incident itself, we are empowered to remove ourselves from the patient encounter. Historically, HCWs have had strong opinions on the next steps, either deciding, “Yes, I am a professional and I will not be bullied,” or “No, I am a professional and I don’t need to deal with this.” Just as we prioritize our patients’ dignities, we should also respect our own and our colleagues’ dignities.

How harassment is handled at our facility

HCWs are commonly unsure whether to “call out” abusive comments during the encounter itself or afterwards. In our hospital, HCWs are encouraged to independently choose to immediately respond, immediately report to a supervisor or hospital security, or defer and report to leadership afterwards via the Patient Safety Network (PSN). The PSN is our hospital’s reporting system for medical errors, near misses, and abuse, neglect, and workplace violence. Relevant examples of abuse, neglect, and workplace violence include:

- Threats. Expression of intent to cause harm, including verbal or written threats and threatening body language

- Physical assault. Attacks ranging from slapping and beating to rape, the use of weapons, or homicide

- Sexual assault. Any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient, such as forced sexual intercourse, forcible sodomy, child molestation, incest, fondling, and attempted rape.

Continue to: Once complete...

Once complete, the PSN report is sent to Risk Management and other relevant groups, such as a 5-person team of security investigators, who are trained in trauma-informed interviewing and re-directive techniques. This team can immediately speak to the patient face-to-face in the inpatient setting or follow-up via phone in the outpatient setting.

The PSN report may result in the creation of a behavior plan for the patient that outlines the behaviors of concern, staff interventions, and consequences for persistent violations. The behavior plan is saved in the patient’s medical chart, and an alert pops up every time the chart is opened. The behavior plan is reviewed once annually for revision or deletion, as appropriate.

Lessons from our facility’s policy

In our health care system, our primary response to HCW harassment is to create a patient behavior plan that lays out specific expectations, care parameters, and consequences (up to terminating a patient from the entire health care system, except for EMTALA-level care). Clinicians are encouraged to report harassment to hospital administration, and a team of security investigators discusses expectations with the patient and/or visitors to prevent further abuse. We believe that describing our policies may be helpful to other health care systems and HCWs who confront this widespread issue.

During the course of my residency training, I have experienced and witnessed patients and visitors harassing health care workers (HCWs) by cursing or directing racial slurs at them, making sexist comments, or threatening their lives. What should be the correct response to this harassment? To say nothing may avoid conflict, but the silence perpetuates such abuse. To speak up may provoke aggression or even a physical assault. Further, does our response change if it is not the patient but someone who is accompanying them who exhibits this behavior?

I conducted a survey of psychiatry HCWs at our institution to evaluate the prevalence of and factors associated with such harassment.

An all-too-common problem

In a December 2020 internal survey at the University of Missouri Department of Psychiatry, 59 of 158 HCWs responded, and 26 (44%) reported experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse. Factors that were statistically significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included being non-White, working in a patient-facing position, and being a nonphysician patient-facing HCW (Table 1). Factors that were not significantly associated with experiencing or witnessing on-the-job harassment or abuse included clinical setting, HCW age, and HCW gender (Table 2).

In addition to comments from patients and visitors, respondents stated that the harassment or abuse also included:

- physically threatening behavior and assault

- reporting a HCW for HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) violations after the HCW declined to provide an early refill of a controlled substance

- being accused of being a bad person for declining to prescribe a specific medication

- insults about not being intelligent enough to be on the treatment team

- comments from colleagues.

At the most basic level of response, the emergency department (ED) remains under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) obligation to see, screen, and stabilize any patient, and if psychiatry is consulted in the ED, we should similarly provide this standard of care. Beyond this, we can create behavioral plans for when a relevant diagnosis exists or does not exist, and patients and/or visitors can be terminated from their stay at the location/service/health care system. Whether or not a patient is receiving psychiatric care and/or treatment is irrelevant to the responses to harassment we might consider.

During the incident itself, we are empowered to remove ourselves from the patient encounter. Historically, HCWs have had strong opinions on the next steps, either deciding, “Yes, I am a professional and I will not be bullied,” or “No, I am a professional and I don’t need to deal with this.” Just as we prioritize our patients’ dignities, we should also respect our own and our colleagues’ dignities.

How harassment is handled at our facility

HCWs are commonly unsure whether to “call out” abusive comments during the encounter itself or afterwards. In our hospital, HCWs are encouraged to independently choose to immediately respond, immediately report to a supervisor or hospital security, or defer and report to leadership afterwards via the Patient Safety Network (PSN). The PSN is our hospital’s reporting system for medical errors, near misses, and abuse, neglect, and workplace violence. Relevant examples of abuse, neglect, and workplace violence include:

- Threats. Expression of intent to cause harm, including verbal or written threats and threatening body language

- Physical assault. Attacks ranging from slapping and beating to rape, the use of weapons, or homicide

- Sexual assault. Any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient, such as forced sexual intercourse, forcible sodomy, child molestation, incest, fondling, and attempted rape.

Continue to: Once complete...

Once complete, the PSN report is sent to Risk Management and other relevant groups, such as a 5-person team of security investigators, who are trained in trauma-informed interviewing and re-directive techniques. This team can immediately speak to the patient face-to-face in the inpatient setting or follow-up via phone in the outpatient setting.

The PSN report may result in the creation of a behavior plan for the patient that outlines the behaviors of concern, staff interventions, and consequences for persistent violations. The behavior plan is saved in the patient’s medical chart, and an alert pops up every time the chart is opened. The behavior plan is reviewed once annually for revision or deletion, as appropriate.

Lessons from our facility’s policy

In our health care system, our primary response to HCW harassment is to create a patient behavior plan that lays out specific expectations, care parameters, and consequences (up to terminating a patient from the entire health care system, except for EMTALA-level care). Clinicians are encouraged to report harassment to hospital administration, and a team of security investigators discusses expectations with the patient and/or visitors to prevent further abuse. We believe that describing our policies may be helpful to other health care systems and HCWs who confront this widespread issue.

Private practice: The basics for psychiatry trainees

Many psychiatry trainees consider private practice as a career option or form of supplemental income. In my experience, however, residency training may provide limited introduction to the general steps involved in starting a practice. In this article, I briefly summarize what I learned while exploring the private practice option as a psychiatry resident.

A good specialty for private practice

Trainees in the earlier stages of their education should be aware that the first step toward private practice may actually occur during medical school, when they are considering which specialty to pursue. If a student is particularly interested in solo private practice, they may want to select a specialty with the potential for less overhead in an independent setting. Psychiatry typically has lower overhead costs than some other specialties. This gap widens even further with the increased popularity and acceptance of telepsychiatry.

Budgeting and finance

Once you decide to pursue private practice, you will want to consider whether you prefer solo practice or group practice, and part-time or full-time. If working for yourself, you will need to understand business planning and budgeting, including how to project revenue and expenses. When first starting in solo practice—especially if you are not taking over a previously established practice—it is useful to have secondary sources of income. This can be a part-time clinical position, working with on-demand health care companies, contracting, consulting, etc. Many new physicians begin with a full-time position and decide to initiate their private practice on a part-time basis. This approach provides a level of financial security that you otherwise would not have. However, a full-time position requires full-time energy, hours, and attention, and it can be challenging to balance full-time and part-time work. Whichever approach you decide to take, it can be most helpful to simply keep an open mind and always consider looking further into any new opportunity that interests you.

Insurance and licensing

You don’t have to wait to establish your own practice to purchase malpractice insurance. Shop around for the best rates and the coverage that most comprehensively fits your needs. If your training program allows “moonlighting,” you might need your own insurance to work at sites other than your training hospital. Many residents begin to apply for independent state licensure at the same time they begin pursuing moonlighting opportunities. It may be helpful not to wait until the last minute to do this, because the process has quite a few steps and can take a while. If your state requires letters of reference, think about which of your supervisors you can ask for one. If you plan to work in a state other than that of your training location, it may be helpful to simultaneously apply for your medical license in that state, because you will already be going through the process. Certain states offer reciprocity regarding medical licenses. The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact offers an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who want to practice in multiple states.1

Marketing your practice

Potential sources for building a panel of patients include referral networks, insurance panels, professional organizations, social media, networking, directories, and word of mouth. If you plan to accept health insurance, the directories provided by insurance panels will allow potential patients to find you when searching for practitioners who accept their plan. Professional organizations offer similar directories, and some private companies also provide directories, either for free or for a fee.

Use technology to your advantage

The exciting thing about starting a private practice today is that the technology available to support a small practice has drastically improved. Many software applications can help with scheduling and billing, which minimizes the need for office staff and enables you to be more productive. These programs typically are available via an online subscription that gives you access to an electronic medical record and other features for a monthly fee. Many of these programs provide add-ons such as a website for your practice and integrated telehealth services. While these programs typically perform many of the same functions, each has a different setup and varying workflows. An online search can facilitate a side-by-side comparison of the software programs that most closely meet your needs.

Seek out mentors and consultants

Finally, try to find a private practice mentor, and reach out to as many people as possible who have worked in any type of private practice setting. A mentor can alert you to factors you might not otherwise have considered. It also may be helpful to establish some form of supervision; such opportunities can be found through professional societies and other groups for private practice clinicians. In these groups, you also can ask other clinicians to recommend private practice and practice management consultants.

Stepping into the unknown can be an intimidating experience; however, you will not know what you are capable of until you try. Fortunately, psychiatry offers the flexibility to create a hybrid career that allows you to follow your passion and maintain your level of comfort. The American Psychiatric Association offers members additional information in the practice management resources section of its website.2

1. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. Information for physicians. 2020. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://www.imlcc.org/information-for-physicians

2. American Psychiatric Association. Online practice handbook. 2021. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/practice-management/starting-a-practice/online-practice-handbook

Many psychiatry trainees consider private practice as a career option or form of supplemental income. In my experience, however, residency training may provide limited introduction to the general steps involved in starting a practice. In this article, I briefly summarize what I learned while exploring the private practice option as a psychiatry resident.

A good specialty for private practice

Trainees in the earlier stages of their education should be aware that the first step toward private practice may actually occur during medical school, when they are considering which specialty to pursue. If a student is particularly interested in solo private practice, they may want to select a specialty with the potential for less overhead in an independent setting. Psychiatry typically has lower overhead costs than some other specialties. This gap widens even further with the increased popularity and acceptance of telepsychiatry.

Budgeting and finance

Once you decide to pursue private practice, you will want to consider whether you prefer solo practice or group practice, and part-time or full-time. If working for yourself, you will need to understand business planning and budgeting, including how to project revenue and expenses. When first starting in solo practice—especially if you are not taking over a previously established practice—it is useful to have secondary sources of income. This can be a part-time clinical position, working with on-demand health care companies, contracting, consulting, etc. Many new physicians begin with a full-time position and decide to initiate their private practice on a part-time basis. This approach provides a level of financial security that you otherwise would not have. However, a full-time position requires full-time energy, hours, and attention, and it can be challenging to balance full-time and part-time work. Whichever approach you decide to take, it can be most helpful to simply keep an open mind and always consider looking further into any new opportunity that interests you.

Insurance and licensing

You don’t have to wait to establish your own practice to purchase malpractice insurance. Shop around for the best rates and the coverage that most comprehensively fits your needs. If your training program allows “moonlighting,” you might need your own insurance to work at sites other than your training hospital. Many residents begin to apply for independent state licensure at the same time they begin pursuing moonlighting opportunities. It may be helpful not to wait until the last minute to do this, because the process has quite a few steps and can take a while. If your state requires letters of reference, think about which of your supervisors you can ask for one. If you plan to work in a state other than that of your training location, it may be helpful to simultaneously apply for your medical license in that state, because you will already be going through the process. Certain states offer reciprocity regarding medical licenses. The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact offers an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who want to practice in multiple states.1

Marketing your practice

Potential sources for building a panel of patients include referral networks, insurance panels, professional organizations, social media, networking, directories, and word of mouth. If you plan to accept health insurance, the directories provided by insurance panels will allow potential patients to find you when searching for practitioners who accept their plan. Professional organizations offer similar directories, and some private companies also provide directories, either for free or for a fee.

Use technology to your advantage

The exciting thing about starting a private practice today is that the technology available to support a small practice has drastically improved. Many software applications can help with scheduling and billing, which minimizes the need for office staff and enables you to be more productive. These programs typically are available via an online subscription that gives you access to an electronic medical record and other features for a monthly fee. Many of these programs provide add-ons such as a website for your practice and integrated telehealth services. While these programs typically perform many of the same functions, each has a different setup and varying workflows. An online search can facilitate a side-by-side comparison of the software programs that most closely meet your needs.

Seek out mentors and consultants

Finally, try to find a private practice mentor, and reach out to as many people as possible who have worked in any type of private practice setting. A mentor can alert you to factors you might not otherwise have considered. It also may be helpful to establish some form of supervision; such opportunities can be found through professional societies and other groups for private practice clinicians. In these groups, you also can ask other clinicians to recommend private practice and practice management consultants.

Stepping into the unknown can be an intimidating experience; however, you will not know what you are capable of until you try. Fortunately, psychiatry offers the flexibility to create a hybrid career that allows you to follow your passion and maintain your level of comfort. The American Psychiatric Association offers members additional information in the practice management resources section of its website.2

Many psychiatry trainees consider private practice as a career option or form of supplemental income. In my experience, however, residency training may provide limited introduction to the general steps involved in starting a practice. In this article, I briefly summarize what I learned while exploring the private practice option as a psychiatry resident.

A good specialty for private practice

Trainees in the earlier stages of their education should be aware that the first step toward private practice may actually occur during medical school, when they are considering which specialty to pursue. If a student is particularly interested in solo private practice, they may want to select a specialty with the potential for less overhead in an independent setting. Psychiatry typically has lower overhead costs than some other specialties. This gap widens even further with the increased popularity and acceptance of telepsychiatry.

Budgeting and finance

Once you decide to pursue private practice, you will want to consider whether you prefer solo practice or group practice, and part-time or full-time. If working for yourself, you will need to understand business planning and budgeting, including how to project revenue and expenses. When first starting in solo practice—especially if you are not taking over a previously established practice—it is useful to have secondary sources of income. This can be a part-time clinical position, working with on-demand health care companies, contracting, consulting, etc. Many new physicians begin with a full-time position and decide to initiate their private practice on a part-time basis. This approach provides a level of financial security that you otherwise would not have. However, a full-time position requires full-time energy, hours, and attention, and it can be challenging to balance full-time and part-time work. Whichever approach you decide to take, it can be most helpful to simply keep an open mind and always consider looking further into any new opportunity that interests you.

Insurance and licensing

You don’t have to wait to establish your own practice to purchase malpractice insurance. Shop around for the best rates and the coverage that most comprehensively fits your needs. If your training program allows “moonlighting,” you might need your own insurance to work at sites other than your training hospital. Many residents begin to apply for independent state licensure at the same time they begin pursuing moonlighting opportunities. It may be helpful not to wait until the last minute to do this, because the process has quite a few steps and can take a while. If your state requires letters of reference, think about which of your supervisors you can ask for one. If you plan to work in a state other than that of your training location, it may be helpful to simultaneously apply for your medical license in that state, because you will already be going through the process. Certain states offer reciprocity regarding medical licenses. The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact offers an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who want to practice in multiple states.1

Marketing your practice

Potential sources for building a panel of patients include referral networks, insurance panels, professional organizations, social media, networking, directories, and word of mouth. If you plan to accept health insurance, the directories provided by insurance panels will allow potential patients to find you when searching for practitioners who accept their plan. Professional organizations offer similar directories, and some private companies also provide directories, either for free or for a fee.

Use technology to your advantage

The exciting thing about starting a private practice today is that the technology available to support a small practice has drastically improved. Many software applications can help with scheduling and billing, which minimizes the need for office staff and enables you to be more productive. These programs typically are available via an online subscription that gives you access to an electronic medical record and other features for a monthly fee. Many of these programs provide add-ons such as a website for your practice and integrated telehealth services. While these programs typically perform many of the same functions, each has a different setup and varying workflows. An online search can facilitate a side-by-side comparison of the software programs that most closely meet your needs.

Seek out mentors and consultants

Finally, try to find a private practice mentor, and reach out to as many people as possible who have worked in any type of private practice setting. A mentor can alert you to factors you might not otherwise have considered. It also may be helpful to establish some form of supervision; such opportunities can be found through professional societies and other groups for private practice clinicians. In these groups, you also can ask other clinicians to recommend private practice and practice management consultants.

Stepping into the unknown can be an intimidating experience; however, you will not know what you are capable of until you try. Fortunately, psychiatry offers the flexibility to create a hybrid career that allows you to follow your passion and maintain your level of comfort. The American Psychiatric Association offers members additional information in the practice management resources section of its website.2

1. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. Information for physicians. 2020. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://www.imlcc.org/information-for-physicians

2. American Psychiatric Association. Online practice handbook. 2021. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/practice-management/starting-a-practice/online-practice-handbook

1. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. Information for physicians. 2020. Accessed March 8, 2021. https://www.imlcc.org/information-for-physicians

2. American Psychiatric Association. Online practice handbook. 2021. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/practice-management/starting-a-practice/online-practice-handbook

COVID-19: One Patient at a Time

I will never forget the first time I cared for a patient who tested positive for COVID-19. It was March 2020, and I was evaluating a patient in the emergency department (ED). At the time we knew very little about this virus and how it is transmitted. We had all seen the images from Wuhan, China, and had appropriate fear of the lethality of the virus, but there was not yet a clear understanding as to how best to keep health care practitioners safe as they cared for patients with COVID-19.

That evening I received a page that a middle-aged man who had tested positive for COVID-19 was in the ED with fever, cough, and hypoxia. As a hospitalist, my role is to care for these patients, those admitted to stay overnight in the hospital. Before going to see the patient, I watched a video on how to properly don personal protective equipment (PPE). I walked to the ED and suited up with a surgical mask, goggles, disposable gown, and gloves. I was very conscious of the amount of time I spent in that patient’s room, and tried to stand at the foot of the bed as much as possible so as to maximize the distance between our faces when we talked.

Upon finishing my assessment, I took off my PPE and exited the room but kept wondering if I had done so correctly. That night when I came home, I slept in the guest bedroom to minimize the risk of transmission of the virus to my wife. For the next 7 days I was terrified that I had been exposed to the virus, worried that I hadn’t worn my mask properly, or that I exposed myself to contamination when taking off my goggles and gown. I was hyperaware of my breathing and temperature, wondering if that scratch in my throat was the first sign of something worse. I never did develop any symptoms of illness but the amount of stress I felt that week was enormous.

Over the subsequent weeks I became much more comfortable with putting on and taking off PPE since the volume of COVID patients kept increasing to the point that more than 80% of the hospital patient census consisted of COVID-19 infections. Those patient interactions became less awkward once I could stop worrying about the PPE and focus on providing patient care.

Unfortunately, patient after patient entered the hospital, all with the same symptoms: cough, fever, and hypoxia. Medically there was little decision-making necessary as care was mostly supportive with supplemental oxygen to give these patients time to recover. Instead, I focused on understanding each patient’s symptoms and thinking about what could be offered to relieve bothersome symptoms. These patients were isolated in their hospital rooms – denied visitors and their interactions with hospital staff involved layers and layers of protective barrier. I sought to overcome those physical barriers through personal connection – learning about a patient’s hobbies, asking about their families, or reminiscing about one of their favorite trips.

Despite this supportive care, many patients ended up intubated in the intensive care unit. Many eventually improved, and we celebrated those individuals – a victory at a time. We even counted the COVID discharges with a running tally; first 10, then a few dozen, and eventually the number climbed into the triple digits. But not every patient was so fortunate. Hearing about a 40-something who passed away hit too close to home – what if that were me?

The hospitalists I work with rose to the occasion. We feared the virus but still showed up for work because the patients needed us and we had job obligations to honor. Everyone else was stuck at home during lockdown but we still got in our cars and drove to the hospital, suited up in our PPE, and cared for terrified patients that were struggling to breathe.

There was a satisfaction in having a job to do and being able to contribute during this time of global crisis. Staying busy gave our minds something to focus on and helped us feel a sense of purpose. Some of us stayed late to coordinate staffing. Others helped to disseminate practice guidelines and clinical knowledge. While others lent a hand wherever they could to pitch in. That sense of camaraderie served as plenty of motivation.

During the early stages of the pandemic, there was a sense that this crisis that would end after a few months and life would return to normal. By May, we experienced a dramatic decline in the number of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, which resulted in a real sense of optimism. But soon it became apparent that this pandemic was not going away anytime soon.

Cases nationwide began rising again over the summer. We saw a steady trickle of new admissions at our hospital month after month until the fall when the rate of admissions accelerated again. The hospital reactivated our surge plan, increased staffing, and confronted the new surge with growing dread. That first surge was all endorphins – but fatigue set in by the time the second wave hit. The volunteerism and sense of “we are in this together” just did not exist anymore. The stories about health care heroes in the broader community waned and the outside world seemingly had moved on from thinking about the pandemic.

Yet we remained, caring for patients with cough, fever, and low oxygen saturation. It was like living through a movie we had already seen before. We knew what we were supposed to do and we followed the script. But now it felt too much like a routine.

It has been a very long 14 months since I first cared for a patient with COVID-19. For much of this time it felt like we were just stuck on a treadmill, passing the time but not making any significant progress towards a post-COVID future state. How many times over this year did we push that date forward in our minds when “life would go back to normal”?

Now, we have reason for hope. More than 100 million Americans have been vaccinated and that number rises daily. The vaccines are remarkably effective, they are making a real difference in reducing the number of patients with COVID-19 at the hospital, and our level of daily anxiety is lower. There is still much uncertainty about the future, but at least we can feel proud of our service over the last year — proud of showing up and donning that PPE. And so, we continue one patient at a time.

Corresponding author: James A. Colbert, MD, Attending Hospitalist, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, 2014 Washington St, Newton, MA, 02462, Senior Medical Director, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

I will never forget the first time I cared for a patient who tested positive for COVID-19. It was March 2020, and I was evaluating a patient in the emergency department (ED). At the time we knew very little about this virus and how it is transmitted. We had all seen the images from Wuhan, China, and had appropriate fear of the lethality of the virus, but there was not yet a clear understanding as to how best to keep health care practitioners safe as they cared for patients with COVID-19.

That evening I received a page that a middle-aged man who had tested positive for COVID-19 was in the ED with fever, cough, and hypoxia. As a hospitalist, my role is to care for these patients, those admitted to stay overnight in the hospital. Before going to see the patient, I watched a video on how to properly don personal protective equipment (PPE). I walked to the ED and suited up with a surgical mask, goggles, disposable gown, and gloves. I was very conscious of the amount of time I spent in that patient’s room, and tried to stand at the foot of the bed as much as possible so as to maximize the distance between our faces when we talked.

Upon finishing my assessment, I took off my PPE and exited the room but kept wondering if I had done so correctly. That night when I came home, I slept in the guest bedroom to minimize the risk of transmission of the virus to my wife. For the next 7 days I was terrified that I had been exposed to the virus, worried that I hadn’t worn my mask properly, or that I exposed myself to contamination when taking off my goggles and gown. I was hyperaware of my breathing and temperature, wondering if that scratch in my throat was the first sign of something worse. I never did develop any symptoms of illness but the amount of stress I felt that week was enormous.

Over the subsequent weeks I became much more comfortable with putting on and taking off PPE since the volume of COVID patients kept increasing to the point that more than 80% of the hospital patient census consisted of COVID-19 infections. Those patient interactions became less awkward once I could stop worrying about the PPE and focus on providing patient care.

Unfortunately, patient after patient entered the hospital, all with the same symptoms: cough, fever, and hypoxia. Medically there was little decision-making necessary as care was mostly supportive with supplemental oxygen to give these patients time to recover. Instead, I focused on understanding each patient’s symptoms and thinking about what could be offered to relieve bothersome symptoms. These patients were isolated in their hospital rooms – denied visitors and their interactions with hospital staff involved layers and layers of protective barrier. I sought to overcome those physical barriers through personal connection – learning about a patient’s hobbies, asking about their families, or reminiscing about one of their favorite trips.

Despite this supportive care, many patients ended up intubated in the intensive care unit. Many eventually improved, and we celebrated those individuals – a victory at a time. We even counted the COVID discharges with a running tally; first 10, then a few dozen, and eventually the number climbed into the triple digits. But not every patient was so fortunate. Hearing about a 40-something who passed away hit too close to home – what if that were me?

The hospitalists I work with rose to the occasion. We feared the virus but still showed up for work because the patients needed us and we had job obligations to honor. Everyone else was stuck at home during lockdown but we still got in our cars and drove to the hospital, suited up in our PPE, and cared for terrified patients that were struggling to breathe.

There was a satisfaction in having a job to do and being able to contribute during this time of global crisis. Staying busy gave our minds something to focus on and helped us feel a sense of purpose. Some of us stayed late to coordinate staffing. Others helped to disseminate practice guidelines and clinical knowledge. While others lent a hand wherever they could to pitch in. That sense of camaraderie served as plenty of motivation.

During the early stages of the pandemic, there was a sense that this crisis that would end after a few months and life would return to normal. By May, we experienced a dramatic decline in the number of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, which resulted in a real sense of optimism. But soon it became apparent that this pandemic was not going away anytime soon.

Cases nationwide began rising again over the summer. We saw a steady trickle of new admissions at our hospital month after month until the fall when the rate of admissions accelerated again. The hospital reactivated our surge plan, increased staffing, and confronted the new surge with growing dread. That first surge was all endorphins – but fatigue set in by the time the second wave hit. The volunteerism and sense of “we are in this together” just did not exist anymore. The stories about health care heroes in the broader community waned and the outside world seemingly had moved on from thinking about the pandemic.

Yet we remained, caring for patients with cough, fever, and low oxygen saturation. It was like living through a movie we had already seen before. We knew what we were supposed to do and we followed the script. But now it felt too much like a routine.

It has been a very long 14 months since I first cared for a patient with COVID-19. For much of this time it felt like we were just stuck on a treadmill, passing the time but not making any significant progress towards a post-COVID future state. How many times over this year did we push that date forward in our minds when “life would go back to normal”?

Now, we have reason for hope. More than 100 million Americans have been vaccinated and that number rises daily. The vaccines are remarkably effective, they are making a real difference in reducing the number of patients with COVID-19 at the hospital, and our level of daily anxiety is lower. There is still much uncertainty about the future, but at least we can feel proud of our service over the last year — proud of showing up and donning that PPE. And so, we continue one patient at a time.

Corresponding author: James A. Colbert, MD, Attending Hospitalist, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, 2014 Washington St, Newton, MA, 02462, Senior Medical Director, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

I will never forget the first time I cared for a patient who tested positive for COVID-19. It was March 2020, and I was evaluating a patient in the emergency department (ED). At the time we knew very little about this virus and how it is transmitted. We had all seen the images from Wuhan, China, and had appropriate fear of the lethality of the virus, but there was not yet a clear understanding as to how best to keep health care practitioners safe as they cared for patients with COVID-19.

That evening I received a page that a middle-aged man who had tested positive for COVID-19 was in the ED with fever, cough, and hypoxia. As a hospitalist, my role is to care for these patients, those admitted to stay overnight in the hospital. Before going to see the patient, I watched a video on how to properly don personal protective equipment (PPE). I walked to the ED and suited up with a surgical mask, goggles, disposable gown, and gloves. I was very conscious of the amount of time I spent in that patient’s room, and tried to stand at the foot of the bed as much as possible so as to maximize the distance between our faces when we talked.

Upon finishing my assessment, I took off my PPE and exited the room but kept wondering if I had done so correctly. That night when I came home, I slept in the guest bedroom to minimize the risk of transmission of the virus to my wife. For the next 7 days I was terrified that I had been exposed to the virus, worried that I hadn’t worn my mask properly, or that I exposed myself to contamination when taking off my goggles and gown. I was hyperaware of my breathing and temperature, wondering if that scratch in my throat was the first sign of something worse. I never did develop any symptoms of illness but the amount of stress I felt that week was enormous.

Over the subsequent weeks I became much more comfortable with putting on and taking off PPE since the volume of COVID patients kept increasing to the point that more than 80% of the hospital patient census consisted of COVID-19 infections. Those patient interactions became less awkward once I could stop worrying about the PPE and focus on providing patient care.

Unfortunately, patient after patient entered the hospital, all with the same symptoms: cough, fever, and hypoxia. Medically there was little decision-making necessary as care was mostly supportive with supplemental oxygen to give these patients time to recover. Instead, I focused on understanding each patient’s symptoms and thinking about what could be offered to relieve bothersome symptoms. These patients were isolated in their hospital rooms – denied visitors and their interactions with hospital staff involved layers and layers of protective barrier. I sought to overcome those physical barriers through personal connection – learning about a patient’s hobbies, asking about their families, or reminiscing about one of their favorite trips.

Despite this supportive care, many patients ended up intubated in the intensive care unit. Many eventually improved, and we celebrated those individuals – a victory at a time. We even counted the COVID discharges with a running tally; first 10, then a few dozen, and eventually the number climbed into the triple digits. But not every patient was so fortunate. Hearing about a 40-something who passed away hit too close to home – what if that were me?

The hospitalists I work with rose to the occasion. We feared the virus but still showed up for work because the patients needed us and we had job obligations to honor. Everyone else was stuck at home during lockdown but we still got in our cars and drove to the hospital, suited up in our PPE, and cared for terrified patients that were struggling to breathe.

There was a satisfaction in having a job to do and being able to contribute during this time of global crisis. Staying busy gave our minds something to focus on and helped us feel a sense of purpose. Some of us stayed late to coordinate staffing. Others helped to disseminate practice guidelines and clinical knowledge. While others lent a hand wherever they could to pitch in. That sense of camaraderie served as plenty of motivation.

During the early stages of the pandemic, there was a sense that this crisis that would end after a few months and life would return to normal. By May, we experienced a dramatic decline in the number of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, which resulted in a real sense of optimism. But soon it became apparent that this pandemic was not going away anytime soon.

Cases nationwide began rising again over the summer. We saw a steady trickle of new admissions at our hospital month after month until the fall when the rate of admissions accelerated again. The hospital reactivated our surge plan, increased staffing, and confronted the new surge with growing dread. That first surge was all endorphins – but fatigue set in by the time the second wave hit. The volunteerism and sense of “we are in this together” just did not exist anymore. The stories about health care heroes in the broader community waned and the outside world seemingly had moved on from thinking about the pandemic.

Yet we remained, caring for patients with cough, fever, and low oxygen saturation. It was like living through a movie we had already seen before. We knew what we were supposed to do and we followed the script. But now it felt too much like a routine.

It has been a very long 14 months since I first cared for a patient with COVID-19. For much of this time it felt like we were just stuck on a treadmill, passing the time but not making any significant progress towards a post-COVID future state. How many times over this year did we push that date forward in our minds when “life would go back to normal”?

Now, we have reason for hope. More than 100 million Americans have been vaccinated and that number rises daily. The vaccines are remarkably effective, they are making a real difference in reducing the number of patients with COVID-19 at the hospital, and our level of daily anxiety is lower. There is still much uncertainty about the future, but at least we can feel proud of our service over the last year — proud of showing up and donning that PPE. And so, we continue one patient at a time.

Corresponding author: James A. Colbert, MD, Attending Hospitalist, Newton-Wellesley Hospital, 2014 Washington St, Newton, MA, 02462, Senior Medical Director, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

The COVID-19 pandemic and changes in pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses

The COVID-19 pandemic upended the U.S. health care market and disrupted much of what was thought to be consistent and necessary hospital-based care for children. Early in the pandemic, clinics closed, elective surgeries were delayed, and well visits were postponed. Mitigation strategies were launched nationwide to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 including mask mandates, social distancing, shelter-in-place orders, and school closures. While these measures were enacted to target COVID-19, a potential off-target effect was reductions in transmission of other respiratory illness, and potentially nonrespiratory infectious illnesses and conditions exacerbated by acute infections.1 These measures have heavily impacted the pediatric population, wherein respiratory infections are common, and also because daycares and school can be hubs for disease transmission.2

To evaluate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric health care utilization, we performed a multicenter, cross-sectional study of 44 children’s hospitals using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database.3 Children aged 2 months to 18 years discharged from a PHIS hospital with nonsurgical diagnoses from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30 over a 4-year period (2017-2020) were included in the study. The primary exposure was the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which was divided into three study periods: pre–COVID-19 (January–February 2020), early COVID-19 (March-April 2020), and COVID-19 (May-September 2020). The primary outcomes were the observed-to-expected ratio of respiratory and nonrespiratory illness encounters of the study period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic. For these calculations, the expected encounters for each period was derived from the same calendar periods from prepandemic years (2017-2019).

A total of 9,051,980 pediatric encounters were included in the analyses: 6,811,799 with nonrespiratory illnesses and 2,240,181 with respiratory illnesses. We found a 42% reduction in overall encounters during the COVID-19 period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic, with a greater reduction in respiratory, compared with nonrespiratory illnesses, which decreased 62% and 38%, respectively. These reductions were consistent across geographic and encounter type (ED vs. hospitalization). The frequency of hospital-based encounters for common pediatric respiratory illnesses was substantially reduced, with reductions in asthma exacerbations (down 76%), pneumonia (down 81%), croup (down 84%), influenza (down 87%) and bronchiolitis (down 91%). Differences in both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses varied by age, with larger reductions found in children aged less than 12 years. While adolescent (children aged over 12 years) encounters diminished during the early COVID period for both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses, their encounters returned to previous levels faster than those from younger children. For respiratory illnesses, hospital-based adolescents encounters had returned to prepandemic levels by the end of the study period (September 2020).

These findings warrant consideration as relaxation of SARS-CoV-2 mitigation are contemplated. Encounters for respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses declined less and recovered faster in adolescents, compared with younger children. The underlying contributors to this trend are likely multifactorial. For example, respiratory illnesses such as croup and bronchiolitis are more common in younger children and adolescents may be more likely to transmit SARS-CoV-2, compared with younger age groups.4,5 However, adolescents may have had less strict adherence to social distancing measures.6 Future efforts to halt transmission of SARS-CoV-2, as well as other respiratory pathogens, should inform mitigation efforts in the adolescent population with considerations of the intensity of social mixing in different pediatric age groups.

While reductions in encounters caused by respiratory illnesses were substantial, more modest but similar age-based trends were seen in nonrespiratory illnesses. Yet, reduced transmission of infectious agents may not fully explain these findings. For example, it is possible that families sought care for mild to moderate nonrespiratory illness in clinics or via telehealth rather than the EDs.7 Provided there were no unintended negative consequences, such transition of care to non-ED settings would suggest there was overutilization of hospital resources prior to the pandemic. Additional assessments would be helpful to examine this more closely and to clarify the long-term impact of those transitions.

It is also possible that the pandemic effects on financial, social, and family stress may have led to increases in some pediatric health care encounters, such as those for mental health conditions,8 nonaccidental trauma or inability to adhere to treatment because of lack of resources.9,10 Additional study on the evolution and distribution of social and stress-related illnesses is critical to maintain and improve the health of children and adolescents.

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in rapid and marked changes to both communicable and noncommunicable illnesses and care-seeking behaviors. Some of these findings are encouraging, such as large reductions in respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses. However, other trends may be harbingers of negative health consequences of the pandemic, such as increases in health care utilization later in the pandemic. Further study of the evolving pandemic’s effects on disease and health care utilization is needed to benefit our children now and during the next pandemic.

Dr. Antoon is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University and a pediatric hospitalist at the Monroe Carroll Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, both in Nashville, Tenn.

References

1. Kenyon CC et al. Initial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric asthma emergency department utilization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Sep;8(8):2774-6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.045.

2. Luca G et al. The impact of regular school closure on seasonal influenza epidemics: A data-driven spatial transmission model for Belgium. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2934-3.

3. Antoon JW et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and changes in healthcare utilization for pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2021 Mar 8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3608.

4. Park YJ et al. Contact tracing during coronavirus disease outbreak, South Korea, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Oct;26(10):2465-8. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.201315.

5. Davies NG et al. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Med. 2020 Aug;26(8):1205-11. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9.

6. Andrews JL et al. Peer influence in adolescence: Public health implications for COVID-19. Trends Cogn Sci. 2020;24(8):585-7. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.001.

7. Taquechel K et al. Pediatric asthma healthcare utilization, viral testing, and air pollution changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Nov-Dec;8(10):3378-87.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.057.

8. Hill RM et al. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e2020029280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280.

9. Sharma S et al. COVID-19: Differences in sentinel injury and child abuse reporting during a pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020 Dec;110:104709. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709.

10. Lauren BN et al. Predictors of households at risk for food insecurity in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000355.

The COVID-19 pandemic upended the U.S. health care market and disrupted much of what was thought to be consistent and necessary hospital-based care for children. Early in the pandemic, clinics closed, elective surgeries were delayed, and well visits were postponed. Mitigation strategies were launched nationwide to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 including mask mandates, social distancing, shelter-in-place orders, and school closures. While these measures were enacted to target COVID-19, a potential off-target effect was reductions in transmission of other respiratory illness, and potentially nonrespiratory infectious illnesses and conditions exacerbated by acute infections.1 These measures have heavily impacted the pediatric population, wherein respiratory infections are common, and also because daycares and school can be hubs for disease transmission.2

To evaluate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric health care utilization, we performed a multicenter, cross-sectional study of 44 children’s hospitals using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database.3 Children aged 2 months to 18 years discharged from a PHIS hospital with nonsurgical diagnoses from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30 over a 4-year period (2017-2020) were included in the study. The primary exposure was the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which was divided into three study periods: pre–COVID-19 (January–February 2020), early COVID-19 (March-April 2020), and COVID-19 (May-September 2020). The primary outcomes were the observed-to-expected ratio of respiratory and nonrespiratory illness encounters of the study period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic. For these calculations, the expected encounters for each period was derived from the same calendar periods from prepandemic years (2017-2019).

A total of 9,051,980 pediatric encounters were included in the analyses: 6,811,799 with nonrespiratory illnesses and 2,240,181 with respiratory illnesses. We found a 42% reduction in overall encounters during the COVID-19 period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic, with a greater reduction in respiratory, compared with nonrespiratory illnesses, which decreased 62% and 38%, respectively. These reductions were consistent across geographic and encounter type (ED vs. hospitalization). The frequency of hospital-based encounters for common pediatric respiratory illnesses was substantially reduced, with reductions in asthma exacerbations (down 76%), pneumonia (down 81%), croup (down 84%), influenza (down 87%) and bronchiolitis (down 91%). Differences in both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses varied by age, with larger reductions found in children aged less than 12 years. While adolescent (children aged over 12 years) encounters diminished during the early COVID period for both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses, their encounters returned to previous levels faster than those from younger children. For respiratory illnesses, hospital-based adolescents encounters had returned to prepandemic levels by the end of the study period (September 2020).

These findings warrant consideration as relaxation of SARS-CoV-2 mitigation are contemplated. Encounters for respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses declined less and recovered faster in adolescents, compared with younger children. The underlying contributors to this trend are likely multifactorial. For example, respiratory illnesses such as croup and bronchiolitis are more common in younger children and adolescents may be more likely to transmit SARS-CoV-2, compared with younger age groups.4,5 However, adolescents may have had less strict adherence to social distancing measures.6 Future efforts to halt transmission of SARS-CoV-2, as well as other respiratory pathogens, should inform mitigation efforts in the adolescent population with considerations of the intensity of social mixing in different pediatric age groups.

While reductions in encounters caused by respiratory illnesses were substantial, more modest but similar age-based trends were seen in nonrespiratory illnesses. Yet, reduced transmission of infectious agents may not fully explain these findings. For example, it is possible that families sought care for mild to moderate nonrespiratory illness in clinics or via telehealth rather than the EDs.7 Provided there were no unintended negative consequences, such transition of care to non-ED settings would suggest there was overutilization of hospital resources prior to the pandemic. Additional assessments would be helpful to examine this more closely and to clarify the long-term impact of those transitions.

It is also possible that the pandemic effects on financial, social, and family stress may have led to increases in some pediatric health care encounters, such as those for mental health conditions,8 nonaccidental trauma or inability to adhere to treatment because of lack of resources.9,10 Additional study on the evolution and distribution of social and stress-related illnesses is critical to maintain and improve the health of children and adolescents.

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in rapid and marked changes to both communicable and noncommunicable illnesses and care-seeking behaviors. Some of these findings are encouraging, such as large reductions in respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses. However, other trends may be harbingers of negative health consequences of the pandemic, such as increases in health care utilization later in the pandemic. Further study of the evolving pandemic’s effects on disease and health care utilization is needed to benefit our children now and during the next pandemic.

Dr. Antoon is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University and a pediatric hospitalist at the Monroe Carroll Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, both in Nashville, Tenn.

References

1. Kenyon CC et al. Initial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric asthma emergency department utilization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Sep;8(8):2774-6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.045.

2. Luca G et al. The impact of regular school closure on seasonal influenza epidemics: A data-driven spatial transmission model for Belgium. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2934-3.

3. Antoon JW et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and changes in healthcare utilization for pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2021 Mar 8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3608.

4. Park YJ et al. Contact tracing during coronavirus disease outbreak, South Korea, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Oct;26(10):2465-8. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.201315.

5. Davies NG et al. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Med. 2020 Aug;26(8):1205-11. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9.

6. Andrews JL et al. Peer influence in adolescence: Public health implications for COVID-19. Trends Cogn Sci. 2020;24(8):585-7. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.001.

7. Taquechel K et al. Pediatric asthma healthcare utilization, viral testing, and air pollution changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Nov-Dec;8(10):3378-87.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.057.

8. Hill RM et al. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e2020029280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280.

9. Sharma S et al. COVID-19: Differences in sentinel injury and child abuse reporting during a pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020 Dec;110:104709. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709.

10. Lauren BN et al. Predictors of households at risk for food insecurity in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000355.

The COVID-19 pandemic upended the U.S. health care market and disrupted much of what was thought to be consistent and necessary hospital-based care for children. Early in the pandemic, clinics closed, elective surgeries were delayed, and well visits were postponed. Mitigation strategies were launched nationwide to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 including mask mandates, social distancing, shelter-in-place orders, and school closures. While these measures were enacted to target COVID-19, a potential off-target effect was reductions in transmission of other respiratory illness, and potentially nonrespiratory infectious illnesses and conditions exacerbated by acute infections.1 These measures have heavily impacted the pediatric population, wherein respiratory infections are common, and also because daycares and school can be hubs for disease transmission.2

To evaluate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric health care utilization, we performed a multicenter, cross-sectional study of 44 children’s hospitals using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database.3 Children aged 2 months to 18 years discharged from a PHIS hospital with nonsurgical diagnoses from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30 over a 4-year period (2017-2020) were included in the study. The primary exposure was the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which was divided into three study periods: pre–COVID-19 (January–February 2020), early COVID-19 (March-April 2020), and COVID-19 (May-September 2020). The primary outcomes were the observed-to-expected ratio of respiratory and nonrespiratory illness encounters of the study period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic. For these calculations, the expected encounters for each period was derived from the same calendar periods from prepandemic years (2017-2019).

A total of 9,051,980 pediatric encounters were included in the analyses: 6,811,799 with nonrespiratory illnesses and 2,240,181 with respiratory illnesses. We found a 42% reduction in overall encounters during the COVID-19 period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic, with a greater reduction in respiratory, compared with nonrespiratory illnesses, which decreased 62% and 38%, respectively. These reductions were consistent across geographic and encounter type (ED vs. hospitalization). The frequency of hospital-based encounters for common pediatric respiratory illnesses was substantially reduced, with reductions in asthma exacerbations (down 76%), pneumonia (down 81%), croup (down 84%), influenza (down 87%) and bronchiolitis (down 91%). Differences in both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses varied by age, with larger reductions found in children aged less than 12 years. While adolescent (children aged over 12 years) encounters diminished during the early COVID period for both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses, their encounters returned to previous levels faster than those from younger children. For respiratory illnesses, hospital-based adolescents encounters had returned to prepandemic levels by the end of the study period (September 2020).

These findings warrant consideration as relaxation of SARS-CoV-2 mitigation are contemplated. Encounters for respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses declined less and recovered faster in adolescents, compared with younger children. The underlying contributors to this trend are likely multifactorial. For example, respiratory illnesses such as croup and bronchiolitis are more common in younger children and adolescents may be more likely to transmit SARS-CoV-2, compared with younger age groups.4,5 However, adolescents may have had less strict adherence to social distancing measures.6 Future efforts to halt transmission of SARS-CoV-2, as well as other respiratory pathogens, should inform mitigation efforts in the adolescent population with considerations of the intensity of social mixing in different pediatric age groups.

While reductions in encounters caused by respiratory illnesses were substantial, more modest but similar age-based trends were seen in nonrespiratory illnesses. Yet, reduced transmission of infectious agents may not fully explain these findings. For example, it is possible that families sought care for mild to moderate nonrespiratory illness in clinics or via telehealth rather than the EDs.7 Provided there were no unintended negative consequences, such transition of care to non-ED settings would suggest there was overutilization of hospital resources prior to the pandemic. Additional assessments would be helpful to examine this more closely and to clarify the long-term impact of those transitions.

It is also possible that the pandemic effects on financial, social, and family stress may have led to increases in some pediatric health care encounters, such as those for mental health conditions,8 nonaccidental trauma or inability to adhere to treatment because of lack of resources.9,10 Additional study on the evolution and distribution of social and stress-related illnesses is critical to maintain and improve the health of children and adolescents.

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in rapid and marked changes to both communicable and noncommunicable illnesses and care-seeking behaviors. Some of these findings are encouraging, such as large reductions in respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses. However, other trends may be harbingers of negative health consequences of the pandemic, such as increases in health care utilization later in the pandemic. Further study of the evolving pandemic’s effects on disease and health care utilization is needed to benefit our children now and during the next pandemic.

Dr. Antoon is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University and a pediatric hospitalist at the Monroe Carroll Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, both in Nashville, Tenn.

References

1. Kenyon CC et al. Initial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric asthma emergency department utilization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Sep;8(8):2774-6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.045.

2. Luca G et al. The impact of regular school closure on seasonal influenza epidemics: A data-driven spatial transmission model for Belgium. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2934-3.

3. Antoon JW et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and changes in healthcare utilization for pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2021 Mar 8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3608.

4. Park YJ et al. Contact tracing during coronavirus disease outbreak, South Korea, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Oct;26(10):2465-8. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.201315.

5. Davies NG et al. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Med. 2020 Aug;26(8):1205-11. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9.

6. Andrews JL et al. Peer influence in adolescence: Public health implications for COVID-19. Trends Cogn Sci. 2020;24(8):585-7. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.001.

7. Taquechel K et al. Pediatric asthma healthcare utilization, viral testing, and air pollution changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Nov-Dec;8(10):3378-87.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.057.

8. Hill RM et al. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e2020029280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280.

9. Sharma S et al. COVID-19: Differences in sentinel injury and child abuse reporting during a pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020 Dec;110:104709. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709.

10. Lauren BN et al. Predictors of households at risk for food insecurity in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000355.

Psychiatry is Neurology: White matter pathology permeates psychiatric disorders

Ask neurologists or psychiatrists to name a white matter (WM) brain disease and they are very likely to say multiple sclerosis (MS), a demyelinating brain disorder caused by immune-mediated destruction of oligodendrocytes, the glial cells that manufacture myelin without which brain communications would come to a standstill.

MS is often associated with mood or psychotic disorders, yet it is regarded as a neurologic illness, not a psychiatric disorder.

Many neurologists and psychiatrists may not be aware that during the past few years, multiple diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have revealed that many psychiatric disorders are associated with WM pathology.1

Most people think that the brain is composed mostly of neurons, but in fact the bulk of brain volume (60%) is comprised of WM and only 40% is gray matter, which includes both neurons and glial cells (astroglia, microglia, and oligodendroglia). WM includes >137,000 km of myelinated fibers, an extensive network that connects all brain regions and integrates its complex, multifaceted functions, culminating in a unified sense of self and agency.

The role of the corpus callosum

Early in my research career, I became interested in the corpus callosum, the largest interhemispheric WM commissure connecting homologous areas across the 2 cerebral hemispheres. It is comprised of 200 million fibers of various diameters. Reasons for my fascination with the corpus callosum were:

The studies of Roger Sperry, the 1981 Nobel Laureate who led the team that was awarded the prize for split-brain research, which involved patients whose corpus callosum was cut to prevent the transfer of intractable epilepsy from 1 hemisphere to the other. Using a tachistoscope that he designed, Sperry discovered that the right and left hemispheres are 2 independent spheres of consciousness (ie, 2 individuals) with different skills.2 Cerebral dominance (laterality) fully integrates the 2 hemispheres via the corpus callosum, with a verbal hemisphere (the left, in 90% of people) dominating the other hemisphere and serving as the “spokesman self.” Thus, we all have 2 persons in our brain completely integrated into 1 “self.”2 This led me to wonder about the effects of an impaired corpus callosum on the “unified self.”