User login

Tips for getting involved with industry

Introduction

The professional activity of physicians has traditionally consisted of patient care, teaching/education, and research in varying proportions. These aims, especially education and research, have traditionally been achieved in academic health settings. However, involvement with industry can afford all physicians an opportunity to increase patient referrals, gain exposure to colleagues through a variety of educational opportunities, and participate in meaningful research projects they could not initiate independently.

How to initiate relationships with industry

Here are several ways to initiate a collaboration with industry. A few of the most common ways are to become a site investigator of a multicenter device or pharmaceutical trial, participate as a member of a speaker’s bureau, or obtain training on a new technology and subsequently incorporate it into your clinical practice. To find out what trials are enrolling and looking for additional sites or new studies that are being planned, I would suggest contacting the company’s local representative and have them put you in touch the appropriate personnel in the clinical trials division. For individuals who become involved in trials, this can be a great way to improve your understanding of how to design and conduct clinical trials as well as gain exposure to colleagues with similar clinical and research interests. Some of my closest long-term collaborators and friends have been individuals who I initially met as part of industry trials at investigator meetings. Another approach is to participate in a speaker’s bureau, which can be an excellent way to improve one’s presentation skills as well as gain knowledge with respect to a specific disease state. It is also a great way to network, meet colleagues, and develop a local and regional reputation as a content expert on a specific topic. Methods to find out about such opportunities include touring the exhibit halls during educational meetings and reading scientific journals to identify new products that are launching. I have found these sorts of opportunities can significantly increase topic-based referrals. Finally, obtaining training on a new diagnostic or therapeutic technology (usually through an industry-sponsored course) can allow individuals an opportunity to offer a unique or distinctive service to their community. In addition, as further clinical expertise is gained, the relationship can be expanded to offer local, regional, or even national training courses to colleagues via either on-site or virtual courses. Similarly, opportunities to speak about or demonstrate the technology/technique at educational courses may also follow.

Navigating and expanding the relationship

Once an individual establishes a relationship with a company or has established a reputation as a key opinion leader, additional opportunities for engagement may become available. These include serving as a consultant, becoming a member of an advisory board, participating or directing educational courses for trainees/practitioners, or serving as the principal investigator of a future clinical trial. Serving as a consultant can be quite rewarding as it can highlight clinical needs, identify where product improvement can be achieved, and focus where research and development funds should be directed. Serving on the advisory board can afford an even higher level of influence where corporate strategy can be influenced. Such input is particularly impactful with smaller companies looking to enter a new field or expand a limited market share. There are also a variety of educational opportunities offered by industry including local, regional, and national courses that focus on utilizing a new technology or education concerning a specific disease state. These courses can be held locally at the physician’s clinical site or off site to attract the desired target audience. Finally, being involved in research studies, especially early-stage projects, can be critical as many small companies have limited capital, and it is essential for them to design studies with appropriate endpoints that will ideally achieve both regulatory approval as well as payor coverage. Of note, in addition to relationships directly involving industry, the American Gastroenterological Association Center for GI Innovation and Technology (CGIT) also offers the opportunity to be part of key opinion leader meetings arranged and organized by the AGA. This may allow for some individuals to participate who may be restricted from direct relationships with industry partners. The industry services offered by the CGIT also include clinical trial design and registry management services.

Entrepreneurship/intellectual property

A less commonly explored opportunity with industry involves the development of one’s own intellectual property. Some of the most impactful technologies in my advanced endoscopy clinical practice have been developed from the ideas of gastroenterology colleagues that have been successfully commercialized. These include radiofrequency ablation technology to treat Barrett’s esophagus and the development of lumen-apposing stents. There are several options for physicians with an idea for an innovation. These can include working with a university technology transfer department if they are in an academic setting, creation of their own company, or collaborating with industry to develop the device through a licensing/royalty agreement. The AGA CGIT offers extensive resources to physicians with new ideas on how to secure their intellectual property as well as to evaluate the feasibility of the aforementioned options to choose which may be most appropriate for them.

Important caveats

It is important that physicians with industry relations be aware of their local institutional policies. Some institutions may prohibit such activities while others may limit the types of relationships or the amount of income that can be received. It is the physician’s responsibility to be aware of their institution’s guidelines prior to formalizing industry agreements. If intellectual property is involved, it is essential to know the specific rules regarding physician remuneration, especially pertaining to royalty or equity agreements. Furthermore, with regard to presentations and publications, it is required to acknowledge industry relations and potential conflicts of interest. Failure to do so may adversely affect an individual’s reputation as well as lead to additional consequences such as the potential for retraction of publications or restrictions regarding future educational speaking opportunities. In addition, key opinion leaders often consult for several companies that may be in competition with each other. Therefore, it is essential that there is no disclosure of confidential proprietary information among companies. Finally, the financial incentives resulting from industry collaboration should never influence physician judgment when interpreting or speaking about data regarding product efficacy or safety.

Conclusions

In summary, there are numerous opportunities for physicians to collaborate with industry. These relationships can be very rewarding and can serve to expedite the introduction of new diagnostic or treatment modalities and provide the opportunity to network and interact with colleagues as well as to participate in important research that improves clinical practice. The nature of these relationships should always be transparent, and it is the physician’s responsibility to ensure that the types of relationships that are engaged in are permitted by their employer. Over the course of my career, I have participated in nearly all forms of these relationships and have seen that participation lead to important publications, changes in corporate strategy, the fostering of acquisitions, and the rapid development and utilization of new endoscopic technologies. It is my personal belief than industry relationships can improve professional satisfaction, enhance one’s brand, and most importantly, expedite clinical innovation to improve patient care.

Dr. Muthusamy is professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and medical director of endoscopy, UCLA Health System. He disclosed ties with Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Motus GI, Endogastric Solutions, and Capsovision.

Introduction

The professional activity of physicians has traditionally consisted of patient care, teaching/education, and research in varying proportions. These aims, especially education and research, have traditionally been achieved in academic health settings. However, involvement with industry can afford all physicians an opportunity to increase patient referrals, gain exposure to colleagues through a variety of educational opportunities, and participate in meaningful research projects they could not initiate independently.

How to initiate relationships with industry

Here are several ways to initiate a collaboration with industry. A few of the most common ways are to become a site investigator of a multicenter device or pharmaceutical trial, participate as a member of a speaker’s bureau, or obtain training on a new technology and subsequently incorporate it into your clinical practice. To find out what trials are enrolling and looking for additional sites or new studies that are being planned, I would suggest contacting the company’s local representative and have them put you in touch the appropriate personnel in the clinical trials division. For individuals who become involved in trials, this can be a great way to improve your understanding of how to design and conduct clinical trials as well as gain exposure to colleagues with similar clinical and research interests. Some of my closest long-term collaborators and friends have been individuals who I initially met as part of industry trials at investigator meetings. Another approach is to participate in a speaker’s bureau, which can be an excellent way to improve one’s presentation skills as well as gain knowledge with respect to a specific disease state. It is also a great way to network, meet colleagues, and develop a local and regional reputation as a content expert on a specific topic. Methods to find out about such opportunities include touring the exhibit halls during educational meetings and reading scientific journals to identify new products that are launching. I have found these sorts of opportunities can significantly increase topic-based referrals. Finally, obtaining training on a new diagnostic or therapeutic technology (usually through an industry-sponsored course) can allow individuals an opportunity to offer a unique or distinctive service to their community. In addition, as further clinical expertise is gained, the relationship can be expanded to offer local, regional, or even national training courses to colleagues via either on-site or virtual courses. Similarly, opportunities to speak about or demonstrate the technology/technique at educational courses may also follow.

Navigating and expanding the relationship

Once an individual establishes a relationship with a company or has established a reputation as a key opinion leader, additional opportunities for engagement may become available. These include serving as a consultant, becoming a member of an advisory board, participating or directing educational courses for trainees/practitioners, or serving as the principal investigator of a future clinical trial. Serving as a consultant can be quite rewarding as it can highlight clinical needs, identify where product improvement can be achieved, and focus where research and development funds should be directed. Serving on the advisory board can afford an even higher level of influence where corporate strategy can be influenced. Such input is particularly impactful with smaller companies looking to enter a new field or expand a limited market share. There are also a variety of educational opportunities offered by industry including local, regional, and national courses that focus on utilizing a new technology or education concerning a specific disease state. These courses can be held locally at the physician’s clinical site or off site to attract the desired target audience. Finally, being involved in research studies, especially early-stage projects, can be critical as many small companies have limited capital, and it is essential for them to design studies with appropriate endpoints that will ideally achieve both regulatory approval as well as payor coverage. Of note, in addition to relationships directly involving industry, the American Gastroenterological Association Center for GI Innovation and Technology (CGIT) also offers the opportunity to be part of key opinion leader meetings arranged and organized by the AGA. This may allow for some individuals to participate who may be restricted from direct relationships with industry partners. The industry services offered by the CGIT also include clinical trial design and registry management services.

Entrepreneurship/intellectual property

A less commonly explored opportunity with industry involves the development of one’s own intellectual property. Some of the most impactful technologies in my advanced endoscopy clinical practice have been developed from the ideas of gastroenterology colleagues that have been successfully commercialized. These include radiofrequency ablation technology to treat Barrett’s esophagus and the development of lumen-apposing stents. There are several options for physicians with an idea for an innovation. These can include working with a university technology transfer department if they are in an academic setting, creation of their own company, or collaborating with industry to develop the device through a licensing/royalty agreement. The AGA CGIT offers extensive resources to physicians with new ideas on how to secure their intellectual property as well as to evaluate the feasibility of the aforementioned options to choose which may be most appropriate for them.

Important caveats

It is important that physicians with industry relations be aware of their local institutional policies. Some institutions may prohibit such activities while others may limit the types of relationships or the amount of income that can be received. It is the physician’s responsibility to be aware of their institution’s guidelines prior to formalizing industry agreements. If intellectual property is involved, it is essential to know the specific rules regarding physician remuneration, especially pertaining to royalty or equity agreements. Furthermore, with regard to presentations and publications, it is required to acknowledge industry relations and potential conflicts of interest. Failure to do so may adversely affect an individual’s reputation as well as lead to additional consequences such as the potential for retraction of publications or restrictions regarding future educational speaking opportunities. In addition, key opinion leaders often consult for several companies that may be in competition with each other. Therefore, it is essential that there is no disclosure of confidential proprietary information among companies. Finally, the financial incentives resulting from industry collaboration should never influence physician judgment when interpreting or speaking about data regarding product efficacy or safety.

Conclusions

In summary, there are numerous opportunities for physicians to collaborate with industry. These relationships can be very rewarding and can serve to expedite the introduction of new diagnostic or treatment modalities and provide the opportunity to network and interact with colleagues as well as to participate in important research that improves clinical practice. The nature of these relationships should always be transparent, and it is the physician’s responsibility to ensure that the types of relationships that are engaged in are permitted by their employer. Over the course of my career, I have participated in nearly all forms of these relationships and have seen that participation lead to important publications, changes in corporate strategy, the fostering of acquisitions, and the rapid development and utilization of new endoscopic technologies. It is my personal belief than industry relationships can improve professional satisfaction, enhance one’s brand, and most importantly, expedite clinical innovation to improve patient care.

Dr. Muthusamy is professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and medical director of endoscopy, UCLA Health System. He disclosed ties with Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Motus GI, Endogastric Solutions, and Capsovision.

Introduction

The professional activity of physicians has traditionally consisted of patient care, teaching/education, and research in varying proportions. These aims, especially education and research, have traditionally been achieved in academic health settings. However, involvement with industry can afford all physicians an opportunity to increase patient referrals, gain exposure to colleagues through a variety of educational opportunities, and participate in meaningful research projects they could not initiate independently.

How to initiate relationships with industry

Here are several ways to initiate a collaboration with industry. A few of the most common ways are to become a site investigator of a multicenter device or pharmaceutical trial, participate as a member of a speaker’s bureau, or obtain training on a new technology and subsequently incorporate it into your clinical practice. To find out what trials are enrolling and looking for additional sites or new studies that are being planned, I would suggest contacting the company’s local representative and have them put you in touch the appropriate personnel in the clinical trials division. For individuals who become involved in trials, this can be a great way to improve your understanding of how to design and conduct clinical trials as well as gain exposure to colleagues with similar clinical and research interests. Some of my closest long-term collaborators and friends have been individuals who I initially met as part of industry trials at investigator meetings. Another approach is to participate in a speaker’s bureau, which can be an excellent way to improve one’s presentation skills as well as gain knowledge with respect to a specific disease state. It is also a great way to network, meet colleagues, and develop a local and regional reputation as a content expert on a specific topic. Methods to find out about such opportunities include touring the exhibit halls during educational meetings and reading scientific journals to identify new products that are launching. I have found these sorts of opportunities can significantly increase topic-based referrals. Finally, obtaining training on a new diagnostic or therapeutic technology (usually through an industry-sponsored course) can allow individuals an opportunity to offer a unique or distinctive service to their community. In addition, as further clinical expertise is gained, the relationship can be expanded to offer local, regional, or even national training courses to colleagues via either on-site or virtual courses. Similarly, opportunities to speak about or demonstrate the technology/technique at educational courses may also follow.

Navigating and expanding the relationship

Once an individual establishes a relationship with a company or has established a reputation as a key opinion leader, additional opportunities for engagement may become available. These include serving as a consultant, becoming a member of an advisory board, participating or directing educational courses for trainees/practitioners, or serving as the principal investigator of a future clinical trial. Serving as a consultant can be quite rewarding as it can highlight clinical needs, identify where product improvement can be achieved, and focus where research and development funds should be directed. Serving on the advisory board can afford an even higher level of influence where corporate strategy can be influenced. Such input is particularly impactful with smaller companies looking to enter a new field or expand a limited market share. There are also a variety of educational opportunities offered by industry including local, regional, and national courses that focus on utilizing a new technology or education concerning a specific disease state. These courses can be held locally at the physician’s clinical site or off site to attract the desired target audience. Finally, being involved in research studies, especially early-stage projects, can be critical as many small companies have limited capital, and it is essential for them to design studies with appropriate endpoints that will ideally achieve both regulatory approval as well as payor coverage. Of note, in addition to relationships directly involving industry, the American Gastroenterological Association Center for GI Innovation and Technology (CGIT) also offers the opportunity to be part of key opinion leader meetings arranged and organized by the AGA. This may allow for some individuals to participate who may be restricted from direct relationships with industry partners. The industry services offered by the CGIT also include clinical trial design and registry management services.

Entrepreneurship/intellectual property

A less commonly explored opportunity with industry involves the development of one’s own intellectual property. Some of the most impactful technologies in my advanced endoscopy clinical practice have been developed from the ideas of gastroenterology colleagues that have been successfully commercialized. These include radiofrequency ablation technology to treat Barrett’s esophagus and the development of lumen-apposing stents. There are several options for physicians with an idea for an innovation. These can include working with a university technology transfer department if they are in an academic setting, creation of their own company, or collaborating with industry to develop the device through a licensing/royalty agreement. The AGA CGIT offers extensive resources to physicians with new ideas on how to secure their intellectual property as well as to evaluate the feasibility of the aforementioned options to choose which may be most appropriate for them.

Important caveats

It is important that physicians with industry relations be aware of their local institutional policies. Some institutions may prohibit such activities while others may limit the types of relationships or the amount of income that can be received. It is the physician’s responsibility to be aware of their institution’s guidelines prior to formalizing industry agreements. If intellectual property is involved, it is essential to know the specific rules regarding physician remuneration, especially pertaining to royalty or equity agreements. Furthermore, with regard to presentations and publications, it is required to acknowledge industry relations and potential conflicts of interest. Failure to do so may adversely affect an individual’s reputation as well as lead to additional consequences such as the potential for retraction of publications or restrictions regarding future educational speaking opportunities. In addition, key opinion leaders often consult for several companies that may be in competition with each other. Therefore, it is essential that there is no disclosure of confidential proprietary information among companies. Finally, the financial incentives resulting from industry collaboration should never influence physician judgment when interpreting or speaking about data regarding product efficacy or safety.

Conclusions

In summary, there are numerous opportunities for physicians to collaborate with industry. These relationships can be very rewarding and can serve to expedite the introduction of new diagnostic or treatment modalities and provide the opportunity to network and interact with colleagues as well as to participate in important research that improves clinical practice. The nature of these relationships should always be transparent, and it is the physician’s responsibility to ensure that the types of relationships that are engaged in are permitted by their employer. Over the course of my career, I have participated in nearly all forms of these relationships and have seen that participation lead to important publications, changes in corporate strategy, the fostering of acquisitions, and the rapid development and utilization of new endoscopic technologies. It is my personal belief than industry relationships can improve professional satisfaction, enhance one’s brand, and most importantly, expedite clinical innovation to improve patient care.

Dr. Muthusamy is professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and medical director of endoscopy, UCLA Health System. He disclosed ties with Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Motus GI, Endogastric Solutions, and Capsovision.

Artificial intelligence applications in colonoscopy

Considerable advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-learning (ML) methodologies have led to the emergence of promising tools in the field of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Computer vision is an application of AI/ML that has been successfully applied for the computer-aided detection (CADe) and computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) of colon polyps and numerous other conditions encountered during GI endoscopy. Outside of computer vision, a wide variety of other AI applications have been applied to gastroenterology, ranging from natural language processing (NLP) to optimize clinical documentation and endoscopy quality reporting to ML techniques that predict disease severity/treatment response and augment clinical decision-making.

In the United States, colonoscopy is the standard for colon cancer screening and prevention; however, precancerous polyps can be missed for various reasons, ranging from subtle surface appearance of the polyp or location behind a colonic fold to operator-dependent reasons such as inadequate mucosal inspection. Though clinical practice guidelines have set adenoma detection rate (ADR) thresholds at 20% for women and 30% for men, studies have shown a 4- to 10-fold variation in ADR among physicians in clinical practice settings,1 with an estimated adenoma miss rate (AMR) of 25% and a false-negative colonoscopy rate of 12%.2 Variability in adenoma detection affects the risk of interval colorectal cancer post colonoscopy.3,4

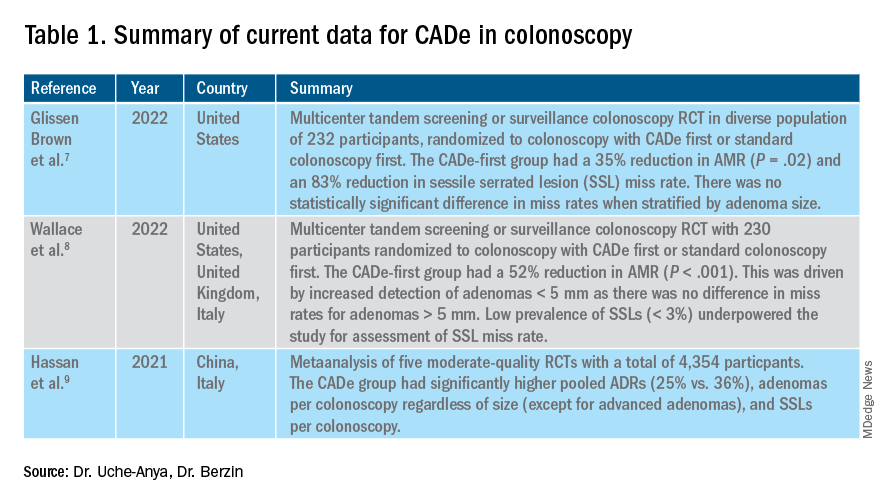

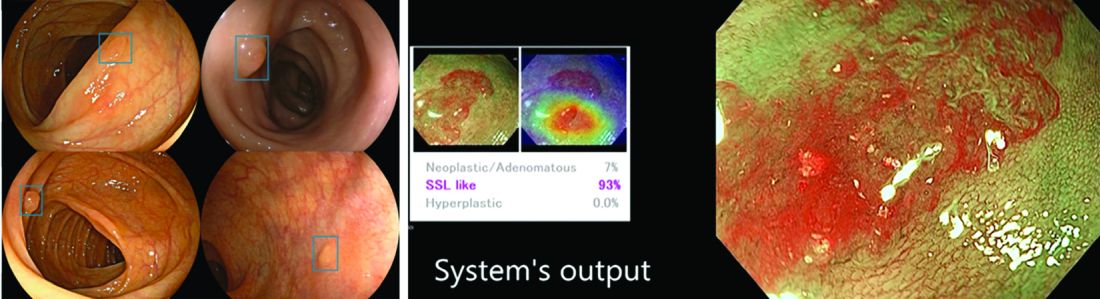

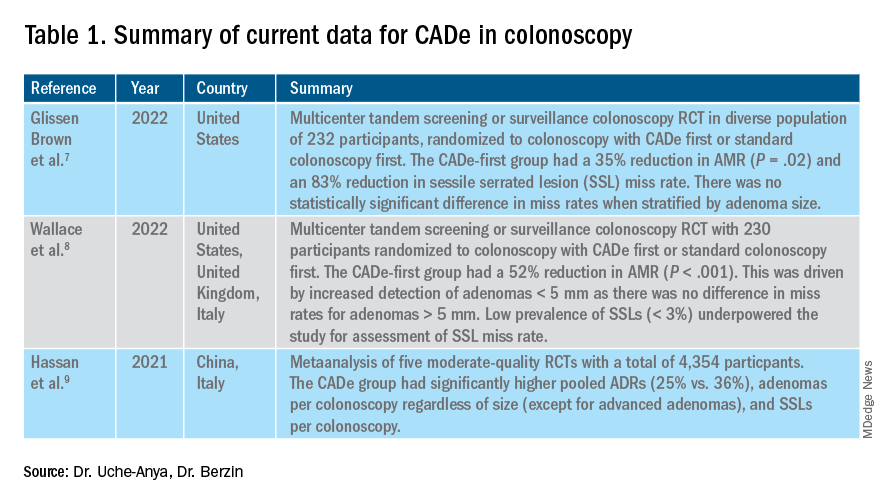

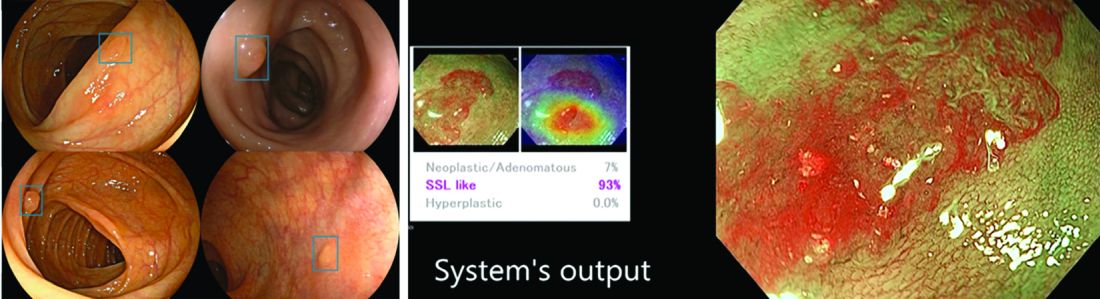

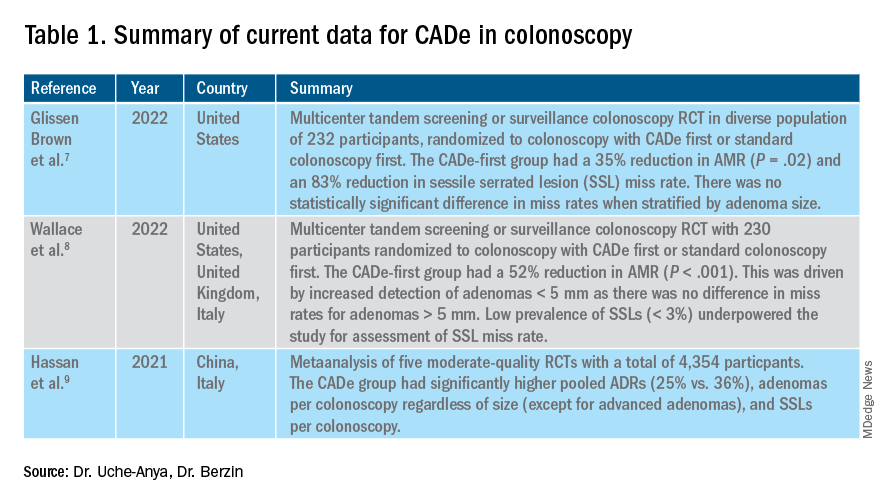

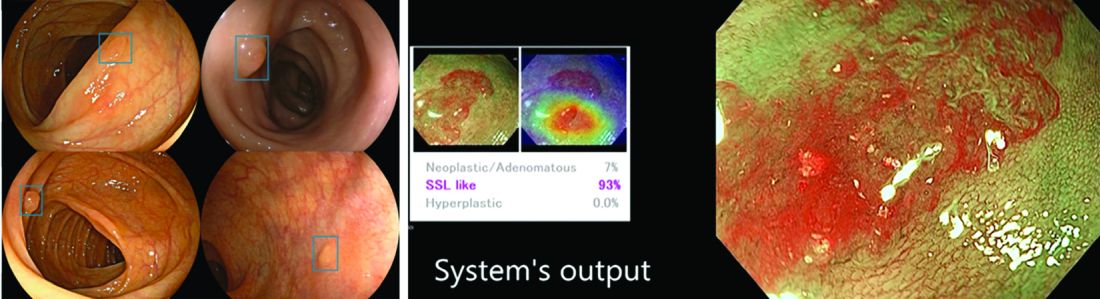

AI provides an opportunity for mitigating this risk. Advances in deep learning and computer vision have led to the development of CADe systems that automatically detect polyps in real time during colonoscopy, resulting in reduced adenoma miss rates (Table 1). In addition to polyp detection, deep-learning technologies are also being used in CADx systems for polyp diagnosis and characterization of malignancy risk. This could aid therapeutic decision-making: Unnecessary resection or histopathologic analysis could be obviated for benign hyperplastic polyps. On the other end of the polyp spectrum, an AI tool that could predict the presence or absence of submucosal invasion could be a powerful tool when evaluating early colon cancers for consideration of endoscopic submucosal dissection vs. surgery. Examples of CADe polyp detection and CADx polyp characterization are shown in Figure 1.

Other potential computer vision applications that may improve colonoscopy quality include tools that help measure adequacy of mucosal exposure, segmental inspection time, and a variety of other parameters associated with polyp detection performance. These are promising areas for future research. Beyond improving colonoscopy technique, natural language processing tools already are being used to optimize clinical documentation as well as extract information from colonoscopy and pathology reports that can facilitate reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics such as ADR, cecal intubation rate, withdrawal time, and bowel preparation adequacy. AI-powered analytics may help unlock large-scale reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics on a health-systems level5 or population-level,6 helping to ensure optimal performance and identifying avenues for colonoscopy quality improvement.

The majority of AI research in colonoscopy has focused on CADe for colon polyp detection and CADx for polyp diagnosis. Over the last few years, several randomized clinical trials – two in the United States – have shown that CADe significantly improves adenoma detection and reduces adenoma miss rates in comparison to standard colonoscopy. The existing data are summarized in Table 1, focusing on the two U.S. studies and an international meta-analysis.

In comparison, the data landscape for CADx is nascent and currently limited to several retrospective studies dating back to 2009 and a few prospective studies that have shown promising results.10,11 There is an expectation that integrated CADx also may support the adoption of “resect and discard” or “diagnose and leave” strategies for low-risk polyps. About two-thirds of polyps identified on average-risk screening colonoscopies are diminutive polyps (less than 5 mm in size), which rarely have advanced histologic features (about 0.5%) and are sometimes non-neoplastic (30%). Malignancy risk is even lower in the distal colon.12 As routine histopathologic assessment of such polyps is mostly of limited clinical utility and comes with added pathology costs, CADx technologies may offer a more cost-effective approach where polyps that are characterized in real-time as low-risk adenomas or non-neoplastic are “resected and discarded” or “left in” respectively. In 2011, prior to the development of current AI tools, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy set performance thresholds for technologies supporting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. The ASGE recommended 90% histopathologic concordance for “resect and discard” tools and 90% negative predictive value for adenomatous histology for “diagnose and leave,” tools.13 Narrow-band imaging (NBI), for example, has been shown to meet these benchmarks14,15 with a modeling study suggesting that implementing “resect and discard” strategies with such tools could result in annual savings of $33 million without adversely affecting efficacy, although practical adoption has been limited.16 More recent work has directly explored the feasibility of leveraging CADx to support “leave-in-situ” and “resect-and-discard” strategies.17

Similarly, while CADe use in colonoscopy is associated with additional up-front costs, a modeling study suggests that its associated gains in ADR (as detailed in Table 1) make it a cost-saving strategy for colorectal cancer prevention in the long term.18 There is still uncertainty on whether the incremental CADe-associated gains in adenoma detection will necessarily translate to significant reductions in interval colorectal cancer risk, particularly for endoscopists who are already high-performing polyp detectors. A recent study suggests that, although higher ADRs were associated with lower rates of interval colorectal cancer, the gains in interval colorectal cancer risk reduction appeared to level off with ADRs above 35%-40% (this finding may be limited by statistical power).19 Further, most of the data from CADe trials suggest that gains in adenoma detection are not driven by increased detection of advanced lesions with high malignancy risk but by small polyps with long latency periods of about 5-10 years, which may not significantly alter interval cancer risk. It remains to be determined whether adoption of CADe will have an impact on hard outcomes, most importantly interval colorectal cancer risk, or merely result in increased resource utilization without moving the needle on colorectal cancer prevention. To answer this question, the OperA study – a large-scale randomized clinical trial of 200,000 patients across 18 centers from 13 countries – was launched in 2022. It will investigate the effect of colonoscopy with CADe on a number of critical measures, including long-term interval colon cancer risk.20

Despite commercial availability of regulatory-approved CADe systems and data supporting use for adenoma detection in colonoscopy, mainstream adoption in clinical practice has been sluggish. Physician survey studies have shown that, although there is considerable interest in integrating CADe into clinical practice, there are concerns about access, cost and reimbursement, integration into clinical work-flow, increased procedural times, over-reliance on AI, and algorithmic bias leading to errors.21,22 In addition, without mandatory requirements for ADR reporting or clinical practice guideline recommendations for CADe use, these systems may not be perceived as valuable or ready for prime time even though the evidence suggests otherwise.23,24 For CADe systems to see widespread adoption in clinical practice, it is important that future research studies rigorously investigate and characterize these potential barriers to better inform strategies to address AI hesitancy and implementation challenges. Such efforts can provide an integration framework for future AI applications in gastroenterology beyond colonoscopy, such as CADe of esophageal and gastric premalignant lesions in upper endoscopy, CADx for pancreatic cysts and liver lesions on imaging, NLP tools to optimizing efficient clinical documentation and reporting, and many others.

Dr. Uche-Anya is in the division of gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is with the Center for Advanced Endoscopy, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is a consultant for Wision AI, Medtronic, Magentiq Eye, RSIP Vision, and Docbot.

Corresponding Author: Eugenia Uche-Anya [email protected] Twitter: @UcheAnyaMD @tberzin

References

1. Corley DA et al. Can we improve adenoma detection rates? A systematic review of intervention studies. Gastrointest Endosc. Sep 2011;74(3):656-65. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.017.

2. Zhao S et al. Magnitude, risk factors, and factors associated with adenoma miss rate of tandem colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 05 2019;156(6):1661-74.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.260.

3. Kaminski MF et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. May 13 2010;362(19):1795-803. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907667.

4. Corley DA et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. Apr 03 2014;370(14):1298-306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309086.

5. Laique SN et al. Application of optical character recognition with natural language processing for large-scale quality metric data extraction in colonoscopy reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 03 2021;93(3):750-7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.08.038.

6. Tinmouth J et al. Validation of a natural language processing algorithm to identify adenomas and measure adenoma detection rates across a health system: a population-level study. Gastrointest Endosc. Jul 14 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.07.009.

7. Glissen Brown JR et al. Deep learning computer-aided polyp detection reduces adenoma miss rate: A United States multi-center randomized tandem colonoscopy study (CADeT-CS Trial). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 07 2022;20(7):1499-1507.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.009.

8. Wallace MB et al. Impact of artificial intelligence on miss rate of colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):295-304.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.007.

9. Hassan C et al. Performance of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 01 2021;93(1):77-85.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.059.

10. Glissen Brown JR and Berzin TM. Adoption of new technologies: Artificial intelligence. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. Oct 2021;31(4):743-58. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2021.05.010.

11. Larsen SLV and Mori Y. Artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A review on the current status. DEN open. Apr 2022;2(1):e109. doi: 10.1002/deo2.109.

12. Gupta N et al. Prevalence of advanced histological features in diminutive and small colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. May 2012;75(5):1022-30. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.020.

13. Rex DK et al. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy PIVI (Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations) on real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2011;73(3):419-22. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.023.

14. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. ASGE Technology Committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2015;81(3):502.e1-16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.022.

15. Mori Y et al. Real-time use of artificial intelligence in identification of diminutive polyps during colonoscopy: A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. Sep 18 2018;169(6):357-66. doi: 10.7326/M18-0249.

16. Hassan C et al.. A resect and discard strategy would improve cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Oct 2010;8(10):865-9, 869.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.018.

17. Hassan C et al. Artificial intelligence allows leaving-in-situ colorectal polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Nov 2022;20(11):2505-13.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.045.

18. Areia M et al. Cost-effectiveness of artificial intelligence for screening colonoscopy: a modelling study. Lancet Digit Health. 06 2022;4(6):e436-44. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00042-5.

19. Schottinger JE et al. Association of physician adenoma detection rates with postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2022 Jun 7;327(21):2114-22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.6644.

20. Oslo Uo. Optimising colorectal cancer prevention through personalised treatment with artificial intelligence. 2022.

21. Wadhwa V et al. Physician sentiment toward artificial intelligence (AI) in colonoscopic practice: a survey of US gastroenterologists. Endosc Int Open. Oct 2020;8(10):E1379-84. doi: 10.1055/a-1223-1926.

22. Kader R et al. Survey on the perceptions of UK gastroenterologists and endoscopists to artificial intelligence. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2022;13(5):423-9. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2021-101994.

23. Rex DKet al. Artificial intelligence improves detection at colonoscopy: Why aren’t we all already using it? Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):35-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.042.

24. Ahmad OF et al. Establishing key research questions for the implementation of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A modified Delphi method. Endoscopy. 09 2021;53(9):893-901. doi: 10.1055/a-1306-7590

Considerable advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-learning (ML) methodologies have led to the emergence of promising tools in the field of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Computer vision is an application of AI/ML that has been successfully applied for the computer-aided detection (CADe) and computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) of colon polyps and numerous other conditions encountered during GI endoscopy. Outside of computer vision, a wide variety of other AI applications have been applied to gastroenterology, ranging from natural language processing (NLP) to optimize clinical documentation and endoscopy quality reporting to ML techniques that predict disease severity/treatment response and augment clinical decision-making.

In the United States, colonoscopy is the standard for colon cancer screening and prevention; however, precancerous polyps can be missed for various reasons, ranging from subtle surface appearance of the polyp or location behind a colonic fold to operator-dependent reasons such as inadequate mucosal inspection. Though clinical practice guidelines have set adenoma detection rate (ADR) thresholds at 20% for women and 30% for men, studies have shown a 4- to 10-fold variation in ADR among physicians in clinical practice settings,1 with an estimated adenoma miss rate (AMR) of 25% and a false-negative colonoscopy rate of 12%.2 Variability in adenoma detection affects the risk of interval colorectal cancer post colonoscopy.3,4

AI provides an opportunity for mitigating this risk. Advances in deep learning and computer vision have led to the development of CADe systems that automatically detect polyps in real time during colonoscopy, resulting in reduced adenoma miss rates (Table 1). In addition to polyp detection, deep-learning technologies are also being used in CADx systems for polyp diagnosis and characterization of malignancy risk. This could aid therapeutic decision-making: Unnecessary resection or histopathologic analysis could be obviated for benign hyperplastic polyps. On the other end of the polyp spectrum, an AI tool that could predict the presence or absence of submucosal invasion could be a powerful tool when evaluating early colon cancers for consideration of endoscopic submucosal dissection vs. surgery. Examples of CADe polyp detection and CADx polyp characterization are shown in Figure 1.

Other potential computer vision applications that may improve colonoscopy quality include tools that help measure adequacy of mucosal exposure, segmental inspection time, and a variety of other parameters associated with polyp detection performance. These are promising areas for future research. Beyond improving colonoscopy technique, natural language processing tools already are being used to optimize clinical documentation as well as extract information from colonoscopy and pathology reports that can facilitate reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics such as ADR, cecal intubation rate, withdrawal time, and bowel preparation adequacy. AI-powered analytics may help unlock large-scale reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics on a health-systems level5 or population-level,6 helping to ensure optimal performance and identifying avenues for colonoscopy quality improvement.

The majority of AI research in colonoscopy has focused on CADe for colon polyp detection and CADx for polyp diagnosis. Over the last few years, several randomized clinical trials – two in the United States – have shown that CADe significantly improves adenoma detection and reduces adenoma miss rates in comparison to standard colonoscopy. The existing data are summarized in Table 1, focusing on the two U.S. studies and an international meta-analysis.

In comparison, the data landscape for CADx is nascent and currently limited to several retrospective studies dating back to 2009 and a few prospective studies that have shown promising results.10,11 There is an expectation that integrated CADx also may support the adoption of “resect and discard” or “diagnose and leave” strategies for low-risk polyps. About two-thirds of polyps identified on average-risk screening colonoscopies are diminutive polyps (less than 5 mm in size), which rarely have advanced histologic features (about 0.5%) and are sometimes non-neoplastic (30%). Malignancy risk is even lower in the distal colon.12 As routine histopathologic assessment of such polyps is mostly of limited clinical utility and comes with added pathology costs, CADx technologies may offer a more cost-effective approach where polyps that are characterized in real-time as low-risk adenomas or non-neoplastic are “resected and discarded” or “left in” respectively. In 2011, prior to the development of current AI tools, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy set performance thresholds for technologies supporting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. The ASGE recommended 90% histopathologic concordance for “resect and discard” tools and 90% negative predictive value for adenomatous histology for “diagnose and leave,” tools.13 Narrow-band imaging (NBI), for example, has been shown to meet these benchmarks14,15 with a modeling study suggesting that implementing “resect and discard” strategies with such tools could result in annual savings of $33 million without adversely affecting efficacy, although practical adoption has been limited.16 More recent work has directly explored the feasibility of leveraging CADx to support “leave-in-situ” and “resect-and-discard” strategies.17

Similarly, while CADe use in colonoscopy is associated with additional up-front costs, a modeling study suggests that its associated gains in ADR (as detailed in Table 1) make it a cost-saving strategy for colorectal cancer prevention in the long term.18 There is still uncertainty on whether the incremental CADe-associated gains in adenoma detection will necessarily translate to significant reductions in interval colorectal cancer risk, particularly for endoscopists who are already high-performing polyp detectors. A recent study suggests that, although higher ADRs were associated with lower rates of interval colorectal cancer, the gains in interval colorectal cancer risk reduction appeared to level off with ADRs above 35%-40% (this finding may be limited by statistical power).19 Further, most of the data from CADe trials suggest that gains in adenoma detection are not driven by increased detection of advanced lesions with high malignancy risk but by small polyps with long latency periods of about 5-10 years, which may not significantly alter interval cancer risk. It remains to be determined whether adoption of CADe will have an impact on hard outcomes, most importantly interval colorectal cancer risk, or merely result in increased resource utilization without moving the needle on colorectal cancer prevention. To answer this question, the OperA study – a large-scale randomized clinical trial of 200,000 patients across 18 centers from 13 countries – was launched in 2022. It will investigate the effect of colonoscopy with CADe on a number of critical measures, including long-term interval colon cancer risk.20

Despite commercial availability of regulatory-approved CADe systems and data supporting use for adenoma detection in colonoscopy, mainstream adoption in clinical practice has been sluggish. Physician survey studies have shown that, although there is considerable interest in integrating CADe into clinical practice, there are concerns about access, cost and reimbursement, integration into clinical work-flow, increased procedural times, over-reliance on AI, and algorithmic bias leading to errors.21,22 In addition, without mandatory requirements for ADR reporting or clinical practice guideline recommendations for CADe use, these systems may not be perceived as valuable or ready for prime time even though the evidence suggests otherwise.23,24 For CADe systems to see widespread adoption in clinical practice, it is important that future research studies rigorously investigate and characterize these potential barriers to better inform strategies to address AI hesitancy and implementation challenges. Such efforts can provide an integration framework for future AI applications in gastroenterology beyond colonoscopy, such as CADe of esophageal and gastric premalignant lesions in upper endoscopy, CADx for pancreatic cysts and liver lesions on imaging, NLP tools to optimizing efficient clinical documentation and reporting, and many others.

Dr. Uche-Anya is in the division of gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is with the Center for Advanced Endoscopy, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is a consultant for Wision AI, Medtronic, Magentiq Eye, RSIP Vision, and Docbot.

Corresponding Author: Eugenia Uche-Anya [email protected] Twitter: @UcheAnyaMD @tberzin

References

1. Corley DA et al. Can we improve adenoma detection rates? A systematic review of intervention studies. Gastrointest Endosc. Sep 2011;74(3):656-65. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.017.

2. Zhao S et al. Magnitude, risk factors, and factors associated with adenoma miss rate of tandem colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 05 2019;156(6):1661-74.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.260.

3. Kaminski MF et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. May 13 2010;362(19):1795-803. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907667.

4. Corley DA et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. Apr 03 2014;370(14):1298-306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309086.

5. Laique SN et al. Application of optical character recognition with natural language processing for large-scale quality metric data extraction in colonoscopy reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 03 2021;93(3):750-7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.08.038.

6. Tinmouth J et al. Validation of a natural language processing algorithm to identify adenomas and measure adenoma detection rates across a health system: a population-level study. Gastrointest Endosc. Jul 14 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.07.009.

7. Glissen Brown JR et al. Deep learning computer-aided polyp detection reduces adenoma miss rate: A United States multi-center randomized tandem colonoscopy study (CADeT-CS Trial). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 07 2022;20(7):1499-1507.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.009.

8. Wallace MB et al. Impact of artificial intelligence on miss rate of colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):295-304.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.007.

9. Hassan C et al. Performance of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 01 2021;93(1):77-85.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.059.

10. Glissen Brown JR and Berzin TM. Adoption of new technologies: Artificial intelligence. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. Oct 2021;31(4):743-58. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2021.05.010.

11. Larsen SLV and Mori Y. Artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A review on the current status. DEN open. Apr 2022;2(1):e109. doi: 10.1002/deo2.109.

12. Gupta N et al. Prevalence of advanced histological features in diminutive and small colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. May 2012;75(5):1022-30. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.020.

13. Rex DK et al. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy PIVI (Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations) on real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2011;73(3):419-22. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.023.

14. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. ASGE Technology Committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2015;81(3):502.e1-16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.022.

15. Mori Y et al. Real-time use of artificial intelligence in identification of diminutive polyps during colonoscopy: A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. Sep 18 2018;169(6):357-66. doi: 10.7326/M18-0249.

16. Hassan C et al.. A resect and discard strategy would improve cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Oct 2010;8(10):865-9, 869.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.018.

17. Hassan C et al. Artificial intelligence allows leaving-in-situ colorectal polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Nov 2022;20(11):2505-13.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.045.

18. Areia M et al. Cost-effectiveness of artificial intelligence for screening colonoscopy: a modelling study. Lancet Digit Health. 06 2022;4(6):e436-44. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00042-5.

19. Schottinger JE et al. Association of physician adenoma detection rates with postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2022 Jun 7;327(21):2114-22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.6644.

20. Oslo Uo. Optimising colorectal cancer prevention through personalised treatment with artificial intelligence. 2022.

21. Wadhwa V et al. Physician sentiment toward artificial intelligence (AI) in colonoscopic practice: a survey of US gastroenterologists. Endosc Int Open. Oct 2020;8(10):E1379-84. doi: 10.1055/a-1223-1926.

22. Kader R et al. Survey on the perceptions of UK gastroenterologists and endoscopists to artificial intelligence. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2022;13(5):423-9. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2021-101994.

23. Rex DKet al. Artificial intelligence improves detection at colonoscopy: Why aren’t we all already using it? Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):35-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.042.

24. Ahmad OF et al. Establishing key research questions for the implementation of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A modified Delphi method. Endoscopy. 09 2021;53(9):893-901. doi: 10.1055/a-1306-7590

Considerable advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-learning (ML) methodologies have led to the emergence of promising tools in the field of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Computer vision is an application of AI/ML that has been successfully applied for the computer-aided detection (CADe) and computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) of colon polyps and numerous other conditions encountered during GI endoscopy. Outside of computer vision, a wide variety of other AI applications have been applied to gastroenterology, ranging from natural language processing (NLP) to optimize clinical documentation and endoscopy quality reporting to ML techniques that predict disease severity/treatment response and augment clinical decision-making.

In the United States, colonoscopy is the standard for colon cancer screening and prevention; however, precancerous polyps can be missed for various reasons, ranging from subtle surface appearance of the polyp or location behind a colonic fold to operator-dependent reasons such as inadequate mucosal inspection. Though clinical practice guidelines have set adenoma detection rate (ADR) thresholds at 20% for women and 30% for men, studies have shown a 4- to 10-fold variation in ADR among physicians in clinical practice settings,1 with an estimated adenoma miss rate (AMR) of 25% and a false-negative colonoscopy rate of 12%.2 Variability in adenoma detection affects the risk of interval colorectal cancer post colonoscopy.3,4

AI provides an opportunity for mitigating this risk. Advances in deep learning and computer vision have led to the development of CADe systems that automatically detect polyps in real time during colonoscopy, resulting in reduced adenoma miss rates (Table 1). In addition to polyp detection, deep-learning technologies are also being used in CADx systems for polyp diagnosis and characterization of malignancy risk. This could aid therapeutic decision-making: Unnecessary resection or histopathologic analysis could be obviated for benign hyperplastic polyps. On the other end of the polyp spectrum, an AI tool that could predict the presence or absence of submucosal invasion could be a powerful tool when evaluating early colon cancers for consideration of endoscopic submucosal dissection vs. surgery. Examples of CADe polyp detection and CADx polyp characterization are shown in Figure 1.

Other potential computer vision applications that may improve colonoscopy quality include tools that help measure adequacy of mucosal exposure, segmental inspection time, and a variety of other parameters associated with polyp detection performance. These are promising areas for future research. Beyond improving colonoscopy technique, natural language processing tools already are being used to optimize clinical documentation as well as extract information from colonoscopy and pathology reports that can facilitate reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics such as ADR, cecal intubation rate, withdrawal time, and bowel preparation adequacy. AI-powered analytics may help unlock large-scale reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics on a health-systems level5 or population-level,6 helping to ensure optimal performance and identifying avenues for colonoscopy quality improvement.

The majority of AI research in colonoscopy has focused on CADe for colon polyp detection and CADx for polyp diagnosis. Over the last few years, several randomized clinical trials – two in the United States – have shown that CADe significantly improves adenoma detection and reduces adenoma miss rates in comparison to standard colonoscopy. The existing data are summarized in Table 1, focusing on the two U.S. studies and an international meta-analysis.

In comparison, the data landscape for CADx is nascent and currently limited to several retrospective studies dating back to 2009 and a few prospective studies that have shown promising results.10,11 There is an expectation that integrated CADx also may support the adoption of “resect and discard” or “diagnose and leave” strategies for low-risk polyps. About two-thirds of polyps identified on average-risk screening colonoscopies are diminutive polyps (less than 5 mm in size), which rarely have advanced histologic features (about 0.5%) and are sometimes non-neoplastic (30%). Malignancy risk is even lower in the distal colon.12 As routine histopathologic assessment of such polyps is mostly of limited clinical utility and comes with added pathology costs, CADx technologies may offer a more cost-effective approach where polyps that are characterized in real-time as low-risk adenomas or non-neoplastic are “resected and discarded” or “left in” respectively. In 2011, prior to the development of current AI tools, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy set performance thresholds for technologies supporting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. The ASGE recommended 90% histopathologic concordance for “resect and discard” tools and 90% negative predictive value for adenomatous histology for “diagnose and leave,” tools.13 Narrow-band imaging (NBI), for example, has been shown to meet these benchmarks14,15 with a modeling study suggesting that implementing “resect and discard” strategies with such tools could result in annual savings of $33 million without adversely affecting efficacy, although practical adoption has been limited.16 More recent work has directly explored the feasibility of leveraging CADx to support “leave-in-situ” and “resect-and-discard” strategies.17

Similarly, while CADe use in colonoscopy is associated with additional up-front costs, a modeling study suggests that its associated gains in ADR (as detailed in Table 1) make it a cost-saving strategy for colorectal cancer prevention in the long term.18 There is still uncertainty on whether the incremental CADe-associated gains in adenoma detection will necessarily translate to significant reductions in interval colorectal cancer risk, particularly for endoscopists who are already high-performing polyp detectors. A recent study suggests that, although higher ADRs were associated with lower rates of interval colorectal cancer, the gains in interval colorectal cancer risk reduction appeared to level off with ADRs above 35%-40% (this finding may be limited by statistical power).19 Further, most of the data from CADe trials suggest that gains in adenoma detection are not driven by increased detection of advanced lesions with high malignancy risk but by small polyps with long latency periods of about 5-10 years, which may not significantly alter interval cancer risk. It remains to be determined whether adoption of CADe will have an impact on hard outcomes, most importantly interval colorectal cancer risk, or merely result in increased resource utilization without moving the needle on colorectal cancer prevention. To answer this question, the OperA study – a large-scale randomized clinical trial of 200,000 patients across 18 centers from 13 countries – was launched in 2022. It will investigate the effect of colonoscopy with CADe on a number of critical measures, including long-term interval colon cancer risk.20

Despite commercial availability of regulatory-approved CADe systems and data supporting use for adenoma detection in colonoscopy, mainstream adoption in clinical practice has been sluggish. Physician survey studies have shown that, although there is considerable interest in integrating CADe into clinical practice, there are concerns about access, cost and reimbursement, integration into clinical work-flow, increased procedural times, over-reliance on AI, and algorithmic bias leading to errors.21,22 In addition, without mandatory requirements for ADR reporting or clinical practice guideline recommendations for CADe use, these systems may not be perceived as valuable or ready for prime time even though the evidence suggests otherwise.23,24 For CADe systems to see widespread adoption in clinical practice, it is important that future research studies rigorously investigate and characterize these potential barriers to better inform strategies to address AI hesitancy and implementation challenges. Such efforts can provide an integration framework for future AI applications in gastroenterology beyond colonoscopy, such as CADe of esophageal and gastric premalignant lesions in upper endoscopy, CADx for pancreatic cysts and liver lesions on imaging, NLP tools to optimizing efficient clinical documentation and reporting, and many others.

Dr. Uche-Anya is in the division of gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is with the Center for Advanced Endoscopy, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is a consultant for Wision AI, Medtronic, Magentiq Eye, RSIP Vision, and Docbot.

Corresponding Author: Eugenia Uche-Anya [email protected] Twitter: @UcheAnyaMD @tberzin

References

1. Corley DA et al. Can we improve adenoma detection rates? A systematic review of intervention studies. Gastrointest Endosc. Sep 2011;74(3):656-65. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.017.

2. Zhao S et al. Magnitude, risk factors, and factors associated with adenoma miss rate of tandem colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 05 2019;156(6):1661-74.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.260.

3. Kaminski MF et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. May 13 2010;362(19):1795-803. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907667.

4. Corley DA et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. Apr 03 2014;370(14):1298-306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309086.

5. Laique SN et al. Application of optical character recognition with natural language processing for large-scale quality metric data extraction in colonoscopy reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 03 2021;93(3):750-7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.08.038.

6. Tinmouth J et al. Validation of a natural language processing algorithm to identify adenomas and measure adenoma detection rates across a health system: a population-level study. Gastrointest Endosc. Jul 14 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.07.009.

7. Glissen Brown JR et al. Deep learning computer-aided polyp detection reduces adenoma miss rate: A United States multi-center randomized tandem colonoscopy study (CADeT-CS Trial). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 07 2022;20(7):1499-1507.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.009.

8. Wallace MB et al. Impact of artificial intelligence on miss rate of colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):295-304.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.007.

9. Hassan C et al. Performance of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 01 2021;93(1):77-85.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.059.

10. Glissen Brown JR and Berzin TM. Adoption of new technologies: Artificial intelligence. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. Oct 2021;31(4):743-58. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2021.05.010.

11. Larsen SLV and Mori Y. Artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A review on the current status. DEN open. Apr 2022;2(1):e109. doi: 10.1002/deo2.109.

12. Gupta N et al. Prevalence of advanced histological features in diminutive and small colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. May 2012;75(5):1022-30. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.020.

13. Rex DK et al. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy PIVI (Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations) on real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2011;73(3):419-22. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.023.

14. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. ASGE Technology Committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2015;81(3):502.e1-16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.022.

15. Mori Y et al. Real-time use of artificial intelligence in identification of diminutive polyps during colonoscopy: A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. Sep 18 2018;169(6):357-66. doi: 10.7326/M18-0249.

16. Hassan C et al.. A resect and discard strategy would improve cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Oct 2010;8(10):865-9, 869.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.018.

17. Hassan C et al. Artificial intelligence allows leaving-in-situ colorectal polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Nov 2022;20(11):2505-13.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.045.

18. Areia M et al. Cost-effectiveness of artificial intelligence for screening colonoscopy: a modelling study. Lancet Digit Health. 06 2022;4(6):e436-44. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00042-5.

19. Schottinger JE et al. Association of physician adenoma detection rates with postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2022 Jun 7;327(21):2114-22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.6644.

20. Oslo Uo. Optimising colorectal cancer prevention through personalised treatment with artificial intelligence. 2022.

21. Wadhwa V et al. Physician sentiment toward artificial intelligence (AI) in colonoscopic practice: a survey of US gastroenterologists. Endosc Int Open. Oct 2020;8(10):E1379-84. doi: 10.1055/a-1223-1926.

22. Kader R et al. Survey on the perceptions of UK gastroenterologists and endoscopists to artificial intelligence. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2022;13(5):423-9. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2021-101994.

23. Rex DKet al. Artificial intelligence improves detection at colonoscopy: Why aren’t we all already using it? Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):35-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.042.

24. Ahmad OF et al. Establishing key research questions for the implementation of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A modified Delphi method. Endoscopy. 09 2021;53(9):893-901. doi: 10.1055/a-1306-7590

February 2023 - ICYMI

Gastroenterology

October 2022

Cryer B et al. Bridging the Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Gap in Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):800-5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.037. PMID: 36137708.

Bajaj JS and Nagy LE. Natural History of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: Understanding the Changing Landscape of Pathophysiology and Patient Care. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):840-51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.031. Epub 2022 May 19. PMID: 35598629; PMCID: PMC9509416.

November 2022

Grunvald E et al; AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on Pharmacological Interventions for Adults With Obesity. Gastroenterology. 2022 Nov;163(5):1198-225. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.045. Epub 2022 Oct 20. PMID: 36273831.

December 2022

Blackett JW et al. Comparison of Anorectal Manometry, Rectal Balloon Expulsion Test, and Defecography for Diagnosing Defecatory Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2022 Dec;163(6):1582-92.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.034. Epub 2022 Aug 19. PMID: 35995074; PMCID: PMC9691522.

de Voogd F et al. Intestinal Ultrasound Is Accurate to Determine Endoscopic Response and Remission in Patients With Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis: A Longitudinal Prospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2022 Dec;163(6):1569-81. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.038. Epub 2022 Aug 24. PMID: 36030056.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

October 2022

Bhavsar-Burke I et al. How to Promote Professional Identity Development and Support Fellows-In-Training Through Teaching, Coaching, Mentorship, and Sponsorship. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Oct;20(10):2166-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.043. Epub 2022 Aug 7. PMID: 35948073.

van Megen F et al. A Low FODMAP Diet Reduces Symptoms in Treated Celiac Patients With Ongoing Symptoms – A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Oct;20(10):2258-66.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.01.011. Epub 2022 Jan 17. PMID: 35051648.

November 2022

Sharzehi K et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Subepithelial Lesions Encountered During Routine Endoscopy: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Nov;20(11):2435-43.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.054. Epub 2022 Jul 13. PMID: 35842117.

December 2022

Kardashian A et al. Food Insecurity is Associated With Mortality Among U.S. Adults With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Advanced Fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Dec;20(12):2790-9.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.029. Epub 2021 Dec 16. PMID: 34958747.

Schuitenmaker JM et al. Sleep Positional Therapy for Nocturnal Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Dec;20(12):2753-62.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.058. Epub 2022 Mar 14. PMID: 35301135.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Azizian JM et al. Yield of Post-Acute Diverticulitis Colonoscopy for Ruling Out Colorectal Cancer. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;24(3):254-61. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2022.04.001. Epub 2022 Apr 18. PMID: 36540108; PMCID: PMC9762736.

Gastro Hep Advances

Kim RW et al. Timely Albumin Improves Survival in Patients With Cirrhosis on Diuretic Therapy Who Develop Acute Kidney Injury: Real-World Evidence in the United States. Gastro Hep Advances. 2023;2(2):252-60. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2022.10.008.

Gastroenterology

October 2022

Cryer B et al. Bridging the Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Gap in Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):800-5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.037. PMID: 36137708.

Bajaj JS and Nagy LE. Natural History of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: Understanding the Changing Landscape of Pathophysiology and Patient Care. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):840-51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.031. Epub 2022 May 19. PMID: 35598629; PMCID: PMC9509416.

November 2022

Grunvald E et al; AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on Pharmacological Interventions for Adults With Obesity. Gastroenterology. 2022 Nov;163(5):1198-225. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.045. Epub 2022 Oct 20. PMID: 36273831.

December 2022

Blackett JW et al. Comparison of Anorectal Manometry, Rectal Balloon Expulsion Test, and Defecography for Diagnosing Defecatory Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2022 Dec;163(6):1582-92.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.034. Epub 2022 Aug 19. PMID: 35995074; PMCID: PMC9691522.

de Voogd F et al. Intestinal Ultrasound Is Accurate to Determine Endoscopic Response and Remission in Patients With Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis: A Longitudinal Prospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2022 Dec;163(6):1569-81. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.038. Epub 2022 Aug 24. PMID: 36030056.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

October 2022

Bhavsar-Burke I et al. How to Promote Professional Identity Development and Support Fellows-In-Training Through Teaching, Coaching, Mentorship, and Sponsorship. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Oct;20(10):2166-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.043. Epub 2022 Aug 7. PMID: 35948073.

van Megen F et al. A Low FODMAP Diet Reduces Symptoms in Treated Celiac Patients With Ongoing Symptoms – A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Oct;20(10):2258-66.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.01.011. Epub 2022 Jan 17. PMID: 35051648.

November 2022

Sharzehi K et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Subepithelial Lesions Encountered During Routine Endoscopy: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Nov;20(11):2435-43.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.054. Epub 2022 Jul 13. PMID: 35842117.

December 2022

Kardashian A et al. Food Insecurity is Associated With Mortality Among U.S. Adults With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Advanced Fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Dec;20(12):2790-9.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.029. Epub 2021 Dec 16. PMID: 34958747.

Schuitenmaker JM et al. Sleep Positional Therapy for Nocturnal Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Dec;20(12):2753-62.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.058. Epub 2022 Mar 14. PMID: 35301135.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Azizian JM et al. Yield of Post-Acute Diverticulitis Colonoscopy for Ruling Out Colorectal Cancer. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;24(3):254-61. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2022.04.001. Epub 2022 Apr 18. PMID: 36540108; PMCID: PMC9762736.

Gastro Hep Advances

Kim RW et al. Timely Albumin Improves Survival in Patients With Cirrhosis on Diuretic Therapy Who Develop Acute Kidney Injury: Real-World Evidence in the United States. Gastro Hep Advances. 2023;2(2):252-60. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2022.10.008.

Gastroenterology

October 2022

Cryer B et al. Bridging the Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Gap in Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):800-5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.037. PMID: 36137708.

Bajaj JS and Nagy LE. Natural History of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: Understanding the Changing Landscape of Pathophysiology and Patient Care. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):840-51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.031. Epub 2022 May 19. PMID: 35598629; PMCID: PMC9509416.

November 2022

Grunvald E et al; AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on Pharmacological Interventions for Adults With Obesity. Gastroenterology. 2022 Nov;163(5):1198-225. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.045. Epub 2022 Oct 20. PMID: 36273831.

December 2022

Blackett JW et al. Comparison of Anorectal Manometry, Rectal Balloon Expulsion Test, and Defecography for Diagnosing Defecatory Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2022 Dec;163(6):1582-92.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.034. Epub 2022 Aug 19. PMID: 35995074; PMCID: PMC9691522.

de Voogd F et al. Intestinal Ultrasound Is Accurate to Determine Endoscopic Response and Remission in Patients With Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis: A Longitudinal Prospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2022 Dec;163(6):1569-81. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.038. Epub 2022 Aug 24. PMID: 36030056.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

October 2022

Bhavsar-Burke I et al. How to Promote Professional Identity Development and Support Fellows-In-Training Through Teaching, Coaching, Mentorship, and Sponsorship. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Oct;20(10):2166-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.043. Epub 2022 Aug 7. PMID: 35948073.

van Megen F et al. A Low FODMAP Diet Reduces Symptoms in Treated Celiac Patients With Ongoing Symptoms – A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Oct;20(10):2258-66.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.01.011. Epub 2022 Jan 17. PMID: 35051648.

November 2022

Sharzehi K et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Subepithelial Lesions Encountered During Routine Endoscopy: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Nov;20(11):2435-43.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.054. Epub 2022 Jul 13. PMID: 35842117.

December 2022

Kardashian A et al. Food Insecurity is Associated With Mortality Among U.S. Adults With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Advanced Fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Dec;20(12):2790-9.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.029. Epub 2021 Dec 16. PMID: 34958747.

Schuitenmaker JM et al. Sleep Positional Therapy for Nocturnal Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Dec;20(12):2753-62.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.058. Epub 2022 Mar 14. PMID: 35301135.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Azizian JM et al. Yield of Post-Acute Diverticulitis Colonoscopy for Ruling Out Colorectal Cancer. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;24(3):254-61. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2022.04.001. Epub 2022 Apr 18. PMID: 36540108; PMCID: PMC9762736.

Gastro Hep Advances

Kim RW et al. Timely Albumin Improves Survival in Patients With Cirrhosis on Diuretic Therapy Who Develop Acute Kidney Injury: Real-World Evidence in the United States. Gastro Hep Advances. 2023;2(2):252-60. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2022.10.008.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor–related gastrointestinal adverse events

Introduction

The field of cancer immunotherapy has exploded in recent years, with new therapies showing promising results for effective treatment of various cancer types. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) work by blocking checkpoint proteins that prevent breakdown of tumor cells by T-lymphocytes. Checkpoint proteins exist to prevent autoimmunity and destruction of healthy cells, but may allow tumor cells to grow unchallenged. Three checkpoint proteins – cytotoxic T-lymphocyte protein–4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell-death protein–1 (PD-1), and programmed cell-death protein ligand–1 (PDL-1) – are therapeutic targets for current ICIs.1

ICIs are used to treat various cancer types (e.g., lung, renal-cell, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma). Immune-related adverse events (irAE) are frequently seen with ICI use, ranging from 15% to 90%, and can occur at any point during, or even after, treatment.2

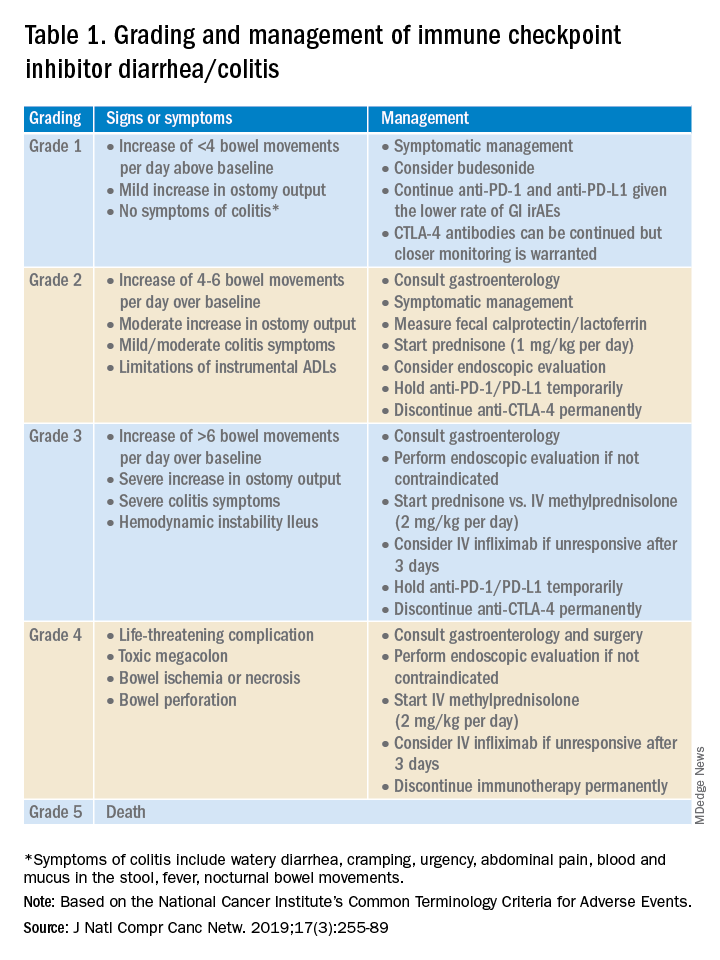

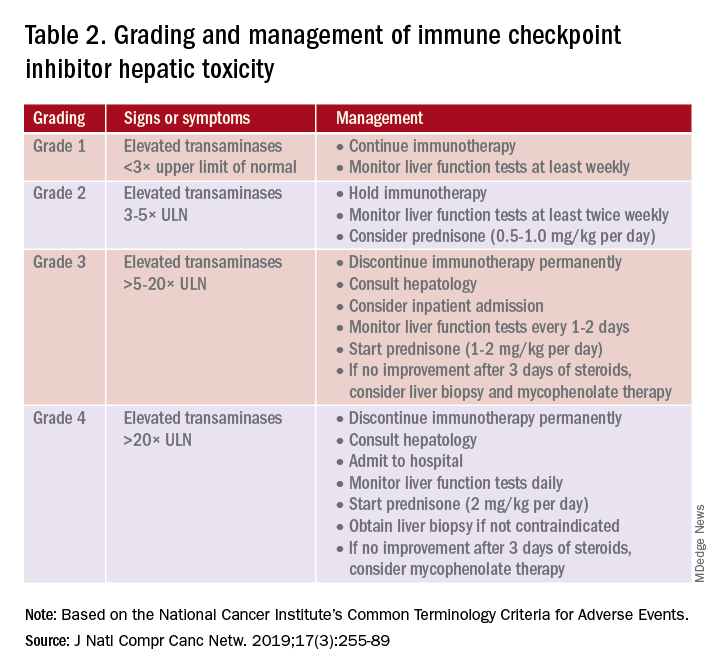

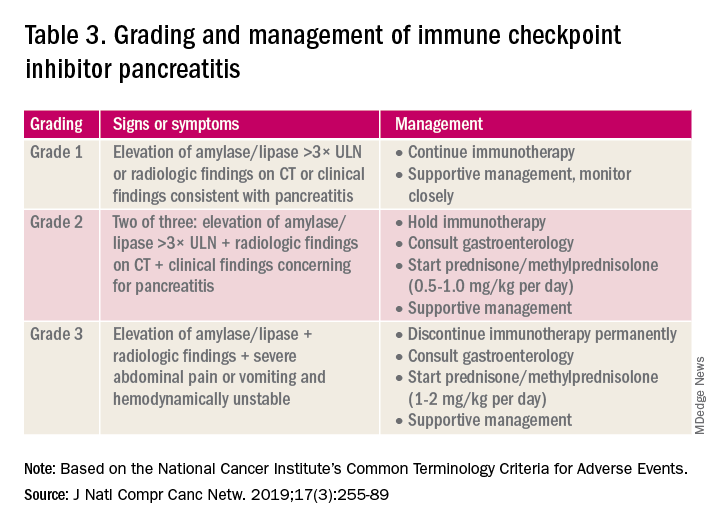

Immune checkpoint inhibitor–related gastrointestinal adverse reactions