User login

Approach to dysphagia

Introduction

Dysphagia is the sensation of difficulty swallowing food or liquid in the acute or chronic setting. The prevalence of dysphagia ranges based on the type and etiology but may impact up to one in six adults.1,2 Dysphagia can cause a significant impact on a patient’s health and overall quality of life. A recent study found that only 50% of symptomatic adults seek medical care despite modifying their eating habits by either eating slowly or changing to softer foods or liquids.1 The most common, serious complications of dysphagia include aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration.3 According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, dysphagia may be responsible for up to 60,000 deaths annually.3

The diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia can be challenging. An initial, thorough history is essential to delineate between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia and guide subsequent diagnostic testing. In recent years, there have been a number of advances in the approach to diagnosing dysphagia, including novel diagnostic modalities. The goal of this review article is to discuss the current approach to esophageal dysphagia and future direction to allow for timely diagnosis and management.

History

The diagnosis of dysphagia begins with a thorough history. Questions about the timing, onset, progression, localization of symptoms, and types of food that are difficult to swallow are essential in differentiating oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia.3,4 Further history taking must include medication and allergy review, smoking history, and review of prior radiation or surgical therapies to the head and neck.

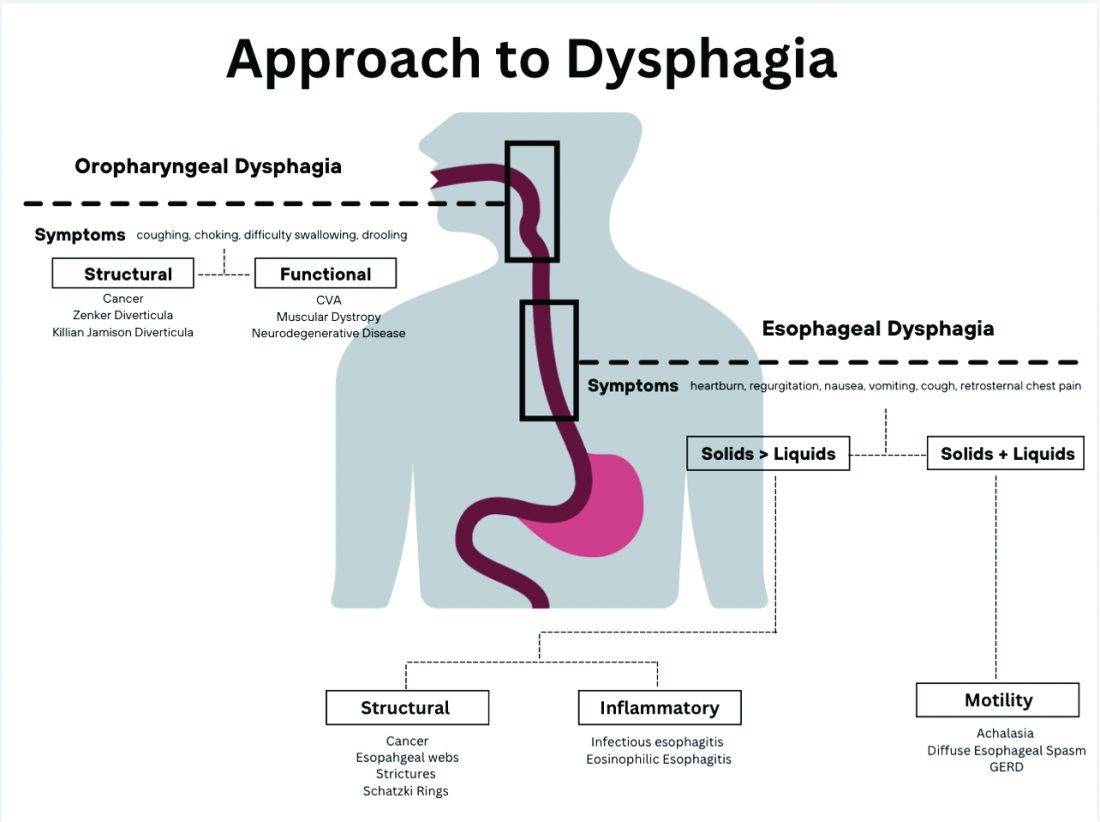

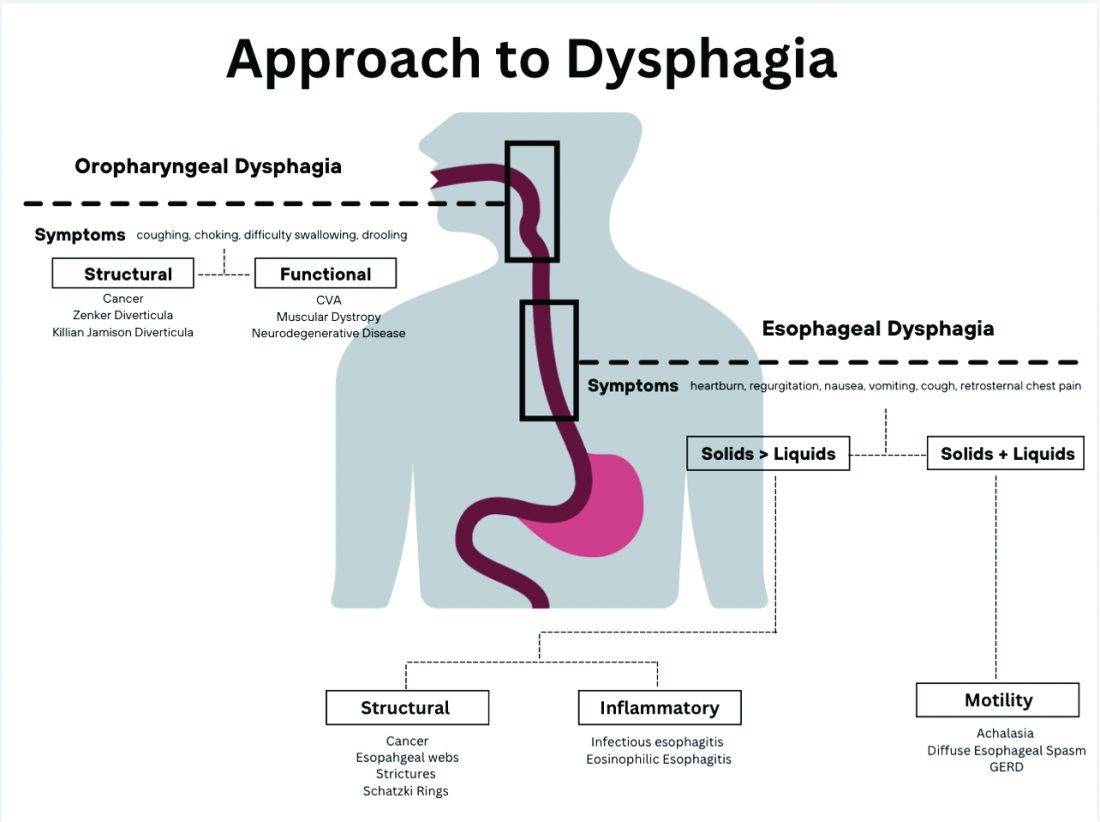

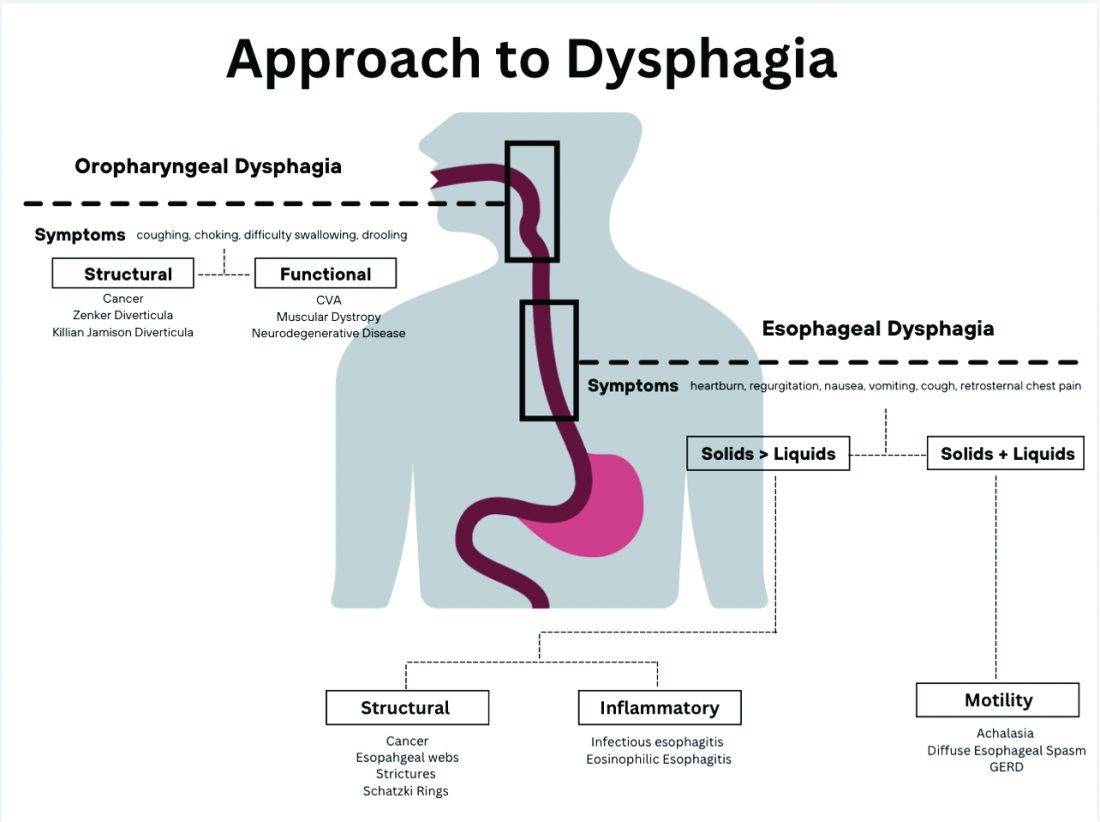

Briefly, oropharyngeal dysphagia is difficulty initiating a swallow or passing food from the mouth or throat and can be caused by structural or functional etiologies.5 Clinical presentations include a sensation of food stuck in the back of the throat, coughing or choking while eating, or drooling. Structural causes include head and neck cancer, Zenker diverticulum, Killian Jamieson diverticula, prolonged intubation, or changes secondary to prior surgery or radiation.3 Functional causes may include neurologic, rheumatologic, or muscular disorders.6

Esophageal dysphagia refers to difficulty transporting food or liquid down the esophagus and can be caused by structural, inflammatory, or functional disorders.5 Patients typically localize symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, cough, or chest pain along the sternum or epigastric region. Alarm signs concerning for malignancy include unintentional weight loss, fevers, or night sweats.3,7 Aside from symptoms, medication review is essential, as dysphagia is a common side effect of antipsychotics, anticholinergics, antimuscarinics, narcotics, and immunosuppressant drugs.8 Larger pills such as NSAIDs, antibiotics, bisphosphonates, potassium supplements, and methylxanthines can cause drug-induced esophagitis, which can initially present as dysphagia.8 Inflammatory causes can be elucidated by obtaining a history about allergies, tobacco use, and recent infections such as thrush or pneumonia. Patients with a history of recurrent pneumonias may be silently aspirating, a complication of dysphagia.3 Once esophageal dysphagia is clinically suspected based on history, workup can begin.

Differentiating etiologies of esophageal dysphagia

The next step in diagnosing esophageal dysphagia is differentiating between structural, inflammatory, or dysmotility etiology (Figure 1).

Patients with a structural cause typically have difficulty swallowing solids but are able to swallow liquids unless the disease progresses. Symptoms can rapidly worsen and lead to odynophagia, weight loss, and vomiting. In comparison, patients with motility disorders typically have difficulty swallowing both solids and liquids initially, and symptoms can be constant or intermittent.5

Prior to diagnostic studies, a 4-week trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is appropriate for patients with reflux symptoms who are younger than 50 with no alarm features concerning for malignancy.7,9 If symptoms persist after a PPI trial, then an upper endoscopy (EGD) is indicated. An EGD allows for visualization of structural etiologies, obtaining biopsies to rule out inflammatory etiologies, and the option to therapeutically treat reduced luminal diameter with dilatation.10 The most common structural and inflammatory etiologies noted on EGD include strictures, webs, carcinomas, Schatzki rings, and gastroesophageal reflux or eosinophilic esophagitis.4

If upper endoscopy is normal and clinical suspicion for an obstructive cause remains high, barium esophagram can be utilized as an adjunctive study. Previously, barium esophagram was the initial test to distinguish between structural and motility disorders. The benefits of endoscopy over barium esophagram as the first diagnostic study include higher diagnostic yield, higher sensitivity and specificity, and lower costs.7 However, barium studies may be more sensitive for lower esophageal rings or extrinsic esophageal compression.3

Evaluation of esophageal motility disorder

If a structural or inflammatory etiology of dysphagia is not identified, investigation for an esophageal motility disorder (EMD) is warranted. Examples of motility disorders include achalasia, ineffective esophageal motility, hypercontractility, spasticity, or esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO).10,11 High-resolution esophageal manometry (HRM) remains the gold standard in diagnosis of EMD.12 An HRM catheter utilizes 36 sensors placed two centimeters apart and is placed in the esophagus to evaluate pressure and peristalsis between the upper and lower esophageal sphincters.13 In 2009, the Chicago Classification System was developed to provide a diagnostic algorithm that categorizes EMD based on HRM testing, with the most recent version (4.0) being published in 2020.12,14 Motility diagnoses are divided into two general classifications of disorders of body peristalsis and disorders of EGJ outflow. The most recent updates also include changes in swallow protocols, patient positioning, targeted symptoms, addition of impedance sensors, and consideration of supplemental testing when HRM is inconclusive based on the clinical context.12 There are some limitations of HRM to highlight. One of the main diagnostic values used with HRM is the integrated relaxation pressure (IRP). Despite standardization, IRP measurements vary based on the recorder and patient position. A minority of patients with achalasia may have IRP that does not approach the accepted cutoff and, therefore, the EGJ is not accurately assessed on HRM.15,16 In addition, some swallow protocols have lower sensitivity and specificity for certain motility disorders, and the test can result as inconclusive.14 In these scenarios, supplemental testing with timed barium esophagram or functional luminal imaging probe (EndoFLIP) is indicated.10,11

Over the past decade, EndoFLIP has emerged as a novel diagnostic tool in evaluating EMD. EndoFLIP is usually completed during an upper endoscopy and utilizes impedance planimetry to measure cross-sectional area and esophageal distensibility and evaluate contractile patterns.16 During the procedure, a small catheter with an inflatable balloon is inserted into the esophagus with the distal end in the stomach, traversing the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). The pressure transducer has electrodes every centimeter to allow for a three-dimensional construction of the esophagus and EGJ.17 EndoFLIP has been shown to accurately measure pyloric diameter, pressure, and distensibility at certain balloon volumes.18 In addition, FLIP is being used to further identify aspects of esophageal dysmotility in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, thought primarily to be an inflammatory disorder.19 However, limitations include minimal accessibility of EndoFLIP within clinical practice and a specific computer program needed to generate the topographic plots.20

When used in conjunction with HRM, EndoFLIP provides complementary data that can be used to better detect major motility disorders.15,20,21 Each study adds unique information about the different physiologic events comprising the esophageal response to distention. Overall, the benefits of EndoFLIP include expediting workup during index endoscopy, patient comfort with sedation, and real-time diagnostic data that supplement results obtained during HRM.10,16,20,2223

Of note, if the diagnostic evaluation for structural, inflammatory, and motility disorders are unrevealing, investigating for atypical reflux symptoms can be pursued for patients with persistent dysphagia. Studies investigating pH, or acidity in the esophagus, in relation to symptoms, can be conducted wirelessly via a capsule fixed to the mucosa or with a nasal catheter.3

Normal workup – hypervigilance

In a subset of patients, all diagnostic testing for structural, inflammatory, or motility disorders is normal. These patients are classified as having a functional esophageal disorder. Despite normal testing, patients still have significant symptoms including epigastric pain, chest pain, globus sensation, or difficulty swallowing. It is theorized that a degree of visceral hypersensitivity between the brain-gut axis contributes to ongoing symptoms.24 Studies for effective treatments are ongoing but typically include cognitive-behavioral therapy, brain-gut behavioral therapy, swallow therapy antidepressants, or short courses of proton pump inhibitors.9

Conclusion

In this review article, we discussed the diagnostic approach for esophageal dysphagia. Initial assessment requires a thorough history, differentiation between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia, and determination of who warrants an upper endoscopy. Upper endoscopy may reveal structural or inflammatory causes of dysphagia, including strictures, masses, or esophagitis, to name a few. If a structural or inflammatory cause is ruled out, this warrants investigation for esophageal motility disorders. The current gold standard for diagnosing EMD is manometry, and supplemental studies, including EndoFLIP, barium esophagram, and pH studies, may provide complimentary data. If workup for dysphagia is normal, evaluation for esophageal hypervigilance causing increased sensitivity to normal or mild sensations may be warranted. In conclusion, the diagnosis of dysphagia is challenging and requires investigation with a systematic approach to ensure timely diagnosis and treatment

Dr. Ronnie and Dr. Bloomberg are in the department of internal medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill. Dr. Venu is in the division of gastroenterology at Loyola. He is on the speakers bureau at Medtronic.

References

1. Adkins C et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1970-9.e2.

2. Bhattacharyya N. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(5):765-9.

3. McCarty EB and Chao TN. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105(5):939-54.

4. Thiyagalingam S et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(2):488-97.

5. Malagelada JR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(5):370-8.

6. Rommel, N and Hamdy S. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(1):49-59.

7. Liu LWC et al. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2018;1(1):5-19.

8. Schwemmle C et al. HNO. 2015;63(7):504-10.

9. Moayyedi P et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(7):988-1013.

10. Triggs J and Pandolfino J. F1000Res. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18900.1.

11. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14058.

12. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14053.

13. Fox M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(5):533-42.

14. Sweis R and Fox M. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(10):49.

15. Carlson DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1742-51.

16. Donnan EN and Pandolfino JE. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):427-35.

17. Carlson DA. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32(4):310-8.

18. Zheng T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34(10):e14386.

19. Carlson DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(8):1719-28.e3.

20. Carlson DA et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1726-35.

21. Carlson DA et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(10):e14116.

22. Carlson DA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(6):915-923.e1.

23. Fox MR et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(4):e14120.

24. Aziz Q et al. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012.

Introduction

Dysphagia is the sensation of difficulty swallowing food or liquid in the acute or chronic setting. The prevalence of dysphagia ranges based on the type and etiology but may impact up to one in six adults.1,2 Dysphagia can cause a significant impact on a patient’s health and overall quality of life. A recent study found that only 50% of symptomatic adults seek medical care despite modifying their eating habits by either eating slowly or changing to softer foods or liquids.1 The most common, serious complications of dysphagia include aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration.3 According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, dysphagia may be responsible for up to 60,000 deaths annually.3

The diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia can be challenging. An initial, thorough history is essential to delineate between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia and guide subsequent diagnostic testing. In recent years, there have been a number of advances in the approach to diagnosing dysphagia, including novel diagnostic modalities. The goal of this review article is to discuss the current approach to esophageal dysphagia and future direction to allow for timely diagnosis and management.

History

The diagnosis of dysphagia begins with a thorough history. Questions about the timing, onset, progression, localization of symptoms, and types of food that are difficult to swallow are essential in differentiating oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia.3,4 Further history taking must include medication and allergy review, smoking history, and review of prior radiation or surgical therapies to the head and neck.

Briefly, oropharyngeal dysphagia is difficulty initiating a swallow or passing food from the mouth or throat and can be caused by structural or functional etiologies.5 Clinical presentations include a sensation of food stuck in the back of the throat, coughing or choking while eating, or drooling. Structural causes include head and neck cancer, Zenker diverticulum, Killian Jamieson diverticula, prolonged intubation, or changes secondary to prior surgery or radiation.3 Functional causes may include neurologic, rheumatologic, or muscular disorders.6

Esophageal dysphagia refers to difficulty transporting food or liquid down the esophagus and can be caused by structural, inflammatory, or functional disorders.5 Patients typically localize symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, cough, or chest pain along the sternum or epigastric region. Alarm signs concerning for malignancy include unintentional weight loss, fevers, or night sweats.3,7 Aside from symptoms, medication review is essential, as dysphagia is a common side effect of antipsychotics, anticholinergics, antimuscarinics, narcotics, and immunosuppressant drugs.8 Larger pills such as NSAIDs, antibiotics, bisphosphonates, potassium supplements, and methylxanthines can cause drug-induced esophagitis, which can initially present as dysphagia.8 Inflammatory causes can be elucidated by obtaining a history about allergies, tobacco use, and recent infections such as thrush or pneumonia. Patients with a history of recurrent pneumonias may be silently aspirating, a complication of dysphagia.3 Once esophageal dysphagia is clinically suspected based on history, workup can begin.

Differentiating etiologies of esophageal dysphagia

The next step in diagnosing esophageal dysphagia is differentiating between structural, inflammatory, or dysmotility etiology (Figure 1).

Patients with a structural cause typically have difficulty swallowing solids but are able to swallow liquids unless the disease progresses. Symptoms can rapidly worsen and lead to odynophagia, weight loss, and vomiting. In comparison, patients with motility disorders typically have difficulty swallowing both solids and liquids initially, and symptoms can be constant or intermittent.5

Prior to diagnostic studies, a 4-week trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is appropriate for patients with reflux symptoms who are younger than 50 with no alarm features concerning for malignancy.7,9 If symptoms persist after a PPI trial, then an upper endoscopy (EGD) is indicated. An EGD allows for visualization of structural etiologies, obtaining biopsies to rule out inflammatory etiologies, and the option to therapeutically treat reduced luminal diameter with dilatation.10 The most common structural and inflammatory etiologies noted on EGD include strictures, webs, carcinomas, Schatzki rings, and gastroesophageal reflux or eosinophilic esophagitis.4

If upper endoscopy is normal and clinical suspicion for an obstructive cause remains high, barium esophagram can be utilized as an adjunctive study. Previously, barium esophagram was the initial test to distinguish between structural and motility disorders. The benefits of endoscopy over barium esophagram as the first diagnostic study include higher diagnostic yield, higher sensitivity and specificity, and lower costs.7 However, barium studies may be more sensitive for lower esophageal rings or extrinsic esophageal compression.3

Evaluation of esophageal motility disorder

If a structural or inflammatory etiology of dysphagia is not identified, investigation for an esophageal motility disorder (EMD) is warranted. Examples of motility disorders include achalasia, ineffective esophageal motility, hypercontractility, spasticity, or esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO).10,11 High-resolution esophageal manometry (HRM) remains the gold standard in diagnosis of EMD.12 An HRM catheter utilizes 36 sensors placed two centimeters apart and is placed in the esophagus to evaluate pressure and peristalsis between the upper and lower esophageal sphincters.13 In 2009, the Chicago Classification System was developed to provide a diagnostic algorithm that categorizes EMD based on HRM testing, with the most recent version (4.0) being published in 2020.12,14 Motility diagnoses are divided into two general classifications of disorders of body peristalsis and disorders of EGJ outflow. The most recent updates also include changes in swallow protocols, patient positioning, targeted symptoms, addition of impedance sensors, and consideration of supplemental testing when HRM is inconclusive based on the clinical context.12 There are some limitations of HRM to highlight. One of the main diagnostic values used with HRM is the integrated relaxation pressure (IRP). Despite standardization, IRP measurements vary based on the recorder and patient position. A minority of patients with achalasia may have IRP that does not approach the accepted cutoff and, therefore, the EGJ is not accurately assessed on HRM.15,16 In addition, some swallow protocols have lower sensitivity and specificity for certain motility disorders, and the test can result as inconclusive.14 In these scenarios, supplemental testing with timed barium esophagram or functional luminal imaging probe (EndoFLIP) is indicated.10,11

Over the past decade, EndoFLIP has emerged as a novel diagnostic tool in evaluating EMD. EndoFLIP is usually completed during an upper endoscopy and utilizes impedance planimetry to measure cross-sectional area and esophageal distensibility and evaluate contractile patterns.16 During the procedure, a small catheter with an inflatable balloon is inserted into the esophagus with the distal end in the stomach, traversing the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). The pressure transducer has electrodes every centimeter to allow for a three-dimensional construction of the esophagus and EGJ.17 EndoFLIP has been shown to accurately measure pyloric diameter, pressure, and distensibility at certain balloon volumes.18 In addition, FLIP is being used to further identify aspects of esophageal dysmotility in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, thought primarily to be an inflammatory disorder.19 However, limitations include minimal accessibility of EndoFLIP within clinical practice and a specific computer program needed to generate the topographic plots.20

When used in conjunction with HRM, EndoFLIP provides complementary data that can be used to better detect major motility disorders.15,20,21 Each study adds unique information about the different physiologic events comprising the esophageal response to distention. Overall, the benefits of EndoFLIP include expediting workup during index endoscopy, patient comfort with sedation, and real-time diagnostic data that supplement results obtained during HRM.10,16,20,2223

Of note, if the diagnostic evaluation for structural, inflammatory, and motility disorders are unrevealing, investigating for atypical reflux symptoms can be pursued for patients with persistent dysphagia. Studies investigating pH, or acidity in the esophagus, in relation to symptoms, can be conducted wirelessly via a capsule fixed to the mucosa or with a nasal catheter.3

Normal workup – hypervigilance

In a subset of patients, all diagnostic testing for structural, inflammatory, or motility disorders is normal. These patients are classified as having a functional esophageal disorder. Despite normal testing, patients still have significant symptoms including epigastric pain, chest pain, globus sensation, or difficulty swallowing. It is theorized that a degree of visceral hypersensitivity between the brain-gut axis contributes to ongoing symptoms.24 Studies for effective treatments are ongoing but typically include cognitive-behavioral therapy, brain-gut behavioral therapy, swallow therapy antidepressants, or short courses of proton pump inhibitors.9

Conclusion

In this review article, we discussed the diagnostic approach for esophageal dysphagia. Initial assessment requires a thorough history, differentiation between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia, and determination of who warrants an upper endoscopy. Upper endoscopy may reveal structural or inflammatory causes of dysphagia, including strictures, masses, or esophagitis, to name a few. If a structural or inflammatory cause is ruled out, this warrants investigation for esophageal motility disorders. The current gold standard for diagnosing EMD is manometry, and supplemental studies, including EndoFLIP, barium esophagram, and pH studies, may provide complimentary data. If workup for dysphagia is normal, evaluation for esophageal hypervigilance causing increased sensitivity to normal or mild sensations may be warranted. In conclusion, the diagnosis of dysphagia is challenging and requires investigation with a systematic approach to ensure timely diagnosis and treatment

Dr. Ronnie and Dr. Bloomberg are in the department of internal medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill. Dr. Venu is in the division of gastroenterology at Loyola. He is on the speakers bureau at Medtronic.

References

1. Adkins C et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1970-9.e2.

2. Bhattacharyya N. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(5):765-9.

3. McCarty EB and Chao TN. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105(5):939-54.

4. Thiyagalingam S et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(2):488-97.

5. Malagelada JR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(5):370-8.

6. Rommel, N and Hamdy S. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(1):49-59.

7. Liu LWC et al. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2018;1(1):5-19.

8. Schwemmle C et al. HNO. 2015;63(7):504-10.

9. Moayyedi P et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(7):988-1013.

10. Triggs J and Pandolfino J. F1000Res. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18900.1.

11. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14058.

12. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14053.

13. Fox M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(5):533-42.

14. Sweis R and Fox M. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(10):49.

15. Carlson DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1742-51.

16. Donnan EN and Pandolfino JE. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):427-35.

17. Carlson DA. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32(4):310-8.

18. Zheng T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34(10):e14386.

19. Carlson DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(8):1719-28.e3.

20. Carlson DA et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1726-35.

21. Carlson DA et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(10):e14116.

22. Carlson DA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(6):915-923.e1.

23. Fox MR et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(4):e14120.

24. Aziz Q et al. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012.

Introduction

Dysphagia is the sensation of difficulty swallowing food or liquid in the acute or chronic setting. The prevalence of dysphagia ranges based on the type and etiology but may impact up to one in six adults.1,2 Dysphagia can cause a significant impact on a patient’s health and overall quality of life. A recent study found that only 50% of symptomatic adults seek medical care despite modifying their eating habits by either eating slowly or changing to softer foods or liquids.1 The most common, serious complications of dysphagia include aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration.3 According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, dysphagia may be responsible for up to 60,000 deaths annually.3

The diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia can be challenging. An initial, thorough history is essential to delineate between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia and guide subsequent diagnostic testing. In recent years, there have been a number of advances in the approach to diagnosing dysphagia, including novel diagnostic modalities. The goal of this review article is to discuss the current approach to esophageal dysphagia and future direction to allow for timely diagnosis and management.

History

The diagnosis of dysphagia begins with a thorough history. Questions about the timing, onset, progression, localization of symptoms, and types of food that are difficult to swallow are essential in differentiating oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia.3,4 Further history taking must include medication and allergy review, smoking history, and review of prior radiation or surgical therapies to the head and neck.

Briefly, oropharyngeal dysphagia is difficulty initiating a swallow or passing food from the mouth or throat and can be caused by structural or functional etiologies.5 Clinical presentations include a sensation of food stuck in the back of the throat, coughing or choking while eating, or drooling. Structural causes include head and neck cancer, Zenker diverticulum, Killian Jamieson diverticula, prolonged intubation, or changes secondary to prior surgery or radiation.3 Functional causes may include neurologic, rheumatologic, or muscular disorders.6

Esophageal dysphagia refers to difficulty transporting food or liquid down the esophagus and can be caused by structural, inflammatory, or functional disorders.5 Patients typically localize symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, cough, or chest pain along the sternum or epigastric region. Alarm signs concerning for malignancy include unintentional weight loss, fevers, or night sweats.3,7 Aside from symptoms, medication review is essential, as dysphagia is a common side effect of antipsychotics, anticholinergics, antimuscarinics, narcotics, and immunosuppressant drugs.8 Larger pills such as NSAIDs, antibiotics, bisphosphonates, potassium supplements, and methylxanthines can cause drug-induced esophagitis, which can initially present as dysphagia.8 Inflammatory causes can be elucidated by obtaining a history about allergies, tobacco use, and recent infections such as thrush or pneumonia. Patients with a history of recurrent pneumonias may be silently aspirating, a complication of dysphagia.3 Once esophageal dysphagia is clinically suspected based on history, workup can begin.

Differentiating etiologies of esophageal dysphagia

The next step in diagnosing esophageal dysphagia is differentiating between structural, inflammatory, or dysmotility etiology (Figure 1).

Patients with a structural cause typically have difficulty swallowing solids but are able to swallow liquids unless the disease progresses. Symptoms can rapidly worsen and lead to odynophagia, weight loss, and vomiting. In comparison, patients with motility disorders typically have difficulty swallowing both solids and liquids initially, and symptoms can be constant or intermittent.5

Prior to diagnostic studies, a 4-week trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is appropriate for patients with reflux symptoms who are younger than 50 with no alarm features concerning for malignancy.7,9 If symptoms persist after a PPI trial, then an upper endoscopy (EGD) is indicated. An EGD allows for visualization of structural etiologies, obtaining biopsies to rule out inflammatory etiologies, and the option to therapeutically treat reduced luminal diameter with dilatation.10 The most common structural and inflammatory etiologies noted on EGD include strictures, webs, carcinomas, Schatzki rings, and gastroesophageal reflux or eosinophilic esophagitis.4

If upper endoscopy is normal and clinical suspicion for an obstructive cause remains high, barium esophagram can be utilized as an adjunctive study. Previously, barium esophagram was the initial test to distinguish between structural and motility disorders. The benefits of endoscopy over barium esophagram as the first diagnostic study include higher diagnostic yield, higher sensitivity and specificity, and lower costs.7 However, barium studies may be more sensitive for lower esophageal rings or extrinsic esophageal compression.3

Evaluation of esophageal motility disorder

If a structural or inflammatory etiology of dysphagia is not identified, investigation for an esophageal motility disorder (EMD) is warranted. Examples of motility disorders include achalasia, ineffective esophageal motility, hypercontractility, spasticity, or esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO).10,11 High-resolution esophageal manometry (HRM) remains the gold standard in diagnosis of EMD.12 An HRM catheter utilizes 36 sensors placed two centimeters apart and is placed in the esophagus to evaluate pressure and peristalsis between the upper and lower esophageal sphincters.13 In 2009, the Chicago Classification System was developed to provide a diagnostic algorithm that categorizes EMD based on HRM testing, with the most recent version (4.0) being published in 2020.12,14 Motility diagnoses are divided into two general classifications of disorders of body peristalsis and disorders of EGJ outflow. The most recent updates also include changes in swallow protocols, patient positioning, targeted symptoms, addition of impedance sensors, and consideration of supplemental testing when HRM is inconclusive based on the clinical context.12 There are some limitations of HRM to highlight. One of the main diagnostic values used with HRM is the integrated relaxation pressure (IRP). Despite standardization, IRP measurements vary based on the recorder and patient position. A minority of patients with achalasia may have IRP that does not approach the accepted cutoff and, therefore, the EGJ is not accurately assessed on HRM.15,16 In addition, some swallow protocols have lower sensitivity and specificity for certain motility disorders, and the test can result as inconclusive.14 In these scenarios, supplemental testing with timed barium esophagram or functional luminal imaging probe (EndoFLIP) is indicated.10,11

Over the past decade, EndoFLIP has emerged as a novel diagnostic tool in evaluating EMD. EndoFLIP is usually completed during an upper endoscopy and utilizes impedance planimetry to measure cross-sectional area and esophageal distensibility and evaluate contractile patterns.16 During the procedure, a small catheter with an inflatable balloon is inserted into the esophagus with the distal end in the stomach, traversing the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). The pressure transducer has electrodes every centimeter to allow for a three-dimensional construction of the esophagus and EGJ.17 EndoFLIP has been shown to accurately measure pyloric diameter, pressure, and distensibility at certain balloon volumes.18 In addition, FLIP is being used to further identify aspects of esophageal dysmotility in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, thought primarily to be an inflammatory disorder.19 However, limitations include minimal accessibility of EndoFLIP within clinical practice and a specific computer program needed to generate the topographic plots.20

When used in conjunction with HRM, EndoFLIP provides complementary data that can be used to better detect major motility disorders.15,20,21 Each study adds unique information about the different physiologic events comprising the esophageal response to distention. Overall, the benefits of EndoFLIP include expediting workup during index endoscopy, patient comfort with sedation, and real-time diagnostic data that supplement results obtained during HRM.10,16,20,2223

Of note, if the diagnostic evaluation for structural, inflammatory, and motility disorders are unrevealing, investigating for atypical reflux symptoms can be pursued for patients with persistent dysphagia. Studies investigating pH, or acidity in the esophagus, in relation to symptoms, can be conducted wirelessly via a capsule fixed to the mucosa or with a nasal catheter.3

Normal workup – hypervigilance

In a subset of patients, all diagnostic testing for structural, inflammatory, or motility disorders is normal. These patients are classified as having a functional esophageal disorder. Despite normal testing, patients still have significant symptoms including epigastric pain, chest pain, globus sensation, or difficulty swallowing. It is theorized that a degree of visceral hypersensitivity between the brain-gut axis contributes to ongoing symptoms.24 Studies for effective treatments are ongoing but typically include cognitive-behavioral therapy, brain-gut behavioral therapy, swallow therapy antidepressants, or short courses of proton pump inhibitors.9

Conclusion

In this review article, we discussed the diagnostic approach for esophageal dysphagia. Initial assessment requires a thorough history, differentiation between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia, and determination of who warrants an upper endoscopy. Upper endoscopy may reveal structural or inflammatory causes of dysphagia, including strictures, masses, or esophagitis, to name a few. If a structural or inflammatory cause is ruled out, this warrants investigation for esophageal motility disorders. The current gold standard for diagnosing EMD is manometry, and supplemental studies, including EndoFLIP, barium esophagram, and pH studies, may provide complimentary data. If workup for dysphagia is normal, evaluation for esophageal hypervigilance causing increased sensitivity to normal or mild sensations may be warranted. In conclusion, the diagnosis of dysphagia is challenging and requires investigation with a systematic approach to ensure timely diagnosis and treatment

Dr. Ronnie and Dr. Bloomberg are in the department of internal medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill. Dr. Venu is in the division of gastroenterology at Loyola. He is on the speakers bureau at Medtronic.

References

1. Adkins C et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1970-9.e2.

2. Bhattacharyya N. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(5):765-9.

3. McCarty EB and Chao TN. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105(5):939-54.

4. Thiyagalingam S et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(2):488-97.

5. Malagelada JR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(5):370-8.

6. Rommel, N and Hamdy S. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(1):49-59.

7. Liu LWC et al. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2018;1(1):5-19.

8. Schwemmle C et al. HNO. 2015;63(7):504-10.

9. Moayyedi P et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(7):988-1013.

10. Triggs J and Pandolfino J. F1000Res. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18900.1.

11. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14058.

12. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14053.

13. Fox M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(5):533-42.

14. Sweis R and Fox M. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(10):49.

15. Carlson DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1742-51.

16. Donnan EN and Pandolfino JE. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):427-35.

17. Carlson DA. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32(4):310-8.

18. Zheng T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34(10):e14386.

19. Carlson DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(8):1719-28.e3.

20. Carlson DA et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1726-35.

21. Carlson DA et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(10):e14116.

22. Carlson DA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(6):915-923.e1.

23. Fox MR et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(4):e14120.

24. Aziz Q et al. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012.

Spring reflections

Dear friends,

I celebrate my achievements (both personal and work related), try not to be too hard on myself with unaccomplished tasks, and plan goals for the upcoming year. Most importantly, it’s a time to be grateful for both opportunities and challenges. Thank you for your engagement with The New Gastroenterologist, and as you go through this issue, I hope you can find time for some spring reflections as well!

In this issue’s In Focus, Dr. Tanisha Ronnie, Dr. Lauren Bloomberg, and Dr. Mukund Venu break down the approach to a patient with dysphagia, a common and difficult encounter in GI practice. They emphasize the importance of a good clinical history as well as understanding the role of diagnostic testing. In our Short Clinical Review section, Dr. Noa Krugliak Cleveland and Dr. David Rubin review the rising role of intestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease, how to be trained, and how to incorporate it in clinical practice.

As early-career gastroenterologists, Dr. Samad Soudagar and Dr. Mohammad Bilal were tasked with establishing an advanced endoscopy practice, which may be overwhelming for many. They synthesized their experiences into 10 practical tips to build a successful practice. Our Post-fellowship Pathways article highlights Dr. Katie Hutchins’s journey from private practice to academic medicine; she provides insights into the life-changing decision and what she learned about herself to make that pivot.

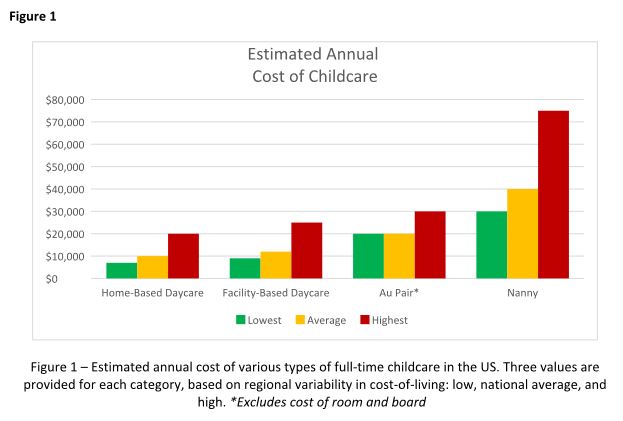

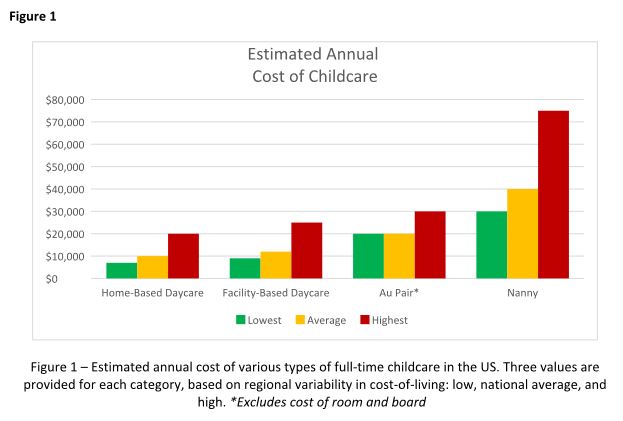

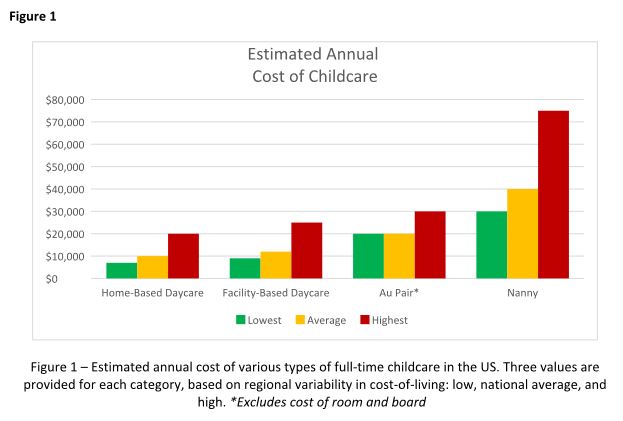

In our Finance section, Dr. Kelly Hathorn and Dr. David Creighton reflect on navigating as new parents while both working full time in medicine; their article weighs the pros and cons of various childcare options in the post–COVID pandemic world.

In an additional contribution this issue, gastroenterology and hepatology fellowship program leaders at the University of Florida, Gainesville, describe their experience with virtual recruitment, including feedback from their candidates, especially as we enter another cycle of GI Match.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact, because we would not be where we are without appreciating where we were: The first formalized gastroenterology fellowship curriculum was a joint publication by four major GI and hepatology societies in 1996 – just 27 years ago!

Yours truly,

Judy A Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Advanced Endoscopy Fellow

Division of gastroenterology & hepatology

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Dear friends,

I celebrate my achievements (both personal and work related), try not to be too hard on myself with unaccomplished tasks, and plan goals for the upcoming year. Most importantly, it’s a time to be grateful for both opportunities and challenges. Thank you for your engagement with The New Gastroenterologist, and as you go through this issue, I hope you can find time for some spring reflections as well!

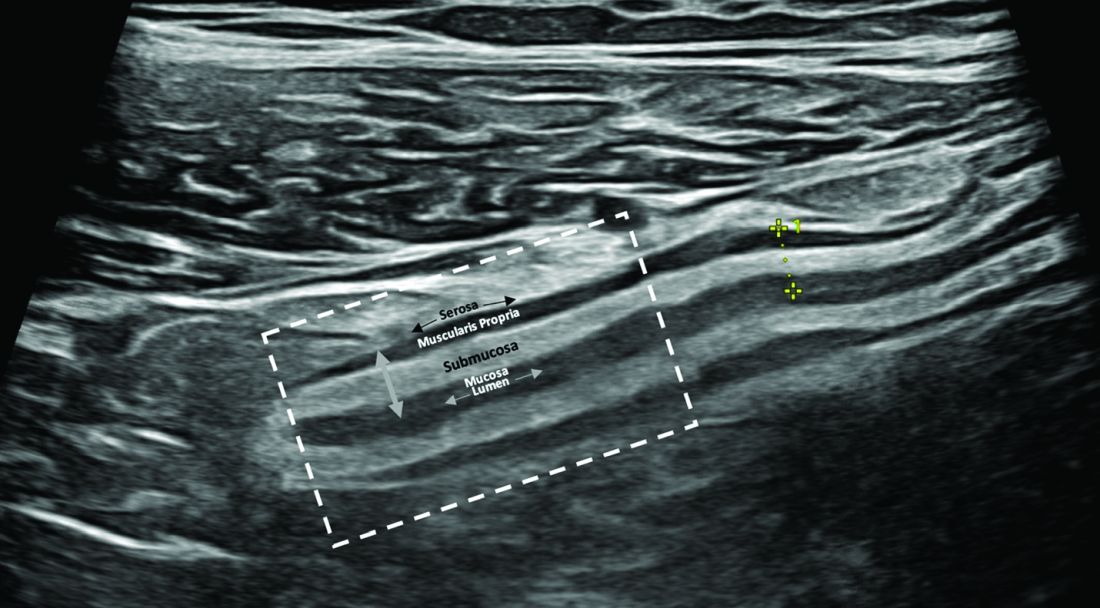

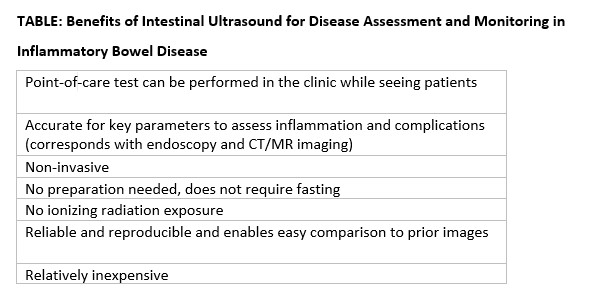

In this issue’s In Focus, Dr. Tanisha Ronnie, Dr. Lauren Bloomberg, and Dr. Mukund Venu break down the approach to a patient with dysphagia, a common and difficult encounter in GI practice. They emphasize the importance of a good clinical history as well as understanding the role of diagnostic testing. In our Short Clinical Review section, Dr. Noa Krugliak Cleveland and Dr. David Rubin review the rising role of intestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease, how to be trained, and how to incorporate it in clinical practice.

As early-career gastroenterologists, Dr. Samad Soudagar and Dr. Mohammad Bilal were tasked with establishing an advanced endoscopy practice, which may be overwhelming for many. They synthesized their experiences into 10 practical tips to build a successful practice. Our Post-fellowship Pathways article highlights Dr. Katie Hutchins’s journey from private practice to academic medicine; she provides insights into the life-changing decision and what she learned about herself to make that pivot.

In our Finance section, Dr. Kelly Hathorn and Dr. David Creighton reflect on navigating as new parents while both working full time in medicine; their article weighs the pros and cons of various childcare options in the post–COVID pandemic world.

In an additional contribution this issue, gastroenterology and hepatology fellowship program leaders at the University of Florida, Gainesville, describe their experience with virtual recruitment, including feedback from their candidates, especially as we enter another cycle of GI Match.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact, because we would not be where we are without appreciating where we were: The first formalized gastroenterology fellowship curriculum was a joint publication by four major GI and hepatology societies in 1996 – just 27 years ago!

Yours truly,

Judy A Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Advanced Endoscopy Fellow

Division of gastroenterology & hepatology

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Dear friends,

I celebrate my achievements (both personal and work related), try not to be too hard on myself with unaccomplished tasks, and plan goals for the upcoming year. Most importantly, it’s a time to be grateful for both opportunities and challenges. Thank you for your engagement with The New Gastroenterologist, and as you go through this issue, I hope you can find time for some spring reflections as well!

In this issue’s In Focus, Dr. Tanisha Ronnie, Dr. Lauren Bloomberg, and Dr. Mukund Venu break down the approach to a patient with dysphagia, a common and difficult encounter in GI practice. They emphasize the importance of a good clinical history as well as understanding the role of diagnostic testing. In our Short Clinical Review section, Dr. Noa Krugliak Cleveland and Dr. David Rubin review the rising role of intestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease, how to be trained, and how to incorporate it in clinical practice.

As early-career gastroenterologists, Dr. Samad Soudagar and Dr. Mohammad Bilal were tasked with establishing an advanced endoscopy practice, which may be overwhelming for many. They synthesized their experiences into 10 practical tips to build a successful practice. Our Post-fellowship Pathways article highlights Dr. Katie Hutchins’s journey from private practice to academic medicine; she provides insights into the life-changing decision and what she learned about herself to make that pivot.

In our Finance section, Dr. Kelly Hathorn and Dr. David Creighton reflect on navigating as new parents while both working full time in medicine; their article weighs the pros and cons of various childcare options in the post–COVID pandemic world.

In an additional contribution this issue, gastroenterology and hepatology fellowship program leaders at the University of Florida, Gainesville, describe their experience with virtual recruitment, including feedback from their candidates, especially as we enter another cycle of GI Match.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact, because we would not be where we are without appreciating where we were: The first formalized gastroenterology fellowship curriculum was a joint publication by four major GI and hepatology societies in 1996 – just 27 years ago!

Yours truly,

Judy A Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Advanced Endoscopy Fellow

Division of gastroenterology & hepatology

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Why my independent GI practice started a GI fellowship program

In this video Naresh Gunaratnam, MD, discusses the gastroenterology fellowship program that Huron Gastroenterology developed with Trinity Health in Ann Arbor, Mich. Dr. Gunaratnam helped create the program because he and his colleagues felt that traditional fellowship programs don’t always provide information or guidance about non-academic career pathways in gastroenterology. Hear from Dr. Gunaratnam how the fellowship program at Huron Gastroenterology is training fellows to become excellent clinicians who care for patients in the community setting. He has no financial conflicts relative to the topics in this video.

In this video Naresh Gunaratnam, MD, discusses the gastroenterology fellowship program that Huron Gastroenterology developed with Trinity Health in Ann Arbor, Mich. Dr. Gunaratnam helped create the program because he and his colleagues felt that traditional fellowship programs don’t always provide information or guidance about non-academic career pathways in gastroenterology. Hear from Dr. Gunaratnam how the fellowship program at Huron Gastroenterology is training fellows to become excellent clinicians who care for patients in the community setting. He has no financial conflicts relative to the topics in this video.

In this video Naresh Gunaratnam, MD, discusses the gastroenterology fellowship program that Huron Gastroenterology developed with Trinity Health in Ann Arbor, Mich. Dr. Gunaratnam helped create the program because he and his colleagues felt that traditional fellowship programs don’t always provide information or guidance about non-academic career pathways in gastroenterology. Hear from Dr. Gunaratnam how the fellowship program at Huron Gastroenterology is training fellows to become excellent clinicians who care for patients in the community setting. He has no financial conflicts relative to the topics in this video.

AGA News – May 2023

Season 2 of Small Talk, Big Topics is here!

AGA’s podcast for trainees and early career GIs, Small Talk, Big Topics, is back for season two. To kick off the new season, hosts Drs. Matthew Whitson, Nina Nandy, and CS Tse sit down with AGA President Dr. John Carethers in a two-part special to chat about his career and how his involvement with AGA has impacted him.

In episode one, Drs. Whitson, Nandy and Tse take a deep dive with Dr. Carethers to reflect on how he first got involved with AGA, his experience with different committees, and how those roles paved the way to leadership positions.

Now, as president, he says, “I am having so much fun. AGA has been with me for my entire GI career. It’s really the voice of the science and practice of gastroenterology.”

In episode two, Dr. Carethers examines the career advice he’s received, how it shaped his leadership style and provides guidance to early career GIs.

“What’s important about some of these higher-level [decisions] is to set a vision. You can’t be a leader if you have no followers, and people have to believe in something, that they’re moving toward something.”

Listen to more of Dr. Carethers’ insight in the first two episodes of Small Talk, Big Topics wherever you listen to podcasts and subscribe to stay up to date on new episodes.

Maximize your first day at DDW® 2023

Held during the first day of Digestive Disease Week®, this year’s AGA Postgraduate Course will be held live on Saturday, May 6, from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. CT. This year’s theme – Advances in Gastroenterology: News You Can Use – will help you cut through the noise surrounding best practices for GI physicians.

Pricing is the same for both in-person and virtual attendees, giving you the flexibility to experience the course in-person or from the comfort of your home. All registrants will have on-demand access to the course for three months and the opportunity to earn up to 17.5 total credits when you complete all on-demand content.

What’s new this year?

General session format

Presentations will be given in an engaging format that will feel less didactic and more akin to a discussion among faculty, or a conversation with the experts! It’s also an exciting opportunity to mix junior and senior lecturers on the same platform.

Recent clinical practices

Session panelists will work together to select the key papers in their topic areas for discussion. Only the newest — within one year — and most important papers, clinical guidelines and pathways in the field will be selected.

Register to attend DDW and the Postgraduate Course today.

And the winner of this year’s Shark Tank is …

The 13th annual AGA Tech Summit took place in San Francisco, Calif., recently, bringing together GI entrepreneurs, clinicians, medical technology companies, venture capitalists, and regulatory agencies working to improve patient care in the field. A highlight of the event is the annual Shark Tank competition, where forward-thinking companies showcase and pitch their innovations to a panel of expert judges.

Congratulations to this year’s winner – Endiatx!

From devices providing rapid cancer detection to technology that makes endoscopy safer, the five companies selected for the 2023 AGA Shark Tank represented a glimpse of the future of GI patient care.

While each team offered a creative solution to modern-day GI challenges, only one could be declared the winner. Congratulations to our 2023 winner, Endiatx! Endiatx will represent AGA in the upcoming Shark Tank competition at DDW®.

Endiatx has developed a vitamin-sized intrabody robot

PillBot is a miniature robotic capsule endoscopy. Shipped to a patient’s home or picked up from a pharmacy, the standard size capsule is swallowed and then controlled by an external joystick-like device or a phone app by a physician in a physically separate location. Using real-time video transmissions visible to both operator and patient, the capsule navigates the entire stomach in a few minutes without anesthesia and ultimately is excreted outside the body without the need for recapture.

Future GI physician innovators

This year the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology (CGIT) welcomed 22 first-year to advanced endoscopy fellows to the AGA Innovation Fellows Program. The program provides a unique opportunity for the fellows to learn from GI clinicians, innovators, entrepreneurs, and medical technology executives on how new technologies are developed and brought to market.

The fellows received an exclusive behind-the-scenes tour of Medtronic’s R&D facility in Santa Clara, Calif., and got to experience hands-on demonstrations of GI GeniusTM, PillCamTM, EndoflipTM, NexpowderTM, BravoTM, BarrxTM and ProdiGITM technologies. The group was also hosted by Boston Scientific Corporation, Castle Biosciences and PENTAX Medical at a dinner that included an innovators panel discussion. The program will continue throughout the year with monthly educational sessions moderated by members of the AGA CGIT committee.

- Mohd Amer Alsamman, MD, Georgetown University

- Mohammad Arfeen, MD, Franciscan Health Olympia Fields

- Alexis Bayudan, MD, University of California, San Francisco

- Aileen Bui, MD, University of Southern California

- Divya Chalikonda, MD, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital

- Alec Faggen, MD, University of California, San Francisco

- Sweta Ghosh, PhD, University of Louisville School of Medicine

- Hemant Goyal, MD, University of Texas Houston

- Averill Guo, MD, Brown University

- Omar Jamil, MD, University of Chicago

- Christina Kratschmer, MD, Washington University in St. Louis

- Thi Khuc, MD, University of Maryland School of Medicine

- Anand Kumar, MD, Northwell Health – Lenox Hill Hospital

- Xing Li, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital

- Alana Persaud, MD, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Itegbemie Obaitan, MD, Indiana University School of Medicine

- Chethan Ramprasad, MD, University of Pennsylvania

- Abhishek Satishchandran, MD, University of Michigan

- Kevin Shah, MD, Emory University School of Medicine

- Shifa Umar, MD, University of Chicago

- Kornpong Vantanasiri, MD, Mayo Clinic Rochester

- Shaleen Vasavada, MD, Baylor College of Medicine

Highlights from social media

See what else attendees shared with #AGATech on Twitter.

The 2023 AGA Tech Summit was made possible by support from Castle Biosciences and Medtronic (Diamond Sponsors), AI Medical Services, Boston Scientific, Exact Sciences Corporation, FUJIFILM Medical Systems and Olympus Corporation (Gold Sponsors), Cook Medical Inc., and STERIS Endoscopy (Silver Sponsors), and Apollo Endosurgery and EvoEndo (Bronze Sponsors).

AGA takes CRC month to Capitol Hill

Participating in Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month in Washington, D.C., means one thing – taking the fight to save lives from CRC to Capitol Hill and advocating for increased access to screening and research to improve outcomes.

In March, AGA joined the national advocacy organization Fight Colorectal Cancer (Fight CRC) and partners in the colorectal cancer community for events in our nation’s capital. The goal was to destigmatize talking about gut health and CRC and to collaboratively develop solutions that will improve and increase access to CRC screening.

Fight CRC working lunch

Former AGA president Dr. David Lieberman and fellow AGA member and FORWARD graduate Dr. Fola May served as facilitators for the coalition of public and private leaders assembled by Fight CRC. The group is working to develop an action plan to further equitable CRC screening and lower the number of lives impacted by CRC. Among the participants were insurers, industry, federal agencies, healthcare providers, retail businesses, and patients.

White House Cancer Moonshot colorectal cancer forum

In partnership with President Biden’s reignited Cancer Moonshot initiative, we joined Fight CRC and other advocacy and industry leaders in the colorectal cancer community for the Cancer Moonshot Colorectal Cancer Forum, hosted by the White House.

Dr. May participated as a panelist during the forum and discussed how we should address disparities in CRC. “Research dollars are essential in [combating CRC inequity]. We do not know how to effectively deliver care and preventive services to these populations unless we do deep dives into these particular settings to understand how to best deliver that care. This is not a “pick a model and apply broadly” approach. We need to go to the people, and we need to go to the people with the methods that work for that particular setting, and that’s going to be different in every community.”

In addition to Dr. Lieberman, who attended on behalf of AGA, fellow AGA members Drs. Austin Chiang, Swati Patel and AGA FORWARD Scholar Rachel Issaka were in attendance. We are appreciative of the opportunity to be included in these important discussions with the Administration and partners in the CRC community as we work together to reduce the burden of CRC and save lives.

Fight CRC United in Blue rally on the National Mall

It’s become an annual tradition for us to join Fight CRC’s United in Blue rally and blue flag installation on the National Mall, and this year was no different. We joined industry and patient advocacy groups in the CRC community to raise our voices about the need for screening, research, and advocacy to improve colon cancer outcomes.

The rally included inspiring calls to action and CRC testimonials from individuals who have been personally impacted by the disease, including Rep. Donald Payne Jr. (D-NJ), who lost his father to CRC and who personally underwent screening, which led to the discovery of 13 polyps.

Dr. Manish Singla from Capital Digestive Care spoke on behalf of AGA and provided encouragement and a reminder for patients and providers.

“What I keep hearing here is patients feel like they’re not being heard – so we’re listening. We’re trying and we’re here to fight the disease with you all. Everyone here knows somebody who is due for a colonoscopy and isn’t getting it, so use your persuasion – talk about it, convince, cajole, shame – use whatever you need so that everyone gets the screenings they need,” Dr. Singla said.

Our work is just beginning: Let’s work together to encourage screenings for colorectal cancer and save lives. Join us as we remind everyone that 45 is the new 50.

Season 2 of Small Talk, Big Topics is here!

AGA’s podcast for trainees and early career GIs, Small Talk, Big Topics, is back for season two. To kick off the new season, hosts Drs. Matthew Whitson, Nina Nandy, and CS Tse sit down with AGA President Dr. John Carethers in a two-part special to chat about his career and how his involvement with AGA has impacted him.

In episode one, Drs. Whitson, Nandy and Tse take a deep dive with Dr. Carethers to reflect on how he first got involved with AGA, his experience with different committees, and how those roles paved the way to leadership positions.

Now, as president, he says, “I am having so much fun. AGA has been with me for my entire GI career. It’s really the voice of the science and practice of gastroenterology.”

In episode two, Dr. Carethers examines the career advice he’s received, how it shaped his leadership style and provides guidance to early career GIs.

“What’s important about some of these higher-level [decisions] is to set a vision. You can’t be a leader if you have no followers, and people have to believe in something, that they’re moving toward something.”

Listen to more of Dr. Carethers’ insight in the first two episodes of Small Talk, Big Topics wherever you listen to podcasts and subscribe to stay up to date on new episodes.

Maximize your first day at DDW® 2023

Held during the first day of Digestive Disease Week®, this year’s AGA Postgraduate Course will be held live on Saturday, May 6, from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. CT. This year’s theme – Advances in Gastroenterology: News You Can Use – will help you cut through the noise surrounding best practices for GI physicians.

Pricing is the same for both in-person and virtual attendees, giving you the flexibility to experience the course in-person or from the comfort of your home. All registrants will have on-demand access to the course for three months and the opportunity to earn up to 17.5 total credits when you complete all on-demand content.

What’s new this year?

General session format

Presentations will be given in an engaging format that will feel less didactic and more akin to a discussion among faculty, or a conversation with the experts! It’s also an exciting opportunity to mix junior and senior lecturers on the same platform.

Recent clinical practices

Session panelists will work together to select the key papers in their topic areas for discussion. Only the newest — within one year — and most important papers, clinical guidelines and pathways in the field will be selected.

Register to attend DDW and the Postgraduate Course today.

And the winner of this year’s Shark Tank is …

The 13th annual AGA Tech Summit took place in San Francisco, Calif., recently, bringing together GI entrepreneurs, clinicians, medical technology companies, venture capitalists, and regulatory agencies working to improve patient care in the field. A highlight of the event is the annual Shark Tank competition, where forward-thinking companies showcase and pitch their innovations to a panel of expert judges.

Congratulations to this year’s winner – Endiatx!

From devices providing rapid cancer detection to technology that makes endoscopy safer, the five companies selected for the 2023 AGA Shark Tank represented a glimpse of the future of GI patient care.

While each team offered a creative solution to modern-day GI challenges, only one could be declared the winner. Congratulations to our 2023 winner, Endiatx! Endiatx will represent AGA in the upcoming Shark Tank competition at DDW®.

Endiatx has developed a vitamin-sized intrabody robot

PillBot is a miniature robotic capsule endoscopy. Shipped to a patient’s home or picked up from a pharmacy, the standard size capsule is swallowed and then controlled by an external joystick-like device or a phone app by a physician in a physically separate location. Using real-time video transmissions visible to both operator and patient, the capsule navigates the entire stomach in a few minutes without anesthesia and ultimately is excreted outside the body without the need for recapture.

Future GI physician innovators

This year the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology (CGIT) welcomed 22 first-year to advanced endoscopy fellows to the AGA Innovation Fellows Program. The program provides a unique opportunity for the fellows to learn from GI clinicians, innovators, entrepreneurs, and medical technology executives on how new technologies are developed and brought to market.

The fellows received an exclusive behind-the-scenes tour of Medtronic’s R&D facility in Santa Clara, Calif., and got to experience hands-on demonstrations of GI GeniusTM, PillCamTM, EndoflipTM, NexpowderTM, BravoTM, BarrxTM and ProdiGITM technologies. The group was also hosted by Boston Scientific Corporation, Castle Biosciences and PENTAX Medical at a dinner that included an innovators panel discussion. The program will continue throughout the year with monthly educational sessions moderated by members of the AGA CGIT committee.

- Mohd Amer Alsamman, MD, Georgetown University

- Mohammad Arfeen, MD, Franciscan Health Olympia Fields

- Alexis Bayudan, MD, University of California, San Francisco

- Aileen Bui, MD, University of Southern California

- Divya Chalikonda, MD, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital

- Alec Faggen, MD, University of California, San Francisco

- Sweta Ghosh, PhD, University of Louisville School of Medicine

- Hemant Goyal, MD, University of Texas Houston

- Averill Guo, MD, Brown University

- Omar Jamil, MD, University of Chicago

- Christina Kratschmer, MD, Washington University in St. Louis

- Thi Khuc, MD, University of Maryland School of Medicine

- Anand Kumar, MD, Northwell Health – Lenox Hill Hospital

- Xing Li, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital

- Alana Persaud, MD, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Itegbemie Obaitan, MD, Indiana University School of Medicine

- Chethan Ramprasad, MD, University of Pennsylvania

- Abhishek Satishchandran, MD, University of Michigan

- Kevin Shah, MD, Emory University School of Medicine

- Shifa Umar, MD, University of Chicago

- Kornpong Vantanasiri, MD, Mayo Clinic Rochester

- Shaleen Vasavada, MD, Baylor College of Medicine

Highlights from social media

See what else attendees shared with #AGATech on Twitter.

The 2023 AGA Tech Summit was made possible by support from Castle Biosciences and Medtronic (Diamond Sponsors), AI Medical Services, Boston Scientific, Exact Sciences Corporation, FUJIFILM Medical Systems and Olympus Corporation (Gold Sponsors), Cook Medical Inc., and STERIS Endoscopy (Silver Sponsors), and Apollo Endosurgery and EvoEndo (Bronze Sponsors).

AGA takes CRC month to Capitol Hill

Participating in Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month in Washington, D.C., means one thing – taking the fight to save lives from CRC to Capitol Hill and advocating for increased access to screening and research to improve outcomes.

In March, AGA joined the national advocacy organization Fight Colorectal Cancer (Fight CRC) and partners in the colorectal cancer community for events in our nation’s capital. The goal was to destigmatize talking about gut health and CRC and to collaboratively develop solutions that will improve and increase access to CRC screening.

Fight CRC working lunch

Former AGA president Dr. David Lieberman and fellow AGA member and FORWARD graduate Dr. Fola May served as facilitators for the coalition of public and private leaders assembled by Fight CRC. The group is working to develop an action plan to further equitable CRC screening and lower the number of lives impacted by CRC. Among the participants were insurers, industry, federal agencies, healthcare providers, retail businesses, and patients.

White House Cancer Moonshot colorectal cancer forum

In partnership with President Biden’s reignited Cancer Moonshot initiative, we joined Fight CRC and other advocacy and industry leaders in the colorectal cancer community for the Cancer Moonshot Colorectal Cancer Forum, hosted by the White House.

Dr. May participated as a panelist during the forum and discussed how we should address disparities in CRC. “Research dollars are essential in [combating CRC inequity]. We do not know how to effectively deliver care and preventive services to these populations unless we do deep dives into these particular settings to understand how to best deliver that care. This is not a “pick a model and apply broadly” approach. We need to go to the people, and we need to go to the people with the methods that work for that particular setting, and that’s going to be different in every community.”

In addition to Dr. Lieberman, who attended on behalf of AGA, fellow AGA members Drs. Austin Chiang, Swati Patel and AGA FORWARD Scholar Rachel Issaka were in attendance. We are appreciative of the opportunity to be included in these important discussions with the Administration and partners in the CRC community as we work together to reduce the burden of CRC and save lives.

Fight CRC United in Blue rally on the National Mall

It’s become an annual tradition for us to join Fight CRC’s United in Blue rally and blue flag installation on the National Mall, and this year was no different. We joined industry and patient advocacy groups in the CRC community to raise our voices about the need for screening, research, and advocacy to improve colon cancer outcomes.

The rally included inspiring calls to action and CRC testimonials from individuals who have been personally impacted by the disease, including Rep. Donald Payne Jr. (D-NJ), who lost his father to CRC and who personally underwent screening, which led to the discovery of 13 polyps.

Dr. Manish Singla from Capital Digestive Care spoke on behalf of AGA and provided encouragement and a reminder for patients and providers.

“What I keep hearing here is patients feel like they’re not being heard – so we’re listening. We’re trying and we’re here to fight the disease with you all. Everyone here knows somebody who is due for a colonoscopy and isn’t getting it, so use your persuasion – talk about it, convince, cajole, shame – use whatever you need so that everyone gets the screenings they need,” Dr. Singla said.

Our work is just beginning: Let’s work together to encourage screenings for colorectal cancer and save lives. Join us as we remind everyone that 45 is the new 50.

Season 2 of Small Talk, Big Topics is here!

AGA’s podcast for trainees and early career GIs, Small Talk, Big Topics, is back for season two. To kick off the new season, hosts Drs. Matthew Whitson, Nina Nandy, and CS Tse sit down with AGA President Dr. John Carethers in a two-part special to chat about his career and how his involvement with AGA has impacted him.

In episode one, Drs. Whitson, Nandy and Tse take a deep dive with Dr. Carethers to reflect on how he first got involved with AGA, his experience with different committees, and how those roles paved the way to leadership positions.

Now, as president, he says, “I am having so much fun. AGA has been with me for my entire GI career. It’s really the voice of the science and practice of gastroenterology.”

In episode two, Dr. Carethers examines the career advice he’s received, how it shaped his leadership style and provides guidance to early career GIs.

“What’s important about some of these higher-level [decisions] is to set a vision. You can’t be a leader if you have no followers, and people have to believe in something, that they’re moving toward something.”

Listen to more of Dr. Carethers’ insight in the first two episodes of Small Talk, Big Topics wherever you listen to podcasts and subscribe to stay up to date on new episodes.

Maximize your first day at DDW® 2023

Held during the first day of Digestive Disease Week®, this year’s AGA Postgraduate Course will be held live on Saturday, May 6, from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. CT. This year’s theme – Advances in Gastroenterology: News You Can Use – will help you cut through the noise surrounding best practices for GI physicians.

Pricing is the same for both in-person and virtual attendees, giving you the flexibility to experience the course in-person or from the comfort of your home. All registrants will have on-demand access to the course for three months and the opportunity to earn up to 17.5 total credits when you complete all on-demand content.

What’s new this year?

General session format

Presentations will be given in an engaging format that will feel less didactic and more akin to a discussion among faculty, or a conversation with the experts! It’s also an exciting opportunity to mix junior and senior lecturers on the same platform.

Recent clinical practices

Session panelists will work together to select the key papers in their topic areas for discussion. Only the newest — within one year — and most important papers, clinical guidelines and pathways in the field will be selected.

Register to attend DDW and the Postgraduate Course today.

And the winner of this year’s Shark Tank is …

The 13th annual AGA Tech Summit took place in San Francisco, Calif., recently, bringing together GI entrepreneurs, clinicians, medical technology companies, venture capitalists, and regulatory agencies working to improve patient care in the field. A highlight of the event is the annual Shark Tank competition, where forward-thinking companies showcase and pitch their innovations to a panel of expert judges.

Congratulations to this year’s winner – Endiatx!

From devices providing rapid cancer detection to technology that makes endoscopy safer, the five companies selected for the 2023 AGA Shark Tank represented a glimpse of the future of GI patient care.

While each team offered a creative solution to modern-day GI challenges, only one could be declared the winner. Congratulations to our 2023 winner, Endiatx! Endiatx will represent AGA in the upcoming Shark Tank competition at DDW®.

Endiatx has developed a vitamin-sized intrabody robot

PillBot is a miniature robotic capsule endoscopy. Shipped to a patient’s home or picked up from a pharmacy, the standard size capsule is swallowed and then controlled by an external joystick-like device or a phone app by a physician in a physically separate location. Using real-time video transmissions visible to both operator and patient, the capsule navigates the entire stomach in a few minutes without anesthesia and ultimately is excreted outside the body without the need for recapture.

Future GI physician innovators

This year the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology (CGIT) welcomed 22 first-year to advanced endoscopy fellows to the AGA Innovation Fellows Program. The program provides a unique opportunity for the fellows to learn from GI clinicians, innovators, entrepreneurs, and medical technology executives on how new technologies are developed and brought to market.

The fellows received an exclusive behind-the-scenes tour of Medtronic’s R&D facility in Santa Clara, Calif., and got to experience hands-on demonstrations of GI GeniusTM, PillCamTM, EndoflipTM, NexpowderTM, BravoTM, BarrxTM and ProdiGITM technologies. The group was also hosted by Boston Scientific Corporation, Castle Biosciences and PENTAX Medical at a dinner that included an innovators panel discussion. The program will continue throughout the year with monthly educational sessions moderated by members of the AGA CGIT committee.

- Mohd Amer Alsamman, MD, Georgetown University

- Mohammad Arfeen, MD, Franciscan Health Olympia Fields

- Alexis Bayudan, MD, University of California, San Francisco

- Aileen Bui, MD, University of Southern California

- Divya Chalikonda, MD, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital

- Alec Faggen, MD, University of California, San Francisco

- Sweta Ghosh, PhD, University of Louisville School of Medicine

- Hemant Goyal, MD, University of Texas Houston

- Averill Guo, MD, Brown University

- Omar Jamil, MD, University of Chicago

- Christina Kratschmer, MD, Washington University in St. Louis

- Thi Khuc, MD, University of Maryland School of Medicine

- Anand Kumar, MD, Northwell Health – Lenox Hill Hospital

- Xing Li, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital

- Alana Persaud, MD, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Itegbemie Obaitan, MD, Indiana University School of Medicine

- Chethan Ramprasad, MD, University of Pennsylvania

- Abhishek Satishchandran, MD, University of Michigan

- Kevin Shah, MD, Emory University School of Medicine

- Shifa Umar, MD, University of Chicago

- Kornpong Vantanasiri, MD, Mayo Clinic Rochester

- Shaleen Vasavada, MD, Baylor College of Medicine

Highlights from social media

See what else attendees shared with #AGATech on Twitter.

The 2023 AGA Tech Summit was made possible by support from Castle Biosciences and Medtronic (Diamond Sponsors), AI Medical Services, Boston Scientific, Exact Sciences Corporation, FUJIFILM Medical Systems and Olympus Corporation (Gold Sponsors), Cook Medical Inc., and STERIS Endoscopy (Silver Sponsors), and Apollo Endosurgery and EvoEndo (Bronze Sponsors).

AGA takes CRC month to Capitol Hill

Participating in Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month in Washington, D.C., means one thing – taking the fight to save lives from CRC to Capitol Hill and advocating for increased access to screening and research to improve outcomes.

In March, AGA joined the national advocacy organization Fight Colorectal Cancer (Fight CRC) and partners in the colorectal cancer community for events in our nation’s capital. The goal was to destigmatize talking about gut health and CRC and to collaboratively develop solutions that will improve and increase access to CRC screening.

Fight CRC working lunch

Former AGA president Dr. David Lieberman and fellow AGA member and FORWARD graduate Dr. Fola May served as facilitators for the coalition of public and private leaders assembled by Fight CRC. The group is working to develop an action plan to further equitable CRC screening and lower the number of lives impacted by CRC. Among the participants were insurers, industry, federal agencies, healthcare providers, retail businesses, and patients.

White House Cancer Moonshot colorectal cancer forum

In partnership with President Biden’s reignited Cancer Moonshot initiative, we joined Fight CRC and other advocacy and industry leaders in the colorectal cancer community for the Cancer Moonshot Colorectal Cancer Forum, hosted by the White House.

Dr. May participated as a panelist during the forum and discussed how we should address disparities in CRC. “Research dollars are essential in [combating CRC inequity]. We do not know how to effectively deliver care and preventive services to these populations unless we do deep dives into these particular settings to understand how to best deliver that care. This is not a “pick a model and apply broadly” approach. We need to go to the people, and we need to go to the people with the methods that work for that particular setting, and that’s going to be different in every community.”

In addition to Dr. Lieberman, who attended on behalf of AGA, fellow AGA members Drs. Austin Chiang, Swati Patel and AGA FORWARD Scholar Rachel Issaka were in attendance. We are appreciative of the opportunity to be included in these important discussions with the Administration and partners in the CRC community as we work together to reduce the burden of CRC and save lives.

Fight CRC United in Blue rally on the National Mall

It’s become an annual tradition for us to join Fight CRC’s United in Blue rally and blue flag installation on the National Mall, and this year was no different. We joined industry and patient advocacy groups in the CRC community to raise our voices about the need for screening, research, and advocacy to improve colon cancer outcomes.

The rally included inspiring calls to action and CRC testimonials from individuals who have been personally impacted by the disease, including Rep. Donald Payne Jr. (D-NJ), who lost his father to CRC and who personally underwent screening, which led to the discovery of 13 polyps.

Dr. Manish Singla from Capital Digestive Care spoke on behalf of AGA and provided encouragement and a reminder for patients and providers.

“What I keep hearing here is patients feel like they’re not being heard – so we’re listening. We’re trying and we’re here to fight the disease with you all. Everyone here knows somebody who is due for a colonoscopy and isn’t getting it, so use your persuasion – talk about it, convince, cajole, shame – use whatever you need so that everyone gets the screenings they need,” Dr. Singla said.