User login

Supporting career development for women in gastroenterology

When I was in fellowship in the late 1990s, it was rare to see women at many of the big gastroenterology conferences. And in terms of presentations, there was maybe one session led by or for women at lunchtime. These conferences were the only events I had ever been to where the line for the men’s room was longer than the line for the women’s room.

Over the years, the lines for the women’s room have gotten longer, and the sessions led by female gastroenterologists have grown exponentially. However, women are still underrepresented in our field. Two out of five GI fellows are women, but women constitute less than 18% of practicing gastroenterologists. And the number of women in leadership positions is even lower.

Women in medicine face many challenges

According to a report in JAMA Network Open, women have lower starting salaries more than 90% of the time, which can create income disparities in earning potential throughout our entire careers.

Other studies suggest that female physicians also spend more time with patients and answering messages from patients and colleagues as well. This extra time, although it is done in small increments, adds up quickly and could suggest the pay gap between women and men is wider than we think.

Of course, female physicians still spend more time parenting children and doing household labor. A study found that female physicians spent 8.5 hours more per week on activities that support the family and household.

We’ve been discussing equity for women in medicine, and in the workplace, for decades. But events over the past several years – such as the killing of George Floyd and the formation of the #MeToo movement in response to workplace sexual harassment – have accelerated a paradigm shift in how organizations are focusing on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and creating cultures that support leadership development for women.

The Gastro Health Women’s Network

In 2020, the leadership of Gastro Health reiterated its commitment to fight discrimination and support equity by sending out a company-wide correspondence that encouraged us to be good stewards within our communities during these turbulent times.

This led to the development of the Gastro Health DEI Council and the Gastro Health Women’s Network, led by Dr. Asma Khapra and based on the framework developed by Dr. Dawn Sears. The programs developed by Dr. Sears are focused on facilitating authentic and supportive relationships, and they helped us create a network for women focused on recruitment, mentorship and retention, networking and social events, and leadership development.

Our network started with a meet & greet, inviting all women in Gastro Health to join a virtual call and get to know each other in an informal setting. This was a great way to introduce people to each other in our natural elements. It was wonderful to see how people are when they are at home and not working.

Recruiting female gastroenterologists

Even though about half of gastroenterology fellows choose independent GI, most fellowship programs don’t educate students about private practice careers or promote that path. In addition, a lot of the national GI conferences are geared toward the academic experience.

It’s incumbent on those of us in private practice to educate students about the benefits and challenges we face as members of independent GI groups, and Gastro Health set out to hold networking and recruitment events at different national conferences with GI fellows and residents.

We’re also working to develop partnerships with fellowship programs. This past year, we’ve held several educational dinners for fellows and residents. Most recently, Dr. Khapra and others took a road trip to New York for dinners with fellows from Mount Sinai, Westchester Medical Center, and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

While it was beneficial for Gastro Health to provide information about life as private practice gastroenterologists, it was also helpful for us to hear how the GI leaders of tomorrow are navigating their career choices and what is impacting their decisions about the future.

Mentorship and retention are vital to practice sustainability

Once you’ve recruited physicians to join your practice, how do you ensure their success? Many practices are rightly concerned about their long-term sustainability and are exploring ways to help early-career physicians maintain the clinical skills they need to treat patients and learn the business skills they need to succeed in private practice.

Sometimes it’s as simple as reaching out to new associates on the first day to let them know you’re glad they’ve joined the practice and to let them know you’re available if they need anything. But there’s also growing recognition that implementing a formal mentorship program can help people feel included and supported.

The Women’s Network worked to pair its members with Gastro Health partners as mentors, and we’ve learned some things along the way. Initially, we tried to pair people with similar lifestyles and interests. What we found is that while this sometimes works, we may have overcomplicated the process. We learned that sometimes people would prefer mentors who have backgrounds that are different from their own. We were reminded that mentorship has many faces, and letting those relationships develop naturally can sometimes be more effective.

Networking and social events deter isolation and keep people engaged

Private practice can be different from working within a hospital because oftentimes your colleagues are working in different offices or facilities. In the case of our organization, those offices may be in different states hundreds of miles away. Within a hospital, there might be more potential to interact with your colleagues, whether in clinical conferences or through a chance encounter in the cafeteria.

In private practice, you may need to be more intentional about creating opportunities for people to network and get to know each other outside of work. This year, we developed an email and WhatsApp group so that women throughout the network can connect with each other. We have used it to disseminate information about upcoming events, fellowship opportunities with the national GI societies, interesting articles, and anything important that we think other women within Gastro Health would like to know.

In March, Gastro Health sponsored five women to attend the Scrubs & Heels Summit, which was developed by Dr. Anita Afzali and Dr. Aline Charabaty to create opportunities for women in GI at different stages of their GI careers and help them succeed and achieve their professional goals. There were 2 days of educational talks, but it also included plenty of events for our colleagues to get to know each other and network with other amazing female GI leaders from across the nation.

Where’s the boardroom?

A recent study found that the percentage of women on the boards of the 1,000 largest public companies in America is a little more than 28%, even though research shows that S&P 500 companies headquartered in California with 30% or more women on their boards had 29% higher revenue.

We’re working to develop opportunities for women to be in leadership positions, within our practices and on the national stage in terms of representation, within our national GI societies. It’s very exciting that we have women in leadership within AGA and ASGE, and that Dr. Latha Alaparthi has made increasing the focus on leadership and pipeline development one of her main priorities as the president and board chair of the Digestive Health Physicians Association (DHPA).

Another way private practices can support women who are leaders is by making recommendations for committees within our national societies and by recognizing that time spent developing presentations and speaking at national conferences is beneficial to the practice in terms of thought leadership, branding, and recruitment of the next generation of practice leaders.

While we have a long way to go, we’re also making strides in the board room at the practice level. I’m the first woman, and notably a woman of color, to join the Gastro Health board of directors under the guidance of support of CEO Joseph Garcia. Dr. Aja McCutchen, who serves as the chair of the DHPA Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion committee, is similarly the first woman and woman of color on the board of directors for United Digestive in Atlanta.

What to look for in joining a practice

When determining which practice you might join, ask how committed the leadership of the organization is to supporting career development for women. Does the practice have a network, a committee or other internal group that supports female physicians? What steps does the practice leadership take to support women who are interested in executive opportunities?

If the practice does have an internal organization, how does it measure progress? For example, we’ve implemented focus groups to measure what is working and where we face the most challenges. Gastro Health partnered with a consultant to hold three confidential sessions with 10 women at a time. This will allow for us to collect depersonalized data that can be compiled into a report for the Gastro Health Board and leadership.

If you’re a woman who is considering a career in independent GI, seek out women in private practice and ask about their experiences. Ask about their path and what opportunities they sought out when starting their careers. They may know of some great opportunities that are available to build your leadership skills.

By creating a network for women, Gastro Health is hoping to make it easier to develop relationships and create productive partnerships. We are certain that working to address the specific challenges that female physicians face in their careers will strengthen our group, and ultimately independent gastroenterology overall.

Dr. Adams is a practicing gastroenterologist and partner at Gastro Health Fairfax in Virginia and serves on the Digestive Health Physicians Association’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee. Dr. Adams has no conflicts to declare.

When I was in fellowship in the late 1990s, it was rare to see women at many of the big gastroenterology conferences. And in terms of presentations, there was maybe one session led by or for women at lunchtime. These conferences were the only events I had ever been to where the line for the men’s room was longer than the line for the women’s room.

Over the years, the lines for the women’s room have gotten longer, and the sessions led by female gastroenterologists have grown exponentially. However, women are still underrepresented in our field. Two out of five GI fellows are women, but women constitute less than 18% of practicing gastroenterologists. And the number of women in leadership positions is even lower.

Women in medicine face many challenges

According to a report in JAMA Network Open, women have lower starting salaries more than 90% of the time, which can create income disparities in earning potential throughout our entire careers.

Other studies suggest that female physicians also spend more time with patients and answering messages from patients and colleagues as well. This extra time, although it is done in small increments, adds up quickly and could suggest the pay gap between women and men is wider than we think.

Of course, female physicians still spend more time parenting children and doing household labor. A study found that female physicians spent 8.5 hours more per week on activities that support the family and household.

We’ve been discussing equity for women in medicine, and in the workplace, for decades. But events over the past several years – such as the killing of George Floyd and the formation of the #MeToo movement in response to workplace sexual harassment – have accelerated a paradigm shift in how organizations are focusing on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and creating cultures that support leadership development for women.

The Gastro Health Women’s Network

In 2020, the leadership of Gastro Health reiterated its commitment to fight discrimination and support equity by sending out a company-wide correspondence that encouraged us to be good stewards within our communities during these turbulent times.

This led to the development of the Gastro Health DEI Council and the Gastro Health Women’s Network, led by Dr. Asma Khapra and based on the framework developed by Dr. Dawn Sears. The programs developed by Dr. Sears are focused on facilitating authentic and supportive relationships, and they helped us create a network for women focused on recruitment, mentorship and retention, networking and social events, and leadership development.

Our network started with a meet & greet, inviting all women in Gastro Health to join a virtual call and get to know each other in an informal setting. This was a great way to introduce people to each other in our natural elements. It was wonderful to see how people are when they are at home and not working.

Recruiting female gastroenterologists

Even though about half of gastroenterology fellows choose independent GI, most fellowship programs don’t educate students about private practice careers or promote that path. In addition, a lot of the national GI conferences are geared toward the academic experience.

It’s incumbent on those of us in private practice to educate students about the benefits and challenges we face as members of independent GI groups, and Gastro Health set out to hold networking and recruitment events at different national conferences with GI fellows and residents.

We’re also working to develop partnerships with fellowship programs. This past year, we’ve held several educational dinners for fellows and residents. Most recently, Dr. Khapra and others took a road trip to New York for dinners with fellows from Mount Sinai, Westchester Medical Center, and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

While it was beneficial for Gastro Health to provide information about life as private practice gastroenterologists, it was also helpful for us to hear how the GI leaders of tomorrow are navigating their career choices and what is impacting their decisions about the future.

Mentorship and retention are vital to practice sustainability

Once you’ve recruited physicians to join your practice, how do you ensure their success? Many practices are rightly concerned about their long-term sustainability and are exploring ways to help early-career physicians maintain the clinical skills they need to treat patients and learn the business skills they need to succeed in private practice.

Sometimes it’s as simple as reaching out to new associates on the first day to let them know you’re glad they’ve joined the practice and to let them know you’re available if they need anything. But there’s also growing recognition that implementing a formal mentorship program can help people feel included and supported.

The Women’s Network worked to pair its members with Gastro Health partners as mentors, and we’ve learned some things along the way. Initially, we tried to pair people with similar lifestyles and interests. What we found is that while this sometimes works, we may have overcomplicated the process. We learned that sometimes people would prefer mentors who have backgrounds that are different from their own. We were reminded that mentorship has many faces, and letting those relationships develop naturally can sometimes be more effective.

Networking and social events deter isolation and keep people engaged

Private practice can be different from working within a hospital because oftentimes your colleagues are working in different offices or facilities. In the case of our organization, those offices may be in different states hundreds of miles away. Within a hospital, there might be more potential to interact with your colleagues, whether in clinical conferences or through a chance encounter in the cafeteria.

In private practice, you may need to be more intentional about creating opportunities for people to network and get to know each other outside of work. This year, we developed an email and WhatsApp group so that women throughout the network can connect with each other. We have used it to disseminate information about upcoming events, fellowship opportunities with the national GI societies, interesting articles, and anything important that we think other women within Gastro Health would like to know.

In March, Gastro Health sponsored five women to attend the Scrubs & Heels Summit, which was developed by Dr. Anita Afzali and Dr. Aline Charabaty to create opportunities for women in GI at different stages of their GI careers and help them succeed and achieve their professional goals. There were 2 days of educational talks, but it also included plenty of events for our colleagues to get to know each other and network with other amazing female GI leaders from across the nation.

Where’s the boardroom?

A recent study found that the percentage of women on the boards of the 1,000 largest public companies in America is a little more than 28%, even though research shows that S&P 500 companies headquartered in California with 30% or more women on their boards had 29% higher revenue.

We’re working to develop opportunities for women to be in leadership positions, within our practices and on the national stage in terms of representation, within our national GI societies. It’s very exciting that we have women in leadership within AGA and ASGE, and that Dr. Latha Alaparthi has made increasing the focus on leadership and pipeline development one of her main priorities as the president and board chair of the Digestive Health Physicians Association (DHPA).

Another way private practices can support women who are leaders is by making recommendations for committees within our national societies and by recognizing that time spent developing presentations and speaking at national conferences is beneficial to the practice in terms of thought leadership, branding, and recruitment of the next generation of practice leaders.

While we have a long way to go, we’re also making strides in the board room at the practice level. I’m the first woman, and notably a woman of color, to join the Gastro Health board of directors under the guidance of support of CEO Joseph Garcia. Dr. Aja McCutchen, who serves as the chair of the DHPA Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion committee, is similarly the first woman and woman of color on the board of directors for United Digestive in Atlanta.

What to look for in joining a practice

When determining which practice you might join, ask how committed the leadership of the organization is to supporting career development for women. Does the practice have a network, a committee or other internal group that supports female physicians? What steps does the practice leadership take to support women who are interested in executive opportunities?

If the practice does have an internal organization, how does it measure progress? For example, we’ve implemented focus groups to measure what is working and where we face the most challenges. Gastro Health partnered with a consultant to hold three confidential sessions with 10 women at a time. This will allow for us to collect depersonalized data that can be compiled into a report for the Gastro Health Board and leadership.

If you’re a woman who is considering a career in independent GI, seek out women in private practice and ask about their experiences. Ask about their path and what opportunities they sought out when starting their careers. They may know of some great opportunities that are available to build your leadership skills.

By creating a network for women, Gastro Health is hoping to make it easier to develop relationships and create productive partnerships. We are certain that working to address the specific challenges that female physicians face in their careers will strengthen our group, and ultimately independent gastroenterology overall.

Dr. Adams is a practicing gastroenterologist and partner at Gastro Health Fairfax in Virginia and serves on the Digestive Health Physicians Association’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee. Dr. Adams has no conflicts to declare.

When I was in fellowship in the late 1990s, it was rare to see women at many of the big gastroenterology conferences. And in terms of presentations, there was maybe one session led by or for women at lunchtime. These conferences were the only events I had ever been to where the line for the men’s room was longer than the line for the women’s room.

Over the years, the lines for the women’s room have gotten longer, and the sessions led by female gastroenterologists have grown exponentially. However, women are still underrepresented in our field. Two out of five GI fellows are women, but women constitute less than 18% of practicing gastroenterologists. And the number of women in leadership positions is even lower.

Women in medicine face many challenges

According to a report in JAMA Network Open, women have lower starting salaries more than 90% of the time, which can create income disparities in earning potential throughout our entire careers.

Other studies suggest that female physicians also spend more time with patients and answering messages from patients and colleagues as well. This extra time, although it is done in small increments, adds up quickly and could suggest the pay gap between women and men is wider than we think.

Of course, female physicians still spend more time parenting children and doing household labor. A study found that female physicians spent 8.5 hours more per week on activities that support the family and household.

We’ve been discussing equity for women in medicine, and in the workplace, for decades. But events over the past several years – such as the killing of George Floyd and the formation of the #MeToo movement in response to workplace sexual harassment – have accelerated a paradigm shift in how organizations are focusing on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and creating cultures that support leadership development for women.

The Gastro Health Women’s Network

In 2020, the leadership of Gastro Health reiterated its commitment to fight discrimination and support equity by sending out a company-wide correspondence that encouraged us to be good stewards within our communities during these turbulent times.

This led to the development of the Gastro Health DEI Council and the Gastro Health Women’s Network, led by Dr. Asma Khapra and based on the framework developed by Dr. Dawn Sears. The programs developed by Dr. Sears are focused on facilitating authentic and supportive relationships, and they helped us create a network for women focused on recruitment, mentorship and retention, networking and social events, and leadership development.

Our network started with a meet & greet, inviting all women in Gastro Health to join a virtual call and get to know each other in an informal setting. This was a great way to introduce people to each other in our natural elements. It was wonderful to see how people are when they are at home and not working.

Recruiting female gastroenterologists

Even though about half of gastroenterology fellows choose independent GI, most fellowship programs don’t educate students about private practice careers or promote that path. In addition, a lot of the national GI conferences are geared toward the academic experience.

It’s incumbent on those of us in private practice to educate students about the benefits and challenges we face as members of independent GI groups, and Gastro Health set out to hold networking and recruitment events at different national conferences with GI fellows and residents.

We’re also working to develop partnerships with fellowship programs. This past year, we’ve held several educational dinners for fellows and residents. Most recently, Dr. Khapra and others took a road trip to New York for dinners with fellows from Mount Sinai, Westchester Medical Center, and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

While it was beneficial for Gastro Health to provide information about life as private practice gastroenterologists, it was also helpful for us to hear how the GI leaders of tomorrow are navigating their career choices and what is impacting their decisions about the future.

Mentorship and retention are vital to practice sustainability

Once you’ve recruited physicians to join your practice, how do you ensure their success? Many practices are rightly concerned about their long-term sustainability and are exploring ways to help early-career physicians maintain the clinical skills they need to treat patients and learn the business skills they need to succeed in private practice.

Sometimes it’s as simple as reaching out to new associates on the first day to let them know you’re glad they’ve joined the practice and to let them know you’re available if they need anything. But there’s also growing recognition that implementing a formal mentorship program can help people feel included and supported.

The Women’s Network worked to pair its members with Gastro Health partners as mentors, and we’ve learned some things along the way. Initially, we tried to pair people with similar lifestyles and interests. What we found is that while this sometimes works, we may have overcomplicated the process. We learned that sometimes people would prefer mentors who have backgrounds that are different from their own. We were reminded that mentorship has many faces, and letting those relationships develop naturally can sometimes be more effective.

Networking and social events deter isolation and keep people engaged

Private practice can be different from working within a hospital because oftentimes your colleagues are working in different offices or facilities. In the case of our organization, those offices may be in different states hundreds of miles away. Within a hospital, there might be more potential to interact with your colleagues, whether in clinical conferences or through a chance encounter in the cafeteria.

In private practice, you may need to be more intentional about creating opportunities for people to network and get to know each other outside of work. This year, we developed an email and WhatsApp group so that women throughout the network can connect with each other. We have used it to disseminate information about upcoming events, fellowship opportunities with the national GI societies, interesting articles, and anything important that we think other women within Gastro Health would like to know.

In March, Gastro Health sponsored five women to attend the Scrubs & Heels Summit, which was developed by Dr. Anita Afzali and Dr. Aline Charabaty to create opportunities for women in GI at different stages of their GI careers and help them succeed and achieve their professional goals. There were 2 days of educational talks, but it also included plenty of events for our colleagues to get to know each other and network with other amazing female GI leaders from across the nation.

Where’s the boardroom?

A recent study found that the percentage of women on the boards of the 1,000 largest public companies in America is a little more than 28%, even though research shows that S&P 500 companies headquartered in California with 30% or more women on their boards had 29% higher revenue.

We’re working to develop opportunities for women to be in leadership positions, within our practices and on the national stage in terms of representation, within our national GI societies. It’s very exciting that we have women in leadership within AGA and ASGE, and that Dr. Latha Alaparthi has made increasing the focus on leadership and pipeline development one of her main priorities as the president and board chair of the Digestive Health Physicians Association (DHPA).

Another way private practices can support women who are leaders is by making recommendations for committees within our national societies and by recognizing that time spent developing presentations and speaking at national conferences is beneficial to the practice in terms of thought leadership, branding, and recruitment of the next generation of practice leaders.

While we have a long way to go, we’re also making strides in the board room at the practice level. I’m the first woman, and notably a woman of color, to join the Gastro Health board of directors under the guidance of support of CEO Joseph Garcia. Dr. Aja McCutchen, who serves as the chair of the DHPA Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion committee, is similarly the first woman and woman of color on the board of directors for United Digestive in Atlanta.

What to look for in joining a practice

When determining which practice you might join, ask how committed the leadership of the organization is to supporting career development for women. Does the practice have a network, a committee or other internal group that supports female physicians? What steps does the practice leadership take to support women who are interested in executive opportunities?

If the practice does have an internal organization, how does it measure progress? For example, we’ve implemented focus groups to measure what is working and where we face the most challenges. Gastro Health partnered with a consultant to hold three confidential sessions with 10 women at a time. This will allow for us to collect depersonalized data that can be compiled into a report for the Gastro Health Board and leadership.

If you’re a woman who is considering a career in independent GI, seek out women in private practice and ask about their experiences. Ask about their path and what opportunities they sought out when starting their careers. They may know of some great opportunities that are available to build your leadership skills.

By creating a network for women, Gastro Health is hoping to make it easier to develop relationships and create productive partnerships. We are certain that working to address the specific challenges that female physicians face in their careers will strengthen our group, and ultimately independent gastroenterology overall.

Dr. Adams is a practicing gastroenterologist and partner at Gastro Health Fairfax in Virginia and serves on the Digestive Health Physicians Association’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee. Dr. Adams has no conflicts to declare.

November 2022 - ICYMI

Gastroenterology

August 2022

Johnson-Laghi KA, Mattar MC. Integrating cognitive apprenticeship into gastroenterology clinical training. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):364-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.013.

Wood LD et al. Pancreatic cancer: Pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):386-402.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.056.

Calderwood AH and Robertson DJ. Stopping surveillance in gastrointestinal conditions: Thoughts on the scope of the problem and potential solutions. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):345-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.009.

September 2022

Donnangelo LL et al. Disclosure and reflection after an adverse event: Tips for training and practice. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):568-71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.07.003.

Chey WD et al. Vonoprazan triple and dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States and Europe: Randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):608-19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.055.

Bushyhead D and Quigley EMM. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-pathophysiology and its implications for definition and management. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):593-607. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.002.

Long MT et al. AGA Clinical practice update: Diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals: Expert review. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):764-74.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.023.

CGH

August 2022

Lennon AM and Vege SS. Pancreatic cyst surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1663-7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.002.

Crockett SD et al. Large Polyp Study Group Consortium. Clip closure does not reduce risk of bleeding after resection of large serrated polyps: Results from a randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1757-17--65.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.036.

Martin P et al. Treatment algorithm for managing chronic hepatitis b virus infection in the United States: 2021 update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1766-75. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.036.

September 2022

Pawlak KM et al. How to train the next generation to provide high-quality peer-reviews. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1902-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.018.

Choung RS et al. Collagenous gastritis: Characteristics and response to topical budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1977-85.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.033.

Basnayake C et al. Long-term outcome of multidisciplinary versus standard gastroenterologist care for functional gastrointestinal disorders: A randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2102-11.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.005.

Deutsch-Link S et al. Alcohol-associated liver disease mortality increased from 2017 to 2020 and accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2142-4.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.017.

TIGE

Nakamatsu, Dai et al. Safety of cold snare polypectomy for small colorectal polyps in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Apr 8;24[3]:246-53. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2022.03.008.

Gastro Hep Advances

Brindusa Truta et al. Outcomes of continuation vs. discontinuation of adalimumab therapy during third trimester of pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastro Hep Advances. 2022 Jan 1;1[5]:785-91. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2022.04.009.

Gastroenterology

August 2022

Johnson-Laghi KA, Mattar MC. Integrating cognitive apprenticeship into gastroenterology clinical training. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):364-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.013.

Wood LD et al. Pancreatic cancer: Pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):386-402.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.056.

Calderwood AH and Robertson DJ. Stopping surveillance in gastrointestinal conditions: Thoughts on the scope of the problem and potential solutions. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):345-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.009.

September 2022

Donnangelo LL et al. Disclosure and reflection after an adverse event: Tips for training and practice. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):568-71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.07.003.

Chey WD et al. Vonoprazan triple and dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States and Europe: Randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):608-19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.055.

Bushyhead D and Quigley EMM. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-pathophysiology and its implications for definition and management. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):593-607. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.002.

Long MT et al. AGA Clinical practice update: Diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals: Expert review. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):764-74.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.023.

CGH

August 2022

Lennon AM and Vege SS. Pancreatic cyst surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1663-7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.002.

Crockett SD et al. Large Polyp Study Group Consortium. Clip closure does not reduce risk of bleeding after resection of large serrated polyps: Results from a randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1757-17--65.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.036.

Martin P et al. Treatment algorithm for managing chronic hepatitis b virus infection in the United States: 2021 update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1766-75. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.036.

September 2022

Pawlak KM et al. How to train the next generation to provide high-quality peer-reviews. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1902-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.018.

Choung RS et al. Collagenous gastritis: Characteristics and response to topical budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1977-85.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.033.

Basnayake C et al. Long-term outcome of multidisciplinary versus standard gastroenterologist care for functional gastrointestinal disorders: A randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2102-11.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.005.

Deutsch-Link S et al. Alcohol-associated liver disease mortality increased from 2017 to 2020 and accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2142-4.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.017.

TIGE

Nakamatsu, Dai et al. Safety of cold snare polypectomy for small colorectal polyps in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Apr 8;24[3]:246-53. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2022.03.008.

Gastro Hep Advances

Brindusa Truta et al. Outcomes of continuation vs. discontinuation of adalimumab therapy during third trimester of pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastro Hep Advances. 2022 Jan 1;1[5]:785-91. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2022.04.009.

Gastroenterology

August 2022

Johnson-Laghi KA, Mattar MC. Integrating cognitive apprenticeship into gastroenterology clinical training. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):364-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.013.

Wood LD et al. Pancreatic cancer: Pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):386-402.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.056.

Calderwood AH and Robertson DJ. Stopping surveillance in gastrointestinal conditions: Thoughts on the scope of the problem and potential solutions. Gastroenterology. 2022 Aug;163(2):345-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.009.

September 2022

Donnangelo LL et al. Disclosure and reflection after an adverse event: Tips for training and practice. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):568-71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.07.003.

Chey WD et al. Vonoprazan triple and dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States and Europe: Randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):608-19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.055.

Bushyhead D and Quigley EMM. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-pathophysiology and its implications for definition and management. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):593-607. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.002.

Long MT et al. AGA Clinical practice update: Diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals: Expert review. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):764-74.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.023.

CGH

August 2022

Lennon AM and Vege SS. Pancreatic cyst surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1663-7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.002.

Crockett SD et al. Large Polyp Study Group Consortium. Clip closure does not reduce risk of bleeding after resection of large serrated polyps: Results from a randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1757-17--65.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.036.

Martin P et al. Treatment algorithm for managing chronic hepatitis b virus infection in the United States: 2021 update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;20(8):1766-75. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.036.

September 2022

Pawlak KM et al. How to train the next generation to provide high-quality peer-reviews. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1902-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.018.

Choung RS et al. Collagenous gastritis: Characteristics and response to topical budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):1977-85.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.033.

Basnayake C et al. Long-term outcome of multidisciplinary versus standard gastroenterologist care for functional gastrointestinal disorders: A randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2102-11.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.005.

Deutsch-Link S et al. Alcohol-associated liver disease mortality increased from 2017 to 2020 and accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;20(9):2142-4.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.017.

TIGE

Nakamatsu, Dai et al. Safety of cold snare polypectomy for small colorectal polyps in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Apr 8;24[3]:246-53. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2022.03.008.

Gastro Hep Advances

Brindusa Truta et al. Outcomes of continuation vs. discontinuation of adalimumab therapy during third trimester of pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastro Hep Advances. 2022 Jan 1;1[5]:785-91. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2022.04.009.

Lean and clean: Minimally invasive endoscopic and pharmacologic approaches to obesity

Obesity currently affects more than 40% of the U.S. population. It is the second-leading preventable cause of mortality behind smoking with an estimated 300,000 deaths per year.1,2 Weight loss can reduce the risk of metabolic comorbidities such as diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. However, 5%-10% total body weight loss (TBWL) is required for risk reduction.3 Sustained weight loss involves dietary alterations and physical activity, although it is difficult to maintain long term with lifestyle changes alone. Less than 10% of Americans with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 will achieve 5% TBWL each year, and nearly 80% of people will regain the weight within 5 years, a phenomenon known as “weight cycling.”4,5 Not only can these weight fluctuations make future weight-loss efforts more difficult, but they can also negatively impact cardiometabolic health in the long term.5 Thus, additional therapies are typically needed in conjunction with lifestyle interventions to treat obesity.

Current guidelines recommend bariatric surgery for patients unable to achieve or maintain weight loss through lifestyle changes.6 Surgeries like Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy lead to improvements in morbidity and mortality from metabolic diseases but are often only approved for select patients with a BMI of at least 40 or at least 35 with obesity-related comorbidities.7 These restrictions exclude patients at lower BMIs who may have early metabolic disease. Furthermore, only a small proportion of eligible patients are referred or willing to undergo surgery because of access issues, socioeconomic barriers, and concerns about adverse events.8,9 Endoscopic bariatric therapy and antiobesity medications (AOMs) have blossomed because of the need for other less-invasive options to stimulate weight loss.

Minimally invasive and noninvasive therapies in obesity

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies

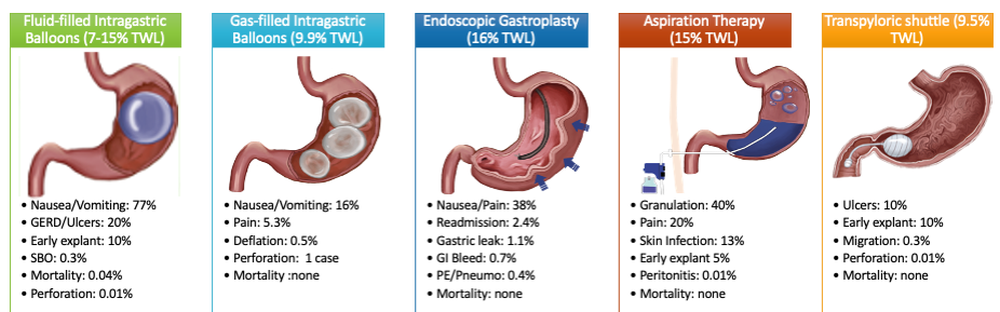

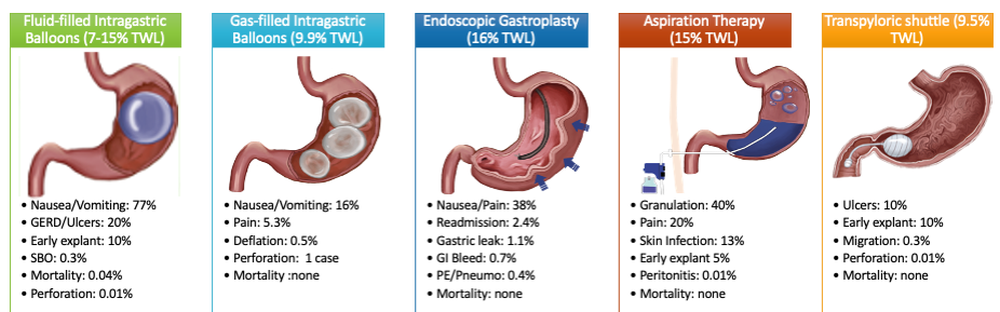

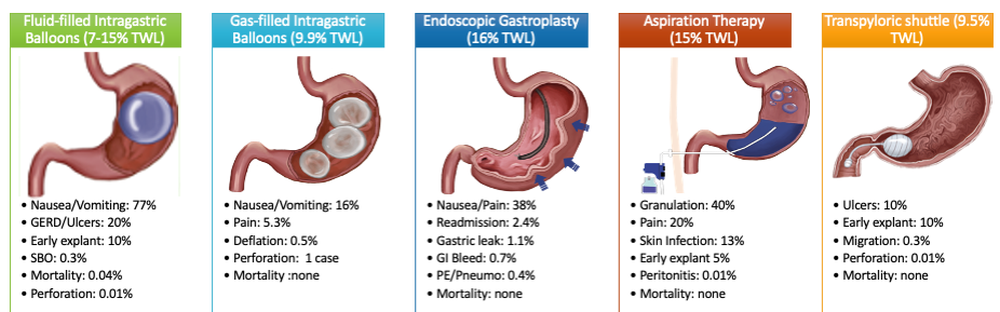

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) are used for the treatment of obesity in patients with a BMI of 30 kg/m2, a cohort that may be ineligible for bariatric surgery.10,11 EBMTs involve three categories: space-occupying devices (intragastric balloons [IGBs], transpyloric shuttle [TPS]), aspiration therapy, and gastric remodeling (endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty [ESG]).21,13 Presently, TPS and aspiration therapy are not commercially available in the United States. There are three types of IGB approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and Apollo ESGTM recently received de novo marketing authorization for the treatment of obesity. TBWL with EBMTs is promising at 12 months post procedure. Ranges include 7%-12% TBWL for IGBs and 15%-19% for ESG, with low rates of serious adverse events (AEs).13-18 Weight loss often reaches or exceeds the 10% TBWL needed to improve or completely reverse metabolic complications.

Obesity pharmacotherapy

Multiple professional societies support the use of obesity pharmacotherapy as an effective adjunct to lifestyle interventions.19 AOMs are classified as peripherally-acting to prevent nutrition absorption (e.g. orlistat), centrally acting to suppress appetite and/or cravings (e.g., phentermine/topiramate or naltrexone/bupropion), or incretin mimetics such as glucagonlike peptide–1 agonists (e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide).20 With the exception of orlistat, most agents have some effects on the hypothalamus to suppress appetite.21 Obesity medications tend to lead to a minimum weight loss of 3-10 kg after 12 months of treatment, and newer medications have even greater efficacy.22 Despite these results, discontinuation rates of the popular GLP-1 agonists can be as high as 47.7% and 70.1% at 12 and 24 months, respectively, because of the high cost of medications, gastrointestinal side effects, and poor tolerance.23,24

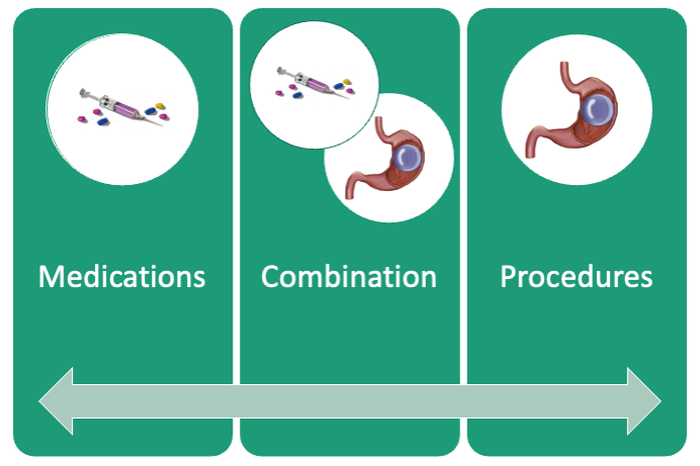

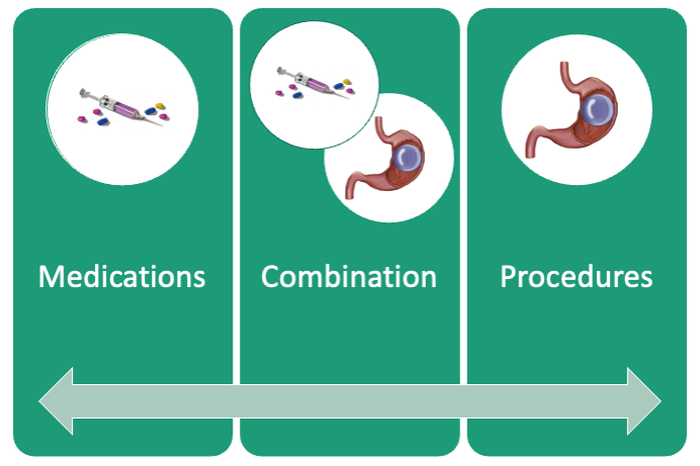

An ongoing challenge for patients is maintaining weight loss following cessation of pharmacotherapy when weight loss goals have been achieved. In this context, the combination of obesity pharmacotherapy and EBMTs can be utilized for long-term weight loss and weight maintenance given the chronic, relapsing, and complex nature of obesity.25

Advantages of less-invasive therapies in obesity management

The advantages of both pharmacologic and endoscopic weight-loss therapies are numerous. Pharmacotherapies are noninvasive, and their multiple mechanisms allow for combined use to synergistically promote weight reduction.26,27 Medications can be used in both the short- and long-term management of obesity, allowing for flexibility in use for patients pending fluctuations in weight. Furthermore, medications can improve markers of cardiovascular health including total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, and glycemic control.28

As minimally invasive therapies, EBMTs have less morbidity and mortality, compared with bariatric surgeries.29 The most common side effects of IGBs or ESG include abdominal pain, nausea, and worsening of acid reflux symptoms, which can be medically managed unlike some of the AEs associated with surgery, such as bowel obstruction, anastomotic dehiscence, fistulization, and postoperative infections.30 Long-term AEs from surgery also include malabsorption, nutritional deficiencies, cholelithiasis, and anastomotic stenosis.31 Even with improvement in surgical techniques, the rate of perioperative and postoperative mortality in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is estimated to be 0.4% and 0.7%, respectively, compared with only 0.08% with IGBs.30,32

In addition, EBMTs are also more cost effective than surgery, as they are often same-day outpatient procedures, leading to decreased length of stay (LOS) for patients. In ongoing research conducted by Sharaiha and colleagues, it was found that patients undergoing ESG had an average LOS of only 0.13 days, compared with 3.09 days for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 1.68 for laparoscopic gastric banding. The cost for ESG was approximately $12,000, compared with $15,000-$22,000 for laparoscopic bariatric surgeries.33 With their availability to patients with lower BMIs and their less-invasive nature, EBMTs and pharmacotherapy can be utilized on the spectrum of obesity care as bridge therapies both before and after surgery.

Our clinical approach

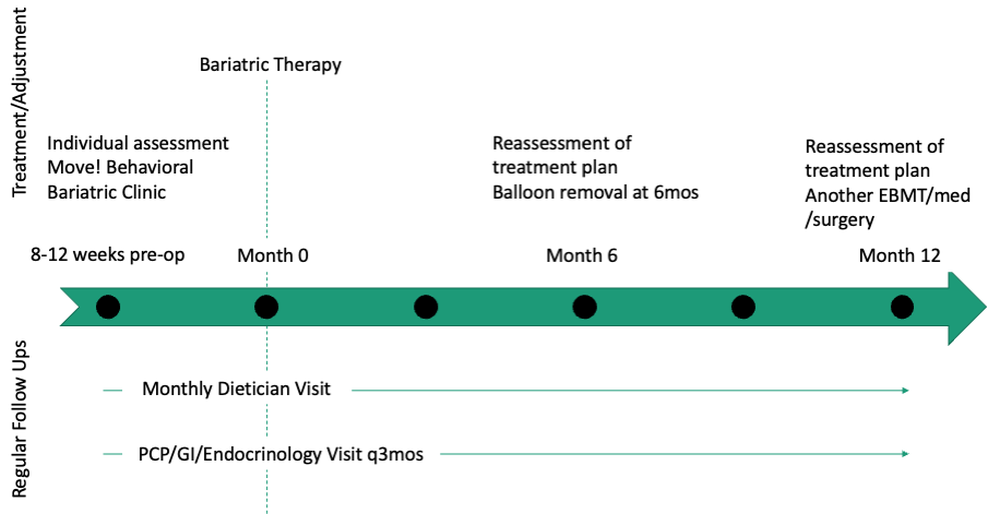

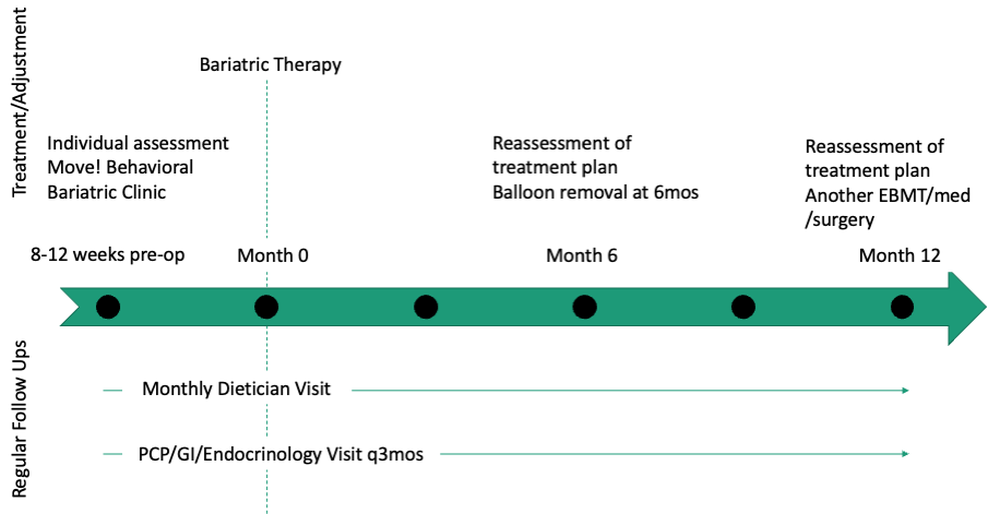

In 2015, the first Veterans Affairs hospital-based endoscopic bariatric program was established at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System utilizing IGBs and weight loss pharmacotherapy in conjunction with the VA MOVE! Program to treat obesity and metabolic comorbidities in veterans. Since then, EBMTs have expanded to include ESG and novel medications. Our treatment algorithm accounts for the chronic nature of obesity, the risk of weight regain after any intervention, and the need for longitudinal patient care.

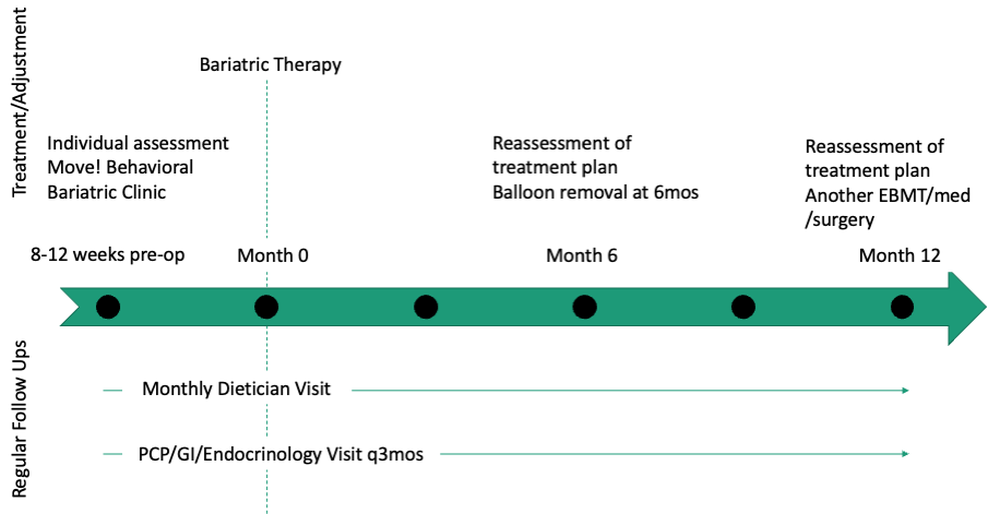

Patients undergo work-up by a multidisciplinary team (MD team) with a nutritionist, psychologist, primary care physician, gastroenterologist, and endocrinologist to determine the optimal treatment plan (Fig. 1).29

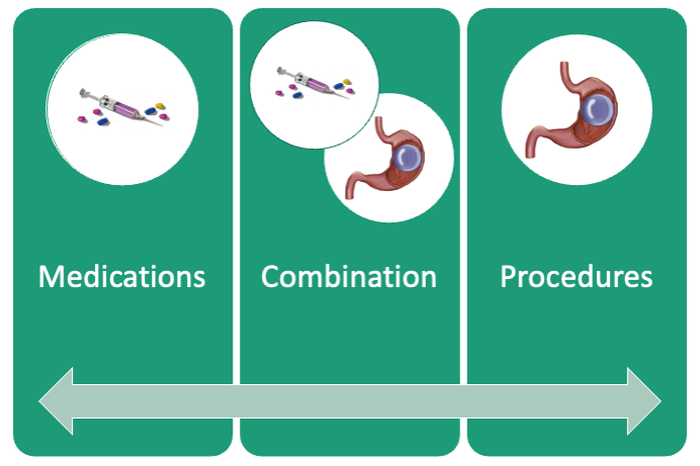

Patients are required to attend multiple information sessions, where all weight-loss methods are presented, including surgery, bariatric endoscopy, and pharmacotherapy. Other specialists also help manage comorbid conditions. Prior to selecting an initial intervention, patients undergo intensive lifestyle and behavioral therapy (Fig. 2 and 3). Depending on the selected therapy, initial treatment lasts between 3 and 12 months with ongoing support from the MD team.

If patients do not achieve their targeted weight loss after initial treatment, a new strategy is selected. This includes a different EBMT such as ESG, alternate pharmacotherapy, or surgery until the weight and health goals of the patient are achieved and sustained (Fig. 3). From the start, patients are informed that our program is a long-term intervention and that active participation in the MOVE! Program, as well as follow-up with the MD team are keys to success. EBMTs and medications are presented as effective tools that only work to enhance the effects of lifestyle changes.

Our multidisciplinary approach provides flexibility for patients to trial different options depending on their progress. Research on long-term outcomes with weight loss and metabolic parameters is ongoing, though early results are promising. Thus far, we have observed that patients undergoing a combination therapy of EBMTs and AOMs have greater weight loss than patients on a single therapeutic approach with either EBMT or AOMs alone.34 Racial and socioeconomic disparities in referrals to bariatric surgery are yet another barrier for patients to access weight reduction and improvement in cardiovascular health.35 EBMTs and pharmacotherapy are no longer just on the horizon; they are here as accessible, effective, and long-term treatments for all patients with obesity. More expansive insurance coverage is needed for EBMTs and AOMs in order to prevent progression of obesity-related comorbidities, reduce high costs, and ensure more equitable access to these effective therapies.

Dr. Young and Dr. Zenger are resident physicians in the department of internal medicine at New York University. Dr. Holzwanger is an advanced endoscopy fellow in the division of gastroenterology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Popov is director of bariatric endoscopy at VA New York Harbor Healthcare System, and assistant professor of medicine at New York University. Dr. Popov reported relationships with Obalon, Microtech, and Spatz, but the remaining authors reported no competing interests.

References

1. Ward ZJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(25):2440-50.

2. Stein CJ and Colditz GA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2522-5.

3. Ryan DH and Yockey SR. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(2):187-94.

4. Fildes A et al. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e54-9.

5. Rhee E-J. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2017;26(4):237-42.

6. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines OEP. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22 Suppl 2:S5-39.

7. Adams TD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):93-6.

8. Wharton S et al. Clin Obes. 2016;6(2):154-60.

9. Iuzzolino E and Kim Y. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2020;14(4):310-20.

10. Goyal D, Watson RR. Endoscopic Bariatric Therapies. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2016;18(6):26.

11. Ali MR et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(3):462-467.

12. Turkeltaub JA, Edmundowicz SA. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2019;17(2):187-201.

13. Reja D et al. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:21.

14. Force ABET et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(3):425-38e5.

15. Thompson CC et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(3):447-57.

16. Nystrom M et al. Obes Surg. 2018;28(7):1860-8.

17. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(8):1423-4.

18. Sharaiha RZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(4):504-10.

19. Apovian CM et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-62.

20. Son JW and Kim S. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(6):802-18.

21. Holst JJ. Int J Obes (Lond). Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(9):1161-8.

22. Joo JK and Lee KS. J Menopausal Med. 2014;20(3):90-6.

23. Weiss T et al. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:2337-45.

24. Sikirica MV et al. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017;10:403-12.

25. Kahan S et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;22(3):154-8.

26. Bhat SP and Sharma A. Curr Drug Targets. 2017;18(8):983-93.

27. Pendse J et al. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29(2):308-16.

28. Rucker D et al. BMJ. 2007;335(7631):1194-9.

29. Jirapinyo P and Thompson CC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(5):619-30.

30. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(5):1073-86.

31. Schulman AR and Thompson CC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(11):1640-55.

32. Ma IT and Madura JA, 2nd. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2015;11(8):526-35.

33. Sharaiha RZ. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty as a nonsurgical weight loss alternative. Digestive Disease Week, oral presentation. 2017.

34. Young S et al. Long-term efficacy of a multidisciplinary minimally invasive approach to weight management compared to single endoscopic therapy: A cohort study. P0865. American College of Gastroenterology Meeting, Abstract P0865. 2021.

35. Johnson-Mann C et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(4):615-20.

Obesity currently affects more than 40% of the U.S. population. It is the second-leading preventable cause of mortality behind smoking with an estimated 300,000 deaths per year.1,2 Weight loss can reduce the risk of metabolic comorbidities such as diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. However, 5%-10% total body weight loss (TBWL) is required for risk reduction.3 Sustained weight loss involves dietary alterations and physical activity, although it is difficult to maintain long term with lifestyle changes alone. Less than 10% of Americans with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 will achieve 5% TBWL each year, and nearly 80% of people will regain the weight within 5 years, a phenomenon known as “weight cycling.”4,5 Not only can these weight fluctuations make future weight-loss efforts more difficult, but they can also negatively impact cardiometabolic health in the long term.5 Thus, additional therapies are typically needed in conjunction with lifestyle interventions to treat obesity.

Current guidelines recommend bariatric surgery for patients unable to achieve or maintain weight loss through lifestyle changes.6 Surgeries like Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy lead to improvements in morbidity and mortality from metabolic diseases but are often only approved for select patients with a BMI of at least 40 or at least 35 with obesity-related comorbidities.7 These restrictions exclude patients at lower BMIs who may have early metabolic disease. Furthermore, only a small proportion of eligible patients are referred or willing to undergo surgery because of access issues, socioeconomic barriers, and concerns about adverse events.8,9 Endoscopic bariatric therapy and antiobesity medications (AOMs) have blossomed because of the need for other less-invasive options to stimulate weight loss.

Minimally invasive and noninvasive therapies in obesity

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) are used for the treatment of obesity in patients with a BMI of 30 kg/m2, a cohort that may be ineligible for bariatric surgery.10,11 EBMTs involve three categories: space-occupying devices (intragastric balloons [IGBs], transpyloric shuttle [TPS]), aspiration therapy, and gastric remodeling (endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty [ESG]).21,13 Presently, TPS and aspiration therapy are not commercially available in the United States. There are three types of IGB approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and Apollo ESGTM recently received de novo marketing authorization for the treatment of obesity. TBWL with EBMTs is promising at 12 months post procedure. Ranges include 7%-12% TBWL for IGBs and 15%-19% for ESG, with low rates of serious adverse events (AEs).13-18 Weight loss often reaches or exceeds the 10% TBWL needed to improve or completely reverse metabolic complications.

Obesity pharmacotherapy

Multiple professional societies support the use of obesity pharmacotherapy as an effective adjunct to lifestyle interventions.19 AOMs are classified as peripherally-acting to prevent nutrition absorption (e.g. orlistat), centrally acting to suppress appetite and/or cravings (e.g., phentermine/topiramate or naltrexone/bupropion), or incretin mimetics such as glucagonlike peptide–1 agonists (e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide).20 With the exception of orlistat, most agents have some effects on the hypothalamus to suppress appetite.21 Obesity medications tend to lead to a minimum weight loss of 3-10 kg after 12 months of treatment, and newer medications have even greater efficacy.22 Despite these results, discontinuation rates of the popular GLP-1 agonists can be as high as 47.7% and 70.1% at 12 and 24 months, respectively, because of the high cost of medications, gastrointestinal side effects, and poor tolerance.23,24

An ongoing challenge for patients is maintaining weight loss following cessation of pharmacotherapy when weight loss goals have been achieved. In this context, the combination of obesity pharmacotherapy and EBMTs can be utilized for long-term weight loss and weight maintenance given the chronic, relapsing, and complex nature of obesity.25

Advantages of less-invasive therapies in obesity management

The advantages of both pharmacologic and endoscopic weight-loss therapies are numerous. Pharmacotherapies are noninvasive, and their multiple mechanisms allow for combined use to synergistically promote weight reduction.26,27 Medications can be used in both the short- and long-term management of obesity, allowing for flexibility in use for patients pending fluctuations in weight. Furthermore, medications can improve markers of cardiovascular health including total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, and glycemic control.28

As minimally invasive therapies, EBMTs have less morbidity and mortality, compared with bariatric surgeries.29 The most common side effects of IGBs or ESG include abdominal pain, nausea, and worsening of acid reflux symptoms, which can be medically managed unlike some of the AEs associated with surgery, such as bowel obstruction, anastomotic dehiscence, fistulization, and postoperative infections.30 Long-term AEs from surgery also include malabsorption, nutritional deficiencies, cholelithiasis, and anastomotic stenosis.31 Even with improvement in surgical techniques, the rate of perioperative and postoperative mortality in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is estimated to be 0.4% and 0.7%, respectively, compared with only 0.08% with IGBs.30,32

In addition, EBMTs are also more cost effective than surgery, as they are often same-day outpatient procedures, leading to decreased length of stay (LOS) for patients. In ongoing research conducted by Sharaiha and colleagues, it was found that patients undergoing ESG had an average LOS of only 0.13 days, compared with 3.09 days for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 1.68 for laparoscopic gastric banding. The cost for ESG was approximately $12,000, compared with $15,000-$22,000 for laparoscopic bariatric surgeries.33 With their availability to patients with lower BMIs and their less-invasive nature, EBMTs and pharmacotherapy can be utilized on the spectrum of obesity care as bridge therapies both before and after surgery.

Our clinical approach

In 2015, the first Veterans Affairs hospital-based endoscopic bariatric program was established at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System utilizing IGBs and weight loss pharmacotherapy in conjunction with the VA MOVE! Program to treat obesity and metabolic comorbidities in veterans. Since then, EBMTs have expanded to include ESG and novel medications. Our treatment algorithm accounts for the chronic nature of obesity, the risk of weight regain after any intervention, and the need for longitudinal patient care.

Patients undergo work-up by a multidisciplinary team (MD team) with a nutritionist, psychologist, primary care physician, gastroenterologist, and endocrinologist to determine the optimal treatment plan (Fig. 1).29

Patients are required to attend multiple information sessions, where all weight-loss methods are presented, including surgery, bariatric endoscopy, and pharmacotherapy. Other specialists also help manage comorbid conditions. Prior to selecting an initial intervention, patients undergo intensive lifestyle and behavioral therapy (Fig. 2 and 3). Depending on the selected therapy, initial treatment lasts between 3 and 12 months with ongoing support from the MD team.

If patients do not achieve their targeted weight loss after initial treatment, a new strategy is selected. This includes a different EBMT such as ESG, alternate pharmacotherapy, or surgery until the weight and health goals of the patient are achieved and sustained (Fig. 3). From the start, patients are informed that our program is a long-term intervention and that active participation in the MOVE! Program, as well as follow-up with the MD team are keys to success. EBMTs and medications are presented as effective tools that only work to enhance the effects of lifestyle changes.

Our multidisciplinary approach provides flexibility for patients to trial different options depending on their progress. Research on long-term outcomes with weight loss and metabolic parameters is ongoing, though early results are promising. Thus far, we have observed that patients undergoing a combination therapy of EBMTs and AOMs have greater weight loss than patients on a single therapeutic approach with either EBMT or AOMs alone.34 Racial and socioeconomic disparities in referrals to bariatric surgery are yet another barrier for patients to access weight reduction and improvement in cardiovascular health.35 EBMTs and pharmacotherapy are no longer just on the horizon; they are here as accessible, effective, and long-term treatments for all patients with obesity. More expansive insurance coverage is needed for EBMTs and AOMs in order to prevent progression of obesity-related comorbidities, reduce high costs, and ensure more equitable access to these effective therapies.

Dr. Young and Dr. Zenger are resident physicians in the department of internal medicine at New York University. Dr. Holzwanger is an advanced endoscopy fellow in the division of gastroenterology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Popov is director of bariatric endoscopy at VA New York Harbor Healthcare System, and assistant professor of medicine at New York University. Dr. Popov reported relationships with Obalon, Microtech, and Spatz, but the remaining authors reported no competing interests.

References

1. Ward ZJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(25):2440-50.

2. Stein CJ and Colditz GA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2522-5.

3. Ryan DH and Yockey SR. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(2):187-94.

4. Fildes A et al. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e54-9.

5. Rhee E-J. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2017;26(4):237-42.

6. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines OEP. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22 Suppl 2:S5-39.

7. Adams TD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):93-6.

8. Wharton S et al. Clin Obes. 2016;6(2):154-60.

9. Iuzzolino E and Kim Y. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2020;14(4):310-20.

10. Goyal D, Watson RR. Endoscopic Bariatric Therapies. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2016;18(6):26.

11. Ali MR et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(3):462-467.

12. Turkeltaub JA, Edmundowicz SA. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2019;17(2):187-201.

13. Reja D et al. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:21.

14. Force ABET et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(3):425-38e5.

15. Thompson CC et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(3):447-57.

16. Nystrom M et al. Obes Surg. 2018;28(7):1860-8.

17. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(8):1423-4.

18. Sharaiha RZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(4):504-10.

19. Apovian CM et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-62.

20. Son JW and Kim S. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(6):802-18.

21. Holst JJ. Int J Obes (Lond). Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(9):1161-8.

22. Joo JK and Lee KS. J Menopausal Med. 2014;20(3):90-6.

23. Weiss T et al. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:2337-45.

24. Sikirica MV et al. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017;10:403-12.

25. Kahan S et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;22(3):154-8.

26. Bhat SP and Sharma A. Curr Drug Targets. 2017;18(8):983-93.

27. Pendse J et al. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29(2):308-16.

28. Rucker D et al. BMJ. 2007;335(7631):1194-9.

29. Jirapinyo P and Thompson CC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(5):619-30.

30. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(5):1073-86.

31. Schulman AR and Thompson CC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(11):1640-55.

32. Ma IT and Madura JA, 2nd. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2015;11(8):526-35.

33. Sharaiha RZ. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty as a nonsurgical weight loss alternative. Digestive Disease Week, oral presentation. 2017.

34. Young S et al. Long-term efficacy of a multidisciplinary minimally invasive approach to weight management compared to single endoscopic therapy: A cohort study. P0865. American College of Gastroenterology Meeting, Abstract P0865. 2021.

35. Johnson-Mann C et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(4):615-20.

Obesity currently affects more than 40% of the U.S. population. It is the second-leading preventable cause of mortality behind smoking with an estimated 300,000 deaths per year.1,2 Weight loss can reduce the risk of metabolic comorbidities such as diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. However, 5%-10% total body weight loss (TBWL) is required for risk reduction.3 Sustained weight loss involves dietary alterations and physical activity, although it is difficult to maintain long term with lifestyle changes alone. Less than 10% of Americans with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 will achieve 5% TBWL each year, and nearly 80% of people will regain the weight within 5 years, a phenomenon known as “weight cycling.”4,5 Not only can these weight fluctuations make future weight-loss efforts more difficult, but they can also negatively impact cardiometabolic health in the long term.5 Thus, additional therapies are typically needed in conjunction with lifestyle interventions to treat obesity.

Current guidelines recommend bariatric surgery for patients unable to achieve or maintain weight loss through lifestyle changes.6 Surgeries like Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy lead to improvements in morbidity and mortality from metabolic diseases but are often only approved for select patients with a BMI of at least 40 or at least 35 with obesity-related comorbidities.7 These restrictions exclude patients at lower BMIs who may have early metabolic disease. Furthermore, only a small proportion of eligible patients are referred or willing to undergo surgery because of access issues, socioeconomic barriers, and concerns about adverse events.8,9 Endoscopic bariatric therapy and antiobesity medications (AOMs) have blossomed because of the need for other less-invasive options to stimulate weight loss.

Minimally invasive and noninvasive therapies in obesity

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) are used for the treatment of obesity in patients with a BMI of 30 kg/m2, a cohort that may be ineligible for bariatric surgery.10,11 EBMTs involve three categories: space-occupying devices (intragastric balloons [IGBs], transpyloric shuttle [TPS]), aspiration therapy, and gastric remodeling (endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty [ESG]).21,13 Presently, TPS and aspiration therapy are not commercially available in the United States. There are three types of IGB approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and Apollo ESGTM recently received de novo marketing authorization for the treatment of obesity. TBWL with EBMTs is promising at 12 months post procedure. Ranges include 7%-12% TBWL for IGBs and 15%-19% for ESG, with low rates of serious adverse events (AEs).13-18 Weight loss often reaches or exceeds the 10% TBWL needed to improve or completely reverse metabolic complications.

Obesity pharmacotherapy

Multiple professional societies support the use of obesity pharmacotherapy as an effective adjunct to lifestyle interventions.19 AOMs are classified as peripherally-acting to prevent nutrition absorption (e.g. orlistat), centrally acting to suppress appetite and/or cravings (e.g., phentermine/topiramate or naltrexone/bupropion), or incretin mimetics such as glucagonlike peptide–1 agonists (e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide).20 With the exception of orlistat, most agents have some effects on the hypothalamus to suppress appetite.21 Obesity medications tend to lead to a minimum weight loss of 3-10 kg after 12 months of treatment, and newer medications have even greater efficacy.22 Despite these results, discontinuation rates of the popular GLP-1 agonists can be as high as 47.7% and 70.1% at 12 and 24 months, respectively, because of the high cost of medications, gastrointestinal side effects, and poor tolerance.23,24

An ongoing challenge for patients is maintaining weight loss following cessation of pharmacotherapy when weight loss goals have been achieved. In this context, the combination of obesity pharmacotherapy and EBMTs can be utilized for long-term weight loss and weight maintenance given the chronic, relapsing, and complex nature of obesity.25

Advantages of less-invasive therapies in obesity management

The advantages of both pharmacologic and endoscopic weight-loss therapies are numerous. Pharmacotherapies are noninvasive, and their multiple mechanisms allow for combined use to synergistically promote weight reduction.26,27 Medications can be used in both the short- and long-term management of obesity, allowing for flexibility in use for patients pending fluctuations in weight. Furthermore, medications can improve markers of cardiovascular health including total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, and glycemic control.28

As minimally invasive therapies, EBMTs have less morbidity and mortality, compared with bariatric surgeries.29 The most common side effects of IGBs or ESG include abdominal pain, nausea, and worsening of acid reflux symptoms, which can be medically managed unlike some of the AEs associated with surgery, such as bowel obstruction, anastomotic dehiscence, fistulization, and postoperative infections.30 Long-term AEs from surgery also include malabsorption, nutritional deficiencies, cholelithiasis, and anastomotic stenosis.31 Even with improvement in surgical techniques, the rate of perioperative and postoperative mortality in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is estimated to be 0.4% and 0.7%, respectively, compared with only 0.08% with IGBs.30,32

In addition, EBMTs are also more cost effective than surgery, as they are often same-day outpatient procedures, leading to decreased length of stay (LOS) for patients. In ongoing research conducted by Sharaiha and colleagues, it was found that patients undergoing ESG had an average LOS of only 0.13 days, compared with 3.09 days for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and 1.68 for laparoscopic gastric banding. The cost for ESG was approximately $12,000, compared with $15,000-$22,000 for laparoscopic bariatric surgeries.33 With their availability to patients with lower BMIs and their less-invasive nature, EBMTs and pharmacotherapy can be utilized on the spectrum of obesity care as bridge therapies both before and after surgery.

Our clinical approach

In 2015, the first Veterans Affairs hospital-based endoscopic bariatric program was established at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System utilizing IGBs and weight loss pharmacotherapy in conjunction with the VA MOVE! Program to treat obesity and metabolic comorbidities in veterans. Since then, EBMTs have expanded to include ESG and novel medications. Our treatment algorithm accounts for the chronic nature of obesity, the risk of weight regain after any intervention, and the need for longitudinal patient care.

Patients undergo work-up by a multidisciplinary team (MD team) with a nutritionist, psychologist, primary care physician, gastroenterologist, and endocrinologist to determine the optimal treatment plan (Fig. 1).29

Patients are required to attend multiple information sessions, where all weight-loss methods are presented, including surgery, bariatric endoscopy, and pharmacotherapy. Other specialists also help manage comorbid conditions. Prior to selecting an initial intervention, patients undergo intensive lifestyle and behavioral therapy (Fig. 2 and 3). Depending on the selected therapy, initial treatment lasts between 3 and 12 months with ongoing support from the MD team.

If patients do not achieve their targeted weight loss after initial treatment, a new strategy is selected. This includes a different EBMT such as ESG, alternate pharmacotherapy, or surgery until the weight and health goals of the patient are achieved and sustained (Fig. 3). From the start, patients are informed that our program is a long-term intervention and that active participation in the MOVE! Program, as well as follow-up with the MD team are keys to success. EBMTs and medications are presented as effective tools that only work to enhance the effects of lifestyle changes.

Our multidisciplinary approach provides flexibility for patients to trial different options depending on their progress. Research on long-term outcomes with weight loss and metabolic parameters is ongoing, though early results are promising. Thus far, we have observed that patients undergoing a combination therapy of EBMTs and AOMs have greater weight loss than patients on a single therapeutic approach with either EBMT or AOMs alone.34 Racial and socioeconomic disparities in referrals to bariatric surgery are yet another barrier for patients to access weight reduction and improvement in cardiovascular health.35 EBMTs and pharmacotherapy are no longer just on the horizon; they are here as accessible, effective, and long-term treatments for all patients with obesity. More expansive insurance coverage is needed for EBMTs and AOMs in order to prevent progression of obesity-related comorbidities, reduce high costs, and ensure more equitable access to these effective therapies.

Dr. Young and Dr. Zenger are resident physicians in the department of internal medicine at New York University. Dr. Holzwanger is an advanced endoscopy fellow in the division of gastroenterology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Popov is director of bariatric endoscopy at VA New York Harbor Healthcare System, and assistant professor of medicine at New York University. Dr. Popov reported relationships with Obalon, Microtech, and Spatz, but the remaining authors reported no competing interests.

References

1. Ward ZJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(25):2440-50.

2. Stein CJ and Colditz GA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2522-5.

3. Ryan DH and Yockey SR. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(2):187-94.

4. Fildes A et al. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e54-9.

5. Rhee E-J. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2017;26(4):237-42.

6. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines OEP. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22 Suppl 2:S5-39.

7. Adams TD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):93-6.

8. Wharton S et al. Clin Obes. 2016;6(2):154-60.

9. Iuzzolino E and Kim Y. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2020;14(4):310-20.

10. Goyal D, Watson RR. Endoscopic Bariatric Therapies. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2016;18(6):26.

11. Ali MR et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(3):462-467.

12. Turkeltaub JA, Edmundowicz SA. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2019;17(2):187-201.

13. Reja D et al. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:21.

14. Force ABET et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(3):425-38e5.

15. Thompson CC et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(3):447-57.

16. Nystrom M et al. Obes Surg. 2018;28(7):1860-8.

17. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(8):1423-4.

18. Sharaiha RZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(4):504-10.

19. Apovian CM et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-62.

20. Son JW and Kim S. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(6):802-18.

21. Holst JJ. Int J Obes (Lond). Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(9):1161-8.

22. Joo JK and Lee KS. J Menopausal Med. 2014;20(3):90-6.

23. Weiss T et al. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:2337-45.

24. Sikirica MV et al. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017;10:403-12.

25. Kahan S et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;22(3):154-8.

26. Bhat SP and Sharma A. Curr Drug Targets. 2017;18(8):983-93.

27. Pendse J et al. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29(2):308-16.

28. Rucker D et al. BMJ. 2007;335(7631):1194-9.

29. Jirapinyo P and Thompson CC. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(5):619-30.

30. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(5):1073-86.

31. Schulman AR and Thompson CC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(11):1640-55.

32. Ma IT and Madura JA, 2nd. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2015;11(8):526-35.

33. Sharaiha RZ. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty as a nonsurgical weight loss alternative. Digestive Disease Week, oral presentation. 2017.

34. Young S et al. Long-term efficacy of a multidisciplinary minimally invasive approach to weight management compared to single endoscopic therapy: A cohort study. P0865. American College of Gastroenterology Meeting, Abstract P0865. 2021.

35. Johnson-Mann C et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(4):615-20.

Passive income for the astute gastroenterologist

I don’t think I heard the term “passive income” until I was already an attending gastroenterologist.

That was no surprise. Why would I as a gastroenterologist with a focus in inflammatory bowel diseases be even remotely interested in that term?

Like most physicians, I went into medicine to take care of patients. That was my entire dream. It was a pleasant surprise to hear that gastroenterologists were relatively well paid compared to many other internal medicine specialties.