User login

Establishing a formalized mentorship program in a community practice

Most GI physicians will tell you that we didn’t get where we are without help along the way. Each of us can point to one – or in most cases, several – specific mentors who provided invaluable guidance when we were in medical school, fellowship, and starting our careers. This is true for gastroenterologists across the spectrum, whether they chose careers in private practice, academic medicine, or within a hospital system.

The leadership at Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates, where I practice, has always recognized the importance of mentorship and its role in developing fulfilling careers for its physicians and a healthy practice culture in which people feel valued and supported. But only recently have we begun to create a formalized program to ensure that everyone has access to mentors.

When I started my career, formalized programs for mentorship did not exist. While I reached out to various doctors in my office and the senior partners throughout the practice, not everyone is comfortable proactively reaching out to ask practice leadership for help and guidance. And as independent GI practices continue to get bigger, there may not be as many opportunities to interact with senior leadership or executives, which means new associates could be left to “cold call” potential mentors by phone or email.

New associates face many challenges

When I was an associate, the path to partnership looked much different than it does in our practice now, and it definitely varies from practice to practice. In our practice, physicians remain associates for 2-3 years before they have the option to become a partner. As they work diligently to provide the best care to patients, new associates face many challenges, like learning how to build a practice and interact with referring physicians, understanding the process to become a partner, and figuring out how to juggle other commitments, such as the balance between work and home life.

Then there are things like buying a home, getting life and disability insurance, and understanding the financial planning aspects of being a business owner. For those whose group model requires buying into the practice to become a partner, medical school doesn’t teach you how to analyze the return on an investment. Providing access to people who have this experience through a mentorship program can help associates be more prepared to become partners, and hopefully be happier and more successful while doing so.

Formalizing a mentorship program

The mentorship program at Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates matches new physicians with a partner-level mentor with whom they are encouraged to meet monthly. We’ve even provided a budget so that mentees and mentors can meet for dinner or coffee and get to know each other better.

The program starts with a meeting of volunteer partners and associates, who then rank their preferred choices for potential mentors. This helps to ensure that the associates are able get to know the mentors a little bit and decide who might be the best fit for their needs. This is also important for new associates who don’t feel comfortable proactively searching for a mentor as they’re able to provide a list of partners they think would be the best match for them.

Each associate is then assigned a partner-level mentor who is responsible for guiding them and providing education around not only clinical care, but also business, marketing, health policy, and all the other critical components of running a successful private practice. Our program specifically pairs mentors and mentees who do not work in the same location. We wanted the mentors to be paired with associates they are not interacting with daily, to ensure our associates get exposed to different perspectives.

As a group, program participants get together every quarter – twice a year in person, and twice virtually. One of the in-person meetings brings together the mentors and mentees with C-suite executives to meet and network with the practice leadership. We organized the program this way because otherwise, most associates wouldn’t get many opportunities to interact with the CEO, chief medical officer, or chief operating officer in any capacity, let alone in a small gathering where they can engage on a personal level.

The second in-person meeting is a dinner with the mentors and mentees, along with their significant others. We understand that all our physicians have responsibilities outside of work, and bringing families together helps provide new associates with a network of support for questions that aren’t work-related. For associates who are not from Atlanta, this can be especially helpful in figuring out housing, schools, and other aspects of work/life balance.

The other two virtual meetings include the C-suite executives and our physician executive board. We develop specific agenda topics related to a career in private practice and provide a forum for the associates to ask practice leadership questions about challenges they may face on their path to becoming a partner.

At the end of each year, we survey the current program participants to see what was successful and what can be improved for the next cohort of incoming associates. So far, the feedback we’ve received from the mentors and mentees has been overwhelmingly positive.

Mentorship benefits the entire practice

As groups continue to grow, more practices may begin to formalize their mentorship programs, particularly those who see the merit they provide in helping recruit and retain valuable associates. To supplement our internal mentorship program, we’ve also started reaching out to local fellowship programs to provide resources to fellows who are considering private practice.

Even though about half of gastroenterology fellows choose independent GI, many aren’t educated about what it means to choose a career in private practice. Our outreach to provide information at the fellowship level is aimed at giving early career physicians an opportunity to know the benefits and challenges associated with private practice. Furthermore, we strive to educate fellows about the resources that are available to guide them through not only joining a group, but also having a successful career.

Leaders of independent GI groups need physicians who want the practice to succeed. Medical school trains physicians to take care of patients but falls short on training physicians to run a business. And building good, strong businesses makes sure that the next generation of leaders are prepared to take over.

Supporting the next generation of practice leaders helps current leadership make changes that will ensure practice sustainability. Often, associates are at the forefront of new technologies, both in terms of patient care, and in terms of practice management, communications, marketing, and advertising. As times change, having associates who are engaged and excited will help any practice be positioned positively for whatever the future holds.

What to look for in joining a practice

Ideally, people should start looking for mentors when they’re looking for a residency program. Joining a practice isn’t much different. If you’re an early career physician who is considering private practice, find an independent GI physician who can tell you about their experiences. And when you’re interviewing with practices, be sure to ask questions about how the group approaches mentorship. If a practice doesn’t have a formal mentorship program, it doesn’t mean it’s an environment where mentorship relationships won’t flourish. In many practices, informal mentorship programs are very successful.

Ask questions about how the practice provides or supports mentorship. Does the practice leadership make themselves available as mentors? Does the practice expect new physicians to find and nurture mentorship relations on their own? Ask about the path to becoming a partner and who is available to discuss challenges, concerns, or any questions that arise.

Independent GI practices are partnerships that seek to provide high-quality care at a lower cost to our community. Strengthening and sustaining that partnership requires us to take the time and continuously invest in the future of new physicians who will go on to serve our community as partner physicians retire. By formalizing a mentorship program, we’re hoping to make it easier for our mentors and mentees to create productive partnerships that will strengthen our group, and ultimately independent gastroenterology overall.

Dr. Sonenshine is a practicing gastroenterologist at Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates, and a partner in United Digestive. He previously served as the chair of communications as a member of the Executive Committee of the Digestive Health Physicians Association. Dr. Sonenshine has no conflicts to declare.

Most GI physicians will tell you that we didn’t get where we are without help along the way. Each of us can point to one – or in most cases, several – specific mentors who provided invaluable guidance when we were in medical school, fellowship, and starting our careers. This is true for gastroenterologists across the spectrum, whether they chose careers in private practice, academic medicine, or within a hospital system.

The leadership at Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates, where I practice, has always recognized the importance of mentorship and its role in developing fulfilling careers for its physicians and a healthy practice culture in which people feel valued and supported. But only recently have we begun to create a formalized program to ensure that everyone has access to mentors.

When I started my career, formalized programs for mentorship did not exist. While I reached out to various doctors in my office and the senior partners throughout the practice, not everyone is comfortable proactively reaching out to ask practice leadership for help and guidance. And as independent GI practices continue to get bigger, there may not be as many opportunities to interact with senior leadership or executives, which means new associates could be left to “cold call” potential mentors by phone or email.

New associates face many challenges

When I was an associate, the path to partnership looked much different than it does in our practice now, and it definitely varies from practice to practice. In our practice, physicians remain associates for 2-3 years before they have the option to become a partner. As they work diligently to provide the best care to patients, new associates face many challenges, like learning how to build a practice and interact with referring physicians, understanding the process to become a partner, and figuring out how to juggle other commitments, such as the balance between work and home life.

Then there are things like buying a home, getting life and disability insurance, and understanding the financial planning aspects of being a business owner. For those whose group model requires buying into the practice to become a partner, medical school doesn’t teach you how to analyze the return on an investment. Providing access to people who have this experience through a mentorship program can help associates be more prepared to become partners, and hopefully be happier and more successful while doing so.

Formalizing a mentorship program

The mentorship program at Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates matches new physicians with a partner-level mentor with whom they are encouraged to meet monthly. We’ve even provided a budget so that mentees and mentors can meet for dinner or coffee and get to know each other better.

The program starts with a meeting of volunteer partners and associates, who then rank their preferred choices for potential mentors. This helps to ensure that the associates are able get to know the mentors a little bit and decide who might be the best fit for their needs. This is also important for new associates who don’t feel comfortable proactively searching for a mentor as they’re able to provide a list of partners they think would be the best match for them.

Each associate is then assigned a partner-level mentor who is responsible for guiding them and providing education around not only clinical care, but also business, marketing, health policy, and all the other critical components of running a successful private practice. Our program specifically pairs mentors and mentees who do not work in the same location. We wanted the mentors to be paired with associates they are not interacting with daily, to ensure our associates get exposed to different perspectives.

As a group, program participants get together every quarter – twice a year in person, and twice virtually. One of the in-person meetings brings together the mentors and mentees with C-suite executives to meet and network with the practice leadership. We organized the program this way because otherwise, most associates wouldn’t get many opportunities to interact with the CEO, chief medical officer, or chief operating officer in any capacity, let alone in a small gathering where they can engage on a personal level.

The second in-person meeting is a dinner with the mentors and mentees, along with their significant others. We understand that all our physicians have responsibilities outside of work, and bringing families together helps provide new associates with a network of support for questions that aren’t work-related. For associates who are not from Atlanta, this can be especially helpful in figuring out housing, schools, and other aspects of work/life balance.

The other two virtual meetings include the C-suite executives and our physician executive board. We develop specific agenda topics related to a career in private practice and provide a forum for the associates to ask practice leadership questions about challenges they may face on their path to becoming a partner.

At the end of each year, we survey the current program participants to see what was successful and what can be improved for the next cohort of incoming associates. So far, the feedback we’ve received from the mentors and mentees has been overwhelmingly positive.

Mentorship benefits the entire practice

As groups continue to grow, more practices may begin to formalize their mentorship programs, particularly those who see the merit they provide in helping recruit and retain valuable associates. To supplement our internal mentorship program, we’ve also started reaching out to local fellowship programs to provide resources to fellows who are considering private practice.

Even though about half of gastroenterology fellows choose independent GI, many aren’t educated about what it means to choose a career in private practice. Our outreach to provide information at the fellowship level is aimed at giving early career physicians an opportunity to know the benefits and challenges associated with private practice. Furthermore, we strive to educate fellows about the resources that are available to guide them through not only joining a group, but also having a successful career.

Leaders of independent GI groups need physicians who want the practice to succeed. Medical school trains physicians to take care of patients but falls short on training physicians to run a business. And building good, strong businesses makes sure that the next generation of leaders are prepared to take over.

Supporting the next generation of practice leaders helps current leadership make changes that will ensure practice sustainability. Often, associates are at the forefront of new technologies, both in terms of patient care, and in terms of practice management, communications, marketing, and advertising. As times change, having associates who are engaged and excited will help any practice be positioned positively for whatever the future holds.

What to look for in joining a practice

Ideally, people should start looking for mentors when they’re looking for a residency program. Joining a practice isn’t much different. If you’re an early career physician who is considering private practice, find an independent GI physician who can tell you about their experiences. And when you’re interviewing with practices, be sure to ask questions about how the group approaches mentorship. If a practice doesn’t have a formal mentorship program, it doesn’t mean it’s an environment where mentorship relationships won’t flourish. In many practices, informal mentorship programs are very successful.

Ask questions about how the practice provides or supports mentorship. Does the practice leadership make themselves available as mentors? Does the practice expect new physicians to find and nurture mentorship relations on their own? Ask about the path to becoming a partner and who is available to discuss challenges, concerns, or any questions that arise.

Independent GI practices are partnerships that seek to provide high-quality care at a lower cost to our community. Strengthening and sustaining that partnership requires us to take the time and continuously invest in the future of new physicians who will go on to serve our community as partner physicians retire. By formalizing a mentorship program, we’re hoping to make it easier for our mentors and mentees to create productive partnerships that will strengthen our group, and ultimately independent gastroenterology overall.

Dr. Sonenshine is a practicing gastroenterologist at Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates, and a partner in United Digestive. He previously served as the chair of communications as a member of the Executive Committee of the Digestive Health Physicians Association. Dr. Sonenshine has no conflicts to declare.

Most GI physicians will tell you that we didn’t get where we are without help along the way. Each of us can point to one – or in most cases, several – specific mentors who provided invaluable guidance when we were in medical school, fellowship, and starting our careers. This is true for gastroenterologists across the spectrum, whether they chose careers in private practice, academic medicine, or within a hospital system.

The leadership at Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates, where I practice, has always recognized the importance of mentorship and its role in developing fulfilling careers for its physicians and a healthy practice culture in which people feel valued and supported. But only recently have we begun to create a formalized program to ensure that everyone has access to mentors.

When I started my career, formalized programs for mentorship did not exist. While I reached out to various doctors in my office and the senior partners throughout the practice, not everyone is comfortable proactively reaching out to ask practice leadership for help and guidance. And as independent GI practices continue to get bigger, there may not be as many opportunities to interact with senior leadership or executives, which means new associates could be left to “cold call” potential mentors by phone or email.

New associates face many challenges

When I was an associate, the path to partnership looked much different than it does in our practice now, and it definitely varies from practice to practice. In our practice, physicians remain associates for 2-3 years before they have the option to become a partner. As they work diligently to provide the best care to patients, new associates face many challenges, like learning how to build a practice and interact with referring physicians, understanding the process to become a partner, and figuring out how to juggle other commitments, such as the balance between work and home life.

Then there are things like buying a home, getting life and disability insurance, and understanding the financial planning aspects of being a business owner. For those whose group model requires buying into the practice to become a partner, medical school doesn’t teach you how to analyze the return on an investment. Providing access to people who have this experience through a mentorship program can help associates be more prepared to become partners, and hopefully be happier and more successful while doing so.

Formalizing a mentorship program

The mentorship program at Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates matches new physicians with a partner-level mentor with whom they are encouraged to meet monthly. We’ve even provided a budget so that mentees and mentors can meet for dinner or coffee and get to know each other better.

The program starts with a meeting of volunteer partners and associates, who then rank their preferred choices for potential mentors. This helps to ensure that the associates are able get to know the mentors a little bit and decide who might be the best fit for their needs. This is also important for new associates who don’t feel comfortable proactively searching for a mentor as they’re able to provide a list of partners they think would be the best match for them.

Each associate is then assigned a partner-level mentor who is responsible for guiding them and providing education around not only clinical care, but also business, marketing, health policy, and all the other critical components of running a successful private practice. Our program specifically pairs mentors and mentees who do not work in the same location. We wanted the mentors to be paired with associates they are not interacting with daily, to ensure our associates get exposed to different perspectives.

As a group, program participants get together every quarter – twice a year in person, and twice virtually. One of the in-person meetings brings together the mentors and mentees with C-suite executives to meet and network with the practice leadership. We organized the program this way because otherwise, most associates wouldn’t get many opportunities to interact with the CEO, chief medical officer, or chief operating officer in any capacity, let alone in a small gathering where they can engage on a personal level.

The second in-person meeting is a dinner with the mentors and mentees, along with their significant others. We understand that all our physicians have responsibilities outside of work, and bringing families together helps provide new associates with a network of support for questions that aren’t work-related. For associates who are not from Atlanta, this can be especially helpful in figuring out housing, schools, and other aspects of work/life balance.

The other two virtual meetings include the C-suite executives and our physician executive board. We develop specific agenda topics related to a career in private practice and provide a forum for the associates to ask practice leadership questions about challenges they may face on their path to becoming a partner.

At the end of each year, we survey the current program participants to see what was successful and what can be improved for the next cohort of incoming associates. So far, the feedback we’ve received from the mentors and mentees has been overwhelmingly positive.

Mentorship benefits the entire practice

As groups continue to grow, more practices may begin to formalize their mentorship programs, particularly those who see the merit they provide in helping recruit and retain valuable associates. To supplement our internal mentorship program, we’ve also started reaching out to local fellowship programs to provide resources to fellows who are considering private practice.

Even though about half of gastroenterology fellows choose independent GI, many aren’t educated about what it means to choose a career in private practice. Our outreach to provide information at the fellowship level is aimed at giving early career physicians an opportunity to know the benefits and challenges associated with private practice. Furthermore, we strive to educate fellows about the resources that are available to guide them through not only joining a group, but also having a successful career.

Leaders of independent GI groups need physicians who want the practice to succeed. Medical school trains physicians to take care of patients but falls short on training physicians to run a business. And building good, strong businesses makes sure that the next generation of leaders are prepared to take over.

Supporting the next generation of practice leaders helps current leadership make changes that will ensure practice sustainability. Often, associates are at the forefront of new technologies, both in terms of patient care, and in terms of practice management, communications, marketing, and advertising. As times change, having associates who are engaged and excited will help any practice be positioned positively for whatever the future holds.

What to look for in joining a practice

Ideally, people should start looking for mentors when they’re looking for a residency program. Joining a practice isn’t much different. If you’re an early career physician who is considering private practice, find an independent GI physician who can tell you about their experiences. And when you’re interviewing with practices, be sure to ask questions about how the group approaches mentorship. If a practice doesn’t have a formal mentorship program, it doesn’t mean it’s an environment where mentorship relationships won’t flourish. In many practices, informal mentorship programs are very successful.

Ask questions about how the practice provides or supports mentorship. Does the practice leadership make themselves available as mentors? Does the practice expect new physicians to find and nurture mentorship relations on their own? Ask about the path to becoming a partner and who is available to discuss challenges, concerns, or any questions that arise.

Independent GI practices are partnerships that seek to provide high-quality care at a lower cost to our community. Strengthening and sustaining that partnership requires us to take the time and continuously invest in the future of new physicians who will go on to serve our community as partner physicians retire. By formalizing a mentorship program, we’re hoping to make it easier for our mentors and mentees to create productive partnerships that will strengthen our group, and ultimately independent gastroenterology overall.

Dr. Sonenshine is a practicing gastroenterologist at Atlanta Gastroenterology Associates, and a partner in United Digestive. He previously served as the chair of communications as a member of the Executive Committee of the Digestive Health Physicians Association. Dr. Sonenshine has no conflicts to declare.

This insurance agent thinks disability insurance deserves a rebrand, and he's a doctor

If you already have disability insurance, keep reading as well. I have a great tip for you from personal experience that made a difference in the job I selected.

Let’s start with an important rebrand for “disability insurance.” What does it protect? Income! Car insurance is not called crash insurance. House insurance is not called burnt house insurance. And unlike a car or a house, it protects an asset with 10-20 times as much value as a million-dollar house.

So, let’s call it what it is: “income protection insurance.”

It’s always a bit nerdy when I talk about how much I appreciate insurance that protects lifelong income. I often make an argument that it is simply one of the best products that exists, especially for high-income earners with lots of debt. Many of us doctors are in that category and are not even slightly jealous of our friends whose parents paid for school (I’m looking at you not-her-real-name-Mary).

Disability is not the catchiest name for a product, but it is more pronounceable than “ophthalmology” and way easier to spell. This is my specialty, and I can’t believe we still haven’t gone with “eye surgeon,” but I digress.

So, let’s rebrand “disability insurance” for the sake of clarity:

I personally like to think of it as a monthly subscription for a soft landing in a worst-case scenario. Call me a millennial, but it just goes down smoother in my mind as a subscription a la Netflix ... and the four other streaming services that someone gave me a password to – if you’re a 55-year-old GI specialist, I know you’re on the Spotify family plan, too. No judgment from me.

So, for $15, you get a bunch of movies with Netflix, and, for $150-$300, you cover a lifetime of income. That’s a pretty decent service even without “The Office.”

Disability insurance often covers at least $15-$20 million dollars over a lifetime of earnings for only 1%-2% of your salary per year.

But I’ll pause here. The numbers are irrelevant if you never get the insurance.

I have one goal for this article, and it is simply to try to help you break down that procrastination habit we all have. I will have added immense value to at least one family’s life if you go and get a policy this week that saves your family from substantial loss of income. This is why I love insurance.

Doctors sacrifice essential life steps to get through training. But we are not alone in that.

Tim Kasser, PhD, puts it well when he said: “We live in a machine that is designed to get us to neglect what is important about life.” Here he is talking about relationships, but securing financial protection is loving to those closest to us.

So, what holds us back from taking a seemingly easy step like locking in disability insurance early in training?

Is it the stress of residency? Studying for Step 1? Moving cities and finding a home during a housing crisis? Job change during COVID? Is it because we have already put it off so long that we don’t want to think about it?

Totally fair.

For all of us busy doctors, the necessity and obviousness of buying disability insurance, *ehem*, income protection insurance makes you feel like you can get to it when you get to it because you know you will, so ... what’s the rush?

Or, is it our desire to bet on ourselves, and every month that goes by without insurance is one less payment? Roll the dice! Woo!

The reason to not put off the important things in life

I will give you a few reasons of “the why of” how we can all benefit from disability insurance and the reason there is no benefit in waiting to get a policy.

But, most importantly, I want to talk to you about your life and why you are putting off a lot of important things.

That diet you’ve been wanting to start? Yep.

That ring you haven’t purchased? Maybe that!

That article you’ve been meaning to write for the GI journal? Yes, especially that.

Remember: Take a deep breath in and exhaaaaale.

So, why do we put off the important?

First, even though the “why” of purchasing income protection is a bit basic, I do find it helpful to have discrete reasons for accomplishing an important task.

Why get disability insurance at all?

Let’s look at the value we get out of covering our income.

Reason No. 1. It softens the landing in the event you have an illness. The stats on disability claims are heavily on the side of illness over accidents or trauma. As you know, many autoimmune conditions show up in the 20’s and 30’s, so those are the things your friends will have first.

Unfortunately, if you have a medical issue before you have a disability policy, you will either not have coverage for that specific condition or you will not be approved for insurance. Unlike health insurance, the company can afford to pay out policies because it is picky on who it is willing to cover. It tries to select healthy people, so apply when you are most healthy, if possible.

Reason No. 2. It’s cheap. When you compare with a $2 million policy for life insurance, it might cost $1,000-$2,000 or so per year for a term policy covering about 25 years. With disability insurance, you can cover about 10x as much for the same annual payment. One could easily make a case that if you do not have dependents, disability insurance should be your first stop even before life insurance. You are more likely to be disabled than to die when you’re in your thirties. Act accordingly.

(Please note for obvious reasons they don’t call life insurance “death insurance.” Disability insurance needs that same rebrand – I’m telling you!)

Reason No. 3. Unless you are independently wealthy, it will be nearly impossible to replace your income and live a similar lifestyle. Lock in the benefits of the work you have already accomplished, and lock in the coverage of ALL of your health while you are healthy.

Time to take action

As Elvis famously sang: “A little less conversation, a little more action please.”

Alright, so how do we get ourselves to ACT and get a policy to protect our income?

Tip No. 1. As doctors we often shoot for perfection. It’s no surprise, therefore, that we have an illusion that we need to find the “perfect policy.”

One of my friends is a great financial adviser, and he often tells me about first meetings with clients to create a long-lasting plan. Often, somewhere along the way when discussing risks of stocks going down and up, someone will ask, “Why don’t we pick one that is low risk but tends to go up in value?” Of course, the reality is that if it were that easy ... everyone would do it!

Fortunately, with disability insurance, the policies are fairly straight forward. You can skip the analysis paralysis with disability insurance by talking with an agent who consistently works with physicians. I enjoy talking policies and helping doctors protect their financial health, so I started selling policies shortly after residency because so many of my co-residents were making me nervous putting it off. Some I helped, and some put it off and are unable to get policies after health issues even just 3 years after residency.

Tip No. 2. Having a policy is better than not having one, and if you’re worried about getting the wrong one, just get two! Seriously, some companies let you split coverage between two and this can even increase the maximum coverage you can get later in life, too. Does it add cost? Surprisingly, it typically does not, and it does not make the agent more money either. In most cases it’s actually more work for them for the same amount of commission. Don’t be afraid to ask about this.

Tip No. 3. This is my hot tip for current policy owners: ask for the full version of your policy, and read the entire policy. I recently asked for my policy because I was doing some international work abroad and wanted to know if I could reside abroad if I made a disability claim. My policy stated that I would need to reside in the United States within 12 months of disability. I likely would do this in the event of disability, but it is quite important to know these aspects.

While reading the fine print, I found that a minimum number of work-hours per week (35 for my policy) was required to qualify for my physician-specific coverage. This was an important part of my job criteria when looking for a new position and is worth investigating for anyone considering part-time employment.

Tip No. 4. The obvious tip: The fear of failure gets a lot of perfectionists from even starting a task unless they know everything about it.

Just start.

That’s my go-to for overcoming fear of failure. You won’t fail. You just won’t. You will learn!

Pretend you are curious about it and try with any of these actionable steps:

- Google disability insurance.

- Email me at [email protected].

- Read an article on a doctor-based blog.

I personally geeked out on insurance so much in residency that I became an insurance agent. I am an independent broker, so I have no bias toward any particular policies (email me anytime even if just with questions). Personally, I believe in this product and the value of this type of insurance, and I would hate for anyone to not have coverage of their most valuable asset: lifelong income!

The steps of applying for disability insurance

Now you know all the great reasons to get going! What are the next steps?

No matter where you get your policy, you can expect the process to be fairly simple. If it’s not then shoot me an email and I’m happy to help chat and discuss further.

The general process is:

Step 1. Initial phone call or email: Chat with an agent to discuss your needs and situation. Immediately after, you can sign initial application documents with DocuSign. (20 minutes).

Step 2. Complete health questionnaire on the phone with the insurance company. (20-40 minutes).

Step 3. Sign the final documents and confirm physician-specific language in their policies. (20 minutes).

The whole application period typically lasts only 2-4 weeks from start to finish and, if you pay up front, you are covered from the moment you send in the check. If you don’t accept the policy, you even get the money back.

I genuinely enjoy talking with my colleagues from all over the world and learning about their lives and plans, so, if you have any questions, please do not hesitate to email me at [email protected]. Also, feel free to check out my mini-blog at curiousmd.com or listen to me chat with Jon Solitro, CFP, on his FinancialMD.com podcast. Similar to this article, it is fairly informal and covers real life, tough career decisions, and actionable financial planning tips.

If you made it to the end of this article, you are a perfectionist and should go back and read Tip No. 1.

Reference

The Context of Things. “We live in a machine that is designed to get us to neglect what’s important about life,” 2021 Aug 24.

Dr. Smith is an ophthalmologist and consultant with Advanced Eyecare Professionals, Grand Rapids, Mich., and founder of DigitalGlaucoma.com. He is cohost of The FinancialMD Show podcast. He is an insurance producer and assists clients with advising and decision-making related to disability insurance at FinancialMD.

If you already have disability insurance, keep reading as well. I have a great tip for you from personal experience that made a difference in the job I selected.

Let’s start with an important rebrand for “disability insurance.” What does it protect? Income! Car insurance is not called crash insurance. House insurance is not called burnt house insurance. And unlike a car or a house, it protects an asset with 10-20 times as much value as a million-dollar house.

So, let’s call it what it is: “income protection insurance.”

It’s always a bit nerdy when I talk about how much I appreciate insurance that protects lifelong income. I often make an argument that it is simply one of the best products that exists, especially for high-income earners with lots of debt. Many of us doctors are in that category and are not even slightly jealous of our friends whose parents paid for school (I’m looking at you not-her-real-name-Mary).

Disability is not the catchiest name for a product, but it is more pronounceable than “ophthalmology” and way easier to spell. This is my specialty, and I can’t believe we still haven’t gone with “eye surgeon,” but I digress.

So, let’s rebrand “disability insurance” for the sake of clarity:

I personally like to think of it as a monthly subscription for a soft landing in a worst-case scenario. Call me a millennial, but it just goes down smoother in my mind as a subscription a la Netflix ... and the four other streaming services that someone gave me a password to – if you’re a 55-year-old GI specialist, I know you’re on the Spotify family plan, too. No judgment from me.

So, for $15, you get a bunch of movies with Netflix, and, for $150-$300, you cover a lifetime of income. That’s a pretty decent service even without “The Office.”

Disability insurance often covers at least $15-$20 million dollars over a lifetime of earnings for only 1%-2% of your salary per year.

But I’ll pause here. The numbers are irrelevant if you never get the insurance.

I have one goal for this article, and it is simply to try to help you break down that procrastination habit we all have. I will have added immense value to at least one family’s life if you go and get a policy this week that saves your family from substantial loss of income. This is why I love insurance.

Doctors sacrifice essential life steps to get through training. But we are not alone in that.

Tim Kasser, PhD, puts it well when he said: “We live in a machine that is designed to get us to neglect what is important about life.” Here he is talking about relationships, but securing financial protection is loving to those closest to us.

So, what holds us back from taking a seemingly easy step like locking in disability insurance early in training?

Is it the stress of residency? Studying for Step 1? Moving cities and finding a home during a housing crisis? Job change during COVID? Is it because we have already put it off so long that we don’t want to think about it?

Totally fair.

For all of us busy doctors, the necessity and obviousness of buying disability insurance, *ehem*, income protection insurance makes you feel like you can get to it when you get to it because you know you will, so ... what’s the rush?

Or, is it our desire to bet on ourselves, and every month that goes by without insurance is one less payment? Roll the dice! Woo!

The reason to not put off the important things in life

I will give you a few reasons of “the why of” how we can all benefit from disability insurance and the reason there is no benefit in waiting to get a policy.

But, most importantly, I want to talk to you about your life and why you are putting off a lot of important things.

That diet you’ve been wanting to start? Yep.

That ring you haven’t purchased? Maybe that!

That article you’ve been meaning to write for the GI journal? Yes, especially that.

Remember: Take a deep breath in and exhaaaaale.

So, why do we put off the important?

First, even though the “why” of purchasing income protection is a bit basic, I do find it helpful to have discrete reasons for accomplishing an important task.

Why get disability insurance at all?

Let’s look at the value we get out of covering our income.

Reason No. 1. It softens the landing in the event you have an illness. The stats on disability claims are heavily on the side of illness over accidents or trauma. As you know, many autoimmune conditions show up in the 20’s and 30’s, so those are the things your friends will have first.

Unfortunately, if you have a medical issue before you have a disability policy, you will either not have coverage for that specific condition or you will not be approved for insurance. Unlike health insurance, the company can afford to pay out policies because it is picky on who it is willing to cover. It tries to select healthy people, so apply when you are most healthy, if possible.

Reason No. 2. It’s cheap. When you compare with a $2 million policy for life insurance, it might cost $1,000-$2,000 or so per year for a term policy covering about 25 years. With disability insurance, you can cover about 10x as much for the same annual payment. One could easily make a case that if you do not have dependents, disability insurance should be your first stop even before life insurance. You are more likely to be disabled than to die when you’re in your thirties. Act accordingly.

(Please note for obvious reasons they don’t call life insurance “death insurance.” Disability insurance needs that same rebrand – I’m telling you!)

Reason No. 3. Unless you are independently wealthy, it will be nearly impossible to replace your income and live a similar lifestyle. Lock in the benefits of the work you have already accomplished, and lock in the coverage of ALL of your health while you are healthy.

Time to take action

As Elvis famously sang: “A little less conversation, a little more action please.”

Alright, so how do we get ourselves to ACT and get a policy to protect our income?

Tip No. 1. As doctors we often shoot for perfection. It’s no surprise, therefore, that we have an illusion that we need to find the “perfect policy.”

One of my friends is a great financial adviser, and he often tells me about first meetings with clients to create a long-lasting plan. Often, somewhere along the way when discussing risks of stocks going down and up, someone will ask, “Why don’t we pick one that is low risk but tends to go up in value?” Of course, the reality is that if it were that easy ... everyone would do it!

Fortunately, with disability insurance, the policies are fairly straight forward. You can skip the analysis paralysis with disability insurance by talking with an agent who consistently works with physicians. I enjoy talking policies and helping doctors protect their financial health, so I started selling policies shortly after residency because so many of my co-residents were making me nervous putting it off. Some I helped, and some put it off and are unable to get policies after health issues even just 3 years after residency.

Tip No. 2. Having a policy is better than not having one, and if you’re worried about getting the wrong one, just get two! Seriously, some companies let you split coverage between two and this can even increase the maximum coverage you can get later in life, too. Does it add cost? Surprisingly, it typically does not, and it does not make the agent more money either. In most cases it’s actually more work for them for the same amount of commission. Don’t be afraid to ask about this.

Tip No. 3. This is my hot tip for current policy owners: ask for the full version of your policy, and read the entire policy. I recently asked for my policy because I was doing some international work abroad and wanted to know if I could reside abroad if I made a disability claim. My policy stated that I would need to reside in the United States within 12 months of disability. I likely would do this in the event of disability, but it is quite important to know these aspects.

While reading the fine print, I found that a minimum number of work-hours per week (35 for my policy) was required to qualify for my physician-specific coverage. This was an important part of my job criteria when looking for a new position and is worth investigating for anyone considering part-time employment.

Tip No. 4. The obvious tip: The fear of failure gets a lot of perfectionists from even starting a task unless they know everything about it.

Just start.

That’s my go-to for overcoming fear of failure. You won’t fail. You just won’t. You will learn!

Pretend you are curious about it and try with any of these actionable steps:

- Google disability insurance.

- Email me at [email protected].

- Read an article on a doctor-based blog.

I personally geeked out on insurance so much in residency that I became an insurance agent. I am an independent broker, so I have no bias toward any particular policies (email me anytime even if just with questions). Personally, I believe in this product and the value of this type of insurance, and I would hate for anyone to not have coverage of their most valuable asset: lifelong income!

The steps of applying for disability insurance

Now you know all the great reasons to get going! What are the next steps?

No matter where you get your policy, you can expect the process to be fairly simple. If it’s not then shoot me an email and I’m happy to help chat and discuss further.

The general process is:

Step 1. Initial phone call or email: Chat with an agent to discuss your needs and situation. Immediately after, you can sign initial application documents with DocuSign. (20 minutes).

Step 2. Complete health questionnaire on the phone with the insurance company. (20-40 minutes).

Step 3. Sign the final documents and confirm physician-specific language in their policies. (20 minutes).

The whole application period typically lasts only 2-4 weeks from start to finish and, if you pay up front, you are covered from the moment you send in the check. If you don’t accept the policy, you even get the money back.

I genuinely enjoy talking with my colleagues from all over the world and learning about their lives and plans, so, if you have any questions, please do not hesitate to email me at [email protected]. Also, feel free to check out my mini-blog at curiousmd.com or listen to me chat with Jon Solitro, CFP, on his FinancialMD.com podcast. Similar to this article, it is fairly informal and covers real life, tough career decisions, and actionable financial planning tips.

If you made it to the end of this article, you are a perfectionist and should go back and read Tip No. 1.

Reference

The Context of Things. “We live in a machine that is designed to get us to neglect what’s important about life,” 2021 Aug 24.

Dr. Smith is an ophthalmologist and consultant with Advanced Eyecare Professionals, Grand Rapids, Mich., and founder of DigitalGlaucoma.com. He is cohost of The FinancialMD Show podcast. He is an insurance producer and assists clients with advising and decision-making related to disability insurance at FinancialMD.

If you already have disability insurance, keep reading as well. I have a great tip for you from personal experience that made a difference in the job I selected.

Let’s start with an important rebrand for “disability insurance.” What does it protect? Income! Car insurance is not called crash insurance. House insurance is not called burnt house insurance. And unlike a car or a house, it protects an asset with 10-20 times as much value as a million-dollar house.

So, let’s call it what it is: “income protection insurance.”

It’s always a bit nerdy when I talk about how much I appreciate insurance that protects lifelong income. I often make an argument that it is simply one of the best products that exists, especially for high-income earners with lots of debt. Many of us doctors are in that category and are not even slightly jealous of our friends whose parents paid for school (I’m looking at you not-her-real-name-Mary).

Disability is not the catchiest name for a product, but it is more pronounceable than “ophthalmology” and way easier to spell. This is my specialty, and I can’t believe we still haven’t gone with “eye surgeon,” but I digress.

So, let’s rebrand “disability insurance” for the sake of clarity:

I personally like to think of it as a monthly subscription for a soft landing in a worst-case scenario. Call me a millennial, but it just goes down smoother in my mind as a subscription a la Netflix ... and the four other streaming services that someone gave me a password to – if you’re a 55-year-old GI specialist, I know you’re on the Spotify family plan, too. No judgment from me.

So, for $15, you get a bunch of movies with Netflix, and, for $150-$300, you cover a lifetime of income. That’s a pretty decent service even without “The Office.”

Disability insurance often covers at least $15-$20 million dollars over a lifetime of earnings for only 1%-2% of your salary per year.

But I’ll pause here. The numbers are irrelevant if you never get the insurance.

I have one goal for this article, and it is simply to try to help you break down that procrastination habit we all have. I will have added immense value to at least one family’s life if you go and get a policy this week that saves your family from substantial loss of income. This is why I love insurance.

Doctors sacrifice essential life steps to get through training. But we are not alone in that.

Tim Kasser, PhD, puts it well when he said: “We live in a machine that is designed to get us to neglect what is important about life.” Here he is talking about relationships, but securing financial protection is loving to those closest to us.

So, what holds us back from taking a seemingly easy step like locking in disability insurance early in training?

Is it the stress of residency? Studying for Step 1? Moving cities and finding a home during a housing crisis? Job change during COVID? Is it because we have already put it off so long that we don’t want to think about it?

Totally fair.

For all of us busy doctors, the necessity and obviousness of buying disability insurance, *ehem*, income protection insurance makes you feel like you can get to it when you get to it because you know you will, so ... what’s the rush?

Or, is it our desire to bet on ourselves, and every month that goes by without insurance is one less payment? Roll the dice! Woo!

The reason to not put off the important things in life

I will give you a few reasons of “the why of” how we can all benefit from disability insurance and the reason there is no benefit in waiting to get a policy.

But, most importantly, I want to talk to you about your life and why you are putting off a lot of important things.

That diet you’ve been wanting to start? Yep.

That ring you haven’t purchased? Maybe that!

That article you’ve been meaning to write for the GI journal? Yes, especially that.

Remember: Take a deep breath in and exhaaaaale.

So, why do we put off the important?

First, even though the “why” of purchasing income protection is a bit basic, I do find it helpful to have discrete reasons for accomplishing an important task.

Why get disability insurance at all?

Let’s look at the value we get out of covering our income.

Reason No. 1. It softens the landing in the event you have an illness. The stats on disability claims are heavily on the side of illness over accidents or trauma. As you know, many autoimmune conditions show up in the 20’s and 30’s, so those are the things your friends will have first.

Unfortunately, if you have a medical issue before you have a disability policy, you will either not have coverage for that specific condition or you will not be approved for insurance. Unlike health insurance, the company can afford to pay out policies because it is picky on who it is willing to cover. It tries to select healthy people, so apply when you are most healthy, if possible.

Reason No. 2. It’s cheap. When you compare with a $2 million policy for life insurance, it might cost $1,000-$2,000 or so per year for a term policy covering about 25 years. With disability insurance, you can cover about 10x as much for the same annual payment. One could easily make a case that if you do not have dependents, disability insurance should be your first stop even before life insurance. You are more likely to be disabled than to die when you’re in your thirties. Act accordingly.

(Please note for obvious reasons they don’t call life insurance “death insurance.” Disability insurance needs that same rebrand – I’m telling you!)

Reason No. 3. Unless you are independently wealthy, it will be nearly impossible to replace your income and live a similar lifestyle. Lock in the benefits of the work you have already accomplished, and lock in the coverage of ALL of your health while you are healthy.

Time to take action

As Elvis famously sang: “A little less conversation, a little more action please.”

Alright, so how do we get ourselves to ACT and get a policy to protect our income?

Tip No. 1. As doctors we often shoot for perfection. It’s no surprise, therefore, that we have an illusion that we need to find the “perfect policy.”

One of my friends is a great financial adviser, and he often tells me about first meetings with clients to create a long-lasting plan. Often, somewhere along the way when discussing risks of stocks going down and up, someone will ask, “Why don’t we pick one that is low risk but tends to go up in value?” Of course, the reality is that if it were that easy ... everyone would do it!

Fortunately, with disability insurance, the policies are fairly straight forward. You can skip the analysis paralysis with disability insurance by talking with an agent who consistently works with physicians. I enjoy talking policies and helping doctors protect their financial health, so I started selling policies shortly after residency because so many of my co-residents were making me nervous putting it off. Some I helped, and some put it off and are unable to get policies after health issues even just 3 years after residency.

Tip No. 2. Having a policy is better than not having one, and if you’re worried about getting the wrong one, just get two! Seriously, some companies let you split coverage between two and this can even increase the maximum coverage you can get later in life, too. Does it add cost? Surprisingly, it typically does not, and it does not make the agent more money either. In most cases it’s actually more work for them for the same amount of commission. Don’t be afraid to ask about this.

Tip No. 3. This is my hot tip for current policy owners: ask for the full version of your policy, and read the entire policy. I recently asked for my policy because I was doing some international work abroad and wanted to know if I could reside abroad if I made a disability claim. My policy stated that I would need to reside in the United States within 12 months of disability. I likely would do this in the event of disability, but it is quite important to know these aspects.

While reading the fine print, I found that a minimum number of work-hours per week (35 for my policy) was required to qualify for my physician-specific coverage. This was an important part of my job criteria when looking for a new position and is worth investigating for anyone considering part-time employment.

Tip No. 4. The obvious tip: The fear of failure gets a lot of perfectionists from even starting a task unless they know everything about it.

Just start.

That’s my go-to for overcoming fear of failure. You won’t fail. You just won’t. You will learn!

Pretend you are curious about it and try with any of these actionable steps:

- Google disability insurance.

- Email me at [email protected].

- Read an article on a doctor-based blog.

I personally geeked out on insurance so much in residency that I became an insurance agent. I am an independent broker, so I have no bias toward any particular policies (email me anytime even if just with questions). Personally, I believe in this product and the value of this type of insurance, and I would hate for anyone to not have coverage of their most valuable asset: lifelong income!

The steps of applying for disability insurance

Now you know all the great reasons to get going! What are the next steps?

No matter where you get your policy, you can expect the process to be fairly simple. If it’s not then shoot me an email and I’m happy to help chat and discuss further.

The general process is:

Step 1. Initial phone call or email: Chat with an agent to discuss your needs and situation. Immediately after, you can sign initial application documents with DocuSign. (20 minutes).

Step 2. Complete health questionnaire on the phone with the insurance company. (20-40 minutes).

Step 3. Sign the final documents and confirm physician-specific language in their policies. (20 minutes).

The whole application period typically lasts only 2-4 weeks from start to finish and, if you pay up front, you are covered from the moment you send in the check. If you don’t accept the policy, you even get the money back.

I genuinely enjoy talking with my colleagues from all over the world and learning about their lives and plans, so, if you have any questions, please do not hesitate to email me at [email protected]. Also, feel free to check out my mini-blog at curiousmd.com or listen to me chat with Jon Solitro, CFP, on his FinancialMD.com podcast. Similar to this article, it is fairly informal and covers real life, tough career decisions, and actionable financial planning tips.

If you made it to the end of this article, you are a perfectionist and should go back and read Tip No. 1.

Reference

The Context of Things. “We live in a machine that is designed to get us to neglect what’s important about life,” 2021 Aug 24.

Dr. Smith is an ophthalmologist and consultant with Advanced Eyecare Professionals, Grand Rapids, Mich., and founder of DigitalGlaucoma.com. He is cohost of The FinancialMD Show podcast. He is an insurance producer and assists clients with advising and decision-making related to disability insurance at FinancialMD.

Repeat endoscopy for deliberate foreign body ingestions

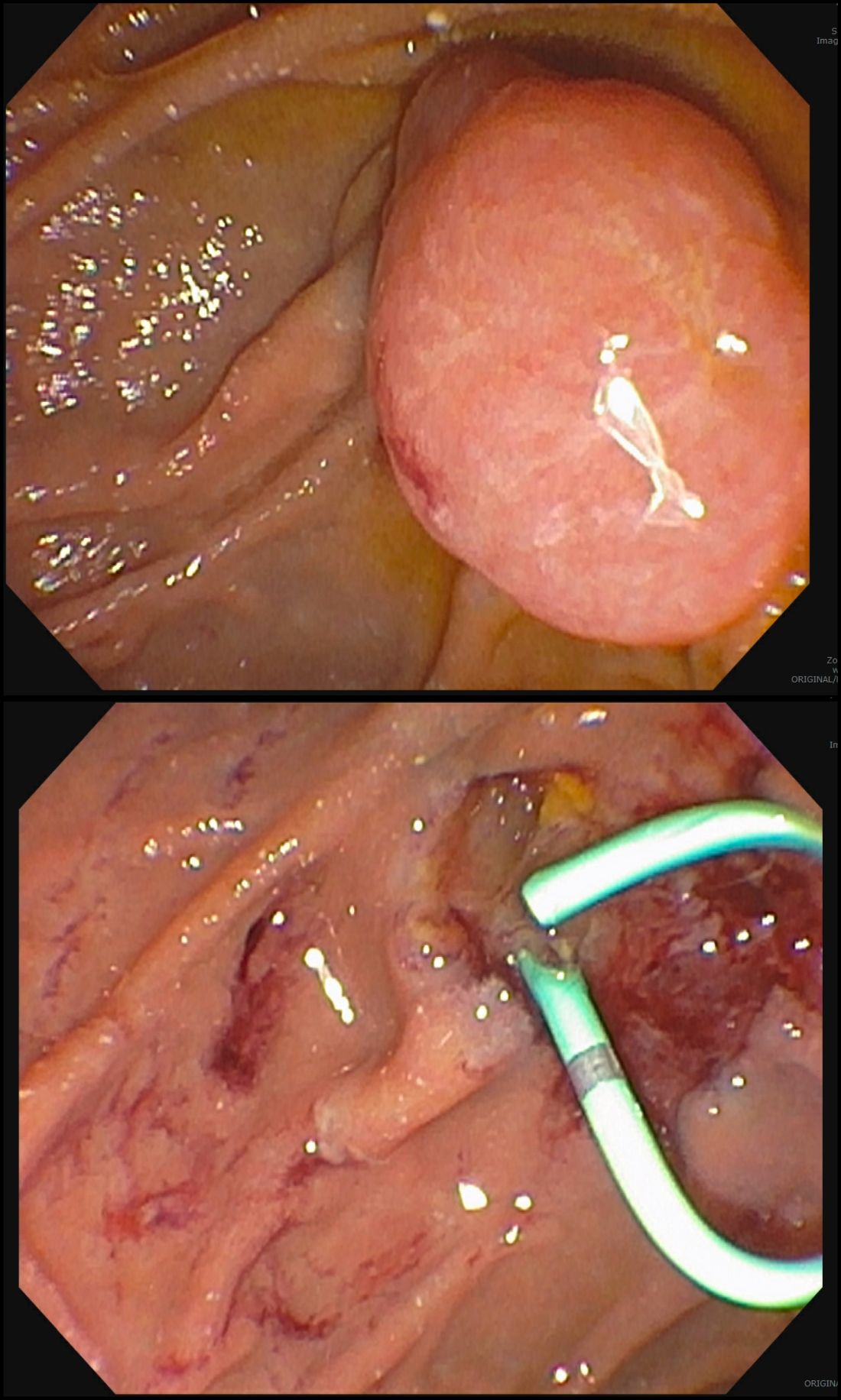

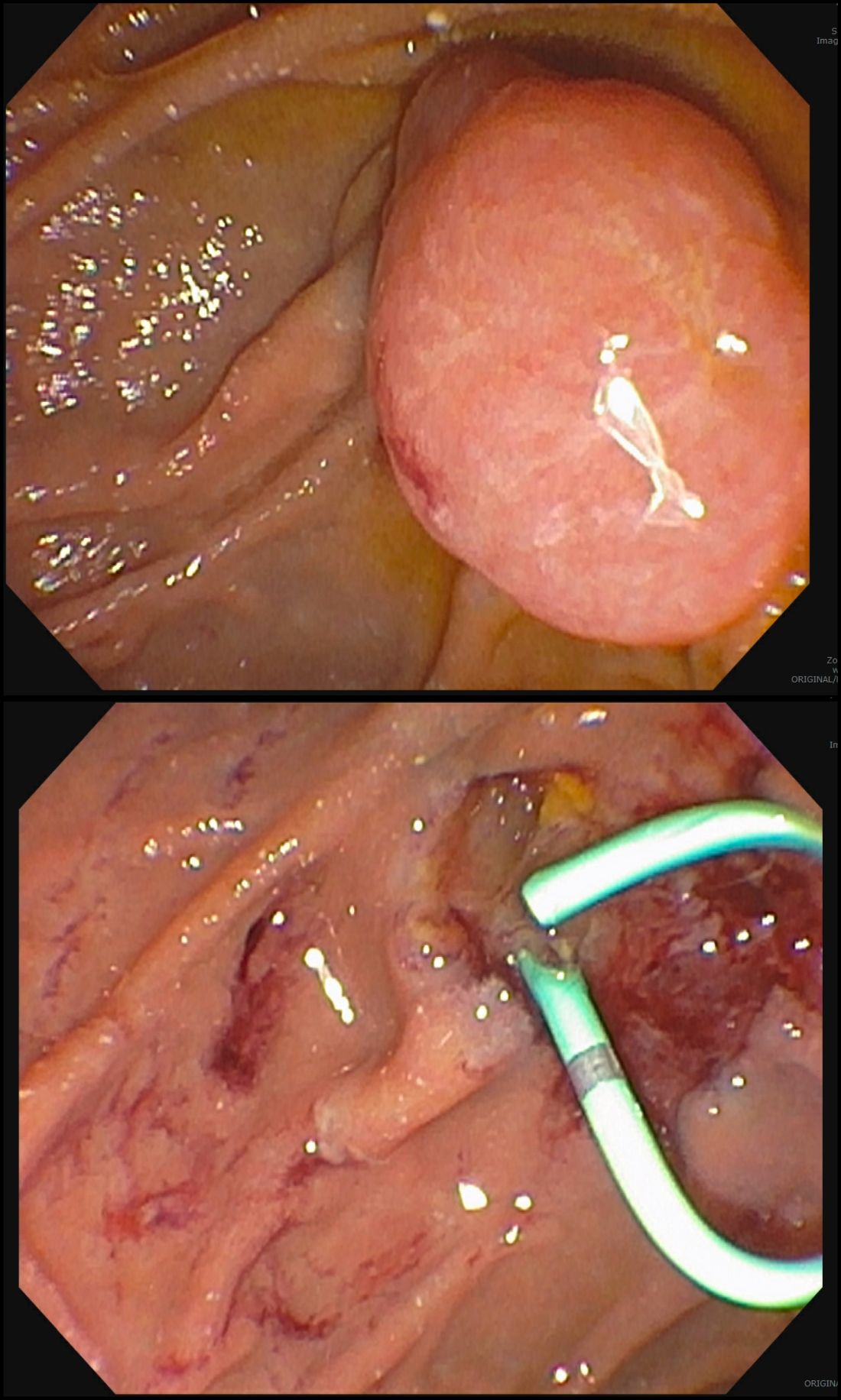

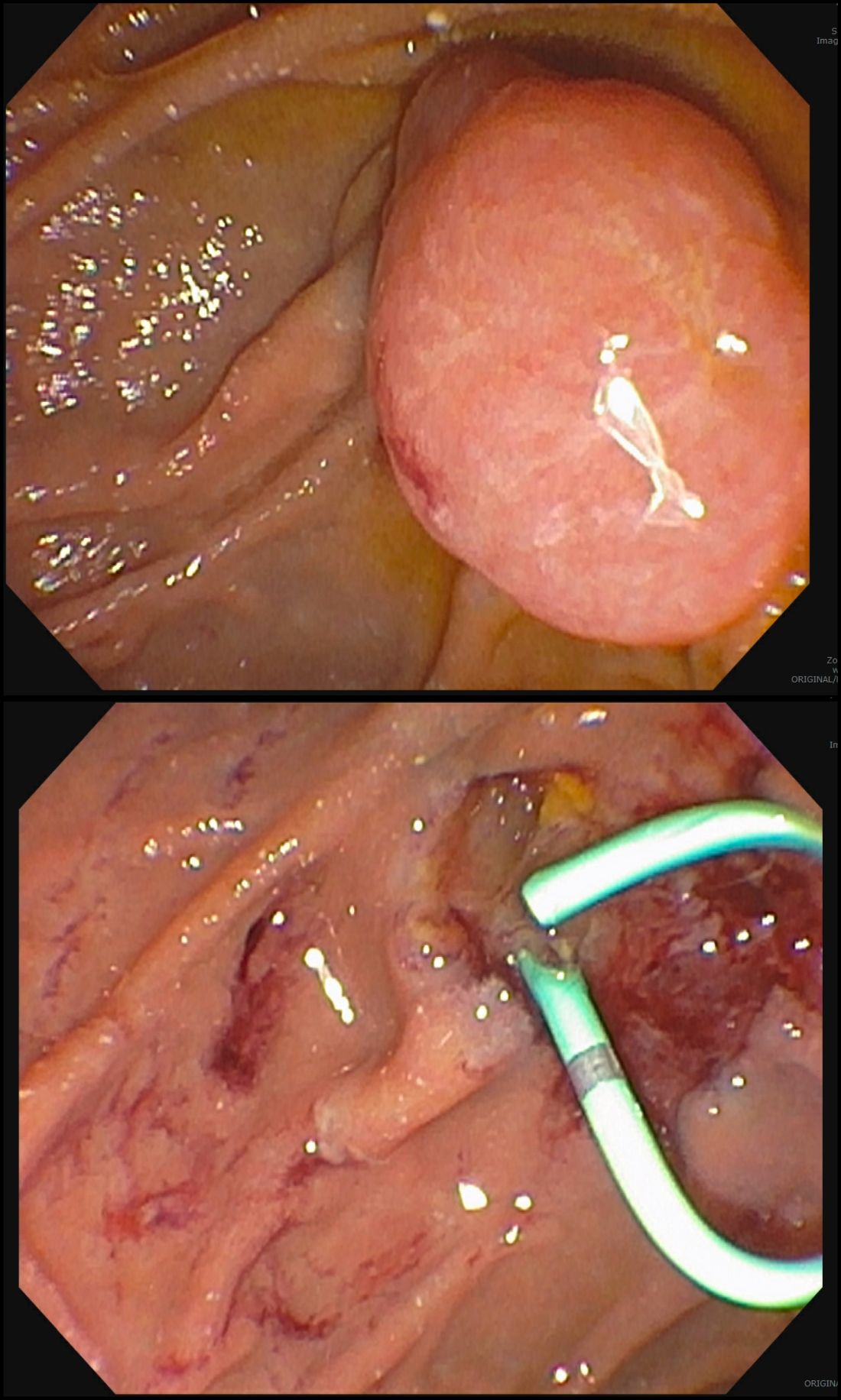

A 35-year-old female with a complex psychiatric history and polysubstance use presents to the emergency department following ingestion of three sewing needles. The patient has a long history of multiple suicide attempts and foreign-body ingestions requiring repeated endoscopy. Prior ingestions include, but are not limited to, razor blades, screws, toothbrushes, batteries, plastic cutlery, and shower curtain rings. The patient has had over 50 upper endoscopies within the past year in addition to a laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy for retrieval of foreign bodies. Despite intensive inpatient psychiatric treatment and outpatient behavioral therapy, the patient continues to present with recurrent ingestions, creating frustration among multiple health care providers. Are gastroenterologists obligated to perform repeated endoscopies for recurrent foreign-body ingestions? Is there a point at which it would be medically and ethically appropriate to defer endoscopy in this clinical scenario?

Deliberate foreign-body ingestion (DFBI) is a psychological disorder in which patients swallow nonnutritive objects. The disorder is commonly seen in young female patients with psychiatric disorders.1 It is also associated with substance abuse, intellectual disabilities, and malingering (such as external motivation to avoid jail). Of those with psychiatric disorders, repeat ingestions are primarily seen in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) or part of a syndrome of self-mutilation or attention-seeking behavior.2 Patients with BPD are thought to have atrophic changes in the brain causing neurocognitive dysfunction accounting for such behaviors.1 Self-injurious behavior is also associated with a history of abandonment and childhood abuse.3 Studies show that 85% of patients evaluated for DFBI have a prior psychiatric diagnosis and 84% of these patients have a history of prior ingestions.4

In this case, the patient’s needles were successfully removed endoscopically. The psychiatry service adjusted her medication regimen and conducted a prolonged behavioral therapy session focused on coping strategies and impulse control. The following morning, the patient managed to overpower her 24-hour 1:1 sitter to ingest a pen. Endoscopy was performed again, with successful removal of the pen.

Although intentional ingestions occur in a small subset of patients, DFBI utilizes significant hospital and fiscal resources. The startling economic impact of caring for these patients was demonstrated in a cost analysis at a large academic center in Rhode Island. It found 33 patients with repeated ingestions accounted for over 300 endoscopies in an 8-year period culminating in a total hospitalization cost of 2 million dollars per year.5 Another study estimated the average cost of a patient with DFBI per hospital visit to be $6,616 in the United States with an average length of stay of 5.6 days.6 The cost burden is largely caused by the repetitive nature of the clinical presentation and involvement of multiple disciplines, including emergency medicine, gastroenterology, anesthesia, psychiatry, social work, security services, and in some cases, otolaryngology, pulmonology, and surgery.

In addition to endoscopy, an inpatient admission for DFBI centers around preventing repeated ingestions. This entails constant observation by security or a sitter, limiting access to objects through restraints or room modifications, and psychiatry consultation for management of the underlying psychiatric disorder. Studies show this management approach rarely succeeds in preventing recurrent ingestions.6 Interestingly, data also shows inpatient psychiatric admission is not beneficial in preventing recurrent DFBI and can paradoxically increase the frequency of swallowing behavior in some patients.6 This patient failed multiple inpatient treatment programs and was noncompliant with outpatient therapies. Given the costly burden to the health care system and propensity of repeated behavior, should this patient continue to receive endoscopies? Would it ever be justifiable to forgo endoscopic retrieval?

One of the fundamental principles of medical ethics is beneficence, supporting the notion that all providers should act in the best interest of the patient. Adults may make poor or self-destructive choices, but that does not preclude our moral obligation to treat them. Patients with substance abuse disorders may repeatedly use emergency room services for acute intoxication and overdose treatment. An emergency department physician would not withhold Narcan from a patient simply because of the frequency of repeated overdoses. A similar rationale could be applied to patients with DFBI – they should undergo endoscopy if they are accepting of the risks/benefits of repeated procedures. Given that this patient’s repeated ingestions are suicide attempts, it could be argued that not removing the object would make a clinician complicit with a patient’s suicide attempt or intent of self-harm.

From an alternative vantage point, patients with repeated DFBI have an increased risk of complications with repeated endoscopy, especially when performed emergently. Patients may have an increased risk of aspiration because of insufficient preoperative fasting, and attempted removal of ingested needles and other sharp objects carries a high risk of penetrating trauma, bleeding, and perforation. The patient’s swallowing history predicts a high likelihood of repeat ingestion which, over time, makes subsequent endoscopies seem futile. Endoscopic treatment does not address the underlying problem and only serves as a temporary fix to bridge the patient to their next ingestion. Furthermore, the utilization of resources is substantial – namely, the repeated emergency use of anesthesia and operating room and endoscopy staff, as well as the psychiatry, surgical, internal medicine, and gastroenterology services. Inevitably, treatment of a patient such as this diverts limited health care resources away from other patients who may have equally or more pressing medical needs.

Despite the seemingly futile nature of these procedures and strain on resources, it would be difficult from a medicolegal perspective to justify withholding endoscopy. In 1986, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act was enacted that requires anyone presenting to an emergency department to be stabilized and treated.7 In this particular patient case, an ethics consultation was obtained and recommended that the patient continue to undergo endoscopy. However, the team also suggested that a multidisciplinary meeting with ethics, the primary and procedural teams, and the hospital’s medicolegal department be held to further elucidate a plan for future admissions and to decide if or when it may be appropriate to withhold invasive procedures. This case was presented at our weekly gastroenterology grand rounds, and procedural guidelines were reviewed. Given the size and nature of most of the objects the patient ingests, we reviewed that it would be safe in the majority of scenarios to wait until the morning for removal if called overnight – providing some relief to those on call while minimizing utilization of emergency anesthesia resources as well as operating room and endoscopy staff.

Caring for these patients is challenging as providers may feel frustrated and angry after repeated admissions. The patient may sense the low morale from providers and feel judged for their actions. It is theorized that this leads to repeated ingestions as a defense mechanism and a means of acting out.1 Additionally, friction can develop between teams as there is a common perception that psychiatry is not “doing enough” to treat the psychiatric disorder to prevent recurrences.8

In conclusion, DFBIs occur in a small number of patients with psychiatric disorders, but account for a large utilization of health care recourses. Gastroenterologists have an ethical and legal obligation to provide treatment including repeat endoscopies as long as the therapeutic benefit of the procedure outweighs risks. A multidisciplinary approach with individualized care plans can help prevent recurrent hospitalizations and procedures which may, in turn, improve outcomes and reduce health care costs.1 Until the patient and clinicians can successfully mitigate the psychiatric and social factors perpetuating repeated ingestions, gastroenterologists will continue to provide endoscopic management. Individual cases should be discussed with the hospital’s ethics and medicolegal teams for further guidance on deferring endoscopic treatment in cases of medically refractory psychological disease.

Dr. Sims is a gastroenterology fellow in the section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of internal medicine, University of Chicago Medicine. Dr. Rao is assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of internal medicine, University of Chicago Medicine. They had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

1. Bangash F et al. Cureus. 2021 Feb;13(2):e13179. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13179

2. Palese C et al. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012 July;8(7):485-6

3. Gitlin GF et al. Psychosomatics, 2007 March;48(2):162-6. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.2.162

4. Palta R et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009 March;69(3):426-33. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.072

5. Huang BL et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Nov;8(11):941-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.07.013

6. Poynter BA et al. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011 Sep-Oct;33(5):518-24. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.06.011

7. American College of Emergency Physicians, EMTALA Fact Sheet. https://www.acep.org/life-as-a-physician/ethics--legal/emtala/emtala-fact-sheet/

8. Grzenda A. Carlat Hosp Psych Report. 2021 Jan;1(1 ):5-9

A 35-year-old female with a complex psychiatric history and polysubstance use presents to the emergency department following ingestion of three sewing needles. The patient has a long history of multiple suicide attempts and foreign-body ingestions requiring repeated endoscopy. Prior ingestions include, but are not limited to, razor blades, screws, toothbrushes, batteries, plastic cutlery, and shower curtain rings. The patient has had over 50 upper endoscopies within the past year in addition to a laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy for retrieval of foreign bodies. Despite intensive inpatient psychiatric treatment and outpatient behavioral therapy, the patient continues to present with recurrent ingestions, creating frustration among multiple health care providers. Are gastroenterologists obligated to perform repeated endoscopies for recurrent foreign-body ingestions? Is there a point at which it would be medically and ethically appropriate to defer endoscopy in this clinical scenario?

Deliberate foreign-body ingestion (DFBI) is a psychological disorder in which patients swallow nonnutritive objects. The disorder is commonly seen in young female patients with psychiatric disorders.1 It is also associated with substance abuse, intellectual disabilities, and malingering (such as external motivation to avoid jail). Of those with psychiatric disorders, repeat ingestions are primarily seen in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) or part of a syndrome of self-mutilation or attention-seeking behavior.2 Patients with BPD are thought to have atrophic changes in the brain causing neurocognitive dysfunction accounting for such behaviors.1 Self-injurious behavior is also associated with a history of abandonment and childhood abuse.3 Studies show that 85% of patients evaluated for DFBI have a prior psychiatric diagnosis and 84% of these patients have a history of prior ingestions.4

In this case, the patient’s needles were successfully removed endoscopically. The psychiatry service adjusted her medication regimen and conducted a prolonged behavioral therapy session focused on coping strategies and impulse control. The following morning, the patient managed to overpower her 24-hour 1:1 sitter to ingest a pen. Endoscopy was performed again, with successful removal of the pen.

Although intentional ingestions occur in a small subset of patients, DFBI utilizes significant hospital and fiscal resources. The startling economic impact of caring for these patients was demonstrated in a cost analysis at a large academic center in Rhode Island. It found 33 patients with repeated ingestions accounted for over 300 endoscopies in an 8-year period culminating in a total hospitalization cost of 2 million dollars per year.5 Another study estimated the average cost of a patient with DFBI per hospital visit to be $6,616 in the United States with an average length of stay of 5.6 days.6 The cost burden is largely caused by the repetitive nature of the clinical presentation and involvement of multiple disciplines, including emergency medicine, gastroenterology, anesthesia, psychiatry, social work, security services, and in some cases, otolaryngology, pulmonology, and surgery.

In addition to endoscopy, an inpatient admission for DFBI centers around preventing repeated ingestions. This entails constant observation by security or a sitter, limiting access to objects through restraints or room modifications, and psychiatry consultation for management of the underlying psychiatric disorder. Studies show this management approach rarely succeeds in preventing recurrent ingestions.6 Interestingly, data also shows inpatient psychiatric admission is not beneficial in preventing recurrent DFBI and can paradoxically increase the frequency of swallowing behavior in some patients.6 This patient failed multiple inpatient treatment programs and was noncompliant with outpatient therapies. Given the costly burden to the health care system and propensity of repeated behavior, should this patient continue to receive endoscopies? Would it ever be justifiable to forgo endoscopic retrieval?

One of the fundamental principles of medical ethics is beneficence, supporting the notion that all providers should act in the best interest of the patient. Adults may make poor or self-destructive choices, but that does not preclude our moral obligation to treat them. Patients with substance abuse disorders may repeatedly use emergency room services for acute intoxication and overdose treatment. An emergency department physician would not withhold Narcan from a patient simply because of the frequency of repeated overdoses. A similar rationale could be applied to patients with DFBI – they should undergo endoscopy if they are accepting of the risks/benefits of repeated procedures. Given that this patient’s repeated ingestions are suicide attempts, it could be argued that not removing the object would make a clinician complicit with a patient’s suicide attempt or intent of self-harm.

From an alternative vantage point, patients with repeated DFBI have an increased risk of complications with repeated endoscopy, especially when performed emergently. Patients may have an increased risk of aspiration because of insufficient preoperative fasting, and attempted removal of ingested needles and other sharp objects carries a high risk of penetrating trauma, bleeding, and perforation. The patient’s swallowing history predicts a high likelihood of repeat ingestion which, over time, makes subsequent endoscopies seem futile. Endoscopic treatment does not address the underlying problem and only serves as a temporary fix to bridge the patient to their next ingestion. Furthermore, the utilization of resources is substantial – namely, the repeated emergency use of anesthesia and operating room and endoscopy staff, as well as the psychiatry, surgical, internal medicine, and gastroenterology services. Inevitably, treatment of a patient such as this diverts limited health care resources away from other patients who may have equally or more pressing medical needs.

Despite the seemingly futile nature of these procedures and strain on resources, it would be difficult from a medicolegal perspective to justify withholding endoscopy. In 1986, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act was enacted that requires anyone presenting to an emergency department to be stabilized and treated.7 In this particular patient case, an ethics consultation was obtained and recommended that the patient continue to undergo endoscopy. However, the team also suggested that a multidisciplinary meeting with ethics, the primary and procedural teams, and the hospital’s medicolegal department be held to further elucidate a plan for future admissions and to decide if or when it may be appropriate to withhold invasive procedures. This case was presented at our weekly gastroenterology grand rounds, and procedural guidelines were reviewed. Given the size and nature of most of the objects the patient ingests, we reviewed that it would be safe in the majority of scenarios to wait until the morning for removal if called overnight – providing some relief to those on call while minimizing utilization of emergency anesthesia resources as well as operating room and endoscopy staff.

Caring for these patients is challenging as providers may feel frustrated and angry after repeated admissions. The patient may sense the low morale from providers and feel judged for their actions. It is theorized that this leads to repeated ingestions as a defense mechanism and a means of acting out.1 Additionally, friction can develop between teams as there is a common perception that psychiatry is not “doing enough” to treat the psychiatric disorder to prevent recurrences.8