User login

My path: Challenges and decisions along the way

It took me a little while to get started on this assignment. What would be most useful to young gastroenterologists embarking on their careers? When I asked around, I heard that many of you wanted me to describe challenges and decision points. The following list is vaguely chronological, surely noncomprehensive, and meant to serve as a starting point.

1. To stay in basic science or return to patient care

My start in science was rocky. I had come to the United States for a post-doc after medical school in Germany. I had never pipetted before. It was the early days of array technologies, and the lab was very technical and basic. We made our own arrays and our own analytics, and none of my experiments worked. So, I spent 1 year feeling like I made no progress – but in hindsight I appreciate the tremendous growth in these formative years honing inquiry and persistence, as well as building resilience. I added a third year as some results were finally emerging; however, the bedside started to feel very far away. I could not ignore the tug back to the patient care, and after contemplating a PhD program, I decided to apply for residency in a physician-scientist pathway. Given the streamlined training that allowed for science and clinical education in an organized fashion, I also decided to stay in the U.S. This of course had vast personal consequences, which I did not fully appreciate at the time.

Residency was another time of immense growth, I was the only “foreign medical graduate” and had a lot to catch up on, but I enjoyed my amazing peers and the hands-on learning.

Pearl: Follow your passion. Not what makes most sense or what someone wants for you or what you could achieve given your past work. Do what will get you up in the morning and add a bounce to your step.

2. To go for big impact or climate

At UCSD at the time, there was a culture of impactful mega-labs, up 30 post-docs, often with many working on the same project with the ones finishing first garnering the publication. This created a “go big or go home” (literally) atmosphere. As part of the PSTP program, I was supported by the GI T32 and, being “free labor,” had a pretty wide array of labs to choose from. To the program director’s surprise, I settled on a fairly junior investigator, who was a fellow gastroenterologist and took a personal interest in my career. When making that decision, I prioritized climate over outcome. I remember thinking to myself that how I spent my time was just as important as the potential outcome of the time spent. Through my years in Dr. John Carethers’ lab, I gained insight into his administrative and leadership roles which added another dimension to our mentorship relationship. These years were fun and productive, and our mentorship grew into a friendship.

Pearl: Look for the right people to work with. Particularly who you work for. Everything else is secondary as the right people will set the tone and most influence your day-to-day experience, which is the foundation of your success.

3. To cultivate a life outside of academia

When I turned 30, I remember driving down Interstate 5 in San Diego and taking stock. Yes, I loved clinical work, I felt valued, and was in a stimulating supportive environment. Yet, I was so immersed that everything else seemed to take a back seat. I made the conscious decision on that drive to prioritize life outside of academia. It is not like I did not have one, I just decided to set an intention so it would not get away from me. I continue to make a conscious effort to be present for my husband, my kids, my family – to take time and spend it together without work bleeding into it. And since this is a goal in and of itself, there is no conflict! Through less travel and no more late nights or weekends, your nonacademic life will flourish.

Pearl: Deliberately prioritize your family and hobbies in the long run. Make key decisions with that in mind.

4. To grow your own program or lead others

When we moved to Chicago for my husband’s residency (he went to medical school as his third career at age 35), I was very excited to build my own comprehensive GI cancer genetics program at Northwestern. It was a little scary but also fun to now run my own lab and try to connect the clinical community around hereditary GI cancers. The program was moving along nicely when I received a generic letter asking for applications to become division chief at the neighboring University of Illinois. The letter concluded with an enticing “Chicago is a vibrant city,” so clearly it was meant for a broad audience. I was not sure what to do and again took stock. Did I want to continue to increase the impact of my own work – clearly there was a lot more ground to cover. Or, did I want to be part of making further-reaching decisions? I had been approached by fellows who wanted to be recruited, and I had ideas for programs and thoughts around processes. While my input was valued, I was not the ultimate decision maker. I decided that I either focus on one or the other and so applied for the position and then took the leap.

Pearl: There are many forks and they will present when you do not expect them. Assess and consider. Also know yourself – not everything that is attainable is desirable.

5. To have greater influence or stay with what you know

Becoming a division chief was transformative. Learning to integrate the needs of various and sometimes conflicting stakeholders, running an operation but also thinking strategically and mission-based – I was drinking from a firehose. How to measure success as a leader? I was fortunate to enter the division at a turbulent time where much rebuilding was needed and it was easy to implement and see change.

Pearl: Again know yourself – not everything that is attainable is desirable. But also – take risks. What is the worst that can happen? Growth may not be attained by waiting.

6. To be spread too thin or close doors

As you develop your focus and expertise while implementing No. 3, you will run out of hours in the day. This means you will need to become more and more efficient, as in delegating (and letting go) where you can and doing fewer nonessential tasks. However, you want to think hard about closing doors completely. I have been careful to hone and keep my endoscopy skills as well as my scientific output. To leave the doors ajar, I have tried to find ways to be very deliberate with my involvement and also understand that at some point it may make sense to close a door.

Pearl: Do not try to do everything well, you will risk doing everything poorly. Work on “good enough” for tasks that can be very involved. Think hard before permanently leaving something behind as you may lose flexibility down the road.

7. To enjoy fruits of labor or continue to grow

A question I get asked often is regarding the ideal time to move. In my mind, there is no perfect time. It depends on your satisfaction with your current position (see No. 2), your personal situation (see No. 3), and what you want at that juncture (see No. 5). At some point, one may want to stay awhile and enjoy. Or continue to change and grow – both have their merits and there is no right or wrong.

Pearl: When contemplating next steps, go back to your passion and priorities. Has anything shifted? Are your goals being met? Are you enjoying yourself? Advice can be helpful but also confusing. Remember, no one knows you like you do.

8. To show tangible results or build out relationships

Over time, as you become more and more efficient, you simultaneously need to spend more time fostering relationships. This feels strange at first as it is the opposite of a fast-paced to-do list and the “results” appear elusive. Build in time for relating – with peers, superiors, fellows, members of your lab.

Pearl: Form relationships early and often. Take care of them (No. 3) and include relationship building into your workstream – I promise it will make your path more successful and satisfying.

I hope this list shows that there are many forks and no one right way. Advice is helpful and subjective. No path is the same, and it truly is yours to shape. Be thoughtful and enjoy – your journey will be amazing and full of surprises.

Dr. Jung is professor and chair, and the Robert G. Petersdorf Endowed Chair in Medicine, in the department of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. She is on Twitter @barbarahjung. She has no conflicts of interest.

It took me a little while to get started on this assignment. What would be most useful to young gastroenterologists embarking on their careers? When I asked around, I heard that many of you wanted me to describe challenges and decision points. The following list is vaguely chronological, surely noncomprehensive, and meant to serve as a starting point.

1. To stay in basic science or return to patient care

My start in science was rocky. I had come to the United States for a post-doc after medical school in Germany. I had never pipetted before. It was the early days of array technologies, and the lab was very technical and basic. We made our own arrays and our own analytics, and none of my experiments worked. So, I spent 1 year feeling like I made no progress – but in hindsight I appreciate the tremendous growth in these formative years honing inquiry and persistence, as well as building resilience. I added a third year as some results were finally emerging; however, the bedside started to feel very far away. I could not ignore the tug back to the patient care, and after contemplating a PhD program, I decided to apply for residency in a physician-scientist pathway. Given the streamlined training that allowed for science and clinical education in an organized fashion, I also decided to stay in the U.S. This of course had vast personal consequences, which I did not fully appreciate at the time.

Residency was another time of immense growth, I was the only “foreign medical graduate” and had a lot to catch up on, but I enjoyed my amazing peers and the hands-on learning.

Pearl: Follow your passion. Not what makes most sense or what someone wants for you or what you could achieve given your past work. Do what will get you up in the morning and add a bounce to your step.

2. To go for big impact or climate

At UCSD at the time, there was a culture of impactful mega-labs, up 30 post-docs, often with many working on the same project with the ones finishing first garnering the publication. This created a “go big or go home” (literally) atmosphere. As part of the PSTP program, I was supported by the GI T32 and, being “free labor,” had a pretty wide array of labs to choose from. To the program director’s surprise, I settled on a fairly junior investigator, who was a fellow gastroenterologist and took a personal interest in my career. When making that decision, I prioritized climate over outcome. I remember thinking to myself that how I spent my time was just as important as the potential outcome of the time spent. Through my years in Dr. John Carethers’ lab, I gained insight into his administrative and leadership roles which added another dimension to our mentorship relationship. These years were fun and productive, and our mentorship grew into a friendship.

Pearl: Look for the right people to work with. Particularly who you work for. Everything else is secondary as the right people will set the tone and most influence your day-to-day experience, which is the foundation of your success.

3. To cultivate a life outside of academia

When I turned 30, I remember driving down Interstate 5 in San Diego and taking stock. Yes, I loved clinical work, I felt valued, and was in a stimulating supportive environment. Yet, I was so immersed that everything else seemed to take a back seat. I made the conscious decision on that drive to prioritize life outside of academia. It is not like I did not have one, I just decided to set an intention so it would not get away from me. I continue to make a conscious effort to be present for my husband, my kids, my family – to take time and spend it together without work bleeding into it. And since this is a goal in and of itself, there is no conflict! Through less travel and no more late nights or weekends, your nonacademic life will flourish.

Pearl: Deliberately prioritize your family and hobbies in the long run. Make key decisions with that in mind.

4. To grow your own program or lead others

When we moved to Chicago for my husband’s residency (he went to medical school as his third career at age 35), I was very excited to build my own comprehensive GI cancer genetics program at Northwestern. It was a little scary but also fun to now run my own lab and try to connect the clinical community around hereditary GI cancers. The program was moving along nicely when I received a generic letter asking for applications to become division chief at the neighboring University of Illinois. The letter concluded with an enticing “Chicago is a vibrant city,” so clearly it was meant for a broad audience. I was not sure what to do and again took stock. Did I want to continue to increase the impact of my own work – clearly there was a lot more ground to cover. Or, did I want to be part of making further-reaching decisions? I had been approached by fellows who wanted to be recruited, and I had ideas for programs and thoughts around processes. While my input was valued, I was not the ultimate decision maker. I decided that I either focus on one or the other and so applied for the position and then took the leap.

Pearl: There are many forks and they will present when you do not expect them. Assess and consider. Also know yourself – not everything that is attainable is desirable.

5. To have greater influence or stay with what you know

Becoming a division chief was transformative. Learning to integrate the needs of various and sometimes conflicting stakeholders, running an operation but also thinking strategically and mission-based – I was drinking from a firehose. How to measure success as a leader? I was fortunate to enter the division at a turbulent time where much rebuilding was needed and it was easy to implement and see change.

Pearl: Again know yourself – not everything that is attainable is desirable. But also – take risks. What is the worst that can happen? Growth may not be attained by waiting.

6. To be spread too thin or close doors

As you develop your focus and expertise while implementing No. 3, you will run out of hours in the day. This means you will need to become more and more efficient, as in delegating (and letting go) where you can and doing fewer nonessential tasks. However, you want to think hard about closing doors completely. I have been careful to hone and keep my endoscopy skills as well as my scientific output. To leave the doors ajar, I have tried to find ways to be very deliberate with my involvement and also understand that at some point it may make sense to close a door.

Pearl: Do not try to do everything well, you will risk doing everything poorly. Work on “good enough” for tasks that can be very involved. Think hard before permanently leaving something behind as you may lose flexibility down the road.

7. To enjoy fruits of labor or continue to grow

A question I get asked often is regarding the ideal time to move. In my mind, there is no perfect time. It depends on your satisfaction with your current position (see No. 2), your personal situation (see No. 3), and what you want at that juncture (see No. 5). At some point, one may want to stay awhile and enjoy. Or continue to change and grow – both have their merits and there is no right or wrong.

Pearl: When contemplating next steps, go back to your passion and priorities. Has anything shifted? Are your goals being met? Are you enjoying yourself? Advice can be helpful but also confusing. Remember, no one knows you like you do.

8. To show tangible results or build out relationships

Over time, as you become more and more efficient, you simultaneously need to spend more time fostering relationships. This feels strange at first as it is the opposite of a fast-paced to-do list and the “results” appear elusive. Build in time for relating – with peers, superiors, fellows, members of your lab.

Pearl: Form relationships early and often. Take care of them (No. 3) and include relationship building into your workstream – I promise it will make your path more successful and satisfying.

I hope this list shows that there are many forks and no one right way. Advice is helpful and subjective. No path is the same, and it truly is yours to shape. Be thoughtful and enjoy – your journey will be amazing and full of surprises.

Dr. Jung is professor and chair, and the Robert G. Petersdorf Endowed Chair in Medicine, in the department of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. She is on Twitter @barbarahjung. She has no conflicts of interest.

It took me a little while to get started on this assignment. What would be most useful to young gastroenterologists embarking on their careers? When I asked around, I heard that many of you wanted me to describe challenges and decision points. The following list is vaguely chronological, surely noncomprehensive, and meant to serve as a starting point.

1. To stay in basic science or return to patient care

My start in science was rocky. I had come to the United States for a post-doc after medical school in Germany. I had never pipetted before. It was the early days of array technologies, and the lab was very technical and basic. We made our own arrays and our own analytics, and none of my experiments worked. So, I spent 1 year feeling like I made no progress – but in hindsight I appreciate the tremendous growth in these formative years honing inquiry and persistence, as well as building resilience. I added a third year as some results were finally emerging; however, the bedside started to feel very far away. I could not ignore the tug back to the patient care, and after contemplating a PhD program, I decided to apply for residency in a physician-scientist pathway. Given the streamlined training that allowed for science and clinical education in an organized fashion, I also decided to stay in the U.S. This of course had vast personal consequences, which I did not fully appreciate at the time.

Residency was another time of immense growth, I was the only “foreign medical graduate” and had a lot to catch up on, but I enjoyed my amazing peers and the hands-on learning.

Pearl: Follow your passion. Not what makes most sense or what someone wants for you or what you could achieve given your past work. Do what will get you up in the morning and add a bounce to your step.

2. To go for big impact or climate

At UCSD at the time, there was a culture of impactful mega-labs, up 30 post-docs, often with many working on the same project with the ones finishing first garnering the publication. This created a “go big or go home” (literally) atmosphere. As part of the PSTP program, I was supported by the GI T32 and, being “free labor,” had a pretty wide array of labs to choose from. To the program director’s surprise, I settled on a fairly junior investigator, who was a fellow gastroenterologist and took a personal interest in my career. When making that decision, I prioritized climate over outcome. I remember thinking to myself that how I spent my time was just as important as the potential outcome of the time spent. Through my years in Dr. John Carethers’ lab, I gained insight into his administrative and leadership roles which added another dimension to our mentorship relationship. These years were fun and productive, and our mentorship grew into a friendship.

Pearl: Look for the right people to work with. Particularly who you work for. Everything else is secondary as the right people will set the tone and most influence your day-to-day experience, which is the foundation of your success.

3. To cultivate a life outside of academia

When I turned 30, I remember driving down Interstate 5 in San Diego and taking stock. Yes, I loved clinical work, I felt valued, and was in a stimulating supportive environment. Yet, I was so immersed that everything else seemed to take a back seat. I made the conscious decision on that drive to prioritize life outside of academia. It is not like I did not have one, I just decided to set an intention so it would not get away from me. I continue to make a conscious effort to be present for my husband, my kids, my family – to take time and spend it together without work bleeding into it. And since this is a goal in and of itself, there is no conflict! Through less travel and no more late nights or weekends, your nonacademic life will flourish.

Pearl: Deliberately prioritize your family and hobbies in the long run. Make key decisions with that in mind.

4. To grow your own program or lead others

When we moved to Chicago for my husband’s residency (he went to medical school as his third career at age 35), I was very excited to build my own comprehensive GI cancer genetics program at Northwestern. It was a little scary but also fun to now run my own lab and try to connect the clinical community around hereditary GI cancers. The program was moving along nicely when I received a generic letter asking for applications to become division chief at the neighboring University of Illinois. The letter concluded with an enticing “Chicago is a vibrant city,” so clearly it was meant for a broad audience. I was not sure what to do and again took stock. Did I want to continue to increase the impact of my own work – clearly there was a lot more ground to cover. Or, did I want to be part of making further-reaching decisions? I had been approached by fellows who wanted to be recruited, and I had ideas for programs and thoughts around processes. While my input was valued, I was not the ultimate decision maker. I decided that I either focus on one or the other and so applied for the position and then took the leap.

Pearl: There are many forks and they will present when you do not expect them. Assess and consider. Also know yourself – not everything that is attainable is desirable.

5. To have greater influence or stay with what you know

Becoming a division chief was transformative. Learning to integrate the needs of various and sometimes conflicting stakeholders, running an operation but also thinking strategically and mission-based – I was drinking from a firehose. How to measure success as a leader? I was fortunate to enter the division at a turbulent time where much rebuilding was needed and it was easy to implement and see change.

Pearl: Again know yourself – not everything that is attainable is desirable. But also – take risks. What is the worst that can happen? Growth may not be attained by waiting.

6. To be spread too thin or close doors

As you develop your focus and expertise while implementing No. 3, you will run out of hours in the day. This means you will need to become more and more efficient, as in delegating (and letting go) where you can and doing fewer nonessential tasks. However, you want to think hard about closing doors completely. I have been careful to hone and keep my endoscopy skills as well as my scientific output. To leave the doors ajar, I have tried to find ways to be very deliberate with my involvement and also understand that at some point it may make sense to close a door.

Pearl: Do not try to do everything well, you will risk doing everything poorly. Work on “good enough” for tasks that can be very involved. Think hard before permanently leaving something behind as you may lose flexibility down the road.

7. To enjoy fruits of labor or continue to grow

A question I get asked often is regarding the ideal time to move. In my mind, there is no perfect time. It depends on your satisfaction with your current position (see No. 2), your personal situation (see No. 3), and what you want at that juncture (see No. 5). At some point, one may want to stay awhile and enjoy. Or continue to change and grow – both have their merits and there is no right or wrong.

Pearl: When contemplating next steps, go back to your passion and priorities. Has anything shifted? Are your goals being met? Are you enjoying yourself? Advice can be helpful but also confusing. Remember, no one knows you like you do.

8. To show tangible results or build out relationships

Over time, as you become more and more efficient, you simultaneously need to spend more time fostering relationships. This feels strange at first as it is the opposite of a fast-paced to-do list and the “results” appear elusive. Build in time for relating – with peers, superiors, fellows, members of your lab.

Pearl: Form relationships early and often. Take care of them (No. 3) and include relationship building into your workstream – I promise it will make your path more successful and satisfying.

I hope this list shows that there are many forks and no one right way. Advice is helpful and subjective. No path is the same, and it truly is yours to shape. Be thoughtful and enjoy – your journey will be amazing and full of surprises.

Dr. Jung is professor and chair, and the Robert G. Petersdorf Endowed Chair in Medicine, in the department of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. She is on Twitter @barbarahjung. She has no conflicts of interest.

Management of gastroparesis in 2022

Introduction

Patients presenting with the symptoms of gastroparesis (Gp) are commonly seen in gastroenterology practice.

Presentation

Patients with foregut symptoms of Gp have characteristic presentations, with nausea, vomiting/retching, and abdominal pain often associated with bloating and distension, early satiety, anorexia, and heartburn. Mid- and hindgut gastrointestinal and/or urinary symptoms may be seen in patients with Gp as well.

The precise epidemiology of gastroparesis syndromes (GpS) is unknown. Classic gastroparesis, defined as delayed gastric emptying without known mechanical obstruction, has a prevalence of about 10 per 100,000 population in men and 30 per 100,000 in women with women being affected 3 to 4 times more than men.1,2 Some risk factors for GpS, such as diabetes mellitus (DM) in up to 5% of patients with Type 1 DM, are known.3 Caucasians have the highest prevalence of GpS, followed by African Americans.4,5

The classic definition of Gp has blurred with the realization that patients may have symptoms of Gp without delayed solid gastric emptying. Some patients have been described as having chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting or gastroparesis like syndrome.6 More recently the NIH Gastroparesis Consortium has proposed that disorders like functional dyspepsia may be a spectrum of the two disorders and classic Gp.7 Using this broadened definition, the number of patients with Gp symptoms is much greater, found in 10% or more of the U.S. population.8 For this discussion, GpS is used to encompass this spectrum of disorders.

The etiology of GpS is often unknown for a given patient, but clues to etiology exist in what is known about pathophysiology. Types of Gp are described as being idiopathic, diabetic, or postsurgical, each of which may have varying pathophysiology. Many patients with mild-to-moderate GpS symptoms are effectively treated with out-patient therapies; other patients may be refractory to available treatments. Refractory GpS patients have a high burden of illness affecting them, their families, providers, hospitals, and payers.

Pathophysiology

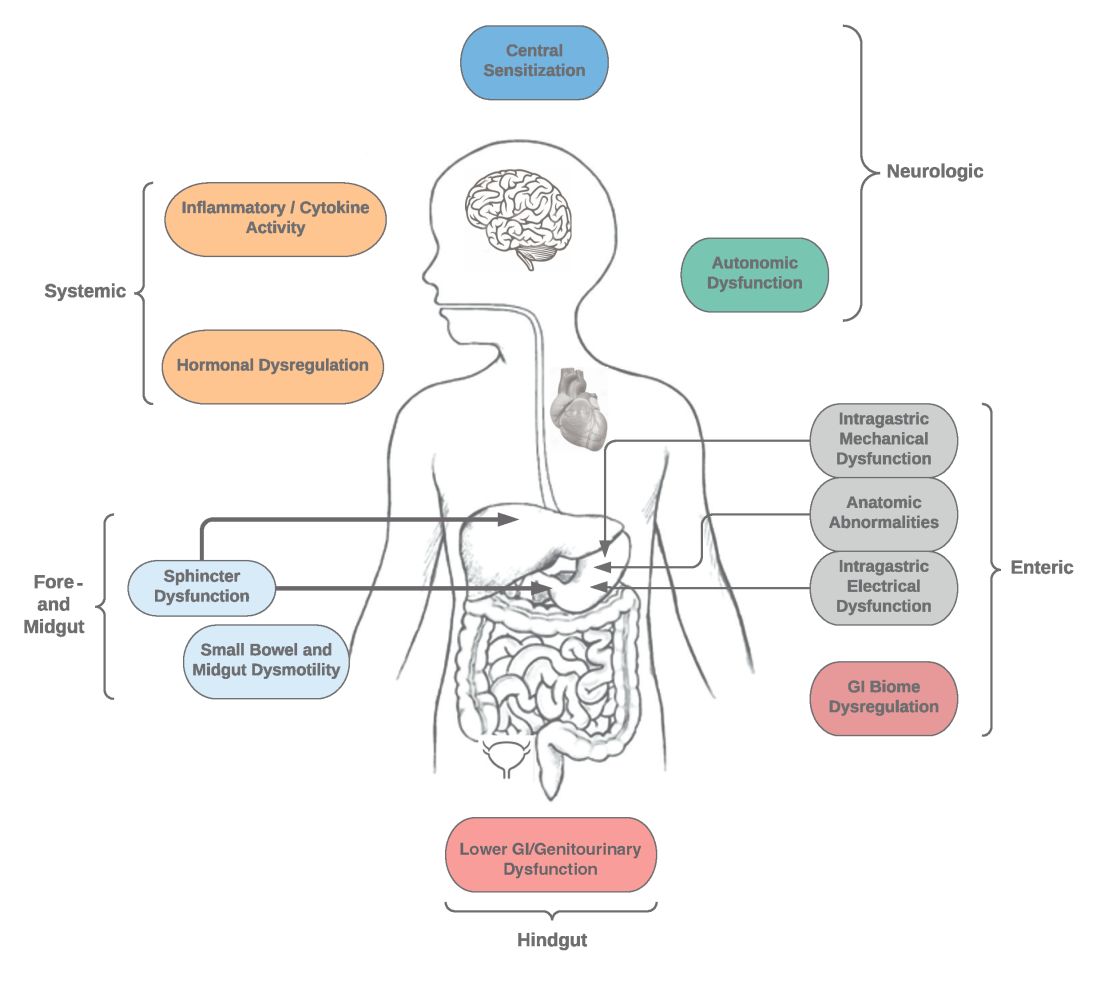

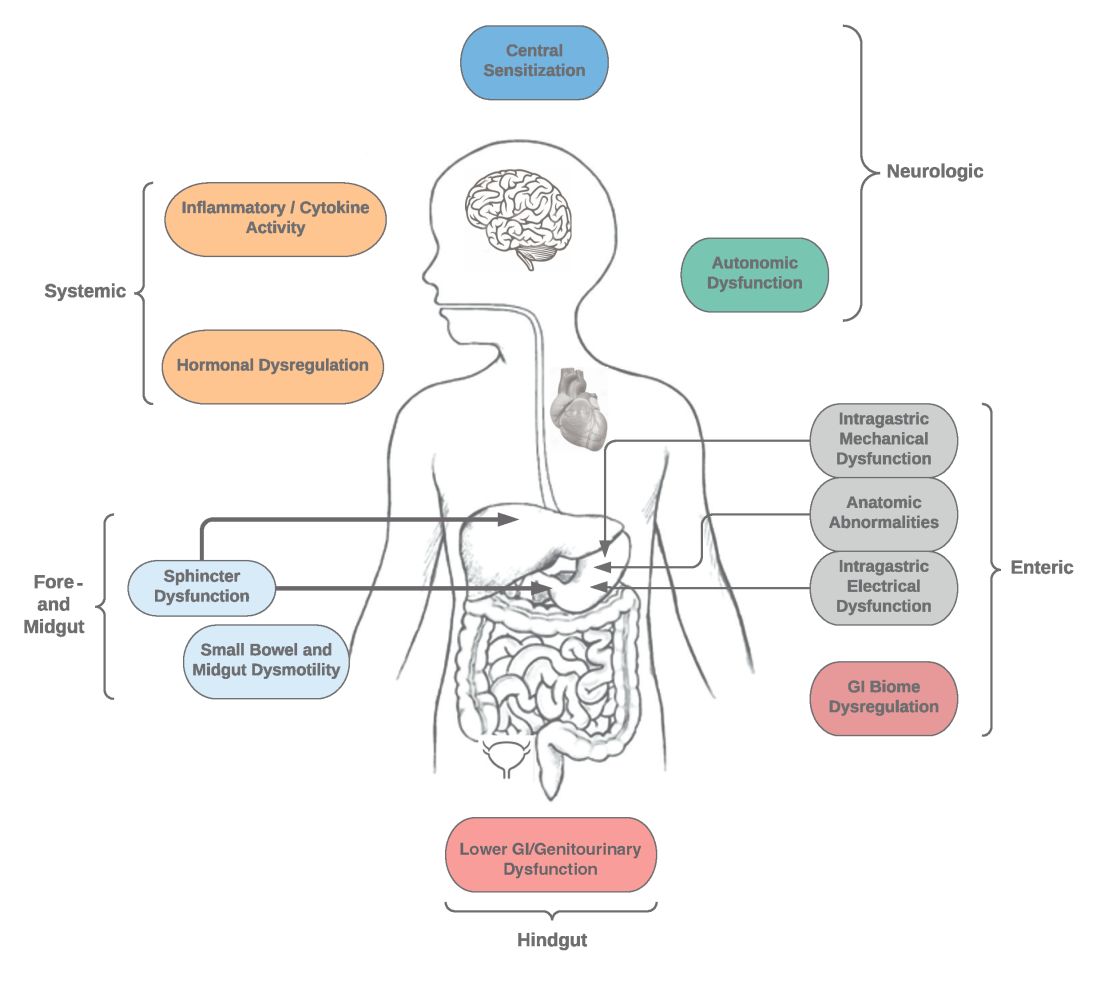

Specific types of gastroparesis syndromes have variable pathophysiology (Figure 1). In some cases, like GpS associated with DM, pathophysiology is partially related to diabetic autonomic dysfunction. GpS are multifactorial, however, and rather than focusing on subtypes, this discussion focuses on shared pathophysiology. Understanding pathophysiology is key to determining treatment options and potential future targets for therapy.

Intragastric mechanical dysfunction, both proximal (fundic relaxation and accommodation and/or lack of fundic contractility) and distal stomach (antral hypomotility) may be involved. Additionally, intragastric electrical disturbances in frequency, amplitude, and propagation of gastric electrical waves can be seen with low/high resolution gastric mapping.

Both gastroesophageal and gastropyloric sphincter dysfunction may be seen. Esophageal dysfunction is frequently seen but is not always categorized in GpS. Pyloric dysfunction is increasingly a focus of both diagnosis and therapy. GI anatomic abnormalities can be identified with gastric biopsies of full thickness muscle and mucosa. CD117/interstitial cells of Cajal, neural fibers, inflammatory and other cells can be evaluated by light microscopy, electron microscopy, and special staining techniques.

Small bowel, mid-, and hindgut dysmotility involvement has often been associated with pathologies of intragastric motility. Not only GI but genitourinary dysfunction may be associated with fore- and mid-gut dysfunction in GpS. Equally well described are abnormalities of the autonomic and sensory nervous system, which have recently been better quantified. Serologic measures, such as channelopathies and other antibody mediated abnormalities, have been recently noted.

Suspected for many years, immune dysregulation has now been documented in patients with GpS. Further investigation, including genetic dysregulation of immune measures, is ongoing. Other mechanisms include systemic and local inflammation, hormonal abnormalities, macro- and micronutrient deficiencies, dysregulation in GI microbiome, and physical frailty. The above factors may play a role in the pathophysiology of GpS, and it is likely that many of these are involved with a given patient presenting for care.9

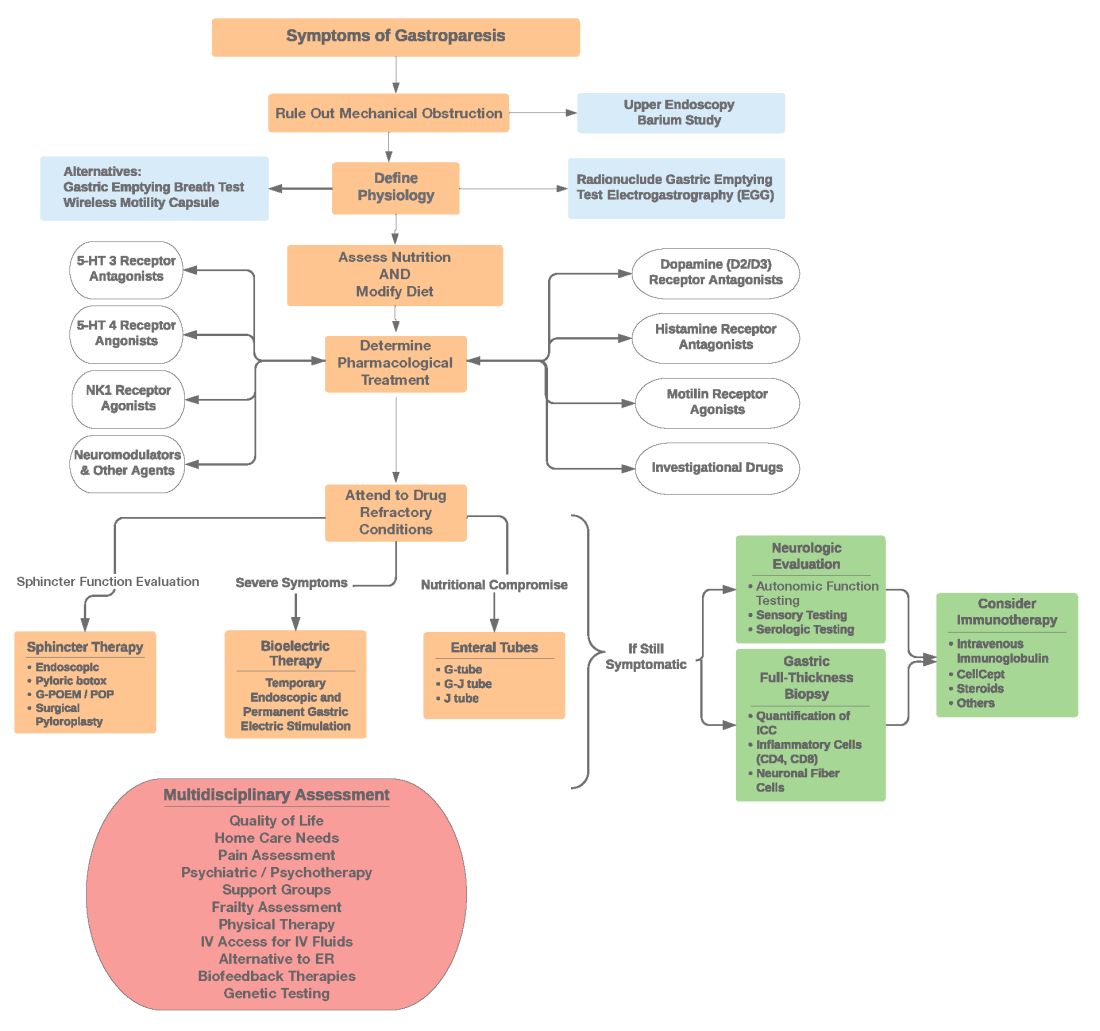

Diagnosis of GpS

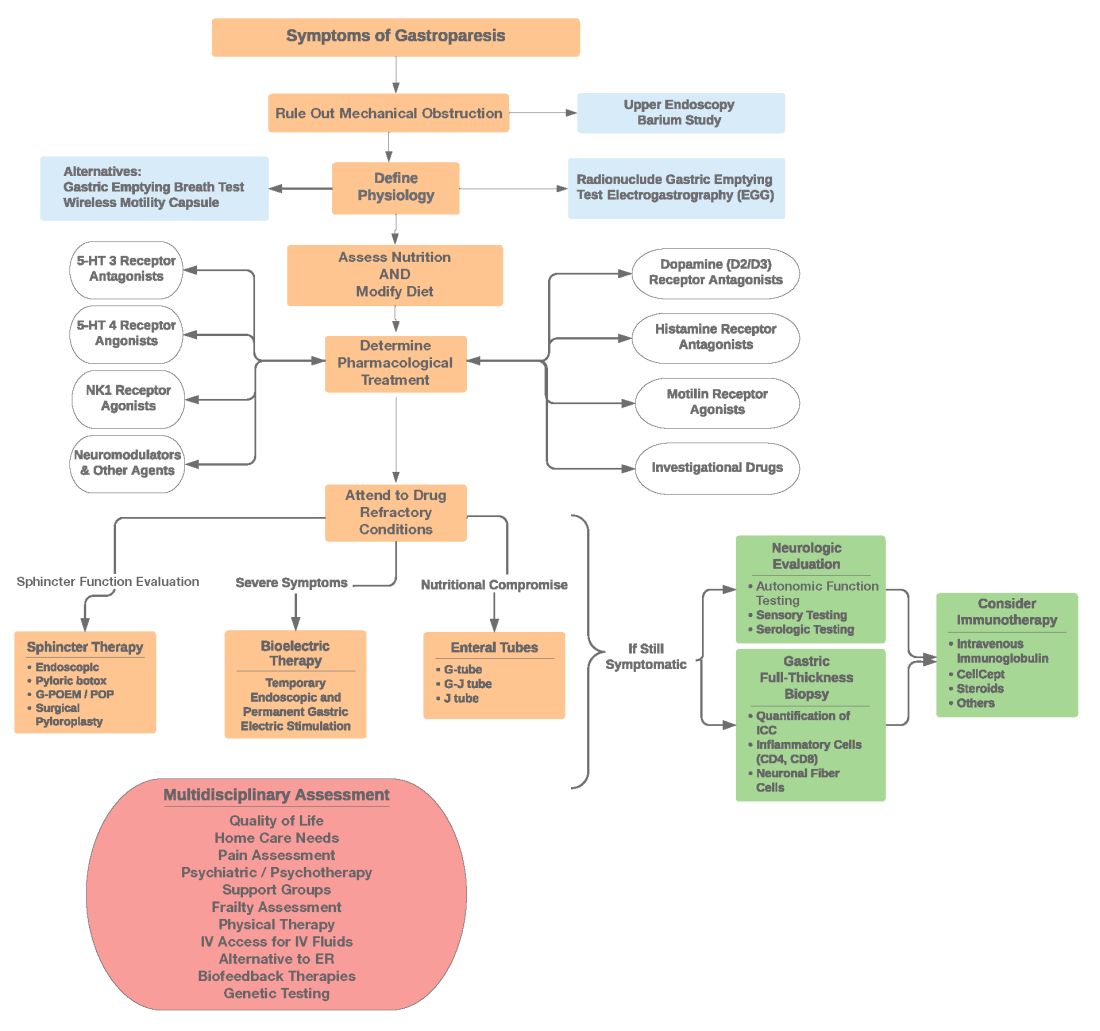

Diagnosis of GpS is often delayed and can be challenging; various tools have been developed, but not all are used. A diagnostic approach for patients with symptoms of Gp is listed below, and Figure 2 details a diagnostic approach and treatment options for symptomatic patients.

Symptom Assessment: Initially Gp symptoms can be assessed using Food and Drug Administration–approved patient-reported outcomes, including frequency and severity of nausea, vomiting, anorexia/early satiety, bloating/distention, and abdominal pain on a 0-4, 0-5 or 0-10 scale. The Gastrointestinal Cardinal Symptom Index or visual analog scales can also be used. It is also important to evaluate midgut and hindgut symptoms.9-11

Mechanical obstruction assessment: Mechanical obstruction can be ruled out using upper endoscopy or barium studies.

Physiologic testing: The most common is radionuclide gastric emptying testing (GET). Compliance with guidelines, standardization, and consistency of GETs is vital to help with an accurate diagnosis. Currently, two consensus recommendations for the standardized performance of GETs exist.12,13 Breath testing is FDA approved in the United States and can be used as an alternative. Wireless motility capsule testing can be complimentary.

Gastric dysrhythmias assessment: Assessment of gastric dysrhythmias can be performed in outpatient settings using cutaneous electrogastrogram, currently available in many referral centers. Most patients with GpS have an underlying gastric electrical abnormality.14,15

Sphincter dysfunction assessment: Both proximal and distal sphincter abnormalities have been described for many years and are of particular interest recently. Use of the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) shows patients with GpS may have decreased sphincter distensibility when examining the comparisons of the cross-sectional area relative to pressure Using this information, sphincter therapies can be offered.16-18

Other testing: Neurologic and autonomic testing, along with psychosocial, genetic and frailty assessments, are helpful to explore.19 Nutritional evaluation can be done using standardized scales, such as subjective global assessment and serologic testing for micronutrient deficiency or electrical impedance.20

Treatment of GpS

Therapies for GpS can be viewed as the five D’s: Diet, Drug, Disruption, Devices, and Details.

Diet and nutrition: The mainstay treatment of GpS remains dietary modification. The most common recommendation is to limit meal size, often with increased meal frequency, as well as nutrient composition, in areas that may retard gastric emptying. In addition, some patients with GpS report intolerances of specific foods, such as specific carbohydrates. Nutritional consultation can assist patients with meals tailored for their current nutritional needs. Nutritional supplementation is widely used for patients with GpS.20

Pharmacological treatment: The next tier of treatment for GpS is drugs. Review of a patient’s medications is important to minimize drugs that may retard gastric emptying such as opiates and GLP-1 agonists. A full discussion of medications is beyond the scope of this article, but classes of drugs available include: prokinetics, antiemetics, neuromodulators, and investigational agents.

There is only one approved prokinetic medication for gastroparesis – the dopamine blocker metoclopramide – and most providers are aware of metoclopramide’s limitations in terms of potential side effects, such as the risk of tardive dyskinesia and labeling on duration of therapy, with a maximum of 12 weeks recommended. Alternative prokinetics, such as domperidone, are not easily available in the United States; some mediations approved for other indications, such as the 5-HT drug prucalopride, are sometimes given for GpS off-label. Antiemetics such as promethazine and ondansetron are frequently used for symptomatic control in GpS. Despite lack of positive controlled trials in Gp, neuromodulator drugs, such as tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline or mirtazapine are often used; their efficacy is more proven in the functional dyspepsia area. Other drugs such as the NK-1 drug aprepitant have been studied in Gp and are sometimes used off-label. Drugs such as scopolamine and related compounds can also provide symptomatic relief, as can the tetrahydrocannabinol-containing drug, dronabinol. New pharmacologic agents for GpS include investigational drugs such as ghrelin agonists and several novel compounds, none of which are currently FDA approved.21,22

Fortunately, the majority of patients with GpS respond to conservative therapies, such as dietary changes and/or medications. The last part of the section on treatment of GpS includes patients that are diet and drug refractory. Patients in this group are often referred to gastroenterologists and can be complex, time consuming, and frustrating to provide care for. Many of these patients are eventually seen in referral centers, and some travel great distances and have considerable medical expenses.

Pylorus-directed therapies: The recent renewed interest in pyloric dysfunction in patients with Gp symptoms has led to a great deal of clinical activity. Gastropyloric dysfunction in Gp has been documented for decades, originally in diabetic patients with autonomic and enteric neuropathy. The use of botulinum toxin in upper- and lower-gastric sphincters has led to continuing use of this therapy for patients with GpS. Despite initial negative controlled trials of botulinum toxin in the pyloric sphincter, newer studies indicate that physiologic measures, such as the FLIP, may help with patient selection. Other disruptive pyloric therapies, including pyloromyotomy, per oral pyloromyotomy, and gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy, are supported by open-label use, despite a lack of published positive controlled trials.17

Bioelectric therapy: Another approach for patients with symptomatic drug refractory GpS is bioelectric device therapies, which can be delivered several ways, including directly to the stomach or to the spinal cord or the vagus nerve in the neck or ear, as well as by electro-acupuncture. High-frequency, low-energy gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is the best studied. First done in 1992 as an experimental therapy, GES was investigational from 1995 to 2000, when it became FDA approved as a humanitarian-use device. GES has been used in over 10,000 patients worldwide; only a small number (greater than 700 study patients) have been in controlled trials. Nine controlled trials of GES have been primarily positive, and durability for over 10 years has been shown. Temporary GES can also be performed endoscopically, although that is an off-label procedure. It has been shown to predict long-term therapy outcome.23-26

Nutritional support: Nutritional abnormalities in some cases of GpS lead to consideration of enteral tubes, starting with a trial of feeding with an N-J tube placed endoscopically. An N-J trial is most often performed in patients who have macro-malnutrition and weight loss but can be considered for other highly symptomatic patients. Other endoscopic tubes can be PEG or PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Some patients may require surgical placement of enteral tubes, presenting an opportunity for a small bowel or gastric full-thickness biopsy. Enteral tubes are sometimes used for decompression in highly symptomatic patients.27

For patients presenting with neurological symptoms, findings and serologic abnormalities have led to interest in immunotherapies. One is intravenous immunoglobulin, given parenterally. Several open-label studies have been published, the most recent one with 47 patients showing better response if glutamic acid decarboxylase–65 antibodies were present and with longer therapeutic dosing.28 Drawbacks to immunotherapies like intravenous immunoglobulin are cost and requiring parenteral access.

Other evaluation/treatments for drug refractory patients can be detailed as follows: First, an overall quality of life assessment can be helpful, especially one that includes impact of GpS on the patients and family. Nutritional considerations, which may not have been fully assessed, can be examined in more detail. Frailty assessments may show the need for physical therapy. Assessment for home care needs may indicate, in severe patients, needs for IV fluids at home, either enteral or parenteral, if nutrition is not adequate. Psychosocial and/or psychiatric assessments may lead to the need for medications, psychotherapy, and/or support groups. Lastly, an assessment of overall health status may lead to approaches for minimizing visits to emergency rooms and hospitalizations.29,30

Conclusion

Patients with Gp symptoms are becoming increasingly recognized and referred to gastroenterologists. Better understandings of the pathophysiology of the spectrum of gastroparesis syndromes, assisted by innovations in diagnosis, have led to expansion of existing and new therapeutic approaches. Fortunately, most patients can benefit from a standardized diagnostic approach and directed noninvasive therapies. Patients with refractory gastroparesis symptoms, often with complex issues referred to gastroenterologists, remain a challenge, and novel approaches may improve their quality of life.

Dr. Mathur is a GI motility research fellow at the University of Louisville, Ky. He reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Abell is the Arthur M. Schoen, MD, Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Louisville. His main funding is NIH GpCRC and NIH Definitive Evaluation of Gastric Dysrhythmia. He is an investigator for Cindome, Vanda, Allergan, and Neurogastrx; a consultant for Censa, Nuvaira, and Takeda; a speaker for Takeda and Medtronic; and a reviewer for UpToDate. He is also the founder of ADEPT-GI, which holds IP related to mucosal stimulation and autonomic and enteric profiling.

References

1. Jung HK et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-33.

2. Ye Y et al. Gut. 2021;70(4):644-53.

3. Oshima T et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;27(1):46-54.

4. Soykan I et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(11):2398-404.

5. Syed AR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(1):50-4.

6.Pasricha PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(7):567-76.e1-4.

7. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):2006-17.

8. Almario CV et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1701-10.

9. Abell TL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Apr;66(4):1127-41.

10. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(3):e13534.

11. Elmasry M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Oct 26;e14274.

12. Maurer AH et al. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(3):11N-7N.

13. Abell TL et al. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008 Mar;36(1):44-54.

14. Shine A et al. Neuromodulation. 2022 Feb 16;S1094-7159(21)06986-5.

15. O’Grady G et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(5):G527-g42.

16. Saadi M et al. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). Oct-Dec 2018;83(4):375-84.

17. Kamal F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(2):168-77.

18. Harberson J et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(2):359-70.

19. Winston J. Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2021;3(2):78-83.

20. Parkman HP et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):486-98, 98.e1-7.

21. Heckroth M et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(4):279-99.

22. Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):19-24.

23. Payne SC et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(2):89-105.

24. Ducrotte P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):506-14.e2.

25. Burlen J et al. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11(5):349-54.

26. Hedjoudje A et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(11):e13949.

27. Petrov RV et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):539-56.

28. Gala K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Dec 31. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001655.

29. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(4):263-83.

30. Camilleri M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(1):18-37.

Introduction

Patients presenting with the symptoms of gastroparesis (Gp) are commonly seen in gastroenterology practice.

Presentation

Patients with foregut symptoms of Gp have characteristic presentations, with nausea, vomiting/retching, and abdominal pain often associated with bloating and distension, early satiety, anorexia, and heartburn. Mid- and hindgut gastrointestinal and/or urinary symptoms may be seen in patients with Gp as well.

The precise epidemiology of gastroparesis syndromes (GpS) is unknown. Classic gastroparesis, defined as delayed gastric emptying without known mechanical obstruction, has a prevalence of about 10 per 100,000 population in men and 30 per 100,000 in women with women being affected 3 to 4 times more than men.1,2 Some risk factors for GpS, such as diabetes mellitus (DM) in up to 5% of patients with Type 1 DM, are known.3 Caucasians have the highest prevalence of GpS, followed by African Americans.4,5

The classic definition of Gp has blurred with the realization that patients may have symptoms of Gp without delayed solid gastric emptying. Some patients have been described as having chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting or gastroparesis like syndrome.6 More recently the NIH Gastroparesis Consortium has proposed that disorders like functional dyspepsia may be a spectrum of the two disorders and classic Gp.7 Using this broadened definition, the number of patients with Gp symptoms is much greater, found in 10% or more of the U.S. population.8 For this discussion, GpS is used to encompass this spectrum of disorders.

The etiology of GpS is often unknown for a given patient, but clues to etiology exist in what is known about pathophysiology. Types of Gp are described as being idiopathic, diabetic, or postsurgical, each of which may have varying pathophysiology. Many patients with mild-to-moderate GpS symptoms are effectively treated with out-patient therapies; other patients may be refractory to available treatments. Refractory GpS patients have a high burden of illness affecting them, their families, providers, hospitals, and payers.

Pathophysiology

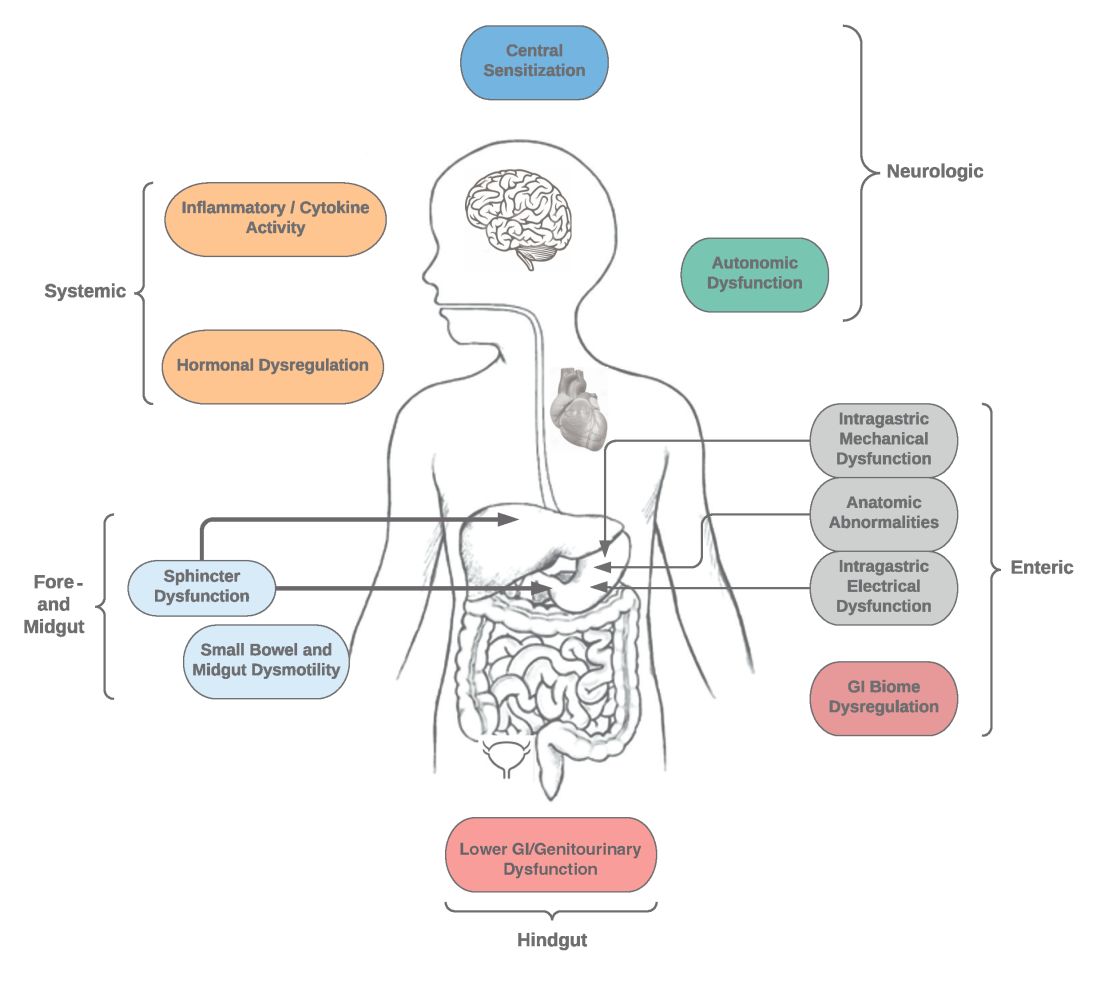

Specific types of gastroparesis syndromes have variable pathophysiology (Figure 1). In some cases, like GpS associated with DM, pathophysiology is partially related to diabetic autonomic dysfunction. GpS are multifactorial, however, and rather than focusing on subtypes, this discussion focuses on shared pathophysiology. Understanding pathophysiology is key to determining treatment options and potential future targets for therapy.

Intragastric mechanical dysfunction, both proximal (fundic relaxation and accommodation and/or lack of fundic contractility) and distal stomach (antral hypomotility) may be involved. Additionally, intragastric electrical disturbances in frequency, amplitude, and propagation of gastric electrical waves can be seen with low/high resolution gastric mapping.

Both gastroesophageal and gastropyloric sphincter dysfunction may be seen. Esophageal dysfunction is frequently seen but is not always categorized in GpS. Pyloric dysfunction is increasingly a focus of both diagnosis and therapy. GI anatomic abnormalities can be identified with gastric biopsies of full thickness muscle and mucosa. CD117/interstitial cells of Cajal, neural fibers, inflammatory and other cells can be evaluated by light microscopy, electron microscopy, and special staining techniques.

Small bowel, mid-, and hindgut dysmotility involvement has often been associated with pathologies of intragastric motility. Not only GI but genitourinary dysfunction may be associated with fore- and mid-gut dysfunction in GpS. Equally well described are abnormalities of the autonomic and sensory nervous system, which have recently been better quantified. Serologic measures, such as channelopathies and other antibody mediated abnormalities, have been recently noted.

Suspected for many years, immune dysregulation has now been documented in patients with GpS. Further investigation, including genetic dysregulation of immune measures, is ongoing. Other mechanisms include systemic and local inflammation, hormonal abnormalities, macro- and micronutrient deficiencies, dysregulation in GI microbiome, and physical frailty. The above factors may play a role in the pathophysiology of GpS, and it is likely that many of these are involved with a given patient presenting for care.9

Diagnosis of GpS

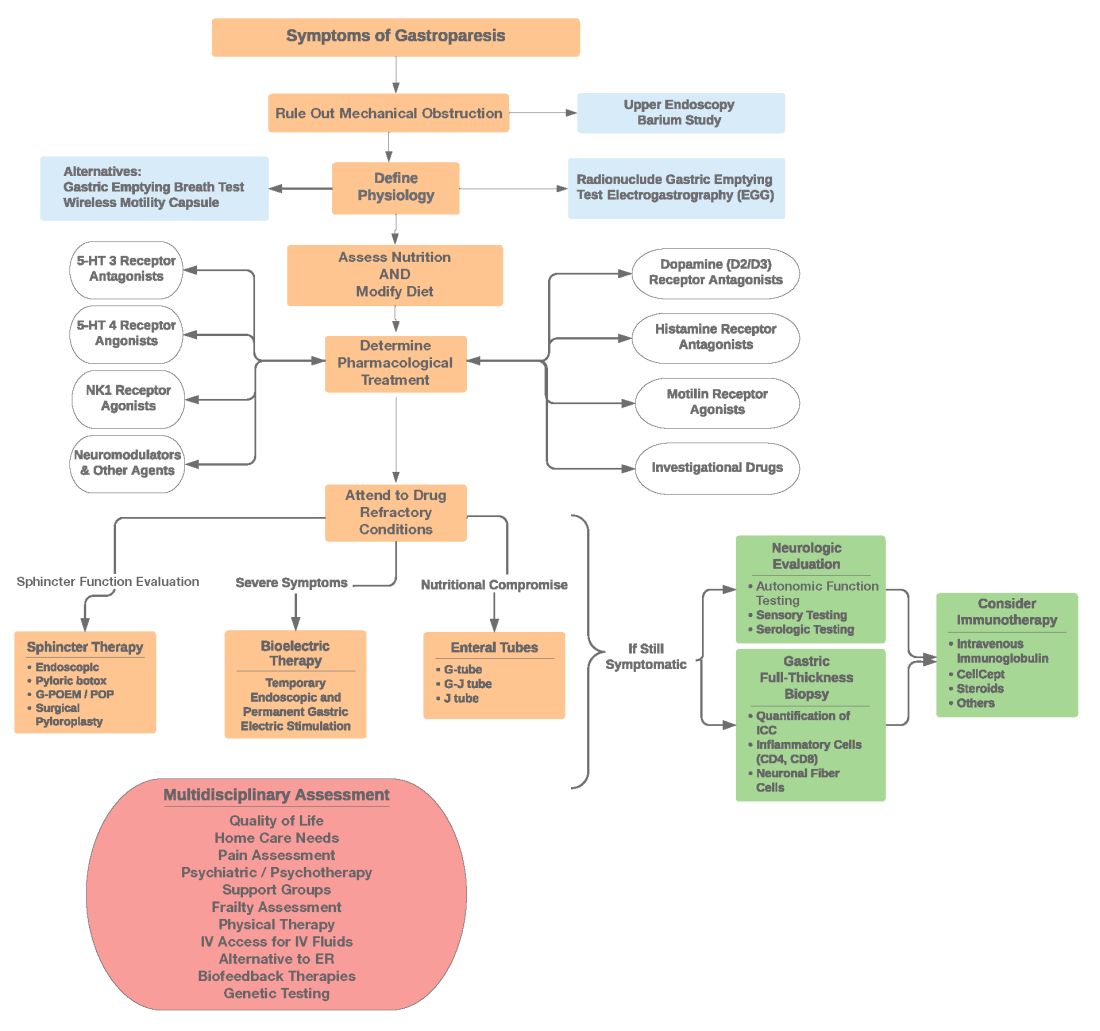

Diagnosis of GpS is often delayed and can be challenging; various tools have been developed, but not all are used. A diagnostic approach for patients with symptoms of Gp is listed below, and Figure 2 details a diagnostic approach and treatment options for symptomatic patients.

Symptom Assessment: Initially Gp symptoms can be assessed using Food and Drug Administration–approved patient-reported outcomes, including frequency and severity of nausea, vomiting, anorexia/early satiety, bloating/distention, and abdominal pain on a 0-4, 0-5 or 0-10 scale. The Gastrointestinal Cardinal Symptom Index or visual analog scales can also be used. It is also important to evaluate midgut and hindgut symptoms.9-11

Mechanical obstruction assessment: Mechanical obstruction can be ruled out using upper endoscopy or barium studies.

Physiologic testing: The most common is radionuclide gastric emptying testing (GET). Compliance with guidelines, standardization, and consistency of GETs is vital to help with an accurate diagnosis. Currently, two consensus recommendations for the standardized performance of GETs exist.12,13 Breath testing is FDA approved in the United States and can be used as an alternative. Wireless motility capsule testing can be complimentary.

Gastric dysrhythmias assessment: Assessment of gastric dysrhythmias can be performed in outpatient settings using cutaneous electrogastrogram, currently available in many referral centers. Most patients with GpS have an underlying gastric electrical abnormality.14,15

Sphincter dysfunction assessment: Both proximal and distal sphincter abnormalities have been described for many years and are of particular interest recently. Use of the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) shows patients with GpS may have decreased sphincter distensibility when examining the comparisons of the cross-sectional area relative to pressure Using this information, sphincter therapies can be offered.16-18

Other testing: Neurologic and autonomic testing, along with psychosocial, genetic and frailty assessments, are helpful to explore.19 Nutritional evaluation can be done using standardized scales, such as subjective global assessment and serologic testing for micronutrient deficiency or electrical impedance.20

Treatment of GpS

Therapies for GpS can be viewed as the five D’s: Diet, Drug, Disruption, Devices, and Details.

Diet and nutrition: The mainstay treatment of GpS remains dietary modification. The most common recommendation is to limit meal size, often with increased meal frequency, as well as nutrient composition, in areas that may retard gastric emptying. In addition, some patients with GpS report intolerances of specific foods, such as specific carbohydrates. Nutritional consultation can assist patients with meals tailored for their current nutritional needs. Nutritional supplementation is widely used for patients with GpS.20

Pharmacological treatment: The next tier of treatment for GpS is drugs. Review of a patient’s medications is important to minimize drugs that may retard gastric emptying such as opiates and GLP-1 agonists. A full discussion of medications is beyond the scope of this article, but classes of drugs available include: prokinetics, antiemetics, neuromodulators, and investigational agents.

There is only one approved prokinetic medication for gastroparesis – the dopamine blocker metoclopramide – and most providers are aware of metoclopramide’s limitations in terms of potential side effects, such as the risk of tardive dyskinesia and labeling on duration of therapy, with a maximum of 12 weeks recommended. Alternative prokinetics, such as domperidone, are not easily available in the United States; some mediations approved for other indications, such as the 5-HT drug prucalopride, are sometimes given for GpS off-label. Antiemetics such as promethazine and ondansetron are frequently used for symptomatic control in GpS. Despite lack of positive controlled trials in Gp, neuromodulator drugs, such as tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline or mirtazapine are often used; their efficacy is more proven in the functional dyspepsia area. Other drugs such as the NK-1 drug aprepitant have been studied in Gp and are sometimes used off-label. Drugs such as scopolamine and related compounds can also provide symptomatic relief, as can the tetrahydrocannabinol-containing drug, dronabinol. New pharmacologic agents for GpS include investigational drugs such as ghrelin agonists and several novel compounds, none of which are currently FDA approved.21,22

Fortunately, the majority of patients with GpS respond to conservative therapies, such as dietary changes and/or medications. The last part of the section on treatment of GpS includes patients that are diet and drug refractory. Patients in this group are often referred to gastroenterologists and can be complex, time consuming, and frustrating to provide care for. Many of these patients are eventually seen in referral centers, and some travel great distances and have considerable medical expenses.

Pylorus-directed therapies: The recent renewed interest in pyloric dysfunction in patients with Gp symptoms has led to a great deal of clinical activity. Gastropyloric dysfunction in Gp has been documented for decades, originally in diabetic patients with autonomic and enteric neuropathy. The use of botulinum toxin in upper- and lower-gastric sphincters has led to continuing use of this therapy for patients with GpS. Despite initial negative controlled trials of botulinum toxin in the pyloric sphincter, newer studies indicate that physiologic measures, such as the FLIP, may help with patient selection. Other disruptive pyloric therapies, including pyloromyotomy, per oral pyloromyotomy, and gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy, are supported by open-label use, despite a lack of published positive controlled trials.17

Bioelectric therapy: Another approach for patients with symptomatic drug refractory GpS is bioelectric device therapies, which can be delivered several ways, including directly to the stomach or to the spinal cord or the vagus nerve in the neck or ear, as well as by electro-acupuncture. High-frequency, low-energy gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is the best studied. First done in 1992 as an experimental therapy, GES was investigational from 1995 to 2000, when it became FDA approved as a humanitarian-use device. GES has been used in over 10,000 patients worldwide; only a small number (greater than 700 study patients) have been in controlled trials. Nine controlled trials of GES have been primarily positive, and durability for over 10 years has been shown. Temporary GES can also be performed endoscopically, although that is an off-label procedure. It has been shown to predict long-term therapy outcome.23-26

Nutritional support: Nutritional abnormalities in some cases of GpS lead to consideration of enteral tubes, starting with a trial of feeding with an N-J tube placed endoscopically. An N-J trial is most often performed in patients who have macro-malnutrition and weight loss but can be considered for other highly symptomatic patients. Other endoscopic tubes can be PEG or PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Some patients may require surgical placement of enteral tubes, presenting an opportunity for a small bowel or gastric full-thickness biopsy. Enteral tubes are sometimes used for decompression in highly symptomatic patients.27

For patients presenting with neurological symptoms, findings and serologic abnormalities have led to interest in immunotherapies. One is intravenous immunoglobulin, given parenterally. Several open-label studies have been published, the most recent one with 47 patients showing better response if glutamic acid decarboxylase–65 antibodies were present and with longer therapeutic dosing.28 Drawbacks to immunotherapies like intravenous immunoglobulin are cost and requiring parenteral access.

Other evaluation/treatments for drug refractory patients can be detailed as follows: First, an overall quality of life assessment can be helpful, especially one that includes impact of GpS on the patients and family. Nutritional considerations, which may not have been fully assessed, can be examined in more detail. Frailty assessments may show the need for physical therapy. Assessment for home care needs may indicate, in severe patients, needs for IV fluids at home, either enteral or parenteral, if nutrition is not adequate. Psychosocial and/or psychiatric assessments may lead to the need for medications, psychotherapy, and/or support groups. Lastly, an assessment of overall health status may lead to approaches for minimizing visits to emergency rooms and hospitalizations.29,30

Conclusion

Patients with Gp symptoms are becoming increasingly recognized and referred to gastroenterologists. Better understandings of the pathophysiology of the spectrum of gastroparesis syndromes, assisted by innovations in diagnosis, have led to expansion of existing and new therapeutic approaches. Fortunately, most patients can benefit from a standardized diagnostic approach and directed noninvasive therapies. Patients with refractory gastroparesis symptoms, often with complex issues referred to gastroenterologists, remain a challenge, and novel approaches may improve their quality of life.

Dr. Mathur is a GI motility research fellow at the University of Louisville, Ky. He reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Abell is the Arthur M. Schoen, MD, Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Louisville. His main funding is NIH GpCRC and NIH Definitive Evaluation of Gastric Dysrhythmia. He is an investigator for Cindome, Vanda, Allergan, and Neurogastrx; a consultant for Censa, Nuvaira, and Takeda; a speaker for Takeda and Medtronic; and a reviewer for UpToDate. He is also the founder of ADEPT-GI, which holds IP related to mucosal stimulation and autonomic and enteric profiling.

References

1. Jung HK et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-33.

2. Ye Y et al. Gut. 2021;70(4):644-53.

3. Oshima T et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;27(1):46-54.

4. Soykan I et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(11):2398-404.

5. Syed AR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(1):50-4.

6.Pasricha PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(7):567-76.e1-4.

7. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):2006-17.

8. Almario CV et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1701-10.

9. Abell TL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Apr;66(4):1127-41.

10. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(3):e13534.

11. Elmasry M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Oct 26;e14274.

12. Maurer AH et al. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(3):11N-7N.

13. Abell TL et al. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008 Mar;36(1):44-54.

14. Shine A et al. Neuromodulation. 2022 Feb 16;S1094-7159(21)06986-5.

15. O’Grady G et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(5):G527-g42.

16. Saadi M et al. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). Oct-Dec 2018;83(4):375-84.

17. Kamal F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(2):168-77.

18. Harberson J et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(2):359-70.

19. Winston J. Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2021;3(2):78-83.

20. Parkman HP et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):486-98, 98.e1-7.

21. Heckroth M et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(4):279-99.

22. Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):19-24.

23. Payne SC et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(2):89-105.

24. Ducrotte P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):506-14.e2.

25. Burlen J et al. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11(5):349-54.

26. Hedjoudje A et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(11):e13949.

27. Petrov RV et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):539-56.

28. Gala K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Dec 31. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001655.

29. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(4):263-83.

30. Camilleri M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(1):18-37.

Introduction

Patients presenting with the symptoms of gastroparesis (Gp) are commonly seen in gastroenterology practice.

Presentation

Patients with foregut symptoms of Gp have characteristic presentations, with nausea, vomiting/retching, and abdominal pain often associated with bloating and distension, early satiety, anorexia, and heartburn. Mid- and hindgut gastrointestinal and/or urinary symptoms may be seen in patients with Gp as well.

The precise epidemiology of gastroparesis syndromes (GpS) is unknown. Classic gastroparesis, defined as delayed gastric emptying without known mechanical obstruction, has a prevalence of about 10 per 100,000 population in men and 30 per 100,000 in women with women being affected 3 to 4 times more than men.1,2 Some risk factors for GpS, such as diabetes mellitus (DM) in up to 5% of patients with Type 1 DM, are known.3 Caucasians have the highest prevalence of GpS, followed by African Americans.4,5

The classic definition of Gp has blurred with the realization that patients may have symptoms of Gp without delayed solid gastric emptying. Some patients have been described as having chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting or gastroparesis like syndrome.6 More recently the NIH Gastroparesis Consortium has proposed that disorders like functional dyspepsia may be a spectrum of the two disorders and classic Gp.7 Using this broadened definition, the number of patients with Gp symptoms is much greater, found in 10% or more of the U.S. population.8 For this discussion, GpS is used to encompass this spectrum of disorders.

The etiology of GpS is often unknown for a given patient, but clues to etiology exist in what is known about pathophysiology. Types of Gp are described as being idiopathic, diabetic, or postsurgical, each of which may have varying pathophysiology. Many patients with mild-to-moderate GpS symptoms are effectively treated with out-patient therapies; other patients may be refractory to available treatments. Refractory GpS patients have a high burden of illness affecting them, their families, providers, hospitals, and payers.

Pathophysiology

Specific types of gastroparesis syndromes have variable pathophysiology (Figure 1). In some cases, like GpS associated with DM, pathophysiology is partially related to diabetic autonomic dysfunction. GpS are multifactorial, however, and rather than focusing on subtypes, this discussion focuses on shared pathophysiology. Understanding pathophysiology is key to determining treatment options and potential future targets for therapy.

Intragastric mechanical dysfunction, both proximal (fundic relaxation and accommodation and/or lack of fundic contractility) and distal stomach (antral hypomotility) may be involved. Additionally, intragastric electrical disturbances in frequency, amplitude, and propagation of gastric electrical waves can be seen with low/high resolution gastric mapping.

Both gastroesophageal and gastropyloric sphincter dysfunction may be seen. Esophageal dysfunction is frequently seen but is not always categorized in GpS. Pyloric dysfunction is increasingly a focus of both diagnosis and therapy. GI anatomic abnormalities can be identified with gastric biopsies of full thickness muscle and mucosa. CD117/interstitial cells of Cajal, neural fibers, inflammatory and other cells can be evaluated by light microscopy, electron microscopy, and special staining techniques.

Small bowel, mid-, and hindgut dysmotility involvement has often been associated with pathologies of intragastric motility. Not only GI but genitourinary dysfunction may be associated with fore- and mid-gut dysfunction in GpS. Equally well described are abnormalities of the autonomic and sensory nervous system, which have recently been better quantified. Serologic measures, such as channelopathies and other antibody mediated abnormalities, have been recently noted.

Suspected for many years, immune dysregulation has now been documented in patients with GpS. Further investigation, including genetic dysregulation of immune measures, is ongoing. Other mechanisms include systemic and local inflammation, hormonal abnormalities, macro- and micronutrient deficiencies, dysregulation in GI microbiome, and physical frailty. The above factors may play a role in the pathophysiology of GpS, and it is likely that many of these are involved with a given patient presenting for care.9

Diagnosis of GpS

Diagnosis of GpS is often delayed and can be challenging; various tools have been developed, but not all are used. A diagnostic approach for patients with symptoms of Gp is listed below, and Figure 2 details a diagnostic approach and treatment options for symptomatic patients.

Symptom Assessment: Initially Gp symptoms can be assessed using Food and Drug Administration–approved patient-reported outcomes, including frequency and severity of nausea, vomiting, anorexia/early satiety, bloating/distention, and abdominal pain on a 0-4, 0-5 or 0-10 scale. The Gastrointestinal Cardinal Symptom Index or visual analog scales can also be used. It is also important to evaluate midgut and hindgut symptoms.9-11

Mechanical obstruction assessment: Mechanical obstruction can be ruled out using upper endoscopy or barium studies.

Physiologic testing: The most common is radionuclide gastric emptying testing (GET). Compliance with guidelines, standardization, and consistency of GETs is vital to help with an accurate diagnosis. Currently, two consensus recommendations for the standardized performance of GETs exist.12,13 Breath testing is FDA approved in the United States and can be used as an alternative. Wireless motility capsule testing can be complimentary.

Gastric dysrhythmias assessment: Assessment of gastric dysrhythmias can be performed in outpatient settings using cutaneous electrogastrogram, currently available in many referral centers. Most patients with GpS have an underlying gastric electrical abnormality.14,15

Sphincter dysfunction assessment: Both proximal and distal sphincter abnormalities have been described for many years and are of particular interest recently. Use of the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) shows patients with GpS may have decreased sphincter distensibility when examining the comparisons of the cross-sectional area relative to pressure Using this information, sphincter therapies can be offered.16-18

Other testing: Neurologic and autonomic testing, along with psychosocial, genetic and frailty assessments, are helpful to explore.19 Nutritional evaluation can be done using standardized scales, such as subjective global assessment and serologic testing for micronutrient deficiency or electrical impedance.20

Treatment of GpS

Therapies for GpS can be viewed as the five D’s: Diet, Drug, Disruption, Devices, and Details.

Diet and nutrition: The mainstay treatment of GpS remains dietary modification. The most common recommendation is to limit meal size, often with increased meal frequency, as well as nutrient composition, in areas that may retard gastric emptying. In addition, some patients with GpS report intolerances of specific foods, such as specific carbohydrates. Nutritional consultation can assist patients with meals tailored for their current nutritional needs. Nutritional supplementation is widely used for patients with GpS.20

Pharmacological treatment: The next tier of treatment for GpS is drugs. Review of a patient’s medications is important to minimize drugs that may retard gastric emptying such as opiates and GLP-1 agonists. A full discussion of medications is beyond the scope of this article, but classes of drugs available include: prokinetics, antiemetics, neuromodulators, and investigational agents.

There is only one approved prokinetic medication for gastroparesis – the dopamine blocker metoclopramide – and most providers are aware of metoclopramide’s limitations in terms of potential side effects, such as the risk of tardive dyskinesia and labeling on duration of therapy, with a maximum of 12 weeks recommended. Alternative prokinetics, such as domperidone, are not easily available in the United States; some mediations approved for other indications, such as the 5-HT drug prucalopride, are sometimes given for GpS off-label. Antiemetics such as promethazine and ondansetron are frequently used for symptomatic control in GpS. Despite lack of positive controlled trials in Gp, neuromodulator drugs, such as tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline or mirtazapine are often used; their efficacy is more proven in the functional dyspepsia area. Other drugs such as the NK-1 drug aprepitant have been studied in Gp and are sometimes used off-label. Drugs such as scopolamine and related compounds can also provide symptomatic relief, as can the tetrahydrocannabinol-containing drug, dronabinol. New pharmacologic agents for GpS include investigational drugs such as ghrelin agonists and several novel compounds, none of which are currently FDA approved.21,22

Fortunately, the majority of patients with GpS respond to conservative therapies, such as dietary changes and/or medications. The last part of the section on treatment of GpS includes patients that are diet and drug refractory. Patients in this group are often referred to gastroenterologists and can be complex, time consuming, and frustrating to provide care for. Many of these patients are eventually seen in referral centers, and some travel great distances and have considerable medical expenses.

Pylorus-directed therapies: The recent renewed interest in pyloric dysfunction in patients with Gp symptoms has led to a great deal of clinical activity. Gastropyloric dysfunction in Gp has been documented for decades, originally in diabetic patients with autonomic and enteric neuropathy. The use of botulinum toxin in upper- and lower-gastric sphincters has led to continuing use of this therapy for patients with GpS. Despite initial negative controlled trials of botulinum toxin in the pyloric sphincter, newer studies indicate that physiologic measures, such as the FLIP, may help with patient selection. Other disruptive pyloric therapies, including pyloromyotomy, per oral pyloromyotomy, and gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy, are supported by open-label use, despite a lack of published positive controlled trials.17

Bioelectric therapy: Another approach for patients with symptomatic drug refractory GpS is bioelectric device therapies, which can be delivered several ways, including directly to the stomach or to the spinal cord or the vagus nerve in the neck or ear, as well as by electro-acupuncture. High-frequency, low-energy gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is the best studied. First done in 1992 as an experimental therapy, GES was investigational from 1995 to 2000, when it became FDA approved as a humanitarian-use device. GES has been used in over 10,000 patients worldwide; only a small number (greater than 700 study patients) have been in controlled trials. Nine controlled trials of GES have been primarily positive, and durability for over 10 years has been shown. Temporary GES can also be performed endoscopically, although that is an off-label procedure. It has been shown to predict long-term therapy outcome.23-26

Nutritional support: Nutritional abnormalities in some cases of GpS lead to consideration of enteral tubes, starting with a trial of feeding with an N-J tube placed endoscopically. An N-J trial is most often performed in patients who have macro-malnutrition and weight loss but can be considered for other highly symptomatic patients. Other endoscopic tubes can be PEG or PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Some patients may require surgical placement of enteral tubes, presenting an opportunity for a small bowel or gastric full-thickness biopsy. Enteral tubes are sometimes used for decompression in highly symptomatic patients.27

For patients presenting with neurological symptoms, findings and serologic abnormalities have led to interest in immunotherapies. One is intravenous immunoglobulin, given parenterally. Several open-label studies have been published, the most recent one with 47 patients showing better response if glutamic acid decarboxylase–65 antibodies were present and with longer therapeutic dosing.28 Drawbacks to immunotherapies like intravenous immunoglobulin are cost and requiring parenteral access.

Other evaluation/treatments for drug refractory patients can be detailed as follows: First, an overall quality of life assessment can be helpful, especially one that includes impact of GpS on the patients and family. Nutritional considerations, which may not have been fully assessed, can be examined in more detail. Frailty assessments may show the need for physical therapy. Assessment for home care needs may indicate, in severe patients, needs for IV fluids at home, either enteral or parenteral, if nutrition is not adequate. Psychosocial and/or psychiatric assessments may lead to the need for medications, psychotherapy, and/or support groups. Lastly, an assessment of overall health status may lead to approaches for minimizing visits to emergency rooms and hospitalizations.29,30

Conclusion

Patients with Gp symptoms are becoming increasingly recognized and referred to gastroenterologists. Better understandings of the pathophysiology of the spectrum of gastroparesis syndromes, assisted by innovations in diagnosis, have led to expansion of existing and new therapeutic approaches. Fortunately, most patients can benefit from a standardized diagnostic approach and directed noninvasive therapies. Patients with refractory gastroparesis symptoms, often with complex issues referred to gastroenterologists, remain a challenge, and novel approaches may improve their quality of life.

Dr. Mathur is a GI motility research fellow at the University of Louisville, Ky. He reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Abell is the Arthur M. Schoen, MD, Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Louisville. His main funding is NIH GpCRC and NIH Definitive Evaluation of Gastric Dysrhythmia. He is an investigator for Cindome, Vanda, Allergan, and Neurogastrx; a consultant for Censa, Nuvaira, and Takeda; a speaker for Takeda and Medtronic; and a reviewer for UpToDate. He is also the founder of ADEPT-GI, which holds IP related to mucosal stimulation and autonomic and enteric profiling.

References

1. Jung HK et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-33.

2. Ye Y et al. Gut. 2021;70(4):644-53.

3. Oshima T et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;27(1):46-54.

4. Soykan I et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(11):2398-404.

5. Syed AR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(1):50-4.

6.Pasricha PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(7):567-76.e1-4.

7. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):2006-17.

8. Almario CV et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(11):1701-10.

9. Abell TL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Apr;66(4):1127-41.

10. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(3):e13534.

11. Elmasry M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Oct 26;e14274.

12. Maurer AH et al. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(3):11N-7N.

13. Abell TL et al. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008 Mar;36(1):44-54.

14. Shine A et al. Neuromodulation. 2022 Feb 16;S1094-7159(21)06986-5.

15. O’Grady G et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(5):G527-g42.

16. Saadi M et al. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). Oct-Dec 2018;83(4):375-84.

17. Kamal F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(2):168-77.

18. Harberson J et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(2):359-70.

19. Winston J. Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2021;3(2):78-83.

20. Parkman HP et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):486-98, 98.e1-7.

21. Heckroth M et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(4):279-99.

22. Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):19-24.

23. Payne SC et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(2):89-105.

24. Ducrotte P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):506-14.e2.

25. Burlen J et al. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11(5):349-54.

26. Hedjoudje A et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(11):e13949.

27. Petrov RV et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):539-56.

28. Gala K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Dec 31. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001655.

29. Abell TL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(4):263-83.

30. Camilleri M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(1):18-37.

AGA News - May 2022

AGA Fellow (AGAF) applications now open

AGA is proud to formally recognize its exemplary members whose accomplishments and contributions demonstrate a deep commitment to gastroenterology through the AGA Fellows Program. Those in clinical practice, education, or research (basic or clinical) are encouraged to apply today.

Longstanding members who apply and meet the program criteria are granted the distinguished honor of AGA Fellowship and receive the following:

- The privilege of using the designation “AGAF” in professional activities.

- An official certificate and pin denoting your status.

- International acknowledgment at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

- A listing on the AGA website alongside esteemed peers.

- A prewritten, fill-in press release, and a digital badge to inform others of your accomplishment.

Learn more

Apply for consideration and gain recognition worldwide for your commitment to the field. The deadline is Aug. 24, 2022.

If you have any questions, contact AGA Member Relations at [email protected] or 301-941-2651.

AGA Fellow (AGAF) applications now open

AGA is proud to formally recognize its exemplary members whose accomplishments and contributions demonstrate a deep commitment to gastroenterology through the AGA Fellows Program. Those in clinical practice, education, or research (basic or clinical) are encouraged to apply today.

Longstanding members who apply and meet the program criteria are granted the distinguished honor of AGA Fellowship and receive the following:

- The privilege of using the designation “AGAF” in professional activities.

- An official certificate and pin denoting your status.

- International acknowledgment at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

- A listing on the AGA website alongside esteemed peers.

- A prewritten, fill-in press release, and a digital badge to inform others of your accomplishment.

Learn more

Apply for consideration and gain recognition worldwide for your commitment to the field. The deadline is Aug. 24, 2022.

If you have any questions, contact AGA Member Relations at [email protected] or 301-941-2651.

AGA Fellow (AGAF) applications now open

AGA is proud to formally recognize its exemplary members whose accomplishments and contributions demonstrate a deep commitment to gastroenterology through the AGA Fellows Program. Those in clinical practice, education, or research (basic or clinical) are encouraged to apply today.

Longstanding members who apply and meet the program criteria are granted the distinguished honor of AGA Fellowship and receive the following:

- The privilege of using the designation “AGAF” in professional activities.

- An official certificate and pin denoting your status.

- International acknowledgment at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

- A listing on the AGA website alongside esteemed peers.

- A prewritten, fill-in press release, and a digital badge to inform others of your accomplishment.

Learn more

Apply for consideration and gain recognition worldwide for your commitment to the field. The deadline is Aug. 24, 2022.

If you have any questions, contact AGA Member Relations at [email protected] or 301-941-2651.

May 2022 - ICYMI

Gastroenterology

February 2022

How to Succeed in Digestive Research

Sonnenberg A, Inadomi JM. Gastroenterology. 2022 Feb;162(2):385-389. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.229.

Incidence and Mortality in Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer After Negative Endoscopy for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Holmberg H et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Feb;162(2):431-438.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.003.

March 2022

Global Prevalence and Impact of Rumination Syndrome

Josefsson A et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Mar;162(3):731-742.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.11.008.

A Clinical Approach to Chronic Diarrhea

Dutra B et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Mar;162(3):707-709. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.038.