User login

Progress still needed for pregnant and postpartum gastroenterologists

Despite increasing numbers joining the field, women remain a minority group in gastroenterology, where they constitute only 18% of these physicians.1 Additionally, women continue to be underrepresented among senior faculty and in leadership roles in both academic and private practice settings.2 While women now make up a majority of medical school matriculants3,4 women trainees are frequently dissuaded from pursuing specialty fellowships following residency, particularly in procedurally based fields like gastroenterology, because of perceived incompatibility with childbearing and child-rearing.5-8 For many who choose to enter the field despite these challenges, gastroenterology training and early practice often coincide with childbearing years.910 These structural impediments may contribute to the “leaky pipeline” and female physician attrition during the first decade of independent practice after fellowship.11-13 Urgent changes are needed in order to retain and support clinicians and physician-scientists through this period so that they, their offspring, their patients, and the field are able to thrive.

Fertility and pregnancy

The decision to have a child is a major milestone for many physicians and often occurs during gastroenterology training or early practice.10 Medical-training and early-career environments are not yet optimized to support women who become pregnant. At baseline, the formative years of a career are challenging ones, punctuated by long hours and both intellectually and emotionally demanding work. They are also often physically grueling, particularly while one is learning and becoming efficient in endoscopy. The ergonomics in the endoscopy suite (as in other areas of medicine) are not optimized for physicians of shorter stature, smaller hand sizes, and those who may have difficulty pushing a several-hundred-pound endoscopy cart bedside, all of which contribute to increased injury risk for female proceduralists.7,14-16 Methods to reduce endoscopic injuries in pregnant endoscopists have not yet been studied. Additionally, the existence of maternity and gender bias has been well-documented, in our field and beyond.17-20 Not surprisingly, women in gastroenterology commonly report delayed childbearing, with expected consequences, including increased infertility rates, compared with nonphysician peers.21 After 5 and 10 years as attendings, female gastroenterologists continue to report fewer children than male colleagues.22,23 Once pregnant, there are a number of field-specific challenges to navigate. These include decisions about the safety of performing procedures involving fluoroscopy or high infectious risk, particularly early in pregnancy when organogenesis occurs.7,24 Additionally, engaging in appropriate obstetric care can be challenging given the need for regular physician and ultrasound appointments.

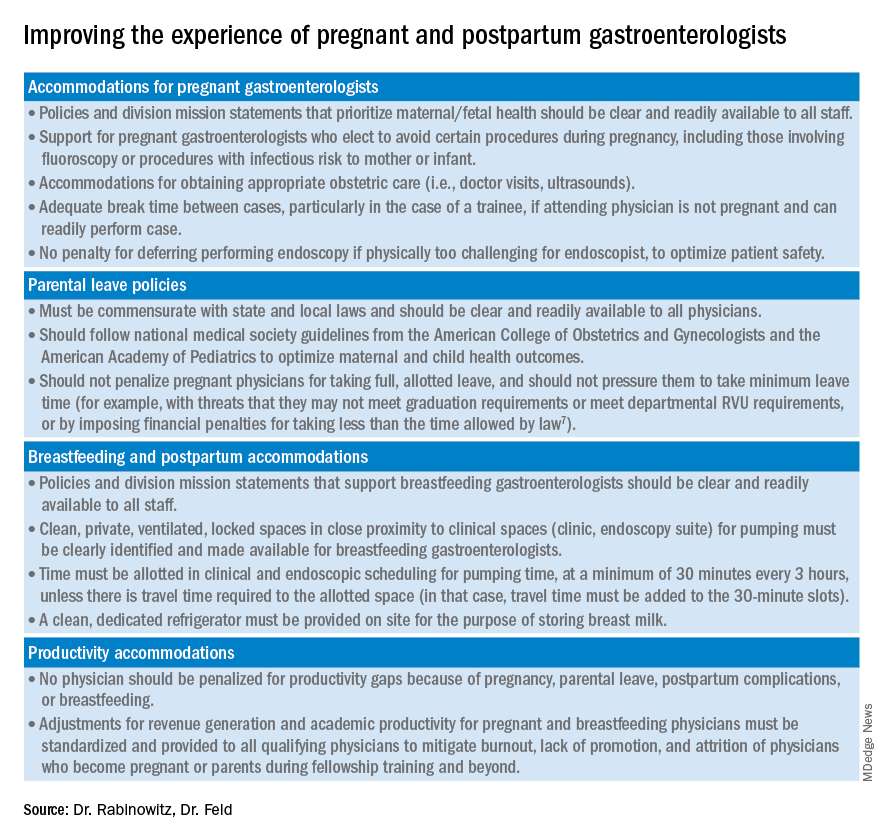

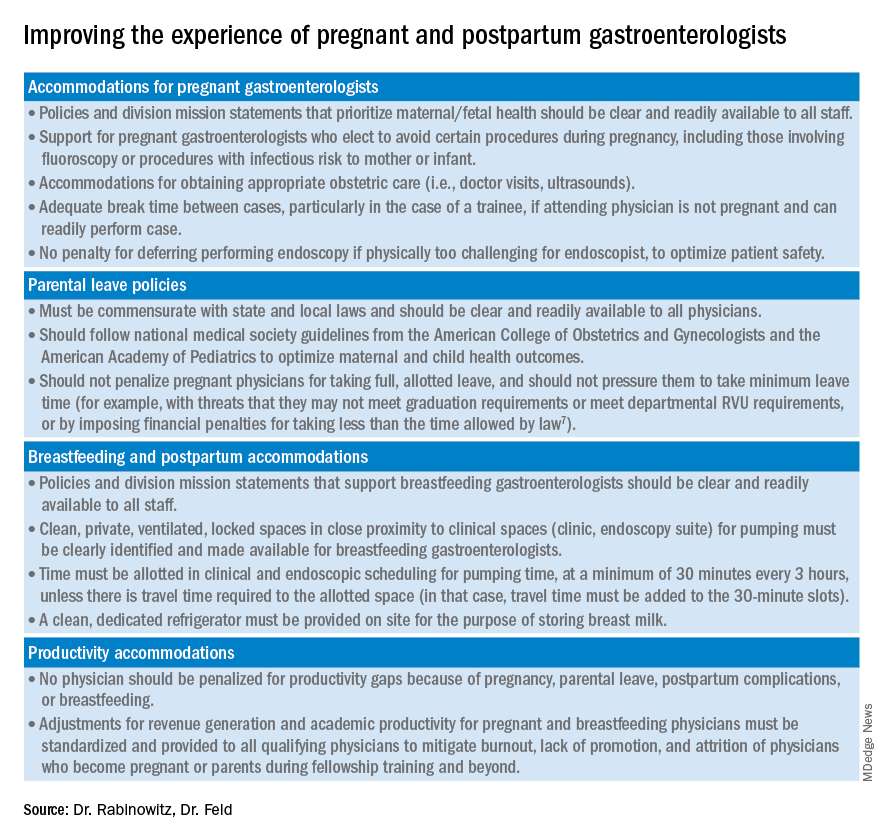

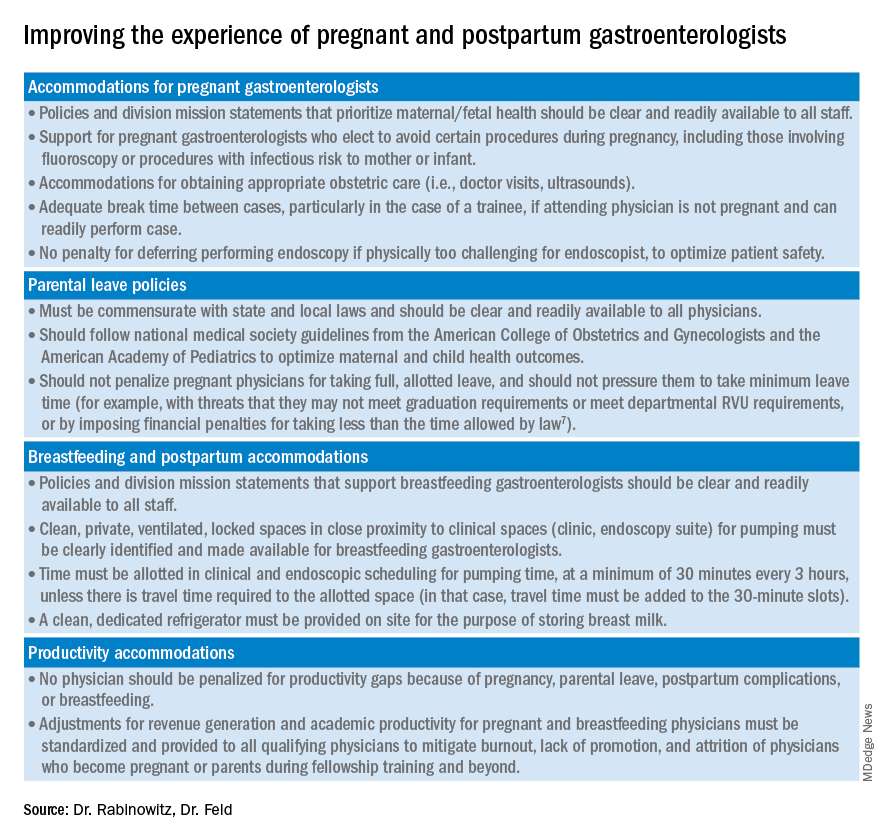

Simple, cost-efficient interventions may be effective in decreasing infertility rates, pregnancy loss, and poor physician experiences during pregnancy. For one, all gastroenterology divisions could craft written policies that include a no-tolerance approach to expressions of maternity bias against pregnant or postpartum trainees and faculty.12,25 Additionally, ergonomic improvements, such as standing pads, dial extenders, and adjusted screen heights may decrease injury rates and increase comfort for female endoscopists.26,27 There should also be a no-penalty, no-questions-asked approach for any female endoscopist who defers performance of an obstetrically high-risk procedure to a nonpregnant colleague. Additionally, pregnant gastroenterologists should be supported in obtaining high-quality obstetric care. At an individual level, nonpregnant gastroenterologists, and particularly male allies, can support pregnant colleagues by agreeing to perform higher-risk procedures, stepping in if a fellow is unable to perform endoscopy because of pregnancy, and by offering to push the endoscopy cart on behalf of a pregnant colleague to bedside, if necessary.10,28

Parental leave

Following delivery, parental leave presents an additional challenge for the physician parent. Paid maternal leave has been associated with improved child and maternal outcomes and is widely available to physicians outside the United States.29,30 At present, duration of leave varies significantly by career stage (fellows versus attending), practice setting (academic center versus private practice), and geographic location. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a minimum of 12 weeks of leave.31 This length has been associated with lower rates of postpartum depression and higher rates of sustained breastfeeding, with subsequent improved health outcomes for mother and child.32-34 An increasing number of states have passed laws mandating minimum paid and unpaid parental leave time (for example, in Massachusetts, gastroenterology trainees and faculty are afforded 12 weeks of leave, in accordance with state law).35 Recent changes to board eligibility and training requirements via the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Council for Graduate Medical Education now provide 6 weeks for parental leave. This is an improvement over prior policies which rendered many physician-parents board-ineligible if they took more than 4 weeks of leave, although it must be noted that even the revised policies allow for less time than either that of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or than the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends.

Our data, presented at the 2021 ACG conference, suggest that many trainees report receiving 4 weeks or less of parental leave, despite the ACGME and ABMS policies described above. We also found that physicians were frequently not aware of their institution or division leave policies.10 Ideally, all gastroenterology divisions in the United States would follow the recommended leave duration set forth by the medical societies of specialties that care for pregnant and postpartum mothers and their infants. Additionally, the impact of leave time on graduation and board eligibility, as well as academic and practice promotion, should be made clear at the time of leave and should minimize adverse consequences for the careers of pregnant and postpartum gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology trainees and faculty should be educated in the existence and details of their institution or practice policies, and these policies should be made readily available to all physicians and administrators.

Postpartum period

The transition back to work is a challenging one for mothers in all fields of medicine, particularly for those returning to procedurally based subspecialties such as gastroenterology. This is especially true for trainees and faculty who have returned to work sooner than the recommended 12 weeks and for those who are post cesarean section, for whom physical healing may not be complete. Long days performing endoscopy may be physically challenging or impossible for some women during the postpartum period. Additionally, expressing breast milk, a metabolically intensive activity, also necessitates time, space, and privacy to perform and is frequently made more difficult by insufficient lactation accommodations. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased logistic challenges for lactating mothers, because of the need for well-ventilated lactation spaces to minimize infectious risk.19 Our colleagues have reported pumping in their vehicles, in supply closets, and in spaces that require so much travel time (in addition to time required to express milk, store milk, and clean pump equipment) that the practice was unsustainable, and the physician stopped breastfeeding prematurely.36

The benefits of breastfeeding for mother and infant are well-established, and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, whose position statement reads as follows: “Policies that protect the right of a woman and her child to breastfeed ... and that accommodate milk expression, such as ... paid maternity leave, on-site childcare, break time for expressing milk, and a clean, private location for expressing milk, are essential to sustaining breastfeeding.”37 We would add to these recommendations provision of dedicated milk storage space and establishment of clear, supportive policies that allow lactating physicians to breastfeed and express breast milk if they choose without career penalty. Several institutions offer scheduled protected clinical time and modified work relative value units (RVU) for lactating physicians, such that returning parents can have protected time for expressing breast milk and still meet RVU targets.38 Additionally, many academic institutions offer productivity adjustments for tenure-track faculty who have recently had children.

Creating a more supportive environment for women gastroenterologists who desire children allows the field to be more representative of our patient population and has been shown to positively impact outcomes from improved colorectal cancer screening rates to more guideline-directed informed consent conversations.39-41 Gastroenterology should comprise a physician workforce predicated on clinical and research excellence alone and should not require its practitioners to delay or abstain from pregnancy and child rearing. Robust, clear, and generous parental leave and postpartum accommodations will allow the field to retain and promote talented physicians, who will then contribute to the betterment of patients and the field over decades.

Dr. Rabinowitz is a faculty member in the department of medicine and division of gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Feld is a transplant hepatology fellow, division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Rabinowitz and Dr. Feld have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

1. AAMC. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. 2018.

2. Colleges AoAM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2015-2016. 2016. www.aamc.org/download/481206/data/2015table11.pdf.

3. AAMC. Table B-3: Total U.S. Medical School Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2014-2015 through 2018-2019, 2019.

4. Rabinowitz LG. Recognizing blind spots – a remedy for gender bias in medicine? (N Engl. J Med. 2018; 378[24]: 2253-5).

5. Douglas PS et al. Career preferences and perceptions of cardiology among US internal medicine trainees: Factors influencing cardiology career choice. JAMA Cardiol 2018; 3(8):682-91.

6. Stack SW et al. Childbearing decisions in residency: A multicenter survey of female residents. Acad Med 2020;95(10):1550-7.

7. David YN et al. Pregnancy and the working gastroenterologist: Perceptions, realities, and systemic challenges. Gastroenterology 2021;161(3):756-60.

8. Rembacken BJ et al. Barriers and bias standing in the way of female trainees wanting to learn advanced endoscopy. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(8):1141-5.

9. Arlow FL et al. Gastroenterology training and career choices: A prospective longitudinal study of the impact of gender and of managed care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(2):459-69.

10. Feld L et al. Parental leave for gastroenterology fellows: A national survey of current fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S611-2.

11. Rabinowitz LG et al. Addressing gender in gastroenterology: opportunities for change. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(1):155-61.

12. Feld LD. Baby steps in the right direction: Toward a parental leave policy for gastroenterology fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):505-8.

13. Feld LD. Interviewing for two. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;116(3):445-6

14. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender dynamics in education and practice of gastroenterology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1047-56.e5.

15. Harvin G. Review of musculoskeletal injuries and prevention in the endoscopy practitioner. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(7):590-4.

16. LabX Oecs. www.labx.com/product/endoscopy-cart (accessed 2021 Nov 19.

17. Heilman ME and Okimoto TG. Motherhood: A potential source of bias in employment decisions. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(1):189-98.

18. Robinson K et al. Racism, bias, and discrimination as modifiable barriers to breastfeeding for African American women: A scoping review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64(6):734-42.

19. Rabinowitz LG and Rabinowitz DG. Women on the Frontline: A Changed Workforce and the Fight Against COVID-19. Acad Med. 2021 Jun 1;96(6):808-12.

20. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender in the endoscopy suite. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec;5(12):1032-4.

21. Stentz NC et al. Fertility and childbearing among American female physicians. J Womens Health. 2016; 25(10):1059-65.

22. Burke CA et al. Gender disparity in the practice of gastroenterology: The first 5 years of a career. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(2):259-64.

23. Singh A et al. Women in gastroenterology committee of American College of G. Do gender disparities persist in gastroenterology after 10 years of practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(7):1589-95.

24. Krueger KJ and Hoffman BJ. Radiation exposure during gastroenterologic fluoroscopy: Risk assessment for pregnant workers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(4):429-31.

25. Krause ML et al. Impact of pregnancy and gender on internal medicine resident evaluations: A retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):648-53.

26. Pawa S et al. Are all endoscopy-related musculoskeletal injuries created equal? Results of a national gender-based survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):530-8.

27. David YN et al. Gender-specific factors influencing gastroenterologists to pursue careers in advanced endoscopy: perceptions vs reality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):539-50.

28. Bilal M et al. The need for allyship in achieving gender equity in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Oct 19. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001508. Online ahead of print.

29. Jou J et al. Paid maternity leave in the United States: Associations with maternal and infant health. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(2):216-25.

30. Aitken Z et al. The maternal health outcomes of paid maternity leave: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:32-41.

31. Dodson NA and Talib HJ. Paid parental leave for mothers and fathers can improve physician wellness. AAP News. 2020 Jul 1. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/12432.

32. Kornfeind KR and Sipsma HL. Exploring the link between maternity leave and postpartum depression. Womens Health Issues 2018;28(4):321-6.

33. Navarro-Rosenblatt D and Garmendia ML. Maternity leave and its impact on breastfeeding: A review of the literature. Breastfeed Med 2018;13(9):589-97.

34. Stack SW et al. Maternity leave in residency: A multicenter study of determinants and wellness outcomes. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1738-45.

35. Mass.gov. Paid Family and Medical Leave Information for Massachusetts Employers. 2020.

36. Ares Segura S et al. en representacion del Comite de Lactancia Materna de la Asociacion Espanola de P. [The importance of maternal nutrition during breastfeeding: Do breastfeeding mothers need nutritional supplements?]. An Pediatr. (Barc) 2016;84(6):347 e1-7.

37. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 658: Optimizing Support for Breastfeeding as Part of Obstetric Practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):e86-92.

38. Porter KK et al. A lactation credit model to support breastfeeding in radiology: The new gold standard to support “liquid gold.” Clin Imaging 2021;80:16-8.

39. Davis J et al. Clinical practice patterns suggest female patients prefer female endoscopists. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(10):3149-50.

40. Menees SB et al. Women patients’ preference for women physicians is a barrier to colon cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(2):219-23.

41. Feld LD et al. Management of code status in the periendoscopic period: A national survey of current practices and beliefs of U.S. gastroenterologists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(1):172-7.e2.

Despite increasing numbers joining the field, women remain a minority group in gastroenterology, where they constitute only 18% of these physicians.1 Additionally, women continue to be underrepresented among senior faculty and in leadership roles in both academic and private practice settings.2 While women now make up a majority of medical school matriculants3,4 women trainees are frequently dissuaded from pursuing specialty fellowships following residency, particularly in procedurally based fields like gastroenterology, because of perceived incompatibility with childbearing and child-rearing.5-8 For many who choose to enter the field despite these challenges, gastroenterology training and early practice often coincide with childbearing years.910 These structural impediments may contribute to the “leaky pipeline” and female physician attrition during the first decade of independent practice after fellowship.11-13 Urgent changes are needed in order to retain and support clinicians and physician-scientists through this period so that they, their offspring, their patients, and the field are able to thrive.

Fertility and pregnancy

The decision to have a child is a major milestone for many physicians and often occurs during gastroenterology training or early practice.10 Medical-training and early-career environments are not yet optimized to support women who become pregnant. At baseline, the formative years of a career are challenging ones, punctuated by long hours and both intellectually and emotionally demanding work. They are also often physically grueling, particularly while one is learning and becoming efficient in endoscopy. The ergonomics in the endoscopy suite (as in other areas of medicine) are not optimized for physicians of shorter stature, smaller hand sizes, and those who may have difficulty pushing a several-hundred-pound endoscopy cart bedside, all of which contribute to increased injury risk for female proceduralists.7,14-16 Methods to reduce endoscopic injuries in pregnant endoscopists have not yet been studied. Additionally, the existence of maternity and gender bias has been well-documented, in our field and beyond.17-20 Not surprisingly, women in gastroenterology commonly report delayed childbearing, with expected consequences, including increased infertility rates, compared with nonphysician peers.21 After 5 and 10 years as attendings, female gastroenterologists continue to report fewer children than male colleagues.22,23 Once pregnant, there are a number of field-specific challenges to navigate. These include decisions about the safety of performing procedures involving fluoroscopy or high infectious risk, particularly early in pregnancy when organogenesis occurs.7,24 Additionally, engaging in appropriate obstetric care can be challenging given the need for regular physician and ultrasound appointments.

Simple, cost-efficient interventions may be effective in decreasing infertility rates, pregnancy loss, and poor physician experiences during pregnancy. For one, all gastroenterology divisions could craft written policies that include a no-tolerance approach to expressions of maternity bias against pregnant or postpartum trainees and faculty.12,25 Additionally, ergonomic improvements, such as standing pads, dial extenders, and adjusted screen heights may decrease injury rates and increase comfort for female endoscopists.26,27 There should also be a no-penalty, no-questions-asked approach for any female endoscopist who defers performance of an obstetrically high-risk procedure to a nonpregnant colleague. Additionally, pregnant gastroenterologists should be supported in obtaining high-quality obstetric care. At an individual level, nonpregnant gastroenterologists, and particularly male allies, can support pregnant colleagues by agreeing to perform higher-risk procedures, stepping in if a fellow is unable to perform endoscopy because of pregnancy, and by offering to push the endoscopy cart on behalf of a pregnant colleague to bedside, if necessary.10,28

Parental leave

Following delivery, parental leave presents an additional challenge for the physician parent. Paid maternal leave has been associated with improved child and maternal outcomes and is widely available to physicians outside the United States.29,30 At present, duration of leave varies significantly by career stage (fellows versus attending), practice setting (academic center versus private practice), and geographic location. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a minimum of 12 weeks of leave.31 This length has been associated with lower rates of postpartum depression and higher rates of sustained breastfeeding, with subsequent improved health outcomes for mother and child.32-34 An increasing number of states have passed laws mandating minimum paid and unpaid parental leave time (for example, in Massachusetts, gastroenterology trainees and faculty are afforded 12 weeks of leave, in accordance with state law).35 Recent changes to board eligibility and training requirements via the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Council for Graduate Medical Education now provide 6 weeks for parental leave. This is an improvement over prior policies which rendered many physician-parents board-ineligible if they took more than 4 weeks of leave, although it must be noted that even the revised policies allow for less time than either that of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or than the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends.

Our data, presented at the 2021 ACG conference, suggest that many trainees report receiving 4 weeks or less of parental leave, despite the ACGME and ABMS policies described above. We also found that physicians were frequently not aware of their institution or division leave policies.10 Ideally, all gastroenterology divisions in the United States would follow the recommended leave duration set forth by the medical societies of specialties that care for pregnant and postpartum mothers and their infants. Additionally, the impact of leave time on graduation and board eligibility, as well as academic and practice promotion, should be made clear at the time of leave and should minimize adverse consequences for the careers of pregnant and postpartum gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology trainees and faculty should be educated in the existence and details of their institution or practice policies, and these policies should be made readily available to all physicians and administrators.

Postpartum period

The transition back to work is a challenging one for mothers in all fields of medicine, particularly for those returning to procedurally based subspecialties such as gastroenterology. This is especially true for trainees and faculty who have returned to work sooner than the recommended 12 weeks and for those who are post cesarean section, for whom physical healing may not be complete. Long days performing endoscopy may be physically challenging or impossible for some women during the postpartum period. Additionally, expressing breast milk, a metabolically intensive activity, also necessitates time, space, and privacy to perform and is frequently made more difficult by insufficient lactation accommodations. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased logistic challenges for lactating mothers, because of the need for well-ventilated lactation spaces to minimize infectious risk.19 Our colleagues have reported pumping in their vehicles, in supply closets, and in spaces that require so much travel time (in addition to time required to express milk, store milk, and clean pump equipment) that the practice was unsustainable, and the physician stopped breastfeeding prematurely.36

The benefits of breastfeeding for mother and infant are well-established, and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, whose position statement reads as follows: “Policies that protect the right of a woman and her child to breastfeed ... and that accommodate milk expression, such as ... paid maternity leave, on-site childcare, break time for expressing milk, and a clean, private location for expressing milk, are essential to sustaining breastfeeding.”37 We would add to these recommendations provision of dedicated milk storage space and establishment of clear, supportive policies that allow lactating physicians to breastfeed and express breast milk if they choose without career penalty. Several institutions offer scheduled protected clinical time and modified work relative value units (RVU) for lactating physicians, such that returning parents can have protected time for expressing breast milk and still meet RVU targets.38 Additionally, many academic institutions offer productivity adjustments for tenure-track faculty who have recently had children.

Creating a more supportive environment for women gastroenterologists who desire children allows the field to be more representative of our patient population and has been shown to positively impact outcomes from improved colorectal cancer screening rates to more guideline-directed informed consent conversations.39-41 Gastroenterology should comprise a physician workforce predicated on clinical and research excellence alone and should not require its practitioners to delay or abstain from pregnancy and child rearing. Robust, clear, and generous parental leave and postpartum accommodations will allow the field to retain and promote talented physicians, who will then contribute to the betterment of patients and the field over decades.

Dr. Rabinowitz is a faculty member in the department of medicine and division of gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Feld is a transplant hepatology fellow, division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Rabinowitz and Dr. Feld have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

1. AAMC. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. 2018.

2. Colleges AoAM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2015-2016. 2016. www.aamc.org/download/481206/data/2015table11.pdf.

3. AAMC. Table B-3: Total U.S. Medical School Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2014-2015 through 2018-2019, 2019.

4. Rabinowitz LG. Recognizing blind spots – a remedy for gender bias in medicine? (N Engl. J Med. 2018; 378[24]: 2253-5).

5. Douglas PS et al. Career preferences and perceptions of cardiology among US internal medicine trainees: Factors influencing cardiology career choice. JAMA Cardiol 2018; 3(8):682-91.

6. Stack SW et al. Childbearing decisions in residency: A multicenter survey of female residents. Acad Med 2020;95(10):1550-7.

7. David YN et al. Pregnancy and the working gastroenterologist: Perceptions, realities, and systemic challenges. Gastroenterology 2021;161(3):756-60.

8. Rembacken BJ et al. Barriers and bias standing in the way of female trainees wanting to learn advanced endoscopy. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(8):1141-5.

9. Arlow FL et al. Gastroenterology training and career choices: A prospective longitudinal study of the impact of gender and of managed care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(2):459-69.

10. Feld L et al. Parental leave for gastroenterology fellows: A national survey of current fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S611-2.

11. Rabinowitz LG et al. Addressing gender in gastroenterology: opportunities for change. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(1):155-61.

12. Feld LD. Baby steps in the right direction: Toward a parental leave policy for gastroenterology fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):505-8.

13. Feld LD. Interviewing for two. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;116(3):445-6

14. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender dynamics in education and practice of gastroenterology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1047-56.e5.

15. Harvin G. Review of musculoskeletal injuries and prevention in the endoscopy practitioner. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(7):590-4.

16. LabX Oecs. www.labx.com/product/endoscopy-cart (accessed 2021 Nov 19.

17. Heilman ME and Okimoto TG. Motherhood: A potential source of bias in employment decisions. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(1):189-98.

18. Robinson K et al. Racism, bias, and discrimination as modifiable barriers to breastfeeding for African American women: A scoping review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64(6):734-42.

19. Rabinowitz LG and Rabinowitz DG. Women on the Frontline: A Changed Workforce and the Fight Against COVID-19. Acad Med. 2021 Jun 1;96(6):808-12.

20. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender in the endoscopy suite. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec;5(12):1032-4.

21. Stentz NC et al. Fertility and childbearing among American female physicians. J Womens Health. 2016; 25(10):1059-65.

22. Burke CA et al. Gender disparity in the practice of gastroenterology: The first 5 years of a career. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(2):259-64.

23. Singh A et al. Women in gastroenterology committee of American College of G. Do gender disparities persist in gastroenterology after 10 years of practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(7):1589-95.

24. Krueger KJ and Hoffman BJ. Radiation exposure during gastroenterologic fluoroscopy: Risk assessment for pregnant workers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(4):429-31.

25. Krause ML et al. Impact of pregnancy and gender on internal medicine resident evaluations: A retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):648-53.

26. Pawa S et al. Are all endoscopy-related musculoskeletal injuries created equal? Results of a national gender-based survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):530-8.

27. David YN et al. Gender-specific factors influencing gastroenterologists to pursue careers in advanced endoscopy: perceptions vs reality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):539-50.

28. Bilal M et al. The need for allyship in achieving gender equity in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Oct 19. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001508. Online ahead of print.

29. Jou J et al. Paid maternity leave in the United States: Associations with maternal and infant health. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(2):216-25.

30. Aitken Z et al. The maternal health outcomes of paid maternity leave: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:32-41.

31. Dodson NA and Talib HJ. Paid parental leave for mothers and fathers can improve physician wellness. AAP News. 2020 Jul 1. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/12432.

32. Kornfeind KR and Sipsma HL. Exploring the link between maternity leave and postpartum depression. Womens Health Issues 2018;28(4):321-6.

33. Navarro-Rosenblatt D and Garmendia ML. Maternity leave and its impact on breastfeeding: A review of the literature. Breastfeed Med 2018;13(9):589-97.

34. Stack SW et al. Maternity leave in residency: A multicenter study of determinants and wellness outcomes. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1738-45.

35. Mass.gov. Paid Family and Medical Leave Information for Massachusetts Employers. 2020.

36. Ares Segura S et al. en representacion del Comite de Lactancia Materna de la Asociacion Espanola de P. [The importance of maternal nutrition during breastfeeding: Do breastfeeding mothers need nutritional supplements?]. An Pediatr. (Barc) 2016;84(6):347 e1-7.

37. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 658: Optimizing Support for Breastfeeding as Part of Obstetric Practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):e86-92.

38. Porter KK et al. A lactation credit model to support breastfeeding in radiology: The new gold standard to support “liquid gold.” Clin Imaging 2021;80:16-8.

39. Davis J et al. Clinical practice patterns suggest female patients prefer female endoscopists. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(10):3149-50.

40. Menees SB et al. Women patients’ preference for women physicians is a barrier to colon cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(2):219-23.

41. Feld LD et al. Management of code status in the periendoscopic period: A national survey of current practices and beliefs of U.S. gastroenterologists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(1):172-7.e2.

Despite increasing numbers joining the field, women remain a minority group in gastroenterology, where they constitute only 18% of these physicians.1 Additionally, women continue to be underrepresented among senior faculty and in leadership roles in both academic and private practice settings.2 While women now make up a majority of medical school matriculants3,4 women trainees are frequently dissuaded from pursuing specialty fellowships following residency, particularly in procedurally based fields like gastroenterology, because of perceived incompatibility with childbearing and child-rearing.5-8 For many who choose to enter the field despite these challenges, gastroenterology training and early practice often coincide with childbearing years.910 These structural impediments may contribute to the “leaky pipeline” and female physician attrition during the first decade of independent practice after fellowship.11-13 Urgent changes are needed in order to retain and support clinicians and physician-scientists through this period so that they, their offspring, their patients, and the field are able to thrive.

Fertility and pregnancy

The decision to have a child is a major milestone for many physicians and often occurs during gastroenterology training or early practice.10 Medical-training and early-career environments are not yet optimized to support women who become pregnant. At baseline, the formative years of a career are challenging ones, punctuated by long hours and both intellectually and emotionally demanding work. They are also often physically grueling, particularly while one is learning and becoming efficient in endoscopy. The ergonomics in the endoscopy suite (as in other areas of medicine) are not optimized for physicians of shorter stature, smaller hand sizes, and those who may have difficulty pushing a several-hundred-pound endoscopy cart bedside, all of which contribute to increased injury risk for female proceduralists.7,14-16 Methods to reduce endoscopic injuries in pregnant endoscopists have not yet been studied. Additionally, the existence of maternity and gender bias has been well-documented, in our field and beyond.17-20 Not surprisingly, women in gastroenterology commonly report delayed childbearing, with expected consequences, including increased infertility rates, compared with nonphysician peers.21 After 5 and 10 years as attendings, female gastroenterologists continue to report fewer children than male colleagues.22,23 Once pregnant, there are a number of field-specific challenges to navigate. These include decisions about the safety of performing procedures involving fluoroscopy or high infectious risk, particularly early in pregnancy when organogenesis occurs.7,24 Additionally, engaging in appropriate obstetric care can be challenging given the need for regular physician and ultrasound appointments.

Simple, cost-efficient interventions may be effective in decreasing infertility rates, pregnancy loss, and poor physician experiences during pregnancy. For one, all gastroenterology divisions could craft written policies that include a no-tolerance approach to expressions of maternity bias against pregnant or postpartum trainees and faculty.12,25 Additionally, ergonomic improvements, such as standing pads, dial extenders, and adjusted screen heights may decrease injury rates and increase comfort for female endoscopists.26,27 There should also be a no-penalty, no-questions-asked approach for any female endoscopist who defers performance of an obstetrically high-risk procedure to a nonpregnant colleague. Additionally, pregnant gastroenterologists should be supported in obtaining high-quality obstetric care. At an individual level, nonpregnant gastroenterologists, and particularly male allies, can support pregnant colleagues by agreeing to perform higher-risk procedures, stepping in if a fellow is unable to perform endoscopy because of pregnancy, and by offering to push the endoscopy cart on behalf of a pregnant colleague to bedside, if necessary.10,28

Parental leave

Following delivery, parental leave presents an additional challenge for the physician parent. Paid maternal leave has been associated with improved child and maternal outcomes and is widely available to physicians outside the United States.29,30 At present, duration of leave varies significantly by career stage (fellows versus attending), practice setting (academic center versus private practice), and geographic location. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a minimum of 12 weeks of leave.31 This length has been associated with lower rates of postpartum depression and higher rates of sustained breastfeeding, with subsequent improved health outcomes for mother and child.32-34 An increasing number of states have passed laws mandating minimum paid and unpaid parental leave time (for example, in Massachusetts, gastroenterology trainees and faculty are afforded 12 weeks of leave, in accordance with state law).35 Recent changes to board eligibility and training requirements via the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Council for Graduate Medical Education now provide 6 weeks for parental leave. This is an improvement over prior policies which rendered many physician-parents board-ineligible if they took more than 4 weeks of leave, although it must be noted that even the revised policies allow for less time than either that of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or than the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends.

Our data, presented at the 2021 ACG conference, suggest that many trainees report receiving 4 weeks or less of parental leave, despite the ACGME and ABMS policies described above. We also found that physicians were frequently not aware of their institution or division leave policies.10 Ideally, all gastroenterology divisions in the United States would follow the recommended leave duration set forth by the medical societies of specialties that care for pregnant and postpartum mothers and their infants. Additionally, the impact of leave time on graduation and board eligibility, as well as academic and practice promotion, should be made clear at the time of leave and should minimize adverse consequences for the careers of pregnant and postpartum gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology trainees and faculty should be educated in the existence and details of their institution or practice policies, and these policies should be made readily available to all physicians and administrators.

Postpartum period

The transition back to work is a challenging one for mothers in all fields of medicine, particularly for those returning to procedurally based subspecialties such as gastroenterology. This is especially true for trainees and faculty who have returned to work sooner than the recommended 12 weeks and for those who are post cesarean section, for whom physical healing may not be complete. Long days performing endoscopy may be physically challenging or impossible for some women during the postpartum period. Additionally, expressing breast milk, a metabolically intensive activity, also necessitates time, space, and privacy to perform and is frequently made more difficult by insufficient lactation accommodations. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased logistic challenges for lactating mothers, because of the need for well-ventilated lactation spaces to minimize infectious risk.19 Our colleagues have reported pumping in their vehicles, in supply closets, and in spaces that require so much travel time (in addition to time required to express milk, store milk, and clean pump equipment) that the practice was unsustainable, and the physician stopped breastfeeding prematurely.36

The benefits of breastfeeding for mother and infant are well-established, and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life is supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, whose position statement reads as follows: “Policies that protect the right of a woman and her child to breastfeed ... and that accommodate milk expression, such as ... paid maternity leave, on-site childcare, break time for expressing milk, and a clean, private location for expressing milk, are essential to sustaining breastfeeding.”37 We would add to these recommendations provision of dedicated milk storage space and establishment of clear, supportive policies that allow lactating physicians to breastfeed and express breast milk if they choose without career penalty. Several institutions offer scheduled protected clinical time and modified work relative value units (RVU) for lactating physicians, such that returning parents can have protected time for expressing breast milk and still meet RVU targets.38 Additionally, many academic institutions offer productivity adjustments for tenure-track faculty who have recently had children.

Creating a more supportive environment for women gastroenterologists who desire children allows the field to be more representative of our patient population and has been shown to positively impact outcomes from improved colorectal cancer screening rates to more guideline-directed informed consent conversations.39-41 Gastroenterology should comprise a physician workforce predicated on clinical and research excellence alone and should not require its practitioners to delay or abstain from pregnancy and child rearing. Robust, clear, and generous parental leave and postpartum accommodations will allow the field to retain and promote talented physicians, who will then contribute to the betterment of patients and the field over decades.

Dr. Rabinowitz is a faculty member in the department of medicine and division of gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Feld is a transplant hepatology fellow, division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Rabinowitz and Dr. Feld have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

1. AAMC. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. 2018.

2. Colleges AoAM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2015-2016. 2016. www.aamc.org/download/481206/data/2015table11.pdf.

3. AAMC. Table B-3: Total U.S. Medical School Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2014-2015 through 2018-2019, 2019.

4. Rabinowitz LG. Recognizing blind spots – a remedy for gender bias in medicine? (N Engl. J Med. 2018; 378[24]: 2253-5).

5. Douglas PS et al. Career preferences and perceptions of cardiology among US internal medicine trainees: Factors influencing cardiology career choice. JAMA Cardiol 2018; 3(8):682-91.

6. Stack SW et al. Childbearing decisions in residency: A multicenter survey of female residents. Acad Med 2020;95(10):1550-7.

7. David YN et al. Pregnancy and the working gastroenterologist: Perceptions, realities, and systemic challenges. Gastroenterology 2021;161(3):756-60.

8. Rembacken BJ et al. Barriers and bias standing in the way of female trainees wanting to learn advanced endoscopy. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(8):1141-5.

9. Arlow FL et al. Gastroenterology training and career choices: A prospective longitudinal study of the impact of gender and of managed care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(2):459-69.

10. Feld L et al. Parental leave for gastroenterology fellows: A national survey of current fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S611-2.

11. Rabinowitz LG et al. Addressing gender in gastroenterology: opportunities for change. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(1):155-61.

12. Feld LD. Baby steps in the right direction: Toward a parental leave policy for gastroenterology fellows. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):505-8.

13. Feld LD. Interviewing for two. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;116(3):445-6

14. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender dynamics in education and practice of gastroenterology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(5):1047-56.e5.

15. Harvin G. Review of musculoskeletal injuries and prevention in the endoscopy practitioner. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(7):590-4.

16. LabX Oecs. www.labx.com/product/endoscopy-cart (accessed 2021 Nov 19.

17. Heilman ME and Okimoto TG. Motherhood: A potential source of bias in employment decisions. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(1):189-98.

18. Robinson K et al. Racism, bias, and discrimination as modifiable barriers to breastfeeding for African American women: A scoping review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64(6):734-42.

19. Rabinowitz LG and Rabinowitz DG. Women on the Frontline: A Changed Workforce and the Fight Against COVID-19. Acad Med. 2021 Jun 1;96(6):808-12.

20. Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender in the endoscopy suite. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec;5(12):1032-4.

21. Stentz NC et al. Fertility and childbearing among American female physicians. J Womens Health. 2016; 25(10):1059-65.

22. Burke CA et al. Gender disparity in the practice of gastroenterology: The first 5 years of a career. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(2):259-64.

23. Singh A et al. Women in gastroenterology committee of American College of G. Do gender disparities persist in gastroenterology after 10 years of practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(7):1589-95.

24. Krueger KJ and Hoffman BJ. Radiation exposure during gastroenterologic fluoroscopy: Risk assessment for pregnant workers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(4):429-31.

25. Krause ML et al. Impact of pregnancy and gender on internal medicine resident evaluations: A retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):648-53.

26. Pawa S et al. Are all endoscopy-related musculoskeletal injuries created equal? Results of a national gender-based survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):530-8.

27. David YN et al. Gender-specific factors influencing gastroenterologists to pursue careers in advanced endoscopy: perceptions vs reality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):539-50.

28. Bilal M et al. The need for allyship in achieving gender equity in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Oct 19. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001508. Online ahead of print.

29. Jou J et al. Paid maternity leave in the United States: Associations with maternal and infant health. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(2):216-25.

30. Aitken Z et al. The maternal health outcomes of paid maternity leave: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:32-41.

31. Dodson NA and Talib HJ. Paid parental leave for mothers and fathers can improve physician wellness. AAP News. 2020 Jul 1. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/12432.

32. Kornfeind KR and Sipsma HL. Exploring the link between maternity leave and postpartum depression. Womens Health Issues 2018;28(4):321-6.

33. Navarro-Rosenblatt D and Garmendia ML. Maternity leave and its impact on breastfeeding: A review of the literature. Breastfeed Med 2018;13(9):589-97.

34. Stack SW et al. Maternity leave in residency: A multicenter study of determinants and wellness outcomes. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1738-45.

35. Mass.gov. Paid Family and Medical Leave Information for Massachusetts Employers. 2020.

36. Ares Segura S et al. en representacion del Comite de Lactancia Materna de la Asociacion Espanola de P. [The importance of maternal nutrition during breastfeeding: Do breastfeeding mothers need nutritional supplements?]. An Pediatr. (Barc) 2016;84(6):347 e1-7.

37. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 658: Optimizing Support for Breastfeeding as Part of Obstetric Practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):e86-92.

38. Porter KK et al. A lactation credit model to support breastfeeding in radiology: The new gold standard to support “liquid gold.” Clin Imaging 2021;80:16-8.

39. Davis J et al. Clinical practice patterns suggest female patients prefer female endoscopists. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(10):3149-50.

40. Menees SB et al. Women patients’ preference for women physicians is a barrier to colon cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(2):219-23.

41. Feld LD et al. Management of code status in the periendoscopic period: A national survey of current practices and beliefs of U.S. gastroenterologists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(1):172-7.e2.

AGA News - February 2022

Registration now open: Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit 2022

Registration is now open for the Gut Microbiota for Health (GMFH) World Summit 2022, taking place March 12-13 in Washington, D.C., and virtually.

Organized by AGA and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM), the GMFH World Summit is the preeminent international meeting on the gut microbiome for clinicians, dietitians, and researchers.

Now in its tenth year, this year’s program will focus on “The Gut Microbiome in Precision Nutrition and Medicine.” Join us to gain a deeper understanding of the role of the gut microbiome in precision medicine and discover personalized approaches to modulating the gut microbiome that may promote health and improve patient outcomes for a variety of disorders and diseases.

https://www.gutmicrobiotaforhealth.com/summit

See Gastroenterology’s curated Equity in GI journal collection

Gastroenterology is proud to announce the release of a special collection of articles focused on the intersection of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and gastroenterology and hepatology. This curated collection, under the guidance of the journal’s new DEI section editor Dr. Chyke Doubeni, includes original research, reviews, commentaries and editorials on matters of health disparities, socioeconomic determinants of health outcomes, and population-based studies on disease incidence among races and ethnicities, among other topics. New articles are added to the collection as they are published.

View the special collection on Gastroenterology’s website, which is designed to help you quickly and easily look over the latest DEI articles and content of interest. Recent articles include:

- How to incorporate health equity training into GI/hepatology fellowships by Jannel Lee-Allen and Brijen J. Shah

- Disparities in preventable mortality from colorectal cancer: are they the result of structural racism? By Chyke A. Doubeni, Kevin Selby and Theodore R. Levin

- COVID-19 pediatric patients: GI symptoms, presentations and disparities by race/ethnicity in a large, multicenter U.S. study by Yusuf Ashktorab, Anas Brim, Antonio Pizuorno, Vijay Gayam, Sahar Nikdel and Hassan Brim

View all of Gastroenterology’s curated article collections.

Registration now open: Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit 2022

Registration is now open for the Gut Microbiota for Health (GMFH) World Summit 2022, taking place March 12-13 in Washington, D.C., and virtually.

Organized by AGA and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM), the GMFH World Summit is the preeminent international meeting on the gut microbiome for clinicians, dietitians, and researchers.

Now in its tenth year, this year’s program will focus on “The Gut Microbiome in Precision Nutrition and Medicine.” Join us to gain a deeper understanding of the role of the gut microbiome in precision medicine and discover personalized approaches to modulating the gut microbiome that may promote health and improve patient outcomes for a variety of disorders and diseases.

https://www.gutmicrobiotaforhealth.com/summit

See Gastroenterology’s curated Equity in GI journal collection

Gastroenterology is proud to announce the release of a special collection of articles focused on the intersection of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and gastroenterology and hepatology. This curated collection, under the guidance of the journal’s new DEI section editor Dr. Chyke Doubeni, includes original research, reviews, commentaries and editorials on matters of health disparities, socioeconomic determinants of health outcomes, and population-based studies on disease incidence among races and ethnicities, among other topics. New articles are added to the collection as they are published.

View the special collection on Gastroenterology’s website, which is designed to help you quickly and easily look over the latest DEI articles and content of interest. Recent articles include:

- How to incorporate health equity training into GI/hepatology fellowships by Jannel Lee-Allen and Brijen J. Shah

- Disparities in preventable mortality from colorectal cancer: are they the result of structural racism? By Chyke A. Doubeni, Kevin Selby and Theodore R. Levin

- COVID-19 pediatric patients: GI symptoms, presentations and disparities by race/ethnicity in a large, multicenter U.S. study by Yusuf Ashktorab, Anas Brim, Antonio Pizuorno, Vijay Gayam, Sahar Nikdel and Hassan Brim

View all of Gastroenterology’s curated article collections.

Registration now open: Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit 2022

Registration is now open for the Gut Microbiota for Health (GMFH) World Summit 2022, taking place March 12-13 in Washington, D.C., and virtually.

Organized by AGA and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM), the GMFH World Summit is the preeminent international meeting on the gut microbiome for clinicians, dietitians, and researchers.

Now in its tenth year, this year’s program will focus on “The Gut Microbiome in Precision Nutrition and Medicine.” Join us to gain a deeper understanding of the role of the gut microbiome in precision medicine and discover personalized approaches to modulating the gut microbiome that may promote health and improve patient outcomes for a variety of disorders and diseases.

https://www.gutmicrobiotaforhealth.com/summit

See Gastroenterology’s curated Equity in GI journal collection

Gastroenterology is proud to announce the release of a special collection of articles focused on the intersection of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and gastroenterology and hepatology. This curated collection, under the guidance of the journal’s new DEI section editor Dr. Chyke Doubeni, includes original research, reviews, commentaries and editorials on matters of health disparities, socioeconomic determinants of health outcomes, and population-based studies on disease incidence among races and ethnicities, among other topics. New articles are added to the collection as they are published.

View the special collection on Gastroenterology’s website, which is designed to help you quickly and easily look over the latest DEI articles and content of interest. Recent articles include:

- How to incorporate health equity training into GI/hepatology fellowships by Jannel Lee-Allen and Brijen J. Shah

- Disparities in preventable mortality from colorectal cancer: are they the result of structural racism? By Chyke A. Doubeni, Kevin Selby and Theodore R. Levin

- COVID-19 pediatric patients: GI symptoms, presentations and disparities by race/ethnicity in a large, multicenter U.S. study by Yusuf Ashktorab, Anas Brim, Antonio Pizuorno, Vijay Gayam, Sahar Nikdel and Hassan Brim

View all of Gastroenterology’s curated article collections.

February 2022 – ICYMI

Gastroenterology

November 2021

How to navigate national societal organizations for leadership development and academic promotion: A guide for trainees and young faculty

Aby ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1361-1365. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.044.

Value of pH impedance monitoring while on twice-daily proton pump inhibitor therapy to identify need for escalation of reflux management

Gyawali CG et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1412-1422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.004.

The sulfur microbial diet is associated with increased risk of early-onset colorectal cancer precursors

Nguyen LH et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1423-1432.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.008.

Underwater vs conventional endoscopic mucosal resection of large sessile or flat colorectal polyps: A prospective randomized controlled trial

Nagl S et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1460-1474.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.044.

December 2021

How to approach long-term enteral and parenteral nutrition

Hadefi A, Arvanitakis M. Gastroenterology. 2021 Dec;161(6):1780-1786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.030.

Regular use of proton pump inhibitor and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: Pooled analysis of 3 prospective cohorts

Xia B et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Dec;161(6):1842-1852.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.005.

January 2022

Serologic response to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Sakuraba A et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):88-108.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.055.

Advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion in scientific publishing

Doubeni CA et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):59-62.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.043.

How we approach difficult to eradicate Helicobacter pylori

Argueta EA, Moss SF. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):32-37. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.048.

Global incidence of acute pancreatitis is increasing over time: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Iannuzzi JP et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):122-134. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.043.

Epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of gastroparesis: Real-world evidence from a large US national claims database

Ye Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):109-121.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.064.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

November 2021

AGA Clinical Practice Update on endoscopic management of perforations in gastrointestinal tract: Expert Review

Lee JH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2252-2261.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.045.

Food allergies and intolerances: A clinical approach to the diagnosis and management of adverse reactions to food

Onyimba F et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2230-2240.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.025.

Management of gastrointestinal side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors

Lui RN et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2262-2265. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.038.

December 2021

Optimizing the endoscopic examination in eosinophilic esophagitis

Dellon ES. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec;19(12):2489-2492.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.011.

Diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin concentration in evaluating therapeutic outcomes of patients with ulcerative colitis

Stevens TW et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2333-2342. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.019.

Factors associated with inpatient endoscopy delay and its impact on hospital length-of-stay and 30-day readmission

Jacobs CC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec;19(12):2648-2655. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.009.

January 2022

Comparing costs and outcomes of treatments for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: Cost-benefit analysis

Shah ED et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):136-144.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.043.

Next generation academic gastroenterology

Allen JI, Berry S. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):5-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.038.

Beyond metoclopramide for gastroparesis

Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):19-24. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.08.052.

Comparative safety and effectiveness of vedolizumab to tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy for ulcerative colitis

Lukin D et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):126-135. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.10.003.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on utilization of EGD and colonoscopy in the United States: An analysis of the GIQuIC registry

Calderwood AH et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(4):313-321. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.07.003.

How to approach small polyps in colon: Tips and tricks

Mahmood S et al. Tech Inov Gastroinest Endosc. 2021;23(4):238-335. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.06.007

Gastroenterology

November 2021

How to navigate national societal organizations for leadership development and academic promotion: A guide for trainees and young faculty

Aby ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1361-1365. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.044.

Value of pH impedance monitoring while on twice-daily proton pump inhibitor therapy to identify need for escalation of reflux management

Gyawali CG et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1412-1422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.004.

The sulfur microbial diet is associated with increased risk of early-onset colorectal cancer precursors

Nguyen LH et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1423-1432.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.008.

Underwater vs conventional endoscopic mucosal resection of large sessile or flat colorectal polyps: A prospective randomized controlled trial

Nagl S et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1460-1474.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.044.

December 2021

How to approach long-term enteral and parenteral nutrition

Hadefi A, Arvanitakis M. Gastroenterology. 2021 Dec;161(6):1780-1786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.030.

Regular use of proton pump inhibitor and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: Pooled analysis of 3 prospective cohorts

Xia B et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Dec;161(6):1842-1852.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.005.

January 2022

Serologic response to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Sakuraba A et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):88-108.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.055.

Advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion in scientific publishing

Doubeni CA et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):59-62.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.043.

How we approach difficult to eradicate Helicobacter pylori

Argueta EA, Moss SF. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):32-37. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.048.

Global incidence of acute pancreatitis is increasing over time: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Iannuzzi JP et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):122-134. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.043.

Epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of gastroparesis: Real-world evidence from a large US national claims database

Ye Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):109-121.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.064.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

November 2021

AGA Clinical Practice Update on endoscopic management of perforations in gastrointestinal tract: Expert Review

Lee JH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2252-2261.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.045.

Food allergies and intolerances: A clinical approach to the diagnosis and management of adverse reactions to food

Onyimba F et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2230-2240.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.025.

Management of gastrointestinal side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors

Lui RN et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2262-2265. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.038.

December 2021

Optimizing the endoscopic examination in eosinophilic esophagitis

Dellon ES. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec;19(12):2489-2492.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.011.

Diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin concentration in evaluating therapeutic outcomes of patients with ulcerative colitis

Stevens TW et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2333-2342. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.019.

Factors associated with inpatient endoscopy delay and its impact on hospital length-of-stay and 30-day readmission

Jacobs CC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec;19(12):2648-2655. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.009.

January 2022

Comparing costs and outcomes of treatments for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: Cost-benefit analysis

Shah ED et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):136-144.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.043.

Next generation academic gastroenterology

Allen JI, Berry S. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):5-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.038.

Beyond metoclopramide for gastroparesis

Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):19-24. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.08.052.

Comparative safety and effectiveness of vedolizumab to tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy for ulcerative colitis

Lukin D et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):126-135. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.10.003.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on utilization of EGD and colonoscopy in the United States: An analysis of the GIQuIC registry

Calderwood AH et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(4):313-321. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.07.003.

How to approach small polyps in colon: Tips and tricks

Mahmood S et al. Tech Inov Gastroinest Endosc. 2021;23(4):238-335. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.06.007

Gastroenterology

November 2021

How to navigate national societal organizations for leadership development and academic promotion: A guide for trainees and young faculty

Aby ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1361-1365. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.044.

Value of pH impedance monitoring while on twice-daily proton pump inhibitor therapy to identify need for escalation of reflux management

Gyawali CG et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1412-1422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.004.

The sulfur microbial diet is associated with increased risk of early-onset colorectal cancer precursors

Nguyen LH et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1423-1432.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.008.

Underwater vs conventional endoscopic mucosal resection of large sessile or flat colorectal polyps: A prospective randomized controlled trial

Nagl S et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1460-1474.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.044.

December 2021

How to approach long-term enteral and parenteral nutrition

Hadefi A, Arvanitakis M. Gastroenterology. 2021 Dec;161(6):1780-1786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.030.

Regular use of proton pump inhibitor and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: Pooled analysis of 3 prospective cohorts

Xia B et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Dec;161(6):1842-1852.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.005.

January 2022

Serologic response to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Sakuraba A et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):88-108.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.055.

Advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion in scientific publishing

Doubeni CA et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):59-62.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.043.

How we approach difficult to eradicate Helicobacter pylori

Argueta EA, Moss SF. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):32-37. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.048.

Global incidence of acute pancreatitis is increasing over time: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Iannuzzi JP et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):122-134. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.043.

Epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of gastroparesis: Real-world evidence from a large US national claims database

Ye Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jan;162(1):109-121.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.064.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

November 2021

AGA Clinical Practice Update on endoscopic management of perforations in gastrointestinal tract: Expert Review

Lee JH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2252-2261.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.045.

Food allergies and intolerances: A clinical approach to the diagnosis and management of adverse reactions to food

Onyimba F et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2230-2240.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.025.

Management of gastrointestinal side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors

Lui RN et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2262-2265. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.038.

December 2021

Optimizing the endoscopic examination in eosinophilic esophagitis

Dellon ES. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec;19(12):2489-2492.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.011.

Diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin concentration in evaluating therapeutic outcomes of patients with ulcerative colitis

Stevens TW et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;19(11):2333-2342. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.019.

Factors associated with inpatient endoscopy delay and its impact on hospital length-of-stay and 30-day readmission

Jacobs CC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec;19(12):2648-2655. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.009.

January 2022

Comparing costs and outcomes of treatments for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: Cost-benefit analysis

Shah ED et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):136-144.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.043.

Next generation academic gastroenterology

Allen JI, Berry S. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):5-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.038.

Beyond metoclopramide for gastroparesis

Camilleri M. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):19-24. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.08.052.

Comparative safety and effectiveness of vedolizumab to tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy for ulcerative colitis

Lukin D et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jan;20(1):126-135. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.10.003.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on utilization of EGD and colonoscopy in the United States: An analysis of the GIQuIC registry

Calderwood AH et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(4):313-321. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.07.003.

How to approach small polyps in colon: Tips and tricks

Mahmood S et al. Tech Inov Gastroinest Endosc. 2021;23(4):238-335. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.06.007

Gender-based pay inequity in gastroenterology

In 2017, the number of women students entering medical school surpassed that of men.1 However, the future generation of women doctors is unlikely to be paid the same as their male colleagues for equal work unless something changes in health care. About 34% of gastroenterology fellows are women,2 and there are increasing proportions of women in all academic and community practices, as well as in leadership positions.

Despite this progress, equity in pay between male and female physicians has been unequal in many areas of the country, despite the same level of training.3 Doximity, a social network for physicians, surveyed 65,000 doctors in the United States and found a difference in pay between male and female physicians who worked full time.4 This is an issue that the medical field has been aware of for many years, and articles have been published on this topic in several medical journals.5-11 Doximity found that women physicians are paid less than men, although the extent of the difference varies among regions.

In 2017, per the Doximity report, the field of gastroenterology was one of the top five specialties with the biggest pay gap: Women gastroenterologists earn 19% less (or $86,447) than men gastroenterologists. This study did not differentiate among practice types (academic, private practice, hospital, or multispecialty), but it did break down the data for all physicians into general groups of owner/partner, independent contractor, and employee – it found a gender-based gap in pay among all three of these groups. For owner/partners, the gap was a $114,590 (27.2%) difference.4 According to Doximity survey data from 2018, gastroenterology is no longer in the top five specialties with the largest gender pay gap, indicating the gap is shrinking but still exists.12

A questionnaire sent to gastroenterologists 3, 5, or 10 years after they completed their fellowships (in 1993 or 1995) revealed that after 3 years women earned 23% less per hour than men, and at 5 years, the gap had decreased to 19% less per hour.6-7 The statistical data showed that the mean annual gross income of males was significantly higher at 3 years and 5 years.7 Unfortunately, at 10 years the income gap increased up to 22%.6 The researchers found that female gastroenterologists at academic centers earned 39% less than male gastroenterologists at academic centers, whereas women at nonacademic centers earned 24% less than men, despite similar work hours and call schedules.6-7

Desai and colleauges analyzed health care provider reimbursement data for various medical specialties using the 2014 Medicare Fee-for-Service Provider Utilization and Payment Data Physician and Other Supplier Public Use File, and they found a disparity in reimbursements of female versus male physicians.11 Female physicians received significantly lower Medicare reimbursements in 11 of 13 medical specialties,4 despite adjustments for productivity, work hours, and years of experience. Factors that might affect Medicare reimbursement include variations in payment among different locations, types of service provided, location of procedures performed (hospital vs. clinic), and missing data because of privacy concerns.

Among medical specialties, the gender-based payment gap is highest among vascular surgeons, followed by occupational medicine physicians, gastroenterologists, pediatric endocrinologists, and rheumatologists. In these specialties, men earn approximately 20% more than women (approximately $89,000 more for a male vascular surgeon or about $45,000 more for a male pediatric rheumatologist).4

Gender-based gaps in pay, leadership opportunities, and other opportunities exist in the health care field regardless of whether physicians are employed at academic institutions, community-based private practices, or large health care systems. Women physicians occupy fewer leadership positions, and female physician leaders have greater disparities in pay, compared with men than women who are not in leadership positions.6,10 A 2016 survey of the 50 medical schools with the largest amounts of funding from the National Institutes of Health revealed that only 13% of the department leaders were women.

The Fair Pay Act of 2013 and the Paycheck Fairness Act of 2014 aimed to close the salary gap between men and women.13 So why are women paid less than men for the same work? Some researchers have proposed “gender differences in negotiation skills, lack of opportunities to join networks of influence within organizations, and implicit or explicit bias and discrimination.”8,10

The fee for service model based on relative value units can result in lower pay for female physicians, who spend more time with patients, compared with male physicians, because of fewer billable RVUs per hour and per day.15

What should be done?

The American Medical Women’s Association leadership stated that the key to pay equity is transparency, which has been a struggle. Some states, such as New York, require state contractors, including providers that work with the state health department, to disclose salary information. Because of the persistent gender gap in pay in all medical specialties (even after adjustments for age, experience, faculty rank, and measures of research productivity and clinical revenue), the American Medical Association House of Delegates announced a plan to balance salaries within the AMA, and in medicine overall, by promoting research, action, and advocacy.14 In the American College of Physicians, 37% of the members are women. This organization published a position paper in 2018 on gender disparity in pay, and proposed solutions included reviewing and addressing recruitment and advancement of women and other underrepresented groups.15

The executive director of Indiana University’s National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health in Indianapolis, Theresa Rohr-Kirchgraber, MD, who is a professor of clinical care and pediatrics, said that women physicians should bill and code in ways that better reflect the services they provide. Women should also demand more transparency in salaries and push to remove patient satisfaction scores from being a factor in salary determination.16

It is also important to note that there are medical groups and hospitals at which disparities in gender pay might not be an issue, because of physician compensation models. These include but are not limited to Kaiser Permanente and large private practice groups (such as MNGI Digestive Health). For example, with MNGI Digestive Health, shareholder track, ambulatory surgical center distributions are based on full-time equivalent status and not on production. Shareholder compensation is transparent and communicated to all. For Kaiser Permanente, salary is based on specialty and years of service. We will have the opportunity to evaluate the effects of different compensation models as health care delivery moves toward value-based care.

There is a limitation in data presented, as we were unable to obtain specialty salary data from the Association of American Medical Colleges or Medical Group Management Association to confirm findings from the Doximity survey, etc.

Conclusions

It is important to acknowledge that we have made great strides in ensuring gender diversity in the field of gastroenterology. All professional medical and gastroenterological societies are working to address gender disparities in compensation and leadership opportunities. Medical schools and fellowship programs have incorporated training on negotiation skills into their curriculums. The medical profession and overall society will benefit from providing thriving workplaces to female physicians, allowing them to achieve their full potential by ensuring gender equity in compensation and opportunities.

Dr. Perera is a gastroenterologist at Advocate Aurora Health, Grafton, Wisc. Dr. Toriz is a gastroenterologist, treasurer, and board member, MNGI Digestive Health, Bloomington, Minn. They disclosed having no relevant conflicts of interest.

References