User login

AGA News

New patient care resource: NASH Clinical Care Pathway

The American Gastroenterological Association – in collaboration with seven professional associations – assembled a multidisciplinary taskforce of 15 experts to develop an action plan to develop a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) Clinical Care Pathway providing practical guidance across multiple disciplines of care. The guidance ranges from screening and diagnosis to management of individuals with NAFLD and NASH, as well as facilitating value-based, efficient, and safe care that is consistent with evidence-based guidelines.

This clinical care pathway is intended to be applicable in any setting in which care for patients with NAFLD is provided, including primary care, endocrine, obesity medicine, and gastroenterology practices.

Read the special report: Clinical Care Pathway for the Risk Stratification and Management of Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.

To learn more about the development of this publication, visit NASH.gastro.org.

GI societies push CMS for payment rules favorable for practices

As part of our longstanding collaboration and ongoing efforts on critical policy and payment issues impacting GI clinicians, AGA, the American College of Gastroenterology, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy submitted comments on proposed 2022 Medicare payments to physicians, ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), and hospital outpatient departments to the CMS. We advocated for the following:

Increased and more accurate valuation for peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) and capsule endoscopy services.

Continued flexibility and payment parity for telehealth and telephone services.

Elimination of the secondary scalar for ASCs, which contributes to the widening differential in payments to ASCs compared to the hospital outpatient department.

You can access our letter here.

New patient care resource: NASH Clinical Care Pathway

The American Gastroenterological Association – in collaboration with seven professional associations – assembled a multidisciplinary taskforce of 15 experts to develop an action plan to develop a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) Clinical Care Pathway providing practical guidance across multiple disciplines of care. The guidance ranges from screening and diagnosis to management of individuals with NAFLD and NASH, as well as facilitating value-based, efficient, and safe care that is consistent with evidence-based guidelines.

This clinical care pathway is intended to be applicable in any setting in which care for patients with NAFLD is provided, including primary care, endocrine, obesity medicine, and gastroenterology practices.

Read the special report: Clinical Care Pathway for the Risk Stratification and Management of Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.

To learn more about the development of this publication, visit NASH.gastro.org.

GI societies push CMS for payment rules favorable for practices

As part of our longstanding collaboration and ongoing efforts on critical policy and payment issues impacting GI clinicians, AGA, the American College of Gastroenterology, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy submitted comments on proposed 2022 Medicare payments to physicians, ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), and hospital outpatient departments to the CMS. We advocated for the following:

Increased and more accurate valuation for peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) and capsule endoscopy services.

Continued flexibility and payment parity for telehealth and telephone services.

Elimination of the secondary scalar for ASCs, which contributes to the widening differential in payments to ASCs compared to the hospital outpatient department.

You can access our letter here.

New patient care resource: NASH Clinical Care Pathway

The American Gastroenterological Association – in collaboration with seven professional associations – assembled a multidisciplinary taskforce of 15 experts to develop an action plan to develop a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) Clinical Care Pathway providing practical guidance across multiple disciplines of care. The guidance ranges from screening and diagnosis to management of individuals with NAFLD and NASH, as well as facilitating value-based, efficient, and safe care that is consistent with evidence-based guidelines.

This clinical care pathway is intended to be applicable in any setting in which care for patients with NAFLD is provided, including primary care, endocrine, obesity medicine, and gastroenterology practices.

Read the special report: Clinical Care Pathway for the Risk Stratification and Management of Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.

To learn more about the development of this publication, visit NASH.gastro.org.

GI societies push CMS for payment rules favorable for practices

As part of our longstanding collaboration and ongoing efforts on critical policy and payment issues impacting GI clinicians, AGA, the American College of Gastroenterology, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy submitted comments on proposed 2022 Medicare payments to physicians, ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), and hospital outpatient departments to the CMS. We advocated for the following:

Increased and more accurate valuation for peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) and capsule endoscopy services.

Continued flexibility and payment parity for telehealth and telephone services.

Elimination of the secondary scalar for ASCs, which contributes to the widening differential in payments to ASCs compared to the hospital outpatient department.

You can access our letter here.

November 2021 – ICYMI

Gastroenterology

August 2021

How to perform a high-quality endoscopic submucosal dissection

Saito Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):405-10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.051.

Comparative effectiveness of multiple different first-line treatment regimens for Helicobacter pylori infection: A network meta-analysis

Rokkas T et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):495-507.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.012.

The optimal age to stop endoscopic surveillance of patients with Barrett’s esophagus based on sex and comorbidity: A comparative cost-effectiveness analysis

Omidvari AH et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):487-94.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.003.

Development and validation of test for “leaky gut” small intestinal and colonic permeability using sugars in healthy adults

Khoshbin K et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):463-75.e13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.020.

September 2021

Pregnancy and the working gastroenterologist: Perceptions, realities, and systemic challenges

David YN et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):756-60. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.053.

New drugs on the horizon for functional and motility gastrointestinal disorders

Camilleri M. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):761-4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.079.

A randomized trial comparing the specific carbohydrate diet to a Mediterranean diet in adults with Crohn’s disease

Lewis JD et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):837-52.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.047.

How to promote career advancement and gender equity for women in gastroenterology: a multifaceted approach

Chua SG et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):792-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.057.

October 2021

How to approach a patient with difficult-to-treat IBS

Chang L. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1092-8.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.034.

Early-age onset colorectal neoplasia in average-risk individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Kolb JM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1145-55.e12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.006.

Adalimumab subcutaneous in participants with ulcerative colitis (VARSITY)

Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1156-67.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.015.

Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: Current concepts, treatment, and implications for disease management

Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1118-32. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.042.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

August 2021

Health equity and telemedicine in gastroenterology and hepatology

Wegermann K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1516-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.024.

AGA Clinical Practice Update on evaluation and management of early complications after bariatric/metabolic surgery: Expert review

Kumbhari V et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1531-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.020.

Clinical, pathology, genetic, and molecular features of colorectal tumors in adolescents and adults 25 years or younger

de Voer RM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1642-51.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.034.

Safety of tofacitinib in a real-world cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis

Deepak P et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1592-601.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.050.

September 2021

Association of adenoma detection rate and adenoma characteristics with colorectal cancer mortality after screening colonoscopy

Waldmann E et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Sep;19(9):1890-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.023.

Prevalence and characteristics of abdominal pain in the United States

Lakhoo K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Sep;19(9):1864-72.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.065.

Model using clinical and endoscopic characteristics identifies patients at risk for eosinophilic esophagitis according to updated diagnostic guidelines

Cotton CC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Sep;19(9):1824-34.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.068.

October 2021

A high-yield approach to effective endoscopy teaching and assessment

Huang HZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):1999-2001. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.013.

2021 E/M code changes: Forecasted impacts to gastroenterology practices

Francis DL et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2002-5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.008.

You can’t have one without the other: Innovation and ethical dilemmas in gastroenterology and hepatology

Couri T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2015-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.024.

Psychiatric disorders in patients with a diagnosis of celiac disease during childhood from 1973 to 2016

Lebwohl B et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2093-101.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.018.

Mast cell and eosinophil counts in gastric and duodenal biopsy specimens from patients with and without eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Reed CC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2102-2111. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.013.

Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Sex differences in the exocrine pancreas and associated diseases

Wang M et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12(2):427-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.04.005.

Mesenteric neural crest cells are the embryological basis of skip segment Hirschsprung’s disease

Yu Q et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12(1):1-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.12.010.

Helicobacter pylori–induced rev-erbα fosters gastric bacteria colonization by impairing host innate and adaptive defense

Mao MY et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12(2):395-425. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.02.013.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Staying (mentally) healthy: The impact of COVID-19 on personal and professional lives

Alkandari A et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):199-206. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.01.003.

Establishing new endoscopic programs in the unit pitfalls and tips for success

Siddiqui UD. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(3):263-7. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.03.002.

Chief of endoscopy: Specific challenges to leading the team and running the unit

Michelle A. Anderson MA et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(3):249-55. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.03.004.

Safety in endoscopy for patients and healthcare workers During the COVID-19 pandemic

Lui RN. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):170-178. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.10.004.

Gastroenterology

August 2021

How to perform a high-quality endoscopic submucosal dissection

Saito Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):405-10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.051.

Comparative effectiveness of multiple different first-line treatment regimens for Helicobacter pylori infection: A network meta-analysis

Rokkas T et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):495-507.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.012.

The optimal age to stop endoscopic surveillance of patients with Barrett’s esophagus based on sex and comorbidity: A comparative cost-effectiveness analysis

Omidvari AH et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):487-94.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.003.

Development and validation of test for “leaky gut” small intestinal and colonic permeability using sugars in healthy adults

Khoshbin K et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):463-75.e13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.020.

September 2021

Pregnancy and the working gastroenterologist: Perceptions, realities, and systemic challenges

David YN et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):756-60. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.053.

New drugs on the horizon for functional and motility gastrointestinal disorders

Camilleri M. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):761-4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.079.

A randomized trial comparing the specific carbohydrate diet to a Mediterranean diet in adults with Crohn’s disease

Lewis JD et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):837-52.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.047.

How to promote career advancement and gender equity for women in gastroenterology: a multifaceted approach

Chua SG et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):792-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.057.

October 2021

How to approach a patient with difficult-to-treat IBS

Chang L. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1092-8.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.034.

Early-age onset colorectal neoplasia in average-risk individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Kolb JM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1145-55.e12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.006.

Adalimumab subcutaneous in participants with ulcerative colitis (VARSITY)

Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1156-67.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.015.

Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: Current concepts, treatment, and implications for disease management

Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1118-32. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.042.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

August 2021

Health equity and telemedicine in gastroenterology and hepatology

Wegermann K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1516-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.024.

AGA Clinical Practice Update on evaluation and management of early complications after bariatric/metabolic surgery: Expert review

Kumbhari V et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1531-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.020.

Clinical, pathology, genetic, and molecular features of colorectal tumors in adolescents and adults 25 years or younger

de Voer RM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1642-51.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.034.

Safety of tofacitinib in a real-world cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis

Deepak P et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1592-601.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.050.

September 2021

Association of adenoma detection rate and adenoma characteristics with colorectal cancer mortality after screening colonoscopy

Waldmann E et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Sep;19(9):1890-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.023.

Prevalence and characteristics of abdominal pain in the United States

Lakhoo K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Sep;19(9):1864-72.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.065.

Model using clinical and endoscopic characteristics identifies patients at risk for eosinophilic esophagitis according to updated diagnostic guidelines

Cotton CC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Sep;19(9):1824-34.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.068.

October 2021

A high-yield approach to effective endoscopy teaching and assessment

Huang HZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):1999-2001. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.013.

2021 E/M code changes: Forecasted impacts to gastroenterology practices

Francis DL et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2002-5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.008.

You can’t have one without the other: Innovation and ethical dilemmas in gastroenterology and hepatology

Couri T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2015-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.024.

Psychiatric disorders in patients with a diagnosis of celiac disease during childhood from 1973 to 2016

Lebwohl B et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2093-101.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.018.

Mast cell and eosinophil counts in gastric and duodenal biopsy specimens from patients with and without eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Reed CC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2102-2111. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.013.

Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Sex differences in the exocrine pancreas and associated diseases

Wang M et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12(2):427-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.04.005.

Mesenteric neural crest cells are the embryological basis of skip segment Hirschsprung’s disease

Yu Q et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12(1):1-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.12.010.

Helicobacter pylori–induced rev-erbα fosters gastric bacteria colonization by impairing host innate and adaptive defense

Mao MY et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12(2):395-425. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.02.013.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Staying (mentally) healthy: The impact of COVID-19 on personal and professional lives

Alkandari A et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):199-206. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.01.003.

Establishing new endoscopic programs in the unit pitfalls and tips for success

Siddiqui UD. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(3):263-7. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.03.002.

Chief of endoscopy: Specific challenges to leading the team and running the unit

Michelle A. Anderson MA et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(3):249-55. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.03.004.

Safety in endoscopy for patients and healthcare workers During the COVID-19 pandemic

Lui RN. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):170-178. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.10.004.

Gastroenterology

August 2021

How to perform a high-quality endoscopic submucosal dissection

Saito Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):405-10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.051.

Comparative effectiveness of multiple different first-line treatment regimens for Helicobacter pylori infection: A network meta-analysis

Rokkas T et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):495-507.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.012.

The optimal age to stop endoscopic surveillance of patients with Barrett’s esophagus based on sex and comorbidity: A comparative cost-effectiveness analysis

Omidvari AH et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):487-94.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.003.

Development and validation of test for “leaky gut” small intestinal and colonic permeability using sugars in healthy adults

Khoshbin K et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Aug;161(2):463-75.e13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.020.

September 2021

Pregnancy and the working gastroenterologist: Perceptions, realities, and systemic challenges

David YN et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):756-60. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.053.

New drugs on the horizon for functional and motility gastrointestinal disorders

Camilleri M. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):761-4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.079.

A randomized trial comparing the specific carbohydrate diet to a Mediterranean diet in adults with Crohn’s disease

Lewis JD et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):837-52.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.047.

How to promote career advancement and gender equity for women in gastroenterology: a multifaceted approach

Chua SG et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Sep;161(3):792-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.057.

October 2021

How to approach a patient with difficult-to-treat IBS

Chang L. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1092-8.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.034.

Early-age onset colorectal neoplasia in average-risk individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Kolb JM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1145-55.e12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.006.

Adalimumab subcutaneous in participants with ulcerative colitis (VARSITY)

Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1156-67.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.015.

Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: Current concepts, treatment, and implications for disease management

Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Oct;161(4):1118-32. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.042.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

August 2021

Health equity and telemedicine in gastroenterology and hepatology

Wegermann K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1516-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.024.

AGA Clinical Practice Update on evaluation and management of early complications after bariatric/metabolic surgery: Expert review

Kumbhari V et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1531-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.020.

Clinical, pathology, genetic, and molecular features of colorectal tumors in adolescents and adults 25 years or younger

de Voer RM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1642-51.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.034.

Safety of tofacitinib in a real-world cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis

Deepak P et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Aug;19(8):1592-601.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.050.

September 2021

Association of adenoma detection rate and adenoma characteristics with colorectal cancer mortality after screening colonoscopy

Waldmann E et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Sep;19(9):1890-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.023.

Prevalence and characteristics of abdominal pain in the United States

Lakhoo K et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Sep;19(9):1864-72.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.065.

Model using clinical and endoscopic characteristics identifies patients at risk for eosinophilic esophagitis according to updated diagnostic guidelines

Cotton CC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Sep;19(9):1824-34.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.068.

October 2021

A high-yield approach to effective endoscopy teaching and assessment

Huang HZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):1999-2001. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.013.

2021 E/M code changes: Forecasted impacts to gastroenterology practices

Francis DL et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2002-5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.008.

You can’t have one without the other: Innovation and ethical dilemmas in gastroenterology and hepatology

Couri T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2015-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.024.

Psychiatric disorders in patients with a diagnosis of celiac disease during childhood from 1973 to 2016

Lebwohl B et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2093-101.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.018.

Mast cell and eosinophil counts in gastric and duodenal biopsy specimens from patients with and without eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Reed CC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct;19(10):2102-2111. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.013.

Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Sex differences in the exocrine pancreas and associated diseases

Wang M et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12(2):427-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.04.005.

Mesenteric neural crest cells are the embryological basis of skip segment Hirschsprung’s disease

Yu Q et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12(1):1-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.12.010.

Helicobacter pylori–induced rev-erbα fosters gastric bacteria colonization by impairing host innate and adaptive defense

Mao MY et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12(2):395-425. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.02.013.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Staying (mentally) healthy: The impact of COVID-19 on personal and professional lives

Alkandari A et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):199-206. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.01.003.

Establishing new endoscopic programs in the unit pitfalls and tips for success

Siddiqui UD. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(3):263-7. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.03.002.

Chief of endoscopy: Specific challenges to leading the team and running the unit

Michelle A. Anderson MA et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(3):249-55. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.03.004.

Safety in endoscopy for patients and healthcare workers During the COVID-19 pandemic

Lui RN. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):170-178. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.10.004.

Developing a career in medical pancreatology: An emerging postfellowship career path

Although described by the Greek physician Herophilos around 300 B.C., it was not until the 19th century that enzymes began to be isolated from pancreatic secretions and their digestive action described, and not until early in the 20th century that Banting, Macleod, and Best received the Nobel prize for purifying insulin from the pancreata of dogs. For centuries in between, the pancreas was considered to be just a ‘beautiful piece of flesh’ (kallikreas), the main role of which was to protect the blood vessels in the abdomen and to serve as a cushion to the stomach.1 Certainly, the pancreas has come a long way since then but, like most other organs in the body, is oft ignored until it develops issues.

Like many other disorders in gastroenterology, pancreatic disorders were historically approached as mechanical or “plumbing” issues. As modern technology and innovation percolated through the world of endoscopy, a wide array of state-of-the-art tools were devised. Availability of newer “toys” and development of newer techniques also means that an ever-increasing curriculum has been squeezed into a generally single year of therapeutic endoscopy training, such that trainees can no longer limit themselves to learning only endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or intervening on pancreatic disease alone. Modern, subspecialized approaches to disease and economic considerations often dictate that the therapeutic endoscopist of today must perform a wide range of procedures besides ERCP and EUS, such as advanced resection using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), endoscopic bariatric procedures, and newer techniques and acronyms that continue to evolve on a regular basis. This leaves the therapeutic endoscopist with little time for outpatient management of many patients that don’t need interventional procedures but are often very complex and need ongoing, long-term follow-up. In addition, any clinic slots available for interventional endoscopists may be utilized by patients coming in to discuss complex procedures or for postprocedure follow-up. Endoscopic management is not the definitive treatment for most pancreatic disorders. In fact, as our knowledge of pancreatic disease has continued to evolve, endoscopic intervention is now required in a minority of cases.

Role of the medical pancreatologist

Patient Care

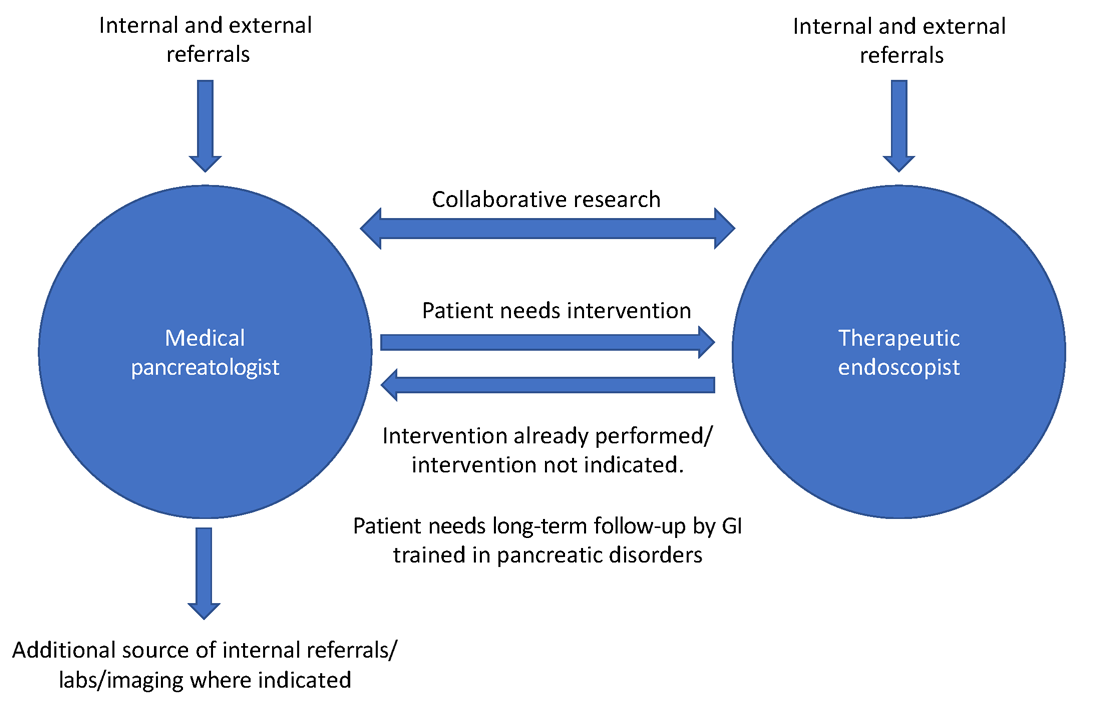

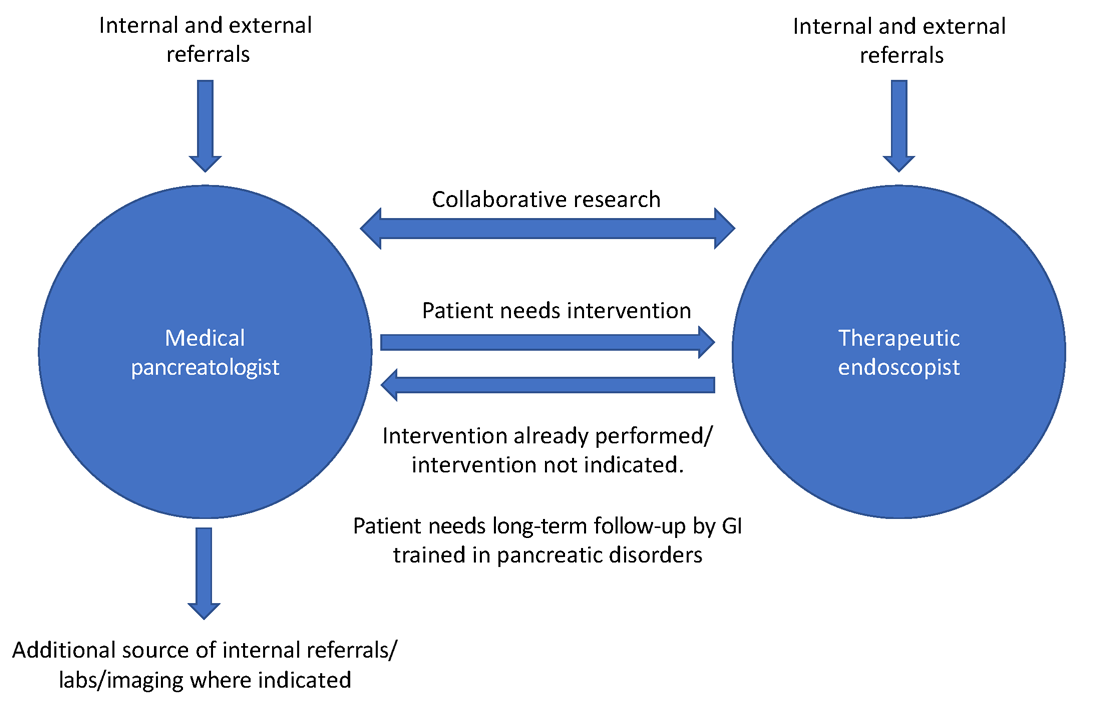

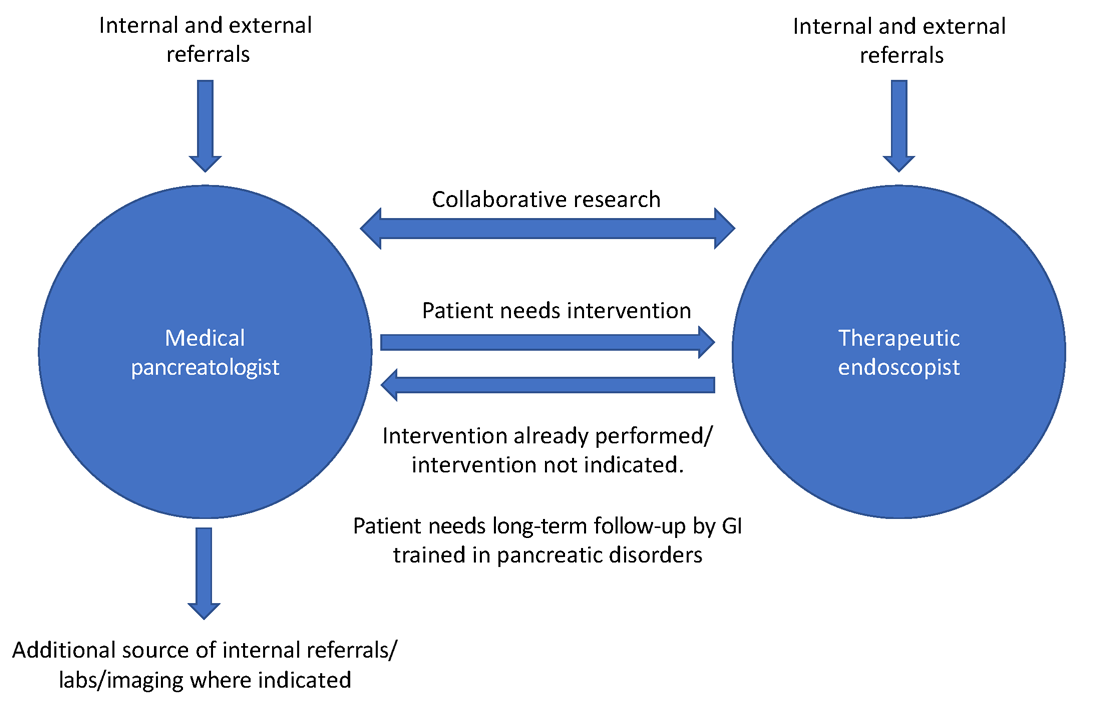

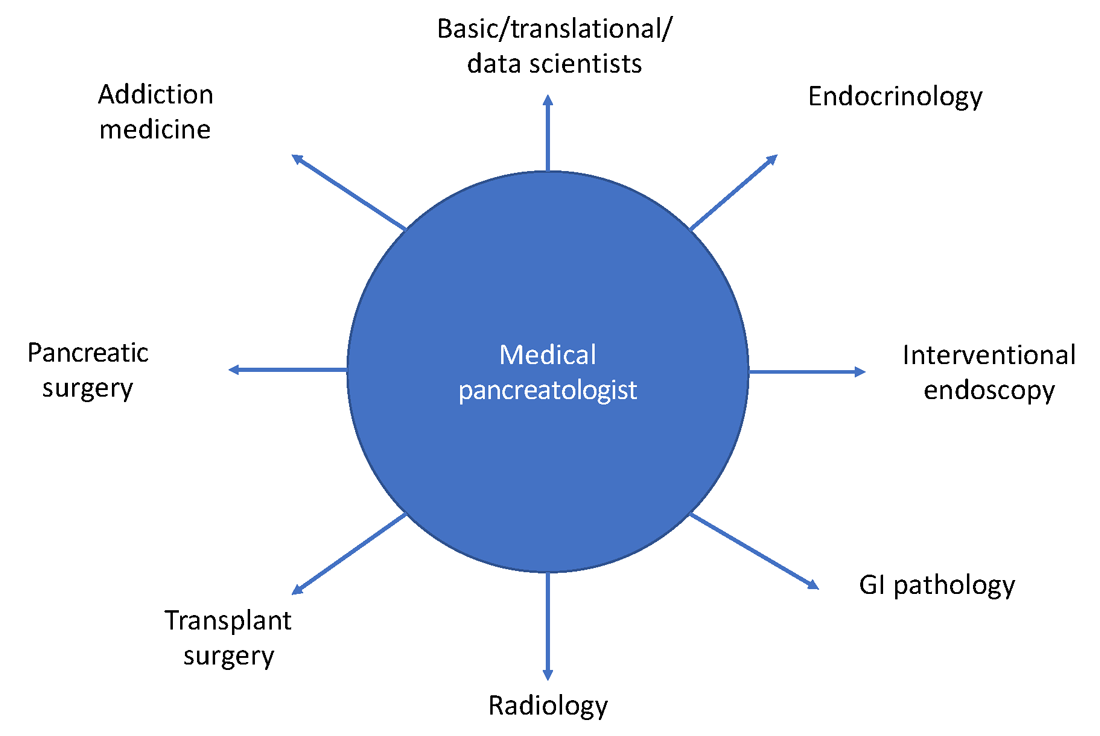

As part of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary team that also includes an interventional gastroenterologist, pancreatic surgeon, transplant surgeon (in centers offering islet autotransplantation with total pancreatectomy), radiology, endocrinology, and GI pathologist, the medical pancreatologist helps lead the care of patients with pancreatic disorders, such as pancreatic cysts, acute and chronic pancreatitis (especially in cases where there is no role for active endoscopic intervention), autoimmune pancreatitis, indeterminate pancreatic masses, as well as screens high-risk patients for pancreatic cancer in conjunction with a genetic counselor. The medical pancreatologist often also serves as a bridge between various members of a large multidisciplinary team that, formally in the form of conferences or informally, discusses the management of complex patients, with each member available to help the other based on the patient’s most immediate clinical need at that time. A schematic showing how the medical pancreatologist collaborates with the therapeutic endoscopist is provided in Figure 1.

Uzma Siddiqui, MD, director for the Center for Endoscopic Research and Technology (CERT) at the University of Chicago said, “The management of pancreatic diseases is often challenging. Surgeons and endoscopists can offer some treatments that focus on one aspect or symptom, but the medical pancreatologist brings focus to the patient as a whole and helps organize care. It is only with everyone’s combined efforts and the added perspective of the medical pancreatologist that we can provide the best care for our shared patients.”

David Xin, MD, MPH, a medical pancreatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, added, “I am often asked what it means to be a medical pancreatologist. What do I do if not EUS and ERCP? I provide longitudinal care, coordinate multidisciplinary management, assess nutritional status, optimize quality of life, and manage pain. But perhaps most importantly, I make myself available for patients who seek understanding and sympathy regarding their complex disease. I became a medical pancreatologist because my mentors during training helped me recognize how rewarding this career would be.”

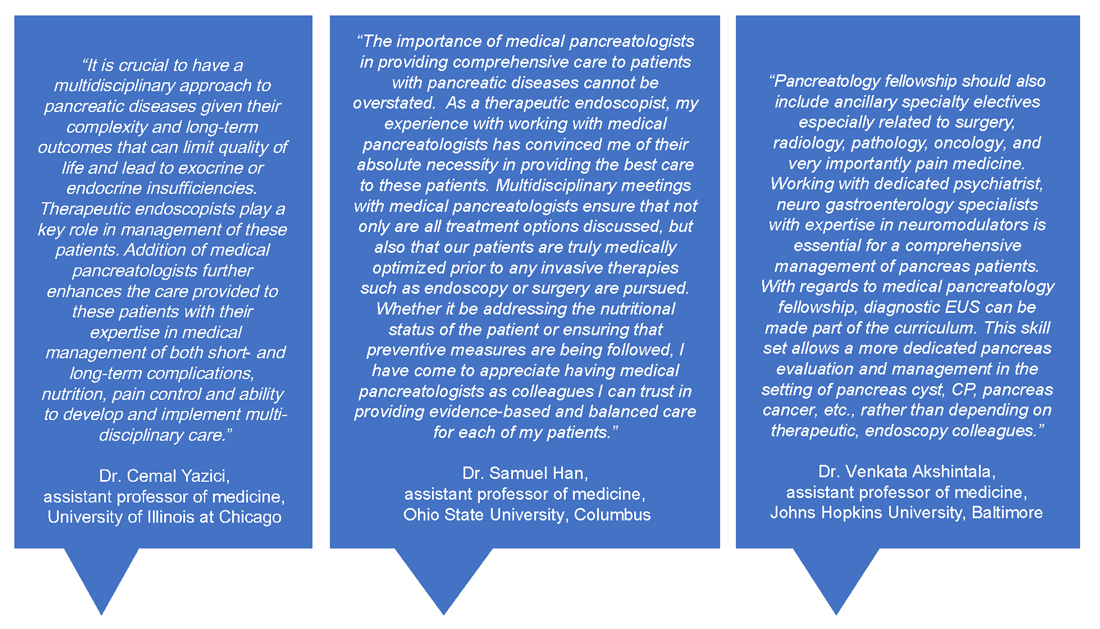

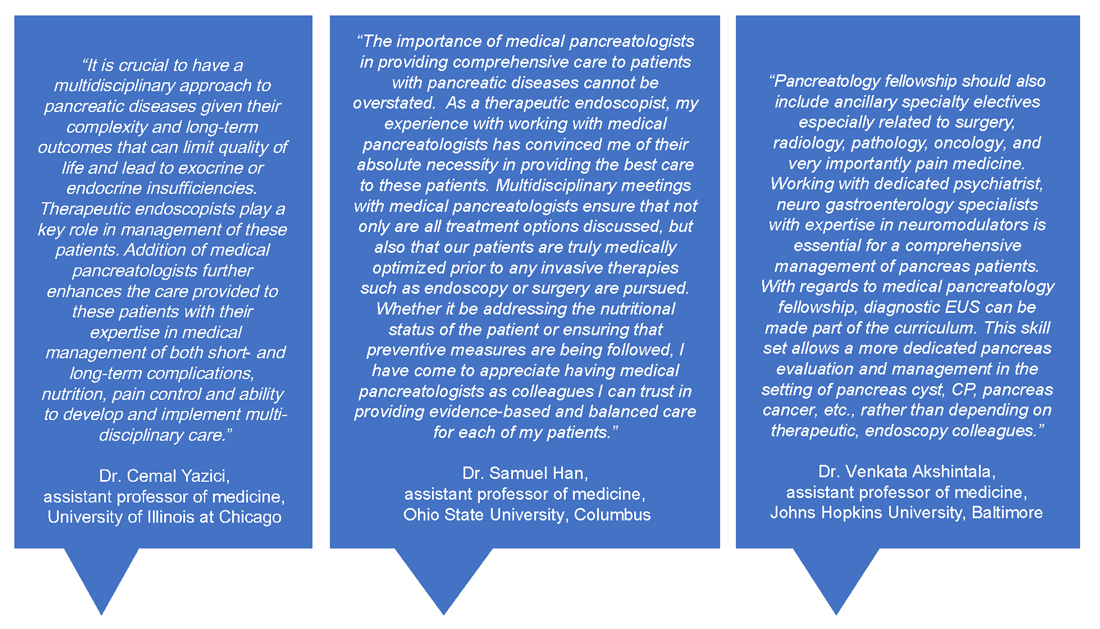

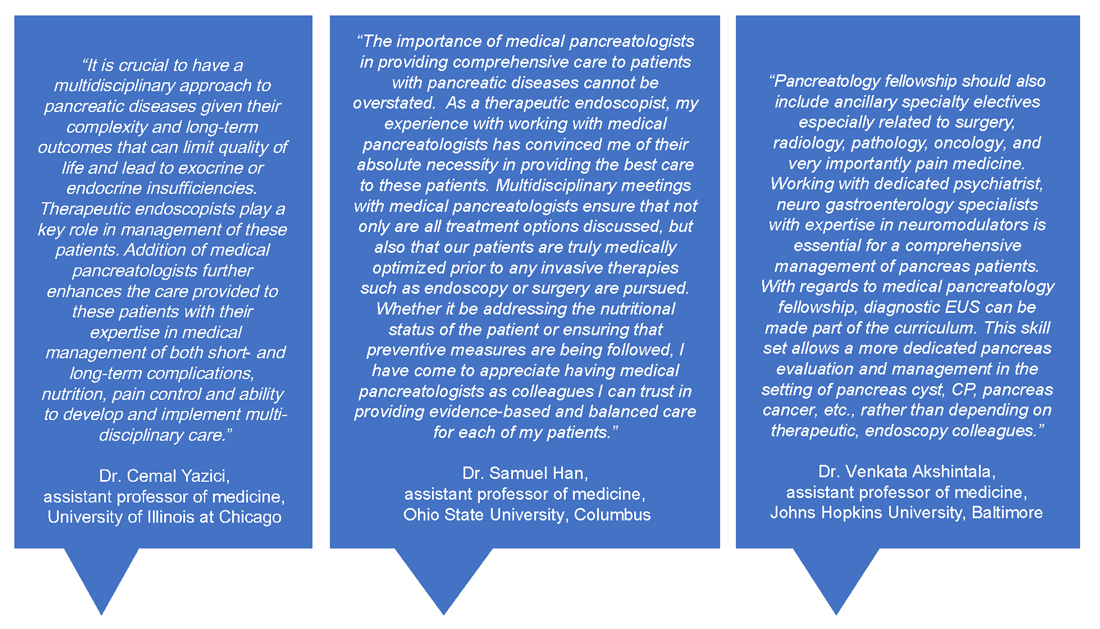

Insights from other medical pancreatologists and therapeutic endoscopists are provided in Figure 2.

Education

Having a dedicated medical pancreatology clinic has the potential to add a unique element to the training of gastroenterology fellows. In my own experience, besides fellows interested in medical pancreatology, even those interested in therapeutic endoscopy find it useful to rotate through the pancreas clinic and follow patients after or leading to their procedures, becoming comfortable with noninterventional pain management of patients with pancreatic disorders and risk stratification of pancreatic cystic lesions, and learning about the management of rare disorders such as autoimmune pancreatitis. Most importantly, this allows trainees to identify cases where endoscopic intervention may not offer definitive treatment for complex conditions such as pancreatic pain. Trainee-centered organizations such as the Collaborative Alliance for Pancreatic Education and Research (CAPER) enable trainees and young investigators to network with other physicians who are passionate about the pancreas and establish early research collaborations for current and future research endeavors that will help advance this field.

Research

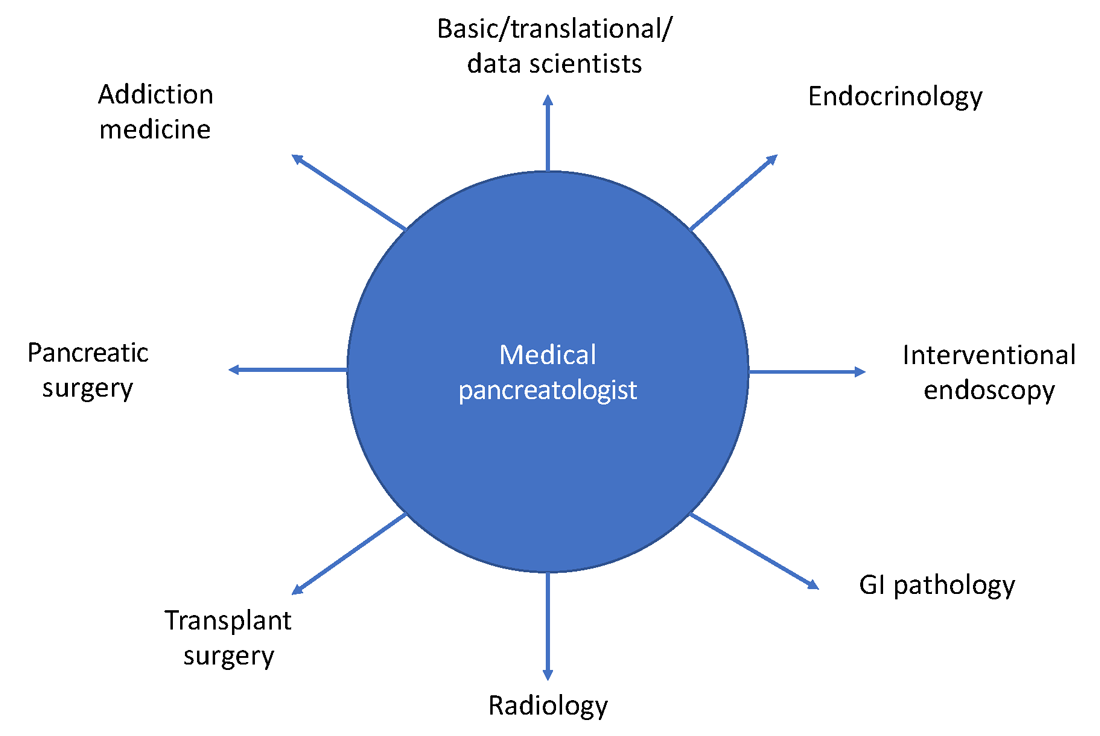

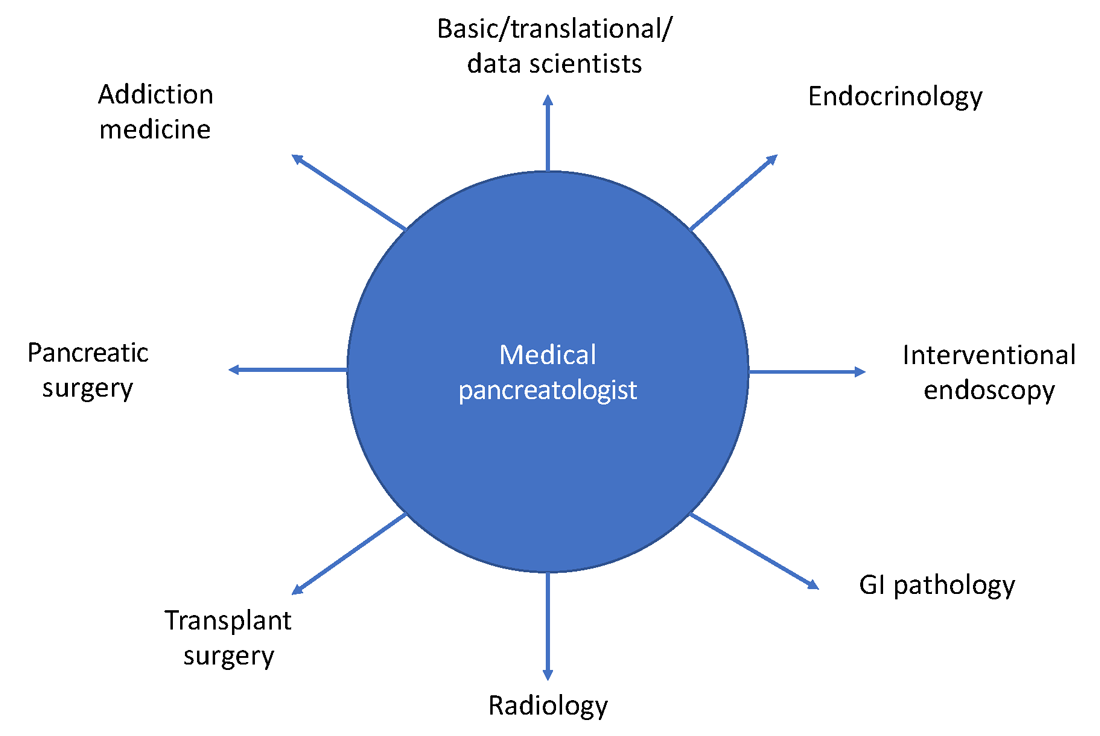

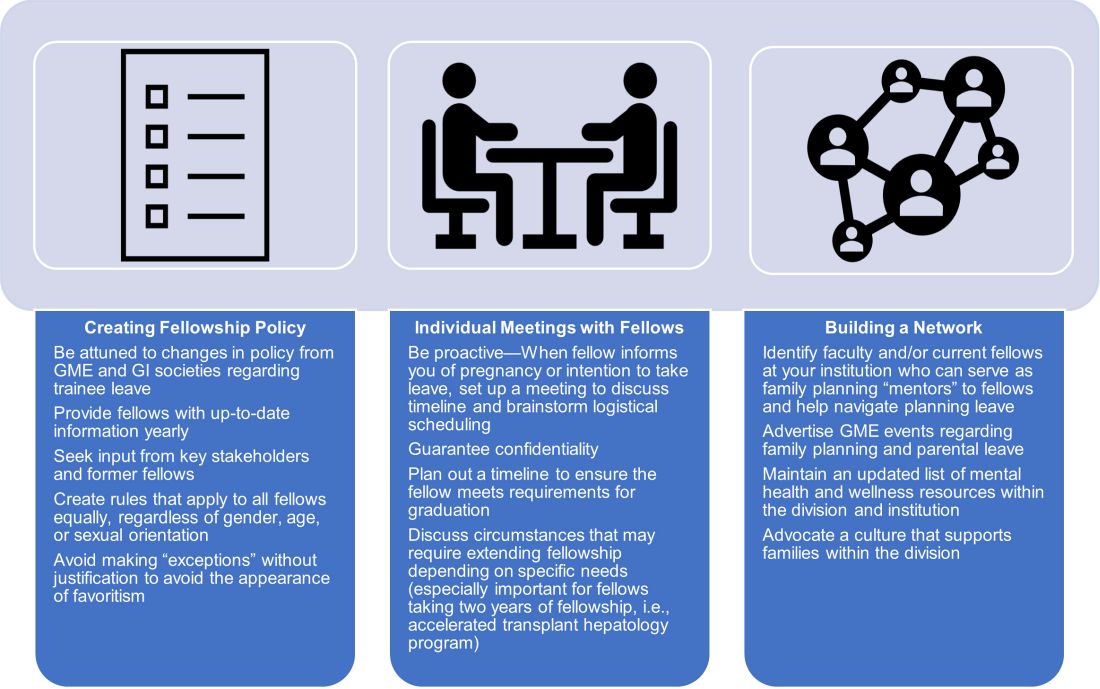

Having a trained medical pancreatologist adds the possibility of adding a unique angle to ongoing research within a gastroenterology division, especially in collaboration with others. For example, during my fellowship training I was able to focus on histological changes in pancreatic islets of patients with pancreatic cancer that develop diabetes, compared with those that do not, in collaboration with a pathologist who focused on studying islet pathology and under the guidance of my mentor, Dr. Suresh Chari, a medical pancreatologist.2 I was also part of other studies within the GI division with other medical pancreatologists, such as Dr. Santhi Vege and Dr. Shounak Majumder, who have continued to serve as career and research mentors.3 Collaborative, multicenter studies on pancreatic disease are also conducted by CAPER, the organization mentioned above. A list of potential collaborations for the fellow interested

in medical pancreatology is provided in Figure 3.

Marketing considerations for the gastroenterology division

Having a medical pancreatologist in the team is not only attractive for referring physicians within an institution but is often a great asset from a marketing standpoint, especially for tertiary care academic centers and large community practices with a broad referral base. Given that there are a limited number of medical pancreatologists in the country, having one as part of the faculty can certainly provide a competitive edge to that center within the area, especially with an ever-increasing preference of patients for hyperspecialized care.

How to develop a career in medical pancreatology

Gastroenterology fellows often start their fellowships “undifferentiated” and try to get exposed to a wide variety of GI pathology, either through general GI clinics or as part of subspecialized clinics, as they attempt to decide how they want their careers to look down the line. Similar to other subspecialities, if a trainee has already decided to pursue medical pancreatology (as happened in my case), they should strongly consider ranking programs with available opportunities for research/clinic in medical pancreatology and ideally undergo an additional year of training. Fellows who decide during the course of their fellowship that they want to pursue a career in medical pancreatology should consider applying for a 4th year in the subject to not only obtain further training in the field but to also conduct research in the area and become more “marketable” as a person that could start a medical pancreatology program at their future academic or community position. Trainees interested in medical pancreatology should try to focus their time on long-term, clinical management of patients with pancreatic disorders, engaging a multidisciplinary team composed of interventional endoscopists, pancreatic surgeons, transplant surgeons (if total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation is available), radiology, addiction medicine (if available), endocrinology, and pathology. The list of places that offer a 4th year in medical pancreatology is increasing every year, and as of the writing of this article there are six programs that have this opportunity, which include:

- Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

- University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Penn.

The CAPER website is also a great resource for education as well as for identifying potential medical pancreatology programs.

In summary, medical pancreatology is an evolving and rapidly growing career path for gastroenterology fellows interested in providing care to patients with pancreatic disease in close collaboration with multiple other subspecialties, especially therapeutic endoscopy and pancreatic surgery. The field is also ripe for fellows interested in clinical, translational, and basic science research related to pancreatic disorders.

Dr. Nagpal is assistant professor of medicine, director, pancreas clinic, University of Chicago. He had no conflicts to disclose.

References

1. Feldman M et al. “Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease,” 11th ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2021).

2. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2020 Jul;20(5):929-35.

3. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2019 Mar;19(2):290-5.

Although described by the Greek physician Herophilos around 300 B.C., it was not until the 19th century that enzymes began to be isolated from pancreatic secretions and their digestive action described, and not until early in the 20th century that Banting, Macleod, and Best received the Nobel prize for purifying insulin from the pancreata of dogs. For centuries in between, the pancreas was considered to be just a ‘beautiful piece of flesh’ (kallikreas), the main role of which was to protect the blood vessels in the abdomen and to serve as a cushion to the stomach.1 Certainly, the pancreas has come a long way since then but, like most other organs in the body, is oft ignored until it develops issues.

Like many other disorders in gastroenterology, pancreatic disorders were historically approached as mechanical or “plumbing” issues. As modern technology and innovation percolated through the world of endoscopy, a wide array of state-of-the-art tools were devised. Availability of newer “toys” and development of newer techniques also means that an ever-increasing curriculum has been squeezed into a generally single year of therapeutic endoscopy training, such that trainees can no longer limit themselves to learning only endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or intervening on pancreatic disease alone. Modern, subspecialized approaches to disease and economic considerations often dictate that the therapeutic endoscopist of today must perform a wide range of procedures besides ERCP and EUS, such as advanced resection using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), endoscopic bariatric procedures, and newer techniques and acronyms that continue to evolve on a regular basis. This leaves the therapeutic endoscopist with little time for outpatient management of many patients that don’t need interventional procedures but are often very complex and need ongoing, long-term follow-up. In addition, any clinic slots available for interventional endoscopists may be utilized by patients coming in to discuss complex procedures or for postprocedure follow-up. Endoscopic management is not the definitive treatment for most pancreatic disorders. In fact, as our knowledge of pancreatic disease has continued to evolve, endoscopic intervention is now required in a minority of cases.

Role of the medical pancreatologist

Patient Care

As part of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary team that also includes an interventional gastroenterologist, pancreatic surgeon, transplant surgeon (in centers offering islet autotransplantation with total pancreatectomy), radiology, endocrinology, and GI pathologist, the medical pancreatologist helps lead the care of patients with pancreatic disorders, such as pancreatic cysts, acute and chronic pancreatitis (especially in cases where there is no role for active endoscopic intervention), autoimmune pancreatitis, indeterminate pancreatic masses, as well as screens high-risk patients for pancreatic cancer in conjunction with a genetic counselor. The medical pancreatologist often also serves as a bridge between various members of a large multidisciplinary team that, formally in the form of conferences or informally, discusses the management of complex patients, with each member available to help the other based on the patient’s most immediate clinical need at that time. A schematic showing how the medical pancreatologist collaborates with the therapeutic endoscopist is provided in Figure 1.

Uzma Siddiqui, MD, director for the Center for Endoscopic Research and Technology (CERT) at the University of Chicago said, “The management of pancreatic diseases is often challenging. Surgeons and endoscopists can offer some treatments that focus on one aspect or symptom, but the medical pancreatologist brings focus to the patient as a whole and helps organize care. It is only with everyone’s combined efforts and the added perspective of the medical pancreatologist that we can provide the best care for our shared patients.”

David Xin, MD, MPH, a medical pancreatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, added, “I am often asked what it means to be a medical pancreatologist. What do I do if not EUS and ERCP? I provide longitudinal care, coordinate multidisciplinary management, assess nutritional status, optimize quality of life, and manage pain. But perhaps most importantly, I make myself available for patients who seek understanding and sympathy regarding their complex disease. I became a medical pancreatologist because my mentors during training helped me recognize how rewarding this career would be.”

Insights from other medical pancreatologists and therapeutic endoscopists are provided in Figure 2.

Education

Having a dedicated medical pancreatology clinic has the potential to add a unique element to the training of gastroenterology fellows. In my own experience, besides fellows interested in medical pancreatology, even those interested in therapeutic endoscopy find it useful to rotate through the pancreas clinic and follow patients after or leading to their procedures, becoming comfortable with noninterventional pain management of patients with pancreatic disorders and risk stratification of pancreatic cystic lesions, and learning about the management of rare disorders such as autoimmune pancreatitis. Most importantly, this allows trainees to identify cases where endoscopic intervention may not offer definitive treatment for complex conditions such as pancreatic pain. Trainee-centered organizations such as the Collaborative Alliance for Pancreatic Education and Research (CAPER) enable trainees and young investigators to network with other physicians who are passionate about the pancreas and establish early research collaborations for current and future research endeavors that will help advance this field.

Research

Having a trained medical pancreatologist adds the possibility of adding a unique angle to ongoing research within a gastroenterology division, especially in collaboration with others. For example, during my fellowship training I was able to focus on histological changes in pancreatic islets of patients with pancreatic cancer that develop diabetes, compared with those that do not, in collaboration with a pathologist who focused on studying islet pathology and under the guidance of my mentor, Dr. Suresh Chari, a medical pancreatologist.2 I was also part of other studies within the GI division with other medical pancreatologists, such as Dr. Santhi Vege and Dr. Shounak Majumder, who have continued to serve as career and research mentors.3 Collaborative, multicenter studies on pancreatic disease are also conducted by CAPER, the organization mentioned above. A list of potential collaborations for the fellow interested

in medical pancreatology is provided in Figure 3.

Marketing considerations for the gastroenterology division

Having a medical pancreatologist in the team is not only attractive for referring physicians within an institution but is often a great asset from a marketing standpoint, especially for tertiary care academic centers and large community practices with a broad referral base. Given that there are a limited number of medical pancreatologists in the country, having one as part of the faculty can certainly provide a competitive edge to that center within the area, especially with an ever-increasing preference of patients for hyperspecialized care.

How to develop a career in medical pancreatology

Gastroenterology fellows often start their fellowships “undifferentiated” and try to get exposed to a wide variety of GI pathology, either through general GI clinics or as part of subspecialized clinics, as they attempt to decide how they want their careers to look down the line. Similar to other subspecialities, if a trainee has already decided to pursue medical pancreatology (as happened in my case), they should strongly consider ranking programs with available opportunities for research/clinic in medical pancreatology and ideally undergo an additional year of training. Fellows who decide during the course of their fellowship that they want to pursue a career in medical pancreatology should consider applying for a 4th year in the subject to not only obtain further training in the field but to also conduct research in the area and become more “marketable” as a person that could start a medical pancreatology program at their future academic or community position. Trainees interested in medical pancreatology should try to focus their time on long-term, clinical management of patients with pancreatic disorders, engaging a multidisciplinary team composed of interventional endoscopists, pancreatic surgeons, transplant surgeons (if total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation is available), radiology, addiction medicine (if available), endocrinology, and pathology. The list of places that offer a 4th year in medical pancreatology is increasing every year, and as of the writing of this article there are six programs that have this opportunity, which include:

- Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

- University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Penn.

The CAPER website is also a great resource for education as well as for identifying potential medical pancreatology programs.

In summary, medical pancreatology is an evolving and rapidly growing career path for gastroenterology fellows interested in providing care to patients with pancreatic disease in close collaboration with multiple other subspecialties, especially therapeutic endoscopy and pancreatic surgery. The field is also ripe for fellows interested in clinical, translational, and basic science research related to pancreatic disorders.

Dr. Nagpal is assistant professor of medicine, director, pancreas clinic, University of Chicago. He had no conflicts to disclose.

References

1. Feldman M et al. “Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease,” 11th ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2021).

2. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2020 Jul;20(5):929-35.

3. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2019 Mar;19(2):290-5.

Although described by the Greek physician Herophilos around 300 B.C., it was not until the 19th century that enzymes began to be isolated from pancreatic secretions and their digestive action described, and not until early in the 20th century that Banting, Macleod, and Best received the Nobel prize for purifying insulin from the pancreata of dogs. For centuries in between, the pancreas was considered to be just a ‘beautiful piece of flesh’ (kallikreas), the main role of which was to protect the blood vessels in the abdomen and to serve as a cushion to the stomach.1 Certainly, the pancreas has come a long way since then but, like most other organs in the body, is oft ignored until it develops issues.

Like many other disorders in gastroenterology, pancreatic disorders were historically approached as mechanical or “plumbing” issues. As modern technology and innovation percolated through the world of endoscopy, a wide array of state-of-the-art tools were devised. Availability of newer “toys” and development of newer techniques also means that an ever-increasing curriculum has been squeezed into a generally single year of therapeutic endoscopy training, such that trainees can no longer limit themselves to learning only endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or intervening on pancreatic disease alone. Modern, subspecialized approaches to disease and economic considerations often dictate that the therapeutic endoscopist of today must perform a wide range of procedures besides ERCP and EUS, such as advanced resection using endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), endoscopic bariatric procedures, and newer techniques and acronyms that continue to evolve on a regular basis. This leaves the therapeutic endoscopist with little time for outpatient management of many patients that don’t need interventional procedures but are often very complex and need ongoing, long-term follow-up. In addition, any clinic slots available for interventional endoscopists may be utilized by patients coming in to discuss complex procedures or for postprocedure follow-up. Endoscopic management is not the definitive treatment for most pancreatic disorders. In fact, as our knowledge of pancreatic disease has continued to evolve, endoscopic intervention is now required in a minority of cases.

Role of the medical pancreatologist

Patient Care

As part of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary team that also includes an interventional gastroenterologist, pancreatic surgeon, transplant surgeon (in centers offering islet autotransplantation with total pancreatectomy), radiology, endocrinology, and GI pathologist, the medical pancreatologist helps lead the care of patients with pancreatic disorders, such as pancreatic cysts, acute and chronic pancreatitis (especially in cases where there is no role for active endoscopic intervention), autoimmune pancreatitis, indeterminate pancreatic masses, as well as screens high-risk patients for pancreatic cancer in conjunction with a genetic counselor. The medical pancreatologist often also serves as a bridge between various members of a large multidisciplinary team that, formally in the form of conferences or informally, discusses the management of complex patients, with each member available to help the other based on the patient’s most immediate clinical need at that time. A schematic showing how the medical pancreatologist collaborates with the therapeutic endoscopist is provided in Figure 1.

Uzma Siddiqui, MD, director for the Center for Endoscopic Research and Technology (CERT) at the University of Chicago said, “The management of pancreatic diseases is often challenging. Surgeons and endoscopists can offer some treatments that focus on one aspect or symptom, but the medical pancreatologist brings focus to the patient as a whole and helps organize care. It is only with everyone’s combined efforts and the added perspective of the medical pancreatologist that we can provide the best care for our shared patients.”

David Xin, MD, MPH, a medical pancreatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, added, “I am often asked what it means to be a medical pancreatologist. What do I do if not EUS and ERCP? I provide longitudinal care, coordinate multidisciplinary management, assess nutritional status, optimize quality of life, and manage pain. But perhaps most importantly, I make myself available for patients who seek understanding and sympathy regarding their complex disease. I became a medical pancreatologist because my mentors during training helped me recognize how rewarding this career would be.”

Insights from other medical pancreatologists and therapeutic endoscopists are provided in Figure 2.

Education

Having a dedicated medical pancreatology clinic has the potential to add a unique element to the training of gastroenterology fellows. In my own experience, besides fellows interested in medical pancreatology, even those interested in therapeutic endoscopy find it useful to rotate through the pancreas clinic and follow patients after or leading to their procedures, becoming comfortable with noninterventional pain management of patients with pancreatic disorders and risk stratification of pancreatic cystic lesions, and learning about the management of rare disorders such as autoimmune pancreatitis. Most importantly, this allows trainees to identify cases where endoscopic intervention may not offer definitive treatment for complex conditions such as pancreatic pain. Trainee-centered organizations such as the Collaborative Alliance for Pancreatic Education and Research (CAPER) enable trainees and young investigators to network with other physicians who are passionate about the pancreas and establish early research collaborations for current and future research endeavors that will help advance this field.

Research

Having a trained medical pancreatologist adds the possibility of adding a unique angle to ongoing research within a gastroenterology division, especially in collaboration with others. For example, during my fellowship training I was able to focus on histological changes in pancreatic islets of patients with pancreatic cancer that develop diabetes, compared with those that do not, in collaboration with a pathologist who focused on studying islet pathology and under the guidance of my mentor, Dr. Suresh Chari, a medical pancreatologist.2 I was also part of other studies within the GI division with other medical pancreatologists, such as Dr. Santhi Vege and Dr. Shounak Majumder, who have continued to serve as career and research mentors.3 Collaborative, multicenter studies on pancreatic disease are also conducted by CAPER, the organization mentioned above. A list of potential collaborations for the fellow interested

in medical pancreatology is provided in Figure 3.

Marketing considerations for the gastroenterology division

Having a medical pancreatologist in the team is not only attractive for referring physicians within an institution but is often a great asset from a marketing standpoint, especially for tertiary care academic centers and large community practices with a broad referral base. Given that there are a limited number of medical pancreatologists in the country, having one as part of the faculty can certainly provide a competitive edge to that center within the area, especially with an ever-increasing preference of patients for hyperspecialized care.

How to develop a career in medical pancreatology

Gastroenterology fellows often start their fellowships “undifferentiated” and try to get exposed to a wide variety of GI pathology, either through general GI clinics or as part of subspecialized clinics, as they attempt to decide how they want their careers to look down the line. Similar to other subspecialities, if a trainee has already decided to pursue medical pancreatology (as happened in my case), they should strongly consider ranking programs with available opportunities for research/clinic in medical pancreatology and ideally undergo an additional year of training. Fellows who decide during the course of their fellowship that they want to pursue a career in medical pancreatology should consider applying for a 4th year in the subject to not only obtain further training in the field but to also conduct research in the area and become more “marketable” as a person that could start a medical pancreatology program at their future academic or community position. Trainees interested in medical pancreatology should try to focus their time on long-term, clinical management of patients with pancreatic disorders, engaging a multidisciplinary team composed of interventional endoscopists, pancreatic surgeons, transplant surgeons (if total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation is available), radiology, addiction medicine (if available), endocrinology, and pathology. The list of places that offer a 4th year in medical pancreatology is increasing every year, and as of the writing of this article there are six programs that have this opportunity, which include:

- Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore

- University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Penn.

The CAPER website is also a great resource for education as well as for identifying potential medical pancreatology programs.

In summary, medical pancreatology is an evolving and rapidly growing career path for gastroenterology fellows interested in providing care to patients with pancreatic disease in close collaboration with multiple other subspecialties, especially therapeutic endoscopy and pancreatic surgery. The field is also ripe for fellows interested in clinical, translational, and basic science research related to pancreatic disorders.

Dr. Nagpal is assistant professor of medicine, director, pancreas clinic, University of Chicago. He had no conflicts to disclose.

References

1. Feldman M et al. “Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease,” 11th ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2021).

2. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2020 Jul;20(5):929-35.

3. Nagpal SJS et al. Pancreatology. 2019 Mar;19(2):290-5.

The importance of education and screening for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

For the past 18 months, we’ve all been focused on defeating the COVID-19 pandemic and preparing for the effects of cancer screenings that were delayed or put off entirely. But COVID isn’t the only epidemic we’re facing in the United States. Obesity is the second leading cause of preventable death in the United States. and its related diseases account for $480.7 billion in direct health care costs, with an additional $1.24 trillion in indirect costs from lost economic productivity.

More than two in five Americans are obese and that number is predicted to grow to more than half of the U.S. population by 2030. Obesity is a risk factor for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a buildup of fat in the liver with little or no inflammation or cell damage that affects one in three (30%-37%) of adults in the U.S.

NAFLD can progress to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which affects about 1 in 10 (8%-12%) of adults in the U.S. NASH is fat in the liver with inflammation and cell damage, and it can lead to fibrosis and liver failure. The number of patients we see with NALFD and NASH continues to rise and it’s taking its toll. One in five people who have NASH will have the disease progress to liver cirrhosis. NASH is expected to be the leading cause of liver transplant in the U.S. for the next 5 years.

Stemming the tide of NAFLD and NASH

In terms of diet, limiting sugar and eating a diet rich in vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats can prevent the factors that lead to liver disease.

If this were easy, we wouldn’t be facing the obesity epidemic that is plaguing the United States. One of the issues is that medicine has only recognized obesity as a disease for less than 10 years. We aren’t trained in medical school, residencies, or fellowships in managing obesity, beyond advising people to exercise and eat right. We know this doesn’t work.

That’s why many independent GI groups are exploring comprehensive weight management programs that take a holistic approach to weight management involving a team of health care providers and educators helping patients gradually exercise more and eat healthy while providing a social support system to lose weight and keep it off.

The best way to educate is to listen first

As gastroenterologists, we see many obesity-related issues and have an opportunity to intervene before other more serious issues show up – like cancer, hypertension, and stroke. And educating the public and primary care physicians is key to ensuring that patients who are high risk are screened for liver disease.

Some GI practices leverage awareness events such as International NASH Day in June, or National Liver Cancer Awareness Month in October, to provide primary care physicians and patients with educational materials about making healthier choices and what options are available to screen for NAFLD and NASH.

While the awareness events offer a ready-made context for outreach, the physicians in my practice work year-round to provide information on liver disease. When patients are brought in for issues that may indicate future problems, we look for signs of chronic liver disease and educate them and their family members about liver disease and cirrhosis.

Discussions of weight are very personal, and it’s important to approach the conversation with sensitivity. It’s also good to understand as best as possible any cultural implications of discussing a person’s weight to ensure that the patient or their family members are not embarrassed by the discussion. I find that oftentimes the best approach is to listen to the patient and hear what factors are influencing their ability to exercise and eat healthy foods so that you can work together to find the best solution.

It’s also important to recognize that racial disparities exist in many aspects of NAFLD, including prevalence, severity, genetic predisposition, and overall chance of recovery. For instance, Hispanics and Asian Americans have a higher prevalence of NAFLD, compared with other ethnic and racial groups.

Early detection is key

Screenings have become a lot simpler and more convenient. There are alternatives to the painful, expensive liver biopsy. There are blood biomarker tests designed to assess liver fibrosis in patients. Specialized vibration-controlled transient elastography, such as Fibroscan, can measure scarring and fat buildup in the liver. And because it’s noninvasive, it doesn’t come with the same risks as a traditional liver biopsy. It also costs about four or five times less, which is important in this era of value-based care.

These simple tests can be reassuring, or they can lead down another path of treating the disease, but not being screened at all can come at a steep price. Severe fibrosis can lead to cirrhosis, a dangerous condition where the liver can no longer function correctly. NAFLD and NASH can also lead to liver cancer.

There are some medications that are in phase 2 and some in phase 3 clinical trials that aim to reduce fatty liver by cutting down fibrosis and steatosis, and there are other medications that can be used to help with weight loss. But the reality is that lifestyle changes are currently the best way to reverse NAFLD or stop it from progressing to NASH or cirrhosis.

Join an innovative practice

For the next 20 years, the obesity epidemic will be the biggest issue facing our society and a major focus of our cancer prevention efforts. Early-career physicians who are looking to join an independent GI practice should ask questions to determine whether the partners in the practice are taking a comprehensive approach to treating issues of obesity, NAFLD, NASH, and liver disease. Discuss what steps the practice takes to educate primary care physicians and their patients about the dangers of NAFLD and NASH.

We’re looking for early-career physicians who are entrepreneurial, not just for the sake of the practice, but because the future is in digital technologies and chronic care management, such as Chronwell, that help people maintain health through remote care and coaching. We want people who are thinking about fixing the problems of today and tomorrow with new technologies and scalable solutions. Through education and new screening and treatment options, we can ensure that fewer people develop serious liver disease or cancer.

Dr. Sanjay Sandhir is a practicing gastroenterologist at Dayton Gastroenterology, One GI in Ohio and is an executive committee member of the Digestive Health Physicians Association. He has no conflicts to declare.

For the past 18 months, we’ve all been focused on defeating the COVID-19 pandemic and preparing for the effects of cancer screenings that were delayed or put off entirely. But COVID isn’t the only epidemic we’re facing in the United States. Obesity is the second leading cause of preventable death in the United States. and its related diseases account for $480.7 billion in direct health care costs, with an additional $1.24 trillion in indirect costs from lost economic productivity.

More than two in five Americans are obese and that number is predicted to grow to more than half of the U.S. population by 2030. Obesity is a risk factor for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a buildup of fat in the liver with little or no inflammation or cell damage that affects one in three (30%-37%) of adults in the U.S.

NAFLD can progress to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which affects about 1 in 10 (8%-12%) of adults in the U.S. NASH is fat in the liver with inflammation and cell damage, and it can lead to fibrosis and liver failure. The number of patients we see with NALFD and NASH continues to rise and it’s taking its toll. One in five people who have NASH will have the disease progress to liver cirrhosis. NASH is expected to be the leading cause of liver transplant in the U.S. for the next 5 years.

Stemming the tide of NAFLD and NASH

In terms of diet, limiting sugar and eating a diet rich in vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats can prevent the factors that lead to liver disease.

If this were easy, we wouldn’t be facing the obesity epidemic that is plaguing the United States. One of the issues is that medicine has only recognized obesity as a disease for less than 10 years. We aren’t trained in medical school, residencies, or fellowships in managing obesity, beyond advising people to exercise and eat right. We know this doesn’t work.

That’s why many independent GI groups are exploring comprehensive weight management programs that take a holistic approach to weight management involving a team of health care providers and educators helping patients gradually exercise more and eat healthy while providing a social support system to lose weight and keep it off.

The best way to educate is to listen first

As gastroenterologists, we see many obesity-related issues and have an opportunity to intervene before other more serious issues show up – like cancer, hypertension, and stroke. And educating the public and primary care physicians is key to ensuring that patients who are high risk are screened for liver disease.

Some GI practices leverage awareness events such as International NASH Day in June, or National Liver Cancer Awareness Month in October, to provide primary care physicians and patients with educational materials about making healthier choices and what options are available to screen for NAFLD and NASH.

While the awareness events offer a ready-made context for outreach, the physicians in my practice work year-round to provide information on liver disease. When patients are brought in for issues that may indicate future problems, we look for signs of chronic liver disease and educate them and their family members about liver disease and cirrhosis.

Discussions of weight are very personal, and it’s important to approach the conversation with sensitivity. It’s also good to understand as best as possible any cultural implications of discussing a person’s weight to ensure that the patient or their family members are not embarrassed by the discussion. I find that oftentimes the best approach is to listen to the patient and hear what factors are influencing their ability to exercise and eat healthy foods so that you can work together to find the best solution.

It’s also important to recognize that racial disparities exist in many aspects of NAFLD, including prevalence, severity, genetic predisposition, and overall chance of recovery. For instance, Hispanics and Asian Americans have a higher prevalence of NAFLD, compared with other ethnic and racial groups.

Early detection is key

Screenings have become a lot simpler and more convenient. There are alternatives to the painful, expensive liver biopsy. There are blood biomarker tests designed to assess liver fibrosis in patients. Specialized vibration-controlled transient elastography, such as Fibroscan, can measure scarring and fat buildup in the liver. And because it’s noninvasive, it doesn’t come with the same risks as a traditional liver biopsy. It also costs about four or five times less, which is important in this era of value-based care.

These simple tests can be reassuring, or they can lead down another path of treating the disease, but not being screened at all can come at a steep price. Severe fibrosis can lead to cirrhosis, a dangerous condition where the liver can no longer function correctly. NAFLD and NASH can also lead to liver cancer.

There are some medications that are in phase 2 and some in phase 3 clinical trials that aim to reduce fatty liver by cutting down fibrosis and steatosis, and there are other medications that can be used to help with weight loss. But the reality is that lifestyle changes are currently the best way to reverse NAFLD or stop it from progressing to NASH or cirrhosis.

Join an innovative practice

For the next 20 years, the obesity epidemic will be the biggest issue facing our society and a major focus of our cancer prevention efforts. Early-career physicians who are looking to join an independent GI practice should ask questions to determine whether the partners in the practice are taking a comprehensive approach to treating issues of obesity, NAFLD, NASH, and liver disease. Discuss what steps the practice takes to educate primary care physicians and their patients about the dangers of NAFLD and NASH.

We’re looking for early-career physicians who are entrepreneurial, not just for the sake of the practice, but because the future is in digital technologies and chronic care management, such as Chronwell, that help people maintain health through remote care and coaching. We want people who are thinking about fixing the problems of today and tomorrow with new technologies and scalable solutions. Through education and new screening and treatment options, we can ensure that fewer people develop serious liver disease or cancer.

Dr. Sanjay Sandhir is a practicing gastroenterologist at Dayton Gastroenterology, One GI in Ohio and is an executive committee member of the Digestive Health Physicians Association. He has no conflicts to declare.

For the past 18 months, we’ve all been focused on defeating the COVID-19 pandemic and preparing for the effects of cancer screenings that were delayed or put off entirely. But COVID isn’t the only epidemic we’re facing in the United States. Obesity is the second leading cause of preventable death in the United States. and its related diseases account for $480.7 billion in direct health care costs, with an additional $1.24 trillion in indirect costs from lost economic productivity.

More than two in five Americans are obese and that number is predicted to grow to more than half of the U.S. population by 2030. Obesity is a risk factor for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a buildup of fat in the liver with little or no inflammation or cell damage that affects one in three (30%-37%) of adults in the U.S.

NAFLD can progress to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which affects about 1 in 10 (8%-12%) of adults in the U.S. NASH is fat in the liver with inflammation and cell damage, and it can lead to fibrosis and liver failure. The number of patients we see with NALFD and NASH continues to rise and it’s taking its toll. One in five people who have NASH will have the disease progress to liver cirrhosis. NASH is expected to be the leading cause of liver transplant in the U.S. for the next 5 years.

Stemming the tide of NAFLD and NASH

In terms of diet, limiting sugar and eating a diet rich in vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats can prevent the factors that lead to liver disease.

If this were easy, we wouldn’t be facing the obesity epidemic that is plaguing the United States. One of the issues is that medicine has only recognized obesity as a disease for less than 10 years. We aren’t trained in medical school, residencies, or fellowships in managing obesity, beyond advising people to exercise and eat right. We know this doesn’t work.

That’s why many independent GI groups are exploring comprehensive weight management programs that take a holistic approach to weight management involving a team of health care providers and educators helping patients gradually exercise more and eat healthy while providing a social support system to lose weight and keep it off.

The best way to educate is to listen first

As gastroenterologists, we see many obesity-related issues and have an opportunity to intervene before other more serious issues show up – like cancer, hypertension, and stroke. And educating the public and primary care physicians is key to ensuring that patients who are high risk are screened for liver disease.

Some GI practices leverage awareness events such as International NASH Day in June, or National Liver Cancer Awareness Month in October, to provide primary care physicians and patients with educational materials about making healthier choices and what options are available to screen for NAFLD and NASH.

While the awareness events offer a ready-made context for outreach, the physicians in my practice work year-round to provide information on liver disease. When patients are brought in for issues that may indicate future problems, we look for signs of chronic liver disease and educate them and their family members about liver disease and cirrhosis.

Discussions of weight are very personal, and it’s important to approach the conversation with sensitivity. It’s also good to understand as best as possible any cultural implications of discussing a person’s weight to ensure that the patient or their family members are not embarrassed by the discussion. I find that oftentimes the best approach is to listen to the patient and hear what factors are influencing their ability to exercise and eat healthy foods so that you can work together to find the best solution.

It’s also important to recognize that racial disparities exist in many aspects of NAFLD, including prevalence, severity, genetic predisposition, and overall chance of recovery. For instance, Hispanics and Asian Americans have a higher prevalence of NAFLD, compared with other ethnic and racial groups.

Early detection is key

Screenings have become a lot simpler and more convenient. There are alternatives to the painful, expensive liver biopsy. There are blood biomarker tests designed to assess liver fibrosis in patients. Specialized vibration-controlled transient elastography, such as Fibroscan, can measure scarring and fat buildup in the liver. And because it’s noninvasive, it doesn’t come with the same risks as a traditional liver biopsy. It also costs about four or five times less, which is important in this era of value-based care.

These simple tests can be reassuring, or they can lead down another path of treating the disease, but not being screened at all can come at a steep price. Severe fibrosis can lead to cirrhosis, a dangerous condition where the liver can no longer function correctly. NAFLD and NASH can also lead to liver cancer.

There are some medications that are in phase 2 and some in phase 3 clinical trials that aim to reduce fatty liver by cutting down fibrosis and steatosis, and there are other medications that can be used to help with weight loss. But the reality is that lifestyle changes are currently the best way to reverse NAFLD or stop it from progressing to NASH or cirrhosis.

Join an innovative practice

For the next 20 years, the obesity epidemic will be the biggest issue facing our society and a major focus of our cancer prevention efforts. Early-career physicians who are looking to join an independent GI practice should ask questions to determine whether the partners in the practice are taking a comprehensive approach to treating issues of obesity, NAFLD, NASH, and liver disease. Discuss what steps the practice takes to educate primary care physicians and their patients about the dangers of NAFLD and NASH.

We’re looking for early-career physicians who are entrepreneurial, not just for the sake of the practice, but because the future is in digital technologies and chronic care management, such as Chronwell, that help people maintain health through remote care and coaching. We want people who are thinking about fixing the problems of today and tomorrow with new technologies and scalable solutions. Through education and new screening and treatment options, we can ensure that fewer people develop serious liver disease or cancer.

Dr. Sanjay Sandhir is a practicing gastroenterologist at Dayton Gastroenterology, One GI in Ohio and is an executive committee member of the Digestive Health Physicians Association. He has no conflicts to declare.

Sharing notes with our patients: Ethical considerations

Even a decade ago, the idea of providers sharing clinical notes with patients was almost unfathomable to most in medicine. We have since seen a sea change regarding the need for transparency in health care, leading to dramatic legislative and policy shifts in recent years.

On April 5, 2021, the federal program rule on Interoperability, Information Blocking, and ONC Health IT Certification took effect, which implemented a part of the bipartisan 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 requiring most of a patient’s electronic health information (EHI) be made easily accessible free of charge and “without delay.”1

Included in this defined set of EHI, known as the United States Core Data for Interoperability, are eight types of clinical notes that must be shared with patients, including: progress notes, history and physical notes, consultation notes, discharge summary notes, procedure notes, laboratory report narratives, imaging narratives, and pathology report narratives. Many clinicians viewed this federally mandated transition to note sharing with patients with concern, fearing increased documentation burdens, needless patient anxiety, and inevitable deluge of follow-up questions and requests for chart corrections.

In reality, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) granted virtually all patients the right to review a paper copy of their medical records, including all clinical notes, way back in 1996. Practically speaking, though, the multiple steps required to formally make these requests kept most patients from regularly accessing their health information.