User login

Finding room for hope

Dear colleagues,

I’m thrilled to introduce the August edition of The New Gastroenterologist, which features an excellent line-up of articles! Summer has been in full swing, and gradually, we eased into aspects of our prepandemic routine. The fear, caution, and isolation that characterized the last year and a half was less pervasive, and the ability to reconnect in person felt both refreshing and liberating. While new threats of variants and rising infection rates have emerged, there is hope that, with the availability of vaccines, the worst of the pandemic may still be behind us.

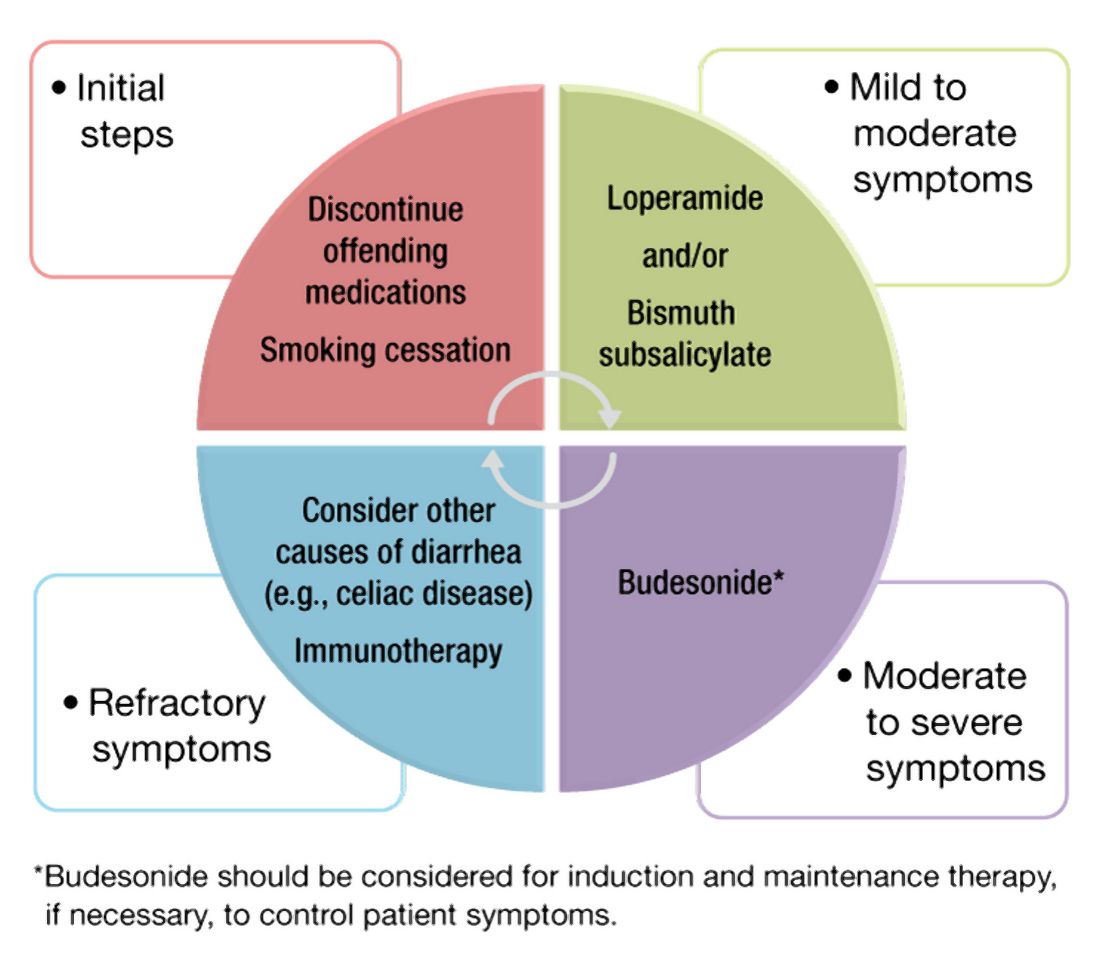

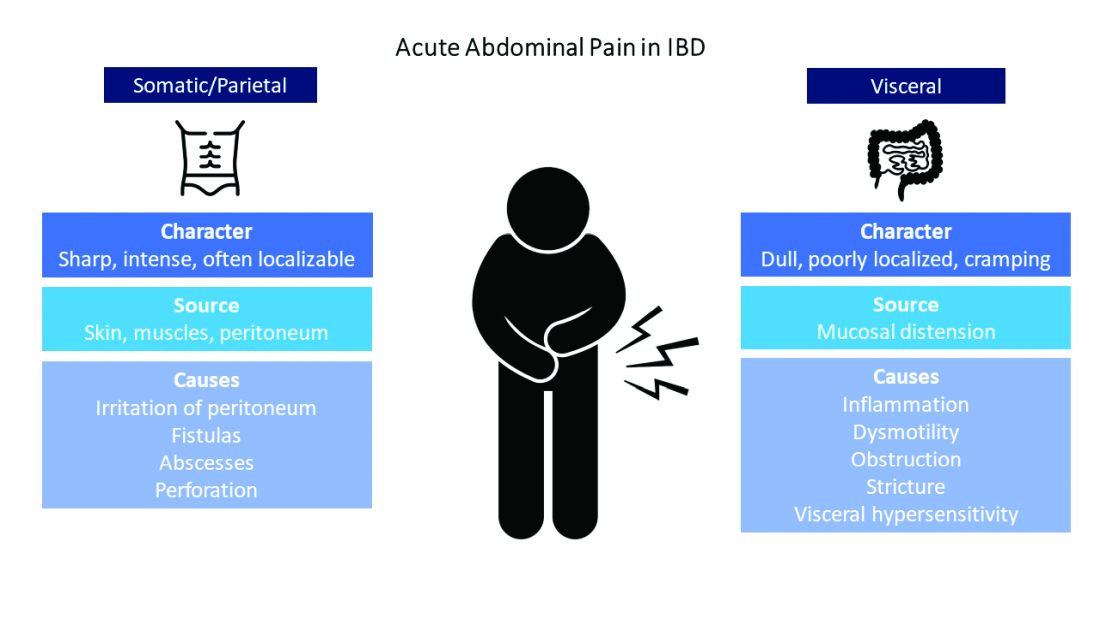

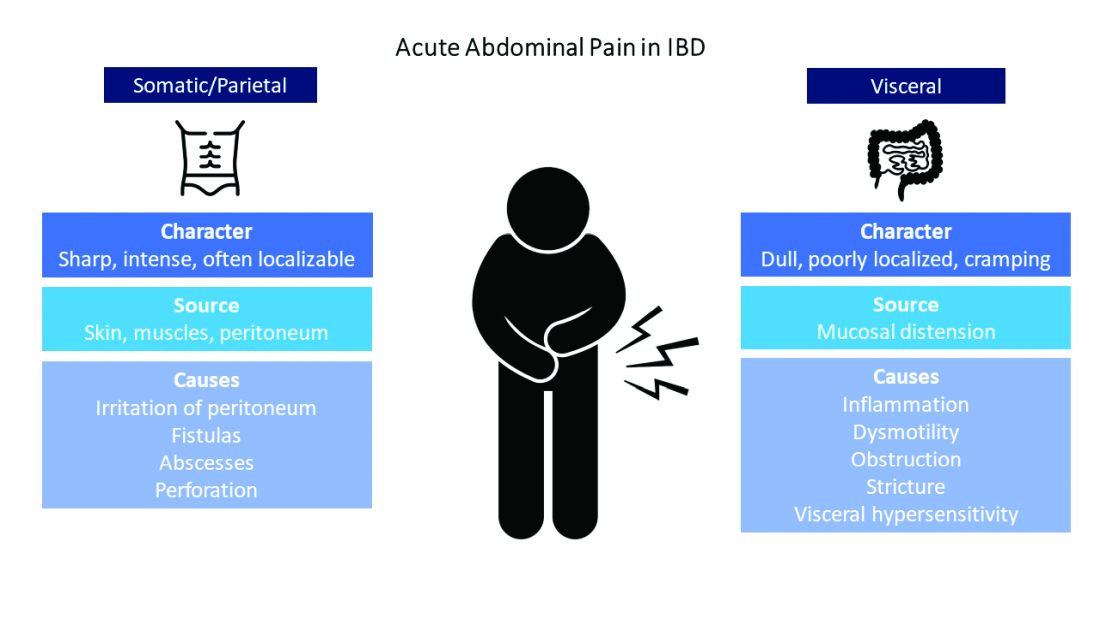

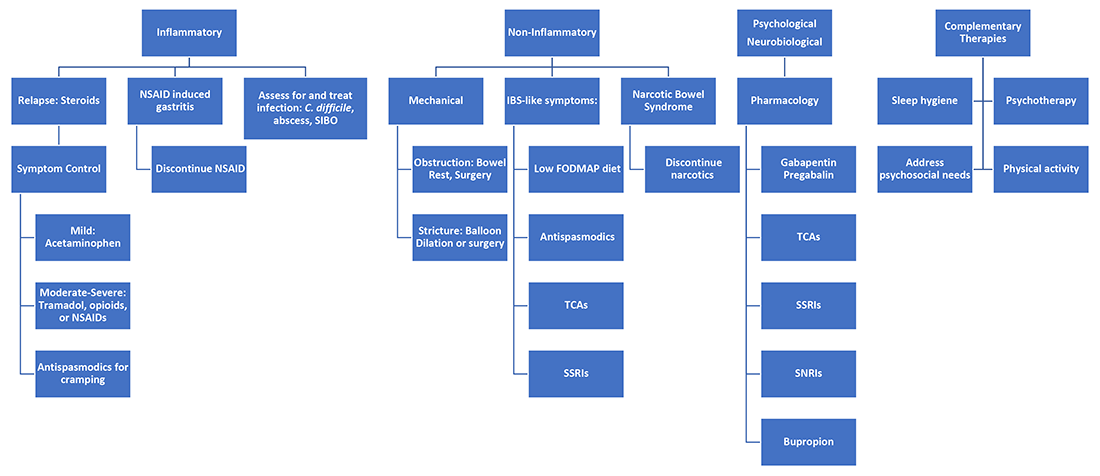

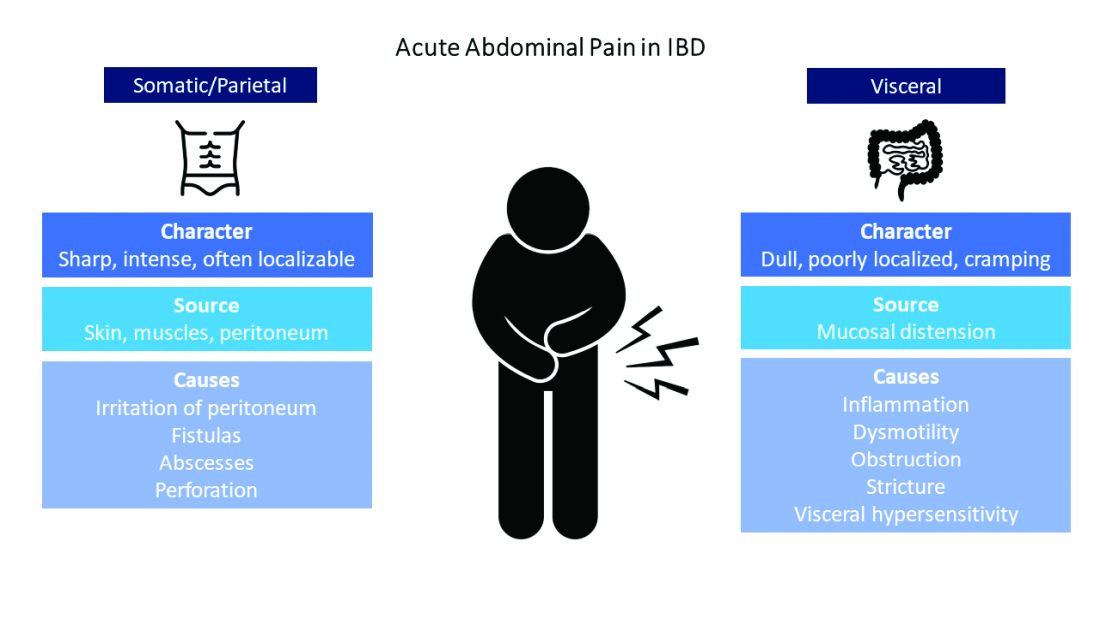

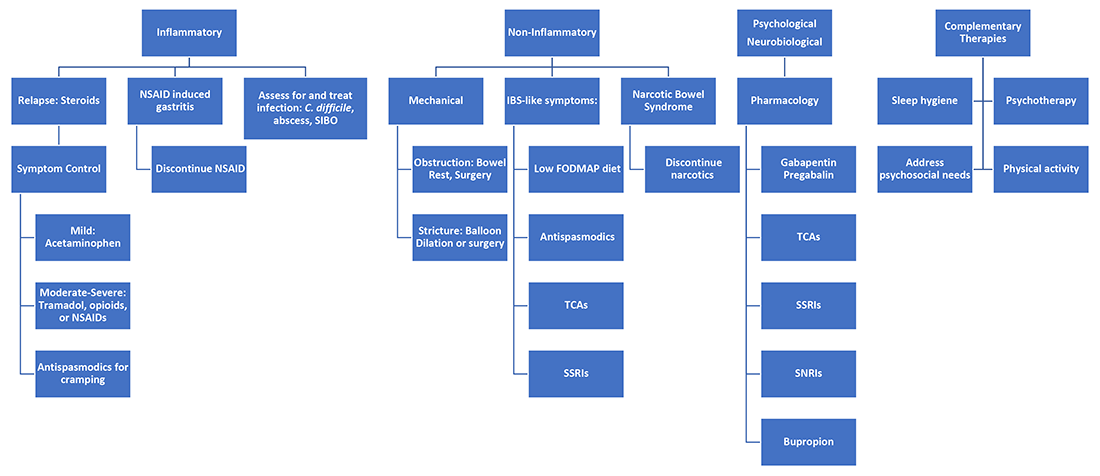

One of the most difficult aspects of treating patients with inflammatory bowel disease is acute pain management. Dr. Jami Kinnucan and Dr. Mehwish Ahmed (University of Michigan) outline an expert approach on differentiating between visceral and somatic pain and how to manage each accordingly.

The diagnosis of microscopic colitis can be elusive because colonic mucosa typically appears endoscopically normal and the pathognomonic findings are histologic. Management can also be challenging given the frequently relapsing and remitting nature of its clinical course. The “In Focus” feature for August, written by Dr. June Tome, Dr. Amrit Kamboj, and Dr. Darrell Pardi (Mayo Clinic), is an absolute must-read as it provides a detailed review on the diagnosis, management, and therapeutic options for microscopic colitis.

As gastroenterologists, we are often asked to place percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. This can be a difficult situation to navigate especially when the indication or timing of placement seems questionable. In our ethics case for this quarter, Dr. David Seres and Dr. Jane Cowan (Columbia University) unpack the ethical considerations of PEG tube placement in order to facilitate discharge to subacute nursing facilities.

Months in quarantine have incited many to crave larger living spaces, lending to a chaotic housing market. Jon Solitro (FinancialMD) offers sound financial advice for physicians interested purchasing a home – including factors to consider when choosing a home, how much to spend, and whether or not to consider a doctor’s loan.

Success in research can be particularly difficult for fellows and early career gastroenterologists as they juggle the many responsibilities inherent to busy training programs or adjust to independent practice. Dr. Dionne Rebello and Dr. Michelle Long (Boston University) compile a list of incredibly helpful tips on how to optimize productivity. For those interested in ways to harness experiences in clinical medicine into health technology, Dr. Simon Matthews (Johns Hopkins) discusses his role as chief medical officer in a health tech start-up in our postfellowship pathways section.

Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. George Dickstein (Greater Boston Gastroenterology), nicely summarizes lessons learned from the pandemic and how a practice can be adequately prepared for a post-pandemic surge of procedures.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Dear colleagues,

I’m thrilled to introduce the August edition of The New Gastroenterologist, which features an excellent line-up of articles! Summer has been in full swing, and gradually, we eased into aspects of our prepandemic routine. The fear, caution, and isolation that characterized the last year and a half was less pervasive, and the ability to reconnect in person felt both refreshing and liberating. While new threats of variants and rising infection rates have emerged, there is hope that, with the availability of vaccines, the worst of the pandemic may still be behind us.

One of the most difficult aspects of treating patients with inflammatory bowel disease is acute pain management. Dr. Jami Kinnucan and Dr. Mehwish Ahmed (University of Michigan) outline an expert approach on differentiating between visceral and somatic pain and how to manage each accordingly.

The diagnosis of microscopic colitis can be elusive because colonic mucosa typically appears endoscopically normal and the pathognomonic findings are histologic. Management can also be challenging given the frequently relapsing and remitting nature of its clinical course. The “In Focus” feature for August, written by Dr. June Tome, Dr. Amrit Kamboj, and Dr. Darrell Pardi (Mayo Clinic), is an absolute must-read as it provides a detailed review on the diagnosis, management, and therapeutic options for microscopic colitis.

As gastroenterologists, we are often asked to place percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. This can be a difficult situation to navigate especially when the indication or timing of placement seems questionable. In our ethics case for this quarter, Dr. David Seres and Dr. Jane Cowan (Columbia University) unpack the ethical considerations of PEG tube placement in order to facilitate discharge to subacute nursing facilities.

Months in quarantine have incited many to crave larger living spaces, lending to a chaotic housing market. Jon Solitro (FinancialMD) offers sound financial advice for physicians interested purchasing a home – including factors to consider when choosing a home, how much to spend, and whether or not to consider a doctor’s loan.

Success in research can be particularly difficult for fellows and early career gastroenterologists as they juggle the many responsibilities inherent to busy training programs or adjust to independent practice. Dr. Dionne Rebello and Dr. Michelle Long (Boston University) compile a list of incredibly helpful tips on how to optimize productivity. For those interested in ways to harness experiences in clinical medicine into health technology, Dr. Simon Matthews (Johns Hopkins) discusses his role as chief medical officer in a health tech start-up in our postfellowship pathways section.

Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. George Dickstein (Greater Boston Gastroenterology), nicely summarizes lessons learned from the pandemic and how a practice can be adequately prepared for a post-pandemic surge of procedures.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Dear colleagues,

I’m thrilled to introduce the August edition of The New Gastroenterologist, which features an excellent line-up of articles! Summer has been in full swing, and gradually, we eased into aspects of our prepandemic routine. The fear, caution, and isolation that characterized the last year and a half was less pervasive, and the ability to reconnect in person felt both refreshing and liberating. While new threats of variants and rising infection rates have emerged, there is hope that, with the availability of vaccines, the worst of the pandemic may still be behind us.

One of the most difficult aspects of treating patients with inflammatory bowel disease is acute pain management. Dr. Jami Kinnucan and Dr. Mehwish Ahmed (University of Michigan) outline an expert approach on differentiating between visceral and somatic pain and how to manage each accordingly.

The diagnosis of microscopic colitis can be elusive because colonic mucosa typically appears endoscopically normal and the pathognomonic findings are histologic. Management can also be challenging given the frequently relapsing and remitting nature of its clinical course. The “In Focus” feature for August, written by Dr. June Tome, Dr. Amrit Kamboj, and Dr. Darrell Pardi (Mayo Clinic), is an absolute must-read as it provides a detailed review on the diagnosis, management, and therapeutic options for microscopic colitis.

As gastroenterologists, we are often asked to place percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. This can be a difficult situation to navigate especially when the indication or timing of placement seems questionable. In our ethics case for this quarter, Dr. David Seres and Dr. Jane Cowan (Columbia University) unpack the ethical considerations of PEG tube placement in order to facilitate discharge to subacute nursing facilities.

Months in quarantine have incited many to crave larger living spaces, lending to a chaotic housing market. Jon Solitro (FinancialMD) offers sound financial advice for physicians interested purchasing a home – including factors to consider when choosing a home, how much to spend, and whether or not to consider a doctor’s loan.

Success in research can be particularly difficult for fellows and early career gastroenterologists as they juggle the many responsibilities inherent to busy training programs or adjust to independent practice. Dr. Dionne Rebello and Dr. Michelle Long (Boston University) compile a list of incredibly helpful tips on how to optimize productivity. For those interested in ways to harness experiences in clinical medicine into health technology, Dr. Simon Matthews (Johns Hopkins) discusses his role as chief medical officer in a health tech start-up in our postfellowship pathways section.

Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. George Dickstein (Greater Boston Gastroenterology), nicely summarizes lessons learned from the pandemic and how a practice can be adequately prepared for a post-pandemic surge of procedures.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Microscopic colitis: A common, yet often overlooked, cause of chronic diarrhea

Microscopic colitis is an inflammatory disease of the colon and a frequent cause of chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. MC consists of two subtypes, collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC). While the primary symptom is diarrhea, other signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities may also be present depending on disease severity.1 In MC, the colonic mucosa usually appears normal on colonoscopy, and the diagnosis is made by histologic findings of intraepithelial lymphocytosis with (CC) or without (LC) a prominent subepithelial collagen band. The management approaches to CC and LC are similar and should be directed based on the severity of symptoms.2 We review the epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management for this condition, as well as novel therapeutic approaches.

Epidemiology

Although the incidence of MC increased in the late twentieth century, more recently, it has stabilized with an estimated incidence varying from 1 to 25 per 100,000 person-years.3-5 A recent meta-analysis revealed a pooled incidence of 4.85 per 100,000 persons for LC and 4.14 per 100,000 persons for CC.6 Proposed explanations for the rising incidence in the late twentieth century include improved clinical awareness of the disease, possible increased use of drugs associated with MC, and increased performance of diagnostic colonoscopies for chronic diarrhea. Since MC is now well-recognized, the recent plateau in incidence rates may reflect decreased detection bias.

The prevalence of MC ranges from 10%-20% in patients undergoing colonoscopy for chronic watery diarrhea.6,7 The prevalence of LC is approximately 63.1 cases per 100,000 person-years and, for CC, is 49.2 cases per 100,000 person-years.6-8 Recent studies have demonstrated increasing prevalence of MC likely resulting from an aging population.9,10

Risk stratification

Female gender, increasing age, concomitant autoimmune disease, and the use of certain drugs, including NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been associated with an increased risk of MC.11,12 Autoimmune disorders, including celiac disease (CD), rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, are more common in patients with MC. The association with CD, in particular, is clinically important, as CD is associated with a 50-70 times greater risk of MC, and 2%-9% of patients with MC have CD.13,14

Several medications have been associated with MC. In a British multicenter prospective study, MC was associated with the use of NSAIDs, PPIs, and SSRIs;15 however, recent studies have questioned the association of MC with some of these medications, which might worsen diarrhea but not actually cause MC.16

An additional risk factor for MC is smoking. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that current and former smokers had an increased risk of MC (odds ratio, 2.99; 95% confidence interval, 2.15-4.15 and OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.37-1.94, respectively), compared with nonsmokers.17 Smokers develop MC at a younger age, and smoking is associated with increased disease severity and decreased likelihood of attaining remission.18,19

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of MC remains largely unknown, although there are several hypotheses. The leading proposed mechanisms include reaction to luminal antigens, dysregulated collagen metabolism, genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, and bile acid malabsorption.

MC may be caused by abnormal epithelial barrier function, leading to increased permeability and reaction to luminal antigens, including dietary antigens, certain drugs, and bacterial products, 20,21 which themselves lead to the immune dysregulation and intestinal inflammation seen in MC. This mechanism may explain the association of several drugs with MC. Histological changes resembling LC are reported in patients with CD who consume gluten; however, large population-based studies have not found specific dietary associations with the development of MC.22

Another potential mechanism of MC is dysregulated collagen deposition. Collagen accumulation in the subepithelial layer in CC may result from increased levels of fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor–beta and vascular endothelial growth factor.23 Nonetheless, studies have not found an association between the severity of diarrhea in patients with CC and the thickness of the subepithelial collagen band.

Thirdly, autoimmunity and genetic predisposition have been postulated in the pathogenesis of MC. As previously discussed, MC is associated with several autoimmune diseases and predominantly occurs in women, a distinctive feature of autoimmune disorders. Several studies have demonstrated an association between MC and HLA-DQ2 and -DQ3 haplotypes,24 as well as potential polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene promoter.25 It is important to note, however, that only a few familial cases of MC have been reported to date.26

Lastly, bile acid malabsorption may play a role in the etiology of MC. Histologic findings of inflammation, along with villous atrophy and collagen deposition, have been reported in the ileum of patients with MC;27,28 however, because patients with MC without bile acid malabsorption may also respond to bile acid binders such as cholestyramine, these findings unlikely to be the sole mechanism explaining the development of the disease.

Despite the different proposed mechanisms for the pathogenesis of MC, no definite conclusions can be drawn because of the limited size of these studies and their often conflicting results.

Clinical features

Clinicians should suspect MC in patients with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. Other risk factors include female gender, use of certain culprit medications, smoking, and presence of other autoimmune diseases. The clinical manifestations of MC subtypes LC and CC are similar with no significant clinical differences.1,2 In addition to diarrhea, patients with MC may have abdominal pain, fatigue, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities depending on disease severity. Patients may also present with fecal urgency, incontinence, and nocturnal stools. Quality of life is often reduced in these patients, predominantly in those with severe or refractory symptoms.29,30 The natural course of MC is highly variable, with some patients achieving spontaneous resolution after one episode and others developing chronic symptoms.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic watery diarrhea is broad and includes malabsorption/maldigestion, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, and medication side effects. In addition, although gastrointestinal infections typically cause acute or subacute diarrhea, some can present with chronic diarrhea. Malabsorption/maldigestion may occur because of CD, lactose intolerance, and pancreatic insufficiency, among other conditions. A thorough history, regarding recent antibiotic and medication use, travel, and immunosuppression, should be obtained in patients with chronic diarrhea. Additionally, laboratory and endoscopic evaluation with random biopsies of the colon can further help differentiate these diseases from MC. A few studies suggest fecal calprotectin may be used to differentiate MC from other noninflammatory conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, as well as to monitor disease activity. This test is not expected to distinguish MC from other inflammatory causes of diarrhea, such as IBD, and therefore, its role in clinical practice is uncertain.31

The diagnosis of MC is made by biopsy of the colonic mucosa demonstrating characteristic pathologic features.32 Unlike in diseases such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, the colon usually appears normal in MC, although mild nonspecific changes, such as erythema or edema, may be visualized. There is no consensus on the ideal location to obtain biopsies for MC or whether biopsies from both the left and the right colon are required.2,33 The procedure of choice for the diagnosis of MC is colonoscopy with random biopsies taken throughout the colon. More limited evaluation by flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsies may miss cases of MC as inflammation and collagen thickening are not necessarily uniform throughout the colon; however, in a patient that has undergone a recent colonoscopy for colon cancer screening without colon biopsies, a flexible sigmoidoscopy may be a reasonable next test for evaluation of MC, provided biopsies are obtained above the rectosigmoid colon.34

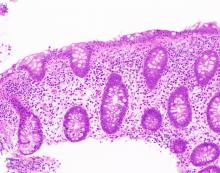

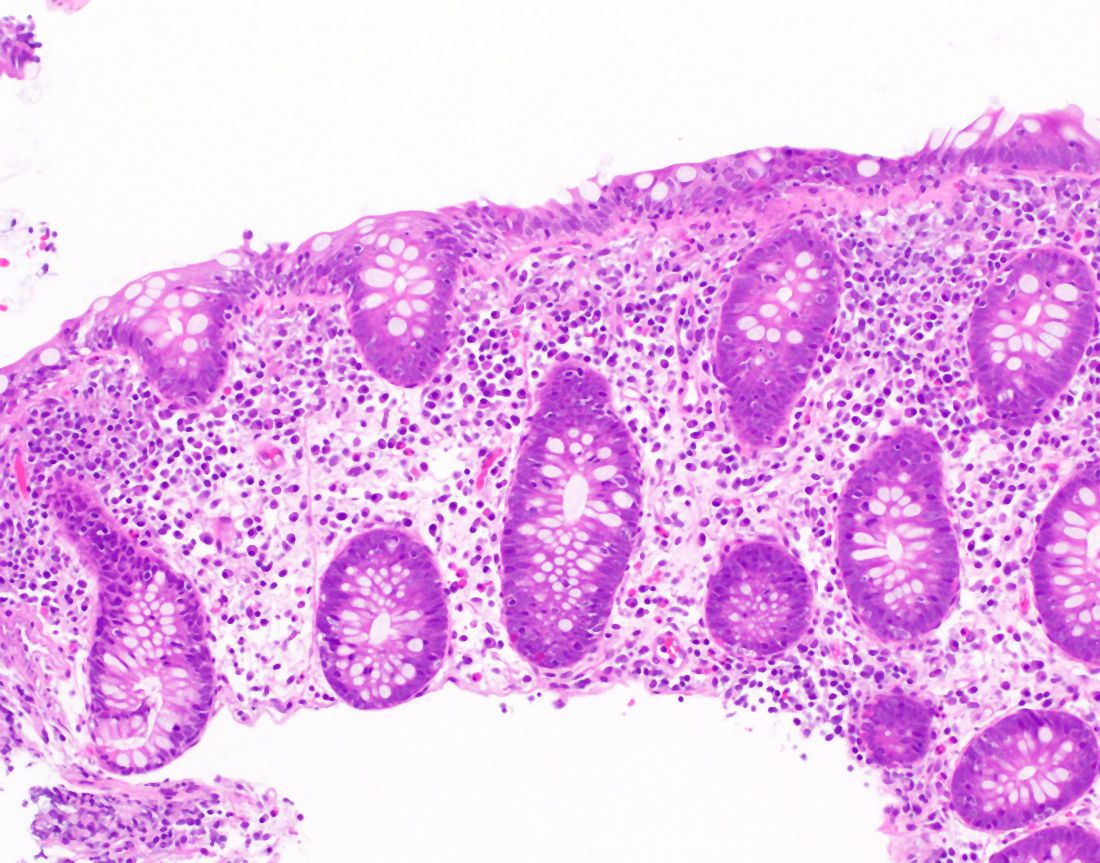

The MC subtypes are differentiated based on histology. The hallmark of LC is less than 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1A). CC is characterized by a thickened subepithelial collagen band greater than 7-10 micrometers (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1B). For a subgroup of patients with milder abnormalities that do not meet these histological criteria, the terms “microscopic colitis, not otherwise specified” or “microscopic colitis, incomplete” may be used.35 These patients often respond to standard treatments for MC. There is an additional subset of patients with biopsy demonstrating features of both CC and LC simultaneously, as well as patients transitioning from one MC subtype to another over time.32,35

Management approach

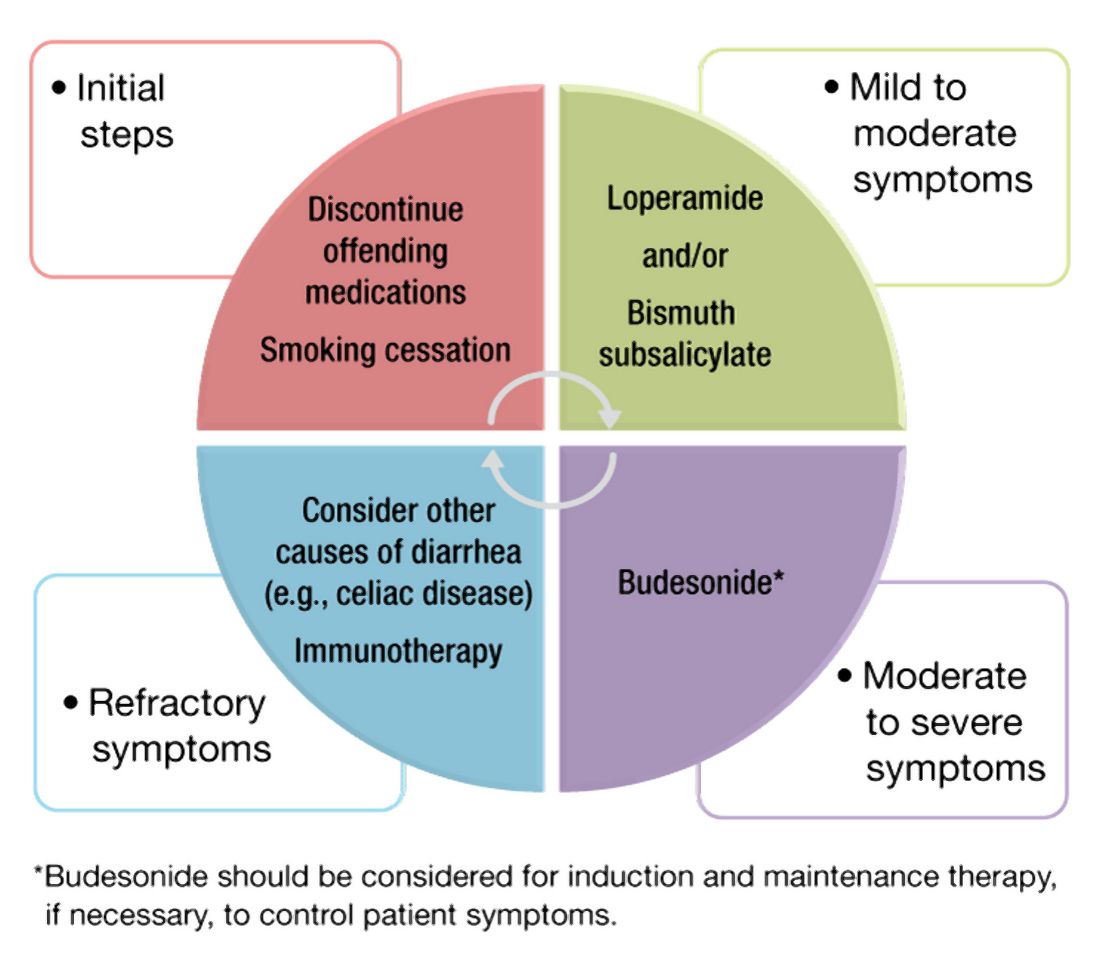

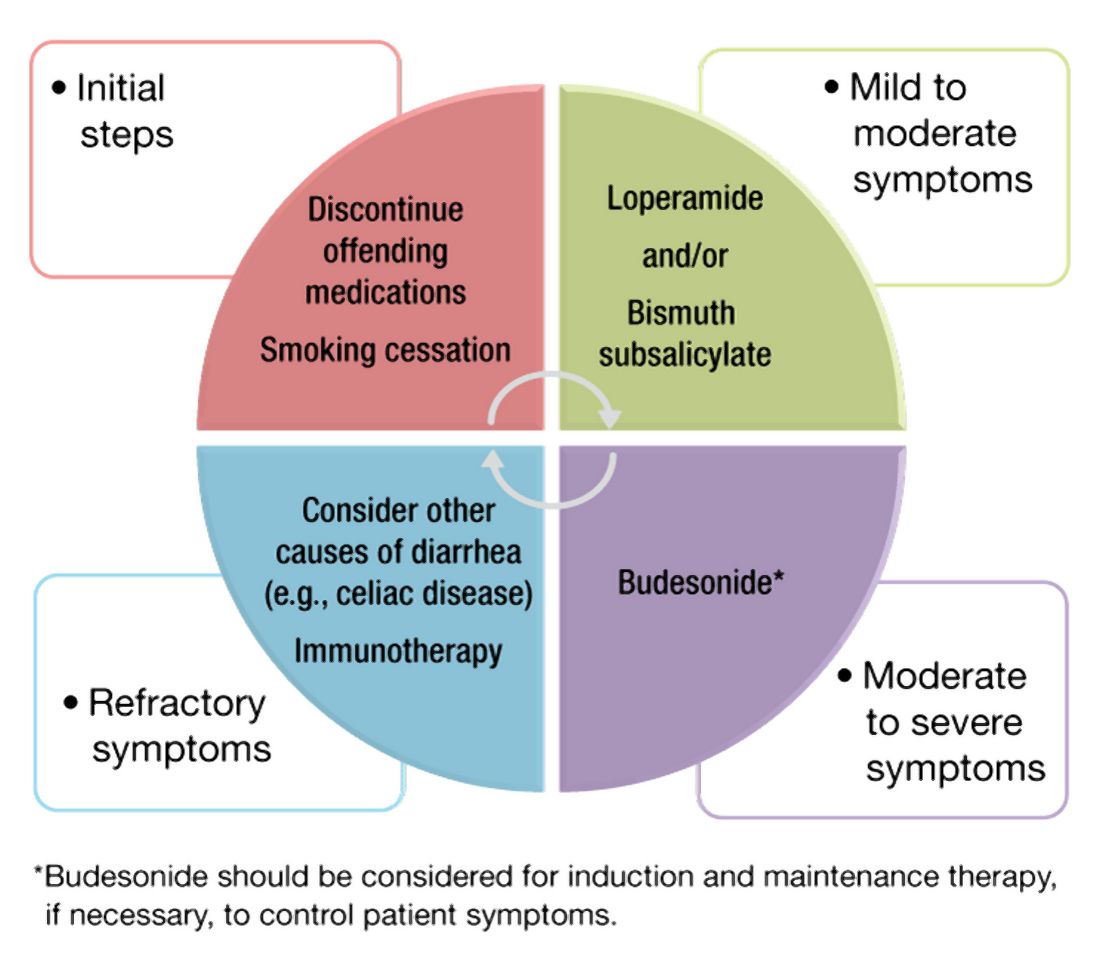

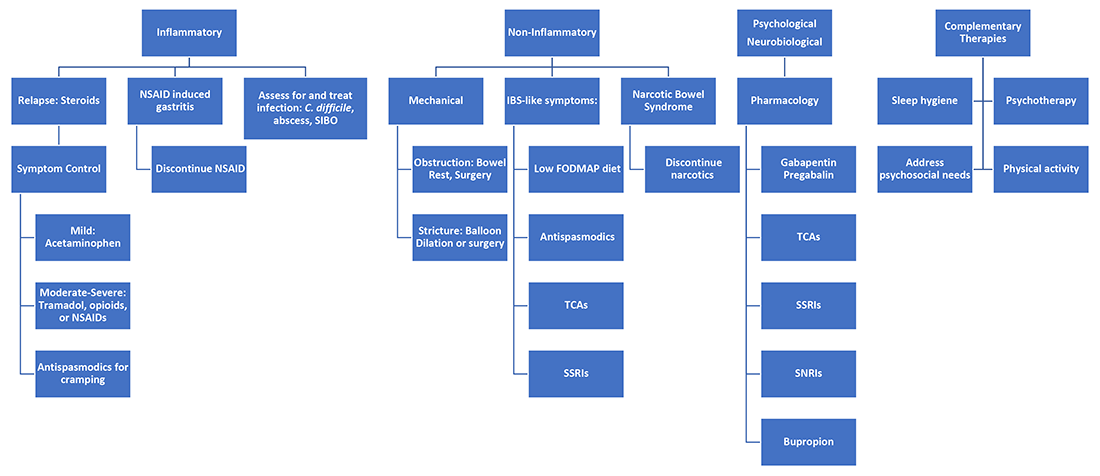

The first step in management of patients with MC includes stopping culprit medications if there is a temporal relationship between the initiation of the medication and the onset of diarrhea, as well as encouraging smoking cessation. These steps alone, however, are unlikely to achieve clinical remission in most patients. A stepwise pharmacological approach is used in the management of MC based on disease severity (Figure 2). For patients with mild symptoms, antidiarrheal medications, such as loperamide, may be helpful.36 Long-term use of loperamide at therapeutic doses no greater than 16 mg daily appears to be safe if required to maintain symptom response. For those with persistent symptoms despite antidiarrheal medications, bismuth subsalicylate at three 262 mg tablets three times daily for 6-8 weeks can be considered. Long-term use of bismuth subsalicylate is not advised, especially at this dose, because of possible neurotoxicity.37

For patients refractory to the above treatments or those with moderate-to-severe symptoms, an 8-week course of budesonide at 9 mg daily is the first-line treatment.38 The dose was tapered before discontinuation in some studies but not in others. Both strategies appear effective. A recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials demonstrated pooled ORs of 7.34 (95% CI, 4.08-13.19) and 8.35 (95% CI, 4.14-16.85) for response to budesonide induction and maintenance, respectively.39

Cholestyramine is another medication considered in the management of MC and warrants further investigation. To date, no randomized clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate bile acid sequestrants in MC, but they should be considered before placing patients on immunosuppressive medications. Some providers use mesalamine in this setting, although mesalamine is inferior to budesonide in the induction of clinical remission in MC.40

Despite high rates of response to budesonide, relapse after discontinuation is frequent (60%-80%), and time to relapse is variable41,42 The American Gastroenterological Association recommends budesonide for maintenance of remission in patients with recurrence following discontinuation of induction therapy. The lowest effective dose that maintains resolution of symptoms should be prescribed, ideally at 6 mg daily or lower.38 Although budesonide has a greater first-pass metabolism, compared with other glucocorticoids, patients should be monitored for possible side effects including hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis, as well as ophthalmologic disease, including cataracts and glaucoma.

For those who are intolerant to budesonide or have refractory symptoms, concomitant disorders such as CD that may be contributing to symptoms must be excluded. Immunosuppressive medications – such as thiopurines and biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors or vedolizumab – may be considered in refractory cases.43,44 Of note, there are limited studies evaluating the use of these medications for MC. Lastly, surgeries including ileostomy with or without colectomy have been performed in the most severe cases for resistant disease that has failed numerous pharmacological therapies.45

Patients should be counseled that, while symptoms from MC can be quite bothersome and disabling, there appears to be a normal life expectancy and no association between MC and colon cancer, unlike with other inflammatory conditions of the colon such as IBD.46,47

Conclusion and future outlook

As a common cause of chronic watery diarrhea, MC will be commonly encountered in primary care and gastroenterology practices. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients presenting with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, especially with female gender, autoimmune disease, and increasing age. The management of MC requires an algorithmic approach directed by symptom severity, with a subgroup of patients requiring maintenance therapy for relapsing symptoms. The care of patients with MC will continue to evolve in the future. Further work is needed to explore long-term safety outcomes with budesonide and the role of immunomodulators and newer biologic agents for patients with complex, refractory disease.

Dr. Tome is with the department of internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Kamboj, and Dr. Pardi are with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Pardi has grant funding from Pfizer, Vedanta, Seres, Finch, Applied Molecular Transport, and Takeda and has consulted for Vedanta and Otsuka. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Nyhlin N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:963-72.

2. Miehlke S et al. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;20-8.

3. Pardi DS et al. Gut. 2007;56:504-8.

4. Fernández-Bañares F et al. J Crohn’s Colitis.2016;10(7):805-11.

5. Gentile NM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):838-42.

6. Tong J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:265-76.

7. Olesen M et al. Gut. 2004;53(3):346-50.

8. Bergman D et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(11):1395-400.

9. Guagnozzi D et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(5):384-8.

10. Münch A et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(9):932-45.

11. Macaigne G et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 09(9):1461-70.

12. Verhaegh BP et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(9):1004-13.

13. Stewart M et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(12):1340-9.

14. Green PHR et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1210-6.

15. Masclee GM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:749-59.

16. Zylberberg H et al. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jun;53(11)1209-15.

17. Jaruvongvanich V et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(4):672-8.

18. Fernández-Bañares F et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19(7):1470-6.

19. Yen EF et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(10):1835-41.

20. Barmeyer C et al. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(10):1090-100.

21. Morgan DM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(4):984-6.

22. Larsson JK et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1309-17.

23. Madisch A et al.. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):2295-8.

24. Stahl E et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):549-61.

25. Sikander A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015; 60:887-94.

26. Abdo AA et al. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15(5):341-3.

27. Fernandez-Bañares F et al. Dig Dis Sci.2001;46(10):2231-8.

28. Lyutakov I et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;1;33(3):380-7.

29. Hjortswang H et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2011 Feb;43(2):102-9.

30. Cotter TG= et al. Gut. 2018;67(3):441-6.

31. Von Arnim U et al. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:97-103.

32. Langner C et al. Histopathology. 2015;66:613-26.

33. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee and Sharaf RN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:216-24.

34. Macaigne G et al. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41(3):333-40.

35. Bjørnbak C et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(10):1225-34.

36. Pardi DS et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):247-74.

37. Masannat Y and Nazer E. West Virginia Med J. 2013;109(3):32-4.

38. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(1):242-6.

39. Sebastian S et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Aug;31(8):919-27.

40. Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1222-30.

41. Gentile NM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:256-9.

42. Münch A et al. Gut. 2016; 65(1):47-56.

43. Cotter TG et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46(2):169-74.

44. Esteve M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(6):612-8.

45. Cottreau J et al. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:140-4.

46. Kamboj AK et al. Program No. P1876. ACG 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American College of Gastroenterology.

47. Yen EF et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:161-9.

Microscopic colitis is an inflammatory disease of the colon and a frequent cause of chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. MC consists of two subtypes, collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC). While the primary symptom is diarrhea, other signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities may also be present depending on disease severity.1 In MC, the colonic mucosa usually appears normal on colonoscopy, and the diagnosis is made by histologic findings of intraepithelial lymphocytosis with (CC) or without (LC) a prominent subepithelial collagen band. The management approaches to CC and LC are similar and should be directed based on the severity of symptoms.2 We review the epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management for this condition, as well as novel therapeutic approaches.

Epidemiology

Although the incidence of MC increased in the late twentieth century, more recently, it has stabilized with an estimated incidence varying from 1 to 25 per 100,000 person-years.3-5 A recent meta-analysis revealed a pooled incidence of 4.85 per 100,000 persons for LC and 4.14 per 100,000 persons for CC.6 Proposed explanations for the rising incidence in the late twentieth century include improved clinical awareness of the disease, possible increased use of drugs associated with MC, and increased performance of diagnostic colonoscopies for chronic diarrhea. Since MC is now well-recognized, the recent plateau in incidence rates may reflect decreased detection bias.

The prevalence of MC ranges from 10%-20% in patients undergoing colonoscopy for chronic watery diarrhea.6,7 The prevalence of LC is approximately 63.1 cases per 100,000 person-years and, for CC, is 49.2 cases per 100,000 person-years.6-8 Recent studies have demonstrated increasing prevalence of MC likely resulting from an aging population.9,10

Risk stratification

Female gender, increasing age, concomitant autoimmune disease, and the use of certain drugs, including NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been associated with an increased risk of MC.11,12 Autoimmune disorders, including celiac disease (CD), rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, are more common in patients with MC. The association with CD, in particular, is clinically important, as CD is associated with a 50-70 times greater risk of MC, and 2%-9% of patients with MC have CD.13,14

Several medications have been associated with MC. In a British multicenter prospective study, MC was associated with the use of NSAIDs, PPIs, and SSRIs;15 however, recent studies have questioned the association of MC with some of these medications, which might worsen diarrhea but not actually cause MC.16

An additional risk factor for MC is smoking. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that current and former smokers had an increased risk of MC (odds ratio, 2.99; 95% confidence interval, 2.15-4.15 and OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.37-1.94, respectively), compared with nonsmokers.17 Smokers develop MC at a younger age, and smoking is associated with increased disease severity and decreased likelihood of attaining remission.18,19

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of MC remains largely unknown, although there are several hypotheses. The leading proposed mechanisms include reaction to luminal antigens, dysregulated collagen metabolism, genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, and bile acid malabsorption.

MC may be caused by abnormal epithelial barrier function, leading to increased permeability and reaction to luminal antigens, including dietary antigens, certain drugs, and bacterial products, 20,21 which themselves lead to the immune dysregulation and intestinal inflammation seen in MC. This mechanism may explain the association of several drugs with MC. Histological changes resembling LC are reported in patients with CD who consume gluten; however, large population-based studies have not found specific dietary associations with the development of MC.22

Another potential mechanism of MC is dysregulated collagen deposition. Collagen accumulation in the subepithelial layer in CC may result from increased levels of fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor–beta and vascular endothelial growth factor.23 Nonetheless, studies have not found an association between the severity of diarrhea in patients with CC and the thickness of the subepithelial collagen band.

Thirdly, autoimmunity and genetic predisposition have been postulated in the pathogenesis of MC. As previously discussed, MC is associated with several autoimmune diseases and predominantly occurs in women, a distinctive feature of autoimmune disorders. Several studies have demonstrated an association between MC and HLA-DQ2 and -DQ3 haplotypes,24 as well as potential polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene promoter.25 It is important to note, however, that only a few familial cases of MC have been reported to date.26

Lastly, bile acid malabsorption may play a role in the etiology of MC. Histologic findings of inflammation, along with villous atrophy and collagen deposition, have been reported in the ileum of patients with MC;27,28 however, because patients with MC without bile acid malabsorption may also respond to bile acid binders such as cholestyramine, these findings unlikely to be the sole mechanism explaining the development of the disease.

Despite the different proposed mechanisms for the pathogenesis of MC, no definite conclusions can be drawn because of the limited size of these studies and their often conflicting results.

Clinical features

Clinicians should suspect MC in patients with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. Other risk factors include female gender, use of certain culprit medications, smoking, and presence of other autoimmune diseases. The clinical manifestations of MC subtypes LC and CC are similar with no significant clinical differences.1,2 In addition to diarrhea, patients with MC may have abdominal pain, fatigue, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities depending on disease severity. Patients may also present with fecal urgency, incontinence, and nocturnal stools. Quality of life is often reduced in these patients, predominantly in those with severe or refractory symptoms.29,30 The natural course of MC is highly variable, with some patients achieving spontaneous resolution after one episode and others developing chronic symptoms.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic watery diarrhea is broad and includes malabsorption/maldigestion, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, and medication side effects. In addition, although gastrointestinal infections typically cause acute or subacute diarrhea, some can present with chronic diarrhea. Malabsorption/maldigestion may occur because of CD, lactose intolerance, and pancreatic insufficiency, among other conditions. A thorough history, regarding recent antibiotic and medication use, travel, and immunosuppression, should be obtained in patients with chronic diarrhea. Additionally, laboratory and endoscopic evaluation with random biopsies of the colon can further help differentiate these diseases from MC. A few studies suggest fecal calprotectin may be used to differentiate MC from other noninflammatory conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, as well as to monitor disease activity. This test is not expected to distinguish MC from other inflammatory causes of diarrhea, such as IBD, and therefore, its role in clinical practice is uncertain.31

The diagnosis of MC is made by biopsy of the colonic mucosa demonstrating characteristic pathologic features.32 Unlike in diseases such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, the colon usually appears normal in MC, although mild nonspecific changes, such as erythema or edema, may be visualized. There is no consensus on the ideal location to obtain biopsies for MC or whether biopsies from both the left and the right colon are required.2,33 The procedure of choice for the diagnosis of MC is colonoscopy with random biopsies taken throughout the colon. More limited evaluation by flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsies may miss cases of MC as inflammation and collagen thickening are not necessarily uniform throughout the colon; however, in a patient that has undergone a recent colonoscopy for colon cancer screening without colon biopsies, a flexible sigmoidoscopy may be a reasonable next test for evaluation of MC, provided biopsies are obtained above the rectosigmoid colon.34

The MC subtypes are differentiated based on histology. The hallmark of LC is less than 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1A). CC is characterized by a thickened subepithelial collagen band greater than 7-10 micrometers (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1B). For a subgroup of patients with milder abnormalities that do not meet these histological criteria, the terms “microscopic colitis, not otherwise specified” or “microscopic colitis, incomplete” may be used.35 These patients often respond to standard treatments for MC. There is an additional subset of patients with biopsy demonstrating features of both CC and LC simultaneously, as well as patients transitioning from one MC subtype to another over time.32,35

Management approach

The first step in management of patients with MC includes stopping culprit medications if there is a temporal relationship between the initiation of the medication and the onset of diarrhea, as well as encouraging smoking cessation. These steps alone, however, are unlikely to achieve clinical remission in most patients. A stepwise pharmacological approach is used in the management of MC based on disease severity (Figure 2). For patients with mild symptoms, antidiarrheal medications, such as loperamide, may be helpful.36 Long-term use of loperamide at therapeutic doses no greater than 16 mg daily appears to be safe if required to maintain symptom response. For those with persistent symptoms despite antidiarrheal medications, bismuth subsalicylate at three 262 mg tablets three times daily for 6-8 weeks can be considered. Long-term use of bismuth subsalicylate is not advised, especially at this dose, because of possible neurotoxicity.37

For patients refractory to the above treatments or those with moderate-to-severe symptoms, an 8-week course of budesonide at 9 mg daily is the first-line treatment.38 The dose was tapered before discontinuation in some studies but not in others. Both strategies appear effective. A recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials demonstrated pooled ORs of 7.34 (95% CI, 4.08-13.19) and 8.35 (95% CI, 4.14-16.85) for response to budesonide induction and maintenance, respectively.39

Cholestyramine is another medication considered in the management of MC and warrants further investigation. To date, no randomized clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate bile acid sequestrants in MC, but they should be considered before placing patients on immunosuppressive medications. Some providers use mesalamine in this setting, although mesalamine is inferior to budesonide in the induction of clinical remission in MC.40

Despite high rates of response to budesonide, relapse after discontinuation is frequent (60%-80%), and time to relapse is variable41,42 The American Gastroenterological Association recommends budesonide for maintenance of remission in patients with recurrence following discontinuation of induction therapy. The lowest effective dose that maintains resolution of symptoms should be prescribed, ideally at 6 mg daily or lower.38 Although budesonide has a greater first-pass metabolism, compared with other glucocorticoids, patients should be monitored for possible side effects including hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis, as well as ophthalmologic disease, including cataracts and glaucoma.

For those who are intolerant to budesonide or have refractory symptoms, concomitant disorders such as CD that may be contributing to symptoms must be excluded. Immunosuppressive medications – such as thiopurines and biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors or vedolizumab – may be considered in refractory cases.43,44 Of note, there are limited studies evaluating the use of these medications for MC. Lastly, surgeries including ileostomy with or without colectomy have been performed in the most severe cases for resistant disease that has failed numerous pharmacological therapies.45

Patients should be counseled that, while symptoms from MC can be quite bothersome and disabling, there appears to be a normal life expectancy and no association between MC and colon cancer, unlike with other inflammatory conditions of the colon such as IBD.46,47

Conclusion and future outlook

As a common cause of chronic watery diarrhea, MC will be commonly encountered in primary care and gastroenterology practices. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients presenting with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, especially with female gender, autoimmune disease, and increasing age. The management of MC requires an algorithmic approach directed by symptom severity, with a subgroup of patients requiring maintenance therapy for relapsing symptoms. The care of patients with MC will continue to evolve in the future. Further work is needed to explore long-term safety outcomes with budesonide and the role of immunomodulators and newer biologic agents for patients with complex, refractory disease.

Dr. Tome is with the department of internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Kamboj, and Dr. Pardi are with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Pardi has grant funding from Pfizer, Vedanta, Seres, Finch, Applied Molecular Transport, and Takeda and has consulted for Vedanta and Otsuka. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Nyhlin N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:963-72.

2. Miehlke S et al. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;20-8.

3. Pardi DS et al. Gut. 2007;56:504-8.

4. Fernández-Bañares F et al. J Crohn’s Colitis.2016;10(7):805-11.

5. Gentile NM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):838-42.

6. Tong J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:265-76.

7. Olesen M et al. Gut. 2004;53(3):346-50.

8. Bergman D et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(11):1395-400.

9. Guagnozzi D et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(5):384-8.

10. Münch A et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(9):932-45.

11. Macaigne G et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 09(9):1461-70.

12. Verhaegh BP et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(9):1004-13.

13. Stewart M et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(12):1340-9.

14. Green PHR et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1210-6.

15. Masclee GM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:749-59.

16. Zylberberg H et al. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jun;53(11)1209-15.

17. Jaruvongvanich V et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(4):672-8.

18. Fernández-Bañares F et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19(7):1470-6.

19. Yen EF et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(10):1835-41.

20. Barmeyer C et al. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(10):1090-100.

21. Morgan DM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(4):984-6.

22. Larsson JK et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1309-17.

23. Madisch A et al.. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):2295-8.

24. Stahl E et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):549-61.

25. Sikander A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015; 60:887-94.

26. Abdo AA et al. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15(5):341-3.

27. Fernandez-Bañares F et al. Dig Dis Sci.2001;46(10):2231-8.

28. Lyutakov I et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;1;33(3):380-7.

29. Hjortswang H et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2011 Feb;43(2):102-9.

30. Cotter TG= et al. Gut. 2018;67(3):441-6.

31. Von Arnim U et al. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:97-103.

32. Langner C et al. Histopathology. 2015;66:613-26.

33. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee and Sharaf RN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:216-24.

34. Macaigne G et al. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41(3):333-40.

35. Bjørnbak C et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(10):1225-34.

36. Pardi DS et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):247-74.

37. Masannat Y and Nazer E. West Virginia Med J. 2013;109(3):32-4.

38. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(1):242-6.

39. Sebastian S et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Aug;31(8):919-27.

40. Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1222-30.

41. Gentile NM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:256-9.

42. Münch A et al. Gut. 2016; 65(1):47-56.

43. Cotter TG et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46(2):169-74.

44. Esteve M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(6):612-8.

45. Cottreau J et al. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:140-4.

46. Kamboj AK et al. Program No. P1876. ACG 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American College of Gastroenterology.

47. Yen EF et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:161-9.

Microscopic colitis is an inflammatory disease of the colon and a frequent cause of chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. MC consists of two subtypes, collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC). While the primary symptom is diarrhea, other signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities may also be present depending on disease severity.1 In MC, the colonic mucosa usually appears normal on colonoscopy, and the diagnosis is made by histologic findings of intraepithelial lymphocytosis with (CC) or without (LC) a prominent subepithelial collagen band. The management approaches to CC and LC are similar and should be directed based on the severity of symptoms.2 We review the epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management for this condition, as well as novel therapeutic approaches.

Epidemiology

Although the incidence of MC increased in the late twentieth century, more recently, it has stabilized with an estimated incidence varying from 1 to 25 per 100,000 person-years.3-5 A recent meta-analysis revealed a pooled incidence of 4.85 per 100,000 persons for LC and 4.14 per 100,000 persons for CC.6 Proposed explanations for the rising incidence in the late twentieth century include improved clinical awareness of the disease, possible increased use of drugs associated with MC, and increased performance of diagnostic colonoscopies for chronic diarrhea. Since MC is now well-recognized, the recent plateau in incidence rates may reflect decreased detection bias.

The prevalence of MC ranges from 10%-20% in patients undergoing colonoscopy for chronic watery diarrhea.6,7 The prevalence of LC is approximately 63.1 cases per 100,000 person-years and, for CC, is 49.2 cases per 100,000 person-years.6-8 Recent studies have demonstrated increasing prevalence of MC likely resulting from an aging population.9,10

Risk stratification

Female gender, increasing age, concomitant autoimmune disease, and the use of certain drugs, including NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been associated with an increased risk of MC.11,12 Autoimmune disorders, including celiac disease (CD), rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, are more common in patients with MC. The association with CD, in particular, is clinically important, as CD is associated with a 50-70 times greater risk of MC, and 2%-9% of patients with MC have CD.13,14

Several medications have been associated with MC. In a British multicenter prospective study, MC was associated with the use of NSAIDs, PPIs, and SSRIs;15 however, recent studies have questioned the association of MC with some of these medications, which might worsen diarrhea but not actually cause MC.16

An additional risk factor for MC is smoking. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that current and former smokers had an increased risk of MC (odds ratio, 2.99; 95% confidence interval, 2.15-4.15 and OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.37-1.94, respectively), compared with nonsmokers.17 Smokers develop MC at a younger age, and smoking is associated with increased disease severity and decreased likelihood of attaining remission.18,19

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of MC remains largely unknown, although there are several hypotheses. The leading proposed mechanisms include reaction to luminal antigens, dysregulated collagen metabolism, genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, and bile acid malabsorption.

MC may be caused by abnormal epithelial barrier function, leading to increased permeability and reaction to luminal antigens, including dietary antigens, certain drugs, and bacterial products, 20,21 which themselves lead to the immune dysregulation and intestinal inflammation seen in MC. This mechanism may explain the association of several drugs with MC. Histological changes resembling LC are reported in patients with CD who consume gluten; however, large population-based studies have not found specific dietary associations with the development of MC.22

Another potential mechanism of MC is dysregulated collagen deposition. Collagen accumulation in the subepithelial layer in CC may result from increased levels of fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor–beta and vascular endothelial growth factor.23 Nonetheless, studies have not found an association between the severity of diarrhea in patients with CC and the thickness of the subepithelial collagen band.

Thirdly, autoimmunity and genetic predisposition have been postulated in the pathogenesis of MC. As previously discussed, MC is associated with several autoimmune diseases and predominantly occurs in women, a distinctive feature of autoimmune disorders. Several studies have demonstrated an association between MC and HLA-DQ2 and -DQ3 haplotypes,24 as well as potential polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene promoter.25 It is important to note, however, that only a few familial cases of MC have been reported to date.26

Lastly, bile acid malabsorption may play a role in the etiology of MC. Histologic findings of inflammation, along with villous atrophy and collagen deposition, have been reported in the ileum of patients with MC;27,28 however, because patients with MC without bile acid malabsorption may also respond to bile acid binders such as cholestyramine, these findings unlikely to be the sole mechanism explaining the development of the disease.

Despite the different proposed mechanisms for the pathogenesis of MC, no definite conclusions can be drawn because of the limited size of these studies and their often conflicting results.

Clinical features

Clinicians should suspect MC in patients with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, particularly in older persons. Other risk factors include female gender, use of certain culprit medications, smoking, and presence of other autoimmune diseases. The clinical manifestations of MC subtypes LC and CC are similar with no significant clinical differences.1,2 In addition to diarrhea, patients with MC may have abdominal pain, fatigue, and dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities depending on disease severity. Patients may also present with fecal urgency, incontinence, and nocturnal stools. Quality of life is often reduced in these patients, predominantly in those with severe or refractory symptoms.29,30 The natural course of MC is highly variable, with some patients achieving spontaneous resolution after one episode and others developing chronic symptoms.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic watery diarrhea is broad and includes malabsorption/maldigestion, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome, and medication side effects. In addition, although gastrointestinal infections typically cause acute or subacute diarrhea, some can present with chronic diarrhea. Malabsorption/maldigestion may occur because of CD, lactose intolerance, and pancreatic insufficiency, among other conditions. A thorough history, regarding recent antibiotic and medication use, travel, and immunosuppression, should be obtained in patients with chronic diarrhea. Additionally, laboratory and endoscopic evaluation with random biopsies of the colon can further help differentiate these diseases from MC. A few studies suggest fecal calprotectin may be used to differentiate MC from other noninflammatory conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, as well as to monitor disease activity. This test is not expected to distinguish MC from other inflammatory causes of diarrhea, such as IBD, and therefore, its role in clinical practice is uncertain.31

The diagnosis of MC is made by biopsy of the colonic mucosa demonstrating characteristic pathologic features.32 Unlike in diseases such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, the colon usually appears normal in MC, although mild nonspecific changes, such as erythema or edema, may be visualized. There is no consensus on the ideal location to obtain biopsies for MC or whether biopsies from both the left and the right colon are required.2,33 The procedure of choice for the diagnosis of MC is colonoscopy with random biopsies taken throughout the colon. More limited evaluation by flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsies may miss cases of MC as inflammation and collagen thickening are not necessarily uniform throughout the colon; however, in a patient that has undergone a recent colonoscopy for colon cancer screening without colon biopsies, a flexible sigmoidoscopy may be a reasonable next test for evaluation of MC, provided biopsies are obtained above the rectosigmoid colon.34

The MC subtypes are differentiated based on histology. The hallmark of LC is less than 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 surface epithelial cells (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1A). CC is characterized by a thickened subepithelial collagen band greater than 7-10 micrometers (normal, less than 5) (Figure 1B). For a subgroup of patients with milder abnormalities that do not meet these histological criteria, the terms “microscopic colitis, not otherwise specified” or “microscopic colitis, incomplete” may be used.35 These patients often respond to standard treatments for MC. There is an additional subset of patients with biopsy demonstrating features of both CC and LC simultaneously, as well as patients transitioning from one MC subtype to another over time.32,35

Management approach

The first step in management of patients with MC includes stopping culprit medications if there is a temporal relationship between the initiation of the medication and the onset of diarrhea, as well as encouraging smoking cessation. These steps alone, however, are unlikely to achieve clinical remission in most patients. A stepwise pharmacological approach is used in the management of MC based on disease severity (Figure 2). For patients with mild symptoms, antidiarrheal medications, such as loperamide, may be helpful.36 Long-term use of loperamide at therapeutic doses no greater than 16 mg daily appears to be safe if required to maintain symptom response. For those with persistent symptoms despite antidiarrheal medications, bismuth subsalicylate at three 262 mg tablets three times daily for 6-8 weeks can be considered. Long-term use of bismuth subsalicylate is not advised, especially at this dose, because of possible neurotoxicity.37

For patients refractory to the above treatments or those with moderate-to-severe symptoms, an 8-week course of budesonide at 9 mg daily is the first-line treatment.38 The dose was tapered before discontinuation in some studies but not in others. Both strategies appear effective. A recent meta-analysis of nine randomized trials demonstrated pooled ORs of 7.34 (95% CI, 4.08-13.19) and 8.35 (95% CI, 4.14-16.85) for response to budesonide induction and maintenance, respectively.39

Cholestyramine is another medication considered in the management of MC and warrants further investigation. To date, no randomized clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate bile acid sequestrants in MC, but they should be considered before placing patients on immunosuppressive medications. Some providers use mesalamine in this setting, although mesalamine is inferior to budesonide in the induction of clinical remission in MC.40

Despite high rates of response to budesonide, relapse after discontinuation is frequent (60%-80%), and time to relapse is variable41,42 The American Gastroenterological Association recommends budesonide for maintenance of remission in patients with recurrence following discontinuation of induction therapy. The lowest effective dose that maintains resolution of symptoms should be prescribed, ideally at 6 mg daily or lower.38 Although budesonide has a greater first-pass metabolism, compared with other glucocorticoids, patients should be monitored for possible side effects including hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis, as well as ophthalmologic disease, including cataracts and glaucoma.

For those who are intolerant to budesonide or have refractory symptoms, concomitant disorders such as CD that may be contributing to symptoms must be excluded. Immunosuppressive medications – such as thiopurines and biologic agents, including tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors or vedolizumab – may be considered in refractory cases.43,44 Of note, there are limited studies evaluating the use of these medications for MC. Lastly, surgeries including ileostomy with or without colectomy have been performed in the most severe cases for resistant disease that has failed numerous pharmacological therapies.45

Patients should be counseled that, while symptoms from MC can be quite bothersome and disabling, there appears to be a normal life expectancy and no association between MC and colon cancer, unlike with other inflammatory conditions of the colon such as IBD.46,47

Conclusion and future outlook

As a common cause of chronic watery diarrhea, MC will be commonly encountered in primary care and gastroenterology practices. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients presenting with chronic or recurrent watery diarrhea, especially with female gender, autoimmune disease, and increasing age. The management of MC requires an algorithmic approach directed by symptom severity, with a subgroup of patients requiring maintenance therapy for relapsing symptoms. The care of patients with MC will continue to evolve in the future. Further work is needed to explore long-term safety outcomes with budesonide and the role of immunomodulators and newer biologic agents for patients with complex, refractory disease.

Dr. Tome is with the department of internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Kamboj, and Dr. Pardi are with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Pardi has grant funding from Pfizer, Vedanta, Seres, Finch, Applied Molecular Transport, and Takeda and has consulted for Vedanta and Otsuka. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Nyhlin N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:963-72.

2. Miehlke S et al. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;20-8.

3. Pardi DS et al. Gut. 2007;56:504-8.

4. Fernández-Bañares F et al. J Crohn’s Colitis.2016;10(7):805-11.

5. Gentile NM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):838-42.

6. Tong J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:265-76.

7. Olesen M et al. Gut. 2004;53(3):346-50.

8. Bergman D et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(11):1395-400.

9. Guagnozzi D et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(5):384-8.

10. Münch A et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(9):932-45.

11. Macaigne G et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 09(9):1461-70.

12. Verhaegh BP et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(9):1004-13.

13. Stewart M et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(12):1340-9.

14. Green PHR et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1210-6.

15. Masclee GM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:749-59.

16. Zylberberg H et al. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jun;53(11)1209-15.

17. Jaruvongvanich V et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(4):672-8.

18. Fernández-Bañares F et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19(7):1470-6.

19. Yen EF et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(10):1835-41.

20. Barmeyer C et al. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(10):1090-100.

21. Morgan DM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(4):984-6.

22. Larsson JK et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1309-17.

23. Madisch A et al.. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):2295-8.

24. Stahl E et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):549-61.

25. Sikander A et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2015; 60:887-94.

26. Abdo AA et al. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15(5):341-3.

27. Fernandez-Bañares F et al. Dig Dis Sci.2001;46(10):2231-8.

28. Lyutakov I et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;1;33(3):380-7.

29. Hjortswang H et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2011 Feb;43(2):102-9.

30. Cotter TG= et al. Gut. 2018;67(3):441-6.

31. Von Arnim U et al. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:97-103.

32. Langner C et al. Histopathology. 2015;66:613-26.

33. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee and Sharaf RN et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:216-24.

34. Macaigne G et al. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41(3):333-40.

35. Bjørnbak C et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(10):1225-34.

36. Pardi DS et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):247-74.

37. Masannat Y and Nazer E. West Virginia Med J. 2013;109(3):32-4.

38. Nguyen GC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(1):242-6.

39. Sebastian S et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Aug;31(8):919-27.

40. Miehlke S et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1222-30.

41. Gentile NM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:256-9.

42. Münch A et al. Gut. 2016; 65(1):47-56.

43. Cotter TG et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46(2):169-74.

44. Esteve M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(6):612-8.

45. Cottreau J et al. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:140-4.

46. Kamboj AK et al. Program No. P1876. ACG 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American College of Gastroenterology.

47. Yen EF et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:161-9.

August 2021 – ICYMI

Gastroenterology

May 2021

Understanding GI Twitter and its major contributors. Elfanagely Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):1917-21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.232.

Long-term safety of fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Saha S et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):1961-9.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.010.

How to incorporate health equity training into gastroenterology and hepatology fellowships. Lee-Allen J, Shah BJ. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):1924-8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.018.

Functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis in tertiary care are interchangeable syndromes with common clinical and pathologic features. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):2006-17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.230.

June 2021

How to manage the large nonpedunculated colorectal polyp. Shahidi N, Bourke MJ. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun;160(7):2239-43.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.029.

Mortality, reoperation, and hospital stay within 90 days of primary and secondary antireflux surgery in a population-based multinational study. Yanes M et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun;160(7):2283-90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.022.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection in north america: A large prospective multicenter study. Draganov PV et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun;160(7):2317-27.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.036.

July 2021

Gluten degradation, pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of TAK-062, an engineered enzyme to treat celiac disease. Pultz IG et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jul;161(1):81-93.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.019.

Paternal exposure to immunosuppressive and/or biologic agents and birth outcomes in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Meserve J et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jul;161(1):107-115.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.020.

Ethnicity associations with food sensitization are mediated by gut microbiota development in the first year of life. Tun Hm et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jul;161(1):94-106. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.016.

How to incorporate bariatric training into your fellowship program. Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):9-13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.034.

CGH

May 2021

Intestinal failure: What all gastroenterologists should know. Jansson-Knodell CL et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 May;19(5):885-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.038.

When and how to use endoscopic tattooing in the colon: An international Delphi agreement. Medina-Prado L et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 May;19(5):1038-50. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.024.

Five-year outcomes of endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for the treatment of obesity. Sharaiha RZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 May;19(5):1051-57.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.055.

June 2021

GA Clinical Practice Update on management of bleeding gastric varices: Expert review. Henry Z et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;19(6):1098-107.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.027.

Inter- and intra-individual variation, and limited prognostic utility, of serum alkaline phosphatase in a trial of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis

Palak J. Trivedi PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;19(6):1248-57. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.032.

Low-fat, high-fiber diet reduces markers of inflammation and dysbiosis and improves quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis. Julia Fritsch J et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;19(6):1189-99.e30. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.026.

July 2021

Scoping out a better parental leave policy for gastroenterology fellows. Wegermann K. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1307-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.040.

An impetus for change: How COVID-19 will transform the delivery of GI health care. Leiman DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1310-1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.042.

Untangling nonerosive reflux disease from functional heartburn. Patel D et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1314-26. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.057.

AGA Clinical Practice Update on chemoprevention for colorectal neoplasia: Expert review. Liang PS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1327-36. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.02.014.

CMGH

Drug inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication in human pluripotent stem cell–derived intestinal organoids. Krüger J et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;11(4):935-48. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.11.003.

TIGE

Virtual interviews during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A survey of advanced endoscopy fellowship applicants and programs. Amrit K. Kamboj AK et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):159-68. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.02.001.

Triage of general gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a national Delphi consensus panel. Feuerstein JD et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):113-21. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.12.005.

Development of a scoring system to predict a positive diagnosis on video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel bleeding. Marya NB et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;22(4):178-84. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.06.001.

Gastroenterology

May 2021

Understanding GI Twitter and its major contributors. Elfanagely Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):1917-21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.232.

Long-term safety of fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Saha S et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):1961-9.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.010.

How to incorporate health equity training into gastroenterology and hepatology fellowships. Lee-Allen J, Shah BJ. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):1924-8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.018.

Functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis in tertiary care are interchangeable syndromes with common clinical and pathologic features. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):2006-17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.230.

June 2021

How to manage the large nonpedunculated colorectal polyp. Shahidi N, Bourke MJ. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun;160(7):2239-43.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.029.

Mortality, reoperation, and hospital stay within 90 days of primary and secondary antireflux surgery in a population-based multinational study. Yanes M et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun;160(7):2283-90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.022.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection in north america: A large prospective multicenter study. Draganov PV et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun;160(7):2317-27.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.036.

July 2021

Gluten degradation, pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of TAK-062, an engineered enzyme to treat celiac disease. Pultz IG et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jul;161(1):81-93.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.019.

Paternal exposure to immunosuppressive and/or biologic agents and birth outcomes in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Meserve J et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jul;161(1):107-115.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.020.

Ethnicity associations with food sensitization are mediated by gut microbiota development in the first year of life. Tun Hm et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jul;161(1):94-106. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.016.

How to incorporate bariatric training into your fellowship program. Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):9-13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.034.

CGH

May 2021

Intestinal failure: What all gastroenterologists should know. Jansson-Knodell CL et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 May;19(5):885-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.038.

When and how to use endoscopic tattooing in the colon: An international Delphi agreement. Medina-Prado L et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 May;19(5):1038-50. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.024.

Five-year outcomes of endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for the treatment of obesity. Sharaiha RZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 May;19(5):1051-57.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.055.

June 2021

GA Clinical Practice Update on management of bleeding gastric varices: Expert review. Henry Z et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;19(6):1098-107.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.027.

Inter- and intra-individual variation, and limited prognostic utility, of serum alkaline phosphatase in a trial of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis

Palak J. Trivedi PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;19(6):1248-57. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.032.

Low-fat, high-fiber diet reduces markers of inflammation and dysbiosis and improves quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis. Julia Fritsch J et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;19(6):1189-99.e30. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.026.

July 2021

Scoping out a better parental leave policy for gastroenterology fellows. Wegermann K. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1307-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.040.

An impetus for change: How COVID-19 will transform the delivery of GI health care. Leiman DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1310-1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.042.

Untangling nonerosive reflux disease from functional heartburn. Patel D et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1314-26. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.057.

AGA Clinical Practice Update on chemoprevention for colorectal neoplasia: Expert review. Liang PS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1327-36. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.02.014.

CMGH

Drug inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication in human pluripotent stem cell–derived intestinal organoids. Krüger J et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;11(4):935-48. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.11.003.

TIGE

Virtual interviews during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A survey of advanced endoscopy fellowship applicants and programs. Amrit K. Kamboj AK et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):159-68. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.02.001.

Triage of general gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a national Delphi consensus panel. Feuerstein JD et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):113-21. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.12.005.

Development of a scoring system to predict a positive diagnosis on video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel bleeding. Marya NB et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;22(4):178-84. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.06.001.

Gastroenterology

May 2021

Understanding GI Twitter and its major contributors. Elfanagely Y et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):1917-21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.232.

Long-term safety of fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Saha S et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):1961-9.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.010.

How to incorporate health equity training into gastroenterology and hepatology fellowships. Lee-Allen J, Shah BJ. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):1924-8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.018.

Functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis in tertiary care are interchangeable syndromes with common clinical and pathologic features. Pasricha PJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):2006-17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.230.

June 2021

How to manage the large nonpedunculated colorectal polyp. Shahidi N, Bourke MJ. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun;160(7):2239-43.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.029.

Mortality, reoperation, and hospital stay within 90 days of primary and secondary antireflux surgery in a population-based multinational study. Yanes M et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun;160(7):2283-90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.022.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection in north america: A large prospective multicenter study. Draganov PV et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun;160(7):2317-27.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.036.

July 2021

Gluten degradation, pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of TAK-062, an engineered enzyme to treat celiac disease. Pultz IG et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jul;161(1):81-93.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.019.

Paternal exposure to immunosuppressive and/or biologic agents and birth outcomes in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Meserve J et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jul;161(1):107-115.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.020.

Ethnicity associations with food sensitization are mediated by gut microbiota development in the first year of life. Tun Hm et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jul;161(1):94-106. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.016.

How to incorporate bariatric training into your fellowship program. Jirapinyo P, Thompson CC. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):9-13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.034.

CGH

May 2021

Intestinal failure: What all gastroenterologists should know. Jansson-Knodell CL et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 May;19(5):885-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.038.

When and how to use endoscopic tattooing in the colon: An international Delphi agreement. Medina-Prado L et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 May;19(5):1038-50. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.024.

Five-year outcomes of endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for the treatment of obesity. Sharaiha RZ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 May;19(5):1051-57.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.055.

June 2021

GA Clinical Practice Update on management of bleeding gastric varices: Expert review. Henry Z et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;19(6):1098-107.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.027.

Inter- and intra-individual variation, and limited prognostic utility, of serum alkaline phosphatase in a trial of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis

Palak J. Trivedi PJ et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;19(6):1248-57. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.032.

Low-fat, high-fiber diet reduces markers of inflammation and dysbiosis and improves quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis. Julia Fritsch J et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;19(6):1189-99.e30. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.026.

July 2021

Scoping out a better parental leave policy for gastroenterology fellows. Wegermann K. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1307-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.040.

An impetus for change: How COVID-19 will transform the delivery of GI health care. Leiman DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1310-1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.042.

Untangling nonerosive reflux disease from functional heartburn. Patel D et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1314-26. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.057.

AGA Clinical Practice Update on chemoprevention for colorectal neoplasia: Expert review. Liang PS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;19(7):1327-36. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.02.014.

CMGH

Drug inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication in human pluripotent stem cell–derived intestinal organoids. Krüger J et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;11(4):935-48. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.11.003.

TIGE

Virtual interviews during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A survey of advanced endoscopy fellowship applicants and programs. Amrit K. Kamboj AK et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):159-68. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2021.02.001.

Triage of general gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a national Delphi consensus panel. Feuerstein JD et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(2):113-21. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.12.005.

Development of a scoring system to predict a positive diagnosis on video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel bleeding. Marya NB et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;22(4):178-84. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.06.001.

Top 12 tips for research success in fellowship and early academic faculty years

Congratulations! You have matched in a competitive medical subspecialty or you have secured your first faculty position. But what do you do now? Success in your early career – as a new fellow or a new attending – requires both hard work and perseverance. We present our top 12 tips for how to be successful as you transition into your new position.

Tip #1: Be kind to yourself

As you transition from medical resident to GI fellow or from GI fellow to first-time attending, it is important to recognize that you are going through a major career transition (not as major as fourth year to intern, but probably a close second). First and foremost, remember to be kind to yourself and set reasonable expectations. You need to allow yourself time to transition to a new role which may also be in a new city or state. Take care of yourself – don’t forget to exercise, eat well, and sleep. You are in the long game now. Work to get yourself in a routine that is sustainable. Block out time to exercise, explore your new city, meal plan, and pursue your interests outside of medicine.

Tip #2: Set up for success