User login

Pediatric HM Literature Review

Clinical question: What is the relationship between duration of intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in infants <6 months of age hospitalized with urinary tract infections (UTIs)?

Background: There is an inadequate evidence base to drive decisions regarding duration of IV antibiotic therapy in young infants hospitalized with UTIs. Documented variability exists in length of stay (LOS) and resource utilization for these infants, which might be a direct result of practice variation with respect to IV therapy.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Twenty-four freestanding children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) administrative database was used to identify healthy infants <6 months of age admitted with a primary or secondary diagnosis of UTI or pyelonephritis from 1999 to 2004 to participating hospitals. Duration of IV therapy was defined as a dichotomous variable with three days (short course: three days) selected because it was the median length of therapy. Treatment failure was defined as readmission within 30 days.

More than 12,300 records were analyzed. Male gender, neonatal status, black race, Hispanic ethnicity, nonprivate insurance, severity of illness, known bacteremia, known genitourinary tract disorders, and specific hospital were independently associated with increased likelihood of long-course (four days) therapy.

Unadjusted analysis initially revealed that long-course therapy was significantly associated with a higher rate of treatment failure. After multivariate (to include propensity scores) adjustment, a significant association between treatment duration and failure was no longer identified. Treatment failure association with known genitourinary abnormalities and higher severity of illness remained.

A significant limitation of this study is the potential for multivariate analysis to fail to mitigate a bias toward sicker patients receiving longer duration of antibiotic therapy and, thus, having a higher likelihood of treatment failure. In addition, the greater question of when IV antibiotics (and hospital admission) are indicated in this population was not addressed by the study design.

Nonetheless, the data likely support a limited utility to long-course IV antibiotic therapy in this population. The study also adds to the evolving picture of considerable and widespread variation in physician practice.

Bottom line: Short-course IV therapy for infants with UTIs does not increase risk of treatment failure.

Citation: Brady PW, Conway PH, Goudie A. Length of intravenous antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in infants with urinary tract infections. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):196-203.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the relationship between duration of intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in infants <6 months of age hospitalized with urinary tract infections (UTIs)?

Background: There is an inadequate evidence base to drive decisions regarding duration of IV antibiotic therapy in young infants hospitalized with UTIs. Documented variability exists in length of stay (LOS) and resource utilization for these infants, which might be a direct result of practice variation with respect to IV therapy.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Twenty-four freestanding children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) administrative database was used to identify healthy infants <6 months of age admitted with a primary or secondary diagnosis of UTI or pyelonephritis from 1999 to 2004 to participating hospitals. Duration of IV therapy was defined as a dichotomous variable with three days (short course: three days) selected because it was the median length of therapy. Treatment failure was defined as readmission within 30 days.

More than 12,300 records were analyzed. Male gender, neonatal status, black race, Hispanic ethnicity, nonprivate insurance, severity of illness, known bacteremia, known genitourinary tract disorders, and specific hospital were independently associated with increased likelihood of long-course (four days) therapy.

Unadjusted analysis initially revealed that long-course therapy was significantly associated with a higher rate of treatment failure. After multivariate (to include propensity scores) adjustment, a significant association between treatment duration and failure was no longer identified. Treatment failure association with known genitourinary abnormalities and higher severity of illness remained.

A significant limitation of this study is the potential for multivariate analysis to fail to mitigate a bias toward sicker patients receiving longer duration of antibiotic therapy and, thus, having a higher likelihood of treatment failure. In addition, the greater question of when IV antibiotics (and hospital admission) are indicated in this population was not addressed by the study design.

Nonetheless, the data likely support a limited utility to long-course IV antibiotic therapy in this population. The study also adds to the evolving picture of considerable and widespread variation in physician practice.

Bottom line: Short-course IV therapy for infants with UTIs does not increase risk of treatment failure.

Citation: Brady PW, Conway PH, Goudie A. Length of intravenous antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in infants with urinary tract infections. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):196-203.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the relationship between duration of intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in infants <6 months of age hospitalized with urinary tract infections (UTIs)?

Background: There is an inadequate evidence base to drive decisions regarding duration of IV antibiotic therapy in young infants hospitalized with UTIs. Documented variability exists in length of stay (LOS) and resource utilization for these infants, which might be a direct result of practice variation with respect to IV therapy.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Twenty-four freestanding children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) administrative database was used to identify healthy infants <6 months of age admitted with a primary or secondary diagnosis of UTI or pyelonephritis from 1999 to 2004 to participating hospitals. Duration of IV therapy was defined as a dichotomous variable with three days (short course: three days) selected because it was the median length of therapy. Treatment failure was defined as readmission within 30 days.

More than 12,300 records were analyzed. Male gender, neonatal status, black race, Hispanic ethnicity, nonprivate insurance, severity of illness, known bacteremia, known genitourinary tract disorders, and specific hospital were independently associated with increased likelihood of long-course (four days) therapy.

Unadjusted analysis initially revealed that long-course therapy was significantly associated with a higher rate of treatment failure. After multivariate (to include propensity scores) adjustment, a significant association between treatment duration and failure was no longer identified. Treatment failure association with known genitourinary abnormalities and higher severity of illness remained.

A significant limitation of this study is the potential for multivariate analysis to fail to mitigate a bias toward sicker patients receiving longer duration of antibiotic therapy and, thus, having a higher likelihood of treatment failure. In addition, the greater question of when IV antibiotics (and hospital admission) are indicated in this population was not addressed by the study design.

Nonetheless, the data likely support a limited utility to long-course IV antibiotic therapy in this population. The study also adds to the evolving picture of considerable and widespread variation in physician practice.

Bottom line: Short-course IV therapy for infants with UTIs does not increase risk of treatment failure.

Citation: Brady PW, Conway PH, Goudie A. Length of intravenous antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in infants with urinary tract infections. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):196-203.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Sound Advice

Recent media reports about the dangers surrounding unused prescription medications, including abuse by teens and medications finding their way into the water supply, have prompted an increase in inquiries to healthcare providers about disposing of unused medication. These issues are complicated when controlled substances are involved.

Often, providers are unsure how to respond to patient questions about medication disposal. For example, what would you do if a patient requests an alternative medication because of an unwanted side effect and brings the originally prescribed medication back to you? What if the family of a recently expired patient brings unused medication to you and asks you to donate it to other patients? What if you have a colleague who performs mission work; could you accept and donate unused medication for use in another country?

Unfortunately, the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) does not provide a readily available mechanism to accomplish efficient, secure, and environmentally sound methods to collect and use or dispose of unwanted controlled substances. This article explains the rules physicians must adhere to and guidelines for “taking back” controlled substances.

The Legislation

Enacted in 1970, the CSA combined all existing federal drug laws into a single statute. It created five “schedules” in which certain drugs are classified. These “scheduled” drugs are commonly referred to as controlled substances. A drug’s classification depends on its potential for abuse and its currently accepted medical use in the U.S. Additionally, provisions of international treaties impact classification.

Under the classification system, Schedule I drugs have a high potential for abuse and have no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the U.S. In contrast, Schedule V drugs have a low potential for abuse and do have a currently accepted medical use in treatment in the U.S.

The CSA governs the manufacture, import, export, possession, use, and distribution of controlled substances. In doing so, the CSA established a system to register those authorized to handle controlled substances. Manufacturers, dispensers, distributors, and individual practitioners who prescribe controlled substances must be registered with the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

The CSA requires registrants to keep certain records for at least two years related to their handling of controlled substances. For example, physician registrants must keep records of controlled substances in Schedules II, III, IV, and V that are dispensed via methods other than prescribing or administering (e.g., industry samples). Inventories of controlled substances are required. Most notably, physicians generally are not required to keep records of prescribed medications; however, records must be kept if drugs are dispensed or administered. Moreover, there are heightened recordkeeping responsibilities for providers who prescribe, dispense, or administer for maintenance or detoxification.

Controlled Substance “Takeback”

The system of registration established by the CSA prohibits a DEA registrant from acquiring controlled substances from nonregistered entities and, in turn, bars an end-user from distributing pharmaceutical controlled substances to a DEA registrant. In other words, physicians cannot receive controlled substances from anyone who does not also have a registration. Thus, physicians may not “take back” prescribed medications from patients or their family members. Similarly, except in cases of a drug being recalled or a dispensing error, patients are not allowed to return controlled medications to a pharmacy.

Information on how a patient or family member should properly dispose of medication is commonly misunderstood. DEA regulations provide a process for nonregistrants to dispose of unused medication; however, it is cumbersome and meant to be used only when dealing with large quantities of controlled substances (e.g., large quantities of abandoned drugs). In such cases, the DEA special agent in charge (SAC) may instruct on disposal, which may include transfer of the substance to a DEA registrant, delivery to a DEA agent or office, destruction in the presence of an agent of the administration or other authorized person, or by other means. The person must submit a letter to the local SAC, which includes:

- Name and address of the person;

- Name and quantity of each controlled substance to be disposed of;

- Explanation of how the applicant obtained the controlled substance, if known; and

- Name, address, and registration number, if known, of the person who possessed the controlled substances prior to the applicant.

Federal legislation also provides a way for the DEA to grant approval to law-enforcement agencies to operate “takeback” programs. The regulation states that “any person in possession of a controlled substance and desiring to dispose of such substance may request assistance from the SAC in the area in which the person is located.” The regulation allows the SAC to authorize and specify the means of disposal to assure that the controlled substances do not become available to unauthorized persons.

State and local government agencies and community associations might hold takeback programs only if law enforcement makes the request, takes custody of the controlled substances, and is responsible for the disposal.

The U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy has published guidelines for medication disposal. These guidelines advise flushing medications only if the prescription label or accompanying patient information specifically states to do so. Instead of flushing, the guidelines recommend that medications be disposed of through a takeback program or by:

- Taking the prescription drugs out of their original containers;

- Mixing the drugs with an undesirable substance, such as cat litter or used coffee grounds;

- Placing the mixture into a disposable container with a lid, such as an empty margarine tub, or into a sealable bag;

- Concealing or removing personal information, including Rx number, on the empty containers by covering it with black permanent marker or duct tape, or by scratching it off; and

- Placing the sealed container with the mixture, and the empty drug containers, in the trash.

Unused Medication Donation

The rising cost of prescription medication leaves many questioning whether there is a need for a safe method to allow unused medication to be donated to others. At least 10 states have passed laws allowing or encouraging the donation of unused pharmaceutical drugs. Many of these programs involve healthcare facilities, nursing homes, or pharmacies. The CSA and current DEA regulations, however, prohibit patients from delivering or distributing controlled substances to a DEA registrant, even if it is for the purpose of a donation. Moreover, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not permit redistribution of medications, except under limited circumstances.

Consequently, state law may be inconsistent with federal law for donation and reuse of controlled substances.

Conclusion

Physicians who fail to comply with CSA handling requirements are subject to criminal charges, discipline against their DEA registration, and discipline against their license to practice medicine. Consequently, physicians should use caution whenever handling unused medication.

The application of various aspects of the CSA and implementing rules is situation-specific. Moreover, the DEA may issue additional regulations. Accordingly, if you have a question about a specific situation, consult an attorney, or contact your local DEA field division office and ask for the diversion duty agent. TH

Patrick O’Rourke works in the Office of University Counsel, Department of Litigation, University of Colorado Denver.

Recent media reports about the dangers surrounding unused prescription medications, including abuse by teens and medications finding their way into the water supply, have prompted an increase in inquiries to healthcare providers about disposing of unused medication. These issues are complicated when controlled substances are involved.

Often, providers are unsure how to respond to patient questions about medication disposal. For example, what would you do if a patient requests an alternative medication because of an unwanted side effect and brings the originally prescribed medication back to you? What if the family of a recently expired patient brings unused medication to you and asks you to donate it to other patients? What if you have a colleague who performs mission work; could you accept and donate unused medication for use in another country?

Unfortunately, the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) does not provide a readily available mechanism to accomplish efficient, secure, and environmentally sound methods to collect and use or dispose of unwanted controlled substances. This article explains the rules physicians must adhere to and guidelines for “taking back” controlled substances.

The Legislation

Enacted in 1970, the CSA combined all existing federal drug laws into a single statute. It created five “schedules” in which certain drugs are classified. These “scheduled” drugs are commonly referred to as controlled substances. A drug’s classification depends on its potential for abuse and its currently accepted medical use in the U.S. Additionally, provisions of international treaties impact classification.

Under the classification system, Schedule I drugs have a high potential for abuse and have no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the U.S. In contrast, Schedule V drugs have a low potential for abuse and do have a currently accepted medical use in treatment in the U.S.

The CSA governs the manufacture, import, export, possession, use, and distribution of controlled substances. In doing so, the CSA established a system to register those authorized to handle controlled substances. Manufacturers, dispensers, distributors, and individual practitioners who prescribe controlled substances must be registered with the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

The CSA requires registrants to keep certain records for at least two years related to their handling of controlled substances. For example, physician registrants must keep records of controlled substances in Schedules II, III, IV, and V that are dispensed via methods other than prescribing or administering (e.g., industry samples). Inventories of controlled substances are required. Most notably, physicians generally are not required to keep records of prescribed medications; however, records must be kept if drugs are dispensed or administered. Moreover, there are heightened recordkeeping responsibilities for providers who prescribe, dispense, or administer for maintenance or detoxification.

Controlled Substance “Takeback”

The system of registration established by the CSA prohibits a DEA registrant from acquiring controlled substances from nonregistered entities and, in turn, bars an end-user from distributing pharmaceutical controlled substances to a DEA registrant. In other words, physicians cannot receive controlled substances from anyone who does not also have a registration. Thus, physicians may not “take back” prescribed medications from patients or their family members. Similarly, except in cases of a drug being recalled or a dispensing error, patients are not allowed to return controlled medications to a pharmacy.

Information on how a patient or family member should properly dispose of medication is commonly misunderstood. DEA regulations provide a process for nonregistrants to dispose of unused medication; however, it is cumbersome and meant to be used only when dealing with large quantities of controlled substances (e.g., large quantities of abandoned drugs). In such cases, the DEA special agent in charge (SAC) may instruct on disposal, which may include transfer of the substance to a DEA registrant, delivery to a DEA agent or office, destruction in the presence of an agent of the administration or other authorized person, or by other means. The person must submit a letter to the local SAC, which includes:

- Name and address of the person;

- Name and quantity of each controlled substance to be disposed of;

- Explanation of how the applicant obtained the controlled substance, if known; and

- Name, address, and registration number, if known, of the person who possessed the controlled substances prior to the applicant.

Federal legislation also provides a way for the DEA to grant approval to law-enforcement agencies to operate “takeback” programs. The regulation states that “any person in possession of a controlled substance and desiring to dispose of such substance may request assistance from the SAC in the area in which the person is located.” The regulation allows the SAC to authorize and specify the means of disposal to assure that the controlled substances do not become available to unauthorized persons.

State and local government agencies and community associations might hold takeback programs only if law enforcement makes the request, takes custody of the controlled substances, and is responsible for the disposal.

The U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy has published guidelines for medication disposal. These guidelines advise flushing medications only if the prescription label or accompanying patient information specifically states to do so. Instead of flushing, the guidelines recommend that medications be disposed of through a takeback program or by:

- Taking the prescription drugs out of their original containers;

- Mixing the drugs with an undesirable substance, such as cat litter or used coffee grounds;

- Placing the mixture into a disposable container with a lid, such as an empty margarine tub, or into a sealable bag;

- Concealing or removing personal information, including Rx number, on the empty containers by covering it with black permanent marker or duct tape, or by scratching it off; and

- Placing the sealed container with the mixture, and the empty drug containers, in the trash.

Unused Medication Donation

The rising cost of prescription medication leaves many questioning whether there is a need for a safe method to allow unused medication to be donated to others. At least 10 states have passed laws allowing or encouraging the donation of unused pharmaceutical drugs. Many of these programs involve healthcare facilities, nursing homes, or pharmacies. The CSA and current DEA regulations, however, prohibit patients from delivering or distributing controlled substances to a DEA registrant, even if it is for the purpose of a donation. Moreover, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not permit redistribution of medications, except under limited circumstances.

Consequently, state law may be inconsistent with federal law for donation and reuse of controlled substances.

Conclusion

Physicians who fail to comply with CSA handling requirements are subject to criminal charges, discipline against their DEA registration, and discipline against their license to practice medicine. Consequently, physicians should use caution whenever handling unused medication.

The application of various aspects of the CSA and implementing rules is situation-specific. Moreover, the DEA may issue additional regulations. Accordingly, if you have a question about a specific situation, consult an attorney, or contact your local DEA field division office and ask for the diversion duty agent. TH

Patrick O’Rourke works in the Office of University Counsel, Department of Litigation, University of Colorado Denver.

Recent media reports about the dangers surrounding unused prescription medications, including abuse by teens and medications finding their way into the water supply, have prompted an increase in inquiries to healthcare providers about disposing of unused medication. These issues are complicated when controlled substances are involved.

Often, providers are unsure how to respond to patient questions about medication disposal. For example, what would you do if a patient requests an alternative medication because of an unwanted side effect and brings the originally prescribed medication back to you? What if the family of a recently expired patient brings unused medication to you and asks you to donate it to other patients? What if you have a colleague who performs mission work; could you accept and donate unused medication for use in another country?

Unfortunately, the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) does not provide a readily available mechanism to accomplish efficient, secure, and environmentally sound methods to collect and use or dispose of unwanted controlled substances. This article explains the rules physicians must adhere to and guidelines for “taking back” controlled substances.

The Legislation

Enacted in 1970, the CSA combined all existing federal drug laws into a single statute. It created five “schedules” in which certain drugs are classified. These “scheduled” drugs are commonly referred to as controlled substances. A drug’s classification depends on its potential for abuse and its currently accepted medical use in the U.S. Additionally, provisions of international treaties impact classification.

Under the classification system, Schedule I drugs have a high potential for abuse and have no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the U.S. In contrast, Schedule V drugs have a low potential for abuse and do have a currently accepted medical use in treatment in the U.S.

The CSA governs the manufacture, import, export, possession, use, and distribution of controlled substances. In doing so, the CSA established a system to register those authorized to handle controlled substances. Manufacturers, dispensers, distributors, and individual practitioners who prescribe controlled substances must be registered with the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

The CSA requires registrants to keep certain records for at least two years related to their handling of controlled substances. For example, physician registrants must keep records of controlled substances in Schedules II, III, IV, and V that are dispensed via methods other than prescribing or administering (e.g., industry samples). Inventories of controlled substances are required. Most notably, physicians generally are not required to keep records of prescribed medications; however, records must be kept if drugs are dispensed or administered. Moreover, there are heightened recordkeeping responsibilities for providers who prescribe, dispense, or administer for maintenance or detoxification.

Controlled Substance “Takeback”

The system of registration established by the CSA prohibits a DEA registrant from acquiring controlled substances from nonregistered entities and, in turn, bars an end-user from distributing pharmaceutical controlled substances to a DEA registrant. In other words, physicians cannot receive controlled substances from anyone who does not also have a registration. Thus, physicians may not “take back” prescribed medications from patients or their family members. Similarly, except in cases of a drug being recalled or a dispensing error, patients are not allowed to return controlled medications to a pharmacy.

Information on how a patient or family member should properly dispose of medication is commonly misunderstood. DEA regulations provide a process for nonregistrants to dispose of unused medication; however, it is cumbersome and meant to be used only when dealing with large quantities of controlled substances (e.g., large quantities of abandoned drugs). In such cases, the DEA special agent in charge (SAC) may instruct on disposal, which may include transfer of the substance to a DEA registrant, delivery to a DEA agent or office, destruction in the presence of an agent of the administration or other authorized person, or by other means. The person must submit a letter to the local SAC, which includes:

- Name and address of the person;

- Name and quantity of each controlled substance to be disposed of;

- Explanation of how the applicant obtained the controlled substance, if known; and

- Name, address, and registration number, if known, of the person who possessed the controlled substances prior to the applicant.

Federal legislation also provides a way for the DEA to grant approval to law-enforcement agencies to operate “takeback” programs. The regulation states that “any person in possession of a controlled substance and desiring to dispose of such substance may request assistance from the SAC in the area in which the person is located.” The regulation allows the SAC to authorize and specify the means of disposal to assure that the controlled substances do not become available to unauthorized persons.

State and local government agencies and community associations might hold takeback programs only if law enforcement makes the request, takes custody of the controlled substances, and is responsible for the disposal.

The U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy has published guidelines for medication disposal. These guidelines advise flushing medications only if the prescription label or accompanying patient information specifically states to do so. Instead of flushing, the guidelines recommend that medications be disposed of through a takeback program or by:

- Taking the prescription drugs out of their original containers;

- Mixing the drugs with an undesirable substance, such as cat litter or used coffee grounds;

- Placing the mixture into a disposable container with a lid, such as an empty margarine tub, or into a sealable bag;

- Concealing or removing personal information, including Rx number, on the empty containers by covering it with black permanent marker or duct tape, or by scratching it off; and

- Placing the sealed container with the mixture, and the empty drug containers, in the trash.

Unused Medication Donation

The rising cost of prescription medication leaves many questioning whether there is a need for a safe method to allow unused medication to be donated to others. At least 10 states have passed laws allowing or encouraging the donation of unused pharmaceutical drugs. Many of these programs involve healthcare facilities, nursing homes, or pharmacies. The CSA and current DEA regulations, however, prohibit patients from delivering or distributing controlled substances to a DEA registrant, even if it is for the purpose of a donation. Moreover, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not permit redistribution of medications, except under limited circumstances.

Consequently, state law may be inconsistent with federal law for donation and reuse of controlled substances.

Conclusion

Physicians who fail to comply with CSA handling requirements are subject to criminal charges, discipline against their DEA registration, and discipline against their license to practice medicine. Consequently, physicians should use caution whenever handling unused medication.

The application of various aspects of the CSA and implementing rules is situation-specific. Moreover, the DEA may issue additional regulations. Accordingly, if you have a question about a specific situation, consult an attorney, or contact your local DEA field division office and ask for the diversion duty agent. TH

Patrick O’Rourke works in the Office of University Counsel, Department of Litigation, University of Colorado Denver.

Malpractice Chronicle

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Signs and Symptoms of Preeclampsia Repeatedly Overlooked

During her second pregnancy, a 23-year-old Michigan woman received prenatal care from Dr. L., beginning in April 2004. Her due date was December 2004.

In late November, the woman presented to a hospital emergency department (ED) with chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath. She was admitted with noted high blood pressure and tachycardia. During her hospitalization, the patient was examined by an emergency physician, who discharged her with a diagnosis of bronchitis and dyspnea.

Two days later, the patient returned to Dr. L. for a scheduled prenatal visit, at which time she still had high blood pressure. She was instructed to go to a second hospital; there, she was seen by a PA, who noted edema in her extremities. Attempts to draw blood for arterial blood gas analysis were unsuccessful, and crackles were noted throughout the woman’s lungs. An obstetrician/gynecologist, Dr. D., was contacted regarding worsening preeclampsia with pulmonary edema. It was decided to perform a cesarean delivery.

The woman became unresponsive on the way to surgery. After delivery, she experienced cardiopulmonary arrest and sustained an anoxic brain injury. She was declared brain dead and died after life support was withdrawn.

Upon autopsy, the cause of death was determined to be anoxic encephalopathy due to respiratory arrest caused by preeclampsia. The plaintiff claimed that Dr. L. failed to provide proper prenatal care and failed to recognize the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia, which the plaintiff alleged were evident in October. The plaintiff also claimed that the emergency physician at the first hospital failed to recognize the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia and failed to contact a specialist and to hospitalize the decedent immediately for monitoring and treatment.

As for the PA and Dr. D., the plaintiff claimed that they negligently administered a bolus of IV fluids when the decedent showed signs of preeclampsia, failed to administer proper dosages of furosemide, and failed to admit the decedent in a timely fashion.

The defendants all denied any negligence.

According to a published report, a $1.5 million settlement was reached.

No Action Taken on Abnormal Blood Cultures

Headache, fever, chills, vomiting, and wide-ranging muscle pain prompted an Indiana woman, age 44, to present to a hospital ED. She was examined by the defendant emergency physician, Dr. M., who ordered tests and made a diagnosis of influenza.

He ordered acetaminophen and prescription-strength ibuprofen and discharged the woman to home with instructions to consume copious amounts of fluid. Two days later, the laboratory staff contacted the ED by phone to report that the patient’s blood culture results were abnormal, indicating a possible bacterial infection. No one on the ED staff acted on this information.

Shortly before midnight the following evening, the patient returned to the ED complaining of similar symptoms. Based on the results of additional testing, acute renal failure and shock secondary to necrotizing soft tissue were diagnosed. The patient was transferred to another hospital, where she underwent extensive treatment, including several surgeries to remove infected tissue. The woman died, however, as a result of multiple organ failure and septic shock secondary to group A streptococcal infection.

The plaintiff alleged negligence by Dr. M. for his failure to investigate the possibility that the patient had a bacterial infection. The plaintiff also alleged negligence on the part of the ED personnel for their failure to act on the notification from the lab. The defendants denied any negligence.

According to a published report, a defense verdict was returned.

Claim Heart Spasm, Not MI, After Treadmill Stress Test

A California man, age 51, saw his primary care physician and internist, Dr. C., and reported a 20-minute-long episode of chest pain in bed that morning. He also said he had had chest pain two mornings earlier, also in bed, that lasted longer than an hour. The patient had cardiac risk factors of obesity, hypertension, a history of smoking, and a strong family history of dyslipidemia and heart disease.

Dr. C. performed an ECG, with results interpreted as normal. He then prescribed a treadmill stress test, which was administered four days later by a cardiologist, Dr. W. The patient was able to complete the test, with his heart rate measured as high as 160 beats/min. Dr. W. interpreted the stress test as normal. The man did not complain of chest pain during the test. His blood pressure, which was expected to rise during the test, remained flat.

About 30 minutes after leaving the treadmill lab, the patient was found in full cardiac arrest at his desk at work. Paramedics were called, but he could not be resuscitated.

An autopsy revealed evidence of MI on the posterior portion of the heart, which corresponded with the complaints of chest pain about a week earlier. The decedent had 75% narrowing of the left anterior descending coronary artery, 75% narrowing of the right circumflex artery, and 30% narrowing of the right coronary artery. No thrombus or plaque rupture was identified. The cause of death was determined to be MI secondary to fatal arrhythmia, associated with coronary artery disease.

The plaintiffs claimed that Dr. C. should have included unstable angina in the differential diagnosis and should have assumed that the decedent had had a heart attack until proven otherwise. The plaintiffs claimed that the ECG taken in Dr. C.’s office was subtly abnormal and that the decedent should have been sent to a hospital immediately; there, they argued, blood would have been drawn and abnormal troponin levels detected. The plaintiffs claimed that the decedent would have then been sent to the catheterization lab for treatment—most likely, stenting.

The plaintiffs further claimed that Dr. W. took an inadequate history and that a treadmill test should not have been performed. The plaintiffs claimed that a myocardial perfusion test or nuclear imaging should have been performed. Further, the plaintiffs maintained that the ECG portion of the treadmill test had subtle abnormalities that Dr. W. overlooked, and that Dr. W. failed to appreciate the abnormality in the decedent’s blood pressure remaining flat during the test.

Dr. C. claimed that the decedent’s claims of chest pain at night suggested that the pain was not cardiac in origin. Dr. C. also claimed that he had acted reasonably in performing and interpreting the ECG. Dr. W. claimed that a treadmill stress test was appropriate for the decedent and that test results were normal.

The defendants both argued that the cause of death was not coronary artery disease, but coronary spasm. They maintained that there was only 50% narrowing in the coronary arteries and that the absence of thrombus or plaque rupture was inconsistent with a classic cardiac death resulting from coronary artery occlusion.

According to a published account, a defense verdict was returned for Dr. W. The jury was undecided in the case against Dr. C.

Obstetrician “Forgets” to Perform Tubal Ligation

A young woman in California became pregnant with her fourth child, although she was using birth control. During her prenatal care, she and her husband told the defendant obstetrician that they did not want, nor could they afford, any more children. They requested a bilateral tubal ligation at the time of a cesarean delivery, which was scheduled for a week before the projected due date.

The woman went into labor two days before the scheduled surgery. The prenatal records could not be found and the obstetrician’s office was closed. He delivered the baby by cesarean section but did not perform the tubal ligation. The mother was in the hospital for three days and was seen by the defendant for a six-week postpartum visit, but she claimed he never told her that he had not performed the tubal ligation. The mother did not take precautions to prevent pregnancy and subsequently conceived her fifth child. The plaintiffs did not opt to abort.

The plaintiffs alleged negligence and wrongful birth, contending that they were never told the tubal ligation had not been performed until after the fifth child was conceived.

The defendant claimed he told the mother at her six-week visit that the tubal ligation had not been performed and advised her to use birth control until she recovered from the cesarean delivery, when she could then undergo a tubal ligation. The obstetrician acknowledged that he had forgotten to perform the tubal ligation but insisted that there was no negligence involved.

According to a published account, a defense verdict was returned.

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Signs and Symptoms of Preeclampsia Repeatedly Overlooked

During her second pregnancy, a 23-year-old Michigan woman received prenatal care from Dr. L., beginning in April 2004. Her due date was December 2004.

In late November, the woman presented to a hospital emergency department (ED) with chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath. She was admitted with noted high blood pressure and tachycardia. During her hospitalization, the patient was examined by an emergency physician, who discharged her with a diagnosis of bronchitis and dyspnea.

Two days later, the patient returned to Dr. L. for a scheduled prenatal visit, at which time she still had high blood pressure. She was instructed to go to a second hospital; there, she was seen by a PA, who noted edema in her extremities. Attempts to draw blood for arterial blood gas analysis were unsuccessful, and crackles were noted throughout the woman’s lungs. An obstetrician/gynecologist, Dr. D., was contacted regarding worsening preeclampsia with pulmonary edema. It was decided to perform a cesarean delivery.

The woman became unresponsive on the way to surgery. After delivery, she experienced cardiopulmonary arrest and sustained an anoxic brain injury. She was declared brain dead and died after life support was withdrawn.

Upon autopsy, the cause of death was determined to be anoxic encephalopathy due to respiratory arrest caused by preeclampsia. The plaintiff claimed that Dr. L. failed to provide proper prenatal care and failed to recognize the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia, which the plaintiff alleged were evident in October. The plaintiff also claimed that the emergency physician at the first hospital failed to recognize the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia and failed to contact a specialist and to hospitalize the decedent immediately for monitoring and treatment.

As for the PA and Dr. D., the plaintiff claimed that they negligently administered a bolus of IV fluids when the decedent showed signs of preeclampsia, failed to administer proper dosages of furosemide, and failed to admit the decedent in a timely fashion.

The defendants all denied any negligence.

According to a published report, a $1.5 million settlement was reached.

No Action Taken on Abnormal Blood Cultures

Headache, fever, chills, vomiting, and wide-ranging muscle pain prompted an Indiana woman, age 44, to present to a hospital ED. She was examined by the defendant emergency physician, Dr. M., who ordered tests and made a diagnosis of influenza.

He ordered acetaminophen and prescription-strength ibuprofen and discharged the woman to home with instructions to consume copious amounts of fluid. Two days later, the laboratory staff contacted the ED by phone to report that the patient’s blood culture results were abnormal, indicating a possible bacterial infection. No one on the ED staff acted on this information.

Shortly before midnight the following evening, the patient returned to the ED complaining of similar symptoms. Based on the results of additional testing, acute renal failure and shock secondary to necrotizing soft tissue were diagnosed. The patient was transferred to another hospital, where she underwent extensive treatment, including several surgeries to remove infected tissue. The woman died, however, as a result of multiple organ failure and septic shock secondary to group A streptococcal infection.

The plaintiff alleged negligence by Dr. M. for his failure to investigate the possibility that the patient had a bacterial infection. The plaintiff also alleged negligence on the part of the ED personnel for their failure to act on the notification from the lab. The defendants denied any negligence.

According to a published report, a defense verdict was returned.

Claim Heart Spasm, Not MI, After Treadmill Stress Test

A California man, age 51, saw his primary care physician and internist, Dr. C., and reported a 20-minute-long episode of chest pain in bed that morning. He also said he had had chest pain two mornings earlier, also in bed, that lasted longer than an hour. The patient had cardiac risk factors of obesity, hypertension, a history of smoking, and a strong family history of dyslipidemia and heart disease.

Dr. C. performed an ECG, with results interpreted as normal. He then prescribed a treadmill stress test, which was administered four days later by a cardiologist, Dr. W. The patient was able to complete the test, with his heart rate measured as high as 160 beats/min. Dr. W. interpreted the stress test as normal. The man did not complain of chest pain during the test. His blood pressure, which was expected to rise during the test, remained flat.

About 30 minutes after leaving the treadmill lab, the patient was found in full cardiac arrest at his desk at work. Paramedics were called, but he could not be resuscitated.

An autopsy revealed evidence of MI on the posterior portion of the heart, which corresponded with the complaints of chest pain about a week earlier. The decedent had 75% narrowing of the left anterior descending coronary artery, 75% narrowing of the right circumflex artery, and 30% narrowing of the right coronary artery. No thrombus or plaque rupture was identified. The cause of death was determined to be MI secondary to fatal arrhythmia, associated with coronary artery disease.

The plaintiffs claimed that Dr. C. should have included unstable angina in the differential diagnosis and should have assumed that the decedent had had a heart attack until proven otherwise. The plaintiffs claimed that the ECG taken in Dr. C.’s office was subtly abnormal and that the decedent should have been sent to a hospital immediately; there, they argued, blood would have been drawn and abnormal troponin levels detected. The plaintiffs claimed that the decedent would have then been sent to the catheterization lab for treatment—most likely, stenting.

The plaintiffs further claimed that Dr. W. took an inadequate history and that a treadmill test should not have been performed. The plaintiffs claimed that a myocardial perfusion test or nuclear imaging should have been performed. Further, the plaintiffs maintained that the ECG portion of the treadmill test had subtle abnormalities that Dr. W. overlooked, and that Dr. W. failed to appreciate the abnormality in the decedent’s blood pressure remaining flat during the test.

Dr. C. claimed that the decedent’s claims of chest pain at night suggested that the pain was not cardiac in origin. Dr. C. also claimed that he had acted reasonably in performing and interpreting the ECG. Dr. W. claimed that a treadmill stress test was appropriate for the decedent and that test results were normal.

The defendants both argued that the cause of death was not coronary artery disease, but coronary spasm. They maintained that there was only 50% narrowing in the coronary arteries and that the absence of thrombus or plaque rupture was inconsistent with a classic cardiac death resulting from coronary artery occlusion.

According to a published account, a defense verdict was returned for Dr. W. The jury was undecided in the case against Dr. C.

Obstetrician “Forgets” to Perform Tubal Ligation

A young woman in California became pregnant with her fourth child, although she was using birth control. During her prenatal care, she and her husband told the defendant obstetrician that they did not want, nor could they afford, any more children. They requested a bilateral tubal ligation at the time of a cesarean delivery, which was scheduled for a week before the projected due date.

The woman went into labor two days before the scheduled surgery. The prenatal records could not be found and the obstetrician’s office was closed. He delivered the baby by cesarean section but did not perform the tubal ligation. The mother was in the hospital for three days and was seen by the defendant for a six-week postpartum visit, but she claimed he never told her that he had not performed the tubal ligation. The mother did not take precautions to prevent pregnancy and subsequently conceived her fifth child. The plaintiffs did not opt to abort.

The plaintiffs alleged negligence and wrongful birth, contending that they were never told the tubal ligation had not been performed until after the fifth child was conceived.

The defendant claimed he told the mother at her six-week visit that the tubal ligation had not been performed and advised her to use birth control until she recovered from the cesarean delivery, when she could then undergo a tubal ligation. The obstetrician acknowledged that he had forgotten to perform the tubal ligation but insisted that there was no negligence involved.

According to a published account, a defense verdict was returned.

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Signs and Symptoms of Preeclampsia Repeatedly Overlooked

During her second pregnancy, a 23-year-old Michigan woman received prenatal care from Dr. L., beginning in April 2004. Her due date was December 2004.

In late November, the woman presented to a hospital emergency department (ED) with chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath. She was admitted with noted high blood pressure and tachycardia. During her hospitalization, the patient was examined by an emergency physician, who discharged her with a diagnosis of bronchitis and dyspnea.

Two days later, the patient returned to Dr. L. for a scheduled prenatal visit, at which time she still had high blood pressure. She was instructed to go to a second hospital; there, she was seen by a PA, who noted edema in her extremities. Attempts to draw blood for arterial blood gas analysis were unsuccessful, and crackles were noted throughout the woman’s lungs. An obstetrician/gynecologist, Dr. D., was contacted regarding worsening preeclampsia with pulmonary edema. It was decided to perform a cesarean delivery.

The woman became unresponsive on the way to surgery. After delivery, she experienced cardiopulmonary arrest and sustained an anoxic brain injury. She was declared brain dead and died after life support was withdrawn.

Upon autopsy, the cause of death was determined to be anoxic encephalopathy due to respiratory arrest caused by preeclampsia. The plaintiff claimed that Dr. L. failed to provide proper prenatal care and failed to recognize the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia, which the plaintiff alleged were evident in October. The plaintiff also claimed that the emergency physician at the first hospital failed to recognize the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia and failed to contact a specialist and to hospitalize the decedent immediately for monitoring and treatment.

As for the PA and Dr. D., the plaintiff claimed that they negligently administered a bolus of IV fluids when the decedent showed signs of preeclampsia, failed to administer proper dosages of furosemide, and failed to admit the decedent in a timely fashion.

The defendants all denied any negligence.

According to a published report, a $1.5 million settlement was reached.

No Action Taken on Abnormal Blood Cultures

Headache, fever, chills, vomiting, and wide-ranging muscle pain prompted an Indiana woman, age 44, to present to a hospital ED. She was examined by the defendant emergency physician, Dr. M., who ordered tests and made a diagnosis of influenza.

He ordered acetaminophen and prescription-strength ibuprofen and discharged the woman to home with instructions to consume copious amounts of fluid. Two days later, the laboratory staff contacted the ED by phone to report that the patient’s blood culture results were abnormal, indicating a possible bacterial infection. No one on the ED staff acted on this information.

Shortly before midnight the following evening, the patient returned to the ED complaining of similar symptoms. Based on the results of additional testing, acute renal failure and shock secondary to necrotizing soft tissue were diagnosed. The patient was transferred to another hospital, where she underwent extensive treatment, including several surgeries to remove infected tissue. The woman died, however, as a result of multiple organ failure and septic shock secondary to group A streptococcal infection.

The plaintiff alleged negligence by Dr. M. for his failure to investigate the possibility that the patient had a bacterial infection. The plaintiff also alleged negligence on the part of the ED personnel for their failure to act on the notification from the lab. The defendants denied any negligence.

According to a published report, a defense verdict was returned.

Claim Heart Spasm, Not MI, After Treadmill Stress Test

A California man, age 51, saw his primary care physician and internist, Dr. C., and reported a 20-minute-long episode of chest pain in bed that morning. He also said he had had chest pain two mornings earlier, also in bed, that lasted longer than an hour. The patient had cardiac risk factors of obesity, hypertension, a history of smoking, and a strong family history of dyslipidemia and heart disease.

Dr. C. performed an ECG, with results interpreted as normal. He then prescribed a treadmill stress test, which was administered four days later by a cardiologist, Dr. W. The patient was able to complete the test, with his heart rate measured as high as 160 beats/min. Dr. W. interpreted the stress test as normal. The man did not complain of chest pain during the test. His blood pressure, which was expected to rise during the test, remained flat.

About 30 minutes after leaving the treadmill lab, the patient was found in full cardiac arrest at his desk at work. Paramedics were called, but he could not be resuscitated.

An autopsy revealed evidence of MI on the posterior portion of the heart, which corresponded with the complaints of chest pain about a week earlier. The decedent had 75% narrowing of the left anterior descending coronary artery, 75% narrowing of the right circumflex artery, and 30% narrowing of the right coronary artery. No thrombus or plaque rupture was identified. The cause of death was determined to be MI secondary to fatal arrhythmia, associated with coronary artery disease.

The plaintiffs claimed that Dr. C. should have included unstable angina in the differential diagnosis and should have assumed that the decedent had had a heart attack until proven otherwise. The plaintiffs claimed that the ECG taken in Dr. C.’s office was subtly abnormal and that the decedent should have been sent to a hospital immediately; there, they argued, blood would have been drawn and abnormal troponin levels detected. The plaintiffs claimed that the decedent would have then been sent to the catheterization lab for treatment—most likely, stenting.

The plaintiffs further claimed that Dr. W. took an inadequate history and that a treadmill test should not have been performed. The plaintiffs claimed that a myocardial perfusion test or nuclear imaging should have been performed. Further, the plaintiffs maintained that the ECG portion of the treadmill test had subtle abnormalities that Dr. W. overlooked, and that Dr. W. failed to appreciate the abnormality in the decedent’s blood pressure remaining flat during the test.

Dr. C. claimed that the decedent’s claims of chest pain at night suggested that the pain was not cardiac in origin. Dr. C. also claimed that he had acted reasonably in performing and interpreting the ECG. Dr. W. claimed that a treadmill stress test was appropriate for the decedent and that test results were normal.

The defendants both argued that the cause of death was not coronary artery disease, but coronary spasm. They maintained that there was only 50% narrowing in the coronary arteries and that the absence of thrombus or plaque rupture was inconsistent with a classic cardiac death resulting from coronary artery occlusion.

According to a published account, a defense verdict was returned for Dr. W. The jury was undecided in the case against Dr. C.

Obstetrician “Forgets” to Perform Tubal Ligation

A young woman in California became pregnant with her fourth child, although she was using birth control. During her prenatal care, she and her husband told the defendant obstetrician that they did not want, nor could they afford, any more children. They requested a bilateral tubal ligation at the time of a cesarean delivery, which was scheduled for a week before the projected due date.

The woman went into labor two days before the scheduled surgery. The prenatal records could not be found and the obstetrician’s office was closed. He delivered the baby by cesarean section but did not perform the tubal ligation. The mother was in the hospital for three days and was seen by the defendant for a six-week postpartum visit, but she claimed he never told her that he had not performed the tubal ligation. The mother did not take precautions to prevent pregnancy and subsequently conceived her fifth child. The plaintiffs did not opt to abort.

The plaintiffs alleged negligence and wrongful birth, contending that they were never told the tubal ligation had not been performed until after the fifth child was conceived.

The defendant claimed he told the mother at her six-week visit that the tubal ligation had not been performed and advised her to use birth control until she recovered from the cesarean delivery, when she could then undergo a tubal ligation. The obstetrician acknowledged that he had forgotten to perform the tubal ligation but insisted that there was no negligence involved.

According to a published account, a defense verdict was returned.

Lethal liver injury blamed on birth trauma...and more

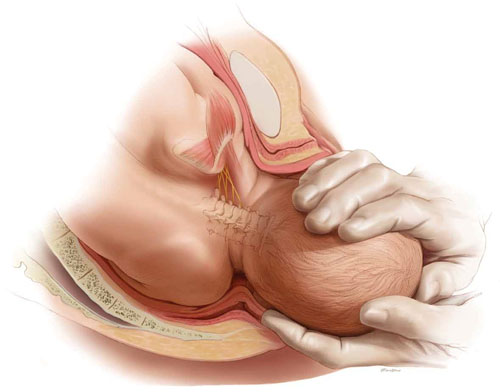

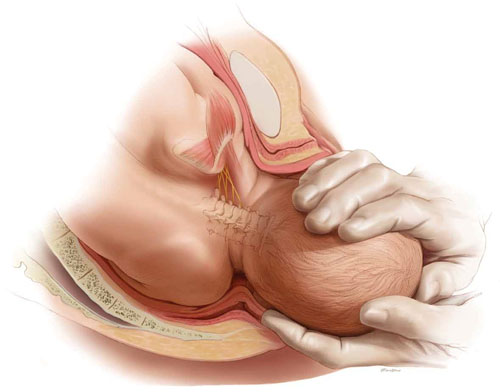

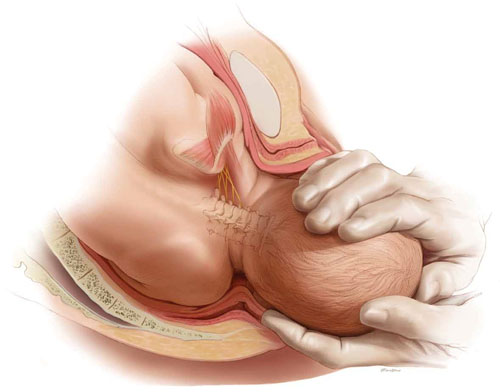

BECAUSE OF PREMATURE CONTRACTIONS and bleeding, a woman underwent cesarean delivery by her ObGyns. When Dr. A reached in to extract the fetus, it floated away. Dr. B then attempted delivery while Dr. A applied fundal pressure. Photographs of the baby taken by the father 2 minutes after birth showed severe bruising over the liver area. Sonography performed shortly after birth revealed a liver laceration. Surgery to repair the liver was unsuccessful. The infant died.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The trauma from improper fundal pressure and improper manipulation when extracting the infant through an inadequately sized incision caused the liver to rupture. A vertical incision should have been made initially, instead of a transverse incision, because of the small size of the fetus and uterus. When the fetus could not be extracted, a reverse “T” incision should have been made so the fetus could be extracted without trauma.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The mother had a preexisting disorder that caused bleeding before delivery; the liver laceration occurred hours before delivery.

VERDICT A $1,461,507 Maryland verdict was returned, including $461,507 to the infant’s estate, and $500,000 to each parent.

Perforated colon after hysteroscopy

A 44-YEAR-OLD WOMAN UNDERWENT hysteroscopic surgery to remove polyps and a fibroid tumor. During the procedure, the ObGyn used a hysteroscopic resection loop. Two days later, the patient developed peritonitis. A perforation was detected, requiring resection of part of the colon and a temporary colostomy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The injury occurred when the ObGyn pushed the resection loop of the hysteroscope through the uterus, burning a hole in the uterus and the colon. The ObGyn should have performed a more extensive check to ensure that no perforation had occurred.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Perforation was a delayed thermal effect that did not occur until 2 days after the procedure. There was no negligence.

VERDICT A $1.55 million New York verdict was returned.

Did retractors cause neuropathy?

AFTER CERVICAL CANCER was diagnosed, a 37-year-old woman was referred to a gynecologic oncologist. He performed a modified radical hysterectomy with pelvic node dissection and lymphadenectomy. A Pfannenstiel incision was used, and the procedure involved removal of the uterus, cervix, upper quarter of the vagina, pelvic lymph nodes, and surrounding tissue. Surgery lasted longer than 5 hours.

The next day, the patient reported pain, burning, tingling, and numbness in her left thigh, which was eventually diagnosed as lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy. This condition did not resolve.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The surgeon failed to reposition retractors with sufficient frequency. He allowed the retractor blades to press on the psoas muscles, thus injuring the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The retractors were used properly; they were periodically shifted to gain better exposure to the surgical area. The surgeon also used his hands to determine that the retractors were properly positioned.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

“I would have terminated my pregnancy if…”

A PREGNANT WOMAN UNDERWENT a blood test that indicated that the fetus had an elevated risk of being born with Down syndrome. The child was born 7 months later with Down syndrome.

PATIENT’S CLAIM She was not told of the increased risk that her child would have Down syndrome. If she had been informed, she would have terminated the pregnancy.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE According to the physician’s records, the mother was told the blood test results many times. Amniocentesis was recommended, but the mother had declined.

VERDICT A Maryland defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

BECAUSE OF PREMATURE CONTRACTIONS and bleeding, a woman underwent cesarean delivery by her ObGyns. When Dr. A reached in to extract the fetus, it floated away. Dr. B then attempted delivery while Dr. A applied fundal pressure. Photographs of the baby taken by the father 2 minutes after birth showed severe bruising over the liver area. Sonography performed shortly after birth revealed a liver laceration. Surgery to repair the liver was unsuccessful. The infant died.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The trauma from improper fundal pressure and improper manipulation when extracting the infant through an inadequately sized incision caused the liver to rupture. A vertical incision should have been made initially, instead of a transverse incision, because of the small size of the fetus and uterus. When the fetus could not be extracted, a reverse “T” incision should have been made so the fetus could be extracted without trauma.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The mother had a preexisting disorder that caused bleeding before delivery; the liver laceration occurred hours before delivery.

VERDICT A $1,461,507 Maryland verdict was returned, including $461,507 to the infant’s estate, and $500,000 to each parent.

Perforated colon after hysteroscopy

A 44-YEAR-OLD WOMAN UNDERWENT hysteroscopic surgery to remove polyps and a fibroid tumor. During the procedure, the ObGyn used a hysteroscopic resection loop. Two days later, the patient developed peritonitis. A perforation was detected, requiring resection of part of the colon and a temporary colostomy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The injury occurred when the ObGyn pushed the resection loop of the hysteroscope through the uterus, burning a hole in the uterus and the colon. The ObGyn should have performed a more extensive check to ensure that no perforation had occurred.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Perforation was a delayed thermal effect that did not occur until 2 days after the procedure. There was no negligence.

VERDICT A $1.55 million New York verdict was returned.

Did retractors cause neuropathy?

AFTER CERVICAL CANCER was diagnosed, a 37-year-old woman was referred to a gynecologic oncologist. He performed a modified radical hysterectomy with pelvic node dissection and lymphadenectomy. A Pfannenstiel incision was used, and the procedure involved removal of the uterus, cervix, upper quarter of the vagina, pelvic lymph nodes, and surrounding tissue. Surgery lasted longer than 5 hours.

The next day, the patient reported pain, burning, tingling, and numbness in her left thigh, which was eventually diagnosed as lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy. This condition did not resolve.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The surgeon failed to reposition retractors with sufficient frequency. He allowed the retractor blades to press on the psoas muscles, thus injuring the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The retractors were used properly; they were periodically shifted to gain better exposure to the surgical area. The surgeon also used his hands to determine that the retractors were properly positioned.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

“I would have terminated my pregnancy if…”

A PREGNANT WOMAN UNDERWENT a blood test that indicated that the fetus had an elevated risk of being born with Down syndrome. The child was born 7 months later with Down syndrome.

PATIENT’S CLAIM She was not told of the increased risk that her child would have Down syndrome. If she had been informed, she would have terminated the pregnancy.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE According to the physician’s records, the mother was told the blood test results many times. Amniocentesis was recommended, but the mother had declined.

VERDICT A Maryland defense verdict was returned.

BECAUSE OF PREMATURE CONTRACTIONS and bleeding, a woman underwent cesarean delivery by her ObGyns. When Dr. A reached in to extract the fetus, it floated away. Dr. B then attempted delivery while Dr. A applied fundal pressure. Photographs of the baby taken by the father 2 minutes after birth showed severe bruising over the liver area. Sonography performed shortly after birth revealed a liver laceration. Surgery to repair the liver was unsuccessful. The infant died.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The trauma from improper fundal pressure and improper manipulation when extracting the infant through an inadequately sized incision caused the liver to rupture. A vertical incision should have been made initially, instead of a transverse incision, because of the small size of the fetus and uterus. When the fetus could not be extracted, a reverse “T” incision should have been made so the fetus could be extracted without trauma.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The mother had a preexisting disorder that caused bleeding before delivery; the liver laceration occurred hours before delivery.

VERDICT A $1,461,507 Maryland verdict was returned, including $461,507 to the infant’s estate, and $500,000 to each parent.

Perforated colon after hysteroscopy

A 44-YEAR-OLD WOMAN UNDERWENT hysteroscopic surgery to remove polyps and a fibroid tumor. During the procedure, the ObGyn used a hysteroscopic resection loop. Two days later, the patient developed peritonitis. A perforation was detected, requiring resection of part of the colon and a temporary colostomy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The injury occurred when the ObGyn pushed the resection loop of the hysteroscope through the uterus, burning a hole in the uterus and the colon. The ObGyn should have performed a more extensive check to ensure that no perforation had occurred.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Perforation was a delayed thermal effect that did not occur until 2 days after the procedure. There was no negligence.

VERDICT A $1.55 million New York verdict was returned.

Did retractors cause neuropathy?

AFTER CERVICAL CANCER was diagnosed, a 37-year-old woman was referred to a gynecologic oncologist. He performed a modified radical hysterectomy with pelvic node dissection and lymphadenectomy. A Pfannenstiel incision was used, and the procedure involved removal of the uterus, cervix, upper quarter of the vagina, pelvic lymph nodes, and surrounding tissue. Surgery lasted longer than 5 hours.

The next day, the patient reported pain, burning, tingling, and numbness in her left thigh, which was eventually diagnosed as lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy. This condition did not resolve.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The surgeon failed to reposition retractors with sufficient frequency. He allowed the retractor blades to press on the psoas muscles, thus injuring the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The retractors were used properly; they were periodically shifted to gain better exposure to the surgical area. The surgeon also used his hands to determine that the retractors were properly positioned.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

“I would have terminated my pregnancy if…”

A PREGNANT WOMAN UNDERWENT a blood test that indicated that the fetus had an elevated risk of being born with Down syndrome. The child was born 7 months later with Down syndrome.

PATIENT’S CLAIM She was not told of the increased risk that her child would have Down syndrome. If she had been informed, she would have terminated the pregnancy.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE According to the physician’s records, the mother was told the blood test results many times. Amniocentesis was recommended, but the mother had declined.

VERDICT A Maryland defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Sound strategies to avoid malpractice hazards on labor and delivery

CASE: Is TOLAC feasible?

Your patient is a 33-year-old gravida 3, para 2002, with a previous cesarean delivery who was admitted to labor and delivery with premature ruptured membranes at term. She is not contracting. Fetal status is reassuring.

Her obstetric history is of one normal, spontaneous delivery followed by one cesarean delivery, both occurring at term.

She wants to know if she can safely undergo a trial of labor, or if she must have a repeat cesarean delivery. How should you counsel her?

At the start of any discussion about how to reduce your risk of being sued for malpractice because of your work as an obstetrician, in particular during labor and delivery, two distinct, underlying avenues of concern need to be addressed. Before moving on to discuss strategy, then, let’s consider what they are and how they arise: Allegation (perception). You are at risk of an allegation of malpractice (or of a perception of malpractice) because of an unexpected event or outcome for mother or baby. Allegation and perception can arise apart from any specific clinical action you undertook, or did not undertake. An example? Counseling about options for care that falls short of full understanding by the patient.

Allegation and perception are the subjects of this first installment of our two-part article on strategies for avoiding claims of malpractice in L & D that begin with the first prenatal visit.

Causation. Your actions—what you do in the course of providing prenatal care and delivering a baby—put you at risk of a charge of malpractice when you have provided medical care that 1) is inconsistent with current medical practice and thus 2) harmed the mother or newborn.

For a medical malpractice case to go forward, it must meet a well-defined paradigm that teases apart components of causation, beginning with your duty to the patient (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1 Signposts in the medical malpractice paradigm

| When the clinical issue at hand is … | … Then the legal term is … |

|---|---|

| A health-care professional’s obligation to provide care | “Duty” |

| A deviation in the care that was provided | “Standard of care” |

| An allegation that a breach in the standard of care resulted in injury | “Proximate cause” |

| An assertion or finding that an injury is “compensable” | “Damages” |

| Source: Yale New Haven Medical Center, 1997.5 | |

Allegation of malpractice arises from a range of sources, as we’ll discuss, but it is causation that reflects the actual, hands-on practice of medicine. We’ll examine strategies for avoiding charges of causation in the second part of this article.

(For now, we’ll just note that a recent excellent review of intrapartum interventions and their basis in evidence1 offers a model for evaluating a number of widely utilized practices in obstetrics. The goal, of course, is to minimize bad outcomes that follow from causation. Regrettably, that evidence-based approach is a limited one, because of a paucity of adequately controlled studies about OB practice.)

CASE: Continued

You consider your patient’s comment that she would like to avoid a repeat cesarean delivery, and advise her that she may safely attempt vaginal birth.

When spontaneous labor does not occur in 6 hours, oxytocin is administered. She dilates to 9 cm and begins to push spontaneously.

The fetal heart rate then drops to 70/min; fetal station, which had been +2, is now -1. A Stat cesarean delivery is performed. Uterine rupture with partial fetal expulsion is found. Apgar scores are 1, 3, and 5 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes.

Your patient requires a hysterectomy to control bleeding.

Some broad considerations for the physician arising from this CASE

- The counseling that you provide to a patient should be nondirective; it should include your opinion, however, about the best option available to her. Insert yourself into this hypothetical case, for discussion’s sake: Did you provide that important opinion to her?

- You must make certain that she clearly understands the risks and benefits of a procedure or other action, and the available alternatives. Did you undertake a check of her comprehension, given the anxiety and confusion of the moment?

- When an adverse outcome ensues—however unlikely it was to occur—it is necessary for you to review the circumstances with the patient as soon as clinically possible. Did you “debrief” and counsel her before and after the hysterectomy?

No more “perfect outcomes”: Our role changed, so did our risk

From the moment an OB patient enters triage, until her arrival home with her infant, this crucial period of her life is colored by concern, curiosity, myth, and fear.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy infant. In an earlier era, the patient and her family relied on the sage advice of their physician to ensure this outcome. To an extent, physicians themselves reinforced this reliance, embracing the notion that they were, in fact, able to provide such a perfect outcome.

With advances that have been made in reproductive medicine, pregnancy has become more readily available to women with increasingly advanced disease; this has made labor and delivery more challenging to them and to their physicians. Realistically, our role as physicians is now better expressed as providing advice to help a woman achieve the best possible outcome, recognizing her individual clinical circumstances, instead of ensuring a perfect outcome.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy baby. But the role of the OB is better expressed as helping her achieve the best possible outcome, not a perfect outcome. ABOVE: Shoulder dystocia is one of the most treacherous and frightening—and litigated—complications of childbirth, yet it is, for the most part, unpredictable and unpreventable in the course of even routine delivery.

Key concept #1

COMMUNICATION

Communication is central to patients’ comprehension about the care that you provide to them. But to enter a genuine dialogue with a patient under your care, and with her family, can challenge your communication skills.

First, you need written and verbal skills. Second, you need to know how to read visual cues.

Third, the messages that you deliver to the patient are influenced by:

- your style of communication

- your cultural background

- the setting in which you’re providing care (office, hospital).

Where are such skills developed? For one, biopsychosocial models that are employed in medical student education and resident training aid the physician in developing appropriate communication skills.